Perovskite vs. CdSe Quantum Dots: A Comparative Analysis of Surface Electronics for Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) and Cadmium Selenide (CdSe) QDs, with a focused examination of their surface electronics and its direct impact on performance...

Perovskite vs. CdSe Quantum Dots: A Comparative Analysis of Surface Electronics for Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) and Cadmium Selenide (CdSe) QDs, with a focused examination of their surface electronics and its direct impact on performance in biomedical environments. We explore the foundational chemical and electronic properties of each QD type, detail synthesis methodologies and their influence on surface states, and address critical challenges in stability and toxicity. A thorough comparative analysis equips researchers and drug development professionals with the insights needed to select and optimize QD materials for targeted drug delivery, bioimaging, biosensing, and other clinical applications, highlighting future directions for this rapidly evolving field.

Unraveling Core Structures and Surface Electronic Properties

Fundamental Crystal Structures and Composition

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) exhibit an ABX₃ crystal structure, where A is a monovalent cation (e.g., Cs⁺, CH₃NH₃⁺ (MA⁺), or CH(NH₂)₂⁺ (FA⁺)), B is a divalent metal cation (typically Pb²⁺), and X is a halide anion (Cl⁻, Br⁻, or I⁻). The structure consists of corner-sharing [BX₆]⁴⁻ octahedra with A-site cations occupying the cavities between them [1]. This ionic crystal lattice is characterized by low formation energy and high defect tolerance, meaning many defects do not create deep-level traps that quench luminescence [1].

CdSe Quantum Dots typically crystallize in either zincblende (cubic) or wurtzite (hexagonal) structures [2]. In core-shell structures like CdSe@CdS, the shell grows epitaxially on the core due to the small lattice mismatch (3.9%), often resulting in a coherent interface that is challenging to distinguish at the atomic level [2]. Unlike perovskites, CdSe QDs are more covalent and susceptible to performance-degrading deep-level trap states unless properly passivated with a shell [1].

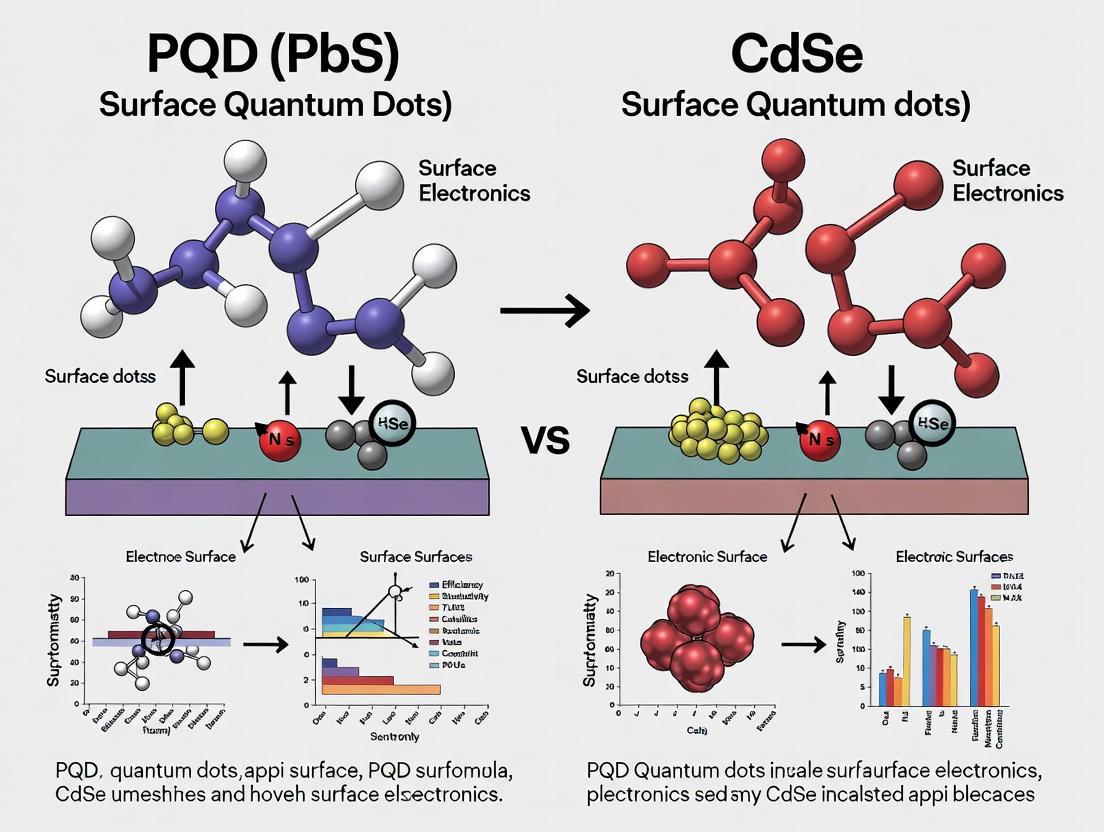

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental structural differences between these two types of quantum dots.

Comparative Optical Properties and Performance Data

Table 1: Comparative Optical Properties of PQDs and CdSe-based QDs

| Property | Perovskite QDs (PQDs) | CdSe-based QDs | Experimental Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | >90% without passivation [1] | >95% with optimized core/shell structure [3] | Relative method using integrating sphere & calibrated standards |

| Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) | <20 nm [1] | 21-25 nm [3] | Fluorescence spectroscopy with spectral correction |

| Color Gamut (NTSC Standard) | ~140% [1] | ~104% [1] | CIE chromaticity coordinates calculation from emission spectra |

| Emission Wavelength Tuning | Halide composition (Cl, Br, I) [4] | Core size & alloying (e.g., CdZnSe) [3] | Absorption & photoluminescence spectroscopy |

| External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) in LEDs | 23.5% (Red), 24.94% (Green), 15% (Blue) [4] | >25% over wide voltage range (1.8-3.0 V) [3] | Integrating sphere measurement in calibrated LED setup |

Table 2: Structural Stability and Device Performance Comparison

| Characteristic | Perovskite QDs (PQDs) | CdSe-based QDs | Testing Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Stability | Low; degrades under moisture, heat, UV [4] | High; robust core/shell structure [3] | Accelerated aging at 85°C/85% RH with PL monitoring |

| Ligand Binding | Weak (OA, OAm easily detached) [4] | Strong; various ligand options [3] [2] | TGA analysis and NMR spectroscopy |

| Operational Lifetime (T₉₅ at 1000 cd/m²) | Limited; significant challenge [1] | 72,968 hours [3] | Constant current driving with luminance tracking |

| Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | 18.3% (solar cells) [5] | 27.3% (LEDs) [3] | IV measurement under standard AM1.G illumination |

| Bohr Exciton Radius | CsPbBr₃: 7 nm; CsPbI₃: 12 nm [6] | CdSe: 5.6 nm [6] | Analysis of quantum confinement effects via absorption spectra |

Synthesis Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The synthesis routes for these quantum dots differ significantly, reflecting their distinct chemical natures. The workflow below outlines the primary methods for each QD type.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Hot-Injection Synthesis for CdSe/CdS Core-Shell QDs [2]

- Preparation: Synthesize CdSe core QDs (4 nm diameter) using standard hot-injection with Cd-oleate and Se precursors.

- Shell Growth: Use the Successive Ionic Layer Adsorption and Reaction (SILAR) method for precise shell thickness control.

- Precursor Injection: Add Cd and S precursors alternately at 240°C for epitaxial shell growth (3-12 monolayers).

- Characterization: Analyze final QDs (≈19.6 nm) via TEM, HAADF-STEM, and XRD to confirm core-shell structure and coherent interface.

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) for PQDs [4]

- Precursor Solution: Dissolve CsX and PbX₂ (X=Cl, Br, I) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) ligands.

- Reprecipitation: Rapidly inject precursor solution into vigorously stirring toluene (poor solvent).

- Purification: Centrifuge precipitated PQDs and redisperse in organic solvent.

- Ligand Exchange (Optional): Post-treat with short-chain ligands (e.g., 2-aminoethanethiol) for enhanced stability.

