Surface Reconstruction Strategies for Stable Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals: Mitigating Ion Migration in Mixed-Halide Systems

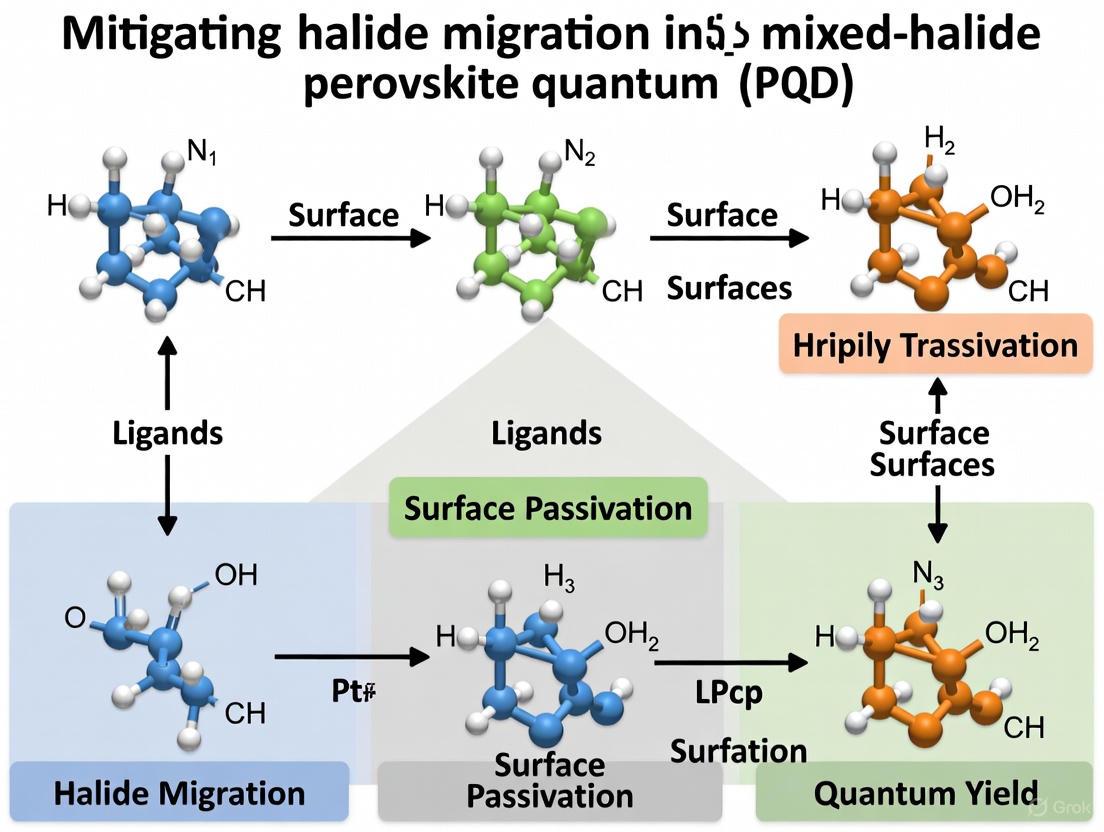

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of halide ion migration in mixed-halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), which significantly undermines the operational stability and performance of optoelectronic devices.

Surface Reconstruction Strategies for Stable Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals: Mitigating Ion Migration in Mixed-Halide Systems

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of halide ion migration in mixed-halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), which significantly undermines the operational stability and performance of optoelectronic devices. Targeting researchers and scientists in material science and nanotechnology, we systematically explore the fundamental mechanisms driving ion migration, advanced characterization techniques for mapping ionic pathways, and innovative surface engineering strategies to suppress this deleterious phenomenon. By integrating foundational knowledge with methodological applications, troubleshooting frameworks, and comparative validation approaches, this article provides a multidisciplinary perspective on developing stable, high-performance PQD-based systems with enhanced spectral stability and extended operational lifetimes, ultimately bridging the gap between laboratory innovation and commercial viability.

Understanding Halide Migration: Fundamental Mechanisms and Characterization Challenges in PQDs

The Crystal Structure and Defect Landscape of Mixed-Halide Perovskites

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues in Mixed-Halide Perovskite Research

FAQ 1: Why does my mixed-halide perovskite film exhibit unstable photoluminescence (PL) under illumination?

Issue: The bandgap of your material is not stable during operation, often manifesting as a continuous red-shift in the PL peak under constant illumination [1].

Underlying Cause: This is characteristic of photoinduced halide segregation [1]. In mixed iodide-bromide perovskites (e.g., MAPb(I₁₋ₓBrₓ)₃ or CsPb(I₁₋ₓBrₓ)₃), illumination creates electron-hole pairs whose energy can be transferred to the lattice, providing the activation energy for halide ions to migrate. This leads to the phase separation into I-rich (lower bandgap) and Br-rich (higher bandgap) domains [1]. The I-rich domains act as low-energy traps for charge carriers, causing the observed red-shift in emission [1].

Solutions:

- Application of a Passivation Layer: Cap the perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) with an insulating layer. PbSO₄-oleate has been shown to form a peapod-like morphology over CsPbX₃ PQDs, physically hindering halide exchange between neighboring dots. This can retard the kinetics of halide segregation for several hours [2].

- Surface Defect Passivation: Employ pseudohalogen engineering. A post-synthetic treatment using pseudohalogen inorganic ligands (e.g., in acetonitrile) can etch lead-rich surfaces and passivate halide vacancies in-situ. This suppresses halide migration and non-radiative recombination, enhancing both stability and photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) [3].

- Stoichiometry Optimization: Carefully control the precursor stoichiometry during synthesis. Deviations from ideal ratios (e.g., PbI₂ vs MAI content) directly influence the density of halide vacancies ((VI^+)) and methylammonium vacancies ((V{MA}^-)), which are primary mobile ionic defects [4].

FAQ 2: Why is the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of my synthesized mixed-halide PQDs low?

Issue: The synthesized PQDs exhibit weak emission, indicating a high rate of non-radiative recombination.

Underlying Cause: Surface defects, particularly halide vacancies, are dominant. In mixed-halide systems, these vacancies are not only non-radiative recombination centers but also provide pathways for accelerated halide migration [2]. The trapped electrons at these vacancy sites undergo non-radiative recombination, directly lowering the PLQY [2].

Solutions:

- Ligand Engineering: Introduce surface-capping ligands that specifically bind to undercoordinated lead atoms on the PQD surface. Molecules containing sulfonate, thiol, or pseudohalogen (e.g., SCN⁻) groups can effectively passivate these sites [3].

- Use of Molecular Additives: Incorporate additives like dodecyl dimethylthioacetamide (DDASCN) and pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-mercaptopropionate) (PTMP) directly into the PQD ink. These molecules can enhance surface passivation and improve the conductivity of the subsequent PQD film, leading to higher efficiency in light-emitting devices [3].

- Control Synthesis Environment: Ensure rigorous removal of water and oxygen from solvents using molecular sieves and N₂ purging during synthesis, as these can exacerbate defect formation [2].

FAQ 3: Why does my perovskite solar cell exhibit significant current-voltage (J-V) hysteresis?

Issue: The power conversion efficiency (PCE) measured in a solar cell changes depending on the voltage scan direction (forward vs. reverse).

Underlying Cause: The migration of mobile ionic defects under an applied electric field [4]. These ions redistribute at the interfaces between the perovskite and charge transport layers, modifying the local electric field and leading to hysteresis. The most common mobile ions are iodide interstitials ((Ii^-)) and methylammonium interstitials ((MAi^+)) [4].

Solutions:

- Stoichiometric Precision: As with halide segregation, optimizing the precursor stoichiometry to minimize the formation of native point defects is crucial. Capacitance-voltage profiling shows that the effective doping density ((N_{eff})) increases with non-stoichiometry, correlating with higher defect densities [4].

- Interface Engineering: Introduce efficient charge extraction layers (e.g., PC61BM and BCP for electrons) that can selectively extract charges while blocking the movement of ionic species to the contacts [4].

- Characterization to Guide Optimization: Use techniques like Impedance Spectroscopy (IS) and Deep-Level Transient Spectroscopy (DLTS) to quantify the ionic defect landscape in your specific films and understand the impact of processing changes [4].

Experimental Protocols for Key Mitigation Strategies

Aim: To synthesize a protective inorganic shell around PQDs to suppress anion migration.

Materials:

- Synthesized CsPbBr₃ and CsPbI₃ PQDs.

- Tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulfate (TBAHS).

- Oleic acid.

- Lead precursors (e.g., PbCl₂, PbBr₂, or PbI₂).

- Anhydrous n-hexane, chloroform, acetone.

Methodology:

- PQD Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbX₃ PQDs via the standard hot-injection method in a 1-Octadecene/Oleic acid/Oleylamine solvent system.

- PbSO₄-Oleate Cluster Formation: React a lead precursor (e.g., PbCl₂) with TBAHS in a binary solvent of chloroform and acetone. This precipitates PbSO₄-oleate clusters.

