Strategies for Enhancing the Environmental Stability of Perovskite Quantum Dots in Biomedical and Electronic Applications

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) exhibit exceptional optoelectronic properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield and tunable bandgaps, making them highly promising for applications in biosensing, drug discovery, and medical imaging.

Strategies for Enhancing the Environmental Stability of Perovskite Quantum Dots in Biomedical and Electronic Applications

Abstract

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) exhibit exceptional optoelectronic properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield and tunable bandgaps, making them highly promising for applications in biosensing, drug discovery, and medical imaging. However, their commercial viability is severely limited by inherent instability when exposed to environmental factors such as moisture, heat, and light. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest strategies to overcome these challenges. It explores the fundamental mechanisms of PQD degradation, reviews advanced stabilization methodologies including encapsulation and surface engineering, discusses optimization techniques for maintaining electronic properties, and evaluates the performance of stabilized PQDs in real-world biomedical applications. The insights presented aim to guide researchers and drug development professionals in creating robust PQD-based technologies for clinical use.

Understanding PQD Instability: The Fundamental Challenge for Biomedical Applications

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our perovskite quantum dot (PQD) films show a rapid decline in Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) upon exposure to ambient laboratory lighting. What are the primary degradation pathways and how can we mitigate them?

A: The degradation is likely due to photo-oxidation and ligand desorption. To mitigate:

- Primary Degradation Pathways:

- Photo-oxidation: Exposure to light and oxygen causes irreversible degradation of the PQD crystal structure [1].

- Ligand Desorption: Dynamic binding of surface ligands leads to their loss over time, creating surface defects that quench luminescence [2].

- Moisture-Induced Defects: Water molecules penetrate the PQD lattice, leading to decomposition [1].

- Recommended Protocol for Enhanced Stability:

- Synthesis & Ligand Engineering: Incorporate long-chain, cross-linkable ligands (e.g., containing acrylate or thiol groups) during synthesis [2].

- Post-Synthesis Treatment: After film fabrication, expose the PQD film to UV light (e.g., 365 nm) in an inert atmosphere (N₂ glovebox). This triggers polymerization, creating a protective cross-linked ligand network [2].

- Encapsulation: Immediately encapsulate the treated film with a glass coverslip using a UV-curable epoxy to create a hermetic seal against oxygen and moisture [1].

Q2: We are developing a high-resolution QD display. Traditional photolithography using photoresists severely damages our PQDs, reducing PLQY. What alternative patterning method should we use?

A: We recommend adopting Polymerization-Induced Direct Photolithography. This method eliminates the need for aggressive etchants and preserves QD integrity [2].

- Detailed Methodology:

- Material Preparation: Formulate a PQD ink mixed with a photo-initiator (e.g., Irgacure 819) and cross-linkable monomers/ligands (e.g., pentaerythritol tetraacrylate) [2].

- Film Deposition: Spin-coat the ink onto your substrate to form a uniform film.

- Soft Bake: Perform a soft bake on a hotplate at 70°C for 1 minute to remove residual solvent.

- Patterned Exposure: Expose the film to UV light through a photomask with your desired pattern. The exposed areas will polymerize, becoming insoluble.

- Development: Develop the pattern by immersing the substrate in a mild solvent (e.g., toluene or hexane) for 30-60 seconds. The unexposed areas will dissolve away, leaving a high-fidelity PQD pattern with maintained optical properties [2].

Q3: What are the key figures of merit we should measure to quantitatively evaluate the performance and stability of our PQD photodetectors?

A: The key quantitative metrics are listed in the table below. Track these over time and under environmental stress to assess stability.

| Figure of Merit | Definition & Equation | Measurement Instrument | Target for High-Performance PDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoresponsivity (R) | Ratio of photocurrent (Iph) to incident optical power (Pin).R = I_ph / P_in [1] | Source meter, calibrated light source | >0.1 A/W [1] |

| External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | Ratio of collected charge carriers to incident photons.EQE = (Number of e⁻ collected / Number of incident photons) * 100% [1] | Spectrometer, monochromator, source meter | >50% [1] |

| Specific Detectivity (D*) | Normalizes detectivity to the noise equivalent power and active area, allowing comparison between devices.D = √(A · Δf) / NEP* (where A is area, Δf is bandwidth) [1] | Spectrum analyzer, source meter | >10¹² Jones [1] |

| Photoconductive Gain (G) | Ratio of the number of collected carriers per second to the number of absorbed photons per second. Indicates carrier multiplication [1]. | Source meter, calibrated light source | Can be >10⁸ in photoconductors [1] |

| Rise/Fall Time | Time taken for the photocurrent to rise from 10% to 90% of its peak value (rise) or fall from 90% to 10% (fall). Indicates response speed [1]. | Pulsed laser, high-speed oscilloscope | Micro- to nanoseconds [1] |

Q4: Our heavy metal (Pb, Cd)-based QDs raise environmental and safety concerns. What are the most promising classes of heavy metal-free QDs for optoelectronics?

A: Several environmentally friendly QD classes show great promise for replacing toxic alternatives. Their properties are summarized below.

| Material Class | Example Compositions | Key Advantages | Reported Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanodots | Graphene QDs, Carbon Dots | High biocompatibility, low cost, tunable photoluminescence [1] | Lower charge carrier mobility, limited absorption in the visible range [1] |

| Group III-V QDs | InP, InAs | Size-tunable emission, high quantum yield, already used in some commercial displays [1] | Synthesis requires high temperatures, narrower size tunability compared to PbS/CdSe [1] |

| Group I-III-VI QDs | CuInS₂, AgBiS₂ | Broadband absorption, low toxicity, composition-dependent bandgap [1] | Broader emission spectra, lower photoluminescence quantum yield in some compositions [1] |

| Halide Perovskites (Sn/Ge) | CsSnI₃, MASnBr₃ | Similar crystal structure to Pb-based perovskites, strong light absorption [1] | Poor environmental stability, susceptibility to oxidation (especially Sn²⁺) [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Lead-Free Precursors (e.g., Tin(II) iodide (SnI₂), Bismuth(III) iodide (BiI₃)) | The foundational materials for synthesizing heavy metal-free perovskite quantum dots (e.g., CsSnI₃, MA₃Bi₂I₉) to address core toxicity concerns [1]. |

| Cross-Linkable Ligands (e.g., Acrylate-functionalized, Thiol-terminated ligands) | Surface ligands that, upon UV exposure, form a robust polymer network around the QD. This drastically enhances environmental stability by preventing ligand desorption and shielding the core [2]. |

| Photo-initiators (e.g., Irgacure 819, LAP) | Molecules that generate reactive species (radicals) upon absorption of UV light, which is essential for initiating the polymerization reaction in direct photolithography and ligand cross-linking protocols [2]. |

| Inert Atmosphere Glovebox (N₂ or Ar) | A critical piece of equipment for all synthesis and device fabrication steps involving air- and moisture-sensitive PQDs, preventing immediate degradation by O₂ and H₂O [1]. |

| Encapsulation Epoxy (UV-curable) | A transparent, barrier material used to hermetically seal fabricated PQD devices, providing the final layer of defense against environmental stressors [1]. |

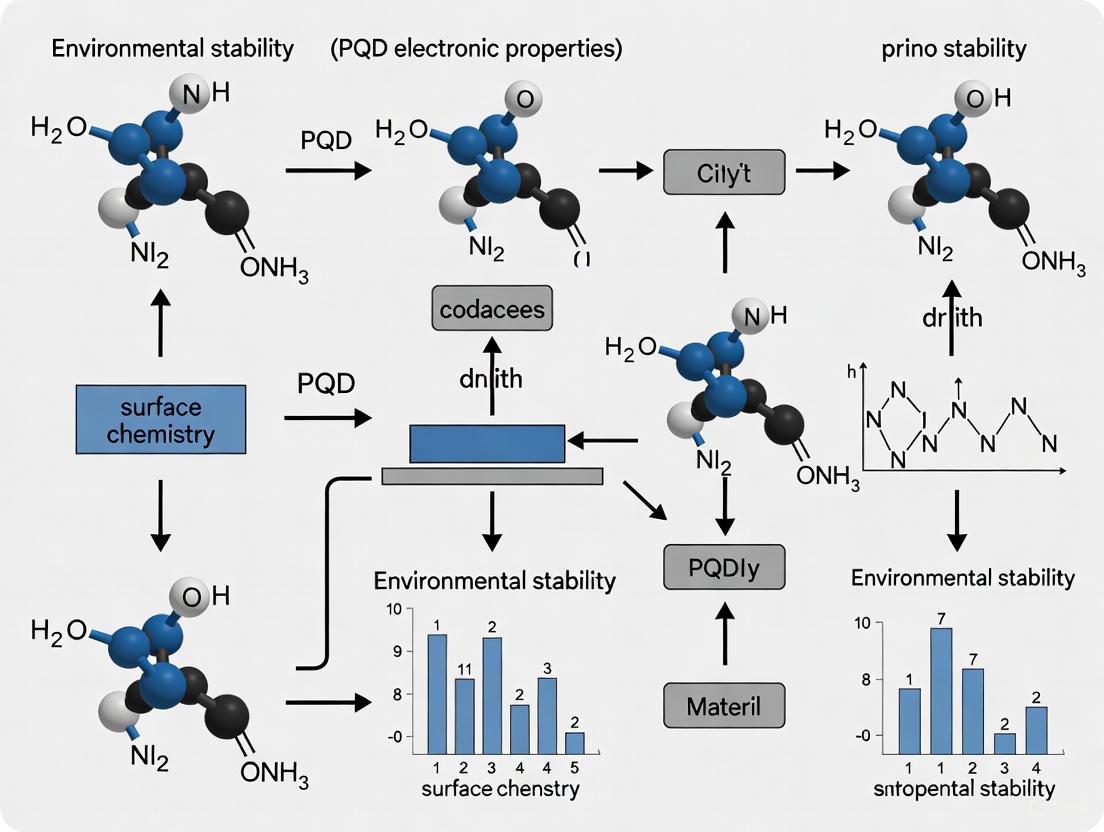

Experimental Workflow: Enhancing PQD Environmental Stability

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing environmentally stable perovskite quantum dots, from synthesis to final device encapsulation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary environmental factors that cause CsPbX3 PQD degradation? The primary environmental factors leading to the degradation of CsPbX3 Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) are moisture, oxygen, heat, and light. These factors can act synergistically. For instance, exposure to light and oxygen can generate reactive oxygen species that accelerate decomposition [3]. The specific degradation pathway often depends on the halide composition (X); iodide-based red-emitting PQDs are particularly susceptible to photo-oxidation, where iodide ions are oxidized to iodine, destroying the perovskite crystal structure [4].

Q2: How does encapsulation improve PQD stability, and what materials are effective? Encapsulation creates a physical barrier that shields the PQDs from environmental stressors like moisture and oxygen. Effective materials include:

- SiO2 (Silicon Dioxide): Forms a protective matrix that significantly enhances air and moisture stability and can prevent halide exchange between different QDs [5] [6].

- Porous Y2O3 (Yttrium Oxide): The porous structure immobilizes PQDs, improving stability against heat, light, and humidity [7].

- Polymers (e.g., PMMA): Coating with polymers like PMMA (poly(methyl methacrylate)) can increase photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and protect the QD surface [8].

Q3: What is the role of surface ligand engineering in stabilizing PQDs? Surface ligands passivate uncoordinated lead and halide ions on the QD surface, reducing defect sites that act as non-radiative recombination centers and initiation points for degradation [8]. Strategies include:

- Ligand Exchange: Replacing native ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) with more robust ones like phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) or dodecanoic acid (DA) [8].

- Redox Protection: Modifying surface chemistry with reductive sulfide salts can suppress the oxidation of iodide to iodine, a key degradation pathway for red-emitting PQDs [4].

Q4: Why are red-emitting mixed-halide (e.g., CsPbBrI2) PQDs less stable? Red-emitting CsPbBrI2 PQDs undergo a specific degradation pathway initiated by iodide desorption from the crystal lattice. The desorbed iodide ions are then easily oxidized by environmental oxygen to form iodine, which irreversibly damages the perovskite structure [4]. This process is accelerated by electric fields and light exposure [6] [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Rapid Quenching of Luminescence in Ambient Conditions

This typically indicates degradation due to moisture and/or oxygen.

- Step 1: Diagnosis: Confirm the issue is environmental by testing PLQY and absorption in a controlled, inert (e.g., nitrogen or argon) glovebox. If values are stable inside the glovebox but drop rapidly outside, moisture/oxygen is the cause.

- Step 2: Solution - Implement Encapsulation:

- Protocol: SiO2 Nanocomposite Encapsulation [5]:

- Materials: Cs2CO3, PbX2 (X = Br, I), oleylamine (OAm), tetraoctylammonium bromide (TOAB), oleic acid (OA), (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), toluene.

- Procedure: Synthesize the PQDs at room temperature in air by injecting the cesium and lead precursor solution into toluene containing ligands (OA, OAm) and APTES. APTES hydrolyzes and condenses to form a protective SiO2 matrix around the in-situ-formed PQDs.

- Key Parameter: APTES provides the Si-O-Si framework for encapsulation. The one-step, room-temperature synthesis is facile and effective.

- Protocol: SiO2 Nanocomposite Encapsulation [5]:

- Step 3: Validation: Compare the PL intensity and PLQY of encapsulated and unencapsulated QD films after exposure to air (e.g., 50% relative humidity) over 1-2 weeks. The encapsulated samples should retain >80% of initial performance [5].

Issue: Color Instability and Performance Drop in Red (CsPbBrI2) PQD-based Devices

This is often due to iodide migration and oxidation.

- Step 1: Diagnosis: Use techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy to check for the appearance of PbI2 or a shift in emission wavelength, which indicates halide segregation or decomposition.

- Step 2: Solution - Apply a Core-Shell Structure and Redox Protection [6] [4]:

- Protocol: Core-Shell PQDs with Stable Gradient Iodide Concentration [6]:

- Concept: Design a CsPbBrI2/SiO2 core-shell structure where the shell suppresses the key step of defective gradient iodide distribution, halting the sequential degradation pathway that ends in I2 vaporization.

- Outcome: This approach can improve the operational stability of light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs) by a factor of ~5000 compared to devices using pristine PQDs.

- Protocol: Redox Protection Strategy [4]:

- Materials: A reductive sulfide salt (specific identity may be proprietary).

- Procedure: Modify the surface of the synthesized CsPbBrI2 PQDs with the sulfide salt. This agent blocks the iodide-to-iodine oxidation reaction.

- Key Parameter: This method, combined with ligand engineering, can yield CsPbBrI2 PQDs with near-unity PLQY and exceptional stability against oxygen and continuous light irradiation.

- Protocol: Core-Shell PQDs with Stable Gradient Iodide Concentration [6]:

- Step 3: Validation: Monitor the electroluminescence spectrum and device lifetime under constant current operation. Stable red emission and extended half-lifetime are indicators of successful stabilization.

Issue: Thermal Degradation During Device Operation or Processing

Heat can induce phase transitions or direct decomposition.

- Step 1: Diagnosis: Perform in-situ XRD or thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) while heating the PQDs to identify the degradation temperature and products (e.g., transition to a yellow δ-phase or decomposition to PbI2) [3].

- Step 2: Solution - Utilize Porous Oxide Matrices [7]:

- Protocol: CsPbX3/P-Y2O3 Composite Synthesis:

- Materials: Cs2CO3, PbBr2, PbI2, oleic acid (OA), oleylamine (OLAM), YCl3•6H2O, urea.

- Procedure:

- Synthesize spherical, amorphous Y(OH)CO3 precursor nanoparticles.

- Calcinate the precursor to form porous Y2O3 (P-Y2O3) nanoparticles.

- Disperse the P-Y2O3 in cyclohexane and mix with the perovskite precursor solution. The PQDs form within and on the pores of the P-Y2O3 nanoparticles.

- Key Parameter: The porous structure of Y2O3 confines the PQDs, suppressing aggregation and hampering ion migration under thermal stress.

- Protocol: CsPbX3/P-Y2O3 Composite Synthesis:

- Step 3: Validation: Test the photostability of P-Y2O3 encapsulated PQDs under continuous UV irradiation compared to bare PQDs. The composite should retain most of its initial PL intensity for a significantly longer time [7].

Table 1: Summary of Stabilization Strategies and Their Performance Outcomes

| Stabilization Method | Targeted Stressor | Key Performance Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 Nanocomposite | Moisture, Air, Halide Exchange | • High stability in ambient conditions.• Prevention of halide exchange between green & red PNCs.• WLED CIE coordinates: (0.375, 0.362). | [5] |

| Porous Y2O3 Encapsulation | Humidity, Heat, Light | • WLED CIE coordinates: (0.34, 0.35).• Luminous Efficiency: 61 lm/W.• Color Rendering Index (CRI): 83. | [7] |

| Gradient Core-Shell (SiO2) | Electric Field, Iodide Loss | • Operational stability of PeLEDs increased by ~5000x. | [6] |

| Redox Protection (Sulfide) | Oxygen, Light (Iodide Oxidation) | • Near-unity PLQY.• Exceptional stability against O₂ and continuous-wave irradiation. | [4] |

| PMMA Polymer Encapsulation | Ambient Environment | • PLQY increased from 60.2% to 90.1%. | [8] |

Table 2: Thermal Degradation Behavior of CsxFA1-xPbI3 PQDs [3]

| A-Site Composition | Primary Thermal Degradation Mechanism | Ligand Binding Energy |

|---|---|---|

| Cs-Rich | Phase transition from black γ-phase to yellow δ-phase. | Lower |

| FA-Rich | Direct decomposition into PbI2. | Higher |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PQD Synthesis and Stabilization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| APTES ((3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane) | Silicon precursor for forming a protective SiO2 matrix via hydrolysis and condensation. | In-situ encapsulation of PQDs for enhanced air/moisture stability [5]. |

| Porous Y2O3 Nanoparticles | A porous inorganic matrix to host and confine PQDs, suppressing aggregation and ion migration. | Enhancing stability of CsPbBrI2 PQDs for WLED application [7]. |

| PEABr (Phenethylammonium Bromide) | A ligand for surface passivation via partial substitution or post-synthesis exchange. | Replacing native OAm ligands to improve surface defect passivation and stability [8]. |

| PMMA (Poly(methyl methacrylate)) | A transparent polymer for coating and encapsulating PQD films. | Protecting CsPbBr3 QD films from the ambient environment, boosting PLQY and longevity [8]. |

| Reductive Sulfide Salts | Surface modifier that acts as a redox agent to suppress iodide oxidation. | Preventing the iodide oxidation pathway in red-emitting CsPbBrI2 PQDs [4]. |

Degradation and Protection Pathways

The following diagrams summarize the key degradation mechanisms and stabilization strategies discussed in the FAQs and troubleshooting guides.

FAQs: Understanding Core Stability Concepts

FAQ 1: What makes the ionic crystal nature of Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) a source of instability?

The ionic bonding in crystal structures, unlike strong covalent networks, creates inherent vulnerabilities. In ionic crystals, stability is heavily influenced by point defects (e.g., ion vacancies, interstitial atoms) and charged impurities [9]. These defects are not static; they can migrate through the crystal lattice under the influence of electric fields or heat, leading to property degradation. For instance, in many minerals, charged species like ferric iron or protons are highly mobile and can substantially enhance electrical conductivity, which is a marker of ionic movement and instability [9]. In PQDs, this ionic mobility is a primary driver of phase segregation, ion migration, and ultimately, device failure.

FAQ 2: How does low formation energy relate to the thermodynamic stability of a crystal?

Formation energy measures the energy difference between a compound and its constituent elements in their standard states. A low or negative formation energy indicates a thermodynamically stable compound is likely to form [10] [11]. However, for a crystal to be truly stable, it must not only have a low formation energy but also be stable with respect to other competing phases in its chemical system. This is quantified by its distance to the convex hull of the phase diagram [10]. A material with low formation energy can still be unstable if another atomic configuration has an even lower energy, meaning it lies above the convex hull.

FAQ 3: Why can a material with low formation energy still be unstable or difficult to synthesize?

This highlights the critical difference between thermodynamic and kinetic stability. A low formation energy suggests thermodynamic favorability, but the actual synthesis and stability are governed by kinetics—the energy barriers involved in atomic rearrangement and crystal growth [12]. A material might have a low formation energy but a high energy barrier for nucleation, making it difficult to form. Conversely, a metastable material (one slightly above the convex hull) might form easily if the kinetic pathway is favorable but will eventually degrade to the more stable phase. Furthermore, low formation energy does not account for dynamic stability; a crystal must also withstand thermal vibrations and external stimuli without collapsing, which can be evaluated using potentials like the Lennard-Jones potential to assess molecular dynamics stability [12].

FAQ 4: What is the practical impact of these structural vulnerabilities on PQD-based devices like solar cells?

These vulnerabilities directly undermine device performance and longevity. Ionic migration and structural instability lead to:

- Non-radiative recombination: Defects at grain boundaries and surfaces act as traps for charge carriers, causing them to recombine without emitting light, which reduces efficiency [13].

- Hysteresis and performance decay: The movement of ions under operational bias causes unpredictable shifts in device characteristics over time [13].

- Environmental degradation: The ionic lattice is susceptible to attack by moisture and oxygen, leading to rapid decomposition [14] [13]. Advanced passivation strategies, such as in-situ growth of core-shell PQDs, are required to mitigate these issues and improve operational lifetime [13].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Issues

Issue: Rapid Degradation of PQD Films in Ambient Conditions

Problem: Perovskite films or quantum dots decompose quickly when exposed to air.

Solution: Implement a dual-passivation strategy targeting grain boundaries and surfaces.

Recommended Protocol: In-situ epitaxial passivation using core-shell PQDs [13].

- Synthesize core-shell PQDs (e.g., MAPbBr3 core with a tetraoctylammonium lead bromide shell) via colloidal synthesis.

- During the antisolvent-assisted crystallization step of your perovskite film, introduce the core-shell PQDs at a concentration of 15 mg/mL.

- The PQDs will spontaneously embed at grain boundaries and surfaces, with the shell providing a protective, epitaxially matched layer that suppresses ion migration and environmental ingress.

Diagnostic Table:

| Observation | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Film color turns from dark brown to yellow | Decomposition of perovskite phase due to moisture/oxygen [13] | Improve glovebox conditions; implement encapsulation immediately after fabrication. |

| Loss of photoluminescence (PL) intensity | Increase in non-radiative recombination at surface defects [13] | Apply the core-shell PQD passivation strategy to pacify surface defects. |

| Presence of PbI2 crystals on film surface | Lead halide separation due to ion migration and instability [14] | Optimize precursor stoichiometry and introduce passivating agents to suppress halide migration. |

Issue: Inaccurate Prediction of Material Stability from Computational Screening

Problem: A hypothetical material predicted to be stable by a machine learning (ML) model fails to be stable when synthesized or calculated with higher-fidelity methods.

Solution: Refine your computational screening workflow to better align with real-world discovery tasks [10].

Recommended Protocol: Utilize the Matbench Discovery framework or similar evaluation tools that address key challenges [10].

- Use Relevant Targets: Move beyond simple formation energy regression. Use the distance to the convex hull (Ehull) as the primary target for stability classification.

- Employ Robust Metrics: Evaluate ML models based on classification performance (e.g., false-positive rate) near the stability boundary, not just global regression metrics like MAE. A model with a low MAE can still have a high false-positive rate if its errors cluster near the decision boundary.

- Leverage Advanced Models: Consider using Universal Interatomic Potentials (UIPs), which have been shown to outperform other methodologies for pre-screening thermodynamically stable hypothetical materials [10].

Diagnostic Table:

| Observation | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High false-positive rate in stability predictions | Model trained only on formation energy, not Ehull [10] | Retrain or select models using Ehull as the target property. |

| Poor performance on new, prospectively generated data | Overfitting to retrospective benchmark data splits [10] | Use models and benchmarks that incorporate realistic covariate shift, testing on data generated from the intended discovery workflow. |

| Long wait times for DFT relaxation of candidates | DFT structural relaxation is a computational bottleneck [11] | Use a structure translation model (e.g., Cryslator) to predict relaxed structures and energies directly from unrelaxed inputs, bypassing expensive DFT cycles. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential research reagents for investigating and improving PQD stability.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Methylammonium Bromide (MABr) & Lead Bromide (PbBr2) | Core precursors for synthesizing MAPbBr3 perovskite quantum dots, forming the base ionic crystal structure [13]. |

| Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (t-OABr) | Shell precursor used to create a protective, higher-bandgap layer around PQDs, enhancing chemical and thermal robustness [13]. |

| Oleylamine & Oleic Acid | Surface ligands used in colloidal synthesis to control nanocrystal growth, prevent aggregation, and provide initial surface passivation [13]. |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) & Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Common solvent systems for preparing perovskite precursor solutions. The DMSO adduct can help control crystallization kinetics [13]. |

| Chlorobenzene & Toluene | Antisolvents used to initiate rapid crystallization of perovskite films and as solvents for dispersing synthesized PQDs [13]. |

Experimental Protocol: In-situ Growth of Core-Shell PQDs for Passivation

Objective: Integrate core-shell MAPbBr3@tetra-OAPbBr3 PQDs during perovskite film crystallization to enhance efficiency and stability [13].

Materials: See Table 1 for key reagents.

Methodology:

- PQD Synthesis:

- Prepare the core precursor by dissolving MABr and PbBr2 in DMF with oleylamine and oleic acid.

- Prepare the shell precursor by dissolving t-OABr and PbBr2 separately.

- Rapidly inject the core precursor into heated toluene (60°C) to form MAPbBr3 nanoparticles.

- Immediately inject the shell precursor to form the core-shell structure. Purify the resulting PQDs via centrifugation and redisperse in chlorobenzene.

- Solar Cell Fabrication with In-situ Passivation:

- Clean and pattern FTO glass substrates, followed by deposition of compact and mesoporous TiO2 layers.

- Prepare the main perovskite precursor solution (e.g., containing PbI2, FAI, MABr, etc.).

- During the spin-coating of the perovskite layer, at the antisolvent dripping step, use the chlorobenzene solution containing the core-shell PQDs (at 15 mg/mL) as the antisolvent.

