Overcoming SCF Convergence Challenges in Transition Metal Complexes: A Computational Chemistry Guide for Drug Development

This comprehensive guide addresses the persistent challenge of Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence failures in quantum chemical calculations of transition metal complexes, a critical hurdle in computational drug discovery and materials...

Overcoming SCF Convergence Challenges in Transition Metal Complexes: A Computational Chemistry Guide for Drug Development

Abstract

This comprehensive guide addresses the persistent challenge of Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence failures in quantum chemical calculations of transition metal complexes, a critical hurdle in computational drug discovery and materials science. We explore the foundational causes rooted in electronic structure complexity, including near-degeneracies, open-shell configurations, and strong correlation effects. The article provides actionable methodological strategies, from initial guess selection and basis set choices to advanced convergence accelerators. We detail systematic troubleshooting protocols and optimization techniques for recalcitrant systems, followed by validation frameworks and comparative analyses of computational methods (DFT vs. Wavefunction). Tailored for researchers and computational chemists in pharmaceutical R&D, this guide synthesizes current best practices to enhance reliability and efficiency in modeling metalloenzymes, catalysts, and metal-based therapeutics.

Why Do Transition Metal Complexes Break SCF Solvers? Decoding Electronic Structure Challenges

In the computational modeling of transition metal complexes (TMCs) and lanthanide/actinide systems, achieving self-consistent field (SCF) convergence is a persistent and fundamental challenge. A primary root of this difficulty lies in the electronic structure of these systems, specifically the multi-reference character arising from near-degeneracies in partially filled d- and f-orbitals. Traditional single-reference methods, such as standard Density Functional Theory (DFT) or Hartree-Fock, assume a single dominant electronic configuration. This assumption breaks down when multiple electronic configurations are close in energy (near-degenerate), leading to poor SCF convergence, incorrect prediction of spin states, bond energies, reaction barriers, and spectroscopic properties. This whitepaper details the core problem, its quantitative impact, and advanced methodological protocols to address it.

Quantitative Analysis of Orbital Near-Degeneracies

The energy separation between d- or f-orbitals in a ligand field is central to the degree of multi-reference character. Small splitting leads to near-degeneracy.

Table 1: Typical d-Orbital Splitting Energies (Δ) in Common Ligand Fields

| Metal Ion | Geometry | Representative Complex | Ligand Field Splitting (Δ, cm⁻¹) | Key Consequence for SCF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti³⁺ (d¹) | Octahedral | [Ti(H₂O)₆]³⁺ | ~20,000 | Mild, typically manageable |

| Cr³⁺ (d³) | Octahedral | [Cr(NH₃)₆]³⁺ | ~21,600 | Stable, low multi-reference |

| Fe²⁺ (d⁶) | Octahedral, High-Spin | [Fe(H₂O)₆]²⁺ | ~10,000 | Near-degeneracy; strong multi-reference |

| Co³⁺ (d⁶) | Octahedral, Low-Spin | [Co(NH₃)₆]³⁺ | ~23,000 | Large Δ, but LS/HS competition possible |

| Ni²⁺ (d⁸) | Square Planar | [Ni(CN)₄]²⁻ | Very Large (~30,000+) | Large Δ, but open-shell singlet issues |

Table 2: Diagnostic Metrics for Multi-Reference Character

| Diagnostic Metric | Calculation Method | Single-Reference Threshold | Problematic Range for TMCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| T₁ Amplitude | CCSD(T) | T₁ < 0.02 | Often > 0.05 in TMCs |

| D₁ Diagnostic | CCSD | D₁ < 0.05 | 0.10 - 0.15+ |

| % Hartree-Fock in DFT | ωB97X, etc. | - | < 50% may indicate issues |

| Natural Orbital Occupancy | CASSCF | 2.0 / 0.0 (for closed-shell) | Occupancies far from 2 or 0 (e.g., 1.8, 0.2) |

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol: Diagnosing Multi-Reference Character with CASSCF

Objective: Quantify active space orbital occupancies to confirm near-degeneracy.

- Initial Geometry: Obtain structure from X-ray crystallography or optimize with a robust functional (e.g., B3LYP-D3/def2-SVP).

- Orbital Localization: Perform a preliminary ROHF/DFT calculation. Use intrinsic bond orbital (IBO) or Pipek-Mezey localization to identify metal d/f and ligand donor orbitals.

- Active Space Selection (Define CAS(n,m)):

- n (electrons): Include all valence d/f electrons (e.g., 6 for Fe(II)).

- m (orbitals): Include all metal d/f orbitals plus key ligand-based orbitals (e.g., σ-donor, π-acceptor). For [Fe(H₂O)₆]²⁺, start with CAS(6,5) (d-orbitals only).

- CASSCF Calculation: Perform state-averaged CASSCF over all spin states of interest. Use a basis set like cc-pVDZ or ANO-RCC for metals.

- Analysis: Inspect natural orbital occupancies. Occupancies deviating significantly from 2 or 0 (e.g., 1.7, 1.3, 0.4) confirm strong static correlation.

Protocol: Robust SCF Convergence for Problematic Systems

Objective: Achieve SCF convergence for a system with suspected strong multi-reference character.

- Initial Guess Strategy:

- Use

fragment=MOguess in software like ORCA orguess=fragmentin Gaussian. - Construct guess from superposition of atomic densities or pre-converged calculations on ligand and high-spin metal ion.

- Use

- SCF Stabilization:

- Algorithm: Use

SCF=XQCorDIIS=Noin initial cycles to avoid false convergence. - Damping: Apply severe damping (e.g., 70%) or Fermi-smearing (finite electronic temperature) in early cycles.

- Level Shifting: Employ level shifting (~0.3-0.5 Hartree) to virtual orbitals to depopulate unstable orbitals.

- Algorithm: Use

- Method Selection for Initial Convergence:

- Start with a pure GGA functional (e.g., BP86) and a modest basis set (def2-SVP).

- Use unrestricted formalism (UKS/UHF) and a high spin state as initial target.

- Convergence Refinement:

- Once converged, use the orbitals as a guess for a more advanced functional (e.g., hybrid like TPSSh, range-separated like ωB97X-D3).

- Systematically reduce damping/level shifting parameters.

Protocol: High-Accuracy Energy Calculation with DMRG-CASSCF/NEVPT2

Objective: Perform a numerically accurate calculation for a system with large active spaces (e.g., lanthanides).

- Preparation: Follow Protocol 3.1 to define a large active space (e.g., CAS(7,10) for Eu³⁺).

- DMRG-CASSCF Setup:

- Use an interface like

CheMPS2(in PySCF) orDMRG(in ORCA). - Set maximum bond dimension (M) initially to ~500, sweeping until energy convergence.

- Specify number of sweeps (typically 10-20).

- Use an interface like

- Correlation Treatment:

- Use the DMRG-CASSCF wavefunction as reference for N-electron valence perturbation theory (NEVPT2).

- Specify

ICMODE=4(strongly contracted) orICMODE=5(partially contracted) in ORCA for the NEVPT2 step.

- Basis Set: Employ correlating basis sets (e.g., ANO-RCC-VTZP for metals, VTZ for ligands).

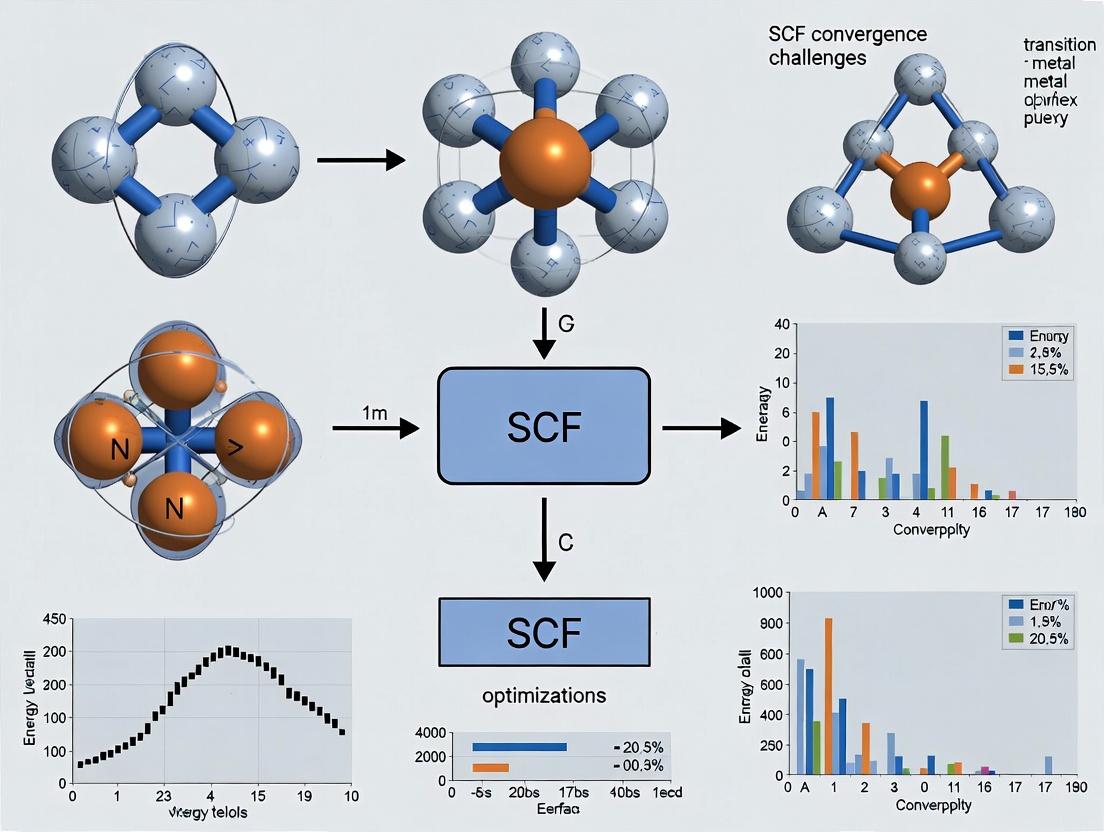

Visualizations

Title: SCF Convergence Decision Tree for TMCs

Title: CASSCF Diagnostic Protocol Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Multi-Reference Systems