Stability Enhancement Strategies

Table 3: Approaches to Improve Quantum Dot Stability

| Strategy | Application to PQDs | Application to CdSe-based QDs |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Engineering | Exchange OA/OAm with short, bidentate ligands (e.g., AET) [4] | Use diverse ligands to control surface chemistry & packing [3] |

| Core-Shell Structure | Limited due to ionic lattice; polymer or oxide coating used [4] | Epitaxial shell (ZnS, ZnSe) for effective passivation [2] |

| Crosslinking | Crosslinkable ligands via light/heat to prevent dissociation [4] | Not typically required due to stable covalent bonds |

| Doping/Metal Ion Addition | Doping at A- or B-sites to strengthen lattice [4] | Alloying (e.g., CdZnSe) to flatten energy landscape [3] |

| Matrix Encapsulation | Incorporation into inorganic oxides or stable polymers [7] | Embedded in glass or polymer matrices for commercial displays [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for QD Synthesis and Processing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in QD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Cadmium oleate, Lead halides (PbBr₂, PbI₂), Cesium carbonate | Provide metal cations (Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cs⁺) for QD core formation |

| Anion Precursors | Selenium (Se) powder, Sulfur (S) in ODE, Trimethylsilyl halides | Source of chalcogenide or halide anions for crystal lattice |

| Surface Ligands | Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm), 2-Aminoethanethiol (AET) | Control growth during synthesis; passivate surface defects post-synthesis |

| Solvents | 1-Octadecene (ODE), Toluene, Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Medium for synthesis (ODE) and reprecipitation (Toluene) |

| Antisolvents | Methyl Acetate, Butanol, Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Purify QDs by removing excess ligands & byproducts [5] |

Inherent Surface Defect Tolerance vs. Surface Defect Susceptibility

The surface properties of quantum dots (QDs) fundamentally dictate their performance and applicability in advanced technologies. Inherent surface defect tolerance refers to a material's ability to maintain excellent electronic and optical properties despite the presence of surface imperfections or dangling bonds. In contrast, surface defect susceptibility describes materials whose functionality rapidly degrades due to surface defects, which act as traps for charge carriers and quench luminescence. Understanding this dichotomy is crucial for developing next-generation optoelectronic devices, as surface defects are inevitable in nanoscale materials due to their high surface-to-volume ratio.

For perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly lead-halide perovskites, this defect tolerance originates from their unique electronic structure. The optoelectronic properties of PQDs are governed by the band edges primarily composed of Pb s and p orbitals, with the valence band maximum from Pb 6p and halogen p orbitals, and conduction band minimum from Pb 6p orbitals [8]. This specific electronic configuration means that common surface defects typically form within the band gap, having minimal impact on non-radiative recombination. Conversely, CdSe QDs exhibit high surface defect susceptibility because their surface states create deep trap levels within the band gap that efficiently capture charge carriers and promote non-radiative recombination, significantly diminishing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and device performance [9].

Fundamental Mechanisms: Electronic Structure and Defect Dynamics

Electronic Origins of Defect Tolerance in PQDs

The defect tolerance in PQDs stems from their bonding characteristics and electronic structure. Research indicates that the Pb s and p orbitals contribute significantly to both valence and conduction bands, creating a symmetric electronic distribution that pushes defect states outside the band edges [8]. Furthermore, the high dielectric constant of perovskite materials provides effective screening of charge carriers, reducing their capture by defect states. This fundamental property enables PQDs to maintain high PLQY even without sophisticated surface passivation strategies.

The Goldschmidt tolerance factor (TF) provides crucial insights into the structural stability of perovskite materials. For stable 3D perovskite structures, the TF typically falls between 0.8 and 1.0, with CsPbI3 having a TF value of 0.89 [8]. This appropriate TF value contributes to the structural stability of PQDs, albeit with remaining challenges in environmental stability against moisture, heat, and light.

Defect Susceptibility Mechanisms in CdSe QDs

CdSe QDs lack the electronic structure that confers defect tolerance. Their surface defects, particularly selenium vacancies and cadmium dangling bonds, create deep trap states within the band gap that act as efficient centers for non-radiative recombination [9]. Raman spectroscopic studies reveal that surface defects are particularly prominent in smaller CdSe QDs (~2.5 nm), while larger QDs (>4.5 nm) show better crystallinity with lower surface defects [9]. This size-dependent defect profile directly impacts optical properties and device performance.

The lattice strain in CdSe QDs further exacerbates their defect susceptibility. XRD analyses demonstrate significant lattice contraction in smaller CdSe QDs, with lattice parameter contraction of approximately 0.44% for 2.5nm QDs compared to 0.10% for 5.2nm QDs [9]. This compressive strain, arising from surface reconstruction during growth, creates additional surface states that trap charge carriers.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties Governing Defect Behavior in PQDs vs. CdSe QDs

| Property | Perovskite QDs (PQDs) | CdSe QDs |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure | Pb s and p orbitals dominate band edges | Cd d and Se p orbitals form band edges |

| Defect State Energy | Typically shallow or outside band gap | Deep trap states within band gap |

| Dielectric Constant | Relatively high (~6-10) | Moderate (~5-6) |

| Lattice Strain | Low formation energy, dynamic structure | Significant compressive strain in small QDs |

| Primary Defect Types | Halide vacancies, organic cation disorder | Se vacancies, Cd dangling bonds |

Experimental Comparison: Methodologies and Quantitative Data

Thermal Stability Assessment

The thermal degradation pathways of PQDs with different A-site compositions were systematically investigated through in situ XRD and TGA measurements under argon flow from 30°C to 500°C [10]. For Cs-rich PQDs (CsPbI3), thermal degradation begins with a phase transition from black γ-phase to yellow δ-phase around 150°C, followed by complete decomposition to PbI2 at higher temperatures. In contrast, FA-rich PQDs (FAPbI3) directly decompose into PbI2 without phase transition, beginning at approximately 150°C [10].

The ligand binding energy plays a crucial role in thermal stability. DFT calculations reveal that FA-rich PQDs with higher ligand binding energy demonstrate slightly better thermal stability than all-inorganic CsPbI3 PQDs, despite the organic-inorganic hybrid composition [10]. This counterintuitive result highlights the importance of surface chemistry in stabilizing PQDs against thermal degradation.

Defect Characterization Techniques

Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) measurements provide critical insights into charge carrier dynamics and defect-mediated recombination. For CdSe QDs, TRPL reveals significantly shortened PL lifetimes when deposited on ITO substrates (approximately 75% of QDs become negatively charged due to direct contact with ITO), leading to accelerated non-radiative Auger processes [11]. This charging effect results in a redshift of ~19 meV in emission energy compared to neutral QDs [11].

Raman spectroscopy offers detailed information about structural defects and phonon interactions in QDs. Studies show that FA-rich PQDs possess stronger electron-longitudinal optical (LO) phonon coupling compared to Cs-rich QDs, suggesting that photogenerated excitons in FA-rich QDs have higher probability of dissociation by phonon scattering [10]. For CdSe QDs, the dominant asymmetric Raman mode between 204-208 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the first-order longitudinal optical phonon (LO1), with its overtone (LO2) observed at ~408 cm⁻¹ [9]. The asymmetric broadening of the LO1 mode requires inclusion of surface optical (SO) phonon modes for adequate fitting, indicating significant surface disorder [9].

Table 2: Experimental Stability Metrics for PQDs vs. CdSe QDs

| Stability Parameter | Perovskite QDs (PQDs) | CdSe QDs |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Degradation Onset | 150°C (Cs-rich, phase transition); 150°C (FA-rich, direct decomposition) [10] | >200°C (size-dependent) |

| PLQY Range | Extremely high (~100% achievable) [8] | Moderate to high (up to ~80% with optimal passivation) |

| PL Lifetime | FA-rich: Longer; Cs-rich: Shorter [10] | Significantly shortened on conductive substrates [11] |

| Charging Effect | Less pronounced | Severe on ITO substrates (75% QDs charged) [11] |

| LO Phonon Coupling | Stronger in FA-rich PQDs [10] | Moderate, dominated by surface optical phonons [9] |

Stability Enhancement Strategies

PQD Stability Improvement Methods

Multiple approaches have been developed to enhance PQD stability against environmental factors:

Ligand Engineering: Strategic modification of surface ligands using long-chain organic molecules like oleic acid and oleylamine improves surface coverage and binding affinity [8] [10]. DFT calculations confirm that stronger ligand binding correlates directly with enhanced thermal stability [10].

Inorganic Shell Coating: Encapsulating PQDs with stable inorganic materials such as oxides or metal fluorides creates a physical barrier against moisture and oxygen penetration while maintaining optoelectronic properties [8].

Ion Doping: Incorporation of specific metal ions (e.g., Mn²⁺, Zn²⁺) into the perovskite lattice enhances structural stability without compromising optical properties [8].

Polymer Matrix Encapsulation: Embedding PQDs in polymer matrices (PMMA, polystyrene) provides mechanical stability and protection from environmental stressors [8].

CdSe QD Defect Passivation Techniques

Ligand Exchange Processes: Replacing long-chain native surfactants with shorter conductive ligands like 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) or atomic S²⁻ ligands reduces interdot distance and improves charge transport while providing limited surface passivation [9].

Core/Shell Structures: Growing epitaxial shells of wider bandgap semiconductors (e.g., ZnS, CdS) on CdSe cores effectively confines charge carriers to the core and reduces surface state accessibility [12] [9].

Size Optimization: Controlling QD size during synthesis, as larger CdSe QDs (>4.5nm) naturally exhibit fewer surface defects and lower lattice strain compared to smaller counterparts (~2.5nm) [9].

Performance in Optoelectronic Devices

Solar Cell Applications

In photovoltaic devices, the defect tolerance of PQDs translates to higher open-circuit voltages (VOC) and reduced voltage deficits compared to CdSe QDs. PQD solar cells have achieved remarkable power conversion efficiencies exceeding 16% through the formation of highly orientated PQD solids that promote charge-carrier transport and diminish trap-assisted non-radiative recombination [13].

For CdSe QDSSCs, performance is fundamentally limited by surface defect-mediated recombination. The highest reported efficiency for CdSe-based QDSSCs using TiO₂ photoanodes and I⁻/I₃⁻ liquid electrolyte reaches only 2.74%, despite optimization of QD size and photoanode structure [9]. Composite photoanodes utilizing TiO₂ nanosheets with high (001)-exposed facets have been shown to enhance performance in CdS/CdSe QDSSCs, achieving 4.42% efficiency—a 54% improvement over conventional nanoparticle-based photoanodes [12].

Light Emission Applications

The defect tolerance of PQDs enables exceptionally high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY) approaching 100% without complex core/shell structures [8]. This makes PQDs particularly suitable for light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and displays. Mixed A-site CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃ PQDs have demonstrated external quantum efficiencies (EQE) surpassing 20% for both red and green LEDs [10].

CdSe QDs require elaborate core/shell structures and sophisticated surface passivation to achieve high PLQY values comparable to PQDs. Furthermore, CdSe QDs exhibit severe performance degradation when integrated with conductive substrates like ITO, where approximately 75% of QDs become negatively charged, leading to quenching of amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) and lasing capabilities [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for QD Surface Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand for PQDs; controls growth and provides steric stabilization [10] [14] | Standard ligand in hot-injection synthesis of PQDs |

| Oleylamine (OLA) | Co-ligand for PQDs; enhances solubility and affects crystal faceting [10] [14] | Used in combination with OA for balanced surface coverage |

| Titanium Butoxide (Ti(OBu)₄) | Precursor for TiO₂ nanostructures with high (001)-exposed facets [12] | Preparation of optimized photoanodes for QDSSC studies |

| 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | Short-chain ligand for CdSe QDs; enables charge transport in devices [9] | Ligand exchange to link CdSe QDs to metal oxide surfaces |

| CdCl₂ / Na₂SeSO₃ | Precursors for CdSe QD growth via SILAR and CBD methods [12] [9] | In situ deposition of CdSe QDs on photoanodes |

| Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) | Transparent conductive substrate for device integration [11] | Studying QD-substrate interactions in optoelectronic devices |

| Octadecene (ODE) | Non-polar solvent for high-temperature QD synthesis [14] | Common reaction medium for both PQD and CdSe QD synthesis |

The fundamental difference in surface defect tolerance between PQDs and CdSe QDs has profound implications for their research and development trajectories. PQDs' inherent defect tolerance enables simpler fabrication processes and outstanding performance in optoelectronic devices, though challenges remain in environmental stability. CdSe QDs require more complex engineering to mitigate their inherent defect susceptibility but benefit from more established synthesis protocols and superior material stability.

Future research directions include developing machine learning approaches to optimize PQD synthesis parameters and properties prediction [14], designing multifunctional ligands that enhance stability without compromising charge transport, and creating advanced composite structures that leverage the advantages of both material systems. Understanding the fundamental contrast between inherent defect tolerance and defect susceptibility continues to drive innovation in quantum dot research and applications across optoelectronics, sensing, and energy technologies.

Electronic Band Structures and Charge Carrier Dynamics

Quantum dots (QDs) are semiconductor nanocrystals whose electronic properties are dominated by quantum confinement effects due to their nanoscale dimensions, typically ranging from 2-10 nanometers [15]. This confinement results in discrete energy levels and size-tunable bandgaps that fundamentally govern their charge carrier dynamics and optoelectronic performance [16] [17]. The electronic band structure of QDs determines critical processes including excitation, energy relaxation, and charge transfer, which are paramount for applications ranging from light-emitting diodes and displays to photodetectors and quantum dot-based non-volatile memory devices [18] [15].

This review provides a comprehensive comparison between perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and traditional cadmium selenide (CdSe) QDs, focusing on their fundamental electronic structures, charge carrier dynamics, and experimental characterization. By examining their distinct photophysical behaviors through standardized experimental frameworks, we aim to establish structure-property relationships that guide material selection for specific electronic and optoelectronic applications.

Fundamental Electronic Band Structures

CdSe Quantum Dot Band Architecture

CdSe QDs exhibit a Type-I core/shell band alignment when encapsulated in wider bandgap materials such as CdS. Detailed spectroscopic studies combining optical and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) have determined the conduction band offset between CdSe and CdS to be approximately 0.15-0.30 eV [17]. This modest offset facilitates partial electron delocalization while maintaining confinement of both electrons and holes within the core region, balancing oscillator strength with environmental stability.

The excited-state dynamics of CdSe QDs reveal complex relaxation pathways. As illustrated in Figure 1, upon photoexcitation, carriers initially populate high-energy states before relaxing to the band edge through a multi-step process. Time-resolved spectroscopic measurements at 77 K have quantified the relaxation from the |e5⟩ state (2S1/2(h) - 1S(e)) at 19700 cm⁻¹ to occur with a 100 femtosecond time constant for initial relaxation, followed by band-edge state rise within 700 femtoseconds [16]. This rapid thermalization is governed by electron-phonon coupling and defect-mediated trapping processes.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Excited States in CdSe Quantum Dots

| State Designation | Electronic Transition | Energy (cm⁻¹) | Energy (eV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| e1⟩ | 1S₃/₂(h) – 1S(e) | 16,200 | 2.01 | |

| e2⟩ | 2S₃/₂(h) – 1S(e) | 16,900 | 2.10 | |

| e3⟩ | 1S₁/₂(h) – 1S(e) | 17,800 | 2.21 | |

| e4⟩ | 1P₃/₂(h) – 1P(e) | 18,300 | 2.27 | |

| e5⟩ | 2S₁/₂(h) – 1S(e) | 19,700 | 2.44 |

Perovskite Quantum Dot Band Structure

Perovskite QDs, particularly lead-halide variants (CsPbX₃, where X = Cl, Br, I), possess a distinctly different electronic structure characterized by defect-tolerant electronic bands originating from the antibonding coupling between Pb-6s and X-np orbitals [19]. This unique bonding arrangement results in electronic transitions that are relatively insensitive to surface defects, enabling high photoluminescence quantum yields (50-90%) even without elaborate passivation schemes [19].

The bandgap tunability in PQDs spans the entire visible spectrum (1.8-3.1 eV) through both quantum confinement effects and facile halide exchange, offering broader compositional flexibility compared to CdSe-based materials. Lead-free perovskite variants (e.g., Cs₃Bi₂X₉, CsSnX₃) demonstrate similar band structure advantages while addressing toxicity concerns, though often with somewhat compromised optoelectronic performance [19].

Experimental Methodologies for Charge Dynamics Analysis

Two-Color Two-Dimensional Electronic Spectroscopy (2DES)

Protocol Objective: To resolve many-body interactions and energy transfer pathways in quantum dots with high temporal and spectral resolution.

Detailed Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute QD solutions in appropriate solvents (e.g., toluene for CdSe QDs) to optical densities of 0.2-0.3 at the first excitonic absorption peak. For low-temperature measurements (77 K), load samples into cryostats with optical windows [16].

- Laser System Configuration: Employ a femtosecond laser system split into three pump pulses and one probe pulse. For two-color measurements, tune the first two pulses to resonate with high-energy states (18,800-21,300 cm⁻¹) and the third probe pulse with lower-energy states (15,200-18,800 cm⁻¹) [16].

- Data Acquisition: Scan coherence time (τ) and population time (T) while recording the heterodyne-detected signal as a function of detection time (t). Measure rephasing and non-rephasing signals separately to construct the 2D spectrum [16].

- Data Analysis: Identify diagonal peaks (representing individual excited states) and cross-peaks (indicating energy transfer between states) through Fourier transformation. Analyze peak evolution during population time to extract relaxation dynamics.

Key Parameters: Pulse durations <50 fs, spectral resolution <100 cm⁻¹, temporal resolution <20 fs, temperature control ±1 K.

Time-Resolved Electroluminescence for QD-LED Dynamics

Protocol Objective: To characterize charge injection and recombination dynamics in operational quantum dot light-emitting diodes.

Detailed Procedure:

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate QD-LEDs with structure ITO/PEDOT:PSS/PVK/QDs/TPBi/LiF/Al. Spin-coat functional layers under nitrogen atmosphere. For QD layer deposition, utilize solution processing with concentration optimization for uniform films [18].

- Pulse Generation: Apply square pulse voltages with varying frequencies (1 Hz-1 MHz) and duty cycles (10-90%) using a pulse generator. Ensure fast rise/fall times (<100 ns) to resolve transient effects [18].

- Emission Detection: Collect electroluminescence signals through a microscope objective coupled to a high-speed photodetector (response time <1 ns) connected to a digital oscilloscope. For spectral resolution, incorporate a monochromator or bandpass filters [18].

- Data Interpretation: Analyze emission rise/fall times, overshoot phenomena, and intensity stabilization periods. Model dynamics using specialized charge transport simulations accounting for carrier injection balance and Auger recombination effects [18].

Key Parameters: Voltage range 2-10 V, temporal resolution <1 ns, spectral range 400-800 nm, controlled atmosphere (O₂, H₂O <1 ppm).

Comparative Analysis of Charge Carrier Dynamics

Excited-State Relaxation Pathways

The relaxation dynamics of photoexcited carriers differ significantly between CdSe and perovskite QDs due to their distinct electronic structures and electron-phonon coupling strengths.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Charge Carrier Dynamics

| Parameter | CdSe QDs | Perovskite QDs |

|---|---|---|

| Hot Carrier Relaxation | 100-700 fs [16] | <100 fs [19] |

| Radiative Recombination | 10-30 ns | 1-20 ns [19] |

| Non-Radiative Recombination | Highly sensitive to surface traps | Suppressed due to defect tolerance [19] |

| Auger Recombination | Significant in charged QDs | Enhanced due to soft lattice [18] |

| Charge Injection in Devices | Can be unbalanced due to energy misalignment [18] | More balanced but susceptible to ionic migration [18] |

| PL Quantum Yield | 50-90% (requires sophisticated shells) | 50-90% (achievable with simple synthesis) [19] |

In CdSe QDs, excited-state absorption signals rise with a time constant of 700 fs, corresponding to electrons arriving at the conduction-band edge [16]. The relaxation pathway involves discrete transitions through quantized states (Table 1), with potential trapping at surface states that can reduce photoluminescence efficiency. In contrast, perovskite QDs exhibit exceptionally fast hot-carrier cooling (<100 fs) due to strong carrier-phonon interactions and a degeneracy of band-edge states that facilitates rapid thermalization [19].

Charge Transport in Functional Devices

In QD-LEDs, both material systems exhibit emission response anomalies including intensity drops and spikes during pulsed operation, though the underlying mechanisms differ. For CdSe QDs, these phenomena primarily result from charge injection imbalance caused by energy band misalignment between transport layers and the QDs themselves [18]. This imbalance leads to space-charge accumulation that quenches luminescence through non-radiative pathways.

Perovskite QD-based devices demonstrate different challenges related to their ionic character and labile surface ligands. While they typically achieve more balanced charge injection, their dynamic emission response is influenced by field-induced ion migration that redistributes potential within the device during operation [18]. This effect contributes to the emission overshoot and stabilization behaviors observed in transient electroluminescence measurements.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for QD Electronic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cadmium Precursors | CdSe QD synthesis | Cadmium oxide (CdO), Cadmium acetate (Cd(Ac)₂) [16] [17] |

| Selenium Precursors | CdSe QD synthesis | Trioctylphosphine selenide (TOP-Se), Selenium powder [16] [17] |

| Perovskite Cation Sources | PQD synthesis | Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃), Cs-oleate, Methylammonium bromide (MABr) [19] [14] |

| Halide Sources | PQD composition tuning | Lead bromide (PbBr₂), Lead chloride (PbCl₂), Ammonium halides [19] [14] |

| Surface Ligands | Size control & passivation | Oleic acid (OA), Oleylamine (OLA), Octadecene (ODE) [19] [14] [20] |

| Solvents | Synthesis medium | 1-Octadecene (ODE), Toluene, Hexane [14] |

| Charge Transport Materials | Device fabrication | PEDOT:PSS, PVK, TPBi, LiF [18] |

| Spectroscopy Standards | Instrument calibration | Fluorophores with known lifetimes, NIST-traceable standards |

Implications for Electronic Applications

Display Technologies

The charge carrier dynamics directly impact key performance parameters in display applications. CdSe QDs benefit from their established core/shell architectures (e.g., CdSe/ZnS) that provide excellent stability and charge confinement, making them suitable for demanding display environments [21]. However, their charge injection limitations require careful device engineering to balance electron and hole fluxes [18].

Perovskite QDs offer superior color purity with narrow emission linewidths (12-40 nm FWHM) and high photoluminescence quantum yields that enhance display color gamut [19] [20]. Their more balanced charge injection simplifies device architecture but necessitates additional stabilization strategies to counter environmental degradation [19].

Memory Devices

Quantum dot-based non-volatile memories leverage the discrete charge storage capability of QDs, with performance dictated by their band structure and interface properties. CdSe QDs have demonstrated endurance of approximately 10⁵ cycles in resistive memory applications, with retention times exceeding 10 years in optimized devices [15]. The well-defined surface chemistry of CdSe facilitates integration with various dielectric materials.

Perovskite QDs present opportunities for photoactive memory elements that can be optically programmed and electrically read, exploiting their strong light-matter interactions [15]. However, their ionic mobility presents challenges for retention that require innovative encapsulation approaches [19].

The electronic band structures and charge carrier dynamics of CdSe and perovskite quantum dots reveal complementary strengths for different electronic applications. CdSe QDs offer precisely characterized excited states and established passivation approaches that make them suitable for applications requiring long-term stability and predictable performance. Their well-understood relaxation pathways (100-700 fs) and controllable charge trapping provide a solid foundation for memory and display technologies.

Perovskite QDs excel through their defect-tolerant band structure and rapid thermalization (<100 fs), enabling high performance with simpler processing. Their balanced charge injection and superior color purity make them particularly attractive for display applications, though challenges regarding environmental stability and lead content require continued research attention.

Future developments in both material systems will likely focus on hybrid approaches that combine the advantageous properties of each, while computational methods like machine learning are increasingly employed to predict optimal synthesis parameters and device architectures for specific electronic applications [14]. The continued refinement of time-resolved spectroscopic methods will further elucidate the fundamental charge carrier dynamics that govern performance in advanced electronic devices.

Quantum dots (QDs) are semiconducting nanocrystals whose small size (typically 1-10 nm) confers unique optical properties due to quantum confinement effects [22] [23]. Among these properties, Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) and color purity are critically important for evaluating performance in optoelectronic applications. PLQY measures the efficiency of photon conversion, calculated as the ratio of emitted to absorbed photons. Color purity, often indicated by a narrow Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of the emission peak, enables vibrant, saturated colors [22] [24] [19].

This guide objectively compares these key properties between two leading QD types: Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) and traditional Cadmium Selenide (CdSe) QDs. The analysis is framed within surface electronics research, highlighting how material composition and surface engineering dictate performance in devices like displays, lighting, and sensors [25] [24].

Property Comparison: PQDs vs. CdSe QDs

The table below summarizes the core optical properties and characteristics of PQDs and CdSe-based QDs.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Optical Properties between PQDs and CdSe QDs

| Property | Perovskite QDs (PQDs) | CdSe-Based QDs |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Chemical Formula | APbX₃ (A=Cs⁺, MA⁺, FA⁺; X=Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) [19] [23] | CdSe (core), often with shell (e.g., CdS) [26] |

| Bandgap Tunability | Via quantum size effect & halogen composition [22] [19] | Primarily via quantum size effect [24] |

| PLQY Range | Up to ~90% (CsPbBr₃ in glass) [27]; ~79% (MAPbBr₃ in MOF) [28]; Up to 100% reported in some studies [22] | Up to 85-100% for core/shell (colloidal) [24]; ~60% in fluorophosphate glass [29] |

| PLQY (Typical Surface/Device) | High defect tolerance enables high "as-synthesized" PLQY [22] | Often requires shelling/advanced ligands for high PLQY [24] [30] |

| Emission FWHM | Very narrow; 12-40 nm [19], e.g., 24 nm (CsPbBr₃) [27] | Generally narrow; can be broader than PQDs [24] |

| Color Purity | Excellent due to narrow FWHM [22] [23] | Very good, a key display technology feature [23] |

| Defect Tolerance | High [22] [19] | Low; surface defects are major non-radiative recombination centers [29] [24] |

| Key Stability Issues | Susceptible to light, heat, moisture, oxygen (ionic lattice) [25] [28] | Good inherent chemical stability; protected by shell [26] |

| Common Stabilization Methods | Encapsulation in glass [27], MOFs [28], polymers [22] | Growth of inorganic shells (e.g., ZnS, CdS) [24] |

Experimental Data and Performance Benchmarks

The following table compiles quantitative data from recent experimental studies, providing a benchmark for the state-of-the-art in both QD technologies.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from Recent Studies

| QD Material & Structure | PLQY | FWHM | Key Experimental Condition / Host Matrix | Reported Application / Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ in Glass [27] | 88.15% | 24 nm | Borosilicate glass (modulated Si/B ratio) | Green emitter in WLED (CCT: 5863 K) |

| MAPbBr₃ in UIO-66 (MOF) [28] | 78.9% | - | Metal-Organic Framework (UIO-66) encapsulation | Green and white LEDs (stable operation for 2.5 hrs) |

| CdSe/CdS Core/Shell [26] | Nearly 100% | - | Colloidal suspension | Optical refrigeration studies |

| CdSe in Fluorophosphate Glass [29] | 60% (max) | - | Fluorophosphate glass matrix; 2.5 nm QDs size | Trap state emission study |

| Colloidal CdSe with Z* Ligands [30] | >55% | - | Amine-assisted ligand engineering in ambient air | Surface passivation study |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To contextualize the data in Table 2, this section outlines the standard and advanced methodologies used to fabricate and stabilize high-performance QDs.