- Capping Reaction:

- Purify the as-synthesized PQDs by centrifugation and re-disperse in hexane.

- Mix the PQD solution with the precipitated PbSO₄-oleate clusters.

- Stir the mixture at a controlled temperature (e.g., 30-60°C) for several hours to allow the clusters to assemble onto the PQD surfaces, forming the peapod-like structure.

- Purification: Centrifuge the capped PQDs to remove unbound clusters and re-disperse in an anhydrous solvent for further use.

Validation: Monitor the success of the capping and its effect on halide exchange kinetics using in situ UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence spectroscopy. Mix capped CsPbBr₃ and CsPbI₃ PQDs and track the shift in their absorption and emission peaks over time compared to uncapped controls.

Aim: To characterize the type, density, and migration properties of ionic defects in a perovskite film.

Materials:

- Completed perovskite solar cell device (e.g., Glass/ITO/PEDOT:PSS/Perovskite/PC61BM/BCP/Ag).

- Precision impedance analyzer.

- Cryostat for temperature control (200-350 K).

Methodology for IS:

- Measurement: Perform impedance measurements over a wide frequency range (e.g., 0.6 Hz to 3.2 MHz) at different temperatures (5 K increments from 200 to 350 K).

- Analysis:

- Model the cell as a combination of resistors and capacitors.

- The capacitance is calculated as (C=\frac{\text{Im}(1/Z)}{\omega}).

- The low-frequency response (<10² Hz) at high temperatures is often associated with the response of mobile ions.

- Extract the relative permittivity (εᵣ) from the geometrical capacitance at reverse bias.

Methodology for DLTS:

- Measurement: Apply a voltage pulse to fill trap states, then monitor the transient capacitance as the traps emit their charge carriers.

- Analysis: Use an extended regularization algorithm for inverse Laplace transform on the transient data. This reveals a distribution of migration rates for the ionic species, rather than a single rate, providing a more detailed picture of the defect landscape.

Data Presentation

| Defect Type | Formation Condition | Impact on Electronic Landscape | Characterization Signature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iodide Vacancies ((V_I^+)) | Slight MAI deficiency in precursors | Increases effective doping density ((N{eff})); can reduce built-in potential ((V{bi})) | Contributes to low-frequency capacitance in IS; detected by DLTS as a fast species (t < ms) |

| Iodide Interstitials ((I_i^-)) | Excess Iodide / MAI-rich conditions | Increases (N_{eff}); acts as recombination center; linked to J-V hysteresis | DLTS signal as a fast species with a specific activation energy |

| MA Vacancies ((V_{MA}^-)) | MAI deficiency | Increases (N_{eff}); can influence ionic transport | Impacts the diode characteristics and (V_{bi}) |

| MA Interstitials ((MA_i^+)) | MAI-rich conditions | Increases (N_{eff}); linked to J-V hysteresis | DLTS signal as a slow species (t ~ s) with a different activation energy |

| PQD System | Capping Layer / Treatment | Activation Energy (Eₐ) for Halide Exchange | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ / CsPbI₃ Mix | Uncapped (Control) | Lower Eₐ | Rapid halide exchange completes within minutes, leading to a single, intermediate emission wavelength. |

| CsPbBr₃ / CsPbI₃ Mix | PbSO₄-oleate | Increased Eₐ | Halide exchange kinetics are significantly hindered, preserving original emission for >3 hours. |

| CsPb(Br/I)₃ | Pseudohalogen (SCN⁻) Ligands | N/A (Study showed suppressed migration) | In-situ defect passivation led to suppressed halide migration and enhanced PLQY. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing and mitigating halide segregation, integrating the troubleshooting and protocols outlined above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Mitigating Halide Migration

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| PbSO₄-oleate clusters | Forms an insulating, peapod-like shell on PQD surfaces to physically impede halide ion exchange between dots [2]. | The capping reaction temperature can be varied to control the coverage and thus the degree of kinetic retardation [2]. |

| Pseudohalogen Ligands (e.g., SCN⁻) | Passivates surface halide vacancies and etches lead-rich surfaces, reducing pathways for halide migration and non-radiative recombination [3]. | Often applied in a post-synthetic treatment using solvents like acetonitrile [3]. |

| Tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulfate (TBAHS) | Used as a sulfate source for the synthesis of PbSO₄-oleate capping clusters [2]. | Reacts with lead precursors in a chloroform/acetone binary solvent system [2]. |

| Dodecyl dimethylthioacetamide (DDASCN) | An organic pseudohalogen additive that passivates defects and improves film conductivity when incorporated into PQD inks [3]. | Used in combination with other ligands for synergistic effects [3]. |

| Stoichiometric Precursor Solutions (MAI, PbI₂, etc.) | Fundamental for controlling the intrinsic defect chemistry (vacancies, interstitials) in the bulk perovskite crystal [4]. | Precise fractional changes are used to systematically tune the defect landscape [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary external drivers that trigger ion migration in mixed-halide Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs)? Ion migration in mixed-halide PQDs is primarily activated by three external forces: electric fields, light illumination, and thermal energy [5] [6]. Under an electric field, halide ions (e.g., I⁻, Br⁻) can become highly mobile, leading to phase segregation and device degradation [5]. Light illumination provides the energy for ions to migrate, with studies showing it causes iodide ions to move from the PQD surface, creating halide vacancies and quenching photoluminescence [7]. Finally, thermal energy at elevated temperatures accelerates ion diffusion by providing the necessary activation energy for ions to overcome migration barriers, exacerbating material instability [6].

Q2: Why does the photoluminescence (PL) of my mixed-halide PQD film quench under continuous illumination, and can it recover? Yes, this quenching can be reversible. The phenomenon is attributed to light-induced halide ion migration [7]. Under illumination, iodide ions migrate out from the PQD surface and associate with adjacent lead ions, creating halide vacancies and lattice distortions that cause fluorescence quenching [7]. This is not necessarily permanent degradation. When the light is turned off, a spontaneous "self-healing" process can occur at room temperature where the migrated iodide ions drift back to fill the vacancies, restoring the original structure and fluorescence emission [7].

Q3: What are the most effective experimental strategies to suppress ion migration in PQDs? Several core strategies have proven effective in suppressing ion migration:

- Ligand Engineering: Replacing dynamic, long-chain ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) with shorter, multidentate, or cross-linkable ligands strengthens the binding to the PQD surface, passivating surface defects and inhibiting ion migration pathways [8] [6].

- Metal Ion Doping: Doping the PQD lattice with suitable metal cations (e.g., at the B-site) can alter bond lengths and strengthen the crystal structure, thereby reducing halide vacancy formation and increasing the activation energy for ion migration [6].

- Steric Confinement: Designing the crystal structure to create physical barriers, such as through inorganic layers in low-dimensional perovskites or specific dopants, can effectively block ion diffusion channels [9] [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Photoluminescence Quenching Under Light

Symptoms: The photoluminescence intensity of your PQD film or solution drops significantly within minutes of light exposure.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High density of surface defects | Measure Time-Resolved PL (TRPL); a short lifetime indicates defect-assisted recombination. | Implement post-synthesis ligand passivation with strong-binding ligands like 2-aminoethanethiol (AET) or triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) to heal uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites [6] [11]. |

| Weak ligand binding | Perform FT-IR spectroscopy before and after purification; a significant drop in ligand-related peaks indicates detachment. | Employ ligand engineering to replace OA/OAm with bidentate or covalent short-chain ligands (e.g., TPPO dissolved in non-polar solvents) for more robust surface passivation [8] [11]. |

| Intense light exposure | Check if quenching is power-dependent. | For characterization, use lower illumination intensities to minimize photo-driving force for ion migration [7]. |

Problem: Phase Segregation in Mixed-Halide Perovskites

Symptoms: Under light bias or electric field, the emission spectrum of your mixed-halide PQDs (e.g., for white light) shifts, or new emission peaks appear, indicating the formation of halide-rich domains.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low activation energy for halide migration | First-principles calculations can quantify migration energy barriers. | Apply steric confinement strategies. For low-dimensional perovskites, inorganic CsI layers in Ruddlesden-Popper structures can inhibit halide diffusion between octahedral slabs [9]. |

| Presence of internal electric fields | Characterize current-voltage (I-V) hysteresis. | Optimize device interfaces and charge transport layers to minimize charge accumulation and internal fields that drive ion migration [5]. |

| High halide vacancy concentration | Conduct thermal admittance spectroscopy. | Incorporate metal doping (e.g., Ag⁺) to act as a vacancy filler, which has been shown to suppress Cu⁺ electromigration in other ionic systems and can be adapted for PQDs [10] [6]. |

The following table summarizes key quantitative data related to ion migration drivers and material properties.

Table 1: Quantified Driving Forces and Material Properties in Ion Migration

| Driver/Material Property | Quantified Value / Metric | Impact/Observation | Source Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Illumination | Complete PL recovery in the dark at room temperature. | Supports reversible "self-healing" mechanism, not permanent degradation. | [7] |

| Crystal Phase Stability (CsPbI₃) | Phase transition from black phase (α, β, γ) to non-perovskite yellow phase (δ) at room temperature. | Intrinsic structural instability facilitates ion migration and material degradation. | [8] |

| Ligand Engineering (TPPO) | PCE of CsPbI₃ PQD solar cells improved to 15.4%; >90% initial efficiency retained after 18 days in ambient conditions. | Covalent ligands in non-polar solvents effectively passivate surface traps and improve stability. | [11] |

| Steric Confinement (Ag/Se doping) | A peak zT of 1.33 @ 873 K and superior electrical stability under dynamic DC-current achieved in Cu–S system. | Demonstrated the efficacy of steric confinement for suppressing ion (Cu⁺) migration. | [10] |

| Ligand Engineering (AET) | PLQY improved from 22% to 51%; PL intensity remained >95% after 60 min water/120 min UV exposure. | Strong ligand-Pb²⁺ affinity creates a dense barrier, inhibiting defect formation from ion loss. | [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Post-Synthesis Surface Passivation with TPPO Ligand

This protocol details surface stabilization of ligand-exchanged CsPbI₃ PQD solids using covalent TPPO ligands dissolved in a non-polar solvent, a method shown to significantly reduce surface traps and improve optoelectrical properties and ambient stability [11].

Workflow:

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OLA) | Long-chain ligands used in initial synthesis for nucleation control and size stabilization. Dynamic binding leads to easy detachment [8] [11]. |

| Sodium Acetate (NaOAc) in Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Polar solvent-based ionic ligand solution for solid-state exchange, replacing anionic OA ligands. Polar solvents can damage PQD surface [11]. |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) in Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) | Ionic ligand solution for replacing cationic OLA ligands with short-chain ammonium cations [11]. |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) in Octane | Critical Solution: Covalent short-chain ligand in non-polar solvent. TPPO strongly coordinates to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites via Lewis-base interaction. Non-polar octane prevents further PQD surface damage [11]. |

Protocol: Enhancing Stability via Metal Ion Doping

This strategy involves doping metal ions into the PQD lattice during synthesis to enhance intrinsic stability by modifying the bond strength and energy landscape for ion migration [6].

Workflow:

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Lead Precursor (e.g., PbO, PbI₂) | Source of Pb²⁺ cations for the B-site of the ABX₃ perovskite structure. The bond strength with halides influences halide vacancy formation energy [6]. |

| Dopant Metal Salt | Source of doping ions (e.g., Ag⁺, Sn²⁺). The selected metal ion should have a suitable ionic radius to maintain the perovskite structure (consider Goldschmidt tolerance factor) and can strengthen the lattice or fill vacancies [10] [6]. |

| Cesium Precursor (e.g., Cs₂CO₃) | Source of Cs⁺ cations for the A-site of the perovskite structure [8]. |

| Halide Precursors (e.g., PbBr₂, NH₄I) | Source of halide anions (I⁻, Br⁻, Cl⁻). The low formation energy of their vacancies is the root cause of halide migration [6]. |

Experimental Toolsets for Observing and Quantifying Ionic Movement

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My experiment shows no detectable single-channel current, even though I am confident the synthetic ion channels are present. What could be wrong? Several factors in your experimental setup could prevent detection [12]:

- Lipid Bilayer Composition: The specific lipid composition of your bilayer membrane (BLM) is critical and influenced by numerous variables. An incorrect composition can prevent proper channel incorporation or function.

- Channel Partitioning: The synthetic ion channels may not be partitioning sufficiently into the BLM. This can be due to an overly small bilayer surface area or because the channels are excessively hydrophobic.

- Low Transport Rates: The ion transport rate of your channels might be below the detection threshold of your potentiostat.

- Electrode Connection: A faulty electrode connection can create pA-level currents that mask the true signal. Always use a potentiostat designed for pA-level measurements and verify your connections.

Q2: I observe multiple, varying current levels instead of a single, stable open-state current. What does this mean? This sample heterogeneity often indicates the coexistence of two or more distinct ion channels or pores with different active structures [12]. This is more common in supramolecular assemblies than in unimolecular channels. Time-dependent variations in current levels can also suggest the presence of intermediate states during the final pore formation.

Q3: What are the key software considerations for analyzing Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry (IM-MS) data? The availability of robust, open-source software for IM-MS data is still developing [13]. Key steps in the workflow where software is needed include:

- CCS Calibration: Converting raw drift time measurements into collision-cross section (CCS) values, which are reproducible structural descriptors.

- Peak Detection and Annotation: Identifying and assigning ions based on their mobility and mass-to-charge ratio.

- Data Extraction and Filtering: Especially for targeted analyses in fields like proteomics and lipidomics. Tools like Skyline and MS-DIAL are commonly used for these tasks [13].

Q4: My electrolyte conductivity measurements are inconsistent. How can I improve the reliability of my analysis? Ensure you are using a standardized, automated analysis platform to minimize human error [14]. For conductivity data derived from Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), you should:

- Use software like the Modular and Autonomous Data Analysis Platform (MADAP) to automate the fitting of EIS data and the subsequent Arrhenius analysis for determining activation energy [14].

- Implement pre-processing steps to detect and handle outliers in your dataset automatically [14].

- Maintain full data provenance tracking to ensure all analysis parameters are recorded and reproducible [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low or Unstable Ionic Current in Lipid Bilayer Experiments

This guide addresses the problem of measuring faint picoampere (pA) level currents across an artificial lipid bilayer, a technique crucial for studying single ion channel behavior [12].

Step 1: Verify Bilayer Integrity Confirm a stable bilayer has formed by monitoring capacitance, which is typically 80-150 pF for a stable membrane [12]. An unstable or leaking bilayer will not provide reliable results.

Step 2: Confirm Channel Incorporation Ensure the synthetic ion channel solution is added to the chamber (e.g., cis side) under gentle stirring. The hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions will drive the molecules to incorporate spontaneously into the bilayer. The final concentration in the chamber should be around 1 µM [12].

Step 3: Optimize Potentiostat Settings Using a potentiostat with high sensitivity is non-negotiable. For example, the Reference 620 potentiostat has dedicated 60 pA and 600 pA full-scale current ranges for this purpose [12]. Using a less sensitive instrument will result in poor resolution and an inability to detect small currents. Configure the chronoamperometry method to apply a constant voltage (e.g., ±50 mV or ±150 mV) across the bilayer [12].

Step 4: Run Controls and Seek Corroborating Evidence Always perform a control experiment under identical conditions but without the synthetic ion channel present. The current trace should be silent, with no stochastic on-off transitions [12]. Furthermore, single-molecule experiments are prone to artifacts, so it is highly recommended to use complementary methods, such as fluorescence spectroscopy with large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs), to validate your findings [12].

Issue 2: Interpreting Complex Signals in Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry (IM-MS)

This guide helps navigate the computational challenges of analyzing IM-MS data, particularly for complex mixtures where ion separation is crucial [13].

Step 1: Select the Appropriate Software Tool Choose a software based on your analysis type (targeted vs. untargeted) and the molecules of interest (proteomics, lipidomics, metabolomics). For a broad overview of available tools, refer to the table in the "Research Reagent Solutions" section below [13].

Step 2: Ensure Proper CCS Calibration The method for calibrating drift time into a collision-cross section (CCS) value depends on your instrument type [13]. Drift Tube IMS (DTIMS) and Trapped IMS (TIMS) use a linear calibration function, while Traveling Wave IMS (TWIMS) requires a non-linear calibration. Using the wrong calibration will produce inaccurate structural data.

Step 3: Leverage Multi-Dimensional Data The power of IM-MS lies in combining separation dimensions. Use software that can align and score data based on retention time (LC), collision-cross section (IM), mass-to-charge ratio (MS), and fragmentation spectra (MS/MS) to confidently identify isomers and isobaric species [13].

Step 4: Account for Instrument-Specific Limitations Be aware of your platform's resolving power. While standard TWIMS might have a resolving power of 30-40, newer technologies like cyclic TWIMS or SLIM TWIMS can achieve much higher resolution (e.g., >750 for multi-pass cycles), which may be necessary to separate very similar ions [13].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Single-Channel Currents Across a Lipid Bilayer

Objective: To characterize the single-channel conductance of synthetic ion channels or pores incorporated into a planar lipid bilayer [12].

Materials:

- Diphytanoylphosphatidylcholine (diPhyPC) in chloroform (10 mg/mL)

- n-decane

- Delrin cup with a 200 µm aperture

- Ag/AgCl electrodes

- Aqueous NaCl solution or buffer

- Potentiostat with pA-level sensitivity (e.g., Reference 620)

- Solution of synthetic ion channel in DMSO

Method:

- Lipid Membrane Preparation: Evaporate 20 µL of diPhyPC solution under nitrogen gas to form a thin film. Re-dissolve this film in 20 µL of n-decane. Inject 0.5 µL of this lipid solution onto the aperture of a Delrin cup and spread it with a nitrogen gas flow to form the bilayer [12].

- Chamber Setup: Fill both the chamber (cis side) and the Delrin cup (trans side) with your aqueous electrolyte solution (e.g., 1 M NaCl) [12].

- Electrode Connection: Place Ag/AgCl electrodes in both the cis and trans solutions. Ground the cis electrode and connect it to the working/work sense leads of the potentiostat. Connect the trans electrode to the counter/reference leads [12].

- Channel Incorporation: Add a small volume (< 5 µL) of your synthetic ion channel solution (in DMSO) to the cis chamber with stirring to reach a final concentration of ~1 µM [12].

- Data Acquisition: Using a chronoamperometry script, apply a constant voltage (e.g., +50 mV, +150 mV) across the bilayer. Record the current over time. The incorporation of a single channel will be observed as a stochastic "jump" in the current to a higher, stable level (the "on" state) [12].

- Data Analysis: Average the current from multiple "on" events at different applied voltages to create a current-voltage (I–V) plot. The slope of the linear fit gives the single-channel conductance [12].

Protocol 2: Determining Ionic Conductivity and Activation Energy of Electrolytes

Objective: To measure the ionic conductivity of a liquid electrolyte formulation across a temperature range and determine the activation energy for ionic conduction [14].

Materials:

- High-throughput electrolyte formulation system (e.g., robotic dispenser)

- Electrochemical cell and potentiostat

- Temperature chamber

- Analysis software (e.g., MADAP Python package) [14]

Method:

- Electrolyte Formulation: Prepare a series of electrolyte solutions by varying the composition (e.g., mass ratios of ethylene carbonate, propylene carbonate, ethyl methyl carbonate) and the concentration of the conducting salt (e.g., LiPF₆) using gravimetric dosing [14].

- Impedance Measurement: Perform Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) measurements on each electrolyte. A typical protocol uses an AC voltage of 40 mV over a frequency range of 50 Hz to 20 kHz [14].

- Temperature Series: Place the electrochemical cell in a temperature chamber. Equilibrate at each target temperature (e.g., from -30 °C to 60 °C in 10 °C steps) for 2 hours before performing the EIS measurement [14].

- Data Analysis:

- Use the EIS data to extract the bulk resistance of the electrolyte, which is then used to calculate the ionic conductivity [14].

- Input the temperature and corresponding conductivity data into an analysis tool like MADAP.

- The software will perform an Arrhenius fit (plotting ln(σ) vs. 1/T, where σ is conductivity and T is temperature). The activation energy (Eₐ) is derived from the slope of the linear fit (Slope = -Eₐ/R, where R is the gas constant) [14].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Commercial IM-MS Platforms

This table compares different Ion Mobility Spectrometry platforms coupled with Mass Spectrometry, highlighting key characteristics for instrument selection [13].

| Acronym | Full Name | Separation Principle | CCS Calibration Function | Typical Resolving Power (Max Reported) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTIMS | Drift Tube Ion Mobility Spectrometry | Temporal dispersive | Linear | 50 - 60 (200 for Atmospheric Pressure) |

| TIMS | Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry | Trapping & release | Linear | 200 - 400 |

| TWIMS | Traveling Wave Ion Mobility Spectrometry | Temporal dispersive | Nonlinear | 30 - 40 |

| Cyclic TWIMS | Cyclic Traveling Wave IMS | Temporal dispersive | Nonlinear | 60 - 80 (one pass), >750 (multi-pass) |

| SLIM TWIMS | Structures for Lossless Ion Manipulations | Temporal dispersive | Nonlinear | 200 - 1500 |

| FAIMS | Field Asymmetric IMS | Spatial dispersive | Not Applicable | < 30 |

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Ion Channel and Conductivity Experiments

This table details essential materials used in experiments for observing ionic movement [14] [12].

| Item | Function / Application | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Diphytanoylphosphatidylcholine (diPhyPC) | Forms stable planar lipid bilayers (BLMs) for single-channel recording [12]. | Branched lipid tails increase membrane stability and reduce phase transitions. |

| Ag/AgCl Electrodes | Provide a stable, non-polarizable interface for applying potential and measuring current in electrochemical cells [12]. | Essential for accurate potential control in low-current experiments. |

| Ethylene Carbonate (EC) / Propylene Carbonate (PC) | Solvents in liquid electrolyte formulations for batteries [14]. | High dielectric constant solvents that dissociate lithium salts (e.g., LiPF₆). Their ratio affects viscosity and conductivity. |

| Lithium Hexafluorophosphate (LiPF₆) | Conducting salt in lithium-ion battery electrolytes [14]. | Concentration and identity of the salt directly impact ionic conductivity. |

| Reference 620 Potentiostat | Measures ultra-low currents (picoampere level) for single-channel experiments [12]. | Features dedicated 60 pA and 600 pA current ranges for high accuracy and resolution. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Single-Channel Conductance Workflow

Electrolyte Conductivity Analysis

Impact of Halide Segregation on Optoelectronic Properties and Device Performance

FAQs: Understanding Halide Segregation

What is halide segregation and why does it occur in mixed-halide perovskites? Halide segregation, also known as phase segregation, is a phenomenon in mixed-halide perovskites (e.g., APb(BrₓI₁₋ₓ)₃) where the material separates into distinct iodide-rich and bromide-rich domains under external stimuli like light, electric fields, or heat. This occurs due to the relatively low ionic migration energy within the perovskite lattice, which facilitates the movement of halide ions (I⁻ and Br⁻) under operational stresses. The soft ionic lattice of perovskites allows ions to easily diffuse through the corner-sharing octahedral network, leading to this demixing process [15] [16] [17].

How does halide segregation directly impact solar cell performance? Halide segregation primarily accelerates charge-carrier recombination in mixed-halide perovskite solar cells, which can translate into significant voltage losses. However, research shows that the increased radiative efficiency of the phase-segregated material can sometimes counterbalance these voltage losses to some extent. Surprisingly, charge-carrier mobilities remain largely unaffected despite the formation of segregated domains, meaning transport properties are relatively preserved even as recombination dynamics change dramatically [15].

Why is halide segregation particularly problematic for light-emitting diodes (LEDs)? In perovskite LEDs (PeLEDs), halide segregation causes spectral instability and color shift because the I-rich domains that form have narrower bandgaps and emit light at different wavelengths. This effect is pronounced due to the comparatively large electric field magnitude across the thin (~30 nm) emitter layer used in LED devices, which drives ion migration. The resulting compositional changes lead to unpredictable emission color and reduced device lifetime [17] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Performance Degradation in Mixed-Halide Perovskite Solar Cells

Symptoms:

- Decreasing open-circuit voltage (VOC) over time under illumination

- Color changes in the active layer visible under microscope

- Increased non-radiative recombination observed in photoluminescence measurements

Solutions:

- Implement lower-dimensional perovskite structures: Incorporate large cations such as guanidinium (GA⁺), phenylethylammonium (PEA⁺), or butyl ammonium (BA⁺) to disrupt 3D phase continuity. This reduces ion diffusion coefficients (Dion) from 10⁻⁸-10⁻¹¹ cm²/s in 3D perovskites to 10⁻¹²-10⁻¹⁵ cm²/s in 2D/3D mixed structures [17].

- Optimize extraction layers and contacts: Use non-reactive interface materials that can tolerate migrating ions without triggering degradation pathways. Proper interface engineering has demonstrated improvement in T80 stability (time for 20% degradation) from a few hours to over 10,000 hours for MA₀.₁Cs₀.₀₅FA₀.₈₅Pb(I₀.₉₅Br₀.₀₅)₃ formulations [17].

- Control environmental factors: Implement strict management of temperature and illumination intensity during operation and testing, as both factors significantly accelerate halide segregation processes [16].

Problem: Spectral Instability in Mixed-Halide PeLEDs

Symptoms:

- Shift in emission wavelength during device operation

- Reduced color purity over time

- Appearance of multiple emission peaks in electroluminescence spectra

Solutions:

- Surface reconstruction of perovskite nanocrystals: Implement resurfacing strategies to passivate surface defects that facilitate halide ion migration. This approach directly addresses the primary factor causing performance degradation in PeLEDs [18].

- Ligand engineering: Replace conventional ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) with alternatives that provide better surface coverage and stronger binding to surface atoms. For example, 2-aminoethanethiol (AET) with thiolate groups binds strongly with Pb²⁺ sites, creating a dense barrier layer that inhibits halide migration [6].

- Metal doping: Introduce appropriate metal ions at A- or B-sites to strengthen the perovskite lattice. This approach changes B-X bond lengths and increases migration activation energy, significantly improving structural stability against halide segregation [6].

Table 1: Charge-Carrier Mobility in Mixed-Halide Perovskites Before and After Phase Segregation

| Material Condition | Photoexcitation Wavelength | Charge-Carrier Mobility (cm²/(Vs)) | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before segregation (MAPb(I₀.₅Br₀.₅)₃) | 400 nm | 37.3 ± 2.7 | Optical-pump terahertz-probe (OPTP) spectroscopy [15] |

| After segregation (MAPb(I₀.₅Br₀.₅)₃) | 400 nm | 37.2 ± 0.6 | Optical-pump terahertz-probe (OPTP) spectroscopy [15] |

| I-rich domains after segregation | 720 nm | 49 (range: 35-66) | Optical-pump terahertz-probe (OPTP) spectroscopy [15] |

Table 2: Impact of Perovskite Dimensionality on Ion Migration and Device Stability

| Perovskite Formulation | Dimensionality | Ion Diffusion Coefficient (Dion, cm²/s) | Typical T80 Stability | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAPbI₃ | 3D | ~10⁻⁸ | 5-12 hours | High PCE but poor stability [17] |

| FA-based mixed compositions | 3D | 10⁻⁸-10⁻¹¹ | Few hours | Better efficiency but still degrades quickly [17] |

| GA/MA formulations | Quasi-2D/3D | 10⁻¹² | ~750 hours | Moderate PCE, improved stability [17] |

| Ruddlesden-Popper (n=2-5) | 2D/3D | 10⁻¹²-10⁻¹⁵ | Hundreds of hours | Lower mobility but high stability [17] |

| CsPbBr₃ | 3D | 10⁻¹²-10⁻¹³ | High | Suitable for LEDs and radiation detectors [17] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Halide Segregation via Photoluminescence Spectroscopy

Purpose: To monitor phase segregation dynamics in mixed-halide perovskite films under controlled illumination.

Materials:

- Mixed-halide perovskite film (e.g., MAPb(I₀.₅Br₀.₅)₃)

- Continuous-wave (CW) laser source (532 nm)

- Spectrometer with fiber-coupled detection

- Neutral density filters for intensity control

- Temperature-controlled sample stage

Procedure:

- Mount the perovskite film in the measurement setup and ensure no prior light exposure.

- Collect initial photoluminescence (PL) spectrum using low-intensity pulsed photoexcitation (400 nm, 11 μJ/cm²) to establish baseline without inducing segregation.

- Expose the film to segregation-driving CW illumination (532 nm, 100 W/cm² intensity) while maintaining constant temperature.

- Monitor PL spectral changes at regular time intervals during CW exposure.

- Continue measurements until PL spectrum stabilizes, indicating completion of the segregation process.

- Analyze the emergence and growth of low-energy PL peak associated with I-rich domains.

Expected Results: The initial single PL peak of the mixed-halide phase will gradually develop a second red-shifted peak around 720-780 nm, indicating formation of I-rich domains through halide segregation [15].

Protocol 2: Measuring Ion Migration Effects via Optical-Pump Terahertz-Probe (OPTP) Spectroscopy

Purpose: To investigate charge-carrier dynamics and transport properties in phase-segregated mixed halide perovskite films.

Materials:

- Mixed-halide perovskite films on suitable substrates

- Femtosecond laser system for photoexcitation

- Terahertz generation and detection apparatus

- CW laser source for inducing segregation

- Environmental chamber for controlled atmosphere

Procedure:

- Align OPTP setup and characterize THz transmission without photoexcitation.

- Measure initial photoconductivity using 400 nm pulsed photoexcitation before inducing segregation.

- Extract charge-carrier mobility from photoconductivity amplitude at zero time delay.

- Expose film to CW illumination to induce halide segregation while monitoring PL changes.

- Repeat OPTP measurements after PL stabilization to assess mobility changes in segregated material.

- Perform additional measurements with 720 nm photoexcitation to selectively probe I-rich domains.

- Analyze frequency-resolved photoconductivity spectra for Drude behavior and phonon modulations.

Expected Results: Charge-carrier mobilities remain largely unchanged despite dramatic PL changes, indicating preserved transport properties in the majority phase. Direct excitation of I-rich domains reveals high mobilities (35-66 cm²/Vs), suggesting minimal carrier localization in segregated domains [15].

Visualization: Halide Segregation Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Halide Migration Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI) | Forming 2D perovskite layers at interfaces | Enhances stability in FAPbI₃-based solar cells, enables PCE >25% [19] |

| 2-Aminoethanethiol (AET) | Surface ligand for PQD passivation | Thiolate groups strongly bind with Pb²⁺ sites, creating dense barrier layer [6] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Conventional ligands for PQD synthesis | Cause steric hindrance due to bent structures; low packing density [6] |

| Alkylammonium chlorides (RACl) | Volatile additives for crystalline phase control | Enable α-phase FAPbI₃ formation on SnO₂/FTO/glass substrates [19] |

| Guanidinium (GA⁺) cations | Large cations for low-dimensional perovskites | Reduces ion diffusion coefficients, improves stability [17] |

| Formamidinium (FA⁺) cations | Larger A-site cation for bandgap reduction | Provides higher photocurrent but phase stability challenges [19] [17] |

| Cesium (Cs⁺) cations | Inorganic cation for stability enhancement | Improves chemical stability in triple-cation formulations [19] |

The Role of Surface Defects versus Bulk Defects in Migration Pathways

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Under light illumination, my perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) lose their luminescence. Is this permanent degradation? Not necessarily. Research indicates that quenched emission can completely recover in the dark at room temperature through a spontaneous "self-healing" mechanism [7]. This reversible process is often linked to surface halide ion migration rather than permanent photo-degradation [7].

Q2: What is the primary mechanistic difference between surface and bulk halide ion migration?

- Surface Migration: Under illumination, iodide ions on the PQD surface migrate out and associate with adjacent lead ions. This creates halide vacancies and lattice distortions, leading to fluorescence quenching. This process is often reversible [7].

- Bulk Migration: In wide-bandgap mixed-halide perovskites, halide ion migration within the bulk lattice can lead to phase segregation, forming I-rich domains. This causes performance loss in solar cells (reducing voltage and current) and is often a more persistent issue [20].

Q3: How can I experimentally distinguish between performance issues caused by surface defects versus bulk defects? Monitor the reversibility of the phenomenon. A problem that "self-heals" after the light source is removed or under mild annealing is likely dominated by surface defect dynamics [7]. Performance losses that are persistent and linked to changes in absorption or emission wavelengths are indicative of bulk phase segregation caused by halide migration [20].

Q4: What are the most effective strategies to suppress surface-ion migration? Surface passivation is a key strategy. The introduction of bidentate ligands, such as 2-bromohexadecanoic acid (BHA), has been shown to effectively passivate surface defects, resulting in photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY) as high as 97% and improved stability under ultraviolet irradiation [21].

Defect Characteristics and Impact: Surface vs. Bulk

The table below summarizes the core differences between surface and bulk defects in halide perovskites, helping to diagnose the root cause of experimental issues.

| Feature | Surface Defects | Bulk Defects |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Location | Outer layer of the nanocrystal; interface with ligands or environment [7] | Within the internal crystal lattice [20] |

| Key Migration Species | Iodide ions (I⁻) on the surface [7] | Halide ions (I⁻, Br⁻) within the bulk structure [20] |

| Primary Experimental Manifestations | Reversible photoluminescence quenching; "self-healing" in the dark [7] | Phase heterogeneity (separation into I-rich and Br-rich domains); persistent voltage (VOC) and current (JSC) loss [20] |

| Impact on Optoelectronic Properties | Creates non-radiative recombination pathways, quenching emission [7] | Alters bandgap; causes carrier funneling and reduces charge collection efficiency [20] |

| Common Mitigation Strategies | Ligand engineering (e.g., bidentate ligands); surface coating [21] | Additive engineering; compositional grading; interface engineering [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Defects

Protocol 1: Probing Reversible Surface Ion Migration

This methodology is adapted from studies on the emission quenching and recovery of CsPbX3 PQDs [7].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Synthesize all-inorganic CsPbI3 or mixed-halide PQDs using a standard hot-injection or ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) method [21]. Disperse the PQDs in a non-polar solvent and deposit as a thin film on a substrate.

- 2. Illumination Stress Test: Place the sample under constant, high-intensity light illumination (e.g., a blue or UV LED) in an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen glovebox). Monitor the photoluminescence (PL) intensity in real-time until a significant quenching (e.g., >50% of initial intensity) is observed.

- 3. Recovery in Dark: Turn off the illumination source and allow the sample to rest in complete darkness at room temperature. Continuously monitor the PL intensity over a period of several minutes to hours.

- 4. Data Interpretation: A complete or near-complete recovery of the PL signal indicates a reversible process dominated by surface ion migration. The recovery kinetics can provide insights into the activation energy for ion migration back to vacancy sites [7].

Protocol 2: Mapping Bulk Halide Migration via Phase Segregation

This protocol is based on research into performance loss in wide-bandgap mixed-halide perovskite solar cells [20].

- 1. Device Fabrication: Fabricate solar cells using a mixed-halide (e.g., I/Br) perovskite absorber layer with a bandgap ≥1.60 eV.

