Why Does My SPR Baseline Drift Upward? A Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers

Upward baseline drift in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a common challenge that can compromise kinetic data and affinity measurements.

Why Does My SPR Baseline Drift Upward? A Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers

Abstract

Upward baseline drift in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a common challenge that can compromise kinetic data and affinity measurements. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational causes of drift, methodological best practices for prevention, step-by-step troubleshooting protocols, and advanced validation techniques. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical optimization strategies, this resource empowers scientists to diagnose drift issues accurately, implement effective solutions, and generate high-quality, publication-ready SPR data.

Understanding SPR Baseline Drift: Root Causes and Underlying Mechanisms

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful analytical technique used to study molecular interactions in real-time, providing critical insights into binding kinetics, affinity, and specificity. At the heart of SPR data interpretation lies the sensorgram, a dynamic plot that visually captures the entire interaction lifecycle between a ligand immobilized on a sensor surface and an analyte in solution. The stability of the baseline—the initial flat line on the sensorgram before analyte injection—is fundamental to obtaining accurate and reliable data. Baseline drift, defined as a gradual increase or decrease in the response signal when no binding should be occurring, represents a frequent challenge that can compromise data quality and lead to erroneous results. Understanding the distinction between normal system equilibration and problematic signal shifts is therefore essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals relying on SPR technology.

The Fundamentals of an SPR Sensorgram and Baseline

A sensorgram is a real-time plot of the SPR response (in Response Units, RU) against time, providing a visual representation of a biomolecular interaction. The baseline corresponds to the signal when only running buffer flows over the sensor chip surface, establishing the reference point from which all binding events are measured. A perfectly stable, flat baseline indicates an equilibrated system where changes in signal can be confidently attributed to specific molecular binding events during the association and dissociation phases.

Normal, expected baseline shifts typically occur during system start-up or after changes to the experimental setup. For instance, a new sensor chip often requires rehydration, and chemicals used during immobilization procedures need to be washed out, which can cause initial drift that stabilizes over time. Similarly, a change in running buffer can cause waviness as the previous buffer mixes with the new one in the fluidic system, but this should resolve after several pump strokes.

Characterizing Problematic vs. Normal Baseline Drift

Distinguishing between acceptable system equilibration and problematic drift is crucial for effective troubleshooting. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each.

Table 1: Characteristics of Normal vs. Problematic Baseline Drift

| Feature | Normal/Expected Drift | Problematic Drift |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | System equilibration (e.g., after docking a chip, buffer change) | System contamination, buffer issues, or surface deterioration |

| Typical Magnitude | Low, typically leveling out within a few to 30 minutes | Often significant and/or persistent |

| Duration | Self-limiting, stabilizes after equilibration period | Continuous, does not stabilize over time |

| Impact on Data | Minimal if system is allowed to stabilize before experiments | Can obscure real binding signals, leading to inaccurate kinetics and affinity calculations |

| Common Solutions | Waiting for a stable signal; incorporating start-up cycles with buffer injections | Cleaning the system and sensor chip; preparing fresh, filtered, and degassed buffers |

Problematic drift is a persistent, often substantial shift in the baseline signal that interferes with accurate data analysis. It can manifest as an upward or downward trend and is frequently a symptom of an underlying issue that must be rectified. Failing to equilibrate the system properly will result in continued drift, making it difficult to distinguish specific binding from background signal artifacts.

Quantitative Assessment of Baseline Stability

For rigorous data quality control, researchers should move beyond qualitative assessment and quantify baseline stability. The following table provides key parameters and their acceptable thresholds, which can be measured during a buffer injection cycle on an equilibrated system.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Baseline Assessment

| Parameter | Description | Acceptable Threshold | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Baseline Response | The steady-state response level before any analyte injection. | Established as the reference point for the experiment. | Monitor the baseline after system equilibration. |

| Noise Level | The short-term variability or "jitter" of the baseline signal. | < 1 RU is considered low noise [1]. | Observe the standard deviation of the baseline signal over time. |

| Drift Rate | The steady change in baseline over a defined period (RU/min). | Should be minimal and consistent across flow channels. | Measure the slope of the baseline over a 5-10 minute period before sample injection. |

A well-performing SPR instrument with a properly prepared system should exhibit a very low noise level, often below 1 RU. Significant deviation from these parameters indicates a need for system investigation and troubleshooting.

Root Causes and Troubleshooting of Problematic Drift

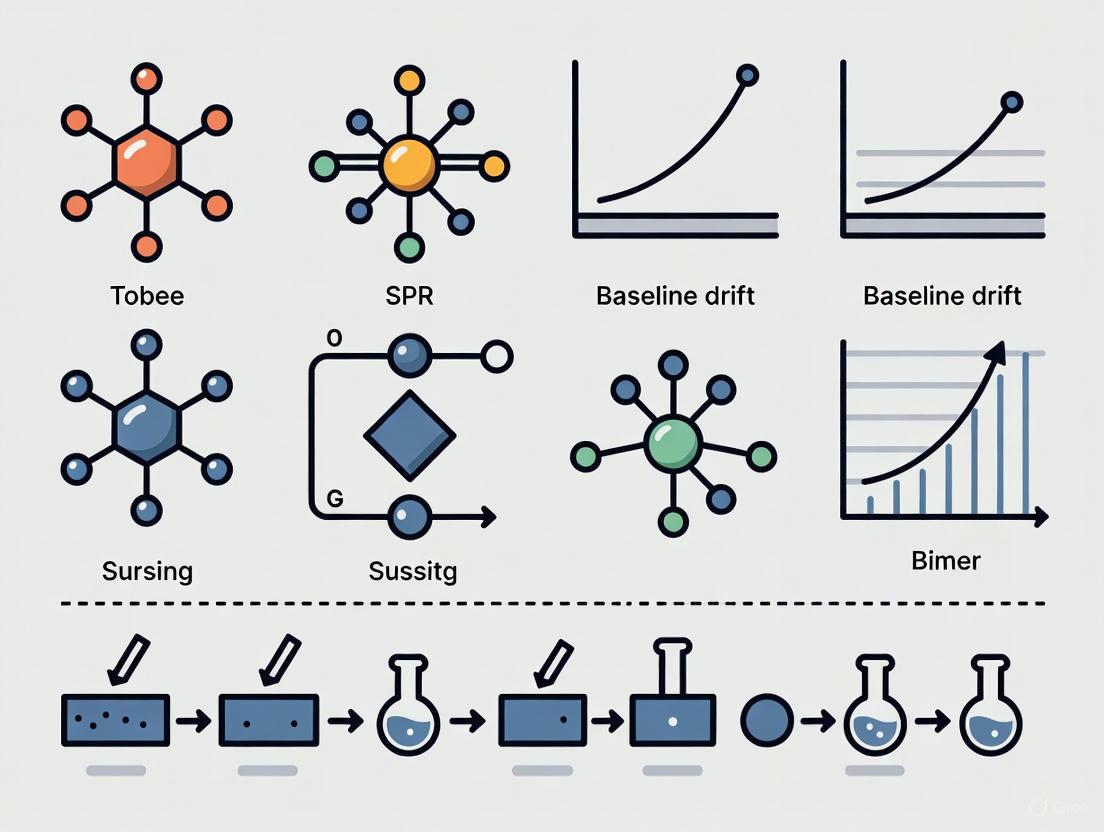

Effective resolution of persistent baseline drift requires a systematic approach to identify and address its root cause. The following decision diagram outlines a logical troubleshooting workflow.

Diagram 1: Troubleshooting Problematic Baseline Drift

Detailed Explanation of Root Causes

System Contamination: Residual analytes or impurities on the sensor chip or within the microfluidic system are a primary cause of drift. Contamination can accumulate over multiple runs, leading to a progressively unstable baseline. Adhering to a strict buffer hygiene protocol is essential; buffers should be prepared fresh daily, filtered through a 0.22 µm filter, and degassed to remove dissolved air that can form spikes or microbubbles [1] [2]. It is considered bad practice to add fresh buffer to old stock, as microbial growth or chemical degradation in the old buffer can introduce contaminants.