Synthesis of High-PLQY CsPbBr₃ QDs in Glass Matrix

This melt-quenching method enhances PQD stability for practical applications [27].

- Glass Preparation: A borosilicate glass composition is designed, typically within the system 80((69-x) SiO₂-xB₂O₃-ZnO)-20(Cs₂CO₃-PbBr₂-NaBr), where the Si/B ratio (x) is modulated (e.g., 31-43 mol%).

- Melting and Quenching: The raw material mixture is ground thoroughly and melted in a muffle furnace at ~1150°C for 20 minutes. The molten glass is then rapidly poured onto a preheated (400°C) plate and pressed to form a plate.

- Thermal Annealing for QD Growth: The as-quenched glass is heat-treated at a temperature above its glass transition temperature (e.g., 450-500°C) for several hours. This step promotes the nucleation and growth of CsPbBr₃ QDs within the glass matrix.

- Characterization: The glass samples are ground and polished for optical measurements. PLQY is measured using an integrating sphere, and absorption/emission spectra are recorded to determine FWHM.

In-situ Growth of MAPbBr₃ QDs in a Metal-Organic Framework (MOF)

This protocol describes a composite approach to achieve high PLQY and stability for organic-inorganic PQDs [28].

- Synthesis of UIO-66 MOF: ZrCl₄, terephthalic acid (H₂BDC), and benzoic acid (modulator) are dissolved in DMF via ultrasonication and stirring. The mixture is transferred to an autoclave and heated at 120°C for 24 hours. The resulting white precipitate (UIO-66) is collected by centrifugation, washed with isopropanol (IPA), and dried. Critical Note: Drying at 160°C for 12 hours is recommended to completely remove residual DMF from the MOF pores, which is crucial for optimal optical performance.

- Lead Ion Loading: UIO-66 powder is dispersed in an aqueous solution of Pb(Ac)₂·3H₂O at varying concentrations and stirred at room temperature for 60 minutes. The resulting Pb-UIO-66 powder is collected, washed, and dried.

- Perovskite Formation: The Pb-UIO-66 powder is dispersed in an IPA solution of methylammonium bromide (MABr) and stirred at room temperature for 12 hours. The MABr diffuses into the MOF pores and reacts with the incorporated Pb²⁺ to form MAPbBr₃ QDs in-situ, yielding the final MAPbBr₃@UIO-66 composite.

- Characterization: The composite material exhibits bright green photoluminescence. Its PLQY and stability against moisture are significantly enhanced compared to unprotected PQDs.

Ligand Engineering for High-Efficiency CdSe QDs

This protocol focuses on surface chemistry to improve the PLQY of colloidal CdSe QDs without shell growth [30].

- Synthesis of CdSe Cores: CdSe QDs are synthesized via the hot-injection method, typically involving the rapid injection of a selenium precursor into a hot cadmium precursor solution in the presence of coordinating solvents and ligands.

- Z* Ligand Passivation: Instead of traditional ligand exchange, an amine-assisted approach is used. Alkylamines (e.g., oleylamine) are introduced, which combine with native Z-type ligands (cadmium carboxylate) on the QD surface to form a more effective passivating layer, termed "Z* ligands".

- Purification and Processing: The QDs are purified to remove excess reactants and byproducts. The Z* ligand treatment minimizes surface etching and significantly enhances the fluorescence of the as-synthesized QDs, enabling the synthesis of CdSe QDs with a PLQY >55% in ambient air conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key materials and their functions for research in high-performance QDs.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Quantum Dot Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in QD Research |

|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) / Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Precursors for inorganic CsPbBr₃ perovskite QDs [27]. |

| Methylammonium Bromide (MABr) | Organic cation source for hybrid organic-inorganic MAPbBr₃ QDs [28]. |

| Cadmium Oleate / Selenium (Se) Precursors | Common metal and chalcogenide sources for the synthesis of CdSe QD cores [24]. |

| Oleylamine / Oleic Acid | Common surface ligands (L-type and X-type) to control growth and provide initial surface passivation during colloidal synthesis [30] [19]. |

| Zirconium Chloride (ZrCl₄) / Terephthalic Acid | Metal cluster and organic linker precursors for constructing UIO-66 MOF host matrices [28]. |

| Zinc Oleate / Sulfur (S) Precursors | Precursors for growing wide-bandgap shells (e.g., ZnS) on CdSe cores to enhance PLQY and stability [24]. |

Research Workflow and Property Determinants

The diagram below illustrates the core research workflow and the critical factors influencing the key optical properties of PQDs and CdSe QDs.

Diagram 1: Research workflow for developing high-performance QDs, highlighting material-specific strategies.

The choice between Perovskite QDs and CdSe QDs involves a trade-off between intrinsic optical performance and stability. PQDs demonstrate a formidable combination of high native PLQY, exceptional color purity, and simpler bandgap tunability, making them a compelling candidate for future optoelectronics. However, their commercial translation is currently hindered by inherent instability under environmental stressors. CdSe-based QDs, particularly core/shell structures, offer robust stability and have already reached high performance levels, facilitating their current use in commercial displays. The ongoing research in surface electronics, focused on advanced encapsulation for PQDs and refined ligand engineering for CdSe QDs, is key to unlocking the full potential of both materials for next-generation applications.

The Role of Surface Ligands in Determining Electronic Properties

In quantum dot (QD) science, surface ligands are far more than passive stabilizing agents; they are fundamental determinants of electronic properties. These molecular capping agents directly influence charge carrier mobility, defect passivation, and environmental stability by mediating the complex interface between the nanoscale semiconductor core and its environment. The strategic selection and engineering of surface ligands enable precise control over the electronic landscape of both individual QDs and their assembled solid films. This comparative analysis examines how ligand chemistry distinctly shapes the electronic performance of two prominent QD families: lead sulfide (PbS) and cadmium selenide (CdSe) colloidal quantum dots (CQDs), and perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). Understanding these relationships is paramount for advancing optoelectronic devices, including solar cells, photodetectors, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

Ligand Functions and Electronic Property Modulation

Surface ligands govern electronic properties through several interconnected mechanisms, with notable differences observed across QD material systems.

Charge Transport in QD Solids: In films of PbS and CdSe CQDs, long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid) create significant potential barriers between dots, severely hindering inter-dot charge transport. Ligand exchange to shorter molecules (e.g., halides, metal chalcogenide complexes) reduces dot-to-dot spacing, dramatically increasing carrier mobility by facilitating stronger electronic coupling [31] [32]. For PQDs, the ligand exchange process is equally critical but often leads to a more pronounced trade-off, where improved transport is accompanied by a significant increase in non-radiative recombination and a drastic reduction in photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) from near 100% to below 0.1% in device-ready films [33].

Defect Passivation and Trap State Reduction: Under-coordinated surface atoms (e.g., Pb or Cd) act as electronic trap states, promoting non-radiative recombination. Ligands passivate these sites by donating electron density. The effectiveness is highly specific: in CdSe QDs, Z-type ligands (e.g., cadmium carboxylates) directly bind to surface Se atoms, with cadmium-based Z-type ligands proving most effective at restoring bright light emission [34]. For CsPbI3 PQDs, ligands like trioctylphosphine (TOP) and trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO) coordinate with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions, suppressing non-radiative recombination and boosting PLQY [35]. Computational studies on CdSe reveal that L-type ligands (e.g., amines, phosphines) binding directly to under-coordinated Cd sites can prevent their reduction, thereby enhancing stability in negatively charged QDs [36].

Electronic Structure and Doping: Surface ligands function as powerful dipolar layers, shifting the absolute energy positions of QD band edges. This effect allows for the tuning of ionization potential and electron affinity, which is critical for optimizing energy level alignment with charge transport layers in devices [31]. Furthermore, certain ligands can introduce intentional electronic doping. In CsPbI3 PQD films, the specific ligand chemistry used during solid-state exchange can lead to a high background free charge carrier concentration, orders of magnitude greater than in perovskite thin films, which influences the open-circuit voltage in solar cells [33].

