Mastering Drift Correction in SPR Kinetics: From Foundations to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to identifying, troubleshooting, and correcting for baseline drift in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) kinetic analysis.

Mastering Drift Correction in SPR Kinetics: From Foundations to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to identifying, troubleshooting, and correcting for baseline drift in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) kinetic analysis. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the fundamental causes of drift, explores both experimental and computational correction methodologies, and offers practical optimization strategies to enhance data quality. By comparing traditional and emerging techniques, including novel hardware-based focus correction and unified software solutions, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to obtain highly reliable and reproducible kinetic parameters for critical decision-making in biomolecular interaction studies.

Understanding Drift in SPR: The Silent Saboteur of Kinetic Data

What is baseline drift in SPR and how can I identify it in my sensorgrams?

Baseline drift is an unstable signal in the absence of analyte and is typically observed as a gradual increase or decrease in response units (RU) over time before analyte injection [1] [2]. It usually indicates a sensor surface that is not optimally equilibrated with the running buffer [1] [3].

You can identify drift in your sensorgrams by looking for:

- A non-flat baseline that steadily rises or falls during the initial buffer phase before analyte injection [1] [2].

- Sensorgram curves that do not return to the original baseline level between analyte injections in multi-cycle kinetics experiments [1].

- A wavy baseline pattern following changes in running buffer, indicating insufficient system equilibration [1].

How does baseline drift specifically impact the calculation of kinetic parameters?

Baseline drift introduces errors in the calculation of all key kinetic parameters by distorting the true binding response. The table below summarizes these specific impacts:

Table 1: Impact of Baseline Drift on Kinetic Parameters

| Kinetic Parameter | Impact of Baseline Drift | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Association rate constant (ka) | Distorts the true association phase slope [4] | Incorrect calculation of binding onset rate |

| Dissociation rate constant (kd) | Alters the apparent dissociation trajectory [4] | Inaccurate measurement of complex stability |

| Maximum Response (Rmax) | Prevents accurate saturation level determination [4] | Error in estimating binding capacity and stoichiometry |

| Equilibrium Dissociation Constant (KD) | Affects both kinetic (kd/ka) and steady-state calculations [4] | Compromised accuracy of affinity measurements |

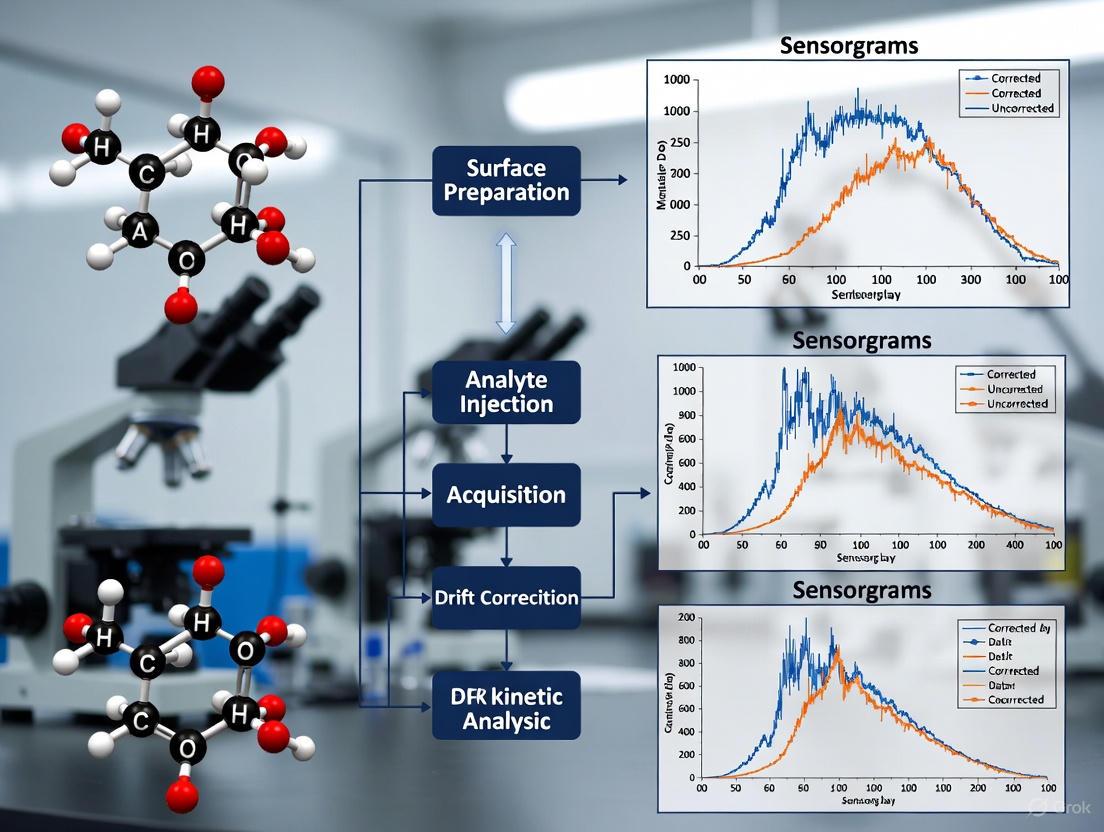

The following diagram illustrates how drift distorts the sensorgram and affects parameter calculation:

What are the primary causes of baseline drift in SPR experiments?

The main causes of baseline drift can be categorized as follows:

Table 2: Common Causes of Baseline Drift and Their Mechanisms

| Cause | Mechanism | Typical Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient System Equilibration | Sensor surface rehydrating or adjusting to running buffer [1] | Drift after docking new chip or immobilization |

| Buffer-Related Issues | Poorly degassed buffers releasing air bubbles; temperature differences; buffer contamination [1] [2] | Continuous drift with waviness; pump strokes visible |

| Flow System Changes | Pressure differences when initiating flow after standstill [1] | Start-up drift that levels out over 5-30 minutes |

| Regeneration Effects | Residual regeneration solution affecting reference and active surfaces differently [1] | Unequal drift rates between channels |

What experimental protocols can I implement to minimize or correct for baseline drift?

A. Prevention Protocols

Buffer Preparation and System Equilibration

- Prepare fresh running buffer daily and 0.22 µM filter and degas before use [1] [2].

- Prime the system several times after each buffer change and wait for a stable baseline [1].

- For persistently drifting surfaces, flow running buffer overnight to fully equilibrate [1] [3].

- Ensure all buffers are at the same temperature before starting experiments [2].

Experimental Design Strategies

- Incorporate at least three start-up cycles at the beginning of each experiment, injecting buffer instead of analyte to prime the surface [1].

- Add blank injections (buffer alone) every five to six analyte cycles and end with one to facilitate double referencing [1].

- Allow 5-30 minutes after initiating flow for the baseline to stabilize before first injection [1].

B. Correction Methods

Double Referencing Procedure

- First subtraction: Subtract the reference channel (without ligand) from the active channel to compensate for bulk effects and drift [1].

- Second subtraction: Subtract blank injections (buffer only) to compensate for differences between reference and active channels [1].

- Space blank injections evenly throughout the experiment for optimal correction [1].

Software-Based Drift Correction

The following workflow outlines a comprehensive approach to addressing baseline drift:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Drift Mitigation

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Managing Baseline Drift

| Reagent/Material | Function in Drift Management | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Buffer Components | Ensure consistent refractive index; minimize chemical contaminants causing drift [1] [6] | Prepare fresh daily; 0.22 µM filter |

| Degassing Equipment | Remove dissolved air that creates bubbles and spikes [1] [2] | Degas after filtering; avoid buffers stored at 4°C |

| Appropriate Sensor Chips | Provide stable surface for ligand immobilization [7] [6] | Select based on ligand characteristics |

| Filter Units (0.22 µm) | Remove particulate contaminants that cause drift [1] [2] | Use before degassing step |

| Reference Channel Components | Enable double referencing for drift compensation [1] [4] | Should closely match active surface |

| Regeneration Solutions | Properly clean surface without damaging ligand activity [7] [6] | Optimize to balance efficacy and ligand preservation |

How can I distinguish baseline drift from other common SPR artifacts?

Baseline drift can be distinguished from other artifacts by its characteristic gradual, continuous change in response units. Unlike bulk shifts which show immediate square-shaped responses at injection start/end [6], or spikes which are abrupt response changes [1], drift manifests as a steady baseline slope. When observing drift, check for mismatched buffer conditions and insufficient equilibration rather than the sample-related issues that typically cause bulk effects [1] [6].

