Solving SPR Regeneration Drift: A Complete Guide to Stable Baselines and Reliable Data

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on understanding, troubleshooting, and preventing baseline drift caused by regeneration solutions in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments.

Solving SPR Regeneration Drift: A Complete Guide to Stable Baselines and Reliable Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on understanding, troubleshooting, and preventing baseline drift caused by regeneration solutions in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it explains the mechanistic causes of drift, including matrix effects and ligand conformational changes. The content details systematic methodologies for scouting optimal regeneration conditions using cocktail approaches, offers practical troubleshooting strategies for immediate drift mitigation, and presents validation techniques to ensure data integrity. By synthesizing these core intents, this guide empowers scientists to achieve highly reproducible binding data, which is critical for accurate kinetic analysis in drug discovery and biomolecular interaction studies.

Understanding the Root Causes: Why Regeneration Solutions Disrupt SPR Baselines

Defining Regeneration-Induced Drift and Its Impact on Data Quality

What is Regeneration-Induced Drift?

Regeneration-induced drift is a phenomenon in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments where the sensor's baseline signal fails to return to its original pre-injection level after a regeneration step. This manifests as a gradual, persistent shift in the baseline, indicating that the sensor surface has not been fully returned to its initial state. Instead of completely removing the bound analyte, incomplete regeneration leaves residual material on the sensor surface, which changes the properties of the sensing layer and compromises the surface for subsequent analysis cycles [1] [2].

How Does Regeneration-Induced Drift Impact Data Quality?

This drift directly compromises the reliability of the collected interaction data in several critical ways:

- Inaccurate Binding Response: A drifting baseline makes it challenging to accurately measure the specific binding response in subsequent analyte injections, potentially leading to overestimation or underestimation of binding levels [3].

- Compromised Kinetic Parameters: The calculation of kinetic parameters, such as association (

k_on) and dissociation (k_off) rate constants, depends on a stable baseline. Baseline drift introduces errors into these calculations, reducing the reliability of the derived affinity constants (K_D) [1]. - Poor Reproducibility: Inconsistent surfaces caused by carryover effects lead to high variability between replicate experiments, undermining the validity and reproducibility of the data [1] [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Regeneration-Induced Drift

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Carryover Effects | Regeneration solution too weak; incomplete analyte removal [1]. | Optimize regeneration buffer composition, pH, and ionic strength; increase flow rate or regeneration time [1] [2]. |

| Sensor Surface Degradation | Harsh or overly acidic/basic regeneration conditions damage the ligand or chip surface [1]. | Use milder regeneration buffers; follow manufacturer's guidelines for surface maintenance; avoid extreme pH conditions [1]. |

| Residual Analyte Buildup | Repeated regeneration cycles without a deep clean lead to cumulative fouling [4]. | Implement a more rigorous cleaning protocol between experimental cycles; monitor surface condition [1] [4]. |

| Improper Surface Equilibration | Sensor surface and fluidic system are not fully equilibrated after regeneration [3]. | Allow longer stabilization time after regeneration; run multiple buffer injections; match flow and analyte buffer composition to avoid bulk shifts [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Optimization of Regeneration Conditions

A methodical approach is required to identify the optimal regeneration conditions for a specific molecular interaction.

Step 1: Preliminary Scouting

Inject a short pulse of your analyte over the ligand surface. Then, test short injections (30-60 seconds) of various regeneration solutions in sequence. Common candidates include:

- Acidic solutions: 10 mM glycine-HCl pH 2.0 - 3.0, or 10 mM phosphoric acid [2].

- Basic solutions: 10 mM - 50 mM NaOH [2].

- High salt solutions: 1 - 4 M NaCl [2].

- Additive-enhanced solutions: Adding 10% glycerol to the regeneration buffer can help maintain target stability [2].

Step 2: Evaluate Regeneration Efficiency

After each regeneration pulse, monitor the baseline. A successful regeneration will return the signal to the original baseline. An unsuccessful one will show carryover and drift [1] [3].

Step 3: Assess Ligand Stability

Inject the analyte again over the regenerated surface. A stable, reproducible binding response indicates the regeneration conditions are effective and do not damage the ligand. A significant drop in response indicates ligand degradation or inactivation [1] [2].

Step 4: Implement and Validate

Once optimal conditions are found, standardize the protocol for all experiments. Include control injections to periodically verify that surface activity remains consistent throughout the run [4].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Regeneration Context |

|---|---|

| Glycine-HCl Buffer (pH 2.0-3.0) | Acidic solution that disrupts hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions; effective for many antibody-antigen complexes [2]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) 10-50 mM | Basic solution that denatures and removes tightly bound proteins; useful for robust ligands [2]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl), High Concentration (1-4 M) | High ionic strength solution disrupts electrostatic interactions [2]. |

| Glycerol | Additive to regeneration buffers; helps stabilize the immobilized ligand's structure during harsh regeneration, preserving activity [2]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Strong ionic detergent for removing stubborn, non-specifically bound analytes; use with caution as it can denature many ligands [4]. |

Research Methodology & Data Analysis Workflow

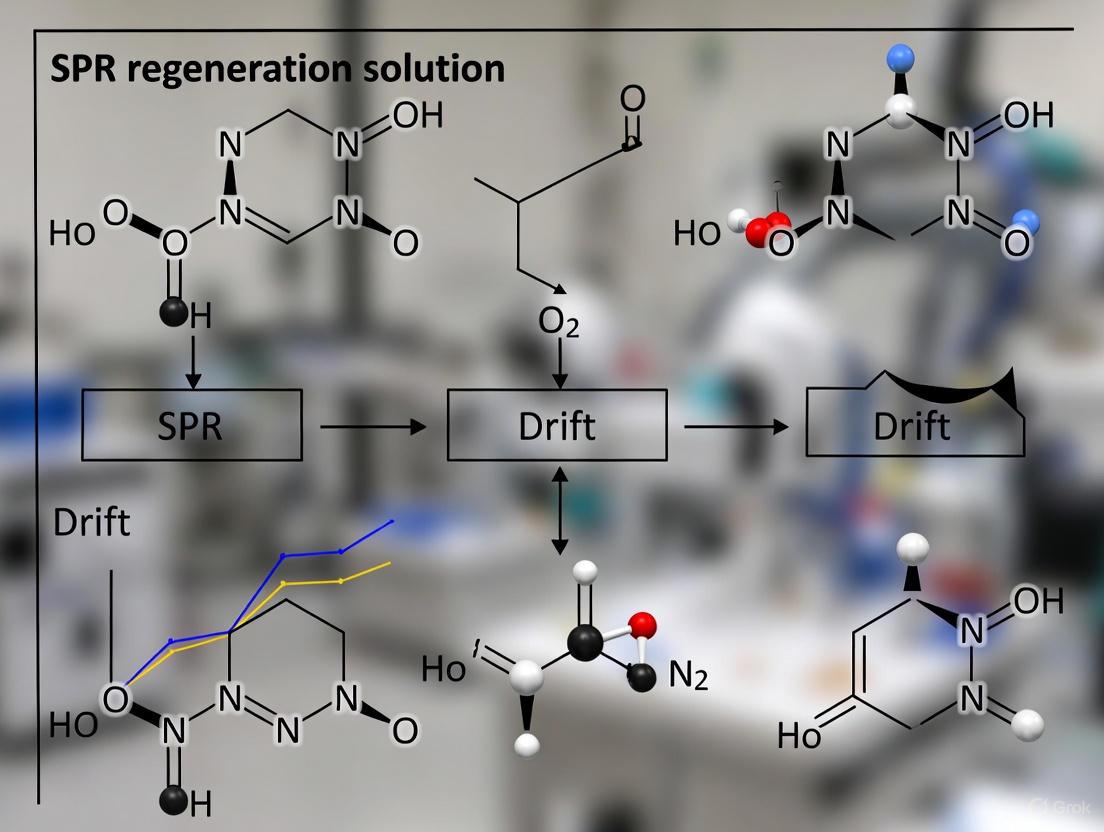

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving regeneration-induced drift, integrating the concepts and protocols outlined above.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are "matrix effects" in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)? Matrix effects are changes in the dextran polymer hydrogel (the immobilization matrix on common sensor chips like CM5) that occur due to variations in the buffer environment, such as pH or ionic strength [5]. These physical changes in the matrix can cause shifts in the baseline response, mimicking binding events or causing drift, which can interfere with the interpretation of binding kinetics [5].

Q2: How do regeneration solutions cause baseline drift? Regeneration solutions often use harsh conditions (e.g., low or high pH, high salt) to break analyte-ligand bonds. These same conditions can temporarily or permanently alter the physical structure of the dextran matrix. When the buffer is switched back to the running buffer, the matrix slowly re-equilibrates, causing a gradual shift in the baseline known as drift [5] [6].

