Overcoming Basis Set Dependency in Quantum Chemistry: A Practical Guide to Confinement Methods

This article provides a comprehensive overview of confinement as a critical solution to the challenge of basis set dependency in quantum chemical calculations, particularly relevant for drug discovery and materials...

Overcoming Basis Set Dependency in Quantum Chemistry: A Practical Guide to Confinement Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of confinement as a critical solution to the challenge of basis set dependency in quantum chemical calculations, particularly relevant for drug discovery and materials science. It explores the foundational theory of Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE), details practical methodological implementations of confinement, offers troubleshooting advice for common convergence issues, and discusses validation protocols. Aimed at computational chemists and drug development researchers, the content synthesizes current best practices to enhance the accuracy and reliability of calculating molecular interaction energies and properties in confined environments.

Understanding Basis Set Dependency and the Critical Role of Confinement

Defining Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) and Its Impact on Energy Calculations

BSSE FAQs: Core Concepts

What is Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE)?

Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) is an inherent error in quantum chemistry calculations that arises from the use of finite basis sets. When atoms or molecules approach each other, their basis functions begin to overlap. This allows each monomer to "borrow" basis functions from nearby atoms or molecules, effectively increasing its basis set size and artificially lowering the computed energy. This error is particularly problematic when comparing energies between complexed and isolated states, such as in binding energy calculations [1] [2].

Why does BSSE occur?

BSSE occurs because the wavefunction of a monomer in a complex has access to more basis functions than the same monomer calculated in isolation. In a dimer complex AB, monomer A can utilize the basis functions of monomer B (and vice versa) to achieve a more complete description of its electron density. This results in an artificial stabilization of the complex relative to the separated monomers, leading to overestimated binding energies [1] [3].

Is BSSE only relevant for non-covalent interactions between different molecules?

No. While BSSE was first identified and is most commonly discussed in the context of intermolecular non-covalent interactions (like hydrogen bonding and dispersion forces), it also affects intramolecular interactions and processes involving covalent bond formation or cleavage. This intramolecular BSSE can influence conformational energies, reaction barriers, and properties of single molecules, especially when using smaller basis sets [1] [2].

How does the choice of basis set affect the magnitude of BSSE?

The magnitude of BSSE is highly dependent on the size and quality of the basis set. Smaller basis sets (e.g., minimal basis sets like STO-3G) typically lead to larger BSSE because the opportunity for "borrowing" functions provides a relatively greater improvement. Larger, more complete basis sets reduce BSSE because the monomer's own basis set is already more adequate. The error diminishes as the basis set approaches completeness [1] [3].

Table: BSSE Effects on Helium Dimer Interaction Energy at Various Theoretical Levels [3]

| Method | Basis Functions per He | Interaction Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| RHF/6-31G | 2 | -0.0035 |

| RHF/cc-pVDZ | 5 | -0.0038 |

| RHF/cc-pVTZ | 14 | -0.0023 |

| RHF/cc-pVQZ | 30 | -0.0011 |

| RHF/cc-pV5Z | 55 | -0.0005 |

| QCISD/cc-pV6Z | 91 | -0.0468 |

| Best Estimate | -0.091 |

Troubleshooting BSSE: A Practical Guide

Problem: My computed binding energies are too large compared to experimental values.

Potential Cause and Solution: This is a classic symptom of significant BSSE. When using small to medium-sized basis sets, the uncorrected binding energy is often overestimated. To address this:

- Apply a BSSE correction, such as the Counterpoise (CP) method [1] [3].

- Use larger basis sets, as BSSE decreases with increasing basis set size [1].

- For very accurate work, use a composite approach: a high-level method with a large basis set and CP correction.

Problem: After applying the counterpoise correction, my interaction energy becomes repulsive (positive).

Potential Cause and Solution: An over-correction can occur, particularly when using very small basis sets (e.g., STO-3G or 3-21G). In these cases, the CP correction can be similar in magnitude to the interaction energy itself, leading to unreliable results [3]. Solution: Use a larger basis set of at least triple-zeta quality (e.g., cc-pVTZ) before applying the CP correction. The structure of the complex optimized with a small basis set may also be inaccurate, exacerbating the problem [3] [4].

Problem: I am studying a chemical reaction within a single molecule, and my relative energies seem anomalous.

Potential Cause and Solution: You may be observing the effects of intramolecular BSSE. This error is not limited to interactions between separate molecules but can also occur between different parts of the same molecule, especially when the chemical process involves significant changes in electron distribution (like proton transfers or bond cleavage) [2]. Solution: Be aware that intramolecular BSSE can affect any calculation of relative energies with limited basis sets. Using larger basis sets or designing fragment-based CP corrections for the changing parts of the molecule can help mitigate this issue.

Problem: I am using DFT-D3 to account for dispersion. Is BSSE still a concern?

Potential Cause and Solution: Yes. While empirical dispersion corrections accurately capture dispersion interactions, they do not automatically correct for BSSE. The BSSE originates from the incomplete basis set description of the monomers and is a separate issue. For accurate results, a BSSE correction (like CP) should be applied in addition to the dispersion correction [4].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Counterpoise Correction for a Dimer using Ghost Atoms

This protocol outlines the steps to correct the interaction energy of a dimer (A-B) for BSSE using the standard Counterpoise method with ghost atoms [5] [3] [4].

- Calculate the Energy of the Complex: Compute the total energy of the optimized dimer A-B in its own basis set. This value is E(AB, rc)AB, where rc is the geometry of the complex.

- Calculate the Monomer Energies in the Full Dimer Basis Set: a. Create a Ghost System: In the geometry of the complex A-B, convert all atoms of monomer B into ghost atoms. Ghost atoms have zero nuclear charge and zero electrons but retain their basis functions [5] [6]. b. Compute Energy of A: Calculate the energy of monomer A in the presence of the ghost atoms of B. This yields E(A, rc)AB. c. Repeat for B: Similarly, convert all atoms of A to ghost atoms and calculate the energy of monomer B to get E(B, rc)AB.

- Calculate the CP-Corrected Interaction Energy: Use the following formula to compute the BSSE-corrected interaction energy:

- E_int,cp = E(AB, rc)AB - E(A, rc)AB - E(B, rc)AB

Workflow Diagram: Counterpoise Correction for a Dimer

Protocol 2: Investigating Intramolecular BSSE on Proton Affinities

This protocol, inspired by research, demonstrates how to systematically investigate the effect of intramolecular BSSE on a chemical property like proton affinity (PA) in a series of molecules [2].

- System Selection: Choose a systematic series of molecules where the chemical change is local (e.g., a series of hydrocarbons of increasing size for proton affinity studies) [2].

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the geometry of both the base (B) and its conjugate acid (BH+) for each molecule in the series. Use a high-quality grid and tight convergence criteria for accurate results [2].

- Single-Point Energy Calculations: Perform single-point energy calculations on the optimized geometries using a range of basis sets from small to large (e.g., Pople-style 6-31G, 6-311G, and Dunning-style cc-pVnZ with n=D, T, Q) [2] [7].

- Thermochemical Analysis: Calculate the proton affinity (PA) and gas-phase basicity (GPB) for each molecule at each level of theory. This involves combining the electronic energies with thermal corrections and using the standard thermodynamic values for the proton [2].

- Data Analysis: Plot the computed PA/GPB values against the basis set size and the molecular size. Intramolecular BSSE and basis set incompleteness error (BSIE) will be revealed as systematic deviations that converge as the basis set becomes larger [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for BSSE Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function in BSSE Context | Example Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Sets | Mathematical functions centered on atoms to describe electron orbitals. Incompleteness leads to BSSE. | Pople (6-31G, 6-311G), Dunning (cc-pVnZ, aug-cc-pVnZ) [2] [7] |

| Ghost Atoms | Atoms with basis functions but no nuclear charge or electrons; used to "loan" basis functions in CP corrections. | Designated by Gh in Gaussian or via the @ symbol [5] |

| Counterpoise (CP) Method | An a posteriori correction technique that calculates the BSSE by comparing monomer energies in different basis sets. | Standard CP, Modified CP for geometry deformation [1] [3] |

| Chemical Hamiltonian Approach (CHA) | An a priori method that prevents BSSE by modifying the Hamiltonian to exclude basis set mixing. | - [1] |

| Absolutely Localized Molecular Orbitals (ALMO) | An alternative method for BSSE evaluation that offers computational advantages and automation. | As implemented in Q-Chem [5] |