For persistent drift that remains after implementing these protocols, consult your instrument manual for specific maintenance procedures, as some drift issues may indicate need for fluidic system maintenance or detector recalibration [1] [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on SPR Drift

FAQ 1: What is baseline drift in SPR and why is it a problem? Baseline drift is an unstable or gradually shifting signal recorded in the absence of analyte. It is a problem because it can obscure genuine binding events, lead to inaccurate calculation of binding kinetics (association and dissociation rates), and result in incorrect affinity measurements, thereby compromising the entire experiment.

FAQ 2: Can the choice of running buffer really cause drift? Yes. Incompatibility between the running buffer and the sensor chip surface or the immobilized ligand can cause instability. Furthermore, if the buffer used for the analyte injection is not perfectly matched with the running buffer, it can cause small, reversible shifts in the baseline. While a reference flow cell can compensate for minor shifts, larger differences will cause significant drift and bulk effects [3].

FAQ 3: I've immobilized my ligand, but the baseline is still drifting. What is wrong? An improperly equilibrated sensor surface is a common cause of drift. Even after immobilization, the dextran matrix on the sensor chip may require extended time to stabilize. It is sometimes necessary to run the flow buffer overnight or perform several buffer injections before starting the actual experiment to minimize this drift [3].

FAQ 4: How does sample quality contribute to drift and poor data? Impurities in your sample, such as protein aggregates, denatured molecules, or contaminants, can bind non-specifically to the sensor surface. This non-specific binding (NSB) can cause a continuous, slow increase in the signal that mimics drift and interferes with the analysis of the specific interaction [8]. Inconsistent sample handling can also lead to poor reproducibility between experimental runs [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Drift

| Source of Drift | Symptoms | Diagnostic Checks & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Air Bubbles/Leaks [2] | Sudden, sharp spikes or sustained baseline instability. | Ensure buffers are properly degassed. Check the entire fluidic system for leaks and ensure all connections are secure. |

| Electrical/Mechanical Noise [2] | High-frequency fluctuations or "noisy" baseline. | Place the instrument in a stable environment with minimal vibrations and temperature fluctuations. Ensure proper electrical grounding. |

| Improper Calibration [8] | Consistent drift across all experiments. | Follow the manufacturer's guidelines for regular instrument calibration. |

| Sensor Surface Degradation [2] | Gradual loss of ligand activity and increasing baseline instability over multiple cycles. | Avoid harsh chemicals and follow recommended storage and handling procedures for sensor chips. Monitor surface performance. |

| Source of Drift | Symptoms | Diagnostic Checks & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer Mismatch [3] | Sharp "bulk" shifts at the start and end of analyte injection, followed by drift. | Precisely match the composition, pH, and ionic strength of the running buffer and the analyte sample buffer. |

| Poor Surface Equilibration [3] | Continuous, slow baseline drift at the beginning of an experiment. | Extend the initial buffer flow (stabilization time). Perform multiple "blank" buffer injections before analyte injections to fully equilibrate the surface. |

| Non-Specific Binding (NSB) [8] [9] | A steady, slow signal increase not accounted for by specific binding; poor reproducibility. | Use blocking agents like BSA or casein. Optimize surface chemistry. Add low concentrations of surfactants (e.g., Tween-20) to the running buffer. |

| Inefficient Regeneration [2] | Gradual rise in baseline over multiple analyte injection cycles due to carryover. | Systematically optimize regeneration conditions (e.g., pH, ionic strength). Test solutions like glycine (pH 2-3), NaOH, or high salt. Increase regeneration time or flow rate. |

| Low Sample Quality [8] | Weak signal, high noise, and inconsistent binding responses. | Purify samples to remove aggregates and contaminants. Use fresh, properly prepared samples and standardize handling procedures. |

Experimental Protocol: A Systematic Approach to Diagnosing Drift

- Isolate the Cause: Begin with a buffer-buffer injection. If drift persists without any analyte, the issue is likely instrumental or related to the running buffer and surface equilibration.

- Check for Bulk Effects: Inject a buffer that is deliberately mismatched (e.g., slightly higher salt) over the sensor surface. A sharp, square-shaped signal that returns to baseline indicates a bulk effect, highlighting the need for perfect buffer matching [3].

- Test for Carryover: Perform consecutive injections of a high-salt solution (e.g., 0.5 M NaCl) and buffer. The signal should return completely to the original baseline after the buffer injection. If not, regeneration is incomplete [3].

- Evaluate Sample: Inject your analyte over a blank, non-functionalized sensor surface. Any signal increase indicates non-specific binding, requiring optimization of blocking strategies or buffer additives [9].

Diagnostic and Resolution Workflow for SPR Drift

The following diagram outlines a logical, step-by-step process for identifying and correcting the root causes of baseline drift in SPR experiments.

Research Reagent Solutions for Drift Mitigation

The following table details key reagents and materials used to prevent and correct for baseline drift in SPR experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function in Drift Mitigation |

|---|---|

| Blocking Agents (BSA, Casein) [8] [9] | Occupies remaining reactive sites on the sensor surface after ligand immobilization to prevent non-specific binding of the analyte. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Tween-20) [8] | Added to the running buffer to reduce hydrophobic interactions between the analyte and sensor surface, thereby minimizing non-specific binding. |

| Ethanolamine [2] [8] | A common blocking agent used to deactivate and block unreacted ester groups on the sensor surface after covalent coupling. |

| Regeneration Solutions [2] [9] | Low pH (e.g., Glycine, Phosphoric acid), high pH (e.g., NaOH), or high salt (e.g., NaCl) solutions used to completely remove bound analyte without damaging the ligand, preventing carryover. |

| High-Quality Buffers & Additives [8] | Properly formulated and filtered buffers maintain ligand and analyte stability, prevent aggregation, and provide optimal conditions to minimize non-specific interactions. |

| Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5, C1, NTA) [8] | Choosing a chip with appropriate surface chemistry (e.g., low non-specific binding, suitable for capture) is fundamental to a stable baseline. |

FAQ: What are the primary artefacts that can be confused with drift in SPR analysis?

In Surface Plasmon Resonance analysis, several artefacts can manifest as baseline shifts that resemble true drift. Correctly identifying the source is crucial for accurate data interpretation and kinetic analysis. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each artefact to aid in diagnosis [8] [10].

| Artefact | Primary Cause | Key Characteristic | Impact on Kinetic Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drift | System instability (e.g., temperature fluctuations, slow ligand leaching, improper buffer equilibration) [10]. | A gradual, continuous change in the baseline signal across the entire experiment [8]. | Leads to inaccurate determination of association ((ka)) and dissociation ((kd)) rate constants. |

| Non-Specific Binding (NSB) | Analyte interacting with the sensor surface via hydrophobic, charge-based, or other non-target forces [11] [12]. | Causes an increase in response units (RU) that can mimic specific binding, but occurs even on a reference surface without the specific ligand [11]. | Inflates the measured RU, leading to erroneously high calculated affinity and incorrect kinetics [11]. |

| Bulk Effect | A difference in refractive index between the running buffer and the sample solution [13]. | A sharp, square signal pulse that occurs immediately at the start of injection and disappears immediately at the end [13]. | Can obscure the initial association phase; can be corrected for with an appropriate reference surface [13]. |

| Mass Transport | The rate of analyte diffusing to the sensor surface is slower than the rate of its binding to the ligand [8]. | Binding curves are often sharper and the dissociation phase can be artificially slowed due to rebinding [8]. | Results in underestimated association rates and overestimated dissociation rates, affecting the calculated affinity ((K_D)). |

The following decision diagram can help you systematically identify the artefact affecting your experiment.

FAQ: What experimental protocols can I use to confirm and reduce non-specific binding?

Non-specific binding (NSB) is a common cause of artefactual signals. The protocol below outlines how to diagnose NSB and provides optimized reagent solutions to mitigate it [11] [12].

Experimental Protocol: Diagnosis and Mitigation of NSB

Step 1: Diagnose NSB with a Control Surface

- Procedure: Before immobilizing your ligand, inject your analyte over a bare sensor surface or a surface immobilized with an irrelevant ligand.

- Interpretation: A significant response on this control surface indicates the presence of NSB that must be addressed before collecting kinetic data [11] [12].

