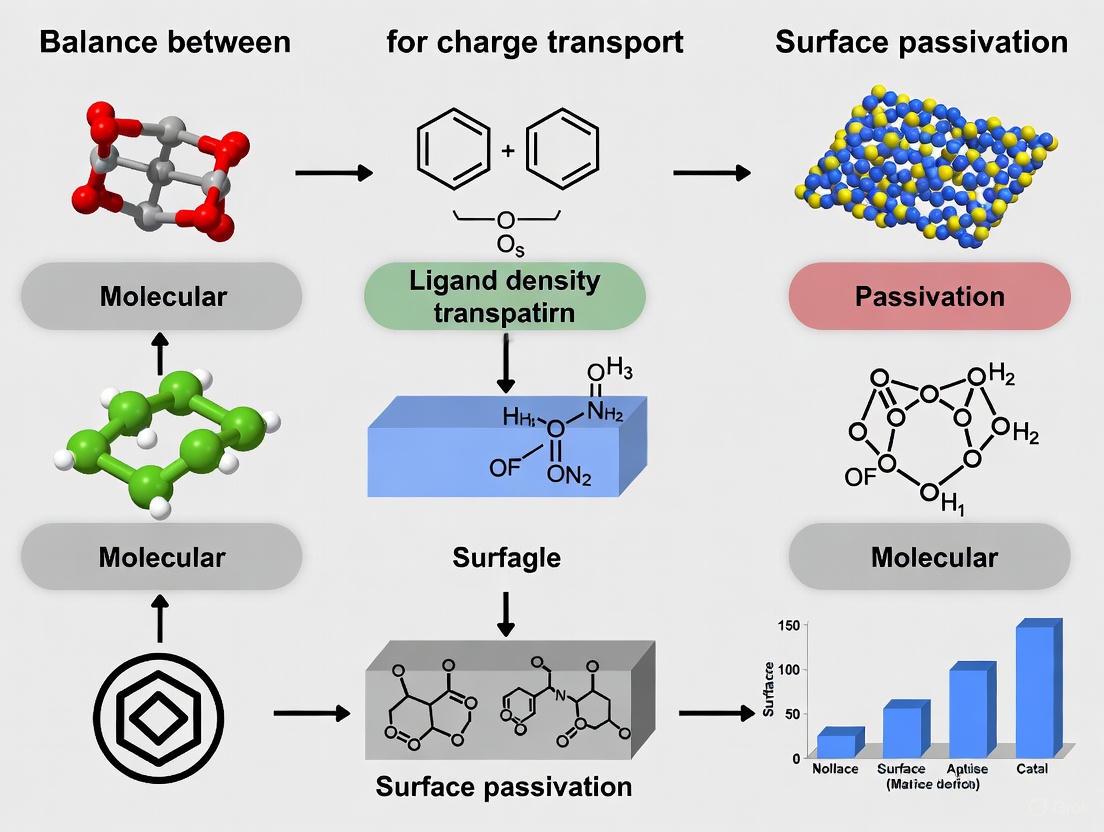

Strategic Ligand Engineering: Balancing Surface Passivation and Charge Transport in Nanomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical challenge of optimizing ligand density on nanomaterial surfaces.

Strategic Ligand Engineering: Balancing Surface Passivation and Charge Transport in Nanomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical challenge of optimizing ligand density on nanomaterial surfaces. It explores the fundamental trade-off where high ligand density ensures colloidal stability and effective surface passivation but hinders charge transport—a property vital for sensing, imaging, and therapeutic applications. The content covers foundational principles of chemical and field-effect passivation, advanced methodological strategies for in-situ and post-synthesis ligand engineering, troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing recent scientific advances, this review offers a strategic framework for designing next-generation nanomedicines and diagnostic tools with precisely tuned functionalities.

The Fundamental Dilemma: How Ligand Chemistry Dictates Passivation and Conductivity

What is surface passivation and why is it critical for semiconductor devices?

Surface passivation is a fundamental process in semiconductor technology that minimizes the influence of electrically active defects at the material's surface. These defects, where the crystal lattice is disrupted, serve as sites where charge carriers (electrons and holes) can recombine, rather than contributing to device function. This undesired recombination significantly reduces device efficiency and performance. Passivation is achieved through treatments that either chemically saturate these defective bonds or create electric fields that shield charge carriers from the surface. As devices continue to shrink and adopt higher surface-to-volume ratios (e.g., in finFETs, nanosheets, and thinner solar cells), effective surface passivation has become a cornerstone of modern semiconductor technology [1].

What are the two primary mechanisms of surface passivation?

The two primary mechanisms are chemical passivation and field-effect passivation. Both aim to reduce surface recombination but achieve this through fundamentally different principles [1] [2]:

- Chemical Passivation: This method focuses on the "defect sites" themselves. It reduces the density of electronic defect states at the semiconductor surface by saturating the dangling bonds with chemical species. A common example is the use of a thin film that bonds to the semiconductor surface, lowering the interface defect density (D~it~) [1].

- Field-Effect Passivation: This method addresses the "charge carriers" required for recombination. It uses fixed electrical charges (Q~f~) within a thin film applied to the semiconductor surface to create an internal electric field. This field repels one type of charge carrier from the surface region, drastically reducing the probability that electrons and holes will meet and recombine [1] [2].

The following diagram illustrates these core mechanisms and their components.

Troubleshooting Common Passivation Issues

Why is my device performance still poor after applying a passivation layer?

Effective passivation requires addressing both mechanisms. Poor performance can persist if only one mechanism is optimized. The table below outlines common issues and their solutions.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| High surface recombination | Incomplete chemical passivation; high interface defect density (D~it~). | Measure D~it~ using capacitance-voltage or photoconductance decay. | Optimize pre-treatment cleaning; use a film known for superior chemical passivation (e.g., Al~2~O~3~ for Si). |

| Low field-effect passivation | Insufficient fixed charge (Q~f~) in the passivation layer. | Characterize Q~f~ using Kelvin Probe or similar techniques. | Use a material with high intrinsic fixed charge; consider a stacked layer (e.g., PO~x~/Al~2~O~3~ for n-type Si). |

| Inconsistent results | Unstable or contaminated surface before deposition. | Check for native oxide or organic residues via XPS or AES. | Implement atomic-scale cleaning (e.g., atomic layer cleaning, HF dip) immediately before deposition. |

| Performance degradation over time | Damage to the passivation layer or underlying interface. | Perform long-term stability testing (damp heat, bias stress). | Apply a capping layer (e.g., Al~2~O~3~ over a hygroscopic PO~x~ layer on InP). |

How do I choose between chemical and field-effect passivation strategies?

The choice is not mutually exclusive; the most effective passivation schemes often leverage both. Your strategy should be guided by the semiconductor material and the dominant charge carrier in your device.

- For Silicon Solar Cells: A combination is industry standard. Aluminum oxide (Al~2~O~3~) deposited via Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) provides excellent field-effect passivation due to its high negative fixed charge, which repels electrons and creates a hole-rich layer at the surface of p-type silicon. It also offers good chemical passivation [1] [2].

- For Germanium and III-V Semiconductors: These materials often have more challenging surface chemistries. Germanium's native oxide is defective and unstable, requiring a stack approach. A successful method uses amorphous silicon for chemical passivation followed by Al~2~O~3~ for field-effect passivation [1]. For Indium Phosphide (InP), a PO~x~/Al~2~O~3~ stack works well, where PO~x~ acts as a phosphorus reservoir to fill vacancies (chemical passivation) and Al~2~O~3~ provides field-effect passivation and environmental protection [1].

- For Nanocrystal Devices: The focus is on ligand engineering. Long, insulating ligands used in synthesis must be exchanged for shorter ones to facilitate charge transport. The choice of ligand (e.g., alkylammonium iodides for PbS quantum dots) directly affects passivation quality and trap state density [3]. The steric bulk and acidity of the ligand can be tuned to optimize the exchange process [4] [3].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

What is a standard workflow for achieving atomic-scale surface passivation?

A robust experimental protocol for high-quality surface passivation, particularly for research on novel materials, involves multiple critical steps as shown in the workflow below.

Detailed Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation and Cleaning: Begin with a standard solvent cleaning sequence (e.g., acetone, isopropanol in an ultrasonic bath) to remove organic contaminants. This is a universal first step referenced in both semiconductor and stainless steel passivation guides [5].

- Surface Pre-Treatment: This is critical for removing the native oxide layer and achieving a pristine, H-terminated surface. A common method is a 1-2% HF acid dip for 60-90 seconds, followed by a deionized water rinse. For the highest quality, atomic layer etching (ALE) can be used for ultimate precision [1].

- Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD): ALD is preferred for its unparalleled conformality and atomic-scale thickness control. Deposit your chosen passivation material (e.g., Al~2~O~3~, SiO~2~). A typical thermal ALD process for Al~2~O~3~ uses trimethylaluminum (TMA) and H~2~O as precursors, with a substrate temperature of 150-300°C and cycles defining the thickness (e.g., ~10-30 nm) [1].

- Post-Deposition Annealing: Anneal the sample in a nitrogen or forming gas (N~2~/H~2~) atmosphere. A standard condition for Al~2~O~3~ on Si is 30 minutes at 400-450°C. This step is crucial for activating the field-effect passivation by driving hydrogen to the interface to saturate dangling bonds and stabilizing the fixed charges [1].

- Passivation Quality Characterization: Use quasi-steady-state photoconductance (QSSPC) to measure the effective carrier lifetime (τ~eff~) and calculate the surface recombination velocity (SRV). Lower SRV indicates better passivation. Complement this with C-V measurements to determine the fixed charge density (Q~f~) and interface defect density (D~it~) [1].

How do I systematically investigate the trade-off between surface passivation and molecular sensitization?

This trade-off is central to applications like lanthanide-doped nanoparticles (LnNPs) for photonics. The core conflict is that a thick, high-quality passivation shell minimizes surface quenching but also impedes energy transfer from surrounding sensitizer molecules.

Experimental Protocol:

- Material Synthesis: Fabricate core-shell nanoparticles (e.g., NaGdF~4~:Yb,Er@NaGdF~4~) with precisely controlled shell thicknesses, ranging from sub-nanometer (e.g., 0.8 nm) to several nanometers (e.g., 3.0 nm). Precise control is key, achieved by varying the amount of injected shell precursor [6].

- Hybrid System Fabrication: Create the nanohybrid system by grafting sensitizer molecules (e.g., 9-anthracenecarboxylic acid) onto the nanoparticle surface via ligand exchange [6].

- Spectroscopic Characterization:

- Steady-State Spectroscopy: Measure upconversion and downshifting luminescence intensities under standardized excitation. Plot enhancement factor versus shell thickness.

- Time-Resolved Spectroscopy: Measure luminescence lifetimes (e.g., of Er~3+~ at 1530 nm) to directly track the suppression of non-radiative decay pathways.

- Advanced Dynamics: Use transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy to elucidate the temporal dynamics of energy-transfer processes, including intersystem crossing and triplet energy transfer [6].

Key Quantitative Findings from a Model System: The data below, derived from a systematic study, highlights the non-monotonic nature of this trade-off [6].

| Shell Thickness (nm) | Upconversion Enhancement (fold) | Downshifting Enhancement (fold) | Er³⁺ Lifetime at 1530 nm (ms) | Energy Transfer Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Core only) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 0.4 | High but luminescence is weak |

| ~0.8 | 26 | Not Specified | Not Specified | Optimal |

| ~1.5 | ~70 | ~2 | ~1.5 | Good |

| ~2.2 | ~140 | ~4 | ~2.8 | Moderate |

| ~3.0 | 290 | 25 | 4.6 | Low |

Conclusion: The optimal shell thickness for balancing luminescence intensity and sensitization efficiency was found to be an intermediate value of ~0.8 nm, not the thickest shell nor no shell at all [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

This table details key materials used in surface passivation experiments across different platforms.

| Item | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum Oxide (Al₂O₃) | Passivation layer for Si, Ge, and III-V materials. Provides high negative fixed charge for field-effect passivation. | Typically deposited via ALD. Requires post-deposition annealing for activation [1]. |

| Tetra-n-butylammonium iodide (TBAI) | Standard ligand for iodide passivation of PbS quantum dots (n-type layer). Replaces long-chain oleate ligands. | Steric crowding of alkyl groups can limit ligand exchange efficiency [3]. |

| Triethylamine hydroiodide (tri-EAHI) | Less sterically crowded alternative to TBAI for PbS CQDs. Enables more effective iodide passivation. | Higher acidity and greater ionic dissociation improve oleate removal and defect passivation [3]. |

| Citric Acid / Nitric Acid | Chemicals for the passivation of stainless steel, removing free iron to form a protective chromium oxide layer. | Citric acid is a safer, more environmentally friendly alternative to nitric acid [5]. |

| Alkylammonium Iodides (AMIs) | A class of ligands for CQD passivation. The structure (chain length, primary/tertiary/quaternary) dictates passivation efficacy. | Less sterically crowded and more acidic AMIs generally perform better [3]. |

| Phosphorus Oxide (POₓ) | Used in passivation stacks (e.g., POₓ/Al₂O₃) for InP and n-type Si. Acts as a phosphorus reservoir and source of high fixed charge. | Hygroscopic; requires an Al₂O₃ capping layer for stability [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What's the difference between passivation and electropolishing?

Passivation is a chemical process that improves corrosion resistance by removing free iron and enhancing the native oxide layer, but it does not significantly alter the surface appearance or remove material. Electropolishing is an electrochemical process that acts as a micro-etch, removing a thin layer of surface material to deburr, smooth, and brighten the surface, while also improving corrosion resistance [7].

Can passivation be performed more than once?

Yes, stainless steel can be repassivated, especially if the surface has become contaminated or damaged. However, for semiconductor thin films, the process is typically integral to device fabrication and is not repeated [8].

How is the success of a passivation treatment verified?

Verification depends on the application:

- For Semiconductor Wafers: The effectiveness is quantified by measuring the effective minority carrier lifetime (τ~eff~) or the derived surface recombination velocity (SRV) using techniques like photoconductance decay. Lower SRV indicates superior passivation [1].

- For Stainless Steel: Tests like the Salt Spray (ASTM B-117) or Copper Sulfate test are used to check for free iron and corrosion resistance. Advanced analytical techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) can quantitatively determine the Chromium-to-Iron ratio in the surface oxide layer [9].

For researchers engineering functional nanomaterials, from nanoparticles for drug delivery to perovskites for photovoltaics, ligand engineering is a powerful tool. A central challenge lies in optimizing ligand surface density to balance two competing imperatives: effective surface passivation for defect suppression and efficient electronic coupling for charge transport. This technical guide provides troubleshooting and methodologies to navigate these trade-offs in your experimental work.

FAQs: Core Concepts for Researchers

Q1: What is the fundamental trade-off between ligand density and electronic coupling? High ligand density provides superior surface passivation by saturating dangling bonds and reducing defect states, which minimizes charge carrier recombination. However, as the ligand shell becomes denser and thicker, it can physically separate the conductive cores of nanomaterials or create insulating barriers that disrupt the electronic wavefunction overlap between sites. This leads to a crossover from band-like to hopping charge transport, significantly reducing charge carrier mobility [10] [11]. The optimal density is a compromise that provides sufficient passivation without excessively degrading conductivity.

Q2: How does ligand density influence the passivation mechanism? Ligand density directly impacts two primary passivation mechanisms:

- Chemical Passivation: High ligand density ensures maximum coverage of surface atoms, eliminating dangling bonds that act as electronic trap states. This reduces the interface defect density (D~it~), a key parameter for device performance [1] [12].

- Field-Effect Passivation: In some systems, the ligand layer itself can contain fixed electrical charges (Q~f~). A well-controlled, dense layer of such ligands can induce an electric field that repels one type of charge carrier (electrons or holes) from the surface, thereby reducing the probability of surface recombination even further [1].

Q3: Which experimental techniques can characterize ligand density and its effects? Several techniques are essential for correlating ligand density with functional outcomes:

- Solution NMR Spectroscopy: Can probe ligand-NP interactions, providing structural, kinetic, and thermodynamic information on sorption equilibria. It is particularly powerful for investigating dynamic processes at nanoparticle surfaces [13].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Identifies chemical states and confirms passivation by showing binding energy shifts, providing direct evidence of ligand interaction with under-coordinated surface ions (e.g., Pb2+ in perovskites) [14].

- Electrical Characterization: Techniques like space-charge-limited current (SCLC) measurements can quantify the reduction in defect density upon passivation, while field-effect transistor measurements can track the mobility degradation as ligand density increases [10] [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent performance results despite using the same ligand concentration.

- Potential Cause: The actual ligand surface density is not controlled, leading to variable coverage. The Langmuir model for adsorption assumes a homogeneous surface, but real-world nanoparticle samples have heterogenous surfaces and morphologies [13].

- Solution: Do not rely solely on the concentration of ligand in solution. Use a surfactant mixture strategy during synthesis to directly control the number of reactive sites on the nanomaterial surface. Systematically vary the ratio of functional (e.g., carboxyl-terminated) to non-functional (e.g., hydroxyl-terminated) surfactants to fine-tune the density of conjugated ligands [15]. Always use complementary analytical techniques (e.g., XPS, NMR) to quantify the achieved surface density.

Problem: Significant voltage loss (V~OC~ deficit) in a perovskite solar cell after ligand treatment.

