Strategies for Enhancing Batch-to-Batch Reproducibility of Perovskite Quantum Dots for Reliable Electronic and Biomedical Applications

This article addresses the critical challenge of batch-to-batch reproducibility in Perovskite Quantum Dot (PQD) synthesis, a key bottleneck for their reliable integration into advanced electronics and biomedical devices.

Strategies for Enhancing Batch-to-Batch Reproducibility of Perovskite Quantum Dots for Reliable Electronic and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of batch-to-batch reproducibility in Perovskite Quantum Dot (PQD) synthesis, a key bottleneck for their reliable integration into advanced electronics and biomedical devices. We explore the fundamental sources of property variation, from nucleation kinetics to ligand chemistry. The scope covers advanced synthetic methodologies, stabilization strategies to combat environmental degradation, and rigorous statistical and biological validation frameworks. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this review provides a holistic roadmap for achieving consistent PQD performance, which is paramount for developing robust biosensors, diagnostic tools, and other clinical applications.

Understanding PQD Complexity and Reproducibility Challenges

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Tunable Bandgap

Q1: Why is my measured bandgap inconsistent with literature values for the same PQD composition? A: This is a common batch-to-batch issue. The bandgap is highly sensitive to nanocrystal size and halide distribution.

- Cause 1: Inaccurate Size Control. Slight variations in reaction temperature, precursor injection speed, or ligand concentration can alter the final nanocrystal size.

- Troubleshooting:

- Calibrate your thermocouple and ensure vigorous, consistent stirring.

- Precisely control the injection rate using a syringe pump.

- Monitor growth by withdrawing aliquots for UV-Vis measurement during synthesis.

- Cause 2: Halide Segregation. In mixed-halide perovskites (e.g., Br/I), phase separation under illumination can lead to a shifting bandgap.

- Troubleshooting:

- Synthesize under a controlled atmosphere (e.g., N₂ glovebox) to prevent surface defects that catalyze segregation.

- Incorporate passivating ligands (e.g., Phenethylammonium Iodide) to stabilize the mixed halide lattice.

Q2: How can I precisely tune the bandgap of my PQD batch? A: The primary method is through compositional engineering and quantum confinement.

- For CsPbX₃ PQDs: Systematically vary the halide ratio (X = Cl, Br, I) during synthesis. A higher Br/I ratio yields a larger bandgap (blue-shifted emission).

- For Size Control: Adjust the reaction time and temperature. Longer reaction times and higher temperatures generally yield larger particles with a smaller bandgap.

Experimental Protocol: Bandgap Measurement via Tauc Plot

- Sample Preparation: Disperse your purified PQDs in a non-solvent (e.g., toluene) to create an optically clear, dilute solution.

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Acquire an absorbance spectrum from a wavelength range of 300-800 nm.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot (αhν)² vs. hν (photon energy), where α is the absorption coefficient and hν is the photon energy. This assumes a direct bandgap.

- Extrapolate the linear region of the plot to the x-axis. The intercept is the direct bandgap energy.

Bandgap Ranges for Common CsPbX₃ PQDs

| PQD Composition | Approximate Bandgap Range (eV) | Corresponding Emission Wavelength (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ | 1.70 - 1.80 | 690 - 730 |

| CsPbBr₃ | 2.30 - 2.50 | 500 - 540 |

| CsPbCl₃ | 2.90 - 3.10 | 400 - 430 |

| CsPb(Br/I)₃ | 1.80 - 2.30 | 540 - 690 |

Diagram: Bandgap Tuning Workflow

Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)

Q1: My PQD batch has a low PLQY (< 60%). How can I improve it? A: Low PLQY indicates a high density of non-radiative recombination centers, often due to surface defects.

- Cause 1: Incomplete Surface Passivation. Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions and halide vacancies on the PQD surface act as trap states.

- Troubleshooting:

- Optimize the concentration of surface ligands (e.g., Oleic Acid, Oleylamine). Too little leads to defects; too much can cause aggregation.

- Introduce specific passivating ligands like Zwitterionic molecules or PbSO₄ that strongly bind to surface sites.

- Cause 2: Synthesis Quenching. If the reaction is quenched too early or too late, it can result in a high defect density.

- Troubleshooting: Determine the optimal reaction time by tracking PL intensity in aliquots over time.

Q2: Why does my PQD solution's PLQY decrease over time (hours/days)? A: This is typically a stability issue related to ligand dynamics and environmental factors.

- Cause: Ligand Desorption. Dynamic binding of ligands means they can fall off over time, exposing surface defects.

- Troubleshooting:

- Store PQD solutions in the dark and at low temperatures (e.g., 4°C).

- Perform all purification and handling in an inert atmosphere to prevent oxidation.

- Consider post-synthetic treatment with a "passivation soup" to replenish ligands.

Experimental Protocol: Absolute PLQY Measurement using an Integrating Sphere

- Setup: Place a cuvette containing your PQD dispersion (in a transparent solvent) inside the integrating sphere.

- Excitation Measurement: Direct the excitation laser beam into the empty sphere and record the signal (Iexempty). Then, place the sample in the beam path and record the signal (Iexsample).

- Emission Measurement: With the sample in place, move the beam to excite the sample directly inside the sphere. Record the total luminescence signal (Iemsample).

- Calculation:

- PLQY = Iemsample / [Iexempty - Iexsample]

Factors Affecting PLQY Reproducibility

| Factor | Impact on PLQY | Method to Improve Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Purity | Impurities compete for binding sites. | Use high-purity (>99%) ligands. |

| Precursor Ratio | Off-stoichiometry creates defects. | Maintain precise Pb:X (halide) ratio. |

| Reaction Temperature | Affects crystallization kinetics. | Use a calibrated, high-stability bath. |

| Purification | Incomplete removal of precursors/quenching solvents. | Standardize antisolvent volume & centrifuge speed/time. |

Diagram: PLQY Optimization Logic

Charge Carrier Mobility

Q1: My measured charge carrier mobility values have high variance between batches. Why? A: Mobility is extremely sensitive to inter-dot coupling and film morphology.

- Cause 1: Inconsistent Film Morphology. Variations in solvent, drying temperature, and ligand shell thickness affect how close PQDs pack, changing tunneling probability.

- Troubleshooting:

- Use a consistent film deposition technique (e.g., spin-coating with fixed speed, time, and acceleration).

- Implement a controlled post-deposition treatment (e.g., solvent vapor annealing) to gently reduce inter-dot distance.

- Cause 2: Variable Ligand Shell. Long, insulating ligands (e.g., Oleic Acid) are necessary for stability but hinder charge transport.

- Troubleshooting: Develop a reproducible ligand exchange protocol to replace long-chain ligands with shorter ones (e.g., formate, acetate) after film formation.

Q2: Which measurement technique is most suitable for PQD films? A: The choice depends on your device structure and the specific property you wish to isolate.

- Space-Charge-Limited Current (SCLC): Good for measuring mobility in diode structures (hole-only or electron-only devices). It probes the bulk transport of the majority carrier.

- Field-Effect Transistor (FET): Measures mobility in a transistor configuration. Can be challenging for PQDs due to ionic migration and instability under gate bias.

- Time-of-Flight (ToF): Provides direct measurement of carrier drift mobility but requires thick, high-quality films, which are difficult to achieve with PQDs.

Experimental Protocol: Hole Mobility by SCLC

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate a hole-only device (e.g., ITO/PEDOT:PSS/PQD Film/MoO₃/Ag).

- Current-Voltage (I-V) Measurement: Sweep the voltage and measure the current in the dark.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot log(Current) vs log(Voltage).

- Identify the region where the slope is 2 (the Child's Law region).

- Use the Mott-Gurney Law to calculate the hole mobility (μh):

- J = (9/8)εε₀μh(V²/d³)

- Where J is current density, ε is dielectric constant, ε₀ is vacuum permittivity, V is voltage, and d is film thickness.

