Physisorption vs Chemisorption: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a definitive guide to adsorption phenomena, specifically tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical science.

Physisorption vs Chemisorption: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide to adsorption phenomena, specifically tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical science. We dissect the fundamental principles distinguishing physical adsorption from chemical adsorption, exploring the underlying forces, energetics, and kinetics. The content extends to practical methodologies for characterization, application-based selection of processes, and troubleshooting for system optimization. With a focus on validation techniques and a forward-looking perspective, this review synthesizes key concepts to inform material selection, catalytic processes, and contaminant removal in pharmaceutical and clinical research, bridging foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications.

Core Principles: Unraveling the Fundamental Forces of Adsorption

Adsorption is a fundamental surface process with critical applications across environmental technology, catalysis, and pharmaceutical development. This phenomenon involves the accumulation of atoms, ions, or molecules from a gas, liquid, or dissolved solid onto a surface, creating a film of the adsorbate on the adsorbent material [1] [2]. Understanding the distinction between adsorption (surface accumulation) and absorption (bulk penetration) is essential, with sorption serving as the umbrella term encompassing both processes [1] [3].

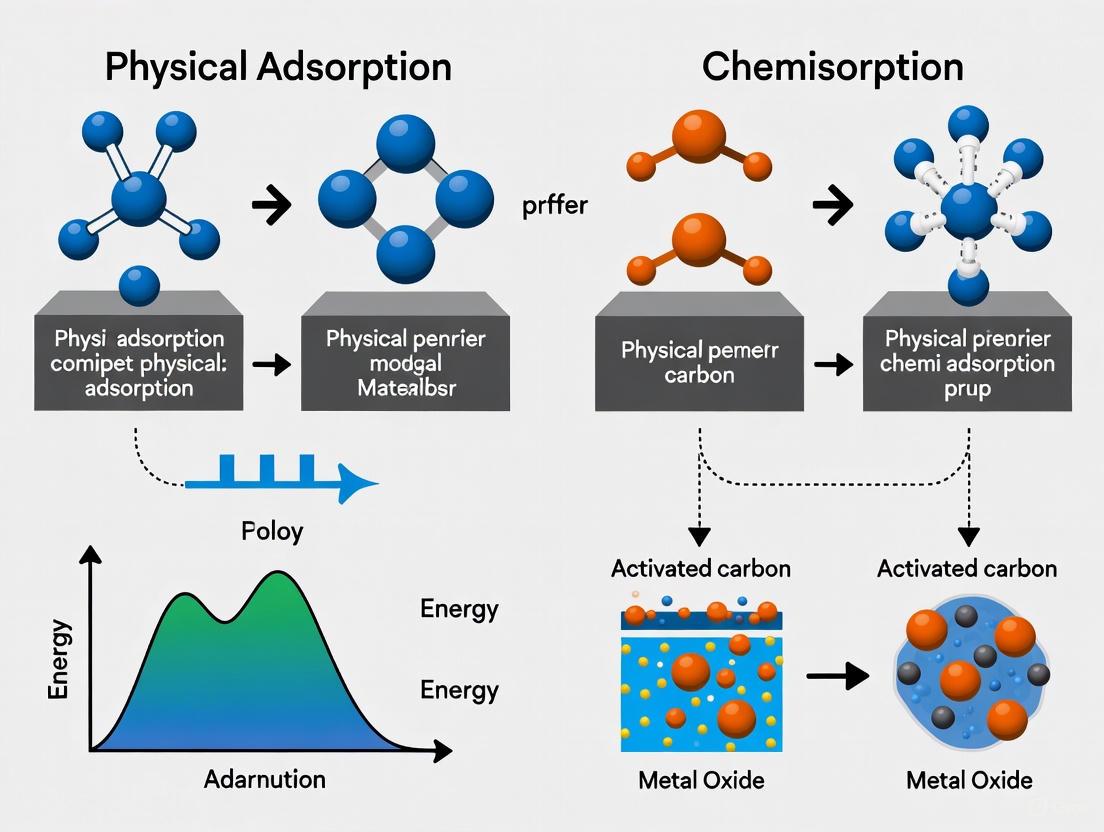

The adsorption system comprises three fundamental components, as illustrated in Figure 1:

- Adsorbent: The solid material on which accumulation occurs, characterized by high surface area and porosity [2]

- Adsorbate: The substance that becomes adsorbed at the interface [2]

- Medium: The fluid phase (gas or liquid) containing the adsorbate

Figure 1. Components and relationships in an adsorption system, showing key adsorbent materials.

This process arises from unbalanced surface forces that create surface energy, driving the adhesion of substances to interfaces between condensed and fluid phases [1] [4]. The following sections provide a comprehensive technical examination of adsorption fundamentals, classification, and experimental characterization.

Adsorption Fundamentals and Classification

Physisorption versus Chemisorption

Adsorption mechanisms are primarily categorized as physical adsorption (physisorption) or chemical adsorption (chemisorption), distinguished by their fundamental interaction forces, energetics, and reversibility characteristics [5] [4].

Table 1. Comparative analysis of physisorption and chemisorption properties

| Property | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Interaction Forces | Weak van der Waals forces [5] [2] | Strong chemical bonding [5] [2] |

| Enthalpy Range | Low (20–40 kJ/mol) [5] | High (80–240 kJ/mol) [5] |

| Reversibility | Reversible [5] [2] | Irreversible [5] [2] |

| Temperature Dependence | Favored at low temperatures [5] | Increases with temperature then decreases [5] |

| Specificity | Non-specific [5] | Highly specific [5] |

| Adsorbate State | No change in state [5] | May change state [5] |

| Typical Layers | Multilayer formation possible [1] | Monolayer limited [1] |

The potential energy curves in Figure 2 illustrate the distinct interaction profiles and energy barriers between physisorption and chemisorption processes, explaining their different temperature dependencies and bonding characteristics.

Figure 2. Potential energy curves distinguishing physisorption and chemisorption mechanisms.

Adsorption Isotherm Models

The quantitative relationship between adsorbed quantity and pressure or concentration at constant temperature is described by adsorption isotherms. Several models have been developed to characterize this relationship, with the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms being most fundamental [1].

Langmuir Isotherm: Derived by Irving Langmuir in 1918, this model assumes: (1) all adsorption sites are equivalent, (2) each site accommodates one molecule, (3) no interactions between adsorbed molecules, and (4) monolayer coverage [1]. The model is expressed as:

θ = KP / (1 + KP)

Where θ represents surface coverage, K is the equilibrium constant, and P is pressure. The Langmuir model is particularly applicable to chemisorption systems and homogeneous surfaces [1].

Freundlich Isotherm: An empirical relationship describing adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces, expressed as:

x/m = kP^(1/n)

Where x/m is quantity adsorbed per mass unit, P is pressure, and k and n are constants [1]. Unlike the Langmuir model, Freundlich accounts for surface heterogeneity and is applicable to multilayer adsorption.

BET Theory: Developed by Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller, this model extends Langmuir theory to describe multilayer physisorption, particularly important for surface area characterization of porous materials [1].

Experimental Characterization and Methodology

Case Study: COâ‚‚ Adsorption on Activated Carbon

A 2025 investigation of COâ‚‚ adsorption on activated carbon (AC) provides a representative experimental protocol for physisorption analysis [6]. The study employed a probabilistic modeling framework combined with adsorption experiments to quantify multilayer adsorption behavior.

Materials and Reagents:

- Powdered Activated Carbon (PAC) from bituminous coal (Surface area: 879 m²/g, Pore volume: 0.540 cm³/g) [6]

- High-purity COâ‚‚ gas (>95%)

- Characterization gases: Nâ‚‚ for BET surface area analysis

Experimental Conditions:

- Temperature range: 26°C, 43°C, 51°C, and 62.5°C

- Pressure variation across appropriate ranges for isotherm generation

- Equilibrium establishment at each condition

Instrumentation and Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: AC washed with distilled water to neutral pH and dried at 109°C for 18 hours [6]

- Surface Characterization:

- BET analysis using Nâ‚‚ adsorption at 77K for surface area determination

- BJH method for mesopore size distribution

- SEM for morphological analysis

- XRD for crystallographic structure

- Adsorption Experiments:

- Gravimetric or volumetric measurement of COâ‚‚ uptake at varying pressures

- Establishment of adsorption isotherms at four temperatures

- Kinetic analysis to determine adsorption rates

- Statistical Modeling:

- Application of grand canonical ensemble for theoretical framework

- Fitting of experimental isotherm data to Langmuir and other models

- Parameter extraction including adhesion energy (ΔEa) and internal energy (Eint)

Key Findings:

- COâ‚‚ adsorption on AC formed 3-4 distinct layers under optimal conditions

- Adsorption identified as exothermic physisorption (ΔEa: 23.08–23.78 kJ/mol) with no chemical bonding

- Elevated temperatures reduced adsorption layers but increased interaction energy

- Multilayer adsorption compensated for AC's high density of active sites, enhancing capture efficiency [6]

Advanced In Situ Monitoring Techniques

Recent methodological advances enable real-time quantitative monitoring of adsorption processes. A 2024 study demonstrated an integrated approach coupling in situ UV-Vis spectroscopy with a two-step algorithm strategy for heterogeneous reaction quantification [7].

