Preventing SPR Baseline Drift: A Complete Guide to Sensor Chip Storage and Handling

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on preventing baseline drift in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments.

Preventing SPR Baseline Drift: A Complete Guide to Sensor Chip Storage and Handling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on preventing baseline drift in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments. Covering foundational principles to advanced troubleshooting, it details how proper sensor chip storage, handling, and system equilibration are critical for obtaining high-quality, reproducible kinetic data. Readers will learn practical methodologies for chip preconditioning, strategies to identify and correct drift sources, and validation techniques to ensure data integrity, ultimately saving time and resources in biophysical characterization and drug discovery workflows.

Understanding SPR Baseline Drift: Causes, Impacts, and Underlying Principles

Baseline Drift? Defining the Signal Instability Problem in SPR Sensorgrams

What is Baseline Drift?

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments, the baseline is the signal recorded when only the running buffer flows over the sensor chip, in the absence of any analyte injection. A stable baseline is the fundamental prerequisite for obtaining accurate and reliable data on biomolecular interactions. Baseline drift is a common problem where this signal is unstable and gradually increases or decreases over time, rather than remaining constant [1] [2].

This instability can make it difficult to accurately measure binding responses, leading to erroneous kinetic and affinity calculations. In essence, a drifting baseline acts as a moving baseline, distorting the real-time binding signal and compromising data quality.

What Causes Baseline Drift? – FAQs

FAQ 1: I've just docked a new sensor chip or completed an immobilization, and now I see drift. Why? This is a very common occurrence. Freshly docked or immobilized sensor chips often require a period of equilibration [1] [3]. The drift results from the rehydration of the sensor surface and the wash-out of chemicals used during the immobilization procedure. The ligand itself may also be adjusting to the flow buffer [1]. It can sometimes be necessary to flow running buffer overnight to fully equilibrate the surface [1] [3].

FAQ 2: I changed my running buffer, and now the baseline is unstable. What happened? Any change in the running buffer composition can cause drift until the system is completely flushed and equilibrated with the new solution [1]. Failing to prime the system adequately after a buffer change can result in a wavy "pump stroke" signal as the previous buffer mixes with the new one in the tubing [1]. Always prime the system thoroughly after preparing a new buffer.

FAQ 3: My baseline drifts when I start the flow after a standstill. Is this normal? Yes, this is known as start-up drift [1]. Some sensor surfaces are sensitive to the initiation of flow, which can be visible as a drift that levels out over 5–30 minutes. It is advised to wait for a stable baseline before injecting your first sample.

FAQ 4: Can my protein sample cause baseline drift? Indirectly, yes. While not a direct cause, poor protein quality can lead to issues that manifest as drift. For example, aggregated protein can stick to the tubing or sensor chip surface and be randomly dislodged later, causing unstable signals and baseline shifts [4]. Ensuring high-quality, monodisperse protein samples is crucial for a stable experiment.

FAQ 5: Are some instruments better at minimizing drift? Yes, instrument design impacts drift. Systems with open fluidics may be less prone to clogging, which can cause pressure-related drift [5]. Some manufacturers specifically engineer their instruments for low drift (e.g., 0.1 μRIU) to improve data fitting [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Baseline Drift

The table below summarizes the common causes and direct solutions for baseline drift.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Baseline Drift

| Cause of Drift | Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|

| System & Surface Not Equilibrated | Prime the system after every buffer change. Flow running buffer until baseline is stable (may require 30 min to overnight). | [1] [3] |

| Air Bubbles or Contaminated Buffer | Always degas and filter (0.22 µm) buffers freshly each day. Use clean, sterile bottles. | [1] [2] |

| Start-up Drift after Flow Standstill | Wait 5-30 minutes after initiating flow for the baseline to level out. Incorporate "start-up cycles" (dummy buffer injections) before the actual experiment. | [1] |

| Poor Sample Quality / Aggregation | Improve protein quality and ensure sample homogeneity. Avoid samples that are prone to aggregation. | [4] |

| Insufficient Surface Regeneration | Optimize regeneration conditions to completely remove bound analyte between cycles, preventing carryover and drift. | [2] [6] |

Visual Guide to Diagnosing Baseline Drift

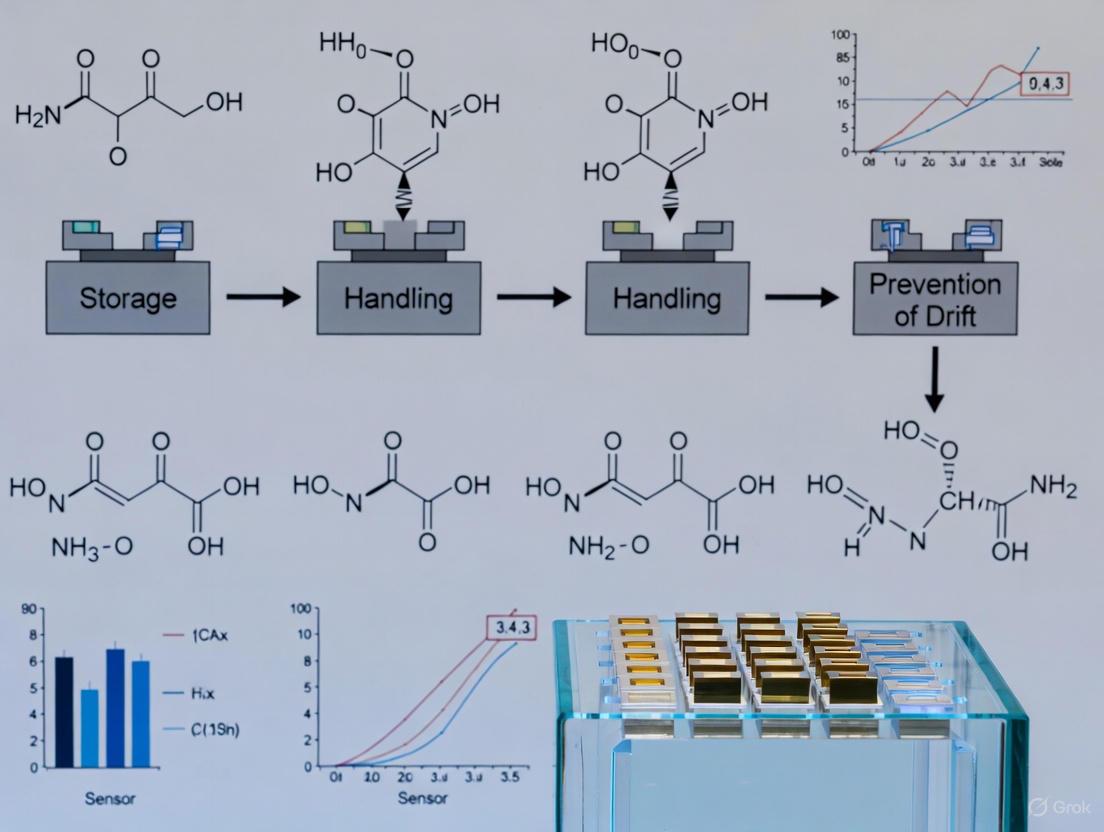

The following diagram illustrates the primary causes of baseline drift and the corresponding solutions, providing a quick diagnostic workflow.

Experimental Protocols for Preventing Drift

Protocol 1: Proper Buffer Preparation and System Startup

This protocol is your first line of defense against baseline drift.

- Buffer Preparation: Ideally, prepare buffers fresh daily. Filter 2 liters of buffer through a 0.22 µM filter and degas it. Store it in a clean, sterile bottle at room temperature to prevent dissolved air from forming spikes later. Do not add fresh buffer to old stock [1].

- System Priming: After any buffer change, prime the system several times to thoroughly replace the liquid in the pumps and tubing [1] [3].

- System Equilibration: Flow the running buffer at your experimental flow rate and monitor the baseline. A stable baseline is crucial before starting injections. If drift is high, continue flowing buffer. For new chips or after immobilization, this may take overnight [1] [3].

- Start-up Cycles: In your experimental method, program at least three start-up cycles or "dummy injections." These are identical to your analyte cycles but inject only running buffer. This primes the surface and fluidics, stabilizing the system before real data collection. Do not use these cycles in your final analysis [1].

Protocol 2: Double Referencing to Compensate for Drift

Even with a well-equilibrated system, minor drift can persist. The data analysis technique of double referencing is used to compensate for it mathematically [1].

