SPR Surface Preconditioning: A Foundational Guide to Reliable Biomolecular Interaction Data

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) surface preconditioning, a critical step for obtaining high-quality, reproducible binding data.

SPR Surface Preconditioning: A Foundational Guide to Reliable Biomolecular Interaction Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) surface preconditioning, a critical step for obtaining high-quality, reproducible binding data. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the fundamental principles of why preconditioning is essential for minimizing noise and maximizing sensitivity, especially in demanding applications like fragment-based screening. The content details step-by-step methodological protocols, advanced troubleshooting for common pitfalls like baseline drift and non-specific binding, and a validation framework comparing SPR data with other biophysical methods. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical optimization strategies, this guide aims to empower users to enhance the reliability and throughput of their SPR-based analyses in drug discovery and diagnostic development.

The Critical Role of Preconditioning in SPR Assay Success

Surface preconditioning is a critical preparatory step in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments, encompassing the series of cleaning, stabilizing, and conditioning treatments applied to the sensor chip surface before ligand immobilization. This process is foundational to the entire experimental workflow, directly determining the reliability and quality of the subsequent biomolecular interaction data. In the context of a broader thesis on SPR surface preconditioning methods, this article establishes that proper preconditioning is not merely a preliminary step but a fundamental determinant of data integrity. It ensures that the sensor surface achieves optimal chemical stability, uniform binding capacity, and minimal non-specific interactions, thereby enabling the collection of kinetically accurate and reproducible binding data essential for drug discovery and development [1].

The absence of or inadequacy in surface preconditioning introduces significant systematic errors, including baseline drift, poor immobilization efficiency, and unreliable kinetic constants. For challenging targets such as G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs), which exhibit intrinsic instability outside their native membrane environment, rigorous and tailored preconditioning protocols are indispensable for maintaining receptor stability and function on the sensor chip [2]. This document provides detailed protocols and a scientific framework for implementing surface preconditioning to uphold the highest standards of data quality.

The Critical Role of Surface Preconditioning

The primary purpose of surface preconditioning is to create a pristine, reactive, and stable surface on the sensor chip that is ready for the efficient and oriented immobilization of ligands. Its impact on data quality is profound and multi-faceted.

Purpose and Scientific Rationale

A newly unpacked or stored sensor chip surface can contain microscopic contaminants, manufacturing residues, or adsorbed atmospheric particles. Preconditioning addresses this by:

- Cleaning the Surface: Removing any contaminants that could block activation sites or contribute to non-specific binding, ensuring that the maximum number of functional groups are available for ligand coupling [1].

- Hydrating and Stabilizing the Matrix: For hydrogel-based chips (e.g., CM5), the dextran matrix must be fully hydrated and swollen to its operational state. Preconditioning with aqueous buffers achieves this, preventing baseline shifts and ensuring consistent analyte diffusion.

- Standardizing Surface Chemistry: It brings the sensor chip to a known, reproducible chemical state. This standardization is crucial for achieving consistent ligand immobilization levels across different experiments, days, and even different operators, which is a prerequisite for comparing kinetic data across screening campaigns [1].

Impact on Key Data Quality Metrics

The direct consequences of surface preconditioning on data are quantifiable. The table below summarizes its impact on critical data quality parameters.

Table 1: Impact of Surface Preconditioning on Data Quality Parameters

| Data Quality Parameter | Effect without Proper Preconditioning | Effect with Proper Preconditioning | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Stability | Significant drift and instability [1] | Stable, flat baseline | Removal of loosely bound contaminants; surface equilibration. |

| Ligand Immobilization Efficiency | Low, variable density; incomplete coupling | High, consistent, and reproducible density | Maximized availability of active ester groups for coupling. |

| Non-Specific Binding (NSB) | Elevated, inconsistent background signal | Minimized and consistent background | Blocking of non-specific adsorption sites on the gold film/matrix. |

| Binding Signal Reproducibility | High variability between replicate runs | High inter- and intra-assay reproducibility | Standardized and uniform surface properties. |

| Accuracy of Kinetic Constants | Inaccurate ka (association) and kd (dissociation) rates due to mass transport or surface heterogeneity | Accurate determination of ka and kd | A homogeneous and accessible ligand layer. |

For sensitive applications like GPCR drug discovery, where the receptor must be stabilized in a lipid bilayer or nanodiscs, preconditioning the surface to properly anchor these membrane mimetics is especially critical. An improperly prepared surface can lead to receptor denaturation or inadequate orientation, completely compromising the binding assay [2].

Experimental Protocols for Surface Preconditioning

The following section provides detailed, step-by-step methodologies for preconditioning different types of sensor chips. These protocols are designed to be integrated directly into experimental documentation.

General Preconditioning Workflow for Carboxymethylated Dextran Chips

This protocol is optimized for common chips like CM5, CMS, or C1, which utilize a carboxymethylated dextran matrix and are activated via EDC/NHS chemistry.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Preconditioning

| Reagent/Solution | Function / Purpose | Typical Composition / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer | Establishes a stable baseline and serves as the solvent for all other solutions. | HEPES Buffered Saline (HBS): 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. |

| Gly-HCl Regeneration Solution | A strong, low-pH solution that strips non-covalently bound material from the surface for cleaning. | 10-100 mM Glycine-HCl, pH 1.5-3.0. |

| NaOH/SDS Solution | A strong, high-pH solution and detergent that removes hydrophobic contaminants and deeply cleans the surface. | 10-50 mM Sodium Hydroxide, sometimes with 0.1% SDS. |

| EDC/NHS Activation Mix | Chemically activates the carboxyl groups on the dextran matrix for covalent ligand immobilization. | 0.4 M EDC + 0.1 M NHS, mixed 1:1 (v/v). |

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Initial System Prime: Prime the SPR instrument (e.g., Biacore systems) with the designated, filtered, and degassed running buffer at least three times to ensure the entire fluidics system is equilibrated.

- Chip Docking and Initial Baseline: Dock the new sensor chip and initiate a continuous flow of running buffer (e.g., 10-30 µL/min). Allow the baseline to stabilize for 10-20 minutes. A large initial drop followed by a slow stabilization is normal.

- Pulsed Regeneration Cleaning:

- Inject a series of short pulses (e.g., 30-60 seconds each) of regeneration solutions across all flow cells.

- A typical sequence is: 2-3 pulses of Gly-HCl (pH 1.5-2.0) followed by 1-2 pulses of NaOH (50 mM).

- A final pulse of a mild acid (e.g., 10 mM HCl) can be used.

- After each pulse, wash extensively with running buffer for 1-2 minutes to re-equilibrate the pH and surface.

- Surface Activation (Optional but Recommended for a Fresh Chip): To test the surface reactivity and ensure it is primed for immobilization, perform a test activation and deactivation.

- Inject the EDC/NHS mixture for 5-7 minutes.

- Immediately follow with an injection of a blocking agent, such as 1 M Ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5), for 5-7 minutes.

- Final Stabilization: After the final cleaning or deactivation step, allow the baseline to stabilize under a continuous flow of running buffer for a final 15-30 minutes. The surface is now preconditioned and ready for ligand immobilization.

