SPR Drift Correction Algorithms: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Advanced Applications

This article provides a systematic comparison of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) drift correction algorithms, essential for ensuring data accuracy in biomolecular interaction analysis.

SPR Drift Correction Algorithms: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) drift correction algorithms, essential for ensuring data accuracy in biomolecular interaction analysis. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the fundamental causes of baseline and focus drift, explores traditional and cutting-edge computational correction methods, and offers practical troubleshooting guidance. By validating algorithm performance against real-world experimental challenges and presenting a comparative analysis of their applications, this guide serves as a critical resource for selecting and implementing the optimal drift correction strategy to obtain reliable kinetic and affinity data.

Understanding SPR Drift: Sources, Impact, and the Critical Need for Correction

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) research, maintaining data integrity requires addressing two distinct forms of instrumental drift: baseline drift and focus drift. While both can compromise data quality, they originate from different physical phenomena, affect measurements differently, and require specialized correction approaches. Baseline drift manifests as a gradual shift in the SPR response signal over time without any analyte interaction, primarily affecting the accuracy of binding quantification [1]. In contrast, focus drift occurs when the optical components of an SPR microscope move relative to the sample, leading to image blurring and reduced spatial resolution, particularly critical in SPR microscopy (SPRM) applications [2]. This guide examines the fundamental differences between these challenges, their impact on data quality, and the algorithmic solutions developed to address them within the broader context of SPR drift correction research.

Fundamental Definitions and Physical Origins

Baseline Drift: Signal Instability in Sensing Systems

Baseline drift refers to the slow deviation of the SPR sensor response from its established baseline under constant conditions. This phenomenon typically arises from instrumental factors rather than biological interactions. The primary sources include temperature fluctuations causing refractive index changes in the buffer solution, imperfect surface equilibration after immobilization or docking of a new sensor chip, and variations in flow pressure or buffer composition [1]. In electronic-hybrid SPR systems, additional contributors may include instability in the light source intensity or detector dark signal [3] [4]. The drift is quantified in Resonance Units (RU) over time and becomes particularly problematic during long dissociation phases or when studying slow binding interactions, as it becomes challenging to distinguish drift from genuine molecular dissociation.

Focus Drift: Optical Degradation in Imaging Systems

Focus drift specifically affects SPR microscopy systems, where it describes the unintended movement of the imaging plane away from the optimal focus on the sensor surface. This occurs due to thermal expansion or contraction of mechanical components, environmental vibrations, or mechanical relaxation in the microscope system [2]. In SPRM, which employs high-magnification objectives with short depths of field (often < 1 μm), even nanometer-scale drift can significantly degrade image quality by introducing abnormal interference fringes, reducing contrast, and lowering the signal-to-noise ratio [2]. This poses a substantial challenge for long-term nanoscale observations, such as tracking single viruses or monitoring dynamic cellular processes, where spatial precision is paramount.

Comparative Analysis: Key Differentiating Factors

The table below systematically compares the fundamental characteristics, impact, and correction strategies for baseline versus focus drift in SPR systems.

| Characteristic | Baseline Drift | Focus Drift |

|---|---|---|

| System Type | Conventional SPR sensors (angular/spectral interrogation) | SPR Microscopy (SPRM) imaging systems |

| Primary Manifestation | Gradual shift in resonance angle/wavelength signal over time | Blurring, reduced contrast, and spatial resolution in SPR images |

| Root Causes | Temperature fluctuations, buffer changes, surface equilibration issues, light source instability [1] [3] | Thermal expansion of components, mechanical vibrations, relaxation in microscope staging [2] |

| Impact on Data | Compromised binding quantification, inaccurate kinetics/affinity determination [1] | Degraded image quality, impaired nanoparticle tracking and single-molecule detection [2] |

| Typical Correction Methods | Dynamic baseline algorithms, double referencing, proper buffer equilibration [3] [1] | Reflection-based positional detection, hardware stabilization, software autofocus [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Drift Characterization

Protocol 1: Quantifying Baseline Drift in Conventional SPR

Objective: To measure and characterize baseline drift stability in standard SPR instrumentation.

Materials:

- SPR instrument with continuous flow capability

- Freshly prepared, filtered, and degassed running buffer

- Appropriate sensor chip (e.g., CM5 for Biacore systems)

- Data acquisition software

Methodology:

- System Preparation: Dock a new sensor chip and prime the system with running buffer thoroughly to remove air bubbles and ensure complete equilibration [1].

- Baseline Acquisition: Initiate continuous buffer flow at the experimental flow rate (typically 10-30 μL/min) and monitor the SPR signal (in RU) over an extended period (30-60 minutes minimum).

- Data Collection: Record the sensorgram without any analyte injections to observe pure baseline behavior.

- Drift Quantification: Calculate the drift rate as the slope of the baseline signal (RU/min) after excluding initial stabilization periods.

- Optimization Testing: Repeat with different equilibration protocols to establish the minimum conditioning time required for acceptable drift (< 1 RU/min for high-sensitivity work).

Expected Outcomes: A properly equilibrated system should exhibit minimal baseline drift (< 1-2 RU/min), allowing accurate distinction of binding events from instrumental artifact [1].

Protocol 2: Characterizing Focus Drift in SPR Microscopy

Objective: To measure focus drift and its impact on image quality in SPRM systems.

Materials:

- SPR microscope with high-numerical-aperture objective

- Gold film sensor surface with immobilized fiducial markers or nanoparticles

- Reflection-based focus detection system [2]

- Image acquisition and analysis software

Methodology:

- System Setup: Prepare sensor surface with sparsely distributed nanoparticles (100 nm gold or polystyrene) as resolution references.

- Initial Focusing: Bring the sample into precise focus using standard Köhler illumination or reflection-based optimization.

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Acquire sequential images of the same field of view over 30-60 minutes without adjusting focus.

- Drift Monitoring: Simultaneously track the position of reflection spots from the sensor surface using a positional detection camera [2].

- Image Analysis: Quantify changes in image sharpness (via gradient analysis) and measure displacement of fixed nanoparticles between frames.

- Correlation: Correlate image quality degradation with measured physical displacement of the focal plane.

Expected Outcomes: This protocol quantifies both the physical focal displacement (nm/min) and its functional impact on image resolution, enabling validation of focus stabilization systems [2].

Algorithmic Correction Approaches: Comparative Evaluation

Dynamic Baseline Algorithm for Signal Drift

The dynamic baseline algorithm represents a computational approach to compensate for signal drift in conventional SPR data. This method dynamically adjusts the analysis baseline according to a pre-defined ratio between the areas of the SPR curve below and above the baseline [3]. The mathematical implementation for centroid-based analysis is expressed as:

Where PB is the dynamically adjusted baseline, P(θ) is the detector response at incidence angle θ, and θres is the calculated resonance angle [3]. This approach maintains consistency in the selected data range despite fluctuations in optical power or background signal, making it mathematically insensitive to correlated noise and drift [3].

Reflection-Based Focus Drift Correction

For SPR microscopy, focus drift correction (FDC) employs a fundamentally different approach based on monitoring the positional deviations of inherent reflection spots from the sensor surface [2]. The relationship between defocus displacement (ΔZ) and reflected spot position (ΔX) is characterized by a correction factor (FDC-F1 for prefocusing and FDC-F2 for continuous monitoring):

This method enables non-invasive focus stabilization without additional optical components or fiducial markers, achieving focus accuracy of 15 nm/pixel and allowing precise distinction between 50 nm and 100 nm nanoparticles during long-term observation [2].