Buffer and Solution Problems: As outlined in the diagram, the buffer itself is a frequent culprit. Beyond contamination, evaporation or degradation of the running buffer can alter its composition and refractive index, causing drift. Furthermore, a failure to properly prime the system after a buffer change means the previous buffer is mixing with the new one in the pump and tubing, creating a wavy baseline until the system is fully equilibrated with the new solution [1].

Sensor Surface Issues: The sensor chip surface must be optimally equilibrated. Drift is often seen directly after docking a new sensor chip or after the immobilization of a ligand, due to rehydration of the surface and the wash-out of immobilization chemicals [1]. Surfaces that are susceptible to flow changes may also exhibit start-up drift when flow is initiated after a standstill. This effect can last 5-30 minutes, depending on the sensor type and immobilized ligand [1]. In severe cases, a deteriorated or aged sensor chip may need replacement.

Temperature Fluctuations: The SPR signal is sensitive to temperature because the refractive index of the buffer is temperature-dependent. Even minor fluctuations in the laboratory environment or instability in the instrument's temperature control can manifest as baseline drift. Ensuring the instrument is located in a stable environment is critical.

Experimental Design for Drift Mitigation

Proactive experimental design is the most effective strategy for minimizing baseline drift. The following protocols should be incorporated into standard SPR practice.

Protocol 1: System Startup and Equilibration

- Prepare Fresh Buffer: Create 2 liters of running buffer, filter through a 0.22 µm membrane, and degas. Store in a clean, sterile bottle at room temperature [1].

- Prime the System: After any buffer change, prime the system several times to ensure the fluidic path is completely filled with the new buffer.

- Equilibrate with Flow: Flow running buffer over the sensor surface at the experimental flow rate until a stable baseline is obtained. This can take 5–30 minutes [1].

- Incorporate Start-up Cycles: Add at least three start-up cycles to the experimental method that inject buffer instead of analyte, including any regeneration steps. These cycles "prime" the surface and stabilize the system; they should be excluded from the final analysis [1].

Protocol 2: Double Referencing

This data processing technique is essential for compensating for residual drift, bulk refractive index effects, and differences between flow channels.

- Reference Channel Subtraction: First, subtract the signal from a reference surface (which should closely match the active surface but lack the specific ligand) from the active channel signal. This compensates for the majority of the bulk effect and drift.

- Blank Injection Subtraction: Second, subtract the response from blank injections (running buffer only) that are spaced evenly throughout the experiment. This further compensates for any differences between the reference and active channels [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for preventing and managing baseline drift in SPR experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Baseline Management

| Item | Function in Drift Prevention | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Buffers | Provides a stable, clean environment for molecular interactions. | Use high-purity reagents; prepare fresh daily to prevent microbial growth or degradation. |

| 0.22 µm Filters | Removes particulate matter and microbes from buffers and samples. | Filter all buffers before degassing and use. |

| Degassing Unit | Removes dissolved air from buffers to prevent bubble formation in the microfluidics. | Bubbles cause sudden spikes and baseline instability. |

| Appropriate Sensor Chips | Provides a stable surface for ligand immobilization. | Select chip type (e.g., CM5, NTA, SA) based on ligand properties and immobilization chemistry. |

| System Cleaning Solution | Removes contaminants from the instrument's fluidic path. | Use according to manufacturer's instructions for regular maintenance or after contaminated runs. |

| Regeneration Buffers | Removes bound analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand. | Inefficient regeneration causes carryover and baseline drift over multiple cycles. |

Baseline drift in SPR biosensing exists on a spectrum, from the normal and self-limiting shifts of a system reaching equilibrium to the problematic and persistent drift indicative of an underlying issue. The ability to distinguish between the two is a fundamental skill for any researcher relying on this technology. By understanding the root causes—primarily contamination, buffer issues, surface instability, and temperature fluctuations—and implementing proactive mitigation strategies such as stringent buffer hygiene, system equilibration protocols, and double referencing, scientists can significantly enhance the quality and reliability of their SPR data. A stable baseline is not merely a cosmetic feature of a sensorgram; it is the foundational guarantee of data integrity, ensuring that the rich kinetic and affinity information yielded by SPR technology is accurate, trustworthy, and fit for purpose in advancing scientific research and drug development.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a label-free detection technique that provides real-time, in-situ analysis of biomolecular interactions by monitoring changes in the refractive index at a sensor surface [3]. For researchers investigating the critical question, "why does my SPR baseline drift upward?", understanding surface equilibration processes is fundamental to obtaining reliable data. Baseline drift, particularly in an upward direction, often indicates that the sensor surface has not reached a state of equilibrium, leading to compromised data quality and erroneous results in drug discovery pipelines [1] [4].

The processes of rehydration and chemical wash-out constitute a critical phase in SPR experimentation, directly impacting baseline stability. Immediately after docking a new sensor chip or following immobilization procedures, the surface undergoes substantial physical and chemical changes [1]. Sensor surfaces require adequate hydration to function optimally, and chemicals from immobilization protocols must be thoroughly removed to prevent gradual release during subsequent experimental cycles. This guide examines the role of surface equilibration within the broader context of SPR baseline drift, providing researchers with detailed methodologies to identify, troubleshoot, and prevent these issues in their experimental workflows.

The Science of Surface Equilibration

Fundamental Principles of SPR Baseline Stability

SPR instruments function as refractometric sensing devices that detect changes in mass concentration at the sensor surface [5]. The baseline response represents the system's equilibrium state when only running buffer flows over the sensor surface. A stable baseline indicates that the refractive index at the surface is constant, which occurs when the sensor chip is properly equilibrated with the running buffer and free from ongoing physical or chemical processes [1] [3].

Upward baseline drift specifically signifies a gradual increase in mass or density at the sensor surface. Within the context of surface equilibration, this phenomenon can result from multiple factors related to rehydration and wash-out processes. When a dry sensor chip is initially docked or when a freshly immobilized surface is first exposed to aqueous buffer, the hydrogel matrix and immobilized ligands begin absorbing water molecules, changing the local refractive index [1]. Similarly, incomplete wash-out of immobilization chemicals leads to their gradual release from the sensor surface during buffer flow, creating a sustained increase in baseline response as these molecules enter the flow system.

Rehydration Dynamics in Sensor Surfaces

The rehydration process for sensor surfaces involves complex physical interactions between water molecules and the sensor matrix. Most SPR sensor chips incorporate a carboxymethylated dextran matrix that undergoes significant swelling as it hydrates [1] [2]. This swelling not only changes the physical dimensions of the matrix but also alters its refractive properties, manifesting as baseline drift in sensorgrams. The duration of this effect depends on the type of sensor and the ligand bound to it, typically lasting from 5 to 30 minutes under optimal conditions [1].

The susceptibility of different sensor chips to rehydration-related drift varies significantly based on their surface chemistry and storage conditions. Chips stored in desiccated conditions before use demonstrate more pronounced rehydration effects. The presence of immobilized ligands further complicates this process, as protein matrices hydrate differently than dextran alone, creating differential drift rates between reference and active flow cells [1].

Chemical Wash-Out Kinetics

Chemical wash-out refers to the process of removing non-covalently bound chemicals from the sensor surface following immobilization procedures. Common immobilization chemicals including EDC (Dimethylaminopropyl-N'-Ethylcarbodiimide N-3-hydrochloride), NHS (N-Hydroxy Succinimide), and ethanolamine can become trapped within the sensor matrix if not properly flushed [6]. These chemicals gradually leach into the running buffer during experiments, changing the local refractive index and causing upward baseline drift.

The kinetics of chemical wash-out depend on several factors, including flow rate, buffer composition, and the porosity of the sensor matrix. Chemicals with higher molecular weights or greater hydrophobicity may require extended wash times for complete removal. Inadequate wash-out not only causes baseline instability but can also interfere with molecular interactions by creating localized concentration gradients or directly modifying analyte behavior [1] [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Equilibration Factors

The following table summarizes the primary factors contributing to baseline drift through inadequate surface equilibration, their physical manifestations, and typical timeframes for stabilization:

Table 1: Factors Influencing Surface Equilibration and Baseline Stability

| Factor | Physical Process | Impact on Baseline | Typical Stabilization Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chip Rehydration | Swelling of dextran matrix upon hydration | Upward drift as refractive index changes | 5-30 minutes [1] |

| Chemical Wash-Out | Gradual leaching of immobilization chemicals | Upward drift as chemicals enter buffer | Variable (minutes to hours) [1] |

| Buffer Equilibration | Mixing of previous and new buffers in system | Waviness with pump strokes | Until homogeneous mixing occurs [1] |

| Ligand Adjustment | Structural reorganization of immobilized ligands | Direction varies based on ligand conformation | May require overnight equilibration [1] |

The stabilization times represent optimal conditions with proper experimental setup. Actual timeframes may extend significantly when using dense immobilization surfaces or complex ligand structures.

