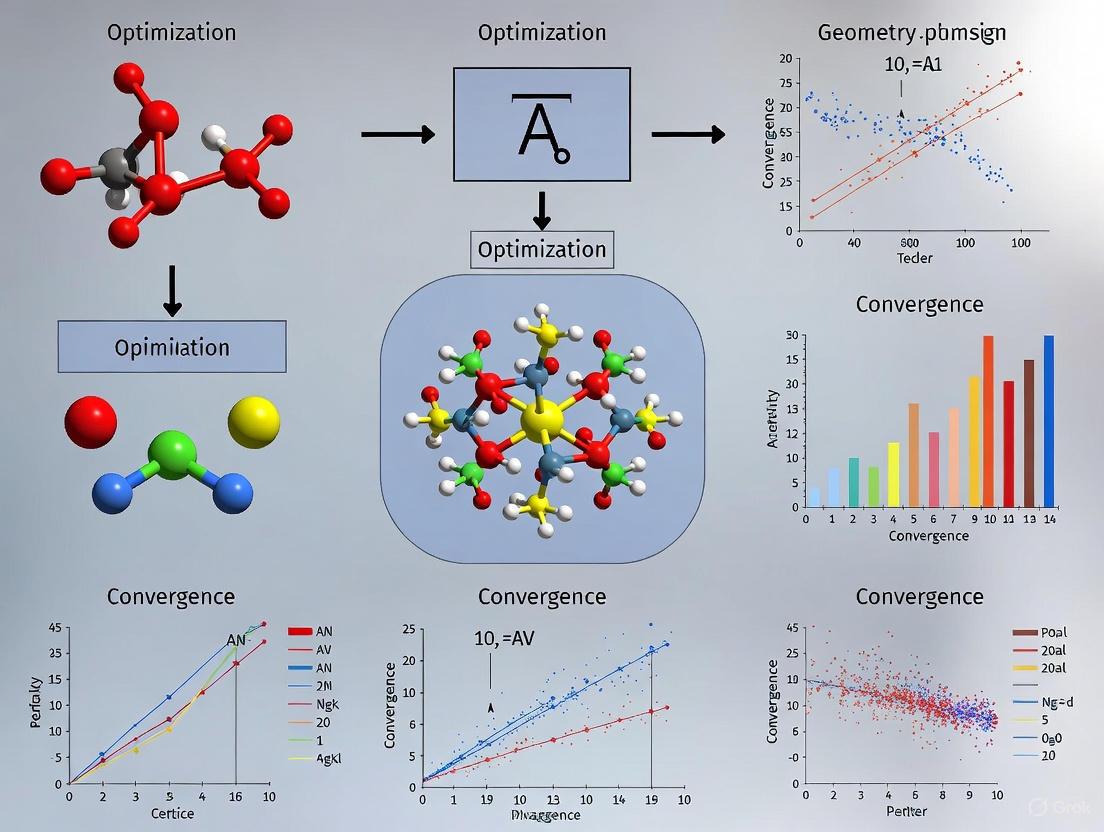

Why Geometry Optimization Fails for Surface Chemistry and How to Fix It

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists struggling with non-converging geometry optimizations in surface chemistry simulations.

Why Geometry Optimization Fails for Surface Chemistry and How to Fix It

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists struggling with non-converging geometry optimizations in surface chemistry simulations. It explores the fundamental reasons for convergence failure, from the complex potential energy surfaces of low-coordination atoms to challenges with k-point sampling and lattice stress. The content details robust methodological choices in computational software like AMS and ORCA, offers a systematic troubleshooting protocol, and outlines validation strategies to ensure result reliability. By integrating foundational theory, practical application, and problem-solving techniques, this guide aims to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of computational studies in drug development and materials science.

Understanding the Root Causes: Why Surface Chemistry Poses Unique Challenges for Geometry Optimization

The Complex Potential Energy Surface of Surface Atoms

# FAQs: Understanding Potential Energy Surfaces and Geometry Optimization

Q: What is a Potential Energy Surface (PES) and why is it important in surface chemistry?

A: A Potential Energy Surface (PES) represents the relationship between a molecule's geometry and its energy [1]. It maps out the energy landscape for chemical reactions and molecular dynamics, allowing researchers to visualize energy changes during processes like bond breaking and formation [1]. In surface chemistry and geometry optimization, the PES is crucial for finding stable molecular configurations (local minima) and understanding the pathways and barriers between them [2] [1].

Q: What does it mean when a geometry optimization "does not converge"?

A: Geometry optimization failure means the computational process of finding a local energy minimum on the PES was unsuccessful within the allowed number of steps [2]. This is typically diagnosed by checking convergence criteria, which often include:

- The maximum force on atoms remains above a set threshold

- The root mean square (RMS) of the forces remains too high

- The maximum displacement of atoms between steps is too large

- The RMS of the displacement is insufficiently small [2] [3]

For example, an error might show: "Maximum Force: 0.043390, Threshold: 0.000450 → NO", indicating convergence was not achieved [3].

Q: What are the common causes of geometry optimization failure for surface systems?

A: Failures often arise from these key issues:

- Insufficient convergence criteria: Loosely set thresholds can stop the optimization before a true minimum is found [2].

- Incomplete physical models: Missing critical physical interactions, such as dispersion corrections, can lead to inaccurate potential energy surfaces, especially for flexible structures or non-covalent interactions [3].

- Problematic initial structures: Starting geometries may be too far from a reasonable structure or lie in a flat region of the PES, causing slow or failed convergence [2].

- Electronic structure challenges: For large conjugated systems, self-interaction error can create an unrealistic PES. Using a functional with higher exact exchange (e.g., M06-2X, wB97XD) can sometimes help, though it may make the PES less smooth and convergence more difficult [3].

Q: What practical steps can I take to fix a non-converging optimization?

A: A systematic troubleshooting approach is recommended:

- Tighten Convergence Criteria: Gradually tighten the

GradientsandEnergythresholds. TheQualitysetting in AMS software can automate this [2]. - Apply Dispersion Corrections: Add an empirical dispersion correction (e.g.,

em=gd3bjin Gaussian) to better describe weak interactions [3]. - Verify the Initial Geometry: Use computational or experimental data to ensure your starting structure is chemically sensible.

- Characterize the Stationary Point: After optimization, use

PESPointCharacterto check if you found a minimum (all real frequencies) or a saddle point (imaginary frequencies). Some software can automatically restart from a saddle point [2]. - Consider Functional and Basis Set: For specific systems, switching to a more appropriate functional or larger basis set may be necessary.

# Troubleshooting Guide: Geometry Optimization Failure

Step 1: Analyze the Optimization Output

Check the optimization log file for the convergence criteria table. Identify which specific criteria have not been met (e.g., Maximum Force, RMS Force, Maximum Displacement) [2] [3].

Step 2: Adjust Convergence Settings

If the optimization is slowly progressing but fails to meet thresholds, systematically tighten the convergence criteria. The following table summarizes standard and tightened settings:

Table: Geometry Optimization Convergence Criteria (based on AMS documentation) [2]

| Convergence Criterion | Unit | 'Normal' Quality | 'Good' Quality | 'VeryGood' Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Change | Hartree | 1.0 × 10⁻⁵ | 1.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 1.0 × 10⁻⁷ |

| Maximum Gradients | Hartree/Ångstrom | 1.0 × 10⁻³ | 1.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 1.0 × 10⁻⁵ |

| Maximum Step | Ångstrom | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.0001 |

Step 3: Address Physical Model Deficiencies

- Add Dispersion Corrections: A common cause of failure, especially for systems with flexible rings or non-covalent interactions, is the lack of dispersion corrections in the density functional theory (DFT) functional [3]. Always use validated dispersion models (e.g., D3-BJ) for surface and supramolecular systems.

- Switch Functional: For systems prone to self-interaction error (e.g., large conjugated molecules), consider using a hybrid functional with higher exact exchange, but be aware this may slow convergence [3].

Step 4: Refine the Computational Approach

- Improve Initial Geometry: If the initial guess is poor, consider generating it from a molecular fragment database or a lower-level of theory calculation.

- Enable Automatic Restarts: If the optimization converges to a saddle point (transition state), software like AMS can automatically restart the optimization after displacing the geometry along the imaginary mode. This requires setting

MaxRestartsto a value >0 and enablingPESPointCharacter[2]. - Increase Maximum Iterations: For difficult cases, increasing the

MaxIterationslimit can allow the optimizer more time to find the minimum [2].

