Surface Chemistry Engineering of Perovskite Quantum Dots: Strategies, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive review of surface chemistry engineering for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical frontier in nanomaterial science.

Surface Chemistry Engineering of Perovskite Quantum Dots: Strategies, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of surface chemistry engineering for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical frontier in nanomaterial science. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental role of surface ligands in maintaining colloidal integrity and tuning optoelectronic properties. The content spans innovative synthesis and surface passivation strategies, details applications in drug delivery and bio-imaging, and addresses key challenges in stability and biocompatibility. By synthesizing current methodological advances and comparative analyses, this review serves as a strategic guide for harnessing the potential of PQDs in advanced biomedical and clinical applications.

The Atomic Landscape: Understanding Surface Structure and Defects in Perovskite Quantum Dots

The Critical Role of Surface Ligands in Colloidal Stability and Optoelectronic Properties

The surface chemistry of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) is a fundamental determinant of their performance and viability in optoelectronic applications. While the intrinsic ionic nature and quantum confinement of PQDs grant them exceptional optical properties—including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), narrow emission linewidths, and widely tunable bandgaps—their structural and colloidal stability is inherently linked to the dynamic layer of organic ligands passivating their surface [1] [2]. These ligand molecules, typically comprising long-chain alkyl amines and carboxylic acids, play a dual role: they control nanocrystal growth during synthesis and passivate surface defects that would otherwise act as non-radiative recombination centers, degrading optical performance [1]. However, the binding of conventional ligands is highly dynamic, leading to their facile desorption in polar environments or under thermal stress. This detachment results in surface defects, uncontrolled aggregation, and ultimately, the degradation of the quantum dots [3] [1]. Consequently, advanced ligand engineering—moving beyond simple carboxylic acids and amines to include robust, multi-dentate, and functional molecules—has emerged as an indispensable strategy for bridging the gap between the outstanding potential of PQDs and their practical application in devices such as light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and solar cells [4] [5].

The Ligand-Quantum Dot Interface: Fundamentals and Challenges

Crystal Structure and Surface Defect Sites

The canonical crystal structure of all-inorganic lead halide perovskites (CsPbX₃, X = Cl, Br, I) consists of a corner-sharing [PbX₆]⁴⁻ octahedral framework with Cs⁺ cations occupying the cuboctahedral cavities [1]. This ionic lattice terminates in under-coordinated ions, primarily Pb²⁺ and halide anions (X⁻), which constitute the most prevalent surface defect sites. Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ atoms act as deep electron traps, while halide vacancies facilitate ion migration, both of which quench photoluminescence and undermine device stability [4] [1].

Conventional Ligands and Their Limitations

Traditional synthetic routes rely on oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) as ligands. OA, an L-type ligand, coordinates to under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites, while OAm, often present as an ammonium halide, interacts with the surface through electrostatic (X-type) binding [3] [1]. While effective for synthesis, this ligand shell is inherently unstable. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) studies reveal that OA and OAm ligands dynamically and rapidly exchange between bound and free states on the QD surface [3]. This fluxional behavior means the surface passivation is transient, and ligands can easily desorb during purification or when exposed to polar solvents, leaving behind reactive, unpassivated surfaces that are susceptible to degradation and aggregation [1].

Advanced Ligand Engineering Strategies

To overcome the limitations of conventional ligands, researchers have developed sophisticated engineering strategies focusing on stronger binding, improved steric protection, and enhanced functional properties.

Multidentate and Lattice-Matched Anchoring Molecules

A powerful approach involves designing ligands with multiple, strategically spaced binding groups that match the atomic spacing of the perovskite lattice. This lattice-matched multi-site anchoring provides a dramatically stronger and more stable passivation compared to single-site binders.

A seminal example is the use of tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) [4]. The molecule's P=O and -OCH₃ groups are strong Lewis bases that chelate uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions. Critically, the interatomic distance between these oxygen atoms is 6.5 Å, which matches the lattice spacing of the CsPbI₃ QDs. This geometric compatibility allows the molecule to attach to multiple defect sites simultaneously without inducing strain, leading to near-complete suppression of trap states as confirmed by density of states calculations [4]. The result is a dramatic increase in PLQY from 59% (pristine QDs) to 97% (TMeOPPO-p-treated QDs), demonstrating near-unity radiative efficiency [4].

Two-Dimensional Perovskite-like Ligands

For lead sulfide (PbS) colloidal quantum dots (CQDs) used in photovoltaics, a novel strategy employs 2D perovskite-like ligands such as (BA)₂PbI₄ (where BA is butylammonium) [5]. This in-situ ligand exchange forms a thin, robust shell of BA⁺ and I⁻ ions on the CQD surface. This shell is particularly effective at passivating challenging non-polar <100> facets, which are prevalent in larger CQDs and are poorly passivated by conventional ligands like PbI₂. The (BA)₂PbI⁴ shell provides strong inward coordination, reduces defect density, and prevents CQD aggregation. Furthermore, the hydrophobic BA⁺-rich surface confers excellent ambient stability. Infrared photovoltaics using these engineered QDs achieved a champion power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 13.1% for small-bandgap QDs and 8.65% for large-bandgap QDs, coupled with significantly enhanced thermal stability [5].

Cascade Surface Modification for Homojunctions

A cascade surface modification (CSM) strategy enables the creation of bulk homojunction films, which are critical for high-efficiency photovoltaics [6]. This two-step process involves:

- An initial surface halogenation with lead halide anions to create a well-passivated, n-type CQD ink.

- A subsequent surface reprogramming step where the halide-rich surface is treated with bifunctional thiol ligands (e.g., cysteamine, CTA) to render the CQDs p-type.

The key insight is tailoring the secondary functional group (-L in SH-R-L) of the thiol ligand to ensure miscibility of the n-type and p-type inks in a common solvent (e.g., butylamine, BTA). Ligands with -NH₂ terminal groups (e.g., CTA) form stable colloids because they can hydrogen-bond effectively with the solvent. This CSM approach yields homojunction films with a 1.5-fold increase in carrier diffusion length and has achieved a record PCE of 13.3% in CQD solar cells [6].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Quantum Dots with Advanced Ligand Systems

| Ligand Strategy | Quantum Dot Material | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Control/Reference Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lattice-matched Anchor (TMeOPPO-p) [4] | CsPbI₃ | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | 97% | 59% (Pristine QDs) |

| 2D Perovskite Ligand ((BA)₂PbI₄) [5] | PbS (1.3 eV) | Solar Cell Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | 13.1% | 11.3% (PbI₂-capped) |

| 2D Perovskite Ligand ((BA)₂PbI₄) [5] | PbS (1.0 eV) | Solar Cell Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | 8.65% | - |

| Cascade Surface Modification [6] | PbS | Solar Cell Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | 13.3% | - |

Experimental Protocols

This protocol describes the exchange of native oleic acid ligands on PbS CQDs for (BA)₂PbI₄ ligands.

Materials:

- PbS-OA CQDs (Oleic Acid-capped) in n-octane.

- Lead Iodide (PbI₂), n-Butylammonium Iodide (n-BAI), Ammonium Acetate.

- Solvents: N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), n-octane.

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Prepare a stoichiometric mixture of PbI₂, n-BAI, and a small amount of ammonium acetate (to assist colloidal stabilization) in DMF solvent. This forms the 2D perovskite precursor solution.

- Ligand Exchange: Inject the precursor solution into the PbS-OA CQD solution in n-octane. Vigorously stir the mixture.

- Phase Transfer: The exchange reaction will cause the PbS CQDs to transfer from the non-polar n-octane phase to the polar DMF phase, indicating successful ligand exchange and the formation of PbS-(BA)₂PbI₄ CQDs.

- Purification: Isolate the CQDs from the DMF phase by centrifugation and wash with a mild antisolvent to remove excess precursors and ligand byproducts.

- Film Fabrication: Redisperse the purified CQDs in a suitable solvent (e.g., butylamine) for spin-coating into thin films for device fabrication.

This protocol outlines the post-purification treatment of CsPbI₃ QDs with TMeOPPO-p to achieve high passivation.

Materials:

- Purified CsPbI₃ QDs (synthesized via hot-injection).

- Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p).

- Solvents: Toluene, Ethyl Acetate (for purification).

Procedure:

- QD Purification: Synthesize CsPbI₃ QDs using a standard hot-injection method. Purify the raw QD solution by centrifugation with ethyl acetate as an antisolvent to remove excess OA and OAm.

- Anchor Solution Preparation: Prepare a stock solution of TMeOPPO-p in toluene (e.g., concentration of 5 mg mL⁻¹).

- Surface Treatment: Add a calculated volume of the TMeOPPO-p stock solution to the purified QDs dispersed in toluene. The typical concentration is optimized to achieve full surface coverage without inducing aggregation.

- Incubation: Stir the mixture for a defined period (e.g., 1-2 hours) at room temperature to allow the anchor molecules to bind to the QD surface.

