Surface Passivation Strategies for Perovskite Quantum Dots: Enhancing Stability and Performance for Biomedical Applications

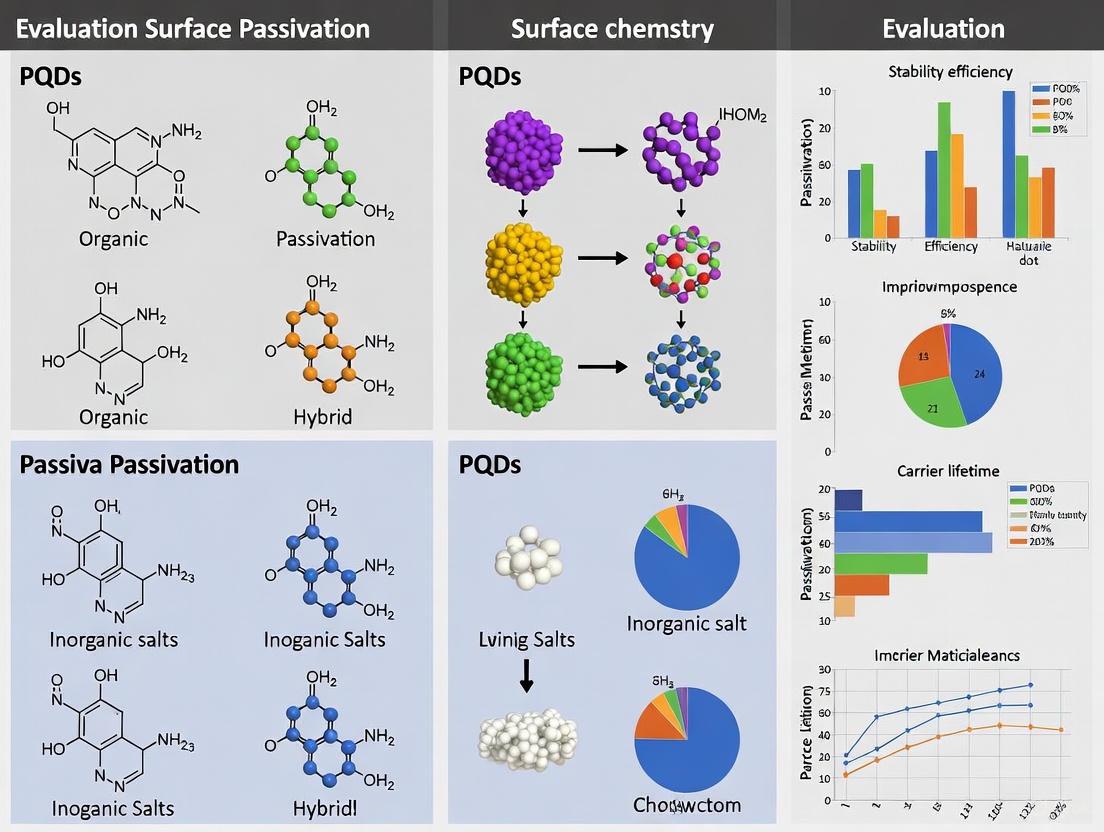

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of surface passivation strategies for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a class of nanomaterials with exceptional optoelectronic properties poised to revolutionize biosensing and biomedical diagnostics.

Surface Passivation Strategies for Perovskite Quantum Dots: Enhancing Stability and Performance for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of surface passivation strategies for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a class of nanomaterials with exceptional optoelectronic properties poised to revolutionize biosensing and biomedical diagnostics. We explore the foundational science behind PQD instability and surface defects, detailing a wide array of methodological approaches from ligand engineering and inorganic encapsulation to advanced bilateral and in-situ techniques. The content systematically addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges, including lead toxicity mitigation and long-term stability enhancement. Finally, we present a rigorous comparative analysis of these strategies, validating their performance through key optical and electronic metrics to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting optimal passivation methods for specific clinical and point-of-care applications.

Understanding PQD Surface Defects and the Critical Need for Passivation

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) represent a revolutionary class of semiconductor nanomaterials that have transformed the landscape of optoelectronics and photovoltaics over the past decade. These metal halide perovskite nanostructures, with their characteristic ABX3 crystal architecture (where A = Cs+, MA+, FA+; B = Pb2+, Sn2+; X = Cl-, Br-, I-), exhibit extraordinary optoelectronic properties that surpass many conventional semiconductor nanomaterials [1] [2]. The quantum confinement effect in these nanoscale crystals, combined with their innate defect tolerance, creates an unparalleled platform for developing advanced optoelectronic devices, from high-purity displays to next-generation solar cells [1] [3].

The unique value proposition of PQDs lies in their synergistic combination of high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs), widely tunable emission spectra, and exceptional defect tolerance - properties that are rarely found together in traditional quantum dot systems [1]. Unlike conventional II-VI and III-V quantum dots that suffer from severe carrier non-radiative recombination due to deep-level trap states, lead-based PQDs possess a peculiar defect-tolerant lattice where electronic traps tend to form within bands rather than deep in the bandgap, enabling highly efficient luminescence even without extensive passivation treatments [1]. This fundamental characteristic, coupled with their facile synthesis and cost-effective processing, positions PQDs as formidable competitors to established quantum dot technologies in the relentless pursuit of superior optoelectronic materials.

Performance Comparison: PQDs Versus Alternative Quantum Dot Technologies

The remarkable optoelectronic properties of PQDs become particularly evident when directly compared with traditional quantum dot systems. The following analysis quantitatively compares the key performance metrics across different quantum dot technologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Different Quantum Dot Technologies

| Property | Perovskite QDs (PQDs) | CdSe-Based QDs | InP-Based QDs | Organic Fluorophores |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLQY (%) | >95% [1] [2] | ~90% (with passivating shell) [1] | ~90% (with passivating shell) [1] | ~90% [1] |

| FWHM (nm) | ~20 [1] | ~20-30 [1] | ~35-45 [1] | 40-100 [1] |

| Color Gamut (% NTSC) | ~140% [1] | ~104% [1] | N/A | ~90% [1] |

| Emission Tuning | Size & Composition [1] [2] | Size [1] | Size [1] | Molecular Structure |

| Defect Tolerance | High [1] [3] | Low (requires shell) [1] | Low (requires shell) [1] | N/A |

| Synthesis Complexity | Low (facile, room temperature possible) [1] [2] | High (high-temperature, inert conditions) [1] | High (high-temperature, inert conditions) [1] | Varies |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of PQDs in Different Optoelectronic Applications

| Application | Key Metric | PQD Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green LEDs | Maximum EQE | >23% [1] | [1] |

| Red LEDs | Maximum EQE | >23% [1] | [1] |

| Solar Cells (as passivators) | PCE Improvement | 19.2% → 22.85% (relative ~19% increase) [4] | [4] |

| Solar Cells (as active layer) | Record PCE | 18.1% [3] | [3] |

| Stability (PSCs with PQD passivation) | PCE Retention | >92% after 900 h [4] | [4] |

The comparative data reveals PQDs' distinctive advantages in optical performance and processing efficiency. Their wide color gamut covering approximately 140% of the NTSC standard significantly surpasses both CdSe-based QDs (104%) and organic fluorophores (90%), making them particularly suitable for high-color-purity display applications [1]. The symmetrical and narrow photoluminescence peaks with full width at half maximum (FWHM) around 20 nm provide exceptional color purity comparable to conventional CdSe-based QDs and superior to InP-based alternatives and organic LEDs [1]. Furthermore, PQDs achieve their outstanding performance without requiring complex core-shell architectures that are essential for conventional QDs to reach comparable PLQYs, significantly simplifying manufacturing processes [1].

Surface Passivation Strategies for Enhancing PQD Performance

The Critical Role of Surface Manipulation in PQD Technology

Despite their inherent defect tolerance, the practical implementation of PQDs faces significant challenges related to environmental stability and surface-mediated non-radiative recombination due to their high surface-to-volume ratio [1] [3]. The surface of PQDs contains numerous undercoordinated sites and ionic defects that can deteriorate optoelectronic performance by creating trap states that facilitate non-radiative recombination pathways [3]. Consequently, surface passivation has emerged as an indispensable strategy for maximizing the potential of PQD-based devices, with various innovative approaches demonstrating remarkable improvements in both efficiency and operational stability.

Epitaxial Core-Shell PQD Passivation

One of the most advanced passivation strategies involves the integration of core-shell structured PQDs through in situ epitaxial growth during device fabrication. A groundbreaking study demonstrated this approach by incorporating MAPbBr3@tetra-OAPbBr3 core-shell PQDs during the antisolvent-assisted crystallization of perovskite solar cells [4]. The epitaxial compatibility between the PQDs and the host perovskite matrix enables effective passivation of grain boundaries and surface defects, thereby suppressing non-radiative recombination and facilitating more efficient charge transport [4].

Experimental Protocol:

- PQD Synthesis: MAPbBr3@tetra-OAPbBr3 core-shell PQDs were synthesized via colloidal synthesis where core precursor solution (MABr and PbBr2 in DMF with oleylamine and oleic acid) was rapidly injected into heated toluene (60°C), followed by controlled injection of shell precursor (tetraoctylammonium bromide-PbBr3) [4].

- Device Integration: The PQDs were integrated during the antisolvent step of perovskite film fabrication, with optimal concentration found at 15 mg/mL in chlorobenzene [4].

- Characterization: Structural properties were analyzed through TEM, XRD, and spectroscopic methods; device performance was evaluated through J-V measurements, IPCE, and long-term stability tests under ambient conditions [4].

Results: The core-shell PQD passivation strategy dramatically enhanced photovoltaic performance, increasing PCE from 19.2% to 22.85%, with simultaneous improvements in Voc (1.120V to 1.137V), Jsc (24.5 mA/cm2 to 26.1 mA/cm2), and fill factor (70.1% to 77%) [4]. Notably, the passivated devices retained over 92% of their initial PCE after 900 hours under ambient conditions, significantly outperforming control devices (~80% retention) [4].

Diagram 1: Core-Shell PQD Passivation Mechanism. The diagram illustrates how core-shell perovskite quantum dots with organic ligands integrate into the host perovskite matrix to passivate grain boundaries and surface defects through epitaxial growth and surface stabilization.

Strategic Interfacial Engineering with Molecular Passivators

Complementary to nanostructured passivation, molecular surface functionalization has demonstrated exceptional results in stabilizing PQD interfaces. A prominent example utilizes sodium heptafluorobutyrate (SHF) to create a comprehensive ion shield that tunes the perovskite surface work function and increases defect formation energy [5]. This approach addresses the fundamental instability of perovskite surfaces, particularly PbI-terminated surfaces which computational analysis revealed have lower defect formation energy compared to FAI-terminated surfaces [5].

Experimental Protocol:

- Surface Treatment: SHF solution was applied as a post-treatment on perovskite films via spin-coating [5].

- Mechanism Analysis: DFT calculations quantified defect formation energy and charge transfer; KPFM measured work function changes; GIWAXS characterized crystal structure modifications [5].

- Device Fabrication: PSCs with p-i-n architecture were fabricated with SHF-treated perovskite layers, using C60 as the electron transport layer [5].

Results: SHF treatment significantly increased the formation energy of surface vacancies, particularly Pb vacancies, enhancing surface stability [5]. The treatment created an interfacial dipole moment (8.97 D from DFT) that tuned the surface work function, enhanced the built-in potential, and improved charge extraction [5]. This approach yielded a record PCE of 27.02% for p-i-n PSCs with exceptional stability - retaining 100% of initial efficiency after 1,200 hours of continuous 1-sun illumination and 92% after 1,800 hours at 85°C [5].

Ligand-Based Surface Engineering Strategies

Traditional ligand engineering remains a vital tool for optimizing PQD properties. Surface manipulation using various organic ligands, including mercaptoacetic acid, mercaptoethylamine, and polyethylene glycol, has been extensively employed to enhance PQD stability and functionality [3] [6]. These ligands typically bind to the PQD surface through carboxylate or ammonium groups, with oleylammonium ligands shown to bind by replacing surface A-site cations with their ammonium head group [3].

Experimental Protocol:

- Ligand Exchange: Long-chain native ligands (OA/OA) are replaced with shorter or more functional ligands through precipitation-redispersion processes or solid-state ligand exchange [3].

- Characterization: FTIR and NMR spectroscopy confirm binding mechanisms; TEM and XRD analyze structural integrity; PLQY measurements quantify optical improvements [3].

Results: Proper ligand engineering enhances PQD stability against moisture and oxygen, improves charge transport between dots by reducing inter-dot distance, and maintains high PLQY by passivating surface traps [3]. Strategic ligand selection also enables compatibility with various solvent systems and deposition techniques essential for device integration [3].

Diagram 2: Surface Passivation Workflow and Outcomes. This diagram outlines the relationship between different surface passivation strategies for PQDs and their corresponding effects on defect mitigation, ultimately leading to enhanced device performance metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Passivation Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Surface Passivation Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in PQD Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Native capping ligand for PQD synthesis [3] | Surface stabilization during synthesis; colloid formation [3] |

| Oleylamine (OLA) | Co-ligand for PQD synthesis [3] | Surface coordination; charge balance [3] |

| Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (t-OABr) | Shell precursor for core-shell PQDs [4] | Formation of protective shell in MAPbBr3@tetra-OAPbBr3 PQDs [4] |

| Sodium Heptafluorobutyrate (SHF) | Molecular passivator [5] | Surface functionalization to increase defect formation energy; work function tuning [5] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Surface ligand for biocompatibility [6] | Hydrophilic coating; biological applications [6] |

| Mercaptocarboxylic Acids | Short-chain binding ligands [6] | Surface anchoring for charge transport improvement [6] |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr2) | Perovskite precursor [4] | B-site source in ABX3 structure; shell formation [4] |

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs2CO3) | Cesium source for all-inorganic PQDs [1] | A-site cation in CsPbX3 PQDs [1] |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Polar solvent [4] | Precursor dissolution; synthesis medium [4] |

| Toluene | Non-polar solvent [4] | Antisolvent for crystallization; PQD dispersion [4] |

The strategic implementation of surface passivation methodologies has profoundly enhanced the performance and stability of PQD-based devices, bridging the gap between their theoretical potential and practical implementation. The exceptional optoelectronic properties of PQDs - including PLQYs exceeding 95%, tunable emission across the visible spectrum, and high defect tolerance - combined with advanced passivation strategies position them as leading candidates for next-generation optoelectronic devices [1] [2].

Future research directions should focus on developing multifunctional passivation systems that simultaneously address electronic, ionic, and environmental degradation pathways while maintaining charge transport efficiency. The exploration of lead-free alternatives and scalable manufacturing processes will be crucial for commercial translation. Additionally, the integration of passivated PQDs in emerging applications such as quantum computing, single-photon sources, and advanced biomedical imaging represents fertile ground for scientific exploration [2]. As passivation strategies continue to evolve from simple ligand exchanges to sophisticated epitaxial and molecular designs, PQDs are poised to redefine the performance benchmarks for quantum dot technologies across optoelectronics, photovoltaics, and beyond.

Metal halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly cesium lead halide (CsPbX3) variants, have emerged as a revolutionary class of semiconducting nanomaterials for optoelectronic applications. Their exceptional properties include high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs), widely tunable emission spectra with high color purity covering the entire visible region, and strong defect tolerance [1]. These characteristics make them promising candidates for next-generation displays, lighting technologies, and quantum information applications. However, the very properties that make PQDs exceptional also create fundamental vulnerabilities. The ionic character of their crystal lattice, characterized by relatively weak ionic bonding, coupled with their low lattice formation energy, facilitates facile crystal growth but simultaneously renders them inherently susceptible to degradation under environmental stressors [1]. Furthermore, the dynamic nature of surface ligands—organic molecules that passivate surface defects and provide colloidal stability—introduces a critical point of failure, as ligand desorption or degradation can rapidly compromise both optical performance and structural integrity. This review objectively compares the efficacy of various surface passivation strategies in mitigating these inherent vulnerabilities, providing researchers with a structured analysis of experimental data and methodologies to guide material selection and protocol development.

Fundamental Vulnerabilities and Their Experimental Manifestations

The operational stability of PQDs is fundamentally challenged by three interconnected material properties. Understanding these vulnerabilities is crucial for developing effective mitigation strategies.

Ionic Character: The PQD lattice, represented as ABX3 (where A = Cs⁺, MA⁺, FA⁺; B = Pb²⁺; X = Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻), is held together primarily by ionic bonds. This ionic nature makes the structure particularly susceptible to polar environments. The high mobility of ionic species within the lattice facilitates defect migration and phase segregation under operational biases, leading to rapid performance decay in devices such as light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [7].

Low Formation Energy: The low energy required for crystal formation, while beneficial for facile synthesis and low-temperature processing, inherently implies lower thermodynamic stability. This manifests as a propensity for phase transitions (e.g., from the photoactive cubic phase to non-perovskite phases) and surface defect formation, particularly under thermal stress [1].

Ligand Lability: The large surface-to-volume ratio of PQDs means that surface chemistry dominates their properties. Native ligands, typically long-chain organic acids and amines (e.g., oleic acid and oleylamine), coordinate weakly to surface sites. This dynamic binding nature ensures good colloidal stability during synthesis but results in easy desorption during purification, film formation, or device operation, leaving behind undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions that act as non-radiative recombination centers [8] [1].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Synthesis Temperature on CsPbI3 PQD Properties [8]

| Synthesis Temperature (°C) | Emission Wavelength (nm) | Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM, nm) | PL Intensity Trend | Structural Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140 | 698 | 24-28 | Moderate | - |

| 170 | ~713 | Narrowest | Highest | Optimal phase purity |

| 180 | - | - | Pronounced decline | Phase transition onset |

Comparative Analysis of Surface Passivation Strategies

Surface passivation functions by coordinating with undercoordinated surface atoms, thereby suppressing defect states within the bandgap that trap charge carriers and facilitate non-radiative recombination. The following section compares the performance of different ligand classes based on experimental findings.

Organic Ligand Passivation

Organic ligands, including phosphines and amines, passivate defects through coordinate bonds with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions. Their effectiveness varies significantly based on the functional group's donor strength and molecular structure.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Organic Ligands on CsPbI3 PQDs [8]

| Ligand | Chemical Type | PL Enhancement (%) | Key Stability Findings | Proposed Passivation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | Amino Acid | 3% | Superior photostability: retained >70% initial PL after 20 days UV exposure | Coordination via amine and carboxylate groups |

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | Phosphine | 16% | - | Coordination with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Phosphine Oxide | 18% | - | Strong coordination via P=O with Pb²⁺ sites |

Halide-Anion-Based Passivation

Anionic passivation, particularly with halide ions, directly addresses halide vacancy defects, which are among the most common and detrimental defects in PQDs. This strategy involves the introduction of halide salts (e.g., PbBr₂) or ionic compounds during or post-synthesis to fill vacancy sites, thereby reducing charge trapping and non-radiative losses. The efficacy is highly dependent on the anion size and binding affinity. For instance, bromide passivation has been widely reported to effectively suppress iodide vacancy formation in mixed-halide perovskites, enhancing both PLQY and phase stability [9]. This approach often works synergistically with cationic ligand passivation.

Multi-component & Core-Shell Strategies

Beyond molecular ligands, advanced structural engineering offers a more robust defense against degradation:

- Multi-component Perovskites (MCPs): Incorporating a mixture of cations (e.g., Cs⁺, FA⁺, MA⁺) and/or halides (e.g., I⁻, Br⁻) into the perovskite lattice can synergistically compensate for compositional instability. This mixture increases the activation energy for ion migration, a primary degradation pathway, thereby stabilizing the lattice against moisture, heat, and light-induced degradation [7].

- Core-Shell Structures: Coating PQDs with an inert shell (e.g., SiO₂) or a wider-bandgap perovskite material provides a physical barrier against environmental stressors like oxygen and moisture [9]. This method directly tackles the vulnerability originating from low formation energy by isolating the sensitive core from the environment.

Experimental Protocols for Passivation Performance Evaluation

This section details standardized methodologies for synthesizing, passivating, and characterizing PQDs, enabling direct comparison of the strategies outlined above.

Synthesis of CsPbI3 PQDs

Objective: To synthesize high-quality, red-emitting CsPbI3 PQDs with precise control over size and crystallinity [8].

Detailed Protocol:

- Precursor Preparation: Combine 0.407 mmol cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) and 10 mL of 1-octadecene (ODE) in a three-neck flask. Add 0.25 mL of oleic acid (OA). Heat the mixture to 120 °C under N₂ atmosphere with constant stirring until the Cs₂CO₃ is completely dissolved to form a cesium oleate precursor.

- Lead Precursor Preparation: In a separate flask, combine 0.125 mmol lead iodide (PbI₂), 10 mL ODE, 1 mL oleylamine (OAm), and 1 mL OA. Heat this mixture to 120 °C under N₂ with stirring until a clear solution is obtained.

- Hot-Injection Synthesis: Rapidly inject 1.5 mL of the cesium oleate precursor into the lead precursor solution, maintained at the optimal temperature of 170 °C.

- Reaction Quenching: After 5-10 seconds of reaction, cool the mixture immediately using an ice-water bath to terminate crystal growth.

- Purification: Precipitate the PQDs by adding an excess of methyl acetate or anhydrous toluene followed by centrifugation (8,000-12,000 rpm for 5-10 minutes). Decant the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in a non-polar solvent (e.g., hexane or octane). Repeat this process 2-3 times to remove unreacted precursors and excess ligands.

Ligand Exchange Passivation

Objective: To introduce functional ligands (TOP, TOPO, L-PHE) post-synthesis to suppress surface defects [8].

Detailed Protocol:

- Stock Solution Preparation: Dissolve the desired passivating ligand (e.g., TOP, TOPO, or L-PHE) in a suitable solvent (e.g., toluene or hexane) at a concentration of 10-50 mg/mL.

- Ligand Introduction: Add the ligand stock solution to the purified CsPbI3 PQD dispersion. The ligand concentration should be in significant molar excess relative to the estimated surface Pb sites (typical ligand:PQD ratios range from 100:1 to 1000:1).

- Incubation: Stir the mixture gently at room temperature or mild heating (40-60 °C) for 1-2 hours to allow for ligand exchange and binding to surface sites.

- Purification: Precipitate the passivated PQDs by adding a polar anti-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or acetone) and centrifuge. Re-disperse the purified PQDs in an anhydrous solvent for storage and characterization.

Characterization Techniques & Workflow

A multi-faceted characterization approach is essential for quantifying the efficacy of any passivation strategy. The following workflow connects key experiments to the specific vulnerabilities they probe.

Table 3: Key Characterization Methods for Evaluating Passivation Efficacy

| Method | Key Measurable Parameters | Directly Probes | Interpretation of Improved Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Percentage of emitted vs. absorbed photons | Defect density & non-radiative recombination | Higher PLQY indicates successful suppression of non-radiative pathways. |

| Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) | Carrier lifetime (τavg, τ₁, τ₂) | Charge carrier recombination dynamics | Longer average lifetime suggests reduced trap-assisted recombination. |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Crystal structure, phase purity | Structural stability & phase transitions | Maintained cubic phase; absence of secondary peaks. |

| Accelerated Stability Testing | PL intensity decay over time (T₅₀, T₇₀) | Resistance to environmental stressors (UV, O₂, H₂O, heat) | Slower decay rate (higher retained PL) signifies enhanced stability. |

| Electroluminescence in LEDs | External Quantum Efficiency (EQE), operational lifetime | Performance in functional devices | Higher EQE and longer device lifetime confirm practical utility of passivation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for PQD Passivation Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cs⁺ precursor for all-inorganic PQD synthesis | Requires careful drying and storage due to hygroscopicity. |

| Lead Iodide (PbI₂) | Pb²⁺ and I⁻ source for the perovskite lattice. | High purity (>99%) is critical to minimize unintentional doping. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | High-boiling, non-coordinating solvent for synthesis. | Must be purified and degassed before use to remove peroxides. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Native surface ligands for colloidal stabilization. | Ratio and concentration control initial QD size and dispersion. |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Lewis base passivant for undercoordinated Pb²⁺. | Strong coordinating agent; excess can affect charge transport. |

| L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | Bifunctional (amine/carboxylate) passivating ligand. | Can enhance photostability via a different binding motif. |

| Methyl Acetate / Toluene | Anti-solvents for precipitation and purification. | Must be anhydrous to prevent PQD degradation during washing. |

The direct comparison of passivation strategies presented herein reveals a critical trade-off: strategies offering the strongest initial performance boost (e.g., TOPO with 18% PL enhancement) may not yield the best long-term stability, for which alternative ligands like L-phenylalanine show distinct promise. The inherent vulnerabilities of PQDs—their ionic character, low formation energy, and ligand lability—are interconnected, and thus, the most promising path forward lies in multi-modal passivation. Combining molecular ligands (to address specific defect sites) with multi-component lattices (to enhance intrinsic stability) and protective shells (to provide extrinsic shielding) presents a robust approach to overcoming these fundamental challenges. Future research must focus on deciphering the molecular-level interactions at the PQD surface and their evolution under device operational stresses. Furthermore, developing universal, high-resolution patterning techniques compatible with these advanced PQDs is essential for their integration into real-world micro-LED displays and other optoelectronic devices [10].

Lead Halide Perovskites (LHPs), particularly in the form of colloidal nanocrystals and quantum dots (PQDs), have emerged as leading semiconductor materials for next-generation optoelectronic devices, including light-emitting diodes (QLEDs) and solar cells [11]. Their defect-tolerant nature—where certain point defects do not create deep-level traps—has been key to their rapid performance advances [11]. Despite this tolerance, surface defects at the interfaces of PQDs and grain boundaries in thin films remain critical performance-limiting factors that promote non-radiative recombination, degrading photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), device efficiency, and operational stability [12] [11].

The high surface-to-volume ratio of PQDs makes their optical properties exceptionally susceptible to surface chemistry [11]. During film assembly, solvent evaporation and ligand loss lead to defect regeneration, creating non-radiative recombination centers that severely affect carrier injection, transport, and recombination in final devices [12]. This review objectively compares prominent surface passivation strategies, analyzing their efficacy in mitigating uncoordinated lead and halide vacancies to minimize non-radiative recombination losses.

Characterizing Common Surface Defects

Types and Origins of Defects

In real-world perovskite crystals, the ideal perovskite lattice (ABX₃) is interrupted by various defects introduced during crystal growth and post-treatment processes [13]. These include:

- Point Defects: Native atomic-scale defects, including vacancies (atoms missing from lattice sites), interstitial defects (atoms located between lattice sites), and anti-site defects (atoms occupying another species' lattice site) [11].

- Extended Defects: Structural imperfections like dislocations and grain boundaries [11].

- Surface Defects: The most critical for PQDs, these arise from insufficiently coordinated anions or cations and the loss of surface ligands during processing [12] [13].

Fortunately, common A-site (e.g., Cs⁺, MA⁺, FA⁺) and X-site (halide) vacancies in Br- or I-based perovskites typically form only shallow-level defects with minimal impact on performance [11]. The most detrimental defects are uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions and related charged surface defects [11]. Their high formation energy means deep-level traps like interstitial or anti-site defects are rare in perovskites [11].

Impact on Non-Radiative Recombination

Defects with transition energy levels located in the one-third of the band gap create deep-level traps that act as potent Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) recombination centers [13]. This trap-assisted recombination is a primary non-radiative loss pathway, directly limiting open-circuit voltage (VOC) in solar cells and external quantum efficiency (EQE) in LEDs [13]. In PQD films, these defects are prone to regenerate at the interfaces between the QD layer and charge transport layers (CTLs), severely affecting carrier injection and transportation [12]. Theoretical calculations using density functional theory (DFT) show significant trap states at band edges due to non-coordinating Pb atoms, which are greatly weakened after effective passivation [12].

Diagram: Classification of common defects in perovskite quantum dots and their impact on device performance. Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ and halide vacancies are highlighted as primary sources of non-radiative recombination.

Comparative Analysis of Passivation Strategies

Bilateral Interfacial Passivation

A groundbreaking bilateral interfacial passivation strategy addresses defects on both top and bottom interfaces of the QD film [12]. This approach involves evaporating organic molecules between the QD film and charge transport layers on both sides, creating a comprehensive protective barrier.

Experimental Protocol: Researchers applied the phosphine oxide molecule TSPO1 (diphenylphosphine oxide-4-(triphenylsilyl)phenyl) as a typical passivator through evaporation [12]. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations revealed a forming energy of -1.1 eV between Pb and O from TSPO1, indicating strong interaction between uncoordinated Pb and the P=O group [12]. Bond order analysis showed phosphorus oxygen groups exhibited superior binding with Pb (bond order 0.2) compared to carboxyl and amidogen ligands, which showed no bonding capability [12]. Transient absorption spectra and space charge-limited current measurements verified decreased defect traps [12].

Ligand Engineering Passivation

Ligand engineering focuses on enhancing the native capping ligands on PQD surfaces to improve passivation stability and charge transport.

Experimental Protocol: In one approach, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) with -OSO₃⁻ molecules was employed as a surface ligand to synthesize PQDs using a room-temperature ligand-assisted reprecipitation method [14]. The SDS concentration was systematically varied, and the resulting PQDs were characterized through absorbance and PL spectroscopy. PQD films were fabricated with different spin-coating speeds (2000-4000 rpm) to optimize thickness, and devices were completed with PEDOT:PSS/PTAA hole transport layers and TPBi/LiF electron transport layers [14].

Synergistic Bimolecular Interface (SBI)

The synergistic bimolecular interface strategy employs multiple molecules in sequence to address different aspects of surface defects and energetics simultaneously.

Experimental Protocol: Researchers developed an SBI using 4-methoxyphenylphosphonic acid (MPA) and 2-phenylethylammonium iodide (PEAI) sequentially deposited between the perovskite and PCBM electron transport layer [15]. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy confirmed the formation of strong covalent P-O-Pb bonds rather than weak coordination bonds [15]. Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy measured work function changes, showing the SBI modified perovskite surface WF decreased from 4.54 eV to 4.20 eV, creating a more n-type surface for enhanced electron extraction [15]. Fourier-transform infrared spectra identified the P-O-Pb vibration signal near 1076 cm⁻¹ [15].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Passivation Strategies

| Passivation Strategy | Key Reagents | PLQY Improvement | Maximum EQE | Stability Enhancement | Defect Reduction Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral Interfacial Passivation [12] | TSPO1 (phosphine oxide) | 43% → 79% (film) | 18.7% | 20x operational lifetime (0.8 h → 15.8 h) | DFT calculations, SCLC measurements |

| Ligand Engineering [14] | Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) | Not explicitly quantified | 10.13% | 4.5x T50 improvement (2.96 h → 13.51 h) | Reduced trap density, increased carrier mobility |

| Synergistic Bimolecular Interface [15] | MPA & PEAI | Not explicitly quantified | 25.53% (solar cell PCE) | 95% efficiency retention after 1000 h | XPS, UPS, KPFM showing covalent bonding and energetics shift |

Table 2: Experimental Methodologies for Defect Characterization and Passivation Validation

| Characterization Technique | Physical Principle | Information Obtained | Applicable Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [12] | Quantum mechanical modeling | Bond formation energy, density of states, bond order | Bilateral passivation |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) [15] | Photoelectric effect analysis | Chemical bonding states, element composition, covalent bond formation | SBI, Bilateral passivation |

| Space Charge-Limited Current (SCLC) [12] | Charge transport in trap-states | Trap density, defect density of states | Bilateral passivation, Ligand engineering |

| Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS) [15] | Photoelectron energy analysis | Work function, valence band maximum, energy level alignment | SBI |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) [15] | Molecular vibration absorption | Chemical bond vibrations, functional group identification | SBI |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Surface Passivation Studies

| Reagent | Chemical Function | Passivation Role | Compatible Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSPO1 [12] | Phosphine oxide group | Coordinates with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ via P=O bond | CsPbBr₃ QLEDs |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) [14] | Sulfate group (-OSO₃⁻) | Binds to PQD surface, suppresses non-radiative recombination | CsPbBr₃ QLEDs |

| 4-Methoxyphenylphosphonic Acid (MPA) [15] | Phosphonic acid group | Forms covalent P-O-Pb bonds with perovskite surface | p-i-n perovskite solar cells |

| 2-Phenylethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) [15] | Ammonium halide | Creates negative surface dipole, improves energy alignment | p-i-n perovskite solar cells |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) [12] [14] | Quaternary ammonium salt | Surface ligand, enhances colloidal stability | Various PQD systems |

The comparative analysis reveals that while all three strategies effectively address surface defects, their mechanisms and optimal applications differ significantly. Bilateral passivation provides comprehensive interface protection ideal for high-performance QLEDs. Ligand engineering with SDS offers a robust solution for improving charge transport and reducing efficiency roll-off. The synergistic bimolecular approach demonstrates the power of covalent bonding combined with energetic alignment for ultimate performance in solar cells.

Future research should explore combining these approaches—developing strongly-coordinating bilateral passivators with optimized energy level alignment. The creation of a more n-type perovskite surface through molecular design, as demonstrated in the SBI strategy, presents a promising direction for enhancing electron extraction across various PQD applications. As passivation strategies evolve from simple defect masking to sophisticated interface engineering, the performance and stability ceilings for perovskite-based optoelectronic devices will continue to rise.

Diagram: Relationship between passivation strategies, their molecular mechanisms, and resulting device performance outcomes.

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly all-inorganic CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) nanocrystals, have emerged as promising semiconductor materials for optoelectronic applications due to their exceptional properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), narrow emission linewidths, and tunable bandgaps across the visible spectrum [16]. Despite these advantageous characteristics, the widespread commercialization of PQD-based devices faces significant challenges related to their environmental instability and susceptibility to degradation under various stressors [17]. The consequences of defects in PQDs manifest primarily through three interconnected phenomena: photoluminescence quenching, ion migration, and rapid degradation in aqueous environments.

Understanding these degradation pathways is fundamental to developing effective surface passivation strategies that can enhance PQD stability for practical applications. This review systematically examines the intrinsic and extrinsic factors governing PQD instability, analyzes the mechanistic relationships between defect types and observed degradation phenomena, and provides a comparative evaluation of surface engineering approaches aimed at mitigating these challenges within the broader context of advancing PQD-based technologies.

Fundamental Defect Types and Their Consequences in PQDs

Structural Defects and Surface Imperfections

The crystal structure of CsPbX3 perovskites consists of a Cs+ cation at the cube corners, Pb2+ at the body center, and X- halide ions at the face centers, forming [PbX6] octahedra that constitute the inorganic framework [16]. This ionic crystal lattice inherently contains various defect types that significantly impact material properties and stability. Table 1 summarizes the primary defect categories in PQDs and their specific consequences on optoelectronic properties.

Table 1: Defect Types in PQDs and Their Consequences

| Defect Category | Specific Defect Types | Primary Consequences | Impact on Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Halide Vacancies (VX) | Bromide, Iodide, Chloride vacancies | • Create deep trap states• Facilitate ion migration• Reduce PLQY | High - initiates degradation cascade |

| Lead-Related Defects | Lead vacancies (VPb), Unsaturated Pb sites | • Non-radiative recombination centers• Reduce charge carrier lifetime | Moderate-High - promotes PL quenching |

| Cesium Vacancies (VCs) | Cesium vacancies | • Alter crystal structure stability• Affect charge balance | Moderate - impacts structural integrity |

| Surface Defects | Uncoordinated Pb2+ sites, Halide vacancies | • Drastic PL quenching• Surface-initiated degradation• Reduced defect tolerance | Very High - primary degradation initiation sites |

The high percentage of surface atoms in PQDs creates a substantial density of uncoordinated ions (dangling bonds) that function as trap states for photoinduced charge carriers [18]. These surface defects are particularly detrimental because they directly facilitate non-radiative recombination pathways, leading to significant PL quenching even when internal defect concentrations remain low. Traditional ligands such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) dynamically bind to these surface sites but readily detach over time, exposing unsaturated lead atoms and halide vacancies that initiate degradation processes [16].

Environmental Stressors and Defect Activation

PQDs exhibit pronounced sensitivity to environmental factors that activate and exacerbate inherent defects. Moisture represents perhaps the most destructive environmental stressor, with water molecules penetrating the crystal lattice and disrupting ionic bonds [16]. This penetration leads to irreversible decomposition through the formation of hydrated phases and eventual dissolution. Oxygen molecules under illumination can catalyze the deprotonation of organic cations in hybrid perovskites, though all-inorganic CsPbX3 demonstrates somewhat improved resistance [17].

Temperature fluctuations induce phase transitions in PQDs that alter their optical properties and structural stability. For instance, CsPbI3 undergoes transitions from cubic (α-) to tetragonal (β-) to orthorhombic (γ-) phases with decreasing temperature, eventually transforming to a non-perovskite orthorhombic (δ-) phase at room temperature that lacks optoelectronic functionality [16]. Light exposure, particularly high-energy photons, generates excess charge carriers that activate migration pathways and accelerate degradation processes [17].

Mechanistic Pathways of Defect-Induced Degradation

Photoluminescence Quenching Mechanisms

Photoluminescence quenching in PQDs occurs through multiple defect-mediated pathways that compete with radiative recombination. Figure 1 illustrates the primary mechanistic routes through which defects lead to PL quenching and subsequent degradation.

Figure 1: Defect-mediated pathways leading to PL quenching and degradation in PQDs. Surface and bulk defects, activated by external stressors, initiate ion migration and non-radiative recombination that manifest as observable degradation phenomena.

The dynamic binding of conventional organic ligands to PQD surfaces creates an equilibrium where ligand detachment constantly occurs, exposing undercoordinated sites that function as efficient traps for charge carriers [16]. These trap states capture photogenerated electrons and holes, providing non-radiative recombination pathways that compete directly with radiative recombination, thereby reducing PLQY. In experimental studies, light-induced PL quenching in quasi-2D perovskite films occurred at different rates depending on illumination wavelength and intensity, with blue light (447 nm) causing more rapid quenching than red light (635 nm) under equivalent intensity [17]. This wavelength dependence suggests that higher-energy photons generate more charge carriers that can activate defect sites.

Ion Migration Pathways and Consequences

Ion migration in PQDs occurs primarily through halide vacancy defects that provide low-energy pathways for halide ion movement through the crystal lattice [16]. This migration leads to several detrimental effects including phase segregation, where halide ions separate into distinct domains under electrical bias or illumination. Phase segregation manifests as spectral shifts in emission and absorption profiles, particularly problematic in mixed-halide PQDs designed for specific emission wavelengths.

The migration of halide ions follows pathways through vacancy sites and grain boundaries, accelerated by the electric fields present in operational devices. This ion movement not only alters local composition and optoelectronic properties but also contributes to non-radiative recombination at accumulation points. Furthermore, migrating ions can reach electrode interfaces, causing chemical reactions that degrade device performance over time [19].

Degradation in Aqueous Environments

The interaction of PQDs with moisture represents one of the most rapid degradation pathways. Water molecules readily penetrate the porous ligand shell and initiate dissolution of the ionic crystal lattice [16]. The degradation mechanism proceeds through a intermediate hydrated perovskite phase before complete decomposition into precursor salts such as CsX, PbX2, and their hydrated forms [17]. This process is markedly accelerated when combined with other stressors such as oxygen and light.

In controlled studies, quasi-2D perovskite films exhibited significantly different degradation behaviors depending on their environment. When illuminated in ambient atmosphere (25°C, ~30% relative humidity) with 635 nm laser light at 50 mW/cm², PL intensity decreased by nearly 50% within 1900 seconds [17]. However, when the same film was placed in vacuum conditions, the PL quenching was substantially suppressed, decreasing by only 20% over the same duration, highlighting the synergistic effect of moisture and illumination in accelerating degradation.

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Defect Consequences

Characterization Techniques for Defect Analysis

Researchers employ multiple advanced characterization techniques to investigate defect consequences in PQDs. Table 2 summarizes the primary experimental methods used to study defect-related phenomena in PQDs, along with their specific applications and limitations.

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Analyzing Defect Consequences in PQDs

| Technique | Primary Application | Key Measurable Parameters | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Resolved PL Spectroscopy | Quantifying non-radiative recombination | Carrier lifetime, recombination kinetics | Does not identify specific defect types |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Monitoring structural changes | Phase transitions, crystal structure degradation | Limited surface sensitivity |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Analyzing surface chemistry | Ligand binding, detachment dynamics | Indirect defect characterization |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis | Assessing thermal stability | Decomposition temperatures, weight loss | Bulk measurement, less surface-specific |

| Electron Microscopy | Visualizing structural degradation | Morphological changes, lattice defects | Vacuum environment may alter samples |

Experimental protocols for stability assessment typically involve controlled exposure to environmental stressors followed by periodic measurements of optical and structural properties. For instance, in studies of light-induced degradation, perovskite films are illuminated with lasers of specific wavelengths (e.g., 447 nm or 635 nm) at controlled intensities (e.g., 50-500 mW/cm²) in either ambient atmosphere or vacuum chambers, with in situ monitoring of PL spectra and intensity [17]. XRD measurements before and after exposure track structural degradation, while FTIR spectroscopy monitors changes in surface ligand binding.

Standardized Testing Protocols

To enable meaningful comparison between different passivation strategies, researchers have developed standardized testing protocols for PQD stability. These typically include:

- Light stability testing: Continuous illumination under controlled intensity and environmental conditions

- Thermal stability testing: Accelerated aging at elevated temperatures (e.g., 60-85°C)

- Environmental stability testing: Exposure to controlled humidity levels (e.g., 30-80% RH)

- Operational stability testing: Performance monitoring under simulated device operation conditions

For each test, quantitative metrics such as PLQY retention, emission peak stability, and phase purity are tracked over time to provide comparative stability data across different material systems and passivation approaches [19].

Surface Passivation Strategies: A Comparative Analysis

Ligand Engineering Approaches

Surface ligand engineering represents the most extensively investigated strategy for mitigating defect consequences in PQDs. Different ligand classes offer distinct mechanisms for stabilizing the PQD surface and reducing defect densities. Table 3 provides a comparative analysis of major ligand categories used for PQD passivation.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Ligand Strategies for PQD Passivation

| Ligand Category | Representative Examples | Binding Mechanism | Impact on PLQY | Stability Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Long-Chain | OA, OAm | Dynamic ionic binding | Moderate (60-80%) | Limited - prone to detachment |

| Multidentate Ligands | 12-AA, 8-AA, 6-AA | Chelation with multiple sites | High (80-95%) | Significant - enhanced binding |

| Conjugated Ligands | BZA, BA, TCA | π-π stacking, coordination | High (80-90%) | Moderate - improved charge transport |

| Branched/Large Volume | APTES, NH2-POSS | Steric hindrance, encapsulation | Moderate-High (70-90%) | Very High - physical barrier |

| Zwitterionic Ligands | Sulfobetaine, phosphatidylcholine | Ionic pairing with surface | High (85-95%) | High - simultaneous cation/anion passivation |

Multidentate ligands containing multiple binding groups in a single molecule demonstrate particularly effective passivation. For example, peptide-like molecules such as 12-aminododecanoic acid (12-AA) provide both carboxylic acid and amine functional groups that simultaneously coordinate with surface sites, creating a more stable ligand shell than traditional OA/OAm mixtures [18]. Similarly, amino acids like phenylalanine (Phe) and leucine (Leu) have been successfully employed as bifunctional ligands, where the carboxylic group coordinates with Pb²⁺ ions while the amino group terminates growth and stabilizes the PQDs [18].

Inorganic Shell and Matrix Encapsulation

Beyond molecular ligands, researchers have developed various encapsulation strategies to physically separate PQDs from environmental stressors. These include:

- Oxide shell encapsulation: Coating PQDs with thin layers of stable oxides (e.g., SiO₂, Al₂O₃) through sol-gel processes or atomic layer deposition

- Polymer composite embedding: Dispersing PQDs in polymer matrices (e.g., PMMA, epoxy) that provide barrier properties while maintaining optical transparency

- Metal-organic framework (MOF) encapsulation: Confining PQDs within MOF structures that offer molecular-scale protection while allowing transport of charge carriers

Each approach presents trade-offs between protection effectiveness, charge transport properties, and processing complexity. For instance, while oxide shells provide excellent barrier properties, they may introduce interfacial defects during deposition and impede charge injection in electroluminescent devices [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Defect Studies and Passivation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salts | Cs₂CO₃, PbBr₂, PbI₂ | Quantum dot synthesis | High purity (>99.99%) critical for low defects |

| Traditional Ligands | Oleic acid, Oleylamine | Surface stabilization during synthesis | Dynamic binding requires optimization of ratios |

| Solvents | Octadecene, DMF, DMSO | Reaction medium, precursor dissolution | Anhydrous conditions essential for reproducibility |

| Multidentate Ligands | 12-AA, APTES, Amino acids | Enhanced surface passivation | Improve stability but may affect charge transport |

| Antisolvents | Ethyl acetate, Methyl acetate | PQD purification, ligand exchange | Polarity affects purification efficiency |

| Stability Enhancers | Zwitterionic polymers, NH2-POSS | Environmental protection | Create physical and chemical barrier to stressors |

The consequences of defects in PQDs—manifested through PL quenching, ion migration, and environmental degradation—present significant challenges that must be addressed through sophisticated surface engineering approaches. This comparative analysis demonstrates that while traditional ligand systems provide basic stabilization, advanced strategies employing multidentate ligands, conjugated molecules, and encapsulation architectures offer substantially improved protection against defect-mediated degradation pathways.

Future research directions should focus on developing quantitative structure-property relationships that connect specific ligand architectures to their protective efficacy, enabling rational design of next-generation passivation systems. Additionally, standardized testing protocols encompassing multiple environmental stressors simultaneously will provide more realistic assessments of PQD stability under operational conditions. As understanding of defect consequences deepens and passivation strategies become more sophisticated, the pathway toward commercially viable PQD-based optoelectronic devices becomes increasingly clear, potentially unlocking the full potential of these remarkable nanomaterials.

Surface passivation has emerged as a critical strategy for mitigating defect-mediated degradation in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), directly addressing the fundamental challenge of reconciling their exceptional optoelectronic properties with commercial-grade stability and performance. The inherent ionic nature and high surface-to-volume ratio of PQDs create a landscape rich in unsaturated bonds and ionic vacancies at their surface, serving as primary centers for non-radiative recombination and environmental degradation [3]. The core principle of passivation involves the targeted application of chemical agents or engineering strategies to saturate these coordinatively unsaturated "dangling bonds," thereby suppressing charge recombination losses and enhancing structural integrity. This review objectively compares contemporary passivation strategies—ranging from ligand engineering to dielectric encapsulation—within the broader thesis of advancing PQD research, providing researchers with a structured analysis of their mechanisms, experimental protocols, and resultant performance metrics to guide material selection and innovation.

Passivation Mechanisms and Strategy Comparison

The efficacy of a passivation strategy is governed by its mechanism of interaction with the PQD surface. Defects in lead halide perovskites predominantly originate from under-coordinated lead atoms and halide (e.g., Br⁻) vacancies, which create charge traps within the bandgap, facilitating non-radiative recombination and ion migration [20] [3]. Effective passivation functions through several core mechanisms:

- Ligand Binding and Vacancy Fillings: Polar molecules or ions selectively bond with under-coordinated surface sites. Short-chain ligands like 2-phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) demonstrate high efficacy by providing halide anions (Br⁻) to fill Br⁻ vacancies while the ammonium group (R-NH₃⁺) can coordinate with the perovskite lattice, simultaneously suppressing defects and improving film morphology [20].

- Dielectric Encapsulation: Inorganic dielectrics or polymers form a physical barrier that shields the PQD surface from environmental stressors like moisture and oxygen. Furthermore, in electronic devices, this layer prevents current leakage by blocking undesired electrochemical pathways in ionic solutions, a critical consideration for biosensor field-effect transistors (BioFETs) [21].

- Surface Dipole Manipulation: The removal of polar surface species, such as hydroxyl groups (-OH) from metal oxide electron transport layers (e.g., ZnMgO nanoparticles), reduces charge trap states and disruptive dipole moments. This leads to more efficient electron injection and extraction in device architectures [22].

The table below provides a comparative summary of distinct passivation strategies, highlighting their primary mechanisms and the resulting enhancements in key performance indicators.

Table 1: Comparison of Surface Passivation Strategies for Enhanced Performance and Stability

| Passivation Strategy | Targeted Defect/Issue | Key Mechanism | Performance Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Ligand (PEABr) | Br⁻ vacancies, poor film morphology | Anion provision and surface binding | PLQY: 78.64%; LED EQE: 9.67% (3.88x increase) | [20] |

| Dielectric Stack (SU-8 + HfO₂) | Gate leakage current in ionic solutions | Physical insulation of conductive components | Leakage current: ~2 nA; Device yield: ~90% | [21] |

| Alcohol Treatment (on ZnMgO NP) | Surface -OH groups on ET layer | Proton transfer and hydrogen bonding | LED lifetime: 4 min → 28 h (operational) | [22] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A critical evaluation of passivation strategies requires an understanding of their implementation. The following section details the experimental protocols for key methodologies cited in this review.

Ligand Exchange Passivation for PQD Light-Emitting Diodes (QLEDs)

The passivation of CsPbBr₃ QDs using 2-phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) involves a solution-phase treatment to replace native long-chain ligands and fill halogen vacancies [20].

- Materials: CsPbBr₃ QDs stabilized with oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA); 2-phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) powder; non-polar solvents (e.g., toluene, hexane).

- Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: The pristine CsPbBr₃ QD solution is synthesized or obtained commercially. A separate PEABr solution is prepared by dissolving the powder in a polar solvent like isopropanol.

- Mixing and Reaction: The PEABr solution is introduced to the QD solution under constant stirring. The short-chain PEA⁺ cations and Br⁻ anions interact competitively with the QD surface.

- Purification: The mixture is centrifuged to separate the passivated QDs from the supernatant containing displaced long-chain ligands and excess PEABr.

- Re-dispersion: The resulting pellet of passivated QDs is re-dispersed in a clean solvent for subsequent film fabrication.

- Film Formation & Device Fabrication: The passivated QD ink is spin-coated onto the substrate. Subsequent layers (electron transport layer, metal electrodes) are deposited to complete the QLED device architecture. The entire process significantly reduces surface roughness, leading to a denser, more uniform emission layer [20].

The following diagram visualizes the ligand exchange passivation workflow for QLEDs.

Multi-Layer Dielectric Passivation for Biosensor FETs (BioFETs)

For carbon nanotube (CNT) thin-film transistors operating in ionic solutions, a combination of photoresist and high-k dielectric materials is used to passivate the contacts and channel, effectively suppressing parasitic leakage currents [21].

- Materials: Fabricated CNT TFTs; SU-8 photoresist; Hafnium dioxide (HfO₂) precursor for Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD).

- Procedure:

- Photoresist Application: SU-8 photoresist is spin-coated onto the device. Photolithography is used to pattern the resist, typically leaving the CNT channel exposed while covering the metallic source/drain contacts.

- Dielectric Layer Deposition: A uniform, conformal layer of HfO₂ is deposited over the entire device (covering both the exposed channel and the photoresist) using Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD). This low-temperature process ensures precise, pinhole-free coverage.

- Curing and Annealing: The device may undergo a thermal treatment to cure the photoresist and improve the quality of the ALD dielectric layer.

- Outcome: This hybrid passivation stack provides robust defense against current leakage, ensuring that the detected electrical signal originates from the semiconducting channel's interaction with biomolecules rather than from parasitic electrochemical reactions [21].

Surface Hydroxyl Removal for Electron Transport Layers

A critical passivation step involves treating the metal oxide electron transport layer to remove surface hydroxyl groups that act as charge traps [22].

- Materials: Synthesized ZnMgO nanoparticles (ZMO NPs) dispersed in ethanol; Alcohol solvents (Methanol, Ethanol, Isopropanol).

- Procedure:

- ETL Deposition: The ZMO NP dispersion is spin-coated onto an ITO glass substrate to form the ETL.

- Alcohol Treatment (AT): Immediately after deposition, the film is subjected to one or more "rinse-spin" cycles with an alcohol solvent. The solvent is dispensed onto the spinning substrate, where it facilitates proton transfer, disrupting the hydrogen bonds between the ZMO surface and the -OH groups.

- Annealing: The treated film is annealed at a moderate temperature (e.g., 80°C) to remove residual solvent.

- Outcome: This simple treatment significantly reduces trap states, improves electron transport, and dramatically enhances the operational stability of the final QLED device [22].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The successful implementation of the described passivation strategies relies on a specific toolkit of reagents and materials. The table below details key components and their functions in surface passivation experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Passivation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Property | Associated Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Phenylethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) | Short-chain passivating ligand | Provides Br⁻ anions and coordinates with A-site; improves carrier transport | Ligand Exchange [20] |

| SU-8 Photoresist | Polymer-based dielectric for electrode insulation | Photosensitive; forms robust, patterned insulating layer | Dielectric Encapsulation [21] |

| Hafnium Dioxide (HfO₂) | High-k dielectric layer | Excellent conformality via ALD; high dielectric constant | Dielectric Encapsulation [21] |

| ZnMgO Nanoparticles (ZMO NPs) | Electron transport layer (ETL) | Solution processability; tunable band alignment | Hydroxyl Removal [22] |

| Methanol / Ethanol | Alcohol treatment solvent | Polar protic solvents that remove -OH via proton transfer | Hydroxyl Removal [22] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OLA) | Native long-chain surfactants for QD synthesis | Provides colloidal stability during synthesis; replaced during passivation | Ligand Exchange [3] |

The strategic implementation of surface passivation is indispensable for unlocking the full potential of perovskite quantum dots in optoelectronics and sensing. As demonstrated, the core principle hinges on a deep understanding of surface chemistry to select a mechanism—be it ionic vacancy filling, physical encapsulation, or trap state removal—that directly targets the dominant degradation pathway. The comparative data reveals that while ligand engineering with molecules like PEABr can dramatically boost luminescent efficiency, hybrid dielectric stacks are paramount for electronic stability in liquid environments. The progression of this field relies on the development of novel passivation agents with enhanced binding affinity and environmental resilience. Future research must focus on deciphering the atomic-scale interface between passivants and the PQD surface and optimizing these protocols for scalability, paving the way for PQD-based technologies that are both high-performing and durable.

A Toolkit of Surface Passivation Techniques: From Ligands to Encapsulation

Organic ligand engineering plays a pivotal role in modulating the surface chemistry and optoelectronic properties of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). Ligands cap the surface of PQDs during colloidal synthesis, influencing everything from defect passivation and charge transport to morphological control and environmental stability [23]. The dynamic binding nature of ligands to the ionic perovskite lattice presents both challenges and opportunities for surface optimization. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of insulating long-chain ligands, represented by oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), against conductive short-chain alternatives, notably phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) and didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB), within the broader context of optimizing surface passivation strategies for PQDs.

Performance Comparison: Short-Chain vs. Long-Chain Ligands

The choice between short-chain and long-chain ligands involves a fundamental trade-off between superior electronic performance and enhanced colloidal stability. The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of both ligand types.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Short-Chain and Long-Chain Ligands on PQDs

| Performance Characteristic | Short-Chain Ligands (PEABr, DDAB) | Long-Chain Ligands (OA, OAm) |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical Conductivity | High; reduces inter-dot distance, boosting charge transport [24] [23] | Low; creates insulating barrier, hindering charge injection [24] [23] |

| Film Morphology | Enables dense, compact films with minimal cracks [25] | Can lead to porous, rough films prone to agglomeration [25] |

| Defect Passivation | Effective; strongly coordinates to surface sites, reducing trap states [24] | Moderate; dynamic binding leads to ligand detachment, creating vacancies [25] |

| Colloidal Stability | Lower; requires carefully controlled purification [23] | High; provides excellent steric stabilization [23] |

| Ligand Binding Affinity | Stronger, more stable binding reduces defect density [24] | Weaker, reversible binding prone to detachment and vacancy formation [25] |

| Representative Device Performance | PQD Solar Cell: 18.3% certified efficiency [25]QLED: EQE up to 13.4% [23] | Performance is typically inferior to devices using optimized short-chain ligands [25] [23] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Ligand Exchange and Post-Synthesis Treatment

A critical step in employing short-chain ligands is the post-synthetic treatment of PQDs initially capped with long-chain OA/OAm. The following workflow details a standard ligand exchange and purification procedure.

Detailed Protocol:

- Purification of Parent PQDs: The synthesized PQDs, capped with pristine OA and OAm, are precipitated by adding an antisolvent (e.g., methyl acetate) and centrifuged. This removes excess ligands and reaction residues [25] [23].

- Ligand Exchange Solution Preparation: A solution of the short-chain ligand (e.g., DDAB or PEABr) is prepared in a suitable solvent like hexane or toluene [23].

- Incubation and Exchange: The purified PQD pellet is re-dispersed in the ligand exchange solution and stirred for several hours to facilitate the substitution of long-chain ligands with short-chain ones [23].

- Final Purification: The PQDs are precipitated again via centrifugation to remove the displaced long-chain ligands and any excess short-chain ligands. The final pellet is dispersed in an anhydrous solvent for film deposition [23].

In-Situ Ligand Exchange During Film Fabrication

For PQD solar cells, an in-situ ligand exchange strategy during the layer-by-layer film deposition is commonly employed. The "alkali-augmented antisolvent hydrolysis" (AAAH) strategy is a advanced example:

- Film Casting: A layer of OA/OAm-capped PQDs is spin-coated onto a substrate [25].

- Antisolvent Rinsing: Immediately after deposition, the film is rinsed with a blend of methyl benzoate (MeBz) antisolvent and potassium hydroxide (KOH). The alkaline environment facilitates the hydrolysis of the ester antisolvent, rapidly generating conductive short-chain ligands (e.g., benzoate) that replace the insulating OA- ligands. This process is repeated for each layer [25].

- A-site Cation Exchange: After building the desired thickness, a post-treatment with a protic solvent like 2-pentanol containing cationic salts (e.g., FAI, MAI) can be applied to substitute the pristine OAm+ ligands, further enhancing electronic coupling [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful ligand engineering requires a suite of specific reagents and materials. The following table outlines key components and their functions in typical experiments.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for PQD Ligand Engineering Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Ligand Engineering | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Long-chain capping ligands for initial PQD synthesis and stabilization [25] [23] | Provides excellent colloidal stability but insulates charge transport. |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Short-chain ligand for post-synthesis exchange [23] | Ammonium-based; improves charge injection and transport in films. |

| Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) | Short-chain conjugated ligand for surface passivation [23] | Aromatic group enhances binding; passivates defects, improves stability. |

| Methyl Acetate / Methyl Benzoate | Antisolvent for purifying PQDs and mediating in-situ ligand exchange [25] | Polarity selectively precipitates PQDs; esters hydrolyze to generate new ligands. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Alkaline additive for antisolvent [25] | Catalyzes ester hydrolysis, making ligand exchange more thermodynamically spontaneous. |

| 2-Pentanol | Solvent for A-site cation exchange post-treatment [25] | Protic solvent with moderate polarity ideal for dissolving cationic salt solutions. |

| Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (TOAB) | Co-ligand in multi-ligand engineering strategies [23] | Helps maintain colloidal stability during and after ligand exchange processes. |

The strategic selection and application of organic ligands is a cornerstone of advanced PQD research. While long-chain ligands like OA and OAm are indispensable for achieving stable, high-quality PQD syntheses, their insulating nature ultimately limits device performance. Short-chain ligands, such as PEABr and DDAB, address this bottleneck by enabling superior charge transport and more effective defect passivation, leading to significant gains in the efficiency of solar cells and light-emitting diodes. The choice is not merely a binary substitution but often involves sophisticated multi-step protocols for ligand exchange and surface functionalization. The ongoing development of novel ligands and exchange strategies, including alkaline-enhanced hydrolysis and the use of conjugated molecular backbones, continues to push the boundaries of PQD-based optoelectronics, paving the way for more efficient and stable devices.

The pursuit of advanced materials for environmental shielding represents a critical frontier in nanotechnology and surface science. Among various strategies, the application of inorganic coatings, particularly those based on silicon dioxide (SiO2) and titanium dioxide (TiO2), has emerged as a highly effective approach for protecting sensitive materials and components from harsh environmental conditions. These coatings provide robust barriers against moisture, corrosion, UV radiation, and chemical attack while often incorporating additional functionalities such as self-cleaning, thermal insulation, and photocatalytic activity.

This guide objectively compares the performance of SiO2 and TiO2 coating technologies across multiple applications, from perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) to industrial materials, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies for evaluating these protection strategies. The fundamental protection mechanism involves the formation of a dense, often nanoporous, physical barrier that chemically bonds to substrate surfaces, preventing direct exposure to degradative elements [26]. The integration of these materials leverages their complementary properties: SiO2 contributes enhanced mechanical robustness, hydrophilicity, and structural stability, while TiO2 provides photocatalytic self-cleaning capabilities and UV absorption [27] [28].

Performance Comparison of Coating Strategies

Protection for Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs)

Perovskite quantum dots show exceptional optoelectronic properties but suffer from environmental instability. Surface coating has emerged as a crucial stabilization strategy, with various SiO2 and TiO2 approaches demonstrating significant effectiveness.

Table 1: Comparison of Coating Strategies for Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Coating Strategy | Material System | Key Performance Metrics | Environmental Stability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic-Inorganic Hybrid | Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/DDAB/SiO₂ | Maintained >90% initial efficiency after 8 hours; Enhanced photoluminescence | High stability in ambient conditions | [29] |

| Eco-Friendly Synthesis | Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/Castor Oil (CO-Cs₃Bi₂Br₉) | PLQY of 21.2%; Maintained 97.3% fluorescence intensity after 72 hours | Excellent retention under environmental exposure | [30] |

| Lead-Free Perovskite | Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/DDAB/SiO₂ | Blue light emission at 485 nm; Used as emission layer in electroluminescent devices | Improved stability for optoelectronic applications | [29] |

Functional Coatings for Industrial Applications

Beyond PQD protection, SiO₂ and TiO₂ coatings provide critical protective functions across industrial sectors including construction, automotive, and aerospace applications.

Table 2: Performance of SiO₂-TiO₂ Coatings in Industrial Applications

| Application Domain | Coating Composition | Protective Function | Performance Data | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automotive Shielding | Ceramic Coating (SiO₂ + TiO₂) | Hydrophobic layer; Prevents damage from road salt/de-icing chemicals | Reduces snow accumulation by 30%; 50% less ice removal effort | [26] |

| Aeronautical Corrosion Protection | SiO₂-TiO₂ nanostructured films | Corrosion resistance on aluminum substrates | Hardness reached 4.6 GPa; Moderate corrosion protection | [31] |

| Building Thermal Insulation | High-precision SiO₂/TiO₂ multilayer | FP cavity structure for thermal insulation | Visible light transmittance >90%; NIR reflectance >90%; 10°C indoor temp reduction | [32] |

| Self-Cleaning Surfaces | SiO₂-TiO₂ superhydrophilic coating | Photocatalytic activity; Anti-fogging; Stain resistance | Water contact angle of 3.5°; Good mechanical properties | [28] |

| Battery Thermal Management | Aerogel composites (SiO₂-based) | Thermal insulation; Fireproofing | Thermal conductivity 0.013-0.018 W/(m·K); Temperature resistance >1100°C | [33] |

| Polymer Photostabilization | Al₂O₃-SiO₂ coated TiO₂ pigments | Reduced photocatalytic degradation of polymers | Gloss retention: 36% (high Al₂O₃-SiO₂) vs 21% (low alumina) | [34] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis of SiO₂-TiO₂ Hybrid Nanocoatings

The sol-gel method represents the most widely employed approach for creating homogeneous SiO₂-TiO₂ composite coatings with precise compositional control:

- Sol Preparation: Combine tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) and tetrabutyl titanate (TBOT) precursors in ethanol under acidic conditions (HCl catalyst). Typical molar ratios vary from 1:1 to 3:1 (SiO₂:TiO₂) depending on desired properties [28].

- Hydrolysis and Condensation: Conduct controlled hydrolysis with deionized water at room temperature with continuous stirring for 24 hours to form a stable, transparent sol.

- Substrate Preparation: Clean substrates (glass, aluminum, etc.) thoroughly with ethanol and deionized water, followed by plasma treatment or chemical activation to ensure proper adhesion.

- Coating Application: Apply the sol using dip-coating at controlled withdrawal speeds (typically 1-5 mm/s) or spray-coating methods to achieve uniform thickness.

- Curing Process: For low-temperature processes, employ hydrothermal treatment at 100°C for 2 hours to induce crystallization without high-temperature calcination. Alternatively, thermal curing at 400-500°C may be used for heat-resistant substrates [28].

Mechanical and Environmental Testing Protocols

Standardized testing methodologies ensure reproducible evaluation of coating performance:

- Nanoindentation Testing: Use diamond tip indenters with continuous stiffness measurement method. Apply loads ranging from 0.1 to 500 mN while measuring displacement to determine hardness and elastic modulus. Create finite element models to verify mechanical response at film-contact interfaces [31].

- Corrosion Resistance: Perform electrochemical tests including potentiodynamic polarization and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in 3.5% NaCl solution. Measure corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion current density (Icorr) to quantify protection effectiveness [31].

- Photocatalytic Activity: Evaluate by monitoring degradation of organic dyes (rhodamine B, methylene blue) under UV or visible light irradiation. Measure concentration decrease spectrophotometrically at characteristic absorption wavelengths [28].

- Accelerated Weathering: Expose coated samples to UV radiation in aging chambers (UVA lamp, 0.8 W/m²/nm at 340 nm) with cyclic condensation at 50°C. Assess durability through gloss retention, carbonyl index formation, and mechanical property retention at defined intervals [34].

Protection Mechanisms and Coating Architectures

Figure 1: Protection mechanisms of SiO₂-TiO₂ coating systems against environmental stressors

The protective efficacy of SiO₂-TiO₂ coatings derives from multiple complementary mechanisms that operate synergistically. The nanoporous network structure of silica aerogel components provides exceptional thermal insulation properties with thermal conductivity measurements ranging from 0.013–0.018 W/(m·K) at room temperature, effectively blocking heat transfer [33]. Simultaneously, TiO₂ components offer photocatalytic self-cleaning functionality by generating electron-hole pairs under UV irradiation that decompose organic pollutants through radical-mediated oxidation processes [28].