Phosphine Oxide Ligands: Suppressing Ion Migration for Stable and Efficient Perovskite QLEDs

This article comprehensively reviews the strategic use of phosphine oxide-based ligands to suppress ion migration in perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (QLEDs).

Phosphine Oxide Ligands: Suppressing Ion Migration for Stable and Efficient Perovskite QLEDs

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the strategic use of phosphine oxide-based ligands to suppress ion migration in perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (QLEDs). Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, we explore the molecular design principles, including lattice-matching and multi-site anchoring, that enable effective defect passivation and lattice stabilization. The discussion extends to practical synthesis methods, bilateral interfacial passivation strategies, and troubleshooting for common device issues like efficiency roll-off. By validating performance through record external quantum efficiencies exceeding 27% and operational lifetimes over 23,000 hours, this analysis highlights the transformative potential of phosphine oxide ligands in creating high-performance, commercially viable optoelectronic devices for future biomedical imaging and sensing technologies.

Understanding Ion Migration: The Fundamental Challenge in Perovskite QLEDs

Ion migration is a fundamental challenge hindering the advancement of quantum-dot light-emitting diodes (QLEDs). This process, exacerbated by inherent defects in quantum dots (QDs), leads to operational instability and efficiency loss, critically limiting the commercial potential of perovskite QLEDs [1] [2]. Defects such as halide vacancies and uncoordinated lead (Pb²⁺) ions act as channels for ion movement under an electric field, accelerating non-radiative recombination and material degradation [1] [2]. This technical support center details the mechanisms of this degradation and provides actionable, evidence-based strategies for researchers aiming to suppress ion migration, with a specific focus on advanced phosphine oxide ligands.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing Ion Migration in QLEDs

| Symptom | Underlying Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid efficiency roll-off at high current density | Auger recombination exacerbated by defect-mediated ion migration [2] | Transient electroluminescence (EL) measurement [2] | Implement multi-site passivation to eliminate trap states [1] |

| Progressive shift in emission wavelength during operation | Field-induced halide vacancy migration altering local composition [1] [2] | Real-time electroluminescence spectrum monitoring | Use lattice-matched anchors to block ion migration channels [1] |

| Hysteresis in current-voltage (I-V) characteristics | Ionic movement in response to applied electric field [3] | Hysteresis measurement in FET transfer characteristics [3] | Employ cross-linked polymer dielectrics or 2D protective caps [3] |

| Decrease in operational lifetime (T50, T95) | Cumulative damage from ion migration and interface deterioration [2] | Accelerated lifetime testing under constant current stress | Engineer charge-injection balance and incorporate stable shell structures [2] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary origins of ion migration in perovskite quantum dots? The primary origins are intrinsic surface defects generated during the synthesis and purification processes. Polar solvents used to wash away excess long-chain ligands (like oleyl amine and oleic acid) can accidentally remove ligands bound to halogen atoms, creating halide vacancies and uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites. These defects then act as pathways for ion movement under electrical bias [1].

Q2: How do phosphine oxide-based ligands specifically suppress ion migration? Phosphine oxide groups (P=O) possess a strong binding affinity with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the QD surface. This interaction passivates these defect sites, preventing them from initiating or participating in ion migration. Multi-site anchoring molecules, such as TMeOPPO-p, are particularly effective. Their design matches the atomic lattice spacing of the perovskite (e.g., 6.5 Å), allowing multiple functional groups (P=O and -OCH₃) to bind simultaneously to the surface, creating a more robust and stable lock that stabilizes the lattice and blocks migration channels [1].

Q3: Beyond phosphine oxides, what other molecular strategies can control ionic drift? Research has shown that spacer cations with medium alkyl chains, π-conjugated bonds, or diammonium linkers can significantly improve layered network integrity and minimize vacancy formation in 2D perovskite structures. Furthermore, the incorporation of additives that supply sulfur donors or extra metal halides has been shown to improve crystal continuity and maintain the desired metal oxidation state, thereby reducing ionic mobility [3].

Q4: What non-destructive characterization techniques are best for probing ion migration in operating devices? Key techniques include:

- Impedance Spectroscopy: Probes ionic and electronic charge dynamics within the device [2].

- Transient Photoluminescence (PL) & Electroluminescence (EL): Reveals charge recombination kinetics and trap states [2].

- Electroabsorption Spectroscopy: Can monitor field distribution changes due to ion movement in real-time [2].

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Confirms the interaction between passivating molecules and the QD surface [1] [2].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Quantitative Performance of Passivation Strategies

The table below summarizes key performance metrics achieved with advanced passivation strategies, demonstrating the profound impact of defect passivation on device performance and stability.

| Passivation Molecule / Strategy | PL Quantum Yield (%) | Max. EQE (%) | Operating Lifetime (T50 or T95, hours) | Key Stability Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMeOPPO-p (Lattice-matched) | 97% [1] | 26.91% @ 693 nm [1] | > 23,000 h (Operating half-life) [1] | EQE roll-off: >20% @ 100 mA cm⁻² [1] |

| Core/Shell Architecture (CdSe-based) | N/R | ~25% [2] | 1,600,000 @ 100 cd/m² [2] | High stability for Cd-based red QLEDs [2] |

| Cd-Free (InP-based, Red) | N/R | N/R | 110,000 @ 100 cd/m² [2] | Progress for RoHS-compliant devices [2] |

| 2D Perovskite with Spacer Cations | N/R | N/R | N/R | Reduced ion migration, stable FET threshold voltage [3] |

N/R: Not explicitly reported in the provided search results.

Detailed Protocol: Passivating QDs with Lattice-Matched TMeOPPO-p

This protocol is adapted from the work of Chen et al. (2025) [1].

1. Objective: To synthesize CsPbI₃ QDs with a near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and suppressed ion migration by surface passivation with tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p).

2. Materials:

- Precursors: Cs₂CO₃, PbI₂, 1-Octadecene (ODE), Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm).

- Solvents: Toluene, Ethyl Acetate.

- Passivation Molecule: Synthesized TMeOPPO-p.

- Equipment: Three-neck flask, Schlenk line, syringe pumps, centrifuge.

3. Methodology: * QD Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbI₃ QDs using a modified hot-injection method. Typically, a Cs-OA precursor is swiftly injected into a hot (~160-180 °C) solution of PbI₂ in ODE, OA, and OAm. * Purification & Passivation: After the reaction, cool the solution and centrifuge the crude solution to separate the QDs. Re-disperse the QD precipitate in a non-polar solvent like toluene. * Anchoring Reaction: Add a solution of TMeOPPO-p (e.g., concentration of 5 mg mL⁻¹ in ethyl acetate) to the dispersed QDs. Stir the mixture for several hours to allow the phosphine oxide molecules to bind to the uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the QD surface. * Final Purification: Precipitate the passivated QDs by adding an anti-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) and centrifuge. Repeat this washing step to remove unbound ligands and impurities. Finally, disperse the purified QDs in a solvent like toluene for film fabrication.

4. Validation & Characterization: * Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Measure using an integrating sphere. Target: >95% [1]. * Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Confirm the presence of TMeOPPO-p on the QD surface by observing weakened C-H stretching modes (2700-3000 cm⁻¹) from original OA/OAm ligands [1]. * X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): A shift in the Pb 4f peaks to lower binding energies indicates enhanced electron shielding due to successful interaction with TMeOPPO-p [1]. * Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Use ¹H and ³¹P NMR to detect signals from the -OCH₃ and P=O groups of TMeOPPO-p in the passivated QDs, confirming successful anchoring [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) | A lattice-matched anchoring molecule; its P=O and -OCH₃ groups bind strongly with uncoordinated Pb²⁺, while its 6.5 Å interatomic O-O distance matches the QD lattice to provide multi-site defect passivation [1]. |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) Derivatives | Function as defect passivators; the P=O group is a strong Lewis base that coordinates with Lewis acidic uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites, reducing surface traps [1] [4]. |

| Spacer Cations (e.g., medium alkyl chains, π-conjugated) | Used in 2D perovskite FETs to improve layered network integrity, minimize vacancy formation, and restrict ion migration [3]. |

| Metal Halide Additives (e.g., ZnTeSe) | Particularly for Cd-free blue QLEDs; help control defects and maintain the desired oxidation state of the metal cation (e.g., Sn²⁺), improving crystal continuity [2] [3]. |

| Cross-linked Polymer Dielectrics | Used in device stacks to significantly reduce leakage currents and help control ionic drift [3]. |