- Potential Cause: Incomplete surface coverage, where unpassivated defect sites remain, leading to non-radiative recombination [14].

- Solution: Increase the ligand density to ensure full monolayer coverage. For example, employing a strong anchoring ligand like triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) can effectively passivate uncoordinated Pb2+ sites, as proven by a shift in the Pb 4f binding energy in XPS, leading to a high open-circuit voltage (V~OC~) [14].

Problem: Poor charge carrier mobility or device conductivity after successful passivation.

- Potential Cause: The ligand layer is too dense or too thick, disrupting electronic coupling and promoting charge carrier localization. This forces charge transport into a slower, hopping-dominated regime [10].

- Solution: Reduce the ligand density to a level that maintains adequate passivation while restoring electronic connectivity. Explore the use of shorter or conjugated organic ligands that can mediate electronic coupling more effectively than long, aliphatic chains.

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Controlling Ligand Density on Polymer Nanoparticles

- Objective: To systematically vary the surface density of a targeting peptide (cLABL) on Poly(dl-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles [15].

- Materials: PLGA polymer, Pluronic F108-COOH (reactive surfactant), Pluronic F68-OH (non-reactive surfactant), cLABL peptide, EDC, sulfo-NHS.

- Methodology:

- Nanoparticle Fabrication: Prepare aqueous surfactant phases with different molar ratios of Pluronic F108-COOH to Pluronic F68-OH (e.g., 100:0, 75:25, 50:50, 25:75).

- Inject a PLGA solution in acetone into the surfactant phase under stirring using a syringe pump. NPs form spontaneously via solvent displacement.

- Ligand Conjugation: Activate the terminal carboxyl groups on the NPs with EDC/sulfo-NHS. Add the cLABL peptide for conjugation.

- Characterization: Purify NPs and use techniques like the BCA assay to quantify the conjugated peptide density. Correlate this density with cellular uptake studies.

Protocol 2: Passivating Perovskite Films with Molecular Ligands

- Objective: To suppress interfacial recombination and ion migration in a perovskite solar cell by optimizing TPPO ligand density [14].

- Materials: Perovskite precursor solution (e.g., MA-free formulation), Triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) solution in an appropriate solvent (e.g., isopropanol), PCBM, Ag for electrode.

- Methodology:

- Film Deposition: Fabricate the perovskite thin film on your substrate (e.g., ITO/NiOx/SAM).

- Ligand Treatment: Spin-coat the TPPO solution at varying concentrations onto the perovskite surface. Anneal to facilitate interaction.

- Device Completion: Deposit the electron transport layer (PCBM) and the metal electrode (Ag) to complete the solar cell stack.

- Characterization:

- Use XPS to confirm the passivation by observing a shift in the Pb 4f core level.

- Perform current-voltage (J-V) measurements to track V~OC~ and efficiency.

- Conduct maximum power point tracking under illumination to assess long-term operational stability.

Table 1: Correlation between Ligand Density and Functional Outcomes in Selected Studies

| Material System | Ligand | Key Performance Metric | Optimal Density Observation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA Nanoparticles | cLABL Peptide | Cellular Uptake | Uptake increased with density up to an optimum, beyond which no further improvement was seen. | [15] |

| Perovskite Solar Cell | TPPO | V~OC~ Deficit & Stability | Sufficient density for full surface coverage yielded a minimal V~OC~ deficit of 0.32 V and 90% stability retention after 1200 hours. | [14] |

| Organic Semiconductors | --- | Charge Carrier Mobility | High-density, insulating ligands force a crossover from band-like to hopping transport, reducing mobility. | [10] [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Ligand Density and Passivation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Pluronic Surfactants (COOH-/OH-) | To control reactive sites and ligand density on nanoparticle surfaces during synthesis. | Creating a tunable density of conjugation sites for peptides on PLGA NPs [15]. |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) | A polar anchoring ligand for passivating metal ion defects in perovskite materials. | Passivating under-coordinated Pb2+ at the perovskite/ETL interface to boost V~OC~ and stability [14]. |

| EDC / sulfo-NHS | A carbodiimide crosslinker system for activating carboxyl groups for conjugation with amine-containing ligands. | Covalently attaching targeting peptides to functionalized nanoparticle surfaces [15]. |

| Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) | A technique for depositing ultrathin, conformal passivation layers with precise thickness control. | Applying Al₂O₃ or tailored oxide stacks for surface passivation in semiconductors and solar cells [1]. |

Visualizing Relationships and Workflows

Diagram: Ligand Density Trade-offs

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Optimization

A fundamental challenge in optimizing passivation layers for advanced optoelectronic materials lies in balancing ligand density for effective surface defect suppression against the need for efficient charge carrier transport. While effective passivation is crucial for mitigating non-radiative recombination and enhancing device stability, overly dense or insulating passivation layers can create resistive barriers that impede current flow and limit device performance. This technical guide explores material-specific passivation challenges and solutions, providing researchers with practical troubleshooting frameworks and experimental protocols to navigate these complex trade-offs.

FAQs: Fundamental Passivation Principles

Q1: What is the primary function of passivation in optoelectronic materials?

Passivation serves to reduce performance-degrading defects at surfaces and interfaces of materials like silicon and perovskites. These defects act as centers for non-radiative recombination, where charge carriers (electrons and holes) recombine without emitting light, thereby reducing the efficiency of solar cells and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Effective passivation suppresses this recombination, enhancing both device efficiency and operational stability [16].

Q2: Why is there a trade-off between passivation quality and charge transport?

This trade-off arises because conventional passivating ligands typically bind to material surfaces through only a single active site. To achieve effective defect coverage, a high density of these ligands is often required. However, dense packing of organic ligands can create an insulating barrier at the interface, impeding the extraction and injection of charge carriers. This results in increased series resistance and reduced fill factor in solar cells, or higher operating voltages in LEDs [17].

Q3: What are the key differences between passivation strategies for silicon versus perovskites?

While both materials require surface defect management, their chemical nature dictates different approaches. Silicon passivation often uses thin, inorganic dielectric layers (e.g., AlOx, SiNx) that provide both chemical passivation and a field effect that repels minority carriers from the surface. Perovskites, being ionic and softer materials, are more commonly passivated using organic or organometallic molecules (e.g., alkylammonium salts, phosphonic acids) that coordinate with undercoordinated lead (Pb²⁺) ions on the surface [18]. Perovskites are also more susceptible to degradation under environmental stressors, requiring passivators that can also enhance moisture and thermal resistance [17].

Q4: What are multi-site passivation agents and how do they address classic trade-offs?

Multi-site passivation agents are molecules designed with multiple functional groups that can simultaneously bind to several defect sites on a material's surface. For example, an antimony chloride-N,N-dimethyl selenourea complex (Sb(SU)₂Cl₃) can bind to four adjacent sites on a perovskite surface via two Se and two Cl atoms. This architecture provides stronger, more stable binding than single-site ligands, allowing for effective defect suppression with a lower ligand density, thereby minimizing resistive barriers and facilitating better charge transport [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Defects and Solutions

Table 1: Common Passivation-Related Defects and Remedial Actions

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Method | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low open-circuit voltage (VOC) in solar cells | High surface recombination at perovskite/C60 interface [18] | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) measurement to quantify non-radiative losses [18] | Implement a bimolecular passivation strategy (e.g., phosphonic acid + piperazinium halide) to simultaneously passivate surface and interface defects [18] |

| Low fill factor & high series resistance | Overly dense insulating passivation layer blocking charge transport [17] | J-V curve analysis; Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy | Employ multi-site binding ligands (e.g., Sb(SU)₂Cl₃) for effective passivation with lower ligand density [17] |

| Poor operational stability | Incomplete passivation leaving defects; lack of ion migration suppression | Maximum power point (MPP) tracking over time; Dark storage tests | Use a bilayer passivation structure (e.g., AlOx/PDAI₂) acting as both passivation and ion diffusion barrier [19] |

| Inhomogeneous performance across device area | Inconsistent surface coverage of passivation layer | Photoluminescence (PL) mapping; Laser Beam Induced Current (LBIC) mapping | Adopt passivation molecules (e.g., piperazinium chloride) that homogenize surface potential and improve wetting [18] |

| Rust on stainless steel components | Compromised chromium oxide passive film exposing iron | Copper sulfate test (ASTM A967); Visual inspection for "pink" coloring after test [20] [21] | Chemical passivation with nitric or citric acid to remove surface iron and restore the protective oxide layer [20] [21] |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Bilayer Passivation Strategy for Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Cells

This protocol details the deposition of an AlOx/PDAI₂ bilayer, a strategy that has enabled a certified efficiency of 30.8% and enhanced stability in tandem cells [19].

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with a textured silicon bottom cell featuring a hole-selective contact. Ensure the surface is clean and dry.