# The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Models

Table: Key Reagents and Models for Surface PES Exploration

| Reagent / Model | Function / Explanation | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Slab Model | A computational model using multiple atomic layers to approximate a solid surface, crucial for calculating surface properties [4]. | Modeling the Pt(111) surface to calculate surface energy; 5-8 layer slabs are typical [4]. |

| Dispersion Correction (e.g., DFT-D3) | An empirical addition to DFT functionals to better describe van der Waals (dispersion) forces, which are often poorly described in standard functionals [3]. | Essential for optimizing structures with flexible dihedrals, non-covalent interactions, or layered materials [3]. |

| Solvation Model (e.g., PCM) | A continuum model that approximates the effects of a solvent on the molecular system, creating a Potential of Mean Force [5] [3]. | Modeling surface chemistry or molecular properties in liquid-phase environments (e.g., SCRF=(PCM,solvent=CH₂Cl₂)) [3]. |

| Hydroxylamine (HDA)-based Chemistry | A reactive chemistry used in "Post Etch Residual Removal" in semiconductor fabrication; its cleaning ability is concentration and temperature-dependent [6]. | Back-end-of-line (BEOL) surface preparation for semiconductor devices [6]. |

| Total Ionic Strength Adjustor Buffer (TISAB) | A buffer solution used in potentiometry to maintain constant ionic strength and pH, and to mask interfering ions, ensuring accurate measurements [7]. | Used when calibrating Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) for surface ion concentration measurements [7]. |

# Advanced PES Analysis: Transition States and Reaction Pathways

Locating Transition States on the PES

The transition state is a first-order saddle point on the PES—the highest energy point along the minimum energy path connecting reactants and products [1]. It is characterized by:

- One imaginary vibrational frequency (negative force constant) corresponding to motion along the reaction coordinate.

- Partially formed or broken bonds, with a structure intermediate between reactants and products [1].

Hammond's Postulate provides a practical guide: for an exothermic reaction, the transition state resembles the reactants ("early" transition state), while for an endothermic reaction, it resembles the products ("late" transition state) [1].

Navigating the Multidimensional PES Landscape

The diagram above illustrates the key concepts of PES navigation. The Minimum Energy Path (MEP) is the lowest-energy route connecting reactants and products [1]. The Reaction Coordinate is a geometric parameter (or combination of parameters) that describes the progress of the reaction along this path [1]. The point of highest energy along the MEP is the Transition State [1]. In more complex reactions, features like valley-ridge inflection (VRI) points can lead to a "two-step, no-intermediate" mechanism, which can be revealed through multi-dimensional PES exploration [5].

Challenges of Low-Coordination Atoms and Defect Sites

In surface chemistry research, particularly in fields like catalysis and energy storage, the presence of low-coordination atoms and defect sites presents a significant double-edged sword. While these sites often enhance catalytic activity, they are also inherently less stable and can be hotspots for material degradation. This instability frequently manifests in computational studies as failing geometry optimizations, where the search for a stable energy minimum on the potential energy surface (PES) does not converge to a solution [8]. This technical guide addresses these convergence challenges, linking them directly to the physical and thermodynamic properties of defective surfaces to provide practical troubleshooting strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do my geometry optimizations of nanoparticle models consistently fail to converge? The convergence of a geometry optimization is highly sensitive to the initial system geometry and the quality of the Hessian (second derivative) matrix [9]. Nanoparticle models rich in low-coordination sites often reside in shallow, complex regions of the PES. A poor initial guess for the Hessian can lead the optimization algorithm to predict steps that do not successfully locate a minimum, causing oscillation or divergence instead of convergence [9] [10].

FAQ 2: My optimization converges, but a subsequent frequency calculation reveals imaginary frequencies. What does this mean? This indicates that the optimization has likely converged to a saddle point (like a transition state) rather than a local minimum [11] [10]. A true minimum should have no imaginary frequencies. Small imaginary frequencies can be hard to eliminate and may require re-optimization with stricter convergence criteria or an improved initial Hessian [11]. Some software packages can automatically restart the optimization from a saddle point by displacing the geometry along the imaginary mode [2].

FAQ 3: How do low-coordination sites directly cause instability during an optimization? Low-coordination sites, such as adatoms or step edges, have a higher surface free energy and are thermodynamically less stable [8]. During the iterative optimization process, atoms at these sites can experience large, unstable forces (gradients) as the algorithm seeks a minimum. Furthermore, these sites facilitate the formation of strong bonds with oxygen intermediates, which can promote surface reconstruction or dissolution, leading to drastic geometry changes that disrupt the optimization path [8].

FAQ 4: What is the functional link between defect sites and electrochemical durability? Research has established a direct functional link: a higher density of low-coordination/defect sites on a surface leads to significantly lower electrochemical durability [8]. These sites are preferential points for Pt dissolution and Ostwald ripening under harsh conditions, as they have lower dissolution potentials. Studies show that reducing these sites, for example through electrochemical annealing, can improve mass activity by nearly three times after durability testing [8].

Troubleshooting Guide: Optimization Failure and Defect Stability

The following table outlines common issues, their diagnostic signals, and recommended solutions.

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Diagnostic Signals | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial System Setup | Overly defective or unrealistic initial nanoparticle model. | Large, unstable forces in first steps; severe atom clashes. | Use a thermodynamically equilibrated structure as a starting point; consider experimental data or well-tested templates. |

| Optimization Algorithm & Coordinates | Poor choice of coordinate system. | Slow convergence; many small, ineffective steps. | Switch to delocalized internal coordinates, which are often optimal for complex molecules [9] [10]. |

| Inadequate convergence criteria. | Optimization halts with large residual forces or energies. | Tighten convergence thresholds (e.g., to "Good" or "VeryGood" quality) [2]. | |

| Hessian (Frequency) Matrix | Low-quality initial Hessian guess. | Erratic optimization steps; convergence to a saddle point. | Calculate an initial Hessian using a faster, lower-level method (e.g., semi-empirical or neural network potential) [11] [10]. |

| Defect-Specific Strategies | High mobility of low-coordination surface atoms. | Unphysical bond lengths/angles; large displacements of surface atoms. | Apply harmonic constraints to freeze positions of key bulk atoms while allowing surface atoms to relax. |

| Intentional study of defect stability. | Need to quantify the effect of defect density on stability. | Use the Mori-Tanaka method (MTM) or similar micromechanical models to relate defect morphology to elastic properties [12]. |

Advanced Protocol: Characterizing Defect Populations from Mechanical Properties

For researchers studying additively manufactured materials or porous solids, mechanical testing can be used to quantitatively characterize defect populations, bypassing the need for extensive imaging. This protocol is adapted from recent research [12].

1. Principle: The effective elastic properties of a material (Young's modulus, Poisson's ratio) are directly influenced by the volume fraction, shape, and orientation of defects (pores, microcracks). By inverting micromechanics models, one can infer defect characteristics from measured mechanical properties.

2. Methodology:

- Sample Preparation and Testing: Fabricate tensile specimens. Measure the elastic moduli (E11, E33) and Poisson's ratio (ν13) in different orientations, as anisotropic properties indicate aligned defects [12].

- Micromechanical Modeling - Mori-Tanaka Method (MTM): Model the material as a solid matrix containing populations of spheroidal voids. The stiffness of these inclusions is set to zero.

- For microcracks, model as a population of oblate voids (e.g., aspect ratio α = 10⁻²).

- For gas porosity, model as a population of more spherical voids (e.g., α = 0.5) [12].

- Input the experimentally measured elastic properties into the inverted MTM model.

- Defect Quantification: The model outputs the effective volume fraction and aspect ratio of the defect populations that are consistent with the measured mechanical data.

3. Validation: Compare the model's predictions against defect characteristics obtained from micro-computed tomography (μCT) and machine learning-based image analysis [12].