- Subtract the Reference Channel: First, subtract the signal from a reference flow cell (which should have no active ligand) from the signal of the active flow cell. This compensates for the bulk refractive index shift and a significant portion of the drift.

- Subtract Blank Injections: Second, subtract the signal obtained from injections of blank buffer (zero analyte concentration). This step corrects for any residual drift and systematic differences between the reference and active channels. It is recommended to space blank injections evenly throughout the experiment, about one every five to six analyte cycles [1].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials to Prevent Drift

| Item | Function in Preventing Drift |

|---|---|

| 0.22 µM Filters | Removes particulates and microbes from buffers to prevent clogs and contamination. |

| Buffer Degassing Unit | Removes dissolved air to prevent bubble formation in the microfluidics, a major cause of spikes and drift. |

| High-Quality, Clean Water | The foundation of all buffers; impurities can contribute to noise and drift. |

| Fresh, Analytical Grade Reagents | Ensures buffer consistency and prevents chemical degradation products from affecting the surface. |

| Appropriate Sensor Chips | A well-suited and properly stored sensor chip is the foundation of a stable baseline. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA) | Blocks unused active sites on the sensor surface after immobilization, reducing non-specific binding. |

Visualizing the Drift Compensation Workflow

The following chart outlines the step-by-step workflow for setting up an SPR experiment to minimize and correct for baseline drift.

What is baseline drift in SPR, and why is it a problem for my kinetic data?

Baseline drift in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a gradual, unidirectional change in the response signal (in Resonance Units, RU) over time, even when no analyte is being injected. It appears as a sensorgram that does not remain flat during the baseline or dissociation phases [1].

This is a critical problem for kinetic and affinity measurements because SPR is a real-time monitoring technology that relies on precise, quantitative tracking of binding events [7]. Drift introduces errors at a fundamental level:

- Skews Kinetic Rate Constants: The calculation of association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants depends on an accurate baseline. Drift during the dissociation phase can make a slow-dissociating complex appear to dissociate faster or slower than it truly does, directly leading to incorrect koff and kon values [8].

- Compromises Affinity Constants: The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) is derived from the ratio koff/kon. Errors in the kinetic rate constants due to drift therefore propagate directly into the affinity calculation, making the measured KD unreliable [8].

- Hinders Accurate Fitting: The software models used to fit binding data assume a stable baseline. A drifting baseline can cause increased chi-squared (χ2) values and sum of residuals, indicating a poor fit between the model and the experimental data [8].

What are the primary causes of baseline drift?

Baseline drift can originate from several sources, many of which are related to sensor chip handling and storage.

- Poor System Equilibration: The most common cause is a sensor surface that is not fully equilibrated with the running buffer. This is frequently seen after docking a new sensor chip or immediately after ligand immobilization, as the surface rehydrates and chemicals from the immobilization process wash out [1].

- Temperature Fluctuations: Changes in the temperature of the instrument or the laboratory environment can cause expansion or contraction of components and changes in the buffer's refractive index, leading to drift.

- Suboptimal Storage or Handling of Sensor Chips: Improperly stored sensor chips can degrade or become contaminated, leading to unstable surfaces. Furthermore, dirty or air-bubbled fluidic systems can cause significant baseline disturbances [1].

- Buffer-Related Issues:

- Un-degassed Buffers: Buffers stored cold contain dissolved air that can come out of solution in the instrument, causing spikes and drift [1].

- Buffer Evaporation: Evaporation from the buffer reservoir can change the buffer's salt concentration and refractive index.

- Poor Buffer Hygiene: Using old or contaminated buffer is a frequent source of instability. It is "bad practice to add fresh buffer to the old since all kind of nasty things can happen/growing in the old buffer" [1].

- Unstable Ligand Surface: A decaying sensor surface, where the immobilized ligand is slowly leaching off, will produce a continuous negative drift [8].

How can I systematically troubleshoot and correct for baseline drift?

A systematic approach to troubleshooting drift is essential for obtaining high-quality data.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Fixing Drift

| Step | Observation | Likely Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Inspect Baseline | Slow, continuous drift after chip docking or immobilization. | Surface not equilibrated; wash-out of immobilization chemicals. | Flow running buffer until stable (can take 30 mins to overnight) [1]. |

| Sudden drift after changing buffer. | System not equilibrated with new buffer; buffer mismatch. | Prime the system multiple times with the new buffer and wait for stability [1]. | |

| Drift after a period of flow standstill. | Sensor surface sensitive to flow changes. | Wait 5-30 minutes after initiating flow before starting an experiment [1]. | |

| 2. Check Buffers | Drift with increased noise or spikes. | Degassing issues; contaminated or old buffer. | Prepare fresh buffer daily, 0.22 µM filter, and degas thoroughly. Use a clean bottle [1]. |

| 3. Examine Method | Consistent drift in specific phases across all cycles. | Insufficient equilibration time in method. | Add 3-5 "start-up cycles" (injecting buffer instead of analyte) to prime the surface before data collection [1]. |

| 4. Apply Data Correction | Low-level, consistent drift after other fixes. | Minor, inherent system or surface instability. | Apply "double referencing" in data analysis [1]. |

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving baseline drift.

Essential Protocol: Double Referencing

Double referencing is a powerful data analysis technique to correct for residual drift and bulk refractive index effects [1]. The procedure involves two steps:

- Reference Surface Subtraction: First, subtract the sensorgram from a reference flow cell (with no ligand or a non-interacting ligand) from the sensorgram of the active flow cell. This removes signal from bulk refractive index shifts and system-wide drift.

- Blank Injection Subtraction: Second, subtract the response from a blank injection (running buffer only) from the analyte injection responses. This corrects for any drift or artifacts specific to the injection cycle itself. For best results, include several blank injections evenly spaced throughout the experiment [1].

How does proper sensor chip storage and handling prevent drift?

The core thesis of this research underscores that proper sensor chip storage and handling is the first and most critical defense against baseline drift. A poorly stored chip is a primary source of instability.

- Prevents Degradation: Sensor chips have a finite shelf life. Storing them according to manufacturer specifications (often at 4°C, in a dark, dry environment) prevents the degradation of the functional chemical coatings (e.g., dextran polymers, capture molecules) [9].

- Maintains Surface Reactivity: Proper storage ensures that the reactive groups on the chip surface (e.g., carboxyl groups for amine coupling) remain functional for consistent and stable ligand immobilization.

- Avoids Contamination: Sealed storage protects the sensitive gold surface from dust, aerosols, and other contaminants that can create unstable binding sites and cause non-specific binding, leading to drift.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for a Stable SPR System

| Reagent / Material | Function in Preventing Drift & Ensuring Data Quality |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Water | Base for all buffers; minimizes contamination from impurities. |

| Fresh Running Buffer | Prevents drift caused by bacterial growth, evaporation, or pH shifts. Must be filtered (0.22 µm) and degassed [1]. |

| Appropriate Detergent (e.g., Tween 20) | Added to running buffer after degassing to minimize non-specific binding and surface fouling. |

| Regeneration Solution (e.g., Glycine pH 1.5-3.0) | Consistently removes analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand, ensuring surface stability over multiple cycles [8] [10]. |

| Sensor Chip Storage Solution | Specific solution (if provided) for storing sensor chips to maintain surface integrity and hydration. |

| EDC/NHS Coupling Kit | For covalent immobilization; fresh reagents ensure efficient and stable ligand attachment [11] [12]. |

FAQ: Common Questions on Drift and Data Quality

Q: What level of baseline noise is acceptable? A: After proper equilibration, the overall noise level should be very low, typically < 1 RU [1]. Injecting running buffer and observing the signal is a good way to measure your system's inherent noise level.

Q: Can I use a drifting baseline for analysis if the drift is small and constant? A: It is not recommended. Even small, constant drift should be corrected for, ideally at the source by better equilibration or in software using double referencing. Kinetic fitting is highly sensitive to an accurate baseline [8].

Q: My sensor chip has been used for over 500 cycles. Could this cause drift? A: Yes. The usage time and alteration of the sensor surface is a major influential factor on kinetic performance. Over time and many regeneration cycles, the ligand can slowly denature or be stripped from the surface, leading to a decaying surface and negative drift. Monitoring performance over time with a control system is advised [8].

Q: Are some sensor chip types more prone to drift than others? A: Yes, distinct differences in precision have been observed between sensor chips from different manufacturers and with different surface chemistries [8]. Surfaces with high immobilization levels or those with three-dimensional hydrogel matrices (like carboxymethylated dextran) may require longer equilibration times than planar surfaces.

