Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation for Perovskite Quantum Dots: Mechanism, Synthesis, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) method for synthesizing perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a promising class of nanomaterials for biomedical and clinical research.

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation for Perovskite Quantum Dots: Mechanism, Synthesis, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) method for synthesizing perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a promising class of nanomaterials for biomedical and clinical research. It covers the foundational principles of LARP, including the thermodynamic and kinetic mechanisms governing nanocrystal formation. The content details advanced methodological approaches and their applications in creating PQDs for biosensing and drug development. It further addresses critical challenges in stability and reproducibility, presenting ligand engineering and high-throughput optimization strategies. Finally, the article examines validation frameworks and compares LARP with other synthesis techniques, offering researchers a complete guide to harnessing PQDs for next-generation diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

Unraveling LARP: Core Principles and Mechanistic Insights into PQD Nucleation

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) has emerged as a foundational synthetic method for producing perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs) and quantum dots (PQDs). This room-temperature technique distinguishes itself from traditional hot-injection methods by offering a simpler, scalable, and low-temperature approach that eliminates the need for high-temperature precursors and complex setups [1]. The core principle of LARP involves the controlled crystallization of perovskite precursors from a polar solvent into a non-polar anti-solvent, where ligands dynamically adsorb to the growing crystal surfaces to control nanocrystal size, stabilize the structure, and passivate surface defects. The significance of LARP extends across multiple application domains, enabling the synthesis of quantum dots for high-resolution micro-displays [2], biosensors for pathogen detection [3], fluorescent sensors for food safety monitoring [4], and lead-free alternatives for environmentally sustainable optoelectronics [5]. This technical guide delineates the fundamental mechanisms, experimental protocols, and parameter optimizations that define the LARP process within the broader context of PQD research.

Fundamental Mechanisms of LARP

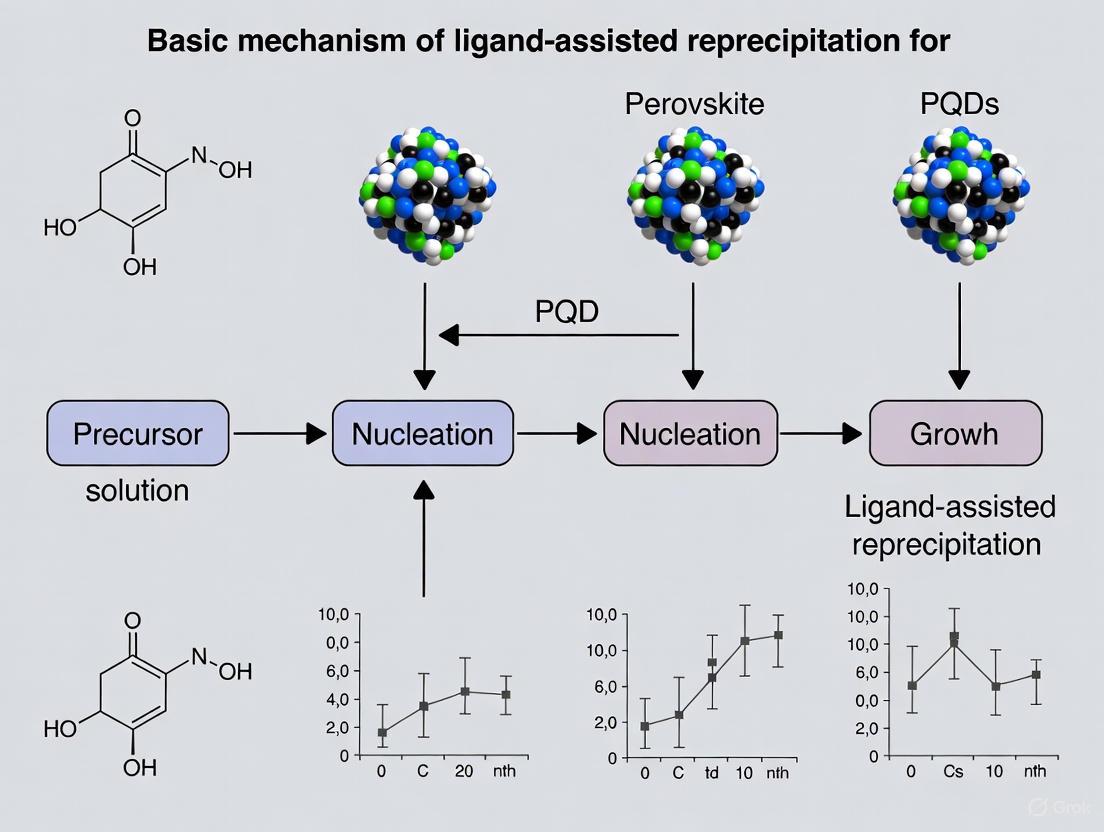

The LARP process operates on the principle of supersaturation-driven crystallization mediated by molecular ligands. The transformation from a homogeneous precursor solution to discrete quantum dots involves a sequence of coordinated physicochemical events, which can be visualized in the following mechanistic diagram:

LARP Mechanistic Pathway to Quantum Dot Formation

This mechanistic pathway illustrates the sequential process from precursor preparation to final quantum dot formation. The initial stage involves dissolving perovskite precursors in a polar solvent such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or acetonitrile (ACN), creating a homogeneous mixture of metal cations (e.g., Pb²⁺, Bi³⁺) and halide anions (e.g., Br⁻, I⁻) coordinated with ligand molecules [1] [5]. Upon injection into a non-polar anti-solvent (typically toluene or chloroform), the solubility of precursors dramatically decreases, creating a state of rapid supersaturation [6]. This instantaneous supersaturation triggers the spontaneous formation of critical nuclei, which quickly evolve into nanoclusters with nascent perovskite crystal structures.

