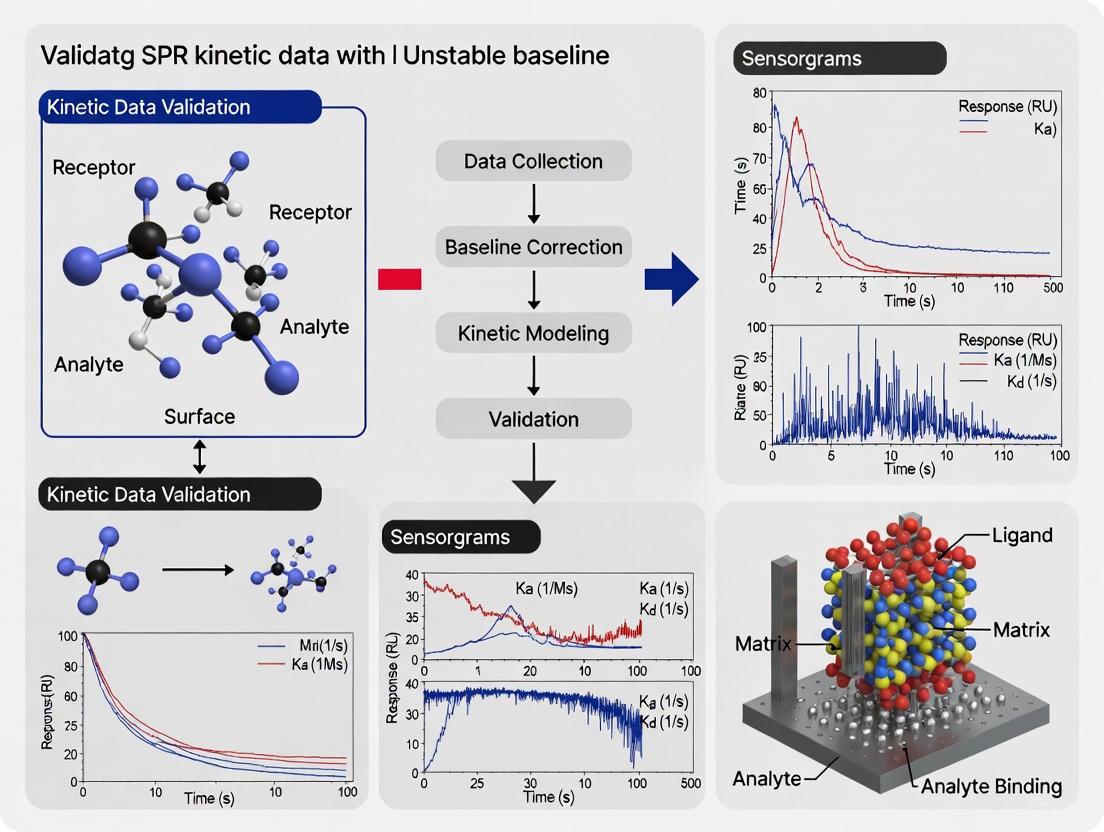

Validating SPR Kinetic Data Despite Unstable Baselines: A Troubleshooting and Optimization Guide

Unstable baselines in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments pose a significant challenge, potentially compromising the accuracy of kinetic data.

Validating SPR Kinetic Data Despite Unstable Baselines: A Troubleshooting and Optimization Guide

Abstract

Unstable baselines in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments pose a significant challenge, potentially compromising the accuracy of kinetic data. This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for identifying, troubleshooting, and validating data collected under unstable baseline conditions. Covering foundational principles, methodological adjustments, systematic optimization, and robust validation techniques, this guide offers practical strategies to ensure data reliability and confidence in kinetic parameters for critical applications in drug discovery and biomolecular interaction analysis.

Understanding SPR Baseline Instability: Root Causes and Impact on Data Integrity

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) analysis, a sensorgram provides real-time, label-free monitoring of molecular interactions. The baseline—the initial flat portion of the sensorgram before analyte injection—serves as the critical reference point from which all binding events are measured. Baseline drift refers to the gradual increase or decrease of this signal when no analyte is present, representing a significant source of experimental artifact that can compromise data integrity [1] [2]. For researchers validating SPR kinetic data, particularly in unstable baseline conditions, recognizing and correcting for baseline drift is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental prerequisite for obtaining reliable kinetic parameters (kₐ, kₑ, and Kᴅ). Uncorrected drift can distort binding curves, leading to inaccurate calculation of association and dissociation rates, ultimately affecting conclusions about binding affinity and mechanism [3]. This guide examines the symptomatic presentation of baseline drift across SPR platforms and provides methodologies for its identification and correction within the context of rigorous kinetic data validation.

Recognizing Visual Symptoms in Sensorgrams

The manifestation of baseline drift can vary from subtle, slow deviations to pronounced, directional trends. The following table categorizes the primary visual symptoms observed in sensorgrams and their immediate implications for data quality.

Table 1: Symptom Profiles of Common Baseline Drift Types

| Symptom Profile | Visual Description | Impact on Sensorgram | Common Causes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upward Drift | Gradual, often linear increase in Response Units (RU) before analyte injection [4]. | Overestimation of binding response and complex stability; can inflate Rmax values [3]. | Slow surface equilibration, ligand leaching from a capture surface, contamination [1] [3]. |

| Downward Drift | Gradual, often linear decrease in RU during the dissociation phase or pre-injection baseline [4]. | Underestimation of binding response and complex stability; can skew dissociation rate calculations [3]. | Surface dehydration, ligand instability, buffer mismatch, or air bubbles in the fluidic system [1] [4]. |

| Start-up Drift | A pronounced drift immediately after initiating flow or docking a new chip, which levels off after 5-30 minutes [1]. | Makes the initial baseline unreliable as a reference point, affecting all subsequent binding cycles. | Rehydration of the sensor surface, wash-out of immobilization chemicals, or temperature equilibration [1]. |

| Post-Regeneration Drift | Failure of the baseline to return to the original pre-injection level after a regeneration step [5]. | Causes carryover effects between analysis cycles, leading to inconsistent analyte binding responses. | Incomplete regeneration (leaving residual analyte) or overly harsh regeneration damaging the ligand [6] [5]. |

Quantitative Characterization of Drift

Beyond visual inspection, quantifying the rate and magnitude of drift is essential for determining its severity and for applying mathematical corrections during data analysis.

Measuring Drift Magnitude and Rate

The most straightforward metric is the drift rate, expressed in Resonance Units per minute (RU/min). This is calculated by measuring the total change in RU (ΔRU) over a defined time period (Δt) during a stable, analyte-free baseline region [3]:

Drift Rate (RU/min) = ΔRU / Δt

For kinetic analysis to be considered reliable, the total drift over the duration of a single analyte injection cycle should be negligible compared to the specific binding signal. As a general guideline, a drift rate that contributes to less than 5% of the Rmax value for that interaction is often considered acceptable, though this threshold depends on the specific affinity and signal strength of the system.

Data Analysis and Modeling Approaches

Modern SPR analysis software incorporates models to account for drift. The Langmuir with Drift model, for instance, is specifically designed for experiments using capture surfaces where ligand loss causes a linear, time-dependent signal change [3]. This model fits the baseline drift as a constant linear variable in addition to the standard kinetic parameters, thereby deconvoluting the drift artifact from the true binding signal. Judging the quality of the fit, often by examining the chi-squared (χ²) value, is crucial for validating that the model adequately accounts for the observed drift [3].

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosis and Validation

A systematic experimental approach is key to diagnosing the root cause of baseline drift and validating kinetic data acquired under potentially unstable conditions.

Baseline Stability Assessment Protocol

This protocol evaluates the intrinsic stability of the SPR system and surface prior to any kinetic experiment.

- Surface Preparation: Dock a clean sensor chip and prime the system with degassed, filtered running buffer [1] [5].

- Initial Equilibration: Flow running buffer at the intended experimental flow rate for 30-60 minutes, monitoring the baseline continuously [1].

- Data Collection: Record the baseline response without any injections. Note the drift rate (RU/min) over the final 20 minutes.

- Acceptance Criterion: A system is considered stable for high-quality kinetics if the baseline exhibits a drift of < 1.0 RU/min over this period [1].