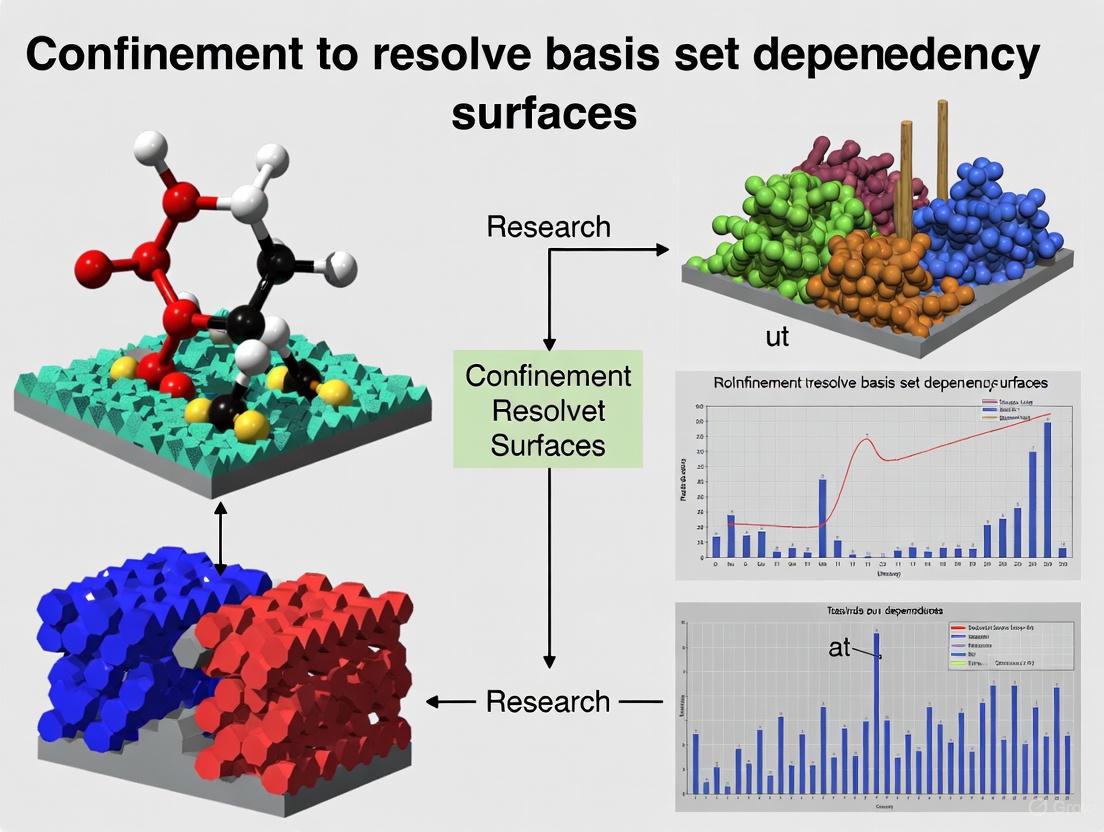

Advanced Topics: BSSE in the Context of Confinement and Basis Set Dependency

The investigation of BSSE is crucial for research on confinement effects, where molecular systems are placed in restricted spaces. In such environments, the electronic structure is altered, and the dependency of results on the basis set can be even more pronounced. Accurately correcting for BSSE ensures that computed energy changes due to confinement are physical and not artifacts of the basis set. Understanding and mitigating BSSE paves the way for creating more reliable "basis set dependency surfaces," which map how molecular properties evolve with both the basis set and the degree of spatial confinement. This is fundamental for achieving high-accuracy, predictive simulations in complex environments like enzyme active sites or porous materials.

The Core Issue: Why Linear Dependency Occurs

Diffuse basis functions, characterized by their very small exponents, are essential for accurate quantum chemical calculations, particularly for studying anions, excited states, and non-covalent interactions [8] [9]. However, their addition to a basis set is the most common cause of linear dependency [10].

These functions are spatially extended, meaning their electron density is spread over a large volume. In molecular systems, especially large ones or those with specific geometries where atoms are close together, these diffuse orbitals on different atoms can become nearly identical [10]. When the overlap between basis functions becomes too great, the overlap matrix develops very small eigenvalues. This indicates that the basis set is over-complete—the functions are no longer linearly independent, and some do not provide unique information to the calculation [8]. This is akin to trying to define a 3D space with multiple vectors that are all nearly parallel.

How to Diagnose Linear Dependency

Most quantum chemistry software packages will automatically check for linear dependence during the calculation. The diagnostic typically involves analyzing the eigenvalues of the overlap matrix.

- The Primary Sign: The calculation fails with an explicit error message, such as

ERROR CHOLSK BASIS SET LINEARLY DEPENDENT[10] or a similar warning. - The Underlying Metric: The software computes the eigenvalues of the overlap matrix. The presence of eigenvalues very close to zero indicates linear dependence. The threshold for what constitutes "too small" is often user-configurable [8].

- Associated Symptoms: Before a fatal error occurs, you may observe a poorly behaved or erratic Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence, where the energy oscillates wildly and fails to stabilize [8] [11].

The diagram below illustrates a typical diagnostic workflow.

Troubleshooting and Solutions Guide

If you encounter linear dependency, here are several methods to resolve it, from quick fixes to more advanced strategies.

FAQ: How can I resolve linear dependency in my calculation?

Q: My calculation with a diffuse basis set (e.g., def2-TZVPPD, aug-cc-pVDZ) has failed due to linear dependency. What can I do? A: You have multiple options, which can sometimes be used in combination:

Use the Built-in Linear Dependency Removal: Many codes have a built-in keyword to automatically remove linearly dependent functions.

- In Q-Chem: Use the

BASIS_LIN_DEP_THRESHrem variable. It sets the threshold for eigenvalue removal to10^-n. The default is6(10⁻⁶). For a poorly behaved SCF, try increasing this to5or smaller (e.g.,10⁻⁵), which removes more functions [8]. - In CRYSCA L: Use the

LDREMOkeyword, which removes functions with overlap eigenvalues below<integer> * 10^-5[10].

- In Q-Chem: Use the

Manually Remove Diffuse Functions: A common approach is to manually eliminate the most diffuse basis functions, typically those with exponents below 0.1 [10]. This directly addresses the root cause but requires manual editing of the basis set.

Adjust the SCF Solver Settings: If linear dependency is mild, it can cause slow or noisy SCF convergence [11]. Techniques like level shifting can sometimes stabilize the convergence. Using a better initial guess (e.g.,

SCF_GUESS) can also help.Employ a More Advanced Approach: For non-covalent interactions where diffuse functions are crucial, one proposed solution is using the complementary auxiliary basis set (CABS) singles correction in combination with compact, low quantum-number basis sets. This can help maintain accuracy while mitigating the "curse of sparsity" caused by diffuse functions [9].

The following table compares the common software-specific remdies.

Table 1: Software-Specific Remedies for Linear Dependency

| Software | Remedy / Keyword | Function | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q-Chem | BASIS_LIN_DEP_THRESH |

Sets threshold (10^-n) for removing linearly dependent basis functions [8]. |

Start with a value of 5 if the default of 6 fails [8]. |

| CRYSCA L | LDREMO |

Systematically removes functions based on overlap matrix eigenvalues [10]. | Use in serial execution mode to see which functions are removed [10]. |

| General | Manual Basis Set Pruning | Removing basis functions with exponents < 0.1 [10]. | Effective but requires care to avoid losing necessary accuracy. |

Advanced Context: The Sparsity-Accuracy Trade-off and Confinement

The problem of linear dependency is part of a larger conundrum in electronic structure theory: the trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency, or "The Blessing for Accuracy yet a Curse for Sparsity" [9].

- The Blessing of Accuracy: Diffuse functions are absolutely essential for achieving high accuracy in key areas like non-covalent interaction energies, properties of anions, and excited states [9]. Without them, results can be severely deficient.

- The Curse of Sparsity: The addition of diffuse functions drastically reduces the sparsity of the one-particle density matrix. This "curse of sparsity" undermines the efficiency of linear-scaling algorithms and is a direct precursor to linear dependency in large systems [9].

