Mastering Dynamic Ligand Binding on Perovskite Quantum Dot Surfaces: Strategies for Enhanced Stability and Performance in Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of dynamic ligand binding on perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces, a critical factor governing their optoelectronic properties and stability for biomedical and drug development...

Mastering Dynamic Ligand Binding on Perovskite Quantum Dot Surfaces: Strategies for Enhanced Stability and Performance in Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of dynamic ligand binding on perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces, a critical factor governing their optoelectronic properties and stability for biomedical and drug development applications. We explore the fundamental principles of PQD surface chemistry, including ligand classification and binding motifs. The review details advanced ligand engineering methodologies, from in-situ techniques to post-synthesis treatments, and addresses common challenges such as ligand desorption and surface defects. Through comparative analysis of validation techniques and performance metrics, we synthesize best practices for optimizing PQD systems. This work serves as an essential resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to harness PQDs' potential in biosensing, imaging, and therapeutic applications.

The Dynamic PQD Surface: Understanding Ligand Binding Fundamentals and Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the role of surface ligands in Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs)? Surface ligands are organic molecules that coordinate with the atoms on the surface of PQDs. They are critical for multiple reasons [1]:

- Colloidal Stability: They prevent the QDs from aggregating in solution, ensuring good dispersion.

- Defect Passivation: They bind to undercoordinated surface ions (like Pb²⁺), suppressing non-radiative recombination pathways that would otherwise diminish photoluminescence (PL) and performance [2].

- Electronic Coupling: The ligand's chain length and functional groups dictate the distance between adjacent QDs, thus influencing charge transport in solid films. Long-chain ligands insulate dots, while short-chain ligands enhance electronic coupling [3].

2. Why is ligand exchange necessary after synthesizing PQDs? PQDs are typically synthesized using long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) to ensure high-quality, monodisperse nanocrystals [3]. However, these long-chain ligands act as insulators, hindering the charge transfer between QDs that is essential for optoelectronic devices. Ligand exchange replaces these with shorter ligands (e.g., phenethylammonium iodide) that maintain passivation while enabling better electronic coupling and carrier transport in device films [3].

3. What causes the degradation of CsPbI3 PQDs, and how can it be mitigated? CsPbI3 PQDs are highly susceptible to degradation from environmental factors like moisture, oxygen, and prolonged illumination [2]. A primary degradation pathway is the structural phase transition from the photoactive cubic phase to a non-photoactive orthorhombic phase. This can be mitigated through precise surface ligand engineering. For instance, passivation with ligands like l-phenylalanine (L-PHE) has been shown to significantly improve photostability, helping PQDs retain over 70% of their initial PL intensity after 20 days of UV exposure [2].

4. How does ligand binding affect the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY)? Ligands that effectively passivate surface defects reduce non-radiative recombination, directly leading to an increase in PLQY. For example, in CsPbBr3 QDs, ligand exchange with strongly binding amines or phosphonic acids has been shown to increase steady-state PL intensities [4]. In CsPbI3 PQDs, passivation with trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO) and trioctylphosphine (TOP) led to PL enhancements of 18% and 16%, respectively [2].

5. Are the interactions between ligands and the PQD surface static or dynamic? The binding of ligands to the PQD surface is highly dynamic. Research using ¹H NMR spectroscopy has shown that native ligands like oleate and oleylamine rapidly associate and dissociate from the surface [4]. This dynamic nature means the ligand shell is in constant flux, which must be accounted for in synthesis and post-processing treatments.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)

A low PLQY indicates a high density of surface defects acting as non-radiative recombination centers.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action & Protocol | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Identify Defect Type | Analyze the synthesis method. Undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions are common defects that require passivation with electron-donating ligands (e.g., Lewis bases like phosphines or amines) [2] [1]. | Targeted selection of passivating ligands. |

| Apply Ligand Passivation | Implement a surface treatment. Protocol: Dissolve the passivating ligand (e.g., TOPO, L-PHE) in a solvent like octane. Add this solution to the purified PQD solution and stir for several hours. Purify the PQDs to remove unbound ligands [2]. | An increase in the solution's PL intensity and measured PLQY. |

| Optimize Synthesis Temperature | Ensure the reaction temperature does not induce phase changes. Protocol: For CsPbI3 PQDs, synthesize at 170 °C. Temperatures that are too high (e.g., 180 °C) can cause a phase transition and a pronounced decline in PL intensity [2]. | PQDs with the highest PL intensity and narrowest emission linewidth. |

Problem 2: Poor Charge Transport in PQD Solid Films

This issue often arises from excessive insulating ligands remaining in the film, creating barriers between quantum dots.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action & Protocol | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Perform Solid-State Ligand Exchange | Replace long-chain ligands with short, conductive ones during film deposition. Protocol: Use a layer-by-layer (LBL) spin-coating method. After depositing each layer of PQDs, treat the film with a solution of the short-chain ligand (e.g., Phenethylammonium Iodide, PEAI, in ethyl acetate). Rinse with methyl acetate to remove the displaced long-chain ligands and by-products [3]. | A dense, electronically coupled PQD film with improved conductivity. |

| Choose Conjugated Ligands | Select ligands that can facilitate charge transport. Using a conjugated ligand like PEAI, which has a phenyl group, not only passivates defects but can also enhance inter-dot coupling compared to aliphatic chains [3]. | Balanced transport and injection of electrons and holes within the device. |

| Verify Film Quality | Characterize the film after exchange. Techniques like FTIR can confirm the replacement of OA/OAm ligands, and mobility measurements can directly quantify improved charge transport [3]. | Higher performance in solar cells (PCE) and LEDs (EQE). |

Problem 3: Poor Environmental and Operational Stability

PQDs can degrade when exposed to moisture, oxygen, or light, leading to loss of optical properties.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action & Protocol | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Employ Bifunctional Ligands | Use ligands that strongly chelate to the surface. Ligands with multiple binding groups (e.g., phosphonic acids) form a more robust bond with the QD surface compared to carboxylic acids, making them less likely to desorb [4] [1]. | Improved colloidal and structural stability over time. |

| Enhance Hydrophobicity | Introduce hydrophobic ligands. Protocol: Incorporate ligands with long alkyl chains or aromatic rings (e.g., PEA+) during the LBL exchange process. This creates a more hydrophobic surface on the PQD film [3]. | Devices that retain performance over time, even in high-humidity environments (e.g., 30-50% RH). |

| Monitor Phase Stability | For CsPbI3, ensure the cubic phase is stabilized. Using a proper ligand shell that suppresses the transition to the orthorhombic phase is key. Monitor phase purity with X-ray diffraction (XRD) [2] [3]. | Long-term retention of the desired crystal phase and optical properties. |

Quantitative Data on Ligand Performance

The following table summarizes experimental data on the effectiveness of different surface ligands, providing a reference for selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Ligand Performance on CsPbI3 PQDs [2]

| Ligand | Functional Group | PL Enhancement | Photostability (PL Retention) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Phosphine Oxide | 18% | N/A | Most effective at passivating defects and boosting PL intensity. |

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | Phosphine | 16% | N/A | Also highly effective for passivation. |

| l-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | Amino Acid / Carboxylate & Amine | 3% | >70% after 20 days UV | Provides superior long-term photostability despite a lower initial PL boost. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for PQD Surface Chemistry Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard long-chain ligands used in the hot-injection synthesis of PQDs to control growth and ensure colloidal stability [3]. |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | A short, conjugated ligand used in solid-state ligand exchange to replace OA/OAm, improving charge transport and passivating surface defects in devices [3]. |

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) & TOPO | Lewis base ligands used for surface passivation to coordinate with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites, significantly enhancing PLQY [2]. |

| Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) | A common short-chain ligand and cation source used in post-treatment of PQD films for passivation and ligand exchange [3]. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) & Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) | Polar, non-solvents used to wash away excess ligands and by-products during the purification and layer-by-layer film deposition process [3]. |