Step 2: Systematically Optimize Buffer Conditions If NSB is detected, systematically test the following buffer additives. Prepare a stock of your running buffer and create separate aliquots for each condition.

| Research Reagent Solution | Function | Typical Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A protein blocker that surrounds the analyte to shield it from non-specific protein-protein interactions and surface adsorption [11] [12]. | 0.5 - 1.0% (w/v) [11] [14] |

| Tween 20 | A non-ionic surfactant that disrupts hydrophobic interactions between the analyte and the sensor surface or tubing [11] [12]. | 0.005 - 0.1% (v/v) [11] [14] |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Shields charge-based interactions by reducing the electrostatic attraction between the analyte and the charged sensor surface [11] [12]. | 150 - 500 mM [11] [14] |

- Procedure: Add the reagent to your running buffer and the analyte sample. Re-run the NSB diagnosis test from Step 1.

- Critical Consideration: Always consider the stability of your biomolecules. Extreme pH or high salt concentrations could denature your protein [11] [12].

Step 3: Alternative Surface Chemistries

- If buffer optimization is insufficient, consider changing the sensor chip. A planar chip or one with a different surface chemistry (e.g., a hydrogel with less charge) can sometimes reduce NSB compared to a standard carboxymethyl dextran chip [14].

FAQ: How can I formally confirm that the issue is drift and not another artefact?

Confirming true instrumental drift involves a systematic diagnostic experiment to rule out other common artefacts.

Experimental Protocol: Isolating System Drift

Step 1: Establish a Stable Baseline

- Equilibrate the SPR instrument with running buffer for an extended period (e.g., 30-60 minutes) while monitoring the baseline signal. A stable baseline should show minimal long-term change [8].

Step 2: Execute a Blank Run

- Perform a mock experiment with sequential injections of running buffer (without analyte) over your prepared ligand surface.

- Interpretation: A gradual, continuous shift in the baseline signal during this blank run is a clear indicator of system drift [10]. This drift can be caused by temperature fluctuations, slow leaching of the immobilized ligand, or improper system cleaning and equilibration [8] [10].

Step 3: Differentiate from Bulk Effect

- In the same blank run, the injections of running buffer should cause little to no disturbance in the signal. A significant pulse during injection would indicate a bulk effect, often due to improper buffer matching [13].

Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Artefact Troubleshooting

The following table lists essential reagents used to diagnose and resolve the SPR artefacts discussed in this guide.

| Reagent | Primary Function in SPR | Specific Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| BSA | Protein blocking agent to minimize NSB [11] [12]. | Added to buffer and sample to shield hydrophobic and charged analytes. |

| Tween 20 | Non-ionic surfactant to disrupt hydrophobic interactions [11] [12]. | Used in running buffer to prevent NSB and analyte loss to tubing. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Salt to shield electrostatic interactions [11] [12]. | Added to buffer at high concentrations to reduce charge-based NSB. |

| Ethylenediamine | Alternative blocking agent for amine-coupled surfaces [14]. | Used instead of ethanolamine to create a less negatively charged surface, reducing NSB for positively charged analytes. |

| Glycerol | Stabilizing agent for regeneration solutions [14]. | Added (5-10%) to regeneration buffers to help maintain ligand activity during repeated cycles. |

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (FAQS)

Q1: What does "baseline drift" look like in my SPR data, and why is it a problem? Baseline drift is observed as an unstable or slowly shifting signal when no analyte is being injected, indicating that the system has not reached equilibrium [2]. For kinetic analysis, particularly with very slow-dissociating complexes (kd < 1x10⁻⁴ s⁻¹), this drift can obscure the true dissociation signal, making accurate calculation of residence time and other kinetic parameters impossible [15] [2].

Q2: I've immobilized my ligand, but the baseline is still drifting. What are the most common causes? The most frequent causes are related to the sensor surface and fluidic system not being fully equilibrated [2] [3]. This can include:

- Improperly Degassed Buffer: Bubbles forming in the fluidic system [2].

- Insufficient Equilibration: The sensor surface requires more time to stabilize. In some cases, it may be necessary to run the flow buffer overnight or perform several buffer injections before the experiment [3].

- Temperature Fluctuations: The instrument is in an environment with unstable temperature [2].

- Contamination: Contaminants on the sensor surface or in the buffer [2].

Q3: My analyte has a very slow off-rate. How can I accurately measure its dissociation if the baseline is drifting? Conventional direct measurement of slow dissociation is challenging with SPR due to signal drift. A robust solution is the competitive SPR chaser assay [15]. This method involves saturating the immobilized target with your test molecule. Then, instead of monitoring dissociation into a blank buffer, a high-concentration competitive molecule (the "chaser") is injected at intervals. The binding of the chaser provides a time-course measurement of how many target sites have been vacated by the test molecule, allowing for accurate calculation of the slow dissociation rate constant [15].

Q4: How can I distinguish between a true binding signal and a "bulk response"? The bulk response is a signal from molecules in solution that do not bind to the surface, complicating data interpretation [16]. The standard method is reference subtraction, using a channel with a non-binding surface to measure and subtract the bulk effect [17] [16]. For the most accurate correction, advanced physical models that use the total internal reflection (TIR) angle response from the same sensor surface have been developed, eliminating the need for a perfectly matched reference surface [16].

TROUBLESHOOTING GUIDES

Guide 1: Resolving Baseline Drift

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable/Drifting Baseline | Buffer not degassed; Air bubbles in fluidics [2] | Degas buffer thoroughly before use. |

| Sensor surface not equilibrated [3] | Extend stabilization time; perform multiple buffer injections; run buffer overnight if needed [3]. | |

| Temperature fluctuations or vibrations [2] | Place instrument in stable environment; ensure proper grounding. | |

| Contaminated buffer or sensor chip [2] | Use fresh, filtered buffer; clean or regenerate sensor surface. |

Guide 2: Addressing Signal and Surface Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No or Weak Binding Signal | Low ligand immobilization level [2] | Optimize immobilization chemistry to achieve higher density. |

| Low analyte concentration [2] | Increase analyte concentration if feasible. | |

| Non-specific binding (NSB) masking signal | Block surface with agent like BSA; optimize running buffer; use site-directed immobilization [2]. | |

| Inconsistent Replicate Data | Inconsistent immobilization [2] | Standardize the immobilization procedure. |

| Sample precipitation or instability [2] | Check sample stability; use consistent handling techniques. | |

| Carryover from incomplete regeneration [2] | Optimize regeneration conditions (pH, buffer); increase flow rate or time [2]. |

RESEARCH REAGENT SOLUTIONS

The following table details key materials used in critical SPR experiments, such as the competitive chaser assay.

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | Example & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Competitive Chaser Molecule | A high-affinity binder used to displace the test molecule during the dissociation phase, enabling measurement of very slow off-rates [15]. | A small molecule or antibody that binds the same site on the target protein; used in the SPR chaser assay [15]. |

| Sensor Chip with Immobilized Target | The solid support on which the target protein (receptor) is fixed, forming the foundation for the binding interaction. | Recombinant human protein (e.g., from Sino Biologicals Inc.) immobilized via amine or capture coupling on a CM5 chip [15]. |

| High-Quality Running Buffer | The solution that maintains pH and ionic strength, ensuring stable baseline and proper biomolecular function. | Filtered and degassed PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline) at physiological pH [15] [16]. |

| Regeneration Buffer | A solution that removes bound analyte from the ligand without damaging the sensor surface, allowing for chip re-use. | Solutions with low pH (e.g., Glycine-HCl) or high salt; conditions must be optimized for each interaction [2]. |

EXPERIMENTAL PROTOCOLS

Protocol 1: Competitive SPR Chaser Assay for Slow-Dissociating Complexes

Principle: This protocol uses a competitive probe (chaser) to track the dissociation of a tight-binding test molecule over time, bypassing the limitations imposed by baseline drift [15].

Methodology:

- Surface Preparation: Immobilize the target protein on an SPR sensor chip using standard coupling chemistry [15].

- Saturation: Inject the test molecule (e.g., a small molecule inhibitor) at a saturating concentration over the target surface to form a stable complex [15].

- Initiate Dissociation & Chaser Injection: Switch to running buffer to begin the dissociation phase. At specified time intervals (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120 minutes), inject a fixed concentration of the competitive chaser molecule [15].

- Data Collection: The repeated chaser injections generate a binding response. A high response indicates many vacant target sites, meaning significant test molecule dissociation has occurred. A low response indicates the test molecule is still bound [15].

- Data Analysis:

- The percentage of test molecule remaining bound over time is calculated based on the chaser's binding signal [15].

- Plot the decay curve and fit the data to a decay function (e.g., Y=Y₀exp(-kdX) in GraphPad Prism) to determine the dissociation rate constant (kd*) [15].

- Using this fixed kd, the association rate constant (ka) can be determined by fitting the association phase data [15].

- The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) is calculated as kd/ka [15].

This experimental workflow is outlined in the following diagram:

Protocol 2: Double Referencing for Bulk Response and Drift Correction

Principle: This standard data processing technique subtracts signals from a reference surface and blank injections to correct for bulk refractive index shifts and systematic drift [17].

Methodology:

- Reference Surface Subtraction: Inject your analyte over both the active surface (with ligand) and a reference surface (without ligand or with a non-binding protein). Subtract the reference sensorgram from the active sensorgram to remove the bulk response and some non-specific binding [17].

- Blank Subtraction: Also referred to as "double referencing," this involves subtracting the signal from a blank injection (zero analyte concentration) from all other sample sensorgrams. This step compensates for drift and minor differences between flow channels [17].

The data processing workflow is as follows:

Corrective Strategies: A Toolkit for Drift Mitigation in SPR Assays

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

1. How can I minimize baseline drift in my SPR experiment? Baseline drift is often a sign of a sensor surface that is not optimally equilibrated [3]. To minimize drift:

- Thoroughly equilibrate the system: It can be necessary to run the flow buffer overnight or perform several buffer injections before the actual experiment [3].

- Ensure buffer compatibility: Match the flow buffer and analyte buffer compositions exactly to avoid bulk shifts [3]. Even small differences in refractive index can cause shifts that complicate data interpretation [6].

- Check instrument calibration: Drift can also result from instrument calibration issues, so ensure the system is properly calibrated before starting experiments [8].

2. What are the best strategies to reduce non-specific binding (NSB)? Non-specific binding occurs when the analyte interacts with non-target sites on the sensor surface, inflating the response and skewing calculations [6]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Adjust buffer pH: A positively charged analyte can interact with a negatively charged sensor surface. Adjusting the pH to the isoelectric point of your protein can neutralize these interactions [6].

- Use blocking additives: Incorporate bovine serum albumin (BSA) at around 1% or non-ionic surfactants like Tween 20 into your buffer to shield molecules from non-specific hydrophobic or charge-based interactions [6] [9].

- Increase salt concentration: Adding salts like NaCl can shield charged proteins and reduce charge-based NSB [6].

- Switch sensor chemistry: Select a sensor chip with a surface chemistry that reduces opposite charges between the chip and your analyte [6].

3. My ligand surface is difficult to regenerate. What can I do? Regeneration strips bound analytes from the ligand between analyte injections. An optimal regeneration buffer is harsh enough to remove the analyte but mild enough to not damage ligand functionality [6].

- Employ a scouting approach: Start with the mildest conditions and progressively increase the intensity. Use short contact times (high flow rates of 100-150 µL/min) to minimize potential ligand damage [6].

- Consider Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK): For surfaces that are difficult or impossible to regenerate, the SCK method is advantageous. It uses sequential injections of increasing analyte concentrations without regeneration between them, thus preserving the ligand surface [18].

- Try common regeneration solutions: The table below lists typical regeneration buffers based on the type of analyte-ligand bond [6].

4. How do I identify and address mass transport limitations? Mass transport limitations occur when the diffusion of the analyte to the sensor surface is slower than its association rate, skewing the kinetic data [6]. To identify this:

- Examine the binding curve: A linear association phase with a lack of curvature can signal mass transport limitations [6].

- Conduct a flow rate experiment: Run your assay at different flow rates. If the observed association rate (ka) decreases at lower flow rates, the interaction is likely mass transport limited [6].

- Solutions: To address this, increase the flow rate, decrease the ligand density on the sensor chip, or use a sensor chip with a thinner matrix to improve analyte diffusion [6].

5. How do I choose which binding partner to immobilize as the ligand? The decision on which molecule to immobilize is crucial for a successful experiment. Key factors to consider are [6]:

- Size: The smaller binding partner is often better suited as the analyte, with the larger one immobilized, to maximize the response signal.

- Purity: For covalent coupling methods, use the purest binding partner as the ligand to ensure only the molecule of interest is attached to the surface.

- Number of binding sites: Multivalent analytes should generally not be immobilized, as they can bind to multiple ligands and provide an artificially low affinity measurement.

- Tags: If one binding partner has a tag (e.g., His, biotin), it is often easier to use it as the ligand with a compatible sensor chip (e.g., NTA, Streptavidin) to ensure proper orientation.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Optimizing Analyte Concentration Series

For reliable kinetic analysis, a well-prepared dilution series of your analyte is essential [6]. The table below summarizes key considerations.

Table 1: Guidelines for Analyte Concentration Series in SPR

| Aspect | Kinetics Analysis | Affinity (Steady-State) Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Concentrations | Minimum of 3, ideally 5 [6] | 8 to 10 concentrations [6] |

| Concentration Range | 0.1 to 10 times the expected KD value [6] | Sufficient to reach saturation [6] |

| If KD is Unknown | Start at low nM and increase until binding is observed [6] | Start at low nM and increase until saturation is reached [6] |

| Dilution Method | Serial dilution to avoid pipetting errors [6] | Serial dilution to avoid pipetting errors [6] |

Selecting a Sensor Chip and Immobilization Strategy

The choice of sensor chip and immobilization method must align with the properties of your ligand to ensure activity and minimize non-specific binding [8].

Table 2: Common SPR Sensor Chips and Their Applications

| Sensor Chip Type | Immobilization Chemistry | Ideal Ligand Type | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CM5 (Dextran) | Covalent (e.g., amine coupling via NHS/EDC) [7] | Proteins, antibodies [8] | Versatile; can lead to heterogeneous attachment [7]. |

| NTA | Non-covalent capture of His-tagged ligands [7] | His-tagged proteins [6] | Requires oriented capture; can be stabilized by cross-linking [7]. |

| SA (Streptavidin) | Non-covalent capture of biotinylated ligands [7] | Biotinylated DNA, proteins [8] | High-affinity, oriented capture [7]. |

| L1 (Lipid) | Hydrophobic interaction for liposomes [6] | Lipids, membrane proteins in liposomes [6] | Preserves lipid environment for membrane-associated molecules [6]. |

Advanced Protocol: Innovative Immobilization for Membrane Proteins A pioneering technique for studying membrane proteins uses the SpyCatcher-SpyTag system with membrane scaffold protein (MSP)-based nanodiscs [19].

- Engineer MSP fused to SpyTag: This facilitates the construction of nanodiscs that house the target membrane protein in a near-native lipid environment [19].

- Immobilize SpyCatcher on a CM5 chip: Use standard amine coupling chemistry to covalently attach SpyCatcher to the sensor surface [19].

- Capture SpyTag-labeled nanodiscs: The SpyCatcher on the surface covalently and specifically captures the SpyTag on the nanodiscs, permanently attaching the membrane protein in a functional orientation [19]. This method overcomes challenges of protein denaturation and instability, enabling high-fidelity kinetic studies of membrane protein interactions with lipids, antibodies, and small molecules [19].

Comparison of Kinetic Measurement Methods

The two primary methods for collecting kinetic data are Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) and Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK). The choice depends on your specific experimental needs and the stability of your ligand surface [18].

Table 3: Multi-Cycle Kinetics vs. Single-Cycle Kinetics

| Feature | Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) | Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK) |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow | Each analyte concentration is injected in a separate cycle followed by a regeneration step [18]. | Sequential injections of increasing analyte concentrations without regeneration between them; a single dissociation phase follows the highest concentration [18]. |

| Advantages | - Easier diagnosis of fitting problems with multiple curves [18].- Allows for buffer blank subtraction for baseline drift correction [18]. | - Faster assay time [18].- Ideal for ligand surfaces that are difficult to regenerate [18].- Reduces potential ligand damage from regeneration [18]. |

| Disadvantages | - Requires a robust regeneration condition [18].- More time-consuming [18]. | - Reduced informational content from a single dissociation phase [18].- More difficult to troubleshoot complex binding kinetics [18]. |

Visualization of SPR Experimental Workflow and Drift Correction

The following diagram illustrates a generalized SPR experimental workflow, highlighting key steps and decision points for optimizing immobilization, buffer conditions, and flow rates to mitigate drift and other artifacts.

