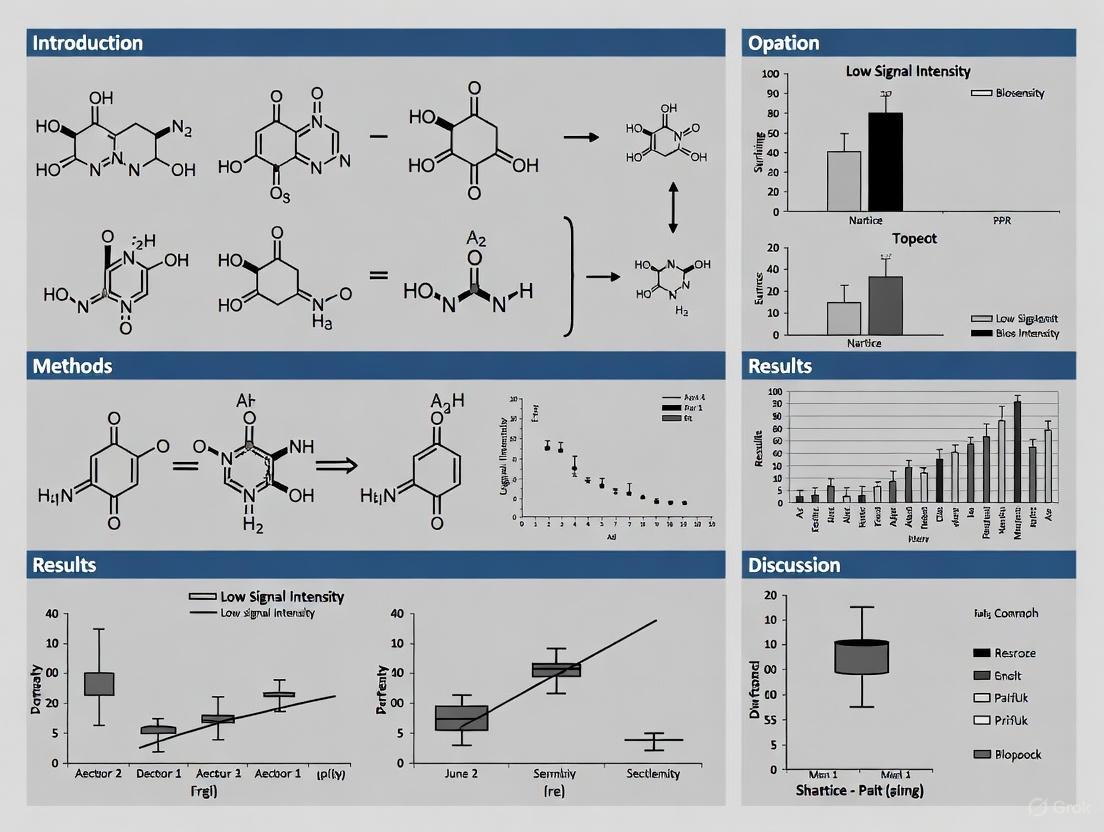

Overcoming Low Signal Intensity in SPR: A Comprehensive Guide to Optimization Strategies for Reliable Biomolecular Data

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the common challenge of low signal intensity in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments.

Overcoming Low Signal Intensity in SPR: A Comprehensive Guide to Optimization Strategies for Reliable Biomolecular Data

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the common challenge of low signal intensity in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments. Covering foundational principles to advanced optimization techniques, it details the root causes of weak signals—from insufficient ligand density and poor immobilization to suboptimal buffer conditions. The content delivers actionable methodologies for surface chemistry selection, immobilization strategy refinement, and sample preparation. Furthermore, it explores advanced troubleshooting protocols, the integration of algorithmic tools and nanomaterials for signal enhancement, and validation frameworks to ensure data reproducibility and accuracy, ultimately empowering scientists to achieve highly sensitive and reliable kinetic data.

Understanding the Roots of Low SPR Signal: A Deep Dive into Core Principles and Common Pitfalls

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is considered "low signal intensity" in an SPR experiment? Low signal intensity refers to a response unit (RU) signal that is too weak to be distinguished from the background noise of the instrument, making it difficult to obtain reliable data for calculating binding affinity (KD) and kinetics (kon and koff). This typically manifests as a flat or barely detectable sensorgram. A signal is often problematic if it is less than 10-20 RU for kinetic analysis on many commercial systems, though the exact acceptable threshold can depend on the specific instrument and application [1] [2].

Q2: How does low signal intensity negatively impact my affinity and kinetic measurements? Low signal intensity directly compromises data quality and reliability in several ways [1]:

- Increased Noise: The signal-to-noise ratio becomes poor, making it impossible to accurately determine the start and end points of binding events.

- Unreliable Kinetics: The calculation of association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants requires a clear, measurable change in the binding curve. A weak signal provides an insufficient dataset for fitting to kinetic models, leading to high errors or failed analysis.

- Inaccurate Affinity: The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) is derived from the kinetic constants (KD = koff/kon). If the kinetics are unreliable, the calculated affinity will also be incorrect.

Q3: My ligand is immobilized, but I see no binding signal. What are the primary causes? A lack of binding signal can be attributed to several factors, often related to the ligand, analyte, or sensor surface [1] [2]:

- Insufficient Ligand Activity or Density: The immobilized ligand may be inactive due to denaturation or improper orientation, or the density on the sensor chip may be too low.

- Low Analyte Concentration: The analyte concentration may be far below the expected KD value.

- Poor Immobilization Efficiency: The coupling chemistry may be inefficient, or the ligand may not have stably attached to the sensor surface.

- Non-Specific Binding (NSB) to Reference Surface: If NSB is high on the reference surface, subtraction can artifactually remove the specific signal.

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Signal Intensity

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Procedure

Follow this workflow to systematically identify and address the root cause of low signal intensity.

Detailed Troubleshooting Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing Ligand Immobilization

- Objective: To ensure sufficient and active ligand is present on the sensor surface.

- Procedure:

- Increase Ligand Density: Use a higher concentration of the ligand during the immobilization step. Aim for a density that gives a robust signal, but avoid levels that cause steric hindrance or mass transport limitation (typically 50-200 RU for proteins) [1] [2].

- Improve Coupling Efficiency: For covalent coupling, ensure the surface activation with EDC/NHS is fresh and efficient. Optimize the pH of the coupling buffer to ensure the ligand has the appropriate charge for attachment [1].

- Change Immobilization Strategy: If using amine coupling, try an alternative method such as streptavidin-biotin capture or use of NTA chips for His-tagged proteins. These can often provide better orientation and higher activity [2].

- Expected Outcome: A significant increase in the maximum response (Rmax) observed when a saturating concentration of analyte is injected.

Protocol 2: Evaluating and Preparing the Analyte

- Objective: To confirm the analyte is present, active, and capable of binding.

- Procedure:

- Concentration Series: Inject a wide range of analyte concentrations (e.g., from nM to µM) to ensure you are testing above and below the expected KD. If the KD is unknown, start with high concentrations and perform serial dilutions [2].

- Analyte Quality Control: Verify analyte purity using SDS-PAGE or other methods. Remove aggregates or degraded material through size-exclusion chromatography or centrifugation [1].

- Positive Control: If possible, use a known binding partner for your analyte to confirm its activity in an independent assay.

- Expected Outcome: A concentration-dependent binding response should become apparent.

Protocol 3: Mitigating Non-Specific Binding (NSB)

- Objective: To ensure the measured signal originates from specific interactions.

- Procedure:

- Include Blocking Agents: Add non-ionic detergents like Tween-20 (0.005-0.05%) or proteins like BSA (0.1-1%) to the running buffer and sample dilution buffer to block hydrophobic and charged sites on the sensor surface [1] [2].

- Adjust Buffer Conditions: Increase the ionic strength of the buffer (e.g., with 150-500 mM NaCl) to shield charge-based interactions. Adjust the pH to neutralize the surface or analyte charge [1].

- Use a Different Sensor Chip: Switch to a sensor chip with a different surface chemistry (e.g., from carboxymethyl dextran to a flat hydrogel or lipophilic surface) that is less prone to NSB with your specific molecules [2].

- Expected Outcome: A reduced signal in the reference flow cell and a cleaner specific binding signal.

