Surface Chemistry and Electronic Transport: From Molecular Design to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how surface chemistry dictates the electronic transport properties of nanomaterials, a critical consideration for developing advanced biomedical technologies.

Surface Chemistry and Electronic Transport: From Molecular Design to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how surface chemistry dictates the electronic transport properties of nanomaterials, a critical consideration for developing advanced biomedical technologies. It explores fundamental interfacial interactions, state-of-the-art characterization and computational methods, strategies to overcome common experimental challenges, and comparative validation of material systems. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes insights from recent experimental and theoretical studies to guide the rational design of more efficient drug delivery systems, biosensors, and electronic therapeutic devices by mastering surface-level phenomena.

The Interface Frontier: How Surface Chemistry Dictates Electronic Pathways

The interactions at the interfaces between materials and biological systems fundamentally govern electronic transport properties, molecular recognition, and the efficacy of advanced materials. In research ranging from biosensor development to nanomedicine design, understanding the precise nature and relative strengths of covalent, ionic, and non-covalent forces is paramount. These interactions collectively determine how molecules adsorb to surfaces, how signal transduction occurs across interfaces, and how efficiently charge transfers in electronic devices. While covalent bonds provide permanent linkage, non-covalent interactions offer dynamic, reversible associations that are crucial for adaptive biological systems and responsive materials. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these fundamental forces, with specific emphasis on their roles in surface chemistry effects on electronic transport properties research, enabling researchers to make informed decisions in experimental design and data interpretation.

Comparative Analysis of Fundamental Interactions

The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the key characteristics of covalent, ionic, and non-covalent interactions, highlighting their relative strengths, length scales, and functional roles in material and biological systems.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Fundamental Chemical Interactions

| Interaction Type | Strength Range (kcal/mol) | Bond Length | Role in Molecular Systems | Directionality | Reversibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent | 50-200 [1] [2] | 0.7-2.0 Å | Primary molecular structure; linear connectivity | High | Irreversible under biological conditions |

| Ionic | 10-250 (highly context-dependent) [3] | 2.0-3.5 Å (for simple salts) | Electrostatic attraction between full charges; crystal formation | Low in solids; medium in solutions | Moderate (dependent on dielectric environment) |

| Hydrogen Bond | 1-40 (typically 1-5) [4] | 2.5-3.2 Å | Secondary structure; molecular recognition | High | Highly reversible |

| Van der Waals | 0.1-4 [4] | 3.0-4.0 Å | Tertiary structure; physical adsorption | Low | Highly reversible |

| Hydrophobic Effect | Not applicable (entropy-driven) | Variable | Membrane formation; protein folding; micellization | Not directional | Driven by system thermodynamics |

| π-Effects (π-π, cation-π, etc.) | 1-15 [4] | 3.0-4.0 Å | Aromatic stacking; drug intercalation; surface binding | Moderate | Highly reversible |

The data reveals a clear hierarchy in interaction strengths, with covalent bonds being the strongest and most directional, while non-covalent interactions span a wide range of energies that collectively enable complex molecular organization. The strength of ionic interactions shows significant contextual variation, being strongest in gas phase and crystalline solids but substantially weakened in aqueous environments due to water's high dielectric constant [1] [3]. Non-covalent interactions, while individually weak, can collectively generate substantial binding energies when numerous interactions act cooperatively, as seen in protein-ligand complexes and molecular self-assembly processes [1] [5].

Table 2: Electronic Properties and Relevance to Transport Phenomena

| Interaction Type | Electronic Character | Influence on Electronic Transport | Role at Interfaces | Experimental Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent | Electron sharing; orbital overlap | Direct pathway for electron transfer; determines band structure | Permanent functionalization of surfaces | Vibrational spectroscopy (IR, Raman); XPS |

| Ionic | Complete electron transfer; full charges | Ion conduction; electrostatic gating; space charge regions | Charge separation; double layer formation | Impedance spectroscopy; zeta potential |

| Hydrogen Bond | Dipole-dipole with H participation | Proton conduction; modifies local dielectric constant | Molecular recognition; mediates electron transfer | NMR chemical shifts; FTIR |

| Van der Waals | Transient/induced dipoles | Tunneling barrier modification; weakly modulates conductivity | Physical adsorption; non-specific binding | AFM force measurements; adsorption isotherms |

| Hydrophobic Effect | Entropic (water restructuring) | Indirect through organization of non-polar domains | Membrane formation; partitioning | Calorimetry; contact angle measurements |

| π-Effects | Orbital interaction with π-systems | Electron hopping; charge transport pathways | Aromatic molecule adsorption; graphene functionalization | UV-Vis spectroscopy; cyclic voltammetry |

The electronic properties column highlights how each interaction type participates differently in electronic transport phenomena. Covalent bonds enable direct electron transfer through connected molecular frameworks, while ionic interactions facilitate ion conduction and establish electric fields that can gate electronic transport. Non-covalent interactions primarily modify the local environment for charge transport and create organizational structures that position molecular components for optimal electronic coupling [5] [6].

Experimental Methodologies for Interface Characterization

Quantifying Non-Covalent Interactions via Electron Density Analysis

Advanced computational methods have been developed to directly map and quantify non-covalent interactions in real space using electron density and its derivatives, providing researchers with powerful tools for interface characterization [6].

Protocol: Reduced Density Gradient (RDG) Analysis

Principle: The method identifies non-covalent interactions as regions of low electron density (ρ) and low reduced density gradient (s). The interaction type is distinguished by the sign of the second eigenvalue (λ₂) of the electron density Hessian matrix, where λ₂ < 0 indicates attractive interactions and λ₂ > 0 indicates non-bonded overlap [6].

Procedure:

- Obtain molecular geometry through X-ray crystallography or DFT optimization

- Calculate electron density (ρ) and its derivatives using quantum chemistry software

- Compute the reduced density gradient: s = (1/2)(3π²)¹/³ × |∇ρ|/ρ⁴/³

- Generate 3D isosurfaces colored according to sign(λ₂)ρ values

- Interpret results: Blue surfaces indicate strong attractive interactions (hydrogen bonds), green indicates weak van der Waals interactions, and red indicates steric repulsion [6]

Applications: This method has been successfully applied to small molecules, molecular complexes, proteins, and DNA, requiring only atomic coordinates and being efficient enough for large systems [6].

Nanoparticle-Mediated Drug Delivery as a Model System

The study of nanoparticle-drug interactions provides a relevant experimental framework for understanding how multiple interaction types cooperate at interfaces in biological environments [5].

Protocol: Evaluating Drug Loading Efficiency on Nanoparticles

Objective: Quantify the immobilization of drug molecules onto nanoparticle vectors through non-covalent interactions, a process critical to nanomedicine development [5].

Methods:

- Surface-Mediated Loading: Drug molecules are directly adsorbed to functionalized nanoparticle surfaces through hydrophobic, electrostatic, or hydrogen bonding interactions [5]

- Encapsulation Techniques: Drugs are physically trapped within porous nanoparticle matrices or polymeric shells [5]

- Solvent Replacement: Hydrophobic drugs are loaded by initially dispersing nanoparticles in organic solvent, adding drug, then exchanging with aqueous buffer [5]

Efficiency Assessment:

- Purify conjugates from free drug via centrifugation, dialysis, or filtration

- Quantify bound drug using spectroscopic methods (e.g., fluorescence quenching by metallic nanoparticles) [5]

- Calculate loading efficiency = (amount of bound drug / total drug) × 100%

Key Considerations: Drug loading is typically the summation of multiple cooperating forces within the system, with efficiency depending on accessible binding sites and drug diffusion kinetics to the nanoparticle surface [5].

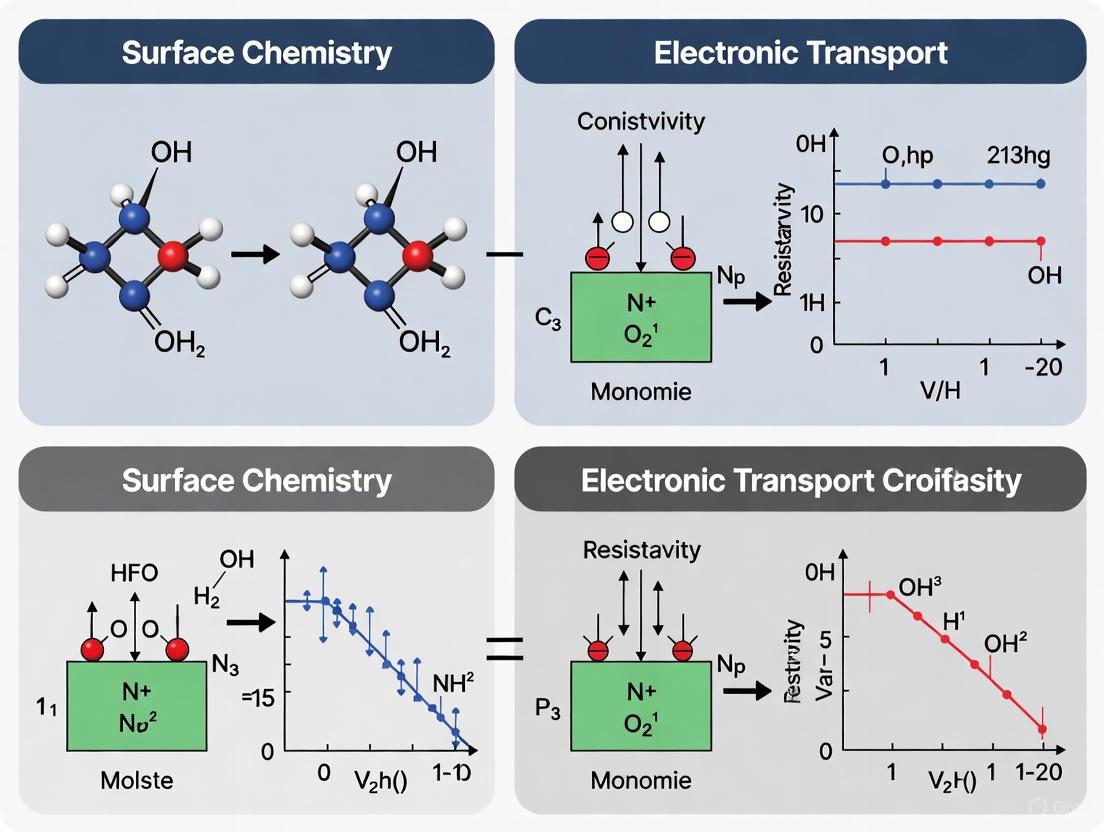

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for comprehensive analysis of non-covalent interactions at interfaces, combining sample preparation, computational analysis, and data interpretation stages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below outlines key materials and their functions in studying interfacial interactions, particularly in contexts relevant to electronic transport and drug delivery applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Interface Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles | Versatile plasmonic platform for surface functionalization | Model system for studying drug loading kinetics; surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy [5] |

| PEGylated Surfaces | Provide stealth properties and prevent non-specific adsorption | Studying the role of hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity in interfacial interactions [5] |

| Zwitterionic SAMs | Model surfaces with controlled charge distribution | Investigating the balance of electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions [5] |

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles | High surface area scaffolds with tunable pore size | Studying confinement effects on molecular interactions and loading efficiency [5] |

| Quantum Dots | Fluorescent probes with size-tunable emission | Tracking molecular interactions and energy transfer at interfaces |

| DNA/RNA Oligonucleotides | Programmable biomolecules with specific recognition | Modeling biological interfaces and molecular recognition events [2] |

| Boron Cluster Anions (e.g., [B₁₀H₁₀]²⁻) | Electron-deficient species for unconventional interactions | Studying dihydrogen bonds and halogen bonding in coordination chemistry [7] |

These materials serve as standardized platforms for systematically investigating how different interaction types contribute to overall interfacial behavior. Their well-characterized properties enable researchers to deconvolute complex interfacial phenomena into contributions from individual force components.

Implications for Electronic Transport Research

The interplay between different interaction types at interfaces directly influences electronic transport properties through multiple mechanisms. Covalent linkages provide robust, conductive pathways for electron transfer, but their formation often requires harsh conditions that may damage sensitive materials. Ionic interactions establish electric double layers that can dramatically modulate conductivity through gating effects, particularly in semiconductor devices and electrochemical systems. Non-covalent interactions, while not directly conductive, enable precise molecular positioning that optimizes electron tunneling distances and facilitates interfacial charge transfer.

In drug delivery systems, the same principles govern cellular uptake and release kinetics. Nanoparticles functionalized with targeting ligands through covalent bonds maintain their surface functionality during circulation, while drugs loaded through non-covalent interactions can be released in response to specific cellular environments [5]. This balance between stability and reversibility mirrors the requirements for many electronic devices that need both durable interfaces and responsive behavior.

The hydrophobic effect, while not a direct force, drives the organization of non-polar molecules and surfaces in aqueous environments, creating segregated domains that can template the assembly of conductive pathways or block undesirable charge leakage. Similarly, π-π interactions between aromatic systems facilitate electron hopping along stacked molecular arrays, enabling charge transport across non-covalently linked systems [4].

Diagram 2: Causal relationships between different interaction types and their effects on electronic transport properties at interfaces.

The strategic integration of covalent, ionic, and non-covalent interactions enables precise control over interfacial properties in both electronic and biological systems. Covalent bonds provide the foundational stability for device architectures and permanent functionalization, ionic interactions enable field-effect modulation and responsive behavior, while non-covalent forces facilitate adaptive assembly and reversible binding. The quantitative parameters and experimental methodologies outlined in this guide provide researchers with a framework for designing interfaces with tailored electronic transport properties, whether for biosensing applications, drug delivery systems, or molecular electronics. Future advances in this field will likely emerge from more sophisticated combinations of these interaction types, leveraging their complementary strengths to create interfaces with unprecedented functionality and responsiveness.

The performance of modern electronic devices, sensors, and energy technologies is fundamentally governed by electron transport properties at surfaces and interfaces. As device dimensions continue to shrink toward the nanoscale, surface effects increasingly dominate overall performance characteristics. This comprehensive analysis examines three critical surface parameters—charge, composition, and structure—that collectively govern electron flow across diverse material systems. By comparing experimental data and theoretical frameworks from multiple research domains, this review establishes foundational principles for predicting and optimizing electron transport behavior in advanced materials systems, with particular relevance for microelectronics, electrochemistry, and energy applications where surface-mediated processes determine operational efficiency and limitations.

Surface Charge Effects on Electron Transport

Surface charge distribution plays a pivotal role in establishing electric fields that guide electron movement through conductive pathways. In metallic conductors, surface charges arrange themselves to produce internal electric fields oriented parallel to the conductor's axis, thereby facilitating directional electron flow [8]. The charge density distribution varies significantly based on conductor geometry, with curvilinear conductors requiring more complex distributions than rectilinear ones to maintain the proper field orientation [8].

At resistor interfaces, charge separation creates functionally critical potential differences. Electrons accumulate at the resistor entrance, creating a negatively charged layer, while a positively charged layer forms at the exit as electrons are depleted [8]. These charged layers establish attracting and repelling forces that collectively drive electron movement through resistive components [8]. The resulting potential differences represent the fundamental origin of voltage in both electrostatic conditions and current-carrying circuits [8].

In electrochemical systems, surface charge manifestations differ notably. During electrolysis, electron flow occurs exclusively through the external circuit, while ions serve as charge carriers within the electrolyte itself [9]. This charge transfer mechanism enables non-spontaneous redox reactions, with oxidation occurring at the anode (electron loss) and reduction at the cathode (electron gain) [10]. The spatial separation of these half-reactions creates a directional electron flow that can be harnessed for material deposition, energy storage, and chemical synthesis applications.

Table 1: Surface Charge Effects Across Different Material Systems

| Material System | Charge Carrier | Spatial Distribution | Primary Effect on Electron Flow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Conductors | Electrons | Higher density on outer surfaces | Creates internal electric fields parallel to conductor axis [8] |

| Resistor Interfaces | Electrons & ions | Charge separation at boundaries | Establishes potential difference driving force [8] |

| Electrolytic Cells | Ions (electrolyte), Electrons (external) | Anions→Anode, Cations→Cathode | Facilitates redox reactions through charge separation [9] |

| Semiconductor Films | Electrons & holes | Depth-dependent trapping states | Reduces diffusion coefficients by several orders of magnitude [11] |

Composition and Material-Dependent Electron Transport

Material composition profoundly influences electron transport characteristics, particularly through surface scattering phenomena that become increasingly dominant at reduced length scales. In cointerconnect applications, copper suffers from strong surface scattering that limits performance as dimensions decrease [12]. Research reveals that the crystallographic orientation of copper surfaces significantly impacts conductivity, with (111) surfaces exhibiting lower conductivity than (001) surfaces due to electronic structure symmetry considerations [12].

In semiconductor photoelectrodes, composition-dependent trap states dramatically impact electron mobility. Nanostructured TiO₂ films exhibit electron diffusion coefficients (~5×10⁻⁵ cm²/s) several orders of magnitude lower than single-crystal TiO₂ due to their multicrystalline nature which creates abundant electron traps [11]. This reduction occurs because electron transport in nanostructured materials occurs through a combination of percolation through networked sites and thermal accessibility to energy states, both highly sensitive to compositional defects and impurities [11].

Environmental electron transfer systems demonstrate how composition enables unexpected transport phenomena. Specialized "cable bacteria" utilize conductive filaments to transfer electrons across centimeter scales, connecting otherwise isolated redox zones in subsurface environments [13]. Simultaneously, conductive minerals and organic molecules like humic substances can form extended "electron highways" that span from nanometers to meters, dramatically influencing contaminant degradation and nutrient cycling processes [14].

Table 2: Composition-Dependent Electron Transport Properties

| Material Category | Specific Composition | Key Transport Parameter | Value/Range | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Films | Cu (111) surface | Conductivity | Lower than (001) surface [12] | First-principles calculation [12] |

| Metal Films | Cu (001) surface | Conductivity | Higher than (111) surface [12] | First-principles calculation [12] |

| Semiconductor Nanostructures | TiO₂ nanoparticle film | Electron diffusion coefficient | ~5×10⁻⁵ cm²/s [11] | EIS, IMPS, IMVS [11] |

| Semiconductor Single Crystal | TiO₂ single crystal | Electron diffusion coefficient | Several orders higher than nanoparticle [11] | EIS, IMPS, IMVS [11] |

| Biological Systems | Cable bacteria | Electron transport distance | Centimeters [13] | Electrochemical sensors [14] |

Structural and Morphological Influences

Surface and interface structures fundamentally determine electron transport pathways and scattering probabilities. Morphological parameters including porosity, surface area, pore size, particle diameter, and elemental crystal size distribution collectively influence both electron diffusion coefficients and energetic properties of materials [11]. In nanostructured photoelectrodes, these structural characteristics create distributions of trap energy states that limit excited electron lifetimes and consequently reduce diffusion coefficients [11].

Surface excitation phenomena occur when electrons traverse solid interfaces, providing an additional energy-loss channel particularly relevant for low-energy electron transport [15]. For electrons with energies up to several kiloelectronvolts, surface excitations account for a sizeable fraction of the intensity in reflection-electron-energy-loss spectra and play a key role in secondary electron emission regardless of primary energy [15]. The probability of surface excitation is approximately proportional to the surface dwell time (t∝1/√E×1/cosθ), where E represents electron energy and θ is the surface crossing angle relative to the surface normal [15].

Structural in-out asymmetry manifests in differential electron energy loss between impinging and emerging trajectories across surfaces [15]. This directional asymmetry arises from boundary conditions imposed on electric fields at interfaces and must be accounted for in accurate electron transport modeling [15]. In focused-electron-beam-induced deposition (FEBID) processes, both incoming primary electrons and emitted secondary electrons influence nanostructure growth, with secondary electrons primarily determining lateral resolution [15].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

First-Principles Surface Scattering Calculations

Objective: To predict electron transport properties under surface scattering without phenomenological parameters [12].

Protocol:

- Model Setup: Define surface orientation, such as Cu(111) or Cu(001), and establish computational cell with periodic boundary conditions

- Electronic Structure Calculation: Employ density functional theory (DFT) to determine band structures and wavefunction symmetries

- Scattering Matrix Computation: Calculate electron-surface scattering probabilities from first principles

- Conductivity Integration: Integrate scattering probabilities across the Fermi surface to obtain surface-dependent conductivity

- Validation: Compare predicted conductivity trends with experimental measurements where available

Key Parameters: Surface orientation, electronic structure symmetry, Fermi surface properties, temperature

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy for Electron Transport Characterization

Objective: To determine electron transport and recombination parameters in nanostructured materials [11].

Protocol:

- Cell Assembly: Construct symmetric or complete device cells with appropriate electrode configuration

- Frequency Sweep: Apply AC voltage signal (typically 0.01 Hz - 1 MHz) with small amplitude (10-20 mV) under illumination or bias

- Data Collection: Measure amplitude and phase shift of current response at each frequency

- Nyquist Plot Analysis: Plot imaginary versus real impedance components and identify characteristic features

- Equivalent Circuit Fitting: Model impedance data using appropriate equivalent circuit to extract parameters:

- Recombination resistance (Rₖ)

- Transport resistance (Rw)

- Chemical capacitance (Cμ)

- Parameter Calculation:

- Electron lifetime: τₙ = RₖCμ

- Effective diffusion coefficient: Deff = (Rₖ/Rw)(L_f²/τₙ)

- Diffusion length: Lₙ = Lf√(Rₖ/Rw)

Key Parameters: Film thickness (L_f), porosity, surface area, charge carrier density

Objective: To quantify surface excitation contributions to electron energy loss spectra [15].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare clean, well-defined surfaces with characterized orientation

- Electron Beam Alignment: Direct focused electron beam (1-5 keV) at specific incidence angles relative to surface normal

- Energy Loss Spectroscopy: Measure reflected electron energy distribution with high resolution

- Spectral Deconvolution: Separate bulk and surface excitation contributions through lineshape analysis

- Angle-Dependent Studies: Measure excitation probabilities as function of incidence angle (θ)

- Data Modeling: Fit results to theoretical models based on dielectric formalism

Key Parameters: Primary electron energy, surface crossing angle, dielectric function, inelastic mean free path

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Electron Transport Studies

| Category | Specific Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive Materials | Copper (Cu) films with different surface orientations | Study of surface scattering effects [12] | Crystallographic orientation: (111) vs (001) |

| Semiconductor Electrodes | TiO₂ nanoparticle films | Photoelectrode for electron transport studies [11] | High surface area, ~5×10⁻⁵ cm²/s diffusion coefficient |

| Electrolytes | Iodide-based redox couples (e.g., I⁻/I₃⁻) | Charge mediation in electrochemical systems [11] | Regeneration of oxidized dyes, viscosity affects regeneration rate |

| Biological Conductors | Cable bacteria (Desulfobulbaceae) | Study of long-distance biological electron transport [13] | Filamentous bacteria capable of cm-scale electron transfer |

| Mineral Conductors | Conductive minerals (e.g., hematite, pyrite) | Electron bridge formation in environmental systems [14] | Enable electron transfer between redox zones |

| Organic Mediators | Humic substances | Natural organic electron shuttles [14] | Quinone groups facilitate electron transfer |

| Computational Tools | First-principles electron transport code [12] | Parameter-free calculation of surface scattering | Available from: sites.utexas.edu/yuanyue-liu/codes/EDI/ |

Comparative Analysis Across Material Systems

The interplay between surface charge, composition, and structure creates distinct electron transport regimes across material classes. Metallic systems exhibit surface scattering dominated by crystallographic orientation and electronic structure symmetry, with conductivity variations between different surface orientations [12]. Semiconductor nanostructures demonstrate trap-limited transport where morphological parameters control diffusion coefficients through trap state distributions [11]. Electrochemical interfaces operate through spatially separated charge carriers, with electrons moving externally and ions mediating internal charge transfer [9]. Environmental systems utilize diverse conductive pathways including minerals, organic matter, and biological structures to achieve surprisingly long-range electron transfer [14].

A fundamental distinction emerges between internal field-driven transport in metallic conductors, where surface charges arrange to create axial electric fields [8], and diffusion-mediated transport in nanostructured semiconductors, where random thermal motion and trapping events govern carrier movement [11]. This dichotomy reflects the different relative importance of mean free path, scattering probabilities, and density of states across material systems.

Table 4: Cross-System Comparison of Surface Parameters Governing Electron Flow

| Parameter | Microelectronic Metals | Nanostructured Semiconductors | Electrochemical Systems | Environmental Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Charge Carrier | Electrons | Electrons & holes | Electrons (external), Ions (internal) | Electrons (minerals), Ions (pore water) |

| Dominant Surface Effect | Surface scattering | Trap state limited diffusion | Charge separation at interfaces | Redox zone connectivity |

| Key Structural Factor | Crystallographic orientation | Porosity & particle size | Electrode architecture & surface area | Mineral connectivity & biofilm structure |

| Characteristic Length Scale | Nanometers to micrometers | Nanometers to micrometers | Micrometers to millimeters | Centimeters to meters |

| Typical Measurement Technique | First-principles calculation [12] | EIS, IMPS, IMVS [11] | Voltammetry, impedance spectroscopy | Electrochemical sensors, geochemical profiling |

| Primary Performance Metric | Conductivity | Diffusion coefficient & lifetime | Current density & overpotential | Contaminant degradation rate |

Surface parameters governing electron flow demonstrate both universal principles and material-specific manifestations across different physical systems. Surface charge distributions establish fundamental driving forces through potential differences and interface dipoles. Material composition determines intrinsic scattering probabilities and charge carrier concentrations through electronic structure and defect chemistry. Surface structure and morphology govern transport pathways through geometric constraints and interface quality. The continuing development of parameter-free computational approaches [12], sophisticated electrochemical characterization methods [11], and multiscale experimental techniques [15] provides an expanding toolkit for precisely controlling these surface parameters to optimize electron transport in applications ranging from nanoelectronic devices to environmental remediation technologies. Future advances will require increasingly integrated approaches that simultaneously address charge, composition, and structural aspects of surface-mediated electron transport.

The solid-liquid interface represents a dynamic and complex frontier where the orchestrated interactions between electrolytes, biomolecules, and material surfaces dictate the efficiency and selectivity of transport phenomena. Understanding these interactions is paramount for advancing numerous scientific and technological fields, from energy storage and conversion to drug delivery and bioelectronics. This guide objectively compares the performance of two predominant investigative approaches within this domain: the analysis of electrolyte behavior at electrified interfaces and the study of electron transport across solid-state biomolecular junctions. The broader thesis context centers on how surface chemistry effects critically influence electronic transport properties research, determining the mechanistic pathways and ultimate performance of integrated systems. By juxtaposing experimental data and methodologies, this article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a structured comparison of these distinct yet complementary research paradigms.

Electrolyte Interactions at Electrified Interfaces

The electrochemical double layer (EDL) is a fundamental concept describing the interface between a charged electrode surface and an electrolyte solution. Its structure governs charge transfer processes critical for electrocatalysis, energy storage, and ion transport [16].

Experimental Protocol: Direct Probing of the EDL

A pioneering methodology for directly probing the electrical potential profile at the EDL involves Ambient Pressure X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (APXPS) under polarization conditions [16].

- Sample Preparation: A polycrystalline gold working electrode is used. A thin electrolyte layer (approximately 30 nm thick) is formed on the electrode surface using the 'dip and pull' method. The electrolyte consists of an aqueous solution of potassium hydroxide (KOH, 0.1–80 mM) with 1.0 M pyrazine added as a neutral molecular probe [16].

- In-Situ Polarization: The electrode is polarized within a double-layer potential range (typically -450 to +650 mV vs. a Ag/AgCl reference electrode) to avoid Faradaic reactions [16].

- Spectroscopic Measurement: Using tender X-rays (4.0 keV), core-level spectra (O 1s from water and N 1s from pyrazine) are collected. The local electric potential within the EDL is deduced from the binding energy shifts and spectral broadening of the core-level peaks from species in the liquid phase. The full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of these peaks is the key parameter, as it broadens proportionally to the potential drop within the EDL [16].

- Data Analysis: The potential of zero charge (PZC) is identified as the applied potential where minimal spectral broadening is observed, indicating no net charge on the electrode surface. The potential drop profile across the EDL is then reconstructed by analyzing the broadening and shifts as a function of the applied potential [16].

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters for EDL Probing via APXPS

| Parameter | Specification | Function/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Polycrystalline Gold | Inert, well-defined surface for EDL studies. |

| Electrolyte Layer | ~30 nm Aqueous KOH + Pyrazine | Thickness matches EDL dimension for dilute solutions; allows direct probing of potential drop. |

| Probe Molecule | 1.0 M Pyrazine (C₄H₄N₂) | Spectator molecule uniformly distributed in liquid; its N 1s peak serves as an independent probe of the electric field. |

| X-ray Source | 4.0 keV ("Tender" X-rays) | Provides optimal photoelectron inelastic mean free path (~10 nm) to probe the entire EDL. |

| Key Spectroscopic Signal | FWHM of O 1s (H₂O) and N 1s (Pyrazine) | Directly correlates with the potential drop across the EDL; maximum at PZC. |

Performance and Data

This approach directly measures the electrical potential, a significant advancement over traditional indirect electrochemical methods. The data quantitatively shows how the EDL structure changes with applied potential and electrolyte concentration [16]. For instance, in a 0.4 mM KOH solution, the potential drop occurs over a distance of about 15.2 nm. The FWHM of the LPPy N 1s peak exhibits a characteristic V-shaped trend when plotted against applied potential, mirroring the electrochemical double-layer capacitance and allowing for precise PZC determination [16].

Biomolecular Electron Transport in Solid-State Junctions

Proteins are increasingly considered as active components in bioelectronic devices. Research focuses on measuring and understanding electron transport (ETp) across proteins sandwiched between solid electrodes [17].

Experimental Protocol: Solid-State Protein Junction Characterization

A standard protocol for creating and measuring electron transport through solid-state protein junctions involves the following steps:

- Substrate Functionalization: A solid substrate (e.g., Au or Si wafer with a regrown oxide layer) is chemically functionalized with a monolayer of linker molecules (e.g., via silane chemistry for Si or thiols for Au). This creates a surface for specific protein immobilization [17].

- Protein Immobilization: A monolayer of the protein of interest (e.g., Azurin, Bacteriorhodopsin, or multi-heme cytochromes) is assembled on the functionalized surface. Orientation is often controlled by exploiting specific binding sites, such as a surface-exposed histidine residue binding to a Ni-NTA functionalized surface [17].

- Top Electrode Deposition: A top electrode (e.g., Au) is deposited onto the protein monolayer using a gentle evaporation technique to minimize damage, creating a metal/protein/metal junction. Alternatively, a conducting probe AFM tip can be used as the top electrode [17].

- Electronic Measurement: Current-voltage (I-V) characteristics are measured at various temperatures (e.g., from 80 K to 320 K). In some setups, a third (gate) electrode is used to electrostatically shift the energy levels of the protein [17].

- Data Analysis: The I-V curves and their temperature dependence are analyzed to determine the dominant transport mechanism (e.g., tunneling or hopping). Conductance values are calculated, and in some cases, inelastic tunneling spectroscopy (IETS) is used to probe electron-phonon interactions [17].

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters for Solid-State Biomolecule Transport Studies

| Parameter | Specification | Function/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Junction Configuration | Metal/Protein/Metal (e.g., Au/Azurin/Au) | Creates a solid-state device for measuring electron transport across a biomolecule. |

| Common Proteins | Azurin, Bacteriorhodopsin, Multi-heme Cyt c | Model proteins with different internal structures (redox cofactors, heme chains). |

| Linker Chemistry | Thiols on Au; Silanes on Si/SiO₂ | Covalently anchors proteins to the electrode, controlling coupling and orientation. |

| Key Measurement | I-V-T (Current-Voltage-Temperature) | Determines conductance and identifies transport mechanism (tunneling vs. hopping). |

| Advanced Probe | Inelastic Tunneling Spectroscopy (IETS) | Detects molecular vibrations during transport, confirming protein presence and coupling. |

Performance and Data

Studies reveal that proteins can be efficient electronic conductors. For example, multi-heme cytochromes show a conductance ~1000 times higher than single-heme or heme-free proteins, comparable to monolayers of conjugated organic molecules [17]. A key finding is the critical role of protein-electrode coupling, which can be a more significant factor than intrinsic protein transport properties. The electrostatic landscape at the interface can dominate charge transport, even inducing a shift between temperature-independent tunneling and temperature-activated hopping [17]. For instance, electron transport via the protein Azurin, when well-coupled to the electrodes, is LUMO-mediated and can be both efficient and near resonance [17].

Comparative Analysis of Transport Phenomena

The following table provides a direct comparison of the two researched areas based on the gathered experimental data.

Table 3: Comparison of Electrolyte Interface and Biomolecule Transport Studies

| Aspect | Electrolyte Interface (EDL) | Biomolecule Electron Transport |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Transport Subject | Ions (e.g., K⁺, OH⁻) and solvent molecules in a confined liquid phase. | Electrons (and holes) through a solid-state, ordered protein layer. |

| Dominant Driving Force | Applied electrical potential (ΔE), concentration gradient (ΔC). | Applied source-drain voltage (VSD), sometimes gated by electrostatic potential. |

| Key Measured Output | Potential drop profile, PZC, ion selectivity. | Current-voltage (I-V) characteristics, conductance, activation energy. |

| Role of Surface Chemistry | Determines surface charge density, specific ion adsorption, and EDL structure. | Dictates protein-electrode coupling efficiency and electrostatic gating effects. |

| Primary Investigative Tool | APXPS under polarization. | Solid-state junction I-V-T measurements. |

| Impact of Hydration | Critical; defines the EDL thickness and pore swelling in membranes. | Less relevant in solid-state, solvent-free measurement conditions. |

| Performance Metric | Ion selectivity, capacitive behavior. | Electronic conductance, transport mechanism (tunneling vs. hopping). |

Cross-Paradigm Insights and the Research Toolkit

Despite their differences, both fields highlight the supremacy of interface properties over bulk transport. In EDL studies, the surface charge dictates the entire potential and ion distribution profile [16]. In biomolecular electronics, the electrode-protein coupling often limits transport more than the intrinsic protein properties [17]. This underscores the broader thesis that surface chemistry is a decisive factor in designing and optimizing electronic transport properties in hybrid systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions, as derived from the cited experimental protocols.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Polycrystalline Gold Electrode | Provides a clean, definable, and catalytically inert surface for fundamental EDL studies and as a substrate for biomolecule junctions. |

| Pyrazine (C₄H₄N₂) | Acts as a neutral, pH-insensitive molecular probe in APXPS studies to independently map the electric potential within the EDL. |

| Azurin (Blue Copper Protein) | A model redox protein for solid-state electron transport studies due to its stability and well-characterized redox-active copper center. |

| Functionalized Si/SiO₂ Wafers | A versatile substrate for bio-junctions; the oxide layer allows for electrostatic gating and functionalization with linker molecules. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) Electrolyte | Provides a well-understood alkaline environment for probing basic EDL properties without complex ion-specific effects. |

| Specific Linker Molecules | (e.g., MPA for Au, Silanes for Si): Form a self-assembled monolayer to covalently and specifically immobilize biomolecules, controlling interface coupling. |

The comparative analysis of electrolyte and biomolecule transport at the solid-liquid interface reveals a shared principle: the interface is not merely a boundary but the primary determinant of system performance. Whether the goal is achieving exquisite ion selectivity through controlled pore hydration or enabling efficient electron tunneling via optimized protein-electrode coupling, success hinges on a deep understanding and strategic engineering of surface chemistry. For researchers in drug development, these principles are translatable to designing delivery vehicles that must navigate complex biological membranes. The experimental protocols and data summarized here provide a foundation for the continued development of high-performance materials and devices across electrochemistry, bioelectronics, and nanomedicine.

Visual Appendix: Experimental Workflows

Workflow for EDL Probing via APXPS

Workflow for Solid-State Biomolecule Transport

The energy difference between the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) is a fundamental electronic property governing molecular reactivity, optical characteristics, and charge transport behavior. Molecular functionalization—the chemical modification of molecules or surfaces with specific functional groups—serves as a powerful strategy for precisely engineering this HOMO-LUMO gap. Within molecular electronics and materials science, controlling this gap is a critical step in designing novel components for optoelectronic applications, logic units, and memory devices [18]. This case study examines how deliberate functionalization tunes the HOMO-LUMO gap across diverse molecular systems, including diamondoids, carbon chains, and semiconductor surfaces, and explores the direct consequences on electronic transport properties.

Comparative Analysis of Functionalized Molecular Systems

The effect of molecular functionalization has been systematically investigated in several key material systems. The table below summarizes the outcomes for diamondoids, carbyne, and functionalized semiconductors.

Table 1: Impact of Molecular Functionalization on HOMO-LUMO Gap and Electronic Properties

| Molecular System | Functionalization Type | HOMO-LUMO Gap / Band Gap | Key Electronic & Structural Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adamantane (Diamondoid) [19] [20] | Inverse design for minimal gap (S, N, thiol, nitro, carbonyl groups) | Reduced from 9.45 eV (pure) to 2.42 eV | Apparent push-pull character; structures with maximal gap used electronegative groups. |

| Adamantane (Diamondoid) [19] [20] | Inverse design for maximal gap (electronegative groups) | Increased from 9.45 eV (pure) to 10.63 eV | Introduction of numerous electronegative groups. |

| Carbyne (Pristine) [21] | None (polyyne structure) | 0.408 eV (PBE), 0.744 eV (HSE06) | Semiconducting behavior with alternating single/triple bonds. |

| Carbyne (H-/F-) [21] | Hydrogenation or Fluorination | 0.00 eV (Metallic) | Structural buckling, equidistant C-C spacing, strong delocalization of electronic states. |

| Carbyne (Double H-) [21] | Two H atoms on a single carbon | 7.52 eV (PBE), 6.87 eV (HSE06) | Increased interatomic distance (1.531 Å), insulating behavior. |

Experimental Protocols for Gap Tuning and Transport Measurement

Inverse Molecular Design for Diamondoid Functionalization

The systematic tuning of diamondoid HOMO-LUMO gaps was achieved through a computational inverse design methodology [19] [20].

- Objective: To find adamantane and diamantane derivatives with minimal and maximal HOMO-LUMO energy gaps by considering all possible functionalization sites (up to 10 for adamantane, 6 for diamantane).

- Optimization Algorithm: A best-first search algorithm was employed, combined with a Monte Carlo component to escape local optima during the search for optimal functional group combinations.

- Functional Groups: A wide range of groups was explored, with analyses showing that minimal gaps were achieved with structures exhibiting a strong push-pull character. The 'push' character was primarily provided by sulfur or nitrogen dopants and thiol groups, while the 'pull' character was dominated by electron-withdrawing nitro or carbonyl groups, often assisted by amino and hydroxyl groups forming intramolecular hydrogen bonds [19].

First-Principles Analysis of Functionalized Carbyne

The electronic transport properties of functionalized carbyne were investigated using first-principles calculations [21].

- Computational Framework: Geometry optimization and electronic structure calculations were performed using Density Functional Theory (DFT) within the Generalized Gradient Approximation (PBE).

- Dispersion Corrections: Grimme's PBE empirical dispersion correction was applied to account for van der Waals interactions during geometry optimizations.

- Band Structure Validation: For more accurate band gap estimation, especially for semiconductors, hybrid HSE06 functional calculations were conducted, which corrects the band gap underestimation typical of standard PBE.

- Transport Calculations: Electronic transport was modeled using the Landauer-Büttiker formalism and the nonequilibrium Green's function (NEGF) technique. The current-voltage (I-V) characteristics were computed to quantify conductance changes post-functionalization.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Functionalization Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Models electronic structure, computes HOMO-LUMO energies, and performs geometry optimization of molecules. |

| Nonequilibrium Green's Function (NEGF) | Formalism for calculating quantum electronic transport in nanoscale junctions and devices. |

| Best-First Search + Monte Carlo Algorithm | An inverse molecular design strategy to efficiently search vast chemical space for target properties. |

| Landauer-Büttiker Formalism | Relates the electronic transmission probability through a device to its conductance and current. |

| Hybrid HSE06 Functional | Provides more accurate electronic band gap calculations compared to standard DFT functionals. |

Electronic Transport Properties in Functionalized Systems

Molecular functionalization directly impacts electronic transport by altering the underlying electronic structure. The relationship between the HOMO-LUMO gap, the alignment of these orbitals with electrode Fermi levels, and the resulting transmission spectrum dictates the conductance of a molecular junction [18].

In the case of pristine carbyne, its semiconducting nature results in a transmission spectrum with a gap around the Fermi level, leading to zero current at low bias voltages [21]. Conversely, hydrogenation or fluorination induces a metallic character, resulting in a finite density of states and high transmission at the Fermi level. This produces a dramatic increase in current, with functionalized chains exhibiting over an order of magnitude higher current than pristine carbyne, as shown by I-V characteristics [21]. Furthermore, creating interface structures with alternating pristine and functionalized carbyne segments can lead to current rectification, demonstrating the potential for designing molecular-scale diodes through selective functionalization [21].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow connecting molecular functionalization to its ultimate impact on electronic transport properties, integrating computational and experimental validation methods.

This comparison demonstrates that molecular functionalization is a profoundly effective and versatile strategy for tuning the HOMO-LUMO gap across diverse material systems. From inducing a 10 eV range in diamondoid gaps to triggering a semiconductor-to-metal transition in carbyne, the targeted attachment of functional groups allows for precise control over electronic properties. The resulting changes are not merely academic; they directly translate to significant modifications in electronic transport, enabling enhanced conductance, current rectification, and the creation of novel molecular-scale electronic components. As inverse design methodologies and precise surface functionalization techniques continue to advance, the rational engineering of molecular electronic properties promises to be a cornerstone in the development of next-generation optoelectronic and computational devices.

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have emerged as a transformative solution in nanomedicine, addressing critical limitations of conventional drug delivery systems such as poor permeability, suboptimal efficacy, and inadequate targeting [22]. These inorganic nanocarriers, with pore diameters ranging from 2 to 50 nm, combine exceptional structural tunability with multifunctionality [23]. Since their first pharmaceutical application in 2001 for ibuprofen release, MSNs have evolved into sophisticated platforms capable of responding to specific biological stimuli for controlled drug release [22] [23]. Their significance stems from unique physicochemical properties—including high surface area (700–1300 m²/g), substantial pore volume (0.5–1.5 cm³/g), and flexible surface chemistry—that enable precise modulation of drug loading and release kinetics [23] [24]. This review examines how surface chemistry engineering in MSNs directs drug release profiles, positioning them advantageously against other nanocarriers in the context of electronic transport properties at the bio-nano interface.

The Interplay of Surface Chemistry and Electronic Properties in MSNs

Fundamentals of MSN Surface Charge and Internal Electrostatics

The surface chemistry of MSNs is predominantly governed by silanol groups (Si-OH) which ionize in biological environments, creating a negative surface charge that promotes electrostatic interactions with positively charged therapeutic agents [23]. However, the internal electrostatic environment within mesoporous structures diverges significantly from theoretical predictions based on planar surfaces due to nanoscale confinement effects [25]. When the size of pore throats becomes comparable to the thickness of the ionic layering forming on surfaces, the ionic layers from opposite surfaces overlap, creating a non-zero electric potential at pore throat centers that differs from the potential in larger pore voids [25].

This phenomenon creates axial ionic variation along the pore structure, meaning that surface charge density is not uniform throughout the MSN architecture. The charge distribution becomes a function of both the electrical double layer (EDL) overlap ratio and the porosity of the system [25]. These intricate electrostatic relationships directly influence how drug molecules navigate, adhere to, and ultimately release from the mesoporous network, making surface charge engineering a critical parameter for controlled release applications.

Comparative Surface Properties: MSNs vs. Alternative Nanocarriers

Table 1: Comparison of Surface Properties Between MSNs and Other Nanocarriers

| Nanocarrier Type | Surface Charge Control | Surface Functionalization Flexibility | Stability Under Physiological Conditions | Electrostatic Modulation Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSNs | High (via pH, functionalization) | Excellent (multiple chemistry routes) | High (rigid framework) | Precise (internal & external control) |

| Polymeric NPs | Moderate | Good (limited by polymer chemistry) | Variable (degradation issues) | Moderate (mainly external surface) |

| Liposomes | Limited (membrane integrity concern) | Moderate (phospholipid constraints) | Low (sensitivity to temperature/pH) | Limited (bilayer stability issues) |

| Dendrimers | High (terminal group control) | Good (generation-dependent) | Moderate (structural compaction) | High (but limited drug loading capacity) |

| Gold NPs | Moderate | Good (thiol chemistry) | High (inert metal core) | Limited (conductive surface effects) |

The surface properties of MSNs provide distinct advantages over organic and other inorganic nanocarriers. Unlike polymeric nanoparticles and liposomes, which face stability challenges in physiological environments, MSNs maintain structural integrity against enzymatic degradation, pH variations, and mechanical stress [23]. While dendrimers offer precise surface charge control, their limited drug loading capacity restricts therapeutic applications. MSNs combine high loading capacity with exceptional surface functionalization flexibility through well-established silane chemistry [22] [24]. This enables attachment of various functional groups (-NH₂, -COOH, -SH) that profoundly alter surface electronics and interaction capabilities [23].

Surface Engineering Strategies for Controlled Drug Release

Chemical Functionalization and Charge Modulation

The surface charge of MSNs can be systematically engineered through functionalization with specific organic groups, dramatically altering their electrostatic interactions with drug molecules. Experimental studies demonstrate that unfunctionalized MSNs typically exhibit a negative zeta potential of approximately -21 mV to -26 mV, while amination converts the surface charge to positive values around +30 mV [23]. This charge reversal enables electrostatic binding of negatively charged therapeutic molecules, particularly nucleic acids and anionic proteins, that would poorly associate with native MSN surfaces.

The strategic application of functional groups extends beyond simple charge reversal to create stimuli-responsive gatekeeping systems. For instance, sodium alginate coatings attached to aminated MSN surfaces through electrostatic interactions have demonstrated excellent pH-responsive release profiles, remaining stable at physiological pH but dissolving in acidic environments such as tumor microenvironments or intracellular compartments [26]. These functionalization strategies effectively create "molecular gates" that regulate drug release based on specific biological triggers.

Surface Electronic States and Their Impact on Drug Release Kinetics

The electronic properties of functionalized surfaces play a crucial role in determining drug release profiles through their influence on charge transfer processes and adsorption thermodynamics. Surface electronic states, similar to those characterized in 2D materials and single-atom catalysts, govern how MSNs interact with their biological surroundings [27]. When MSN surfaces are functionalized with organic molecules, complex bonding mechanisms—including hydrogen bonding, dative bonding, and π-π stacking—significantly alter the electronic structure and charge distribution at the interface [28].

These electronic modifications directly impact drug release kinetics by changing the binding energy between the carrier and therapeutic cargo. Experimental and theoretical studies indicate that functionalization-induced changes in the HOMO-LUMO gap and charge distribution correlate with altered release profiles, as the electronic compatibility between drug molecules and the MSN surface determines retention and release characteristics [28]. The ability to tune these electronic interactions through surface engineering enables precise control over release rates for different therapeutic applications.

Experimental Approaches for Characterizing MSN Surface Properties

Methodologies for Surface Charge and Release Kinetics Assessment

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Characterizing MSN Surface Chemistry and Release Properties

| Characterization Method | Experimental Protocol Summary | Key Parameters Measured | Applications in Release Modulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeta Potential Measurement | MSNs dispersed in aqueous solution at physiological pH; laser Doppler electrophoresis | Surface charge magnitude and polarity | Predict electrostatic drug loading capacity and cellular interaction |

| Potentiometric Titration | Acid-base titration of MSN suspension with monitoring of pH changes | Internal surface charge density, proton adsorption/desorption | Quantify available silanol groups for functionalization |

| Streaming Potential Analysis | Pressure-driven flow through MSN compact with simultaneous potential measurement | Zeta potential under flow conditions, electrokinetic charge | Model drug release behavior under physiological flow conditions |

| In Vitro Release Testing | Incubation of drug-loaded MSNs in buffers at various pH with periodic sampling | Cumulative drug release over time, release kinetics | Validate stimuli-responsive release triggered by pH, enzymes, or redox potential |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Surface irradiation with X-rays under ultra-high vacuum; measurement of ejected electrons | Elemental composition, chemical states of surface elements | Confirm successful surface functionalization and quantify coating efficiency |

Probing Internal Surface Charge and Electronic Properties

Characterizing the internal surface charge of MSNs presents unique challenges due to nanoscale confinement effects. Advanced electrochemical techniques including scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM) provide localized information about surface reactivity and charge transfer processes at the nanocarrier interface [27]. These methods have revealed that the internal surface charge density of mesoporous systems deviates almost twofold from theoretical calculations based on flat surfaces, with particularly pronounced effects in regions where pore throats connect to larger voids [25].

The Poisson-Nernst-Planck (PNP) equations combined with charge regulation (CR) models have emerged as powerful computational tools for predicting surface charging behavior in nanoconfinement [25]. These models consider protonation/deprotonation surface reactions based on the site density of functional groups, providing more accurate predictions of internal surface charge than classical Boltzmann distribution-based approaches. When correlated with experimental drug release data, these characterization techniques enable rational design of MSNs with tailored release profiles for specific therapeutic applications.

Impact of Surface-Modified MSNs on Biological Performance

Cellular Uptake and Epithelial Permeability

The surface properties of MSNs significantly influence their biological interactions and performance. Studies demonstrate that cellular uptake of MSNs occurs in a time-, concentration-, and size-dependent manner [23]. Smaller MSNs (below 100 nm) exhibit more efficient cellular internalization but may become trapped in mucin layers covering epithelial surfaces, while larger particles (around 500 nm) show stronger interactions with cell membranes but limited uptake due to size constraints [23].

Surface charge plays a crucial role in these biological interactions. Cationic MSNs typically demonstrate enhanced cellular uptake compared to their anionic or neutral counterparts due to favorable electrostatic interactions with negatively charged cell membranes. However, this enhanced uptake must be balanced against potential cytotoxicity concerns, as highly positive surfaces may exhibit greater membrane disruption. Optimal biological performance requires careful tuning of surface charge density to balance efficient cellular internalization with maintained biocompatibility.

Therapeutic Efficacy in Disease Models

Surface-engineered MSNs have demonstrated remarkable efficacy across various disease models. In diabetes management, MSN-based nanocomposites have successfully delivered therapeutic molecules including insulin, GLP-1, exenatide, and DPP-4 inhibitors through functionalization strategies that enable controlled and stimuli-responsive release [29]. For anticancer therapy, pH-responsive systems like alginate-coated MSNs have shown triggered release in acidic tumor microenvironments, significantly improving therapeutic efficacy while reducing systemic side effects [26].

The ability to coordinate multiple functionalization approaches on a single MSN platform enables sophisticated targeting strategies. For instance, MSNs can be conjugated with biological markers for tissue-specific delivery while simultaneously incorporating magnetic nanoparticles for organ-specific targeting using external magnetic fields [30]. These multi-functional systems represent the next generation of targeted therapeutics, with surface chemistry serving as the foundation for their sophisticated behavior.

Visualization of MSN Surface Chemistry and Drug Release Mechanisms

Electronic Charge Distribution in Mesoporous Structures

This diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism behind variable surface charge distribution within MSN architectures. The pore void regions exhibit a lower negative potential compared to the pore throat regions where spatial confinement creates enhanced EDL overlap. This potential difference drives axial ionic concentration variations along the pore structure, creating heterogeneous drug binding sites with different affinities that collectively determine overall release kinetics [25].

Surface Functionalization for pH-Responsive Drug Release

This workflow depicts the operational mechanism of pH-responsive MSNs. The system utilizes an aminated MSN surface that provides positive charge for electrostatic interaction with negatively charged alginate coatings [26]. At neutral pH (bloodstream), the coating remains intact, retaining drugs within the porous structure. When the MSNs encounter acidic environments (tumor tissues, intracellular compartments), the alginate coating dissolves, triggering controlled drug release through the newly accessible pores.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for MSN Surface Engineering

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MSN Surface Functionalization

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Surface Engineering | Application in Drug Release Modulation |

|---|---|---|

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Amines introduce positive surface charge | Enhances binding of negatively charged drugs; enables further conjugation |

| Carboxyethylsilanetriol (CTES) | Carboxyl groups create negative surface charge | Increases hydrophilicity; repels negatively charged biomolecules |

| Triethoxyvinylsilane (VTES) | Vinyl groups enable click chemistry | Provides versatile platform for advanced bioorthogonal functionalization |

| N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) | Activates carboxyl groups for amide bonding | Facilitates covalent attachment of targeting ligands and polymers |

| 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) | Carboxyl-to-amine crosslinker | Couples targeting molecules to functionalized MSN surfaces |

| Polyethylene glycol (PEG) silanes | Creates stealth coating against opsonization | Prolongs circulation time; enhances accumulation in target tissues |

| Sodium Alginate | Forms pH-responsive coating over aminated MSNs | Creates gatekeeping system for triggered drug release in acidic environments |

| Gadolinium(III) chloride | Doping agent for imaging functionality | Enables theranostic applications with MRI visibility alongside drug delivery |

Surface chemistry engineering in mesoporous silica nanoparticles represents a powerful strategy for controlling drug release profiles and enhancing therapeutic efficacy. The intricate relationship between surface functionalization, electronic properties, and release kinetics enables precise tuning of MSN performance for specific biomedical applications. As characterization techniques advance, particularly in probing internal surface charge distribution and electronic states at the nanoscale, our understanding of structure-function relationships in MSN-based drug delivery will continue to deepen. Future research directions will likely focus on multi-stimuli responsive systems, advanced targeting modalities, and enhanced biocompatibility profiles—all founded on sophisticated surface engineering approaches. These developments position MSNs as indispensable platforms in the evolving landscape of precision medicine and controlled drug delivery.

Tools and Techniques: Characterizing and Harnessing Surface-Mediated Transport

The investigation of surface chemistry and its profound impact on electronic transport properties is a cornerstone of advanced materials research. The performance of materials in applications ranging from microelectronics and energy storage to drug development is heavily influenced by the outermost atomic layers. To fully understand these critical interfaces, researchers rely on a powerful, complementary suite of characterization techniques. Among the most vital are X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR), and Raman Spectroscopy. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these three core techniques, detailing their fundamental principles, specific applications, and the synergistic data they provide for correlating surface chemical effects with electronic properties.

Each technique in this spectroscopic toolkit probes a different aspect of a material's composition and structure. The table below summarizes their core operating principles and key characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of XPS, FT-IR, and Raman Spectroscopy

| Feature | XPS (X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy) | FT-IR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Elemental identity, chemical state, and empirical formula of the surface [31] | Molecular functional groups and chemical bonding [31] | Molecular structure, crystallinity, phase, and molecular interactions [31] |

| Probed Phenomenon | Kinetic energy of ejected photoelectrons [31] | Molecular bond vibrations (stretching, bending) from infrared light absorption [31] | Molecular bond vibrations from inelastic light scattering [31] |

| Typical Depth Sensitivity | ~1-10 nm (highly surface-specific) [32] | ~0.1-10 µm (can be bulk-sensitive or surface-sensitive with ATR mode) | ~0.5-100 µm (bulk-sensitive, but can be surface-enhanced) [32] [33] |

| Detection Limit | ~0.1 - 1 at% [31] | ~1% | ~0.1 - 1% (can be single-molecule with SERS) [33] |

The complementary nature of these techniques is further visualized in the following workflow, which outlines a logical approach for comprehensive surface analysis.

Diagram 1: A complementary workflow for surface analysis using XPS, FT-IR, and Raman spectroscopy.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To obtain reliable and reproducible data, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following sections detail common methodologies for each technique.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS is a quantitative technique that measures the elemental composition and chemical state of surfaces [31].

- Sample Preparation: Samples are typically used as solid slabs, powders, or thin films. Powders are often pressed into indium foil or mounted on double-sided adhesive tape. For highly insulating samples, a low-energy electron flood gun is used to neutralize surface charging [31].

- Data Acquisition: The sample is irradiated with a monochromatic X-ray beam (e.g., Al Kα or Mg Kα) in an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber. The kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectrons is measured by a hemispherical analyzer. Survey scans (wide energy range) are first acquired to identify all elements present, followed by high-resolution scans of specific core-level peaks (e.g., C 1s, O 1s) to determine chemical states [31].

- Data Analysis: Elemental concentrations are calculated from peak areas and known sensitivity factors. Chemical state identification is performed by analyzing binding energy shifts. For example, the difference in binding energy between carbon in a C-C bond and carbon in a C-O bond can be resolved [31].

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

FT-IR identifies molecular functional groups by measuring the absorption of infrared light [31].

- Sample Preparation: The preparation method depends on the sample's physical state [31].

- Transmission Mode: Solid powders are mixed with KBr and pressed into a pellet. Liquids are placed between two salt plates (e.g., KBr, NaCl).

- Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR): A solid or liquid sample is placed in direct contact with a high-refractive-index crystal (e.g., diamond, ZnSe). The infrared beam reflects within the crystal, generating an evanescent wave that penetrates the sample. ATR requires minimal preparation and is highly surface-sensitive due to the shallow penetration depth of the evanescent wave [31].

- Data Acquisition: An infrared source is passed through an interferometer and then through (or onto) the sample. The detector measures an interferogram, which is then Fourier-transformed to produce a spectrum of absorbance or transmittance versus wavenumber (cm⁻¹) [31].

- Data Analysis: Peaks in the spectrum are assigned to specific vibrational modes of molecular bonds. For example, a strong, broad peak around 3300 cm⁻¹ is characteristic of O-H stretching, while a sharp peak near 1700 cm⁻¹ is typical of C=O stretching [31].

Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy provides information on molecular vibrations, phonons, and crystal structure through inelastic light scattering [31].

- Sample Preparation: Raman spectroscopy requires minimal sample preparation. Solids, powders, and liquids can be analyzed directly. The sample should not fluoresce excessively, as fluorescence can swamp the weaker Raman signal. For surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), the sample is adsorbed onto or placed near a nanostructured noble metal surface (e.g., gold or silver nanoparticles) to dramatically enhance the signal [33].

- Data Acquisition: A monochromatic laser source (e.g., 532 nm, 633 nm, 785 nm) is focused onto the sample. The scattered light is collected, and a spectrometer analyzes its wavelength. A notch or edge filter is used to block the intense elastically scattered Rayleigh light, allowing the weak inelastically scattered Raman light to be detected [31].

- Data Analysis: The resulting spectrum plots intensity versus Raman shift (cm⁻¹). The positions, widths, and intensities of the peaks reveal molecular structure, stress/strain in materials, crystallinity, and phase. For instance, the characteristic G and D bands in carbon materials provide information on graphitic ordering and defect density [31].

Applications in Electronic Transport and Surface Chemistry

The combination of XPS, FT-IR, and Raman is exceptionally powerful for linking surface chemistry to electronic properties, as demonstrated in key research areas.

Analysis of Two-Dimensional (2D) Materials

Materials like graphene and molybdenum disulfide are central to next-generation electronics and sensors [32].

- XPS quantifies the elemental composition and identifies contaminants (e.g., oxygenated groups on graphene) that can act as scattering sites, degrading electron mobility [32].

- Raman confirms the number of layers, defect density (via the D/G band ratio), and strain within the crystal lattice, all of which directly influence electrical conductivity and band structure [31] [32].

- The correlation is clear: XPS-identified surface contaminants often correlate with a higher Raman D-band intensity, together explaining a measured decrease in electronic transport performance.

Characterization of Lithium-Ion Battery Electrodes

The performance and degradation of batteries are governed by complex surface phenomena [32] [34].

- XPS is indispensable for analyzing the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer that forms on the anode surface. It identifies the chemical states of lithium (e.g., in Li₂O, LiF, or organic Li compounds) within this passivating layer [34].

- Raman probes the bulk structural changes of electrode materials during cycling. For example, it can detect phase transitions in the cathode or the disordering of graphite in the anode, which lead to capacity fade [32] [34].

- FT-IR can identify organic components and decomposition products within the electrolyte and at the electrode-electrolyte interface [34].

- Together, these techniques connect surface chemistry (from XPS) with bulk structural degradation (from Raman) to provide a complete picture of capacity fading and impedance growth.

Interfacial Analysis in Organic Electronics and Pharmaceuticals

Understanding molecular interactions at interfaces is critical for device efficiency and drug stability [35].

- XPS determines the elemental composition and oxidation states at the interface of an organic semiconductor and a metal electrode, which is critical for understanding charge injection barriers [31].

- FT-IR and Raman are used to study organic ion pairs, which are relevant in pharmaceutical applications. They can reveal intermolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding (e.g., N–H···O), which stabilizes the structure and can influence solubility and dissolution rates—key factors in drug development [35].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and reagents commonly used in experiments involving this spectroscopic toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Indium Foil | A ductile, conductive substrate for mounting powdered samples for XPS analysis to prevent charging [31]. |

| KBr (Potassium Bromide) | An infrared-transparent material used to prepare pellets for FT-IR transmission measurements of solid powders [31]. |

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe) | Durable crystals used in ATR-FT-IR for direct, minimal-preparation analysis of solids and liquids [31]. |

| SERS Substrates (Au/Ag NPs) | Nanostructured gold or silver films/colloids used to enhance the Raman signal by many orders of magnitude, enabling trace-level detection [33]. |

| Conductive Adhesive Tapes (e.g., Carbon Tape) | For mounting samples to a holder in vacuum-based techniques like XPS, ensuring electrical and thermal contact [31]. |

| Calibration Standards (e.g., Au, Ag, Si) | Reference materials with known binding energies (for XPS) or Raman shifts (e.g., silicon wafer at 520.7 cm⁻¹) for instrument calibration [31]. |

Advanced and Synergistic Approaches

The integration of these techniques, both conceptually and in combined instrumentation, represents the cutting edge of surface analysis.

- Combined XPS and Raman Instrumentation: Commercially available systems now integrate a Raman spectrometer directly into an XPS instrument. This allows for analysis at the exact same sample spot without breaking vacuum, providing perfectly correlated surface chemical (XPS) and molecular structural (Raman) data [32].

- The Role of Metamaterials: The field of metamaterials is revolutionizing surface-enhanced spectroscopy. By designing subwavelength structures that support resonances like localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), researchers can create "hot spots" of intense electromagnetic fields. This principle is the foundation of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) and Surface-Enhanced Infrared Absorption (SEIRA), pushing detection limits to the single-molecule level and opening new possibilities for ultrasensitive detection [33].

- Theoretical Calculations: Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations are increasingly used in conjunction with experimental data. DFT can predict the vibrational frequencies observed in FT-IR and Raman spectra, as well as the core-level binding energies measured by XPS, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for peak assignment and a deeper understanding of molecular and electronic structure [35].

The synergy between Density Functional Theory (DFT) and the Non-Equilibrium Green's Function (NEGF) formalism provides a powerful, first-principles framework for modeling quantum transport in nanoscale and molecular-scale devices. This combined DFT-NEGF approach enables researchers to predict how electrons flow through materials and molecular junctions under an applied bias, which is fundamental to designing next-generation electronic components, sensors, and energy conversion devices [36] [37]. The accuracy of this method hinges on its ability to self-consistently compute a non-equilibrium electron density in the presence of open boundaries, represented by semi-infinite electrodes held at different electrochemical potentials [36]. This guide offers a comparative analysis of leading DFT-NEGF implementations, detailing their theoretical underpinnings, performance characteristics, and practical applications in probing surface chemistry effects on electronic transport.

Theoretical Framework of DFT-NEGF

The DFT-NEGF method partitions a system into three distinct regions: a left electrode, a central scattering region, and a right electrode. The core objective is to solve for the electronic structure and electron density of the central region under the non-equilibrium conditions imposed by the electrodes.

Core Formalisms and Equations