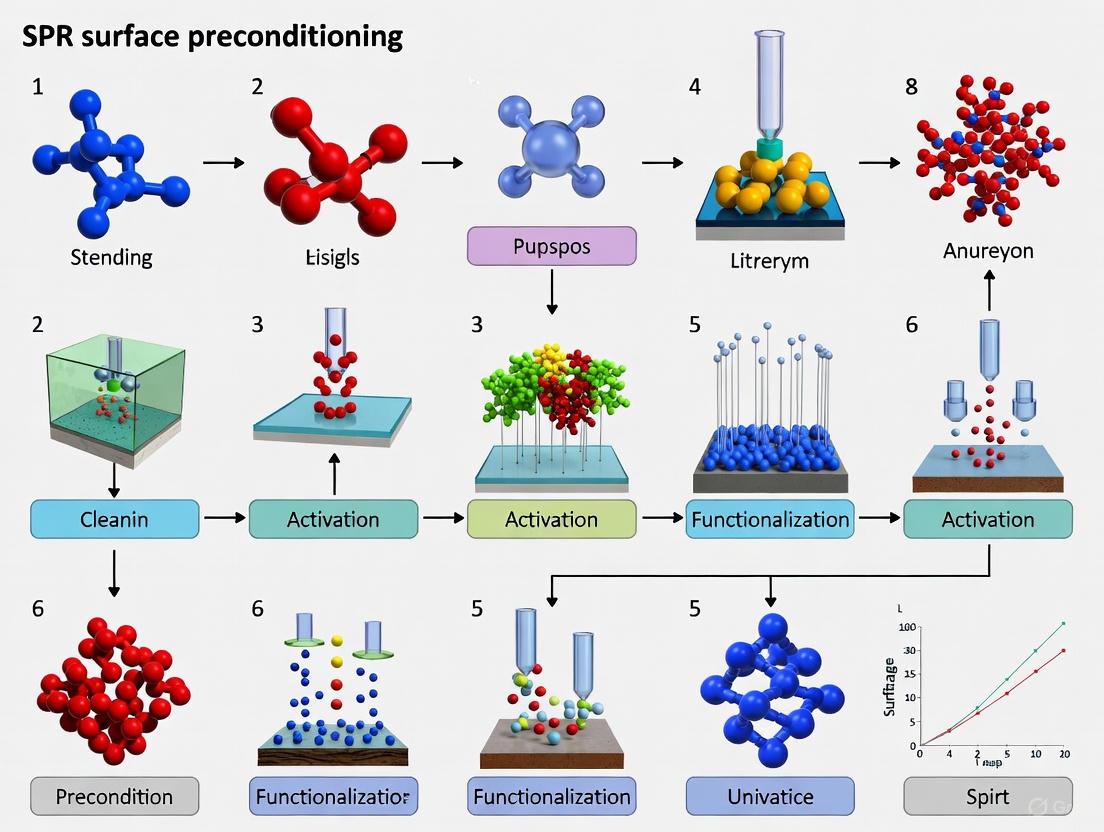

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-stage process and its role in the complete SPR experiment.

Diagram 1: SPR Surface Preconditioning Workflow

Specialized Preconditioning for GPCR and Membrane Protein Studies

Preconditioning surfaces for GPCR analyses requires additional steps to ensure the stable incorporation of the target into a membrane-mimetic environment on the chip. The strategy depends on the immobilization method [2].

Protocol 1: Preconditioning for Liposome or Nanodisc Capture

- Surface Cleaning: Follow the general protocol (Steps 1-3) to ensure the underlying sensor chip (e.g., an L1 chip with lipophilic anchors) is clean.

- Lipid Surface Preparation: Inject a solution of small, sonicated liposomes (e.g., POPC:POPG mixtures) to form a uniform lipid bilayer on the surface. This may require multiple injections.

- Surface Stabilization: Wash extensively with running buffer containing a low concentration of a mild, GPCR-compatible detergent (e.g., 0.01% DDM) to stabilize the layer and remove poorly associated material.

- Receptor Loading: The preconditioned lipid surface is now ready for the injection of GPCRs reconstituted in liposomes, nanodiscs, or proteoliposomes.

Protocol 2: Preconditioning for Direct Receptor Immobilization via Tags

- Surface Cleaning: Precondition a NTA or SA sensor chip using the general protocol. For NTA chips, include a pulse injection of a chelator (e.g., EDTA) to remove any bound metal ions, followed by a recharge with fresh NiCl₂.

- Receptor Stabilization: The running buffer must be optimized with specific lipids (e.g., cholesterol) and detergents to maintain GPCR stability during the immobilization process [2].

- Receptor Capture: Inject the His-tagged or biotinylated GPCR sample. The preconditioned surface will ensure oriented capture and maximal retention of functional receptor.

Data Validation and Troubleshooting

Even with a standardized protocol, researchers must validate the success of preconditioning through data inspection.

Quantifying Preconditioning Success

A successfully preconditioned surface should exhibit the following in the sensorgram before any ligand immobilization:

- A Flat and Stable Baseline: The response signal (RU) should show minimal drift (< 5-10 RU over 5 minutes) after the stabilization period.

- Low Noise Level: The signal noise should be minimal, typically < 0.5-1 RU peak-to-peak.

- Appropriate Activation Response: If a test activation is performed, a large, sharp increase in RU upon EDC/NHS injection confirms high surface reactivity.

Common Preconditioning Issues and Resolutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Preconditioning Problems

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Baseline Drift | Buffer incompatibility; contaminated buffer; improperly cleaned surface. | Filter and degass buffers; increase number and duration of regeneration pulses; ensure buffer and chip chemistry are compatible [1]. |

| Low Immobilization Level | Inactive surface; insufficient preconditioning; old EDC/NHS. | Perform a fresh test activation/deactivation cycle to verify surface reactivity; use freshly prepared EDC/NHS reagents. |

| High Non-Specific Binding | Incomplete blocking of non-specific sites on the gold surface. | Incorporate a blocking step with an inert protein (e.g., BSA, casein) after preconditioning but before immobilization [1]. |

| Poor Reproducibility | Inconsistent preconditioning protocol between runs or users. | Strictly adhere to a documented Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for preconditioning, specifying exact solution concentrations, pulse times, and flow rates. |

Surface preconditioning is a scientifically rigorous and non-negotiable practice in SPR. It transforms a variable sensor chip into a reliable scientific platform. As outlined in these application notes, a meticulously executed preconditioning protocol, tailored to the specific sensor chip and biological target, is the most effective strategy to mitigate experimental artifacts at their source. For the ongoing research into SPR preconditioning methods, this establishes a foundational protocol from which further innovations—such as preconditioning for novel two-dimensional nanomaterial sensor surfaces or automated high-throughput preconditioning routines—can be developed and validated. By mastering surface preconditioning, researchers ensure that the high-quality data driving critical decisions in drug development is built upon a solid and dependable foundation.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique used to study biomolecular interactions in real-time, providing critical insights into kinetics, affinity, and specificity. Achieving reliable and reproducible data, however, demands meticulous experimental preparation, with surface preconditioning standing as a critical foundational step. This process directly determines the success of subsequent immobilization and binding steps. Within the context of a broader thesis on SPR surface preconditioning methods, this application note details how a rigorous and optimized preconditioning protocol serves as a core principle to minimize experimental noise and maximize system sensitivity. By ensuring a clean, stable, and reactive sensor surface from the outset, researchers can significantly enhance data quality, improve detection limits for low-abundance analytes, and obtain more accurate kinetic parameters [1].

The necessity for preconditioning arises from the need to create a uniform and predictable surface chemistry on the sensor chip. A poorly prepared surface can lead to high baseline drift, non-specific binding, and low immobilization efficiency, all of which introduce noise and obscure true binding signals. Furthermore, an inconsistent surface can cause variations in ligand density, directly impacting the measured binding affinity and kinetics. Preconditioning protocols are therefore not merely routine cleaning steps but are instrumental in activating the sensor surface's full potential, ensuring that the immobilized ligand is biologically active and that the resulting data is a true reflection of the molecular interaction under investigation [1].

Core Principles Linking Preconditioning to Performance

The relationship between preconditioning and enhanced SPR performance is governed by several core principles. Understanding these mechanisms allows for the intelligent optimization of protocols for specific experimental needs.

Minimization of Non-Specific Binding

Non-specific binding (NSB) is a primary source of noise in SPR experiments, occurring when molecules interact with the sensor surface through means other than the specific interaction of interest. Preconditioning combats NSB by removing adsorbed contaminants and deactivating promiscuous binding sites on the sensor chip surface. A clean surface ensures that the subsequent immobilization chemistry targets only the intended functional groups. Furthermore, a key part of the preconditioning workflow involves the use of blocking agents, such as ethanolamine, to cap any remaining activated sites after ligand coupling, which prevents random attachment of analytes during the binding phase [1].

Enhancement of Surface Stability and Baseline Flatness

Baseline drift is a common issue that compromises the accuracy of binding response measurements. Drift can originate from several sources, including the slow release of contaminants from the sensor chip matrix or instability in the surface chemistry itself. Preconditioning directly addresses this by stabilizing the sensor surface through rigorous cleaning and conditioning cycles. By subjecting the chip to controlled pulses of buffer, sometimes at extreme pH, the dextran matrix and its chemical modifications are stabilized before the actual experiment begins. This results in a flatter, more stable baseline, which is crucial for accurately quantifying both high-affinity interactions with slow dissociation rates and low-affinity interactions with weak signals [1].