Diagram 1: SPR experimental workflow highlighting key optimization and troubleshooting points for drift correction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents and materials used in SPR experiments to achieve high-quality, reproducible data.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for SPR Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A versatile dextran-coated chip for covalent immobilization of proteins via amine coupling [7]. | Can lead to heterogeneous ligand orientation; suitable for a wide range of ligands [7]. |

| NTA Sensor Chip | For capturing His-tagged ligands via nickel chelation, providing a uniform orientation [6] [7]. | Requires a his-tagged ligand; surface can be stabilized by cross-linking after capture [7]. |

| Running Buffer (e.g., HEPES, PBS) | Provides the liquid medium for the interaction and maintains pH and ionic strength [7]. | Must be matched exactly between running buffer and sample buffer to avoid bulk shift [6]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A blocking agent used to reduce non-specific binding by occupying reactive sites on the sensor surface [6] [9]. | Typically used at 1% concentration; add to buffer during analyte runs only [6]. |

| Tween 20 | A non-ionic surfactant used to disrupt hydrophobic interactions that cause non-specific binding [6]. | Use at low concentrations (e.g., 0.05%) to avoid interfering with the specific interaction [6]. |

| Regeneration Solutions | Used to remove tightly bound analyte from the ligand surface without damaging its activity [6]. | Common solutions: 10 mM Glycine (pH 2-3), 10 mM NaOH, 2 M NaCl. Must be empirically determined [6] [9]. |

| MSP-Nanodiscs | Membrane scaffold proteins that form lipid bilayers to solubilize membrane proteins in a native-like environment [19]. | Crucial for studying membrane protein interactions while preserving their structural integrity [19]. |

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) research, baseline drift is a frequent technical challenge that can compromise the accuracy of kinetic data. Drift is the unintended, gradual change in the baseline signal when no active binding occurs, often resulting from instrument instability or environmental factors. For thesis research focused on robust kinetic analysis, understanding and correcting for drift is paramount. This guide details the software tools and data processing methodologies available within unified analysis platforms to automatically identify and correct for baseline drift, ensuring the integrity of your kinetic parameters.

Implementing Drift Correction: Core Methodologies

Software-Enabled Corrective Procedures

Modern SPR analysis software incorporates specific models and procedures to manage drift.

- Langmuir with Drift Model: This is a primary tool within many analysis suites (e.g., Bio-Rad's ProteOn Manager). It fits sensorgram data to a standard 1:1 interaction model while simultaneously calculating a linear drift component that is constant with time. This model is particularly useful for experiments employing capture surfaces where the captured ligand may slowly dissociate, causing baseline drift before, during, and after analyte injection [20].

- Double Referencing: This is a fundamental data processing technique used to compensate for drift and other artifacts. It involves two sequential subtractions [1]:

- A reference surface subtraction to account for bulk refractive index shift and systemic drift.

- A blank injection (buffer alone) subtraction to correct for any differences between the reference and active channels and to account for injection-specific artifacts. For optimal results, blank cycles should be spaced evenly throughout the experiment [1].

Pre-Experimental System Equilibration

Software correction is most effective on a stable system. A key preventive methodology is thorough system equilibration [1] [2].

- Protocol: After docking a new sensor chip or changing the running buffer, prime the fluidic system and flow the running buffer over the sensor surface at the experimental flow rate.

- Duration: Monitor the baseline until it stabilizes; this can take 5–30 minutes or, in some cases, overnight following immobilization to fully rehydrate the surface and wash out chemicals [1].

- Start-up Cycles: Incorporate at least three start-up cycles into your method that inject buffer instead of analyte. These cycles "prime" the surface and stabilize the system without contributing to experimental data [1].

The following workflow outlines the integrated process of experimental preparation and data processing for effective drift management:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful SPR experiment relies on high-quality reagents to minimize artifacts like drift. The table below lists key materials and their functions.

| Item | Function in Experiment | Importance for Drift Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh Running Buffer | The liquid phase that carries the analyte over the ligand surface. | Prevents contamination-related drift; must be 0.22 µM filtered and degassed daily to avoid air spikes [1]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A common blocking agent. | Reduces non-specific binding to the sensor surface, a potential source of signal drift [2]. |

| Regeneration Solution (e.g., low/high pH buffer) | Removes bound analyte from the ligand to regenerate the surface. | Proper regeneration prevents carryover, but harsh conditions can damage the ligand and cause future drift [2]. |

| EDC/NHS | Cross-linking reagents for covalent ligand immobilization. | A stable, well-executed immobilization creates a more robust surface with less baseline drift [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Baseline Issues

- Problem: Significant baseline drift is observed during the dissociation phase or between cycles.

- Problem: The baseline is noisy or shows large fluctuations.

- Solution: Confirm the buffer is freshly prepared, filtered, and degassed. Place the instrument in a stable environment free from temperature fluctuations and vibrations. Check for contamination on the sensor surface [2].

Signal & Analysis Issues

- Problem: Sensorgram fitting is poor, and the software reports high chi-squared (χ²) values.

- Solution: This can indicate that the chosen model (e.g., simple 1:1) does not fit the data, possibly due to unaccounted-for drift or other artifacts. Try switching to a "Langmuir with Drift" model or review the quality of your reference and blank subtractions [20].

- Problem: Data from replicate experiments are inconsistent.

- Solution: Standardize your immobilization and sample handling procedures. Verify the instrument is properly calibrated and that the sensor surface is consistently regenerated without damage [2].

Experimental Design FAQs

- Which kinetic method is better for managing drift: Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) or Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK)?

- Answer: MCK allows for a buffer blank injection to be subtracted from each analyte curve, which effectively corrects for baseline drift in that cycle. SCK has fewer regeneration steps, which is beneficial for delicate surfaces, but it relies on a single dissociation phase, making drift correction more dependent on robust referencing and software models [18].

- How can I tell if my drift correction is working?

- Answer: A successfully corrected sensorgram will show a flat baseline before injection and a stable signal returning to baseline (or a new steady state for a capture system) during the dissociation phase. The residual plots (difference between fitted curve and raw data) should be randomly distributed around zero [20].

Various software platforms offer functionalities for data processing and drift correction. The table below compares several key tools.

| Software Platform | Primary Use | Key Features Related to Drift & Data Processing |

|---|---|---|

| ProteOn Manager (Bio-Rad) | Data acquisition & analysis | Includes a dedicated "Langmuir with Drift" kinetic model for fitting data with a linear drift component [20]. |

| TraceDrawer (Ridgeview) | Post-processing & analysis | Offers extensive tools for data processing, including reference subtraction and curve comparison, facilitating double referencing [21] [22]. |

| Anabel | Open source analysis | A browser-based tool for analyzing binding datasets; provides guidance on selecting optimal parts of the sensorgram for analysis, which can exclude unstable drift regions [21]. |

| SCRUBBER (Biologic Software) | Data "cleaning" | Specializes in aligning and preparing sensorgram data, including zeroing, reference subtraction, and blank subtraction in a structured, recordable manner [21]. |

Reflection-Based Positional Detection and Auto-Focus Scanning SPRM

Troubleshooting Guides

Auto-Focus System Calibration Failure

Problem Description The Auto Focus calibration procedure fails to measure the focal length correctly, often indicated by an error message on the instrument touchscreen [23].

Possible Causes and Solutions

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Height Incorrect | Check if engraved lines appear discontinuous during calibration [23]. | Manually adjust laser height to 21.0 mm or lower (e.g., 19.0 mm) via Settings > Laser > Adjust Laser Height [23]. |

| Outdated Firmware | Verify firmware version on instrument console. | Download the latest firmware and update via USB drive [23]. |

| Hardware Malfunction | Check for persistent failure after troubleshooting software and laser height. | Contact technical support and submit a ticket with troubleshooting results and media [23]. |

Step-by-Step Recovery Protocol

- If calibration fails, tap

Failedon the touchscreen. - Swipe the scale to your right and select the

-5.0 mmline, then tapSave. - Return to the application list and tap

Calibrationto retry Auto Focus. - If the problem persists, repeat the steps or proceed to manual laser height adjustment [23].

Signal Drift in Kinetic Analysis

Problem Description A steady, gradual change in the baseline response (signal drift) is observed, which can corrupt kinetic measurements and affinity calculations [18].

