Non-Specific Binding in SPR Experiments: A Complete Troubleshooting Guide from Detection to Validation

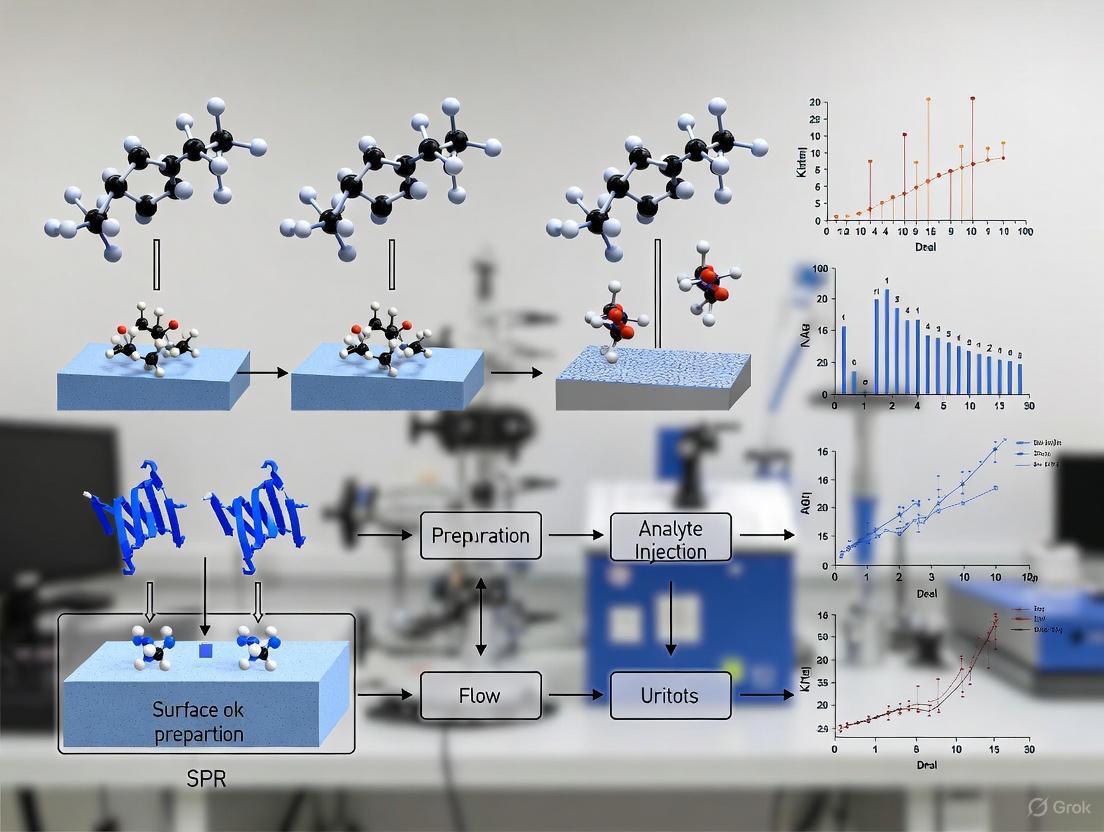

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on tackling non-specific binding (NSB) in Surface Plasmon Resonance experiments.

Non-Specific Binding in SPR Experiments: A Complete Troubleshooting Guide from Detection to Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on tackling non-specific binding (NSB) in Surface Plasmon Resonance experiments. Covering foundational concepts to advanced validation techniques, it details how to identify NSB origins, implement effective mitigation strategies using buffer additives and surface engineering, optimize experimental protocols, and rigorously validate data to ensure kinetic and affinity parameters are accurate and reliable.

Understanding Non-Specific Binding: Defining the Problem and Its Impact on SPR Data Quality

What is Non-Specific Binding? Distinguishing Specific vs. Non-Specific Signals

FAQ: What is non-specific binding (NSB)?

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and other binding assays, non-specific binding (NSB) occurs when an analyte interacts with surfaces or sites other than the intended target binding site [1] [2]. This includes binding to the sensor chip itself, non-target molecules, or assay components like filters [3]. In contrast, specific binding is the desired interaction between the analyte and its cognate receptor or ligand [4]. NSB creates a background signal that can obscure true specific interactions, leading to inaccurate data and erroneous conclusions about binding affinity and kinetics [1] [2].

FAQ: How does non-specific binding occur?

NSB is primarily driven by non-covalent molecular forces, such as hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic (charge-based) attractions [1] [3]. In SPR, if the sensor surface has a negative charge, a positively charged analyte may bind to it irrespective of the specific ligand [1]. Sample impurities or suboptimal experimental conditions like buffer composition, pH, or ionic strength can further exacerbate NSB [2] [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Non-Specific Binding

How to Identify Non-Specific Binding

Recognizing NSB is the critical first step in troubleshooting. The table below outlines common hallmarks and their descriptions.

Table 1: Identifying Signs of Non-Specific Binding

| Observation | Description |

|---|---|

| Signal on Reference Channel | In SPR, a significant response on the reference surface (without the specific ligand) indicates NSB. If this signal is more than a third of the sample channel response, NSB is likely interfering [6]. |

| Lack of Saturation | Specific binding is saturable. If binding does not plateau with increasing analyte concentration and instead shows a linear increase, it suggests a significant non-specific component [4]. |

| Promiscuous Binding | An inhibitor or analyte appears to bind to multiple, unrelated targets, which is a classic sign of aggregation-based inhibition [7]. |

| Unusual Kinetic Curves | NSB can manifest as rapid, non-saturable association and slow dissociation, which differs from the characteristic curves of specific interactions [2]. |

Core Strategies to Reduce Non-Specific Binding

Once identified, the following strategies can be employed to minimize NSB.

Optimize Buffer Composition and Additives

The buffer is a powerful tool for controlling the chemical environment to discourage NSB.

Table 2: Common Buffer Additives to Minimize NSB

| Additive | Function | Typical Usage | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSA or Casein | Protein blocking agent [1] [2] [5] | 0.5 - 2 mg/mL [6] | Coats the surface and tubing, shielding hydrophobic and charged sites from nonspecific interactions [1]. |

| Non-Ionic Surfactants (Tween 20) | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions [1] [8] | 0.005% - 0.1% [6] | Reduces hydrophobic binding by coating surfaces and analyte [1]. A key tool to attenuate aggregation-based inhibition (ABI) [7]. |

| Salt (NaCl) | Shields electrostatic interactions [1] | Up to 500 mM [6] | Ionic strength shields charged groups on the analyte and surface, preventing charge-based attraction [1]. |

| Dextran or PEG | Polymer-based blocking [8] [6] | ~1 mg/mL [6] | Acts as a physical barrier to block unused sites on specific sensor chip surfaces like carboxymethyl dextran [6]. |

Refine Experimental Design and Surface Chemistry

- Optimize Sensor Surface: Choose a sensor chip with surface chemistry that minimizes interactions with your specific analyte. If using a dextran chip shows high NSB, try a planar surface, and vice versa [5] [6]. After immobilization, use a blocking agent like ethanolamine to cap any remaining active sites [5].

- Improve Sample Quality: Contaminants or aggregates in your sample are a major source of NSB. Purify your analyte using methods like centrifugation, dialysis, or size-exclusion chromatography before the experiment [2] [5].

- Include Proper Controls: Always run a reference channel with no specific ligand immobilized, or with an irrelevant ligand. The signal from this channel represents NSB and can be subtracted from the sample channel signal to isolate the specific binding [2] [3].

The following workflow provides a logical pathway for diagnosing and addressing NSB in your experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key reagents used to troubleshoot and minimize non-specific binding.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NSB Troubleshooting

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Protein-based blocking agent to shield hydrophobic/charged surfaces [1]. | Standard concentration is 1%, but should be optimized for each experiment [1]. |

| Tween 20 | Non-ionic surfactant to disrupt hydrophobic interactions [1] [8]. | Use at low concentrations (0.005%-0.1%); higher concentrations may disrupt specific binding [6]. |

| NaCl | Salt to shield charge-based electrostatic interactions [1]. | Can be used at varying concentrations up to 500 mM [6]. Test for protein stability at high salt. |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent to attenuate aggregation-based inhibition (ABI) [7]. | Converts protein-binding aggregates into non-binding coaggregates, preventing false positives [7]. |

| Human Serum Albumin (HSA) | Carrier protein that acts as a reservoir for hydrophobic inhibitors [7]. | Prevents ligand self-association (aggregation) but may also suppress specific binding, risking false negatives [7]. |

| Carboxymethyl Dextran | Polymer additive for blocking specific sensor chip types [6]. | Used at ~1 mg/mL in running buffer to block unused sites on dextran chips [6]. |

| Ethylenediamine | Surface charge modifier for amine-coupled chips [6]. | Used instead of ethanolamine to block the surface, resulting in a less negative surface to repel positively charged analytes [6]. |

A technical guide for researchers troubleshooting non-specific binding in Surface Plasmon Resonance experiments.

Non-specific binding (NSB) occurs when analyte molecules interact with the sensor surface through molecular forces unrelated to the specific biological interaction of interest. These unintended interactions are primarily driven by hydrophobic interactions, charge-based (electrostatic) interactions, and hydrogen bonding [1] [9]. In an SPR experiment, NSB manifests as a response on the reference channel and can lead to erroneous calculated kinetics, inflating the measured response units (RU) and compromising data accuracy [1]. This guide provides a structured approach to diagnosing and mitigating NSB based on the underlying molecular forces.

FAQ: Diagnosing Non-Specific Binding

Q1: How can I confirm that non-specific binding is occurring in my experiment? A1: NSB can be verified by examining the response on the reference channel. If the response on the reference channel is greater than about a third of the sample channel response, the non-specific binding contribution is significant and should be reduced [6]. A simple preliminary test is to run your analyte over a bare sensor surface (without any immobilized ligand). A significant signal on this surface confirms the presence of NSB [1].

Q2: My analyte is positively charged. What is a specific strategy I can use to reduce charge-based NSB? A2: For positively charged analytes, the negative charge of a standard carboxymethyl dextran sensor chip can be a primary cause of NSB. After standard amine coupling, you can block the sensor chip with ethylenediamine instead of the more common ethanolamine. Ethylenediamine introduces a primary amine that reduces the net negative charge of the sensor surface, thereby decreasing electrostatic attraction to your positively charged analyte [6].

Q3: What are the hallmarks of mass transport limitation, and how does it relate to my immobilization level? A3: Mass transport limitation occurs when the rate of analyte diffusion to the sensor surface is slower than its binding rate. Sensorgrams will appear linear during the association phase, lacking the expected curvature [10]. While a sufficient immobilization level is needed for a detectable signal, excessively high ligand density can promote mass transport effects. A low immobilization level and a low Rmax are often better for obtaining reliable kinetics [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Molecular Forces and Corrective Actions

The table below summarizes the primary molecular forces behind NSB and the corresponding optimization strategies.

Table: Molecular Forces Behind Non-Specific Binding and Corrective Strategies

| Molecular Force | Manifestation in SPR | Recommended Corrective Action | Key Reagents & Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Interactions | NSB due to non-polar surface/analyte domains [1] | Introduce mild, non-ionic surfactants to disrupt hydrophobic forces [1] [8] | Tween-20 (0.005% - 0.1%) [1] [6] |

| Charge-Based (Electrostatic) Interactions | Attraction/repulsion between charged analyte and surface [1] | Adjust buffer pH or increase ionic strength to shield charges [1] | NaCl (up to 500 mM) [1] [6]; Buffer pH adjustment [1] |

| Hydrogen Bonding & Other NSB | Multivalent, non-specific adhesion to surface chemistries [9] | Use protein blockers to occupy non-specific binding sites [1] [9] [8] | BSA (0.5 - 2 mg/ml) [1] [6]; Casein [9] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for NSB Reduction

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of Running Buffer

This protocol outlines a stepwise approach to incorporate additives into your running buffer to mitigate NSB.

- Prepare a Stock Running Buffer: Start with a standard buffer (e.g., HBS-EP) that is compatible with your biomolecules and sensor chip.

- Test a Surfactant Additive: To address hydrophobic interactions, add Tween-20 to the running buffer from a stock solution to a final concentration of 0.005% to 0.1% [1] [6]. Inject the analyte and evaluate the reduction in reference channel signal.

- Test a Charge-Shielding Additive: To address electrostatic interactions, supplement the buffer with NaCl. A final concentration of 150-200 mM is a common starting point, with up to 500 mM being acceptable [1] [6]. Re-inject the analyte and assess the signal.

- Test a Protein Blocking Additive: To occupy remaining non-specific sites, add Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to the running buffer at a concentration of 0.5 to 2 mg/mL [1] [6]. Re-evaluate the binding signal.

- Combine Effective Additives: Based on the results, combine the most effective additives (e.g., 0.01% Tween-20 and 150 mM NaCl) into a single, optimized running buffer for all subsequent experiments.

Protocol 2: Surface Blocking with Ethylenediamine for Positively Charged Analytes

Use this protocol after ligand immobilization via amine coupling to reduce surface charge.

- Complete Ligand Immobilization: Perform the standard EDC/NHS activation and ligand coupling steps on your chosen sensor chip.

- Prepare Ethylenediamine Solution: Dissolve ethylenediamine in deionized water to a concentration of 1 M, and adjust the pH to 8.0 [6].

- Inject Blocking Solution: Instead of the standard ethanolamine injection, inject the ethylenediamine solution for 5-7 minutes to covalently couple to the remaining activated carboxyl groups.

- Wash and Stabilize: Wash the system with running buffer to remove excess ethylenediamine and stabilize the baseline before starting analyte injections.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents used to troubleshoot and reduce non-specific binding in SPR experiments.

Table: Essential Reagents for Troubleshooting Non-Specific Binding

| Reagent | Function in NSB Reduction | Typical Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Tween-20 | Non-ionic surfactant that disrupts hydrophobic interactions [1] [8] | 0.005% - 0.1% [1] [6] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Protein blocker that adsorbs to and shields non-specific binding sites on the sensor surface [1] [9] | 0.5 - 2 mg/mL [1] [6] |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Salt that shields electrostatic charges, reducing charge-based attraction/repulsion [1] | Up to 500 mM [6] |

| Ethylenediamine | Charged blocking agent used after amine coupling to reduce the net negative charge of the sensor surface [6] | 1 M, pH 8.0 [6] |

| Carboxymethyl Dextran | Can be added to running buffer when using CMx chips to compete for non-specific interactions with the dextran matrix [6] | 1 mg/mL [6] |

NSB Troubleshooting Logic Flow

The following diagram outlines a systematic decision-making process for diagnosing and resolving NSB based on the underlying molecular forces.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is non-specific binding (NSB) in SPR, and why is it a problem? Non-specific binding (NSB) occurs when your analyte interacts with the sensor surface or the immobilized ligand through non-targeted, unintended forces like hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, or charge-based attraction [11] [1]. This inflates the measured response units (RU), leading to inaccurate data and erroneous calculations of binding affinity and kinetics [1].

Q2: My analyte is a membrane protein. How can I immobilize it effectively? A novel and robust method involves using the SpyCatcher-SpyTag system combined with membrane scaffold protein (MSP)-based nanodiscs [12] [13]. You can engineer an MSP-SpyTag fusion to incorporate the target membrane protein into lipid nanodiscs. These SpyTag-labeled nanodiscs are then covalently and specifically captured by SpyCatcher proteins pre-immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip. This strategy maintains the protein in a near-native lipid environment, preserving its structure and activity [12] [13].

Q3: How can I tell if my SPR data is affected by mass transport limitation? Mass transport limitation can be identified by examining your binding curve for a linear association phase that lacks curvature [14]. You can also perform a flow rate experiment: inject the analyte at several different flow rates. If the observed association rate constant (ka) decreases at lower flow rates, your interaction is likely mass transport limited [11] [14].

Q4: What is a "bulk shift," and how can I correct for it? Bulk shift, or solvent effect, appears as a large, rapid, square-shaped response change at the start and end of an injection [14]. It is caused by a difference in the refractive index between your analyte solution and the running buffer. The most effective mitigation is to match the components of your analyte buffer to the running buffer as closely as possible, particularly for components like DMSO, glycerol, or sucrose [15] [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Non-Specific Binding (NSB)

NSB is one of the most common artifacts in SPR data. The table below summarizes the common causes and solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Non-Specific Binding

| Cause of NSB | Description | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Charge Interactions | Positively charged analyte attracted to a negatively charged sensor surface [1] [14]. | - Adjust buffer pH to the isoelectric point (pI) of the analyte [1] [14].- Increase salt concentration (e.g., NaCl) to shield charges [1] [14]. |

| Hydrophobic Interactions | Hydrophobic patches on the analyte interact with the surface [1]. | - Add non-ionic surfactants like Tween 20 to the running buffer [1] [14]. |

| General Protein Adsorption | Non-specific sticking of proteins to surfaces or tubing [1]. | - Add protein blocking additives like 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to the buffer [1] [14]. |

Experimental Protocol: Preliminary NSB Test Before collecting formal data, always run this test to gauge NSB levels:

- Use a bare sensor with no immobilized ligand.

- Inject your highest concentration of analyte over this surface.

- Observe the response. A significant signal indicates NSB is present, and you should apply the mitigation strategies listed in Table 1 before proceeding [1] [14].

Guide 2: Optimizing Sensor Surface Regeneration

Regeneration removes bound analyte from the immobilized ligand so the surface can be reused. An ideal regeneration buffer completely strips the analyte without damaging the ligand.

Table 2: Common Regeneration Buffers by Interaction Type

| Type of Analyte-Ligand Bond | Recommended Regeneration Solution |

|---|---|

| Electrostatic | 2 M NaCl [15] [14] |

| Hydrophobic | 10-50% Ethylene Glycol [14] |

| Strong affinity (e.g., antibody-antigen) | 10-100 mM Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0) or 10-100 mM Phosphoric Acid [8] [14] |

Experimental Protocol: Scouting for Regeneration Conditions

- Start Mild: Begin with the mildest potential regeneration buffer (e.g., high salt).

- Inject: Use a short contact time (e.g., 15-30 seconds at 100-150 µL/min) [14].

- Evaluate: Check if the response returns to the original baseline. Then, inject a positive control (a known concentration of analyte) to verify the ligand is still active [14].

- Escalate if Needed: If regeneration is incomplete, progressively try harsher conditions (e.g., acidic buffers) until the surface is fully regenerated without damaging ligand activity [8] [14].

Guide 3: Selecting the Right Immobilization Strategy

The method you use to attach your ligand to the sensor chip is critical for activity and data quality.

Table 3: Common Sensor Chips and Immobilization Methods

| Sensor Chip / Chemistry | Immobilization Principle | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxylated (e.g., CM5) | Covalent coupling via NHS/EDC chemistry to primary amines on the ligand [15] [16]. | General purpose; untagged proteins. | Can lead to heterogeneous attachment if binding site is near the coupling point [8] [15]. |

| NTA | Captures polyhistidine-tagged (His-tag) ligands via chelated nickel ions [15] [16]. | His-tagged ligands. | Provides oriented immobilization. Ligand can be stripped with imidazole or EDTA [16] [14]. |

| Streptavidin | Captures biotinylated ligands [16]. | Biotinylated ligands. | Very stable, high-affinity binding. Excellent for capture from crude samples [16]. |

Workflow Diagrams

SPR Troubleshooting Logic

Membrane Protein Immobilization via SpyTag/Catcher

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Reagents for SPR Troubleshooting

| Reagent | Function / Purpose | Typical Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Protein blocking additive. Shields the analyte from non-specific interactions with surfaces and tubing [1] [14]. | 1% in running buffer and sample solution [1]. |

| Tween 20 | Non-ionic surfactant. Disrupts hydrophobic interactions that cause NSB [1] [14]. | Low concentration (e.g., 0.005-0.05%) in running buffer. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Salt used to shield charge-based interactions. Reduces NSB caused by electrostatic attraction [1] [14]. | Varying concentrations (e.g., 150-500 mM) in running buffer. |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 2-3) | Acidic regeneration solution. Efficiently disrupts strong antibody-antigen and protein-protein interactions [8] [14]. | 10-100 mM, injected for short durations (15-60 sec). |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Basic regeneration solution. Effective for removing tightly bound analytes and cleaning surfaces [8]. | 10-50 mM, injected for short durations. |

| Imidazole | Competitive agent for His-tag capture. Used to regenerate NTA sensor surfaces by displacing the His-tagged ligand [14]. | Varying concentrations (e.g., 300-500 mM) in buffer. |

The Critical Impact of NSB on Kinetic and Affinity Calculations

FAQs: Understanding and Identifying NSB

Q1: What is Non-Specific Binding (NSB) and how does it critically impact my SPR data?

Non-Specific Binding (NSB) occurs when the analyte interacts with non-target sites on the sensor surface or the immobilized ligand, rather than binding specifically to the intended ligand [1] [14]. This inflates the measured response units (RU) and directly leads to erroneous calculations of association rates (ka), dissociation rates (kd), and equilibrium constants (KD) [1] [17]. Essentially, NSB signal masks the true specific binding event, compromising the accuracy and reliability of your kinetic and affinity data.

Q2: How can I quickly test if my experiment has a significant NSB problem?

A simple preliminary test is to run your analyte over a bare sensor surface without any immobilized ligand [1] [14]. If you observe a significant binding response, this indicates the presence of NSB that must be addressed before proceeding with kinetic experiments.

Q3: What are the common visual signs of NSB in my sensorgrams?

Sensorgrams affected by NSB may show a high baseline or a significant response on reference surfaces [14]. The binding curves might also appear unusual or not fit standard binding models well. NSB can manifest as a signal that looks very similar to specific binding, making it crucial to run the proper control tests [18].

Q4: My analyte is a protein with a high isoelectric point (pI). Why am I experiencing severe NSB?

Proteins with a high pI are positively charged at neutral pH. Since many sensor surfaces (like carboxyl or NTA sensors) are negatively charged, this leads to strong charge-based NSB [1] [14]. In this case, you can adjust the buffer pH, use a different sensor chemistry, or add salts to shield these charge interactions.

Troubleshooting Guides: Mitigating NSB

Guide 1: Choosing the Right Strategy to Combat NSB

The table below summarizes the primary sources of NSB and the corresponding solutions.

Table 1: Common Sources of Non-Specific Binding and Recommended Solutions

| Source of NSB | Description | Recommended Solution | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge-Based Interactions [1] [14] | Attraction between a charged analyte and an oppositely charged sensor surface. | - Adjust buffer pH [1] [14]- Increase salt concentration [1] [14] | - pH near protein pI [1]- 150-200 mM NaCl [1] [19] |

| Hydrophobic Interactions [1] [14] | Hydrophobic patches on the analyte interact with the sensor surface. | - Add non-ionic surfactants [1] [14] | - 0.005%-0.01% Tween-20 [14] |

| General Surface Adsorption | Analyte binds indiscriminately to surfaces, tubing, or container walls. | - Use protein blocking additives [1] [14] [18]- Use low-adsorption consumables [20] | - 1% BSA [1] [18]- Carrier proteins or polymers [21] |

Guide 2: Advanced and Combinatorial Blocking Strategies

For challenging cases, especially with weak protein-protein interactions requiring high analyte concentrations (>10 µM), common blockers like BSA may be insufficient [18]. Research has shown that a combinatorial admixture can be far more effective.

Table 2: Advanced Combinatorial NSB-Blocking Admixture

| Component | Function | Final Concentration | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A general protein blocker that shields surfaces from NSB [18]. | 1% | A standard, first-line additive for protein analytes [1]. |

| Sucrose | An osmolyte that enhances protein solvation and reduces aggregation/adsorption. Highly effective as an NSB blocker [18]. | 0.6 M | Non-ionic, highly soluble, and compatible with biosensor tips. More effective than glucose or trehalose [18]. |

| Imidazole | Blocks free sites on Ni-NTA biosensors, preventing analyte binding to the sensor moiety itself [18]. | 20 mM | Use a concentration high enough to block NSB but low enough to not displace His-tagged ligands [18]. |

Protocol: Testing the Combinatorial Blocker

- Prepare your standard running buffer.

- Supplement it with 1% BSA, 0.6 M sucrose, and 20 mM imidazole.

- Use this buffer for dilution of your analyte and as the running buffer.

- Repeat the NSB test on a bare sensor. The NSB signal should be significantly reduced compared to using BSA alone [18].

Guide 3: Experimental Design to Minimize NSB

Optimize Ligand and Sensor Selection:

- Ligand Choice: When possible, choose the smaller, purer, and more negatively charged molecule as the ligand to minimize NSB [14].

- Sensor Chemistry: Select a sensor surface that minimizes charge opposition with your analyte. For example, avoid using a negatively charged carboxyl sensor for a positively charged analyte [14].

Proper Controls are Essential: Always use a reference channel on your SPR instrument. Immobilize a non-interacting ligand or leave the surface bare on the reference channel. The system will then subtract the signal from this reference channel, correcting for bulk refractive index shifts and some level of NSB [14]. If NSB cannot be completely eliminated but accounts for <10% of your total signal, you can correct your data by subtracting the NSB signal from the specific binding signal [1] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Overcoming NSB Challenges

| Reagent / Material | Function in NSB Mitigation | Typical Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A globular carrier protein that adsorbs to exposed hydrophobic and charged surfaces, blocking the analyte from binding non-specifically [1] [21]. | 0.5 - 1% [1] [18] |

| Tween 20 | A non-ionic surfactant that disrupts hydrophobic interactions between the analyte and the sensor surface or tubing [1] [14]. | 0.005 - 0.01% [14] |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Shields charge-based interactions by increasing the ionic strength of the buffer, reducing electrostatic attraction/repulsion [1] [14]. | 150 - 500 mM [1] |

| Sucrose | An effective NSB blocker that works by enhancing protein solvation. Particularly useful for weak PPI studies at high analyte concentrations [18]. | 0.2 - 0.6 M [18] |

| Casein | A milk-derived protein mixture often used as a blocking agent to passivate surfaces [18]. | 0.1 - 0.5% |

| Low-Adsorption Tubes | Consumables made from specially treated polymers that minimize the surface area available for analyte adsorption [20]. | N/A |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates a systematic, decision-tree workflow for diagnosing and mitigating NSB in SPR experiments.

Systematic NSB Troubleshooting Workflow

Proactive Assay Design: Strategic Methods to Prevent and Detect NSB

Non-specific binding (NSB) is a critical challenge in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments that can directly compromise the accuracy of kinetic data [1]. During an SPR experiment, the measured response is intended to reflect the specific interaction between an immobilized ligand and a solubilized analyte. However, when the analyte also interacts with the sensor surface itself or non-target molecules through hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, or Van der Waals forces, this NSB inflates the response units (RU), leading to erroneous calculated kinetics [1] [8].

Preliminary testing for NSB by running the analyte over a bare or deactivated sensor surface is a fundamental and essential first step in any well-optimized SPR experiment [1]. This simple test helps researchers identify the presence and extent of NSB before committing to full experimental runs, saving time and resources while ensuring data quality. When the response on a reference channel exceeds approximately one-third of the sample channel response, the NSB contribution must be systematically reduced [6].

Experimental Protocol for Preliminary NSB Testing

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for conducting preliminary NSB testing:

Detailed Methodology

Surface Preparation: Select an appropriate bare sensor chip (e.g., gold surface) or a deactivated surface. A deactivated surface can be prepared by subjecting a standard sensor chip to the same coupling chemistry used in the main experiment (e.g., amine coupling with EDC/NHS) but without immobilizing the ligand, followed by blocking with ethanolamine [8] [22]. This control surface accurately mimics the chemical environment of the active surface while lacking the specific ligand.

Analyte Injection and Data Collection: Prepare the analyte in the intended running buffer at the highest concentration planned for the main experiment. Inject this analyte solution over the prepared reference surface using the same flow rate and temperature conditions as planned for the actual binding study. Monitor and record the response on the reference channel in real-time [1] [6].

Response Evaluation: Compare the response unit (RU) signal obtained from the reference channel to the expected specific binding signal on the sample channel. As a general guideline, if the NSB response exceeds one-third of the specific binding response, mitigation strategies are required before proceeding [6].

Quantitative Data on Common NSB Reduction Strategies

The table below summarizes the most effective buffer additives and their optimal concentration ranges for reducing non-specific binding, as evidenced by experimental data:

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Non-Specific Binding

| Reagent Solution | Mechanism of Action | Typical Concentration Range | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [1] [8] [6] | Shields analyte from non-specific interactions with charged surfaces and tubing by acting as a protein blocker. | 0.5 - 2 mg/mL (or 0.05% - 0.2%) | Effective for preventing non-specific protein-protein interactions and sample loss. |

| Tween 20 [1] [8] [6] | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions between analyte and sensor surface via mild, non-ionic surfactant action. | 0.005% - 0.1% (v/v) | Ideal when NSB is driven by hydrophobic effects. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) [1] [6] | Shields charged molecules via ionic strength, preventing electrostatic interactions with the surface. | Up to 500 mM | Particularly effective for charged analytes or surfaces. |

| Carboxymethyl Dextran [6] | Acts as a blocking agent specific to carboxymethyl dextran sensor chips. | 1 mg/mL | Used when working with CM5 or similar dextran-based chips. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [8] [6] | Reduces NSB through steric hindrance and surface passivation. | 1 mg/mL | Suitable for planar COOH sensor chips. |

Table 2: Buffer pH Adjustment Strategies Based on Analyte Properties

| Analyte Characteristic | Recommended pH Adjustment | Intended Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Positively Charged [1] [6] | Adjust buffer pH to the isoelectric point (pI) of the analyte OR neutralize the sensor surface (e.g., with ethylenediamine). | Reduces electrostatic attraction between analyte and negatively charged sensor surface. |

| Negatively Charged [1] | No adjustment or slight acidification may be needed, but requires empirical testing. | Minimizes charge-based repulsion or attraction. |

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

FAQ 1: What should I do if my preliminary test shows high NSB on the bare surface?

High NSB indicates a need to optimize your running buffer. Begin by systematically introducing additives from Table 1. A combination of 0.1% BSA and 0.01% Tween 20 is an excellent starting point for protein analytes. If the analyte is highly charged, incrementally increase the NaCl concentration (e.g., 150 mM, 250 mM, 500 mM) while monitoring for improvements. Always verify that these conditions do not denature your biomolecules or disrupt the specific interaction under investigation [1] [5].

FAQ 2: My analyte binds strongly to the reference surface. How can I distinguish this from specific binding?

This is the precise purpose of the reference channel. In the main experiment, the response you measure on the sample channel (with immobilized ligand) is the sum of specific binding, any remaining NSB, and bulk refractive index shift. The reference channel (with a bare or deactivated surface) measures only the NSB and bulk effect. The specific binding signal is obtained in real-time by digitally subtracting the reference channel response from the sample channel response [6]. If NSB is still too high after optimization, this subtraction becomes less reliable, underscoring the need for effective NSB reduction.

FAQ 3: After trying common additives, NSB is still unacceptably high. What are my next steps?

Consider a more fundamental change to your experimental setup:

- Alternative Sensor Chips: If using a dextran-based chip (e.g., CM5), switch to a chip with a different surface chemistry, such as a planar hydrophobic or lipophilic sensor chip, which may present different non-specific binding properties [8] [6].

- Different Immobilization Chemistry: If the ligand's binding pocket is near the coupling site, it might be partially obstructed, leading to misleading signals. Try an alternative coupling strategy, such as capture-based immobilization (e.g., using a His-tag and NTA chip) or covalent coupling via thiol groups instead of amines [8].

- Ligand Coupling on Reference: For the reference channel, couple a compound that is structurally similar to your ligand but does not bind the analyte. This provides a more accurate surface for subtraction [8] [6].

Preliminary NSB testing is a non-negotiable step in robust SPR experimental design. By running the analyte over a bare or deactivated sensor surface, researchers can diagnose the severity of NSB and take informed, systematic steps to mitigate it through buffer optimization and surface chemistry selection. A methodical approach to NSB troubleshooting, beginning with the protocols outlined here, ensures that the resulting binding data accurately reflects the biology of interest, thereby enhancing the reliability of kinetic and affinity determinations in drug development and basic research.

Troubleshooting Guides

How do I identify and troubleshoot issues with my reference surface?

A faulty or poorly chosen reference surface is a common source of error in SPR experiments, often leading to inaccurate data. The table below outlines common symptoms, their likely causes, and recommended solutions.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Binding Signals: The analyte appears to bind more strongly to the reference than to the target surface. [8] | Buffer mismatch or high non-specific binding to the reference surface. [8] | - Supplement running buffer with additives like BSA or surfactants. [8] [1]- Test the suitability of your reference by injecting a high analyte concentration over different surfaces. [8] |

| High Non-Specific Binding (NSB): Significant signal is detected on the reference flow cell. [23] | The reference surface is not adequately blocking interactions between the analyte and the sensor chip matrix. | - Optimize the surface deactivation method after ligand immobilization. [23]- Use a matched reference surface with an identical, but non-functional, ligand. [8] |

| Inconsistent Baseline or Noisy Sensorgram | Contamination on the reference surface or unstable ligand immobilization. | - Clean and regenerate the sensor surface. [23]- Ensure proper sample preparation to remove impurities. [24] |

| Data Inconsistency Between Replicates | Inconsistent preparation of the reference surface from one experiment to the next. | - Standardize the immobilization and deactivation protocol. [23]- Use a consistent sample handling technique. [23] |

What should I do if I see a negative binding signal in my sensorgram?

A negative binding signal, where it appears the analyte binds more strongly to the reference surface, is a clear indicator that your reference surface is not functioning correctly. [8] Follow this systematic protocol to identify and resolve the issue.

Experimental Protocol: Troubleshooting Negative Binding Signals

Test Reference Surface Suitability: Inject the highest concentration of your analyte over different surfaces to benchmark its behavior:

- Unmodified Surface: A bare, underivatized sensor chip.

- Deactivated Surface: A sensor chip that has been activated (e.g., with EDC/NHS) and then blocked with a non-reactive molecule like ethanolamine. [23]

- Protein-Coated Surface: A surface immobilized with a non-specific protein like BSA or an irrelevant IgG. [8]

- Interpretation: Significant binding to the deactivated or protein-coated surfaces indicates general NSB that must be addressed before proceeding.

Optimize Running Buffer: NSB is often caused by electrostatic or hydrophobic interactions. Modify your running buffer to suppress these:

- Adjust pH: If your analyte is positively charged, it may interact with a negatively charged dextran matrix. Adjust the buffer pH to the isoelectric point of your analyte to neutralize its charge. [1]

- Increase Ionic Strength: Add NaCl to your buffer (e.g., 200 mM) to shield charge-based interactions. [1]

- Add Detergents: Incorporate a non-ionic surfactant like Tween 20 (e.g., 0.05%) to disrupt hydrophobic binding. [1]

- Add Blocking Proteins: Supplement buffer with BSA (e.g., 1%) to block non-specific sites on the sensor surface and system tubing. [1]

Re-evaluate Surface Chemistry: If buffer optimization is insufficient, consider changing the sensor chip type or the method of ligand coupling to better present the target and minimize non-specific interactions. [8]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental purpose of a reference surface in an SPR experiment?

The reference surface serves as an essential internal control. Its primary purpose is to generate a signal from all non-specific interactions and systemic effects (such as bulk refractive index changes, injection noise, or matrix effects) so that this signal can be subtracted from the signal obtained from the active ligand surface. This subtraction yields a sensorgram that reflects only the specific binding interaction of interest. [25]

What are the main types of reference surfaces, and when should I use each one?

The choice of reference surface is critical for a successful experiment. The table below compares the three primary designs.

| Reference Surface Type | Description | Ideal Use Case | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unmodified | A sensor chip flow cell that has not been chemically derivatized or coupled with any molecule. [8] | Preliminary tests to assess the level of non-specific binding of your analyte to the bare chip matrix. | Does not account for NSB introduced by the chemical groups used during ligand immobilization on the active surface. |

| Deactivated | A flow cell that has been activated with the same chemistry as the active surface (e.g., EDC/NHS) but is then "blocked" or deactivated with a non-reactive compound like ethanolamine. [23] | Standard experiments where the ligand is covalently immobilized. It controls for the chemical environment of the dextran matrix. | The gold standard for most covalent coupling experiments. It effectively controls for the immobilized chemical groups. |

| Matched | A surface that is intentionally immobilized with a ligand that is identical to the active ligand but is mutated, inactivated, or otherwise unable to bind the analyte specifically. [8] | Complex experiments where the analyte may have low-level affinity for the ligand's scaffold or structure itself. | Provides the highest level of specificity, as the chemical and structural environment is nearly identical to the active surface. Can be difficult to produce. |

How can I reduce non-specific binding to my reference surface?

Reducing NSB requires a multi-faceted approach targeting the sample, buffer, and surface: [24]

- Optimize Sample Preparation: Purify your analyte to remove contaminants using centrifugation, dialysis, or size-exclusion chromatography. [24]

- Use Buffer Additives: As outlined in the troubleshooting protocol, additives like BSA (a protein blocker), Tween 20 (a surfactant), and NaCl (to shield charge) are highly effective. [1]

- Employ a Robust Deactivated Surface: Ensure your deactivation step (e.g., with ethanolamine) is thorough to cover all reactive sites. [23]

My regeneration step doesn't fully return the signal to baseline. Could this be related to my reference surface?

Yes, an incomplete regeneration can affect both your active and reference surfaces, leading to signal carry-over and inaccurate data for subsequent cycles. While regeneration is typically focused on the active surface, a poorly regenerated reference will not provide a clean baseline for subtraction. Optimize your regeneration conditions (e.g., testing glycine pH 2.0, NaOH, or high salt solutions) to completely remove all bound analyte from both surfaces without damaging the immobilized ligand. [8] [23]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents used to prepare and optimize reference surfaces and minimize non-specific binding.

| Reagent | Function in SPR Reference Surfaces |

|---|---|

| Ethanolamine | A common deactivation agent used to block unreacted NHS-ester groups on the sensor chip surface after covalent ligand immobilization, creating a neutral chemical environment. [23] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A globular protein used as a blocking agent at 1% concentration in buffers to coat hydrophobic or charged sites on the sensor surface and fluidic system, preventing loss of analyte and reducing NSB. [1] |

| Tween 20 | A non-ionic surfactant added to running buffers at low concentrations (e.g., 0.05%) to disrupt hydrophobic interactions between the analyte and the sensor surface. [1] |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | A salt used to increase the ionic strength of the running buffer, which shields electrostatic interactions between charged analytes and the sensor surface. [1] |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0) | A low-pH solution commonly used as a regeneration agent to disrupt protein-protein interactions and remove bound analyte from the sensor surface, allowing for chip re-use. [8] |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | A high-pH solution used as a regeneration agent for robust cleaning of the sensor surface. [8] |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and validating an appropriate reference surface for an SPR experiment.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for studying biomolecular interactions in real-time, providing invaluable insights into kinetics, affinity, and specificity. The sensor chip is the heart of any SPR system, serving as the platform where these molecular interactions occur. Choosing the appropriate sensor chip chemistry is a foundational decision that directly impacts data quality, experimental success, and troubleshooting frequency, particularly concerning non-specific binding (NSB). NSB occurs when molecules interact with the sensor surface through unintended mechanisms, leading to inaccurate data and erroneous kinetic calculations. A well-chosen chip, matched to the experimental system, forms the first and most crucial line of defense against this pervasive challenge. This guide provides a detailed comparison of common sensor chips—CM5, NTA, and SA—and introduces advanced low-fouling alternatives, offering researchers a framework to select the optimal surface chemistry for their specific needs.

Sensor Chip Comparison Table

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, optimal use cases, and troubleshooting priorities for the most common sensor chip types.

| Chip Type | Immobilization Chemistry | Ligand Requirements | Typical Applications | Key Advantages | Primary NSB Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM5 | Covalent coupling (e.g., amine coupling via NHS/EDC) to a carboxymethylated dextran matrix [5] [26] | None (native protein) | General protein-protein interactions; high immobilization capacity [5] | High binding capacity; versatile for many biomolecules | Hydrophobic/electrostatic interactions with dextran matrix [1] [8] |

| NTA | Affinity capture via His-tag to Ni²⁺-nitrilotriacetic acid [27] | His-tagged ligand | Protein-nucleic acid interactions; tagged protein kinetics [28] [27] | Controlled orientation; surface regeneration [27] | Chelation of serum proteins; metal-ion-mediated NSB [27] |

| SA (Streptavidin) | Affinity capture via biotin-streptavidin interaction [5] | Biotinylated ligand | Antibody-antigen studies; nucleic acid hybridization [5] | Very stable binding; excellent orientation | Hydrophobic patches on streptavidin surface; non-specific analyte adhesion [5] |

| Low-Fouling | Varies (e.g., PEG, zwitterionic polymers, self-assembled monolayers) [29] | Varies (often covalent) | Analysis in complex matrices (serum, plasma, crude lysate) [29] | Designed to minimize NSB from complex samples | Minimal by design, but dependent on correct polymer coating [29] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: How do I select the right sensor chip to minimize non-specific binding from the start?

Answer: The optimal chip choice depends on your ligand, analyte, and sample matrix. Follow this decision logic:

- For general protein studies with purified components, the CM5 chip is a versatile starting point. However, its dextran matrix can contribute to NSB, requiring careful optimization of buffer conditions and surface blocking [5] [8].

- For controlled orientation and easy regeneration of His-tagged proteins, the NTA chip is ideal. Be aware that nickel ions can chelate certain serum proteins, leading to NSB in complex media [27].

- For extremely stable immobilization of biotinylated ligands (e.g., antibodies, DNA), the SA chip is superior. Its primary NSB risk comes from hydrophobic interactions [5].

- For experiments using complex biological fluids like serum, plasma, or cell lysates, low-fouling chips are strongly recommended. These surfaces are specifically engineered with coatings like poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) or zwitterionic polymers to resist protein adsorption, thereby preserving signal integrity and assay sensitivity [29].

FAQ 2: I am using a CM5 chip and see high baseline drift and non-specific binding. What should I do?

Answer: High NSB and baseline drift on CM5 chips are common but manageable issues. Implement the following strategies:

- Optimize Surface Blocking: After ligand immobilization, inject a blocking agent like ethanolamine, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), or casein to occupy any remaining reactive sites on the dextran matrix [5] [1].

- Adjust Buffer Composition: Modify the pH of your running buffer to ensure your analyte is not positively charged and interacting with the negatively charged dextran. Adding non-ionic surfactants like Tween 20 (0.005%-0.05%) can disrupt hydrophobic interactions, while increasing salt concentration (e.g., 150-200 mM NaCl) can shield electrostatic attractions [1].

- Verify Surface Regeneration: Inefficient regeneration between cycles can lead to a buildup of residual material, causing baseline drift. Ensure you are using a robust regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM glycine pH 2.0, 10 mM NaOH, or 2 M NaCl) that fully removes the analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand [5] [8].

FAQ 3: My NTA chip results are inconsistent between experiments and chips. Is this normal?

Answer While some variability is inherent to commercial NTA chips, it is not uncontrollable. This inconsistency often stems from differences in Ni²⁺ loading and ligand immobilization efficiency across different chips and channels [27].

- Calibrate for Each Chip: Do not assume the same ligand concentration will yield identical immobilization levels on different chips. Perform a ligand titration to establish a calibration curve for each new chip, identifying the linear range of analyte response and avoiding steric crowding at high density [27].

- Ensure Consistent Handling: Standardize the chip preconditioning, Ni²⁺ activation, and ligand immobilization protocols, carefully controlling time, temperature, and pH [5] [27].

- Buffer Exchange Ligand: If your protein ligand is stored in a buffer containing glycerol or imidazole, perform a buffer exchange into the SPR running buffer before immobilization to prevent interference with the Ni²⁺-NTA chemistry [28].

FAQ 4: Can I use low-fouling chips for kinetic studies, and what are their limitations?

Answer: Yes, low-fouling chips are excellent for kinetic studies, especially when working with complex samples like serum or cell culture supernatants. Their primary advantage is the significant reduction of background noise from NSB, which leads to more reliable and interpretable sensorgrams [29] [30].

Their limitations include:

- Potentially Lower Immobilization Capacity: Compared to the porous dextran matrix of a CM5 chip, some planar low-fouling surfaces may offer lower capacity for ligand immobilization.

- Specialized Immobilization Chemistry: The covalent chemistry for attaching your ligand to the low-fouling surface may differ from standard chips and requires validation.

- Cost and Availability: These specialized chips can be more expensive and may not be available for all SPR instruments.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Immobilization Procedure for a CM5 Chip via Amine Coupling

This is a foundational protocol for covalently attaching a protein ligand to a CM5 chip [5] [26].

- Surface Activation: Inject a 1:1 mixture of NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) and EDC (N-ethyl-N'-(dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) for 7-10 minutes to activate the carboxyl groups on the dextran matrix.

- Ligand Injection: Dilute your ligand to 10-100 µg/mL in a low-salt buffer with a pH below its isoelectric point (e.g., 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0-5.5). Inject this solution over the activated surface for a sufficient time to achieve the desired immobilization level (response units, RU).

- Blocking: Inject 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 5-7 minutes to deactivate any remaining activated ester groups.

- Conditioning: Perform several short injections (30-60 seconds) of your regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM glycine pH 2.0) to stabilize the surface and remove loosely bound ligand before starting analyte injections.

Protocol 2: Reducing NSB in Complex Serum Samples

This protocol, adapted from research on detecting anti-HLA antibodies in serum, is highly effective for analyzing targets in complex media [30].

- Use a Capture Assay: Instead of direct immobilization, use a capture molecule (e.g., an antibody) to specifically immobilize your target ligand onto a series of flow cells.

- Establish a NSB Baseline: In the first cycle, capture a non-cognate target (a structurally similar protein that does not bind your analyte of interest) on the surface. Inject the complex sample (e.g., serum) and record the NSB signal.

- Measure Specific Binding: In a new binding cycle on the same flow cell, capture the target of interest. Inject the same complex sample.

- Subtract the Signal: The specific binding signal is obtained by subtracting the response from the non-cognate surface (Step 2) from the response on the target surface (Step 3). This controls for the variable and heterogeneous NSB inherent to individual serum samples.

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

Sensor Chip Selection and NSB Troubleshooting Pathway

This diagram outlines a systematic approach to selecting a sensor chip and addressing non-specific binding issues.

Key Experimental Workflow for SPR with NSB Controls

This workflow illustrates the critical steps in a robust SPR experiment, integrating NSB controls and surface regeneration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for SPR

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip [5] | Versatile surface for covalent immobilization of proteins via amine coupling. | High capacity requires aggressive blocking to mitigate NSB from the dextran matrix. |

| NTA Sensor Chip [27] | For capturing and orienting His-tagged ligands via Ni²⁺ coordination. | Prone to variability; requires chip-specific calibration and is sensitive to chelating agents. |

| Streptavidin (SA) Sensor Chip [5] | For immobilizing biotinylated ligands with high stability and specificity. | Excellent for DNA, RNA, and biotinylated antibodies. NSB can arise from hydrophobic patches. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) [1] | Protein-based blocking agent used to passivate unused surface sites and reduce NSB. | Typically used at 0.1-1% concentration. Ensure it does not interfere with the interaction. |

| Tween 20 [1] | Non-ionic surfactant added to running buffer (0.005%-0.05%) to reduce hydrophobic interactions. | Critical for preventing analyte loss to tubing and surfaces. |

| Ethanolamine [5] | Small molecule used to deactivate (block) NHS-ester activated surfaces after coupling. | Standard final step in amine coupling protocols. |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 1.5-2.5) [8] [27] | Common, mild regeneration solution for disrupting antibody-antigen and many protein-protein interactions. | Effectiveness and required concentration must be empirically determined for each pair. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid) [27] | Regeneration agent for NTA chips; chelates Ni²⁺ to strip the His-tagged ligand from the surface. | Allows for chip re-use but requires re-charging with Ni²⁺. |

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides for researchers using advanced surface coatings to minimize non-specific binding (NSB) in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments. Non-specific adsorption remains a critical barrier to obtaining reliable, high-quality data in biomolecular interaction analysis, leading to false-positive signals, reduced sensitivity, and compromised kinetic data [31] [32]. The following FAQs and guides address common challenges with PEG-based coatings, zwitterionic polymers, and alkanethiol self-assembled monolayers (SAMs), providing practical solutions to enhance assay performance within the broader context of SPR troubleshooting research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Coating Performance and NSB

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Coating-Related Issues in SPR

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| High baseline drift after coating | Unstable or poorly formed alkanethiol SAM; oxidation of thiol groups | Ensure clean gold surface prior to SAM formation (piranha or O2 plasma treatment); use fresh thiol solutions; extend SAM formation time (e.g., 12+ hours). | [33] |

| Significant NSB despite coating | Inadequate surface coverage; hydrophobic surface patches | Add non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Tween-20, 0.005%-0.1%) to running buffer; use protein blockers like BSA (0.5-2 mg/ml). | [6] [14] |

| Low ligand immobilization capacity | Steric hindrance from dense polymer brush (e.g., PEG); incorrect SAM terminal chemistry | Use mixed SAMs with short-chain spacers (e.g., 6-mercapto-1-hexanol) to reduce steric hindrance. | [33] |

| Coating failure in complex matrices | Coating thickness or hydration insufficient for complex samples like serum | Consider switching to or incorporating a zwitterionic polymer coating, known for its strong surface hydration and excellent anti-fouling properties. | [34] |

| Inconsistent results between runs | SAM degradation over time; loss of lubricant in slippery surfaces | Avoid long-term storage of SAM-coated chips at room temperature; for liquid-infused surfaces, ensure lubricant layer stability. | [35] [33] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can I quickly determine if non-specific binding is affecting my SPR data?

A preliminary test is to inject a high concentration of your analyte over a bare sensor surface or a reference channel functionalized with a non-interacting compound. If a significant response is observed, NSB is present. A useful rule of thumb is that if the response on the reference channel is greater than a third of the sample channel response, the NSB contribution should be actively reduced [6].

FAQ 2: My analyte is positively charged and sticks to my negatively charged dextran chip. What are my options?

This is a common issue due to electrostatic interactions. You can:

- Adjust Buffer Conditions: Increase the ionic strength of your running buffer with NaCl (up to 500 mM) to shield electrostatic charges [6] [14].

- Modify Surface Charge: For amine-coupled ligands, you can block the sensor chip with ethylenediamine instead of ethanolamine to reduce the negative charge of the surface [6].

- Change Sensor Chips: Consider switching to a sensor chip with less inherent negative charge, such as a planar chip, instead of a carboxymethyl dextran chip [6].

FAQ 3: Are there effective, non-toxic alternatives to traditional antifouling coatings?

Yes, research is advancing towards bio-inspired, non-toxic solutions. A prominent example is slippery liquid-infused porous surfaces (SLIPS). These coatings work by infusing a lubricating liquid into a nanostructured surface, creating a smooth, defect-free layer that effectively repels biomolecules, bacteria, and complex fluids like blood [35]. These are being developed for marine and medical applications to avoid environmental and health impacts of biocides.

FAQ 4: Beyond passive coatings, what active methods can remove NSB?

Active removal methods use external energy to shear away weakly adsorbed molecules. These include:

- Electromechanical Transducers: Using piezoelectric materials to generate surface waves.

- Acoustic Devices: Applying ultrasound to create surface forces.

- Hydrodynamic Removal: Optimizing fluid flow in microfluidic channels to generate high shear forces [31]. These methods are particularly valuable for micro/nano-scale biosensors where traditional coatings may not be compatible.

Experimental Protocols for Key Coating Strategies

Protocol 1: Forming a Mixed Alkanethiol SAM for Reduced Steric Hindrance

This protocol outlines the creation of a mixed self-assembled monolayer to immobilize ligands while minimizing non-specific interactions [33].

Principle: A long-chain thiol (e.g., 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid, 11-MUA) provides a functional group for ligand coupling, while a short-chain thiol (e.g., 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol, MCH) dilutes the surface, reduces steric hindrance, and improves ligand accessibility.

Materials:

- Gold sensor chip

- Ethanol (absolute)

- 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA)

- 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH)

- Piranha solution (H₂SO₄/H₂O₂) or O₂ plasma cleaner (Handle with extreme care)

Procedure:

- Surface Activation: Clean the gold sensor chip to remove organic contaminants. This can be done by immersion in a piranha solution (with extreme caution) or via O₂ plasma etching for 5-10 minutes. Rinse thoroughly with pure ethanol and water if using piranha [33].

- SAM Formation: Prepare a 1:1 molar ratio ethanolic solution of 11-MUA and MCH with a total thiol concentration of 1 mM.

- Incubation: Immerse the activated gold chip in the mixed thiol solution for at least 12 hours at room temperature.

- Rinsing and Drying: After incubation, rinse the chip copiously with pure ethanol to remove physically adsorbed thiols. Dry under a stream of nitrogen gas.

- The resulting surface will have exposed carboxyl groups from 11-MUA ready for activation with EDC/NHS for ligand immobilization.

Protocol 2: Utilizing Zwitterionic Polymers for Low-Fouling Surfaces

This protocol describes the application of zwitterionic polymers, which achieve superior antifouling performance through strong surface hydration [34].

Principle: Zwitterionic polymers possess both positive and negative charged groups that create a tightly bound layer of water molecules via electrostatically induced hydration. This hydration layer forms a physical and energy barrier that prevents the adsorption of proteins and other biomolecules.

Materials:

- Functionalized SPR sensor chip (e.g., with gold or carboxyl groups)

- Zwitterionic polymer (e.g., poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) or poly(carboxybetaine methacrylate))

- Appropriate coupling buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer saline, PBS)

- EDC and NHS (for carboxyl-functionalized surfaces)

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: If using a gold chip, first form a SAM with a terminal functional group (e.g., carboxyl or amine) to facilitate polymer grafting.

- Surface Activation (for carboxyl surfaces): Activate the carboxyl groups on the surface with a fresh mixture of EDC and NHS for 7-15 minutes to form NHS esters.

- Polymer Immobilization: Expose the activated surface to a solution of the zwitterionic polymer. The polymer must contain functional groups (e.g., amines) that can react with the activated surface. Incubate for several hours.

- Blocking and Rinsing: After immobilization, rinse the surface with coupling buffer to remove unbound polymer. Any remaining active esters can be blocked with a small molecule like ethanolamine.

- Validation: The resulting surface should exhibit significant resistance to protein adsorption when tested with complex samples like 100% serum or blood plasma.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Anti-Fouling Surface Coating and Troubleshooting

| Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tween-20 | Non-ionic surfactant that disrupts hydrophobic interactions, reducing NSB. | Use at low concentrations (0.005%-0.1%); compatible with most biomolecules. | [6] [14] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Protein blocker that adsorbs to vacant surface sites, preventing NSB. | Typical concentration 0.5-2 mg/ml; do not use during ligand immobilization. | [6] [31] [14] |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Salt used to shield electrostatic interactions between analyte and surface. | Can be used at concentrations up to 500 mM. | [6] [14] |

| 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA) | Alkanethiol for forming SAMs on gold; provides carboxyl groups for ligand coupling. | Requires long incubation times (>12 hrs); prone to oxidation over time. | [33] |

| Zwitterionic Polymers | Creates a highly hydrated surface that is extremely resistant to protein adsorption. | Ideal for applications in complex media (e.g., serum, blood); requires specific surface chemistry for grafting. | [34] |

| Dextran or Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Can be added to running buffer to reduce NSB on corresponding chip types. | Add 1 mg/ml carboxymethyl dextran for dextran chips or 1 mg/ml PEG for planar COOH chips. | [6] |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Surface Coating Selection Workflow

This diagram outlines a logical decision process for selecting and troubleshooting surface coatings to minimize fouling in SPR experiments.

Mechanism of Non-Specific Adsorption (NSA)

This diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms by which molecules adsorb non-specifically to sensor surfaces, leading to fouling.

Proven Strategies for NSB Reduction: A Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Protocol

FAQ

What is the core principle behind adjusting pH to the isoelectric point (pI) to reduce non-specific binding (NSB)?

The principle is based on charge neutralization. At a solution's pH equal to a protein's isoelectric point (pI), the protein carries no net electrical charge [1]. If your analyte is positively charged and your sensor surface is negatively charged, they will attract each other non-specifically [1]. By adjusting your buffer's pH to the pI of your analyte, you neutralize its overall charge, thereby eliminating these non-specific, charge-based interactions with the sensor surface [1] [11].

How do I determine the isoelectric point (pI) of my analyte?

The isoelectric point can be theoretically predicted using bioinformatics software that calculates the net charge from the amino acid sequence [1]. Alternatively, it can be experimentally determined using techniques such as isoelectric focusing (IEF) [36].

What are the potential risks of using a buffer pH at the analyte's pI?

A significant risk is reduced solubility and potential precipitation of the analyte, as the absence of net charge minimizes electrostatic repulsion between molecules [1]. Furthermore, a pH that is not optimal for your specific biomolecule could lead to a loss of activity or denaturation if the protein's native state is compromised [1]. It is crucial to confirm that your protein remains stable, soluble, and functional at the chosen pH.

My analyte is a protein mixture. Can I still use this strategy?

This strategy is most effective for a single, purified analyte with a known pI. For complex mixtures like serum, different proteins have different pIs. Adjusting the pH to the pI of one protein will leave others with net charges, potentially causing widespread NSB [30]. In such cases, alternative strategies like using blocking agents (BSA) or surfactants (Tween 20) are often more suitable [1] [6].

What should I do if I cannot eliminate all NSB with pH adjustment?

If the level of specific binding is significantly greater than the NSB, you can correct your data by subtracting the NSB signal from the specific binding signal [1] [14]. This is typically done using a reference channel on the SPR instrument. If NSB persists, a combination of strategies is recommended, such as adjusting pH along with adding low concentrations of salt or a non-ionic detergent [1] [5].

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Buffer pH

Objective

To empirically determine the optimal buffer pH that minimizes non-specific binding while maintaining the biological activity of your analyte.

Materials

- Purified analyte

- SPR instrument and sensor chips

- Running buffers at different pH values

- Ligand (immobilized partner)

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Theoretical Calculation: Begin by calculating the theoretical pI of your analyte using software tools.

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare a series of running buffers (e.g., citrate-phosphate buffer for pH 3-7, Tris buffer for pH 7-9) covering a range around the predicted pI (e.g., pI ± 1.5 pH units).

- Ligand Immobilization: Immobilize your ligand on the sensor chip using a standard, well-optimized protocol [5].

- NSB Test Surface: Prepare a reference surface without the specific ligand. This could be a blank, deactivated surface or one coated with an irrelevant protein like BSA [14] [37].

- Analyte Injection and Data Collection:

- Dilute your analyte into each of the different pH buffers.