Optimization of Ligand Immobilization Efficiency

The efficiency and homogeneity of ligand immobilization are paramount for obtaining high-quality kinetic data. Preconditioning prepares the surface for optimal ligand attachment by ensuring uniform surface activation and by facilitating pre-concentration. Pre-concentration is an electrostatic process where the ligand is attracted to the sensor surface prior to covalent coupling. This is achieved by using a low ionic strength buffer with a pH slightly below the isoelectric point (pI) of the ligand, which creates opposing charges on the ligand and the carboxymethylated dextran surface. This process results in a high local concentration of the ligand at the surface, leading to a more efficient and dense immobilization, which directly boosts the final signal intensity [3]. A well-preconditioned surface provides a consistent foundation for this process, leading to highly reproducible immobilization levels across multiple sensor chips or flow cells.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Preconditioning on Key SPR Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | Without Preconditioning | With Preconditioning | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Drift | High (e.g., >5 RU/min) | Low (e.g., <1 RU/min) | Enables accurate measurement of slow dissociation rates |

| Immobilization Level Variation | High (>10% RSD) | Low (<5% RSD) | Essential for reproducible affinity and kinetics measurements |

| Non-Specific Binding Signal | Can be significant | Minimized | Improves signal-to-noise ratio, crucial for low-abundance analytes |

| Ligand Activity | Unpredictable, potentially low | High and consistent | Ensures measured kinetics reflect true biological interaction |

Experimental Protocols for Surface Preconditioning

A comprehensive preconditioning protocol is tailored to the specific sensor chip type and the ligand to be immobilized. The following section provides a generalized step-by-step protocol for carboxymethylated dextran chips (e.g., CM5), which are among the most commonly used.

Preconditioning Protocol for CM5 Sensor Chips

This protocol is designed to be performed on the SPR instrument immediately prior to ligand immobilization.

Research Reagent Solutions

- Flow Buffer: 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA, 0.005% surfactant P20, pH 7.4 [3]. This is the standard running buffer for the experiment.

- Activation Solutions: 0.4 M EDC (N-Ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and 0.1 M NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide). These are used for covalent coupling [3].

- Pre-concentration Buffers: A series of low ionic strength (10 mM) buffers, such as acetate (pH 4.0-5.5), formate (pH 3.5-4.5), or maleate (pH 5.5-6.5). The appropriate buffer is selected based on the ligand's pI [3].

- Blocking Solution: 1 M ethanolamine hydrochloride, pH 8.5 [3].

- Regeneration Solutions: Solutions like 10 mM glycine-HCl (pH 1.5-3.0) or NaOH (10-50 mM) are used for preconditioning cycles and later for regenerating the surface between analyte injections.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for SPR Preconditioning and Immobilization

| Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| EDC / NHS | Cross-linking agents that activate carboxyl groups on the sensor chip surface for covalent ligand immobilization. |

| Ethanolamine | A blocking agent that deactivates any remaining ester groups on the surface after ligand coupling, preventing non-specific binding. |

| Acetate Buffer (10 mM, pH 4.0-5.5) | A low-ionic-strength buffer used to create a favorable electrostatic environment for pre-concentration of positively charged ligands. |

| Glycine-HCl (10 mM, pH 2.0) | A mild regeneration solution used to remove non-covalently bound material during preconditioning cycles and between analyte injections. |

| Surfactant P20 | A detergent added to the running buffer to reduce non-specific hydrophobic interactions with the sensor chip surface. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Initial Surface Sanitization: Dock the sensor chip and prime the system with the desired flow buffer at the standard operating flow rate (e.g., 10-30 µL/min). Allow the baseline to stabilize for at least 10-15 minutes. A stable baseline is an initial indicator of a clean system.

Preconditioning Cycles: Inject a series of short pulses (e.g., 30-60 seconds) of regeneration solutions. A typical regimen might include 2-3 injections of 10-50 mM NaOH followed by 2-3 injections of 10 mM glycine-HCl (pH 2.0). This process serves to remove any non-specifically adsorbed contaminants and stabilizes the dextran matrix.

Surface Activation: Inject a 1:1 mixture of EDC and NHS for 7-10 minutes. This reaction activates the carboxyl groups on the dextran matrix, forming reactive NHS esters.

Ligand Pre-concentration and Immobilization: a. pH Scouting: To identify the optimal condition for pre-concentration, inject the ligand diluted in a series of pre-concentration buffers at different pH values. A strong, rapid increase in signal indicates successful pre-concentration. b. Immobilization: Using the optimal buffer identified, inject the ligand for a sufficient duration to achieve the desired immobilization level (Response Units, RU). The ligand is covalently attached to the activated esters.

Surface Blocking: Inject ethanolamine hydrochloride for 5-7 minutes to block any remaining activated ester groups. This critical step minimizes future non-specific binding.

Post-Conditioning Stability Check: Wash the surface with flow buffer and monitor the baseline for stability. A minimal and rapidly stabilizing drift indicates a successful preconditioning and immobilization procedure. The surface is now ready for analyte binding experiments.

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow and decision points in this protocol.

Data Analysis and Validation

The success of the preconditioning protocol must be validated through quantitative data analysis both during and after the process.

Quantitative Benchmarks for Success

A well-preconditioned surface should meet several key benchmarks, which can be directly measured from the sensorgram data:

- Low Baseline Drift: After the final blocking step and a return to flow buffer, the baseline drift should be minimal. A common benchmark is a drift of less than 1-2 RU per minute over a 10-minute period. High drift suggests incomplete surface stabilization or contamination [1].

- Stable Immobilization Level: The immobilization level of the ligand, measured in RU, should remain stable after the final wash. A significant drop in RU indicates that the ligand was not properly covalently coupled and was washed away, pointing to a failure in the activation or pre-concentration steps.

- High Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Reference Flow Cell: The signal from a reference flow cell (which should have no ligand or an irrelevant ligand) during analyte injection should be flat, indicating minimal non-specific binding. The ratio of the specific binding signal to the reference signal should be high.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Preconditioning and Immobilization Issues

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| High Baseline Drift | Inefficient surface regeneration; buffer incompatibility; contaminated sensor chip. | Extend preconditioning cycles; ensure buffer compatibility with chip chemistry; use fresh, filtered buffers. |

| Low Immobilization Level | Incorrect pre-concentration pH; low ligand activity or concentration; expired EDC/NHS. | Perform a comprehensive pH scouting experiment; check ligand integrity and concentration; prepare fresh activation solutions. |

| High Non-Specific Binding | Incomplete surface blocking; suboptimal buffer conditions. | Ensure fresh, pH-adjusted ethanolamine is used; add a non-ionic detergent (e.g., 0.005% P20) to the running buffer. |

| Poor Reproducibility | Inconsistent preconditioning protocol; variation in ligand stock solutions. | Standardize the preconditioning cycle regimen across all experiments; use highly concentrated ligand stocks and consistent dilution methods. |

Surface preconditioning is far more than a preliminary step in SPR experimentation; it is a fundamental practice that directly dictates data quality and reliability. By adhering to the core principles and detailed protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can systematically minimize noise and maximize the sensitivity of their SPR systems. A rigorously preconditioned surface ensures a stable, homogeneous, and reactive foundation for ligand immobilization, which in turn leads to more accurate and reproducible measurements of biomolecular interactions. As SPR technology continues to evolve, playing a critical role in drug discovery and basic research, mastering these foundational techniques remains essential for any scientist seeking to generate robust, publication-quality data [1] [4] [5].

Within the framework of research on Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) surface preconditioning methods, achieving a stable, low-noise baseline is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant for successful kinetic and affinity analyses. SPR biosensors detect biomolecular interactions in real-time by monitoring changes in the refractive index at a sensor surface [6]. A drifting baseline or excessive noise can obscure the detection of weak binding events, compromise data quality, and lead to erroneous interpretation of kinetic parameters [7] [1]. This application note details the essential goals and provides validated protocols for surface preconditioning, enabling researchers to establish a robust foundation for reliable data acquisition.

The process of preconditioning equilibrates the sensor chip, the fluidic system, and the immobilized ligand with the running buffer, minimizing inherent signal instabilities. Instabilities often arise from factors such as sensor chip rehydration, wash-out of immobilization chemicals, temperature fluctuations, and buffer mismatches [7] [8]. Proper preconditioning directly addresses these sources of drift and noise, which is especially crucial for sensitive applications like fragment-based drug discovery where binding signals are minimal [9].

Core Principles of Baseline Stability

A stable baseline is characterized by minimal drift and low noise, forming a reliable horizontal line from which binding responses can be accurately measured. Drift is a gradual, monotonic change in the baseline signal over time, while noise constitutes rapid, stochastic signal fluctuations [7].