Comparison of Mobility Measurement Techniques

| Technique | Required Sample Form | Key Output | Pros & Cons for PQDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCLC | Diode (Hole/Electron-only) | Bulk Mobility (μ) | Pro: Relatively simple analysis. Con: Requires trap-free film for accurate result. |

| FET | Transistor (Gate, Source, Drain) | Field-Effect Mobility (μ_FE) | Pro: Measures tunable transport. Con: Highly sensitive to interface; ionic effects can distort data. |

| ToF | Thick Film (>1 μm) between contacts | Drift Mobility (μ_drift) | Pro: Direct measurement, less ambiguous. Con: Difficult sample preparation for PQDs. |

Diagram: Mobility Measurement Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function | Critical for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Precursor for Cs⁺ ions. | Use high-purity (>99.9%) source. Dry thoroughly before use to prevent hydroxide formation. |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Precursor for Pb²⁺ and Br⁻ ions. | Purify via recrystallization to remove trace metals and Pb⁰. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand; binds to Pb sites, provides colloidal stability. | Monitor acid value; store under inert gas to prevent oxidation. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Surface ligand; passivates halide vacancies. | Use in a precise ratio with OA; batch variability is high, so test new batches. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-coordinating solvent for high-temperature synthesis. | Purify by heating under vacuum to remove polar impurities and water. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Antisolvent for purifying and precipitating PQDs. | Use anhydrous grade and ensure consistent volume across batches. |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Short-chain ligand for post-synthetic treatment to improve mobility. | Standardize the concentration and treatment time for ligand exchange. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Nucleation Kinetics Defects

Problem: Inconsistent crystal nucleation between batches. High supersaturation, often essential to promote nucleation of macromolecular crystals, is far from ideal for growth and leads to competition between crystal formation and amorphous precipitates [1]. This variation in the early stage of crystallization is a primary source of batch differences.

- Issue: Uncontrolled secondary nucleation

- Root Cause: Supersaturation levels that are too high, leading to excessive nucleation sites and inconsistent crystal growth initiation [1].

- Impact: Variable crystal size, morphology, and electronic properties in final batches [1].

- Solution: Implement controlled supersaturation profiling and use seeding techniques to ensure consistent primary nucleation events.

Experimental Protocol for Seeding:

- Prepare a saturated solution of your material at precisely controlled temperature

- Generate seed crystals by creating a brief, high supersaturation pulse

- Characterize seed size distribution using dynamic light scattering

- Introduce standardized seed quantity to new batches at precisely 5% below metastable zone width

- Monitor nucleation events with in-situ particle size analysis

Surface Ligand Dynamics Variation

Problem: Inconsistent surface chemistry between batches. Surface ligand dynamics significantly impact the electronic properties of quantum dots and other crystalline materials, where inconsistent ligand binding or exchange creates batch-to-batch variability in performance.

- Issue: Fluctuating ligand coverage and binding stability

- Root Cause: Variable reaction kinetics during ligand exchange processes and inconsistent purification efficacy [2].

- Impact: Altered surface electronic states, variable charge transport properties, and inconsistent device performance [2].

- Solution: Standardize ligand exchange protocols with real-time monitoring and implement rigorous purification quality control.

Experimental Protocol for Ligand Exchange Monitoring:

- Establish baseline ligand coverage using FTIR spectroscopy

- Implement real-time UV-Vis monitoring during exchange processes

- Standardize quenching methodology across all batches

- Deploy consistent precipitation/redispersion cycles (recommended: 3 cycles minimum)

- Verify final ligand density through TGA analysis

Crystal Defects and Imperfections

Problem: Structural defects that vary between production batches. Crystal defects significantly impact the degree of molecular and lattice order, which affects functional properties like charge carrier mobility and recombination kinetics [1].

- Issue: Variable dislocation density and point defect concentrations

- Root Cause: Non-uniform thermal profiles during growth, impurity incorporation, and inconsistent lattice matching [1] [3].

- Impact: Reduced charge carrier lifetime, altered bandgap characteristics, and inconsistent electronic performance between batches [1].

- Solution: Implement optimized thermal protocols with verification through structural characterization.

Experimental Protocol for Defect Characterization:

- Perform X-ray diffraction analysis to determine crystalline size and strain

- Conduct photoluminescence spectroscopy to identify defect states

- Use atomic force microscopy to visualize surface defects

- Employ transmission electron microscopy for lattice-level defect identification

- Correlate defect density with electronic performance metrics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the primary factors influencing batch-to-batch variation in crystal growth? A: The major factors include: (1) Nucleation kinetics controlled by supersaturation levels [1], (2) Surface ligand dynamics affecting interfacial properties [2], and (3) Crystal defect formation during growth processes [1]. Controlling these parameters through standardized protocols is essential for reproducibility.

Q: How can I quantify batch-to-batch variation in my experimental system? A: Implement a rigorous characterization protocol including:

- Size exclusion chromatography for molecular weight distribution [4] [5]

- Cyclic voltammetry for electrochemical consistency [2]

- X-ray diffraction for crystalline structure analysis [1]

- Spectroscopic methods for surface chemistry verification [2]

Q: What analytical techniques are most sensitive for detecting batch variations? A: The most sensitive techniques include:

- Cyclic voltammetry (detects variation in electrochemical properties) [2]

- Chromatographic methods (SE-UPLC detects physicochemical differences) [4] [5]

- Mass spectrometry (identifies compositional variations) [6]

- Atomic force microscopy (visualizes nanoscale defects) [1]

Q: How does nucleation kinetics specifically impact batch reproducibility? A: Nucleation kinetics determines critical parameters including:

- Crystal size distribution

- Polymorph selection

- Defect density

- Molecular order within the lattice [1]

Variation in nucleation conditions leads to divergent crystalline materials with different properties, even with identical chemical composition.

Table 1: Measured Batch-to-Batch Variation Across Material Systems

| Material System | Measurement Type | Observed Variation | Impact on Properties | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser-Inscribed Graphene (LIG) | Electrochemical Performance | <5% (bare LIG), ~30% (metallized LIG) | Specific capacitance, peak current | [2] |

| Transferon (Biopharmaceutical) | Chromatographic Profile | <0.2% (retention time), <30% (peak area) | Biological activity, consistency | [4] [5] |

| Advair Diskus (Pharmaceutical) | Pharmacokinetic Parameters | Failed bioequivalence tests | Drug absorption, therapeutic effect | [7] |

| Direct Infusion Mass Spectrometry | Analytical Precision | 15.9% median RSD | Metabolite detection accuracy | [6] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Solutions for Common Batch Variation Issues

| Problem Category | Detection Methods | Corrective Actions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleation Inconsistency | Light scattering, microscopy | Seeding protocols, supersaturation control | Standardized nucleation triggers |

| Surface Ligand Variability | FTIR, XPS, TGA | Ligand exchange optimization | Real-time reaction monitoring |

| Crystal Defects | XRD, TEM, AFM | Thermal profile adjustment | Lattice matching protocols |

| Impurity Incorporation | Chromatography, spectrometry | Purification process enhancement | Raw material quality control |

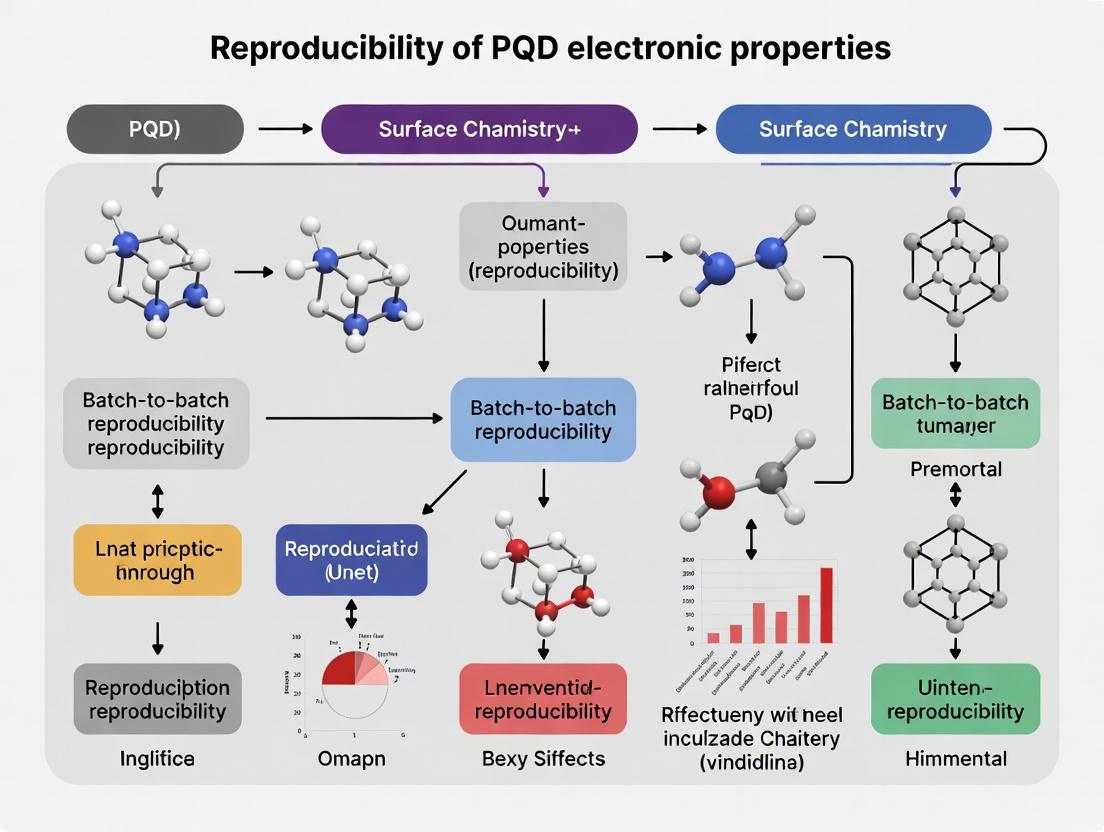

Workflow Visualization

Experimental Optimization Pathway

Material Characterization Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Batch Reproducibility Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polyimide Film | Substrate for LIG formation | Electrical grade, 0.0050" thickness recommended [2] |