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Baseline Drift in SPR Experiments

This guide addresses the key physical causes of baseline drift, a common issue where the sensor's signal is unstable in the absence of analyte, to ensure high-quality, reliable data [2].

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Underlying Physical Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Surface & Storage | Baseline drift after chip storage | Sensor surface rehydration and equilibration; insufficient stabilization post-storage [2] [3]. | Prime the system and run buffer over the sensor surface for an extended period (e.g., overnight) to fully equilibrate [3]. Perform several buffer injections before the experiment [3]. |

| Buffer Compatibility | Unstable or drifting baseline | Chemical incompatibility between the running buffer and the sensor chip surface chemistry; improper buffer degassing [2] [6]. | Ensure buffers are properly degassed to eliminate air bubbles [2]. Check for and avoid bulk refractive index differences between the sample and running buffer [3]. Optimize buffer composition to be compatible with the chip surface [6]. |

| Environmental Fluctuations | Noisy or fluctuating baseline | Physical instabilities in the instrument environment, primarily temperature fluctuations and vibrations [2]. | Place the instrument in a stable environment with minimal temperature variations and vibrations [2]. Use a temperature-controlled cabinet or ensure lab air handling systems are stable [6]. |

| System Maintenance | Gradual baseline shift over time | Leaks in the fluidic system that introduce air or microscopic bubbles [2]; Contamination on the sensor surface [2]. | Check the fluidic system for leaks and ensure all connections are secure [2]. Clean and regenerate the sensor surface according to manufacturer guidelines [2]. Perform regular instrument calibration [2] [6]. |

Summary of Key Principles: Achieving a stable baseline hinges on ensuring the sensor surface is perfectly equilibrated with the running buffer, the chemical and physical properties of the buffer are fully compatible with the system, and the instrument operates in a tightly controlled physical environment.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my baseline drift upwards or downwards as soon as I start an experiment after loading a stored sensor chip? This is primarily a rehydration and equilibration issue. A dry or stored sensor chip needs time to establish a stable equilibrium with the aqueous running buffer flowing over it. An insufficiently equilibrated surface will cause significant baseline drift as it hydrates. The solution is to prime the system thoroughly and allow the buffer to flow over the chip for an extended period, sometimes even overnight, until the signal stabilizes [3].

Q2: How can I tell if my buffer is incompatible with the SPR experiment? Buffer incompatibility often manifests as baseline drift, high noise, or sudden "spikes" in the signal. It can be caused by improper degassing (leading to bubbles), high salt concentrations, or the presence of components that weakly and non-specifically interact with the sensor chip surface. To troubleshoot, ensure your buffer is freshly prepared, properly degassed, and filtered. Also, perform a buffer injection over a blank surface to check for unexpected interactions [2] [3].

Q3: My lab temperature is fairly stable; can small fluctuations really affect my SPR data? Yes. SPR instruments are highly sensitive to minute changes in the physical environment. Even small temperature variations can cause the sensor chip's gold layer and the buffer to expand or contract slightly, leading to measurable baseline drift and noise. Placing the instrument away from air vents, doors, and sunlight, and ensuring it is on a stable, vibration-free bench are critical steps for optimal performance [2].

Q4: What is the first thing I should check if I observe persistent baseline drift? After confirming the sensor surface is equilibrated, the most common culprits are the buffer and the fluidic system. First, prepare a fresh batch of properly degassed running buffer. Second, meticulously inspect the entire fluidic path for any minor leaks or air bubbles. These two areas resolve the majority of baseline drift problems [2].

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology to diagnose the root causes of baseline drift.

1. Aim To methodically identify and resolve the key physical causes—sensor surface rehydration, buffer incompatibility, and temperature fluctuations—that lead to baseline drift in SPR experiments.

2. Materials and Reagents

- SPR instrument (e.g., systems from Cytiva or Reichert Technologies)

- Fresh running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP), properly degassed

- New, sealed sensor chip or a freshly regenerated chip

- 70% (v/v) glycerol in water (for normalization, if required) [13]

3. Procedure Step 1: Initial System Preparation. Prime the entire fluidic system with freshly prepared and degassed running buffer. Inspect all tubing, connections, and the sample injection needle for any signs of leaks or air bubbles [2].

Step 2: Sensor Chip Installation and Hydration. Install a new or freshly regenerated sensor chip. Initiate a continuous flow of running buffer and monitor the baseline signal. Note the initial drift rate. For a new chip, this equilibration may require an extended period (30+ minutes) to stabilize fully [3].

Step 3: Buffer versus Buffer Injection. Inject a plug of running buffer over a reference flow cell. Analyze the sensorgram. A stable, flat line indicates good buffer compatibility and no fluidic issues. A drifting signal or large bulk shifts suggest buffer problems or sample dispersion [3].

Step 4: Environmental and System Calibration. Ensure the instrument's cabinet is closed and the ambient environment is stable. Run any available system calibration and normalization routines (e.g., using a 70% glycerol solution as per manufacturer instructions) to account for instrumental variations [13].

Step 5: Data Interpretation and Next Steps.

- If drift persists after Step 2: The primary cause is likely sensor surface rehydration. Continue buffer flow until stabilization is achieved.

- If drift or noise appears during Step 3: The issue is likely related to buffer composition or degassing, or a fluidic leak. Prepare a new buffer batch and re-check fluidics.

- If the baseline is stable: The system is ready for a ligand immobilization experiment.

The logical workflow for this diagnostic procedure is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents critical for preventing and troubleshooting baseline drift in SPR experiments.

| Item | Function in Preventing Drift | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| HBS-EP Buffer | A standard running buffer (HEPES with EDTA & surfactant); its consistent pH and ionic strength prevent surface-induced drift, while P20 surfactant minimizes non-specific binding [13]. | Always degas before use; avoid repeated warming/cooling cycles; prepare fresh from high-purity components. |

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A widely used carboxymethylated dextran chip. Proper surface chemistry is foundational for stable ligand attachment and low non-specific binding, which prevents drift [13]. | Must be fully hydrated and equilibrated before use; store as recommended to prevent dehydration. |

| Ethanolamine | Used to "block" or deactivate remaining reactive groups on the sensor surface after ligand immobilization. This prevents uncontrolled binding of analyte to the chip surface, a source of drift [13]. | Standard concentration is 1 M, pH 8.5. Ensures a chemically inert background surface. |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | A cross-linking chemistry (N-ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide / N-hydroxysuccinimide) for covalent immobilization of ligands. Creates a stable, irreversible attachment, preventing ligand leakage and drift [13]. | Freshly prepared solutions are critical for efficient coupling and a stable sensor surface. |

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments, a stable baseline is fundamental for obtaining reliable, high-quality data on biomolecular interactions. Baseline drift, the phenomenon where the sensor's signal deviates from the true value over time even when the measured system is unchanged, is a common challenge that can severely compromise data integrity [14]. Effectively troubleshooting drift requires understanding its origin, which broadly falls into two categories:

- Systemic (Instrument) Drift: Arises from the instrument itself or general experimental setup, such as temperature fluctuations, power supply variations, or buffer issues [2] [14].

- Surface-Related (Chip-Specific) Drift: Originates from the sensor chip or its immobilized components, such as an improperly equilibrated surface, leaching ligand, or non-specific binding [2] [1] [3].

This guide provides a structured approach to diagnosing and resolving these distinct types of drift, ensuring the robustness of your SPR research.

Diagnostic Guide: Identifying the Source of Drift

The first step is to identify the type of drift you are encountering. The following flowchart outlines a systematic diagnostic process.

Diagnosing SPR Baseline Drift

Key Characteristics of Different Drift Types

The table below summarizes the common features and specific causes of systemic and surface-related drift to aid in diagnosis.

| Feature | Systemic (Instrument) Drift | Surface-Related (Chip) Drift |

|---|---|---|

| Common Causes | Temperature fluctuations, unstable power supply, improperly degassed buffer, air bubbles in fluidics [2] [14]. | Slow surface rehydration, leaching ligand, non-specific binding, inefficient regeneration, carryover from previous runs [2] [1] [3]. |

| Typical Manifestation | Often a gradual, continuous drift that affects all flow cells similarly [14]. | Frequently observed after docking a new chip, post-immobilization, or after a change in running buffer [1]. |

| Response to Priming | Often improves after system priming and buffer equilibration [1]. | May persist despite priming; requires surface-specific conditioning [1]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs

Systemic (Instrument-Related) Drift

Q: My baseline is continuously drifting upward or downward across all flow cells. What should I check first?