The growth phase represents the most critical regulatory step, where ligand dynamics determine the final nanocrystal characteristics. Long-chain organic ligands, predominantly oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) or octylamine (OctAm), diffuse through the solution and competitively adsorb to the surface of growing nanocrystals [6]. This ligand shell acts as a dynamic barrier that modulates crystal growth by controlling ion addition rates, ultimately determining the final particle size and size distribution. The ligands simultaneously passivate surface defects and coordinatively unsaturated sites, which is essential for achieving high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs) reported up to 62% for Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PNCs [5] and exceeding 90% for optimized CsPbBr₃ PQDs [2]. The diffusion kinetics of these ligands throughout the reaction system has been identified as a crucial factor determining the structural and functional properties of the resulting PNCs [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized LARP Synthesis Workflow

The following diagram outlines the generalized experimental workflow for LARP synthesis, integrating both material preparation and purification stages:

LARP Experimental Workflow

This workflow provides the structural framework for specific LARP protocols. The actual experimental execution varies based on the target perovskite composition, as detailed in the following section.

Detailed Protocol for CsPbBr₃ Nanocrystals

For the model system of all-inorganic CsPbBr₃ PNCs, the LARP protocol involves specific reagent combinations and processing conditions. In a typical synthesis, cesium precursors (Cs⁺ salts) and lead bromide (PbBr₂) are dissolved in a polar solvent such as DMF or DMSO, with precise stoichiometric ratios controlling the final composition [6]. The ligand system typically consists of oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) in varying ratios, which critically influence nucleation and growth kinetics. This precursor solution is then rapidly injected into toluene under vigorous stirring, immediately producing a brightly luminescent colloidal suspension indicating PNC formation. The reaction mixture is often temperature-quenched in an ice-water bath to arrest growth and stabilize the desired size distribution. Subsequent purification involves centrifugation at 6000-9000 rpm for 10-15 minutes to remove aggregates and unreacted precursors, followed by redispersion in non-polar solvents such as hexane or chloroform [6] [2]. High-throughput robotic synthesis platforms have revealed that the delicate adjustment of ligand ratios and antisolvent selection is particularly crucial for controlling the growth behaviors and colloidal stability of LARP-synthesized PNCs [6].

Protocol for FAPbI₃ Colloidal Quantum Dots

The synthesis of formamidinium lead iodide (FAPbI₃) CQDs demonstrates the versatility of LARP for hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites. In a modified LARP approach, PbI₂ (0.1 mmol, 0.045 g) is dissolved in anhydrous acetonitrile (2 mL) with OA (200 μL) and OctAm (20 μL) under continuous stirring [1]. Separately, a formamidinium iodide (FAI) solution is prepared by mixing FAI (0.08 mmol, 0.0137 g) with OA (40 μL), OctAm (6 μL), and ACN (0.5 mL). The FAI solution is added dropwise to the PbI₂ solution, and the resulting mixture is injected into preheated toluene (10 mL, 70°C) under rapid stirring, followed immediately by quenching in an ice/water bath. The crude product is collected via ultracentrifugation at 9000 rpm for 15 minutes, then redispersed in hexane (1 mL) and centrifuged again at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes to remove agglomerated particles, yielding purified FAPbI₃ CQDs with average sizes of approximately 11 nm [1]. This protocol highlights the importance of precursor segregation and temperature control in achieving phase-pure FAPbI₃ quantum dots with optimal optical properties.

Protocol for Lead-Free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ Nanocrystals

For environmentally sustainable alternatives, LARP effectively produces lead-free perovskite derivatives. Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PNCs are synthesized using DMSO and chloroform as the solvent and anti-solvent pair, respectively [5]. Precursors including cesium salts and bismuth bromide are dissolved in DMSO with oleylamine and oleic acid as ligands. The concentration of oleic acid demonstrates significant influence over the crystal structure and bandgap energy, which can be tuned from 3.85 eV to 3.29 eV through ligand concentration variations [5]. Synthesis temperature represents another critical parameter that governs the direct and indirect bandgap nature of the resulting PNCs. After rapid injection into chloroform, the nanocrystals are purified through centrifugation and can achieve exceptional PLQYs up to 62% [5]. This protocol establishes LARP as a viable method for producing high-efficiency lead-free alternatives to conventional lead-halide perovskites.