| Size Exclusion UPLC | Physicochemical characterization | Validated method for batch comparison [4] [5] |

| Reference Electrodes (Ag/AgCl) | Electrochemical standardization | Essential for consistent voltammetry [2] |

| Calibrated Weights | Weighing system verification | Prevention of dosing inaccuracies [8] |

| Standardized Solvents | Purification and processing | High purity with lot-to-lot consistency |

| Ligand Libraries | Surface modification | Pre-characterized for purity and reactivity |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their critical functions in ensuring reproducible Perovskide Quantum Dot (PQD) synthesis and electronic properties.

| Reagent/ Material | Primary Function | Impact on Reproducibility & Electronic Properties |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Precursors (e.g., CsX, PbX₂) | Source of primary elements for perovskite crystal structure. | Purity directly dictates defect density and trap states, profoundly influencing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and charge carrier mobility [9]. |

| Spectrophotometric Grade Solvents (e.g., DMF, DMSO, γ-butyrolactone) | Dissolving precursors to form the reaction medium. | Solvent purity (e.g., water content), coordinating ability, and viscosity affect precursor reactivity, nucleation rates, and final nanocrystal stability, impacting batch-to-burst size distribution [10] [11]. |

| Ligands (e.g., Oleic Acid, Oleylamine) | Capping agents that control nanocrystal growth and stabilize the colloidal suspension. | The ligand chain length, concentration, and binding affinity determine surface passivation, influencing PLQY and electronic properties by mitigating surface defects [9]. |

| Silica, Polymer, or MOF Coatings | Encapsulating matrix to enhance PQD stability. | Protects the sensitive PQDs from environmental degradation (moisture, oxygen, heat), preserving their electronic and optical properties over time and across batches [9]. |

| Antisolvents (e.g., Toluene, Hexane, Ethyl Acetate) | Triggering supersaturation and nanocrystal precipitation. | The chemical nature, purity, and addition kinetics of the antisolvent are critical for achieving a narrow size distribution during the crystallization process [9]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Optical Properties (PLQY and Emission Wavelength)

Problem: Batch-to-batch variations in photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and emission peak position.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Corrective Action & Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Variable Precursor Purity & Stoichiometry | - Perform elemental analysis of precursors.- Titrate Pb:Cs molar ratio in small increments (e.g., ±5%) and monitor optical output. | - Source precursors from a single, reputable supplier with Certificate of Analysis.- Establish and strictly adhere to a fixed stoichiometric ratio. Pre-mix large batches of precursor stock solutions for multi-batch studies [12]. |

| Uncontrolled Hydrolysis of Solvents | - Test solvents for water content via Karl Fischer titration.- Compare PL results from "as-opened" vs. dried/stored solvents (over molecular sieves). | - Use anhydrous, spectrophotometric-grade solvents. Employ proper storage and handling under inert atmosphere to prevent water absorption [10] [11]. |

| Irregular Ligand Binding Dynamics | - Characterize PQDs via FTIR to monitor ligand binding states.- Systematically vary the OA:OAm ratio while keeping other parameters constant. | - Standardize the purity, concentration, and ratio of all surface ligands. Pre-mix ligand stocks. Implement a highly consistent injection and reaction temperature protocol [9]. |

Experimental Protocol for Diagnosing Solvent-Induced Variability:

- Prepare a master batch of precursor solution (e.g., 1.5 M CsPbBr₃ in anhydrous DMF).

- Split this master batch into three equal parts.

- Control: Use one part immediately with dry antisolvent.

- Test 1: Intentionally add 0.1% v/v water to the second precursor part, then proceed with synthesis.

- Test 2: Use the third part with an antisolvent batch known to have higher water content.

- Characterize all three resulting PQD batches using UV-Vis absorption, PL spectroscopy, and calculate PLQY. The difference in emission intensity and peak shift between the control and test samples will quantify the impact of solvent purity.

Issue 2: Poor Batch-to-Batch Size Uniformity

Problem: Wide variations in particle size and size distribution between syntheses.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Corrective Action & Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Fluctuating Reaction Temperature | - Calibrate the heating mantle/oil bath thermometer.- Run replicates with tight (±1°C) vs. loose (±5°C) temperature control. | - Use a calibrated thermocouple in the reaction flask. Employ heating systems with high stability and use a stirring hotplate to ensure even heat distribution [13]. |

| Inconsistent Antisolvent Addition | - Record the addition rate (drops/sec) and vigor of stirring.- Synthesize batches with manual vs. syringe pump addition. | - Replace manual, dropwise addition with an automated syringe pump for a fixed, reproducible addition rate (e.g., 5 mL/min). Standardize stirring speed (e.g., 800 rpm) [13]. |

| Unoptimized Ligand Concentration | - Conduct a synthesis series where ligand concentration is the only variable.- Use TEM to measure the resulting nanocrystal size and size distribution. | - Determine the optimal ligand concentration that provides the smallest, most monodisperse particles and adhere to it strictly. Avoid under- or over-passivation of surfaces [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is precursor purity so critical for the electronic properties of PQDs? Impurities in precursor materials (e.g., metal ions, halides, organic contaminants) act as defect sites within the perovskite crystal lattice. These defects create electronic trap states that non-radiatively capture charge carriers (electrons and holes). This process severely quenches photoluminescence (low PLQY) and degrades charge transport properties, which are essential for electronic devices like LEDs and solar cells. High-purity precursors minimize these defects, leading to more efficient and predictable electronic performance [9].

FAQ 2: How do solvent properties beyond purity affect my PQD reaction? The choice of solvent is not merely a passive medium. Its properties—such as dielectric constant, viscosity, boiling point, and coordinating ability—directly influence:

- Solvation of Precursors: How well ions are separated, affecting reactivity.

- Nucleation Rate: A higher dielectric constant can promote rapid nucleation, leading to smaller particles.

- Growth Kinetics: Viscosity affects diffusion rates and thus crystal growth.

- Stability of Intermediate Complexes: Solvents like DMSO strongly coordinate with Pb²⁺, forming complexes that can alter the reaction pathway. Changing the solvent system changes the fundamental energy landscape of the synthesis, making consistency paramount [10] [11].

FAQ 3: What are the most common sources of variability in the reaction environment? The most pervasive yet often overlooked sources of variability are:

- Temperature Gradients: Inconsistent heating within the reaction vessel.

- Ambient Atmosphere: Exposure to oxygen and moisture during synthesis or purification.

- Human Operational Factors: Inconsistent timing, manual injection rates, and stirring efficiency.

- Reagent Age and Storage: Degradation of precursors or solvents over time, especially under improper storage. Implementing automation for fluid handling, using inert atmosphere gloveboxes, and standardizing all timings and physical setups are the most effective ways to mitigate these issues [13].

FAQ 4: How can I quickly assess if my new batch of PQDs is consistent with previous ones? Perform a set of rapid, routine characterizations immediately after synthesis and purification:

- UV-Vis Absorption Spectroscopy: Check the position and sharpness of the first excitonic absorption peak. A shift indicates a change in bandgap or size distribution.

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: Measure the emission peak wavelength and, crucially, the full width at half maximum (FWHM). A broadening FWHM signals increased size dispersion.

- PL Quantum Yield (PLQY): Measure the absolute or relative PLQY to confirm the intrinsic optoelectronic quality has been maintained. A significant drop in PLQY suggests a high density of defects [9].

Experimental Workflow for Reproducible PQD Synthesis

The following diagram outlines a standardized workflow that integrates quality control checkpoints to enhance batch-to-batch reproducibility.

Quality Control Verification Pathway

This decision tree helps troubleshoot a new batch of PQDs that shows inconsistent properties, guiding you to the most likely root cause.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: Why is there significant variation in the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) between my synthesis batches?

A: PLQY is highly sensitive to the halide ratio and reaction temperature. Even minor deviations can lead to large variations in defect density and non-radiative recombination.

- Root Cause: Non-stoichiometric Pb:Br ratios and temperature fluctuations during injection and growth.

- Solution: Precisely control precursor stoichiometry and implement a rigorous temperature control system for the reaction flask. Use an excess of PbBr2 (e.g., 5-10%) to ensure full conversion and reduce lead vacancy defects.

Q2: My synthesized CsPbBr3 PQDs exhibit broad size distribution and poor crystallinity. What step is most critical to control?

A: The ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) process is highly sensitive to the antisolvent addition rate and the choice of ligands/cosolvents.

- Root Cause: Rapid antisolvent addition causes uncontrolled nucleation and Ostwald ripening. Ineffective ligand binding leads to particle aggregation.

- Solution: Use a syringe pump for slow, dropwise addition of the precursor solution into the antisolvent under vigorous stirring. Optimize the ratio of oleic acid (OA) to oleylamine (OAm) to enhance surface passivation.

Q3: How does the ligand ratio (OA:OAm) specifically affect the electronic properties of the final PQD film?

A: The OA:OAm ratio directly influences surface defect passivation and charge transport in films. An imbalance can create insulating layers or trap states.

- Root Cause: Oleylamine alone passivates lead-rich sites but can create excess ligands. Oleic acid passivates bromine-rich sites. An imbalance leaves unpassivated surface sites.

- Solution: A balanced molar ratio (e.g., 1:1 to 3:1 OA:OAm) is typically optimal. See Table 1 for quantitative data on its impact.

Q4: Why do my PQD films have poor charge carrier mobility and high trap density?

A: This is often a result of poor inter-dot coupling due to long, insulating ligand chains and residual solvent trapped in the film.

- Root Cause: Long-chain OA/OAm ligands create large inter-dot distances. Incomplete purification leaves oleate/oleylammonium species that act as traps.

- Solution: Implement a solid-state ligand exchange process post-deposition using short-chain ligands like ethylenediamine bromide (EDABr). Ensure thorough washing with polar antisolvents (e.g., methyl acetate) during purification.

Table 1: Impact of Synthesis Parameters on CsPbBr3 PQD Properties

| Parameter | Typical Range Tested | Optimal Value | Effect on PLQY | Effect on FWHM (nm) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb:Br Precursor Ratio | 1:2 to 1:4 | 1:3 (with 5% Pb excess) | 45% -> 85% | 22 -> 18 | Slight Pb excess suppresses Br vacancies, boosting PLQY. |

| Reaction Temperature (°C) | 20 - 80 | 40 ± 2 | 30% -> 75% | 25 -> 19 | Higher temps increase defect density; precise control is vital. |

| OA:OAm Molar Ratio | 1:5 to 5:1 | 3:1 | 60% -> 90% | 20 -> 17 | Balanced ratio ensures complete surface passivation. |

| Antisolvent Addition Rate (mL/min) | 0.5 - 5 | 1.0 | 50% -> 80% | 28 -> 20 | Slower rate promotes monodisperse nucleation. |

| Purification Solvent | Toluene, EA, MA | Methyl Acetate (MA) | 70% -> 90%* | - | MA most effectively removes unbound ligands without damaging PQDs. |

*PLQY after purification.

Experimental Protocol: Optimized LARP Synthesis for High-Reproducibility CsPbBr3 PQDs

Methodology (Based on ):

- Precursor Solution: Dissolve 0.16 mmol CsBr, 0.21 mmol PbBr2 (5% excess Pb) in 1 mL of Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO). Add Oleic Acid (0.5 mL) and Oleylamine (0.25 mL) to achieve a 3:1 OA:OAm ratio. Stir at 60°C until fully dissolved.

- Antisolvent: Load 20 mL of Toluene into a 50 mL three-neck flask. Equip the flask with a magnetic stirrer and a temperature probe. Set and maintain the temperature at 40°C.

- Injection and Nucleation: Using a syringe pump, inject 0.5 mL of the precursor solution into the vigorously stirring (1000 rpm) toluene at a constant rate of 1.0 mL/min.

- Reaction and Growth: Allow the reaction to proceed for 10 minutes at 40°C. The solution will turn from clear to a bright greenish-yellow, indicating PQD formation.

- Purification: Centrifuge the crude solution at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes. Discard the supernatant. Re-disperse the pellet in 1 mL of hexane and add 4 mL of methyl acetate (MA) to precipitate the PQDs again. Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes. Repeat this washing step once more.

- Storage: Finally, disperse the purified PQD pellet in 2 mL of hexane for storage and characterization.

Workflow and Parameter Relationship Diagrams

PQD Synthesis Workflow & Critical Parameters

Parameter Impact on Electronic Properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for CsPbBr3 PQD Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Critical Consideration for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Bromide (CsBr) | Cs+ precursor for the perovskite lattice. | High purity (>99.99%) is essential to minimize ionic impurities. Must be stored in a desiccator. |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr2) | Pb2+ and Br- precursor for the lattice. | High purity (>99.99%). Slight excess (5-10%) is often used to compensate for Pb-related defects. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Solvent for precursor salts. | Anhydrous grade. Acts as a coordinating solvent, influencing precursor stability. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand (L-type). Passivates bromine-rich sites. | Must be stored under inert atmosphere. Titrate to determine acid content if reproducibility is an issue. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Surface ligand (L-type). Passivates lead-rich sites. | Technical grade (~70%) is common but can introduce variability. Use high-purity (>98%) for better control. |

| Toluene | Antisolvent for the LARP process. | Anhydrous grade. Polarity and saturation pressure critically influence nucleation kinetics. |

| Methyl Acetate (MA) | Purification solvent (polar antisolvent). | Effectively precipitates PQDs and removes unbound ligands without causing degradation. |

Advanced Synthesis and Stabilization Techniques for Consistent PQDs

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Hot-Injection (HI) Method Troubleshooting

Q1: Why do I observe a wide photoluminescence (PL) full width at half maximum (FWHM) in my HI-synthesized perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), indicating poor size uniformity?

A: A wide PL FWHM (>25 nm for CsPbBr3) typically stems from non-uniform nucleation and growth. This is often caused by:

- Insufficient Temperature: The injection temperature is too low, leading to slow nucleation.

- Improper Injection Speed: Slow injection causes a gradient in precursor concentration, resulting in sequential nucleation events.

- Unstable Ligand Coverage: An imbalance in the ratio of oleic acid (OA) to oleylamine (OAm) fails to effectively passivate the PQD surface and control growth.

Protocol for Optimization:

- Calibrate the thermocouple in your heating mantle to ensure accurate temperature reporting.

- Systematically vary the injection temperature between 140-180°C for CsPbBr3.

- Practice a rapid, single-motion injection. Use syringes with wide-bore needles.

- Optimize the OA:OAm ratio. A common starting point is 1:1, but this should be tuned for your specific precursors and target size.

Q2: Why is my HI synthesis batch-to-batch reproducibility poor, with significant variations in PL peak wavelength and quantum yield (QY)?

A: Batch-to-batch variance is frequently due to inconsistent reaction conditions or precursor quality.

- Precursor Degradation: Metal halide precursors (e.g., PbBr2) are hygroscopic. Absorbed water leads to inconsistent reactivity.

- Oxygen and Moisture: The reaction is sensitive to O2 and H2O, which can create defect states.

- Timing Inconsistencies: The time between injection and cooling (reaction quenching) is critical.

Protocol for Optimization:

- Precursor Handling: Always use high-purity, anhydrous precursors. Store them in a nitrogen-filled glovebox and dry them under vacuum before use.

- Schlenk Line Technique: Ensure your Schlenk line provides a consistent, high-quality vacuum and inert gas flow. Purge the reaction flask for at least 30 minutes before heating.

- Standardize Quenching: Use a precise timer and a standardized cooling method (e.g., transferring the flask to a water bath at a specific time, such as 10 seconds post-injection).

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) Method Troubleshooting

Q3: Why does my LARP synthesis result in immediate precipitation or cloudiness instead of a clear, luminescent colloid?

A: Immediate precipitation indicates uncontrolled, bulk crystallization instead of confined nanocrystal growth. The primary cause is an excessive anti-solvent polarity or a too-rapid mixing process.

Protocol for Optimization:

- Modify Anti-Solvent Polarity: Instead of using pure toluene or chloroform as the anti-solvent, create a gradient by pre-mixing it with a small percentage (5-20%) of a solvent that has higher solubility for the precursors, such as N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) or Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

- Optimize Mixing Dynamics: Implement vigorous stirring (e.g., using a vortex mixer) during the anti-solvent addition to ensure instantaneous and homogeneous mixing, preventing local supersaturation spikes.

Q4: How can I improve the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and stability of my LARP-synthesized PQDs?

A: Low PLQY and poor stability are linked to surface defects and inadequate ligand binding.

- Ligand Concentration: The concentration of ligands (OA and OAm) in the "good solvent" is too low to effectively cap all nucleation sites.

- Ligand Ratio: An improper OA:OAm ratio can lead to non-stoichiometric surfaces and unpassivated lead or halide sites.

Protocol for Optimization:

- Systematically vary the total ligand concentration from 50-200 µL per mL of DMF.

- Titrate the OA:OAm ratio. A slight excess of OAm is often beneficial for lead-rich surfaces, but too much can destabilize the colloid. A ratio between 0.8:1 to 1.2:1 (OA:OAm) is a good range to explore.

- Consider post-synthesis treatments like dilution with anti-solvent and centrifugation to remove unbound ligands and poorly emitting aggregates.

Table 1: Optimized HI Synthesis Parameters for CsPbBr3 PQDs

| Parameter | Sub-optimal Range | Optimal Range | Typical Target Value | Key Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injection Temp. | 120-140 °C | 150-170 °C | 160 °C | Controls nucleation burst; higher temp = smaller size. |

| OA:OAm Ratio | <0.5 or >2.0 | 0.8 - 1.5 | 1:1 | Determines surface passivation & stability. |

| Reaction Time | >30 s | 5 - 15 s | 10 s | Governs growth phase; longer time = larger dots. |

| Pb:Br Ratio | <0.9 or >1.1 | 1:2 - 1:3 | 1:2.5 | Affects stoichiometry & defect density. |

| PL FWHM | >25 nm | 18 - 22 nm | ~20 nm | Indicator of size distribution uniformity. |

| PLQY | <50% | 70 - 95% | >80% | Measure of emissive efficiency. |

Table 2: Optimized LARP Synthesis Parameters for CsPbBr3 PQDs

| Parameter | Sub-optimal Range | Optimal Range | Typical Target Value | Key Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Conc. | >0.1 M | 0.05 - 0.08 M | 0.06 M | High conc. leads to aggregation. |

| Good:Anti-Solvent | <1:3 | 1:5 - 1:10 | 1:7 | Governs supersaturation level. |

| Total Ligand Vol. | <50 µL/mL | 75 - 150 µL/mL | 100 µL/mL | Ensures sufficient surface coverage. |

| Mixing Method | Gentle stirring | Vortex / Vigorous | Vortex | Ensures instantaneous mixing. |

| PL FWHM | >28 nm | 20 - 25 nm | ~22 nm | Indicator of size distribution uniformity. |

| PLQY | <40% | 50 - 85% | >70% | Measure of emissive efficiency. |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Title: Hot-Injection Synthesis Workflow

Title: LARP Cloudiness Troubleshooting

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Metal cation precursor for the PQD lattice. | Must be high-purity (≥99.99%), anhydrous, and stored in a glovebox. Hygroscopicity is a major source of batch variance. |

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Source for Cs-oleate precursor. | Reacts with oleic acid to form the Cs-Oleate stock solution used in HI. Must be thoroughly dried. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Primary surface ligand (carboxylate). | Passivates the PQD surface, controlling growth and preventing aggregation. Quality and age can affect deprotonation. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Primary surface ligand (amine). | Co-passivates the surface, often acts as the proton scavenger. The ratio to OA is critical for stability and PLQY. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-coordinating solvent for HI. | High boiling point allows for high-temperature reactions. Must be purified and stored over molecular sieves. |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | "Good solvent" for LARP. | Highly polar solvent that dissolves perovskite precursors. Anhydrous grade is essential. |

| Toluene | Common "anti-solvent" for LARP. | Low polarity induces supersaturation and nucleation when added to the DMF precursor solution. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Perovskite Quantum Dot (PQD) Research

This guide addresses frequent challenges in PQD research, providing solutions to improve the consistency and performance of your materials.

Table 1: Common PQD Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Properties | Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Surface defects (e.g., uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites) acting as non-radiative recombination centers. [14] [15] | Implement post-synthetic passivation with Lewis base ligands (e.g., trioctylphosphine oxide, didodecyldimethylammonium bromide). [16] [15] | |

| Batch-dependent emission wavelength | Uncontrolled growth/aggregation due to variable ligand coverage during synthesis or purification. [15] | Standardize purification protocols (precipitant volume, centrifugation speed/time). Monitor ligand concentration in supernatant. [17] [18] | ||

| Material Stability | Rapid degradation in aqueous environments | Instability of lead-based compositions; ligand desorption. [16] | Develop core-shell structures or encapsulate PQDs within stable matrices (e.g., Metal-Organic Frameworks, SiO₂). [16] [19] | |

| Loss of colloidal stability over time | Dynamic binding nature of traditional ligands (e.g., oleate) leading to aggregation. [15] | Employ multidentate or zwitterionic ligands that offer stronger, more stable surface binding. [15] | ||

| Electrical & Device Performance | Poor charge carrier transport in films | Excessive insulating organic ligands creating barriers between NCs. [14] | Perform controlled ligand exchange to shorter, conductive ligands (e.g., formate, acetate) or use inorganic ligands (e.g., halide salts). [14] [15] | |

| High device-to-device variation (e.g., in LEDs) | Inconsistent surface passivation and uncontrolled grain boundaries in thin films. [14] [17] | Adopt multi-functional passivation strategies (e.g., combining ionic and coordinate bonds) and implement statistical quality control for film characterization. [14] [17] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most effective chemical strategies for passivating defects on PQD surfaces? Effective passivation leverages specific chemical interactions to tie up surface defects, primarily uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions and halide vacancies. The most successful strategies often combine multiple approaches [14]:

- Ionic Bonding: Using alkylammonium halides (e.g., oleylammonium iodide) to provide halide ions that fill vacancies and ammonium groups to electrostatically interact with the surface. [14] [15]

- Coordinate Bonding: Employing Lewis base molecules (e.g., trioctylphosphine oxide, thiocyanates) that donate electron pairs to coordinate with under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites. This is highly effective for boosting PLQY. [14] [16]

- Hydrogen Bonding: Molecules with appropriate donor/acceptor groups can stabilize the surface crystal lattice and help bind other passivating agents. [14]

Q2: How can we quantitatively track and improve batch-to-batch reproducibility in PQD synthesis? Improving reproducibility requires a two-pronged approach: rigorous process control and statistical quality assessment.

- Process Standardization: Precisely control synthesis parameters (temperature, injection speed, ligand ratios) and establish fixed, documented purification protocols to minimize procedural drift. [18]

- Adopt Statistical Quality Control (QC): Implement a QC workflow similar to those used for other nanomaterials like laser-inscribed graphene. [17] This involves:

- High-Throughput Screening: Use rapid characterization techniques like photoluminescence spectroscopy or cyclic voltammetry on a large number of samples (e.g., n ≥ 36). [17]

- Statistical Clustering: Apply hierarchical clustering algorithms to the characterization data (e.g., PL spectra, voltammogram shapes) to group batches with similar performance and identify outliers. [17] This data-driven method allows researchers to select high-quality, consistent batches for device fabrication, reducing performance variation.

Q3: What are the best characterization techniques to verify successful surface passivation? A combination of techniques is necessary to confirm both the chemical and functional outcomes of passivation:

- Optical Spectroscopy: A direct increase in PLQY and a reduction in PL emission linewidth (FWHM) are primary indicators of successful defect passivation. [16] [15]

- Structural & Chemical Analysis: Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy can confirm the binding of passivating ligands to the PQD surface. [15] X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) can reveal changes in surface elemental composition and chemical states. [15]

- Functional Performance: In devices, improved external quantum efficiency (EQE) in LEDs and solar cells, along with enhanced operational stability, is the ultimate validation of effective passivation. [14] [15]

Experimental Protocols for Reproducible PQD Passivation

Protocol 1: Post-Synthetic Halide-Anion Exchange Passivation

This protocol details a method to enrich the surface halide coverage of CsPbX₃ PQDs, mitigating halide vacancy defects. [14] [15]

1. Principle Lead-halide PQDs are prone to losing surface halide ions (e.g., Br⁻), creating positive charges and uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites that quench luminescence. This passivation method introduces a source of halide ions (e.g., from PbX₂) in the presence of a Lewis acid scavenger (e.g., Lewis acid M⁺), which promotes the dissolution of PbX₂ and the subsequent binding of X⁻ to the PQD surface. [15]

2. Materials

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Synthesized CsPbBr₃ PQDs in non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene, hexane).

- Lead Bromide (PbBr₂): Source of halide ions for passivation.

- Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB): Provides both halide ions and ammonium-based surface stabilization.

- Anhydrous Solvents (e.g., N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO)): For dissolving PbBr₂.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. Pre-treatment Solution Preparation: Dissolve 10 mg of PbBr₂ in 1 mL of DMSO. In a separate vial, dissolve 20 mg of DDAB in 1 mL of toluene. 2. PQD Preparation: Transfer a known quantity (e.g., 5 mL) of the as-synthesized CsPbBr₃ PQD solution to a clean vial. 3. Passivation: Under vigorous stirring, add the DDAB solution (e.g., 100-200 µL) to the PQD solution. 4. Incubation: Continue stirring the mixture for 5-10 minutes at room temperature. 5. Purification: Precipitate the passivated PQDs by adding a polar anti-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate). Centrifuge the mixture, discard the supernatant, and re-disperse the pellet in a non-polar solvent. 6. Characterization: Compare the PLQY and PL lifetime of the PQDs before and after passivation to quantify the improvement.

Protocol 2: Quality Control Screening Using Hierarchical Clustering

This protocol adapts a statistical QC method from LIG manufacturing for assessing batch-to-batch consistency in PQD optical properties. [17]

1. Principle By characterizing a large batch of samples and using an unbiased clustering algorithm, researchers can objectively group similar-performing PQDs and identify outliers. This moves beyond single-point measurements to a more robust, data-driven selection process.

2. Workflow The following diagram illustrates the sequential steps for implementing this quality control process.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. High-Throughput Characterization: Prepare a large batch of PQD samples (e.g., n=36). Acquire PL emission spectra for all samples under identical instrument settings. 2. Data Extraction & Pre-processing: Extract key parameters from each spectrum, such as peak emission wavelength, Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM), and integrated PL intensity. Normalize the data if necessary. 3. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis: Use statistical software (e.g., R, Python) to perform hierarchical clustering on the extracted dataset. The open-source algorithm from Qian et al. (2024) for LIG electrodes can be adapted for this purpose. [17] This will group PQD samples with similar optical properties into distinct clusters on a dendrogram. 4. Cluster Identification & Selection: Analyze the dendrogram to identify the cluster(s) that contain samples with the desired properties (e.g., highest PL intensity, narrowest FWHM). Samples outside these clusters are considered outliers and can be excluded. 5. Validation: Use the selected PQDs from the optimal cluster for device fabrication. The performance variation (e.g., in LED efficiency) across devices should be significantly reduced compared to using randomly selected batches. [17]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for PQD Surface Engineering and Defect Mitigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Example(s) | Primary Function | Brief Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lewis Base Ligands | Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO), Oleylamine | Coordinate bonding to under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites. [15] | Electron pair donation from the P=O or amine group fills the empty orbital of Pb²⁺, suppressing non-radiative recombination. [15] |

| Halide Source Ligands | Oleylammonium Iodide (OAmI), Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Ionic bonding to fill halide vacancies. [14] [15] | Provides halide anions (I⁻, Br⁻) to fill vacancies, while the ammonium cation provides electrostatic stabilization. [14] [15] |

| Inorganic Salts | Lead Bromide (PbBr₂), Cesium Oleate (Cs-Ol) | Post-synthetic surface reconstruction and defect healing. [15] | Provides a source of both metal and halide ions to repair the perovskite lattice at the surface, often driven by Lewis acid-base interactions. [15] |

| Polymeric / Multidentate Ligands | Poly(ethylenimine) (PEI), Multidentate Zwitterions | Enhanced binding stability and aqueous compatibility. [16] | Multiple binding sites per molecule reduce ligand desorption, while hydrophilic groups can impart stability in water or buffer solutions. [16] |

| Encapsulation Matrices | Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), SiO₂ precursors | Formation of a core-shell structure. [16] | Creates a physical barrier that protects the PQD core from environmental factors (moisture, oxygen) and inhibits ion migration. [16] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Crystallinity in Composite COF Materials

Problem: The synthesized COF composite exhibits poor crystallinity, as evidenced by weak or absent peaks in Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) analysis.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient interaction with matrix | Analyze hydroxyl group density on matrix via FTIR; test different wood pre-treatment methods (e.g., delignification, plasma etching). | Pre-treat wood substrate to increase hydroxyl groups for stronger chemical bonding with COF building blocks [20]. |

| Unoptimized synthesis conditions | Perform PXRD after varying reaction time, temperature, and monomer concentration. | For quinoline-linked COFs (e.g., TFPA-TAPT-COF-Q), use a one-pot Povarov reaction with BF₃·OEt₂ catalyst in 1,4-dioxane/mesitylene to improve crystallinity over post-modification approaches [21]. |

| Rapid, irreversible reaction | Compare crystallinity of frameworks formed with reversible vs. irreversible linkers. | Introduce a degree of reversibility in linkage formation where possible, as this allows for error correction and defect healing, which are critical for achieving high crystallinity [22]. |

Weak Bonding Between COF and Stabilizing Matrix

Problem: The COF material detaches or leaches from the stabilizing matrix (e.g., wood, polymer) during application, especially in liquid-phase environments.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor interfacial compatibility | Use SEM to inspect the COF-matrix interface for gaps or poor adhesion. | Select a matrix with functional groups that can chemically interact with the COF. The abundant hydroxyl groups in wood can chemically bond with the functional groups of MOFs/COFs, enhancing the stability of the composite material [20]. |

| Physical adsorption only | Perform a stability test by vigorously stirring or sonicating the composite in a solvent. | Design the synthesis to promote covalent bonding or strong coordination between the COF and the matrix, rather than relying on weaker physical adsorption [20]. |

| Matrix pore size mismatch | Characterize the pore size distribution of the matrix (e.g., wood channels) and compare it with COF particle size. | Use a matrix with a hierarchical pore structure that can accommodate COF growth and interlocking. The microporous structure of wood provides ample physical space for the efficient loading of COFs [20]. |

Inadequate Chemical Stability in Harsh Conditions

Problem: The COF-based composite degrades, dissolves, or loses its structural integrity when exposed to harsh conditions such as strong acids, bases, or oxidants.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inherently weak imine linkages | Perform stability tests by immersing the COF in aqueous solutions of varying pH and analyzing the supernatant and solid residue via NMR or PXRD. | Replace inherently labile linkages (e.g., imine) with more robust ones. Convert imine linkages in photoactive COFs into quinoline groups, which display improved stability and maintained crystallinity under harsh photocatalytic conditions [21]. |

| Unstable matrix | Test the stability of the bare matrix separately under the target application conditions. | Select a chemically resistant matrix. For example, certain wood treatments can enhance its stability. Combine this with a robust COF to create a composite suitable for applications in harsh environments [20]. |

| Framework lacks cross-linking | Evaluate the dimensionality and connectivity of the COF structure via molecular modeling. | Employ building blocks that promote the formation of 3D COF networks, which can exhibit higher stability compared to some 2D structures [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the batch-to-batch reproducibility of my COF-composite's electronic properties so poor? Reproducibility issues often stem from inconsistencies in the COF's crystallinity, porosity, and the uniformity of its integration with the stabilizing matrix. Key factors to control include:

- Linkage Robustness: Using chemically robust linkages (e.g., quinoline, triazine) reduces framework degradation during synthesis and application, leading to more consistent electronic structures [22] [21].

- Matrix Functionalization: Ensure consistent pre-treatment of the stabilizing matrix (e.g., wood) to guarantee a uniform density of functional groups (e.g., -OH) available for bonding with the COF [20].

- Synthetic Protocol: Precisely adhere to reaction parameters (catalyst amount, solvent ratio, temperature, time). For example, the one-pot synthesis of TFPA-TAPT-COF-Q provides higher yield and better reproducibility than post-synthetic modification routes [21].

Q2: Which stabilizing matrices are most effective for enhancing the mechanical robustness of COFs? Natural wood is a highly promising matrix due to its unique compositional and structural advantages [20].

- Mechanical Support: Wood provides a strong, lightweight scaffold that enhances the overall mechanical strength of the composite.

- Chemical Bonding: The abundance of hydroxyl groups on wood fibers can form chemical bonds with COF functional groups, preventing shedding and enhancing interfacial stability.

- Hierarchical Porosity: The natural pore structure of wood allows for efficient loading of COFs and provides a rich network of transport pathways.

Q3: How can I rapidly screen for COF-composites with the desired thermal and mechanical properties? Traditional trial-and-error is time-consuming. A more efficient strategy involves the synergistic use of computational tools [24] [23]:

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Use to calculate electronic structure, binding energies, and predict intrinsic thermal/mechanical stability at the atomic level.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD): Employ to simulate ion transport, polymer chain dynamics, and framework response to mechanical stress or heat flow.

- Machine Learning (ML): Leverage data-driven models trained on existing COF databases to predict properties like thermal conductivity and bulk modulus for new structures, dramatically accelerating the design cycle.

Q4: My COF-composite performs well in the lab but fails in real-world harsh condition applications. How can I improve its operational stability? The key is to proactively design for stability under application-relevant harsh conditions [21]:

- Strong Oxidative Environments: For applications like photocatalytic H₂O₂ production, imine-linked COFs can decompose. Replacing them with quinoline-linked COFs (e.g., TFPA-TAPT-COF-Q) can yield a stable photocatalyst with high efficiency (up to 11831.6 μmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹) and long-term recyclability.

- Extreme pH: Select a COF linkage known for its stability in acidic or basic environments (e.g., β-ketoenamine, quinoline) and pair it with a matrix that is similarly inert under those conditions.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Synthesis of a Robust Quinoline-Linked COF (TFPA-TAPT-COF-Q)

This protocol describes a one-pot synthesis for creating a highly stable, photoactive COF, suitable for harsh condition applications [21].

1. Reagents and Equipment:

- Tris(4-formylphenyl)amine (TFPA)

- 1,3,5-tris-(4-aminophenyl)triazine (TAPT)

- Phenylacetylene

- Boron trifluoride diethyl etherate (BF₃·OEt₂)

- Anhydrous 1,4-dioxane

- Anhydrous mesitylene

- Pyrex tube (10 mL)

- Freeze-pump-thaw setup

- Oven (120°C)

2. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: In a 10 mL Pyrex tube, combine TFPA (0.05 mmol), TAPT (0.05 mmol), and phenylacetylene (0.4 mmol).

- Step 2: Add a solvent mixture of 1,4-dioxane (1.0 mL) and mesitylene (1.0 mL).

- Step 3: Add BF₃·OEt₂ (0.2 mL) as a catalyst to the reaction mixture.

- Step 4: Sonicate the mixture until all solids are fully dissolved.

- Step 5: Subject the solution to three freeze-pump-thaw cycles to remove oxygen.

- Step 6: Seal the tube under vacuum and heat it in an oven at 120°C for 3 days.

- Step 7: After cooling, collect the resulting yellow solid by filtration.

- Step 8: Wash the solid thoroughly with anhydrous 1,4-dioxane and anhydrous acetone.

- Step 9: Activate the product by drying under vacuum at 120°C for 12 hours to yield TFPA-TAPT-COF-Q.

3. Characterization:

- PXRD: Confirm crystallinity. Key peaks for TFPA-TAPT-COF-Q should appear at 2θ = 4.48° (100), 7.74° (110), 8.92° (200), and 11.82° (210) [21].

- FTIR: Monitor the disappearance of aldehyde C=O stretches and the formation of C=N and C=C stretches characteristic of the quinoline ring.

- N₂ Sorption: Analyze porosity and surface area (BET).

Quantitative Comparison of Robust COF Linkages

The following table summarizes key performance data for different COF linkages, highlighting the superiority of robust designs.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of COF Linkages and Composites

| Material / Linkage Type | Key Stability Feature | Performance Metric | Application & Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quinoline-linked COF (TFPA-TAPT-COF-Q) [21] | High stability under strong oxidative conditions | H₂O₂ production: 11,831.6 μmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹; Maintains crystallinity over multiple cycles | Photocatalysis: Effective and recyclable under conditions that decompose imine-linked COFs. |

| COF/Wood Composite [20] | Chemical bonding between wood -OH and COFs | Significant improvement in composite stability and functionality vs. powdered COFs. | Environmental Remediation: Enhanced adsorption properties, catalytic activity, and separation efficiency. |

| Theoretical Screening (High-throughput) [23] | Identification of COFs with high bulk modulus and thermal conductivity | Bulk Modulus: <0.1 to 100 GPA; Thermal Conductivity: ~0.02 to 50 W m⁻¹ K⁻¹ | Multifunctional Design: Data-driven discovery of COFs with tailored mechanical and thermal properties. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

COF Stabilization Strategy Map

Composite Material Synthesis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Robust COF and Composite Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Tris(4-formylphenyl)amine (TFPA) | Electron-donating, photoactive aldehyde monomer for COF synthesis. | Building block for constructing photoactive COFs like TFPA-TAPT-COF-Q for photocatalysis [21]. |

| 1,3,5-tris-(4-aminophenyl)triazine (TAPT) | Electron-accepting, planar triazine-based amine monomer. | Co-monomer with TFPA to create donor-acceptor COFs with enhanced π-communication and crystallinity [21]. |

| Boron Trifluoride Diethyl Etherate (BF₃·OEt₂) | Lewis acid catalyst for facilitating specific linkage formation. | Catalyst for the Povarov reaction, converting imine linkages into more robust quinoline groups in COFs [21]. |

| Phenylacetylene | A reactant in the Povarov cyclization reaction. | Used as a dienophile to convert imine bonds in COFs into substituted quinoline linkages, enhancing stability [21]. |

| Delignified Wood Scaffolds | A natural, porous, and mechanically strong stabilizing matrix. | Serves as a substrate for in-situ growth of COFs, enhancing composite stability via chemical bonding with wood hydroxyl groups [20]. |

| Anhydrous 1,4-Dioxane & Mesitylene | Solvent system for COF synthesis. | Mixed solvent used in the one-pot synthesis of quinoline-linked COFs (e.g., TFPA-TAPT-COF-Q) to achieve optimal crystallinity [21]. |

Leveraging Machine Learning for Predictive Synthesis and Inverse Design

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Model Performance and Poor Reproducibility Between Experimental Batches

Problem Description: A model that accurately predicts Perovskite Quantum Dot (PQD) properties, such as photoluminescence (PL) or absorbance, during training performs erratically when used to guide new synthesis batches, leading to inconsistent electronic properties in the final product.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Check Data Consistency and Versioning: Inconsistent data is a primary culprit for poor reproducibility [25]. Ensure that the exact dataset version used for model training is employed for all predictions. Implement data version control tools like DVC (Data Version Control) to create immutable snapshots of your training data [25].

- Control Randomness: Machine learning training processes inherently involve randomness from weight initialization, data shuffling, and dropout layers, which can lead to significant variations in outcomes [25]. Set and record random seeds for all random number generators in your code (e.g., in Python, NumPy, and deep learning frameworks like TensorFlow/PyTorch) to ensure consistent model initialization and data sampling [25].

- Verify Hyperparameters and Environment: Even minor undocumented changes to hyperparameters or the software environment can drastically alter results [25]. Meticulously log all hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, batch size, number of layers) and use environment management tools like Docker or Conda to replicate the exact software library versions and system dependencies used during the initial successful training [25] [26].

- Audit the Surrogate Model: In iterative design workflows, the performance of the ML surrogate model (e.g., a Graph Convolutional Neural Network) can degrade when applied to newly generated molecules that are structurally different from its original training data [27]. Continuously evaluate the model's prediction error (e.g., Mean Absolute Error) on new batches and retrain the model with data from the new chemical space to maintain accuracy [27].

Issue 2: Failure of Inverse Design to Generate Feasible or High-Performing Candidates

Problem Description: The generative model (e.g., a Masked Language Model or Variational Autoencoder) produces molecular structures that are chemically invalid, have low synthetic accessibility, or do not possess the target electronic properties.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Validate and Filter Outputs: Implement a post-generation filtering step. Use validity, uniqueness, and similarity metrics to assess generated ligands or molecules [28]. Leverage tools like RDKit to check molecular validity and compute synthetic accessibility scores to prioritize candidates that are feasible to synthesize in the lab [28].

- Refine Model Conditioning: The generative model may not be adequately constrained by the target property. Ensure the model is correctly conditioned on the desired outcome (e.g., a specific HOMO-LUMO gap for PQDs) [27]. In architecture design, this involves learning the conditional distribution of design features relative to performance objectives [29].

- Expand and Rebalance Training Data: If the model consistently generates structures with little diversity or poor performance, the training data may lack sufficient examples of high-performing candidates or be biased towards certain structural motifs [27]. Curate a larger, more balanced dataset that includes both positive and negative examples (failed syntheses) to improve the model's coverage of the chemical space [28].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most suitable machine learning models for predicting the properties of Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs)? Different ML models offer varying advantages. A study focusing on predicting the size, absorbance, and photoluminescence of CsPbCl₃ PQDs found that Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Nearest Neighbour Distance (NND) models demonstrated the highest accuracy [30]. The table below summarizes the performance of various models evaluated in this context.

Table 1: Performance of ML Models for Predicting CsPbCl₃ PQD Properties [30]

| Machine Learning Model | Reported Strengths / Performance |

|---|---|

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | One of the best for accurate property prediction, achieving high R², low RMSE, and low MAE on test data. |

| Nearest Neighbour Distance (NND) | One of the best for accurate property prediction, achieving high R², low RMSE, and low MAE on test data. |

| Random Forest (RF) | High performance; often used for predicting synthesis parameters like time and temperature. |

| Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) | Used for property prediction. |

| Decision Tree (DT) | Used for property prediction. |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Used for property prediction; neural networks can learn faster with growing dataset sizes. |

Q2: Our dataset of successful PQD syntheses is relatively small. Can we still use machine learning effectively? Yes. The study on CsPbCl₃ PQDs utilized a dataset of 708 data points (531 input parameters, 177 output properties) and found it sufficient for accurate prediction of nanocrystal properties [30]. The key is to use models that perform well with smaller datasets, such as SVR, Random Forest, or Gradient Boosting [30]. Furthermore, you can employ techniques like data augmentation and leverage pre-trained models on larger chemical databases, fine-tuning them on your specific PQD data.

Q3: In an inverse design workflow, what is a common reason for a large discrepancy between a surrogate model's prediction and the actual measured property of a synthesized molecule? This is often a problem of generalization error. The surrogate model (e.g., a Graph Neural Network) may have been trained on a molecular dataset that does not adequately cover the region of chemical space explored by the generative model [27]. For instance, if your generative model creates molecules with more atoms or strained rings not present in the original training data, the surrogate model's predictions become less reliable. The solution is to implement an iterative workflow where the surrogate model is periodically retrained using new experimental data from the generated candidates, thus improving its accuracy for the relevant chemical space [27].

Q4: What core technical components are required to build a reproducible ML-driven inverse design pipeline? A reproducible pipeline rests on three core pillars [25] [26]:

- Code Versioning and Tracking: Use Git to track every change to model architecture, hyperparameters, and preprocessing steps.

- Data Versioning and Consistency: Use tools like DVC to create immutable snapshots of training datasets, preventing silent failures from data drift.

- Environment and Dependency Management: Use Docker or Conda to document and replicate the exact software environment, including library versions and system dependencies.

Experimental Protocol: Iterative Inverse Design for Molecules with Target Electronic Properties

This protocol details a workflow for the inverse design of molecules, such as PQDs, with a target HOMO-LUMO gap (HLG), integrating elements from several successful studies [28] [27] [31].

1. Objective To iteratively generate and screen novel molecular structures with a user-specified HOMO-LUMO gap.

2. Materials and Computational Resources

- High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster: For running quantum chemical calculations.

- Quantum Chemistry Software: For example, a Density-Functional Tight-Binding (DFTB) package [27] or Density Functional Theory (DFT) software for generating reference property data.

- Machine Learning Libraries: Python libraries such as scikit-learn, PyTorch/TensorFlow, and RDKit.

3. Methodology The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow for inverse molecular design:

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Workflow

| Item / Software | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| DFTB/DFT Software | Generates high-fidelity ground truth data for molecular properties (e.g., HOMO-LUMO gap) used to train the surrogate model [27]. |

| Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GCNN) | Acts as a fast surrogate model to predict the target property (e.g., HLG) for new molecules, bypassing slow quantum chemistry calculations [27]. |

| Masked Language Model (MLM) | A generative model that creates novel molecular structures by mutating selected molecular data from the database [27]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used to handle molecular descriptors, check chemical validity, and compute synthetic accessibility scores [28]. |

| SynMOF Database / Similar | Example of a specialized database (here for Metal-Organic Frameworks) that provides structured data linking synthesis parameters to resulting structures, essential for training [31]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initial Data Preparation: Begin with a curated database of molecular structures and their associated properties. For organic molecules, a common starting point is the GDB-9 database [27].

- Generate Ground Truth Data: Use an approximate quantum chemical method like DFTB (or higher-accuracy DFT if resources allow) to calculate the target property, the HOMO-LUMO gap, for all molecules in the starting database. This creates the "ground truth" dataset [27].

- Train Surrogate Model: Train a Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GCNN) as a surrogate model. The input is the molecular structure (e.g., from a SMILES string), and the output is the predicted HLG. Validate the model's performance using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [27].

- Generate New Candidates: Use a pre-trained generative model, such as a Masked Language Model (MLM), to create new molecular structures. This is done by mutating the molecular structures in the current database [27].

- Predict and Filter: Use the trained GCNN surrogate model to rapidly predict the HLG for the newly generated molecules. Filter the candidates to select those with HLG values closest to your target.

- Iterate and Retrain: Add the newly generated molecules and their predicted properties to the database. To maintain prediction accuracy, periodically retrain the GCNN surrogate model on the expanded dataset. This step is crucial for keeping the model accurate as the generative process explores new regions of chemical space [27].

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize the top-performing candidate molecules predicted by the final iteration of the workflow and experimentally characterize their electronic properties to validate the model's predictions.

Transitioning a synthesis from laboratory to industrial production presents significant challenges for researchers and scientists, particularly in achieving consistent batch-to-batch reproducibility. At the laboratory scale, processes are conducted under ideal, controlled conditions. However, scaling up introduces new physical constraints and variables that can drastically alter process outcomes and final product properties [32] [33]. A successful scale-up strategy requires meticulous planning, a deep understanding of chemical processes, and anticipation of potential issues that do not manifest at smaller scales [32]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help bridge this critical gap, with a specific focus on maintaining electronic property consistency in advanced materials.

Troubleshooting Common Scale-Up Issues

Troubleshooting Guide: Process Inconsistencies

Problem: Inconsistent product quality or yield between laboratory and pilot-scale batches.

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Heat Transfer [32] | Inefficient heating/cooling at larger scales; different surface-to-volume ratios. | Implement advanced heating/cooling systems; adjust process parameters to maintain optimal reaction temperature. |

| Mixing & Mass Transfer Inefficiencies [32] | Altered flow patterns; formation of dead zones; insufficient shear. | Optimize reactor design and impeller type/ speed; adjust viscosity; consider staged addition of reagents. |

| Inconsistent Reaction Kinetics [33] | Changes in oxygen transfer or concentration gradients. | Conduct pilot tests (e.g., 10-100 L); monitor and control dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, and agitation. |

| Unoptimized Scale-Up Ratio [32] | Linear scaling without accounting for nonlinear changes in process dynamics. | Use simulation tools and pilot trials to determine the optimal scale-up factor; employ step-wise scaling. |

| Raw Material Variability [32] | Differences in quality or purity between lab and production-grade materials. | Secure a consistent supply; evaluate and qualify suppliers; implement strict raw material quality control. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Equipment & Operational Issues

Problem: Equipment malfunctions or operational failures during scaled-up production.

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Failed Batches [33] | Unforeseen process deviations; equipment not suited for the scaled process. | Use pilot-scale equipment for validation; develop robust Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs); invest in automation for traceability. |

| Equipment Not to Specification [34] | Incorrect equipment selection for the specific product or process requirements. | Consult with equipment suppliers early; select machinery based on product characteristics (viscosity, shear sensitivity). |

| Supply Chain Disruptions [32] | Inability to secure consistent quantities of required raw materials for larger batches. | Develop robust supply chain strategies; diversify suppliers; explore alternative materials where possible. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Scale-Up

Q1: What is the most critical first step in planning a scale-up? A: The most critical step is to thoroughly understand and document your lab-scale process, including all key steps and critical parameters like mixing speed, temperature, and time [34]. This documentation provides the essential baseline for identifying which parameters are most sensitive to change during scaling.

Q2: Why is heat transfer often a problem during scale-up? A: Heat transfer does not scale linearly. As batch size increases, the surface area-to-volume ratio decreases, making heat dissipation less efficient [32] [34]. This can lead to hot spots, degraded product quality, or safety hazards. Advanced cooling systems and process adjustments are often required.

Q3: How can we improve batch-to-batch reproducibility at the industrial scale? A: Key strategies include: 1) Implementing rigorous quality control protocols with in-process checks [32]; 2) Developing and adhering to detailed Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) [34]; 3) Using automation and monitoring systems to control process parameters like pH, DO, and temperature in real-time [33]; and 4) Ensuring raw material consistency [32].

Q4: What role does pilot plant testing play? A: Pilot testing (typically at 10-100 L scales) is essential for validating process parameters, identifying unforeseen challenges like mixing inefficiencies, and generating data for the design of the full-scale commercial process [32] [33]. It is a critical risk-reduction step.

Q5: How do we choose the right equipment for scale-up? A: Equipment selection should be driven by the product and process needs, not just a desire for larger capacity. Key factors include the type of agitation, heating/cooling capabilities, material of construction (e.g., 316L stainless steel), and scalability. Consulting with an experienced equipment supplier is highly recommended [34].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

General Scale-Up Workflow

The following workflow outlines a systematic approach for transitioning a process from laboratory synthesis to industrial production.