Experimental Workflow and Ligand Binding Dynamics

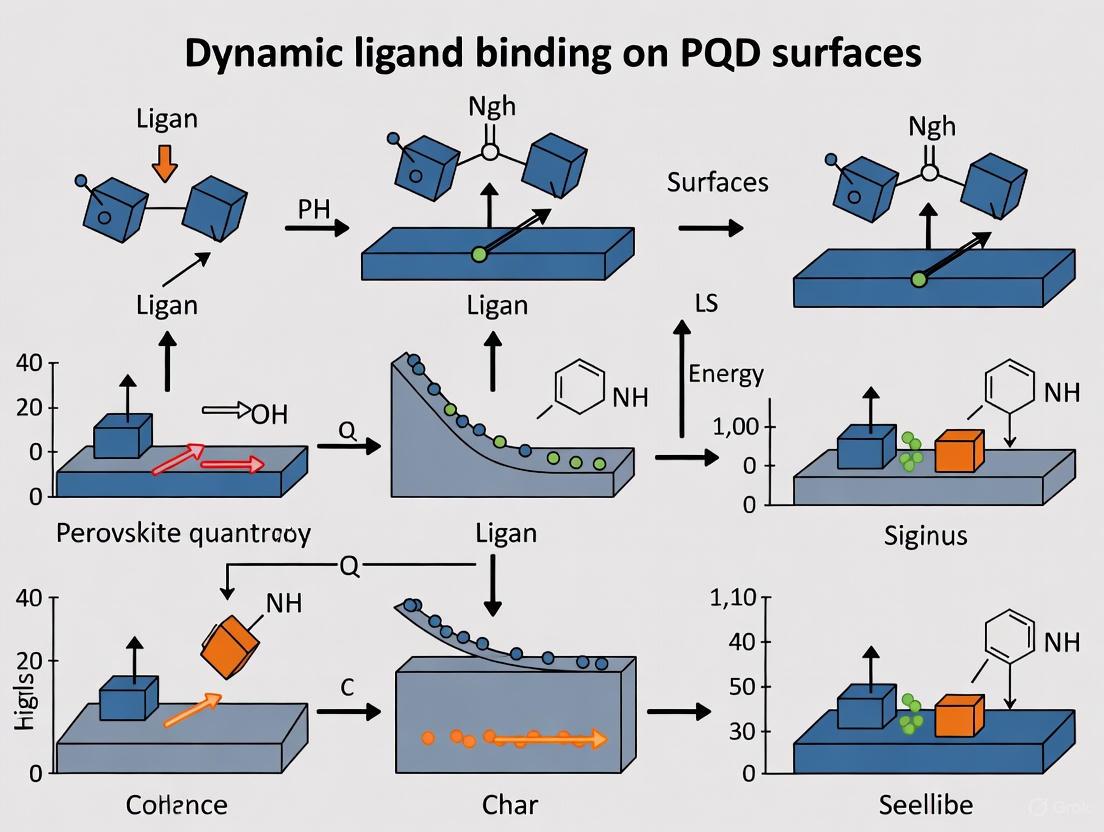

The diagrams below illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows in PQD surface chemistry.

Diagram 1: PQD Surface Chemistry and Ligand Binding

Diagram 2: Layer-by-Layer Ligand Exchange Workflow

Within the context of a broader thesis on addressing dynamic ligand binding on PQD surfaces, understanding the Covalent Bond Classification (CBC) method is fundamental. This system categorizes ligands based on the number of electrons they donate to the metal center, which in turn dictates the binding motif and stability on the nanocrystal surface [5] [6]. For perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and other semiconductor nanocrystals, this is not a static classification; the dynamic binding and exchange of these ligands are critical factors influencing material stability and optoelectronic properties [7] [8] [9].

The following diagram illustrates the logical process for classifying a ligand according to the CBC method.

FAQ & Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses specific, common issues researchers encounter when working with surface ligands, providing targeted solutions based on the underlying binding chemistry.

FAQ 1: Why does my PQD film lose photoluminescence (PL) after washing or processing?

Answer: This is a classic sign of ligand destabilization. Washing with polar solvents (e.g., alcohols, acetone) can strip L-type and X-type ligands from the QD surface [10]. This removal creates unsaturated "dangling bonds" on surface atoms, which act as trap states for charge carriers. These trap states provide non-radiative recombination pathways, effectively quenching the luminescence that would otherwise be released as light [7] [10].

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Step 1: Diagnosis. Use vibrational sum frequency generation (vSFG) spectroscopy or NMR to directly probe the ligand coverage and ordering after washing. vSFG is particularly sensitive to subtle changes in ligand disorder [10].

- Step 2: Solution. Implement a post-synthesis ligand exchange or passivation step. Replace the dynamically bound long-chain ligands (e.g., oleate) with more robust, multidentate ligands that have a higher binding affinity to the surface [8].

- Step 3: Validation. Monitor the PL quantum yield (PLQY) before and after processing. A stable or improved PLQY after ligand engineering confirms successful surface passivation.

FAQ 2: What is the "third ligand state" beyond simply bound and free?

Answer: Recent quantitative studies have moved beyond the simple two-state (bound/free) model. A third, weakly bound (Wbound) state has been identified, particularly for ligands like oleic acid on PbS QDs [9]. This state is hypothesized to represent ligands weakly coordinating to specific crystal facets (e.g., (100) facets of PbS) through their headgroups, distinct from the strongly bound (Sbound) chemisorbed ligands on other facets (e.g., (111)) [9]. This weakly associated population is in rapid dynamic equilibrium with the free ligand pool and can influence packing density and exchange kinetics.

Experimental Quantification Method:

- Technique: Multimodal Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, combining diffusometry (DOSY) and 1D ¹H spectroscopy [9].

- Procedure: Titrate excess ligand (e.g., oleic acid) into a solution of purified QDs. DOSY can separate species based on their diffusion coefficients, distinguishing Sbound, Wbound, and free ligands. Line shape analysis of 1D ¹H NMR spectra as a function of temperature (dynamic NMR) can then quantify the rapid exchange rates between the W_bound and free states [9].

- Output: Population fractions and exchange rate constants for the different ligand states, providing a deeper understanding of the binding landscape.

FAQ 3: How do I choose a ligand to improve charge transport in a QD film?

Answer: Long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) are major barriers to charge transport. The solution is ligand exchange to replace them with shorter or inorganic ligands.

Mechanism and Rationale: Long hydrocarbon chains create a physical and electronic barrier between QDs. Replacing them with shorter ligands or inorganic species (e.g., S²⁻, I⁻, metal chalcogenide complexes) reduces the interparticle distance, which exponentially increases the wavefunction overlap between neighboring dots, facilitating charge carrier tunneling and boosting film conductivity [11].

Experimental Workflow: The following diagram outlines a standard workflow for conducting a ligand exchange to improve film conductivity.

Quantitative Data & Ligand Properties

The following tables summarize key characteristics and quantitative data for the different ligand classes, essential for informed experimental design.

Table 1: Classification and Properties of Ligand Types

| Ligand Type | Electron Donation | Formal Charge | Common Examples | Key Binding Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Type [5] [6] | 2-electron donor | Neutral | Amines (R-NH₂), Phosphines (R₃P), CO |

Lewis base. Dative bond. Common in synthesis but can be dynamically bound [10]. |

| X-Type [5] [6] | 1-electron donor | Anionic | Carboxylates (R-COO⁻), Halides (Cl⁻, I⁻), Thiolates (RS⁻) |

Compensates for cationic surface charge. Can be displaced by acids [9] [10]. |

| Z-Type [5] [9] | 2-electron acceptor | Neutral | Metal complexes (e.g., Pb(oleate)₂, Cd(oleate)₂) |

Lewis acid. Binds to anionic surface sites. Often considered as a metal with two X-type ligands [9]. |

Table 2: Quantified Ligand Binding States on PbS QDs [9]

| Ligand State | Proposed Binding Site | Population Fraction (Example) | Exchange Kinetics | Characterization Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Bound (S_bound) | (111) facets as X-type | ~40% of total OAH | Slow exchange | ¹H NMR, DOSY |

| Weakly Bound (W_bound) | (100) facets as L-type | ~25% of total OAH | Rapid exchange (0.09–2 ms) | Dynamic ¹H NMR, DOSY |

| Free | Solution | ~35% of total OAH | N/A | ¹H NMR, DOSY |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key materials and their functions for experiments focused on ligand engineering.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Ligand Engineering Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OAH) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard L-type and X-type ligands for colloidal synthesis; stabilize nanoparticles and prevent aggregation [8] [11]. | Dynamic binding leads to easy detachment, causing instability. The ratio during synthesis can control crystal shape [8]. |

| Short-Chain Carboxylic Acids (e.g., Butyric Acid) | Used in ligand exchange to replace long-chain OA; reduce interparticle distance in films [11]. | Improved conductivity but may reduce colloidal stability due to weaker van der Waals forces between short chains. |

| Halide Salts (e.g., PbI₂, CsI) | Provide X-type halide ligands for passivation of PQDs; crucial for stabilizing ionic perovskite surfaces and tuning optoelectronic properties [8]. | Effective for defect passivation. Inorganic nature enhances conductivity in films [8] [11]. |

| Alkane Thiols (e.g., 1,2-ethanedithiol) | Multidentate X-type ligands for strong binding to metal sites; used to create cross-linked, stable QD films [11]. | The multidentate "chelating" effect enhances binding stability compared to monodentate ligands [8]. |

| Lead Oleate (Pb(OA)₂) | Example of a Z-type ligand; a metal complex that can coordinate to anionic chalcogen sites on the QD surface [9]. | Represents a common surface species where a metal cation is coordinated by two X-type ligands. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Non-Exponential Dissociation Curves

Problem: The time course curve for ligand dissociation does not fit a single-phase exponential decay model.

Explanation: A two-phase dissociation curve often indicates that the binding mechanism is more complex than a simple single-site interaction [12]. This is a common finding in dynamic systems like perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces, where multiple ligand populations with different binding strengths can coexist [13] [9].

Solutions:

- Use Appropriate Models: Employ alternative equations designed for complex binding mechanisms, such as a two-site or multi-phase binding model [12].

- Investigate Ligand States: Consider that your system may involve multiple ligand populations. For example, on PbS QD surfaces, oleic acid (OAH) ligands can exist in at least three states: strongly bound oleate (OA) on (111) facets, weakly bound OAH on (100) facets, and free ligands in solution [13] [9]. A model accounting for these states will provide a better fit.

- Check for Compartmentalization: In whole cell or membrane binding assays, ensure the unlabeled ligand can access all compartments. Adding a small amount of membrane-permeabilizing agent (e.g., 50 μg/ml saponin) can resolve this [12].

Guide 2: Addressing High Background Noise in Binding Assays

Problem: The assay exhibits high background noise, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio.

Explanation: High background is frequently caused by non-specific binding, where ligands or analytes interact with surfaces or components other than the intended target [14].

Solutions:

- Optimize Blocking: Use effective blocking agents like BSA or casein to coat unused binding sites on surfaces [14].

- Refine Washing Steps: Increase the number or stringency of wash steps after the binding reaction to remove loosely associated molecules.

- Validate Reagent Quality: Ensure all reagents, especially antibodies, are of high quality and specificity to minimize cross-reactivity [14].

Guide 3: Resolving Ligand Desorption from Quantum Dot Surfaces

Problem: Ligands dynamically desorb from the perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surface, leading to nanoparticle aggregation, defect formation, and reduced performance in devices like solar cells [15] [16].

Explanation: The native long-chain ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylammonium) on PQDs have a highly dynamic and labile binding nature. This leads to incomplete surface coverage and ligand loss during processing [15] [16].

Solutions:

- Employ Tight-Binding Ligands: Use ligands with higher binding energy. For example, the liquid bidentate ligand formamidine thiocyanate (FASCN) has a binding energy fourfold higher than original oleate ligands on FAPbI3 QDs, effectively suppressing ligand loss [16].

- Implement Complementary Dual-Ligand Systems: Strategies using multiple ligands that form complementary networks (e.g., through hydrogen bonds) can stabilize the PQD surface lattice and improve inter-dot electronic coupling [17].

- Optimize Ligand Exchange Conditions: During post-synthesis treatment, avoid the use of high-polarity solvents that can damage the ionic perovskite core. Using liquid ligands can help avoid this issue [15] [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How much ligand should be immobilized on a sensor chip for kinetic studies?

For kinetic studies using surface plasmon resonance (SPR), the general recommendation is to use the lowest ligand density possible that still provides a measurable and reliable signal. A very low density minimizes mass transfer limitations and rebinding effects, allowing for more accurate determination of association and dissociation rate constants [18].

FAQ 2: Is it possible to study ligand binding without labels or immobilization?

Yes. Transient Induced Molecular Electronic Spectroscopy (TIMES) is a method that detects protein-ligand interactions without the need for fluorescent labels, molecular probes, or surface immobilization. It works by measuring the change in dipole moment when a protein and ligand form a complex, offering a way to study interactions in native, physiological conditions [19].

FAQ 3: Our purified intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) for NMR studies is prone to degradation. How can we improve its stability?

Intrinsically disordered proteins are extremely sensitive to proteolytic cleavage due to their flexible, exposed backbones [20].

- Use Protease Inhibitors: Always include a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktail in all purification buffers.

- Work Quickly: Keep samples on ice and minimize the time between purification and analysis.

- Consider Tags: Use solubility-enhancing tags (e.g., GST, MBP) that can be cleaved off just before the final purification step.

- Purify in Denaturing Conditions: A key advantage with IDPs is that you can use denaturing conditions (e.g., urea) during purification without the worry of refolding, as they lack a native structure. This can help stabilize them against proteases and aggregation [20].

Quantitative Data on Ligand Binding and Exchange

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent research on ligand dynamics, essential for informing experimental design and data interpretation.

Table 1: Quantified Ligand Populations on PbS Quantum Dots via Multimodal NMR [13] [9]

| Ligand State | Binding Facet / Type | Population Fraction (Example) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Bound (S_bound) | (111) / X-type (Oleate, OA) | Varies with conditions | Chemisorbed; stable binding |

| Weakly Bound (W_bound) | (100) / L-type (Oleic Acid, OAH) | Varies with conditions | Rapid exchange with free state; weak coordination |

| Free | Solution / Unbound | Varies with conditions | Fast diffusion; in dynamic equilibrium |

Table 2: Measured Exchange Kinetics and Binding Energies from Recent Studies

| System | Parameter | Value | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| PbS QDs (OAH) | Exchange rate (weakly bound ⇌ free) | 0.09 - 2 ms [13] | Dynamic NMR |

| FAPbI3 PQDs (FASCN) | Binding Energy (Eb) | -0.91 eV [16] | DFT Calculation |

| FAPbI3 PQDs (Oleate) | Binding Energy (Eb) | -0.22 eV [16] | DFT Calculation |

| CsPbI3 PQDs (Dual-Ligand) | Solar Cell Efficiency (PCE) | 17.61% (Record) [17] | Device Measurement |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Ligand Populations and Exchange on QD Surfaces using Multimodal NMR

Objective: To quantify the populations and kinetics of ligands in different states (strongly bound, weakly bound, free) on quantum dot surfaces.

Materials:

- Purified quantum dot sample (e.g., OA-capped PbS QDs).

- Deuterated solvent (e.g., CDCl3).

- Ligand for titration (e.g., oleic acid).

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectrometer.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Purify the QDs thoroughly to remove excess free ligands. Confirm the absence of free ligand signals in the initial 1H NMR spectrum [9].

- NMR Diffusometry (DOSY):

- Acquire a DOSY spectrum to separate NMR signals based on their diffusion coefficients.

- Free ligands will have a high diffusion coefficient (~10-9 m2/s).

- Bound/Associated ligands will have a significantly lower diffusion coefficient, similar to that of the QDs themselves (~10-10 m2/s) [9].

- Titration and Population Quantification:

- Titrate known amounts of excess ligand (e.g., OAH) into the QD solution.

- After each addition, acquire 1H NMR spectra.

- Integrate the peaks corresponding to the bound and free states. The presence of a third, broadened component may indicate weakly bound ligands.

- Calculate the population fractions of each state as a function of titrant concentration and temperature [13] [9].

- Kinetics Measurement (Dynamic NMR):

- Record 1H NMR spectra at varying temperatures.

- Perform line shape analysis on the resonances that change with temperature.

- Quantify the exchange rate between the weakly bound and free ligand states from the line broadening and coalescence phenomena [13].

Protocol 2: Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange on Perovskite QDs for Enhanced Performance

Objective: To replace native long-chain insulating ligands with short-chain or bidentate ligands to improve charge transport and passivation in PQD solids.

Materials:

- Colloidal suspension of PQDs (e.g., CsPbI3 or FAPbI3).

- Exchange ligand solution (e.g., Formamidine thiocyanate (FASCN) in a mild solvent) [16].

- Anti-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate, methyl acetate).

- Centrifuge.

Method:

- Purification: Precipitate the pristine PQDs from their crude solution by adding anti-solvent and centrifuging. Discard the supernatant to remove excess original ligands [15].

- Ligand Exchange:

- Re-disperse the purified PQD pellet in a small volume of a non-polar solvent (e.g., hexane, toluene).

- Add the ligand exchange solution (e.g., FASCN) dropwise under vigorous stirring. The liquid characteristic of FASCN avoids the need for high-polarity solvents that could damage the PQDs [16].

- Continue stirring for a short, optimized period (typically seconds to minutes).

- Purification of Exchanged QDs:

- Add anti-solvent to precipitate the ligand-exchanged QDs.

- Centrifuge the sample and carefully discard the supernatant, which contains the displaced original ligands and reaction by-products.

- Repeat the dispersion-precipitation cycle if necessary to ensure complete removal of free ligands [15].

- Film Formation: Re-disperse the final pellet in a suitable solvent for film deposition (e.g., octane for spin-coating).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Ligand Binding on Nanocrystal Surfaces

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OAH) / Oleate (OA) | Common native X-type capping ligand for synthesizing and stabilizing PbS and Pb-based Perovskite QDs [13] [15]. | Serves as a model system for studying acid-base ligand exchange mechanisms; exhibits dynamic binding equilibrium. |

| Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) | Bidentate liquid ligand for post-synthesis treatment of PQDs. Passivates surface traps and improves charge transport [16]. | Provides high binding energy (-0.91 eV) and full surface coverage without requiring polar solvents. |

| Trimethyloxonium Tetrafluoroborate & Phenylethyl Ammonium Iodide | Complementary dual-ligand system for surface reconstruction of CsPbI3 PQDs [17]. | Forms a hydrogen-bonded network on the PQD surface, enhancing stability and electronic coupling. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl3) | Solvent for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) studies of ligand binding [13] [9]. | Allows for quantitative analysis of ligand populations and kinetics without interfering proton signals. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Workflow for analyzing ligand dynamics on quantum dot surfaces.

Diagram 2: A logical troubleshooting guide for common ligand binding issues.

Troubleshooting Guide: Uncoordinated Lead Defects

Q1: Why does the photoluminescence intensity of my perovskite quantum dot (PQD) solution or film decrease significantly over time?

A: A primary cause is the formation of uncoordinated lead defects on the PQD surface. These defects act as non-radiative recombination centers, meaning they dissipate excited state energy as heat instead of light [21]. The dynamic nature of the ligand binding to the PQD surface means that native ligands like oleate (OA) can detach over time, exposing unpassivated lead ions (Pb²⁺) and creating these highly efficient quenching sites [21] [8].

Q2: What experimental evidence confirms the presence of uncoordinated lead on the PQD surface?

A: The effectiveness of specific chemical treatments that target lead atoms provides strong indirect evidence. For instance, the addition of trioctylphosphine (TOP), an L-type ligand where the phosphorus atom donates electrons, instantly recovers the photoluminescence of aged PQDs [22]. This occurs because TOP coordinates with the uncoordinated lead, passivating the defect sites and restoring radiative recombination [22]. Furthermore, techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) can be used to directly probe the chemical states and coordination environment of lead atoms on the surface [23].

Q3: My PQDs are losing their structural stability and degrade in polar solvents. Is this related to surface defects?

A: Yes, this is directly related. Uncoordinated lead sites, often resulting from ligand loss, disrupt the ionic lattice stability of the perovskite structure [8]. These sites make the crystal more susceptible to attack by polar molecules, such as ethanol or water, leading to rapid degradation and loss of emission [22]. Strengthening the ligand binding through surface passivation is key to improving stability.

Q4: Are all ligand binding sites on the PQD surface the same?

A: No, research shows ligand binding is more complex than a simple two-state model. On PbS QDs, for example, ligands can exist in at least three states: strongly bound (e.g., oleate on Pb-rich (111) facets), weakly bound (e.g., oleic acid on (100) facets), and free in solution [9]. This suggests that uncoordinated lead defects may preferentially form at specific crystal facets where ligand binding is inherently weaker or more dynamic.

Experimental Protocols for Defect Analysis and Passivation

Protocol 1: Emission Recovery via L-Type Ligand Passivation

This protocol is adapted from studies on using trioctylphosphine (TOP) to treat CsPbBr₁.₂I₁.₈ PQDs [22].

- Objective: To recover the photoluminescence (PL) of aged PQDs and passivate uncoordinated lead defects.

- Materials: Aged PQD solution (in toluene or hexane), trioctylphosphine (TOP), inert atmosphere glovebox or Schlenk line, spectrophotometer.

- Procedure:

- Place the aged, non-luminescent PQD solution in a vial under an inert atmosphere.

- Add a controlled volume of TOP directly to the solution. A typical starting range is 20-100 µL of TOP per mL of PQD solution [22].

- Mix the solution gently. An immediate recovery of photoluminescence under UV light should be visually observable.

- Characterize the sample using UV-vis absorption and PL spectroscopy to quantify the recovery of the emission intensity and peak position.

- Key Measurements: Monitor the increase in PL intensity and the lengthening of the PL lifetime, which indicates a reduction in non-radiative recombination pathways [22].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Ligand Binding Dynamics via NMR Spectroscopy

This protocol is based on studies analyzing ligand populations on OA-capped PbS QDs [9].

- Objective: To quantify the populations and exchange kinetics of ligands in different binding states (strongly bound, weakly bound, free).

- Materials: Purified PQD sample, deuterated solvent, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectrometer capable of diffusometry (DOSY) and dynamic NMR experiments.

- Procedure:

- Dissolve the purified PQD sample in a deuterated solvent.

- Acquire ¹H NMR spectra to identify signals from bound ligands, which are characteristically broadened.

- Perform Diffusion-Ordered Spectroscopy (DOSY) to separate NMR signals based on their diffusion coefficients, distinguishing between strongly bound, weakly bound, and free ligands [9].

- Use dynamic NMR line shape analysis as a function of temperature to quantify the rapid exchange rates between the weakly bound and free ligand states [9].

- Key Measurements: Determine the fraction of ligands in each state and calculate the exchange rate constants between states.

Quantitative Data on Defect Impact and Passivation

Table 1: Impact of Surface Passivation on PQD Optical Properties

| PQD Sample | Relative PL Intensity | Average PL Lifetime (ns) | Key Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh CsPb(Br/I)₃ PQDs [22] | 1.00 | 41.5 | As-synthesized |

| Aged CsPb(Br/I)₃ PQDs [22] | 0.02 | 32.5 | Aged 15 days |

| Aged PQDs + TOP [22] | 1.10 | 61.8 | 80-120 µL TOP |

| Fresh PQDs + TOP [22] | >1.00 | 61.8 | 80-120 µL TOP |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Passivation

| Reagent | Type / Classification | Primary Function in Passivation |

|---|---|---|

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) [22] | L-type ligand | Electron donor that coordinates with uncoordinated lead atoms, neutralizing defect sites. |

| Oleic Acid (OAH) [9] | L-type / X-type ligand | Can bind as an L-type acid to Pb sites or dissociate to form a strongly-bound X-type oleate. |

| Oleate (OA) [9] | X-type ligand | Anionic ligand that compensates for cationic charge on metal sites; strongly bound to (111) facets. |

| Thiocyanate Salts (e.g., NaSCN) [22] | X-type ligand | Effective for passivating CsPbBr₃ PQDs, though may not work on iodided-based PQDs. |

Visualization of Ligand Dynamics and Defect Passivation

This technical support center is established to assist researchers in navigating the complexities of ligand binding analysis, with a specific focus on spectroscopic techniques and their application in cutting-edge fields like the study of dynamic ligand binding on Perovskite Quantum Dot (PQD) surfaces. The following guides and FAQs are designed to address common experimental challenges, ensure data accuracy, and promote reproducible results in characterizing the spectrum of ligand binding states.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does a "shift in the amide-I band" in ATR-FTIR spectra signify, and how do I interpret it?

- Answer: The amide-I band (approximately 1600-1700 cm⁻¹) in ATR-FTIR spectroscopy primarily arises from the C=O stretch of the protein backbone and is highly sensitive to secondary structure and hydrogen bonding. A downshift (e.g., from 1666 cm⁻¹ to 1656 cm⁻¹) typically indicates a weakening of hydrogen bonds, often associated with conformational changes towards an active state, such as the outward movement of a transmembrane helix in a GPCR. An upshift suggests stronger hydrogen bonding or a different conformational change, often linked to antagonist binding. The direction and magnitude of the shift serve as a spectral fingerprint for ligand efficacy [24].

Q2: My ligand binding assay shows high background noise. What are the primary causes and solutions?

- Answer: High background noise often stems from non-specific binding. To mitigate this:

- Optimize Blocking: Use effective blocking agents like BSA or casein to cover exposed surfaces on your assay plates [14].

- Validate Reagents: Ensure your antibodies or other detection reagents are of high quality and specificity. Monoclonal antibodies can improve consistency [14].

- Wash Stringently: Increase the number or stringency of wash steps to remove unbound or loosely bound material [14].

Q3: How can I determine if a ligand is a full agonist, partial agonist, or antagonist using spectroscopic methods?

- Answer: ATR-FTIR spectroscopy can distinguish efficacies by monitoring specific spectral features. As demonstrated for the M2 muscarinic receptor:

- Full Agonists (e.g., acetylcholine) cause a characteristic down-shift of the amide-I band (e.g., 1666 cm⁻¹ to 1656 cm⁻¹) [24].

- Super Agonists (e.g., Iperoxo) may induce an even larger spectral down-shift (~20-30 cm⁻¹), indicating more profound conformational changes [24].

- Antagonists (e.g., Atropine) often show an opposite spectral shift (e.g., 1643 cm⁻¹ to 1656 cm⁻¹), reflecting a stabilizing, inactive conformation [24]. These spectral changes correlate with functional G-protein activation levels in cells [24].

Q4: What are the critical factors for ensuring reproducible results in ligand binding assays?

- Answer: Reproducibility hinges on strict control of experimental conditions:

- Reagent Consistency: Prepare and aliquot reagents in large batches to minimize batch-to-batch variability [14].

- Standardized Protocols: Develop and adhere to detailed, step-by-step protocols for all assay procedures [14] [25].

- Environmental Control: Maintain consistent temperature, pH, and ionic strength throughout the assay, as these factors directly influence binding kinetics [14].

- Calibration and QC: Regularly calibrate equipment and include quality control samples in every assay run [14] [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Interpreting Atypical ATR-FTIR Spectral Data

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No observable shift in amide-I band upon ligand addition. | Ligand not binding; protein inactivity; incorrect buffer interference. | Confirm protein activity with a reference ligand. Check for buffer absorption overlaps (e.g., water vapor) and ensure proper background subtraction [24]. |

| Excessive noise in difference spectra. | Incomplete buffer subtraction; protein degradation; ligand precipitation. | Ensure careful matching of sample and reference buffer conditions. Centrifuge protein samples before measurement. Filter ligand solutions [24]. |

| Spectral shifts are inconsistent with expected ligand efficacy. | Protein misfolding; mixed ligand populations; complex multi-step binding. | Validate protein structure and purity. Perform ligand concentration-dependence studies to probe binding affinity and heterogeneity [24] [26]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Instability in Perovskite Quantum Dot (PQD) Ligand Studies

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid degradation of PQD photoluminescence. | Ligand detachment due to dynamic binding nature; intrinsic phase instability. | Employ multidentate ligands (e.g., dicarboxylic acids) for stronger surface binding. Use ligand mixtures to create a complementary, stabilizing surface layer [15] [8]. |

| Poor charge transport in PQD films. | Insulating long-chain ligands (e.g., OA, OAm) creating barriers. | Implement post-synthesis ligand exchange to replace long-chain insulators with shorter, conductive ligands [15] [8]. |

| PQD aggregation during processing. | Insufficient ligand coverage during synthesis or purification. | Optimize the ratio of ligands (e.g., OA to OAm) during synthesis. Consider in-situ ligand engineering to ensure complete surface passivation [8]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy for Ligand Efficacy Profiling

This protocol outlines the steps to characterize ligand-induced conformational changes in membrane receptors like GPCRs using ATR-FTIR, based on the methodology applied to the human M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor [24].

Protein Reconstitution:

- Reconstitute the purified receptor protein (typically <5 μg) into a lipid bilayer compatible with the ATR crystal. This preserves the native membrane environment [24].

Baseline Acquisition:

- Perfuse the sample cell with ligand-free buffer to establish a stable baseline. Collect and average multiple IR spectra to define the "apo" or unbound state of the receptor [24].

Ligand Binding:

- Introduce the ligand solution at the desired concentration using a continuous flow or two-liquid exchange system. Monitor the spectra in real-time to capture binding events [24].

Difference Spectrum Calculation:

- Subtract the averaged baseline spectrum (Step 2) from the spectrum obtained after ligand binding (Step 3). This difference spectrum highlights the vibrational changes induced solely by ligand binding [24].

Data Analysis:

- Identify key peaks in the difference spectrum, particularly in the amide-I region (1600-1700 cm⁻¹). The direction and magnitude of shifts (e.g., 1666 cm⁻¹ → 1656 cm⁻¹ for agonists) are correlated with ligand efficacy [24].

ATR-FTIR Ligand Efficacy Workflow

Protocol 2: Competition Kinetics Binding Assay

This protocol describes how to quantify the binding kinetics of an unlabeled test ligand by competing it against a labeled tracer ligand, a common method in drug discovery [26].

Pre-incubation:

- Incubate the target (e.g., receptor) with a range of concentrations of the unlabeled test ligand for varying time points.

Tracer Addition:

- Add a fixed concentration of a labeled tracer ligand (e.g., fluorescent or radioactive) to the mixture. The tracer and test ligand compete for the same binding site.

Real-time Measurement:

- Immediately begin measuring the bound tracer signal at multiple time points using an appropriate detector (e.g., plate reader for fluorescence). Continue until the signal reaches a steady state.

Data Fitting:

- Fit the resulting time-course data for each test ligand concentration to an exponential association curve to determine the observed association rate (k_obs) [26].

Kinetic Constant Calculation:

- Plot the k_obs values against the corresponding test ligand concentrations. The slope of this linear plot provides the association rate constant (k₁), and the y-intercept provides an estimate of the dissociation rate constant (k₂) of the tracer ligand [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Ligand Binding and PQD Surface Studies

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| High-Affinity Monoclonal Antibodies | Used as specific capture or detection reagents in ligand binding assays (LBAs) to ensure high sensitivity and minimal cross-reactivity [14]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard long-chain ligands used in the synthesis of PQDs to control growth and provide initial colloidal stability. Their dynamic binding is a common source of instability [8]. |

| Reference Standards (GMP Grade) | Qualified standards with known potency and stability, critical for calibrating assays, calculating relative potency, and ensuring consistency across batches in regulated environments [25]. |

| Blocking Agents (BSA, Casein) | Proteins used to coat unused surfaces on microplates or sensors to minimize non-specific binding of ligands and detection reagents, thereby reducing background noise [14]. |

| Multidentate Ligands (e.g., Dicarboxylic Acids) | Used in PQD surface engineering to provide stronger, more stable binding compared to monodentate ligands, significantly enhancing PQD environmental stability [8]. |

| Formamidinium Iodide / Phenylethylammonium Iodide | Examples of salts used in post-synthesis ligand exchange on PQDs to replace insulating OA/OAm, improving dot-to-dot electronic coupling and charge transport in films [15] [17]. |

Data Interpretation Diagrams

Interpreting ATR-FTIR Spectral Shifts

Advanced Ligand Engineering Techniques: From Synthesis to Surface Reconstruction

In-Situ Ligand Engineering During PQD Synthesis

In-situ ligand engineering has emerged as a pivotal strategy to address the fundamental challenge of dynamic ligand binding on perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces. The intrinsic ionic nature of lead halide perovskites (CsPbX3, where X = Cl, Br, I) creates a highly dynamic surface where traditional long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) exhibit weak binding interactions [8] [15]. This dynamic equilibrium leads to continuous ligand detachment and reattachment, resulting in surface defects, compromised optoelectronic properties, and ultimately limiting the performance and stability of PQD-based devices [8] [15]. Within the context of a broader thesis on addressing dynamic ligand binding, in-situ approaches offer a proactive methodology by engineering stable ligand configurations during the synthetic process itself, rather than attempting remedial post-synthesis treatments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on In-Situ Ligand Engineering

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of in-situ ligand engineering over post-synthesis treatment? In-situ ligand engineering integrates stable ligand binding directly during PQD synthesis, creating a more thermodynamically favorable surface configuration. This proactive approach minimizes the formation of surface vacancies and trap states that inevitably occur when removing native ligands in post-synthesis exchanges. It better preserves the structural integrity of the ionic perovskite core by avoiding exposure to harsh polar solvents typically required for ligand exchange processes [8] [15].

Q2: How does the complementary dual-ligand strategy improve PQD stability? The complementary dual-ligand system establishes a network of hydrogen bonds between different ligand types on the PQD surface. This synergistic interaction creates a more robust and cooperative capping layer that resists detachment. For example, research demonstrates that trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate and phenylethyl ammonium iodide can form such a complementary system, which not only stabilizes the surface lattice but also improves inter-dot electronic coupling in solid films, leading to record solar cell efficiencies [17].

Q3: What role do alkaline environments play in ester-based ligand hydrolysis? Recent studies show that creating alkaline environments during synthesis significantly enhances the hydrolysis efficiency of ester antisolvents. This environment renders ester hydrolysis thermodynamically spontaneous and lowers the reaction activation energy by approximately 9-fold, facilitating rapid substitution of pristine insulating oleate ligands with conductive counterparts. This approach enables up to twice the conventional amount of hydrolyzed conductive ligands to cap the PQD surface [27].

Q4: Can ligand engineering preserve PQD structure under operational stresses? Yes, strategic ligand selection can significantly enhance electrochemical stability. Studies on zeolitic imidazolate frameworks demonstrate that mixed-ligand systems can preserve the fundamental framework structure by in-situ formation of a protective surface layer, facilitating both conductivity and catalytic activity while considerably enhancing (photo)electrochemical stability [28].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Excessive surface defects due to insufficient ligand coverage; Ligand mismatch with crystal facets; Incomplete coordination during synthesis. | Optimize ligand-to-precursor ratio; Utilize multidentate ligands for stronger binding; Incorporate complementary ligand systems [17] [8]. |

| Poor Solvent Dispersion | Inadequate ligand surface coverage; Incorrect ligand chain length; Formation of ligand aggregates. | Adjust ligand concentration during synthesis; Employ ligand mixtures with balanced steric properties; Verify solvent polarity compatibility [8] [15]. |

| Phase Instability | Weak ligand binding unable to stabilize perovskite phase; Ligand-induced lattice strain; Incomplete surface passivation. | Implement ligands with higher binding energy (e.g., aromatic amines); Utilize ligand combinations that stabilize the α-phase [8] [3]. |

| Low Charge Carrier Mobility | Excessive insulating ligand residues; Poor inter-dot coupling in films; Incomplete replacement of long-chain ligands. | Incorporate short-chain conductive ligands during synthesis; Employ strategies that promote ligand condensation [17] [29]. |

Quantitative Data: Ligand Engineering Performance

Table 1: Performance Metrics of In-Situ Ligand Engineering Strategies in PQD Solar Cells

| PQD Material | Ligand Engineering Strategy | Device Efficiency (%) | Key Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ PQDs | Complementary dual-ligands (Trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate & PEAI) | 17.61% | Record high efficiency for inorganic PQDSCs; Improved environmental stability [17]. | [17] |

| FAPbI₃ PQDs | Consecutive Surface Matrix Engineering (CSME) | 19.14% | Record efficiency for FAPbI₃ PQDSCs; Enhanced operational stability [29]. | [29] |

| FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQDs | Alkaline-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH) with KOH/MeBz | 18.37% (Certified 18.30%) | Highest among hybrid A-site PQDSCs; Improved storage/operational stability [27]. | [27] |

| CsPbI₃ PQDs | Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) Layer-by-Layer | 14.18% | Balanced electron/hole transport; Enabled electroluminescence [3]. | [3] |

Table 2: Ligand Types and Their Impact on PQD Properties

| Ligand Type | Binding Mechanism | Impact on Stability | Impact on Charge Transport | Typical Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-type (Lewis base) | Electron pair donation to Pb²⁺ sites | Good halide vacancy passivation | Moderate (depends on chain length) | Oleylamine (OAm), Alkyl ammonium salts [8] [15] |

| X-type (Anionic) | Ionic binding to Pb²⁺ & Cs⁺ sites | Stabilizes surface ions | Can be high with short chains | Oleate (OA⁻), Benzoate [8] [27] |

| Multidentate | Multiple binding sites to surface | Excellent stability against detachment | Variable | Dicarboxylic acids, Diamines [8] |

| Conjugated Ligands | π-π interaction with aromatic groups | Enhanced environmental stability | High due to π-conjugation | Phenethylammonium (PEA⁺) [29] [3] |

Core Experimental Protocols

Complementary Dual-Ligand Resurfacing Protocol

This methodology describes the in-situ incorporation of two complementary ligands to create a hydrogen-bonded network on the CsPbI₃ PQD surface, stabilizing the lattice and enhancing electronic coupling [17].

Materials and Equipment:

- Lead iodide (PbI₂, 99.99%)

- Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99.99%)

- 1-Octadecene (ODE, 90%)

- Oleic acid (OA, 90%)

- Oleylamine (OAm, 80-90%)

- Trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate

- Phenylethyl ammonium iodide (PEAI)

- Three-neck flask

- Schlenk line

- Syringe pumps

- Heating mantle

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Load Cs₂CO₃, ODE, and OA in a three-neck flask. Dry under vacuum at 120°C for 1 hour. Then heat under N₂ to 150°C until complete dissolution to form Cs-oleate.

- Reaction Mixture: In a separate flask, combine PbI₂, ODE, OA, and OAm. Dry under vacuum at 120°C for 1 hour.

- Ligand Introduction: Add calculated stoichiometric amounts of trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate and PEAI to the reaction mixture.

- QD Synthesis: Rapidly inject the Cs-oleate precursor into the reaction flask at 150-180°C.

- Purification: Cool the reaction mixture immediately in an ice-water bath. Centrifuge the crude solution and redisperse the precipitate in anhydrous hexane.

- Characterization: Analyze structural integrity via XRD, surface chemistry via FTIR, and optical properties via UV-Vis and PL spectroscopy.

Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis Workflow

This protocol utilizes alkaline environments to enhance ester hydrolysis during synthesis, enabling efficient substitution of insulating ligands with conductive counterparts [27].

Key Reagents:

- Methyl benzoate (MeBz) antisolvent

- Potassium hydroxide (KOH)

- FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQD precursor solution

Procedure:

- Alkaline Environment Setup: Prepare MeBz antisolvent with controlled concentrations of KOH (typically 0.1-1 mM).

- Synthesis: Execute standard hot-injection synthesis of PQDs under inert atmosphere.

- Ligand Exchange: During the purification and washing steps, use the KOH/MeBz solution as antisolvent to simultaneously precipitate PQDs and facilitate ligand exchange.

- Validation: Confirm ligand density through NMR analysis of washed PQDs and measure conductivity of resulting films.

Essential Visualizations

Ligand Binding Dynamics Diagram

In-Situ Ligand Engineering Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for In-Situ Ligand Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salts | Cs₂CO₃, PbI₂, FAI | Provides metal and cation sources for perovskite structure | High purity (>99.99%) critical for low defects [3] |

| Traditional Ligands | Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) | Controls nucleation/growth; prevents aggregation | Dynamic binding requires replacement [8] [15] |

| Short-Chain Conductive Ligands | Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI), Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) | Enhances inter-dot coupling; improves charge transport | Can induce phase change if overused [29] [3] |

| Ester Antisolvents | Methyl Acetate (MeOAc), Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Precipitates PQDs; facilitates ligand exchange | Hydrolysis efficiency critical [27] |

| Alkaline Additives | Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Enhances ester hydrolysis kinetics; promotes ligand substitution | Concentration must be controlled to avoid degradation [27] |

| Multidentate Ligands | Dicarboxylic acids, Aromatic diamines | Strong binding to surface; reduced detachment | May affect crystallization kinetics [8] |

Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange Strategies and Solvent Considerations

Fundamental Concepts: Ligand Exchange Mechanisms

What are the primary mechanistic pathways for ligand exchange? Ligand substitution reactions are broadly characterized by their mechanism, which exists on a continuum between two extremes: associative and dissociative [30].

- Associative Mechanism (A): The incoming ligand bonds to the metal center before the original ligand departs, forming a transient, higher-coordination-number intermediate. This mechanism is common for 16-electron complexes and is characterized by a rate law that depends on the concentrations of both the metal complex and the incoming ligand [31].

- Dissociative Mechanism (D): The original ligand dissociates from the metal center first, creating a lower-coordination-number intermediate. The incoming ligand then coordinates to this reactive intermediate. This pathway is typical for 18-electron complexes, as an associative mechanism would lead to a disfavored 20-electron intermediate [30].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for identifying the dominant exchange mechanism based on your complex.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does solvent choice impact the ligand exchange process? Solvent choice is critical and can directly participate in the reaction. Polar solvents can significantly increase the rate of ligand exchange. In some cases, the solvent itself can act as an incoming ligand. For associative reactions with square planar complexes, the solvent may first coordinate to the metal in a slow step, after which the intended ligand displaces the solvent in a faster step. Because the solvent is present in vast excess, its concentration remains effectively constant, which can lead to observed rate constants that include a solvent-dependent pathway (k_s) [31].

2. Why is my ligand exchange incomplete, especially in thick films? Incomplete exchange is a common issue, particularly in thicker films, due to diffusion limitations. The original organic ligands (e.g., oleic acid) must diffuse out, while the new exchanging ligands (e.g., iodide from TBAI) must diffuse in. In thick or dense films, this process can be hindered, leaving unexchanged ligands in the interior that act as trap states and degrade electronic performance [32]. Solution: Implement post-synthesis washing cycles on the quantum dots before film deposition to reduce the initial ligand load and optimize the concentration and time of the exchange process [32].

3. Can ligand exchange be used to create complex nanostructures? Yes. The Solvent-Assisted Ligand Exchange (SALE) method is a powerful technique for transforming the structure and composition of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs). This process involves a balance between the dissolution of the original "mother" MOF and the recrystallization of a new "daughter" MOF. By carefully controlling the reaction conditions—such as the concentration of the new ligand, temperature, and time—you can achieve complex architectures like core-shell, yolk-shell, and multi-shelled hollow structures from a single MOF precursor [33].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Exchange Efficiency | Diffusion-limited process in thick films; excessive initial ligand load [32]. | - Optimize number of post-synthesis washing cycles [32].- Increase exchange solution concentration/time.- Use a solvent that swells the film to improve permeability. |

| Structural Collapse or Loss of Crystallinity | The dissolution rate of the original framework outpaces the recrystallization rate of the new framework [33]. | - Reduce the concentration of the exchanging ligand solution.- Lower the reaction temperature to slow down kinetics.- Use a solvent mixture that modulates the exchange rate. |

| Poor Material Performance (e.g., low PCE in solar cells) | Incomplete ligand exchange creating electronic trap states [32]. | - Ensure complete removal of original ligands and exchange byproducts via thorough washing.- Characterize trap state density to link device performance to exchange efficacy [32]. |

| Unpredictable Reaction Kinetics | Solvent participation in the mechanism or an unaccounted-for exchange pathway [31]. | - Run control experiments with different solvent polarities.- Determine the rate law under pseudo-first-order conditions to identify the mechanism [31]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimized Ligand Exchange for PbS QD Solar Cells

This protocol is adapted from a study achieving 5.55% power conversion efficiency and focuses on achieving complete exchange in thick films (~240 nm) [32].

1. Materials and Reagents

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| PbS Quantum Dots | The core semiconductor material, typically capped with oleic acid (OA) ligands [32]. |

| Tetrabutylammonium Iodide (TBAI) | The exchanging ligand source. Iodide provides passivation for high-performance PbS QD solar cells [32]. |

| Solvents (e.g., Acetone, Octane) | Acetone: A polar solvent for washing and precipitating QDs to remove excess OA [32]. Octane: A non-polar solvent for dispersing OA-capped QDs and film deposition. |

| 2-Methylimidazole (Hmim) | A ligand used in SALE processes for MOFs, demonstrating the versatility of nitrogen-donor ligands [33]. |

2. Pre-Exchange Purification (Critical Step)

- Procedure: Perform multiple washing cycles on the synthesized OA-capped PbS QDs. This involves adding a polar solvent (e.g., acetone) to the QD solution to induce flocculation, centrifuging, and decanting the supernatant containing excess OA and reaction byproducts.

- Importance: A sufficient number of washing cycles reduces the initial OA ligand burden, which is crucial for enabling a complete and uniform ligand exchange in subsequent steps, especially in thicker films [32].

3. Film Deposition and Ligand Exchange

- Deposit a thick film (~240 nm) of the purified PbS QDs onto your substrate via a suitable method like spin-coating.

- Immerse the film in a TBAI solution (e.g., 10 mg/mL in methanol) for a predetermined time to execute the solid-state ligand exchange.

- Terminate the reaction by rinsing the film thoroughly with fresh methanol to remove exchanged ligands and excess TBAI.

The workflow for this optimized exchange process is outlined below.

Table 1: Influence of Purification and Exchange Parameters on Outcomes in PbS QD Systems [32]

| Parameter | Condition | Outcome & Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Washing Cycles | Insufficient cycles | High residual OA, incomplete TBAI exchange, lower device performance [32]. |

| Optimal cycles | Reduced OA load, complete TBAI exchange in thick films, achieved 5.55% PCE [32]. | |

| Exchange Reaction Kinetics | Dissociative (18-e⁻ complex) | Rate = k[MLn], positive ΔS‡ [30]. |

| Associative (16-e⁻ complex) | Rate = k[MLn][Li], negative ΔS‡ [31]. | |

| Solvent Polarity | Low to High Polarity | Can markedly increase pre-equilibrium constant (Ke) and rate constant (k2) [34]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

This technical support center addresses common experimental challenges in the synthesis and application of advanced ligand systems, with a special focus on resolving dynamic ligand binding on perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces.

Bidentate Ligand Systems

Q1: My bidentate Schiff base metal complexes are precipitating from solution. What could be the cause? Precipitation often results from poor ligand stability or incorrect metal-to-ligand ratio. For bidentate NS ligands derived from S-benzyldithiocarbazate and methoxybenzaldehyde, ensure a 1:2 (metal:ligand) ratio for complexes with Cu(II), Ni(II), and Zn(II) [35]. Characterize your complexes using elemental analysis and infrared spectroscopy to confirm coordination via the azomethine nitrogen and thiolate sulfur atoms [35].

Q2: How can I confirm the distorted square-planar geometry of my synthesized nickel Schiff base complex? Use a combination of X-ray crystallographic analysis and spectroscopic techniques. Crystallographic determination at low temperatures (e.g., 170 K) confirms the structure, showing coordination through the iminic nitrogen and phenoxy oxygen atoms [36]. The complex typically crystallizes in the triclinic space group P-1 [36].

Short-Chain and Conductive Ligands

Q3: The pristine long-chain insulating ligands on my PQDs hinder charge transfer in the assembled film. How can I replace them effectively? Implement an Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH) strategy [37]. Using an alkaline environment with methyl benzoate (MeBz) antisolvent coupled with potassium hydroxide (KOH) facilitates rapid substitution of insulating oleate (OA-) ligands with conductive short-chain ligands. This method reduces the activation energy for ester hydrolysis by approximately 9-fold, making the reaction thermodynamically spontaneous [37].

Q4: My lead-based PQDs suffer from stability and toxicity issues. Are there safer alternatives? Consider bismuth-based PQDs like Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ for photoelectrochemical applications [38]. They offer extended serum stability and already meet current safety standards without additional coating, unlike lead-based compositions (e.g., CsPbBr₃ PQDs) whose Pb²⁺ release typically exceeds permitted levels [38].

Q5: How can I rapidly screen thousands of ligands to find the one that suppresses back electron transfer in my photoexcited palladium catalyst system? Use the Virtual Ligand-Assisted Screening (VLAS) computational approach [39]. This method analyzes electronic and steric properties of phosphine ligands to predict their performance. For alkyl ketone reduction, VLAS identified tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine (L4) as most effective at suppressing back electron transfer, enabling high-yield ketyl radical transformations [39].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Ligand Synthesis and Application Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low yield in Schiff base synthesis [36] | Incomplete condensation reaction | Ensure strict anhydrous conditions and use molecular sieves. |

| Poor charge transport in PQD films [37] | Inefficient replacement of long-chain OA- ligands | Adopt the AAAH strategy with KOH/MeBz for interlayer rinsing [37]. |

| Catalyst system fails with alkyl ketones [39] | Back electron transfer (BET) | Use the computationally identified ligand tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine [39]. |

| PQD film degradation in aqueous phase [38] | Lead leaching & structural instability | Switch to lead-free compositions (e.g., Cs₃Bi₂Br₉) or apply surface passivation [38]. |

| Non-specific binding in assays [40] | Target interaction with buffer components | Use techniques like Microfluidic Diffusional Sizing (MDS) to detect size deviations indicating non-specific binding [40]. |

Quantitative Data for Experimental Planning

Table 2: Key Performance Data for Ligand and PQD Systems

| System / Parameter | Value / Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Certified PQD Solar Cell Efficiency [37] | 18.3% | Achieved via AAAH strategy for conductive capping. |

| Steady-state PQD Solar Cell Efficiency [37] | 17.85% | Average over 20 devices was 17.68% [37]. |

| Activation Energy Reduction [37] | ~9-fold lower | Ester hydrolysis in alkaline treatment vs. conventional. |

| Schiff Base Ni Complex Crystallography [36] | Space Group P-1, a=6.233(5) Å, b=8.586(5) Å, c=15.247(5) Å, β=98.324(5)° | X-ray structural analysis at 170 K. |

| Cu(II) Complex Cytotoxicity [35] | Active against MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines | Marked cytotoxicity observed, unlike Ni(II) or Zn(II) complexes. |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Methodology:

- Ligand Synthesis: Conduct a condensation reaction in methanolic solution between the primary amine (e.g., 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethylamine or S-2-methylbenzyldithiocarbazate) and the carbonyl compound (e.g., 3,5-dichlorosalicylaldehyde or methoxybenzaldehyde) [36] [35].

- Complex Formation: React the purified ligand with metal acetates (e.g., Ni(CH₃COO)₂, Cu(CH₃COO)₂·H₂O) in a 2:1 (ligand:metal) molar ratio in methanol [36] [35].

- Purification: Isolate the complex via filtration or evaporation, and recrystallize from a suitable solvent [36].

Characterization:

- Elemental Analysis: Confirm composition.

- Spectroscopy: Use IR to identify coordination shifts (e.g., C=N stretch), NMR, and electronic spectroscopy [36].

- Molar Conductivity: Confirm non-electrolytic nature in DMSO solution (5×10⁻⁴ M) [36].

- X-ray Crystallography: For definitive structural determination [36] [35].

Materials:

- PQD Solids: FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQDs (~12.5 nm average size).

- Antisolvent: Methyl benzoate (MeBz).

- Alkaline Source: Potassium hydroxide (KOH).

Workflow:

- Spin-coat the PQD colloids to form an initial solid film.

- Rinse the film with the MeBz antisolvent containing a tailored concentration of KOH under ambient conditions (~30% relative humidity). This step hydrolyzes the ester and substitutes the pristine insulating oleate (OA⁻) ligands.

- Repeat the layer-by-layer deposition and rinsing until the desired film thickness is achieved.

- Post-treat (if needed) with short cationic ligands (e.g., FA⁺) in 2-pentanol to enhance electronic coupling [37].

Methodology:

- Define the System: Identify the core catalytic transformation (e.g., photoexcited palladium catalysis for ketyl radical generation).

- Select Ligand Library: Choose a representative set of ligands (e.g., 38 phosphine ligands).

- Run VLAS: Use the Virtual Ligand-Assisted Screening (VLAS) method to compute electronic and steric properties, generating a predictive heat map.

- Laboratory Validation: Select top-ranked computational candidates (e.g., 2-3 ligands) for experimental testing in the target reaction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Ligand and PQD Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Feature / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 3,5-Dichlorosalicylaldehyde [36] | Synthesis of dihalogenated bidentate Schiff base ligands. | Provides a versatile precursor for complex formation with metals like Ni(II) and Cu(II). |

| S-2-Methylbenzyldithiocarbazate [35] | Synthesis of bidentate NS Schiff base ligands. | Coordinates via azomethine nitrogen and thiolate sulfur. |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) [37] | Ester-based antisolvent for interlayer rinsing of PQD solids. | Hydrolyzes into conductive short-chain ligands; suitable polarity for PQD stability. |

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine (L4) [39] | Ligand for photoexcited palladium catalysis. | Computationally identified to suppress back electron transfer for alkyl ketone reactions. |

| Cesium Bismuth Bromide (Cs₃Bi₂Br₉) [38] | Lead-free perovskite quantum dot composition. | Offers sub-femtomolar sensitivity in biosensing and meets safety standards. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) [37] | Alkaline additive for antisolvent hydrolysis (AAAH). | Facilitates rapid, spontaneous ester hydrolysis for efficient ligand exchange. |

Dual-Ligand and Multi-Ligand Surface Reconstruction Approaches

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: My PQD solar cell efficiency is lower than expected after ligand exchange. What could be the cause? A: Reduced Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) often stems from incomplete surface passivation or improper ligand binding during exchange. If long-chain insulating ligands are not fully replaced, charge transport remains hindered. Conversely, if short-chain ligands do not adequately passivate surface defects (e.g., Cs⁺ or I⁻ vacancies), non-radiative recombination increases, lowering Voc and efficiency [41]. Ensure your multifaceted ligand, such as ThMAI, has strong binding affinity to both cationic and anionic surface sites [41]. Monitor carrier lifetime measurements; a shorter lifetime indicates persistent surface defects.

Q2: The black phase (α, β, or γ) of my CsPbI3 PQDs is unstable and transitions to the yellow δ-phase after ligand treatment. How can I prevent this? A: Phase instability is frequently caused by a loss of surface tensile strain during ligand exchange. The removal of initial long-chain ligands (like OA and OLA) can induce severe lattice distortion [41]. To mitigate this, employ ligands with a larger ionic radius than Cs⁺, such as ThMA⁺. These ligands can restore compressive surface strain, stabilizing the black perovskite phase [41]. Techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) can be used to monitor lattice parameters and phase purity.

Q3: How can I achieve uniform orientation of PQDs in a solid film? A: Non-uniform orientation often arises from weak or non-specific ligand binding, leading to disordered aggregation during film formation. Multifaceted anchoring ligands promote uniform orientation by simultaneously binding to multiple surface sites with high affinity. For example, a ligand with a thiophene group (binding to Pb²⁺) and an ammonium group (binding to I⁻ or Cs⁺ vacancies) creates a more deterministic and uniform binding configuration, guiding a consistent PQD alignment [41].

Q4: My ligand exchange process is inconsistent between batches. What parameters should I control most strictly? A: Key parameters to control include:

- Ligand Concentration and Reaction Time: These directly affect the completeness of exchange and defect passivation.

- Ambient Conditions: Moisture and oxygen can degrade PQD surfaces during the exchange process. Perform the exchange in an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen glovebox) [41].

- Washing Process: The type and volume of antisolvent used for washing can inadvertently remove necessary ligands or induce lattice distortion. Standardize this step precisely [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of using a dual/multi-ligand approach over a single ligand? A: A single ligand typically passivates only one type of surface defect (e.g., an ammonium group targets metal cation vacancies). A dual-ligand system or a multifaceted single ligand molecule can concurrently passivate multiple defect types (e.g., both cation and anion vacancies), leading to superior surface coverage, reduced trap states, and enhanced electronic coupling between PQDs for better charge transport [41].

Q2: Can I use the same ligand exchange protocol for different types of PQDs (e.g., CsPbI3 vs. CsPbBr3)? A: The core principle is applicable, but the protocol may require optimization. Different halide compositions affect the surface energy and binding affinity of ligands. The optimal concentration, solvent, and reaction time may vary. It is crucial to validate the protocol for each specific PQD composition [41].

Q3: How can I verify the successful binding of my new ligands to the PQD surface? A: Several characterization techniques can confirm ligand binding:

- Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Identifies changes in functional groups, confirming the presence of new ligands.

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Detects elemental shifts on the PQD surface, providing evidence of chemical bonding between the ligand and the surface atoms.

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Can quantify ligand density and confirm the replacement of original ligands.

Experimental Protocols & Data

This protocol details the ligand exchange process using 2-Thiophenemethylammonium Iodide (ThMAI) to create conductive and stable CsPbI3 PQD solid films.

1. Materials and Reagents

- Synthesized CsPbI3 PQDs (stabilized with OA/OLA in n-hexane)

- Ligand solution: 0.1 mM ThMAI in anhydrous acetonitrile

- Solvents: Anhydrous acetonitrile, n-hexane, n-octane

- Substrates (e.g., FTO glass)

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

- PQD Precipitation: Centrifuge the CsPbI3 PQD solution in n-hexane. Discard the supernatant to remove excess solvent and weakly bound ligands.

- Redispersion: Re-disperse the PQD precipitate in a small volume of n-octane to create a concentrated dispersion.

- Ligand Exchange: Slowly add the ThMAI solution in acetonitrile to the PQD dispersion under constant stirring. The ratio of ThMAI solution to PQD dispersion should be optimized (e.g., 3:1 v/v).

- Reaction: Allow the mixture to react for 60-120 seconds with continuous stirring.

- Washing: Centrifuge the mixture to obtain a solid pellet. Carefully discard the supernatant containing the displaced long-chain ligands and reaction by-products.

- Film Fabrication: Re-disperse the treated PQDs in anhydrous acetonitrile to form a clean ink. Deposit the ink onto the substrate via spin-coating or drop-casting.

- Drying: Allow the film to dry under an inert atmosphere.

3. Critical Notes

- Timing: The ligand exchange reaction time is critical. Too short may lead to incomplete exchange; too long may damage the PQD core.

- Environment: All steps must be performed in an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen glovebox) to prevent degradation by moisture and oxygen.

- Antisolvent: Acetonitrile acts as a solvent for ThMAI and an antisolvent for PQDs, driving the ligand exchange process.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CsPbI3 PQD Solar Cells with Different Ligand Treatments [41]

| Ligand Treatment | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Stability (PCE retention after 15 days) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Short-chain only) | 13.6% | ~8.7% | Poor phase stability, numerous surface defects |

| ThMAI (Multifaceted) | 15.3% | ~83% | Improved carrier lifetime, uniform orientation, restored tensile strain |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for PQD Surface Reconstruction [41]

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OLA) | Long-chain native ligands for initial PQD synthesis and phase stabilization. |

| 2-Thiophenemethylammonium Iodide (ThMAI) | Multifaceted anchoring ligand for exchange; passivates defects and induces strain. |

| Anhydrous Acetonitrile | Solvent and antisolvent; facilitates ligand exchange and purification. |

| n-Octane | Non-polar solvent for creating concentrated PQD dispersions post-precipitation. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: Ligand exchange experimental workflow.

Diagram 2: Multifaceted ligand binding mechanism.

Interfacial Passivation Techniques for Enhanced PQD Stability

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This technical support center is designed within the context of a broader thesis on addressing dynamic ligand binding on PQD surfaces. It provides targeted solutions for common experimental challenges encountered in the laboratory, helping researchers achieve more stable and efficient perovskite quantum dot (PQD) materials and devices.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: The power conversion efficiency (PCE) of my perovskite quantum dot solar cell (QDSC) is lower than expected. What is a likely cause and how can I address it? A primary cause is poor charge transport between PQDs due to the presence of long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid/OA and oleylamine/OAm) on the dot surfaces. These ligands create energy barriers that impede electron and hole movement [ [42] [15]].