Suppressing Ion Migration in Perovskite Quantum Dot Memory: Strategies for Stable Neuromorphic Devices

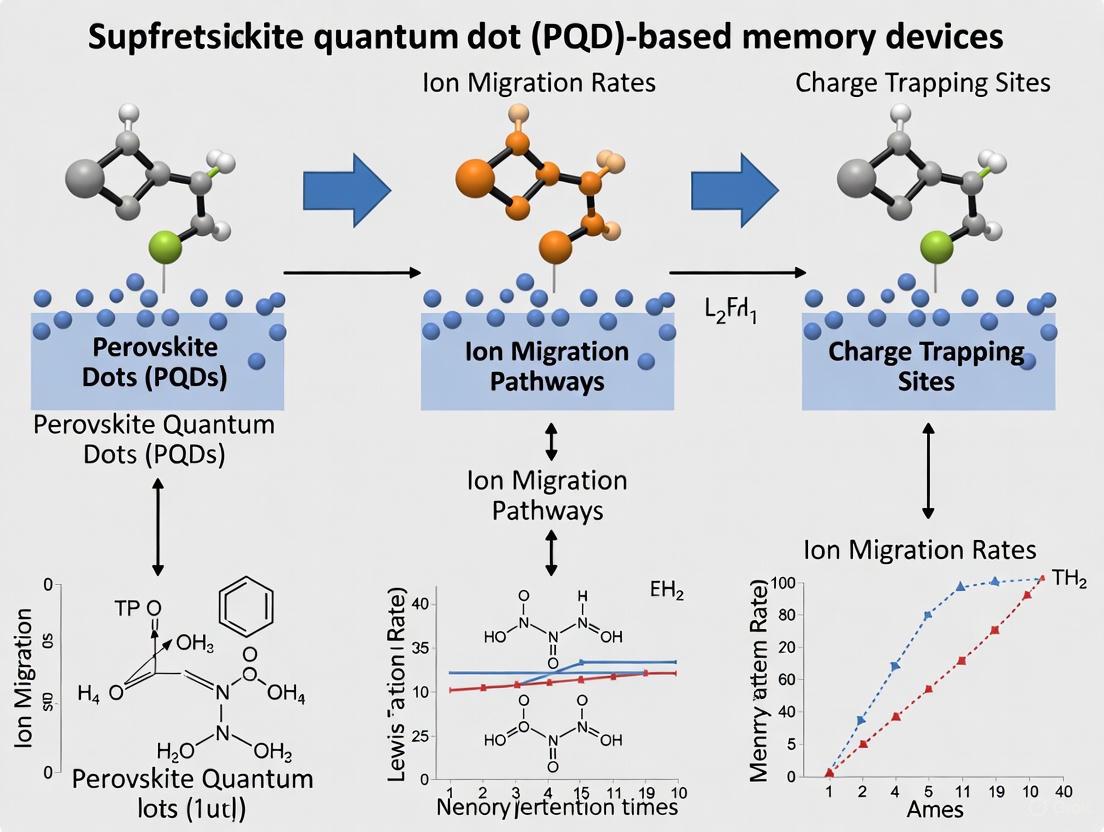

Ion migration is a critical challenge that compromises the performance and reliability of perovskite quantum dot (PQD)-based memory and neuromorphic devices.

Suppressing Ion Migration in Perovskite Quantum Dot Memory: Strategies for Stable Neuromorphic Devices

Abstract

Ion migration is a critical challenge that compromises the performance and reliability of perovskite quantum dot (PQD)-based memory and neuromorphic devices. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists, exploring the fundamental mechanisms of ionic conduction, advanced material and interface engineering strategies for suppression, and troubleshooting for enhanced operational stability. We detail methodologies including surface passivation, compositional tuning, and novel device architectures, validated through comparative analysis of key performance metrics. The review concludes with future directions for developing commercially viable and robust PQD memory technologies for biomedical and computing applications.

Understanding Ion Migration: The Fundamental Challenge in PQD Memory

The Role of Ionic Migration in Resistive Switching Mechanisms

Resistive Random-Access Memory (RRAM) operates on the principle of electrically-induced resistance switching in a metal-insulator-metal (MIM) structure. Ionic migration is the fundamental process driving this switching behavior, where the reversible movement of cations or anions forms and dissolves conductive filaments within the switching layer [1] [2]. Understanding and controlling this phenomenon is crucial for developing reliable memory devices, especially in emerging materials like perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) where uncontrolled ion migration can undermine device performance and stability.

Two primary resistive switching mechanisms are governed by ionic migration: the Electrochemical Metallization Memory (ECM) mechanism, which involves the migration of cationic species from an electrochemically active electrode (such as Ag or Cu), and the Valence Change Mechanism (VCM), which relies on the migration of anionic species (typically oxygen vacancies) within the switching layer [3] [1] [2]. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these mechanisms:

Table 1: Fundamental Mechanisms of Ionic Migration in Resistive Switching

| Feature | Electrochemical Metallization (ECM) | Valence Change Mechanism (VCM) |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Species | Metal cations (Ag⁺, Cu²⁺) [3] | Anions (O²⁻) / Oxygen vacancies [1] |

| Active Electrode | Electrochemically active metal (e.g., Ag) [3] | Inert metal (e.g., Pt, Au) [1] |

| Filament Type | Metallic (e.g., Ag, Cu) [3] | Oxygen vacancy (Vₒ) filament [1] |

| Typical Switching | Bipolar [1] | Bipolar [1] |

| Key Challenge | Filament instability, variability [3] | Precise control of oxygen vacancy profile [4] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Why does my RRAM device exhibit high cycle-to-cycle and device-to-device variability?

- Problem: High variability in switching parameters (SET/RESET voltages, resistance states) is a common issue.

- Root Cause: This is often due to the stochastic and uncontrolled nature of ionic filament formation and dissolution [4] [1]. In ECM cells, the precise location and shape of the metallic filament can vary between cycles. In VCM cells, the random distribution of oxygen vacancies leads to similar variability.

- Solution:

- Current Compliance: Strictly control the current compliance during the electroforming and SET processes to limit the maximum current flowing through the filament, preventing overgrowth [4].

- Bilayer Structures: Implement a bilayer switching stack (e.g., HfOₓ/TiOₓ) where one layer promotes ion migration and the other layer helps confine the filament, improving uniformity [1].

- Material Engineering: Dope the switching matrix with elements that can guide or nucleate filament growth in a more predictable location [5].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the retention and endurance of my perovskite quantum dot (PQD) memory device?

- Problem: Device performance degrades over time (poor retention) or fails after a limited number of switching cycles (low endurance).

- Root Cause: Unsuppressed ion migration within the PQD layer is a primary source of instability [6] [7]. Mobile ions can lead to unintended changes in the conductive filament or interface properties over time.

- Solution:

- Alloying: As demonstrated in all-inorganic perovskites, alloying (e.g., Sn-Pb) can tighten the lattice structure and enhance ionic bonds, effectively immobilizing halide ions [7].

- Defect Passivation: Reduce the density of deep-level defects (e.g., anti-site defects like Iₚᵦ) which act as pathways for ion migration, through chemical passivation techniques [7].

- Interface Engineering: Insert a stable charge transport layer or buffer layer between the electrode and the PQD film to prevent interfacial reactions and ion diffusion into the electrode [6].

FAQ 3: My device shows high operating power. How can I achieve low-voltage switching?

- Problem: The voltages required for SET and RESET operations are too high, leading to excessive power consumption.

- Root Cause: High switching voltage is often related to a thick or high-energy-barrier switching layer that impedes ion migration.

- Solution:

- Thickness Optimization: Reduce the thickness of the switching layer to lower the electric field required for ion migration [5] [1].

- Material Selection: Use switching materials with lower activation energy for ion migration. ECM-based devices using Ag or Cu are often promising for low-voltage operation [1].

- Interface Modification: Employ a thin interface layer or an oxygen exchange layer at the electrode to reduce the barrier for ion injection/extraction [1].

FAQ 4: How can I achieve stable multi-level cell (MLC) operation in my HfO₂-based device?

- Problem: Inability to reliably program and maintain stable intermediate resistance states.

- Root Cause: The intermediate states in filamentary switching are often unstable because they rely on a partially formed or dissolved filament, which is inherently meta-stable.

- Solution:

- Precise Pulse Control: Use carefully engineered sequences of identical pulses (e.g., identical pulse trains) instead of variable-amplitude pulses to gradually modulate the filament diameter in a more controlled manner [4].

- Programmable Compliance Current: Utilize a transistor (1T1R structure) to provide a precise and programmable compliance current, which directly controls the filament's size and thus the resistance level [4].

- Verify Retention per State: Ensure that all intermediate resistance states, not just the HRS and LRS, exhibit non-volatile retention for >10⁴ seconds to be suitable for inference applications [4].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Ionic Migration

Protocol: In-situ TEM Observation of Filament Dynamics

This protocol allows for the direct, real-time observation of conductive filament formation and dissolution, which is critical for understanding the fundamental ionic migration process [3].

- Objective: To visually characterize the dynamics of filament growth and rupture in an ECM or VCM cell at the nanoscale.

- Materials and Equipment:

- Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) with in-situ electrical biasing holder.

- TEM sample preparation tools (FIB/SEM).

- RRAM device cross-section or nanoscale lamella.

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Fabricate a cross-sectional lamella of the RRAM device (e.g., Pt/Cu/HfO₂/Pt) using a Focused Ion Beam (FIB).

- Setup: Mount the lamella onto a specialized in-situ TEM holder with electrical probing contacts.

- Imaging and Biasing: Insert the holder into the TEM. While observing in real-time, apply a series of voltage sweeps or pulses to the device electrodes to induce switching.

- Data Collection: Record high-resolution video and images during the SET (filament formation) and RESET (filament rupture) processes. Correlate the observed structural changes with the simultaneously measured current-voltage (I-V) characteristics.

- Expected Outcome: Direct visualization of the filament's morphology, growth direction, and rupture point, providing unambiguous evidence of the switching mechanism [3].

Protocol: Quantifying Ion Migration in Perovskite Films

This methodology is adapted from research on all-inorganic perovskites and is highly relevant for characterizing ion migration in PQD films [7].

- Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of suppression strategies (e.g., Sn-Pb alloying) on ion migration in perovskite films.

- Materials and Equipment:

- Perovskite films (e.g., CsPbBrI₂ and CsPb₀.₉Sn₀.₁BrI₂).

- Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS).

- Optical Microscope.

- Galvanostatic measurement setup.

- Methodology:

- TOF-SIMS Profiling: Use TOF-SIMS to perform depth profiling on the perovskite films. Monitor the distribution of halide ions (I⁻, Br⁻) before and after applying a constant electric field (e.g., 0.5 V/µm for 10 min). A steeper concentration gradient in the control film indicates stronger ion migration [7].

- Optical Microscopy: Observe the surface of the perovskite film under an optical microscope after applying a DC bias. The formation of dark clusters or color changes is a direct indicator of halide ion migration and segregation [7].

- Galvanostatic Measurement: Measure the ionic conductivity of the films by applying a small constant current and measuring the resulting voltage drop over time. A lower ionic conductivity in the alloyed film confirms suppressed ion migration [7].

- Expected Outcome: A multi-faceted dataset proving that Sn-Pb alloying tightens the lattice, enhances ionic bonding, reduces defect density, and thereby significantly suppresses ion migration [7].

Visualization of Ionic Migration and Device Structure

The following diagram illustrates the two primary resistive switching mechanisms and the corresponding device structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Ionic Migration and Resistive Switching Research

| Material / Reagent | Function in Research | Key Characteristics & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hafnium Oxide (HfO₂) | Benchmark VCM switching layer [4]. | CMOS compatibility, controllable oxygen vacancy concentration, can exhibit ferroelectricity in doped forms. |

| Silver (Ag) / Copper (Cu) | Active electrode for ECM cells [3] [1]. | High mobility of Ag⁺/Cu²⁺ cations, enables low-voltage switching, but can suffer from filament instability. |

| All-inorganic Perovskites (e.g., CsPbX₃) | Emerging switching/semiconductor layer [7]. | Tunable bandgap, high absorption coefficient, but susceptible to ion migration; requires suppression strategies. |

| Tin (Sn) precursor | Alloying agent for PQDs [7]. | Suppresses ion migration in Pb-based perovskites by tightening the lattice and reducing deep-level defects. |

| Tungsten (W) / Titanium (Ti) | Material for micro-heaters [8]. | Used in electrically programmed devices for localized Joule heating to induce phase transitions or ion migration. |

| Ge₂Sb₂Se₅ (GSSe) | Low-loss phase-change material [8]. | Used in photonic memory; ultralow optical absorption in amorphous state, high contrast upon crystallization. |

Link Between Ion Migration, Hysteresis, and Non-Radiative Recombination

Core Mechanism and FAQs

How are ion migration, hysteresis, and non-radiative recombination fundamentally linked in perovskite devices?

In perovskite materials, these three phenomena form a disruptive cycle. Ion migration—the field-induced movement of ionic defects (e.g., halide vacancies, A-site cations)—triggers the problem. [9] [10] These mobile ions accumulate at interfaces with charge transport layers, causing electronic band bending and energy level misalignment. [9] [11] This misalignment severely impedes charge injection in light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and charge extraction in solar cells and memory devices. [11] [10] The resulting inefficient charge collection manifests as current-density–voltage (J–V) hysteresis, where the measured current differs between forward and reverse voltage scans. [9] [11] Critically, the accumulated ions and the defects they create at interfaces act as potent non-radiative recombination centers. [6] [11] When injected electrons and holes recombine at these defect sites instead of radiating light or contributing to photocurrent, their energy is lost as heat, a process known as non-radiative recombination. [6] [11] This directly degrades device efficiency, stability, and performance. [6]

My perovskite memory device shows significant performance drift. Could ion migration be the cause?

Yes, performance drift is a classic symptom of ion migration in perovskite-based non-volatile memory (NVM). [12] [10] Mobile ions within the perovskite structure can lead to:

- Unstable Schottky Barriers: Ion migration to electrode interfaces can modify the local doping concentration, altering the Schottky barrier height and width. [10] This causes the device's resistance state (ON/OFF ratio) to drift over time, compromising data integrity. [12] [10]

- Charge Leakage: The movement of ions can create transient conduction paths, leading to charge leakage from the charge-storage nodes (e.g., quantum dots) in the memory device. [12] This degrades the crucial charge retention capability. [12]

- Inductive Loops and Negative Capacitance: The slow response of ions at interfaces can interfere with electronic processes, leading to anomalous electrical signatures like inductive loops and negative capacitance, which complicate performance assessment and signal readout. [10]

What experimental observation confirms that ion migration occurs even in devices with minimal hysteresis?

Transient optoelectronic measurements on CH₃NH₃PbI₃ solar cells provide direct evidence. [9] Electric-field screening consistent with ion migration was observed to be similar in both high-hysteresis and low-hysteresis cells. [9] The key difference was that in low-hysteresis devices, interfacial recombination was effectively passivated. [9] This results in higher concentrations of photogenerated charge carriers at forward bias, which screen the ionic charge and mitigate its negative impact on current collection, thereby reducing the observable hysteresis. [9] This proves that ion migration is still present, but its detrimental effects on J–V curves are masked by superior interface properties. [9]

Quantitative Data on Defects and Ion Migration

Table 1: Experimentally Measured Activation Energies (Eₐ) for Ion Migration in Various Perovskite Compositions. A higher Eₐ indicates more suppressed ion migration.

| Perovskite Material | Migrating Species | Activation Energy (Eₐ) | Impact on Device Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Cs₂AgBiBr₆ (Baseline) | Halide Vacancies (V₋Br) | ~0.09 eV / ~360 meV [11] [13] | High ion migration, leading to large dark current and detection limit in X-ray detectors. [13] |

| Quasi-2D (BA)₂Cs₉Ag₅Bi₅Br₃₁ | Halide Vacancies (V₋Br) | 419 meV [13] | Suppressed ion migration, lower dark current density (66 nA cm⁻²), and enhanced operational stability. [13] |

| MAPbBr₃ | Br⁻ Vacancies | 0.09 eV [11] | Contributes to hysteresis and trap-assisted non-radiative recombination. [11] |

| MAPbBr₃ | MA⁺ Cations | 0.56 eV [11] | Slower migration, can act as deep traps for non-radiative recombination. [11] |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Quantum Dot-Based Non-Volatile Memory (NVM) Affected by Ion Migration.

| Parameter | Conventional Floating-Gate NVM | QD-Based NVM (Potential) | Impact of Suppressing Ion Migration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge Retention | Lower due to leakage through thin oxide [12] | Enhanced due to discrete charge storage [12] | Prevents charge drift, enabling retention >1 year [12] |

| Endurance (P/E Cycles) | Limited by dielectric breakdown [12] | Improved with thicker tunnel oxide [12] | Reduces defect generation, enhancing longevity [12] |

| Operating Voltage | Higher [12] | Lower (efficient charge trapping) [12] | Enables lower power consumption [12] |

| ON/OFF Ratio | - | Can exceed 10⁵ [12] | Ensures stable and distinguishable memory states [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigation and Suppression

Protocol: Transient Optoelectronic Measurement for Probing Ion Migration

This method directly probes the internal electric field screening caused by ion migration. [9]

- Device Preconditioning: Polarize the device by holding it at a specific bias voltage (e.g., short circuit 0 V or forward bias +1 V) in the dark for a set duration (e.g., 1 minute). [9]

- Transient Measurement: Simultaneously switch the device to open circuit and turn on a constant bias light. Monitor the evolution of the open-circuit voltage (V_OC) over time (from microseconds to hundreds of seconds). [9]

- Small Perturbation Superimposition: While monitoring the background V_OC, superimpose a series of short (e.g., 500 ns) laser pulses. Analyze the resulting transient photovoltage decays. [9]

- Data Interpretation: Changes in the amplitude and time constants of the small perturbation transients during the slow V_OC evolution indicate ion movement and its interaction with photogenerated charges. A negative deflection in the transient photovoltage is a key signature of ionic current. [9]

Protocol: Fabricating Quasi-2D Perovskites to Suppress Ion Migration

Introducing large organic cations (e.g., Butylammonium, BA⁺) creates a natural barrier to ion migration. [13] [10]

- Precursor Solution Preparation: For a lead-free double perovskite system, dissolve CsBr, AgBr, BiBr₃, and Butylammonium Bromide (BABr) in a molar ratio targeting the desired quasi-2D phase (e.g., (BA)₂Cs₉Ag₅Bi₅Br₃₁) in dimethylformamide (DMF). [13]

- Film Fabrication: Employ ultrasonic spraying for large-area, uniform polycrystalline thick films. This is more suitable than spin-coating for eventual device upscaling. [13]

- Characterization: Use X-ray diffraction (XRD) to confirm the crystal structure and phase purity. Measure the ion migration activation energy (Eₐ) via thermal admittance spectroscopy or dark current drift analysis. An increase in Eₐ from 360 meV (3D) to 419 meV (quasi-2D) confirms successful suppression. [13]

Protocol: Surface Passivation via Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD)

Effective passivation reduces surface and grain boundary defects, which are primary pathways for ion migration and non-radiative recombination. [14]

- Device Preparation: Fabricate your perovskite memory or LED device up to the point where the perovskite layer is patterned (mesa formation for µLEDs). [14]

- ALD Deposition: Place the device in an ALD chamber. Deposit a conformal thin film (e.g., 10-50 nm) of a high-κ dielectric material such as HfO₂. Other materials like Al₂O₃ can also be tested. [14]

- Performance Evaluation: Compare the electrical characteristics of passivated and unpassivated devices. Effective HfO₂ passivation can improve external quantum efficiency (EQE) by over 50% and significantly reduce surface recombination velocity by nearly 20% by terminating dangling bonds. [14]

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Investigating and Mitigating Ion Migration.

| Material / Reagent | Function / Role | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Butylammonium Bromide (BABr) | Large organic cation to construct quasi-2D perovskite structures, physically blocking ion migration pathways. [13] | Synthesizing (BA)₂Cs₉Ag₅Bi₅Br₃₁ for X-ray detectors with low dark current. [13] |

| Hafnium Oxide (HfO₂) | High-κ dielectric passivation layer deposited via ALD to coat sidewalls and suppress surface recombination and ion leakage. [14] | Passivating AlGaInP-based red μLEDs, boosting EQE by up to 57.9%. [14] |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ligand with -SO₃⁻ group for strong binding to PQD surface, suppressing non-radiative recombination and improving film morphology. [15] | Fabricating high-efficiency PQD-LEDs with low efficiency roll-off (1.5% at 200 mA/cm²). [15] |

| Phenyl-C₆₁-butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM) | Electron transport layer material that also passivates interfacial traps, reducing hysteresis by minimizing recombination. [9] | Used in low-hysteresis CH₃NH₃PbI₃ solar cells to enable efficient charge collection despite ion migration. [9] |

Troubleshooting FAQs

1. Why does my PQD-based memory device suffer from rapid data retention loss?

Rapid data retention loss is frequently caused by charge leakage from the quantum dot storage nodes. This occurs due to inadequate electrical isolation between dots or the presence of surface defects that create charge migration pathways. To mitigate this, ensure proper surface passivation of the perovskite quantum dots. Implementing a core-shell structure or using cladding materials like germanium oxide (GeOx) can provide superior electrical and physical isolation, preventing lateral dot-to-dot conduction. Studies on GeOx-cladded Ge quantum dots have shown a negligible shift in threshold voltage over one year, demonstrating excellent retention [12].

2. What causes operational instability and device degradation during thermal stress testing?

Operational instability under thermal stress is heavily influenced by the A-site cation composition and surface ligand binding energy of the perovskite quantum dots. Cs-rich PQDs (e.g., CsPbI₃) typically degrade via a phase transition from a black γ-phase to a non-functional yellow δ-phase. In contrast, FA-rich PQDs (e.g., FAPbI₃) with higher ligand binding energy directly decompose into PbI₂ at elevated temperatures. This degradation is often accompanied by quantum dot grain growth and merging. Improving thermal tolerance requires optimizing the A-site cation mixture (CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃) and selecting ligands with high binding energy to stabilize the nanocrystal surface [16].

3. How does ion migration lead to increased leakage current and a reduced ON/OFF ratio?

Ion migration, particularly of halide ions and A-site cation vacancies, creates conductive filaments or temporary shunt paths within the perovskite matrix. These paths facilitate unwanted charge leakage, which diminishes the stored charge in the QDs. This directly translates to a smaller memory window (the difference between programmed and erased states) and a lower ON/OFF ratio, as the 'OFF' state current becomes higher. This phenomenon is often exacerbated by defects at grain boundaries and interfaces, which act as channels for ion movement [12] [6].

4. What experimental techniques can I use to diagnose ion migration and degradation pathways in situ?

Key techniques for in-situ diagnosis include:

- In-situ X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Monitors phase transitions (e.g., from black γ-phase to yellow δ-phase in CsPbI₃) and decomposition into secondary phases like PbI₂ as a function of temperature or applied bias [16].

- In-situ Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: Tracks changes in emission intensity and peak position, which can indicate defect formation, phase segregation, or thermal degradation in real-time [16].

- In-situ Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA): Coupled with mass spectrometry, this can help identify the temperature at which organic ligands or A-site cations decompose and leave the material, providing insight into thermal stability [16].

Table 1: Comparison of QD-Based and Conventional NVMs on Key Performance Parameters [12]

| Aspect | Quantum Dots (QDs) | Conventional Bulk Materials |

|---|---|---|

| Scalability | Better scaling with discrete charge storage nodes | Limited by gate dielectric thickness and reliability issues |

| Power Consumption | Lower operating voltages; Reduced leakage currents | Higher power consumption; Significant leakage currents at smaller scales |

| Endurance | Improved endurance due to isolated nodes and reduced defect formation | Higher risk of charge leakage and degradation over time |

| Retention | Enhanced retention; Can be improved with cladding (e.g., GeOx) | Lower retention due to higher charge leakage |

| Retention Example | GeOx-cladded Ge QDs: Negligible Vth shift over 1 year | Varies, but generally lower than QD-based counterparts |

Table 2: Thermal Degradation Pathways of CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃ PQDs [16]

| A-site Composition | Primary Degradation Mechanism | Onset Temperature Notes | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| FA-rich (e.g., FAPbI₃) | Direct decomposition to PbI₂ | Begins ~150°C | Higher ligand binding energy; No intermediate phase transition; Grain growth observed before decomposition. |

| Cs-rich (e.g., CsPbI₃) | Phase transition from black γ-phase to yellow δ-phase | Varies, but generally less stable than FA-rich under thermal stress | Lower ligand binding energy; Phase transition precedes final decomposition. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In-situ XRD for Monitoring Thermal Degradation Phases

Objective: To identify the crystalline phase transitions and decomposition pathways of perovskite quantum dots under thermal stress.

Materials:

- Synthesized PQD powder or thin film (e.g., CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃).

- In-situ XRD stage with a heating element and temperature controller.

- Inert environment chamber (e.g., argon gas flow) to prevent oxidation.

Methodology:

- Sample Loading: Place the PQD sample on the Pt holder in the in-situ XRD stage.

- Environment Purge: Purge the chamber with an inert gas (Argon) for at least 30 minutes to create an oxygen- and moisture-free environment.

- Baseline Measurement: Collect a baseline XRD pattern at room temperature (e.g., 30°C).

- Ramped Heating & Data Collection: Program the heater to ramp temperature at a constant rate (e.g., 5-10°C/min) from room temperature to a target temperature (e.g., 500°C). Continuously or intermittently collect XRD patterns at regular temperature intervals (e.g., every 25°C).

- Data Analysis: Analyze the sequence of XRD patterns. Identify the appearance, disappearance, and shift of diffraction peaks. Correlate these changes to known reference patterns for phases like the black perovskite phase (cubic/γ), yellow phase (δ), and PbI₂.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Data Retention in QD-Based Memory Devices

Objective: To measure the ability of a memory device to retain a programmed charge state over time.

Materials:

- Fabricated QD-based non-volatile memory device.

- Semiconductor parameter analyzer (e.g., Keithley 4200).

- Environmental probe station (temperature control is optional but recommended).

Methodology:

- Initial Characterization: Perform current-voltage (I-V) sweeps to determine the device's initial threshold voltage (Vth₁).

- Programming: Apply a programming voltage pulse (e.g., +10V for 1 ms) to inject charge into the QD layer.

- Immediate Verification: Perform a quick I-V sweep immediately after programming to determine the shifted threshold voltage (Vth_programmed).

- Retention Baking: Maintain the device at a constant elevated temperature (e.g., 85°C) without any applied bias. This accelerates the aging process.

- Periodic Measurement: At predefined time intervals (e.g., 1h, 10h, 100h, 1000h), cool the device to room temperature (if heated) and measure the threshold voltage (Vth_retention).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of charge loss over time using the formula:

[(Vth_programmed - Vth_retention) / (Vth_programmed - Vth₁)] * 100%.Plot Vth_retention or charge loss versus time to extract retention lifetime.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for PQD-Based Memory Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Oleylamine & Oleic Acid | Surface ligands for QD synthesis and stabilization. | Control the growth, dispersion, and electronic passivation of PQDs during colloidal synthesis. FA-rich PQDs with higher ligand binding energy show better thermal stability [16]. |

| GeOx Cladding Precursor | Forms an insulating shell around QDs. | Used to clad Germanium QDs, providing electrical and physical isolation that drastically reduces charge leakage and improves data retention [12]. |

| Uracil Additive | A molecular binder and defect passivator. | Strengthens grain boundaries and passivates defects in perovskite films, enhancing mechanical and operational stability in solar cells—a strategy transferable to memory devices [17]. |

| Guanabenz Acetate Salt | Prevents perovskite hydration during fabrication. | Enables the fabrication of high-performance PSCs in ambient air, mitigating moisture-induced degradation—a critical step for reproducible device manufacturing [17]. |

| β-poly(1,1-difluoroethylene) | A dipolar polymer for phase stabilization. | Used to stabilize the perovskite black phase and improve thermal cycling stability by controlling crystallization and energy alignment [17]. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Root Cause Analysis and Mitigation Workflow for PQD Memory Instability.

Diagram 2: Stressor-Mechanism-Impact Pathway in PQD Memory Devices.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the primary intrinsic factors that lead to ion migration in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) memory devices?

Intrinsic factors originate from the material's inherent properties and structural defects. Key issues include:

- Low Activation Energy for Migration: The perovskite crystal lattice itself has a low energy barrier for ion movement, making migration a spontaneous process even without external triggers [18].

- Point Defects and Vacancies: Crystallographic defects, such as halide anti-site defects (e.g., ICs and IPb), create pathways that facilitate ion movement within the lattice [7].

- Composition and Stoichiometry: The specific chemical composition of the perovskite (e.g., the ratio of formamidinium (FA), methylammonium (MA), or cesium (Cs)) influences defect density and the strength of ionic bonds, thereby affecting intrinsic migration rates [18].

FAQ 2: Which external, extrinsic stressors most significantly accelerate ion migration and device failure?

Extrinsic factors are environmental stresses applied during operation or testing. The most critical are:

- Thermal Stress: High temperatures, especially during operation (e.g., 85 °C), provide the thermal energy needed for ions to overcome activation barriers, dramatically accelerating migration [19] [18].

- Electrical Bias: The application of voltage, particularly a strong built-in electric-field, creates a drift force that drives ion movement across the perovskite film and into adjacent transport layers [18].

- Illumination (Photo-Stress): Light exposure can generate excess charge carriers that interact with ionic species, exacerbating migration and related degradation processes [18].

- Humidity: Although all-inorganic perovskites offer improved resistance, moisture can infiltrate the device, leading to corrosion and secondary reactions that compound ion migration issues [7] [20].

FAQ 3: How can I experimentally distinguish between failures caused by intrinsic material defects versus extrinsic environmental stress?

A combination of characterization techniques is required to pinpoint the failure mechanism:

- Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS): Use this to depth-profile and directly track the movement of specific ions (e.g., I⁻) across device layers after aging under different stress conditions [7] [18].

- Rutherford Backscattering Spectroscopy (RBS): Employ this non-destructive technique to quantitatively analyze extrinsic and intrinsic ion migration without damaging the sample [21].

- Electrical and Optical Monitoring: Perform stability tests under controlled stressors (e.g., maximum power point tracking at 85 °C) while monitoring performance metrics like hysteresis and steady-state efficiency. Intrinsic defects often manifest as gradual performance decay, while extrinsic stress can cause rapid, specific failure signatures [18].

FAQ 4: What are the most effective material engineering strategies to suppress intrinsic ion migration?

Strategies focus on stabilizing the perovskite lattice and passivating defects:

- Cation Alloying: Incorporating small-radius cations like Tin (Sn²⁺) into the lead-based lattice can tighten the crystal structure, enhance the strength of Pb-X (halide) ionic bonds, and reduce the concentration of anti-site defects, thereby immobilizing halide ions [7].

- Barrier Layer Deposition: Depositing an ultra-thin, dense scattering layer (e.g., atomic-layer-deposited HfO₂) on the perovskite surface provides a physical barrier that blocks the path of migrating ions. A layer of 1.5 nm has been shown to reduce iodide diffusion by 30-50% without impeding charge carrier transport [18].

- Dipole Monolayer Engineering: Following the scattering layer, a self-assembled dipole monolayer (e.g., using CF3-PBAPy molecules) can create a uniform drift electric-field that further repels approaching ions, increasing the total barrier energy beyond the required threshold [18].

FAQ 5: What quantitative metrics can I use to evaluate the effectiveness of an ion migration suppression strategy?

The effectiveness of suppression strategies can be evaluated using the following quantitative metrics, which should be presented in experimental results.

| Metric | Description | Target/Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Barrier Energy (eV) | The quantified energy threshold required to prevent ion loss from the perovskite film. | >0.911 eV for FAPbI₃ to confine I⁻ ions [18] |

| Ion Migration Reduction | The percentage reduction in migrated ions measured by techniques like TOF-SIMS. | Up to 99.9% reduction compared to control devices [18] |

| Operational Stability | The retention of initial performance under continuous stress (e.g., light, heat). | >95% of initial efficiency after 1500 hours at 85°C [18] |

| Hysteresis Reduction | The decrease in current-voltage hysteresis, indicating suppressed ion migration. | Significant reduction in hysteresis index [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Quantifying the Barrier Energy for Iodide Migration Suppression

- Objective: To determine the minimum energy barrier required to prevent iodide ions from migrating out of the perovskite layer.

- Materials: Completed perovskite solar cell (PSC) devices, reverse bias source, X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) equipment.

- Methodology:

- Age the PSC devices under illumination for a set period (e.g., 500 hours).

- Apply a series of reverse bias voltages (e.g., -0.8 V) to another set of devices during the aging process. The bias enhances the drift component of ion movement.

- Use XPS to analyze the surface of the hole transport layer (HTL), such as PTAA, for the presence of iodine (I 3d peaks).

- The specific reverse bias at which the I 3d peaks disappear from the HTL surface indicates that a dynamic equilibrium between ion diffusion and drift has been achieved.

- Calculate the potential drop within the HTL depletion region under this equilibrium bias. This calculated potential drop (in eV) is the quantified barrier energy required for suppression [18].

Protocol 2: Assessing Ion Migration via Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS)

- Objective: To directly visualize and measure the distribution and migration of ions within a device stack.

- Materials: Fresh and aged perovskite device samples, TOF-SIMS instrument.

- Methodology:

- Encapsulate the device cross-section or prepare a sample for top-down depth profiling.

- Use a focused primary ion beam to sputter the sample surface, releasing secondary ions.

- A mass spectrometer measures the mass-to-charge ratio of these secondary ions, allowing for the identification of specific isotopes and elements (e.g., I⁻, Cs⁺).

- As the sputtering continues, a depth profile is built, showing the concentration of each ion as a function of depth.

- Compare the depth profiles of fresh and aged devices. The diffusion or accumulation of ions (e.g., iodine on the HTL surface) in the aged device provides direct evidence of migration [7] [18].

Protocol 3: Environmental Stress Screening (ESS) for Accelerated Lifetime Testing

- Objective: To uncover latent defects and accelerate failure mechanisms induced by extrinsic stressors.

- Materials: Memory devices or test structures, thermal cycling chamber, temperature-humidity chamber.

- Methodology:

- Thermal Cycling/Shock: Expose devices to rapid cycles of extreme high and low temperatures. This reveals vulnerabilities like solder joint fatigue or delamination caused by coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) mismatch [19] [20].

- Temperature-Humidity Bias (THB) Testing: Subject devices to high temperatures (e.g., 85°C) and high relative humidity (e.g., 85%) while potentially applying an electrical bias. This test assesses the robustness of seals and the device's resistance to corrosion and current leakage from moisture infiltration [20].

- Moisture Sensitivity Level (MSL) Testing: Determine the sensitivity of packages to moisture absorption before soldering to avoid "popcorning" or internal delamination during reflow [20].

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and mitigating ion migration in PQD memory devices.

Diagram: Ion Migration Diagnosis and Mitigation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for experiments focused on suppressing ion migration.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Tin (Sn) Precursors (e.g., SnI₂) | Used for cation alloying (Sn-Pb). Tightens the perovskite lattice, enhances ionic bonds, and reduces deep-level defect density to suppress intrinsic ion migration [7]. |

| Hafnium Oxide (HfO₂) | Deposited via Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) to form an ultra-thin (e.g., 1.5 nm) scattering layer on the perovskite surface. Blocks ion migration via a physical barrier mechanism [18]. |

| Dipole Molecules (e.g., CF3-PBAPy) | Forms an ordered self-assembled monolayer on the HfO₂ layer. Creates a drift electric-field that repels migrating iodide ions, adding an energy barrier to their movement [18]. |

| Poly(N-vinylcarbazole) (PVK) | A hole transport material (HTM) with a high work function. Used to address band shifts caused by interfacial dipole layers, thereby maintaining efficient hole extraction while ion migration is suppressed [18]. |

| Time-of-Flight SIMS (TOF-SIMS) | An analytical instrument for depth profiling. Critical for directly tracking and quantifying the migration of specific ions (e.g., I⁻, Cs⁺) across device layers after aging [7] [18]. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | A surface-sensitive quantitative spectroscopy technique. Used to detect the presence and quantity of elements (e.g., Iodine) on the surface of transport layers to confirm ion migration [18]. |

Material and Interface Engineering for Ion Suppression

Advanced Surface Passivation Techniques with Organic Semiconductors and Ligands

Perovskite Quantum Dot (PQD)-based memory technologies represent a promising frontier for next-generation data storage and neuromorphic computing. These materials exhibit exceptional properties such as quantum confinement, bandgap tunability, and optoelectronic synergy. However, a significant challenge impedes their commercial viability: ion migration. Within the crystal lattice, halide ions (e.g., I⁻) are highly mobile, leading to uncontrolled ionic movement that degrades charge transport layers, triggers interfacial chemical reactions, and causes severe operational instability in memory devices [18] [22].

Advanced surface passivation is a cornerstone strategy for suppressing this detrimental ion migration. By applying organic semiconductors and functional ligands to the PQD surface, researchers can effectively pacify surface defects, suppress non-radiative recombination, and create energy barriers that confine ionic movement. This technical support center provides a practical guide for researchers tackling the experimental challenges associated with implementing these sophisticated passivation techniques to develop durable and high-performance PQD-based memory devices [23] [6].

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Rapid Photoluminescence (PL) Quenching After Passivation

- Problem: After applying a passivation layer, the PL intensity of your PQD film decreases significantly or quenches rapidly, indicating a failure to properly pacify surface trap states.

- Diagnosis & Solution:

- Cause 1: Incomplete Surface Coverage. The passivation ligand or organic semiconductor did not form a uniform monolayer, leaving surface defects exposed.

- Solution: Optimize your deposition technique. For ligand exchange, ensure sufficient reaction time and ligand concentration. For solution-based coating, optimize spin-coating speed and solvent engineering to promote uniform spreading [23].

- Cause 2: Quenching by Energy Transfer. The energy levels of the passivation material are not aligned with the PQD, leading to non-radiative energy transfer instead of defect passivation.

- Solution: Carefully select passivation materials with appropriate highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) levels that align with the band structure of your PQDs to facilitate charge transfer or blocking as desired [6].

- Cause 3: Chemical Damage During Processing. The solvent or processing conditions (e.g., temperature) used to apply the passivation layer degrades the underlying PQDs.

- Solution: Use orthogonal solvents that dissolve the passivation material but do not dissolve or degrade the PQDs. Test processing temperature thresholds to avoid thermal degradation [23].

- Cause 1: Incomplete Surface Coverage. The passivation ligand or organic semiconductor did not form a uniform monolayer, leaving surface defects exposed.

Operational Instability in Memory Devices

- Problem: Your PQD-based memristor shows significant performance degradation (e.g., resistance drift, reduced ON/OFF ratio) after a few operation cycles.

- Diagnosis & Solution:

- Cause 1: Persistent Iodide Migration. The passivation layer is insufficient to block the migration of iodide ions from the perovskite layer into the electrodes.

- Solution: Implement a composite blocking strategy. A quantitative study found that a barrier energy of approximately 0.911 eV is required to completely suppress I⁻ migration from an FAPbI₃ film. Consider a bilayer structure: a thin, dense metal oxide (e.g., HfO₂) for scattering ions, topped with an ordered dipole monolayer (e.g., CF3-PBAPy) to create a drift electric-field that meets the required energy barrier [18].

- Cause 2: Inadequate Environmental Encapsulation. The passivation layer addresses surface defects but does not protect the PQDs from environmental stressors like moisture and oxygen.

- Solution: Integrate a matrix encapsulation strategy. As demonstrated in display applications, a synergistic approach combining chemical passivation with rigid encapsulation in a mesoporous silica (MS) matrix can provide excellent water resistance and photostability, retaining over 95% of initial PL intensity after aging tests [23].

- Cause 1: Persistent Iodide Migration. The passivation layer is insufficient to block the migration of iodide ions from the perovskite layer into the electrodes.

High Leakage Current and Low ON/OFF Ratio

- Problem: The memory device exhibits high leakage current in the High Resistance State (HRS), resulting in a low ON/OFF ratio, which is critical for data storage.

- Diagnosis & Solution:

- Cause: Defect-Mediated Charge Tunneling. Surface defects and grain boundaries in the PQD film act as pathways for unwanted charge injection and tunneling.

- Solution: Employ multifunctional passivation ligands. Sulfonic acid-based surfactants (e.g., SB3-18) have been shown to coordinate strongly with unpassivated Pb²⁺ sites on CsPbBr₃ QD surfaces, effectively suppressing surface trap states. This reduces non-radiative recombination and decreases leakage currents, which can enhance the ON/OFF ratio in memristive devices [23] [6].

- Cause: Defect-Mediated Charge Tunneling. Surface defects and grain boundaries in the PQD film act as pathways for unwanted charge injection and tunneling.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental mechanism by which organic ligands passivate PQD surfaces? Organic ligands passivate PQDs primarily through coordination bonding between functional groups on the ligand and unsaturated sites (defects) on the QD surface. Common defects include unpassivated Pb²⁺ ions (Lewis acid sites) and halide vacancies. Ligands with sulfonate (-SO₃⁻), carboxylate (-COO⁻), or phosphonate (-PO₃²⁻) groups can strongly coordinate with these Pb²⁺ sites, effectively filling the vacancies and eliminating trap states that would otherwise facilitate non-radiative recombination and ion migration [23].

Q2: How do I choose between a simple ligand and a complex organic semiconductor for passivation? The choice depends on the primary failure mode you are addressing in your memory device.

- Use small functional ligands (e.g., SB3-18, oleic acid) when the main goal is to pacify intrinsic surface defects and improve photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY). These are ideal for solving problems like rapid PL quenching [23].

- Use complex organic semiconductors (e.g., PVK, PTAA) or composite layers when you need additional functionality, such as:

- Charge Transport: To improve hole or electron extraction/injection.

- Energy Barrier Creation: To physically block ion migration using a dense, compact layer.

- Drift Electric-Field: Using dipole molecules to create an electric-field that repels migrating ions [18].

Q3: We often see a trade-off between passivation efficacy and charge transport. How can this be mitigated? This is a common challenge. Thick or insulating passivation layers can hinder carrier transport. Strategies to mitigate this include:

- Using Conductive Passivators: Select organic semiconductors that not only passivate but also facilitate charge transport.

- Ultra-Thin Layers: Employ atomic-layer deposition to create thin, pinhole-free layers (e.g., 1.5 nm HfO₂) that allow carrier tunneling via the quantum effect while effectively blocking ions [18].

- Synergistic Strategies: Combine a thin chemical passivation layer with a conductive matrix. The chemical layer handles defect pacification, while the matrix provides structural stability without severely impeding transport [23].

Q4: Are there quantitative metrics for determining if passivation is sufficient to suppress ion migration? Yes, recent research provides a key quantitative benchmark. For a standard FAPbI₃ perovskite film, a barrier energy of 0.911 eV is quantified as the threshold needed at the interface to completely suppress the loss of iodide ions. You can indirectly evaluate your passivation scheme's effectiveness by measuring device stability under operational conditions (e.g., maximum power point tracking at 85°C) and using techniques like XPS or TOF-SIMS to detect iodide diffusion into charge transport layers [18].

Experimental Protocols for Key Passivation Techniques

Protocol: Synergistic Surface Passivation and Matrix Encapsulation

This protocol is adapted from methods used to achieve highly stable CsPbBr₃ QDs for displays, which is highly relevant for creating durable memory devices [23].

- Objective: To simultaneously passivate surface defects and provide a robust physical barrier against environmental degradation and ion migration.

- Materials:

- CsPbBr₃ QD precursor (CsBr, PbBr₂)

- Passivation ligand: Sulfonic acid-based surfactant (e.g., SB3-18)

- Encapsulation matrix: Mesoporous silica (MS)

- Solvents (e.g., Toluene, DMF)

- Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Weigh CsBr and PbBr₂ in a 1:1 molar ratio. Weigh MS powder at a mass ratio of 1:3 (precursors:MS).

- Grinding: Place the precursors and MS in an agate mortar and grind thoroughly until a homogeneous mixture is obtained.

- Calcination: Transfer the mixture to a furnace and calcine at 650 °C for a set time (e.g., 30-60 minutes) under an inert atmosphere. This high temperature causes the precursors to diffuse into the MS pores and the MS framework to collapse and densify, encapsulating the formed QDs.

- Passivation: After calcination and cooling, the composite is dispersed in a toluene solution containing the SB3-18 ligand. The SO₃⁻ group of the ligand will coordinate with unsaturated Pb²⁺ sites on the QD surface.

- Purification: Centrifuge the solution to remove unreacted ligands and large aggregates, then re-disperse the passivated and encapsulated QDs in a clean solvent for film deposition.

- Key Parameters:

- Calcination Temperature: Critical for inducing MS pore collapse.

- Ligand Concentration: Must be optimized for full surface coverage without causing aggregation.

- Expected Outcome: A composite material with enhanced PLQY (e.g., from 49.59% to 58.27%) and excellent stability, retaining >95% of initial PL after water resistance and light radiation tests [23].

Protocol: Constructing a Composite Ion-Migration Barrier

This protocol is based on a proven method for suppressing iodide migration in perovskite solar cells, a technique directly transferable to enhancing the endurance of PQD memory devices [18].

- Objective: To deposit a quantifiably sufficient barrier that blocks the migration of iodide ions from the PQD layer.

- Materials:

- Fabricated PQD film

- HfO₂ precursor for atomic-layer deposition (e.g., TEMAHf)

- Dipole molecule solution (e.g., (4-(2-(trifluoromethyl)pyrimidin-5-yl)phenyl) boronic acid, CF3-PBAPy)

- Procedure:

- PQD Film Preparation: Prepare a uniform and dense film of your chosen PQD (e.g., FAPbI₃) using your standard method (e.g., spin-coating).

- Scattering Barrier (HfO₂) Deposition:

- Load the PQD film into an atomic-layer deposition (ALD) system.

- Deposit an ultra-thin, conformal layer of HfO₂. A thickness of ~1.5 nm is optimal, as it provides a scattering barrier for ions while allowing carriers to tunnel through without significant resistance.

- Drift Barrier (Dipole Monolayer) Assembly:

- Immerse the HfO₂-coated film in a dilute solution of the CF3-PBAPy molecule.

- The boronic acid anchoring group will covalently bond to the hydroxyl groups on the ALD HfO₂ surface, forming a dense, ordered monolayer.

- Remove the film and rinse gently with an orthogonal solvent to remove physisorbed molecules.

- Key Parameters:

- HfO₂ Thickness: Must be controlled precisely via ALD cycle number.

- Dipole Solution Concentration & Immersion Time: Critical for forming a dense, uniform monolayer.

- Verification: Use XPS to confirm the presence and chemical state of the dipole layer. The effectiveness of the barrier can be validated by TOF-SIMS, showing a >99.9% reduction in iodide diffusion after aging [18].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Performance of Passivation Strategies

The following table summarizes key quantitative data from recent studies on advanced passivation techniques, providing benchmarks for researchers.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Advanced Passivation Strategies

| Passivation Strategy | Material System | Key Performance Improvement | Stability Enhancement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synergistic Passivation & Encapsulation | CsPbBr₃-SB3–18/MS | PLQY increased from 49.59% to 58.27% | Retained 95.1% of PL after water resistance test; 92.9% after light radiation test | [23] |

| Composite Ion-Migration Barrier | FAPbI₃ with HfO₂/CF3-PBAPy | Certified steady-state efficiency of 25.7% | >95% initial efficiency retained after 1500 h at 85°C under operation | [18] |

| Barrier Energy Quantification | FAPbI₃ / HTL Interface | Barrier energy of 0.911 eV quantified as sufficient to suppress I⁻ migration | Iodide migration suppressed by 99.9% compared to control | [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Advanced Surface Passivation Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfonic Acid-Based Surfactants (e.g., SB3-18) | Chemical passivator; coordinates with unpassivated Pb²⁺ sites to suppress surface trap states. | Optimize concentration to achieve full surface coverage without disrupting colloidal stability. [23] |

| Mesoporous Silica (MS) | Rigid encapsulation matrix; provides a physical barrier against moisture, oxygen, and ion diffusion. | High-temperature sintering (~650°C) is required to collapse pores and form a dense protective layer. [23] |

| Hafnium Oxide (HfO₂) | Scattering barrier; deposited via ALD to form an ultra-thin, conformal layer that blocks ion migration via scattering. | Thickness must be kept minimal (~1.5 nm) to allow carrier tunneling and avoid impeding charge transport. [18] |

| Dipole Molecules (e.g., CF3-PBAPy) | Drift barrier; forms an ordered self-assembled monolayer that creates a drift electric-field to repel migrating ions. | Requires a functional anchoring group (e.g., boronic acid) to covalently bind to the underlying oxide surface. [18] |

| Poly(N-vinylcarbazole) (PVK) | Hole transport material (HTM) with high work function; used to address band shifts caused by interfacial electric-fields from dipole layers. | Improves hole extraction efficiency when used in conjunction with electric-field-inducing passivation layers. [18] |

Visualization of Workflows and Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this guide.

Diagram 1: Mechanism of Composite Ion-Migration Barrier

Diagram Title: Ion Migration Blocking Mechanism

Diagram 2: Synergistic Passivation & Encapsulation Workflow

Diagram Title: PQD Stabilization Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of ion migration in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) memory devices, and why is it a critical issue? Ion migration, particularly of halide anions (e.g., iodine vacancies) and metal cations, is an intrinsic property of metal halide perovskites. In PQD-based memory devices, this phenomenon is pronounced due to the high concentration of surface ionic vacancies resulting from weak ligand interactions and detachment during film processing [24]. Ion migration is critical because it leads to uncontrolled formation of conductive filaments, current-voltage (J-V) hysteresis, and device degradation, ultimately compromising the operational stability and reliability of memory devices [25] [24].

Q2: How does compositional tuning with potassium (K+) improve the performance of lead-free double perovskites? Alloying the B-site (e.g., Ag+ site) in lead-free double perovskites like Cs₂AgInCl₆ with potassium (K+) ions serves as an effective strategy to enhance photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and regulate optoelectronic properties. The addition of K+ (e.g., Cs₂Ag₀.₈₀K₀.₂₀In₀.₈₇₅Bi₀.₁₂₅Cl₆) leads to a significant increase in radiative recombination of self-trapped excitons. Research has demonstrated that an optimized K+ alloying content of 0.20 can improve the PLQY from approximately 2.70% to 15.96%, a five-fold enhancement, while also ensuring high stability over 180 days [26].

Q3: What role does dimensional engineering (2D/3D) play in enhancing perovskite device stability? Employing hybrid two-dimensional/three-dimensional (2D/3D) architectures creates a synergistic effect. The 3D perovskite provides high charge mobility, while the 2D perovskite layers, often achieved using bulky organic cations, impart superior environmental robustness. This structure effectively passivates surface defects and isolates the moisture-sensitive 3D bulk perovskite from environmental factors, significantly enhancing the long-term operational stability of the devices [27] [28].

Q4: Which characterization techniques are crucial for assessing ionic migration in perovskite films and devices? A combination of techniques is essential to probe ionic migration:

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Used to prove that resistive switching is achieved by the migration of mobile iodine vacancies under an electric field to form conductive filaments [24].

- In-situ Conductive Atomic Force Microscopy (c-AFM): Directly visualizes the formation and growth of conductive filaments from grain boundaries to grain interiors, revealing the multilevel resistive switching properties [24].

- Ferromagnetic Resonance (FMR) and Anisotropy Magnetoresistance (AMR): These toolsets help investigate magnetodynamic properties and changes in resistance related to ionic movement and composition changes [25] [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) in Lead-Free Double Perovskites

Potential Cause: Indirect bandgap nature and high non-radiative recombination rates due to defects in materials like Cs₂AgInCl₆ [26]. Solution: B-site Alkali Metal Alloying This protocol outlines the synthesis of K+-alloyed Cs₂AgInCl₆ double perovskites to enhance PLQY [26].

- Objective: To improve the optical performance of lead-free double perovskites via compositional engineering.

- Materials:

- Precursors: Cesium chloride (CsCl), Silver chloride (AgCl), Indium chloride (InCl₃), Bismuth chloride (BiCl₃), Potassium chloride (KCl).

- Solvents: Hydrochloric acid (HCl), Deionized water.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve stoichiometric amounts of CsCl, AgCl, InCl₃, BiCl₃, and KCl in a mixture of deionized water and concentrated HCl under vigorous stirring. The Bi³⁺ co-doping (e.g., 12.5%) is used to create emissive centers.

- Recrystallization: Slowly evaporate the solution at room temperature to facilitate the growth of Cs₂Ag₁₋ₓKₓIn₀.₈₇₅Bi₀.₁₂₅Cl₆ crystals.

- Optimization: Systematically vary the value of

x(K+ content, e.g., x ≤ 0.60) to find the optimal composition. Studies indicate that x = 0.20 often yields the highest PLQY [26]. - Purification: Collect the recrystallized powder via centrifugation and wash multiple times with an anti-solvent to remove unreacted precursors.

- Characterization: Perform UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence spectroscopy to determine the bandgap and PLQY. Use X-ray diffraction to confirm the crystal structure and successful alloying.

Problem: Uncontrolled Resistive Switching and Low ON/OFF Ratio in PQD Memory

Potential Cause: Uncontrolled migration of ionic defects (e.g., iodine vacancies, Vᵢ) leading to random and unstable conductive filament formation [24]. Solution: Engineering Multilevel Resistive Switching via Defect Control This protocol describes the fabrication of a CsPbI₃ PQD-based write-once-read-many-times (WORM) memory device with controlled ion migration.

- Objective: To achieve reliable, multilevel resistive switching in a simple Ag/CsPbI₃ PQDs/ITO device structure.

- Materials:

- CsPbI₃ PQDs synthesized via the hot-injection method [24].

- Oleic Acid (OA) and Oleylamine (OAm) as surface ligands.

- Substrates: ITO-coated glass.

- Top electrode: Silver (Ag).

- Experimental Protocol:

- PQD Synthesis & Film Formation: Synthesize CsPbI₃ PQDs using the standard hot-injection method with OA and OAm ligands [24] [30]. Spin-coat the PQD dispersion (e.g., 80 mg/mL in toluene:hexane) onto the cleaned ITO substrate to form a dense, ~190 nm thick film. Anneal the film to remove residual solvent.

- Device Fabrication: Thermally evaporate Ag top electrodes through a shadow mask to define the device area (e.g., 100 × 100 μm²).

- Electrical Formation: Apply a sweeping voltage (0 → -2.5 V → 0 → +3 V → 0) to the Ag electrode (with ITO grounded). This process initially forms conductive filaments (CFs) via VI migration.

- Multilevel State Control: The device exhibits intrinsic ternary states:

- High Resistance State (HRS): The initial state.

- Intermediate Resistance State (IRS): Achieved at a SET voltage of ~1.0 V.

- Final Low Resistance State (fLRS): Achieved at a second SET voltage of ~2.0 V.

- Validation: Use electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and in-situ c-AFM to confirm that the resistive switching is due to the formation and growth of VI-based conductive filaments, preferentially at grain boundaries before propagating into grain interiors [24].

Problem: Rapid Performance Degradation and Poor Operational Stability

Potential Cause: Intrinsic material instability and high sensitivity to environmental factors like moisture and oxygen [27] [6]. Solution: Implementing 2D/3D Hybrid Perovskite Architectures This protocol involves creating a protective 2D perovskite layer on top of a 3D perovskite film to enhance stability.

- Objective: To improve the environmental and operational stability of perovskite devices without significantly compromising charge transport.

- Materials:

- 3D perovskite precursors (e.g., FAPbI₃, MAPbI₃).

- Bulky ammonium salts for 2D layer formation (e.g., Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI), Butylammonium Bromide (BABr)).

- Common solvents (e.g., DMF, DMSO, Isopropanol).

- Experimental Protocol:

- 3D Perovskite Deposition: Fabricate the standard 3D perovskite film (e.g., FAPbI₃) using your preferred method (e.g., anti-solvent quenching).

- 2D Capping Layer Formation: Immediately after the 3D film formation, spin-coat a solution of the bulky ammonium salt (e.g., 2-10 mg/mL in isopropanol) onto the still-hot 3D perovskite substrate.

- Annealing: Anneal the stack at a moderate temperature (e.g., 100°C for 10-30 minutes) to facilitate the reaction between the ammonium salt and the top layer of the 3D perovskite, converting it into a thin, stable 2D perovskite layer.

- Device Completion: Proceed with the deposition of subsequent charge transport layers and electrodes.

- Stability Testing: Characterize the stability by monitoring the device performance under continuous illumination or in ambient conditions (controlled humidity and temperature) and compare it with a reference device without the 2D capping layer [27] [28].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Enhancement of Lead-Free Double Perovskites via K⁺ Alloying

Data derived from the synthesis of Cs₂Ag₁₋ₓKₓIn₀.₈₇₅Bi₀.₁₂₅Cl₆ crystals [26].

| K⁺ Alloying Content (x) | PLQY (%) | Emission Peak (λmax, nm) | Bandgap (eV) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | ~2.70 | ~629 | ~3.3 (Direct) | Baseline performance |

| 0.20 | ~15.96 | ~629 | ~3.3 (Direct) | Optimal performance, 5x PLQY increase |

| ≤ 0.60 | Varied | ~629 | ~3.3 (Direct) | Maintains direct bandgap, properties regulated |

Table 2: Resistive Switching States in CsPbI₃ PQD WORM Memory Device

Summary of the intrinsic ternary states observed in Ag/CsPbI₃ PQDs/ITO memory devices [24].

| Resistance State | Set Voltage (V) | Typical Resistance (Ω) | ON/OFF Ratio | Retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (HRS) | N/A (Initial) | ~10⁶ | 10³ : 1 | > 10⁴ s |

| Intermediate (IRS) | ~1.0 | ~10⁴ | 10² : 1 | > 10⁴ s |

| Final Low (fLRS) | ~2.0 | ~10³ | 1 : 1 | > 10⁴ s |

Experimental Workflow and Mechanism Visualization

Ion Migration and Conductive Filament Formation in PQD Memory

Lead-Free Perovskite Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Lead-Free Perovskite and PQD Memory Research

| Research Reagent | Function / Role in Experiment | Key Consideration / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Salts (CsCl, CsBr, CsI) | A-site cation in all-inorganic perovskites (e.g., CsPbI₃, Cs₂AgInCl₆) [26] [30]. | Provides thermal stability compared to organic cations like MA⁺ or FA⁺. |

| Silver Salts (AgCl, AgNO₃) | B⁺-site cation in lead-free double perovskites (e.g., Cs₂AgInCl₆) [26]. | Paired with a trivalent cation (e.g., In³⁺, Bi³⁺) to replace two Pb²⁺ ions. |

| Potassium Salts (KCl, KI) | Alloying agent for B-site engineering. Substitutes for Ag⁺ in double perovskites [26]. | Similar ionic radius to Ag⁺ allows lattice incorporation. Enhances PLQY by modifying recombination dynamics. |

| Bismuth Salts (BiCl₃, BiI₃) | Trivalent B³⁺-site dopant or cation in low-dimensional perovskites [26] [27]. | Creates emissive centers in double perovskites. Used in Bismuth-based lead-free perovskites (e.g., A₃Bi₂I₉). |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Surface ligands for colloidal PQD synthesis and stabilization [24] [30]. | Control nanocrystal growth and prevent aggregation. Weak binding can lead to surface vacancies, which is a key factor for ion migration in memory devices. |

| Bulky Ammonium Salts (e.g., PEAI, BAI) | Precursors for forming 2D perovskite capping layers on 3D perovskites [27] [28]. | Improves environmental stability by forming a hydrophobic barrier and passivating surface defects at the 3D perovskite interface. |

Core-Shell and Matrix Encapsulation Strategies (e.g., PQD@MOF Composites)

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts and Material Selection

Q1: What are the primary advantages of creating PQD@MOF composites for memory devices? The primary advantage lies in the synergistic combination of the properties of Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) and Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs). MOFs provide a stable, porous crystalline matrix that can encapsulate PQDs, shielding them from environmental degradation factors like moisture and oxygen [22]. This encapsulation is crucial for suppressing undesirable ion migration, a major source of instability and performance hysteresis in PQD-based memory devices [22]. The composite structure enhances the material's thermal and chemical stability while maintaining the excellent optoelectronic properties of the PQDs [31].

Q2: Why is ion migration a critical problem in perovskite quantum dot memory devices, and how does encapsulation help? Ion migration in PQDs leads to unstable switching behavior, low ON/OFF ratios, and poor retention in memristive devices [22]. In polycrystalline films, grain boundaries act as fast pathways for ion movement and serve as high-defect areas [22]. Encapsulation within a MOF matrix directly addresses this by physically confining the PQDs and passivating their surface, which reduces the pathways and driving forces for ion migration, leading to more reliable and predictable device performance.

Q3: What are the key considerations when choosing a MOF for encapsulating PQDs? The selection of a MOF is critical and depends on several factors:

- Pore Size and Aperture: The MOF pores must be large enough to host the PQDs or allow for their in-situ synthesis within the cages, yet the apertures should help confine the PQDs and suppress leaching.

- Chemical Compatibility: The MOF should be chemically stable under the synthesis and operational conditions of the PQDs.

- Functional Groups: The organic linkers in the MOF can be chosen to interact favorably with the PQD surface, promoting stability and influencing charge transfer properties [31].

Q4: My PQD@MOF composite precipitates out of solution. How can I improve its colloidal stability? Colloidal stability is essential for processing uniform films. Strategies to improve stability include:

- Surface Functionalization: Introducing charged or sterically bulky functional groups (e.g., sulfonates, long alkyl chains) on the MOF linkers or the PQD capping ligands can prevent aggregation [32].

- Core-Shell Structures: Designing a magnetic core-MOF shell composite, where a stable silica (SiO₂) shell is first coated on the magnetic core before MOF growth, can significantly enhance dispersion stability [32].

- Solvent Optimization: Ensure you are using a solvent that provides good solvation for the external surface of your composite material.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Incomplete or Non-Uniform Encapsulation of PQDs within the MOF

Symptoms:

- Poor reproducibility in device performance (e.g., varying ON/OFF ratios).

- Presence of free, unencapsulated PQDs observed in photoluminescence microscopy or separated during centrifugation.

- Rapid degradation of optoelectronic properties, indicating insufficient protection.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Mismatched PQD and MOF pore size | Perform N₂ physisorption to determine MOF pore size distribution. TEM imaging of the composite. | Synthesize a MOF with a larger cavity size or use a post-synthetic infusion method where PQDs are diffused into a pre-formed MOF. |

| Poor surface interaction | Use FT-IR or XPS to analyze the surface chemistry of PQDs and MOF linkers. | Functionalize the PQD surface with ligands that have affinity for the MOF's metal nodes or organic linkers (e.g., carboxylate or pyridine groups). |

| Overly rapid MOF crystallization | Monitor crystallization kinetics. Rapid crystallization often leads to defects and surface deposition. | Optimize synthesis by reducing reagent concentration, lowering temperature, or using a modulated synthesis approach with coordination modulators. |

Experimental Protocol: Post-Synthetic Infusion of PQDs into MOF

- Activation: Dehydrate and activate the pre-synthesized MOF crystals (e.g., ZIF-8, MIL-101) by heating under vacuum at 150°C for 12 hours.

- Infusion: In a nitrogen-filled glovebox, prepare a concentrated solution of PQDs (e.g., CsPbBr₃) in a low-boiling-point, anhydrous solvent (e.g., toluene or hexane).

- Incubation: Add the activated MOF crystals to the PQD solution. Gently stir or sonicate the mixture for 24-48 hours to allow for pore diffusion.

- Washing: Collect the composite by centrifugation and wash thoroughly with fresh solvent multiple times to remove any surface-adsorbed PQDs.

- Drying: Dry the final PQD@MOF composite under a mild vacuum before further use.

Problem 2: Low ON/OFF Ratio and High Operational Variability in Memory Devices

Symptoms:

- The resistance difference between the High Resistance State (HRS) and Low Resistance State (LRS) is minimal.

- The switching voltage and HRS/LRS currents vary significantly from cycle to cycle.

- Poor data retention, with the device state decaying rapidly over time.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Significant ion migration | Conduct capacitive-frequency (C-f) measurements or thermally stimulated depolarization current (TSDC) analysis. | Optimize the MOF encapsulation to better confine halide ions. Consider using a lead-free perovskite composition (e.g., Cs₃Bi₂Br₉) which may exhibit different ion dynamics [33]. |

| High defect density at interfaces | Use impedance spectroscopy to analyze interface-dominated effects. | Introduce an ultrathin interfacial layer (e.g., Al₂O₃ via atomic layer deposition) between the composite film and the electrode to block charge injection and stabilize the interface. |

| Inhomogeneous composite film | Characterize film morphology with SEM and AFM. Map electrical characteristics with conductive-AFM. | Optimize the film deposition process (e.g., spin-coating parameters, ink formulation) to achieve a smooth, pinhole-free layer. |

Problem 3: Poor Chemical and Operational Stability of the Composite

Symptoms:

- Rapid quenching of photoluminescence intensity over time.

- Structural degradation or phase segregation of the PQDs observed under TEM or XRD after device operation.

- Device failure after a limited number of switching cycles.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| MOF matrix degradation | Perform PXRD before and after stability tests to check for loss of crystallinity. | Choose a hydrothermally and chemically stable MOF (e.g., UiO-66, ZIF-8). For magnetic composites, a dense SiO₂ shell can protect the core from acidic environments [32]. |

| Incomplete surface passivation | Analyze trap density via thermal admittance spectroscopy or space-charge-limited current (SCLC) measurements. | Employ a multi-step encapsulation strategy. For example, first passivate PQDs with a thin oxide shell, then embed them within the MOF matrix for enhanced protection. |

| Lead leakage from PQDs | Use ICP-MS to measure lead content in solutions after aging the composite. | Develop and use lead-free PQD@MOF composites (e.g., based on Cs₃Bi₂Br₉), which already meet stricter safety standards and can offer better operational stability [33]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in PQD@MOF Composites |

|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ Quantum Dots | The active optoelectronic material whose ion migration and stability are being studied. Provides the memristive switching layer [22]. |

| ZIF-8 (Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8) | A common MOF for encapsulation. Its relatively small pores and high stability make it suitable for confining PQDs and suppressing ion diffusion. |

| Magnetic Fe₃O₄ Nanoparticles | Used as a core material to create magnetically retrievable core-shell MOF composites, facilitating easy separation and reuse during synthesis and processing [31]. |

| APTES ((3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane) | A silane coupling agent used to functionalize surfaces (e.g., of magnetic nanoparticles or PQDs) with amine groups, promoting stronger interaction with MOF precursors and better encapsulation [32]. |

| Lead-Free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs | A more environmentally benign alternative to lead-halide PQDs. They are being explored for their intrinsic stability and potential for reduced ion migration in composite structures [33]. |

| Perovskite Precursor Salts (e.g., Cs₂CO₃, PbBr₂, BiBr₃) | Used in the direct in-situ synthesis of PQDs within the MOF pores. |

Experimental Workflow and Diagnostic Pathways

Diagram 1: PQD@MOF Composite Synthesis and Troubleshooting

Diagram 2: Ion Migration Suppression Mechanism

Interface Engineering for Blocking Ionic Pathways and Enhancing Stability

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary role of interface engineering in suppressing ion migration in Perovskite Quantum Dot (PQD) memory devices?

Interface engineering is a foundational strategy to enhance the operational stability and performance of PQD-based memory devices. Its primary role is to create robust, chemically compatible interfaces that act as physical barriers to block the unintended movement of ions. This is achieved by passivating surface defects and dangling bonds on the PQDs, which are the primary pathways for ion migration. Effective interface engineering suppresses ion migration, leading to reduced leakage currents, enhanced charge retention capabilities, and improved endurance against program/erase cycles [34] [35] [6].

Q2: Why are PQDs particularly susceptible to ion migration and instability?

PQDs possess an ionic crystal lattice and inherently soft ionic bonds, making them susceptible to ion migration under electrical bias and environmental stressors. Key factors contributing to their instability include:

- High Surface-to-Volume Ratio: The large surface area of QDs presents a high density of surface defects and unpassivated sites that facilitate ion movement and serve as non-radiative recombination centers [36] [6].

- Environmental Sensitivity: Exposure to moisture, oxygen, and light can accelerate degradation and ion migration by disrupting the ionic lattice [33] [37].

- Ligand Instability: The original organic ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) used in synthesis are dynamically bound and can desorb over time, creating unstable interfaces and exposing ionic surfaces [34] [37].

Q3: What are the most effective material strategies for creating stable interfaces on PQDs?

The most effective strategies involve creating a protective, often inorganic, shell around the PQD core.

- Aminosilane Passivation: Using molecules like (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) forms a protective silica-like shell through a hydrolysis-condensation reaction, effectively passivating surface defects and enhancing compatibility with polymer matrices like PVDF [34].

- Core-Shell PQD Structures: Engineering PQDs with a wider-bandgap shell, such as a

MAPbBr3@tetra-OAPbBr3core-shell structure, can epitaxially passivate the core's surface, suppressing non-radiative recombination and blocking ionic pathways [36]. - Lead-Free Compositions: Exploring lead-free alternatives (e.g., Cs₃Bi₂Br₉) can inherently reduce toxicity and improve environmental stability, though their performance often lags behind lead-based counterparts [33].

Q4: How can I diagnose ion migration as the cause of failure in my PQD memory device?

Ion migration typically manifests through several measurable device characteristics:

- Poor Retention Time: A rapid loss of stored charge (e.g., a quick decay of the "ON" or "OFF" state) is a classic symptom of charge leakage via ionic pathways [35].