Minimizing Drift: Baseline drift is frequently a sign of a non-optimally equilibrated sensor surface [7]. It is commonly observed immediately after docking a new sensor chip or following ligand immobilization, largely due to the rehydration of the surface and the wash-out of chemicals used during the immobilization procedure [7]. Furthermore, a change in running buffer composition can cause significant drift until the system is fully equilibrated. In systems where temperature control is imperfect, fluctuations in the temperature of the instrument or the buffer can induce drift because the SPR signal is sensitive to the refractive index of the bulk solution, which is temperature-dependent [8] [6].

Reducing Noise: A high noise level can mask small binding responses, effectively raising the detection limit of the assay. Noise can originate from multiple sources, including air bubbles in the fluidic path, particulate matter in the buffer or samples, mechanical pump vibrations, and electronic instabilities in the optical detection system [7] [1]. Impurities in the sample or buffer can also contribute to non-specific binding and stochastic signal spikes.

The Role of Preconditioning: Preconditioning is the systematic process of addressing these issues before data collection begins. It involves preparing the buffer, priming the fluidic system, and conditioning the sensor surface to a state of equilibrium with the experimental conditions. A well-preconditioned system exhibits a flat, stable baseline, which is the ultimate goal and a prerequisite for high-quality SPR data.

Preconditioning Protocols

The following protocols provide a step-by-step guide to achieving a stable, low-noise baseline. Adherence to these procedures is essential for generating publication-quality data.

Protocol 1: Buffer Preparation and System Priming

Objective: To eliminate buffer-related causes of drift and noise by ensuring the use of clean, compatible, and degassed buffers and by thoroughly equilibrating the fluidic system.

Materials:

- Running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP, PBS)

- High-purity water

- 0.22 µm membrane filter unit

- Buffer degassing apparatus (or a vacuum degasser integrated into some SPR instruments)

- Clean, sterile glassware or bottles

Method:

- Prepare Fresh Buffer: Ideally, prepare running buffer fresh daily using high-purity reagents and water [7].

- Filter and Degas: Pass the buffer through a 0.22 µm filter to remove particulate matter. Subsequently, degas the buffer thoroughly to prevent the formation of air bubbles during the experiment, which can cause spikes and noise in the sensorgram [7].

- Buffer Hygiene: Store filtered and degassed buffer in clean, sterile bottles. Avoid adding fresh buffer to old stock, as microbial growth or contaminants can introduce noise and drift [7].

- Prime the System: After a buffer change or at the start of a new experiment, prime the fluidic system according to the instrument manufacturer's guidelines. This process flushes out the previous buffer and ensures the entire flow path is filled with the new, degassed running buffer [7]. Failing to equilibrate the system can result in a "waviness" in the baseline corresponding to pump strokes as the old and new buffers mix.

- Flow Stabilization: Flow running buffer at the experimental flow rate until a stable baseline is observed. This may take 5–30 minutes or longer, depending on the system and the nature of the sensor surface [7].

Protocol 2: Sensor Surface Equilibration

Objective: To stabilize the sensor chip surface and the immobilized ligand, minimizing initial drift.

Materials:

- Docked sensor chip

- Running buffer

- Regeneration solution (if applicable)

Method:

- Initial Docking Drift: After docking a new sensor chip, expect and allow for an initial period of drift. This is often due to the rehydration of the dextran matrix on the sensor chip and thermal equilibration [7] [9].

- Post-Immobilization Equilibration: Following ligand immobilization, flow running buffer over the surface for an extended period. For surfaces with significant drift, it "can be necessary to run the running buffer overnight to equilibrate the surfaces" [7].

- Start-up Cycles and Blank Injections: Incorporate at least three start-up cycles into the experimental method. These cycles should mimic the analyte injection cycles but inject only running buffer. If a regeneration step is used, it should also be included. These cycles serve to "prime" the surface, stabilizing it before actual analyte injections begin, and should not be used in data analysis [7]. Additionally, intersperse blank (buffer) injections evenly throughout the experiment to facilitate double referencing.

Protocol 3: Establishing a Low-Noise Baseline

Objective: To characterize and minimize the system's noise level, ensuring optimal detection sensitivity.

Materials:

- Equilibrated SPR system with buffer flowing

Method:

- System Equilibration: Ensure the system is fully equilibrated using Protocols 1 and 2 to minimize drift, which can interfere with noise assessment.

- Buffer Injection Test: Perform several consecutive injections of running buffer and observe the baseline response [7]. A system with a low noise level will show a flat baseline with random variations of less than <1 RU [7].

- Noise Diagnosis: If the noise level is high (>1 RU), investigate potential sources. Check for air bubbles in the fluidic path, ensure buffers are properly filtered and degassed, verify that the instrument is placed on a stable surface free from vibrations, and confirm that the detector is properly calibrated [7] [1].

Table 1: Quantitative Baseline Performance Targets

| Parameter | Ideal Performance | Acceptable Performance | Diagnostic Action if Unacceptable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Drift | < 5 RU/hour | < 10 RU/hour | Extend surface equilibration; check for buffer mismatch or temperature fluctuations [7]. |

| Static Noise | < 0.3 RU (RMS) | < 1 RU (RMS) | Check for air bubbles, particulate contamination, or electronic issues [7]. |

| Bulk Refractive Index Noise | Minimal shift upon buffer switch | < 10 RU shift | Ensure thorough system priming with new buffer; verify buffer degassing [7]. |

Experimental Workflow and Data Analysis

A standardized workflow is crucial for consistent success in achieving a stable baseline. The following diagram and table outline the logical sequence of operations and the key reagents required.

Diagram 1: Preconditioning workflow for baseline stability.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Preconditioning

| Reagent / Material | Function in Preconditioning | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer | Creates the solvent environment for interactions; defines pH and ionic strength. | Must be fresh, filtered, and degassed to minimize noise and drift [7] [1]. |

| Detergent (e.g., Tween-20) | Additive to reduce non-specific binding and prevent bubble formation. | Add after filtering and degassing to avoid foam [7]. |

| Regeneration Solution | Remains bound analyte from the ligand between cycles. | Must effectively regenerate without damaging the immobilized ligand to prevent baseline drift over multiple cycles [1]. |

| 0.22 µm Filter | Removes particulate matter from buffers to prevent clogging and noise. | Essential for all buffers and samples introduced into the fluidic system [7]. |

| Sensor Chip | The platform where biomolecular interactions occur. | Requires time for rehydration and chemical equilibration after docking and immobilization [7] [9]. |

Data Analysis and Referencing

Once a stable baseline is secured, proper data referencing is vital to isolate the specific binding signal from residual drift and bulk effects.

Double Referencing: This is the recommended procedure to compensate for drift, bulk refractive index effects, and channel differences [7].

- Step 1: Reference Surface Subtraction: First, subtract the signal from a reference flow cell (which lacks the ligand or has an irrelevant ligand) from the signal of the active flow cell. This compensates for the majority of the bulk effect and system drift.

- Step 2: Blank Injection Subtraction: Second, subtract the response from injections of running buffer (blank injections) from the analyte injections. This corrects for any residual differences between the reference and active surfaces that are not due to specific binding.

Baseline Validation in Analysis: Before fitting kinetic models, ensure the pre-injection baseline is flat and the post-dissociation phase returns to a stable baseline. Persistent drift after dissociation can indicate incomplete regeneration or surface heterogeneity.

Achieving a stable, low-noise baseline through meticulous preconditioning is a non-negotiable foundation for any rigorous SPR study. The protocols outlined herein—focusing on impeccable buffer preparation, systematic fluidic priming, and thorough sensor surface equilibration—provide a reliable roadmap for researchers. By investing time in this essential preparatory phase, scientists can significantly enhance data quality, improve the reliability of kinetic and affinity parameters, and ultimately accelerate drug discovery and biomolecular research.

The Link Between Preconditioning and Immobilization Efficiency

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) technology, the precise immobilization of a ligand to the sensor chip is a foundational step that directly dictates the success and reliability of subsequent biomolecular interaction analyses. Immobilization efficiency affects everything from the signal-to-noise ratio to the accuracy of determined kinetic parameters. Preconditioning, often manifested as a "pre-concentration" step, is a critical preparatory procedure designed to enhance this efficiency by optimizing the local environment at the sensor chip surface. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on SPR surface preconditioning methods, details the intrinsic link between preconditioning and immobilization efficiency. It provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with structured data, detailed protocols, and visual guides to implement these methods effectively, thereby improving the sensitivity and robustness of their SPR assays.

The Principle and Importance of Preconditioning

Preconditioning, specifically in the form of electrostatic pre-concentration, is the process of accumulating ligand molecules at the sensor chip surface prior to their covalent attachment. This is a standard and recommended procedure for carboxyl-group-based sensor chips (such as CM4 or CM5 chips) where immobilization relies on amine coupling [3].

The fundamental goal is to increase the local concentration of the ligand at the dextran matrix of the sensor chip. This is achieved by carefully manipulating the electrostatic interactions between the charged ligand and the charged sensor surface. A successful pre-concentration step results in a rapidly increasing SPR signal as the ligand accumulates at the surface, followed by a stable signal plateau. This process makes the subsequent covalent immobilization more efficient, uniform, and controllable [3].

The absence of a pre-concentration step can lead to suboptimal immobilization levels, wasted precious ligand, and surfaces with heterogeneous activity. The procedure is particularly crucial when working with low-abundance or valuable ligands, as it maximizes the immobilization yield from a limited sample.

Key Factors Governing Preconditioning Efficiency

The efficacy of the pre-concentration step is governed by a interplay of several chemical and physical factors. Understanding and optimizing these parameters is key to achieving high immobilization efficiency.

Buffer pH and Ionic Strength

The pH of the immobilization buffer is the most critical variable, as it determines the net charge of both the ligand and the carboxymethylated dextran matrix.

- pH Relative to Ligand pI: For effective pre-concentration, the ligand must carry a net positive charge to be attracted to the negatively charged dextran surface. This is achieved by using a buffer with a pH slightly below the isoelectric point (pI) of the protein ligand. General guidelines suggest [3]:

- For pI 3.5–5.5, use a buffer 0.5 pH units below the pI.

- For pI 5.5–7, use a buffer 1.0 pH unit below the pI.

- For pI >7, a buffer at approximately pH 6.0 is often suitable.

- Low Ionic Strength: The buffer must have a low ionic strength (e.g., 10 mM). High salt concentrations mask the electrostatic charges on both the ligand and the surface, effectively nullifying the attractive forces and diminishing the pre-concentration effect [3].

Ligand Concentration and Buffer Composition

- Ligand Concentration: A ligand concentration between 5 and 25 µg/mL is typically sufficient for effective pre-concentration. Using highly concentrated stock solutions is advised to avoid diluting the coupling buffer and altering its pH and ionic strength. Alternative buffer exchange methods like gel filtration or dialysis can also be used [3].

- Buffer Additives: Additives such as sodium azide must be avoided during immobilization as they can react with the activated surface and lower immobilization efficiency. Detergents may be necessary for solubilizing membrane proteins or other hydrophobic ligands, but their impact on surface chemistry must be considered [10] [11].

Table 1: Summary of Key Preconditioning Parameters and Their Optimal Ranges

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Impact on Preconditioning |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer pH | 0.5–1.0 units below ligand pI | Determines net charge of ligand; positive charge enables attraction to surface. |

| Ionic Strength | Low (e.g., 10 mM) | Prevents masking of electrostatic charges, enabling strong attraction. |

| Ligand Concentration | 5–25 µg/mL | Provides sufficient molecules for surface accumulation without rapid saturation. |

| Ligand Stock Solution | Highly concentrated | Prevents dilution and alteration of the coupling buffer's properties. |

| Additives | Avoid azide; use compatible detergents | Prevents unintended reactions with activated surface; maintains ligand solubility. |

Experimental Protocol: Preconditioning and Immobilization via Amine Coupling

The following protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for immobilizing a protein ligand onto a CM-series sensor chip, incorporating a pre-concentration step. The example of immobilizing the cannabinoid receptor CB2 is used to illustrate a real-world application [10].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Immobilization

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| HBS-N Buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA, 0.005% surfactant P20, pH 7.4) | Standard running buffer for SPR; used for equilibration and dilution. |

| Sodium Acetate Buffer (10 mM, pH 4.0-5.5) | Low-ionic-strength buffer for pre-concentration and ligand dilution. |

| EDC (N-ethyl-N'-(dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) | Activates carboxyl groups on the sensor chip surface. |

| NHS (N-Hydroxysuccinimide) | Works with EDC to form an amine-reactive NHS ester on the surface. |

| Ethanolamine-HCl (1 M, pH 8.5) | Quenches unreacted NHS esters after ligand immobilization. |

| Ligand Solution | The protein of interest, solubilized in a compatible, low-ionic-strength buffer. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

System and Sensor Chip Preparation

- Dock a new CM4 or CM5 sensor chip into the SPR instrument.

- Prime the system with HBS-N running buffer to equilibrate the fluidics and establish a stable baseline.

- Perform a brief surface conditioning with a gentle regeneration solution if recommended by the manufacturer.

Surface Activation

- Inject a 1:1 mixture of EDC and NHS (e.g., for 7 minutes) over the target flow cell. This creates reactive NHS esters on the dextran matrix. A significant bulk shift in the SPR signal will be observed.

Pre-concentration and Ligand Immobilization

- Dilute the ligand to a concentration of 5–25 µg/mL in a low-ionic-strength buffer (e.g., 10 mM sodium acetate) at a predetermined optimal pH (see Table 1).

- Inject the diluted ligand solution for 2-7 minutes at a low flow rate (e.g., 5-10 µL/min).

- Monitor the SPR signal in real-time:

- A rapid increase followed by a plateau indicates successful pre-concentration.

- A flat line indicates no accumulation, requiring adjustment of pH.

- Once a stable pre-concentration level is achieved, proceed with the injection. The ligand will covalently attach to the activated surface during this period.

Quenching

- Inject 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 5-7 minutes to block any remaining unreacted NHS esters.

Post-Immobilization Wash

- Wash the surface with running buffer to remove any non-covalently bound ligand. The final, stable SPR signal level (in Resonance Units, RU) indicates the total amount of immobilized ligand.

Diagram 1: Workflow for preconditioning and immobilization.

Case Study and Data Analysis

Immobilization of Cannabinoid Receptor CB2

A study on the human cannabinoid receptor CB2, a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), highlights the importance of controlled immobilization. The researchers utilized a Rho-tag/1D4 antibody system for capture. While not a classic pre-concentration, this method achieves a similar goal: it concentrates the receptor on the sensor surface in a uniform orientation, maximizing the availability of active binding sites [10].

- Method: The 1D4 antibody was first immobilized on a CM4 chip. Subsequently, a cell lysate or purified preparation containing the Rho-tagged CB2 receptor was injected over the surface.

- Result: The CB2 receptor was captured quantitatively and in a uniform orientation, as demonstrated by the SPR signal. This efficient "pre-positioning" enabled high-quality binding studies with a monoclonal antibody (NAA-1) targeting CB2, confirming the accessibility and functionality of the immobilized receptor [10].

Data Interpretation and Optimization

Analyzing the pre-concentration sensorgram is vital for diagnostics and optimization.

Diagram 2: Idealized SPR sensorgram during pre-concentration and immobilization.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Preconditioning and Immobilization

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No pre-concentration signal | Buffer pH is at or above protein pI; high ionic strength; ligand concentration too low. | Lower buffer pH relative to pI; ensure buffer is 10 mM; increase ligand concentration. |

| Very fast, massive signal jump | Ligand concentration is too high; very strong electrostatic attraction. | Lower ligand concentration; consider a buffer with a slightly higher pH (closer to pI). |

| Signal decreases after quenching/wash | Insufficient covalent coupling; non-specific binding. | Ensure fresh EDC/NHS; check that pre-concentration pH is not too low, which can hinder covalent chemistry. |

| High non-specific binding | Inadequate surface blocking or quenching. | Extend quenching time with ethanolamine; include a non-ionic surfactant in the buffer. |

Advanced Considerations and Future Outlook

Beyond standard amine coupling, preconditioning principles apply to advanced immobilization strategies. The development of Molecularly Imprinted Bio-Polymers (MIBPs) as antibody substitutes offers a new paradigm. These polymers, such as polynorepinephrine (PNE), can be grown directly on bare gold chips and, crucially, can be completely removed using a mild oxidizing treatment (e.g., 3.5% NaOCl), allowing for the reconditioning and reuse of the gold chip itself for multiple cycles without performance loss [12]. This represents a sustainable extension of the preconditioning concept to the entire sensor chip lifecycle.

Furthermore, for membrane proteins like GPCRs, preconditioning also involves maintaining the protein in a functional state throughout the process. This often requires the use of specific detergents (e.g., DDM, CHAPS) and lipids (e.g., CHS) in all buffers to stabilize the protein and prevent denaturation during surface capture [10] [11].

Preconditioning is an indispensable strategy for maximizing immobilization efficiency in SPR biosensing. By strategically controlling the pH and ionic strength of the ligand solution, researchers can electrostatically pre-concentrate the target molecule at the sensor surface, leading to higher and more consistent immobilization levels. The implementation of the protocols and guidelines outlined in this application note will enable scientists to standardize and optimize this critical step, thereby enhancing the data quality of kinetic and affinity analyses, accelerating drug discovery pipelines, and contributing to more reliable and reproducible biosensor research.

Instrument and Sensor Chip Preparation as a Preconditioning Prerequisite

Within the framework of advanced Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) research, the preparatory steps of instrument and sensor chip preconditioning are not merely preliminary tasks; they are foundational prerequisites that dictate the success and reliability of the entire biomolecular interaction analysis. Preconditioning encompasses the systematic procedures required to stabilize the SPR instrument, activate the sensor chip surface, and optimize the chemical environment to ensure that the collected data on binding kinetics and affinity is both accurate and reproducible. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these protocols is essential for studying even the most challenging interactions, from high-throughput drug candidate screening to the detailed analysis of low-abundance protein complexes. This application note provides detailed methodologies and structured data, contextualized within broader thesis research on SPR surface preconditioning methods, to serve as a definitive laboratory guide.

Instrument Preparation and System Calibration

A stable and well-calibrated SPR instrument is the first non-negotiable prerequisite for any binding experiment. Before engaging with precious samples, the system must be prepared to minimize operational variability.

System Sanitization and Fluidic Priming: Begin by flushing the fluidic system with recommended sanitization solutions (e.g., 50 mM NaOH or 6 M guanidine hydrochloride) to remove any residual biomolecules or contaminants from previous experiments [1]. Following sanitization, the system must be thoroughly primed with the designated running buffer—absent of any additives like azide that could interfere with surface chemistry—to establish a stable refractive index baseline and remove air bubbles from the microfluidics [3] [1].

Baseline Stabilization and Calibration: Allow the instrument and buffer to reach thermal equilibrium, as temperature fluctuations are a primary cause of signal drift. Monitor the baseline signal for a sufficient period to confirm stability. Subsequently, perform any instrument-specific calibration routines as mandated by the manufacturer to ensure the optical detection unit and liquid handling system are operating within specified tolerances [1]. A drifting baseline often indicates unresolved air bubbles, buffer incompatibility, or insufficient thermal equilibration, necessitating troubleshooting before proceeding [1].

Sensor Chip Selection and Surface Chemistry

The sensor chip is the heart of the SPR experiment, and its selection must be a deliberate choice based on the biochemical properties of the ligand and the experimental goals. The surface chemistry directly influences ligand activity, immobilization capacity, and the propensity for non-specific binding.

Table 1: Guide to Sensor Chip Selection for Common Experimental Goals

| Sensor Chip Type | Surface Chemistry | Key Applications | Immobilization Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxylated Dextran (e.g., CM5) | 3D hydrogel matrix (carboxymethylated dextran) | General purpose; protein-protein interactions; small molecule analytes [13] [14] | Covalent coupling (e.g., amine) |

| NTA | Immobilized Nitrilotriacetic Acid | Capture of poly-histidine tagged ligands [13] [14] | Affinity capture |

| Streptavidin (SA) | Immobilized Streptavidin | Capture of biotinylated ligands [13] [14] | Affinity capture |

| Protein A | Immobilized Protein A | Capture of IgG antibodies [13] [14] | Affinity capture |

| Planar / C1 | Short-chain or self-assembled monolayer (SAM) | Large analytes (viruses, cells); lipid monolayer studies [13] [14] | Covalent or adsorptive |

The choice between a 3D hydrogel surface (e.g., CM5 dextran) and a 2D planar surface is critical. The 3D matrix offers a high surface area, ideal for immobilizing a large number of ligands and for enhancing sensitivity towards small molecules [13] [14]. Conversely, planar surfaces are better suited for studying large analytes like vesicles or whole cells, where steric hindrance within a dextran matrix can become prohibitive [14].

Detailed Preconditioning and Immobilization Protocols

Sensor Chip Preconditioning and Activation

Once a chip is selected and loaded, a universal preconditioning and activation cycle is required to prepare the surface for ligand attachment.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Sensor Chip Preconditioning and Immobilization

| Research Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Formulation/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer | Establishes a stable baseline and sample solvent | 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% surfactant P20, pH 7.4 [3] |

| Regeneration Solution | Removes bound analyte while preserving ligand activity | 10 mM HCl; or 10 mM Glycine, pH 2.0-3.0 [15] [16] |

| Low pH Buffer | For surface conditioning and pH scouting | 10-50 mM Acetate, Formate, or Maleate buffer (pH 3.5-5.5) [3] |

| EDC / NHS Mix | Activates carboxyl groups on the sensor surface for covalent coupling | 0.4 M EDC mixed with 0.1 M NHS (freshly prepared or from aliquots) [3] |

| Ethanolamine | Blocks unreacted NHS-esters after ligand immobilization | 1 M ethanolamine-HCl, pH 8.5 [3] |

The following workflow details the core steps for surface activation and ligand immobilization.

Diagram 1: Core preconditioning and immobilization workflow.

Advanced Preconcentration Screening Protocol

For covalent immobilization on carboxylated surfaces, preconcentration is a powerful preconditioning technique that electrostatically concentrates the ligand onto the sensor surface prior to covalent coupling, dramatically improving immobilization efficiency and conserving precious protein samples [15] [3].

Principle: By using a low ionic strength immobilization buffer with a pH slightly below the isoelectric point (pI) of the ligand, the ligand acquires a net positive charge. This is attracted to the negatively charged carboxylated dextran matrix, leading to a high local concentration at the surface [15] [3]. Starting with a ligand concentration of 5-25 µg/mL, the local concentration at the surface can exceed 100 mg/mL [15].

Step-by-Step Preconcentration Screening to Determine Optimal pH:

This protocol uses a single, non-activated carboxyl sensor chip that can be regenerated between tests [15].

- Prepare Ligand Solutions: Dissolve the ligand to a low concentration (e.g., 5-25 µg/mL) in a series of 10 mM acetate buffers (or other suitable low ionic strength buffers) covering a pH range from 4.0 to 5.5, or more broadly depending on the protein's pI. Ensure the ligand concentration is identical in all buffers [15] [3].

- Prepare Regeneration Solution: A solution of 10 mM HCl is typically effective for regenerating the non-activated surface between tests [15].

- Initial Surface Wash: Load the carboxyl sensor and wash with the regeneration solution to ensure a clean starting state [15].

- pH Screening Cycle: For each acetate buffer pH, perform the following cycle:

- Inject Ligand: Inject the ligand solution in the current acetate buffer at a low flow rate (e.g., 10 µL/min) and monitor the response [15].

- Regenerate Surface: Inject the 10 mM HCl regeneration solution at a high flow rate (e.g., 100 µL/min) to remove the electrostatically bound ligand, resetting the surface for the next test [15].

- Data Analysis: Plot the response units (RU) from each ligand injection. The optimal immobilization buffer is the one with the highest pH that still produces a large signal increase during the injection phase. This balances efficient electrostatic preconcentration with the more favorable conditions for subsequent covalent coupling at a higher pH [15].

Diagram 2: Preconcentration screening to determine optimal pH.

Troubleshooting Common Preconditioning Challenges

Even with meticulous preparation, challenges can arise. The following table addresses common issues linked to inadequate preconditioning.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Preconditioning and Immobilization Issues

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| High Non-Specific Binding (NSB) | Inactive surface sites or incompatible buffer [16] [1] | Optimize surface blocking with BSA or casein; add non-ionic surfactant (e.g., 0.05% Tween-20) to running buffer [16] [1]. |

| Low Immobilization Level | Suboptimal pH for preconcentration; inefficient surface activation [15] [1] | Perform preconcentration screening; ensure fresh EDC/NHS aliquots are used; extend activation time [15] [3]. |

| Unstable Baseline (Drift) | Buffer mismatch; residual contaminants on chip or in system; temperature fluctuations [1] | Ensure buffer compatibility; perform system and chip sanitization; allow more time for temperature equilibration [1]. |

| Poor Reproducibility | Inconsistent surface regeneration; variable ligand activity [16] [1] | Establish a robust regeneration protocol between analyte cycles; always include control samples; standardize ligand purification and storage [1]. |

| Unexpected Negative SPR Shifts | Complex interfacial phenomena, bulk refractive index changes, or charge effects [8] [17] | Include appropriate reference surfaces; ensure careful buffer matching between sample and running buffer [8] [17]. |

Instrument and sensor chip preconditioning is a sophisticated and multi-faceted prerequisite that transforms an SPR system from a mere optical instrument into a precise tool for biomolecular analytics. The protocols detailed herein—from systematic instrument priming and strategic chip selection to the advanced optimization of immobilization conditions via preconcentration—provide a robust foundation for generating publication-quality data. As SPR technology continues to evolve, integrating with electrochemical methods and other novel sensing modalities [8] [17], the principles of rigorous surface preparation will remain a constant cornerstone of reliable research and drug development.

Step-by-Step Protocols for Effective SPR Surface Preconditioning

Standard Preconditioning Procedure for Dextran-Based Sensor Chips

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technology used extensively in biomedical research and drug development to study biomolecular interactions in real-time [6]. The sensor chip is the core of this technology, and among the various available surfaces, dextran-based sensor chips are one of the most prevalent for general-purpose applications [14]. These chips feature a hydrophilic carboxymethylated dextran matrix that provides a three-dimensional structure ideal for immobilizing ligands, ranging from proteins to small molecules [14].

A critical, yet often overlooked, step in ensuring the success and reproducibility of SPR experiments is the standardized preconditioning of these dextran-based chips. Proper preconditioning prepares the sensor surface by removing any preservatives, stabilizing the matrix, and ensuring consistent and efficient ligand immobilization. This protocol details a robust preconditioning procedure for dextran-based sensor chips, framed within broader research on SPR surface preconditioning methods. Implementing this protocol minimizes baseline drift, reduces non-specific binding, and enhances the reliability of the kinetic and affinity data obtained [1].

Technical Background

A typical dextran-based SPR biosensor chip consists of a glass substrate coated with a thin gold layer. An adhesive linker layer anchors the dextran-based immobilization matrix [14]. For chips with a gold surface, this linker often comprises self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) of alkylthiol compounds [14]. The carboxymethylated dextran matrix is a hydrophilic polymer that extends 100-200 nm from the surface, forming a flexible, non-cross-linked, brush-like structure [14]. This three-dimensional hydrogel is particularly suitable for studying interactions involving small molecular weight analytes, as it offers a large surface area for ligand binding [14].

The surface chemistry of these chips allows for the covalent immobilization of ligands, most commonly via amine coupling [14]. The preconditioning process is designed to hydrate and swell this dextran matrix, ensuring it is chemically uniform and reactive for subsequent activation steps. A well-preconditioned surface is fundamental for achieving a stable baseline, which is crucial for accurate measurement of binding responses [1].

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential reagents and equipment required for the preconditioning protocol.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Equipment

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Dextran-based Sensor Chips | e.g., CM5 (Cytiva). The protocol is optimized for carboxymethylated dextran surfaces. |

| Running Buffer | HBS-EP (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% surfactant P20, pH 7.4) is recommended for its ability to minimize non-specific binding [1]. |

| SPR Instrument | Any commercial SPR system (e.g., from Cytiva, Reichert Technologies, or OpenSPR) [18]. |

| Regeneration Solutions | Mild acidic (e.g., 10 mM Glycine-HCl, pH 2.0-3.0) or basic (e.g., 10 mM Glycine-NaOH, pH 9.0) solutions, or surfactants (e.g., 0.05% SDS). Choice depends on ligand stability [1]. |

Preconditioning Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the logical flow of the standard preconditioning procedure, from initial setup to final ligand immobilization.

Preconditioning Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

This section provides a detailed methodology for preconditioning a dextran-based sensor chip prior to ligand immobilization. The entire process is designed to be completed within approximately 30-45 minutes.

Table 2: Detailed Preconditioning Steps and Parameters

| Step | Procedure | Parameters & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. System Preparation | 1. Power on the SPR instrument and software. 2. Diligently flush the microfluidic system with filtered, degassed running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP) to remove air bubbles and particulates. | Critical: Use filtered (0.22 µm) and degassed buffers to prevent system blockages and signal artifacts. |

| 2. Chip Loading | 1. Carefully remove the sensor chip from its storage case. 2. Gently dry the surrounding glass and contacts, if necessary, ensuring the dextran surface is not touched or scratched. 3. Load the chip according to the manufacturer's instructions. | Handle the chip only by its edges to avoid contaminating or damaging the sensitive dextran surface. |

| 3. Initial Hydration & Stabilization | 1. Initiate a continuous flow of running buffer over the sensor surface at the recommended operational flow rate (e.g., 10-30 µL/min). 2. Allow the baseline to stabilize for 10-15 minutes. | A stable baseline is characterized by a drift of less than 5-10 Response Units (RU) per minute [1]. |

| 4. Surface Activation & Regeneration Cycles | 1. Inject a series of short pulses (30-60 seconds) of a regeneration solution. A common choice is Glycine-HCl (pH 1.5-2.0). 2. Follow each pulse with a 2-3 minute stabilization period with running buffer. | Typically, 2 to 4 cycles are sufficient. This step removes any loosely adsorbed contaminants and conditions the dextran matrix. |

| 5. Final Baseline Check | After the final regeneration cycle, observe the baseline in running buffer for 5-10 minutes to confirm stability. | The baseline should be flat and stable, with minimal drift, before proceeding to ligand coupling. |

Results and Data Interpretation

A successful preconditioning procedure yields a sensor chip with a stable baseline and low non-specific binding properties.

- Successful Preconditioning: The sensorgram will show a flat and stable baseline after the regeneration cycles, with minimal drift when the running buffer is flowing. The response during the glycine pulses will be consistent across cycles, indicating a clean and uniform surface.

- Incomplete Preconditioning: A drifting or "noisy" baseline after the procedure suggests residual contaminants or an improperly conditioned surface. This can lead to poor ligand immobilization efficiency and unreliable binding data in subsequent assays.

This preconditioning protocol directly enhances data quality by improving the signal-to-noise ratio. A stable baseline allows for the precise measurement of small binding responses, which is especially critical for detecting interactions involving low molecular weight analytes or characterizing weak affinity interactions [1] [6].

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Even with a standard protocol, challenges may arise. The table below lists common issues and recommended solutions.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Preconditioning

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Baseline Drift | Buffer incompatibility; air bubbles; contaminated buffer or system. | Ensure buffer is fresh, filtered, and degassed. Perform a more thorough system prime. Check for air bubbles in the flow cell. |

| Low Ligand Binding After Immobilization | Deactivated ligand; insufficient preconditioning; poor surface chemistry choice. | Ensure the preconditioning regeneration solution does not denature the ligand. Verify ligand activity off-line. |

| High Non-Specific Binding (NSB) | Inadequate blocking after immobilization; sample impurities. | After immobilization, use blocking agents like ethanolamine or BSA [1]. Optimize buffer additives (e.g., 0.005% Tween-20) to minimize NSB [17]. |

| Poor Reproducibility | Inconsistent preconditioning between runs; variable sample quality. | Strictly adhere to the preconditioning timeline and reagent concentrations. Ensure consistent sample preparation and purification. |

The implementation of a standardized preconditioning protocol for dextran-based sensor chips is a fundamental component of robust SPR biosensing. This document has outlined a detailed procedure that serves as a reliable foundation for researchers. The broader context of SPR surface preconditioning research points to several advanced considerations.

Future developments in this field are likely to integrate machine learning algorithms for the automated evaluation of surface quality and preconditioning efficacy [12]. Furthermore, the drive towards more sustainable and cost-effective biosensing has spurred research into regenerable sensor surfaces. For instance, innovative approaches using polynorepinephrine-based Molecularly Imprinted BioPolymers (MIBPs) have demonstrated the potential for up to 10 reconditioning and reuse cycles of the same gold chip without compromising analytical performance [12]. Similarly, the use of a regenerable biotin–SwitchAvidin–biotin bridging system has been shown to enable high-throughput determination of kinetic parameters for irreversible covalent inhibitors, significantly reducing cost and time [19].

In conclusion, meticulous preconditioning is not merely a preparatory step but a critical determinant of the success of an entire SPR experiment. By following this standardized protocol, researchers in drug development and related fields can enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and quality of their biomolecular interaction data, thereby accelerating research outcomes.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions. The reliability of the data generated, however, is profoundly dependent on the integrity of the liquid handling system and the stability of the molecular layer on the sensor chip. Two of the most critical, yet often overlooked, aspects of a robust SPR assay are appropriate buffer selection and thorough buffer degassing. This application note details the protocols for selecting compatible running buffers and effective degassing procedures, framing them as essential components of surface preconditioning within a comprehensive SPR research methodology. Proper execution of these steps minimizes system artifacts, prevents air bubble formation, and ensures the generation of high-quality, publication-ready binding kinetics data.

The Critical Role of Buffer Selection

The running buffer serves as the liquid environment for the analyte and the medium through which all interactions are monitored. Its composition and pH are therefore paramount, influencing not only the biomolecular interaction itself but also the stability of the baseline and the efficiency of ligand immobilization.

Key Considerations for Buffer Choice

- Refractive Index Matching: The running buffer should ideally be identical to the buffer in which the analyte is stored. Even minor differences in salt concentration, pH, or other components can cause significant refractive index changes, leading to bulk effect shifts in the sensorgram that can obscure true binding signals [20].

- Biomolecular Compatibility: The buffer must maintain the stability and native conformation of both the immobilized ligand and the flowing analyte. This often requires the inclusion of stabilizing agents like glycerol (at 5% for glycerol-stocked proteins) or mild detergents to prevent non-specific binding [20].

- Immobilization Efficiency: For covalent coupling, the pH of the immobilization buffer must be optimized to promote electrostatic preconcentration of the ligand onto the sensor surface. A buffer pH just below the isoelectric point (pI) of the protein ligand encourages attraction to the negatively charged carboxylated sensor surface, dramatically increasing the local ligand concentration and final immobilization level [15].

Table 1: Common Buffers and Their Applications in SPR

| Buffer Type | Typial pH Range | Key Characteristics | Ideal for Ligand/Analyte | Compatibility Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEPES-based (HBS-N, HBS-EP) | 7.2 - 7.4 | Physiologically relevant, common for protein interactions. | Antibodies, soluble proteins, protein-lipid interactions [20] [21]. | Often includes surfactants (P20) and EDTA to reduce non-specific binding [21]. |

| Acetate | 4.0 - 5.5 | Acidic; used for electrostatic preconcentration during amine coupling. | Proteins with pI > 5; ideal for covalent immobilization pH scouting [15] [21]. | Not suitable as a running buffer for most biological analytes. |

| Phosphate (PBS) | 7.0 - 7.4 | Another physiologically relevant buffer. | General protein interactions, serological samples [22] [21]. | Can form precipitates; ensure filtration and compatibility with system components. |

| Borate | 8.5 - 9.0 | Basic; used for immobilization of ligands stable at high pH. | Ligands with very low pI. | Less common; requires verification of ligand activity post-immobilization. |

Experimental Protocol: Buffer pH Scouting for Optimal Immobilization

This protocol allows for the rapid determination of the optimal pH for ligand immobilization using a single sensor chip, saving time and precious sample [15].

Principle: By testing a series of low-pH acetate buffers, the condition that provides the strongest electrostatic attraction between the ligand and the sensor surface can be identified, maximizing immobilization density.

Materials:

- OpenSPR Immobilization Buffer Optimization Kit (or self-prepared 10 mM acetate buffers at pH 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5) [15].

- Ligand protein (dissolved at 5-25 µg/mL in each acetate buffer) [15].

- Regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM HCl) [15].

- Standard Carboxyl Sensor chip [15].

- SPR instrument (e.g., OpenSPR or equivalent).

Method:

- Surface Preparation: Load a carboxyl sensor chip into the instrument. Wash the surface with regeneration solution to ensure it is clean [15].

- Ligand Injection: Inject the ligand solution prepared in pH 5.5 acetate buffer over the sensor surface at a low flow rate (e.g., 10 µL/min) [15].

- Surface Regeneration: Inject the regeneration solution at a high flow rate (e.g., 100 µL/min) to remove the electrostatically concentrated, but not covalently bound, ligand [15].

- Iterative Testing: Repeat steps 2 and 3 for each acetate buffer pH (e.g., 5.0, 4.5, 4.0). Each pH condition should be tested in duplicate for reliability [15].

- Data Analysis: Plot the resulting response curves. The optimal immobilization buffer is the one with the highest pH that produced a large signal increase during the injection phase. This balances efficient preconcentration with favorable conditions for the subsequent covalent coupling reaction [15].

The following workflow summarizes the key steps for SPR surface preconditioning, from initial buffer preparation to final system readiness:

Figure 1: SPR Surface Preconditioning and Buffer Preparation Workflow

The Necessity of Buffer Degassing

The formation of air bubbles within the microfluidic path of an SPR instrument is a major operational hazard. Bubbles can obstruct flow cells, create severe air-liquid interfaces that denature proteins, and cause massive, irreversible signal spikes and baseline drift. Efficient degassing is a non-negotiable step to prevent these issues.

Consequences of Inadequate Degassing

Air bubbles introduced into the system can disrupt measurements by blocking the flow cell, leading to sudden drops in response and unstable baselines. The technical director of BioNavis confirms that efficient degassing techniques are critical for eliminating bubbles and preserving sample stability, which in turn ensures reliable data [23].

Recommended Degassing Protocols

- Vacuum Degassing: This is the most effective and common method. It involves pulling a vacuum on the buffer solution for approximately 20-30 minutes while stirring. Commercially available in-line degassers on many SPR instruments automate this process, ensuring that buffer is degassed immediately before entering the fluidics system [23].

- Sparging with Inert Gas: Bubbling an inert gas like helium or argon through the buffer can help displace dissolved air. However, this method is generally less effective than vacuum degassing.

- Sonication: While useful for removing gas from small sample volumes, sonication is impractical for the large volumes of running buffer required for most SPR experiments.

Best Practice: All buffers and aqueous solutions injected into the SPR instrument must be thoroughly degassed and 0.2 µm filtered to remove particulates and microorganisms [20]. This should be performed as a routine part of buffer preparation before starting the instrument.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for SPR Buffer and Surface Preconditioning

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Acetate Buffers (10 mM, pH 4.0-5.5) | pH scouting for amine coupling; enables electrostatic preconcentration of protein ligands on carboxylated surfaces [15]. | Used to determine optimal ligand immobilization pH before covalent coupling [15]. |

| HEPES Buffered Saline (HBS-N/EP) | A standard, physiologically compatible running buffer for biomolecular interaction analysis. | HBS-EP includes EDTA and surfactant P20 to reduce non-specific binding and chelate metal ions [21]. |

| EDC & NHS | Amine-coupling reagents that activate carboxyl groups on the sensor chip surface to form reactive esters [22] [21]. | Always prepared fresh or from frozen aliquots to ensure efficient surface activation [21]. |

| Ethanolamine-HCl | A blocking agent used to deactivate and quench remaining activated ester groups after ligand immobilization [21]. | Prevents non-specific binding of analyte to the activated sensor surface [21]. |

| Regeneration Solutions (e.g., Glycine-HCl, NaOH) | Solutions of low or high pH used to disrupt the ligand-analyte complex without damaging the immobilized ligand [22] [21]. | Allows for repeated use of the same ligand surface; condition must be empirically determined [22]. |

| BIAdesorb / Sanitize Solutions | Specialized cleaning solutions (e.g., 0.5% SDS, 50 mM glycine-NaOH, 10% bleach) for rigorous maintenance of the instrument's fluidics [20] [21]. | Used for routine maintenance or if system contamination is suspected [20]. |

The relationship between buffer conditions, surface chemistry, and the resulting assay performance can be conceptualized as follows:

Figure 2: Impact of Buffer and Fluidics Management on Key Assay Outcomes

Buffer selection and degassing are not mere preparatory chores but are foundational to the success of any SPR experiment. They are integral components of a surface preconditioning strategy that ensures system compatibility and operational stability. By meticulously selecting running buffers that match the analyte's storage conditions and support the biological interaction, by optimizing immobilization buffers through systematic pH scouting, and by rigorously degassing all solutions, researchers can eliminate major sources of experimental artifact. Adherence to the protocols outlined in this application note will significantly enhance data quality, improve reproducibility, and increase the overall efficiency of SPR-based research and drug development programs.