Methodological Framework:

- In Situ UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Real-time monitoring of adsorption kinetics in aqueous suspension

- Inverse Adding-Doubling (IAD) Method: Correction for light scattering effects in heterogeneous systems

- Multivariate Curve Resolution-Alternating Least Squares (MCR-ALS): Spectral deconvolution without prior reference spectra requirements

- Computational Spectroscopy Simulations: Connection of MCR-ALS solutions with molecular structural evolution

Application Workflow:

- Continuous monitoring of reflectance and transmittance spectral kinetics during adsorption

- Extraction of pure optical absorption properties after scattering correction

- Identification of spectral profiles of chemical compositions and their abundance

- Quantification of adsorption kinetics through spectral evolution tracking

This methodology successfully quantified bisphenol A adsorption onto polyamide microparticles, demonstrating applicability for pharmaceutical and environmental adsorption studies [7].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 2. Essential research reagents and materials for adsorption studies

| Material/Reagent | Function & Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Activated Carbon [6] | Broad-spectrum adsorbent for gases, organics, and pollutants | High surface area (600-1500 m²/g), microporous structure |

| Zeolites [2] | Selective gas adsorption, ion exchange, and catalysis | Crystalline aluminosilicates, uniform pore structure, acidity |

| Silica Gel [2] [3] | Humidity control, chromatography, and separation | Amorphous SiOâ‚‚, high hydrophilicity, tunable porosity |

| Activated Alumina [2] [3] | Drying, purification, and catalyst support | Porous Al₂O₃, thermal stability, surface acidity |

| Molecular Sieves [6] | Size-selective separation and drying | Uniform pore size, high selectivity, regenerability |

| Nanoparticle Adsorbents [2] | Enhanced adsorption capacity and kinetics | High surface area-to-volume ratio, tunable surface chemistry |

| Minocycline-d6 | Minocycline-d6, MF:C23H27N3O7, MW:463.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Yonkenafil-d8 | Yonkenafil-d8, MF:C24H33N5O4S, MW:495.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The selection of appropriate adsorbent materials depends on specific application requirements, including surface chemistry, pore structure, regeneration capability, and selectivity for target adsorbates.

The accumulation of molecules, atoms, or ions from a fluid onto the surface of a solid material represents a fundamental process known as adsorption [8]. This phenomenon, distinct from absorption where molecules penetrate the bulk material, plays a critical role in numerous scientific and industrial applications, including purification, separation, catalytic transformation, and drug development [8]. Adsorption mechanisms are primarily categorized into physisorption (physical adsorption) and chemisorption (chemical adsorption), with the nature of the intermolecular forces involved serving as the key differentiator between these processes [9] [8].

Physisorption is characterized by weak, reversible interactions, predominantly van der Waals forces, which include dipole-dipole, dipole-induced dipole, and London dispersion forces [10]. These forces arise from transient fluctuations in electron distribution within molecules and do not involve significant electronic rearrangement or chemical bond formation. In contrast, chemisorption involves the formation of strong, irreversible chemical bonds through substantial electron transfer or sharing between the adsorbate and adsorbent [9]. This fundamental distinction in bonding mechanisms leads to dramatic differences in adsorption behavior, including enthalpy changes, temperature dependence, reversibility, and the formation of monolayer versus multilayer structures [9] [8].

Understanding these mechanisms is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical research and development, where surface interactions influence drug stability, formulation, delivery, and efficacy [11] [12]. The following sections provide a comprehensive technical examination of physisorption, with emphasis on its quantitative characterization, experimental protocols, and applications in drug development.

Fundamental Principles of Physisorption

Molecular Interactions and Energetics

Physisorption occurs when gas or liquid molecules adhere to a surface through weak van der Waals forces without forming chemical bonds [13] [9]. This process is characterized by low adsorption enthalpies, typically ranging between 5 and 40 kJ/mol [8]. The weakness of these interactions makes physisorption generally reversible and favored at lower temperatures, as increased thermal energy can readily overcome these forces [9] [8].

Several types of van der Waals forces contribute to physisorption:

- London dispersion forces: Temporary fluctuating dipoles due to uneven electron distribution in adjacent atoms or molecules.

- Dipole-dipole interactions: Electrostatic forces between permanent molecular dipoles.

- Dipole-induced dipole forces: Interactions between a permanent dipole and an induced dipole in a polarizable molecule.

Unlike chemisorption, which typically forms a unimolecular layer due to specific chemical bonding requirements, physisorption can result in multimolecular layers as additional layers can form through the same weak forces that initial layers formed [9]. The non-specific nature of physisorption means it occurs across a wide variety of surfaces without requiring particular chemical compatibility between adsorbate and adsorbent [9].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Physisorption versus Chemisorption

| Property | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Forces Involved | Van der Waals forces | Chemical bonds |

| Enthalpy (kJ/mol) | 5-40 | 40-800 |

| Reversibility | Reversible | Irreversible |

| Temperature Dependence | Decreases with increasing temperature | Increases with increasing temperature |

| Specificity | Non-specific | Highly specific |

| Layer Formation | Multimolecular layers | Uni-molecular layers |

| Activation Energy | Low | High |

Factors Influencing Physisorption

Multiple factors govern the extent and strength of physisorption interactions:

- Nature of the Adsorbate: Compounds that are easier to liquefy generally exhibit greater physisorption, with adsorption tendency increasing with the critical temperature of the gas [8].

- Surface Area: Materials with larger surface areas provide more sites for molecular attachment, significantly enhancing adsorption capacity [10] [8].

- Temperature: Unlike chemisorption, physisorption decreases with rising temperature due to the exothermic nature of the process and the weak binding forces involved [9].

- Pressure: Adsorption capacity initially increases rapidly with pressure as available surface sites fill, then gradually slows as surface coverage approaches maximum [8].

In porous materials, pore size distribution significantly impacts physisorption behavior. Micropores (diameter < 2 nm) demonstrate enhanced adsorption potential due to the overlapping potential fields from opposite pore walls, while mesopores (2-50 nm) often exhibit capillary condensation phenomena [8].

Quantitative Analysis of Physisorption

Adsorption Isotherm Models

Adsorption isotherms describe how the amount of adsorbate on the adsorbent varies with pressure or concentration at constant temperature [8]. Several mathematical models have been developed to quantify and interpret physisorption behavior:

Langmuir Isotherm: This model assumes monolayer adsorption onto a homogeneous surface with identical, independent adsorption sites and no lateral interactions between adsorbed molecules [8]. The nonlinear form of the Langmuir equation is represented as: [ \frac{Q}{Q0} = \frac{KL C}{1 + KL C} ] where Q is the amount adsorbed, Qâ‚€ is the maximum monolayer capacity, KL is the Langmuir constant related to adsorption energy, and C is the equilibrium concentration [8].

Freundlich Isotherm: An empirical model used for heterogeneous surfaces, expressing the relationship between adsorption capacity and equilibrium concentration as: [ Q = KF C^{1/n} ] where KF and n are Freundlich constants related to adsorption capacity and intensity, respectively [8].

BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) Theory: Extending the Langmuir model to multilayer adsorption, the BET theory is particularly valuable for determining the specific surface area of porous materials [8]. The BET equation is expressed as: [ \frac{P}{V(P0 - P)} = \frac{1}{Vm C} + \frac{C - 1}{Vm C} \left(\frac{P}{P0}\right) ] where P is the equilibrium pressure, Pâ‚€ is the saturation pressure, V is the adsorbed gas quantity, V_m is the monolayer capacity, and C is the BET constant [8].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters in Physisorption Analysis

| Parameter | Description | Typical Range for Physisorption | Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Area | Total specific surface area of adsorbent | 10-1500 m²/g for activated carbons | BET analysis from N₂ adsorption isotherms |

| Pore Volume | Total volume of pores | 0.2-1.5 cm³/g | Single point adsorption at P/P₀ ≈ 0.95 |

| Pore Size Distribution | Distribution of pore diameters | Micropores (<2 nm), Mesopores (2-50 nm) | DFT, BJH method |

| Isosteric Heat of Adsorption | Energy released during adsorption | 5-40 kJ/mol | Calorimetry, temperature-dependent isotherms |

| Mean Pore Width | Average pore diameter | 0.5-10 nm | DFT methods |

Advanced Computational Methods

Modern computational approaches provide atomic-level insights into physisorption mechanisms. Density Functional Theory (DFT) with advanced van der Waals functionals (such as SCAN-rvv10, optPBE-vdW, optB88-vdW) enables accurate prediction of binding affinities and adsorption configurations [14]. These methods are particularly valuable for studying the adsorption of small organic molecules (CHâ‚„, COâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚O) on novel materials like MXenes, where weak dispersion interactions dominate [14].

For pharmaceutical applications, Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling utilizes topological indices as molecular descriptors to correlate molecular structure with physicochemical properties relevant to adsorption behavior, including boiling points, enthalpy of vaporization, and molar refraction [15]. These computational approaches facilitate early-stage screening and optimization of drug candidates without extensive laboratory experimentation [15].

Experimental Characterization of Physisorption

Gas Sorption Analysis

Gas sorption analysis represents the primary method for characterizing physisorption in porous materials. The following protocol details the standard approach for determining surface area and pore characteristics:

Equipment and Reagents:

- Physisorption analyzer (e.g., Micromeritics, Quantachrome, Belsorp instruments) [13]

- High-purity analysis gases (Nâ‚‚ at 77 K or Ar at 87 K)

- Degassing system for sample preparation

- Cryogenic bath (liquid Nâ‚‚ or Ar)

- Reference and sample tubes

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Weigh 50-200 mg of sample into a clean, dry analysis tube

- Secure the tube to the degas port and begin evacuation

- Heat the sample to an appropriate temperature (typically 100-300°C) under vacuum for 2-12 hours to remove contaminants

- Monitor pressure rise to verify complete degassing

- Transfer the degassed sample to the analysis station

Analysis Procedure:

- Immerse the sample tube in a cryogenic bath (typically liquid Nâ‚‚ at 77 K)

- Introduce known quantities of adsorbate gas (Nâ‚‚) into the sample chamber

- Allow the system to reach equilibrium at each pressure point

- Measure the quantity of gas adsorbed at each relative pressure (P/Pâ‚€)

- Continue measurements across the relative pressure range from 10â»âµ to 0.995

- Perform desorption measurements to assess hysteresis

Data Analysis:

- Apply the BET equation to the relative pressure range 0.05-0.30 P/Pâ‚€ to calculate specific surface area

- Use the t-plot or αs-plot method to determine micropore volume and external surface area

- Apply appropriate methods (DFT, BJH) to calculate pore size distribution from the adsorption isotherm

Diagram 1: Gas Sorption Analysis Workflow

Distinguishing Physisorption from Chemisorption in Experimental Systems

Experimental differentiation between physisorption and chemisorption is crucial for accurate material characterization. Research on carbon nanotube (CNT) gas sensors demonstrates a methodology for identifying both processes through analysis of response curves [16].

Voltage Response Measurement Protocol:

- Prepare multi-walled CNTs grown on SiOâ‚‚ substrate with silver-flake electrical junctions

- Place samples in high vacuum conditions (10â»â¶ mbar) with constant temperature control

- Apply a constant current (5 mA) to the CNT system using a sourcemeter (e.g., Keithley 2400)

- Measure voltage across CNTs as a function of time with 500 ms sampling

- Collect background data for 5 minutes to establish voltage offset

- Introduce target gases (Hâ‚‚, COâ‚‚) at various concentrations via leak valve

- Monitor voltage response during gas exposure (adsorption) and pump-out (desorption) phases

Data Analysis for Mechanism Identification:

- Calculate responsiveness as (V(t) - Vâ‚€)/Vâ‚€, where Vâ‚€ is equilibrium voltage

- Fit both adsorption and desorption curves with double exponential function:

- Ascending branch: Responsiveness = A(1 - e^(-(t-tâ‚€)/Ï„)) + B

- Descending branch: Responsiveness = Ae^(-(t-tâ‚€)/Ï„) + B

- Extract characteristic time constants (Ï„) from fitting

- Identify faster processes as physisorption (shorter Ï„) and slower processes as chemisorption (longer Ï„) based on timescale separation [16]

This approach capitalizes on the fundamental kinetic difference between physisorption (generally faster physi(de)sorption) and chemisorption (slower chemi(de)sorption) [16].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Physisorption Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| BET Analyzer | Measures specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution through gas adsorption | Characterization of pharmaceutical carriers, activated carbons, metal-organic frameworks [13] |

| Activated Carbons | High-surface-area adsorbents with tunable porosity | Environmental remediation, pharmaceutical impurity removal, gas separation [13] [8] |

| Silica and Aluminum Gels | Desiccants with controlled pore structures | Humidity control, moisture removal in pharmaceutical packaging [9] |

| Van der Waals Density Functionals (SCAN-rvv10) | Computational methods for modeling weak dispersion interactions | Predicting binding affinities of small organic molecules on novel materials [14] |

| Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) Models | Mathematical correlation of molecular structure with adsorption properties | Early-stage drug screening, prediction of physicochemical properties [15] |

| MXenes (Vâ‚‚C) | Novel 2D materials with tunable surface chemistry | Gas separation, carbon capture, sensing applications [14] |

| Atr-IN-12 | Atr-IN-12, MF:C22H27N5O3S, MW:441.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ganoderterpene A | Ganoderterpene A | Ganoderterpene A is a lanostane-type triterpenoid from Ganoderma lucidum with potent anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic research applications. For Research Use Only. |

Pharmaceutical Applications of Physisorption

Drug Development and Formulation

In pharmaceutical sciences, physisorption principles find application across multiple stages of drug development:

Drug Polymorphism and Cocrystal Engineering: Physisorption analysis helps characterize different crystalline forms of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), which directly impact stability, solubility, and bioavailability [12]. Techniques including dynamic vapor sorption (DVS) quantify water uptake in various polymorphic forms, informing selection of optimal solid forms for development [12].

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD): Physisorption parameters contribute to quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models that predict drug behavior, enabling more efficient lead optimization and reducing late-stage failures [11]. These approaches integrate physicochemical properties, including those governed by surface interactions, into predictive frameworks for absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) [11].

Enhancing Bioavailability: For Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) Class II and IV drugs with low solubility, adsorption onto high-surface-area carriers can improve dissolution rates and oral bioavailability [12]. Physisorption onto mesoporous silica or other inert carriers presents a strategy for enhancing the performance of poorly soluble APIs without chemical modification.

Material Characterization in Pharma

Surface Area and Porosity Analysis: BET surface area measurements represent a critical quality attribute for many pharmaceutical excipients and active ingredients, influencing dissolution, stability, and processing behavior [12]. Regulatory guidelines often require thorough characterization of porous drug carriers to ensure consistent performance.

Dynamic Vapor Sorption (DVS): This technique measures water uptake by materials under controlled humidity conditions, providing insights into hygroscopicity, hydrate formation, and physical stability [12]. Such information is crucial for predicting shelf life, selecting appropriate packaging, and designing stable formulations.

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of physisorption continues to evolve with several emerging trends:

Integration with Artificial Intelligence: Machine learning algorithms are increasingly applied to predict adsorption properties and optimize adsorbent materials, reducing experimental screening time [11] [13]. AI-driven analysis of large-scale biological, chemical, and clinical datasets enhances prediction accuracy for drug adsorption and release profiles [11].

Advanced Materials Design: Novel 2D materials like MXenes and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) with tailored surface properties offer unprecedented control over physisorption behavior [14] [8]. These materials demonstrate potential for selective gas separation, targeted drug delivery, and energy storage applications.

Miniaturization and Automation: Trends toward miniaturized physisorption instruments enable in-field analysis and real-time monitoring of adsorption processes [13]. Automated systems with integrated data analysis streamline material characterization in quality control environments.

Despite these advances, challenges remain in standardizing physisorption measurements across materials and instruments, scaling adsorption technologies for industrial applications, and fully understanding complex adsorption mechanisms in heterogeneous systems. Future research will likely focus on developing more sophisticated computational models, designing multifunctional adsorbents with precisely controlled properties, and integrating physisorption principles into broader pharmaceutical development frameworks.