Diagnostic Run for Kinetic Validation

When analyzing an interaction with a suspected unstable baseline, the following modified kinetic experiment is recommended.

- Start-up Cycles: Incorporate at least three "start-up" or "dummy" cycles at the beginning of the method. These cycles should use buffer injections instead of analyte over the ligand surface, including any regeneration steps. Their purpose is to condition the surface and stabilize the system; these cycles are not used in the final analysis [1].

- Extended Dissociation: For interactions with slow off-rates, include a long dissociation phase (e.g., 1-2 hours) following a mid-range analyte concentration injection.

- Blank Referencing: Intersperse regular blank (buffer) injections throughout the analyte concentration series. These are critical for double referencing—a data processing step that subtracts both signal from a reference flow cell and systemic artifacts from the buffer injection itself [1].

- Data Processing:

- Double Referencing: Subtract the reference surface data and then the average blank injection response from all analyte sensorgrams [1].

- Model Fitting: Fit the processed data to both the standard Langmuir model and the Langmuir with Drift model. Compare the chi-squared (χ²) values and the residual plots. A significantly better fit with the drift model, along with random (non-systematic) residuals, validates the use of drift correction for that data set [3].

The logical workflow for a systematic diagnosis is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for experiments focused on diagnosing and mitigating baseline drift.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Baseline Drift Management

| Tool | Function in Drift Management | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh Running Buffer (e.g., HBS-EP, PBS) [1] [7] | Maintains a stable refractive index; old or contaminated buffer is a primary cause of drift. | Prepare fresh daily, 0.22 µm filter and degas thoroughly before use [1]. |

| Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5, NTA, SA) [7] [6] | Provides a stable surface for ligand immobilization. Chip type impacts surface equilibration time. | Allow sufficient time for surface hydration and equilibration with running buffer after docking [1]. |

| Regeneration Buffers (e.g., Glycine-HCl pH 1.5-3.0, 10-50 mM NaOH) [7] [6] | Resets the baseline by removing bound analyte without damaging the ligand. | Must be optimized for each ligand-analyte pair to balance completeness of regeneration with ligand activity preservation [6]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., Ethanolamine, BSA) [7] [5] | Reduces non-specific binding (NSB) to the sensor surface, a potential source of drift. | Apply after ligand immobilization to block unreacted functional groups on the sensor surface [5]. |

| Detergents & Additives (e.g., Surfactant P20, Tween-20) [7] [6] | Minimizes NSB by disrupting hydrophobic and charge-based interactions. | Use at low concentrations (e.g., 0.005% P20) in running buffer to reduce drift from NSB [7] [6]. |

| Software with Drift Correction (e.g., ProteOn Manager) [3] | Mathematically corrects for linear drift during data analysis, validating kinetic parameters. | Use models like "Langmuir with Drift" for a more accurate fit when residual drift is present post-referencing [3]. |

Cross-Platform Comparison of Drift Artifacts

The manifestation and impact of baseline drift can be influenced by the specific SPR instrument and its fluidics. The table below provides a generalized comparison of how drift management is approached across different experimental setups.

Table 3: Approach to Baseline Drift Across SPR Contexts

| Experimental Context | Typical Drift Profile | Recommended Correction Strategy | Data Validation Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biacore-style Systems (Multi-channel) | Start-up drift; differences in drift rates between active and reference surfaces [1]. | Double referencing; use of a dedicated, untreated reference flow cell [1]. | After referencing, residual systematic errors in residuals indicate inadequate drift compensation. |

| Capture-Based Assays (e.g., His-tag / NTA) | Linear, continuous downward drift due to ligand loss from the capture surface [3]. | Use of "Langmuir with Drift" kinetic model in data fitting [3]. | The fitted drift rate should be consistent across all analyte concentrations for the model to be valid. |

| Single-Cycle Kinetics | Potential for progressive drift to accumulate over multiple, sequential analyte injections. | Inclusion of blank injections within the cycle and careful pre-equilibration [1]. | Compare the pre-injection baseline for each injection to quantify accumulated drift. |

| High-Throughput Screening | Variability in drift between different ligand spots or channels. | Robust referencing and normalization to internal controls are critical. | The z'-factor for the assay should be calculated incorporating baseline noise and drift to assess quality. |

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensing, the integrity of kinetic data is paramount for accurate determination of biomolecular interactions in drug discovery and basic research. A stable baseline is the foundational prerequisite for reliable data, serving as the indicator of system equilibrium before analyte introduction. Instabilities in the baseline—manifesting as drift, injection spikes, or high buffer noise—directly compromise the accuracy of extracted kinetic parameters (association rate k_on, dissociation rate k_off, and equilibrium dissociation constant K_D). This guide provides a systematic framework for researchers to diagnose the root causes of baseline instability, categorizing them into surface, buffer, and instrumental origins, and offers validated experimental protocols for effective troubleshooting and data validation [8].

The SPR Sensorgram: A Diagnostic Blueprint

A well-defined sensorgram provides the real-time signature of a binding interaction and the first clues for diagnosing issues. The initial phase is the baseline, established by flowing a running buffer over the sensor surface. A flat, stable baseline confirms system equilibrium. Any deviation indicates potential problems requiring investigation. The subsequent phases—association (analyte binding), steady-state (binding equilibrium), dissociation (analyte wash-off), and regeneration (surface preparation for a new cycle)—are all interpreted relative to this initial baseline [8].

The following diagram illustrates the ideal sensorgram phases and common instability signatures that point to specific problem categories.

Systematic Diagnostic Framework

A systematic approach to diagnosing baseline issues efficiently isolates the root cause. The following workflow guides users from initial observation to targeted resolution.

Experimental Protocols for Cause Isolation

Protocol 1: Buffer Mismatch and Purity Test

- Objective: To isolate buffer-related causes from surface or instrumental factors.

- Method: Perform multiple, consecutive injections of the running buffer alone (with no analyte) over a freshly prepared and stabilized sensor surface [8].

- Expected Result: A flat, stable baseline with minimal noise (<1-2 Resonance Units (RU) deviation).

- Diagnostic Interpretation:

- If the baseline is stable: The buffer system and instrument are not the primary causes. Underlying surface chemistry or analyte-specific issues (e.g., non-specific binding) are more likely.

- If instability persists: The problem lies with the buffer or the instrument. Proceed to degas and filter all buffers (0.22 µm filter) to remove air bubbles and particulates. Ensure the running buffer and sample buffer are perfectly matched in composition, pH, and salt concentration.

Protocol 2: Surface Integrity and Immobilization Stability Test

- Objective: To evaluate the stability of the ligand immobilization and the sensor surface itself.

- Method: Dock a new sensor chip with a bare surface or a freshly immobilized ligand. Condition the surface with multiple short injections of a regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.0-2.5), followed by extensive re-equilibration in running buffer [8] [9].

- Expected Result: The baseline should return to its original position after each regeneration cycle, demonstrating a stable and reusable surface.

- Diagnostic Interpretation:

- If the baseline is stable and recovers fully: The surface chemistry is robust.

- If the baseline shows irreversible drift or poor recovery: The ligand may be degrading, the coupling chemistry may be unstable, or the sensor surface may be contaminated. Consider optimizing the immobilization level, using a different coupling chemistry, or employing a more stringent blocking agent to reduce non-specific binding.

Protocol 3: Instrumental and Fluidic System Diagnostic

- Objective: To identify hardware-related issues, such as clogging, bubbles, or temperature fluctuations.

- Method: Run the instrument's built-in priming and cleaning procedure. Then, test the system with a blank buffer flow across multiple independent flow cells or channels [10].

- Expected Result: All flow cells should exhibit identical, stable baseline responses.

- Diagnostic Interpretation:

- If instability is localized to one flow cell: A clog or a bubble is likely present in that specific microfluidic path.

- If instability is consistent across all flow cells: A systemic instrumental issue is probable, such as a failing pump, a leak in the fluidic system, or an unstable temperature controller. Consult the instrument's service manual.

Quantitative Data Comparison of Common Issues

The table below summarizes the characteristic signatures, diagnostic tests, and solutions for the three primary categories of baseline instability.