Experimental Protocols for Surface Equilibration

Comprehensive Surface Preparation Methodology

Proper surface preparation is fundamental to minimizing equilibration-related baseline drift. The following protocol, adapted from established SPR methodologies [1] [6], ensures optimal surface conditions:

Surface Activation and Ligand Immobilization

- Initial System Priming: Prime the SPR system with degassed running buffer for at least three cycles to remove air bubbles and stabilize the fluidics system [1].

- Surface Activation: For amine coupling, inject a 1:1 mixture of 400 mM EDC and 100 mM NHS across the sensor surface at a flow rate of 10 μL/min for 7 minutes to activate carboxyl groups on the dextran matrix [6].

- Ligand Immobilization: Dilute the ligand in appropriate immobilization buffer (typically 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0-4.5) and inject over the activated surface for 5-15 minutes until the desired immobilization level is achieved (typically 5,000-10,000 RU for protein ligands) [5] [7].

- Blocking: Deactivate remaining active esters by injecting 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 7 minutes [6].

Extended Surface Equilibration Protocol

- Initial Chemical Wash-Out: Following immobilization, run continuous buffer flow at experimental flow rate for 30-60 minutes to remove loosely bound chemicals [1].

- Start-up Cycles: Implement at least three start-up cycles with buffer injection (mimicking experimental conditions but without analyte) including regeneration steps if used in the actual experiment [1].

- Overnight Equilibration: For surfaces exhibiting persistent drift, flow running buffer overnight at a low flow rate (1-5 μL/min) to ensure complete rehydration and chemical wash-out [1].

- Baseline Stability Assessment: Monitor baseline for 15-30 minutes before experiments; acceptable drift should be <1 RU/min [1].

Buffer Preparation and System Equilibration

The role of proper buffer preparation in surface equilibration cannot be overstated. Buffer-related issues constitute a frequent source of baseline instability:

Table 2: Buffer Preparation Guidelines for Optimal Surface Equilibration

| Component | Specification | Rationale | Quality Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Quality | Ultra-pure (18.2 MΩ·cm resistance) | Minimizes particulate contamination | Filtration through 0.22 μm membrane [1] |

| Buffer Freshness | Prepared daily | Prevents microbial growth or degradation | Aliquot from master stock [1] |

| Filtration | 0.22 μm filter | Removes particulates that accumulate on surfaces | Visual inspection for clarity [1] |

| Degassing | Under vacuum for 20-30 minutes | Prevents air spike formation in fluidics | No visible bubbles after agitation [1] |

| Detergent Addition | 0.005% Tween-20 (optional) | Reduces non-specific binding | Added after degassing to prevent foaming [1] |

After buffer changes, always prime the system multiple times and wait for a stable baseline before initiating experiments [1]. Failing to properly equilibrate the system after buffer changes results in waviness pump stroke patterns as the previous buffer mixes with the new buffer in the pump [1].

Visualization of Equilibration Processes

The following diagram illustrates the key processes in surface equilibration and their relationship to baseline stability:

Diagram 1: Surface equilibration processes leading to baseline drift

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful management of surface equilibration requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details essential components for effective rehydration and chemical wash-out protocols:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Equilibration

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Equilibration | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chip CM5 | Carboxymethylated dextran surface | Provides hydrogel matrix for immobilization | Standard for protein ligands; requires controlled hydration [2] |

| Sodium Acetate Buffer | 10 mM, pH 4.0-4.5 | Immobilization buffer for amine coupling | Optimal pH depends on isoelectric point of ligand [5] |

| EDC/NHS Mixture | 400 mM EDC, 100 mM NHS | Activates carboxyl groups for amine coupling | Fresh preparation recommended for optimal activation [6] |

| Ethanolamine-HCl | 1 M, pH 8.5 | Blocks residual activated groups | Critical for reducing non-specific binding [6] |

| HBS-EP Buffer | 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% Tween-20, pH 7.4 | Standard running buffer | Maintains pH and ionic strength; detergent reduces nonspecific binding [5] |

| Regeneration Solutions | Varied (e.g., 10 mM glycine pH 2.0, 2 M NaCl) | Removes bound analyte without damaging ligand | Must be validated for each ligand-analyte pair [7] |

| NaOH Solution | 10-50 mM | Cleaning solution for removal of residual contaminants | Effective for removing precipitated materials; concentration depends on application [5] |

Surface equilibration through proper rehydration and chemical wash-out represents a critical foundation for successful SPR experimentation. Within the context of investigating upward baseline drift, these processes directly impact data quality and reliability. The protocols and methodologies presented here provide researchers with comprehensive strategies to address equilibration challenges systematically.

Implementation of rigorous surface preparation protocols, including extended wash-out periods and strategic start-up cycles, significantly reduces equilibration-related artifacts. Furthermore, proper buffer management and surface regeneration practices maintain baseline stability throughout experimental runs. By mastering these fundamental techniques, researchers can minimize baseline drift complications and focus on extracting meaningful biological insights from their SPR data, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and development processes.

Impact of Buffer Changes and System Priming on Signal Stability

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) analysis, a stable baseline is the fundamental foundation for acquiring accurate, reproducible data on biomolecular interactions, such as determining the affinity and kinetics of a drug candidate binding to its protein target. Baseline drift—a gradual increase or decrease in the signal response when no active binding is occurring—is a common yet challenging problem that can compromise data integrity and lead to erroneous conclusions [1] [8]. This drift is frequently a direct consequence of non-optimal system equilibration, particularly following changes in the running buffer or at the initiation of a new experiment [1]. Within the context of a broader thesis investigating "why does my SPR baseline drift upward," this guide provides an in-depth examination of how buffer changes and system priming procedures are intrinsically linked to signal stability. By understanding and controlling these factors, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their SPR data.

Understanding Baseline Drift: Causes and Identification

Baseline drift manifests as a gradual shift in resonance units (RU) and can be either positive (upward) or negative (downward). Its origins are often tied to physical and chemical imbalances within the microfluidic system and sensor surface.

Primary Causes of Drift

- System Equilibration Issues: A newly docked sensor chip or a surface freshly modified via immobilization requires time to equilibrate fully. This process involves the rehydration of the surface and the wash-out of chemicals used during immobilization, which can cause significant drift until the system stabilizes [1].

- Buffer-Related Changes: Any alteration in the running buffer composition, including its pH, ionic strength, or chemical constituents, can lead to a refractive index mismatch. Failing to prime the system adequately after a buffer change results in the previous buffer mixing with the new one within the pump and tubing, creating a "waviness pump stroke" and subsequent drift as the system slowly reaches a new equilibrium [1].

- Start-Up Drift: Initiating fluid flow after a period of stagnation can cause a temporary drift, as some sensor surfaces are particularly sensitive to sudden changes in flow dynamics. This drift typically levels out within 5-30 minutes [1].

- Contamination: Residual analytes, impurities, or microbial growth in the buffer or fluidic system can adsorb to the sensor surface or tubing, causing a gradual signal change [8] [2].

Table 1: Common Causes and Signatures of Baseline Drift

| Cause of Drift | Typical Direction | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Equilibration | Upward or Downward | Most pronounced immediately after docking a chip or immobilization; decreases over time with continuous buffer flow [1]. |

| Buffer Change without Priming | Upward or Downward | Signal exhibits a wavy pattern as buffers mix in the pump; stabilizes after sufficient priming and flow [1]. |

| Contaminated Buffer | Upward | Gradual, continuous drift; may be accompanied by increased noise or spikes [8]. |

| Sensor Surface Susceptibility | Upward | Observed when flow is started after a standstill; duration is sensor- and ligand-dependent [1]. |

A Systematic Workflow for Diagnosing Drift

The following diagram outlines a logical pathway for diagnosing and resolving upward baseline drift, with a specific focus on buffer and priming-related issues.

