Quantum Confinement and Surface Electronics in Perovskite Quantum Dots: Fundamentals, Biomedical Applications, and Challenges

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how quantum confinement effects govern the surface electronic and optical properties of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), with a specific focus on implications for...

Quantum Confinement and Surface Electronics in Perovskite Quantum Dots: Fundamentals, Biomedical Applications, and Challenges

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how quantum confinement effects govern the surface electronic and optical properties of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), with a specific focus on implications for biomedical research and drug development. We explore the foundational principles of zero-dimensional confinement in PQDs, detailing how size and surface chemistry tune band gaps and create unique photophysical properties. The content covers advanced synthesis methodologies and functionalization strategies that enable applications in targeted drug delivery, bioimaging, and theranostics. A significant portion is dedicated to addressing critical challenges such as surface instability, toxicity, and biocompatibility, while also reviewing computational and experimental validation techniques, including the emerging role of machine learning for accurate property prediction. This resource is tailored for researchers and scientists seeking to harness PQDs for advanced clinical applications.

The Quantum Realm: Unraveling Confinement and Surface Dynamics in Perovskite Nanostructures

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) represent a class of zero-dimensional semiconductor nanocrystals that exhibit distinct chemical, physical, electrical, and optical properties compared to their bulk counterparts, primarily due to quantum confinement effects [1]. These materials are typically 2-10 nanometers in diameter, falling within the range where quantum mechanical effects dominate over classical physics [2] [3]. When a quantum dot is illuminated by UV light, an electron can be excited to a higher energy state, corresponding to the transition from the valence band to the conduction band in semiconducting materials [4]. The subsequent relaxation of this electron back to the valence band releases energy as light, a process known as photoluminescence, with the specific color determined by the energy difference between discrete quantum mechanically allowed energy levels [4].

The quantum confinement effect occurs when the size of PQDs is less than or equal to the Bohr exciton radius of the material [2]. Under these conditions, the charge carriers (electrons and holes) are spatially confined in all three dimensions, leading to discrete atomic-like energy states rather than the continuous energy bands found in bulk semiconductors [4]. This phenomenon fundamentally alters the electronic and optical properties of the material, making the electronic wave functions in quantum dots resemble those in real atoms, hence the description of quantum dots as "artificial atoms" [4]. For PQDs, this quantum confinement enables precise tuning of their band gap through size control—smaller dots emit higher energy photons (bluer light) while larger dots emit lower energy photons (redder light) [4]. This size-dependent tunability, combined with their high quantum yield and solution processability, makes PQDs highly promising for applications spanning photovoltaics, light-emitting diodes, lasers, and quantum technologies [1] [3].

Fundamental Principles of Zero-Dimensional Confinement

Quantum Confinement Theory

The electronic structure of quantum dots is governed by the quantum confinement effect, which becomes significant when the particle size approaches or falls below the Bohr exciton radius of the semiconductor material [2]. In bulk semiconductors, electrons and holes are bound together by Coulomb interaction to form excitons with a characteristic Bohr radius specific to the material. When the physical dimensions of the semiconductor nanocrystal become smaller than this Bohr radius, the motion of charge carriers is restricted in all three spatial dimensions, leading to discrete energy levels akin to those in atoms or molecules [4]. This phenomenon is described by the particle-in-a-box model in quantum mechanics, where the bandgap energy increases as the size of the quantum dot decreases [4].

The relationship between quantum dot size and bandgap energy can be quantitatively described for lead sulfide (PbS) PQDs using the following equation [2]:

[ E(R) = \sqrt{ Eg^2 + \frac{2h^2Eg}{m^*R^2} } ]

Where E(R) is the size-dependent bandgap, E_g is the bulk bandgap, h is Planck's constant, m* is the reduced effective mass, and R is the quantum dot radius. This size-dependent tunability of optical properties is a direct consequence of quantum confinement and forms the basis for tailoring PQDs for specific applications. As the diameter of the particle decreases, the specific surface area increases significantly, leading to a higher ratio of surface atoms with unsaturated bonds that create electronic defect states [2]. These surface states significantly influence exciton behavior and must be carefully managed through appropriate surface engineering techniques.

Surface Effects and Electronic Structure

The surface properties of PQDs have a profound impact on their electronic structure and overall performance. With decreasing size, the number of surface atoms increases dramatically, resulting in heightened surface energy and a large number of unsaturated bonds that破坏 the periodicity of the crystal lattice [2]. This leads to the formation of numerous hole and electronic defect states on the quantum dot surface [2]. Since the size of quantum dots is within the radius of the bulk exciton, the excitons in quantum dots always exist proximate to the surface, making them particularly susceptible to surface chemistry and defects [2].

Table 1: Size-Dependent Properties of Quantum Dots

| Property | Bulk Semiconductor | Quantum Dots (2-10 nm) | Impact of Reduced Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy States | Continuous bands | Discrete atomic-like levels | Size-tunable bandgap |

| Surface-to-Volume Ratio | Low | High (~30-50% surface atoms) | Enhanced surface effects |

| Exciton Location | Bulk of material | Near surface | Increased surface susceptibility |

| Optical Properties | Fixed absorption/emission | Size-tunable absorption/emission | Precise color control |

| Defect Influence | Minimal | Significant | Dominates recombination processes |

The surface effects distinguish quantum dots from bulk materials and create both challenges and opportunities for device applications [2]. Proper passivation of these surface states is crucial for achieving high performance in PQD-based devices, as unpassivated surfaces lead to non-radiative recombination pathways that diminish photoluminescence quantum yield and overall device efficiency [1].

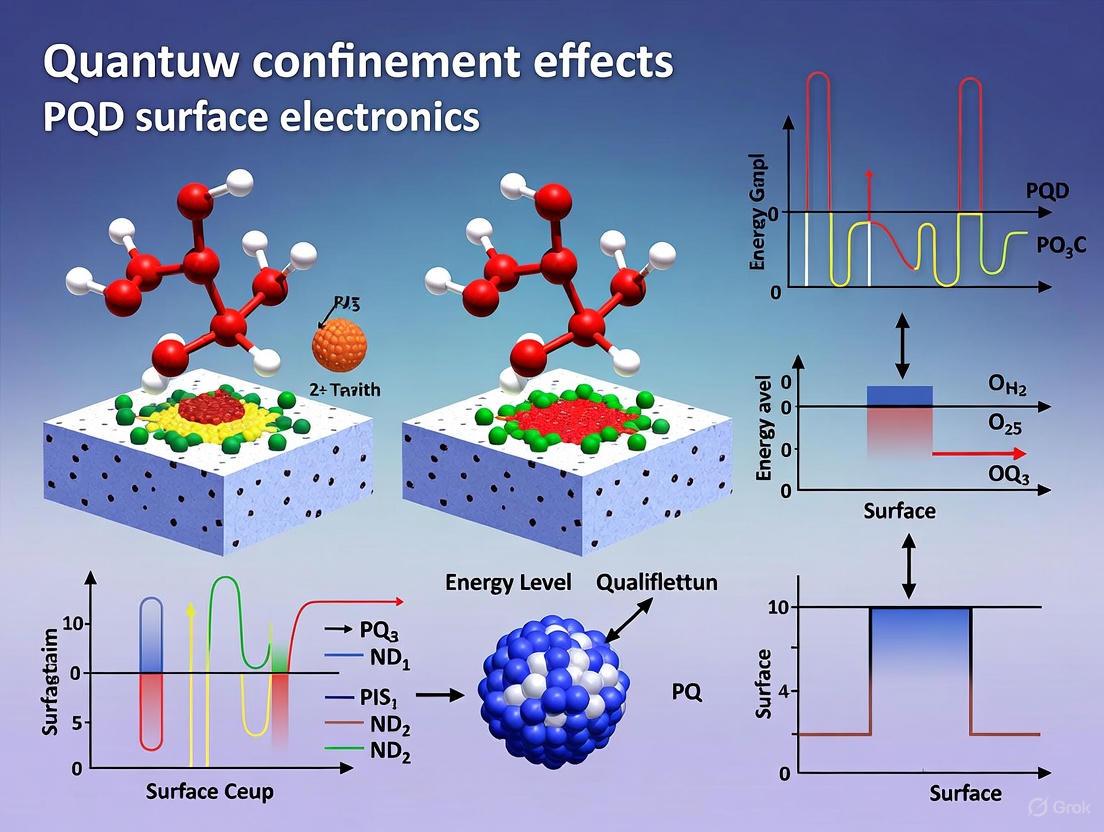

Diagram 1: Quantum confinement effects relationship map illustrating how zero-dimensional confinement influences the electronic structure and optical properties of PQDs, leading to both advantageous characteristics and challenges for applications.