- Perovskite Deposition: Fabricate the wide-bandgap perovskite top cell using your standard method (e.g., spin-coating, blade-coating) up to the formation of the perovskite absorber layer.

- ALD AlOx Deposition:

- Tool: Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) system.

- Precursors: Trimethylaluminum (TMA) and H₂O.

- Conditions: Chamber temperature 100-150°C. Pulse sequence: TMA dose → N₂ purge → H₂O dose → N₂ purge.

- Thickness: Deposit an ultrathin layer (typically 1-5 nm). The AlOx forms a homogeneous coating over perovskite grains and island-like structures at grain boundaries, serving as a initial passivation and ion barrier [19].

- PDAI₂ Layer Application:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve propane-1,3-diammonium iodide (PDAI₂) in a suitable anhydrous solvent (e.g., isopropanol) at a concentration of 0.5-1.0 mg/ml.

- Deposition: Spin-coat the PDAI₂ solution onto the AlOx layer at 3000-5000 rpm for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: Thermally anneal the stack on a hotplate at 100°C for 10 minutes. The PDAI₂ interacts with the AlOx, fine-tuning energy level alignment and providing further chemical passivation [19].

- Device Completion: Proceed with the deposition of the electron transport layer (e.g., C₆₀) and the top metal electrode.

Protocol 2: Multi-Site Passivation for Air-Processed Perovskite Solar Cells

This protocol uses the Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex to achieve high efficiency (25.03%) in fully air-processed devices, addressing the ligand-versus-transport trade-off [17].

- Synthesis of Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ Passivator:

- Reagents: Antimony chloride (SbCl₃), N,N-dimethylselenourea (SU), and dichloromethane (DCM) as the solvent.

- Procedure: Dissolve SbCl₃ and SU in a 1:2 molar ratio in DCM. Stir the reaction mixture at room temperature for 4-6 hours under an inert atmosphere. Recover the solid product via filtration and dry under vacuum [17].

- Perovskite Film Fabrication with Passivation:

- Two-Step Method: First, deposit a PbI₂ layer. The protocol can incorporate the passivator in this stage.

- Passivation Integration: Add the synthesized Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex directly into the PbI₂ precursor solution at a controlled molar percentage (e.g., 0.5-2.0% relative to PbI₂).

- Crystallization: Proceed with the second step, depositing the organic halide salt (e.g., FAI) to convert the film to perovskite. The complex will incorporate into the growing film, passivating defects at grain boundaries and surfaces via its multi-site (2Se + 2Cl) binding capability [17].

- Characterization Validation:

- Use Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to confirm the presence of the complex (characteristic Se-Sb vibrational band at 350-300 cm⁻¹) [17].

- Perform X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to verify the suppression of metallic Pb⁰ signals, indicating successful defect passivation.

Diagram 1: Bilayer passivation process flow and functional outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Passivation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphonic Acids (e.g., pFBPA) | Passivates top-surface defects in perovskites by forming P–O–Pb bonds and suppressing Pb⁰ defects [18]. | Fluorinated derivatives (e.g., pentafluorobenzyl) show superior passivation due to favorable energy of substitution on the perovskite surface [18]. |

| Diammonium Salts (e.g., PDAI₂) | Suppresses recombination at the perovskite/electron-transport layer interface; improves energy level alignment [19] [18]. | Often used in a bilayer with a dielectric (e.g., AlOx, LiF) to combine field-effect and chemical passivation [19]. |

| Multi-site Ligands (e.g., Sb(SU)₂Cl₃) | Binds to multiple adjacent undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites simultaneously, enabling strong passivation with lower ligand density to minimize transport barriers [17]. | The complex also forms a hydrogen-bonding network, enhancing moisture resistance and overall film stability [17]. |

| Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) AlOx | Creates an ultrathin, pinhole-free dielectric layer that acts as both a passivation interlayer and a barrier against ion migration [19]. | Requires precise control over thickness (1-5 nm) to ensure effective passivation without completely blocking charge tunneling. |

| Citric Acid-Based Passivators (e.g., CitriSurf) | Removes surface iron from stainless steel components to restore the protective chromium oxide layer, preventing rust [21]. | A less hazardous alternative to nitric acid passivation; does not etch the surface or change its finish [21]. |

Strategic Visualization of Passivation Concepts

Diagram 2: Multi-site versus single-site ligand binding strategy.

Advanced Ligand Engineering Strategies for Optimal Performance

In-situ passivation is a critical technique for enhancing the performance of materials, particularly in cutting-edge fields like perovskite photovoltaics. It involves treating a material during its synthesis to minimize defects that form on its surface. For researchers and scientists, especially in drug development and materials science, mastering this process is key to creating more efficient and stable products. The core challenge, and the central theme of modern research, is achieving an optimal balance: using enough passivating ligands to pacify all surface defects, but not so many that they form a thick, insulating layer that hinders essential charge transport [22] [23] [24]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and methodological support for navigating these complex experimental landscapes.

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

FAQ 1: How can I tell if poor charge transport in my device is caused by excessive ligand density?

Problem: After in-situ passivation, your perovskite solar cell or light-emitting diode shows a significant drop in fill factor (FF) and short-circuit current density (Jsc), or your sensor has sluggish response times.

Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of overly dense ligand packing on the material's surface. While the ligands successfully passivate defects, they also create a resistive barrier that impedes the flow of electrons or holes [23]. The insulating organic layer acts as a bottleneck.

Solutions:

- Switch to Multidentate Ligands: Replace single-site binding ligands with bidentate or multi-anchoring ligands. A single-site ligand like a simple ammonium salt can pack densely. In contrast, a bidentate ligand (e.g., nicotinimidamide, N,N-diethyldithiocarbamate) or a multi-site ligand (e.g., the Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex) can passivate multiple defect sites with fewer molecules, reducing layer density and improving charge transfer [22] [23].

- Optimize Ligand Concentration: Systematically vary the concentration of the passivating ligand in your precursor solution. Use a design-of-experiments (DoE) approach to find the concentration that maximizes photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) without compromising conductivity.

- Conduct Advanced Characterization: Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to quantitatively measure the series resistance and charge transfer resistance at interfaces. An increasing trend in these parameters with higher ligand load confirms the diagnosis.

FAQ 2: My in-situ passivation results are inconsistent between batches. What key factors should I control?

Problem: The power conversion efficiency (PCE) and operational stability of perovskite devices vary widely from one synthesis batch to another, despite using the same ligand.

Diagnosis: Inconsistent results typically stem from uncontrolled variables during the synthesis and passivation process that affect ligand coordination and film formation.

Solutions:

- Strictly Control Ion Diffusion: In two-step fabrication methods, the reaction between the PbI₂ layer and organic salts is governed by ion interdiffusion. Uncontrolled diffusion leads to asynchronous crystallization and varying defect densities. Introduce controlled moisture exposure to promote intermediate hydrate phases, which can regulate ion diffusion kinetics and lead to more uniform films [23].

- Standardize the "Aging" of Precursor Solutions: Some ligand complexes require time to form. For example, the antimony chloride-N,N-dimethyl selenourea complex (Sb(SU)₂Cl₃) is synthesized before use [23]. Ensure consistent aging time for precursor solutions containing complexes.

- Monitor and Report Environmental Conditions: Document the temperature and relative humidity during film deposition and annealing. These factors strongly influence crystallization kinetics and ligand binding efficacy. Fabrication in an inert atmosphere (glovebox) versus ambient air can lead to dramatically different outcomes [23].

FAQ 3: Why is my passivated film unstable in moist conditions, and how can I improve its stability?

Problem: The passivated film or device rapidly degrades, losing its optical or electronic properties when exposed to ambient air with moderate humidity.

Diagnosis: The passivation strategy may be effective for defect suppression but fails to provide a hydrophobic barrier against water incursion. Alternatively, the ligand itself may not form a stable enough bond with the surface, desorbing over time.

Solutions:

- Select Hydrophobic Ligands: Incorporate ligands with hydrophobic functional groups, such as long alkyl chains or fluorinated groups. The methyl groups in N,N-dimethylselenourea and the chloride ions in the Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex, for instance, contribute to improved moisture resistance [23].

- Utilize Ligands that Form Cross-Linked Networks: Choose ligands that can form additional hydrogen bonds or other intermolecular interactions. The Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex creates an extended hydrogen-bonding network through N-H...Cl bonds, which stabilizes the passivation layer and enhances its barrier properties [23].

- Verify Binding Stability: Use Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to monitor characteristic bonds (e.g., N-H, C-Se, Se-Sb) before and after environmental aging. A stable spectrum indicates robust ligand anchoring [23].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: In-Situ Passivation of Perovskites Using a Multi-Site Binding Ligand

This protocol describes the use of the Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex for highly effective passivation during the two-step fabrication of formamidinium lead iodide (FAPbI₃) perovskite solar cells, achieving high efficiency and stability [23].

1. Synthesis of Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ Passivation Complex

- Reagents: Antimony chloride (SbCl₃), N,N-dimethylselenourea (SU), and anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM).

- Procedure: Dissolve stoichiometric amounts of SbCl₃ and SU in DCM under an inert atmosphere. Stir the reaction mixture for several hours at room temperature. Recover the synthesized crystalline complex through standard methods [23].

- Verification: Confirm complex formation using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and FTIR spectroscopy. FTIR should show bands for N-H stretching (~3300 cm⁻¹), N-H bending (~1650 cm⁻¹), and C-Se stretching (1000-800 cm⁻¹) [23].

2. Preparation of PbI₂ Precursor Solution with Passivator

- Procedure: Co-dissolve PbI₂ and the synthesized Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex in a polar aprotic solvent (e.g., DMF/DMSO) to create your precursor solution. The complex is integrated directly into the one-step or two-step fabrication process.

3. Film Deposition and Crystallization

- Procedure: Spin-coat the precursor solution onto your substrate. For two-step methods, this involves depositing the PbI₂+passivator solution first. Control the crystallization process during thermal annealing. The complex will co-crystallize with the perovskite, binding to undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions via its Se and Cl atoms [23].

4. Characterization of Passivated Films

- Defect Density Analysis: Use photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy and time-resolved PL (TRPL). A significant increase in PL intensity and carrier lifetime indicates effective defect passivation.

- Morphology: Analyze film crystallinity and grain structure with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and XRD.

- Device Performance: Fabricate full solar cell devices (e.g., structure: ITO/SnO₂/Perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au) and current-voltage (J-V) measurements to determine PCE, Voc, Jsc, and FF [23].

Protocol 2: In-Situ Passivation of Perovskite Nanoplatelets (NPLs) with Multidentate Ligands

This protocol is tailored for low-dimensional materials, where high surface-to-volume ratios create a high density of defects [24].

1. Synthesis Setup

- Reagents: Lead bromide (PbBr₂), cesium bromide (CsBr), oleic acid (OA), oleylamine (OAm), and selected multidentate ligands (e.g., dicarboxylic acids, bidentate phosphines).

- Procedure: Set up a standard hot-injection or ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) synthesis for CsPbBr₃ NPLs in a three-neck flask under inert atmosphere.

2. Introduction of Passivating Ligands

- In-Situ Method: Add the multidentate ligand directly to the reaction flask alongside the standard ligands (OA and OAm) before the initiation of crystallization. The ligands will compete for binding sites during the growth of the NPLs.

- Key Consideration: The ratio of multidentate to standard ligands is critical. A systematic variation is required to achieve full surface coverage without causing aggregation or dissolution of the nanocrystals.

3. Purification and Dispersion

- Procedure: After synthesis, precipitate the NPLs using a non-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate/tert-butanol) and centrifuge. Re-disperse the pellet in an appropriate solvent (e.g., toluene, hexane). Repeat as needed.

- Monitoring: During purification, monitor the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) to ensure the multidentate ligands are not being stripped from the surface. A stable PLQY indicates strong ligand binding.

4. Characterization

- Optical Properties: Measure UV-Vis absorption and PL spectra to confirm the bandgap and assess the PLQY.

- Surface Analysis: Use FTIR to confirm the presence of the multidentate ligands on the purified NPL surface.

Data Presentation: Ligand Performance and Outcomes

Table 1: Performance of Selected Bidentate and Multi-Site Ligands in Perovskite Solar Cells

| Ligand Name | Binding Mode | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Key Stability Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotinimidamide | Bidentate | 25.30% | - | [22] |

| N,N-Diethyldithiocarbamate | Bidentate | 24.52% | Improved stability in FAPbI₃ vs. MAPbI₃ | [22] |

| Isobutylhydrazine | Bidentate | 24.25% | - | [22] |

| Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ Complex | Multi-site (4 anchors) | 25.03% (air-processed) | T80 lifetime: 23,325 h (dark storage); 5,004 h (85°C); 5,209 h (operational) | [23] |

Table 2: Essential Reagent Solutions for In-Situ Passivation Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration for Success | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bidentate Ligands (e.g., Nicotinimidamide) | Passivate undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions by forming a stable 5- or 6-membered chelate ring. | Superior to monodentate ligands in stability and reduced resistance. | [22] |

| Multi-Site Binding Complexes (e.g., Sb(SU)₂Cl₃) | Bind to multiple adjacent defect sites simultaneously, offering deep trap passivation and lower interfacial resistance. | Synthesize the complex beforehand; ensures correct stoichiometry and binding geometry. | [23] |

| Short-Chain Ligands | Passivate defects while minimizing insulating barrier thickness due to their reduced length. | Can improve charge transport but may offer less steric protection against moisture. | [24] |

| Polymer & Zwitterionic Ligands | Provide a robust, cross-linked passivation layer that enhances both electronic and environmental stability. | Can be more difficult to process and may require optimization of molecular weight. | [24] |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

In-Situ Passivation with Multi-Site Ligand

Balancing Ligand Density and Charge Transport

Colloidal quantum dots (QDs), such as PbS and perovskite nanocrystals, are typically synthesized with long-chain insulating organic ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) to ensure colloidal stability and prevent uncontrolled growth [25] [26]. However, these native ligands form an insulating barrier that severely impedes charge transport between adjacent QDs, rendering the resulting QD solids unsuitable for direct use in optoelectronic devices [25] [26]. Post-synthesis ligand exchange is a critical chemical strategy to replace these long-chain ligands with shorter, more conductive alternatives while aiming to preserve surface passivation and quantum dot integrity. This process is fundamentally governed by the thermodynamics and kinetics of ligand exchange reactions, where the equilibrium position depends on the relative binding strengths and concentrations of the competing ligands [27] [28]. The central challenge lies in balancing the reduction of ligand density to enhance charge transport with the maintenance of sufficient surface coverage to prevent defect formation, a crucial trade-off that dictates the final performance of QD-based devices [25] [29].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Q1: My ligand exchange process is inconsistent, especially in thicker films, leading to variable device performance. How can I improve reproducibility?

A: Incomplete ligand exchange in thicker films is a frequently reported issue [25]. This often stems from insufficient removal of the original long-chain ligands before the exchange process.

- Solution: Implement an optimized pre-washing procedure for the QDs. Systematically increase the number of washing cycles using an ethanol-methanol mixture before film deposition and solid-state ligand exchange. This reduces the initial load of OA, facilitating a more complete exchange [25].

- Protocol: After synthesis, precipitate the QDs using a non-solvent (e.g., acetone, methanol). Redisperse the pellet in a solvent like hexane or chloroform, and re-precipitate. This constitutes one washing cycle. The optimal number of cycles (e.g., 3-5) should be determined experimentally for your system, as it directly influences the final ligand exchange efficiency [25].

- Data: The table below summarizes the effect of washing cycles on PbS QDs, as demonstrated in one study [25].

Table 1: Effect of Washing Cycles on Ligand Exchange Efficiency in PbS QDs [25]

| Number of Washing Cycles | Residual OA after Exchange | Ligand Exchange Efficiency | Film Quality & Device PCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (e.g., 1-2) | High | Low | Poor, low PCE (~2-3%) |

| Medium (e.g., 3) | Moderate | High | Good, optimal PCE (5.55%) |

| High (e.g., >5) | Low | High | Potential solubility issues |

Q2: After ligand exchange, my QD films become more prone to aggregation and lose solubility. What is causing this?

A: This is typically a sign of poor surface passivation following ligand removal. The new short-chain ligands may not adequately coordinate the QD surface atoms, leading to surface defects and loss of colloidal stability [29].

- Solution 1: In-situ ligand regulation. For perovskite QDs (e.g., FAPbI₃), directly use protonated-OAm (e.g., from oleylammonium iodide) during synthesis instead of free OAm. This suppresses the dynamic proton exchange between OA and OAm, creating a more stable ligand shell that is less prone to degradation and detachment during subsequent processing [29].

- Solution 2: Employ conjugated short-chain ligands. Consider using ligands like 3-phenyl-2-propen-1-amine bromide (PPABr) or its derivatives. Their rigid, conjugated backbone promotes π-π stacking between adjacent ligands, which enhances the stability of the QD film and improves charge transport without requiring long insulating chains [26].

Q3: The charge transport in my QD solid is improved after ligand exchange, but the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) drops significantly. How can I mitigate this?

A: This indicates a trade-off between passivation and transport. The new short-chain ligands, while improving electronic coupling, are likely not fully passivating the surface traps, leading to non-radiative recombination [26].

- Solution: Explore functionalized short-chain ligands that combine good conductivity with strong binding to the QD surface. For instance, PPABr-derived ligands with electron-donating substituents (e.g., 4-CH₃ PPABr) have been shown to enhance hole transport while effectively passivating surface defects, thereby maintaining a high PLQY [26].