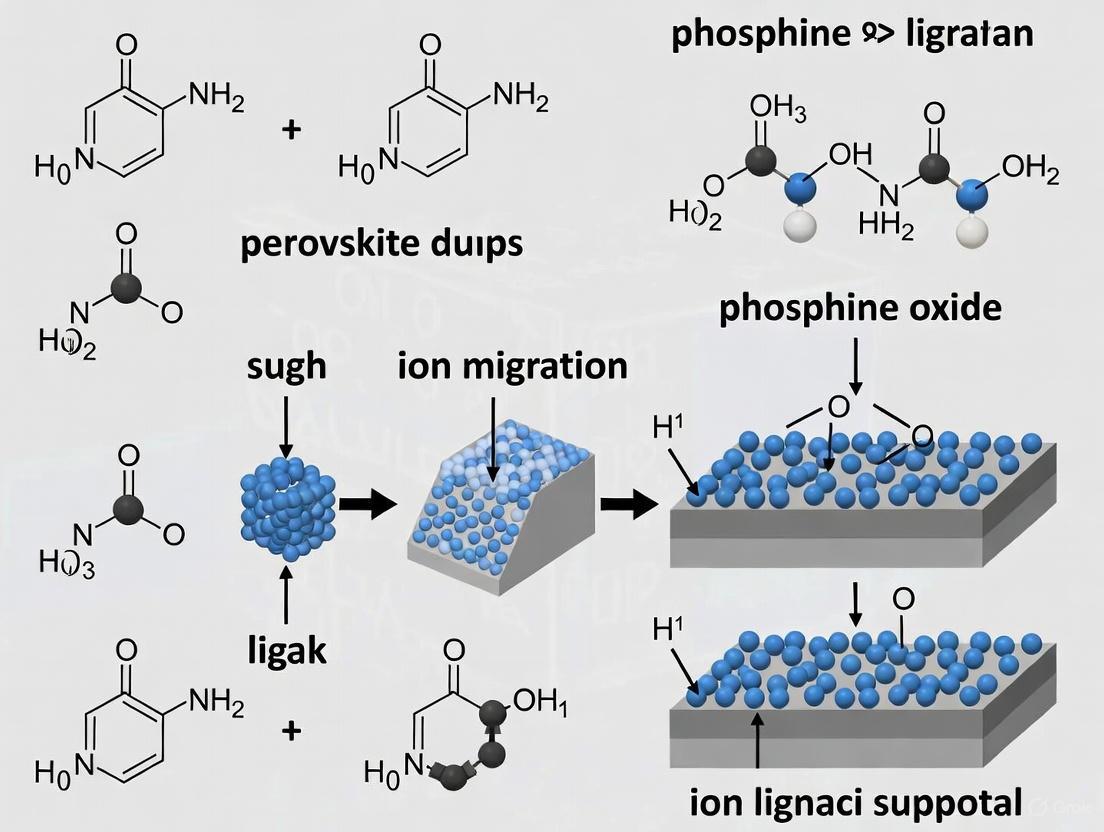

Visualization: Multi-Site Anchoring Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates how a lattice-matched phosphine oxide molecule passivates multiple defect sites on a quantum dot surface.

In perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (QLEDs), the exceptional optoelectronic properties of the materials are often compromised by inherent instabilities. A primary source of this instability is ion migration, a process initiated by intrinsic atomic defects within the perovskite crystal lattice. The soft, ionic nature of the lead halide perovskite lattice makes it particularly vulnerable to the formation and migration of these defects under operational stresses such as electric fields and photoexcitation [5] [6]. This technical support document outlines the atomic-scale origins of ion migration and provides practical, experimentally-validated solutions centered on phosphine oxide ligands to suppress these pathways, thereby enhancing the performance and operational lifetime of perovskite QLEDs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary atomic defects that act as ion migration pathways? The two most significant defects are uncoordinated lead ions (Pb²⁺) and halide vacancies.

- Uncoordinated Pb²⁺: These are under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the quantum dot surface, where the original organic ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) have been lost. These sites act as deep electron traps and facilitate the movement of ions by creating localized charge imbalances [7] [8].

- Halide Vacancies: These are empty lattice sites where a halide ion (e.g., I⁻, Br⁻) is missing. They are the most mobile species in the perovskite lattice and their migration under an electric field is a major cause of phase segregation and device degradation [5] [6].

Q2: How do phosphine oxide-based ligands suppress these migration pathways? Phosphine oxide molecules, characterized by their P=O functional group, function as highly effective multi-site passivators. The strongly nucleophilic oxygen atom in the P=O group has a potent affinity for the uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions. This interaction:

- Passivates Surface Traps: By coordinating with the electrophilic Pb²⁺, the molecules eliminate the trap states within the bandgap, reducing non-radiative recombination [7] [8].

- Anchors the Lattice: The strong bond formed between P=O and Pb²⁺ acts as a structural anchor, stabilizing the quantum dot surface and physically impeding the formation and movement of halide vacancies [7]. This directly blocks the channels through which ions migrate.

Q3: Why is a "bilateral interfacial passivation" strategy often necessary in devices? In a standard QLED sandwich structure, the perovskite quantum dot (PQD) film is interfaced with charge transport layers (CTLs) on both its top and bottom surfaces. Defects are prone to regenerate at both of these interfaces during device fabrication and operation. A unilateral passivation strategy only addresses one interface, leaving the other vulnerable. Bilateral passivation ensures that both the top and bottom surfaces of the PQD film are stabilized, leading to superior device efficiency and operational stability by ensuring balanced charge injection and suppressing interfacial recombination [8].

Q4: What specific properties make a phosphine oxide molecule an ideal passivator? An ideal phosphine oxide passivator possesses two key properties:

- Strong Binding Affinity: The P=O group must have a high bond order with the Pb²⁺ ion. Theoretical calculations show a bond order of 0.2 for P=O...Pb, which is significantly stronger than the interaction with common carboxyl or amine ligands, making the passivation more robust under electric fields [8].

- Lattice-Matched Multi-site Design: Advanced molecules are designed with multiple binding sites whose interatomic distances match the spacing of the perovskite crystal lattice (e.g., ~6.5 Å). This geometric matching allows a single molecule to passivate multiple uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites simultaneously, leading to near-complete elimination of trap states and exceptional lattice stabilization [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) in QD Films

A low PLQY indicates a high density of non-radiative recombination centers, typically from unpassivated defects.

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low film PLQY (<80%) after purification | Massive surface defects from ligand loss during film formation [8] | Implement post-deposition passivation. Spin-coat or evaporate a solution of TMeOPPO-p (1-5 mg/mL in ethyl acetate) onto the QD film. This directly passivates defects introduced during processing [7] [8]. |

| PLQY of colloids is high but drops significantly in films | Defect regeneration at interfaces with charge transport layers | Employ a bilateral passivation strategy. Evaporate a thin layer (e.g., TSPO1) onto the bottom charge transport layer before depositing QDs, and another layer on top of the QDs before depositing the opposite charge transport layer [8]. |

Rapid Efficiency Roll-off and Device Degradation

Quickly diminishing efficiency at high currents and short operational lifetimes are hallmarks of field-induced ion migration.

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Significant efficiency roll-off at high current density | Ion migration under high electric field leading to non-radiative pathways [5] | Use a lattice-matched multi-site anchor molecule like TMeOPPO-p. Its strong, multi-dentate binding effectively suppresses ion migration under high bias, as evidenced by a low efficiency roll-off (e.g., >20% EQE at 100 mA cm⁻²) [7]. |

| Short operational lifetime (T₅₀) | Ionic migration leads to irreversible decomposition and halide expulsion [5] [6] | Ensure robust passivation with phosphine oxides. Molecules like TSPO1 form a strong barrier that blocks ion migration channels. This has been shown to enhance device lifetime by over 20-fold [8]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key phosphine oxide molecules and their demonstrated efficacy in suppressing ion migration.

| Reagent Name | Function & Mechanism | Key Performance Data |

|---|---|---|

| TMeOPPO-p (tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide) | Lattice-matched multi-site anchor. P=O and -OCH3 groups bind to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ with 6.5 Å spacing, matching the QD lattice [7]. | - PLQY: 97% [7]- Max EQE: 27% [7]- Operating Lifetime (T₅₀): >23,000 h [7] |

| TSPO1 (diphenylphosphine oxide-4-(triphenylsilyl)phenyl) | Bilateral interfacial passivator. P=O group passivates Pb²⁺, while the molecular structure blocks ion migration at interfaces [8]. | - Film PLQY increase: 43% → 79% [8]- Max EQE: 18.7% [8]- Lifetime enhancement: 20-fold (0.8 h → 15.8 h) [8] |

| DDAB (didodecyldimethylammonium bromide) | Surface passivator. DDA⁺ cation binds to Br⁻ sites, improving stability and charge transfer. Shorter chain enhances passivation density [9]. | - Detectivity (D*): 7.93 × 10¹² Jones [9]- Response times: 3.64 μs (rise), 1.97 μs (fall) [9] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Bilateral Interfacial Passivation for QLED Fabrication

This protocol details the integration of TSPO1 as a passivation layer on both sides of a CsPbBr₃ QD film, as validated in high-performance devices [8].

Materials:

- Synthesized CsPbBr₃ QDs (PLQY >85%)

- TSPO1 (≥99.0% purity)

- Anhydrous solvents (e.g., toluene, ethyl acetate)

- Substrates with pre-patterned ITO and electron transport layer (e.g., PCBM)

Procedure:

- Bottom Interface Passivation: Load the substrate into a thermal evaporation chamber. Thermally evaporate a thin layer of TSPO1 (≈1-2 nm) directly onto the electron transport layer at a rate of 0.1-0.2 Å/s under high vacuum.

- QD Film Deposition: Immediately transfer the substrate with the bottom TSPO1 layer into a nitrogen-filled glovebox. Deposit the CsPbBr₃ QD film via spin-coating (e.g., 2000 rpm for 30 s) from a colloidal solution (e.g., 10 mg/mL in octane).

- Top Interface Passivation: Prepare a solution of TSPO1 in anhydrous ethyl acetate (0.5-1.0 mg/mL). Spin-coat this solution (e.g., 3000 rpm for 30 s) directly onto the dry QD film. This step passivates the top surface of the QD layer.

- Device Completion: Continue with the standard fabrication process by depositing the hole transport layer (e.g., TAPC) and the metal anode (e.g., Ag/MoO₃) [8].

Validation:

- Characterize the passivated QD film using FTIR and XPS to confirm the interaction between the P=O group and Pb²⁺ [7] [8].

- Measure the PLQY of the bilateral-passivated film; a successful passivation should yield a value >75% [8].

Protocol: Lattice-Matched Passivation of QD Inks

This protocol describes the post-synthesis treatment of CsPbI₃ QDs with TMeOPPO-p to achieve near-unity PLQY and superior stability [7].

Materials:

- CsPbI₃ QDs synthesized via hot-injection method.

- Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p, ≥99.0% purity)

- Anhydrous ethyl acetate and hexane.

Procedure:

- Purification: After synthesis, purify the crude QD solution by standard precipitation/centrifugation steps using an anti-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) to remove excess precursors and ligands.

- Passivation: Re-disperse the purified QD pellet in 5 mL of anhydrous hexane. Add a stock solution of TMeOPPO-p in ethyl acetate (10 mg/mL) to the QD dispersion under vigorous stirring. The optimal mass ratio of TMeOPPO-p to QDs is approximately 1:10.

- Incubation: Stir the mixture for 10 minutes at room temperature to allow the TMeOPPO-p molecules to bind to the QD surface.

- Final Purification: Precipitate the passivated QDs by adding an excess of ethyl acetate, then centrifuge. Re-disperse the final pellet in anhydrous octane or toluene for film deposition [7].

Validation:

- Measure the PLQY of the final QD ink using an integrating sphere. The PLQY should approach 97% for successful passivation [7].

- Aberration-corrected STEM can be used to confirm the uniform cubic morphology and clear lattice fringes of the passivated QDs [7].

Mechanism and Workflow Diagrams

Defect Passivation Mechanism

Bilateral Passivation Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary observable consequences of ion migration in perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (QLEDs)?

Ion migration, particularly of halide ions, is a major driver of performance degradation in perovskite QLEDs. The primary consequences are [10]:

- Phase Segregation: Under an electric field, mobile halide ions can separate into iodide-rich and bromide-rich domains. This changes the local bandgap, leading to undesirable color shifts and spectral instability in the emitted light [10].

- Efficiency Roll-off: At high injection currents, the external quantum efficiency (EQE) of the device drops significantly. Ion migration-induced field screening and increased non-radiative recombination at defects are dominant factors in this initial efficiency loss [10].

- Operational Instability: Mobile ions accelerate device degradation under operational stresses (electric field, light, heat), leading to a short operational lifetime. They are responsible for anomalies like current-voltage hysteresis and slow conductivity response [10].

FAQ 2: How do surface defects on quantum dots (QDs) contribute to efficiency roll-off and instability?

Surface defects on perovskite QDs, such as halide vacancies and uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions, create non-radiative recombination centers. This reduces the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and the efficiency of the device [7]. Furthermore, these vacancy defects act as channels for ion migration, directly linking surface imperfections to operational instability. The dissociation of excitons into free carriers in the bulk layer, partly due to weak electron-hole binding, also leads to high leakage current and low luminous efficiency, contributing to roll-off [11].

FAQ 3: What strategies can be used to suppress ion migration and improve stability?

Research points to several effective strategies:

- Lattice-Matched Molecular Anchors: Designing passivation molecules whose functional groups match the atomic spacing of the perovskite lattice (e.g., 6.5 Å). Molecules like tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) can provide multi-site anchoring, effectively passivating defects and suppressing ion migration [7].

- B-site Doping: Substituting the Pb²⁺ (B-site) cation with elements like alkaline-earth metals (e.g., Ca) or lanthanides (e.g., Eu) strengthens the lattice, suppresses octahedral oscillations, and increases the energy barrier for ion migration. Co-doping and multiple-element doping at the B-site are particularly effective [10].

- Dual-Interface Passivation: Employing solvent-free methods to passivate both the top and bottom interfaces of the perovskite film can improve charge transport and device longevity without creating secondary defects [11].

Troubleshooting Experimental Issues

Issue: My fabricated perovskite QLEDs exhibit a significant efficiency roll-off at high current densities.

| Possible Cause | Investigation Method | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High density of surface defects | Measure the Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) of the QD solution. A low PLQY indicates significant non-radiative recombination. | Implement a post-synthesis passivation treatment. Use multi-site anchoring molecules like TMeOPPO-p to bind to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions [7]. |

| Uncontrolled ligand density | Use Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to analyze the surface ligand composition on the QDs. | Optimize the purification process to maintain an optimal ligand density. Consider acid-assisted ligand exchange to replace weak long-chain ligands with stable coordination bonds [11]. |

| Active ion migration | Perform current-voltage (I-V) hysteresis measurements. A large hysteresis is a key indicator of ion migration. | Introduce B-site dopants (e.g., Eu, Ca) into the perovskite lattice to increase the ion migration barrier [10]. |

Issue: The electroluminescence spectrum of my devices shifts during operation (phase segregation).

| Possible Cause | Investigation Method | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Halide migration under bias | Monitor the electroluminescence spectrum in real-time under constant current stress. | Use B-site doping to lock the halide ions in place by strengthening lattice interactions [10]. |

| Weak lattice stability | Characterize the film crystallinity and phase stability using X-ray diffraction (XRD) under light/heat stress. | Employ passivation strategies that enhance the lattice stability, such as the lattice-matched molecular anchor TMeOPPO-p, which stabilizes the lattice and suppresses halide vacancy formation [7]. |

Table 1: Performance Enhancement via Lattice-Matched Anchoring Molecules[a]

| Parameter | Pristine QDs | TPPO-treated QDs | TMeOPPO-p-treated QDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average PLQY | 59% | 70% | 97% |

| Maximum EQE | — | — | 27% |

| EQE at 100 mA cm⁻² | — | — | >20% |

| Operating Half-life | — | — | >23,000 h |

[a] Data adapted from the study on tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Ion Migration Suppression Strategies

| Strategy | Key Mechanism | Impact on Iodine Migration Barrier | Key Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lattice-Matched Anchor (TMeOPPO-p) | Multi-site defect passivation & lattice stabilization | Not quantified, but near-unity PLQY and long device lifetime indicate effective suppression [7]. | PLQY of 97%; Device T₅₀ > 23,000 h; eliminated trap states in PDOS [7]. |

| B-site Doping (Eu, Ca) | Strengthens lattice interactions & restrains octahedral oscillation | Significantly increases the barrier [10]. | Hysteresis-free current-voltage curves; remarkable improvement in ambient stability [10]. |

| Applied Compressive Strain | Reduces unit cell volume and lattice void | Increases migration barrier [10]. | First-principles calculations and machine learning molecular dynamics simulations [10]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis and Purification of CsPbI₃ QDs with Lattice-Matched Molecular Anchors

This protocol is adapted from the hot-injection method used in the cited research [7].

QD Synthesis:

- Prepare precursor solutions: Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) in octadecene with oleic acid, and Lead iodide (PbI₂) in octadecene with oleic acid and oleylamine.

- Heat the PbI₂ solution to a specific high temperature (e.g., 150-180 °C) under inert atmosphere.

- Rapidly inject the Cs-oleate solution into the hot PbI₂ solution and let the reaction proceed for 5-60 seconds.

- Cool the reaction mixture rapidly using an ice bath to terminate the reaction.

Purification and Passivation:

- Precipitate the crude QD solution by adding a polar solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or methyl acetate) and centrifuging.

- Discard the supernatant and re-dissolve the QD pellet in a non-polar solvent (e.g., hexane or octane).

- Add the lattice-matched anchor molecule (e.g., TMeOPPO-p) to the QD solution at a controlled concentration. Sonicate or stir to ensure interaction.

- Precipitate and wash the passivated QDs multiple times with a polar solvent to remove excess ligands and by-products.

- Finally, disperse the purified and passivated QDs in an anhydrous solvent for film deposition.

Protocol 2: B-site Doping for Ion Migration Suppression

This protocol outlines the strategy for incorporating dopants into the perovskite lattice [10].

- Dopant Selection: Based on computational screening, select one or multiple B-site dopant elements, such as Europium (Eu) and Calcium (Ca).

- Precursor Preparation: Incorporate the chosen dopant salts (e.g., EuI₃, CaI₂) into the perovskite precursor solution alongside lead halide (PbI₂). The stoichiometry should be carefully controlled.

- Crystal/Film Growth: For single crystals, use slow crystallization methods. For thin films, use one-step spin-coating or thermal evaporation. The growth conditions (temperature, atmosphere) must be optimized for the specific dopants.

- Validation: Characterize the doped crystals/films using techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) to confirm successful incorporation and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) to examine morphology.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Suppressing Ion Migration

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) | Lattice-matched multi-site anchoring molecule; passivates uncoordinated Pb²⁺ via P=O and -OCH₃ groups, stabilizing the lattice and suppressing ion migration [7]. | Used as a post-synthesis passivator to achieve QDs with 97% PLQY and high-stability QLEDs [7]. |

| Europium (Eu) & Calcium (Ca) Salts | B-site dopants; strengthen ionic interactions within the inorganic lattice, restrain octahedral rocking, and increase the energy barrier for iodine ion migration [10]. | Used in co-doping to create hysteresis-free perovskite single crystals with improved ambient stability [10]. |

| Octylammonium Iodide (OAI) | Additive for crystallization modulation and defect passivation; suppresses uncontrolled grain growth and minimizes grain boundaries, reducing defect density [11]. | Employed in a dual-role approach to create improved perovskite films for pure red PeLEDs [11]. |

| Phenanthroline-based compound (BUPH1) | In-situ passivator for vacuum-deposited films; coordinates with under-coordinated Pb(II) ions during film formation, passivating halide vacancies [11]. | Co-evaporated with perovskite precursors to enhance film morphology and stabilize the emission spectrum without additional steps [11]. |

Mechanism and Workflow Diagrams

Fundamental Mechanisms of Defect Passivation

What are the primary defects that phosphine oxide groups target in perovskite quantum dots?

Phosphine oxide groups, specifically the P=O functional group, primarily target undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the surface of perovskite quantum dots (QDs) [7]. These defects form when halide vacancies are created or when native ligands (like oleyl amine or oleic acid) are accidentally removed during purification with polar solvents [7]. The P=O group acts as a Lewis base that donates electron density to the electron-deficient, undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions, which act as Lewis acids [4] [7]. This coordination saturates the dangling bonds, effectively eliminating trap states that would otherwise promote non-radiative recombination and ion migration [7].

How does the molecular structure of a phosphine oxide influence its passivation efficiency?

The passivation efficiency is profoundly influenced by the molecular design beyond just the presence of the P=O group. Recent research highlights the critical importance of a lattice-matched multi-site anchoring strategy [7].

- Single-site vs. Multi-site Anchoring: Traditional molecules like triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) offer only a single P=O binding site. While this can passivate one defect, it often leaves other uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions untouched, leading to residual trap states [7]. In contrast, advanced designs like tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) feature multiple electron-donating groups (P=O and -OCH₃) positioned to match the crystal lattice of the perovskite.

- Lattice Matching: The interatomic distance between the oxygen atoms in the passivator molecule must match the spacing of the potential binding sites on the QD surface. For TMeOPPO-p, the calculated O-O distance is 6.5 Å, which precisely matches the lattice spacing of CsPbI₃ QDs. This allows the molecule to bind strongly to multiple undercoordinated sites simultaneously without introducing strain [7].

- Electronic Effects: The nucleophilicity of the binding groups also matters. Electron-donating substituents like methoxy groups (-OCH₃) enhance the electron-donating capability of the phosphine oxide, strengthening the interaction with Pb²⁺ ions [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Phosphine Oxide-Based Passivation Molecules

| Molecule Name | Binding Groups | Site Spacing | Key Finding | Reported PLQY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPPO [7] | P=O | Single Site | Eliminates some trap states, but consecutive trap states remain. | ~70% |

| TMeOPPO-p [7] | P=O and three -OCH₃ | 6.5 Å (Lattice-matched) | Multi-site anchoring eliminates trap states completely and stabilizes the lattice. | ~97% |

| TMeOPPO-o [7] | P=O and -OCH₃ | 2.6 Å (Mismatched) | Enforced coordination introduces strain and structural distortion. | ~82% |

Experimental Protocols for Defect Analysis and Passivation

Protocol: Validating Passivation Effectiveness via Spectroscopic Techniques

This protocol outlines the key experiments to confirm the successful passivation of QD surface defects by phosphine oxide molecules.

Objective: To provide evidence of the interaction between the phosphine oxide molecule (e.g., TMeOPPO-p) and the perovskite QD surface.

Materials:

- Synthesized perovskite QDs (e.g., CsPbI₃)

- Phosphine oxide passivator (e.g., TMeOPPO-p, dissolved in ethyl acetate)

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectrometer

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscope (XPS)

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectrometer

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare two batches of QDs: a control (pristine) and a target batch treated with the phosphine oxide additive during or after purification [7].

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy:

- Procedure: Acquire FTIR spectra for both pristine and target QD films.

- Expected Outcome: In target QDs, the intensity of C–H stretching modes (2700-3000 cm⁻¹) from the long-chain oleyl amine/oleic acid ligands is weakened. This indicates that the phosphine oxide molecule has partially replaced or supplemented the original ligands, forming a stronger connection to the QD surface [7].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS):

- Procedure: Analyze the Pb 4f core-level spectra of pristine and target QDs.

- Expected Outcome: A shift of the Pb 4f characteristic peaks to lower binding energies in the target QDs. This confirms a strong interaction between the passivator and the Pb²⁺ ions, which enhances the shielding effect on the inner electrons [7].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy:

- Procedure: Record ¹H and ³¹P NMR spectra of the pure passivator molecule and the target QDs.

- Expected Outcome: The presence of signature peaks from the passivator (e.g., the -OCH₃ peak at δ 3.81 in ¹H NMR) in the spectra of the target QDs confirms that the TMeOPPO-p is successfully incorporated onto the QD surface. Chemical shifts in these peaks further evidence the coordination bonding [7].

Protocol: Quantifying the Reduction of Ion Migration

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of the passivator in suppressing the migration of ionic species, a primary failure mechanism in perovskite QLEDs.

Materials:

- Fabricated QLED devices (with and without passivation)

- Impedance Spectroscopy Setup

- Transient Current Measurement Setup

Methodology:

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate QLEDs using passivated and non-passivated QDs as the emissive layer [7].

- Impedance Spectroscopy:

- Procedure: Measure the impedance of the devices over a range of frequencies.

- Data Analysis: Fit the resulting spectra to an appropriate equivalent circuit model to extract the ionic conductivity (σ) [12].

- Transient Current Measurements:

- Procedure: In the dark, apply a voltage step and measure the resulting current transient.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the current decay to calculate the mobile ion concentration (N₀) [12].

- Calculation of Ionic Mobility (μ): Using the values obtained from the above techniques, calculate the ionic mobility with the formula: σ = q * N₀ * μ, where q is the elementary charge [12].

Interpretation: Effective passivators like lattice-matched phosphine oxides significantly reduce both N₀ and μ by filling halide vacancies and stabilizing the lattice, thereby suppressing ion migration pathways [7] [13] [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Researchers

Q1: My passivated quantum dots show high PLQY in solution, but the performance of my fabricated LED is poor. What could be the issue?

A: This is a common problem often related to charge injection imbalance. While the phosphine oxide passivator effectively eliminates non-radiative recombination centers (hence high PLQY), it may also influence the electrical properties of the QD film.

- Cause 1: The passivation layer might be too thick or insulating, hindering charge carrier injection into the QDs [7]. This is a trade-off with the native long-chain ligands.

- Solution: Optimize the concentration of the phosphine oxide additive and the post-treatment process to achieve optimal passivation without completely blocking charge transport. A lattice-matched, multi-site anchor like TMeOPPO-p is designed to bind strongly without excessive, poorly-conducting organic chains [7].

- Cause 2: The passivation may have altered the energy level alignment at the QD/charge transport layer interface.

- Solution: Use ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) to check the work function and ionization energy of the passivated QD film. You may need to adjust the charge transport layers to ensure efficient hole and electron injection.

Q2: I've used a phosphine oxide additive, but my device stability is still low. Why?

A: Incomplete passivation or the presence of other degradation pathways could be the cause.

- Cause 1: The molecule may not be effectively passivating all major defect sites. A single-site passivator might be insufficient.

- Solution: Consider switching to a multi-site anchoring molecule like TMeOPPO-p, which is designed to passivate multiple uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions simultaneously, offering more robust lattice stabilization [7].

- Cause 2: Ion migration can still occur through grain boundaries or from other ionic species not targeted by the phosphine oxide group [13].

- Solution: Implement a multi-pronged strategy. Combine surface passivation with compositional engineering (e.g., using mixed halides or cations) to increase the intrinsic activation energy for ion migration [13]. Also, ensure your charge transport layers and electrodes are robust and resistant to corrosion from any residual migrating ions [13].

Q3: How critical is the "lattice-matching" principle in designing new phosphine oxide passivators?

A: It is a breakthrough concept for achieving high-performance devices. Research shows that a mismatch between the molecule's binding site distance and the perovskite lattice spacing can be detrimental.

- Evidence: A molecule with a site spacing of 2.6 Å (TMeOPPO-o) was shown to introduce substantial strain upon binding, leading to structural distortion and a lower PLQY (82%) compared to the lattice-matched TMeOPPO-p (97%) [7].

- Guidance: When designing new molecules, use computational chemistry (e.g., DFT calculations) to project the density of states (PDOS) and simulate the binding configuration. A successful passivator should connect the trap states with the conduction band minimum, indicating complete defect elimination, which is only achievable with a well-matched, multi-site design [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Phosphine Oxide-Based Passivation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) | A lattice-matched, multi-site anchoring passivator. The P=O and three -OCH₃ groups coordinatively bind to uncoordinated Pb²⁺, suppressing defects and ion migration. | The representative molecule in [7], enabling a record EQE of 27% and enhanced stability in QLEDs. |

| Triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) | A single-site passivator benchmark. Serves as a basic framework for understanding the passivation mechanism of the P=O group. | Used as a control molecule to demonstrate the limitations of single-site passivation compared to multi-site anchors [7]. |

| CsPbI₃ Quantum Dots | The model perovskite semiconductor system for studying passivation effects in optoelectronic devices. | The base material passivated by TMeOPPO-p in the cited research, showing a near-unity PLQY [7]. |

| Oleyl Amine / Oleic Acid | Native surface ligands for QD synthesis and stabilization. They are dynamically bound and can be displaced, creating defects. | Their partial replacement by stronger-binding phosphine oxide molecules is a key step in the enhanced passivation process [7]. |

Visualizing the Passivation Mechanism and Workflow

Passivation Mechanism Diagram

Experimental Workflow

Molecular Engineering and Practical Implementation of Phosphine Oxide Ligands

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Problem 1: Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)

- Problem Description: The synthesized perovskite quantum dots (QDs) exhibit a photoluminescence quantum yield significantly below the near-unity (>95%) values reported in literature, indicating insufficient defect passivation [7].

- Potential Causes:

- Lattice Mismatch: The site spacing of the multi-site anchoring molecule does not match the 6.5 Å lattice spacing of the perovskite QDs, leading to enforced coordination and structural distortion [7].

- Incorrect Purification: The polar solvent washing step may have accidentally removed ligands binding with halogen atoms, creating halide vacancies or uncoordinated Pb²⁺ [7].

- Weak Binding Groups: The functional groups on the anchor molecule (e.g., -F, -Cl, -Br) may have nucleophilicity that is too low for strong interaction with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ [7].

- Solution Steps:

- Verify Molecular Design: Confirm that the interatomic distance of the binding sites (e.g., O atoms from P=O and -OCH₃) on your anchor molecule is approximately 6.5 Å to ensure lattice matching [7].

- Optimize Purification Protocol: Carefully control the type and volume of polar solvent used during washing to remove excess ligands without stripping those crucial for surface integrity [7].

- Select Strong Binding Groups: Prioritize molecules with strongly nucleophilic groups like -OCH₃ and P=O, which show stronger interactions with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ compared to halogens [7].

Common Problem 2: Significant Efficiency Roll-Off in QLEDs

- Problem Description: The fabricated quantum dot light-emitting diode (QLED) shows a rapid decrease in external quantum efficiency (EQE) as the current density increases.

- Potential Causes:

- Residual Surface Defects: Incomplete passivation leaves trap states that promote non-radiative recombination at higher current densities [7].

- Ion Migration: The presence of halide vacancies or uncoordinated Pb²⁺ provides channels for field-induced ion migration under electrical stress, degrading performance [7].

- Poor Charge Injection: Excessively long insulating ligand chains can block efficient charge injection into the QD layer, a problem exacerbated at higher currents [7].

- Solution Steps:

- Implement Multi-Site Anchors: Use lattice-matched multi-site anchoring molecules (e.g., TMeOPPO-p) instead of single-site passivators. Theoretical calculations confirm these can completely eliminate trap states from Pb-6pz orbitals, unlike single-site anchors [7].

- Characterize Trap States: Use techniques like projected density of states (PDOS) calculation or transient photoluminescence to verify the elimination of trap states around the Fermi level [7].

- Balance Ligand Density: Achieve an optimal ligand density that provides sufficient passivation without overly compromising electrical conductivity [7].

Common Problem 3: Poor Operational Stability of QLEDs

- Problem Description: The QLED device degrades rapidly during operation, showing a short operating half-life.

- Potential Causes:

- Weak/ Dynamic Ligand Binding: Traditional ligands (e.g., oleyl amine, oleic acid) have a weak and dynamic connection to the QD surface, making them susceptible to desorption under electric field or thermal stress [7].

- Incomplete Surface Coverage: The anchor molecule does not provide sufficient coverage of all surface defect sites.

- Solution Steps:

- Employ Strong Multi-Site Anchors: Utilize molecules like TMeOPPO-p designed for strong, multi-site interaction. The triple-attached nucleophilic groups increase the probability of binding with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ and stabilize the lattice [7].

- Confirm Surface Binding: Use Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to check for the weakening of C-H stretching modes from original ligands and the appearance of signatures from the new anchor molecule. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) can show a shift in Pb 4f peaks to lower binding energies, confirming enhanced electron shielding due to successful anchor binding [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is lattice matching so critical in the design of anchor molecules for perovskite QDs?

A1: Lattice matching is crucial because it allows the anchor molecule to approach close enough to the perovskite crystal lattice without introducing substantial steric strain. A precisely matched interatomic distance (e.g., 6.5 Å for CsPbI₃ QDs) enables multiple binding sites on the molecule to simultaneously interact with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ on the QD surface. This multi-site anchoring provides a strong interaction that effectively eliminates trap states and stabilizes the lattice, leading to high PLQY and operational stability. A mismatched molecule cannot offer adequate passivation and may even cause structural distortion [7].

Q2: How do phosphine oxide-based anchors like TMeOPPO-p compare to traditional oleyl amine/oleic acid ligands?

A2: The comparison can be summarized as follows:

| Feature | Traditional Ligands (Oleyl amine/Oleic acid) | Phosphine Oxide Anchors (e.g., TMeOPPO-p) |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Strength | Weak, dynamic connection [7] | Strong, multi-site interaction [7] |

| Primary Function | Basic passivation, colloidal stability [7] | Targeted, multi-site defect passivation [7] |

| Electrical Properties | Long alkyl chains can block charge injection [7] | Can be designed for rational ligand density to balance passivation and conductivity [7] |

| Stability | Can be accidentally removed during purification [7] | Stabilizes lattice, resists desorption under electric field [7] |

Q3: What experimental techniques can confirm the successful binding of an anchor molecule to the QD surface?

A3: Several techniques can provide conclusive evidence:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): ¹H and ³¹P NMR spectra can show the presence of the anchor molecule (e.g., signals for -OCH₃ and P=O groups) in the purified QD sample, confirming it remains on the surface [7].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): A shift in the binding energy of core levels (e.g., Pb 4f shifting to lower energies) indicates an enhanced shielding effect due to electron donation from the anchor molecule, proving a strong electronic interaction [7].