Core Principles: Buffer Composition and Preparation

The running buffer is not merely a carrier for the analyte; it is a critical component of the SPR environment. Its properties directly influence the refractive index, the stability of the sensor surface, and the biomolecular interactions being studied.

Buffer Selection and Optimization

The ideal running buffer should match the analyte's storage buffer to minimize refractive index differences [9]. Common buffers include HEPES, Tris, or Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) [7] [10]. For lipid-protein interaction studies, it is crucial that the buffer is free of detergents, as these can destabilize lipid vesicles on sensor chips like the L1 chip [11] [9]. Additives like glycerol, used for protein stability, should be matched in the running buffer to prevent a bulk refractive index shift [9].

Essential Buffer Preparation Protocol

Proper buffer preparation is a primary defense against baseline drift and noise. The following detailed protocol is compiled from established laboratory practices [1] [9]:

- Fresh Preparation: Buffers should be prepared fresh each day. Avoid adding new buffer to old stock, as this can introduce contaminants or lead to microbial growth [1].

- Filtration: Filter the buffer through a 0.22 µm membrane filter. This step removes particulate matter that could clog the microfluidic channels or introduce scattering elements into the optical path [1].

- Degassing: Degas the buffer before use. Buffers stored at 4°C contain more dissolved air, which can form microbubbles during the experiment. These bubbles cause sudden, large spikes in the sensorgram and contribute to baseline instability [1].

- Hygiene: Store prepared buffer in clean, sterile bottles. Just before use, transfer an aliquot to a new clean bottle for degassing. After degassing, add any necessary detergents (if compatible with the experiment) to avoid foam formation [1].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Stable SPR Baselines

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Specification & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer (e.g., HEPES-KCl) | Dissolves and transports analyte; defines chemical environment. | Should be detergent-free for lipid surfaces [11] [9]. Match analyte storage buffer exactly [9]. |

| 0.22 µm Membrane Filter | Removes particulates from buffers to prevent microfluidic blockages and noise. | Essential for clean, spike-free baselines [1]. |

| Degassing Unit | Removes dissolved air to prevent bubble formation in the IFC. | Critical for preventing spikes and drift [1]. |

| NaOH Solution (e.g., 50 mM) | Used for sanitizing the fluidic system and as a regeneration solution. | Sterile-filtered; effective for removing residual bound protein [11] [9]. |

| Detergent Solutions (e.g., CHAPS, Octyl-β-Glucoside) | For deep cleaning the fluidic system and stripping lipid surfaces from L1 chips. | Use for routine instrument maintenance and when changing sensor chip types [11] [9]. |

Experimental Protocols for System Priming and Equilibration

System priming and equilibration are active processes that establish a chemically and physically stable environment before data collection begins.

Comprehensive Priming and Equilibration Procedure

Priming is the process of flushing the entire integrated fluidic system (IFC) with the running buffer to ensure the liquid path is completely filled with—and the surfaces are saturated by—the new buffer [1].

- Prime after Buffer Change: Always execute the instrument's prime command after changing the running buffer bottle. This forces several milliliters of the new buffer through the entire fluidic path, displacing the old buffer and minimizing mixing zones [1] [8].

- Equilibrate the Sensor Surface: After priming, flow the running buffer over the sensor surfaces at the experimental flow rate and monitor the baseline. A stable baseline (minimal drift over 5-10 minutes) indicates good equilibration. For new or freshly immobilized chips, this may require flowing buffer for an extended period, sometimes overnight [1].

- Incorporate Start-Up Cycles: In the experimental method, program at least three start-up cycles before actual sample injections. These cycles should be identical to the sample runs but inject only running buffer. If a regeneration step is used, include it in these cycles. This practice "conditions" the surface and stabilizes the system, ensuring that drift from the initial cycles does not affect your experimental data. These start-up cycles should not be used in the final analysis [1].

- Add Blank Injections: Space blank (buffer-only) injections evenly throughout the experiment, approximately one every five to six analyte cycles. These blanks are crucial for the data analysis technique of double referencing, which compensates for residual drift and bulk refractive index effects [1].

Workflow for a Stable Experiment Start

The following diagram integrates buffer preparation, priming, and start-up cycles into a complete pre-experimental workflow.

Advanced Troubleshooting and Data Analysis

When standard priming and equilibration are insufficient, advanced troubleshooting and analytical techniques are required.

Troubleshooting Persistent Drift

If baseline drift continues after following the above protocols, consider these additional checks:

- Fluidic System Cleaning: Residual biomaterial or contaminants can adsorb to the internal tubing. Perform a desorb procedure using the instrument's recommended solutions (e.g., 0.5% SDS followed by 50 mM glycine-NaOH) to deep-clean the fluidic path [9] [10].

- Sensor Surface Regeneration: Inefficient regeneration between cycles can leave analyte bound, causing a cumulative upward drift. Ensure the regeneration solution is strong enough to remove all analyte but not so harsh that it damages the immobilized ligand [7] [2].

- Control Environmental Factors: Fluctuations in laboratory temperature can cause baseline drift. Ensure the instrument is in a temperature-stable environment and that the running buffer temperature is properly controlled [2].

Compensating for Drift via Data Analysis

Even with the best preparation, minor drift can occur. The powerful technique of double referencing can mathematically compensate for this in the data analysis phase [1].

- Reference Surface Subtraction: First, subtract the signal from a reference flow cell (which lacks the ligand or has a non-interacting surface) from the signal of the active flow cell. This step removes the majority of the bulk refractive index shift and some systemic drift.

- Blank Injection Subtraction: Second, subtract the response from the blank (buffer-only) injections from the analyte injections. This step corrects for any remaining differences in drift or response between the active and reference channels that are not due to the specific binding interaction.

Upward baseline drift in SPR is a multifaceted problem, but its connection to buffer changes and system priming is one of the most critical and controllable factors. A disciplined approach that emphasizes the use of fresh, properly prepared buffers, a rigorous priming protocol after any buffer change, and a patient system equilibration process will dramatically improve baseline stability. By integrating these practices with a structured diagnostic workflow and robust data analysis techniques like double referencing, researchers can confidently minimize this pervasive issue, leading to more reliable and interpretable kinetic and affinity data.

Within the broader thesis of "why does my SPR baseline drift upward," start-up drift presents a critical, often overlooked, challenge. This specific drift occurs during the initial phase of an experiment or upon flow cell activation and is characterized by a positive, non-equilibrium shift in the baseline signal. A primary driver of this artifact is the sensor surface's inherent susceptibility to sudden changes in liquid flow, which induces mechanical and thermal stresses on the sensor chip and microfluidic system. This guide details the mechanisms, measurement, and mitigation of flow-induced start-up drift.

Core Mechanisms Linking Flow Changes to Drift

The initiation of fluid flow perturbs the system in two primary ways, leading to an upward drift in the baseline response.

2.1 Thermal Mismatch (The Thermo-Optic Effect) The running buffer, often stored at ambient temperature, is introduced into a temperature-controlled flow cell. The resulting heat transfer changes the local refractive index (RI) at the sensor surface. Since SPR measures RI changes, this is detected as a drift.

2.2 Mechanical Stress (The Strain-Optic Effect) The sudden application of hydrodynamic pressure from the pump deforms the sensor chip substrate and the associated optical components (prism, flow cell gasket). This strain alters the optical path of the incident light, shifting the resonance angle and causing a signal drift.

Title: Flow-Induced Drift Mechanisms

Quantitative Analysis of Flow-Induced Drift

The magnitude of start-up drift is a function of flow rate change and system properties. The following data, compiled from recent instrument characterization studies, illustrates typical drift magnitudes.

