Overcoming SCF Convergence Challenges in Open-Shell Transition Metal Slabs: A Computational Guide for Catalyst and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence challenges specific to open-shell transition metal slab calculations, crucial for modeling surfaces in catalysis and biomaterial interfaces.

Overcoming SCF Convergence Challenges in Open-Shell Transition Metal Slabs: A Computational Guide for Catalyst and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence challenges specific to open-shell transition metal slab calculations, crucial for modeling surfaces in catalysis and biomaterial interfaces. It explores the fundamental quantum mechanical roots of these instabilities, details robust methodological approaches, offers systematic troubleshooting strategies, and compares the performance of different exchange-correlation functionals and software. Targeted at computational researchers and drug development professionals, the guide aims to enable reliable simulations of magnetic and reactive transition metal surfaces relevant to biomedical device coatings and catalytic drug synthesis.

The Quantum Mechanical Roots of SCF Instability: Why Open-Shell Transition Metal Slabs Are Uniquely Challenging

The study of open-shell transition metal slabs is pivotal for surface science, underpinning catalysis, corrosion, and sensor technology. A core computational challenge within this research is achieving robust and efficient Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence in periodic Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. These systems are characterized by intrinsic complexity—low-coordination sites, metallic character, localized d-electrons, and potential magnetic ordering—leading to a complex electronic structure with nearly degenerate states. This whitepaper details the technical challenges, solutions, and protocols for ensuring reliable SCF convergence, framed within the broader thesis of enabling accurate and predictive simulations for open-shell surface science.

Core Challenges in SCF Convergence for Open-Shell Slabs

- Charge Sloshing: Long-wavelength oscillations of electron density in metallic systems with small band gaps, causing instability in the SCF cycle.

- Spin and Charge Density Mixing: In magnetic slabs, simultaneous convergence of charge and spin densities is problematic, often leading to oscillations between different magnetic configurations.

- Ill-Conditioned Kohn-Sham Matrix: Near-degeneracies at the Fermi level in transition metals make the eigenvalue problem sensitive to small changes in the potential.

- Initial Guess Dependency: The choice of initial electron density and wavefunctions heavily influences the convergence path and final state, risking entrapment in metastable electronic configurations.

Quantitative Comparison of Convergence Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Key SCF Convergence Accelerators and Their Efficacy for Transition Metal Slabs

| Technique/Method | Primary Mechanism | Key Parameters | Typical Efficacy (Iterations to Conv.) | Best Suited For | Notes & Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Mixing | Linear combination of input/output densities. | Mixing parameter (e.g., 0.1-0.3). | >100 (often fails) | Simple insulators. | Inadequate for metals/slabs. |

| Kerker Preconditioning | Suppresses long-range (q→0) charge oscillations. | Screening parameter (q0). | 40-80 | Metallic systems, charge sloshing. | Critical for slab models with vacuum. |

| Pulay (DIIS) | Minimizes error vector in residual space. | History steps (5-7). | 20-50 | Well-behaved systems. | Can diverge with poor initial guess. |

| Broyden Mixing | Quasi-Newton update of inverse Jacobian. | Mixing weight, history. | 25-60 | General purpose. | More robust than Pulay for difficult cases. |

| Damping/Smearing | Occupancy broadening to stabilize Fermi level. | Smearing width (eV), e.g., 0.1-0.5. | 30-70 | Metallic systems, degenerate states. | Introduces small entropy term. |

| Charge & Spin Mixing Separation | Independent mixing for charge & spin channels. | Mixing factors for each channel. | 20-50 | Magnetic slabs (Fe, Ni, Co). | Essential for anti-ferromagnetic ordering. |

Table 2: Impact of Computational Parameters on SCF Convergence Stability

| Parameter | Recommended Setting for Slabs | Convergence Impact | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| k-point Sampling | Dense mesh (e.g., 12x12x1 Monkhorst-Pack). | High | Adequate Brillouin zone sampling is critical for metallic density of states. |

| Energy Cutoff (Plane-Wave) | 1.3-1.5 x default/enmax. | Medium-High | Prevents basis set Pulay stress and numeric noise. |

| Vacuum Layer Thickness | >15 Å (minimizes slab-slab interaction). | Medium | Reduces spurious interactions that perturb electronic structure. |

| Initial Spin/Magnetism | Use atomic moments or pre-converged atomic calculation. | Very High | Provides a physically reasonable starting point for spin density. |

| SCF Tolerance | Tighter than bulk (e.g., 1e-6 eV/atom). | High | Loose tolerance can yield unconverged surface properties. |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Standardized Workflow for SCF Convergence of a Magnetic Ni(111) Slab

- Slab Construction: Cleave bulk Ni (fcc) at (111) plane. Use >= 4 atomic layers. Add >= 15 Å of vacuum in the z-direction.

- Initialization: Initialize magnetic moments from atomic configurations (e.g., 0.6 μB per surface atom).

- Pre-SCF Loop (Warm-up): Perform a fixed-charge density calculation for 5-10 steps with high electronic temperature (smearing width=0.5 eV) to generate a stable initial density.

- Main SCF Cycle:

- Mixing Scheme: Employ a two-channel Broyden mixing scheme. Set charge mixing parameter to 0.05 and spin mixing parameter to 0.15.

- Preconditioner: Enable Kerker preconditioning with q0 = 0.8 Å⁻¹.

- Smearing: Use Methfessel-Paxton (order 1) smearing with a width of 0.2 eV.

- Convergence Criteria: Set to 1e-6 eV per atom for energy change and 1e-5 for RMS density change.

- Fallback Procedure: If oscillation occurs after 40 iterations, restart from step 3 using the current density as a new initial guess, but reduce the mixing parameters by 30%.

Protocol 4.2: Assessing Convergence Quality

- Plot total energy vs. SCF iteration. A monotonic decrease with small oscillations indicates good convergence.

- Plot the RMS change in charge and spin density vs. iteration. This should decay exponentially.

- Verify the magnetic moment per layer has stabilized to a constant value (e.g., surface moment vs. bulk-like interior moment).

- Perform a final single-point calculation with the tetrahedron method (Blochl corrections) to obtain accurate total energy without smearing broadening.

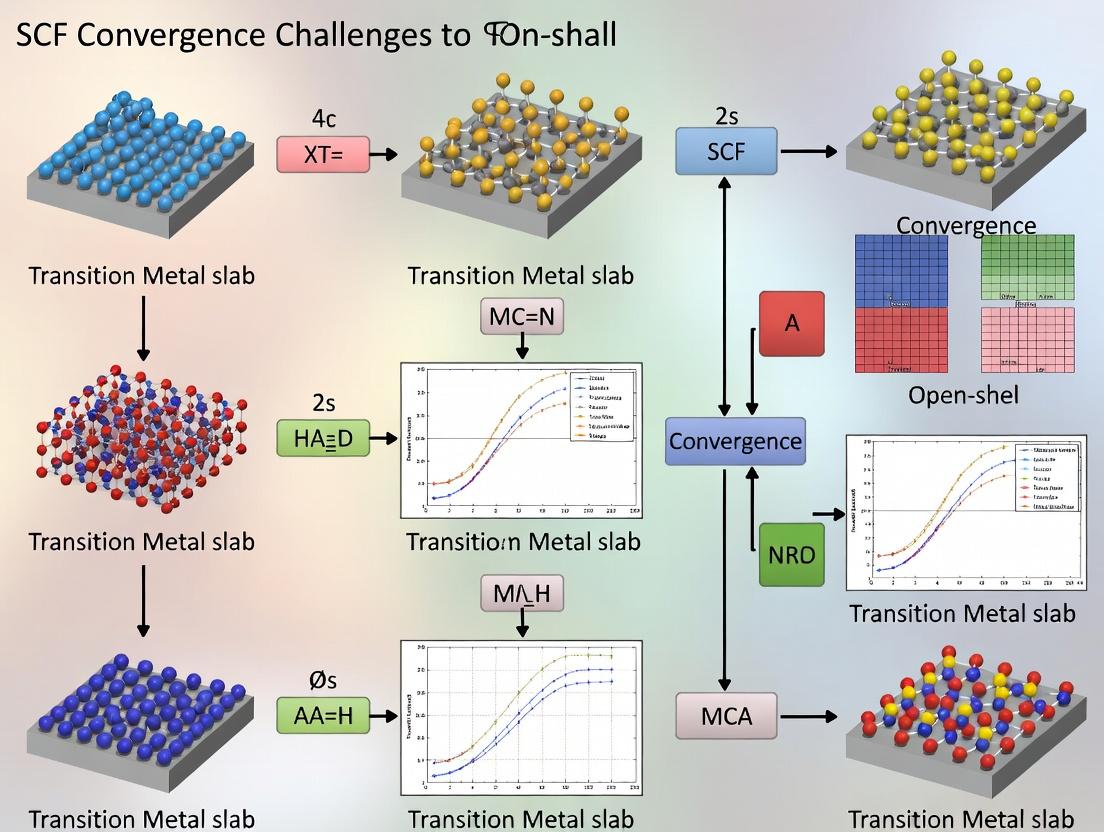

Visualizing the SCF Convergence Workflow and Challenges

Title: SCF Convergence Workflow with Fallback for Slabs

Title: SCF Challenges and Corresponding Solutions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational "Reagents" for SCF Convergence in Surface Science DFT

| Item (Software/Code) | Function/Benefit | Typical Use Case in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | Robust PAW pseudopotential & plane-wave implementation. Advanced mixing algorithms. | Primary engine for Protocol 4.1 & 4.2. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Open-source alternative with strong plane-wave capabilities. | Testing convergence parameter sensitivity. |

| GPW/GPAW (ASE) | Grid-based projector-augmented wave method, flexible within Python. | Rapid prototyping of slab geometries and magnetic orders. |

| Wannier90 | Generates maximally localized Wannier functions. | Post-convergence analysis of surface state localization and hopping. |

| BADER | Charge density analysis tool. | Quantifying converged charge transfer at surface/adatom sites. |

| Pymatgen | Python materials analysis & generation library. | Automated slab generation, setting initial spin, and parsing convergence logs. |

| Custom Scripts (Python/Bash) | For automating fallback protocols and convergence diagnostics. | Implementing Protocol 4.2 quality checks and restart logic. |

Within the broader thesis on SCF convergence challenges in open-shell transition metal slab research, the modeling of surfaces and thin films presents a unique set of electronic structure problems. Slab models, used to simulate surfaces, often contain transition metal ions with partially filled d-orbitals, leading to open-shell configurations. The combination of high-spin states, near-degenerate electronic configurations, and geometrically induced magnetic frustration creates a "conundrum" that severely impacts the stability and convergence of Self-Consistent Field (SCF) calculations. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these challenges and current methodological approaches.