This is where the thesis concept of confinement becomes highly relevant. Spatial confinement, which can model high-pressure conditions or a restricting molecular environment, has been shown to cause significant changes in molecular properties, including bond shortening and altered electric properties [12]. From a basis set perspective, confinement naturally counteracts the diffuseness of orbitals, potentially acting as a physical remedy to the mathematical problem of linear dependency. By compressing the electron density, confinement may reduce the excessive overlap between diffuse basis functions, thereby restoring numerical stability and enhancing sparsity. Exploring this connection offers a promising research direction for handling large, diffuse basis sets in complex systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Concepts

| Item / Concept | Function / Description | Relevance to Linear Dependency |

|---|---|---|

| Overlap Matrix | A matrix representing the overlap between pairs of basis functions. | Its eigenvalues are the primary diagnostic for linear dependency [8]. |

| Diffuse Basis Functions | Atomic orbitals with small exponents, providing a more extended electron density. | The primary cause of linear dependency due to their large spatial overlap [8] [10]. |

| BASISLINDEP_THRESH | A Q-Chem input parameter controlling the linear dependency threshold [8]. | The main tool for automated remediation in Q-Chem. |

| def2-TZVPPD / aug-cc-pVXZ | Examples of standard and augmented diffuse basis sets [11] [9]. | Common sources of linear dependency issues in practice [11] [13]. |

| CABS Singles Correction | An advanced method that can improve accuracy with smaller basis sets [9]. | A potential strategy to bypass the need for highly diffuse functions. |

Theoretical Foundations: Confinement and Orbital Restriction

What is the primary theoretical effect of spatial confinement on an atomic orbital? Spatial confinement primarily compresses the atomic orbital, restricting its natural diffuseness. This compression optimizes the orbital for the effective atomic charge in its molecular environment, making it more contracted if the atom is somewhat cationic and more diffuse if it is somewhat anionic. This "breathing" response is a key feature of Natural Atomic Orbitals (NAOs), which automatically incorporate this adjustment, a effect that typically requires multiple basis functions of variable range in standard basis sets [14].

How does confinement help address the problem of basis set dependency in quantum chemistry calculations? Confinement, as realized in the formalism of Natural Atomic Orbitals (NAOs), condenses significant electron occupancy into a much smaller set of core and valence-shell orbitals, known as the "natural minimal basis" (NMB). This allows the large residual set of extra-valence Rydberg-type orbitals from the original basis to be effectively ignored. This dramatic simplification reduces the effective dimensionality of the orbital space, thereby mitigating the problem of basis set dependency by providing an intrinsic, occupancy-ordered set of orbitals that are optimal for the wavefunction's own description [14].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: My calculations for a confined system (e.g., an atom inside a fullerene cage) show unexpected oscillations in the photoionization cross-section. Is this an error? No, this is likely not an error but a physical phenomenon known as a confinement resonance. These resonances arise from the interference of the photoelectron wave with itself after being scattered by the confining potential. They are a genuine feature of confined quantum systems and indicate a strong interaction between the atomic electron and the confining boundary [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Convergence in Confined Atom Calculations

- Problem: Your full configuration-interaction (FCI) calculation for two atoms in an isotropic harmonic trap is converging poorly.

- Potential Cause & Solution: The issue may lie with the treatment of the interparticle interaction. Using a simplified pseudopotential (like a regularized δ-function) can lead to convergence failures in beyond-mean-field approaches because it fails to accurately represent the interaction when the trap dimension is comparable to the effective atom-atom interaction length [16].

- Recommended Action: Implement a more realistic interaction potential, such as a Morse model potential, and use Gaussian-type orbitals to evaluate the necessary two-particle integrals. This approach has been shown to yield results that compare favorably with quasi-exact references [16].

FAQ: What is the fundamental definition of a "Natural Orbital," and why is it important for confined systems? A Natural Orbinal (NO) is uniquely defined as an eigenorbital of the first-order reduced density operator. Mathematically, it is the solution to ΓΘ~k~ = p~k~Θ~k~, where p~k~ is the orbital's occupancy. Crucially, NOs are intrinsic to the wavefunction itself and are independent of the initial choice of basis orbitals (e.g., Slater or Gaussian types). This makes them a powerful and unbiased tool for analyzing electronic structure in confined systems, as they are not affected by basis set artifacts [14].

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Adopting Gaussian Basis Functions for Confined Ultracold Atoms

This protocol is inspired by quantum-chemistry-inspired approaches to studying atoms confined in optical tweezers [16].

- System Definition: Define the confining potential (e.g., an isotropic harmonic trap or a multi-well tweezer array geometry) and the realistic interparticle interaction (e.g., a Morse potential).

- Basis Set Selection: Select a set of single-particle basis functions. Cartesian or spherical Gaussian-type orbitals are often preferred, positioned at the centers of the trap potential wells.

- Integral Evaluation: Implement the efficient evaluation of the six-dimensional two-particle integrals involving the Gaussian basis functions and the chosen interaction potential.

- Wavefunction Construction: Express the many-particle wavefunction as a linear combination of properly symmetrized (for bosons) or antisymmetrized (for fermions) product states (configurations).

- Solving the System: Perform full configuration-interaction calculations (exact diagonalization) to solve for the energy spectrum and eigenfunctions.

- Validation: Assess the performance and convergence of the implementation by comparing results with quasi-exact numerical benchmarks where available [16].

Protocol 2: Natural Atomic Orbital (NAO) Analysis for Confined Electronic Structure

This protocol outlines the numerical algorithm for obtaining NAOs, which are critical for analyzing confinement effects on atomic orbitals in molecules [14].

- Initial Calculation: Begin with a wavefunction Ψ computed using a standard atom-centered basis set {χ~j~}.

- Occupancy-Weighted Symmetric Orthogonalization (OWSO): Apply the T~OWSO~ transformation to the initial, overlapping basis orbitals {χ~j~} to obtain a set of basis orbitals {oχ~j~} that are orthogonal between different nuclear centers. This transformation maximally preserves the character of the initial high-occupancy orbitals.

- Subsystem Definition: For the atom of interest A, define the subsystem density operator Γ(A) within the matrix representation of the orthogonalized orbitals for that atom.

- Diagonalization: Solve the eigenvalue problem for the subsystem: Γ(A)Θ~k~(A) = p~k~(A)Θ~k~(A). The resulting eigenfunctions {Θ~k~(A)} are the Natural Atomic Orbitals for atom A, and their eigenvalues {p~k~(A)} are their orbital occupancies [14].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Conceptual Comparison of Orbital Types in Confined Systems

| Orbital Type | Definition | Key Feature in Confinement | Basis Set Dependency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Basis Orbital (e.g., Gaussian) | A non-unique "fitting function" chosen for numerical convenience. | Fixed form; does not automatically adapt to confinement. | High - Results can vary with basis set choice and size. |

| Natural Orbital (NO) | The unique eigenorbital of the wavefunction's density operator [14]. | Intrinsic to the wavefunction; optimal for describing the confined density. | Low - In principle, independent of the initial basis set. |

| Natural Atomic Orbital (NAO) | A localized, 1-center orbital defined as the "natural orbital of atom A" in a molecule [14]. | Automatically incorporates "breathing" contraction/diffusion and steric nodal features. | Very Low - Forms a natural minimal basis, condensing most occupancy. |

Table 2: Physiological and Behavioral Changes in a 180-Day Confinement Study

This data illustrates the tangible effects of macroscopic confinement on human systems, providing a comparative context [17].

| Parameter | Pre-Confinement Value/Baseline | Change After 180-Day Confinement |

|---|---|---|

| Body Weight | 64.5 ± 6.1 kg | Decreased by ~2 kg (mostly lean mass) |

| Carotid IMT | Baseline measurement | Increased by 10-15% |

| Endothelium-dependent Vasodilation | Baseline function | Decreased |

| Masseter Muscle Tone | Baseline tone | Increased by 6-14% |

| Behavioral Flow (Global Activity) | Baseline level | Decreased 1.5 to 2-fold after the first month |

| Negative Emotions | Baseline score | Decreased (per psychological questionnaires) |

Visualization of Key Concepts

Confinement Effect on Orbital Properties

Workflow for Confined Atom FCI Calculation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Theoretical Studies of Confined Atoms

| Material / Computational Tool | Function in Confinement Research | Key Reference / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian-type Orbitals | Single-particle basis functions used to expand the wavefunction of particles in arbitrarily arranged confining potentials, such as optical tweezers [16]. | Study of ultracold atoms in tweezer arrays [16]. |

| Morse Model Potential | A realistic analytical potential used to describe the interparticle interaction between confined atoms, enabling accurate beyond-mean-field treatments [16]. | Implementation of six-dimensional two-particle integrals in full CI calculations [16]. |

| Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) Program | A software package that performs Natural Population Analysis, transforming standard basis sets into Natural Atomic Orbitals (NAOs) and Natural Bond Orbitals (NBOs) for chemical interpretation [14]. | Analysis of electron density and bonding in molecules, providing orbitals intrinsic to the wavefunction [14]. |

| C~60~ Fullerene Cage | A near-spherical confining environment used to study the electronic structure and dynamics of encapsulated atoms (A@C~60~) [15]. | Investigation of confinement effects on properties like ionization potentials and photoionization dynamics [15]. |

Chemical Systems Most Vulnerable to Basis Set Dependency Issues

## Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Basis Set Errors

Common Problem 1: Inaccurate Electron Affinities and Anion Properties

The Problem: Your calculations on anions or systems with lone pairs show significant errors in electron affinities, molecular orbitals, or dipole moments. The electron binding seems poorly described.