Research Reagent Solutions for Drift Management

The table below outlines essential materials and reagents used in experimental protocols for characterizing and mitigating SPR drift phenomena.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Drift Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Polyelectrolyte Solutions (PDADMAC/PSS) | Model system for layer-by-layer assembly to test sensor response stability [4] | Baseline drift characterization |

| BSA/Glycine Solutions | Defined molecular mixtures for diffusion-based drift assessment [5] | Buffer-related drift studies |

| Polystyrene Nanoparticles (50-100 nm) | Fiducial markers for quantifying spatial resolution degradation [2] | Focus drift measurement in SPRM |

| Gold Nanoparticles (100 nm) | Alternative fiducial markers with different refractive properties [2] | Focus drift measurement |

| Freshly Prepared Buffers with Proper Filtering/Degassing | Minimize buffer-derived signal fluctuations [1] | Baseline stabilization |

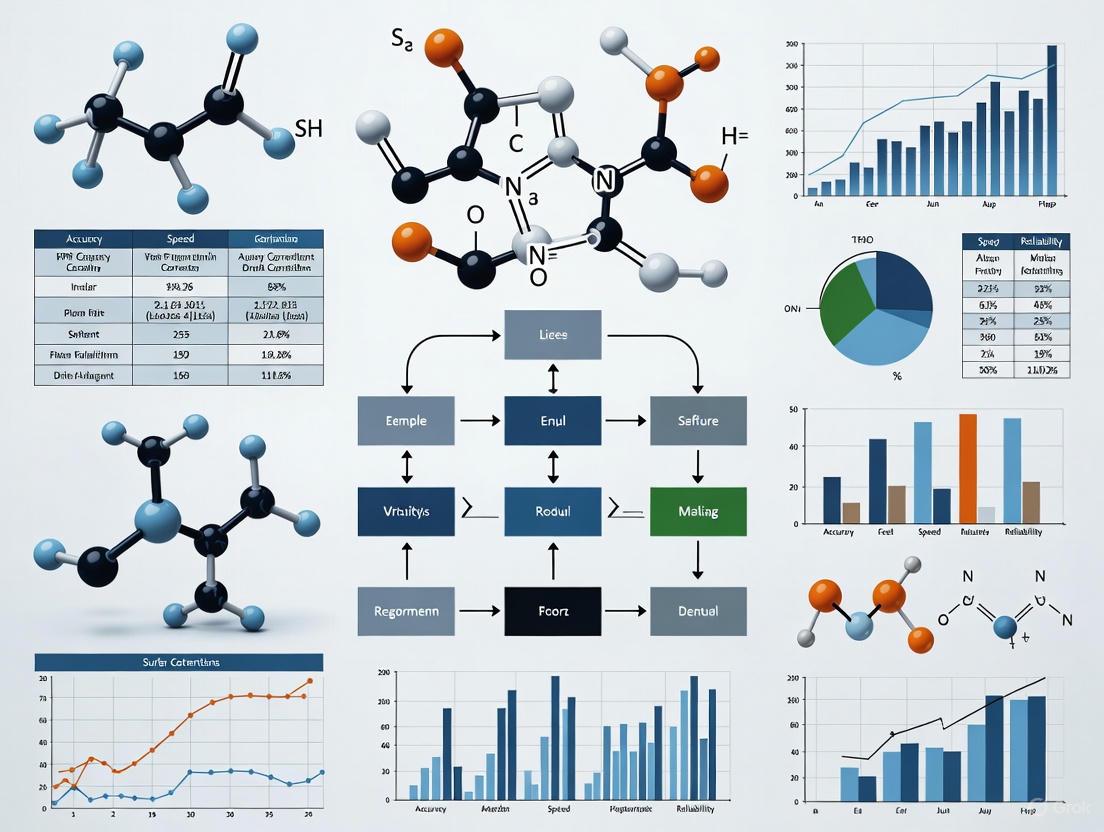

Visualization of Drift Correction Workflows

Baseline Drift Correction Algorithm

Focus Drift Correction in SPR Microscopy

Baseline drift and focus drift present fundamentally different challenges in SPR research, requiring specialized correction approaches tailored to their distinct characteristics and impact mechanisms. Baseline drift correction relies primarily on signal processing algorithms and careful experimental design to maintain measurement accuracy for binding quantification. In contrast, focus drift correction demands optical stabilization methods to preserve spatial resolution in imaging applications. The strategic selection of appropriate correction methodologies—whether dynamic baseline algorithms for conventional SPR or reflection-based positional detection for SPR microscopy—proves essential for generating high-quality, reproducible data across diverse SPR applications. As SPR technology continues to evolve toward higher sensitivity and more complex applications, the development of integrated correction systems addressing both forms of drift will become increasingly vital for advancing biomedical research and drug discovery.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) technology has become a cornerstone in the study of biomolecular interactions, providing real-time, label-free analysis critical for drug discovery and diagnostic development [6] [7]. However, the reliability of SPR data is consistently challenged by drift, a phenomenon where the baseline signal shifts over time despite no change in analyte concentration. This drift primarily stems from three interconnected causes: environmental fluctuations (particularly temperature), buffer incompatibility, and gradual surface re-equilibration following ligand immobilization. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate drift correction strategy is paramount, as the choice between hardware-based and algorithm-based solutions significantly impacts data integrity, with each approach offering distinct advantages for specific experimental conditions. This guide provides a structured comparison of contemporary drift correction methodologies, empowering scientists to make informed decisions that enhance the validity of their kinetic and affinity measurements.

Comparative Analysis of SPR Drift Correction Algorithms

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, experimental backing, and optimal use cases for the primary drift correction strategies identified in current research.

| Correction Method | Underlying Principle | Reported Performance/Experimental Data | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware-Based Focus Drift Correction (FDC) [2] | Uses inherent reflection spot displacements from brightfield images to calculate and correct defocus in real-time. | Focus accuracy reached 15 nm/pixel; enabled distinction between 50 nm and 100 nm nanoparticles [2]. | Real-time correction; does not require fiducial markers or complex algorithms; universal application [2]. | Integrated into the microscope system; may not correct for all forms of signal drift (e.g., bulk refractive index changes). |

| PPBM4D Denoising Algorithm [8] | An advanced algorithm using inter-polarization correlations and collaborative filtering to suppress instrumental noise in phase-sensitive SPR. | Achieved a refractive index resolution of 1.51 × 10⁻⁶ RIU; reduced instrumental noise by 57% [8]. | Exceptional noise suppression without compromising temporal resolution; works with existing hardware. | Primarily addresses high-frequency noise; may require adaptation for different SPR platforms. |

| Fiducial-Free Post-Processing [9] | Corrects drift post-experiment by combining 3D brightfield registration with a computational method that uses localization data. | Provides robust, sub-pixel drift correction indefinitely; effective with low localization counts [9]. | Does not require fiducial markers; robust to low signal levels; suitable for long-term experiments. | Post-processing step; requires brightfield images and computational analysis. |

| Time-Varying Bayesian Optimization (TVBO) [10] | A data-driven approach that actively adjusts optical components to maintain optimal beam trajectory over time. | In simulations, maintained sub-micron and nanoradian beam stability over several hours in a complex optical system [10]. | Actively counters slow, complex drift patterns; suitable for highly stable light sources and complex setups. | Can be computationally intensive; may require system-specific adaptation. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Drift Correction Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and facilitate a deeper understanding of the comparative data, this section outlines the detailed experimental methodologies from the key studies cited.

Focus Drift Correction (FDC) Protocol

This protocol is designed for SPR microscopy (SPRM) systems to correct for optomechanical drift during long-term nanoscale observation [2].

- Step 1: System Setup. A standard Kretschmann-configuration SPRM system with a high-magnification objective is used. The system must be capable of capturing both brightfield and SPR images.

- Step 2: Reference Image Acquisition. Before data collection, a 3D z-stack of brightfield reference images of the sample area is acquired.

- Step 3: Pre-focusing (FDC-F1). Before each imaging dataset, a new brightfield z-stack is taken. A scaled 3D cross-correlation between this new stack and the reference stack is computed. The calculated spatial offset (ΔX, ΔY, ΔZ) is used to adjust the stage position, bringing the sample back into the original focal plane.

- Step 4: Focus Monitoring (FDC-F2). During the actual SPR imaging process, the positional deviations of inherent reflection spots are continuously calculated for each frame using a second auxiliary function (FDC-F2), enabling continuous nanometer-scale focus monitoring without special imaging patterns.

- Validation: The method's efficacy was validated by statically and dynamically observing polystyrene and gold nanoparticles (50 nm and 100 nm), showing improved image clarity and the ability to distinguish different nanoparticle types [2].

PPBM4D Denoising Algorithm Protocol

This protocol is for enhancing the resolution of phase-sensitive SPR imaging systems through advanced computational denoising [8].

- Step 1: Data Acquisition with Quad-Polarization Camera. An SPR imaging system is configured with a quad-polarization filter array (PFA) camera. The PFA camera simultaneously captures four images of the SPR reflected light, each at a different polarization angle (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°).

- Step 2: Virtual Measurement Generation. The raw intensity images from the four polarization channels are processed. The PPBM4D algorithm leverages the high correlation and textural similarity between these channels to generate "virtual" independent measurements for each polarization state.

- Step 3: Collaborative 4D Filtering. The algorithm organizes the data from the real and virtual measurements into 4D groups (stacking 3D patches from different polarizations along a fourth dimension). It then applies collaborative Wiener filtering in this 4D transform domain to separate the signal from noise effectively.

- Step 4: Signal Reconstruction. The denoised polarization images are reconstructed, leading to a significantly cleaner SPR phase difference signal.

- Validation: The system's performance was quantified by measuring the refractive index resolution, achieving 1.51 × 10⁻⁶ RIU. It was further validated through ultra-dilute NaCl solution switching experiments and protein interaction assays (antibody-protein binding down to 0.15625 μg/mL) [8].

Visualization of Drift Correction Strategies

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and decision-making pathway for selecting an appropriate drift correction strategy based on the primary cause of drift.

Decision Workflow for SPR Drift Correction Strategies

The experimental workflow for a combined hardware and algorithmic correction approach, as used in advanced SPR imaging, is detailed below.

Combined Hardware-Algorithmic Correction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of drift correction protocols requires specific materials and reagents. The following table lists key components used in the featured experiments.

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Sensor Chip | The plasmonic-active metal film (typically ~30-50 nm thick) on a glass substrate that serves as the sensing surface. | 30 nm Au layer on ZF5 glass prism (n=1.734) used in phase-imaging systems [8]. |

| Polystyrene/Gold Nanoparticles | Standardized nanoscale particles used for system calibration, resolution testing, and validating drift correction performance. | 50 nm and 100 nm PS and Au nanoparticles used to demonstrate FDC-enhanced imaging precision [2]. |

| Quad-Polarization Filter Array (PFA) Camera | A specialized imaging sensor that simultaneously captures light intensity at multiple polarization angles for phase extraction and noise reduction. | Sony IMX250 CRZ sensor, crucial for the PPBM4D denoising algorithm [8]. |

| Half-Wave Plate | An optical component used to rotate the polarization plane of light, essential for modulating SPR signals in differential detection systems. | Fast axis oriented at 22.5° to generate complementary interference patterns for phase calculation [8]. |

| Ligand Immobilization Reagents | Chemicals for covalently attaching biomolecules (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) to the gold sensor surface to create the active sensing layer. | N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) for covalent coupling [2]. |

| Aptamers | Engineered oligonucleotide or peptide affinity probes used as stable, customizable alternatives to antibodies for target capture. | Utilized in SPR aptasensors for their thermal stability and ease of functionalization [7]. |

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) technology stands as a cornerstone in biomolecular interaction analysis, enabling label-free, real-time determination of binding affinity and kinetic parameters critical for drug discovery and basic research. However, the integrity of this high-precision data is fundamentally threatened by instrumental and environmental drift—a persistent challenge that, if left uncorrected, systematically compromises the accuracy of calculated rate constants and equilibrium constants. Drift manifests as gradual signal changes unrelated to molecular binding events, arising from temperature fluctuations, mechanical instabilities, or bulk refractive index variations. This article examines how uncorrected drift introduces substantive errors in key interaction parameters, compares methodological approaches for drift correction, and provides experimental guidance for distinguishing artifact from authentic binding signals. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these consequences is not merely technical but essential for generating reliable, reproducible interaction data that informs critical project decisions.

How Uncorrected Drift Compromises Key Interaction Parameters

Fundamental Mechanisms of Drift-Induced Error

Drift interferes with SPR measurements by creating a non-zero baseline slope that distorts the sensorgram's association and dissociation phases. During the association phase, a positive drift (upward slope) can be misinterpreted as continued binding, leading to overestimation of the association rate constant (kon). Conversely, during the dissociation phase, the same positive drift opposes the signal decrease from complex dissociation, resulting in underestimation of the dissociation rate constant (koff). Since the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) is calculated as koff/kon, these correlated errors compound in the final affinity measurement, potentially shifting reported KD values by an order of magnitude or more. The bulk response effect further complicates this picture, as molecules in solution but not binding to the surface contribute to the refractive index change within the evanescent field, creating a false signal that masks true binding interactions, particularly at high analyte concentrations necessary for probing weak affinities [11].

Experimental Evidence of Parameter Distortion

The practical impact of drift is not theoretical—it manifests consistently in experimental data. A systematic comparison of SPR biosensors revealed that even different commercial instruments can produce varying kinetic parameters for the same interaction, partly due to differing susceptibilities and correction methods for instrumental drift [12]. For instance, when measuring the interaction between IgG antibodies and protein A, values for association rate constants obtained across devices varied within one order of magnitude, while dissociation constants showed greater consistency for some antibody subtypes but not others [12]. This variability underscores how drift sensitivity can directly impact cross-platform reproducibility.

Furthermore, investigations into weak affinity interactions, such as between poly(ethylene glycol) brushes and lysozyme, demonstrate that proper correction for bulk effects—a form of drift—is essential to reveal true binding events. Without appropriate correction, the weak equilibrium affinity (KD = 200 μM) and short-lived interaction (1/koff < 30 s) between PEG and lysozyme remained obscured [11]. This case illustrates how drift correction transcends mere signal quality improvement to actually enabling detection of otherwise invisible interactions.

Table 1: Consequences of Uncorrected Drift on SPR Kinetic Parameters

| SPR Phase | Impact of Positive Drift | Effect on Kinetic Parameters | Resulting KD Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association | Overestimates binding rate | Overestimated kon | Underestimated (Tighter apparent affinity) |

| Dissociation | Opposes signal decay | Underestimated koff | Underestimated (Tighter apparent affinity) |

| Equilibrium | Shifts baseline binding level | Misrepresents steady state | Incorrect by order of magnitude |

Comparative Analysis of Drift Correction Methodologies

Hardware-Based and Signal Processing Approaches

Multiple technological approaches have been developed to address the drift challenge, each with distinct mechanisms and limitations. Hardware-based stabilization methods employ additional detectors and feedback elements to maintain focus and position stability, achieving remarkable precision down to 5 nm in some hyperspectral nanoimaging systems [2]. However, these approaches increase optical path complexity and require specialized instrumentation that may not be accessible to all laboratories.

Reference channel subtraction represents a common software-based approach that utilizes a separate surface region to measure and subtract bulk response contributions. While implemented in many commercial instruments, this method depends critically on the reference surface perfectly repelling injected molecules while maintaining identical optical properties to the sample channel—conditions difficult to achieve in practice [11]. Even minor deviations introduce artifacts that persist in corrected sensorgrams, as evidenced by residual bulk responses visible in studies utilizing commercial correction features [11].

Reflection-based positional detection offers an alternative that eliminates the need for separate reference surfaces. This approach correlates defocus displacement with positional deviations of reflection spots, enabling both initial prefocusing and continuous drift monitoring during experiments. Implemented in Focus Drift Correction (FDC)-enhanced SPR microscopy, this method achieves focus accuracy of 15 nm/pixel without additional optical components or special imaging patterns, significantly improving image quality for nanoparticle observation [2].

Advanced Computational and Physical Models

Recent algorithmic advances provide additional powerful approaches to drift compensation. The Nearest Paired Cloud (NP-Cloud) algorithm, developed for single-molecule localization microscopy but conceptually relevant to SPR, demonstrates how iterative nearest-neighbor pairing within a small search radius can efficiently extract and correct spatial shifts between data segments [13]. This approach substantially improves robustness and computational speed compared to traditional cross-correlation methods, achieving drift corrections within seconds [13].

For addressing the specific challenge of bulk response, physical model-based correction utilizes the total internal reflection (TIR) angle response as input to directly calculate and subtract bulk contributions without a reference channel. This method accounts for the thickness of surface receptor layers, correctly revealing weak interactions that remain hidden with conventional correction approaches [11]. The accuracy of this physical model has been verified experimentally, showing it outperforms built-in correction methods in commercial instruments.

Table 2: Comparison of Drift Correction Methodologies for SPR

| Methodology | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Channel Subtraction | Measures bulk response on separate surface | Widely implemented in commercial systems | Requires perfectly non-adsorbing reference surface with identical properties |

| Focus Drift Correction (FDC) | Tracks reflection spot positional deviations | No extra optics needed; 15 nm/pixel accuracy | Primarily addresses focus drift specifically |

| Physical Model-Based Bulk Correction | Uses TIR angle response to calculate bulk effect | No reference surface needed; reveals weak interactions | Requires accurate modeling of layer thicknesses |

| Spectral Shaping | Controls light intensity with mask for uniform spectral response | ~70% SNR difference reduction; cost-effective | Addresses SNR variation rather than drift directly |

| NP-Cloud Algorithm | Iterative nearest-neighbor pairing within search radius | >100-fold faster; robust to uncorrelated localizations | Developed for SMLM; adaptation to SPR may be needed |

Experimental Protocols for Drift Assessment and Correction

Protocol for Validating Bulk Response Correction

Accurate drift correction begins with rigorous validation of the chosen methodology. The following protocol adapts the physical model approach for general SPR applications:

Surface Preparation: Immobilize the receptor of interest using standard coupling chemistry. Precisely determine the dry and hydrated thickness of the surface layer using SPR spectra fits to Fresnel models, as this dimension critically influences the bulk response calculation [11].

System Equilibration: Maintain constant temperature throughout the experiment, as temperature fluctuations represent a primary source of drift. Allow sufficient time for system stabilization before data collection.

Data Collection with TIR Monitoring: Simultaneously record both SPR angle and TIR angle signals during analyte injections. The TIR signal serves as an intrinsic reference for bulk refractive index changes.

Baseline Correction: Apply linear baseline correction if drift is consistent throughout the experiment (typically <10⁻⁴ °/min). Subtract injection artifacts (typically ~0.002°) evident in both SPR and TIR angles when protein concentration approaches zero.

Physical Model Application: Correct the SPR signal using the corresponding TIR angle signal based on the derived relationship between bulk refractive index and SPR response. Account for the specific thickness of the surface receptor layer in these calculations.

Validation with Negative Controls: Include non-interacting analyte concentrations to verify that the correction eliminates nonspecific bulk responses while preserving genuine binding signals.

High-Throughput Workflow for Kinetic Parameter Determination

For studies requiring characterization of multiple interactions, such as antibody affinity screening, implement the following high-throughput workflow adapted from the "BreviA" system:

Library Transformation: Transform Brevibacillus with plasmid library containing variant antibody sequences. Culture single colonies in 96-well plates for 60 hours [14].

Parallel Processing: Centrifuge cultures; process supernatant for interaction analysis and precipitate for plasmid sequencing.

Sample Preparation: Precipitate supernatant with ammonium sulfate to remove low-molecular-weight culture medium components that interfere with immobilization [14].

Immobilization and Kinetics: Immobilize antibodies from precipitated samples onto NTA sensor chips. Perform interaction kinetics with antigen at 4-5 concentrations in a fourfold dilution series using non-regenerative kinetics method [14].

Data Integration: Combine sequence data from plasmid miniprep with kinetic parameters to create a comprehensive dataset of antibody variants and their binding characteristics.

This integrated system enables acquisition of up to 384 sequence-kinetic datasets within one week, dramatically accelerating the characterization process while maintaining data quality [14].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The relationship between uncorrected drift and parameter miscalculation follows a logical pathway that researchers must understand to properly diagnose data quality issues. The diagram below maps this cascading effect from initial causes to ultimate consequences:

The experimental workflow for proper drift correction involves multiple decision points and methodological considerations, particularly when designing high-throughput interaction analyses:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for SPR Drift Correction Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chips | Standard chip for amine coupling of receptors | Cytiva CM5 chips (used in Biacore systems) [15] |

| NTA Sensor Chips | Immobilization of histidine-tagged proteins | Used in high-throughput antibody screening [14] |

| PEG Brushes | Model system for studying weak interactions and bulk response | 20 kg/mol thiol-terminated PEG on gold sensors [11] |

| Lysozyme | Model protein for weak affinity interaction studies | Chicken egg white lysozyme (Product #L6876) [11] |

| Reference Proteins | Negative controls for bulk response validation | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [11] |

| Coupling Reagents | Immobilization chemistry for ligand attachment | NHS/EDC mixture for amine coupling [15] |

| Regeneration Solutions | Surface regeneration between analyte cycles | Ethanolamine hydrochloride for blocking [15] |

Uncorrected drift in SPR measurements represents more than a minor technical inconvenience—it systematically distorts the fundamental kinetic and affinity parameters that drive scientific conclusions and development decisions. The evidence clearly demonstrates that drift artifacts can obscure weak interactions, falsely enhance apparent affinities, and undermine reproducibility across platforms. As SPR technology expands into high-throughput applications and increasingly challenging molecular systems, implementing robust drift correction methodologies transitions from optional refinement to essential practice. The continuing development of physical model-based approaches that eliminate dependency on reference surfaces, combined with computational algorithms adapted from other microscopy fields, promises more accurate and accessible correction capabilities. For the research and drug development community, prioritizing these advances ensures that SPR remains a reliable cornerstone for biomolecular interaction analysis, producing data whose validity matches its potential impact.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) technology is a cornerstone of label-free biomolecular interaction analysis, but its precision is often compromised by signal drift and noise. The scientific community has addressed this challenge through two distinct philosophical approaches: instrumental solutions, which enhance hardware stability and optical components, and algorithmic solutions, which use computational methods to purify acquired signals. This guide provides an objective comparison of these correction philosophies, supported by recent experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

The Instrumental Philosophy: Enhancing Hardware Stability

The instrumental philosophy seeks to eliminate the physical sources of drift at their origin. This approach focuses on refining optical configurations and implementing real-time hardware feedback systems to maintain optimal measurement conditions.

Focus Drift Correction (FDC) in SPR Microscopy

A prime example of this philosophy is the Focus Drift Correction (FDC) enhanced SPR microscopy. In SPRM, the use of high-magnification objectives with short depths of field (<1 μm) makes imaging highly susceptible to tiny drifts from thermal fluctuations or mechanical instability, leading to aberrant interference fringes and reduced image quality [2].

Experimental Protocol & Workflow: The developed FDC system operates in two distinct steps [2]:

- Prefocusing (FDC-F1): Before imaging begins, an image processing program calculates the initial defocus displacement (ΔZ) by tracking the positional deviation (ΔX) of a reflection spot on the camera. The system is then automatically adjusted to the focal plane.

- Focus Monitoring (FDC-F2): During continuous imaging, the system constantly monitors the reflection spot position and makes nanoscale corrections to counteract any focus drift occurring in real-time.

This method is notable for not requiring extra optical components or special sample markers [2]. The diagram below illustrates this feedback-driven instrumental workflow.

Performance Data: This instrumental approach achieved a focus accuracy of 15 nm/pixel, enabling the system to visually distinguish between 50 nm and 100 nm nanoparticles, as well as between 100 nm nanoparticles of different materials [2].

Spectral Shaping with a Mask

Another instrumental solution tackles the wavelength-dependent signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in SPR sensors. A 2025 study employed a simple, cost-effective mask placed within a multi-field-of-view spectrometer to control the amount of light received by the sensor at different wavelengths [16].

Experimental Protocol: The mask is designed to create uniform spectral intensity across the SPR's resonance wavelengths. This equalizes the measurement accuracy that would otherwise vary due to the sensor's and optics' differential response to light [16].

Performance Data:

| Metric | Improvement |

|---|---|

| Difference in SNR across wavelengths | Reduced by ~70% [16] |

| Difference in measurement accuracy | Reduced by ~85% [16] |

The Algorithmic Philosophy: Purifying Data Post-Acquisition

In contrast, the algorithmic philosophy accepts that some noise is inherent to the measurement process and focuses on using advanced computational models to separate the signal of interest from the noise.