| Tool / "Reagent" | Category | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| CASSCF | Wavefunction Method | Provides reference wavefunction for strongly correlated electrons by treating active space exactly. |

| DMRG Solver | Active Space Solver | Enables handling of very large active spaces (e.g., >16 orbitals) for lanthanides/clusters. |

| NEVPT2 / MRCI | Dynamic Correlation | Adds remaining electron correlation on top of CASSCF reference for accurate energies. |

| ωB97X-D3 / TPSSh | Density Functional | Robust hybrid functionals with improved stability for challenging open-shell systems. |

| def2-TZVP / ANO-RCC | Basis Set | Triple-zeta quality basis with polarization, essential for describing correlation effects. |

| Q-Chem / ORCA / PySCF | Software Suite | Packages with specialized algorithms for SCF stabilization and multi-reference methods. |

| IBO / Pipek-Mezey | Analysis Utility | Localizes orbitals to facilitate chemically intuitive active space selection. |

| Level Shifter / Damping | SCF Stabilizer | Numerical "stabilizing agents" to force convergence in problematic cycles. |

The study of open-shell systems, particularly transition metal complexes (TMCs), is a cornerstone of modern inorganic chemistry and catalysis, with direct implications for drug development in metalloenzyme targeting and MRI contrast agents. A central computational challenge in this field is achieving robust Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence. The presence of near-degenerate molecular orbitals leads to multiple accessible electronic states—primarily high-spin (HS), low-spin (LS), and broken symmetry (BS) solutions—each representing a local minimum on the potential energy surface. The selection of an inappropriate initial guess or convergence algorithm often traps the SCF procedure in an unphysical or undesired state, leading to erroneous predictions of geometry, magnetism, and reactivity. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these states, their physical significance, and methodological protocols for their controlled calculation and analysis, directly addressing the SCF convergence challenges prevalent in TMC research.

Fundamental Concepts: Spin States and Symmetry Breaking

High-Spin and Low-Spin States

In TMCs with partially filled d-shells, electron-electron repulsion (Hund's rule) favors parallel spin alignment (HS), while ligand field splitting (Δ) favors electron pairing in lower-energy orbitals (LS). The competition between these energies determines the ground state.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Properties for Idealized High-Spin and Low-Spin States

| Property | High-Spin (HS) State | Low-Spin (LS) State |

|---|---|---|

| Spin Alignment | Maximizes unpaired electrons | Minimizes unpaired electrons |

| Total Spin (S) | Larger | Smaller |

| Spin Multiplicity | 2S+1 (High) | 2S+1 (Low) |

| Magnetic Moment | Larger (≈√[n(n+2)] μB) | Smaller (often diamagnetic) |

| Ligand Field | Weak field (Δ < P) | Strong field (Δ > P) |

| Typical Geometry | Often longer metal-ligand bonds | Often shorter metal-ligand bonds |

| SCF Convergence | Often easier, more stable | Can be challenging if close in energy to HS |

The Broken Symmetry Approach

The Broken Symmetry (BS) state is a conceptual and computational construct used primarily within Density Functional Theory (DFT) to approximate the electronic structure of antiferromagnetically coupled systems (e.g., binuclear clusters). It is not a pure spin eigenstate but a mixture. It allows the α and β spin densities to localize on different magnetic centers with opposite spin alignment, providing a way to estimate the Heisenberg exchange coupling constant (J).

Methodological Protocols for State-Specific Calculations

Protocol A: Targeting Specific Spin States for SCF Convergence

Objective: Converge to a specific HS or LS solution for a mononuclear TMC.

- Initial Guess Construction:

- For HS: Use the Aufbau principle with maximum spin polarization. Employ an atomic guess with high-spin metal ion configuration.

- For LS: Use a restricted or restricted open-shell guess. Sometimes, converging the HS state first, then using its orbitals as a guess for the LS calculation, is effective.

- SCF Algorithm Selection:

- Use level shifting or direct inversion in the iterative subspace (DIIS) with damping for problematic cases.

- For difficult LS cases, consider fractional occupation or smearing techniques to initially bypass orbital degeneracy, followed by annealing to zero smearing.

- Stability Analysis: After convergence, perform a wavefunction stability check (e.g.,

STABLEin Gaussian). If unstable, follow the eigenvector of the unstable mode to relax to a more stable solution.

Protocol B: Computing the Broken Symmetry State and Exchange Coupling

Objective: Calculate the BS state and estimate the Heisenberg J for a dinuclear system.

- Reference HS Calculation: Calculate the pure high-spin state (e.g., S₁+S₂ for two metal centers A and B). This is usually straightforward. Record energy: Eₕₛ.

- BS State Setup: Construct an initial guess where α spin density is localized on center A and β spin density on center B (or vice-versa). This often requires modifying the initial density matrix or using fragment guesses.

- Convergence: Use a broken symmetry initial guess and SCF constraints. Severe convergence issues may require constraining orbital occupations initially and then relaxing.

- Energy Evaluation: Converge the BS solution and record its energy: E_BS.

- Calculate J: Using the Yamaguchi relation (preferred for DFT): J = (EBS − *E*ₕₛ) / [〈Ŝ²〉ₕₛ − 〈Ŝ²〉BS]. Calculate the expectation value of the total spin squared 〈Ŝ²〉 for both states.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Broken Symmetry & J Calculation

Quantitative Data and Case Study: Fe(II) Complex

Recent benchmark studies (2023-2024) highlight the dependence of spin-state energetics on functional choice and the critical role of stability analysis.

Table 2: Calculated Spin-State Energy Splittings (ΔE_HS-LS in kcal/mol) for [Fe(NCH)₆]²⁺

| DFT Functional | ΔE_HS-LS | Recommended For | SCF Convergence Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | +13.5 | Organic/Main Group | Stable HS/LS, BS needs care |

| PBE0 | +10.2 | General purpose | Good DIIS convergence |

| TPSS (meta-GGA) | +5.8 | Solid-state, materials | Sensitive to initial guess |

| r²SCAN (meta-GGA) | +7.1 | Modern benchmark | Robust with damping |

| M06-L | +3.5 | Transition metals | Can have multiple solutions |

| TPSSh | +8.0 | Spin-state energetics | Reliable for BS states |

| Experimental Ref. | ~8-12 | - | - |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Open-Shell TMC Research

| Item / Software | Function in Research | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Suite (Gaussian, ORCA, NWChem) | Performs electronic structure calculations (DFT, CASSCF). | SCF optimization, energy calculation, property prediction. |

| Visualization Software (VMD, Chimera, GaussView) | Model building and analysis of spin density, orbitals. | Visualizing α/β spin density separation in BS states. |

Stability Analysis Tool (Internal/ e.g., STABLE) |

Checks if SCF solution is a true minimum. | Diagnosing failed convergence and finding lower-energy states. |

| Fractional Occupation/ Smearing Algorithm | Occupies near-degenerate orbitals fractionally. | Aiding initial SCF convergence in difficult LS or metallic systems. |

| Effective Core Potentials (ECPs) | Replaces core electrons with a potential. | Modeling heavier transition metals (e.g., Ru, Pt) efficiently. |

| Solvation Model (e.g., SMD, COSMO) | Implicitly models solvent effects. | Providing realistic energetics for drug-relevant complexes. |

| Magnetic Property Calculator | Computes magnetic susceptibility, J-coupling. | Connecting computed states to experimental NMR/EPR data. |

Diagram 2: SCF Problem-Solving Decision Tree

Mastering the intricacies of high-spin, low-spin, and broken symmetry states is non-negotiable for accurate computational research on open-shell transition metal complexes. This understanding directly informs strategies to overcome persistent SCF convergence challenges. By employing systematic protocols—careful initial guess selection, algorithmic damping, and mandatory stability analysis—researchers can reliably converge to the intended physical state. This rigor is essential for generating predictive insights into the electronic structure, magnetic properties, and reactivity of TMCs, thereby accelerating rational design in catalysis and pharmaceutical development.

This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence challenges in transition metal complexes, explores the critical role of charge transfer and metal-ligand covalency in SCF convergence instability. Accurate electronic structure calculation for drug-relevant transition metal complexes (e.g., catalysts, metalloenzyme mimics) is often hampered by persistent SCF convergence failures. These failures frequently originate from the intricate balance between metal-centered and ligand-centered orbitals, where significant electron delocalization (covalency) and low-lying charge-transfer states create a flat energy landscape that challenges iterative diagonalization algorithms.

Theoretical Background and Convergence Challenges

The SCF Cycle and Instability Points

The SCF procedure seeks a converged set of molecular orbitals (MOs) by iteratively solving the Roothaan-Hall equations, F C = S C ε. In transition metal complexes, the Fock matrix (F) is highly sensitive to the initial guess due to:

- Near-degeneracies: Close-lying metal d-orbitals and ligand donor orbitals.

- Strong orbital mixing: Significant covalent interaction leads to heavily hybridized MOs.

