Surface Treatment Strategies for Reduced Auger Recombination in Perovskite Quantum Dots

Auger recombination is a critical non-radiative process that plagues the performance of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs), causing efficiency roll-off and limiting achievable brightness, which directly impacts...

Surface Treatment Strategies for Reduced Auger Recombination in Perovskite Quantum Dots

Abstract

Auger recombination is a critical non-radiative process that plagues the performance of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs), causing efficiency roll-off and limiting achievable brightness, which directly impacts their utility in biomedical imaging and diagnostic applications. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the fundamental mechanisms of Auger recombination and detailing advanced surface treatment methodologies to suppress it. We examine the critical role of dielectric confinement, passivation techniques, and ligand engineering in mitigating losses. A troubleshooting guide addresses common challenges in synthesis and film formation, while a comparative evaluation validates the performance of treated PQDs through photoluminescence quantum yields and device efficiency metrics. The synthesized insights aim to guide the development of highly stable and efficient PQD systems for future clinical and diagnostic tools.

Understanding Auger Recombination: The Fundamental Challenge in PQD Performance

Defining Auger Recombination and Its Impact on PQD Optoelectronic Properties

Auger recombination is a non-radiative process that represents a significant energy loss pathway in semiconductors, including perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). In this process, an electron recombines with a hole, but instead of releasing the energy as a photon (as in radiative recombination), the energy is transferred to a third charge carrier (either an electron or a hole), which is excited to a higher energy state within the same band. This excited carrier then relaxes back to the band edge, dissipating its excess energy as heat through lattice vibrations or phonons [1] [2].

This three-particle interaction makes Auger recombination a dominant loss mechanism, particularly at high charge carrier densities common in operating optoelectronic devices. The recombination rate for an electron-electron-hole process is proportional to n²p, and for an electron-hole-hole process to np², where n and p are the electron and hole concentrations, respectively [1]. Auger recombination is especially detrimental in quantum-confined systems like PQDs due to enhanced Coulomb interactions between charge carriers [3] [4].

Quantitative Impact on PQD Properties

Auger recombination substantially impacts key optoelectronic properties of PQDs, primarily through the reduction of emission efficiency and acceleration of efficiency roll-off at high excitation densities.

Table 1: Impact of Auger Recombination on PQD Optoelectronic Properties

| Property Affected | Impact of Auger Recombination | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Significant reduction at high carrier densities due to non-radiative decay channel | Quasi-2D perovskite films show pronounced PLQY decline beyond critical excitation density [4] |

| Efficiency Roll-Off | Accelerated decline in efficiency at high current densities in LEDs | QD-LEDs exhibit efficiency roll-off due to Auger recombination; heterostructured QDs improve roll-off threshold [3] |

| Charge Carrier Lifetime | Substantial reduction, particularly at high carrier densities | Auger lifetimes in QD solids can be as short as 0.4-1.6 ps, becoming dominant at densities >10⁻³ per QD [5] |

| Operational Brightness | Limits maximum achievable luminance in LEDs | Suppressing Auger recombination enabled PeLEDs with record luminance of 82,480 cd m⁻² [4] |

The Auger recombination rate is proportional to the cube of the carrier density, making it particularly severe in quasi-2D perovskites where efficient energy transfer creates amplified carrier density at recombination centers [4]. In conductive quantum-dot solids, Auger recombination becomes the dominant charge carrier decay path even at exceptionally low excitation densities of approximately 10⁻³ per quantum dot [5].

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Auger Recombination

Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) Spectroscopy

Objective: To measure carrier recombination dynamics and extract Auger recombination rates in PQDs.

Materials:

- Pulsed laser source (wavelength above PQD bandgap)

- Spectrometer with time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) capability

- Cryostat for temperature-dependent measurements

- Optical cryostat and neutral density filters

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Deposit PQD film on quartz substrate using spin-coating. Maintain consistent film thickness (~100 nm) across samples.

- System Calibration: Measure instrument response function using a scattering solution. Align optical path for maximum signal collection.

- Excitation Density Series: Conduct TRPL measurements across varying excitation densities (0.001-100 μJ/cm²) using neutral density filters.

- Data Acquisition: Collect decay traces at PQD emission peak. Ensure adequate signal-to-noise ratio without detector saturation.

- Lifetime Analysis: Fit decay curves to appropriate models:

- Single exponential at low fluence: I(t) = I₀exp(-t/τ)

- Stretched exponential or multi-exponential at high fluence

- Auger Coefficient Extraction: Plot decay rate (1/τ) versus carrier density (n). Auger coefficient (C) is derived from the slope of the linear fit: 1/τ = 1/τ₀ + Cn², where τ₀ is the radiative lifetime.

Two-Photon TRPL for Bulk Lifetime Measurement

Objective: To decouple surface and bulk recombination processes by exciting carriers below the surface.

Materials:

- Mode-locked Ti:Sapphire laser (wavelength: 800-1000 nm)

- Confocal microscope with high NA objective (>0.8)

- Avalanche photodiode detector

- Three-axis piezoelectric stage

Procedure:

- System Alignment: Confirm two-photon absorption by verifying quadratic dependence of PL intensity on excitation power.

- Depth Profiling: Focus laser beam at different depths within PQD film (1-5 μm). Acquire TRPL decays at each depth.

- Bulk Lifetime Extraction: Use decays from deepest focal positions (>2 μm) to determine bulk lifetime unaffected by surface recombination.

- Lifetime Mapping: Generate 2D spatial maps of carrier lifetime by raster scanning the beam across sample area.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Auger Recombination Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| p-Fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA) iodide | Organic cation for reducing exciton binding energy | Decreasing Auger recombination in quasi-2D perovskites by weakening dielectric confinement [4] |

| Zinc halide salts (ZnCl₂, ZnI₂) | Doping agent for enhancing PL stability | Zn doping in CsPb(Cl/Br)₃ and CsPb(Br/I)₃ PQDs to suppress non-radiative recombination [6] |

| 1,2-ethanediamine (EDA) | Short-chain ligand for QD film fabrication | Enhancing inter-dot coupling in conductive QD solids for Auger recombination studies [5] |

| CdSe/CdS core/shell QDs | Model system for Auger studies | Engineering heterostructures with suppressed Auger recombination through alloyed interfaces [3] |

| Al₂O₃ passivation layer | Surface passivation material | Atomic layer deposition for reducing surface recombination in nanostructured semiconductors [7] |

Mitigation Strategies and Surface Treatment Protocols

Doping Protocol for Auger Suppression in PQDs

Objective: Incorporate zinc dopants to enhance PL stability and suppress non-radiative recombination in mixed halide PQDs.

Materials:

- Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99.9%)

- Lead bromide (PbBr₂, >98%)

- Lead iodide (PbI₂, 99%)

- Zinc chloride (ZnCl₂, 98%)

- Oleic acid (OA, 90%)

- Oleylamine (OAm, 90%)

- 1-Octadecene (ODE, 90%)

- Methyl acetate (MeOAC, 99%)

- Toluene (C₇H₈, 99.8%)

Synthesis Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation:

- Cesium oleate: Load 0.4 g Cs₂CO₃, 1.25 mL OA, and 15 mL ODE into 50 mL flask. Heat at 120°C under N₂ until completely dissolved.

- Zinc-doped lead precursor: Mix 0.3 mmol PbBr₂, 0.03 mmol ZnCl₂ (10% doping), 5 mL ODE, 0.5 mL OA, and 0.5 mL OAm in 25 mL flask. Heat at 120°C until dissolved.

Hot-Injection Synthesis:

- Heat zinc-doped lead precursor to 160°C under N₂ atmosphere.

- Rapidly inject 0.4 mL cesium oleate solution. Observe immediate color change.

- After 10 seconds, cool reaction flask in ice-water bath.

Purification:

- Transfer crude solution to centrifuge tubes. Add methyl acetate (1:1 volume ratio).

- Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes. Discard supernatant.

- Redisperse precipitate in toluene. Centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 3 minutes to remove undispersed aggregates.

- Collect supernatant containing purified Zn-doped PQDs.

Characterization:

- Confirm doping success through X-ray diffraction (XRD) peak shifts.

- Measure PLQY using integrating sphere before and after doping.

- Perform time-resolved PL to assess carrier lifetime improvement.

Surface Passivation for Reduced Auger Recombination

Objective: Implement a surface treatment protocol to reduce trap-assisted recombination, a precursor to Auger processes.

Materials:

- Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB)

- Lead bromide (PbBr₂)

- Anhydrous toluene

Procedure:

- Surface Ligand Engineering:

- Prepare DDAB solution (10 mg/mL in toluene).

- Mix PQD solution with DDAB solution at 2:1 volume ratio.

- Stir mixture for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Precipitate with ethyl acetate and centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Redisperse in anhydrous toluene for further use.

- Halide-Rich Surface Passivation:

- Prepare PbBr₂ solution (0.1 M in DMF).

- Add 100 μL PbBr₂ solution to 5 mL PQD solution (in toluene) under vigorous stirring.

