Solving SCF Convergence Problems in Surface Calculations: A Comprehensive Guide for Pd and Fe Slabs

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and computational chemists tackling self-consistent field (SCF) convergence challenges in metallic surface calculations, particularly focusing on Palladium (Pd) and Iron (Fe) slabs.

Solving SCF Convergence Problems in Surface Calculations: A Comprehensive Guide for Pd and Fe Slabs

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and computational chemists tackling self-consistent field (SCF) convergence challenges in metallic surface calculations, particularly focusing on Palladium (Pd) and Iron (Fe) slabs. Drawing from current documentation and community knowledge, we explore the foundational causes of convergence difficulties, present methodological approaches across multiple computational packages (ADF, ORCA, Quantum ESPRESSO), detail advanced troubleshooting and optimization techniques, and establish validation protocols to ensure physical reliability. The content is specifically tailored to assist scientists in obtaining robust, converged results for these notoriously challenging systems, which are crucial in catalysis and materials science applications.

Understanding SCF Convergence Challenges in Metallic Slab Systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is SCF convergence and why does it fail for metallic slabs like Pd and Fe?

The Self-Consistent Field (SCF) method is an iterative procedure for finding electronic structure configurations in density functional theory calculations. Convergence failures occur when successive iterations fail to reach a consistent electronic structure. This is particularly problematic for metallic slabs like Pd and Fe due to their small HOMO-LUMO gaps, localized open-shell configurations (especially in Fe), and the presence of many near-degenerate electronic states at surfaces. These factors cause charge sloshing and oscillations in the electron density during iterations [1] [2].

Why are Fe slabs typically more challenging than Pd slabs for SCF convergence?

Fe slabs often present greater convergence difficulties due to their localized 3d-electrons and significant spin polarization. The presence of unpaired electrons in open-shell configurations creates complex potential energy surfaces with multiple local minima, making it harder for the SCF procedure to find a stable solution. Pd, while also a transition metal, generally has a more delocalized electron density [3] [1].

How does slab thickness affect SCF convergence?

Increasing slab thickness introduces more electronic states and can exacerbate convergence problems due to quantum size effects. The surface formation energy calculated as the difference between slab and bulk energies may diverge linearly with slab thickness if not properly handled. Using established linear fitting procedures helps achieve convergent surface energies [4].

What are the most effective initial strategies for improving SCF convergence?

Begin with these conservative adjustments to increase stability:

- Reduce mixing parameters (e.g.,

SCF%Mixing 0.05) - Increase DIIS subspace size (e.g.,

DIIS%Dimix 0.1orN 25) - Implement electron smearing with a small value to occupy near-degenerate states

- Ensure accurate initial guess and proper spin multiplicity [3] [1] [2]

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Non-Converging SCF Cycles

SCF convergence problems manifest as continuous oscillation of energies or failure to meet convergence criteria within the maximum cycle limit. The following workflow provides a systematic approach to resolve these issues:

Step-by-Step Implementation:

Foundation Checks

Adjust SCF Acceleration Parameters

Improve Numerical Accuracy

Advanced Techniques

Guide 2: Resolving Geometry Optimization Failures Caused by SCF Issues

When geometry optimizations fail due to underlying SCF convergence problems:

Prerequisite: Ensure SCF convergence at each geometry step using the techniques in Guide 1.

Accuracy Enhancements:

- Increase radial grid points (

RadialDefaults NR 10000) [3] - Improve overall numerical quality (

NumericalQuality Good) [3] - Tighten geometry convergence criteria (

GeoOpt%Converge) once SCF is stable [3]

Step Size Considerations:

- For phonon calculations with negative frequencies, reduce step size (

PhononConfig%StepSize) [3] - Ensure geometry is truly at minimum before frequency analysis [3]

Guide 3: Overcoming Basis Set Dependency Errors

Basis set dependency errors occur when Bloch functions become nearly linearly dependent, particularly problematic in periodic slab calculations.

Symptoms:

- Program termination with "dependent basis" message [3]

- Small eigenvalues of the overlap matrix below threshold [3]

Resolution Strategies:

Table: Basis Set Dependency Solutions

| Approach | Implementation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Confinement | Apply Confinement to diffuse functions |

Inner slab layers where diffuseness isn't needed [3] |

| Basis Function Removal | Remove STOs with large dependency coefficients | When one eigenvalue is below threshold [3] |

| Function Modification | Replace two problematic functions with an averaged one | When multiple coefficients are large [3] |

Systematic Resolution:

- Examine dependency coefficients printed after error message [3]

- Identify basis functions with largest coefficients as most problematic [3]

- Apply confinement to inner layer atoms while preserving surface atom basis quality [3]

- Iteratively test modified basis sets until all k-points pass dependency checks [3]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Surface Science SCF Convergence

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function |

|---|---|---|

| SCF Algorithms | DIIS, LISTi, GDM, QC, MESA | Provide alternative convergence pathways for difficult systems [3] [1] [5] |

| Mixing Schemes | Plain, local-TF, Anderson | Control how electron density is updated between cycles [2] |

| Smearing Methods | Fermi, Gaussian | Broaden electron occupation to handle small HOMO-LUMO gaps [2] [6] |

| Numerical Grids | BeckeGrid, Integration grids | Determine accuracy of numerical integration [3] [7] |

| Basis Sets | STOs, Numerical orbitals | Represent electron wavefunctions throughout the slab [3] |

| k-point Sampling | Monkhorst-Pack, Gamma-centered | Sample the Brillouin Zone of periodic systems [3] |

Advanced Protocols

Protocol: Surface Energy Convergence for Pd and Fe Slabs

Background: Surface energy calculation requires comparing slab energies with independently determined bulk energies, which can diverge linearly with slab thickness if not properly handled [4].

Procedure:

- Compute bulk energy with high k-point sampling and tight SCF convergence

- Create slabs of increasing thickness (3-7 layers)

- For each slab thickness:

- Use SCF convergence techniques from Guide 1

- Employ

SCF=Tightor equivalent convergence criteria - Ensure forces are converged to < 0.01 eV/Å

- Calculate surface energy as: γ = (Eslab - N × Ebulk) / (2 × A)

- Plot surface energy versus 1/N (inverse slab thickness)

- Extract convergent surface energy from linear fit [4]

Validation:

- Compare results with different mixing parameters and k-point sets

- Achieve surface energy convergence within 0.08 eV or better [4]

Protocol: DeltaSCF for Excited States at Surfaces

Application: Calculating excited states at surfaces using single-reference wavefunctions [8].

Implementation (ORCA):

Key Considerations:

- Use

ALPHACONForBETACONFto specify desired electron configuration [8] - Start from converged ground-state orbitals [8]

- Employ L-SR1 Hessian update (not L-BFGS) for saddle point convergence [8]

- Use MOM or PMOM to maintain reference state during optimization [8]

Validation:

- Check for imaginary frequencies in vibrational analysis [8]

- Verify spin contamination values for open-shell singlets [8]

FAQ: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

What are the most common causes of SCF convergence problems in Pd and Fe slab calculations? SCF convergence issues in transition metal slabs like Pd and Fe primarily arise from their complex electronic structures. Palladium (Pd) slabs are generally easier to converge than Iron (Fe) slabs [3]. Key difficulties include:

- Localized Open-Shell Configurations: Iron, in particular, often has localized d-electrons and can exhibit open-shell configurations, leading to challenging convergence [1] [9].

- Small HOMO-LUMO Gaps: Metallic systems or those with many near-degenerate electronic levels around the Fermi energy have a very small or vanishing HOMO-LUMO gap. This can cause oscillations between different orbital occupancies during the SCF procedure [1] [10].

- Insufficient Numerical Accuracy: Problems can be caused by inadequate quality in the numerical integration grid, an insufficient number of k-points for sampling the Brillouin zone, or a poor-quality density fit [3].

Why are Fe slabs typically more difficult to converge than Pd slabs? The core difference lies in the nature of their d-electrons. Fe slabs are more problematic due to the presence of localized open-shell configurations and more complex magnetic behavior [3] [1]. These localized electrons lead to challenging potential energy surfaces and can cause strong oscillations in the spin density and magnetic moments during the SCF cycle, making it difficult for the algorithm to find a stable solution [11].

What are the primary SCF algorithms and when should I use them? Different SCF algorithms offer a trade-off between speed and robustness. The table below summarizes the key options.