Why This Happens: This occurs when your basis set lacks diffuse functions [18] [19]. Standard basis functions decay too rapidly to accurately capture the more extended electron density of anions and lone pairs, which are farther from the nucleus [18].

Solutions:

- Add Diffuse Functions: Switch to a basis set that explicitly includes diffuse functions. Look for notations like

aug-(in Dunning family),+or++(in Pople family) [18] [19]. - Verify with Larger Basis Sets: Perform a single-point energy calculation with a larger, diffuse-rich basis set (e.g.,

aug-cc-pVQZ) to check for consistency with your results from a smaller basis set.

Preventive Measures:

- Always use basis sets with diffuse functions (

aug-or+) when studying anions, dipole moments, van der Waals complexes, or reaction pathways involving lone pairs [18] [19].

Common Problem 2: Unreliable Atomic Charges and Population Analysis

The Problem: Your calculated atomic charges (e.g., Mulliken, NPA, ESP) show large, unphysical variations when you change the basis set, making it difficult to interpret chemical bonding or parameterize force fields.

Why This Happens: Certain population analysis methods, particularly orbital-based schemes like Mulliken analysis, are highly sensitive to basis set size and composition [7]. The arbitrary partitioning of the overlap population in Mulliken analysis can lead to significant basis set dependence [7].

Solutions:

- Choose a Less Sensitive Method: For charge analysis, prefer Electrostatic Potential (ESP) methods (e.g., CHELPG, Merz-Kollman) or volume-based methods (e.g., Hirshfeld). These generally show lower basis set dependence compared to Mulliken analysis [7].

- Use Consistent, Larger Basis Sets: When comparing charges across a series of molecules, use the same, sufficiently large basis set for all calculations. A polarized triple-zeta basis is a good starting point [19] [7].

- Avoid Minimal Basis Sets: Never use minimal basis sets (e.g., STO-3G) for population analysis, as they yield particularly poor results [18] [7].

Table 1: Basis Set Sensitivity of Common Population Analysis Methods

| Method Type | Examples | Basis Set Sensitivity | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orbital-Based | Mulliken, Löwdin | High [7] | Simple but often unreliable; avoid for property analysis [7]. |

| Volume-Based | Hirshfeld, AIM (Atoms-in-Molecules) | Low to Moderate [7] | AIM requires topological analysis; Hirshfeld charges tend to be small in magnitude [7]. |

| Electrostatic Potential (ESP) | CHELPG, Merz-Kollman (MK) | Low [7] | Recommended for force field development; less computationally expensive than AIM [7]. |

Common Problem 3: Poor Convergence in Post-Hartree-Fock Energy Calculations

The Problem: Your correlated wavefunction theory calculations (e.g., MP2, CCSD(T)) for interaction or reaction energies fail to converge or show large errors, even with seemingly large basis sets.

Why This Happens: Post-Hartree-Fock methods have a slower convergence to the complete basis set (CBS) limit. Standard Pople-style basis sets (e.g., 6-31G*) were primarily designed for Hartree-Fock and DFT calculations and are less efficient for correlated methods [18] [19].

Solutions:

- Use Correlation-Consistent Basis Sets: Switch to the cc-pVnZ (n=D,T,Q,5,6) family of basis sets developed by Dunning and coworkers [18] [19]. These are systematically designed to converge to the CBS limit for correlated calculations.

- Employ Basis Set Extrapolation: For high-accuracy work, perform calculations with two or three basis sets in the

cc-pVnZhierarchy (e.g., TZ and QZ) and extrapolate to the CBS limit [18] [19]. - Include Diffuse Functions for Weak Interactions: When studying weak interactions like hydrogen bonding or dispersion, use the aug-cc-pVnZ series, as diffuse functions are critical for describing the interacting electron tails [19] [20].

Table 2: Recommended Basis Sets for Different Computational Methods

| Computational Method | Recommended Basis Set Families | Minimum Recommended | For High Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | def2-XVP, Pople (e.g., 6-31G*) | def2-SVP or 6-31G* | def2-TZVP or 6-311+G [19] |

| Wavefunction Theory (MP2, CCSD) | Dunning cc-pVnZ [18] [19] | cc-pVTZ [19] | CBS extrapolation from cc-pVQZ/5Z [19] |

| Geometry Optimizations | def2-SVP, 6-31G* [19] | def2-SVP | def2-TZVP (single-point on optimized geometry) [19] |

Common Problem 4: Basis Set Errors in Heavy Element and Transition Metal Chemistry

The Problem: Calculations involving transition metals, lanthanides, or actinides produce unrealistic geometries, energies, or property predictions.

Why This Happens: Heavy elements have complex electron correlation and relativistic effects that are not captured by standard non-relativistic basis sets designed for main-group elements [19] [7]. Their core electrons require a more flexible description.

Solutions:

- Use Relativistic Effective Core Potentials (ECPs): Replace the core electrons of heavy atoms with an ECP and use a matched valence basis set. This is an efficient way to include relativistic effects [19].

- Employ Relativistically-Optimized Basis Sets: For all-electron calculations, use basis sets specifically designed for relativistic methods like ZORA or DKH2 (e.g.,

ZORA-def2-TZVPin ORCA) [21] [19]. - Select Appropriate Basis Sets for Correlation: For correlated calculations on heavy elements, use specialized correlation-consistent basis sets like

cc-pVnZ-DK3orcc-pwCVnZ-DK3, which are optimized for use with relativistic Hamiltonians [7].

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My molecule contains both main-group elements and transition metals. Can I use different basis sets for different atoms?

A: Yes, this is not only possible but often recommended to save computational resources. A common strategy is to use a larger, more polarized basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) on the metal center and a smaller one (e.g., def2-SVP) on the surrounding ligands. This can be specified in the input of most quantum chemistry software (e.g., using the newgto keyword in ORCA) [19].

Q2: What does the "decontraction" of a basis set do, and when should I use it? A: Decontraction removes the fixed linear combinations of primitive Gaussian functions in a basis set, giving the variational procedure complete freedom to mix all primitives. This is sometimes necessary for achieving high accuracy in molecular property calculations where the standard contraction might introduce a basis set dependency. However, decontracted basis sets are larger and require more accurate numerical integration grids in DFT [19].

Q3: What is the connection between atomic confinement potentials and basis set dependency? A: Confinement potentials are used in the generation of Numerical Atomic Orbitals (NAOs) to force the radial functions to vanish smoothly beyond a cutoff radius, ensuring strict locality in calculations [22]. This is physically motivated, as orbitals contract when atoms form bonds [22]. In the context of resolving basis set dependencies, confinement provides a controlled way to generate localized and efficient basis sets. By simulating a confined atomic environment, one can produce NAOs that are better suited for describing atoms within molecules or materials, thereby reducing the errors that arise from using unconfined, isolated-atom basis sets [22].

## The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Materials for Basis Set Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

Correlation-Consistent Basis Sets (cc-pVnZ) |

Systematically converge correlated (e.g., MP2) energies to the Complete Basis Set (CBS) limit [18] [19]. | Accurate calculation of binding energies and reaction barriers [18]. |

Diffuse-Augmented Basis Sets (aug-cc-pVnZ, 6-31+G*) |

Describe extended electron densities in anions, Rydberg states, and weak interactions [18] [19]. | Modeling electron affinities or hydrogen bonding networks [19]. |

| ZORA/DKH2 Relativistic Basis Sets | Account for relativistic effects in calculations involving heavy elements (Z > 36) [21] [19]. | Studying catalysis with transition metals or optical properties of lead-halide perovskites [19]. |

| Auxiliary Basis Sets | Enable the Resolution-of-Identity (RI) approximation to speed up integral evaluation in DFT and MP2 [19]. | Accelerating geometry optimizations and property calculations on large systems [19]. |

| Confinement Potentials | Generate localized Numerical Atomic Orbitals (NAOs) with finite support, improving efficiency and sparsity in solid-state calculations [22]. | Linear-scaling DFT calculations on large molecules and periodic systems [22]. |

## Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing Basis Set Dependency

Objective: To systematically assess and mitigate basis set errors for a given chemical system.

Workflow Overview: The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving basis set dependency issues.

Methodology:

- Initial Calculation: Perform your target calculation (e.g., single-point energy, geometry optimization) using a standard, moderate basis set like

6-31G*ordef2-SVP. - System Identification: Classify your system based on its key characteristics, which determines the solution path in the workflow.

- Targeted Re-calculation: Repeat the calculation using a basis set specifically chosen to address the potential deficiency of the initial one. Refer to the workflow paths (A-D) and Table 2 for guidance.

- Convergence Check: Compare the results (energies, properties, geometries) from the initial and targeted calculations. A significant difference indicates a basis set error.