Chemisorption, or chemical adsorption, is a fundamental surface phenomenon where a chemical reaction occurs between an adsorbate (gas or vapor) and the solid surface of a material. This process results in the formation of strong chemical bonds via electron sharing and valence bonding, creating a distinct chemical species at the surface [17]. Unlike physical adsorption, chemisorption is characterized by the splitting of adsorbing gas or vapor molecules into atoms, radicals, or ions that chemically bond to specific adsorption sites on the surface [17]. This interaction is typically characterized by high binding energy and is often irreversible under standard conditions [18] [17].

The process plays a vital role in numerous industrial applications and scientific fields, particularly in heterogeneous catalysis, where it enables the formation of chemisorbed intermediates that react with each other to form products [19]. Understanding chemisorption is essential for researchers and scientists working in catalyst characterization, petroleum refining, biofuel production, plastic manufacturing, and environmental technology [20]. The specificity and strength of chemisorption make it a critical phenomenon for drug development professionals who utilize surface interactions in various analytical and synthetic processes.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Chemisorption

The Chemisorption Process

The mechanism of chemisorption follows a distinct sequence of events that begins when an adsorbate particle approaches a solid surface. The first stage involves the particle becoming trapped on the surface by losing sufficient momentum through an inelastic collision, forming a precursor state bonded to the surface by weak forces similar to physisorption [19]. In this precursor state, the particle diffuses across the surface until it encounters a deep chemisorption potential well. The particle then reacts with the surface, forming new types of electronic bonds, or simply desorbs after gaining sufficient energy [19].

The reaction between the surface and adsorbate depends on the chemical species involved and follows fundamental thermodynamic principles. Applying the Gibbs energy equation for reactions (ΔG = ΔH - TΔS), the spontaneity of chemisorption requires a negative change in free energy (ΔG) at constant temperature and pressure [19]. Since a free particle becomes restrained to a surface (decreasing entropy, ΔS < 0), the enthalpy term (ΔH) must be sufficiently negative (exothermic) to drive the process [19]. This results in the characteristically high binding energy associated with chemisorption processes.

Bond Formation in Chemisorption

The formation of chemical bonds during chemisorption occurs when a molecule moves sufficiently close to surface atoms that their electron clouds overlap [20]. This overlap allows the adsorbate and adsorbent to share electrons, leading to the formation of chemical bonds that are typically ionic or covalent in nature [19]. The strong interaction between the adsorbate and substrate surface creates these new electronic bonds, fundamentally distinguishing chemisorption from physisorption [19].

Two primary mechanisms describe the bonding process in catalytic systems. In molecular adsorption, the adsorbate remains intact during the bonding process, such as occurs with alkene binding using platinum catalysts [20]. In dissociative adsorption, chemical bonds within the adsorbate molecule break concomitantly with bond formation to the surface. A classic example is the binding of Hâ‚‚ to metal catalysts, where the hydrogen molecule dissociates into atoms that individually bond to the surface [20]. The barrier to dissociation significantly impacts the adsorption rate, with the energy to overcome the activation potential typically coming from translational and vibrational energy [19].

Comparative Analysis: Chemisorption vs. Physisorption

Understanding the distinctions between chemisorption and physisorption is essential for researchers studying surface phenomena. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of these two adsorption processes based on key characteristics.

| Characteristic | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Type | Weak van der Waals forces [21] [20] | Strong chemical bonds (ionic/covalent) [19] [21] |

| Reversibility | Reversible [21] | Often irreversible [21] [17] |

| Specificity | Not specific [21] | Highly specific [21] |

| Enthalpy of Adsorption | Low (20-40 kJ/mol) [21] [20] | High (80-240 kJ/mol) [21] [20] |

| Temperature Dependence | Favors low temperature, decreases with increasing temperature [21] | Favors high temperature, increases with increasing temperature [21] |

| Layer Formation | Multimolecular layers [21] | Monolayer only [21] |

| Activation Energy | Low [21] | Significant [21] |

Energetics and the Potential Energy Diagram

The potential energy diagram provides a conceptual framework for understanding the energetics of adsorption processes. This diagram represents the variation in the energy of a system as a function of the distance (d) of an adsorbate from a surface [4]. In the case of pure physisorption, weak van der Waals forces create a shallow minimum in the potential energy curve at a relatively large distance from the surface (typically d > 0.3 nm) [4]. This physisorption well is characterized by the absence of an activation barrier, making the kinetics of physisorption invariably fast.

For systems capable of chemisorption, the potential energy curve features a much deeper chemisorption minimum at shorter distances, representing the strong chemical bond formation [4]. The overall potential energy curve for such systems combines both physisorption and chemisorption characteristics, with a curve crossing point where chemisorption forces begin to dominate over physisorption forces [4]. The depth of the chemisorption well corresponds directly to the energy of adsorption, while the location of the global minimum on the distance axis represents the equilibrium bond distance (d_ch) for the adsorbed molecule on the surface [4].

Figure 1: Potential Energy Diagram Showing Physisorption and Chemisorption Pathways

Experimental Methodologies for Chemisorption Analysis

Static Volumetric Chemisorption

The static volumetric technique is performed using instruments like the Micromeritics 3Flex and ASAP 2020 Plus, which operate over a range of pressures [17]. In this method, two adsorption isotherms (quantities of gas adsorbed as functions of pressure at constant temperature) are collected at sub-atmospheric pressures [17]. The first isotherm represents total adsorption (both physisorption and chemisorption), while the second represents reversible adsorption (primarily physisorption) [17]. The difference between these two isotherms provides a measure of the irreversible adsorption, which is operationally defined as chemisorption [17]. This technique yields quantitative information on the number of adsorption sites available on the catalyst surface, enabling subsequent calculations of active surface area. When the active surface area analysis is performed at one specific temperature, it is termed isothermal chemisorption [17].

Protocol for Static Volumetric Chemisorption:

- Sample Preparation: The catalyst sample is placed in the analysis tube and subjected to pre-treatment (often degassing) to remove contaminants and moisture.

- Conditioning: The sample may undergo reduction or oxidation cycles to activate the surface.

- First Isotherm Measurement: The sample is exposed to the probe gas (e.g., Hâ‚‚, CO) at increasing pressures while maintaining constant temperature.

- Evacuation: The system is evacuated to remove reversibly adsorbed species.

- Second Isotherm Measurement: The process is repeated to measure reversible adsorption.

- Calculation: The difference between the first and second isotherms gives the chemisorbed quantity.

Dynamic Chemisorption Techniques

Dynamic chemisorption utilizes flowing gas systems to characterize catalytic surfaces through various temperature-programmed methods. Instruments such as the ChemiSorb and AutoChem series implement these techniques using pulse chemisorption in a dynamic flow system to titrate the active surface [17]. In these experiments, the identity, quantity, and strength of active sites can be quantified by adsorption, desorption, or reaction under isothermal or temperature-programmed conditions [17]. The dynamic approach employs several specialized techniques:

- Temperature Programmed Reduction (TPR): Measures the reduction profile of catalytic materials as temperature increases in a reducing atmosphere [17].

- Temperature Programmed Desorption (TPD): Analyzes desorbed species as temperature increases, providing information on adsorption strength and active site distribution [22] [17].

- Temperature Programmed Oxidation (TPO): Characterizes the oxidation behavior of catalysts in an oxidizing environment [22] [17].

- Pulse Chemisorption: Involves injecting precise volumes of probe gas into a carrier stream flowing over the catalyst to titrate active sites [17].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Chemisorption Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions for Chemisorption Studies

The table below outlines key reagents and materials commonly used in chemisorption experiments, along with their specific functions in catalyst characterization.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Chemisorption Studies | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) | Probe molecule for metal surface sites; participates in dissociative chemisorption [20] | Determination of metal dispersion in supported metal catalysts [17] |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) | Probe for both metallic and cationic sites; forms various surface complexes [20] | Titration of surface active sites; IR spectroscopy studies [17] |

| Ammonia (NH₃) | Acidic probe molecule for characterization of solid acid catalysts [20] | Measurement of acid site density and strength distribution [17] |

| Oxygen (Oâ‚‚) | Oxidizing agent for temperature-programmed oxidation studies [17] | Determination of oxidation characteristics and carbonaceous deposits [22] |

| Nitrogen (Nâ‚‚) | Relatively inert carrier gas; can chemisorb dissociatively on certain surfaces [19] | Carrier gas in pulse chemisorption; study of ammonia synthesis catalysts [18] |

Applications in Research and Industry

Heterogeneous Catalysis

Chemisorption serves a fundamental role in heterogeneous catalysis, where it facilitates the formation of chemisorbed intermediates that react with each other on catalyst surfaces [19]. After these chemisorbed species combine through bond formation, the resulting products desorb from the surface, regenerating the active sites for subsequent catalytic cycles [19]. This mechanism is crucial for numerous industrial processes, including petroleum refining, biofuel production, and plastic manufacturing [20]. The strong interaction between adsorbates and catalyst surfaces enables the breaking and formation of chemical bonds under controlled conditions, significantly accelerating reaction rates and improving selectivity.