- Stir for 1 hour to allow halide ion exchange and surface defect passivation.

- Purify by centrifugation and redisperse in toluene.

Auger recombination represents a fundamental limitation in PQD optoelectronic devices, particularly affecting performance at high operating currents required for bright displays and lighting. The strategies outlined here—including structural engineering with alloyed layers [3], dielectric confinement manipulation through polar organic cations [4], and strategic doping with elements like zinc [6]—provide effective pathways for suppressing this loss mechanism.

The experimental protocols and surface treatment methods detailed in this application note enable researchers to quantitatively characterize and mitigate Auger recombination in PQD systems. Implementation of these approaches has already demonstrated remarkable improvements in device performance, including PeLEDs with external quantum efficiencies exceeding 20% and record luminance levels above 80,000 cd m⁻² [4]. Future research directions should focus on developing more precise doping techniques, exploring novel heterostructure designs, and establishing standardized characterization protocols for Auger recombination across different PQD compositions.

The Critical Link Between Exciton Binding Energy and Auger Recombination Rates

In semiconductor physics, excitons are quasi-particles consisting of a bound electron-hole pair attracted to each other by the electrostatic Coulomb force. These electrically neutral quasiparticles form when a material absorbs photon energy, promoting an electron to the conduction band and leaving a positively charged hole in the valence band [8]. The strength of this electron-hole bond is quantified by its exciton binding energy (Eb), which represents the energy required to dissociate an exciton into its free charge carriers [9].

The value of Eb varies significantly across different semiconductor materials. In traditional inorganic semiconductors like GaAs, binding energies are relatively small (4.9 meV), while in organic semiconductors, they can reach 0.1-1.0 eV [9]. In low-dimensional systems such as quantum dots and quasi-2D perovskites, quantum confinement and dielectric confinement effects can lead to substantially enhanced exciton binding energies [4] [8].

Auger recombination represents a non-radiative process involving three carriers, where an electron and hole recombine but instead of emitting light, transfer their energy to a third carrier (either an electron or hole), exciting it higher within its energy band [10] [11]. This process becomes particularly significant at high carrier densities and is a major efficiency-loss mechanism in optoelectronic devices, leading to efficiency "droop" in light-emitting diodes and reduced performance in other semiconductor devices [4] [11].

Table: Key Properties of Exciton Types

| Exciton Type | Binding Energy Range | Spatial Extent | Typical Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wannier-Mott | 0.01 - 0.1 eV | Large (many unit cells) | Inorganic semiconductors (GaAs, CdTe) |

| Frenkel | 0.1 - 1.0 eV | Small (single molecule/atom) | Organic semiconductors, insulators |

| Quasi-2D Perovskite | 1 - 20 meV | Intermediate | Layered perovskite semiconductors |

Theoretical Framework: The Eb-Auger Relationship

Recent research has established a critical theoretical link between exciton binding energy and Auger recombination rates. In strongly confined one-dimensional systems, the Auger recombination rate demonstrates a cubic dependence on exciton binding energy [12]. This powerful relationship explains why materials with large Eb values experience dramatically accelerated Auger recombination.

The underlying physical mechanism stems from enhanced Coulomb electron-hole interactions in systems with large binding energies. These strengthened interactions cause carriers to become non-uniformly distributed in space, substantially increasing the probability of finding two electrons and one hole at the same position - the fundamental requirement for Auger recombination to occur [4]. The dielectric confinement effect in low-dimensional structures further amplifies this phenomenon by reducing dielectric screening of Coulomb interactions [4].

For quasi-2D perovskites, this relationship presents a particular challenge. These materials naturally exhibit strong quantum and dielectric confinement, leading to large Eb values that consequently accelerate Auger recombination [4]. This fundamental materials property manifests practically as efficiency roll-off in light-emitting devices, especially under high injection currents where carrier densities are elevated [4].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Evidence

Experimental studies across multiple material systems have provided quantitative validation of the Eb-Auger relationship. In quasi-2D perovskite systems, strategic manipulation of organic cations has demonstrated dramatic changes in Auger recombination constants.

Table: Experimental Data on Eb and Auger Recombination

| Material System | Intervention | Exciton Binding Energy (Eb) | Auger Recombination Constant | Device Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEA₂MAₙ₋₁PbₙBr₃ₙ₊₁ (reference) | None | High (reference) | Reference value | Severe efficiency roll-off |

| p-FPEA₂MAₙ₋₁PbₙBr₃ₙ₊₁ | Polar organic cation | Several times smaller | >1 order of magnitude lower | Peak EQE: 20.36%, Luminance: 82,480 cd m⁻² |

| PbS QD/rGO System | Charge transfer-induced hole accumulation | N/A | Dominant recombination pathway | PL lifetime reduction from 1950 ns to 4 ns |

In a compelling demonstration, researchers employed a polar molecule, p-fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA⁺), to generate quasi-2D perovskites with reduced Eb. The resulting materials exhibited Auger recombination rates more than one order of magnitude lower compared to PEA⁺ analogues [4]. This suppression of Auger recombination enabled the demonstration of highly efficient perovskite light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs) with a peak external quantum efficiency of 20.36% and a record luminance of 82,480 cd m⁻² [4].

In quantum dot systems, research on PbS QDs covalently attached to reduced graphene oxide (rGO) revealed that Auger recombination dominated photoluminescence quenching when excess holes remained in QDs after charge transfer processes [13]. This system exhibited substantial PL lifetime reduction from 1950 ns in pristine QDs to just 4 ns in rGO/QD composites with 1:15 weight ratio, directly correlating with increased Auger processes [13].

Diagram Title: Eb-Auger Relationship Flowchart

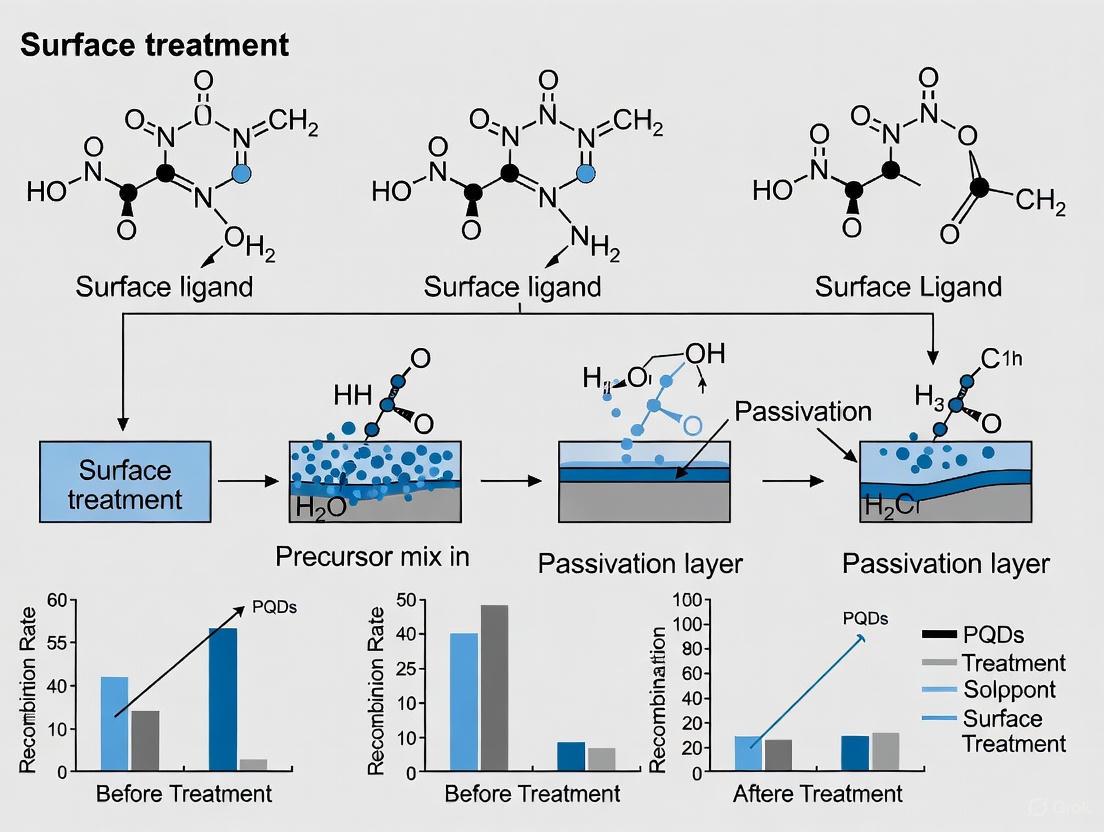

Surface Treatment Strategies for Reduced Auger Recombination

Surface treatment represents a powerful strategy for mitigating Auger recombination in semiconductor nanomaterials, particularly perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). The fundamental approach involves modifying the interface between the semiconductor core and its environment to reduce non-radiative recombination pathways.