Possible Causes and Solutions

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Surface Regeneration | Observe if the baseline does not return to its original level after regeneration [18]. | Optimize regeneration conditions (e.g., harsher pH, different ionic strength) between analyte injections [18]. |

| Ligand Inactivation | Monitor for a consistent drop in binding capacity over multiple cycles. | Switch to a Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK) method to eliminate repeated regeneration steps [18]. |

| Buffer or Temperature Instability | Check for fluctuations in system temperature or buffer composition. | Ensure thorough buffer degassing, use temperature control, and flush the system to prevent salt or cation buildup [24]. |

Workflow for Diagnosing Signal Drift

Poor Reproducibility Between Sensor Chips

Problem Description Experimental results, particularly binding kinetics, show high variability when different sensor chips from the same or different production batches are used.

Possible Causes and Solutions

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Chip Surface Variability | Check specifications for gold film thickness and roughness. | Source chips from suppliers with stringent quality control; use chips from the same batch for a related series of experiments [25]. |

| Inconsistent Immobilization | Compare immobilization levels and binding responses across chips. | Standardize surface functionalization and ligand immobilization protocols rigorously [25]. |

| Improper Calibration | Run a reference analyte with known kinetic parameters. | Implement thorough calibration and use reference samples or internal standards to normalize results across chips [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of using a reflection-based positional detection system in SPR? The core advantage is its exceptional sensitivity to minute changes in the refractive index (RI) at the sensor surface—often down to picomolar (pM) concentrations [25]. This is because the SPR angle (θSPR) is exquisitely dependent on the RI of the medium in the ~200 nm vicinity of the metal film [26]. Any molecular binding event that changes the local mass concentration, such as an analyte binding to an immobilized ligand, will alter the RI and cause a measurable shift in θSPR, enabling real-time, label-free detection [27] [26].

Q2: How does the Auto-Focus mechanism in Scanning SPR Microscopy (SPRM) enhance data quality for kinetic analysis? A stable, precisely focused laser spot is critical for obtaining high-fidelity kinetic data. The Auto-Focus mechanism maintains this optimal focus by automatically compensating for mechanical drift or thermal expansion in the system that could otherwise alter the incident angle of the light beam [23]. This directly minimizes one source of instrumental drift in the baseline signal, ensuring that observed shifts in the SPR angle are truly due to biomolecular interactions and not optical artifacts, leading to more reliable kinetic parameters [18].

Q3: Our lab observes significant signal drift when studying interactions requiring calcium-containing buffers. What is the likely cause and how can we mitigate it? This is a common issue. Calcium ions tend to precipitate over time, especially in alkaline conditions, leading to a buildup of material in the fluidic system and on the sensor chip, which increases the baseline [24]. The solution is proactive system maintenance: flush the instrument with a calcium-free buffer or a mild EDTA-containing solution between runs to chelate and remove residual Ca²⁺. Adhere strictly to the manufacturer's recommended cleaning procedures (e.g., "desorb" and "sanitize" programs) to prevent long-term damage [24].

Q4: When should I choose the Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK) method over the traditional Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) to combat drift and other issues? SCK is particularly advantageous when your immobilized ligand is sensitive to the surface regeneration steps required in MCK [18]. Since SCK sequentially injects increasing analyte concentrations in a single, continuous cycle with only one final dissociation phase, it drastically reduces the number of regeneration steps. This minimizes ligand inactivation and the associated signal decay (drift) over time, preserving the binding capacity of your surface [18].

Q5: What are the limitations of the SCK method? The primary trade-off for the robustness of SCK is a reduction in informational content. Having only a single dissociation phase for all analyte concentrations makes it more difficult to diagnose complex binding kinetics (e.g, heterogeneous binding) compared to MCK, which provides multiple, distinct sensorgrams for easier diagnosis [18]. If SCK data fitting is poor, reverting to an MCK experiment is often necessary for a clearer understanding of the interaction [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Application in SPR | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chip CM5 | A widely used gold sensor chip with a carboxymethylated dextran matrix that facilitates ligand immobilization [24]. | The dextran matrix provides a hydrophilic environment for biomolecules and offers various covalent coupling chemistries [24]. |

| HBS-EP Buffer | A standard running buffer (HEPES-buffered saline with EDTA and Polysorbate 20) used in many SPR experiments [24]. | Provides a consistent, physiologically relevant pH and ionic strength. The surfactant (Polysorbate 20) minimizes non-specific binding. |

| Amine Coupling Kit | Contains the reagents (EDC, NHS, and ethanolamine) required to covalently immobilize ligands containing primary amines onto CM5 chips [24]. | EDC and NHS activate the carboxyl groups on the dextran matrix, enabling ligand coupling. Ethanolamine blocks unused activated groups. |

| Sodium Acetate Buffer | A low-pH immobilization buffer used during ligand coupling to CM5 chips [24]. | The pH must be optimized for each specific protein/peptide to ensure it is positively charged and thus attracted to the negatively charged dextran surface. |

| Regeneration Solution | A solution that dissociates bound analyte from the ligand, resetting the sensor surface for the next injection [18] [24]. | Must be strong enough to remove all analyte but gentle enough to not damage the immobilized ligand. Common examples include low pH (e.g., Glycine-HCl), high salt, or EDTA to chelate metal ions [24]. |

Standard Experimental Protocol for Kinetic Analysis with Drift Correction

Methodology for Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) with Regeneration Scouting

This protocol outlines the steps for determining the kinetic parameters of a biomolecular interaction while accounting for and correcting signal drift.

1. Surface Preparation (Ligand Immobilization)

- Activation: Inject a 1:1 mixture of EDC and NHS from the Amine Coupling Kit over the chosen flow cell for 7 minutes to activate the carboxyl groups on the CM5 chip surface [24].

- Immobilization: Dilute the ligand to 1-10 µg/mL in a suitable low-pH buffer (e.g., 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0-5.0) and inject it over the activated surface until the desired immobilization level (Response Units, RU) is achieved [24].

- Blocking: Inject 1 M ethanolamine-HCl pH 8.5 for 7 minutes to deactivate and block any remaining activated ester groups [24].

- Reference Surface: Use a blank flow cell (activated and blocked, but with no ligand immobilized) or a surface immobilized with an irrelevant protein for double-referencing during data processing.

2. Regeneration Scouting

- Inject a single, mid-range concentration of analyte in running buffer and allow the complex to fully associate and partially dissociate.

- Test short (15-30 second) pulses of various regeneration solutions (e.g., 10 mM Glycine-HCl pH 2.0-3.0, 1-3 M NaCl, 1-10 mM NaOH, 1-10 mM EDTA).

- Identify the solution that returns the signal to the pre-injection baseline with minimal change to the ligand's activity over 5-10 regeneration cycles. This is your optimal regeneration condition [18].

3. Multi-Cycle Kinetics Experiment

- Design: Prepare a series of analyte concentrations in a running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP), typically using a 2- or 3-fold serial dilution spanning a range above and below the expected equilibrium dissociation constant (KD).

- Injection Cycle: For each analyte concentration, run the following cycle in sequence:

- Baseline: Stabilize with running buffer for 60-180 seconds.

- Association: Inject analyte for 120-300 seconds.

- Dissociation: Replace with running buffer for 300-600 seconds (or longer for slow off-rates).

- Regeneration: Inject the pre-optimized regeneration solution for 15-60 seconds [18].

- Include a blank (0 M analyte) injection to correct for bulk refractive index shifts and instrument drift [18].

Data Processing Workflow for Drift Correction

4. Data Analysis

- Process the data by sequentially subtracting the signal from the reference flow cell and the blank buffer injection.

- Fit the processed, drift-corrected sensorgrams globally to a suitable binding model (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir) using the instrument's evaluation software to extract the association (ka) and dissociation (kd) rate constants, and calculate the affinity (KD = kd/ka) [18].

Understanding Regeneration-Induced Drift and the SCK Advantage

What is regeneration-induced drift? In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) analysis, baseline drift is a persistent signal change in the absence of analyte, often indicating a non-optimally equilibrated sensor surface [1]. Regeneration-induced drift specifically occurs when the chemical solutions used to remove bound analyte from the immobilized ligand between binding cycles in Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) cause gradual, irreversible changes to the ligand or sensor matrix. These changes can manifest as conformational alterations in the immobilized ligand or matrix effects from variations in pH or ionic strength, leading to a drifting baseline that complicates kinetic analysis [28].

How does SCK minimize this issue? Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK) substantially reduces regeneration-induced drift by drastically cutting the number of regeneration steps required. Unlike MCK, which requires a regeneration step after each analyte concentration injection, SCK performs sequential injections of increasing analyte concentrations with only a single regeneration step at the end of the complete cycle [18]. This approach minimizes repeated exposure of the sensor surface to potentially harsh regeneration conditions, thereby preserving ligand functionality and surface integrity while yielding kinetic constants consistent with traditional MCK methods [18] [29].

MCK vs. SCK: A Direct Comparison

Table: Key Characteristics of Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) vs. Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK)

| Feature | Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) | Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK) |

|---|---|---|

| Regeneration Frequency | After each analyte concentration injection [18] | Only once, after the highest concentration injection [18] |

| Assay Run Time | Longer due to multiple regeneration and re-equilibration steps [18] | Shorter by eliminating regeneration between concentrations [18] |

| Risk of Ligand Damage | Higher due to repeated regeneration exposures [18] | Lower due to minimal regeneration steps [18] |

| Data Information Content | Multiple, independent dissociation phases for easier diagnosis [18] | Single dissociation phase; less suitable for complex kinetics [18] |

| Ligand & Surface Longevity | Reduced, especially with harsh regeneration conditions [29] | Extended, as surface is subjected to fewer regeneration cycles [29] |

| Ideal Use Cases | Interactions with simple 1:1 kinetics; abundant, robust ligand [18] | Ligands sensitive to regeneration; limited sample availability [18] |

SCK Experimental Protocol for Drift Reduction

Step 1: Preliminary SCK Assay Design

- Simulate Sensorgrams: Use simulation software (e.g., Biacore's BiaEvaluation software) to predict the best experimental conditions, including the maximum analyte concentration needed for saturation, appropriate dilution factors for serial dilutions, and optimal durations for association and dissociation phases [29].

- Plan Concentrations: Prepare five analyte concentrations, typically using a 2- or 3-fold serial dilution series [18].

Step 2: System Equilibration to Minimize Initial Drift

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare fresh running buffer daily. Filter (0.22 µm) and degas the buffer thoroughly to eliminate air bubbles that cause spikes and drift [1] [2].

- System Priming: Prime the fluidic system extensively with running buffer until a stable baseline is achieved. Incorporate at least three start-up cycles (dummy injections of running buffer, including regeneration if used) to stabilize the system before actual analyte injections. Do not use these start-up cycles as blanks in analysis [1].

Step 3: Executing the Single-Cycle Run

- Sequential Injections: Inject the analyte concentrations sequentially from lowest to highest, without any regeneration steps between injections [18].

- Dissociation Phase: After the final (highest) concentration injection, allow for a single, extended dissociation phase [18].

- Final Regeneration: Perform one regeneration step at the very end of the cycle to prepare the surface for the next experiment [18].

Step 4: Data Processing with Double Referencing

- Reference Subtraction: Subtract the signal from a reference flow cell from the active cell signal to correct for bulk refractive index effects and some baseline drift [1].

- Blank Subtraction: Incorporate blank injections (buffer alone) evenly throughout the experiment. Subtract the average blank response from the analyte sensorgrams to compensate for differences between reference and active channels (double referencing) [1].

Troubleshooting Common SCK Challenges

FAQ 1: The baseline remains unstable even in an SCK experiment. What should I check?

- Solution: Verify your buffer is freshly prepared, filtered, and thoroughly degassed [1]. Ensure the system is adequately primed and equilibrated before starting analyte injections. Continuous drift often indicates insufficient system equilibration, which may require flowing running buffer for an extended period (sometimes overnight) to stabilize [1].

FAQ 2: My SCK sensorgram shows an abnormal signal drop during analyte injection. What does this mean?

- Solution: This typically indicates sample dispersion, where the sample mixes with the flow buffer, resulting in a lower effective analyte concentration [3]. Check that your instrument's fluidics are properly washing and separating the sample from the running buffer. Verify that your sample solution is compatible with the running buffer to prevent precipitation.

FAQ 3: The single dissociation phase in my SCK data is difficult to fit. What are my options?

- Solution: The SCK method provides less informational content from its single dissociation phase compared to MCK, which can be problematic for complex binding kinetics [18]. If poor fits persist, consider switching to an MCK experiment. The multiple, independent curves generated by MCK facilitate easier diagnosis of fitting issues and underlying binding phenomena [18].

FAQ 4: Non-specific binding is high in my SCK run. How can I reduce it?

- Solution: Block the sensor surface with a suitable agent (e.g., BSA) before ligand immobilization [2]. Optimize your running buffer conditions (e.g., pH, ionic strength, add a detergent) to reduce non-specific interactions [2]. Ensure your final regeneration step is efficient at completely removing all bound analyte.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Robust SCK Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in SCK Experiment | Considerations for Drift Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh Running Buffer | Liquid medium for analyte transport and surface stability. | Must be freshly prepared, filtered (0.22 µm), and degassed daily to prevent bubbles and contamination that cause drift [1] [2]. |

| Regeneration Cocktail | Solution to remove bound analyte after the SCK cycle. | Use the mildest effective solution (e.g., low pH glycine) [28]. Empirical testing using a "cocktail approach" targeting multiple binding forces gently is often needed [28]. |

| Blocking Agent (e.g., BSA, Ethanolamine) | Blocks unused active groups on the sensor surface to reduce non-specific binding. | Proper blocking after ligand immobilization is crucial to minimize background signal and drift associated with non-specific interactions [2]. |

| High-Purity Ligand & Analyte | The interacting molecules under study. | Ensure samples are soluble, stable, and free of aggregates in the running buffer. Precipitation can cause massive signal instability and clog fluidics [2]. |

| Sensor Chip (e.g., CM5) | The platform for ligand immobilization. | Handle and store chips carefully. Monitor surface condition. A degraded chip will never produce a stable baseline [2]. |

The SPR Troubleshooter's Guide to a Stable Baseline

Within the context of a broader thesis on correcting for drift in SPR kinetic analysis research, proactive system maintenance is not merely a preliminary task but a fundamental prerequisite for obtaining reliable kinetic data. Baseline drift, a gradual shift in the sensor's signal over time, is a common manifestation of a poorly maintained system and directly compromises the accuracy of kinetic parameter estimation [8] [1]. Such drift can stem from multiple sources, including air bubbles in the fluidic path, buffer-sensor surface mismatch, or the presence of contaminants. This guide details the essential degassing, priming, and cleaning protocols designed to preempt these issues, ensuring system stability and the collection of high-fidelity, publication-quality data.

Fundamental Maintenance Protocols

Buffer Preparation and Degassing

The foundation of a stable SPR experiment is a properly prepared running buffer.

- Preparation: Ideally, fresh buffers should be prepared daily. After preparation, the buffer should be 0.22 µM filtered to remove particulate contaminants [1].

- Degassing: Filtered buffer must be degassed before use. Buffers stored at 4°C contain more dissolved air, which can form small air bubbles ("air-spikes") in the sensorgram when warmed, causing sudden spikes and baseline perturbations [1]. Degassing is typically performed using an in-line degasser on the instrument or by stirring the buffer under vacuum for a sufficient period.

- Hygiene: It is considered bad practice to add fresh buffer to old buffer remaining in the system, as microbial growth or chemical changes in the old buffer can introduce instability [1]. Always use a fresh, clean bottle for the aliquot of buffer you place on the instrument.

System Priming

Priming is the process of flushing the new, degassed running buffer through the entire fluidic system (tubing, injection needle, integrated fluidic cartridges - IFCs, and sensor surface) to establish equilibrium.

- Purpose: Priming removes any air bubbles, eliminates residue from previous buffers or samples, and ensures the sensor surface and fluidic path are fully equilibrated with the current running buffer. A failure to prime properly will result in a wavy baseline due to the mixing of the old and new buffers within the pump [1].

- Procedure: After a buffer change or at the start of a new experiment, execute the instrument's prime command multiple times (typically 2-3 cycles) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Following priming, allow the system to stabilize by flowing running buffer at the experimental flow rate until a stable baseline is achieved, which can sometimes take 30 minutes or more [1].

System and Sensor Chip Cleaning

Regular cleaning prevents the accumulation of contaminants that can cause drift, high noise levels, and non-specific binding.

- Routine Cleaning: The instrument's wash procedures with recommended cleaning solutions (e.g., dilute sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), glycine-based solutions) should be performed regularly, especially after analyzing complex samples like cell lysates or serum.