Table 1: Drift Magnitude vs. Flow Rate Change

| Initial Flow Rate (µL/min) | Final Flow Rate (µL/min) | Average Drift Magnitude (RU) | Stabilization Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 150 - 300 | 10 - 20 |

| 0 | 50 | 400 - 700 | 15 - 30 |

| 0 | 100 | 600 - 1200 | 20 - 40 |

| 10 | 100 | 300 - 600 | 10 - 25 |

| 100 | 10 | -200 to -500 | 10 - 20 |

Table 2: System Factors Influencing Drift Susceptibility

| System Factor | High Drift Condition | Low Drift Condition | Impact on Drift Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chip Substrate | Glass (High CTE*) | Fused Silica (Low CTE) | High CTE increases mechanical strain. |

| Flow Cell Material | Polymer | Metal/Alloy | Metal dissipates heat more effectively. |

| Temperature Control | Poorly equilibrated | Fully equilibrated (>1 hr) | Reduces thermal mismatch. |

| Pressure Rating | Low (<100 psi) | High (>500 psi) | Stiffer systems resist deformation. |

*CTE: Coefficient of Thermal Expansion

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing System-Specific Start-Up Drift

This protocol allows researchers to quantify the flow-induced drift profile of their specific SPR instrument.

Objective: To measure the amplitude and duration of baseline drift resulting from a step-change in flow rate.

Materials:

- SPR Instrument with precise temperature control

- Running Buffer (e.g., 1X PBS, HBS-EP)

- Sterile, particle-free buffer reservoir

- Data analysis software (e.g., Scrubber, OriginLab)

Procedure:

- System Equilibration: Install a clean, bare gold sensor chip. Prime the system with running buffer and set the temperature to the desired experimental set point (e.g., 25°C). Allow the system to equilibrate until the baseline signal varies by less than 0.5 RU/min for at least 10 minutes.

- Initial Baseline Acquisition: Set the flow rate to 0 µL/min. Wait for 60 seconds to establish a stable, static baseline.

- Flow Initiation: Initiate a constant flow of buffer at the target rate (e.g., 30 µL/min). Do not inject any analyte.

- Data Recording: Continuously record the baseline signal for a minimum of 30 minutes or until the signal stabilizes (drift < 1 RU/min for 5 minutes).

- Data Analysis: Plot the sensorgram. The drift magnitude is the difference between the maximum signal post-flow initiation and the initial static baseline. Stabilization time is the duration from flow start to signal stabilization.

Mitigation Strategy Workflow

A systematic approach is required to minimize flow-induced start-up drift's impact on data quality.

Title: Drift Mitigation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Drift Management

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Degassed Running Buffer | Prevents micro-bubble formation in flow cells, which causes severe signal spikes and drift. |

| Low CTE Sensor Chips (e.g., Fused Silica) | Minimizes mechanical deformation from pressure and thermal changes, reducing strain-optic effects. |

| In-line Buffer Heater/Cooler | Pre-conditions buffer to the instrument's set temperature, eliminating thermal mismatch. |

| High-Precision Syringe Pumps | Provide smooth, pulseless flow initiation, avoiding sudden pressure shocks. |

| System Equilibration Buffer | Identical to running buffer; used for extended priming to ensure thermal and mechanical equilibrium is reached before data collection. |

How Regeneration Solutions Induce Differential Drift Between Channels

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for studying biomolecular interactions in real time. A common challenge in obtaining high-quality kinetic data is managing baseline stability. This technical guide examines a specific phenomenon: differential baseline drift between measurement channels induced by regeneration solutions. This drift occurs when the reference and active sensor surfaces respond differently to regeneration conditions, complicating data analysis and impacting the accuracy of binding affinity and kinetic measurements. We explore the underlying mechanisms, present quantitative data on common regeneration agents, and provide detailed methodologies for diagnosing and mitigating this issue, framing the discussion within the broader context of SPR baseline drift research.

In SPR experiments, baseline drift refers to the gradual change in the response signal over time when no active binding or dissociation events are occurring. An ideal baseline is perfectly stable, allowing for precise measurement of binding-induced response changes. Differential drift is a particular problem where the baseline in the active flow cell (with immobilized ligand) and the reference flow cell (without ligand, or with a non-interacting control) drift at different rates. This mismatch invalidates the simple subtraction of the reference signal and can lead to significant errors in the determination of binding kinetics and affinities.

Regeneration—the process of removing bound analyte from the immobilized ligand to prepare the surface for a new interaction cycle—is a primary contributor to differential drift. The chemicals used in regeneration can alter the properties of the sensor surface or the immobilized ligand itself to different degrees on the active and reference surfaces, leading to divergent drift behavior [1]. Understanding and controlling this effect is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on the high accuracy of SPR data.

Mechanisms of Regeneration-Induced Differential Drift

Regeneration solutions induce differential drift through several physical and chemical mechanisms that disproportionately affect the active channel.

Chemical Alteration of the Sensor Surface

- Ligand Degradation: Repeated exposure to harsh regeneration conditions can partially denature or degrade the immobilized ligand on the active surface. This gradual alteration changes the hydrodynamic properties or mass of the ligand layer, causing a steady drift in the baseline signal that is not mirrored on the reference surface [1] [2].

- Surface Matrix Erosion: Regeneration solutions, especially those with extreme pH (e.g., Glycine pH 2.0-3.0 or NaOH), can slowly hydrolyze or degrade the dextran matrix common on sensor chips like the CM5. If the immobilization levels between channels differ, the erosion rate and its consequent effect on the baseline can also differ [2].

Incomplete Regeneration and Residual Analyte

- Carryover Effects: Incomplete removal of the analyte from the active surface leaves residual bound material. This buildup over multiple cycles increases the baseline response in the active channel, while the reference channel remains unaffected, creating a growing differential between them [2].

Differential Re-equilibration

- Buffer Equilibration: After a regeneration step, which often uses a buffer different from the running buffer, the system must re-equilibrate. The chemical microenvironment of the active ligand surface may interact with the new buffer ions differently than the reference surface, leading to a period of differential drift as the two surfaces equilibrate at different rates [1].

The following diagram illustrates the primary pathways through which a regeneration solution leads to the problem of differential drift.

Quantitative Analysis of Regeneration Effects

The choice of regeneration solution and its specific conditions profoundly impacts the degree and rate of baseline drift. The following table summarizes the effects of common regeneration agents, as observed in experimental settings.

Table 1: Characteristics of Common SPR Regeneration Solutions and Their Impact on Drift

| Regeneration Solution | Typical Concentration Range | Primary Mechanism | Risk of Differential Drift | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine-HCl | 10-100 mM, pH 1.5-3.0 | Disrupts electrostatic & hydrophobic interactions | Medium-High | Can gradually denature sensitive proteins, leading to cumulative drift [2]. |

| NaOH | 1-100 mM | Creates a high-pH environment disrupting interactions | Medium | Can hydrolyze dextran matrix over time; 10-50 mM is common [12]. |

| SDS | 0.01%-0.1% (w/v) | Ionic detergent solubilizes proteins | High | Highly effective but can cause significant ligand denaturation and persistent drift; requires thorough washout [2]. |

| MgCl₂ or NaCl | High (1-4 M) | Disrupts ionic and polar interactions | Low-Medium | Generally milder, but high salt can cause precipitation or non-specific disruption of some ligands. |

| Acid (e.g., H₃PO₄) | 10-100 mM, pH 1.0-2.5 | Similar to Glycine-HCl, protonates residues | Medium-High | Requires careful conditioning to avoid sudden, large response shifts. |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosing and Mitigating Drift

A systematic experimental approach is essential to identify regeneration-induced differential drift and implement effective countermeasures.

Protocol: Diagnostic Test for Regeneration-Induced Drift

This protocol helps isolate drift specifically caused by the regeneration solution.

- Surface Preparation: Immobilize the ligand on the active flow cell and prepare an appropriate reference surface (e.g., blocked-deactivated surface).

- Initial Baseline Acquisition: Flow running buffer over both channels until a stable baseline is achieved (drift < 5 RU/min).

- Regeneration Challenge Cycle:

- Inject a buffer sample (blank) over both surfaces and monitor the dissociation for 5-10 minutes to establish a post-injection baseline.

- Inject the regeneration solution for the typical contact time (e.g., 30-60 seconds).

- Immediately return to running buffer flow and monitor the baseline response for a prolonged period (15-30 minutes).

- Repeat this cycle 5-10 times to observe cumulative effects.

- Data Analysis: Compare the baseline drift rates (RU/min) in the active and reference channels immediately after each regeneration. A consistent, growing divergence indicates regeneration-induced differential drift.

Protocol: Optimization of Regeneration Conditions

Once a problem is identified, optimize the regeneration strategy to minimize drift.