Synthesis and Surface Engineering of PQDs

Colloidal Synthesis Methods

Colloidal synthesis represents the most widely employed approach for fabricating high-quality PQDs with controlled size and composition [4]. This solution-based method involves heating precursor solutions at high temperatures, causing decomposition into monomers that subsequently nucleate and generate nanocrystals [4]. Temperature control is a critical factor during synthesis as it must be sufficiently high to allow atomic rearrangement and annealing while being low enough to promote controlled crystal growth [4]. Monomer concentration represents another crucial parameter that must be stringently controlled throughout nanocrystal growth.

The growth process of PQDs occurs through two distinct regimes: "focusing" and "defocusing" [4]. At high monomer concentrations, the critical size (where nanocrystals neither grow nor shrink) is relatively small, resulting in growth of nearly all particles. In this regime, smaller particles grow faster than larger ones since larger crystals require more atoms to grow, leading to size distribution focusing that yields nearly monodispersed particles [4]. Size focusing is optimal when the monomer concentration maintains the average nanocrystal size slightly larger than the critical size. Over time, as monomer concentration diminishes, the critical size becomes larger than the average size present, and the distribution defocuses [4]. Recent advances have enabled the synthesis of colloidal perovskite quantum dots, which typically contain 100 to 100,000 atoms within the quantum dot volume, corresponding to diameters of approximately 2-10 nanometers [4].

Diagram 2: PQD colloidal synthesis workflow showing the key stages in solution-based synthesis of perovskite quantum dots, highlighting the temperature-dependent and concentration-dependent processes that control final PQD size and distribution.

Surface Ligand Engineering

Surface ligand engineering plays a pivotal role in determining the properties and stability of PQDs. Initially, long-chain organic ligands such as oleic acid (OA) and trioctyl phosphine oxide (TOPO) are employed during synthesis as surfactants to maintain colloidal stability and ensure good monodispersity [2]. However, these insulating organic ligands can impede charge transport in optoelectronic devices [2]. Consequently, post-synthetic ligand exchange processes are often employed to replace long-chain ligands with shorter alternatives that improve inter-dot coupling and charge carrier mobility while maintaining sufficient passivation of surface states.

Table 2: Surface Ligand Engineering Techniques for PQDs

| Technique | Mechanism | Key Ligands | Impact on PQD Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Ligand Exchange | Replacement of long-chain with short-chain organic ligands | MPA, EDT, BDT | Improved charge transport, maintained solubility |

| Inorganic Ligand Passivation | Coordination bonding between atoms and metal cations | Halides (I⁻, Br⁻, Cl⁻), Chalcogenides (S²⁻) | Enhanced stability, reduced trap states |

| Cation Exchange | Partial or complete replacement of surface cations | Pb²⁺, Cs⁺, FA⁺, MA⁺ | Bandgap tuning, lattice engineering |

| Core/Shell Structures | Growing semiconductor shell around PQD core | ZnS, ZnSe, SiO₂ | Defect passivation, environmental protection |

Ligand exchange processes follow distinct chemical principles depending on the approach. For organic ligand exchange, small molecules containing sulfhydryl or carboxyl groups act as Lewis bases, providing at least one electron while participating in bonding and exhibiting strong binding affinity with heavy metal cations such as lead [2]. In contrast, inorganic ligand passivation typically involves halide anions or chalcogenides that form direct coordination bonds with surface metal atoms [2]. These inorganic ligands often provide superior passivation of surface traps and enhanced stability compared to their organic counterparts.

For particularly challenging applications, core/double-shell systems have been developed, such as CdSe/ZnSe/ZnS nanocrystals, where an intermediate ZnSe layer reduces lattice mismatch between the CdSe core and ZnS outer shell, improving fluorescent efficiency by 70% compared to single-shell structures [4]. These sophisticated architectures significantly enhance resistance against photo-oxidation, which contributes to degradation of emission spectra in PQDs [4].

Characterization and Experimental Methodologies

Structural and Optical Characterization

Comprehensive characterization of PQDs requires multiple complementary techniques to correlate structural properties with optical behavior and electronic characteristics. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) provides direct visualization of quantum dot size, shape, and distribution, with high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) enabling atomic-scale analysis of crystal structure and defects [3]. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns reveal information about crystal phase, strain, and preferential orientation in PQD films [3].

Optical characterization techniques include ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy for determining absorption onset and bandgap energy, and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy for evaluating emission properties, quantum yield, and lifetime [3]. The photoluminescence quantum yield (PL QY) represents a critical parameter defined as the ratio of emitted to absorbed photons, with high-quality PQDs typically exhibiting values exceeding 70-80% when properly passivated [3]. Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) provides insights into charge carrier dynamics, including recombination pathways and trap states.

Table 3: Key Characterization Techniques for PQD Analysis

| Technique | Parameters Measured | Information Obtained | Typical Values for PQDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEM/HRTEM | Size, morphology, lattice fringes | Size distribution, crystallinity, defects | 2-10 nm diameter, spherical shape |

| XRD | Diffraction peak positions, widths | Crystal structure, phase purity, strain | Cubic perovskite phase, peak broadening |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Absorption onset, excitonic peaks | Bandgap energy, quantum confinement | Bandgap tunable from 1.7-3.0 eV |

| PL Spectroscopy | Emission wavelength, intensity, FWHM | Optical quality, defect states, quantum yield | FWHM: 20-40 nm, QY: 70-90% |

| XPS | Elemental composition, binding energy | Surface chemistry, oxidation states, ligand binding | Pb 4f, I 3d, Cs 3d core levels |

Surface-Specific Analytical Techniques

Surface-specific characterization is particularly important for PQDs due to the significant influence of surface states on their optoelectronic properties. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) provides quantitative information about elemental composition, chemical states, and the effectiveness of surface ligand binding [3]. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) identifies organic functional groups and confirms successful ligand exchange processes through characteristic vibrational modes [3].

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) and Spectroscopy (STS) enable direct probing of electronic structure at the single quantum dot level, mapping local density of states and identifying surface trap states with atomic-scale resolution [3]. For investigating dynamic processes at PQD surfaces, time-resolved electrical measurements including impedance spectroscopy and transient photovoltage/photocurrent decay provide insights into charge separation, transport, and recombination kinetics at interfaces [3].

Applications and Performance Metrics

Optoelectronic Devices

PQDs have found diverse applications across multiple optoelectronic domains due to their exceptional properties. In photovoltaics, quantum dot-sensitized solar cells (QDSSCs) leverage the size-tunable bandgap of PQDs to optimize sunlight harvesting [3]. Recent advances have demonstrated power conversion efficiencies (PCE) exceeding 16% for single-junction devices, with theoretical models suggesting potential efficiencies above 30% for tandem architectures [3] [5]. The key advantages of PQDs in photovoltaics include their bandgap tunability, potential for multiple exciton generation, and compatibility with low-cost solution processing techniques [3].

In light-emitting applications, PQD-based light-emitting diodes (LEDs) have achieved external quantum efficiencies (EQE) over 20% with exceptionally pure color emission [1] [3]. Their narrow emission bandwidth (typically 20-40 nm full width at half maximum) enables wide color gamuts exceeding 100% of the NTSC standard for display applications [3]. For lighting applications, PQD-based white LEDs demonstrate high color rendering index (CRI > 90) and tunable correlated color temperature (CCT) [3]. Additionally, PQDs have shown promising performance in laser diodes (LDs), reaching threshold currents compatible with practical applications, and in photodetectors with responsivities competitive with conventional semiconductor technologies [2] [3].

Emerging Applications and Research Frontiers

Beyond conventional optoelectronics, PQDs are enabling emerging technologies in several frontier domains. In quantum information technologies, PQDs serve as single-photon sources with high purity and indistinguishability, critical requirements for quantum computing and quantum cryptography applications [1]. Their quantum confinement enables triggered single-photon emission with g(2)(0) values below 0.1, approaching the ideal single-photon source characteristic [1].

In biological imaging and sensing, the narrow emission spectra, high brightness, and photostability of PQDs provide advantages over traditional organic fluorophores [3]. Recent developments have produced PQDs with biocompatible coatings that maintain high quantum yield in aqueous environments while reducing potential toxicity concerns [3]. For infrared imaging applications, PbS-based PQDs have enabled focal plane arrays with pixel counts up to 512 × 640, achieving detectivity values exceeding 10¹² Jones at 970 nm wavelength while operating at elevated temperatures [2].