- Sensor Chip Care: A new or freshly docked sensor chip often requires extensive equilibration. "It can be necessary to run the running buffer overnight to equilibrate the surfaces," as the surface rehydrates and washes out storage chemicals [1]. Similarly, surfaces after ligand immobilization need thorough washing to remove excess reagents.

The following workflow illustrates the logical relationship between these core maintenance procedures and their direct impact on stabilizing the SPR baseline and ensuring data quality.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Common Maintenance Issues

Q1: My baseline is continuously drifting upwards/downwards after I start my experiment. What is the most likely cause and how can I fix it?

- A: The most common cause of baseline drift is a non-optimally equilibrated sensor surface [1]. This frequently occurs after docking a new chip or following an immobilization procedure.

- Solution: Ensure the system has been thoroughly primed. Flow running buffer over the sensor surface for an extended period until the baseline stabilizes. In methods, incorporate several "start-up cycles" that mimic your experimental cycle but inject buffer instead of analyte. These cycles prime the surface and are discarded from the final analysis [1].

Q2: I see sudden, large spikes in my sensorgram at the beginning or end of injections. What does this indicate?

- A: Sudden spikes often signal a bulk refractive index (RI) shift [6]. This happens when the composition of your analyte buffer (e.g., salt concentration, DMSO percentage) does not perfectly match the running buffer.

Q3: I have followed the priming procedure, but the noise level of my baseline is still unacceptably high. What should I check?

- A: High noise can be caused by air bubbles in the fluidic path or a contaminated system/sensor chip [1].

- Solution:

- Re-degas your buffer and perform additional prime cycles.

- Check for contaminants: Run a more stringent system cleaning procedure as recommended by the instrument manufacturer.

- Inspect the sensor chip: The sensor chip or IFC may need replacement if the high noise persists across multiple chips [1].

- Solution:

Q4: How can I systematically test if my fluidics are clean and functioning properly?

- A: You can perform a diagnostic run by injecting an elevated salt solution (e.g., 0.5 M NaCl) and a flow buffer solution [3].

- Expected Result: The NaCl injection should produce a sharp rise and fall with a flat steady-state region. The buffer injection should give an almost flat line. Deviations from this (e.g., slow rise/fall, drifting steady state) indicate issues with carryover, sample dispersion, or a dirty fluidic path [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key reagents and materials essential for the proactive care of an SPR system.

| Reagent/Material | Function & Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Buffers | To provide a stable chemical environment for interactions and system operation. | Use high-purity reagents. Prepare fresh daily and 0.22 µM filter to remove particles [1]. |

| Non-ionic Detergent (e.g., Tween-20) | Added to running buffers to reduce non-specific binding (NSB) by disrupting hydrophobic interactions [8] [6]. | Use at low concentrations (e.g., 0.005-0.01%) to avoid foam formation. Add after filtering and degassing the buffer [1]. |

| System Cleaning Solution | To remove contaminants, lipids, and denatured proteins from the fluidic system. | Common solutions include 0.5% SDS, 50-100 mM glycine (low pH), or 10-50 mM NaOH. Follow manufacturer guidelines [6]. |

| Regeneration Solutions | To remove strongly bound analyte from the ligand between analysis cycles without damaging the ligand [6]. | Scope from mild (e.g., mild acid/base) to harsh (e.g., 10 mM HCl, 3-5 M MgCl₂). Start mild and increase strength as needed [6]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Ethanolamine) | To occupy any remaining active sites on the sensor chip surface after immobilization, minimizing non-specific binding [8]. | Ethanolamine is used after covalent coupling with EDC/NHS. BSA (e.g., 1%) can be used in running buffers for analyte injections [8] [6]. |

This guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice to overcome a common challenge in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments: optimizing the regeneration step to fully remove bound analyte while preserving the activity and integrity of your immobilized ligand.

► FAQ: The Regeneration Balancing Act

Q: What is regeneration in SPR, and why is it critical for kinetic analysis?

Regeneration is the process of removing bound analyte from the immobilized ligand on the sensor chip between binding cycles. In the context of kinetic analysis, complete regeneration is essential because any residual analyte (carryover) leads to inaccurate baseline measurements. This baseline drift directly compromises the calculation of reliable kinetic constants (ka and kd) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) [2] [6].

Q: How can I tell if my regeneration is incomplete?

Incomplete regeneration is often visible in the sensorgram. Key indicators include:

- A progressively rising baseline over multiple analyte injections [2].

- A loss of binding response in subsequent cycles because binding sites remain occupied [6].

- A failure of the sensorgram to return to the pre-injection baseline level before the next sample is injected [2].

Q: What is the first step if my regeneration is too harsh?

If you suspect ligand damage from a harsh regeneration buffer, the solution is to systematically scout for milder conditions. Start with buffers of low pH or ionic strength and gradually increase the intensity. Using a short contact time and a high flow rate (e.g., 100-150 µL/min) can also help minimize exposure to the regeneration solution and protect ligand activity [6].

► Troubleshooting Guide: Common Regeneration Problems and Solutions

The table below summarizes frequent regeneration issues, their causes, and actionable solutions.

| Problem Observed | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Regeneration (Carryover, rising baseline) [2] | Regeneration buffer is too mild; insufficient to disrupt analyte-ligand bonds. | Optimize conditions: Increase pH, ionic strength, or use a different buffer chemistry. Extend contact time slightly [6]. |

| Ligand Damage/Inactivation (Loss of binding capacity over cycles) [6] | Regeneration buffer is too harsh, denaturing the immobilized ligand. | Scount for milder conditions: Start with low pH/low salt and gradually increase. Use shorter contact times and higher flow rates [6]. |

| Baseline Drift [2] [3] | Sensor surface is not fully equilibrated, or regeneration leaves residual material. | Extend buffer equilibration before the experiment. Ensure regeneration is complete. Match flow and analyte buffers to avoid bulk shifts [3]. |

► Experimental Protocol: A Systematic Approach to Regeneration Scouting

Follow this detailed methodology to identify the optimal regeneration condition for your specific interaction.

1. Define Your Test Cycle Immobilize your ligand on the sensor chip. Then, design a cycle that includes:

- Injection of a single, medium concentration of analyte.

- A dissociation phase in running buffer.

- Injection of a candidate regeneration solution for a short duration (e.g., 30-60 seconds).

- A second injection of the same analyte concentration to test the ligand's remaining activity [6].

2. Test Regeneration Buffers Systematically Begin with the mildest condition and progressively move to stronger solutions. The table below lists common reagents based on the type of analyte-ligand bond [6].

| Type of Interaction | Common Regeneration Solutions |

|---|---|

| Acidic Conditions | Glycine-HCl (pH 1.5 - 3.0), HCl, Phosphoric Acid |

| Basic Conditions | Sodium Hydroxide, Glycine-NaOH (pH 8.5 - 10.0) |

| High Salt / Chaotropic | Magnesium Chloride, Guanidine HCl |

| Other | SDS, Ethylene Glycol |

3. Evaluate the Results An optimal regeneration condition will show:

- Complete Return to Baseline: The response returns to the level before analyte injection.

- Stable Baseline: The baseline is stable after regeneration.

- Consistent Binding: The binding response in the second analyte injection is consistent with the first, confirming full ligand activity [6].

4. Condition the Surface Before starting a full kinetic experiment, perform 1-3 injections of your optimized regeneration buffer on the sensor chip to condition the surface and ensure stability [6].

Regeneration Scouting Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for systematically optimizing your regeneration conditions.

► The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key reagents used in SPR regeneration experiments and their primary functions.

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Regeneration |

|---|---|

| Glycine-HCl [6] | A low-pH buffer used to disrupt electrostatic and some hydrophobic interactions. |

| NaOH [6] | A high-pH solution effective for breaking a wide range of interactions, including those involving antibodies. |

| MgCl₂ [6] | A high salt concentration solution used to disrupt ionic and polar interactions. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) [6] | An ionic detergent effective at denaturing proteins and disrupting strong hydrophobic interactions. Use with caution as it can destroy ligand activity. |

| Running Buffer [8] | Used to re-equilibrate the sensor surface to a stable pH and ionic strength after regeneration. |

| Ethanolamine [2] | A blocking agent used after ligand immobilization to deactivate and block unused activated groups on the sensor surface, reducing non-specific binding. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Causes of SPR Drift and Solutions

The following table summarizes the most frequent issues related to buffers and samples that cause drift and disturbances in SPR sensorgrams, along with their recommended solutions.

| Issue | Description | Primary Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|