- Charge transfer character: Low-energy excitations involving metal-to-ligand (MLCT) or ligand-to-metal (LMCT) charge transfer.

These factors can cause oscillatory behavior between different electron configurations, preventing convergence.

Quantifying Covalency and Its Impact

Metal-ligand covalency is not merely a bonding descriptor; it directly dictates the hardness of the SCF convergence problem. High covalency leads to:

- Diffuse orbital character: Reduces overlap differences, flattening the energy functional.

- Configuration mixing: Increases multi-reference character, challenging single-reference methods.

- Small HOMO-LUMO gaps: In charge-transfer states, this shrinks the gap, a known source of divergence.

Table 1: Correlation Between Covalency Metrics and SCF Convergence Difficulty

| Covalency Metric | Low Covalency (Ionic) | High Covalency | Direct Impact on SCF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mulliken Metal d-Population | >8.5 e⁻ | <7.8 e⁻ | Larger density shifts per iteration |

| Löwdin Bond Order | <0.3 | >0.6 | Stronger off-diagonal Fock matrix elements |

| Charge Transfer Energy (Δ_CT) | >4.0 eV | <1.5 eV | Near-degeneracy induces oscillation |

| Overlap Population (Metal-Ligand) | <0.1 | >0.25 | Increased initial guess sensitivity |

Experimental and Computational Protocols for Diagnosis

Protocol: Diagnosing Charge-Transfer Instability

Objective: Identify if convergence failure is due to low-lying charge-transfer states. Methodology:

- Initial Calculation: Perform a single-point energy calculation at a low level of theory (e.g., RHF/LANL2DZ) with a stable convergence algorithm (e.g., Quadratic Convergence, Direct Inversion of the Iterative Subspace (DIIS) with damping).

- Orbital Analysis: Inspect the virtual orbitals. Look for low-lying (< 3.0 eV above HOMO) orbitals with significant simultaneous amplitude on the metal center and ligand set (MLCT or LMCT character).

- Excited State Probe: Run a Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculation on the converged low-level structure for the first 10-20 excited states. A high density of charge-transfer states within 2 eV of the ground state is a strong indicator of potential SCF instability at higher theory levels.

- Verification: Use the stable=opt keyword (in Gaussian) or similar "stable" calculation to test if the purported ground state is a true minimum on the wavefunction stability surface.

Protocol: Quantifying Metal-Ligand Covalency

Objective: Obtain quantitative metrics to correlate with observed SCF behavior. Methodology:

- Calculation: Run a single-point calculation with a method/basis set appropriate for property analysis (e.g., B3LYP/def2-TZVP with an effective core potential for the metal). Ensure use of an integration grid of at least "Fine" quality (e.g., 75 radial, 302 angular pruned points).

- Population Analysis: Perform both Mulliken and Löwdin population analyses. Record the electron population on the metal d orbitals.

- Density of States (DOS) / Crystal Orbital Overlap Population (COOP): Generate a projected DOS (pDOS) plot. Integrate the metal d and key ligand orbital contributions across the bonding region. The overlap population (from a COOP analysis) provides a direct measure of covalency.

- Energy Decomposition Analysis (EDA): For a more rigorous breakdown, perform an EDA (e.g., using the ADF package) to separate the interaction energy into Pauli repulsion, electrostatic attraction, and orbital mixing (covalent) components.

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

Title: SCF Convergence Instability Diagnostic Flow

Title: Metal-Ligand Covalency Leading to SCF Instability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Reagents for SCF Stability Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Purpose | Example Source / Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Stable=Opt Keyword | Performs a wavefunction stability analysis to verify if the SCF solution is a true minimum or a saddle point. Critical for diagnosing false convergence. | Gaussian, ORCA (Stable keyword) |

| DIIS with Damping | A modified DIIS algorithm that mixes the new Fock matrix with the previous one (damping factor ~0.5). Suppresses oscillatory divergence. | Gaussian (SCF=Damping), PySCF |

| Level Shifting | Artificially increases the energy of virtual orbitals during SCF cycles to prevent occupancy swapping and enforce Aufbau principle. | Gaussian (SCF=VShift), Q-Chem |

| Quadratic Convergence (QC) | Alternative to DIIS; uses second-order methods (Newton-Raphson) to find the energy minimum. More robust but memory intensive. | Gaussian (SCF=QC), TURBOMOLE |

| Broken-Symmetry Initial Guess | For open-shell systems, starting from an asymmetric electron distribution can help converge to a stable, symmetric solution. | User-defined guess in most quantum chemistry packages. |

| Effective Core Potentials (ECPs) | Replaces core electrons with a pseudopotential, reducing the number of basis functions and mitigating linear dependence issues. | Stuttgart/Dresden ECPs, LANL2DZ basis set. |

| Enhanced Integration Grids | Using a denser numerical grid for integrating exchange-correlation functionals improves accuracy and can aid convergence in difficult cases. | Gaussian (Int=UltraFineGrid), "Grid 5" in ORCA. |

| Density Fitting (RI) Approximations | Resolution of the Identity techniques accelerate integral calculation and can improve convergence behavior by reducing numerical noise. | RIJCOSX in ORCA, DensityFit in PySCF. |

The Role of Strong Electron Correlation in SCF Divergence

Within the critical research challenge of achieving Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence in transition metal complexes (TMCs), the issue of divergence remains a significant bottleneck. These systems, ubiquitous in catalysis, biomimetic chemistry, and drug development (e.g., metalloenzyme inhibitors, platinum-based anticancer agents), are plagued by strong electron correlation effects. This technical guide examines how the multi-configurational character, driven by near-degenerate d- or f-orbitals, fundamentally destabilizes the standard SCF iterative procedure, leading to divergence and unreliable electronic structure predictions.

Theoretical Foundations: Correlation and SCF Instability

The Hartree-Fock (HF) method assumes a single Slater determinant, an approximation that fails for strongly correlated systems. In TMCs, electron correlation is partitioned into:

- Dynamic Correlation: Short-range electron-electron repulsion.

- Static (Strong) Correlation: Arises from near-degeneracies where multiple electronic configurations contribute significantly to the ground state. This is quantified by a large weight of secondary determinants in a Complete Active Space Configuration Interaction (CAS-CI) expansion.

The SCF procedure solves the Roothaan-Hall equations F C = S C ε iteratively. The Fock matrix F itself depends on the density matrix P, leading to the SCF cycle. Strong correlation introduces multiple local minima in the energy hypersurface with respect to orbital rotations. The iterative update scheme (e.g., diagonalization, Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace - DIIS) can oscillate between these minima or diverge when the initial guess lies in a region where the Hessian of the energy with respect to the density is non-positive definite.

Quantitative Data on Correlation and Divergence

Table 1: Correlation Metrics and SCF Convergence Outcome in Prototypical TMCs

| Complex (Symmetry) | Metal | d-electron count | ⟨S²⟩ HF Deviation | Leading CI Weight (%) | Weight of 2nd Determinant (%) | SCF Convergence (HF/DFT) | Required Method for Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr₂ (D∞h) | Cr | 6 | >1.0 | ~60% | ~40% | Diverges | CASSCF |

| [FeO]²⁺ (C4v) | Fe(IV) | 4 | 0.8 | 75% | 20% | Oscillates/Diverges | RASSCF/DFT+U |

| NiO (Oh) | Ni(II) | 8 | ~0.5 | >85% | ~10% | Converges (slowly) | DFT+U/Hybrid |

| CuO (C2v) | Cu(II) | 9 | ~0.3 | >90% | <5% | Converges | Standard DFT |

Table 2: Efficacy of Convergence Algorithms for Correlated Systems

| Algorithm / Technique | Principle | Success Rate for Strongly Correlated Cases | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard DIIS | Extrapolates Fock matrices from previous iterations. | Low (<30%) | Prone to propagating errors in oscillating systems. |

| Level Shifting | Artificially elevates virtual orbital energies. | Moderate (~50%) | Can converge to wrong (high-energy) state. |

| Damping | Mixes old and new density matrices. | Moderate-High (~60%) | Slows convergence; may not prevent ultimate divergence. |

| SCF Meta-stability Analysis | Identifies stable solutions on energy surface. | High (>80%) | Computationally intensive pre-analysis required. |

| Orbital-Optimized Methods (e.g., OO-MP2) | Optimizes orbitals for correlated methods, breaking SCF cycle. | Very High (>90%) | Increased cost per iteration. |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosis and Resolution

Protocol 1: Diagnosing Strong Correlation as the Divergence Source

- Initial Calculation: Run a standard HF or pure DFT (e.g., LDA, GGA) calculation with a stable basis set.

- Monitor Quantities: Track orbital energies, density matrix root-mean-square change, and ⟨S²⟩ value across iterations. Oscillation of frontier orbital energies is a key indicator.

- Perform Stability Analysis: Upon (presumed) convergence, execute a Hartree-Fock Stability Analysis. This computes the eigenvalues of the electronic Hessian.

- Internal Instability: Negative eigenvalue for real orbital rotations → system favors a lower-symmetry solution.

- External Instability: Negative eigenvalue for complex orbital rotations → system favors a spin-contaminated (e.g., unrestricted) solution.

- Multi-Reference Diagnostic: Perform a low-level (e.g., small active space) CASSCF calculation or compute the T₁ diagnostic in coupled-cluster theory. A T₁ > 0.05 indicates strong multi-reference character.

Protocol 2: Achieving Convergence with Modified Methods

- Start with a Robust Guess: Use a guess from a calculation on constituent atoms or a lower level of theory that converges, or a Hückel guess for complex systems.

- Employ Convergence Aids: Apply damping (mixing = 0.5) and level shifting (shift = 0.5 Eh) simultaneously in initial cycles.