Table 1: Primary Ligand Types and Their Electronic Functions

| Ligand Type | Binding Mechanism | Key Electronic Influences | Example Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Type (Lewis Base) | Electron pair donation to metal cations | Passivates metal-site traps; can increase PLQY | Amines, Phosphines (TOP, TOPO) [35] [36] |

| X-Type (Anionic) | Ionic bond exchange with surface anions | Modulates band energy levels; enables charge transport | Halides (I⁻, Br⁻, Cl⁻), carboxylates [31] [36] |

| Z-Type (Lewis Acid) | Electron pair acceptance from chalcogen anions | Passivates anion-site traps; restores luminescence | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺ complexes (e.g., Cd oleate) [34] |

Comparative Analysis: PbS/CdSe CQDs vs. Perovskite QDs

While all QDs share a reliance on surface chemistry, the nature and consequences of ligand interactions differ significantly between traditional chalcogenides and perovskites.

Stability and Defect Tolerance

- PbS/CdSe CQDs: These materials are generally more robust, with degradation often being a slower process. Their surfaces exhibit a wider range of thermodynamically stable ligand binding modes. The primary challenge is managing the trade-off between passivation and transport [32] [36].

- PQDs: Ionic crystal structures make them highly susceptible to degradation by polar solvents, moisture, and light. While they are often described as defect-tolerant, their surfaces are highly dynamic and reactive. Ligand binding is weaker, and ligand loss is a major pathway for degradation and trap formation. The stability of PQDs, such as CsPbI3, is highly dependent on rigorous surface passivation to inhibit structural phase transitions [35] [33].

Impact of Ligand Exchange on Optoelectronic Properties

- PbS/CdSe CQDs: The ligand exchange process typically causes a measurable but often manageable drop in PLQY. The primary goal is to replace long insulating ligands with shorter conductive ones while preserving as much of the initial passivation as possible [32].

- PQDs: The contrast is stark. As-synthesized PQDs in solution can have PLQYs of ~57%, and thin films with native ligands can maintain ~5.3%. However, the solid-state ligand exchange necessary for device fabrication catastrophically reduces the PLQY to ~0.02%, indicating a massive introduction of non-radiative recombination centers and highlighting the extreme sensitivity of PQD surfaces to processing conditions [33].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Ligand Effects on Different QD Systems

| Property | PbS/CdSe CQDs | Perovskite QDs (CsPbI3) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Initial PLQY | High (Up to ~50% or more) [32] | Very High (Up to ~100%) [33] |

| PLQY After Device Ligand Exchange | Moderately reduced | Catastrophically reduced (to <0.1%) [33] |

| Primary Stability Concern | Oxidation over time [36] | Rapid degradation from moisture, light, phase transition [35] |

| Impact of A-site Cation | Not applicable | Significant; FA⁺ reduces trap density by 40x vs. Cs⁺ [33] |

| Effect of Top Passivators | TOPO: 18% PL enhancement; L-PHE: Superior photostability (70% intensity after 20 days UV) [35] | Lead nitrate/MeOAc exchange enables transport but kills luminescence [33] |

Experimental Methodologies and Data

Reliable data on ligand-effects requires a suite of complementary characterization techniques.

Synthesis and Ligand Exchange Protocols

- PbS CQD Synthesis: A common method is the high-temperature heat injection, where a sulfur precursor (e.g., bis(trimethylsilyl) sulfide, TMS) is swiftly injected into a lead precursor (e.g., PbO) dissolved in a coordinating solvent (e.g., 1-octadecene) with oleic acid at 150°C. This yields monodisperse PbS CQDs [32].

- PQD (CsPbI3) Synthesis and Exchange: High-quality CsPbI3 PQDs are synthesized by precisely controlling temperature (~170°C), precursor injection volume, and reaction duration. Surface passivation employs ligands like TOP, TOPO, and L-phenylalanine (L-PHE) [35]. For solar cell fabrication, a critical solid-state ligand exchange is performed using a lead nitrate solution in methyl acetate (Pb(NO₃)₂/MeOAc) to replace long native ligands with shorter iodides and nitrates [33].

Key Characterization Techniques

- Photoluminescence Spectroscopy (PL): Measures emission intensity, quantum yield (PLQY), and lifetime. A drop in PLQY after ligand exchange directly quantifies the introduction of non-radiative defects [35] [33].

- Dynamic Nuclear Polarization NMR (DNP-NMR): Provides atomic-level insights into the local chemical environment of atoms (e.g., ¹¹³Cd) on the QD surface, revealing different ligand binding configurations and surface stoichiometry [37].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Computational modeling used to predict the energetics of ligand binding, charge localization, and the formation of surface defects upon charging, helping to explain experimental observations [36].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for QD ligand exchange and characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for QD Surface Ligand Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Long-chain L-type ligands for synthesis & initial stabilization | Standard surfactants for achieving monodisperse QDs during synthesis [35] [32] |

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) / TOPO | Strong L-type ligands for surface passivation | Passivating undercoordinated Pb²⁺ in PQDs; enhancing PL intensity [35] |

| Lead Nitrate (Pb(NO₃)₂) | Source of metal cations and halides for solid-state exchange | Replaces organic ligands with iodide on PQD surfaces for conductive films [33] |

| Halide Salts (e.g., Tetrabutylammonium Iodide) | X-type ligands for charge transport tuning | Replaces long carboxylates to reduce inter-dot spacing and boost mobility in CQD films [31] [32] |

| Metal Carboxylates (e.g., Cd oleate) | Z-type ligands for defect passivation | Binds to chalcogen sites on CdSe QDs to fix defects and improve luminescence [34] |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Polar, non-solvent for purification and exchange | Used as a washing solvent to remove excess ligands without redissolving QD film [33] |

| Deuterated Toluene / AMUPol Radical | Solvent and polarizing agent for DNP-NMR | Enables high-sensitivity NMR to probe ligand distribution and surface structure [37] |

The critical role of surface ligands in determining the electronic properties of quantum dots is an indisputable cornerstone of nanoscience. While significant progress has been made in understanding ligand chemistry for both CQDs and PQDs, the path forward requires a more nuanced, system-specific approach. For PbS and CdSe CQDs, future research will likely focus on developing multifunctional hybrid ligands that provide simultaneous excellent passivation and high charge transport, pushing device efficiencies closer to their theoretical limits. For PQDs, the most pressing challenge remains bridging the enormous gap between the superb luminescence of as-synthesized dots and the poor luminescence of device-ready films. This will necessitate innovative mild exchange processes and defect-healing strategies that minimize surface damage. Ultimately, the rational design of surface ligands, informed by advanced characterization and computational modeling, will be the key to unlocking the full potential of quantum dots in next-generation optoelectronic technologies.

Synthesis, Surface Engineering, and Biomedical Implementation

The synthesis of quantum dots (QDs) dictates their structural perfection, optical properties, and ultimate utility in devices ranging from light-emitting diodes to biological sensors. For cadmium selenide (CdSe) and metal halide perovskite (CsPbBr3) nanocrystals (NCs)—two of the most prominent QD families—the hot-injection (HI) and ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) methods represent two fundamentally different philosophical and technical approaches to nanocrystal formation [38]. The HI method is a high-temperature, organometallic approach pioneered for CdSe QDs, offering exceptional monodispersity and crystallinity. In contrast, LARP is a room-temperature, solution-based pathway that has gained prominence for its simplicity and efficacy in synthesizing perovskite NCs [39] [38]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two methods, framing the analysis within a broader research context that contrasts the surface electronics and defect physics of CdSe and perovskite QDs. We summarize quantitative experimental data, detail essential protocols, and visualize key concepts to equip researchers with the knowledge to select the optimal synthesis for their specific application.

Methodological Foundations & Experimental Protocols

Hot-Injection (HI) Synthesis

The HI method relies on the rapid injection of precursor compounds into a high-boiling-point coordinating solvent to induce a sudden supersaturation event, leading to the synchronous nucleation and growth of nanocrystals [40] [41].

- Typical Protocol for CdSe/CdS Core/Shell QDs [41]:

- Reaction Setup: The selenium (Se) precursor (e.g., trioctylphosphine selenide) is prepared separately. A flask containing the cadmium (Cd) precursor (e.g., cadmium oxide) and a mixture of coordinating solvents (e.g., 1-octadecene, oleic acid, and trioctylphosphine oxide) is heated to 240°C under inert gas.

- Nucleation: The Se precursor is swiftly injected into the hot Cd solution, causing an immediate color change. The high temperature (240-300°C) ensures rapid decomposition of precursors and the formation of CdSe cores.

- Growth & Shelling: The temperature is reduced to 250-280°C for growth. A shell of CdS can be epitaxially grown by the successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) method, involving the dropwise addition of cationic (Cd) and anionic (S) precursors.

- Purification: The synthesized CdSe/CdS core/shell QDs are purified by repeated precipitation using a non-solvent (e.g., N-butyl ether) and centrifugation to remove excess ligands and unreacted precursors.

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) Synthesis

LARP is a thermodynamically controlled synthesis performed at room temperature. It involves dissolving perovskite precursors in a polar solvent and then triggering crystallization by mixing with a non-polar antisolvent, with ligands present to control growth and stabilization [39] [42].