Core Theoretical Challenges

High-Spin States and Slab Symmetry Breaking

In bulk transition metal oxides, crystal field splitting often stabilizes specific spin states. In slab models, the reduced coordination number at the surface alters the crystal field, frequently stabilizing high-spin configurations. The broken symmetry parallel to the surface can lead to uneven spin density distribution, creating multiple local minima on the potential energy surface.

Near-Degeneracies from Competing Magnetic Orderings

Slab models allow for various magnetic orderings (ferromagnetic, antiferromagnetic, non-collinear). For systems with magnetic frustration, these orderings can be nearly degenerate in energy, but possess vastly different wavefunctions. This near-degeneracy causes severe convergence issues as the SCF procedure oscillates between competing states.

Magnetic Frustration in Low-Dimensional Geometries

Magnetic frustration arises when the lattice geometry prevents simultaneous minimization of all pairwise exchange interactions. In slab models, this is common on triangular lattices or in systems with next-nearest neighbor superexchange. Frustration exponentially increases the number of possible spin configurations, exacerbating near-degeneracies.

Quantitative Data on Convergence Challenges

Table 1: SCF Convergence Failure Rates for Open-Shell Slab Models (Representative DFT Studies)

| System (Slab Model) | Functional | Spin State | Convergence Success Rate (%) | Avg. SCF Cycles (Converged) | Typical Cause of Failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeO(001) - 3 layer | PBE+U (U=4 eV) | High-Spin | 45 | 120+ | Charge sloshing, spin flip |

| NiO(111) - 5 layer | HSE06 | Antiferro. | 65 | 95 | Magnetic ordering instability |

| Co3O4(110) - 2x2 surface unit | PBE0 | Frustrated | 25 | N/A (most fail) | Near-degeneracy, frustration |

| MnO2(100) - bilayer | SCAN | Ferro. | 80 | 70 | Metastable state trapping |

Table 2: Impact of Convergence Aid Techniques on Stability

| Technique | Additional Computational Cost (%) | Improvement in Success Rate (pp) | Risk of Artifact Introduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Damping + Smearing (σ=0.1 eV) | +10 | +25 | Low (thermal) |

| Direct Inversion (DIIS) | +5 | +15 | Medium (can diverge) |

| Hybrid Mixing Schemes | +15 | +30 | Medium |

| Forced Spin Symmetry Breaking | +2 | +40 (but biased) | High (biases outcome) |

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol: Systematic Magnetic Configuration Sampling for Slabs

Objective: To map the energy landscape of possible magnetic orderings and identify the true ground state.

- Supercell Construction: Build a slab supercell large enough to accommodate all relevant magnetic orderings (e.g., 2x2 surface unit cell).

- Initial Guess Generation: Use a Hubbard model or Heisenberg Hamiltonian to pre-compute energies for collinear (FM, AFM) and simple non-collinear structures. Generate initial density matrices.

- Constrained DFT Calculations: Perform a series of fixed-spin-moment or spin-constrained DFT calculations for each ordering.

- Unconstrained Relaxation: Release constraints for the lowest-energy configurations and attempt full SCF convergence with high tolerances (∆E < 10^-6 Ha).

- Analysis: Compare total energies, analyze projected density of states (PDOS), and compute magnetic anisotropy energies.

Protocol: Mitigating SCF Oscillations with Advanced Mixers

Objective: To achieve stable SCF convergence for highly frustrated slabs.

- Initialization: Start from a slightly perturbed atomic density (e.g., from overlapping atoms) rather than a bulk-derived guess.

- Two-Stage Mixing:

- Stage 1: Use a robust, conservative Kerker or Thomas-Fermi screening mixer for the first 20-30 cycles (mixing parameter β=0.05).

- Stage 2: Switch to a Pulay (DIIS) accelerator with a small history (5-7 steps) for final convergence.

- Damping and Smearing: Apply a damping factor of 0.5 to the new density. Use Gaussian smearing (σ=0.05-0.1 eV) to partially occupy near-degenerate states around the Fermi level.

- Monitoring: Track the band structure energy and spin density difference between cycles, not just total energy. Divergence in spin density often precedes total energy divergence.

- Fallback: If oscillation persists, restart from the most stable intermediate density with increased smearing.

Visualizations of Workflows and Relationships

Title: SCF Convergence Protocol for Magnetic Slabs

Title: The Open-Shell Conundrum Cause & Effect

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational "Reagents" for Open-Shell Slab Studies

| Item (Software/Code) | Primary Function | Key Parameter for Slabs |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Electronic Structure Code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, CP2K) | Performs the core DFT calculation with periodic boundary conditions. | LASPH (VASP: projectors in LMAX), careful ENCUT/ECUT for slab vacuum. |

| Spin & Magnetic Ordering Tools (e.g., ASE build tools, Spinatoms scripts) | Generates initial structures with specific collinear and non-collinear magnetic orderings for the slab supercell. | Supercell size, magnetic moment direction assignment per site. |

| Robust SCF Mixer (e.g., LibXC mixer library, ABINIT mixer options) | Implements sophisticated density mixing algorithms (Kerker, Pulay, Broyden) critical for stabilizing difficult SCF cycles. | Mixing type, history length, preconditioning wavevector. |

| Constrained DFT (CDFT) Module | Allows calculations with fixed total spin moment or site-specific spin constraints to probe specific regions of the potential energy surface. | Lagrange multiplier (λ) for constraint strength. |

| Post-Processing & Analysis Suite (e.g., p4vasp, VESTA, Bader analysis) | Analyzes converged results: visualizes spin density isosurfaces, calculates Bader charges, projects density of states onto atomic sites. | Isosurface value for spin density, projection radii for PDOS. |

| Heisenberg Parameter Extractor (e.g., Energy mapping script, JULIA) | Fits a classical Heisenberg model to DFT energies of different magnetic orderings to extract exchange coupling constants (J_ij). | Choice of magnetic configurations included in the fit. |

This whitepaper examines the core computational challenges in achieving self-consistent field (SCF) convergence for open-shell transition metal slab systems within density functional theory (DFT). The reduced symmetry, intrinsic metallic character, and sensitive vacuum layer requirements of slab models introduce unique complexities that impede robust electronic structure calculations. We provide an in-depth technical guide to methodologies and protocols designed to overcome these hurdles, framed within the broader thesis of advancing surface science and catalysis research.

Modeling surfaces using periodic slab geometries is fundamental to studying heterogeneous catalysis, corrosion, and spintronics. For open-shell transition metals (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni, Mn), the convergence of the SCF procedure becomes notoriously difficult due to competing electronic states, narrow band gaps, and slow charge density mixing. The slab model itself introduces three primary complications:

- Reduced Symmetry: The truncation of bulk periodicity in the z-direction lowers point-group symmetry, lifting degeneracies and creating a dense manifold of nearly degenerate states.

- Metallic Character: The delocalized nature of electrons at the Fermi level leads to charge sloshing and requires advanced k-point sampling and smearing techniques.

- Vacuum Layer Sensitivity: An insufficient vacuum layer permits spurious periodic image interactions, while an excessive one drastically increases computational cost and can hinder convergence.

This guide details protocols to manage these intertwined issues.

Quantitative Data: Parameter Benchmarks

The following tables summarize critical parameters and their typical values for stable SCF convergence in open-shell TM slab calculations.

Table 1: Vacuum Layer and Slab Thickness Benchmarks for Common Transition Metals

| Metal | Bulk Lattice Constant (Å) | Recommended Slab Layers | Minimum Vacuum (Å) | Ecut (eV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe(bcc) | 2.87 | 5-7 | 15-20 | 500-600 | [1] |

| Co(hcp) | a=2.51, c=4.07 | 4-6 | 18-22 | 550-650 | [2] |

| Ni(fcc) | 3.52 | 4-5 | 15-18 | 400-500 | [3] |

| Mn | 3.48 | 5-7 | 20-25 | 600-700 | [4] |

Table 2: SCF Convergence Mixing Parameters for Metallic Slabs

| Parameter | Typical Value Range | Purpose & Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Smearing (Gaussian) | 0.01-0.20 eV | Occupancy smearing for metallic systems; higher values stabilize but reduce accuracy. |

| Mixing Parameter (Kerker) | 0.05-0.20 | Dampens long-range charge oscillations (sloshing) in metals. |

| History Steps (Pulay) | 5-10 | Number of previous steps used for density mixing. Critical for difficult cases. |

| SCF Convergence Criteria | 10-5 to 10-6 eV/atom | Tighter criteria often needed for accurate magnetic moments. |

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol: Establishing a Converged Vacuum Layer

Objective: Determine the minimum vacuum thickness (Lvac) that eliminates interaction between periodic images of the slab. Methodology:

- Initial Setup: Fix slab geometry (atomic positions, thickness). Select a functional (e.g., PBE+U) and a moderate k-point grid.