Table 1: Systematic Diagnosis of Baseline Instability Causes

| Problem Category | Characteristic Sensorgram Signature | Key Diagnostic Test | Most Effective Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Causes | Gradual, irreversible downward drift after regeneration; slow stabilization; high binding in reference cell [8] [9] | Surface Integrity Test (Protocol 2) | Optimize ligand density; use different coupling chemistry; improve surface blocking with inert proteins [9]. |

| Buffer Causes | Sharp injection spikes; increased baseline noise (>"chatter"); steady upward/drift during buffer flow [8] | Buffer Mismatch Test (Protocol 1) | Degas and filter all buffers; ensure perfect match between running and sample buffer; use high-purity reagents. |

| Instrumental Causes | Consistent drift across all flow cells; large, sudden signal jumps (bubbles); complete signal dropout [10] | Instrumental Diagnostic Test (Protocol 3) | Execute system prime and purge; inspect for fluidic leaks or clogs; verify instrument temperature stability. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful SPR experimentation and troubleshooting rely on a set of core reagents and materials. The following table details key items for surface preparation, analysis, and regeneration.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SPR

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip (or equivalent) | A gold sensor surface with a carboxymethylated dextran matrix that facilitates ligand immobilization via amine coupling [9]. | The standard choice for most applications; other chips (e.g., lipophilic, nitrilotriacetic acid) are available for specific needs like membrane protein studies [11]. |

| HEPES-NaCl Buffer (HBS-EP) | A standard running buffer (e.g., 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% surfactant P20, pH 7.4) for conditioning and maintaining the sensor surface [8]. | The surfactant reduces non-specific binding. Buffer must be degassed and filtered (0.22 µm) before use to prevent air bubbles and particulates. |

| NHS/EDC Mixture | A mixture of N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and N-ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) used to activate carboxyl groups on the sensor chip surface for covalent amine coupling of ligands [9]. | Fresh preparation is recommended for optimal activation efficiency. |

| Ethanolamine Hydrochloride | A blocking reagent used to deactivate and quench any remaining activated ester groups on the sensor surface after ligand immobilization, minimizing non-specific binding [9]. | A critical step to ensure a stable, non-reactive surface post-immobilization. |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-2.5) | A low-ppH regeneration solution used to break the binding interaction between the ligand and analyte, effectively "resetting" the sensor surface for a new analysis cycle [8]. | The exact pH and composition must be optimized for each specific ligand-analyte pair to ensure complete regeneration without damaging the immobilized ligand. |

A stable baseline is the cornerstone of valid SPR kinetic data. By applying this systematic diagnostic framework—differentiating between surface, buffer, and instrumental origins through targeted experimental protocols—researchers can efficiently troubleshoot their systems, minimize experimental artifacts, and significantly enhance the reliability of their biomolecular interaction data. This rigorous approach to data validation is indispensable for accelerating drug discovery and ensuring the accuracy of scientific conclusions.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for determining the kinetic parameters of biomolecular interactions, including the association rate constant (ka), dissociation rate constant (kd), and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD). However, the accuracy of these measurements is critically dependent on the stability of the baseline signal. Baseline drift, a gradual shift in the signal when no binding occurs, is a common artifact that can significantly skew derived kinetic parameters. Within the context of validating SPR kinetic data, understanding, identifying, and mitigating drift is essential for producing reliable and publication-quality data. This guide explores the impact of drift, provides protocols for its identification and correction, and compares these strategies against alternative experimental approaches.

What is Baseline Drift and What Causes It?

In SPR, the baseline is the signal recorded from the sensor surface when only the running buffer is flowing over it, representing a state of no binding activity. A stable baseline is fundamental for accurately measuring the response units (RU) change upon analyte injection.

Baseline drift is the phenomenon where this baseline signal unstablely increases or decreases over time instead of remaining constant. A good fit is characterized by a drift contribution of less than ± 0.05 RU s⁻¹ [12].

The primary causes of baseline drift include:

- Insufficient System Equilibration: The instrument and sensor surface are not fully stabilized before the experiment begins. This is a frequent cause of initial drift [12] [4].

- Buffer Incompatibility: Differences in temperature, composition, or degassing between the running buffer and the sample buffer can cause refractive index shifts and drift [5] [4].

- Surface Contamination or Incomplete Regeneration: Residual material buildup on the sensor surface over multiple injection cycles can alter the baseline [5].

- Environmental Factors: Fluctuations in ambient temperature or vibrations can introduce instrumental noise and drift [4].

How Drift Skews Kinetic Parameters

Baseline drift introduces a non-random error that the fitting algorithms for standard binding models (like the 1:1 Langmuir model) cannot account for. This leads to systematic inaccuracies in the calculated kinetic constants, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Impact of Baseline Drift on Key SPR Kinetic Parameters

| Kinetic Parameter | Impact of Upward Drift | Impact of Downward Drift |

|---|---|---|

| Association Rate Constant (ka) | Artificially inflated; the binding appears faster as the drifting baseline adds to the binding signal. | Artificially lowered; the binding appears slower as the drift subtracts from the binding signal. |

| Dissociation Rate Constant (kd) | Artificially lowered; the complex appears more stable because the upward drift counteracts the signal decrease from dissociation. | Artificially inflated; the complex appears less stable because the downward drift accelerates the apparent signal loss. |

| Equilibrium Dissociation Constant (KD) | Inaccurate; the overall affinity (KD = kd/ka) is skewed, typically resulting in an underestimated KD (falsely high affinity). | Inaccurate; the overall affinity is skewed, typically resulting in an overestimated KD (falsely low affinity). |

The following diagram illustrates the causal pathway of how drift originates and ultimately compromises data integrity.

Experimental Protocols for Detection and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Visual and Statistical Detection of Drift

A robust workflow for detecting drift combines visual inspection of sensorgrams with quantitative goodness-of-fit metrics.

Detailed Methodology:

- Visual Inspection: Before any data correction or fitting, examine the raw sensorgrams. Focus on the baseline regions immediately before analyte injection and during the final dissociation phase. A sloping line, rather than a flat one, indicates drift [13].

- Residuals Analysis: After fitting the data to a kinetic model (e.g., 1:1 binding), plot the residuals—the difference between the experimental data and the fitted curve.

- Interpretation: A good fit with no significant drift will show residuals randomly scattered around zero. A systematic pattern (e.g., a U-shape or a slope) in the residuals indicates that the model cannot account for the drift, and the fit is poor [12].

- Chi² (Chi-Squared) Value: The Chi² value is a statistical measure of the accuracy of the fit. While it increases with the number of curves fitted, a high Chi² value suggests a poor fit, which can be caused by significant drift or other artifacts [12].

Protocol 2: Mitigation and Correction Strategies

The most effective approach to drift is to prevent it through careful experimental design. The following protocol outlines key steps.

Detailed Methodology:

- Extended System Equilibration:

- Buffer Matching:

- Prepare the analyte samples in the exact same running buffer used in the instrument. This is critical to avoid bulk refractive index (RI) shifts and associated drift [6] [14].

- For analytes dissolved in DMSO, ensure the DMSO concentration is identical in all analyte samples and the running buffer [14].

- Instrument and Surface Maintenance:

- Degas Buffers: Always degas buffers to prevent the formation of air bubbles in the microfluidics, a common cause of baseline noise and drift [4].

- Proper Regeneration: Develop a regeneration scouting protocol to find conditions that completely remove bound analyte without damaging the ligand. Incomplete regeneration leads to carryover and a drifting baseline over multiple cycles [6] [5].

- Environmental Control: Place the instrument in a stable environment with minimal temperature fluctuations and vibrations [4].

- Data Processing:

- Double Referencing: This standard data processing technique involves subtracting both the signal from a reference flow cell (with no ligand or an irrelevant ligand) and the signal from a blank injection (buffer alone). This effectively corrects for systemic drift and bulk effects [12].

