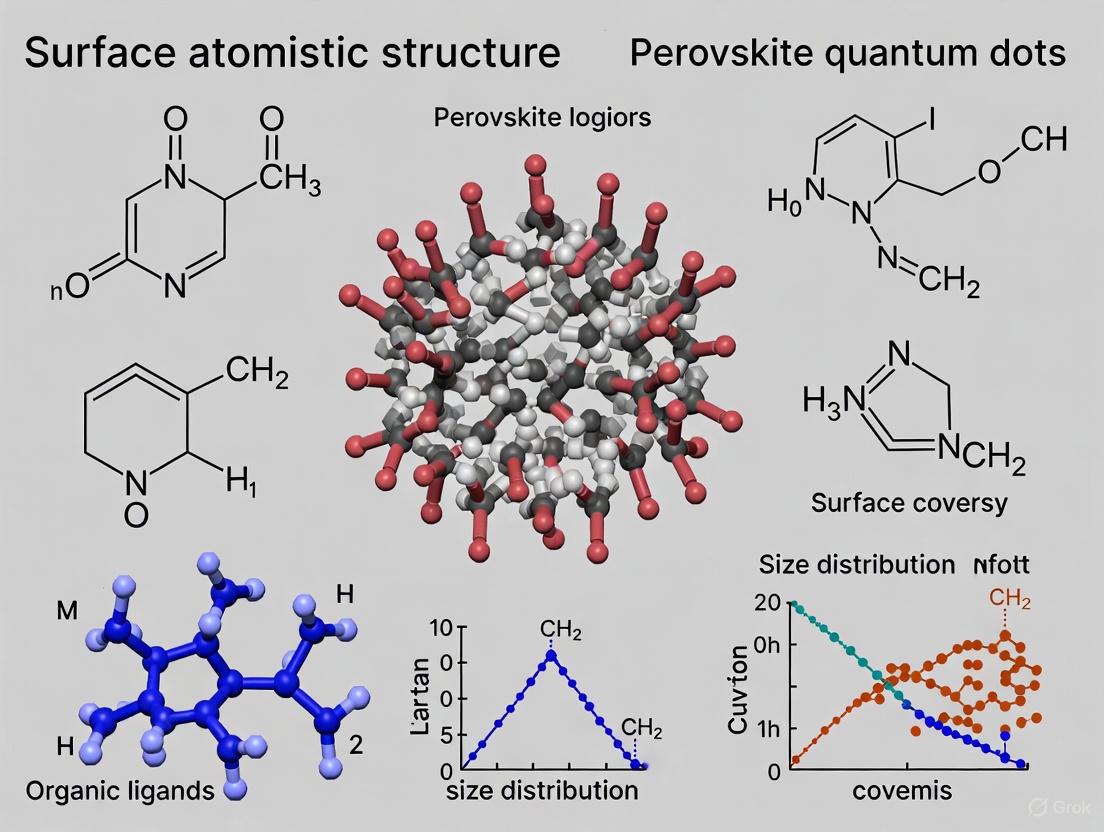

Surface Atomistic Structure of Perovskite Quantum Dots: Engineering Strategies for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the surface atomistic structure of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and its pivotal role in determining their optoelectronic properties and functional efficacy.

Surface Atomistic Structure of Perovskite Quantum Dots: Engineering Strategies for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the surface atomistic structure of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and its pivotal role in determining their optoelectronic properties and functional efficacy. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the fundamental principles of PQD surface chemistry, advanced engineering methodologies for stability and biocompatibility, and troubleshooting for aqueous instability and lead toxicity. The review critically evaluates PQDs against conventional nanomaterials, highlighting their superior photoluminescence quantum yield and tunability for biosensing, bioimaging, and therapeutic applications. By synthesizing recent breakthroughs and future directions, this work serves as a roadmap for translating surface-engineered PQDs into transformative clinical tools.

Decoding the Surface Blueprint: Fundamental Principles of Perovskite Quantum Dot Atomistic Structure

The term "perovskite" describes a class of crystalline materials sharing a structure similar to the mineral calcium titanium oxide (CaTiO₃), first discovered in the Ural Mountains in 1839 and named after Russian mineralogist L. A. Perovski [1]. These materials possess the general chemical formula ABX₃, where 'A' and 'B' are cations of different sizes and 'X' is an anion that bonds to both [1]. The versatility of this structure allows for a wide range of elemental substitutions, leading to an impressive array of properties including superconductivity, ferroelectricity, and exceptional optoelectronic performance [2].

In the idealized cubic unit cell, the larger 'A' cation sits at the cube corners (0, 0, 0), the smaller 'B' cation sits at the body-center position (1/2, 1/2, 1/2), and the 'X' anions (typically halogens like I⁻, Br⁻, Cl⁻ in halide perovskites) sit at the face-centered positions (1/2, 1/2, 0), (1/2, 0, 1/2), and (0, 1/2, 1/2) [1]. This arrangement forms a network of corner-sharing BX₆ octahedra, with the A cation occupying the cuboctahedral cavity, coordinating with 12 X anions to stabilize the structure [1] [3].

Table 1: Cation and Anion Roles in the ABX₃ Perovskite Quantum Dot Structure

| Site | Ionic Characteristic | Coordination Number | Common Elements in PQDs | Function in Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-site | Larger, monovalent cation | 12 | Cesium (Cs⁺), Formamidinium (FA⁺), Methylammonium (MA⁺) [2] [4] | Occupies cuboctahedral voids, stabilizes the 3D framework [1] |

| B-site | Smaller, divalent cation | 6 (Octahedral) | Lead (Pb²⁺), Tin (Sn²⁺) [2] | Forms the BX₆ octahedron core; determines electronic properties [1] [3] |

| X-site | Halogen anion | 2 | Iodide (I⁻), Bromide (Br⁻), Chloride (Cl⁻) [2] [4] | Bridges A and B sites; corner-sharing ligand that defines octahedral network [1] |

The stability and formation of the perovskite structure are governed by the Goldschmidt tolerance factor (t) and the octahedral factor (μ). The tolerance factor, calculated as ( t = (rA + rX) / [ \sqrt{2} (rB + rX) ] ), where ( rA ), ( rB ), and ( r_X ) are the respective ionic radii, predicts structural stability. A value between 0.8 and 1.0 generally indicates a stable perovskite structure [3]. Slight deviations from the ideal cubic structure are common, leading to non-cubic variants such as tetragonal and orthorhombic structures, which can influence the material's electronic and ferroelectric properties [1].

ABX3 Structure in Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs)

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) are nanoscale semiconducting crystals, typically with diameters between 2-10 nanometers, that inherit the ABX₃ crystal structure [2]. At this scale, quantum confinement effects dominate, causing the optoelectronic properties to become highly tunable based on both the size of the dot and its composition [2] [4]. The ability to fine-tune the bandgap by adjusting the halide component (X) or the particle size makes PQDs exceptionally suitable for applications like light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and quantum dot solar cells [2] [5].

The electronic structures of ABX₃ perovskites are crucial for their performance. The overlap between the electron orbitals of the A-site cation and the BX₆ octahedron can significantly affect the crystal structure's stability and the material's carrier mobility [6]. For instance, in copper-based perovskite chlorides (CuMCl₃), the calculated carrier effective mass ratios suggest a carrier mobility similar to or higher than that of common CsPbCl₃, highlighting the profound influence of the A-site cation on electronic properties [6].

Table 2: Effect of Quantum Confinement and Composition on PQD Properties

| Tuning Parameter | Experimental Method | Effect on Optical Property | Typical Range/Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size | Controlling reaction time and temperature during synthesis [4] | Size-dependent bandgap; smaller dots emit higher energy (bluer) light [2] | 3 nm to 15 nm [4] |

| Halide Composition (X-site) | Mixing halide precursors (e.g., CsPbBr₃ₓIₓ) [2] [5] | Continuous bandgap tuning; emission across the entire visible spectrum [5] | CsPbCl₃ (blue), CsPbBr₃ (green), CsPbI₃ (red) [2] [4] |

| A-site Cation | Substituting Cs⁺ with Cu⁺ or organic cations [6] | Affects structural stability, crystal phase, and carrier mobility [6] | Cs⁺, Cu⁺, Formamidinium, Methylammonium [6] [2] |

A significant challenge in PQD technology is the inherent instability and susceptibility to performance degradation, largely originating from the surface atomistic structure [7]. Due to their high surface-area-to-volume ratio, a large proportion of atoms reside on the surface. These surface atoms are often under-coordinated, leading to the formation of trap states that can non-radiatively recombine charge carriers, quenching photoluminescence and reducing quantum yields [8] [9]. This intrinsic vulnerability necessitates advanced surface engineering strategies to achieve commercial viability [7].

Surface Atomistic Structure and Defects in PQDs

The surface of a PQD is a critical interface where the periodic ABX₃ crystal lattice terminates. This termination creates under-coordinated ions—primarily under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions—which act as deep trap states for charge carriers [8] [9]. These defects are a primary source of non-radiative recombination, a process that converts excited electronic energy into heat instead of light, thereby reducing the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and overall efficiency of optoelectronic devices [9]. Furthermore, these surface defects facilitate ion migration, especially in mixed-halide perovskites, leading to phase segregation and spectral instability [2].

The bond-valence vector sum (BVVS) is a valuable descriptor for quantifying the distortion of the BX₆ octahedron, which is intrinsically linked to these surface defects [3]. In a perfect octahedron, the BVVS is zero, but distortion caused by under-coordinated surface ions or lattice strain leads to a non-zero value, providing a quantifiable metric for structural imperfection and its associated detrimental effects [3].

Diagram: Impact of surface defects on PQD properties. Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions lead to optical losses and ion migration, resulting in overall property degradation.

Experimental Protocols for Synthesis and Surface Engineering

Core Synthesis of PQDs

Two primary colloidal synthesis methods are employed to fabricate high-quality PQDs:

Hot-Injection Method: This is the most common technique for producing monodisperse PQDs with high crystallinity [5] [4]. The protocol involves:

- Preparation of Cs-Oleate Precursor: Cs₂CO₃ is mixed with oleic acid (OA) and 1-octadecene (ODE) and stirred at 150°C until clear [5] [4].

- Preparation of Pb-Halide Precursor: Lead halide (e.g., PbBr₂) is dried and dissolved in ODE with coordinating ligands (OA and oleylamine - OLA) at a high temperature (e.g., 180°C).

- Injection and Reaction: The prepared Cs-oleate is swiftly injected into the vigorously stirred Pb-halide solution. The reaction proceeds for a few seconds before being rapidly cooled in an ice-water bath to terminate nanocrystal growth [5] [4].

- Purification: The crude solution is centrifuged to precipitate the PQDs, which are then redispersed in a non-solvent like hexane or toluene.

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) at Room Temperature: A simpler, lower-energy alternative [5].

- Precursor Solution Preparation: The lead halide (PbX₂) and cesium halide (CsX) are dissolved in a polar aprotic solvent like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

- Ligand Addition: Capping ligands, typically oleylamine (OLA) and oleic acid (OA), are added to the precursor solution under stirring.

- Precipitation: A small amount of this precursor solution is added to a poor solvent (e.g., toluene), triggering the instantaneous crystallization and precipitation of PQDs.

- Separation: The PQDs are separated via centrifugation [5].

Diagram: Workflow of primary PQD synthesis methods, showing hot-injection and room-temperature pathways.

Advanced Surface Passivation Protocols

To address surface defects, several advanced surface chemistry engineering strategies have been developed:

Post-Synthetic Pseudohalogen Treatment: A robust method for passivating defects in mixed-halide PQDs.

- Procedure: A solution of pseudohalogen inorganic ligands (e.g., pseudohalide salts in acetonitrile) is used to treat the synthesized PQDs. This treatment simultaneously etches the lead-rich surface and passivates the resulting defects in situ [2].

- Outcome: This approach produces PQDs with suppressed halide migration, enhanced photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), and improved film conductivity [2].

Imide-Derivative Molecular Passivation:

- Procedure: Various imide derivatives, such as caffeine and 6-amino-1,3-dimethyluracil, are introduced to the PQD solution [9]. These molecules bind to under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites via their carbonyl oxygen atoms.

- Outcome: This method significantly improves optical properties and thermal stability by effectively neutralizing trap states. Molecular calculations confirm that the atomic charge of the carbonyl oxygen is proportional to the efficacy of passivation [9].

Core/Shell Nanostructure Engineering:

- Procedure: A protective shell layer is grown epitaxially around the PQD core. This strategy, successful in traditional quantum dots, is now applied to perovskites [7].

- Outcome: The shell physically protects the core from environmental degradation (oxygen, moisture) and electronically passivates surface states, controlling surface defects and improving stability against external environments [7].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PQD Synthesis and Passivation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cs⁺ (A-site) cation source [4] | Precursor for Cs-oleate in hot-injection synthesis [4] |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Pb²⁺ (B-site) and Br⁻ (X-site) source [4] | The metal-halide precursor for synthesis [4] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OLA) | Surface capping ligands [4] | Coordinate surface atoms to control growth and provide colloidal stability [5] [4] |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-coordinating solvent [4] | High-booint solvent for precursor dissolution and reaction [4] |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Polar aprotic solvent [5] | Solvent for precursor salts in the LARP method [5] |

| Caffeine (1,3,7-Trimethylxanthine) | Molecular passivator [9] | Binds to under-coordinated Pb²⁺ via carbonyl groups to suppress non-radiative recombination [9] |

| Pseudohalogen Salts (e.g., SCN⁻) | Inorganic passivating ligand [2] | Post-synthetic treatment to etch defective surfaces and passivate vacancies in situ [2] |

Characterization and Machine Learning in PQD Research

Accurately characterizing the crystal structure and properties of PQDs is essential. Techniques such as X-ray diffraction (XRD) are used to determine the space group, crystal system, and lattice constant [3]. However, traditional computational methods like density functional theory (DFT) and experimental XRD curve fitting are resource-intensive [3] [4].

Machine Learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool to overcome these hurdles. ML models can rapidly predict the crystal structures and optical properties of PQDs from synthesis parameters, significantly accelerating materials design [3] [4]. For instance, models like Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Nearest Neighbour Distance (NND) have demonstrated high accuracy (high R², low RMSE) in predicting the size, absorbance, and photoluminescence of CsPbCl₃ PQDs using synthesis features like injection temperature, precursor amounts, and ligand volumes as input [4]. A key ML model for crystal structure identification uses a descriptor known as the bond-valence vector sum (BVVS), which effectively captures the intricate geometry and octahedral distortion in perovskites, enabling precise prediction of space groups and lattice constants with limited feature descriptors [3].

The ABX₃ crystal lattice provides the fundamental framework for the exceptional and tunable optoelectronic properties of Perovskite Quantum Dots. However, the surface atomistic structure, rich with under-coordinated ions and defects, remains the central challenge limiting their stability and performance. Ongoing research, leveraging advanced surface passivation protocols, core/shell engineering, and data-driven machine learning approaches, is critically focused on understanding and controlling this surface interface. Mastering the surface is the key to unlocking the full commercial potential of PQDs in next-generation displays, photovoltaics, and other optoelectronic devices.

The surface atomistic structure of metal halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) is a foundational element governing their optoelectronic properties and operational stability. The significantly large surface-area-to-volume ratio of PQDs makes them highly susceptible to surface defects, which act as non-radiative recombination centers, quenching photoluminescence and degrading performance in devices such as light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and solar cells [9]. The inherent ionic character of perovskites further complicates this dynamic, as it leads to low formation energies for defects and heightened susceptibility to degradation from environmental stimuli like moisture and oxygen [10]. Understanding the dynamics of surface atoms—their bonding, coordination, and the nature of the defects they form—is therefore critical for advancing PQD-based technologies. This guide, framed within a broader thesis on PQD surface science, details the origin of defects, quantitative performance metrics, and the experimental methodologies employed to passivate these surfaces for superior device performance.

Core Defect Dynamics and Ionic Instability

The optoelectronic performance of PQDs is primarily dictated by the dynamics at their surface, where the crystalline periodicity terminates. This termination leads to under-coordinated ions and vacancies that define the defect landscape.

Dominant Defect Types: The most common and detrimental defects in lead-halide PQDs (e.g., CsPbX₃, FAPbBr₃) are under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions and halide anion vacancies (X⁻) [9] [10]. Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions, resulting from the absence or detachment of surface ligands, create deep trap states that capture charge carriers and promote non-radiative energy loss. Concurrently, the high mobility of the ionic lattice facilitates the formation of halide vacancies, which further act as trap states and serve as initiation points for chemical degradation.

The Role of Ionic Character: The perovskite's ionic bonding nature means that surface ions are not covalently bound with the same strength as in semiconductor materials like silicon. This leads to a highly dynamic and "soft" lattice [10]. While this defect-tolerance is beneficial in the bulk, at the surface, it translates to low energy barriers for ion migration and defect formation. When PQDs are purified or subjected to external stimuli (light, heat, polar solvents), the dynamic binding of surface ligands can be disrupted, causing them to peel off and expose under-coordinated ions, leading to rapid fluorescence quenching [10].

Consequences of Defects: The presence of these surface defects directly diminishes the Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY), increases non-radiative recombination, and accelerates degradation. Furthermore, these defects promote anion exchange when QDs of different halide compositions are mixed, broadening the emission spectrum and reducing color purity [10].

Quantitative Analysis of Passivation Strategies

Advanced passivation strategies target the suppression of these surface defects. The table below summarizes the performance outcomes of three prominent approaches, highlighting their impact on key optoelectronic metrics.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of PQD Passivation Strategies

| Passivation Strategy | Key Functional Group/Material | Reported PLQY | Key Stability Outcome | Optoelectronic Application Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imide Derivatives [9] | Carbonyl oxygen (e.g., in Caffeine) | Significantly improved | Thermal stability significantly improved | LED Current & External Quantum Efficiency "significantly improved"; Color gamut up to 130% NTSC |

| Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) [10] | Al₂O₃ coating | Maintained post-passivation | Excellent reliability in 60°C/90% humidity tests; stable in long-term light aging | Enabled high-speed visible-light communication at 1 Gbit/s |

| Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) with Post-Synthesis Optimization [10] | Excess Br⁻ ions | High (referenced as "high PLQY") | Addressed aggregation & surface defects from purification | Improved crystal quality for film preparation |

The data demonstrates that effective passivation directly enhances both the intrinsic optical properties (PLQY) and the extrinsic operational stability under thermal, humid, and optical stress. The success of carbonyl-containing molecules like caffeine underscores the importance of molecular functionality in defect passivation [9].

Experimental Protocols for Surface Passivation

Defect Passivation with Imide Derivatives

This protocol details the surface treatment of synthesized PQDs with molecular passivators [9].

- PQD Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbX₃ PQDs using standard hot-injection or ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) methods to achieve the desired crystal phase and size.

- Passivator Preparation: Prepare solutions of the imide derivatives (e.g., caffeine, 4-amino-N-methylphthalimide, 6-amino-1,3-dimethyluracil) in a suitable solvent compatible with the PQD dispersion (e.g., toluene, hexane).

- Surface Treatment: Add the passivator solution dropwise to the purified PQD solution under vigorous stirring. The reaction is typically allowed to proceed at room or slightly elevated temperatures for a specific duration (e.g., 5-60 minutes).

- Purification: Precipitate the passivated PQDs by adding a non-solvent (e.g., methyl acetate for toluene solutions) followed by centrifugation.

- Characterization: Redisperse the pellet in an anhydrous solvent for characterization. Key techniques include:

- UV-Vis and PL Spectroscopy: To measure absorption, emission wavelength, and calculate PLQY.

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): To confirm the binding of passivators to surface Pb²⁺ ions.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): To assess crystal quality, size distribution, and the presence of "black dots" (trap states).

Atomic Layer Deposition for Encapsulation

This protocol describes the formation of a conformal inorganic shield around PQDs using ALD [10].

- Sample Loading: Load dry, synthesized PQD powder or a solid PQD film into the ALD reaction chamber.

- ALD Process Parameters: Set the chamber temperature to 150°C. Use Trimethylaluminum (TMA, Al(CH₃)₃) as the aluminum precursor and ozone (O₃) or water (H₂O) as the co-reactant.

- Cycle Execution: Run the ALD process for a predetermined number of cycles (e.g., 200 cycles). A typical cycle consists of: a. TMA Pulse: Introduce the TMA precursor into the chamber. b. Purge Step: Flush the chamber with an inert gas to remove unreacted precursor and by-products. c. Reactant Pulse: Introduce the O₃ or H₂O co-reactant. d. Purge Step: Flush the chamber again.

- Thickness Control: The thickness of the Al₂O₃ layer is controlled by the number of cycles, with a typical growth rate of ~2.5 Å/cycle.

- Characterization: Analyze the encapsulated PQDs (termed PeQD) for:

- PLQY Retention: Measure PLQY before and after ALD to ensure the process does not quench emission.

- Stability Testing: Subject the samples to harsh conditions (e.g., 60°C/90% relative humidity, high-intensity UV light) and monitor PL intensity and wavelength over time.

- Electron Microscopy: Use TEM/STEM to confirm the presence and uniformity of the Al₂O₃ coating.

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation with Halide Compensation

This is a specific synthesis and post-synthesis optimization method to minimize defects during PQD formation [10].

- Precursor Preparation: Mix oleic acid (OA), formamidinium bromide (FABr), lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂), and octylamine in a polar solvent (e.g., DMF, DMSO).

- Reprecipitation: Rapidly inject this mixture into a large volume of a non-solvent (toluene) under stirring, causing instantaneous crystallization of FAPbBr₃ QDs.

- Purification: Centrifuge the solution to separate the QDs. Discard the supernatant.

- Halide Compensation (Post-Synthesis Optimization): Redissolve the QD pellet in toluene. Add an excess-lead-ion solution (containing PbBr₂) and oleic acid. This step provides excess Br⁻ ions to compensate for halogen anion vacancies generated during purification.

- Final Purification: Add methyl acetate to precipitate the optimized QDs, centrifuge, and redisperse the final product in toluene.

Visualizing the Passivation Workflow and Defect Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression from defect formation to the application of passivated PQDs, integrating the strategies discussed.

Diagram 1: Defect formation and passivation workflow in perovskite QDs.

The molecular interaction between a passivating agent and a surface defect is a key atomistic dynamic, as shown below.

Diagram 2: Atomistic mechanism of molecular surface passivation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for PQD Defect Passivation Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role in Research | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Imide Derivatives | Molecular surface passivators; bind to under-coordinated Pb²⁺ via carbonyl oxygen, suppressing trap states [9]. | Caffeine, 6-amino-1,3-dimethyluracil |

| ALD Precursors | Gaseous reactants used to form a conformal, inorganic encapsulation layer that protects QDs from environmental degradation [10]. | Trimethylaluminum (TMA) + O₃/H₂O for Al₂O₃ |

| Halide Salts | Provide excess halide ions (X⁻) to compensate for surface halide vacancies created during synthesis and purification [10]. | Formamidinium Bromide (FABr), PbBr₂ |

| Surface Ligands | Organic molecules that coordinate surface ions during synthesis, controlling growth and providing initial colloidal stability [10]. | Oleic Acid (OA), Octylamine |

| Precision Solvents | High-purity solvents for synthesis, purification, and processing; critical for achieving high PLQY and avoiding unintended surface reactions. | Toluene, Acetonitrile, Methyl Acetate, n-Hexane |

| Scattering Particles | Used in solid-state films to enhance light extraction and management by reducing internal reflection [10]. | Nanoscale TiO₂ |

The surface atomistic structure of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) is a critical frontier in nanoscience and optoelectronics. While the bulk crystal structure of perovskites dictates fundamental properties such as bandgap, it is the surface—and the organic ligand species bound to it—that governs colloidal stability, defect formation, non-radiative recombination pathways, and ultimately, device performance. Surface ligands are molecular entities that coordinate to undercoordinated atoms on the PQD surface, forming a dynamic interface between the inorganic crystal and its environment. This technical guide examines the multifaceted roles of surface ligands, framing them not merely as passive stabilizers but as active components in tuning the optoelectronic properties of PQDs. Within the broader context of surface atomistic research, understanding ligand chemistry is paramount for advancing PQD applications from laboratory curiosities toward robust commercial technologies.

Fundamental Roles of Surface Ligands

Surface ligands perform several essential functions that are interdependent and crucial for the performance of PQDs in any application. The primary roles can be categorized as follows:

- Colloidal Stabilization: Ligands create a protective shell around the PQD core, preventing aggregation and precipitation by providing steric hindrance. This is essential for maintaining phase purity and processability from solution.

- Surface Passivation: Undercoordinated surface atoms (e.g., Pb²⁺ ions) act as trap states for charge carriers, leading to non-radiative recombination that quenches photoluminescence (PL) and reduces device efficiency. Ligands donate electron density to these undercoordinated sites, neutralizing traps and enhancing radiative recombination [11].

- Optoelectronic Tuning: The strength of the quantum confinement effect, and thus the emission wavelength, is partially determined by the physical size of the PQD. Ligands influence crystal growth kinetics and final size distribution, thereby tuning the optical bandgap.

- Charge Transport Mediation: In solid-state films for devices like solar cells and light-emitting diodes (LEDs), the insulating nature of long-chain ligands can impede charge transfer between adjacent QDs. Strategic ligand engineering is required to balance stability with efficient charge transport [12] [13].

Table 1: Core Functions of Surface Ligands in Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Function | Mechanism | Impact on PQD Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Colloidal Stabilization | Steric hindrance from long hydrocarbon chains prevents aggregation. | Enables synthesis of discrete nanocrystals and stable colloidal solutions. |

| Surface Passivation | Coordination with undercoordinated surface atoms (e.g., Pb²⁺). | Reduces non-radiative recombination; increases Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY). |

| Morphology Control | Modulating surface energy and growth kinetics during synthesis. | Controls nanocrystal size, shape, and size distribution (uniformity). |

| Charge Transport Tuning | Determining the electronic coupling and dielectric environment between QDs. | Governs conductivity in QD solids; critical for device efficiency. |

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Effects on PQD Properties

The impact of specific ligand engineering strategies on the photophysical properties of PQDs can be quantitatively assessed across recent studies. The following table summarizes key performance metrics achieved through targeted ligand modification.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics from Recent Ligand Engineering Studies

| PQD Material | Ligand Strategy | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ | Dual-functional acetate & 2-hexyldecanoic acid | PLQY: 99%; FWHM: 22 nm; ASE threshold: 0.54 μJ·cm⁻² (70% reduction) | [14] |

| Cs₂NaInCl₆:Sb³⁺ | Optimization of OAm to OA ratio | Highest PLQY achieved with 10% Sb³⁺ doping; OAm passivates defects, OA improves stability. | [15] |

| CsPbI₃ | Passivation with TOPO, TOP, L-PHE | PL increase: TOPO (18%), TOP (16%), L-PHE (3%); L-PHE retained >70% initial PL after 20 days UV. | [11] |

| FAPbI₃ | Consecutive Surface Matrix Engineering (CSME) | Solar cell efficiency: 19.14%; enhanced electronic coupling from ligand desorption. | [12] |

| CsPbI₃ | Complementary Dual-Ligand Reconstruction | Solar cell efficiency: 17.61%; improved inter-dot electronic coupling and stability. | [13] |

Advanced Ligand Engineering Methodologies

Defect Passivation and Auger Recombination Suppression

Non-radiative recombination pathways, such as trap-assisted recombination and Auger recombination, are detrimental to laser and LED applications. Advanced ligand systems directly target these loss mechanisms. In CsPbBr₃ QDs, a novel cesium precursor recipe incorporating acetate (AcO⁻) as a short-branched-chain ligand significantly improved precursor purity from 70.26% to 98.59%, minimizing by-product formation and enhancing batch-to-batch reproducibility. The AcO⁻ anion also functioned as a surface ligand, passivating dangling bonds. Furthermore, replacing oleic acid with 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) provided a stronger binding affinity to the QD surface, which effectively suppressed biexciton Auger recombination. This synergistic approach resulted in a high PLQY of 99% and a 70% reduction in the Amplified Spontaneous Emission (ASE) threshold [14].

Complementary Dual-Ligand Systems and Surface Reconstruction

For photovoltaic applications, achieving efficient charge transport in QD solids is a major challenge. A "complementary dual-ligand reconstruction" strategy for CsPbI₃ PQDs used trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate and phenylethyl ammonium iodide to form a system stabilized by hydrogen bonds. This system not only stabilized the surface lattice but also significantly improved electronic coupling between dots, leading to a record solar cell efficiency of 17.61% for inorganic PQDSCs [13]. Similarly, for FAPbI₃ PQDs, a "Consecutive Surface Matrix Engineering" (CSME) strategy was employed. This process induced an amidation reaction between native OA and OAm ligands, disrupting their dynamic equilibrium and facilitating the desorption of these insulating ligands. The resulting surface vacancies were then filled by short-chain conjugated ligands, which suppressed trap-assisted recombination and enhanced electronic coupling, yielding a champion solar cell efficiency of 19.14% [12].

Thermodynamics of Ligand Coordination

The stability of the ligand-shell is governed by the thermodynamics of ligand coordination. Research utilizing Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) to quantify the enthalpy and equilibrium constants of ligand exchange reactions on CsPbBr₃ QDs has shown that replacing native ligands with stronger-binding ones, such as zwitterionic ligands or primary amines, is crucial for achieving a stable, chemically well-defined QD surface. Without this exchange, the native ligands lead to Ostwald ripening and poor colloidal stability [16].

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Studies

Protocol: Optimized Synthesis of CsPbBr₃ QDs with High Reproducibility

This protocol is adapted from the high-quality synthesis method detailed in [14].

- Primary Materials: Cesium precursor (e.g., Cs₂CO₃), Lead (II) bromide (PbBr₂, 99%), Oleic Acid (OA, 90%), Oleylamine (OAm, 70%), 1-Octadecene (ODE, 90%), Acetate compound, 2-Hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA).

- Synthesis Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Design a novel cesium precursor by combining a dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) and 2-HA as a short-branched-chain ligand. This combination aims to achieve a high-purity precursor (target >98%).

- Reaction Setup: Load the cesium precursor, PbBr₂, and ligands (with optimized OA/OAm ratio) into a three-neck flask with ODE.

- Degassing: Heat the mixture to 110°C under vacuum with vigorous stirring for 50 minutes to remove water and oxygen.

- Reaction Initiation: Under an inert nitrogen atmosphere, rapidly raise the temperature to 170°C. Swiftly inject a predefined volume of GeCl₄ precursor solution (77 μL GeCl₄ per 1 mL ODE) to initiate nucleation and growth.

- Crystallization: Maintain the reaction at 180°C for 5 minutes to allow for crystal growth.

- Termination and Purification: Rapidly cool the reaction mixture in an ice-water bath. Purify the resulting QDs by centrifugation (9500 rpm for 5 min), redisperse the precipitate in chlorobenzene, and centrifuge again. The final QD product is dispersed in a non-polar solvent like hexane.

- Key Characterization: UV-Vis and PL spectroscopy to determine absorption/emission profiles, FWHM, and PLQY. TEM for size and morphology analysis. XRD for crystal structure.

Protocol: Investigating Ligand Roles in Double Perovskite QDs

This protocol outlines the methodology for systematically studying the distinct roles of OA and OAm in double perovskite QDs [15].

- Primary Materials: Cs(OAc), Na(OAc), In(OAc)₃, Sb(OAc)₃, OAm, OA, ODE, GeCl₄.

- Experimental Workflow:

- QD Synthesis with Varied Ligand Ratios: Synthesize multiple batches of Cs₂NaInCl₆:Sb³⁺ (10%) QDs, varying the [OA]/[OAm] volume ratio systematically (e.g., 4, 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25) while keeping the total ligand volume constant.

- Purification: For each batch, precipitate the QDs using centrifugation, wash, and redisperse in hexane.

- Ligand Binding Analysis:

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Analyze the purified QD samples to identify the specific functional groups (e.g., -COO⁻, -NH₃⁺) bound to the QD surface. This identifies which ligand is directly coordinating.

- NMR Spectroscopy: Use NMR to further characterize the state and binding of the ligands.

- Performance Correlation:

- Optical Measurements: For each batch, measure the PLQY, absorption, and PL spectra.

- Stability Test: Monitor the colloidal and optical stability of the QD solutions over time.

- Structural Analysis: Use XRD and TEM to correlate ligand ratio with crystallinity and particle size/morphology.

- Expected Outcome: The data will reveal that OAm is primarily bound to the surface and is critical for achieving high PLQY via defect passivation, while OA plays a greater role in determining long-term colloidal stability [15].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for selecting a ligand engineering strategy based on target application and material constraints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section catalogs critical reagents and materials used in advanced PQD ligand research, as referenced in the studies.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Perovskite Quantum Dot Ligand Research

| Reagent/Material | Chemical Function | Role in Ligand Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Long-chain carboxylic acid | Traditional X-type ligand; passivates Pb²⁺ sites; impacts colloidal stability. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Long-chain primary amine | Traditional L-type ligand; passivates halide vacancies; crucial for PLQY. |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Phosphine oxide | Strong L-type ligand; effective surface passivator for Pb²⁺ ions. |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | Branched carboxylic acid | Alternative to OA; stronger binding affinity reduces Auger recombination. |

| Acetate (AcO⁻) | Short-chain carboxylate | Dual-function: improves precursor purity and acts as a passivating ligand. |

| L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | Amino acid | Bifunctional ligand; enhances photostability and provides passivation. |

| Phenylethyl Ammonium Iodide | Bulky ammonium salt | Used in dual-ligand systems; improves surface coverage and stability. |

| Trimethyloxonium Tetrafluoroborate | Methylating agent | Used in dual-ligand systems; participates in surface reconstruction. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | High-booint solvent | Non-coordinating solvent providing medium for high-temperature synthesis. |

| GeCl₄ | Chloride precursor | Used in double perovskite synthesis (e.g., Cs₂NaInCl₆) as a halide source. |

Surface ligand engineering has evolved from a simple synthesis requirement to a sophisticated tool for atomistic-level control over the properties of perovskite quantum dots. The dynamic ligand shell directly dictates key performance parameters, including PLQY, ASE thresholds, charge transport, and operational stability. Strategies such as the use of strongly-binding alternative ligands, complementary dual-ligand systems, and consecutive surface matrix engineering are pushing the boundaries of what is possible with PQDs in optoelectronic devices. Future research within the broader thesis of surface atomistic structure will likely focus on developing a more quantitative understanding of ligand binding thermodynamics, designing novel multi-functional ligands, and integrating these advanced PQDs into complex device architectures. The precise command of surface chemistry remains the key to unlocking the full theoretical potential of perovskite quantum dots.

The optical properties of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) are governed by the intricate interplay between two fundamental phenomena: quantum confinement effects arising from their nanoscale dimensions and surface effects determined by their atomistic surface structure. Quantum confinement dictates the electronic band structure and initial optoelectronic potential of these nanomaterials, while surface effects ultimately determine the stability and practical performance through defect-mediated non-radiative recombination.

In the broader context of perovskite quantum dot research, understanding this interplay is paramount for advancing both fundamental science and practical applications. This whitepaper comprehensively examines the governing principles, experimental evidence, and methodological approaches for investigating and optimizing these critical phenomena, providing researchers with a technical framework for advancing PQD-based technologies.

Theoretical Foundations

Quantum Confinement in Nanocrystal Systems

Quantum confinement effects describe the phenomenon where electrons in semiconductor nanocrystals are spatially confined, leading to discrete energy levels and altered electronic properties compared to bulk materials. This confinement becomes significant when the physical dimensions of the material approach the de Broglie wavelength of its charge carriers (typically electrons or holes) [17] [18].

The most direct manifestation of quantum confinement is the quantization of energy levels. In bulk semiconductors, electrons can occupy a quasi-continuous range of energy states within bands, but when confined to nanoscale dimensions (quantum dots representing zero-dimensional confinement), these energy levels become discrete, analogous to the electronic states of atoms [17]. This energy quantization follows the particle-in-a-box model from quantum mechanics, where the confinement length directly determines the energy separation between states.

For semiconductor quantum dots, this spatial restriction of charge carriers causes a widening of the effective band gap as particle size decreases. The relationship between bandgap energy and particle size can be described by the Brus equation:

[ E{QD} = Eg + \frac{\hbar^2\pi^2}{2R^2} \left( \frac{1}{me} + \frac{1}{mh} \right) - \frac{1.786e^2}{\varepsilon R} ]

where (E{QD}) is the quantum dot bandgap, (Eg) is the bulk bandgap, (R) is the particle radius, (me) and (mh) are the effective masses of electrons and holes, and (\varepsilon) is the dielectric constant [17]. This size-dependent bandgap enables precise tuning of optical absorption and emission wavelengths across the visible spectrum by controlling quantum dot dimensions.

Surface Atomistic Structure and Defect Formation

The surface atomistic structure of PQDs plays an equally critical role in determining their ultimate optical properties and environmental stability. Due to their high surface-to-volume ratio, a significant proportion of atoms in quantum dots reside on the surface, where they experience different coordination environments compared to bulk atoms [11] [8].

In perovskite quantum dots with the ABX₃ crystal structure (where A is cesium, formamidinium, or methylammonium; B is lead or tin; and X is a halide), surface defects primarily occur as undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions and halide vacancies [11]. These defective sites create trap states within the bandgap that facilitate non-radiative recombination of charge carriers, thereby reducing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and accelerating degradation under environmental stressors [8].

The dynamic binding nature of native surface ligands (typically oleic acid and oleylamine) further complicates the surface chemistry, as weakly bound ligands can desorb during processing or operation, creating additional defect sites [8] [19]. This underscores the critical importance of surface chemistry engineering in PQD research and development.

Experimental Evidence and Quantitative Relationships

Quantum Confinement Manifestations

The quantum confinement effect enables precise tuning of PQD optical properties through size control. In CsPbI₃ PQDs, synthesis temperature variations between 140°C and 180°C produce emission wavelengths tunable from 698 nm to 713 nm, demonstrating direct size control over optoelectronic properties [11]. Similarly, full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) values ranging between 24 nm and 28 nm indicate narrow size distributions achievable through optimized synthesis protocols.

The dimensions of PQDs typically range from approximately 3 nm to 15 nm, within which strong quantum confinement effects operate [4]. This size range corresponds to bandgap energies that can be tuned across the visible spectrum, enabling applications requiring specific emission wavelengths from blue to red and near-infrared regions.

Table 1: Size-Dependent Optical Properties of CsPbI₃ PQDs

| Synthesis Temperature (°C) | Emission Wavelength (nm) | FWHM (nm) | PL Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 140 | 698 | 24 | Baseline |

| 150 | 705 | 26 | Baseline |

| 160 | 709 | 27 | Baseline |

| 170 | 712 | 28 | Maximum |

| 180 | 713 | 28 | Significant decrease |

Surface Effects on Optical Performance

Surface ligand engineering directly impacts PQD optical performance and stability. Systematic studies with CsPbI₃ PQDs demonstrate that surface passivation using trioctylphosphine (TOP), trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO), and l-phenylalanine (L-PHE) effectively suppresses non-radiative recombination through coordination with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions [11].

Photoluminescence enhancements of 3%, 16%, and 18% were observed for L-PHE, TOP, and TOPO-modified PQDs, respectively, highlighting the critical role of ligand selection in optimizing optical performance [11]. Notably, L-PHE-modified PQDs demonstrated superior photostability, retaining over 70% of their initial PL intensity after 20 days of continuous UV exposure, despite providing more modest initial PL enhancement [11].

Table 2: Surface Ligand Effects on CsPbI₃ PQD Properties

| Ligand | PL Enhancement (%) | Photostability (After 20 days UV) | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-PHE | 3% | >70% retention | Defect passivation |

| TOP | 16% | Not specified | Coordination with Pb²⁺ |

| TOPO | 18% | Not specified | Coordination with Pb²⁺ |

Advanced surface encapsulation techniques further enhance PQD stability. Atomic layer deposition (ALD) of Al₂O₃ passivation layers effectively protects PQDs from moisture infiltration and oxidation while maintaining high photoluminescence quantum yield [20]. These passivated PQDs exhibit excellent wavelength stability and reliability in current variation tests, long-term light aging tests, and temperature/humidity tests (60°/90%), making them suitable for commercial applications [20].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Synthesis Approaches for Controlled Quantum Confinement

Hot-Injection Method for CsPbI₃ PQDs:

- Prepare precursor solutions: cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99%) in 1-octadecene with oleic acid; lead iodide (PbI₂, 99%) in 1-octadecene with oleylamine [11]

- Heat lead precursor to temperatures between 140°C and 180°C under inert atmosphere

- Rapidly inject cesium precursor with precise volume control (optimal volume: 1.5 mL)

- Control reaction duration to achieve desired size and narrow size distribution

- Quench reaction using ice bath to terminate growth [11]

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) for FAPbBr₃ PQDs:

- Mix oleic acid (500 μL), formamidinium bromide (FABr, 0.16 mmol), lead bromide (PbBr₂, 0.2 mmol), and octylamine (20 μL) [20]

- Add toluene (10 mL) followed by acetonitrile (5 mL) under stirring

- Centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 25 minutes, discard supernatant

- Redissolve pellet in toluene and add excess-lead-ion solution

- Introduce oleic acid (500 μL) and methyl acetate (10 mL), centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 25 minutes [20]

- Recover purified FAPbBr₃ PQDs in toluene for further surface modification

Surface Engineering Techniques

Ligand Exchange Protocol:

- Purify as-synthesized PQDs using standard centrifugation/washing procedure

- Prepare ligand solution (TOP, TOPO, or L-PHE) in non-polar solvent

- Incubate PQD solution with ligand solution at elevated temperature (60-80°C) for 1-2 hours

- Precipitate and purify surface-modified PQDs using antisolvent

- Redisperse in appropriate solvent for characterization or device integration [11]

Atomic Layer Deposition Passivation:

- Use ALD system with powder "dust flow field" design for uniform coating

- Employ trimethylaluminum (TMA) and ozone (O₃) as precursors with water co-reactant

- Maintain substrate temperature at 150°C

- Execute 200 cycles at deposition rate of 2.5 Å/cycle

- Form conformal Al₂O₃ protective layer on individual PQDs [20]

Advanced Characterization and Computational Approaches

Machine Learning for Property Prediction

Machine learning (ML) approaches enable accurate prediction of PQD properties based on synthesis parameters. For CsPbCl₃ PQDs, ML models including Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Nearest Neighbour Distance (NND) demonstrate high accuracy in predicting size, absorbance (1S abs), and photoluminescence properties [4].

These models utilize synthesis parameters as input features, including injection temperature, precursor molar ratios (Cs:Pb, Cl:Pb), ligand volumes (oleic acid, oleylamine), and reaction times. With adequate training data (~700 data points), ML algorithms can identify complex relationships between synthesis conditions and resulting optical properties, accelerating materials optimization without resource-intensive trial-and-error approaches [4].

Structural and Optical Characterization

High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) confirms lattice matching between perovskite matrices and quantum dots in heterocrystal structures, providing direct evidence of epitaxial relationships [21]. Photoluminescence quantum yield measurements quantify emission efficiency, while time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) assesses carrier lifetimes and trap state densities [22].

Environmental stability tests evaluate PL intensity retention under continuous UV exposure, thermal stress, and humidity exposure (60°C/90% relative humidity) to determine practical suitability for device applications [11] [20].

Interplay Visualization and Research Toolkit

Diagram 1: Interplay between quantum confinement and surface effects in determining PQD optical properties. Blue elements represent quantum confinement phenomena, red elements represent surface effects, and green represents the resulting optical properties. Dashed lines indicate key interactions between the two domains.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PQD Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cesium precursor | CsPbI₃ PQD synthesis [11] |

| Lead Iodide/Bromide (PbI₂/PbBr₂) | Lead precursor | ABX₃ perovskite formation [11] [20] |

| Formamidinium Bromide (FABr) | Organic cation source | FAPbBr₃ PQD synthesis [20] |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-polar solvent reaction medium | High-temperature synthesis [11] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand, coordination | Colloidal stability, surface passivation [11] [4] |

| Oleylamine (OLA) | Surface ligand, coordination | Colloidal stability, surface passivation [11] [4] |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Surface passivation ligand | Defect passivation for PL enhancement [11] |

| l-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | Surface passivation ligand | Photostability enhancement [11] |

| Trimethylaluminum (TMA) | ALD precursor | Al₂O₃ passivation layer [20] |

The optical properties of perovskite quantum dots emerge from the complex interplay between quantum confinement effects—which establish the fundamental electronic structure—and surface effects—which determine practical performance through defect-mediated processes. Quantum confinement enables bandgap tuning and size-dependent emission, while surface chemistry governs non-radiative recombination, environmental stability, and ultimate device performance.

Strategic surface ligand engineering combined with precise size control represents the most effective approach for optimizing PQD optical properties. Passivation using phosphine-based ligands (TOP, TOPO) provides significant PL enhancement, while amino acid ligands (L-PHE) offer superior photostability. Advanced encapsulation techniques, particularly atomic layer deposition of metal oxides, further enhance environmental stability without compromising optical performance.

Future research directions should focus on developing multifunctional ligands that simultaneously optimize optical performance, charge transport, and environmental stability, alongside machine-learning accelerated discovery of synthesis parameters for tailored PQD properties. This integrated approach will advance PQD technologies toward commercial viability in photovoltaics, displays, quantum technologies, and memory applications.

The exceptional optoelectronic properties of metal halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), such as their high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and tunable bandgap, have positioned them as leading materials for next-generation light-emitting diodes (LEDs), lasers, and quantum light sources [23] [24]. However, their commercial viability is critically hampered by intrinsic instabilities originating from their fundamental material nature. The "soft" ionic lattice, characterized by weak Pb-X (X = Cl, Br, I) bonds, and a dynamic surface equilibrium, where ligands are in constant exchange with the surrounding medium, are recognized as the primary culprits [25] [26] [27]. These features lead to rapid degradation under thermal, light, and atmospheric stresses, posing a significant barrier to practical applications. This whitepaper delves into the atomistic origins of these challenges, synthesizes current understanding from cutting-edge research, and outlines advanced experimental and engineering strategies developed to stabilize the surface structure of PQDs, thereby framing the pathway toward their technological maturation.

Fundamental Challenges in Perovskite Quantum Dot Surface Stability

The surface of a PQD is a region of high energy and activity, where the periodic crystal structure terminates. For PQDs, which possess a high surface-area-to-volume ratio, the surface atoms dictate the overall stability and optoelectronic properties. The core challenges can be dissected into two interrelated phenomena.

The "Soft" Ionic Lattice

The term "soft" describes the low lattice energy and highly dynamic nature of the ionic bonds in lead halide perovskites. Unlike covalent semiconductors (e.g., CdSe), the ionic bonds in ABX₃ perovskites are weaker and more susceptible to breakage.

- Inherent Bond Weakness: The Pb-X bond strength is insufficient to robustly withstand external stimuli such as heat, light, or chemical attack. This softness is inversely related to the crystal's cohesive energy, making the structure inherently prone to decomposition [27].

- Phase Instability: This soft lattice culminates in phase instability, particularly for iodide-based compositions like CsPbI₃. At room temperature, the photoactive black phase (γ-phase or α-phase) is metastable and tends to transition to a non-perovskite, non-photoactive yellow phase (δ-phase) [28] [26]. Thermal stress exacerbates this, with Cs-rich PQDs undergoing a phase transition, while FA-rich PQDs directly decompose into PbI₂ [26].

- Ion Migration and Phase Segregation: Under operational stresses like electric fields or photo-excitation, halide ions become highly mobile within the lattice. In mixed-halide PQDs (e.g., CsPb(BrₓI₁₋ₓ)₃), this leads to phase segregation, where halides separate into domains of different bandgaps, causing spectral instability and efficiency losses [27].

Dynamic Surface Equilibrium and Ligand Lability

The surface of as-synthesized PQDs is typically passivated by a layer of organic ligands, such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm). However, the binding of these ligands is highly labile.

- Acid-Base Equilibrium: Conventional OA and OAm ligands exist in a dynamic equilibrium on the PQD surface (OA⁻ + OAmH⁺ ⇋ OAm + OA). This equilibrium is easily disturbed during purification, film formation, or device operation, leading to ligand desorption [29] [30].

- Creation of Surface Defects: Ligand desorption exposes under-coordinated surface ions, creating vacancies (e.g., A-site, Pb²⁺, and X-site) that act as traps for charge carriers. These defects non-radiatively recombine excitons, quench PL, and serve as entry points for further degradation [29] [31].

- Colloidal and Structural Disintegration: The loss of ligands destabilizes the colloidal suspension, leading to agglomeration and precipitation. More critically, excessive ligand loss can trigger the dissolution of the surface ionic layer itself, fundamentally destroying the nanocrystal [32].

The following diagram illustrates the degradation pathways initiated by these inherent challenges.

Advanced Characterization and Experimental Protocols

Understanding and mitigating these challenges requires sophisticated characterization techniques to probe the surface chemistry, crystal structure, and optical properties of PQDs under various conditions.

In Situ Structural and Thermal Analysis

Objective: To monitor the real-time structural evolution of PQDs under thermal stress and elucidate composition-dependent degradation mechanisms [26].

Protocol:

- Synthesis: Prepare a series of CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃ PQDs across the entire compositional range (x = 0 to 1) using a standard hot-injection or ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) method.

- Sample Preparation: Deposit concentrated PQD solutions onto a Pt substrate to form a thin film for X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis.

- In Situ XRD Measurement:

- Place the sample in a temperature-controlled stage under an inert argon atmosphere.

- Heat the sample from 30 °C to 500 °C at a controlled ramp rate (e.g., 5-10 °C/min).

- Continuously acquire XRD patterns at regular temperature intervals.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify the appearance, shift, or disappearance of diffraction peaks corresponding to the perovskite phases (black γ-/α-phase at ~27.7° and ~31.0°), non-perovskite δ-phase, and degradation products like PbI₂ (peaks at 25.2°, 29.0°, and 41.2°).

- Correlate the specific degradation pathways (phase transition vs. direct decomposition) with the A-site composition.

Surface Binding Affinity Assessment via Spectroscopy and Simulation

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the binding strength and mode of engineered ligands to the PQD surface [32].

Protocol:

- Ligand Design and Synthesis: Design zwitterionic phospholipid ligands with varying headgroups (e.g., phosphocholine, PC, vs. phosphoethanolamine, PEA) and tail structures.

- Post-Synthetic Ligand Exchange: Synthesize PQDs (e.g., FAPbBr₃, CsPbBr₃) via a standard method. Subsequently, displace the native ligands by introducing the target phospholipid in solution, followed by purification.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations:

- Model the PQD surface as a slab of the bulk crystal structure (e.g., FAPbBr₃ (100) plane).

- Simulate the interaction and free energy of different ligand binding modes (physisorption, ion displacement) to identify the most stable configuration.

- Experimental Validation:

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Analyze the ligand-capped PQDs to identify shifts in characteristic vibrational modes (e.g., P=O stretching), confirming coordination to surface Pb atoms.

- Solid-State NMR: Employ techniques like ³¹P–²⁰⁷Pb Rotational-Echo Double-Resonance (REDOR) to directly probe the spatial proximity between the ligand's phosphorus atoms and the PQD's lead atoms, providing atomic-level evidence of binding.

Single Quantum Dot Photostability Measurement

Objective: To assess the photoluminescence (PL) intermittency (blinking) and photostability of single PQDs, which are critical for quantum light source applications [31].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the PQD solution to a very low concentration in a non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene). Spin-coat the solution onto a clean, inert substrate (e.g., SiO₂/Si) to ensure spatial isolation of individual QDs.

- Confocal Microscopy Setup: Use a confocal fluorescence microscope equipped with a high-numerical-aperture (NA > 0.9) objective, a continuous-wave laser (e.g., 405 nm), and single-photon avalanche photodiodes (SPADs) in a Hanbury Brown and Twiss (HBT) interferometer configuration.

- Data Acquisition:

- Scan the sample to locate individual QDs.

- For a selected single QD, record the PL intensity trajectory over time (e.g., 10-300 seconds) under constant laser excitation.

- Simultaneously, perform a second-order correlation (g²(τ)) measurement using the HBT setup to confirm single-photon emission (g²(0) < 0.5).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the ON fraction (the percentage of time the QD spends in a bright state) from the PL trajectory.

- Monitor the time until photodarkening (a permanent drop in PL intensity) occurs to evaluate resistance to photodegradation.

Table 1: Key Characterization Techniques for Surface and Stability Analysis

| Technique | Key Measurable Parameters | Insights Gained |

|---|---|---|

| In Situ XRD [26] | Phase transition temperatures, decomposition products, crystal grain growth. | Thermal degradation mechanism, composition-stability relationship. |

| FTIR Spectroscopy [32] | Vibrational frequency shifts of ligand functional groups (e.g., P=O, -COO⁻). | Confirmation of ligand binding to the surface and identification of binding moieties. |

| Solid-State NMR (REDOR) [32] | Nuclear spin coupling between ligand atoms (³¹P) and surface ions (²⁰⁷Pb). | Atomistic-level proof of ligand coordination and binding mode. |

| Single-QD Microscopy [31] | PL intensity trajectory, ON fraction, g²(0) value, photodarkening time. | Blinking behavior, single-photon purity, and intrinsic photostability of surface-passivated QDs. |

Engineering Solutions for Stable Surface Atomistic Structures

Addressing the inherent instability of PQDs requires innovative strategies that move beyond conventional ligands to engineer robust surface interfaces.

Zwitterionic Ligand Engineering

Zwitterionic ligands, which contain both positive and negative charges within the same molecule, offer a charge-neutral and stable passivation strategy that avoids the adverse ionic metathesis of cationic/anionic ligands [32] [29].

- Headgroup Optimization: The geometric fitness of the zwitterionic headgroup into the PQD surface lattice is paramount. MD simulations and experimental studies show that phosphoethanolamine (PEA) headgroups, with primary ammonium cations, fit better into the A-site cation pockets on the PQD surface compared to bulkier phosphocholine (PC) headgroups. This allows for near-complete surface coverage and significantly enhanced colloidal and structural integrity [32].

- Tail-Group Engineering: The ligand tail governs dispersibility and intermolecular interactions in solid films. Short-chain ligands or those with aromatic groups (e.g., phenethylammonium, PEA) enable dense packing and attractive π-π stacking between adjacent ligands. This creates a nearly epitaxial, low-energy ligand layer that drastically reduces surface defects, suppresses blinking, and improves photostability [31]. In contrast, bulky, long-chain tails introduce steric repulsion that prevents complete passivation.

"Whole-Body" Fluorination Strategy

A groundbreaking approach to strengthening the PQD's internal lattice is the "whole-body" fluorination strategy [27]. This involves the partial substitution of halide ions (X⁻) with highly electronegative fluoride ions (F⁻) throughout the entire nanocrystal, including the interior lattice and the surface.

- Enhanced Cohesive Energy: The strong Pb-F ionic bond increases the crystal's overall cohesive energy, effectively "hardening" the soft ionic lattice.

- Defect Passivation: Fluorination simultaneously passivates surface defects, mitigating non-radiative recombination and suppressing ion migration and phase segregation.

- Stability Outcome: This dual action results in PQDs with exceptional operational stability in devices like LEDs, significantly outperforming their non-fluorinated counterparts [27].

Synthesis Control and Nucleation Kinetics

The synthesis process itself can be engineered to produce more uniform and stable PQDs from the outset. Replacing traditional OA/OAm with short-chain acids and bases like octanoic acid (OTAc) and octylamine (OTAm) controls the precursor chemistry [30].

- Elimination of Cluster Intermediates: OTAc/OTAm prevents the formation of less reactive {OAmH⁺·[PbBr₃]ₙ} cluster intermediates, leading to a homogeneous one-route nucleation pathway.

- Uniform Nucleation and Growth: This results in PQDs with narrow size distribution, better crystallinity, and fewer intrinsic defects, which translates to higher PLQY and superior environmental stability against humidity [30].

Table 2: Summary of Advanced Surface Stabilization Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Ligands [32] [29] | Charge-neutral binding avoids ionic metathesis. Headgroup geometry optimizes surface fit. | Enhanced colloidal stability, improved PLQY, reduced defect density. |

| Aromatic Tail Stacking [31] | π-π stacking between ligand tails creates a dense, epitaxial-like layer on the solid-state QD surface. | Near-non-blinking emission, unprecedented photostability (>12 hours), high-purity single-photon emission. |

| Whole-Body Fluorination [27] | Substitution with F⁻ strengthens internal Pb-X bonds and increases crystal cohesive energy. | Mitigated phase segregation, ultra-stable lattice, enhanced device operational lifetime. |

| Kinetic-Controlled Synthesis [30] | Using short-chain acids/bases to eliminate cluster intermediates and promote homogeneous nucleation. | Uniform size distribution, high crystallinity, stability in high-humidity air. |

The following diagram synthesizes these strategies into a coherent experimental workflow for developing stable PQDs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and materials central to the advanced research on stabilizing perovskite quantum dots, as discussed in this whitepaper.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for PQD Surface Stabilization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Phospholipids | Engineered ligands for robust, charge-neutral surface passivation. Superior headgroup geometry (e.g., PEA) enhances binding affinity. [32] | Hexadecyl-phosphoethanolamine (PEA) |

| Aromatic Ammonium Salts | Small ligands whose tails undergo π-π stacking, creating a dense, stabilizing layer on the QD surface in solid state. [31] | Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) |

| Short-Chain Acids/Amines | Used in synthesis to control precursor chemistry, prevent cluster intermediates, and enable homogeneous nucleation of uniform QDs. [30] | Octanoic Acid (OTAc), Octylamine (OTAm) |

| Fluorine-based Precursors | Source of F⁻ ions for "whole-body" fluorination strategy to strengthen the ionic lattice and passivate defects. [27] | Not specified (Commercial F-salts e.g., PbF₂, CsF) |

| Betaine | A short zwitterionic molecule used for surface treatment; carboxylate and quaternary ammonium groups passivate defects and stabilize the dynamic surface. [29] | Betaine (BET) |

Precision Engineering and Biomedical Translation: From Synthesis to Clinical Applications

The pursuit of precise control over the surface atomistic structure of inorganic halide perovskite quantum dots (IHPQDs) is a central theme in modern nanomaterials research. The synthesis method employed directly dictates critical surface characteristics, including ligand density, defect concentration, and ionic stability, which ultimately govern the optoelectronic properties and environmental resilience of the resulting quantum dots [33]. Techniques such as hot-injection, ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP), and microwave-assisted synthesis represent foundational approaches for fabricating IHPQDs, each offering distinct pathways for manipulating surface morphology and crystallinity.

Advanced characterization techniques, particularly integrated differential-phase-contrast scanning transmission electron microscopy, have enabled researchers to atomically resolve local structures in QDs, including surfaces and interfaces [34]. These studies reveal that the structural evolution of IHPQDs under external stimuli is intrinsically linked to their initial synthesis conditions, highlighting the importance of selecting and optimizing synthetic protocols to achieve desired surface properties for specific applications.

Synthesis Techniques: Mechanisms and Methodologies

Hot-Injection Method

The hot-injection technique is a high-temperature colloidal synthesis approach that enables precise control over quantum dot size, size distribution, and crystallinity through rapid nucleation and controlled growth phases [33]. This method involves the rapid injection of precursor compounds into a heated solvent containing coordinating ligands, resulting in instantaneous nucleation. The subsequent crystal growth phase is carefully controlled by maintaining specific temperature profiles.

Key Experimental Protocol (CsPbX₃ QDs via Hot-Injection):

- Precursor Preparation: Cesium precursor (e.g., Cs₂CO₃) is combined with oleic acid (OA) and octadecene (ODE) in a three-neck flask, then heated to 150°C under inert gas until completely dissolved [14]. Lead halide precursor (e.g., PbBr₂) is separately mixed with ODE, OA, and oleylamine (OLA) in another flask.

- Reaction Process: The lead precursor solution is heated to 150-200°C under nitrogen atmosphere with vigorous stirring. The cesium precursor solution is swiftly injected into the reaction vessel.

- Nucleation and Growth: Immediate nucleation occurs upon injection. The reaction temperature and time (typically 5-60 seconds) precisely control QD size and size distribution.

- Purification: The reaction is cooled using an ice bath. Quantum dots are isolated by centrifugation with anti-solvents (typically ethyl acetate or methyl acetate) and redispersed in non-polar solvents [33].

This method facilitates nearly atomic-level control over surface termination, allowing researchers to engineer defect-tolerant structures through careful ligand selection and reaction condition optimization [35].

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP)

LARP is a room-temperature synthesis method conducted under ambient atmospheric conditions, offering significant advantages for scalability and reduced energy consumption compared to hot-injection techniques [35]. The process relies on the supersaturation of precursors in a solvent system that undergoes dramatic polarity changes.

Key Experimental Protocol (CsPbX₃ QDs via LARP):

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Perovskite precursors (cesium and lead halide salts) are dissolved in a polar aprotic solvent (typically dimethylformamide or dimethyl sulfoxide) containing coordinating ligands (OA and OLA).

- Antisolvent Addition: A small volume of the precursor solution (typically 0.1-0.5 mL) is rapidly injected into a larger volume (5-10 mL) of a poor solvent (typically toluene or chloroform) under vigorous stirring.

- Nucleation Mechanism: The immediate reduction of solvent polarity induces supersaturation, triggering rapid nucleation and formation of quantum dots at room temperature.

- Stabilization: Ligands in the solution immediately coordinate to the surface of the nascent nanocrystals, controlling growth and providing colloidal stability [36].

Life-cycle assessments comparing LARP to traditional hot-injection methods have demonstrated reductions in environmental impact by up to 50% in terms of hazardous solvent usage and waste generation [35].

Microwave-Assisted Synthesis

Microwave-assisted synthesis utilizes dielectric heating to achieve rapid, uniform temperature increases throughout the reaction mixture, enabling significantly shortened reaction times and enhanced reproducibility [36]. This method provides exceptional control over thermal gradients, minimizing internal temperature variations that can lead to batch inconsistencies.

Key Experimental Protocol (CsPbX₃ QDs via Microwave Synthesis):

- Reaction Vessel Preparation: Precursor solutions similar to those used in hot-injection are combined in a microwave-safe vessel.

- Microwave Irradiation: The reaction mixture is subjected to microwave irradiation with precise control over power, temperature, and time. Typical reactions require only minutes or even seconds to complete.

- Kinetic Control: Rapid heating rates promote homogeneous nucleation while suppressing Ostwald ripening, resulting in narrow size distributions.

- Scalability: The method demonstrates excellent reproducibility and can be scaled using continuous-flow microwave reactors [36].

Machine learning models have recently been employed to optimize microwave synthesis parameters, achieving exceptional predictability for QD properties including size, absorbance, and photoluminescence characteristics [4].

Comparative Analysis of Synthesis Techniques

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Advanced Synthesis Techniques for Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Parameter | Hot-Injection | LARP | Microwave-Assisted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature Range | 120-200°C | Room temperature | 60-150°C |

| Reaction Time | 5-60 seconds | <10 seconds | 1-10 minutes |

| Atmosphere | Inert (N₂/Ar) required | Ambient air | Inert or ambient |

| Energy Consumption | High | Low | Moderate |

| Scalability | Moderate | High | High |

| Size Distribution (FWHM) | <20 nm | 20-35 nm | <25 nm |

| PLQY Range | 50-99% [14] | 50-90% | 60-95% |

| Environmental Impact | High | Low (-50%) [35] | Moderate |

| Surface Defect Density | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Batch-to-Batch Reproducibility | Moderate | Variable | High |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Synthesis Techniques for CsPbBr₃ QDs

| Performance Metric | Hot-Injection | LARP | Microwave-Assisted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average PLQY (%) | 99% [14] | 70-85% | 80-95% |

| FWHM (nm) | 22 [14] | 25-35 | 20-28 |

| ASE Threshold (μJ·cm⁻²) | 0.54 [14] | 2.5-5.0 | 1.0-2.0 |

| Stability (PLQY retention after 30 days) | >95% [35] | 70-85% | 85-95% |

| Size Deviation Batch-to-Batch | 9.02% [14] | 15-25% | 5-10% |

| LOD for Heavy Metal Ions (nM) | 0.1-1.0 [36] | 1.0-10.0 | 0.5-5.0 |

Advanced Synthesis Workflow and Surface Structure Relationship

The following diagram illustrates the strategic decision-making pathway for selecting and optimizing synthesis techniques based on desired surface structures and application requirements:

Synthesis Technique Selection Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Perovskite Quantum Dot Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Precursors (Cs₂CO₃, Cs-Oleate) | Provides Cs⁺ ions for perovskite structure | CsPbBr₃ synthesis with 98.59% purity [14] |

| Lead Halides (PbBr₂, PbI₂, PbCl₂) | Provides Pb²⁺ and halide ions | CsPbX₃ (X=Cl, Br, I) formation [33] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand for passivation and colloidal stability | Defect passivation in hot-injection (0.5-2.0 mL) [14] |

| Oleylamine (OLA) | Co-ligand for enhanced surface binding | Improved morphology in LARP [36] |

| Octadecene (ODE) | Non-polar solvent for high-temperature reactions | Reaction medium in hot-injection (10-20 mL) [33] |

| Polar Solvents (DMF, DMSO) | Dissolves precursor salts for LARP | Precursor solvent in reprecipitation method [35] |

| Non-polar Solvents (Toluene, Hexane) | Anti-solvent for nucleation and dispersion | Colloidal stabilization in LARP [36] |

| Acetate Salts (e.g., CsOAc) | Dual-functional precursor and ligand | Enhanced cesium conversion and surface passivation [14] |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | Branched-chain ligand | Suppression of Auger recombination [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Surface Structure Optimization

High-Reproducibility CsPbBr₃ Synthesis with Acetate Chemistry

Objective: To achieve CsPbBr₃ QDs with exceptional batch-to-batch reproducibility and minimized surface defects through novel cesium precursor design [14].

Detailed Methodology:

- Cesium Precursor Optimization:

- Combine Cs₂CO₃ (0.2 mmol) with 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA, 0.6 mmol) in octadecene (5 mL)

- Heat at 120°C under N₂ atmosphere with stirring until complete dissolution (approximately 30 minutes)

- Add acetate source (CsOAc, 0.1 mmol) to enhance conversion purity to 98.59%

Lead Precursor Preparation:

- Dissolve PbBr₂ (0.2 mmol) in octadecene (10 mL) with oleic acid (0.5 mL) and oleylamine (0.5 mL)

- Degas at 100°C for 30 minutes, then heat to 150°C under N₂ atmosphere

Reaction and Purification:

- Rapidly inject cesium precursor into lead precursor solution with vigorous stirring

- React for 10 seconds, then immediately cool in ice bath

- Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes, discard supernatant

- Redisperse precipitate in toluene (5 mL) and centrifuge at 3000 rpm for 3 minutes to remove aggregates

Key Outcomes: This protocol yields QDs with uniform size distribution, green emission at 512 nm, PLQY of 99%, narrow emission linewidth of 22 nm, and enhanced amplified spontaneous emission with threshold reduced by 70% from 1.8 μJ·cm⁻² to 0.54 μJ·cm⁻² [14].

Stabilized PQD Synthesis for Sensing Applications

Objective: To develop water-stable perovskite quantum dots for heavy metal ion detection with limits of detection as low as 0.1 nM [36].

Detailed Methodology:

- Matrix Encapsulation Approach:

- Synthesize CsPbBr₃ QDs via standard hot-injection method

- Prepare metal-organic framework (MOF) precursor solution (zinc nitrate and 2-methylimidazole in methanol)

- Combine QDs with MOF precursors under gentle stirring for 24 hours at room temperature

- Collect PQD@MOF composite by centrifugation and wash with methanol

- Surface Ligand Engineering for Aqueous Stability:

- Replace native oleic acid/oleylamine ligands with poly(ethylenimine) (PEI) via solid-state ligand exchange

- Dissolve PEI (10 mg/mL) in toluene and add to purified QD solution

- Stir for 12 hours at 50°C, then precipitate with acetonitrile

- Redisperse in aqueous buffer for sensing applications

Key Outcomes: The resulting composites demonstrate enhanced stability in aqueous environments while maintaining high sensitivity to heavy metal ions through fluorescence quenching mechanisms, enabling detection of Hg²⁺, Cu²⁺, Cd²⁺, Fe³⁺, Cr⁶⁺, and Pb²⁺ at nanomolar concentrations [36].

The strategic selection and optimization of synthesis techniques directly enables precise manipulation of the surface atomistic structure in perovskite quantum dots, facilitating tailored material properties for specific applications. Hot-injection remains the benchmark for high-quality QDs with superior optoelectronic properties, while LARP offers an environmentally sustainable alternative with room-temperature processing. Microwave-assisted synthesis emerges as a promising approach for industrial-scale production with exceptional reproducibility. Future developments will likely focus on hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of multiple techniques, further enhanced by machine learning optimization, to achieve unprecedented control over surface properties and quantum dot performance [4]. The continued refinement of these synthetic methodologies will be essential for advancing perovskite quantum dots from laboratory curiosities to commercially viable technologies across optoelectronics, sensing, and biomedical applications.