Critical Parameter Optimization

The controlled synthesis of PNCs via LARP requires precise optimization of multiple interconnected parameters. The following table summarizes the key chemical variables and their impact on final product characteristics:

Table 1: Optimization of LARP Chemical Parameters

| Parameter | Impact on Synthesis | Effect on PNC Properties | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Type & Ratio | Controls nucleation rate & growth kinetics [6] | Determines size distribution, stability & PLQY [6] | OA:OAm (1:1 to 10:1) [6] |

| Anti-Solvent Selection | Affects supersaturation rate & nucleation density [7] | Influences crystal phase, emission wavelength [7] | Toluene, Chloroform [6] [5] |

| Precursor Concentration | Determines nucleation density & growth duration | Affects particle size, size distribution & yield | 0.05-0.2 M [1] |

| Temperature | Modulates reaction kinetics & diffusion rates [5] | Controls bandgap nature, PL intensity [5] | Room temp to 70°C [1] |

| Purification Method | Removes excess ligands & unreacted precursors [1] | Affects inter-dot spacing, charge transport [1] | MeOAc volume optimization [1] |

Beyond these chemical parameters, processing conditions significantly influence the structural and optical properties of LARP-synthesized PNCs. Injection rate determines the initial supersaturation level, with faster injection producing higher nucleation densities and consequently smaller nanocrystals. Stirring efficiency ensures homogeneous mixing during the critical nucleation phase, preventing localized aggregation and ensuring narrow size distributions. Post-synthesis processing, including purification with methyl acetate (MeOAc) and ligand exchange protocols, enables further optimization of surface chemistry and thin-film properties for specific applications [1]. For instance, sequential solid-state multiligand exchange using 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) and formamidinium iodide (FAI) has been shown to significantly enhance the current density and power conversion efficiency of photovoltaic devices by approximately 28% by reducing inter-dot spacing and improving thin-film conductivity [1].

Advanced LARP Techniques and Modifications

High-Throughput Robotic Synthesis

The integration of high-throughput robotic synthesis platforms with machine learning algorithms represents a cutting-edge advancement in LARP methodology. This approach enables rapid exploration of the multidimensional synthesis space for complex compositions such as CsPb(BrₓI₁₋ₓ)₃ PNCs, where traditional one-variable-at-a-time optimization proves prohibitively time-consuming [7]. By systematically varying parameters including halide ratios, ligand concentrations, antisolvent compositions, and processing conditions, these platforms generate extensive datasets that machine learning algorithms, particularly SHAP analysis, process to identify critical parameter influences and predictive synthesis models [6]. This data-driven approach has revealed inherent disparities between the latent features in machine-learning-refined synthesis space and the manifested functionality space, highlighting how the colloidal nature in the precursor state governs both synthesizability and functionality control of LARP-PNCs [7]. Such advanced methodologies not only accelerate optimization but provide fundamental insights into the complex interparameter relationships that govern LARP synthesis outcomes.

Ligand Engineering and Exchange Strategies

Surface ligand management has emerged as a crucial aspect of advanced LARP protocols, directly impacting both synthetic control and application performance. Research has demonstrated that short-chain ligands cannot produce functional PNCs with desired sizes and shapes, whereas long-chain ligands provide homogeneous and stable PNCs with superior optical properties [6]. However, these insulating long-chain ligands hinder charge transport in electronic devices, necessitating sophisticated exchange strategies. Sequential solid-state multiligand exchange processes have been developed where solutions of short-chain ligands like 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) and formamidinium iodide (FAI) in methyl acetate replace the original long-chain octylamine (OctAm) and oleic acid (OA) ligands [1]. This approach achieves approximately 85% ligand removal confirmed by ¹H NMR while effectively passivating surface defects, significantly enhancing charge transport in subsequent device applications [1]. Such ligand engineering strategies preserve the excellent optical properties of LARP-synthesized PNCs while enabling their integration into high-performance optoelectronic devices.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful LARP synthesis requires precise selection and combination of specialized reagents, each fulfilling specific functions in the synthetic pathway:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for LARP Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in LARP Process |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salts | PbI₂, PbBr₂, CsX, FAI, BiX₃ [1] [5] | Provides metal & halide ions for perovskite lattice formation |

| Polar Solvents | DMSO, DMF, ACN [1] [5] | Dissolves precursor salts to create homogeneous solution |

| Non-Polar Anti-Solvents | Toluene, Chloroform, Hexane [6] [1] [5] | Induces supersaturation & nucleation upon injection |

| Acidic Ligands | Oleic Acid (OA), Octanoic Acid [6] [1] | Binds to metal sites, controls growth, passivates surfaces |

| Basic Ligands | Oleylamine (OAm), Octylamine (OctAm) [6] [1] | Binds to halide sites, controls nucleation, stabilizes colloid |

| Purification Solvents | Methyl Acetate (MeOAc), Acetone [1] | Removes excess ligands & precursors during purification |

The Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation method represents a versatile and robust platform for the synthesis of perovskite nanocrystals and quantum dots with tailored optoelectronic properties. Through precise control of chemical parameters—including ligand ratios, antisolvent selection, precursor concentration, and processing conditions—researchers can navigate the complex synthesis space to achieve target functionalities across diverse applications from photovoltaics to sensing. The mechanistic understanding of ligand-mediated nucleation and growth, coupled with advanced techniques such as high-throughput robotic synthesis and machine learning optimization, continues to expand the boundaries of LARP synthesis. Furthermore, the development of sophisticated ligand exchange protocols addresses critical challenges in charge transport, enabling the transition from colloidal stability to device functionality. As LARP methodologies evolve, particularly through the refinement of lead-free compositions and integration with patterning technologies for device fabrication, this synthetic approach promises to remain indispensable for advancing perovskite quantum dot research and applications.