Table 1: Overview of SCF Convergence Algorithms

| Algorithm | Description | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DIIS (Direct Inversion in Iterative Subspace) | Default in many codes; fast but can be unstable for difficult systems [12]. | Standard systems with a good initial guess and no near-degeneracies [12]. |

| GDM (Geometric Direct Minimization) | Robust method that accounts for the spherical geometry of orbital rotation space [12]. | Recommended fallback when DIIS fails; default for restricted open-shell calculations in some codes [12]. |

| DIISGDM / DIISDM | Hybrid approach; uses DIIS initially then switches to (G)DM [12]. | Combines DIIS speed in early cycles with GDM robustness for final convergence [12]. |

| LIST / LISTi | An alternative DIIS variant that may reduce the number of SCF cycles [3]. | When standard DIIS shows slow convergence or oscillations [3]. |

| TRAH (Trust Region Augmented Hessian) | A robust second-order converger, more expensive but reliable [9]. | Pathological cases where other methods struggle; can activate automatically in some modern codes [9]. |

How does the initial guess impact convergence, and how can I improve it? The initial guess for the electron density is critical. A poor guess can lead to convergence on an incorrect electronic state or failure to converge [13]. For difficult slabs:

- Use a Restart: A moderately converged density from a previous calculation is often the best guess [1].

- Converge a Simpler System: First converge a calculation with a simpler functional (e.g., BP86) or smaller basis set, then read the resulting orbitals as a guess for the target calculation [9].

- Manually Alter Orbitals: For open-shell systems, the initial orbital occupancy can be manually altered to guide the calculation towards the desired electronic state (e.g., a specific spin configuration) [13].

Experimental Protocols for Reliable Convergence

Standard Protocol for Troubleshooting SCF Convergence

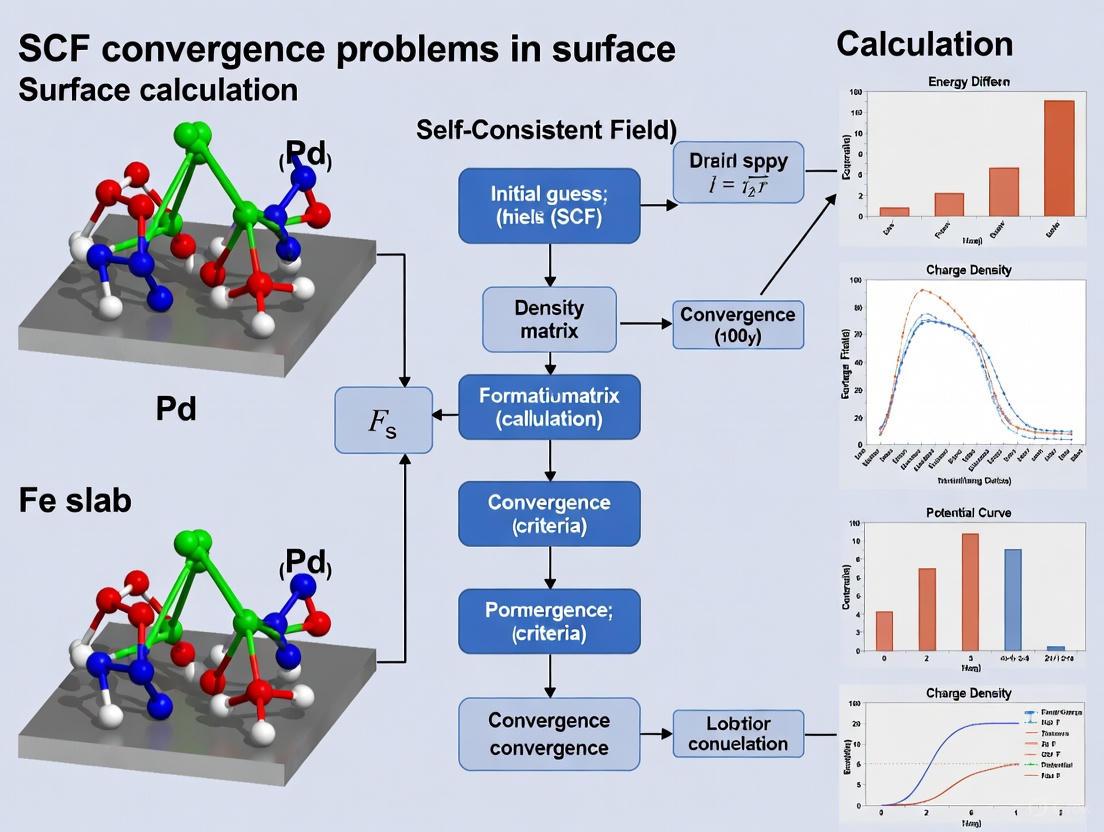

This workflow provides a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving SCF convergence issues in surface slab calculations. The process is illustrated in the diagram below.

Phase 1: Foundational Checks

- Verify Geometry and Spin: Ensure the slab geometry is physically realistic (correct bond lengths, angles) and that the vacuum spacing is sufficient to prevent interaction between periodic images [1] [14]. Confirm the correct spin multiplicity and initial magnetic moments are set, especially for Fe [1] [11].

- Adjust SCF Control Parameters:

- Decrease Mixing: Reduce the mixing parameter (e.g., to 0.05 or lower) to take more conservative steps between SCF cycles. This is a primary recommendation for problematic cases like Fe slabs [3].

- Increase DIIS Subspace: Using more previous Fock matrices (e.g.,

DIIS%DimixorDIIS_SUBSPACE_SIZEof 20-25) can stabilize the extrapolation [3] [1] [15].

Phase 2: Systematic Adjustments

- Improve the Initial Guess: As outlined in the FAQ, use a restart file or orbitals from a converged calculation of a simpler system [1] [9].

- Increase Numerical Accuracy:

- k-points: Ensure the Brillouin zone is sampled with a sufficient k-point grid. Using only the Γ-point can cause problems [3] [10] [14]. For slabs, use a grid like k1 × k2 × 1.

- Density Fitting and Grids: Improve the quality of the numerical integration (Becke grid) and density fit (ZlmFit) from 'Basic' to 'Normal' or 'Good' [3].

- Switch the SCF Algorithm: If DIIS fails, switch to a more robust algorithm like Geometric Direct Minimization (GDM) or a hybrid DIIS_GDM approach [12]. Alternatively, try the LISTi method [3].

Phase 3: Advanced Techniques

- Employ Electron Smearing: Apply a small amount of electron smearing (e.g., a finite electronic temperature) to occupy orbitals around the Fermi level fractionally. This is particularly helpful for metallic systems with small gaps. Keep the smearing value as low as possible to avoid altering the total energy significantly [1].

- Use Level Shifting: Artificially raising the energy of unoccupied orbitals can help break oscillations. Note that this may invalidate properties that depend on virtual orbitals, such as excitation energies [1].

Protocol for Handling Linear Dependency and Basis Set Issues

A calculation aborting due to a "dependent basis" error indicates that the basis set is too diffuse or large, leading to near-linear-dependent Bloch functions. This is common in slabs with highly coordinated atoms [3].

- Diagnose: The program output will list "Dependency Coefficients" – basis functions with large coefficients are the most problematic [3].

- Apply Confinement: Use a confinement potential to reduce the diffuseness of basis functions, particularly on atoms in the inner layers of the slab [3].

- Remove Functions: Manually remove one or more of the most diffuse basis functions identified in the output [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Materials for Surface Slab Calculations

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Basis Set | Provides the atomic orbital functions to construct Bloch waves. Must balance accuracy and computational cost to avoid linear dependence [3]. |

| k-point Grid | Samples the Brillouin zone of the slab. Critical for accuracy in periodic systems; a dense grid in the slab plane (e.g., k1 x k2) with 1 point in the vacuum direction is typical [10] [14]. |

| SCF Converger (DIIS, GDM, TRAH) | The algorithm that drives the SCF cycle to a self-consistent solution. Choice is crucial for robustness and efficiency [12] [9]. |

| Mixing Parameter | Controls the fraction of the new Fock matrix used to update the density. A key parameter to stabilize difficult calculations [3] [1]. |

| Electron Smearing | A numerical "reagent" that fractionally occupies orbitals near the Fermi level, smoothing energy landscapes and aiding convergence in metallic systems [1]. |

| Initial Orbital Guess | The starting point for the SCF procedure. A good guess (e.g., from a restart) is essential for complex electronic structures [13] [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common symptoms of a non-converging SCF calculation? The most common symptoms include oscillating energy values instead of a steady approach to a minimum, a complete stall where the energy change between iterations becomes negligible or zero, and dependency errors where the program aborts due to a linearly dependent basis set [3] [15] [16].

Why does my calculation of an Fe slab show more convergence problems than a Pd slab? Some systems are intrinsically more difficult to converge than others. For example, an Fe slab is known to be more challenging than a Pd slab [3]. This can be due to the electronic structure, requiring more conservative SCF settings and higher numerical accuracy.