- Scouting for Milder Conditions: Test a panel of regeneration solutions, starting with the mildest option (e.g., high salt) and progressively moving to stronger conditions (low/high pH, detergents) only if necessary.

- Minimize Contact Time and Concentration: For an effective solution, determine the minimum concentration and contact time required to remove >95% of the analyte without causing significant drift in a diagnostic test.

- Incorporation of Start-up Cycles: In the final experimental method, include at least three start-up cycles that perform a full injection and regeneration with buffer instead of analyte. These cycles "prime" the surface, allowing it to stabilize after the initial, most impactful regenerations. Do not use these cycles for data analysis [1].

- Baseline Stabilization Period: After each regeneration step in the main experiment, include a stabilization period of 5-10 minutes with running buffer flow before injecting the next analyte sample. This allows the differential drift to subside or equalize [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful management of regeneration-induced drift relies on the use of specific reagents and materials.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Managing Differential Drift

| Reagent/Material | Function in Drift Management | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Buffers | Consistent running buffer ionic strength and pH minimize baseline fluctuations unrelated to regeneration. | Prepare fresh daily, 0.22 µM filter and degas to prevent spikes and drift [1]. |

| Glycine Buffer (Low pH) | Common, effective regeneration agent for antibodies and many proteins. | Start scouting at pH 2.5; can be combined with additives like salt to reduce required strength [2]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Effective for disrupting a wide range of protein-protein interactions. | A versatile choice; 10-30 mM is often a good starting point for scouting [12]. |

| Ethanolamine Hydrochloride | Used for blocking remaining active esters on the sensor chip after ligand immobilization. | Proper blocking reduces non-specific binding and subsequent need for harsh regeneration [2]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A blocking agent for surfaces to reduce non-specific binding. | Can minimize analyte carryover, a contributor to drift. Use a high-purity, protease-free grade. |

| HBS-EP/EP+ Buffer | A standard running buffer containing a carboxymethylated dextran matrix and surfactant. | The surfactant (Polysorbate 20) reduces non-specific binding and helps stabilize the baseline [2]. |

Data Analysis and Compensation Strategies

When differential drift cannot be fully eliminated, analytical techniques are vital for compensation.

- Double Referencing: This is the most critical data processing step for compensating for residual differential drift. It involves two stages:

- Reference Surface Subtraction: The response from the reference flow cell is subtracted from the active flow cell response. This compensates for the bulk refractive index shift and a significant portion of the systemic drift.

- Blank Injection Subtraction: The sensorgram from a buffer-only injection (blank) is subtracted from the analyte injection sensorgrams. This blank injection, performed at regular intervals throughout the experiment, captures the unique drift characteristics of the active surface relative to the reference surface post-regeneration. Subtracting it corrects for the differential component of the drift [1].

- Drifting Baseline Algorithm: During kinetic evaluation, use a fitting algorithm that incorporates a drifting baseline parameter. This allows the model to account for a linear drift during the association or dissociation phase, preventing the drift from being misinterpreted as very slow binding or dissociation events. This is often necessary for long dissociation phases [12].

Differential drift induced by regeneration solutions is a significant, yet manageable, challenge in SPR analysis. It originates from the dissimilar chemical and physical alterations that regeneration conditions impose on active and reference sensor surfaces. Successful mitigation requires a holistic strategy, combining the systematic optimization of regeneration protocols with rigorous experimental design—including start-up cycles and regular blank injections—and concluding with robust data analysis techniques like double referencing. A deep understanding of these principles enables researchers to produce highly reliable and reproducible kinetic data, which is the ultimate goal of any SPR investigation within a broader research context aimed at conquering baseline drift.

Proactive Methodologies: Designing Experiments to Minimize Drift

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) research, an unstable or upwardly drifting baseline is a frequent challenge that can compromise data integrity and impede accurate kinetic analysis. A significant proportion of baseline instability originates from suboptimal buffer preparation. Proper buffer preparation is not merely a preliminary step but a critical factor in ensuring the stability of the refractive index at the sensor surface, which directly manifests as a stable baseline. This protocol provides an in-depth technical guide for the preparation of SPR running buffers, with a specific focus on methodologies to eliminate the common causes of upward baseline drift, thereby ensuring the collection of publication-quality data.

The Critical Role of Buffer in SPR Baseline Stability

The SPR signal is exquisitely sensitive to changes in the refractive index at the sensor surface. An upwardly drifting baseline often signals a gradual change in the composition of the liquid environment at this surface. Inadequate buffer preparation introduces artifacts such as air bubbles, particulate matter, and microbial growth, all of which alter the local refractive index and cause the baseline to drift [1] [13].

The core principle of reliable SPR is buffer homogeneity and stability. Any inconsistency between the running buffer and the analyte buffer, or the introduction of physical or chemical instabilities, will generate a refractive index mismatch. This mismatch is detected as a bulk effect or, when gradual, as a persistent baseline drift [14]. Consequently, stringent buffer hygiene, proper degassing, and meticulous filtration are non-negotiable practices for diagnosing and resolving upward baseline drift.

Comprehensive Buffer Preparation Protocol

Materials and Reagents

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Buffer Preparation

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer Salts | To create the desired chemical environment (e.g., HEPES, PBS). | Use high-purity grades. Ensure pH is adjusted at the temperature of the experiment. |

| Ultrapure Water | Solvent for all buffer components. | Resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm at 25°C to minimize organic and ionic contaminants [5]. |

| Detergent (e.g., Tween-20) | Reduces non-specific binding and minimizes bubble formation. | Add after filtering and degassing to avoid foam formation [1]. Concentration typically 0.005% v/v [5]. |

| 0.22 µm Filter | Removes particulate matter and microbial contaminants. | Use a low-protein-binding membrane material (e.g., PES). |

| Clean (Sterile) Bottles | For buffer storage. | Prevents introduction of contaminants from the container. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Solution Preparation Weigh all buffer components accurately and dissolve them in ultrapure water. Adjust the pH using an appropriately calibrated pH meter. A final volume of 2 litres is recommended to ensure sufficient buffer for system equilibration and the experimental run [1].

Step 2: Filtration Filter the buffer solution through a 0.22 µm membrane filter [1] [13]. This step is critical for two reasons: it removes particulate matter that can cause spikes or block microfluidic channels, and it sterilizes the buffer, preventing microbial growth that can consume components and alter buffer composition over time.

Step 3: Degassing Degas the filtered buffer thoroughly before use. Dissolved air can form minute bubbles within the SPR instrument's microfluidic system, especially at higher temperatures or low flow rates, leading to severe signal spikes and baseline instability [13] [14]. Use a vacuum degasser or sonication to remove dissolved gases. Note that buffers stored at 4°C contain more dissolved air and require extra attention during this step [1].

Step 4: Addition of Detergent After degassing, add a suitable detergent like Tween-20. Adding detergent post-degassing prevents the formation of excessive foam, which can interfere with buffer handling and introduce air [1].

Step 5: Storage and Handling Store the prepared buffer in clean, sterile bottles at room temperature to minimize gas solubility and prevent compositional shifts. It is bad practice to add fresh buffer to old buffer remaining in the system or storage bottle, as this can introduce contaminants [1]. Prepare fresh buffer daily for the most critical applications.

Quantitative Data and Buffer Specifications

Table 2: Buffer-Related Parameters and Their Impact on SPR Baseline

| Parameter | Target Specification | Consequence of Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Filtration Pore Size | 0.22 µm | Larger pores fail to remove microbes and small particles, leading to clogs and drift [1]. |

| Daily Buffer Preparation | Fresh buffer each day | Prevents microbial growth and chemical degradation that cause progressive baseline drift [1]. |

| Storage Temperature | Room Temperature | Cold storage increases dissolved gas, leading to air-spikes upon warming [1]. |

| DMSO Concentration Matching | Exact match between running and analyte buffer | A 1% DMSO mismatch can cause a response jump >1000 RU, obscuring the binding signal [14]. |

| Salt Concentration Matching | Exact match between running and analyte buffer | Every 1 mM salt difference can cause a ~10 RU bulk refractive index shift [14]. |

Integration with SPR Experimental Workflow

Proper buffer preparation is the first and most critical step in a chain of procedures designed to stabilize the SPR baseline. The following workflow illustrates how buffer preparation integrates with subsequent system setup and experimental steps to mitigate upward baseline drift.