Dielectric Engineering via Organic Cations

In quasi-2D perovskites, introducing polar organic cations at the "A-site" effectively weakens dielectric confinement, thereby reducing Eb and subsequent Auger recombination [4]. The p-fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA⁺) cation, with its strong molecular dipole moment (2.39 D versus 1.28 D for PEA⁺), increases the dielectric constant of the organic barrier layer [4]. This reduced dielectric mismatch between inorganic wells and organic barriers diminishes the dielectric confinement effect, leading to several times smaller Eb and more than one-order-of-magnitude lower Auger recombination rates [4].

Surface Passivation Techniques

Beyond dielectric engineering, direct surface defect passivation is crucial for comprehensive performance improvement. In AlGaInP red micro-LEDs, steam oxidation treatment of mesa sidewalls has proven effective in suppressing nonradiative recombination [14]. This process converts the metal components (Al, Ga, In) in the quaternary epi-layers into their respective native oxides, creating an insulating layer that diverts current flow from damaged sidewall regions [14]. Optimal oxidation parameters are size-dependent, with smaller devices (5×5 μm²) requiring shorter oxidation times (15 minutes) compared to larger devices (100×100 μm², 60 minutes) [14].

For 4H-SiC semiconductors, oxidation followed by post-oxidation annealing (POA) significantly reduces surface recombination velocity, demonstrating effective passivation of both Si and C faces [15]. This approach addresses surface states that act as enhanced Shockley-Read-Hall recombination centers [15].

Chemical Passivation and Functionalization

In quantum dot systems, surface ligand engineering plays a critical role in controlling recombination dynamics. For PbS QD/rGO composites, covalent attachment via (3-mercaptopropyl) trimethoxysilane (MPTS) linkers enables controlled charge transfer while potentially mitigating detrimental Auger effects through proper surface coordination [13]. The thiol group binds to the QD surface while the silane group covalently functionalizes rGO, creating a stable composite architecture [13].

Diagram Title: Surface Treatment Strategies for Auger Suppression

Experimental Protocols for Eb and Auger Characterization

Exciton Binding Energy Measurement Protocol

Temperature-Dependent Photoluminescence (TD-PL) Method

- Objective: Quantitatively determine exciton binding energy through temperature-dependent spectral analysis.

- Materials: Closed-cycle helium cryostat (1.5-300 K range), spectrometer with InGaAs detector for NIR applications, laser excitation source (e.g., 532 nm Nd:YAG), computer-controlled temperature controller [4].

- Procedure:

- Mount sample in cryostat and establish vacuum environment.

- Collect PL spectra across temperature range (1.5-300 K) with constant excitation power.

- Observe PL intensity reduction and spectral line broadening with increasing temperature.

- Extract Eb from the thermal activation energy of exciton dissociation.

- Data Analysis: Fit temperature-dependent PL intensity to Arrhenius plot, where the activation energy corresponds to Eb [4].

Optical Absorption Spectroscopy Method

- Objective: Qualitatively assess Eb through excitonic feature analysis.

- Materials: UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (e.g., Shimadzu UV3600), temperature-controlled sample holder [4].

- Procedure:

- Measure absorption spectra at low temperatures (4-10 K) to resolve excitonic features.

- Identify excitonic absorption peaks below the band-edge transition.

- Compare with room-temperature spectra where excitonic features may be obscured.

- Data Analysis: For n=1 2D perovskites, clearly resolved excitonic peaks (e.g., at 3.08 eV for PEA₂PbBr₄) indicate large Eb, while diminished features (kink at 3.04 eV for p-FPEA₂PbBr₄) indicate reduced Eb [4].

Auger Recombination Characterization Protocol

Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TR-PL) Method

- Objective: Determine carrier recombination dynamics and quantify Auger coefficients.

- Materials: Pulsed laser system (1 ns pulse duration), InGaAs/InP avalanche photodiode (APD) operating in photon-counting mode, time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) electronics, custom NIR PL analysis setup [13].

- Procedure:

- Excite sample with pulsed laser at varying excitation densities.

- Record PL decay curves using TCSPC methodology.

- Fit decay curves to multiexponential functions.

- Calculate average PL lifetime using: τₐᵥ = Σ(Aᵢτᵢ)/ΣAᵢ, where Aᵢ and τᵢ are amplitudes and lifetimes [13].

- Data Analysis: Extract Auger coefficient from excitation-density-dependent lifetime measurements. Dominant cubic dependence of decay rate on carrier density indicates Auger processes.

ABC Model Fitting Protocol

- Objective: Quantify contributions of radiative, SRH, and Auger recombination.

- Materials: Light output power vs. current density (L-J) data, variable-temperature EQE measurements [14].

- Procedure:

- Measure EQE as function of injection current density.

- Record light output power versus current density characteristics.

- Perform measurements at multiple temperatures if possible.

- Data Analysis: Fit data to ABC model: Rtotal = An + Bn² + Cn³, where A is SRH coefficient, B is radiative coefficient, and C is Auger coefficient [14].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Eb and Auger Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| p-Fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA⁺) | Polar organic cation for dielectric engineering | Eb reduction in quasi-2D perovskites [4] |

| (3-Mercaptopropyl) trimethoxysilane (MPTS) | Bifunctional linker for QD composite formation | Covalent attachment of PbS QDs to rGO [13] |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | Charge transfer/acceptor material | QD composite studies for Auger process investigation [13] |

| Lead Oxide (PbO) | Precursor for QD synthesis | PbS QD fabrication for recombination studies [13] |

| Hexamethyldisilathiane | Sulfur source for QD synthesis | PbS QD fabrication [13] |

The established critical link between exciton binding energy and Auger recombination rates provides a fundamental design principle for developing high-performance optoelectronic materials. Surface treatment strategies, particularly dielectric engineering with polar molecules and defect passivation through oxidation techniques, represent powerful approaches for managing this relationship to achieve superior device performance.

Future research directions should focus on refining surface treatment protocols for specific material systems, developing advanced characterization techniques for direct observation of Eb-Auger dynamics, and exploring novel chemical approaches for simultaneous Eb reduction and defect passivation. The integration of these strategies with device architecture optimization will enable next-generation optoelectronic devices with minimized efficiency losses at high operating intensities.

How Dielectric Confinement in Quasi-2D Perovskites Amplifies Auger Losses

Quasi-two-dimensional (quasi-2D) perovskites have emerged as promising materials for optoelectronic devices, particularly light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs), due to their exceptional stability and favorable photophysical properties. These materials feature self-assembled multiple-quantum-well structures where inorganic semiconductor layers are sandwiched between organic insulating spacers. This architecture creates two significant confinement effects: quantum confinement and dielectric confinement [4]. The dielectric confinement effect arises from the substantial mismatch between the high dielectric constant of the inorganic layers (εw) and the low dielectric constant of the surrounding organic ligands (εb) [16]. This mismatch reduces the dielectric screening of the Coulomb interaction between electrons and holes, leading to strongly bound excitons with large exciton binding energies (Eb) [4].

While this strong excitonic character boosts radiative recombination efficiency at low excitation densities, it unfortunately comes with a significant drawback: amplified Auger recombination [4]. Auger recombination is a non-radiative process where the energy from one recombining electron-hole pair is transferred to a third carrier, which is promoted to a higher energy state. This process becomes particularly detrimental in quasi-2D perovskites under high excitation densities or electrical injection, leading to efficiency roll-off in PeLEDs and limiting their achievable brightness and commercial potential [4] [17]. Understanding and mitigating this trade-off between beneficial excitonic effects and detrimental Auger losses is crucial for advancing quasi-2D perovskite optoelectronics.

Theoretical Foundation: The Fundamental Link Between Dielectric Confinement and Auger Recombination

The intrinsic connection between dielectric confinement and Auger recombination in quasi-2D perovskites can be understood through several interrelated physical mechanisms. First, the dielectric confinement effect directly enhances the exciton binding energy (Eb). In quasi-2D Ruddlesden-Popper perovskites with the general formula (RNH₃)₂(A)ₙ₋₁BₙX₃ₙ₊₁, the surrounding organic ligands with small dielectric constants are less polar, which diminishes the dielectric screening of electron-hole Coulomb interaction [4]. This results in Eb values that can reach several hundred millielectronvolts, significantly higher than those in their 3D counterparts [4].

The Auger recombination rate in strongly confined systems exhibits a power-law dependence on Eb. Research has established that in quasi-2D perovskites, the Auger recombination rate is proportional to the third power of the exciton binding energy [4]. This strong correlation occurs because enhanced Coulomb electron-hole interaction leads to carriers no longer being uniformly distributed in space, thus increasing the probability of finding two electrons and one hole at the same position to accelerate the Auger process [4].

Furthermore, the energy transfer dynamics in quasi-2D perovskites further exacerbate Auger losses. These materials naturally form a distribution of domains with different dimensionality (n-values). The ultrafast energy transfer from smaller-n to larger-n domains creates an amplified carrier density at the recombination centers (typically the lowest-bandgap domains) [4]. Since the Auger recombination rate is proportional to the cube of carrier density, this localized high carrier density significantly enhances Auger losses [4]. The combination of these factors makes Auger recombination a dominant loss mechanism in quasi-2D perovskites under operational conditions.