This pattern strongly suggests a systemic issue. Follow this protocol:

- Buffer Preparation and Degassing: Prepare a fresh running buffer daily. Filter (0.22 µm) and degas the buffer thoroughly before use to eliminate air bubbles, which are a primary cause of drift and spikes [2] [1]. Buffers stored at 4°C contain more dissolved air and should be warmed and degassed before use.

- Instrument Environment and Calibration: Ensure the instrument is located in a stable environment with minimal temperature fluctuations and vibrations [2]. Check that the instrument is properly grounded to minimize electrical noise. Perform instrument calibration according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

- Fluidic System Check: Inspect the fluidic system for leaks that could introduce air or cause pressure variations [2]. Prime the system thoroughly after any buffer change to ensure complete fluidic equilibration.

Q: I observe sudden spikes and high-frequency noise on my baseline. Is this drift and how do I fix it?

This is typically classified as noise rather than drift, but it often shares systemic causes.

- Check for Bubbles: Sudden spikes are frequently caused by micro-bubbles in the fluidic path. Ensure buffers are properly degassed and that the system has been primed adequately [2] [1].

- Electrical Grounding: Verify that the instrument is correctly grounded to eliminate electrical noise [2].

- Power Supply: Fluctuations in the power supply can introduce noise. Use a stable power source and consider conditioning equipment if the problem persists [14].

Surface-Related (Chip-Specific) Drift

Q: I have docked a new sensor chip (or just finished immobilization) and see significant drift. What is the cause and solution?

This is a classic sign of a non-equilibrated sensor surface. The dextran matrix or other surface chemistries require time to fully hydrate and adjust to the running buffer.

- Cause: After docking or chemical immobilization procedures, the sensor surface undergoes rehydration, and chemicals from the process are washed out, leading to a drifting baseline until equilibrium is reached [1].

- Solution: Equilibrate the surface by flowing running buffer over the sensor chip. This can take 30 minutes to several hours; in some cases, it may be necessary to run the buffer overnight to achieve perfect stability [1] [3]. Incorporate several "start-up cycles" (injecting buffer instead of analyte) at the beginning of your experiment to stabilize the surface before collecting data [1].

Q: The drift started after I injected my analyte or performed a regeneration step. How can I resolve this?

This indicates an issue with the interaction or the surface regeneration process.

- Post-Analyte Injection Drift: This can be caused by non-specific binding of the analyte to the sensor surface or a slow, continuous binding event [2] [6]. Ensure your surface is properly blocked with an agent like BSA or ethanolamine. Optimize your running buffer conditions (e.g., add a detergent like Tween-20) to minimize non-specific interactions [2] [6].

- Post-Regeneration Drift: Inefficient regeneration that fails to completely remove the bound analyte is a common culprit. The residual analyte can cause carryover effects and baseline drift [2]. Optimize your regeneration conditions (e.g., harsher pH, different buffer, longer contact time, or higher flow rate) to fully strip the analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand.

Experimental Protocols for Drift Management and Correction

Protocol 1: System and Surface Equilibration

A proper start-up procedure is the most effective way to prevent drift.

- Fresh Buffer Preparation: Prepare 2 liters of fresh buffer. Filter through a 0.22 µm filter and degas thoroughly. Store in a clean, sterile bottle at room temperature. Do not add fresh buffer to old stock [1].

- System Priming: Prime the instrument with the new buffer at least three times to ensure the entire fluidic path is equilibrated.

- Surface Equilibration: Dock the sensor chip and initiate a continuous flow of running buffer at your experimental flow rate. Monitor the baseline.

- Start-Up Cycles: Program an experimental method that includes at least three start-up cycles. These cycles should mimic your analyte injections but use running buffer instead. Include regeneration steps if they are part of your method. Do not use these cycles for data analysis [1].

- Baseline Stability Check: Wait until the baseline is stable (variation < 1-2 RU over 5-10 minutes) before beginning actual analyte injections [1].

Protocol 2: Double Referencing for Data Correction

Even with the best practices, minor drift can occur. Double referencing is a standard data processing technique to compensate for residual drift and bulk refractive index effects [1].

- Incorporate Blank Injections: Throughout your experimental run, intersperse blank injections (running buffer alone). It is recommended to have one blank cycle for every five to six analyte cycles, with blanks evenly spaced and one at the end [1].

- Subtract Reference Channel: First, subtract the signal from the reference flow cell from the signal of the active flow cell. This compensates for the majority of the bulk effect and systemic drift.

- Subtract Blank Injection: Second, subtract the averaged response from the blank injections from the reference-subtracted data. This step compensates for any remaining differences between the reference and active channels, providing a clean sensorgram for analysis [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate sensor chip and reagents is a critical pre-experimental step to minimize surface-related issues.

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| COOH1 Sensor Chip (e.g., Octet SPR) | Low-capacity, matrix-free surface for large analytes (cells, viruses) [15]. | Minimizes steric hindrance; sensitive due to minimal distance between analyte and surface. |

| PCH Sensor Chip (e.g., Octet SPR) | High-capacity surface for small molecules, fragments, and low MW compounds [15]. | Useful in conditions not favorable for dextran; long matrix (~150 nm). |

| CDH Sensor Chip (e.g., Octet SPR) | High-capacity dextran matrix for a wide range of molecules [15]. | Produces stable covalent bonds; general purpose for proteins and viruses. |

| Streptavidin (SA) Sensor Chip | Captures biotinylated ligands for controlled orientation [15] [16]. | Reduces non-specific binding; ideal for capturing specific antibodies or receptors. |

| Ni-NTA (HisCap) Sensor Chip | Captures poly-histidine tagged ligands [15] [16]. | Suitable alternative for proteins not amenable to amine coupling. |

| Ethanolamine / BSA | Blocking agents to deactivate and occupy unused active sites on the sensor surface [2] [6]. | Critical for reducing non-specific binding after ligand immobilization. |

| Filtered (0.22 µm) & Degassed Buffer | The running buffer for the SPR experiment [2] [1]. | Prevents baseline drift and spikes caused by air bubbles and particulate contamination. |

Proactive Protocols: Step-by-Step Sensor Chip Storage, Handling, and System Equilibration

For researchers in drug discovery and biologics development, the integrity of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) data is paramount. Sensor chips are the heart of the SPR instrument, and their proper storage and handling are critical first steps in preventing experimental drift and ensuring the generation of robust, reproducible results [15] [16]. This guide provides essential protocols for sensor chip storage, troubleshooting common issues, and maintaining data integrity from the moment a chip is selected until it is used in an assay.

Sensor Chip Storage Fundamentals

Proper storage begins with understanding the chip's construction. A typical SPR biosensor chip is a glass substrate coated with a thin gold layer and a functionalized immobilization matrix [11]. This sensitive surface is vulnerable to environmental factors and physical contamination, which can introduce artifacts and drift into your sensorgrams.

Core Storage Guidelines

While manufacturer-specific instructions should always be prioritized, the following general principles apply to most SPR sensor chips.

| Storage Factor | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Store at 4°C or as specified by the manufacturer. Always allow sealed chip to reach room temperature before opening. | Prevents condensation from forming on the sensitive surface, which can cause contamination or dissolution of the matrix [16]. |

| Humidity | Store in a controlled, dry environment. Use supplied desiccant in original packaging. | Moisture can compromise the chemical functional groups on the sensor surface and promote microbial growth [16]. |

| Packaging | Keep in original, light-protective casing until ready for use. Do not remove protective sheets prematurely. | Protects the gold layer and matrix from dust, scratches, and exposure to ambient light and vapors [16]. |

| Handling | Always use clean, blunt-ended forceps. Avoid contact with the sensor surface. | Prevents fingerprints, skin oils, and particulates from contaminating the surface, which can distort SPR measurements [16]. |

Figure 1: Proper sensor chip retrieval and handling workflow to minimize risks of condensation and surface contamination.