What should I check first if my geometry optimization does not converge? First, ensure that the SCF (single-point energy) calculation itself converges correctly. If it does, the problem likely lies in the forces. You can improve the situation by increasing the accuracy of the gradient calculation using more radial points and higher numerical quality [3].

I get 'negative frequencies' in my phonon calculation. Is this related to convergence? Yes, unphysical negative frequencies can stem from two primary convergence-related issues: the geometry was not fully optimized to a minimum, or the step size used in the phonon calculation is too large [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: SCF Convergence Failures

Oscillating Energy Values

Oscillations in the total energy during the self-consistent field (SCF) procedure indicate that the iterative process is unstable and unable to find a steady solution [16].

- Primary Solution: Conservative Mixing Adjust the parameters that control how the electron density is mixed between SCF cycles to dampen the oscillations.

- Alternative Solution: Change Algorithm

Switching to a different algorithm like

LISTican sometimes resolve oscillations that DIIS cannot handle, though it may increase the cost per iteration [3].

Stalled or Stagnated Convergence

The SCF process stalls when the energy change between iterations becomes extremely small but the convergence criteria are not met, often seen in large or complex systems like a 500-atom Fe5C2 slab [15].

- Primary Solution: Improve Numerical Accuracy Stalls can be caused by insufficient numerical precision in integrals or k-point sampling.

- System-Specific Tuning: For challenging systems like iron slabs, you may need to experiment with recommended settings for

mixing_beta,mixing_ndim, andmixing_gg0[15].

Basis Set Dependency Errors

The calculation aborts with a "dependent basis" error when the set of Bloch functions is nearly linearly dependent, threatening numerical accuracy [3].

- Diagnosis: The program prints dependency coefficients and eigenvalues of the overlap matrix. Basis functions with the largest coefficients are the most suspicious [3].

- Solution 1: Use Confinement Apply spatial confinement to diffuse basis functions, particularly on atoms in the inner layers of a slab, to reduce their range and overlap [3].

- Solution 2: Modify the Basis Set Remove one or more problematic basis functions identified by the large dependency coefficients. If both STO and numerical orbitals are problematic, prioritize removing the STO [3].

Geometry Optimization Does Not Converge

The process of finding the energy-minimum structure fails to converge even when forces seem small.

- Solution: Increase Gradient Accuracy The gradients (forces) may be calculated with insufficient accuracy. To improve this:

Negative Frequencies in Phonon Calculations

The appearance of unphysical negative frequencies in an otherwise stable system's phonon spectrum.

- Solution 1: Verify Geometry Convergence

Ensure the geometry optimization has truly reached a minimum by tightening its convergence criteria (

GeoOpt%Converge) [3]. - Solution 2: Adjust Phonon Calculation Settings

Reduce the

PhononConfig%StepSizeused for the numerical differentiation of forces [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational parameters and their functions for troubleshooting SCF convergence problems in surface calculations.

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| SCF%Mixing | Controls the fraction of the new electron density mixed with the old. Lower, more conservative values (e.g., 0.05) stabilize oscillating calculations [3]. |

| DIIS%Dimix | Parameter for the Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace (DIIS) algorithm. Reducing it (e.g., to 0.1) provides a more conservative convergence strategy [3]. |

| K-Space Quality | Defines the fineness of k-point sampling. Upgrading from Basic to Normal ensures adequate Brillouin Zone integration, crucial for metallic slabs [3]. |

| ZlmFit Quality | Determines the accuracy of the density fit. Using Normal or Good quality can resolve precision-related stalls [3]. |

| BeckeGrid Quality | Specifies the quality of the numerical integration grid. Normal or Good setting is vital for accurate integration near heavy nuclei [3]. |

| Basis Set Confinement | A technique to make diffuse basis functions more localized, reducing linear dependency issues in slabs and highly coordinated systems [3]. |

Workflow for Diagnosing SCF Convergence

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and treating common SCF convergence problems.

The Role of HOMO-LUMO Gaps, Near-Degenerate States, and Metallic Character

Troubleshooting Guides

SCF Convergence Failure in Metallic Slab Systems

Problem Description The Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure fails to converge during electronic structure calculations of metallic slabs, particularly in challenging systems like iron (Fe) slabs compared to more straightforward systems like palladium (Pd) slabs [3]. This manifests as continuous oscillation of energies or a complete stall in the convergence cycle, especially problematic in large systems (e.g., ~500 atoms) [15].

Root Causes

- Near-Degenerate States and Small HOMO-LUMO Gaps: Metallic systems are characterized by vanishing band gaps and high densities of near-degenerate states near the Fermi level. This electronic structure leads to rapid charge sloshing during the SCF cycle, where small changes in the electron density cause large shifts in the Kohn-Sham orbitals, preventing convergence [17].

- Insufficient Numerical Precision: Low-quality numerical integration grids (Becke grid), insufficient k-point sampling, or a poor-quality density fit can prevent the accurate resolution of these near-degenerate states, exacerbating convergence problems [3].

- Overly Aggressive Mixing Parameters: Standard mixing parameters for insulators or molecules can be too aggressive for metallic systems, failing to dampen the oscillations caused by charge sloshing [3] [15].

Solutions and Protocols

Table 1: Parameter Adjustments for SCF Convergence

| Parameter/Block | Recommended Setting | Function | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

SCF%Mixing |

0.05 (reduced) | Controls the fraction of the new density mixed with the old. | More conservative mixing dampens oscillations from charge sloshing [3]. |

DIIS%Dimix |

0.1 (reduced) | Weight for the DIIS error vector in the density update. | A more conservative DIIS strategy stabilizes convergence [3]. |

DIIS%Variant |

LISTi |

Switches to the LISTi algorithm for the SCF solver. | Can reduce the number of SCF cycles in difficult cases [3]. |

NumericalQuality |

Good |

Improves the general accuracy of numerical integration. | Ensures sufficient precision to handle near-degenerate states [3]. |

KSpace%Quality |

Normal or Good |

Increases the number of k-points for Brillouin zone sampling. | Critical for metals; better samples the Fermi surface [3]. |

ZlmFit%Quality |

Normal or Good |

Improves the quality of the density fit. | Prevents errors from propagating into the SCF cycle [3]. |

BeckeGrid%Quality |

Normal or Good |

Uses a more accurate grid for numerical integration. | Essential for systems with heavy elements [3]. |

Experimental Protocol

- Initial Assessment: Confirm the system is metallic and check the k-point grid. A single k-point is often insufficient [3].

- Apply Conservative Parameters: Begin by applying the reduced

MixingandDimixparameters from Table 1. - Increase Numerical Accuracy: If convergence issues persist (e.g., many iterations after the "HALFWAY" message), systematically increase the quality of the numerical settings (

NumericalQuality,KSpace,ZlmFit,BeckeGrid) [3]. - Advanced Solver: For systems resistant to the above steps, switch the DIIS variant to

LISTi[3]. - Validation: Always compare the total energy of a converged calculation with previous attempts to ensure physical consistency.

Geometry Optimization Failure

Problem Description Geometry optimization (GeoOpt) does not converge, even when the SCF procedure is stable.

Root Causes Inaccurate forces and stresses due to poor SCF convergence or low-quality gradient evaluation [3].

Solutions and Protocols Table 2: Parameters for Geometry Convergence

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Function |

|---|---|---|

NumericalQuality |

Good |

Improves the general accuracy of all numerical integrations, including gradients [3]. |

RadialDefaults%NR |

10000 | Increases the number of radial points in the atomic integration grids [3]. |

Experimental Protocol

- Ensure the SCF is fully converged at each geometry step using the guidelines above.

- Implement the higher-accuracy settings for force calculations shown in Table 2.

Basis Set Dependency Error

Problem Description Calculation aborts with a "dependent basis" error. This occurs when the set of Bloch basis functions for a k-point is nearly linearly dependent, threatening numerical accuracy [3].

Root Causes Overly diffuse basis functions on highly coordinated atoms (common in slabs) leading to excessive overlap between functions on neighboring atoms [3].

Solutions and Protocols

- Confinement: Apply the

Confinementkeyword to reduce the range of diffuse basis functions. In a slab, consider applying confinement only to atoms in the inner layers, leaving surface atom basis functions unmodified to describe vacuum decay [3]. - Basis Set Modification: Remove one or more problematic diffuse basis functions. The program output provides "Dependency Coefficients" to identify the most suspicious functions [3].

Experimental Protocol

- Analyze the "Dependency Coefficients" in the output file. Functions with large coefficients are suspects.

- Prefer removing a numerical Slater-type orbital (STO) over a Dirac valence function.

- If two coefficients are large, remove one function and consider modifying the other.