- This step simultaneously triggers the crystallization of the bulk perovskite film and integrates the pre-synthesized PQDs at grain boundaries and interfaces.

- Complete device fabrication by depositing hole-transport and electrode layers.

Expected Outcome: The modified devices should show a significant increase in Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE), open-circuit voltage, and fill factor. Stability assessments should demonstrate over 92% retention of initial PCE after 900 hours under ambient conditions, outperforming control devices [13].

Stability Evaluation & Computational Workflows

FAQs: Understanding the Phase Transition

What is the black-to-yellow phase transition in CsPbI3? The black-to-yellow transition is a spontaneous, detrimental transformation of cesium lead iodide (CsPbI3) from a photoactive "black" perovskite phase (cubic α-phase, or its low-temperature variants like orthorhombic γ-phase) to a photo-inactive, wide-bandgap "yellow" non-perovskite phase (orthorhombic δ-phase) at room temperature. This transition destroys the material's excellent optoelectronic properties, making it unsuitable for solar cells or LEDs [15] [16].

Why is the black phase of CsPbI3 metastable? The metastability originates from structural and chemical factors. The Goldschmidt's tolerance factor (t) for CsPbI3 is approximately 0.8, which is outside the ideal range for a stable perovskite structure (0.9-1.0). A more accurate revised tolerance factor (τ) of 4.99 also indicates an unstable structure (τ < 4.18 is considered stable). This structural instability is due to the small size of the Cs+ ion relative to the Pb-I lattice cavity, making the non-perovskite yellow phase thermodynamically favored at room temperature [15].

What environmental factors accelerate this phase transition? Moisture is the primary accelerator, as water molecules readily facilitate the rearrangement of the crystal lattice into the yellow phase. Elevated temperatures can also drive the transition, although all-inorganic perovskites are generally more thermally stable than their organic-inorganic counterparts. The phase transition can also be induced by photoexcitation itself, as observed in related all-inorganic perovskites like CsPbBr3, where light can cause impulsive heating and lattice rearrangement [17] [18] [16].

How does this instability impact device performance and commercialization? The instability directly leads to rapid degradation of optoelectronic device performance. Solar cells experience a catastrophic drop in power conversion efficiency (PCE) as the light-absorbing black phase disappears. This lack of operational longevity is the most critical barrier preventing the widespread commercialization of CsPbI3-based photovoltaics, despite their high theoretical efficiency [15] [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Phase Degradation in Ambient Air

Symptoms:

- Loss of dark brown/black color in thin films, turning yellow or transparent.

- Significant drop in photocurrent and overall device efficiency during testing.

- Appearance of a dominant peak around 11° (2θ) in X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, corresponding to the yellow δ-phase.

Solutions:

- Implement Strict Environmental Control: Process and test films inside a nitrogen or argon-filled glovebox. Ensure oxygen and moisture levels are maintained below 0.1 ppm.

- Optimize Film Crystallization: Use high-temperature annealing (≥300°C) to promote a more robust black phase. Follow a two-step annealing process: a low-temperature step (e.g., 100°C) for solvent removal, immediately followed by a high-temperature step for crystallization.

- Apply Encapsulation: Immediately encapsulate finished devices with glass covers using UV-curable epoxy to create a hermetic seal against ambient air [16].

Problem: Inconsistent Film Quality Leading to Localized Degradation

Symptoms:

- Non-uniform color or patchy appearance of the perovskite film.

- Inconsistent device performance across different areas of the same substrate.

- Pinholes or incomplete surface coverage observed under a microscope.

Solutions:

- Improve Precursor Solution Chemistry: Use additives like Hydroiodic Acid (HI) or Hypophosphorous Acid (HPA) in the precursor solution. These act as stabilizers, control crystallization kinetics, and lead to more uniform, pinhole-free films.

- Employ Compositional Engineering: Partially substitute Pb²⁺ with smaller cations like Sn²⁺, Ge²⁺, or dope with bismuth (Bi³⁺) or antimony (Sb³⁺). This can tailor the tolerance factor and strain within the lattice, enhancing phase stability.

- Explore Alternative Deposition Techniques: If spin-coating is inconsistent, consider vacuum deposition methods. This allows for precise control over film thickness and morphology, often resulting in higher-quality, more stable layers [15] [16] [19].

Problem: Phase Instability Under Operating Conditions (Light & Heat)

Symptoms:

- Performance degradation (reduced PCE) during continuous light soaking.

- Phase transition observed even in encapsulated devices under standard solar cell operating conditions.

Solutions:

- Surface Passivation: Treat the surface of the CsPbI3 film with large organic cations, such as Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI). These ligands passivate under-coordinated lead atoms, reducing surface defects that can initiate phase degradation. Be cautious of ligand penetration, which can sometimes negatively affect stability [20] [15].

- Strain Engineering: Introduce slight compressive strain into the perovskite lattice through substrate engineering or interfacial layers. A compressed lattice is more resistant to the expansion associated with the transition to the yellow phase.

- Dimensional Engineering: Create a 2D/3D hybrid structure by incorporating bulky organic cations. The stable 2D perovskite layers act as a protective barrier, shielding the 3D CsPbI3 from environmental factors and improving overall stability [21] [15].

Quantitative Data on Stabilization Strategies

The following table summarizes key strategies and their impact on phase stability and device performance.

Table 1: Strategies for Stabilizing Black-Phase CsPbI3

| Stabilization Method | Specific Example(s) | Impact on Phase Stability | Reported Solar Cell Efficiency | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compositional Doping | B-site doping (Sn²⁺, Ge²⁺, Bi³⁺, Sb³⁺) | Increases formation energy of black phase, tailoring tolerance factor [15] [19]. | Varies; high-performing doped devices can exceed 15% [19]. | Modifies lattice parameters and electronic structure. |

| Additive Engineering | HI, HPA, organic halide salts | Suppresses yellow phase nucleation, improves crystallinity, passivates defects [15] [16]. | Crucial for achieving efficiencies >17% [15]. | Controls crystallization kinetics and defect density. |

| Surface Ligand Passivation | Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Protects surface from moisture, reduces defect-mediated degradation [20]. | Contributes to high-efficiency, stable devices [20]. | Forms a protective layer or penetrates to form low-dimensional phases. |

| Dimensional Engineering | 2D/3D Hybrid Structures | 2D layers act as moisture-resistant barriers, enhancing environmental stability [21]. | Promising for operational stability, with PCE > 18% [21]. | Provides superior environmental shielding. |

| Processing Optimization | High-temperature annealing (>300°C), solvent engineering | Directly forms a stable, low-strain black phase with good crystallinity [16]. | Foundational for all high-efficiency devices [16]. | Determines initial film quality and phase purity. |

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Stability

Protocol: Surface Passivation with Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI)

Objective: To reduce surface defects and improve the moisture resistance of CsPbI3 films, thereby delaying the black-to-yellow phase transition.

Materials:

- Precursor solution: CsPbI3 in DMF/DMSO.

- PEAI solution: Phenethylammonium Iodide dissolved in isopropanol (typical concentration 1-5 mg/mL).

- Substrates (e.g., TiO2-coated FTO glass).

- Spin coater, hotplate, and glovebox.

Methodology:

- Film Deposition: Inside a nitrogen-filled glovebox, deposit the CsPbI3 precursor solution onto the substrate via spin-coating. Execute the anti-solvent dripping step during spinning to initiate crystallization.

- Annealing: Immediately transfer the wet film to a hotplate and anneal at 300-350°C for 5-10 minutes to form the black perovskite phase.

- Passivation: After the film cools to room temperature, dynamically spin-coat the prepared PEAI solution onto the CsPbI3 film.

- Rinsing: Spin-cast pure isopropanol for 30 seconds to remove any unbound excess ligands.

- Characterization: Proceed with the deposition of subsequent charge transport layers and the metal electrode, or perform characterization techniques like XRD and UV-Vis to confirm phase stability [20].

Protocol: Stabilization via Additive Engineering (Hypophosphorous Acid - HPA)

Objective: To stabilize the precursor solution and improve the morphology and phase stability of the resulting CsPbI3 film.

Materials:

- Cesium Lead Iodide precursor (e.g., CsI and PbI2 in DMF).

- Hypophosphorous Acid (HPA, typically 50% aqueous solution).

Methodology:

- Precursor Modification: Add a small volume of HPA (e.g., 1-5% by volume) to the CsPbI3 precursor solution.

- Stirring: Stir the mixture thoroughly for several hours to ensure homogeneity. The HPA acts as a reducing agent, preventing the oxidation of I⁻ to I₂, which is a common degradation pathway in the precursor.

- Film Deposition: Spin-coat the additive-containing precursor solution following the standard procedure, including anti-solvent quenching.

- Annealing: Anneal the film at the required high temperature (≥300°C). The additive promotes the formation of a more uniform and pinhole-free black phase film with larger grain sizes.

- Validation: Use photoluminescence (PL) mapping and XRD to verify the improved phase purity and uniformity of the film [15] [16].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Phase Transition Pathway in CsPbI3

Diagram Title: CsPbI3 Black-to-Yellow Phase Transition Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Phase-Stable CsPbI3

Diagram Title: Workflow for Stable CsPbI3 Fabrication

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for CsPbI3 Phase Stability Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Iodide (CsI) | A-site precursor for CsPbI3 synthesis. | High purity (99.99%) is critical to minimize impurities that act as nucleation sites for the yellow phase. |

| Lead Iodide (PbI2) | B-site and X-site precursor. | Source of lead toxicity; requires careful handling. Purity directly impacts defect density in the final film. |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) & Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Solvents for precursor preparation. | DMSO helps stabilize the precursor colloids. Anhydrous grades are mandatory to prevent premature degradation. |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Surface passivating ligand. | Can penetrate the perovskite surface; the substituents on the benzene ring can affect the extent of penetration and stability [20]. |

| Hypophosphorous Acid (HPA) | Additive for precursor stabilization. | Acts as a reducing agent to prevent I⁻ oxidation in the precursor solution, leading to more reproducible film formation [15] [16]. |

| Chlorobenzene / Diethyl Ether | Anti-solvents for crystallization. | Dripped during spin-coating to rapidly remove the host solvent and induce the crystallization of the perovskite film. |

| Inert Gas (N₂/Ar) | Environment for processing. | Used in gloveboxes or sealed systems to exclude O₂ and H₂O during all fabrication and testing steps. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and their functions in the synthesis and stabilization of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs).

| Reagent Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Precursor for the cesium (Cs) component in the perovskite crystal structure [22]. |

| Lead Halides (PbX₂, X=Cl, Br, I) | Precursors providing lead and the respective halide ions (Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) [22]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | A common surface ligand that coordinates with the PQD surface, stabilizing the nanocrystals and preventing aggregation [22]. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Often used synergistically with OA as a co-ligand to effectively passivate the PQD surface and improve stability [23] [22]. |

| 4-Bromo-butyric Acid (BBA) | A ligand used in dual-ligand strategies to create a hydrophobic protective shell, enabling water-dispersible and stable PQDs [23]. |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | A surface passivation ligand that coordinates with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions, suppressing non-radiative recombination and enhancing photoluminescence [24]. |

| L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | A ligand demonstrated to offer superior photostability, helping PQDs retain over 70% of initial photoluminescence intensity after extended UV exposure [24]. |

| Octadecene (ODE) | A high-boiling-point, non-polar solvent used as the reaction medium in hot-injection synthesis methods [22]. |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | A polar solvent used to dissolve precursor salts in the ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) synthesis method [22]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary factors determining the stability of CsPbX₃ PQDs? The stability is predominantly governed by the halide anion and surface chemistry. The halide ion affects the intrinsic thermodynamic stability of the crystal lattice, with CsPbI₃ being prone to phase degradation. The organic ligands (e.g., OA, OAm, BBA) passivating the surface are critical for protecting the ionic crystal from environmental factors like moisture, oxygen, and polar solvents [23] [22] [24].

Q2: Why does CsPbI₃ have poor phase stability compared to CsPbBr₃ and CsPbCl₃? CsPbI₃ has a smaller tolerance factor. The large Cs⁺ and I⁻ ions result in a crystal structure that is only stable in the photoactive black phase at high temperatures. At room temperature, it tends to transition to a non-perovskite, photoinactive yellow phase, which lacks the desired optoelectronic properties.

Q3: How can I improve the water stability of CsPbBr₃ PQDs for sensing applications? Employ a synergistic dual-ligand passivation strategy. Research has shown that using ligands like 4-bromo-butyric acid (BBA) and oleylamine (OLA) can form a robust hydrophobic protective shell. This allows CsPbBr₃ PQDs to maintain their photoluminescence and structural integrity in aqueous solutions for extended periods (e.g., over 140 hours) [23].

Q4: What is a common cause of low photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) in newly synthesized PQDs, and how can it be addressed? Low PLQY is typically caused by surface defects that act as traps for charge carriers, leading to non-radiative recombination. This can be addressed through ligand engineering—using specific passivation ligands like trioctylphosphine (TOP) or trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO) which coordinate with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the surface, effectively suppressing these defects and enhancing PLQY [24].

Q5: My blue-emitting CsPb(Br/Cl)₃ PQDs show spectral instability. What might be the cause? This is a common challenge in mixed-halide blue-emitting PQDs. The instability often arises from halide segregation, where the Br⁻ and Cl⁻ ions separate under photoexcitation, leading to a shift in the emission wavelength. Strategies to mitigate this include precise compositional control, using a matrix for encapsulation, and advanced surface ligand engineering to lock the halides in place [22].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: Rapid Degradation of PQDs in Polar Solvents or Water

- Potential Cause: Inadequate surface passivation, allowing polar molecules to attack and disrupt the ionic perovskite lattice.

- Solution: Implement a robust ligand exchange or co-passivation protocol. For example, use a combination of long-chain and short-chain ligands (e.g., BBA and OLA) to create a dense, hydrophobic ligand shell [23]. Ensure that polar solvents like DMF are thoroughly removed after synthesis via repeated washing and centrifugation.

Issue: Broad Size Distribution and Poor Morphology of Synthesized PQDs

- Potential Cause: Uncontrolled nucleation and growth kinetics during synthesis.

- Solution: Optimize synthetic parameters. For the hot-injection method, ensure precise control of injection and reaction temperatures. For the LARP method, consider a two-step supersaturated recrystallization approach for better size control. Adding additives like didodecyl dimethyl ammonium bromide (DDAB) to the poor solvent can also improve nucleation control [22].

Issue: Significant Drop in PL Intensity Over Time During Storage

- Potential Cause: Ligand desorption from the PQD surface, leading to increased surface defects and aggregation.

- Solution: Utilize ligands with stronger binding affinity or multiple binding sites. Studies show that ligands like L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) can significantly enhance photostability, helping PQDs retain a large percentage of their initial PL intensity over weeks [24]. Store PQDs in an inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂ glovebox) and in non-polar solvents like toluene or hexane.

Quantitative Data Comparison

The table below summarizes key stability and optical properties of CsPbCl₃, CsPbBr₃, and CsPbI₃ PQDs based on current research.

| Property / PQD Type | CsPbCl₃ | CsPbBr₃ | CsPbI₃ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bandgap (eV) / Emission Range | Deep Blue (~410 nm) [22] | Green (~510 nm) [23] | Red/NIR (~700 nm) [24] |

| Typical PLQY | Low (Challenging for pure blue) [22] | High (Can exceed 80-90%) [23] | High (Can be >90%) [24] |

| Phase Stability | High | High | Low (Prone to phase transition) |

| Environmental Stability (Moisture, Light) | Moderate | Can be made High with passivation [23] | Moderate to Low |

| Key Stability Challenge | Halide segregation in mixed Cl/Br systems; low PLQY [22] | Maintaining stability in water/polar environments [23] | Phase instability at room temperature [24] |

| Effective Passivation Strategy | Synthesis of ultrasmall, confined QDs; mixed halides [22] | Dual-ligand strategies (e.g., BBA & OLA) [23] | Surface passivation with TOPO, L-PHE, etc. [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Stability

Protocol: Dual-Ligand Passivation for Water-Dispersible CsPbBr₃ PQDs

This protocol is adapted from methods used to create super-stable PQDs for chemical sensing [23].

- Preparation of Precursors: In a standard synthesis, prepare a cesium-oleate precursor and a lead bromide (PbBr₂) solution in octadecene (ODE).

- Ligand Introduction: To the PbBr₂ solution, add the ligands 4-bromo-butyric acid (BBA) and oleylamine (OLA) in optimized molar ratios. The synergistic interaction of these two ligands is crucial.

- Synthesis Reaction: Inject the cesium-oleate precursor into the hot PbBr₂/ligands solution under inert atmosphere with continuous stirring.

- Purification: After the reaction is quenched, purify the resulting CsPbBr₃@BBA QDs by centrifugation and washing with a antisolvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or methyl acetate).

- Dispersion: The final product can be dispersed in polar solvents, including water, forming a stable colloidal solution for subsequent applications.

Protocol: Ligand Engineering for High PLQY and Photostability in CsPbI₃ PQDs

This protocol is based on research into surface ligand modification [24].

- Synthesis of Base PQDs: Synthesize CsPbI₃ PQDs using a standard hot-injection method, controlling reaction temperature and duration to obtain high-quality, crystalline dots.

- Ligand Exchange Solution: Prepare a solution containing the desired passivation ligand (e.g., Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) or L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE)) in an appropriate solvent.

- Surface Treatment: Mix the purified CsPbI₃ PQDs with the ligand exchange solution. Stir the mixture for a set period to allow the new ligands to coordinate with the PQD surface, effectively displacing weaker native ligands.

- Purification and Characterization: Purify the passivated PQDs to remove excess ligands. Characterize the PLQY and photostability by monitoring the PL intensity over time under continuous UV illumination. PQDs treated with L-PHE have been shown to retain over 70% of initial PL intensity after 20 days [24].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

PQD Stability Optimization Pathway

PQD Synthesis and Passivation Workflow

Advanced Stabilization Strategies: From Encapsulation to Surface Engineering

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary stability advantage of using a glass matrix to encapsulate Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) compared to other methods?

Glass matrix encapsulation is considered one of the most effective strategies for enhancing the extrinsic stability of PQDs. The rigid, inorganic glass structure provides an exceptional barrier that physically shields the encapsulated PQDs from degrading environmental factors such as oxygen, water (moisture), heat, and light. This protection is superior to organic polymer coatings or surface ligand passivation alone, as the glass is impermeable and chemically inert, preventing the ionic crystal structure of the perovskites from breaking down [25].

Q2: My PQD@glass composite has low photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY). What could be the cause?

A low PLQY often indicates poor formation or crystallization of the quantum dots within the glass matrix. This can be influenced by several factors related to the fabrication protocol:

- Incorrect Heat Treatment Parameters: The temperature and duration during the heat treatment crystallization step are critical. If the temperature is too low or the time is too short, the PQDs may not properly nucleate and grow. Conversely, excessive heat can lead to oversized crystals or degradation [25].

- Glass Composition: The composition of the precursor glass directly affects the diffusion of ions necessary for PQD formation. An imbalance in components like halides (Br, I) or network formers (B, Si) can inhibit the growth of high-quality, luminescent dots [25].

- Improper Melting or Quenching: Inhomogeneity in the initial precursor glass, resulting from insufficient melting time or temperature, can create zones with varied composition, leading to inconsistent PQD formation during subsequent heat treatment [25].

Q3: Why are there bubbles or haziness in my PQD@glass sample, and how does it affect performance?

Bubbles or haziness are typically defects introduced during the melting and quenching stages of precursor glass fabrication. These defects act as light scattering centers, which reduce the optical clarity of the material. For display and LED applications, this scattering directly compromises the color purity and luminous efficiency. Furthermore, bubbles can create pathways for environmental gases and moisture to penetrate deeper into the glass, potentially compromising the long-term stability of the encapsulated PQDs. Ensuring a homogeneous melt and controlled quenching rate is key to minimizing these defects [25].

Q4: How does the composition of the glass matrix influence the properties of the final PQD@glass composite?

The glass composition is a critical variable that dictates both the optical properties and the stability of the composite. The key influences are summarized in the table below [25]:

| Glass Matrix Type | Key Influences on PQD@glass Properties |

|---|---|

| Borosilicate | Offers a good balance of chemical durability, thermal stability, and water resistance. A common and robust choice. |

| Phosphosilicate | Can influence the crystallization kinetics of PQDs and the resulting optical properties. |

| Tellurite | Allows for a lower melting temperature, which can be beneficial but may offer slightly lower chemical resistance. |

| Borogermanate | The presence of germanium can modify the glass network structure, potentially enhancing the photostability of the encapsulated PQDs. |

Q5: What are the best practices for storing PQD@glass composites to ensure long-term stability?

Although the glass matrix offers significant protection, proper storage is still essential for maximizing shelf life. Composites should be stored in a dry, controlled environment. It is recommended to keep them in desiccators or sealed containers with desiccant packs to minimize exposure to ambient moisture. While the glass matrix itself is stable, protecting the composite from prolonged exposure to intense UV light or extreme temperatures will help maintain optimal performance over time [25].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent PQD Crystallization Across the Glass Matrix

- Observed Issue: The PQD@glass sample exhibits uneven color or varying luminescence intensity when examined under UV light.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inhomogeneous precursor glass due to insufficient melting or mixing of raw materials.

- Solution: Ensure raw materials are thoroughly mixed and that the melting is performed at the correct temperature for a sufficient duration to achieve a homogeneous melt. Use high-purity, analytical-grade reagents [26].

- Cause: Non-uniform temperature profile during the heat treatment crystallization step.

- Solution: Use a calibrated furnace with good temperature stability and uniformity. Avoid overcrowding the furnace to ensure consistent heat flow around all samples.

- Cause: Incorrect cooling rate after melting.

- Solution: Standardize the quenching process. Pouring the melt onto a pre-heated or massive metal plate can help achieve a consistent and rapid quench, leading to a more uniform glass [25].

- Cause: Inhomogeneous precursor glass due to insufficient melting or mixing of raw materials.

Problem: Poor Water Resistance and Lead Leakage

- Observed Issue: The glass matrix shows signs of surface degradation or cloudiness after immersion in water, and tests indicate lead ion leakage.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: A glass composition with poor chemical durability, potentially low in network formers like SiO₂ or B₂O₃.

- Solution: Optimize the glass composition. Increasing the content of SiO₂ or incorporating oxides like ZrO₂ or Al₂O₃ can significantly enhance the chemical stability and resistance to leaching, forming a more durable network [26].

- Cause: Inadequate encapsulation that fails to fully isolate the PQDs.

- Solution: Research indicates that proper glass encapsulation can achieve a lead leakage inhibition rate of up to 99% [27]. Ensure your fabrication protocol, particularly the melting and crystallization steps, is designed to achieve a dense, non-porous glass matrix that fully encapsulates the PQD crystals.

- Cause: A glass composition with poor chemical durability, potentially low in network formers like SiO₂ or B₂O₃.

Problem: Low Quantum Yield and Broad Emission Linewidth

- Observed Issue: The final PQD@glass composite has dim photoluminescence and the emitted light color is not pure (broad FWHM).

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Poor quality PQDs with internal defects or a wide size distribution.

- Solution: Fine-tune the heat treatment parameters. A specific nucleation temperature followed by a crystal growth temperature can help create a more uniform population of PQDs. The use of a controlled two-step heat treatment protocol is often more effective than a single high-temperature step [25].

- Cause: The glass matrix itself is causing scattering or absorption.

- Solution: Verify the purity of your raw materials to avoid contamination from ions like Fe or Cu, which can quench luminescence. Also, ensure the glass is fully vitreous and free from unintended crystallization.

- Cause: Poor quality PQDs with internal defects or a wide size distribution.

Experimental Protocols for Key Processes

Protocol 1: Fabrication of CsPbBr₃ PQD@glass via Melt-Quenching and Heat Treatment

This is a standard method for creating bulk PQD@glass composites [25] [26].

1. Materials Preparation:

- Reagents: High-purity SiO₂, H₃BO₃, Na₂CO₃, Cs₂CO₃, PbBr₂, NaBr. (Note: B₂O₃ enriched in the ¹¹B isotope can be used to minimize neutron absorption for certain structural studies [26]).

- Equipment: Platinum crucible, high-temperature furnace (capable of >1450°C), stainless steel quenching plate, grinder/mixer mill.

2. Synthesis of Precursor Glass:

- Weighing: Calculate the batch composition for a target glass, e.g., 55SiO₂·10B₂O₃·25Na₂O·5BaO·5ZrO₂ (mol%), with additional Cs, Pb, and Br precursors for the PQDs [26].

- Melting: Transfer the thoroughly mixed powders to a platinum crucible. Place in a furnace and melt at 1450°C for 2 hours to ensure complete reaction and homogeneity.

- Quenching: Quickly remove the crucible and pour the molten glass onto a pre-heated stainless-steel plate. Press with another plate to form a flat, thin disc, facilitating rapid cooling.

3. Heat Treatment for Crystallization:

- Annealing: Anneal the precursor glass at a temperature just below its glass transition temperature (Tg) to relieve internal stresses.

- Nucleation and Growth: Place the glass pieces in a furnace and heat to a specific temperature range (typically 400-550°C) for a controlled period (e.g., 10-30 minutes). This step drives the nucleation and growth of CsPbBr₃ nanocrystals within the glass matrix.

- Cooling: After heat treatment, turn off the furnace and allow the samples to cool to room temperature inside.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-stage process:

Protocol 2: Structural Confirmation via X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

Purpose: To verify the successful crystallization of the perovskite phase within the amorphous glass matrix [25].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Gently grind a small piece of the PQD@glass composite into a fine, uniform powder using an agate mortar and pestle.

- Measurement: Load the powder into an XRD sample holder. Run the XRD measurement with Cu Kα radiation, typically from 10° to 80° (2θ).

- Expected Results: The diffraction pattern should show sharp Bragg peaks superimposed on a broad, diffuse hump. The sharp peaks are characteristic of the crystalline CsPbX₃ phase (e.g., CsPbBr₃), while the broad hump is the signature of the amorphous glass matrix. The absence of sharp peaks suggests failed crystallization, and the presence of unexpected peaks indicates impurity phases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key materials used in the fabrication of PQD@glass composites and their primary functions [25] [26].

| Material Category | Examples | Function in PQD@glass Fabrication |

|---|---|---|

| Glass Network Formers | SiO₂, B₂O₃ | Form the rigid, continuous structural backbone of the glass matrix, providing mechanical strength and chemical durability. |

| Glass Network Modifiers | Na₂O, K₂O, BaO | Break up the glass network, lower the melting temperature, and facilitate ion mobility during PQD crystallization. |

| Perovskite Precursors | Cs₂CO₃, PbO/PbX₂, NaX/KX (X=Cl, Br, I) | Source of Cs⁺, Pb²⁺, and halide ions (Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) required to form the CsPbX₃ crystal structure within the glass. |

| Chemical Stabilizers | ZrO₂, Al₂O₃ | Enhance the chemical resistance of the glass matrix against water and other solvents, reducing lead leakage and improving long-term stability. |

| Crucible Material | Platinum (Pt) Crucible | Withstands very high temperatures (≥1450°C) without reacting with the corrosive glass melt. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Ligand Exchange Efficiency

Problem: Poor charge transport in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) films after ligand exchange.

- Potential Cause 1: Incomplete removal of long-chain insulating ligands. The original long-chain oleate (OA) ligands may not have been fully displaced, creating a barrier to electron flow between quantum dots [28] [29].

- Solution: Implement a sequential ligand exchange strategy. First, use dipropylamine (DPA) to remove the long-chain oleylamine (OAm) ligands, then use benzoic acid (BA) to passivate surface defects and replace the OA ligands [28].

- Potential Cause 2: Weak binding of new short-chain ligands. Acetate (Ac⁻) ligands from methyl acetate (MeOAc) antisolvent hydrolysis may bind too weakly to the PQD surface, leading to poor capping and defect formation [30].

- Solution: Use an antisolvent with a more robust binding group, such as methyl benzoate (MeBz). Enhance its hydrolysis into conductive ligands by creating an alkaline environment (e.g., with KOH) during the interlayer rinsing process to ensure dense, conductive capping [30].

Problem: Low power conversion efficiency (PCE) in the final PQD solar cell device.

- Potential Cause: Low current density due to high trap-state density from surface defects. Inefficient ligand exchange can leave behind unpassivated surfaces on the PQDs, which act as traps for charge carriers [28] [30].

- Solution: Optimize the concentration and type of short-chain ligands. Ensure the ligand exchange process effectively passivates surface defects. The use of DPA and BA has been shown to suppress carrier non-radiative recombination, leading to a champion PCE of 12.13% on a flexible substrate [28].

Material Stability and Compatibility

Problem: Structural degradation or aggregation of PQDs during film processing.

- Potential Cause: Destabilization of the PQD surface. If the pristine insulating ligands are removed during antisolvent rinsing and are not sufficiently replenished by new conductive ligands, the PQD surfaces become unstable, leading to aggregation during subsequent processing steps [30].

- Solution: Carefully control the antisolvent polarity and rinsing time. Esters of moderate polarity, such as MeOAc, MeBz, and EtOAc, are recommended to remove ligands without disrupting the perovskite core [30]. The alkaline treatment (AAAH) strategy can ensure rapid and sufficient ligand substitution to stabilize the dots [30].

Problem: Poor environmental stability of the fabricated PQD film or device.

- Potential Cause 1: Use of ligands that do not provide a protective barrier. The new short-chain ligand shell may be ineffective at shielding the PQD core from environmental factors like moisture and oxygen [28].

- Solution: Select ligands that offer both conductivity and protection. Ligand-capped PQDs have been demonstrated to exhibit extraordinary mechanical and environmental stability compared to bulk thin films [28].

- Potential Cause 2: Lead leakage from lead-based PQDs. CsPbBr₃ PQDs can release Pb²⁺, which poses toxicity concerns and can degrade performance [31].

- Solution: Consider developing or switching to lead-free alternatives, such as bismuth-based Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs, which offer superior stability and already meet current safety standards without additional coating [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is ligand exchange necessary in PQD-based optoelectronics?

- A1: Ligands play a critical dual role. First, they provide stability by passivating surface defects and preventing the quantum dots from aggregating. Second, they mediate electronic properties. The long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) used in synthesis are excellent for colloidal stability but hinder charge transport between dots in a solid film. Ligand exchange replaces these with shorter, conductive ligands to facilitate efficient electron hopping, which is essential for device performance [28] [29].

Q2: What are the key considerations when selecting a new short-chain ligand?

- A2: The ideal short-chain ligand should:

- Bind Robustly: Form a strong bond with the PQD surface to ensure durable capping [30].

- Facilitate Charge Transport: Be short and conductive to minimize the barrier for charge transfer between adjacent PQDs [28] [29].

- Passivate Defects: Effectively coordinate with surface atoms to reduce trap states that cause non-radiative recombination [28].

- Provide Stability: Help shield the PQD core from environmental degradation [28].

Q3: My ligand exchange process is inconsistent. How can I improve its reliability?

- A3: The traditional layer-by-layer (LBL) deposition with antisolvent rinsing can be time-consuming and poorly reproducible [28]. For better consistency, consider these approaches:

- Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH): This method makes ester hydrolysis for ligand generation more thermodynamically spontaneous and lowers the reaction activation energy, leading to a more uniform and efficient ligand exchange [30].

- One-Step Fabrication: Explore simplified one-step fabrication techniques via sequential ligand exchange, which can enhance repeatability and is compatible with future commercial applications [28].

Q4: How does ligand engineering improve the mechanical stability of flexible devices?

- A4: Surface ligand-capped PQDs exhibit intrinsic mechanical stability compared to their bulk counterparts. This property is crucial for flexible electronics. For instance, a flexible PQD solar cell fabricated using a sequential ligand exchange strategy maintained approximately 90% of its initial PCE after 100 bending cycles at a 7 mm bending radius [28].

Key Experimental Data

The table below summarizes quantitative data from key studies on ligand engineering in PQDs.

Table 1: Performance of PQD Solar Cells with Different Ligand Engineering Strategies

| Ligand System | PQD Material | Device Type | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Key Stability Metric | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Exchange (DPA + BA) | FAPbI₃ | Flexible | 12.13% (0.06 cm²) | ~90% initial PCE after 100 bending cycles | [28] |

| Alkali-Augmented Hydrolysis (KOH + MeBz) | FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ | Rigid | 18.30% (certified) | Improved storage & operational stability | [30] |

| Conventional MeOAc Rinsing | Lead Halide PQDs | Rigid | <16% (typically) | Lower due to weak ligand binding and defects | [30] |

Experimental Protocols

This protocol outlines a one-step fabrication method for creating stable and efficient flexible PQD solar cells.

- PQD Synthesis: Synthesize FAPbI₃ PQDs using a standard hot-injection method. The as-synthesized PQDs will be capped with long-chain insulating oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) ligands.

- Film Deposition & First Ligand Exchange:

- Spin-coat the PQD colloid onto your substrate to form a solid film.

- While the film is still wet, treat it with a solution of dipropylamine (DPA). DPA acts to remove the long-chain OAm ligands.

- Second Ligand Exchange & Passivation:

- Following the DPA treatment, immediately treat the film with a solution of benzoic acid (BA). The BA serves to passivate the surface defects created in the previous step and replaces the OA ligands.

- Film Processing: Repeat the layer-by-layer deposition (steps 2-3) until the desired film thickness is achieved.

- Device Fabrication: Complete the solar cell device by depositing the remaining charge transport layers and electrodes.

This protocol enhances the conductive capping on PQD surfaces by promoting ester hydrolysis.

- Antisolvent Preparation: Select an ester antisolvent of moderate polarity, such as methyl benzoate (MeBz). Add a carefully regulated amount of potassium hydroxide (KOH) to the MeBz to create an alkaline environment.

- PQD Film Rinsing: After spin-coating a layer of PQD solids, rinse the film using the KOH/MeBz solution. The alkaline environment facilitates the rapid hydrolysis of the ester, generating a high density of short-chain conductive ligands that replace the pristine insulating OA⁻ ligands.

- Drying: Allow the antisolvent to evaporate completely after rinsing.

- Iteration and Post-Treatment: Repeat the deposition and rinsing steps to build the film thickness. A post-treatment with short cationic ligands (e.g., FAI) can be subsequently performed to exchange the pristine OAm⁺ ligands on the A-site of the PQD surface.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Sequential ligand exchange workflow for one-step fabrication of PQD films.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Ligand Engineering in PQDs

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Dipropylamine (DPA) | Removes long-chain oleylamine (OAm) ligands during sequential exchange [28]. | Mildly strips ligands but may introduce extra surface defects, requiring a second passivation step [28]. |

| Benzoic Acid (BA) | Short-chain ligand that replaces OA, passivates surface defects, and enhances electronic coupling [28]. | Provides a more robust and conductive capping compared to acetate ligands [28]. |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Ester antisolvent used for interlayer rinsing; hydrolyzes to form conductive benzoate ligands [30]. | Its moderate polarity preserves the PQD core structure while enabling efficient ligand exchange [30]. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Additive to create an alkaline environment for antisolvent hydrolysis (AAAH strategy) [30]. | Lowers the activation energy for ester hydrolysis, enabling rapid and dense conductive capping. Concentration must be optimized [30]. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Conventional ester antisolvent; hydrolyzes to form acetate ligands [28] [30]. | Results in weakly bound ligands and less effective capping compared to alternatives like MeBz [30]. |

| Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) | Source of short A-site cation (FA⁺) for post-treatment to replace OAm⁺ ligands [30]. | Further enhances electronic coupling between PQDs after anionic ligand exchange [30]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Material Synthesis and Integration

Q1: How can I improve the aqueous-phase stability of lead halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) when integrating them with MXenes?

A: Lead halide PQDs (e.g., CsPbBr₃) are prone to degradation in water, which can be accelerated by the hydrophilic surfaces of MXenes [31]. To mitigate this:

- Surface Passivation: Implement a robust surface passivation layer using ligands like oleic acid and oleylamine, or explore inorganic shelling methods. This can extend the stability of PQDs from days to several weeks in aqueous environments [31].

- Lead-Free Alternatives: Consider substituting CsPbBr₃ with lead-free alternatives such as bismuth-based PQDs (e.g., Cs₃Bi₂Br₉). These exhibit significantly higher inherent aqueous stability and circumvent lead toxicity concerns, making them more suitable for biomedical and environmental applications [31].

- Matrix Encapsulation: Use the COF component as a protective matrix. The porous and stable structure of COFs can shield PQDs from direct contact with moisture, thereby enhancing the overall composite's stability [32].

Q2: What are the common issues when mixing MXenes with polymer matrices like PLA, and how can they be resolved?

A: A primary challenge is the interfacial incompatibility between the hydrophilic MXene and the hydrophobic polymer matrix, leading to poor dispersion and weak interfacial adhesion [33].

- Problem: Poor MXene dispersion in PLA, resulting in aggregation.

- Solution: Functionalize MXene surfaces with compatible coupling agents. For instance, the organic structures in COFs (e.g., melamine-derived units) can improve compatibility with both MXenes and PLA, leading to a more uniform composite with a smoother surface and smaller particle size [32].

- Problem: Degradation of MXene's electrical properties due to oxidation.

- Solution: The synthesis and storage environment is critical. Process and store MXene dispersions in an inert atmosphere (e.g., Argon glovebox) and use degassed solvents to minimize exposure to oxygen and water [34] [33]. Incorporating MXenes into a COF-PLA composite can also create a more controlled microenvironment, reducing the rate of oxidative degradation [32].

Q3: Which MXene synthesis method is recommended for minimizing environmental impact while maintaining good quality for composite fabrication?

A: Traditional hydrofluoric acid (HF) etching is highly effective but poses significant safety and environmental hazards [35].

- Recommended Method: Fluoride Salt Etching (e.g., using LiF/HCl mixtures). This method generates HF in situ, reducing direct handling risks and is widely regarded as a safer and more scalable alternative [35] [36].

- Alternative Methods:

- Molten Salt Etching: Uses salts like ZnCl₂ at high temperatures to remove the 'A' layer from MAX phases. This method can produce MXenes with unique surface terminations (e.g., Cl⁻) without using fluorine-based etchants [33].

- Electrochemical Etching: An environmentally friendly approach that selectively removes the 'A' layer by applying an electric current in a mild electrolyte solution [34] [33].

Performance and Characterization

Q4: The electronic properties of my PQD-COF-MXene composite are unstable. What could be the cause?

A: Instability often originates from the degradation of individual components and their interfaces.

- PQD Degradation: As noted in Q1, the degradation of PQDs in the composite is a primary factor. The release of Pb²⁺ ions from lead-based PQDs can disrupt charge transport pathways [31].

- MXene Oxidation: MXenes readily oxidize in aqueous or ambient environments, converting into their corresponding metal oxides (e.g., TiO₂ from Ti₃C₂Tx). This process drastically reduces their electrical conductivity and compromises the composite's performance [34] [33] [37]. Characterize the composite after aging using techniques like X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to detect the appearance of TiO₂ peaks, indicating MXene oxidation [34].

- Interface Defects: Poor interfacial bonding can lead to trap states that capture charge carriers, reducing mobility and causing performance drift. Ensure thorough mixing and consider compatibility agents, as suggested in Q2.

Q5: How can I characterize the success of the integration between PQDs, COFs, and MXenes?

A: A multi-technique approach is necessary to confirm successful integration and understand the composite structure.

- Microscopy: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) to observe the morphology and confirm the uniform dispersion of PQDs and MXenes within the COF matrix without severe aggregation [32].

- Spectroscopy: Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy can verify the chemical bonds and identify the presence of specific functional groups from each component, confirming successful composite formation [32].

- Thermal Analysis: Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) can demonstrate enhanced thermal stability. For example, a COF-PLA composite showed an increased initial pyrolysis temperature (313.7 °C) compared to pure PLA (297.5 °C), indicating successful reinforcement [32].

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Analyze the crystallinity of the composite. The XRD pattern should show characteristic peaks from all three components, confirming their presence and indicating whether the crystal structures are preserved during integration [32].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Ti₃C₂Tx MXene via LiF/HHCl Etching Method

Objective: To safely synthesize multilayer Ti₃C₂Tx MXene from Ti₃AlC₂ MAX phase for composite fabrication [35] [36].

Materials:

- Ti₃AlC₂ MAX phase powder (1 g)

- Lithium Fluoride (LiF), powder

- Hydrochloric Acid (HCl), 9 M solution

- Deionized (DI) water

- Argon gas supply

Procedure:

- Etchant Preparation: In a polypropylene (PP) beaker, slowly add 1 g of LiF into 20 mL of 9 M HCl under continuous stirring (500 rpm). Allow the mixture to stir for 10 minutes to ensure complete dissolution and in-situ generation of HF.

- Etching: Gradually add 1 g of Ti₃AlC₂ powder to the etchant mixture. Maintain the reaction at 35 °C for 24 hours with continuous stirring (500 rpm).

- Washing: After etching, transfer the suspension to PP centrifuge tubes and centrifuge at 3500 rpm for 5 minutes. Discard the supernatant.

- Neutralization: Re-disperse the sediment in DI water and centrifuge. Repeat this washing cycle 5-7 times until the supernatant reaches a pH of approximately 6.

- Storage: Finally, disperse the obtained multilayer MXene sediment in DI water. Store the dispersion in a sealed container under an Argon atmosphere at 4 °C to minimize oxidation.

Protocol 2: Fabrication of a PQD-COF-MXene Composite Film

Objective: To fabricate a thin-film composite for enhanced environmental stability and electronic performance.

Materials:

- Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQD dispersion (in toluene, 10 mg/mL) [31]

- COF (TpTt) suspension (in DMAc, 5 mg/mL) [32]

- Ti₃C₂Tx MXene dispersion (in water, 2 mg/mL) from Protocol 1

- Polylactic Acid (PLA) pellets

- Chloroform (anhydrous)

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation:

- COF-PLA Masterbatch: Dissolve 1 g of PLA pellets in 20 mL of chloroform by stirring at 50 °C for 1 hour. Add 10 mL of COF suspension dropwise and stir for another 2 hours.

- PQD-MXene Blend: Slowly add 5 mL of Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQD dispersion to 10 mL of Ti₃C₂Tx MXene dispersion under vigorous stirring. Sonicate for 15 minutes to achieve a homogeneous blend.

- Composite Integration: Combine the COF-PLA masterbatch with the PQD-MXene blend. Stir the mixture for 4 hours at room temperature to ensure thorough integration.

- Film Casting: Pour the final composite solution onto a clean glass substrate.

- Solvent Evaporation: Allow the film to dry slowly under a covered Petri dish at room temperature for 12 hours, followed by vacuum drying at 40 °C for 6 hours to remove residual solvents.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of MXene Synthesis Methods

| Method | Key Reagents | Typical Yield | Advantages | Disadvantages | Suitability for Bio/Enviro Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF Etching [34] [33] | Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | 35-50 wt.% | High efficiency, reliable, produces well-etched layers | Highly toxic, corrosive, requires extreme safety measures, hazardous waste | Low (due to toxic residues and environmental impact) |

| Fluoride Salt Etching [35] [36] | LiF + HCl | 35-50 wt.% | Safer (in-situ HF generation), scalable, good control over terminations | Still generates fluoride-containing waste, requires careful pH control | Medium (requires thorough purification to remove fluoride ions) |

| Molten Salt Etching [33] | ZnCl₂, KF | Varies | HF-free, can create unique surface terminations (e.g., Cl, OH) | High temperatures required, can be energy-intensive | High (can produce halogen-terminated MXenes without fluorine) |