- 2. Operational Stability Testing: Operate the solar cell under continuous light soaking (1 Sun equivalent) at maximum power point or open-circuit conditions while maintaining a constant temperature (e.g., 45-50°C).

- 3. In-Situ Characterization:

- Electroluminescence (EL) or Photoluminescence (PL) Imaging: Use a hyperspectral imager to track the emergence of low-bandgap, I-rich domains (emitting at longer wavelengths) over time.

- Current-Voltage (J-V) Curves: Periodically measure J-V curves to quantify the loss in open-circuit voltage (VOC) and short-circuit current density (JSC) [20].

- 4. Data Interpretation: Correlate the appearance of red-shifted emission peaks in PL/EL maps with the observed drops in VOC and JSC. This spatial and electrical correlation is a hallmark of bulk halide migration and phase segregation [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The table below lists essential materials for synthesizing stable PQDs and investigating defect pathways.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | A common cesium precursor for the hot-injection synthesis of all-inorganic CsPbX3 PQDs [21]. |

| Lead Bromide/Iodide (PbBr₂, PbI₂) | The lead and halide source for the perovskite crystal structure. The ratio of I/Br can be tuned for desired bandgap [21]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Common ligand pairs used in synthesis to control nanocrystal growth, stabilize the surface, and prevent aggregation [21]. |

| 2-Bromohexadecanoic Acid (BHA) | A bidentate ligand that provides superior surface passivation compared to OA/OAm, leading to higher PLQY and photostability [21]. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | A high-boiling-point, non-coordinating solvent used as the reaction medium in the hot-injection synthesis method [21]. |

Visualization of Defect Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core concepts and experimental logic discussed.

Diagram 1: Reversible surface ion migration cycle in PQDs.

Diagram 2: Irreversible bulk halide migration leading to performance loss.

Surface Engineering and Synthesis Approaches to Suppress Halide Migration

Advanced Surface Ligand Engineering for Defect Passivation

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly lead halide perovskites with the formula ABX₃ (where A = Cs⁺, MA⁺, FA⁺; B = Pb²⁺; X = Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻), have emerged as promising materials for optoelectronic applications due to their exceptional optical and electrical properties [22] [6]. These materials exhibit high color purity, tunable bandgaps, high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs), and remarkable defect tolerance [23] [24]. Despite these advantageous properties, PQDs face significant stability challenges that hinder their commercial application. The primary issues stem from their inherent ionic nature, which makes them susceptible to degradation under external stimuli such as moisture, heat, light, and polar solvents [6] [23].

The structural degradation of PQDs occurs mainly through two mechanisms: (1) defect formation on the surface caused by ligand dissociation, where weakly bound ligands detach from the PQD surface, and (2) vacancy formation in the crystal lattice due to halide migration with low activation energy [6]. These degradation pathways lead to surface defects that act as non-radiative recombination centers, reducing PLQY and overall device performance [22]. Surface ligand engineering has emerged as a crucial strategy to address these challenges by enhancing binding strength, improving surface coverage, and effectively passivating defects to create more stable and efficient PQDs [23].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges & Solutions

Rapid Degradation During Purification

Observed Problem: Significant decrease in photoluminescence intensity and quantum yield after purification steps.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand detachment during polar solvent exposure [6] | Monitor PLQY before and after each centrifugation step; use FTIR to confirm ligand loss. | Implement post-synthesis ligand exchange with strongly-binding ligands (e.g., thiols) [6]. | Reduce purification cycles; use less polar antisolvents; add new ligands before purification. |

| Surface defect formation [6] [23] | Characterize with TEM (morphology changes) and XRD (phase changes). | Apply halide-rich ligand solutions to maintain surface stoichiometry [23]. | Optimize ligand-to-precursor ratio during synthesis; use excess halide sources. |

| Quantum dot aggregation [23] | Observe solution turbidity; use DLS to measure size distribution. | Introduce branched or multidentate ligands to enhance steric protection [23]. | Increase initial ligand concentration; use solvents with appropriate polarity. |

Poor Film Quality in Device Fabrication

Observed Problem: Non-uniform films with poor surface coverage and low conductivity in LED or solar cell devices.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient ligand removal [22] | Measure film conductivity; use TGA to analyze ligand content. | Perform controlled washing with polar solvent mixtures [22]. | Optimize ligand chain length balance for desired film properties. |

| Excessive inter-dot distance [6] | Characterize with TEM; measure charge transport properties. | Employ ligand exchange with short-chain conductive ligands [6]. | Use hybrid ligand systems with mixed chain lengths. |

| Incompatible surface energy [23] | Measure contact angle; inspect film morphology. | Add solvent additives to modulate drying dynamics [23]. | Pre-treat substrate with self-assembled monolayers. |

Halide Segregation in Mixed-Halide Compositions

Observed Problem: Color shift and phase separation under operational conditions.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low halide migration activation energy [25] | Track emission spectra under illumination; use XRD to detect phase separation. | Incorporate metal dopants (e.g., Zn²⁺, Mn²⁺) to strengthen lattice [6]. | Optimize halide composition to minimize thermodynamic driving force. |

| Surface halide vacancies [25] | Measure PL lifetime; use XPS to quantify surface composition. | Passivate with halide-rich ligands (e.g., ammonium halides) [23]. | Maintain halide-rich environment during synthesis and processing. |

| Strain in crystal lattice [22] | Analyze XRD peak shifts; calculate tolerance factor. | Use larger A-site cations to improve lattice matching [22]. | Fine-tune composition with mixed cations (Cs⁺/FA⁺). |

Core Defect Passivation Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the primary defect passivation mechanisms employed in advanced surface ligand engineering for PQDs:

Experimental Protocols: Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange with Short-Chain Ligands

Objective: Replace long-chain native ligands (OA/OAm) with short-chain conductive ligands to enhance charge transport while maintaining stability [6].

Materials:

- CsPbX₃ PQDs stabilized with OA/OAm

- Short-chain ligand (e.g., 2-aminoethanethiol hydrochloride, butylamine)

- Solvents: hexane, methyl acetate, toluene

- Centrifuge tubes

Procedure:

- Purify Native PQDs: Precipitate 5 mL of as-synthesized PQD solution with 10 mL methyl acetate, centrifuge at 7500 rpm for 5 minutes, discard supernatant [6].

- Prepare Ligand Solution: Dissolve short-chain ligand in toluene at 10 mg/mL concentration.

- Ligand Exchange: Redisperse purified PQD pellet in 2 mL hexane, add 5 mL ligand solution, stir for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Purification: Add methyl acetate (1:2 v/v) to precipitate PQDs, centrifuge at 7500 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Final Dispersion: Redisperse final product in 2 mL toluene for characterization and device fabrication.

Critical Parameters:

- Timing: Complete entire process within 2 hours to minimize degradation

- Molar Ratio: Maintain ligand:PQD ratio of 1000:1 for complete surface coverage

- Atmosphere: Perform under inert atmosphere (N₂ glovebox) for oxygen-sensitive ligands

Protocol 2: Multidentate Ligand Passivation for Enhanced Stability

Objective: Implement bidentate or tridentate ligands for stronger binding and improved resistance to environmental stressors [23].

Materials:

- Purified CsPbBr₃ PQDs

- Multidentate ligand (e.g., 2,2'-iminodibenzoic acid, thioglycolic acid)

- Dimethylformamide (DMF), toluene

- Ultrasonic bath

Procedure:

- Ligand Solution Preparation: Dissolve multidentate ligand in minimal DMF (0.1 M concentration).

- PQD Preparation: Purify PQDs twice using standard procedure to remove excess native ligands.

- Surface Treatment: Add ligand solution dropwise to 5 mL PQD solution (1 µM in toluene) under vigorous stirring.

- Annealing: Heat mixture to 60°C for 30 minutes with stirring to facilitate ligand binding.

- Purification: Precipitate with methyl acetate, centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Washing: Wash pellet twice with hexane to remove unbound ligands.

- Storage: Redisperse in anhydrous toluene at desired concentration for further use.

Critical Parameters:

- Solvent Compatibility: Use minimal DMF (≤ 5% v/v) to prevent PQD dissolution

- Binding Confirmation: Monitor PLQY increase (typically 20-30%) as indicator of successful passivation

- Storage: Store in dark at 4°C for long-term stability

Protocol 3: In Situ Halide-Rich Ligand Engineering

Objective: Incorporate halide-rich ligands during synthesis to suppress halide vacancy formation and mitigate ion migration [23] [25].

Materials:

- Precursors: Cs₂CO₃, PbBr₂, oleic acid, oleylamine

- Halide-rich ligand (e.g., didodecyldimethylammonium bromide, octylammonium bromide)

- 1-octadecene (ODE)

- Syringe pumps, three-neck flask, thermocouple

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation:

- Cs-oleate: 0.4 g Cs₂CO₃ in 15 mL ODE with 1.25 mL OA at 120°C under N₂

- Pb-precursor: 0.3 g PbBr₂ in 15 mL ODE with 1.5 mL OA and 1.5 mL OAm at 120°C

- Hot-Injection Synthesis:

- Heat Pb-precursor to 170°C under N₂ atmosphere

- Quickly inject 1 mL Cs-oleate solution with rapid stirring

- After 5 seconds, cool reaction mixture in ice bath

- Ligand Addition: Immediately add halide-rich ligand (0.1 M in toluene) at 50°C

- Purification: Centrifuge crude solution at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes, redisperse in toluene

Critical Parameters:

- Timing: Add halide-rich ligands immediately after synthesis for optimal surface coverage

- Temperature: Maintain below 80°C during ligand addition to prevent Ostwald ripening

- Stoichiometry: Use 20% molar excess of halide-rich ligands relative to surface sites

Ligand Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the properties and performance characteristics of different ligand classes used in PQD surface engineering:

| Ligand Class | Representative Examples | Binding Strength | PLQY Improvement | Stability Enhancement | Conductivity | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain amines [6] | Butylamine, Octylamine | Medium | 10-20% | Moderate | High | LEDs, Solar cells |

| Thiol-based ligands [6] | 2-aminoethanethiol, Thioglycolic acid | High | 20-30% | High | Medium | Photodetectors, Stable LEDs |

| Multidentate ligands [23] | Iminodiacetic acid, 2,2'-iminodibenzoic acid | Very High | 30-50% | Very High | Low | High-stability applications |

| Halide-rich ammonium [23] [25] | Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide | Medium | 15-25% | High | Medium | Mixed-halide systems |

| Polymeric ligands [6] | Zwitterionic polymers | High | 20-40% | Very High | Low | Flexible devices, patterning |

| Crosslinkable ligands [6] | Vinyl-containing amines, Acrylic acids | Medium (pre) → High (post) | 25-35% | Extreme | Low | Extreme environments |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials for implementing advanced surface ligand engineering strategies:

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Supplier Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Ligands [23] | Oleic acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) | Initial stabilization during synthesis, size control | Sigma-Aldrich (≥99% purity), store under N₂ |

| Short-chain Ligands [6] | Butylamine, Octylamine, Propylamine | Enhance charge transport, reduce inter-dot distance | TCI Chemicals (anhydrous grades recommended) |

| Strong-binding Ligands [6] [23] | 2-aminoethanethiol, Thioglycolic acid, Cysteamine | Defect passivation, stability improvement | Alfa Aesar (store in amber vials, moisture-sensitive) |

| Halide-rich Ligands [23] [25] | Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide, Octylammonium bromide | Suppress halide vacancies, mitigate ion migration | Sigma-Aldrich (handle in glovebox, hygroscopic) |

| Multidentate Ligands [23] | Iminodiacetic acid, 2,2'-iminodibenzoic acid | Enhanced binding strength, stability | TCI Chemicals (purify before use if needed) |

| Crosslinking Agents [6] | Divinylbenzene, Bisfunctional azides | Create networked ligand shells, extreme stability | Fisher Scientific (includes radical initiators) |

| Solvents [23] | Octadecene, Toluene, Hexane, Methyl acetate | Synthesis, purification, processing | Sigma-Aldrich (anhydrous grades, store over molecular sieves) |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do we need to replace the native OA and OAm ligands if they work well during synthesis?

A1: While OA and OAm are excellent for controlling nucleation and growth during synthesis, they create several limitations in final devices: (1) Their long insulating chains impede charge transport between quantum dots, reducing device efficiency [6]; (2) Their bent molecular structure creates steric hindrance that reduces packing density, leaving significant surface areas unprotected [6]; (3) They bind weakly to the PQD surface and easily detach during purification steps or under operational stress, creating surface defects [23].

Q2: How do I choose between short-chain ligands and multidentate ligands for my specific application?

A2: The choice depends on your priority in the target application:

- Short-chain ligands (butylamine, octylamine): Choose when high electrical conductivity is priority (solar cells, LEDs) [6]

- Multidentate ligands (iminodiacetic acid): Choose when environmental stability is priority (outdoor applications, harsh environments) [23]

- Thiol-based ligands (2-aminoethanethiol): Choose for balanced requirements, offering both reasonable conductivity and enhanced stability [6]

- Hybrid approaches: Using mixed ligand systems can sometimes provide balanced properties [23]

Q3: What is the fundamental mechanism by which ligand engineering suppresses halide migration?

A3: Ligand engineering addresses halide migration through multiple mechanisms: (1) Surface vacancy passivation - Halide-rich ligands provide extra halide ions to fill vacancies that initiate migration pathways [25]; (2) Lattice stabilization - Strong-binding ligands reduce surface dynamics and prevent the initiation of vacancy chains [23]; (3) Barrier formation - Crosslinked ligand shells create physical barriers that impede ion diffusion between PQDs [6]; (4) Strain reduction - Properly engineered ligand surfaces reduce lattice strain that facilitates ion migration [22].

Q4: How can I quantitatively characterize the effectiveness of my ligand passivation strategy?

A4: Several characterization methods provide quantitative assessment:

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Measure before and after passivation (target >90% for excellent passivation) [23]

- Time-resolved PL decay: Calculate lifetime improvement (2-3x increase indicates reduced non-radiative recombination) [6]

- FTIR spectroscopy: Quantify ligand binding and surface coverage [23]

- XPS analysis: Measure surface elemental composition and halide-to-lead ratios [25]

- Stability testing: Track PL retention under continuous illumination or environmental stress (target >80% after 100 hours for good stability) [6]

Q5: What are the most common pitfalls in ligand exchange procedures and how can I avoid them?

A5: Common pitfalls and solutions:

- Pitfall 1: Complete loss of colloidal stability during ligand exchange

- Solution: Optimize solvent mixture polarity gradually; use bridging solvents [23]

- Pitfall 2: Significant red-shift in emission wavelength after processing

- Solution: Reduce processing temperature and time to prevent Ostwald ripening [6]

- Pitfall 3: Incomplete ligand exchange leaving mixed ligand populations

- Solution: Use excess new ligand (1000:1 molar ratio) and multiple exchange cycles [23]

- Pitfall 4: Introduction of new defects during the exchange process

- Solution: Perform exchange under inert atmosphere with carefully purified ligands [6]

Ligand Engineering Workflow

The following diagram outlines the comprehensive workflow for implementing advanced surface ligand engineering strategies:

Nanocrystal Resurfacing Techniques for Robust Surface Reconstruction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of surface defects in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) during fabrication?

Surface defects in PQDs primarily occur during the ligand exchange process, where native insulating ligands are replaced with conductive alternatives. This process often introduces structural defects that act as traps for charge carriers, greatly reducing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and colloidal stability [26]. Furthermore, the conventional purification process using anti-solvents like methyl acetate (MeOAc) inevitably removes surface ligands, creating a large number of defects such as halide (I⁻) vacancies and suspended Pb²⁺ ions [27] [6].

Q2: How does halide ion migration relate to surface defects, and why is it a critical issue?

Halide ion migration is closely related to defects on the PQD surface and at the grain boundaries of their thin films. Due to the low ionic migration energy within PQD lattices, halide vacancies form easily. This ion migration is a primary factor causing performance degradation in PQD-based light-emitting diodes (LEDs), leading to spectral instability and reduced device operational lifetime [18] [6].

Q3: Can the photoluminescence of aged or "dead" PQDs be recovered?

Yes, the photoluminescence of aged PQDs that have lost their emission can be effectively recovered. Research demonstrates that trioctylphosphine (TOP) can instantly restore the luminescence of aged red-emitting CsPbBr₁.₂I₁.₈ PQDs. This treatment also results in a narrower emission profile (full width at half maximum reduced from 46 nm to 36 nm) and significantly enhances stability against long-term storage, heat, UV irradiation, and polar solvents [28].

Q4: What is the role of multidentate ligands in surface resurfacing?

Multidentate ligands, such as ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), perform a "surface surgery treatment." They can chelate and remove suspended Pb²⁺ ions from the PQD surface and simultaneously passivate I⁻ vacancies. A key advantage is their ability to crosslink adjacent PQDs, acting as a "charger bridge" to improve electronic coupling between dots, which substantially facilitates charge carrier transport within PQD solid films [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges & Solutions

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Root Cause | Proposed Solution & Supporting Data |

|---|---|---|

| Severe drop in PLQY after ligand exchange | Introduction of structural defects (lattice perforations) and non-radiative recombination centers during ligand exchange [26]. | Post-treatment with L-type ligands: Add Lewis base ligands like DMP. Result: Tenfold increase in PLQY and recovery of structural integrity [26]. |

| Aged PQDs lose all emission ("dead" QDs) | Accumulation of surface defects over time, creating non-radiative pathways [28]. | Chemical treatment with TOP: Add 80-120 µL of TOP to aged PQD solution. Result: PL intensity recovers to 110% of original fresh QDs and the emission profile narrows [28]. |

| Poor charge transport in PQD solid films | Inefficient electronic coupling between PQDs due to insulating native ligands or chaotic surface states [27]. | Resurfacing with multidentate ligands: Use EDTA for surface surgery. Result: Power conversion efficiency in QD solar cells increased from 13.67% to 15.25% [27]. |

| Structural degradation under polar solvents or heat | Weak binding of native ligands (OA/OAm) and low formation energy of halide vacancies [28] [6]. | Ligand modification with short-chain, strong-binding ligands: Perform ligand exchange with AET. Result: PLQY improved from 22% to 51%; PQDs maintained >95% PL intensity after 60 min water/120 min UV exposure [6]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Surface Reconstruction via Wet Annealing

This protocol is adapted from a method proven to heal ligand exchange-induced defects in CdSe nanoplatelets, resulting in a 230-fold PLQY recovery [26].

- Starting Material: Begin with a dispersion of ligand-exchanged, damaged nanocrystals in water. The example in the study used CdSe nanoplatelets with thiostannate ligands after a damaging exchange process using NH₄OH [26].

- Heating Process: Place the dispersion in a suitable reaction vial and heat it to 100 °C while stirring. This process is known as "wet annealing" (WA) [26].

- Monitoring Reaction Progress:

- At 5 minutes of WA: Immediately take an aliquot. Characterize via UV-Vis and PL spectroscopy. A red-shift of about 10 nm in both absorption and PL peaks is expected, indicating structural modification. PLQY should show significant recovery (up to 4.5% in the cited study) [26].

- At 10 minutes of WA: Take another aliquot. Further red-shifting (additional ~5 nm) and broadening of the excitonic absorption peaks may occur, suggesting continued surface reconstruction and potential onset of nanocrystal "soldering" [26].

- Termination: Cool the dispersion to room temperature to stop the healing process. The NPs are now reconstituted with whole surfaces and significantly improved optoelectronic properties [26].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Emission Recovery of Aged PQDs using TOP

This protocol details the use of TOP to recover the luminescence of fully aged, non-emissive PQDs [28].

- Preparation: Start with a toluene solution of aged CsPbBr₁.₂I₁.₈ PQDs that have visually lost their fluorescence emission under UV light [28].

- Titration:

- To the aged PQD solution, add trioctylphosphine (TOP) in incremental amounts.

- For example, add 20 µL of TOP at a time to a standard solution volume, mixing thoroughly.

- Optimization: After each addition, measure the PL intensity. The intensity will increase with added TOP until it plateaus. The cited study found that adding 80-120 µL of TOP restored the PL intensity to 104%-110% of the original value of the fresh PQDs [28].

- Characterization: The treated PQDs will show a longer average PL lifetime (e.g., an increase from 32.5 ns to 51.9 ns), indicating effective surface passivation and suppression of non-radiative recombination pathways [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Resurfacing | Key Experimental Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | Emission recovery agent and stabilizer for aged PQDs [28]. | Instantly recovers PL of "dead" PQDs; enhances stability against heat, UV light, and polar solvents like ethanol [28]. |

| Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid (EDTA) | Multidentate ligand for surface surgery; chelator and crosslinker [27]. | Removes suspended Pb²⁺; passivates I⁻ vacancies; crosslinks PQDs to improve electronic coupling in solid films [27]. |

| 2-Aminoethanethiol (AET) | Short-chain, strong-binding surface ligand [6]. | Thiol group binds strongly to Pb²⁺; creates a dense passivation layer; significantly improves stability against moisture and UV [6]. |

| DMP (2,6-Dimethylpyridine) | L-type (Lewis base) promoter ligand for defect healing [26]. | Repairs structural damage (e.g., holes) from prior ligand exchange; leads to a tenfold increase in PLQY [26]. |

| Na₄SnS₄ / (NH₄)₄Sn₂S₆ | Conductive thiostannate ligands for enhanced charge transport [26]. | Replaces insulating oleate ligands; enables high conductance but can introduce defects requiring subsequent healing steps [26]. |

Workflow Diagram: Nanocrystal Resurfacing Strategies

Compositional Engineering and Dopant Strategies for Intrinsic Stability

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center provides solutions for common experimental challenges in mitigating halide migration in mixed-halide Perovskite Quantum Dot (PQD) surfaces. The guidance is based on current research in compositional engineering and dopant strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary mechanisms causing structural degradation in my PQD samples? The structural degradation of PQDs is primarily caused by two intrinsic mechanisms:

- Ligand Dissociation: Weakly bound surface ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) can detach during purification or when exposed to ambient conditions. This creates surface defects and facilitates PQD aggregation, accelerating degradation from moisture and oxygen [29].

- Halide Migration and Vacancy Formation: Due to the low migration energy of halide ions within the PQD lattice, halide vacancies can form easily. This ion migration is a major driver of phase segregation and decomposition under external stimuli like heat and electric fields [29].

Q2: When I incorporate Methylammonium (MA) into my FAPbI₃-based perovskites to improve efficiency, I observe faster degradation. Why? Research indicates that incorporating MA into FAPbI₃-based perovskites can be harmful to long-term operational stability. This is primarily due to defect-induced degradation. Even low dopant content (e.g., 1%) can increase the trap density of the perovskite film, making it more susceptible to degradation over time [30].

Q3: Which compositional strategies are most effective for enhancing intrinsic stability against halide migration? Effective strategies focus on suppressing the trap density and strengthening the perovskite lattice. Key approaches include:

- Bromine Incorporation: Adding Bromine (Br) into FAPbI₃-based perovskites has been shown to suppress trap density, thereby enhancing intrinsic operational stability [30].

- Mixed-Metal Alloying: Simultaneously alloying with a trivalent metal cation (e.g., Sb³⁺) and a divalent chalcogen anion (e.g., S²⁻) into the perovskite structure (e.g., FAPbI₃) enhances ionic binding energy and alleviates lattice strain. This suppresses humidity- and thermal-induced degradation at an intrinsic level [31].

- Metal Doping: Doping the B-site with specific metal ions (e.g., Bi³⁺) can tune the crystal structure and bond lengths, improving structural stability. The efficacy of a dopant is highly dependent on the host composition, a critical factor in doping design [29] [32].

Q4: My doped perovskite films show inconsistent results. What could be a key factor I'm overlooking? The effectiveness of a dopant is not solely an intrinsic property but is critically dependent on its interplay with the host material's existing elements. For example, in a Co-free, Ni-rich cathode system, the benefits of Al, B, and Mg dopants were diminished due to functional overlap with Manganese (Mn) already present. In contrast, Titanium (Ti) provided a complementary stabilizing function, leading to significantly enhanced performance [32]. Always consider synergistic or antagonistic interactions within the doped system.

Quantitative Data on Stability-Enhancing Additives

The following table summarizes data on various additives used to improve the intrinsic stability of perovskite materials.

Table 1: Compositional Additives for Enhanced Perovskite Stability

| Additive/Dopant | Host Perovskite | Key Finding on Stability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bromine (Br) | FAPbI₃ | Beneficial; suppresses trap density in films, enhancing long-term stability. | [30] |

| Methylammonium (MA) | FAPbI₃ | Harmful; increases defect-induced degradation despite unchanged morphological/optical properties. | [30] |

| Sb³⁺ and S²⁻ (alloyed) | FAPbI₃ | Significantly enhances humidity & thermal stability; promotes α-(200)c crystal growth and minimizes lattice strain. Unencapsulated solar cells retained ~95% of initial PCE after 1080 hours. | [31] |

| Silver Iodide (AgI) | CsPbIBr₂ | Improves film quality; acts as a nucleation promoter, leading to uniform films with larger grain size and fewer boundaries, which reduces defects. | [33] |

| Bismuth (Bi³⁺) | MASn₀.₆Pb₀.₄I₃ | Maintains crystal structure and enables bandgap narrowing; stability effect is highly dependent on the A-site cation (e.g., adverse in Cs-based Sn-Pb perovskites). | [34] |

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Stability

Protocol 1: Sequential Air-Processed Alloying for FAPbI₃ Stability

This methodology details the incorporation of Sb³⁺ and S²⁻ into FAPbI₃ to enhance intrinsic stability [31].

- Preparation of Sb-TU Complex Solution: Dissolve SbCl₃ and Thiourea (TU) in a suitable solvent (e.g., DMSO) to form a complex. Concentrations of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mol% (with respect to PbI₂) are typical for optimization.

- Deposition of Precursor Layer: Mix the Sb-TU complex solution with PbI₂. Spin-coat this mixture onto the substrate.

- Annealing: Anneal the spin-coated film at 150°C to form the precursor layer.

- Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) Deposition: Apply a solution of FAI onto the precursor layer to initiate the perovskite formation reaction via a sequential intramolecular exchange process.

- Final Crystallization: Anneal the film again to crystallize the final Sb³⁺ and S²⁻ alloyed FAPbI₃.

Workflow Diagram: Sequential Alloying Process