- Repeat the process until all k-points pass the dependency check [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is an Fe slab much harder to converge than a Pd slab? The difference originates from the electronic structure. Iron, with its more complex and spatially localized d-electrons near the Fermi level, has a higher density of near-degenerate states compared to palladium. This leads to more pronounced charge sloshing and greater sensitivity to the initial guess and SCF mixing parameters [3] [15].

Q2: What is the connection between the HOMO-LUMO gap and SCF convergence? A small or zero HOMO-LUMO gap (a hallmark of metallic character) directly challenges SCF convergence. The HOMO-LUMO gap represents the energy cost for electron excitation; a small gap means many low-energy electronic excitations are possible. During the SCF cycle, this results in instability, as the electron density can easily fluctuate between many near-degenerate configurations [17]. In the limit of a large gap (as in insulators), these fluctuations are suppressed, leading to robust convergence.

Q3: My phonon calculation shows negative frequencies, but my geometry is optimized. What is wrong? Unphysical negative frequencies in a phonon spectrum typically indicate one of two issues:

- The geometry is not a true minimum: Ensure your geometry optimization has converged tightly (check

GeoOpt%Convergecriteria). - Insufficient numerical accuracy in the phonon calculation: The numerical step size used to calculate the force constants (

PhononConfig%StepSize) may be too large, or there could be underlying errors from numerical integration or k-space sampling [3].

Q4: The calculation aborts due to a "frozen core too large" error. What should I do?

The program checks the overlap of the frozen core orbitals, and if it deviates too much from the unit matrix (default criterion >0.02), it stops. The safest solution is to use a smaller frozen core. If performance is critical, you can loosen the dependency criterion (e.g., to 0.8 via the Dependency keyword), but you must validate the results against a calculation with a smaller core on a test system [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Parameters and Methods

| Item | Function in Calculation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SCF Mixing (SCF%Mixing) | Controls the damping of the new electron density guess. Lower values (0.05) are more stable for metals [3]. | Primary knob for combating charge sloshing. |

| DIIS Solver (DIIS%Variant) | An algorithm to accelerate SCF convergence. The LISTi variant can be more robust for difficult cases [3]. |

Alternative to standard Pulay DIIS. |

| k-point Grid (KSpace) | Samples the Brillouin zone. Crucial for metallic systems to describe the Fermi surface accurately [3]. | A single k-point is often a cause of failure. |

| Numerical Grid (BeckeGrid) | Defines the points for numerical integration. Higher quality is needed for heavy elements and accurate gradients [3]. | Affects all integrated quantities. |

| Density Fitting (ZlmFit) | Approximates the electron density with an auxiliary basis set for computational efficiency [3]. | Poor quality can introduce SCF errors. |

| Basis Set Confinement | Limits the spatial extent of diffuse basis functions to avoid linear dependency in periodic systems [3]. | Key for avoiding "dependent basis" errors in slabs. |

Impact of Basis Set Diffusiveness and Linear Dependency in Slab Models

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the signs of a linear dependency problem in a slab calculation? The calculation may abort with an explicit error message stating "dependent basis". This occurs when the program detects that the set of Bloch functions constructed from your basis set is numerically too close to being linearly dependent, threatening the numerical accuracy of the results. The program performs an internal check by computing and diagonalizing the overlap matrix of the basis; if the smallest eigenvalue is below a critical threshold, the calculation stops [18].

2. Why are slab models particularly susceptible to SCF convergence and basis set issues? Slab models, especially those with symmetric terminations and vacuum layers, can be challenging for several reasons. Systems with metallic character or complex electronic structures, like Fe slabs, are inherently more difficult to converge than simpler systems like Pd slabs [18]. Furthermore, the inclusion of vacuum in the model often necessitates diffuse basis functions to describe the decay of the electron density correctly. The diffuseness of these functions, particularly on highly coordinated atoms in the inner layers of the slab, can lead to significant overlap and linear dependency problems [18].

3. My SCF calculation oscillates and won't converge, even for a simple Pd slab. What are the first steps I should take?

Before investigating more complex causes, you should first try to use more conservative electronic minimization settings. A primary strategy is to decrease the mixing parameter (often called Mixing or mixing_beta) to a value like 0.05 or 0.1 to stabilize the convergence [18] [19]. You can also try switching from the default DIIS algorithm to a MultiSecant method, which can be more robust for difficult systems without a significant increase in cost per iteration [18].

4. How can I fix a linear dependency error without compromising the physical accuracy of my calculation? The two most effective strategies are using confinement or removing overly diffuse basis functions [18].

- Confinement: This technique reduces the spatial range of basis functions, mitigating their unwanted overlap. In a slab, you can apply stronger confinement to atoms in the inner layers, as their wavefunctions do not need to be as diffuse as those on the surface atoms, which must describe the decay into the vacuum [18].

- Basis Set Adjustment: Manually removing the most diffuse basis functions from your set is a direct way to eliminate the source of the linear dependency. It is strongly recommended to adjust the basis set rather than simply lowering the internal dependency criterion to bypass the error [18].

5. Are there any advanced automation strategies for difficult geometry optimizations?

Yes, you can configure the calculation to use a higher electronic temperature and looser SCF convergence criteria during the initial optimization steps when atomic forces are large. As the geometry converges and forces become smaller, the automation can gradually tighten these parameters. This approach prevents the calculation from getting stuck in the early stages while ensuring high accuracy in the final structure [18]. For example, you can automate the ElectronicTemperature to decrease from 0.01 Ha to 0.001 Ha as the gradient norm falls below a certain threshold [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving SCF Convergence Failure

Problem: The self-consistent field (SCF) calculation oscillates, exceeds the maximum number of iterations, or shows a non-monotonic change in total energy [19] [20].

Diagnosis: This is a common issue for systems with complex electronic structures. It can be caused by an inaccurate initial guess, overly tight convergence criteria, or a problematic charge density from a previous calculation step [20] [19].

Resolution Protocol:

Stabilize the SCF Procedure:

- Decrease the mixing parameter (

Mixingormixing_beta) to a value between0.05and0.1to reduce oscillations [18] [19]. - For DIIS-based methods, reduce the

DiMixparameter (e.g., to0.1) and consider settingAdaptabletofalseto disable automatic adjustments [18]. - Alternatively, change the SCF method to

MultiSecantor a LIST variant (e.g.,LISTi), which can be more stable for difficult cases [18].

- Decrease the mixing parameter (

Employ a Sequential Restart Strategy:

- If the calculation stalls, do not simply continue it. Restart the entire calculation from scratch using the latest atomic structure and charge density from the previous, nearly-converged calculation. This can sometimes reset a "stuck" charge density and lead to convergence [19].

Use a Finite Electronic Temperature:

- Applying a small electronic temperature (e.g.,

kT = 0.001to0.01Ha) can smear the Fermi surface and help convergence in metallic systems. This can be automated to be higher at the start of a geometry optimization and lower at the end [18].

- Applying a small electronic temperature (e.g.,

Simplify and Rebuild:

- Start the convergence process with a minimal basis set (e.g., SZ). Once the SCF is converged, use the resulting wavefunctions as a starting point for a restart calculation with the full, desired basis set [18].

The following workflow outlines the systematic troubleshooting process for SCF convergence failure.

Guide 2: Resolving Linear Dependency in the Basis Set

Problem: The calculation terminates immediately with a "dependent basis" error.

Diagnosis: The basis functions on adjacent atoms are too diffuse, leading to an overlap that makes the resulting Bloch functions numerically linearly dependent in reciprocal space [18].

Resolution Protocol:

Apply Spatial Confinement:

- Use the

Confinementkeyword to reduce the range of basis functions. This is often the most physically justified approach for slab systems. - Implement a stratified confinement scheme: Apply strong confinement to atoms in the inner layers of the slab, while using the normal, more diffuse basis for surface atoms. This ensures the surface electronic tail into the vacuum is described correctly while preventing numerical issues in the bulk-like region [18].

- Use the

Modify the Basis Set:

- Manually remove the most diffuse basis functions from the basis set. This is a direct solution but requires careful consideration to ensure the remaining basis set is still sufficient for the desired accuracy [18].

Increase Numerical Precision (Use with Caution):

- While not recommended as a first solution, you can try increasing the

NumericalAccuracyto improve the quality of the integrals, which might alleviate mild dependency issues caused by numerical noise. However, adjusting the basis set itself is a more robust solution [18].

- While not recommended as a first solution, you can try increasing the

The logical flow for diagnosing and resolving a linear dependency error is summarized in the following diagram.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Stratified Confinement for Slab Models

Objective: To eliminate linear dependency while maintaining an accurate description of the surface electronic structure.

Methodology:

- Identify Atom Layers: Classify atoms in your slab model into "surface" and "inner" layers.

- Apply Differential Confinement: In the computational input, apply a standard (or no) confinement potential to the atoms in the surface layers. Apply a stronger confinement potential (e.g., with a smaller radius) to all atoms in the inner layers.

- Convergence Test: Systematically test the total energy and key properties (e.g., work function, surface energy) as a function of the inner-layer confinement radius to ensure the results are physically meaningful.

The following table lists common parameters in quantum chemistry codes that can be adjusted to improve SCF convergence, based on strategies found in the literature [19] [18].

| Parameter | Default (Typical) | Troubleshooting Value | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

Mixing / mixing_beta |

0.2 - 0.4 | 0.05 - 0.1 | Controls the fraction of new density mixed with the old; lower values stabilize convergence [18] [19]. |

SCF Method |

DIIS | MultiSecant or LIST | Alternative algorithms that can be more robust for difficult systems [18]. |

Electronic Temperature (kT) |

0 Ha | 0.001 - 0.01 Ha | Smears orbital occupations, aiding convergence in metallic or small-gap systems [18]. |

DIIS %DiMix |

Varies | 0.1 | A more conservative mixing parameter within the DIIS algorithm itself [18]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines essential computational "reagents" and their functions for managing basis set diffusiveness and linear dependency.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Confinement Potential | A computational tool that restricts the spatial extent of atomic orbital basis functions, directly mitigating excessive overlap and linear dependency between nearby atoms [18]. |

| MultiSecant / LIST SCF Solver | Advanced algorithms for converging the SCF equations. They serve as alternatives to the standard DIIS method and can often achieve convergence where DIIS fails, without a significant computational overhead [18]. |

| Stratified Confinement Scheme | A methodology where different confinement strengths are applied to different regions of a model (e.g., strong in slab interior, weak on surface). It is key to maintaining accuracy while solving numerical issues [18]. |

| Automation Scripts for Geometry Optimization | Scripts or input parameters that dynamically adjust SCF criteria (like electronic temperature and convergence threshold) based on the optimization step, preventing early termination and improving efficiency [18]. |

| Minimal Basis Set (e.g., SZ) | A simplified basis set used as a starting point to generate a stable initial wavefunction and charge density, which is then used to restart the calculation with a larger, target basis set [18]. |

Initial Guess Quality and Its Critical Role in Starting the SCF Procedure

FAQs on SCF Initial Guesses

What is the primary goal of a good SCF initial guess? A good initial guess serves two critical purposes: it ensures the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure converges to the appropriate electronic ground state rather than a local minimum, and it significantly reduces computational time by providing a starting point close to the final solution, thereby decreasing the number of SCF iterations required [21].

Why do my slab calculations (e.g., Pd, Fe) have particular difficulty converging? Systems such as Fe slabs are notably more difficult to converge than Pd slabs. This is often due to the complex electronic structure of transition metals, including closely spaced orbitals and the presence of unpaired electrons. A poor initial guess can exacerbate these convergence problems [18] [15].

What are the common initial guess methods available? Different computational packages offer various initial guess procedures. The most common include [21]:

- SAD (Superposition of Atomic Densities): Constructs a trial density matrix from spherically averaged atomic densities. It is generally superior for large molecules and basis sets.

- Core Hamiltonian: Diagonalizes the core Hamiltonian matrix. Its quality degrades with increasing system and basis set size.

- GWH (Generalized Wolfsberg-Helmholtz): Uses a combination of overlap and core Hamiltonian matrix elements, satisfactory mainly for small molecules in small basis sets.

- READ: Reads molecular orbitals from a previous calculation's disk file.

How can I manipulate the initial guess to converge to a specific electronic state? You can modify the occupied guess orbitals to break spatial or spin symmetry, which is crucial for converging to states of different symmetry or for unrestricted calculations on molecules with an even number of electrons. This can be achieved by [21]:

- Explicitly listing the orbitals to be occupied in the alpha and beta spaces.

- Swapping specific occupied and virtual orbitals in the initial guess.

- Using options like

SCF_GUESS_MIXto add a percentage of the LUMO into the HOMO to break symmetry.

My calculation failed with a "dependent basis" error. Is this related to the initial guess? While a "dependent basis" error is directly related to the basis set itself (indicating near-linear dependency), the strategies to resolve it can influence the SCF procedure. Using confinement to reduce the range of diffuse basis functions or removing specific functions can alleviate this problem. A more stable basis often makes obtaining a good initial guess easier and improves overall SCF convergence [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: SCF Does Not Converge for a Difficult System (e.g., Fe Slab)

Diagnosis: The default SCF settings and initial guess are insufficient for systems with complex electronic structures, leading to oscillatory behavior or divergence in the energy.

Solutions:

- Use a Conservative Mixing Scheme: In the BAND code, decreasing the mixing parameters can stabilize convergence [18].

- Employ Alternative SCF Algorithms: If the standard DIIS method fails, consider switching to the MultiSecant method, which has a similar computational cost per cycle, or a LIST method [18].

- Implement a Two-Stage Strategy:

- Leverage Basis Set Projection (Q-Chem): Use the

BASIS2$rem variable to automatically perform a calculation in a small basis set and project the resulting density into your large target basis, providing an excellent initial guess [21].

Problem: SCF Converges to the Wrong Electronic State

Diagnosis: The initial guess has incorrect orbital occupancy or symmetry, causing convergence to an excited state or a state with unintended symmetry (e.g., ^2A₁ instead of ^2B₁ for the NH₂ radical) [13].

Solutions:

- Manually Alter Orbital Occupancy: After a standard initial guess, swap the intended SOMO (Singly Occupied Molecular Orbital) with a virtual orbital. In Gaussian, this is done with the

guess=alterkeyword and specifying the orbitals to swap after the molecular specification [13]. - Specify Occupied Orbitals Directly: In Q-Chem, use the

$occupiedor$swap_occupied_virtualinput groups to explicitly define the orbitals considered occupied in the initial guess [21]. - Enforce Symmetry: Use options like

SCF=Symmin Gaussian to retain the orbital symmetry of the initial guess throughout the SCF process, which can help in maintaining a specific state [13].

Problem: SCF is Slow to Converge in Geometry Optimizations

Diagnosis: Using an inappropriately tight SCF convergence criterion in the early stages of a geometry optimization, when the nuclear gradients are still large, wastes computational resources.

Solutions:

- Use Loose Initial SCF Convergence: Implement "automations" (e.g., in the BAND code) that tighten the SCF convergence criterion as the geometry optimization progresses [18].

- Employ Finite Electronic Temperature: A finite electronic temperature can smear orbital occupations and aid convergence when far from the minimum. This temperature can be automated to decrease as the geometry converges [18].

- Reuse the Previous Guess: By default, most programs use the wavefunction from the previous geometry step as the guess for the next. Ensure this is active and not overridden by settings like

SCF_GUESS_ALWAYS = TRUEin Q-Chem, which forces a new guess for every point [21].

Initial Guess Methods: A Comparative Table

Table 1: Common SCF initial guess methods, their principles, and best-use contexts.

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAD [21] | Superposition of atomic densities | Robust; excellent for large systems and basis sets | Not orbital-based; not available for general basis sets | Default for standard basis sets |

| Core Hamiltonian [21] | Diagonalization of the core Hamiltonian | Simple | Quality degrades with system/basis set size | Small molecules and basis sets |

| GWH [21] | Approximation using overlap & core Hamiltonian | Better than core guess for small systems | Less effective for large systems | Small molecules where SAD is unavailable |

| READ [21] [13] | Read MOs from a previous calculation | Can be very accurate if system is similar | Requires a previous calculation; basis sets must be compatible | Restarting or modifying a previous calculation |

| Basis Projection [21] | Projects density from small to large basis | High-quality guess for large basis sets | Requires an automated two-step process | Bootstrapping a calculation in a large basis set |

Experimental Protocols for Challenging Systems

Protocol 1: Converging a Difficult Fe Slab System

This protocol is designed for systems where standard SCF procedures fail, as reported for a large Fe~5~C~2~ slab system [15].

Preliminary Minimal Basis Calculation:

- Basis Set: Start with a minimal basis set (e.g., SZ in ADF/BAND).

- SCF Settings: Use default settings or conservative mixing (

mixing_beta=0.1). - Goal: Achieve SCF convergence in this reduced space. The resulting density and orbitals will be used as the initial guess for the next stage [18].

Target Calculation with Large Basis:

- Initial Guess: Use

guess=read(Gaussian) orSCF_GUESS=READ(Q-Chem) to import the wavefunction from the preliminary calculation [21] [13]. - SCF Algorithm: If convergence struggles persist, switch to a more robust algorithm:

- Damping/CDIIS: For systems with severe oscillations, using

SCF=FermiorSCF=CDIISin Gaussian, which implies damping, can help stabilize the early iterations [6].

- Initial Guess: Use

Protocol 2: Targeting a Specific Electronic State in a Radical

This protocol uses the NH₂ radical example to demonstrate how to converge to the ^2A₁ state instead of the default ^2B₁ state [13].

Perform a Standard Calculation:

- Run a standard SCF calculation (e.g.,

#ROHF/STO-3G scf=(symm,tight)in Gaussian) to generate a baseline wavefunction.

- Run a standard SCF calculation (e.g.,

Analyze the Initial Guess Orbitals:

- Use

guess=onlyto run the initial guess without proceeding to the full SCF. Examine the output to identify the orbital symmetries and the order of occupied and virtual orbitals [13].

- Use

Alter the Orbital Occupancy:

- In the input for the new calculation, specify

guess=alter. - After the molecular specification, list the pairs of orbitals to be swapped. For example, to make the 6th orbital (virtual, A1 symmetry) occupied and the 5th orbital (occupied, B1 symmetry) virtual, you would add the line:

5 6[13]. - Execute the job. The SCF procedure will now start from the altered guess and converge to the ^2A₁ state.

- In the input for the new calculation, specify

Verify the Result:

- Check the final output to confirm the electronic state and the orbital occupancy match the target.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational "reagents" and their functions in managing SCF convergence.

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| SAD Initial Guess [21] | Provides a high-quality, physically motivated starting density from atomic fragments. | Default guess in Q-Chem for standard basis sets; excellent for large molecules. |

| DIIS/EDIIS Algorithms [6] | Extrapolates the Fock matrix to accelerate SCF convergence. | Default in many codes (Gaussian, BAND). Conservative Dimix or Mixing parameters help difficult cases [18]. |

| Quadratic Convergence (QC) [6] | A robust, non-Pulay algorithm that guarantees convergence close to a minimum. | SCF=QC in Gaussian for systems where DIIS fails completely. Not available for ROHF. |

| Orbital Swapping Tools [21] [13] | Allows manual reordering of orbital occupancy in the initial guess. | guess=alter in Gaussian or $occupied in Q-Chem to converge to a specific electronic state. |

| Finite Electronic Temperature [18] | Smears orbital occupations, aiding convergence by preventing oscillatory behavior between near-degenerate states. | Useful in the early stages of geometry optimization of metals or systems with small band gaps. |

| Basis Set Projection [21] | Generates a superior initial guess for a large basis set by leveraging a pre-converged calculation in a smaller basis. | Using the BASIS2 $rem variable in Q-Chem to automate the process. |

Workflow Diagram: Initial Guess Selection and Troubleshooting

The following diagram provides a logical roadmap for diagnosing SCF convergence issues and selecting the appropriate initial guess strategy.

Systematic Methodologies and Computational Approaches for Stable SCF

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My SCF calculation for a metallic Fe slab is oscillating and won't converge. What is the first parameter I should adjust?

The two most effective initial parameters to adjust for a problematic metallic slab are reducing the SCF mixing parameter and/or the DIIS mixing parameter (Dimix). Using more conservative (lower) mixing values stabilizes the SCF iteration. For an Fe slab, you might start with:

Guide 2: System-Specific Protocol: Fe and Pd Slabs

Converging SCF for transition metal slabs like Fe and Pd is a common challenge in surface science research. Fe slabs, in particular, are noted to be more difficult to converge than Pd slabs. [3] [18] [22] The table below summarizes a recommended step-by-step protocol.

| Step | Action | Example Parameters / Code | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial Check | Verify spin polarization and use a reasonable k-point grid. | scf.SpinPolarization on scf.Kgrid 24 24 1 [22] |

Fe is magnetic; a dense k-grid is crucial for metallic states. [22] |

| 2. Stable Guess | Begin with a conservative DIIS setup. | SCF{Mixing 0.05} Diis{Dimix 0.1 Adaptable false} [3] [18] |

Low mixing prevents large, unstable density updates. |

| 3. Method Switch | If DIIS fails, switch to MultiSecant or LISTi. | SCF{Method MultiSecant} or Diis{Variant LISTi} [18] |

These methods can be more robust for difficult cases. [1] [18] |

| 4. Smearing | Apply a small electronic temperature. | scf.ElectronicTemperature 1500.0 [22] or Convergence%ElectronicTemperature 0.001 [18] |

Smearing fractional occupancies helps overcome small gap issues. [1] |

| 5. Final Touch | For a hard failure, use a slow-and-steady DIIS. | SCF{DIIS{N 25 Cyc 30} Mixing 0.015 Mixing1 0.09} [1] |

Uses many DIIS vectors and very low mixing for maximum stability. [1] |

Accelerator Comparison and Selection Table

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of the major SCF convergence accelerators.

| Method | Key Principle | Best For | Pros | Cons | Key Tuning Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIIS (Direct Inversion in Iterative Subspace) [1] | Extrapolates new Fock matrix by minimizing the commutator [F, PS] from previous iterations. |

Standard systems with reasonable HOMO-LUMO gap. | Well-established, fast for "well-behaved" systems. | Can diverge for difficult cases (e.g., small-gap, open-shell). | Mixing (aggresiveness), N (number of history vectors), Cyc (start cycle). [1] |

| EDIIS + DIIS (Energy-DIIS) [23] [24] | Combines energy minimization (EDIIS) with standard DIIS commutator minimization. | Robust general-purpose use; considered top-tier in method comparisons. [23] | More robust than DIIS alone; less likely to diverge. | (Implementation dependent) | |

| LISTi (Linear Expansion Shooting Technique) [1] | Uses a direct minimization of the total energy with respect to the density matrix. | Problematic systems where DIIS fails (e.g., Fe slabs). [1] [18] | Can converge cases where DIIS oscillates or diverges. | Higher computational cost per SCF iteration. [1] [18] | Diis{Variant LISTi} [18] |

| MultiSecant [18] | A quasi-Newton method that satisfies multiple previous secant conditions simultaneously. | Difficult systems like slabs; a good first alternative to try. | Robust performance at a cost per cycle similar to DIIS. [18] | SCF{Method MultiSecant} [18] |

|

| MESA [1] | Not detailed in results, but presented as an alternative convergence acceleration method. | Systems where other methods fail. | Can achieve convergence where others cannot. | Performance is system-dependent. | (Implementation dependent) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

In computational chemistry, the "reagents" are the key input parameters and numerical settings that determine the quality and success of a calculation.

| Reagent (Parameter) | Function / Purpose | Recommended Values / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SCF Mixing (mixing_beta) [1] [3] | Controls the fraction of the new Fock/Density matrix used in the next iteration. Lower values are more stable. | Default: ~0.2-0.3. Problematic systems: 0.015 - 0.05. [1] [3] |

| DIIS History (mixing_ndim) [1] [15] | Number of previous Fock/Density matrices used for extrapolation. More vectors can increase stability. | Default: ~10-20. Problematic systems: Up to 25-35. [1] [15] |

| Electronic Temperature (degauss) [1] [22] | Applies fractional occupations via smearing to help converge metallic/small-gap systems. | Keep as low as possible (e.g., 0.001-0.01 Ha, or 300-1500 K). Successively reduce it in restarts. [1] [22] |

| Level Shift [1] | Artificially increases the energy of virtual orbitals to stabilize the SCF procedure. | Helpful for small-gap systems but invalidates properties relying on virtual orbitals (e.g., excitation energies). [1] |

| Numerical Quality [3] [18] | Controls the accuracy of numerical integration (grid) and density fitting. | If SCF has many cycles after "HALFWAY" message, try NumericalQuality Good and better BeckeGrid/ZlmFit quality. [3] [18] |

Why are some systems, like Fe slabs, more difficult to converge than Pd slabs?

The inherent electronic structure of the system dictates the difficulty of achieving Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence. Systems with complex electronic configurations, such as those containing iron (Fe), are generally more challenging than others, like palladium (Pd) [18]. This is often due to the presence of closely spaced orbitals, localized d-electrons, or multiple possible spin states in transition metal complexes like Fe, which can lead to multiple locally stable wavefunctions and oscillations in the SCF cycle [25] [26]. For problematic cases, a move to more conservative settings is the primary strategy [18].

Optimal Mixing Parameters for Pd and Fe Slabs

The core conservative strategy involves reducing the mixing parameters to dampen oscillations between iterations. The following table summarizes the recommended starting ranges for Fe systems, with Pd typically being less sensitive [18].

Table 1: Key SCF Mixing Parameters for Difficult Convergence

| Parameter | Function | Typical "Easy" System Range | Recommended "Fe-like" Conservative Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCF%Mixing / SCF.Mixer.Weight | Damping factor for new density/potential in the next SCF cycle. | Higher values (e.g., 0.2 - 0.5) | 0.05 - 0.1 [18] |

| DIIS%Dimix | Weight for the DIIS (Pulay) error vector in the mixing scheme. | Higher values (e.g., >0.2) | ~0.1 [18] |

| SCF.Mixer.History | Number of previous steps used for Pulay/Broyden extrapolation. | Default (e.g., 2-5) | Can be reduced for stability or slightly increased (e.g., 4-6) to provide more history [27]. |

Advanced Mixing Strategies

Beyond basic damping, you can employ more sophisticated algorithms:

- Alternative Methods: If standard DIIS (Pulay) fails, consider switching to the MultiSecant method, which has a similar computational cost, or the LIST method, which may reduce the number of SCF cycles at a higher cost per iteration [18].

- Mixing Variable: The system can be set to mix either the Hamiltonian (H) or the Density Matrix (DM). The default in some codes, like SIESTA, is to mix the Hamiltonian, which often provides better results and stability [27].

Troubleshooting Workflow for SCF Convergence

For a structured approach to resolving SCF convergence issues, follow this workflow:

Experimental Protocol: Converging a Difficult Fe Slab System

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for applying the troubleshooting workflow.

1. Initial System Preparation:

- Construct Slab Model: Ensure your Fe slab model has a sufficient number of atomic layers (e.g., 5-8 layers) and adequate vacuum spacing (e.g., 10-20 Å) to avoid spurious interactions with periodic images [28].

- Set Convergence Criteria: Define appropriate tolerances. For high accuracy, consider using

TightSCFcriteria, which may include a total energy change (TolE) below 1e-8 Hartree and a maximum density change (TolMaxP) below 1e-7 [26].

2. Multi-Stage SCF Procedure:

- Stage 1: Conservative Mixing

- Set the primary mixing parameter (

SCF%MixingorSCF.Mixer.Weight) to 0.05 [18]. - Set the DIIS mixing parameter (

DIIS%Dimix) to 0.1 and, if available, setAdaptabletofalseto prevent automatic adjustments [18]. - Run the SCF calculation. If it converges, proceed to geometry optimization. If not, move to Stage 2.

- Set the primary mixing parameter (

Stage 2: Two-Step Initial Guess with Basis Set Reduction

Stage 3: Application of Finite Electronic Temperature

- Introduce a finite electronic temperature (e.g.,

Convergence%ElectronicTemperature= 0.01 Hartree) to smear the orbital occupations. This can help escape metastable states in the initial stages of optimization [18]. - This can be automated in a geometry optimization to use a higher temperature initially and a lower value (e.g., 0.001 Hartree) as the geometry nears convergence [18].

- Introduce a finite electronic temperature (e.g.,

3. Validation:

- Once the SCF has converged, perform an SCF stability analysis to ensure the solution found is a true local minimum and not a saddle point [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for SCF Convergence

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative Mixing Parameters | Stabilizes the SCF cycle by damping updates. | First response for oscillating or diverging systems like Fe slabs [18]. |

| Minimal Basis Set (e.g., SZ) | Provides a simpler, more stable initial wavefunction. | Generating a good initial guess for a subsequent calculation with a larger basis set [18]. |

| Finite Electronic Temperature | Smears orbital occupancy, preventing oscillations between near-degenerate states. | Aiding convergence in metallic systems or complexes with small band gaps [18]. |

| Advanced Mixing Algorithms (MultiSecant, LIST) | Alternative convergence acceleration methods. | When standard DIIS/Pulay mixing fails to converge or is inefficient [18]. |

| Fragmentation Methods (FLMO) | Divides a large system into smaller, manageable fragments. | Enabling SCF calculations for very large systems (>300 atoms) that are otherwise intractable [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What should I check if my geometry optimization does not converge, even with a converged SCF?

Ensure the gradients (forces) are calculated with sufficient accuracy. You can improve this by increasing the number of radial points in the numerical integration (RadialDefaults NR 10000) and setting the general numerical quality to Good [18].

How can I manage SCF convergence in large systems where calculations become prohibitively expensive?

For large systems (e.g., >300 atoms), traditional SCF methods can fail. Consider using fragmentation approaches like the Fragment Localized Molecular Orbital (FLMO) method. This technique divides the system into smaller fragments, converges the SCF for each fragment individually, and uses these localized orbitals to construct an accurate initial guess for the entire system, often leading to much faster and more robust convergence [25].

My calculation failed due to a "dependent basis" error. What does this mean and how can I fix it?

This error indicates near-linear dependence in your basis set, often caused by overly diffuse functions in highly coordinated atoms. Do not simply loosen the dependency criterion. Instead, adjust the basis set itself by using confinement to reduce the range of diffuse functions or by manually removing the most diffuse basis functions [18].

Leveraging Finite Electronic Temperature and Electron Smearing for Metallic Systems

FAQ 1: Why does my Pd or Fe slab calculation fail to converge, and how can smearing help?

Answer: SCF convergence problems in metallic systems like Pd or Fe slabs are primarily due to the vanishing HOMO-LUMO gap and the presence of many near-degenerate electronic states around the Fermi level. This leads to level-crossing instabilities, where electrons abruptly jump between energy levels during the iterative SCF process, causing oscillations in the total energy [1] [29].

Electron smearing is a crucial technique to overcome this. It works by assigning fractional occupation numbers to electronic states near the Fermi energy, effectively smoothing the discrete occupation of levels. This creates a more continuous charge density update between SCF cycles, which dampens oscillations and stabilizes convergence [1] [29]. For metallic systems, this is not just a convergence trick; it is essential for achieving physically meaningful results and accurate k-point integration [29] [30].

Table: Common Smearing Methods for Metallic Systems

| Smearing Method | ISMEAR (VASP) | Key Characteristics | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methfessel-Paxton [31] [30] | 1 (First-order) | High accuracy for total energy in metals; not recommended for insulators [30]. | Force and phonon calculations in metals [30]. |

| Gaussian [31] [30] | 0 | Stable and reliable; requires extrapolation to SIGMA→0 for exact energy [30]. | General-purpose, safe for unknown systems [30]. |

| Fermi-Dirac [31] [30] | -1 | Smearing width corresponds to physical electronic temperature [30]. | Properties dependent on physical electron temperature [30]. |

| Tetrahedron (Blöchl) [31] [30] | -5 | Very precise total energies and DOS; forces can be inaccurate for metals [30]. | Accurate DOS and total energy calculations (no relaxation) [30]. |

The following workflow can guide your choice and application of smearing for slab calculations:

FAQ 2: What are the best practices for selecting smearing parameters for my transition metal slab?

Answer:

Selecting optimal parameters involves a trade-off between numerical stability and physical accuracy. The key is to use the smallest smearing width (SIGMA) that ensures stable convergence.

1. Initial Setup and Convergence:

For an unknown system, start with Gaussian smearing (ISMEAR = 0) and a small SIGMA value between 0.03 and 0.1 eV [30]. This provides a safe starting point. For production relaxations of metals, switch to Methfessel-Paxton (ISMEAR = 1) with a SIGMA that keeps the entropy term (T*S) in the OUTCAR file below 1 meV/atom [30].

2. Systematic Parameter Testing:

Convergence testing is essential. You should plot the force on a symmetrically unique atom in your slab (from a slightly distorted structure) against the smearing width for increasingly dense k-point meshes. The correct SIGMA and k-point density are achieved when the forces no longer change significantly with either parameter [29].

Table: Parameter Selection and Troubleshooting Guide

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Purpose & Effect |

|---|---|---|

| SIGMA | 0.1 - 0.2 eV (Metals) [30] | Smearing width. Larger values stabilize SCF but can unphysically raise energy. |

| ISMEAR | 1 (Metals, relaxation), -5 (Metals, static DOS) [30] | Selects the smearing method. |

| KSPACING | Smaller than default (e.g., 0.15) | Ensures sufficient k-point sampling to integrate smoothed occupations [29]. |

| EDIFF | 1E-5 (default) | SCF energy convergence threshold. |

| NEDOS | 1000 or higher | Number of points for DOS, important for accurate Fermi level finding. |

FAQ 3: What other SCF settings can I adjust for a stubbornly non-converging Fe/Pd slab?

Answer: If smearing alone does not resolve convergence, combine it with other SCF accelerator settings. For difficult systems, a "slow and steady" approach often works best.

1. DIIS and Mixing Parameters: You can make the DIIS algorithm more stable by increasing the number of previous cycles it considers and reducing the mixing parameter. This is less aggressive but helps dampen oscillations [1]. A sample input block for such a setup is:

This configuration uses more DIIS vectors (N) and starts DIIS after more cycles (Cyc), combined with a low mixing fraction for stability [1].

2. Advanced Techniques:

- Level Shifting (VASP): Using

SCF=vshift=300in Gaussian artificially increases the HOMO-LUMO gap by raising the energy of virtual orbitals, reducing state mixing. This only affects the convergence process, not the final results [7]. - Alternative Algorithms: Switch to more robust but potentially more expensive SCF convergence accelerators like the Augmented Roothaan-Hall (ARH) method, which directly minimizes the total energy [1].

Table: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for Metallic Slab Simulations

| Tool / Parameter | Function / Purpose | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Methfessel-Paxton Smearing | Smoothens orbital occupations for integration in metals; minimizes finite-T error [29] [30]. | Structural relaxation of a Pd(111) slab. |

| Tetrahedron Method (Blöchl) | Provides high-fidelity k-point integration for DOS and accurate total energies [30]. | Calculating the electronic DOS of an Fe slab for analysis. |

| Fermi-Dirac Smearing | Uses physical temperature for electron occupations [30]. | Studying properties at finite electronic temperatures. |

| K-Point Convergence Test | Determines the minimal k-mesh for energetically converged results. | Ensuring calculated surface energy of a slab is converged. |

| DIIS & Mixing Parameters | Controls the SCF extrapolation process; critical for damping oscillations [1]. | Stabilizing SCF in a magnetic Fe slab with convergence issues. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why is SCF convergence more difficult for my Fe slab compared to a Pd slab? Some systems, like Fe slabs, are inherently more difficult to converge than others, such as Pd slabs, due to their electronic structure. For problematic cases, using more conservative SCF settings is recommended. This includes decreasing the mixing parameter and using a more conservative DIIS strategy [3] [18].

2. My calculation fails with a "dependent basis" error. What should I do? This error indicates that your basis set is nearly linearly dependent, which threatens numerical accuracy. Instead of loosening the dependency criterion, you should adjust the basis set itself. The two primary methods are:

- Using Confinement: This reduces the range of diffuse basis functions, which are often the cause of the problem, especially in highly coordinated atoms or slabs [3] [18].

- Removing Basis Functions: The program prints "Dependency Coefficients" that help identify the most problematic functions. Those with the largest coefficients should be removed or modified first [3].

3. How can I manage disk space for large systems with many k-points?

For systems with many basis functions or k-points, disk space demands can grow significantly. You can change how temporary matrices are stored by setting the KMIOSTORAGEMODE. Using Programmer Kmiostoragemode=1 enables a fully distributed storage mode, which can help mitigate this issue [18].

4. What can I do if my geometry optimization does not converge? First, ensure that the SCF cycle is converging. If it is, the problem may be inaccurate gradients. You can improve gradient accuracy by increasing the number of radial points and setting a higher numerical quality [3] [18]:

5. How can a finite electronic temperature help with convergence? Applying a finite electronic temperature can make systems easier to converge. This is particularly useful during the initial steps of a geometry optimization when gradients are still large. You can automate this process so that the temperature is higher at the start and decreases as the geometry converges [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

SCF Convergence Failure

The self-consistent field (SCF) procedure is iterative and may not converge for challenging systems.

Symptoms:

- The SCF cycle exceeds the maximum number of iterations without reaching the specified energy criterion.

- Large oscillations in the energy or density are observed between cycles.

Solutions: Implement the following strategies systematically.

- Strategy 1: Conservative SCF Settings Begin with more stable, though potentially slower-converging, mixing parameters.

- Strategy 2: Alternative SCF Solvers If the DIIS method fails, try switching to the MultiSecant or LIST methods [18].

- Strategy 3: Improved Numerical Accuracy Convergence problems after the "HALFWAY" message often indicate insufficient numerical precision. Improve the quality of critical integrations [3].

- Strategy 4: Two-Step Restart Procedure

This is a robust method to obtain a good initial density for a difficult calculation.

- Initialization with a Small Basis: Perform a calculation with a minimal (e.g., SZ) basis set, which is often easier to converge [18].

- Restart with Target Basis: Use the electron density from the SZ calculation as the starting point for a new calculation with your desired larger basis set (e.g., TZP). This leverages the checkpoint/restart capability found in many electronic structure codes [18] [32].

The following workflow outlines this systematic troubleshooting process.

Basis Set Dependency Error

This error arises when the overlap matrix of the basis functions is nearly singular, jeopardizing the numerical stability of the calculation.

Symptoms:

- Calculation aborts with a "dependent basis" message.

- The program outputs a list of very small eigenvalues of the overlap matrix and large "Dependency Coefficients."

Solutions:

- Solution 1: Apply Confinement Diffuse functions are a common cause. Apply a confinement potential to reduce their range, particularly for atoms in the inner layers of a slab while leaving surface atoms unconfined to describe vacuum decay [3] [18].

- Solution 2: Remove Problematic Functions

Use the "Dependency Coefficients" from the output to identify which basis functions contribute most to the linear dependency. Functions with the largest coefficients are the best candidates for removal. The procedure for identifying functions is:

- Loop over all atom types in your input order.

- For each atom of a type, list all its basis functions (first Dirac/valence, then STOs).

- Each L-quantum number corresponds to 2L+1 functions [3].

The logic for resolving basis set dependency issues is summarized below.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" and parameters essential for managing basis sets and SCF convergence in slab calculations.

| Item/Reagent | Function & Purpose | Example Usage / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Small (SZ) Basis Set | Provides a quick-to-converge initial electron density; used as a starting point for more accurate calculations [18]. | PAO.BasisSize SZ (Siesta) or basis-set SZ (other codes). |

Mixing Parameter (Mixing) |

Controls how much of the new density is mixed with the old in each SCF step. Lower values are more stable but slower [3] [18]. | SCF { Mixing 0.05 } (more conservative). |

DIIS History (Dimix) |

Determines how many previous steps are used to extrapolate the next density. A smaller history can improve stability [3]. | Diis { DiMix 0.1 }. |

| Confinement Potential | Reduces the spatial range of diffuse basis functions, mitigating linear dependency issues in periodic systems [3] [18]. | Typically applied per atom type, especially to inner slab layers. |

| Numerical Quality Settings | Governs the accuracy of numerical integrations (k-points, density fitting, grids). Poor quality can cause convergence failure [3] [18]. | NumericalQuality Good, KSpace { Quality Normal }. |

Electronic Temperature (ElectronicTemperature) |

Smears electronic occupations, helping to converge metallic systems and initial geometry steps [18]. | Convergence { ElectronicTemperature 0.01 } (in Hartree). |

| Checkpoint File | Saves the state of a calculation (density, orbitals) to allow for restarts and as an initial guess for subsequent jobs [32]. | %chk=caffeine.chk (Gaussian). Essential for the SZ-to-TZP restart strategy. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic SCF Convergence for Challenging Slabs

This protocol is designed for systems like an Fe slab where standard SCF settings fail.

- Initial Attempt: Start with the default SCF parameters for your code.

- Stabilize Mixing: If the default fails, reduce the

SCF%Mixingparameter (e.g., to 0.05) and/or theDIIS%Dimixparameter (e.g., to 0.1). Disable adaptable DIIS if oscillations persist [3] [18]. - Change Solver: If conservative mixing fails, switch the SCF method to

MultiSecantorLISTi[18]. - Increase Precision: If many iterations occur after the "HALFWAY" point, systematically increase the

NumericalQualityand the quality of the k-space sampling, density fit (ZlmFit), and integration grid (BeckeGrid) [3]. - Final Restart Strategy: If the above steps fail, converge the system using a minimal SZ basis set. Then, restart the calculation using the obtained density as the initial guess for a larger, target basis set (e.g., DZP or TZP) [18].

Protocol 2: Basis Set Optimization and Dependency Resolution

This protocol guides the process of refining a basis set to avoid linear dependency.

- Identify the Problem: When a "dependent basis" error occurs, examine the output file for the smallest eigenvalue of the overlap matrix and the list of "Dependency Coefficients" [3].

- Apply Confinement: As a first remedy, add a

Confinementpotential to the basis sets of atoms identified as having diffuse functions (often those with the largest dependency coefficients). In a slab, prioritize atoms in the inner layers [3]. - Remove Functions: If confinement is insufficient or undesirable, remove the basis function(s) with the largest dependency coefficient(s). If two functions have similarly large coefficients, consider replacing them with a single, averaged function [3].

- Iterate: Repeat steps 1-3. Solving the dependency for one k-point may reveal problems at another k-point. Continue the process until all k-points pass the dependency check [3].

Essential Code Snippets and Input Parameters

Conservative SCF and DIIS Settings:

Improved Numerical Quality:

Automation for Geometry Optimization: This automation relaxes SCF criteria in the early stages of optimization for faster convergence, tightening them as the geometry improves [18].

Frequently Asked Questions