XPS vs AES vs SIMS: A Comprehensive Guide to Surface Analysis Techniques for Biomedical Research

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of three cornerstone surface analysis techniques—X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), and Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS).

XPS vs AES vs SIMS: A Comprehensive Guide to Surface Analysis Techniques for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of three cornerstone surface analysis techniques—X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), and Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles, methodological applications, and common challenges associated with each technique. The scope ranges from foundational knowledge and material-specific selection to troubleshooting experimental artifacts and validating findings through complementary use. By synthesizing current capabilities and emerging trends, this guide aims to empower professionals in making informed decisions to advance biomedical and clinical research, from optimizing medical implants and drug delivery systems to characterizing novel biomaterials.

Understanding Surface Analysis: Core Principles of XPS, AES, and SIMS

Understanding the elemental and chemical composition of material surfaces is fundamental in fields ranging from drug development to advanced battery and semiconductor research. Among the most powerful techniques for such analysis are X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS). These methods probe the topmost atomic layers of a sample, providing critical information that bulk analysis techniques cannot capture. XPS operates by irradiating a sample with X-rays and measuring the kinetic energy of emitted photoelectrons to identify elements and their chemical states. AES uses an electron beam to excite atoms, resulting in the emission of Auger electrons whose energies are characteristic of the emitting element. SIMS, in contrast, uses a focused primary ion beam to sputter material from the surface, and the ejected secondary ions are mass-analyzed to determine the surface composition.

Each technique has its own physical basis, strengths, and limitations. XPS is renowned for its excellent quantitative capabilities and sensitivity to chemical state information. AES offers high spatial resolution, making it ideal for microanalysis and failure analysis. SIMS provides extremely high sensitivity (down to parts-per-billion for some elements) and the ability to detect all elements, including hydrogen and isotopes. The choice between them depends on the specific analytical requirements, such as the need for spatial resolution, chemical sensitivity, or detection limits. This guide provides a objective, data-driven comparison of these three core surface analysis techniques to inform researchers and scientists in their methodological selections.

Theoretical Foundations and Physical Processes

Photoelectron Emission (XPS)

The XPS process is initiated when a sample is irradiated with X-rays of a known energy. These X-rays can cause the photoemission of core-level electrons from atoms within the top 1-10 nanometers of the material [1]. The kinetic energy (KE) of the emitted photoelectron is measured by the spectrometer, and the electron's binding energy (BE) is calculated using the equation: BE = hν - KE - Φ, where hν is the energy of the incident X-ray photon and Φ is the work function of the spectrometer. The binding energy is a unique characteristic of both the element and the specific electron orbital from which it originated, and it is sensitive to the chemical environment of the atom. This chemical shift allows XPS to identify not only the presence of elements but also their oxidation states and the local bonding arrangements. As a surface-sensitive technique, the information depth of XPS is limited by the escape depth of the photoelectrons, which is typically a few nanometers, making it exquisitely sensitive to surface composition [2].

The Auger Effect (AES)

The Auger process is a competing mechanism to photoelectron emission that occurs when an atom relaxes following the removal of a core-level electron. This initial ionization is typically caused by a focused electron beam in AES, though it can also be induced by X-rays. The resulting core-hole is filled by an electron from a higher energy level, and the energy released in this transition can either be emitted as a characteristic X-ray (fluorescence) or transferred to another electron, which is then ejected from the atom. This ejected electron is known as an Auger electron. Its kinetic energy, which is characteristic of the element and independent of the incident beam energy, is what is measured in AES. The Auger process involves three electrons and is described using X-ray notation, such as KL₁L₂₃, indicating the initial hole and the subsequent transitions involved. Like XPS, AES is highly surface-sensitive due to the short inelastic mean free path of the emitted Auger electrons [3].

Sputtered Ion Emission (SIMS)

SIMS is fundamentally different from both XPS and AES, as it is based on the interaction of a primary ion beam (typically O₂⁺, Cs⁺, or Ga⁺) with the sample surface. When these high-energy ions (typically 1-30 keV) strike the surface, they transfer their momentum to the atoms of the sample through a series of collisions in a process known as the collision cascade. This can lead to the ejection (sputtering) of atoms, molecules, and molecular fragments from the top one or two atomic layers of the surface. A small fraction of these sputtered particles are ionized (positive or negative), and these secondary ions are then extracted into a mass analyzer (e.g., a time-of-flight or quadrupole mass spectrometer) where they are separated according to their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) and detected [4] [5]. The intensity of a specific secondary ion provides a measure of the concentration of that species in the surface, while the mass spectrum provides a detailed map of the surface's molecular and elemental composition.

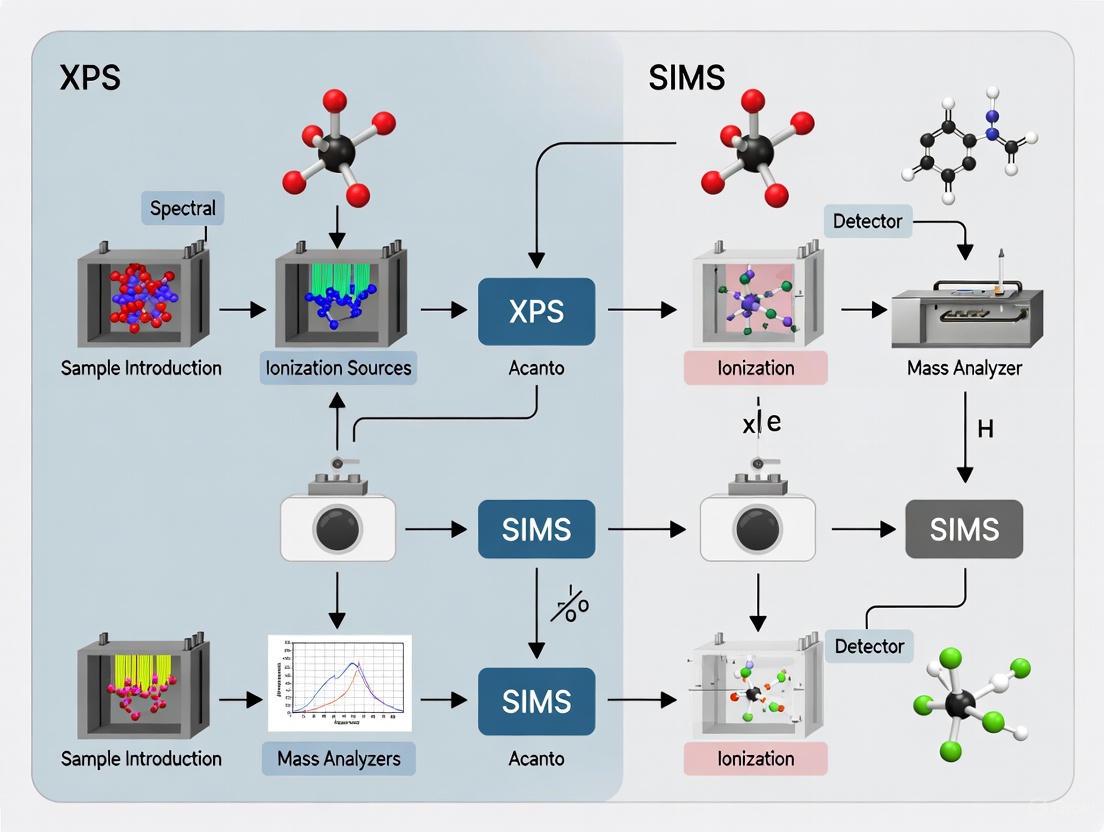

Diagram 1: Core physical processes in XPS, AES, and SIMS, showing the different incident probes and emitted particles used for surface analysis.

Technical Comparison and Performance Data

The following tables provide a consolidated, quantitative comparison of the core capabilities, performance metrics, and practical considerations for XPS, AES, and SIMS, based on experimental data and established technical specifications.