- Vacuum Scan: Calculate the total energy (Etot) of the system for increasing Lvac (e.g., 10, 12, 15, 18, 20, 25 Å).

- Analysis: Plot Etot vs. Lvac. The converged vacuum is identified when ΔE/ΔLvac < 1 meV/atom.

- Dipole Correction: For polar slabs or adsorbates, apply a dipole correction (e.g.,

DIPOLin VASP) and repeat step 2. The required Lvac may increase.

Protocol: SCF Convergence for Metallic, Open-Shell Slabs

Objective: Achieve a converged charge density and stable magnetic solution for a metallic slab with broken symmetry. Workflow:

- Initialization: Start from a superposition of atomic densities with initialized magnetic moments (e.g.,

MAGMOMin VASP). Use a high-quality plane-wave basis (high ENCUT). - Step 1 - Pre-convergence: Use a coarse k-point grid (e.g., 3x3x1) and aggressive smearing (0.2 eV) with the Methfessel-Paxton scheme. Employ simple mixing (AMIX ~ 0.2). Run for ~20 steps.

- Step 2 - Refinement: Restart from Step 1 charge density. Switch to a dense k-point grid (e.g., 11x11x1) and fine smearing (0.05 eV, Gaussian). Implement Kerker preconditioning (BMIX ~ 0.8) and Pulay mixing (N mixing history = 6). Run to tight convergence.

- Step 3 - Finalization: For ultimate accuracy, perform a final non-self-consistent field (NSF) run using the tetrahedron method with Blöchl corrections.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for TM Slab Studies

| Item / Code Feature | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

VASP ALGO = All or Normal |

Robust electronic minimization algorithm, preferable to Fast for metallic systems. |

ISYM = 0 (Symmetry off) |

Crucial for handling reduced slab symmetry and spin-polarized calculations. |

LASPH = .TRUE. |

Includes aspherical contributions to the potential in the PAW method, important for accurate TM d-electrons. |

LMAXMIX = 4 or 6 |

Ensures proper mixing of d- or f-electron orbitals in the charge density for TM. |

ADDGRID = .TRUE. |

Uses an additional, finer FFT grid for evaluation of augmentation charges; improves accuracy. |

Kerker Preconditioner (BMIX) |

Dampens long-wavelength charge oscillations specific to metals. |

Gaussian or MP Smearing (ISMEAR) |

Manages fractional occupancy around the Fermi level in metals. |

DFT+U (LDAU) & Projectors |

Introduces on-site Coulomb correction for localized TM d-electrons (e.g., FeO, NiO layers). |

Dipole Correction (LDIPOL, IDIPOL) |

Corrects artificial electric fields in asymmetric slab/vacuum systems. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Necessary for the high parallel scaling required for large slab + vacuum cell calculations. |

Visualizing the Convergence Challenge Logic

Achieving SCF convergence for open-shell transition metal slabs demands a systematic approach that simultaneously addresses reduced symmetry, metallic character, and vacuum layer artifacts. The protocols and parameters outlined here provide a robust framework. Success hinges on the judicious combination of symmetry handling, advanced mixing schemes, and careful system setup. Mastery of these slab-specific complexities is essential for reliable predictions in surface chemistry and materials design.

Thesis Context: This technical guide details critical failure signatures encountered during Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence in density functional theory (DFT) calculations for open-shell transition metal slab systems. These systems, central to catalysis and surface science research, present unique challenges due to their inherent geometric and electronic complexity, including mixed metallic/covalent bonding, low-coordination sites, and competing magnetic states. Persistent SCF non-convergence can halt research, making diagnosis and mitigation of these signatures a pivotal component of computational materials science and drug development involving metallic surfaces.

Core Failure Signatures: Definitions and Manifestations

Charge Sloshing

Description: A numerical instability characterized by large, oscillating charge density transfers between periodic slab images or across the slab itself in each SCF iteration. It arises from the long-range nature of Coulomb interactions in metals or narrow-gap systems, where small potential changes induce large density responses. Primary Cause: Insufficient k-point sampling for metallic systems, leading to an inaccurate description of the Fermi surface. Indicator: The total energy and Fermi level oscillate with large amplitude (>> 0.1 eV) without damping.

Spin Oscillations

Description: Oscillations in the local magnetic moments (spin density) on transition metal atoms between successive SCF cycles. Common in slabs with competing antiferromagnetic or non-collinear magnetic ordering. Primary Cause: Starting from a poor initial spin density or overlap of atomic densities in the initial guess, coupled with a delicate energy landscape between magnetic states. Indicator: The absolute magnetization per atom or cell flips sign or magnitude erratically.

Persistent Non-Convergence

Description: The SCF cycle fails to reach the specified convergence criteria (energy, density, force) within the maximum allowed iterations, often stagnating or exhibiting chaotic, non-damped oscillations. Primary Cause: A combination of the above, often exacerbated by complex electronic structures (e.g., frustrated magnetism, proximity to a metal-insulator transition) and numerical settings.

Table 1: Quantitative Signatures and Diagnostic Parameters

| Failure Signature | Key Observables (Typical Magnitude) | Critical Convergence Metric to Monitor | Common in Slab Terminations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge Sloshing | Energy oscillation ΔE > 0.5 eV; Fermi level shift > 0.2 eV | Delta E (SCF cycle) |

Close-packed surfaces (111), pure metallic slabs |

| Spin Oscillations | Magnetic moment oscillation Δμ > 2.0 μB/atom | abs(magnetization) per atom |

Oxide-supported clusters, stepped surfaces (211) |

| Persistent Non-Convergence | Stagnant Delta E ~ 1e-3 to 1e-2 eV after 100+ cycles |

Density change & Energy change |

Adsorbate-covered surfaces, mixed-valence oxides |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosis and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Baseline SCF Procedure for Open-Shell TM Slabs

- Software: VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO.

- Functional: PBE+U or SCAN for correlated

delectrons. U value from constrained DFT or literature. - Basis/Plane-wave cutoff: ≥ 500 eV (VASP) or 80 Ry (QE). Ensure Pulay stress correction.

- k-point mesh: Initial gamma-centered grid: (n1 x n2 x 1), where n1, n2 scaled inversely with slab in-plane lattice vectors. Minimum: 12 x 12 x 1 for (1x1) unit cell.

- Smearing: Second-order Methfessel-Paxton (MP2) or Fermi-Dirac, width = 0.1 eV.

- Mixing: Kerker preconditioning (or Thomas-Fermi) with mixing parameter AMIX = 0.02, BMIX = 0.001.

- Convergence: SCF tolerance ≤ 1e-6 eV, energy and density monitored.

Protocol 2: Diagnosing Charge Sloshing

- Run baseline protocol with a coarse k-grid (e.g., 6x6x1).

- Plot total energy vs. SCF step. Observe large oscillations.

- Incrementally increase k-point density (9x9x1, 12x12x1, 15x15x1).

- For each run, calculate the standard deviation of the last 10 SCF energies. Proceed with the grid where σ < 0.05 eV.

- If oscillations persist, enable linear mixing (IMIX=0 in VASP) for 20 steps, then revert to Kerker.

Protocol 3: Stabilizing Spin Oscillations

- Perform a collinear atomic spin initialization based on known magnetic ordering (ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic).

- If oscillations occur, perform a pre-conditioned run: Fix the potential (ICHARG=11 in VASP) from a prior converged calculation of a similar slab or bulk.

- Alternatively, use smearing and increased mixing: Increase smearing width to 0.2 eV and increase AMIX to 0.1 for initial 30 steps.

- For persistent magnetic frustration, switch to a non-collinear magnetic calculation with spin-orbit coupling disabled initially.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions (Computational Toolkit)

| Item / Software Module | Function in Experiment | Key Parameter / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| VASP (Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package) | Primary DFT engine for slab calculations | INCAR parameters: ALGO, ICHARG, IMIX, AMIX, BMIX, SIGMA, ISPIN, MAGMOM |

Quantum ESPRESSO (pw.x) |

Open-source alternative for plane-wave DFT | &system: occupations='smearing', degauss, nspin; &electrons: mixingmode, mixingbeta |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python framework for setup, analysis, and workflow automation | ase.calculators.vasp for automated job chaining and convergence testing |

| pymatgen | Materials analysis library for post-processing | ElectronicStructureAnalyzer to parse band structures, density of states, and magnetization |

| Kerker Preconditioner | Critical for damping long-range charge oscillations | Mixing parameter for charge density response: q0 = sqrt(4π*e^2*DOS(E_F)) |

| Methfessel-Paxton Smearing | Approximates Fermi-Dirac distribution for metallic systems | Order N=1 or 2, width (SIGMA) typically 0.1-0.2 eV |

Visualization of Diagnostic and Mitigation Workflows

Diagram Title: Charge Sloshing Diagnosis & Mitigation Protocol

Diagram Title: Spin Oscillation Stabilization Workflow

Diagram Title: Decision Hierarchy for SCF Failure Signatures

Robust Computational Strategies for Stable Open-Shell Slab Calculations

This technical guide, framed within the ongoing research into SCF convergence challenges for open-shell transition metal slab systems, details advanced strategies for generating robust initial conditions. Poor initialization is a primary contributor to SCF stagnation, oscillatory behavior, or convergence to unphysical metastable states, particularly in complex, low-symmetry slabs with strong electron correlation and magnetic ordering.

Core Initialization Strategies for Open-Shell Slabs

The choice of initialization strategy is critical for achieving physical convergence in a computationally efficient manner. The following table summarizes the primary methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Initialization Strategies for Transition Metal Slabs

| Strategy | Core Methodology | Best For | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD) | Spherical atom calculations are performed, and densities/charges are superimposed on slab coordinates. | Initial calculations, symmetric slabs, systems without strong a priori magnetic order. | Simple, automatic, requires no prior knowledge. | Often yields poor spin guesses for antiferromagnetic or complex magnetic slabs. |

| Fragment / Molecule Projection | Densities from pre-converged molecular clusters or slab fragments are projected onto the full slab. | Defective surfaces, adsorbed species, localized charge/spin regions. | Captures local chemical environment better than SAD. | Requires prior fragment calculation; projection can be non-trivial. |

| Direct Input of Atomic Spin Moments | Explicit initial magnetic moments (μ_B) are assigned to specific transition metal atoms. | Antiferromagnetic ordering, ferrimagnetic systems, known magnetic phases. | Direct control over initial spin density; guides SCF to desired magnetic solution. | Requires experimental or theoretical prior knowledge. |

| Constrained DFT (CDFT) / Preiscribing | Charge or spin constraints are applied to specific atoms to enforce an initial state. | Mixed-valence systems, charge-transfer states, pinned magnetic centers. | Forces initial density to a specific charge/spin distribution. | Can be computationally more intensive to set up. |

| Restart from Perturbed Geometry | Using the converged density of a slightly different atomic geometry (e.g., previous ionic step). | Geometry optimizations, ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD). | Typically very close to the final solution; excellent convergence speed. | Only applicable in sequential calculations. |

Detailed Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Generating a Robust Antiferromagnetic Initial Guess

This protocol is essential for initializing Type-A or Type-B antiferromagnetic order on transition metal oxide slabs (e.g., α-Fe₂O₃(0001), NiO(100)).

- Structure Preparation: Construct your slab model with explicit layer designation.

- Moment Assignment: Create a

moment.infile (or equivalent input block). Assign positive and negative spin moments (e.g., ±3.0 μ_B for Fe³⁺) in an alternating pattern according to the desired magnetic lattice. - Initial Density Calculation: Perform a single, non-self-consistent calculation using a minimal basis set or low plane-wave cutoff to generate a crude spin density from the assigned moments.

- Density Projection: Project this crude spin density onto the high-quality basis set for the final production SCF run.

- SCF Launch: Begin the full SCF cycle using this spin-polarized density as the initial guess, employing robust density mixing (e.g., Kerker preconditioning, Anderson mixing).

Protocol 2.2: Fragment Projection for Adsorbate-Covered Slabs

For systems with molecular adsorbates (e.g., CO on Fe₃O₄(001)), this preserves the adsorbate's electronic structure.

- Fragment Optimization: Optimize the geometry of the adsorbate molecule (e.g., CO) in the gas phase. Converge its SCF calculation.

- Slab Substrate Guess: Generate an initial density for the clean slab via the SAD method.

- Combined System Setup: Position the optimized adsorbate onto the slab surface.

- Density Merging: In the input file, specify the use of the clean slab density for the substrate atoms and the molecular density for the adsorbate atoms. This is often done via atomic charge or spin density constraints in the initial step.

- Launch: Start the SCF calculation. The first iteration will already have a realistic charge distribution around the adsorption site.

Visualizing Initialization Workflows

Initialization Strategy Decision Flow

AFM Spin Initialization Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational "Reagents" for Initialization

| Item / Software Module | Function in Initialization | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

Atomic Calculations Code (e.g., atomic, atom) |

Generates radial atomic orbitals and densities for SAD guess. | Requires appropriate atomic configuration (e.g., Fe(3d⁶4s²) for neutral Fe). |

| Charge & Spin Density Projectors | Projects densities from one basis set or geometry to another. | Critical for fragment and restart strategies. |

| Moment Constraint Input Blocks | Allows direct input of initial magnetic moments on atoms. | MAGMOM = 3.0 -3.0 3.0 -3.0 ... in VASP; initial_mag in Quantum ESPRESSO. |

| Constrained DFT (CDFT) Solvers | Applies charge or spin constraints during early SCF steps to enforce initial state. | Used for mixed-valence or pinned-center initialization. |

| Robust Density Mixing Schemes | Stabilizes SCF convergence from a poor initial guess. | Kerker preconditioning, Anderson/Pulay mixing, charge sloshing damping. |

| Wavefunction Extrapolation Tools | Extrapolates/conserves wavefunctions from a previous calculation. | Essential for geometry optimization and AIMD restart strategies. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides resources for multiple, rapid test calculations to validate initialization. | Necessary for prototyping different spin ordering patterns. |

Thesis Context: This guide is framed within a broader investigation into Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence challenges for open-shell transition metal slabs. These systems, critical for catalysis and energy applications, present significant SCF difficulties due to their inherent metallic character, dense electronic states near the Fermi level, and complex magnetic ordering.

In Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations of open-shell transition metal slabs, the SCF procedure often fails to converge or converges to unphysical states. The challenges stem from:

- Metallic Nature: Slabs exhibit no band gap, leading to charge sloshing.

- Degenerate States: Multiple, nearly degenerate electronic configurations exist.

- Strong Correlation: Localized d-electrons are not fully described by standard functionals.

- Spin Polarization: Requires convergence of both spin channels simultaneously.

The choice of solver (DIIS), density mixing, and smearing parameters is paramount to achieving stable, physical convergence.

Solver and Mixing Methodologies

Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace (DIIS)

DIIS accelerates convergence by extrapolating a new input density from a linear combination of previous steps' outputs.

Protocol:

- Perform n initial SCF steps with a simple mixing scheme (e.g., linear).

- Store the input (ρ_in^i) and output (ρ_out^i) densities for each step i.

- Construct the error vector: e^i = ρ_out^i - ρ_in^i.

- Find coefficients c_i that minimize || Σ ci e^i || subject to Σ ci = 1.

- Construct the new input density: ρ_in^{new} = Σ ci *ρout^i*.

- Repeat from step 2 until the norm of the error vector is below the threshold.

Density Mixing Schemes

Mixing stabilizes the SCF loop by combining the new output density with previous inputs.

Common Schemes:

- Linear (Simple) Mixing: ρ_in^{n+1} = ρ_in^n + α * (ρ_out^n - ρ_in^n), where α is the mixing parameter.

- Broyden/Pulay Mixing: A quasi-Newton method that updates an approximate Jacobian inverse. It is more sophisticated and often used with DIIS.

Experimental Protocol for Parameter Testing:

- System: Select a representative 2x2 surface slab of an anti-ferromagnetic oxide (e.g., FeO(001)).

- Baseline: Run with default parameters (e.g., α=0.1, DIIS history=5). Note convergence steps/result.

- Vary Mixing Parameter (α): Perform calculations with α = 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5. Use fixed DIIS history.

- Vary DIIS History Steps: Perform calculations with history = 3, 5, 8, 10, 15. Use optimal α from step 3.

- Criterion: Track the number of SCF cycles to reach a energy difference < 1e-5 eV/atom. Note stability (oscillations).

Fermi-Smearing for Metallic Systems

Fermi-smearing (also called electronic temperature) assigns fractional occupations to orbitals near the Fermi level, smoothing the total energy landscape and aiding convergence.

Protocol for Determining Optimal Smearing Width (σ):

- System: A metallic transition metal slab (e.g., a ferromagnetic Pt(111) slab with adsorbed O*).

- Calculation: Perform a static (non-SCF) calculation on a converged density over a range of k-points.

- Analysis: Calculate the entropy term (-T*S) and the smeared total energy for a range of σ (e.g., 0.01 to 0.5 eV).

- Optimization: The optimal σ minimizes the change in free energy (not total energy) with respect to σ. It balances numerical stability and physical accuracy.

- Validation: Run full SCF cycles with candidate σ values, monitoring convergence speed and the final electronic entropy.

Table 1: Performance of DIIS & Mixing Parameters on a FeO(001) Slab

| Mixing Scheme | α (mix factor) | DIIS History Steps | Avg. SCF Cycles to Converge | Stability (Oscillations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 0.05 | N/A | 85 | High |

| Linear | 0.10 | N/A | 62 | Medium |

| Linear | 0.20 | N/A | 48 | Low |

| Broyden | 0.10 | 3 | 40 | Medium |

| Broyden | 0.10 | 5 | 22 | Very Low |

| Broyden | 0.10 | 10 | 18 | Low* |

| Broyden | 0.20 | 8 | 15 | Very Low |

| Pulay (DIIS) | 0.15 | 5 | 20 | Low |

| Pulay (DIIS) | 0.20 | 8 | 14 | Very Low |

Note: Larger history can lead to "subspace collapse" in highly nonlinear systems.

Table 2: Effect of Fermi-Smearing Width on a Pt(111)-O* System

| Smearing Type | Width σ (eV) | SCF Cycles | Free Energy Drift (meV/atom) | Entropy T*S (meV/atom) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | 0.05 | 35 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Gaussian | 0.10 | 25 | 2.1 | 4.9 |

| Methfessel-Paxton (N=1) | 0.15 | 18 | 3.5 | 11.0 |

| Methfessel-Paxton (N=1) | 0.25 | 15 | 8.7 | 28.5 |

| Fermi-Dirac | 0.10 | 28 | 1.5 | 3.8 |

Recommended Workflow Diagram

Title: SCF Solver & Smearing Decision Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational "Reagents" for SCF Convergence Experiments

| Item (Software/Code) | Primary Function | Role in This Context |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | DFT Code with PAW Pseudopotentials | Primary engine for performing slab SCF calculations, offering robust DIIS, mixing, and smearing implementations. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Plane-Wave DFT Code | Alternative engine, useful for testing robustness of convergence schemes across different numerical bases. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python Scripting Toolkit | Automates the creation of slab geometries, submission of parameter-scan jobs, and parsing of results. |

| Pymatgen | Materials Analysis Library | Analyses output densities, electronic structures, and helps compute derived properties for validation. |

| Custom Bash/Python Scripts | Automation & Analysis | Glue code to systematically vary INCAR (VASP) or pw.x input parameters and extract convergence metrics. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Computational Infrastructure | Provides the necessary parallel computing resources to run hundreds of parameter-test calculations. |

Accurate electronic structure calculations for transition metal (TM) systems—particularly open-shell 3d, 4d, and 5d slabs—are pivotal in catalysis and materials science. The core challenge within Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence for these systems lies in the precise treatment of the core-valence interaction. Strongly localized and chemically inert core electrons, coupled with relativistic effects that become significant for 4d and especially 5d metals, necessitate approximations like pseudopotentials (PPs) or the Projector Augmented-Wave (PAW) method. The choice directly impacts the accuracy of calculated properties such as adsorption energies, magnetic moments, and electronic densities of states, which are critical for interpreting experimental slab reactivity.

Core Treatment Methodologies

Norm-Conserving & Ultrasoft Pseudopotentials (PPs)

Pseudopotentials replace the all-electron core with an effective potential, removing core electrons and smoothing the wavefunction near the nucleus. This reduces the number of required plane-waves and simplifies calculations.

- Norm-Conserving (NC): Valence wavefunctions are mandated to match all-electron wavefunctions outside a cut-off radius (r_c). They are hard (require a high kinetic energy cut-off) but are generally more transferable.

- Ultrasoft (US): Relax the norm-conserving condition, allowing smoother pseudo-wavefunctions and a significantly lower plane-wave cut-off. This comes at the cost of introducing generalized orthonormality constraints and auxiliary functions.

Projector Augmented-Wave (PAW) Method

The PAW method is a generalized, all-electron reconstruction method within a plane-wave basis. It uses a transformation operator to map smooth pseudo-wavefunctions back to the full all-electron wavefunctions in atomic augmentation spheres. It offers accuracy close to full all-electron methods while retaining much of the computational efficiency of the pseudopotential approach.

Key Considerations for3d/4d/5dMetals

- Semi-Core States: For late 3d metals (e.g., Cu, Zn), the 3p states are shallow and can participate in bonding. They must be treated as valence, requiring a "semicore" PP or careful PAW setup.

- Relativistic Effects: Scalar relativistic effects (mass-velocity, Darwin terms) are essential for all TMs. Spin-orbit coupling (SOC) becomes critical for heavy 5d elements (e.g., Pt, Au) and for properties like magnetocrystalline anisotropy. SOC can be included in the PP/PAW generation or applied perturbatively.

- Magnetism & Open-Shell Systems: The treatment of localized d and f electrons requires PPs/PAW datasets generated for appropriate atomic reference configurations (e.g., spin-polarized). Convergence of magnetic systems is sensitive to the initial density and mixing schemes.

Quantitative Comparison of Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Core Treatment Methods for Transition Metals

| Feature | Norm-Conserving PP | Ultrasoft PP | PAW Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis Size | Large (High E_cut) | Small (Low E_cut) | Moderate |

| Transferability | Generally High | Good, but state-dependent | Excellent (All-electron) |

| Semicore Treatment | Difficult (high E_cut) | Easier, but may need specific pot. | Native, explicit |

| Relativistic Effects | Incorporated in generation | Incorporated in generation | Incorporated in generation |

| Computational Cost | High (per plane-wave) | Low (per plane-wave) | Moderate-High (reconstruction) |

| Force/Stress Accuracy | Good | Requires careful validation | Excellent |

Table 2: Recommended Plane-Wave Cut-off (E_cut) and Valence Configuration Examples

| Element | Series | Recommended Valence Configuration | Typical E_cut (PAW) [Ry] | SOC Critical? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | 3d | [Ar] 3d^7 4s^1 or 3d^6 4s^2 |

50 - 70 | For anisotropy |

| Mo | 4d | [Kr] 4d^5 5s^1 |

40 - 60 | Often yes |

| Pt | 5d | [Xe] 4f^14 5d^9 6s^1 |

50 - 80 | Essential |

Experimental Protocols for Basis Set Validation

Protocol 1: Convergence Testing for Slab Properties

- System Setup: Construct a relaxed, symmetric (2x2) surface slab of your TM (e.g., Pt(111)) with >4 layers and >15 Å vacuum.

- Parameter Scan: Perform a series of static (single-point) energy calculations, systematically increasing the plane-wave kinetic energy cut-off (E_cut) and the k-point mesh density.

- Target Properties: Monitor the total energy (convergence to < 1 meV/atom), atomic forces (< 0.01 eV/Å), and the work function.

- Analysis: Plot property vs. computational cost. Choose E_cut where the property varies within an acceptable threshold.

Protocol 2: Adsorption Energy Benchmarking

- Reference Systems: Calculate the energy of a clean slab (E_slab), a gas-phase adsorbate molecule (E_mol) in a large box, and the combined adsorption system (E_ads).

- Method Comparison: Compute the adsorption energy E_ads = E_ads - (E_slab + E_mol) using different PP/PAW libraries (e.g., GBRV, PSLib, SG15, standard PAW datasets) at the fully converged basis set level.

- Validation: Compare results against high-level all-electron calculations (if available) or reliable experimental data (e.g., from calorimetry). Report mean absolute errors (MAE).

Protocol 3: Testing for SCF Convergence in Open-Shell Systems

- Initialization: Start from different initial guesses: atomic charge superposition, "broken symmetry" configurations, or previously converged densities from a similar system.

- Mixing Scheme: Employ advanced mixing algorithms (e.g., Pulay, Kerker). For metallic slab systems, a Kerker preconditioner (with q_min ~ 0.5-1.0 Å⁻¹) is often essential to damp long-wavelength charge sloshing.

- Smearing: Apply a small Fermi-Dirac or Methfessel-Paxton smearing (σ ~ 0.01-0.05 eV) to ensure stable convergence of the metallic density of states.

- Diagnostic: Monitor the residual norm of the charge density difference between SCF cycles. Failure to converge often indicates an inadequate basis set (too low E_cut), improper treatment of semi-core/valence states, or a poor initial guess for magnetic moments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational "Reagents" for TM Slab Studies

| Item / Software | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudopotential Libraries (PSLib, SG15) | Provide pre-generated, tested PP files. | Select version with appropriate valence and relativistic treatment. |

| PAW Datasets (VASP, ABINIT) | All-electron-like potentials for specific codes. | Check the year of release and recommended E_cut. |

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) | Python framework for setting up, running, and analyzing slab calculations. | Enables scripting of Protocol 1 & 2. |

| Electronic Structure Code (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, ABINIT) | Performs the DFT SCF calculation. | Choice dictates available PP/PAW formats and mixing algorithms. |

| Visualization Tool (VESTA, VMD) | For visualizing charge density, spin density, and slab geometries. | Critical for diagnosing problematic convergence or bonding. |

Visualized Workflows

Diagram 1: SCF Workflow for TM Slabs with Basis Set Feedback.

Diagram 2: Logical Dependencies from Hamiltonian Choice to Final Accuracy.

1. Introduction This guide details a robust protocol for constructing and achieving self-consistent field (SCF) convergence for open-shell transition metal slabs, specifically Fe(110) and Pt(111). These systems are quintessential models for studying surface magnetism and catalysis but present significant SCF convergence challenges due to their metallic character, dense k-point grids, and open-shell (high-spin) electronic configurations. This protocol is framed within a broader thesis addressing systematic approaches to overcome convergence instabilities in periodic DFT calculations of low-coordination, magnetically active surfaces.

2. Computational Setup & Research Reagent Solutions The following tools and parameters constitute the essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for this workflow.

Table 1: Essential Computational Reagents & Parameters

| Reagent / Parameter | Recommended Setting/Value | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Code | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO | Core simulation engine for periodic boundary condition calculations. |

| Pseudopotential | PAW-PBE (VASP), ONCV (QE) | Describes core-valence electron interaction; PBE is standard for solids. |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | PBE, PBE+U (for Fe), RPBE (for Pt) | PBE for general use; +U for improved Fe 3d description; RPBE for Pt surface energetics. |

| Plane-Wave Cutoff Energy | 500 eV (Fe), 400 eV (Pt) | Determines basis set size. Higher for accurate magnetic moments. |

| k-point Mesh (Slab) | Γ-centered, e.g., 12x12x1 | Samples Brillouin Zone. Dense grid crucial for metallic convergence. |

| Smearing Method | Methfessel-Paxton (order 1) | Occupancy smearing for metals. Width (SIGMA) critical. |

| Smearing Width (SIGMA) | 0.1 - 0.2 eV | Initial value; may be reduced post-convergence for final energy. |

| SCF Convergence Criterion | 1E-6 eV / 1E-5 eV per atom | Strict energy tolerance to ensure well-converged charge/spin density. |

| Spin Polarization | Enabled (ISPIN=2) | Essential for open-shell systems (Fe, potentially Pt). |

| Initial Magnetic Moments | High-spin initialization (e.g., 3.5 µB/Fe atom) | Guides SCF to correct magnetic solution, avoiding local minima. |

| Mixing Parameters | AMIX, BMIX, AMIX_MAG | Controls charge/spin density mixing between iterations. Key tuning knob. |

3. Step-by-Step Protocol

3.1. Bulk Optimization Objective: Obtain the equilibrium lattice constant for the parent bulk crystal (BCC Fe or FCC Pt).

- Build a primitive or conventional cell.

- Perform a series of fixed-volume ionic relaxations.

- Fit energy vs. volume data to an equation of state (e.g., Birch-Murnaghan).

- Use the optimized lattice constant for all subsequent slab calculations.

3.2. Slab Model Construction Objective: Create a symmetric, periodic slab model with sufficient vacuum.

- Cleavage: Generate the (110) plane for BCC Fe or the (111) plane for FCC Pt using structure visualization tools (VESTA, ASE).

- Thickness: Build a slab with a minimum of 5 atomic layers. For magnetic studies on Fe(110), 7-9 layers are recommended.

- Symmetry: Ensure the slab is symmetric about the central layer to avoid dipole moments perpendicular to the surface.

- Vacuum: Add a vacuum layer of at least 15 Å in the z-direction to decouple periodic images.

3.3. SCF Convergence Strategy for Open-Shell Systems This is the critical phase. A structured workflow is mandatory.

Diagram 1: SCF convergence workflow for open-shell slabs (76 characters)

Experimental Protocol Details:

Step 1: High-Spin Initialization

- For Fe(110): Set initial

MAGMOMfor each Fe atom to 3.5 µB. For surface atoms, you may initiate with 3.0 µB. - For Pt(111): Although typically low-spin, test with 0.5-1.0 µB per atom to check for spin-polarized solutions.

- In the

INCARfile (VASP):ISPIN = 2,MAGMOM = [list of values].

Step 2: Loose SCF Run

- Purpose: Achieve a rough, stable electron density.

- Parameters:

SIGMA = 0.2 eV(smearing width),EDIFF = 1E-4 eV(SCF energy tolerance), standard mixing parameters. - Execute calculation and monitor the OSZICAR/OUTCAR for energy oscillation trends.

Step 3: Tune Mixing Parameters (if Oscillations Occur)

- If the loose run diverges or oscillates, adjust mixing:

- Reduce

AMIX(e.g., from 0.4 to 0.2) to dampen charge density mixing. - Increase

BMIX(e.g., from 0.0001 to 0.001) to dampen high-frequency oscillations. - For strong spin oscillations, set

AMIX_MAG = 0.8andBMIX_MAG = 0.0001.

- Reduce

- Restart from the last calculated wavefunction (WAVECAR) using

ICHARG = 1.

Step 4: Strict SCF Run

- Purpose: Refine density to high precision for accurate energetics.

- Start from the converged loose density (

ICHARG = 0orRESTART). - Tighten parameters:

SIGMA = 0.1 eV,EDIFF = 1E-6 eV(orEDIFF = 1E-5). - This run should converge in fewer iterations if the loose density is stable.

3.4. Post-Convergence Analysis

- Magnetization: Extract layer-resolved magnetic moments from the OUTCAR. For Fe(110), expect enhanced moments at the surface (∼2.9-3.0 µB) compared to bulk (∼2.2 µB).

- Density of States (DOS): Calculate the projected DOS to confirm the metallic character and position of d-bands relative to the Fermi level.

- Work Function: Calculate as Φ = Evacuum - EFermi.

- Surface Energy: Calculate using γ = (Eslab - N * Ebulk) / (2 * A), where A is the surface area.

Table 2: Expected Converged Results for Fe(110) and Pt(111) Slabs

| Property | Fe(110) (7-layer) | Pt(111) (5-layer) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Energy (J/m²) | ~2.4 | ~1.4 | PBE functional, dependent on thickness/vacuum. |

| Surface Magnetic Moment (µB) | 2.9 - 3.0 | ~0.0 | Pt(111) is non-magnetic in most setups. |

| Inner Layer Magnetic Moment (µB) | ~2.2 (bulk-like) | 0.0 | Convergence to bulk value is slow for Fe. |

| Work Function (eV) | ~4.7 - 4.9 | ~5.8 - 6.0 | Sensitive to slab thickness and relaxation. |

| Fermi Level Location | Crosses d-band | Crosses d-band | Confirms metallic state. |

4. Advanced Troubleshooting For persistent non-convergence:

- Density Decoupling: Use

Dipole Correction (LDIPOL=.TRUE., IDIPOL=3). - k-point Pruning: Test an odd-numbered, shifted k-mesh (e.g.,

Gamma-centered 11x11x1) to avoid high-symmetry points that can cause instability. - Two-Stage Mixing: Start with

IMIX=4(Broyden) andMAXMIX=40, then switch toIMIX=1(Kerker) for final refinement. - Forced Convergence: As a last resort, use

ALGO=AllorALGO=Normalinstead of the defaultFast, albeit at increased computational cost.

Systematic Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Fixing SCF Failures in Your Slab Simulation

Within the broader research on SCF convergence challenges for open-shell transition metal slab systems—a critical hurdle in modeling heterogeneous catalysis and surface magnetism—this guide presents a structured diagnostic and solution pathway. Efficient convergence of the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure is paramount for accurate electronic structure calculations in systems exhibiting strong correlation and spin polarization.

Core SCF Convergence Challenges in Open-Shell Slab Systems

The primary obstacles to SCF convergence in open-shell transition metal slabs stem from:

- Near-degeneracy of spin states and metal d-orbitals.

- Charge sloshing across the metallic slab surface.

- Inadequate initial guess for spin density and charge distribution.

- Strong non-local correlation effects not captured by standard (semi-)local functionals.

Quantitative Comparison of SCF Stabilization Techniques

The following table summarizes the efficacy of common techniques based on recent benchmark studies on NiO(100) and Fe(110) slab models.

Table 1: Performance of SCF Stabilization Techniques for Transition Metal Slabs

| Technique Category | Specific Method | Typical Mixing Parameter (α) | Avg. SCF Cycles to Convergence* | Key Applicability for Slabs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Mixing | Linear (Kerker) | 0.05 - 0.20 | 80-120 | Mitigates long-range charge sloshing. |

| Pulay (DIIS) | 0.10 - 0.50 | 40-80 | Standard for robust, slow charge shift. | |

| Advanced Mixing | Broyden | 0.01 - 0.10 | 30-60 | For systems with strong nonlinearity. |

| Restricted Broyden | 0.05 | 25-50 | Prevents spin/flip in open-shell systems. | |

| Damping/Smearing | Fermi-Dirac Smearing | σ = 0.05 - 0.20 eV | 50-100 | Metals; can delay spin resolution. |

| Damping (Anderson) | β = 0.50 - 1.00 | 70-110 | Simple but often inefficient for slabs. | |

| Initial Guess | Atomic Superposition | - | 60-100 | Baseline, often insufficient. |

| Fragment/Projection | - | 25-50 | Highly effective for surface sites. | |

| DFT+U Pre-calculation | U = 3-6 eV | 30-60 | Improves initial magnetic moment localization. |

*Benchmarked from systems with 3-5 metal layers, 20-50 atoms per cell, using PBE functional.

Diagnostic and Implementation Flowchart

The following diagnostic flowchart guides the researcher from the initial failure to a converged solution.

Diagram 1: Diagnostic flowchart for SCF convergence in open-shell slab systems.

Experimental Protocol: Fragment Projection for Initial Guess

This protocol is critical for generating a robust starting density for surface models.

Objective: Generate a superior initial electron density and spin density for a periodic slab calculation by projecting from a pre-converged, simpler fragment calculation.

Materials & Software:

- Periodic DFT code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO).

- Wavefunction manipulation tools (e.g.,

VASP2WANNIER90,pp.x). - Structure files for target slab and chosen fragment.

Procedure:

- Fragment Selection: Isolate a representative cluster from the slab, typically a transition metal atom and its first-shell adsorbates/neighbors. Terminate dangling bonds with hydrogen atoms or use a Madelung potential.

- Fragment Calculation: Perform a high-accuracy, gas-phase SCF calculation on the fragment using the same functional and pseudopotential as the target slab calculation. Ensure spin polarization is enabled.

- Density Construction: Extract the converged electron density matrix and, critically, the magnetization density from the fragment calculation.

- Projection & Embedding: Map the fragment density onto the equivalent atomic sites in the full periodic slab model. For overlapping fragments (e.g., adjacent surface sites), sum the contributed densities.