Q3: Why is the dextran matrix sensitive to pH and ionic strength? The carboxymethylated dextran matrix contains charged carboxyl groups. Changes in pH affect the ionization state of these groups, causing the polymer chains to swell (at high pH, when charged) or contract (at low pH, when neutral) due to electrostatic repulsion or lack thereof. Similarly, high ionic strength buffers shield these charges, reducing repulsion and causing the matrix to collapse [5] [7].

Q4: What are the practical consequences of matrix effects on my SPR data? Matrix effects can lead to:

- Baseline Instability: Drift after regeneration makes it difficult to obtain a stable starting point for the next analyte injection [5] [6].

- Inaccurate Quantification: Drift can be mistaken for very slow dissociation or for non-specific binding, leading to errors in kinetic and affinity calculations [5].

- Poor Data Quality: Significant drift and bulk effects reduce the signal-to-noise ratio and the reliability of the fitted data [5].

Q5: How can I minimize matrix effects in my experiments?

- Use Milder Regeneration: Find the mildest possible regeneration solution (pH, salt, contact time) that still fully dissociates your complex [5] [6].

- Allow for Stabilization: Introduce a stabilization period after regeneration and before the next injection to allow the baseline to fully stabilize [5].

- Optimize Pre-concentration: During ligand immobilization, use low-ionic-strength buffers and a pH slightly below the ligand's pI to promote efficient pre-concentration without promoting non-specific matrix effects later [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Matrix Effects and Baseline Drift

Problem: Significant baseline drift observed immediately after regeneration.

| Step | Action | Rationale & Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check Regeneration Stringency | Overly harsh conditions (e.g., pH <2 or >10) cause large, slow matrix rearrangements. Expected Outcome: Milder conditions should reduce the magnitude of drift. [5] |

| 2 | Increase Equilibration Time | The matrix requires time to re-equilibrate with the running buffer. Use the instrument's washing command and extend the stabilization time post-regeneration. Expected Outcome: Baseline stabilizes before the next analyte injection. [5] [6] |

| 3 | Verify Running Buffer Consistency | Ensure the running buffer after regeneration is identical in pH and ionic strength to the pre-regeneration buffer to prevent an osmotic imbalance. Expected Outcome: A more stable baseline. [5] |

| 4 | Inspect Ligand Density | Very high ligand density can amplify matrix effects. Expected Outcome: A lower ligand density may reduce drift and also mitigate mass transport limitations. [5] [6] |

Problem: A large bulk refractive index shift is obscuring the specific binding signal.

| Step | Action | Rationale & Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Match Analyte & Running Buffer | A large shift indicates a difference in composition between the analyte sample and the running buffer. Dialyze the analyte into the running buffer or use a desalting column. Expected Outcome: A significantly reduced bulk shift. [8] |

| 2 | Include a Blank Injection | Always inject your sample buffer (blank) in the same cycle as the analyte. This allows for subtraction of the bulk shift during data processing. Expected Outcome: Cleaner sensorgrams after double-referencing. [8] |

| 3 | Use a Reference Flow Cell | An activated and blocked but unliganded flow cell, or one with an irrelevant ligand, is essential for subtracting systemic artifacts and bulk effects [8] [6]. |

The table below summarizes how different solution conditions physically affect the dextran matrix and provides recommended starting points for experimentation.

Table 1: Effects of Solution Conditions on the Dextran Matrix and Recommended Ranges

| Condition | Effect on Dextran Matrix | Typical Range for Regeneration | Recommended Pre-concentration Buffer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low pH (Acidic) | Protonates carboxyl groups, reducing electrostatic repulsion. Causes matrix contraction [5] [7]. | pH 1.5 - 3.0 (e.g., Glycine/HCl) [5]. | 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0 - 5.5 [8] [7]. |

| High pH (Basic) | Deprotonates carboxyl groups, increasing negative charge and electrostatic repulsion. Causes matrix swelling [5]. | pH 9 - 10 (e.g., Glycine/NaOH, NaOH) [5]. | Not typically used for pre-concentration on carboxylated surfaces [7]. |

| High Ionic Strength | Shields charges on the polymer chains, reducing repulsion and causing matrix contraction [5] [7]. | 0.5 - 4 M NaCl or MgCl₂ [5]. | 10 mM buffer, low salt ( |

Experimental Protocol: The "Cocktail Method" for Finding Optimal Regeneration Conditions

This protocol, adapted from Andersson et al., provides a systematic, multivariate approach to identify effective yet mild regeneration conditions that minimize matrix damage and drift [5].

Objective: To empirically determine the most effective regeneration cocktail by targeting multiple binding forces simultaneously.

Principle: By mixing different chemicals, it is possible to disrupt the analyte-ligand interaction under less harsh conditions than a single strong reagent, thereby preserving ligand activity and matrix integrity [5].

Stock Solutions to Prepare [5]:

- Acidic Stock: Equal volumes of 0.15 M oxalic acid, H₃PO₄, formic acid, and malonic acid, adjusted to pH 5.0 with NaOH.

- Basic Stock: Equal volumes of 0.20 M ethanolamine, Na₃PO₄, piperazine, and glycine, adjusted to pH 9.0 with HCl.

- Ionic Stock: A solution of 0.46 M KSCN, 1.83 M MgCl₂, 0.92 M urea, and 1.83 M guanidine-HCl.

- Detergent Stock: A solution of 0.3% (w/w) CHAPS, 0.3% (w/w) Zwittergent 3-12, 0.3% (v/v) Tween 80, 0.3% (v/v) Tween 20, and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100.

Workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Investigating Matrix Effects

Table 2: Essential Reagents for SPR Regeneration and Matrix Studies

| Reagent Category | Example | Function & Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Acidic Buffers | 10-50 mM Glycine/HCl, pH 1.5-2.5 [5] [8]. | Unfolds proteins and adds positive charge, causing repulsion. Contracts dextran matrix by protonating carboxyl groups [5]. |

| Basic Buffers | 10-100 mM NaOH; 10 mM Glycine/NaOH, pH 9-10 [5] [8]. | Disrupts hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions. Swells dextran matrix by deprotonating carboxyl groups [5]. |

| High Salt Solutions | 1-4 M MgCl₂ or NaCl [5]. | Shields ionic and polar interactions. Contracts dextran matrix by shielding charged groups [5] [7]. |

| Chaotropic Agents | 6 M Guanidine-HCl; Urea [5]. | Disrupts hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, denatures proteins [5]. |

| Chelating Agents | 3-20 mM EDTA [5] [6]. | Removes divalent metal ions that may be essential for coordination in some binding complexes [5]. |

Ligand Conformational Changes and Unfolding Post-Regeneration

FAQs: Addressing Core Challenges

Q1: Why does my baseline drift after a regeneration step, and how is this linked to ligand damage?

Baseline drift following regeneration is a classic sign that the regeneration solution may have caused unintended changes to your immobilized ligand or the sensor chip surface itself. This drift can occur because the regeneration conditions were too harsh, leading to:

- Ligand Conformational Changes: The ligand may refold slowly or incorrectly after being exposed to extreme pH or chemicals, creating an unstable surface that slowly equilibrates, causing a drifting baseline [5] [9].

- Ligand Unfolding or Denaturation: Strong acids or bases can partially denature the protein ligand, causing it to lose its native structure and biological activity. This altered state can have a different refractive index and binding properties, manifesting as drift [5].

- Matrix Effects: The dextran polymer matrix on the sensor chip itself can swell or shrink in response to sudden changes in pH or ionic strength from the regeneration solution. This change in the physical environment of the ligand can take minutes or even hours to stabilize, leading to a drifting baseline [5].

Q2: How can I tell if my regeneration protocol is causing ligand unfolding instead of simply removing the analyte?

Distinguishing between successful regeneration and ligand damage requires looking at the data across multiple cycles:

- Monitor Ligand Activity: After regeneration, inject a known, high-concentration analyte sample. A consistent binding response (Response Units, RU) cycle-after-cycle indicates a healthy ligand. A steady decline in maximum RU is a direct indicator that your ligand is losing activity, likely due to unfolding or denaturation [5] [1].

- Check for Altered Kinetics: If the shape of the binding sensorgram changes in subsequent cycles (e.g., slower association or faster dissociation), it suggests the ligand's binding site has been altered conformationally [4].

- Observe Baseline Stability: A failure to return to the original baseline or persistent drift after regeneration are key signs of surface instability, potentially from a damaged ligand or a compromised sensor chip matrix [9] [1].

Q3: What are the first steps to take if I suspect my ligand has undergone conformational changes post-regeneration?

Your immediate actions should focus on using milder conditions and better system equilibration:

- Use Milder Regeneration: Immediately switch to a milder regeneration solution (e.g., higher pH for acidic solutions, or lower pH for basic solutions) and/or shorten the contact time [5] [1].

- Employ a "Cocktail" Approach: Target multiple binding forces simultaneously with a mixture of milder chemicals instead than one harsh solution. This can be more effective and less damaging [5].

- Increase Equilibration Time: After regeneration, allow more time for the system to stabilize with running buffer flowing. In severe cases, it may be necessary to flow buffer for an extended period (even overnight) to achieve a stable baseline [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Post-Regeneration Artifacts

| Observed Problem | Primary Underlying Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Progressive loss of binding signal (RUmax) | Ligand denaturation or irreversible unfolding due to harsh regeneration conditions [5]. | Optimize regeneration by starting with the mildest possible conditions (e.g., short contact time, low concentration). Use a empirical "cocktail" approach to find an effective yet gentle solution [5]. |

| Continuous baseline drift after regeneration | Slow re-folding of the ligand; slow re-equilibration of the sensor chip matrix (dextran) after a change in pH/ionic strength; or residual analyte remaining on the surface [5] [9]. | Extend the post-regeneration stabilization time; ensure complete regeneration; consider using a different, more stable sensor chip surface chemistry (e.g., C1 for large molecules) [9] [10]. |

| Poor Reproducibility & Inconsistent Data | Inconsistent regeneration leading to a variable mix of active, partially unfolded, and denatured ligands on the surface [4] [1]. | Standardize the regeneration protocol meticulously. Include several "start-up" cycles (buffer injections with regeneration) at the beginning of an experiment to condition the surface before collecting data [9]. |

| Change in binding kinetics in later cycles | Conformational changes in the ligand that alter the binding site but do not completely destroy it [5]. | Use a different, milder regeneration buffer. If possible, switch the immobilization chemistry to a more robust method (e.g., covalent capture) that better withstands regeneration [4] [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing Regeneration-Induced Ligand Damage

This protocol provides a systematic method to test and identify a regeneration solution that effectively removes the analyte while preserving ligand integrity.

Methodology: An empirical, iterative screening of regeneration solutions.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Prepare Stock Solutions: Prepare the six stock solution categories as defined by Andersson et al.: Acidic, Basic, Ionic, Non-polar water-soluble solvents, Detergents, and Chelating [5].

- Create Regeneration Cocktails: Mix new regeneration solutions from the basic stock solutions. Each cocktail should consist of three parts, which can be three different stock solutions or one stock solution plus two parts water [5].

- Initial Analyte Injection: Inject your analyte over the ligand surface to form a complex and record the maximum response (RU).

- First Regeneration Injection: Inject the first regeneration candidate solution.

- Evaluate Regeneration Efficiency: Calculate the percentage of analyte removed (percentage regeneration).

- If regeneration is < 10%: The solution is ineffective. Proceed to inject the next regeneration candidate solution [5].

- If regeneration is between 10% and 50%: The solution has partial effect. Note its composition and proceed to test the next candidate [5].

- If regeneration is > 50%: This is a promising candidate. Inject fresh analyte to begin the next test cycle [5].

- Iterate and Refine: Repeat this process with all candidates. Identify the common components in the most effective solutions. Use these components to mix a new set of refined regeneration solutions and repeat the testing cycle until an optimal, mild solution is found [5].

Key Reagents:

- Running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP)

- Ligand and analyte samples

- Stock solutions for regeneration cocktails (Acidic, Basic, Ionic, etc.) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function in Troubleshooting Regeneration Issues |

|---|---|

| Glycine-HCl Buffer (pH 1.5-3.0) | A common, mild acidic regeneration solution. Useful for disrupting interactions involving electrostatic or hydrogen bonding. Start testing at a higher pH (e.g., 2.5-3.0) to minimize unfolding risk [5]. |

| NaOH Solution (10-100 mM) | A common basic regeneration solution. Effective for hydrophobic interactions. Start with low concentrations (e.g., 10 mM) to avoid damaging the ligand or sensor chip matrix [5]. |

| Ethylene Glycol (25-50%) | A non-polar solvent used in regeneration cocktails to disrupt hydrophobic interactions under milder pH conditions, helping to preserve ligand conformation [5]. |

| MgCl₂ or NaCl (High Salt) | High ionic strength solutions (0.5-2 M) can disrupt electrostatic interactions. Useful as a component in cocktail solutions to reduce reliance on extreme pH [5]. |

| Detergent Mix (e.g., Tween-20, CHAPS) | A mixture of mild detergents can help disrupt hydrophobic binding and prevent non-specific adsorption without denaturing many proteins [5]. |

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A versatile, carboxymethylated dextran chip common for covalent immobilization. Note that its matrix is susceptible to swelling/shrinking with pH changes, contributing to drift [4] [10]. |

| C1 Sensor Chip | A matrix-free, flat surface sensor chip. Can be used to eliminate matrix-related effects and baseline drift associated with dextran chips post-regeneration [10]. |

| SA Sensor Chip | Streptavidin-coated chip for capturing biotinylated ligands. Offers a highly specific and stable immobilization base, but the streptavidin itself can be sensitive to extreme pH regeneration [10]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What causes baseline drift in my SPR experiments, and how is it linked to regeneration?

Baseline drift, a gradual shift in the sensor's baseline signal over time, can severely impact data accuracy. Incomplete regeneration and persistent non-specific binding are two primary sources of this problem.

- Incomplete Regeneration: This occurs when the regeneration solution fails to completely dissociate the analyte from the ligand. Residual analyte remains on the sensor surface, causing the baseline to shift to a higher level and reducing the number of available binding sites for the next injection. This leads to a gradual increase in baseline and a decrease in binding capacity over multiple cycles [5] [12].

- Persistent Non-Specific Binding: This happens when analytes bind to the sensor surface itself rather than specifically to the immobilized ligand. These unwanted interactions can be difficult to remove with standard regeneration protocols, causing a buildup of material on the surface and resulting in a drifting baseline [5] [4].

The diagram below illustrates how these issues lead to an unstable baseline.

FAQ 2: How can I minimize non-specific binding (NSB) on my sensor chip?

Non-specific binding makes interactions appear stronger than they are and is a common source of drift. The following strategies can help minimize it [4] [2] [13]:

- Optimize Surface Chemistry: Select a sensor chip with surface chemistry tailored to reduce NSB. For example, use planar chips instead of dextran-based chips if you see high NSB, or switch to a chip with a different charge [4] [13].

- Use Buffer Additives: Supplement your running buffer with additives that reduce unwanted interactions. Common additives include:

- Effective Surface Blocking: After ligand immobilization, block any remaining active sites on the sensor chip with a suitable agent like ethanolamine, casein, or BSA [4].

- Tune Flow Conditions: Optimize the buffer flow rate. A moderate flow rate that matches the analyte's diffusion rate can help reduce non-specific adsorption [4].

FAQ 3: My regeneration is either damaging the ligand or is incomplete. How can I find the optimal conditions?

Finding a regeneration solution that completely removes the analyte without damaging the ligand is empirical. The recommended strategy is the "cocktail approach," which systematically tests mixtures targeting different binding forces [5].

- Start Mild: Always begin with the mildest possible conditions and short contact times [5] [12].

- Systematic Scouting: Test different types of solutions, typically starting with acidic conditions (e.g., 10 mM Glycine pH 1.5-3.0), then basic (e.g., 10-100 mM NaOH), and high salt (e.g., 1-2 M NaCl) [5] [14] [12].

- Use a Cocktail: Mix chemicals from different stock solutions (acidic, basic, ionic, detergent, etc.) to target multiple binding forces simultaneously, which can be effective under less harsh conditions [5].

- Preserve Ligand Activity: Add 5-10% glycerol to your regeneration solution. Glycerol can help preserve the ligand's biological activity during the regeneration process [14].

- Evaluate Success: A good regeneration returns the baseline to its original level and maintains consistent analyte binding responses across multiple cycles [12].

The workflow below outlines this systematic scouting process.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Scouting for Regeneration Solutions

This protocol is based on the multivariate cocktail method to efficiently identify the best regeneration conditions [5].

Methodology:

- Prepare Stock Solutions: Create the following six stock solutions [5]:

- Acidic: Equal volumes of 0.15 M oxalic acid, H₃PO₄, formic acid, and malonic acid, mixed and adjusted to pH 5.0 with NaOH.

- Basic: Equal volumes of 0.20 M ethanolamine, Na₃PO₄, piperazin, and glycine, mixed and adjusted to pH 9.0 with HCl.

- Ionic: A solution of 0.46 M KSCN, 1.83 M MgCl₂, 0.92 M urea, and 1.83 M guanidine-HCl.

- Non-polar solvents: Equal volumes of DMSO, formamide, ethanol, acetonitrile, and 1-butanol.

- Detergents: A solution of 0.3% (w/w) CHAPS, 0.3% (w/w) Zwittergent 3-12, 0.3% (v/v) Tween 80, 0.3% (v/v) Tween 20, and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100.

- Chelating: A 20 mM EDTA solution.

- Mix Initial Cocktails: Create new regeneration solutions by mixing three parts from different stock solutions (or one stock with two parts water).

- Test and Evaluate:

- Immobilize your ligand and inject the analyte.

- Inject the first regeneration solution and calculate the percentage of regeneration (0-100%).

- If regeneration is below 10%, try the next, harsher solution. If it is above 50%, inject a new analyte and continue testing.

- Refine the Solution: Identify common components in the top three performing solutions. Mix new regeneration solutions focusing on these best-performing stock solutions and repeat the testing cycle until an optimal solution is found [5].

Protocol 2: A Method to Evaluate Regeneration Efficiency and Ligand Integrity

This protocol assesses whether your regeneration strategy is effective and sustainable over multiple cycles.

Methodology:

- Condition the Surface: Before starting kinetic measurements, perform 1-3 injections of your chosen regeneration buffer to condition the ligand surface [12].

- Establish a Baseline: Immobilize the ligand and achieve a stable baseline in running buffer.

- Run Repeated Cycles: For a single, medium concentration of analyte, run multiple cycles of:

- Association phase (analyte injection)

- Dissociation phase (running buffer)

- Regeneration phase (regeneration solution injection)

- Monitor Key Metrics:

- Baseline Stability: The baseline should return to the same level after each regeneration. A rising baseline indicates incomplete regeneration; a falling baseline indicates ligand damage [12].

- Binding Response Consistency: The maximum response (Rmax) for the same analyte concentration should be consistent across all cycles. A decreasing Rmax indicates loss of ligand activity [12].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Regeneration Buffers and Their Applications

This table summarizes typical regeneration solutions, their formulations, and the types of interactions they are suited for [5] [12].

| Type of Solution | Example Formulations | Target Interaction/Bond | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic | 10-50 mM Glycine/HCl (pH 1.5-2.5); 0.5 M Formic acid; 10 mM HCl [5] [14] | Ionic, Hydrogen bonding [5] | Proteins, Antibodies [12] |

| Basic | 10-100 mM NaOH; 10 mM Glycine/NaOH (pH 9-10) [5] [2] | Ionic, Hydrogen bonding [5] | Nucleic acids [12] |

| High Salt | 0.5-4 M NaCl; 1-2 M MgCl₂ [5] | Ionic, Hydrophobic [5] | Various, depending on salt concentration |

| Detergent | 0.01-0.5% SDS; 0.3% Triton X-100 [5] [12] | Hydrophobic [5] | Peptides, Protein/Nucleic acid complexes [12] |

| Chaotropic | 6 M Guanidine chloride; 0.92 M Urea [5] | Strong multiple bonds [5] | Very strong interactions |

Table 2: The Researcher's Toolkit for Regeneration and Drift Control

This table lists essential reagents and materials used to troubleshoot regeneration and drift problems.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Glycerol | Added to regeneration buffers (5-10%) to help preserve ligand activity and prevent denaturation during the regeneration process [14]. |

| Tween-20 | A non-ionic surfactant added to running buffers (0.005-0.1%) to minimize non-specific binding to the sensor chip surface [4] [13]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A blocking agent used to occupy remaining active sites on the sensor surface after ligand immobilization, reducing non-specific binding [4] [13]. |

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A carboxymethylated dextran chip commonly used for covalent immobilization of ligands via amine coupling [4]. |

| NTA Sensor Chip | A nitrilotriacetic acid-coated chip used to capture His-tagged proteins, offering an alternative, reversible immobilization strategy [4]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing Common Regeneration Challenges

1. What are the signs that my regeneration solution is too harsh? A regeneration solution that is too harsh will damage the ligand, leading to a loss of activity over multiple cycles. You will observe a decreasing baseline and a lower analyte binding response when the same analyte concentration is injected in subsequent cycles [12]. This indicates that the ligand is being denatured or removed from the sensor chip surface.

2. What indicates that my regeneration is too mild? If the regeneration is too mild, it will not fully remove the bound analyte. This results in carryover and a higher baseline in the next injection cycle because analyte remains on the surface [1] [12]. This residual analyte occupies binding sites, reducing the available ligand for the next injection and skewing kinetic data.

3. Why does my baseline drift after regeneration, and how is it related to my thesis research? Baseline drift following regeneration is a classic symptom of matrix or conformational effects induced by the regeneration solution [5]. Within the context of thesis research on SPR regeneration-induced drift, this is a primary area of investigation. The drift can occur because the regeneration solution causes slow, reversible changes in the dextran matrix of the sensor chip (matrix effect) or alters the structure of the immobilized ligand (conformational change) [5]. Introducing a stabilization period after regeneration is often necessary for the baseline to re-equilibrate [5] [9].

4. How can I systematically find the best regeneration conditions? The most robust method is the "cocktail" approach [5]. This involves creating stock solutions targeting different binding forces (acidic, basic, ionic, detergent, etc.) and systematically testing mixtures of these stocks. You start with mild conditions and progressively test harsher cocktails until you find a solution that achieves complete analyte removal with minimal impact on ligand activity [5].

Troubleshooting Common Regeneration Problems

| Problem | Primary Symptom | Underlying Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overly Harsh Regeneration | Decreasing baseline & signal over cycles [12] | Ligand denaturation or removal from surface [5] | Use a milder regeneration solution; shorten contact time [5] [12] |

| Incomplete Regeneration | Rising baseline; carryover effect [1] | Analyte not fully dissociated [12] | Use a stronger regeneration solution; use a "cocktail" approach [5] |

| Regeneration-Induced Drift | Baseline instability post-regeneration [5] | Matrix effects or slow ligand re-folding [5] | Increase stabilization time; use double referencing [5] [9] |

| Inconsistent Results | Variable binding responses between cycles [1] | Uneven ligand coverage or damaged ligand [1] | Standardize immobilization; check ligand stability; calibrate instrument [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Scouting for an Initial Regeneration Condition

This protocol provides a starting point for identifying an effective regeneration buffer.

1. Principle Empirically test a series of common regeneration buffers to find which is most effective at disrupting the specific ligand-analyte interaction while preserving ligand activity [5] [12].

2. Materials

- Research Reagent Solutions: See Table 1.

- SPR Instrument and Sensor Chip

- Ligand and Analyte samples

- Running Buffer

3. Procedure

- Immobilize your ligand on the sensor chip.

- Inject a single concentration of analyte to achieve a high binding response.

- Inject a candidate regeneration buffer for 15-60 seconds.

- Monitor the response: a sharp drop back to the original baseline indicates successful regeneration.

- Inject the same analyte concentration again. If the binding response is similar to the first injection, the regeneration buffer has preserved ligand activity. A lower signal indicates the buffer is too harsh [12].

- Repeat steps with different regeneration buffers, starting with the mildest conditions.

Protocol 2: The Cocktail Regeneration Method

For difficult interactions, a systematic cocktail approach is recommended to target multiple binding forces simultaneously with milder conditions [5].

1. Principle By mixing chemicals from different stock classes (acidic, basic, ionic, etc.), you can often achieve complete regeneration under less harsh conditions than a single, strong chemical would allow, thereby better preserving ligand integrity [5].

2. Materials

- Stock Solutions [5]:

- Acidic Stock: Equal volumes of oxalic acid, H₃PO₄, formic acid, and malonic acid (each 0.15 M), mixed and adjusted to pH 5.0.

- Basic Stock: Equal volumes of ethanolamine, Na₃PO₄, piperazin, and glycine (each 0.20 M), mixed and adjusted to pH 9.0.

- Ionic Stock: A solution of KSCN (0.46 M), MgCl₂ (1.83 M), urea (0.92 M), and guanidine-HCl (1.83 M).

- Detergent Stock: A solution of 0.3% (w/w) CHAPS, 0.3% (w/w) Zwittergent 3-12, 0.3% (v/v) Tween 80, 0.3% (v/v) Tween 20, and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100.

- Chelating Stock: 20 mM EDTA solution.

- SPR Instrument and Prepared Sensor Chip

3. Procedure

- Create regeneration "cocktails" by mixing three different stock solutions, or one stock with two parts water.

- After analyte injection, inject the first cocktail. Calculate the percentage of regeneration.

- If regeneration is <10%, inject a stronger cocktail. If regeneration is >50%, inject new analyte to test ligand activity.

- Repeat this process, testing different cocktails.

- Identify the best-performing stock solutions and mix new, refined cocktails from them.

- Iterate until an optimal regeneration solution is found [5].

Regeneration Optimization Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Common regeneration buffer types and their typical applications.

| Regeneration Type | Example Formulations | Primary Mechanism | Typical Interaction Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic | 10-150 mM Glycine-HCl, pH 1.5-3.0 [5] [12] | Protein unfolding; charge repulsion [5] | Antibodies, protein-protein [12] |

| Basic | 10-100 mM NaOH, 10 mM Glycine-NaOH, pH 9-10 [5] | Charge disruption; mild denaturation | Nucleic acids, specific protein classes [12] |

| High Ionic Strength | 0.5 - 4 M NaCl, 1-2 M MgCl₂ [5] | Disruption of electrostatic and ionic bonds | Ionic interactions, hydrophobic interfaces |

| Chaotropic | 0.5-1 M Formic Acid [5], 6 M Guanidine-HCl [5] | Competes for hydrogen bonds; denaturation | Strong hydrophobic, protein complexes |

| Detergent | 0.01-0.5% SDS [12] | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions | Peptides, protein-lipid [12] |

| Hydrophobic Disruptor | 25-50% Ethylene Glycol [5] | Reduces hydrophobic effect; alters solvation | Hydrophobic interactions [5] |

Regeneration Balance and Effects

Troubleshooting and Optimization: Practical Solutions for Drift Correction

FAQ: What are matrix effects and ligand damage in the context of SPR regeneration?

Matrix effects are physical or chemical changes to the sensor chip's dextran matrix or the buffer environment caused by the regeneration solution. These changes, such as swelling or shrinking of the matrix due to shifts in pH or ionic strength, alter the baseline refractive index, causing a drift. This effect is usually reversible with sufficient buffer equilibration [5].

Ligand damage refers to the irreversible loss of biological activity of the immobilized ligand due to overly harsh regeneration conditions. This can involve denaturation (unfolding) or conformational changes in the ligand, preventing future analyte binding. Unlike matrix effects, ligand damage causes a permanent, often progressive, decrease in binding capacity over multiple cycles [5] [12].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics to differentiate them.

| Feature | Matrix Effects | Ligand Damage |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Changes in pH, ionic strength, or buffer composition affecting the sensor matrix [5] | Overly harsh regeneration conditions denaturing or altering the ligand [5] [12] |

| Nature of Effect | Primarily physical change in the sensor surface; often reversible [5] | Irreversible loss of ligand function and binding activity [5] |

| Impact on Baseline | Causes a baseline drift that typically stabilizes after re-equilibration [9] | Leads to a permanent drop in the baseline level and, crucially, a reduced binding capacity (lower Rmax) [12] |

| Impact on Binding Signal | Little to no direct impact on the ligand's ability to bind analyte once baseline stabilizes. | Progressive decrease in analyte binding response with each regeneration cycle [12] |

| Visual Clue on Sensorgram | Baseline does not return to its original zero point but is stable; subsequent binding responses are consistent if baseline is corrected [12] | Baseline may be lower, and the maximum response (Rmax) for the same analyte concentration is progressively lower in subsequent cycles [12] |

FAQ: What is the step-by-step protocol for diagnosing the cause of drift?

Follow the logical workflow below to diagnose the source of drift in your SPR experiments.

Diagnostic Protocol:

Observe and Document: After regeneration, note the baseline level. Does it drift upwards or downwards? Does it eventually stabilize at a different level than the pre-regeneration baseline? [9]

Test for Matrix Effects:

- Allow the system to re-equilibrate with a steady flow of running buffer. In cases of significant drift, this may require an extended period (even overnight) for the surface to stabilize fully [9].

- Perform several "dummy" injections of running buffer only (including the regeneration step). Monitor whether the baseline eventually stabilizes and returns to the original level after each cycle [9].

Test for Ligand Damage:

- Once the baseline is stable, inject a known concentration of analyte.

- Compare the maximum binding response (Rmax) with the response from the same analyte concentration in a previous, successful cycle.

- If the baseline is stable but the analyte binding signal is consistently and significantly lower (e.g., >10% loss) compared to earlier cycles, it indicates the ligand has been damaged and has lost activity [12].

FAQ: How can I prevent matrix effects and ligand damage?

To Prevent Matrix Effects:

- Adequate Equilibration: Always prime the system thoroughly after changing buffers and before starting an experiment. Incorporate several "start-up cycles" that include buffer injections and regeneration to stabilize the surface before collecting data [9].

- Buffer Matching: Ensure your running buffer and regeneration buffer are compatible. After injecting a harsh regeneration buffer, the system needs time and buffer flow to return to the original chemical environment [9].

- Double Referencing: Use a reference flow cell and subtract blank injections (buffer only) from your analyte sensorgrams. This standard data processing technique helps to compensate for baseline drift and bulk refractive index changes [9].

To Prevent Ligand Damage:

- Start Mild, Then Escalate: When scouting for regeneration conditions, always begin with the mildest possible solution (e.g., slight pH change, low salt) and progressively increase the strength only if needed [5] [12].

- Use the "Cocktail" Approach: Target multiple binding forces simultaneously with a mixture of mild chemicals instead of one harsh solution. For example, a mix of different stock solutions (acidic, ionic, detergent) can effectively disrupt binding while preserving ligand activity [5].

- Minimize Contact Time: Use the shortest possible injection time for regeneration that still effectively removes the analyte.

- Condition the Surface: Perform 1-3 initial cycles of analyte injection and regeneration before starting the actual experiment. This "conditions" the ligand surface and can improve stability for subsequent cycles [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Regeneration Scouting

The table below lists essential reagents used to develop and optimize SPR regeneration protocols.

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Regeneration |

|---|---|

| Glycine-HCl Buffer (Low pH) | A common acidic reagent. Low pH can cause protein unfolding and introduce positive charges, leading to electrostatic repulsion that breaks the ligand-analyte complex [5]. |

| NaOH (High pH) | A common basic reagent. High pH can alter the charge and structure of proteins, disrupting interactions [5] [15]. |

| High-Salt Solutions (e.g., MgCl₂, NaCl) | Disrupts ionic or electrostatic bonds between the ligand and analyte by shielding opposite charges [5] [15]. |

| Chaotropic Agents (e.g., Guanidine-HCl, Urea) | Disrupts hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions by denaturing proteins [5]. |

| Detergents (e.g., SDS) | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions and solubilizes proteins. Typically used at low concentrations (0.01-0.5%) [5] [12]. |

| Ethylene Glycol | Reduces hydrophobic interactions by altering the polarity of the solvent environment [5]. |

| Cocktail Stock Solutions | Pre-mixed stocks (Acidic, Basic, Ionic, Detergent, etc.) used in the empirical "cocktail" method to efficiently find effective, mild regeneration conditions by targeting multiple bond types at once [5]. |

Optimizing Post-Regeneration Equilibration and Stabilization Times

Why Does My Baseline Drift After Regeneration?

Post-regeneration baseline drift is a frequent challenge in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments. It is often a matrix effect, where the regeneration solution causes a physical change in the sensor chip's dextran matrix, such as swelling or shrinking, which alters the refractive index [5]. These changes can have time constants ranging from seconds to hours, causing a slow baseline drift that stabilizes only after the matrix fully re-equilibrates with the running buffer [5]. Other causes include:

- Conformational Changes: The regeneration buffer may cause slow, reversible changes in the structure of the immobilized ligand [5].

- Incomplete Regeneration: Residual analyte remains bound to the ligand, preventing a true return to baseline [1].

- Carryover: Harsh regeneration solutions are not thoroughly washed away, contaminating the fluidics and running buffer [1].

A Troubleshooting Guide for Post-Regeneration Drift

Systematically address post-regeneration drift using the following guide.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action & Purpose | Key Details & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Evaluate Regeneration Solution | Switch to a milder regeneration buffer or shorten contact time [5] [16]. | Goal: Remove all analyte while keeping ligand intact. Start mild, increase harshness gradually [5]. |

| 2. Increase Stabilization Time | After regeneration, extend the equilibration period before injecting the next sample [5]. | Matrix effects can be slow. Allow minutes or hours for baseline to fully stabilize [5]. |

| 3. Use a Washing Step | Implement a post-regeneration washing command with running buffer [6]. | Ensures complete removal of regeneration solution from fluidic system [6]. |

| 4. Verify Ligand Activity | Check if repeated regeneration has damaged ligand function [5]. | Inject a positive control analyte. A diminished response indicates ligand degradation [16]. |

| 5. Check for System Issues | Ensure running buffer is fresh, properly degassed, and free of contaminants [1]. | Bubbles or buffer inconsistencies cause drift unrelated to regeneration [1]. |

The flowchart below outlines the systematic troubleshooting process.

Optimizing Your Regeneration and Equilibration Protocol

A proactive experimental design minimizes drift. The "Cocktail Method" is a systematic empirical approach to find the mildest yet effective regeneration solution by targeting multiple binding forces simultaneously [5].

Objective: Find a regeneration buffer that completely removes the analyte while preserving ligand activity and minimizing matrix effects.

Methodology:

- Prepare Stock Solutions: Create acidic, basic, ionic, non-polar solvent, detergent, and chelating stock solutions [5].

- Create Cocktails: Mix new regeneration solutions from the stock solutions. Each cocktail can contain three different stock solutions or one stock with two parts water [5].

- Test Systematically:

- Immobilize your ligand and inject the analyte.

- Inject the first regeneration cocktail and calculate the percentage of regeneration (0-100%).

- If regeneration is below 10%, the solution is too mild; inject the next, stronger cocktail.

- If regeneration is above 50%, inject new analyte to test if the ligand remains active.

- Repeat until all cocktails are tested [5].

- Refine: Identify the best-performing stock solutions and mix new, refined cocktails from them. Repeat the testing cycle until an optimal solution is found [5].

Key Optimization Parameters:

- Analyte Concentration Range: Use a range that spans from 0.1 to 10 times the expected KD value [16].

- Ligand Immobilization Level: Immobilize enough ligand for a clear signal above the noise level, but keep it low to avoid mass transport effects or steric hindrance. A starting point of 100 RU is often recommended [6].

- Post-Regeneration Wash: Use the instrument's washing command after regeneration to ensure all buffer is flushed from the fluidic system [6].

- Stabilization Time: After regeneration and washing, allow sufficient time for the baseline to stabilize fully before starting the next injection cycle. This may require extending the equilibration time in your method [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists common reagents used to combat post-regeneration drift.

| Reagent | Function in Optimization | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Glycine-HCl Buffer (pH 1.5-3.0) | Mild acidic regeneration; disrupts interactions via protein unfolding and charge repulsion [5]. | A first-line choice for many protein-protein interactions. |

| NaOH (10-100 mM) | Basic regeneration solution; effective for disrupting hydrophobic and ionic bonds [5]. | Can be harsh; contact time should be minimized. |

| Ethylene Glycol (25-50%) | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions by altering solvent polarity [5]. | Often used in cocktail solutions. |

| MgCl₂ or NaCl (0.5-4 M) | High-salt solutions disrupt ionic and polar interactions by shielding charges [5]. | High concentrations may require extended washing. |

| Detergents (e.g., SDS 0.02-0.5%) | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions and solubilizes proteins [5]. | Can be difficult to wash off completely, potentially causing drift. |

| EDTA (e.g., 3 mM) | Chelating agent; regenerates interactions dependent on metal ions [6]. | Highly specific to metal-dependent binding systems. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My baseline stabilizes after regeneration, but it returns to a different level than the previous cycle. Is this a problem? A persistent shift in baseline level after regeneration is a classic sign of a matrix effect [5]. The dextran matrix has not fully returned to its original state. While data can sometimes be corrected mathematically, it is preferable to optimize regeneration conditions to minimize this shift, as it can affect the accuracy of kinetic measurements, especially for low-response interactions.

Q2: How long is too long for baseline stabilization? I've waited 30 minutes and it's still drifting. If your baseline has not stabilized after 30 minutes, the regeneration conditions are likely too harsh and are causing significant, slow-recovering changes to the sensor surface or matrix [5]. You should re-evaluate your regeneration strategy. Consider using a milder regeneration solution, even if it requires a slightly longer contact time, as this will often reduce the equilibration time overall.

Q3: I found a regeneration solution that works perfectly, but after 5 cycles, my ligand signal drops. What's happening? This indicates that your regeneration solution, while effective at removing the analyte, is gradually damaging or stripping the immobilized ligand from the surface [5] [11]. The solution is not as mild as initially thought. You may need to find an even gentler alternative or use an immobilization strategy that is more resistant to your regeneration conditions, such as the switchavidin or dual-His-tag systems developed for this purpose [11].

Implementing Double Referencing to Compensate for Residual Drift

A essential technique for ensuring data integrity in SPR experiments, particularly after regeneration.

What is double referencing and why is it critical after regeneration?

Double referencing is a two-step data processing method in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) used to compensate for non-specific binding, bulk refractive index (RI) shifts, and baseline drift [9] [17]. This is especially crucial following a regeneration step, as regeneration solutions can induce differential drift rates between the active and reference flow channels due to their effect on the sensor surface and the immobilized ligand [9] [5].

Residual drift can obscure true dissociation kinetics and lead to inaccurate calculation of rate constants. Double referencing effectively cleans the sensorgram, providing a more accurate representation of the specific binding interaction [9] [18].

How to implement double referencing: A step-by-step protocol

Prerequisites and experimental design

Before data collection, a properly designed experiment is essential.

- Stable Baseline: Ensure the system is fully equilibrated. Flow running buffer until the baseline is stable, as start-up drift is common after docking a chip or changing buffers [9].

- Reference Surface: Use a reference flow cell with a surface that closely matches your active surface but lacks the specific ligand. This can be a blank channel, a channel with a non-functional ligand, or a surface coupled with an inert protein [9] [19] [16].

- Plan Blank Injections: Incorporate "blank" injections (injections of running buffer only) evenly throughout your experimental cycle. It is recommended to have one blank cycle for every five to six analyte cycles [9].

The double referencing procedure

Once data is collected, follow this two-step subtraction process.

Step 1: Reference Channel Subtraction Subtract the sensorgram from the reference channel from the sensorgram of the active channel [9]. This first subtraction removes the signal from:

- Bulk Refractive Index Effects: Caused by differences in buffer composition between the sample and running buffer [19] [17] [16].

- Systematic Drift: Instrumental or environmental drift affecting both channels similarly [9].

Step 2: Blank Injection Subtraction Subtract the signal from a blank injection (running buffer) from the interim sensorgram obtained in Step 1 [9]. This second subtraction removes:

- Residual Drift Differences: Any remaining minor drift discrepancies between the active and reference channels [9].

- Injection Artifacts: Spikes or disturbances caused by the injection process itself [9].

Key research reagents for reliable double referencing

| Reagent or Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Running Buffer | Used for equilibration, sample dilution, and blank injections. Must be 0.22 µM filtered and degassed to prevent spikes and drift [9]. |

| Reference Surface | A non-active surface that mimics the properties of the active sensor surface to provide a signal for non-specific effects [9] [19]. |

| Regeneration Solution | Removes bound analyte between cycles. Must be optimized to be effective without damaging the ligand or causing excessive baseline drift [5] [19]. |

| Ligand & Analyte | The interaction partners. The ligand is immobilized, while the analyte is injected in a concentration series. Purity is critical for clean data [18] [16]. |

Troubleshooting common issues with double referencing

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Residual Drift After Referencing | System not equilibrated; regeneration solution causing slow surface rearrangement [9] [5]. | Extend buffer flow after regeneration; include a stabilization period in the method; use milder regeneration conditions [9] [5]. |

| Poor Fit After Referencing | Drift is too severe for the model to fit; the 1:1 binding model is incorrect [18]. | Ensure drift is minimal before fitting. For a 1:1 model, the fitted drift contribution should be less than ± 0.05 RU/s [18]. |

| Inconsistent Blank Signals | Surface instability or incomplete regeneration between cycles [9] [16]. | Re-optimize the regeneration step to ensure complete analyte removal without damaging the ligand [5] [16]. |

Key takeaways for effective drift compensation

- Prevention is paramount: A well-equilibrated system and a stable, fully regenerated surface are the foundations for low drift. Double referencing is a correction for residual drift, not a substitute for good experimental practice [9] [18].

- Strategic blanking: Distribute blank injections evenly throughout the experiment to accurately track and correct for drift that may change over time [9].

- Validate with diagnostics: Always inspect the residuals (difference between fitted curve and data) after fitting. Randomly scattered residuals indicate a good fit, while structured residuals suggest unaccounted-for artifacts like drift [18].

Why is buffer hygiene critical in SPR experiments, and what are the consequences of poor practices?

Poor buffer hygiene is a primary source of experimental artifacts in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). Inconsistent or contaminated buffers directly cause baseline drift, noise, and spikes in sensorgrams, making data difficult to interpret and analyze accurately [1] [20]. These issues can obscure genuine binding events and lead to erroneous kinetic calculations.

Specifically, improper buffer handling leads to:

- Baseline Drift: Unstable baselines often result from inadequate system equilibration or leaching of chemicals from the sensor surface, which is exacerbated by using old or contaminated buffers [1] [9].

- Spikes and Noise: The formation of small air bubbles is a frequent cause of spikes in the sensorgram. Bubbles are more likely to form when buffers are not properly degassed, especially at higher experimental temperatures (e.g., 37°C) or low flow rates [20].

- Bulk Refractive Index Shifts: Large, abrupt shifts in the signal occur when the running buffer and the sample buffer are not perfectly matched. Even small differences in components like salt concentration or organic solvents (e.g., DMSO) can cause significant jumps that obscure the kinetic data [20].

What is the standard protocol for preparing SPR running buffer?

A rigorous, standardized protocol for buffer preparation is the foundation of good buffer hygiene. The following table summarizes the key steps and their purposes [20] [9].

Table: Standard Protocol for SPR Running Buffer Preparation

| Step | Procedure | Purpose & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Preparation | Prepare a sufficient volume of buffer (e.g., 2 liters) daily. | Ensures a consistent supply and avoids the need to add fresh buffer to old stocks, which can promote contamination [20]. |

| 2. Filtration | Filter the buffer through a 0.22 µM filter. | Removes particulate matter, dust, and microbial contaminants that can cause scratches, blockages, or non-specific binding [20]. |

| 3. Storage | Store filtered buffer in clean, sterile bottles at room temperature. | Prevents increased dissolved air content, which occurs when buffers are stored at 4°C and can lead to air-spikes later [20]. |

| 4. Degassing | Before use, transfer an aliquot to a clean bottle and degas. | Eliminates dissolved air that can form disruptive bubbles in the microfluidic system during the experiment [1] [20]. |

| 5. Additive Introduction | Add detergents (e.g., Tween-20) or other additives after filtering and degassing. | Prevents excessive foam formation during the degassing process [9]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical sequence for proper buffer preparation and system equilibration.

How do poor buffer practices relate to drift caused by regeneration solutions?

Regeneration solutions are a common but often overlooked source of baseline drift, and their effects are tightly linked to buffer hygiene. These solutions are designed to be harsh to remove tightly bound analyte, but they can disrupt the sensor surface and the immobilized ligand.

- Carryover and Surface Incompatibility: Inefficient regeneration leaves residual material on the sensor surface. If the running buffer is not pristine, contaminants can interact with this residue, leading to a gradual accumulation of material and a drifting baseline [1] [4]. Furthermore, some regeneration buffers (e.g., those with low pH or high salt) may not be fully compatible with the sensor chip matrix or the running buffer, causing slow leaching of the ligand or gradual surface changes that manifest as drift [9].

- Post-Regeneration Equilibration: After a regeneration step, the system must be re-equilibrated with the running buffer. If the buffer is not fresh and well-degassed, this equilibration will be slow and unstable, resulting in prolonged drift. Incorporating several "start-up cycles" or "dummy injections" of buffer after regeneration is essential to re-stabilize the surface before collecting data [9].

What are the essential reagents for maintaining proper buffer hygiene?

The following toolkit lists key materials and reagents necessary for implementing the buffer hygiene protocols described above.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Buffer Hygiene

| Reagent / Material | Function in Buffer Hygiene |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Water | The foundation for all buffers; ensures no background contaminants interfere with interactions or baseline stability. |

| Buffer Salts & Chemicals | For preparing the chosen running buffer (e.g., HEPES, PBS). Use high-purity grades to minimize contaminants. |

| 0.22 µm Membrane Filters | For removing particulate matter and microbial contamination from the buffer solution prior to use [20]. |

| Degassing Apparatus | A dedicated system (e.g., in-line degasser, vacuum chamber) for removing dissolved air to prevent bubble formation [1] [20]. |

| Clean, Sterile Storage Bottles | For storing filtered buffer to prevent introduction of contaminants or growth of microbes between experiments [20]. |

| Detergent (e.g., Tween-20) | An additive to reduce non-specific binding and improve surface wetting. It should be added after filtering and degassing to prevent foaming [20] [9]. |

How can I systematically troubleshoot baseline drift and noise?

When experiencing baseline issues, a systematic approach to troubleshooting is required. The following table guides you through investigating buffer-related causes.

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Buffer-Related Baseline Issues

| Observed Problem | Potential Buffer-Related Cause | Solution & Action |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Drift | Buffer not properly degassed [1]. | Degas buffer thoroughly before use. |

| System not equilibrated after buffer change or regeneration [9]. | Prime the system multiple times and flow running buffer until stable. Use start-up cycles. | |

| Contaminated or old buffer [1]. | Use fresh, filtered buffer prepared daily. | |

| High Noise or Fluctuations | Unfiltered buffer with particulates [1]. | Filter all buffers through a 0.22 µm filter. |

| Electrical or environmental interference. | Ensure proper instrument grounding and place in a stable environment [1]. | |

| Sharp Spikes | Air bubbles in the fluidic system [20]. | Use degassed buffers. Increase flow rate temporarily to flush out bubbles. |

| Pump refill events or pressure changes [20]. | Schedule washing and pump refill commands to avoid critical data collection periods. | |

| Bulk Shift Jumps | Mismatch between running buffer and sample buffer [20]. | Dialyze the sample into the running buffer or use size exclusion columns for buffer exchange. |

| Evaporation from sample vial changing solute concentration [20]. | Cap sample vials securely to prevent evaporation. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Why does my baseline drift after using a regeneration solution, and how can I fix it?

Answer: Baseline drift following regeneration is a common issue often caused by the regeneration solution itself. Harsh conditions can induce slow, reversible changes in the sensor chip's dextran matrix or the conformation of the immobilized ligand, which manifest as a drifting baseline as the surface slowly re-equilibrates with the running buffer [5]. To resolve this:

- Use Milder Regeneration Conditions: Always start with the mildest effective regeneration solution. A "regeneration cocktail" approach that combines different chemicals at lower concentrations can effectively disrupt binding while preserving ligand activity and surface stability [5].

- Implement a Stabilization Period: Introduce a stabilization time in your method immediately after the regeneration step. Flowing running buffer for 5–30 minutes allows the surface to fully re-equilibrate, which will level out the drift before the next sample injection [5] [9].

- Incorporate Start-Up Cycles: Execute at least three start-up cycles at the beginning of your experiment. These cycles should use buffer injections instead of analyte but include the regeneration step. This "primes" the surface, allowing it to stabilize after the initial regeneration cycles. These cycles should not be used in the final analysis [9].

FAQ: How can I ensure my kinetic data is reproducible despite necessary regeneration steps?

Answer: Reproducibility is paramount for reliable kinetics. Inconsistent regeneration is a major source of error, as it can lead to varying levels of active ligand or residual analyte on the surface [5]. Strategic experimental design is key to compensation:

- Standardize Regeneration Protocols: Ensure surface activation, ligand immobilization, and regeneration protocols are standardized, with careful monitoring of time, temperature, and pH in every experiment [4].

- Utilize Strategic Blank Injections: Throughout your experimental run, regularly intersperse blank injections (buffer alone). It is recommended to include one blank cycle for every five to six analyte cycles and to finish with a blank. These are essential for a data processing technique called double referencing [9].

- Employ Double Referencing: This is a two-step data subtraction procedure. First, subtract the signal from a reference flow cell (with no ligand or an irrelevant ligand) from the active flow cell signal. This compensates for bulk refractive index shifts and systemic drift. Second, subtract the response from the blank injections to correct for any remaining differences between the reference and active channels [9].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: The Cocktail Method for Finding Optimal Regeneration Solutions

Objective: To empirically determine a effective yet mild regeneration condition by systematically testing mixtures that target different binding forces.

Background: Molecular interactions are stabilized by a combination of forces (e.g., ionic, hydrophobic). This method uses a multivariate approach to simultaneously disrupt multiple forces with milder conditions, preserving ligand integrity and reducing baseline drift [5].

Materials:

- Stock solutions as detailed in Table 1.

- Standard SPR running buffer.

- Ligand and analyte samples.

Method:

- Prepare Stock Solutions: Create the six stock solution types listed in Table 1.

- Mix Initial Cocktails: Create new regeneration solutions by mixing three parts from your stock solutions (these can be three different stocks, or one stock plus two parts water).

- Initial Screen:

- Immobilize your ligand and inject the analyte to form a complex.

- Inject the first regeneration cocktail and measure the percentage of regeneration.

- If regeneration is below 10%, the solution is ineffective. Proceed to inject the next, potentially stronger, cocktail.

- If regeneration exceeds 50%, inject a new analyte sample to test the surface's binding capacity remains intact. Repeat this process for all cocktails.

- Refine the Cocktail: Identify the common components in the top-performing cocktails. Select the three best-performing stock solution types and mix new regeneration solutions from them.

- Repeat Screening: Repeat the injection and regeneration process with these new, refined cocktails.

- Final Validation: Continue this iterative procedure until an optimal regeneration solution is found that provides complete regeneration with minimal impact on ligand activity and baseline stability [5].

Protocol: Implementing Start-Up Cycles and Blank Injections for Stable Baselines

Objective: To stabilize the sensor surface and system baseline before data collection, and to generate reference data for robust analysis.

Background: Freshly docked chips or newly immobilized surfaces require time to rehydrate and equilibrate, which can cause initial drift. Start-up cycles and blank injections manage this instability and enable data correction [9].

Method:

- System Equilibration: After priming the system with your running buffer, initiate a constant flow and allow the baseline to stabilize. This may take 5–30 minutes [9].

- Program Start-Up Cycles: In your method software, program at least three initial cycles. These cycles should mirror your experimental cycles in all aspects (flow rate, contact time, dissociation time) except that buffer is injected instead of analyte. Include the regeneration step in these cycles.

- Execute Start-Up Cycles: Run these cycles to condition the surface. Do not use the data from these cycles in your final analysis [9].

- Program Strategic Blank Injections: Within the main experimental method, program blank injections (buffer) to occur at regular intervals. A robust design includes one blank for every five to six analyte cycles and a final blank at the end of the run [9].

- Data Analysis with Double Referencing: During data processing, use the signal from the blank injections to perform a second subtraction after the initial reference channel subtraction, which corrects for residual drift and channel-specific effects [9].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Stock Solutions for Regeneration Cocktail Screening

This table outlines the stock solutions used for empirically determining optimal regeneration conditions, as proposed by Andersson et al. [5].

| Solution Type | Purpose | Example Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Acidic | Disrupts ionic and hydrogen bonds | Equal volumes of 0.15 M oxalic acid, H₃PO₄, formic acid, and malonic acid, pH 5.0 |

| Basic | Disrupts ionic and hydrogen bonds | Equal volumes of 0.20 M ethanolamine, Na₃PO₄, piperazin, and glycine, pH 9.0 |

| Ionic | Disrupts electrostatic interactions | 0.46 M KSCN, 1.83 M MgCl₂, 0.92 M urea, 1.83 M guanidine-HCl |

| Non-polar Solvents | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions | Equal volumes of DMSO, formamide, ethanol, acetonitrile, and 1-butanol |

| Detergents | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions | 0.3% (w/w) CHAPS, 0.3% (w/w) Zwittergent 3-12, 0.3% (v/v) Tween 80, 0.3% (v/v) Tween 20, 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100 |

| Chelating | Removes divalent cations | 20 mM EDTA |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Baseline Drift and Reproducibility Issues

This table summarizes common problems and their solutions related to regeneration-induced drift.

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Post-Regeneration Drift | Slow re-equilibration of sensor matrix/ligand [5] | Use milder regeneration; add post-regeneration stabilization time (5-30 min) [5] [9]. |

| Irreproducible Binding Levels | Incomplete or overly harsh regeneration damaging the ligand [4] [5] | Optimize regeneration solution via cocktail method; standardize regeneration contact time [5]. |

| High Noise & Instability | System not fully equilibrated; air bubbles in buffer; contaminated buffer [9] | Prime system thoroughly; use fresh, filtered, and degassed buffers; include start-up cycles [9]. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Workflow for Stable SPR Data

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key solutions and materials required for implementing the advanced techniques described in this guide.

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Regeneration Cocktail Stocks | Empirical finding of optimal, mild regeneration conditions. | Includes acidic, basic, ionic, detergent, solvent, and chelating stock solutions [5]. |

| High-Purity Running Buffer | Maintains sample and surface stability; reduces noise. | Must be fresh, 0.22 µM filtered, and degassed before use to prevent air spikes [9]. |

| Sensor Chips (e.g., SA, NTA, CM5) | Platform for ligand immobilization. | Choice of chip chemistry (streptavidin, NTA, carboxymethyl dextran) depends on ligand properties and immobilization strategy [4]. |

| Start-up & Blank Cycle Buffers | System conditioning and data referencing. | Identical in composition to the running buffer; used in non-analyte cycles for stabilization and double referencing [9]. |

Validation and Comparative Analysis: Ensuring Regeneration Efficacy and Data Reproducibility

Within the broader context of research on Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) regeneration-induced drift, achieving a successful regeneration protocol is a critical yet often challenging step. A poorly executed regeneration step can lead to significant baseline drift, compromising the accuracy of kinetic data and the reproducibility of experiments across multiple cycles. This guide provides a systematic framework for benchmarking regeneration success, helping you to distinguish ideal sensorgrams from suboptimal ones and to implement robust solutions that preserve ligand activity and ensure data integrity.

FAQ: Diagnosing Regeneration Problems

Q1: What are the primary visual indicators of a successful regeneration step in a sensorgram?

A successful regeneration is characterized by a stable and reproducible baseline. After the regeneration solution is injected and replaced with running buffer, the baseline signal should return to its original level prior to the analyte injection [12]. The binding response (response unit, RU) for identical, consecutive analyte injections should be consistent, demonstrating that the ligand's activity remains undamaged and that the analyte has been completely removed [12].

Q2: How does an unsuccessful regeneration step contribute to baseline drift in longitudinal studies?

Regeneration-induced baseline drift is a key challenge in multi-cycle experiments. This drift manifests in two primary ways:

- Upward Drift: If the regeneration is too mild and fails to remove all analyte, residual molecules accumulate on the sensor surface with each cycle. This causes the baseline to step upwards after each regeneration, a phenomenon known as "carryover" [4] [12].

- Downward Drift: If the regeneration solution is too harsh, it can gradually denature or remove the immobilized ligand itself. This leads to a decreasing baseline and a corresponding drop in the binding capacity (lower Rmax) for subsequent analyte injections [4] [12]. Both scenarios undermine the stability required for reliable, long-term data collection.

Q3: What is the strategic advantage of including glycerol in a regeneration scouting protocol?

Adding glycerol (at a concentration of around 10%) to a regeneration solution can act as a stabilizing agent [14]. It helps to protect the immobilized ligand from denaturation caused by harsh pH or chemical conditions, thereby preserving its biological activity over multiple regeneration cycles without compromising the solution's ability to dissociate the analyte [14]. This simple modification can significantly extend the functional lifespan of a sensor chip.

Troubleshooting Guide: Ideal vs. Suboptimal Regeneration Outcomes

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of regeneration outcomes to help you diagnose your experimental results.

| Benchmarking Parameter | Ideal Regeneration Outcome | Suboptimal Regeneration Outcome & Underlying Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Stability | Returns precisely to the pre-injection level; remains stable and flat across all cycles [12]. | Upward Drift: Baseline does not fully return, indicating incomplete regeneration and analyte carryover [4] [12]. Downward Drift: Baseline decreases progressively, indicating ligand degradation/denaturation from overly harsh conditions [4] [12]. |

| Binding Response (Rmax) Consistency | The maximum binding response for identical analyte injections is highly reproducible across all cycles [12]. | A consistent decrease in Rmax with each cycle signals a loss of active ligand due to surface damage or inactivation [12]. |

| Sensorgram Shape | The association and dissociation curves for replicate analyte injections are superimposable [12]. | Changes in the shape of binding curves (e.g., slower association or dissociation) in later cycles suggest altered binding kinetics from a compromised ligand surface [4]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Systematic Workflow for Regeneration Scouting

This detailed protocol is designed to help you efficiently identify the optimal regeneration solution for your specific molecular interaction.

1. Pre-Conditioning and Ligand Immobilization

- Begin by conditioning your sensor chip with 1-3 injections of a mild regeneration buffer to stabilize the surface [12].

- Immobilize your ligand using a standard, well-optimized coupling method (e.g., amine coupling) to ensure a uniform and active surface [4].

2. Regeneration Solution Scouting

- Start with the mildest potential regeneration solution and progressively increase stringency only if needed [12].

- Common solutions to test include:

- Inject your analyte at a medium concentration, allow for dissociation, and then inject a short pulse (30-60 seconds) of the first candidate regeneration solution.

3. Surface Integrity Validation

- After regeneration, inject the same medium concentration of analyte again.

- Closely monitor two parameters: 1) whether the baseline returns to its original level, and 2) whether the binding response (Rmax) is identical to the first injection [12].