Visualizing the Dielectric Confinement-Auger Recombination Relationship

The diagram below illustrates the mechanistic relationship between dielectric confinement and Auger recombination:

Quantitative Data: Experimental Evidence of Dielectric Engineering Effects

Impact of Organic Spacer Dielectric Constant on Exciton Binding and Auger Recombination

Table 1: Experimental parameters of quasi-2D perovskites with different organic spacers

| Organic Spacer | Dielectric Constant | Exciton Binding Energy (Eb) | Auger Recombination Rate | PLQY | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEA⁺ | Low (~1.28 D dipole moment) | 135.9 meV (⟨n⟩=4) | High (reference) | Moderate | [16] |

| p-FPEA⁺ | Intermediate (~2.39 D dipole moment) | 75.3 meV (⟨n⟩=4) | >10× lower than PEA⁺ | High (with passivation) | [16] [4] |

| EA⁺ | Not specified | 57.4 meV (⟨n⟩=4) | Intermediate | Variable | [16] |

| BDA²⁺ | Not specified | 108.6 meV (n=5) | Lower than longer chains | 5.5% (device EQE) | [17] |

| HDA²⁺ | Not specified | 138.1 meV (n=5) | Balanced | 8.2% (device EQE) | [17] |

| ODA²⁺ | Not specified | 168.6 meV (n=5) | Highest among series | 7.3% (device EQE) | [17] |

The data in Table 1 clearly demonstrates the correlation between organic spacer properties, exciton binding energy, and Auger recombination. The dipole moment of the organic cation, which influences its effective dielectric constant, plays a crucial role in determining the material's electronic properties. Introducing polar molecules like p-FPEA⁺ with higher dipole moments (2.39 D) compared to conventional PEA⁺ (1.28 D) reduces the dielectric constant mismatch, thereby weakening dielectric confinement and reducing Eb [4]. This reduction in Eb directly translates to suppressed Auger recombination, with p-FPEA⁺-based quasi-2D perovskites showing more than one-order-of-magnitude lower Auger recombination rates compared to PEA⁺ analogues [4].

Device Performance Metrics from Dielectric Engineering

Table 2: Performance characteristics of PeLEDs employing dielectric confinement modulation

| Device Strategy | Peak EQE (%) | Maximum Luminance (cd/m²) | Efficiency Roll-Off | Stability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-FPEA⁺ with passivation | 20.36% | 82,480 | Suppressed | Enhanced (reduced Joule heating) | [4] [18] |

| HDA²⁺ quasi-2D DJ phase | 21.9% | Not specified | Moderate | T₅₀ = 479 h at 20 mA cm⁻² | [17] |

| ODA²⁺ quasi-2D DJ phase | 7.3% | Not specified | Severe | Inferior to HDA²⁺ | [17] |

| Volatile PEAAc phase reconstruction | Low-threshold lasing: 17.3 μJ cm⁻² | Not specified | Not applicable | Improved film quality | [19] |

The device performance metrics in Table 2 highlight the significant benefits of rationally engineering dielectric confinement. The use of polar organic spacers like p-FPEA⁺, combined with appropriate passivation strategies, has enabled some of the most efficient and bright PeLEDs reported to date [4] [18]. The substantial improvement in maximum luminance directly results from suppressed efficiency roll-off, which stems from reduced Auger recombination at high carrier densities. Furthermore, suppressed Auger recombination reduces Joule heating, thereby enhancing device operational stability [4]. The chain-length dependence observed with alkyldiammonium cations further confirms the delicate balance required in dielectric engineering - while longer chains can increase exciton binding energy and radiative recombination rates, they also exacerbate Auger recombination and charge transport barriers [17].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Characterizing and Mitigating Auger Losses

Protocol: Fabrication of Dielectric-Engineered Quasi-2D Perovskite Films

Objective: Prepare quasi-2D perovskite films with controlled dielectric confinement using organic spacers with varying dielectric constants.

Materials:

- Lead bromide (PbBr₂)

- Methylammonium bromide (MABr)

- Organic spacer salts: PEABr, p-FPEABr, or other derivatives

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF)

- Solvent engineering agents (chloroform, toluene)

- Substrates (glass, ITO, etc.)

Procedure:

- Prepare precursor solutions by dissolving PbBr₂, MABr, and the selected organic spacer salt (e.g., PEA₂MAn−1PbnBr3n+1 or p-FPEA₂MAn−1PbnBr3n+1 stoichiometry) in DMSO/DMF mixture [4].

- For p-FPEA⁺-based perovskites, utilize the higher polarity cation to reduce dielectric confinement [4].

- Stir the precursor solution overnight at room temperature to ensure complete dissolution and complex formation.

- Clean substrates thoroughly with sequential sonication in detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropanol.

- Deposit perovskite films using spin-coating: typically a two-step program (1000-4000 rpm for 30-60 s) [4].

- During the spin-coating process, initiate crystallization by dripping anti-solvent (chloroform or toluene) onto the spinning substrate 10-15 seconds before the end of the program [16].

- Anneal the films at 60-100°C for 10-30 minutes to remove residual solvent and improve crystallinity [4].

- For additional passivation, implement post-treatment strategies using organic halide solutions or other passivating agents [4] [20].

Quality Control:

- Characterize film morphology using scanning electron microscopy to ensure pinhole-free, uniform coverage [19].

- Verify phase purity and crystallinity through X-ray diffraction [4].

- Confirm target n-value distribution through absorption spectroscopy, identifying characteristic excitonic peaks [16] [19].

Protocol: Transient Absorption Spectroscopy for Auger Recombination Kinetics

Objective: Quantify Auger recombination rates in quasi-2D perovskite films using femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy.

Materials and Equipment:

- Femtosecond laser system (e.g., Ti:Sapphire amplifier, 1 kHz repetition rate)

- Optical parametric amplifier for tunable pump pulses

- Helios or similar broadband pump-probe spectrometer [16]

- White-light continuum probe generation system (380-600 nm range) [16]

- Cryostat for temperature-dependent measurements (optional)

Procedure:

- Set up the pump-probe system with pump excitation energy tuned to the primary excitonic absorption of the perovskite film [16].

- Generate white-light continuum probe pulses by focusing a portion of the fundamental 800 nm laser pulses onto a sapphire crystal [16].

- Measure differential transmission (ΔT/T) or absorption (ΔA) signals across temporal delays from femtoseconds to nanoseconds [16].

- Systematically vary pump fluence from low excitation (≤1 μJ/cm²) to high excitation (≥100 μJ/cm²) densities [16] [21].

- For each fluence, record the kinetics at the ground-state bleaching peak of the dominant emitting phase [16].

- Perform measurements on films with different organic spacers under identical conditions for comparative analysis [16].

Data Analysis:

- Fit the decay dynamics with multi-exponential functions including energy transfer, trap-assisted recombination, and Auger recombination components [16].

- Extract the fast decay component that scales quadratically with excitation fluence, characteristic of biexciton Auger recombination [16].

- Calculate the Auger recombination rate (k₃) from the cubic dependence of the decay rate on carrier density [4].

- Compare Auger rates across samples with different dielectric confinement strengths [16] [4].

Protocol: Exciton Binding Energy Measurement via Temperature-Dependent Photoluminescence

Objective: Determine the exciton binding energy (Eb) of quasi-2D perovskite films through temperature-dependent PL spectroscopy.

Materials and Equipment:

- Closed-cycle cryostat with temperature control (4-300 K)

- Continuous-wave laser excitation source (e.g., 405 nm)

- Spectrometer with CCD detector

- Optical cryostat with temperature controller

Procedure:

- Mount the perovskite film in the cryostat and ensure good thermal contact.

- Set initial temperature to lowest achievable point (typically 10 K).

- Excite the sample with low laser power density to avoid heating effects.

- Record PL spectra at temperature intervals (e.g., 10 K steps) from 10 K to 300 K.

- Maintain consistent acquisition parameters throughout the temperature series.

- Monitor integrated PL intensity, peak position, and full-width at half-maximum at each temperature.

Data Analysis:

- Plot the integrated PL intensity as a function of inverse temperature (1/T).

- Fit the high-temperature region (where thermal quenching occurs) with the Arrhenius equation:

I(T) = I₀ / [1 + A exp(-Eb/kBT)]

where I₀ is the intensity at 0 K, A is a constant, Eb is the exciton binding energy, and kB is the Boltzmann constant [16].

- Extract Eb from the fitting parameter [16].

