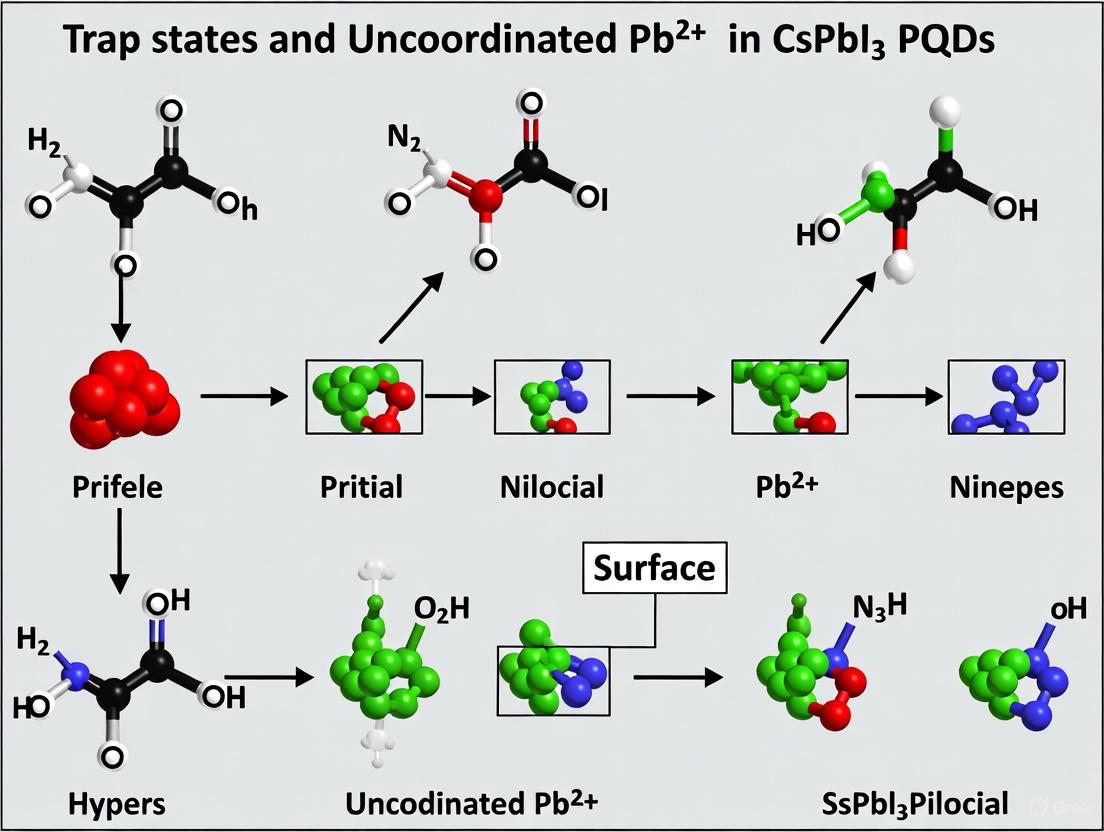

Unraveling and Controlling Trap States and Uncoordinated Pb2+ in CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dots for Advanced Optoelectronic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of defect engineering in CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), focusing on the origins and consequences of trap states and uncoordinated Pb2+ ions.

Unraveling and Controlling Trap States and Uncoordinated Pb2+ in CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dots for Advanced Optoelectronic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of defect engineering in CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), focusing on the origins and consequences of trap states and uncoordinated Pb2+ ions. We explore the fundamental nature of these defects, including the role of mobile ionic vacancies and surface ligand dynamics. The review covers advanced characterization techniques and a suite of ligand engineering strategies—from in-situ passivation to post-synthetic exchange—for effective defect suppression. We further evaluate the impact of defect management on the performance and stability of optoelectronic devices, such as solar cells and light-emitting diodes, providing a validated framework for optimizing CsPbI3 PQD-based technologies for research and development applications.

The Fundamental Nature of Defects in CsPbI3 PQDs: Origins and Impacts of Trap States and Uncoordinated Pb2+

In the pursuit of high-performance optoelectronic devices based on CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs), a profound understanding of intrinsic ionic defects is paramount. Among these defects, iodine vacancies (VIs) represent a critical class of point defects that significantly influence both the operational efficiency and long-term stability of devices. Their characteristically low formation and migration energies facilitate rapid ion movement under operational biases, leading to phenomena such as hysteresis, accelerated degradation, and the formation of trap states that promote non-radiative recombination [1] [2]. This technical guide delves into the atomic-scale dynamics of VIs, framing their behavior within the broader research context of mitigating trap states and passivating uncoordinated Pb2+ ions in CsPbI3 PQDs. A precise understanding of these defects is not merely academic; it is the foundation for developing robust strategies to enhance the commercial viability of perovskite-based technologies, from photovoltaics to memory devices and light-emitting diodes.

The Atomic-Scale Nature of Iodine Vacancies

Iodine vacancies are intrinsic point defects that form when an iodide ion (I⁻) is missing from its designated lattice site within the perovskite crystal structure of CsPbI3. The all-inorganic CsPbI3 perovskite adopts a cubic unit cell where corner-sharing [PbI6]4⁻ octahedra create a three-dimensional network, with Cs+ cations occupying the interstitial cavities [2]. The removal of an I⁻ ion creates a localized charge imbalance, effectively constituting a positive charge center within the lattice.

The formation energy for these vacancies is remarkably low, typically calculated to be in the range of 0.1–0.2 eV [1]. This low energy barrier means that VIs can form spontaneously during synthesis or under mild external stimuli such as heat, light, or electric fields. The prevalence of VIs is particularly pronounced in PQDs compared to their bulk counterparts. The high surface-to-volume ratio of quantum dots means a significant proportion of atoms reside on the surface, where the binding of passivating ligands is often weak. Long-chain insulating ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), commonly used in synthesis, can detach during purification, aging, or thermal annealing processes, leaving behind surface iodine vacancies [1] [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Iodine Vacancies (VIs) in CsPbI3 PQDs

| Property | Typical Value/Range | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy | 0.1 - 0.2 eV | The energy required to create a vacancy; low value indicates easy formation [1]. |

| Migration Energy | 0.1 - 0.6 eV | The energy barrier for vacancy movement through the lattice; low value enables high ionic conductivity [1]. |

| Primary Locations | Surfaces, Grain Boundaries | Regions of high energy and incomplete atomic coordination [1]. |

| Charge State | Positive | Results from the absence of a negatively charged I⁻ ion. |

Impact on Carrier Dynamics and Trap State Formation

The presence and migration of VIs have a direct and detrimental impact on the carrier recombination dynamics within CsPbI3 PQDs. Ab initio non-adiabatic molecular dynamics studies reveal that the exact influence of a VI is highly dependent on its position and the local atomic configuration.

- Surface VIs: Even when they do not create a new electronic state within the band gap, outermost layer VIs can significantly accelerate the electron-hole (e-h) recombination rate—by a factor of approximately 2 compared to a defect-free surface. This acceleration is primarily driven by the enhanced electron-phonon coupling induced by the vacancy, which facilitates non-radiative energy loss [3].

- Subsurface VIs and Pb-Dimers: When VIs occur just beneath the surface, the situation is more severe. These defects can create a localized hole-trapping state. This state enables the swift capture of holes from the valence band, subsequently accelerating their recombination with conduction band electrons by a factor of 6.5. In the specific case of Pb-dimer formations associated with VI complexes, this recombination rate can escalate dramatically, by a factor of 13 [3].

The critical link between VIs and the user's thesis context on trap states and uncoordinated Pb2+ is precisely this localized hole trapping. The formation of a VI leaves behind under-coordinated Pb2+ ions. These Pb2+ ions, lacking their full complement of I⁻ ligands, possess dangling bonds that introduce electronic states within the bandgap. These states act as efficient traps for charge carriers (electrons or holes). Once trapped, the carriers are much more likely to recombine non-radiatively, converting their energy into heat (lattice vibrations) rather than light or electrical current. This process severely diminishes the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of the PQDs and reduces the operational efficiency of devices such as solar cells and LEDs [3] [2].

Experimental Methodologies for Probing VI Dynamics

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

Objective: To indirectly prove that resistive switching is achieved by the migration of mobile iodine vacancies under an electric field to form conductive filaments (CFs) [1].

- Protocol:

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate a metal-semiconductor-metal device with a structure such as Ag/CsPbI3 PQDs/ITO.

- Measurement Setup: Apply a small AC voltage signal (typically 10-50 mV) over a range of frequencies (e.g., 1 Hz to 1 MHz) across the device while it is held at a specific DC bias.

- Data Analysis: Model the resulting impedance spectrum using an equivalent circuit. The response, particularly at low frequencies, is sensitive to ionic motion. The observed changes in the impedance under different bias conditions can be correlated with the formation and rupture of VI-based conductive filaments, providing evidence of ion migration as the core mechanism behind resistive switching [1].