Workflow for mechanical defect characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Computational Solutions

| Category | Item / Technique | Primary Function / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Methods | Delocalized Internal Coordinates | Preferred coordinate system for most geometry optimizations, improving convergence rate [9]. |

| Eigenvector-Following (EF) Algorithm | Robust algorithm for locating both minima and transition states by walking uphill from minima [9]. | |

| GDIIS Algorithm | An alternative minimization algorithm, effective for accelerating convergence [9]. | |

| Mori-Tanaka Mean Field Theory (MTM) | An analytical homogenization method to predict effective material properties and quantify defects from elastic moduli [12]. | |

| Experimental & Characterization Techniques | CO Bulk Oxidation (Annealing) | An electrochemical method to eliminate low-coordination sites and surface irregularities on Pt nanoparticles, enhancing stability [8]. |

| Accelerated Durability Test (ADT) | A standardized cycling protocol to evaluate the electrochemical stability of electrocatalysts over time [8]. | |

| Micro-Computed Tomography (μCT) | A 3D imaging technique for visualizing and quantifying internal defect morphology (void space, cracks) [12]. | |

| X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (XAFS) | Used to confirm changes in coordination number and local structure after surface treatments [8]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Defect Engineering to Stability Validation

The following diagram and protocol outline an integrated approach for modifying and validating the stability of surfaces with controlled defect densities.

Integrated defect engineering and validation workflow.

Detailed Protocol: Electrochemical Annealing for Stable Pt Nanoparticles

This protocol is based on research that established a functional link between low-coordination sites and durability [8].

1. Surface Modification via CO Annealing:

- Setup: Use a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell (e.g., with a glassy carbon working electrode, Pt wire counter electrode, and a reference electrode). Prepare an ink of Pt/C catalyst deposited on the working electrode.

- Procedure: Saturate the electrolyte with CO gas. Perform potential cycling (e.g., between 0.05 V and 1.20 V vs. RHE) for a set number of cycles. This process, known as CO bulk oxidation, promotes surface reconstruction that selectively eliminates low-coordination sites and adatoms without significant particle agglomeration [8].

2. Ex-situ Characterization:

- X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (XAFS): Collect XAFS data to determine the average coordination number of Pt atoms. A successful treatment will show an increase in the average coordination number, confirming the reduction of low-coordination sites [8].

- Electrochemical Probe Reactions: Use adsorbed CO (COad) electro-oxidation as a probe. A positive shift in the COad oxidation peak potential indicates a smoother surface with fewer defective sites [8].

3. Computational Modeling & Stability Validation:

- Model Building: Construct computational models representing both the initial (defect-rich) and annealed (defect-reduced) surfaces.

- Geometry Optimization: Perform geometry optimizations using tight convergence criteria (e.g., energy change < 10⁻⁶ Ha, gradients < 10⁻⁴ Ha/Å) [2]. The model of the annealed surface should converge more readily and to a lower energy minimum.

- Durability Testing: Subject both the initial and annealed catalysts to an Accelerated Durability Test (ADT), which involves thousands of potential cycles in an acidic electrolyte. The annealed catalyst is expected to show significantly lower activity loss and less Pt dissolution, directly validating the enhanced stability from reduced defect density [8].

The Critical Role of k-Space Sampling in Periodic Systems

FAQs on k-Space Fundamentals

What is k-space and why is it critical in periodic calculations?

In computational studies of periodic systems, k-space (or reciprocal space) is the Fourier transform of real space and is fundamental for describing the periodicity of electronic wavefunctions. The Brillouin zone, the primitive unit cell in reciprocal space, must be sampled to solve the electronic structure equations for crystals [13]. The quality of this sampling directly impacts the accuracy of computed properties such as total energy, electron density, and forces. Inaccurate sampling can lead to failure in geometry optimization, as forces on atoms become unreliable, preventing convergence to the correct minimum [14] [13].

How does k-space sampling affect geometry optimization convergence in surface chemistry?

Geometry optimization requires highly accurate forces, which are sensitive to k-space sampling [13]. Insufficient k-point density can result in:

- Noisy Potential Energy Surfaces (PES): The energy landscape becomes jagged, causing the optimization algorithm to oscillate or fail to find a lower energy state.

- Incorrect Atomic Forces: Forces acting on atoms are miscalculated, leading to steps that increase, rather than decrease, the total energy.

- Wrong Adsorption Configurations: For surface chemistry, this can mean predicting a metastable adsorption site as the most stable one, as debated for NO on MgO(001) [15]. Consequently, the optimization process may not converge or may converge to an incorrect geometry.

My geometry optimization does not converge. Could k-space sampling be the issue?

Yes. If you have verified other parameters (basis set, energy cutoff, SCF procedure), k-space sampling is a primary suspect. This is particularly true for:

- Metallic systems: Which require very dense k-point sets to capture the sharp features at the Fermi level [14] [13].

- Small unit cells: Which have large Brillouin zones that require more k-points for adequate sampling [14].

- Systems with known fine electronic structure: Such as those involving topological states or electronic transport [13].

What are the best practices for choosing a k-point grid?

The optimal grid is system-dependent and should be determined through a convergence test [14].

- Start with a standard grid, such as a Monkhorst-Pack grid [13].

- Systematically increase the k-point density (e.g., from 2x2x2 to 4x4x4, 6x6x6, etc.).

- Monitor a key property (e.g., total energy per atom, forces, or lattice parameters) until the change with increasing k-points is below a desired threshold (e.g., 1 meV/atom) [13].

- Use the converged grid for all production calculations. Automated frameworks for high-throughput computing sometimes use very high densities, such as 5,000 k-points per Å⁻³, to ensure universal accuracy [13].

When can I use only the Gamma-point?

The Gamma-point (k=0) alone is often sufficient for large supercells or systems without long-range periodicity, such as amorphous materials or liquids [13]. As the supercell size increases, the Brillouin zone shrinks, and the Gamma-point becomes a better approximation of the full integral. However, this should be verified with a convergence test for your specific property of interest.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Geometry Optimization Fails to Converge

Issue Identification

The optimization cycle exceeds the maximum number of steps or oscillates without reducing the total energy and forces. This often manifests as a "ping-pong" effect where atoms move back and forth.

Diagnostic Steps

- Check Force Norms: Plot the maximum and root-mean-square (RMS) forces over the optimization cycle. A non-decaying pattern indicates a problem.

- Perform a Single-Point Energy Test: Calculate the energy and forces for the current geometry using a significantly denser k-point grid. If the results differ substantially from your standard calculation, k-space sampling is likely insufficient.

- Visualize Electronic Structure: Plot the band structure or density of states. If features appear "grainy" or change dramatically with small geometry changes, k-point sampling may be too coarse [13].

Resolution Procedures

- Immediate Action: Restart the optimization using a k-point grid one level higher (e.g., move from "Normal" to "Good" quality in DFTB/BAND, or from 4x4x4 to 6x6x6 in VASP/Quantum ESPRESSO) [14].

- Systematic Solution: Conduct a k-point convergence study on a fixed (e.g., experimentally known) geometry to determine the appropriate grid for your system before attempting a full optimization [14].

- Advanced Technique: For metals, consider using the Methfessel-Paxton or Gaussian smearing methods to slightly occupy states above the Fermi level. This improves SCF convergence and mimics the effect of a denser k-point grid at a lower cost, but requires careful selection of the smearing width [13].

Verification Method

After successful convergence, perform a final single-point energy calculation with an even denser k-point grid to confirm the stability of the optimized geometry's energy.

Problem: Inaccurate Adsorption Enthalpy (Hₐds) on Surfaces

Issue Identification

The computed adsorption energy differs significantly from experimental values (e.g., from temperature-programmed desorption) or is inconsistent with benchmark calculations from correlated wavefunction theory (e.g., CCSD(T)) [15].

Diagnostic Steps

- Benchmark Your Functional: Compare your DFT-predicted Hₐds for a well-studied system (e.g., CO on MgO) against high-quality theoretical or experimental benchmarks [15].

- Check for Spurious Configurations: Inaccurate k-sampling can stabilize a wrong adsorption configuration. Explore multiple adsorption sites to ensure the identified global minimum is not an artifact of poor sampling, as was the case for several proposed NO configurations on MgO(001) [15].

- Analyze k-point Density for Surfaces: Surface calculations often use a slab model. Ensure the k-point grid is equally dense in the surface plane directions. A 1x1x1 grid is almost always inadequate.

Resolution Procedures

- Convergence Test for the Slab: Perform a k-point convergence test for the total energy of the clean, relaxed slab model.

- Use of Primitive Cells: For k-point convergence studies, use the primitive cell of the surface, which requires fewer k-points for the same sampling density, reducing computational cost [14].

- Leverage Automated Frameworks: For ionic materials, use automated frameworks like

autoSKZCAMto obtain CCSD(T)-quality benchmarks for assessing the accuracy of your DFT protocol [15].

K-Point Sampling Guidelines for Different System Types

Table 1: Recommended starting points for k-space sampling. Always perform a convergence test for definitive results.

| System Type | Recommended K-Space Setting | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Metals | Very dense grids (e.g., Excellent quality, 8x8x8 or finer) [14] [13] |

Required to capture the Fermi surface. Use of smearing techniques is highly recommended. |

| Insulators & Semiconductors | Moderate grids (e.g., Good quality, 4x4x4 to 6x6x6) [14] |

Fewer k-points are needed due to the band gap. |

| Large Supercells / Molecules | Gamma-point or minimal grid (e.g., 2x2x2, 1x1x1) [13] | The large real-space cell leads to a small Brillouin zone. |

| Surfaces (Slab Models) | Dense sampling in surface plane (e.g., 6x6x1), often 1 point in z-direction [14] | The limited periodicity in the z-direction (vacuum) requires only one k-point along that axis. |

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential "reagents" for reliable k-space sampling and surface chemistry studies.

| Item / Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Monkhorst-Pack Grids | A systematic method for generating k-point sets in the Brillouin zone [13]. | The standard for most periodic DFT calculations in VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO. |

| AutoSKZCAM Framework | An automated, open-source tool to obtain CCSD(T)-level accuracy for adsorption energies on ionic surfaces [15]. | Benchmarking DFT functionals and obtaining reliable Hₐds for surface chemistry. |

| Symmetric K-Space Grid | A k-point grid that respects the point-group symmetry of the crystal, improving efficiency [14]. | Used in codes like DFTB and BAND to reduce the number of irreducible k-points. |

| Tetrahedron Method | An integration technique for the Brillouin zone that is often more accurate than smearing for DOS calculations [13]. | Calculating accurate densities of states, especially for semiconductors and insulators. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: K-Point Convergence Study for Lattice Optimization

Purpose: To determine the k-point sampling density required for a converged lattice parameter optimization.

Materials/Methods:

- Software: A periodic DFT code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, BAND, DFTB).

- System: The primitive unit cell of the material of interest.

- Task: Single-point energy or single-parameter lattice optimization.

Procedure:

- Initial Setup: Import the crystal structure of the primitive unit cell [14].

- Define K-Point Series: Select a series of k-point grids of increasing density (e.g., 2x2x2, 3x3x3, 4x4x4, 6x6x6). For hexagonal systems, ensure grids respect symmetry (e.g., 6x6x4).

- Run Calculations: For each k-point grid, run a single-point energy calculation on the fixed experimental geometry, or a simple lattice parameter optimization.

- Data Collection: Record the total energy per atom and the optimized lattice parameters for each calculation.

- Analysis: Plot the total energy per atom and lattice parameters against the k-point grid density. The value is considered converged when the change is below your target threshold (e.g., energy change < 1 meV/atom) [13].

Visual Workflow:

Protocol: Benchmarking Adsorption Enthalpy with an Automated Framework

Purpose: To obtain a highly accurate adsorption enthalpy (Hₐds) for assessing the performance of DFT functionals.

Materials/Methods:

- Software: The

autoSKZCAMframework or similar tools [15]. - System: A relaxed slab model with the adsorbate in the putative most stable configuration.

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: Create a slab model from the conventional cell of the surface using Miller indices. Ensure the slab is thick enough to mimic bulk-like properties in the central layers [14].

- Configuration Screening: Use DFT to pre-screen multiple adsorption sites and configurations to identify low-energy candidates.

- Framework Input: Prepare input files for the

autoSKZCAMframework, specifying the adsorbate-surface system and the candidate configurations. - Execution: Run the automated framework. It will leverage multilevel embedding and correlated wavefunction theory (like CCSD(T)) to compute accurate Hₐads values [15].

- Validation: Compare the framework's predicted Hₐds and most stable configuration against your DFT results and experimental data. Use this to validate or correct your DFT protocol.

Visual Workflow:

Lattice Stress and the Need for Simultaneous Atom and Lattice Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does my Self-Consistent Field (SCF) calculation fail to converge during a geometry optimization? SCF convergence failures are common in systems with metallic character or when using insufficient numerical precision. This can be addressed by using more conservative mixing schemes, increasing the electronic temperature initially, or employing more robust algorithms like the MultiSecant method [16].

2. My geometry optimization is oscillating and will not converge. What should I check?

First, ensure your SCF calculations are converging. If they are, the problem may be inaccurate gradients due to insufficient numerical quality. Try improving the numerical integration settings (e.g., increasing radial points) and set NumericalQuality to Good [16].

3. How can I accelerate my geometry optimization calculations? Machine learning (ML) methods can significantly reduce the number of required DFT calculations. Neural Network (NN) ensemble active learning methods can accelerate local geometry optimization, while global optimization protocols use surrogate ML potentials to explore complex potential energy surfaces efficiently [17] [18].

4. What specific settings can help with lattice optimization for GGAs?

Lattice optimization with GGAs can be stabilized by using analytical stress instead of numerical stress. This requires three key changes: setting a fixed SoftConfinement Radius, enabling StrainDerivatives Analytical=yes, and using a GGA functional from the libxc library [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: SCF Does Not Converge

The SCF procedure is the foundation of geometry optimization. Failure to converge halts the entire process.

Methodology & Protocols:

- Conservative SCF Settings: Begin with more robust, albeit slower, SCF mixing.

- Code Example:

- Finite Electronic Temperature: Smearing the electron occupation can help initial convergence.

- Protocol: Use a higher electronic temperature (

Convergence%ElectronicTemperatureorkT) at the start of the optimization when forces are large, and automatically reduce it as the geometry converges [16].

- Protocol: Use a higher electronic temperature (

- Alternative Algorithms: Switch from the default DIIS algorithm to the MultiSecant method, which is similarly efficient, or to the LIST method, which may reduce the number of SCF cycles at a higher cost per iteration [16].

- Improve Numerical Accuracy: Convergence problems can stem from poor numerical precision.

- Protocol: Increase the

NumericalAccuracysetting and ensure the quality of the density fit and Becke grid is sufficient, especially for systems with heavy elements [16].

- Protocol: Increase the

Issue 2: Geometry or Lattice Optimization Does Not Converge

This issue occurs when the atomic forces or lattice stresses are not minimized to the desired tolerance.

Methodology & Protocols:

- Ensure SCF Convergence: A geometry optimization cannot converge if the underlying SCF does not. Resolve SCF issues first [16].

- Increase Gradient Accuracy: Inaccurate force calculations prevent convergence.

- Protocol: Use a higher

NumericalQuality(e.g.,Good) and increase the number of radial points in the integration grid [16]. - Code Example:

- Protocol: Use a higher

- Automate Key Parameters: Use engine automations to relax convergence criteria in the early optimization stages.

- Protocol: Implement an iterative automation that tightens the

Convergence%CriterionandSCF%Iterationslimit as the geometry optimization progresses. This prevents early failure and saves computational resources [16].

- Protocol: Implement an iterative automation that tightens the

- Analytical Stress for Lattice Optimization: For GGA functionals, use analytical stress derivatives.

- Protocol: Implement the following settings to enable efficient and stable lattice optimization [16]:

SoftConfinement Radius=10.0StrainDerivatives Analytical=yes- Use a GGA functional via

XC libxc [Functional Name]

- Protocol: Implement the following settings to enable efficient and stable lattice optimization [16]:

| Table 1: SCF Convergence Acceleration Protocol | Step | Parameter | Action / Value | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SCF%Mixing |

Decrease to 0.05 | Uses more conservative electron density mixing for stability [16]. | |

| 2 | Diis%DiMix |

Set to 0.1 | Applies a conservative strategy for the DIIS procedure [16]. | |

| 3 | SCF%Method |

Switch to MultiSecant |

Employs an alternative algorithm that can converge difficult systems without extra cost per cycle [16]. | |

| 4 | Convergence%ElectronicTemperature (kT) |

Start at 0.01 Ha, final 0.001 Ha | Finite temperature smearing helps initial convergence; automated reduction ensures final result is near the ground state [16]. |

| Table 2: Key Parameters for Lattice Optimization with GGA | Parameter | Required Setting | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

SoftConfinement |

Radius=10.0 |

Uses a fixed confinement radius compatible with the analytical stress code [16]. | |

StrainDerivatives |

Analytical=yes |

Triggers the use of analytical first derivatives for strain, which is more efficient and accurate than numerical stress [16]. | |

XC |

libxc PBE (or other GGA) |

Utilizes a library that provides the necessary derivatives for calculating analytical stress [16]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated machine-learning accelerated workflow for global geometry optimization, which addresses both atom position and lattice stress.

ML-Driven Global Optimization Workflow [17]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Geometry Optimization | Tool / Solution | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | The foundational quantum mechanical method for calculating electronic structure, energies, and forces. | All electronic structure calculations; essential for evaluating energy in geometry optimization [17] [19]. | |

| Gaussian Approximation Potentials (GAP) | A machine-learning potential trained on-the-fly to act as a surrogate for expensive DFT calculations. | Enables efficient global exploration of complex potential energy surfaces for adsorbates and lattices [17]. | |

| Minima Hopping (MH) Algorithm | A global optimization algorithm that escapes local minima to find the global minimum structure. | Used in conjunction with ML potentials to perform an unbiased search for optimal adsorbate/surface geometries [17]. | |

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) | A Python package for setting up, controlling, and analyzing atomistic simulations. | Provides optimizers and utilities to interface with different DFT codes and ML protocols [18]. | |

| Neural Network (NN) Ensemble | An active learning method using multiple NNs to predict energies and forces and estimate uncertainty. | Accelerates local geometry optimization by reducing the number of required DFT calculations [18]. |

Building a Robust Workflow: Method Selection and Setup for Stable Surface Convergence

In the specialized field of surface chemistry research, achieving a converged geometry optimization is a critical yet often challenging step. The choice of computational method—traditional density functional theory (DFT) or modern neural network potentials (NNPs)—can significantly impact the success of these calculations. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate common pitfalls and select the appropriate functional for their investigations of surfaces, interfaces, and adsorption phenomena.

Troubleshooting Guide: Geometry Optimization Does Not Converge

Q1: My geometry optimization for a surface slab is oscillating and will not converge. What are the primary settings I should adjust?

A: Non-convergence often stems from an inaccurate initial guess or issues with the electronic structure calculation. Follow this systematic protocol [16] [20] [21]:

- Verify the Initial Geometry and Hessian: A poor initial guess for the Hessian (second derivative matrix) is a common cause. For systems far from equilibrium, using a conservative

HESS=UNITkeyword can help. For more accurate results, generate a high-quality Hessian by first running a frequency calculation (IR calculation) at your target theory level before restarting the geometry optimization [20]. - Improve SCF Convergence: Oscillations can originate from the self-consistent field (SCF) cycle. Use more conservative settings by decreasing the mixing parameter (e.g.,

SCF%Mixing 0.05). Alternatively, switch to the MultiSecant method (SCF Method MultiSecant). For systems with a small HOMO-LUMO gap, using a finite electronic temperature can stabilize the initial steps [16]. - Increase Computational Accuracy: The default accuracy settings may be insufficient for complex surfaces. Increase the

NumericalQualitytoGood, tighten the SCF convergence criterion (e.g., to1e-8), and consider using theExactDensitykeyword for a more precise exchange-correlation potential calculation [21].

Q2: My calculation involves a transition state search on a catalyst surface. The optimization is unstable. What is the recommended strategy?

A: Transition state searches are inherently more sensitive. The strategy of a good starting geometry and a high-quality Hessian is paramount [20].

- Starting Geometry: Use a transition state builder or an energy profile calculation to obtain a structure as close as possible to the suspected transition state. The starting geometry must be near the saddle point on the potential energy surface [20].

- Hessian Quality: The default semi-empirical Hessian may be inadequate. The best practice is to perform a frequency calculation at the beginning of the transition state search to compute an initial Hessian at the correct theory level. After the calculation, validate that the imaginary frequency corresponds to the desired reaction coordinate [20].

Q3: I am using a neural network potential (NNP) for a large-scale simulation of a surface reaction. How can I ensure the reliability of the NNP for my specific system?

A: The reliability of an NNP depends on the quality and coverage of its training data. Before applying a general-purpose NNP, you must validate its performance [22] [23].

- Employ Transfer Learning: For systems not well-represented in the pre-trained model, use a transfer learning strategy. Incorporate a small amount of new, system-specific DFT data to retrain and refine the pre-trained NNP (e.g., the DP-GEN framework). This enhances accuracy for your target system without requiring massive datasets [22].

- Check Error Metrics: Systematically compare the NNP's predictions for energies and forces against DFT reference calculations for a set of validation structures. Ensure that the mean absolute error (MAE) for energy is within ± 0.1 eV/atom and for forces is within ± 2 eV/Å to confirm chemical accuracy [22].

Quantitative Comparison: Traditional vs. Neural Network Approaches

The table below summarizes key performance indicators to guide your choice of functional.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional DFT and Neural Network Potentials for Surface Chemistry

| Feature | Traditional DFT | Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | High (often prohibitive for >1,000 atoms or >ns scales) | Low (can be 1,000+ times faster than DFT for dynamics) [22] |

| Accuracy | Well-established, but can be limited for specific interactions (e.g., dispersion) [23] | Can achieve DFT-level accuracy for energies and forces if trained properly [22] |

| Scalability to Large Systems | Poor (cubic scaling with electron count) | Excellent (linear scaling enables millions of atoms) [22] |

| Data Requirements | None (first-principles) | High (requires extensive DFT datasets for training) [22] [23] |

| Best Use Cases | • Single-point calculations on small models• Precise electronic property analysis• Systems with no relevant training data | • Large-scale molecular dynamics (MD)• Long-time-scale reactive processes• High-throughput screening across chemical space [22] [23] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Robust Workflow for Surface Structure Optimization

This methodology outlines a stepwise approach to overcome convergence issues in surface calculations [20] [21].

- Start Simple: Begin with a geometry optimization at a lower level of theory (e.g., semi-empirical or Hartree-Fock with a small basis set like 3-21G*) to generate a reasonable starting structure.

- Validate Electronic State: Perform a single-point calculation at your target level of theory (e.g., DFT/GGA) on the pre-optimized structure. Check that it is a true ground state by verifying the spin-polarization and ensuring no lower-energy high-spin states exist [21].

- Progress to Higher Theory: Use the optimized geometry from the lower-level calculation as the starting point for a new geometry optimization at the higher, target theory level.

- Final Validation: Run a frequency calculation on the final optimized structure to confirm it is a minimum (no imaginary frequencies) or a transition state (one imaginary frequency).

Protocol 2: Development and Application of a Neural Network Potential

This protocol describes the process for creating and deploying a specialized NNP, such as the EMFF-2025 model for high-energy materials [22].

- Database Construction: Build a diverse training database of atomic structures relevant to your chemical space (e.g., C, H, N, O systems for energetic materials). Generate reference energies and forces for these structures using DFT calculations.

- Model Training: Train the NNP (e.g., using a Deep Potential framework) on the DFT database. The model learns to map atomic configurations to their corresponding energies and forces.

- Model Validation: Benchmark the trained NNP against a held-out set of DFT data. Key metrics include the mean absolute error (MAE) of energy (target: ~0.1 eV/atom) and forces (target: ~2 eV/Å) [22].

- Application in Simulation: Deploy the validated NNP in molecular dynamics (MD) or structure optimization simulations to predict properties like crystal structures, mechanical behavior, and thermal decomposition pathways at a fraction of the cost of direct DFT.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and applying the appropriate functional in a surface chemistry research project.

Diagram 1: Functional Selection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential computational tools and their functions for modern surface chemistry simulations.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Surface Science

| Tool Name / Keyword | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| SCF%Mixing / DIIS%Dimix | Keywords to adjust the self-consistent field (SCF) convergence behavior by controlling how electron density from previous cycles is mixed. Decreasing values leads to more stable, conservative mixing [16]. |

| NumericalQuality Good | An input keyword that increases the precision of numerical integration grids and other accuracy-related parameters, leading to more reliable forces and energies during geometry optimization [21]. |

| HESS=UNIT | A keyword that instructs the code to use a unit matrix as the initial Hessian. This is a conservative and stable, though sometimes slower, starting point for geometry optimization [20]. |

| Deep Potential (DP) | A machine learning framework for developing neural network potentials. It enables large-scale molecular dynamics simulations with near-DFT accuracy but much lower cost [22]. |

| GOFEE / BEACON | ML-based global optimization algorithms (Global Optimization with First-Principles Energy Expressions / Bayesian Exploration of Atomic Configurations). They use surrogate models to efficiently find minimum energy structures of surfaces and adsorbates [23]. |

| Transfer Learning | A machine learning technique where a pre-trained model (e.g., a general NNP) is fine-tuned on a small, system-specific dataset. This drastically reduces the amount of new DFT data needed for accurate simulations [22]. |

FAQs on Cell Selection and Geometry Optimization

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a primitive and a conventional unit cell?

A primitive cell is the smallest possible unit cell of a crystalline material, containing exactly one lattice point. It is the most minimal repeating unit [24]. In contrast, a conventional cell is chosen primarily to make the symmetry of the crystal structure obvious. It is not necessarily the smallest possible unit and may contain more than one lattice point [24] [25].

Q2: For geometry optimization, which cell type is generally recommended and why?

The primitive cell is usually recommended for geometry optimization calculations [26]. Because it contains the fewest atoms, it is computationally more efficient, making calculations faster [25]. This is particularly crucial for complex systems like Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), where reducing the atom count from a conventional cell can make calculations feasible on standard hardware [25].

Q3: My geometry optimization is not converging. What are some key convergence criteria I should check?

Geometry optimization convergence is based on several criteria being met simultaneously. The table below outlines the primary criteria monitored during an optimization, based on common computational software documentation [2].

| Criterion | Description | Common Threshold (Normal Quality) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Change | The difference in total energy between successive optimization steps. | < 10⁻⁵ Ha per atom [2] |

| Maximum Gradients | The largest force on any atom. Indicates how far the system is from a stationary point. | < 10⁻³ Ha/Å [2] |

| RMS Gradients | The root mean square of the forces on all atoms. | < (2/3) * 10⁻³ Ha/Å [2] |

| Maximum Step | The largest movement of any atom between steps. | < 0.01 Å [2] |

| RMS Step | The root mean square of the movements of all atoms. | < (2/3) * 0.01 Å [2] |

Q4: Why might my optimized structure lose its original space group symmetry?

This can occur if the initial geometry was not the true minimum or if the optimization algorithm introduces small displacements that break symmetry. To preserve symmetry during optimization, ensure that your calculation is configured to constrain the Bravais lattice type [26]. Additionally, using a conventional cell can sometimes make it easier to maintain and observe the full symmetry of the crystal structure throughout the optimization process [24].

Q5: When is it better to use a conventional cell for property calculation?

While the primitive cell is preferred for optimization, the choice for calculating properties like band structure depends on the specific analysis. The conventional cell might be necessary if you need to analyze properties in relation to the full, easy-to-interpret symmetry of the crystal [26]. Note that the electronic band structure will appear different in a conventional cell compared to a primitive cell due to different Brillouin zone folding [26].

Experimental Protocols for Cell Selection and Conversion

Protocol 1: Selecting a Unit Cell for Efficient Optimization

- Objective: Identify the computationally most efficient cell for geometry optimization.

- Methodology:

- Start by obtaining the crystal structure.

- If the conventional cell is large (e.g., over 100 atoms), convert it to its primitive counterpart [25].

- Perform the geometry optimization on the primitive cell using standard convergence criteria (e.g., "Normal" quality) [2].

- This approach reduces computational cost significantly, allowing for faster convergence and freeing resources for more accurate electronic structure calculations [26] [25].

Protocol 2: Converting a Conventional Cell to a Primitive Cell

This protocol outlines a general method using visualization software like VESTA, which can be adapted for various computational codes [25].

- Preparation: Start with a structure file (e.g., a POSCAR file for VASP) where atomic positions are specified in Cartesian coordinates [25].

- Visualization: Open the conventional cell file in VESTA.

- Lattice Vector Determination:

- Choose a reference atom in the conventional cell.

- Using the distance tool in VESTA, identify the vectors from this reference atom to its nearest equivalent atoms in the lattice. These vectors define your new primitive lattice vectors [25].

- VESTA provides "fractional coordinates" for these vectors. Convert these fractional vectors into Cartesian coordinates by multiplying them with the original conventional lattice vectors [25].

- File Modification: In your structure file, replace the old conventional lattice vectors with the new primitive lattice vectors.

- Atom Selection:

- In the original conventional cell in VESTA, identify one copy of each unique atom that will constitute the primitive cell.

- In the structure file, remove all other redundant atoms.

- Update the atom count in the structure file header to reflect the new number of atoms in the primitive cell [25].

- Validation: Open the final modified structure file in VESTA to verify that the new cell is correct and contains no overlapping atoms [25].

Decision Workflow for Unit Cell Selection

The following diagram illustrates the logical process for choosing between a primitive and conventional unit cell for your calculation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

In computational surface chemistry research, "reagents" refer to the essential software, algorithms, and numerical settings that enable successful simulations.

| Tool/Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| Crystal Visualization Software (e.g., VESTA) | Used to visualize crystal structures, identify symmetry, and manually convert between conventional and primitive unit cells [25]. |

| Geometry Optimizer (e.g., Quasi-Newton, L-BFGS) | The core algorithm that iteratively adjusts atomic coordinates and lattice vectors to find a local energy minimum on the potential energy surface [2]. |

| Convergence Criteria Profile (e.g., 'Normal', 'Good') | A set of pre-defined thresholds for energy, force, and step size that determine when an optimization is considered complete. Using a profile like "Good" tightens these thresholds for a more accurate result [2]. |

| PES Point Characterization | A calculation of the lowest Hessian eigenvalues to check if the optimized structure is a true minimum or a saddle point. Essential for diagnosing faulty optimizations [2]. |

| High-Quality Numerical Basis Set | A set of functions used to represent electron orbitals. Higher quality (larger) basis sets provide greater numerical accuracy, which is necessary when using tight convergence criteria [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My geometry optimization does not converge. What are the primary checks I should perform?

The first step is to verify the accuracy of your calculated gradients. Inaccurate gradients prevent the optimizer from finding a correct descent direction. Ensure the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure is fully converged at each point, as an unconverged SCF leads to noisy gradients [16]. You can improve numerical accuracy by increasing the integration grid size or using a higher NumericalQuality setting [2] [16]. Finally, review your convergence criteria; for quick preliminary optimizations, you can use Quality Basic, but for final results, Quality Good or VeryGood is recommended [2].

Q2: What does it mean if my optimization converges to a saddle point instead of a minimum?

A saddle point, or transition state, is characterized by having exactly one imaginary frequency in the calculated Hessian (vibrational frequencies). This can happen if the initial structure was too close to this higher-order stationary point. You can configure your optimizer to perform automatic restarts upon detecting a saddle point. Using the PESPointCharacter property and setting MaxRestarts to a value greater than 0 will displace the geometry along the imaginary mode and restart the optimization [2]. Note that this typically requires symmetry to be disabled (UseSymmetry False).

Q3: The L-BFGS optimizer is slow for my large molecular system. Are there more efficient variants? Yes, a parallel-preconditioned L-BFGS (PP-LBFGS) algorithm has been developed to address this. The standard L-BFGS algorithm is serial, but PP-LBFGS performs multiple gradient calculations in parallel in each step to improve the Hessian estimate. This algorithm uses molecular connectivity to selectively update the most important Hessian elements, leading to a 2x–4x speedup in terms of optimization cycles and real time compared to the plain L-BFGS method [27].

Q3: Can I use tighter convergence criteria for the final steps of an optimization only?

Yes, this is possible and often efficient through engine automations. You can define rules that tighten the convergence criteria as the optimization progresses. For example, you can specify that the Convergence%Criterion (for the SCF) starts at a loose value (e.g., 1.0e-3) and tightens to a strict value (e.g., 1.0e-6) over a specified number of geometry iterations. Similarly, the electronic temperature can be automated to help with initial SCF convergence [16].

Q4: My lattice vector optimization for a periodic GGA system fails to converge. What can I do? For lattice optimizations, using analytical stress tensors is more efficient and accurate than numerical ones. To enable this, you must ensure three settings are correct [16]:

- Set

SoftConfinementto a fixed radius (e.g.,Radius=10.0). - Set

StrainDerivatives Analytical=yes. - Use a GGA functional (e.g., PBE) via the

libxclibrary.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Geometry Optimization is Stagnating or Diverging

A geometry optimization fails when the total energy and molecular structure do not settle into a stable minimum after many cycles. This guide outlines a systematic approach to diagnose and fix the issue.

Diagnosis Workflow: The following diagram outlines the logical steps for diagnosing convergence failure, from basic checks to advanced techniques.

Detailed Protocols & Solutions:

Protocol 1: Ensuring SCF Convergence

- Objective: Achieve a stable electronic ground state at each geometry step.

- Procedure:

- Decrease the SCF mixing parameter (e.g.,

SCF%Mixing 0.05). - For DIIS, reduce

DIIS%Dimix(e.g., to0.1) and setAdaptable false[16]. - As an automation, use a finite electronic temperature (e.g.,

Convergence%ElectronicTemperature 0.01) at the start of the optimization and reduce it as gradients become smaller [16]. - Alternatively, try switching the SCF method to

MultiSecant[16].

- Decrease the SCF mixing parameter (e.g.,

Protocol 2: Improving Gradient Accuracy for Numeric Methods

- Objective: Obtain precise nuclear gradients when analytic gradients are unavailable or noisy.

- Procedure:

- If using numerical gradients, be aware that the cost is 6 × (number of atoms) × (single point cost) [10].

- Increase the quality of numerical integration grids. Use the

RadialDefaultskey to increase the number of radial points (e.g.,NR 10000) [16]. - Set

NumericalQualitytoGoodorVeryGoodto improve the overall precision of the calculation [2] [16].

Protocol 3: Selecting Convergence Criteria

- Objective: Define a physically meaningful endpoint for the optimization without wasteful over-calculation.

- Procedure: The

Convergence%Qualitykeyword offers a quick way to set thresholds. The table below details the standard values [2].

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha/atom) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10⁻³ | 10⁻¹ | 1 |

| Basic | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻² | 0.1 |

| Normal | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻³ | 0.01 |

| Good | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ | 0.001 |

| VeryGood | 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻⁵ | 0.0001 |

- Protocol 4: Generating a Good Initial Hessian

- Objective: Provide the optimizer with a realistic estimate of the potential energy surface curvature to accelerate convergence.

- Procedure:

- For minimizations, the

Almloefmodel Hessian is the default and recommended [10]. - For transition metal complexes where semi-empirical methods like AM1 fail, compute an initial Hessian at a lower level of theory (e.g., ZINDO/1 or a quick RI-DFT calculation like

BP def2-sv(p)) [10]. - In a compound calculation, run a frequency job at the lower level first, then read the resulting Hessian (

InHess Read) for the higher-level optimization [10].

- For minimizations, the

Problem: Optimization Converges to a Saddle Point

Solution: Implement an automatic restart protocol.

- Enable Characterization: In the

Propertiesblock, setPESPointCharacter Trueto compute the lowest Hessian eigenvalues at the end of the optimization [2]. - Enable Restarts: In the

GeometryOptimizationblock, setMaxRestartsto a number greater than 0 (e.g.,5) [2]. - Disable Symmetry: Add

UseSymmetry Falseto the input, as the symmetry-breaking displacements required for restarts are otherwise not allowed [2]. - Configure Displacement: The

RestartDisplacementkeyword (default 0.05 Å) controls the size of the displacement along the imaginary mode [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key computational "reagents" – essential parameters and algorithms that are crucial for successful geometry optimization experiments.

| Item/Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence Criteria | Defines the stopping point for the optimization based on energy, gradients, and step size [2]. | Loose criteria (Basic) speed up calculations but may yield imprecise geometries. Tight criteria (VeryGood) are necessary for accurate vibrational frequency calculations [2]. |

| Initial Hessian | Provides an initial guess for the second derivatives of the energy, critical for the optimizer's first steps [10]. | A poor guess (e.g., unit matrix) leads to slow convergence. Model Hessians (Almloef) or those from lower-level calculations significantly improve performance [10]. |

| Coordinate System | The internal coordinate system used to represent molecular movements during optimization [10]. | Redundant internal coordinates are typically most efficient. If they fail, switching to Cartesian coordinates (COPT) can be more stable, though possibly slower [10]. |

| PP-LBFGS Optimizer | A parallel variant of the L-BFGS algorithm that accelerates convergence for large systems [27]. | Most efficient when using the one-color variant, which requires only 4 parallel gradient calculations per step for a 2x-4x speedup [27]. |

| NumericalQuality | Controls the accuracy of numerical integrations, affecting the precision of energies and gradients [2] [16]. | Essential to set to Good or VeryGood when performing geometry optimizations with tight convergence criteria to ensure gradients are noise-free [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What does it mean when a geometry optimization does not converge? Non-convergence means the computational algorithm could not find a geometry that satisfies all the specified convergence criteria within the allowed number of steps. This indicates that the calculation was stopped before a stationary point (like a minimum or transition state) on the potential energy surface was confidently located [20].

2. My optimization is converging very slowly. What can I do? Slow convergence is a common issue. You can try the following strategies:

- Increase the maximum number of optimization cycles. This gives the algorithm more time to find the minimum [20].

- Improve the initial geometry guess. A starting geometry that is far from the minimum can slow down convergence. Consider pre-optimizing at a lower level of theory [20].

- Check the initial Hessian (force constant matrix). A poor-quality initial Hessian can impede progress. Using a more accurate Hessian, perhaps calculated at a lower theory level, can significantly speed up convergence [20].

3. My optimization converges for energy but not for gradients or displacements. What is the issue? This situation often points to a very flat potential energy surface. While the energy change between steps becomes negligible, the atoms may still be experiencing significant forces or need to move a considerable distance. You can:

- Loosen the convergence criteria for forces and displacements [20].

- Use internal coordinates instead of Cartesian coordinates, as they can better describe molecular motions during optimization [20].

4. For lattice optimization, what are the specific convergence criteria?

In addition to atomic forces and displacements, lattice optimization also involves converging the stress tensor. One common criterion is the maximum stress energy per atom, which is the maximum value of the matrix (stress_tensor * cell_volume) / number_of_atoms [14]. The optimization is considered converged when this value, along with the forces and displacements, falls below a predefined threshold.

5. How does SCF convergence relate to geometry optimization convergence? The Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure calculates the electronic energy for a given nuclear geometry. If the SCF does not converge at any point during the geometry optimization, the forces on the atoms cannot be accurately determined, causing the entire optimization to fail [28]. Therefore, ensuring robust SCF convergence is a prerequisite for a successful geometry optimization.

Troubleshooting Guide: Geometry Optimization Does Not Converge

This guide provides a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving geometry optimization failures.

Initial Checks and Geometry Setup

- Verify Molecular Identity: Ensure the specified charge and spin multiplicity are correct for your system. An incorrect setting is a common source of failure [20].

- Inspect the Starting Geometry: Manually check that bond lengths and angles are reasonable. A poor initial geometry can lead to unrealistic forces or "new chemistry" like unintended bond formation/breaking [20].

- Break Symmetry: If the starting geometry is highly symmetric, the calculation might struggle. Try turning off symmetry constraints or physically distorting the structure slightly to break the symmetry [20].

Adjusting Calculation Parameters and Algorithms

- Simplify the Problem: A highly effective strategy is to start with a lower level of theory (e.g., Semi-Empirical or Hartree-Fock with a small basis set) to get a reasonable geometry, and then use that optimized geometry as a starting point for a higher-level calculation [20].

- Increase Iteration Limits: The most straightforward fix is to increase the maximum number of geometry optimization cycles (

Opt=MaxCycle=Nin some software) [20]. - Improve the Initial Hessian: The Hessian guides the optimization direction. For difficult cases, provide a better initial Hessian by:

- Using a

Hessian=Calculatekeyword to compute it at the start of the job. - Calculating the Hessian via a frequency calculation at a lower theory level and reading it in for the higher-level optimization [20].

- Using a

- Modify Convergence Criteria: If the defaults are too strict, you can loosen them. The table below outlines standard and relaxed criteria for key parameters in a common format [14] [29].

| Criterion | Standard Threshold | Relaxed Threshold | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Force | 0.00045 | 0.001 | Largest component of the force (gradient) on any atom. |

| RMS Force | 0.0003 | 0.001 | Root-mean-square of all force components. |

| Maximum Displacement | 0.0018 | 0.005 | Largest predicted atomic displacement for the next step. |

| RMS Displacement | 0.0012 | 0.005 | Root-mean-square of all predicted atomic displacements. |

| Stress (for lattices) | User defined | User defined | Maximum stress energy per atom (stresstensor * volume / numberof_atoms) [14]. |

System-Specific Considerations

- Metals and Open-Shell Systems: These often have challenging electronic structures. For SCF convergence issues, use keywords like

SlowConv,VerySlowConv, orDIISMaxEqto increase damping and improve stability [28]. - Lattice Optimizations: Ensure your k-point sampling is sufficient. Metals and small unit cells require denser k-point grids. Always perform a k-point convergence study for production calculations [14].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the troubleshooting process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential computational "reagents" and their roles in ensuring successful geometry optimizations.

| Tool/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Lower Theory Level Pre-Optimization | Provides a reliable starting geometry. | Use a fast method (e.g., Semi-Empirical, HF) to generate an input structure for expensive DFT or MP2 calculations [20]. |

| Improved Initial Hessian | Guides the optimization direction more effectively. | Crucial for transition state searches and overcoming slow convergence in complex systems [20]. |

| Internal Coordinates (RIC/DLC) | Describes molecular structure using bonds, angles, and dihedrals. | Speeds up optimization for standard organic molecules; can be turned off for high-coordination systems if problematic [20]. |

| SCF Convergence Aids | Stabilizes the electronic structure calculation. | Essential for converging difficult systems like open-shell transition metal complexes (e.g., SlowConv, DIISMaxEq) [28]. |

| k-point Grid | Samples the Brillouin zone in periodic calculations. | Determines accuracy in crystal and surface calculations; density required depends on unit cell size and material type (metal/insulator) [14]. |

The Importance of Initial Guesses and Hessian Matrices

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Poor Initial Guesses

Problem: Geometry optimization fails to converge or converges to an unrealistic, high-energy structure. Primary Cause: The initial molecular geometry is too far from the true minimum, causing the optimizer to diverge or become trapped in an incorrect region of the potential energy surface (PES).

| Observation | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization stops after excessive steps without meeting convergence criteria. [30] | Initial guess is in a flat, low-gradient region of the PES. | Use a pre-optimized structure from a lower-level of theory (e.g., Molecular Mechanics) as a starting point. [30] |

| Converged structure has distorted bond lengths/angles inconsistent with chemical knowledge. | Initial guess was in the basin of attraction of an incorrect local minimum. | Employ a global optimization algorithm (e.g., Stochastic methods like Genetic Algorithms) to sample multiple starting points. [31] |

| Severe oscillations in energy and gradients during optimization. | Initial geometry is near a saddle point or has symmetry that conflicts with the target minimum. | Apply small, random displacements to the atomic coordinates to break symmetry and displace the structure. [2] |

Workflow for Generating Robust Initial Guesses:

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Hessian Matrix Issues

Problem: Optimization is slow, exhibits oscillatory behavior, or fails to converge even with a reasonable initial guess. Primary Cause: Problems with the Hessian matrix (or its approximation), which describes the curvature of the PES and is critical for determining step direction and size.

| Observation | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization takes many small, inefficient steps. | Initial Hessian is a poor approximation (e.g., default unit matrix is used). | Calculate an initial Hessian numerically or at a lower level of theory. [32] |

| Optimization fails with "imprecise M matrix" or similar errors. | Hessian update has become corrupted or non-positive definite. | Restart the optimization from the last geometry, allowing it to rebuild the Hessian. [32] |

| Performance degrades significantly for large systems (>1000 atoms). | Memory and cost of storing/explicitly updating the full Hessian become prohibitive. | Switch to a Limited-memory BFGS (LBFGS) optimizer, which does not store the full Hessian. [32] |

Diagnostic and Recovery Workflow for Hessian Problems:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my geometry optimization not converging? A1: Failure to converge is one of the most common issues. Systematically check the following, which are summarized in the table below:

- Initial Geometry: Is it chemically reasonable and close to the expected minimum?

- Convergence Criteria: Are the thresholds for energy, gradient, and step size too tight? Loosening them can sometimes lead to acceptable structures with significant computational savings, especially in fragmentation methods. [33]

- Hessian: Is the initial Hessian appropriate? For difficult cases, a computed Hessian is better than a default guess.

- Method and Basis Set: Ensure the electronic structure method itself is converging reliably at each point.

Q2: How loose can I set the SCF convergence criteria before my results become unreliable? A2: The acceptable looseness depends on your specific goal. For single-point energy calculations in fragmentation methods, looser criteria (e.g., 10^-5 to 10^-6 Eh in energy change) may still yield energies accurate to ~1 kcal/mol and gradients suitable for dynamics simulations. [33] However, for final production calculations, especially for sensitive properties, always use tighter, standard criteria. Always perform benchmark tests on a smaller system to validate your chosen thresholds.

Q3: What is the difference between BFGS and LBFGS, and when should I use which? A3: The key differences and use cases are:

| Feature | BFGS | LBFGS |

|---|---|---|

| Hessian Storage | Stores a dense approximation of the full Hessian matrix. [32] | Stores only a few vectors to approximate the Hessian, using less memory. [32] |

| Memory Usage | High (O(N²)), where N is the number of degrees of freedom. [32] | Low (O(mN)), where m is a small number (~5-20). [32] |

| Ideal Use Case | Small to medium-sized molecules (typically <100 atoms). | Large systems (proteins, polymers, surfaces) and coarse-grained models. [32] |

Q4: My optimization converged to a stationary point. How can I be sure it's a minimum and not a saddle point? A4: After a geometry optimization, you must perform a frequency calculation. This computes the Hessian matrix at the optimized geometry.

- If all vibrational frequencies are real (positive), the structure is a local minimum.

- If one (and only one) frequency is imaginary (negative), the structure is a transition state (first-order saddle point). [31]

- Some optimization packages, like AMS, offer PESPointCharacter functionality to automatically check the nature of the stationary point and can even restart the optimization if a saddle point is found. [2]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in Geometry Optimization |

|---|---|

| Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS) | A quasi-Newton optimizer that builds and updates an approximation to the Hessian matrix, leading to quadratic convergence near the minimum. [32] |

| Limited-memory BFGS (LBFGS) | A variant of BFGS for large systems; it avoids storing the full Hessian, using only a few vectors to represent it, thus saving memory. [32] |

| Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace (DIIS) | A standard convergence acceleration algorithm for the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure in quantum chemistry, which is critical for obtaining accurate energies and gradients at each optimization step. [33] |

| Global Optimization Algorithms (e.g., Genetic Algorithms, Basin Hopping) | Stochastic methods used to generate reliable initial guesses by broadly exploring the PES to find the global minimum or low-lying local minima. [31] |

| Fragmentation Methods (e.g., EE-GMFCC) | Approaches that partition a large molecule into smaller fragments for QM calculation, enabling energy and gradient computations for systems like proteins that would otherwise be too large. [33] |

| Automatic Differentiation (PySCFAD) | An extension for quantum chemistry packages like PySCF that provides automatic differentiation capabilities, allowing for the precise computation of gradients and Hessians. [34] |

A Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Protocol for Stalled or Oscillating Optimizations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does changing the numerical quality from 'Normal' to 'Good' actually do to improve convergence?

Increasing the numerical quality to Good is a comprehensive strategy that enhances the precision of critical numerical integrations in the calculation. This primarily involves using a higher-quality integration grid for calculating the exchange-correlation potential and improving the accuracy of the density fit [16]. For geometry optimizations, this directly translates to more accurate forces (energy gradients), which are essential for the optimization algorithm to reliably find a minimum energy structure [21].

Q2: My geometry optimization oscillates without converging. The SCF converges, but the energy oscillates around a value. What should I do?

This is a common issue where the energy oscillates and gradients stop improving. The root cause is often insufficient accuracy in the calculated forces. We recommend the following systematic protocol [21]:

- Increase Numerical Accuracy: Set

NumericalQuality Goodin the input. This is often the most effective first step. - Tighten SCF Convergence: A tighter SCF convergence criterion ensures the electronic energy is well-converged at each geometry step. Set

SCF%Converge 1e-8or similar [21]. - Use Exact Density (if feasible): For the highest accuracy, add the

ExactDensitykeyword. Note that this can make the calculation 2-3 times slower and should be used if the first two steps are insufficient [21].