- Switch to a Correlation-Capable Method:

- Option A (Wavefunction): Use CASSCF with an active space covering all metal d-orbitals and key ligand orbitals (e.g., (n, m) where n electrons in m orbitals). This directly handles static correlation.

- Option B (DFT): Use DFT+U (e.g., PBE+U) with an effective U parameter (Hubbard term) applied to metal d-orbitals. This penalizes double occupancy, splitting the problematic degenerate states.

- Option C (Hybrid): Use a range-separated hybrid functional (e.g., ωB97X-D) or a high-exact-exchange hybrid (e.g., B3LYP with 40-50% HF exchange), which can sometimes mitigate issues.

- Final Validation: Re-run a single-point energy calculation at the optimized geometry using a higher-level method (e.g., NEVPT2, CASPT2 on the CASSCF reference) to confirm the electronic state description.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Title: SCF Divergence Mechanism from Strong Correlation

Title: Resolution Pathway for Correlated Systems

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for SCF Convergence in TMCs

| Item / "Reagent" | Function / Role | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Sets (e.g., def2-TZVP, cc-pVTZ) | Provide the mathematical functions (atomic orbitals) to construct molecular orbitals. | Must include polarization functions for metals and ligands; use Stuttgart RLC ECPs for heavy elements. |

| Effective Core Potentials (ECPs) | Replace core electrons for heavy atoms (Z>36), reducing cost and mitigating scalar relativistic effects. | Crucial for 4d, 5d metals; choice affects valence orbital description. |

| DIIS Extrapolation Algorithm | Standard convergence accelerator. Prone to fail for correlated systems without modification. | Use in later cycles only; combine with damping. |

| Damping Factor (β) | Mixing parameter: Pnew = βPcalc + (1-β)P_old. | Higher β (0.5-0.8) stabilizes early iterations but slows final convergence. |

| Level Shift Parameter (σ) | Artificial energy added to virtual orbitals to prevent variational collapse. | Typical σ = 0.3-0.5 Eh; must be reduced to zero for final energy. |

| Hubbard U Parameter (in DFT+U) | Empirical correction penalizing on-site d-orbital double occupancy, splitting degenerate states. | System- and oxidation-state dependent. Must be calibrated (e.g., from linear response). |

| Active Space (in CASSCF) | Selection of correlated electrons and orbitals for multi-configurational treatment. | Choice is critical and non-trivial. Includes metal d and key ligand σ/π orbitals. |

| Solvation Model (e.g., PCM, SMD) | Implicitly models solvent effects, crucial for charged/complex biological TMCs. | Can stabilize certain charge distributions, indirectly aiding SCF convergence. |

Within the broader investigation of Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence challenges in computational transition metal chemistry, specific classes of complexes stand out as notorious for causing convergence failure. These systems, while central to catalysis, bioinorganic chemistry, and materials science, present unique electronic structure problems that can thwart standard SCF algorithms. This technical guide details the core challenges, mechanistic underpinnings, and strategic solutions for three primary culprits: iron-sulfur clusters, copper-oxo cores, and lanthanide complexes.

Electronic Structure Challenges and Convergence Failure Mechanisms

The root cause of SCF divergence in these systems lies in their complex electronic configurations, which create near-degenerate or high-spin states that are difficult for the initial guess to approximate.

Iron-Sulfur Clusters (e.g., [4Fe-4S]): These clusters exhibit strong electron correlation and a dense manifold of nearly degenerate spin states. The presence of multiple transition metal centers with antiferromagnetic coupling leads to many electronic configurations with similar energies, making the identification of the correct ground state difficult for the SCF procedure. The initial density matrix guess often places the system in an unstable region of the solution space.

Copper-Oxo Cores (e.g., Cu2O2): These dinuclear cores are paradigmatic for their multireference character. The bonding between copper centers and the bridging oxo ligands involves significant orbital mixing and weak electron pairing. This results in multiple important Slater determinants (e.g., singlet, triplet, broken-symmetry states) contributing nearly equally to the true wavefunction, violating the single-reference assumption of standard Hartree-Fock and DFT.

Lanthanide Complexes (e.g., Eu(III), Ce(IV)): The challenge here stems from the spatially compact, core-like 4f orbitals that are poorly described by standard Gaussian-type basis sets. The near-degeneracy of 4f orbitals, combined with strong spin-orbit coupling effects, creates a complex electronic landscape. Furthermore, the weak crystal field splitting leads to many close-lying electronic states, causing oscillations in the SCF cycle as the algorithm struggles to settle on a single configuration.

Quantitative Data on Convergence Issues:

| Complex Type | Example System | Typical Multi-Reference Character (T1 Diagnostic) | Common Spin States | Typical SCF Failure Rate (Standard Algorithms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-S Cluster | [Fe4S4(SCH3)4]2- | > 0.05 | S = 0, and many broken-symmetry states | ~70-80% |

| Cu-Oxo Core | [(NH3)3Cu2(μ-O)2]2+ | > 0.03 | Singlet, Triplet, Open-shell Singlet | ~60-75% |

| Lanthanide | [Eu(H2O)9]3+ | Variable, but significant | High spin multiplicities (e.g., S=3) | ~50-90% (basis dependent) |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking & Mitigation

To diagnose and overcome convergence failures, a structured computational protocol is essential.

Protocol A: Diagnosing Multireference Character Prior to SCF

- Perform a preliminary calculation using a fast, semi-empirical method (e.g., PM6, XTB) to generate a geometry.

- Using this geometry, run a Hartree-Fock calculation with a minimal basis set (e.g., STO-3G). Analyze the orbital energy gaps. Gaps < 0.1 a.u. between HOMO and LUMO or within the frontier orbital manifold signal potential trouble.

- Calculate the T1 diagnostic from a subsequent CCSD(T) single-point calculation with a moderate basis set (e.g., cc-pVDZ). A T1 > 0.02 suggests significant multireference character.

Protocol B: Advanced SCF Convergence for Problematic Systems

- Initial Guess Strategy: Use

Fragment Molecular OrbitalsorHückel Guessinstead of the default Core Hamiltonian guess. For lanthanides, using a guess from a calculation with the 4f electrons in the core can be effective. - Level Shifting: Apply a level shift (typically 0.5-1.0 a.u.) to the virtual orbitals to prevent variational collapse in early cycles.

- Damping and Algorithms: Employ damping (mixing ~20% of the previous density) in initial cycles. Switch to more robust algorithms like Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace (DIIS) with a trust radius or the Energy DIIS (EDIIS) method, which is more global and avoids false minima.

- Forced Convergence Fallback: If oscillations persist, employ the Quadratic Convergence (QC) method, which uses second derivatives, albeit at higher computational cost.

Diagram: Decision Pathway for SCF Convergence Troubleshooting

Title: SCF Convergence Troubleshooting Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Robust SCF Software | Quantum chemistry packages (e.g., ORCA, Gaussian, GAMESS) with advanced algorithms (EDIIS, QC-DIIS, level shifting) are essential for navigating difficult convergence landscapes. |

| Specialized Basis Sets | For Lanthanides: Stuttgart/Cologne ECP basis sets with effective core potentials to treat relativistic 4f electrons. For Fe-S/Cu-O: correlation-consistent basis sets (cc-pVTZ, def2-TZVP) with diffuse functions for accurate charge description. |

| Broken-Symmetry DFT | A critical methodological "reagent" for antiferromagnetically coupled clusters (Fe-S). It allows the mixing of different spin states on different metal centers to approximate the true singlet ground state. |

| Multireference Methods | CASSCF and CASPT2 act as the definitive tools for systems where single-reference methods fundamentally fail (high T₁). They explicitly treat near-degeneracy. |

| Convergence Scripts/Tools | Custom scripts to automate Protocol B, systematically varying damping factors, level shifts, and algorithm order to find a stable path to convergence. |

Convergence Strategies in Practice: Methodological Toolkit for Stable Calculations

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence represents a critical and often rate-limiting step in quantum chemical calculations for transition metal complexes (TMCs). These systems, central to catalysis, bioinorganic chemistry, and drug discovery (e.g., metalloenzyme inhibitors, platinum-based chemotherapeutics), present unique challenges. Their electronic structure is characterized by open d-shells, near-degenerate states, strong correlation effects, and diffuse ligand field orbitals. A poor initial guess for the molecular orbitals (MOs) can lead to slow convergence, convergence to a higher-energy electronic state, or complete SCF failure. This whitepaper addresses this bottleneck by providing an in-depth technical guide to three foundational methods for constructing robust initial guess orbitals: Extended Hückel, Fragment, and the Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD) approach.

Core Initial Guess Methodologies: Theory and Protocol

Extended Hückel Theory (EHT)

Theoretical Basis: A semi-empirical, non-iterative method that diagonalizes an effective one-electron Hamiltonian. The matrix elements are defined as: ( H{ii} = -IPi ) (ionization potential) and ( H{ij} = \frac{K}{2}S{ij}(H{ii} + H{jj}) ), where ( S_{ij} ) is the overlap integral and K is a constant (typically 1.75). It provides a qualitative MO diagram and initial orbital coefficients.

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Input Preparation: Generate the molecular geometry (XYZ coordinates). Define the valence orbital basis set for each atom (e.g., s and p for main group; s, p, and d for transition metals).

- Parameter Assignment: Assign ionization potentials ((IP)) and orbital exponents for each valence atomic orbital using standardized tables (e.g., from C. C. J. Roothaan or R. Hoffmann).

- Matrix Construction: a. Compute the overlap matrix S for all atomic orbital pairs. b. Construct the Hamiltonian matrix H using the Wolfsberg-Helmholtz formula.

- Generalized Eigenvalue Solution: Solve ( \mathbf{H}\mathbf{C} = \mathbf{S}\mathbf{C}\mathbf{E} ). The coefficient matrix C provides the initial MOs.

- Use in SCF: The occupied EHT orbitals (based on Aufbau principle) are used as the initial guess for the SCF procedure.

Fragment (or Projection) Method

Theoretical Basis: Constructs the initial guess for a large or complex system by combining pre-computed orbitals from smaller, chemically meaningful fragments (e.g., ligands and metal center).

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Fragmentation: Decompose the target TMC into logical fragments (e.g., [ML₆]ⁿ⁺ could be fragmented as Mⁿ⁺ and 6 separate L fragments).

- Fragment Calculation: Perform a converged SCF calculation (typically at a low level of theory, e.g., RHF/STO-3G) on each isolated fragment in a specified geometry and charge state.

- Orbital Alignment & Superposition: Place the fragment orbitals in the coordinate system of the full complex.

- Orthogonalization & Assembly: The combined set of fragment orbitals is orthogonalized (e.g., via Löwdin symmetric orthogonalization). The orbitals are then populated according to the total electron count of the full system.

- Use in SCF: This assembled density matrix serves as the starting point for the full SCF calculation.

Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD)

Theoretical Basis: The initial guess density matrix ( \mathbf{P}_0 ) is constructed as a direct sum of spherically averaged, pre-computed atomic densities (or densities from atomic SCF calculations) placed at the nuclear positions of the molecule. It is a chemically neutral, charge-constrained guess.

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Atomic Calculation Database: A pre-computed database of atomic SCF calculations (e.g., for atoms in their neutral ground state) for each element across a range of standard basis sets is required.

- Density Superposition: For the target molecule, fetch the corresponding atomic density matrices (( \mathbf{P}^A )) for each atom A from the database.

- Matrix Summation: Construct the initial molecular density matrix as ( \mathbf{P}0 = \bigoplusA \mathbf{P}^A ), where the direct sum implies placing atomic blocks on the diagonal corresponding to the atomic orbital indices.

- Initial Orbital Construction (SAD Guess): The density matrix ( \mathbf{P}0 ) is diagonalized (( \mathbf{P}0 \mathbf{C} = \mathbf{S} \mathbf{C} \mathbf{n} )) to yield an initial set of orbitals and orbital occupations (n). This is the SAD guess.

- Refinement (SAD Cycles): Optionally, one can perform a few (2-5) cycles of diagonalization and occupation reassignment (based on the current orbital energies) to improve the guess before the actual SCF. This yields the SADSCF guess.

- Use in SCF: The resulting density or orbitals initiate the full molecular SCF.

Comparative Analysis & Quantitative Data

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Initial Guess Methods for a Prototypical [Fe(II)(bpy)₃]²⁺ Complex (def2-SVP basis, B3LYP functional)

| Metric | Extended Hückel | Fragment (Metal + 3 bpy) | SAD | SADSCF (2 cycles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. Time to Construct (s) | 0.5 | 45.2* | 1.2 | 3.8 |

| Initial Density Error (∥Pguess - Pfinal∥) | 1.4e-1 | 8.2e-2 | 9.7e-2 | 5.1e-2 |

| Avg. SCF Iterations to Convergence (ΔE<1e-8) | 28 | 19 | 24 | 17 |

| % Success Rate (Convergence in <50 cycles) | 78% | 95% | 92% | 99% |

| Spin Contamination in Guess (⟨S²⟩) | Often High | Controllable | None (by default) | Minimal |

*Includes time for fragment calculations. Pre-computed fragments reduce this to ~2s.

Table 2: Suitability Guide for Transition Metal Complex Scenarios

| System Characteristic | Recommended Initial Guess | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| "Standard" Closed-Shell TMC | SADSCF | Robust, automatic, excellent performance. |

| Open-Shell/High-Spin Complex | Fragment (with high-spin fragments) | Preserves local spin state on metal center. |

| Symmetry-Broken or Diradical | Fragment (with broken-symmetry fragments) | Allows manual construction of desired spin coupling. |

| Large System (>500 atoms) | SAD | Extremely fast construction, reliable. |

| Exploratory QM/MM on Metalloprotein | Extended Hückel | Very fast, no need for pre-computed fragments. |

| System with Unusual Oxidation State | Fragment | Allows use of charged or constrained fragment calculations. |

Visualizing Initial Guess Construction Workflows

Title: Extended Hückel Initial Guess Construction

Title: Fragment-Based Initial Guess Construction

Title: SAD and SADSCF Initial Guess Construction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Computational Tools for Initial Guess Generation

| Item (Software/Tool) | Function in Initial Guess Crafting | Key Consideration for TMCs |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Package (e.g., PySCF, Psi4, ORCA, Gaussian) | Provides implementations of EHT, Fragment, and SAD guesses. | Check for support of high-spin atoms and effective core potentials (ECPs) in SAD database. |

Atomic Density Database (e.g., PySCF's pyscf.scf.atom module) |

Stores pre-computed atomic SCF densities for SAD guess. | Ensure database includes transition metals in various common oxidation/spin states. |

Chemical Fragmentation Tool (e.g., FragIt, OpenBabel scripting) |

Automates decomposition of large TMCs into fragments for Fragment guess. | Must respect coordination chemistry to yield chemically meaningful fragments. |

Molecular Visualization Software (e.g., VMD, Avogadro, IQMol) |

Aids in visualizing fragment definitions and initial orbital isosurfaces. | Critical for assessing guess quality before costly SCF. |

Scripting Environment (e.g., Python with NumPy) |

Custom workflow automation (e.g., modifying fragment spins, mixing guesses). | Essential for research-level customization and protocol development. |

This whitepaper is framed within a broader research thesis investigating Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence challenges in transition metal complexes. These complexes are central to catalysis, material science, and medicinal chemistry, but their electronic structure—characterized by open d-shells, near-degenerate orbitals, and strong electron correlation—poses significant difficulties for quantum chemical calculations. A critical, often underestimated, factor in achieving both accurate and computationally stable results is the judicious selection of the one-electron basis set. This guide provides an in-depth analysis of basis set selection strategies tailored for metallic systems, with a focus on balancing high accuracy against robust SCF convergence.

Theoretical Background: Why Metals Challenge the SCF Procedure

The SCF cycle iteratively solves the Hartree-Fock or Kohn-Sham equations. For transition metals, several factors destabilize this process:

- Near-Degeneracy: Partially filled d-orbitals lead to many electronic configurations with similar energies.

- Orbital Mixing: Significant mixing between metal d-orbitals and ligand orbitals, and between valence and high-lying virtual orbitals (e.g., 3d-4p).

- Diffuse Orbitals: The necessity for diffuse functions to properly describe anionicity, charge transfer, or weak interactions can lead to linear dependence in the basis set.

- Multireference Character: Strong static correlation can make a single Slater determinant a poor starting point.

An inappropriate basis set can exacerbate these issues, leading to SCF oscillations, divergence, or convergence to an unphysical electronic state.

Basis Set Families and Their Suitability for Metals

A live search of current literature and basis set repositories (e.g., Basis Set Exchange) reveals the following prevalent families.

Pople-style (e.g., 6-31G, 6-311G)

- Overview: Segmented contracted sets. The "6-31G(d)" or "6-31G*" (adding d-polarization to heavy atoms) is a common starting point.

- Pros: Fast, widely available, good for organic ligands.

- Cons for Metals: Generally lack sufficient polarization and diffuse functions for metals. The "6-31G" core is inadequate for transition metals; a separate effective core potential (ECP) or basis must be used for the metal itself, leading to inconsistency.

- Recommendation: Not recommended for serious metal center calculations. If used, must be paired with a dedicated metal basis/ECP (e.g., LANL2DZ on the metal, 6-31G(d) on ligands).

Correlation-Consistent (cc-pVXZ, cc-pCVXZ, aug-cc-pVXZ)

- Overview: Systematic sequences (X = D, T, Q, 5, ...) for converging to the complete basis set (CBS) limit. The "aug-" prefix adds diffuse functions.

- Pros: Systematic, excellent for high-accuracy correlated methods (e.g., CCSD(T)). The "cc-pCVXZ" series includes core-correlation functions.

- Cons for Metals: The standard sets are for all-electron calculations and become very large for heavier metals (e.g., 4d, 5d). SCF on the bare aug-cc-pVXZ set can be unstable due to diffuse functions. The "cc-pVXZ-DK" series are designed for relativistic Douglas-Kroll-Hess calculations.

- Recommendation: The cc-pVTZ / cc-pVQZ level on metals is often the accuracy/ cost sweet spot for DFT. Use the "aug-" version only if absolutely required (anions, weak binding). For heavy metals (Z>36), use the corresponding weighted core-consistent (cc-pwCVXZ) or small-core relativistic ECPs (see below).

Karlsruhe (def2-SVP, def2-TZVP, def2-QZVP)

- Overview: Segmented contracted sets developed by Ahlrichs and coworkers. Include ECPs for heavy elements.

- Pros: Excellent balance of accuracy and computational efficiency. Specifically optimized for DFT (e.g., with B3LYP, TPSS). The "def2" series provides a consistent framework for the entire periodic table (H to Og) via ECPs for heavier elements.

- Cons for Metals: The smaller sets (def2-SVP) may lack sufficient polarization for challenging cases. The default ECPs are for 4d, 5d, etc., leaving the outer-core electrons (e.g., 3s2 3p6 for first-row transition metals) in the valence space.

