Strategies for Reducing Auger Recombination in Perovskite Quantum Dots: From Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

Auger recombination is a critical non-radiative process that plagues perovskite quantum dots (QDs), leading to efficiency roll-off in light-emitting devices and limiting their performance in biomedical applications.

Strategies for Reducing Auger Recombination in Perovskite Quantum Dots: From Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

Auger recombination is a critical non-radiative process that plagues perovskite quantum dots (QDs), leading to efficiency roll-off in light-emitting devices and limiting their performance in biomedical applications. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms and impacts of Auger recombination, exploring advanced suppression strategies including compositional engineering, surface passivation, and dielectric confinement manipulation. We examine methodological breakthroughs that enhance photoluminescence quantum yield and operational stability, while addressing troubleshooting approaches for defect management and synthesis optimization. Furthermore, we present a comparative evaluation of perovskite QDs against other nanomaterials, discussing validation techniques and the ongoing challenges for clinical translation in drug delivery and bioimaging.

Understanding Auger Recombination: Fundamentals and Challenges in Perovskite QDs

Troubleshooting Guide: Auger Recombination in Quantum-Confined Systems

Symptom: Efficiency Droop in Light-Emitting Devices

Problem: Device efficiency decreases significantly at high current densities or excitation levels.

- Underlying Cause: Auger recombination becomes the dominant decay pathway at high carrier densities, outcompeting radiative recombination. Its rate scales with the cube of the carrier density (R~n³), making it severely impact performance under high injection conditions [1] [2].

- Diagnostic Check: Measure external quantum efficiency (EQE) as a function of injection current. A distinct peak at low current followed by a rapid decrease indicates efficiency droop.

- Solution: Implement band structure engineering to reduce the Auger coefficient. For quasi-2D perovskites, using polar organic cations like p-fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA+) can reduce exciton binding energy, suppressing Auger rates by more than an order of magnitude [3].

Symptom: Photoluminescence Blinking in Single Quantum Dot Studies

Problem: Random switching between bright and dim emission states in single-particle tracking.

- Underlying Cause: Random charging/discharging events create charged excitons (trions) that undergo rapid non-radiative Auger recombination [4] [5].

- Diagnostic Check: Perform single-dot fluorescence correlation spectroscopy to identify characteristic "on" and "off" times.

- Solution: Use heterostructured quantum dots with alloyed interfacial layers (e.g., CdSe/CdSeS/CdS core/alloy/shell). The smoothed confinement potential suppresses Auger recombination by reducing wavefunction overlap [6] [4].

Symptom: Reduced Open-Circuit Voltage in Solar Cells

Problem: Lower-than-expected open-circuit voltage (VOC) under concentrated sunlight.

- Underlying Cause: Auger recombination in heavily doped regions or at high carrier concentrations reduces charge carrier lifetimes [2].

- Diagnostic Check: Measure carrier lifetime as a function of injection level; cubic dependence indicates Auger dominance.

- Solution: Optimize doping profiles and implement passivation techniques to reduce the intrinsic Auger coefficient. For conductive quantum-dot solids, minimize energy disorder to prevent carrier congregation in "Auger hot spots" [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is Auger recombination and why is it problematic for quantum-confined systems?

Auger recombination is a non-radiative process where an electron and hole recombine, but instead of emitting a photon, the energy is transferred to a third carrier (electron or hole) which is excited to a higher energy state [1] [8]. This process is particularly efficient in quantum-confined systems due to enhanced Coulomb interactions and spatial confinement, leading to significant efficiency losses in optoelectronic devices at operational carrier densities [2] [4].

Q2: How does Auger recombination cause efficiency droop in LEDs?

In LEDs, as current density increases, carrier concentration in the active region rises. Since the Auger recombination rate scales with the cube of carrier density (R~n³), it becomes dominant at high injection levels, causing a sublinear increase in light output power and decreasing overall efficiency—a phenomenon known as "efficiency droop" [2]. This is especially problematic in blue and green LEDs where Auger coefficients are typically higher.

Q3: What experimental techniques can detect and quantify Auger recombination?

- Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL): Measures carrier decay dynamics; fast components at high excitation indicate Auger processes [6].

- Transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy: Monitors bleach recovery dynamics; accelerated decay at high fluences reveals Auger recombination [7].

- Electron emission spectroscopy: Directly detects energetic Auger electrons emitted from devices under electrical injection [1].

- Photoconductance decay: Higher-order dependence on carrier density indicates Auger dominance [7].

Q4: What strategies effectively suppress Auger recombination in perovskite quantum dots?

- Dielectric constant engineering: Using polar organic cations (e.g., p-FPEA+) to reduce dielectric confinement and exciton binding energy [3].

- Surface passivation: Strong-binding ligands like 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) passivate surface defects and suppress biexciton Auger recombination [9].

- Interface alloying: Creating graded core/alloy/shell structures to smooth confinement potentials and reduce wavefunction overlaps [6] [4].

- Charge balance engineering: Modifying shell composition to impede unbalanced carrier injection and reduce trion formation [6].

Quantitative Data on Auger Recombination

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Auger Coefficients for Various Materials

| Material System | Auger Coefficient (cm⁶/s) | Measurement Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quasi-2D Perovskite (p-FPEA⁺) | ~1-2 × 10⁻³¹ | TRPL & recombination kinetics | [3] |

| In₀.₁₀Ga₀.₉₀N/GaN | 1.5 × 10⁻³⁰ | Device performance modeling | [1] |

| InGaN/GaN | 3.5 × 10⁻³¹ | Electro-optical characterization | [1] |

| CdSe/CdS Core/Shell QDs | Varies with geometry: 10⁸-10⁹ s⁻¹ (rate) | Single-dot spectroscopy | [4] |

Table 2: Biexciton Lifetimes in Engineered Quantum Dots

| Quantum Dot Structure | Biexciton Lifetime (τXX) | Auger Rate Enhancement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| InP/1CdS (1.6 ML shell) | 58 ± 12 ps | Baseline | [5] |

| InP/4CdS (5.6 ML shell) | 99 ± 5 ps | 1.7× slower | [5] |

| InP/7CdS (8.2 ML shell) | 612 ± 49 ps | 10.6× slower | [5] |

| InP/10CdS (11.4 ML shell) | 7,212 ± 1,073 ps | 124× slower | [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Auger Characterization

Protocol 1: Time-Resolved Photoluminescence for Auger Coefficient Extraction

- Sample Preparation: Deposit quantum dot films on quartz substrates using spin-coating to create optically smooth surfaces.

- Excitation Source: Use a pulsed laser system (e.g., Ti:Sapphire) with tunable wavelength and pulse width <100 fs.

- Excitation Density Variation: Systematically vary laser fluence from 10⁻³ to >1 excitons per QD, carefully measuring absorbed photons.

- Lifetime Analysis: Fit decay traces with multi-exponential models; extract fast components attributed to Auger processes.

- Auger Coefficient Calculation: Plot decay rate vs. carrier density squared; slope yields Auger coefficient using Rᴬᵘᵍᵉʳ = C·n³ [3] [4].

Protocol 2: Single Quantum Dot Blinking Suppression Assessment

- Sample Preparation: Dilute QD solution and spin-coat on cover slides for single-particle isolation.

- Microscopy Setup: Use confocal microscope with high-NA objective and sensitive single-photon detectors.

- Data Acquisition: Record fluorescence time traces (typically 5-10 minutes) with 10-100 ms time bins.

- Blinking Analysis: Calculate probability density functions of "on" and "off" times from intensity trajectories.

- Auger Suppression Validation: Compare trion lifetimes from blinking dynamics; longer "off" times indicate suppressed Auger recombination [4] [5].