- Drift Correction in Software: Some analysis software allows for the inclusion of a drift parameter in the fitting model. This should be used as a last resort, and its contribution should be minimal. As one source states, "Fit the curves first without a drift component. Then add a drift component in the final fitting" [12].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Drift Mitigation

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Drift Mitigation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Matched Running Buffer | Prevents bulk refractive index shifts and associated drift by ensuring analyte and buffer composition are identical. | Use for dissolving/diluting the analyte and as the system running buffer [6] [14]. |

| Ethanolamine | Blocks unused active sites on the sensor surface after ligand immobilization, reducing non-specific binding that can cause drift. | Standard blocking agent for carboxymethylated dextran chips (e.g., CM5) after NHS/EDC coupling [5]. |

| Regeneration Buffer (e.g., Glycine pH 2.0) | Removes all bound analyte from the ligand surface between cycles, preventing carryover and baseline drift. | Must be optimized for each ligand-analyte pair to be effective without damaging the ligand [6] [14]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Acts as a blocking agent to reduce non-specific binding (NSB) to the sensor chip, a potential source of drift. | Typically used at 0.1-1% concentration in running buffer during analyte injections only [6]. |

| High-Salt Regeneration (e.g., 2 M NaCl) | A mild regeneration solution that disrupts electrostatic interactions to remove bound analyte. | An alternative to low-pH regeneration for sensitive ligands [14]. |

Comparison of Kinetic Methods Under Drift-Prone Conditions

The choice of kinetic method can influence a study's resilience to drift. The two primary methods, Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) and Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK), offer different advantages and vulnerabilities.

Table 3: Method Comparison: MCK vs. SCK in the Context of Drift

| Feature | Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) | Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Each analyte concentration is injected in a separate cycle, with a regeneration step in between [15]. | Increasing analyte concentrations are injected sequentially in a single, continuous cycle without intermediate regeneration [15]. |

| Advantages for Drift Management | - Individual fitting of cycles allows for diagnosis of drift in specific segments.- A buffer blank can be injected and subtracted from each cycle to correct for baseline drift [15]. | - Fewer regeneration steps reduce the risk of surface-based drift caused by incomplete regeneration or ligand damage [15]. |

| Vulnerabilities to Drift | - Cumulative surface damage or contamination over many regeneration cycles can cause progressive baseline drift [5]. | - A single, long run is more susceptible to system-wide drift (e.g., from temperature changes) affecting the entire dataset [15]. |

| Best Suited For | Interactions where a robust regeneration condition is available and the ligand surface is stable over many cycles. | Interactions where regeneration is difficult or damages the ligand, or for capture-based immobilization [15]. |

Baseline drift is not merely a cosmetic issue in SPR data but a significant source of systematic error that directly compromises the accuracy of kinetic parameters. Unchecked drift leads to miscalculated ka and kd values, resulting in a fundamentally skewed understanding of molecular affinity (KD). Through rigorous experimental practice—including thorough system equilibration, meticulous buffer matching, and proper surface regeneration—researchers can effectively mitigate drift. Furthermore, selecting the appropriate kinetic method and diligently using referencing techniques are critical for validating SPR data. In the broader context of a thesis on data validation, establishing and adhering to a strict protocol for identifying and correcting for baseline instability is a cornerstone of generating reliable, reproducible, and scientifically defensible kinetic data.

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) studies, particularly those focused on validating kinetic data amidst unstable baselines, the experimental setup phase is paramount. The integrity of pre-experimental choices—specifically in sensor chip selection, buffer formulation, and sample quality—directly dictates the robustness, reproducibility, and ultimate validity of the derived kinetic constants (association rate constant, ka; dissociation rate constant, kd; and equilibrium constant, KD). An unstable baseline is a frequent challenge that can stem from inadequate buffer compatibility, poor surface preparation, or sample impurities, leading to significant drift and compromising the accuracy of kinetic measurements [5] [16]. This guide objectively compares available options and provides foundational protocols to safeguard your data from these common pitfalls, ensuring that your kinetic analysis rests on a solid experimental foundation.

Sensor Chip Selection: A Comparative Guide

The sensor chip is the stage upon which biomolecular interactions occur. Its surface chemistry must be meticulously chosen to ensure proper ligand orientation, stability, and minimal non-specific binding, all of which are critical for obtaining clean data with a stable baseline [6] [5].

Comparative Analysis of Common Sensor Chips

Table 1: Comparison of key sensor chip types for SPR kinetics.

| Chip Type | Immobilization Chemistry | Ideal Ligand Type | Key Advantages | Limitations & Baseline Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM5 (Dextran) | Covalent (amine coupling) | Proteins, antibodies | High binding capacity; widely applicable | Prone to non-specific binding; dextran matrix can cause mass transport limitations and baseline drift if not properly blocked [6] [5] |

| NTA | Capture (His-tag) | His-tagged proteins | Controlled orientation; surface regenerable | Requires low imidazole; ligand leaching during runs can cause instability and inaccurate dissociation rates [6] [16] |

| SA (Streptavidin) | Capture (biotin) | Biotinylated molecules | High-affinity, stable capture; excellent orientation | High surface density can lead to avidity effects for multivalent analytes, distorting kinetic fits [6] |

| C1 / Flat Carboxyl | Covalent (amine coupling) | Large particles, cells | Minimal steric hindrance; no hydrogel | Lower binding capacity; more susceptible to non-specific binding on the flat surface, increasing noise [5] |

Experimental Protocol: Chip Surface Preparation and Validation

A standardized protocol for surface preparation is essential for minimizing baseline drift from the outset.

- Surface Cleaning/Activation: For covalent chips like CM5, inject a 1:1 mixture of EDC (N-ethyl-N'-(dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) for 5-7 minutes at a flow rate of 10 µL/min to activate the carboxyl groups [5].

- Ligand Immobilization: Dilute the ligand in a low-salt buffer at a pH 0.5 units below its isoelectric point (pI) to ensure a positive charge for efficient coupling to the activated surface. Inject until the desired immobilization level (Response Units, RU) is achieved. For kinetic studies, lower ligand densities (e.g., 50-100 RU for a 50 kDa protein) are recommended to minimize mass transport effects [6] [16].

- Surface Blocking: Inject 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 5-7 minutes to deactivate and block any remaining activated ester groups. This is a critical step to reduce non-specific binding and stabilize the baseline [5].

- Validation: Perform a buffer blank injection (0 nM analyte). A stable, flat baseline with minimal drift (< 5 RU over 5 minutes) and a small, square bulk shift indicates a well-prepared surface. Significant drift suggests incomplete blocking or buffer incompatibility [16].

Buffer Formulation and Optimization

The running buffer serves as the solvent environment for the interaction, and its composition is a frequent source of baseline instability and experimental artifacts [6] [5].

Key Buffer Components and Their Impact on Baseline Stability

Table 2: Critical buffer components, their functions, and optimization strategies to ensure stability.

| Component | Primary Function | Risk to Baseline & Kinetics | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffering Agent | pH Stability (e.g., HEPES, PBS) | Inadequate buffering can cause pH drift, altering binding kinetics and ligand activity. | Use 10-20 mM buffer concentration. Match the pH of analyte samples exactly to the running buffer [6]. |

| Salts (e.g., NaCl) | Maintain Ionic Strength | High salt can promote non-specific hydrophobic binding; low salt can increase electrostatic non-specific binding. | Titrate salt concentration (typically 150 mM NaCl). Use additives to shield charges if NSB is charge-based [6]. |

| Detergents (e.g., Tween-20) | Reduce Non-Specific Binding | Can coat the sensor surface or form micelles, causing baseline drift and signal suppression. | Use low, consistent concentrations (e.g., 0.005-0.01% v/v). Ensure it is present in both running buffer and analyte samples [6] [5]. |

| Carrier Proteins (e.g., BSA) | Blocking Agent | Can bind to the sensor surface or the ligand, increasing signal and drift. Inconsistent use between cycles causes major instability. | Use sparingly (e.g., 0.1 mg/mL BSA) and only in analyte samples, not during immobilization. Avoid if possible by optimizing other parameters [6]. |

Experimental Protocol: Buffer Scouting and Bulk Shift Correction

- Buffer Scouting: Prepare running buffer and analyte samples using the same stock solutions of all components to ensure perfect matching. A tell-tale "square" shape in the sensorgram at the start and end of injection indicates a bulk refractive index (RI) difference, often due to mismatched buffer composition [6].

- Reference Surface Subtraction: Always use a reference flow cell immobilized with an irrelevant ligand or a mock-coupled surface. The signal from this channel is automatically subtracted to correct for bulk RI shifts and instrument noise [6] [16].

- Additive Titration: If non-specific binding (NSB) is observed on the reference surface, systematically titrate additives like Tween-20 or BSA into the running buffer and analyte samples, starting from low concentrations (0.002% Tween-20, 0.1 mg/mL BSA) [6].

Sample Quality and Preparation

The quality of the interacting molecules is non-negotiable for reliable kinetics. Impurities or aggregates are a major source of instability and complex binding artifacts [5].

Essential Reagent Solutions for SPR Kinetics

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions and materials required for high-quality SPR experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function in SPR Experiment | Critical Specification for Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Pure Water | Solvent for all buffers and samples | ≥18 MΩ·cm resistivity to minimize particulate and organic contaminants. |

| Chromatography System | Post-purification of analyte and ligand | For size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to remove aggregates immediately before the experiment. |

| EDC/NHS Crosslinkers | Activation of carboxylated sensor surfaces | Freshly prepared or single-use aliquots to ensure efficient coupling. |

- Ethanolamine-HCl: Used to block the activated sensor surface after ligand immobilization, quenching remaining esters.

- Regeneration Solutions: Harsh buffers (e.g., low pH glycine, high salt, mild detergent) used to remove bound analyte without damaging the ligand. Must be empirically scouted [6].

- Serial Dilution Tools: Automated liquid handlers or reverse pipetting techniques are recommended to prepare an accurate analyte dilution series for kinetics, minimizing pipetting errors [6].

Experimental Protocol: Sample Quality Control and Concentration Series

- Sample Purification and Clarification: Purify the analyte using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) immediately prior to the SPR experiment to remove aggregates. Centrifuge all samples at >14,000 × g for 10 minutes and use the supernatant to remove particulates that can clog the microfluidics [5].

- Analyte Concentration Series: For kinetic analysis, a minimum of five analyte concentrations is recommended. The concentrations should span a range from 0.1 to 10 times the expected KD value to adequately define the association and dissociation phases [6] [16]. A serial dilution method should be used to maintain constant buffer composition across all concentrations.

- Positive Control: Include a well-characterized interaction (e.g., a known antibody-antigen pair) in the experimental run to verify instrument performance and surface functionality.

Integrated Workflow for Pre-Experimental Safeguards

The following diagram synthesizes the critical pre-experimental decisions and their interrelationships into a single, logical workflow designed to preemptively address unstable baselines and ensure kinetic data validity.

SPR Pre-Experimental Safeguards Workflow

This integrated approach ensures that the foundational elements of your SPR experiment are aligned to produce the most reliable kinetic data, providing a robust defense against the confounding effects of an unstable baseline.

Methodological Adjustments for Stable Baselines and Reliable Data Acquisition

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) technology has established itself as a gold-standard technique for directly measuring the kinetics of molecular interactions in real-time, providing crucial data on association rates (ka), dissociation rates (kd), and equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) [17]. These parameters are particularly vital in drug discovery and development, where understanding the precise binding characteristics of therapeutic candidates can determine success in clinical trials. The validation of SPR kinetic data becomes especially critical when working with systems exhibiting unstable baselines, which can compromise data integrity and lead to erroneous conclusions about binding behavior [18].

Unstable baselines in SPR experiments may arise from various sources, including instrumental drift, temperature fluctuations, buffer mismatches, or improper surface conditioning. Within the context of a broader thesis on validating SPR kinetic data with unstable baseline research, this guide objectively compares experimental design strategies that incorporate start-up cycles and blank injections to enhance data reliability. These methodological elements serve not merely as procedural formalities but as critical components for distinguishing specific binding signals from experimental artifacts, particularly when investigating challenging molecular interactions with fast kinetics that might otherwise yield false-negative results in traditional endpoint assays [17].

Theoretical Foundation: The Role of Start-up Cycles and Blank Injections

Start-up Cycles: Stabilizing the Measurement System

Start-up cycles, often referred to as system conditioning cycles, constitute the initial series of buffer injections performed before sample analysis. These cycles serve multiple essential functions in SPR experimental design:

- System Equilibration: Start-up cycles allow the instrument fluidics and sensor surface to reach thermal and chemical equilibrium with the running buffer, minimizing baseline drift during subsequent analyte injections [18].

- Surface Validation: Initial cycles verify the integrity and functionality of the immobilized ligand before valuable samples are introduced.

- Signal Stabilization: Modern SPR instruments, particularly high-throughput systems like those described by Carterra, require stable baselines for accurate kinetic measurements across hundreds or even thousands of interactions simultaneously [19].

The implementation of start-up cycles becomes particularly crucial when working with unstable baselines, as these preliminary cycles help identify whether instability originates from the experimental system itself rather than the molecular interaction under investigation.

Blank Injections: The Cornerstone of Signal Referencing

Blank injections, comprising running buffer or sample buffer without analyte, provide the reference signals necessary for proper data interpretation through a process termed "double referencing" [18]. This approach offers two critical functions:

- Bulk Refractive Index Correction: Blank injections account for signal contributions arising from minor differences in composition between running buffer and sample buffers [18].

- Non-specific Binding Assessment: Control injections help identify and quantify non-specific binding to the sensor surface or reference regions.

The strategic incorporation of blank injections throughout the experimental run, not merely at the beginning, enables researchers to account for temporal changes in baseline behavior, which is especially valuable when working with extended run times or complex sample matrices.

Table 1: Strategic Implementation of Start-up Cycles and Blank Injections

| Experimental Phase | Purpose | Recommended Practice | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Start-up Cycles | System equilibration & stabilization | 3-5 buffer injections before first sample | Reduces baseline drift; validates surface functionality |

| Interspersed Blank Injections | Double referencing & baseline correction | Regular intervals throughout experiment | Corrects for bulk shift; identifies non-specific binding |

| Pre-concentration Blank | Analyte-specific background | Blank matching sample buffer composition | Accounts for buffer-specific refractive index effects |

| Post-regeneration Blank | Surface integrity verification | After regeneration steps | Confirms successful regeneration without ligand damage |

Comparative Analysis of Experimental Strategies

Multi-Cycle Kinetics vs. Single-Cycle Kinetics

SPR experimental design offers several injection strategies, each with distinct advantages and limitations concerning baseline management and data validation:

Multi-Cycle Kinetics represents the most common approach, where each analyte concentration is injected in a separate cycle with regeneration steps between injections [20] [18]. This method provides several advantages for unstable baseline scenarios:

- Individual reference subtraction for each concentration

- Opportunity for baseline re-equilibration between injections

- Capacity to identify and exclude outliers without losing entire dataset

Single-Cycle Kinetics (kinetic titration) involves injecting increasing analyte concentrations sequentially without regeneration between steps [20] [18]. This approach offers particular benefits for systems with challenging regeneration requirements or ligand instability but presents different baseline considerations:

- Reduced total experiment time minimizes long-term drift

- Single baseline reference point for multiple concentrations

- Potential for cumulative baseline effects during consecutive injections

Table 2: Strategic Comparison of Injection Approaches for Unstable Baselines

| Parameter | Multi-Cycle Kinetics | Single-Cycle Kinetics | Steady-State Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Management | Individual correction per concentration | Global correction for all concentrations | Requires stable baseline throughout |

| Regeneration Impact | Frequent potential for baseline shifts | Minimal regeneration requirements | Dependent on dissociation characteristics |

| Data Validation | Internal replication through multiple cycles | Limited validation within single experiment | Direct measurement at equilibrium |

| Optimal Application | Interactions with stable regeneration | Difficult-to-regenerate ligands [20] | Fast-dissociating interactions (kd > 10-³ s⁻¹) [18] |

High-Throughput SPR Implementation

Advanced SPR platforms like Carterra's LSAXT instrument and SPOC technology enable unprecedented throughput, with capacity for up to 1,152 binding interactions in a single automated run [17] [19]. These systems present unique baseline challenges and solutions:

- Parallel Processing: High-throughput systems perform simultaneous measurements across multiple flow cells, requiring careful normalization of baseline behavior across all channels [19].

- Integrated Referencing: Modern SPR software incorporates automated referencing protocols that systematically employ blank injections throughout extended runs [19].

- Data Quality Metrics: Advanced analytics provide quantitative assessment of baseline stability as a key parameter for validating individual binding curves within large datasets.

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Data Validation

Comprehensive Start-up Cycle Protocol

The following detailed methodology ensures optimal system stabilization before sample analysis:

Initial System Preparation:

- Clean instrument according to manufacturer specifications using recommended solutions [18]

- Filter (0.22 µm) and degas all buffers to minimize air spikes and particulate contamination

- Equilibrate all solutions to experimental temperature

Surface Conditioning:

- Prime system with running buffer until stable baseline is achieved (±5 RU/min)

- Perform 3-5 initial start-up injections of running buffer using planned experimental flow rate and contact time

- Monitor baseline return after each injection; consistent performance indicates proper equilibration

Ligand Validation:

- Confirm immobilization level matches experimental design parameters

- Verify consistent ligand activity across all spots/channels through control analyte injection

Strategic Blank Injection Implementation

Incorporate blank injections systematically throughout the experimental workflow:

Pre-Analyte Blank Sequence:

- Inject running buffer as initial reference

- Follow with sample matrix buffer to identify buffer-specific effects

- Include at least two replicate blanks to establish reproducibility

Intra-Run Blank Monitoring:

- Insert blank injections after every 3-5 sample injections to monitor baseline stability

- Vary blank placement to avoid rhythmic patterns that might confound data interpretation

Data Processing Integration:

- Apply double referencing using both interspersed blanks and reference surface data [18]

- Validate referencing by confirming blank injections yield flat, response-free sensorgrams

Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced Baseline Stability

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SPR Experiments with Unstable Baselines

| Reagent/Chemical | Specification | Function in Experimental Design | Considerations for Unstable Baselines |

|---|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | Carboxymethylated dextran matrix [9] | Standard immobilization surface for amine coupling | Batch variability can affect baseline stability; pre-screening recommended |

| HBS-EP Buffer | 10mM HEPES, 150mM NaCl, 3mM EDTA, 0.05% surfactant P20 [9] | Standard running buffer for reduced non-specific binding | Surfactant concentration critical for minimizing drift; filter before use |

| NHS/EDC Mixture | 1:1 mixture of 0.4M NHS and 0.1M EDC [9] | Carboxyl group activation for covalent immobilization | Fresh preparation required; degradation increases baseline noise |

| Ethanolamine HCl | 1.0M, pH 8.5 [9] | Quenching reagent after immobilization | Proper pH essential for complete quenching without surface damage |

| Glycine-HCl | 10-100mM, pH 1.5-3.0 | Regeneration solution for surface stripping | Concentration optimization required to maintain ligand activity over cycles |

| Fatty Acid-Free BSA | 1-5% in running buffer | Blocking agent for reduced non-specific binding | Quality varies by supplier; impurities contribute to baseline instability |

Data Analysis and Interpretation Framework

Quality Assessment Metrics for Baseline Validation

Implement systematic quality control measures to validate kinetic data derived from experiments with initial baseline instability:

Baseline Stability Quantification:

- Calculate baseline drift rate (RU/min) during pre-analyte phase

- Establish acceptance criteria (typically <5 RU/min for kinetic analysis)

- Document stabilization time required after start-up cycles

Reference Channel Performance:

- Verify reference surface responses remain <5% of active surface signals

- Confirm consistent reference behavior throughout experimental run

- Identify and exclude data segments with reference channel anomalies

Blank Injection Validation:

- Quantify response variability between replicate blank injections

- Establish threshold for maximum acceptable blank response (<3 RU)

- Confirm blank sensorgrams lack characteristic binding shapes

Advanced Analytical Approaches for Challenging Data

When working with data affected by residual baseline instability despite optimized experimental design, several advanced analytical approaches can enhance data interpretation:

- Global Fitting Analysis: Simultaneously fit multiple concentrations with shared kinetic parameters to improve parameter confidence [19]

- Mass Transport Evaluation: Incorporate mass transport limitations into kinetic models when rapid binding kinetics are observed [21]

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Methods: Implement Bayesian approaches for robust parameter estimation with uncertainty quantification [21]

The integration of start-up cycles and strategic blank injections represents a foundational element in validating SPR kinetic data, particularly within research contexts addressing unstable baselines. By implementing the systematic approaches and comparative strategies outlined in this guide, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of kinetic parameters essential for informed decision-making in therapeutic development programs.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a label-free, real-time technology for monitoring biomolecular interactions, widely used in drug discovery and basic research [22] [17]. A fundamental challenge in SPR biosensing is distinguishing the specific binding signal from non-specific signals caused by instrumental drift, buffer mismatches, and non-specific binding to the sensor matrix [1] [23]. Effective referencing is not merely a data processing step but is critical for validating kinetic data, especially in experiments characterized by unstable baselines. Without proper compensation, these artifacts can lead to significant errors in the determination of kinetic parameters (ka, kd) and equilibrium constants (KD), undermining the validity of the research [24] [16].

Drift, often observed as a gradual baseline shift, is frequently a sign of a non-optimally equilibrated sensor surface. This can occur after docking a new sensor chip, following immobilization procedures, or after a change in running buffer [1]. In the context of kinetic data validation, uncompensated drift directly compromises the integrity of the dissociation phase, leading to inaccurate calculation of the dissociation rate constant (kd) [24] [16]. Similarly, bulk refractive index (RI) effects from buffer mismatches can mask the true association kinetics. Therefore, implementing robust referencing techniques is a foundational prerequisite for generating reliable and kinetically meaningful SPR data.

Comparing Referencing Techniques for Drift Compensation

Several referencing strategies are employed in SPR to compensate for non-specific effects. The choice of technique directly impacts the quality of the resulting sensorgrams and the confidence in the fitted kinetic parameters. The table below summarizes the core principles and limitations of common methods.

Table 1: Comparison of SPR Referencing and Drift Compensation Techniques

| Technique | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Impact on Kinetic Data Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Reference Subtraction | Subtract signal from a separate reference flow cell. | Compensates for bulk refractive index shifts and system noise [23]. | Does not correct for baseline drift or differences between channels [1]. | Limited utility for validating data with unstable baselines; kd values susceptible to drift artifacts. |

| Blank Buffer Subtraction | Subtract sensorgram from a blank (buffer) injection. | Simple to implement. | Ineffective for drift occurring between injections; does not account for bulk effects during analyte injection. | Does not reliably improve kinetic parameter confidence. |

| Double Referencing | 1. Subtract reference flow cell signal.2. Subtract blank injection sensorgram [25]. | Comprehensively compensates for bulk RI, drift, and channel differences [25] [1]. | Requires careful experimental design with evenly spaced blank injections. | Gold standard for producing clean data; essential for accurate ka and kd determination in drift-prone systems [16]. |

| In-Line Referencing | Use a reference surface with an immobilized, non-interacting ligand. | Better matches the physicochemical properties of the active surface. | Challenging to find a suitable ligand and immobilize it at a matched density [23]. | Can reduce but not eliminate all non-specific signals and drift. |

As illustrated, double referencing stands out as the most comprehensive strategy. It is a two-step process that first removes the bulk effect via a reference surface and then compensates for residual drift and inter-channel differences using blank injections [25]. This technique is highly recommended for rigorous kinetic analysis as it directly addresses the sources of noise that can invalidate a kinetic model fit.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Double Referencing

A successful double referencing experiment requires careful planning in both the experimental setup and the data processing workflow. The following section provides a detailed methodology.

Experimental Design and Setup

- Surface Preparation: Immobilize your ligand on the active flow cell. Create a reference surface that closely mimics the active surface. For a carboxylated dextran chip, this typically involves activating and then deactivating the surface with ethanolamine, resulting in a surface with hydroxyl groups that is less negatively charged [23]. For more advanced in-line referencing, immobilize a non-interacting protein (e.g., BSA or a non-specific IgG) at a density similar to the ligand of interest to match volume exclusion effects [23].

- Buffer Matching: Ensure the running buffer and the analyte dilution buffer are perfectly matched to minimize bulk refractive index shifts. Dialyzing the analyte into the running buffer is the most effective method [23].

- System Equilibration: After docking the chip or changing buffers, prime the system extensively and allow the baseline to stabilize. Drift can be minimized by flowing running buffer until a stable baseline is obtained, which can take 5-30 minutes or even overnight for new surfaces [1].

- Incorporating Blank and Start-up Cycles:

- Add at least three start-up cycles at the beginning of the method. These cycles should inject buffer instead of analyte but include any regeneration steps. Their purpose is to "prime" the surface and stabilize the system; they are not used in the final analysis [1].

- Incorporate blank injections (running buffer only) evenly throughout the experiment. It is recommended to have one blank cycle for every five to six analyte cycles, including one at the end. These blanks are crucial for the second step of double referencing [1].

Data Processing Workflow

The data processing procedure for double referencing follows a sequential path to yield a fully referenced sensorgram ready for kinetic analysis. The workflow can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Double referencing data workflow.

The steps outlined in the diagram are executed as follows [25]:

- Zero in Y: Select a small timeframe just before the injection start and set the response to zero for all curves. This overlays the curves relative to a common baseline.

- Align to Injection Start (Zero in X): Align the sensorgrams so that the injection start is defined as t=0. This corrects for small phase differences between flow cells.

- Crop Data: Remove all unwanted parts of the sensorgram, such as stabilization periods, washing, or regeneration steps, focusing only on the relevant association and dissociation phases.

- Reference Subtraction: Subtract the sensorgram from the reference flow cell from the sensorgram of the active ligand flow cell. This is the first critical step that removes the bulk refractive index signal and some system noise.

- Blank Subtraction: Subtract the sensorgram from a blank (buffer) injection from all analyte injection sensorgrams. This second step compensates for residual baseline drift and differences between the reference and active channels, completing the double referencing process.

Validating Kinetic Data After Referencing

After processing data with double referencing, the resulting sensorgrams must be rigorously validated before trusting the fitted kinetic parameters.

Visual and Residual Inspection

The most effective way to assess the quality of a fit is through visual inspection [16].

- Fit Overlay: The fitted curve should closely follow the measured data throughout the association and dissociation phases [24].

- Residuals Plot: The residuals (difference between measured and fitted data) should be small and randomly distributed, indicating they are due to instrument noise and not a systematic deviation of the model. The noise level should not exceed the instrument's normal noise level, typically resulting in residuals below 1-2 RU [16]. Systematic patterns in the residuals indicate an inadequate model or poorly processed data.

Parameter Consistency Checks

After a visually acceptable fit is obtained, the calculated parameters should be checked for biological and experimental sense [16].

- Rmax: The calculated maximum response should be consistent with the theoretical Rmax based on the immobilized ligand level and the molecular weights of the ligand and analyte. A fitted Rmax that is very high compared to the actual responses can indicate a wrong model.

- Kinetic Constants: The association rate constant (ka) and dissociation rate constant (kd) should fall within the instrument's valid range (e.g., for a Biacore T200, ka is typically between 10³ and 10⁷ M⁻¹s⁻¹, and kd between 10⁻⁵ and 10⁻¹ s⁻¹) [24] [16].

- Self-Consistency: The equilibrium constant calculated from the ratio KD = kd/ka should be comparable to the value obtained from an equilibrium analysis of the steady-state response (Req) versus concentration [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for SPR Referencing

| Item | Function in Experiment | Application in Drift Compensation |

|---|---|---|

| Carboxylated Dextran Sensor Chip (e.g., CM5) | Standard matrix for ligand immobilization. | The reference surface is created by activating and deactivating a flow cell without ligand attachment. |

| Ethanolamine-HCl | Standard reagent for blocking remaining activated ester groups after amine coupling. | Used to prepare a deactivated reference surface, providing a chemically matched control. |

| BSA or non-specific IgG | Inert proteins. | Used to create an in-line reference surface with matched physical properties to the ligand surface, helping to compensate for volume exclusion effects [23]. |

| HBS-EP Buffer | Common running buffer (HEPES, Saline, EDTA, Polysorbate). | A well-defined, filtered, and degassed buffer is essential for minimizing baseline drift and bulk effects [1]. |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 1.5-3.0) | Regeneration solution. | Removes bound analyte from the ligand surface without damaging activity, allowing for multiple cycles and blank injections on the same surface [26]. |

In the pursuit of validated and reliable SPR kinetic data, particularly when dealing with unstable baselines, double referencing is an indispensable technique. It provides a robust methodological framework for compensating for the primary non-specific signals that plague SPR biosensing: bulk refractive index changes and instrumental drift. As demonstrated, its implementation requires careful experimental design, including the use of a matched reference surface and strategic blank injections, followed by a systematic data processing workflow. When combined with rigorous post-fitting validation through residual analysis and parameter checks, double referencing allows researchers to place a high degree of confidence in their reported kinetic parameters, thereby strengthening the conclusions drawn from SPR-based research in drug development and molecular interaction studies.

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) studies, particularly those focused on validating kinetic data with unstable baselines, the critical role of buffer management is often underappreciated. SPR is a powerful, label-free technology that measures biomolecular interactions in real-time by detecting changes in the refractive index at a metal surface [27]. It has become indispensable in drug discovery and basic research for determining the affinity and kinetics of molecular interactions [17] [9]. The sensitivity of this technique, however, makes it exceptionally vulnerable to experimental artifacts caused by improper buffer preparation. Air bubbles formed in non-degassed buffers can disrupt fluidics and create signal noise, while particulate matter can clog delicate microfluidic systems. More subtly, mismatches in buffer composition between running and sample buffers can cause profound baseline shifts due to bulk refractive index effects, potentially obscuring true binding signals and compromising kinetic data [28]. For researchers investigating complex systems with inherent instability, such as G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) or other membrane proteins, rigorous buffer protocols are not merely a best practice but a fundamental prerequisite for obtaining reliable, publishable data [11]. This guide objectively compares the performance impact of various buffer management strategies, providing the experimental data and methodologies needed to establish a robust foundation for SPR research.

The Critical Role of Buffer Management in SPR Data Quality

The exquisite sensitivity of SPR biosensors to changes in the refractive index (RI) is the very property that enables the detection of biomolecular binding events without labels. This same sensitivity, however, renders the technique susceptible to signal noise and drift stemming from inadequate buffer management. Three primary buffer-related issues can corrupt SPR data: bubbles, particulates, and refractive index mismatch.

Bubble Formation: Air bubbles precipitating within the microfluidic system or fluid cell of an SPR instrument cause sudden, massive spikes in the sensorgram due to the drastic difference in RI between liquid and gas phases. These events can permanently disrupt an experiment by introducing air-liquid interfaces that denature proteins or by blocking flow channels [28].

Particulate Contamination: Unfiltered buffers contain microscopic particles that can accumulate and clog the instrument's fluidic path, leading to increased backpressure, inconsistent flow rates, and unstable baselines. This compromises the delivery of analyte to the sensor surface and the accuracy of kinetic measurements.

Refractive Index Shifts: The most insidious problem is the bulk refractive index shift. This occurs when the composition of the buffer in the sample plug differs from that of the running buffer flowing through the instrument. Even minor differences in salt concentration, DMSO content, or other additives between the two buffers create a sharp, square-wave "injection peak" as the sample passes over the sensor surface. This artifact can mask the beginning of a binding reaction, complicate data analysis, and for weak binders, make accurate kinetic determination impossible. In the context of validating data from unstable proteins like GPCRs, where the baseline itself may be inherently drift-prone, such artifacts can render an experiment uninterpretable.

The following diagram illustrates how these buffer-related issues directly interfere with the SPR signal and the binding events under investigation.

Figure 1: Impact of Buffer Protocols on SPR Data Quality. This workflow illustrates how failures in degassing, filtration, or composition matching introduce artifacts that compromise kinetic data validation, a critical concern in studies with unstable baselines.

Experimental Protocols for Buffer Management

Standardized protocols are essential for minimizing experimental variability in SPR. The following sections detail the core methodologies for proper buffer preparation.

Buffer Filtration Protocol

Filtration removes particulate contaminants that can clog fluidic systems and increase noise.

- Materials: Cellulose acetate or polyethersulfone (PES) membrane filters with a 0.22 µm pore size are recommended for their low protein binding characteristics [28].

- Procedure: For small volumes (less than 50 mL), use a disposable syringe and an attached syringe filter. For larger volumes, use a vacuum filtration unit with a bottle-top filter. Filter the buffer directly into a clean, sterile container. The choice between cellulose acetate and PES may depend on the specific additives in the buffer; cellulose acetate is generally preferred for its broad compatibility.

Buffer Degassing Protocol

Degassing prevents bubble formation within the microfluidic cartridges and flow cells of the SPR instrument.

- Methods: Two primary methods are effective:

- Vacuum Degassing: Place the filtered buffer in a sealed vessel connected to a vacuum source. Apply a vacuum for approximately 15 minutes while gently stirring. This method reduces the dissolved oxygen content efficiently [28].

- Ultrasonic Bath Degassing: Submerge the sealed container of filtered buffer in an ultrasonic bath for approximately 15 minutes. The ultrasonic energy encourages microbubbles to coalesce and escape from the solution.

- Timing: For optimal results, buffers should be freshly filtered and degassed daily before use. Storing degassed buffers for extended periods allows gas to slowly re-dissolve [28].

Composition Matching Protocol

Matching the composition of the running buffer and the sample buffer (including the analyte dilution buffer) is critical to avoid bulk refractive index shifts.

- Procedure: The sample containing the analyte must be prepared through serial dilution or buffer exchange into the same running buffer that is flowing through the instrument. Dialysis or desalting columns can be used for buffer exchange if the analyte is stored in a different buffer.

- Critical Consideration: Pay close attention to the concentration of all components, including salts, detergents, and DMSO. For instance, when testing small molecule drugs dissolved in DMSO, the DMSO concentration in the running buffer must be precisely matched to that in the sample dilutions. Even a 0.5% difference can cause a significant injection peak.

Performance Comparison of Buffer Management Strategies

The following table summarizes the experimental outcomes and performance impact of implementing versus neglecting key buffer management protocols.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Buffer Management Strategies in SPR Analysis

| Management Factor | Experimental Outcome with Proper Protocol | Experimental Outcome with Neglected Protocol | Impact on Kinetic Data (ka, kd, KD) | Suitability for Unstable Baseline Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degassing | Stable baseline with minimal spike artifacts [28]. | Sudden, large signal spikes; erratic fluidics and potential protein denaturation from air-liquid interfaces [28]. | High Impact. Bubbles render specific sensorgrams unusable, reducing data points for kinetic fitting. | Unsuitable. Introduces unpredictable noise that confounds intrinsic baseline instability. |

| Filtration (0.22 µm) | Consistent flow rates and reduced non-specific binding [28]. | Increased backpressure, clogged fluidics, and drift from accumulated particulates. | Medium Impact. Clogging causes gradual signal drift, affecting equilibrium and steady-state analysis. | Unsuitable. Particulates compound baseline drift, complicating data validation. |

| Composition Matching | Clean injection profiles with minimal bulk RI shift, enabling clear observation of binding onset [17]. | Large injection peaks at start and end of sample injection, obscuring the initial binding phase. | Critical Impact. RI shifts mask early association (ka) and dissociation (kd) phases, corrupting kinetic fitting. | Essential. Separates buffer artifact from genuine signal drift, which is mandatory for validation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and reagents essential for implementing the buffer management protocols described in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for SPR Buffer Management

| Item | Function/Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 0.22 µm Cellulose Acetate Filter | Removal of particulate matter from buffers to prevent fluidic clogging. | Preferred for low protein binding, preserving the concentration of sensitive protein additives. |

| Vacuum Filtration Unit | Sterile filtration of large-volume (>100 mL) running buffers. | Enables efficient preparation of a single, consistent buffer batch for multi-cycle experiments. |

| Vacuum Degassing Apparatus | Removal of dissolved gases to prevent bubble formation in microfluidics. | More consistent and controllable than ultrasonic baths for a wide range of buffer compositions. |

| DMSO (Hybridoma Grade) | Solvent for small molecule analytes; requires precise matching in running buffer. | High-purity grade ensures low UV absorbance and contaminant levels that can foul sensor surfaces. |

| High-Purity Detergents | Maintaining solubility of membrane proteins like GPCRs in SPR analysis [11]. | Critical for stabilizing immobilized receptors; type and concentration must be matched exactly in all buffers. |

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A widely used SPR sensor chip with a carboxymethylated dextran matrix for ligand immobilization. | The quality and consistency of the gold film and surface functionalization are critical for reproducible results [27]. |

Integrated Workflow for Reliable SPR Kinetics

To achieve reliable kinetic data, especially with challenging targets, all buffer management steps must be integrated into a single, standardized workflow. The following diagram outlines this comprehensive experimental process, from buffer preparation to data acquisition, highlighting the points where specific artifacts are mitigated.

Figure 2: Integrated SPR Buffer Management Workflow. This comprehensive protocol ensures the preparation of high-quality buffers to minimize artifacts, forming the foundation for reliable kinetic analysis, particularly with unstable proteins.

Within the rigorous framework of validating SPR kinetic data, particularly for systems with unstable baselines such as those involving GPCRs [11] or transient biomolecular interactions [17], buffer management transcends routine preparation to become a critical experimental variable. As the comparative data in this guide demonstrates, neglecting protocols for degassing, filtration, and composition matching directly introduces artifacts that corrupt the primary kinetic measurements of association (ka) and dissociation (kd). The implementation of these protocols is a non-negotiable prerequisite for data integrity. By adopting the standardized methodologies and workflows outlined here—filtering with 0.22 µm membranes, rigorously degassing buffers, and exactly matching buffer compositions—researchers can eliminate significant sources of noise and error. This establishes a stable experimental foundation, enabling them to confidently distinguish true binding kinetics from experimental artifact and thereby accelerate reliable drug discovery and biological research.

In the rigorous field of drug discovery, the validity of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) kinetic data is foundational to candidate selection. SPR technology has established itself as a gold standard for directly measuring the association (ka) and dissociation (kd) rates of molecular interactions, providing essential parameters such as bound complex half-life (t1/2) and equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) [17]. However, a pervasive challenge in generating publication-quality data is the validation of results against artifacts introduced by an unstable instrument baseline, a pre-conditioning variable often relegated to the periphery of method sections. An unstable baseline can obscure true binding events, lead to inaccurate fitting of kinetic parameters, and ultimately compromise the selection of therapeutic candidates.

This guide objectively compares the performance of contemporary SPR platforms and experimental approaches, with a focused lens on their capacity to facilitate and maintain stable system equilibration. The broader thesis posits that without standardized start-up and conditioning procedures, even advanced high-throughput systems risk generating kinetic data that is not robust, particularly for the detection of weak or transient interactions that are critical for profiling therapeutic specificity [17]. We present experimental data and detailed protocols to equip researchers with the framework necessary to validate their SPR kinetic data, starting from the moment of system initiation.

Performance Comparison: Throughput, Sensitivity, and Stability

The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of several SPR-related technologies and configurations, highlighting aspects relevant to system stability and data quality.

Table 1: Comparison of SPR Technologies and Configurations

| Technology / Configuration | Key Feature | Reported Sensitivity | Throughput / Sample Consumption | Stability & Conditioning Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carterra LSA [19] | High-throughput kinetics via microfluidic printing | Not Specified | Up to 1,152 clones per run; minimal sample (e.g., 200 ng/clone) [19] | Microfluidic flow cells require precise priming and buffer equilibration; high flow rates for efficient capture. |

| SPOC Technology [17] | Cell-free protein synthesis directly on biosensor | Not Specified | ~864 protein ligand spots (high multiplex capacity) [17] | On-chip protein production minimizes surface handling variability; in-situ capture standardizes surface density. |

| ZnO/Ag/Si3N4/WS2 Sensor [29] | Novel nanomaterial architecture for cancer detection | 342.14 deg/RIU (Blood Cancer) [29] | N/A | Material layers (e.g., Si3N4) can protect the plasmonic metal (Ag), potentially improving baseline drift from oxidation. |

| Copper/MXene Sensor [30] | Cost-effective copper enhanced with MXene | 312° RIU−1 (Breast T2 model) [30] | N/A | Dielectric-MXene coatings impede copper oxidation, a key factor in long-term baseline stability. |

| Spectral Shaping Method [31] | Optical method to improve signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) | N/A | N/A | Reduces SNR difference at resonance wavelengths by ~70%, directly enhancing baseline consistency and measurement accuracy [31]. |

Experimental Protocols for System Validation

Protocol 1: Ligand Immobilization and Surface Stability Assessment

This protocol is foundational for ensuring a stable sensor surface, a prerequisite for reliable kinetic analysis. It is adapted from general SPR practices and specific studies documenting immobilization [9].

1. Surface Activation: