Surface Modification Strategies for High-Performance Perovskite Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes

This article provides a comprehensive review of surface modification techniques for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) to enhance the performance and stability of light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

Surface Modification Strategies for High-Performance Perovskite Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of surface modification techniques for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) to enhance the performance and stability of light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Targeting researchers and scientists in materials science and optoelectronics, it explores the foundational role of surface chemistry in determining PQD optoelectronic properties, details advanced ligand engineering and passivation methodologies, addresses critical stability challenges, and validates these approaches through comparative performance analysis. The synthesis of recent research offers a strategic framework for developing next-generation, high-efficiency PQD-LEDs for display and lighting applications.

The Surface Science of Perovskite Quantum Dots: Understanding the Foundation of Luminescence and Stability

The ABX3 Crystal Structure and Its Intrinsic Defect Tolerance

The ABX₃ crystal structure, named after the naturally occurring mineral calcium titanate (CaTiO₃), provides the foundational framework for halide perovskite materials critical to modern optoelectronics, including light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [1]. This structure is characterized by a cubic unit cell where:

- A larger monovalent cation (e.g., Cs⁺, MA⁺, FA⁺) occupies the body-center position in a 12-fold cuboctahedral coordination [2] [1].

- A smaller divalent metal cation (e.g., Pb²⁺, Sn²⁺) resides at the cube corners in a 6-fold octahedral coordination, forming the [BX₆]⁴⁻ octahedron [2] [3].

- The X-site anion (a halogen: I⁻, Br⁻, Cl⁻) sits at the face centers, bridging the B-site cations [2] [1].

This arrangement, with a general chemical formula of ABX₃, exhibits remarkable structural and compositional flexibility. The Goldschmidt tolerance factor and octahedral factor are key parameters for predicting the stability of the perovskite structure, allowing for extensive substitution and mixing of ions at the A, B, and X sites to precisely tune material properties [3].

The Principle of Defect Tolerance

Defect tolerance in halide perovskites (HaPs) refers to the unique phenomenon where structural defects do not necessarily translate into detrimental electronic states within the bandgap that act as efficient charge recombination centers [4]. In conventional semiconductors (e.g., silicon, GaAs), such defects severely degrade performance, necessitating high-purity, single-crystal materials. In contrast, HaPs, even polycrystalline films processed from solution at low temperatures, can exhibit excellent optoelectronic properties, a characteristic explained by defect tolerance [4].

Direct experimental evidence for defect tolerance comes from comparing the structural quality of Pb-haplide perovskite single crystals with their optoelectronic characteristics. High-sensitivity measurements, including X-ray diffraction rocking curves, show that despite the presence of structural defects, these materials maintain high optoelectronic quality, as evidenced by their excellent emission and transport properties [4]. This indicates that the majority of structural defects in HaPs are "electrically benign" [4].

The defect tolerance in lead-halide perovskites is theorized to stem from several key electronic structure properties:

- The valence band maximum and conduction band minimum are primarily formed by anti-bonding coupling of Pb(6s) and I(5p) orbitals [4].

- This specific orbital contribution leads to a high dielectric constant and strong electronic screening, which can render the electrostatic potential of charged defects less effective at trapping charge carriers [4].

- Computational studies suggest that charge trapping at intrinsic defects may be suppressed by large, picosecond-scale fluctuations in the energy levels of defect states, a consequence of the soft, dynamic lattice [4].

Table 1: Key Evidence and Rationale for Defect Tolerance in ABX₃ Halide Perovskites

| Evidence/Rationale | Description | Experimental/Computational Support |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk Optoelectronic Quality | High performance despite structural defects in bulk material [4]. | XRD rocking curves, photoluminescence (PL) decay, transport measurements on single crystals [4]. |

| Electronic Screening | High dielectric constant screens charge carrier trapping at defect sites [4]. | Theory and computation of electronic structure and defect formation [4]. |

| Soft, Dynamic Lattice | Low-frequency phonon modes and large, picosecond-level fluctuations of defect energy levels [4]. | Combined molecular dynamics and density functional theory (DFT) computations [4]. |

| Contrast with Classical Semiconductors | Performance less sensitive to grain boundaries and structural defects than Si or GaAs [4]. | Comparative device performance of polycrystalline films prepared under mild conditions [4]. |

Implications for Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) and LEDs

The principle of defect tolerance is profoundly significant for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) used in light-emitting diodes (LEDs). The quantum confinement in PQDs enhances radiative recombination, making them exceptional emitters. While the ABX₃ bulk structure may be defect-tolerant, the high surface-to-volume ratio of PQDs means surface defects dominate their optoelectronic properties [5] [6]. Unpassivated surface defects, such as under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions, become major sources of non-radiative recombination, quenching photoluminescence (PL) and reducing the external quantum efficiency (EQE) of LEDs [5] [6]. Therefore, research shifts from mitigating bulk defects to engineering surface chemistry via ligands to control the surface states of PQDs.

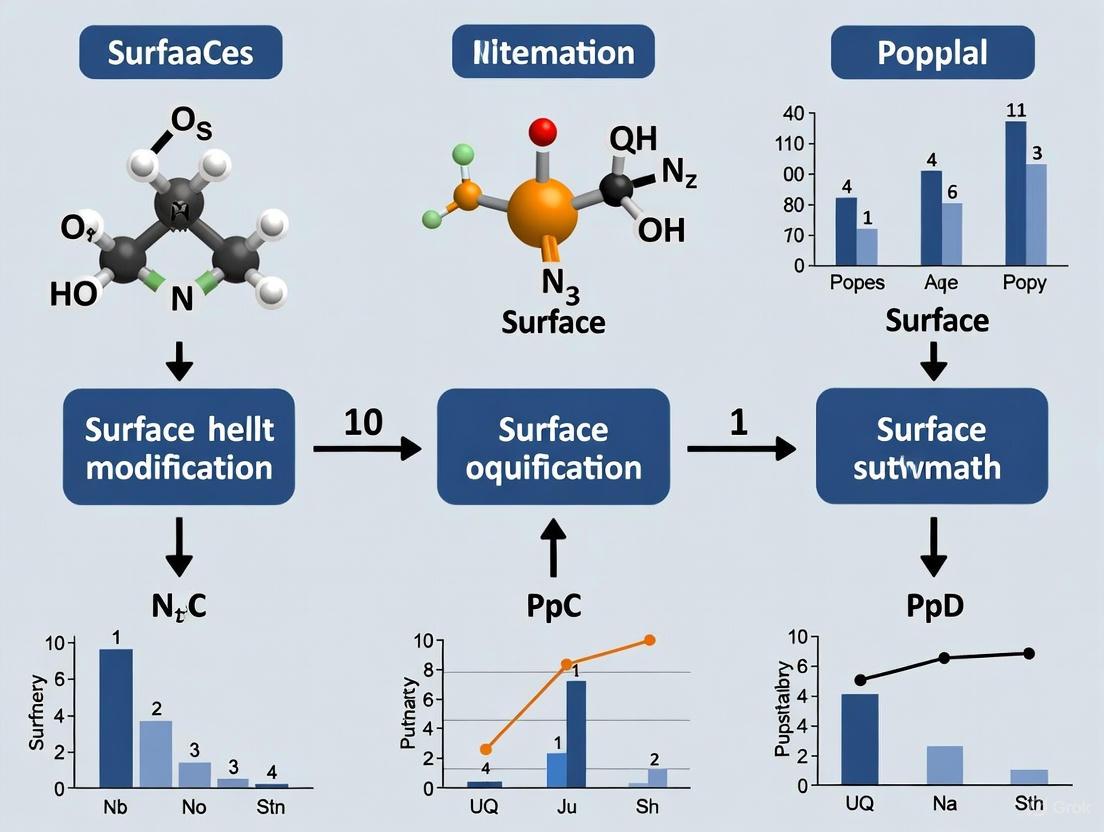

Diagram 1: Contrasting impact of defects in bulk perovskites versus perovskite quantum dots, highlighting the critical role of surface ligand engineering for PQD-based LEDs.

Surface Engineering Strategies for Defect Management

Surface ligand engineering is a critical protocol for passivating defects in PQDs, enhancing their performance in LEDs. Effective ligands coordinate with under-coordinated surface ions, suppressing non-radiative recombination pathways.

Ligand Exchange and Passivation Protocols

A robust protocol for ligand exchange on CsPbX₃ PQDs involves replacing native ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) with functionalized ligands to improve passivation and imprint new functionalities [6].

Detailed Protocol: Enhanced Ligand Exchange with Ultrasonic Treatment

- Objective: To achieve high ligand exchange efficiency for improved spin selectivity and optoelectronic properties in chiral PQDs for spin-LEDs [6].

- Materials:

- Pre-synthesized CsPbBr₃ PQDs: Capped with oleic acid (OAc) and oleylamine (OAm) ligands, dispersed in non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene, hexane) [6].

- Chiral Ligand Solution: R- or S-methylbenzylamine (MBA) dissolved in a polar solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) [6]. Other ligands like l-phenylalanine can be used for specific passivation [5].

- Equipment: Ultrasonic bath, centrifuge, inert atmosphere glovebox.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Transfer the pristine PQD solution to a vial. Prepare the chiral ligand solution with a typical concentration of 10-20 mM [6].

- Mixing: Add the ligand solution to the PQD solution under vigorous stirring. The typical volume ratio of ligand solution to PQD solution is 1:1 [6].

- Ultrasonic Treatment: Place the mixture in an ultrasonic bath and treat for 10-20 minutes. The ultrasonic energy assists the desorption of original OAc/OAm ligands, promoting the adsorption of chiral ligands [6].

- Purification: Precipitate the PQDs by adding anti-solvent (e.g., methyl acetate) and centrifuging at 8000-10000 rpm for 5-10 minutes [6].

- Washing: Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in a clean solvent. Repeat the purification cycle 1-2 times to remove excess ligands and by-products [6].

- Storage: Finally, disperse the exchanged PQDs in an appropriate solvent (e.g., octane) for film deposition. Store in a dark and cool environment [6].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Aggregation: If PQDs aggregate during exchange, reduce ultrasonic power or treatment time. Ensure anti-solvent is added slowly and with gentle stirring.

- Incomplete Passivation: Increase ligand concentration or extend ultrasonic treatment duration. Confirm the ligand is adequately dissolved in the solvent.

- PL Quenching: Optimize purification steps to remove unbound ligands effectively, which can introduce charge traps.

Quantitative Performance of Ligand Modifications

The effectiveness of surface ligand engineering is quantitatively assessed through enhancements in photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), emission linewidth, and device efficiency.

Table 2: Impact of Surface Ligand Modification on the Optical Properties of CsPbI₃ PQDs [5]

| Ligand Treatment | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) Enhancement | Key Findings and Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| l-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | +3% | Effective passivation of surface defects; demonstrated superior photostability, retaining >70% of initial PL intensity after 20 days of UV exposure [5]. |

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | +16% | Coordination with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions effectively suppresses non-radiative recombination [5]. |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | +18% | Strong coordination with surface Pb²⁺ ions, leading to the highest PLQY enhancement among the tested ligands [5]. |

For LED applications, this ligand engineering directly translates to improved device performance. Chiral CsPbBr₃ PQDs treated with R-/S-MBA via the ultrasonic-assisted ligand exchange protocol demonstrated high-performance spin-LEDs with an external quantum efficiency (EQE) of up to 16.8% and a high electroluminescence dissymmetric factor (gEL) of 0.285 [6]. This protocol synergistically enhances both spin selectivity and optoelectronic properties by improving chiral ligand coverage, which concurrently passivates surface defects and imprints chirality [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PQD Surface Engineering and Characterization

| Item/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PQD Cores | Light-emitting material; platform for surface studies [5] [6]. | CsPbI₃ PQDs (red emission), CsPbBr₃ PQDs (green emission) [5] [6]. |

| Passivating Ligands | Coordinate with undercoordinated surface ions to suppress non-radiative recombination [5] [6]. | L-Phenylalanine, Trioctylphosphine (TOP), Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO), R-/S-Methylbenzylamine (MBA) [5] [6]. |

| Precursor Salts | Synthesis of PQDs and precursor solutions for film deposition [5]. | Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃), Lead Iodide (PbI₂) [5]. |

| Solvents | Medium for synthesis, ligand exchange, purification, and film processing [5] [6]. | 1-Octadecene (non-polar), Dimethylformamide (polar), Ethyl Acetate (polar), Toluene (non-polar) [5] [6]. |

| Characterization Equipment | Quantifying structural, optical, and electronic properties of surface-engineered PQDs [4] [5] [6]. | Photoluminescence (PL) Spectrometer, X-ray Diffractometer (XRD), Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) with magnetic conductive probe (mCP-AFM) [4] [5] [6]. |

Diagram 2: A generalized experimental workflow for the surface engineering and characterization of perovskite quantum dots, from synthesis to device integration.

In the pursuit of high-performance perovskite quantum dot (PQD)-based light-emitting diodes (LEDs), the manipulation of material dimensions has emerged as a pivotal strategy. Low-dimensional halide perovskite nanostructures, including quantum dots (QDs), nanowires (NWs), and nanosheets (NSs), exhibit distinctive quantum confinement effects, adjustable bandgaps, superior carrier dynamics, and cost-effective solution processability [7]. A fundamental characteristic defining the behavior of these nanomaterials is their high surface-to-volume ratio (SVR), which becomes increasingly dominant as material dimensions shrink. This application note delineates the critical influence of SVR on the optoelectronic properties of PQDs, framed within a thesis investigating surface modification strategies. We provide a structured quantitative comparison, detailed experimental protocols for synthesis and surface modification, and essential reagent information to guide research in this field.

Theoretic Background: SVR and Nanostructure Properties

The high SVR in low-dimensional perovskites directly governs their performance and stability. In contrast to the continuous [BX6]4- octahedral network of traditional 3D perovskites, low-dimensional structures feature discrete perovskite units. This architectural difference profoundly enhances the Coulomb interaction between electrons and holes, resulting in significantly higher exciton binding energies and enabling efficient radiative recombination at room temperature [7]. Furthermore, the expansive surface area of PQDs, while beneficial for ligand anchoring and defect passivation, also presents a higher density of potential defect sites, such as uncoordinated lead atoms and halide vacancies, which can act as traps for charge carriers and instigate non-radiative recombination [7]. The high SVR also facilitates more extensive interactions with environmental factors like moisture and oxygen, making surface integrity a critical determinant of operational stability [8] [7]. Consequently, sophisticated surface modification protocols are not merely supplementary but are essential for achieving high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and device longevity.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Low-Dimensional Halide Perovskite Nanostructures for Optoelectronics.

| Nanostructure Type | Typical Dimensions | Key Optoelectronic Properties | Impact of High SVR | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0D Quantum Dots (QDs) | 2-10 nm | High PLQY (>90%), narrow emission linewidth (FWHM ~20-30 nm), tunable bandgap [9] [7] | Dominant quantum confinement; vast surface for ligand binding and defect formation; high susceptibility to environmental degradation [7] | LEDs, displays, lasers [7] |

| 1D Nanowires (NWs) | Diameter: 10-100 nm, Length: several µm | Efficient charge transport, high gain, ultrafast response [7] | Anisotropic charge transport; reduced grain boundaries in the long axis; surface states can scatter carriers [7] | Photodetectors, transistors [7] |

| 2D Nanosheets (NSs) | Thickness: single/few layers, Lateral: >1 µm | Confined electron-hole pairs, enhanced PLQY and monochromaticity, excellent environmental stability from hydrophobic ligands [7] | Large, uniform emission surface; interlayer spacers block environmental ingress; surface ligands critically control stability [7] | LEDs, photocatalysis [7] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of CsPbX3 PQDs via Hot-Injection Method

This protocol describes the synthesis of high-quality cesium lead halide (CsPbX₃) PQDs with tunable emission, adapted from established methods [7]. The hot-injection technique offers superior control over size and size distribution.

Workflow Overview

Materials and Equipment

- Chemicals: Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99.9%), Lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂, 99.999%), 1-Octadecene (ODE, 90%), Oleic acid (OA, 90%), Oleylamine (OAm, 70%), Octylamine (95%).

- Solvents: Toluene, Hexane, Acetone.

- Equipment: Three-neck round-bottom flask (100 mL), Schlenk line, Thermostatic heating mantle, Syringes and needles, Centrifuge.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Cs-oleate Precursor: Combine 0.4 g Cs₂CO₃, 1.25 mL OA, and 20 mL ODE in a 50 mL flask. Dry and degas under vacuum at 120°C for 1 hour. Heat under N₂ atmosphere until all Cs₂CO₃ reacts, forming a clear solution (~150°C). Maintain at 100°C for use.

- PbX₂ Precursor: In a 100 mL three-neck flask, load 0.069 mmol PbBr₂, 5 mL ODE, 0.5 mL OA, and 0.5 mL OAm. Dry under vacuum at 120°C for 30 minutes.

- Nucleation and Growth: Under N₂ flow, raise the temperature of the Pb-precursor to 150°C. Rapidly inject 0.4 mL of the preheated Cs-oleate solution and stir vigorously.

- Reaction Quenching: After 5 seconds, immediately cool the reaction flask in an ice-water bath to terminate crystal growth.

- Purification: Transfer the crude solution to centrifuge tubes. Add an equal volume of acetone and centrifuge at 8,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the PQD pellet in 5-10 mL of toluene or hexane. Repeat centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 5 minutes to remove any aggregates.

- Storage: Store the purified PQD solution in an inert atmosphere glovebox at 4°C for further use and characterization.

Protocol 2: Surface Passivation of PQDs using Bidentate Ligands

This protocol details the post-synthetic treatment of CsPbX₃ PQDs with 2-bromohexadecanoic acid (BHA) to significantly improve PLQY and photostability by passivating surface defects [7].

Workflow Overview

Materials and Equipment

- Chemicals: 2-Bromohexadecanoic acid (BHA, >95%), Purified CsPbX₃ PQDs in toluene.

- Solvents: Toluene, Ethyl Acetate.

- Equipment: Centrifuge, Vortex mixer, UV-Vis spectrophotometer, Fluorometer.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- PQD Preparation: Purify as-synthesized PQDs per Protocol 1 and disperse in toluene to a concentration of ~10 mg/mL.

- BHA Solution: Prepare a BHA solution in toluene at a concentration of 10 mM.

- Passivation Reaction: Add the BHA solution to the PQD solution with a molar ratio of BHA:Pb²⁺ between 1:1 and 3:1. Vortex the mixture for 30 seconds.

- Incubation: Stir the reaction mixture at room temperature for 2-4 hours.

- Purification: Precipitate the passivated PQDs by adding ethyl acetate (2:1 v/v to the PQD solution) and centrifuging at 8,000 rpm for 5 minutes. Re-disperse the pellet in toluene.

- Validation: Measure the absorption and photoluminescence spectra. The PLQY of the passivated PQDs is expected to be significantly enhanced, reaching values as high as 97% [7], indicating effective suppression of non-radiative recombination pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for PQD Synthesis and Surface Modification.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Characteristics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cesium cation (Cs⁺) precursor for ABX₃ structure [7] | High purity (≥99.9%) required for optimal luminescence and reduced impurities. |

| Lead(II) Bromide (PbBr₂) | Lead (B-site) and halide source [7] | High purity (≥99.999%) critical for minimizing defect states. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-coordinating solvent [7] | Acts as a high-booint reaction medium. Must be purified and stored over molecular sieves. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Surface capping ligands [7] | Dynamic binding passivates surfaces; controls crystal growth; concentration affects morphology and stability. |

| 2-Bromohexadecanoic Acid (BHA) | Bidentate passivating ligand [7] | The bromine moiety enhances binding to the PQD surface, providing robust passivation and boosting PLQY. |

| Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene): Poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) | Hole-injection layer (HIL) in PeLED devices [8] [10] | Facilitates efficient hole injection into the PQD emissive layer; forms a smooth, conductive film. |

| MXene Composites | Flexible electrode material [8] | Used in composite electrodes (e.g., with AgNWs, PEDOT:PSS) to optimize charge transport and heat dissipation in flexible devices. |

In the development of perovskite quantum dot-based light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs), surface defects on PQDs are a primary source of non-radiative recombination centers, severely limiting device performance and stability. These defects trap charge carriers, promoting non-radiative energy loss through processes such as the Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) mechanism, thereby reducing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), operational lifetime, and overall electroluminescence efficiency [11] [12] [13]. Within the broader research on surface modification for PeLEDs, the precise identification and characterization of these defects is a critical first step toward developing effective passivation strategies. This Application Note details the common surface defects in PQDs, provides protocols for their identification and quantification, and presents quantitative data on their impact, serving as a foundational guide for researchers aiming to mitigate non-radiative losses in optoelectronic devices.

Common Surface Defects and Their Quantitative Impact

Surface defects in PQDs primarily arise from incomplete surface passivation by organic ligands, leading to under-coordinated ions and structural imperfections at the nanocrystal surface [14]. The table below summarizes the primary defect types, their atomic-scale origins, and their specific impacts on device performance.

Table 1: Common Surface Defects in Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) and Their Impact on Device Performance

| Defect Type | Atomic Origin | Impact on PQD Properties & Device Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Vacancies (V_Pb) | Missing Pb²⁺ ions in the crystal lattice | Acts as a hole trap; increases non-radiative recombination, reducing PLQY and open-circuit voltage (V_OC) in devices [12] [13]. |

| Halide Vacancies (V_X) | Missing halide ions (I⁻, Br⁻, Cl⁻) | Creates shallow trap states; facilitates ion migration, leading to spectral instability and a slow EL response time in LEDs [11]. |

| Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ | Pb atoms not fully bonded to halides, often at edges/corners | Serves as a strong electron trap center; significantly reduces PLQY and external quantum efficiency (EQE) [11] [14]. |

| Dangling Bonds | Unsatisfied bonds at the PQD surface, often from ligand loss | Introduces mid-gap states that are efficient SRH recombination centers; increases surface recombination velocity (S) and reduces carrier lifetime [13]. |

The presence of these defects directly enables non-radiative recombination. While the classic SRH model often assumes a single mid-gap defect level, a more complex two-level recombination process can occur. In this mechanism, one type of carrier is first captured at a defect level, forming a metastable state; this is followed by a rapid local structural change, after which the other carrier is captured and recombined through a different defect level. This process can enhance the non-radiative recombination rate by orders of magnitude, even for defects with relatively shallow energy levels [12].

Quantitative Characterization of Defects and Recombination

The efficacy of any surface modification is quantitatively assessed by measuring the reduction in defect density and the consequent enhancement in optical and electronic properties. The following table compiles key performance metrics from recent studies employing different surface modification strategies, highlighting the direct correlation between defect passivation and device improvement.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Surface Modification Strategies on PQD Properties and PeLED Performance

| Surface Modification Strategy | PLQY | Average Recombination Lifetime (τ_avg) | Device EQE | EL Response Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquid ([BMIM]OTF) | Increased from 85.6% to 97.1% | Increased from 14.26 ns to 29.84 ns | Improved from 7.57% to 20.94% | Reduced by over 75%; achieved 700 ns | [11] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) Ligands | Improved from 18.7% to 31.85% | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | [15] |

| SiO₂ Encapsulation (in s-MSNs) | Achieved 90.0% | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | [16] |

| Unpassivated/Control PQDs (Baseline) | Low (Reference) | Short (Reference) | Low (Reference) | Slow (Reference) | [11] [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Defect Identification and Analysis

Protocol: Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) for Recombination Kinetics

Objective: To determine the carrier recombination dynamics and quantify the relative rates of radiative and non-radiative recombination in PQD samples.

Materials:

- Pulsed Laser Source: Wavelength suitable for bandgap excitation (e.g., ~400 nm for CsPbBr₃).

- Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting (TCSPC) system or a streak camera.

- Spectrometer with high spectral resolution.

- Cryostat (for temperature-dependent studies).

- PQD sample in solution or as a solid film.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Deposit a homogeneous film of PQDs on a clean substrate (e.g., quartz) or place the solution in a quartz cuvette.

- System Calibration: Calibrate the TRPL system using a standard fluorophore with a known lifetime.

- Data Acquisition: Excite the sample with a low-intensity pulsed laser to avoid non-linear effects like Auger recombination. Record the photoluminescence decay curve at the peak emission wavelength.

- Data Fitting: Fit the decay curve using multi-exponential functions (e.g., bi- or tri-exponential). The function is typically: I(t) = A₁exp(-t/τ₁) + A₂exp(-t/τ₂) + A₃exp(-t/τ₃) + ...

- Analysis: Calculate the amplitude-weighted average lifetime (τavg). A longer τavg generally indicates a lower density of non-radiative trap states, as seen in [11] where τ_avg increased after defect passivation. The presence of multiple time constants can reveal different recombination pathways (e.g., band-edge recombination, trap-assisted recombination).

Protocol: Measuring External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) of PeLEDs

Objective: To quantify the efficiency of a light-emitting diode by measuring the number of photons emitted per electron injected.

Materials:

- Completed PeLED device on a substrate.

- Source Measure Unit (SMU).

- Integrating sphere coupled to a calibrated spectrometer.

- Software for controlling the SMU and spectrometer.

Procedure:

- Device Connection: Place the PeLED inside the integrating sphere and connect its electrodes to the SMU.

- Light Emission Measurement: Drive the device with a defined current density using the SMU. The emitted light is collected by the integrating sphere, ensuring capture of all photons regardless of angle.

- Spectral Acquisition: The spectrometer measures the electroluminescence (EL) spectrum of the captured light.

- EQE Calculation: The EQE is calculated using the formula: EQE = (Number of photons emitted per second) / (Number of electrons injected per second) = (Luminous Flux / Photon Energy) / (Current / Elementary Charge). The software typically performs this calculation directly. A higher EQE signifies more efficient charge injection and radiative recombination, directly reflecting successful defect passivation [11].

Pathways and Workflows for Defect Management

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for identifying surface defects and developing effective passivation strategies, integrating the characterization techniques and performance metrics discussed.

Diagram 1: Workflow for PQD Defect Management. This chart outlines the process from quantum dot synthesis to performance enhancement, linking defect identification, characterization, passivation strategies, and final device outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Effective surface modification relies on specific chemical reagents. The table below lists key materials used for passivating surface defects in PQDs.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Surface Passivation of PQDs

| Reagent / Material | Function / Mechanism | Key Outcome / Performance Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquid [BMIM]OTF | Enhances crystallinity and passivates surface defects via coordination of [BMIM]+ with Br⁻ and OTF− with Pb²⁺. Reduces charge injection barrier. | Increased PLQY to 97.1%; boosted EQE to 20.94%; achieved nanosecond EL response (700 ns) [11]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) | Acts as an organic ligand, forming a hydrogen-bonding network for strong surface binding and defect passivation. | Enhanced fluorescence intensity by 144%; improved PLQY from 18.7% to 31.85% [15]. |

| Surface-functionalized Mesoporous Silica Nanospheres (s-MSNs) & SiO₂ | Provides physical encapsulation, shielding PQDs from environmental factors (O₂, H₂O) and passivating surface defects. | Achieved high PLQY of 90.0% and significantly enhanced environmental stability [16]. |

| Amino Acid Ligands | Provides dual passivation for PQD solar cells; chelates under-coordinated surface ions. | Improved photovoltaic performance and stability of CsPbI₃ quantum dot solar cells [14]. |

The Critical Role of Surface Ligands in Stabilizing the Perovskite Lattice

The intrinsic ionic nature of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) renders their lattice structure highly dynamic and susceptible to degradation, primarily through the formation of surface defects such as uncoordinated lead ions (Pb²⁺) and halide vacancies [5] [17]. These defects act as non-radiative recombination centers, quenching photoluminescence and undermining the performance of PQD-based light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs). Surface ligand engineering emerges as a critical strategy to address this instability. By forming coordinated bonds with undercoordinated surface ions, ligands effectively passivate defects, suppress ion migration, and enhance the overall robustness of the perovskite lattice [18] [19]. This application note details the mechanisms, quantitative outcomes, and practical protocols for employing surface ligands to stabilize the perovskite lattice, with a specific focus on applications in PeLEDs.

Ligand Classification and Binding Mechanisms

Surface ligands for PQDs can be categorized based on their binding affinity, molecular structure, and the resulting impact on material properties. The choice of ligand directly influences the optoelectronic quality and stability of the final PQD solid film.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Key Surface Ligands for PQDs

| Ligand Type | Representative Examples | Binding Mechanism | Key Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lewis Base Ligands | Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO), Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) [5] [17] | Coordinate with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites via electron-donating oxygen atoms [5]. | Strong covalent binding; effective suppression of non-radiative recombination [17]. | Requires dissolution in non-polar solvents (e.g., octane) to prevent PQD surface damage [17]. |

| Ionic Short-Chain Ligands | Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) [18] [17] | Ammonium group occupies A-site cation vacancies; anionic group (e.g., I⁻) passivates halide vacancies [18]. | Improves inter-dot charge transport compared to long-chain ligands [17]. | Labile ionic bonding can lead to ligand loss; may not fully suppress phase transition [18]. |

| Multifunctional Anchoring Ligands | 2-thiophenemethylammonium iodide (ThMAI) [18] | Thiophene ring (Lewis base) binds to Pb²⁺; ammonium group occupies Cs⁺ vacancies [18]. | Multidentate binding enhances passivation and restores beneficial lattice strain [18]. | Molecular design is complex to ensure simultaneous binding of multiple functional groups. |

| Multi-Site Binding Ligands | Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex [19] | Coordinates with up to four adjacent undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions via Se and Cl atoms [19]. | Creates a robust, cross-linked surface network; dramatically increases defect formation energy [19]. | Synthesis of the complex can be more involved than for simple organic ligands. |

Quantitative Impact of Ligands on PQD Properties

The effectiveness of surface ligands is quantitatively reflected in key performance metrics of PQDs and their resulting devices. The following table summarizes experimental data from recent studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Ligand-Modified PQDs

| Ligand Strategy | Material System | Optical Performance | Device Performance & Stability | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lewis Base Passivation (TPPO in octane) [17] | CsPbI₃ PQD Solar Cells | Increased PL intensity after ligand exchange [17]. | PCE: 15.4%; Ambient Stability: >90% of initial PCE after 18 days [17]. | Non-polar solvent prevents surface damage during treatment. |

| Multifunctional Anchoring (ThMAI) [18] | CsPbI₃ PQD Solar Cells | Improved carrier lifetime; uniform PQD orientation [18]. | PCE: 15.3%; Ambient Stability: 83% of initial PCE after 15 days (vs. 8.7% for control) [18]. | Simultaneously passivates defects and restores lattice strain. |

| Ligand-Assisted Purification (OA/OAm addition) [20] | Mixed-Halide CsPbBr₃₋ₓIₓ PNCs | Achieved near-unity PLQY for both green- and red-emissive NCs [20]. | Enhanced color purity for display applications [20]. | Prevents ligand detachment during anti-solvent washing. |

| Multi-Site Binding (Sb(SU)₂Cl₃) [19] | FAPbI₃ Perovskite Film | Enhanced crystallinity and reduced defect density [19]. | PCE: 25.03% (air-processed); T80 Lifetime: ~2.7 years (shelf storage) [19]. | Unprecedented stability for ambient-fabricated devices. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Surface Passivation with Covalent Lewis Base Ligands

This protocol describes the post-synthetic treatment of CsPbI₃ PQD solids with TPPO to achieve stable and highly luminescent films, adapted from [17].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- TPPO Solution in Octane: Dissolve triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) in anhydrous octane at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. The non-polar octane solvent is critical to prevent stripping of surface ions from the PQDs.

- PQD Solid Film: CsPbI₃ PQD films deposited on a substrate via layer-by-layer (LbL) spin-coating, with long-chain oleate/oleylamine ligands exchanged for short-chain ionic ligands (e.g., acetate and phenethylammonium iodide) using standard procedures [17].

Procedure:

- Film Preparation: Fabricate a conductive CsPbI₃ PQD solid film of desired thickness using the standard LbL method and ligand exchange process.

- TPPO Treatment: Dynamically spin-coat the TPPO solution in octane onto the freshly prepared PQD solid film at 3000 rpm for 30 seconds.

- Washing: Gently rinse the film with pure octane to remove any unbound TPPO ligand.

- Drying: Anneal the film on a hotplate at 70°C for 5 minutes to remove residual solvent.

Validation:

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Confirm the presence of TPPO on the PQD surface by detecting characteristic P=O stretching vibrations.

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: Measure the PL intensity and lifetime. A significant increase in both indicates successful passivation of non-radiative recombination centers [17].

Protocol: Ligand-Assisted Purification of Mixed-Halide PQDs

This protocol outlines a purification strategy that incorporates ligand supplementation to maintain high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) by minimizing ligand loss, adapted from [20].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Crude PQD Solution: As-synthesized mixed-halide (e.g., CsPbBr₃₋ₓIₓ) PQDs in a non-polar solvent like hexane.

- Ligand Supplement: A mixture of oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) in a 1:1 volume ratio.

- Anti-Solvent: Anhydrous tert-butanol (t-BuOH).

Procedure:

- Ligand Addition: To the crude PQD solution, add a controlled amount of the OA/OAm ligand supplement (e.g., 0.1 mL per 10 mL of crude solution). Mix thoroughly.

- Precipitation: Slowly add a reduced volume of anti-solvent (e.g., 3 mL of t-BuOH) to the mixture to induce precipitation. Using a minimized volume of anti-solvent is key to reducing ligand detachment [20].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture at 15,000 rpm for 10 minutes. A tightly packed precipitate will form.

- Re-dispersion: Carefully decant the supernatant and re-disperse the purified PQD precipitate in an appropriate anhydrous solvent (e.g., hexane or toluene) for further use.

Validation:

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Measure the PLQY of the re-dispersed PQDs using an integrating sphere. This method has been shown to achieve near-unity PLQY [20].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Quantify the ligand density on the purified PQDs to confirm effective retention of surface passivation.

Ligand Binding Mechanisms and Experimental Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate the multi-site binding mechanism of an advanced ligand and the general workflow for fabricating and passivating PQD solids.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Ligand Engineering in PQDs

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) [5] | Lewis base ligand for passivating uncoordinated Pb²⁺ defects. | Showed a 16% PL enhancement in CsPbI₃ PQDs [5]. |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) [17] | Covalent short-chain ligand for post-treatment passivation. | Must be dissolved in non-polar solvents (e.g., octane) to preserve the PQD surface [17]. |

| 2-Thiophenemethylammonium Iodide (ThMAI) [18] | Multifunctional ligand for strain restoration and defect passivation. | Its larger ionic size helps restore beneficial tensile strain on the PQD surface [18]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) [20] | Standard long-chain ligands for synthesis; used as supplements during purification. | Adding small quantities prior to anti-solvent washing prevents detachment and preserves PLQY [20]. |

| Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ Complex [19] | Multi-site binding passivator for dramatically enhanced stability. | Its quadruple-site binding configuration massively increases defect formation energy [19]. |

| Non-Polar Solvents (e.g., Octane) [17] | Medium for post-synthetic ligand exchange treatments. | Prevents the polar-solvent-induced loss of surface ions and ligands from PQDs [17]. |

In the development of perovskite quantum dot (PQD)-based light-emitting diodes (LEDs), surface modification is a critical determinant of device performance. The dynamic nature of the ligands passivating the PQD surface directly governs two pivotal properties: the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), indicative of optoelectronic quality, and charge transport, essential for electrical efficiency. Ligand dynamics encompass the binding affinity, which influences passivation stability, and the resultant surface coverage, which affects both defect passivation and inter-dot coupling. This application note details the quantitative relationships, measurement protocols, and practical methodologies for engineering ligand dynamics to achieve high-performance PQD-LEDs, framed within a broader thesis on surface modification strategies.

Quantitative Data on Ligand Impact

The properties of ligands, including their binding energy and steric effects, directly correlate with key performance metrics of PQDs and their resulting devices. The data below summarizes these critical relationships.

Table 1: Impact of Ligand Type on PQD Performance Metrics

| Ligand Type | Binding Energy (eV) | Reported PLQY | Exciton Binding Energy (meV) | Key Characteristics and Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleate (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | -0.22 / -0.18 [21] | Low / Variable [22] | 39.1 (Control) [21] | Dynamic binding; long chains hinder charge transport; low coverage [21] [22]. |

| Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) | -0.91 [21] | Notable Improvement [21] | 76.3 [21] | Bidentate, short-chain, liquid ligand; tight binding; high conductivity [21]. |

| Multidentate Ligands | High (General) | High [22] | Information Missing | Improved stability via multiple binding points; reduces ligand loss [22]. |

Table 2: Correlations between Ligand Properties and Device Performance

| Ligand Property | Impact on PLQY | Impact on Charge Transport | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Binding Affinity | Increases (Effective trap passivation) [21] | Improves (Stable surface coverage) [21] | 4x higher binding energy vs. oleate; suppressed ligand desorption [21]. |

| Full Surface Coverage | Increases (Reduces non-radiative sites) [21] | Improves (Reduces interfacial traps) [21] | FASCN treatment yields full coverage; eliminates interfacial quenching centers [21]. |

| Short Chain Length | Secondary Effect | Significantly Improves (Reduces inter-dot distance) | FASCN (C<3) enables 8x higher film conductivity [21]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange with FASCN

This protocol describes the treatment of synthesized CsPbX₃ PQDs with formamidine thiocyanate (FASCN) to enhance binding affinity and surface coverage [21].

Materials:

Procedure:

- PQD Purification: Transfer the crude PQD solution to centrifuge tubes. Add a non-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) to precipitate the QDs. Centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes. Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in 1 mL of anhydrous toluene.

- Ligand Treatment: To the purified PQD solution, add the 10 mM FASCN solution in a 1:1 volume ratio. Vortex the mixture vigorously for 30 seconds to ensure complete mixing.

- Incubation: Allow the mixture to stand for 10 minutes at room temperature to facilitate ligand exchange.

- Purification of Treated PQDs: Precipitate the FASCN-treated PQDs by adding a non-solvent (e.g., methyl acetate). Centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes. Discard the supernatant containing displaced oleate ligands and excess FASCN.

- Redispersion: Redisperse the final pellet in 1-2 mL of anhydrous hexane or toluene for further film fabrication or characterization.

Protocol: Measuring Binding Affinity via DFT Calculation

Computational determination of ligand binding energy (E₆) provides a quantitative metric for predicting ligand stability on the PQD surface [21].

- Software Requirement: Density-Functional Theory (DFT) code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO).

- Model Setup:

- Surface Model: Construct a slab model of a stable Pb-rich (100) surface of CsPbX₃. A minimum of 3-4 atomic layers is recommended, with the bottom 1-2 layers fixed.

- Ligand Model: Isolate the functional head group of the ligand (e.g., -SCN for FASCN, -COO⁻ for OA).

- Calculation Parameters:

- Functional: Use a generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functional like PBE.

- Basis Set: Employ plane-wave basis sets with a cutoff energy of 400-500 eV.

- k-points: Use a Γ-centered k-point grid for surface Brillouin zone sampling.

- Convergence: Set energy convergence criteria to 10⁻⁵ eV and force convergence to 0.01 eV/Å.

- Energy Calculation:

- Calculate the total energy of the optimized bare surface (Esurface).

- Calculate the total energy of the isolated ligand molecule in a vacuum (Eligand).

- Calculate the total energy of the surface with the ligand adsorbed at the most stable coordination site (E_complex).

- Analysis:

- Compute the binding energy using the formula: E₆ = Ecomplex - (Esurface + E_ligand). A more negative E₆ value indicates stronger, more favorable binding [21].

Visualization of Ligand Dynamics and Impact

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz, illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows.

Ligand Impact on PQD Performance

Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Ligand Engineering Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) | Bidentate ligand for post-synthesis treatment [21]. | Short-chain liquid ligand with high binding energy (-0.91 eV); enables high surface coverage and conductivity [21]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard L-type and X-type ligands for in-situ synthesis [22]. | Most common ligands for nucleation/growth control; dynamic binding leads to instability, serving as a baseline for improvement [22]. |

| 1,2-Ethanedithiol (EDT) | Short-chain bidentate crosslinker for solid-state films [23]. | Facilitates the formation of conductive NC solids; used in layer-by-layer deposition for photovoltaic devices [23]. |

| Lead Halide Salts (PbX₂) | Inorganic precursors for PQD synthesis. | Source of Pb²⁺ and halide ions (Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) for the perovskite lattice formation. |

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cesium precursor for all-inorganic CsPbX₃ PQDs. | Provides Cs⁺ ions upon reaction with acids in the synthesis mixture. |

| Anhydrous Solvents | Medium for synthesis and processing (e.g., Octadecene, Toluene). | High-purity, water-free solvents prevent degradation of ionic perovskite crystals during synthesis and ligand exchange. |

Advanced Surface Engineering Techniques: From Ligand Chemistry to Practical Device Integration

In the pursuit of high-performance perovskite quantum dot-based light-emitting diodes (PQD-LEDs), surface modification has emerged as a critical research frontier. The intrinsic ionic nature and dynamic ligand binding of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) create a high density of surface defects that serve as non-radiative recombination centers, severely limiting both device efficiency and operational stability [22] [21]. Ligand passivation strategies directly address this fundamental challenge by coordinating with undercoordinated surface ions—primarily Pb²⁺ and halide anions—to suppress trap states and enhance optoelectronic properties. This application note provides a systematic examination of three strategically significant ligand classes: conventional oleylamine, phosphine-based trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO), and carboxylic acids, detailing their performance characteristics, quantitative outcomes, and implementation protocols for PQD-LED applications.

Ligand Functions and Performance Comparison

The Role of Ligands in PQD Stability and Performance

Ligands bound to the PQD surface serve dual critical functions: they passivate surface defects to enhance photoluminescence and provide a steric barrier to maintain colloidal stability and prevent aggregation [22]. The binding strength, molecular structure, and coordination mode of these ligands directly determine the extent of defect passivation and the electrical conductivity of PQD films. Strong, stable binding suppresses ligand desorption and associated defect regeneration, while compact ligand structures enhance inter-dot charge transport—both essential for efficient PQD-LED operation [24] [21].

Quantitative Comparison of Ligand Performance

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for the featured ligand types, as established in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Ligand Passivation Strategies

| Ligand Type | Specific Ligand | Binding Group | PLQY Enhancement | Stability Performance | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Amine | Oleylamine (OAm) | Amine Group | Not Quantified | Limited; dynamic binding leads to detachment [22] | Facilitates synthesis & crystal growth [22] |

| Phosphine Oxide | Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | P=O Group | 18% PL enhancement [5] | Superior photostability [5] | Strong coordination with Pb²⁺; effective defect passivation [5] |

| Carboxylic Acid | Oleic Acid (OA) | Carboxyl Group | Not Quantified | Limited; dynamic binding leads to detachment [22] | Chelates with lead atoms; inhibits aggregation [22] |

| Bidentate Ligand | Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) | Thiocyanate Group | Notable PLQY improvement [21] | Excellent thermal & humidity stability [21] | Short chain, bidentate binding; high surface coverage & conductivity [21] |

| Polymer Ligand | PVP/PEG | Carbonyl & Ether Groups | 76% PLQY achieved [25] | >96% PL retention after 50h UV/humidity [25] | Multi-point attachment; robust physical barrier [25] |

Table 2: Electrical and Optoelectronic Properties of Ligand-Modified PQD Films

| Ligand Treatment | Film PLQY | Exciton Binding Energy (meV) | Relative Conductivity | LED Device Performance (EQE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleate-capped (Control) | Low (Reference) | 39.1 [21] | Reference | Low (Reference) |

| FASCN Treatment | High | 76.3 [21] | 8x higher [21] | ~23% (NIR-I LEDs) [21] |

| Bilateral TSPO1 | 79% (from 43%) [24] | Not Reported | Not Reported | 18.7% [24] |

Experimental Protocols

In Situ Ligand Passivation During Synthesis

This protocol describes the hot-injection synthesis of CsPbI₃ PQDs with simultaneous surface passivation using TOPO, adapted from established methodologies [5].

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PQD Synthesis and Passivation

| Reagent Name | Function/Role | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cesium (Cs⁺) precursor | 99% Purity |

| Lead Iodide (PbI₂) | Lead (Pb²⁺) and Iodide (I⁻) precursor | 99% Purity |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-coordinating solvent | Anhydrous |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Conventional ligand (Carboxylic acid) | 90% Technical Grade |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Conventional ligand (Amine) | 90% Technical Grade |

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | Phosphorus precursor & ligand | 99% Purity |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Phosphine oxide ligand | 99% Purity |

| L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | Bidentate amino acid ligand | 98% Purity |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: In a three-neck flask, combine 0.2 mmol Cs₂CO₃, 5 mL ODE, and 0.5 mL OA. Heat the mixture to 120°C under inert gas (N₂ or Ar) with constant stirring until the Cs₂CO₃ is completely dissolved, forming a clear Cs-oleate solution. Maintain this solution at 100°C for subsequent use.

- Reaction Mixture Setup: In a separate 50 mL three-neck flask, load 0.2 mmol PbI₂, 5 mL ODE, 1 mL OA, and 1 mL OAm. Add the specific ligand modifier (e.g., 0.2 mmol TOPO) at this stage for in situ passivation.

- Degassing and Heating: Evacuate the PbI₂-containing flask under vacuum with stirring at 100°C for 60 minutes to remove residual oxygen and water. Then, purge the flask with inert gas and raise the temperature to the target reaction temperature of 170°C [5].

- Hot-Injection and Nucleation: Rapidly inject 1.5 mL of the preheated Cs-oleate solution into the vigorously stirring reaction flask. The reaction mixture will immediately turn turbid, indicating rapid nucleation of PQDs.

- Crystallization and Growth: Allow the reaction to proceed for 10-15 seconds to facilitate PQD growth and crystallization.

- Quenching and Purification: Immediately cool the reaction flask using an ice-water bath to terminate the reaction. Centrifuge the crude solution at high speed (e.g., 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes) to precipitate the PQDs. Carefully discard the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in a non-polar solvent like hexane or toluene. Repeat this centrifugation and re-dispersion cycle at least twice to remove unreacted precursors and excess ligands.

- Storage: Store the purified PQD ink in an inert atmosphere glovebox or sealed vials to prevent degradation.

Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange

Post-synthesis treatment is highly effective for introducing short, conductive ligands or replacing weakly-bound native ligands to enhance charge transport in PQD films [26] [21].

Procedure for Solvent-Mediated Ligand Exchange:

- PQD Solid Film Preparation: Deposit a thin film of purified, oleate-capped PQDs onto the target substrate via spin-coating or drop-casting.

- Ligand Solution Preparation: Prepare a treatment solution of short-chain ligands (e.g., 5-10 mg/mL choline halides or formamidine thiocyanate (FASCN)) in a protic solvent with appropriate dielectric constant and acidity, such as 2-pentanol [26] [21].

- Film Treatment: Gently drop-cast the ligand solution onto the PQD film and let it incubate for 30-60 seconds. The solvent mediates the exchange, where short ligands in the solution replace the long-chain oleylamine/oleic acid on the PQD surface.

- Rinsing and Annealing: Spin the substrate to remove excess treatment solution and gently rinse with a pure 2-pentanol solvent to remove the displaced ligands. Finally, anneal the film at a mild temperature (e.g., 70°C for 10 minutes) to remove residual solvent and consolidate the film.

Advanced and Emerging Strategies

Bilateral Interfacial Passivation

For device integration, a bilateral passivation strategy can drastically enhance performance. This involves evaporating or spin-coating organic molecules (e.g., TSPO1, a phosphine oxide) onto both the top and bottom interfaces of the QD film within the LED device stack [24]. This method passivates defects introduced during film assembly and shields the PQDs from damaging interactions with charge transport layers, leading to reported maximum external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 18.7% and a 20-fold enhancement in operational lifetime [24].

All-Polymer Ligand Systems

Replacing conventional ligands entirely with polymer matrices represents a radical approach for extreme stability. A combination of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and polyethylene glycol (PEG) can be used to synthesize and passivate CsPbBr₃ PQDs at room temperature without OA or OAm [25]. This strategy achieves excellent properties, including 76% PLQY and remarkable stability, retaining 96.81% of initial PL after 50 hours under extreme conditions (80% relative humidity and high-intensity UV) [25].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the strategic decision-making pathway for selecting and implementing ligand passivation strategies, from objective definition to final application.

The experimental workflow for synthesizing and passivating PQDs, from precursor preparation to final film treatment, is outlined in the diagram below.

The strategic selection and implementation of ligand passivation are fundamental to advancing PQD-LED technology. While conventional ligands like oleylamine and oleic acid facilitate synthesis, their weak binding limits device performance. Phosphine-based ligands (TOPO) and advanced strategies using bidentate molecules (FASCN) or polymer systems (PVP/PEG) demonstrate superior defect passivation and stability by enabling stronger coordination and higher surface coverage. The optimal ligand strategy is application-dependent, requiring careful consideration of the trade-offs between conductivity, stability, and photoluminescence efficiency. Future developments will likely focus on sophisticated multi-dentate ligands and composite passivation schemes that collectively address the multifaceted challenges of surface defects, ion migration, and charge transport in PQD films.

Innovative Pseudohalide Engineering for Defect Suppression and Halide Migration Inhibition

Within the field of perovskite quantum dot (PQD)-based light-emitting diodes (LEDs), achieving high efficiency and operational stability is paramount for commercialization. A significant challenge is inherent material instability, primarily caused by defect-mediated non-radiative recombination and ion migration, particularly halide migration, which leads to phase segregation and spectral shift. This document details innovative application notes and protocols on pseudohalide engineering, a cutting-edge surface modification strategy that effectively suppresses defects and inhibits halide migration in perovskites. By integrating these methodologies into your research on PQD-based LEDs, you can significantly enhance the optoelectronic performance and longevity of your devices.

Pseudohalide Engineering: Mechanisms and Quantitative Benefits

Pseudohalides are anions whose chemical behavior resembles that of true halides but often with enhanced functionality due to their molecular nature. Examples include thiocyanate (SCN−), trifluoroacetate (TFA−), and tricyanomethanide (C4N3−). Their incorporation into perovskite structures, either as direct substitutes for halides or as surface-modifying ligands, addresses core instability issues through multiple synergistic mechanisms.

Table 1: Mechanisms of Action for Key Pseudohalides in Perovskite Systems

| Mechanism | Pseudohalide Example | Chemical Function | Observed Outcome in Perovskites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defect Passivation | Trifluoroacetate (TFA⁻) | CO group coordinates with under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions [27]. | Reduction of Pb-related defects; Non-radiative recombination suppression [27]. |

| Lattice Stabilization | Thiocyanate (SCN⁻) | Can bridge between perovskite layers, enhancing structural rigidity [28] [29]. | Tightened lattice structure; Improved thermal stability [28] [30]. |

| Halide Migration Inhibition | 2-Methoxyethylamine Trifluoroacetate (MeOEA-TFA) | Electrostatic interaction between -NH₃⁺ and halide ions, reinforced by O-atom polarization, anchors halides [27]. | Significant suppression of halogen migration; Improved operational stability [27]. |

| Phase Distribution Regulation | Trifluoroacetate (TFA⁻) | CF group forms H-bonds with organic cations (e.g., PEA⁺/BA⁺), retarding their diffusion and delaying crystallization [27]. | Increased proportion of desired n=2 phase in quasi-2D perovskites; Reduced n=1 phase [27]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Enhancements from Pseudohalide Engineering

| Performance Metric | Control System | Pseudohalide-Modified System | Pseudohalide Used | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | Reported as lower | 7.41% (pure-blue PeLED) | MeOEA-TFA [27] | [27] |

| Luminance (cd m⁻²) | Reported as lower | 3123 cd m⁻² (pure-blue PeLED) | MeOEA-TFA [27] | [27] |

| Operational Stability | Baseline | 5-fold improvement (operational lifetime) | MeOEA-TFA [27] | [27] |

| Thermal Stability | Halide complexes less stable | Exceptional thermal stability surpassing halide counterparts | N₃⁻, NCS⁻ in Cu(I) complexes [30] | [30] |

| Emission Wavelength Tuning | A₂MnBr₄: 512 nm (green) | 549–613 nm (green-red) in (RPh₃P)₂MnBrₓNCS₄₋ₓ | Thiocyanate (NCS⁻) [31] | [31] |

Diagram 1: Mechanisms of pseudohalide engineering for improved perovskite performance, showing how molecular-level interactions lead to enhanced device properties.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Incorporating MeOEA-TFA in Quasi-2D Mixed Halide Perovskites

This protocol details the use of 2-Methoxyethylamine Trifluoroacetate (MeOEA-TFA) as a multi-functional additive to suppress halogen migration and passivate defects in quasi-2D mixed Br/Cl perovskite films for pure-blue PeLEDs [27].

- Objective: To synthesize a high-efficiency, stable pure-blue perovskite emission layer with suppressed ion migration and reduced defect density.

Materials:

- Precursor Salts: CsCl, PbBr₂, PEABr, BABr.

- Solvent: Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

- Additive: 2-Methoxyethylamine Trifluoroacetate (MeOEA-TFA).

- Substrate: Pre-annealed PEDOT:PSS layer on a flexible or rigid substrate.

Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve CsCl, PbBr₂, PEABr, and BABr in DMSO at a molar ratio of 1.1:1:0.6:0.4 to create the base perovskite precursor solution.

- Additive Introduction: Add a optimized molar percentage of MeOEA-TFA (e.g., 5-15 mol%) to the precursor solution. Vortex and stir until a clear, homogeneous solution is obtained.

- Film Deposition: Spin-coat the final precursor solution onto the prepared PEDOT:PSS substrate. A typical two-step spin-coating program is recommended (e.g., 1000 rpm for 10 s, followed by 4000 rpm for 30 s).

- Annealing: Immediately after deposition, transfer the film to a hotplate and anneal at 90-100 °C for 10-15 minutes to remove residual solvent and crystallize the perovskite film.

Key Considerations:

- The electrostatic interaction between the -NH₃⁺ group of MeOEA⁺ and halide ions is crucial for immobilizing halides. This is stronger than hydrogen bonding alone and is reinforced by the electron-withdrawing O atom in MeOEA⁺ [27].

- The TFA⁻ anion simultaneously passivates Pb defects via coordination and regulates phase distribution by forming hydrogen bonds with organic cations.

Protocol: Synthesizing Pseudohalide-Substituted Layered Cobalt Hydroxides

This protocol describes the synthesis of α-cobalt-based layered hydroxides intercalated with pseudohalides (SCN⁻ or C₄N₃⁻) via an epoxide route, useful for exploring fundamental structural and magnetic properties [28] [29].

- Objective: To prepare two-dimensional pseudohalide-modified layered hydroxides and study their structural and magnetic properties.

Materials:

- Metal Salt: CoCl₂·6H₂O.

- Pseudohalide Salts: NaSCN (for thiocyanate) or NaC₄N₃ (for tricyanomethanide).

- Precipitation Agent: Glycidol.

- Solvents: Deionized Water, Ethanol (EtOH).

- Nucleophile (for C₄N₃⁻): NaCl.

Procedure for α-Co-SCN:

- In a mixture of H₂O and EtOH (1:1 v/v), dissolve NaSCN (100 mM), glycidol (500-1000 mM), and CoCl₂ (10 mM).

- Allow the solution to precipitate at room temperature for 24 hours.

- Collect the green solid by filtration, wash thoroughly with Milli-Q water and ethanol, and dry overnight in a desiccator with dry silica.

Procedure for α-Co-C₄N₃:

- In a mixture of H₂O and EtOH (3:1 v/v), dissolve NaC₄N₃ (100 mM), glycidol (1000 mM), CoCl₂ (10 mM), and NaCl (50 mM). The added NaCl acts as a nucleophile to promote precipitation.

- Allow the solution to precipitate at room temperature for 48 hours.

- Collect the solid by filtration, wash multiple times with water and ethanol, and dry in a desiccator.

Characterization:

- Structural: Use Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) to confirm the layered structure and measure interlayer spacing changes.

- Spectroscopic: Employ Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier-Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy to confirm pseudohalide incorporation and its coordination mode (e.g., bridging for SCN⁻).

- Magnetic: Perform DC magnetization measurements using a SQUID magnetometer from 2-300 K to study magnetic ordering behavior.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflows for pseudohalide incorporation in perovskite films and layered hydroxides.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Pseudohalide Engineering Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Methoxyethylamine Trifluoroacetate (MeOEA-TFA) | Multi-functional additive; cation (MeOEA⁺) inhibits halide migration via electrostatic interaction, anion (TFA⁻) passivates defects and regulates phase distribution [27]. | Critical for achieving high EQE (>7%) in pure-blue quasi-2D PeLEDs; improves operational stability 5-fold [27]. |

| Thiocyanate (SCN⁻) Salts (e.g., NaSCN) | Pseudohalide for structural modification; can induce bridging coordination between inorganic layers, tightening the lattice structure [28] [29]. | Used in synthesizing α-cobalt layered hydroxides; induces subtle structural and magnetic modifications [28]. |

| Tricyanomethanide (C₄N₃⁻) Salts (e.g., NaC₄N₃) | A less-explored pseudohalide for modulating the interlayer chemistry and electronic properties of layered materials [28] [29]. | Incorporation into α-layered hydroxide frameworks requires addition of a nucleophile like NaCl to promote precipitation [29]. |

| Cesium Trifluoroacetate (Cs-TFA) | Source of TFA⁻ anions for defect passivation without introducing additional organic cations. | Can be used to study the isolated effect of the TFA⁻ anion on perovskite film properties [27]. |

| Glycidol | Proton-scavenging agent used in the epoxide synthesis route to precipitate layered hydroxide materials [28] [29]. | Standard reagent for the synthesis of Simonkolleite-like α-layered hydroxides. |

Pseudohalide engineering represents a powerful and versatile strategy for advancing PQD-based LED research. By employing the detailed protocols for material synthesis and device fabrication outlined in this document, researchers can directly implement these innovative approaches. The strategic use of pseudohalides like TFA⁻ and SCN⁻, which function through robust mechanisms such as electrostatic halide anchoring and metal-ion defect passivation, addresses the core challenges of defect suppression and halide migration. Integrating these surface modification techniques will be instrumental in developing the next generation of high-performance, spectrally stable, and commercially viable perovskite light-emitting devices.

Bilateral and Multi-Functional Ligand Designs for Comprehensive Surface Coverage

In the development of perovskite quantum dot (PQD)-based light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs), achieving comprehensive and stable surface coverage on nanocrystals is a fundamental challenge. The dynamic nature of ligands traditionally used in synthesis, such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), leads to their detachment from the PQD surface, creating unpassivated defect sites that act as quenching centers and significantly impair device performance and stability [22] [21]. Bilateral and multi-functional ligand designs present a sophisticated strategy to overcome these limitations. These advanced ligands are engineered to feature multiple, strong binding sites that anchor securely to the PQD surface, while their functional molecular backbone enhances inter-ligand interactions and material compatibility. This approach ensures robust surface passivation, suppresses ion migration, and improves charge transport, thereby unlocking the full potential of PQDs in optoelectronic applications [32] [21].

Key Ligand Design Strategies and Mechanisms

Bidentate Ligands for Enhanced Binding Affinity

Bidentate ligands are designed to form two coordinate bonds with the perovskite surface, resulting in a dramatic increase in binding energy compared to conventional monodentate ligands. The significantly stronger attachment prevents ligand desorption during subsequent processing steps, ensuring that the surface remains passivated.

- Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN): This liquid bidentate ligand employs soft sulfur and nitrogen atoms to coordinate with lead atoms on the FAPbI3 QD surface. Density-functional theory (DFT) calculations reveal a binding energy of -0.91 eV, which is approximately fourfold higher than that of standard oleate ligands (OA: -0.22 eV; OAm: -0.18 eV) and about threefold higher than other common halide ligands like FAI (-0.31 eV) and MAI (-0.30 eV) [21]. This tight binding is crucial for achieving full surface coverage and effectively eliminating interfacial quenching sites.

Bilateral Ligand Combinations for Surface Energy Control

Strategically combining ligands with different chain architectures and binding groups allows for precise control over the surface energy of PQDs. This is particularly critical for mitigating detrimental effects in solution-processing techniques like inkjet printing.

- Octanoic Acid/Oleylamine (OcA/OAm) Combination: This specific mixed-ligand system creates a spatial barrier that optimizes the Ohnesorge number (Z), a key parameter governing ink jetting behavior. The branched nature of OcA and OAm results in a high surface energy (2.14 eV), which enhances steric stabilization, reduces particle aggregation, and promotes Marangoni flow during droplet drying. This effectively suppresses the "coffee ring effect," leading to the formation of high-fidelity, uniform patterns on flexible substrates [32].

Short-Chain and Multidentate Ligands for Improved Conductivity

Long-chain insulating ligands create barriers to charge transport between QDs. Engineering shorter ligands or those with multidentate binding motifs can significantly enhance the electrical conductivity of PQD films.

- FASCN as a Short Ligand: With a carbon chain length of less than three atoms, FASCN replaces the long-chain oleates. This change results in an eightfold higher film conductivity (3.95 × 10⁻⁷ S m⁻¹) compared to the control, facilitating efficient charge injection and transportation in LED devices [21].

- Multidentate Ligands: The use of ligands featuring multiple binding groups (e.g., X-type and L-type) can further strengthen the attachment to the PQD surface and improve passivation. These ligands are less prone to detachment and more effectively address surface defects, leading to enhanced luminescence performance and stability [22].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Different Ligand Strategies in PQDs

| Ligand System | Key Feature | Binding Energy (eV) | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FASCN (Bidentate) [21] | Short-chain, liquid | -0.91 | Highest improvement over control | ~23% EQE in NIR-LEDs; Eightfold higher conductivity |

| OcA/OAm (Bilateral) [32] | Mixed acid/amine | N/P | 92% | Suppressed coffee ring effect; High-fidelity printing |

| OA/OAm (Conventional) [22] [21] | Long-chain, dynamic | -0.22 (OA) / -0.18 (OAm) | Baseline | Baseline; Prone to detachment |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange with FASCN

This protocol describes the treatment of pre-synthesized FAPbI₃ QDs with the bidentate ligand FASCN to enhance surface coverage and optoelectronic properties [21].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Precursor QDs: Oleate-capped FAPbI₃ QDs in non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene, hexane).

- Ligand Solution: 10 mM Formamidine thiocyanate (FASCN) in dimethylformamide (DMF).

- Purification Solvents: Anhydrous toluene, methyl acetate (or ethyl acetate).

- Equipment: Centrifuge, vortex mixer, inert atmosphere glovebox (or nitrogen flow setup).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Concentrate Precursor QDs: Precipitate a known volume (e.g., 5 mL) of the pristine FAPbI₃ QD solution by adding a polar anti-solvent (e.g., methyl acetate) at a volume ratio of 1:2. Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes and discard the supernatant.

- Redisperse and Mix: Redisperse the QD pellet in 2 mL of anhydrous toluene. Add this QD solution dropwise to 5 mL of the 10 mM FASCN ligand solution under vigorous vortexing.

- Incubate for Exchange: Allow the mixture to stir for 10 minutes at room temperature to facilitate the complete exchange of oleate ligands with FASCN.

- Purify Treated QDs: Add an excess of methyl acetate (approx. 15 mL) to the mixture to precipitate the FASCN-treated QDs. Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Wash and Finalize: Carefully discard the supernatant. Redisperse the final pellet in a desired non-polar solvent (e.g., octane, octane) to form a stable ink for film deposition. Filter the ink through a 0.22 μm PTFE filter before use.

Protocol: In-Situ Synthesis of CsPbBr₃ QDs with Mixed Bilateral Ligands

This protocol outlines the hot-injection synthesis of CsPbBr₃ QDs using four different bilateral ligand combinations to control surface energy and mitigate the coffee ring effect in printing [32].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cesium Source: Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃).

- Lead Source: Lead bromide (PbBr₂).

- Solvent: 1-Octadecene (ODE).

- Ligand Pairs: Oleic acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm), Octanoic acid (OcA), Octylamine (OcAm). Used in four combinations: OA/OAm, OA/OcAm, OcA/OAm, OcA/OcAm.

- Equipment: Three-neck flask, Schlenk line, heating mantle, thermometer, syringe.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Prepare Cesium Oleate: Load 0.4 g Cs₂CO₃, 1.25 mL OA, and 15 mL ODE into a 50 mL flask. Dry and degas under vacuum at 120°C for 1 hour. Heat under N₂ to 150°C until the Cs₂CO₃ is fully dissolved.

- Prepare Lead Halide Precursor: In a separate 100 mL three-neck flask, load 0.069 g PbBr₂, 5 mL ODE, and the selected ligand pair (e.g., 0.5 mL OcA and 0.5 mL OAm). Dry and degas under vacuum at 120°C for 30 minutes until the solution becomes clear.

- Hot Injection: Under a nitrogen atmosphere, rapidly raise the temperature of the lead precursor solution to 180°C. Swiftly inject 0.4 mL of the preheated cesium oleate solution into the reaction flask.

- Crystallization and Quenching: Allow the reaction to proceed for 5-10 seconds to facilitate QD growth. Immediately cool the reaction flask using an ice-water bath to quench the reaction.

- Purification: Centrifuge the crude solution at high speed (e.g., 10,000 rpm) for 10 minutes. Isolate the precipitate and redisperse it in an anhydrous non-polar solvent (e.g., hexane, toluene). Repeat the centrifugation and redispersion cycle twice to obtain purified QDs.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bilateral Ligand Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis/Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Precursors | Cs₂CO₃, PbBr₂, FAPbI₃ QDs | Provides metal and halide ions for the perovskite crystal structure [32] [21]. |

| Solvents | 1-Octadecene (ODE), Toluene, Dimethylformamide (DMF) | ODE: High-booint solvent for hot-injection; Toluene/DMF: Dispersion and ligand exchange media [32] [21]. |

| Ligands (Acids) | Oleic Acid (OA), Octanoic Acid (OcA) | X-type ligands; Bind to undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the PQD surface [32] [22]. |

| Ligands (Amines) | Oleylamine (OAm), Octylamine (OcAm) | L-type ligands; Interact with halide ions on the PQD surface via hydrogen bonding [32] [22]. |

| Advanced Ligands | Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) | Bidentate ligand; Provides high-binding-energy passivation for full surface coverage [21]. |

Characterization and Validation

Rigorous characterization is essential to validate the efficacy of bilateral and multi-functional ligand designs.

- Photophysical Properties: A successful ligand exchange, such as with FASCN, should result in a substantial increase in Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) and a prolonged photoluminescence lifetime, as measured by Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL). These improvements indicate a reduction in non-radiative recombination pathways due to effective surface passivation [21].

- Binding Affinity Analysis: Density-functional theory (DFT) calculations are used to compute and compare the binding energies of different ligands to the PQD surface, providing a theoretical basis for the observed stability [32] [21].

- Surface Chemistry and Stability: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) can detect shifts in the binding energy of core ions (e.g., Pb 4f, I 3d), confirming the passivation of surface vacancies (e.g., Iodine vacancies) by the new ligands [21]. Furthermore, films treated with robust ligands like FASCN should demonstrate superior thermal and humidity stability, showing minimal photoluminescence quenching or spectral shifts under stress tests [21].

- Morphological and Optoelectronic Assessment: For bilateral ligands like OcA/OAm, a key validation is the elimination of the "coffee ring effect" in printed patterns, resulting in uniform films with low surface roughness [32]. Enhanced film conductivity, verified by two-terminal device measurements, confirms the benefit of short-chain ligands for charge transport [21].

Acid Etching-Driven Ligand Exchange for Ultralow Trap Densities

The performance of perovskite quantum dot-based light-emitting diodes (PQD-LEDs) is predominantly governed by the density of trap states on the PQD surface. These trap states, often originating from ligand desorption and surface ion vacancies, serve as non-radiative recombination centers that quench photoluminescence and limit device efficiency [33] [34]. Surface modification through ligand engineering has emerged as a pivotal strategy to suppress these trap states. Among various approaches, acid etching-driven ligand exchange has proven particularly effective in achieving ultralow trap densities, thereby significantly enhancing the optoelectronic properties of PQDs and the performance of resulting LEDs [14]. This protocol details a methodology for implementing acid etching-driven ligand exchange to create high-performance PQD-LEDs with exceptional color purity and operational stability, contributing to the broader thesis research on surface modification strategies for PQD optoelectronics.

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Oleate-Capped CsPbBr₃ PQDs

Principle: The hot-injection method provides high-quality, monodisperse PQDs with precise size control and excellent crystallinity, which is crucial for reproducible ligand exchange and device performance [34] [35].

Materials:

- Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99.9%)

- Lead bromide (PbBr₂, 99.99%)

- 1-Octadecene (ODE, 90%)

- Oleic acid (OA, 90%)

- Oleylamine (OAm, 80-90%)

- Zinc bromide (ZnBr₂, 99.99%)

- Toluene (anhydrous, 99.8%)

- Methyl acetate (MeOAc, anhydrous, 99.5%)

Procedure:

- Cs-oleate precursor: Load Cs₂CO₃ (0.407 g), OA (1.25 mL), and ODE (25 mL) into a 100 mL three-neck flask. Heat to 120°C under vacuum for 30 min until complete dissolution. Switch to N₂ atmosphere and heat to 135°C until use [35].

- Pb-oleate precursor: In a separate flask, mix OA and OAm in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio. Degas at 120°C for 30 min under vacuum. In another flask, dissolve PbBr₂ (1.2 mmol) and ZnBr₂ (appropriate doping concentration) in ODE (25 mL). Degas at 120°C for 30 min, then purge with N₂ [35].

- PQD synthesis: Add preheated oleate mixture (7.5 mL) to the Pb-oleate solution. Heat to 170°C. Rapidly inject Cs-oleate precursor (3 mL) and maintain for 10 seconds. Immediately cool the reaction in an ice-water bath to terminate growth [35].

- Purification: Precipitate PQDs by adding MeOAc to the crude solution. Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 30 min. Discard supernatant and redisperse precipitate in hexane. Repeat centrifugation and redispersion twice. Store purified PQDs in hexane (10 mg/mL) at 4°C for 24 h before use [35].

Acid Etching-Driven Ligand Exchange