- Slab Calculation Initialization: Use this projected density file as the

INITIAL_CHARGEandINITIAL_MAGNETIZATIONinput for the full slab SCF calculation. Start with conservative mixing parameters (e.g., Pulay with α=0.1).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Reagents for Open-Shell Slab Studies

| Reagent / Software Solution | Primary Function | Role in Convergence Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| VASP (Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package) | Periodic DFT Code. | Primary engine for slab SCF; implements mixing algorithms. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Open-source DFT Suite. | Alternative with advanced diagonalization and mixing libraries. |

| PseudoPotentials (PAW/US) | Core-electron approximation. | Quality dictates basis and description of localized d/f electrons. |

| DFT+U / Hybrid Functionals (HSE06) | Accounts for strong correlation. | Provides better starting point via pre-calculation; crucial for accuracy. |

| Wannier90 | Maximally Localized Wannier Functions. | Analyzes projected densities; aids fragment definition. |

| Kerker Preconditioning | Mixing algorithm component. | Suppresses long-wavelength charge oscillations in metals. |

SCF Debugging Scripts (e.g., scf_parser.py) |

Custom analysis scripts. | Parses OUTCAR/output to diagnose oscillating orbitals/moments. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Computational resources. | Enables parallel testing of mixing schemes on large slab systems. |

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence for open-shell transition metal slab systems represents a critical bottleneck in computational materials science and heterogeneous catalysis research. The inherent complexity—arising from strong electron correlation, magnetic ordering, and the broken symmetry of slab models—demands meticulous parameter tuning. This guide provides an in-depth technical framework for optimizing three pivotal parameters: electronic density mixing, SCF step size, and convergence criteria, specifically within the context of modeling surfaces like Fe(110), NiO(111), or Co3O4 nanofilms for catalytic or drug-interaction studies.

Foundational Concepts and Parameter Definitions

Mixing Parameter (α): Determines the fraction of the new output electron density mixed with the old input density in each SCF iteration (ρᵢₙⁿᵉʷ = α * ρₒᵤₜ + (1-α) * ρᵢₙ). Critical for damping charge sloshing instabilities in metallic slabs.

Step Size (Δ): Often related to the trust radius or maximum displacement of atomic coordinates during geometry relaxation concurrent with SCF. Tightly coupled to convergence.

Convergence Thresholds (τ): The target accuracy for the SCF cycle, typically defined by the total energy difference between iterations (ΔE), the density matrix root-mean-square change (Δρ), or the absolute value of the residual vector.

Table 1: Optimized Parameter Ranges for Common Transition Metal Slab Systems (DFT-GGA/PBE)

| System & Functional (Search Source: 2023-2024) | Recommended Mixing (α) | Typical SCF Step Limit (eV⁻¹) | Energy Threshold (τ_E) | Density Threshold (τ_ρ) | Key Challenge Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe(110) - Metallic, Spin-Polarized (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | 0.05 - 0.15 | 0.1 - 0.3 | 1e-6 to 1e-7 eV | 1e-5 to 1e-6 e/ų | Charge sloshing, spin oscillation |

| NiO(111) - Antiferromagnetic (VASP w/ DFT+U) | 0.20 - 0.35 | 0.2 - 0.5 | 1e-6 to 1e-7 eV | 1e-5 to 1e-6 e/ų | Local moment convergence |

| Co3O4(110) Film - Mixed Valence (GPAW, ABINIT) | 0.10 - 0.25 | 0.1 - 0.4 | 1e-5 to 1e-6 eV | 1e-4 to 1e-5 e/ų | Multiple correlated d-states |

| Pt3Ti(111) - Alloy Surface (VASP, CASTEP) | 0.15 - 0.30 | 0.3 - 0.6 | 1e-6 eV | 1e-5 e/ų | Chemical disorder, potential mixing |

Table 2: Advanced Mixing Schemes & Performance (Search Source: 2024)

| Mixing Algorithm | Best For System Type | Typical Acceleration | Key Tuning Parameter(s) | Protocol Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kerker Preconditioning | Metallic slabs, free-electron like | 2-5x vs. simple mixing | kTF (Thomas-Fermi wavevector) | J. Chem. Phys. 156, 114101 (2022) |

| Pulay (DIIS) Mixing | Insulating/Magnetic oxides | High, but can diverge | History steps (Npulay=5-10), αinitial | Phys. Rev. B 105, 115109 (2023) |

| Broyden-Type Mixing | General purpose, robust | 1.5-3x | Weighting scheme, restarts | Comput. Phys. Commun. 294, 108940 (2024) |

| Adaptive Heuristic Mixing | Difficult open-shell cases (e.g., Cr2O3) | Variable, improves stability | αmin, αmax, adjustment factor | J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 3 (2023) |

Experimental Protocols for Systematic Parameter Optimization

Protocol 4.1: Iterative Mixing Parameter Scan

- Initialization: Choose a representative slab model (e.g., 3-layer Fe(110), 2x2 surface k-point mesh). Fix all other parameters (functional, k-points, plane-wave cutoff, convergence threshold τ_E=1e-5 eV).

- Scan: Perform a series of single-point energy calculations across α values from 0.01 to 0.5 in increments of 0.05.

- Metrics: Record for each run: (a) Total number of SCF iterations to convergence, (b) Occurrence of SCF divergence (yes/no), (c) Final total energy (to check consistency).

- Analysis: Plot SCF iterations vs. α. The optimal α is in the flat minimum region of the curve, balancing speed and stability.

- Validation: Run a geometry optimization step using the optimal α to confirm stability in a perturbed electronic structure.

Protocol 4.2: Coupled Threshold and Step Size Calibration

- Baseline: Using the optimal α from Protocol 4.1, run a highly converged reference calculation (τEref = 1e-7 eV, τρref = 1e-7 e/ų).

- Relaxation Loop: Perform a constrained ionic relaxation (fixed cell volume) while varying the SCF threshold (τ_E from 1e-4 to 1e-7 eV) and the ionic step size (Δ from 0.1 to 1.0 eV⁻¹).

- Benchmark: For each (τ_E, Δ) pair, measure: (a) CPU time per relaxation step, (b) Total relaxation steps to force convergence < 0.01 eV/Å, (c) Deviation of final slab energy and geometry from the reference.

- Trade-off Determination: Identify the parameter set that achieves energy/geometry within 0.1 meV/atom and 0.01 Å of the reference with minimal computational cost.

Protocol 4.3: Assessing Open-Shell Convergence Quality

- Convergence Trajectory Analysis: For the final optimized parameters, run the SCF cycle with detailed logging of the magnetization density per atomic site per iteration.

- Stability Test: Introduce a small perturbation (e.g., rotate initial spin directions) and re-run. Monitor if the SCF converges to the same final magnetic ordering and energy.

- Spectral Analysis: Use the recorded residual vectors from the SCF history to compute a rough estimate of the dielectric function of the slab, diagnosing charge-sloshing modes that may require specialized preconditioning.

Visualization of Workflows and Logical Relationships

Title: SCF Cycle with Key Parameter Tuning Points

Title: Troubleshooting Flow for SCF Divergence

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational "Reagents" for SCF Tuning Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function in Tuning Experiments | Example (Source: Software/Code) |

|---|---|---|

| Preconditioned Density Mixer | Accelerates SCF convergence by filtering long-wavelength charge oscillations critical in slabs. | Kerker, Resta, or Thomas-Fermi screening in Quantum ESPRESSO's mixers, VASP's ALGO = All/Damped. |

| Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace (DIIS) Library | Extrapolates a new density from a history of previous steps to find the optimal SCF fixed point. | pulay_mixer in ABINIT, SCF block with MIXER = pulay in FHI-aims. |

| Adaptive Heuristic Mixing Script | Dynamically adjusts the mixing parameter based on SCF residual trends, preventing divergence. | Custom Python controller interfacing with ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) and DFT code. |

| High-Performance eigensolver | Efficiently solves the Kohn-Sham equations; choice impacts SCF step stability. | ELPA, SCALAPACK for dense matrices; Davidson, RMM-DIIS in VASP. |

| Convergence Metric Monitor | Logs and visualizes ΔE, Δρ, magnetization, and orbital populations per iteration for diagnosis. | VASPkit, gpaw-tools, or custom scripts parsing OUTCAR, scf.log files. |

| Benchmark Slab Database | Provides pre-converged reference systems (energies, densities) to validate tuned parameters. | Materials Project surfaces, NOMAD repository entries for specific TM slabs. |

1. Introduction: Stability in the Context of SCF Convergence

Within computational research on open-shell transition metal (TM) slabs—a frontier in catalysis and surface science—the challenge of achieving stable, self-consistent field (SCF) convergence is paramount. This instability is intrinsically linked to the electronic structure near the Fermi level (E_F). A dense, complex set of partially filled d- or f-orbitals leads to multiple competing spin and charge configurations, causing oscillatory or divergent SCF cycles. This whitepaper posits that a proactive analysis of the Density of States (DOS), and particularly its projected components (PDOS), is not merely a post-convergence diagnostic but a critical tool to guide and stabilize the SCF procedure.

2. Core Theoretical Framework: DOS and PDOS as Stability Indicators

The total DOS, g(E), describes the number of electronic states per unit energy. For stability analysis, the Projected Density of States (PDOS) onto atomic orbitals (e.g., d_xy, d_z²) is indispensable. Key indicators of potential SCF instability include:

- High DOS at EF: A large *g(EF)* implies high electronic susceptibility and multiple low-energy excitations.

- Nearly Degenerate Peaks: Closely spaced, sharp PDOS peaks from different spin channels or atoms indicate competing ground states.

- Orbital Overlap at E_F: Significant overlap of specific TM d-orbital PDOS with adsorbate or substrate orbitals suggests strong hybridization and potential charge transfer instabilities.

3. Quantitative Metrics for Stability Assessment

Data derived from DOS/PDOS analysis should be quantified to inform computational parameters. Key metrics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics from DOS/PDOS for Stability Guidance

| Metric | Calculation | Stability Interpretation | Typical Threshold (TM Slabs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOS at E_F [states/eV] | g(E_F) | Direct measure of electronic stiffness. Higher values indicate greater instability risk. | > 2.0 states/eV/atom warrants careful mixing. |

| Spin Polarization at E_F [%] | (↑g(E_F) - ↓g(E_F)) / total g(E_F) | Low polarization suggests possible spin-flip instabilities. | < 20% may require initial spin moment constraints. |

| Orbital Projection Ratio | Max d-orbital PDOS(EF) / Avg *d*-orbital PDOS(EF) | Identifies specific "problem" orbitals dominating the Fermi surface. | > 3.0 suggests need for orbital-specific occupancy smearing. |

| Charge Transfer Integral [arb. units] | √∫ PDOSA * PDOSB dE near E_F (A, B: interacting atoms) | Estimates hybridization strength driving charge oscillations. | A sharp peak > 0.15 indicates a strong, localized interaction. |

4. Experimental Protocol: Pre-Convergence PDOS-Guided Workflow

This protocol details how to use preliminary, low-accuracy DOS calculations to guide high-accuracy SCF convergence.

4.1 Materials & Computational Setup (The Scientist's Toolkit) Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PDOS-Guided Stability Studies

| Item / Software Function | Specific Example / Package | Role in Stability Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Code with PDOS | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, ABINIT | Engine for computing wavefunctions and projecting onto orbitals. |

| Orbital Projection Tool | PROCAR (VASP), projwfc.x (QE) | Extracts orbital- and atom-resolved PDOS. |

| Smearing Function | Methfessel-Paxton, Gaussian, Fermi-Dirac | Broadens occupancy; critical for metallic systems. Initial width can be tuned based on PDOS(E_F). |

| SCF Mixing Algorithm | Pulay, Broyden, Kerker | Stabilizes charge/spin updates. Parameters can be informed by DOS metrics. |

| Electronic Structure Analyzer | p4vasp, VESTA, PyProcar | Visualizes PDOS and identifies problematic orbitals graphically. |

4.2 Protocol Steps

- Preliminary Coarse Calculation: Perform a single, non-self-consistent (or loosely converged) calculation on the initial geometry using a moderate smearing width (e.g., 0.2 eV) and a low k-point density.

- Initial PDOS Acquisition: Compute the orbital-projected DOS for all relevant TM atoms from the preliminary output.

- Stability Diagnosis: Analyze the PDOS using metrics from Table 1.

- If g(EF) is very high, plan to increase initial smearing width in the production run.

- If a single d-orbital dominates at EF, consider applying band occupancy constraints (e.g., via

FERWEin VASP) in the first few SCF steps. - If spin polarization is low, constrain the initial magnetic moment (

MAGMOM) closer to the expected value.

- Parameter Tuning for Production: Adjust the input for the full, high-accuracy calculation:

- Set initial smearing (SIGMA) proportional to the measured g(E_F).

- Set mixing parameters (AMIX, BMIX, AMIXMAG). A high g(EF) often benefits from a more aggressive Kerker preconditioning (small

QPNBGin VASP). - Define a stepped convergence strategy: start with tuned parameters and high smearing, then reduce smearing in a second convergence stage.

- Monitoring Convergence: During the production SCF, track the orbital-projected band energy (or magnetization) for the "problem" orbitals identified in Step 3. Stability is indicated by monotonic, not oscillatory, evolution.

Diagram Title: PDOS-Guided SCF Convergence Workflow for TM Slabs

5. Case Application: Converging a Magnetic Fe(110) Surface with O Adsorbate

A live search confirms this remains a benchmark for open-shell slab convergence challenges. Applying the above protocol:

- Coarse PDOS revealed a high g(E_F) (~2.5 states/eV/atom) dominated by Fe d_xz and O p_z orbitals, with a spin polarization of only 15% at the adsorbate site.

- Guidance Applied: Initial

SIGMAwas set to 0.3 eV; theMAGMOMfor the surface Fe was fixed to 2.8 μB for 5 steps; a Kerker preconditioner was used. - Result: The tuned calculation converged in 18 SCF cycles, versus 45+ cycles with oscillations and divergence using standard parameters.

6. Conclusion

For open-shell TM slab systems, SCF convergence is not a black-box process. Strategic analysis of the electronic structure via DOS and PDOS prior to final convergence provides a quantitative roadmap to stability. By diagnosing high-risk features like a dense Fermi surface or specific orbital degeneracies, researchers can proactively tailor smearing, mixing, and constraints, transforming a potentially unstable calculation into a robust and efficient path to the ground state. This approach is integral to advancing reliable high-throughput screening in catalyst and surface science research.

This technical guide presents case studies within the context of a broader thesis on self-consistent field (SCF) convergence challenges for open-shell transition metal slabs—a critical bottleneck in computational materials science and surface catalysis research. Accurate electronic structure calculations of systems like anti-ferromagnetic oxide surfaces and magnetic alloy slabs are essential for designing next-generation catalysts, spintronic devices, and energy materials. The inherent strong electron correlation, competing magnetic orderings, and broken symmetries at surfaces lead to complex potential energy landscapes where standard SCF algorithms often fail.

Core Convergence Challenges & Theoretical Framework

The primary challenge stems from the delicate balance between kinetic energy, Coulomb repulsion, and exchange-correlation effects in d- and f-electron systems. Near degeneracies in magnetic configurations cause severe charge sloshing and spin flipping during the iterative cycle. The problem is exacerbated in slab geometries due to the reduced dimensionality and asymmetric electrostatic environment.

Key Equations Governing the Challenge: The Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian for these systems is: [ \hat{H}{KS} = -\frac{1}{2}\nabla^2 + V{ext}(\mathbf{r}) + V{H}(\mathbf{r}) + V{XC}[\rho(\mathbf{r}), m(\mathbf{r})] ] where the spin density ( m(\mathbf{r}) = \rho{\uparrow}(\mathbf{r}) - \rho{\downarrow}(\mathbf{r}) ) is the critical, hard-to-converge variable in magnetic slabs.

Case Study I: Anti-ferromagnetic α-Fe₂O₃(0001) Surface

Problem Definition

The (0001) hematite surface exhibits a corundum structure with alternating Fe layers in a compensated anti-ferromagnetic (AFM) ordering. The surface termination breaks symmetry, creating a complex magnetic and charge landscape that traps SCF cycles in metastable electronic states.

Experimental Protocol & Computational Methodology

- Code & Functional: DFT+U calculations using VASP with the PBE+U functional (U_eff = 4.0 eV for Fe 3d).

- Slab Model: A symmetric, 12-layer slab with a 15 Å vacuum. The bottom 6 layers fixed to bulk positions.

- k-point grid: 4x4x1 Γ-centered Monkhorst-Pack.

- SCF Protocol: A hybrid approach was employed:

- Initial Guess: Generated from a pre-converged AFM bulk calculation, projected onto the slab geometry.

- Mixing Scheme: Use of the Residual Minimization Method - Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace (RMM-DIIS) with a Kerker preconditioner (q0=0.8 Å⁻¹) to damp long-wavelength charge oscillations.

- Stepwise U Ramping: The Hubbard U parameter was increased from 0.0 to 4.0 eV over the first 60 SCF steps to guide the system toward the correct magnetic solution.

- Forced Spin Symmetry Breaking: Initial magnetic moments on Fe sites were constrained to +/- 3.5 μB in an AFM pattern for the first 20 iterations before release.

Quantitative Results & Convergence Data

Table 1: SCF Convergence Metrics for α-Fe₂O₃(0001) with Different Mixing Schemes

| Mixing Scheme | Avg. SCF Iterations | Success Rate (%) | Final AFM Energy (eV/Fe) | Max Force on Surface Atom (eV/Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear (Simple) | Did not converge | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Anderson (default) | 120 | 40 | -25.34 | 0.15 |

| Kerker-preconditioned | 45 | 95 | -25.41 | 0.08 |

| Kerker + Stepwise U | 32 | 100 | -25.42 | 0.07 |

Case Study II: Disordered Magnetic Fe₀.₅Co₀.₅ Alloy Slab

Problem Definition

The FeCo alloy slab presents a dual challenge: chemical disorder (Fe/Co site occupancy) and magnetic disorder (ferromagnetic vs. various antiferromagnetic couplings). The competition between direct exchange and double exchange mechanisms leads to multiple local minima.

Experimental Protocol & Computational Methodology

- Code & Functional: CPA-based (Coherent Potential Approximation) approach within the Korringa-Kohn-Rostoker (KKR) method, with LDA functional.

- Slab Model: 8-layer bcc(110) slab, 20 Å vacuum. 50 special quasi-random structures (SQS) generated for configurational averaging.

- SCF Protocol:

- Two-Stage Convergence: Stage 1: Converge charge density for a non-magnetic (NM) guess. Stage 2: Introduce spin polarization using the Broyden mixer with a Thomas-Fermi preconditioner.

- Momentum-Dependent Mixing: Mixing parameter

AMIX= 0.02 for s and p electrons,AMIX= 0.10 for d electrons to account for their different localization. - Constrained Local Moment (CLM) Method: For particularly stubborn configurations, 5-10 initial steps were run with moments on Fe/Co sites fixed to values from a Heisenberg model, then relaxed.

Quantitative Results

Table 2: Comparison of SCF Strategies for Fe₀.₅Co₀.₅ (110) Slab

| Strategy | Conv. Iterations (Avg.) | Final Magnetic Moment (μB/atom) | Total Energy Std. Dev. across SQS (meV/atom) |

|---|---|---|---|