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: A weakening of signature stretches from original ligands and the appearance of new peaks can indicate ligand exchange and successful binding of the new anchor [7].

Q4: Can these lattice-matched molecular anchors be used in air-processed devices?

A4: Yes, research demonstrates that QDs treated with advanced lattice-matched anchors like TMeOPPO-p exhibit improved resistance to oxygen and water. This allows the fabrication of air-processed QLEDs that can maintain high performance, with reported devices achieving a maximum external quantum efficiency of over 26% even when processed in air [7].

| Molecule | Binding Site Spacing (Å) | Average PLQY (%) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine QDs | - | 59 | Baseline with high defect density |

| TPPO | 5.3 (Single-site) | 70 | Incomplete trap state elimination |

| TMeOPPO-o | 2.6 | 82 | Mismatched spacing, enforced coordination |

| TMeOPPO-p | 6.5 | 96 | Lattice-matched, best performance |

| TFPPO | 6.6 | 92 | Good, but lower nucleophilicity |

| TClPPO | 7.0 | 88 | Larger spacing, lower nucleophilicity |

| TBrPPO | 7.2 | 87 | Largest spacing, lowest nucleophilicity |

| Parameter | Value | Measurement Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Max External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | 26.91% | At 693 nm |

| EQE Roll-off | > 20% | At 100 mA cm⁻² |

| Operating Half-life (T₅₀) | > 23,000 hours | - |

| Air-processed Max EQE | 26.28% | - |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol is adapted from the modified hot-injection method described in the research.

QD Synthesis:

- Prepare precursor solutions: Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) in oleic acid and lead iodide (PbI₂) in 1-octadecene with oleyl amine and oleic acid.

- Heat the PbI₂ solution to a specific temperature (e.g., 150-180°C) under inert atmosphere with vigorous stirring.

- Rapidly inject the Cs-oleate solution into the reaction flask.

- Allow the reaction to proceed for a few seconds before cooling the mixture rapidly in an ice-water bath.

Purification and Ligand Exchange:

- Precipitate the crude QD solution by adding a polar solvent (e.g., methyl acetate or ethyl acetate) and centrifuging.

- Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the QD pellet in a non-polar solvent like hexane or toluene.

- Add the TMeOPPO-p anchor molecule (typical concentration 5 mg mL⁻¹ in ethyl acetate) to the QD solution.

- Stir the mixture for a predetermined period to allow for ligand exchange.

- Precipitate the QDs again with a polar solvent and centrifuge. Repeat this washing step 2-3 times to remove excess ligands and reaction by-products.

- Finally, disperse the purified QDs in an anhydrous solvent (e.g., octane) for film deposition and device fabrication.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Lattice-Matched Anchor Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) | Lattice-matched multi-site anchor; passivates uncoordinated Pb²⁺ via P=O and -OCH₃ groups [7]. |

| CsPbI₃ Quantum Dots | The target perovskite semiconductor material for optoelectronic applications [7]. |

| Oleyl Amine / Oleic Acid | Traditional ligands used in initial QD synthesis for basic passivation and colloidal stability [7]. |

| Ethyl Acetate | Polar solvent used in the purification and washing steps to remove excess ligands [7]. |

| Triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) | Single-site anchoring molecule; useful as a control to demonstrate the superiority of multi-site anchors [7]. |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Molecular Anchoring Mechanism

Experimental Workflow for QD Treatment & Analysis

Defect passivation is an essential strategy for constructing efficient and stable perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (QLEDs). While phosphorus-oxygen (P=O) functional groups have been extensively studied for their excellent coordination with under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions, a broader toolkit of functional groups offers versatile mechanisms for suppressing ion migration and enhancing device performance. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols for researchers leveraging these functional groups, specifically methoxy (-OCH₃) and others, within the context of suppressing ion migration in perovskite QLEDs.

Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Functional Group Passivation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| para-tert-butylbenzene derivatives (e.g., tB-OCH₃, tB-COOH) | Core molecular scaffold for systematically comparing the passivation efficacy of different functional groups attached at the para-position [14]. |

| Pluronic F127 (PF127) | Non-ionic surfactant used for surface passivation to minimize non-specific binding and surface adhesion of perovskites during spectroscopic studies [15]. |

| π-conjugated Lewis base molecules | A class of passivators designed to address the "passivation-transport" contradiction, enabling effective passivation without harming charge carrier transport [16]. |

| Symmetrical silane-based passivators (e.g., SPE) | In-situ passivating agents containing P=O bonds that coordinate with Pb²⁺ and provide hydrophobicity, improving optical performance and stability [17]. |

| Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) | Technique for depositing ultra-thin, conformal passivation layers (e.g., Al₂O₃) on semiconductors to minimize surface recombination [18]. |

| Triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) | A classic phosphine oxide ligand used to stabilize coordination geometries and study steric/electronic effects on passivation and luminescence [19]. |

Comparative Performance of Functional Groups

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Select Passivation Functional Groups

| Functional Group | Example Molecule | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methoxy (-OCH₃) | tB-OCH₃ | Open-circuit voltage (VOC) trend | Intermediate VOC increase, lower than -COOH [14] | [14] |

| Carboxyl (-COOH) | tB-COOH | Champion Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | 21.46% [14] | [14] |

| Carboxyl (-COOH) | tB-COOH | Long-term stability (unencapsulated) | >88% initial PCE retained after 10,080 hours [14] | [14] |

| Phosphine Oxide (P=O) | SPE (silane-based) | Photoluminescence Intensity (PL) | 28% enhancement [17] | [17] |

| Phosphine Oxide (P=O) | SPE (silane-based) | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Increased from 81.53% to 94.57% [17] | [17] |

| Phosphine Oxide (P=O) | TPPO/Phen system | Luminescence Quantum Yield (Eu³⁺) | 26.88% [19] | [19] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Passivation Effect of Functional Groups on Perovskite Films

This protocol is adapted from systematic studies comparing different functional groups [14].

- Material Preparation: Synthesize or procure a series of passivation molecules based on a consistent core structure (e.g., para-tert-butylbenzene) but functionalized with different terminal groups (e.g., -CH₃, -OCH₃, -COOH, -CN, -NH₂).

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate planar n-i-p PSCs with an ITO/SnO₂/perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au structure. Use a one-step spin-coating method for the perovskite active layer (e.g., MAPbI₃).

- Passivation Application: Introduce the passivation molecules at the perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD interface. This is typically done by depositing a solution of the molecule in a suitable solvent (e.g., chlorobenzene) via spin-coating.

- Performance Characterization:

- Current-Voltage (J-V) Measurements: Measure the open-circuit voltage (VOC) of the devices. A higher VOC indicates more effective suppression of non-radiative recombination.

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculation: Perform calculations to determine the binding energy between the functional group and the perovskite surface (e.g., with PbI₂-terminated slab). This quantifies the chemical bonding strength.

- Stability Testing: Store unencapsulated devices in ambient air (e.g., ~45% relative humidity) and track the retention of Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) over time (e.g., up to 10,080 hours).

Protocol 2: In-situ Passivation of Perovskite Quantum Dots (QDs) with Phosphorus-Oxygen Ligands

This protocol outlines the passivation of QDs during synthesis [17].

- Passivator Synthesis: Synthesize the passivating agent, such as the symmetrical silane 1,3-bis(3-diethoxyphosphorylpropyl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyldisiloxane (SPE).

- QD Synthesis and Passivation: Incorporate the SPE passivating agent directly into the precursor solution used for synthesizing CsPbBr₃ QDs. Vary the concentration of SPE (e.g., 0 to 30 mg/mL) to identify the optimal passivation level.

- Optical Characterization:

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: Measure the PL intensity and peak position.

- UV-vis Absorption Spectroscopy: Record absorption spectra to observe any shifts in the absorption edge and calculate the Urbach energy (Eu) to quantify structural disorder.

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Determine the absolute PLQY using an integrating sphere.

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL): Fit the decay curves with a biexponential model to extract the average carrier lifetime (τave).

- Structural and Stability Characterization:

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Analyze the morphology, crystal structure, and defect density of passivated vs. unpassivated QDs.

- Stability Tests: Subject passivated QDs to thermal stress (e.g., 80°C) and high humidity (e.g., 84% RH), monitoring PL degradation over time.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why does my passivated device show high VOC but poor long-term stability?

- Problem: The passivation layer is volatile or lacks robust intermolecular interactions.

- Solution: Select functional groups that form strong, stable bonds with the perovskite and with each other. For example, molecules with carboxyl groups (-COOH) can form crystalline, water-insoluble interlayers with high melting points due to strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding, leading to exceptional long-term stability [14].