2In SituConductive Atomic Force Microscopy (c-AFM)

Objective: To directly visualize the formation and growth of conductive filaments (CFs) and correlate them with the multilevel resistance states observed in devices [1].

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Deposit a thin film of CsPbI3 PQDs on a conductive substrate (e.g., ITO).

- Scanning and Biasing: Use a conductive AFM tip as a mobile top electrode. Scan the topography of the PQD film in standard AFM mode to identify grain interiors (GIs) and grain boundaries (GBs).

- Current Mapping: Apply a localized bias to the tip at specific points on the film while simultaneously measuring the current flowing through the tip. This allows for the creation of a spatial current map.

- Filament Visualization: The c-AFM images reveal that CFs preferentially initiate at GBs, where VI concentration and mobility are higher, before propagating into the GIs. This two-stage growth pathway, with distinct activation energies for each stage, directly explains the intrinsic multilevel resistive states in the WORM memory devices [1].

3Ab InitioNon-Adiabatic Molecular Dynamics

Objective: To theoretically investigate the role of surface VI defects on carrier recombination dynamics and evaluate passivation strategies [3].

- Protocol:

- Model Construction: Create computational models of pristine and defective CsPbI3 perovskite surfaces, introducing VIs at various positions (outermost layer, subsurface) and configurations (including Pb-dimers).

- Dynamics Simulation: Perform non-adiabatic molecular dynamics calculations to simulate the motion of atoms and the coupled evolution of electronic states over time.

- Rate Calculation: Compute the rate of electron-hole recombination for each model system. Compare the rates for defective surfaces against the pristine benchmark to quantify the impact of specific VI configurations.

- Passivation Modeling: Introduce passivating molecules (e.g., the Lewis base HCOO⁻) into the model and simulate their binding with under-coordinated Pb2+ sites. Recalculate the recombination rates to validate the efficacy of the passivation strategy [3].

Harnessing and Mitigating VI Effects in Functional Devices

WORM Memory Devices

The intrinsic property of VI migration can be harnessed for novel electronic applications. In a Write-Once-Read-Many (WORM) memory device with a simple Ag/CsPbI3 PQDs/ITO structure, the migration of VIs under an electric field leads to the formation of stable conductive filaments (CFs), causing a permanent resistive switch [1].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of a CsPbI3 PQD-Based WORM Memory Device [1]

| Performance Parameter | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| ON/OFF Ratio | 10³ : 10² : 1 (fLRS:IRS:HRS) | High ratio allows for clear differentiation between multiple memory states. |

| Retention Time | > 10⁴ seconds | Demonstrates non-volatile, long-term data storage capability. |

| Set Voltages | ~1.0 V (Vset1), ~2.0 V (Vset2) | Distinct voltages enable reliable multilevel operation. |

| Switching Mechanism | Migration of Iodine Vacancies (VIs) | Leverages an intrinsic "defect" for a useful function. |

The multilevel capability (ternary states) arises from the different activation energies for VI migration at grain boundaries versus grain interiors, leading to two distinct pathways for conductive filament growth, as directly visualized by in situ c-AFM [1].

Defect Passivation Strategies

For applications where VI migration is detrimental, such as solar cells and LEDs, effective passivation is essential. The primary target is the uncoordinated Pb2+ ions associated with the VIs.

- Ligand Engineering: Exchanging weakly bound long-chain ligands (OA/OAm) with shorter, bidentate ligands that have a stronger affinity for the PQD surface is a key strategy. For instance, short choline ligands in a tailored solvent like 2-pentanol can effectively remove insulating ligands without introducing new halogen vacancy defects, enhancing conductivity and passivating surfaces [4]. Similarly, molecules like 2-aminoethanethiol (AET) bind strongly to under-coordinated Pb2+ via thiolate groups, forming a dense passivation layer that significantly improves stability against water and UV light [2].

- Lewis Base Passivation: The introduction of Lewis base molecules, such as formate (HCOO⁻), is highly effective. These molecules form stable Pb–O bonds with the lead ions on the surface, which prevents the reconstruction of surface VIs (e.g., via iodine migration) and the formation of Pb-dimers. This passivation successfully reduces the deleterious electron-phonon coupling, restoring carrier recombination dynamics to a level comparable to that of a defect-free surface [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CsPbI3 PQD Synthesis and VI Study

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Precursor (e.g., Cs₂CO₃) | Source of Cs+ cations for the perovskite lattice. | Typically combined with oleic acid at high temp to form Cs-oleate [1]. |

| Lead Iodide (PbI₂) | Source of Pb²⁺ and I⁻ ions for the perovskite framework. | High purity is critical for controlling defect density. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Long-chain surface ligands for colloidal stabilization and growth control. | Weak binding to iodine leads to surface VI formation; source of instability [1] [2]. |

| 2-Pentanol | A protic solvent for post-synthetic ligand exchange. | Tailored dielectric constant and acidity maximize insulating ligand removal without creating new VIs [4]. |

| Short Ligands (e.g., Choline, AET) | Post-treatment passivants to replace OA/OAm. | Improve charge transport and passivate uncoordinated Pb2+ sites, reducing trap states [4] [2]. |

| Lewis Base Passivators (e.g., HCOO⁻) | Molecular passivants for surface VIs and uncoordinated Pb²⁺. | Form strong coordinate bonds with Pb²⁺, suppressing ion migration and non-radiative recombination [3]. |

Iodine vacancies, with their inherently low migration energy, are a double-edged sword in CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dots. They are fundamental drivers of ionic conductivity that can be exploited in memory devices but are also a primary source of trap states, inefficient carrier recombination, and material instability. The path toward high-performance, stable optoelectronic devices lies in a nuanced understanding and precise control of these defects. This involves strategically harnessing their properties for specific functions like resistive switching while aggressively passivating them through advanced ligand and molecular strategies to mitigate their detrimental impacts in photonic and photovoltaic applications. Continued research into the atomistic dynamics of VIs and their interaction with uncoordinated Pb2+ sites remains crucial for advancing the field of perovskite quantum dot technology.

The surface chemistry of CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) represents a fundamental frontier in nanomaterials research, critically determining their optical properties, electronic characteristics, and environmental stability. Within this domain, the dynamic binding and detachment of conventional ligands—specifically oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm)—govern the formation of surface trap states and uncoordinated Pb2+ sites that profoundly impact device performance. These weakly-bound insulating ligands create a persistent challenge in balancing colloidal stability with optimal charge transport in PQD-based devices. The inherent instability of OA/OAm ligands on CsPbI3 surfaces facilitates the creation of uncoordinated Pb2+ atoms, which act as non-radiative recombination centers, quenching photoluminescence and degrading electroluminescent efficiency [5] [6]. Understanding these surface chemistry dynamics is not merely academic but essential for advancing PQD applications in photovoltaics, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and other optoelectronic devices where trap state minimization is crucial for performance enhancement. This technical analysis examines the mechanistic foundations of ligand interactions, quantitative binding dynamics, and experimental methodologies for surface engineering to suppress defect formation in CsPbI3 PQDs.

Fundamental Principles of Quantum Dot Surface Chemistry

Crystal Facets and Surface Atom Coordination

The surface structure of CsPbI3 PQDs dictates the coordination environment for ligand binding. Quantum dot surfaces comprise locally flat regions of truncated crystalline planes with varying atomic arrangements and reactivities. These facets exhibit different surface energies and chemical properties based on their termination and atom coordination numbers [6]. Surface atoms possess reduced coordination numbers compared to bulk atoms, resulting in dangling bonds that create electronic states within the band gap. These undercoordinated surface sites, particularly unpassivated Pb2+ cations, function as trap states for charge carriers, promoting non-radiative recombination and diminishing luminescent efficiency [6]. The high surface-to-volume ratio of PQDs (with 10-50% of atoms surface-localized) amplifies the impact of these surface states on overall material properties, making effective passivation through robust ligand binding a critical requirement for optimal performance.

The OA/OAm Ligand System: Binding Mechanisms and Limitations

The conventional OA/OAm ligand pair operates through a cooperative binding mechanism where OA (carboxylic acid) and OAm (amine) interact with surface sites through acid-base reactions. OA typically coordinates with undercoordinated Pb2+ sites as a carboxylate anion, while OAm binds as an ammonium cation to halide sites or surface vacancies [5]. This ligand system provides adequate steric stabilization during synthesis but suffers from inherent dynamic instability due to relatively weak binding energies (approximately 1.23 eV for OAm) [5]. The labile nature of OA/OAm binding facilitates rapid ligand desorption during processing, purification, or device operation, exposing undercoordinated Pb2+ ions and generating surface traps. Furthermore, the proton transfer equilibrium between OA- (deprotonated OA) and OAmH+ (protonated OAm) creates an unstable interface where ligand detachment can occur spontaneously, especially in the presence of polar antisolvents during purification [5]. This instability is compounded by the long hydrocarbon chains of OA/OAm, which create significant inter-dot separation in solid films, impeding charge transport and limiting device performance.

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Binding Dynamics

Binding Energy Comparisons of Ligand Systems

The effectiveness of surface passivation directly correlates with ligand binding strength. Computational and experimental studies have quantified the binding energies of various ligand classes to CsPbI3 PQD surfaces, revealing significant advantages for strategically designed ligand systems.

Table 1: Comparative Binding Energies of Ligands on CsPbI3 PQD Surfaces

| Ligand Type | Chemical Structure | Binding Energy (eV) | Primary Binding Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Long-chain amine | 1.23 eV [5] | Coordinate bond to Pb²⁺ sites |

| 2-Naphthalene Sulfonic Acid (NSA) | Sulfonic acid with naphthalene ring | 1.45 eV [5] | Sulfonate group coordination to Pb²⁺ |

| PF₆⁻ (from NH₄PF₆) | Hexafluorophosphate anion | 3.92 eV [5] | Ionic interaction with surface cations |

| 5-Aminopentanoic Acid (5AVA) | Short-chain amino acid | Not quantified | Bidentate chelation via NH₂/COOH |

The enhanced binding energy of NSA (1.45 eV) compared to conventional OAm (1.23 eV) demonstrates the effectiveness of sulfonic acid groups for robust surface coordination [5]. The exceptionally high binding energy of PF₆⁻ anions (3.92 eV) highlights the potential of inorganic ligands for creating extremely stable passivation layers [5].

Performance Metrics of Ligand-Engineered PQDs

Ligand exchange strategies directly influence key performance parameters in CsPbI3 PQD optoelectronic devices, particularly light-emitting diodes. Controlled modification of the ligand shell significantly enhances device efficiency and operational stability.

Table 2: Optical and Device Performance of CsPbI3 PQDs with Different Ligand Systems

| Ligand System | PLQY (%) | EQE (%) | Emission Wavelength (nm) | Operational Half-Lifetime | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional OA/OAm | <80% | 18.63% [7] | ~635 [5] | Minimal [7] | |

| NSA + NH₄PF₆ | 94% [5] | 26.04% [5] | 628 [5] | 729 min @ 1000 cd/m² [5] | |

| 5AVAI (Proton-Prompted) | Not specified | 24.45% [7] | 645 [7] | 10.79 h [7] |

The data demonstrate that advanced ligand engineering achieves remarkable performance enhancements, with NSA-treated QDs maintaining over 80% of their high quantum efficiency after 50 days of storage [5]. The proton-prompted 5AVAI ligand exchange increased device operational lifetime by 70-fold compared to conventional OA/OAm-capped QDs [7], highlighting the critical importance of ligand stability for practical applications.

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Ligand Dynamics

Inhibition of Ostwald Ripening with Strong-Binding Ligands

Objective: To synthesize strongly confined CsPbI3 QDs with pure red emission (623 nm) by suppressing Ostwald ripening through strong-binding ligands [5].

Materials:

- Lead iodide (PbI₂, 99.999%)

- Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃)

- Octadecene (ODE, 90%)

- Oleic acid (OA, 90%)

- Oleylamine (OAm, 90%)

- 2-Naphthalene sulfonic acid (NSA)

- Ammonium hexafluorophosphate (NH₄PF₆)

- Non-polar solvents: n-hexane, n-octane

- Polar antisolvents: methyl acetate, ethyl acetate

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Combine 170 mg PbI₂ and 6 mL ODE in a 50 mL three-neck flask. Dry under argon flow at 120°C for 1 hour [5].

- Ligand Injection: Inject 1 mL OA and 2 mL OAm at 120°C under argon atmosphere [5].

- Nucleation: Raise temperature to 150°C and swiftly inject 2.2 mL Cs-oleate precursor solution [5].

- NSA Treatment: After 5 seconds, rapidly cool reaction to 100°C and inject NSA ligand solution (0.6 M in ethyl acetate) [5].

- Purification: Add NH₄PF₆ during antisolvent purification to exchange long-chain ligands and prevent regrowth [5].

- Isolation: Precipitate QDs using ethyl acetate/methyl acetate mixture (1:1:3 volume ratio of crude solution:ethyl acetate:methyl acetate), centrifuge at 7000 rpm for 2 minutes, and redisperse in octane [5].

Key Measurements:

- In-situ PL spectroscopy during synthesis monitors PL evolution and blue shift confirmation of ripening inhibition [5].

- TEM with size statistics quantifies particle size distribution narrowing (average size ~4.3 nm) [5].

- PLQY measurements confirm defect passivation (up to 94% efficiency) [5].

- FTIR and XPS verify ligand binding and surface composition [5].

Proton-Prompted In Situ Ligand Exchange

Objective: To replace long-chain OA/OAm ligands with short-chain 5-aminopentanoic acid (5AVA) ligands during synthesis cooling stage to enhance charge transport while maintaining quantum confinement [7].

Materials:

- Lead iodide (PbI₂, 99.999%)

- Zinc iodide (ZnI₂, 99.99%)

- 5-aminopentanoic acid (5AVA, 97%)

- Hydroiodic acid (HI, 55-58%)

- Ethyl acetate, methyl acetate

- Standard CsPbI3 precursors: Cs₂CO₃, ODE, OA, OAm

Procedure:

- Ligand Solution Preparation: Dissolve 5AVA (0.1-0.3 mmol) in 1.5x molar equivalent HI, add 1 mL ethyl acetate, and heat to 80°C to form 5AVAI solution [7].

- QDs Synthesis: Follow standard CsPbI3 synthesis with PbI₂/ZnI₂ precursor in ODE with OA/OAm ligands [7].

- Proton-Prompted Exchange: After Cs-oleate injection and 5-second reaction, cool mixture to 100°C and swiftly inject preheated 5AVAI solution [7].

- Purification: Use anti-solvent precipitation with ethyl acetate and methyl acetate mixture, followed by centrifugation and redispersion in octane [7].

Mechanistic Insight: HI protons trigger desorption of OA/OAm ligands by protonating amine groups, while 5AVA amine groups are simultaneously protonated, promoting binding to QD surfaces. Iodide ions provide iodine-rich environment to maintain QD size [7].

Figure 1: Proton-prompted ligand exchange workflow showing the replacement of OA/OAm with short-chain 5AVA ligands.

Solvent-Mediated Ligand Exchange for Solar Cells

Objective: To maximize removal of insulating oleylamine ligands from CsPbI3 PQD surfaces using tailored solvent environments without introducing halogen vacancy defects [4].

Materials:

- Protic solvent: 2-pentanol (tailored for appropriate dielectric constant and acidity)

- Short ligands: choline-based compounds

- Polar antisolvents for purification

- CsPbI3 PQDs with initial OA/OAm ligand shell

Procedure:

- Solvent Screening: Select 2-pentanol for optimal ligand solubility with appropriate dielectric constant and acidity [4].

- Film Treatment: Deposit PQD solid film and treat with 2-pentanol solution containing short choline ligands [4].

- Ligand Exchange: Allow solvent-mediated extraction of long-chain ligands and adsorption of short ligands [4].

- Characterization: Evaluate film conductivity, defect passivation, and device performance (solar cells achieving 16.53% efficiency) [4].

Key Advantage: This approach maximizes insulating ligand removal while maintaining quantum confinement and minimizing halogen vacancy formation [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for CsPbI3 PQD Surface Chemistry Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Naphthalene Sulfonic Acid (NSA) | Strong-binding ligand for Pb²⁺ sites | Inhibits Ostwald ripening; enhances stability [5] |

| Ammonium Hexafluorophosphate (NH₄PF₆) | Inorganic ligand for surface passivation | Exchanges long-chain ligands during purification [5] |

| 5-Aminopentanoic Acid (5AVA) | Short bifunctional ligand | Proton-promoted exchange; improves film conductivity [7] |

| Hydroiodic Acid (HI) | Proton source for ligand exchange | Promotes OA/OAm desorption in 5AVA strategy [7] |

| 2-Pentanol | Tailored solvent for ligand exchange | Maximizes ligand removal without defect creation [4] |

| Methyl Acetate/Ethyl Acetate | Polar antisolvents | PQD precipitation and purification [5] [7] |

| Choline-based Compounds | Short conductive ligands | Solar cell applications; enhanced charge transport [4] |

The dynamics of weak OA/OAm ligand binding and detachment present both a fundamental challenge and strategic opportunity for advancing CsPbI3 PQD research. The inherent lability of conventional ligand systems directly generates uncoordinated Pb2+ trap states that degrade device performance and operational stability. Emerging ligand engineering strategies—including strong-binding sulfonic acids, inorganic ligands, proton-promoted exchange, and solvent-mediated approaches—demonstrate that rational surface design can effectively suppress trap state formation while enhancing charge transport. These approaches collectively highlight the critical importance of binding energy optimization, steric consideration, and exchange process control in tailoring PQD surface chemistry. Future research directions should focus on developing multi-functional ligand systems that simultaneously address passivation completeness, charge transport efficiency, and environmental stability while maintaining quantum confinement. The continued refinement of surface chemistry protocols will undoubtedly accelerate the commercialization of CsPbI3 PQD technologies across optoelectronic applications.

Lead halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly cesium lead iodide (CsPbI3), have emerged as a revolutionary semiconductor class for optoelectronic applications, from photovoltaics to light-emitting diodes and visible light communication (VLC) systems. Their exceptional properties—including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), tunable bandgaps, and defect tolerance—position them as formidable competitors to conventional semiconductors. However, the practical deployment of CsPbI3 PQDs is critically hindered by several material instabilities originating from defects. This technical guide examines the fundamental consequences of these defects: non-radiative recombination, ion migration, and phase instability, framing them within the broader research context of understanding trap states and uncoordinated Pb2+ in CsPbI3 PQDs. Although these phenomena are interconnected, they present distinct challenges for device performance and operational stability. A comprehensive atomic-scale understanding of these defect-mediated processes is essential for developing robust mitigation strategies and advancing CsPbI3 PQDs toward commercial viability.

Quantitative Consequences of Defects in CsPbI3 PQDs

The impact of defects on CsPbI3 PQD performance and stability can be quantitatively summarized through key metrics from experimental studies. The following table consolidates critical data illustrating the consequences of defects and the efficacy of various passivation strategies.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Defects and Passivation in CsPbI3 PQDs

| Defect/Parameter | Impact on Performance/Stability | Passivation/Mitigation Strategy | Result after Treatment | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Trap States (Uncoordinated Pb²⁺) | Lowers Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Surface passivation achieving near-complete defect elimination | PLQY up to ~100% (solution) | [8] |

| Trap States in Film | Concentration quenching; low film PLQY | Energy transfer via mixed quantum dots (FRET) | Film PLQY enhanced from 38% (neat) to 52% (mixed) | [9] |

| Excitonic Trap States (below optical gap) | Detrimental to solar cell performance | Growth in presence of chloride (Cl⁻) | Density of excitonic traps reduced by at least one order of magnitude | [10] |

| Ion Migration (Mobile point defects) | Reduces VLC system performance; causes hysteresis & degradation | System stabilization after ion migration | VLC data rate of 90 Mbps achieved (OOK modulation) | [11] |

| Phase Instability (α to δ phase transition) | Poor optical properties; larger bandgap (2.82 eV) | Reduction to nanoscale (quantum confinement) | Stabilization of photoactive α-phase at room temperature | [12] |

The Origins and Nature of Defects in CsPbI3 PQDs

Classification of Trap States

Defect-induced trap states in lead halide perovskites are not a monolith and must be carefully classified to understand their specific influence. A primary distinction exists between surface and bulk trap states. Direct evidence confirms that hole traps localize predominantly on the surfaces of three-dimensional perovskite thin films, while excitonic traps reside below the optical gap within the bulk material [10]. The electronic sub-gap trap states distribution differs significantly from the surface to the bulk, even though surfaces adjacent to charge transport layers can exhibit analogous densities of states (DOS) [13].

The physical origin of these states is often linked to crystal structure deformations. Trap states are enhanced at surfaces and interfaces where the perovskite crystal structure is most susceptible to deformation, likely caused by strong electron-phonon coupling [10]. A critical conceptual clarity is offered by research emphasizing that the nature of localized states should not be oversimplified into generic "defects" or "states," as their causes and characteristics can vary widely [14].

The Central Role of Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ Ions

A predominant source of detrimental surface traps, particularly in CsPbI3 PQDs, is uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions. The crystal structure of CsPbI3 consists of a corner-sharing [PbI6]4− octahedral framework with Cs+ cations occupying the interstitial voids [12]. During synthesis or post-processing, the surface of the QDs can become terminated by CsI- facets, leading to a cesium- and halide-deficient surface. This non-stoichiometric surface leaves Pb²⁺ ions under-coordinated [12]. These under-coordinated sites act as deep-level traps, efficiently capturing photogenerated charge carriers and promoting non-radiative recombination, which severely quenches photoluminescence and reduces device efficiency.

Consequences of Defects

Non-Radiative Recombination

Non-radiative recombination is the primary pathway through which defects degrade the optoelectronic performance of CsPbI3 PQDs. When a photogenerated electron or hole is captured by a trap state (such as an uncoordinated Pb²⁺ site), the carrier's energy is dissipated as heat rather than light. This process directly competes with radiative recombination, leading to a significant reduction in the internal PLQY. In practical devices, this translates to lower open-circuit voltages in solar cells and diminished luminescent efficiency in LEDs.

The severity of this issue is context-dependent. While CsPbI3 QDs can achieve near-unity PLQY in solution with optimal passivation [8], forming dense solid films often reintroduces non-radiative pathways through concentration quenching and increased surface defect interactions [9]. This highlights the critical need for effective surface management not only during synthesis but also throughout device fabrication.

Ion Migration

Ion migration, recognized as a crucial mobile point defect, is a key factor inducing performance degradation in perovskite devices [11]. This phenomenon involves the movement of ions (e.g., FA+, Cs+, I-) through the crystal lattice under the influence of external biases or illumination. The process is facilitated by the relatively low formation energy of vacancies (e.g., V⁻ₐ, V⁺ᵢ) [15].

The consequences of ion migration are multifaceted and detrimental. In visible light communication (VLC) systems, it directly reduces data transmission performance, though the system can recover to its initial state after a stabilization period [11]. In solar cells, ion migration is a primary contributor to current-voltage (J-V) hysteresis and giant dielectric responses [13]. Furthermore, it can accelerate device degradation by triggering irreversible chemical reactions at the electrodes. Atomic-scale studies reveal that ion loss begins randomly, after which the remaining ions migrate unit cell by unit cell into an ordered, more stable superstructure [15].

Phase Instability

Phase instability is a particularly critical challenge for CsPbI3. The photoactive black perovskite phase (α-CsPbI3) is metastable at room temperature and tends to transform into a non-perovskite, optically inactive yellow phase (δ-CsPbI3) with a much wider bandgap (~2.82 eV) [12]. This transition renders the material useless for optoelectronic applications.

Defects, especially vacancies, play a fundamental role in initiating and accelerating this phase transition. The loss of A-site cations (FA+ or Cs+) and halide anions (I-) creates local non-stoichiometry and strain that destabilizes the perovskite lattice [15]. The subsequent migration and ordering of these vacancies can trigger specific octahedral tilt modes, leading to the formation of intermediate tetragonal phases and ultimately the decomposition into thermodynamically stable PbI2 [15]. The A-site cation composition influences this process; for instance, mixed Cs/FA systems exhibit different octahedral tilt modes and enhanced stability compared to pure FAPbI3 [15].

Figure 1: Interrelationship of defect-mediated consequences in CsPbI3 PQDs, leading to overall device degradation.

Experimental Characterization Protocols

A multi-faceted experimental approach is required to definitively characterize defects and their consequences. The following protocols represent state-of-the-art techniques for probing these phenomena.

Probing Ion Migration and Phase Stability with Low-Dose TEM

Objective: To directly observe the atomic-scale structural evolution, including ion migration, vacancy ordering, and phase transitions, in CsPbI3 PQDs under controlled degradation conditions.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Synthesize high-quality CsPbI3 or mixed-cation Cs₁₋ₓFAₓPbI₃ QDs. Deposit them onto TEM grids, ensuring minimal exposure to air and moisture [15].

- Ultra-Low Dose Imaging: Use transmission electron microscopy (TEM) or scanning TEM (STEM) equipped with a direct-detection electron counting camera (DDEC). Maintain total electron dose at minimal levels (e.g., ~44 e⁻/Ų per image) to avoid beam-induced artifacts and observe pristine structures [15].

- Controlled Dose Experiment: Systematically increase the electron dose to act as a proxy for degradation. Acquire sequential atomic-resolution images to capture:

- The initial random loss of A-site cations (FA⁺/Cs⁺) and I⁻ ions.

- The migration and ordering of remaining ions into superstructures (e.g., √2 × √2).

- Subsequent octahedral tilting and formation of intermediate phases (e.g., tetragonal).

- Final decomposition into PbI₂ [15].

- Data Analysis: Analyze image intensity line profiles across different atomic columns to identify vacancies. Compare observed superstructures and phase transitions with proposed structural models.

Quantifying Trap States and Recombination via Impedance Spectroscopy

Objective: To non-destructively characterize the density and distribution of sub-gap trap states in a full device at steady-state conditions.

Methodology:

- Device Fabrication: Fabric a complete device (e.g., a planar solar cell with structure FTO/TiO₂/CsPbI₃ QD Layer/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au) [13].

- AC Impedance Measurement: Place the device under a steady-state bias and/or photo-excitation. Measure the impedance (C-V spectra) over a wide range of ac modulation frequencies (e.g., from mHz to MHz) [13].

- Capacitance Analysis: Extract the chemical capacitance (Cμ) from the impedance data. The frequency-dependent Cμ is directly concerned with the surface and bulk-related density of states (DOS) [13].

- DOS Fitting: Fit the extracted DOS using a Gaussian distribution function. This allows for the quantification of electronic sub-gap trap states and the distinction between their distribution at the surface and in the bulk [13].

Investigating Energy Transfer as a Passivation Pathway

Objective: To utilize Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) between QDs of different sizes to reduce non-radiative recombination in solid films.

Methodology:

- QD Synthesis: Prepare two batches of size-controlled CsPbI₃ QDs with different energy gaps (Eg), such as large QDs (LQDs, 10.7 nm) and small QDs (SQDs, 7.9 nm), ensuring spectral overlap between SQD emission and LQD absorption [9].

- Film Preparation: Create a mixed QD (MQD) film by blending SQDs and LQDs. Prepare control films of neat SQDs and neat LQDs.

- Photophysical Characterization:

- PL Quantum Yield (PLQY): Measure the absolute PLQY of the MQD film and compare it to the neat films. An enhancement indicates reduced non-radiative recombination [9].

- Time-Resolved PL (TRPL): Measure the photoluminescence decay time. A longer PL decay time in the MQD film suggests successful FRET and suppressed trapping [9].

- Photoluminescence Excitation (PLE): Map the PLE spectrum. If the LQD emission is observed when exciting at the absorption wavelength of the SQDs, it confirms the occurrence of energy transfer [9].

Figure 2: Workflow of key experimental techniques for characterizing defects in CsPbI3 PQDs, linking methods to the physical information they provide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CsPbI3 PQD Defect Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Example / Role |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Precursor | Provides the inorganic A-site cation (Cs⁺) for the ABX₃ structure. | Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) or cesium oleate, fundamental for synthesizing all-inorganic CsPbI₃ QDs [12]. |

| Lead Precursor | Provides the B-site cation (Pb²⁺) for the perovskite lattice. | Lead(II) iodide (PbI₂) or lead acetate, reacts with halide source to form the [PbI₆]⁴⁻ octahedra [12]. |

| Halide Source | Provides the X-site anion (I⁻) and controls crystal formation. | e.g., Alkylammonium iodides, critical for tuning halide composition and passivating surface defects [8]. |

| Surface Ligands | Control QD growth during synthesis and passivate surface traps in final product. | Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm): Standard ligands for colloidal synthesis. (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES): Enhances structural stability of QD films [8]. |

| Chloride Additives | Incorporated to reduce trap state density and improve crystallinity. | e.g., Methylammonium chloride (MACl), reduces density of excitonic traps by orders of magnitude [10]. |

| Mixed-Cation Sources | To enhance phase stability via A-site cation engineering. | Formamidinium iodide (FAI), used to create mixed Cs₁₋ₓFAₓPbI₃ compositions, which show altered ion migration pathways [15]. |

| Energy Transfer Partners | QDs of different sizes used to manipulate energy flow and reduce losses. | Small and Large CsPbI₃ QDs, blended to create a FRET system that enhances overall film PLQY [9]. |

The journey to realizing the full potential of CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dots is fundamentally a battle against defects. The intertwined consequences of non-radiative recombination, ion migration, and phase instability, often rooted in uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions and various vacancies, pose significant challenges to device performance and longevity. However, as detailed in this guide, the research community has developed a sophisticated toolkit of atomic-scale characterization techniques and a deepening mechanistic understanding to confront these issues. Strategies such as advanced surface ligand engineering, A-site cation alloying, halide composition tuning, and novel approaches like leveraging energy transfer pathways are demonstrating significant promise in mitigating these defect-mediated consequences. Future research must continue to bridge the gap between fundamental atomic-level understanding and macroscopic device performance, focusing on the long-term stability under operational conditions. By systematically addressing the consequences of defects, the path toward robust, high-performance, and commercially viable CsPbI3 PQD optoelectronics becomes increasingly clear.

Ostwald ripening is a fundamental and often detrimental process in nanomaterial science wherein larger particles grow at the expense of smaller ones due to interfacial energy differences. This phenomenon presents a significant challenge in the synthesis and application of quantum dots (QDs), particularly in the case of perovskite quantum dots like CsPbI3, where it directly contributes to defect formation and performance degradation. The driving force behind this process is the inherent thermodynamic instability of nanoscale systems, where atoms or molecules on the surface of smaller particles (with higher curvature and surface energy) tend to dissolve and redeposit onto larger, more stable particles. This results in a progressive increase in average particle size over time, reducing the quantum confinement effects that make QDs technologically valuable.

Within the specific context of CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) research, controlling Ostwald ripening is critical for mitigating trap state formation and stabilizing uncoordinated Pb2+ sites on the crystal surface. These PQDs exhibit exceptionally promising optoelectronic properties but suffer from structural and optical instability that has hindered their commercial implementation. The dynamic, ionic nature of the bonding in perovskite structures creates a labile surface where ligand binding is inherently less stable than in conventional II-VI or III-V QD systems. This review examines the mechanistic basis of Ostwald ripening in PQDs, explores its direct connection to defect generation, and synthesizes recent methodological advances that offer promising pathways toward ripening suppression and material stabilization.

The Fundamental Link Between Surface Energy and Ripening

Thermodynamic Driving Forces

At the nanoscale, surface energy becomes a dominant factor determining material stability and evolution. The high surface-to-volume ratio of quantum dots means that a significant proportion of atoms reside at the surface with unsatisfied bonds, creating a state of elevated energy relative to bulk material. This energy penalty follows the Gibbs-Thomson relationship, where the solubility of a particle increases exponentially with decreasing radius. The mathematical formulation governing this relationship establishes that the chemical potential of atoms in a spherical particle of radius r is elevated by 2γΩ/r, where γ represents the surface energy and Ω the atomic volume.

This thermodynamic framework creates a natural driving force for mass transport from regions of high chemical potential (smaller particles) to regions of lower chemical potential (larger particles). In CsPbI3 PQD systems, this manifests as the dissolution of smaller dots and the corresponding growth of larger ones, leading to broadened size distribution and eventual loss of quantum confinement effects. The process is particularly pronounced in perovskite systems due to their highly ionic character and dynamic surface chemistry, which facilitates the dissolution and redeposition processes essential for ripening.

Consequences for Quantum Dot Systems

The practical implications of Ostwald ripening in operational QD systems are severe and multifaceted:

- Size Distribution Broadening: The mean particle size increases while the distribution widens, degrading the narrow emission profiles essential for high-color-purity applications.

- Surface Defect Proliferation: As material dissolves from smaller particles, uncoordinated lead cations (Pb2+) become exposed, creating trap states that facilitate non-radiative recombination.

- Morphological Degradation: Cubic perovskite crystals undergo shape transition to spherical forms through preferential dissolution of vertices and edges, further increasing surface energy.

- Optical Performance Decay: Photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) decreases and emission spectra shift due to reduced quantum confinement and increased defect-mediated recombination.

Table 1: Defect Types Arising from Ostwald Ripening in CsPbI3 PQDs

| Defect Type | Structural Origin | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Interface Fusion | Merging of adjacent QDs | Reduced quantum confinement; red-shifted emission |

| Low-Angle Boundary | Slight crystallographic misorientation between domains | Carrier scattering; reduced mobility |

| High-Angle Boundary | Severe crystallographic mismatch | Non-radiative recombination centers |

| Antiphase Boundary | Offset of crystal planes | Trap state formation; PLQY degradation |

| Dislocation | Line defects in crystal structure | Charge trapping; accelerated degradation |

Experimental Evidence of Ostwald Ripening in Quantum Dots

Microscopic Visualization of Ripening Processes

Advanced microscopy techniques have provided direct visual evidence of Ostwald ripening in CsPbI3 PQD systems. Studies comparing pristine QDs with stabilized variants reveal pronounced differences in morphological evolution. Aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) demonstrates that pristine CsPbI3 QDs capped with conventional oleylamine (OAm) and oleic acid (OA) ligands suffer from significant adhesion between individual dots, with boundaries becoming increasingly ambiguous after air exposure [16]. This interfacial fusion represents the initial stage of ripening, where particles begin to lose their structural independence.

The progression of ripening creates characteristic defect structures observable at the atomic scale. These include low-angle and high-angle boundaries between partially merged crystallites, antiphase boundaries where crystal planes become offset, and dislocation defects that create deep trap states for charge carriers [16]. In contrast, stabilized QDs treated with ripening-suppression molecules maintain well-defined cubic morphology with sharp boundaries even after prolonged air exposure, demonstrating the effectiveness of targeted intervention strategies.

Spectroscopic and Compositional Analysis

Complementary techniques provide additional evidence for ripening processes and their chemical consequences. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analyses reveal changes in surface chemical states that correlate with ripening progression. In pristine QD systems, the loss of surface coordination is evidenced by shifts in binding energies associated with lead species, indicating an increase in uncoordinated Pb2+ sites that function as trap states [16].

Optical characterization further supports the connection between ripening and performance degradation. Unstabilized QD systems exhibit decreasing photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs) over time, along with reduced photoluminescence lifetimes, indicating rising non-radiative recombination pathways through surface defects. These changes occur concomitantly with observable ripening in morphological studies, establishing a direct correlation between the physical process of Ostwald ripening and the optical degradation of PQD materials.

Methodological Approaches to Studying Ostwald Ripening

In Situ Monitoring Techniques

Understanding the kinetics of Ostwald ripening requires experimental methods capable of tracking morphological evolution in real time. Reflection high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED) has proven valuable for monitoring surface dynamics during QD formation and transformation. By analyzing Bragg spot intensity kinetics, researchers can quantify morphological changes while excluding confounding factors like thermal decomposition [17]. This approach has elucidated the reversible 2D-3D transitions in Group III-nitride systems, providing insights that may extend to perovskite materials.

For molecular-scale insights into the initial stages of ripening, diffuse reflectance infra-red Fourier transform (DRIFT) spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy offer window into chemical bonding changes during solid-state transformations. When applied to model systems like organozinc single crystals, these techniques have revealed how hydrolytic processes initiate at discrete hydrophilic microcavities on crystal surfaces, leading to the formation of quantum-sized particles through processes analogous to natural chemical weathering [18]. Such fundamental studies provide mechanistic understanding relevant to solution-phase perovskite systems.

Theoretical and Modeling Frameworks

Computational approaches complement experimental observations in unraveling Ostwald ripening mechanisms. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations enable quantification of molecular adsorption energies and surface binding dynamics, revealing how ripening-suppression molecules interact with specific crystal facets and surface sites. For example, DFT analyses of bidentate molecules like PZPY demonstrate electron density shifts toward nitrogen atoms that enhance coordination with uncoordinated Pb2+ sites on CsPbI3 QD surfaces [16].

Kinetic rate equation modeling based on experimental data allows researchers to correlate measured intensity variations in techniques like RHEED with calculated surface energy values governed by adsorbate coverage [17]. These models establish quantitative relationships between processing conditions (such as ammonia flow modulation in GaN systems) and the resulting morphological evolution, providing predictive capability for ripening behavior. Thermodynamic equilibrium models further establish the critical surface energy values necessary to trigger 2D-3D transitions that initiate QD formation and subsequent ripening processes.

Diagram 1: Ostwald ripening mechanism in perovskite quantum dots and the molecular suppression strategy. The process initiates with high surface energy in small QDs, progressing through dissolution and redeposition stages that ultimately generate uncoordinated Pb²⁺ defects. The suppression approach uses bidentate molecules that coordinate with surface sites to reduce surface energy and inhibit ripening.

Solutions and Stabilization Strategies

Molecular Ripening Inhibition

Recent research has demonstrated that specifically designed organic molecules can effectively suppress Ostwald ripening in CsPbI3 PQDs. A prominent example utilizes the bidentate molecule 2-(1H-pyrazol-1-yl)pyridine (PZPY), which features dual nitrogen coordination sites that simultaneously bind to uncoordinated Pb2+ surface sites [16]. The molecular structure of PZPY provides optimal steric characteristics—its relatively small size and flexibility derived from the C-N bond of pyrazole enable efficient surface attachment without significant space hindrance. This strong, bidentate coordination reduces surface energy and disfavors the dissolution step that initiates ripening.

The effectiveness of this approach is evidenced by remarkable stability improvements in treated QD systems. PZPY-modified CsPbI3 QDs maintain cubic morphology and show no significant ripening even after three days of air exposure, whereas pristine QDs undergo substantial aggregation and shape degradation [16]. Optical properties show parallel stability, with PLQYs remaining above 90% in stabilized systems compared to rapid decay in control samples. This molecular strategy represents a significant advancement beyond conventional monodentate ligand systems, which provide insufficient binding strength to resist displacement during processing and operation.

Surface Energy Modulation Through Processing Control

An alternative approach to ripening control involves precise modulation of synthesis and processing conditions to thermodynamically disfavor the ripening process. In GaN QD systems, ammonia flow modulation during growth enables reversible 2D-3D transitions that can be harnessed to create uniform QD arrays while suppressing Ostwald ripening [17]. Though demonstrated in a different material system, this strategy illustrates the broader principle that surface energy can be controlled through ambient conditions during processing.

The thermodynamic modeling supporting this approach establishes that specific surface energy thresholds must be exceeded to trigger the 2D-3D transition that precedes QD formation [17]. By carefully controlling adsorbate coverage of NH2, H, and NH species through ammonia modulation, researchers can tune surface energy to values that favor the formation of stable, uniform QDs while avoiding either uncontrolled ripening or the formation of continuous films. This refined control over nucleation and growth thermodynamics offers a complementary pathway to molecular stabilization for inhibiting ripening-driven defect formation.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Pristine vs. Stabilized CsPbI3 QDs [16]

| Parameter | Pristine QDs | PZPY-Stabilized QDs | Measurement Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLQY | ~80% (initial) | 94% | Fresh solution |

| PLQY Retention | <50% after days | >90% after 3 days | Ambient exposure |

| Film Roughness | 5.48 nm RMS | 4.02 nm RMS | AFM measurement |

| Crystal Morphology | Irregular after air exposure | Maintains cubic shape | 3 days air exposure |

| LED EQE | <20% | 26.0% | Device measurement |

| LED Operating Lifetime | Hundreds of hours | 10,587 hours (extrapolated T₅₀) | Initial radiance 190 mW sr⁻¹ m⁻² |

Research Reagent Solutions for Ostwald Ripening Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ostwald Ripening and Stabilization Studies

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 2-(1H-pyrazol-1-yl)pyridine (PZPY) | Bidentate ripening inhibitor for CsPbI3 QDs | Dual nitrogen coordination sites; molecular flexibility; strong Pb²⁺ binding [16] |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Conventional capping ligand | Monodentate binding; dynamic binding equilibrium; moderate surface coverage |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Co-ligand for charge balance | Acidic proton source; counterion for surface charge neutralization |

| Diethylzinc (Et₂Zn) | Organometallic precursor for model systems | Hydrolytic sensitivity; enables solid-state QD formation studies [18] |

| Benzamide (BA-H) | Ligand for hydrolyzable precursors | Moderate acidity (pKa ~14); forms hydrogen-bonded matrices upon hydrolysis [18] |

| Ammonia (NH₃) | Modulator for 2D-3D transitions | Controls surface adsorbates; modifies surface energy thermodynamics [17] |

The challenge of Ostwald ripening in quantum dot systems represents a critical frontier in nanomaterials research, with particular significance for the development of stable, high-performance perovskite optoelectronics. The fundamental thermodynamic driving forces that promote ripening are inherent to nanoscale systems, but strategic intervention through molecular design and processing control offers promising pathways to suppression. The connection between ripening and defect formation—particularly the creation of uncoordinated Pb2+ trap states—establishes this phenomenon as a central consideration in CsPbI3 PQD research.

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas: the development of multidentate coordination systems with optimized steric and electronic properties for stronger surface binding; the exploration of in situ passivation strategies that automatically heal defects as they form; and the integration of computational screening methods to identify novel ripening inhibitors from molecular libraries. As these approaches mature, the operational lifetime and performance consistency of perovskite QD-based devices should approach the thresholds required for commercial implementation, unlocking the considerable potential of these remarkable materials for advanced optoelectronic applications.

Advanced Characterization and Ligand Engineering Strategies for Defect Passivation

The exceptional optoelectronic properties of cesium lead iodide perovskite quantum dots (CsPbI3 PQDs), including tunable bandgaps and high absorption coefficients, make them highly promising for next-generation devices such as solar cells and memory applications [1] [19]. However, their performance and long-term stability are critically limited by intrinsic defect mechanisms, particularly trap states arising from uncoordinated Pb2+ ions and mobile ionic vacancies [19] [20]. A comprehensive understanding of these defects is essential for advancing CsPbI3 PQD research.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of advanced characterization techniques specifically applied to probe defect dynamics in CsPbI3 PQDs. We focus on three powerful methods: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for quantifying ionic vacancy migration, conductive Atomic Force Microscopy (c-AFM) for nanoscale visualization of conductive filament formation, and in-situ Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy for monitoring defect-related recombination processes in real-time. By integrating these complementary approaches, researchers can obtain a multidimensional understanding of defect mechanisms, ultimately guiding the development of more stable and efficient PQD-based devices.

Key Defect Mechanisms in CsPbI3 PQDs

Defects in CsPbI3 PQDs primarily manifest as surface trap states and mobile ionic vacancies, each playing a distinct role in device performance and degradation.

Uncoordinated Pb2+ and Surface Trap States

The high surface-to-volume ratio of PQDs leads to a significant population of under-coordinated lead ions (Pb2+) on the crystal surface. These uncoordinated sites act as deep-level traps, facilitating non-radiative recombination of charge carriers which reduces photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and compromises solar cell efficiency [19]. Passivation strategies using conjugated polymers with functional groups like -CN and -EG can strongly coordinate with these Pb2+ sites, as confirmed through Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) [19].

Mobile Iodine Vacancies (VI)

Iodine vacancies (VI) are point defects with low formation energy (0.1–0.2 eV) and migration energy (0.1–0.6 eV), making them highly mobile under external electric fields [1]. Unlike trap states, this mobility can be harnessed for memory applications. In resistive switching devices, VI migration forms conductive filaments (CFs), enabling transitions between resistance states [1]. The concentration of these mobile vacancies is particularly high in PQDs due to weak ligand interactions and detachment during purification and processing [1].

Table 1: Key Defect Types in CsPbI3 PQDs and Their Characteristics

| Defect Type | Formation Energy | Primary Impact | Characterization Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncoordinated Pb2+ | - | Non-radiative recombination, reduced PLQY | In-situ PL, XPS, FTIR |

| Iodine Vacancies (VI) | 0.1–0.2 eV [1] | Ionic conduction, resistive switching, device instability | EIS, c-AFM, I-V measurements |

Experimental Techniques for Defect Probing

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

EIS is a powerful technique for characterizing ionic migration and charge transport in CsPbI3 PQDs, particularly for quantifying VI mobility and conductive filament formation.

Experimental Protocol for EIS:

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate a metal-semiconductor-metal sandwich structure (e.g., Ag/CsPbI3 PQDs/ITO) with a defined active area (e.g., 100 × 100 μm²) [1].

- Measurement Setup: Apply a small AC voltage amplitude (typically 10-50 mV) superimposed on a DC bias voltage, sweeping across a frequency range from 1 Hz to 1 MHz.

- Data Collection: Measure the complex impedance (Z) and phase angle (θ) at each frequency point.

- Analysis: Fit the obtained Nyquist plots (Z'' vs. Z') to an equivalent circuit model. The formation and rupture of conductive filaments from VI migration are often represented by a series of resistive and capacitive elements, with resistance changes indicating different conductive states [1].

Key Parameters: The frequency response reveals relaxation times associated with ionic migration, while the bias-dependent impedance changes directly correlate with VI drift and filament dynamics [1].

Conductive Atomic Force Microscopy (c-AFM)

c-AFM provides direct nanoscale visualization of conductive filament formation and growth driven by VI migration, directly correlating morphological features with electronic properties.

Experimental Protocol for c-AFM:

- Sample Preparation: Deposit CsPbI3 PQDs to form densely packed thin films (e.g., ~190 nm thickness) on a conductive substrate (e.g., ITO) [1].

- Measurement Configuration: Use a conductive cantilever tip and apply a DC bias voltage between the tip and the substrate while scanning the surface in contact mode.

- In-situ Biasing: Monitor current distribution in real-time while applying set voltages (e.g., 1.0 V and 2.0 V) to observe the progressive formation of conductive filaments [1].

- Data Acquisition: Simultaneously collect topographical images and current maps to correlate grain structure with local conductivity variations.

Key Findings: In-situ c-AFM has revealed that multilevel resistive switching originates from distinct activation energies for VI migration at grain boundaries versus grain interiors, resulting in two distinct pathways for conductive filament growth [1].

In-situ Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy

In-situ PL spectroscopy monitors defect-related recombination dynamics in real-time under operational stresses such as electric bias or environmental exposure.

Experimental Protocol for In-situ PL:

- Setup Configuration: Integrate a PL spectrometer with a probe station equipped with electrical biasing capabilities and an environmental chamber.

- Real-time Monitoring: Focus excitation laser source on the CsPbI3 PQD film while simultaneously applying voltage cycles or exposing to controlled humidity.

- Spectral Acquisition: Continuously collect PL spectra (e.g., emission peak around 690 nm for CsPbI3) and track intensity, peak position, and full width at half maximum (FWHM) changes [1].

- Data Correlation: Synchronize PL data with applied bias and environmental conditions to identify defect activation mechanisms.

Key Applications: In-situ PL can verify that Joule heat during electrical operation does not induce structural changes (invariant PL peak), confirming that resistance switching originates from ionic migration rather than phase transitions [1].

Integrated Experimental Workflows

Combining EIS, c-AFM, and in-situ PL provides a comprehensive picture of defect mechanisms. The following diagram illustrates a typical integrated workflow for probing defect dynamics in CsPbI3 PQDs.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for multimodal defect analysis in CsPbI3 PQDs (Width: 760px)

Defect Formation and Characterization Pathways

Understanding the sequential process from defect formation to characterization is crucial for targeted analysis. The following diagram maps the pathways from intrinsic material properties to observable defect phenomena and appropriate characterization techniques.

Diagram 2: Defect formation pathways and characterization approaches (Width: 760px)

The application of these characterization techniques generates critical quantitative insights into defect properties and device performance, as summarized in the following tables.

Table 2: Defect and Device Performance Metrics from Characterization Techniques

| Characterization Technique | Key Measurable Parameters | Typical Values for CsPbI3 PQDs | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| EIS | Low Resistance State (LRS) | ~10³ Ω [1] | Stable conductive filament formation |

| High Resistance State (HRS) | ~10⁶ Ω [1] | Filament rupture or dissolution | |

| Retention Time | >10⁴ s [1] | Non-volatile memory capability | |

| c-AFM | Set Voltage 1 (Vset1) | ~1.0 V [1] | VI migration at grain boundaries |

| Set Voltage 2 (Vset2) | ~2.0 V [1] | VI migration through grain interiors | |

| ON/OFF Ratio | 10³:10²:1 (fLRS:IRS:HRS) [1] | Multilevel storage capability | |

| In-situ PL | PL Emission Peak | ~690 nm [1] | Band-edge emission, phase stability |

| PL Intensity Change | Variable with defect density | Trap state population dynamics |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Defect Studies in CsPbI3 PQDs

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Long-chain surface ligands for PQD synthesis and stabilization | Initial synthesis, creates insulating layer with inherent VI [1] |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Ester-based antisolvent for interlayer rinsing | Hydrolyzes to acetate ligands, replaces OA/OAm [21] |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Ester-based antisolvent with KOH additive | Creates alkaline environment for enhanced ligand exchange, improves conductive capping [21] |

| Conjugated Polymers (Th-BDT, O-BDT) | Multifunctional ligands with -CN and -EG functional groups | Passivate uncoordinated Pb²⁺, enhance charge transport, control QD packing [19] |

| Ag/ITO Electrodes | Top and bottom contacts for electrical characterization | Form metal-semiconductor-metal structure for EIS and switching tests [1] |

The multidimensional characterization approach combining EIS, c-AFM, and in-situ PL spectroscopy provides unprecedented insights into defect mechanisms in CsPbI3 PQDs. EIS quantifies the ionic migration responsible for resistive switching, c-AFM directly visualizes the nanoscale conductive filament formation pathways, and in-situ PL monitors trap state dynamics in real-time. Together, these techniques enable researchers to establish critical structure-property relationships, guiding the development of effective passivation strategies such as conjugated polymer ligands and alkaline-enhanced antisolvent treatments. This comprehensive understanding of defect mechanisms is fundamental to advancing CsPbI3 PQD research toward more stable and efficient optoelectronic devices.

The pursuit of pure-red emitters for next-generation displays has positioned all-inorganic CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) as a leading candidate, capable of meeting the stringent Rec. 2020 color standard [5]. However, their path to commercialization is hindered by a fundamental instability: the propensity for surface defects to form and for the nanocrystals to undergo irreversible growth during synthesis and storage [5] [16]. This degradation is primarily driven by two interrelated factors: the presence of uncoordinated lead ions (Pb2+) on the crystal surface and the phenomenon of Ostwald ripening.

Ostwald ripening is a process where smaller, higher-energy nanoparticles dissolve and re-deposit onto larger, more stable particles, leading to a gradual increase in average crystal size and a loss of the quantum confinement effect essential for pure-red emission [5] [22]. The root of this problem lies in the dynamic and labile nature of traditional ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm). These ligands readily desorb from the QD surface, exposing undercoordinated Pb2+ atoms. These sites act as non-radiative recombination centers, reducing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), and serve as points of instability that facilitate atomic rearrangement and crystal growth [5] [16].

This technical guide explores the application of strong-binding sulfonic acid ligands as an in-situ treatment to simultaneously suppress Ostwald ripening and passivate uncoordinated Pb2+ defects in CsPbI3 PQDs. By addressing these issues at their source, this strategy enables the synthesis of highly stable, high-efficiency pure-red PQDs, unlocking their potential for advanced optoelectronic devices.

Core Mechanism: How Sulfonic Acid Ligands Stabilize PQDs

Sulfonic acid ligands, such as 2-naphthalene sulfonic acid (NSA), exert their stabilizing effect through a combination of superior binding chemistry and steric hindrance.

Suppression of Ostwald Ripening

The introduction of NSA ligands after the initial nucleation phase fundamentally alters the growth kinetics of the PQDs. Research involving in-situ photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy has demonstrated that upon NSA injection, the PL spectrum of the QDs undergoes a blue shift and a concurrent increase in intensity. This spectral evolution is direct evidence that the harmful Ostwald ripening process is being inhibited, preserving the small size of the QDs and passivating surface defects that would otherwise quench luminescence [5]. The NSA molecule achieves this through its two key structural features:

- Sulfonic Acid Group: This group possesses a higher dissociation constant and is more polar than the carboxylic acid group of OA. When introduced into the reaction mixture, NSA displaces the weaker native ligands (OA⁻ and OAmH⁺) by promoting a proton transfer process that leads to their debonding from the QD surface [5].

- Naphthalene Ring: The bulky aromatic ring structure of NSA provides significant steric hindrance around the QD. This physical barrier impedes the close approach of other QDs and the addition of further precursor material, thereby mechanically inhibiting overgrowth and fusion [5].

Passivation of Uncoordinated Pb2+

The primary defect sites in CsPbI3 PQDs are uncoordinated Pb2+ ions on the surface, which act as traps for charge carriers and cause non-radiative recombination. Sulfonic acid ligands directly passivate these sites.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations reveal that the binding energy between the sulfonic acid group of NSA and a surface Pb2+ ion is approximately 1.45 eV. This is significantly stronger than the 1.23 eV binding energy of the commonly used OAm ligand [5]. This stronger interaction ensures that the NSA ligand remains anchored to the QD surface even under conditions that would cause traditional ligands to desorb. Experimental evidence from Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) confirms the presence of NSA ligands on the QD surface and a shift in the Pb 4f binding energy, indicating a robust chemical interaction between NSA and the surface Pb atoms [5].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of CsPbI3 PQDs with and without Sulfonic Acid Ligand Treatment

| Parameter | OA/OAm Ligands (Untreated) | NSA-Treated QDs | Measurement Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| PL Emission Peak | 635 nm | 623 nm | Solution [5] |

| FWHM (Color Purity) | 41 nm | 32 nm | Solution [5] |

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Not specified (inferior) | 94% | After synthesis & purification [5] |

| PLQY Retention | Not specified (poor) | >80% | After 50 days of storage [5] |

| Average Particle Size | Larger, broad distribution | ~4.3 nm, monodisperse | TEM analysis [5] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing In-Situ Sulfonic Acid Treatment

The following section provides a detailed methodology for synthesizing stable, pure-red CsPbI3 PQDs using an in-situ treatment with 2-naphthalene sulfonic acid (NSA), based on published protocols [5].

Materials

- Precursors: Cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3, 99.9%), Lead iodide (PbI2, 99.99%).

- Solvents: 1-Octadecene (ODE, 90%).

- Standard Ligands: Oleic acid (OA, 90%), Oleylamine (OAm, 90%).

- Target Ligand: 2-Naphthalene sulfonic acid (NSA, >95%).

- Purification Agents: Methyl acetate, Hexane, Ammonium hexafluorophosphate (NH4PF6, >95%).

Step-by-Step Procedure

Part A: Precursor Preparation

- Cesium Oleate Synthesis: Load 0.4 g of Cs2CO3, 1.25 mL of OA, and 15 mL of ODE into a 50 mL 3-neck flask.

- Reaction: Degas the mixture under vacuum for 1 hour at 120°C to remove residual water and oxygen.

- Dissolution: Subsequently, heat the mixture under a nitrogen (N2) atmosphere to 150°C with vigorous stirring until the Cs2CO3 is completely dissolved and the solution becomes clear. Maintain this cesium oleate solution at 150°C until injection.

Part B: Quantum Dot Synthesis with NSA Treatment

- PbI2 Precursor: In a separate 100 mL 3-neck flask, load 0.276 g of PbI2, 2.5 mL of OA, 2.5 mL of OAm, and 25 mL of ODE.

- Degassing & Heating: Degas the PbI2 mixture for 1 hour at 120°C. Then, under N2, heat the solution to 170°C with stirring until the PbI2 is completely dissolved.

- Nucleation: Rapidly inject 2 mL of the preheated cesium oleate solution into the PbI2 precursor at 170°C. The reaction mixture will immediately turn dark red, indicating the nucleation of CsPbI3 QDs.

- In-Situ NSA Treatment: After 10 seconds of reaction, swiftly inject a pre-dissolved NSA solution (0.6 M in ODE) into the hot reaction mixture.

- Quenching: 5 seconds after the NSA injection, cool the reaction flask using an ice-water bath to arrest further growth and ripening of the QDs.

Part C: Purification and Ligand Exchange

- Separation: Centrifuge the cooled crude solution at high speed (e.g., 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes). Discard the supernatant and collect the QD pellet.

- Redispersion: Redisperse the pellet in 5-10 mL of hexane.

- NH4PF6 Ligand Exchange: To the redispersed QDs, add a solution of NH4PF6 in isopropanol (concentration ~10 mg/mL). Vortex or stir the mixture for a few minutes. This step exchanges any remaining long-chain, labile ligands with the short-chain, strongly-bound PF6⁻ anion, which further passivates the surface and enhances charge transport [5].

- Washing: Precipitate the QDs by adding methyl acetate (a polar anti-solvent) and centrifuge. Repeat this washing step 2-3 times to remove excess ligands and reaction byproducts.

- Final Dispersion: Finally, disperse the purified QDs in anhydrous hexane or toluene at a desired concentration (e.g., 20-30 mg/mL) for film fabrication and characterization. Store the solution in an inert atmosphere.

Critical Workflow and Ligand Action

The diagram below illustrates the experimental workflow and pinpoints the specific stages where the sulfonic acid ligand and other chemical agents act to control ripening and passivation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sulfonic Acid Ligand Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function & Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| 2-Naphthalene Sulfonic Acid (NSA) | The primary strong-binding ligand. Its sulfonic acid group passivates uncoordinated Pb²⁺, while its naphthalene ring provides steric hindrance to suppress Ostwald ripening [5]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard long-chain ligands used during initial nucleation to stabilize the newly formed QD nuclei and control solubility [5] [16]. |

| Ammonium Hexafluorophosphate (NH4PF6) | An inorganic ligand exchange agent. The PF6⁻ anion has an extremely high binding energy (~3.92 eV) and replaces organic ligands during purification, enhancing surface passivation and charge transport in the final QD film [5]. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | A high-boiling-point, non-coordinating solvent that serves as the reaction medium for the hot-injection synthesis [5]. |

| Methyl Acetate | A polar anti-solvent. It is used to precipitate QDs from their colloidal dispersion during the washing and purification steps without damaging them [5]. |

Characterization and Performance Metrics

Rigorous characterization is essential to validate the efficacy of the sulfonic acid ligand treatment. The following data, consolidated from experimental results, provides a quantitative overview of the enhancements achieved [5].

Table 3: Comprehensive Characterization Data of NSA-Treated CsPbI3 PQDs

| Analysis Method | Key Results & Observations for NSA-Treated QDs |

|---|---|

| In-situ PL Spectroscopy | Immediate blue shift and intensity increase post-injection confirms suppressed Ostwald ripening and defect passivation [5]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Monodisperse, cubic QDs with an average size of ~4.3 nm. Untreated QDs show larger size and broader distribution [5]. |

| Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) | Extended PL lifetime, indicating a reduction in non-radiative recombination pathways due to effective surface passivation [5]. |

| Fourier-Transform IR (FTIR) / XPS | FTIR confirms the presence of NSA on QD surface. XPS shows a shift in Pb 4f binding energy, proving strong NSA-Pb²⁺ interaction [5]. |