The PPBM4D Denoising Algorithm

A leading algorithmic solution is the Polarization Pair, Block Matching, and 4D Filtering (PPBM4D) algorithm, designed for high-resolution, large-range phase-sensitive SPR imaging [17].

Experimental Protocol & Workflow: This algorithm is used in conjunction with a quad-polarization filter array (PFA) camera that simultaneously captures four polarization images. PPBM4D extends the BM3D denoising framework by leveraging the textural similarity and intensity redundancy across these different polarization states [17].

- The four polarization images (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°) are captured.

- The algorithm uses inter-polarization correlations to generate "virtual measurements" for each channel.

- These virtual measurements provide additional constraints for a collaborative 4D filtering process, which aggregates similar patches from both the virtual and actual measurements to suppress noise effectively.

The following diagram outlines the core data processing steps of this algorithmic approach.

Performance Data: The PPBM4D algorithm demonstrated a 57% reduction in instrumental noise. When integrated into a specialized phase imaging system, it achieved a refractive index resolution of 1.51 × 10⁻⁶ RIU over a wide dynamic range (1.333–1.393 RIU). The system validated its performance by accurately quantifying antibody-protein binding kinetics at concentrations as low as 0.15625 μg/mL [17].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The table below synthesizes experimental data from key studies to provide a direct, objective comparison of the featured solutions.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Instrumental vs. Algorithmic SPR Correction Solutions

| Correction Philosophy | Specific Method | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental | Focus Drift Correction (FDC) [2] | Focus Accuracy | 15 nm/pixel | Distinguishing 50 nm & 100 nm nanoparticles |

| Instrumental | Spectral Shaping with Mask [16] | SNR Uniformity | ~70% improvement | Equalized accuracy across wavelengths |

| Algorithmic | PPBM4D Denoising [17] | Refractive Index Resolution | 1.51 × 10⁻⁶ RIU | Detection of antibody binding at 0.15625 μg/mL |

| Algorithmic | PPBM4D Denoising [17] | Noise Reduction | 57% reduction | Enhanced signal clarity in protein assays |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of these correction methods, particularly in biomarker interaction studies, relies on a suite of key reagents and materials.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SPR Drift Correction Studies

| Item Name | Function / Role | Specific Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Lab-Grown Diamond with NV Centers | Serves as an ultra-pure substrate for engineered quantum sensors to study magnetic fluctuations at nanoscale [18]. | Diamond with nitrogen-vacancy centers for correlated magnetic noise sensing [18]. |

| Quad-Polarization Filter Array (PFA) | A CMOS sensor that simultaneously captures light intensity at four polarization angles (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°) for differential phase detection and algorithmic denoising [17]. | Sony IMX250 CRZ sensor used in the PPBM4D denoising study [17]. |

| Gold Sensor Chip (with Cr layer) | The standard SPR substrate; a thin gold film on a glass prism that supports surface plasmon excitation. | ZF5 glass prism coated with 3 nm Cr and 30 nm Au layers [17]. |

| Biomolecular Ligands (e.g., Antibodies) | The capture molecule immobilized on the gold chip to study specific binding interactions with an analyte. | Antibodies used in protein interaction assays to validate sensor performance [17]. |

| Chemical Cross-linkers (NHS/EDC) | A common chemistry used to covalently immobilize protein ligands onto the gold sensor chip surface. | N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and N-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC) for amine coupling [2]. |

| Nanoparticle Standards | Used as size and morphology references for calibrating and validating system resolution and focus. | Polystyrene (PS) and gold nanoparticles (50 nm, 100 nm) [2]. |

| Buffer Components (PBS) | Provides a stable, physiologically relevant ionic and pH environment for biomolecular interactions. | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) [19]. |

The choice between instrumental and algorithmic correction philosophies is not a matter of which is universally superior, but which is most appropriate for the specific research problem and system constraints.

- Instrumental solutions like FDC and spectral shaping offer a direct, hardware-based path to stability. They address the root cause of drift but may require specialized equipment or modifications.

- Algorithmic solutions like PPBM4D provide a powerful, software-driven approach to enhance data from existing hardware. They offer great flexibility and can be applied retroactively, but rely on the quality of the initial raw data.

A prevailing trend in the latest SPR research is the integration of both philosophies. For instance, deploying a stable optical configuration with a PFA camera (instrumental) and then processing the data with a sophisticated algorithm like PPBM4D (algorithmic) represents a synergistic approach that pushes the boundaries of SPR performance, enabling breakthroughs in live-cell imaging, high-throughput screening, and trace molecular detection [17].

A Deep Dive into Drift Correction Algorithms: From Dynamic Baselines to AI

Traditional Reference Subtraction and Double Referencing

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technology for the real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions, providing critical insights into binding kinetics and affinity. [20] A significant challenge in generating reliable SPR data is the mitigation of signal drift and bulk refractive index (RI) effects. The "bulk response" is a particularly inconvenient effect that complicates interpretation; it occurs when molecules in solution generate signals without binding to the surface, often because the evanescent field extends hundreds of nanometers into the solution. [11] For decades, Traditional Reference Subtraction has been the primary method for correcting these unwanted signals. More recently, advanced methodologies, including a form of Double Referencing, have been developed to improve accuracy. This guide objectively compares the performance of these established and emerging drift-correction algorithms within the broader context of SPR data refinement.

Explanation of the Methods

Traditional Reference Subtraction

Traditional Reference Subtraction is a foundational correction technique. It involves using a dedicated reference channel on the sensor chip that is functionalized with an inert surface designed to repel the analyte. [11] The core principle is that any signal recorded from this reference channel originates from non-specific system effects, such as bulk RI changes, injection artifacts, or instrumental drift. The specific binding signal from the active channel, which contains the immobilized ligand, is then purified by digitally subtracting the signal from the reference channel.

While this method effectively reduces bulk RI contributions and some drift, its accuracy hinges on a critical assumption: that the reference surface perfectly mimics the active surface in all aspects except for the specific binding activity. Any difference in the physical properties of the two surfaces, such as coating thickness or hydration, can introduce error. [11]

Advanced Referencing and "Double Referencing"

The term "Double Referencing" in SPR often refers to a two-step correction process. The first step is the traditional reference channel subtraction described above. The second step involves an additional subtraction, typically of a blank injection (a buffer solution with no analyte) or the average baseline drift, to account for any remaining minor, systematic artifacts. [21]

A more advanced approach moves beyond the reliance on a separate physical reference channel. One innovative method uses the total internal reflection (TIR) angle response from the very same sensor surface as an internal standard to determine the bulk RI. [11] This signal is then used in a physical model to directly calculate and subtract the bulk contribution, eliminating the potential errors arising from differences between separate channels. [11] For the purpose of this guide, we group these sophisticated, self-referencing techniques under the broader umbrella of advanced double-referencing strategies.

Experimental Comparison

To objectively evaluate these methods, we consider experimental data focused on a challenging model system: the weak interaction between a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) brush and the protein lysozyme (LYZ). This interaction is ideal for testing drift correction because its low affinity requires high analyte concentrations, which exacerbate the bulk response effect. [11]

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following protocol summarizes the key methodologies from the cited research on the PEG-lysozyme model system. [11]

- 1. Sensor Chip Preparation: SPR chips with a 50 nm gold layer are rigorously cleaned using RCA1 and RCA2 cleaning solutions, followed by ethanol rinsing and nitrogen drying. [11]

- 2. Surface Functionalization: The active surface is grafted with 20 kg/mol thiol-terminated PEG by exposing the clean gold surface to a 0.12 g/L PEG solution in 0.9 M Na₂SO₄ for 2 hours. The surface is then rinsed and stored in water. [11] A reference surface (for traditional subtraction) would be prepared with a non-interacting, protein-repellent coating.

- 3. SPR Data Acquisition: Experiments are conducted on a multi-wavelength SPR instrument (e.g., SPR Navi 220A) at 25°C. Lysozyme solutions in PBS buffer are injected over the sensor surface at a flow rate of 20 μL/min. The instrument simultaneously records the SPR angle shift (binding signal) and the TIR angle shift (bulk signal). [11]

- 4. Data Processing with Different Methods:

- Traditional Reference Subtraction: The signal from the dedicated reference channel is subtracted from the active channel signal.

- Advanced Self-Referencing: The bulk response is calculated using a physical model where the SPR angle shift (

Δθ_SPR) is a function of the surface-bound analyte and the bulk RI change, the latter being directly proportional to the TIR angle shift (Δθ_TIR). The formula takes the form:Δθ_corrected = Δθ_SPR - (L_d / L_eff) * Δθ_TIR, whereL_dandL_effare the thickness of the surface-grafted layer and the effective field decay length, respectively. [11] This correction is applied to the data from the single active channel.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The table below details the key reagents and materials used in the featured experiment.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Gold-coated SPR Sensor Chips | Provides the surface for plasmon excitation and ligand immobilization. [11] |

| Thiol-terminated PEG (20 kg/mol) | Forms a grafted polymer brush layer on the gold surface, serving as the ligand for studying weak interactions with lysozyme. [11] |

| Lysozyme (LYZ) | The analyte protein used to probe the interaction with the PEG brush surface. [11] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Running buffer that maintains a physiologically relevant ionic strength and pH for the biomolecular interaction. [11] |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Used as a non-interacting protein to determine the height of the hydrated PEG brush layer. [11] |

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key differences between the Traditional Reference Subtraction and the Advanced Self-Referencing methods.

Performance Data and Comparison

The performance of each method is quantified by its ability to reveal the true binding isotherm and kinetics of the weak PEG-lysozyme interaction, which is obscured by the bulk response in uncorrected data.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Correction Methods

| Method | Corrected Equilibrium Signal (at 1 g/L LYZ) | Calculated Dissociation Constant (K_D) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncorrected Data | ~0.052° SPR shift | Not accurately determinable | N/A | Fails to separate bulk signal; obscures true binding isotherm. [11] |

| Traditional Reference Subtraction | ~0.015° binding signal | Inaccurate due to residual error | Reduces bulk RI and drift; widely available. [11] | Requires perfectly matched reference surface; prone to error from coating differences. [11] |

| Advanced Self-Referencing | ~0.012° binding signal | 200 µM | No separate reference channel needed; uses internal standard (TIR); reveals subtle kinetics (1/k_off < 30 s). [11] | Requires instrument capable of measuring TIR angle; relies on accuracy of physical model. [11] |

The experimental data clearly demonstrates that while Traditional Reference Subtraction is a useful tool for mitigating gross bulk effects, it is not generally accurate for probing weak interactions or in situations where perfect surface matching is impossible. [11] The advanced self-referencing method, which leverages a physical model and internal calibration, provides superior accuracy by directly addressing the bulk response from the active surface itself. This method successfully unveiled a previously obscured weak affinity (K_D = 200 µM) and fast dynamics in the PEG-lysozyme system. [11]

For researchers pursuing the highest data accuracy, particularly for challenging interactions requiring high analyte concentrations, advanced double-referencing techniques represent the future of SPR drift correction. The evolution of commercial instruments to incorporate such features is a positive step, yet the research community must continue to validate these implementations and develop even more robust correction algorithms. [11]

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) microscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for nanoscale observation, enabling researchers to visualize and quantify label-free nano-scale objects near metal surfaces with high sensitivity and temporal resolution. This technology has proven invaluable for imaging and quantitative analysis of diverse targets, including single silica nanoparticles, polystyrene nanoparticles, influenza viruses, T4 phage viruses, and single DNA molecules. A significant advantage of SPR microscopy over traditional fluorescent microscopy lies in its capability for real-time, label-free imaging, making it particularly suitable for long-term tracking applications such as monitoring single organelle transportation in living cells, exosome dynamics on antibody-coated surfaces, and the binding kinetics of single label-free SARS-CoV-2 viruses.

However, the effectiveness of SPR systems for long-term nanoscale observation faces a fundamental challenge: micrometer-scale optomechanical drift-induced defocus. This drift occurs because SPR microscopy systems typically employ high magnification objectives with extremely short depths of field (often less than 1 μm). Consequently, any tiny focus drift caused by optical components or environmental fluctuations can significantly degrade imaging quality. Focus drifts introduce abnormal interference fringes and reduce image contrast, ultimately diminishing image quality and lowering the signal-to-noise ratio of SPR analysis. This limitation has restricted broader applications in quantitative biomolecule interaction detection, prompting the development of sophisticated drift correction algorithms.

The dynamic baseline algorithm represents a significant advancement in addressing these limitations for SPR sensors. This algorithm modifies the traditional approach to SPR curve analysis by dynamically adjusting the baseline according to a pre-defined ratio between the areas of the SPR curve below and above this baseline. This adjustment compensates for fluctuations in input optical power and background signal, ensuring the output response of the SPR sensor remains insensitive to these variations. The implementation has been shown to be mathematically exact, offering a robust solution to a persistent challenge in SPR sensing.

Comparative Analysis of SPR Drift Correction Algorithms

Various approaches have been developed to combat drift in SPR systems and other microscopy techniques. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these methods:

Table 1: Comparison of Drift Correction Algorithms for Sensing and Microscopy

| Algorithm Name | Application Context | Underlying Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Baseline Algorithm [22] [23] | SPR Sensor Data Analysis | Dynamically adjusts baseline to maintain constant area ratio above/below baseline. | Mathematically exact compensation for optical power fluctuations; simple implementation. | Primarily addresses intensity drift, not spatial drift. |

| Focus Drift Correction (FDC) [2] | SPR Microscopy (SPRM) | Calculates positional deviations of reflection spots to correct defocus displacement. | Does not require extra optical systems or special imaging patterns; 15 nm/pixel accuracy. | Requires specific reflection spot analysis. |

| Fiducial Marker-Based | General Microscopy | Tracks known, fixed reference points within the sample. | Conceptually simple; provides direct drift measurement. | Requires introduction of external markers that may interfere. |

| Nearest Paired Cloud (NP-Cloud) [13] | Single-Molecule Localization Microscopy (SMLM) | Pairs nearest molecules between data segments to calculate displacements. | >100x faster than traditional methods; utilizes precise localization data. | Designed for SMLM, not directly applicable to SPR. |

| Image Correlation-Based [13] | SMLM and other microscopies | Computes cross-correlation of binned images from different time segments. | Conceptually simple and widely implemented. | Spatial binning can lose precision; computationally heavy. |

| Mean Shift Algorithm [24] | Localization Microscopy | Peak-finding algorithm for estimating drift in single-molecule data. | Efficient and robust for localization microscopy. | Application-specific to localization datasets. |

The performance of these algorithms can be quantitatively assessed based on critical parameters relevant to high-precision research. The following table compares these metrics across different correction approaches:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Drift Correction Methods

| Algorithm | Spatial Accuracy | Temporal Resolution | Computational Speed | Robustness to Noise | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Baseline (SPR) [22] | N/A (Intensity Correction) | High (Real-time capable) | Fast | High (Insensitive to optical power noise) | Low |

| FDC for SPRM [2] | 15 nm/pixel | High | Fast | High (Withstands continuous nanoscale observation) | Medium |

| NP-Cloud for SMLM [13] | Near ground truth (simulated) | Dependent on segment size | >100x faster than cross-correlation | High in simulated and experimental data | Medium |

| Cross-Correlation for SMLM [13] | Lower than NP-Cloud (grid size dependent) | Dependent on segment size | Slow (baseline for comparison) | Deteriorates with small grid sizes | Low |

Mathematical Principles of the Dynamic Baseline Algorithm

The dynamic baseline algorithm addresses a fundamental vulnerability in traditional SPR curve analysis methods, such as the centroid method and polynomial curve fitting. These conventional approaches are often sensitive to correlated noise or drift from the light source, which can generate significant noise on the SPR response. The dynamic baseline algorithm introduces a mathematically rigorous correction that effectively mitigates these issues.

Core Mathematical Formulation

At the heart of the dynamic baseline algorithm is the maintenance of a constant ratio between the integrated areas of the SPR curve below and above the baseline. For an angular interrogation SPR system, the standard centroid method determines the resonance angle using the equation:

[ \theta{res} = \frac{\int{\theta1}^{\theta2} (PB - P(\theta)) \theta d\theta}{\int{\theta1}^{\theta2} (P_B - P(\theta)) d\theta} ]

where ( PB ) is the baseline, ( P(\theta) ) is the detector response at incidence angle ( \theta ), and the integration occurs between angles ( \theta1 ) and ( \theta_2 ).

The dynamic baseline algorithm modifies this approach by defining two key areas:

- Area A₀: The integrated area of the SPR curve below the baseline ( P_B )

- Area A₁: The integrated area above the baseline ( P_B )

The algorithm dynamically adjusts the baseline ( P_B ) to maintain a constant ratio ( k ) between these two areas, defined by the equation:

[ \frac{A0}{A1} = \frac{\int{\theta1}^{\theta2} [PB - P(\theta)] d\theta}{\int{\theta1}^{\theta2} [P(\theta) - PB] d\theta} = k ]

This relationship ensures that the output response of the SPR sensor remains insensitive to fluctuations in the input optical power and background signal. The adjustment of the baseline provides compensation that has been proven to be mathematically exact for correlated noise sources, making the algorithm particularly valuable in real-world experimental conditions where light source stability is often a limiting factor.

Algorithm Workflow and Implementation

The implementation of the dynamic baseline algorithm follows a logical sequence that can be visualized as a workflow:

This implementation workflow demonstrates the iterative nature of the dynamic baseline algorithm, which continuously adjusts the baseline to maintain the target area ratio despite fluctuations in optical power or background signal.

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Experimental Setup for Dynamic Baseline Validation

The validation of the dynamic baseline algorithm employed a specific experimental setup to quantify its performance advantages. Researchers used an injection-moulded polymer sensor chip incorporating a metal film for SPR sensing and diffractive optical coupling elements (DOCE) for input and output coupling of light. The optical system utilized a GaAIAs/GaAs light emitting diode (LED) with a central emitting wavelength of 670 nm and a spectral bandwidth of 25 nm (full width at half maximum) as the light source. Detection was performed using a 1024 × 1288 Zoran CMOS sensor, which provided the digital output for analysis.

To systematically evaluate the algorithm's performance, the experiments introduced controlled variations in the LED drive current. This manipulation directly altered the output optical power, creating a controlled source of fluctuation that would typically affect SPR measurements. Throughout these variations, the SPR response was calculated using both a constant baseline method and the dynamic baseline algorithm, allowing for direct comparison of performance under destabilizing conditions.

Performance Assessment Methodology

The evaluation of the dynamic baseline algorithm employed both numerical simulations and experimental validation. For the simulations, a digital detector array response ( P(\theta, t) ) was modeled as a function of the angle of incidence ( \theta ) and time ( t ), incorporating several key parameters:

[ P(\theta, t) = G(\alpha(\theta, t) I'_0(t) + \beta(t)) ]

where:

- ( G ) represents a digitizing gain factor dependent on the bit resolution of the detector

- ( I'_0(t) ) is the normalized light intensity

- ( \alpha(\theta, t) ) encompasses the normalized light reflection coefficient ( R(\theta, ns) ), offset drift ( B'1(t) ), and fixed pattern noise ( \Delta F(\theta) )

- ( \beta(t) ) includes background drift ( B'0(t) ) and detector noise ( \Delta N{\text{noise}}(t) )

This comprehensive model allowed researchers to quantify the algorithm's performance under various noise conditions, including optical power fluctuations, background signal changes, and detector noise. The simulations specifically assessed the deterioration of signal linearity, noise levels in the sensor output, and the algorithm's ability to compensate for intensity fluctuations.

The experimental protocol applied these controlled variations in optical power while measuring known analytes, enabling direct comparison between the dynamic baseline algorithm and traditional methods. The results demonstrated negligible deterioration in signal linearity (less than 1% error) when using the dynamic baseline approach, confirming its robustness for quantitative SPR measurements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of SPR drift correction algorithms, including the dynamic baseline method, requires specific materials and reagents. The following table details key components used in the featured experiments and their functions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SPR Experiments

| Material/Reagent | Specification/Properties | Experimental Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene Nanoparticles [2] | Sizes: 50 nm, 100 nm, 1 µm (2.5 wt%) | Calibration and resolution testing | Static and dynamic observation of single nanoparticles |

| Gold Nanoparticles [2] | Size: 100 nm (0.1 mg/mL) | Reference material for signal calibration | Distinguishing nanoparticles of different materials |

| Sensor Chip [22] [23] | Polymer with metal film & diffractive optical elements | SPR signal generation platform | Main sensing element in experimental validation |

| Plasmonic Materials (Gold, Silver) [25] | High chemical stability (Au), sharp resonance (Ag) | Enhancing detection performance | Metal coatings in PCF-SPR sensor configurations |

| N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) [2] | CAS NO: 6066-82-6 | Surface functionalization | Biomolecule immobilization on sensor surface |

| N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC) [2] | CAS NO: 25952-53-8 | Surface functionalization | Covalent coupling with NHS for immobilization |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [2] | CAS NO: 9048-46-8 | Blocking agent | Reducing non-specific binding on sensor surfaces |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) [2] | Standard physiological buffer | Sample dilution and maintenance | Maintaining stable pH and ionic strength |

These materials enable the fabrication, calibration, and experimental validation of SPR systems utilizing drift correction algorithms. The nanoparticles serve as critical tools for system calibration and resolution testing, allowing researchers to quantify the performance improvements offered by the dynamic baseline algorithm. The functionalization chemicals (NHS, EDC) and blocking agents (BSA) facilitate the preparation of biospecific sensing surfaces, which are essential for biomolecular interaction studies.

The dynamic baseline algorithm represents a significant advancement in SPR sensing technology, addressing the critical challenge of optical power fluctuations and background drift through a mathematically rigorous approach. By maintaining a constant ratio between the areas of the SPR curve above and below a dynamically adjusted baseline, this algorithm provides exact compensation for correlated noise sources that have traditionally limited measurement accuracy.

When compared to other drift correction methodologies—including focus drift correction for SPR microscopy, fiducial marker-based approaches, and computational methods like NP-Cloud for single-molecule localization microscopy—the dynamic baseline algorithm offers distinct advantages for specific application contexts. Its mathematical simplicity, computational efficiency, and proven robustness make it particularly valuable for researchers and drug development professionals requiring high-precision, real-time SPR measurements.

The experimental validation, supported by both numerical simulations and physical experiments, demonstrates that the dynamic baseline algorithm maintains signal linearity with less than 1% error while effectively compensating for intensity fluctuations. This performance, combined with its compatibility with common SPR data analysis methods, positions the dynamic baseline algorithm as a foundational tool in the continuing advancement of SPR technology for biomedical research and pharmaceutical development.

Reflection-Based Positional Detection for Focus Drift in SPR Microscopy

Surface Plasmon Resonance Microscopy (SPRM) has emerged as a powerful, label-free tool for nanoscale observation, enabling the visualization and quantification of diverse nano-scale objects near metal surfaces with high sensitivity and temporal resolution. Applications span from imaging single silica and polystyrene nanoparticles to monitoring dynamic biological processes such as single organelle transportation in living cells and the binding of single viruses like SARS-CoV-2 [2]. However, the technique's full potential is often limited by a persistent technical challenge: focus drift.

SPRM systems typically employ high-magnification objectives with a short depth of field (often less than 1 micrometer). Consequently, any tiny focus drift caused by optical components or environmental fluctuations can significantly degrade imaging quality. This drift introduces abnormal interference fringes, reduces image contrast, and lowers the signal-to-noise ratio of SPRM analysis, creating a major obstacle for long-term nanoscale continuous observation and quantitative biomolecular interaction studies [2]. This article provides a comparative analysis of focus drift correction algorithms for SPRM, with a specific focus on evaluating the performance of a reflection-based positional detection method against other computational and hardware-based approaches.

Experimental Protocols for Drift Correction Methodologies

Protocol 1: Reflection-Based Positional Detection (FDC-SPRM)

The Focus Drift Correction (FDC) approach for SPRM utilizes a reflection-based positional detection system that does not rely on extra optomechanical subsystems or special imaging patterns [2].

Workflow Overview:

- Prefocusing (FDC-F1 Function): Before imaging, an image processing program retrieves the positional deviation (ΔX) of the inherent reflection spot on the camera imaging plane. The defocus displacement (ΔZ) is then calculated using the auxiliary focus function FDC-F1, and the system is automatically adjusted to the optimal focus position.

- Focus Monitoring (FDC-F2 Function): During the continuous imaging procedure, the relationship between defocus displacement and the reflection spot deviation (FDC-F2) is used to monitor and correct focus drift in real-time, maintaining nanoscale focus accuracy throughout long-term observations.

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Nanoparticles: Polystyrene (PS) nanoparticles (50 nm, 100 nm, and 1 µm) and gold nanoparticles (100 nm) are used for system validation [2].

- Sensor Chip: A glass substrate coated with a 48-nm gold film serves as the sensing surface [26].

- Chemical Reagents: N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) for surface functionalization, along with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) for blocking and maintaining a biocompatible environment [2].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the FDC-SPRM method:

Protocol 2: Bayesian Sample Drift Inference (BaSDI)

BaSDI treats drift correction as a statistical inference problem, aiming to find the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation of the drift trace from single-molecule localization data [27].

Workflow Overview:

- Initialization: A preliminary superresolution image (θ) is guessed, often from the summed image of all frames without drift correction.

- Expectation Step (E-Step): Given the current estimate of θ, the conditional distribution of the drift trace P(d|o,θ) is computed.

- Maximization Step (M-Step): A new optimization of the superresolution image θ is performed based on the computed distribution of the drift.

- Iteration: The E- and M-steps are repeated iteratively until convergence is achieved, co-optimizing both the most likely drift trace and the final, drift-compensated superresolution image [27].

Protocol 3: Mean Shift (MS) Algorithm

The Mean Shift algorithm is designed for drift correction in single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM) data, operating directly on the acquired localization lists [24] [28].

Workflow Overview:

- Temporal Binning: Localizations are distributed into non-overlapping temporal bins containing an equal number of frames.

- Pairwise Displacement Calculation: All pairwise displacements between localizations across two different temporal bins are calculated.

- Peak Finding: Displacements arising from the same emitter cluster around the true drift value, while those from different emitters form a random background. The MS algorithm iteratively finds the center of this cluster:

- All displacement pairs within a defined radius are selected.

- The centroid of these pairs is calculated, shifting the estimate toward the true drift.

- The observation window is re-centered on the new mean, and the process repeats until convergence [28].

- Trajectory Fitting: A weighted linear least-squares fitting algorithm generates a continuous drift trajectory from the displacement estimates between bin pairs.

Performance Comparison of Drift Correction Algorithms

The following tables summarize the key characteristics and quantitative performance data of the different drift correction methods.

Table 1: Technical Characteristics and Hardware Requirements Comparison

| Method | Principle | Hardware Requirements | Sample/Label Requirements | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reflection-Based (FDC-SPRM) [2] | Correlation of defocus displacement (ΔZ) with reflection spot position (ΔX) | No extra optical components | No fiducial markers; uses inherent reflection | Low; simple image processing |

| Bayesian Inference (BaSDI) [27] | Statistical inference via Expectation-Maximization | Standard imaging setup | No fiducial markers required | High; iterative model fitting |

| Mean Shift Algorithm [28] | Clustering of cross-frame single-molecule displacements | Standard imaging setup | No fiducial markers required | Moderate; efficient peak finding |

| Fiducial Marker-Based [27] | Tracking the position of embedded markers | Standard imaging setup | Requires fiducial markers (e.g., gold nanoparticles) | Low to Moderate |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance and Application Scope

| Method | Reported Focus Accuracy / Precision | Temporal Resolution | Best-Suited Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reflection-Based (FDC-SPRM) [2] | 15 nm/pixel | Continuous, real-time monitoring | Long-term nanoscale observation (e.g., viral binding, nanoparticle dynamics) | Performance tied to reflection spot quality |

| Bayesian Inference (BaSDI) [27] | Significantly higher than correlation-based | Limited by total frames and processing load | SMLM for structures with well-defined geometry | High computational load; complex implementation |

| Mean Shift Algorithm [28] | Robust at high molecular density | Limited by temporal bin size | SMLM for high-density structures (e.g., nuclear pores) | Bias risk with overlapping bins or time-correlated blinking |

| Image Cross-Correlation [27] | Lower than BaSDI and MS methods | Coarse (substack level) | Simple, rapid correction for smooth drifts | Poor performance with mechanical creeps or sudden jumps |

The quantitative data demonstrates that the reflection-based FDC method achieves a high level of focus accuracy (15 nm/pixel), making it suitable for distinguishing nanoparticles as small as 50 nm and differentiating between 100 nm particles of different materials [2]. Its primary advantage lies in its ability to provide continuous, real-time correction without introducing experimental complexity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of advanced SPRM and drift correction methods relies on a set of key reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for SPRM Drift Correction Studies

| Item | Function / Role | Example Application in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Gold-coated Sensor Chips [2] [26] | Substrate for SPR excitation; typically 48 nm gold film on glass. | Serves as the sensing surface in all SPRM protocols. |

| Polystyrene & Gold Nanoparticles [2] | Calibration and validation standards for system resolution and drift correction performance. | Used in FDC-SPRM to validate ability to distinguish 50 nm vs. 100 nm particles. |

| NHS/EDC Chemistry [2] | Standard carboxylated surface activation for covalent ligand immobilization. | Used in FDC-SPRM and BaSDI for attaching proteins or other biomolecules. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) [2] | Blocking agent to minimize non-specific binding on sensor surfaces. | Used in various protocols after surface functionalization. |

| PBS Buffer [2] | Biocompatible buffer to maintain pH and ionic strength during biological experiments. | Standard buffer for dilutions and as a running buffer in most protocols. |

| HaloTag Fusion Protein System [29] | Enables standardized, high-density capture of proteins of interest on biosensor surfaces. | Used in SPOC technology for high-throughput, real-time kinetic screening. |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores that the optimal choice of a drift correction algorithm for SPRM is highly dependent on the specific experimental requirements. The reflection-based positional detection method (FDC-SPRM) offers a compelling solution for applications demanding continuous, real-time nanoscale observation without introducing experimental complexity or relying on specific sample patterns [2]. Its integration directly into the SPRM system provides a robust hardware-software solution for long-term dynamic process monitoring.

In contrast, computational approaches like the Bayesian method (BaSDI) and the Mean Shift algorithm provide powerful post-processing solutions, particularly for single-molecule localization microscopy data where high precision is paramount [27] [28]. The ongoing innovation in SPRM technology, including its expanding applications in drug discovery and biomolecular interaction analysis [30] [29], will continue to drive the development of more sophisticated, accurate, and user-friendly drift correction methodologies. Future advancements will likely focus on the deeper integration of AI and machine learning to further enhance accuracy and computational efficiency, pushing the boundaries of nanoscale biological observation.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a cornerstone technology for label-free biomolecular interaction analysis, enabling researchers to determine affinity and probe binding kinetics in real-time. A significant challenge that has complicated SPR data interpretation for decades is the "bulk response," a signal originating from molecules in solution that do not bind to the sensor surface [11]. This effect occurs because the evanescent field used for detection extends hundreds of nanometers from the surface, far beyond the thickness of typical analytes like proteins. Consequently, when high concentrations of analyte are injected—a necessity for probing weak interactions—a substantial signal is generated from the change in refractive index of the bulk liquid, complicating the separation from the genuine surface binding signal [11]. Traditional methods to compensate for this effect have relied on using a separate reference channel. However, this approach requires a perfect non-adsorbing surface and identical coating thickness to the sample channel to avoid introducing errors [11]. Advanced computational methods are now emerging that eliminate the need for a reference channel, offering a more accurate and streamlined approach to bulk response correction.

The Challenge of Reference-Based Correction Methods