Performance Optimization Data

The following table summarizes key parameters to optimize for enhancing signal intensity, based on established SPR practices [1] [2].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Signal Optimization

| Parameter | Sub-Optimal Condition | Optimized Condition | Impact on Signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Density | Too low (< 10 RU for small molecules) | Adjusted to achieve Rmax ~50-200 RU for kinetics | Direct Increase: Higher density provides more binding sites. |

| Analyte Concentration | Far below KD (e.g., < 0.1 x KD) | 0.1 to 10 x KD (min. 5 concentrations) | Direct Increase: Ensures measurable binding at relevant concentrations. |

| Flow Rate | Too low (e.g., < 10 µL/min) | Moderate to high (e.g., 30-100 µL/min) | Indirect Improvement: Reduces mass transport limitation and rebinding. |

| Buffer Additives | None, leading to high NSB | 0.05% Tween-20, 1% BSA, or increased salt | Noise Reduction: Suppresses non-specific binding, improving signal-to-noise. |

| Surface Chemistry | Prone to NSB or poor orientation | Matched to ligand properties (e.g., SA for biotin) | Efficiency Gain: Improves ligand activity and reduces background. |

Advanced optimization studies have demonstrated that algorithmic approaches can enhance sensor performance metrics by over 200%, pushing detection limits to the attomolar (aM) range, which is critical for detecting very low-abundance analytes [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in SPR Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A carboxymethylated dextran matrix for covalent coupling of ligands via amine groups. | General purpose protein immobilization [1] [2]. |

| NTA Sensor Chip | Coated with nitrilotriacetic acid for capturing His-tagged ligands via nickel chelation. | Reversible capture of His-tagged proteins [1] [2]. |

| Streptavidin (SA) Sensor Chip | Coated with streptavidin for capturing biotinylated ligands. | Highly stable and oriented immobilization of biotinylated antibodies or DNA [1]. |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | Crosslinker system for activating carboxyl groups on the sensor chip for covalent coupling. | Standard amine coupling protocol for proteins and other biomolecules [1] [4]. |

| HBS-EP Buffer | Common running buffer (HEPES, NaCl, EDTA, Surfactant P20) with low NSB. | Standard buffer for maintaining analyte stability and minimizing background [1] [2]. |

| Tween-20 | Non-ionic detergent used as a blocking agent to reduce hydrophobic interactions. | Added to running buffer at 0.005-0.05% to minimize NSB [1] [2]. |

| Ethanolamine | Used to block remaining activated ester groups after ligand coupling. | Final step in amine coupling to deactivate unused sites and reduce NSB [1] [4]. |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 1.5-3.0) | Low pH regeneration solution for breaking antibody-antigen interactions. | Stripping bound analyte from the ligand surface between analysis cycles [2]. |

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free analytical technique that enables real-time monitoring of biomolecular interactions. The core of SPR technology lies in its ability to convert minute refractive index changes at a sensor surface into quantifiable Response Units (RU). This process forms the SPR signal chain, a critical pathway that researchers must optimize to achieve reliable detection, especially when investigating low-abundance analytes or weak interactions. When signal intensity is low, understanding each link in this chain—from the initial biochemical binding event to the final digital readout—becomes paramount. Any disruption or inefficiency in this sequence can lead to failed experiments and inconclusive results. This guide deconstructs the SPR signal chain, provides targeted troubleshooting for low signal scenarios, and outlines advanced optimization strategies to enhance detection sensitivity for demanding applications.

Deconstructing the SPR Signal Chain

The SPR signal chain is a multi-stage process that transforms a molecular binding event into an analytical measurement. The following diagram visualizes this entire pathway, from the initial biochemical interaction to the final data output.

The signal chain begins when an analyte binds to its ligand immobilized on the sensor surface. This binding event increases the mass concentration at the surface, altering the local refractive index (RI) [5] [6]. This RI change is the critical first step; its magnitude directly determines the potential signal strength.

This local RI change modulates the evanescent electromagnetic field generated under surface plasmon resonance conditions. The evanescent wave typically penetrates approximately 100-200 nanometers into the medium adjacent to the metal film, making it exquisitely sensitive to surface events [7].

The altered electromagnetic field changes the surface plasmon resonance condition. Specifically, the resonance angle or wavelength shifts to compensate for the new refractive index environment [5] [8]. In the common Kretschmann configuration with a BK7 glass prism and 635 nm light, a protein layer of 3 nm can produce an angular shift of approximately 0.75 degrees [8].

This resonance shift manifests as a measurable change in the intensity of reflected light at a fixed angle, or a shift in the angle of minimum reflection [5]. The reflected light hits a photodetector, typically a position-sensitive detector (PSD) or charged-coupled device (CCD), which converts the photon flux into an electrical current [5].

Finally, the instrument processes this electrical signal, converting it into the digital Response Units (RU) displayed to the researcher. The relationship is defined such that 1 RU corresponds to a surface coverage of approximately 1 picogram per square millimeter [6]. This standardized unit allows comparison across different experiments and instrument platforms.

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Signal Intensity

Weak signal intensity is a common challenge in SPR experiments, particularly when working with low molecular weight analytes, low concentrations, or low-affinity interactions. The following table provides a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving the root causes of low signals.

Troubleshooting Low Signal Intensity

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| No significant signal change upon analyte injection [9] | - Low analyte concentration- Low ligand activity/immobilization- Incompatible molecular interaction | 1. Verify analyte concentration (spectrophotometry)2. Check ligand immobilization level (RU)3. Confirm binding compatibility (positive control) | - Increase analyte concentration if feasible- Optimize ligand immobilization density- Use different coupling chemistry (e.g., capture assay) [10] |

| Weak binding signal with poor signal-to-noise [9] | - Suboptimal mass transport- Low ligand density- Poor ligand orientation | 1. Examine flow rate dependence2. Compare immobilization levels across runs3. Check ligand functionality assay | - Increase flow rate (30-100 µL/min) [7]- Optimize ligand density for higher capacity- Use site-specific immobilization [9] |

| Rapid signal saturation making kinetics difficult [9] | - Analyte concentration too high- Ligand density too high- Mass transport limitation | 1. Inspect sensorgram shape2. Test lower analyte concentrations3. Evaluate flow rate dependence | - Reduce analyte concentration or injection time- Decrease ligand immobilization density- Increase flow rate to reduce mass transport effects [9] |

| High non-specific binding obscuring specific signal [10] | - Inadequate surface blocking- Non-optimal running buffer- Surface requires regeneration | 1. Compare reference and active flow cells2. Test different buffer additives3. Inject BSA to test surface | - Block with BSA or ethanolamine [9]- Add surfactant (e.g., 0.05% Tween 20) [6]- Optimize regeneration protocol between runs [9] |

| Excessive noise or baseline drift [9] | - Air bubbles in fluidics- Buffer contamination- Temperature fluctuations | 1. Check for sharp signal spikes (bubbles)2. Inspect baseline stability with fresh buffer3. Monitor system temperature | - Degas buffers thoroughly- Use fresh, filtered buffers- Place instrument in stable environment, ensure proper grounding [9] |

Advanced Diagnostics for Persistent Low Signals

When standard troubleshooting fails, these advanced experimental protocols can help isolate the problem:

Mass Transport Limitation Test

- Procedure: Run the same analyte concentration at multiple flow rates (e.g., 10, 30, 50, 100 µL/min).

- Interpretation: If binding response increases significantly with flow rate, mass transport is limiting the interaction. This suggests the observed kinetics are distorted, and higher flow rates or lower ligand densities are needed [9].

Ligand Activity Verification

- Procedure: Immobilize ligand, then inject a high concentration of a known binder with well-characterized kinetics.

- Interpretation: If the expected response is not achieved, the ligand may be inactive or improperly oriented, suggesting a need for alternative immobilization strategies [10].

Reference Surface Evaluation

- Procedure: Inject highest analyte concentration over a non-functionalized reference surface.

- Interpretation: Significant binding indicates non-specific binding, requiring improved surface blocking or buffer optimization [10].

SPR Optimization Strategies: Enhancing Signal Intensity

Recent research has demonstrated powerful optimization strategies that significantly enhance SPR signal intensity and detection limits. The following table summarizes quantitative performance improvements achieved through various advanced approaches.

Performance Comparison of SPR Optimization Strategies

| Optimization Strategy | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Improvement | Detection Limit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-objective PSO Algorithm [3] | - Sensitivity: 230.22% increase- FOM: 110.94% increase- DFOM: 90.85% increase | Bulk RI sensitivity, FOM, and DFOM significantly enhanced vs. conventional design | Mouse IgG: 54 ag/mL (0.36 aM) |

| ML-Optimized PCF-SPR Sensor [11] | - Wavelength Sensitivity: 125,000 nm/RIU- Amplitude Sensitivity: -1422.34 RIU⁻¹- FOM: 2112.15 | Machine learning identified optimal design parameters for maximum sensitivity | Resolution: 8 × 10⁻⁷ RIU |

| Bowtie PCF-SPR Sensor [12] | - Wavelength Sensitivity: 143,000 nm/RIU- Amplitude Sensitivity: 6242 RIU⁻¹- FOM: 2600 | Combination of external and internal sensing mechanisms | Resolution: 6.99 × 10⁻⁷ RIU |

| 2D Material Enhancement (Graphene/MoS₂) [3] | - Large specific surface area- Strong analyte binding capability | Significant sensitivity enhancement due to improved binding and field confinement | - |

Algorithm-Driven Optimization Protocols

Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) Protocol This methodology optimizes multiple sensor parameters simultaneously for comprehensive performance enhancement [3]:

Define Optimization Objectives: Establish sensitivity (S), figure of merit (FOM), and depth-resolved FOM (DFOM) as key performance metrics.

Parameter Selection: Identify critical design parameters to optimize: incident angle, adhesive layer thickness (chromium), and metal layer thickness (gold).

Model Optical Characteristics: Compute SPR reflectivity curves using the iterative transfer matrix method for a four-layer medium model (prism, chromium, gold, sensing medium).

Implement PSO Algorithm: Execute the optimization over approximately 150 iterations to maximize the multi-objective function combining S, FOM, and DFOM.

Experimental Validation: Apply optimized parameters to mouse IgG immunoassay, demonstrating detection down to 54 ag/mL.

Machine Learning-Enhanced Sensor Design Recent work demonstrates how machine learning can accelerate PCF-SPR sensor optimization [11]:

Data Generation: Perform COMSOL Multiphysics simulations to evaluate sensor properties (effective index, confinement loss, sensitivity) across parameter variations.

Model Training: Employ multiple regression algorithms (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, XGBoost) to predict optical properties from design parameters.

Explainable AI Analysis: Apply SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) to identify the most influential design parameters (wavelength, analyte RI, gold thickness, pitch).

Design Optimization: Use ML predictions to iterate toward optimal designs without exhaustive simulations, significantly reducing computational time and cost.

Experimental Workflow for Enhanced SPR Detection

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow that integrates optimization strategies and troubleshooting for low signal scenarios.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the minimum analyte concentration I can detect with SPR? A: The detection limit depends on multiple factors including molecular weight, binding affinity, and instrument sensitivity. With conventional SPR, detection below 1 × 10⁻¹⁵ g/mL is challenging, but recent optimizations using algorithmic approaches have achieved detection of mouse IgG at 54 ag/mL (0.36 aM) [3]. For context, a monolayer of Cytochrome c produces ~0.5° angular shift, and with an angular sensitivity of 0.1 mDeg, the mass sensitivity is approximately 0.6 pg/mm² [8].

Q2: Why does my baseline drift, and how can I stabilize it? A: Baseline drift can result from improperly degassed buffers (introducing air bubbles), leaks in the fluidic system, buffer contamination, or temperature fluctuations [9]. Ensure buffers are thoroughly degassed, check the system for leaks, use fresh filtered buffers, and place the instrument in a stable temperature environment with proper grounding to minimize electrical noise.

Q3: How can I reduce non-specific binding in my SPR experiments? A: Several strategies can minimize non-specific binding: (1) Block the sensor surface with suitable agents like BSA or ethanolamine before ligand immobilization; (2) Supplement running buffer with additives like surfactant (0.05% Tween 20) or BSA; (3) Optimize regeneration steps to efficiently remove bound analyte; (4) Consider alternative immobilization strategies such as site-directed immobilization [9] [10].

Q4: What are the key differences between angular sensitivity and surface sensitivity? A: Angular sensitivity refers to the minimum detectable shift in resonance angle (measured in degrees or mDeg), while surface sensitivity refers to the minimum detectable mass binding (measured in pg/mm² or RU). An instrument with excellent angular sensitivity may not necessarily have good surface sensitivity, as the conversion depends on instrumental conditions like prism material and wavelength [8]. For molecular binding studies, surface sensitivity is the more relevant parameter.

Q5: When should I consider using algorithm-based optimization for my SPR experiments? A: Algorithm-driven optimization is particularly valuable when: (1) Working with ultralow analyte concentrations approaching single-molecule detection; (2) Multiple performance parameters (sensitivity, FOM, DFOM) need simultaneous optimization; (3) Traditional single-variable optimization has failed to achieve desired sensitivity; (4) Designing specialized PCF-SPR sensors where multiple geometric parameters interact complexly [3] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines essential materials and their functions in SPR experiments, particularly for signal optimization.

Essential Research Reagents for SPR Optimization

| Reagent/Chip Type | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| L1 Sensor Chip [7] | Captures intact lipid vesicles using hydrophobic groups on the dextran surface. | Ideal for membrane-protein interactions; coating ranges: 5000-9000 RU; lifespan: 40-60 coatings. |

| HPA Sensor Chip [7] | Forms supported lipid monolayer via hydrophobic interactions with alkanethiol groups. | Preferred for proteins that induce vesicle fusion; creates a more uniform surface. |

| Series S Sensor Chips [6] | Carboxymethyldextran surface for covalent coupling via amine, thiol, or other chemistries. | Versatile for protein/nucleic acid interactions; standard for most applications. |

| Running Buffer Additives [10] [6] | Reduce non-specific binding (surfactants), maintain protein stability (BSA). | Use 0.05% Tween 20; BSA at 0.1-1 mg/mL; avoid detergents with lipid surfaces [7]. |

| Regeneration Solutions [9] [10] | Remove bound analyte while maintaining ligand activity for surface reuse. | Common options: 10 mM glycine (pH 2-3), 10 mM NaOH, 2M NaCl; often with 10% glycerol for stability. |

| Lipid Vesicles [7] | Create biomimetic membrane surfaces on L1 or HPA chips for membrane interaction studies. | Prepare at 0.5 mg/ml in HEPES buffer with 0.16M KCl; extrude through 100nm filter for uniformity. |

| 2D Materials (Graphene, MoS₂) [3] | Enhance sensitivity when used as interface layer between metal and sensing medium. | Large specific surface area and strong analyte binding capabilities improve signal. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Weak Signal Intensity

FAQ: Why is my SPR signal weak or low, and how can I fix it?

Weak signal intensity in SPR experiments often stems from two primary sources: insufficient ligand density on the sensor chip and poor immobilization efficiency. A low signal can compromise data quality, making kinetic parameter determination difficult or impossible.

- Symptom: The change in Response Units (RU) upon analyte injection is insignificant or much lower than expected.

- Primary Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Ligand Density: The amount of ligand immobilized on the sensor surface is too low to generate a detectable mass change upon analyte binding [1] [9].

- Poor Immobilization Efficiency: The ligand may not be attaching to the chip surface effectively, or the process may be resulting in a ligand that is improperly oriented or denatured, rendering it inactive [1] [13].

- Solution: Improve coupling conditions by adjusting the pH of the activation or coupling buffers [1]. Use different immobilization techniques (e.g., switch from amine coupling to a tag-based capture method like biotin-streptavidin or NTA-His tag) to ensure proper orientation and binding site accessibility [1] [2].

- Weak Binding Affinity: The interaction between the ligand and analyte may be inherently weak [1].

- Solution: Increase the concentration of the analyte in the injection solution to boost the signal [1].

- Inappropriate Sensor Chip: Using a standard chip for a specialized application might reduce sensitivity [14].

The following workflow diagram outlines the logical process for diagnosing and resolving weak signal issues.

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Ligand Immobilization

This protocol provides a methodology for establishing and optimizing ligand immobilization conditions to maximize signal intensity [1] [13].

Pre-concentration Test (pH Scouting):

- Purpose: To identify the optimal pH that promotes the attraction between the ligand and the sensor surface, ensuring efficient coupling.

- Method: Inject small volumes of your ligand (e.g., 0.5 mg/mL) in buffers of different pH (e.g., pH 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5 for a standard protein) over a non-activated sensor surface [15]. Use low-salt buffers (e.g., 10 mM sodium acetate) without reactive components like Tris or azide [15].

- Measurement: Monitor the transient binding response. A positive spike indicates the ligand is attracted to the surface at that pH. Choose the pH that gives the strongest response for the actual immobilization.

Ligand Immobilization:

- Surface Activation: For amine coupling, inject a mixture of EDC (N-ethyl-N'-(dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) over the sensor surface to activate the carboxyl groups [14].

- Ligand Coupling: Inject the ligand solution in the pre-determined optimal buffer. A typical immobilization requires about 25 µg of ligand at a concentration > 0.5 mg/mL [15].

- Surface Blocking: Inject ethanolamine to deactivate and block any remaining activated ester groups, minimizing non-specific binding [1].

Density Optimization:

- Purpose: Immobilize the right amount of ligand for your application.

- Method: Perform titrations of the ligand during immobilization. Test different concentrations and contact times to find the optimal surface density [1].

- Guidance:

- For kinetics studies, use the lowest density that gives a proper signal to avoid mass transport limitations and steric hindrance [1] [15].

- For affinity ranking, low to moderate density surfaces are sufficient [15].

- For concentration measurements, the highest ligand density is often needed to facilitate mass transfer limitation [15].

The table below summarizes key quantitative guidelines for ligand and analyte preparation to achieve high-quality data.

Table 1: Ligand and Analyte Preparation Guidelines

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Purpose & Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand for Immobilization | ~25 µg total, > 0.5 mg/mL | Ensures sufficient mass and concentration for a standard immobilization. Buffer must be compatible with chemistry (e.g., no amines in amine coupling buffer). | [15] |

| Analyte for Kinetic Study | 0.1 to 100 x the KD value | Covers a concentration range below and above the KD to define the binding curve accurately. Use a minimum of 3-5 concentrations. | [15] [2] |

| Analyte Volume (Example) | ~100 µL of a 5 µM stock | Example quantity sufficient for initial kinetic experiments (e.g., a two-minute injection at 25 µl/min). | [15] |

| Immobilization Time | 45 - 90 minutes per flow channel | Typical time required when starting from scratch, excluding pre-concentration scouting. | [15] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Immobilization

| Item | Function in SPR Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A carboxymethylated dextran matrix for covalent immobilization of ligands via amine, thiol, or other chemistries. | Versatile "gold standard"; 3D matrix may limit access for very large analytes [1] [14]. |

| NTA Sensor Chip | Captures histidine-tagged ligands via nickel chelation. | Allows for oriented immobilization; ligand can be stripped and surface regenerated [2]. |

| C1 Sensor Chip | A flat carboxymethylated surface without a dextran matrix. | Preferred for large analytes (e.g., nanoparticles, viruses) to prevent steric hindrance [14]. |

| EDC / NHS Chemistry | Activates carboxyl groups on the sensor chip surface for covalent coupling to primary amines on the ligand. | Most common covalent coupling method [14]. |

| Ethanolamine | A blocking agent used to deactivate excess reactive groups on the sensor surface after ligand coupling. | Reduces non-specific binding by quenching the activation reaction [1] [9]. |

| HBS-EP Buffer | A common running buffer (Hepes Buffered Saline with EDTA and Polysorbate). | Provides a consistent, low-non-specific-binding environment; surfactant (Polysorbate 20) helps prevent aggregation and NSB [1]. |

| Regeneration Buffer | Removes bound analyte from the immobilized ligand without destroying its activity, resetting the surface. | Composition is system-specific (e.g., low pH glycine, high salt, mild detergent). Must be optimized to balance efficacy with ligand stability [2] [9]. |

The Role of Molecular Weight and Binding Affinity in Signal Generation

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is an optical technique used to measure molecular interactions in real time without labels [6]. The SPR signal is directly dependent on the refractive index on the sensor chip surface, and when biomolecules bind, this refractive index changes [6]. Critically, the response is proportional to the mass on the surface—for any given interactant, the response is proportional to the number of molecules bound [6]. This fundamental relationship makes molecular weight a central factor in signal intensity, while binding affinity primarily governs the kinetics and stability of the interaction.

The following workflow outlines the systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving low signal intensity in SPR experiments:

Core Concepts: Molecular Weight and Binding Affinity

Molecular Weight Considerations

The relationship between molecular weight and SPR response is quantitative. The maximum response (Rmax) achievable when the ligand is saturated with analyte can be approximated using this fundamental equation [16]:

Rmax = (ResponseLigand × MassAnalyte) / MassLigand

This calculation becomes particularly critical when studying small molecules. For instance, with a 100 kDa protein ligand and a 100 Da small molecule analyte, achieving an Rmax of just 1 RU would require 1000 RU of ligand attached to the chip [16]. This mass-based relationship explains why low molecular weight analytes often produce weak signals.

Binding Affinity Fundamentals

SPR measures both kinetic parameters (association rate ka and dissociation rate kd) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) [16]. The KD represents the affinity between interacting molecules, with lower values indicating tighter binding. For accurate kinetic analysis, a minimum of 3-5 analyte concentrations between 0.1 to 10 times the expected KD value is recommended [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Signal Intensity

FAQ: Common Experimental Challenges

Why is my signal weak even though my analyte should bind? Weak signals frequently result from suboptimal mass ratios or improper experimental design [16] [17]. If your analyte has low molecular weight, you may need to increase ligand density or consider reversing the orientation of the interaction (immobilizing the smaller molecule instead) [2]. Additionally, protein quality issues—such as denaturation during immobilization, aggregation, or improper storage—can render proteins non-functional and unable to perform expected interactions [17].

How does molecular weight difference affect my experiment? Large disparities in molecular weight between ligand and analyte present significant detection challenges [16]. Small molecule binding (<1 kDa) to large macromolecular ligands (>10 kDa) requires special consideration. When kinetics are desired, it may be necessary to use fragments of larger ligands that encapsulate the binding site to improve signal resolution [16].

My binding affinity seems incorrect—what could be wrong? Inaccurate affinity measurements often stem from partially non-functional protein preparations [17]. If a percentage of protein molecules are denatured or improperly folded, the calculated affinity and kinetics will be skewed because the input numbers used in calculations don't reflect the actual concentration of functional molecules [17]. Protein dimerization or oligomerization can similarly distort results [17].

Quantitative Relationship Guide

Table 1: Molecular Weight Impact on SPR Signal Requirements

| Analyte Mass | Ligand Mass | Target Rmax | Required Ligand RU | Feasibility Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 Da (Small molecule) | 100 kDa (Protein) | 1 RU | 1,000 RU | Moderate [16] |

| 100 Da (Small molecule) | 100 kDa (Protein) | 100 RU | 100,000 RU | Not feasible (exceeds standard chip capacity) [16] |

| 10 kDa (Protein fragment) | 10 kDa (Protein) | 100 RU | 1,000 RU | Highly feasible [16] |

Table 2: Analyte Concentration Ranges for Binding Affinity Studies

| Expected KD | Recommended Concentration Range | Number of Concentrations | Steady-State Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Known KD | 0.1 to 10 × KD | Minimum 3, ideally 5 [2] | 8-10 concentrations for single data points [2] |

| Unknown KD | Low nM upward until binding response observed [2] | 5+ for kinetics | Not applicable until saturation observed [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Signal Optimization

Protocol 1: Maximizing Signal for Low MW Analytes

Ligand Selection Strategy: Immobilize the smaller binding partner to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio [2]. For small molecule studies, use protein fragments containing the binding domain rather than full-length proteins to improve mass ratio [16].

Ligand Density Optimization: Calculate theoretical Rmax using the formula Rmax = (ResponseLigand × MassAnalyte)/MassLigand [16]. Aim for lower ligand densities to avoid analyte depletion at the sensor surface during association [2].

Surface Chemistry Selection: Employ high-affinity capture techniques (His-tag/NTA, biotin/streptavidin) that preserve ligand orientation and activity [16] [1]. For covalent immobilization, ensure the method doesn't obscure the binding site.

Signal Amplification: For challenging systems, consider high-sensitivity sensor chips (CM7) designed for greater ligand capture capacity [16].

Protocol 2: Accurate Binding Affinity Determination

Sample Quality Verification: Characterize protein samples for monodispersity and functionality before SPR analysis. Aggregated or denatured proteins will produce skewed affinity measurements [17].

Concentration Series Design: Prepare analyte dilutions in running buffer matched for all components (DMSO, detergent, salts) to avoid buffer mismatch artifacts [16] [2]. Use serial dilution to minimize pipetting errors [2].

Reference Surface Preparation: Include a ligand-free reference flow cell to compensate for bulk refractive index differences and non-specific binding [2] [6].

Regeneration Optimization: Develop regeneration conditions that completely remove bound analyte without damaging ligand functionality [16] [2]. Start with mild conditions and progressively increase stringency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for SPR Signal Optimization

| Reagent/Chip Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | Carboxymethylated dextran surface for covalent immobilization [16] [1] | General protein-protein interactions; amine coupling |

| NTA Sensor Chip | Captures His-tagged ligands with oriented immobilization [16] [1] | Membrane proteins; tagged recombinant proteins |

| SA Sensor Chip | Streptavidin-coated surface for biotinylated ligands [1] | DNA studies; biotinylated antibodies or receptors |

| Running Buffer with Tween-20 | Reduces non-specific binding; maintains sample stability [6] | All applications; particularly important for crude samples |

| Regeneration Solutions | Removes bound analyte between cycles without damaging ligand [16] | High-throughput screening; slow-dissociating interactions |

| MSP1D1 Nanodiscs | Membrane mimetics for studying lipid-protein interactions [16] | Membrane protein studies; lipid-binding analyses |

Advanced Optimization Strategies

Addressing Mass Transport Limitations

When the diffusion rate of analyte to the sensor surface is slower than the association rate constant (ka), binding kinetics become mass transport limited [2]. To identify this effect:

- Examine the binding curve for a linear association phase with lack of curvature [2]

- Conduct flow rate experiments—if ka decreases at lower flow rates, the interaction is mass transport limited [2]

- Compare data fits using both 1:1 Langmuir and 1:1 Langmuir mass transport corrected models [2]

Mitigating Non-Specific Binding (NSB)

Non-specific binding inflates response units and skews calculations [1] [2]. Address NSB by:

- Adjusting buffer pH to neutralize charge-based interactions [2]

- Adding non-ionic surfactants (Tween-20) to disrupt hydrophobic interactions [1] [2]

- Increasing salt concentration to shield charged proteins from sensor surface [2]

- Using protein blocking additives (BSA) in buffer and sample solutions [2]

Buffer Composition and Bulk Shift Control

Bulk shift occurs due to refractive index differences between analyte solution and running buffer [2]. Minimize this by:

- Matching all buffer components between analyte samples and running buffer [16] [2]

- Maintaining consistent DMSO concentrations across all solutions when working with organic molecules [16]

- Including detergent (0.05% Tween-20) in running buffer to reduce non-specific binding [6]

Successful SPR experimentation requires careful consideration of both molecular weight relationships and binding affinity parameters. The mass-based nature of SPR detection means that molecular weight directly influences signal intensity, while binding affinity governs the kinetic and equilibrium parameters of the interaction. By systematically addressing both factors through optimized experimental design, appropriate surface chemistry selection, and rigorous sample preparation, researchers can overcome common challenges associated with low signal intensity and obtain reliable, publication-quality data.

FAQs: Addressing Common SPR Signal Issues

What are the primary causes of low signal intensity in SPR experiments? Low signal intensity, or a weak binding response, can stem from several factors related to the three core areas of assay design [1]:

- Sample Quality: Insufficient ligand density on the sensor chip, low analyte concentration, or low activity of the immobilized ligand due to improper orientation or denaturation.

- Buffer Composition: A significant mismatch between the running buffer and the analyte buffer can cause a bulk shift, obscuring the specific binding signal. The wrong buffer can also fail to stabilize your molecules or promote non-specific binding [2].

- Surface Chemistry: Choosing a sensor chip chemistry that is incompatible with your ligand can lead to low immobilization levels or render the binding site inaccessible. Non-specific binding to the surface can also inflate the background noise, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio [10] [18].

How can I reduce non-specific binding (NSB) in my assay? Non-specific binding occurs when your analyte interacts with the sensor surface itself rather than your specific ligand. You can mitigate it with the following strategies [10] [1] [2]:

- Optimize Buffer Composition: Add blocking agents like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA at ~1%), non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Tween 20), or increase the salt concentration (e.g., NaCl) to shield charged-based interactions.

- Select Appropriate Surface Chemistry: Change to a sensor chip with a different surface charge or properties. Using a capture coupling strategy (e.g., NTA for His-tagged proteins) can improve orientation and reduce NSB.

- Adjust Analyte and Ligand: If possible, use the more negatively charged molecule as the analyte to reduce interaction with commonly used negatively charged sensor surfaces.

My analyte doesn't dissociate, making surface regeneration difficult. What can I do? Successful regeneration removes the bound analyte while keeping the ligand active. It often requires empirical testing [10] [18] [2]:

- Test Different Solutions: Start with mild conditions and progressively increase intensity. Common reagents include:

- Acidic: 10 mM Glycine-HCl, pH 2.0 - 3.0

- Basic: 10 - 50 mM NaOH

- High Salt: 1 - 2 M NaCl

- Additives: 10-50% glycerol can help stabilize the ligand during regeneration.

- Use Short Contact Times: Use high flow rates (100-150 µL/min) for brief injections to minimize ligand damage.

- Verify Ligand Activity: Always include a positive control after regeneration to ensure the ligand remains active and the binding response is consistent.

The binding curve appears linear instead of curved. What does this indicate? A linear association phase often indicates that the binding kinetics are mass transport limited [19] [2]. This means the rate at which analyte molecules diffuse from the bulk solution to the sensor surface is slower than their intrinsic association rate constant. To identify and address this:

- Conduct a Flow Rate Test: Run your assay at multiple flow rates. If the observed association rate (ka) increases with higher flow rates, mass transport is influencing your data.

- Reduce Ligand Density: A lower density of immobilized ligand reduces the analyte consumption at the surface, mitigating the diffusion gradient.

- Use a Laminar Flow Cell: Ensure your instrument's flow cell is designed for efficient mass transport.

Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Guide: Optimizing Sample Quality and Immobilization

Objective: To maximize specific binding signal by ensuring high ligand activity and appropriate surface density.

Protocol for Ligand Immobilization Optimization:

- Ligand Selection: Choose the smaller, purer binding partner as the ligand to maximize the response per unit mass [2]. If it is tagged (e.g., His-tag, Biotin), use a compatible capture sensor chip (e.g., NTA, SA) for better orientation and activity [19].

- Purity Check: Purify and characterize your ligand and analyte beforehand. Impurities like aggregates or denatured proteins can cause non-specific binding or clog the microfluidics [1].

- Immobilization Level: Aim for a lower ligand density (e.g., 50-100 Response Units (RU) for kinetic studies) to avoid mass transport limitations and steric hindrance. For small molecule detection or low-affinity interactions, a higher density may be necessary [2].

- Activity Validation: Test the activity of your immobilized ligand by injecting a known positive control analyte. A low response may indicate inactive ligand due to denaturation or incorrect orientation, necessitating a different immobilization strategy (e.g., covalent coupling via amine vs. thiol groups) [10] [18].

Guide: Systematic Buffer Optimization

Objective: To create an optimal chemical environment for specific binding while minimizing bulk effects and non-specific interactions.

Protocol for Buffer Screening:

- Match Buffers: Prepare the analyte samples in the running buffer to avoid bulk refractive index shifts. If additives (e.g., DMSO, glycerol) are necessary for solubility, include the same concentration in both the running buffer and analyte samples [2].

- Screen Additives: If non-specific binding is suspected, systematically test additives in your running buffer.

- pH Scouting: The buffer pH can affect the charge and stability of your molecules. Perform scouting experiments around the theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of your proteins to find the condition that minimizes non-specific electrostatic interactions [2].

Advanced Optimization: Algorithmic and Machine Learning Approaches

For fundamental sensor enhancement, research is focused on optimizing the physical parameters of the SPR system itself using advanced computational methods. The table below summarizes performance metrics from recent studies that employed such strategies for hardware optimization.

Table 1: Performance Metrics from Algorithm-Optimized SPR Sensors

| Optimization Method | Sensor Type | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-objective PSO [3] | Prism-based SPR | Sensitivity Enhancement | 230.22% improvement | Mouse IgG detection |

| Machine Learning (XGBoost) & XAI [11] | PCF-SPR | Wavelength Sensitivity | 125,000 nm/RIU | Biomedical sensing |

| Nelder-Mead Algorithm [20] | SPR-PCF | Amplitude Sensitivity | -6,202.62 RIU⁻¹ | Sucrose detection |

Protocol for Multi-Parameter Sensor Optimization using PSO:

- Define Objectives: Establish key performance metrics as optimization targets, such as Sensitivity (S), Figure of Merit (FOM), and Depth of Resonant Dip (DRD) [3].

- Set Variable Space: Identify the design parameters to be optimized (e.g., incident light angle, metal layer thickness, adhesive layer thickness) [3].

- Algorithm Execution: Implement a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm to iteratively search the variable space. The algorithm evaluates the fitness (performance) of each parameter set and converges toward the global optimum [3].

- Validation: Fabricate the sensor with the optimized parameters and experimentally validate its performance against the predicted metrics [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for SPR Troubleshooting and Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Usage & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Blocking agent to reduce non-specific binding by occupying hydrophobic sites on the sensor surface. | Used at 0.1-1% in running buffer or sample dilution buffer [10] [2]. |

| Tween 20 | Non-ionic surfactant to disrupt hydrophobic interactions between the analyte and sensor surface. | Use at low concentrations (0.005-0.01%) to avoid protein denaturation [1] [2]. |

| NaCl | Salt used to shield electrostatic, charge-based non-specific interactions. | Concentration can be titrated from 150 mM to 500 mM or higher based on need [2]. |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0) | Acidic regeneration solution for disrupting antibody-antigen and other protein-protein interactions. | A common starting point for regeneration scouting; 10-30 second injection is typical [10] [18]. |

| NaOH (10-50 mM) | Basic regeneration solution for disrupting hydrophobic or protein-nucleic acid interactions. | Effective for many systems; monitor ligand stability over multiple cycles [10] [18]. |

| NTA Sensor Chip | For capturing His-tagged ligands, ensuring proper orientation and allowing for gentle surface regeneration. | Ideal for proteins with a His-tag; ligand can be stripped and re-captured for a fresh surface [19] [2]. |

| CM5 Sensor Chip | Versatile carboxylated dextran matrix for covalent coupling via amine groups. | A standard choice for many protein immobilizations using EDC/NHS chemistry [1]. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Visualization

SPR Low Signal Troubleshooting Guide

SPR Optimization Strategy Map

Advanced Surface Chemistry and Immobilization Strategies to Boost SPR Response

This guide provides a structured approach to selecting and optimizing Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) sensor chips, a critical factor in overcoming low signal intensity and obtaining high-quality, reproducible binding data.

The sensor chip is the heart of any Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiment. Its surface chemistry determines how the ligand is immobilized, which directly influences the activity, orientation, and stability of the captured molecule. Selecting the appropriate chip type is a fundamental first step in designing a robust assay and is a primary strategy for mitigating low signal intensity. An ill-suited chip can lead to low immobilization levels, improper ligand orientation, or high non-specific binding, ultimately compromising data quality and reproducibility. This guide focuses on three common sensor chip types—CM5, NTA, and SA—to help you match the chip chemistry to your specific experimental needs.

Sensor Chip Types and Characteristics

The table below summarizes the key properties, applications, and considerations for CM5, NTA, and SA sensor chips.

Table 1: Comparison of Common SPR Sensor Chips

| Chip Type | Surface Chemistry | Immobilization Method | Optimal For | Key Advantages | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM5 | Carboxymethylated dextran matrix | Covalent coupling (e.g., via amine, thiol groups) | Proteins, antibodies, DNA [1] | High binding capacity; versatile chemistry | Risk of random orientation; requires purified ligand [1] |

| NTA | Nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) on a surface | Capture of His-tagged proteins via Ni²⁺ ions | Recombinant proteins with a His-tag [1] [21] | Controlled, uniform orientation; surface can be regenerated with mild chelators | Baseline drift due to ligand leaching; requires His-tagged ligand [21] |

| SA | Streptavidin covalently attached to surface | Capture of biotinylated molecules | Biotinylated DNA, proteins, carbohydrates [1] | Very stable binding; excellent for capturing biotinylated ligands | Risk of non-specific binding; requires biotinylated ligand [1] |

Sensor Chip Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate sensor chip based on your ligand and assay requirements.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: I am not getting any signal change upon analyte injection. What should I check?

- Verify Ligand Activity: Confirm that your immobilized target protein is still active and functional. Inactivity can arise from denaturation or the binding site being obscured by the surface [10].

- Check Immobilization Level: Ensure a sufficient amount of ligand has been immobilized on the sensor surface. A very low immobilization level will produce a weak signal [9].

- Confirm Analyte Concentration: The analyte concentration may be too low for detection. Perform a concentration series to establish a detectable range [9] [1].

- Assess Surface Functionality: If using a capture chip (like NTA or SA), ensure the capturing moiety (e.g., Ni²⁺, streptavidin) is still active and not saturated or degraded [21].

Q2: How can I reduce non-specific binding (NSB) to my sensor chip?

- Use a Blocking Agent: After immobilization, block any remaining active sites on the sensor surface with inert proteins like BSA or ethanolamine [10] [1].

- Optimize Running Buffer: Supplement your running buffer with additives that minimize NSB, such as surfactants (e.g., Tween-20), BSA, or dextran [10] [1].

- Employ a Reference Channel: Always use a reference flow cell immobilized with a non-interacting ligand or just the blocked surface. This allows for automatic subtraction of bulk refractive index shifts and non-specific signals [10].

- Consider Alternative Chips: Some sensor chips have hydrogels or surface chemistries designed to be more inert. Switching to a chip with a different surface chemistry can sometimes reduce NSB [10].

Q3: My NTA chip surface is unstable and shows significant baseline drift. How can I fix this?

- Stabilize the Surface: The weak interaction between the His-tag and Ni²⁺ can cause ligand dissociation and baseline drift. A proven protocol involves capturing the His-tagged protein on the NTA chip and then using standard chemistry to covalently stabilize the captured protein. This eliminates drift while maintaining a highly active and oriented surface [21].

Q4: The signal saturates too quickly, making kinetic analysis difficult. What can I do?

- Reduce Ligand Density: A surface with an excessively high density of ligand can lead to mass transport limitation and rapid saturation. Aim for a lower immobilization level (e.g., 50-100 RU for kinetics) [9].

- Lower Analyte Concentration: Inject a lower concentration of analyte to slow down the association phase and obtain a more interpretable sensorgram [9].

- Increase Flow Rate: A higher flow rate can help reduce mass transport effects, delivering analyte to the surface more efficiently [9] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for SPR Sensor Chip Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A versatile chip with a carboxymethylated dextran matrix for covalent coupling. | Immobilizing antibodies or proteins via amine coupling [1]. |

| NTA Sensor Chip | A chip functionalized with NTA groups for capturing His-tagged proteins via Ni²⁺ ions. | Capturing recombinant His-CypA for small molecule interaction studies [21]. |

| SA Sensor Chip | A chip with a pre-immobilized streptavidin layer. | Capturing biotinylated DNA or biotinylated antibodies [1]. |

| EDC/NHS | Cross-linking reagents used to activate carboxyl groups on chips like CM5 for covalent coupling. | Activating the CM5 dextran matrix prior to ligand immobilization [1]. |

| Ethanolamine | A blocking agent used to deactivate and block remaining activated ester groups after coupling. | Blocking the CM5 surface post-ligand immobilization to reduce NSB [1]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A common blocking agent used to passivate the sensor surface. | Adding to running buffer or using as a blocking step to minimize non-specific binding [10] [9]. |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0) | A low-pH regeneration solution. | Stripping bound analyte from an antibody-coated surface without damaging the ligand [10]. |

FAQ: Core Concepts and Method Selection

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between covalent coupling and capture methods?

Covalent coupling creates a permanent, stable bond between the ligand and the sensor chip surface, while capture methods use non-covalent, high-affinity interactions to temporarily attach the ligand [22] [23]. This key difference leads to distinct practical implications, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison between Covalent Coupling and Capture Methods

| Feature | Covalent Coupling | Capture Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Type | Permanent covalent bond [23] | Transient, non-covalent (except streptavidin-biotin) [22] [23] |

| Ligand Consumption | Low; surface is reusable [22] [23] | High; fresh ligand often needed for each cycle [22] [23] |

| Ligand Purity Requirement | High, to avoid immobilizing impurities [24] | Lower; capturing acts like affinity purification [22] [2] |

| Orientation Control | Random, which can block binding sites [22] [23] | Specific and controlled, improving activity [22] [23] [24] |

| Surface Stability | High and stable over time [23] | Can be decaying; ligand may be removed during regeneration [23] |

Q2: How do I decide whether to use a covalent or capture method for my ligand?

The choice depends on the properties of your ligand and the goal of your experiment. The following decision flowchart outlines key questions to guide your selection.

Q3: Which covalent coupling chemistry should I use for my protein?

The optimal chemistry depends on the functional groups available on your ligand. Amine coupling is the most common first choice, but alternatives may be superior for specific ligands [22].

Table 2: Suitability of Covalent Coupling Chemistries for Different Ligands

| Ligand Type | Amine Coupling | Thiol Coupling | Aldehyde Coupling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic Proteins (pI < 3.5) | Not suitable [22] | Recommended [22] | Not suitable [22] |

| Neutral/Basic Proteins | Recommended [22] | Acceptable [22] | Requires modification [22] |

| Nucleic Acids | Not suitable [22] | Not suitable [22] | Not suitable [22] |

| Polysaccharides/Glycoconjugates | Not suitable [22] | Not suitable [22] | Best choice [22] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Signal Intensity

Low signal intensity is a common issue often traced back to the immobilization step. The problems and solutions differ between the two methods.

Q4: I used covalent coupling, but my signal is low. What could be wrong?

Low signal after covalent coupling is frequently caused by improper ligand orientation or inactivation.

- Problem: Random Orientation. When ligands are coupled randomly via amine groups, the binding site may be obstructed or facing the sensor surface, making it inaccessible to the analyte [22] [23].

- Solution: Use Unidirectional Immobilization.

- For Antibodies: Biotinylate antibodies via carbohydrate groups for oriented capture on a streptavidin chip. Alternatively, generate Fab' fragments and immobilize them using thiol coupling [22].

- For Other Proteins: Introduce unique functional groups (e.g., cysteine residues) for site-specific coupling, ensuring the binding domain is exposed [22].

- Problem: Ligand Inactivation. The low pH conditions used in amine coupling or the chemical reactions themselves can denature the ligand and reduce its activity [22] [10].

- Solution:

- Switch Coupling Chemistry: Use a milder chemistry like thiol coupling, which is more robust and uses less critical pH conditions [22] [10].

- Use a Capture Approach: Immobilize a capturing molecule (e.g., an antibody) covalently and then bind your ligand under gentle, native conditions [22] [10]. This protects your ligand from harsh coupling chemistry.

Q5: I used a capture method, but my signal is still weak. How can I fix this?

For capture methods, low signal often relates to the capturing efficiency and ligand activity.

- Problem: Low Capture Efficiency. The density of the capturing molecule (e.g., streptavidin, NTA, antibody) on the surface may be too low, or the ligand may not be efficiently binding to it.

- Solution: Optimize Capture Surface Density.

- Increase the immobilization level of the capturing molecule while being mindful that very high densities can cause steric hindrance [1] [25].

- Ensure your ligand is properly tagged (e.g., biotinylated, His-tagged) and that the tag is accessible.

- For His-tagged proteins, ensure the running buffer does not contain high concentrations of imidazole or EDTA, which could compete with or disrupt the NTA-metal interaction [23].

- Problem: Ligand Instability on Surface. Some captured ligands may dissociate over time or during the analyte injection, leading to a decaying surface and lower signal [23].

- Solution:

Troubleshooting Guide: Non-Specific Binding and Regeneration

Q6: How can I reduce high non-specific binding (NSB) after immobilization?

Non-specific binding occurs when the analyte adheres to the sensor surface or the immobilized ligand without specificity, skewing the data [10] [1] [2].

- Strategy 1: Optimize Buffer Composition.

- Add Surfactants: Include non-ionic detergents like Tween-20 (e.g., 0.005%) in the running buffer to disrupt hydrophobic interactions [1] [2].

- Add Protein Blockers: Supplement buffers with BSA (e.g., 1%) to shield the surface from non-specific protein interactions [10] [2].

- Adjust Ionic Strength: Increase salt concentration (e.g., NaCl) to shield charged surfaces from electrostatic interactions with the analyte [2].

- Strategy 2: Optimize Surface and Ligand Charge.

- If using a negatively charged sensor chip (e.g., carboxymethyl dextran), ensure the analyte is not highly positively charged. If it is, consider using the more negatively charged molecule as the analyte to reduce electrostatic NSB [24].

- Strategy 3: Improve Surface Blocking.

- After covalent immobilization, use a blocking agent like ethanolamine to deactivate any remaining reactive groups on the sensor surface [1].

Q7: I cannot regenerate my surface completely. What should I do?

Regeneration removes the bound analyte while leaving the ligand intact and active for the next injection [10] [2]. An incomplete regeneration leads to carryover and inaccurate data.

- Solution: Systematically Scout Regeneration Conditions.

- Start with mild conditions and progressively increase the intensity. A good scouting series includes [10] [2]:

- 10 mM Glycine-HCl, pH 2.0 - 3.0

- 10 mM NaOH

- 2 M NaCl

- 0.1% - 0.5% SDS (use with caution as it can denature the ligand)

- Add Stabilizers: For delicate ligands, adding 10% glycerol to the regeneration solution can help maintain ligand stability [10].

- Use Short Contact Times: Inject the regeneration solution at a high flow rate (e.g., 100-150 µL/min) for a short duration (e.g., 15-60 seconds) to minimize ligand exposure to harsh conditions [2].

- Start with mild conditions and progressively increase the intensity. A good scouting series includes [10] [2]:

Table 3: Common Regeneration Buffers for Different Interaction Types

| Analyte-Ligand Bond Type | Recommended Regeneration Solutions |

|---|---|

| Protein-Protein | 10 mM Glycine pH 2.0 - 3.0, 10 mM NaOH, 2 M NaCl [10] |

| Antibody-Antigen | 10 mM Glycine pH 1.5 - 2.5, 3 M MgCl₂, 0.1% SDS [2] |

| His-tagged Protein - NTA | 350 mM EDTA, 10-300 mM Imidazole [23] [2] |

| Biotin-Streptavidin | 6 M Guanidine HCl, 0.1% SDS (often not regenerable) [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents used in SPR immobilization optimization and their specific functions in troubleshooting.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for SPR Immobilization and Troubleshooting

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A carboxymethyl dextran chip for general-purpose covalent coupling, especially via amine chemistry [1] [23]. | High binding capacity but can induce steric hindrance or mass transport limitations at high density [25]. |

| SA Sensor Chip | Pre-coated with streptavidin for capturing biotinylated ligands, ensuring oriented immobilization [1] [23]. | Provides a highly stable surface due to the strong biotin-streptavidin affinity [23]. |

| NTA Sensor Chip | Coated with nitrilotriacetic acid for capturing His-tagged proteins [22] [1]. | Requires charging with nickel or other metal ions. Regenerated with EDTA/imidazole [23]. |

| EDC / NHS | Cross-linking reagents used to activate carboxyl groups on the sensor chip for covalent amine coupling [1]. | Standard protocol; the low pH of the coupling buffer can inactivate some sensitive proteins [22]. |

| Ethanolamine | Used to block remaining activated ester groups on the sensor surface after covalent coupling [1]. | Reduces non-specific binding by deactivating the reactive surface. |

| Tween-20 | A non-ionic surfactant added to running buffers (e.g., 0.005%) to reduce hydrophobic non-specific binding [1] [2]. | Mild and generally does not disrupt specific biomolecular interactions. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A proteinaceous blocking agent used to coat surfaces and minimize non-specific adsorption of analytes [10] [2]. | Typically used at 0.1-1% concentration. Should not be used during ligand immobilization. |

Core Concepts: Density, Orientation, and Steric Hindrance

What is the fundamental relationship between ligand density, orientation, and steric hindrance in an SPR experiment?

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensors, the immobilization of the ligand (the capture molecule) is a critical step that dictates the success of the entire experiment. The density of the ligand on the sensor surface and its orientation are two pivotal factors that directly influence the accessibility of its binding sites. When these factors are not optimized, they lead to steric hindrance, a phenomenon where closely packed or poorly oriented ligands physically block the analyte from binding, resulting in reduced signal intensity, inaccurate kinetic data, and an underestimation of binding affinity [26] [1].

The following diagram illustrates how different immobilization strategies affect ligand orientation and the resulting analyte binding efficiency, which is a primary cause of steric hindrance.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ: How can I tell if my low signal is due to steric hindrance?

Answer: Several symptoms in your sensorgram can indicate steric hindrance [9] [27]:

- Rapid Saturation: The sensorgram reaches saturation too quickly, even at low analyte concentrations, making it difficult to determine kinetic parameters.

- Weak Signal Change: The overall change in response units (RU) upon analyte injection is lower than expected for the given ligand density.

- Non-1:1 Binding Kinetics: The binding curves do not fit a standard 1:1 interaction model well, often because a portion of the immobilized ligands is inactive due to blocking.

- Mass Transport Limitation: The binding rate is limited by the diffusion of the analyte to the surface, rather than the interaction itself, which becomes more likely with very high-density surfaces.

FAQ: What are the best strategies to control ligand orientation?

Answer: Controlling orientation ensures the binding site is exposed to the solution. Key strategies include [1] [10]:

- Site-Specific Immobilization: Instead of random coupling (e.g., amine coupling), use methods that target a specific site on the ligand.

- Thiol Coupling: For ligands with free cysteine residues, this allows coupling at a defined point.

- Capture Methods: Use a surface pre-immobilized with streptavidin (SA chip) to capture biotinylated ligands, or with an antibody to capture His-tagged or Fc-tagged ligands. This provides a uniform orientation.

- Use of Aptamers: Aptamers, which are oligonucleotide-based affinity probes, can be engineered with specific terminal modifications for highly controlled immobilization, minimizing orientation issues [28].

FAQ: Is there an ideal ligand density to aim for?

Answer: There is no universal "ideal" density, as it depends on the size of the ligand and analyte and the kinetics of the interaction. However, the guiding principle is to use the lowest density that gives a reliable signal above the baseline noise [27]. Low responses are generally preferred over high responses because they are less affected by mass transport and non-1:1 interactions. As a starting point for a new experiment, calculating a target response of around 100 RU for the ligand is often recommended, followed by iterative optimization [27].

Table 1: Symptoms and Diagnostic Steps for Steric Hindrance

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Signal saturation at low analyte concentrations [9] | Excessive ligand density; steric hindrance | Reduce ligand immobilization level by 50-75% and re-run analysis [27]. |

| Poor fit to a 1:1 binding model [9] | Heterogeneous ligand activity due to random orientation | Switch to a site-specific immobilization method (e.g., capture) [1] [10]. |

| Weak binding signal despite sufficient ligand [9] [1] | Binding site is buried or obstructed | Try an alternative coupling chemistry or ligand orientation. |

FAQ: My ligand is inactive after immobilization. What should I do?

Answer: Inactivity often means the binding pocket is inaccessible. To resolve this [10]:

- Change Coupling Method: Perform a capture experiment instead of covalent coupling.

- Alternative Attachment Points: If possible, couple the ligand via a different functional group (e.g., a thiol group) that is away from the active site.

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol 1: Method for Site-Specific Immobilization via Biotin-Streptavidin Capture

This protocol is ideal for controlling orientation and minimizing steric hindrance.

- Chip Selection: Use a streptavidin (SA) sensor chip.

- Ligand Preparation: Biotinylate your ligand using a chemistry that targets a region distant from the binding site (e.g., enzyme-mediated biotinylation of a specific tag).

- Immobilization: Inject the biotinylated ligand solution over the SA chip surface. The strong biotin-streptavidin interaction will capture the ligand in a uniform orientation.

- Blocking (Optional): Inject a low concentration of free biotin to block any unoccupied streptavidin sites, reducing non-specific binding [1].

- Analysis: Proceed with analyte binding experiments.

Protocol 2: Titration Method for Determining Optimal Ligand Density

This empirical method helps find the ideal density for your specific system [27].

- Prepare Multiple Surfaces: Immobilize your ligand on several sensor channels (or separate chips) at different densities, spanning a wide range (e.g., 50 RU, 500 RU, 5000 RU).

- Inject a Standard Analyte: Using the same analyte concentration and buffer conditions, inject over each surface with different ligand densities.

- Analyze Sensorgrams: Compare the binding responses and the quality of the kinetic data.

- Identify the Optimal Range: The optimal density is one that yields a strong, reproducible signal with well-shaped association and dissociation curves that fit a binding model reliably. It is often lower than expected [27].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Ligand Immobilization Strategies

| Strategy | Principle | Advantages for Preventing Steric Hindrance | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amine Coupling | Covalent attachment via primary amines (Lys residues) [26]. | Simple, widely applicable. | Proteins with accessible Lysines away from the binding site. |

| Thiol Coupling | Covalent attachment via free thiols (Cys residues) [10]. | Site-specific, offers controlled orientation. | Proteins/antibodies with engineered or native cysteine residues. |

| Streptavidin-Biotin Capture | High-affinity non-covalent capture [1]. | Excellent orientation control, gentle on ligand activity. | Biotinylated ligands (DNA, aptamers, proteins) [28]. |

| NTA Capture | Coordination chemistry for His-tagged ligands [1]. | Good orientation control, surface can be regenerated. | His-tagged recombinant proteins. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Surface Activity Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chips (SA) | Provides a surface pre-coated with streptavidin for capturing biotinylated ligands. | Used in Protocol 1 for oriented immobilization [1]. |

| EDC / NHS | Cross-linking agents for activating carboxylated surfaces for covalent amine coupling. | Standard chemistry for activating CM5 chips [26] [27]. |

| Ethanolamine | A blocking agent used to deactivate and block any remaining activated ester groups after coupling. | Injected after ligand immobilization to passivate the surface [27]. |

| Biotinylation Kit | A set of reagents for chemically adding a biotin tag to a protein or aptamer. | Used to prepare the ligand for Protocol 1 [1] [28]. |

| Short-Chain Thiols (e.g., MCH) | Used to create mixed self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) to reduce steric hindrance and non-specific binding. | Mixed with a longer thiol (e.g., 11-MUA) on gold surfaces to create a diluted, well-spaced ligand layer [26]. |

Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) and Thiol Chemistry for Stable, High-Performance Surfaces

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide to SAM-Related SPR Signal Issues

Problem: Low or unstable signal intensity in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments, potentially linked to the quality of the self-assembled monolayer (SAM).

Background: A poorly formed SAM can lead to low ligand immobilization, high non-specific binding, or an unstable baseline, all of which directly impact the SPR signal and data reliability within the context of your thesis research [9] [26].

Solution: A systematic approach to SAM formation and characterization is required. The following workflow outlines the key steps for diagnosing and resolving SAM-related signal issues:

Detailed Corrective Actions:

For Noisy or Drifting Baselines [9]:

- Ensure the running buffer is properly degassed to eliminate microbubbles that cause signal fluctuations.

- Check the fluidic system for leaks.

- Use fresh, high-purity solvents for SAM formation to avoid contamination.

For Weak or Absent Binding Signals [9] [1]:

- Verify the substrate is thoroughly cleaned before SAM formation. Common methods include piranha solution (a mixture of sulfuric acid and hydrogen peroxide) or oxygen plasma treatment [26]. Caution: Piranha solution is extremely hazardous and must be handled with extreme care.

- Ensure adequate SAM formation time. While alkanethiolates can form quickly, full organization can take 12 to 72 hours for a well-ordered monolayer [29] [26].

- Confirm the concentration and purity of the thiol solution. Thiols can oxidize into disulfides, leading to inferior SAM quality [30].

For High Non-Specific Binding [26] [10]:

- Use mixed SAMs that incorporate a diluent thiol (e.g., 1-octane thiol or 6-mercapto-1-hexanol) alongside your functional thiol. This reduces steric hindrance and presents a more inert surface to the solution, minimizing unwanted interactions [26].

- Consider the terminal group of the SAM. A non-reactive group like hydroxyl or ethylene glycol can passivate the surface.

Preventive Measures:

- Characterization: Use techniques like ellipsometry or X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to measure SAM thickness and composition, and contact angle measurements to verify surface energy [29].

- Stable Storage: Store formed SAMs in an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon) to prevent oxidation of the thiolate-gold bond [30].

Guide to SAM Formation Defects and Instability

Problem: The self-assembled monolayer is unstable over time, leading to degradation of SPR performance, loss of immobilized ligand, and unreliable data.

Background: Instability can arise from intrinsic factors like oxidation of the sulfur-gold bond, or extrinsic factors such as substrate contamination and impurities in the adsorbates [29] [30].

Solution:

Step 1: Identify the Failure Mode

- Gradual Signal Decay Over Days/Weeks: Likely caused by oxidation of the thiol-gold bond in ambient air [30].

- Immediate Poor Quality or High Defect Density: Likely caused by contaminated gold substrate, impure thiol compounds, or incorrect SAM formation protocol [29].

Step 2: Implement Corrective and Advanced Strategies

- For Oxidative Instability: Consider alternative anchoring chemistries. Recent research demonstrates that selenides form SAMs with extraordinary air stability, maintaining junction integrity for over 200 days due to a stronger Se-Au bond and slower oxidation kinetics compared to thiolates [30].

- For Defect-Related Instability:

- Re-evaluate the substrate cleaning protocol. Oxygen plasma can clean effectively while resulting in a smoother surface than piranha treatment [26].

- Use freshly purified thiols or protected precursors (e.g., thioacetates) to prevent oxidation before SAM formation [30].

- Explore the use of surfactants that can increase the mobility of gold surface atoms during SAM formation, promoting the creation of a nearly defect-free monolayer [29].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical factors for forming a high-quality, low-defect thiol SAM on gold? The most critical factors are substrate cleanliness, thiol purity, and formation time. The gold surface must be free of organic and inorganic contaminants. The thiol compound should be pure, as disulfide impurities can lead to poorly ordered films. While adsorption is fast, allowing 12-72 hours for organization can improve the final order and packing density of the monolayer [29] [26].

Q2: How does SAM quality directly impact my SPR data on low signal intensity? Poor SAM quality is a primary contributor to low signal intensity. A defective, loosely-packed monolayer results in low ligand immobilization density, directly reducing the potential binding signal. Furthermore, a disordered SAM can lead to improper ligand orientation, rendering a fraction of your ligands inactive. Defects in the SAM also create pathways for non-specific binding, which increases background noise and further obscures the specific signal of interest [29] [14] [1].