- Inject a fixed, high concentration of the analyte over both the ligand and reference surfaces at each pH condition.

- Monitor and record the response on both surfaces.

- Data Analysis:

- The response on the reference surface represents pure NSB.

- The optimal pH is identified as the condition that yields the lowest response on the reference surface, indicating minimal NSB, while still preserving a strong, specific signal on the ligand surface.

The following table summarizes experimental data from a model system investigating the interaction between Glycated Albumin (GA) and its aptamer, demonstrating how pH and salt concentration influence the binding response [36].

Table 1: Experimental Binding Responses of Glycated Albumin Under Different Buffer Conditions

| pH Value | Salt Concentration (mM NaCl) | Observed Binding Response (RU) | Notes on Interaction Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.0 | 0 | 110 | Strongest signal, but high NSB risk |

| 5.0 | 0 | 90 | Strong signal |

| 6.0 | 0 | 45 | Moderate signal |

| 7.4 | 0 | 20 | Weak signal |

| 4.0 | 150 | 60 | Signal reduction due to charge shielding |

| 5.0 | 150 | 50 | Signal reduction due to charge shielding |

| 6.0 | 150 | 40 | Signal reduction due to charge shielding |

| 7.4 | 150 | 15 | Weakest signal |

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for troubleshooting and optimizing buffer pH to minimize non-specific binding in SPR experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for pH Optimization

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for pH Optimization Experiments

| Reagent | Function in Experiment | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Buffering Agents | Maintains stable pH in the running and sample buffers during the SPR experiment. | Citrate-Phosphate (pH 3-7), Tris-HCl (pH 7-9), HEPES (pH 7-8) [36]. |

| pH Standard Solutions | Used for precise calibration of pH meters to ensure accuracy of prepared buffers. | Commercial pH standards (e.g., pH 4.01, 7.00, 10.01). |

| Blocking Proteins | Used on reference surfaces to characterize NSB; can also be a buffer additive. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) at 0.5-2 mg/ml [1] [6] [37]. |

| Carboxymethyl Dextran | Additive to block NSB to dextran-based sensor chip matrices. | Used at 0.1 - 1 mg/ml in running buffer [6] [37]. |

| Salts | Used to investigate and shield charge-based interactions; often used in conjunction with pH. | NaCl (up to 500 mM) [1] [6]. |

Core Concepts: Understanding the Additives

What is Non-Specific Binding (NSB) in SPR? In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments, non-specific binding (NSB) occurs when the analyte interacts with the sensor surface or other non-target molecules through unintended forces, rather than binding specifically to the immobilized ligand. These forces can include hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, or electrostatic (charge-based) interactions [1]. NSB leads to an inflated response signal, which can cause erroneous calculations of binding kinetics and affinity, compromising data accuracy [1].

How BSA and Dextran Mitigate NSB BSA and dextran function as blocking agents to prevent these unwanted interactions, but through different mechanisms:

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA): This is a globular protein used as a protein blocker. When added to the buffer or sample solution, BSA surrounds the analyte and occupies potential NSB sites on the sensor surface, tubing, and container walls. This "shielding" effect minimizes non-specific protein-protein interactions and interactions with charged surfaces [1] [38]. It is particularly effective at preventing analyte loss and blocking sites on the sensor chip that remain active after ligand immobilization [1] [5].

- Carboxymethyl (CM) Dextran: This polymer is primarily used to reduce NSB with the dextran sensor chip matrix itself. The dextran matrix in common sensor chips (e.g., CM5) can have a high affinity for certain compounds, especially small molecules [37]. Adding CM-dextran to the running buffer saturates these non-specific sites on the matrix, preventing your analyte from binding to them [37] [39].

The following decision tree guides the selection of the appropriate additive based on the source of non-specific binding in your SPR experiment:

Practical Implementation: Protocols and Data

Experimental Preparation of Additive Solutions Integrating BSA and dextran into your SPR workflow is straightforward. Below are standard protocols for preparing running buffer solutions supplemented with these additives.

- BSA Supplementation: Add Bovine Serum Albumin to your standard SPR running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP or PBS-P) to achieve a final concentration of 0.1 - 1 mg/mL [37] [39]. Gently mix to dissolve without foaming. Filter the buffer using a 0.22 µm filter to ensure sterility and remove particulates.

- CM-Dextran Supplementation: Add Carboxymethyl Dextran to your running buffer to a final concentration of 0.1 - 1 mg/mL [37] [39]. Due to the viscosity of dextran solutions, allow sufficient time for complete dissolution and mixing. Filter the final solution with a 0.22 µm filter.

Summary of Additive Concentrations and Functions

| Additive | Typical Working Concentration | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | 0.1 - 1 mg/mL [37] [39] | Blocks NSB on surfaces and tubing; shields analyte from non-specific protein interactions [1] [38]. | Preventing loss of protein analytes; reducing charge-based and hydrophobic NSB; general-purpose blocking [1] [5]. |

| Carboxymethyl (CM) Dextran | 0.1 - 1 mg/mL [37] [39] | Saturates NSB sites on the dextran matrix of the sensor chip itself [37]. | Studying small molecule interactions; when the analyte shows affinity for the dextran hydrogel [37]. |

| Tween 20 | 0.005% - 0.1% [1] [40] | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions via non-ionic surfactant action [1] [5]. | When NSB is suspected to be hydrophobic in nature [1] [40]. |

Combination Strategies: For complex NSB issues stemming from multiple sources, BSA and CM-Dextran can be used together in the same running buffer within the concentration ranges listed above [39].

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My negative control (reference surface) still shows binding after using BSA. What could be wrong?

- A: This indicates that your reference surface is not adequately matched to your ligand surface. A surface deactivated with ethanolamine post-activation has different chemical properties (-OH group) than a ligand-immobilized surface. A more effective strategy is to immobilize a non-interacting protein (e.g., an irrelevant IgG or BSA itself) on the reference channel to better mimic the surface properties of your ligand channel. Ensure the immobilization level (RU) is similar to your ligand surface to account for volume exclusion effects [37].

Q2: Can high concentrations of BSA or dextran interfere with my specific binding signal?

- A: While generally safe at recommended concentrations, extremely high levels of any additive could theoretically cause steric hindrance or viscosity issues. It is crucial to empirically determine the lowest effective concentration that suppresses NSB without diminishing your specific signal. Perform a titration experiment where you inject your analyte over your ligand surface while incrementally increasing the additive concentration in the running buffer until the NSB signal is minimized [1] [5].

Q3: I am working with small molecule analytes and seeing significant NSB. Which additive should I try first?

- A: Small molecules are particularly prone to NSB with the dextran matrix. In this case, CM-Dextran should be your first choice for additive screening, as it directly competes for matrix binding sites [37]. If NSB persists, you can then screen surfactants like Tween 20 or evaluate BSA.

Q4: Are there any situations where BSA should be avoided?

- A: Yes. BSA itself can bind a wide variety of molecules and should not be used as a reference surface ligand without testing [37]. If your analyte is known to bind to BSA (e.g., certain fatty acids or small molecules), using it in the running buffer could potentially scavenge your analyte or create a new pathway for NSB. In such cases, focus on other additives like detergents or CM-dextran.

Advanced Troubleshooting: The Case of Negative Curves Sometimes, after reference subtraction, the binding signal appears negative. A common cause is that the analyte binds more to the reference surface than to the ligand-coated surface [37]. This underscores the critical importance of a well-matched reference. Strategies to resolve this include:

- Improving the reference surface by immobilizing a non-reactive protein [37].

- Increasing the concentration of additives like BSA or CM-Dextran in the running buffer to further suppress NSB on the reference [37].

- Adding extra salt (e.g., up to 250 mM NaCl) to disrupt charge-based interactions that may be stronger on the reference surface [37] [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent | Function in SPR | Specific Use Case for NSB Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | General-purpose protein blocker | Shields the analyte and blocks NSB sites on surfaces and tubing [1] [38]. |

| Carboxymethyl (CM) Dextran | Matrix blocker for dextran chips | Competes for and saturates non-specific binding sites within the hydrogel matrix of the sensor chip [37]. |

| Tween 20 | Non-ionic surfactant | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions between the analyte and the sensor surface [1] [5]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Ionic strength modifier | Shields electrostatic charges to reduce charge-based NSB; used typically up to 250 mM [1] [39]. |

| HEPES/TRIS Buffers | Buffer system | Provides a stable physiological pH environment to maintain biomolecule stability [39]. |

| Ethanolamine | Surface blocking agent | Standard solution for deactivating remaining active ester groups on the sensor surface after amine coupling [40]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Application