Optimizing Phonon Calculations: A Guide to Step Size and Accuracy Settings for Reliable Results

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the critical parameters of step size and accuracy in phonon calculations.

Optimizing Phonon Calculations: A Guide to Step Size and Accuracy Settings for Reliable Results

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the critical parameters of step size and accuracy in phonon calculations. It covers foundational principles, traditional finite-displacement and modern machine learning methodologies, and troubleshooting techniques for common pitfalls like imaginary frequencies. The content also addresses validation strategies against experimental data and DFT benchmarks, with a special focus on implications for the stability and properties of complex molecular systems relevant to drug development.

Phonon Calculations Explained: From Core Concepts to Accuracy Fundamentals

Understanding Phonons and Their Role in Material Properties

Phonons, the quantized lattice vibrations in crystalline materials, are fundamental to understanding a wide range of material properties including thermal conductivity, superconductivity, and ferroelectricity [1] [2]. Detailed experimental phonon spectra are available for only a limited number of materials, which has driven the development of computational methods for large-scale analysis of vibrational properties and their derived quantities [2]. First-principles phonon calculations, particularly within the harmonic approximation, now enable researchers to obtain full phonon dispersion relations and vibrational density of states for thousands of inorganic compounds [2].

The accuracy of these computational predictions depends critically on the calculation parameters and methodologies employed. This application note provides detailed protocols for phonon calculations, summarizes quantitative performance data across computational methods, and outlines essential research tools for reliable phonon property determination in material science research.

Quantitative Data on Phonon Calculation Methods

Comparison of Phonon Calculation Approaches

Table 1: Computational Methods for Phonon Properties

| Calculation Method | Applicable Systems | Key Advantages | Accuracy Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) [3] [2] | Semilocal DFT (LDA, GGA) with norm-conserving pseudopotentials [3] | Most efficient for compatible systems; calculates IR/Raman intensities [3] | High accuracy for semiconductors/inorganic materials [2] |

| Finite Displacement (Supercell) [3] | Ultrasoft pseudopotentials, DFT+U, hybrid XC, MGGA [3] | Broad Hamiltonian compatibility [3] | Requires larger computational resources [3] |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) [4] | High-throughput screening across chemical spaces [4] | DFT accuracy at fraction of computational cost [4] | Performance varies by model; some achieve high harmonic phonon accuracy [4] |

Performance Benchmarking of Universal MLIPs

Table 2: Benchmarking of Universal MLIPs for Phonon Properties [4]

| Model Name | Geometry Relaxation Failure Rate (%) | Energy MAE (eV/atom) | Force MAE (eV/Å) | Phonon Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHGNet [4] | 0.09 | ~0.1 (uncorrected) | ~0.03 | Reliable for phonons despite higher energy error |

| MatterSim-v1 [4] | 0.10 | ~0.035 | ~0.05 | Good overall performance |

| M3GNet [4] | ~0.15 | ~0.035 | ~0.05 | Moderate phonon capability |

| MACE-MP-0 [4] | ~0.15 | ~0.03 | ~0.04 | Good force prediction |

| SevenNet-0 [4] | ~0.15 | ~0.04 | ~0.05 | Moderate performance |

| ORB [4] | ~0.60 | ~0.025 | ~0.04 | Higher failure rate (forces not exact derivatives) |

| eqV2-M [4] | 0.85 | ~0.025 | ~0.04 | Highest failure rate (forces not exact derivatives) |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol: Geometry Optimization for Phonon Calculations

Principle: Phonon spectra must be calculated on fully optimized geometries, including both internal atomic positions and lattice vectors, to ensure accurate results [5].

Detailed Procedure:

Initial Structure Setup

Geometry Optimization Settings

- Set task to Geometry Optimization [5].

- Enable lattice vector optimization by selecting "Optimize Lattice" in geometry optimization details [5].

- Set convergence criteria to "Very Good" or equivalent tight thresholds for both nuclear and lattice degrees of freedom [5].

- For ab initio methods, use strict convergence criteria: forces < 10⁻⁶ Ha/Bohr and stresses < 10⁻⁴ Ha/Bohr³ [2].

k-Point Grid Selection

Execution and Monitoring

Protocol: DFPT Phonon Calculation at Γ-Point

Principle: DFPT efficiently calculates phonon frequencies and properties at specific q-points, particularly valuable for spectroscopic modeling [3].

Detailed Procedure:

Input File Preparation

Phonon-Specific Parameters

Electronic Structure Parameters

Execution and Output Analysis

Protocol: Finite Displacement Phonon Calculations

Principle: The finite displacement method calculates force constants by displacing atoms in a supercell, applicable to systems where DFPT is not implemented [3].

Detailed Procedure:

Supercell Construction

- Build supercell of sufficient size to capture relevant atomic interactions.

- Maintain periodicity and symmetry of the original crystal structure.

Atomic Displacements

- Apply small displacements (typically 0.01-0.03 Å) to each atom in each independent direction.

- Calculate forces for each displacement configuration using chosen Hamiltonian.

Force Constant Calculation

- Extract force constants from force-displacement relationships.

- Apply acoustic sum rule to enforce translational invariance [2].

Phonon Property Determination

- Fourier transform force constants to obtain dynamical matrix throughout Brillouin zone.

- Diagonalize dynamical matrix to obtain phonon frequencies and eigenvectors.

- Calculate derived properties including phonon DOS and thermal properties.

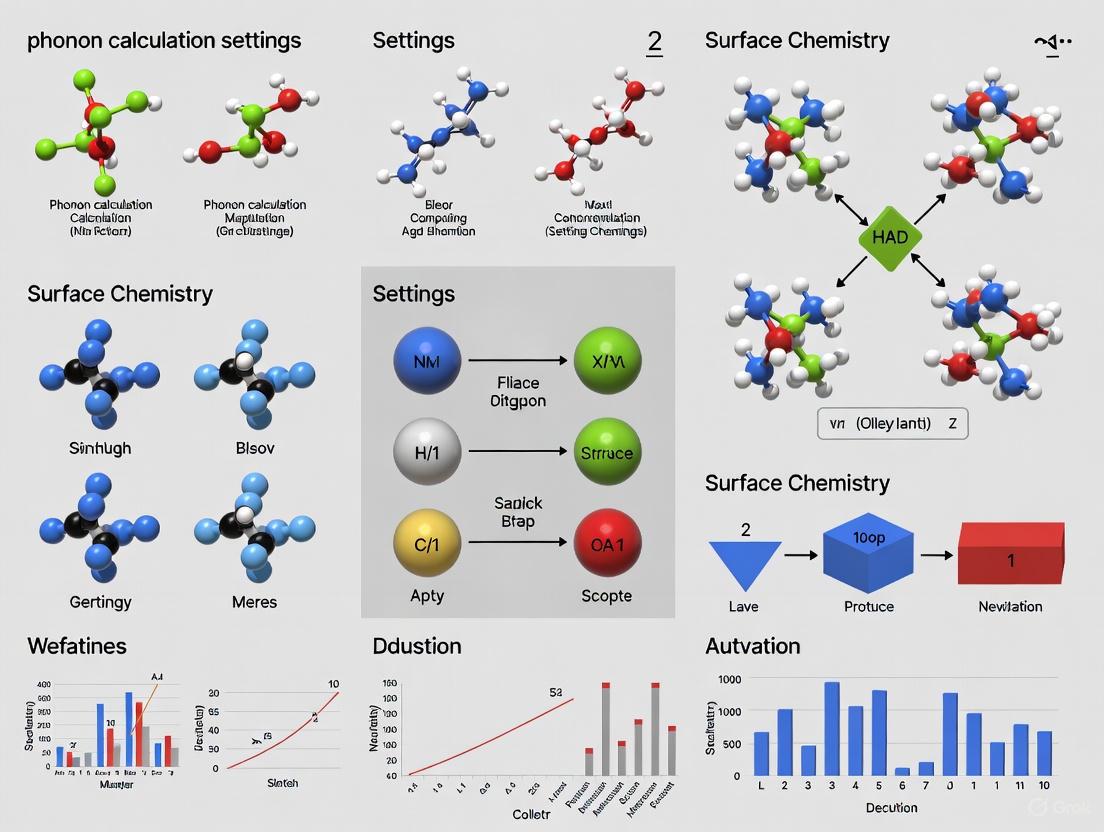

Workflow Visualization

Phonon Calculation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Phonon Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABINIT [2] | Software Package | DFT/DFPT calculations | Used for high-throughput phonon database generation [2] |

| CASTEP [3] | Software Package | DFT/DFPT calculations | Implements both DFPT and finite displacement methods [3] |

| Phonopy [1] | Software Package | Phonon analysis | Open-source code for post-processing force calculations [1] |

| AMS/DFTB [5] | Software Package | Semi-empirical calculation | Efficient for initial screening; includes phonon capabilities [5] |

| Universal MLIPs [4] | Machine Learning Potentials | High-throughput screening | MACE-MP-0, CHGNet show good phonon performance [4] |

| PseudoDojo [2] | Pseudopotential Library | Norm-conserving pseudopotentials | Provides accuracy-tested pseudopotentials for DFPT [2] |

Theoretical Foundation

The dynamical matrix is the fundamental mathematical construct in the computational modeling of phonons—the quantized lattice vibrations in crystalline solids. It transforms the complex, real-space interactions between atoms into a tractable eigenvalue problem in reciprocal space, providing access to a material's vibrational spectrum.

In the harmonic approximation, the potential energy of a system is expressed as a Taylor expansion around the equilibrium positions. The dynamical matrix, D(q), is built from the second derivatives of this potential energy with respect to atomic displacements [6]. For a crystal, the equation of motion for an atom leads to the central eigenvalue equation [6]: [ \sum{a^{\prime}\beta} D{a\alpha,a^{\prime}\beta}(\mathbf{q}) \epsilon{a^{\prime}\beta,\mathbf{q}j} = \omega{\mathbf{q}j}^2 \epsilon{a\alpha,\mathbf{q}j} ] Here, ( \omega{\mathbf{q}j} ) is the vibrational frequency of the phonon mode j with wavevector q, and ( \epsilon{\mathbf{q}j} ) is its corresponding polarization vector (eigenvector). The dynamical matrix itself is constructed from the Fourier transform of the interatomic force constants (IFCs), ( C{a\alpha, a^{\prime}\beta} ), which describe the force in the α direction on atom a when atom a′ is displaced in the β direction [6]: [ D{a\alpha,a^{\prime}\beta}(\mathbf{q}) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{ma m{a^\prime}}} \sum{\mathbf{r}} C{a\alpha, a^{\prime}\beta}(\mathbf{r}) e^{-i\mathbf{q}\cdot \mathbf{r}} ] where ( ma ) is the atomic mass and the sum is over lattice vectors r.

Solving this eigenvalue equation for wavevectors q across the Brillouin zone yields the full phonon dispersion relations ( \omega_{\mathbf{q}j} ) and density of states, which are foundational for predicting thermodynamic properties like vibrational entropy, free energy, and lattice thermal conductivity [6].

Key Computational Methods and Protocols

Calculating the interatomic force constants (IFCs) needed to build the dynamical matrix can be approached through several first-principles methods. The following table summarizes the core computational techniques.

Table 1: Core Computational Methods for Phonon Calculations

| Method | Fundamental Principle | Key Outputs for Dynamical Matrix | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finite-Displacement [7] | Atoms in a supercell are systematically displaced; forces are calculated via Density Functional Theory (DFT) to compute force constants. | Interatomic Force Constants (IFCs) | Standard method for precise harmonic phonon spectra. |

| DFT + Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIP) [8] [7] | A Machine Learning Force Field (MLFF), trained on a dataset of DFT calculations, is used to predict forces/energies for new configurations. | Forces for IFC calculation or direct phonon prediction. | Accelerating high-throughput screening; achieving accuracy close to hybrid-DFT at a fraction of the cost [8]. |

| Linear Response (DFPT) | The linear response of the electron charge density to a phonon perturbation is calculated directly. | Dynamical matrix elements directly for a given q. | Efficient for obtaining full dispersion from few q-points; suitable for polar materials. |

Detailed Protocol: Finite-Displacement Method with DFT

This is the most widely used approach for calculating phonons from first principles.

A. Objectives and Prerequisites

- Primary Objective: To compute the full set of harmonic interatomic force constants and subsequently determine the phonon dispersion and density of states.

- Prerequisites:

- A fully relaxed crystal structure (equilibrium lattice constants and atomic positions).

- A converged plane-wave energy cut-off and k-point grid for the DFT calculations.

B. Required Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| DFT Code | Software (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) to perform electronic structure calculations and obtain energies/forces. |

| Phonopy | A widely used software package for post-processing force sets to produce force constants, phonon dispersion, and DOS. |

| Supercell | A repetition of the primitive cell, large enough to capture the relevant interatomic interactions. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) | A pre-trained or fine-tuned model (e.g., MACE) used as a surrogate for DFT to predict forces [8] [7]. |

C. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Supercell Construction: Generate a supercell from the relaxed primitive cell. The size must be chosen to ensure force constants decay to zero within the supercell.

- Atomic Displacements: Systematically displace each atom in the supercell by a small amount (typically 0.01 - 0.05 Å) in independent Cartesian directions [7].

- Force Calculations: For each displaced configuration, perform a single-point DFT calculation (no electronic relaxation) to compute the Hellmann-Feynman forces on every atom in the supercell.

- Force Constant Calculation: Use the central equation relating the force on atom a in direction α due to a displacement of atom a′ in direction β: [ C{a\alpha, a^{\prime}\beta} = - \frac{\partial F{a\alpha}}{\partial u{a^{\prime}\beta}} \approx -\frac{\Delta F{a\alpha}}{\Delta u_{a^{\prime}\beta}} ] where ( \Delta F ) is the change in force and ( \Delta u ) is the displacement.

- Dynamical Matrix Construction & Diagonalization: Construct the dynamical matrix D(q) for each wavevector q of interest using the Fourier transform of the IFCs. Diagonalize D(q) to obtain the phonon frequencies ( \omega_{\mathbf{q}j} ) and eigenvectors.

The workflow for this protocol is as follows:

Detailed Protocol: Accelerated Workflow using MLIPs

Machine learning offers a paradigm shift, drastically reducing the computational cost of phonon calculations.

A. Objective To achieve phonon spectra with an accuracy comparable to high-level (e.g., hybrid functional) DFT but at a computational cost orders of magnitude lower, by leveraging machine-learned force fields [8].

B. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Dataset Generation (Training): Create a dataset of atomic configurations and their corresponding energies and forces, typically from DFT calculations. This can be done via:

- Atomic Relaxation Trajectory: Using the configurations generated during a standard DFT relaxation of the defect or structure of interest provides a small but valuable dataset for fine-tuning [8].

- Active Learning / On-the-fly: Run molecular dynamics (MD) or randomly perturb atoms, and use Bayesian uncertainty quantification to selectively add configurations with high prediction uncertainty to the training set [9].

- MLIP Training: Train an MLIP model (e.g., MACE) to learn the potential energy surface (PES) from the generated dataset [7].

- Force & IFC Evaluation: Use the trained MLIP to evaluate the forces on atoms in displaced supercells. The MLIP acts as a fast and accurate surrogate for DFT in the finite-displacement method [8] [7].

- Phonon Spectrum Calculation: Proceed with the standard post-processing steps (calculating IFCs, building the dynamical matrix, and diagonalizing it) using the MLIP-predicted forces.

The following diagram illustrates the MLIP-assisted workflow and its integration with the traditional method:

Accuracy, Validation, and Data Presentation

The accuracy of a phonon calculation is highly sensitive to numerical parameters and the underlying physical approximations.

Critical Parameters for Convergence

Table 3: Key Parameters Governing Dynamical Matrix Accuracy

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Results | Convergence Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supercell Size | Dimensions of the repeated cell used for finite-displacement. | Governs the range of interatomic interactions. Too small a cell introduces spurious interactions. | Increase supercell size until phonon frequencies at Brillouin zone boundary converge. |

| DFT Functional | Exchange-correlation functional used (e.g., PBE, HSE06). | Semi-local functionals (PBE) often underestimate phonon frequencies; hybrid functionals (HSE06) are more accurate but costly [8]. | Use MLIPs fine-tuned on hybrid-DFT data to achieve high accuracy efficiently [8]. |

| k-point Grid | Sampling density in the Brillouin zone for the DFT calculation. | Affects the accuracy of the force calculations for each displaced configuration. | Use the same k-point density as for a standard energy calculation on the supercell. |

| Displacement Step Size | Magnitude of atomic displacement (Δu). | A step too large introduces anharmonicity; a step too small amplifies numerical noise. | Test values between 0.01 Å and 0.05 Å; 0.01 Å is a common standard [7]. |

Validation and Comparison with Experiment

A robust computational study must validate its predictions against experimental data where available.

- Phonon Dispersion: Compare calculated dispersion curves along high-symmetry paths with measurements from Inelastic Neutron Scattering (INS) or Inelastic X-ray Scattering.

- Phonon Density of States (DOS): Compare with experimental DOS obtained from INS.

- Γ-Point Vibrational Modes: Compare frequencies and activities of zone-center modes with Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy measurements. The intensities in these spectra are governed by different selection rules derived from the phonon eigenvectors [6]:

The logical relationship between the dynamical matrix, its outputs, and experimental validation techniques is summarized below:

The finite-displacement method is a cornerstone technique in computational materials science for calculating phonons, the quantized vibrational modes of a crystal lattice. It operates by numerically approximating the second and higher-order derivatives of the potential energy surface—the interatomic force constants (IFCs)—through systematic atomic displacements [10]. The choice of displacement step size is a critical parameter in this process. An excessively small step can lead to numerical noise dominated by computational uncertainties, while an overly large step violates the harmonic approximation, introducing anharmonic effects that corrupt the force constants [11]. This application note details the impact of step size on the accuracy of derived force constants and provides validated protocols for its selection.

The Role of Step Size in Force Constant Calculations

Fundamental Principles

Within the finite-displacement framework, the core task is to compute the force constant matrix, defined as:

$$ \Phi{ij}^{ab} = - \frac{\partial Fi^a}{\partial uj^b} \approx -\frac{Fi^a(\mathbf{R} + \Delta uj^b) - Fi^a(\mathbf{R})}{\Delta u_j^b} $$

Here, ( \Phi{ij}^{ab} ) is the force constant coupling atom ( a ) in direction ( i ) and atom ( b ) in direction ( j ), ( Fi^a ) is the force on atom ( a ) in direction ( i ), ( \mathbf{R} ) represents the equilibrium atomic positions, and ( \Delta u_j^b ) is the finite displacement applied to atom ( b ) in direction ( j ) [10]. The step size, ( \Delta u ), is the perturbation magnitude used to probe the potential energy surface. Its value directly controls the accuracy of the finite-difference approximation. A step size that is too small may be susceptible to numerical noise in the force calculations, whereas a step size that is too large engages anharmonic terms in the potential energy, leading to a systematic overestimation or underestimation of the true harmonic force constants [11].

Quantitative Data on Step Size Selection

The following table consolidates recommended displacement step sizes and their associated contexts from recent research and established protocols.

Table 1: Step Size Recommendations in Finite-Displacement Phonon Calculations

| Recommended Step Size | Computational Context | Key Findings / Rationale | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 Å | Conventional finite-displacement method (single-atom displacement) | Considered a typical, standard displacement magnitude. | [7] [12] |

| 0.01 Å to 0.05 Å | Machine learning potential training (random multi-atom perturbations) | This range is used for extracting force constants via compressive sensing. Larger displacements in this range provide richer force signal information. | [7] [12] |

| ~0.04 Å | Defect-specific MLIP training (random multi-atom perturbations) | Identified as an optimal balance, minimizing errors in the resulting force constants. | [11] |

The "one defect, one potential" strategy highlights the importance of step size optimization. In this approach, a machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP) is trained specifically for a single defect system using structures where all atoms are randomly displaced. A study analyzing the error in force constants as a function of the random displacement radius found that a value of 0.04 Å provided the best balance, yielding accurate phonon frequencies and eigenvectors compared to benchmark density functional theory (DFT) calculations [11].

Experimental Protocols

Workflow for Finite-Displacement Phonon Calculation

The standard workflow for a phonon calculation using the finite-displacement method, illustrating the role of step size, is summarized below.

Diagram 1: Finite-displacement phonon calculation workflow.

Step 1: Structure Optimization

- Objective: Obtain the ground-state equilibrium geometry (atomic positions and lattice vectors) of the primitive cell.

- Protocol: Perform a stringent geometry optimization using density functional theory (DFT). It is crucial to optimize both the internal atomic coordinates and the lattice vectors to ensure the correct equilibrium state for phonon calculations [5] [10]. Convergence thresholds for forces and stresses should be set to high precision (e.g., forces < 1 meV/Å).

Step 2: Generate Displaced Supercells

- Objective: Create a set of structures where atoms are displaced from their equilibrium positions.

- Protocol: Build a supercell large enough to capture the necessary interatomic interactions. The finite-displacement method then requires generating multiple supercells.

- Conventional Approach: For a supercell containing ( N ) atoms, create ( 6N ) structures, each with a single atom displaced by a small step (e.g., 0.01 Å) in the positive and negative directions along each Cartesian axis [11].

- Efficient/Sampling Approach: Generate a smaller subset of supercells (e.g., ~6 per material) where all atoms are randomly perturbed with displacements in a defined range (e.g., 0.01 Å to 0.05 Å). This method is highly efficient for training machine learning potentials or for use with compressive sensing lattice dynamics [7] [12].

Step 3: DFT Force Calculations

- Objective: Compute the quantum mechanical forces on every atom in each of the displaced supercells.

- Protocol: Run a single-point DFT calculation (no relaxation) for each displaced supercell to obtain the Hellmann-Feynman forces. These calculations are embarrassingly parallel and constitute the most computationally intensive part of the workflow [13].

Step 4: Construct Force Constant Matrix

- Objective: Calculate the second-order IFCs (( \mathbf{\Phi} )) from the forces and displacements.

- Protocol: Use the finite-difference formula to relate the change in force on atom ( a ) to the displacement of atom ( b ). This is automatically handled by phonon computation software like Phonopy [1] or Alamode, which build the force constant matrix from the calculated forces.

Step 5: Solve the Phonon Eigenvalue Problem

- Objective: Determine the phonon frequencies and eigenvectors.

- Protocol: Construct the dynamical matrix for a wave vector ( \mathbf{q} ) by Fourier transforming the real-space force constants. Diagonalizing this matrix yields the squares of the phonon frequencies ( \omega^2 ) for that ( \mathbf{q} )-point [14]. Repeating this across a path in the Brillouin zone gives the phonon dispersion, and repeating over a dense mesh gives the phonon density of states (DOS).

Protocol for Step Size Optimization

Determining the optimal step size for a specific system is a critical procedure. The following diagram and protocol outline this process.

Diagram 2: Step size optimization protocol.

- Define a Range of Step Sizes: Select a representative set of displacement values. A logical range spans from a very small value (e.g., 0.005 Å) where numerical noise may dominate, to a larger value (e.g., 0.06 Å) where anharmonicity becomes significant [11].

- Calculate Phonons for Each Step Size: For each candidate step size in the defined range, perform a full finite-displacement phonon calculation (as outlined in Section 3.1) on a well-converged supercell.

- Establish an Error Metric: The accuracy of the phonon calculation for each step size must be quantified. Two common approaches are:

- Comparison with DFPT: If available, use phonon frequencies calculated via Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) as a benchmark. DFPT provides an analytic, highly accurate solution for the harmonic force constants [14].

- Self-Consistency Check: Use the results from the smallest step size (e.g., 0.01 Å) as a reference. The error is then the deviation in key outputs, such as the phonon frequencies at high-symmetry points or the vibrational free energy, from this reference.

- Identify the Optimal Step Size: Plot the chosen error metric against the step size. The optimal value is typically located at the minimum of this curve, representing the best compromise between numerical precision and anharmonic contamination [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Software and Computational Resources for Phonon Calculations

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function | Relevance to Step Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP [11] [10] [14] | DFT Code | Performs first-principles electronic structure calculations to compute energies and atomic forces. | The core engine that provides the force data for a given displaced structure. Its numerical precision (e.g., force convergence) limits the smallest viable step size. |

| Phonopy [10] [1] | Phonon Analysis | Automates the generation of displaced supercells, parses force outputs, and constructs the force constants to calculate phonon spectra and DOS. | Directly implements the finite-displacement method. The step size is a user-defined input parameter within its configuration. |

| Phono3py [10] | Anharmonic Phonons | Computes third-order force constants and lattice thermal conductivity using the finite-displacement method. | Extends the finite-displacement concept to higher-order IFCs, where step size selection is equally critical. |

| HiPhive [10] | Force Constant Fitting | Employs compressive sensing or regression to extract harmonic and anharmonic IFCs from forces of randomly displaced structures. | Enables the use of larger, multi-atom displacement ranges (e.g., 0.01-0.05 Å) to efficiently sample the potential energy surface. |

| MACE/Allegro [7] [11] | Machine Learning Potential | Trains a machine-learning model on DFT forces to create a fast and accurate surrogate potential for rapid force prediction. | Training data is generated using specific displacement strategies (e.g., random displacements of ~0.04 Å). The model's accuracy for phonons depends on this step size. |

In the realm of computational materials science, first-principles phonon calculations are indispensable for predicting dynamical, thermal, and vibrational properties of materials. The accuracy of these calculations is paramount and is governed by the convergence of three fundamental numerical parameters: the k-point grid for Brillouin zone sampling, the plane-wave energy cutoff (ENCUT), and the supercell size for force constant evaluation. This document, framed within a broader thesis on phonon calculation step size and accuracy settings, synthesizes current knowledge and protocols to establish robust convergence criteria for researchers and scientists. Insufficient convergence can lead to spurious results, such as imaginary phonon frequencies that incorrectly suggest dynamic instability, thereby jeopardizing the predictive power of the simulation [15].