- Iterate if Necessary: If the results are not converged, move to a larger basis set in the same family (e.g., from

cc-pVTZtocc-pVQZ) or a more specialized type and repeat the comparison. - Final Reporting: Once the results are stable (converged) with respect to further basis set enlargement, the method is considered sufficient, and the final results can be reported with confidence.

Linking BSSE to Inaccuracies in Protein-Ligand Binding Energy Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is BSSE and how does it directly affect my protein-ligand binding energy calculations? Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) is a significant source of error in quantum chemical calculations caused by the use of incomplete basis sets. In protein-ligand binding, fragment A (e.g., the ligand) can artificially use basis functions from a proximal non-bonded fragment B (e.g., the protein) to variationally lower its electronic energy. This results in an overestimation of the strength of non-bonded molecular interactions. The error always leads to an artificial stabilization of the system, meaning your calculated binding energies may be inaccurately too favorable [23].

2. Beyond intermolecular complexes, can BSSE affect my conformational analysis of a single protein? Yes. Intramolecular BSSE (IBSSE) is a documented concern. It can affect the ability to reliably compare different conformations of the same system. Studies on small peptides have estimated that the magnitude of IBSSE can be equal to or even greater than the relative energies between different peptide conformations. This is critical for any study requiring an accurate potential energy surface, such as free energy calculations, molecular dynamics simulations, or geometry optimization [23].

3. My molecular dynamics (MD) binding affinity results are not reproducible. Is BSSE the cause? While BSSE is a quantum chemistry error and not a direct cause of chaos in classical MD, the lack of reproducibility in single MD simulations is a well-known issue rooted in the chaotic nature of the underlying dynamics. For reproducible and statistically robust binding free energies, ensemble-based MD methods are essential. These methods involve running multiple independent replicas of a simulation to compute macroscopic averages with proper uncertainty quantification, thereby mitigating the inherent instability of individual trajectories [24].

4. Are there fast methods to estimate BSSE without performing costly counterpoise corrections? Yes. Research has led to the development of fast estimation methods. One approach involves dividing a system into interacting fragments and using a simple, pre-parameterized statistical model to estimate each fragment's contribution to the overall BSSE. This method uses a geometry-dependent proximity descriptor and requires no additional quantum calculations, only an analysis of the system's interacting fragments, making it significantly faster than the standard counterpoise procedure which requires 2N+1 calculations for N fragments [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Overly Favorable (Too Negative) Binding Energies

Potential Cause: Significant uncorrected Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE).

Diagnosis Steps:

- Check Basis Set Size: Smaller basis sets (e.g., 6-31G*) are more prone to BSSE. Note the magnitude of BSSE is basis-set dependent [23].

- Estimate BSSE Magnitude: Use a fast estimation model [23] or the counterpoise method to quantify the error. Compare the BSSE magnitude to your calculated binding energy.

Solutions:

- Apply a Correction: Implement the counterpoise correction for the specific protein-ligand complex [23].

- Use a Larger Basis Set: Employ a larger, more complete basis set to inherently reduce the BSSE magnitude, though this increases computational cost.

- Fast Estimation: For large systems like proteins, use a fast fragment-based statistical model to obtain a BSSE estimate without additional quantum calculations [23].

Issue 2: Non-Reproducible Binding Free Energies from MD Simulations

Potential Cause: The chaotic nature of classical MD trajectories leads to extreme sensitivity to initial conditions. Results from a single simulation are statistically unreliable [24].

Diagnosis Steps:

- Run Multiple Replicas: Perform several (e.g., 5-25) independent simulations of the same system from different initial conditions.

- Analyze Variance: Calculate the standard deviation of the binding energies from the ensemble. A large variance indicates the single-shot results are not reproducible.

Solutions:

- Adopt Ensemble Methods: Use ensemble-based simulation approaches as a standard practice.

- Leverage Enhanced Sampling: Combine ensemble simulations with enhanced sampling methods (e.g., Thermodynamic Integration with Enhanced Sampling) for more rapid and precise convergence [24].

- Optimize Replica Count: Bootstrap analysis can determine the optimal number of replicas. For example, one study found that 6 replicas of 100 ns or 8 replicas of 10 ns provided a good balance between efficiency and accuracy [25].

Issue 3: Inaccurate Identification of Ligand Binding Sites

Potential Cause: Poor performance of the binding site prediction tool on your specific protein target.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Benchmark Your Tool: Consult independent benchmarks that evaluate different predictors (e.g., P2Rank, fpocket, DeepPocket) on large, curated datasets like LIGYSIS [26].

- Check for Redundant Predictions: Some methods may predict multiple, very similar pockets, which can artificially inflate performance metrics.

Solutions:

- Choose a Top-Performing Predictor: Select a method with high recall and precision, such as P2Rank or re-scored fpocket (e.g., with PRANK or DeepPocket) [26].

- Re-score Predictions: Improve the performance of an existing geometry-based predictor (like fpocket) by re-scoring its candidate pockets with a more robust machine-learning-based scorer like PRANK or DeepPocket, which has been shown to boost performance significantly [26].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fast Estimation of BSSE for a Protein-Ligand Complex

This protocol outlines the steps for the fast, statistical estimation of BSSE as described in the literature [23].

Objective: To quickly estimate the BSSE for a large system without performing additional quantum calculations.

Materials:

- Software: A fragmentation program and a script to compute the proximity descriptor.

- Parameters: Pre-optimized parameters (a, b, c) for different interaction types (e.g., hydrogen bonds, nonpolar, charged).

Methodology:

- System Fragmentation: Divide the protein-ligand complex into small, interacting molecular fragments.

- Fragment Categorization: Classify each interacting fragment pair by its interaction type (e.g., backbone-backbone hydrogen bond, charged, polar, nonpolar).

- Calculate Proximity Descriptor: For each fragment pair (A, B), compute the proximity descriptor, PAB:

PAB = a + b * ΣΣ exp(-c * rij²)where the sum is over all heavy atoms i in fragment A and j in fragment B, and rij is the distance between them [23]. - Estimate Fragment BSSE: Use the pre-parameterized model for the specific interaction type to convert the proximity score PAB into an estimated BSSE contribution for that fragment pair.

- Propagate System Error: Sum the BSSE estimates from all interacting fragment pairs to obtain the total BSSE estimate for the entire protein-ligand system.

Protocol 2: Ensemble MM/GBSA for Reproducible Binding Affinity

This protocol uses ensemble Molecular Mechanics with Generalized Born and Surface Area solvation (MM/GBSA) to calculate a statistically robust binding affinity.

Objective: To calculate a reproducible binding free energy for a protein-ligand complex using an ensemble of MD simulations.

Materials:

- Software: An MD simulation package (e.g., AMBER, GROMACS) and an MM/GBSA tool.

- Hardware: High-performance computing (HPC) resources for parallel simulations.

Methodology:

- System Preparation: Prepare the protein-ligand complex topology and coordinates. Solvate the system and add ions to neutralize.

- Equilibration: Run standard energy minimization and equilibration steps for the system.

- Generate Ensemble: Launch N independent replicas (e.g., 8-25) of the production simulation from different initial velocities [25] [24].

- Simulation: Run each production replica for a sufficient time (e.g., 10-100 ns per replica).

- Trajectory Analysis: For each replica, extract a set of snapshots and calculate the MM/GBSA (or MM/PBSA) binding energy.

- Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate the average binding energy across all replicas.

- Calculate the standard deviation or confidence interval to quantify uncertainty.

- The final reported result is the ensemble average ± uncertainty (e.g., -8.9 ± 1.6 kcal/mol) [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools and Their Functions

| Research Reagent | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Counterpoise Correction | The standard quantum chemistry procedure to correct for intermolecular BSSE by calculating energies with and without the basis functions of the partner fragment [23]. |

| Fast BSSE Estimation Model | A statistical model that uses geometric descriptors to quickly estimate BSSE from fragment interactions without extra QM calculations, ideal for large systems [23]. |

| Ensemble MD Simulations | Multiple independent MD replicas run to obtain statistically robust and reproducible binding free energies, overcoming the chaotic nature of single trajectories [24]. |

| MM/PBSA & MM/GBSA | End-point methods to compute binding free energies from MD trajectories by combining molecular mechanics energies with implicit solvation models (Poisson-Boltzmann or Generalized Born) [25]. |

| Ligand Binding Site Predictors | Computational tools (e.g., P2Rank, fpocket, DeepPocket) that identify potential binding cavities on a protein structure from geometry or machine learning [26]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

BSSE Troubleshooting Pathway

Ensemble MD for Reproducibility

Implementing Confinement: Practical Strategies and Computational Protocols

Step-by-Step Guide to Applying the Confinement Keyword in Electronic Structure Codes

What is a Confinement Potential?