In the synthesis of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), ligands are not mere spectators but are fundamental directors of the nucleation and growth processes. The ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) method has garnered significant attention as a feasible route for the mass production of these nanocrystals due to its relative simplicity and effectiveness [6]. At the heart of this method, and the broader field of PQD research, lies the critical partnership between oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm). These long-chain ligands are indispensable for controlling the crystallization kinetics, passivating surface defects, and determining the ultimate structural and optical properties of the resulting nanocrystals [8] [9]. This guide delves into the fundamental mechanisms by which OA and OAm operate, providing a detailed technical examination of their roles in stabilizing the delicate phases of PQD formation and maturation, thereby enabling the advancement of next-generation optoelectronic devices.

The Chemical Functions of OA and OAm Ligands

The synergistic interaction between OA and OAm forms the cornerstone of successful PQD synthesis. Their individual and cooperative chemical behaviors are crucial for guiding the entire lifecycle of the nanocrystals, from initial precursor dissolution to final surface passivation.

Acid-Base Synergy and Proton Transfer: In the colloidal synthesis environment, OA and OAm exist in a dynamic equilibrium. OA, a carboxylic acid, can deprotonate to form oleate (OA⁻), while OAm, an amine, can protonate to form oleylammonium (OAmH⁺). This pair engages in a continuous proton transfer process: OA⁻ + OAmH⁺ → OA + OAm [8]. This equilibrium is pivotal for the ligand binding dynamics on the perovskite surface and can be manipulated by the introduction of other acidic or basic components.

Surface Binding and Coordination: The ligands bind to the growing crystal surfaces in a complementary fashion. OA chelates with lead (Pb²⁺) atoms on the PQD surface, forming a coordinate covalent bond [9]. Conversely, OAm interacts with halide ions (e.g., I⁻, Br⁻) primarily through hydrogen bonding [9]. This dual passivation effectively neutralizes charged surface sites that would otherwise act as traps for charge carriers, thereby enhancing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and stability.

Steric Stabilization: The long hydrocarbon chains (C18) of both OA and OAm extend outward from the nanocrystal surface, creating a protective hydrophobic shell [6]. This shell physically impedes the close approach and aggregation of individual PQDs, maintaining their colloidal stability in non-polar solvents. The chain length is critical; short-chain ligands cannot provide sufficient steric hindrance to produce functional, stable PNCs with desired sizes and shapes [6].

Table 1: Primary Functions of OA and OAm Ligands in PQD Synthesis

| Ligand | Chemical Role | Binding Target | Impact on Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Carboxylic acid; Proton donor | Pb²⁺ ions on PQD surface [9] | Controls crystal growth; Passivates metal-site defects |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Amine; Proton acceptor | Halide ions (I⁻, Br⁻) [9] | Promotes nucleation; Passivates halide-site defects |

| OA/OAm Pair | Acid-base equilibrium; Steric hindrance | Overall PQD surface | Provides colloidal stability; Determines final size & morphology [6] |

Quantitative Impact on PQD Properties and Stability

The precise ratios and concentrations of OA and OAm are not arbitrary; they are powerful levers that directly control the structural and optical characteristics of the resulting PQDs. High-throughput robotic synthesis studies have systematically explored these effects, revealing that the ligand ratio profoundly influences particle size, size distribution, and most critically, the colloidal and phase stability of the nanocrystals [6].

An imbalance in the OA/OAm system can be detrimental. Excessive amines or the use of polar antisolvents can trigger a phase transformation of the PQDs into a Cs-rich non-perovskite structure, which exhibits poorer emission functionalities and broader size distributions [6]. Furthermore, the dynamic binding nature of these traditional ligands means they can easily desorb from the surface, especially during purification with polar antisolvents. This ligand loss creates unsaturated "active sites" on the perovskite ionic lattice, accelerating detrimental processes like Ostwald ripening and ultimately leading to the degradation of optical properties [8] [9].

Table 2: Impact of Ligand Parameters on CsPbX3 PQD Characteristics

| Parameter | Optimal Range / Condition | Observed Effect on PQDs |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Chain Length | Long-chain (e.g., C18) | Homogeneous, stable PNCs; short-chain ligands fail to produce functional PNCs [6] |

| OA/OAm Ratio | Balanced (varies by specific synthesis) | Controls crystal phase, size, and prevents transformation to non-perovskite structures [6] [9] |

| Ligand Binding Strength | Strong binding energy | Suppresses Ostwald ripening; enhances PLQY and environmental stability [8] |

| Ligand Stability | Resists polar antisolvents | Maintains passivation during purification; prevents defect formation and fusion [8] |

Advanced Ligand Engineering Strategies

Recognizing the inherent limitations of OA and OAm, particularly their dynamic binding and susceptibility to desorption, the field has advanced towards more robust ligand engineering strategies. These approaches aim to retain the beneficial roles of ligands while overcoming instability issues.

A prominent strategy is the post-synthesis ligand exchange, where weakly bound OA/OAm molecules are replaced with ligands that have stronger anchoring groups. For instance, the sulfonic acid group in 2-naphthalene sulfonic acid (NSA) has a calculated binding energy with Pb of 1.45 eV, which is stronger than that of OAm (1.23 eV) [8]. The naphthalene ring also provides large steric hindrance, collectively inhibiting overgrowth and stabilizing the nanocrystals. In a further step, inorganic ligands like ammonium hexafluorophosphate (NH₄PF₆) can be used. The PF₆⁻ anion exhibits an exceptionally high binding energy of 3.92 eV, which strongly passivates the surface and significantly improves the charge transport between QDs in a film [8].

Another innovative approach is the use of complementary dual-ligand systems. For example, a combination of trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate and phenylethyl ammonium iodide can form a hydrogen-bonded network on the PQD surface [10]. This system not only stabilizes the surface lattice but also improves electronic coupling between quantum dots in solid films, leading to record efficiencies in devices like quantum dot solar cells [10].

Experimental Protocols for Ligand-Assisted Synthesis

Standard LARP Synthesis with OA/OAm

A typical LARP synthesis of CsPbBr₃ nanocrystals involves creating a precursor solution in a polar solvent (like DMF or DMSO) containing Cs⁺, Pb²⁺, and Br⁻ ions. This solution is then rapidly injected into a poorly coordinating antisolvent (like toluene) under vigorous stirring. The antisolvent contains OA and OAm, which immediately act to control the crystallization process [6].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve CsBr and PbBr₂ in DMF to form the perovskite precursor solution.

- Ligand Solution: Prepare the antisolvent (e.g., toluene) with specific volumes of OA and OAm. The ratio of OA to OAm is a critical parameter that requires optimization for the target nanocrystal size and phase [6] [9].

- Reprecipitation and Nucleation: Quickly inject the precursor solution into the antisolvent/ligand mixture. The sudden drop in solubility causes supersaturation, triggering rapid nucleation.

- Growth and Stabilization: The OA and OAM ligands immediately coordinate with the newly formed nuclei, limiting growth and preventing aggregation. The reaction mixture is typically centrifuged to isolate the synthesized PQDs.

Inhibition of Ostwald Ripening with NSA

To overcome the limitations of OA/OAm, an advanced protocol introduces a strong-binding ligand like 2-Naphthalene Sulfonic Acid (NSA) after the initial nucleation phase [8].

Detailed Methodology:

- Initial Synthesis: Begin with a standard hot-injection or LARP method using OA and OAm.

- Post-Nucleation Ligand Injection: After the initial nucleation of QDs, inject a solution of NSA (e.g., 0.6 M in toluene) into the reaction mixture.

- Reaction Mechanism: The NSA, being a stronger acid with a higher dissociation constant, pushes the proton transfer equilibrium (OA⁻ + OAmH⁺ → OA + OAm), facilitating the debonding of weak OA/OAm ligands from the QD surface [8].

- Surface Binding: The sulfonic acid group of NSA, with its higher binding energy to Pb (1.45 eV), replaces the original OAm ligands, passivating the surface more effectively and providing greater steric hindrance from its naphthalene ring.

- Purification Enhancement: Further stability during purification is achieved by adding ammonium hexafluorophosphate (NH₄PF₆), whose PF₆⁻ anion has a very high binding energy (3.92 eV), to the polar antisolvent used for washing, preventing ligand loss and defect formation [8].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit - Essential Reagents for Ligand-Based PQD Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Synthesis | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Long-chain carboxylic acid; Binds to Pb²⁺ sites; Controls crystal growth [9] | Must be used with amine; Ratio to OAm is critical for phase stability [6] |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Long-chain amine; Binds to halide sites; Promotes nucleation [9] | Dynamic binding can lead to desorption; source of instability [8] |

| 2-Naphthalene Sulfonic Acid (NSA) | Strong-binding ligand; Suppresses Ostwald ripening [8] | Higher Pb-binding energy (1.45 eV) than OAm; introduces steric hindrance [8] |

| Ammonium Hexafluorophosphate (NH₄PF₆) | Inorganic ligand for post-synthesis exchange; Enhances charge transport [8] | Very high binding energy (3.92 eV); improves stability during purification [8] |

| Polar Solvent (e.g., DMF) | Dissolves inorganic precursor salts for LARP [6] | Enables creation of high-concentration precursor solutions |

| Non-Polar Antisolvent (e.g., Toluene) | Triggers reprecipitation and nucleation in LARP [6] | Must be miscible with polar solvent; contains initial OA/OAm ligands |

OA and OAm serve as the foundational ligands in the synthesis of perovskite quantum dots, masterfully directing the processes of nucleation and growth through their synergistic acid-base chemistry and steric stabilization. However, their dynamic binding nature presents a significant limitation for long-term stability and device performance. The future of ligand engineering in PQD research lies in moving beyond this traditional pair towards sophisticated strategies employing strong-binding organic molecules, complementary dual-ligand systems, and robust inorganic ligands. These advanced approaches, built upon the fundamental understanding of OA and OAm mechanisms, are paving the way for the development of highly stable and efficient perovskite nanocrystals capable of meeting the rigorous demands of commercial optoelectronic applications.

Reprecipitation is a fundamental phase transformation process where a dissolved solute or a metastable solid phase dissolves and a more stable solid phase precipitates from the solution or via an intermediate state. This mechanism plays a crucial role across diverse scientific fields, from materials science to geochemistry and nanotechnology. Within the context of ligand-assisted reprecipitation for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) research, understanding the thermodynamic and kinetic drivers is essential for controlling particle size, morphology, and functional properties. The reprecipitation process is governed by the intricate balance between the thermodynamic driving force for phase transformation and the kinetic pathways that determine the rate and mechanism of this transformation.

In materials science, reprecipitation reactions are widely employed to enhance materials performance by controlling the microstructure evolving during precipitation [11]. In the specific case of PQDs, the ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) method provides a simple route for mass-production of high-quality nanocrystals, rendering promising performances in various optoelectronic applications [12]. The precise control of reaction kinetics allows researchers to tailor the microstructure and thus tune the material properties for specific applications.

Thermodynamic Fundamentals of Reprecipitation

Classical Nucleation Theory

The thermodynamic basis for reprecipitation begins with classical nucleation theory, which describes the formation of stable precipitate particles from a supersaturated matrix. The rate of nucleation (Ȧ) is dominated by an energy barrier ΔG* for the formation of a particle of critical size r* above which the particle becomes stable [11]. This relationship is expressed as:

Ȧ ∝ exp(-ΔG/kT)*

where k is the Boltzmann constant and T is the absolute temperature. For a precipitation reaction, both ΔG* and r* are functions of the change in chemical Gibbs energy Δg~c~(x~α,m~,x~β,p~) upon nucleation, where -Δg~c~(x~α,m~,x~β,p~) represents the chemical driving force for nucleation for given compositions of the α-phase matrix and the β-phase precipitate, and of the interface energy γ per unit area [11].

Competing Energy Contributions

The formation and stability of a precipitate-phase particle are defined by two counteracting thermodynamic factors [11]:

Energy release: The release of energy due to the decomposition of the supersaturated matrix phase into solute-depleted matrix phase and solute-rich precipitate phase. This energy release can be described as a difference of chemical Gibbs energies of the homogeneous phases, defined by their respective compositions.

Energy increase: The increase in energy due to the development of a particle-matrix interface.

These competing contributions are represented in rate equations for nucleation and growth through two key concepts: the energy barrier for nucleation and the Gibbs-Thomson effect that affects particle growth rate.

Gibbs-Thomson Effect

For small particles with a large ratio of interface area to particle volume, the equilibrium between the matrix and precipitate phases deviates significantly from the state of equilibrium between bulk phases. This Gibbs-Thomson effect can be expressed by composition functions that depend on particle size and interface energy [11]:

x~α,int~ = x~α,int~(r,γ) and x~β,int~ = x~β,int~(r,γ)

The Gibbs-Thomson effect in a binary system is often described by the equation:

x~α,int~(r) = x~α~(r→∞) exp(2γV~mol~^β^/RT × 1/r)

where x~α~(r→∞) is the solute concentration of the α phase in the reference state of equilibrium between the α phase and the β phase with r→∞, V~mol~^β^ is the mean molar volume of the β-phase, and R is the gas constant [11]. This equation highlights how interfacial energy becomes increasingly important at the nanoscale, which is particularly relevant for PQD synthesis where control of quantum dot size is critical for optoelectronic properties.

Kinetic Principles Governing Reprecipitation

Growth Kinetics

The growth rate of spherical particles in a binary system follows a diffusion-controlled kinetics model described by [11]:

dr/dt = (x~α,m~ - x~α,int~)/(k'x~β,int~ - x~α,int~) × D/r

where D is the diffusion coefficient of the solute component in the matrix, and x~α,m~, x~α,int~, and x~β,int~ are the atom fractions of solute in the α-phase matrix remote from the particle, in the α-phase matrix at the particle-matrix interface, and in the β-phase particle at the interface, respectively. The factor k' accounts for the difference in molar volume between the α phase and the β phase. When x~α,m~ > x~α,int~, the particle is stable and grows; when x~α,m~ < x~α,int~, the particle becomes unstable and shrinks [11].

Alternative Kinetic Pathways

Recent research has revealed that reprecipitation does not always follow classical dissolution-transport-precipitation pathways. In some systems, element transfer during mineral dissolution and reprecipitation can occur through an alkali-Al-Si-rich amorphous material that forms directly by depolymerization of the crystal lattice [13]. This amorphous material occupies large volumes in an interconnected porosity network, and precipitation of product minerals occurs directly by repolymerization of the amorphous material at the product surface. This mechanism allows for significantly higher element transport and mineral reaction rates than aqueous solutions, with major implications for reaction kinetics in various systems [13].

Johnson-Mehl-Avrami (JMA) Kinetics Model

For the analysis of precipitation kinetics, the Johnson-Mehl-Avrami (JMA) model provides a framework applicable to both isothermal and non-isothermal analysis [14]. The fraction of transformation, Y, is described by:

Y = 1 - exp(-kt^n^)

where n is the Avrami exponent that depends on precipitate growth modes, and k is the rate parameter. For non-isothermal transformations, the integrated form becomes [14]:

Y = 1 - exp[-(k~0~RT^2^/ϕQ)exp(-Q/RT)]^n^

where R is the gas constant, φ is the cooling rate, and Q is the activation energy of the reaction. The Avrami exponent typically falls in the range of 1.5-2.3 for spherical or irregular growth [14], which is relevant for understanding the kinetics of PQD formation via LARP processes.

Table 1: Key Kinetic Parameters in Reprecipitation Processes

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avrami exponent | n | 1.5-2.3 [14] | Determines growth morphology (spherical/irregular) |

| Activation energy | Q | System-dependent | Temperature dependence of reaction rate |

| Rate coefficient | k(T) | k~0~exp(-Q/RT) [14] | Combined nucleation and growth rate parameter |

| Diffusion coefficient | D | Temperature-dependent | Controls solute transport to growing particles |

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation for Perovskite Quantum Dots

Fundamentals of LARP Synthesis

The ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) method provides a simple synthetic route enabling mass-production of high-quality perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs) compared to complex hot-injection methods [12]. This technique is particularly valuable for inorganic cesium lead bromide (CsPbBr~3~) perovskite nanocrystals, which show promising performance in various optoelectronic applications. The LARP process involves controlled precipitation of nanocrystals from precursor solutions through the introduction of antisolvents, with ligands playing a critical role in directing nanocrystal growth and stabilization.

In LARP synthesis, ligands serve multiple functions: they control particle growth, prevent aggregation, passivate surface defects, and determine the colloidal stability of the resulting nanocrystals. The diffusion of ligands within the reaction system crucially determines the final structures and functionalities of the PNCs [12]. Understanding the thermodynamic and kinetic aspects of ligand interaction with growing crystal surfaces is essential for controlling the LARP process.

Ligand Selection and Optimization

Research using high-throughput automated experimental platforms has systematically explored the influence of ligands—including chain lengths, concentration, and ratios—on particle growth and consequent functionalities of PNCs [12]. Key findings include:

- Chain length effects: Short-chain ligands (e.g., octanoic acid-octylamine) generally cannot produce functional PNCs with desired sizes and shapes, whereas long-chain ligands (e.g., oleic acid-oleylamine) provide homogeneous and stable PNCs [12].

- Stoichiometric balance: Excessive amines or polar antisolvent can transform PNCs into a Cs-rich non-perovskite structure with poorer emission functionalities and larger size distributions [12].

- Acid-base pairs: The combination of carboxylic acids and amines as ligand pairs is crucial for controlling the surface chemistry and growth kinetics of PNCs.

Table 2: Ligand Systems in LARP Synthesis of Perovskite Nanocrystals

| Ligand Pair | Chain Length | PNC Characteristics | Functionality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic acid-Oleylamine | Long (C18) | Homogeneous, stable PNCs [12] | Optimal size control, good emission properties |

| Octanoic acid-Octylamine | Short (C8) | Non-functional PNCs [12] | Poor size control, undesirable structures |

| Balanced ratio | - | Desired perovskite structure | Good optical properties, narrow size distribution |

| Excessive amine | - | Cs-rich non-perovskite structure [12] | Poorer emission, larger size distribution |

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Reprecipitation

Characterization Techniques

A comprehensive understanding of reprecipitation mechanisms requires the application of multiple characterization techniques:

- Thermal Analysis: Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) can determine transformation temperatures and measure heat flow during reprecipitation reactions. The fraction of precipitation Y(T) at temperature T is given by Y(T) = A(T)/A(T~f~), where A(T) is the area under the DTA peak between the initial temperature T~i~ and temperature T, and A(T~f~) is the total peak area between T~i~ and the final temperature T~f~ [14].

- Electron Microscopy: Field Emission Gun Scanning Electron Microscopy (FEG-SEM) investigates evolution in morphology and distribution of reprecipitated particles [14]. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) combined with focused ion beam (FIB) sectioning can visualize reaction zones at near-atomic resolution [13].

- SIMS Mapping: Nano-secondary ion mass spectrometer (SIMS) mappings provide elemental distribution information across reaction interfaces [13].

High-Throughput Synthesis Approaches

For ligand-assisted reprecipitation studies, implementing high-throughput automated experimental platforms enables systematic exploration of synthesis parameter spaces [12]. This approach allows researchers to efficiently map the influence of multiple variables—including ligand concentrations, ratios, solvent compositions, and reaction conditions—on the resulting nanocrystal characteristics. The data generated from such high-throughput studies provides guidance for optimizing synthesis routes to achieve desired PNC properties.

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Kampmann-Wagner-Numerical (KWN) Modeling

The KWN-type modeling approach computes the evolution of particle size distribution through numerical integration of composition-dependent nucleation rates and size- and composition-dependent growth rates for discrete time steps and discrete particle-size classes [11]. This method requires numerous evaluations of thermodynamic relations, making computational efficiency a key consideration. A generally valid method for combined, inherently consistent, numerical evaluation of nucleation barrier and Gibbs-Thomson effect has been developed based on the Gibbsian treatment of nucleation and growth [11].

Phase Field Modeling

Phase field modeling visualizes microstructure development and quantifies physical phenomena such as impingement, particle coalescence, or splitting by solving nonlinear time-dependent phase field equations within the framework of irreversible thermodynamics [14]. While powerful, this approach requires extensive experimental work to set realistic values for boundary conditions and determine material parameters, making application to new alloys or materials challenging.

Challenges in Computational Modeling

Computational modeling of reprecipitation processes faces several challenges [14]:

- Computational expense: Full coupling with CALPHAD for calculation of nucleation driving force is computationally expensive.

- Parameter availability: Many physical constants (element diffusion coefficients, surface energies, interface kinetic coefficients, driving forces for phase transformations) are not always readily available for complex compositions.

- Application to new systems: For new alloys or materials, calibration and independent experimental measurements are needed to determine model parameters with high fidelity and minimum overfitting.