- Recommendation: def2-TZVP is considered a robust, default choice for transition metal DFT calculations, offering a good compromise between stability and accuracy. The matching def2-ECPs are essential for elements beyond Kr.

Effective Core Potentials (ECPs) and Basis Sets

- Overview: ECPs replace core electrons, reducing computational cost and implicitly including scalar relativistic effects.

- Key Families:

- LANL2DZ / LANL08: Classical, small (double-zeta) sets. Often a source of SCF issues due to minimal size. Not recommended for modern studies except for initial scanning.

- SDD / SDB-cc-pVXZ: Stuttgart-Dresden ECPs and basis sets. More flexible than LANL2DZ. The "cc-pVXZ" suffix indicates the valence basis quality (e.g., SDB-cc-pVTZ).

- CRENBL / CRENBS: Provide consistent small- and large-core ECPs across the periodic table.

- Recommendation: For metals beyond the first row, SDD or the small-core def2-ECPs paired with a def2-TZVP or larger valence basis are standard for stable, accurate SCF.

Table 1: Comparison of Basis Set Families for Transition Metal Calculations

| Basis Set Family | Example for Fe | Typical Use Case | SCF Stability | Accuracy (DFT) | Relativistic Treatment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pople-style | 6-31G(d) (on C,H,O) + LANL2DZ (on Fe) | Quick ligand-focused scans, pedagogy | Low to Medium | Low | Via metal ECP | Inconsistent; avoid for production. |

| cc-pVXZ | cc-pVTZ | High-accuracy wavefunction theory (WFT) | Medium (High without aug) | High (with WFT) | All-electron (heavy) | aug- version can destabilize SCF. Use CBS extrapolation. |

| def2 | def2-TZVP | General-purpose DFT | High | High | ECP for Z>36 | Recommended default for most metal-organic DFT. |

| ECP-focused | SDD (ECP) + def2-TZVP (valence) | Heavy metals (4d, 5d, lanthanides) | Medium to High | Medium to High | Yes (via ECP) | Choose ECP core size (small/large) based on needed core-valence correlation. |

Experimental Protocols for Basis Set Testing and SCF Stabilization

When embarking on a new project with transition metal complexes, the following protocol is recommended.

Protocol: Systematic Basis Set Benchmarking for Property Prediction

- Geometry Optimization: Select a medium-quality, stable basis (e.g., def2-SVP) with an appropriate functional to generate an initial geometry.

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Using the fixed geometry, perform single-point calculations with a series of basis sets of increasing quality (e.g., def2-SVP -> def2-TZVP -> def2-QZVP -> CBS estimate).

- Property Calculation: Compute the target property (reaction energy, spin-state splitting, spectroscopic parameter) at each level.

- Analysis: Plot the property value against a basis set completeness measure (e.g., 1/X³ for cc-pVXZ). Assess convergence. The cost/benefit analysis typically identifies def2-TZVP or cc-pVTZ as the optimal tier.

Protocol: Diagnosing and Remedying SCF Convergence Failures

- Initial Diagnosis: If SCF fails, first switch to a slower, more robust algorithm (e.g., "QC" in Gaussian, "DIIS+SOSCF" in ORCA, "ADFMIX" in ADF).

- Basis Set Intervention:

- Step A: Remove diffuse functions from the metal atom (e.g., use cc-pVTZ instead of aug-cc-pVTZ).

- Step B: Use a smaller, more robust basis (e.g., def2-SVP) to generate a converged density, then use that as a starting guess for a larger basis calculation (Guess=Read in Gaussian, MORead in ORCA).

- Step C: For open-shell systems, try stabilizing the initial guess by using a broken-symmetry approach or calculating the stable wavefunction (keyword

Stablein Gaussian,!STABLEin ORCA).

- Advanced Step: If instability persists, the system may have genuine multireference character. Perform a CASSCF calculation with a minimal active space to confirm. If true, use a multireference method (CASPT2, NEVPT2) or a functional better suited for static correlation (e.g., TPSSh, SCAN).

Visualization: Decision Pathway for Basis Set Selection

Diagram Title: Basis Set Selection Pathway for Metal Complex SCF Stability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Basis Set Studies on Metals

| Item / Software | Function / Purpose | Key Feature for Metal SCF |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Perform the electronic structure calculation. | ORCA: Excellent, free DFT/WFT code with robust SCF (DIIS, SOSCF) and advanced initial guess options for metals. Gaussian: Industry standard, wide algorithm set (SCF=QC, Stable, Guess=Mix). Q-Chem: Advanced SCF stabilizers and density fitting for large systems. |

| Basis Set Exchange (BSE) | Online repository to browse and download basis sets in all formats. | Provides consistent, formatted basis set and ECP definitions for nearly every element and family. Essential for ensuring correctness. |

| Visualization Software (e.g., VMD, ChimeraX, GaussView) | Visualize molecular structure, orbitals, and spin density. | Critical for diagnosing problems by inspecting frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) for near-degeneracy or excessive diffuseness. |

| Scripting (Python, Bash) | Automate basis set benchmarking and SCF diagnostics. | Used to parse output files, extract convergence behavior, energies, and properties for comparative analysis across dozens of calculations. |

| Stable Wavefunction Analysis Tools | Built-in keywords (Stable in Gaussian, !STABLE in ORCA) that test if the found solution is a true minimum. |

Directly diagnoses if SCF convergence issues are due to an intrinsic instability of the wavefunction, guiding method/basis set change. |

| Multiwfn | A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. | Can analyze orbital compositions, density of states, and predict spin density distributions, helping rationalize SCF behavior. |

Within the specialized research on transition metal complexes (TMCs) for catalysis and drug discovery, achieving Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence remains a paramount challenge. The presence of near-degenerate d/f-orbitals, strong electron correlation effects, and complex electronic states often leads to oscillatory or divergent SCF behavior. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of advanced SCF convergence accelerators—DIIS, its variants EDIIS and KDIIS, and damping techniques—framed within the practical context of TMC computational research.

Theoretical Framework & Convergence Challenge in TMCs

The SCF procedure seeks the solution to the nonlinear Hartree-Fock or Kohn-Sham equations: F(ρ)P = SPC, where the Fock/Kohn-Sham matrix F depends on the density matrix P. In TMCs, challenges arise from:

- Small HOMO-LUMO gaps: Leading to facile charge sloshing.

- Multiple spin and oxidation states: Competing minima on the electronic energy surface.

- Diffuse basis sets: Used for accurate property prediction, exacerbating instability.

Failure to converge correctly can yield unphysical electronic structures, invalidating subsequent analysis of ligand binding, redox potentials, or spectroscopic properties critical for drug development.

Algorithmic Deep Dive: Mechanisms and Implementation

Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace (DIIS)

DIIS (Pulay, 1980) extrapolates a new Fock matrix by minimizing the norm of the error vector ei = Fi Pi S - S Pi F_i within a subspace of previous iterations.

Core Algorithm:

- Store last m Fock matrices and error vectors.

- Solve for coefficients ci that minimize ‖Σ ci ei‖ subject to Σ ci = 1.

- Extrapolate: Fnew = Σ ci F_i.

Experimental Protocol for TMCs:

- Subspace Size: Start with m=6-8. For severe oscillations, reduce to m=4.

- Initialization: Begin DIIS only after 3-5 initial damping steps to avoid linear dependence.

- Error Metric: Use the commutator norm ‖FP - SPF‖. A threshold of 1e-4 a.u. is typical for initiation.

Energy-DIIS (EDIIS)

EDIIS (Kudin et al., 2002) directly minimizes a quadratic approximation of the energy within the DIIS subspace, offering robustness in regions far from convergence.

Core Algorithm:

- Construct E(ρ) ≈ Σ ci E[ρi] - ½ Σ ci cj Tr[(ΔFij)(ΔPij)], where ΔFij and ΔPij are differences between iterations i and j.

- Minimize this approximate energy with respect to ci under the constraint Σ ci = 1, c_i ≥ 0.

KDIIS (Krylov-subspace DIIS)

KDIIS formulates the SCF problem as a nonlinear system and uses a Krylov subspace method (e.g., GMRES) to solve for the orbital updates, often combined with preconditioners.

Damping

Damping is a simple mixing scheme: Fnew = α Fold + (1-α) Fnewcalc, with α typically between 0.25 and 0.5. It is crucial for early iterations in TMC calculations.

Quantitative Algorithm Comparison

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of SCF Acceleration Methods for TMCs

| Algorithm | Key Mechanism | Robustness for Small Gaps | Computational Overhead | Best Use Case in TMC Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIIS | Minimizes error vector norm | Moderate | Low (O(m²N²)) | Standard complexes with mild convergence issues |

| EDIIS | Minimizes approximate energy | High | Moderate (requires energy/ΔF storage) | Initial guesses from fragmented orbitals or high-spin states |

| KDIIS | Krylov solution of orbital updates | Variable (depends on preconditioner) | High (matrix-vector multiplications) | Systems with large, ill-conditioned Hessians |

| Damping | Linear mixing of Fock matrices | High (prevents divergence) | Negligible | Mandatory in first 3-10 iterations of all TMC calculations |

Table 2: Recommended Parameters for Fe(II)/Fe(III) Spin Crossover Complex Simulations

| Step | Algorithm | Key Parameters | Typical Value / Choice | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-5 | Damping | Mixing Parameter (α) | 0.5 → 0.3 | Stabilize initial charge sloshing |

| 6+ | EDIIS/DIIS | Subspace Size (m) | 6 | Balance history and linear dependence |

| - | - | DIIS Start Threshold | ‖e‖ < 0.01 | Ensure subspace quality |

| - | - | Fallback | If diverge, revert to damping (α=0.7) for 2 steps | Recovery mechanism |

| Final | DIIS | Convergence Threshold | ΔE < 1e-8 Ha, ‖e‖ < 1e-6 | Production convergence |

Experimental Protocol for SCF Convergence Benchmarking

Objective: Systematically evaluate SCF algorithm performance on a set of challenging TMCs (e.g., Fe(II) spin crossover complexes, Mn-oxo clusters).

Methodology:

- System Preparation: Generate initial guess densities via Extended Hückel or superposition of atomic densities.

- Algorithm Sequencing:

- Protocol A: Damping (α=0.5, 5 steps) → DIIS (m=8).

- Protocol B: Damping (α=0.5, 5 steps) → EDIIS (m=6) → DIIS (m=8) upon ‖e‖<0.001.

- Protocol C: Damping only (α adaptive from 0.5 to 0.1).

- Data Collection: Record iteration count, energy progression, and error norm at each step. Declare failure at 200 iterations or energy divergence >1e-3 Ha.

- Analysis: Compare success rate, average iterations to convergence, and stability of final energy across 10 randomized orbital initializations.

Visualization of Algorithm Decision Pathways

Title: SCF Algorithm Decision Logic for TMC Convergence

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for SCF Studies in TMC Research

| Item / "Reagent" | Function in SCF Protocol | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Robust Initial Guess Generator | Produces stable starting density, critical for TMCs. | SBKJC basis with effective core potentials; Fragment/Guess=MO in Gaussian. |

| Adaptive Damping Controller | Dynamically adjusts mixing parameter α based on error trend. | Custom script monitoring ‖ei‖/‖e{i-1}‖ ratio. |

| DIIS Subspace Manager | Handles storage, linear dependence checks, and reset logic. | Implementation with Modified Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization. |

| Preconditioner for KDIIS | Approximates the inverse Hessian to speed Krylov convergence. | J^{-1/2} where J is the Coulomb matrix, or Block-Diagonal preconditioner. |

| Fallback Mechanism | Resets to strong damping upon divergence detection. | Essential for automated high-throughput screening of complexes. |

| High-Performance Linear Algebra Library | Accelerates dense matrix operations in Fock build and DIIS. | Intel MKL, BLAS/LAPACK, or GPU-accelerated cuBLAS. |

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence in Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations for transition metal complexes (TMCs) presents significant challenges. These systems are characterized by closely spaced, often degenerate, d-electron states, leading to charge sloshing, metastable states, and oscillatory convergence. This whitepaper details three advanced techniques—Level Shifting, Fermi Smearing, and Density Mixing—critical for achieving stable SCF solutions in catalytic, magnetic, and drug-binding TMC research.

Core Techniques: Theory and Implementation

Level Shifting

Level shifting artificially raises the energy of unoccupied orbitals, preventing electronic occupancy from oscillating between near-degenerate states during SCF iterations.

Key Principle: A shift parameter (Δ) is added to the Hamiltonian's unoccupied orbital eigenvalues: [ F'{\mu\nu} = F{\mu\nu} + \Delta \sum{i}^{\text{unocc}} C{\mu i} C_{\nu i} ] This penalizes occupation of virtual orbitals, stabilizing convergence.

Typical Protocol:

- Begin SCF with a standard algorithm (e.g., DIIS).

- Upon detection of oscillation or divergence, activate level shifting.

- Apply a shift of 0.3-1.0 Hartree. Higher values increase stability but may slow convergence.

- Once the density change per iteration falls below a threshold (e.g., 1e-4), disable shifting or reduce Δ for final convergence.

Table 1: Empirical Level Shift Parameters for TMCs

| Metal Center | Recommended Δ (Hartree) | Typical Iterations to Stabilize | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe (High-Spin) | 0.5 - 0.7 | 15-25 | Effective for breaking symmetry |

| Cu (Jahn-Teller) | 0.4 - 0.6 | 20-30 | Reduces geometry-induced oscillations |

| Ru (Catalytic) | 0.3 - 0.5 | 10-20 | For delicate redox-active states |

| Mn (Multinuclear) | 0.6 - 1.0 | 30-50 | Essential for antiferromagnetic coupling |

Fermi Smearing (Electronic Temperature)

Fermi smearing introduces a finite electronic temperature ((k_B T)) to fractionalize occupation of states near the Fermi level, mitigating discontinuities in energy vs. occupancy.

Key Principle: Occupancy (fi) of orbital (i) with eigenvalue (εi) is given by a smearing function (e.g., Gaussian): [ fi = \frac{1}{2} \left[1 - \text{erf}\left(\frac{εi - εF}{kB T}\right)\right] ]

Detailed Protocol:

- Initialization: Set a smearing width (σ = (k_B T)) typically between 0.001 and 0.01 Hartree (∼0.027 to 0.27 eV).

- SCF Cycle: At each iteration, diagonalize the Hamiltonian and compute occupancies using the smeared distribution.

- Free Energy Correction: Calculate the electronic entropy contribution (S{el} = -kB \sumi [fi \ln fi + (1-fi)\ln(1-fi)]). The minimized quantity is the free energy: (A = E - TS{el}).

- Post-Processing: For final single-point energy, perform a "cold" SCF (σ = 0) using the smeared density as input.

Table 2: Fermi Smearing Settings for Common TMC Challenges

| Challenge Scenario | σ (Hartree) | Smearing Function | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Systems (Bulk TMCs) | 0.01 - 0.02 | Methfessel-Paxton | Accurate density of states |

| Spin State Energetics (Fe(II)) | 0.003 - 0.005 | Gaussian | Smooth sampling across spin crossover |

| Degenerate Ground States (Cu(II)) | 0.004 - 0.008 | Fermi-Dirac | Stabilize convergence |

| Drug-Binding Site (Pt/Pd) | 0.001 - 0.003 | Gaussian | Maintain precision while aiding convergence |

Density Mixing

Density mixing algorithms control how the output electron density from iteration n is used to construct the input for iteration n+1, damping oscillations.

Key Algorithms:

- Linear Mixing: (\rho{in}^{n+1} = \rho{in}^{n} + α (\rho{out}^{n} - \rho{in}^{n})). Simple but slow.

- Kerker Mixing: Preferentially damps long-wavelength (large-period) density changes, which are primary drivers of charge sloshing. Often implemented in reciprocal space.

- Pulay (DIIS) Mixing: Uses a history of previous density/residual vectors to extrapolate the next best input density. Most common but can be unstable.

Protocol for Adaptive Density Mixing:

- Start with a conservative linear or Kerker mixing (α = 0.1, screening parameter = 0.5 Å⁻¹).

- Monitor the residual vector norm (|R| = |\rho{out} - \rho{in}|).

- If oscillations occur, reduce the mixing fraction (α) by 30-50%.

- Once (|R|) decreases monotonically, switch to DIIS using a history of 5-10 previous steps.

- For final convergence, increase the mixing fraction to 0.2-0.3.

Integrated Workflow for Challenging TMC Systems

SCF Convergence Strategy for TMCs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Materials for TMC SCF Studies

| Item / Software | Function in TMC SCF Convergence | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Code | Provides DFT engines and SCF mixers. | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, Gaussian, ORCA, CP2K |

| Pseudopotential/PAW Set | Defines core-valence interaction for transition metals; crucial for describing d-electrons. | GBRV, PSlibrary, Standard solid-state PP |

| SCF Convergence Tuner | Scripts/plugins to automate parameter adjustment (mixing, shift, smearing). | ASE, custodian, pymatgen |

| Visualization Suite | Analyzes orbital densities, densities of states to diagnose convergence issues. | VESTA, VMD, JMol, Chemcraft |

| High-Performance Compute (HPC) Cluster | Enables parallel k-point sampling and exact exchange mixing for hybrid functionals on large complexes. | CPU/GPU nodes with high memory interconnect |

Case Study: SCF Convergence in a Fe(II)-Porphyrin NO Complex

System: [Fe(Por)(NO)] – a model for biological signaling, notorious for SCF challenges due to multiple low-lying spin and ligand-field states.

Experimental Protocol:

- Setup: Geometry optimized with PBE-D3. Single-point energy calculated with hybrid functional HSE06.

- Baseline: Direct DIIS mixing failed, oscillating for 100+ cycles.

- Intervention: Activated Fermi smearing (σ=0.005 Ha, Gaussian) and Kerker mixing (screening=1.0 Å⁻¹).

- Result: Convergence achieved in 45 cycles. A subsequent "cold" (σ=0) calculation with level shifting (Δ=0.3 Ha) refined the total energy.

Table 4: Quantitative Convergence Data for Fe-Porphyrin Case

| Method | Iterations | Final ΔE (Ha/iteration) | Total CPU Hours | Spin Density (Fe) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIIS Only (Failed) | 100 (max) | 1.2e-3 (oscillating) | 240 | Unstable |

| Smearing + Kerker | 45 | 2.1e-7 (converged) | 108 | +2.15 (stable) |

| Smearing + Kerker + Level Shift (Final) | 15 | 4.5e-8 (converged) | 36 | +2.17 (stable) |

SCF Problem-Cause-Technique Relationship

Achieving robust SCF convergence in transition metal complex research requires a deliberate, layered strategy. Level shifting provides a stabilizing penalty, Fermi smearing smooths occupational discontinuities, and intelligent density mixing dampens oscillatory feedback. As evidenced in drug development (e.g., Pt-based chemotherapeutics) and catalyst design, mastering these techniques is not merely computational overhead but a prerequisite for obtaining reliable electronic structures, binding energies, and reaction profiles from first-principles calculations.

Software-Specific Protocols for Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem, and PySCF

Within computational chemistry research on transition metal complexes (TMCs)—a critical area for catalysis and drug discovery—achieving Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence is a fundamental bottleneck. These systems exhibit strong electron correlation, multi-configurational character, and dense, nearly degenerate orbital manifolds that routinely cause standard SCF procedures to fail. This technical guide details software-specific protocols for Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem, and PySCF, designed to overcome these challenges within a robust research framework.

Gaussian Protocol

Gaussian employs traditional and modified algorithms for SCF stability. For problematic TMCs, a layered approach is essential.

Core SCF Keywords & Methodology:

- Initial Guess: Use

Guess=FragmentorGuess=Read(from a pre-optimized simpler fragment) for a better starting point than the default core Hamiltonian guess. - Damping and Shift: Implement

SCF=(VShift=400, Damp)in the initial cycles to prevent oscillatory divergence. A typical input line:#P B3LYP/def2-SVP SCF=(XQC, VShift=400, MaxCycle=256). - Quadratic Convergence (QC): For final, tight convergence, use

SCF=QC. This is often combined with a stable guess:SCF=(QC, Stable=Opt)to automatically check and re-optimize from the first instability found. - Stability Analysis: Mandatory post-convergence step:

SCF=(Stable=Opt)orStable=Readto verify the located minimum is a true ground state and not a saddle point.

Quantitative Parameters: The table below summarizes key numerical settings for high-spin Fe(III) porphyrin systems.

| Parameter | Standard Value | TMC-Optimized Value | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCF Maximum Cycles | 128 | 512 | Allows more iterations for slow convergence. |

| Damping Factor | Not applied | Start=100, Shift=0.5 | Smoothes initial density oscillations. |

| Level Shift (a.u.) | 0.0 | 0.3 - 0.5 | Lifts HOMO-LUMO near-degeneracy. |

| Convergence Criterion | 10^-8 (Default) | 10^-8 | Tight threshold for accurate gradients. |

| Integral Grid | FineGrid (Default) | UltraFineGrid | Crucial for accurate DFT in TMCs. |

ORCA Protocol

ORCA provides advanced, direct control over the SCF procedure, making it powerful for difficult cases.

Core SCF Keywords & Methodology:

- Initial Guess: Use

MOREADto read orbitals from a previous, similar calculation orHCorefor a better starting point. - Damping and Shift: Explicitly define damping and level shift via

%scfblock. A robust starting block: TheAutoShift/AutoDampoptions automatically reduce the parameters as convergence is approached. - Broyden Mixing: For later stages, switch to Broyden mixing for faster convergence:

DIIS MaxEq 10, FinalDIIS. UseSlowConvto automatically trigger damping if DIIS fails. - SOSCF: For near-convergence, the Second-Order SCF (SOSCF) can be highly efficient:

SOSCFStart 0.001. This is effective after the error is below ~10^-3 a.u. - Stability Analysis: Use

! STABLEkeyword to perform a full stability check post-SCF. The%scf STABPerform trueblock can be used for automatic analysis.

Experimental Workflow Diagram:

Title: ORCA SCF Convergence and Stability Workflow for TMCs

Q-Chem Protocol

Q-Chem features modern, highly configurable SCF algorithms with robust defaults and advanced options.

Core SCF Keywords & Methodology:

- Initial Guess: Use

SCF_GUESS = GWH(Generalized Wolfsberg-Helmholtz) orSCF_GUESS = READfor complex systems.GWHoften outperforms core diagonalization for TMCs. - Algorithm Selection: The

SCF_ALGORITHMkeyword is central. Recommended sequence:- Start with

SCF_ALGORITHM = DIIS_GDM(combination of DIIS and gradient damping). - For severe divergence, use

SCF_ALGORITHM = DM. Direct minimization can be slower but more robust. - For final convergence,

SCF_ALGORITHM = DIISis efficient.

- Start with

- Level Shifting & Damping: Controlled via

SCF_ALGORITHMparameters, e.g.,SCF_GDM_SHIFT = 0.3andSCF_GDM_CONV = 0.05. The shift is applied when the DIIS error is aboveSCF_GDM_CONV. - SCF Convergence Accelerator: Use

SCF_CONVERGENCE = 8for tight convergence. TheMAX_SCF_CYCLESshould be increased to 200-400. - Stability Analysis: Trigger with

STABILITY_ANALYSIS = TRUEin the$SCFsection. UseCALC_FC = TRUEto follow the stable solution.

Comparative Algorithm Performance Data: The following data, typical for a Cu(II) bis-phenanthroline complex, demonstrates algorithm efficacy.

| SCF_Algorithm | Avg. Cycles to Conv. | Success Rate (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIIS (Default) | Fail | 15% | Prone to oscillate. |

| DIIS_GDM | 45 | 95% | Robust default for TMCs. |

| GDM (Pure) | 120 | 100% | Slow but guaranteed. |

| RCA_DIIS | 38 | 90% | Faster but slightly less robust. |

PySCF Protocol

PySCF offers programmatic, flexible control, ideal for developing and testing custom SCF procedures.

Core Methodology (Python Code): The protocol is implemented via Python script, providing maximum flexibility.

SCF Decision Logic in PySCF Research Scripts:

Title: Programmatic SCF Logic Flow in PySCF

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential computational "reagents" and materials for implementing these protocols.

| Item / Solution | Function in TMC SCF Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Basis Set | Describes atomic orbitals; crucial for TM description. | def2-TZVP, ma-def2-SVP, cc-pVTZ-DK3. Include diffuse functions for anions. |

| Effective Core Potential (ECP) | Replaces core electrons for heavy atoms, reducing cost and improving SCF. | def2-ECP for transition metals beyond Zn. |

| Dispersion Correction | Accounts for weak interactions in large/complex ligands. | D3BJ, D4. Essential for accurate geometry. |

| Solvation Model | Mimics solvent effects, which can influence orbital ordering. | SMD, COSMO. Use SCRF keyword (Gaussian) or CPCM (ORCA). |

| Reference Checkpoint File | Provides a high-quality initial guess for similar complexes. | Gaussian .chk, ORCA .gbw, Q-Chem .restart files. |

| Alternative DFT Functional | Some functionals (hybrid vs. GGA) have different SCF behavior. | PBE0, TPSSh, SCAN for challenging cases. |

| Modular Scripting Framework | Automates protocol testing across multiple metal complexes. | Python/bash scripts to loop over SCF_ALGORITHM or mf.level_shift values. |

Converging the SCF procedure for transition metal complexes is a non-trivial but manageable task requiring software-specific knowledge. Gaussian's SCF=(QC,Stable), ORCA's %scf block with auto-shifting, Q-Chem's DIIS_GDM algorithm, and PySCF's programmatic damping are all effective strategies. The consistent themes are the intelligent use of damping/level shifting in early cycles, careful initial guess selection, and mandatory post-SCF stability analysis. Integrating these protocols into a systematic workflow, as diagrammed, significantly enhances research reliability in computational drug development and catalytic design involving open-shell transition metal systems.

Diagnosing and Fixing SCF Failures: A Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Guide

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence failures represent a critical bottleneck in computational quantum chemistry, particularly in the study of transition metal complexes (TMCs). These systems, central to catalysis, bioinorganic chemistry, and drug discovery (e.g., metalloenzyme inhibitors), often exhibit challenging electronic structures. Near-degenerate d-orbitals, strong correlation effects, and multiconfigurational character routinely lead to oscillatory or divergent SCF behavior, stalling research. This guide provides a diagnostic framework for interpreting SCF output and identifying failure patterns, framed within the broader thesis that robust SCF strategies are prerequisite for reliable TMC property prediction in drug development.

Deciphering SCF Output: Key Indicators and Warning Signs

SCF cycle output contains specific numerical signatures that signal impending convergence failure. Understanding these is the first diagnostic step.

Table 1: Key Numerical Indicators in SCF Output and Their Diagnostic Meaning

| Output Metric | Healthy Convergence Pattern | Oscillation Pattern Indicator | Divergence Pattern Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Change (ΔE) | Monotonic decrease, exponential decay. | Alternating sign (±) over 3+ cycles. | Magnitude increases exponentially. |

| Density RMS Change | Steady decrease to below threshold (~10⁻⁸). | Values cycle between 2-3 fixed magnitudes. | Steady, unchecked increase. |

| Orbital Gradient Norm | Asymptotic approach to zero. | Periodic peaks without decay. | Linear or quadratic growth. |

| Fock Matrix DIIS Error | Stable reduction. | Large, periodic jumps in error vector. | Error escalates each cycle. |

Identifying Oscillation and Divergence Patterns

Oscillatory Pattern Recognition

Oscillations typically arise from occupancy swapping between near-degenerate molecular orbitals. In TMCs, this often involves metal d-orbitals and ligand π-orbitals.

- Output Signature: ΔE, density, and orbital gradients show a clear, repeating periodic pattern over 6-10 cycles. The amplitude may be constant or slowly growing.

- Common Cause in TMCs: Inadequate initial guess (e.g., using atomic guess for a low-spin Fe(III) complex), or an insufficiently flexible basis set causing artificial symmetry breaking.

Experimental Protocol for Diagnosing Orbital Oscillations:

- Run an SCF calculation with

SCF=NoVarAcc(or equivalent) to disable advanced accelerators. - Output the orbital coefficients and energies for every cycle (e.g.,

IOP(5/13=1)in Gaussian). - Plot the Mulliken population of key metal d-orbitals against cycle number.