- Compare Eb values for different organic spacers to correlate with dielectric confinement strength [16] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents for dielectric confinement engineering in quasi-2D perovskites

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Usage | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-Fluorophenethylammonium bromide (p-FPEABr) | High-polarity organic spacer to reduce dielectric confinement | Partial or complete replacement of PEA⁺ to reduce Eb and Auger recombination [4] | Higher dipole moment (2.39 D) reduces dielectric mismatch [4] |

| Phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) | Standard organic spacer for quasi-2D perovskites | Reference material for strong dielectric confinement studies [16] [4] | Lower dipole moment (1.28 D) creates strong dielectric confinement [4] |

| Alkyldiammonium halides (BDAI₂, HDAI₂, ODAI₂) | Chain-length tunable spacers for Dion-Jacobson phases | Systematic studies of chain length vs. dielectric confinement and Auger rates [17] | Longer chains increase Eb but may hinder charge transport [17] |

| 2-phenylethylammonium acetate (PEAAc) | Volatile ammonium for phase reconstruction | Creates high-quality films with reduced confinement via post-annealing desorption [19] | Volatility enables transition from quasi-2D to 3D phases during annealing [19] |

| Trifluoroacetate anions | Additive for film morphology control | Assisted crystallization for improved film coverage [20] | Often used in conjunction with post-treatment anion exchange methods [20] |

| Organic chlorides (PEACl, DPEACl) | Post-treatment anion exchange and passivation | Chloride source for bandgap tuning and defect passivation [20] | Good solubility addresses limitations of inorganic chlorides [20] |

Visualization: Experimental Workflow for Dielectric Confinement Studies

The diagram below outlines a comprehensive experimental approach for studying and mitigating Auger losses in quasi-2D perovskites:

The intricate relationship between dielectric confinement and Auger recombination in quasi-2D perovskites represents both a fundamental scientific challenge and a technological opportunity. While dielectric confinement enhances exciton stability and radiative efficiency at low carrier densities, it unavoidably amplifies Auger losses under operational conditions, manifesting as efficiency roll-off in PeLEDs. The experimental protocols and data presented herein provide a roadmap for systematically characterizing and mitigating these losses through rational materials design.

Future research directions should focus on developing multi-functional organic spacers that simultaneously optimize dielectric properties, passivate defects, and facilitate efficient charge transport. The exploration of volatile ammonium agents for phase reconstruction represents a promising avenue for achieving high-quality films with minimized confinement effects [19]. Additionally, advanced in-situ characterization techniques during film formation could provide deeper insights into the dynamic evolution of dielectric confinement and its impact on recombination kinetics. As these strategies mature, the fundamental understanding of dielectric confinement effects will continue to enable high-performance perovskite optoelectronics with suppressed Auger losses and enhanced operational stability.

Analyzing the Cube-Law Dependence of Auger Recombination on Carrier Density

Auger recombination is a critical non-radiative process in semiconductors where the energy from an electron-hole recombination event is transferred to a third charge carrier (an electron or a hole), exciting it to a higher energy state within the same band. This excited carrier subsequently relaxes back to its equilibrium state through phonon emission, effectively converting the recombination energy into heat. Unlike Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) recombination which depends linearly on carrier density and radiative recombination which follows a quadratic dependence, the direct Auger recombination process exhibits a characteristic cube-law dependence on carrier density, making it particularly detrimental at high carrier concentrations commonly encountered in optoelectronic devices operating under high injection conditions or in heavily doped materials [22] [23].

The cube-law dependence arises from the fundamental nature of the three-body process, requiring the simultaneous interaction of three carriers. For an n-type semiconductor, the Auger recombination rate can be expressed as ( R{Auger} = Cn n^2 p + Cp n p^2 ), where ( n ) and ( p ) are electron and hole densities, and ( Cn ) and ( Cp ) are the Auger coefficients for the processes involving two electrons and one hole, or two holes and one electron, respectively. Under high injection conditions where ( n \approx p = \Delta n ), this simplifies to ( R{Auger} = C{eff} \Delta n^3 ), where ( C{eff} = Cn + Cp ), clearly demonstrating the cubic dependence on carrier density [22]. This cubic relationship has been experimentally verified in various semiconductor systems, including InN, where carrier lifetime (( \tau )) scales as ( 1/n^2 ) since ( \tau = \Delta n / R{Auger} \propto 1/(C{eff} \Delta n^2) ) [22].

Quantitative Analysis of Auger Recombination Coefficients

Table 1: Experimentally Measured Auger Recombination Coefficients in Various Semiconductor Systems

| Material System | Auger Coefficient (cm⁶/s) | Carrier Density Range | Measurement Technique | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| InN epilayers | (8 ± 1) × 10⁻²⁹ | 10¹⁸ - 5×10¹⁹ cm⁻³ | Light-Induced Transient Grating (LITG) | [22] |

| CdSe/CdS core/shell QDs (H=2.0 nm) | Not specified | >5×10¹⁸ cm⁻³ | Time-resolved PL | [3] |

| CdSe/CdS core/shell QDs (H=5.5 nm) | Not specified | >5×10¹⁸ cm⁻³ | Time-resolved PL | [3] |

| 4H-SiC | Relatively small contribution | >5×10¹⁸ cm⁻³ | Theoretical analysis | [15] |

The cube-law dependence of Auger recombination manifests clearly in experimental data. In InN epilayers, carrier lifetime decreases with the square of carrier density (( \tau \propto 1/n^2 )) in the density range between 8×10¹⁸ cm⁻³ and 5×10¹⁹ cm⁻³, confirming the cubic relationship between recombination rate and carrier density (( R \propto n^3 )) [22]. This relationship deviates at extremely high carrier densities (>5×10¹⁹ cm⁻³) due to phase space filling effects which saturate the Auger recombination rate [22].

In quantum-confined systems such as perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and colloidal quantum dots (QDs), Auger recombination is significantly enhanced due to spatial confinement which relaxes momentum conservation and strengthens carrier-carrier Coulomb interactions [3] [24]. The Auger lifetime (( \tau )) in QDs scales linearly with QD volume, with smaller dots exhibiting faster Auger recombination [3]. For example, in CdSe/CdS core/shell QDs, increasing the shell thickness from 2.0 nm to 5.5 nm increases the biexciton Auger lifetime from 0.13 ns to 0.76 ns, demonstrating the volume dependence of this recombination pathway [3].

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Auger Recombination

Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TR-PL) Spectroscopy

Objective: To measure carrier lifetime dynamics and extract Auger recombination coefficients from the cube-law dependence of decay rates.

Materials and Equipment:

- Femtosecond or picosecond pulsed laser source (wavelength tunable)

- Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) system or streak camera

- Cryostat for temperature-dependent measurements (77K to 300K)

- Spectrometer with high spectral resolution

- Neutral density filters for excitation power adjustment

- Sample mount with precise positioning

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Deposit PQD films on quartz substrates using spin-coating at 2000 rpm for 30 seconds. Maintain uniform film thickness (~100 nm) across all samples.

- Excitation Power Variation: Conduct TR-PL measurements at excitation fluences ranging from 10-1000 μJ/cm² using neutral density filters. Ensure the laser spot size is precisely measured for accurate carrier density calculation.

- Data Acquisition: For each excitation power, record at least 10 decay traces with integration times sufficient for good signal-to-noise ratio. Measure the initial carrier density (( \Delta n )) using the relationship ( \Delta n = \alpha I / h\nu ), where ( \alpha ) is absorption coefficient, ( I ) is excitation energy fluence, and ( h\nu ) is photon energy [22].

- Lifetime Extraction: Fit decay curves to appropriate models (monoexponential, biexponential, or stretched exponential) and extract decay time constants.

- Auger Coefficient Determination: Plot the inverse lifetime (( 1/\tau )) versus the square of the initial carrier density (( \Delta n^2 )). The slope of the linear fit provides the Auger coefficient ( C{eff} ) according to: ( 1/\tau = 1/\tau0 + C{eff} \Delta n^2 ), where ( \tau0 ) is the low-injection lifetime [22].

Light-Induced Transient Grating (LITG) Technique

Objective: To simultaneously measure carrier lifetime and diffusion coefficient across a wide range of carrier densities.

Materials and Equipment:

- Femtosecond laser system (e.g., 250-fs pulses at 1030 nm)

- Optical parametric oscillator for tunable probe pulses

- Holographic beam splitter for creating interference patterns

- Precision translation stages for delay control

- Photodetectors and lock-in amplifiers for signal detection

Procedure:

- Grating Formation: Split the pump beam into two coherent beams and recombine them on the sample surface at an angle θ to create an interference pattern with period ( \Lambda = \lambda / [2 \sin(\theta/2)] ), where λ is the laser wavelength.

- Probe Diffraction: Direct a time-delayed probe beam onto the transient grating and monitor the first-order diffraction efficiency as a function of delay time.

- Multiple Period Measurements: Repeat measurements for different grating periods (typically 1-10 μm) by adjusting the angle between the interfering beams.

- Data Analysis: For each delay time, extract the instantaneous decay time (( \tauG )) by fitting the diffraction efficiency to ( \eta(t) \propto \exp(-2t/\tauG) ). Plot ( 1/\tau_G ) versus ( 4\pi^2/\Lambda^2 ) for each carrier density. The y-intercept gives ( 1/\tau ) (recombination rate) and the slope provides the diffusion coefficient D [22].

- Auger Parameter Extraction: Plot the recombination rate (( 1/\tau )) versus carrier density squared (( n^2 )) and extract the Auger coefficient from the slope of the linear region.