System Equilibration and Start-up Cycles

After preparing the buffer correctly, the following steps are essential to translate this quality into a stable experimental baseline:

- Prime the System: After any buffer change, prime the instrument's fluidic system according to the manufacturer's instructions. This replaces the old liquid in the tubing and pump with the new, properly prepared buffer [1]. Failing to do so results in mixing of different buffers within the pump, creating a wavy baseline due to refractive index fluctuations with each pump stroke [1].

- Equilibrate the System: Flow the running buffer over the sensor surface at the experimental flow rate until a stable baseline is obtained. This can take 5–30 minutes or longer, depending on the sensor chip and immobilized ligand [1]. This step allows for the temperature of the system to stabilize and the sensor surface to fully hydrate and adjust to the buffer chemistry.

- Execute Start-up Cycles: Incorporate at least three start-up cycles into your experimental method. These are identical to analyte injection cycles but inject running buffer instead of sample. If a regeneration step is used, include it in these cycles. This "primes" the fluidic path and the sensor surface, stabilizing the system before actual data collection begins. Data from these cycles should not be used in the final analysis [1].

Troubleshooting Buffer-Induced Baseline Drift

Even with careful preparation, issues can arise. The table below links specific baseline drift symptoms to their potential buffer-related causes and solutions.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Buffer-Induced Baseline Issues

| Observed Problem | Potential Buffer-Related Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Consistent Upward Drift | Buffer evaporation or microbial growth; Buffer not equilibrated to instrument temperature. | Use freshly prepared buffer; Ensure buffer bottles are sealed; Allow more time for system temperature equilibration. |

| Sudden Large Jumps/Spikes | Air bubbles from inadequately degassed buffer; Particulate matter. | Extend degassing time; Ensure buffer is filtered and stored properly; Use high flow rates briefly to flush bubbles [14]. |

| Rising Baseline During Analyte Injection | Buffer mismatch between running buffer and analyte solution. | Dialyze the analyte into the running buffer or use size exclusion columns for buffer exchange [14]. |

| High Noise/Fluttering Baseline | Contaminated buffer or dirty fluidic path; Electrical or environmental interference. | Prepare new buffer with fresh filtration; Clean the instrument's fluidic system as per manual; Ensure stable power supply and minimal vibrations [13]. |

Upward baseline drift in SPR is frequently a symptom of inadequate buffer preparation. This master protocol establishes that rigorous attention to daily buffer preparation, strict filtration (0.22 µm), thorough degassing, and impeccable buffer hygiene forms the foundational strategy for eliminating this problem. By adhering to these standardized procedures—integrating them with careful system priming and equilibration—researchers can achieve the stable baselines required for obtaining reliable, high-quality, and publishable kinetic data. A disciplined approach to buffer management is the most effective first step in troubleshooting and preventing SPR baseline drift.

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) analysis, a stable baseline is the fundamental prerequisite for generating reliable, publication-quality binding data. An upward-drifting baseline is a common yet challenging problem that directly compromises data integrity by making it difficult to distinguish true molecular binding events from system-related artifacts. This drift is frequently a symptom of a system that has not reached full thermodynamic and chemical equilibrium [1]. System equilibration—comprising the meticulous processes of priming, washing, and stabilization—serves as the primary defense against this issue. This guide details the core principles and practical protocols for achieving a stable SPR system, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a methodological framework to eliminate baseline drift at its source. A properly equilibrated instrument ensures that the calculated kinetic parameters (ka, kd, KD) accurately reflect the biology of the interaction under investigation, thereby strengthening conclusions in both basic research and therapeutic candidate profiling.

Understanding the Causes of Baseline Drift

Baseline drift is typically defined as a gradual, monotonic change in Response Units (RU) when only running buffer is flowing over the sensor surface. Effectively troubleshooting this issue requires a systematic understanding of its underlying causes.

Sensor Chip Hydration and Chemical Wash-Out: A newly docked sensor chip, or one freshly subjected to immobilization chemistry, requires time to hydrate fully and equilibrate with the running buffer. Chemicals from the immobilization process (e.g., amine-coupling reagents) can continue to leach out, causing a steady drift until completely washed away [1]. In some cases, it can be necessary to run the running buffer overnight to fully equilibrate the surfaces [1].

Insufficient Buffer Equilibration After Change: Changing the running buffer composition, even slightly, introduces a new solvent environment. Failure to thoroughly prime and equilibrate the system with the new buffer leads to mixing of the old and new buffers within the fluidics, manifesting as a "waviness" in the baseline that only stabilizes after the previous buffer is completely purged [1].

Flow Start-Up Effects: After a period of flow standstill, initiating fluid flow can cause a temporary drift as the system adjusts to the renewed pressure and the sensor surface acclimates to the flow. This effect is particularly pronounced on certain sensor surfaces and can last from 5 to 30 minutes [1].

Regeneration Solution After-Effects: Harsh regeneration solutions can temporarily alter the properties of the hydrogel on certain sensor chips or slightly perturb the immobilized ligand. The reference and active surfaces may drift at different rates after regeneration due to differences in surface chemistry and immobilization levels, necessitating careful matching or computational correction [1].

Table 1: Common Causes of Baseline Drift and Their Characteristics

| Cause of Drift | Typical Drift Direction | Key Identifying Features |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chip Hydration | Upward or Downward | Most prominent immediately after docking a new chip or after immobilization. |

| Buffer Change | Upward or Downward | "Wavy" baseline due to buffer mixing in pump strokes; occurs after changing buffer bottles. |

| Flow Start-Up | Variable | Observed immediately after initiating fluid flow following a standstill period. |

| Regeneration After-Effect | Variable | Drift rate may differ between reference and active flow channels. |

Core Principles of System Equilibration

The Role of Priming

Priming is a proactive cleaning and equilibration procedure that forces running buffer through the entire microfluidic system (IFC - Integrated Fluidic Cartridge). Its primary purpose is to remove any air bubbles, residual solvents, previous buffers, or contaminants, and to ensure the system is uniformly filled with the current running buffer. A prime should always be performed after any buffer change and as the first step in any daily start-up procedure [1] [15].

The Purpose of Washing

While priming addresses the internal fluidics, washing focuses on the sensor surface and the specific flow cells being used for the experiment. A wash step, often performed at a higher flow rate or with a slightly larger volume than a standard prime, helps to rapidly stabilize the sensor surface by establishing consistent flow dynamics and removing any loosely adsorbed material. It is a critical step after docking a chip or following a regeneration step that uses harsh conditions.

Determining Stabilization Times

Stabilization is not an active step but a period of observation. It involves flowing running buffer at the experimental flow rate and waiting until the baseline signal is flat, typically with a drift of less than 1-2 RU per minute. The required duration is not fixed; it depends on the factors listed in Section 2. The system should be considered stable when the baseline drift has minimized to an acceptable level for the specific experiment. For systems requiring the highest sensitivity, a drift of < 1 RU over 5-10 minutes is a good target.

Recommended Equilibration Workflows

The following workflows are designed to be incorporated into standard SPR experimental routines to prevent baseline drift.

Start-Up and Daily Equilibration Protocol

This protocol should be used at the beginning of each experimental session or after the instrument has been idle for an extended period.

- Prepare Fresh Buffer: Prepare at least 2 liters of fresh running buffer each day. Filter through a 0.22 µM filter and degas thoroughly. Storage of buffers at 4°C should be avoided as cold liquid contains more dissolved air, which can lead to air spikes. Always use a clean, sterile bottle [1].

- Initial Prime: Prime the system at least twice with the fresh, degassed running buffer. This removes any storage solution or previous buffer from the fluidic path.

- Stabilization Flow: Initiate a continuous flow of running buffer at your intended experimental flow rate. Monitor the baseline response in real-time.

- Assess Stability: Allow the system to flow until the baseline drift levels out. This may take 5–30 minutes, depending on the sensor chip and history [1].

- Execute Start-Up Cycles: Program and run at least three "start-up" or "dummy" cycles. These are identical to your experimental cycles but inject running buffer instead of analyte. If your method includes a regeneration step, include it in these cycles. The data from these cycles are used to stabilize the system and are discarded from final analysis [1].

Post-Buffer Change and Post-Immobilization Protocol

This more rigorous protocol is critical after any change to the running buffer or after a new ligand has been immobilized on the sensor surface.

- Multiple Primes: After introducing the new buffer, prime the system a minimum of three times. This ensures complete purging of the old buffer from the entire fluidic system to prevent mixing-related waviness [1].

- Extended Equilibration Flow: Flow the new running buffer continuously. For a fresh immobilization, this may require an extended period. In severe cases of drift, it can be necessary to run the running buffer overnight to equilibrate the surfaces [1].

- Buffer Blank Injections: Perform several injections of running buffer (blank injections) over both the active and reference surfaces. This further confirms baseline stability and provides essential data for the double referencing procedure during data analysis [1].

Pre-Experiment Stabilization Checks

Before commencing the actual analyte injections, a final stability check is imperative.

- Baseline Noise Level Check: With the system equilibrated, inject running buffer several times and observe the average baseline response. The overall noise level should be very low (e.g., < 1 RU) [1].

- Drift Rate Quantification: Directly measure the drift rate in RU/minute over a 5-10 minute period of buffer flow immediately before starting the experiment. A stable system should have a near-zero drift rate.

- Visual Inspection: The baseline should be flat and free of spikes or periodic oscillations. Any deviation suggests the need for further priming or washing.

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for establishing a stable baseline, integrating the protocols and checks described above.

Data Presentation: Equilibration Parameters and Reagents

Table 2: Summary of Key Equilibration Steps and Parameters

| Equilibration Step | Recommended Frequency | Typical Duration / Volume | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Priming | After every buffer change; daily start-up. | 2-3 cycles of full system volume. | Purge fluidics of previous buffers/contaminants; remove air bubbles. |

| Stabilization Flow | After priming; after sensor chip docking. | 5 - 30 minutes (or overnight if needed). | Thermally and chemically equilibrate the sensor surface with running buffer. |

| Start-Up Cycles | Start of every new experiment sequence. | Minimum of 3 full cycles. | Condition the surface with regeneration buffers and stabilize system response. |

| Blank Injections | Spaced throughout the experiment. | One blank every 5-6 analyte cycles. | Provide data for double referencing to correct for residual drift and bulk effects. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for SPR Equilibration and Troubleshooting

| Reagent / Material | Function in Equilibration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer | The solvent environment for all interactions; defines the chemical baseline. | Must be 0.22 µm filtered and degassed daily to prevent spikes and drift. Use high-purity chemicals [1]. |

| Regeneration Buffer | Removes tightly bound analyte from the ligand to reset the baseline. | Must be strong enough to regenerate the surface but mild enough to not damage ligand activity (e.g., Glycine-HCl pH 1.5-3.0) [15]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A blocking agent to reduce non-specific binding (NSB) to the sensor surface. | Typically used at 1% in buffer. Should be added to sample solutions during runs only, not during immobilization [15]. |

| Non-ionic Surfactant (e.g., Tween 20) | Reduces NSB by disrupting hydrophobic interactions between analyte and sensor surface. | Use at low concentrations (e.g., 0.005-0.05%) to avoid foaming, which is especially important after degassing [1] [15]. |

Advanced Strategy: Double Referencing for Drift Compensation

Even with meticulous equilibration, minimal residual drift can persist. The data analysis technique of double referencing is a powerful and mandatory strategy to compensate for this. This mathematical correction is a two-step process [1]:

- Reference Channel Subtraction: First, the response from a reference flow cell (a surface without the specific ligand or with a non-interacting control) is subtracted from the active flow cell response. This compensates for the majority of the bulk refractive index shift and any system-wide drift.

- Blank Injection Subtraction: Second, the average response from multiple blank injections (running buffer injected as a sample) is subtracted from the reference-subtracted data. This final step compensates for any remaining differences between the reference and active channels and for any injection artifacts, yielding a sensorgram that reflects only the specific binding interaction.

A stable, drift-free baseline is not a matter of chance but the direct result of rigorous and systematic equilibration. By understanding the root causes of baseline drift and adhering to the detailed protocols for priming, washing, and stabilization outlined in this guide, researchers can transform their SPR data quality. Incorporating these practices, complemented by the essential data analysis tool of double referencing, ensures that the collected kinetic and affinity data are robust, reliable, and truly reflective of the underlying molecular interaction. In the context of drug development, where decisions are data-driven, such rigorous attention to the fundamentals of system equilibration is not just best practice—it is critical to success.

Incorporating Start-Up and Blank Cycles in Experimental Design

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful analytical technique used to study real-time biomolecular interactions, providing critical insights into kinetics, affinity, and specificity for researchers and drug development professionals. At the heart of SPR data quality lies baseline stability—the foundation upon which all binding parameter calculations are built. Baseline drift, particularly upward drift, represents a fundamental challenge that can compromise data integrity, leading to erroneous kinetic parameters and affinity calculations. This technical guide addresses baseline drift within the context of experimental design, specifically focusing on the strategic implementation of start-up and blank cycles as a systematic approach to drift mitigation.

The sensorgram's baseline phase represents the system's stability before analyte introduction, and its proper equilibration is crucial for accurate measurements [8]. Drift is often observed after docking a new sensor chip or following immobilization procedures due to rehydration of the surface and wash-out of chemicals used during immobilization [1]. Furthermore, changes in running buffer composition without proper system equilibration can result in pump stroke-induced waviness as previous buffer mixes with new buffer in the fluidic system [1]. This technical guide provides detailed methodologies for incorporating start-up and blank cycles into SPR experimental designs, offering researchers systematic approaches to stabilize baselines and ensure data reliability for both multi-cycle kinetics (MCK) and single-cycle kinetics (SCK) applications.

Understanding Baseline Drift in SPR Systems

Root Causes of Upward Baseline Drift

Upward baseline drift in SPR systems stems from multiple physicochemical and instrumental factors that researchers must recognize and address:

- Surface Non-Equilibration: Newly docked sensor chips or recently immobilized surfaces require substantial equilibration time as the surface rehydrates and chemicals from immobilization procedures wash out [1]. This process can create significant upward drift as the surface stabilizes in the flow buffer environment.

- Buffer-Related Issues: Changing running buffers without sufficient system priming creates mixing artifacts as the previous buffer gradually exchanges with the new buffer in pump systems [1]. Additionally, buffers stored at 4°C contain more dissolved air which can create artifacts upon warming, and poor buffer hygiene (e.g., adding fresh buffer to old stock) introduces contaminants that contribute to drift [1].

- Start-Up Flow Effects: Sensor surfaces susceptible to flow changes exhibit noticeable drift when flow is initiated after a standstill period, typically leveling out over 5-30 minutes depending on the sensor type and immobilized ligand [1].

- Regeneration Aftermath: Regeneration solutions can differentially affect reference and active surfaces due to variations in protein content and immobilization levels, creating unequal drift rates between channels [1].

- System Contamination: Residual analytes or impurities on the sensor surface, contaminants in running buffer or samples, and gradual surface degradation all contribute to upward signal drift [8] [13].

Impact of Drift on Data Analysis

Baseline drift introduces systematic errors that propagate through data analysis, particularly affecting the accuracy of dissociation rate constants (k~d~) in long experiments and compromising the precision of affinity calculations (K~D~) [1]. For interactions with slow dissociation kinetics, unequal drift rates between reference and active channels create referencing artifacts that distort the true binding signal. In single-cycle kinetics (SCK), where sequential analyte injections occur without regeneration, uncompensated drift can significantly impact the binding curves across concentrations, potentially leading to erroneous conclusions about binding mechanisms [16].

Core Experimental Strategy: Start-Up and Blank Cycles

The Role of Start-Up Cycles

Start-up cycles, also termed "dummy injections" or "system conditioning cycles," are identical to experimental cycles but inject running buffer instead of analyte solution [1]. Their implementation serves critical functions in experimental design:

- Surface Priming: Start-up cycles "prime" the sensor surface by exposing it to initial flow and regeneration conditions, stabilizing the ligand environment before actual data collection begins [1].

- System Equilibration: These cycles allow the fluidics system to stabilize after buffer changes or cleaning procedures, minimizing the pump stroke waviness that occurs during buffer transition periods [1].