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Synthesis and Fabrication

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salts | PbBr₂, PbI₂, Cs₂CO₃, FAI, MABr | Source of metal and halide ions | Purity affects defect formation, hygroscopicity |

| Organic Solvents | DMF, DMSO, GBL, Toluene, Octane | Dissolving precursors, reaction medium | Boiling point, coordinating ability, purity |

| Surface Ligands | Oleic Acid, Oleylamine, TOPO | Colloidal stability, size control | Chain length affects inter-dot distance |

| Short-Chain Ligands | MPA, EDT, BDT | Ligand exchange for charge transport | Binding affinity, passivation quality |

| Inorganic Passivators | PbBr₂, ZnBr₂, CdI₂ | Defect passivation, surface termination | Solubility in processing solvents |

| Antisolvents | Ethyl Acetate, Methyl Acetate, Butanol | Precipitation and purification | Polarity, miscibility with reaction solvent |

The selection and quality of research reagents significantly influence the properties and performance of resulting PQDs. High-purity precursor salts (≥99.99%) are essential for minimizing unintentional doping and defect formation [2] [4]. Solvents must be rigorously dried and purified to prevent hydrolysis and oxidation during synthesis, with oxygen-free environments maintained using standard Schlenk line or glovebox techniques [4]. Ligand purity and precise stoichiometric ratios critically determine surface chemistry and defect passivation efficacy [2].

For specialized applications, additional reagents may be required. In core/shell PQD synthesis, shell precursors such as zinc stearate or cadmium oleate enable the growth of protective semiconductor layers [4]. For inorganic ligand exchange, metal chalcogenide complexes including (NH₄)₄Sn₂S₆ or Na₄SnS₄ provide chalcogenide ions for surface coordination [2]. In cation exchange processes, metal salts like silver nitrate or cadmium perchlorate enable partial cation substitution for band structure engineering [2].

Zero-dimensional confinement in PQDs creates exceptional optoelectronic properties that can be strategically harnessed through precise control of size, composition, and surface chemistry. The discrete energy levels resulting from quantum confinement enable size-tunable bandgaps, while the high surface-to-volume ratio necessitates sophisticated surface engineering approaches to mitigate defect states [2] [1]. Colloidal synthesis methods provide versatile routes to high-quality PQDs with narrow size distributions, while ligand engineering strategies address the critical challenge of balancing stability against charge transport requirements [2] [4].

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in fully leveraging zero-dimensional confinement in PQDs. The translation of PQDs into commercially viable technologies is currently hindered by insufficient understanding of formation mechanisms, complex surface chemistry, dynamic instabilities at PQD surfaces, and inefficient charge transport in PQD-based devices [1]. Future research directions should prioritize developing more comprehensive structure-property relationships through advanced in situ characterization techniques, designing multifunctional ligands that simultaneously optimize passivation and transport properties, and establishing standardized protocols for accelerated stability testing under operational conditions [1] [6]. As these fundamental challenges are addressed, PQDs are positioned to enable transformative technologies across photovoltaics, displays, quantum information processing, and biological imaging, ultimately fulfilling their potential as versatile quantum-confined nanomaterials [1] [3].

This technical guide explores the fundamental principle of quantum confinement and its divergent impacts on the core versus surface electronic structure of semiconductor nanocrystals, with a focus on perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). When material dimensions approach the quantum regime, the electronic wavefunctions become spatially confined, leading to discrete energy levels and a widening bandgap in the core. Concurrently, the surface atoms, possessing incomplete coordination, introduce localized states that can dominate charge carrier dynamics. Framed within ongoing research on PQDs, this review synthesizes how the interplay between core confinement and surface chemistry dictates optoelectronic properties. We provide a quantitative analysis of these effects, detailed experimental methodologies for their investigation, and visualizations of the underlying physics to equip researchers with the tools to harness these phenomena in advanced applications.

Quantum confinement is a phenomenon observed in semiconductor nanostructures, such as quantum dots (QDs), nanowires, and two-dimensional monolayers, when the physical size of the material is reduced to a scale comparable to the Bohr exciton radius of the electron-hole pair [7]. Under these conditions, the charge carriers (electrons and holes) experience spatial confinement in one or more dimensions, leading to a transition from continuous energy bands to discrete atomic-like energy states.

This spatial restriction of the electron and hole wavefunctions results in several key consequences for the material's electronic structure, the most prominent being a widening of the fundamental band gap ((Eg)) as the size of the nanostructure decreases. The electronic and optical properties (band gap, band structure, excited state energy) exhibited by semiconductor nanocrystals of the same chemical composition are found to vary significantly as a function of their size, a direct result of the quantum confinement effect [7]. This effect takes place when the crystal size is smaller than or comparable to the Bohr radius ((aB)), which is a material-specific constant; for example, (a_B) is about 2.34 nm for CdTe and can be as large as 10 nm for related Cd-compounds [7].

The confinement of an electron and hole in nanocrystals significantly depends on these material properties. In the strong confinement regime, where the nanoparticle radius (R) is much smaller than (a_B), the energy of the exciton can be described by models that modify the bulk properties with terms accounting for the kinetic energy of confinement, the Coulomb interaction, and correlation energy [7].

Core Electronic Structure Under Confinement

The core electronic structure of a quantum-confined semiconductor is primarily governed by the particle-in-a-box model, where the potential energy is considered infinite at the boundaries of the nanocrystal. This spatial confinement forces the electron and hole wavefunctions to adopt standing-wave patterns, leading to quantized energy levels.

Theoretical Foundations

In a simplified effective mass model, the exciton energy ((E_x)) for a spherical nanocrystal of radius (R) is given by:

Equation 1: [ Ex = Eg(\text{bulk}) + \frac{\hbar^2 \pi^2}{2R^2} \left( \frac{1}{me} + \frac{1}{mh} \right) - \frac{1.786}{\epsilon R} - 0.248E_{Ry} ] where:

- (E_g(\text{bulk})) is the bulk band gap,

- (me) and (mh) are the effective masses of the electron and hole, respectively,

- (\epsilon) is the dielectric constant,

- (E_{Ry} = \mu e^4 / 2\epsilon^2 \hbar^2) is the effective Rydberg energy, with (\mu) being the reduced mass of the electron-hole pair [7].

The second term represents the kinetic energy of confinement, which is the dominant factor causing band gap widening. The third and fourth terms account for the Coulomb attraction and correlation energy, respectively.

Quantitative Impact of Size Reduction

The following table summarizes the effect of quantum confinement on core electronic properties across different semiconductor materials.

Table 1: Impact of Quantum Confinement on Core Electronic Properties of Selected Semiconductors

| Material | Bulk Band Gap (eV) | Bohr Radius (nm) | Nanocrystal Size (nm) | Resulting Band Gap (eV) | Key Phenomenon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdS (II-VI) | ~2.4 | ~3.0 [7] | 2.0 | ~3.1 | Band gap increase, blue-shifted photoluminescence [7] |

| CdTe (II-VI) | ~1.5 | ~2.34 [7] | 4.0 | ~1.9 | Fluorescent color variation with tiny size differences [7] |

| PbS (IV-VI) | ~0.4 | ~18.0 | 5.0 | ~1.2 | Strong confinement enabling infrared tuning [8] |

| 2D Monolayer (WS₂) | ~1.3 (indirect, bulk) | N/A | Single Layer | ~2.1 (direct) | Indirect-to-direct band gap transition [8] |

For more accurate predictions, especially in small clusters where the effective mass approximation breaks down, microscopic approaches like the empirical pseudopotential method (EPM) are employed [7]. The EPM solves the Schrödinger equation for the crystal using empirically derived atomic potentials, providing a more precise description of the electronic density of states and band structures that are sensitive to the exact atomic lattice of the nanocrystal [7].

Surface Electronic Structure and Ligand Interactions

While quantum confinement dictates the core electronic structure, the surface properties of quantum dots are equally critical. The high surface-to-volume ratio of nanocrystals means a significant fraction of atoms resides on the surface, where they possess dangling bonds and incomplete coordination. These surface states can introduce trap levels within the band gap, leading to non-radiative recombination and quenching of photoluminescence, which often undermines the beneficial effects of quantum confinement.

The Role of Surface Chemistry

The electronic passivation of these surface states is achieved through chemical bonding with organic or inorganic ligands. The nature of this ligand-shell directly influences the optoelectronic properties of the QD. For instance, in lead sulfide (PbS) QDs, replacing native oleate ligands with tetracenedicarboxylate molecules can induce strong electronic coupling [8]. Studies involving comprehensive Fourier-transform infrared analysis, ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy, and density functional theory simulations have shown that ligands adopting a geometry parallel to the nanocrystal facet can split absorption bands by up to 700 meV and enable instantaneous energy transfer from the ligand to the QD [8].

Surface Doping and Phase Engineering

Beyond passivation, surface interactions can be used to actively engineer electronic properties. Research on molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) monolayers has demonstrated that treatments with n-butyl lithium can lead to heavy n-type doping or even a phase conversion from the semiconducting (2H) phase to a metallic/semi-metallic (1T/1T') phase, depending on immersion time [8]. This surface-functionalized state, stabilized by adding specific surface groups, can be maintained for over two weeks, enabling the integration of these monolayers into air-exposed devices like gas sensors and field-effect transistors [8].

Table 2: Surface-Mediated Phenomena and Experimental Outcomes in Quantum-Confined Systems

| Material System | Surface Intervention | Experimental Observation | Impact on Electronic Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| PbS Quantum Dots [8] | Solid-state ligand exchange with tetracenedicarboxylate | Absorption bands split by up to 700 meV; altered photophysics | Strong coupling model; control over energy/charge transfer |

| MoS₂ Monolayers [8] | n-butyl lithium treatment + surface functionalization | Phase conversion (2H to 1T/1T'); heavy n-type doping | Creation of stable metallic or heavily doped semiconducting 2D layers |

| WS₂ Monolayers [8] | Exposure to O₂ vs. H₂O vapor under illumination | Photoluminescence increase & red-shift (O₂) vs. overall increase (H₂O) | Trion vs. exciton emission dominance; application as humidity sensor |

| 2D Perovskite (PEA)₂PbI₄ [8] | Coupling to cavity polaritons in a Fabry-Pérot microcavity | Increased recombination lifetime; controlled exciton/exciton annihilation | Reduced interaction model due to increased photonic character |

Experimental Protocols for Probing Core and Surface States

Distinguishing the contributions of the quantum-confined core and the complex surface requires a multifaceted experimental approach. The following protocols outline key methodologies for characterizing these effects.

Synthesis of Quantum-Confined Nanocrystals

Protocol: Hot-Injection Method for PbS Quantum Dots

- Preparation: In a three-neck flask, degas lead oxide (PbO) and oleic acid (OA) in 1-octadecene (ODE) under inert gas (e.g., N₂ or Ar) at 120°C for one hour.

- Reaction: Raise the temperature to 150°C until a clear solution is formed, indicating the formation of lead oleate.

- Injection: Rapidly inject a solution of bis(trimethylsilyl) sulfide (TMS)₂S dissolved in ODE.

- Growth: Allow the reaction to proceed for 30-120 seconds to control the nanocrystal size. The growth can be monitored by extracting aliquots and measuring the absorption onset.

- Termination: Cool the reaction mixture rapidly by placing the flask in a cold water bath.

- Purification: Precipitate the QDs by adding a non-solvent (e.g., acetone or ethanol), followed by centrifugation. Redisperse the pellet in a non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene or hexane). Repeat this process 2-3 times.

Solid-State Ligand Exchange for Surface Studies

Protocol: Investigating Ligand-QD Electronic Coupling [8]

- Film Fabrication: Cast a thin film of as-synthesized PbS QDs (with bound oleate ligands) onto a substrate via spin-coating.

- Ligand Exchange: Immerse the solid film in a solution of the new ligand (e.g., tetracenedicarboxylate) for a controlled duration (e.g., 1-24 hours). This substitutes the original oleate ligands in the solid state, which is often necessary when the exchange destabilizes QDs in solution.

- Rinsing: Gently rinse the film with a pure solvent to remove any physisorbed ligand molecules.

- Characterization: Analyze the film using:

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: To confirm ligand binding and identify binding modes.

- Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy: To observe changes in the absorption spectrum, including band splitting or shifts.

- Transient Absorption (TA) Spectroscopy: To probe ultrafast energy transfer and charge carrier dynamics.

Probing the Electronic Structure

Protocol: Ultrafast Spectroscopy for Charge Transfer Dynamics

- Sample Preparation: Fabricate the heterostructure of interest, such as a mixed-dimensionality trilayer (2D TMDC/1D carbon nanotube/2D TMDC) [8].

- Pump-Probe Setup: Use a femtosecond laser system split into a pump beam (to photoexcite the sample) and a delayed probe beam (to monitor the sample's response).

- Data Acquisition: Measure the transient reflection or transmission of the probe beam as a function of the time delay after the pump pulse.

- Analysis: Fit the kinetic traces at various wavelengths to extract charge transfer times (often in the femtosecond to picosecond range) and charge recombination lifetimes (which can exceed microseconds in optimized systems) [8].

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Quantum Confinement and Surface Effects

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental concepts of core quantum confinement and surface interactions discussed in this guide.

Diagram 1: The divergent effects of quantum confinement on the core and surface electronic structure of a semiconductor nanocrystal.

Experimental Workflow for Surface Study

This diagram outlines a standard experimental workflow for modifying and characterizing QD surfaces, as described in the protocols.

Diagram 2: A combined experimental and theoretical workflow for investigating surface ligand effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for research in quantum-confined semiconductors, particularly for surface electronics studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Quantum Confinement and Surface Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Oxide (PbO) & Bis(trimethylsilyl) sulfide ((TMS)₂S) | Precursors for the synthesis of PbS quantum dot cores. | Acts as the lead and sulfur source, respectively, in the hot-injection synthesis of size-tunable PbS QDs [8]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | A common surface ligand (surfactant) used during synthesis. | Coordinates with surface Pb atoms, providing colloidal stability in non-polar solvents and passivating surface states [8]. |

| n-Butyl Lithium | A strong reducing agent used for chemical doping. | Heavily n-type dopes or phase-converts transition metal dichalcogenide (e.g., MoS₂) monolayers [8]. |

| Tetracenedicarboxylate Ligands | Aromatic molecules for advanced surface functionalization. | Enables strong electronic coupling with PbS QD surfaces, altering photophysics and enabling energy transfer [8]. |

| 4-(2,2-dicyanovinyl)cinnamic acid | A hydrophilic ligand for creating amphiphilic structures. | Used alongside oleic acid to construct Janus-ligand shells on PbS QDs for forming stable Pickering emulsions [8]. |

| Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD)-Grown TMDCs | High-quality two-dimensional semiconductor substrates. | Used in mixed-dimensionality heterostructures (e.g., with carbon nanotubes) to study ultrafast charge transfer cascades [8]. |

The electronic structure of quantum-confined semiconductors is a tapestry woven from two distinct yet inseparable threads: the core, governed by the fundamental physics of spatial confinement, and the surface, dominated by complex chemical interactions. As detailed in this guide, quantum confinement in the core systematically enlarges the band gap and quantizes energy levels, while the surface landscape, sculpted by ligands and environmental factors, introduces localized states that can either quench or enable novel optoelectronic phenomena. The future of PQD and nanomaterial research lies in moving beyond treating these components in isolation. The most promising advancements, such as strong light-matter coupling in cavities or engineered charge transfer in heterostructures, emerge from the synergistic control of both core and surface electronic states. Mastering this synergy is the key to unlocking the full potential of these materials in next-generation photovoltaics, quantum light sources, and spin-based electronic devices.

The Role of Surface Chemistry and Functional Groups on Electronic Properties

The exploration of quantum confinement effects in semiconductor nanocrystals has fundamentally advanced our understanding of size-tunable electronic and optical properties. While quantum confinement dictates the fundamental band gap of these materials, emerging research reveals that surface chemistry and functional groups play an equally critical role in modulating electronic properties, particularly in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) where surface states dominate charge carrier dynamics. This technical guide examines how strategic surface functionalization serves as a powerful tool for engineering electronic structures, enabling precise control over properties essential for optoelectronic applications and quantum information technologies.

The intrinsic quantum confinement effect in PQDs creates discrete electronic energy levels and size-dependent band gaps, establishing the foundational electronic structure. However, the high surface-to-volume ratio of these nanoscale systems means that a significant portion of atoms reside at the surface, where disrupted periodic potentials create dangling bonds and surface states that can trap charge carriers, facilitating non-radiative recombination and degrading device performance. Surface chemistry management through functional groups provides a methodological framework to pacify these reactive surfaces, engineer interface dipoles, and control interparticle interactions in assembled superlattices.

This review synthesizes current understanding of how specific functional groups—including hydrogen, oxygen, fluorine, hydroxyl, amines, and carboxyl groups—influence electronic properties through various mechanisms including surface passivation, dipole formation, charge transfer, and structural modification. We further provide quantitative analyses and experimental methodologies for researchers pursuing surface engineering of PQDs for enhanced performance in photovoltaics, light-emitting diodes, and quantum computing applications.

Theoretical Foundations

Quantum Confinement and Surface Effects

The electronic structure of quantum dots is governed by the interplay between quantum confinement and surface chemistry. Quantum confinement effects become significant when the particle size approaches the exciton Bohr radius, resulting in discrete energy levels and a size-tunable band gap. However, the high surface-to-volume ratio means surface atoms significantly influence overall electronic behavior.

The surface atoms experience a broken symmetry compared to the bulk crystal structure, creating dangling bonds and surface states within the band gap. These states can act as traps for charge carriers, leading to increased non-radiative recombination and reduced quantum efficiency. Proper surface functionalization passivates these dangling bonds, shifting surface states out of the band gap or enabling efficient radiative recombination.

Electronic Structure Modification Mechanisms

Surface functional groups influence electronic properties through several fundamental mechanisms:

- Surface Passivation: Termination of dangling bonds with appropriate functional groups eliminates mid-gap states, reducing charge carrier trapping. First-principles calculations demonstrate hydrogen termination effectively passivates surface states in PbS QDs [9].

- Dipole Formation: Functional groups with different electronegativities create surface dipoles that modify energy level alignment at interfaces. These dipoles significantly impact charge injection and extraction in optoelectronic devices.

- Charge Transfer: Electron-donating or withdrawing groups directly modify the charge carrier density in quantum dots, enabling n-type or p-doping effects.

- Structural Distortion: Surface bonding can induce structural relaxations that propagate to the quantum dot core, indirectly modifying electronic structure through strain effects.

Table 1: Fundamental Mechanisms of Surface-Mediated Electronic Structure Modification

| Mechanism | Physical Origin | Primary Electronic Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Passivation | Elimination of dangling bonds | Reduction of trap states, enhanced PLQY |

| Dipole Formation | Electronegativity differences between surface atoms and functional groups | Band bending, work function modification |

| Charge Transfer | Electron donation/withdrawal | Doping, Fermi level shifting |

| Structural Distortion | Surface stress and lattice deformation | Band gap modification, polarization effects |

Quantitative Effects of Surface Functionalization

Functional Group Effects on Electronic Properties

Surface termination with different functional groups systematically modulates electronic structure parameters. Time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) studies on MXene quantum dots (Ti₂CT₂) reveal how varying surface terminations (T = O, F, OH) induces notable shifts in both energy gap and absorption spectra [10].

Table 2: Electronic Properties of MXene Quantum Dots with Different Surface Terminations

| Surface Functional Group | Band Gap (eV) | Absorption Range | Stability | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen (-O) | Largest gap | UV region | Highest | Large energy separation, high stability |

| Hydroxyl (-OH) | Intermediate | Visible region | Moderate | Red-shifted absorption |

| Fluorine (-F) | Smallest gap | Near-infrared | Lower | Extended absorption range |

Similar effects are observed in PbS QDs, where hydrogen functionalization introduces shallow defect states near band edges rather than deep-level traps, maintaining electronic integrity while modifying optoelectronic properties [9]. Hydrogenation also stabilizes simple cubic superlattice structures with direct band gaps and interband states, contrasting with stoichiometric nanoparticle assemblies.

Size-Dependent Surface Effects

Quantum dot size significantly influences the impact of surface functionalization. Studies on Ti₂CO₂ QDs demonstrate a pronounced blue shift in absorption spectra as dot size decreases to ~1-2 nm, coupled with increased exciton binding energy up to 75% of the energy gap [10]. This enhanced exciton confinement results from strong quantum coupling effects in small QDs, where excitons delocalize across the entire quantum dot.

The binding energy of the first exciton in functionalized MXene QDs far exceeds typical values in corresponding 2D materials (~25%), critically influencing optical absorption intensity and spectral position [10].

Experimental Methodologies

Computational Investigation Techniques

First-principles density functional theory (DFT) with van der Waals corrections provides atomic-level understanding of surface functionalization effects. The standard computational workflow includes:

Diagram 1: Computational Methodology Workflow

Model Creation: Construct stoichiometric QD models by truncating bulk crystal structures. For PbS QDs, a symmetric stoichiometric cluster of 28 Pb and 28 S atoms (~1 nm size) embedded in a large cubic supercell (30 Å side length) minimizes spurious periodic interactions [9].

Geometry Optimization: Employ plane-wave basis sets with projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials. Set kinetic energy cutoff to 60 Ry for wavefunctions and 360 Ry for charge density. Use the PBE functional for geometry relaxation until forces are below 0.001 Ry/au [9].

Electronic Structure Calculation: Utilize hybrid functionals (HSE06) for more accurate band gap prediction after geometry optimization. Incorporate van der Waals corrections for proper treatment of dispersive forces in superlattice formations [9].

Property Analysis: Calculate projected density of states (PDOS), band structures, charge density differences, and optical absorption spectra. Analyze surface state distribution and functional group contributions to electronic properties.

Experimental Validation: Correlate computational predictions with experimental measurements from techniques such as scanning quantum dot microscopy (SQDM) and photoluminescence spectroscopy [11].

Scanning Quantum Dot Microscopy (SQDM)

SQDM enables quantitative imaging of electric surface potentials with single-atom resolution, providing experimental validation of surface functionalization effects:

Diagram 2: SQDM Imaging Process

Protocol Details:

QD Functionalization: Attach a single molecule quantum dot sensor to the tip of a non-contact atomic force/scanning tunneling microscope (NC-AFM/STM) through controlled manipulation [11].

Surface Approach: Maintain constant height during scanning while measuring the sample bias V± required to maintain the QD at its charging potential Φ±.

Image Processing: Calculate the relative gating efficiency α_rel(r) and equivalent bias potential V*(r) using the relationships:

- α_rel(r) = (V₀⁺ - V₀⁻)/(V⁺(r) - V⁻(r))

- V*(r) = V₀⁻/α_rel(r) - V⁻(r) where V₀± represents reference values [11].

Surface Potential Extraction: Deconvolve V*(r) with the point spread function of the measurement to obtain the quantitative surface potential distribution Φ_s(r') with atomic resolution.

This technique successfully measures work function changes and dipole moments for surface-functionalized systems, providing direct experimental verification of theoretical predictions [11].

Polymerization-Induced Direct Photolithography

Direct photolithography enables patterning of functionalized QDs for device integration through polymerization-based approaches:

Photochemical Reaction Setup:

- Prepare QD-polymer composite solution with photoactive functional groups (alkenes, alkynes, or disulfides) on QD surface ligands [12].

- Deposit thin film via spin-coating or blade-coating.

- Expose to patterned UV light (typically 365 nm) to initiate radical polymerization or cycloaddition reactions.

- Develop pattern by removing unexposed regions with selective solvent.

Key Advantages: This method eliminates sacrificial photoresist layers, minimizing solvent damage to QDs and preserving photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) while enabling high-resolution patterning [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Surface Functionalization Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Passivation Agents | Surface defect passivation | Creating shallow defect states in PbS QDs [9] |

| Oxygen Functionalization | Band gap widening, stability enhancement | MXene QDs with large energy separation [10] |

| Halide Terminations (F, Cl, Br, I) | Band gap reduction, absorption extension | Near-infrared absorption in Ti₂CF₂ QDs [10] |

| Hydroxyl Groups | Intermediate electronic effects | Visible light absorption in Ti₂C(OH)₂ QDs [10] |

| Amine-containing Ligands | Electron donation, n-type doping | Charge carrier density modification [13] |

| Carboxylic Acids | Electron withdrawal, p-type doping | Energy level alignment [14] |

| Thiol Ligands | Strong surface binding, passivation | Trap state reduction in PbS QDs [9] |

| Polymerizable Monomers | Pattern formation, device integration | Direct photolithography of QD arrays [12] |

Surface chemistry and functional groups fundamentally modulate the electronic properties of quantum-confined systems through multiple mechanisms including surface passivation, dipole formation, charge transfer, and structural distortion. Strategic surface functionalization enables precise engineering of band gaps, absorption ranges, exciton binding energies, and charge transport properties. Computational approaches using van der Waals-corrected DFT combined with experimental techniques like SQDM provide comprehensive characterization of these effects at the atomic scale. As quantum dot technologies advance toward broader optoelectronic and quantum information applications, mastery of surface chemistry will remain indispensable for optimizing device performance and enabling novel functionalities.

An exciton is a bound electron-hole pair, a fundamental quasiparticle that forms when a semiconductor absorbs light, prompting an electron to jump to the conduction band and leave a positively charged hole in the valence band. The Coulomb attraction between these two opposite charges binds them together. The energy required to dissociate this bound pair into a free electron and a free hole is defined as the exciton binding energy (Eb). This parameter is critical as it determines the thermal stability of the exciton and significantly influences the optoelectronic properties of a material, including its photoluminescence efficiency and lasing thresholds.

The phenomenon of quantum confinement occurs when the physical dimensions of a material are reduced to a scale comparable to the Bohr radius of its exciton. In such confined systems, such as quantum dots (QDs) or two-dimensional (2D) materials, the continuous energy bands of the bulk material become discrete, atomic-like energy levels. This spatial restriction of the charge carriers leads to two major consequences for excitons:

- Increased Exciton Binding Energy: The confined electron and hole are forced to occupy a smaller volume, which enhances their Coulomb interaction and consequently stabilizes the exciton, leading to a significant increase in Eb.

- Size-Dependent Optical Properties: As the size of the nanocrystal decreases, the energy gap between these discrete levels widens, resulting in a blue shift of the absorption and emission spectra.

Studying excitonic effects in confined systems is therefore paramount for the development of advanced optoelectronic devices, including light-emitting diodes (LEDs), lasers, and photodetectors.

Theoretical Framework: Exciton Binding in Low Dimensions

The strength of excitonic effects is profoundly affected by the dimensionality of a system. The degree of spatial confinement dictates how the electron and wavefunctions are restricted, which in turn governs their Coulomb interaction.

In three-dimensional (3D) bulk semiconductors, confinement is weak, and excitons are typically stable only at low temperatures. The Bohr model is often used to describe them, and their binding energy is relatively modest. In two-dimensional (2D) materials, such as monolayers of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), charge carriers are confined in one dimension. This drastically enhances the electron-hole interaction, leading to exciton binding energies that are orders of magnitude larger than those in their 3D counterparts, often reaching hundreds of meV, making them stable at room temperature.

In one-dimensional (1D) nanotubes and nanowires, and especially in zero-dimensional (0D) quantum dots (QDs), the confinement is even stronger. The exciton is squeezed in all spatial directions, forcing the electron and hole into close proximity. This results in a dramatic increase in the exciton binding energy. For instance, in MXene quantum dots (MXQDs) with lateral sizes of ~1–2 nm, the binding energy of the first exciton can achieve values as high as 75% of the material's energy gap, a stark contrast to the typical ~25% found in corresponding 2D materials [10]. This highlights the critical role of exciton confinement in tailoring optical properties.

Experimental Manifestations and Key Studies

Exciton Confinement in MXene Quantum Dots

Recent research on Ti₂CT₂ MXene quantum dots (where T = O, F, OH) has quantitatively demonstrated the profound impact of quantum dot size and surface chemistry on excitonic properties. A key finding is that the exciton binding energy (Eb) scales inversely with the quantum dot size. As the lateral dimensions of the QDs shrink, the spatial confinement of the electron and hole wavefunctions intensifies, leading to a substantial increase in Eb [10].

Table 1: Effect of Surface Functionalization on Ti₂CT₂ MXQDs Optical Properties [10]

| Surface Termination | Stability | Energy Gap | Absorption Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen (O) | Highest | Largest | Blue-shifted absorption |

| Hydroxyl (OH) | Moderate | Reduced | Shifted towards visible and near-infrared regions |

| Fluorine (F) | Lower | Reduced | Shifted towards visible and near-infrared regions |

Furthermore, the surface termination groups play a critical role by modifying the electronic structure and the dielectric environment. For example, oxygen-terminated dots exhibit the largest energy gap and highest stability, while hydroxyl and fluorine terminations shift the absorption into the visible and near-infrared regions, making them suitable for specific optoelectronic applications [10]. Small MXQDs in the 1–2 nm range exhibit strong quantum coupling effects, with excitons that are delocalized across the entire dot, further enhancing their binding energy.

Weak Confinement in Lead-Free Perovskites

In contrast to traditional lead-based perovskites and other low-dimensional systems, a family of silver/bismuth bromide double perovskites exhibits unusually weak electronic and dielectric confinement effects. Studies on 2D compounds like (PEA)₄AgBiBr₈ (n=1) and (PEA)₂CsAgBiBr₇ (n=2) revealed that, unlike lead-based perovskites where quantum confinement dominates, their photophysics are governed by strong excitonic effects inherent to the double perovskite lattice itself [15].

Both the 3D parent compound (Cs₂AgBiBr₆) and the 2D derivatives show evidence of strong electron-hole interactions. A key experimental signature is a large Stokes shift—the energy difference between absorption and emission peaks—of almost 1 eV. This was attributed not to indirect bandgap recombination, but to the inherent softness of the double-perovskite lattice and strong charge carrier interaction with lattice vibrations (electron-phonon coupling) [15]. This demonstrates that quantum confinement is not the only mechanism that can lead to significant excitonic effects; the intrinsic structural properties of the material can also play a dominant role.

Table 2: Exciton Properties in Confined Systems: Key Comparisons

| Material System | Dimensionality | Key Exciton Feature | Primary Governing Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| MXene QDs (Ti₂CO₂) [10] | 0D | Eb can reach 75% of energy gap; strong blue shift with reduced size. | Strong quantum confinement in all spatial directions. |

| AgBi-Br Double Perovskites [15] | 2D / 3D | Large Stokes shift (~1 eV); strong excitonic effects despite weak confinement. | Strong electron-phonon coupling and inherent lattice softness. |

| Conventional Lead Halide Perovskites [15] | 3D / 2D | Narrow, weakly Stokes-shifted emission (~40 meV). | Moderate quantum confinement in 2D structures. |

Experimental Protocols for Probing Excitonic Effects

Synthesis of Low-Dimensional Perovskite Single Crystals

Method: Slow Crystallization Method [15]

- Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve stoichiometric amounts of precursor salts (e.g., AgBr, BiBr₃, CsBr, and phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) for 2D structures) in a suitable solvent, typically a high-boiling-point polar aprotic solvent like dimethylformamide (DMF) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

- Solution Concentration: Gently heat the solution while stirring to obtain a clear, saturated precursor solution.

- Crystal Growth: Allow the solution to cool slowly to room temperature at a controlled rate (e.g., 0.5-2°C per hour). Alternatively, employ antisolvent vapor diffusion, where a vapor of an antisolvent (e.g., diethyl ether or toluene) is slowly diffused into the precursor solution to reduce solute solubility and induce slow, controlled crystallization.

- Harvesting: After several days, well-formed platelike single crystals (e.g., 3 × 3 × 0.2 mm³) will precipitate. Collect them by filtration, wash with a small amount of antisolvent, and dry under vacuum.

- Characterization: The resulting crystals should be characterized by Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to determine space group and lattice parameters, and by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for morphological analysis [15].

Optical Characterization of Exciton Properties

Method: Steady-State and Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy

- Objective: To measure the exciton emission energy, Stokes shift, and recombination dynamics.

- Procedure:

- Steady-State PL: Irradiate the sample with a continuous-wave (CW) laser source at an energy greater than the material's bandgap. Collect the emitted light and disperse it through a monochromator onto a sensitive detector (e.g., a CCD camera). This provides the PL spectrum and the Stokes shift relative to the absorption edge [15].

- Time-Resolved PL (TRPL): Excite the sample with a pulsed laser. Use a fast detector (e.g., a photomultiplier tube or streak camera) to record the intensity of the PL emission as a function of time after the excitation pulse. This decay profile reveals the lifetime of the excitons.

- Data Analysis: The PL lifetime (τ) is obtained by fitting the decay curve. A short lifetime can indicate efficient non-radiative recombination, while a long lifetime suggests high material quality and dominant radiative recombination. The large Stokes shift, as seen in AgBi-Br double perovskites, provides evidence for strong exciton-phonon coupling or self-trapped excitons [15].

First-Principles Computational Analysis

Method: Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT) [10]

- Objective: To theoretically calculate electronic structures, optical absorption spectra, and exciton binding energies.

- Procedure:

- Model Construction: Build an atomic-scale model of the system (e.g., a MXene quantum dot with specific surface terminations) based on known crystallographic data.

- Ground-State Calculation: Perform a standard DFT calculation to obtain the ground-state electronic structure and the fundamental energy gap (E₉).

- Excited-State Calculation: Use TD-DFT to compute the optical absorption spectrum. The first absorption peak corresponds to the optical gap (Eₒₚₜ).

- Eb Calculation: The exciton binding energy is estimated as the difference between the fundamental and optical gaps: Eb = E₉ - Eₒₚₜ.

- Output: This methodology allows for the dissection of the relative contributions of quantum confinement and surface chemistry to the excitonic properties, as demonstrated in the study of MXQDs [10].

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: The causal pathway from quantum confinement to increased exciton binding energy and its experimental manifestations.

Diagram 2: Integrated experimental and computational workflow for studying excitons in confined systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Research in Confined Excitonic Systems

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Precursor Salts (e.g., AgBr, BiBr₃, CsBr, Ti₂C MXene) [15] | Serves as the source of metal and halide ions for the synthesis of the inorganic perovskite or nanocrystal backbone. |

| Organic Spacers (e.g., Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr), Butylammonium Bromide (BABr)) [15] | Used to break the 3D perovskite structure into lower-dimensional (2D) layers, inducing quantum confinement. |

| Polar Aprotic Solvents (e.g., DMF, DMSO, NMP) [15] | High-boiling-point solvents used to dissolve precursor salts for the synthesis of perovskite crystals and thin films. |

| Antisolvents (e.g., Toluene, Chloroform, Diethyl Ether) [15] | Used in crystallization and precipitation protocols to reduce solubility and initiate controlled nucleation and growth of nanocrystals or thin films. |

| Surface Ligands (e.g., Oleic Acid, Oleylamine) | Used in colloidal synthesis of quantum dots to control growth, prevent aggregation, and passivate surface states. |

| Computational Codes (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) [10] | Software packages for performing first-principles DFT and TD-DFT calculations to model electronic and optical properties. |

Size-Dependent Tuning of Band Gaps and Absorption Spectra

The precise tuning of band gaps and absorption spectra in semiconductor nanocrystals, known as quantum dots (QDs), represents one of the most direct manifestations of quantum confinement effects in nanoscale materials. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles and experimental methodologies underlying size-dependent optical properties, with particular focus on implications for perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surface electronics research. The quantum confinement effect emerges when semiconductor crystal dimensions shrink below the Bohr exciton radius, causing discrete quantization of energy levels and size-tunable electronic transitions that differ fundamentally from bulk semiconductor behavior [16] [17]. This phenomenon enables unprecedented control over optoelectronic properties through nanocrystal size manipulation rather than chemical composition changes.

For perovskite quantum dot research, understanding these quantum confinement principles is particularly crucial due to the complex surface chemistry and dynamic ligand interactions that characterize these materials. The surface electronic structure of PQDs directly influences their stability, charge transport properties, and ultimate device performance [1] [18]. This guide provides a comprehensive technical foundation for researchers investigating quantum confinement effects in PQD systems, with detailed experimental methodologies, quantitative data analysis techniques, and specialized considerations for surface electronic property characterization.

Theoretical Foundation of Quantum Confinement

Quantum Mechanical Principles

The phenomenon of quantum confinement in semiconductor nanocrystals arises from spatial restriction of charge carriers (electrons and holes) within dimensions smaller than their natural Bohr radius. In bulk semiconductors, electrons and holes experience minimal spatial restriction, resulting in continuous energy bands. As crystal dimensions approach the nanoscale, these charge carriers become physically confined, leading to discrete energy levels and a size-dependent increase in the band gap energy [17] [19].

The fundamental relationship between quantum dot size and band gap energy can be understood through the "particle-in-a-box" model, where the confinement energy varies inversely with the square of the box dimensions:

E ∝ ħ²π²/(2m*L²)

Where E represents the confinement energy, ħ is the reduced Planck's constant, m* is the effective mass of the charge carrier, and L is the spatial confinement dimension [17]. For semiconductor quantum dots, this model must be extended to three dimensions with appropriate corrections for the specific material parameters, including dielectric constant and electron-hole pair (exciton) interactions.

The effective mass approximation provides a more accurate description of quantum confinement effects, where the band gap increase (ΔE) for spherical quantum dots can be expressed as:

ΔE = ħ²π²/(2μR²) - 1.8e²/(4πε₀εR) + ...

Where μ is the reduced effective mass of the electron-hole pair, R is the quantum dot radius, ε is the dielectric constant, and the terms represent quantum confinement kinetic energy and electron-hole Coulomb interaction, respectively [19]. More sophisticated theoretical approaches, including tight-binding models and density functional theory (DFT), provide increasingly accurate predictions of size-dependent electronic properties but require substantial computational resources [18] [19].

Bohr Exciton Radius and Confinement Regimes

The Bohr exciton radius represents a critical parameter defining the quantum confinement regime for any semiconductor material. It is defined as:

a_B = 4πε₀εħ²/(μe²)

Where a_B is the Bohr exciton radius, ε is the dielectric constant, and μ is the reduced mass of the electron-hole pair [16]. Three distinct confinement regimes exist:

- Weak confinement: Quantum dot radius (R) > a_B (both electron and hole experience minimal confinement)

- Intermediate confinement: R < a_B but larger than the Bohr radius of one carrier type

- Strong confinement: R < a_B for both electron and hole (both carriers experience quantum confinement) [16]

For CdSe, with a Bohr radius of approximately 5.8 nm, quantum dots smaller than this dimension exhibit strong quantum confinement effects, with band gaps increasing significantly as size decreases [16]. The experimental data from Poudyal et al. demonstrates that this size-dependent lifetime trend holds for QDs smaller than the Bohr radius but does not consistently apply to QDs larger than this critical dimension [16].

Figure 1: Quantum confinement regimes and their effects on semiconductor electronic structure. As quantum dot size decreases relative to the Bohr exciton radius (a_B), energy levels become increasingly discrete and band gaps widen.

Quantitative Data on Size-Dependent Optical Properties

Experimental Size-Band Gap Relationships

Direct experimental measurements across multiple quantum dot material systems have established precise quantitative relationships between nanocrystal dimensions and band gap energies. These relationships enable predictive design of quantum dots with specific optical properties tailored for particular applications.

Table 1: Experimental Size-Dependent Band Gap Data for Different Quantum Dot Materials

| Material | Diameter (nm) | Band Gap (eV) | Absorption Peak (nm) | Emission Peak (nm) | Stokes Shift (meV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdSe | 2.20 | 2.59 | 483.44 | 492.14 | 86.5 | [16] |

| CdSe | 3.73 | 2.12 | 577.39 | 585.21 | 26.5 | [16] |

| CdSe | 6.50 | 1.87 | 633.99 | 638.83 | 11.9 | [16] |

| AgIn₅S₈ | 2.60 | 3.77 | 329 | 385 | 440 | [20] |

| AgIn₅S₈ | ~5.00 | 3.09 | 401 | 450 | 300 | [20] |

| AgIn₅S₈ | ~31.00 | 2.18 | 569 | 610 | 124 | [20] |

| AgIn₅S₈ | ~34.00 | 1.73 | 717 | 760 | 92 | [20] |

The data demonstrates several key trends. For CdSe quantum dots, the band gap decreases from 2.59 eV to 1.87 eV as diameter increases from 2.20 nm to 6.50 nm, with smaller quantum dots exhibiting larger Stokes shifts [16]. AgIn₅S₈ quantum dots show even more dramatic band gap tunability, spanning from 3.77 eV to 1.73 eV—a remarkable 2.04 eV range—encompassing much of the visible spectrum and extending into the near-infrared [20]. This extraordinary tunability exceeds that typically reported for AgInS₂ QDs (2.3-3.1 eV) and highlights the potential of spinel-phase AgIn₅S₈ for applications requiring specific spectral characteristics [20].

Exciton Dynamics and Lifetime Components

Time-resolved photoluminescence spectroscopy reveals complex exciton recombination dynamics in quantum dots, with multiple decay pathways contributing to the overall lifetime. Poudyal et al. identified three distinct lifetime components in CdSe quantum dots:

Table 2: Exciton Lifetime Components in CdSe Quantum Dots

| Lifetime Component | Time Scale | Associated Transition | Size Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| τ₁ (Fast) | Short (~ns) | Band edge to valence band | Increases with size for QDs < Bohr radius |

| τ₂ (Intermediate) | Medium | Surface-trapped state to valence band or band edge to valence trapped state | Variable with surface chemistry |

| τ₃ (Slow) | Long (~μs) | Surface-trapped state to valence trapped state | Less size-dependent |

The study demonstrated that band-edge transitions contribute most significantly to the overall exciton lifetime across all QD sizes. For quantum dots smaller than the Bohr radius, the weighted average exciton lifetime increases with size, while this trend does not consistently hold for dots larger than the Bohr radius [16]. These findings highlight the complex interplay between quantum confinement, surface effects, and charge carrier dynamics in determining the optical properties of semiconductor nanocrystals.

Surface Chemistry and Band Edge Engineering

Ligand-Mediated Band Edge Tuning

Surface chemistry plays a critical role in determining the electronic properties of quantum dots, particularly through its influence on band edge positions. Seminal research on lead sulfide (PbS) quantum dots has demonstrated that solution-phase surface chemistry modification can tune band edge positions over an extraordinary 2.0 eV range—comparable to the tuning achievable through quantum confinement itself [21].

This remarkable control is achieved through ligand exchange processes that replace native surface ligands with functionalized cinnamate ligands. The relationship between ligand properties and band edge shifts involves two primary mechanisms:

- Ligand dipole moment: Functional groups with different electron-withdrawing or donating characteristics introduce interfacial dipoles that shift band edge positions

- Inter-QD ligand shell inter-digitization: In close-packed QD films, ligand interdigitation between adjacent dots creates additional dipole moments that influence electronic structure [21]

The combination of these effects enables precise engineering of ionization energy and work function in quantum dot films, with significant implications for optimizing charge injection and extraction in electronic devices including solar cells, light-emitting diodes, and photodetectors.

Surface Chemistry Effects on PQD Electronic Properties

For perovskite quantum dots, surface chemistry assumes even greater importance due to the ionic nature of the materials and dynamic ligand binding. PQDs typically exhibit high defect tolerance but remain susceptible to surface defects that introduce trap states within the band gap [1] [18]. Proper surface passivation is essential for:

- Reducing non-radiative recombination: Surface ligands passivate dangling bonds and eliminate trap states

- Enhancing environmental stability: Appropriate ligand shells protect the ionic perovskite lattice from moisture and oxygen degradation

- Controlling inter-dot coupling: Ligand length and functionality determine electronic coupling between adjacent dots in films

- Modifying band alignment: Polar ligands can shift band edge positions to optimize energy level alignment with charge transport layers [1]

Recent studies have highlighted the critical importance of understanding the complex chemistry and dynamic instabilities at PQD surfaces for developing commercially viable applications [1]. Advanced characterization techniques including in-situ spectroscopy and computational modeling are providing new insights into ligand binding dynamics and their influence on electronic structure.

Figure 2: Relationship between synthesis parameters, quantum dot properties, and resulting optical characteristics. Precise control of reaction conditions enables targeted tuning of optical properties through manipulation of quantum dot size, surface chemistry, and crystalline structure.

Experimental Methodologies

Quantum Dot Synthesis Protocols

Colloidal Hot-Injection Method for CdSe Quantum Dots

This widely-employed synthesis produces high-quality, monodisperse CdSe quantum dots with precise size control [17]:

- Preparation: Combine cadmium oxide (0.012 mol), trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO, 0.036 mol), and hexadecylamine (0.036 mol) in a three-neck flask under inert atmosphere

- Heating: Heat mixture to 300°C with vigorous stirring until a clear solution forms

- Injection: Rapidly inject selenium precursor (0.009 mol selenium in trioctylphosphine) into the hot reaction mixture

- Growth: Maintain temperature at 250-300°C for specific time periods (1-30 minutes) to control quantum dot size

- Termination: Cool rapidly to room temperature to arrest growth

- Purification: Precipitate quantum dots with methanol, centrifuge, and redisperse in non-polar solvents

Aqueous-Phase Synthesis for AgIn₅S₈ Quantum Dots

This environmentally-friendly approach produces water-dispersible quantum dots under mild conditions [20]:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve AgNO₃ (0.01 M) and In₂(SO₄)₃ (0.04 M) in deionized water with Na₂S₂O₃ (0.3 M) as ligand agent

- Sulfide Source: Add thioacetamide (0.3 M) as sulfide precursor

- Temperature Control: Heat from room temperature to either 55°C or 75°C over 15 minutes

- Reaction: Maintain temperature for 90 minutes with continuous stirring

- Ultrasound Variant: For ultrasound-assisted synthesis, irradiate at 20 kHz and 100 W cm⁻² during heating and reaction

- Isolation: Separate products by filtration, wash with deionized water, and dry at room temperature

Optical Characterization Techniques

Absorption Spectroscopy

UV-Visible-NIR spectroscopy provides direct measurement of quantum dot band gaps through Tauc plot analysis:

- Instrumentation: Use dual-beam spectrophotometer with 1-2 nm spectral resolution

- Sample Preparation: Prepare dilute solutions in non-absorbing solvents to minimize scattering

- Data Collection: Measure absorbance from 250-800 nm with solvent baseline correction

- Band Gap Calculation: Plot (αhν)² versus hν for direct band gap semiconductors, where α is absorption coefficient and hν is photon energy

- Size Estimation: Compare absorption peak positions with established sizing curves [16] [17]

Time-Resolved Photoluminescence Spectroscopy

This technique quantifies exciton recombination dynamics and identifies trap states:

- Excitation Source: Use pulsed laser diode (λ = 375-405 nm) with pulse width < 100 ps

- Detection: Employ time-correlated single photon counting with microchannel plate photomultiplier tube

- Data Fitting: Analyze decay curves with multi-exponential model: I(t) = ΣAᵢexp(-t/τᵢ)

- Component Assignment: Identify lifetime components associated with band-edge and surface-state recombination [16]

Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange Protocol

This method enables precise surface chemistry control for band edge tuning [21]:

- Starting Material: Prepare oleate-capped PbS QDs (3.2 nm diameter) in organic solvent

- Ligand Solution: Dissolve functionalized cinnamic acid ligands (0.1 M) in mixture of acetonitrile and methanol

- Exchange: Add ligand solution to QD dispersion with vigorous stirring for 1-2 hours

- Purification: Precipitate exchanged QDs with hexane, centrifuge, and redisperse in polar solvents

- Characterization: Verify complete exchange using FTIR and ¹H NMR spectroscopy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Quantum Dot Synthesis and Characterization

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Cadmium oxide (CdO), Silver nitrate (AgNO₃), Indium sulfate (In₂(SO₄)₃), Lead acetate (Pb(OAc)₂) | Source of metallic components in quantum dots | Purity >99.99% essential; moisture-sensitive materials require inert atmosphere handling |

| Chalcogenide Sources | Selenium powder, Sulfur powder, Thioacetamide, Trioctylphosphine selenide | Provide chalcogenide components | Air-sensitive; often prepared as stock solutions in coordinating solvents |

| Solvents | Trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO), Octadecene, Hexane, Toluene | Reaction medium and dispersion medium | Anhydrous grade required; TOPO must be pre-purified to remove residual water and acids |

| Ligands | Oleic acid, Oleylamine, Cinnamic acid derivatives, Alkylthiols | Surface passivation and colloidal stability | Chain length and functional groups determine inter-dot spacing and electronic coupling |

| Purification Agents | Methanol, Ethanol, Acetone, Butanol | Precipitation and washing of quantum dots | Solvent polarity selected for specific quantum dot material system |

| Characterization Standards | Tetrachloroethylene, Chloroform-d, Polystyrene | Reference materials for spectroscopic analysis | Spectroscopic grade essential for accurate measurements |

Implications for PQD Surface Electronics Research

The principles of size-dependent band gap tuning and surface-mediated electronic structure control have profound implications for perovskite quantum dot research, particularly in the context of surface electronics. Several key considerations emerge:

Defect Passivation Strategies Perovskite quantum dots exhibit relatively high defect tolerance compared to conventional semiconductors, but surface defects remain significant contributors to non-radiative recombination and charge trapping [1] [18]. Effective passivation requires:

- Anionic site passivation: Lewis base ligands that bind to undercoordinated lead atoms

- Cationic site passivation: Lewis acid ligands that interact with halide vacancies

- Multidentate ligands: Species with multiple binding groups that enhance binding stability

- Conjugated ligands: Molecules that facilitate charge transfer while providing passivation

Surface-Dependent Charge Transport The electronic coupling between PQDs in thin films strongly influences device performance in optoelectronic applications. Key factors include:

- Ligand length and binding strength: Shorter ligands enhance inter-dot coupling but may reduce colloidal stability

- Surface dipole moments: Polar ligands modify energy level alignment at interfaces

- Dynamic binding: Labile ligand binding in PQDs creates time-dependent electronic properties

- Mixed ligand systems: Strategic combinations of long insulating and short conductive ligands

Stability Considerations PQD surface chemistry directly impacts environmental and operational stability:

- Hydrophobic ligands: Long alkyl chains provide moisture barrier protection

- Cross-linkable ligands: Species that form protective networks upon mild treatment

- Inorganic ligands Metal halides, chalcogenides that enhance thermal and photostability

- Zwisitterionic ligands: Molecules that provide electrostatic stabilization in diverse environments

Recent research has highlighted the critical importance of understanding the complex chemistry and dynamic instabilities at PQD surfaces for developing commercially viable applications [1]. Advanced characterization techniques including in-situ spectroscopy and computational modeling are providing new insights into ligand binding dynamics and their influence on electronic structure.