Femtosecond Transient Absorption (TA) Spectroscopy

Objective: To directly monitor multiexciton dynamics and Auger recombination rates in PQDs.

Materials and Equipment:

- Femtosecond amplifier system (e.g., 35 fs pulses at 1 kHz repetition rate)

- Optical parametric amplifier for tunable pump pulses

- White-light continuum probe generation

- Spectrometer with diode array detection

- Automated delay stage with sub-micrometer resolution

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare PQD solutions with optical density of ~0.3 at excitation wavelength in 1mm pathlength cuvettes.

- Pump-Probe Alignment: Overlap spatially and temporally the pump and probe beams on the sample with pump beam diameter slightly larger than probe.

- Multiexciton Dynamics: Conduct excitation fluence-dependent measurements from 10-500 μJ/cm². At high fluences where multiexcitons are created, the decay will show a fast component due to Auger recombination.

- Data Analysis: Extract the biexciton Auger lifetime by global fitting of the decay kinetics. Plot the fast decay component versus excitation fluence to confirm the cubic dependence on carrier density.

Research Reagent Solutions for Auger Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Auger Recombination Studies in PQDs

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite NCs (CsPb(BrxCl1-x)3) | Model system for studying defect-mediated Auger recombination | Blue-emissive NCs for amplified spontaneous emission studies | Control deep-level defects associated with VCl (chlorine vacancies) [24] |

| ZnSeTe Quantum Dots | Eco-friendly QD system with tunable interfacial potential | Investigating Auger suppression through interfacial potential grading | Te distribution affects lattice mismatch and Auger rates [25] |

| Core/Alloy/Shell (C/A/S) Heterostructures | Suppressing Auger recombination through interface engineering | CdSe/CdSe0.5S0.5/CdS QDs with smoothed interfacial potential | Alloyed interface reduces wavefunction overlap for Auger processes [3] |

| HF/ZnCl2 Surface Treatment | Surface passivation to reduce non-radiative channels | Defect passivation in ZnSeTe QDs | Reduces surface defects that contribute to trap-assisted Auger [25] |

| Steam Oxidation Treatment | Sidewall passivation for micro-LEDs | AlGaInP red µLEDs with reduced surface recombination | Creates insulating oxide layers to reduce sidewall recombination [14] |

Mitigation Strategies for Auger Recombination in PQDs

Interfacial Potential Engineering

Graded interfacial potential structures effectively suppress Auger recombination by smoothing the confinement potential between core and shell regions. In ZnSeTe quantum dots, implementing an interfacial potential-graded (IPG) shell between the ZnSeTe core and ZnSe shell significantly reduces Auger recombination rates compared to conventional core/shell structures [25]. The IPG structure features a gradual compositional gradient (e.g., ZnSe0.9Te0.1) that alleviates interfacial lattice mismatch and strain, reducing structural deformation and misfit defects that enhance Auger processes [25]. Experimental verification using excitation-intensity dependent ultrafast transient absorption kinetics confirms suppressed Auger recombination in IPG QDs, leading to enhanced performance in quantum dot light-emitting diodes (QLEDs) with peak external quantum efficiency of 21.7% [25].

Alloyed Interface Design

Inserting an alloyed layer at the core-shell interface effectively suppresses Auger recombination by "smoothing" the interfacial potential. In CdSe/CdSe0.5S0.5/CdS core/alloy/shell (C/A/S) quantum dots, the alloyed interface reduces the overlap between wavefunctions of the initial and final states of the carrier excited in the Auger process, thereby decreasing the Auger recombination rate [3]. Compared to conventional core/shell (C/S) structures with similar volume, C/A/S QDs exhibit significantly longer negative trion (X⁻) and biexciton (XX) lifetimes, indicating suppressed Auger decay [3]. This approach is particularly effective for enhancing the performance of bipolar devices where Auger recombination limits efficiency at high currents.

Deep-Level Defect Control

Deep-level defects significantly influence Auger recombination in perovskite nanocrystals by inducing charge separation states through ultrafast capture of charge carriers (within 10 ps) [24]. These defects preferentially trap electrons, leading to the formation of charged exciton states (trions) that enhance Auger recombination under quantum confinement [24]. In mixed halide (chlorine/bromine) perovskite nanocrystal systems, chlorine-related deep-level defects capture electrons and leave holes, with the excess charges combining with excitons to form charged states that facilitate Auger recombination [24]. Reducing deep-level defect density through optimized synthesis (e.g., hot injection versus room-temperature saturation crystallization) enables pure blue amplified spontaneous emission with record-low threshold of 25 μJ cm⁻² [24].

Auger Recombination Mitigation Strategies

The cube-law dependence of Auger recombination on carrier density presents a fundamental limitation for high-performance optoelectronic devices based on semiconductor nanomaterials, particularly under high injection conditions required for lighting, lasing, and high-brightness applications. Accurate characterization of this dependence through sophisticated experimental techniques like TR-PL, LITG, and transient absorption spectroscopy provides critical insights for developing effective mitigation strategies. The most promising approaches involve interfacial engineering through alloyed layers and compositional grading to smooth confinement potentials, combined with rigorous control of deep-level defects that exacerbate Auger processes through charged exciton formation. Future research should focus on developing quantitative relationships between specific defect types and their contributions to Auger recombination, and exploring novel heterostructure designs that fundamentally alter carrier-carrier interaction potentials to suppress this detrimental non-radiative pathway.

Auger recombination is a non-radiative process in semiconductors where the energy released from electron-hole pair recombination is transferred to a third carrier (electron or hole) instead of being emitted as a photon. This third carrier relaxes back to its original energy state by releasing the excess energy as heat through phonon emission [26]. In the context of perovskite light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs), this process becomes particularly dominant at high carrier densities—precisely the conditions required for high-brightness device operation.

The fundamental challenge for PeLED performance stems from the cube dependence of the Auger recombination rate on carrier concentration (R_Auger ∝ n³) [26]. As injection current increases, the carrier concentration in the perovskite active layer rises dramatically, leading to enhanced Auger recombination that directly competes with radiative processes. This competition results in efficiency roll-off (also known as efficiency droop), where the external quantum efficiency (EQE) of PeLEDs significantly decreases at high current densities, limiting their achievable brightness and commercial viability for display and lighting applications [4] [27].

Quantitative Analysis of Auger-Induced Efficiency Loss

Key Parameters Influencing Auger Recombination

The table below summarizes critical parameters and their impact on Auger recombination in perovskite emissive materials:

Table 1: Key Parameters Affecting Auger Recombination in Perovskites

| Parameter | Impact on Auger Recombination | Experimental Range/Value |

|---|---|---|

| Exciton Binding Energy (E₆) | Proportional to Auger rate; larger E₆ enhances electron-hole interaction [4] | Reduced from PEA⁺ (347 meV) to p-FPEA⁺ analogues [4] |

| Auger Recombination Constant | Material-specific parameter quantifying Auger probability [26] | ~10⁻²⁷–10⁻²⁸ cm⁶/s in 3D perovskites [28]; reduced by order of magnitude with engineering [28] |

| Carrier Concentration | Cube dependence: R_Auger ∝ n³ [26] | Dominates at high injection levels (>100 A/cm²) |

| Dielectric Confinement | Weaker dielectric confinement reduces E₆ and Auger rate [4] | Achieved via high-polarity cations (p-FPEA⁺) [4] |

| Dimensionality | Quasi-2D structures exhibit faster Auger due to energy funneling [4] | 3D perovskites show slower Auger than quasi-2D counterparts [28] |

Efficiency Roll-Off Metrics in Experimental PeLEDs

Recent studies demonstrate how suppressing Auger recombination directly improves key performance metrics:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of PeLEDs With Different Auger Suppression Strategies

| Device Description | Peak EQE | Maximum Luminance | Efficiency Roll-Off Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-FPEA⁺ quasi-2D perovskite | 20.36% | 82,480 cd/m² | Record brightness due to suppressed roll-off [4] | [4] |

| CsTFA-modified 3D perovskite | 21.4% | 2409 W sr⁻¹ m⁻² radiance | EQE >20% at 2270 mA/cm²; negligible roll-off [28] | [28] |

| Annealed+Plasma treated MAPbBr₃ | 20.5% | 68,500 cd/m² | Improved roll-off from enhanced crystallinity [29] | [29] |

| Conventional quasi-2D PeLED | ~20% | <50,000 cd/m² (typical) | Severe roll-off at modest current densities [4] | [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Auger Recombination Characterization

Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) for Recombination Kinetics

Objective: To quantify carrier recombination rates and extract Auger coefficients from excitation-dependent lifetime measurements.

Materials:

- Pulsed laser source (wavelength tunable to perovskite bandgap)

- Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) system

- Cryostat for temperature-dependent measurements (77K-400K)

- Neutral density filters for excitation power variation

- Spectrometer with near-infrared to visible capability

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Deposit perovskite films on glass substrates using optimized fabrication protocols. Ensure uniform coverage without pinholes.

- Excitation Power Series: Measure TRPL decays across at least three orders of magnitude in excitation fluence (10¹⁵–10¹⁸ photons/cm² per pulse).

- Data Analysis:

- Fit decay curves to extract lifetime components at each excitation power.

- Plot initial PL intensity (I₀) versus carrier density to identify recombination order.

- Use rate equation analysis to extract k₁ (monomolecular), k₂ (bimolecular), and k₃ (Auger) coefficients [28].

Interpretation: Quadratic dependence of I₀ on carrier density indicates bimolecular recombination dominance, while cubic dependence signifies Auger-dominated regime [28].

Temperature-Dependent Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)

Objective: To quantify the exciton binding energy and its relationship to Auger recombination.

Materials:

- Integrating sphere with temperature control

- Continuous-wave laser source (405nm, 532nm)

- Spectrometer calibrated for absolute intensity measurements

- Closed-cycle helium cryostat (10K-400K)

Procedure:

- System Calibration: Measure system response function using standardized light sources.

- Temperature Series: Acquire PLQY measurements at minimum 10 temperature points between 10K and 350K.

- Data Fitting: Model temperature-dependent PLQY using Saha-Langmuir equation to extract exciton binding energy [4].

Interpretation: Lower exciton binding energy correlates with reduced Auger recombination rates, as demonstrated with p-FPEA⁺ perovskites showing several times smaller E₆ compared to PEA⁺ analogues [4].

Mitigation Strategies and Research Reagent Solutions

Material Engineering Approaches

Diagram: Comprehensive Strategies for Mitigating Auger Recombination in PeLEDs

Research Reagent Solutions for Auger Suppression

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Suppressing Auger Recombination

| Reagent | Function/Mechanism | Application Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| p-Fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA⁺) | Reduces exciton binding energy via increased dielectric constant; decreases Auger rate by 10x [4] | Incorporate in quasi-2D perovskite precursor solution as A-site cation [4] |

| Cesium Trifluoroacetate (CsTFA) | Decouples electron-hole wavefunction; retards Auger recombination in 3D perovskites [28] | Add to perovskite precursor (0.12 equiv to Pb²⁺); enhances film coverage and passivation [28] |

| 5-Ammonium Valeric Acid Iodide (5AVAI) | Phase stabilizer for α-FAPbI₃; works synergistically with CsTFA for defect passivation [28] | Use in precursor mixture (FAI:PbI₂:5AVAI = 1.28:1:0.1 molar ratio) [28] |

| Argon Plasma Treatment | Post-processing method to improve crystallinity and reduce non-radiative recombination [29] | Treat perovskite films at air pressure for 5 minutes after thermal annealing [29] |

| Thermal Annealing Optimization | Controls grain size and crystallinity; reduces trap-assisted Auger recombination [29] | Optimize temperature (e.g., 60-100°C) for specific perovskite composition [29] |

Advanced Characterization and Theoretical Modeling

Multi-Physics Modeling of Efficiency Roll-Off

Recent theoretical work provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the complex interplay of factors contributing to efficiency roll-off in PeLEDs. The model incorporates:

Self-Consistent Electrical-Thermal Coupling:

- Recombination Current: Jrec = q(k₁n + k₂n² + k₃n³)WP, where k₁, k₂, k₃ represent monomolecular, bimolecular, and Auger recombination coefficients respectively [27].

- Temperature-Dependent Radiative Recombination: k₂ = k₂F × exp(EA/kT), with activation energy E_A ~100 meV [27].

- Joule Heating Effects: Positive feedback mechanism where increased current → higher temperature → reduced radiative efficiency → more heating [27].

Space Charge Effects:

- Potential drop supporting space-charge-limited transport: VSC = KSC × J_rec^α, where α depends on trap distribution [27].

This modeling approach reveals that Auger recombination and Joule heating create a positive feedback mechanism that dominantly contributes to efficiency droop, rather than Auger recombination alone [27].

Experimental Workflow for Auger Analysis

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Analyzing Auger Recombination in PeLEDs

The direct consequence of Auger recombination in PeLEDs—efficiency roll-off at high current densities—represents a fundamental challenge for their commercialization in high-brightness applications. Through advanced material engineering strategies including polar cation incorporation (p-FPEA⁺), anion manipulation (TFA⁻), and optimized processing protocols, significant progress has been made in suppressing Auger rates and mitigating efficiency droop.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Advanced Band Structure Engineering: Further development of perovskite compositions with intrinsically reduced Auger coefficients through computational materials design.

- Nanostructure Optimization: Precise control of quantum confinement effects to naturally suppress three-carrier Auger processes.

- Device Architecture Innovation: Engineering of charge injection profiles to minimize local carrier accumulation and reduce Auger-dominated regimes.

- Multiphoton Management: Exploration of novel phenomena like the spin-exchange Auger process in doped quantum dots for enhanced performance under extreme conditions [30].

The experimental protocols and characterization methodologies outlined in this application note provide a foundation for systematic investigation of Auger recombination in perovskite materials, enabling researchers to develop next-generation PeLEDs with minimal efficiency roll-off for advanced display and lighting technologies.

Advanced Surface Treatments and Passivation Techniques for Auger Suppression

Polar Organic Cation Engineering to Reduce Dielectric Confinement

Low-dimensional organic-inorganic hybrid perovskites, such as two-dimensional (2D) layered structures and quasi-2D systems, naturally form multi-quantum-well (MQW) structures. These structures exhibit not only quantum confinement but also a significant dielectric confinement effect. This effect arises from the substantial mismatch between the high dielectric constant of the inorganic semiconductor layers (εinorganic ≈ 6-25) and the low dielectric constant of the organic cation layers (εorganic ≈ 2-4) [4] [31]. The dielectric mismatch traps photo-generated excitons through inefficient screening of Coulomb interactions, leading to excessively large exciton binding energies (Eb) that can reach 200-470 meV in conventional 2D perovskites [4] [31]. This strong binding impedes the efficient dissociation of excitons into free carriers at room temperature (kT ≈ 26 meV), thereby reducing the quantum yield for photocurrent generation and enhancing non-radiative Auger recombination processes [4].

Polar organic cation engineering presents a powerful strategy to mitigate dielectric confinement. By incorporating organic cations with large dipole moments and higher dielectric constants, the dielectric mismatch between the organic and inorganic layers can be substantially reduced [4] [31] [32]. This enhanced screening weakens the Coulomb interaction between electrons and holes, leading to a dramatic reduction in Eb. A lower Eb facilitates more efficient exciton dissociation into free carriers, which is crucial for photovoltaic and light-emitting applications, and simultaneously suppresses Auger recombination by reducing the electron-hole wavefunction overlap [4]. This application note details the experimental protocols and material design principles for implementing this strategy, with particular emphasis on its role in reducing Auger recombination in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and films.

Polar Organic Cation Design Strategies

The selection and design of polar organic cations are critical for effectively reducing dielectric confinement. The following design approaches have proven successful:

Incorporating Polar Functional Groups: Introducing highly electronegative atoms or polar groups significantly increases the cation's dipole moment and dielectric constant. For instance, fluorination of phenethylammonium (PEA+) creates (S)-ortho-fluorinated-methyl-benzylamine (S-2F-MBA), which increases the organic layer's dielectric constant and reduces Eb [32]. Similarly, ethanolamine (EA+, HOCH2CH2NH3+), featuring a polar hydroxy group, possesses an exceptionally high dielectric constant of 37.7, which drastically diminishes dielectric confinement [31].

Utilizing Cations with Large Intrinsic Dipole Moments: Small cations with large permanent dipole moments, such as methylammonium (MA+, 2.3 D), can be incorporated into the inorganic cage. Their rotational freedom allows for a strong orientational polarizability, which provides additional screening of the electric field between confined charges [33].

The following table summarizes key polar organic cations and their impact on material properties.

Table 1: Properties of Selected Polar Organic Cations and Their Impact on Perovskites

| Organic Cation | Dielectric Constant (ε) | Dipole Moment (D) | Exciton Binding Energy (Eb) | Key Structural Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEA+ [31] | ~3.3 [31] | 1.28 D [4] | ~250 meV [31] | Conventional, low-polarity cation |

| p-FPEA+ [4] | Information Missing | 2.39 D [4] | Several times smaller than PEA+ [4] | Fluorinated aromatic ring |

| S-2F-MBA+ [32] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Significantly reduced vs. non-fluorinated [32] | Fluorinated chiral cation |

| EA+ (HOCH2CH2NH3+) [31] | 37.7 [31] | Information Missing | ~13 meV [31] | Polar hydroxy group |

| Methylammonium (MA+) [33] | Information Missing | 2.3 D [33] | Anomalous QCSE response [33] | Small, rotatable dipolar cation |

The logical relationship between cation properties, the resulting material structure, and the final device performance is outlined below.

Figure 1: Logic of how polar organic cation engineering mitigates Auger recombination and improves device performance.

Quantitative Data on Performance Enhancement

Engineering polar organic cations directly translates to enhanced material properties and device performance. The reduction in Eb through mitigated dielectric confinement is the most critical outcome.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics Enabled by Polar Organic Cations

| Material System | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Comparison / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-FPEA2MAn-1PbnBr3n+1 [4] | Auger Recombination Rate | >1-order magnitude lower | Compared to PEA+ analogue |

| p-FPEA2MAn-1PbnBr3n+1 [4] | LED Peak EQE / Luminance | 20.36% / 82,480 cd m⁻² | Suppressed efficiency roll-off |

| 2D_EA Perovskite(HOCH2CH2NH3)2PbI4 [31] | Exciton Binding Energy (Eb) | ~13 meV | Vs. 250 meV for 2D_PEA perovskite |

| 2D_EA Perovskite [31] | Free Carrier Generation | 3x higher PA signal intensity | From fs-TA measurements vs. 2D_PEA |

| S-2F-MBA cOIHP [32] | Photocurrent Density (for OER) | 4.6 mA cm⁻² | Vs. 3.35 mA cm⁻² for S-MBA cOIHP |

| S-2F-MBA cOIHP [32] | Operational Stability | 6 hours (280% extension) | In polar electrolyte vs. non-fluorinated |

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Fluorinated Cation-Based Perovskite Films

This protocol describes the synthesis of quasi-2D perovskite films using fluorinated organic cations, such as p-FPEA+ or S-2F-MBA+, adapted from methods in the literature [4] [32].

- Primary Reagents: Lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂, >99.99%), methylammonium bromide (MABr, >99.5%), p-fluorophenethylammonium bromide (p-FPEABr, >99%), or other fluorinated ammonium salts. Dimethylformamide (DMF, anhydrous) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, anhydrous) as solvents.

- Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Prepare a 1.0 M precursor solution in a mixture of DMF:DMSO (4:1 v/v). For a typical p-FPEA2MA1Pb2Br7 (n=2) formulation, stoichiometrically weigh p-FPEABr, MABr, and PbBr₂ to achieve the desired molar ratio (e.g., 2:1:2). Dissolve the powders in the solvent mixture.

- Stirring and Filtration: Stir the mixture at 60°C for 4-6 hours until a clear, homogeneous solution is obtained. Filter the solution through a 0.22 μm PTFE syringe filter to remove any undissolved particles or contaminants.

- Film Deposition: Deposit the filtered solution onto the target substrate (e.g., FTO, ITO, or quartz) via a one-step spin-coating process. A typical two-step spin-coating program is 1000 rpm for 10 s (spread step) followed by 4000 rpm for 30 s (thinning step).

- Crystallization Induction: During the second spin-coating step, 10 seconds before the end of the program, drop-cast 100 μL of anhydrous chlorobenzene (CB) or diethyl ether (anti-solvent) onto the center of the spinning substrate to induce instantaneous crystallization.

- Annealing: Immediately transfer the wet film to a hotplate and anneal at 70°C for 5 minutes, then at 100°C for 15 minutes to remove residual solvent and improve crystallinity.

Characterization of Exciton Binding Energy (Eb)

Accurate determination of the Eb is crucial for validating the success of dielectric confinement reduction. The temperature-dependent photoluminescence (PL) method is widely used.

- Equipment: Cryostat system with temperature control (4-400 K), continuous-wave laser source (e.g., 405 nm), spectrometer with a CCD detector, and a calibrated power meter.

- Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Mount the perovskite film in the cryostat under a vacuum to prevent condensation and frost formation at low temperatures.

- PL Data Acquisition: Cool the sample to a low starting temperature (e.g., 20 K). Excite the sample with a low-intensity laser beam to avoid heating and record the steady-state PL spectrum. Repeat this measurement while gradually increasing the temperature in fixed increments (e.g., 10-20 K) up to room temperature (300 K) or beyond.

- Data Analysis: Integrate the area under the PL curve for each temperature to obtain the integrated PL intensity (I_PL(T)).

- Fitting with Arrhenius Equation: Fit the temperature-dependent IPL(T) data using the following modified Arrhenius equation to account for both exciton dissociation and non-radiative recombination: IPL(T) = I₀ / [1 + Aexp(-Eb/kBT) + Bexp(-Ea/kBT)] where I₀ is the intensity at 0 K, A and B are pre-exponential factors, Eb is the exciton binding energy, Ea is the activation energy for non-radiative recombination, and kB is the Boltzmann constant. The value of Eb extracted from this fitting is a reliable measure of the strength of the dielectric and quantum confinement [31].

Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) Spectroscopy

This protocol assesses exciton dissociation and free carrier generation dynamics, providing indirect evidence of low Eb [31].

- Equipment: Femtosecond laser amplifier, optical parametric amplifier (OPA), pump-probe spectrometer with a delay stage, and a sensitive detector.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Use a high-quality, solid thin film on a transparent substrate (e.g., quartz).

- Pump-Probe Setup: Set the pump pulse energy to a low fluence (e.g., <10 μJ/cm²) to minimize multi-exciton generation. The pump wavelength should be tuned above the bandgap (e.g., 330 nm). A white-light continuum probe pulse is used to monitor changes in absorption across the visible and NIR spectrum.

- Data Collection: Record the differential transmission (ΔT/T) or absorption (ΔA) spectra at various time delays between the pump and probe pulses (from sub-ps to ns).

- Kinetic Analysis: Identify the ground-state bleach (GSB), stimulated emission (SE), and photo-induced absorption (PA) features. A more intense and longer-lived PA signal in the NIR region, assigned to free carriers, indicates more efficient exciton dissociation, a signature of low Eb [31].

The workflow for synthesizing and characterizing these advanced materials is summarized in the following diagram.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for synthesizing and characterizing polar cation-engineered perovskites.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Polar Cation Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Purity / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| p-Fluorophenethylammonium Bromide (p-FPEABr) | High-dipole organic cation for Eb reduction [4] | >99.0% (HPLC) |

| (S)-ortho-fluorinated-methyl-benzylamine (S-2F-MBA) | Chiral, fluorinated cation for spin-dependent electronics [32] | >99.0% (Chiral HPLC) |

| Ethanolammonium Iodide/Bromide | High-ε organic cation for extreme dielectric screening [31] | >98.0% |

| Lead(II) Bromide (PbBr₂) | Metal halide precursor for inorganic framework | >99.99% (Trace Metals Basis) |

| Anhydrous N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | High-quality solvent for precursor preparation | Anhydrous, 99.8% |

| Anhydrous Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Co-solvent for perovskite precursor inks | Anhydrous, ≥99.9% |

| Anhydrous Chlorobenzene | Anti-solvent for crystallization during spin-coating | Anhydrous, 99.8% |

The strategic engineering of polar organic cations is a highly effective method for reducing the detrimental dielectric confinement in low-dimensional perovskites. By selecting cations with high dipole moments and dielectric constants, such as fluorinated aromatics or molecules with polar hydroxy groups, researchers can dramatically lower exciton binding energies. This suppression enhances exciton dissociation, improves charge transport, and crucially, mitigates Auger recombination by reducing electron-hole wavefunction overlap. The protocols outlined herein provide a reliable roadmap for synthesizing and characterizing these advanced materials, paving the way for the development of high-performance perovskite optoelectronic devices, including brighter, more efficient LEDs and stable solar cells.

Molecular Passivation Strategies for Defect Mitigation and Trap State Reduction

Molecular passivation has emerged as a critical strategy for mitigating defects and reducing trap states in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and thin films, directly addressing the challenge of non-radiative Auger recombination that plagues advanced optoelectronic devices. By strategically applying organic and inorganic molecules to passivate surface defects, researchers have achieved remarkable improvements in both the efficiency and operational stability of perovskite-based solar cells. This document provides a comprehensive overview of recent advances in molecular passivation techniques, with particular emphasis on their role in suppressing Auger recombination through targeted surface treatment. We present systematically organized quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and key reagent information to equip researchers with practical tools for implementing these strategies in their own laboratories, ultimately contributing to the development of more efficient and stable perovskite optoelectronic devices.

Molecular Passivation Mechanisms and Quantitative Outcomes

Key Passivation Strategies and Performance Metrics

Molecular passivation functions through several complementary mechanisms to reduce defect states and suppress Auger recombination in PQDs. The table below summarizes four prominent strategies, their molecular mechanisms, and resulting performance improvements.

Table 1: Molecular Passivation Strategies for Defect Mitigation in Perovskite Materials

| Passivation Strategy | Molecular Mechanism | Performance Improvement | Impact on Auger Recombination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extended π-Conjugation [34] | Suppresses molecular desorption, improves energy-level alignment, enhances radical-cation stability | Efficiency increased from 22.7% to 24.6%; Retention improved from 61% to 85% after 1000h illumination | Reduced trap-assisted Auger recombination via enhanced surface defect passivation |

| Core-Shell PQDs [35] | Epitaxial compatibility with host perovskite matrix passivates grain boundaries and surface defects | PCE increased from 19.2% to 22.85%; Voc from 1.120V to 1.137V; >92% retention after 900h | Suppressed non-radiative recombination through defect neutralization |