- Typical Protocol for CsPbBr3 NCs [39] [38]:

- Precursor Preparation: Cesium (Cs) and lead halide (PbBr2) salts are dissolved in a polar solvent like dimethylformamide (DMF), forming the precursor solution. Ligands, typically an acid-base pair like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), are added to this solution.

- Crystallization: The precursor solution is added dropwise to a vigorously stirring non-polar antisolvent, such as toluene. Upon mixing, the solubility of the precursors drops drastically, leading to supersaturation and the subsequent nucleation and growth of CsPbBr3 NCs.

- Purification & Stability: The NCs are purified by centrifugation to remove aggregates and excess ligands. The study highlights that long-chain ligands (e.g., OA/OAm) yield homogeneous and stable NCs, whereas short-chain ligands or excessive amine can lead to a transformation into non-perovskite structures with poor emission [39].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The following tables synthesize key experimental data and characteristics from the literature to facilitate a direct comparison of the two synthesis methods.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Synthesis Method Characteristics

| Parameter | Hot-Injection (HI) | Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Temperature | High (240–320 °C) [41] | Room Temperature [39] |

| Synthesis Philosophy | Kinetic control, high supersaturation | Thermodynamic control, solubility shift |

| Energy Consumption | High | Low |

| Required Infrastructure | Schlenk line, high-temperature heating, inert atmosphere | Standard lab glassware, ambient conditions |

| Scalability Potential | Moderate, limited by heat/mass transfer | High, amenable to large-volume processing [39] |

| Typical QD Systems | CdSe, CdS, InP, core/shell structures [41] | CsPbBr3, other metal halide perovskites [38] |

| Key Ligands | Trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO), Oleic Acid, Alkylamines [43] | Oleic Acid, Oleylamine, Octanoic acid, Octylamine [39] |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Resultant Quantum Dot Properties

| Property | Hot-Injection (HI) | Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) |

|---|---|---|

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | High (can exceed 80% for core/shell) [41] | Very High (can reach near-unity, >90%) [38] |

| Size Distribution (Monodispersity) | Excellent (narrow size distribution) | Good to Excellent, dependent on ligand control [39] |

| Crystallinity | Excellent, high-temperature annealing | Good, but may contain more surface disorder [38] |

| Sample Blinking | Suppressed with thick shells, but sensitive to surface traps [41] | Prevalent, with behavior linked to synthetic surface quenchers [38] |

| Surface Trap States | Effectively passivated by inorganic shells (e.g., CdS, ZnS) [41] | More prevalent; significant influence from ligand choice and stoichiometry [38] |

| Stability (Ambient) | Good for core/shell structures | Moderate to Poor; requires matrix encapsulation or ligand engineering [44] |

| Defect Tolerance | Low (requires careful surface passivation) | High (intrinsic property of perovskites) |

The Surface Electronics and Defect Physics Perspective

The fundamental difference in the nature of CdSe and perovskite QDs is most apparent in their surface and defect physics, which is a direct consequence of the synthesis environment.

- CdSe QDs (via HI): CdSe QDs are defect-intolerant; even minor surface defects act as non-radiative recombination centers, quenching PL and causing photoluminescence blinking [41]. The high-temperature HI process facilitates the growth of thick, crystalline inorganic shells (e.g., CdS, ZnS), which structurally passivate these surface traps. However, the surface remains a critical vulnerability. Studies show that direct contact with conductive substrates like ITO can lead to QD charging, where electrons transfer from the substrate to the QD, forming negative trions (T⁻) that accelerate non-radiative Auger recombination and quench light amplification [11].

- Perovskite QDs (via LARP): Metal halide perovskites like CsPbBr3 are renowned for their defect tolerance, where certain intrinsic defects form within the bandgap without creating deep trap states [38]. However, the room-temperature LARP synthesis results in a dynamic and complex surface dominated by organic ligands. The choice of ligands (e.g., acid-base pair, chain length) directly determines surface quenchers' density and energy levels, which govern photophysical phenomena like blinking behavior. NCs synthesized by HI and LARP can have identical crystal structures but exhibit drastically different blinking statistics due to distinct surface quenchers introduced during synthesis [38].

The diagrams below illustrate the distinct workflows and the critical surface-related phenomena associated with each synthesis method.

Diagram 1: The Hot-Injection (HI) synthesis workflow for CdSe QDs. The high-temperature process yields high-crystallinity QDs, often with protective shells. A key subsequent challenge is surface-related, including the need for effective trap passivation and the avoidance of QD charging when integrated into devices on conductive substrates like ITO [11] [41].

Diagram 2: The Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) synthesis workflow for CsPbBr3 nanocrystals. The room-temperature process is heavily governed by ligand chemistry. While the resulting NCs have a defect-tolerant bulk lattice, their optical stability at the single-particle level is critically determined by the nature of surface quenchers, which are a direct consequence of the synthesis parameters [39] [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and their functions in the synthesis of quantum dots via these two methods.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for HI and LARP Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Example Compounds | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Cadmium Oxide (CdO), Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃), Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Source of metallic cations (Cd²⁺, Cs⁺, Pb²⁺) for the inorganic crystal lattice. |

| Chalcogen/Halide Precursors | Trioctylphosphine Selenide (TOP-Se), Elemental Sulfur (S), Bromide Salts | Source of anionic components (Se²⁻, S²⁻, Br⁻) for the crystal lattice. |

| Coordinating Solvents | 1-Octadecene (ODE), Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | High-boiling-point solvent medium (ODE); Strong coordinating ligand and solvent for HI (TOPO). |

| Acid Ligands | Oleic Acid (OA), Octanoic Acid | Binds to surface metal atoms, controlling growth and providing colloidal stability. |

| Amine Ligands | Oleylamine (OAm), Octylamine | Interacts with the precursor/anion complex; affects surface termination and particle morphology. |

| Polar Solvents | Dimethylformamide (DMF), Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Dissolves perovskite precursor salts in the LARP method. |

| Non-Polar Antisolvents | Toluene, Chloroform | Triggers supersaturation and crystallization in the LARP method by reducing precursor solubility. |

The choice between Hot-Injection and Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation is not a matter of identifying a superior technique, but of selecting the right tool for the material system and application at hand. Hot-Injection is the established, robust route for high-quality CdSe and other II-VI QDs, offering unparalleled control over size, structure, and crystallinity, albeit with higher complexity and energy cost. Its primary challenge lies in meticulous surface passivation to mitigate charge trapping and Auger effects. Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation is a simpler, more accessible, and scalable method that has been instrumental in the rapid development of perovskite QDs, leveraging their intrinsic defect tolerance to achieve outstanding optical properties. Its main bottleneck is the control over surface ligand chemistry to ensure environmental stability and suppress dynamic disorder like blinking. For researchers, this comparison underscores that the synthesis pathway is inextricably linked to the core physical properties of the nanocrystals, especially their surface electronics, which must be carefully considered when integrating them into functional devices.

Surface Functionalization Strategies for Aqueous Stability and Biocompatibility

The integration of quantum dots (QDs) into biological and electronic applications represents a frontier in nanotechnology, offering unprecedented opportunities for imaging, sensing, and drug delivery. However, a fundamental challenge persists: as-synthesized QDs are typically incompatible with aqueous biological environments due to their hydrophobic surfaces stabilized by coordinating organic solvents [45] [46]. This incompatibility necessitates sophisticated surface functionalization strategies to bridge the gap between their exceptional innate properties and practical application requirements. The performance of functionalized QDs in biological milieus or electronic devices is not merely a function of their core composition but is predominantly dictated by their surface characteristics [47]. Consequently, surface engineering has emerged as a critical discipline within nanotechnology, determining the hydrodynamic size, colloidal stability, chemical reactivity, and ultimately, the biocompatibility and functionality of these nanoscale materials.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of surface functionalization strategies for two prominent quantum dot classes: cadmium selenide (CdSe) QDs, the well-established workhorses of the field, and emergent perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), noted for their superior optical properties [19]. We objectively analyze the performance of these functionalized QDs based on experimental data, focusing on their aqueous stability, biocompatibility, and performance in biological and electronic contexts. The discussion is framed within a broader thesis on performance comparison of PQD versus CdSe quantum dot surface electronics research, providing researchers with the necessary insights to select and optimize QD platforms for specific applications.

Comparative Analysis of Functionalization Strategies and Outcomes

Surface Functionalization Methodologies

The transition from hydrophobic to hydrophilic QDs can be achieved through several established methodologies, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Ligand Exchange: This method involves replacing native hydrophobic ligands with bifunctional hydrophilic molecules that coordinate with the QD surface via strong-binding groups (e.g., thiols, amines) while presenting hydrophilic groups (e.g., carboxylates, PEG) to the aqueous medium [45] [46]. A prominent example is the use of dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA) conjugated to poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) with terminal functional groups (biotin, carboxyl, amine). This approach creates a compact ligand shell, yielding QDs with hydrodynamic diameters only slightly larger than the core nanocrystal, which is beneficial for applications like FRET sensing [48]. These QDs demonstrate exceptional stability over extended periods and across a broad pH range [48].

Amphiphilic Coating: This strategy encapsulates the native hydrophobic QD within an amphiphilic polymer or lipid layer. The hydrophobic components of the coating intercalate with the native ligands, while hydrophilic segments face outward, conferring water solubility [46]. Although this method better preserves the original photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and provides a robust protective barrier, it significantly increases the hydrodynamic size of the QDs, which can hinder cellular uptake or affect signal transduction in FRET-based applications [46].

Biosynthesis: An emerging environmental-friendly alternative, biosynthesis utilizes biological organisms like E. coli to produce QDs extracellularly in aqueous media. This process results in QDs naturally capped with biomolecular layers (e.g., proteins), granting immediate water solubility, stability, and biocompatibility without requiring post-synthetic modifications [49]. Biosynthesized CdSe QDs exhibit good crystallinity, strong fluorescence emission, and have been successfully used for bio-imaging in yeast cells [49].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Surface Functionalization Strategies for Quantum Dots

| Functionalization Strategy | Mechanism | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Representative QD Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Exchange | Direct replacement of native ligands with hydrophilic analogs | Compact final size; Direct surface functionalization | Potential for reduced QY; Stability dependent on ligand binding strength | DHLA-PEG-functionalized QDs [48]; Thiolated ligands (MPA, MUA) [46] |

| Amphiphilic Coating | Encapsulation of hydrophobic QD-polymer/lipid shell | High stability; Better preservation of initial QY | Large hydrodynamic diameter; Complex multi-step process | Amphiphilic polymer-coated CdSe/ZnS QDs [46] |

| Biosynthesis | In-situ biological synthesis & capping with biomolecules | Innate biocompatibility; Aqueous process | Less control over size distribution; Lower yield | E. coli-mediated CdSe QDs [49] |

Performance Comparison: Aqueous Stability and Biocompatibility

The success of a functionalization strategy is ultimately measured by the performance of the QDs in real-world conditions, particularly their colloidal stability in physiological buffers and their interactions with biological systems.

Aqueous Stability: QDs functionalized with compact multifunctional ligands like DHLA-PEG demonstrate remarkable stability, maintaining solubility over extended periods and across a broad pH range [48]. This stability is crucial for applications in drug delivery and bio-sensing where environmental conditions can vary. In contrast, QDs capped with simple monodentate thiols (e.g., mercaptopropionic acid, MPA) often suffer from colloidal instability over time and at non-neutral pH due to the dynamic nature of the thiol-metal bond, leading to ligand desorption and QD aggregation [46]. The PEG component in advanced ligands provides a steric barrier that significantly reduces non-specific protein binding and opsonization, extending circulation time in vivo [45].

Cytotoxicity and Cellular Response: The surface charge and ligand structure are critical determinants of biocompatibility. A comprehensive analysis on primary human lung cells revealed that positively charged QDs are significantly more cytotoxic than their negative or neutral counterparts [47]. Furthermore, QDs functionalized with long ligands were found to be more cytotoxic than those with short ligands, with negative QDs showing size-dependent cytotoxicity [47]. The study concluded that the hierarchy of influence is charge > functionalization > size [47]. At a molecular level, different surface properties trigger distinct cellular pathways; relatively benign negative QDs can upregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines, while highly toxic positive QDs induce changes in genes associated with mitochondrial function [47].

Optical Performance Retention: A principal challenge in functionalization is retaining the high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of the native QDs. Ligand exchange processes can sometimes lead to a significant drop in QY due to surface trap formation if the new ligands do not effectively passivate all surface sites [46]. Amphiphilic coatings generally perform better in preserving the initial QY, as they disturb the original ligand shell less [46]. Notably, lead-based PQDs like CsPbX3 can achieve high PLQY (50-90%) but often require additional engineering for aqueous stability [19].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data of Functionalized Quantum Dots in Biological Contexts

| QD System & Functionalization | Hydrodynamic Size (nm) | Quantum Yield (%) | Cytotoxicity / Cellular Response | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdSe/ZnS with DHLA-PEG ligands [48] | Compact, size slightly larger than core | Maintained high QY after functionalization | Biocompatible; Enabled cellular internalization and imaging | Stable over extended time and broad pH range; Allowed EDC coupling and specific avidin-biotin binding. |

| CdSe QDs with varying surface charge [47] | Varied by design | Not specified | Positively charged QDs significantly more cytotoxic | Cytotoxicity mechanism was independent of ROS; Gene expression changes varied with surface charge. |

| Biosynthesized CdSe (E. coli) [49] | ~3.1 nm (core size) | Strong fluorescence emission at 494 nm | Biocompatible; Used for yeast cell imaging | Capped with surface protein layer; Good water solubility and stability; Simplified collection without cell disruption. |

| CdTe with Thiol Ligands (e.g., GSH) [46] | Tunable based on synthesis | Can be improved by post-synthesis treatments | Implied biocompatibility due to GSH | Glutathione (GSH) capping provides improved biocompatibility; QY depends on Cd:GSH ratio and pH. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Functionalization and Assessment

Protocol 1: Ligand Exchange with DHLA-PEG Conjugates

This protocol describes the cap exchange process to render hydrophobic QDs water-soluble using engineered DHLA-PEG ligands, based on the work of Susumu et al. [48].

Materials:

- Core QDs: CdSe/ZnS core-shell QDs synthesized via organometallic route, dissolved in toluene or hexane.

- Ligand Solution: DHLA-PEG conjugates (e.g., DHLA-PEG-COOH, DHLA-PEG-NH2, DHLA-PEG-biotin) dissolved in a compatible solvent like DMSO or water.

- Solvents: Anhydrous toluene, tetrahydrofuran (THF), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4).

- Purification Equipment: Centrifuge, ultrafiltration devices (e.g., Amicon filters).

Procedure:

- Transfer a known quantity (e.g., 1 µmol) of purified hydrophobic QDs to a vial and evaporate the organic solvent under a nitrogen stream.

- Redissolve the QD film in a minimal amount of anhydrous THF.

- Add a substantial molar excess (e.g., 10,000:1 ligand-to-QD ratio) of the DHLA-PEG ligand solution to the QD solution. Vigorously stir the mixture for several hours (or overnight) under an inert atmosphere to allow complete cap exchange.

- Slowly add PBS buffer (pH 7.4) to the mixture while stirring to induce the transfer of QDs into the aqueous phase.

- Remove any residual organic solvent and unbound ligands by repeated centrifugation and washing with PBS or using ultrafiltration.

- Filter the final aqueous QD solution through a 0.2 µm membrane filter and store at 4°C.

Validation Metrics: Successful functionalization is confirmed by stable dispersion in aqueous buffers, characterization of hydrodynamic size via Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), and measurement of PLQY using a fluorometer with a reference standard.

Protocol 2: Biosynthesis of CdSe QDs using E. coli

This protocol outlines an extracellular, green synthesis method for producing biocompatible CdSe QDs, as described in the study utilizing E. coli [49].

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: Escherichia coli (E. coli).

- Culture Media: Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and modified Czapek's (M9) medium.

- Precursor Solutions: Cadmium chloride hemipentahydrate (CdCl₂·2.5H₂O, 0.04 M) and sodium selenite (Na₂SeO₃, 0.02 M) in water.

- Additives: Mercaptosuccinic acid (MSA), sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate.

- Equipment: Rotary shaker, centrifuge, UV-Vis spectrophotometer, fluorometer.

Procedure:

- Culture E. coli aerobically in LB medium at 37°C overnight.

- Harvest the bacteria by centrifugation (4000 rpm, 15 min) and transfer to M9 medium. Continue incubation until the culture reaches an OD₆₀₀ of ~0.6.

- Centrifuge again to harvest this "second-generation" E. coli.

- Incubate the bacterial pellet in 100 ml of fresh M9 medium.

- Add the precursor solutions sequentially: 8 ml of CdCl₂, 800 mg of sodium citrate, 1.5 ml of Na₂SeO₃, and an optimized amount of MSA (e.g., 80 mg).

- Incubate the reaction mixture at 37°C on a rotary shaker (200 rpm) for the desired duration (e.g., 24-48 hours).

- Centrifuge the reaction solution at 4000 rpm to remove bacterial cells.

- Collect the supernatant and subject it to high-speed centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 30 min) to pellet the biosynthesized CdSe QDs.

- Wash the QD pellet with 50% ethanol by repeated centrifugation to remove residual chemicals.

Validation Metrics: Monitor QD growth using UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy. Characterize the QDs using photoluminescence spectroscopy, High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HR-TEM) for size and crystallinity, and FTIR spectroscopy to confirm the presence of the surface protein capping layer.

Schematic Workflow and Property Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway from QD synthesis to functionalization and the resulting property-performance relationships that determine biological applicability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials