Surface Ligand Engineering for Enhanced Charge Transport in Perovskite Quantum Dots: Strategies, Challenges, and Computational Tools

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced surface ligand design strategies to overcome the critical challenge of inefficient charge transport in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) films.

Surface Ligand Engineering for Enhanced Charge Transport in Perovskite Quantum Dots: Strategies, Challenges, and Computational Tools

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced surface ligand design strategies to overcome the critical challenge of inefficient charge transport in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) films. Tailored for researchers and scientists in materials science and nanotechnology, we explore the fundamental roles of ligands in passivation and electronic coupling, detail novel material systems like conjugated polymers, and address common synthesis and operational challenges. The scope extends to methodological applications for improving solar cell efficiency and stability, alongside a critical evaluation of computational and experimental validation techniques for benchmarking new ligand designs. This resource synthesizes foundational knowledge with cutting-edge research to guide the rational design of high-performance PQD-based optoelectronics.

The Fundamental Role of Surface Ligands in PQD Electronics and Charge Transport Physics

The Promise of Perovskite Quantum Dots

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) represent a class of semiconductor nanocrystals characterized by the general formula ABX₃, where A is a monovalent cation (e.g., Cs⁺, methylammonium MA⁺), B is a divalent metal cation (e.g., Pb²⁺, Sn²⁺), and X is a halide anion (e.g., Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) [1]. These materials have emerged as transformative platforms for optoelectronic applications due to their exceptional properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs) of 50–90%, narrow emission spectra with full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 12–40 nm, and widely tunable bandgaps across the visible spectrum [1]. Their structural versatility enables precise compositional tuning through substitutions at the A, B, or X sites, allowing tailored optical and electronic properties for specific device requirements [1].

The quantum confinement effects at nanoscale dimensions (2–10 nm) result in discrete energy levels and enhanced oscillator strengths, while their defect-tolerant nature and large absorption coefficients (10⁵ to 10⁶ cm⁻¹) facilitate efficient light harvesting and stable fluorescence signals [1]. These attributes position PQDs as ideal candidates for next-generation displays, lighting, and sensing technologies, with demonstrated potential to surpass the performance of conventional metal chalcogenide quantum dots in several key metrics [2].

Surface Ligand Design: A Critical Determinant of PQD Performance

Surface ligand engineering has emerged as a pivotal strategy for enhancing the charge transport properties and operational stability of PQD-based devices. Ligands play a dual role: they passivate surface defects to improve luminescence efficiency while simultaneously influencing charge injection and transport characteristics [3]. The dynamic binding nature of traditional alkylammonium ligands (e.g., oleylamine, oleic acid) often results in poor electrical conductivity and instability under operational conditions [4] [3].

Advanced Ligand Design Strategies

Recent innovations in ligand chemistry have focused on multifunctional molecular designs that address these limitations:

Benzylammonium Ligands: Introducing benzylammonium (BA) halides for ligand exchange creates a conjugated structure that enhances film conductivity through overlapped orbitals between the PQD surface and π-bonds of the aromatic ring [4]. This approach significantly improves charge injection and transport while reducing surface defects, achieving external quantum efficiency (EQE) increases from 2.4% (pristine) to 5.88% (BA bromide) and 5.50% (BA chloride) in perovskite nanocrystal light-emitting diodes [4].

Lattice-Matched Molecular Anchors: The design of tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) demonstrates the critical importance of spatial compatibility between ligand architecture and the perovskite crystal structure [3]. With an interatomic distance of 6.5 Å between oxygen atoms that precisely matches the PQD lattice spacing, this multi-site anchoring molecule strongly interacts with uncoordinated Pb²⁺, eliminating trap states and stabilizing the lattice [3]. Devices incorporating this strategy achieve remarkable performance metrics, including PLQYs of 97%, maximum EQE of 27%, and operational half-lives exceeding 23,000 hours [3].

Multifunctional Patterning Ligands: Triphenylphosphine (TPP) serves as a compact molecular design that simultaneously functions as a surface ligand, photoinitiator, and oxidation protector [5]. This multifunctionality enables direct optical patterning of PQDs under ambient conditions with resolutions up to 9534 dpi while maintaining high optoelectronic performance, with patterned devices achieving EQEs of 21.6% (blue), 25.6% (green), and 20.2% (red) [5].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of PQD Light-Emitting Diodes with Different Ligand Engineering Strategies

| Ligand Strategy | Device Architecture | Maximum EQE (%) | Current Efficiency (cd A⁻¹) | Operating Stability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzylammonium bromide | CsPbBr₃ NC LEDs | 5.88 | 19.5 | Not specified | [4] |

| Benzylammonium chloride | CsPbBr₃ NC LEDs | 5.50 | 16.6 | Not specified | [4] |

| Lattice-matched TMeOPPO-p | CsPbI₃ QLEDs | 27.0 | Not specified | >23,000 hours (half-life) | [3] |

| Pristine ligands (control) | CsPbBr₃ NC LEDs | 2.4 | 7.8 | Not specified | [4] |

| Triphenylphosphine (patterning) | Blue CdSe/ZnS QLEDs | 21.6 | Not specified | Not specified | [5] |

Pitfalls and Challenges in PQD Implementation

Despite their exceptional optoelectronic properties, PQDs face significant challenges that must be addressed for commercial implementation:

Stability Limitations

PQDs exhibit vulnerability to environmental factors including moisture, oxygen, and heat, leading to rapid degradation of optical properties [6]. Under operational conditions, field-induced ion migration through surface defects further accelerates device failure [3]. The inherent ionic nature of perovskite materials creates susceptibility to halogen vacancy formation and metal cation displacement, particularly in lead-based compositions [1].

Charge Transport Limitations

The presence of insulating long-chain ligands on PQD surfaces creates energy barriers that impede inter-dot charge transport [3] [7]. Achieving balanced charge injection in devices remains challenging, often resulting in efficiency roll-off at high current densities [8]. Solution-processed charge transport layers can damage the emissive PQD layer during fabrication, leading to photoluminescence quenching and reduced device efficiency [2].

Toxicity and Environmental Concerns

Lead-based PQDs raise significant environmental and safety concerns due to Pb²⁺ toxicity [1]. While lead-free alternatives (e.g., Cs₃Bi₂X₉, CsSnX₃) offer promising alternatives, they typically exhibit inferior optoelectronic performance and reduced PLQYs compared to their lead-based counterparts [1].

Experimental Protocols for PQD Synthesis and Fabrication

Ligand Exchange Protocol for Enhanced Charge Transport

Materials: CsPbBr₃ PQDs, benzylammonium bromide, benzylammonium chloride, n-hexane, ethyl acetate, toluene.

Procedure:

- Purify pristine CsPbBr₃ PQDs through standard precipitation/redispersion cycles using n-hexane and ethyl acetate [4].

- Prepare 10 mM solutions of benzylammonium ligands (bromide or chloride forms) in toluene [4].

- Add ligand solution to PQD dispersion at 1:2 volume ratio under continuous stirring.

- Maintain reaction at room temperature for 6 hours to allow complete ligand exchange.

- Precipitate exchanged PQDs by adding anti-solvent (methyl acetate) followed by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes [4].

- Redisperse purified PQDs in toluene for film deposition.

Quality Control: Monitor completion of exchange via FTIR spectroscopy (reduction of C-H stretching modes at 2700-3000 cm⁻¹) and XPS (shift in Pb 4f peaks to lower binding energies) [4].

Lattice-Matched Anchoring Molecule Treatment

Materials: CsPbI₃ PQDs, tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p), ethyl acetate.

Procedure:

- Synthesize CsPbI₃ PQDs using modified hot-injection method [3].

- Purify PQDs through standard precipitation/redispersion cycles.

- Prepare TMeOPPO-p solution in ethyl acetate at concentration of 5 mg mL⁻¹ [3].

- Incubate PQDs with TMeOPPO-p solution for 12 hours under inert atmosphere.

- Recover treated PQDs through centrifugation and redisperse in appropriate solvent for device fabrication.

Characterization: Validate multi-site anchoring through PLQY measurements (target >96%), NMR spectroscopy (appearance of ¹H and ³¹P signals from TMeOPPO-p), and TEM analysis (maintained cubic morphology with clear lattice fringes) [3].

Direct Photopatterning Protocol for PQD Arrays

Materials: CdSe/ZnS core-shell QDs, triphenylphosphine (TPP), toluene, development solvent (chloroform:hexane, 1:4 v/v).

Procedure:

- Prepare photosensitive PQD ink by adding TPP (5% by mass) to QD dispersion in toluene [5].

- Deposit QD-TPP ink onto substrate via spin-coating to form uniform film.

- Expose selected regions to UV light (365 nm, 100 mW cm⁻²) through photomask for 60-120 seconds in ambient atmosphere [5].

- Develop pattern by immersing substrate in development solvent for 30 seconds with gentle agitation.

- Rinse with pure solvent and dry under nitrogen flow.

Quality Assessment: Verify patterning resolution via optical microscopy (up to 9534 dpi achievable) and maintain PLQYs >90% for RGB QDs [5].

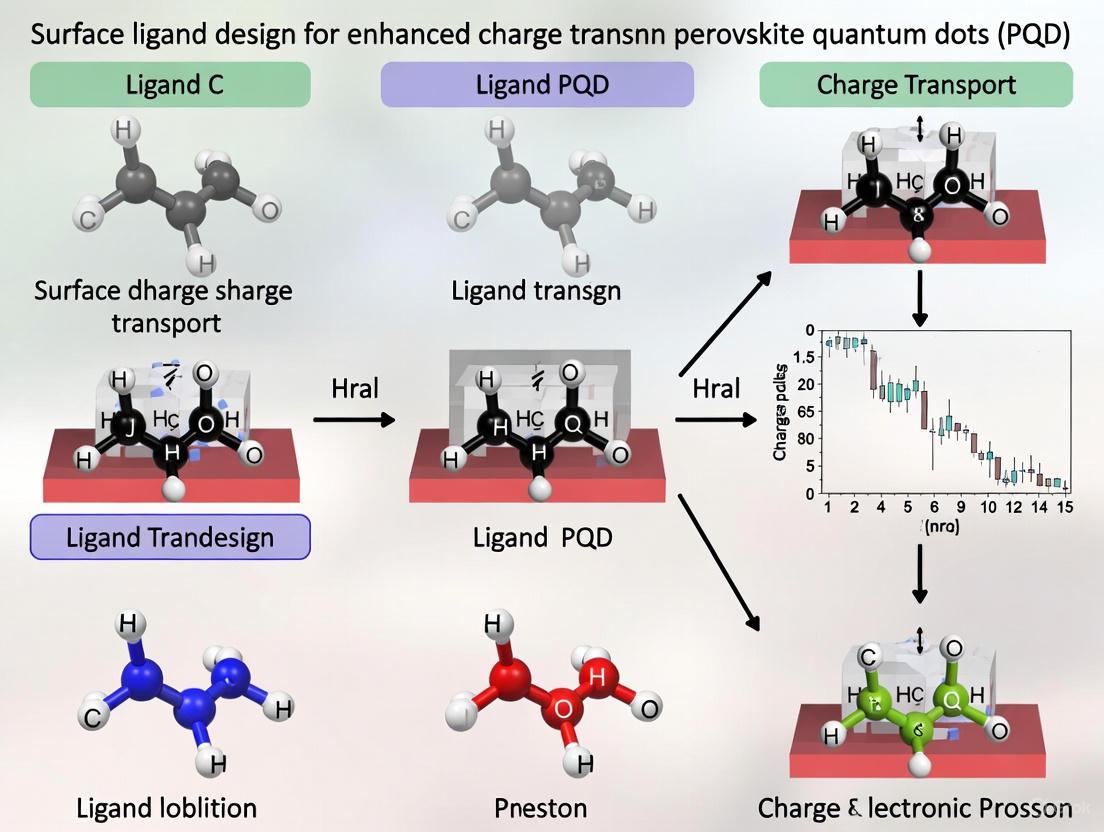

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

Ligand Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Charge Transport

PQD Device Fabrication and Patterning Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PQD Charge Transport Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzylammonium halides | Conjugated ligand for exchange | Enhanced charge transport in PQD films | EQE increase from 2.4% to 5.88% [4] |

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) | Lattice-matched anchor molecule | Multi-site defect passivation | PLQY up to 97%, EQE up to 27% [3] |

| Triphenylphosphine (TPP) | Multifunctional ligand for patterning | Ambient photopatterning of PQD arrays | Enables 9534 dpi patterning, EQE >20% [5] |

| Poly(sodium-4-styrene sulfonate) modified PEDOT:PSS | Hole-buffering layer | Charge balance engineering in QLEDs | Reduces hole over-injection, improves EQE to 22.4% [8] |

| Zinc magnesium oxide (Zn₀.₉₅Mg₀.₀₅O) | Electron transport layer | Inverted device structures | Facilitates electron injection, improves charge balance [7] |

| Pseudohalogen inorganic ligands (e.g., DDASCN) | Surface passivation | Suppression of halide migration | Enhanced PLQY and film conductivity [2] |

Surface ligand design represents a cornerstone in unlocking the full potential of perovskite quantum dots for optoelectronic applications. Through strategic molecular engineering—incorporating conjugated systems for enhanced charge transport, lattice-matched architectures for defect suppression, and multifunctional ligands for ambient stability—researchers have demonstrated remarkable progress in addressing the intrinsic limitations of PQDs. The continued refinement of these approaches, coupled with advanced patterning techniques and device integration strategies, positions PQD technology as a transformative platform for next-generation displays, lighting, and sensing applications. Future research directions will likely focus on developing lead-free compositions with comparable performance, enhancing operational stability under realistic conditions, and scaling fabrication processes for commercial implementation.

The performance of perovskite quantum dot (PQD) solar cells is intrinsically governed by their surface chemistry. While long-chain insulating ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) ensure excellent colloidal stability during synthesis, they severely impede charge carrier transport in solid films, limiting device efficiency [9] [10]. Consequently, surface ligand engineering has emerged as a pivotal research focus, transitioning from a role primarily concerned with stabilization to one that actively mediates electronic coupling and charge transport. Effective ligand strategies must fulfill a dual mandate: effectively passivating surface defects to suppress non-radiative recombination and facilitating efficient charge carrier transport between quantum dots. This Application Note delineates advanced ligand design protocols and their profound impact on the optoelectronic properties of PQD films, providing a structured framework for researchers developing high-performance PQD-based optoelectronic devices.

The following tables consolidate key experimental findings from recent literature, offering a comparative overview of how different ligand engineering strategies influence material properties and final device performance.

Table 1: Impact of Ligand Strategy on PQD Film Properties and Solar Cell Performance

| Ligand Strategy | PQD Material | Key Film Properties | PCE (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multidentate (EDTA) | CsPbI₃ | Reduced defect density, improved electronic coupling | 15.25 | [9] |

| In Situ Core-Shell | MAPbBr₃@ tetra-OAPbBr₃ | Epitaxial passivation of grain boundaries | 22.85 | [11] |

| Sequential Exchange (DPA+BA) | FAPbI₃ | Enhanced electronic coupling, suppressed non-radiative recombination | 14.27 (Rigid) | [10] |

| Solvent-Mediated (Choline/2-pentanol) | CsPbI₃ | Maximized ligand removal, superior defect passivation | 16.53 | [12] |

| Conjugated Polymer (Th-BDT) | CsPbI₃ | Defect passivation, compact crystal packing via π-π stacking | >15.00 | [13] |

Table 2: Charge Transport and Stability Metrics from Selected Studies

| Ligand System | Charge Transport Enhancement | Stability Retention | Key Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Redox Ligands (FcCOO⁻) | Enabled self-exchange charge transport via ligand states | N/R | Cyclic Voltammetry, Transient Absorption [14] |

| Conjugated Polymer (O-BDT) | Improved inter-dot coupling, higher short-circuit current | >85% after 850 hours | J-V Characterization, FTIR, XPS [13] |

| In Situ Core-Shell PQDs | Facilitated efficient charge transport at grain boundaries | >92% after 900 hours | J-V Tracking, IPCE [11] |

| Hybrid Passivation (TBAI+Pyridine) | Reduced trap sites, decreased charge trapping dynamics | N/R | FT-IR, AFM, TEM [15] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Advanced Ligand Engineering

Protocol: Multidentate Ligand Passivation with EDTA

This protocol is adapted from Chen et al. for resurfacing CsPbI₃ PQDs to simultaneously passivate defects and enhance electronic coupling [9].

- Reagents: CsPbI₃ PQDs in hexane (synthesized via hot-injection), Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid (EDTA), Anhydrous Dimethylformamide (DMF), Methyl Acetate (MeOAc), Anhydrous Hexane.

- Procedure:

- Synthesize CsPbI₃ PQDs (~12 nm) using the standard hot-injection method with OA and OAm ligands.

- Deposit a PQD solid film on your substrate using a layer-by-layer spin-coating process. After each layer deposition, rinse with MeOAc to remove the original long-chain ligands.

- Prepare the passivation solution by dissolving EDTA in DMF.

- Surface Surgery Treatment (SST): Immerse the fabricated PQD solid film into the EDTA/DMF solution for a controlled duration.

- Remove the film and rinse thoroughly with anhydrous hexane to remove any residual, unbound EDTA.

- Repeat the layer-by-layer deposition and SST process until the desired film thickness is achieved.

- Mechanism & Notes: EDTA acts as a multidentate ligand that chelates uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the PQD surface. Its functional groups also occupy I⁻ vacancies, effectively passivating these defects. Concurrently, EDTA molecules crosslink adjacent PQDs, forming "charger bridges" that facilitate inter-dot charge transport. The use of DMF is critical for dissolving the EDTA, but care must be taken to avoid excessive exposure that could dissolve the underlying perovskite film.

Protocol: Sequential Ligand Exchange for Flexible Devices

This protocol, based on Wang et al., describes a one-step fabrication of FAPbI₃ PQD films using a sequential ligand exchange, ideal for flexible substrates [10].

- Reagents: FAPbI₃ PQDs in octane, Dipropylamine (DPA), Benzoic Acid (BA), Anhydrous Methyl Acetate (MeOAc), Anhydrous Octane.

- Procedure:

- DPA Treatment: Add a calculated volume of DPA directly into the FAPbI₃ PQD colloidal solution. Mix thoroughly and let it react for a short period. DPA acts as a proton acceptor, efficiently displacing the native oleylammonium ligands.

- BA Treatment: Immediately after the DPA treatment, introduce a solution of BA in MeOAc into the mixture. The BA passivates the surface defects created by the DPA stripping and further replaces any remaining OA ligands.

- Film Fabrication: Immediately spin-coat the treated PQD solution onto the substrate in a single step. This one-step process is facilitated by the ligand exchange occurring primarily in solution.

- Post-Rinsing: Gently rinse the as-deposited film with anhydrous octane to remove any byproducts and excess ligands.

- Mechanism & Notes: The sequential treatment first uses DPA to strip insulating ligands, improving electronic conductivity. The subsequent BA treatment stabilizes the surface, passivating defects and preventing aggregation. This method avoids the time-consuming layer-by-layer process, simplifies fabrication, and produces films with excellent mechanical properties suitable for flexible electronics.

Protocol: In Situ Epitaxial Passivation with Core-Shell PQDs

This advanced protocol involves the synthesis of core-shell PQDs and their integration during perovskite film crystallization for superior grain boundary passivation [11].

- Reagents: Methylammonium Bromide (MABr), Lead Bromide (PbBr₂), Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (t-OABr), Oleylamine, Oleic Acid, Dimethylformamide (DMF), Toluene.

- Part A: Synthesis of MAPbBr₃@t-OAPbBr₃ Core-Shell PQDs

- Prepare core precursor: Dissolve MABr and PbBr₂ in DMF with oleylamine and oleic acid.

- Prepare shell precursor: Dissolve t-OABr in DMF following a similar protocol.

- Inject the core precursor into hot toluene (60°C) under stirring to form MAPbBr₃ nanoparticle cores.

- Immediately inject the shell precursor into the reaction mixture to form the tetra-OAPbBr₃ shell, indicated by a color change.

- Purify the resulting core-shell PQDs by centrifugation and redisperse in chlorobenzene.

- Part B: Integration during Perovskite Film Fabrication

- During the antisolvent-assisted crystallization step of the bulk perovskite film, add the core-shell PQD dispersion (optimal concentration: 15 mg/mL) to the antisolvent.

- Spin-coat the perovskite precursor solution as the antisolvent/PQD mixture is dripped onto the spinning film.

- Anneal the film to facilitate crystallization. The core-shell PQDs integrate epitaxially at grain boundaries and surfaces.

- Mechanism & Notes: The lattice compatibility between the core-shell PQDs and the bulk perovskite matrix enables epitaxial growth at the grain boundaries. This effectively passivates defects and suppresses non-radiative recombination, while also creating favorable pathways for charge transport.

Visualization: Ligand-Mediated Charge Transport Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts and operational workflows for different ligand strategies.

Ligand Engineering Pathways for Enhanced PQD Performance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ligand Engineering

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for PQD Surface Ligand Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Core Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid (EDTA) | Multidentate ligand for defect passivation & crosslinking. | Chelates Pb²⁺; Occupies I⁻ vacancies; Bridges PQDs for enhanced coupling [9]. |

| Choline Chloride/Iodide | Short-chain, conductive halide salt for ligand exchange. | Used with tailored solvents (e.g., 2-pentanol) to maximize insulating ligand removal [12]. |

| Dipropylamine (DPA) & Benzoic Acid (BA) | Sequential ligand exchange pair. | DPA strips ligands; BA passivates defects; Enables one-step film fabrication [10]. |

| Ferrocene Carboxylic Acid (FcCOOH) | Redox-active ligand precursor. | Anchors to QD surface; Provides electronic states for self-exchange charge transport [14]. |

| Conjugated Polymers (Th-BDT/O-BDT) | Dual-function ligands for passivation & charge transport. | Provide strong surface interaction, defect passivation, and enable oriented packing via π-π stacking [13]. |

| Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (t-OABr) | Shell precursor for core-shell PQDs. | Forms wider bandgap shell around PQD core for in situ epitaxial passivation [11]. |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) / Oleylamine | Surface passivation precursors for nanoplatelets. | Added post-synthesis to reduce halide vacancy-related electron traps [16]. |

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) represent a revolutionary class of materials for next-generation optoelectronic devices, offering exceptional properties including tunable bandgaps, high absorption coefficients, and superior charge transport capabilities [17]. Despite their theoretical promise, the practical performance of PQD-based devices consistently falls short of potential, primarily due to a critical bottleneck: the presence of insulating surface ligands. These PQDs are typically synthesized with long-chain, insulating ligands such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), which are essential for maintaining colloidal stability during synthesis and processing [18] [19]. However, when assembled into solid films for device fabrication, these same insulating ligands create significant barriers to charge transport between individual quantum dots, severely limiting device performance [20] [13].

The fundamental conflict is between stability in solution and performance in the solid state. The long alkyl chains of native ligands create a thick, insulating shell around each PQD, leading to poor electronic coupling in films. This results in inefficient charge carrier transport, which manifests in devices as reduced photocurrent, low fill factor, and limited power conversion efficiency in solar cells [19]. Furthermore, imperfect ligand coverage creates surface vacancies and defects that act as traps for charge carriers, promoting non-radiative recombination and further degrading device performance [21]. Addressing this charge transport bottleneck requires sophisticated ligand engineering strategies that balance the need for colloidal stability with the imperative of efficient inter-dot charge transport.

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Impact on Device Performance

The relationship between ligand structure and device performance has been rigorously quantified across numerous studies. The following table summarizes key performance metrics achieved through different ligand engineering strategies, highlighting the significant improvements possible through optimized surface chemistry.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of PQD Solar Cells with Different Ligand Strategies

| Ligand Strategy | PQD Material | Power Conversion Efficiency (%) | Key Improvements | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional OA/OAm Ligands | CsPbI₃ | ~12.7 (Baseline) | Baseline performance with poor charge transport | [13] |

| Conjugated Polymer Ligands | CsPbI₃ | >15.0 | Enhanced inter-dot coupling and charge transport | [13] |

| Consecutive Surface Matrix Engineering | FAPbI₃ | 19.14 | Record efficiency via diminished surface vacancies | [19] |

| Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis | FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ | 18.37 (certified) | Fewer trap-states, homogeneous orientations | [22] |

| Dual-Ligand Synergistic Passivation | CsPbBr₃ | - | Near-unity PLQY (98.56%), suppressed non-radiative decay | [21] |

Beyond final device efficiency, ligand engineering profoundly affects fundamental material properties. The replacement of insulating ligands with conductive alternatives can increase photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) to near-unity values (98.56% reported) through suppressed non-radiative decay [21]. Ligand exchange strategies have also demonstrated the ability to reduce trap-state densities by orders of magnitude, significantly lowering non-radiative recombination losses [22]. Furthermore, proper ligand engineering enhances environmental stability, with some passivated PQDs retaining over 90% of initial device efficiency after extended testing periods [18] and conjugated polymer-based devices maintaining over 85% of initial efficiency after 850 hours [13].

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Exchange and Characterization

Protocol: Dual-Ligand Synergistic Passivation Engineering

This protocol simultaneously addresses bulk and surface defects in CsPbBr₃ PQDs, achieving near-unity PLQY and enhanced solvent compatibility [21].

Materials and Reagents:

- Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99%)

- Lead bromide (PbBr₂, 99%)

- Europium acetylacetonate (Eu(acac)₃)

- Benzamide

- Tetraoctylammonium bromide (TOAB)

- Octanoic acid (OTAc)

- 1-Octadecene (ODE)

Procedure:

- Prepare Cs Precursor: Load Cs₂CO₃ (0.3258 g, 1 mmol) and OTAc (10 mL) into a 20 mL vial. Stir at room temperature for 10 minutes until fully dissolved.

- Synthesize Doped PbBr₂ Precursor: Dissolve PbBr₂ (1 mmol), TOAB (2 mmol), and varying amounts of Eu(acac)₃ (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 mmol) in ODE (10 mL) in a separate flask.

- Quantum Dot Synthesis: Heat the PbBr₂ precursor to 120°C under nitrogen until clear. Rapidly inject the Cs precursor (0.5 mL) into the reaction mixture and quench after 30 seconds using an ice bath.

- Ligand Exchange: Purify the crude solution via centrifugation and redisperse in hexane. Add benzamide (molar ratio 1:2 to Pb) and stir for 2 hours at 60°C to complete surface passivation.

- Purification: Precipitate PQDs with ethyl acetate, centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes, and redisperse in anhydrous hexane for further use.

Characterization Methods:

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield: Use integrating sphere with 365 nm excitation source.

- Fluorescence Lifetime: Employ time-correlated single photon counting with pulsed laser excitation.

- Structural Analysis: Conduct high-resolution XRD to confirm phase purity and structural modulation.

- Surface Chemistry: Analyze via FTIR and XPS to verify ligand binding and surface composition.

Protocol: Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis for Conductive Capping

This protocol enhances the conductive capping on PQD surfaces by facilitating ester hydrolysis, enabling up to twice the conventional amount of hydrolyzed conductive ligands [22].

Materials and Reagents:

- Methyl benzoate (MeBz)

- Potassium hydroxide (KOH)

- FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQDs (synthesized via standard methods)

- 2-pentanol (2-PeOH)

Procedure:

- Prepare Alkaline Antisolvent: Dissolve KOH (0.1 M) in methyl benzoate under anhydrous conditions with continuous stirring until fully dissolved.

- Layer-by-Layer Film Deposition: Spin-coat PQD colloidal solution onto substrate to form initial layer.

- Interlayer Rinsing: Immediately after deposition, rinse the PQD film with the alkaline methyl benzoate solution for 10 seconds, followed by spin drying at 2000 rpm for 30 seconds.

- Repeat Deposition Cycle: Repeat steps 2-3 for 8-10 layers to achieve desired film thickness (~300 nm).

- Post-treatment: Treat the final film with FA⁺ cationic salts dissolved in 2-pentanol to complete A-site ligand exchange.

Characterization Methods:

- Charge Transport Analysis: Measure space-charge-limited current (SCLC) to determine trap-state density.

- Film Morphology: Analyze via SEM and TEM for particle packing and aggregation assessment.

- Surface Ligand Density: Quantify using TGA and NMR spectroscopy to confirm ligand exchange efficiency.

- Device Performance: Fabricate solar cells with structure ITO/SnO₂/PQD Film/Spiro-OMeTAD/MoO₃/Au for complete photovoltaic characterization.

Advanced Ligand Design Strategies for Enhanced Charge Transport

Conjugated Polymer Ligands

Conjugated polymers represent a groundbreaking approach to overcoming the insulation-charge transport trade-off. These polymers feature π-conjugated backbones that facilitate charge transport while incorporating functional groups that strongly bind to PQD surfaces. Studies have demonstrated that conjugated polymers like Poly(BT(EG)-BDT(Th)) (Th-BDT) and Poly(BT(EG)-BDT(O)) (O-BDT) can simultaneously passivate surface defects and enhance inter-dot coupling [13]. The ethylene glycol (-EG) side chains provide strong binding to Pb²⁺ sites on the PQD surface, while the conjugated backbones enable efficient hole transport between dots. Devices incorporating these polymers achieved efficiencies exceeding 15%, compared to 12.7% for pristine devices, with remarkably improved stability retaining over 85% of initial efficiency after 850 hours [13].

Short-Chain Conductive Ligands

Replacing long-chain insulating ligands with shorter conductive alternatives represents a more direct approach. Strategies using ammonium iodide (NH₄I) [20], didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) [18], and various short-chain organic salts have shown significant improvements in charge transport. The key advantage lies in reducing the inter-dot distance, which follows an exponential relationship with electron tunneling probability. These short ligands typically feature binding groups (ammonium, carboxylate, phosphonate) that coordinate with surface atoms while maintaining electronic coupling between adjacent PQDs.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for PQD Ligand Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Mechanism | Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Salt Additives | Eu(acac)₃, MnCl₂ | Compensates for Pb²⁺ vacancies; stabilizes crystal framework | Reduces bulk defects; enhances PLQY [21] |

| Organic Passivators | Benzamide, DDAB, L-PHE | Passivates surface defects via coordination with undercoordinated ions | Suppresses non-radiative recombination; improves stability [18] [21] [23] |

| Conjugated Polymers | Th-BDT, O-BDT | Provides both passivation and charge transport pathways | Enhances inter-dot coupling; improves Jsc and FF [13] |

| Inorganic Coatings | SiO₂ from TEOS | Forms protective barrier; enhances environmental stability | Improves thermal and moisture resistance [18] |

| Alkaline Esters | KOH in MeBz | Facilitates ester hydrolysis for efficient ligand exchange | Increases conductive ligand density; reduces traps [22] |

Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Passivation

Combining organic and inorganic passivation approaches creates synergistic effects that address multiple degradation pathways simultaneously. For instance, lead-free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs stabilized with both DDAB (organic) and SiO₂ coating (inorganic) demonstrate significantly enhanced environmental stability while maintaining favorable charge transport properties [18]. The organic component provides specific defect passivation, while the inorganic coating creates a physical barrier against environmental stressors. This approach is particularly valuable for applications requiring long-term operational stability under real-world conditions.

Visualization of Ligand Exchange Processes and Charge Transport

The following diagrams illustrate key processes in ligand engineering and their impact on charge transport in PQD films.

Diagram 1: Ligand Exchange Process Overcoming Charge Transport Bottleneck

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Ligand Engineering and Characterization

The charge transport bottleneck imposed by insulating ligands represents a fundamental challenge in PQD technology, but also a tremendous opportunity for performance enhancement through sophisticated surface chemistry. The ligand engineering strategies outlined in this application note—from dual-ligand synergistic passivation to conjugated polymer approaches—demonstrate that rational ligand design can dramatically improve both device performance and operational stability. The experimental protocols provide researchers with reproducible methods for implementing these advanced strategies in their own laboratories.

Future developments in PQD ligand engineering will likely focus on multi-functional ligands that simultaneously address charge transport, environmental stability, and phase stability under operational conditions. The integration of machine learning approaches to predict optimal ligand structures for specific applications represents another promising direction. As these strategies mature, the performance gap between laboratory-scale devices and commercial applications will narrow, ultimately enabling the full potential of perovskite quantum dots in next-generation optoelectronics.

Surface ligand engineering is a cornerstone in the development of high-performance perovskite quantum dot (PQD) optoelectronic devices. Ligands dictate key electronic processes by modulating charge transport, influencing energy level alignment, and determining morphological stability within PQD solid films. The strategic design of ligand properties—specifically their binding motifs, molecular length, and consequent energy level alignment—enables researchers to transcend fundamental limitations posed by intrinsic surface defects and inefficient inter-dot coupling. This Application Note details the core ligand characteristics and provides validated experimental protocols for designing enhanced charge transport pathways in PQD-based devices, framing these advancements within the broader research objective of achieving superior photovoltaic performance and operational stability.

Core Ligand Properties and Their Quantitative Impact

The performance of a PQD solid is governed by the synergistic interplay of several key ligand properties. The table below summarizes these properties, their impact on system characteristics, and quantitative performance outcomes.

Table 1: Key Ligand Properties and Their Impact on PQD Film Characteristics and Device Performance

| Ligand Property | Impact on PQD System | Representative Ligands | Reported Device Performance (PCE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Motif & Affinity | Determines surface defect passivation efficacy and colloidal stability. | DDAB (Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide): Passivates halide vacancies [24]. Conjugated Polymers (Th-BDT/O-BDT): Strong interaction via -CN and -EG groups with Pb sites [13]. | ~18.3% (Certified, DDAB-augmented) [25] |

| Molecular Length & Conductivity | Governs inter-dot charge transport efficiency and film packing density. | Short Conductive Ligands (e.g., hydrolyzed from Methyl Benzoate): Enhance inter-dot coupling [25]. Conjugated Polymers: Provide delocalized π-systems for charge transport [13]. | >15% (Conjugated Polymer ligands) [13] |

| Energy Level Alignment | Influences charge injection/extraction efficiency and open-circuit voltage (VOC). | Conjugated Polymers (Th-BDT/O-BDT): Raise HOMO level of perovskites, improving band alignment [13]. | 16.53% (Inorganic CsPbI3 PQDSC with tailored solvent) [12] |

Binding Motifs and Molecular Affinity

The chemical motif with which a ligand binds to the PQD surface is paramount for effective passivation and stability. Strong, robust binding minimizes ligand detachment and provides durable surface coverage.

- Ionic Salts (e.g., DDAB): Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) provides halide ions (Br⁻) to passivate halide vacancies on the PQD surface, significantly suppressing non-radiative recombination centers. This leads to enhanced photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and prolonged exciton lifetimes [24].

- Multidentate Conjugated Polymers: Conjugated polymers functionalized with specific binding groups, such as -cyano (-CN) and ethylene glycol (-EG), exhibit strong multidentate interactions with under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the PQD surface. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy confirms these interactions through characteristic peak shifts, for instance, the ν(─CN) peak shifting from ~2219 cm⁻¹ to ~2224 cm⁻¹ upon binding with PbI₂ [13].

- Short Anionic Ligands from Ester Hydrolysis: An alkaline-augmented antisolvent hydrolysis (AAAH) strategy can be employed to generate short, conductive anionic ligands (e.g., from methyl benzoate) in situ. These ligands rapidly substitute the pristine, long-chain insulating oleate (OA⁻) ligands, providing a denser and more conductive capping layer [25].

Molecular Length and Electronic Structure

The length and electronic nature of the ligand directly control the electronic coupling between adjacent PQDs.

- Insulating vs. Conductive Ligands: Conventional long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) act as insulating barriers, severely hindering charge transport. Replacing them with shorter ligands or conjugated molecules reduces the inter-dot separation and creates efficient pathways for charge carrier hopping or tunneling [25] [13].

- Conjugated Polymer Ligands: Unlike small-molecule ligands, conjugated polymers such as Th-BDT and O-BDT possess delocalized π-electron systems. These systems facilitate charge transport along the polymer backbone and between adjacent PQDs, while also driving compact crystal packing through π-π stacking interactions. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations reveal that these polymers have delocalized HOMO orbitals along their planar backbones, which is conducive to high hole mobility [13].

Energy Level Alignment at Interfaces

The frontier molecular orbitals of the ligands must align favorably with the band edges of the PQD to enable efficient charge transfer and minimize energy losses.

- HOMO Level Modulation: The introduction of conjugated polymers with electron-donating functional groups (e.g., -EG) can raise the HOMO level of the perovskite composite, leading to a more favorable energy level alignment with hole transport layers. This optimization improves hole extraction and reduces open-circuit voltage (VOC) deficits in solar cells [13].

- Theoretical Guidance: Computational methods, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT) and the DFT + Σ approach, are invaluable for predicting the energy level alignment and conductance of molecular junctions. These tools help in screening and designing ligand structures in silico before synthetic efforts [26].

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Engineering and Analysis

Protocol 1: Alkaline-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH) for Conductive Capping

This protocol describes a method to replace pristine long-chain ligands with short, conductive ones during film processing [25].

- PQD Solid Film Deposition: Spin-coat the synthesized CsPbI₃ or hybrid FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQD colloidal solution onto a substrate to form an "as-cast" solid film.

- Preparation of Alkaline Antisolvent: Add a carefully regulated amount of Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) to methyl benzoate (MeBz) antisolvent. The alkaline environment facilitates the thermodynamic spontaneity and kinetics of ester hydrolysis.

- Interlayer Rinsing: Immediately after spin-coating each PQD layer, rinse the film with the KOH/MeBz antisolvent. This step hydrolyzes the ester in situ, generating short anionic ligands that replace the pristine insulating oleate (OA⁻) ligands.

- Solvent Evaporation: Allow the antisolvent to evaporate rapidly, leaving behind a PQD solid film with a conductive surface capping.

- Repetition: Repeat the layer-by-layer deposition and rinsing process until the desired film thickness is achieved.

The workflow for this ligand exchange process is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Post-Treatment with Conjugated Polymer Ligands

This protocol details the application of conjugated polymers as multi-functional ligands for surface passivation and enhanced charge transport [13].

- Synthesis of Conjugated Polymers: Synthesize conjugated polymers (e.g., Th-BDT and O-BDT) via Stille or Suzuki coupling polymerization. Purify the polymers thoroughly.

- Ligand Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution (e.g., 5 mg mL⁻¹) of the conjugated polymer in a suitable solvent (e.g., chlorobenzene).

- PQD Film Deposition: Deposit a layer of PQD solid film via layer-by-layer spin-coating, using a standard ester antisolvent (e.g., methyl acetate) for initial rinsing to remove long-chain ligands.

- Post-Treatment: Spin-coat the conjugated polymer solution directly onto the pre-deposited PQD solid film.

- Annealing: Anneal the film on a hotplate at 70-100 °C for 10 minutes to facilitate strong binding and solvent removal.

- Characterization: Analyze the film via FTIR and XPS to confirm ligand binding. FTIR should show shifts in characteristic peaks (e.g., ν(─CN), ν(C─O─C)) indicating interaction with Pb²⁺ ions.

Analytical Methods for Validation

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Confirm ligand binding to the PQD surface by identifying shifts in characteristic vibrational peaks (e.g., -CN, C-O-C) compared to the pure ligand and pure PbI₂ [13].

- X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Detect chemical state changes and binding energies. A shift in the Pb 4f core level peaks (e.g., from 142.80 eV to 142.70 eV for Pb 4f₇/₂) confirms strong interaction between the ligand and the PQD surface [13].

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL): Quantify the impact of passivation on charge dynamics. DDAB passivation, for example, has been shown to prolong exciton lifetimes (e.g., from 15.48 ns to 48.32 ns), indicating suppressed non-radiative recombination [24].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations: Use DFT and DFT+Σ methods to model the electronic structure of ligand-PQD systems, predict energy level alignment, and calculate junction conductance for different binding motifs [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for PQD Ligand Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Ionic surfactant for defect passivation; supplies Br⁻ to fill halide vacancies. | Suppression of non-radiative recombination in CsPb(Br₀.₈I₀.₂)₃ QDs [24]. |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Ester antisolvent; hydrolyzes to form short-chain benzoate ligands. | Used in AAAH strategy for interlayer rinsing to create conductive capping [25]. |

| Conjugated Polymers (e.g., Th-BDT) | Multifunctional ligands; provide passivation and enhance inter-dot charge transport via π-conjugation. | Post-treatment of CsPbI₃ PQD films to improve efficiency and stability [13]. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Alkaline additive; catalyzes ester hydrolysis in antisolvents. | Augments MeBz antisolvent to enhance the kinetics and completeness of ligand exchange [25]. |

| 2-Pentanol (2-PeOH) | Protic solvent for cationic ligand salts; mediates A-site ligand exchange. | Solvent for formamidinium iodide (FAI) during post-treatment of PQD solids [25]. |

The targeted design of surface ligands—by mastering their binding motifs, molecular length, and influence on energy level alignment—provides a powerful pathway to overcome the intrinsic limitations of perovskite quantum dots. The experimental protocols and analytical methods detailed in this Application Note offer a reproducible framework for constructing high-performance, stable PQD solids. By integrating these ligand engineering strategies, researchers can systematically enhance charge transport, paving the way for the next generation of efficient and durable PQD optoelectronic devices.

The precise interaction between a ligand and its target represents a fundamental principle in biological systems, governing processes from enzyme catalysis to signal transduction. In drug discovery, understanding these interactions is crucial for developing therapeutics with high specificity and efficacy [27]. Remarkably, these biological principles find direct parallels in the field of materials science, particularly in the design of surface ligands for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). In both domains, the molecular-level control of binding interactions dictates functional outcomes—whether modulating biological pathways or optimizing charge transport in optoelectronic materials [23] [22]. This application note explores these interdisciplinary connections, providing detailed methodologies and data frameworks that leverage biological ligand-target insights to advance PQD surface engineering.

Biological Foundations of Ligand-Target Interactions

Key Principles of Molecular Recognition

In biological systems, ligand-target binding depends on complementary molecular features that govern specificity and affinity. Protein-ligand interactions occur when small molecules bind specifically to protein residues within binding sites, facilitated by shape complementarity, electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic effects [27]. The LABind method exemplifies how computational tools can predict these binding sites by integrating protein structural data with ligand chemical information, using graph transformers and cross-attention mechanisms to capture distinct binding characteristics [27].

Biological specificity often arises from precise spatial arrangements of functional groups and the molecular context in which binding occurs. These principles directly inform the rational design of surface ligands for PQDs, where ligand structure and binding mode determine interfacial properties and charge transfer efficiency [23].

Analytical Techniques for Studying Binding Interactions

Experimental characterization of ligand-target interactions employs multiple biophysical techniques:

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Measures binding affinity and kinetics in real-time without labeling [28]

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): Quantifies binding thermodynamics through heat changes [29]

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Models structural stability and binding interactions computationally [29]

These methods provide complementary data on different aspects of molecular recognition, from kinetic parameters to energetic profiles, enabling comprehensive understanding of binding mechanisms.

Parallels in Perovskite Quantum Dot Surface Engineering

Ligand Design Principles from Biological Systems

The surface ligand engineering of PQDs mirrors biological ligand-target principles, where molecular specificity dictates functional outcomes. Biological systems achieve precise molecular recognition through complementary structural features, similar to how PQD surface ligands must specifically bind to crystal surfaces while mediating interfacial interactions [23] [22].

In both contexts, the molecular structure of the ligand determines binding affinity and specificity. Short conductive ligands like those derived from methyl benzoate hydrolysis exhibit stronger binding to PQD surfaces and facilitate better charge transfer, analogous to how optimal drug molecules maximize target binding while minimizing off-target interactions [22].

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Effects on PQD Properties

Table 1: Impact of Ligand Modifications on CsPbI3 PQD Optical Properties and Performance

| Ligand Treatment | Photoluminescence Enhancement | Initial PL Retention (%) | Certified PCE (%) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| l-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | 3% | >70% (after 20 days UV) | - | Superior photostability |

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | 16% | - | - | Effective defect suppression |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | 18% | - | - | Optimal passivation effect |

| Methyl Benzoate + KOH (AAAH) | - | - | 18.3% | Highest PQDSC efficiency |

Table 2: Comparison of Ester Antisolvents for PQD Surface Treatment

| Antisolvent | Relative Polarity | PQD Structural Integrity | Ligand Exchange Efficiency | Practical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl Methanesulfonate | High | Complete degradation | - | Not suitable |

| Methyl Formate | High | Degradation observed | - | Not suitable |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Moderate | Preserved | Limited | Standard reference |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Moderate | Preserved | High (with AAAH) | Optimal performance |

| Ethyl Cinnamate (EtCa) | Lower | Porous morphology | Limited | Suboptimal packing |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH) for PQDs

Principle: This protocol enhances conductive capping on PQD surfaces by creating alkaline conditions that facilitate rapid ester hydrolysis and ligand exchange, analogous to enzymatic processes in biological systems [22].

Materials:

- CsPbI3 PQD colloids (synthesized as in Supplementary Fig. 1 [22])

- Methyl benzoate (MeBz, 99% purity)

- Potassium hydroxide (KOH, reagent grade)

- 1-octadecene (ODE, 90%)

- Lead(II) iodide (PbI₂, 99%)

- Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99%)

Procedure:

- PQD Film Preparation: Spin-coat hybrid FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQD colloids onto substrates at 2000 rpm for 30 seconds to form solid films.

- Alkaline Antisolvent Preparation: Dissolve KOH in methyl benzoate at optimized concentrations (typically 0.5-2 mM) under inert atmosphere.

- Interlayer Rinsing: Immediately after spin-coating, rinse the PQD film with the KOH/MeBz solution using a pulsed spraying method (0.5 mL over 10 seconds).

- Ligand Exchange: Allow the alkaline antisolvent to reside on the film surface for 15-20 seconds, enabling hydrolysis and ligand substitution.

- Spin-off Excess: Spin at 3000 rpm for 20 seconds to remove excess solvent and byproducts.

- Layer Stacking: Repeat steps 1-5 for subsequent layers until desired film thickness is achieved (typically 5-8 layers).

- Post-treatment: For A-site ligand exchange, treat final film with 2-pentanol solution containing FA⁺ or MA⁺ cationic ligands [22].

Validation:

- FTIR spectroscopy to confirm ligand exchange

- TEM analysis of PQD morphology and packing

- Photoluminescence quantum yield measurements

- X-ray diffraction to verify crystal structure preservation

Protocol 2: LABind-Based Computational Prediction of Binding Sites

Principle: This computational protocol predicts protein-ligand binding sites using graph neural networks and cross-attention mechanisms, offering insights applicable to designing PQD surface ligands with specific binding characteristics [27].

Materials:

- Protein structures (PDB format)

- Ligand SMILES strings

- LABind software (available from original publication)

- Molecular pre-trained language model (MolFormer)

- Protein pre-trained language model (Ankh)

- DSSP for protein structural features

Procedure:

- Input Preparation:

- For proteins: Extract sequence and 3D structural features

- Generate protein graphs with node features (angles, distances, directions) and edge features (residue-residue interactions)

- For ligands: Input SMILES sequence into MolFormer to obtain molecular representations

Feature Integration:

- Concatenate protein sequence embeddings from Ankh with DSSP structural features

- Add protein-DSSP embeddings to node spatial features of the protein graph

- Process ligand and protein representations through cross-attention mechanisms

Binding Site Prediction:

- Use graph transformer to capture binding patterns in local spatial contexts

- Employ multi-layer perceptron classifier to predict binding residues

- Generate binding probability scores for each residue

Validation:

- Compare predictions with experimental binding site data

- Calculate recall, precision, F1 score, MCC, AUC, and AUPR metrics

- Perform ablation studies to confirm feature importance

Applications for PQD Research:

- Predict binding affinity of potential surface ligands to perovskite crystals

- Optimize ligand structure for enhanced binding and charge transport

- Design ligand libraries with tailored properties for specific PQD compositions

Visualization of Core Concepts

Ligand-Target Binding Workflow

AAAH Experimental Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Ligand-Targeted Binding Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ester Antisolvents | PQD ligand exchange via hydrolysis | Methyl benzoate, Methyl acetate | Generate short conductive ligands through hydrolysis [22] |

| Alkaline Additives | Enhance hydrolysis kinetics | KOH, NaOH | Lower activation energy for ester hydrolysis (9-fold reduction) [22] |

| Ligand Libraries | Structure-function relationship studies | TOP, TOPO, L-PHE | Passivate surface defects and modulate charge transport [23] |

| Computational Tools | Binding site prediction and analysis | LABind, MolFormer, Ankh | Predict ligand-target interactions and binding sites [27] |

| Characterization Methods | Binding affinity and kinetics | SPR, ITC, Molecular Dynamics | Quantify binding parameters and thermodynamic profiles [28] [29] |

The interdisciplinary transfer of knowledge from biological ligand-target systems to PQD surface engineering offers powerful strategies for advancing materials design. The application of biological principles—such as molecular recognition, binding specificity, and rational ligand design—has demonstrably improved PQD performance through enhanced surface chemistry control. The experimental protocols and analytical frameworks presented here provide researchers with practical tools to further explore these connections. Future research directions include developing more sophisticated computational models that integrate biological binding prediction with materials properties, designing multi-functional ligands that simultaneously address stability and charge transport challenges, and creating high-throughput screening methods for optimal ligand discovery. By continuing to leverage the rich knowledge from biological systems, researchers can accelerate the development of next-generation PQD materials with tailored optoelectronic properties.

Innovative Ligand Design and Synthesis for Superior Inter-Dot Coupling

The performance of perovskite quantum dot (PQD) solar cells is often compromised by inherent material challenges, including surface defects, inefficient charge transport, and instability under ambient conditions. These issues primarily originate from random nanocrystal packing and the presence of long-chain insulating ligands that hinder inter-dot electronic coupling [30] [13]. Conventional ligand exchange processes frequently leave surface vacancies that become susceptible to moisture infiltration and phase transitions, ultimately degrading device performance and operational lifetime [13].

A transformative approach has emerged using conjugated polymer ligands that simultaneously address both passivation and conductivity requirements. Unlike conventional insulating ligands, these specialized polymers interact strongly with PQD surfaces while facilitating preferred packing orientations through π-π stacking interactions—a previously unexplored mechanism in PQD assemblies [30]. Functionalized with ethylene glycol side chains, these polymers effectively reduce defect density, improve crystallinity, and enhance inter-dot coupling, creating superior charge transport pathways while providing robust surface protection [30] [13]. This dual-function strategy represents a significant advancement in surface ligand design, enabling high-performance and stable PQD solar cells suitable for real-world optoelectronic applications.

Key Mechanisms and Principles

Molecular Design Rationale

The conjugated polymer ligands Th-BDT and O-BDT are synthesized from benzothiadiazole (BT) and benzodithiophene (BDT) core components, featuring electron-rich cyano (-CN) and ethylene glycol (-EG) functional groups that facilitate strong interactions with PQD surfaces [13]. The BDT core provides high planarity and symmetry advantageous for achieving high carrier mobility, while the attached side chains significantly influence the polymer's crystallinity and charge transport characteristics [13].

Th-BDT contains vertically attached thienyl side chains, while O-BDT features alkoxy side chains. The thienyl group promotes π-π stacking formation and reduces inter-polymer spacing due to its compact size, thereby enhancing hole transport capability [13]. Density functional theory calculations reveal that both polymers exhibit highest occupied molecular orbitals delocalized along the molecular backbone, suggesting strong π conjugation effects and planar backbones ideal for charge transport [13].

Dual-Function Mechanisms

The conjugated polymer ligands operate through two synchronized mechanisms that address the fundamental limitations of PQD systems:

Defect Passivation: The -CN and -EG functional groups form strong coordinative bonds with undercoordinated lead atoms on the PQD surface. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy confirms these interactions through characteristic peak shifts, with the ν(-CN) peak shifting from ≈2219 cm⁻¹ to ≈2224 cm⁻¹ upon interaction with PbI₂ [13]. Similarly, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy shows shifts in Pb 4f and Cs 3d core level spectra, further confirming strong surface interactions [13].

Enhanced Charge Transport: The conjugated backbones of the polymers create continuous pathways for charge carrier movement between quantum dots. Additionally, the polymers facilitate preferred PQD packing orientation through π-π stacking interactions, improving inter-dot electronic coupling and reducing charge recombination losses [30] [13]. This dual mechanism simultaneously improves both the intrinsic properties of the PQD surfaces and their collective behavior in solid films.

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Conjugated Polymer Ligands

Materials

- Benzothiadiazole (BT) and benzodithiophene (BDT) monomer units

- Ethylene glycol side chain precursors

- Standard Suzuki or Stille polycondensation reagents and catalysts

- Anhydrous solvents (tetrahydrofuran, toluene)

Procedure

- Functionalization of Monomers: Attach ethylene glycol side chains to the BDT monomer unit through etherification reactions under inert atmosphere.

- Polymer Synthesis: Conduct polymerization via Stille or Suzuki polycondensation between functionalized BDT and BT monomers at 80-100°C for 48-72 hours.

- Purification: Precipitate the polymer in methanol, followed by sequential Soxhlet extraction with methanol, hexane, and chloroform to remove oligomers and catalyst residues.

- Characterization: Verify molecular weight via gel permeation chromatography and confirm structure using ¹H NMR spectroscopy.

PQD Synthesis and Ligand Exchange

Materials

- Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃), lead iodide (PbI₂)

- Oleic acid (OA), oleylamine (OAm)

- 1-octadecene (ODE)

- Methyl acetate (MeOAc), conjugated polymer solution (2 mg/mL in chloroform)

CsPbI₃ PQD Synthesis

- Cesium Oleate Preparation: Load Cs₂CO₃ (0.814 g), OA (2.5 mL), and ODE (40 mL) into a 100 mL 3-neck flask. Heat at 120°C under vacuum for 1 hour, then under N₂ at 150°C until complete dissolution.

- Perovskite Precursor: Mix PbI₂ (0.691 g), ODE (10 mL), OA (1 mL), and OAm (1 mL) in a 50 mL 3-neck flask. Heat at 120°C under vacuum for 1 hour, then under N₂ at 180°C until clear.

- Quantum Dot Formation: Quickly inject cesium oleate solution (1.5 mL) into the lead precursor at 180°C. React for 5-10 seconds then cool in ice-water bath.

- Purification: Centrifuge the crude solution at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes. Discard supernatant and redisperse precipitate in hexane. Repeat centrifugation and redispersion twice.

Conjugated Polymer Ligand Exchange

- Layer-by-Layer Deposition: Spin-coat PQD colloidal solution onto substrate at 2000 rpm for 20 seconds to form uniform film.

- Polymer Treatment: Apply conjugated polymer solution (2 mg/mL in chloroform) via spin-coating at 3000 rpm for 30 seconds.

- Solvent Removal: Anneal film at 70°C for 5 minutes to remove residual solvents.

- Repetition: Repeat steps 1-3 until desired film thickness (≈300 nm) is achieved.

Device Fabrication for Solar Cells

Materials

- Indium tin oxide (ITO) coated glass substrates

- Electron transport layer materials (TiO₂, SnO₂)

- Hole transport layer materials (Spiro-OMeTAD, PTAA)

- Metal electrodes (Au, Ag)

Fabrication Procedure

- Substrate Preparation: Clean ITO substrates sequentially with detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropanol via sonication for 15 minutes each. Treat with UV-ozone for 20 minutes.

- Electron Transport Layer: Deposit compact TiO₂ layer via spray pyrolysis or spin-coating followed by annealing at 450°C for 30 minutes.

- PQD Active Layer: Deposit conjugated polymer-treated PQD films using the layer-by-layer method described in section 3.2.3.

- Hole Transport Layer: Spin-coat Spiro-OMeTAD solution (70 mM in chlorobenzene with tert-butylpyridine and lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide additives) at 4000 rpm for 30 seconds.

- Electrode Deposition: Thermally evaporate gold electrodes (80 nm thickness) under high vacuum (<10⁻⁶ Torr).

Characterization Techniques

Structural and Chemical Analysis

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy: Analyze ligand-PQD interactions through characteristic peak shifts.

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy: Examine surface composition and binding energies.

- X-ray Diffraction: Assess crystal structure and phase purity.

Optoelectronic Characterization

- UV-Vis Absorption Spectroscopy: Measure optical absorption properties.

- Photoluminescence Spectroscopy: Quantify emission properties and trap states.

- Current-Voltage Measurements: Characterize device performance under simulated AM 1.5G illumination.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Performance Metrics of PQD Solar Cells

Table 1: Photovoltaic parameters of conjugated polymer-modified PQD solar cells compared to control devices

| Device Type | PCE (%) | VOC (V) | JSC (mA/cm²) | FF (%) | Stability (% initial PCE retained) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine PQD | 12.70 | 1.10 | 16.50 | 70.10 | <50% (after 850 h) |

| Th-BDT Modified | 15.20 | 1.18 | 18.90 | 76.50 | 86% (after 850 h) |

| O-BDT Modified | 15.10 | 1.17 | 18.70 | 76.10 | 85% (after 850 h) |

Table 2: Structural and electronic properties of conjugated polymer ligands

| Polymer | LUMO (eV) | HOMO (eV) | Band Gap (eV) | Side Chain Type | π-π Stacking Ability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th-BDT | -3.49 | -5.01 | 1.52 | Thienyl | High |

| O-BDT | -3.53 | -5.05 | 1.52 | Alkoxy | Moderate |

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials for conjugated polymer ligand experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role |

|---|---|---|

| Conjugated Polymers | Th-BDT, O-BDT | Dual-function ligands for passivation and charge transport |

| PQD Precursors | Cs₂CO₃, PbI₂, FA⁺ salts | Source of perovskite components |

| Solvents | 1-octadecene, chloroform, methyl acetate | Reaction medium, purification, ligand exchange |

| Conventional Ligands | Oleic acid, oleylamine | Initial capping during PQD synthesis |

| Characterization Reagents | FTIR samples, XPS standards | Material analysis and verification |

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Molecular Interaction Mechanism

Diagram Title: Dual-Function Mechanism of Conjugated Polymer Ligands

Experimental Workflow for PQD Solar Cell Fabrication

Diagram Title: PQD Solar Cell Fabrication with Conjugated Polymer Ligands

The implementation of conjugated polymer ligands represents a paradigm shift in surface ligand design for perovskite quantum dots, effectively addressing the traditional trade-off between passivation quality and charge transport efficiency. Through strategic molecular engineering incorporating ethylene glycol side chains and conjugated backbones, these polymers enable compact crystal packing while providing robust defect passivation [30] [13]. The resulting PQD solar cells demonstrate significantly enhanced power conversion efficiency exceeding 15% and exceptional operational stability, retaining over 85% of initial performance after 850 hours [30].

This dual-function strategy unlocks new pathways for high-performance PQD optoelectronics, establishing a versatile platform that can be adapted to various perovskite compositions and device architectures. The protocols and methodologies detailed in this application note provide researchers with comprehensive guidelines for implementing this advanced ligand strategy, accelerating the development of stable, efficient quantum dot-based photovoltaics suitable for commercial applications.

The strategic design of surface ligands is paramount to advancing the performance and stability of perovskite quantum dot (PQD) solar cells. Long-chain insulating ligands provide colloidal stability but impede charge transport, a critical bottleneck in optoelectronic devices. This Application Note details how engineering ligands with specific functional groups, namely cyano (-CN) and ethylene glycol (-EG), can simultaneously enhance PQD surface binding and modify interfacial energetics. Within the broader thesis of surface ligand design for enhanced charge transport, we demonstrate that conjugated polymers functionalized with -CN and -EG groups provide robust passivation, improve inter-dot coupling, and ultimately facilitate superior charge carrier mobility, paving the way for high-efficiency photovoltaics.

Key Binding Interactions and Energetic Modifications

The efficacy of -CN and -EG functional groups stems from their distinct chemical interactions with the PQD surface and their influence on the energy levels of the resultant hybrid material.

Cyano Group (-CN) Interactions

The cyano group acts as a strong electron-withdrawing moiety. Its nitrogen atom, with a lone pair of electrons, forms a robust coordinate covalent bond with undercoordinated lead (Pb²⁺) atoms on the PQD surface [13]. This interaction was confirmed through Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, where the ν(-CN) peak shifted from approximately 2219 cm⁻¹ in the pure polymer to 2224 cm⁻¹ after interaction with PbI₂, indicating a strong chemical bond [13]. This binding effectively passivates surface defects, reducing trap-assisted non-radiative recombination.

Ethylene Glycol (EG) Side Chain Interactions

The ethylene glycol side chains, characterized by their oxygen-rich ether groups, engage in multiple interactions. The oxygen atoms in the -EG chain also possess lone electron pairs, enabling them to interact with Pb²⁺ ions [13]. FTIR analysis showed characteristic peaks for ν(C─O─H) and ν(C─O─C) in the polymers, which underwent shifts upon binding with PbI₂, confirming the involvement of the -EG groups in surface coordination [13]. Furthermore, the long, flexible -EG side chains improve the solubility and processability of the ligands.

Synergistic Effect on Energetics

The combination of these groups within a conjugated polymer backbone creates a powerful synergistic effect. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations and Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) measurements on polymers like Th-BDT and O-BDT revealed that the -EG functional groups significantly influence the energy structure by raising the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) level of the system [13]. This modification of the interfacial energy landscape can lead to more favorable energy level alignment at the electrode interface, thereby facilitating hole extraction and improving the open-circuit voltage (V_OC) in solar cells [13].

Table 1: Spectroscopic Evidence of Functional Group Binding with PQDs

| Functional Group | Analytical Technique | Observed Peak (Pure Polymer) | Shifted Peak (After PQD Binding) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyano (-CN) | FTIR Spectroscopy | ≈ 2219 cm⁻¹ | ≈ 2224 cm⁻¹ | Strong coordination to Pb²⁺ sites [13] |

| Ethylene Glycol (C-O-C) | FTIR Spectroscopy | 1112-1144 cm⁻¹ | Shifted (values not specified) | Coordination of ether oxygen with Pb²⁺ [13] |

| Lead (Pb) | XPS (Pb 4f) | N/A | 142.80 & 137.94 eV → 142.70 & 137.84 eV | Change in chemical environment confirms ligand binding [13] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Ligand Exchange and Passivation of CsPbI₃ PQDs with Functionalized Polymers

This protocol describes the post-synthetic treatment of CsPbI₃ PQD films with conjugated polymer ligands (e.g., Th-BDT or O-BDT) to enhance surface passivation and charge transport [13].

I. Materials

- CsPbI₃ PQD Colloidal Solution: Synthesized via standard hot-injection method.

- Conjugated Polymer Ligands: Th-BDT and O-BDT (see Section 5: Research Reagent Solutions).

- Solvents: Anhydrous toluene, methyl acetate (MeOAc), dimethylformamide (DMF).

- Substrate: Pre-cleaned ITO/glass or similar.

- Equipment: Spin coater, hot plate, nitrogen glovebox, ultrasonic bath.

II. Procedure

- PQD Film Deposition (Layer-by-Layer):

- Place the substrate on the spin coater.

- Pipette ~100 µL of the CsPbI₃ PQD solution (in toluene) onto the substrate.

- Spin-coat at 2500 rpm for 15 seconds.

- Immediately after spinning, pipette ~200 µL of MeOAc onto the film while it is still spinning and spin for an additional 15 seconds. This step removes residual solvents and initiates ligand exchange.

- Repeat this cycle until the desired film thickness (e.g., ~300 nm) is achieved.

- Polymer Passivation Treatment:

- Prepare a solution of the conjugated polymer (Th-BDT or O-BDT) in a mild solvent (e.g., DMF) at a concentration of 5 mg/mL.

- Pipette ~100 µL of the polymer solution onto the as-deposited PQD film.

- Spin-coat at 2000 rpm for 30 seconds.

- Anneal the film on a hotplate at 70°C for 5 minutes inside a nitrogen glovebox to remove residual solvent and improve polymer ordering.

III. Analysis & Validation

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Compare the spectra of the pure polymer and the treated PQD film to confirm the shift in -CN and C-O-C peaks, indicating successful binding.

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Analyze the Pb 4f and Cs 3d core levels. A negative shift in binding energy confirms the change in chemical environment due to ligand attachment [13].

- Photoluminescence (PL) & UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Measure the PL intensity and absorption. A significant increase in PL quantum yield indicates effective passivation of non-radiative recombination centers.

Protocol: Verifying Energetic Modifications via Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)

This protocol outlines the procedure for determining the HOMO/LUMO energy levels of the conjugated polymer ligands, which is crucial for understanding their impact on device energetics [13].

I. Materials

- Polymer Solution: 1 mg/mL of Th-BDT or O-BDT in anhydrous DMF.

- Electrolyte: 0.1 M Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF₆) in acetonitrile.

- Working Electrode: Glassy carbon electrode.

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire.

- Reference Electrode: Ag/Ag⁺ reference electrode.

- Equipment: Potentiostat, nitrogen gas cylinder.

II. Procedure

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the glassy carbon working electrode with alumina slurry and rinse thoroughly with deionized water and the solvent.

- Solution Preparation: Add 5 mL of the polymer solution to the electrochemical cell containing the electrolyte. Purge the solution with nitrogen gas for 10 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Measurement:

- Run the CV measurement at a scan rate of 100 mV/s.

- Record the oxidation onset potential relative to the reference electrode.

- Calculation:

- The HOMO energy level can be estimated using the formula: ( E{HOMO} (eV) = - (E{onset}^{ox} + 4.8) )

- The LUMO level can be approximated from the HOMO level and the optical bandgap ((Eg)) determined from the absorption onset: ( E{LUMO} = E{HOMO} + Eg ).

Schematic Workflow and Binding Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the ligand exchange process and the key binding interactions of the -CN and -EG functional groups with the PQD surface.

Diagram 1: Workflow of PQD Film Treatment with Functionalized Polymer Ligands

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Functional Group Engineering in PQDs

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ Perovskite Quantum Dots | The core light-absorbing and charge-generating nanomaterial. | Synthesized via hot-injection; size ~11.5 nm; bandgap tunable via synthesis parameters [13]. |

| Conjugated Polymer Ligands (Th-BDT, O-BDT) | Dual-function agents for surface passivation and charge transport enhancement. | Th-BDT: Features thienyl side chains, promotes strong π-π stacking. O-BDT: Features alkoxy side chains. Both contain -CN and -EG functional groups [13]. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | A short-chain ligand and washing solvent for initial ligand exchange. | Replaces native long-chain ligands (oleic acid/oleylamine), improving initial dot-to-dot coupling [13]. |

| Lead Iodide (PbI₂) | Model compound for binding studies. | Used in FTIR and XPS experiments to validate the interaction mechanism between functional groups and Pb²⁺ ions [13]. |

| Anhydrous Solvents (Toluene, DMF) | Processing mediums for film deposition and polymer dissolution. | Essential for maintaining PQD stability and preventing degradation during processing. Must be handled in a controlled atmosphere. |

In the field of perovskite quantum dot (PQD) research, surface ligand engineering has emerged as a critical strategy for enhancing charge transport properties. Among various intermolecular forces, π-π stacking interactions between conjugated ligands have proven particularly effective in promoting the compact crystal packing necessary for superior device performance. These noncovalent interactions, characterized by attractive forces between aromatic rings containing π orbitals, enable the design of stable, highly ordered PQD solids with enhanced inter-dot coupling [30] [31]. The application of π-π stacking in materials science represents a convergence of supramolecular chemistry and nanotechnology, leveraging well-established principles from biological systems where such interactions are fundamental to DNA base-pairing and protein folding [31].

This protocol details the implementation of conjugated ligand strategies to exploit π-π stacking for improved PQD packing and charge transport, providing both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for researchers developing next-generation optoelectronic devices.

Theoretical Foundations of π-π Stacking

Fundamental Principles and Energetics

π-π stacking interactions arise from complex interplay between multiple quantum mechanical phenomena:

- Electrostatic Effects: Early models proposed that electrostatic repulsion between negatively charged π-electron clouds favors slipped parallel or T-shape geometries over perfectly face-on configurations [31].

- Dispersion Forces: Van der Waals interactions, driven by the extent of π-orbital overlap between aromatic units, significantly contribute to interaction strength [31].

- Orbital Interactions: At equilibrium distances, intermolecular orbital interactions involving hybridization of molecular orbitals form weak intermolecular bonds that stabilize the stacked structure [32].

The strength of π-π stacking can be modulated through strategic chemical substitution on aromatic rings. Electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups alter electron density distribution, thereby influencing stacking geometry and interaction energy [31]. For indole-based systems relevant to tryptophan stacking in biological contexts, halogenation has been shown to enhance stacking stability in the order F < Cl < Br < I, with interaction energies spanning a range of 3.6 kcal·mol⁻¹ [33].

Role in Supramolecular Assembly

The dynamic, reversible nature of π-π interactions facilitates the self-assembly of complex supramolecular architectures. In noncovalent π-stacked organic frameworks (πOFs), these interactions impart solution processability, self-healing capability, and notable carrier mobility, making them ideal candidates for advanced electronic applications [31]. The flexible and conductive nature of π-delocalized supramolecular frameworks represents a significant advantage over traditional porous materials.

Application in Perovskite Quantum Dot Systems

Conjugated Polymer Ligand Strategy

Recent advances in PQD solar cells demonstrate that conjugated polymer ligands functionalized with ethylene glycol side chains exhibit strong interactions with PQD surfaces while facilitating preferred packing orientation through π-π stacking [30]. Unlike conventional insulating ligands, these conjugated systems simultaneously address multiple challenges:

- Surface Defect Passivation: Strong binding to PQD surfaces reduces trap state density