The following tables summarize the key quantitative parameters and their recommended convergence values as identified from the literature.

Table 1: Energy Cutoff (ENCUT) Convergence Guidelines

| Parameter | Default/Starting Point | Convergence Criterion | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENCUT | Max ENMAX in POTCAR file | Property of interest (e.g., energy differences) is stable with increasing ENCUT [16]. | Always set manually in INCAR for consistent accuracy across calculations [16]. |

| PREC | Normal | Accurate (for high-quality calculations) [16]. | PREC = Accurate avoids wrap-around errors in FFT meshes [16]. |

| ADDGRID | False | True (can reduce noise in forces) [16]. | Use with caution [16]. |

Table 2: Supercell Size Convergence Recommendations

| System Type | Minimum Suggested Size | General Guidance | Reported Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| General 3D Materials | >15 Å supercell diameter [17] | System-specific convergence test is mandatory [14] [17]. | Quartz: ~7.5 Å force constant cutoff [17]. |

| 2D Materials (MoS₂) | 5×5×1 [15] | Smaller supercells (3×3×1, 4×4×1) can show artificial imaginary frequencies [15]. | MoS₂: 5×5×1 supercell required for dynamic stability [15]. |

| Diamond Structure | Nondiagonal supercell of size N for N×N×N q-grid [17] | Use nondiagonal supercells to dramatically reduce the number of atoms vs. diagonal supercells [17]. | Diamond: 48-atom nondiagonal supercell for a 48×48×48 q-grid [17]. |

Convergence Parameters and Protocols

Plane-Wave Energy Cutoff (ENCUT)

The energy cutoff (ENCUT) determines the highest kinetic energy of the plane-waves in the basis set, directly controlling the quality of the wavefunction expansion. An unconverged ENCUT introduces Pulay stress and leads to inaccurate forces, which are the foundation of phonon calculations [18] [16].

Convergence Protocol:

- Initialization: Set

ENCUTto the maximumENMAXvalue found in thePOTCARfiles. Never use a value lower than this [16]. - Systematic Increase: Perform a series of single-point energy calculations (or small supercell phonon calculations) while progressively increasing

ENCUT(e.g., 1.1×, 1.2×, 1.3×, 1.5× the defaultENMAX). - Monitoring Convergence: The target property for convergence should be the total energy difference between configurations of interest (e.g., during ionic relaxation), as it converges faster than absolute total energies [16]. For phonons, the forces are a critical proxy.

- Force Drift Check: Inspect the OUTCAR file for the 'total drift' of forces. This value should be significantly smaller than the forces of interest, typically below 0.1 eV/Å [16].

- Final Selection: Choose the

ENCUTvalue where the change in the target property (energy difference or force) falls below a predefined threshold (e.g., 1 meV/atom).

Advanced Settings:

- Set

PREC = Accurateto ensure the FFT mesh for the Kohn-Sham orbitals is large enough to avoid wrap-around errors, which is crucial for accurate forces [16]. - Consider

ADDGRID = Trueto use a support grid for the evaluation of augmentation charges, which can further reduce noise in the forces [16].

k-point Grid Sampling

The k-point grid governs the sampling of the Brillouin zone for electronic structure calculations. A mesh that is too coarse fails to capture the electronic environment accurately, leading to errors in the force constants.

Convergence Protocol:

- Initial Grid Selection: For a preliminary calculation, use a grid density derived from system-specific recommendations or tools like

KpointDensityin QuantumATK, which allows setting a density per reciprocal angstrom [19]. - Grid Refinement: Systematically increase the density of the k-point grid (e.g., from 4×4×4 to 6×6×6, 8×8×8, etc.) while monitoring the convergence of the total energy. For phonon calculations, the relevant energy is that of the optimized structure in the primitive cell.

- Supercell Consideration: When a supercell is used for phonon calculations, the k-point grid must be correspondingly reduced. The key is to maintain a constant sampling density in reciprocal space. If the supercell is created by doubling the lattice vectors in one direction, the k-point mesh in that direction should be halved [18].

- 2D Material Note: For monolayers, no k-point subdivision is needed in the direction of the surface normal (e.g., using a 12×12×1 grid), as it only describes interaction between periodic images [18].

Supercell Size for Phonons

The supercell size determines the range of interatomic force constants (IFCs) that can be captured. Phonons with wavelengths longer than the supercell dimensions cannot be described, and a cell that is too small leads to unphysical interactions between periodic images of displaced atoms.

Convergence Protocol:

- Generation of Supercells: Create a series of supercells of increasing size. Traditionally, this is done using diagonal supercells (e.g., 2×2×2, 3×3×3, 4×4×4). For efficiency, nondiagonal supercells should be considered, as they can achieve the same q-point sampling with a significantly smaller number of atoms [17].

- Force Constant Calculation: Compute the force constants for each supercell size using the finite-differences method (

IBRION = 5, 6in VASP) or density-functional perturbation theory (DFPT,IBRION = 7, 8) [14]. - Monitoring Convergence: The key metric is the disappearance of imaginary (negative) frequencies in the phonon spectrum, particularly at high-symmetry points. As demonstrated in MoS₂, a 5×5×1 supercell was required to eliminate spurious imaginary frequencies present in smaller 3×3×1 and 4×4×1 supercells [15]. Alternatively, one can monitor the convergence of phonon frequencies at specific q-points.

- Practical Shortcut: A general rule of thumb is to ensure the supercell is large enough that the force constants decay to near-zero, which for many systems translates to a minimum supercell diameter of ~15 Å [17].

Polar Materials: For polar materials like MgO or AlN, the long-range dipole-dipole interaction must be treated by setting LPHON_POLAR = True and providing the Born effective charges (PHON_BORN_CHARGES) and the static dielectric tensor (PHON_DIELECTRIC) obtained from a prior linear-response calculation (LEPSILON = TRUE) [14]. This is critical for correctly capturing the LO-TO splitting.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence for a comprehensive phonon convergence study, integrating the three key parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Parameters for Phonon Calculations

| Tool / Parameter | Category | Function and Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| VASP [18] [14] | Software Package | A widely used ab-initio simulation package for performing electronic structure calculations and calculating forces for phonons. |

| Phonopy [17] [1] | Software Package | An open-source package for post-processing force calculations to obtain phonon band structures and density of states. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO [20] | Software Package | An integrated suite of Open-Source computer codes for electronic-structure calculations and materials modeling, often used with DFPT. |

| IBRION | VASP Input Tag | Determines the ion dynamics method. Set to 5, 6 (finite differences) or 7, 8 (DFPT) for phonon calculations [14]. |

| LPHON_DISPERSION | VASP Input Tag | When set to True, directs VASP to compute the phonon dispersion along a path provided in a QPOINTS file [14]. |

| Pymatgen [18] | Python Library | A robust, open-source Python library for materials analysis, used for tasks like creating supercells from a primitive structure. |

| Born Effective Charges & Dielectric Tensor | Physical Property | Essential input for correcting the force constants in polar materials to account for long-range interactions and LO-TO splitting [14]. |

Achieving converged results in phonon calculations is a non-negotiable prerequisite for reliable scientific insight. There is no universal "one-size-fits-all" parameter set; convergence must be demonstrated for each unique material system. The protocols outlined herein—systematically increasing ENCUT until energy differences and forces stabilize, refining the k-point grid until the total energy converges, and enlarging the supercell until spurious imaginary frequencies vanish—provide a rigorous methodology. By adhering to this framework and leveraging modern techniques like nondiagonal supercells, researchers can ensure the accuracy and predictive power of their computational studies on lattice dynamics, a cornerstone of modern materials science and drug development research.

Phonons, the quanta of lattice vibrations, are fundamental to understanding and predicting the behavior of materials. Their accurate calculation is not merely a numerical exercise but a prerequisite for reliably determining key properties that define a material's real-world applicability. Inaccurate phonon spectra directly compromise predictions of thermodynamic stability, phase transitions, and thermal transport. For instance, imaginary frequencies in phonon dispersion indicate dynamical instability, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about a material's existence or stability under operational conditions [21] [22]. Furthermore, properties like the free energy, entropy, and heat capacity are derived from the complete phonon density of states; errors in phonon frequencies propagate into these thermodynamic quantities, affecting predictions of phase stability at finite temperatures [6]. The critical nature of this link makes precision in phonon calculations a cornerstone of computational materials science and drug development, where stability and thermal properties are paramount.

Key Phonon-Dependent Properties and the Impact of Accuracy

The following table summarizes core material properties governed by phonons and how inaccuracies in their calculation manifest.

Table 1: Linking Phonon Accuracy to Material Property Predictions

| Material Property | Phonon Dependency | Consequence of Phonon Inaccuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamical Stability [21] [22] | Determined by the absence of imaginary frequencies (ω² > 0) in the phonon spectrum. | Presence of spurious imaginary frequencies can incorrectly label a stable phase as unstable, and vice versa. |

| Thermodynamic Properties [6] | Free energy, entropy, and heat capacity are calculated by integrating over all phonon modes. | Errors in phonon frequencies lead to incorrect free energies, compromising phase stability predictions and phase diagrams. |

| Thermal Conductivity [23] [6] | Dictated by anharmonic phonon-phonon scattering rates and phonon group velocities. | Inaccurate scattering rates or group velocities result in poor estimates of thermal conductivity, critical for thermoelectrics and thermal management. |

| Mechanical Stability [22] | Elastic constants can be derived from long-wavelength acoustic phonon limits. | Incorrect acoustic phonon slopes lead to wrong predictions of a material's stiffness and mechanical robustness. |

| Superconducting Critical Temperature (T_c) [21] | Calculated from the electron-phonon coupling strength and phonon frequencies. | Miscalculated phonon frequencies and linewidths directly translate to inaccurate predictions of Tc. |

Computational Protocols for Accurate Phonon Calculations

Achieving accurate phonons requires meticulous methodology, from the choice of potential to the handling of atomic displacements. Below are detailed protocols for two common approaches.

Protocol: Phonons via Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs)

This protocol uses MLIPs to achieve near-ab initio accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, ideal for complex systems like polymers and molecular crystals [23].

Potential Training and Validation:

- Data Generation: Perform ab initio (e.g., DFT) calculations on a diverse set of atomic configurations, including energies, forces, and stresses. Critically, the training set must include off-equilibrium structures (e.g., from molecular dynamics or distorted geometries) to accurately capture the curvature of the potential energy surface, which is essential for phonons [4] [24].

- Active Learning: Employ active learning strategies to iteratively identify and include configurations where the model is uncertain, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the relevant configurational space [23].

- Validation: Rigorously benchmark the trained potential against purely ab initio results for key properties like energy, forces, and, crucially, harmonic phonon frequencies before proceeding [4].

Force Constant Calculation via Frozen Phonon:

- Supercell Construction: Build a supercell of sufficient size to capture the relevant interatomic interactions and avoid finite-size errors.

- Atomic Displacements: Displace each atom in the supercell by a small, finite amount (typically ~0.01 Å) in the ±x, ±y, and ±z directions.

- Force Evaluation: Use the validated MLIP to calculate the forces on all atoms in the supercell for each displacement.

- Matrix Construction: Compute the force constant matrix elements using central finite differences: Φij = - (Fi+ - Fi-) / (2δ), where Fi+ and Fi- are forces on atom i due to positive and negative displacements of atom j, and δ is the displacement magnitude.

Phonon Dispersion and Properties:

- Dynamical Matrix: Fourier transform the real-space force constant matrix to momentum space to build the dynamical matrix for each wavevector q in the Brillouin zone.

- Diagonalization: Diagonalize the dynamical matrix to obtain the phonon eigenvalues (squared frequencies, ω²(q)) and eigenvectors (polarization vectors) for each q.

- Post-Processing: Use the phonon frequencies to compute derived properties, including the phonon density of states, free energy, and thermal conductivity [23].

Protocol: The Minimal Molecular Displacement (MMD) Method for Molecular Crystals

This protocol leverages the molecular nature of crystals (e.g., pharmaceuticals, organic semiconductors) to drastically reduce computational cost while maintaining high accuracy, particularly for low-frequency modes [25].

System Preparation and Molecular Coordinate Definition:

- Equilibrium Structure: Obtain a fully optimized crystal structure of the molecular crystal.

- Define Molecular Units: Identify the distinct, rigid molecular units within the unit cell.

- Basis Generation: For each molecule, define a complete set of internal coordinates. This includes:

- 3N - 6 Internal Vibrational Modes: Calculate these by performing a vibrational analysis on an isolated molecule.

- 6 Rigid-Body Modes (3 translational + 3 rotational).

Minimal Displacement Sampling:

- Instead of displacing every atom individually, displace the entire system along a carefully selected subset of the molecular coordinates defined in Step 1.

- The MMD approximation prioritizes displacements along rigid-body translations and rotations, which are most relevant for the low-frequency, dispersive phonons, and key intramolecular modes [25].

- This strategy can reduce the number of required supercell force calculations by a factor of 4 to 10 compared to the standard frozen phonon method [25].

Specialized Force Constant Calculation:

- Perform ab initio supercell calculations for each selected molecular displacement.

- Compute the forces on all atoms and project them onto the molecular coordinate basis.

- Construct the force constant matrix in this reduced molecular coordinate space.

Phonon Computation and Analysis:

- The subsequent steps for obtaining the phonon dispersion are analogous to the standard method but operate in the efficient molecular coordinate basis.

- The results are especially accurate for the low-frequency (THz) region, which governs thermodynamic properties and is sensitive to crystal packing [25].

Workflow Visualization: Pathways from Calculation to Property Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow connecting accurate phonon calculations to the prediction of key material properties, highlighting critical decision points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

This section details key computational tools and data resources that form the foundation of modern, accurate phonon studies.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Phonon Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Phonon Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [21] [22] | First-Principles Method | Provides fundamental reference data for energies and forces; the gold standard for training MLIPs and single-point calculations. |

| Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) [4] [23] | Machine Learning Potential | Surrogates for DFT that enable phonon calculations in large/complex systems (e.g., polymers, interfaces) at near-DFT accuracy. |

| Universal MLIPs (uMLIPs) [4] | Pre-Trained ML Model | Foundational models (e.g., M3GNet, CHGNet) for rapid phonon screening across diverse chemistries without system-specific training. |

| Stochastic Self-Consistent Harmonic Approximation (SSCHA) [21] | Computational Method | Introduces anharmonic corrections to harmonic phonons, crucial for materials with strong quantum fluctuations or anharmonicity. |

| Phonopy [22] | Software Package | A widely used tool for automating frozen-phonon supercell calculations and post-processing phonon dispersion and DOS. |

| Materials Project Database [4] | Computational Database | Source of initial structures and reference data for high-throughput phonon studies and model training. |

Validating Phonon Accuracy: Metrics and Case Studies

Quantitative benchmarking against experimental data or high-fidelity calculations is the final, essential step.

Table 3: Benchmarking Universal MLIPs for Phonon Prediction (PBE Functional) Data adapted from a benchmark study of ~10,000 non-magnetic semiconductors [4]

| Universal MLIP Model | Performance on Phonon Properties | Noteworthy Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| M3GNet | Moderate accuracy | A pioneering uMLIP; performance is surpassed by newer models. |

| CHGNet | High reliability in convergence | Small architecture; low failure rate in geometry optimization (0.09%). |

| MACE-MP-0 | High accuracy | Uses atomic cluster expansion for data efficiency. |

| eqV2-M | Top-tier accuracy | Ranked highly; uses equivariant transformers. Higher failure rate (0.85%). |

Case Study: Stability in Double Perovskites First-principles phonon calculations for lead-free double perovskites Cs₂AgBiBr₆ and Cs₂AgBiCl₆ confirm their dynamical stability, as evidenced by the absence of any imaginary frequencies in their phonon dispersion spectra. This computational validation is a critical prerequisite for further investigation of their mechanical and thermodynamic properties for optoelectronic applications [22].

Case Study: The Cost of Inaccurate Training Data Models trained exclusively on equilibrium or near-equilibrium atomic configurations can perform well on energy and force predictions for stable structures but exhibit substantial inaccuracies in predicting phonon properties. This is because phonons probe the curvature of the potential energy surface, requiring training data that includes off-equilibrium structures [4] [24].

Setting Up Calculations: Traditional and Machine Learning Approaches

The finite-difference method, often referred to as the "frozen-phonon" approach, is a powerful technique for calculating phonon properties within density functional theory (DFT) simulations using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP). This method explicitly calculates the force-constant matrix by displacing atoms and computing the resulting forces on all atoms in the system through the Hellmann-Feynman theorem [26]. Unlike density functional perturbation theory (DFPT), which computes derivatives analytically, the finite-difference approach relies on numerical differentiation of forces, making it conceptually straightforward and compatible with any exchange-correlation functional [27]. The successful implementation of this method requires careful attention to three critical parameters: IBRION (which algorithm to use), NFREE (how many displacements to perform), and POTIM (displacement step size). This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for configuring these parameters within the broader context of phonon calculation step size and accuracy settings research.

Core Parameter Definitions and Interactions

Table 1: Core parameters for finite-difference phonon calculations in VASP

| Parameter | Function | Recommended Values | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBRION | Determines finite-difference algorithm | 5 (no symmetry), 6 (with symmetry) | IBRION=6 reduces computational cost but may have issues with vacuum dimensions [27] [28] |

| NFREE | Sets number of displacements per ion direction | 2 (central difference), 4 (four displacements) | NFREE=2: ±POTIM; NFREE=4: ±POTIM and ±2×POTIM [29] |

| POTIM | Controls displacement step size | 0.015 Å (default in VASP 5.1+) | Critical for harmonic approximation validity [27] [30] |

Algorithm Selection and Symmetry Considerations

The IBRION parameter serves as the primary switch for activating finite-difference phonon calculations in VASP. Setting IBRION = 5 displaces all atoms in all three Cartesian directions, which can result in significant computational effort even for moderately sized systems [27]. In contrast, IBRION = 6 utilizes crystal symmetry to identify and compute only symmetry-inequivalent displacements, significantly reducing the number of required force calculations [27]. The force-constants matrix is subsequently filled using symmetry operations.

However, a critical consideration when using IBRION = 6 arises for systems with vacuum spaces, such as surfaces, monolayers, or nanowires. In these cases, the symmetry analysis may incorrectly apply in-plane symmetries to directions including vacuum, potentially leading to inaccurate results [28]. For such systems, IBRION = 5 is recommended despite its higher computational cost.

Displacement Scheme Configuration

The NFREE parameter determines the number of displacements used for each direction and ion, directly impacting the numerical accuracy of the force-constant matrix:

NFREE = 2 employs the central-difference formula, displacing each ion by a small positive and negative displacement (±POTIM) along each Cartesian direction [27] [29]. This approach is generally recommended for its balance between accuracy and computational cost.

NFREE = 4 uses four displacements along each Cartesian direction (±POTIM and ±2×POTIM) [29], potentially providing higher accuracy at increased computational expense.

NFREE = 1 applies only a single displacement and is "strongly discouraged" as it provides insufficient data for accurate numerical differentiation [27] [29].

Step Size Optimization

POTIM sets the displacement width for finite-difference calculations. The default value in VASP 5.1 and newer releases is 0.015 Å, which is automatically applied if the user-supplied value is unreasonably large [27] [30]. This default represents "a very reasonable compromise" based on extensive testing [27].

The choice of POTIM is critical because the frozen-phonon method relies on the harmonic approximation, which is only valid for sufficiently small displacements [30]. If POTIM is too large, the system may enter the anharmonic regime, violating this fundamental assumption. Conversely, excessively small displacements may lead to numerical inaccuracies in force calculations.

Workflow and Parameter Interdependencies

Finite-Difference Phonon Calculation Workflow

Diagram 1: Finite-difference phonon calculation workflow showing the sequence from structure preparation to final results, with the parameter selection phase highlighted.

Pre-Calculation Structure Preparation

Before initiating finite-difference phonon calculations, thorough structure preparation is essential:

Complete Structure Relaxation: The crystal must be fully relaxed to its equilibrium geometry, minimizing forces on atoms and stresses in the unit cell [26]. This is typically performed using

IBRION = 1(RMM-DIIS) orIBRION = 2(conjugate gradient) algorithms withISIF = 3(relaxing ions, cell shape, and volume) orISIF = 2(relaxing only ionic positions) [28].Symmetry Enforcement: After relaxation, the resulting structure in the CONTCAR file should be checked and potentially edited to enforce the desired symmetry [28]. Small numerical deviations in lattice constants or atomic positions may reduce the crystal symmetry, adversely affecting phonon calculations. Rounding small values (e.g., -0.00001248932473 to 0.00000000000000) and performing a subsequent relaxation with fixed lattice constants (

ISIF = 2) and enforced symmetry (ISYM = 2) is recommended [28].Electronic Convergence Parameters: Force calculations require high electronic accuracy. Recommended settings include

PREC = Accurate,EDIFF = 1E-8or lower, andEDIFFG = -0.03to-0.05eV/Å for force convergence during preliminary relaxation [27] [31]. TheADDGRID = .TRUE.setting should be used with caution and tested thoroughly [27].

Practical Implementation Protocols

Basic INCAR Configuration for Finite-Difference Phonons

Table 2: Essential INCAR tags for finite-difference phonon calculations

| Tag | Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

IBRION |

5 or 6 | Activates finite-difference method |

NFREE |

2 (recommended) | Sets displacement scheme |

POTIM |

0.015 | Displacement step size (Å) |

PREC |

Accurate | Ensures high accuracy |

EDIFF |

1E-6 to 1E-8 | Tight electronic convergence |

NSW |

1 | Single ionic step (no relaxation) |

ISIF |

2 | Calculates forces and stress |

LEPSILON |

.TRUE. | Computes dielectric properties (optional) |

A typical INCAR configuration for finite-difference phonon calculations:

Convergence Testing Protocol

To ensure accurate and reliable phonon frequencies, a systematic convergence protocol should be implemented:

k-Point Convergence:

- Perform initial convergence tests for the primitive cell

- When increasing supercell size, decrease k-point density proportionally to maintain equivalent sampling [27]

- Example: A 12×12×12 mesh for a primitive cell becomes 6×6×6 for a 2×2×2 supercell

Energy Cutoff (ENCUT) Convergence:

- Systematically increase ENCUT in steps of ~15% beyond the default value

- Monitor Γ-point optical mode frequencies until changes become negligible

- For systems with significant Pulay stresses, ensure

ENCUT > 1.3*ENMAX[31]

Supercell Size Convergence:

- Construct progressively larger supercells until phonon frequencies converge

- Ensure force constants between distant atoms approach zero

- Balance computational cost against accuracy requirements

Force Accuracy Verification:

- Compare results with density-functional-perturbation theory (DFPT) when possible [27]

- Validate against experimental data if available

Advanced Configuration: Elastic Constants Calculation

For IBRION = 6 and ISIF ≥ 3, VASP can calculate elastic constants through six finite distortions of the lattice [27]. Key considerations for this advanced application include:

- Enhanced ENCUT: The plane-wave cutoff may need to be increased by roughly 30% beyond typical values to converge the stress tensor [27]

- Output Interpretation: Results include "SYMMETRIZED ELASTIC MODULI" (clamped ions), "ELASTIC MODULI CONTR FROM IONIC RELAXATION," and "TOTAL ELASTIC MODULI" (combined) [27]

- Memory Considerations: These calculations may require significant computational resources

Post-Processing and Analysis

Output Interpretation

VASP writes phonon modes and frequencies to the OUTCAR file following the header:

For each normal mode, output includes:

The label "f" indicates a stable (real frequency) mode, while "f/i" denotes an imaginary frequency (soft mode) [27]. A system should have 3N normal modes, where N is the number of atoms in the supercell, with the last three typically being translational modes [27].

Phonon Dispersion and DOS Calculation

To obtain full phonon dispersions (not just Γ-point):

- Compute second-order force constants in a sufficiently large supercell

- Use Fourier interpolation to generate dynamical matrices throughout the Brillouin zone

- Employ post-processing tools like phonopy [27] to:

- Extract phonon density of states (DOS)

- Generate phonon dispersion curves

- Calculate thermodynamic properties

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for finite-difference phonon calculations

| Tool/Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | First-principles DFT code | Requires license; version 5.1+ recommended [27] |

| phonopy | Post-processing package | Extracts phonon DOS, dispersion; requires Python [27] [28] |

| convasp | Structure manipulation | Creates supercells from primitive cells [26] |

| VESTA | Visualization | Crystal structure and phonon mode visualization [28] |

| High-Performance Computing Cluster | Computational resource | Essential for large supercells and numerous displacements |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem Resolution Table

Table 4: Common issues and solutions in finite-difference phonon calculations

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Imaginary frequencies | Structure not fully relaxed | Re-relax with tighter force convergence (EDIFFG = -0.01) |

| Inaccurate phonon frequencies | Insufficient k-points or small supercell | Converge k-point grid and supercell size systematically |

| Poor force convergence | Insufficient electronic convergence | Tighten EDIFF (1E-6 to 1E-8), increase NELMIN |

| Symmetry-related errors | Incorrect symmetry detection | Check SYMPREC, manually enforce symmetry in POSCAR |

| Excessive computation time | Too many displacements with IBRION=5 | Switch to IBRION=6 (if appropriate) or reduce supercell size |

The finite-difference approach to phonon calculations in VASP provides a powerful, versatile method for determining vibrational properties of materials. The critical parameters—IBRION, NFREE, and POTIM—require careful configuration based on the specific system under investigation. The recommended protocol begins with thorough structure relaxation and symmetry enforcement, proceeds with appropriate parameter selection (typically IBRION=6 for bulk crystals, NFREE=2, and POTIM=0.015 Å), and concludes with systematic convergence testing and post-processing. Adherence to these application notes and protocols will enable researchers to obtain accurate, reliable phonon properties across a wide range of materials systems, supporting broader investigations into thermal, vibrational, and thermodynamic material behavior.

The accurate calculation of phonon properties is fundamental to understanding material behavior, from thermal conductivity to phase stability. The choice of computational parameters, most critically the step size or displacement magnitude used in finite-difference methods and the time step in molecular dynamics (MD), directly determines the balance between numerical stability and the physical capture of anharmonic effects. An overly large step can violate the harmonic approximation's underlying assumptions, while an excessively small step amplifies numerical noise. Furthermore, the emergence of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) and advanced anharmonicity treatments has introduced new dimensions to this balancing act, requiring refined protocols for different computational frameworks. These guidelines synthesize recent methodological advances to establish robust protocols for step size selection across leading phonon calculation techniques, enabling researchers to achieve reliable results while capturing essential anharmonic physics.

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies and Performance

Table 1: Comparison of Phonon Calculation Methods and Step Size Parameters

| Methodology | Primary Step Parameter | Typical Value / Range | Key Performance Metric | Reported Accuracy/Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frozen Phonon (Finite Displacement) [7] [32] | Atomic Displacement Magnitude | 0.01 - 0.05 Å | Accuracy of Force Constants | Systematic improvability with more displacements |

| Molecular Dynamics (QC + QTB) [33] | MD Time Step | Not Explicitly Specified | Capture of Anharmonicity & NQEs | Accurate anharmonic frequencies in solid Ne |

| Real-time BTE (Adaptive) [34] | Adaptive Numerical Time Step | Dynamic (fs to ps) | Solution Tolerance / Cost | 10x speedup or 3-6 orders accuracy improvement |

| SSCHA + MLIP [35] | Configurational Sampling (γ-select) | γ-select = 2 (extrapolation grade) | % Configurations for DFT | ~96% cost reduction for PdCuH2 |

| GPU 3ph/4ph Scattering [36] | N/A (Post-processing) | N/A | Computational Speed | >25x acceleration for scattering rate step |

Table 2: Universal MLIP Performance on Phonon and Structural Properties (Based on Benchmarking 10,000 Materials) [4]

| Model Name | Energy MAE (eV/atom) | Force MAE (eV/Å) | Volume MAE (ų/atom) | Geometry Optimization Failure Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHGNet | Not Specified (Higher) | Not Specified | < PBE-PBEsol difference | 0.09% |

| MatterSim-v1 | Not Specified | Not Specified | < PBE-PBEsol difference | 0.10% |

| M3GNet | ~0.035 (from literature) | Not Specified | < PBE-PBEsol difference | ~0.2% |

| MACE-MP-0 | Not Specified | Not Specified | < PBE-PBEsol difference | ~0.2% |

| ORB | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | >0.85% |

| eqV2-M | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | 0.85% |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Harmonic Phonons with MLIPs and Finite Displacements

This protocol uses machine learning universal potentials to accelerate high-throughput harmonic phonon calculations, drastically reducing the number of required supercell calculations compared to conventional density functional theory (DFT) [7].

- Initial Structure Optimization: Begin with a fully optimized crystal structure. For reliable phonons, optimize both atomic positions and lattice vectors using tight convergence thresholds (e.g., force convergence < 0.001 eV/Å) [5].

- Supercell Construction and Perturbation:

- Construct a supercell large enough to capture all relevant interatomic interactions. The

Phonopycode or similar can determine the minimum necessary supercell size based on a force constant cutoff distance [1]. - Instead of the traditional single-atom displacement method, generate approximately 6 supercells for the material.

- In each supercell, randomly perturb all atoms with displacement magnitudes ranging from 0.01 Å to 0.05 Å. This strategy efficiently samples many non-zero force components for model training [7].

- Construct a supercell large enough to capture all relevant interatomic interactions. The

- DFT Force Calculations: Perform single-point DFT calculations on this subset of perturbed supercells to obtain the reference energies and interatomic forces.

- MLIP Training: Train a state-of-the-art machine learning interatomic potential (e.g., MACE [7]) on the dataset of supercell structures and their corresponding DFT-calculated forces.

- Phonon Property Prediction: Use the trained MLIP to compute the interatomic force constants (IFCs) via the finite-displacement method, typically employing a standard displacement of 0.01 Å. Finally, post-process the IFCs to obtain the full harmonic phonon spectrum, density of states, and related thermodynamic properties.

Protocol 2: Capturing Anharmonicity and Quantum Effects with SSCHA and MLIPs

This protocol leverages the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation (SSCHA) combined with machine-learned potentials to model anharmonicity and nuclear quantum effects (NQEs) efficiently, crucial for systems like hydrides and quantum crystals [35].

- Initial Harmonic Calculation: Perform a harmonic phonon calculation on a relatively small supercell to obtain an initial guess for the dynamical matrix.

- Active Learning SSCHA Loop:

- Population Generation: The SSCHA generates a population of atomic configurations displaced from their equilibrium positions, sampled from a distribution whose width is linked to the current force constants.

- Extrapolative Configuration Identification: For each configuration, calculate the extrapolation grade (γ) using a criterion like the generalized D-optimality. A conservative threshold of γ-select = 2 is recommended [35].

- DFT and MLIP Evaluation:

- Perform DFT calculations only for configurations with γ > γ-select.

- Use the currently trained MLIP (e.g., a Moment Tensor Potential, MTP) to predict energies and forces for all other configurations in the population.

- SSCHA Optimization: Combine all forces (from DFT and MLIP) and feed them to the SSCHA to re-optimize the force constants and centroid positions.

- Iterate: Repeat the population generation and active learning steps until the SSCHA converges for the current supercell size.

- Upscaling:

- Restart the SSCHA with a larger supercell. Use the converged dynamical matrix from the smaller cell to initialize the guess for the larger one via a tight-binding extrapolation.

- In the upscaled simulation, the MLIP from the previous cycle serves as the primary evaluator, with DFT used sparingly for newly encountered extrapolative configurations. This process is iterated until the phonon properties converge with supercell size.

Protocol 3: Adaptive Time-Stepping for Coupled Electron-Phonon Dynamics

This protocol uses adaptive and multirate numerical methods to solve the real-time Boltzmann transport equation (rt-BTE), enabling efficient simulation of coupled electron and phonon dynamics from femtoseconds to picoseconds [34].

- Precomputation: Calculate all necessary first-principles electron-phonon (e-ph) and phonon-phonon (ph-ph) interaction matrix elements on dense momentum grids before the time propagation.

- Integrator Selection and Setup:

- Employ adaptive step-size Runge-Kutta (RK) methods or multirate infinitesimal (MRI) methods from the SUNDIALS/ARKODE library.

- Set absolute and relative solution tolerances (e.g., between 1e-4 and 1e-7) to control the error and guide the adaptive step size [34].

- Time Propagation:

- The integrator dynamically adjusts the time step for the coupled system of equations. MRI methods are particularly effective as they can use different step sizes for the fast (e-ph) and slow (ph-ph) scattering processes.

- At each step, the algorithm computes the scattering integrals. The ph-ph integral, being the most computationally expensive, is the primary target for acceleration.

- Analysis: The output is the time evolution of electron and phonon populations, from which properties like carrier relaxation times, phonon lifetimes, and thermalization pathways can be extracted.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Workflows for step size control across different phonon calculation methodologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Computational Tools for Advanced Phonon Calculations

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Phonon Calculations | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE [7] | Machine Learning Interatomic Potential | Accurately predicts interatomic forces for force constant calculation. | State-of-the-art message passing neural network; high data efficiency. |

| SSCHA [35] | Computational Method | Models anharmonicity and nuclear quantum effects non-perturbatively. | Combines with active learning and MLIPs for drastic cost reduction. |

| Phonopy [1] | Software Package | Performs harmonic phonon calculations via the finite displacement method. | Open-source, widely used; handles structure optimization and post-processing. |

| PERTURBO [34] | Software Package | Computes electron-phonon couplings and propagates the real-time BTE. | Interface with SUNDIALS for adaptive time-stepping in coupled dynamics. |

| SUNDIALS/ARKODE [34] | Numerical Library | Provides adaptive and multirate time integration algorithms. | Enables dynamic step size control for stiff differential equations like the BTE. |

| FourPhonon_GPU [36] | GPU-Accelerated Code | Calculates three- and four-phonon scattering rates and thermal conductivity. | Uses OpenACC for massive parallelization; >25x speedup for scattering rates. |

| QuantumATK [32] | Commercial Platform | Integrated environment for phonon band structure, DOS, and transmission. | Combines classical potentials, DFT, and automated workflow management. |

Geometry optimization, the process of finding the minimum-energy configuration of a system by adjusting nuclear coordinates and lattice vectors, is a foundational step in computational materials science and drug development [37]. The accuracy of this process is paramount, as virtually all subsequent property calculations—from electronic band structures to phonon dispersions—are performed on the relaxed structures [38]. For researchers investigating phonon properties, which are critically dependent on the precise details of the interatomic force constants, a rigorously optimized geometry is an non-negotiable prerequisite [7] [11]. This application note details the core principles, convergence criteria, and advanced protocols for performing robust geometry optimizations of both atomic positions and lattice parameters, with a specific focus on ensuring the accuracy of downstream phonon calculations.

Foundational Concepts and Convergence Criteria

The Geometry Optimization Landscape

Geometry optimization is typically a local process, meaning it converges to the nearest local minimum on the potential energy surface (PES) based on the initial configuration provided [37]. The optimization involves navigating the PES by utilizing the total energy, atomic forces (the negative gradient of the energy with respect to atomic positions), and, for solid-state systems, the stress tensor (the derivative of the energy with respect to the lattice vectors) [39] [37].

A critical strategic choice is whether to optimize the lattice vectors in addition to the atomic coordinates. Constraining the lattice while relaxing only the atoms is appropriate for studying local defects in an otherwise fixed host matrix. In contrast, full optimization of both is necessary for predicting stable crystal polymorphs or equilibrium bulk properties [39] [37]. Furthermore, the choice of constraints can preserve or break crystal symmetry. One can choose to Constrain space group, which relaxes atom positions, unit cell volume, and shape while preserving the original crystal symmetry, or Constrain Bravais lattice, which allows the relaxation to a different crystal symmetry and is useful for optimizing alloys or amorphous materials [39].

Quantitative Convergence Criteria

Convergence is judged by simultaneous satisfaction of thresholds for energy changes, forces, steps, and, for lattice optimization, stresses. The following table summarizes standard and stringent convergence criteria, with the latter often recommended for pre-phonon calculations [39] [37].

Table 1: Standard and Stringent Convergence Criteria for Geometry Optimization

| Criterion | Description | Standard Setting | Stringent Setting (e.g., for Phonons) | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | Change in total energy between steps | 1×10⁻⁵ | 1×10⁻⁶ | Hartree/atom |

| Gradients (Forces) | Maximum Cartesian force on any atom | 1×10⁻³ | 1×10⁻⁴ | Hartree/Bohr |

| Gradients (Forces) RMS | Root-mean-square of all Cartesian forces | 6.7×10⁻⁴ | 6.7×10⁻⁵ | Hartree/Bohr |

| Step | Maximum displacement of any atom between steps | 0.01 | 0.001 | Ångstrom |

| Stress | Maximum stress tensor component (for lattice optimization) | 5×10⁻⁴ | 5×10⁻⁵ | Hartree/atom |

The "Quality" setting in some software packages offers a convenient way to toggle these thresholds collectively [37]:

Normal: Typically corresponds to the Standard Setting column.Good: Tightens all thresholds by an order of magnitude.VeryGood: Tightens all thresholds by two orders of magnitude.

It is considered good practice to tighten the gradient criterion rather than the step criterion for accurate final coordinates, as the step uncertainty is dependent on the approximate Hessian used by the optimizer [37].

Computational Workflows and Protocols

The following diagram illustrates the standard iterative workflow for a full geometry optimization (lattice + atoms), highlighting key decision points and the role of machine learning-assisted approaches.

Protocol 1: Basic DFT-Based Optimization for Bulk Crystals

This protocol outlines the standard process for optimizing a bulk crystal structure using Density Functional Theory (DFT), as exemplified for SiO₂ (quartz) [39].

- Initial Structure Acquisition: Obtain the initial crystal structure from a validated source, such as the NanoLab Internal Database, the Crystallography Online Database (COD), or the Materials Project [39].

- Calculator Setup: Configure the DFT calculator. For semiconductors and insulators like SiO₂, a hybrid functional (e.g., HSE06) can provide superior accuracy for lattice parameters compared to standard GGA functionals like PBE [39].

- Basis Set: Use a linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) or plane-waves with a medium basis set size and a k-point sampling appropriate for the system.

- Numerical Accuracy: For semiconductors, set a Fermi-Dirac occupation broadening of ~300 K instead of the default 1000 K for improved convergence [39].

- Optimization Block Configuration:

- Constraints: For a general bulk optimization, select "Constrain space group" to relax atomic positions, cell volume, and shape while preserving the original crystal symmetry [39].

- Algorithm: Select a robust optimizer such as Quasi-Newton, L-BFGS, or FIRE [37].

- Convergence Criteria: Adopt the "Good" or "VeryGood" quality settings, or manually input criteria from Table 1. For phonon pre-optimization, aim for a force tolerance of at least 0.0001 Ha/Å and a stress tolerance of 0.00005 Ha/atom [39] [37].

- Job Execution and Monitoring: Run the calculation, monitoring the convergence of energy, forces, and stress over the optimization steps. Tools like the Movie Tool in QuantumATK can visualize the trajectory and structural evolution [39].

- Result Analysis: Upon convergence, compare the optimized and initial lattice constants. Inspect the final forces and stresses to confirm they are below the threshold. The optimized structure is now ready for subsequent property calculations [39].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Accelerated Optimization

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) can dramatically reduce the cost of geometry optimization by providing DFT-level forces at a fraction of the computational cost [7] [11]. Two distinct paradigms exist:

A. Using Foundational MLIPs Foundational models like MACE-OFF23, M3GNet, or CHGNet are pre-trained on extensive datasets and can be used out-of-the-box for organic molecules or specific material classes [38] [40].

- Procedure: Replace the DFT force/stress engine in the standard workflow with a foundational MLIP. The optimization then proceeds identically, but each force evaluation is orders of magnitude faster.

- Caveat: Performance is highly dependent on the system's similarity to the training data. They may fail for molecules with unusual functional groups (e.g., diazo) or organic salts not well-represented in the training set [40].

B. The "One Defect, One Potential" Strategy For systems where high-fidelity phonon properties are critical, such as defect-phonon coupling, a bespoke MLIP strategy is recommended [11].

- Generate Training Data: Start with the DFT-relaxed defect structure. Create a compact training set by generating ~40-50 perturbed supercells. This is done by randomly displacing all atoms in the supercell with a small displacement radius (e.g., 0.04 Å) from their equilibrium positions [11].

- DFT Single-Point Calculations: Perform a single-shot DFT calculation on each of these perturbed structures to obtain the total energy and atomic forces. This constitutes the training dataset.

- Train a Defect-Specific MLIP: Train an equivariant graph neural network potential (e.g., using Allegro or NequLP frameworks) on this limited dataset. The local descriptor of these models ensures high data efficiency [11].

- Optimize with MLIP: Use the newly trained, defect-specific potential to drive the geometry optimization to convergence. The resulting structure and phonon properties show excellent agreement with direct DFT but at a drastically reduced computational cost [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Software and Computational Tools for Geometry Optimization

| Tool / "Reagent" | Type | Primary Function in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | First-Principles Method | Provides fundamental quantum mechanical forces, stresses, and energies; the gold standard for accuracy. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | Machine Learning Force Field | Provides fast, approximate forces and energies; used to accelerate or replace DFT in optimization loops [9] [7]. |

| Optimizers (L-BFGS, FIRE, Quasi-Newton) | Algorithm | Updates atomic positions and lattice vectors using forces/stresses to minimize the total energy [37]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | Experimental Design Algorithm | Guides the selection of new candidate structures (e.g., polymers) for evaluation in an automated design loop, minimizing the number of expensive simulations [41]. |

| Automatic Differentiation | Mathematical Framework | Enables end-to-end training of models that can directly predict relaxed structures, bypassing iterative optimization [38]. |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Phonon Calculations

The choice of geometry optimization protocol directly impacts the efficiency and accuracy of advanced material properties calculations.