- Prevention: When designing or selecting passivation molecules, prioritize those with the potential for secondary intermolecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking) to enhance the durability of the passivation layer.

FAQ 2: Why does adding more passivator beyond an optimal concentration degrade device performance?

- Problem: This is a classic "passivation-transport" contradiction. Excessive insulating passivators can block charge extraction at the interface [16].

- Solution:

- Precisely optimize the concentration of the passivator.

- Consider using π-conjugated Lewis base molecules. Their conjugated structure can provide effective passivation while still allowing for charge transfer, making their passivation effect more tolerant to higher concentrations and thus more durable against increasing defects over time [16].

- Prevention: During optimization, monitor both VOC (indicator of passivation) and the fill factor (FF, indicator of charge transport) to find a balance.

FAQ 3: My perovskite films show high non-specific adhesion to measurement substrates, causing artifacts. How can I prevent this?

- Problem: Strong adhesion to glass or other substrates can alter material properties and increase background noise in sensitive measurements like single-molecule imaging [15].

- Solution: Implement a robust surface passivation protocol for your experimental substrates.

- Make glass slides hydrophobic by treating with Sigmacote.

- Incubate with a solution of the surfactant Pluronic F127 (PF127). The PPO block adsorbs to the hydrophobic surface, while the PEO blocks form a dense, hydrated brush layer that minimizes non-specific binding.

- This method is simple, rapid (active handling <1 hour), and effective across a wide range of pH and salt conditions [15].

FAQ 4: The methoxy (-OCH₃) group shows a weaker passivation effect than phosphine oxide (P=O) in my tests. Is this expected?

- Answer: Yes, this is consistent with systematic studies. The passivation strength of a functional group is directly correlated with its chemical bonding strength to the perovskite surface (e.g., with under-coordinated Pb²⁺). While -OCH₃ provides a moderate improvement, stronger Lewis bases like P=O and -COOH consistently demonstrate higher binding energies and thus more effective defect passivation, as reflected in larger VOC gains and better stability [14]. The P=O group's high coordination capability and electron affinity make it particularly effective for suppressing non-radiative recombination [17].

Mechanisms and Workflow Diagrams

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why are phosphine oxide ligands particularly effective for passivating perovskite QDs? Phosphine oxide ligands, characterized by their P=O functional groups, are highly effective due to their strong interaction with under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the perovskite QD surface. This binding passivates surface defects, which are non-radiative recombination centers, thereby enhancing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and stability. The strong coordination bond (with a calculated bond order of 0.2) also helps prevent ligand detachment under an electric field, suppressing ion migration channels and improving device operational stability [4] [8].

FAQ 2: During which stages of QD processing can phosphine oxide ligands be incorporated? Phosphine oxide ligands can be introduced at two main stages:

- In-situ during synthesis: Added directly to the reaction mixture in the hot-injection method, allowing ligands to bind during QD nucleation and growth.

- Post-synthesis treatment: Applied after QD purification by dispersing or treating the synthesized QDs with a solution containing the phosphine oxide molecules. This method often targets surface defects that may have formed during purification [4] [20].

FAQ 3: What is a "bilateral interfacial passivation" strategy in device fabrication? This strategy involves passifying both the top and bottom interfaces of the perovskite QD emissive layer within the LED device stack. Evaporating a thin layer of organic molecules, such as phosphine oxides, at these interfaces before depositing the charge transport layers can drastically reduce interfacial defects. This improves charge carrier injection and balance, leading to enhanced external quantum efficiency (EQE) and operational stability of the quantum dot light-emitting diodes (QLEDs) [8].

FAQ 4: What common issues cause a drop in PLQY after purifying QDs? The purification process, which uses polar solvents to remove excess precursors and ligands, often accidentally strips the native surface ligands (like oleic acid and oleylamine). This leads to surface defects, such as uncoordinated Pb²⁺ and halide vacancies, which act as non-radiative recombination centers and reduce the PLQY [20]. Post-treatment passivation with strongly-binding ligands like phosphine oxides is designed to heal these defects.

FAQ 5: How does the molecular structure of a phosphine oxide ligand influence its passivation efficiency? The passivation efficiency is highly dependent on the molecular design. Key factors include:

- Number of Binding Sites: Multi-dentate molecules with multiple P=O or other coordinating groups (e.g., -OCH₃) can bind to multiple surface sites simultaneously, creating a stronger anchor.

- Lattice Matching: The spatial distance between the binding groups in the ligand should match the lattice spacing of the perovskite crystal to enable effective multi-site anchoring without introducing strain. For example, a spacing of 6.5 Å between oxygen atoms has been shown to be ideal [1].

- Nucleophilicity: The electron-donating ability of the functional groups influences the strength of the interaction with the Pb²⁺ ions [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) in Synthesized QDs

A low PLQY indicates a high density of defects that cause non-radiative recombination.

| Probable Cause | Recommended Action | Underlying Principle & References |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient surface passivation during synthesis. | Introduce phosphine oxide ligands (e.g., TPPO, TMeOPPO-p) into the precursor solution or reaction flask. | The P=O group coordinates with under-coordinated Pb²⁺, eliminating trap states and enhancing radiative recombination [4] [8]. |

| High defect density from ligand loss during purification. | Implement a post-treatment step: re-disperse purified QDs in a solution containing the phosphine oxide ligand. | Post-treatment heals surface defects created when native ligands detach during washing with polar solvents [20]. |

| Poor ligand design with a single, non-lattice-matched binding site. | Use lattice-matched, multi-site anchoring molecules like TMeOPPO-p. | Multi-site anchors with spacing that matches the perovskite lattice (e.g., 6.5 Å) provide stronger binding and more complete passivation compared to single-site ligands [1]. |

Issue: Poor Stability and Rapid Degradation of QDs or Devices

Rapid degradation can be environmental (oxygen, moisture) or operational (under electric field/light).

| Probable Cause | Recommended Action | Underlying Principle & References |

|---|---|---|

| Weak ligand binding leading to detachment and defect regeneration. | Replace common ligands (OA/OAm) with strongly-coordinating phosphine oxides. | The high bond order (0.2) of P=O with Pb is stronger than that of carboxylate or amine groups, preventing ligand loss and blocking ion migration channels [8]. |

| Ion migration under an electric field in the device. | Apply a bilateral interfacial passivation layer in the QLED stack. | Passivating both interfaces of the QD layer with evaporated TSPO1 suppresses ion migration and protects the QDs from the charge transport layers, enhancing operational lifetime by 20-fold [8]. |

| Susceptibility to environmental factors (O₂, H₂O). | Combine phosphine oxide passivation with encapsulation using polymers (PMMA) or inorganic layers. | Encapsulation creates a physical barrier against moisture and oxygen, while surface passivation improves intrinsic stability [21] [20]. |

Issue: Inefficient Charge Injection and Transport in QLEDs

This manifests as high operating voltage, low efficiency, and severe efficiency roll-off.

| Probable Cause | Recommended Action | Underlying Principle & References |

|---|---|---|

| Insulating long-chain ligands creating barriers. | Use short-chain or conjugated phosphine oxide ligands to improve inter-dot charge transport. | Shorter ligands reduce the inter-particle distance, facilitating charge hopping between QDs [20]. |

| Defects at the QD/charge transport layer interface. | Employ the bilateral passivation strategy with molecules like TSPO1. | Passivating the interfaces reduces charge trapping, leading to more balanced carrier injection and higher efficiency (e.g., EQE increase from 7.7% to 18.7%) [8]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange with Phosphine Oxide Molecules

This protocol describes how to treat already-synthesized and purified CsPbX₃ QDs to improve their PLQY and stability by incorporating phosphine oxide ligands.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Purified CsPbX₃ QDs | The starting material, typically in a non-polar solvent like hexane or toluene. |

| Phosphine Oxide Ligand (e.g., TMeOPPO-p, TSPO1) | The passivating agent that will replace native ligands to heal surface defects. |

| Anhydrous Ethyl Acetate | A polar solvent used for the ligand exchange and washing steps. |

| n-Hexane, Toluene | Non-polar solvents for dispersion and precipitation. |

| Centrifuge | Essential for precipitating and collecting QDs after reactions. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Preparation: Dissolve the purified CsPbX₃ QDs in a minimum amount of anhydrous toluene to create a concentrated solution. Prepare a separate solution of the phosphine oxide ligand (e.g., TMeOPPO-p) in ethyl acetate at a concentration of 5 mg/mL [1].

- Ligand Exchange: Under an inert atmosphere (e.g., in a nitrogen glovebox), add the phosphine oxide solution dropwise to the QD solution under vigorous stirring. A typical volume ratio is 1:1, but this may be optimized. Continue stirring for 10-30 minutes to allow the ligand exchange to occur.

- Precipitation: Add an excess of n-hexane to the mixture to precipitate the surface-modified QDs. Centrifuge the solution (e.g., at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes) to form a pellet.

- Washing: Carefully decant the supernatant. Re-disperse the QD pellet in a small amount of ethyl acetate and centrifuge again to remove any unbound ligands and reaction by-products. This washing step may be repeated.

- Final Dispersion: Finally, disperse the purified QDs in an appropriate anhydrous solvent (e.g., toluene, octane) for film fabrication. The PLQY of the resulting QD solution should be measured to confirm improvement [1].

Protocol: Bilateral Interfacial Passivation in QLED Device Fabrication

This protocol is for integrating a phosphine oxide passivation layer at both interfaces of the QD emissive layer during device stacking.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| TSPO1 (or similar molecule) | The evaporable phosphine oxide passivator for interfacial defect suppression. |

| Pre-fabricated QD Layer | The spin-coated film of perovskite QDs on the substrate/HTL. |

| Thermal Evaporator | Equipment used to deposit the TSPO1 layer and subsequent metal electrodes. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with a cleaned substrate patterned with a bottom electrode (e.g., ITO).

- Deposit Hole Transport Layer (HTL): Spin-coat the HTL (e.g., PEDOT:PSS, TFB) onto the substrate and anneal as required.

- First (Bottom) Passivation: Load the substrate into a thermal evaporation chamber. Evaporate a thin layer (e.g., 1-5 nm) of TSPO1 directly onto the HTL under high vacuum [8].

- QD Layer Deposition: Transfer the substrate back to a glovebox. Spin-coat the perovskite QD ink directly onto the TSPO1/HTL surface to form the emissive layer.

- Second (Top) Passivation: Return the substrate with the QD layer to the thermal evaporator. Evaporate another thin layer of TSPO1 directly on top of the QD film [8].

- Complete Device Stack: Without breaking vacuum, continue to deposit the Electron Transport Layer (ETL, e.g., TPBi) and the top metal electrode (e.g., Al) to complete the QLED device.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Perovskite QDs Treated with Different Phosphine Oxide Ligands

This table summarizes the impact of various phosphine oxide ligands on the optical properties of perovskite QDs, demonstrating the importance of molecular design.

| Ligand Molecule | Key Structural Feature | Reported PLQY | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid / Oleylamine (Reference) | Common ligands, bent chain | ~59% | Baseline performance with high defect density. | [1] |

| TPPO | Single P=O binding site | ~70% | Improvement, but single-site binding offers limited passivation. | [1] |

| TMeOPPO-p | Multi-site, lattice-matched (6.5 Å spacing) | ~97% | Precise lattice matching enables near-unity PLQY by eliminating trap states. | [1] |

| TSPO1 (in device) | Used as bilateral interfacial layer | Film PLQY: 79% (from 43%) | Passivates defects at the QD/charge layer interface, boosting device EQE to 18.7%. | [8] |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Bilateral Interfacial Passivation Workflow

Bilateral Passivation in QLED Stack

Diagram 2: Phosphine Oxide Ligand Binding Mechanism

Ligand Binding Mechanism Comparison

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Failures and Solutions

Problem: Inconsistent Device Performance After Passivation

- Symptoms: Large variations in efficiency (PCE) or open-circuit voltage (Voc) across devices from the same batch.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High performance variation | Incomplete or uneven ligand exchange on QD surface. | - Ensure sufficient reaction time and agitation during passivation.- Verify solvent purity and eliminate moisture contamination.- Characterize surface chemistry via FT-IR or XPS to confirm ligand binding. |

| Low Voc and FF | Inadequate passivation at the charge transport layer interface, leading to increased non-radiative recombination. | - Optimize the concentration and deposition method of the interfacial passivation layer.- Ensure the passivation material's energy levels align with the QD and transport layers. |

| Rapid performance decay under operation | Residual ionic defects facilitating migration under bias. | - Implement bilateral passivation to address both top and bottom interfaces.- Conduct ISOS-L and ISOS-V stability tests to identify specific degradation stressors [22] [23]. |

Problem: Poor Film Quality During Passivation Layer Deposition

- Symptoms: Film non-uniformity, pinholes, or dewetting.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Film non-uniformity | Incorrect solvent choice that damages the underlying QD film. | - Screen orthogonal solvents that do not dissolve the QD layer.- Utilize slower spin-coating speeds or spray-coating techniques. |

| Pinholes | Contamination or particulate matter on the substrate or QD film. | - Perform all fabrication steps in a cleanroom environment (ISO Class 1000 or better).- Filter all solutions immediately before deposition. |

| Dewetting | Poor surface energy matching between the QD film and the passivation layer. | - Employ a thin surface treatment (e.g., UV-Ozone, plasma) to modify surface energy prior to deposition.- Introduce an adhesion-promoting agent into the passivation solution. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is bilateral passivation specifically critical for suppressing ion migration in perovskite QLEDs? Ion migration primarily occurs through grain boundaries and along interfaces between the perovskite quantum dot (QD) film and the charge transport layers. Passivating only one surface leaves a pathway for ions to migrate from the unprotected interface. Bilateral passivation creates a "sandwich" structure that blocks ion migration channels from both sides, thereby significantly enhancing operational stability [23].

Q2: My device efficiency drops after applying the passivation layer. What is the most likely reason? This is often due to incorrect energy level alignment. The passivation material, while effective at defect suppression, may create an energy barrier that impedes charge carrier injection into the QD emissive layer. To resolve this:

- Characterize the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) levels of your passivation material.

- Select a passivation material whose energy levels provide a "staircase" alignment between the charge transport layers and the QDs, facilitating smooth charge transport.

Q3: How can I quantitatively compare the stability improvement offered by my bilateral passivation strategy? Adhere to standardized ISOS protocols for stability testing to ensure your results are comparable with the literature [22] [23]. Key protocols include:

- ISOS-L-1I: Light soaking under inert atmosphere to isolate intrinsic photostability.

- ISOS-V-2: Electrical bias stress in the dark at elevated temperature (e.g., 65°C or 85°C) to specifically accelerate ion migration.

- Report the T80 lifetime (time for efficiency to drop to 80% of initial) under these conditions. For a robust strategy, T80 should be significantly improved compared to a non-passivated control device.

Q4: Which characterization techniques are most effective for confirming successful passivation? A combination of techniques is required to probe both electronic and ionic effects:

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: Confirms the chemical binding of phosphine oxide ligands to the QD surface.

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Quantifies the reduction in surface defect states (e.g., unpassivated Pb atoms).

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL): Measures the increase in carrier lifetime, indicating suppressed non-radiative recombination.

- Thermally Stimulated Current (TSC) Spectroscopy: Directly probes and quantifies the density of ion-migration-related trap states.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standardized Stability Assessment Protocol (Based on ISOS Guidelines)

This protocol provides a framework for assessing the operational stability of your passivated perovskite QLEDs, focusing on suppressing ion migration [22] [23].

- Objective: To evaluate the long-term operational stability of bilateral-passivated perovskite QLEDs under maximum power point (MPP) tracking.

- Protocol Selection: ISOS-L-1I (Light Soaking, Inert Atmosphere).

- Materials:

- Encapsulated perovskite QLED devices (with bilateral passivation and control devices).

- MPP tracking system (e.g., Fluxim LITOS Lite or equivalent) [22].

- Solar simulator or calibrated LED array providing AM 1.5G, 1000 W/m² illumination.

- Environmental chamber or glovebox for maintaining inert (N₂) atmosphere.

- Temperature control stage.

- Procedure:

- Initial Characterization: Place the encapsulated device in the test chamber under inert atmosphere. Measure the initial current-voltage (J-V) characteristic curve to determine the starting PCE, Voc, short-circuit current (Jsc), and fill factor (FF).

- Stress Condition Setup: Set the temperature to 65°C. Illuminate the device continuously at 1 sun equivalent intensity (1000 W/m²).

- MPP Tracking: Operate the device at its maximum power point (MPP), with the tracking system continuously adjusting the bias to maintain maximum power output.

- Periodic Monitoring: The system should periodically (e.g., every hour) record the key performance parameters (PCE, Voc, Jsc, FF) and the applied bias voltage.

- Duration: Continue the test until the device efficiency drops to 80% of its initial value (T80) or for a minimum of 1000 hours.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the normalized PCE versus time to determine the T80 lifetime.

- Compare the T80 of your bilateral-passivated device against a control device.