- Mechanism: The conjugated structure allows for delocalized electron clouds that facilitate charge transport, while the specific functional groups (e.g., -CH₃) strengthen the interaction with the QD surface, reducing defect density.

Advanced Optimization Strategies

Q4: How can I precisely control the ligand density and composition to fine-tune the properties of the QD film?

A: Advanced synthesis and exchange strategies offer superior control.

- Strategy: Decoupled precursor synthesis. For FAPbI₃ QDs, use separate Pb²⁺ and I⁻ sources (e.g., lead acetate and oleylammonium iodide) instead of a single PbI₂ precursor. This allows for precise control of the I/Pb ratio, enabling the creation of a halide-rich surface environment that suppresses iodide vacancy formation and allows for modulation of ligand density without compromising structural integrity [29].

- Strategy: Direct synthesis of ion-coordinated inks. A "low-temperature nucleation followed by high-temperature growth" strategy can balance monomer and ionic ligand supply during the direct synthesis of PbS QD inks. This scalable method produces QDs coordinated by inorganic ions in polar solvents, eliminating the need for a subsequent solid-state ligand exchange and its associated challenges [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents for Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange

| Reagent / Material | Function & Explanation | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Tetrabutylammonium Iodide (TBAI) | A common halide source for atomic ligand exchange. The iodide ions passivate the QD surface, while the TBA⁺ cation assists in the removal of the native OA ligand, leading to n-type QD films [25]. | Solid-state ligand exchange on PbS QD films for solar cells [25]. |

| Conjugated Short-Chain Amines (e.g., PPABr) | Short-chain ligands with a conjugated backbone (e.g., with a -CH₃ or -F substituent). They enhance inter-dot charge transport via π-π stacking and can be functionalized to tune carrier injection (electron-withdrawing for electron transport, donating for hole transport) [26]. | Creating efficient charge transport layers in perovskite QLEDs [26]. |

| Oleylammonium Iodide (OLAI) | A source of both the iodide anion and the protonated oleylamine cation. Using pre-formed OLAI suppresses proton exchange equilibria, leading to a more stable and strongly bound ligand shell on perovskite QDs [29]. | In-situ ligand regulation during FAPbI₃ QD synthesis for improved solar cell efficiency and stability [29]. |

| Ethanol-Methanol Mixture | A common non-solvent used in the washing and purification of QDs. It precipitates QDs out of suspension, allowing for the removal of excess reactants and loosely bound ligands [25]. | Pre-washing cycles to reduce initial oleic acid load on PbS QDs [25]. |

Experimental Workflow and Protocol: TBAI Exchange on PbS QD Films

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating the effect of pre-washing on the solid-state ligand exchange for solar cells [25].

Materials and Synthesis

- PbS QDs: Synthesize OA-capped PbS QDs using standard hot-injection methods [25].

- ZnO Nanoparticles: Synthesize as an electron transport layer following reported procedures [25].

- TBAI Solution: Prepare a solution of TBAI in anhydrous methanol (e.g., 10 mg/mL).

- Solvents: Anhydrous hexane, chloroform, butanol, acetone, methanol, and ethanol.

Pre-Washing and Film Deposition (Critical for Reproducibility)

- Washing Cycles: Dissolve the synthesized PbS QDs in hexane and precipitate them using an ethanol-methanol mixture. Centrifuge to obtain a pellet. Redisperse the pellet in hexane and repeat this process for an optimized number of cycles (e.g., 3 cycles) [25].

- Film Fabrication: Deposit the washed QDs onto a substrate (e.g., ITO/ZnO) via layer-by-layer spin-coating. For each layer:

- Spin-coat the QD solution in hexane (e.g., 50 mg/mL).

- Immediately after deposition, while the film is still wet, spin-coat the TBAI solution in methanol to initiate the solid-state ligand exchange.

- Rinse with anhydrous methanol to remove by-products and excess TBAI.

- Repeat the process to build the desired film thickness (~240 nm can be achieved with fewer cycles using pre-washed QDs) [25].

Ligand Exchange Efficiency: Verification and Characterization

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Use to monitor the disappearance of C-H stretching vibrations (∼2900 cm⁻¹) from OA and the appearance of new peaks associated with the incoming ligand [25].

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Perform on purified QD powders to quantify the amount of organic ligand (OA) before and after the exchange process [25].

- X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Employ to confirm the successful incorporation of the new atomic ligand (e.g., iodide from TBAI) onto the QD surface [25].

Workflow and Logical Diagrams

Ligand Exchange Workflow

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for the post-synthesis ligand exchange process, highlighting the critical pre-washing step for achieving complete exchange in thick films.

Ligand Binding Equilibrium

Diagram 2: The proton exchange equilibrium in standard OA/OAm ligand systems. The strategy of in-situ regulation pushes the equilibrium towards the strongly bound protonated-OAm, enhancing stability [29].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is my zwitterionic conjugated polymer exhibiting low electronic conductivity despite good ionic transport? This common issue often arises from an imbalance in ligand design, where overly dense ionic side chains disrupt the π-conjugation of the polymer backbone. The polar groups enhance ion transport but can interrupt the delocalized π-electron pathway essential for electronic conductivity [31]. To resolve this, try reducing the density of ionic side chains or incorporating more rigid, planar conjugated units (like benzodithiophene) into the backbone to improve orbital overlap and charge carrier mobility [31].

Q2: How can I improve the water uptake and dispersibility of my conjugated polymer network for aqueous applications? Incorporating zwitterionic building blocks, such as sulfopropyl-pyridinium salts, directly into the polymer network can significantly enhance hydrophilicity and water uptake. Research shows that zwitterionic ion-in-conjugation porous polymer networks (IIC-PPNs) can achieve a water uptake of 14.5 g g⁻¹, which is substantially higher than similar non-ionic polymers [32]. Ensure your synthesis, such as Knoevenagel polycondensation, correctly links the zwitterionic monomer with complementary units like triformylbenzene.

Q3: What strategies can I use to fine-tune the band gap of a conjugated polyelectrolyte for photocatalysis? Band gap engineering is primarily achieved through backbone modification. Designing a donor-acceptor (D-A) type polymer backbone, where electron-donating units (e.g., thiophene, carbazole) alternate with electron-accepting units (e.g., perylenediimide, fluorene derivatives), is a highly effective strategy [31]. This D-A interaction facilitates π-electron delocalization and can reduce the band gap. For instance, optical absorption band edges around 512 nm with a band gap of 2.55 eV have been achieved in zwitterionic IIC-PPNs, making them suitable for visible-light photocatalysis [32].

Q4: During nanocrystal synthesis, how do I choose ligands to balance surface passivation and charge transport? Ligand selection is a critical trade-off. Long, insulating ligands (e.g., long-chain alkanes) provide excellent passivation and colloidal stability but hinder charge transport between nanocrystals. To balance this, consider using shorter ligands or conjugated ligands (e.g., arylamines) that facilitate electronic coupling [4]. For simultaneous ionic and electronic transport, zwitterionic ligands are promising as their structure can support both functions. Remember that ligand exchange processes are key for replacing initial long-chain ligands with more conductive shorter or functional ligands [4].

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Solubility in Orthogonal Solvents | High crystallinity of conjugated backbone; insufficient polar side chains. | Introduce polar ionic or zwitterionic side chains via side-chain engineering. Use branched alkyl chains in side groups to disrupt dense packing [31]. |

| Poor Photocatalytic Efficiency | Band gap is too large for visible light; fast charge carrier recombination. | Implement donor-acceptor backbone engineering to narrow the band gap. Use the material as a heterogeneous photocatalyst to facilitate separation and recovery [32]. |

| Low Ionic Conductivity | Insufficient ionic functional groups; low water uptake. | Incorporate zwitterionic units to create a significant ionic dipole. This enhances water uptake, creating ion-transport channels within the material [32]. |

| High Charge Recombination | Poor electronic coupling between nanostructures; trap states from surface defects. | Perform ligand exchange to replace insulating ligands with conjugated or Z-type ligands that passivate traps and improve interparticle electronic coupling [4]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of a Zwitterionic Ion-in-Conjugation Porous Polymer Network (IIC-PPN) via Knoevenagel Polycondensation

This methodology is adapted from the synthesis of IIC-PPNs for photooxidation applications [32].

Key Reagents:

- Monomer A: Zwitterionic N-(3-sulfopropyl)-2,6-(dimethyl)pyridinium salt.

- Monomer B: 1,3,5-Triformylbenzene.

- Catalyst: A base catalyst suitable for Knoevenagel condensation (e.g., piperidine).

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Dissolve the zwitterionic 2,6-lutidine derivative (Monomer A) and 1,3,5-triformylbenzene (Monomer B) in a suitable anhydrous solvent (e.g., DMSO or DMF) in a Schlenk flask under an inert atmosphere (N₂ or Ar).

- Catalyst Addition: Add a catalytic amount of the base catalyst to the reaction mixture.

- Polycondensation: Heat the reaction mixture to a carefully studied temperature (e.g., 90-120°C) and stir for 24-72 hours. The formation of a vinylene-linked network occurs through a Knoevenagel reaction.

- Product Isolation: After cooling to room temperature, precipitate the polymer into a large volume of a poor solvent (e.g., methanol or acetone).

- Purification: Collect the solid product via centrifugation or filtration. Purify the resulting porous network via Soxhlet extraction using solvents like methanol, acetone, and THF to remove any unreacted monomers or oligomers.

- Drying: Dry the final IIC-PPN under high vacuum at an elevated temperature (e.g., 80°C) for at least 24 hours to remove all solvent residues.

Characterization:

- Surface Area: Use nitrogen sorption porosimetry to determine the specific surface area (BET method). Reported values for IIC-PPNs can reach up to 263 m² g⁻¹ [32].

- Optical Properties: Analyze the optical absorption band edge via UV-Vis spectroscopy to estimate the optical band gap (e.g., 512 nm edge) [32].

- Water Uptake: Measure the equilibrium water absorption capacity gravimetrically.

Protocol 2: Ligand Exchange on Nanocrystals for Enhanced Charge Transport

This protocol is derived from strategies for improving conductivity in ligand-capped nanocrystal films [4].

Key Reagents:

- Starting Nanocrystals: Colloidal nanocrystals (NCs) capped with long-chain, insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine).

- Exchange Ligand Solution: A solution containing the new functional ligands (e.g., short-chain mercaptans, conjugated molecules, or zwitterionic ligands) in a solvent that can disperse the NCs.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Purify the original nanocrystals to remove excess free ligands from the solution.

- Mixing: Re-disperse the purified NCs in a minimal amount of solvent. Mix this dispersion with a large excess (e.g., 100-1000 fold) of the exchange ligand solution.

- Incubation: Stir the mixture for a defined period (from hours to days) at a specific temperature to allow the new ligands to replace the original ones on the NC surface.

- Purification: Isolate the ligand-exchanged NCs by precipitation and centrifugation. Wash the pellet multiple times with a solvent that removes the displaced original ligands and any unbound exchange ligands.

- Processing: Re-disperse the final functionalized NCs in an appropriate solvent for thin-film deposition or device integration.

Characterization:

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: Confirm the replacement of old ligands by tracking the disappearance/appearance of characteristic vibrational bands (e.g., C-H stretches of long alkanes vs. S-H or new functional groups).

- TGA (Thermogravimetric Analysis): Quantify the new ligand density on the NC surface.

- Electrical Measurements: Fabricate a thin-film device (e.g., a transistor or a simple resistor) to measure the electronic conductivity or mobility before and after exchange, expecting a significant increase [4].

Table 1: Properties of Zwitterionic Conjugated Polymer Networks

| Material Name | Synthesis Method | Surface Area (m² g⁻¹) | Water Uptake (g g⁻¹) | Optical Band Gap (eV) | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IIC-PPN [32] | Knoevenagel Polycondensation | 263 | 14.5 | 2.55 | Photooxidation of Bisphenol A |

| PAV-CN [32] | Not Specified | Not Specified | 7.0 | Not Specified | Benchmark for Comparison |

| PAV-OMe [32] | Not Specified | Not Specified | 8.5 | Not Specified | Benchmark for Comparison |

| PAV-CHO [32] | Not Specified | Not Specified | 5.3 | Not Specified | Benchmark for Comparison |

Table 2: Ligand Types and Their Impact on Nanocrystal Properties

| Ligand Type | Example | Primary Function | Effect on Charge Transport |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-chain Alkyl [4] | Oleic Acid, Oleylamine | Colloidal Stability, Size/Shape Control | Creates thick insulating shell; poor electronic transport (hopping/tunneling). |

| Conjugated [4] | Arylamines, Thiophenes | Enhances Interparticle π-π Coupling | Facilitates band-like or improved hopping transport; higher electronic conductivity. |

| X-type [4] | Carboxylates, Phosphonates | Strong Binding, Passivation | Variable effect; can be engineered for good passivation and reasonable conductivity. |

| Z-type [4] | Metal Halides (e.g., PbCl₂) | Passivation of Surface Defects/Traps | Reduces charge recombination centers; can indirectly boost conductivity. |

| Zwitterionic [32] [4] | Sulfopropyl-pyridinium | Imparts Dual Ionic/Electronic Character | Can support both ionic and electronic conduction; enhances hydrophilicity. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram Title: Multifunctional Ligand Design Workflow

Diagram Title: Charge Transport Mechanisms in Nanocrystals

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| 1,3,5-Triformylbenzene [32] | A key monomer for constructing covalent organic frameworks (COFs) and porous polymer networks via polycondensation reactions (e.g., Knoevenagel). |

| Zwitterionic Monomers (e.g., sulfopropyl-pyridinium salts) [32] | Imparts ionic character and hydrophilicity to conjugated frameworks, enabling dual ion/electron transport and high water uptake. |

| Conjugated Polyelectrolytes (CPEs) [31] | Serve as the core material combining a π-conjugated backbone for electronics with ionic groups for ion transport and processability. |

| Short/Conjugated Ligands (e.g., thiols, arylamines) [4] | Used in ligand exchange to replace long insulating ligands on nanocrystals, enhancing electronic coupling and charge transport between particles. |

| Z-type Ligands (e.g., metal halides) [4] | Effectively passivate surface defect sites (traps) on nanocrystals, reducing charge recombination and improving performance. |

| D-A Type Polymer Building Blocks [31] | Electron Donor (e.g., carbazole) and Acceptor (e.g., perylenediimide) units used to engineer band gaps and energy levels in conjugated polymers. |

FAQs: Core Principles and Strategic Design

Q1: What is the fundamental challenge that ligand stack engineering aims to solve? The core challenge is balancing sufficient surface passivation to suppress non-radiative recombination with maintaining efficient charge transport. High ligand densities effectively passivate surface defects but can create thick, insulating barriers that impede charge carrier movement between nanocrystals or at perovskite interfaces. Ligand stack engineering addresses this by designing multi-component, layered ligand systems where different molecules work synergistically. [24] [4]

Q2: How does a multi-site binding ligand differ from a conventional single-site ligand?

Conventional ligands typically bind to the perovskite or nanocrystal surface through a single active site (e.g., one amine or carboxyl group). This can lead to densely packed, resistive layers. In contrast, multi-site binding ligands, like the antimony chloride-N,N-dimethyl selenourea complex (Sb(SU)₂Cl₃), use multiple atoms (e.g., two Se and two Cl atoms) to coordinate with four adjacent undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions simultaneously. This provides stronger, more stable passivation without requiring a densely packed monolayer, thereby reducing interfacial resistance and more effectively suppressing defect formation. [17]

Q3: What is "Binary Synergistic Passivation (BSP)" and what are its benefits? BSP is a strategy that employs two different ligand molecules to address multiple issues at an interface. For example, in wide-bandgap perovskite solar cells, a combination of phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) and ethanediamine dihydroiodide (EDAI₂) was used. The PEA⁺ cation improves crystal facet orientation during film formation, while the synergy between PEA⁺ and EDA²⁺ creates an amino-bridged interconnection that enhances defect suppression and optimizes energy level alignment at the charge transport interface. This led to a record-low conduction band offset of 0.04 eV and significantly improved device voltage and fill factor. [33]

Q4: What are the key considerations when selecting ligands for a stack? Selecting ligands requires evaluating several factors:

- Binding Group: Prefer multidentate (e.g., bidentate, quadruple-site) over monodentate ligands for stronger, more stable passivation. [17] [34]

- Functional Moieties: Incorporate groups that actively participate in charge transport (e.g., conjugated systems, carbazoles) or provide additional stability (e.g., hydrophobic chains). [4] [34]

- Synergistic Potential: Choose ligands whose combined action can address different types of defects or improve both passivation and band alignment. [33]

- Processing Compatibility: Ensure the ligands are compatible with your fabrication method, whether it's solution processing, thermal evaporation, or post-synthesis treatment. [24] [34]

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

This guide helps diagnose and resolve frequent problems encountered during ligand stack engineering.