Troubleshooting Sensorgram Drift & Disturbances

Even with proper storage, sensorgram disturbances can occur. The table below links common issues to their potential root causes in storage and handling.

| Symptom | Potential Cause Related to Storage/Handling | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Baseline Drift/Shift [17] | - Chip exposed to moisture during storage.- Condensation on surface due to temperature mismatch.- Contaminated storage environment. | - Ensure chip is at room temperature before opening.- Verify integrity of storage packaging and desiccant.- Store in a clean, stable environment. |

| 'Wave' Curve or Instability [17] | - Particulate contamination (dust) on the sensor surface.- Degradation of the surface matrix. | - Inspect chip surface before use. Keep in sealed packaging.- Adhere to manufacturer's shelf-life and storage conditions. |

| Obvious Error/Spikes [17] | - Physical damage (scratches) to the gold surface.- Fingerprints or residue on the sensor surface. | - Always handle with forceps and avoid contact with the active surface.- Ensure protective sheets are not touched or damaged. |

| Low Binding Capacity | - Ageing or improper storage of functionalized surface leading to loss of activity. | - Use chips within their expiration date.- Monitor lot-specific performance. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can I re-use sensor chips if they have been stored improperly but look fine? It is not recommended. Imperceptible damage, such as a compromised monolayer or oxidation, may not be visible but can significantly increase baseline noise, drift, and non-specific binding, compromising data integrity [16] [11].

Q2: How long can I typically store SPR sensor chips? Shelf life varies by manufacturer and surface chemistry. Always note the expiration date on the original packaging and practice first-in-first-out (FIFO) inventory management. Using an expired chip risks poor performance and unreliable data.

Q3: What is the single most important step to prevent drift from storage issues? The most critical step is to allow a refrigerated chip to fully equilibrate to room temperature while still in its sealed, original packaging [16]. This simple step prevents condensation from forming on the sensitive surface, a common cause of drift and contamination.

Q4: Are there specific storage concerns for capture-type chips (e.g., NTA, Streptavidin)? Yes. The capturing molecules (e.g., streptavidin) on these chips are proteins that can denature over time if exposed to temperature fluctuations or moisture. Strict adherence to cold storage in a dry environment is essential for maintaining their activity and binding capacity [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A well-managed lab includes key materials for proper sensor chip handling and storage.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Blunt-Ended Forceps | For safe handling of sensor chips without contacting the sensitive surface, preventing scratches and oil contamination [16]. |

| Desiccant Packs | Maintains a low-humidity environment within the chip storage container, protecting the surface matrix from moisture [16]. |

| Sealed, Light-Protective Cassettes | Original packaging designed to shield chips from dust, light, and physical damage during storage [16]. |

| Temperature-Monitored Fridge | Provides a stable, cold (typically 4°C) environment for long-term storage of functionalized chips. |

| Degassed Buffer | Although not a storage item, using properly degassed buffer is critical for preventing air bubbles during experiments, a common source of sensorgram disturbance [17]. |

Figure 2: The relationship between proper storage practices and successful experimental outcomes, leading to reliable data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is proper acclimation of a new or stored sensor chip necessary, and what happens if I skip it? Proper acclimation, which involves hydrating the sensor chip surface and equilibrating it with your running buffer, is critical for achieving a stable baseline. If you skip this step, you will likely observe significant baseline drift during your experiment. This drift occurs due to the rehydration of the surface and the wash-out of chemicals used during storage or immobilization procedures. A drifting baseline makes it difficult to obtain accurate and reproducible binding data [1].

Q2: How long should I acclimate my sensor chip before starting an experiment? The required acclimation time can vary. For optimal results, it is recommended to dock the sensor chip and flow running buffer over the surface for at least 12 hours prior to running an experiment. In some cases, it may even be necessary to run the buffer overnight to fully stabilize the surface [1] [18].

Q3: What is the most effective way to clean the SPR instrument itself to prevent contamination? Regular instrument maintenance is essential. This includes daily and weekly tasks to clean the fluidic path. A more thorough "Superdesorb" procedure is recommended approximately once a month. This involves priming the system with a series of solutions like 0.5% SDS, 6 M Urea, 1% acetic acid, and 0.2 M NaHCO₃ to remove adsorbed contaminants, followed by extensive washing with hot water and running buffer [19].

Q4: How can I minimize non-specific binding and baseline instability from my samples and buffers? Always use freshly prepared buffers, filtered (0.22 µm) and degassed on the same day. Storage of buffers in sterile bottles and avoiding the addition of fresh buffer to old stock are key practices to prevent microbial growth, which can cause spikes and drift. Furthermore, ensure your samples are pure and free of aggregates, as impurities can bind non-specifically to the sensor surface [1] [6].

Q5: What are the consequences of touching the gold surface of a sensor chip? Touching the gold surface with bare hands can leave fingerprints, dust, and skin oils. These contaminants can create a non-uniform surface, leading to increased noise, baseline drift, and unreliable data due to non-specific binding of your analyte to the soiled areas [19].

Troubleshooting Common Pre-Experiment Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Baseline Drift | Sensor chip not properly acclimated to running buffer. | Flow running buffer over the docked chip for at least 12 hours before the experiment [1]. |

| System not equilibrated after a buffer change. | Prime the system several times with the new buffer and wait for a stable baseline before starting [1]. | |

| Air Spikes in Sensorgram | Buffers not properly degassed or stored at 4°C. | Always degas buffers after filtering and bring to room temperature before use [1]. |

| Poor Reproducibility | Contamination in tubing or Integrated Fluidic Cartridge (IFC). | Perform regular "Desorb" and "Sanitize" cleaning procedures as part of weekly maintenance [19]. |

| Abnormal Reflectance Dips | Contaminated or heterogeneous sensor surface (e.g., from dust or fingerprints). | Always handle sensor chips by the edges and ensure the gold surface is clean and undamaged [19]. |

Standard Maintenance and Cleaning Schedule

Maintaining a regular cleaning schedule for your SPR instrument is fundamental to preventing contamination and ensuring data quality. The following table summarizes key tasks [19].

| Task | Frequency | Estimated Time |

|---|---|---|

| Syringe Inspection (check for air bubbles and leaks) | Daily | 2 minutes |

| Unclogging (flush system at high speed) | Daily | 4 minutes |

| Injection Port & Needle Cleaning | Weekly | 10 minutes |

| Desorb (remove adsorbed proteins) | Weekly | 22 minutes |

| Sanitize (remove microorganisms with bleach) | Monthly | 45 minutes |

| Superdesorb (thorough chemical cleaning) | Monthly | 90 minutes |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following solutions are critical for sensor chip immobilization, cleaning, and maintenance protocols [20] [19].

| Reagent Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| Acetate Buffer (10 mM, pH 4.0-5.5) | Common buffer for ligand pre-concentration and immobilization via amine coupling. |

| EDC & NHS | Activates carboxyl groups on the sensor chip surface for covalent ligand immobilization. |

| Ethanolamine-HCl | Blocks unused activated ester groups on the surface after immobilization. |

| SDS Solution (0.5% w/v) | A potent detergent used in "Desorb" and "Superdesorb" to remove proteins from the fluidics. |

| Glycine-NaOH (50 mM, pH 9.5) | A high-pH solution used in cleaning protocols to wash away various contaminants. |

| Sodium Hypochlorite (10%) | Used in the "Sanitize" procedure to disinfect the fluidic system and eliminate microbes. |

Experimental Workflow: Sensor Chip Preparation and System Equilibration

The diagram below outlines the critical pre-experiment steps to ensure a clean, stable, and well-acclimated SPR system.

FAQs on Buffer Preparation for SPR

Why is it critical to use fresh buffers for each experiment? Preparing fresh buffers daily is a fundamental step to prevent contamination and ensure experimental consistency. Over time, stored buffers, especially those kept at 4°C, can become a breeding ground for microbial growth, which can introduce contaminants to the sensitive sensor surface. Furthermore, buffers stored at lower temperatures contain more dissolved air, which can form disruptive air-spikes in the sensorgram during the experiment. A common bad practice is to add fresh buffer to an old batch, which should be avoided as it can lead to unpredictable results [1].

What is the purpose of filtering and degassing the running buffer?

- Filtering: Running buffers should be 0.22 µM filtered to remove any particulate matter that could clog the intricate fluidic system of the SPR instrument or introduce non-specific binding to the sensor chip [1].

- Degassing: Dissolved air in the buffer can form small bubbles, particularly under the flow conditions and temperature stability required for SPR. These bubbles can cause sudden spikes, baseline instability, and signal noise. Degassing the buffer aliquot just before use removes this dissolved air, ensuring a smooth, uninterrupted liquid flow and a stable baseline [1] [2].

How does improper buffer preparation lead to baseline drift? Baseline drift is a frequent symptom of a poorly prepared or equilibrated system. Using a buffer that is not properly degassed introduces air bubbles that cause sudden jumps and instability. Furthermore, a change in running buffer composition without thorough system priming can create a "waviness" in the baseline as the old and new buffers mix within the pump and tubing over several pump strokes. Only a fully equilibrated system with a clean, degassed buffer will produce a stable baseline, which is the foundation for accurate kinetic data [1].

What is the recommended protocol for preparing and equilibrating buffer? A robust protocol for buffer preparation and system equilibration is key to success. The recommended steps are [1]:

- Prepare fresh buffer daily.

- Filter the solution through a 0.22 µM filter.

- Degas an aliquot of the filtered buffer just before use.

- Prime the system several times with the new buffer to completely replace the old fluid in the pumps and tubing.

- Flow the running buffer at your experimental flow rate until a stable baseline is obtained, which can sometimes require overnight equilibration, especially for a newly docked chip.

Troubleshooting Guide: Baseline Instability

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Drift | Non-optimal equilibrated sensor surface or buffer [1] | Equilibrate system by flowing running buffer longer (up to overnight); prime after buffer changes [3] [1]. |

| Dissolved air in buffer (not degassed) [2] | Use fresh, properly degassed buffer. Ensure buffer stored at room temperature, not 4°C [1]. | |

| Buffer contamination or old buffer [2] | Prepare fresh buffer daily; do not top off old buffers. Filter with 0.22 µM filter [1]. | |

| Noise or Fluctuations | Air bubbles in fluidic system [2] | Confirm buffer is degassed; check system for leaks. |

| Electrical or environmental interference [2] | Place instrument in stable environment; minimize temperature fluctuations and vibrations. | |

| Particulate matter in buffer or system [2] | Use filtered (0.22 µM), clean buffer; ensure proper cleaning of the fluidic system. | |

| Bulk Shift (Square-shaped injection artifact) | Refractive index (RI) mismatch between analyte solution and running buffer [21] | Match the composition of the analyte buffer to the running buffer as closely as possible; use reference channel subtraction [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Buffer Preparation and System Equilibration

Objective: To prepare a stable, particle-free, and degassed running buffer and to fully equilibrate the SPR instrument to minimize baseline drift and noise.

Materials:

- Buffer salts and reagents (e.g., HEPES, PBS)

- High-purity water

- 0.22 µm vacuum filter unit and sterile bottles

- Degassing unit (e.g., sonicator, vacuum pump)

- SPR instrument and sensor chip

Methodology:

- Preparation: Dissolve all buffer components in high-purity water to the desired concentration to create 2 liters of buffer [1].

- Filtration: Filter the entire buffer volume through a 0.22 µM filter into a clean, sterile bottle for storage. Store at room temperature [1].

- Daily Aliquot: Just before the experiment, transfer a working aliquot (e.g., 500 mL) to a new clean bottle.

- Degassing: Degas the working aliquot of buffer. Note: If using a detergent (e.g., Tween-20) to reduce non-specific binding, add it after the filtering and degassing steps to prevent foam from forming [1].

- System Priming: Prime the SPR instrument's fluidic system several times with the new, degassed buffer to completely displace the previous solution from all pumps and tubing [1].

- Baseline Stabilization: Initiate a constant flow of the running buffer at your experimental flow rate. Monitor the baseline signal. A stable baseline (minimal drift, e.g., < 1 RU) must be achieved before starting analyte injections. This may take 5-30 minutes or, in some cases, overnight for a new sensor chip [1].

- System Check (Optional): Perform several dummy injections of running buffer to verify low noise levels and a flat response, confirming the system is ready for the experiment [1].

This workflow ensures that the fluidic environment of your SPR experiment is stable and free from common physical artifacts that compromise data quality.

Buffer Prep and Equilibration Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for SPR Buffer and Surface Management

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| 0.22 µm Filter | Removes particulate matter from buffers to prevent clogging of microfluidics and non-specific binding on the sensor surface [1]. |

| Degassing Equipment | Removes dissolved air from the running buffer to prevent air bubble formation in the fluidic path, which causes spikes and baseline instability [1] [2]. |

| Detergent (e.g., Tween-20) | A non-ionic surfactant added to running buffer to reduce non-specific binding (NSB) by disrupting hydrophobic interactions [21]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A protein blocking agent used to coat surfaces and occupy non-specific binding sites, minimizing unwanted interactions with the analyte [21]. |

| Ethanolamine | Used as a blocking agent after ligand immobilization via amine-coupling to deactivate and block any remaining reactive groups on the sensor surface [6]. |

| High Salt Solution (e.g., 0.5 M NaCl) | Used for system checks and to reduce charge-based non-specific binding. Injection provides a sharp, square response to verify fluidic integrity [3] [21]. |

| Regeneration Buffers (e.g., Glycine pH 2.0) | Mild acidic or basic solutions used to remove bound analyte from the immobilized ligand without destroying its activity, allowing for surface re-use [21]. |

A guide to achieving a stable baseline for reliable, drift-free SPR data.

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) research, system equilibration is not merely a preliminary step but the foundation for generating kinetically accurate and reproducible data. A poorly equilibrated system manifests as baseline drift and instability, directly compromising the integrity of binding measurements. This guide outlines definitive priming protocols and start-up cycles, framing them within the essential context of proper sensor chip storage and handling to prevent drift.

Troubleshooting FAQs

1. Why is my baseline unstable or drifting significantly during an experiment?

Baseline drift often originates from improper system preparation or sensor chip issues [2].

- Solution [2]:

- Degas Your Buffer: Ensure the running buffer is properly degassed to eliminate microscopic bubbles that cause signal fluctuations.

- Inspect the Fluidics: Check the fluidic system for leaks that can introduce air.

- Fresh Buffer & Stable Environment: Always use a fresh, filtered buffer to avoid contamination and place the instrument in a stable environment with minimal temperature fluctuations and vibrations.

- Sensor Chip Surface: Check for contamination on the sensor surface and clean or regenerate it if necessary.

2. What should I do if I observe no signal change or a very weak signal upon analyte injection?

A weak or absent signal can stem from issues with the analyte, ligand, or surface preparation [2] [6].

- Solution [2] [6]:

- Verify Concentrations: Confirm that the analyte concentration is appropriate and that the ligand immobilization level is sufficient.

- Check Functionality: Ensure the ligand is functional and the interaction is expected under your experimental conditions.

- Optimize Immobilization: Low ligand density or poor immobilization efficiency can lead to weak signals. Optimize the immobilization protocol to achieve an optimal density.

- Review Surface Chemistry: Use a high-sensitivity chip (e.g., Octet SPR PCH for small molecules) if working with low-abundance analytes or weak interactions [15].

3. How can I minimize non-specific binding (NSB) in my assays?

Non-specific binding occurs when molecules other than your target analyte adsorb to the sensor surface, skewing results [6].

- Solution [2] [6]:

- Effective Blocking: After ligand immobilization, block the sensor surface with a suitable agent like BSA or ethanolamine to occupy any remaining active sites.

- Buffer Additives: Incorporate surfactants like Tween-20 into your running buffer to reduce hydrophobic interactions.

- Optimal Surface Selection: Choose a sensor chip with surface chemistry that minimizes NSB for your specific analyte.

- Optimize Regeneration: Develop a robust regeneration step to efficiently remove any non-specifically bound material between cycles [2].

4. My data lacks reproducibility between experimental runs. What could be the cause?

Poor reproducibility often arises from inconsistencies in chip handling, immobilization, or environmental factors [6].

- Solution [6]:

- Standardize Protocols: Ensure surface activation and ligand immobilization procedures are performed consistently with careful control of time, temperature, and pH.

- Use Controls: Always include negative controls to monitor for non-specific binding and validate your assay's specificity.

- Proper Chip Maintenance: Pre-condition sensor chips before use and follow a strict regeneration protocol to maintain surface integrity. Handle chips carefully to avoid physical damage [2].

- Monitor Environment: Perform experiments in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment to minimize external variables.

Best Practices for System Equilibration

Priming and Start-Up Cycle Protocol

A systematic start-up and priming procedure is crucial for stabilizing the SPR instrument and sensor chip surface before data collection.

1. Pre-Experimental Preparation

Sensor Chip Storage and Handling [2]:

- Always store sensor chips according to the manufacturer's specifications to preserve surface chemistry.

- Prior to use, allow the chip to acclimate to the laboratory environment to prevent condensation.

- Handle chips only by the edges to avoid contaminating or damaging the active sensor surface.

Buffer Preparation [6]:

- Use high-purity reagents and water.

- Filter the buffer through a 0.22 µm filter and degas it thoroughly for at least 20-30 minutes before use.

2. Instrument and Sensor Chip Priming

This multi-step protocol ensures the instrument fluidics and sensor surface are fully stabilized.

Step-by-Step Execution:

- Step 1: Install Sensor Chip. Carefully install the sensor chip, ensuring it is properly seated and secured in the instrument [15].

- Step 2: Initial System Prime. Prime the entire fluidic path with your degassed running buffer to remove any air bubbles and condition the system [2].

- Step 3: Execute Start-Up Cycles. Perform a series of buffer-only injections, mimicking the planned experimental cycle (injection followed by buffer flow). This conditions the sensor chip surface and stabilizes the baseline.

- Step 4: Stabilization Check. Monitor the baseline signal. The system is considered equilibrated when the baseline drift is minimal (e.g., < 5 RU/min over a 10-minute period) [2]. If unstable, repeat priming and start-up cycles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the correct sensor chip is a critical parameter for a successful and stable SPR assay [15] [6].

| Sensor Chip Type | Key Function & Immobilization Chemistry | Ideal Application & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Carboxylated (e.g., COOH1, CDH) [15] | Covalent coupling via amine groups (EDC/NHS chemistry). | General purpose for proteins; provides a stable, covalent bond for ligands. |

| Streptavidin (SA) [15] | Captures biotinylated ligands. | For controlled orientation of biomolecules; minimizes interference of the target ligand. |

| High Capacity (e.g., PCH) [15] | Hydrophobic interaction for fragment capture. | Small molecule, fragment, and organic compound studies; high binding capacity. |

| NTA (Nitrilotriacetic acid) [6] | Captures His-tagged proteins. | For studying His-tagged recombinant proteins; reversible binding allows surface regeneration. |

Logical Workflow for Drift Prevention

The following diagram integrates storage, handling, priming, and troubleshooting into a coherent strategy to prevent baseline drift in SPR research.

Why a Stable Baseline is Critical

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments, a stable baseline is the foundation for generating high-quality, interpretable data. It signifies that the instrument and sensor surface are properly equilibrated with the running buffer, minimizing signal drift that can distort the binding sensorgrams. Excessive drift can be mistaken for binding or dissociation, leading to inaccurate kinetic and affinity calculations [1].

The process of establishing a stable baseline is intrinsically linked to proper sensor chip storage and handling. A poorly stored chip can introduce contaminants or cause surface alterations, leading to persistent baseline drift and non-specific binding, which undermines data reliability.

How Long to Equilibrate: Quantitative Guidance

The required equilibration time depends on the specific situation. The following table summarizes evidence-based timeframes for different experimental stages.

Table 1: Recommended Equilibration Times for a Stable Baseline

| Experimental Stage | Recommended Minimum Time | Context and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| After docking a new sensor chip | Overnight (e.g., 12 hours) | This allows for complete rehydration of the sensor surface and wash-out of storage solution contaminants [1] [22]. |

| After ligand immobilization | Overnight | Chemicals used during immobilization (e.g., EDC/NHS) must be thoroughly washed away, and the immobilized ligand must adjust to the flow buffer [1]. |

| After a change in running buffer | Until baseline is stable (Prime system) | Prevents "waviness" from buffer mixing. Prime the system and wait for a stable signal [1]. |

| At the start of a method | 5–30 minutes | The system is sensitive to flow changes after a standstill. A 5-minute wait before the first injection is recommended [1] [22]. |

When to Proceed: Assessing Baseline Stability

Before starting analyte injections, confirm your system is ready by checking the following criteria:

- Drift Rate: The baseline drift should be minimal, ideally less than ± 0.3 Resonance Units (RU) per minute [23].

- Flat Baseline: The signal should be practically flat, with no consistent upward or downward trend [23].

- Successful "Start-Up Cycles": Integrate at least three start-up cycles into your experimental method. These are cycles that mimic your experimental conditions but inject only running buffer, including any regeneration steps. The baseline should stabilize during these dummy runs before you proceed to actual analyte injections [1].

The flowchart below outlines the decision-making process for establishing a stable baseline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Baseline Stability

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Troubleshooting Baseline Drift

| Item | Function & Importance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh, Degassed Buffer | The running buffer must be free of air bubbles and prepared daily to prevent spikes, drift, and bacterial growth [1]. | Always filter (0.22 µm) and degas buffers before use. Do not top off old buffer with new [24] [1]. |

| Appropriate Sensor Chip | The choice of chip (e.g., CM5, C1, L1) depends on the ligand and analyte. Proper storage is critical to its performance. | Sensor chips have a finite shelf life (e.g., 6 months). Store as recommended, either wet at 4°C or dry in a desiccator [9] [22]. |

| Cleaning & Regeneration Solutions | Used to maintain the instrument and sensor surface. Examples include 10 mM Glycine (low pH) and 50 mM NaOH [23] [24]. | Use the mildest effective regeneration conditions to remove analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand [23]. |

| Blocking Agents | Proteins like BSA can be used to create a reference surface or block unused reactive groups on the sensor chip, reducing non-specific binding [9] [22]. | Ensures the reference channel closely mimics the active surface, improving the quality of double referencing [22]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for System Equilibration

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare a fresh batch of running buffer. Filter it through a 0.22 µm filter and degas it thoroughly. Adding a detergent can help minimize non-specific binding, but it should be added after degassing to avoid foam [1].

- System Priming: Prime the SPR instrument with the new buffer several times to flush out the previous buffer completely from the entire fluidic path [1].

- Initial Equilibration: Begin flowing buffer over the docked sensor chip at your intended experimental flow rate. If the chip is new or has just been immobilized, plan for an extended equilibration period, potentially overnight [1].

- Incorporate Start-Up Cycles: Program your method to include at least three start-up cycles. These cycles should be identical to your experimental cycles, including regeneration steps, but should inject running buffer instead of analyte [1].

- Assess and Proceed: After the start-up cycles, verify that the baseline drift is within the acceptable limit (< ± 0.3 RU/min). Once stable, you can confidently begin your analyte injections [23].

Diagnosing and Correcting Drift: Practical Troubleshooting and Optimization Strategies

A stable baseline is the foundation of reliable SPR data.

What is Baseline Drift?

Baseline drift in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) occurs when the signal, recorded in the absence of analyte, is unstable and shifts upward or downward over time. A stable baseline is crucial for obtaining accurate kinetic and affinity data, as drift can distort the sensorgram and lead to incorrect interpretation of binding events [2].

This guide will help you systematically identify and resolve the common causes of baseline drift in your experiments.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying the Source of Drift

Q1: Is your system properly equilibrated?

The Problem: The baseline is unstable or drifting continuously, often at the start of an experiment [2].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| System not equilibrated | Observe if drift is most prominent at start of run | Allow buffer to flow over sensor surface for extended time; "run the flow buffer overnight" or use several buffer injections [3]. |

| Buffer mismatch | Check if sharp signal spikes occur at injection start/end | Ensure the running buffer and analyte sample buffer are identical. Match pH, ionic strength, and composition [3]. |

| Bubbles or contamination | Look for sudden, large shifts or noise | Degas buffers thoroughly before use. Check fluidic system for leaks and ensure all solutions are fresh and filtered [2]. |

Q2: Is the issue coming from your sensor surface?

The Problem: Drift is accompanied by other issues like high non-specific binding or inconsistent data between runs [2].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Deteriorating sensor chip | Monitor surface performance over time and multiple regeneration cycles | Handle chips carefully to avoid damage. Follow manufacturer’s storage guidelines and regeneration protocols. Do not use expired chips [9] [2]. |

| Non-specific binding (NSB) | Check for a rising signal that doesn't plateau during analyte injection | Use a suitable blocking agent (e.g., BSA, ethanolamine) after ligand immobilization. Optimize buffer conditions to minimize non-specific interactions [2]. |

| Unstable ligand immobilization | Observe if baseline is stable before but not after ligand coupling | For capture coupling, ensure the ligand is not slowly dissociating from the surface. For covalent coupling, confirm ligand stability [11] [9]. |

Q3: Are your instrument and environment stable?

The Problem: The baseline is noisy or shows slow, continuous drift even after thorough equilibration [2].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature fluctuations | Check if drift correlates with room temperature changes or instrument thermostat performance | Place the instrument in a stable environment away from drafts, air conditioning vents, or direct sunlight. Allow instrument to warm up sufficiently [2]. |

| Electrical noise or vibrations | Look for high-frequency noise superimposed on the baseline | Ensure proper electrical grounding of the instrument. Place on a stable, vibration-dampening bench [2]. |

Follow the systematic diagnostic workflow below to pinpoint your drift source.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Proper handling of these core materials is critical for preventing drift and ensuring experimental success.

| Item | Function in Drift Prevention | Handling & Storage Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer | Provides consistent solvent environment; mismatch with sample buffer is a primary drift cause [3]. | Always degas before use. Use high-purity reagents. Filter through a 0.22 µm filter. |

| Sensor Chips | The foundation for immobilization; a degraded chip causes instability [9] [2]. | Store as recommended (often 4°C). Do not use beyond expiration date. Handle by edges to avoid damage. |

| EDC & NHS | Activate carboxylated surfaces for covalent amine coupling [9] [25]. | Freshly prepare or reconstitute aliquots. Store dry at -20°C. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. |

| Ethanolamine | Deactivates remaining active esters on sensor surface after coupling, reducing non-specific binding [25]. | Use at the recommended concentration (e.g., 1.0 M, pH 8.5). |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A common blocking agent used to passivate the sensor surface and minimize non-specific binding [2]. | Prepare solutions fresh or store aliquots at -20°C. Filter before use. |

Key Takeaway

Most baseline drift issues can be prevented through meticulous experimental preparation: always degas your buffers, perfectly match your running and sample buffers, and ensure your sensor chip is fresh and properly handled. When drift occurs, use the systematic workflow to efficiently pinpoint the root cause.

FAQs on Immobilization and Regeneration

Q1: Why is my baseline drifting, and how can I stabilize it? Baseline drift is typically a sign of a non-optimally equilibrated sensor surface [1] [3]. Common causes include surfaces that are not fully rehydrated, wash-out of immobilization chemicals, or a system that has not been sufficiently purged after a buffer change [1]. To stabilize the baseline:

- Equilibrate thoroughly: After docking a new sensor chip or performing an immobilization, flow running buffer until the baseline stabilizes. This can sometimes require equilibrating the system overnight [1] [17].

- Use fresh, degassed buffers: Always prepare fresh buffers daily, filter them (0.22 µM), and degas them to prevent air bubbles that can cause spikes and drift [1] [2].

- Prime the system: After every buffer change, prime the instrument to ensure the previous buffer is completely flushed out [1].

- Incorporate start-up cycles: Add at least three dummy cycles at the beginning of your experiment that inject buffer (and regeneration solution if used) to "prime" the surface before collecting data [1].

Q2: How do I choose the right regeneration buffer for my interaction? The optimal regeneration buffer is specific to your molecular interaction and must be strong enough to remove all bound analyte but mild enough to preserve ligand activity for multiple cycles [26] [27]. A general strategy is to start with mild conditions and progressively increase the intensity. The table below summarizes common starting points based on interaction type [26] [27].

Table 1: Common Regeneration Buffers for Different Molecular Interactions

| Interaction Type | Recommended Reagent | Typical Concentration Range |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins / Antibodies | Acid (e.g., Glycine) | 5 - 150 mM [26] |

| Peptides / Proteins / Nucleic Acids | SDS | 0.01% - 0.5% [26] |

| Nucleic Acids / Nucleic Acids | NaOH | 10 mM [26] |

| Lipids | IPA:HCl | 1:1 ratio [26] |

| Strong ionic interactions | High Salt (e.g., MgCl₂) | 1 - 4 M [27] |

| Hydrophobic interactions | Ethylene Glycol | 25 - 50% [27] |

Q3: My regeneration is either damaging the ligand or not removing the analyte. How can I optimize it? Optimization requires empirical testing. The "cocktail method" is a systematic approach that involves mixing different stock solutions to target multiple binding forces (e.g., ionic, hydrophobic) simultaneously with less harsh conditions [27].

- Prepare stock solutions for acidic, basic, ionic, detergent, and solvent regeneration agents [27].

- Create test cocktails by mixing small volumes of different stock solutions.

- Inject analyte and then a test regeneration cocktail. Evaluate the regeneration efficiency.

- Refine the recipe based on the best-performing cocktails, iterating until you find a solution that fully regenerates the surface without damaging the ligand (evidenced by a stable baseline and consistent analyte binding across cycles) [26] [27].

Q4: What is the optimal ligand density for kinetic studies? For accurate kinetic measurements, a low ligand density is crucial to avoid effects like mass transport limitation and steric hindrance. A general guideline is to aim for a maximal analyte response (Rmax) of around 100 RU [25]. This ensures the binding rate is governed by the interaction kinetics rather than by the analyte's diffusion to the surface.

Q5: How can I reduce non-specific binding (NSB) on my sensor surface? Non-specific binding occurs when your analyte adheres to the surface rather than specifically to your ligand [28].

- Effective blocking: After immobilization, block any remaining active sites with a suitable agent like ethanolamine, BSA, or casein [25] [6] [28].

- Use a reference surface: A well-matched reference channel is essential for subtracting bulk refractive index shifts and non-specific binding signals [1].

- Buffer additives: Supplement your running buffer with surfactants like Tween-20 to minimize hydrophobic interactions [6] [28].

- Surface chemistry: Choose a sensor chip with a surface chemistry that minimizes NSB for your specific molecules. For positively charged analytes, consider blocking with ethylenediamine to reduce surface negative charge [25] [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Surface-Related Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Drift [1] [2] [17] | • Surface not equilibrated• Buffer not degassed• Buffer contamination or mismatch• Air bubbles in system | • Extend equilibration time (overnight if needed)• Filter and degas fresh buffer daily• Prime system after buffer change• Use a high-flow flush step (e.g., 100 µl/min) between cycles |

| No or Weak Signal [2] [6] [28] | • Low ligand density• Inactive ligand• Poor ligand orientation / accessibility• Analyte concentration too low | • Optimize immobilization pH and time to increase density• Check ligand activity; use a capture method for better orientation• Increase analyte concentration |

| Carryover / Incomplete Regeneration [26] [27] [17] | • Regeneration solution too mild• Insufficient regeneration contact time• High-viscosity solutions | • Optimize regeneration buffer (try stronger conditions or cocktails)• Increase regeneration flow rate or injection time• Add extra wash steps after regeneration |

| Ligand Inactivation [26] [27] | • Regeneration solution too harsh• Repeated regeneration cycles degrade ligand | • Re-optimize to find milder effective conditions• Condition the surface with 1-3 regeneration cycles before data collection• For analysis, use a local Rmax fitting |

| Non-Specific Binding (NSB) [6] [28] | • Inadequate surface blocking• Electrostatic interactions• Analyte impurities | • Improve blocking with BSA, ethanolamine, etc.• Increase ionic strength in running buffer• Ensure sample purity and include a proper reference surface |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Scouting for Regeneration Conditions

This protocol is based on the multivariate cocktail approach for efficiently finding the optimal regeneration solution [27].

1. Prepare Stock Solutions: Create the following six stock solutions [27]:

- Acidic: Equal volumes of 0.15 M oxalic acid, H₃PO₄, formic acid, and malonic acid, mixed and adjusted to pH 5.0 with NaOH.

- Basic: Equal volumes of 0.20 M ethanolamine, Na₃PO₄, piperazin, and glycine, mixed and adjusted to pH 9.0 with HCl.

- Ionic: A solution of 0.46 M KSCN, 1.83 M MgCl₂, 0.92 M urea, and 1.83 M guanidine-HCl.

- Solvents: Equal volumes of DMSO, formamide, ethanol, acetonitrile, and 1-butanol.

- Detergents: A solution of 0.3% (w/w) CHAPS, 0.3% (w/w) Zwittergent 3-12, 0.3% (v/v) Tween 80, 0.3% (v/v) Tween 20, and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100.

- Chelating: A 20 mM EDTA solution.

2. Create and Test Initial Cocktails:

- Mix new regeneration solutions where each cocktail consists of three parts. These can be three different stock solutions or one stock plus two parts water.

- Follow this testing cycle [27]:

- Inject your analyte over the ligand surface.

- Inject the first regeneration cocktail.

- Measure the regeneration efficiency (0-100%). If it's below 10%, inject the next, potentially stronger cocktail. If it's over 50%, inject a new analyte plug to test ligand activity.

- Repeat until all cocktails are tested.

3. Refine the Best Cocktails:

- Identify the stock solutions common to the top-performing cocktails.

- Use these stocks to mix new, more refined regeneration solutions.

- Repeat the testing cycle until you identify a solution that provides complete regeneration (>95%) while maintaining stable ligand binding activity over multiple cycles.

Protocol 2: Ligand Immobilization via Amine Coupling

This is a standard protocol for covalently immobilizing ligands containing primary amines [25].

Workflow Overview:

Steps:

- Surface Activation: