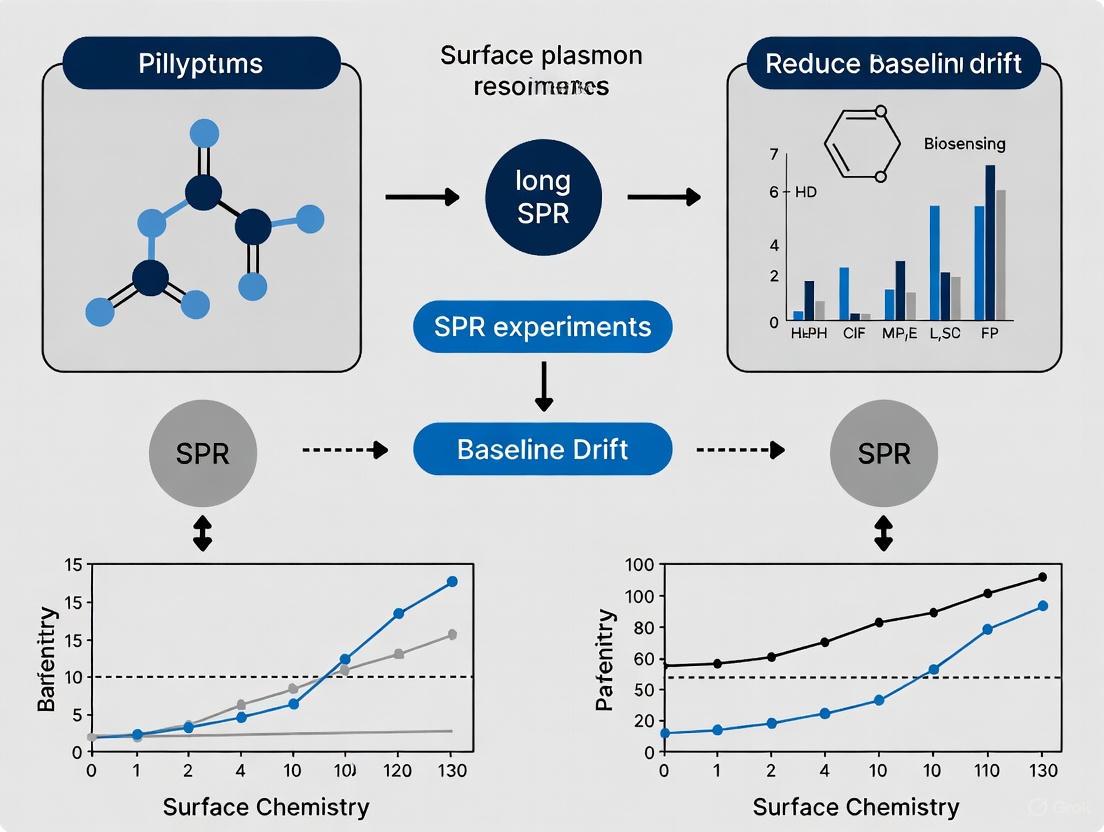

Stable Signals: A Comprehensive Guide to Reducing Baseline Drift in Long SPR Experiments

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for managing baseline drift in extended Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) studies.

Stable Signals: A Comprehensive Guide to Reducing Baseline Drift in Long SPR Experiments

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for managing baseline drift in extended Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) studies. Covering both foundational principles and advanced applications, it details the root causes of instability—from surface equilibration and buffer effects to instrumental factors. The content offers a systematic troubleshooting workflow and proven optimization strategies, including proper buffer hygiene, surface preconditioning, and advanced referencing techniques. Furthermore, it explores next-generation sensor architectures and algorithmic approaches designed to inherently minimize drift, empowering scientists to achieve the high-quality, reproducible data essential for reliable kinetic and affinity analysis in long-duration experiments.

Understanding the Root Causes of SPR Baseline Drift

Defining Baseline Drift and Its Impact on Data Integrity in Kinetic Analysis

FAQs: Understanding Baseline Drift

What is baseline drift?

Baseline drift is a gradual, one-directional change in the background signal of an analytical instrument while only the mobile phase or running buffer is flowing, without any sample injection. In an ideal scenario, the baseline remains stable at a constant steady-state level, but in practice, it can slowly rise or fall over time, from minutes to hours. [1]

Why is a stable baseline critical for reliable kinetic analysis in SPR?

Kinetic analysis requires measuring small changes in response units (RU) over time to determine association and dissociation rates. Baseline drift distorts the sensorgram's starting point, leading to incorrect calculation of these kinetic parameters. A drifting baseline makes it difficult to distinguish true binding events from background noise, compromising data integrity and the accuracy of affinity measurements (Ka/Kd) and rate constants (kon/koff). For interactions with slow dissociation rates, even minor drift can significantly impact the calculated off-rate. [2] [3]

What are the most common causes of baseline drift in long SPR experiments?

The following table summarizes the primary causes and their mechanisms:

| Cause | Mechanism & Impact |

|---|---|

| Improper System Equilibration | Sensor surfaces rehydrate and wash out immobilization chemicals, causing signal drift until fully equilibrated with the flow buffer. [2] |

| Temperature Fluctuations | Changes in lab temperature affect the detector, mobile phase, and sensor surface, causing expansion/contraction and changes in reaction rates, leading to drift. [1] |

| Buffer-Related Issues | Buffer contamination, degradation, or improper degassing causes shifting background absorbance. Changing buffers without thorough priming causes mixing and waviness. [2] [4] |

| Sensor Surface Issues | Residual sample components eluting slowly, leaching from column packing materials, or non-specific binding to the surface can cause a gradual signal change. [1] |

Troubleshooting Guides

My baseline is drifting continuously. What should I do?

Follow this systematic troubleshooting workflow to identify and resolve the root cause.

My baseline is stable at the start but drifts after multiple injection cycles. How can I fix this?

This issue is common in long experiments. The following solutions target cycle-specific drift:

- Optimize Regeneration: Inefficient regeneration can leave residual analyte on the surface, causing a buildup that shifts the baseline over cycles. Optimize your regeneration conditions (e.g., pH, ionic strength, buffer composition) to completely remove bound analyte without damaging the ligand. [5] [6]

- Incorporate Blank Injections: Regularly space blank (buffer alone) injections throughout your experimental method. It is recommended to have one blank cycle for every five to six analyte cycles. These blanks are essential for performing double referencing, which compensates for drift and bulk effects during data analysis. [2]

- Switch to Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK): For surfaces that are difficult to regenerate or where regeneration inactivates the ligand, consider the SCK method. SCK involves sequential injections of increasing analyte concentrations without regeneration between them, followed by a single long dissociation phase. This minimizes surface damage and reduces drift associated with repeated regeneration steps. [3]

- Ensure Sample Purity: Impurities in your analyte sample can accumulate on the sensor surface over multiple cycles, leading to a rising baseline. Ensure thorough purification of your samples before the experiment. [6]

Essential Protocols for Drift Reduction

Protocol 1: Systematic Buffer Preparation and System Equilibration

A rigorous start-up protocol is the most effective defense against drift. [2]

Methodology:

- Fresh Buffer Preparation: Prepare running buffer daily. Filter through a 0.22 µM filter and degas thoroughly. Do not add fresh buffer to old stock. [2]

- System Priming: After a buffer change, prime the system multiple times to fully replace the liquid in the pumps and tubing. [2]

- Initial Equilibration: Flow running buffer at the experimental flow rate until a stable baseline is obtained. This can take 5-30 minutes, or sometimes even overnight for new or heavily used sensor chips. [2] [7]

- Start-Up Cycles: Program at least three start-up cycles into your experimental method. These cycles should be identical to your analyte cycles but inject only running buffer. If regeneration is used, include it. Do not use these cycles for data analysis. [2]

Protocol 2: Double Referencing for Data Correction

Double referencing is a data processing technique that mathematically corrects for residual drift and bulk refractive index effects. [2]

Methodology:

- Reference Channel Subtraction: First, subtract the signal from the reference flow channel (which should have a surface as similar as possible to the active surface but without the ligand) from the active channel signal. This compensates for the majority of the bulk effect and some drift.

- Blank Subtraction: Second, subtract the response from the blank injections (running buffer) from the analyte injection responses. This compensates for differences between the reference and active channels and further corrects for drift. The blanks spaced throughout the experiment allow for tracking and subtracting drift over time. [2]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| 0.22 µM Filters | Removes particulate matter and microbes from buffers to prevent clogging and contamination, a common source of drift and spikes. [2] |

| High-Purity Water & Solvents | Using the highest grade available minimizes UV-absorbing impurities that contribute to baseline rise and noise. A case study showed that switching methanol brands resolved recurrent sensitivity loss and drift. [1] |

| Degassing Equipment | Inline degassers or helium sparging remove dissolved air from the mobile phase, preventing bubble formation in the flow cell which causes sudden spikes and drift. [4] |

| Detergents (e.g., Tween-20) | Added to the running buffer after degassing to reduce non-specific binding to the sensor chip and tubing. Reduces baseline drift caused by slow accumulation of contaminants. [2] [6] |

| Appropriate Sensor Chips | Selecting the correct chip (e.g., CM5 for amine coupling, NTA for His-tagged capture) ensures stable ligand immobilization and minimizes surface-induced drift. [6] |

| Effective Regeneration Solutions | Solutions like glycine-HCl or NaOH are used to clean the sensor surface between cycles without damaging the ligand. Proper selection is key to preventing carryover and drift over multiple cycles. [5] |

The tables below summarize key metrics and thresholds related to baseline performance.

Table 1: Acceptable Operational Standards for Baseline Stability

| Parameter | Target Value / Guideline | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Noise Level | < 1 Response Unit (RU) | Measured after system equilibration with buffer injections. [2] |

| Bulk Shift Compensation | < 10 RU | Low shifts are easily compensated by the reference surface; avoid larger shifts. [7] |

| Start-Up Cycles | Minimum of 3 cycles | Recommended to prime the surface and stabilize the system before data collection. [2] |

| Blank Injection Frequency | 1 per 5-6 analyte cycles | Provides sufficient data points for effective double referencing against drift. [2] |

Table 2: Common Drift Scenarios and Corrective Actions

| Drift Scenario | Most Likely Cause | Immediate Action |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous drift after docking chip | Surface not equilibrated | Continue flowing buffer; can take 30 min to several hours for full hydration. [2] |

| Drift after buffer change | System not adequately primed | Prime system at least 2-3 times with the new buffer. [2] |

| Drift correlated with room temperature | Uncontrolled lab environment | Stabilize room temp 2+ hours prior; use water bath for mobile phase bottles. [1] |

| Drift increasing over many cycles | Inefficient regeneration or sample impurities | Optimize regeneration solution; include regular blank injections and washes. [2] [5] |

FAQs on SPR System Equilibration

1. What is baseline drift and why is it a problem in SPR experiments? Baseline drift is an unstable or gradually shifting signal when no analyte is present. It is a problem because it makes analyzing sensorgrams difficult and can lead to erroneous results, wasting valuable experimental time and resources. A stable baseline is the foundation for accurate kinetic and affinity measurements [2] [5].

2. What are the primary causes of baseline drift? The main causes are:

- Non-optimal surface equilibration: This includes rehydration of a newly docked sensor chip and wash-out of chemicals from the immobilization procedure [2].

- Improper buffer handling: Using old, contaminated, or poorly degassed buffers can introduce drift and spikes [2] [5].

- Systemic issues: Changes in running buffer without sufficient priming, or start-up effects after a flow standstill can cause waviness and drift [2].

- Regeneration solutions: These can cause different drift rates on reference and active surfaces [2].

3. How can I prevent drift after immobilizing a ligand or docking a new chip? It is often necessary to run the running buffer overnight to fully equilibrate the sensor surface. Drift after immobilization is due to the rehydration of the surface and the adjustment of the bound ligand to the flow buffer. Allowing for an extended buffer flow ensures complete stabilization [2] [7].

4. What is the best practice for preparing and using running buffer?

- Prepare fresh buffers daily and filter them through a 0.22 µM filter [2].

- Degas the buffer before use to prevent air spikes [2] [5].

- Store buffers in clean, sterile bottles at room temperature. Avoid storage at 4°C as cold buffers contain more dissolved air [2].

- Do not add fresh buffer to old buffer to avoid contamination [2].

- Add detergents after the degassing step to prevent foam from forming [2].

5. My baseline is noisy and fluctuating. What should I check?

- Instrument environment: Ensure the instrument is in a stable environment with minimal temperature fluctuations and vibrations [5].

- Buffer quality: Use a clean, filtered buffer solution [5].

- Electrical noise: Confirm the instrument is properly grounded [5].

- Surface contamination: Check for contamination on the sensor surface and clean or regenerate it if necessary [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Baseline Drift

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous drift after chip docking | Sensor surface rehydration | Flow running buffer for an extended period (e.g., overnight) for full equilibration [2]. |

| Drift & waviness after buffer change | System not equilibrated with new buffer | Prime the system several times after each buffer change and wait for a stable baseline before starting experiments [2]. |

| Drift after regeneration | Regeneration solution inducing matrix effects | Use milder regeneration conditions and extend the post-regeneration equilibration/wash time. Ensure system is fully re-equilibrated before the next injection [2] [8]. |

| Unstable or noisy baseline | Poor buffer quality; air bubbles; temperature fluctuations | Use fresh, filtered, and degassed buffer. Check for leaks in the fluidic system. Place instrument in a stable environment [2] [5]. |

| Start-up drift after flow is initiated | Sensor surface susceptibility to flow changes | Wait for a stable baseline (5-30 min) before analyte injection. Incorporate start-up cycles with buffer injections [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for System Equilibration

Protocol 1: Standard System and Surface Equilibration

This protocol is designed to stabilize the SPR instrument and sensor surface before critical experiments.

Key Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent | Function in Equilibration |

|---|---|

| Fresh Running Buffer | Maintains a consistent solvent environment; prevents contamination [2]. |

| 0.5 M NaCl Solution | Used in system diagnostics to check for carry-over and sample dispersion [7]. |

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare 2 liters of fresh running buffer. Filter through a 0.22 µM filter and degas. Add appropriate detergents after degassing [2].

- System Priming: Prime the fluidic system several times with the new running buffer to completely replace the old buffer [2].

- Initial Stabilization: Flow running buffer at your experimental flow rate until the baseline is stable. For new or recently immobilized chips, this may require an extended period, even overnight [2] [7].

- Start-up Cycles: Program at least three start-up cycles into your method. These are identical to analyte cycles but inject running buffer instead of sample. If regeneration is used, include the regeneration step. Do not use these cycles in your final analysis [2].

- System Diagnostic Check: Inject a 0.5 M NaCl solution followed by a running buffer injection. The NaCl injection should show a sharp rise and fall with a flat steady-state. The buffer injection should be almost flat, confirming the system is clean and well-washed [7].

Protocol 2: Diagnostic Check for Noise and Drift Levels

This protocol assesses the instrument's stability and noise level after equilibration.

- Equilibrate System: Follow the steps in Protocol 1 to minimize drift [2] [8].

- Inject Running Buffer: Perform several injections of running buffer only [2] [8].

- Observe Baseline Response: Monitor the average baseline response and the shape of the curves. The overall noise level should be very low (e.g., < 1 RU) [2] [8].

- Check for Issues: If there is significant drift or the curves are not level shortly after injection starts, further equilibration or system cleaning is required [8].

System Equilibration Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for achieving a stable SPR system, integrating the key protocols and checks described above.

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments, a stable baseline is the foundation for obtaining reliable kinetic and affinity data. Baseline drift—a gradual shift in the signal when no analyte is binding—is a common challenge that can compromise data integrity, particularly in long-term studies. This instability is frequently traced back to a single, often-overlooked factor: buffer hygiene. This guide details how proper buffer preparation, including degassing, filtration, and fresh preparation, is a critical preventative measure for ensuring baseline stability and data quality.

FAQs on Buffer Hygiene and Baseline Stability

What is buffer hygiene and why is it critical for SPR?

Buffer hygiene refers to the set of practices used to prepare and handle the running buffers in an SPR experiment to ensure they are free from chemical contaminants, particulate matter, and dissolved air. It is critical because the SPR signal is exquisitely sensitive to changes in the refractive index at the sensor surface. Contaminants or air bubbles in the buffer can cause significant baseline drift, noise, and spikes, making it difficult to distinguish true binding events from experimental artifacts [2] [9].

How does dissolved air in buffers cause instability?

Dissolved air in buffers is a primary cause of instability. When buffer stored at 4°C warms to room temperature, dissolved air can come out of solution, forming microscopic bubbles. These bubbles create sudden, sharp spikes in the sensorgram when they pass through the microfluidic system [2]. Furthermore, the presence of dissolved gas can lead to a gradual baseline drift as the system struggles to equilibrate.

What are the consequences of using old or contaminated buffer?

Using old or contaminated buffer introduces multiple risks:

- Chemical Degradation: Buffer components can break down or support microbial growth over time, leading to a change in composition [2].

- Non-Specific Binding: Particulates or contaminants can adsorb non-specifically to the sensor chip surface, gradually changing its properties and causing drift [6].

- System Clogging: Particulate matter can clog the instrument's delicate microfluidic channels. It is considered bad practice to add fresh buffer to old buffer, as this can introduce contaminants and exacerbate these issues [2].

How does proper buffer hygiene prevent baseline drift in long experiments?

For long experiments, system equilibration is paramount. Proper buffer hygiene promotes a stable baseline by:

- Eliminating Bubble-Induced Spikes: Degassing prevents the formation of air spikes [2] [5].

- Ensuring Chemical Consistency: Fresh preparation and filtration maintain consistent buffer composition, preventing slow drift caused by contaminants or microbial metabolites [2].

- Facilitating Surface Equilibration: A clean, consistent buffer allows the sensor surface to fully hydrate and equilibrate, which is especially important after docking a new chip or immobilizing a ligand [2] [7].

Experimental Protocols for Optimal Buffer Preparation

Protocol 1: Standard Procedure for Fresh Buffer Preparation

This protocol is designed to prepare 2 liters of clean, degassed running buffer, suitable for most SPR experiments [2].

Materials Needed:

- High-purity water (e.g., 18 MΩ resistivity)

- Analytical grade buffer salts and reagents

- 0.22 µm bottle-top or vacuum filtration unit

- Clean (preferably sterile) storage bottles

- Degassing unit (e.g., sonicator, in-line degasser, or vacuum degassing)

Step-by-Step Method:

- Preparation: Dissolve all buffer components in high-purity water to the desired concentration. It is advised that the running buffer matches the analyte storage buffer to minimize refractive index changes [10].

- Filtration: Filter the entire volume of buffer through a 0.22 µm filter. This step removes particulate matter and sterilizes the solution, preventing microbial contamination [2] [10].

- Storage: Transfer the filtered buffer to clean, sterile bottles. Store at room temperature. Avoid storage at 4°C, as cold liquid holds more dissolved air, which will form bubbles upon warming [2].

- Aliquot and Degas: Just before use, transfer a working aliquot to a new clean bottle and degas it. If you are using detergents (e.g., Tween-20), add them after filtering and degassing to prevent foam formation [2] [6].

- System Priming: Prime the SPR instrument's fluidic system several times with the new, degassed buffer before starting the experiment to ensure complete equilibration [2].

Protocol 2: Validating Buffer Hygiene and System Equilibration

This method uses a simple injection test to diagnose issues related to buffer quality or system equilibration [7].

Materials Needed:

- Freshly prepared, degassed running buffer (from Protocol 1)

- 0.5 M Sodium Chloride (NaCl) solution, freshly prepared

Step-by-Step Method:

- System Setup: Dock a sensor chip and prime the system with your running buffer.

- Baseline Monitoring: Flow the running buffer and monitor the baseline until it appears stable.

- NaCl Injection: Program a method to inject the 0.5 M NaCl solution.

- Expected Result: A sharp rise and fall in the response signal, with a flat steady-state region during the injection [7].

- Problem Indication: A slow rise/fall or a non-flat steady state suggests issues with sample dispersion or mixing in the fluidic path.

- Buffer Injection: Program a method to inject the running buffer itself.

- Expected Result: An almost flat line, indicating no refractive index change and excellent needle washing [7].

- Problem Indication: Any significant signal change during a buffer injection indicates carry-over from previous samples or insufficient washing.

Troubleshooting Guide: Buffer-Related Baseline Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Frequent sharp spikes in the sensorgram | Air bubbles in the buffer or fluidic system [2] [5] | Ensure buffers are freshly degassed before use. Check for leaks in the fluidic system. Prime the system thoroughly [5]. |

| Continuous baseline drift (up or down) | System not equilibrated; Sensor surface not hydrated; Contaminated buffer [2] [6] | Prepare fresh buffer. Flow running buffer overnight to equilibrate the surface. Add "start-up cycles" with buffer injections to stabilize the system [2]. |

| Large bulk shift at injection start/end | Mismatch between running buffer and analyte buffer [7] | Dialyze or prepare the analyte in the running buffer. Use a desalting column to exchange buffers. |

| High noise level | Particulate matter in buffer; Temperature fluctuations [5] | Filter buffer through a 0.22 µm filter. Ensure the instrument is in a stable environment, free from vibrations. |

| Drift after buffer change | Incomplete system priming; Buffer mixing in pump [2] | Always prime the system after a buffer change. Flow the new buffer for sufficient time to completely purge the old buffer. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Buffer Hygiene | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 0.22 µm Filter | Removes particulate matter and sterilizes the buffer to prevent clogging and non-specific binding [2] [10]. | Use a membrane compatible with your buffer chemistry. Sterile, disposable filters are ideal. |

| Degassing Apparatus | Removes dissolved air to prevent bubble formation in the microfluidics, which causes spikes and drift [2] [5]. | Can be a sonication bath, vacuum degasser, or an in-line degasser on the instrument. |

| Clean Storage Bottles | Prevents introduction of chemical or biological contaminants during buffer storage [2]. | Use sterile, dedicated bottles. Avoid topping off old buffer with new. |

| Detergents (e.g., Tween-20) | Added to the buffer to reduce non-specific binding of analytes to the sensor chip and fluidic walls [6]. | Always add after filtering and degassing to prevent excessive foam formation [2]. |

| High-Purity Water | Serves as the solvent for all buffers; ensures no interference from ionic or organic impurities [10]. | Use ultrapure water (18 MΩ resistivity) [10]. |

Buffer Preparation and Stability Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for preparing SPR running buffers and the consequences of each step on system stability.

Key Takeaways

Meticulous buffer hygiene is not a minor preparatory step but a fundamental requirement for robust SPR data. The core principles are simple yet must be rigorously applied: prepare fresh buffers daily, filter through a 0.22 µm membrane, and degas immediately before use. By integrating these protocols and validation tests into your standard workflow, you can effectively prevent the common instabilities of baseline drift, spikes, and noise, thereby ensuring the integrity of your biomolecular interaction data in even the longest experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does the baseline often drift significantly immediately after I start the fluidic system or dock a new sensor chip?

This is a common phenomenon known as start-up drift and is primarily caused by system equilibration. When a sensor chip is newly docked or the flow is started after a standstill, several processes occur: the sensor surface rehydrates, chemicals from immobilization procedures are washed out, and the immobilized ligand adjusts to the flow buffer. This creates a period of instability that can last from 5 to 30 minutes before the baseline levels out. The exact duration depends on the sensor type and the properties of the immobilized ligand [2].

FAQ 2: Are certain types of sensor chips more prone to specific drift profiles?

Yes, different sensor chips exhibit distinct susceptibility to drift based on their surface chemistry and structure. For instance, negatively charged carboxylated surfaces (e.g., CM5 chips) can experience drift with positively charged analytes due to non-specific electrostatic interactions. Hydrophobic surfaces may drift with certain protein samples due to non-specific hydrophobic binding. Furthermore, capture-based chips (e.g., NTA for His-tagged proteins, SA for biotinylated ligands) can be susceptible to drift if the capture ligand itself is unstable or if the regeneration step is incomplete, leading to gradual ligand loss [11] [6].

FAQ 3: What is the most critical step to minimize drift before starting my experiment?

The single most critical step is thorough system equilibration. This involves flowing running buffer over the sensor surface until a stable baseline is achieved. For a new chip or after a buffer change, this can require priming the system several times and sometimes even flowing buffer overnight to fully equilibrate the surface. Always confirm a stable, low-noise baseline before injecting your first sample [2] [5].

FAQ 4: How can I distinguish between system-related drift and a true, very slow binding event?

True binding events typically show a concentration-dependent response. To distinguish drift from binding, include blank injections (buffer alone) and analyze the response on a reference surface. Drift will manifest as a similar signal change on both the active and reference surfaces, whereas specific binding will only (or primarily) occur on the active surface. Furthermore, a slow binding event will usually reach a plateau during the association phase, while drift often appears as a continuous, linear change [2] [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Baseline Drift

Problem: Significant Baseline Drift Upon Flow Start-Up

Description A continuous rise or fall in the baseline signal is observed immediately after initiating fluid flow or docking a new sensor chip.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| System not equilibrated [2] | Monitor baseline for 5-30 minutes after flow start. | Flow running buffer until baseline stabilizes (≥ 5 min). Prime system after any buffer change [2]. |

| Air bubbles in fluidic system [5] | Check for sudden spikes or irregular noise accompanying drift. | Ensure buffer is properly degassed. Check for and eliminate leaks in the fluidic path [5]. |

| Sensor surface rehydration [2] | Drift occurs after docking a new, dry sensor chip. | Follow manufacturer's chip priming procedure. Allow extended buffer flow for rehydration [2]. |

| Buffer mismatch or contamination [2] [5] | Check if drift persists after thorough priming with fresh buffer. | Prepare fresh, filtered (0.22 µm), and degassed buffer daily. Avoid adding fresh buffer to old stock [2]. |

Problem: Chip-Specific or Sustained Drift During Experiment

Description A persistent drift is observed throughout the experiment, which may vary in intensity depending on the sensor chip type or immobilized ligand.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-specific binding (NSB) [12] [11] | Inject a high analyte concentration over a bare reference surface. A significant signal indicates NSB. | Add blocking agents (e.g., 1% BSA), non-ionic surfactants (e.g., 0.05% Tween 20), or increase salt concentration in the running buffer [11]. |

| Incomplete regeneration [11] | Observe if the baseline does not return to the pre-injection level after regeneration. | Optimize regeneration solution (e.g., glycine pH 2.0, NaOH, high salt). Use short, fast-flow regeneration pulses [11]. |

| Unstable ligand immobilization [2] [13] | Drift is more pronounced on the active surface vs. reference. Check ligand activity with a positive control. | Use a milder immobilization chemistry. Ensure ligand purity and stability. Avoid harsh regeneration conditions that damage the ligand [13]. |

| Inappropriate sensor chip chemistry [11] [6] | Drift is consistently high with a specific chip type and analyte pair. | Switch sensor chip to one with a more compatible surface chemistry (e.g., neutral hydrogel to reduce electrostatic NSB) [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for Drift Mitigation

Protocol for System Equilibration and Start-Up

Purpose: To minimize initial baseline drift caused by fluidic and surface instability at the start of an experiment [2].

Materials:

- Fresh running buffer (filtered through 0.22 µm and degassed)

- Docked sensor chip

Method:

- Prime the System: After docking the chip and changing the buffer, perform a minimum of two prime procedures using the instrument's software to flush the entire fluidic path with the new buffer.

- Initial Stabilization: Initiate a constant flow of running buffer at the experimental flow rate. Allow the system to stabilize for a minimum of 5 minutes, or until the baseline drift falls below an acceptable threshold (e.g., < 5 RU/min).

- Execute Start-Up Cycles: Program and run at least three "start-up" or "dummy" cycles. These should be identical to your experimental cycles but inject running buffer instead of analyte. If your method includes a regeneration step, include it in these cycles.

- Verify Stability: After the start-up cycles, confirm that the baseline is stable. The baseline noise level should be low (e.g., < 1 RU) [2]. Do not use data from start-up cycles for analysis.

- Begin Experiment: Once a stable baseline is confirmed, commence the experimental cycles with analyte injections.

Protocol for Diagnostic Flow Rate Test

Purpose: To determine if observed binding kinetics are distorted by mass transport limitations, which can manifest as a specific type of drift in the association phase [11].

Materials:

- A single concentration of analyte (at a mid-range level, e.g., near the expected KD)

- Immobilized ligand surface

Method:

- Design the Method: Create a method that injects the same analyte concentration over the ligand surface multiple times, but vary the flow rate for each injection (e.g., 10, 30, 50, 100 µL/min). Use a sufficiently long dissociation phase.

- Run the Experiment: Execute the method, ensuring the surface is fully regenerated between injections.

- Analyze the Sensorgrams: Plot the response versus time for the different flow rates.

- Interpretation: If the observed association rate (ka) increases with increasing flow rate, it indicates that the binding is limited by the diffusion of the analyte to the surface (mass transport limitation), not just by the intrinsic kinetics. A lack of flow rate dependence suggests mass transport is not a significant issue [11].

Diagram 1: Diagnostic flowchart for baseline drift.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and materials essential for diagnosing and mitigating baseline drift in SPR experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Drift Mitigation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh, Filtered (0.22 µm), Degassed Buffer [2] | Removes dissolved air (prevents bubbles), particles, and microbial contaminants that cause spikes and drift. | Prepare fresh daily. Do not top up old buffers. Filter before degassing. Add detergents after degassing to prevent foam [2]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [11] | A blocking agent used at ~1% concentration to coat non-specific binding sites on the sensor surface, reducing charge- and hydrophobic-based NSB. | Use during analyte runs only. Do not use during ligand immobilization, as it will bind to the surface [11]. |

| Non-Ionic Surfactant (e.g., Tween 20) [11] | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions that lead to NSB. Typical concentration is 0.005%-0.05%. | Use mild, high-purity detergents to avoid damaging the instrument or ligand. |

| High-Salt Solutions (e.g., 1-2 M NaCl) [11] | Shields electrostatic charges on the sensor surface and analyte, reducing non-specific ionic binding. | The required concentration is analyte-dependent. Test different levels to find the optimum without disrupting the specific interaction. |

| Regeneration Buffers (e.g., 10-100 mM Glycine pH 2.0-3.0, 10-50 mM NaOH, high salt) [11] | Removes bound analyte completely between cycles without damaging the ligand, preventing carryover and baseline rise. | Start with the mildest option and increase stringency. Always include a positive control to verify ligand activity remains after regeneration [11]. |

| Reference Sensor Chip Surface [2] [13] | A surface without the specific ligand, used to measure and subtract signals from NSB and bulk refractive index changes (double referencing). | Should be as chemically and structurally similar as possible to the active surface to provide an accurate reference [2]. |

Diagram 2: Workflow for a low-drift SPR experiment.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are SPR experiments so sensitive to minor temperature changes? Temperature fluctuations cause changes in the refractive index (RI) of the buffer and the optical components of the sensor chip itself. The SPR signal is exquisitely sensitive to RI changes at the sensor surface. Even small temperature variations can induce a baseline drift or shift the resonance signal, mimicking a binding event or obscuring a real one [14] [15]. The gold film's plasma frequency, a critical property, is also temperature-dependent, directly contributing to the resonant wavelength shift [16].

Q2: How do pressure changes affect my SPR baseline? Sudden pressure changes, often from air bubbles in the microfluidic system or irregular flow from pump refilling, can cause instant spikes or a noisy, drifting baseline [17] [5]. These events disrupt the consistent flow and liquid composition over the sensor surface.

Q3: What are the most common instrumental signs of temperature and pressure issues? The table below summarizes the key symptoms to watch for.

Table: Common Symptoms of Temperature and Pressure Issues in SPR

| Symptom | Description | Likely Cause(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Drift [7] [5] | A gradual, continuous rise or fall of the baseline signal before analyte injection. | Slow thermal equilibration of the instrument/sample; temperature fluctuation in the room; undegassed buffer [6] [5]. |

| Signal Spikes [17] | Sudden, sharp increases or decreases in the signal. | Air bubbles passing through the flow cell; pump refill cycles; carry-over from previous injections [17]. |

| Bulk Refractive Index Shifts [17] | A large, instantaneous signal jump at the start and end of an injection, with a flat "steady-state" level during injection. | A mismatch between the running buffer and the analyte buffer (e.g., different salt concentration, DMSO content, or temperature) [17]. |

Q4: How can I minimize the impact of temperature fluctuations?

- Equilibration: Allow the instrument and all solutions to thermally equilibrate completely before starting the experiment. This may require running buffer overnight [7].

- Buffer Handling: Always degas your buffers to prevent bubble formation, especially if they have been stored cold [17] [5].

- Environmental Control: Operate the instrument in a temperature-stable environment, away from drafts, direct sunlight, or heating/cooling vents [5].

Q5: What steps can I take to prevent pressure-related problems?

- Degas Buffers: This is the most critical step for preventing air bubbles [17] [5].

- Avoid Bubbles in Samples: Centrifuge samples before loading them into vials to remove any microscopic bubbles.

- System Maintenance: Perform routine instrument priming and flushing as recommended by the manufacturer to clear the fluidic system of contaminants and bubbles [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Temperature-Induced Baseline Drift

Problem: The baseline signal continuously drifts upward or downward.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

- Confirm Equilibration: Ensure the instrument and all buffers have reached a stable operating temperature. If the system was recently started or the buffer was recently replaced, allow at least 30-60 minutes for stabilization. For new surfaces, overnight equilibration may be necessary [7].

- Check Buffer Quality: Prepare a fresh batch of running buffer, filter (0.22 µm) and degas it thoroughly immediately before use. Do not top off old buffer with new buffer [17].

- Inspect for Environmental Drafts: Verify that the instrument is not in the path of an air conditioning vent or other source of temperature fluctuation.

- Verify System Calibration: Consult your instrument manual to perform a system calibration check if drift persists [5].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Pressure Spikes and Air Bubbles

Problem: Sudden, sharp spikes appear in the sensorgram.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

- Identify Spike Source:

- Pump Refill Spikes: Check if spikes correlate with the instrument's pump refill cycle. These are often periodic [17].

- Air Bubbles: Bubbles typically cause random, large spikes. Visually inspect the fluidic path and sensor surface if possible.

- Degas Solutions: Thoroughly degas all buffers and samples. If your instrument has an in-line degasser, ensure it is functioning correctly [17].

- Purge the System: Run a high flow rate (e.g., 50-100 µL/min) for a few minutes to flush any existing bubbles out of the flow cells [17].

- Review Injection Method:

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Bulk Refractive Index Shifts

Problem: A large, square-shaped signal jump occurs at the beginning and end of an injection.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

- Match Buffer Compositions: The most common cause is a difference between the running buffer and the analyte buffer. Dialyze your analyte into the running buffer or use a size-exclusion column for buffer exchange [17].

- Handle Additives with Care: If using additives like DMSO, ensure the DMSO concentration is identical in the running buffer and the analyte sample. Evaporation from sample vials can change concentration, so cap them securely [17].

- Temperature Matching: Ensure the analyte sample is at the same temperature as the running buffer when injected. A cold sample injected into a warm system will cause a significant bulk shift.

- Use Instrument Features: If available, use features like real-time bulk refractive index compensation (e.g., PureKinetics on BioNavis instruments) to correct for these shifts [17].

Quantitative Data on Temperature Sensitivity

The following table summarizes key experimental findings on the intrinsic temperature sensitivity of SPR systems, which underpins the need for careful control.

Table: Experimental Findings on SPR Temperature Sensitivity

| Study Focus | Key Finding | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Contribution of Gold Film [16] | The temperature-dependent change in the gold film's plasma frequency contributed to 19.6% of the total SPR wavelength shift. | A PCS optical fiber SPR sensor in ethanol, with temperature increase from 0°C to 50°C [16]. |

| Overall Sensor Sensitivity [14] | Instrumental sensitivity (Sθ) in angular interrogation mode deteriorated from 120°/RIU to 30°/RIU as temperature dropped below 300 K (~27°C). | A commercial SPR (SPREETA) device at the gold-water interface, using angular interrogation [14]. |

| Impact of Interrogation Mode [14] | The effect of higher device temperatures (300K |

Theoretical evaluation of SPR performance using a BK7 glass prism, gold film, and aqueous analyte [14]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: System Equilibration and Baseline Stability Test

This protocol is designed to verify that your SPR system is thermally stable and ready for a long-term experiment.

Objective: To achieve a stable baseline with minimal drift (< 10 RU over 30 minutes). Materials:

- Freshly prepared, filtered (0.22 µm), and degassed running buffer.

- A clean, unused or properly regenerated sensor chip.

Methodology:

- Install the sensor chip and prime the fluidic system with the degassed running buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Set the instrument to continuous flow at your experimental flow rate (e.g., 30 µL/min) and temperature.

- Start monitoring the baseline signal and allow the system to equilibrate. A significant initial drift is normal.

- Once the drift slows, continue monitoring for at least 30 minutes. The baseline is considered stable when the drift is minimal and linear [7].

- If the baseline continues to drift significantly, perform several buffer injections and continue equilibration. Persistent drift may indicate a need for more thorough buffer degassing or system cleaning [17].

Protocol 2: Injection System Integrity Test

This protocol checks for issues related to sample dispersion, carry-over, and bulk shifts.

Objective: To verify that the instrument delivers a sharp, consistent sample plug without artifacts. Materials:

- Running buffer.

- High-salt solution (e.g., running buffer + 0.5 M NaCl).

Methodology:

- Prepare a dilution series of the high-salt solution in the running buffer (e.g., 50, 25, 12.5, 0 mM extra NaCl) [17].

- Using a plain gold chip, inject the solutions from low to high concentration in a single-cycle kinetics program. End with an injection of running buffer alone.

- Analyze the sensorgrams:

- The rise and fall of each injection should be sharp and immediate.

- The steady-state response during injection should be flat, indicating no mixing with the running buffer (no sample dispersion) [17].

- The final running buffer injection should show no signal, confirming no carry-over from the high-salt samples [17].

- Any deviation from this ideal behavior indicates a need to optimize the injection routine or wash steps.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for Stable SPR Experiments

| Item | Function | Considerations for Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer Components | To provide a stable chemical and ionic environment for biomolecular interactions. | Always filter (0.22 µm) and degas before use. Prepare fresh daily to prevent microbial growth or contamination [17] [5]. |

| Detergent (e.g., Tween-20) | A common additive to reduce non-specific binding to the sensor surface. | Can also help prevent bubble formation. Use at low, consistent concentrations (e.g., 0.005-0.01%) [6]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Ethanolamine) | To passivate unused active sites on the sensor surface after ligand immobilization. | Reduces non-specific binding, which can be a source of signal drift and noise [6] [5]. |

| Regeneration Solutions | To remove bound analyte from the ligand without damaging it. | An optimized, effective regeneration step is vital for reproducible results and preventing carry-over, which affects baseline stability [5]. |

Diagnostic Workflow Diagram

The following diagram outlines a logical, step-by-step process for diagnosing and resolving baseline instability issues related to instrumental and environmental factors.

Proactive Experimental Design for Drift-Free SPR Assays

Why is buffer optimization critical for Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments?

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), the running buffer is the medium in which molecular interactions occur. A poorly matched buffer can introduce bulk effects (or bulk shifts), which are false signals caused by differences in refractive index between the analyte solution and the running buffer [11]. These artifacts can obscure genuine binding events, complicate data analysis, and reduce the reliability of your kinetic and affinity measurements. Proper buffer optimization, focusing on ionic strength, pH, and additives, is therefore a fundamental step in experimental design to ensure high-quality, publication-ready data.

Troubleshooting Common Buffer-Related Issues

Q: What does a "square-shaped" sensorgram indicate, and how is it resolved? A: A large, square-shaped response at the start and end of an injection is a classic sign of a bulk shift [11]. This occurs when the refractive index of your analyte sample does not match that of your running buffer. To resolve this:

- Match buffer composition: Ensure the running buffer and the buffer used to prepare your analyte dilutions are identical [11].

- Use a reference channel: Always subtract the signal from a reference flow cell to correct for bulk refractive index differences [2] [11].

- Prepare buffers fresh: Always prepare fresh running buffer daily, filter (0.22 µm), and degas it to eliminate air spikes and contamination [2].

Q: How does buffer contribute to baseline drift, and how can it be stabilized? A: Baseline drift is often a sign of a system that is not fully equilibrated, which can be exacerbated by the buffer [2] [7].

- Ensure thorough equilibration: After a buffer change or sensor chip docking, prime the system and flow running buffer until the baseline is stable. For some surfaces, this may require flowing buffer overnight [2] [7].

- Use start-up cycles: Incorporate several "dummy" injections (injecting buffer instead of analyte) at the beginning of your experiment to stabilize the system and sensor surface [2].

- Check for contamination: Use fresh, filtered, and degassed buffers to prevent the introduction of particles or microbes that can cause drift [2] [5].

Q: How can I minimize non-specific binding (NSB) through buffer composition? A: Non-specific binding occurs when analytes interact with the sensor surface or ligand through non-targeted, often charge-based or hydrophobic, interactions [6] [12] [11].

- Adjust pH: A positively charged analyte can interact non-specifically with a negatively charged dextran matrix. Adjusting the buffer pH to your protein's isoelectric point can neutralize these charges [11].

- Increase ionic strength: Adding salt (e.g., NaCl) to your running buffer can shield charge-based interactions [11].

- Add detergents: Incorporating non-ionic surfactants like Tween-20 (e.g., 0.005% P20 in HBS buffers) can disrupt hydrophobic interactions that cause NSB [6] [11].

- Use blocking agents: Adding proteins like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to analyte samples can block non-specific sites [12] [11].

Buffer Composition and Optimization Guidelines

The following table summarizes the role and optimization strategy for key buffer components to minimize bulk effects and other artifacts.

Table 1: Optimization of Key Buffer Components

| Component | Function & Impact | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Strength | Controls electrostatic interactions. Low ionic strength can increase NSB; very high ionic strength can mask charges and hinder specific binding. | Use a moderate starting concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl). Increase to shield charges if NSB is high; decrease to enhance pre-concentration during immobilization [18] [11]. |

| pH | Affects the charge and stability of proteins and the sensor surface. A mismatch can cause NSB and ligand inactivity. | Choose a pH that maintains biological activity. Adjust to the ligand's isoelectric point (pI) to reduce NSB. For immobilization, use a pH 0.5-1.0 unit below the ligand's pI for pre-concentration [18] [11]. |

| Detergents (e.g., Tween-20, P20) | Reduce NSB by disrupting hydrophobic interactions. Can cause foam if added before degassing. | Add after filtering and degassing the buffer to avoid foam formation [2]. Use at low concentrations (e.g., 0.005%-0.05%) [6]. |

| Organic Solvents (e.g., DMSO) | Essential for solubilizing small molecules. Causes significant bulk shifts if mismatched. | Match the DMSO concentration precisely between the running buffer and all analyte samples [19]. Keep the concentration as low as possible (typically ≤1%). |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA) | Occupies non-specific binding sites on the sensor surface. | Add BSA (typically 0.1-1%) to analyte samples during runs only. Do not use during ligand immobilization, as it will coat the surface [11]. |

Optimized Buffer Preparation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for preparing and validating an optimized SPR running buffer.

Protocol:

- Define Base Buffer: Select a biologically relevant buffer such as HEPES, PBS, or Tris [19].

- Add Salts: Incorporate salts like NaCl to a moderate ionic strength (e.g., 150 mM) to minimize non-specific electrostatic interactions [11].

- Adjust pH: Titrate to the desired pH using a calibrated pH meter. Ensure the pH is optimal for your ligand-analyte interaction and surface stability [18] [11].

- Filter and Degas: Pass the buffer through a 0.22 µm filter to remove particulates, then degas to prevent air spikes in the microfluidics [2].

- Add Additives: After degassing, add detergents like Tween-20 or other stabilizers to avoid foam formation [2].

- Match Solvent: For small molecule studies, add the correct percentage of organic solvent (e.g., DMSO) to the running buffer to match the analyte solution [19].

- Validate: Perform a buffer injection test. A flat sensorgram response indicates good buffer matching and a clean system [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for SPR Buffer Optimization and Troubleshooting

| Reagent | Function | Example Usage & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HEPES | A common buffering agent for maintaining stable pH. | Used at 10-50 mM concentration in running buffers for protein interactions [19]. Prefered for its stability at room temperature. |

| NaCl | Modifies the ionic strength of the solution to shield charge-based interactions. | Used to reduce non-specific binding; concentrations can be scouted from 0 to 500 mM [11]. |

| Tween-20 / P20 | Non-ionic surfactant that reduces hydrophobic non-specific binding. | Typically used at 0.005%-0.05% (v/v). Must be added after degassing to prevent foam [2] [6]. |

| DMSO | Organic solvent for solubilizing small molecule analytes. | Concentration must be matched exactly (e.g., 0.5-1%) in running buffer and all analyte samples to prevent major bulk shifts [19]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Blocking agent to occupy non-specific binding sites. | Added to analyte samples at ~1% concentration to reduce NSB. Avoid using during ligand immobilization [11]. |

| Glycine | Used in regeneration buffers to remove bound analyte. | A low-pH (pH 2.0-3.0) glycine solution is a common, mild regeneration scouting solution [19] [12]. |

| NaOH | Used in regeneration buffers to remove bound analyte. | A common, harsher regeneration scouting solution (e.g., 10-50 mM) [12]. |

| Sodium Acetate | Low pH immobilization buffer. | Used for pre-concentration and covalent coupling of ligands to carboxymethylated dextran chips (e.g., CM5) [18]. |

Keywords: Surface Plasmon Resonance, SPR, Baseline Drift, Pre-conditioning, Overnight Equilibration, Start-Up Cycles, Surface Equilibration

Why is my baseline unstable at the beginning of an SPR experiment, and how can I stabilize it?

Baseline drift, often observed as an unstable signal at the start of an experiment, is typically a sign of a non-optimally equilibrated sensor surface [2]. This frequently occurs after docking a new sensor chip or following the immobilization procedure, due to the rehydration of the surface and the wash-out of chemicals used during immobilization [2]. A poorly equilibrated system can lead to drift and changing analyte binding performance in initial cycles, compromising data quality [20].

Solution: Implement a comprehensive surface pre-conditioning protocol.

- Overnight Equilibration: In cases of significant drift, it can be necessary to run the running buffer overnight to equilibrate the surfaces fully [2] [7].

- Stabilization Cycles: Subject the ligand surface to several cycles of analyte injection and regeneration to stabilize it before formal data collection begins. This provides valuable information on the stability and reproducibility of the interaction [20].

- Buffer Matching: Ensure that your analyte and flow buffers are perfectly matched. Buffer mismatches are a common cause of bulk effects and large residuals, which contribute to instability [20] [11].

What is the detailed protocol for implementing start-up cycles?

Start-up cycles, also known as dummy injections, are a critical procedural step to "prime" the system and surface, minimizing drift and other artifacts during the actual analyte injections [20] [2].

Experimental Protocol:

- Initial System Prime: After a buffer change or system start-up, prime the system with your running buffer until a stable baseline is obtained [2].

- Incorporate Start-Up Cycles: In your experimental method, program at least three to five start-up cycles before the first analyte injection [20] [2].

- Cycle Composition: These cycles should be identical to your experimental cycles, but inject running buffer instead of analyte. If your method includes a regeneration step, include the regeneration injection in these start-up cycles as well [2].

- Exclude from Analysis: The data from these start-up cycles are used solely for system stabilization and should be left out of the final analysis. They should not be used as blanks for referencing [2].

Table 1: Components of a Start-Up Cycle Protocol

| Step | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Prime | Flush the system with running buffer | To equilibrate the entire fluidic system and remove air bubbles |

| 2. Buffer Injection | Inject running buffer as a sample | To stabilize the injection system and identify pressure-related spikes |

| 3. Regeneration | Apply the regeneration solution (if used) | To condition the surface to the regeneration process and stabilize ligand activity |

| 4. Repeat | Perform steps 2-3 for 3-5 cycles | To ensure system and surface responses are consistent and stable |

How does overnight equilibration work, and when is it necessary?

Overnight equilibration is an extended process used to achieve a perfectly stable baseline, which is foundational for high-quality, reproducible SPR data, especially in long-duration experiments.

Methodology:

- Procedure: Continuously flow fresh, filtered, and degassed running buffer over the docked sensor chip at a constant flow rate for an extended period, typically overnight [2] [7].

- Purpose: This process allows for the complete rehydration of the sensor surface and the thorough wash-out of any residual chemicals from the immobilization process, allowing the bound ligand to fully adjust to the flow buffer conditions [2].

Table 2: Equilibration Troubleshooting Guide

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent high drift (> ± 0.3 RU/min) after docking | Surface not fully equilibrated | Extend the equilibration time; implement overnight buffer flow |

| Drift after buffer change | System not adequately primed with new buffer | Prime the system several times after each buffer change |

| Drift after regeneration | Differences in surface response between reference and active flow cells | Use double referencing to compensate for drift differences |

| Start-up drift after flow is initiated | Sensor surface susceptibility to flow changes | Allow additional time (5–30 minutes) for baseline to stabilize before first injection |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the strategic decision-making process for implementing these pre-conditioning steps.

What other experimental strategies can I use to minimize drift and improve data quality?

Beyond start-up cycles and extended equilibration, several other strategies are essential for a robust experimental setup.

- Use Fresh Buffers: Prepare running buffer fresh daily. Filter through a 0.22 µM filter and degas before use to eliminate particles and air bubbles, which are common causes of noise and spikes [5] [2]. Avoid adding fresh buffer to old stock, as contamination can occur.

- Implement Double Referencing: This is a powerful data processing technique to compensate for residual drift, bulk refractive index effects, and differences between flow channels. It involves subtracting both a reference surface signal and blank (buffer) injections spaced evenly throughout the experiment [20] [2].

- Include Blank Injections: Throughout your experimental run, incorporate blank cycles (running buffer only) at a rate of approximately one blank every five to six analyte cycles. This provides the necessary data for effective double referencing [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SPR Surface Pre-conditioning

| Reagent / Equipment | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer | Hydrates the surface and provides the solvent for interactions | Must be filtered (0.22 µm) and degassed; composition should match analyte buffer |

| Sensor Chip | Platform for ligand immobilization | Type (e.g., CM5, NTA, SA) must be compatible with ligand and immobilization chemistry |

| Regeneration Solution | Removes bound analyte between cycles in start-up and main experiments | Must be harsh enough to dissociate the complex but mild enough to preserve ligand activity (e.g., 10 mM Glycine pH 1.5–2.5) |

| Blocking Agent (e.g., BSA, Ethanolamine) | Occupies unused active sites on the sensor surface | Reduces non-specific binding, which can contribute to signal instability |

| SPR Instrument | Performs fluidic handling, injection, and real-time detection | Regular calibration and maintenance (e.g., "desorb" and "sanitize" routines) are critical |

How do I know if my pre-conditioning strategy is successful?

A successful pre-conditioning strategy results in a stable baseline with low noise, which is the foundation for acquiring high-quality, publication-ready data.

Success Criteria:

- Baseline Drift: Should be minimal, ideally less than ± 0.3 RU/minute [20].

- Noise Level: The system noise should be very low (e.g., < 1 RU), producing a flat and clean signal when buffer is flowing [2].

- Buffer Injections: Injections of running buffer alone should give low responses (e.g., < 5 RU), indicating a well-behaved system with minimal injection spikes or bulk effects [20].

By systematically implementing strategic surface pre-conditioning through start-up cycles and, when necessary, overnight equilibration, researchers can effectively mitigate baseline drift at its source. This proactive approach significantly enhances the reliability of data generated in long SPR experiments, supporting accurate kinetic and affinity analysis in critical research and drug development projects.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Understanding and Diagnosing Baseline Drift

What is baseline drift and why is it a problem in SPR experiments? Baseline drift is the gradual shift in the signal response when no analyte is present, making analysis difficult and leading to erroneous results [2]. In long experiments, uncompensated drift distorts binding curves, compromises kinetic parameter accuracy, and wastes valuable experimental time [2].

How can I determine if my baseline drift is acceptable? After proper system equilibration, your baseline drift should be minimal. A well-equilibrated system typically exhibits drift of less than ± 0.3 RU/min [20]. Injecting running buffer should yield low responses (under 5 RU), indicating a stable system ready for experiment [20].

What are the most common causes of baseline drift?

- Poor Surface Equilibration: Newly docked sensor chips or recently immobilized surfaces require time to rehydrate and wash out immobilization chemicals [2].

- Buffer Issues: Changing running buffers without sufficient system priming causes mixing and waviness [2].

- Start-up Effects: Flow initiation after standstill causes temporary drift (5-30 minutes) as the system stabilizes [2].

- Regeneration Solutions: These can cause differential drift between reference and active surfaces [2].

Implementing Double Referencing for Drift Compensation

What is double referencing and how does it compensate for drift? Double referencing is a two-step procedure that compensates for drift, bulk effects, and channel differences [2]. First, a reference channel is subtracted from the active channel, compensating for bulk effect and primary drift. Then, blank injections are subtracted, compensating for differences between reference and active channels [2].

What is the optimal strategy for incorporating blank injections? For effective double referencing, include blank cycles evenly throughout your experiment. It's recommended to add one blank cycle every five to six analyte cycles and always finish with a blank [2]. Space blanks evenly within the experiment to track and compensate for drift consistently across the entire run [2].

How should I prepare my system before starting the actual experiment? Incorporate at least three start-up cycles in your method that mimic analyte cycles but inject buffer instead [2]. These cycles prime the surface and eliminate differences from initial regeneration cycles. Do not use start-up cycles as blanks in your final analysis [2].

Advanced Experimental Setup for Drift Reduction

What buffer preparation practices minimize drift?

- Prepare fresh buffers daily and 0.22 µM filter and degas before use [2].

- Store buffers in clean, sterile bottles at room temperature [2].

- Never add fresh buffer to old buffer to avoid contamination [2].

- Add detergents after filtering and degassing to prevent foam formation [2].

How long should I equilibrate my sensor surface? For surfaces with significant drift, it may be necessary to run running buffer overnight to fully equilibrate [2] [7]. Flow running buffer at your experimental flow rate until a stable baseline is obtained, which may take 5-30 minutes after flow initiation [2].

What should I do after changing running buffers or cleaning the system? Always prime the system after each buffer change and method start [2]. Allow extra equilibration time after cleaning the system. Monitor the baseline until it stabilizes before beginning analyte injections [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: System Equilibration and Baseline Stabilization

Purpose: To minimize initial drift before analyte injections through proper system preparation.

Materials:

- Freshly prepared, filtered (0.22 µm), and degassed running buffer

- Primed SPR instrument with docked sensor chip

Method:

- Prime the system several times with fresh running buffer [2].

- Begin continuous buffer flow at your experimental flow rate.

- Monitor the baseline response for stability.

- If drift exceeds ± 0.3 RU/min, continue flowing buffer [20].

- For persistent drift, flow running buffer overnight [2] [7].

- Once stable, inject running buffer several times to determine noise level.

- The system is ready when buffer injections yield responses < 5 RU with minimal spikes [20].

Protocol 2: Double Referencing Experimental Setup

Purpose: To implement double referencing for optimal drift compensation throughout the experiment.

Materials:

- Equilibrated SPR system

- Prepared analyte samples

- Running buffer for blank injections

Method:

- Program your method to include 3+ start-up cycles (buffer + regeneration) [2].

- Design your experimental cycle sequence with blank injections every 5-6 sample cycles [2].

- Include a final blank cycle at the end of the experiment [2].

- Execute the method with randomized analyte injections where possible.

- During analysis, subtract the reference channel from the active channel.

- Subsequently subtract the averaged blank injections from the reference-subtracted data [2].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Guidelines for Optimal Drift Reduction

| Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Purpose & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Drift Rate | < ± 0.3 RU/min [20] | Indicates properly equilibrated system |

| Buffer Injection Response | < 5 RU [20] | Confirms minimal bulk effects and system stability |

| Blank Injection Frequency | 1 per 5-6 analyte cycles [2] | Provides regular drift measurement points |

| Start-up Cycles | ≥ 3 cycles [2] | Stabilizes surface before data collection |

| System Noise Level | < 1 RU [2] | Ensures high-quality data detection |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Drift Management

| Reagent/Solution | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh Running Buffer | Maintains system stability and prevents contamination [2] | Prepare daily, 0.22 µM filter, degas before use [2] |

| Degassed Buffer | Prevents bubble formation in fluidic system [5] | Eliminates air spikes that cause baseline artifacts |

| Detergents/Additives | Reduce non-specific binding and surface interactions [2] | Add after filtering and degassing to prevent foam [2] |

| Regeneration Solutions | Remove bound analyte between cycles [20] | Use mildest effective conditions to preserve ligand activity [20] |

| Blocking Agents | Minimize non-specific binding [12] | BSA, ethanolamine, or casein occupy remaining active sites [12] |

Methodological Visualization

Double Referencing Data Flow

Drift Reduction Experimental Workflow

Incorporating Blank and Control Injections for Continuous Baseline Monitoring

FAQs on Baseline Drift and Control Injections

1. What is baseline drift and why is it problematic in long SPR experiments? Baseline drift is an unstable or gradually shifting signal when no analyte is present. It is usually a sign of a non-optimally equilibrated sensor surface or system [2] [5]. In long experiments, it complicates data analysis by making it difficult to differentiate true binding events from background signal movement, potentially leading to erroneous kinetic parameters and affinity constants [2].

2. How do blank and control injections help monitor and correct for baseline drift? Blank injections (injecting running buffer instead of analyte) are used in the data processing step of double referencing [2] [21]. First, a reference flow cell is subtracted from the active flow cell to compensate for bulk effect and most of the drift. Subsequently, subtracting the blank injections compensates for small differences between the reference and active channels, providing a cleaner baseline for analysis [2]. Spacing these blanks evenly throughout the experiment allows for continuous monitoring and correction of the baseline [2].

3. What is the difference between a start-up cycle and a blank injection? Both involve injecting buffer, but they serve different purposes. Start-up cycles are performed at the very beginning of an experiment, before any analyte is injected, to "prime" and stabilize the sensor surface, especially after a regeneration step [2]. These cycles are not used in the final analysis. Blank injections are interspersed among the analyte injections throughout the entire experiment and are actively used in the double referencing procedure during data analysis [2].

4. How many blank injections should I include in my experiment? It is recommended to add blank cycles evenly within the experiment, with an average of one blank cycle for every five to six analyte cycles, and to end the experiment with a blank [2]. Having more blanks is considered better than having too few [2].

5. My baseline is still drifting even with blank injections. What else should I check? Blank injections are a data correction method; they do not prevent drift from occurring. If significant drift persists, investigate the root cause [2] [7] [5]:

- Buffer and System Equilibration: Ensure your running buffer is fresh, filtered, and degassed. Prime the system after every buffer change and flow running buffer until the baseline is stable; this can sometimes take 5-30 minutes or even overnight [2] [7].

- Sensor Surface: A newly docked chip or a recently immobilized surface needs time to rehydrate and equilibrate, which causes initial drift [2].

- Instrument Maintenance: Check for air bubbles or leaks in the fluidic system and ensure the instrument is in a stable environment with minimal temperature fluctuations [5].

Troubleshooting Guide for Baseline Instability

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Baseline Noise [5] | Electrical noise; contaminated buffer or sensor surface; environmental fluctuations. | Ensure proper instrument grounding; use a clean, filtered buffer; place instrument in a stable environment away from vibrations [5]. |

| Sudden Baseline Jumps | Change in running buffer composition; air spikes; improper priming. | Always prime the system after a buffer change; ensure buffers are thoroughly degassed to prevent air spikes [2] [5]. |

| Carryover Effect [7] | Incomplete regeneration of the sensor surface between analyte injections. | Optimize regeneration conditions (solution, contact time) to completely remove bound analyte without damaging the ligand [7] [11]. |

| Bulk Shift [11] | Refractive index (RI) difference between the running buffer and the analyte sample buffer. | Match the analyte buffer to the running buffer as closely as possible. Use reference subtraction to compensate for remaining shifts [11] [21]. |

| Continuous Drift [2] [7] | Poorly equilibrated system or sensor surface; buffer instability. | Extend the system equilibration time with buffer flow. Incorporate start-up cycles. Prepare fresh running buffer daily [2] [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Establishing a Stable Baseline

This protocol details the methodology for system setup and equilibration to minimize baseline drift, incorporating blank injections for monitoring.

Methodology for System Preparation and Continuous Monitoring

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare running buffer fresh daily. Filter through a 0.22 µM filter and degas to prevent air spikes. If needed, add detergents after degassing to avoid foam [2].

- System Priming: Prime the instrument with the new running buffer several times to ensure the fluidic system is completely filled and free of previous buffer or contaminants [2].

- Initial Equilibration: Flow running buffer over the sensor surface at the experimental flow rate. Monitor the baseline until it is stable. This may take 5–30 minutes, or longer for new chips [2]. In some cases, flowing buffer overnight is necessary [7].

- Incorporate Start-up Cycles: In your experimental method, program at least three start-up cycles before any analyte is injected. These cycles should mimic the experimental cycle (including regeneration if used) but inject only running buffer. Do not use these cycles in the final analysis [2].

- Run the Experiment with Blank Injections:

- Data Processing (Double Referencing):

- Zero the Y-axis: Align all sensorgrams to a baseline region just before an injection [21].

- Reference Subtraction: Subtract the signal from the reference flow channel from the active flow channel [2] [21].

- Blank Subtraction: Subtract the averaged response of the blank injections from the analyte injection curves. This, combined with reference subtraction, constitutes double referencing and effectively compensates for residual drift and channel differences [2] [21].

Double Referencing Data Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequence of data processing steps for double referencing, which uses blank and reference channel injections to correct the baseline.

System Equilibration Protocol

This workflow outlines the key steps for preparing the SPR instrument and sensor surface to minimize initial baseline drift.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their specific functions in maintaining a stable baseline and implementing effective blank controls.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Baseline Monitoring & Stability |

|---|---|

| Fresh Running Buffer | The foundation of stability. Fresh preparation prevents contamination from microbial growth or chemical degradation that causes drift [2]. |

| 0.22 µM Filter | Removes particulate matter from buffers that could clog the fluidic system or bind non-specifically to the sensor surface, causing spikes and drift [2]. |

| Degasser | Removes dissolved air from the buffer to prevent the formation of air bubbles in the fluidic system, which create sudden spikes and baseline disturbances [2] [5]. |

| Reference Sensor Chip | A surface without immobilized ligand (or with an inertly coated ligand) used in a reference flow channel. It is essential for the first step of double referencing to subtract bulk refractive index shifts [2] [21]. |

| Buffer for Blank Injections | Identical to the running buffer. Used in blank injections to distinguish system-derived drift from specific binding signals during data processing [2] [21]. |

| Non-ionic Detergent (e.g., Tween 20) | An additive to running buffer or samples to reduce non-specific binding (NSB) to the sensor surface. Lower NSB results in a cleaner and more stable baseline [11] [6]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide to Diagnosing and Resolving Baseline Drift

Q: What are the primary causes of baseline drift in SPR experiments, and how can I resolve them?

Baseline drift, characterized by a gradual shift in the baseline signal over time, is a common issue that can compromise data quality in long SPR experiments. The table below summarizes the main causes and solutions.

| Cause of Drift | Underlying Issue | Recommended Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Surface Equilibration [2] | Sensor surface is not fully hydrated or adjusted to the flow buffer after docking or immobilization. | Flow running buffer for an extended period (e.g., overnight) to equilibrate the surface [2]. | Incorporate start-up cycles with buffer injections before actual sample runs [2]. |

| Inadequate System Equilibration [2] | System not fully flushed after a buffer change or cleaning procedure. | Prime the system thoroughly after each buffer change. Flow running buffer at the experiment's flow rate until the baseline is stable [2]. | Always prime the system after buffer changes and allow extra equilibration time after cleaning [2]. |

| Unstable Immobilization [6] | Ligand is not stably attached to the sensor chip, leading to gradual shedding. | Optimize the immobilization chemistry and density. Ensure thorough washing to remove contaminants post-immobilization [6]. | Use a covalent immobilization strategy like EDC/NHS chemistry for stable bonds [22]. |

| Inefficient Surface Regeneration [6] | Residual analyte remains bound, causing a cumulative shift in baseline. | Develop a robust regeneration protocol that completely removes analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand [6]. | Test different regeneration buffers and contact times to find the optimal conditions. |

| Buffer Incompatibility [6] | Buffer components interact with the sensor chip or immobilized ligand. | Check buffer compatibility. Use fresh, 0.22 µM filtered, and degassed buffers prepared daily [2] [6]. | Avoid adding fresh buffer to old stocks. Use buffers at room temperature to minimize dissolved air [2]. |

FAQ: Addressing Common Immobilization Challenges

Q: How does ligand density specifically influence baseline drift and data quality?

Ligand density is a critical factor that influences both the stability of the surface and the quality of the kinetic data. An imbalance can lead to drift and artifacts [23].

- Too High Density: Can cause steric hindrance, where analyte molecules cannot access all binding sites. This may lead to mass transport limitations, where the measured kinetics reflect the diffusion of the analyte to the surface rather than the true binding interaction. High-density surfaces can also be more prone to non-specific binding and may take longer to equilibrate, contributing to apparent drift [22] [23].

- Too Low Density: Results in a weak signal, making it difficult to distinguish genuine binding from background noise. For low molecular weight analytes, a sufficiently high density is necessary to generate a detectable signal [23]. A surface with low density may also not stabilize effectively, leading to drift.