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Charge Transport (Low FF, high series resistance) | 1. Excessively thick/insulating ligand shell. 2. Dense packing of long, insulating alkyl-chain ligands. 3. Poor interparticle coupling. | 1. Measure film conductivity & trap density. 2. Use FTIR/XPS to quantify ligand density. 3. Perform TRPL to assess charge extraction. | 1. Implement ligand exchange with short-chain/conjugated ligands. [4] 2. Use a BSP strategy with a conductive ligand (e.g., BUPH1). [34] |

| Insufficient Passivation (Low PLQY, Voltage Deficit) | 1. Incomplete surface coverage. 2. Weak ligand-surface interaction (single-site binding). 3. Ligand desorption during processing. | 1. Characterize with XPS/NMR to check ligand coverage. 2. Calculate ligand binding energy via DFT. 3. Check for surface defects via SEM/TEM. | 1. Adopt multi-site binding ligands (e.g., Sb(SU)₂Cl₃). [17] 2. Combine passivators for synergistic effect (e.g., PEABr/EDAI₂). [33] |

| Spectral Instability (Peak shift under bias/light) | 1. Ligand failure to suppress ion migration. 2. Phase segregation in mixed-halide perovskites. | 1. Perform operational stability tests with in-situ PL. 2. Characterize elemental distribution after stress. | 1. Use bidentate ligands (e.g., phenanthroline-based BUPH1) to pin ions and suppress migration. [34] 2. Employ ligands that form a physical barrier against ion movement. |

| Film Morphology Defects (Pinholes, roughness) | 1. Ligand-induced aggregation during processing. 2. Disrupted crystal growth from bulky ligands. 3. Incompatible solvent/processing conditions. | 1. Analyze film morphology with AFM/SEM. 2. Monitor crystallization kinetics (in-situ GIWAXS). | 1. Optimize ligand concentration and solvent system. 2. Use ligands that guide crystallization (e.g., PEABr for (100) orientation). [33] 3. Employ in-situ passivation during film formation. [34] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Ligand Stack Strategies

Protocol 1: In-situ Molecular Passivation for Evaporated Films

This protocol is adapted from the fabrication of efficient, spectrally stable pure-blue PeLEDs. [34]

Objective: To incorporate a passivating ligand directly during the thermal evaporation of a perovskite layer to suppress defects as the film forms.

Materials:

- Precursors: e.g., PbBr₂, CsCl, CsBr.

- Passivation Ligand: e.g., BUPH1 (4,7-di(9H-carbazol-9-yl)-1,10-phenanthroline).

- Substrate: Pre-patterned ITO/glass with necessary charge transport layers.

- Thermal Evaporation System: High-vacuum chamber (< 3.0 × 10⁻⁶ Torr).

Methodology:

- Preparation: Load perovskite precursors (PbBr₂, CsCl, CsBr) and the BUPH1 ligand into separate, calibrated evaporation crucibles within the high-vacuum chamber.

- Co-evaporation: Simultaneously evaporate all four sources. Precisely control the deposition rates using quartz crystal microbalances.

- Example rates: PbBr₂ at 0.5 Å/s, CsCl at 0.65 Å/s, CsBr at 0.3 Å/s, BUPH1 at a rate determined empirically for optimal performance.

- Film Formation: The ligands coordinate with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions in real-time as the perovskite film grows, passivating halide vacancies.

- Post-processing: After deposition, the film may be subjected to a mild thermal annealing step to improve crystallinity, if necessary.

Key Analysis:

- PLQY & FWHM: Measure photoluminescence quantum yield and full width at half maximum to quantify passivation efficacy and color purity.

- AFM: Use atomic force microscopy to verify improved film morphology and reduced roughness.

- Device Characterization: Fabricate full devices (e.g., LEDs or solar cells) to evaluate external quantum efficiency (EQE) and spectral stability under electrical bias.

Protocol 2: Post-Synthesis Binary Synergistic Passivation (BSP)

This protocol is adapted from high-efficiency perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells. [33]

Objective: To apply a solution-based treatment of two complementary ligands to a pre-formed perovskite film to passivate defects and improve energy level alignment.

Materials:

- Substrate: Pre-formed wide-bandgap perovskite film (e.g., ~1.67 eV).

- Passivation Solution: A blend of PEABr (phenethylammonium bromide) and EDAI₂ (ethanediamine dihydroiodide) in a suitable solvent (e.g., isopropanol). Typical concentrations are in the range of 0.5-1.5 mg/mL.

- Spin Coater.

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve precise molar ratios of PEABr and EDAI₂ in anhydrous isopropanol to create the binary passivation solution.

- Film Treatment: Deposit the passivation solution onto the perovskite film via spin-coating (e.g., 4000 rpm for 30 seconds).

- Reaction & Annealing: Allow the film to react for a short period (e.g., 1-2 minutes), then thermally anneal at a moderate temperature (e.g., 100°C for 10 minutes) to remove solvent and facilitate the formation of a stable passivated interface.

Key Analysis:

- XRD/GIWAXS: Confirm the induction of preferential (100) crystal orientation.

- XPS/UPS: Verify ligand binding via chemical shift analysis and measure the work function to demonstrate improved energy level alignment (e.g., reduced conduction band offset).

- SCLC: Use space-charge-limited-current measurements to quantify the reduction in trap density.

- Device Performance: Measure the open-circuit voltage (VOC) deficit and fill factor (FF) in completed solar cells.

Research Reagent Solutions: A Toolkit for Ligand Stack Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Ligand Stack | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Phenanthroline-based ligands (e.g., BUPH1) | Bidentate chelating ligand for in-situ passivation. Nitrogen lone pairs coordinate undercoordinated Pb²⁺. Carbazole moieties aid hole transport. [34] | Ideal for vacuum-processed devices. Enhances both PLQY and charge balance. |

| Multi-site Binding Complexes (e.g., Sb(SU)₂Cl₃) | Passivates multiple adjacent defect sites simultaneously (e.g., via 2 Se and 2 Cl atoms). Creates a robust, cross-linked surface layer. [17] | Provides superior stability and deep trap passivation. Can be used in solution-based processing. |

| Binary Salt Mixtures (PEABr + EDAI₂) | Synergistic passivation. PEA⁺ improves crystal orientation; EDA²⁺ provides field-effect passivation. Together, they reduce defects and optimize band alignment. [33] | Ratios and concentrations are critical. Must be dissolved in a solvent that does not dissolve the underlying perovskite. |

| Short-Chain / Conjugated Ligands | Improve interparticle charge transport by reducing tunneling distance and potential barriers. Can facilitate band-like transport in nanocrystal solids. [24] [4] | Often used in ligand exchange processes post-synthesis. May trade off some colloidal stability for conductivity. |

| Zwitterionic & Polymer Ligands | Provide strong passivation and enhanced stability. The charged groups can improve solubility and processing while maintaining a compact ligand shell. [24] | Useful for creating stable inks for printing and large-area coating. |

Visualization of Workflows and Mechanisms

Ligand Stack Engineering Workflow

Synergistic Passivation Mechanism

Diagnosing and Solving Common Ligand Engineering Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary observable symptoms of photo-induced phase segregation in mixed-halide perovskite films?

A1: The primary symptoms are distinct changes in the film's photoluminescence (PL) properties and structural composition.

- PL Peak Splitting: Under continuous illumination, a single, sharp PL peak from the initial mixed-halide phase will split into (at least) two separate peaks. A new, red-shifted peak emerges corresponding to the formed Iodine-rich (I-rich) low-bandgap domains, while a blue-shifted peak may correspond to Bromine-rich (Br-rich) regions [35].

- Bandgap Instability: The optical bandgap of the film becomes unstable and changes over the course of light soaking, moving from the initial mixed value towards the bandgaps of the segregated phases [36].

- XRD Peak Splitting: In X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, the main diffraction peaks may split, providing direct evidence of the lattice distortion and the formation of separate crystalline phases with different halide compositions [36].

Q2: How does phase segregation directly lead to a reduction in Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)?

A2: Phase segregation creates a heterogeneous energy landscape that accelerates non-radiative recombination, thereby lowering PLQY.

- Charge Funneling: Photogenerated charge carriers rapidly funnel (on the order of picoseconds) from the wider-bandgap mixed matrix into the lower-bandgap I-rich domains [35].

- Enhanced Recombination: These I-rich domains can act as recombination centers. The local high density of charge carriers and the presence of defects at the interfaces between different phases dramatically enhance the rate of charge-carrier recombination, which is often non-radiative, leading to a drop in PLQY [35].

- Voltage Loss: In solar cells, this accelerated recombination directly translates to a loss in open-circuit voltage (VOC), undermining device performance [35].

Q3: What experimental factors can trigger or accelerate phase segregation during characterization?

A3: Several experimental conditions are known drivers of phase segregation.

- Continuous Illumination: Unlike pulsed light, continuous-wave (CW) illumination provides the steady-state energy input that drives ion migration and segregation [35].

- Illumination Intensity: Higher light intensities typically accelerate the phase segregation process [35].

- Temperature: Elevated temperatures can increase ionic mobility, facilitating the segregation process [35].

- Photoexcitation Wavelength: Illumination with energy above the bandgap of the mixed phase provides the excess energy that can drive the segregation mechanism [35].