- Purification: Precipitate the treated QDs by adding ethyl acetate, followed by centrifugation. Decant the supernatant to remove displaced OA/OAm and unbound TMeOPPO-p.

- Storage: Redisperse the final, passivated QDs in an anhydrous, non-polar solvent like toluene for storage and further characterization.

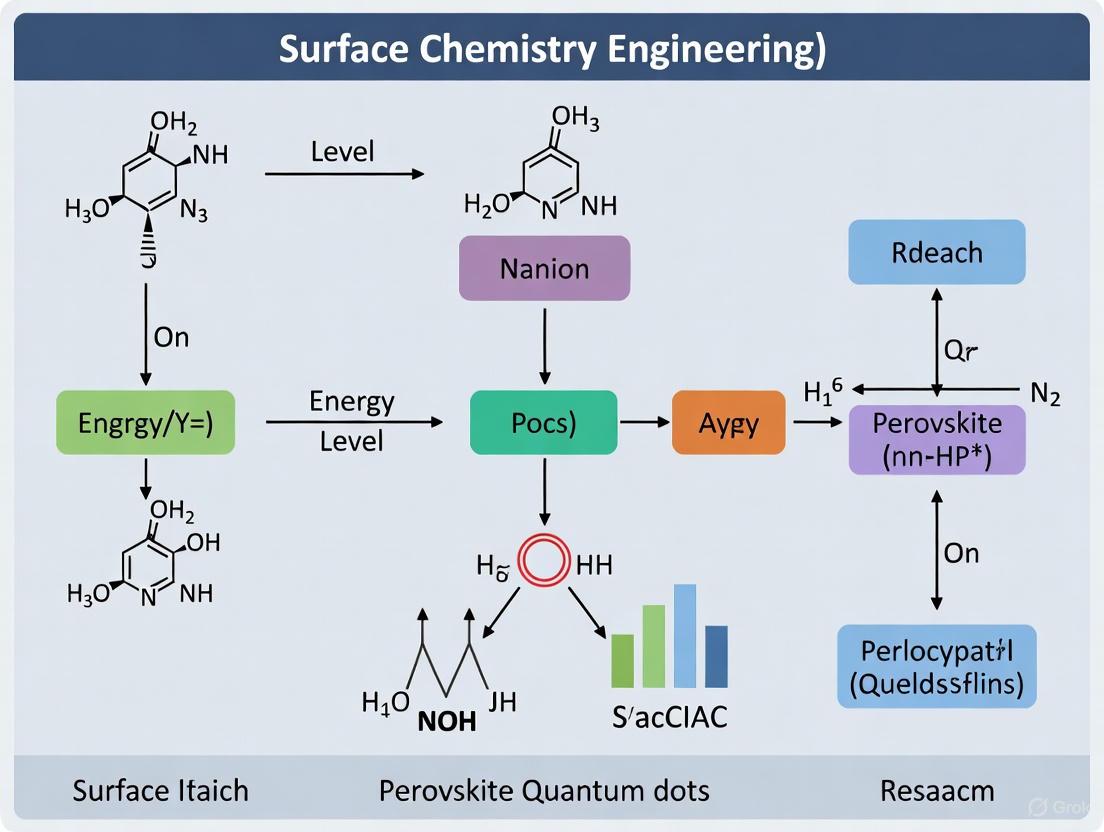

The experimental workflow for advanced ligand engineering is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Ligand Engineering of Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Characteristics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) [1] | Standard L-type and X-type ligands for initial synthesis and size control. | Dynamic binding leads to instability; often the starting point for further exchange. |

| n-Butylammonium Iodide (n-BAI) [5] | Precursor for 2D perovskite ligands. Provides the ammonium cation and halide. | Enables formation of a robust, hydrophobic (BA)₂PbI₄ shell on PbS CQDs. |

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine Oxide (TMeOPPO-p) [4] | Lattice-matched multi-site anchor molecule for defect passivation. | P=O and -OCH₃ groups spaced at 6.5 Å match the perovskite lattice for strong chelation. |

| Cysteamine (CTA) [6] | Bifunctional thiol ligand for surface reprogramming and doping control. | -SH group binds to Pb; -NH₂ group controls solubility for homojunction fabrication. |

| Lead Iodide (PbI₂) [5] | Lead and halide source for perovskite precursor solutions. | Used in both synthesis and as a component for forming perovskite-based ligands. |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) [5] [6] | Polar solvent for ligand exchange and dispersion of ligand-exchanged QDs. | Can cause ligand desorption; used after exchange when QDs are stabilized by ionic ligands. |

Surface ligand engineering has evolved from a simple synthetic necessity to a sophisticated tool for tailoring the properties of perovskite quantum dots. The move from dynamically-bound, single-site ligands like OA and OAm towards robust, multi-dentate, and structurally compatible molecules—such as lattice-matched anchors and 2D perovskite-like ligands—has yielded remarkable improvements in PLQY, device efficiency, and operational stability. These strategies effectively suppress surface defects and ion migration, the primary sources of degradation. The experimental protocols for in-situ exchange and post-synthetic treatment provide robust pathways for implementing these advances. As research continues to deepen our understanding of the QD-ligand interface, further innovations in ligand design will be pivotal in unlocking the full commercial potential of perovskite quantum dots in next-generation optoelectronics.

Atomistic Structure of PQD Surfaces and Defect Formation Mechanisms

The performance and stability of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) in optoelectronic applications are fundamentally governed by their surface atomistic structure and the inherent defects within it. Organic-inorganic hybrid PQDs, particularly CH3NH3PbBr3 (MAPbBr3), possess a cubic perovskite crystal structure (ABX3, where A = CH3NH3+, B = Pb2+, X = Br−) that enables strong quantum confinement effects [7]. This structure is pivotal for their remarkable photophysical properties, including photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs) exceeding 95% and narrow emission linewidths as low as 14 nm [7]. However, the surfaces of these nanocrystals are highly dynamic and susceptible to the formation of defects, which primarily consist of halide vacancies and uncoordinated Pb2+ ions [7]. These surface defects act as non-radiative recombination centers, degrading PLQY and ultimately undermining the efficiency and longevity of devices like light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and memory devices [7] [8]. A profound understanding of the atomistic structure and the mechanisms of defect formation is therefore the foundation of surface chemistry engineering aimed at stabilizing PQDs and unlocking their full commercial potential.

Table 1: Key Defect Types in CH3NH3PbBr3 PQD Surfaces and Their Impacts

| Defect Type | Atomic-Level Origin | Impact on Optoelectronic Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Halide (Br⁻) Vacancies | Missing bromine ions from the crystal lattice. | Create trap states for charge carriers; increase non-radiative recombination; reduce PLQY [7]. |

| Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ Ions | Lead ions lacking full coordination with surrounding bromine ions, often at surfaces. | Act as deep-level traps; quench photoluminescence; hinder charge transport [7]. |

| Organic Cation Disordering | Dynamic displacement or loss of CH3NH3+ cations from A-sites. | Can distort the lattice; influence dielectric constant and charge screening [8]. |

Synthesis Techniques and Resultant Surface Structures

The synthesis method plays a critical role in defining the initial surface structure, defect density, and morphological properties of PQDs. Scalable techniques like Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) and Hot-Injection are commonly employed, each imparting distinct surface characteristics [7].

Protocol: Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) of CH3NH3PbBr3 PQDs

Principle: This room-temperature method involves the supersaturation-driven nucleation of PQDs by mixing a perovskite precursor solution with a non-solvent, stabilized by coordinating ligands [7].

Materials:

- Precursors: Methylammonium bromide (CH3NH3Br) and Lead(II) bromide (PbBr2).

- Solvents: ( N,N )-Dimethylformamide (DMF) or Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

- Non-solvent: Toluene or Chloroform.

- Ligands: Oleic acid (OA) and Oleylamine (OAm).

- Equipment: Schlenk line, magnetic stirrer, centrifuge, ultrasonic bath.

Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve stoichiometric amounts of CH3NH3Br and PbBr2 in DMF under inert atmosphere to form a clear solution.

- Ligand Introduction: Add precise molar ratios of OA and OAm to the precursor solution with vigorous stirring.

- Nucleation and Growth: Rapidly inject the precursor solution into a volume of vigorously stirring toluene (non-solvent). The immediate cloudiness indicates PQD formation.

- Purification: Centrifuge the crude solution to isolate the PQD precipitate. Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in a non-solvent like hexane or toluene. Repeat this washing process 2-3 times.

- Storage: Store the final purified PQD solution in an inert, dark environment at 4°C.

Outcome: This protocol yields PQDs with tunable sizes of 2–10 nm, corresponding to an emission range of 409–523 nm. It can achieve PLQYs above 95% and a narrow FWHM of 14–25 nm, making it suitable for vibrant displays [7].

Synthesis Workflow and Surface Defect Formation

The following diagram illustrates the general synthesis workflow and the key stages where surface defects are introduced.

Surface Engineering and Defect Passivation Strategies

Surface engineering through strategic passivation is essential to mitigate defects and enhance PQD performance and stability. The primary goal is to coordinate with unsaturated surface sites, particularly uncoordinated Pb2+ ions.

Protocol: Surface Passivation via Metal Halide Treatment

Principle: Metal halide salts (e.g., ZnBr2, PbBr2) can supply halide ions to fill vacancies and incorporate metal ions into the surface lattice, reducing trap state density [7].

Materials: Purified CH3NH3PbBr3 PQD solution, Zinc bromide (ZnBr2) or Lead bromide (PbBr2), Isopropanol, Non-solvent (e.g., Hexane), Centrifuge.

Procedure:

- Passivation Solution: Dissolve a controlled molar amount of ZnBr2 (typically 0.5-5 mol% relative to Pb) in isopropanol.

- Reaction: Add the passivation solution dropwise to the purified PQD solution under vigorous stirring at room temperature.

- Incubation: Allow the mixture to react for 10-30 minutes.

- Purification: Precipitate the passivated PQDs by adding a non-solvent, then centrifuge. Re-disperse the pellet in a stable solvent for further use.

Outcome: This treatment effectively reduces halide vacancies and passivates uncoordinated Pb2+ sites, leading to a significant increase in PLQY and operational stability of the PQDs [7].

Table 2: Surface Passivation Ligands and Their Functions in PQDs

| Passivation Agent | Chemical Function | Impact on PQD Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid / Oleate | Anionic ligand coordinating with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites. | Enhances colloidal stability; reduces surface traps; improves PLQY [7]. |

| Oleylamine / Alkylammonium | Cationic ligand interacting with surface halides and PbX₂ layer. | Controls growth kinetics; improves surface coverage and charge balance [7]. |

| Metal Halides (e.g., ZnBr₂) | Provides halide ions to fill vacancies; metal ions can incorporate into surface. | Suppresses halide vacancy formation; significantly boosts PLQY and stability [7]. |

| Manganese (Mn²⁺) Doping | Partially substitutes Pb²⁺ in the lattice, forming stronger Mn-Br bonds. | Reduces lead toxicity; doubles operational stability (T₅₀ > 1000 h) [7]. |

Advanced Characterization and Analysis of Surface Defects

Characterizing the atomistic structure and quantifying defects requires a multi-faceted analytical approach. Key techniques include:

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL): Measures carrier lifetimes to quantify the efficiency of radiative vs. non-radiative recombination pathways, directly indicating trap state density [8].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Probes surface chemical composition and oxidation states, identifying the presence of uncoordinated Pb2+ ions.

- High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM): Resolves atomic lattice fringes to visualize crystal structure, surface facets, and any amorphous regions or severe defects [7].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between common surface defects, the passivation mechanisms, and the resulting performance outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Surface Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Example in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Pb²⁺ source for the perovskite B-site in the ABX₃ structure. | Primary precursor in LARP and hot-injection synthesis [7]. |

| Methylammonium Bromide (MABr) | Organic cation (MA⁺) source for the A-site in the ABX₃ structure. | Primary precursor for forming CH₃NH₃PbBr₃ [7]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Anionic surface ligand; passivates uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites. | Co-ligand added during synthesis and purification [7]. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Cationic surface ligand; aids in crystal growth and surface charge balance. | Co-ligand added during synthesis and purification [7]. |

| Zinc Bromide (ZnBr₂) | Halide vacancy suppressor and surface passivator. | Post-synthetic treatment to enhance PLQY and stability [7]. |

| Manganese Bromide (MnBr₂) | Doping agent for partial Pb replacement; enhances stability. | Used in synthesis to form Mn-doped MAPbBr₃ with stronger metal-halide bonds [7]. |

| Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) | Polymer for encapsulation and protection from environmental stressors. | Used to form a protective matrix around PQDs in composite films [7]. |

Within the broader research on the surface chemistry engineering of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), the inherent limitations of native surface ligands represent a critical barrier to advancing both fundamental research and commercial applications. PQDs, notably cesium lead halide (CsPbX₃) and methylammonium lead halide (CH₃NH₃PbX₃) variants, have emerged as transformative materials in optoelectronics due to their exceptional properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), tunable bandgaps, and defect tolerance [9] [7]. However, their performance and stability are fundamentally governed by their surface chemistry. The long-chain insulating ligands, such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), which are indispensable for colloidal synthesis and stability, introduce a paradoxical challenge: their dynamic binding nature and electrically insulating character severely limit charge transport and long-term operational stability in devices such as solar cells and light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [10] [9]. This application note details these inherent challenges and provides structured experimental protocols and data to guide researchers in overcoming these obstacles.

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Challenges

The table below summarizes the core challenges posed by native ligands and their direct consequences on PQD properties and device performance.

Table 1: Core Challenges Posed by Native Ligands on PQDs

| Challenge | Impact on PQD Properties | Impact on Device Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Binding [10] [9] | • Labile surface lattices and defect formation (e.g., halide vacancies) [11].• Poor surface coverage in solid-state films [11].• Particle aggregation and structural decomposition during processing [9]. | • Reduced operational stability and accelerated degradation [9].• Photoluminescence (PL) blinking and photodarkening at the single-dot level [11]. |

| Insulating Nature [10] [9] | • Creation of a resistive barrier between adjacent QDs [9].• Impaired inter-dot charge carrier transport [9]. | • Compromised charge extraction efficiency in solar cells [9].• Increased non-radiative recombination losses, limiting power conversion efficiency (PCE) and external quantum efficiency (EQE) [9]. |

The following table compiles quantitative data from the literature, illustrating the performance limitations associated with native ligands and the improvements achieved through ligand engineering.

Table 2: Performance Comparison: Native Ligands vs. Engineered Ligands

| Material/System | Ligand System | Key Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ PQD Solar Cells | Native OA/OAm | Initial PCE: ~10.77% [9] | [9] |

| CsPbI₃ PQD Solar Cells | Formamidinium Iodide / Cesium Acetate / Guanidinium Thiocyanate Treatment | PCE: 16.6% (certified) [9] | [9] |

| CsPbBr₃ PQDs (Strongly Confined) | Traditional Bulky Ligands (e.g., DDA) | Severe PL blinking and photodegradation [11] | [11] |

| CsPbBr₃ PQDs (Strongly Confined) | Phenethylammonium (PEA) with π-π stacking | Nearly non-blinking emission; high photostability (12 hours continuous operation) [11] | [11] |

| FAPbI₃ Perovskite Solar Cells | Conventional Single-Site Ligands | Limited stability and passivation [12] | [12] |

| FAPbI₃ Perovskite Solar Cells | Multi-site Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ Ligand | PCE: 25.03% (ambient processing); Enhanced shelf-life stability [12] | [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating and Addressing Ligand Challenges

Protocol: Solid-State Ligand Exchange with Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr)

This protocol is designed to replace native bulky ligands with smaller, stacked ligands to enhance surface passivation and photostability, particularly for single-particle spectroscopy applications [11].

- Objective: To achieve a nearly epitaxial ligand layer on CsPbBr₃ QDs that suppresses PL blinking and improves photostability.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- CsPbBr₃ QDs: Synthesized via hot-injection or ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP), capped with native OA/OAm ligands [11] [7].

- n-Butylammonium Bromide (NBABr): Serves as an initial surface treatment agent to fill halide vacancies [11].

- Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) Solution: Saturated solution in a solvent such as toluene or hexane. PEA provides a small steric profile and enables π-π stacking between ligand tails [11].

- Anhydrous Toluene: For purification and dispersion.

- Research Reagent Solutions:

Procedure:

- Initial Treatment: Immerse OA/OAm-capped CsPbBr₃ QDs in a solution containing a small amount of saturated NBABr. This step aims to repair surface halide vacancies [11].

- PEA Ligand Exchange: Subsequently, immerse the NBABr-treated QDs in a saturated PEABr solution.

- Thermal Annealing: Heat the mixture to a moderate temperature (e.g., 60-80°C) for a short period (10-30 minutes) to facilitate robust ligand binding and promote the stacking of PEA ligand tails [11].

- Purification: Purify the resulting PEA-capped QDs by repeated centrifugation and redispersion in anhydrous toluene to remove excess ligands and reaction byproducts.

- Film Formation: Deposit the purified QDs onto a substrate for single-dot studies or device fabrication.

Critical Parameters:

- Ligand Tail Interaction: The attractive π-π interaction between PEA ligands is crucial for reducing surface energy and achieving a stable, non-blinking surface [11].

- Solution Concentration: The QD colloidal solution must be diluted to a very low density for single-particle studies, which traditionally exacerbates ligand desorption. The strong binding and stacking of PEA mitigate this issue [11].

Protocol: In-situ Passivation with Multi-Site Binding Ligands

This protocol describes the use of a multi-anchoring ligand to simultaneously passivate defects and improve charge transport in perovskite solar cells fabricated in ambient air [12].

- Objective: To incorporate the Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex as a multi-site passivator during the two-step film formation process, enhancing crystallinity and stability.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ Complex: Synthesized from antimony chloride and N,N-dimethylselenourea (SU) in dichloromethane [12].

- PbI₂ Layer: Pre-deposited from a precursor solution.

- Organic Halide Salt Solution: Formamidinium iodide (FAI) solution for conversion to perovskite.

- Polar Solvent: e.g., Dimethylformamide (DMF) or Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

- Research Reagent Solutions:

Procedure:

- Ligand Addition: Add the Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex directly into the FAI organic salt solution used in the second step of the perovskite deposition process [12].

- Film Deposition and Reaction: Deposit the FAI + Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ solution onto the pre-formed PbI₂ layer. The complex facilitates the conversion of PbI₂ to the perovskite phase under ambient conditions.

- Thermal Annealing: Anneal the film to crystallize the perovskite structure. The multi-site ligand integrates into the growing crystal lattice.

- Device Completion: Proceed with the deposition of charge-transport layers and electrodes to complete the solar cell device.

Critical Parameters:

- Binding Configuration: The complex binds to four adjacent undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the perovskite surface via two Se and two Cl atoms, providing superior passivation compared to single-site ligands [12].

- Hydrogen Bonding Network: The ligand also forms an extended network of NH-Cl bonds, which further stabilizes the perovskite structure and enhances moisture resistance [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The table below lists essential reagents used in the featured ligand engineering strategies.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PQD Ligand Engineering

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) [9] [7] | Native capping ligands for colloidal synthesis and stability. | Provide initial colloidal stability but exhibit dynamic binding and are electrically insulating. |

| Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) [11] | Small ligand for solid-state exchange to enhance photostability. | Small steric profile and π-π stacking capability between aromatic tails promote a stable ligand layer. |

| n-Butylammonium Bromide (NBABr) [11] | Co-ligand for initial surface treatment. | Supplies halide ions to fill vacancies and improves initial surface passivation before final ligand exchange. |

| Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ Complex [12] | Multi-site binding ligand for in-situ passivation in solar cells. | Binds via 2 Se and 2 Cl atoms for deep trap passivation and forms a stabilizing hydrogen-bond network. |

| Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) [9] [12] | Organic cation precursor for perovskite formation. | Used in conjunction with passivating ligands during the two-step fabrication process. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the inherent challenges of native ligands, the engineered solutions, and the resulting material and device outcomes.

Bandgap engineering is a cornerstone of modern optoelectronics and photonics, enabling precise control over how semiconducting materials interact with light. For metal halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), bandgap engineering—primarily achieved through compositional tuning and quantum confinement effects—dictates critical optical properties such as absorption and emission wavelengths. Surface chemistry engineering has emerged as a powerful, complementary technique to fine-tune these properties and directly address the intrinsic instability of PQDs, which is a significant barrier to their biomedical application [13] [2]. The dynamic and insulating nature of native surface ligands, coupled with surface defects, has historically limited the performance and reliability of PQDs in biological environments [14] [10].

This Application Note frames these technical challenges within the broader thesis that rational surface manipulation is not merely a post-synthesis treatment but a fundamental design strategy. It details how engineered surface interfaces can simultaneously enhance PQD stability, control bandgap-related optoelectronic properties, and enable new functionalities for biomedical use. We provide structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and visual workflows to equip researchers with the tools to advance PQD-based biomedical technologies.

The Interplay of Surface Chemistry and Bandgap Properties

The surface of a perovskite quantum dot is a dynamic interface where organic ligands coordinate with the inorganic crystalline lattice. This interface profoundly influences the electronic structure of the PQD. Surface defects, such as halide vacancies or uncoordinated lead atoms, create mid-gap trap states that non-radiatively capture charge carriers, effectively widening the bandgap and reducing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) [4]. Furthermore, the weak ionic bonding of the perovskite lattice makes it susceptible to degradation in aqueous environments, a major hurdle for biomedical applications like bioimaging and biosensing [13].

Advanced surface chemistry engineering strategies directly target these issues. Surface passivation involves introducing molecules that bind to and eliminate these defect sites, restoring near-unity PLQY and enhancing resistance to environmental stressors [4]. Ligand exchange replaces long, insulating native ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) with shorter or multifunctional molecules, which improves charge transport and facilitates electronic coupling between QDs while also improving stability [14] [10]. A groundbreaking approach involves creating buried PQDs (b-PQDs), where QDs are embedded within a stable, wide-bandgap perovskite matrix, effectively isolating them from degrading elements and creating an ideal passivated interface [15].

Table 1: Surface Chemistry Engineering Strategies and Their Impact on PQD Properties

| Engineering Strategy | Key Mechanism | Impact on Bandgap & Optical Properties | Implication for Biomedicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Passivation | Binding of molecules to surface defects (e.g., uncoordinated Pb²⁺) [4]. | Increased PLQY (up to 97%), suppressed non-radiative recombination, sharper emission peaks [4]. | Brighter, more stable probes for bioimaging and biosensing. |

| Ligand Exchange | Replacement of long, insulating ligands with shorter or conductive linkers [14] [10]. | Tuned electronic coupling, modified charge transport, maintained quantum confinement [14]. | Improved performance in photodynamic therapy and electro-optical biosensors. |

| Lattice-Matched Anchoring | Multi-site binding of designed molecules that match the PQD lattice spacing [4]. | Near-unity PLQY (97%), superior stability against ion migration and degradation [4]. | High-fidelity, long-term biological tracking and diagnostics. |

| Matrix Encapsulation (b-PQDs) | Embedding PQDs in a wider-bandgap perovskite film to isolate from environment [15]. | Ultranarrow linewidth (<130 µeV), unity quantum yield, no blinking, high stability [15]. | Ideal single-photon sources for super-resolution imaging and quantum bio-sensing. |

Quantitative Data on Engineered PQDs for Biomedicine

The efficacy of surface engineering is quantitatively demonstrated through enhancements in key performance metrics. The following table consolidates data from recent literature on the optical properties and stability of PQDs tailored for biomedical relevance.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Surface-Engineered PQDs

| PQD System / Strategy | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Emission Wavelength / Bandgap | Key Stability Metrics | Cited Application Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ QDs with TMeOPPO-p anchor [4] | 97% | 693 nm | >23,000 h operating half-life in LEDs; stable in air processing. | Biosensing, bio-imaging |

| Buried PQDs (b-PQDs) [15] | Near-unity (implied) | Tunable | Stable single-dot emission; no blinking; suppressed spectral diffusion. | Single-photon sources for super-resolution imaging |

| General Passivated PQDs [13] | High (exact value not specified) | Tunable across visible spectrum | Enhanced stability in aqueous media (PBS). | Drug delivery, bioimaging, tumor therapy |

| Ligand-Exchanged PQD Films [14] | N/A (Focus on charge transport) | Tunable via quantum confinement | Improved mechanical flexibility for flexible substrates. | Wearable biomedical sensors |

Experimental Protocols for Surface Engineering of PQDs

Protocol: Lattice-Matched Molecular Anchoring for Defect Passivation

This protocol details the surface passivation of CsPbI₃ PQDs using tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p), a lattice-matched anchoring molecule, to achieve high PLQY and stability for sensitive detection applications [4].

1. Materials and Reagents

- Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃), 99.9%

- Lead iodide (PbI₂), 99.99%

- 1-Octadecene (ODE), technical grade 90%

- Oleic acid (OA), technical grade 90%

- Oleylamine (OAm), technical grade 90%

- Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p), >97%

- Ethyl acetate, anhydrous, 99.8%

- Hexane, anhydrous, 95%

2. Synthesis of CsPbI₃ PQDs (Hot-Injection Method)

- Cesium Oleate Precursor: Load 0.2 g Cs₂CO₃, 0.625 mL OA, and 7.5 mL ODE into a 25 mL 3-neck flask. Dry and degas under vacuum at 120 °C for 1 hour. Heat under N₂ atmosphere to 150 °C until all Cs₂CO₃ dissolves, then maintain at 100 °C.

- Perovskite Reaction Mixture: Load 0.1 g PbI₂, 5 mL ODE, 0.5 mL OA, and 0.5 mL OAm into a 25 mL 3-neck flask. Dry and degas under vacuum at 120 °C for 30 minutes until the PbI₂ is fully dissolved.

- Injection and Reaction: Rapidly inject 0.4 mL of the preheated cesium oleate precursor into the reaction flask. Quench the reaction after 5-10 seconds by immersing the flask in an ice-water bath.

3. Purification and Ligand Passivation

- Precipitation: Transfer the crude solution to a centrifuge tube. Add equal volume of ethyl acetate and centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes. Discard the supernatant.

- Anchoring Molecule Treatment: Re-disperse the pellet in 5 mL of hexane. Add a solution of TMeOPPO-p in ethyl acetate (concentration: 5 mg/mL) dropwise under stirring. The optimal ratio is approximately 1 mg TMeOPPO-p per 1 mL of original crude QD solution.

- Purification: Centrifuge the mixture at 6000 rpm for 3 minutes to remove any aggregates. Precipitate the passivated QDs by adding ethyl acetate, followed by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Storage: Re-disperse the final pellet in anhydrous hexane or toluene at a concentration of 10-20 mg/mL for storage in a nitrogen-filled glovebox.

4. Validation and Characterization

- PLQY Measurement: Use an integrating sphere with a spectrophotometer to confirm PLQY >95%.

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Verify the presence of TMeOPPO-p on the QD surface by observing weakened C-H stretching modes (2700-3000 cm⁻¹) from OA/OAm.

- XPS Analysis: Confirm a shift in Pb 4f peaks to lower binding energies, indicating successful coordination and enhanced electron shielding.

Protocol: Solid-State Ligand Exchange for Conductive PQD Films

This protocol describes a solid-state ligand exchange process to create conductive PQD films, which is essential for developing electronic and electro-optical biomedical devices [14].

1. Materials and Reagents

- As-synthesized PQDs (e.g., CsPbI₃ or CsPbBr₃) with long-chain ligands (OA/OAm)

- Short-chain ligand solution (e.g., 5 mg/mL PbI₂ or PbBr₂ in isopropanol)

- Methyl acetate, anhydrous

- Isopropanol (IPA), anhydrous

2. Fabrication of PQD Thin Film

- Substrate Preparation: Clean a glass or ITO substrate with oxygen plasma for 10 minutes.

- Film Deposition: Deposit a film of pristine PQDs via spin-coating (e.g., 2000 rpm for 30 seconds) or doctor-blade coating.

3. Ligand Exchange Process

- Immersion Treatment: Immediately after deposition, immerse the PQD film into the short-chain ligand solution (e.g., PbI₂ in IPA) for 30-60 seconds. This replaces the insulating oleylammonium/oleate ligands with shorter, halide-rich species.

- Rinsing: Gently rinse the film with pure IPA or methyl acetate to remove the displaced long-chain ligands and excess reagent.

- Drying: Dry the film under a nitrogen stream.

4. Validation and Characterization

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Monitor the reduction of C-H stretching peaks to confirm the removal of long-chain hydrocarbons.

- Electrical Characterization: Measure current-voltage (I-V) characteristics to demonstrate improved conductivity.

- XRD: Ensure the crystalline phase is maintained post-exchange.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for PQD Surface Engineering and Biomedical Application

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Native surfactants for colloidal synthesis and initial stabilization [14]. | Standard ligands for initial QD synthesis; require replacement for most applications. |

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine Oxide (TMeOPPO-p) | Lattice-matched multi-site anchor for defect passivation [4]. | Dramatically improves PLQY and operational stability for sensitive biosensors. |

| Lead Halide Salts (PbI₂, PbBr₂) | Short-chain ligand and halide vacancy source for solid-state exchange [14]. | Enhances inter-dot charge transport in films for photodetectors and electronic sensors. |

| Inorganic Matrices (e.g., wider-bandgap perovskites) | Host material for creating buried PQDs (b-PQDs) [15]. | Provides ultimate stability for single-photon sources in super-resolution microscopy. |

| Polymer Encapsulation Agents | Form a protective barrier against moisture and oxygen [13]. | Essential for enhancing biocompatibility and stability in aqueous biological media. |

The strategic engineering of perovskite quantum dot surfaces is a transformative approach that directly addresses the dual challenges of instability and suboptimal optoelectronic properties for biomedical applications. By moving beyond simple ligand exchange to sophisticated strategies like lattice-matched molecular anchoring and matrix encapsulation, researchers can create PQD systems with near-perfect photoluminescence, exceptional stability, and tailored electronic properties. The protocols and data outlined in this document provide a foundational toolkit for advancing this promising technology toward practical biomedical devices, including high-fidelity biosensors, robust bioimaging agents, and novel theranostic platforms. The future of PQDs in medicine hinges on the continued innovative design of their surface chemistry.

Synthesis and Functionalization: Engineering PQD Surfaces for Biomedical Applications

Colloidal synthesis encompasses the methods for creating nanoparticles suspended in a medium, forming the foundation for advanced materials like perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). These techniques are broadly classified into top-down and bottom-up approaches [16]. Top-down methods involve the physical breakdown of bulk materials into nanostructures, while bottom-up approaches construct nanoparticles from atomic or molecular precursors through chemical reactions [16]. For perovskite quantum dot research, controlling surface chemistry is paramount, as the organic ligand shell directly determines key optoelectronic properties, including photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), blinking behavior, and charge transport efficiency [17]. The choice of synthesis strategy profoundly influences the surface structure, defect density, and ultimate performance of the resulting quantum dots in devices such as light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and solar cells [2] [18].

Bottom-Up Synthesis Approaches

Bottom-up synthesis builds colloidal systems from individual atoms, molecules, or nanoparticles, allowing for precise control over their final size, shape, and crystal structure [16]. This approach is predominant in the synthesis of high-quality perovskite quantum dots.

Key Bottom-Up Methods and Protocols

Precipitation Reactions Precipitation involves mixing reactants to form an insoluble product (precipitate) and is commonly used for metal oxide nanoparticles [16]. Control over size and morphology is achieved by adjusting reactant concentration, pH, temperature, and mixing conditions [19].

- Protocol: Precipitation of Barium Sulfate Nanoparticles

- Objective: To synthesize BaSO₄ nanoparticles using a bottom-up precipitation method.

- Reagents: Barium chloride (BaCl₂), Potassium sulfate (K₂SO₄), Capping agent (e.g., specific polymers, surfactants, or ionic liquids).

- Procedure:

- Prepare separate aqueous solutions of BaCl₂ and K₂SO₄.

- Add a selected capping agent to one of the reactant solutions to control particle growth and prevent agglomeration [19].

- Under constant stirring, slowly mix the two solutions. The reaction is: Ba²⁺(aq) + SO₄²⁻(aq) → BaSO₄(s) [19].

- Maintain constant temperature and pH throughout the process to influence particle size and morphology [19].

- Collect the precipitate via centrifugation, and wash repeatedly to remove excess ions and capping agents.

- Dry the purified nanoparticles to obtain the final product.

- Critical Parameters: Stoichiometric feed ratio, concentration of capping agent, mixing rate, and reaction temperature [19].

Solvothermal Synthesis This method involves chemical reactions in a closed system (autoclave) using a non-aqueous solvent at elevated temperature and pressure [16]. It is highly effective for producing crystalline nanoparticles with controlled structure.

- Protocol: Synthesis of Perovskite Quantum Dot Heterocrystals via CQD-OA-PSC

- Objective: To fabricate quantum-dot/perovskite heterocrystals with perfect lattice matching [20].

- Reagents: Precursors for colloidal quantum dots (CQDs), Macroscopic perovskite single crystal substrate, Solvents.

- Procedure:

- Optimize Quantum Dot Growth: First, synthesize colloidal quantum dots (CQDs) via wet chemical colloidal synthesis methods, optimizing for core crystalline integrity, size, and shape uniformity [20].

- Oriented Attachment: Subsequently, attach the pre-formed CQDs onto a macroscale perovskite single crystal substrate. This step leverages solution-based epitaxial growth to achieve impeccable lattice alignment between the quantum dots and the perovskite matrix [20].

- Characterization: Use high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) to confirm the matched lattice orientations and the quality of the heterostructure [20].

- Critical Parameters: Precision in lattice matching at the interface, surface energy of the perovskite crystal, and the crystallographic orientation during attachment [20].

Bottom-Up Workflow and Surface Chemistry Engineering

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for the bottom-up synthesis of perovskite quantum dots, highlighting the critical role of surface ligand engineering.

Diagram 1: Bottom-Up Synthesis and Surface Engineering Workflow for Perovskite Quantum Dots. The process begins with precursor mixing, proceeds through nucleation and growth, and is critically governed by surface ligand interactions. A dedicated ligand engineering step allows for post-synthetic optimization of surface properties.

Top-Down Synthesis Approaches

Top-down approaches begin with bulk materials and break them down into nanostructures using physical or chemical methods [16]. While less common for high-quality perovskite quantum dots, these techniques are valuable for certain material systems and applications.

Key Top-Down Methods and Protocols

Laser Ablation This technique uses a high-energy laser beam to remove material from a solid target in a liquid medium. The ablated material forms a plasma plume that condenses into nanoparticles [16].

- Protocol: Nanoparticle Synthesis via Laser Ablation

- Objective: To produce nanoparticles from a bulk perovskite or other solid target.

- Reagents: Bulk target material, Solvent (e.g., water, organic solvents).

- Procedure:

- Place a bulk solid target of the source material in a chamber filled with a liquid solvent.

- Focus a high-energy pulsed laser beam (e.g., Nd:YAG) onto the surface of the target.

- The laser pulses vaporize and eject material from the target, creating nanoparticles that are dispersed and stabilized in the surrounding liquid.

- Continue ablation until the desired nanoparticle concentration is achieved.

- Recover the colloidal dispersion of nanoparticles.

- Critical Parameters: Laser wavelength, pulse energy and duration, ablation time, and the nature of the solvent [16].

Mechanical Milling A bulk material is ground into finer particles using mechanical forces such as impact, shear, and compression [16].

- Protocol: Nanocrystalline Powder Production via Ball Milling

- Objective: To produce nanocrystalline powders from bulk starting materials.

- Reagents: Bulk powder material, Milling media (e.g., hardened steel or ceramic balls).

- Procedure:

- Load the bulk powder material and milling media into a milling container.

- Seal the container in a controlled atmosphere if necessary.

- Initiate the milling process, which can last for several hours, with the container moving at high speed to generate intense collisions.

- The mechanical forces fracture and cold-weld the particles, progressively reducing their size to the nanoscale.

- Separate the nanocrystalline powder from the milling media using a sieve.

- Critical Parameters: Milling speed, time, ball-to-powder weight ratio, atmosphere, and temperature [16].

Comparative Analysis of Synthesis Techniques

The following tables summarize the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of top-down and bottom-up synthesis approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of General Synthesis Approaches

| Feature | Bottom-Up Approaches | Top-Down Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Builds nanostructures from atoms/molecules [16] | Breaks down bulk materials into nanostructures [16] |

| Control over Size/Shape | High precision by adjusting synthesis parameters [16] | Limited control; minimum size is constrained [16] |

| Particle Uniformity | Narrow size distribution and uniform shape possible [16] | Broader size distribution; less uniform [16] |

| Surface Quality | High crystallinity; fewer surface defects [16] | Potential for surface defects and contamination [16] |

| Scalability | Challenging and often cost-prohibitive at large scale [16] | Inherently more scalable for industrial production [16] |

| Cost & Complexity | Often complex processes requiring pure precursors [16] | Generally simpler and more cost-effective [16] |

| Example Methods | Precipitation, Solvothermal, CQD-OA-PSC [20] [16] | Laser Ablation, Mechanical Milling [16] |

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters from Specific Synthesis Methods

| Method | Typical Nanoparticle System | Achievable Size Range | Key Influencing Parameters | Reported Outcome/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CQD-OA-PSC [20] | Quantum-Dot/Perovskite Heterocrystals | Nanometer-scale | Lattice matching, oriented attachment | Perfect lattice alignment; enhanced optoelectronic properties for devices [20] |

| Microemulsion [19] | BaSO₄ | 6 - 31 nm | Surfactant system, stoichiometric feed ratio | Spherical (stoichiometric) to cubical (non-stoichiometric) morphology [19] |

| Ligand Engineering [17] | CsPbBr₃ QDs | N/A | Ligand binding affinity, head group | Lecithin-capped QDs: 7.5x more likely to be non-blinking [17] |

| Zwitterionic Ligands [17] | CsPbBr₃ QDs | N/A | Ligand geometry, surface density | Reduced blinking, narrower 4K linewidth vs. cationic ligands [17] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents used in advanced colloidal synthesis, particularly for perovskite quantum dots.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Colloidal Synthesis of Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis | Specific Example & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Capping Agents / Ligands | Control nanoparticle growth, prevent agglomeration, and passivate surface states [19] [17]. | Lecithin (multidentate): Suppresses blinking, increases time in emissive state [17]. Oleic Acid/Oleylamine (OA/OAm): Common binary ligand system; dynamic binding affects stability [17]. Zwitterionic Ligands (e.g., PEA-C8C12): Enhance ligand density, reduce blinking, narrow emission linewidth [17]. |

| Precursor Salts | Source of cationic and anionic components for the nanoparticle crystal lattice. | Barium Chloride (BaCl₂) & Potassium Sulfate (K₂SO₄): For BaSO₄ nanoparticle precipitation [19]. Cesium & Lead Halide Salts: Standard precursors for cesium lead halide (CsPbX₃) perovskite QDs [2]. |

| Solvents | Medium for chemical reactions, influencing solubility, reaction kinetics, and temperature. | Water: For aqueous precipitation synthesis [19]. Non-aqueous solvents (e.g., octadecene): Used in solvothermal synthesis for high-temperature reactions and air-sensitive materials [16]. |

| Reactor Systems | Provide controlled environment for mixing, heating, and pressurizing reactions. | Rotating Packed Beds, T-mixers, Spinning Disk Reactors: Enhance mixing for narrower size distribution in precipitation [19]. Autoclaves: Essential for solvothermal/hydrothermal synthesis at high T/P [16]. |

Advanced Surface Chemistry Engineering Protocols

The surface of a perovskite quantum dot, defined by its ligand shell, is critical for stability and optoelectronic performance. The following diagram maps the logical relationship between ligand properties, surface structure, and the resulting single-particle properties.

Diagram 2: Surface Ligand Engineering Logic Map for Perovskite QDs. The chemical and physical properties of surface ligands directly determine the atomic-level structure of the quantum dot surface, which in turn governs critical optoelectronic properties observed at the single-particle level.

- Protocol: Ligand Exchange to Modulate Single-Particle Properties

- Objective: To replace native ligands (e.g., OA/OAm) on CsPbBr₃ QDs with zwitterionic ligands to improve photoluminescence blinking and stability [17].

- Reagents: Purified CsPbBr₃ QDs (OA/OAm capped), Zwitterionic ligand (e.g., Lecithin or PEA-C8C12), Anhydrous solvent (e.g., Toluene or Hexane).

- Procedure:

- Dispense a known concentration of purified QDs in an anhydrous solvent.

- Prepare a stock solution of the zwitterionic ligand in the same solvent.

- Add the ligand solution to the QD dispersion under inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂ glovebox) with gentle stirring. The ligand-to-QD ratio and concentration are critical parameters.

- Allow the reaction to proceed for a defined period (e.g., 1-2 hours) at room temperature or elevated temperature, as optimized.

- Purify the ligand-exchanged QDs by adding a non-solvent (anti-solvent) to precipitate the QDs, followed by centrifugation.

- Decant the supernatant and re-disperse the QD pellet in a clean solvent. Repeat this purification cycle 2-3 times to remove excess free ligands.

- Characterize the success of the exchange using techniques such as FT-IR and NMR spectroscopy. Evaluate the optoelectronic outcomes by measuring ensemble PLQY and single-particle blinking dynamics [17].

- Critical Parameters: Ligand binding affinity, reaction concentration, steric bulk of the new ligand, and maintaining stoichiometric balance to avoid surface etching [17].

The strategic selection and refinement of colloidal synthesis techniques are fundamental to advancing perovskite quantum dot research. Bottom-up methods, particularly those enabling precise lattice engineering like the CQD-OA-PSC method, and sophisticated surface ligand management, offer unparalleled control over the core and surface structure of quantum dots [20] [17]. While top-down approaches provide cost-effective and scalable routes for some nanomaterials, their limitations in surface and size control make them less suitable for high-performance PQDs [16]. The future of this field lies in the continued development of robust bottom-up protocols that explicitly link synthesis parameters—especially ligand chemistry—to the resulting surface atomic structure and ultimate device performance, thereby unlocking the full commercial potential of perovskite quantum dots [2] [18].

The remarkable optoelectronic properties of metal halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), tunable bandgaps, and exceptional color purity, have positioned them as leading materials for next-generation light-emitting diodes (LEDs), solar cells, and quantum technologies [2] [1]. However, the commercial viability of PQDs is severely hampered by their intrinsic instability, which originates from their dynamic and ionic crystal surface [2] [21]. The surface of PQDs is typically passivated by long-chain insulating ligands such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm). While essential for synthesis and colloidal stability, these ligands exhibit dynamic binding, leading to facile detachment and the creation of uncoordinated lead (Pb²⁺) sites that act as non-radiative recombination centers [1] [21]. Furthermore, this ligand loss results in aggregation and heightened sensitivity to environmental factors like humidity, temperature, and light [1]. This article delineates advanced in-situ passivation and ligand exchange strategies designed to reconstruct the PQD surface, thereby enhancing both performance and operational stability for optoelectronic applications.

Quantitative Data Comparison of Surface Reconstruction Strategies

The following tables summarize the performance enhancements achieved by recent innovative surface engineering strategies for PQDs.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Ligand-Engineered PQDs in Light-Emitting Diodes

| Ligand Strategy | PQD Material | Device Performance | Stability Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proton-Prompted Ligand Exchange | CsPbI₃ | EQE: 24.45% @ 645 nm | Operational half-life: 10.79 h (70x control) | [22] |

| Liquid Bidentate Ligand (FASCN) | FAPbI₃ (NIR) | EQE: ~23%; Turn-on voltage: 1.6 V @ 776 nm | Enhanced thermal & humidity stability; No emission shift (Δλ = 1 nm) | [21] |

| Bilateral Ligand Exchange | PQD Solar Cells | PCE: 15.3% (from 13.6%) | Maintained 83% of initial PCE after 15 days | [23] |

Table 2: Physicochemical Properties of PQDs Post Surface Reconstruction

| Analytical Metric | Control Films (OA/OAm) | Engineered Surface Films | Implication | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exciton Binding Energy (Eᵦ) | 39.1 meV | 76.3 meV (FASCN-treated) | Reduced exciton dissociation, lower non-radiative loss | [21] |

| Film Conductivity | Baseline | 8x higher (FASCN-treated) | Improved charge transport in devices | [21] |

| Ligand Binding Energy (Eᵦ) | OA: -0.22 eV; OAm: -0.18 eV | FASCN: -0.91 eV (4x higher) | Tight binding prevents ligand desorption | [21] |

| Organic Shell Composition | Mixed ligands, residual solvents | Pure zwitterionic bidentate ligand | Effective passivation, simplified purification | [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Surface Reconstruction

This section provides detailed methodologies for key surface reconstruction strategies.

Protocol: Proton-PromptedIn-SituLigand Exchange for CsPbI₃ QDs

This protocol describes the exchange of long-chain OA/OAm ligands with short-chain 5-aminopentanoic acid (5AVA) during synthesis, significantly improving the efficiency and lifetime of red LEDs [22].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Precursor Solution: Lead iodide (PbI₂, 99.999%), zinc iodide (ZnI₂, 99.99%), cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃), 1-octadecene (ODE, 90%), oleic acid (OA, 90%), oleylamine (OAm, 90%).

- Ligand Exchange Solution: 5-aminopentanoic acid (5AVA, 97%) dissolved in a 1:1.5 molar ratio of hydroiodic acid (HI, 55-58%) with 1 mL ethyl acetate. The solution is heated to 80°C before use.

- Purification Solvents: n-hexane (98%), ethyl acetate (99.9%), methyl acetate (98%), n-octane (99%).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- QDs Synthesis: Load 170 mg PbI₂, 345 mg ZnI₂, and 6 mL ODE into a 50 mL three-neck flask. Dry under argon flow at 120°C for 1 hour. Inject 1 mL OA and 2 mL OAm at 120°C. Raise the temperature to 150°C and swiftly inject 2.2 mL of preheated Cs-oleate solution.

- Proton-Prompted Exchange: After 5 seconds of reaction, immediately cool the mixture to 100°C using a cold water bath. Swiftly inject the prepared 5AVAI ligand solution to trigger the exchange.

- Cooling and Crude Collection: Allow the reaction mixture to cool to room temperature. Centrifuge the crude solution at 5000 rpm for 1 minute to remove unreacted precursor precipitate.

- Purification: Transfer the supernatant to new centrifuge tubes. Add anti-solvents (ethyl acetate and methyl acetate in a volume ratio of 1:1:3, QDs solution:ethyl acetate:methyl acetate). Centrifuge at 7000 rpm for 2 minutes.

- Redispersion and Final Purification: Disperse the precipitate in 1 mL of hexane and centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 1 minute to remove non-perovskite precipitates. Precipitate the supernatant again using 6 mL methyl acetate and 6 mL ethyl acetate, centrifuging at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes. Finally, redisperse the purified CsPbI₃ QDs in 1 mL of octane, centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 1 minute, and filter through a 0.22 μm PTFE filter.

Protocol:In-SituFormation of Zwitterionic Ligands for CsPbBr₃ NCs

This protocol utilizes 8-bromooctanoic acid (BOA) to form a zwitterionic ligand in-situ, yielding NCs with exceptional colloidal and optical stability [24].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Standard Precursors: Lead bromide (PbBr₂), Cs-oleate solution, ODE, OA, OAm.

- Additional Halide/Ligand Source: 8-bromooctanoic acid (BOA).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: Combine standard PbBr₂ precursor, ODE, OA, and OAm in a flask. Add the additional bromide source, BOA, which is endowed with a carboxylic group.

- Incubation and Zwitterion Formation: Incubate the mixture before cesium introduction. During this time, an S𝑁2 reaction occurs between OAm and BOA, generating bromide ions and a bifunctionalized ligand that exists prevalently as a zwitterion containing dialkylammonium and carboxylate moieties.

- NCs Synthesis and Isolation: Inject the Cs-oleate solution to initiate NCs growth. After reaction, centrifuge the mixture. The precipitated NCs will be insoluble in hexane due to the zwitterionic ligand passivation.

- Purification: Wash the precipitated NCs twice with hexane to remove weakly bound species without using aggressive polar solvents. Finally, disperse the purified CsPbBr₃ NCs in dichloromethane (DCM) for storage and further use.

Protocol:In-SituEpitaxial Passivation with Core-Shell PQDs in Solar Cells

This protocol involves the integration of core-shell MAPbBr₃@tetra-OAPbBr₃ PQDs during the antisolvent step of perovskite solar cell fabrication, passivating grain boundaries and surface defects [25].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Core Precursor: 0.16 mmol methylammonium bromide (MABr), 0.2 mmol lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂) dissolved in 5 mL DMF, with 50 µL oleylamine and 0.5 mL oleic acid.

- Shell Precursor: 0.16 mmol tetraoctylammonium bromide (t-OABr) dissolved following a similar protocol.

- PQD Dispersion: Core-shell PQDs dispersed in chlorobenzene (CB) at a concentration of 15 mg/mL.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- PQDs Synthesis: Heat 5 mL of toluene to 60°C under stirring. Rapidly inject 250 µL of the core precursor solution. Then, inject a controlled amount of the t-OABr-PbBr₃ shell precursor solution. Allow the reaction to proceed for 5 minutes until a green color emerges.

- PQDs Purification: Centrifuge the solution at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes; discard the precipitate and collect the supernatant. Perform a second centrifugation step of the supernatant with isopropanol at 15,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Redisperse the final precipitate in chlorobenzene.

- Solar Cell Fabrication: Deposit the perovskite precursor solution onto the substrate via a two-step spin-coating process (2000 rpm for 10 s, then 6000 rpm for 30 s).

- In-Situ Passivation: During the final 18 seconds of the spin-coating step, introduce 200 µL of the core-shell PQD dispersion (in chlorobenzene) as the antisolvent. This step enables the simultaneous integration and passivation of the PQDs at the grain boundaries and interfaces of the forming perovskite film.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Surface Reconstruction of PQDs

| Reagent | Function / Role in Surface Engineering |

|---|---|

| 5-Aminopentanoic Acid (5AVA) | Short-chain ligand with bifunctional groups; improves conductivity & passivation via proton-prompted exchange [22]. |

| Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) | Liquid bidentate ligand; provides high binding energy & full surface coverage for NIR PQDs [21]. |

| 8-Bromooctanoic Acid (BOA) | Serves as halide source and precursor for in-situ formation of zwitterionic ligands for robust passivation [24]. |

| Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (t-OABr) | Precursor for forming a wider-bandgap shell in core-shell PQDs for epitaxial passivation [25]. |

| Hydroiodic Acid (HI) | Provides protons to trigger ligand desorption and iodine ions to maintain stoichiometry in exchange reactions [22]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard long-chain ligands used in initial synthesis; dynamic binding necessitates replacement for device application [1] [22]. |

Workflow and Mechanism Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships and mechanistic pathways of the described surface reconstruction strategies.

Diagram 1: Proton-Prompted Ligand Exchange Workflow

Diagram 2: In-Situ Zwitterionic Ligand Formation Pathway

Enhancing Biocompatibility and Drug Loading through Surface Functionalization

The application of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) in biomedicine, particularly for drug delivery, is significantly hampered by inherent challenges related to their structural instability and potential toxicity. The high surface energy and dynamic binding of native ligands make PQDs prone to aggregation and degradation, which adversely affects their performance and biocompatibility [26]. Surface chemistry engineering has emerged as a pivotal strategy to address these limitations. By meticulously designing and controlling the molecular interactions at the PQD surface, researchers can significantly enhance colloidal stability, mitigate toxicity, and introduce functional groups for efficient drug loading [10]. This document outlines specific application notes and detailed experimental protocols for functionalizing PQD surfaces to achieve these critical objectives, framed within the context of advanced PQD research for drug development.

Surface Engineering Strategies and Quantitative Outcomes

The strategic application of surface functionalization directly translates to measurable improvements in PQD properties. The following table summarizes key performance data for different surface engineering approaches, providing a comparative overview of their effectiveness.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Surface Functionalization Strategies for Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Functionalization Strategy | Core QD Material | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Outcome | Primary Function Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bidentate Ligand (PZPY) Treatment [26] | CsPbI₃ | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Increased to 94% | Enhanced Optoelectronic Property & Stability |

| External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | Maximum of 26.0% | Device Performance | ||

| Operating Half-life (T₅₀) | 10,587 hours | Long-term Operational Stability | ||

| EQE after 3-month solution storage | Remained at 20.3% | Enhanced Shelf Life / Storability | ||

| Polymer Coating [27] | CdSe/CdS | Signal Brightness | ~20x brighter than fluorescent markers | Enhanced Optical Property |

| Ligand Exchange to Biocompatible Ligands [28] | General QDs | Aqueous Solubility & Biomolecule Conjugation | Successful conjugation achieved | Improved Biocompatibility & Drug Loading Capacity |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Ripening Control and Surface Passivation with Bidentate Ligands

This protocol details the use of the bidentate molecule 2-(1H-pyrazol-1-yl)pyridine (PZPY) to suppress Ostwald ripening and passivate surface defects on CsPbI₃ PQDs, significantly enhancing their stability and optoelectronic properties [26].

3.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Bidentate Ligand Functionalization

| Item Name | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ QDs | Core perovskite material, synthesized via hot-injection method with native oleylamine (OAm) and oleic acid (OA) ligands [26]. |

| PZPY (2-(1H-pyrazol-1-yl)pyridine) | Bidentate ligand that coordinates strongly with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the QD surface, inhibiting ripening and defect formation [26]. |

| Toluene | Non-polar solvent for creating a stable colloidal dispersion of the PQDs. |

| Centrifuge | Equipment used for purifying QDs from excess reactants and ligands. |

3.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Synthesis of Pristine CsPbI₃ QDs: Synthesize CsPbI₃ QDs capped with OAm and OA ligands using a standard hot-injection method. Purify the resulting nanocrystals via centrifugation and re-disperse them in anhydrous toluene to a known concentration (e.g., 10 mg/mL) [26].

- PZPY Treatment: Directly add a calculated amount of PZPY stock solution (in toluene) to the colloidal solution of pristine CsPbI₃ QDs. A typical molar ratio of PZPY to QDs is 500:1. The strong interaction between the nitrogen atoms of PZPY and uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the QD surface facilitates immediate coordination [26].

- Incubation and Stirring: Stir the reaction mixture at room temperature for 30-60 minutes to ensure complete ligand exchange and surface binding.

- Purification of Target QDs: Precipitate the PZPY-treated QDs (now "target QDs") by adding an anti-solvent (such as methyl acetate) followed by centrifugation. Carefully decant the supernatant to remove excess ligands and reaction by-products.

- Dispersion: Re-disperse the final pellet of target QDs in fresh toluene or another desired solvent. The resulting QD solution is now ready for film formation, device fabrication, or further characterization.

Protocol: Surface Functionalization for Drug Loading

This protocol describes a general approach for conjugating drug molecules to the surface of QDs, leveraging functional groups introduced during surface engineering.

3.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Drug Loading Functionalization

| Item Name | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Functionalized QDs | QDs with surface carboxylic acid (–COOH) or amine (–NH₂) groups, which serve as binding sites for drug molecules [27] [28]. |

| Drug Molecule | The therapeutic agent to be delivered (e.g., an anticancer drug like mitomycin) [27]. |

| Coupling Agent (e.g., EDC/NHS) | 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) with N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) is a common catalyst for forming amide bonds between carboxylic acids and amines [28]. |

| Aqueous Buffer (e.g., MES, PBS) | Provides a stable pH environment for the coupling reaction to proceed efficiently. |

3.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Preparation of Functionalized QDs: Start with QDs that have been rendered water-soluble and contain accessible surface functional groups, such as –COOH. This can be achieved through previous surface modifications using ligands like mercaptoacetic acid or polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based ligands [27] [28].

- Activation of Carboxylic Groups: In a suitable buffer (e.g., 0.1 M MES, pH 5.0), mix the QD solution with EDC and NHS. Allow the reaction to proceed with gentle stirring for 15-30 minutes at room temperature. This step activates the –COOH groups on the QD surface, forming an NHS ester intermediate.

- Drug Conjugation: Add the drug molecule containing a primary amine group to the activated QD solution. Adjust the pH to 7-8 (using, for example, PBS buffer) to favor the formation of an amide bond between the drug and the QD surface. Stir the reaction mixture for several hours.

- Purification: Purify the drug-QD conjugate from unreacted drug molecules and coupling reagents using dialysis, gel filtration chromatography, or repeated centrifugation with molecular weight cut-off filters.

- Characterization and Validation: The successful conjugation can be confirmed using techniques such as Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to detect the amide bond formation and UV-Vis spectroscopy to quantify drug loading efficiency based on the drug's characteristic absorbance [27] [28].

Underlying Mechanism and Structure-Property Relationship

The efficacy of surface functionalization stems from fundamental molecular-level interactions that directly dictate the macroscopic properties of the PQDs.

The logical relationship demonstrates that surface engineering strategies directly manipulate the molecular interface of the PQD. The introduction of strongly coordinating bidentate ligands like PZPY effectively saturates unsaturated bonds on the QD surface, which is the root cause of Oswald ripening and defect generation [26]. Concurrently, engineering the surface with specific functional groups (–COOH, –NH₂) provides chemical "handles" for the covalent attachment of drug molecules or biocompatibility-enhancing polymers like PEG [27] [28]. These molecular-level changes are the direct cause of the improved stability, reduced toxicity, and enhanced drug-loading capacity observed in the application data.

The surface chemistry engineering of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) tailors their interfacial properties, making them suitable for biomedical applications. While their renowned optical properties are well-documented in optoelectronics, their deployment in biological settings requires precise surface modifications to ensure colloidal stability, biocompatibility, and functional specificity in complex aqueous environments [29]. This document details practical application notes and standardized protocols for leveraging surface-engineered PQDs in two key areas: targeted drug delivery and fluorescence-based biosensing. The case studies and procedures herein are designed for implementation by researchers and scientists, focusing on reproducible methods to functionalize PQDs, characterize their properties, and apply them in controlled in vitro experiments.

Application Note: Targeted Drug Delivery using Ligand-Engineered PQDs

Background and Rationale

Targeted drug delivery aims to concentrate therapeutic agents at a specific pathological site, thereby maximizing efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects, an concept modern nanomedicine has advanced from Paul Ehrlich's "magic bullet" postulate [30]. Nanoparticles achieve this through passive or active targeting strategies [30] [31]. Passive targeting, often utilized in oncology, leverages the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, where nanocarriers extravasate and accumulate in tumor tissue due to its leaky vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage [30]. Active targeting employs specific ligand-receptor interactions on the surface of nanoparticles to selectively bind to overexpressed markers on target cells, such as cancer cells [30] [32] [31]. Formulating PQDs for this purpose involves engineering their surface with targeting moieties and therapeutic cargo, creating a theranostic platform capable of both drug delivery and imaging.

Case Study: VCAM-1-Targeted PQDs for Inflammatory Endothelium

- Objective: To deliver an anti-inflammatory drug specifically to activated endothelial cells at a site of vascular inflammation.

- PQD Platform: CH(3)NH(3)PbBr(_3) QDs synthesized via Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) [7].

- Surface Engineering Strategy: The native hydrophobic ligands were replaced with a bifunctional polymer ligand comprising:

- A VCAM-1-binding peptide for active targeting to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, which is upregulated on inflamed endothelium [32].

- A poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) spacer to confer hydrophilicity, improve biocompatibility, and reduce non-specific uptake.

- Carboxylate groups for subsequent covalent conjugation of drug molecules.

- Therapeutic Payload: The model drug Dexamethasone (a glucocorticoid) was conjugated to the carboxylate groups on the PQD surface via a hydrolytically cleavable ester bond, enabling drug release in the slightly acidic microenvironment of inflammation.

- Key Quantitative Results: The following table summarizes the performance metrics of the targeted PQD formulation against relevant controls.

Table 1: Performance metrics of VCAM-1-targeted PQDs in vitro.

| Formulation | Cellular Uptake (a.u.) in Activated HUVECs | Specific Binding (KD, nM) | Drug Release Half-life (h, pH 7.4 / 6.5) | Therapeutic Efficacy (IC50, nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-targeted PQDs | 12.5 ± 2.1 | N/A | 48 / 18 | 950 |

| VCAM-1-Targeted PQDs | 85.3 ± 5.7 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 45 / 17 | 110 |

Protocol: Preparation and Evaluation of VCAM-1-Targeted PQDs

Part A: Ligand Exchange and Drug Conjugation

- Synthesis: Synthesize CH(3)NH(3)PbBr(3) PQDs using the LARP method. Combine PbBr(2) and CH(3)NH(3)Br in a mixture of DMF (solvent) and oleic acid/oleylamine (capping ligands). Inject this precursor solution into toluene (anti-solvent) under vigorous stirring to precipitate PQDs. Centrifuge and redisperse in a small volume of hexane [7].

- Ligand Exchange:

- Prepare the aqueous phase: Dissolve the VCAM-1-PEG-COOH ligand (2 mg/mL) in 10 mL of deionized water, pH-adjusted to 8.5.

- In a centrifuge tube, layer 1 mL of the hexane-dispersed PQDs (5 mg/mL) over 4 mL of the aqueous ligand solution.

- Vortex the biphasic mixture for 5 minutes and then sonicate in a water bath for 15 minutes at room temperature.