In catalyst characterization, chemisorption measurements provide vital insights into key properties such as the reduction temperature at which metals become catalytically active, the quantity of surface metal or active species available for reaction, the strength of specific active sites, and the material's performance after undergoing reduction or oxidation cycles [17]. For example, the dissociative chemisorption of hydrogen on copper surfaces has been extensively studied, revealing a large activation energy of 0.35–0.85 eV, with vibrational excitation of the hydrogen molecule promoting dissociation on low index copper surfaces [19].

Environmental and Materials Applications

Beyond traditional catalysis, chemisorption principles find applications in environmental remediation and advanced materials development. In environmental technology, chemisorption is employed for the removal of heavy metals and organic pollutants from aquatic media [23]. For instance, chemisorption mechanisms involving metal-organic complexes or cation exchange reactions effectively remove lead ions (Pb²âº) from wastewater [23]. The process has also been applied to capture gaseous pollutants such as mercury, nitrogen dioxide, and carbon dioxide through functionalized carbon-based materials [22].

In materials science, chemisorption enables the creation of self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) by chemisorbing reactive reagents with metal surfaces [19]. A prominent example involves thiols (RS-H) adsorbing onto gold surfaces, forming strong Au-SR bonds while releasing Hâ‚‚ [19]. These densely packed thiol groups protect the surface and provide platforms for sensor development, molecular electronics, and nanotechnology applications. Additionally, chemisorption techniques are utilized to modify carbon black surfaces through oxidation, halogenation, and polymer grafting, enhancing their dispersion, electrochemical properties, and compatibility in composite materials [22].

Advanced Concepts and Recent Developments

Dissociative Chemisorption

Dissociative chemisorption represents a specialized category where diatomic gas molecules, such as hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, separate into atoms upon adsorption onto a surface [19]. The precursor-mediation model describes this process: the gas molecule first adsorbs onto the surface into a precursor state, then diffuses across the surface to chemisorption sites where the molecular bond breaks in favor of new bonds with the surface [19]. The energy required to overcome the activation potential for dissociation typically derives from translational and vibrational energy [19].

The hydrogen-copper system exemplifies dissociative chemisorption and has been extensively studied. This system exhibits a substantial activation energy ranging from 0.35 to 0.85 eV, with vibrational excitation of the hydrogen molecule significantly promoting dissociation on low-index copper surfaces [19]. Such fundamental studies provide insights into surface reactivity and bond formation that inform catalyst design for industrial processes including ammonia synthesis, hydrogenation reactions, and fuel cell technologies.

Theoretical Modeling Challenges

Theoretical modeling of chemisorption presents significant challenges due to the complexity of real-world systems. A multidimensional potential energy surface derived from effective medium theory typically describes the effect of the surface on absorption, though only certain portions are utilized depending on the specific research focus [19]. The basic equation representing the total energy as a function of location is:

[E({Ri}) = E{el}({Ri}) + V{\text{ion-ion}}({R_i})]

where (E{el}) represents the electronic energy contribution and (V{\text{ion-ion}}) accounts for ion-ion interactions [19].

Several factors complicate theoretical calculations of chemisorption processes. Solid surfaces are not necessarily at equilibrium and may contain irregularities, defects, and odd adsorption sites that create a distribution of adsorption energies [19]. Additionally, bonds formed between adsorbates can further alter the surface chemistry [19]. Unlike physisorption where adsorbates simply reside on the surface, chemisorbed species can induce substantial surface restructuring through relaxation (changing interplanar distances) or reconstruction (altering surface structure) [19]. For example, oxygen forms strong bonds (~4 eV) with metals like Cu(110), accompanied by surface bond breaking and large restructuring through "missing row" formations [19].

Two primary models describe surface reactions: the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism, where both reacting species are adsorbed before reaction, and the Eley-Rideal mechanism, where one adsorbed species reacts directly with a gas-phase molecule [19]. Understanding these mechanisms provides crucial insights for designing more efficient and selective catalytic processes across pharmaceutical, environmental, and industrial applications.

Surface chemistry plays a critical role in numerous scientific and industrial processes, from catalytic converters in automobiles to drug development and environmental remediation [24]. At the heart of this field lies adsorption, the process whereby molecules adhere to a surface. For researchers and scientists engaged in drug development and material science, a precise understanding of the two primary adsorption mechanisms—physisorption (physical adsorption) and chemisorption (chemical adsorption)—is fundamental [25]. These processes govern interactions at the solid-gas and solid-liquid interfaces, influencing everything from catalyst design to pollutant removal and pharmaceutical compound behavior. This technical guide provides an in-depth, side-by-side examination of their key characteristics, enabling professionals to select and optimize processes based on the underlying interaction mechanisms.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Theoretical Framework

Physisorption: Weak Surface Interactions Governed by Van der Waals Forces

Physisorption is a process in which the electronic structure of the adsorbate atom or molecule is barely perturbed upon adsorption [26]. The fundamental interacting force is van der Waals attraction, which originates from interactions between induced, permanent, or transient electric dipoles [26]. This force is relatively weak, leading to adsorption energies typically on the same order of magnitude as the heat of liquefaction [24].

The process can be modeled using a quantum-mechanical oscillator approach. When an atom approaches a surface, the motion of its electrons is modified by image charges, effectively lowering the system's vibrational frequencies. The van der Waals binding energy (Vv) can be expressed as Vv = -Cv/(Z-Z0)³, where Cv is a constant related to the atomic polarizability, Z is the distance from the surface, and Z0 is the position of the dynamical image plane, accounting for the spilling of electron wavefunction out of the surface [26]. This model accurately describes the weak, long-range Zâ»Â³ dependence of the physisorption potential.

Chemisorption: Strong Bond Formation via Orbital Overlap

Chemisorption involves the formation of a chemical bond—either covalent or ionic—between the adsorbate molecule and the surface atoms [25]. This process involves sharing or transferring electrons, resulting in a significant perturbation of the electronic structures of both the adsorbate and the adsorbent [25]. The union is much stronger than a physical bond, with heats of adsorption comparable to those of chemical reactions [27]. This often leads to the formation of a new surface compound, such as iron nitride when nitrogen is chemisorbed on iron at high temperatures [27]. Due to this bond strength, chemisorption is typically difficult to reverse [27].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Physisorption and Chemisorption

| Characteristic | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Force | Van der Waals forces [26] | Covalent or Ionic bonds [25] |

| Energy Range | Low (∼10–100 meV; ~20–40 kJ/mol) [26] [5] | High (80–800 kJ/mol) [25] [27] [5] |

| Electronic Perturbation | Barely perturbed [26] | Significant change; electron sharing/transfer [25] |

| Theoretical Model | Image charge, Quantum oscillator [26] | Chemical bonding models (e.g., molecular orbital theory) |

| Nature of Process | Non-specific and reversible [5] | Highly specific and often irreversible [5] |

Potential Energy Curves and Energetics

The interaction of a molecule with a surface is effectively visualized through a one-dimensional potential energy (PE) curve, which plots the system's energy as a function of the molecule's distance from the surface [28].

In the PE diagram above, the red curve depicts the potential energy pathway for chemisorption. It is characterized by a deep minimum at a short distance from the surface, representing the strong bond formation. A significant feature is the possible presence of an activation energy barrier (Eaᵃᵈˢ), which must be overcome for the chemisorption bond to form. The depth of this well corresponds to the energy of adsorption (ΔH꜀ₕₑₘ), which is strongly exothermic [28]. The blue dashed curve shows the physisorption potential, featuring a shallow minimum at a larger distance, governed by long-range van der Waals forces. Its depth (ΔHₚₕᵧₛ) is much smaller [28]. In many real systems, the overall potential is a combination of these two curves. The physisorption well often acts as a precursor state, facilitating the eventual chemisorption process by trapping molecules near the surface before they overcome the activation barrier [28].

Comparative Analysis of Key Properties

A detailed comparison of the properties of physisorption and chemisorption is essential for predicting and controlling surface behavior in applied research.

Table 2: Comparative Properties of Physisorption and Chemisorption

| Property | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Enthalpy (ΔH) | Low (∼20–40 kJ/mol) [5] | High (80–240 kJ/mol, up to 800 kJ/mol) [25] [27] [5] |

| Reversibility | Reversible; equilibrium is quickly established [5] | Irreversible; often forms a stable surface compound [5] |

| Temperature Dependence | Favored at low temperature; decreases with increasing T [5] | Often requires high temperature; rate increases with T (initially) [5] |

| Specificity | Non-specific; occurs on all surfaces [5] | Highly specific; requires chem. affinity [5] |

| State of Adsorbate | No change in the state of the adsorbate [5] | Adsorbate may change its state due to reaction [5] |

| Adsorbate Layer | Multi-layer formation is possible [27] | Typically limited to a monolayer [25] [27] |

| Kinetics | Fast and non-activated [28] | Can be activated; may have an energy barrier [28] |

The temperature dependence of adsorption is a critical distinguishing factor. Physisorption occurs readily at low temperatures and diminishes as temperature increases due to the exothermic nature of the process [5]. In contrast, chemisorption, often being an activated process, may initially increase with temperature as molecules gain sufficient energy to overcome the activation barrier. After reaching an optimum temperature, the extent of chemisorption may decrease due to desorption or decomposition at very high temperatures [5]. Notably, a gas adsorbed via physisorption at low temperatures may transition to chemisorption as the temperature is raised [5].

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Characterizing adsorbents and catalysts requires precise methodologies to quantify surface area, active sites, and adsorption strength.

Volumetric (Static) Chemisorption Analysis

The volumetric technique is a standard method for obtaining high-resolution chemisorption isotherms. It operates by precisely dosing a known quantity of adsorbate gas into a calibrated volume containing the evacuated adsorbent sample [27]. The pressure change is monitored until equilibrium is reached, allowing for the calculation of the quantity adsorbed using gas laws. This process is repeated at various pressures to construct an adsorption isotherm. The technique is highly accurate and can be performed at various temperatures, but requires high vacuum and is best suited for powdered or granular samples [27].

Dynamic (Flowing Gas) Pulse Chemisorption

The dynamic pulse chemisorption technique operates at ambient pressure. After sample pre-treatment, small, precise pulses of the adsorbate gas are injected into a carrier gas stream flowing over the sample [27]. A downstream thermal conductivity detector (TCD) measures the quantity of gas not adsorbed by the sample. The adsorbed quantity per pulse is calculated by subtracting the detected amount from the injected amount. The process continues until the sample is saturated, as indicated by the TCD signal returning to baseline. This method is faster and simpler than the volumetric method and is well-suited for determining total active site capacity, though it provides less detailed isotherm data [27].

Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD)

Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD) is a powerful technique for probing the strength and distribution of adsorption sites. After the adsorbate is adsorbed onto the surface at a specific temperature, the temperature is increased linearly under a flow of inert gas [27]. As the temperature rises, adsorbed molecules gain energy to desorb, causing peaks in the detector signal (e.g., a TCD). The temperature at which desorption occurs indicates the binding strength—higher temperatures correspond to stronger bonds—while the area under the peak quantifies the number of sites. TPD is invaluable for studying catalyst deactivation, surface reaction intermediates, and the energy distribution of active sites [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate materials and probe molecules is critical for designing meaningful adsorption experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function & Characteristics | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (Nâ‚‚) at 77 K | Non-reactive probe gas for physisorption; used to determine total surface area and pore size distribution based on BET theory. | Standard characterization of porous materials (e.g., catalyst supports, zeolites) [27]. |

| Carbon Dioxide (COâ‚‚) at 273 K | Probe molecule for analyzing ultramicropores; its higher temperature use minimizes diffusion limitations. | Characterization of microporous carbons and zeolites [27]. |

| Hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) | Reactive probe for chemisorption on metal sites; can dissociate to form hydrides. | Measurement of metal dispersion and active surface area in transition metal catalysts (e.g., Pt, Pd, Ni) [27] [5]. |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) | Strongly coordinating molecule that chemisorbs on both metallic and oxide sites; can bridge multiple metal atoms. | Probing the coordination and oxidation state of active metal sites in catalysts [27]. |

| Ammonia (NH₃) | Basic probe molecule for characterizing surface acidity via chemisorption. | Acidity measurement of solid acid catalysts (e.g., zeolites, alumina-silica) [27]. |

| Porous Solids (Zeolites, Activated Carbon) | High-surface-area adsorbents with tunable surface chemistry (acidity, hydrophobicity) and pore structures. | Model adsorbents for gas separation, catalysis, and environmental remediation studies [25]. |

| Metal Nanoparticles on Supports (Pt/SiO₂, Pd/Al₂O₃) | Model catalysts with well-defined active phases dispersed on high-surface-area supports. | Studies of structure-activity relationships, metal dispersion, and catalytic performance [27]. |

| Bliretrigine | Bliretrigine, CAS:1233229-75-8, MF:C20H24N4O2, MW:352.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DNA-PK-IN-3 | DNA-PK-IN-3, MF:C19H19N9O, MW:389.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Research and Industry

The distinct characteristics of physisorption and chemisorption make them suitable for different applications.

- Heterogeneous Catalysis: Chemisorption is a fundamental step in heterogeneous catalysis, where reactant molecules form intermediate surface complexes that are more receptive to chemical reaction [27] [24]. The catalytic activity depends critically on the strength of the chemisorption bond; if it is too weak, the molecule may desorb before reacting, and if it is too strong, the product may not be released, poisoning the catalyst [27]. An iconic example is the platinum-catalyzed reaction between hydrogen and oxygen to form water, where the platinum surface provides alternative reaction pathways by breaking the bonds in the gas molecules [24].

- Environmental Remediation and Water Purification: Adsorption is a key purification procedure for removing contaminants like heavy metals and organic dyes from wastewater [25]. Both physisorption and chemisorption play roles, often simultaneously [25]. Chemisorption mechanisms such as complexation reactions are particularly effective. For instance, modified sodium alginate materials can remove arsenic and chromium through complexation with functional groups [25]. Biosorbents, derived from natural biomass, are also gaining interest due to their multiple functional groups that enable sorption via electrostatic interaction, complexation, and ion exchange [25].

- Surface Area and Porosity Analysis: Physical adsorption of gases, particularly nitrogen at 77 K, is the standard method for characterizing the total surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution of porous materials like catalyst supports, zeolites, and activated carbons [27] [24]. The analysis of the resulting physisorption isotherm provides critical information about the material's texture, which influences mass transfer, accessibility of active sites, and overall performance in applications ranging from drug delivery to gas storage.

- Computational Material Design: Modern research leverages molecular dynamics (MD), Monte Carlo (MC) simulations, and density functional theory (DFT) calculations to provide atomic-level insights into adsorption processes [29]. These methods simulate the entire adsorption process, predict equilibrium properties, and help understand stable adsorption configurations and interaction energies. This computational toolkit is invaluable for designing and optimizing new adsorbent materials before their synthetic realization [29].

Physisorption and chemisorption represent two distinct yet interconnected pathways by which molecules interact with surfaces. The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores that physisorption, governed by weak van der Waals forces, is a reversible, non-specific process characterized by low enthalpy and multi-layer formation. In contrast, chemisorption, involving strong covalent or ionic bonding, is specific, often irreversible, and characterized by high enthalpy and monolayer limitation. The choice between these mechanisms—or their synergistic exploitation—dictates the efficiency of processes ranging from industrial catalysis and environmental cleanup to pharmaceutical development. A deep understanding of their side-by-side characteristics, combined with robust experimental and computational tools, empowers researchers to rationally design and optimize materials and processes for the advanced technological challenges of today and tomorrow.

In both chemical engineering and pharmaceutical development, the adsorption of molecules onto solid surfaces is a critical process, influencing applications ranging from drug delivery system design to contaminant removal. The thermodynamic analysis of adsorption provides fundamental insights into the energy changes and spontaneity of these processes, enabling scientists to optimize conditions for desired outcomes. Thermodynamic parameters—specifically Gibbs free energy (ΔG), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS)—serve as essential indicators of adsorption behavior, revealing whether a process occurs spontaneously and the nature of the driving forces involved. Within this framework, adsorption mechanisms are broadly classified as either physisorption, involving weak van der Waals forces, or chemisorption, characterized by strong chemical bonds. The distinction has profound implications for the stability, capacity, and reversibility of adsorption systems, making thermodynamic studies indispensable for researchers designing novel materials or processes.

This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of adsorption thermodynamics, focusing on experimental methodologies, data interpretation, and practical applications relevant to scientific researchers and drug development professionals. By integrating contemporary research case studies and quantitative data analysis, this work establishes a rigorous foundation for understanding how thermodynamic principles govern adsorption phenomena across different systems.

Core Thermodynamic Parameters in Adsorption

The spontaneity and fundamental nature of an adsorption process are quantitatively described by three primary thermodynamic parameters. The Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) determines the spontaneity of a process; a negative ΔG value indicates a thermodynamically favorable, spontaneous reaction [30]. The enthalpy change (ΔH) reveals whether the process is exothermic (releases heat, ΔH < 0) or endothermic (absorbs heat, ΔH > 0), providing insight into the energy changes during adsorption. The entropy change (ΔS) reflects the change in molecular disorder or randomness in the system upon adsorption.

These parameters are intrinsically related through the fundamental equation: ΔG = ΔH - TΔS, where T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin. In adsorption studies, the magnitude and sign of these parameters help distinguish between physisorption and chemisorption. Physisorption typically features lower enthalpy changes (ΔH < 40 kJ/mol), minimal activation energy requirements, and often negative entropy changes due to the reduced freedom of adsorbed molecules [30]. In contrast, chemisorption involves higher enthalpy changes (ΔH > 40 kJ/mol), significant activation energy barriers, and may result in either positive or negative entropy changes depending on the specific molecular rearrangements [30].

Table 1: Characteristic Thermodynamic Parameters for Physisorption vs. Chemisorption

| Parameter | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| ΔH Magnitude | Typically < 40 kJ/mol [30] | Typically > 40 kJ/mol [30] |

| Activation Energy (Eâ‚) | 5–40 kJ/mol [30] | 40–800 kJ/mol [30] |

| ΔS Change | Usually negative (molecules lose freedom) | Variable (can be positive if surface reconstruction occurs) |

| Nature of Bond | Weak van der Waals, electrostatic | Strong covalent, chemical bonds |

| Reversibility | Highly reversible | Often irreversible or requires significant energy for reversal |

| Temperature Dependence | Often decreases with increasing temperature | May increase or decrease with temperature depending on system |

Quantitative Thermodynamic Data from Contemporary Studies

Recent adsorption studies across various material systems provide concrete examples of how thermodynamic parameters are determined and interpreted. The following table summarizes key thermodynamic data from current research, illustrating the range of values encountered in different adsorption scenarios.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Thermodynamic Parameters from Recent Adsorption Studies

| Adsorbate/Adsorbent System | Temperature Range (°C) | ΔH (kJ/mol) | ΔS (J/mol·K) | ΔG (kJ/mol) | Nature of Process | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroquinone/Quartz | 25-80 | -8.02 | 6.12 | Negative (spontaneous) | Exothermic, spontaneous | [31] |

| Hydroquinone/Carbonate Rock | 25-90 | -6.49 | 6.47 | -8.34 to -8.74 | Exothermic, spontaneous | [32] |

| Urotropine/Kaolinite | Not specified | +9.53 | Not specified | Negative (spontaneous) | Endothermic, spontaneous | [33] |

| Ni(II)/GO@Fe₃O₄@Pluronic-F68 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Negative (spontaneous) | Spontaneous | [34] |

The data reveals how different adsorbate-adsorbent systems exhibit distinct thermodynamic signatures. For hydroquinone adsorption on both quartz and carbonate rocks, the consistently negative enthalpy values confirm exothermic processes, while the negative Gibbs free energy across all temperatures indicates spontaneity [31] [32]. Interestingly, the urotropine-kaolinite system demonstrates that endothermic adsorption (positive ΔH) can still proceed spontaneously when driven by sufficiently positive entropy changes [33]. This highlights the compensatory relationship between enthalpy and entropy in determining overall process spontaneity.

Temperature dependence represents another critical aspect of adsorption thermodynamics. For the hydroquinone-quartz system, adsorption capacity decreased significantly from 47.1 mg/g at 25°C to 27.1 mg/g at 80°C, reflecting the exothermic nature of the process where higher temperatures reduce favorability [31]. Similarly, in hydroquinone-carbonate systems, adsorption capacity declined from 45.2 mg/g at 25°C to 34.2 mg/g at 90°C [32]. This consistent pattern across different rock types provides valuable predictive insight for applications such as chemical injection strategies in subsurface environments where temperature variations occur naturally.

Experimental Protocols for Thermodynamic Parameter Determination

Batch Adsorption Experiments

The determination of thermodynamic parameters requires carefully controlled batch adsorption experiments followed by appropriate data analysis. A typical protocol involves preparing a series of adsorbate solutions across a concentration range (e.g., 100-100,000 mg/L for hydroquinone studies) using distilled or deionized water as the solvent [31] [32]. The solutions are mixed thoroughly using magnetic stirrers (commonly at 400 rpm) to ensure complete dissolution and homogeneity [31]. The adsorbent material is then added in precise quantities (e.g., 20 g quartz per 100 mL solution) to each solution, and the mixtures are agitated for a sufficient duration (typically 24 hours) to reach equilibrium at constant temperatures [31].

Post-equilibrium, the solid adsorbent is separated from the liquid phase via centrifugation (e.g., at 6000 rpm), and the residual adsorbate concentration in the supernatant is quantified using appropriate analytical techniques such as UV-Vis spectrophotometry [31]. The adsorption capacity at equilibrium (qe) is calculated using the equation: qe = 1000 × (Ci - Ce) × Vs / mq, where Ci and Ce represent the initial and equilibrium concentrations (mg/L), Vs is the solution volume (L), and mq is the adsorbent mass (g) [31]. This procedure is repeated across a temperature range (commonly 25°C to 90°C or higher) to capture temperature dependence.

Data Analysis and Parameter Calculation

Once equilibrium adsorption capacities are determined across temperatures, thermodynamic parameters are derived through mathematical analysis. The equilibrium constant (Kc) is first calculated from the adsorption data at different temperatures. The values of ΔH and ΔS are then determined from the van't Hoff equation: ln(Kc) = -ΔH/RT + ΔS/R, where R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K) [30]. Plotting ln(K_c) versus 1/T yields a linear relationship where the slope equals -ΔH/R and the intercept equals ΔS/R.

The Gibbs free energy change is calculated at each temperature using the relationship: ΔG = -RT ln(K_c) [30]. Consistent negative ΔG values across temperatures confirm spontaneous processes, as observed in both hydroquinone-quartz and hydroquinone-carbonate systems [31] [32]. For activation energy (Eâ‚) determination, which helps distinguish between physisorption and chemisorption, the Arrhenius equation is employed: ln(kâ‚‚) = ln(A) - Eâ‚/RT, where kâ‚‚ is the pseudo-second-order rate constant at temperature T, and A is the Arrhenius constant [30]. The slope of the Arrhenius plot (ln(kâ‚‚) versus 1/T) provides the Eâ‚ value.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful adsorption thermodynamic studies require specific materials and analytical tools carefully selected based on the research objectives. The following table catalogizes essential components used in contemporary adsorption research, with examples drawn from recent studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Thermodynamic Studies

| Category/Item | Specification Examples | Function/Purpose | Research Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorbents | Quartz (96% purity, 10-250 µm particles) | Provides homogeneous adsorption surface with active sites | [31] |

| Carbonate rocks (>95% calcite, 2-4 µm) | Represents reservoir rocks for oil recovery studies | [32] | |

| Kaolinite (>97% purity, <2 µm) | High-specific surface area clay adsorbent | [33] | |

| GO@Fe₃O₄@Pluronic-F68 nanocomposite | Engineered nanomaterial for heavy metal removal | [34] | |

| Adsorbates | Hydroquinone (>98% purity) | Crosslinker for gelation studies in oil reservoirs | [31] [32] |

| Urotropine (>99% purity) | Crosslinking agent for in-situ gel injection processes | [33] | |

| Ni(II) ions (from NiCl₂·6H₂O) | Model heavy metal contaminant for removal studies | [34] | |

| Analytical Instruments | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Quantifies residual adsorbate concentration in solution | [31] [33] |

| Magnetic Stirrer (400 rpm) | Ensures homogeneous mixing of adsorption mixtures | [31] [32] | |

| Laboratory Centrifuge (6000 rpm) | Separates solid adsorbent from liquid phase post-adsorption | [31] | |

| FT-IR Spectrometer | Characterizes functional groups and surface chemistry | [34] | |

| Characterization Tools | X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Verifies crystallinity and purity of adsorbent materials | [31] [33] |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Visualizes surface morphology and particle size distribution | [31] [34] | |

| BET Surface Area Analyzer | Measures specific surface area and pore characteristics | [34] | |

| Hpk1-IN-10 | Hpk1-IN-10|Potent HPK1 Inhibitor|For Research Use | Hpk1-IN-10 is a potent HPK1 inhibitor for cancer immunotherapy research. This product is for Research Use Only and not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Esomeprazole-d3 | Esomeprazole-d3, MF:C17H19N3O3S, MW:348.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The selection of appropriate adsorbent materials with well-characterized properties proves crucial for generating reproducible and meaningful thermodynamic data. High-purity materials (typically >95-97% purity) minimize interference from impurities, while controlled particle size distributions ensure consistent surface area availability for adsorption [31] [33]. Similarly, high-purity adsorbates enable accurate concentration measurements and reduce experimental uncertainty. The combination of bulk adsorption measurements with sophisticated characterization techniques provides comprehensive insight into both macroscopic thermodynamic behavior and molecular-level adsorption mechanisms.

Thermodynamic Distinctions: Case Studies in Physisorption and Chemisorption

Real-world research examples illustrate how thermodynamic parameters differentiate adsorption mechanisms and guide system optimization. The adsorption of hydroquinone on quartz and carbonate rocks exemplifies physisorption, with ΔH values of -8.02 kJ/mol and -6.49 kJ/mol respectively—well below the 40 kJ/mol threshold typically associated with chemisorption [31] [32] [30]. The negative ΔH values confirm exothermic processes, while negative ΔG across all temperatures demonstrates spontaneity. The decreasing adsorption capacity with increasing temperature further corroborates the exothermic nature, as higher temperatures reduce favorability according to Le Chatelier's principle [31].

In contrast, the adsorption of palladium on poly(m-aminobenzoic acid) polymer demonstrates classic chemisorption, with a reported activation energy of 61.71 kJ/mol, significantly exceeding the physisorption threshold [30]. Similarly, copper adsorption on A. bisporus showed chemisorption behavior with an activation energy of 118.86 kJ/mol, indicating strong chemical bonding between adsorbate and adsorbent [30]. These high activation energy values reflect the substantial energy barrier that must be overcome for chemical bond formation, unlike the minimal barriers in physisorption.

Interestingly, some systems exhibit atypical thermodynamic behavior that reveals complex underlying mechanisms. The adsorption of urotropine on kaolinite demonstrates endothermic character (ΔH = +9.53 kJ/mol) yet proceeds spontaneously, indicating that the process is entropy-driven rather than energy-driven [33]. This suggests that structural rearrangements or solvent effects contribute significantly to the adsorption mechanism. Such cases highlight the importance of measuring all thermodynamic parameters rather than assuming behavior based on limited data.

Thermodynamic analysis provides fundamental insights into adsorption processes that are critical for advancing research across scientific disciplines and industrial applications. The parameters ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS collectively describe system spontaneity, energy changes, and structural reorganizations during adsorption, enabling researchers to distinguish between physisorption and chemisorption mechanisms. Contemporary research demonstrates that these thermodynamic principles apply consistently across diverse systems—from hydroquinone adsorption in reservoir engineering to heavy metal removal using advanced nanomaterials.

The experimental methodologies outlined in this work provide a rigorous framework for determining thermodynamic parameters, while case studies illustrate how these principles manifest in real research scenarios. As adsorption technologies continue to evolve in sophistication—from MOF-based CO₂ capture to targeted drug delivery systems—thermodynamic perspectives will remain essential for optimizing performance, predicting behavior under varying conditions, and designing novel materials with tailored adsorption properties. For researchers and drug development professionals, this thermodynamic foundation enables evidence-based decisions in process design and material selection, ultimately contributing to more efficient and effective technological solutions.

Techniques and Real-World Applications in Science and Industry

In surface chemistry, adsorption describes the process where atoms, ions, or molecules from a substance (gas, liquid, or dissolved solid) adhere to the surface of an adsorbent. This process is distinct from absorption, where a substance permeates into the bulk of a material. The broader term sorption encompasses both phenomena [35]. Understanding the mechanism—whether it is physical adsorption (physisorption) or chemical adsorption (chemisorption)—is fundamental to designing and optimizing materials for applications in catalysis, environmental remediation, and drug development.

The distinction between physisorption and chemisorption is critical. Physisorption is characterized by weak van der Waals forces, is typically reversible, and occurs more readily at low temperatures. In contrast, chemisorption involves the formation of strong chemical bonds, is often irreversible, and may require higher temperatures to proceed [5] [4]. The potential energy curve for an adsorbate approaching a surface clearly shows a shallow physisorption well at a larger distance from the surface, which may be a precursor to a deeper chemisorption well at a shorter distance, separated by an activation energy barrier [4].

Characterizing the adsorbent materials is crucial to linking their physical and chemical properties to their performance. This guide details four core techniques—BET, FTIR, XRD, and SEM—that are indispensable for elucidating the properties of porous materials like Activated Carbon Black Microparticles (ACBMPs) and others used in adsorption studies.

Core Characterization Techniques

Surface Area and Porosity Analysis (BET Theory)

The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory is the standard method for determining the specific surface area of porous materials by analyzing the physical adsorption of gas molecules (typically nitrogen at 77 K) on a solid surface.

- Principle: The theory extends the Langmuir model to multilayer adsorption. It operates by measuring the quantity of adsorbate gas required to form a monomolecular layer on the adsorbent surface, which is then used to calculate the total specific surface area.

- Data Output: The primary result is the specific surface area (m²/g). The analysis of the adsorption and desorption isotherms can also provide information about the pore size distribution, distinguishing between micropores (pores < 2 nm), mesopores (pores between 2-50 nm), and macropores (pores > 50 nm).

- Relevance to Adsorption: Surface area is a primary factor determining the capacity of an adsorbent in physisorption processes. A higher surface area provides more sites for adsorbate molecules to adhere. For instance, Activated Carbon Black typically has a large internal surface area ranging from 500 to 2000 m²/g [36].

Chemical Bonding and Functional Group Analysis (FTIR)

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy is used to identify the chemical functional groups present on the surface of an adsorbent, which is vital for understanding chemisorption mechanisms.

- Principle: The technique measures the absorption of infrared light by a material. Different chemical bonds (e.g., O-H, C=O, C-O) vibrate at characteristic frequencies, producing a unique absorption spectrum that acts as a molecular fingerprint.

- Data Output: An IR spectrum plotting transmittance or absorbance against wavenumber (cmâ»Â¹). Specific peaks are identified and correlated to known functional groups.

- Relevance to Adsorption: FTIR can confirm the successful activation of materials (e.g., by phosphoric acid) and identify surface functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, hydroxyl, carbonyl) that can form strong chemical bonds with adsorbates, facilitating chemisorption [37] [36]. It can also be used to study the mechanism of dye adsorption, such as with Methyl Red (MR) molecules [36].

Crystalline Structure and Phase Identification (XRD)

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) is employed to determine the crystallinity, phase composition, and structural parameters of solid adsorbents.

- Principle: A collimated X-ray beam strikes a powdered sample, and the constructive interference of the scattered X-rays occurs at specific angles according to Bragg's law (nλ = 2d sinθ). This produces a diffraction pattern unique to the material's atomic structure.

- Data Output: A diffractogram plotting intensity against the diffraction angle (2θ). The positions of the peaks identify the crystalline phases, while peak broadening can be used to estimate crystallite size.

- Relevance to Adsorption: XRD reveals the d-spacing (the distance between parallel crystal planes), which can indicate the presence of graphitic structures or other layered materials. For example, in ACBMPs, the parallel planes spacing (dâ‚•â‚–â‚—) of the carbonaceous framework sheets was found to be about 2.98 Ã… to 4.44 Ã… [36]. Changes in d-spacing or crystallinity after activation or adsorption can provide insights into the interaction mechanism.

Surface Morphology and Topography Analysis (SEM)

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) provides high-resolution, topographical images of the adsorbent's surface, revealing its micro- and nano-structure.