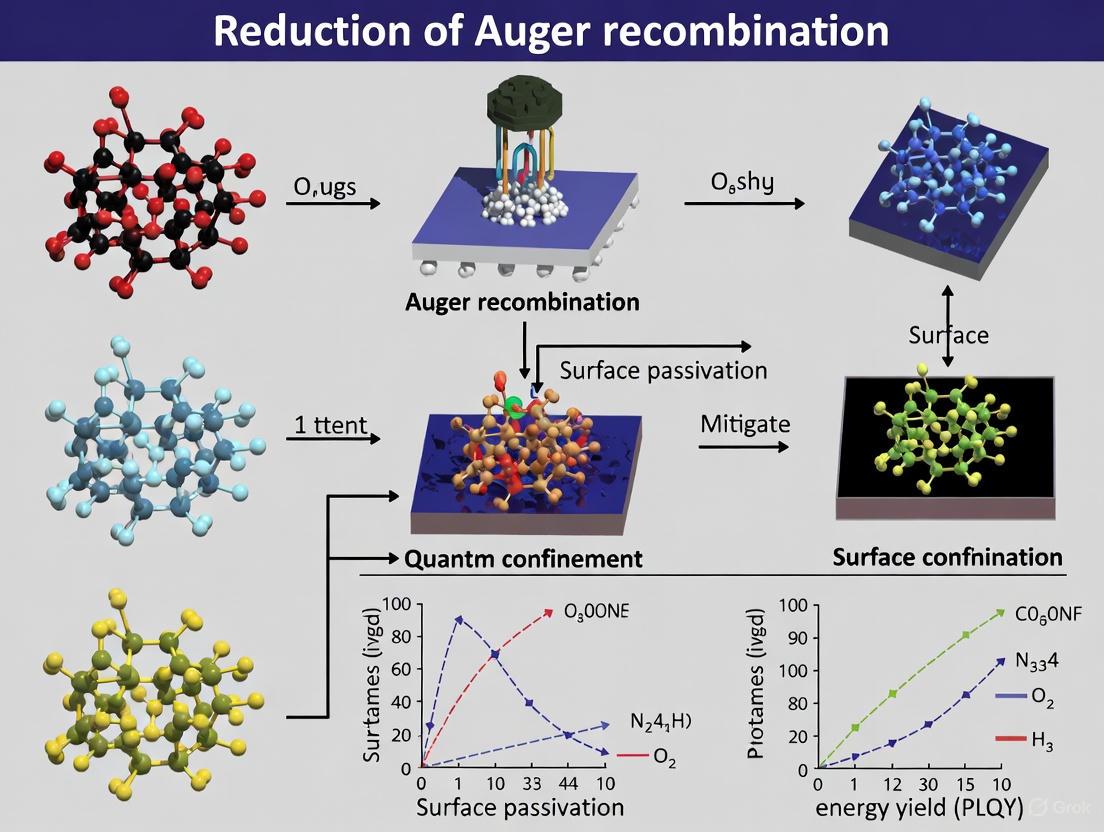

Visualization of Auger Processes and Suppression Strategies

Diagram 1: Auger Recombination Process and Mitigation Strategies. The flowchart illustrates the multi-step nature of Auger recombination and how specific engineering strategies target different stages of the process to suppress non-radiative losses.

Research Reagent Solutions for Auger Suppression

Table 3: Key Reagents for Suppressing Auger Recombination in Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Auger Suppression | Application Protocol | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-Fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA⁺) | Reduces dielectric confinement and exciton binding energy | Incorporate as A-site cation in quasi-2D perovskite synthesis | Lowers Auger rate by >10× [3] |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | Surface ligand with strong binding affinity | Replace oleic acid during QD synthesis or post-treatment | Suppresses biexciton Auger recombination [9] |

| Acetate (AcO⁻) anions | Dual-function: complete precursor conversion & surface passivation | Add to cesium precursor solution during QD synthesis | Enhances reproducibility and reduces trap states [9] |

| CdSe₀.₅S₀.₅ alloy interfacial layer | Smoothes core/shell confinement potential | Grow intermediate layer between core and shell in QD synthesis | Reduces wavefunction overlap for Auger processes [6] |

Core Concepts FAQ

What are efficiency roll-off and limited brightness in the context of perovskite quantum dot (QD) light-emitting devices?

Efficiency roll-off is the undesirable decrease in a device's external quantum efficiency (EQE) as the driving current or brightness increases. Limited brightness refers to the challenge in achieving high luminance levels before this efficiency drop becomes severe or the device degrades. In perovskite QD light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs), these phenomena are primarily driven by Auger recombination, a non-radiative process where the energy from recombining an electron and hole is transferred to a third carrier (another electron or hole) instead of being emitted as light [3] [10]. This process becomes dominant at high excitation densities, quenching light output and limiting performance.

Why is Auger recombination particularly problematic in quantum-confined systems like perovskite QDs?

Quantum confinement in nanocrystals exacerbates Auger recombination through two main mechanisms:

- Enhanced Coulomb Interaction: The strong spatial confinement of electrons and holes within a small volume increases their Coulomb interaction, directly accelerating the Auger recombination rate [10].

- Defect-Mediated Auger Recombination: Deep-level defects, common in mixed-halide perovskites, can trap charge carriers. These trapped charges facilitate the formation of charged excitons (trions), which undergo very fast Auger recombination, often within picoseconds [10]. This defect-mediated pathway significantly contributes to high Auger recombination rates, even under modest excitation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing Efficiency Roll-Off

Problem: Your PeLED shows high efficiency at low current densities but suffers a severe efficiency drop as current increases.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Experimental Investigation |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid roll-off at low to medium brightness | High defect density leading to defect-mediated Auger recombination [10] | Time-resolved PL (TRPL) and transient absorption (TA) to measure carrier trapping dynamics (trapping often occurs in 10 ps) [10]. |

| Severe roll-off and reduced operational stability | Significant triplet-polaron annihilation (TPA) and triplet-triplet annihilation (TTA) due to long-lived triplet states [11]. | Transient electroluminescence measurement to analyze exciton lifetime and identify long-delay tails [12] [13]. |

| Roll-off accompanied by reduced photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) | Incomplete surface passivation, leading to non-radiative recombination and charging of QDs [14]. | Measure PLQY under varying excitation densities; single-dot microscopy to observe PL blinking [14]. |

Achieving High Brightness

Problem: You are unable to achieve high brightness levels without significant efficiency loss or device degradation.

| Challenge | Root Cause | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Threshold for amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) is too high | Auger recombination outcompetes radiative recombination, preventing population inversion [15] [10]. | Measure ASE threshold; fs-transient absorption to directly track Auger recombination rates [10]. |

| Brightness is limited by rapid degradation at high current | Joule heating induced by non-radiative Auger processes and exciton annihilation [3]. | Monitor device temperature and EQE stability under constant high current operation. |

| Emission color instability at high drive currents | Electric-field-induced dissociation of excitons or ion migration exacerbated by heat [12]. | Time-resolved emission spectra under electric field; measure spectral shift versus current density [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for Mitigation

Protocol: Surface Passivation to Suppress Defect-Mediated Auger Recombination

Objective: Passivate surface defects to reduce non-radiative recombination and suppress the formation of charged excitons that drive Auger recombination [15] [14].

Materials:

- CsPbBr₃ QDs synthesized via hot-injection or room-temperature method.

- Precursor: 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA), a short-branched-chain ligand with strong binding affinity [15].

- Precursor: Acetate (AcO⁻) ions, which act as a co-passivator for dangling bonds [15].

- Solvents: Toluene, hexane, ethyl acetate.

- Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) for solid-state ligand exchange to promote π-π stacking [14].

Methodology:

- QD Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbBr₃ QDs using a novel cesium precursor recipe combining AcO⁻ and 2-HA. The AcO⁻ improves precursor purity and passivates surface defects, while 2-HA provides a stable ligand coat [15].

- Purification: Purify the QDs by precipitation with anti-solvent (ethyl acetate) and centrifugation. Redisperse in toluene.

- Solid-State Ligand Engineering: a. Prepare a saturated solution of PEABr in a solvent like isopropanol. b. Mix the QD film with the PEABr solution and anneal at a mild temperature (e.g., 60-80°C) for 10-15 minutes. c. Rinse with pure solvent to remove excess ligands [14].

- Characterization:

Protocol: Reducing Exciton Binding Energy to Suppress Auger Recombination

Objective: Lower the exciton binding energy (Eb) to weaken electron-hole Coulomb interaction, thereby directly reducing the Auger recombination rate [3].

Materials:

- p-Fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA): A polar organic cation with a high dipole moment.

- PbBr₂, MABr, CsBr.

- Common solvents (DMF, DMSO, isopropanol).

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a precursor solution for quasi-2D perovskite (p-FPEA)₂MAn₋₁PbnBr₃n₊₁. The polar p-FPEA cation increases the dielectric constant of the organic barrier, weakening dielectric confinement and reducing Eb [3].

- Film Fabrication: Deposit the perovskite film via spin-coating onto the substrate. Use an anti-solvent drip to induce crystallization.

- Annealing: Anneal the film at an appropriate temperature (e.g., 90°C for 10 minutes) to form the crystalline phase.

- Characterization:

- Temperature-Dependent PL: Measure PL spectra at different temperatures to quantitatively extract the reduced Eb [3].

- Transient Absorption Spectroscopy: Confirm the reduction in Auger recombination rate, which can be one order of magnitude lower than PEA-based analogues [3].

- Device Performance: Fabricate PeLEDs and measure EQE and luminance. Devices should show a high peak EQE (>20%) and a record luminance (>80,000 cd m⁻²) due to suppressed roll-off [3].

Table 1: Impact of Different Strategies on Auger Recombination and Device Performance

| Strategy | Material System | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand & Surface Engineering | CsPbBr₃ QDs with AcO⁻/2-HA | PLQYASE Threshold | 99%Reduced from 1.8 μJ·cm⁻² to 0.54 μJ·cm⁻² (70% decrease) | [15] |

| Reducing Eb with Polar Cations | (p-FPEA)₂MAn₋₁PbnBr₃n₊₁ | Auger Recombination RatePeak EQEMax Luminance | One-order-of-magnitude decrease vs. PEA+20.36%82,480 cd m⁻² | [3] |

| Deep-Level Defect Control | CsPb(Br/Cl)₃ NCs (Low defect) | ASE Threshold (Blue) | 25 μJ·cm⁻² | [10] |

| Ligand Tail Stacking | CsPbBr₃/I₃ QDs with PEA | Photostability | Nearly non-blinking for 12 hours under continuous laser excitation | [14] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced PeLED Development

| Reagent | Function | Key Property / Application |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | Surface ligand | Short-branched-chain ligand providing stronger binding affinity than oleic acid, improving passivation and suppressing Auger recombination [15]. |

| Acetate (AcO⁻) ions | Co-passivator & precursor additive | Dual-function: passivates dangling surface bonds and improves cesium precursor purity to enhance batch reproducibility [15]. |

| p-Fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA) | Polar organic cation | High dipole moment reduces dielectric confinement and exciton binding energy (Eb) in quasi-2D perovskites, suppressing Auger recombination [3]. |

| Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) | Small-sized ligand for solid-state treatment | Promotes attractive π-π stacking between ligand tails, enabling near-epitaxial surface coverage and exceptional photostability in single QDs [14]. |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Surface ligand (colloidal stability) | Provides halide ions and passivates Pb²⁺ sites; effective for initial colloidal synthesis but may limit solid-state passivation due to bulky tails [14]. |

Mechanism and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Primary causes and effects of Auger recombination in PeLEDs.

Diagram 2: Multi-strategy workflow for high-performance PeLED development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the primary factors that influence Auger recombination rates in quantum-confined systems? Auger recombination rates are predominantly influenced by two key factors: the exciton binding energy (Eₕ) and the degree of quantum confinement. A higher exciton binding energy strengthens the Coulomb electron-hole interaction, which accelerates the Auger process [3]. Simultaneously, strong quantum confinement, typically in nanoparticles smaller than the exciton Bohr radius, increases the probability of carrier interactions, further enhancing Auger recombination rates [16] [10].

How can we experimentally reduce Auger recombination in quasi-2D perovskite films? Research demonstrates that Auger recombination can be suppressed by reducing the material's exciton binding energy. One effective method involves incorporating polar organic cations, such as p-fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA⁺), into the perovskite "A-site". This reduces the dielectric constant mismatch, weakening dielectric confinement and thus the binding energy. This approach has been shown to decrease the Auger recombination rate by more than an order of magnitude compared to non-polar analogues [3].

Does the "universal volume scaling law" for Auger recombination always apply? No, recent studies on high-quality, large perovskite nanocrystals in the weak confinement regime (where the nanocrystal size is larger than the exciton Bohr radius) have shown a significant deviation from the universal volume scaling law. In this regime, the Auger recombination lifetime increases exponentially with volume, rather than linearly, due to the emergence of nonlocal effects [16].

What is the role of deep-level defects in Auger recombination? Deep-level defects, particularly those associated with chlorine vacancies in mixed-halide perovskites, can profoundly enhance Auger recombination. These defects can capture electrons within 10 picoseconds, leading to the formation of charged separation states. Under quantum confinement, these excess charges bind with excitons to form trions (charged excitons), which provides a pathway for significantly enhanced Auger recombination, thereby increasing the threshold for achieving optical gain [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Severe Efficiency Roll-Off in Perovskite Light-Emitting Diodes (PeLEDs)

Potential Cause: Rapid Auger recombination, often triggered by high exciton binding energy and amplified carrier density at recombination centers [3]. Solutions:

- Material Engineering: Replace standard organic cations (e.g., PEA⁺) with polar alternatives like p-FPEA⁺. This reduces the dielectric confinement and lowers the exciton binding energy, directly suppressing the Auger rate [3].

- Passivation: Implement a robust molecular passivation strategy post-Eb reduction. While lowering Eₕ also reduces the first-order exciton recombination rate, effective passivation suppresses trap-assisted nonradiative recombination, allowing high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs) to be maintained across a broad range of excitation densities [3].

Problem: Low Amplified Spontaneous Emission (ASE) Performance and High Lasing Threshold

Potential Cause: Significant Auger recombination outcompeting radiative processes, exacerbated by either strong quantum confinement or deep-level defects [9] [10]. Solutions:

- Surface Ligand Engineering: Use ligands with strong binding affinity, such as 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA), to effectively passivate surface dangling bonds. This suppresses non-radiative defect-assisted recombination and biexciton Auger recombination [9].

- Defect Density Management: For mixed-halide blue emitters, optimize the synthesis to minimize deep-level defects, particularly chlorine vacancies. A hot-injection method may yield lower defect density compared to room-temperature synthesis [10].

- Core/Shell Interface Alloying: Engineering an alloyed layer at the core/shell interface of quantum dots can smooth the confinement potential, which has been shown to effectively suppress Auger recombination [17].

Problem: Inconsistent Batch-to-Batch Performance of Perovskite Quantum Dots

Potential Cause: Poor reproducibility in nanocrystal synthesis, leading to variable defect densities and size distributions that affect Auger dynamics [9]. Solutions:

- Precursor Purity Control: Employ a dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) in the cesium precursor recipe. The AcO⁻ anion aids in the more complete conversion of cesium salt, enhancing precursor purity from ~70% to over 98% and improving the homogeneity and reproducibility of the resulting quantum dots [9].

The following table summarizes key quantitative relationships and experimental data related to Auger recombination control.

Table 1: Experimental Data on Auger Recombination Suppression Strategies

| Factor & Strategy | Material System | Key Measurable Outcome | Quantitative Result | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reducing Exciton Binding Energy (Eₕ) | Quasi-2D Perovskite: p-FPEA₂MAₙ₋₁PbₙBr₃ₙ₊₁ | Auger Recombination Rate | Decreased by >10x vs. PEA⁺ analogue [3] | |

| Device Luminance | Record 82,480 cd m⁻² [3] | |||

| Peak External Quantum Efficiency | 20.36% [3] | |||

| Surface Ligand Passivation | CsPbBr₃ QDs with 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | 99% [9] | |

| Amplified Spontaneous Emission (ASE) Threshold | Reduced by 70% (1.8 μJ·cm⁻² to 0.54 μJ·cm⁻²) [9] | |||

| Weak Quantum Confinement | Large CsPbBr₃ Nanocrystals (1000 - 10000 nm³) | Biexciton Efficiency | Up to 80% [16] | |

| Auger Lifetime Scaling | Exponential increase with volume, deviating from universal volume scaling [16] | |||

| Deep-Level Defect Control | CsPb(BrₓCl₁₋ₓ)₃ Nanocrystals | Blue ASE Threshold | 25 μJ·cm⁻² (achieved under low defect density) [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Reducing Auger Recombination via Exciton Binding Energy Engineering in Quasi-2D Perovskites

This protocol is based on the work by Jiang et al. (2021) [3].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare precursor solutions using standard methods for quasi-2D PEA₂MAₙ₋₁PbₙBr₃ₙ₊₁ perovskites.

- Cation Substitution: Synthesize the polar organic cation p-fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA⁺). Substitute the standard PEA⁺ cation with p-FPEA⁺ in the precursor solution to form p-FPEA₂MAₙ₋₁PbₙBr₃ₙ₊₁.

- Film Deposition: Deposit the perovskite film onto your substrate using a suitable method (e.g., spin-coating).

- Post-Treatment/Passivation: Immediately after film deposition, apply a suitable passivation agent (specifics may vary) to suppress trap-assisted nonradiative recombination that becomes more impactful after Eₕ is reduced.

- Characterization:

- Use temperature-dependent photoluminescence (PL) to quantitatively measure the reduction in exciton binding energy.

- Perform time-resolved PL or ultrafast spectroscopy to measure recombination kinetics and confirm the suppression of the Auger recombination rate.

Protocol B: Suppressing Auger Recombination in Quantum Dots via Ligand Engineering

This protocol synthesizes methods from Bi et al. (2025) and Cai et al. [9] [10].

- Precursor Optimization: For CsPbBr₃ QD synthesis, use a cesium precursor recipe combining cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) with a dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) source and 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) as a short-branched-chain ligand instead of oleic acid.

- Synthesis: Execute the synthesis via the hot-injection method to ensure higher crystallinity and lower defect density compared to room-temperature methods.

- Purification: Purify the resulting QDs using standard solvents like ethyl acetate or methyl acetate.

- Characterization:

- Measure the PLQY to confirm high emission efficiency (~99%).

- Perform femtosecond transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy to directly probe multi-exciton dynamics and quantify the Auger recombination rate.

- Test ASE performance by measuring the excitation threshold required to achieve optical gain.

Conceptual Diagrams

Diagram 1: Strategies to Suppress Auger Recombination

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Controlling Auger Recombination

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Property / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| p-Fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA⁺) Iodide/Bromide | Polar organic A-site cation in quasi-2D perovskites. | High dipole moment (~2.39 D) reduces dielectric confinement and exciton binding energy, suppressing Auger recombination [3]. |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | Short-branched-chain surface ligand for QDs. | Stronger binding affinity to QD surface than oleic acid, providing superior passivation of surface defects and suppression of biexciton Auger recombination [9]. |

| Acetate (AcO⁻) Salts | Additive in cesium precursor or surface ligand. | Dual-function: improves cesium precursor purity and completeness of reaction, and acts as a surface passivant for dangling bonds [9]. |

| Lead Acetate Trihydrate (Pb(AC)₂·3H₂O) | Lead precursor for nanocrystal synthesis. | High-purity precursor that can help reduce the formation of lead-based by-products, improving batch reproducibility [10]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Mitigating Defect-Auger Recombination

This guide helps diagnose and resolve the issue of accelerated non-radiative losses in perovskite quantum dots (QDs) caused by deep-level defects.

Problem: My perovskite quantum dot films show a rapid drop in photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) under moderate excitation, and my devices suffer from severe efficiency roll-off.

Question 1: How can I confirm that deep-level defects are accelerating Auger recombination in my samples?

Answer: Deep-level defects act as ultrafast trapping centers, creating a pathway for enhanced Auger recombination. To confirm their role, perform the following diagnostic experiments:

- Perform Time-Resolved Optical Characterization: Use time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) and femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) spectroscopy. A very fast carrier trapping component (often within 10 ps) is a key signature of deep-level defect activity [10]. These measurements track how quickly photogenerated excitons are captured by defect states.

- Conduct Temperature-Dependent PL Measurements: Analyze how the PL intensity and decay dynamics change with temperature. Deep-level defects often exhibit distinct thermal activation energies. An increase in non-radiative losses at higher temperatures can indicate the involvement of these defects [10].

- Look for Signature Dynamics in Pump-Probe Signals: In transient absorption or reflection measurements, a rapid signal decay followed by a slow component can indicate the capture and subsequent slow release of carriers from trap states. The saturation of this trapping effect at high excitation densities can be used to estimate the defect density itself [18].

Question 2: What specific chemical defects should I look for in mixed-halide perovskite nanocrystals?

Answer: In mixed chlorine-bromine systems, the primary culprit is often the chlorine-related deep-level defect, such as a vacancy (V₍Cl₎) or an antisite defect [10]. These defects are characterized by:

- Rapid charge carrier capture (on the timescale of picoseconds).

- Preferential electron trapping, which leads to the formation of charge-separated states [10].

- Under quantum confinement, these trapped charges can bind with excitons to form charged excitons (trions), providing a pathway for efficient, non-radiative Auger recombination [10].

Question 3: What practical strategies can I use to suppress defect-mediated Auger recombination?

Answer: The most effective strategy is a combination of defect passivation and material engineering.

- Implement Robust Surface Passivation: This is the most direct method. Use ligands with strong binding affinity to the QD surface to tie up "dangling bonds" that cause deep-level defects.

- Recommended Reagents: Short-branched-chain ligands like 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) demonstrate stronger binding than traditional oleic acid, effectively suppressing non-radiative recombination and biexciton Auger recombination [9]. Acetate ions (AcO⁻) can also function as effective surface ligands, enhancing passivation [9].

- Reduce Dielectric Confinement: The strong electron-hole interaction in quasi-2D perovskites exacerbates Auger rates. You can reduce the exciton binding energy (E₆), which is proportional to the Auger rate, by using polar organic cations.

- Example: Replacing phenethylammonium (PEA+) with p-fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA+) creates a high-polarity environment, weakening dielectric confinement. This has been shown to reduce the Auger recombination rate by more than an order of magnitude [3].

- Optimize Precursor Synthesis and Purity: Inconsistent precursor quality introduces defects. Employ synthesis recipes that ensure high precursor purity and complete conversion. For example, using acetate-assisted synthesis for cesium precursors can increase purity from ~70% to over 98%, leading to superior homogeneity and fewer defects in the final QDs [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental mechanism linking deep-level defects to Auger recombination?

Answer: Deep-level defects do not typically cause a direct, band-to-band Auger process. Instead, they act as a critical intermediate. The mechanism involves three key steps [10]:

- Ultrafast Trapping: A deep-level defect (e.g., a chlorine vacancy) preferentially captures an electron on an ultrafast timescale (~10 ps).

- Charge Separation: This trapping event creates a long-lived, charge-separated state (a trapped electron and a free hole).

- Trion-Driven Auger Recombination: Under quantum confinement, this charged defect site can bind a neutral exciton, forming a trion (a three-particle complex). The recombination of this trion is an Auger process, where the energy is transferred to the third carrier, which is then excited to a higher energy state within the band.

FAQ 2: My perovskite films have high PLQY at low excitation, but it drops sharply. Is this a sign of defect-Auger problems?

Answer: Yes, this is a classic symptom. A high PLQY at low excitation indicates that shallow defects are effectively passivated or saturated. The sharp drop at higher excitation is a direct result of Auger recombination becoming the dominant loss channel. When deep-level defects are present, this threshold for "efficiency droop" occurs at even lower carrier densities because the defects actively facilitate the Auger process [10] [3].

FAQ 3: Are there quantitative benchmarks for Auger coefficients in perovskites?

Answer: Yes, experimental measurements have provided the following ranges for Auger coefficients (C) in various perovskite materials. This table can help you benchmark your own findings.

| Material System | Auger Coefficient (cm⁶/s) | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|

| Quasi-2D Perovskite (p-FPEA+) | ~ 1 x 10⁻³¹ (estimated) | One-order lower than PEA+ analogue; low droop [3]. |

| InGaN/GaN (for comparison) | ~ 1.5 x 10⁻³⁰ to 3.5 x 10⁻³¹ [1] | Common in high-performance LEDs. |

| CsPb(Br/Cl)₃ NCs (with defects) | Significantly enhanced | Defect-mediated process [10]. |

FAQ 4: Can I distinguish defect-assisted Auger recombination from other non-radiative pathways?

Answer: Absolutely. The key differentiator is the carrier density dependence of the recombination rate.

- Shockley-Read-Hall (Trap) Recombination: Rate is proportional to carrier density (n).

- Radiative Recombination: Rate is proportional to n².

- Band-to-Band Auger Recombination: Rate is proportional to n³.

- Defect-Assisted Auger Recombination: In the "saturation regime" where the defect states are filled, the rate can be proportional to n², mimicking bimolecular recombination. This quadratic dependence under high injection can be a tell-tale sign of this specific mechanism [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key materials used in advanced perovskite QD research to suppress defect-mediated Auger recombination.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Suppressing Defect-Auger Recombination |

|---|---|

| p-Fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA+) Iodide/Bromide | A polar organic cation that reduces dielectric confinement and exciton binding energy, directly lowering the Auger recombination rate [3]. |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | A short-branched-chain ligand with stronger binding affinity to QD surfaces than oleic acid, providing superior surface passivation and suppressing biexciton Auger recombination [9]. |

| Acetate Salts (e.g., Cesium Acetate) | Serves a dual role: improves precursor purity and completeness of reaction to reduce defect formation, and acts as a surface passivant for dangling bonds [9]. |

| Lead Acetate Trihydrate | A high-purity lead precursor often used in combination with acetate salts to create a "clean" reaction environment with fewer intrinsic defects [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: Time-Resolved Characterization of Defect and Auger Dynamics

Objective: To measure the carrier trapping time by deep-level defects and the subsequent Auger recombination rate in perovskite quantum dot films.

Materials:

- Synthesized perovskite QD film sample (e.g., CsPb(BrxCl1-x)3).

- Femtosecond laser system (e.g., Ti:Sapphire amplifier).

- Transient absorption spectrometer or time-resolved photoluminescence setup.

- Cryostat for temperature-dependent measurements.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Spin-coat your QD solution onto a clean substrate (e.g., quartz) to form a smooth, solid film. Ensure the film is encapsulated if sensitive to ambient conditions.

- Transient Absorption Measurement:

- Set the pump laser wavelength to above the bandgap to generate electron-hole pairs.

- Use a white-light continuum probe to monitor the differential transmission (ΔT/T) or absorption (ΔA) over a broad spectral range.

- Collect data at multiple pump fluences, from low (where trap-filling is minimal) to high (where Auger dominates).

- Data Analysis Workflow:

- Identify the Bleach Peak: Locate the ground-state bleach (GSB) feature of the exciton in the transient spectra.

- Fit the Kinetics: Fit the decay kinetics of the GSB at various pump fluences with a multi-exponential or physical model.

- The fastest component (1-30 ps) is typically assigned to carrier trapping by deep-level defects [10] [18].

- The fluence-dependent decay component at higher excitation is attributed to Auger recombination. Its cubic dependence (for band-to-band) or quadratic dependence (for defect-assisted) on carrier density can be used to extract the Auger coefficient.

The following diagram visualizes this experimental workflow and the physical processes it reveals:

Troubleshooting Guides

Transient Absorption Spectroscopy Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions | Relevant to Auger Recombination Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) [20] | Low repetition rate lasers, electronic noise, probe light intensity drift, low pump fluence. | Use noise suppression technologies (NSTs); Average multiple measurements; Ensure laser stability. [20] | Essential for detecting weak signals from suppressed Auger processes. |

| Scattered Excitation Light in Data [21] | Pump laser wavelength within optical detection window. | Use software's "Subtract Scattered Light" function; Average multiple background spectra for correction. [21] | Cleans data for accurate kinetic fitting of Auger components. |

| Sample Degradation [20] | High pump fluence causing non-linear effects and photodegradation. | Reduce pump fluence; Use flow cells or raster scanning for sensitive samples (e.g., Perovskite QDs). [20] | Prevents misleading recombination kinetics from altered samples. |

| Incorrect Interpretation of ΔA Features [21] | Misassignment of positive (ESA) and negative (GSB, SE) signals. | Correlate GSB with steady-state absorption; Note SE matches fluorescence shape. [21] | Critical for identifying band-filling from high carrier densities in Auger analysis. |

Time-Resolved Photoluminescence Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions | Relevant to Auger Recombination Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measuring Fast Decay Processes [22] | Fluorescence lifetimes too short for conventional photodetectors (e.g., picosecond, femtosecond scales). | Use pump-probe techniques instead of direct detection. [22] | Necessary for resolving fast Auger recombination lifetimes. |

| Deviation from Quadratic IPL0 vs. Density [23] | Dominance of Auger recombination at high carrier densities. | Perform fluence-dependent TRPL; Fit data with rate equations including n³ term. [23] | Directly quantifies Auger recombination coefficient. |

| Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) [9] | Defect-assisted non-radiative recombination, Auger recombination. | Passivate surface defects with appropriate ligands (e.g., 2-hexyldecanoic acid, acetate). [9] | Enhancing PLQY is directly linked to suppressing non-radiative Auger pathways. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Transient Absorption (TA) and Time-Resolved PL (TRPL) spectroscopy? TA measures time-dependent changes in a sample's absorption (ΔA) following photoexcitation, allowing observation of both emissive and non-emissive (dark) states like triplets and charge-separated states [20]. TRPL measures the time-dependent emission of light from a sample, providing information about the population of radiative excited states [22]. For perovskite quantum dot studies, TA can track charge carriers and excited-state absorption, while TRPL directly probes the decay of luminescent states, together offering a complete picture of recombination pathways, including Auger recombination [23].

Q2: How can I determine if Auger recombination is significant in my perovskite quantum dot sample? The key indicator is a superlinear decay in the TRPL traces at high excitation fluences. Specifically, plot the initial PL intensity (IPL₀) against the carrier density. A transition from a quadratic dependence (indicative of bimolecular recombination) to a sub-quadratic dependence signals the growing dominance of Auger recombination, a three-body non-radiative process [23]. Additionally, a rapid drop in relative PLQY with increasing carrier density is a characteristic signature of Auger recombination [23].

Q3: My TA data shows a sharp, negative feature that doesn't change with time. What is this likely to be? This is a classic sign of scattered excitation light [21]. It appears as a sharp, non-decaying negative (bleach-like) feature at the wavelength of your pump laser or its diffraction orders. Most TA analysis software (e.g., Surface Xplorer) includes a "Subtract Scattered Light" function to correct for this artifact [21].

Q4: What are some material design strategies to suppress Auger recombination in perovskite QDs, and how can I verify them spectroscopically? Recent advances include:

- Surface Passivation: Using ligands with stronger binding affinity (e.g., 2-hexyldecanoic acid over oleic acid) to passivate surface defects that facilitate Auger recombination [9].

- Anion Engineering: Incorporating electron-withdrawing anions like trifluoroacetate (TFA⁻) to decouple electron-hole wavefunctions, thereby retarding Auger recombination [23].

- Cation Doping: Doping with ions like Indium (In³⁺) to passivate defects and modify crystal structure, suppressing defect-mediated and phonon-assisted Auger recombination [24].

- Verification: Success is verified by a reduced Auger recombination constant extracted from fluence-dependent TRPL, a higher carrier density tolerance in PLQY measurements, and in TA, a reduced amplitude of decay components associated with many-body interactions [23] [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for TA Spectroscopy to Probe Auger Recombination

This protocol is adapted from established methodologies for processing and fitting TA data [21] [23].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Prepare perovskite QD films or solutions with optimized surface chemistry to minimize extrinsic defects [9].

- For solutions, use a stirred flow cell to prevent local heating and degradation during high-repetition-rate measurements [20].

2. Data Collection:

- Collect a "blank" dataset (solvent only) under identical experimental conditions for later artifact correction [21].

- Perform measurements at a range of pump fluences to vary the initial photoexcited carrier density (N). This is crucial for isolating the N³-dependent Auger recombination.

3. Data Processing:

- Load Data: Import the SAMPLE dataset into your analysis software (e.g., Surface Xplorer, Glotaran) [21].

- Subtract Scattered Light: If a sharp, static negative feature is present at the pump wavelength, use the "Subtract Scattered Light" function, averaging ~10 background spectra for a stable correction [21].

- Chirp Correction: Correct for temporal chirp if using a broadband white-light probe to ensure kinetics are aligned across all wavelengths.

4. Global Lifetime Analysis (GLA):

- GLA fits the entire dataset (wavelength and time) simultaneously to a model of decaying components.

- The output is a set of Decay-Associated Difference Spectra (DADS) which show the spectral signature of each decay component.

- A component with a positive DADS that decays faster at higher fluences may be associated with Auger recombination.

Protocol for Fluence-Dependent TRPL

This protocol is used to extract recombination constants, including the Auger coefficient [23].

1. Data Collection:

- Measure TRPL decays at multiple, carefully controlled excitation fluences.

- Ensure the carrier density (N) spans from the low regime (where monomolecular decay may dominate) to the high regime (where bimolecular and Auger recombination are prominent).

2. Data Fitting and Analysis:

- Fit the TRPL decay curves, I(t), to a kinetic model. The simplest form is a rate equation where the decay rate is the derivative of the carrier density:

dn/dt = -k₁n - k₂n² - k₃n³Here,k₁is the monomolecular (defect) recombination constant,k₂is the bimolecular recombination constant, andk₃is the Auger recombination constant. - Plot the initial PL intensity (Iₚₗ₀) as a function of N. The power-law exponent reveals the dominant process: ~1 for monomolecular, ~2 for bimolecular, and a roll-off to <2 for Auger-dominated decay at high N [23].

Experimental Workflow and Data Interpretation

Experimental Workflow for Auger Recombination Study

Data Interpretation Pathway for TA Spectroscopy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Key Materials for Optimizing Perovskite QDs to Suppress Auger Recombination

| Material / Reagent | Function in Reducing Auger Recombination | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) [9] | A short-branched-chain ligand with stronger binding affinity than oleic acid, effectively passivating surface defects and suppressing biexciton Auger recombination. [9] | Use in CsPbBr₃ QD synthesis led to a high PLQY of 99% and a 70% reduction in ASE threshold. [9] |

| Acetate (AcO⁻) Anions [9] | Acts as a dual-functional surface ligand, passivating dangling surface bonds and improving precursor purity, leading to enhanced homogeneity and reduced defect density. [9] | Improved cesium precursor purity from 70.26% to 98.59%, enhancing batch-to-batch reproducibility. [9] |

| Trifluoroacetate (TFA⁻) Anions [23] | Electron-withdrawing anion that incorporates into 3D perovskites, decoupling electron-hole wavefunctions and thereby directly retarding Auger recombination. Also inhibits halide migration. [23] | In FAPbI₃ films, reduced Auger constant by an order of magnitude, enabling PeLEDs with negligible efficiency roll-off at high current densities. [23] |

| Indium (In³⁺) Dopant [24] | Dopant that passifies defects and modifies the bond angle in mixed-cation perovskites, diminishing phonon resonance intensity and suppressing defect-mediated and phonon-assisted Auger recombination. [24] | In SnO₂/M:In³⁺ heterostructures, positive electron extraction efficiency was maintained at high carrier densities, unlike undoped samples. [24] |

Advanced Suppression Strategies and Emerging Biomedical Applications

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can I improve the batch-to-batch reproducibility of my perovskite quantum dot synthesis? A1: Low reproducibility often stems from incomplete precursor conversion and variable ligand binding. Implement a novel cesium precursor recipe combining dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) and 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA). AcO⁻ enhances precursor purity from ~70% to over 98%, while the short-branched-chain 2-HA provides stronger, more consistent binding to QD surfaces compared to oleic acid, yielding a photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 99% with a narrow emission linewidth of 22 nm [15].

Q2: What compositional strategies can suppress Auger recombination in blue-emitting perovskite nanocrystals? A2: Auger recombination is severe in blue emitters due to quantum confinement and deep-level defects. For mixed Cl/Br systems, deep-level defects associated with V˅Cl can capture carriers within 10 ps, enhancing Auger processes. Focus on synthesis methods that minimize these defects. Using a hot-injection method over room-temperature synthesis can yield nanocrystals with lower deep-level defect density, enabling pure blue amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) with a low threshold of 25 μJ cm⁻² [10].

Q3: How can I tune the bandgap of my perovskite film to the ideal range for single-junction solar cells? A3: Employ Pb-Sn mixed-halide compositional engineering. Formamidinium-based FAPb₁₋ₓSnₓ(I₀.₈Br₀.₂)₃ perovskites can target near-optimal bandgaps of ~1.4 eV. A Sn content of x = 0.4 has been shown to provide optimal photovoltaic performance, stabilizing the photoactive phase and promoting dense film formation [25].

Q4: What is a high-throughput method to screen perovskite compositions for stability? A4: Utilize automated platforms like HITSTA (High-Throughput Stability Testing Apparatus). This system can optically characterize and accelerate the aging of up to 49 thin-film samples simultaneously under controlled heat (up to 110 °C) and light intensity (2.2 suns), continuously monitoring absorptance and photoluminescence to assess stability and performance [26].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) and Poor Color Purity

- Potential Cause: High density of non-radiative defect states and inefficient surface passivation.

- Solution: Optimize surface ligand chemistry. A combination of acetate (AcO⁻) for passivating dangling bonds and 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) for strong binding affinity effectively suppresses non-radiative recombination and Auger recombination, leading to PLQY values up to 99% [15].

Issue 2: Rapid Efficiency Roll-off in Light-Emitting Diodes (PeLEDs)

- Potential Cause: Strong Auger recombination, prevalent in quasi-2D perovskites with high exciton binding energy (E˅b).

- Solution: Reduce the E˅b to suppress Auger rates. Incorporate polar organic cations like p-fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA⁺) into quasi-2D perovskites. This weakens dielectric confinement, reducing E˅b and thereby decreasing the Auger recombination rate by more than an order of magnitude, which mitigates efficiency roll-off at high brightness [3].

Issue 3: Phase Instability in Wide-Bandgap Perovskites

- Potential Cause: Halide segregation under stress, leading to phase impurities.

- Solution: Implement a bi-solvent engineering approach. For Cs₀.₁₇FA₀.₈₃PbI₁.₈Br₁.₂, using a binary solvent system (e.g., DMF with additives like DMSO or acetonitrile) improves film quality, suppresses halide segregation, enhances efficiency, and stability. The optimal ratio is unique for each secondary solvent [27].

Issue 4: Poor Environmental and Thermal Stability of Solar Cells

- Potential Cause: Intrinsic lattice instability and susceptibility to moisture/heat.

- Solution: Use mixed-metal chalcohalide alloying. Incorporating trivalent Sb³⁺ and divalent S²⁻ into FAPbI₃ enhances ionic binding energy and alleviates lattice strain. This promotes stable crystal growth, yielding PSCs with a PCE of 25.07% and excellent shelf-life stability (94.9% of initial PCE after 1080 hours in ambient conditions) [28].

Key Data Presentation

Auger Recombination Suppression & ASE Performance

Table 1: Strategies for Suppressing Auger Recombination in Perovskite Nanocrystals and Quasi-2D Films

| Material System | Engineering Strategy | Key Mechanism | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ QDs [15] | AcO⁻ & 2-HA ligand combination | Enhanced precursor purity & surface defect passivation | ASE threshold reduced by 70% (from 1.8 μJ·cm⁻² to 0.54 μJ·cm⁻²) |

| Blue CsPb(BrₓCl₁₋ₓ)₃ NCs [10] | Suppression of Cl-related deep-level defects | Reduced defect-mediated charged exciton formation | Pure blue ASE achieved with a threshold of 25 μJ·cm⁻² |

| Quasi-2D PEA₂MAₙ₋₁PbₙBr₃ₙ₊₁ [3] | p-FPEA⁺ cation substitution | Reduced exciton binding energy (E˅b) | Auger recombination rate reduced by one order of magnitude |

Compositional Engineering for Solar Cells

Table 2: Performance of Compositionally Engineered Perovskite Solar Cells

| Perovskite Composition | Engineering Approach | Key Achievement | Stability Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAPb₁₋ₓSnₓ(I₀.₈Br₀.₂)₃ [25] | Pb-Sn alloying; mixed halide | Near-optimal bandgap (~1.4 eV) for single-junction cells | Optimal performance at x=0.4 under ambient conditions |

| Sb³⁺/S²⁻ alloyed FAPbI₃ [28] | Mixed-metal chalcohalide alloying | PCE of 25.07% fabricated in ambient air | ~94.9% of initial PCE retained after 1080 h (unencapsulated, dark, 20-40% RH) |

| CsPbI₂Br [29] | Inorganic perovskite; transport layer optimization | Simulated PCE of 21.13% (FTO/MZO/CsPbI₂Br/CNTS/Au) | Enhanced thermal stability inherent to all-inorganic composition |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of High-Quality CsPbBr₃ QDs with Low ASE Threshold

This protocol is adapted from the novel cesium precursor recipe for producing highly reproducible, high-PLQY QDs with excellent ASE performance [15].

1. Reagents:

- Cs₂CO₃, Lead bromide (PbBr₂), 1-Octadecene (ODE), Oleylamine (OAm), Oleic acid (OA), 2-Hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA), Acetate source (e.g., lead acetate trihydrate or ammonium acetate).

2. Synthesis Steps:

- Cesium Precursor Preparation: In a 50 mL flask, combine Cs₂CO₃, 2-HA, and ODE. Heat under vacuum at 120 °C for 60 minutes. Then, under N₂ atmosphere, heat to 150 °C until a clear solution is obtained. The use of 2-HA and acetate is critical for high-purity precursor.

- Perovskite QD Synthesis: In a separate 100 mL three-neck flask, mix PbBr₂, the acetate ligand, ODE, OA, and OAm. Heat under vacuum at 120 °C for 60 minutes. Under N₂, raise the temperature to 180 °C. Swiftly inject the pre-heated cesium precursor solution.

- Reaction and Purification: Allow the reaction to proceed for 5-10 seconds before cooling the mixture in an ice-water bath. Add ethyl acetate to precipitate the QDs. Centrifuge the mixture and redisperse the precipitate in hexane or toluene for further characterization.

3. Characterization:

- PLQY: Use an integrating sphere to measure absolute PLQY, targeting values near 99%.

- ASE Measurement: Spin-coat a dense film of QDs onto a clean substrate. Use a pulsed laser source (e.g., femtosecond, 400 nm) for excitation. Focus the beam to a stripe on the film using a cylindrical lens. Measure the output emission from the edge of the film as a function of pump fluence. The ASE threshold is identified as the point where the output intensity superlinearly increases.

Protocol 2: Fabrication of Stable, Mixed-Metal Chalcohalide FAPbI₃ Solar Cells

This protocol outlines a sequential ambient-air process for fabricating efficient and stable PSCs [28].

1. Reagents:

- Lead iodide (PbI₂), Formamidinium iodide (FAI), Antimony chloride (SbCl₃), Thiourea (TU), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Solvent (DMF/NMP).

2. Fabrication Steps:

- Precursor Solution Preparation:

- PbI₂ + Sb-TU Solution: Dissolve PbI₂ and the SbCl₃-Thiourea complex (e.g., 1.0 mol%) in a mixed solvent of DMF and NMP.

- FAI Solution: Dissolve FAI in isopropanol.

- Film Deposition (Sequential Process):

- Spin-coat the PbI₂ + Sb-TU solution onto the pre-cleaned substrate (e.g., FTO/c-TiO₂/mp-TiO₂).

- Anneal the deposited film at 150 °C for 10 minutes.

- While the film is still hot, dynamically spin-coat the FAI solution onto it. This step facilitates the conversion to the perovskite phase.

- Anneal the final film again at 150 °C for 30-60 minutes to crystallize the Sb³⁺/S²⁻ alloyed FAPbI₃.

- Device Completion: Subsequently, deposit the hole transport layer (e.g., Spiro-OMeTAD) and metal electrode (e.g., Au) by thermal evaporation.

3. Characterization:

- XRD: Confirm the formation of the α-FAPbI₃ phase and check for the presence of residual PbI₂.

- J-V Characterization: Perform current density-voltage (J-V) measurements under standard AM 1.5G illumination to determine PCE, V˅OC, J˅SC, and FF.

- Stability Testing: Monitor the unencapsulated device performance over time when stored in the dark under controlled humidity (20-40% RH) at room temperature.

Visualization: Auger Recombination Suppression Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Compositional Engineering and Defect Management

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Acetate Salts (e.g., CH₃COO⁻) | Dual-functional: improves precursor conversion & passivates surface dangling bonds [15]. | Enhancing reproducibility & PLQY of CsPbBr₃ QDs. |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | Short-branched-chain ligand with stronger binding affinity than OA; suppresses Auger recombination [15]. | Surface ligand engineering for low-threshold ASE. |

| p-Fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA⁺) | Polar organic cation; reduces dielectric confinement and exciton binding energy (E˅b) [3]. | Suppressing Auger recombination in quasi-2D PeLEDs. |

| Antimony Chloride (SbCl₃) & Thiourea | Source of Sb³⁺ and S²⁻ for mixed-metal chalcohalide alloying; enhances lattice stability [28]. | Fabricating stable, high-efficiency FAPbI₃ solar cells in air. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Co-solvent in precursor ink; influences crystallization kinetics and final film morphology [27]. | Solvent engineering for high-quality wide-bandgap perovskite films. |

Surface passivation is a critical technology in the development of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), directly addressing the challenges of stability and performance efficiency. For researchers and scientists focused on reducing Auger recombination—a dominant non-radiative loss process at high carrier densities—mastering these techniques is essential. This technical support center provides a practical guide to implementing these strategies, complete with troubleshooting advice and essential resources for your experimental work.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Problem Solving

1. How does surface passivation specifically help in reducing Auger recombination in PQDs?

Auger recombination is a non-radiative process where an electron and hole recombine, transferring their energy to another charge carrier. This process is particularly detrimental in devices like lasers and light-emitting diodes (LEDs) operating at high currents, as it causes efficiency roll-off. Surface passivation mitigates this by:

- Reducing Trap-Assisted Auger Processes: Unpassivated surface defects (dangling bonds) act as traps that promote Auger recombination. Effective passivation eliminates these trap states, thereby suppressing this loss pathway [30] [15].

- Engineering Core-Shell Structures: Applying a perovskite shell with a small band offset to the core quantum dot has been shown to increase the Auger lifetime by up to an order of magnitude. This specific band alignment suppresses the Auger rate without hindering charge confinement [31].

- Decreasing Exciton Binding Energy: In quasi-2D perovskites, introducing polar organic cations (e.g., p-fluorophenethylammonium) can reduce the dielectric confinement and lower the exciton binding energy (Eb). Since the Auger recombination rate is proportional to Eb, this reduction directly leads to a slower Auger process [3].

2. We are experiencing rapid fluorescence quenching in our CsPbBr3 QD films. What is a likely cause and solution?

Likely Cause: The problem often lies with the native long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) used in synthesis. These ligands create barriers that inhibit efficient charge transport between QDs in a solid film, leading to energy loss and quenching [32].

Solution: Implement a ligand exchange strategy.

- Detailed Protocol: A proven method involves a two-step ligand exchange to replace long carbon chain ligands with halide ion-pair ligands like di-dodecyl dimethyl ammonium bromide (DDAB) [32].

- Preparation: Synthesize CsPbBr3 QDs using standard hot-injection or room-temperature methods, resulting in QDs capped with oleic acid/oleylamine.

- Intermediate Desorption: Add a polar solvent (like ethyl acetate) to the QD solution to desorb the protonated oleylamine ligands partially. Centrifuge the mixture to obtain a pellet.

- Ligand Exchange: Redisperse the pellet in a non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene) containing the new short ligand (DDAB). Stir for several hours to allow the exchange.

- Purification: Precipitate and centrifuge the QDs to remove excess ligands and by-products.

- Troubleshooting Tip: Attempting direct ligand exchange without the intermediate desorption step can cause severe photoluminescence degradation. The intermediate step is crucial for maintaining high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) [32].

3. Our PQD-based devices fail quickly when exposed to ambient air. How can we improve their operational stability?

Solution: Employ a shell encapsulation approach to create a physical barrier against environmental factors.

- Encapsulation in Hollow Silica Spheres: A highly effective method is encapsulating CsPbBr3 QDs within dual-shell hollow SiO₂ spheres via a successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) method [33].

- Synthesis of Silica Spheres: Prepare monodisperse silica spheres as a template.

- QD Loading: Infuse the perovskite precursors into the hollow spheres. The QDs form and are anchored on the interior shell surface.

- Sealing: A second silica shell is grown to seal the QDs inside.

- Performance Data: This encapsulation dramatically enhances stability, with the material retaining 89% of its PL intensity after 72 hours of continuous UV light exposure and 65% after heat treatment at 100°C [33].

- Alternative: Self-Encapsulation: Another strategy is to grow a protective laurionite-type PbX(OH) (X=Cl, Br) shell directly on the CsPbX3 QDs during room-temperature crystallization. This shell acts as a water-blocking layer, significantly improving stability in polar solvents [34].

4. Our QD synthesis results in inconsistent batch-to-batch quality and poor reproducibility. How can we address this?

Root Cause: Incomplete conversion of precursors and the formation of by-products during synthesis lead to inhomogeneity and defects [15].

Solution: Optimize the precursor recipe for higher purity and more robust ligand binding.

- Protocol for a Novel Cesium Precursor: Design a cesium precursor using a combination of dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) and 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) as a short-branched-chain ligand [15].

- Function of AcO⁻: Acetate aids in the complete conversion of cesium salt, boosting precursor purity from ~70% to over 98%. It also acts as a surface ligand to passivate dangling bonds.

- Function of 2-HA: This ligand has a stronger binding affinity to the QD surface than oleic acid, leading to better passivation of surface defects and suppression of Auger recombination.

- Outcome: This recipe yields CsPbBr3 QDs with a narrow size distribution, a high PLQY of 99%, and an amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) threshold reduced by 70%, indicating suppressed non-radiative recombination [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

| Problem Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low PLQY in films | Long, insulating ligands hindering charge transport | Perform a two-step ligand exchange with short, conductive ligands (e.g., DDAB) | [32] |

| Efficiency drop (roll-off) in LEDs at high current | Severe Auger recombination | Reduce exciton binding energy using polar organic cations (e.g., p-FPEA+); Apply core-shell structures with small band offsets | [3] [31] |

| Degradation in polar solvents/ambient air | Lack of protective barrier | Encapsulate QDs in inorganic matrices (e.g., hollow SiO₂ spheres) or grow a self-encapsulating PbX(OH) shell | [34] [33] |

| High ASE/lasing threshold | Defect-assisted and Auger recombination | Use optimized precursors (AcO⁻, 2-HA) for defect passivation and Auger suppression | [15] |

| Poor batch-to-batch reproducibility | Impure precursors and inconsistent ligand binding | Employ a novel cesium precursor recipe with acetate and 2-HA to improve purity and binding | [15] |

Table: Quantitative Impact of Different Passivation Strategies

| Passivation Strategy | Material System | Key Performance Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduction of Eb via polar cation | Quasi-2D (p-FPEA+) | Auger recombination rate decreased by one order of magnitude; LED luminance of 82,480 cd m⁻² | [3] |

| Halide ion-pair ligand exchange | CsPbBr₃ QDs | Achieved LED external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 3.9% for green emission | [32] |

| Dual-shell SiO₂ encapsulation | CsPbBr₃ QDs | 89% PL intensity retained after 72h UV light; PLQY of 89% | [33] |

| Self-encapsulating PbBr(OH) shell | CsPbBr₃@PbBr(OH) | Greatly improved stability in polar solvents; Enhanced PLQY and fluorescence lifetime | [34] |

| Optimized precursor (AcO⁻, 2-HA) | CsPbBr₃ QDs | PLQY of 99%; ASE threshold reduced by 70% (from 1.8 to 0.54 μJ·cm⁻²) | [15] |

Essential Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for developing high-performance, stable perovskite quantum dots, integrating the key passivation strategies discussed.

Diagram: Troubleshooting and Passivation Workflow for PQDs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Surface Passivation Experiments

| Reagent | Function / Role in Passivation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| p-Fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA+) Iodide/Bromide | Polar organic cation to reduce dielectric confinement and exciton binding energy, suppressing Auger recombination. | Used in quasi-2D perovskite films for high-efficiency, high-brightness LEDs with reduced efficiency roll-off [3]. |

| Di-dodecyl dimethyl ammonium bromide (DDAB) | Halide ion-pair ligand for exchanging long native ligands; improves charge transport in QD films. | Two-step ligand exchange on CsPbBr₃ QDs to create conductive films for efficient LEDs [32]. |

| Acetate (e.g., Cesium Acetate) | Dual-functional agent in precursor: improves cesium salt conversion purity and passivates surface defects as a ligand. | Key component in a novel precursor recipe for highly reproducible, high-PLQY CsPbBr₃ QDs with low ASE threshold [15]. |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | Short-branched-chain ligand with strong binding affinity to QD surface; suppresses non-radiative and Auger recombination. | Used with acetate in an optimized precursor system for superior surface passivation and stability [15]. |

| Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) | Precursor for forming silica (SiO₂) encapsulation shells via sol-gel chemistry. | Encapsulating CsPbBr₃ QDs in dual-shell hollow silica spheres for extreme stability against light, heat, and moisture [33]. |

Core Concepts: Dielectric Confinement and Exciton Binding Energy

What is the fundamental relationship between dielectric confinement and exciton binding energy (E₆)?

Dielectric confinement arises from the mismatch in dielectric constants between the inorganic semiconductor layer (high dielectric constant) and the surrounding organic layers (low dielectric constant) in low-dimensional materials like 2D perovskites [35] [3]. This mismatch reduces the screening of the Coulomb interaction between an electron and a hole. The unscreened Coulomb force strengthens the bond holding the exciton together, leading to a significantly larger exciton binding energy (E₆) [35] [3]. A large E₆ makes it difficult for excitons to dissociate into free carriers, which is detrimental for devices like solar cells and LEDs where free carriers are needed [35].

How do polar molecules help to reduce this effect?

Polar molecules possess a high dielectric constant due to their intrinsic molecular dipole moment [3]. When used as the organic component in 2D materials, they increase the average dielectric constant of the organic layer. This reduces the dielectric mismatch with the inorganic layer, enhancing the screening of the electron-hole Coulomb interaction [35]. The improved screening weakens the force binding the exciton, resulting in a dramatically reduced exciton binding energy, which facilitates exciton dissociation into free carriers at room temperature [35] [36].

What is the connection to reducing Auger recombination in perovskite quantum dots?

Auger recombination is a non-radiative process where an exciton recombines and transfers its energy to a third carrier. Its rate is strongly correlated with E₆; a higher E₆ leads to a higher Auger recombination rate because it enhances the Coulomb interaction and increases the probability of three carriers meeting at the same location [3]. Therefore, reducing E₆ via dielectric confinement manipulation is an effective strategy to suppress Auger recombination. This has been successfully demonstrated in quasi-2D perovskite light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs), where reducing E₆ led to a more than one-order-of-magnitude decrease in the Auger recombination rate [3]. For quantum dots, surface ligand engineering with molecules that provide better dielectric screening is a key method to achieve similar suppression [9].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Polar Molecules on Material Properties

| Material System | Organic Molecule Used | Dielectric Constant of Organic Layer | Exciton Binding Energy (E₆) | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Perovskite [35] | Ethanolamine (EA) | ~37.7 | ~13 meV | 20x smaller E₆ than PEA-based perovskites; efficient exciton dissociation at room temperature. |

| 2D Perovskite [35] | Phenethylamine (PEA) | ~3.3 | ~250 meV | Strong dielectric confinement; prominent exciton peak in absorption spectra. |

| Quasi-2D Perovskite [3] | p-fluorophenethylammonium (p-FPEA+) | Higher than PEA+ | Several times smaller than PEA+ analog | >10x lower Auger recombination constant; record LED brightness of 82,480 cd m⁻². |

| Ionic Covalent Organic Nanosheets [36] | Hydroxyl-functionalized linker | Significantly increased | Greatly reduced | Promoted exciton dissociation and enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. |

Experimental Approaches & Methodologies

What are the primary molecular engineering strategies for creating high-dielectric organic components?

The main strategy is to introduce functional groups that enhance the molecular dipole moment and polarizability. Effective approaches include:

- Incorporating Hydroxyl Groups (-OH): The hydroxy group in ethanolamine (HOCH₂CH₂NH₃⁺) is a key reason for its high dielectric constant (ε=37.7) [35]. Similarly, integrating -OH groups into the ionic moieties of covalent organic nanosheets significantly boosted orientational polarizability and the material's dielectric constant [36].

- Using Halogenated Aromatic Groups: Substituting a hydrogen atom on an aromatic ring with an electron-withdrawing atom like fluorine (e.g., in p-fluorophenethylammonium) polarizes the electronic state, creating a strong molecular dipole moment (2.39 D for p-FPEA⁺ vs. 1.28 D for PEA⁺) [3].

What are the key experimental protocols for synthesizing and characterizing these materials?

Synthesis of 2D Perovskites with Polar Molecules:

- Crystal Preparation: Bulk single crystals of 2D perovskites like (HOCH₂CH₂NH₃)₂PbI₄ (2D_EA) can be grown using standard single crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) methods [35]. For thin films and quasi-2D structures, solution-processing techniques are common [3].

- Microwave-Assisted Synthesis (for Covalent Organic Nanosheets): Ionic covalent organic nanosheets (iCONs) can be synthesized via a Schiff base condensation reaction in a mixture of dioxane and deionized water under microwave irradiation at 100 °C for 60 minutes [36].

Characterization of Exciton Binding Energy (E₆):

- Temperature-Dependent Photoluminescence (PL): This is a standard method for determining E₆.

- Procedure: Measure the PL intensity of the material over a temperature range (e.g., from 10 K to 300 K).

- Data Analysis: Fit the integrated PL intensity as a function of temperature using the Arrhenius equation: ( I(T) = I0 / [1 + A \exp(-Eb / kB T)] ), where ( I(T) ) is the intensity at temperature T, ( I0 ) is the intensity at 0 K, A is a constant, and ( k_B ) is the Boltzmann constant. The activation energy obtained from the fit corresponds to E₆ [35] [3].

- Optical Absorption Spectroscopy:

- Procedure: Measure the absorption spectrum at room temperature.

- Data Interpretation: The presence of a sharp, prominent exciton peak indicates a large E₆. In materials with successfully reduced dielectric confinement, the exciton peak is greatly diminished or absent, showing a more continuum-like absorption, similar to 3D perovskites [35].

How is the reduction of Auger recombination experimentally verified?

- Time-Resolved Spectroscopy: Use techniques like femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) to track carrier dynamics.

- Procedure: Excite the material with an ultrafast laser pulse and probe the differential absorption changes over time.

- Interpretation: The decay kinetics of the photo-induced absorption signal associated with free carriers can be modeled. A slower decay component in materials with reduced E₆ indicates a longer carrier lifetime and suppressed non-radiative recombination pathways, including Auger recombination [35] [3].

- Power-Dependent Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY):

- Procedure: Measure the PLQY of the film under a broad range of excitation densities.

- Interpretation: A high and invariant PLQY across a wide range of excitation densities indicates that non-radiative losses, such as Auger recombination, have been effectively suppressed [3].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for dielectric confinement manipulation.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: I've incorporated a polar molecule, but my E₆ is not decreasing as expected. What could be wrong? A: Common issues include:

- Insufficient Dipole Moment: The chosen molecule may not be polar enough. Verify its calculated dipole moment and consider molecules with stronger electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., -F, -CN) or hydroxyl groups [35] [3].

- Poor Crystallinity or Orientation: The polar molecules might not be properly aligned within the crystal lattice to maximize the dielectric screening effect. Check the crystal structure and quality via XRD [36].

- Incomplete Conversion or Purity: In covalent organic frameworks, ensure the synthesis reaction has a high conversion rate and purity to achieve the desired functional group density [36].

Q: After reducing E₆, my material's photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) has dropped. Is this normal? A: Yes, this can be an initial side effect. Reducing E₆ decreases the first-order exciton recombination rate. If non-radiative trap-assisted recombination is still present, it can dominate, lowering the PLQY [3]. The solution is to combine your dielectric engineering with a robust passivation strategy. Use Lewis base molecules or other surface ligands to passivate dangling bonds and defects, which suppresses non-radiative pathways and allows the full benefit of a low E₆ to be realized [3] [9].

Q: How can I be sure that the observed improvements in my device performance are due to reduced Auger recombination? A: You need to correlate device metrics with spectroscopic data. For LEDs, a suppressed efficiency roll-off (i.e., the efficiency remains high at high current densities) is a key indicator of reduced Auger recombination [3]. This device-level observation should be supported by time-resolved spectroscopy (e.g., transient absorption) showing slower decay kinetics at high excitation densities, which directly points to a lower Auger recombination rate [35] [3].

Troubleshooting Table

Table 2: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low PLQY after E₆ reduction | High density of non-radiative defects; dominant trap-assisted recombination. | Implement surface passivation with Lewis base ligands (e.g., acetate) [3] [9]. Optimize synthesis to improve crystallinity and reduce defects [36]. |

| Inconsistent results between batches | Variations in precursor purity, reaction conditions, or ligand binding. | Use high-purity precursors. For QDs, design precursor recipes with additives (e.g., acetate) to ensure complete conversion and high reproducibility [9]. Standardize synthesis protocols. |

| Minimal change in absorption spectrum | Dielectric constant of organic component is still too low; weak screening. | Select a molecule with a higher intrinsic dielectric constant (e.g., ethanolamine ε~37.7) [35] or a stronger dipole moment (e.g., p-FPEA⁺) [3]. |

| Severe efficiency roll-off in PeLEDs | Strong Auger recombination has not been sufficiently suppressed. | Ensure E₆ has been effectively reduced. Alternatively, use a composition engineering approach to increase the density of recombination centers, thereby lowering the local carrier density and slowing the Auger process [3]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Dielectric Confinement Manipulation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example & Key Feature |

|---|---|---|