A confinement potential is a mathematical function applied in computational chemistry to restrict the spatial extent of atomic orbital basis functions. It forces the radial basis functions to vanish smoothly at a specific cut-off radius (rc), ensuring strict locality. This technique is crucial for generating efficient Numerical Atomic Orbital (NAO) basis sets and for simulating environmental effects on atoms, such as those in solids, quantum dots, or under high pressure [22].

Purpose in Electronic Structure Calculations

Confinement potentials address the "basis set dependency" problem by creating controlled, reproducible, and localized basis functions. This ensures:

- Strict Locality: Basis functions are non-zero only within a defined cut-off radius (e.g., ~5 Å), leading to sparse operator matrices and enabling linear-scaling calculations on large systems [22].

- Simulation of Environment: They model the physical pressure and spatial restrictions experienced by atoms in confined environments like endohedral fullerenes (e.g., A@C₆₀) or within crystal lattices [15] [22].

- Generation of Virtual Orbitals: They help create a meaningful set of localized unoccupied states for post-Hartree-Fock calculations [22].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Components for Confinement Calculations

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Confinement Potential (Vc(r)) | The mathematical function (e.g., power, Fermi, Woods-Saxon, harmonic) that defines how the orbital is forced to zero. It is added to the atomic Hamiltonian [22]. |

| Cut-off Radius (r_c) | The critical distance from the nucleus beyond which the basis function is forced to be zero. A typical value is around 5 Å [22]. |

| Electronic Structure Code | Software with confinement capabilities, such as CRYSTAL (BDIIS method), FHI-aims, SIESTA, or GPAW [27] [22]. |

| Initial Atomic Guess | The starting electron density or wavefunction, often a moderately converged result from a previous calculation, which is critical for SCF convergence [28]. |

| SCF Convergence Accelerator | Algorithms like DIIS, MESA, LISTi, EDIIS, or ARH to achieve self-consistency in difficult cases induced by confinement [28]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol for Applying Confinement

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for setting up and running a confinement calculation, from system analysis to result validation.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: System Analysis and Potential Selection

- Analyze the System: Determine the chemical nature of your system (e.g., metallic, ionic, covalent, dispersive) and the purpose of confinement (e.g., basis set generation, simulating high pressure) [27] [22].

- Select a Confinement Potential: Choose from established potential forms. The choice influences the smoothness and decay behavior of the orbital.

- Power Potential:

Vc(r) = (r / r_c)^p / (1 - (r / r_c)^p)forr < r_c(diverges atr_c) [22]. - Fermi Potential:

Vc(r) = -V0 / (1 + exp(-a (r_c - r)))(smooth step function) [22]. - Woods-Saxon Potential: Similar to Fermi, used for physical confinement modeling [22].

- Harmonic Potential:

Vc(r) = k * r²(used for quantum dots) [22].

- Power Potential:

Step 2: Parameter Configuration

- Set the Cut-off Radius (

r_c): This is a critical parameter. For NAO generation,r_cis typically chosen to be around 5 Å to balance accuracy and computational efficiency [22]. For physical confinement, this is based on the size of the confining environment (e.g., the radius of a C₆₀ cage) [15]. - Tune Potential-Specific Parameters: Adjust parameters like

pin the power potential orV0andain the Fermi potential to control the steepness and depth of the confinement well [22].

Step 3: Basis Set Generation and Optimization

- Generate NAOs: Solve the atomic Kohn-Sham or Hartree-Fock equations with the chosen confinement potential

Vc(r)added to the Hamiltonian. This yields the confined radial functionsR_nl(r)[22]. - Optimize Basis Sets (Advanced): For system-specific optimization, use algorithms like the Basis-set DIIS (BDIIS). This method minimizes the system's total energy while controlling the condition number of the overlap matrix to prevent linear dependence [27].

- The functional minimized is often:

Ω = E_total + γ * κ({α, d}), whereE_totalis the total energy,γis a small constant (e.g., 0.001), andκis the condition number of the overlap matrix [27].

- The functional minimized is often:

Step 4: SCF Calculation Setup Confinement can make the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure more challenging. Use the following protocol to ensure convergence [28]:

- Provide a Good Initial Guess: Use a converged density from a previous, similar calculation or a slightly perturbed geometry.

- Select an SCF Accelerator: For difficult cases, use robust algorithms like MESA, LISTi, or EDIIS. The Augmented Roothaan-Hall (ARH) method is a viable, though computationally expensive, alternative [28].

- Adjust DIIS Parameters (if using DIIS):

- Mixing: Reduce from the default (e.g., 0.2) to a more stable value like 0.015 for problematic systems.

- N (DIIS expansion vectors): Increase from the default (e.g., 10) to 25 for greater stability.

- Cyc (initial SDIIS steps): Increase from the default (e.g., 5) to 30 for more initial equilibration [28].

Example Input Snippet (Protocol-like)

Source: Adapted from SCM documentation on SCF convergence guidelines [28].

Step 5: Validation of Results

- Check for Convergence: Verify that the SCF energy has converged to the desired threshold and that the electron density is stable.

- Check Physical Properties: Ensure that the calculated properties (e.g., ionization potentials, bond lengths) are physically reasonable. Compare with known experimental or high-level theoretical data if available.

- Assess Basis Set Quality: For NAOs, verify the completeness and accuracy of the basis set by comparing total energies or property convergence against larger basis sets or fully numerical methods [22].

Troubleshooting and FAQs

FAQ 1: My SCF calculation will not converge after applying confinement. What should I do? Answer: This is a common issue. Follow this systematic troubleshooting procedure:

- Action 1: Check your initial geometry and spin multiplicity. Unrealistic bond lengths or an incorrect spin state are a frequent source of convergence failure [28].

- Action 2: Provide a better initial guess. Use a restart file from a previously converged calculation [28].

- Action 3: Switch to a more stable SCF convergence accelerator like MESA or EDIIS [28].

- Action 4: Manually adjust DIIS parameters. Decrease the

Mixingparameter and increase the number of DIIS vectors (N) to stabilize the iteration, as detailed in the protocol above [28]. - Action 5 (Alters result): As a last resort, consider using electron smearing with a small value or level shifting. Be aware that this slightly alters the final result and can affect properties like excitation energies [28].

FAQ 2: How do I choose the right cut-off radius (r_c) for my system?

Answer: The optimal r_c balances accuracy and computational efficiency.

- For general-purpose NAO basis sets, a

r_cof approximately 5 Å is a standard starting point, as it provides a good compromise [22]. - For simulating physical confinement (e.g., atoms inside a fullerene),

r_cshould be based on the physical dimensions of the confining environment [15]. - If high precision is required, perform a convergence test: calculate your property of interest (e.g., total energy) using increasingly larger

r_cvalues until the change is negligible.

FAQ 3: What is the difference between "soft" and "hard-wall" confinement? Answer:

- Soft Confinement: Uses a smooth, continuous potential (e.g., power, Fermi) to force the orbital to zero. This is standard for NAO generation as it improves numerical stability and the quality of the basis functions [22].

- Hard-Wall Confinement: The wavefunction is forced to be exactly zero at

r_c(infinite potential barrier). This is often used in fundamental physical studies but can be numerically more challenging and may produce less smooth orbitals [22]. Soft potentials can be made increasingly steep to approach the hard-wall limit.

FAQ 4: My calculation failed due to "linear dependence" in the basis set. How can confinement help? Answer: Confinement potentials are a direct solution to this problem. When basis sets become large, exponents can become too diffuse, leading to linear dependence and numerical instability. A confinement potential prevents this by:

- Restricting the diffuseness of the basis functions.

- Allowing the optimization of exponents and contraction coefficients while minimizing the condition number of the overlap matrix (

κin the BDIIS method), thus suppressing linear dependencies [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between surface and bulk atom confinement? A1: Surface confinement typically involves restricting atoms or molecules to 2D interfaces or porous surfaces, which primarily affects reaction pathways and transition states. Bulk confinement involves encapsulating species within 3D spaces like supramolecular cages or quantum dots, which can drastically alter chemical stability, photogenerated carrier separation, and even create new stereochemical arrangements not possible in solution [29] [30]. For example, confinement in supramolecular cages can stabilize reactive intermediates and create internal electric fields that facilitate catalysis [29].

Q2: How does confinement strategy differ based on the target—surface atoms versus bulk atoms? A2: The dimensionality of the confinement is a key differentiator [29]:

- Surface Atoms (2D Confinement): Strategies focus on creating patterned surfaces (e.g., using rare gas layers or organic cages on metal surfaces) to control elementary surface reactions. The effects of the confining wall's electronic structure and geometry are critical [29].

- Bulk Atoms (0D/3D Confinement): Strategies involve encapsulation within nano-sized, supramolecular self-assemblies or reverse micelles. The focus is on using the confined space as a nanoreactor to control guest uptake, chemical conversion, and product release, often leveraging quantum confinement effects [29] [31].

Q3: My experimental results on confined systems show poor reproducibility. What could be causing this? A3: Inconsistent results often stem from a lack of control over the confining environment. Key factors to check include:

- Surface Chemistry: Variations in the functional groups of the confining walls (e.g., of a supramolecular cage) can significantly alter host-guest interactions and reactivity [29].

- Geometry and Size: Ensure the size and geometry (0D, 1D, 2D) of your confining system (pores, cages, micelles) are consistent, as these directly influence the confinement effect [29].

- Solvent Effects: The properties of solvent molecules within a confined space can be drastically different from the bulk phase, impacting thermodynamic properties and reaction rates [29].

Q4: Why is my confined catalytic system showing decreased activity over time? A4: This is a common challenge in catalysis. A "self-regeneration" strategy can be employed. For instance, in a photo-Fenton-like system, loading CoBiOx quantum dots onto defect-rich carbon supports facilitates the conversion of bulk electrons to surface electrons. This promotes the regeneration of reductive metal redox couples (e.g., Co and Bi sites), maintaining catalytic activity [31].

Q5: How can I experimentally characterize the effects of confinement on my molecular system? A5: A combination of spectroscopic and computational techniques is often required:

- THz and Vibrational Spectroscopy: Useful for characterizing the low-frequency dynamics of confined molecules and water, as well as internal electric fields within nanocages [29].

- Vibrational Circular Dichroism (VCD): Effective for studying chiral induction and conformational preferences of guest molecules within chiral confined spaces [29].

- Theoretical Calculations: Force field/ab initio molecular dynamics and free energy simulations are crucial for interpreting experimental data and understanding reaction details inside confined spaces [29] [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inefficient Separation of Photogenerated Charge Carriers in Confined Semiconductor Nanoparticles

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low photocatalytic degradation efficiency. | High recombination of bulk-phase electrons and holes. | Integrate defect engineering. Use a defect-rich support (e.g., nitrogen-defect rich carbon, NBC) to act as an "electron trap," promoting the migration of electrons from the bulk to the surface [31]. |

| Poor regeneration of metal redox couples. | Long migration distance for electrons to reach active sites. | Adopt a "two birds with one stone" strategy. Synthesize quantum dots (e.g., CoBiOx) with quantum confinement effects and load them on defect-rich supports. This synergistically enhances bulk-to-surface electron transfer and redox couple regeneration [31]. |

Problem: Uncontrolled Reactivity and Selectivity in Supramolecular Nanoreactors

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unwanted reaction products or pathways. | The confining environment does not provide adequate stereochemical or regiochemical control. | Refine the nano-confinement design. Equip the walls of supramolecular assemblies with specific functions like chiral elements, non-covalent recognition sites, and catalytic groups to guide the reaction along a desired pathway [29]. |

| Rapid catalyst deactivation or product inhibition. | The reaction product binds more strongly to the confinement than the reactants, preventing turnover. | Design "inverted" confinement. Use containers that favor the Michaelis complex (reactants) over the product. Alternatively, design containers with gated pores or stimuli-responsive walls to facilitate product release [30]. |

The following table summarizes key quantitative metrics and requirements related to confinement strategies and system characterization.

Table 1: Confinement Strategies and System Characterization

| Category | Parameter | Target Value / Requirement | Notes / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility (Diagrams) | Text/Background Contrast Ratio | Minimum 4.5:1 (AA), 7:1 (AAA) [32] [33] | For normal text. Large text requires 3:1 (AA), 4.5:1 (AAA) [34]. |

| Non-text Contrast Ratio | Minimum 3:1 [33] | For UI components and graphical objects. | |

| Confinement Effects | Accelerated Reaction Rate | >240 times faster [30] | Bimolecular "click" reaction inside a cylindrical capsule vs. outside in solution. |

| Effective Concentration | >4 M [30] | For a molecule inside a spherical "softball" capsule (volume ~3.5 × 10⁻²⁵ L). | |

| Optimal Space Filling | ~55% [30] | Reported as an optimal filling of space in solution for confined systems. | |

| Theoretical Methods | Particle Treatment | Full-dimensional beyond mean-field [16] | Required for accurate description when trap dimension is similar to atom-atom interaction length. |

| Interaction Potential | Morse model / Gaussian potentials [16] | Realistic potentials used in quantum-chemistry inspired approaches for ultracold atoms. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Synthesis of CoBiOx Quantum Dots on Defect-Rich Carbon for Enhanced Electron Migration

Purpose: To create a confined photocatalyst system that overcomes bulk electron recombination and promotes the self-regeneration of metal redox active sites [31].

Materials:

- Bismuth nitrate (Bi(NO₃)₃)

- Cobalt chloride (CoCl₃)

- Nitric acid (HNO₃)

- Citric acid

- Nitrogen-defect rich carbon (NBC) support

Methodology:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve 1.94 g of Bi(NO₃)₃ in a mixed solvent of 2 mL HNO₃ and 18 mL deionized H₂O. In a separate container, dissolve 0.65 g of CoCl₃ and 2.5 g of citric acid in 20 mL deionized H₂O.

- Combination and Mixing: Combine the two solutions and stir for 30 minutes to ensure homogeneity.

- Solvothermal Synthesis: Transfer the mixture into a Teflon-lined autoclave and conduct a solvothermal reaction at 160°C for 12 hours.

- Isolation and Washing: After cooling, collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation. Wash the solid several times with deionized water and ethanol to remove impurities.

- Drying: Dry the product in an oven at 60°C overnight to obtain the CoBiOx (CBO) quantum dots.

- Loading onto Support: Disperse the NBC support in ethanol and mix it with the CBO QDs suspension. Sonicate and stir to achieve uniform distribution.

- Final Processing: Centrifuge the mixture, wash, and dry to obtain the final NCBO (NBC-loaded CBO) photocatalyst.

Visualization of Workflow:

Protocol: Studying a Bimolecular Reaction in a Synthetic Supramolecular Capsule

Purpose: To investigate the acceleration and regiochemical control of a bimolecular reaction within a confined nano-space [30].

Materials:

- Cylindrical supramolecular capsule (e.g., self-assembled from resorcinarene derivatives)

- Reactants (e.g., phenyl acetylene and phenyl azide for a "click" reaction)

- Anhydrous, deuterated mesitylene as solvent

Methodology:

- Capsule Formation: Prepare the cylindrical capsule by dissolving the constituent cavitands in mesitylene, allowing them to self-assemble via hydrogen bonding.

- Guest Encapsulation: Introduce the two reactants (phenyl acetylene and phenyl azide) into the capsule solution. The capsule will spontaneously form a "Michaelis complex" by encapsulating one molecule of each reactant.

- Reaction Monitoring: Monitor the reaction progress using ¹H NMR spectroscopy. The confined environment will lead to a specific regioisomer of the triazole product.

- Kinetic Analysis: Compare the reaction rate inside the capsule to the background reaction rate in the bulk solvent under the same conditions (e.g., millimolar concentrations) to quantify the rate acceleration.

Visualization of Confinement Concept:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Confinement Experiments

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Supramolecular Cages (e.g., Pd₂L₄) | Provide 0D confined spaces to study guest binding, chiral induction, and promote encapsulated reactions [29]. |

| Defect-Rich Carbon Supports (NBC) | Act as "electron traps" to facilitate bulk-to-surface electron migration in photocatalytic confined systems [31]. |

| Reverse Micelles | Serve as confined nanoreactors in solution for studying nanoparticle precipitation and polymerization reactions [29]. |

| Quantum Dots (e.g., CoBiOx) | Exhibit quantum confinement effects that, when combined with defect engineering, enhance charge carrier separation [31]. |

| Patterned Surfaces (e.g., on NaBr, rare gas layers) | Create 2D confinement environments on surfaces to disentangle geometrical confinement effects from electronic wall effects [29]. |

| Chiral Crown Ethers / Macrocycles | Model systems for studying how a chiral confined space influences the stereoselectivity of a guest molecule's reactions [29]. |

FAQs: Integrating Confinement with Computational Techniques

FAQ 1: What is the frozen core approximation and why is it used with confinement methods? The frozen core (FC) approximation is a computational technique where low-lying core orbitals are kept fixed and excluded from explicit correlation treatment in post-Hartree-Fock calculations. This approximation significantly reduces computational cost while having minimal impact on accuracy for most chemical properties, as core electrons contribute little to chemical bonding. When combined with confinement methods, which study systems in restricted spatial domains, using the frozen core approximation allows researchers to focus computational resources on the valence electrons that participate in confinement effects [35].

FAQ 2: How do I select the appropriate number of frozen core electrons for my system? Most quantum chemistry programs provide default frozen core settings based on the periodic table. ORCA, for example, uses conservative defaults: 2 core electrons for elements Li-Ne, 10 for Na-Ar, 18 for K-Kr, and 36 for Rb-Xe [35]. For heavier elements, these defaults increase further. The BAND software offers predefined tiers (Small, Medium, Large) that automatically select appropriate frozen cores based on the element [36]. For carbon, all three options use the 1s core, while for sodium, Small freezes the 1s electrons and Medium/Large freeze both 1s and 2p electrons [36].

FAQ 3: What numerical accuracy settings are most critical when using confinement methods? Key numerical parameters that require careful attention include:

- Density mesh cutoff: Determines the real-space grid quality for representing the electron density [37]

- k-point sampling: Controls the sampling of the reciprocal space for periodic systems [37]

- Basis set quality: Affects both accuracy and computational cost significantly [36]

- Frozen core size: Balances between computational efficiency and accuracy [35] [36]

FAQ 4: My calculation shows unexpected results with confinement and frozen core - what should I check?

First, verify that your core orbitals are actually being frozen as expected. Some codes, like Q-Chem, may not freeze core orbitals by default for certain methods like ADC calculations, requiring explicit N_FROZEN_CORE=FC specification [38]. Second, check for orbital misordering issues where core orbitals appear in the valence region - ORCA's CheckFrozenCore and CorrectFrozenCore keywords can diagnose and fix this [35]. Finally, ensure your basis set has properly optimized correlation-consistent basis functions if you're using frozen core approximation [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Energy Convergence with Confinement and Frozen Core

Symptoms:

- SCF cycles failing to converge

- Oscillating energy values during optimization

- Large errors in correlation energy

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Problem Area | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Orbital Misordering | Run with CheckFrozenCore true in ORCA; Check for warnings about core orbitals in valence region |

Use CorrectFrozenCore true to automatically rotate orbitals; Consider using FC_EWIN to freeze by energy window instead [35] |

| Insufficient Basis Set | Compare results with larger basis sets; Check for missing polarization functions | Use correlation-consistent basis sets (e.g., cc-pwCVXZ); Upgrade from DZP to TZP or TZ2P [36] |

| Numerical Grid Issues | Check density mesh cutoff errors; Monitor integration accuracy | Increase density_mesh_cutoff; For hybrid functionals, ensure exx_grid_cutoff is appropriately set [37] |

Issue 2: Incorrect Treatment of Core Electrons in Correlation Methods

Symptoms:

- Core orbitals unexpectedly included in correlation treatment

- Much longer computation times than anticipated

- Discrepancies with reference calculations

Resolution:

This commonly occurs when default settings don't match method expectations. For ADC calculations in Q-Chem, explicitly set N_FROZEN_CORE = FC in the $rem section to ensure core orbitals are frozen [38]. When using effective core potentials (ECPs), ensure NewNCore includes both the ECP electrons and any additional frozen electrons [35]. Always verify the printed orbital statistics in your output to confirm which orbitals are designated as frozen, active, and virtual.

Issue 3: Balancing Accuracy and Efficiency in Confinement Studies

Symptoms:

- Unacceptable accuracy with small basis sets

- Prohibitively long computation times with accurate basis sets

- Difficulty comparing confined vs. unconfined systems

Resolution: Systematically test basis set convergence while using frozen core approximations. The table below shows typical accuracy/efficiency tradeoffs:

| Basis Set | Energy Error (eV) | CPU Time Ratio | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| SZ | 1.8 | 1.0 | Initial testing only |

| DZ | 0.46 | 1.5 | Pre-optimization |

| DZP | 0.16 | 2.5 | Geometry optimization |

| TZP | 0.048 | 3.8 | Recommended default |

| TZ2P | 0.016 | 6.1 | High accuracy |

| QZ4P | Reference | 14.3 | Benchmarking |

Data adapted from BAND documentation showing accuracy for a carbon nanotube system [36]

For confinement studies, the TZP basis typically offers the best compromise, providing good accuracy with reasonable computational cost [36]. Note that energy differences (e.g., between confined and unconfined states) converge much faster with basis set size than absolute energies.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Consistent Frozen-Core FCI with Natural Orbital Analysis

This protocol, adapted from the Fbond framework studies, ensures consistent treatment of electron correlation across different molecular systems for confinement studies [39]:

System Preparation

- Generate molecular geometries (XYZ coordinates)

- Select appropriate basis set (STO-3G for method testing, larger for production)

Frozen-Core Setup

- Identify core orbitals based on element-specific defaults [35]

- For first-row elements (Li-Ne): freeze 2 electrons (1s orbital)

- For second-row elements (Na-Ar): freeze 10 electrons (1s, 2s, 2p orbitals)

Natural Orbital Analysis

- Perform frozen-core FCI calculation

- Compute one-particle density matrix

- Diagonalize to obtain natural orbitals and occupation numbers

- Calculate orbital entanglement entropies

Correlation Analysis

- Compute HOMO-LUMO gap from natural orbitals

- Calculate maximum single-orbital entanglement entropy

- Compute Fbond descriptor = (HOMO-LUMO gap) × (max entanglement entropy)

This methodology reliably identifies two correlation regimes: σ-bonded systems (Fbond ≈ 0.03-0.04) and π-bonded systems (Fbond ≈ 0.065-0.072), providing quantitative guidance for method selection in confinement studies [39].

Protocol 2: Numerical Accuracy Optimization for Confined Systems

Basis Set Selection

- Start with TZP basis for all elements [36]

- For final calculations, consider TZ2P for properties dependent on virtual orbital space

- Use DZP for initial geometry optimizations of organic systems

Frozen Core Configuration

Numerical Parameters

Workflow Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

| Tool/Setting | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Frozen Core Approximation | Reduces computational cost by freezing core electrons | Use conservative defaults; Check for heavy elements [35] |

| TZP Basis Set | Triple zeta plus polarization | Optimal balance of accuracy and efficiency [36] |

| Density Mesh Cutoff | Controls real-space grid quality | ≥12.0 Hartree for accurate results [37] |

| CheckFrozenCore | Diagnoses orbital ordering issues | Essential for systems with heavy elements [35] |

| FC_EWIN | Freezes electrons by energy window | Alternative to fixed electron count [35] |

| Fbond Descriptor | Quantifies electron correlation strength | Identifies σ vs. π correlation regimes [39] |

| FNO-CCSDT | Cost-effective coupled cluster with triples | Reduced scaling with minimal accuracy loss [40] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) in Adsorption Energy Calculations

Issue: Calculated adsorption energies are unrealistically high and decrease significantly with larger basis sets, indicating a problem with Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE).

Symptoms:

- Adsorption energy is overly exothermic.

- Energy values do not converge with increasing basis set size.

- Significant energy change when using a counterpoise correction.

Solution: Apply the Counterpoise Correction method to account for the artificial stabilization caused by the basis set of one fragment improving the description of another.

Procedure:

- Calculate Energy of Isolated Molecule: Compute the energy of the isolated molecule (A), ( E_A ), in the full system's basis set.

- Calculate Energy of Isolated Slab: Compute the energy of the isolated slab (B), ( E_B ), in the full system's basis set.

- Calculate Energy of Complex: Compute the energy of the combined molecule-slab system (AB), ( E_{AB} ), in its full basis set.

- Calculate "Ghost" Energies: Compute the energy of the molecule in the presence of the slab's "ghost" basis functions (A in AB's basis), ( E{A}^{ghost} ). Then compute the energy of the slab with the molecule's "ghost" basis functions (B in AB's basis), ( E{B}^{ghost} ).

- Compute Corrected Adsorption Energy: Use the formula: ( E{ads,corrected} = E{AB} - E{A}^{ghost} - E{B}^{ghost} )

Verification: The corrected adsorption energy should be less sensitive to the basis set size. Compare results with a larger, more complete basis set to confirm stabilization.

Guide 2: Addressing Inefficient Global Structure Optimization

Issue: Global optimization of adsorbate placement on a Pd slab is computationally intractable with pure first-principles methods due to the vast configuration space.

Symptoms:

- Structure search fails to converge to a known minimum.

- Computational cost is prohibitively high for the system size.

- Search gets trapped in high-energy local minima.

Solution: Implement a machine-learning-accelerated global optimization workflow that uses a surrogate model to explore the potential energy surface efficiently [41].

Procedure:

- Generate Initial Training Set: Perform a limited number of first-principles calculations on a diverse set of initial adsorbate configurations.

- Train Surrogate Model: Use the initial set to train a machine learning model (e.g., Gaussian Process Regression or a Neural Network Potential) to predict system energy from structure [41].

- Active Learning Loop: