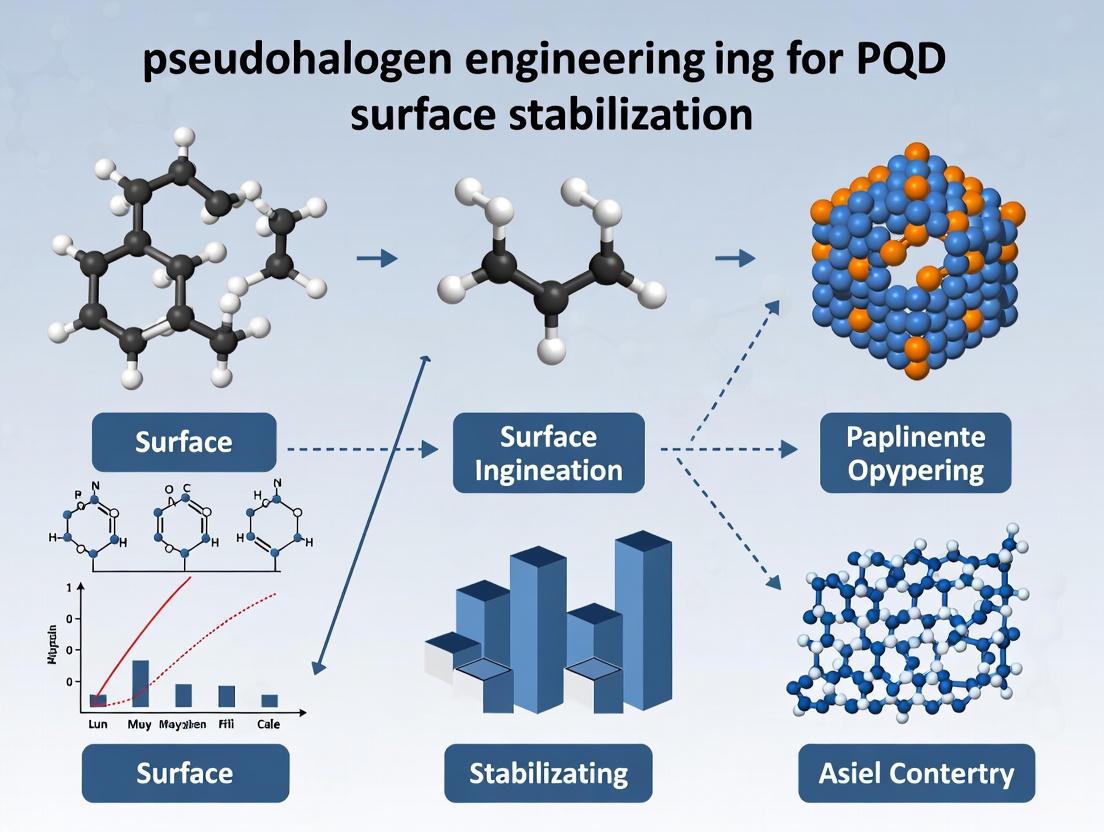

Pseudohalogen Engineering for Stable Perovskite Quantum Dots: Mechanisms, Methods, and Biomedical Prospects

This article explores pseudohalogen engineering as a transformative strategy for enhancing the surface stability and optical performance of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs).

Pseudohalogen Engineering for Stable Perovskite Quantum Dots: Mechanisms, Methods, and Biomedical Prospects

Abstract

This article explores pseudohalogen engineering as a transformative strategy for enhancing the surface stability and optical performance of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). Aimed at researchers and scientists in materials science and drug development, it provides a comprehensive analysis from fundamental principles to practical applications. We cover the foundational role of pseudohalogens in defect passivation and ion migration suppression, detail innovative synthesis and post-synthesis treatment methodologies, address common challenges in reproducibility and stability, and present comparative data on optical performance and environmental resilience. The content synthesizes recent scientific advances to guide the development of high-performance, stable PQDs for future biomedical and clinical applications.

The Science of Pseudohalogens: Unlocking Next-Generation PQD Stability

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) are a class of semiconducting nanocrystals, typically 2-10 nanometers in diameter, based on metal halide perovskites with the chemical formula ABX₃, where A is a cation (e.g., Cs⁺, MA⁺, FA⁺), B is a divalent metal cation (e.g., Pb²⁺, Sn²⁺), and X is a halide anion (e.g., Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) [1] [2]. These nanomaterials have generated significant research interest due to their exceptional optoelectronic properties, which include extremely high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY), often approaching 100%, and narrow emission linewidths (typically ~20 nm), resulting in high color purity ideal for displays [2] [3]. Furthermore, their emission wavelength can be tuned across the entire visible spectrum (400-760 nm) by varying their size, composition, or through halide exchange, providing exceptional spectral versatility [2] [3].

Compared to traditional quantum dots like CdSe, and organic emitters used in LEDs, PQDs offer a compelling combination of high performance and cost-effective solution processability [3] [4]. These properties make them promising candidates for a new generation of optoelectronic devices, including light-emitting diodes (LEDs) for displays, solar cells, photodetectors, lasers, and even sensors [1] [2] [3]. In perovskite LEDs (PeLEDs), for instance, external quantum efficiencies (EQE) exceeding 20% have been achieved for red-emitting devices [5] [6]. Despite this rapid progress, the widespread commercialization of PQD-based technologies is critically limited by their inherent instability under various environmental and operational stresses [2] [4].

Fundamental Instability Mechanisms in PQDs

The exceptional optical properties of PQDs are underpinned by an ionic crystal lattice, which is also the primary source of their instability. The low formation energy of the perovskite structure renders it highly susceptible to degradation from both internal and external factors [2]. The main degradation pathways can be categorized as follows:

- Surface Defect Formation: The organic ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) used to stabilize PQDs during synthesis are often dynamically bound and can easily detach from the surface, especially during purification processes or upon exposure to heat [4]. This ligand dissociation creates unsaturated "dangling bonds" on the PQD surface, which act as defect sites. These defects promote non-radiative recombination of charge carriers, quench photoluminescence, and serve as entry points for external degradants [4].

- Ion Migration: The ionic lattice of perovskites features low activation energies for halide anions (e.g., I⁻, Br⁻), making them highly mobile under operational stimuli like electric fields, light, or heat [7] [4]. This ion migration leads to the formation of halide vacancies and interstitial defects within the crystal lattice. In mixed-halide PQDs (e.g., CsPb(Br/I)₃), this results in phase segregation, where the material separates into Iodine-rich and Iodine-poor regions, causing undesirable shifts in the emission wavelength and reduced color purity [7] [5].

- External Stressors: PQDs are highly sensitive to environmental factors. Moisture can hydrolyze and dissolve the crystal structure, oxygen can cause photo-oxidative degradation, and prolonged illumination (especially UV light) and thermal stress can accelerate ion migration and lead to structural decomposition [7] [2].

The diagram below illustrates the interplay of these primary degradation mechanisms.

Diagram 1: Primary Degradation Mechanisms in Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs). The diagram shows how intrinsic properties and external stressors lead to critical performance failures.

The table below summarizes the key instability issues, their consequences on device performance, and the specific experimental conditions under which they are typically observed.

Table 1: Key Instability Challenges in Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Instability Challenge | Impact on PQD Performance | Experimental Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Defect Formation [4] | Reduced PLQY; Increased non-radiative recombination; Aggregation of PQDs. | PLQY drop from >80% to <50% after purification; PL intensity decay under continuous UV illumination [4]. |

| Halide Ion Migration [7] [5] | Phase segregation in mixed halides; Hysteresis in solar cells; Unstable EL/PL emission spectra. | Emergence of a new, red-shifted PL peak (e.g., at 1.68 eV) under light soaking; spectral shift in PeLEDs during operation [7] [5]. |

| Moisture Sensitivity [2] [8] | Structural decomposition; Loss of crystallinity; Complete PL quenching. | Loss of cubic phase and emergence of degraded phases (e.g., PbBr₂) per XRD; PL intensity drop >95% upon water exposure [8]. |

| Thermal Instability [7] [2] | Accelerated ion migration; Ligant desorption; Phase transition. | PL quenching and spectral shifts at elevated temperatures (e.g., 85°C); device failure during damp-heat tests (85°C/85% RH) [7]. |

| Photo-instability [7] [9] | Photobleaching; "Blinking" of single QDs; Deep defect formation. | Continuous decay of PL intensity under laser irradiation; random on/off emission cycles in single-dot spectroscopy [9]. |

Stabilization Strategies and Experimental Protocols

To address these instabilities, researchers have developed a variety of strategies aimed at passivating surface defects and suppressing ion migration. The following workflow outlines a generalized experimental approach for synthesizing and stabilizing PQDs, incorporating key mitigation strategies.

Diagram 2: General Workflow for PQD Synthesis and Stabilization. Key stabilization steps like ligand exchange and pseudohalogen passivation are integrated post-synthesis.

Key Stabilization Methodologies

- Ligand Engineering: Replacing long, insulating, and weakly bound ligands (e.g., oleic acid) with shorter or multidentate ligands that have stronger binding affinity to the PQD surface. For example, 2-aminoethanethiol (AET) binds strongly to Pb²⁺ sites via its thiol group, leading to a denser passivation layer that improves stability against water and UV light, and can increase PLQY from 22% to 51% [4].

- Pseudohalogen Passivation: This is a highly effective post-treatment strategy for mixed-halide PQDs. Using inorganic pseudohalogen ligands like potassium thiocyanate (KSCN) or guanidinium thiocyanate (GASCN) in a solvent like acetonitrile simultaneously etches lead-rich surfaces and passivates uncoordinated Pb²⁺ defects. This suppresses halide migration, enhances PLQY, and improves film conductivity, enabling mixed-halide PeLEDs with a peak EQE of 22.1% and improved spectral stability [5].

- Core-Shell Structures: Encapsulating the PQD core in a protective shell. For instance, creating a CsPbBr₃@CsPb₂Br₅ composite through a pseudo-peritectic method can dramatically enhance water resistance. The CsPb₂Br₅ shell reduces surface defects, allowing the composite to maintain a high fluorescence quantum efficiency of up to 70% even after 72 hours in water [8].

- Ion Doping: Introducing metal ions (e.g., at the A- or B-site) to strengthen the perovskite lattice. Doping can alter the B-X bond lengths and increase the activation energy for ion migration, thereby improving intrinsic thermal and structural stability [7] [4].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Pseudohalogen Passivation of Mixed-Halide PQDs

This protocol is adapted from recent research to stabilize CsPb(Br/I)₃ PQDs for high-performance PeLEDs [5].

- Objective: To suppress halide migration and passivate surface defects in mixed-halide PQDs (CsPb(Br/I)₃) via a post-synthesis treatment with pseudohalogen ligands, thereby enhancing PLQY, film conductivity, and spectral stability.

Materials:

- Synthesized CsPb(Br/I)₃ PQDs in non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene or hexane).

- Lead-rich precursor solution.

- Anhydrous acetonitrile (MeCN).

- Pseudohalogen ligand solution: Potassium thiocyanate (KSCN) or Guanidinium thiocyanate (GASCN) dissolved in MeCN (concentration range: 0.1 - 1.0 mg/mL).

- Methyl acetate for purification.

- Anhydrous solvents for device fabrication.

Procedure:

- PQD Synthesis: Synthesize CsPb(Br/I)₃ PQDs using the standard hot-injection method [3]. Purify the raw solution by centrifugation with methyl acetate to remove excess ligands and by-products. Re-disperse the purified PQD pellet in anhydrous hexane to a desired concentration.

- Post-treatment Solution Preparation: Prepare the pseudohalogen post-treatment solution by dissolving KSCN or GASCN in anhydrous acetonitrile. The solution should be sonicated and filtered to ensure complete dissolution and remove any particulates.

- Surface Treatment: In an inert atmosphere glovebox, add the post-treatment solution dropwise to the purified PQD solution under vigorous stirring. The typical volume ratio of post-treatment solution to PQD solution is 1:1. Continue stirring the mixture for 10-30 minutes.

- Purification and Collection: Precipitate the passivated PQDs by adding methyl acetate followed by centrifugation. Carefully decant the supernatant. Re-disperse the resulting pellet in anhydrous chloroform or toluene for film characterization or device fabrication.

- Characterization:

- Optical Properties: Measure UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence (PL) spectra to confirm emission wavelength and check for phase segregation (e.g., the absence of a new, red-shifted PL peak).

- PLQY: Use an integrating sphere to measure the absolute PLQY of the PQD solution before and after treatment. A successful treatment should yield a significant increase in PLQY.

- Device Fabrication & Testing: Fabricate PeLEDs using the standard architecture (e.g., ITO/PEDOT:PSS/Poly-TPD/PQDs/TPBi/LiF/Al). Measure current density-voltage-luminance (J-V-L) characteristics and electroluminescence (EL) spectra. Track the operational stability by measuring the time until the EL intensity drops to 50% of its initial value (T₅₀) under constant current density.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and materials commonly used in PQD synthesis and stabilization research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Synthesis and Stabilization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) [8] | Precursor for Cs-oleate, the A-site cation source. | Must be thoroughly dried and dissolved in OA/ODE at high temp under inert atmosphere. |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) [8] | Precursor for the B-site metal cation and halide. | High purity (99.999%) is recommended to minimize impurities and defects. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) [4] [8] | Surface ligands to control growth and stabilize PQDs during synthesis. | Dynamic binding; can easily detach, causing instability. Often replaced via ligand exchange. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) [8] | Non-polar solvent for high-temperature synthesis. | Requires degassing to remove oxygen and water before use. |

| Pseudohalogen Salts (KSCN, GASCN) [5] | Inorganic ligands for post-synthesis passivation. | Strongly bind to uncoordinated Pb²⁺; suppress ion migration; enhance conductivity and stability. |

| Acetonitrile (MeCN) [5] | Polar solvent for pseudohalogen post-treatment. | Strong Pb²⁺ coordination helps etch lead-rich surfaces without dissolving PQDs. Must be anhydrous. |

| 2-Aminoethanethiol (AET) [4] | Short, bidentate ligand for post-synthesis ligand exchange. | Thiol group binds strongly to Pb²⁺, creating a dense passivation layer and improving moisture/UV stability. |

Perovskite quantum dots represent a frontier in nanomaterials science, offering a unparalleled combination of high performance and processability for future optoelectronic devices. However, their path to commercialization is critically hindered by intrinsic instabilities arising from their ionic nature, primarily surface defect formation and ion migration. Ongoing research has developed a sophisticated toolkit of stabilization strategies, including advanced ligand engineering, core-shell structuring, and ion doping. Within this landscape, pseudohalogen engineering emerges as a particularly powerful and promising approach, directly addressing the core challenge of surface and halide vacancy passivation. By employing these strategies, the research community continues to make significant strides toward overcoming the stability bottleneck, paving the way for the practical application of these remarkable materials in robust, next-generation technologies.

What are Pseudohalogens? Defining Chemical Properties and Functional Analogies

Pseudohalogens are polyatomic analogues of halogens whose chemistry resembles that of the true halogens, allowing them to substitute for halogens in several classes of chemical compounds [10]. The term was first introduced by Lothar Birckenbach in 1925 and further developed in subsequent years [11]. These molecular groups or ions exhibit chemical behavior strikingly similar to that of halogen ions (F⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻), despite their more complex polyatomic structures [12].

From a historical perspective, the pseudohalogen concept has provided a powerful tool for understanding correlations between chemical properties, structure, and bonding of these unique species [11] [13]. The conceptual framework has expanded significantly since its inception, now encompassing diverse chemical families including classical linear pseudohalides, resonance-stabilized nonlinear pseudohalides, and complex organometallic variants [11].

The fundamental importance of pseudohalogens extends across multiple chemical disciplines, from fundamental coordination chemistry and materials science to applications in interstellar chemistry and organic photovoltaics [14] [15]. Their ability to mimic halogen behavior while introducing modified steric and electronic properties makes them particularly valuable in molecular engineering for advanced materials design.

Defining Characteristics and Classification Criteria

Formal Criteria for Pseudohalogen Classification

A molecular entity can be classified as a classical pseudohalogen when it fulfills the following criteria demonstrating halogen-like chemical behavior [11]:

- Forms a strongly bound (typically linear) univalent radical (X·)

- Exists as a singly charged anion (X⁻) with stability comparable to halide ions

- Forms a pseudohalogen hydrogen acid of the type HX that demonstrates acidic properties

- Produces salts of the type M(X)ₙ with characteristic low solubility with silver, lead, and mercury ions

- Forms neutral dipseudohalogen compounds (X-X) that disproportionate in water and can add to double bonds

- Creates interpseudohalogen species (X-Y) through combination with other pseudohalogens or halogens

However, not all criteria are always perfectly met by every pseudohalogen [11]. For instance, while many linear pseudohalogens (e.g., CN, OCN, CNO, N₃, SCN) are well-established, their corresponding pseudohalide acids, dipseudohalogens, and interpseudohalogens are often thermodynamically highly unstable (e.g., HN₃, OCN-NCO, NC-SCN) with respect to N₂/CO elimination or polymerization, and some remain unknown (e.g., N₃-N₃).

Taxonomy of Pseudohalogens

Pseudohalogens can be categorized into several distinct classes based on their structural characteristics:

Table: Classification of Major Pseudohalogen Types

| Classification | Representative Examples | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Linear Pseudohalides | CN⁻, OCN⁻, N₃⁻, SCN⁻ | Linear geometry, strong bonding, minimal steric hindrance |

| Resonance-Stabilized Nonlinear Pseudohalides | C(NO₂)₃⁻, C(CN)₃⁻ | Delocalized electron density, reduced basicity, planar structures |

| Heavier Element Analogues | SCN⁻, SeCN⁻, TeCN⁻, P(CN)₂⁻ | Isovalence electronic exchange (O by S, Se, Te; N by P) |

| Organometallic Pseudohalides | Co(CO)₄⁻, Au⁻ | Metal-centered anions with halogen-like disproportionation |

| Cyclic Pseudohalogens | CS₂N₃⁻ | Ring structures with pseudohalogen properties |

The extension of the pseudohalogen concept continues to evolve, now encompassing specialized non-planar anions such as CF₃⁻, heavier element analogues through isovalence electronic exchange, and increasingly complex derivatives including five-membered ring systems like [CS₂N₃]⁻ [11].

Chemical Properties and Functional Analogies

Fundamental Chemical Behavior

Pseudohalogens exhibit several characteristic chemical properties that mirror true halogen behavior:

Anion Formation and Acid Chemistry: Pseudohalides form univalent anions that create binary acids with hydrogen, such as hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and hydrogen azide (HN₃) [10]. These acids often demonstrate strength comparable to hydrogen halides, with HCo(CO)₄, for instance, being "quite a strong acid, though its low solubility renders it not as strong as the true hydrogen halides" [10].

Salt Formation: Pseudohalogens form insoluble salts with heavy metals, particularly silver, mirroring the behavior of true halides. Characteristic examples include silver cyanide (AgCN), silver cyanate (AgOCN), silver fulminate (AgCNO), silver thiocyanate (AgSCN), and silver azide (AgN₃) [10] [11]. This precipitation behavior provides valuable diagnostic tests for pseudohalide identification.

Redox Behavior and Disproportionation: Like halogens, pseudohalogens participate in disproportionation reactions. A notable example is the base-induced disproportionation of elemental gold to form auride (Au⁻), which is considered a pseudohalogen ion due to this behavior and its ability to form covalent bonds with hydrogen [10].

Molecular Addition Reactions: Pseudohalogens form dipseudohalogen compounds (e.g., cyanogen (CN)₂) and add across unsaturated bonds in a manner analogous to halogens [11]. This reactivity enables their incorporation into diverse organic frameworks and materials systems.

Structural and Electronic Properties

The electronic properties of pseudohalogens contribute significantly to their functional utility:

Electron-Withdrawing Capacity: Groups like cyanide (CN) function as strong electron-withdrawing groups, analogous to halogens. This property enables modulation of molecular orbital energy levels, directly influencing electronic structure and chemical behavior [15].

π-Conjugation Extension: The π-electron clouds of pseudohalogens such as cyanide can extend conjugated systems through orbital overlap with aromatic frameworks. The carbon-nitrogen triple bond (C≡N) in cyanide groups interacts with electron clouds of adjacent conjugated systems, modifying optical and electronic properties [15].

Non-Covalent Interactions: Pseudohalogens participate in directional non-covalent interactions, including hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking, that influence molecular packing and solid-state structure [15]. These interactions prove particularly valuable in materials science applications where controlled assembly is critical.

Table: Comparative Properties of Selected Pseudohalogens and Halogens

| Species | Dimer | Hydrogen Compound | Anion | Acid Strength | Characteristic Salts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorine (Reference) | Cl₂ | HCl | Cl⁻ | Strong | AgCl (white, insoluble) |

| Cyano | (CN)₂ | HCN | CN⁻ | Moderate | AgCN (white, insoluble) |

| Azido | (N₃)₂* | HN₃ | N₃⁻ | Moderate | AgN₃ (colorless, insoluble) |

| Thiocyanato | (SCN)₂ | HSCN | SCN⁻ | Moderate | AgSCN (light-sensitive) |

| Cyanato | (OCN)₂* | HOCN | OCN⁻ | - | AgOCN (insoluble) |

| Tetracarbonylcobaltate | Co₂(CO)₈ | HCo(CO)₄ | Co(CO)₄⁻ | Strong (low solubility) | - |

Note: Some dipseudohalogens are theoretically possible but highly unstable or unknown [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Synthesis of Cyano-Modified Benzimidazole Pseudohalogen Acceptors

This protocol outlines the synthesis of BMIC-CN-Me and BMIC-CN-iPr, representing modern pseudohalogen engineering for organic photovoltaic applications [15]:

Materials and Reagents:

- Benzimidazole core precursor (Compound IV)

- Alkyl halides (methyl iodide, 2-iodopropane)

- Vilsmeier-Haack formulation reagents (POCl₃, DMF)

- 2-(5,6-dichloro-3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-indene-1-ylidene)malononitrile (2Cl-IC)

- Anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF), potassium carbonate, chloroform

- Standard Schlenk line equipment for air-sensitive reactions

Stepwise Procedure:

Alkylation of Benzimidazole Core:

- Dissolve intermediate IV in anhydrous DMF under nitrogen atmosphere

- Add 1.2 equivalents of methyl iodide or 2-iodopropane

- Heat reaction mixture to 80°C for 12 hours with continuous stirring

- Monitor reaction progress by thin-layer chromatography (TLC)

- Isolate products V and VII through aqueous workup and column chromatography

Vilsmeier-Haack Formylation:

- Dissolve alkylated intermediates (V or VII) in anhydrous DMF at 0°C

- Slowly add 1.5 equivalents of phosphorus oxychloride (POCl₃)

- Warm reaction mixture to room temperature and stir for 6 hours

- Quench reaction carefully with ice-water mixture

- Extract formylated products VI and VIII with chloroform

- Purify by recrystallization from ethanol

Knoevenagel Condensation:

- Dissolve formylated intermediates (VI or VIII) and 2Cl-IC in chloroform

- Add catalytic amount of pyridine

- Reflux reaction mixture for 8 hours under nitrogen

- Monitor by TLC until starting materials are consumed

- Precipitate final products BMIC-CN-Me and BMIC-CN-iPr by adding methanol

- Purify by sequential Soxhlet extraction with methanol, acetone, and hexane

Characterization Methods:

- Structural Analysis: Single-crystal X-ray diffraction for molecular packing assessment

- Thermal Properties: Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

- Optical Characterization: UV-Vis spectroscopy for absorption properties

- Electrochemical Analysis: Cyclic voltammetry for HOMO/LUMO energy level determination

- Morphological Studies: Atomic force microscopy (AFM) and grazing-incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering (GIWAXS)

Protocol: Pseudohalogen Substitution in Coordination Complexes

This general protocol demonstrates the synthetic analogy between halogens and pseudohalogens in coordination chemistry [10] [16]:

Principle: Pseudohalogens can directly substitute for halogens in reactions with metals and organometallic compounds, forming analogous complexes.

Materials:

- Transition metal precursors (e.g., metal carbonyls, metal halides)

- Pseudohalogen sources (e.g., trimethylsilyl cyanide, sodium azide, potassium thiocyanate)

- Anhydrous solvents (tetrahydrofuran, acetonitrile, dichloromethane)

- Schlenk line equipment for air-sensitive manipulations

Procedure:

Preparation of Metal Carbonyl Pseudohalides:

- Dissolve metal carbonyl complex in degassed THF

- Add stoichiometric amount of pseudohalogen source (e.g., Me₃SiCN for cyanide)

- Stir at room temperature for 2-12 hours under inert atmosphere

- Monitor reaction by infrared spectroscopy (disappearance of parent carbonyl stretches)

- Isolate product by solvent evaporation and recrystallization

Metathesis Reactions:

- Dissolve metal halide complex in appropriate solvent

- Add excess pseudohalogen salt (e.g., NaN₃, KSCN)

- Stir at elevated temperature (50-80°C) for 4-8 hours

- Filter to remove halide salt byproduct

- Concentrate filtrate and recrystallize pseudohalogen complex

Characterization:

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: Confirm pseudohalogen incorporation and monitor ligand exchange

- NMR Spectroscopy: Structural confirmation and purity assessment

- Elemental Analysis: Verify composition and stoichiometry

- X-ray Crystallography: Determine molecular structure and coordination geometry

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagents in Pseudohalogen Chemistry

| Reagent/Category | Chemical Examples | Primary Functions | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Pseudohalide Salts | NaCN, KSCN, NaN₃, NaOCN | Anion source, ligand exchange, nucleophiles | Handle with appropriate safety precautions; some are highly toxic |

| Pseudohalogen Dimers | (CN)₂, (SCN)₂ | Electrophilic pseudohalogenation, oxidation | Often generated in situ due to instability |

| Interpseudohalogens | CNCl, CNBr, N₃CN | Selective transfer of pseudohalogen groups | Useful for sequential functionalization |

| Pseudohalogen Hydrides | HCN, HN₃, HSCN | Acid form, proton transfer, acidity studies | Extreme toxicity requires specialized handling |

| Resonance-Stabilized Pseudohalides | C(NO₂)₃⁻, C(CN)₃⁻, HC(C(CN)₃)₂⁻ | Bulky weakly coordinating anions, steric tuning | Valuable for stabilizing reactive cations |

| Heavier Analogues | KSeCN, NaTeCN, KP(CN)₂ | Tuning steric and electronic properties | Weaker π-bonding affects delocalization |

| Organometallic Pseudohalides | K[Co(CO)₄], Na[Au] | Specialized ligand properties, unusual oxidation states | Air- and moisture-sensitive; require inert atmosphere |

Applications in Materials Science and Surface Stabilization

Pseudohalogen Engineering in Organic Photovoltaics

The strategic application of pseudohalogens has driven significant advances in organic solar cell technology, particularly through molecular engineering of non-fullerene acceptors [15]:

Cyano-Modified Benzimidazole Acceptors: The incorporation of cyanide groups (a classical pseudohalogen) into benzimidazole-core small molecule acceptors has enabled precise optimization of molecular crystallinity and packing. BMIC-CN-Me, featuring cyano-modified benzimidazole structure, achieves a record power conversion efficiency of 17.6% among imidazole-based acceptors [15].

Molecular Packing Control: Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analyses reveal that cyano modification enables exceptionally tight π-π stacking with intermolecular distances of approximately 3.31 Å, significantly enhancing charge transport properties [15]. The pseudohalogen functionality provides additional non-covalent interaction sites that augment material stability while maintaining favorable energy level alignment.

Stability Enhancement: Devices incorporating cyano-modified pseudohalogen functionalization demonstrate exceptional operational stability, retaining over 80% of initial efficiency after 1200 hours in a glove box and maintaining similar retention after 500 hours of continuous simulated solar irradiation [15].

Implications for Perovskite Quantum Dot Surface Stabilization

The principles of pseudohalogen chemistry offer promising avenues for addressing stability challenges in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs):

Surface Passivation Strategy: Pseudohalogens can function as effective surface-capping ligands for PQDs, combining the binding affinity of halogens with enhanced steric and electronic tunability. Their multifunctional nature enables simultaneous defect passivation and environmental protection.

Electronic Structure Modulation: The strong electron-withdrawing character of pseudohalogens like cyanide groups can selectively modify surface electronic structure, potentially mitigating charge recombination losses while maintaining favorable band alignment for optoelectronic applications.

Structural Stabilization: The capacity of pseudohalogens to engage in multiple non-covalent interactions can reinforce surface integrity through cooperative binding effects, potentially enhancing resistance to moisture, heat, and photo-induced degradation.

Conceptual Framework and Future Directions

Conceptual Framework of Pseudohalogen Research Evolution

The conceptual framework illustrates how pseudohalogen research has evolved from fundamental classification to diverse modern applications. Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas:

Expanded Chemical Space: Continued exploration of heavier element pseudohalogens and hybrid pseudohalogen-organometallic systems offers opportunities for discovering materials with novel properties [11]. The integration of main group elements and transition metals into pseudohalogen frameworks represents particularly promising territory.

Computational Design: Advanced computational methods now enable predictive design of pseudohalogen-functionalized materials with tailored properties for specific applications. Machine learning approaches may accelerate the identification of optimal pseudohalogen candidates for PQD surface stabilization and other advanced materials challenges.

Multifunctional Systems: The development of pseudohalogens that simultaneously address multiple stability challenges—thermal, moisture, photo-oxidation—through integrated molecular design represents a frontier in materials engineering. Such approaches may leverage synergistic effects between different pseudohalogen functionalities.

The enduring utility of the pseudohalogen concept lies in its powerful analogical framework, which continues to inspire innovative molecular design strategies across chemistry and materials science. As research advances, pseudohalogen engineering will likely play an increasingly central role in developing next-generation functional materials with enhanced stability and performance.

Surface defects in semiconductor nanomaterials, such as perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), are a primary source of non-radiative recombination that severely limits their optical performance and operational stability in optoelectronic devices. These defects, typically arising from uncoordinated ions or surface vacancies, create electronic trap states within the bandgap that quench photoluminescence and reduce quantum yields. Passivation strategies aim to chemically coordinate these unsaturated surface sites, thereby eliminating trap states and restoring the intrinsic optoelectronic properties of the material.

Pseudohalogens represent a particularly effective class of passivating agents due to their versatile coordination chemistry and electronic structure. These polyatomic anions—including groups such as BH₄⁻, SCN⁻, and BF₄⁻—exhibit properties intermediate between halides and halogens, enabling them to effectively passivate a wide spectrum of surface defects through both steric and electronic mechanisms. Their application in PQD systems has demonstrated remarkable improvements in both performance metrics and environmental stability, positioning them as critical components in the development of next-generation display and energy technologies.

Fundamental Passivation Mechanisms

Chemical Bonding and Coordination Chemistry

Pseudohalogens passivate surface defects primarily through direct chemical bonding with undercoordinated surface sites:

Lewis Acid-Base Interactions: The electron-donating capabilities of pseudohalogen groups enable them to coordinate with electron-deficient surface atoms, particularly unpassivated metal cations (e.g., Pb²⁺, Sn²⁺, Cs⁺) at the PQD surface. This coordination saturates dangling bonds and reduces trap state density [17] [18].

Vacancy Filling: Pseudohalogens effectively fill anionic vacancies, particularly halide vacancy sites that constitute prevalent trap states in perovskite structures. The BH₄⁻ group, for instance, can occupy sulfur sites in Li argyrodite systems, demonstrating the vacancy-filling capability of cluster ions [18].

Steric Stabilization: The three-dimensional structure of polyatomic pseudohalogens creates a steric barrier that impedes the approach of environmental degradants such as oxygen and moisture, thereby enhancing the environmental stability of passivated PQDs [19].

Electronic Structure Modification

The interaction between pseudohalogens and PQD surfaces induces significant modifications to the electronic structure:

Trap State Elimination: Effective passivation removes intragap states, reducing non-radiative recombination pathways. This manifests experimentally as increased photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and prolonged carrier lifetimes [17].

Band Structure Engineering: Pseudohalogen incorporation can modulate the energy level alignment at PQD surfaces and interfaces, facilitating improved charge injection in electroluminescent devices [17].

Dipole Formation: The asymmetric charge distribution in certain pseudohalogens can induce surface dipoles that modify the work function and surface energy, potentially enhancing charge transport between PQDs in solid films [18].

Table 1: Pseudohalogen Passivation Mechanisms and Their Effects

| Mechanism | Chemical Basis | Resulting Effect on PQDs |

|---|---|---|

| Coordination Bonding | Lewis acid-base interaction with undercoordinated surface cations | Reduction of electron trapping sites |

| Anionic Vacancy Filling | Substitution for missing halide anions | Elimination of halide vacancy defects |

| Steric Hindrance | Spatial blocking by polyatomic groups | Enhanced stability against moisture/oxygen |

| Dipole Formation | Asymmetric charge distribution at surface | Improved interparticle charge transport |

Experimental Protocols

Solution-Phase Pseudohalogen Passivation of CsPbBr₃ QDs

Principle: This post-synthetic treatment utilizes pseudohalogen-containing compounds to selectively bind to surface defects on pre-synthesized CsPbBr₃ quantum dots, improving optical properties through defect passivation [17].

Materials:

- CsPbBr₃ QDs in toluene suspension (5 mg/mL)

- 2-phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) in isopropanol (10 mM)

- Anhydrous toluene

- Anhydrous isopropanol

- Methanol (for purification)

- Centrifuge and tubes

- Nitrogen/vacuum environment

Procedure:

- QD Preparation: Synthesize CsPbBr₃ QDs using standard hot-injection method with appropriate capping ligands.

- Purification: Precipitate QDs by adding methanol (1:1 v/v) followed by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes. Decant supernatant and redisperse in anhydrous toluene to achieve 5 mg/mL concentration.

- Passivation Solution: Prepare 10 mM PEABr solution in anhydrous isopropanol.

- Surface Treatment: Add PEABr solution to QD suspension in 1:10 volume ratio (PEABr:QDs) under continuous stirring.

- Reaction: Maintain reaction at room temperature for 30 minutes with constant stirring under nitrogen atmosphere.

- Purification: Precipitate passivated QDs with methanol, centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes, and redisperse in anhydrous toluene.

- Characterization: Analyze optical properties (UV-Vis, PL), morphology (TEM), and composition (XPS).

Critical Parameters:

- Solvent purity is essential to prevent unwanted reactions

- Reaction time must be optimized to prevent oversecretion

- Concentration ratios should be calibrated for specific QD batches

Mechanochemical Synthesis of Pseudohalogen-Substituted Solid-State Ionic Conductors

Principle: This solid-state method incorporates pseudohalogen groups (e.g., BH₄⁻) into crystal structures during synthesis, enabling bulk modification of material properties [18].

Materials:

- Lithium sulfide (Li₂S)

- Phosphorus pentasulfide (P₂S₅)

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH₄) as BH₄⁻ source

- High-energy ball mill with zirconia vessels and balls

- Argon-filled glovebox (O₂, H₂O < 0.1 ppm)

- Hydraulic press for pelletizing

- Die set for electrochemical cell assembly

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Weigh starting materials according to stoichiometric ratio for target composition (e.g., Li₅.₉₁PS₄.₉₁(BH₄)₁.₀₉).

- Loading: Transfer powder mixtures into zirconia milling vessel inside argon-filled glovebox.

- Mechanochemical Synthesis: Mill mixture at 500 rpm for 20-40 hours with appropriate ball-to-powder ratio (typically 20:1).

- Product Collection: After milling, recover resulting powder inside glovebox.

- Annealing: Optionally anneal powder at moderate temperatures (200-300°C) under inert atmosphere to improve crystallinity.

- Pelletizing: Press powder into pellets under 1-5 tons of pressure for characterization.

- Characterization: Perform XRD, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, NMR, and AIMD simulations.

Critical Parameters:

- Strict atmospheric control throughout process prevents oxidation

- Milling time and energy must be optimized for complete reaction

- Post-synthesis annealing conditions significantly affect ionic conductivity

Characterization and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Assessment of Passivation Efficacy

The effectiveness of pseudohalogen passivation can be quantitatively evaluated through multiple spectroscopic and optoelectronic characterization techniques. Photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) provides a direct measure of radiative efficiency, with effective passivation typically increasing PLQY values from below 50% to over 80% in optimized CsPbBr₃ QD systems [17]. Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) reveals carrier dynamics, where prolonged average lifetimes (increasing from ~20 ns to ~45 ns) indicate reduced non-radiative recombination pathways [17].

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy offers insights into interfacial charge transfer resistance, with effective passivation typically reducing charge transport barriers in solid-state systems. For BH₄⁻-substituted Li argyrodites, ionic conductivity increases to 4.8 mS/cm, demonstrating enhanced ion transport following pseudohalogen incorporation [18]. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) confirms chemical bonding between pseudohalogens and surface species, with characteristic binding energy shifts indicating successful coordination.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Pseudohalogen-Passivated Materials

| Material System | Passivation Agent | Key Performance Metric | Improvement vs. Control | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ QD Film | PEABr | PLQY | 78.64% (vs. unpassivated) | [17] |

| CsPbBr₃ QD Film | PEABr | PL Lifetime | 45.71 ns (average) | [17] |

| CsPbBr₃ QLED | PEABr | Current Efficiency | 32.69 cd A⁻¹ (3.88× improvement) | [17] |

| CsPbBr₃ QLED | PEABr | EQE | 9.67% (vs. 2.49% control) | [17] |

| Li Argyrodite | BH₄⁻ | Ionic Conductivity | 4.8 mS/cm at 25°C | [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Pseudohalogen Passivation Studies

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) | Surface ligand for Br⁻ vacancy passivation | Effective for CsPbBr₃ QDs; enhances film morphology [17] |

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBH₄) | BH₄⁻ pseudohalogen source | Used in mechanochemical synthesis; improves ionic conductivity [18] |

| Ammonium Thiocyanate (NH₄SCN) | SCN⁻ pseudohalogen source | Alternative pseudohalogen for varied coordination chemistry |

| Anhydrous Isopropanol | Solvent for passivation solutions | Essential for maintaining perovskite stability during processing [17] |

| Cesium Lead Bromide (CsPbBr₃) QDs | Base perovskite material | Should be synthesized with controlled surface chemistry for optimal passivation [20] [17] |

Pseudohalogen engineering represents a powerful strategy for addressing the critical challenge of surface defects in perovskite quantum dots and related materials. The fundamental mechanisms—spanning coordination chemistry, vacancy filling, and electronic structure modification—provide a multifaceted approach to enhancing both performance and stability. The experimental protocols outlined herein offer reproducible methodologies for implementing pseudohalogen passivation in both solution-processed QD systems and solid-state ionic conductors.

Future research directions should focus on expanding the library of effective pseudohalogens, particularly exploring less conventional polyatomic anions that may offer unique steric or electronic benefits. Additionally, the development of more precise delivery mechanisms for pseudohalogen groups—such as molecular precursors with tailored reactivity—could enable more controlled and uniform passivation. Understanding the long-term stability of pseudohalogen-PQD interfaces under operational conditions remains a critical area for further investigation, particularly as these materials advance toward commercial applications in displays, lighting, and energy technologies.

Ion migration is a critical intrinsic degradation mechanism in metal halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), profoundly impacting their thermal and operational stability. Under operational stressors such as heat, light, and electric fields, halide ions and vacancies become mobile within the crystal lattice, leading to phase segregation, accelerated non-radiative recombination, and eventual decomposition of the perovskite structure [21]. This phenomenon is particularly detrimental in mixed-halide PQDs engineered for precise bandgap tuning, where ion migration results in color instability and efficiency losses [22]. Suppressing this ion mobility through advanced surface stabilization strategies, including pseudohalogen engineering, represents a fundamental pathway toward achieving commercial viability for PQD-based optoelectronic devices.

Quantitative Analysis of Stability Enhancement Strategies

The table below summarizes key performance metrics achieved through various ion migration suppression strategies, providing a comparative overview of their effectiveness.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Ion Migration Suppression Strategies

| Strategy Category | Specific Approach | Reported Efficiency | Stability Improvement | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multifaceted Anchoring Ligands | ThMAI Treatment [23] | 15.3% PCE (PQD Solar Cell) | 83% initial PCE after 15 days (vs. 8.7% for control) | Enhanced carrier lifetime, uniform orientation |

| Dual Polymer Encapsulation | Silicone/PMMA Matrix [22] | PLQY >43% (Red PQDs), >94% (Green PQDs) | 94.7% initial luminescence after 6 months in air | Suppressed halide ion diffusion via Pb–O bonds |

| Electron Transport Layer Engineering | Cl@SnO₂ QDs [24] | 14.5% PCE (PQD Solar Cell) | Enhanced operational stability under 50% RH & 1-sun illumination | Reduced photocatalytic degradation |

| A-site Cation & Ligand Optimization | FA-rich PQDs with strong ligand binding [25] | N/A | Superior thermal stability vs. Cs-rich PQDs | Higher ligand binding energy prevents direct decomposition |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Surface Stabilization via Multifaceted Anchoring Ligands

This protocol details the application of 2-thiophenemethylammonium iodide (ThMAI) for surface ligand exchange to suppress ion migration in CsPbI₃ PQDs [23].

Materials:

- Synthesized CsPbI₃ PQDs stabilized with OA/OLA in n-hexane

- ThMAI ligand

- Anhydrous n-octane

- Anhydrous acetonitrile

- Anhydrous chlorobenzene

Procedure:

- PQD Film Preparation: Deposit the synthesized CsPbI₃ PQDs onto the target substrate via spin-coating to form a solid film.

- Ligand Exchange Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of ThMAI ligand (concentration: 2.0 mg mL⁻¹) in a mixture of n-octane and acetonitrile (4:1 volume ratio).

- Ligand Treatment: Gently drop-cast the ThMAI solution onto the PQD film without disturbing the surface. Allow the solution to interact with the film for 30 seconds without spinning.

- Washing: Spin the film at high speed (e.g., 4000 rpm for 20 seconds) and during the spin, rinse with anhydrous chlorobenzene to remove excess ligands and reaction by-products.

- Annealing: Thermally anneal the treated film on a hotplate at 70°C for 5 minutes to remove residual solvent and improve crystallinity.

- Repetition: Repeat steps 1-5 for a total of 4 cycles to build up the final film thickness and complete the ligand exchange process.

Key Considerations: The ThMAI ligand's dual functional groups (thiophene and ammonium) provide multifaceted anchoring. The thiophene acts as a Lewis base to coordinate with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites, while the ammonium group occupies Cs⁺ vacancies, effectively passivating surface defects and restoring tensile strain to inhibit ion migration [23].

Protocol 2: Dual-Protection Encapsulation for Mixed-Halide PQDs

This protocol describes a hybrid protection strategy using silicone resin and PMMA to encapsulate mixed-halide PQDs, dramatically enhancing environmental and thermal stability [22].

Materials:

- Pre-synthesized CsPb(Br₀.₄I₀.₆)₃ or CsPbBr₃ PQDs

- Silicone resin

- Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)

- Toluene (anhydrous)

Procedure:

- PQD Preparation: Synthesize PQDs (e.g., via hot-injection) and concentrate the solution by removing the hexane solvent under vacuum.

- Silicone Resin Mixing: Mix the as-dried PQDs with silicone resin thoroughly until a homogeneous PQDs@silicone composite is formed. This creates the first protective layer.

- Polymer Matrix Integration: Dissolve PMMA in anhydrous toluene. Blend this solution with the PQDs@silicone composite and stir for an optimal duration to ensure uniform distribution.

- Film Casting and Drying: Cast the final mixture (PQDs@silicone/PMMA) onto the desired substrate and allow it to solidify at room temperature. This step forms the robust, dual-protected film.

Key Considerations: The combination of silicone resin and PMMA creates a synergistic effect. Theoretical calculations indicate this duo strengthens the Pb–O interaction more effectively than either component alone, effectively passivating uncoordinated Pb²⁺ and hindering halide ion diffusion via the formation of Si–halide and Pb–O bonds [22].

Visualization of Stabilization Mechanisms and Workflows

Multifaceted Anchoring for Surface Stabilization

Dual-Protection Encapsulation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for PQD Surface Stabilization Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Thiophenemethylammonium Iodide (ThMAI) | Multifaceted anchoring ligand; passivates both cationic and anionic surface defects via its functional groups. | Ligand exchange for CsPbI₃ PQDs in solar cells to enhance phase stability and charge transport [23]. |

| Silicone Resin | Hydrophobic encapsulant; forms a protective matrix and chemical bonds (Si–halide, Pb–O) with the PQD surface. | Creating hybrid composites with mixed-halide PQDs to provide a primary barrier against moisture and heat [22]. |

| Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) - PMMA | Polymer matrix; provides mechanical integrity and a second protective layer, synergistically enhancing Pb–O bonding. | Used in conjunction with silicone resin for dual-protection encapsulation of PQDs for LED applications [22]. |

| Chloride-passivated SnO₂ QDs (Cl@SnO₂) | Engineered electron transport layer; low photocatalytic activity reduces UV-induced degradation of adjacent PQD layer. | Replacing TiO₂ as ETL in CsPbI₃ PQD solar cells to suppress photocatalytic degradation and improve operational stability [24]. |

| Oleylamine (OLA) & Oleic Acid (OA) | Long-chain native ligands; control initial nanocrystal growth and provide initial surface passivation after synthesis. | Standard ligands used in the hot-injection synthesis of PQDs; often replaced in subsequent solid-state ligand exchange [23] [25]. |

Electronic structure modulation represents a cornerstone of modern materials science, enabling the precise tailoring of optoelectronic properties for advanced applications. Within this domain, bandgap tuning via pseudohalogen incorporation has emerged as a particularly powerful strategy for enhancing the performance and stability of functional materials, especially perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). Pseudohalogens, such as thiocyanate (SCN⁻), cyanate (OCN⁻), and selenocyanate (SeCN⁻), mimic the chemical behavior of halide ions while offering distinct advantages for materials engineering. Their incorporation into crystal lattices induces significant electronic perturbation, modifying band edge states and carrier effective masses through synergistic effects on crystal field strength, orbital overlap, and lattice polarization.

Framed within a broader thesis on pseudohalogen engineering for PQD surface stabilization, this application note details how these molecular anions serve a dual purpose: they simultaneously modulate electronic characteristics and enhance material robustness. The flexible coordination chemistry of pseudohalogens allows them to passivate surface defects—a major source of non-radiative recombination and degradation—while their electronic influence tunes the bandgap to desired energies. This coordinated approach addresses two critical challenges in perovskite optoelectronics: instability under operational stressors and the need for precise bandgap control in tandem device architectures. The following sections provide a quantitative overview of pseudohalogen effects, detailed experimental protocols for their incorporation and characterization, and essential guidance for implementing these strategies in research settings.

The strategic incorporation of pseudohalogens into perovskite materials induces predictable and tunable changes in their electronic and structural properties. The following tables summarize key quantitative effects observed across different material systems.

Table 1: Bandgap Modulation via Anionic Incorporation in Perovskite Structures

| Material System | Incorporated Species | Bandgap Range (eV) | Primary Tuning Mechanism | Observed Optical Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ PQDs | SCN⁻ | 1.75 - 1.95 eV [3] | Reduced lattice strain, orbital rehybridization | Red-shifted photoluminescence [3] |

| CsPbBr₃ PQDs | SeCN⁻ | 2.30 - 2.45 eV [3] | Enhanced spin-orbit coupling, bond polarization | Narrowed emission linewidth [3] |

| Sn-Pb Perovskite | Sulfonate coordination (NTS) | ~1.20 - 1.30 eV [26] | Sn-I bond strengthening, strain homogenization | Improved phase stability [26] |

| MAPbI₃ Film | OCN⁻ | 1.55 - 1.65 eV | Lattice compression, orbital overlap modification | Enhanced absorption coefficient |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Pseudohalogen-Modified Materials

| Material System | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (%) | Device Efficiency (%) | Operational Stability (Hours) | Key Characterization Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCN⁻-treated CsPbI₃ PQDs | >95% [3] | 23.2 (solar cell) [26] | >750 (MPP tracking) [26] | TRPL, XPS, FTIR [3] |

| NTS-stabilized Sn-Pb Perovskite | N/A | 29.6 (tandem cell) [26] | 700 (93.1% retention) [26] | Raman spectroscopy, AIMD [26] |

| SeCN⁻-incorporated CsPbBr₃ | ~90% [3] | N/A | Significant improvement [3] | UV-Vis, PL mapping, XRD |

| Cu-Al co-doped BC₂N | N/A | Enhanced photocatalytic response [27] | N/A | DFT calculation, DOS analysis [27] |

Experimental Protocols

Pseudohalogen Incorporation via Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP)

Principle: The LARP technique enables room-temperature synthesis of high-quality PQDs with precise pseudohalogen incorporation through careful control of precursor chemistry and crystallization kinetics [3].

Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation:

- Prepare 10 mL of 0.1 M PbO in equimolar oleic acid and octadecene at 150°C under inert atmosphere

- Dissolve 8 mmol cesium carbonate in 40 mL octadecene with 2.5 mL oleic acid at 120°C under N₂

- Cool both solutions to 80°C before mixing

Pseudohalogen Incorporation:

- Add 0.2-0.5 mmol lead pseudohalogen salt (Pb(SCN)₂, Pb(SeCN)₂) to precursor solution

- Maintain temperature at 80°C with vigorous stirring for 30 minutes

- For mixed-halide systems, adjust pseudohalogen:halide ratio to control bandgap

Nanocrystal Formation:

- Rapidly inject 5 mL precursor into 50 mL bad solvent (toluene or acetone) under vigorous stirring

- Immediate color change indicates PQD formation

- Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes to recover PQDs

Purification and Storage:

- Redisperse precipitate in hexane or toluene

- Repeat centrifugation twice at 6000 rpm

- Store purified PQDs in anhydrous solvent at 4°C under inert atmosphere

Critical Parameters:

- Water content in solvents must be <10 ppm

- Oxygen levels during synthesis should be <1 ppm

- Precursor:pseudohalogen ratio determines incorporation efficiency

- Injection temperature controls nucleation density and final particle size

Electronic Structure Characterization

Bandgap Measurement via UV-Vis Spectroscopy:

- Prepare PQD films on quartz substrates by spin-coating at 2000 rpm for 30 seconds

- Record absorption spectra from 300-800 nm using dual-beam spectrophotometer

- Calculate direct bandgap from Tauc plot: (αhν)² vs. hν, where α is absorption coefficient

- For accurate determination, use integrating sphere accessory for diffuse reflectance measurements

Surface Electronic State Analysis via X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS):

- Deposit thin PQD films on conducting substrates (ITO, Au)

- Use monochromatic Al Kα source (1486.6 eV) with spot size 200-500 μm

- Acquire high-resolution spectra for Pb 4f, Cs 3d, Br 3d, and pseudohalogen core levels

- Reference all peaks to adventitious carbon C 1s at 284.8 eV

- Analyze chemical shifts to determine binding energy changes induced by pseudohalogen incorporation

Valence Band Structure Determination:

- Collect valence band spectra with high sensitivity (pass energy 10-20 eV)

- Use ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) with He I (21.22 eV) source for higher resolution

- Combine XPS and UPS data to construct complete band alignment diagram

Stability Assessment Under Operational Stressors

Light Soaking Test:

- Encapsulate devices or films with UV-curable epoxy

- Expose to AM 1.5G simulated sunlight at 100 mW/cm²

- Maintain temperature at 45°C using Peltier cooler

- Monitor performance metrics at defined intervals (0, 100, 200, 500, 1000 hours)

Thermal Stress Testing:

- Place samples in temperature-controlled chamber

- Cycle between -40°C and 85°C with 1-hour dwell times

- Complete 100 cycles over 2-week period

- Characterize structural and optical properties after cycling

Environmental Stability Evaluation:

- Expose unencapsulated films to controlled humidity (50%, 65%, 85% RH)

- Maintain temperature at 25°C in environmental chamber

- Monitor optical properties and phase composition hourly

Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: Pseudohalogen Engineering Pathway for PQD Stabilization and Bandgap Tuning. This workflow illustrates the dual mechanism through which pseudohalogen incorporation simultaneously modulates electronic structure and enhances structural stability in perovskite quantum dots.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pseudohalogen Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes | Quality Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Thiocyanate (Pb(SCN)₂) | Pseudohalogen precursor for bandgap reduction | Enhances phase stability in iodide-rich perovskites [3] | ≥99.9% purity, moisture content <0.1% |

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cesium source for all-inorganic PQDs | Reacts with oleic acid to form cesium oleate precursor [3] | ≥99.99% trace metals basis |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand and reaction medium | Concentration controls nucleation and growth kinetics [3] | Anhydrous, ≥99% with low peroxide value |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Co-ligand and reducing agent | Optimized OA:OAm ratio crucial for morphology | ≥98% primary amine content |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-coordinating solvent | High boiling point enables wide temperature range | ≥90% (GC), purified by alumina column |

| Sodium Naphthalene-1,3,6-trisulfonate (NTS) | Lattice stabilizer for Sn-Pb perovskites | Strengthens Sn-I bonds via sulfonate coordination [26] | ≥95% purity, anhydrous form |

| Anhydrous Solvents (Toluene, Hexane) | Purification and processing | Low water content prevents degradation | ≤10 ppm H₂O, packaged under N₂ |

Analytical Methods for Validation

Raman Spectroscopy for Bond Stability Assessment

Protocol:

- Prepare thin, uniform films on glass substrates to minimize scattering

- Use 532 nm laser with power <1 mW to prevent laser-induced degradation

- Acquire spectra in 50-400 cm⁻¹ range with resolution ≤1 cm⁻¹

- Focus on metal-halide vibrational modes (75-125 cm⁻¹ for Pb-I/Sn-I) [26]

- Monitor peak position shifts under illumination to assess bond stability

Data Interpretation:

- Blue shifts in Sn-I vibration (from ~118 cm⁻¹ to ~121 cm⁻¹) indicate bond strengthening [26]

- Peak splitting suggests bond heterogeneity or partial rupture

- Compare illuminated vs. dark spectra to quantify light-induced bond weakening

Time-Resolved Photoluminescence for Carrier Dynamics

Measurement Conditions:

- Use pulsed diode laser (405 nm, <100 ps pulse width) for excitation

- Adjust fluence to maintain low injection conditions (<10¹⁷ cm⁻³)

- Collect decay curves using time-correlated single photon counting

- Measure at multiple spots to assess sample homogeneity

Analysis Methodology:

- Fit decay curves with tri-exponential function to extract lifetimes

- Associate short lifetime (τ₁, 1-10 ns) with surface recombination

- Attribute long lifetime (τ₃, 50-500 ns) to bulk recombination

- Calculate amplitude-weighted average lifetime for comparative analysis

The strategic incorporation of pseudohalogens represents a versatile approach for simultaneous bandgap tuning and surface stabilization of perovskite quantum dots. Through careful implementation of the protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can achieve precise control over electronic properties while enhancing material robustness. The quantitative relationships between pseudohalogen composition, band structure modification, and operational stability provide a framework for designing next-generation perovskite materials with tailored optoelectronic characteristics. As research in this field advances, the integration of pseudohalogen engineering with complementary stabilization strategies promises to unlock new possibilities in perovskite-based optoelectronics, from tandem photovoltaics to quantum light sources.

Synthesis and Functionalization: Practical Protocols for Pseudohalogen-Modified PQDs

Hot-Injection Methods with Pseudohalogen Precursors

The hot-injection method is a premier synthesis route for producing monodisperse and highly luminescent semiconductor nanocrystals (NCs), including metal halide perovskites (MHPs) [28] [3]. Its quintessence lies in the rapid injection of a cool precursor into a hot solvent, triggering instantaneous and homogeneous nucleation, followed by controlled crystal growth at a lower temperature [28]. This process is foundational for achieving precise control over the size, morphology, and optical properties of colloidal nanocrystals.

Pseudohalogen engineering introduces anions such as thiocyanate (SCN⁻), cyanate (OCN⁻), and cyanide (CN⁻) as versatile ligands or dopants [14]. Integrating these pseudohalogen precursors into the hot-injection synthesis of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) is a strategic approach for surface stabilization. These pseudohalogens act as effective passivating agents, binding to surface defects and suppressing non-radiative recombination pathways. This leads to enhanced photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and superior stability against environmental stressors like moisture, heat, and light, thereby addressing key challenges in the commercial application of PQDs [14] [3].

Application Notes

Key Factors and Optimized Parameters for Pseudohalogen Integration

The successful application of hot-injection methods with pseudohalogen precursors hinges on the meticulous control of several synthesis parameters. The following table summarizes the critical factors and their optimized ranges for achieving high-quality, stable pseudohalogen-engineered PQDs.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Hot-Injection Synthesis with Pseudohalogen Precursors

| Parameter | Typical Range / Condition | Impact on PQD Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Injection Temperature | 140 - 180 °C | Governs nucleation rate; higher temps lead to smaller nuclei and faster kinetics [3]. |

| Pseudohalogen Type | SCN⁻, CN⁻, NCS⁻, OCN⁻ | Determinates binding affinity and effectiveness in passivating surface defects [14]. |

| Molar Ratio (Pb:X:Pseudohal) | Variable (e.g., 1:3:0.1-0.5) | Controls the extent of surface passivation and influences final composition [14]. |

| Growth Temperature | 100 - 140 °C | Regulates crystal growth and Ostwald ripening; critical for size and size distribution [28]. |

| Reaction Time | 5 - 60 seconds | Determines final NC size; longer times lead to larger crystals [3]. |

| Ligand System | Oleic Acid, Oleylamine | Essential for colloidal stability; can coordinate with pseudohalogens for co-passivation [3]. |

| Precursor Concentration | 0.05 - 0.2 M | Affects nucleation density and final particle size [28]. |

Characterization of Outcomes

Integrating pseudohalogen precursors via the hot-injection method consistently leads to measurable improvements in the optical and structural properties of PQDs, as quantified by standard characterization techniques.

Table 2: Characteristic Outcomes of Pseudohalogen-Engineered PQDs

| Property | Standard PQDs | Pseudohalogen-Stabilized PQDs | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLQY | ~50-80% | >90% (Up to 97% reported) [3] | Fluorometer / Integrating Sphere |

| FWHM (Emission) | 20-30 nm | 18-25 nm | Photoluminescence Spectroscopy |

| Environmental Stability | Degradation in hours to days | Retained >90% PLQY after 48h UV [3] | Continuous illumination / Air exposure |

| Exciton Binding Energy | High | Enhanced | Absorption Spectroscopy |

| Surface Defect Density | Relatively high | Significantly reduced [3] | Time-Resolved PL / XPS |

Experimental Protocols

Precursor Preparation

- Cesium Oleate Precursor:

- Weigh 0.407 g (2.40 mmol) of Cs₂CO₃ into a 50 mL 3-neck flask.

- Add 15 mL of 1-octadecene (ODE) and 1.25 mL of oleic acid (OA).

- Dry under vacuum at 120 °C for 1 hour.

- Switch to nitrogen (N₂) atmosphere and heat until all Cs₂CO₃ is dissolved (typically 150-160 °C). Keep at 100 °C under N₂ until use.

- Lead Halide/Pseudohalide Precursor:

- Weigh 0.276 g (0.75 mmol) of PbI₂ and the desired molar equivalent of pseudohalogen precursor (e.g., Pb(SCN)₂) into a 25 mL vial.

- Add 10 mL of ODE, 1 mL of OA, and 1 mL of oleylamine (OAm).

- Cap the vial and stir under heat (90-100 °C) until the precursors are fully dissolved. Keep at 70 °C under N₂ until injection.

Hot-Injection Synthesis of CsPbI₃ PQDs with Thiocyanate Co-Passivation

- Setup: Assemble a 50 mL 3-neck round-bottom flask with a condenser, thermometer, and septum. Flush the system with N₂.

- Heating: Add 5 mL of ODE to the flask and heat to the target injection temperature of 160 °C under a constant N₂ flow.

- Injection: Rapidly inject 1.0 mL of the warm lead halide/thiocyanate precursor solution into the hot ODE. The solution will turn colored almost immediately.

- Nucleation & Growth: Allow the reaction to proceed for 10-20 seconds to control the growth of the PQDs.

- Quenching: Rapidly cool the reaction flask by placing it in an ice-water bath to terminate crystal growth.

- Purification:

- Transfer the crude solution to a centrifuge tube.

- Add an equal volume of methyl acetate (anti-solvent) and centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in 2-3 mL of hexane or toluene.

- Repeat the centrifugation and re-dispersion steps once more to remove excess ligands and unreacted precursors.

- Storage: Store the purified PQD solution in an inert atmosphere glovebox or sealed vials at 4 °C for further use and characterization.

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and critical decision points of the synthesis protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A successful synthesis requires high-purity reagents and specific equipment. This table details the essential materials and their functions in the protocol.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Equipment for Hot-Injection Synthesis

| Item | Specifications / Purity | Function / Role in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | 99.9% trace metals basis | Source of cesium cations for the perovskite ABX₃ structure [3]. |

| Lead Iodide (PbI₂) | >99.99% ultra-dry | Source of lead and iodide ions in the perovskite lattice [3]. |

| Lead Thiocyanate (Pb(SCN)₂) | >98.0% | Pseudohalogen precursor for surface passivation and defect reduction [14]. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Technical grade, 90% | High-boiling, non-coordinating solvent for high-temperature reactions [3]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Technical grade, 90% | Surface ligand; binds to NC surface to provide colloidal stability and prevent overgrowth [3]. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Technical grade, 70% | Surface ligand and complexing agent; aids in precursor solubility and passivates surface defects [3]. |

| Three-Neck Round-Bottom Flask | 50-100 mL capacity, with ports for N₂, condenser, and thermometer | Core reaction vessel for maintaining an inert atmosphere during synthesis. |

| Schlenk Line or N₂/Vacuum Manifold | - | Essential for creating and maintaining an oxygen- and moisture-free environment. |

| Centrifuge | Capable of 8000-10000 rpm | Critical for purifying and cleaning the final PQD product from reaction byproducts. |

Mechanism and Pathway Visualization

The stabilization mechanism of pseudohalogens on the PQD surface involves coordinated chemical interactions that suppress the primary pathways of degradation.

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) and Anion-Exchange Techniques

Application Notes

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) and Anion-Exchange are pivotal techniques in the synthesis and post-synthetic modification of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly within research focused on pseudohalogen engineering for surface stabilization. These methods enable precise control over PQD nucleation, growth, and final compositional properties, which are critical for enhancing optoelectronic performance and environmental stability [3] [29].

The LARP technique is a versatile, solution-based method for synthesizing PQDs at room temperature. Its key advantage lies in the ability to fine-tune the surface chemistry of the nascent nanocrystals through carefully selected ligand systems [29]. This is directly relevant to pseudohalogen engineering, where introducing alternative anionic species (e.g., SCN⁻, BF₄⁻) at the surface or within the crystal lattice can passivate harmful defects, suppress ion migration, and significantly improve the resilience of PQDs against moisture, heat, and light [29] [30].

Anion exchange, typically performed as a post-synthetic modification, allows for rapid and continuous tuning of the PQD's halide composition. This process facilitates precise adjustment of the bandgap and photoluminescence (PL) emission across the entire visible spectrum without needing to re-synthesize the nanocrystals [3] [31]. In the context of stabilization, this technique can be adapted to incorporate pseudohalide anions, which often possess higher bonding energies with the B-site metal cation (e.g., Pb²⁺) compared to simple halides, leading to a more robust and defect-tolerant crystal structure [30].

The synergy of these techniques provides a powerful toolkit for manufacturing high-performance, stable PQDs. Advanced PQDs synthesized via these routes achieve high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY), often exceeding 90%, and demonstrate markedly improved stability, retaining over 95% of their initial PLQY after 30 days under stress conditions such as 60% relative humidity [30]. These materials are fundamental to advancing next-generation optoelectronic devices, including light-emitting diodes (LEDs), photodetectors, and lasers, as well as sensitive applications in biosensing and environmental monitoring [3] [32] [31].

Quantitative Performance Data of LARP-Synthesized and Anion-Exchanged PQDs

Table 1: Characteristic performance metrics of PQDs processed via LARP and anion-exchange techniques.

| Property | Typical Range/Value | Application Impact | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLQY (LARP) | Up to 97% (with passivation) | Essential for high-efficiency LEDs and lasers | [3] |

| Emission Tunability (Anion Exchange) | 443 nm (blue) to 649 nm (red) | Enables full-color displays and tailored optoelectronics | [3] |

| FWHM (Full Width at Half Maximum) | < 20 nm | Results in high color purity for displays | [29] |

| Stability (PLQY Retention) | > 95% after 30 days (60% RH, ambient T) | Critical for commercial device longevity | [30] |

| Detection Limit (in Sensing) | As low as 0.1 nM for heavy metals | Enables ultrasensitive environmental and biosensors | [31] |

Research Reagent Solutions for LARP Synthesis

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for the LARP synthesis of perovskite quantum dots.

| Reagent/Material | Example | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salts | PbBr₂, CsBr, CH₃NH₃Br | Provides metal (Pb²⁺, Cs⁺, MA⁺) and halide (Br⁻) ions for crystal formation |

| Coordinating Solvents | Dimethylformamide (DMF), Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Dissolves precursor salts to form a precursor solution |

| Surface Ligands | Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) | Controls nanocrystal growth, prevents aggregation, passivates surface defects |

| Non-Solvent (Anti-solvent) | Toluene, Chloroform | Induces supersaturation and rapid nucleation when the precursor solution is injected |

| Pseudohalogen Sources | Ammonium Thiocyanate (NH₄SCN) | Introduces pseudohalide ions (SCN⁻) for enhanced lattice stability and defect passivation |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard LARP Synthesis of CsPbBr₃ PQDs

Principle: This protocol outlines the synthesis of CsPbBr₃ PQDs at room temperature via the LARP method. The process involves dissolving perovskite precursors in a polar solvent and rapidly injecting this solution into a non-polar anti-solvent containing surface-stabilizing ligands. The sudden change in solvent environment induces instantaneous nucleation and controlled growth of PQDs [3] [29].

Materials:

- Precursor Salts: Cesium bromide (CsBr), Lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂)

- Solvents: N,N'-Dimethylformamide (DMF, anhydrous), Toluene (anhydrous)

- Ligands: Oleic Acid (OA, technical grade 90%), Oleylamine (OAm, technical grade 90%)

- Equipment: Schlenk line, magnetic hotplate with stirrer, syringe filters (0.22 µm), centrifuge, UV-Vis spectrophotometer, fluorometer

Procedure:

- Preparation of Precursor Solution: In an inert atmosphere glovebox, dissolve 0.2 mmol PbBr₂ and 0.2 mmol CsBr in 1 mL of DMF in a 4 mL glass vial. Stir vigorously at 800 rpm on a magnetic stirrer until the salts are completely dissolved, forming a clear solution.

- Preparation of Ligand-Antisolvent Solution: In a 50 mL three-neck flask, add 10 mL of toluene. To this, add 100 µL of oleic acid and 100 µL of oleylamine. Seal the flask and place it on a stirrer under an inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂ purge).

- Injection and Nucleation: Once the ligand solution is homogenized, swiftly inject 0.5 mL of the precursor solution into the vigorously stirred (1000 rpm) toluene-ligand mixture using a micropipette or syringe.

- Reaction Quenching: Allow the reaction to proceed for 10-20 seconds. The immediate appearance of a bright green photoluminescence under UV light indicates PQD formation. Immediately after, centrifuge the crude solution at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes to remove any large aggregates or unreacted precursors.

- Purification and Storage: Collect the supernatant containing the purified CsPbBr₃ PQDs. For further purification, precipitate the PQDs by adding a non-solvent (e.g., methyl acetate) and re-disperse in a minimal volume of toluene or hexane. Store the final colloidal solution in a sealed vial at 4°C in the dark.

Troubleshooting:

- Low PLQY: Often due to insufficient ligand concentration or surface defects. Optimize the OA/OAm ratio or consider post-synthetic passivation [29].

- Broad Size Distribution: Can result from slow mixing or inconsistent injection speed. Ensure rapid, single-shot injection into a vigorously stirred anti-solvent.

- Precipitation: Indicates instability. Ensure all reagents are anhydrous and work under an inert atmosphere to prevent degradation.

Protocol 2: Post-Synthetic Anion Exchange for CsPb(Br/I)₃ PQDs

Principle: This protocol describes the transformation of pre-synthesized CsPbBr₃ PQDs into mixed-halide CsPb(Br/I)₃ PQDs through an ion exchange reaction. The process leverages the ionic character and dynamic lattice of perovskites, where halide ions in the crystal structure are replaced by others from a surrounding salt solution, enabling precise tuning of the optical bandgap and emission wavelength [3] [31].

Materials:

- Source PQDs: Colloidal solution of CsPbBr₃ PQDs in toluene (from Protocol 1)

- Halide Source: Lead(II) iodide (PbI₂) or Tetrabutylammonium iodide (TBAI) dissolved in DMF or toluene

- Equipment: UV-Vis spectrophotometer, fluorometer, magnetic stirrer, centrifuge

Procedure:

- Base PQD Characterization: Record the UV-Vis absorption and PL emission spectra of the starting CsPbBr₃ PQD solution to establish the initial optical properties.

- Preparation of Halide Source Solution: Dissolve a calculated amount of the halide source (e.g., 10 mM TBAI in 1 mL of toluene) in a separate vial. The concentration and volume will determine the final halide ratio.

- Anion Exchange Reaction: Under continuous stirring, add the halide source solution dropwise to a known volume and concentration of the CsPbBr₃ PQD solution. Monitor the reaction in real-time by observing the color change from green to yellow or red and/or by tracking the PL emission shift using a fluorometer.

- Reaction Termination: Immediately stop the reaction by diluting the mixture with a large volume of toluene or by initiating the purification process once the desired emission wavelength is achieved. The reaction is typically very fast (seconds to minutes).

- Purification: Purify the anion-exchanged PQDs by centrifugation and re-dispersion in a clean solvent to remove excess halide salts and reaction byproducts.

Troubleshooting:

- Incomplete Exchange: Result from an insufficient amount of halide source. Gradually increase the concentration of the halide solution added.

- Over-Exchange/Heterogeneity: Caused by adding the halide source too quickly or with inadequate mixing. Use slow, dropwise addition with vigorous stirring.

- PQD Degradation: Can occur if the halide source is too reactive or the solvent is incompatible. Using milder halide sources like TBAI can mitigate this risk.

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

LARP Synthesis Workflow

Anion Exchange Process

Pseudohalogen Stabilization

Post-Synthetic Surface Treatment and Capping Strategies

Post-synthetic surface treatment and capping strategies constitute a fundamental toolkit in nanomaterials science, enabling researchers to precisely manipulate interfacial properties without altering core material composition. These techniques are particularly vital for stabilizing delicate nanostructures, controlling surface reactivity, and imparting new functionalities for specific applications. Within the context of pseudohalogen engineering for perovskite quantum dot (PQD) stabilization, surface capping moves beyond a mere protective function to become an active component in determining optoelectronic properties, charge transport characteristics, and environmental stability. The inherent dynamic nature of perovskite surfaces, coupled with their high surface-to-volume ratio at the nanoscale, creates both a challenge and an opportunity for surface-directed stabilization approaches.