Table 1: Core Technical Capabilities and Performance Metrics

| Feature | XPS | AES | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Probe | X-rays | Electron Beam | Ion Beam |

| Detected Signal | Photoelectrons | Auger Electrons | Sputtered Ions |

| Information Depth | 1-10 nm [1] | 1-5 nm [6] | 1-2 monolayers [5] |

| Lateral Resolution | 1-10 μm [2] (≥150 nm at synchrotrons) | 10-50 nm | < 100 nm |

| Detection Limits (Atomic %) | 0.1 - 1% | 0.1 - 1% | ppm - ppb [5] |

| Elements Detected | All except H and He [2] | All except H and He [2] | All, including H and isotopes [2] |

| Chemical State Information | Excellent | Good (e.g., carbon on metals) [2] | Limited (via cluster ions) |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Excellent (±5-10%) | Good (±10-15%) | Poor (requires standards) |

| Destructive to Sample? | Essentially Non-destructive | Potentially destructive (e-beam damage) [7] | Destructive |

Table 2: Analytical Strengths, Weaknesses, and Common Applications

| Parameter | XPS | AES | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Strengths | Simple quantification, excellent chemical state info, low damage [2] | High-spatial resolution elemental mapping, fast analysis | Ultimate sensitivity, isotope detection, full elemental coverage, molecular information (ToF-SIMS) [2] [8] |

| Main Limitations | Poor lateral resolution vs. AES/SIMS, no H detection, charging on insulators | E-beam damage [7], poorer chemical state info vs. XPS, charging | Complex spectra, strong matrix effects, semi-destructive |

| Typical Applications | Surface chemistry, functional group identification, oxidation states, thin film composition | Micro-contamination analysis, grain boundary chemistry, failure analysis | Trace element mapping, dopant profiling, organic surface analysis (ToF-SIMS), isotope tracing [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Analysis Protocol for XPS

A typical XPS analysis begins with sample introduction, preferably via a load-lock system to maintain ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions and minimize air exposure. The sample is often secured to a holder using conductive tape or clips to mitigate charging. The analysis is performed in a UHV chamber (base pressure typically < 1 × 10⁻⁸ mbar) to prevent surface contamination and allow the emitted electrons to travel to the detector without scattering. A survey spectrum is first acquired over a wide binding energy range (e.g., 0-1200 eV) to identify all elements present. This is followed by high-resolution regional scans over the core-level peaks of the identified elements to extract chemical state information. For insulating samples, a low-energy electron flood gun is used to neutralize positive charge buildup on the surface. Peak fitting of the high-resolution spectra is then performed using appropriate software, applying constraints based on known chemical physics (e.g., fixed peak separations and area ratios for spin-orbit doublets) to accurately identify chemical species and their relative abundances [2]. It is critical to note that a common pitfall, observed in about 40% of published papers, is the incorrect fitting of peaks, such as using symmetrical peaks for inherently asymmetrical metallic line shapes [2].

Depth Profiling with Ion Sputtering

To analyze composition as a function of depth, XPS and AES are often combined with ion sputtering. A beam of inert gas ions (typically Ar⁺) is used to sequentially remove layers of material, with analysis performed intermittently between sputtering cycles. This process, however, introduces artefacts that must be carefully considered. These include atomic mixing (ion bombardment smears the original interface), preferential sputtering (one element is removed faster than others, altering the measured composition), ion-induced roughening (which degrades depth resolution), and chemical reduction (e.g., reduction of oxides to their metallic states) [1] [7]. To mitigate some of these effects, particularly roughening, sample rotation during sputtering has been successfully applied in AES and SIMS. However, in XPS, the large analyzed area can make the technique more susceptible to crater-edge effects, which can still degrade resolution even with rotation [9]. Cluster ion sources (e.g., Arₙ⁺) are now increasingly used for depth profiling of organic materials and inorganic interfaces as they cause less chemical damage and reduce atomic mixing compared to monoatomic ions [1].

Combined XPS and TOF-SIMS Protocol for Complex Materials

For the analysis of complex, multi-component systems like battery electrodes, a combined approach using XPS and Time-of-Flight SIMS (TOF-SIMS) is highly effective [8]. The experimental workflow is as follows:

- Sample Transfer: Electrodes are extracted from cycled cells in an inert atmosphere (e.g., an Ar-filled glovebox) to preserve the native solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI).

- Initial XPS Analysis: Samples are transferred via an airtight vessel to the XPS instrument. Large-area survey and high-resolution spectra (e.g., of C 1s, O 1s, F 1s, and transition metals) are acquired to determine the average surface chemistry and identify key chemical states.

- SXI and Spectral Mapping: Scanning X-ray-induced secondary electron (SXI) imaging provides an overview of the surface morphology. Following this, high-resolution XPS spectral maps (mosaics) of specific regions of interest are collected to correlate chemistry with morphology.

- TOF-SIMS Analysis: The same sample is transferred to the TOF-SIMS instrument. The surface is interrogated with a pulsed primary ion beam (e.g., Bi₃⁺). The high-lateral resolution mass spectral data provides detailed 2D and 3D maps of the distribution of specific molecular and elemental ions (e.g., organic fragments, LiF, phosphates) identified by XPS.

- Data Correlation: The complementary datasets are overlayed, with XPS providing positive chemical identification and TOF-SIMS revealing the spatial distribution of these components with high sensitivity. This protocol has proven essential for understanding how engineered coatings stabilize battery cathode interfaces [8].

Diagram 2: Integrated XPS and TOF-SIMS workflow for analyzing air-sensitive functional materials like battery electrodes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Argon Gas (Monoatomic) | Sputter source for surface cleaning and conventional depth profiling. | XPS, AES, SIMS |

| Argon Gas (Cluster, Arₙ⁺) | Sputter source for reduced damage depth profiling of delicate organics and inorganic interfaces. | XPS, AES |

| C₆₀ Fullerene | Thermal deposition source for a consistent, conductive carbon reference layer for binding energy calibration on challenging samples. | XPS [7] |

| Gold (Au) Wire | Evaporation source for depositing a thin, conductive coating on insulating samples to mitigate charging; also used as a BE reference. | XPS, AES |

| Adventitious Carbon | Ubiquitous hydrocarbon contamination used as an internal reference for charge correction (C 1s at ~284.8 eV). Use with caution on reactive surfaces. | XPS |

| Ionic Liquid Electrolytes | Model systems for studying electrode-electrolyte interfaces and solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation under near-ambient conditions. | XPS, AES [7] |

| Engineered Particle (Ep) Electrodes | Model battery electrodes with controlled surface coatings to study interfacial stabilization mechanisms. | XPS, TOF-SIMS [8] |

| Ni/Cr Multilayer Thin Film | Standard reference material for evaluating and optimizing depth resolution in sputter depth profiling experiments. | XPS, AES [9] |

XPS, AES, and SIMS are complementary pillars of modern surface analysis, each founded on distinct physical principles. XPS excels in providing straightforward quantitative analysis and detailed chemical state information with minimal damage. AES offers superior spatial resolution for elemental mapping at the nanoscale. SIMS delivers unparalleled sensitivity for trace element and isotopic analysis, with TOF-SIMS extending this to molecular surface mapping. The choice of technique is not a question of which is best, but which is most appropriate for the specific analytical question. For complex, real-world problems in advanced materials and drug development, a multi-technique approach—such as the combined use of XPS and TOF-SIMS—is often the most powerful strategy, leveraging the respective strengths of each method to build a comprehensive picture of surface composition and chemistry.

Surface analysis is a critical component in materials science, chemistry, and drug development, providing essential information about the outermost layers of a material that dictate its properties and behavior. Among the most powerful techniques in this field are X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS). Each technique offers unique capabilities and limitations for probing elemental composition, chemical states, and molecular information from surface and near-surface regions. Understanding their complementary strengths is essential for selecting the appropriate analytical method for specific research questions, particularly in pharmaceutical development where surface properties can significantly influence drug efficacy, stability, and delivery mechanisms.

Each technique operates on different physical principles: XPS relies on the photoelectric effect, AES utilizes the Auger emission process, and SIMS is based on sputtering and ionization of surface atoms. These fundamental differences result in varying capabilities for elemental detection, chemical state information, molecular analysis, detection sensitivity, spatial resolution, and depth profiling. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these techniques, supported by experimental data and protocols, to enable researchers to make informed decisions for their specific analytical needs.

Technical Comparison of XPS, AES, and SIMS

The following table summarizes the key characteristics and capabilities of XPS, AES, and SIMS for surface analysis:

Table 1: Comparison of Surface Analysis Techniques

| Parameter | XPS | AES | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Elemental identity & chemical state [10] | Elemental composition [11] [12] | Elemental, isotopic, & molecular composition [13] [14] |

| Chemical State Information | Excellent [10] | Minimal [11] | Limited (except in Static SIMS) [13] |

| Molecular Information | Indirect through chemical shifts | Very limited | Excellent, especially Static SIMS [13] |

| Detection Limits | 0.1-1 at% (can reach 0.01 at% in favorable cases) [15] | 0.1-1 at% [11] | ppm to ppb range [13] [14] |

| Depth Resolution | ~5-10 nm [10] | Top 3-10 nm [11] | 1-2 nm [13] |

| Lateral Resolution | 10-200 μm (can reach 200 nm with synchrotron) [10] | ≥10 nm [11] | Down to 40 nm [14] |

| Elements Detected | All except H and He [10] [16] | All except H and He [11] | All elements including H [13] [14] |

| Primary Damage | Low to moderate (X-ray degradation) [10] | Moderate (electron beam damage) | High (sputtering inherent) [13] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Excellent (90-95% for major peaks) [10] | Semi-quantitative [11] | Requires standards due to matrix effects [13] |

Table 2: Detection Limits Comparison for Selected Elements

| Element | XPS | AES | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Elements (C, N, O) | 0.1-1 at% [15] | 0.1-1 at% [11] | ppb range [14] |

| Heavy Elements in Light Matrix | ~0.01 at% [15] | ~0.1 at% [11] | ppt-ppb range [13] |

| Light Elements in Heavy Matrix | ~3 at% [15] | ~1 at% [11] | ppb-ppm range [13] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Protocol

XPS operates based on the photoelectric effect, where X-rays irradiate a sample, ejecting photoelectrons whose kinetic energies are measured to determine binding energies and elemental identification [10]. A standard XPS experimental protocol involves multiple well-defined steps:

Sample Preparation: Samples must be compatible with ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions (typically 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁹ Pa) [10]. Conducting samples can be mounted directly, while insulating materials may require charge compensation methods such as low-energy electron floods. Sample size is instrument-dependent, with modern systems handling samples from millimeters to several centimeters in dimension [10] [16].

Instrument Setup: Select appropriate X-ray source (typically monochromatic Al Kα at 1486.7 eV or Mg Kα at 1253.7 eV) [10]. The choice depends on the elements of interest and potential overlaps with Auger peaks. Configure the analyzer pass energy based on required resolution (higher pass energy for survey scans, lower for high-resolution regions).

Data Acquisition:

- Begin with a survey scan (0-1100 or 0-1400 eV binding energy) to identify all detectable elements, typically requiring 1-20 minutes [10].

- Acquire high-resolution regional scans for elements of interest with sufficient signal-to-noise ratio, typically requiring 1-15 minutes per region [10].

- For depth profiling, combine with argon ion sputtering (monoatomic or cluster ions) to remove surface layers sequentially [1]. Cluster ions are preferred for organic materials to reduce damage.

Data Analysis: Process data using peak fitting with appropriate background subtraction (e.g., Shirley or Tougaard backgrounds). Quantification is performed using peak areas corrected with relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) [10] [15].

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) Protocol

AES utilizes a focused electron beam (3-25 keV) to excite atoms, which then relax through the emission of Auger electrons [11] [12]. The standard AES protocol includes:

Sample Preparation: Similar to XPS, samples must be UHV-compatible. AES is particularly challenging for insulators due to charging effects, and the technique is generally not recommended for bulk insulating materials [17]. Samples should be sufficiently conducting to dissipate the electron beam charge.

Instrument Setup: Select primary beam energy (typically 3-25 keV) and current based on required spatial resolution and analytical sensitivity. Higher beam energies provide better spatial resolution but may increase sample damage. Configure the electron energy analyzer (typically cylindrical mirror analyzer) [12].

Data Acquisition:

- Locate areas of interest using secondary electron imaging [11].

- Acquire point spectra from specific locations or perform mapping by rastering the electron beam.

- Auger spectra are often displayed in derivative mode (dN(E)/dE) to enhance visibility of small peaks on a high background [12].

- For depth profiling, combine with inert gas sputtering (typically argon) to remove material sequentially [11].

Data Analysis: Elemental identification based on characteristic kinetic energies. Semi-quantitative analysis using sensitivity factors, with more accurate quantification requiring comparison to standard samples of known composition [11] [12].

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) Protocol

SIMS uses a focused primary ion beam to sputter material from the surface, with a fraction of the ejected particles being ionized and analyzed by a mass spectrometer [13] [14]. The protocol varies significantly between static and dynamic modes:

Sample Preparation: Samples must be UHV-compatible. SIMS can analyze any solid material, including insulators, semiconductors, and metals [14]. Careful consideration of electrical properties is needed for insulating samples to maintain surface potential stability.

Instrument Setup: Select primary ion species based on application:

- Oxygen primary ions (O₂⁺, O⁻) enhance positive secondary ion yields [14].

- Cesium primary ions (Cs⁺) enhance negative secondary ion yields [14].

- Liquid metal ion guns (LMIG) with Ga, Au, or Bi provide high spatial resolution (<50 nm) [13].

- Cluster ion sources (C₆₀⁺, Ar₇₀₀⁺) reduce damage for organic analysis [13].

Data Acquisition:

- Static SIMS: Use very low primary ion dose density (<10¹³ ions/cm²) to preserve molecular information from the top monolayer [13]. Typically uses time-of-flight (ToF) mass analyzers for simultaneous detection of all masses.

- Dynamic SIMS: Use higher primary ion currents for depth profiling, sacrificing surface molecular information but enabling bulk composition analysis and depth distribution measurements of trace elements [14].

Data Analysis: Mass spectra are interpreted based on mass-to-charge ratios. Quantification requires comparison with matrix-matched standards due to strong matrix effects on ion yields. Use relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) derived from standards for quantitative analysis [14].

Figure 1: Surface analysis technique selection workflow based on primary information requirements.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful surface analysis requires not only sophisticated instrumentation but also appropriate reference materials and reagents for calibration and quantification. The following table outlines essential research reagents and their functions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Surface Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Standard Reference Materials | Quantification calibration | Required for accurate SIMS quantification; useful for AES and XPS [13] [14] |

| Argon Gas (High Purity) | Sputtering for depth profiling | Used in all three techniques for depth profiling [16] [1] |

| Conductive Coatings (Au, C) | Charge compensation for insulating samples | Used cautiously in AES and XPS; problematic for SIMS [17] |

| Relative Sensitivity Factors (RSFs) | Quantitative analysis | Database required for XPS and AES quantification; matrix-specific for SIMS [10] [14] [15] |

| Charge Compensation Flood Sources | Neutralizing surface charge | Essential for analyzing insulating samples in XPS; challenging for AES [10] [17] |

| Primary Ion Beams (O₂, Cs, C₆₀, Ar clusters) | Sputtering and ionization | SIMS requires specific primary ions tailored to application [13] [14] |

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Combined XPS and TOF-SIMS Analysis of Battery Materials

A compelling case study demonstrating the complementary nature of these techniques involves the analysis of engineered particle (Ep) battery cathodes [8]. Researchers combined XPS and Time-of-Flight SIMS (TOF-SIMS) to understand how specialized coatings stabilize cathode-electrolyte interfaces in high-voltage lithium cobalt oxide (LCO) systems. In this workflow:

- XPS provided chemical state information of the transition metals and oxidation states at the cathode surface before and after electrochemical cycling [8].

- TOF-SIMS delivered high-resolution mapping of organic and inorganic species distribution across the electrode surface, identifying spatial distribution of degradation products [8].

- The combination revealed how Ep coatings create more uniform interfaces that reduce side reactions and transition metal dissolution, leading to improved battery performance and longevity [8].

This approach exemplifies how technique synergy provides insights unattainable by any single method, particularly for complex, multi-component systems.

Depth Profiling of Thin Films and Interfaces

Depth profiling represents a critical application for all three techniques, with each offering distinct advantages:

XPS Depth Profiling: When combined with argon cluster ion sputtering, XPS can provide chemical state information as a function of depth with minimal damage, particularly valuable for organic materials and polymers [1]. The main challenges include ion-induced mixing, preferential sputtering, and surface roughening that must be accounted for during data interpretation [1].

AES Depth Profiling: AES offers excellent spatial resolution for depth profiling of small features, with the ability to characterize particles and defects smaller than 25 nm [11]. This makes it invaluable for failure analysis in microelectronics and investigation of grain boundary chemistry in metallurgical applications [11] [17].

SIMS Depth Profiling: Dynamic SIMS provides the highest sensitivity for trace element depth distribution, with detection limits reaching ppb levels [14]. This exceptional sensitivity makes it the technique of choice for dopant and contaminant profiling in semiconductors, with depth resolution reaching sub-nanometer levels when using low-energy primary ions [14].

Technique Selection Guidelines

Selecting the appropriate surface analysis technique requires careful consideration of research objectives, sample properties, and information requirements. The decision process should address the following key questions:

What is the primary information needed?

What are the detection limit requirements?

What is the sample type?

Is depth information required?

What is the required spatial resolution?

For complex analytical challenges, a combined approach utilizing multiple techniques often provides the most comprehensive understanding of material properties and behavior.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three principal surface analysis techniques: X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS). For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate technique is critical for characterizing material surfaces, thin films, and interfaces. The following data, protocols, and visualizations will aid in making an informed choice based on key performance metrics.

Comparative Performance Metrics at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core performance characteristics of XPS, AES, and SIMS, providing a high-level overview for initial technique evaluation [18] [19] [5].

| Performance Metric | XPS (X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy) | AES (Auger Electron Spectroscopy) | SIMS (Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information Depth | ~3 monolayers (≈10 Å) [18] | ~3 monolayers (≈10 Å) [18] | ~10 monolayers [18] |

| Detection Limits | ~0.1 at% (1000 ppm) [19] [5] | ~0.1 at% (1000 ppm) [19] [5] | Parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-million (ppm) range [18] |

| Spatial Resolution | Tens of micrometers (conventional); sub-micrometer (small-spot systems) [9] | Can be better than 5 nm [18] | High (elemental mapping capability) [18] |

| Chemical State Information | Yes, a key strength [20] | Limited [5] | Limited, complex due to ion-induced effects |

| Depth Profiling | Yes, with sputtering; maximal depth ~500 nm [18] | Yes, excellent with sample rotation [9] | Yes, inherent to the technique [18] |

| Typical Sputtering Rate | Slow (nm/min) [18] | Not specified in results | Slow (nm/min) [18] |

Detailed Metrics and Experimental Protocols

Beyond the high-level overview, a deeper understanding of each metric and how it is determined is essential for rigorous experimental planning.

Analysis Depth & Depth Profiling

The analysis depth defines the thickness of the surface layer from which the analytical signal originates. For depth profiling, this involves repeated surface removal and analysis to characterize layered structures.

- XPS & AES Information Depth: The analysis depth for XPS and AES is limited by the escape depth of the ejected electrons, which is typically on the order of a few nanometers (≈3-10 monolayers) [18]. This makes them highly surface-sensitive.

- SIMS Information Depth: SIMS can probe slightly deeper, up to about 10 monolayers, as the analysis involves the ejection of atoms from the surface [18].

- Experimental Protocol for Depth Profiling:

- Sputter Ion Beam Setup: A focused ion beam (often Ar⁺) is directed at the sample surface to erode material. The ion energy and current density must be optimized to balance sputtering rate and depth resolution [9].

- Data Acquisition Cycle: The instrument alternates between sputtering for a fixed time to remove a layer and performing surface analysis (XPS, AES, or SIMS) on the newly exposed surface.

- Sample Rotation (for AES/XPS): For AES and XPS, sample rotation during sputtering is a critical methodological improvement. It reduces ion-beam-induced topography (e.g., roughening, ripples) by continuously changing the angle of incidence, leading to a higher depth resolution that is independent of the sputtered depth [9].

- Crater Edge Effects: A key challenge in XPS depth profiling is the large analyzed area, which can lead to signal distortion from the sloping sides of the sputter crater. Precise alignment of the X-ray probe, analyzed spot, ion beam, and rotation axis is crucial to mitigate this [9].

Sensitivity & Detection Limits

Sensitivity refers to the minimum amount of an element or isotope that can be detected.

- SIMS Superiority: SIMS offers the highest sensitivity of the three techniques, with detection limits in the parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-million (ppm) range across the periodic table. This is due to its high efficiency in ejecting and detecting ions from the topmost layers [18].

- XPS and AES: These techniques have more modest detection limits, typically around 0.1 atomic percent (1000 ppm) [19] [5].

- Experimental Protocol for Determining Detection Limits:

- Calibration Standards: Use a series of reference materials with known, low concentrations of the analyte in a relevant matrix.

- Signal Measurement: Acquire multiple spectra from the standard materials under identical, optimized instrument conditions.

- Calibration Curve: Plot the measured signal intensity against the known concentration.

- Limit Calculation: The detection limit is typically calculated as the concentration that yields a signal three times the standard deviation of the background signal from a blank or ultra-low concentration sample.

Spatial Resolution

Spatial resolution defines the smallest feature size that can be chemically resolved on the sample surface.

- AES Superiority: AES can achieve the highest spatial resolution, with modern field-emission systems capable of resolutions on the order of 5 nm. This is because the incident electron beam can be focused to a very small spot [18].

- XPS Limitations: Conventional XPS analyzes an area of tens of micrometers. While "small-spot" XPS systems exist, the analyzed area is still generally much larger than in AES, which also makes it more susceptible to crater-edge effects during depth profiling [9].

- SIMS: SIMS also provides high spatial resolution, sufficient for creating element-specific maps of the sample surface [18].

- Experimental Protocol for Spatial Resolution Measurement:

- Standard Sample: Use a certified reference material with well-defined, small-scale features, such as a gold-coated diffraction grating.

- Line Scan: Perform a high-magnification image or a line scan across a sharp edge between two chemically distinct phases.

- Data Analysis: The spatial resolution is often reported as the distance over which the signal intensity changes from 16% to 84% (or 20% to 80%) when scanning across the sharp edge.

Technique Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a logical decision-making process for selecting the most appropriate surface analysis technique based on primary research questions. This workflow synthesizes the comparative performance data to guide researchers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful surface analysis requires not only sophisticated instruments but also a suite of essential materials and reagents for sample preparation, calibration, and analysis.

| Item Name | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Argon Gas Supply | High-purity argon is used in ion guns for sputtering during depth profiling in XPS and AES, and as the sputtering gas in GDOES comparisons [18]. |

| Primary Ion Source (e.g., Cesium, O₂⁺) | These ion beams are used in SIMS to sputter and eject secondary ions from the sample surface. The choice of ion species can significantly enhance the yield of positive or negative secondary ions [18]. |

| Conductive Adhesive Tapes | Used for mounting insulating samples to prevent surface charging during analysis with electron or ion beams. Crucial for non-conductive samples in AES and XPS [18]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Standards with known composition and concentration are essential for quantitative analysis, calibrating instrument response, and determining detection limits for all techniques. |

| Sample Stubs & Holders | Specialized holders are designed for specific instruments to ensure good electrical contact, precise positioning, and, where applicable, sample rotation during depth profiling [9]. |

| Charge Neutralization Filament | A low-energy electron flood gun is used in XPS to neutralize charge buildup on insulating samples, ensuring accurate binding energy measurements [18] [20]. |

The choice between XPS, AES, and SIMS is not a matter of identifying a single "best" technique, but rather selecting the right tool for a specific analytical question. XPS is unparalleled for quantifying chemical states. AES provides superior spatial resolution for nanoscale analysis. SIMS offers the ultimate sensitivity for detecting trace elements and isotopes. Modern research often benefits from a complementary approach, using two or more techniques on the same sample to build a comprehensive picture of its surface composition and chemistry.

Surface analysis techniques are fundamental to advancements in materials science, nanotechnology, and semiconductor development. These techniques provide critical information about the outermost layers of a material, where crucial interactions occur that dictate properties like adhesion, corrosion resistance, and electronic functionality [21]. Among the most prominent methods are X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS). The landscape of these techniques is continuously evolving, driven by technological innovations and shifting research demands. This guide provides an objective comparison of XPS, AES, and SIMS, framing their performance within current publication and adoption trends. It is designed to assist researchers and scientists in selecting the optimal technique for their specific analytical challenges by presenting structured data, detailed methodologies, and a clear framework for decision-making.

Comparative Analysis of Surface Techniques

A comprehensive understanding of the strengths and limitations of XPS, AES, and SIMS is essential for effective technique selection. The following table summarizes their core characteristics based on current technological capabilities.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of XPS, AES, and SIMS

| Feature | XPS/ESCA | AES | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Elemental composition, chemical state, empirical formula [22] [21] | Elemental composition, some chemical information [23] | Elemental, isotopic, and molecular species; depth profiling [23] [24] |

| Detection Limits | ~0.1 atomic % (parts per thousand) [25] | Parts per thousand (ppt) range [23] | Parts per billion (ppb) to parts per million (ppm) [23] |

| Depth Resolution | ~10 nm information depth; depth profiling with sputtering [21] | ~ nm scale for depth profiling [23] | Excellent (nm scale); 1-3 monolayers (static); down to 1 nm (profiling) [23] [24] |

| Lateral Resolution | >10 µm; imaging down to ~1 µm [21] | <10 nm [23] | Sub-micrometer (down to 0.2 µm) [23] [24] |

| Chemical State Info | Excellent, via chemical shifts [23] [21] | Moderate, via Auger peak shapes [23] | Limited, as sputtering breaks molecular bonds [23] |

| Quantitation | Straightforward and quantitative [23] [25] | Straightforward, with corrections [23] | Difficult; requires calibrated standards [23] |

| Elements Detected | All except hydrogen and helium [23] [25] | Cannot detect hydrogen or helium [23] | Full periodic table, including H, plus molecular species [23] [24] |

| Sample Environment | Ultra-high vacuum [22] [25] | High vacuum [23] | Ultra-high vacuum [23] [24] |

| Sample Damage | Less destructive (photon excitation) [23] | Can cause beam damage (electron excitation) [23] | Destructive (sputtering process) [23] |

Key Technological and Adoption Trends

The application of these techniques is influenced by broader market and research trends. The global surface analysis market is a multi-billion dollar industry, projected to grow at a CAGR of 5.18% [26]. Specific trends impacting XPS, AES, and SIMS include:

- Automation and AI Integration: The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for data interpretation and automation is enhancing precision and efficiency, transforming operational workflows [27] [26]. Automation in XPS sample loading has reduced turnaround time by 42% in high-volume testing centers [27].

- Multi-Technique Platforms: There is a growing trend of 22% in the use of multi-technique platforms that integrate XPS, AES, and SIMS to address cross-correlation needs for advanced nanostructure verification [27].

- Demand for High-Resolution: Demand for high-resolution monochromatic XPS systems has risen by 34% within three years due to growing requirements for surface chemistry analysis in nanotechnology [27].

- Semiconductor Drive: The relentless drive for semiconductor miniaturization, with nodes advancing below 7 nm, is a key driver. This requires extremely precise surface characterization, as contamination layers under 0.5 nm can disrupt device yields [27].

Experimental Protocols for Technique Validation

To ensure reliable and reproducible results, standardized experimental protocols must be followed. Below are detailed methodologies for key analyses cited in comparative studies.

XPS for Chemical State Identification

Objective: To determine the elemental composition and chemical bonding states of a silicon-based sample (e.g., a wafer with a thermal oxide layer).

Materials & Reagents:

- Sample: Silicon wafer piece (< 1x1 cm).

- Mounting: Conductive double-sided tape or a dedicated sample stub.

- Charge Neutralizer: Low-energy electron flood gun, required for insulating samples.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Clean the sample with solvents (e.g., isopropanol) to remove atmospheric contaminants and dry in a clean environment. Mount the sample securely on the holder.

- Loading: Introduce the sample into the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) introduction chamber of the XPS instrument (pressure ≤ 1×10⁻⁹ Torr) [25].

- Pump-down: Allow the system to reach UHV in the analysis chamber.

- Data Acquisition:

- Select an analysis area (e.g., 500 x 500 µm).

- Excite the surface with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV).

- Acquire a wide energy range survey scan (e.g., 0-1100 eV binding energy) to identify all elements present.

- Acquire high-resolution, narrow scans for the elements of interest (e.g., Si 2p, O 1s, C 1s).

- Data Analysis:

- Use software to calibrate the spectrum to a known peak (e.g., adventitious carbon C 1s at 284.8 eV).

- Identify elements from the peak positions in the survey scan.

- Analyze the high-resolution Si 2p spectrum. Deconvolute the peak to identify contributions from elemental silicon (Si⁰, ~99.3 eV) and silicon dioxide (Si⁴⁺, ~103.3 eV) based on their chemical shifts [22].

SIMS for High-Sensitivity Depth Profiling

Objective: To obtain a depth profile of a dopant (e.g., Boron) in a semiconductor layer structure with high sensitivity and depth resolution.

Materials & Reagents:

- Sample: Semiconductor cross-section.

- Primary Ion Source: Cs⁺ or O⁻ ion source for enhanced negative or positive secondary ion yields, respectively.

- Reference Standard: A matrix-matched standard with a known concentration of the dopant for quantification.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Cleave or cross-section the sample to expose the region of interest. Ensure it is clean and mount securely.

- Loading: Load the sample into the UHV chamber of the SIMS instrument.

- Instrument Setup:

- Select a primary ion beam (e.g., Cs⁺ for analyzing Boron as B⁻ secondary ions).

- Raster the primary beam over a defined area (e.g., 200 x 200 µm).

- Set the mass spectrometer to detect the specific isotope of interest (e.g., ¹¹B⁻).

- Define the data collection cycle time.

- Data Acquisition:

- Start the primary ion beam to begin sputtering a crater into the sample.

- Continuously monitor the secondary ion signal of the dopant and the substrate matrix as a function of time.

- Data Conversion:

- After the analysis, measure the crater depth with a profilometer.

- Convert the sputtering time to depth using the measured crater depth and the total sputter time.

- Convert the secondary ion counts to concentration using the Relative Sensitivity Factor (RSF) derived from the standard [23].

AES for High-Spatial Resolution Mapping

Objective: To map the lateral distribution of a specific element on a metallized sample with sub-micron resolution.

Materials & Reagents:

- Sample: Conductive or charge-coated sample with micro-features.

- Electron Gun: Field emission gun for high spatial resolution.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: The sample must be conductive. If insulating, apply a thin, continuous conductive coating (e.g., carbon).

- Loading: Introduce the sample into the high vacuum chamber of the AES instrument.

- Instrument Setup:

- Select a primary electron beam energy (e.g., 10 keV) and a small beam current to achieve a probe size < 10 nm.

- Locate the area of interest using secondary electron imaging.

- Data Acquisition:

- Select the specific Auger transition peak for the element of interest (e.g., Cu LMM at ~920 eV).

- Perform a raster scan of the focused electron beam over the selected area.

- At each pixel, acquire the Auger electron spectrum or the signal intensity at the specific energy, creating an elemental map.

- Data Analysis:

- Overlay the elemental map on the secondary electron image to correlate elemental distribution with surface topography.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Tape/Stub | Sample mounting for electrical and thermal contact. | Essential for preventing charging in XPS/AES on insulators. |

| Charge Neutralizer (Flood Gun) | Compensates for surface charging on insulating samples. | Critical for analyzing polymers, ceramics, or oxides with XPS. |

| Primary Ion Source (Cs⁺, O⁻, Ga⁺) | Sputters the sample surface for depth profiling (SIMS, XPS, AES) or primary excitation (SIMS). | The ion species (atomic vs. cluster) affects sputter rate, damage, and molecular information retention. |

| Matrix-Matched Reference Standards | Enables quantitative analysis by providing a calibration reference. | Absolutely essential for achieving accurate quantification in SIMS. |

| Monatomic/Cluster Ion Source (Arn+) | Provides gentle sputtering for organic depth profiling in XPS and SIMS. | Preserves chemical information while depth profiling soft materials. |

A Decision Framework for Technique Selection

The choice between XPS, AES, and SIMS is not a matter of which technique is superior, but which is most appropriate for the specific analytical question. The following diagram and explanation provide a logical pathway for this decision.

Diagram 1: Surface analysis technique selection guide.

Navigating the Decision Tree:

- Pursue XPS when the analytical problem requires definitive information on chemical bonding states, oxidation, or empirical formula determination. It is the preferred tool for quantifying surface composition and understanding chemical reactions at interfaces, such as in corrosion studies, catalyst analysis, or polymer surface modification [28] [21].

- Choose SIMS when the highest sensitivity for trace elements or isotopes is needed, or when detailed depth profiling with excellent depth resolution is the primary requirement. Its ability to detect hydrogen and its ppm to ppb detection limits make it indispensable for dopant profiling in semiconductors and contamination analysis [23] [24].

- Select AES when high spatial resolution for elemental analysis is paramount, such as for analyzing individual grain boundaries, sub-micron particles, or specific defects on a surface [23].

- Opt for a Combined Approach for the most comprehensive understanding. Many advanced research problems require correlative data. For example, using XPS to determine the chemical state of a surface layer and then using SIMS to profile the same layer to see how that chemistry changes with depth [27] [23].

XPS, AES, and SIMS are powerful, complementary techniques that form the cornerstone of modern surface analysis. XPS excels in quantitative chemical state analysis, SIMS offers unparalleled sensitivity and depth resolution, and AES provides superior spatial resolution for elemental mapping. The evolving landscape is characterized by the integration of these techniques into multi-modal platforms, enhanced by automation and AI-driven data analysis. As materials and devices continue to become more complex, particularly in fields like semiconductors and nanotechnology, the synergistic use of XPS, AES, and SIMS will be crucial for driving innovation and ensuring product quality and performance. Researchers are empowered to make informed decisions by applying the comparative data and the logical selection framework provided in this guide.

Choosing the Right Tool: Application-Oriented Analysis of XPS, AES, and SIMS

XPS for Biomaterial Biocompatibility and Chemical State Analysis

The biological performance of a biomaterial is fundamentally determined by its surface properties. Biocompatibility starts at the surface, where interactions with proteins, cells, and biological fluids occur. The chemical composition, molecular orientation, presence of functional groups, and microdomain distribution at the topmost layer of a material directly influence critical processes like protein adsorption, cell attachment, and biofilm formation [29] [30]. Consequently, detailed surface chemical analysis is indispensable for understanding and controlling the biological response to synthetic materials.

Among the available analytical techniques, X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), has emerged as a cornerstone for biomaterial characterization. Its exceptional sensitivity to elemental composition and chemical state information makes it particularly powerful. This guide objectively evaluates the performance of XPS against other major surface analysis techniques—Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS)—within the context of biomaterial research. The comparison focuses on their capabilities in providing the data necessary to ensure biocompatibility and optimize material performance for drug delivery systems, medical implants, and other biomedical applications [31] [32] [33].

Comparative Analysis of XPS, AES, and SIMS

Each surface analysis technique offers unique strengths and limitations. The choice between them depends on the specific information required, such as elemental vs. molecular data, surface vs. depth sensitivity, or qualitative vs. quantitative analysis.

Table 1: Overall Technique Comparison for Biomaterial Analysis

| Feature | XPS (ESCA) | AES | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Elemental composition, empirical formula, chemical state, electronic state [31] [32] | Elemental composition, focusing on Auger transitions [34] | Elemental and molecular structure, isotopic information [29] [30] |

| Underlying Principle | Photoelectric effect [34] | Auger effect [34] | Emission of secondary ions via ion sputtering [5] |

| Depth of Analysis | Top few nanometers (highly surface-sensitive) [34] | Slightly deeper than XPS, but still surface-sensitive [34] | Top monolayer (static SIMS) to deep depth profiling (dynamic SIMS) |

| Spatial Resolution | High lateral and depth resolution [34] | Good lateral resolution, may have lower depth resolution than XPS [34] | High spatial resolution, capable of high-resolution imaging [30] |

| Quantitative Capability | Excellent; provides quantitative data on elemental composition and chemical states [32] | Good for elemental composition [5] | Semi-quantitative; can be hampered by matrix effects [5] |

| Chemical State Info | Excellent; directly identifies oxidation states and functional groups [31] | Limited; less effective for chemical state analysis compared to XPS [5] | Good; fragments can indicate molecular structure and functional groups [29] |

| Key Biomaterial Applications | Surface functionalization, implant analysis, protein adsorption, biocompatibility studies [32] | Metallurgy, semiconductor analysis, thin-film characterization [34] | Characterization of surface-bound proteins, polymer additives, and biological spatial distributions [29] [30] |

Key Performance Differentiators

- Chemical State Information: XPS excels at determining the chemical state of elements, which is crucial for understanding surface functionality. For instance, it can distinguish between C-C/C-H, C-O/C-N, and O=C-O/O=C-N bonds in polymers or proteins, providing insight into surface chemistry that directly affects biocompatibility [30] [32]. AES provides limited chemical state information, while SIMS infers chemistry from molecular fragment patterns [29] [5].

- Detection Sensitivity and Quantification: XPS is highly reliable for quantitative analysis of elemental surface composition. AES also provides good quantitative data. In contrast, SIMS, while extremely sensitive (often to ppm/ppb levels), suffers from matrix effects that can make quantification challenging without standardized reference materials [5].

- Depth Profiling and Spatial Resolution: For in-depth analysis, SIMS is the superior technique for depth profiling of multi-layered structures. AES can also perform effective depth profiling. While XPS can perform depth profiling via ion sputtering, it is less refined for this purpose compared to SIMS and AES [5]. AES typically offers the best lateral resolution for elemental mapping, followed by SIMS and then XPS [34].

Experimental Protocols for Biomaterial Analysis

Standardized protocols are essential for obtaining reliable and reproducible surface analysis data, especially for complex biological interfaces.

Sample Preparation for Hydrated Biomaterials

A significant challenge in analyzing biomaterials is that they function in hydrated environments, while techniques like XPS and SIMS require ultra-high vacuum (UHV). Simply drying the sample can alter its surface structure. To address this, cryogenic preparation methods have been developed [35] [30].

- Fast-Freezing: The hydrated biomaterial sample is rapidly frozen in a suitable medium, a process that vitrifies the water, preserving the spatial structure and composition of the surface.

- Transfer and Analysis: The frozen-hydrated sample is transferred under vacuum to the spectrometer stage, which is maintained at cryogenic temperatures (e.g., liquid nitrogen). Analysis is then performed on the frozen surface, preventing dehydration-induced artifacts [35].

Protocol for Protein Adsorption Studies

Understanding protein adsorption is a cornerstone of biocompatibility assessment. A powerful multi-technique protocol involves:

- Surface Modification: Create a series of model surfaces with controlled functionalities (e.g., -CH3, -OH, -COOH) using methods like self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) or plasma polymerization [30].

- Protein Exposure: Incubate these surfaces in a solution containing a single protein or complex mixture (e.g., blood plasma) for a defined time and temperature.

- Radiolabeling (Quantification): Use 125I radiolabeling of proteins as the "gold standard" to determine the absolute amount of protein adsorbed onto the surface [30].

- XPS Analysis (Thickness and Composition): Analyze the protein-coated surfaces with XPS. The atomic % nitrogen (N) signal, which is unique to the protein layer, can be used to calculate film thickness. The radiolabeling data calibrates the XPS composition, enabling accurate thickness determination [30].

- SIMS Analysis (Molecular Information): Perform static ToF-SIMS analysis on the same samples. The unique fragmentation patterns from different amino acids can help identify the proteins present and provide clues about their conformation and orientation on the surface [30].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterial Surface Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) | Creates well-defined, chemically controlled model surfaces to systematically study the effect of specific functional groups on protein adsorption and cell adhesion [30]. |

| Polymeric Biomaterials (e.g., Polyurethanes, PMMA) | Representative classes of biopolymers used as test substrates for surface modification and to correlate surface characterization with bio- and blood-compatibility [29]. |

| 125I-Radiolabeled Proteins | Provides an absolute quantitative measure of the amount of protein adsorbed onto a material surface, used to calibrate data from XPS and other techniques [30]. |

| Trehalose Coating | A sample preparation method where a disaccharide (trehalose) is used to coat and preserve the native state of biological samples (e.g., cells, proteins) for analysis under UHV conditions [30]. |

| Cryogenic Preparation Stage | A specialized instrument accessory that allows for the fast-freezing and analysis of hydrated biomaterials, preventing structural collapse and preserving the interface as it exists in an aqueous environment [35]. |

Protocol for Surface Contamination and Cleanliness Analysis

Surface contamination can severely compromise biomaterial performance. XPS provides a direct method for assessment.

- Survey Scan: Acquire a wide energy range scan (e.g., 0-1200 eV binding energy) to identify all elements present on the surface.

- High-Resolution Scans: Perform high-resolution scans on key elements (like C 1s, O 1s, N 1s) to determine their chemical states.

- Data Interpretation: A high-resolution C 1s spectrum is particularly informative. A dominant C-C/C-H peak often indicates hydrocarbon contamination. Peaks for C-O, C=O, and O-C=O confirm the presence of organic contaminants and can help identify their source. The absence of expected elements or the presence of unexpected ones (like Si on a polymer surface) indicates issues with processing or handling [29] [32].

Analytical Workflows and Data Interpretation

The integration of multiple techniques often provides the most comprehensive understanding of a biomaterial's surface. The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for a full surface characterization project.

Case Study: Characterizing a Coated Titanium Implant

Consider a titanium alloy (e.g., Ti6Al4V) implant with a surface coating designed to enhance bone integration.

- XPS Analysis: First, XPS would be used to confirm the successful application of the coating. It would verify the elemental composition and, crucially, prove the formation of the desired chemical states. For a titanium dioxide-based coating, XPS can distinguish the presence of TiO2 from other oxides of alloying elements and confirm its oxidation state, which is critical for its photocatalytic and bioactive properties [35].

- SIMS Analysis: Subsequently, ToF-SIMS would be employed to image the homogeneity of the coating at a micron or sub-micron scale and to detect any trace-level contaminants or dopants that might have been incorporated during processing. The molecular ion signals can confirm the identity of the coating material.

- AES Analysis (if needed): If the implant had micro-scale features and required very high-resolution elemental mapping of the coating-substrate interface, AES could be used to provide nanoscale information about the distribution of Ti, O, and coating elements.

This multi-technique approach provides a robust dataset to confidently link the implant's surface properties to its in-vitro and in-vivo performance.

XPS, AES, and SIMS are powerful, complementary techniques in the biomaterial scientist's toolkit. XPS stands out for its excellent quantitative capabilities and unparalleled ability to provide chemical state information directly, which is fundamental for understanding surface functionality and biocompatibility. While SIMS offers superior sensitivity, molecular specificity, and imaging capabilities, and AES provides high spatial resolution, XPS remains the primary workhorse for comprehensive surface composition analysis.

The future of biomaterial surface analysis lies in the continued integration of these techniques, along with the development of more advanced sample handling methods like cryo-XPS [35] and sophisticated data analysis protocols such as multivariate analysis (MVA) for ToF-SIMS data [30]. By leveraging the complementary strengths of XPS, AES, and SIMS, researchers can obtain an unprecedentedly detailed view of the biomaterial-biology interface, accelerating the development of safer and more effective medical devices and therapies.

AES for High-Resolution Surface Mapping and Nanoscale Contaminant Identification

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) is a powerful surface-sensitive analytical technique that provides quantitative elemental information from the top surface of solid materials. With an average analysis depth of approximately 5-10 nanometers and lateral spatial resolution as fine as 8 nanometers, AES delivers exceptional capabilities for high-resolution surface mapping and nanoscale contaminant identification [36] [37] [38]. The technique is particularly valuable for industrial and research applications where surface or thin film composition critically determines material performance, including semiconductors, nanomaterials, catalysis, corrosion studies, and thin film coatings [37]. Modern AES instruments, such as the PHI 710 Scanning Auger Nanoprobe, achieve SEM-like ultra-high resolution elemental characterization, making them indispensable tools for advanced materials research and failure analysis [36].

This guide objectively compares AES with two other major surface analysis techniques: X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS). Understanding the relative strengths and limitations of these techniques enables researchers to select the optimal methodology for specific analytical challenges, particularly in pharmaceutical development and materials science where surface composition and contamination critically influence product performance and safety.

Technical Comparison of Surface Analysis Techniques

The table below summarizes the key technical parameters of AES, XPS, and SIMS for surface analysis applications:

Table 1: Comparison of Surface Analysis Techniques

| Parameter | AES | XPS | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Excitation Source | Focused electron beam (2-25 keV) [36] [38] | X-rays [9] [18] | Focused ion beam (2-5 keV) [18] |

| Detected Species | Auger electrons [38] | Photoelectrons [18] | Secondary ions [18] |

| Analysis Depth | 0.4-10 nm [38] | ~3 monolayers (≈10 Å) [18] | ~10 monolayers [18] |

| Lateral Resolution | <8 nm [36] [37] | Larger than AES (even small-spot instruments) [9] | Typically higher than XPS [39] |

| Elemental Range | All elements except H and He [38] | All elements except H [18] | All elements including H [18] |

| Detection Limits | ~0.1-0.5 at% [38] [40] | ~0.1-1 at% | Parts-per-billion to parts-per-million [18] |

| Chemical Bonding Information | Limited | Excellent [18] | Limited molecular information |

| Quantitative Analysis | Semi-quantitative with sensitivity factors [38] | Good with sensitivity factors [18] | Difficult due to matrix effects [18] |

| Depth Profiling | Yes, with monoatomic Ar⁺ sputtering [36] [38] | Yes, with alternating sputtering and XPS analysis [18] | Inherent to technique [18] |

| Sample Environment | Ultra-high vacuum (<10⁻⁹ torr) [38] | Ultra-high vacuum [18] | High vacuum (<10⁻⁷ torr) [18] |

Key Differentiating Factors

Spatial Resolution vs. Analytical Area: AES excels with sub-10 nm spatial resolution for elemental mapping, while XPS analyzes much larger areas even in small-spot instruments, making AES superior for nanoscale feature analysis [9] [36]. This capability enables identification of contaminants on the scale of individual nanoparticles.

Chemical State Information: XPS provides comprehensive chemical bonding information, whereas AES primarily delivers elemental composition with limited chemical state data [18]. This makes XPS preferable for studying surface reactivity and oxidation states.

Detection Sensitivity: SIMS offers superior detection limits (ppb-ppm range) compared to AES and XPS (~0.1 at%), making it ideal for trace element and dopant analysis [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

AES for Nanoscale Contaminant Identification

Sample Preparation:

- Samples must be solids compatible with ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions [36]. Non-volatile, stable materials under electron beam irradiation are essential to prevent decomposition during analysis.

- For insulating samples, specialized charge compensation methods are required since traditional conductive coatings interfere with AES analysis [38]. Approaches include using small samples mounted on indium substrates, conductive Si wafers with colloidal graphite paint, or analysis at low beam voltages (1-3 keV) [38].

- Surface cleaning via low-energy Ar⁺ sputtering (typically 0.5-5 keV) removes adventitious carbon contamination present on most "as-received" samples [38].

Data Acquisition:

- High-resolution SEM imaging (up to 20,000× magnification) identifies regions of interest using the electron beam [40].

- Auger elemental maps are acquired by scanning the focused electron beam (typically 2-25 keV) across the sample surface while monitoring specific Auger electron energies characteristic of target elements [36] [38].

- For quantitative analysis, multiplex mode monitors specific energy windows corresponding to elements of interest while sputtering to determine depth profiles [38].

- The PHI 710 instrument achieves 8 nm resolution for AES maps and 3 nm for secondary electron images, enabling precise nanoscale characterization [36].

Data Interpretation:

- Auger spectra typically display the differentiated signal (dN(E)/dE) to enhance peak visibility against the background [38].

- Elemental identification relies on the characteristic kinetic energies of Auger electrons, with quantification using published sensitivity factors or comparison with standards [38].

- Spatial elemental distributions are visualized through color overlays of individual element maps, clearly showing contaminant localization [37].

Comparative Experimental Data

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison in Applied Studies

| Application | AES Performance | XPS Performance | SIMS Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thin Film Analysis | Excellent for layer thickness and interfacial analysis [38] | Good for chemical state information at interfaces [18] | Excellent for trace impurities at interfaces [18] |

| Catalyst Characterization (PtNiCo Nanowires) | High-resolution imaging and elemental mapping of individual nanowires [39] | Reveals chemical states influencing surface reactivity [39] | Detects surface-level contamination critical to electrocatalytic activity [39] |

| Depth Profiling (Ni/Cr Multilayer) | High depth resolution independent of sputtered depth with sample rotation [9] | Degradation of depth resolution with sputtered depth due to crater-edge effects [9] | Not specifically reported in search results |

| Oxide Layer Analysis | Light element sensitivity advantageous for oxide characterization [38] | Excellent for chemical state identification in oxides [18] | Matrix effects complicate oxide analysis [18] |

Multi-Technique Approach

Complementary use of multiple techniques provides comprehensive surface characterization. For example, in fuel cell catalyst research (PtNiCo nanowires):

- AES offers high-resolution imaging and elemental mapping of individual nanowires [39].

- XPS reveals chemical states that influence surface reactivity [39].

- TOF-SIMS detects surface-level contamination critical to electrocatalytic activity [39].

This integrated approach delivers insights into surface and subsurface composition, bonding, and contamination essential for optimizing material performance.

Technique Selection Guide

Decision Framework

The following workflow diagram illustrates the technique selection process for surface analysis applications:

Application-Specific Recommendations

Pharmaceutical Contaminant Identification: For particulate contamination on medical devices or drug delivery systems, AES provides unambiguous elemental identification at the nanoscale, crucial for determining contaminant source and composition [37]. When chemical state information is required for understanding reactivity or toxicity, complement with XPS.

Thin Film Pharmaceutical Coatings: AES depth profiling effectively characterizes coating thickness, uniformity, and interfacial layers in controlled-release formulations [38]. The combination with XPS provides additional chemical environment information for polymer-based coatings.

Catalyst and Nanomaterial Development: A multi-technique approach using AES for elemental distribution, XPS for surface chemistry, and SIMS for trace impurities offers comprehensive characterization of advanced nanomaterials [39].

Corrosion and Surface Modification Studies: AES excels in mapping elemental redistribution during corrosion processes and characterizing surface treatments on medical implants [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for AES Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| PHI 710 Scanning Auger Nanoprobe | High-resolution AES analysis with SEM imaging | Sub-8 nm spatial resolution, 25 kV max electron beam, UHV compatibility [36] |

| Field Emission Electron Source | Produces finely focused electron beam for high spatial resolution | Enables spot sizes >25 nm, critical for nanoscale mapping [38] [40] |

| Cylindrical Mirror Analyzer (CMA) | Detects and energy-analyzes Auger electrons | High collection efficiency and energy resolution [38] |

| Argon Ion Sputter Gun | Surface cleaning and depth profiling | Monoatomic Ar⁺ source for controlled material removal [36] [38] |

| Indium Mounting Substrates | Sample preparation for insulating materials | Conductive, malleable substrate minimizes charging [38] |

| Conductive Colloidal Graphite Paint | Sample mounting for difficult-to-analyze materials | Provides electrical connection without interfering with analysis [38] |

| Ultra-High Vacuum System | Maintains necessary vacuum for electron detection | Pressure <10⁻⁹ torr to prevent electron absorption and surface contamination [38] |

| Integrated EDS Detector | Complementary bulk elemental analysis | Provides simultaneous bulk composition data [38] |

| Focused Ion Beam (FIB) Attachment | Cross-sectional analysis and sample preparation | Enables subsurface feature access and in situ cross-sections [37] |

AES establishes itself as the premier technique for high-resolution surface mapping and nanoscale contaminant identification when spatial resolution at the sub-10 nm scale is required. Its exceptional capabilities in elemental mapping, combined with depth profiling functionality, make it invaluable for pharmaceutical development, materials science, and failure analysis. However, AES has limitations in chemical speciation and detection sensitivity compared to XPS and SIMS respectively.

The optimal surface analysis approach often involves complementary use of multiple techniques, leveraging the strengths of each method. For comprehensive material characterization, researchers should consider integrated workflows combining AES for nanoscale elemental distribution, XPS for chemical state information, and SIMS for ultimate detection sensitivity. This multi-technique strategy provides the most complete understanding of surface composition and contamination essential for advancing drug development and materials innovation.

ToF-SIMS for 3D Molecular Imaging and Drug Distribution in Complex Systems

In the field of material and life sciences, understanding the molecular composition and distribution within complex systems is paramount. Among the suite of surface analysis techniques available, Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) has emerged as a powerful tool for label-free molecular imaging, particularly for applications requiring high spatial resolution and detailed chemical information. While X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) are well-established for elemental and chemical state analysis, ToF-SIMS provides unparalleled capabilities in molecular identification and 3D distribution mapping. XPS is the most commonly used surface technique due to its simpler spectra and ease of quantification, but it does not directly detect hydrogen and helium and offers lower spatial resolution than ToF-SIMS or AES [2]. AES can provide superior chemical information for some systems, like carbon on metals, but both XPS and AES have limitations for molecular analysis compared to ToF-SIMS [2]. The unique strength of ToF-SIMS lies in its high sensitivity, ability to detect all elements including isotopes, and its capacity to provide 3D molecular characterization of organic and biological materials, making it indispensable for advanced research in drug development and complex system analysis.

Technique Comparison: ToF-SIMS vs. XPS vs. AES

The selection of an appropriate surface analysis technique depends heavily on the specific information required. The table below provides a comparative overview of the key characteristics of ToF-SIMS, XPS, and AES.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Surface Analysis Techniques

| Feature | ToF-SIMS | XPS | AES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Probe | Pulsed Primary Ions (e.g., Bin+, Aun+, C60+) [41] | X-rays [28] | Electrons [2] |

| Detected Signal | Secondary Ions (positive or negative) [41] | Photoelectrons [28] | Auger Electrons [2] |

| Chemical Information | Elemental, isotopic, and molecular fragment information [41] [2] | Elemental composition and chemical bonding/oxidation state [28] [2] | Primarily elemental, with some chemical state information [2] |

| Spatial Resolution | Tens to hundreds of nanometers [41] | ~1-10 μm (can be 150 nm at synchrotrons) [2] | Higher than XPS, can be focused to small areas [2] |

| Detection Limits | ppm to ppb range [41] | Typically ~0.1 - 1 at% | Varies, but generally high surface sensitivity |

| Strength in Pharma/Bio | 3D molecular imaging of APIs, lipids, and metabolites [41] [42] | Quantifying elemental surface composition and chemical states [28] | High-resolution elemental mapping and surface chemistry |

The Analytical Power of ToF-SIMS: Principles and Instrumentation

ToF-SIMS operates on the principle of bombarding a sample surface with a pulsed, high-energy primary ion beam. This interaction causes the emission of secondary ions (SIs) from the uppermost atomic layers of the sample. These SIs are then analyzed by a time-of-flight mass spectrometer, where their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) is determined by measuring their flight time [41] [43]. A key advantage of the ToF analyzer is its ability to acquire a full mass spectrum from a single ion pulse, maximizing ion utilization efficiency and enabling the static analysis of sensitive biological and organic samples [43].

The development of cluster ion sources (e.g., Aun+, Bi3+, C60+) has been a major advancement for biological and organic analysis using ToF-SIMS. Unlike earlier mono-atomic ion beams (e.g., Ga+), cluster ions distribute their kinetic energy over many atoms, resulting in lower energy per atom and significantly reduced damage to organic molecules. This leads to a higher yield of diagnostic molecular ions and larger fragments, enabling the analysis of more complex biological systems [41].

The fundamental output of a ToF-SIMS analysis is a mass spectrum that provides a detailed chemical fingerprint of the sample surface. By rastering the primary ion beam across the sample, a spectrum can be collected at each pixel, allowing for the reconstruction of 2D images showing the spatial distribution of any ion of interest. Furthermore, by combining this with a sputter ion beam that etches the sample, a series of 2D images can be acquired as a function of depth. This depth profiling capability allows for the creation of 3D chemical maps, revealing the internal molecular architecture of a sample with a best-case depth resolution of less than 1 nm [41].

Table 2: Common Primary Ion Sources in ToF-SIMS Bioimaging

| Primary Ions | Cluster Size | Energy | Imaging Resolution | Selected Application Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aun+ | 3–400 | ~10 keV | < 100 nm | Biological and polymer material imaging, molecular depth profiling [41] |

| Bin+ | 3, 5, 7... | Information Missing | Information Missing | High-resolution molecular imaging [41] |

| C60+ | 60 | Information Missing | Information Missing | Organic and molecular depth profiling [41] |

| (H2O)n+ | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Reduced damage for sensitive biological samples [41] |

Experimental Protocols for ToF-SIMS Analysis

Protocol 1: 3D Drug Distribution on Powder Carriers

This protocol details the methodology for determining the 3D distribution of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and a lubricant on inhalation carrier particles, as exemplified in a recent study [42].

- Objective: To determine the 3D distribution of budesonide (API) and magnesium stearate (Mg-stearate) on the surface of lactose carrier particles in a dry powder inhalation formulation.

- Sample Preparation: Adhesive mixture formulations of lactose carrier particles, budesonide, and Mg-stearate are prepared. Particles are mounted on a suitable substrate (e.g., double-sided adhesive tape) for ToF-SIMS analysis.