Visualization of Reprecipitation Mechanisms

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation Mechanism for PQDs

Experimental Workflow for LARP Synthesis Optimization

Research Reagent Solutions for LARP Experiments

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in LARP Process | Impact on PNC Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salts | CsPbBr~3~ | Provides primary perovskite composition | Determines crystal structure and basic composition |

| Solvents | DMSO, DMF | Dissolves precursor salts | Affects precursor concentration and reaction kinetics |

| Antisolvents | Toluene, Chloroform | Induces supersaturation and nucleation | Controls nucleation rate and final particle size |

| Long-Chain Ligands | Oleic acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) [12] | Directs growth and stabilizes nanocrystals | Produces homogeneous, stable PNCs with desired optoelectronic properties |

| Short-Chain Ligands | Octanoic acid (OctA), Octylamine (OctAm) [12] | Alternative ligand system | Typically cannot produce functional PNCs with desired characteristics |

| Stoichiometry Modifiers | Excess CsBr or PbBr~2~ | Controls final composition | Can lead to non-perovskite structures if unbalanced [12] |

The reprecipitation mechanism is governed by the complex interplay between thermodynamic driving forces and kinetic pathways. In the specific case of ligand-assisted reprecipitation for perovskite quantum dots research, understanding these fundamental principles enables precise control over nanocrystal size, morphology, and functional properties. Thermodynamic factors—particularly the chemical driving force for nucleation and the interface energy governed by the Gibbs-Thomson effect—determine the feasibility and direction of reprecipitation processes. Meanwhile, kinetic factors—including diffusion rates, surface kinetics, and ligand exchange dynamics—control the rate and pathway of the transformation.

The ligand-assisted reprecipitation method represents a significant advancement in perovskite nanocrystal synthesis, offering a simpler route to mass-production compared to traditional hot-injection techniques. However, successful implementation requires careful optimization of ligand systems, with long-chain ligands such as oleic acid and oleylamine proving essential for producing functional nanocrystals with desired properties. The insights from fundamental studies of reprecipitation mechanisms across materials science and geochemistry provide valuable principles that can be applied to the continued development and optimization of PQD synthesis for advanced optoelectronic applications.

The ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) method has emerged as a pivotal technique for the synthesis of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), prized for its feasibility for mass production and room-temperature processing [6] [15] [16]. This method hinges on the precise control of a trifecta of parameters: solvents, antisolvents, and ligand ratios. These components collectively govern the supersaturation, nucleation, and growth stages of nanocrystal formation, thereby dictating the final crystal structure, dimensionality, and optoelectronic properties of the resulting PQDs [6] [17]. Understanding the fundamental mechanisms of LARP is essential for advancing PQD research, as the intrinsic ionic character and low formation energy of perovskites make their synthesis highly sensitive to the chemical environment [17] [18]. This guide provides an in-depth analysis of how these critical parameters control crystal structure, supported by quantitative data, detailed protocols, and mechanistic insights for researchers and scientists.

The Core Mechanism of Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP)

The LARP synthesis of PQDs is a rapid process that can be conceptualized in three key stages, leading from precursor solutions to final nanocrystals.

Diagram 1: The synthetic pathway of anisotropic perovskite nanocrystals via the LARP method, showing the divergent pathways to 1D nanorods and 2D nanoplatelets [17].

The process begins when perovskite precursor salts (e.g., PbBr₂) and Cs-oleate are combined in a solvent containing organic ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm). This mixture instantly forms small, emissive crystalline nanoclusters approximately 5.1 nm in size [17]. The subsequent injection of an antisolvent triggers a critical supersaturation event, inducing a burst of nucleation. The fate of the synthesis then diverges based on antisolvent properties and precursor ratios. As revealed by in-situ studies, the formation of a dense hexagonal mesophase of intermediate nanoclusters leads to their fusion into 1D nanorods. In contrast, the absence of this mesophase results in the growth of freely dispersed 2D nanoplatelets, which can subsequently stack into lamellar superstructures [17]. Throughout this process, ligands dynamically control the reaction kinetics by modulating the diffusion of reactants and passivating the surface of the growing nanocrystals to determine their final size and shape [6] [17].

Governing Parameters and Their Impact on Crystal Structure

The Role of the Antisolvent

The antisolvent is not merely a precipitating agent but a primary structure-directing component. Its physicochemical properties, particularly dipole moment (μ) and Hansen hydrogen bonding parameter (δH), are decisive for the shape and monolayer thickness of anisotropic nanocrystals [17].

- Mechanism of Action: The antisolvent reduces the solubility of the perovskite precursors, driving the system into a supersaturated state that forces nucleation and growth. Its polarity and hydrogen-bonding capacity influence how it interacts with the organic ligands and precursor ions, thereby controlling the self-assembly of intermediate phases [17].

- Divergent Anisotropy: The formation of a dense, hexagonal mesophase of intermediate nanoclusters, induced by specific antisolvent properties, leads to their fusion into 1D nanorods. In the absence of this mesophase, the system follows a thermodynamically driven path to form 2D nanoplatelets [17].

- Solvent Polarity and Ligand Removal: The polarity of the antisolvent used in post-treatment steps critically affects the surface chemistry of PQD solid films. For instance, methyl acetate (MeOAc) has been identified as an effective antisolvent for FAPbI₃ PQDs, as it successfully removes long-chain surface ligands like oleic acid without destroying the underlying perovskite crystal structure [19]. Excessive amounts of polar antisolvents, however, can lead to the transformation of PQDs into non-perovskite structures with poorer optical properties and larger size distributions [6].

Table 1: Effect of Antisolvent Properties on Perovskite Nanocrystal Morphology

| Antisolvent | Key Properties | Impact on Crystal Structure | Typical Application/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Moderate polarity | Effectively removes ligands without destroying the FAPbI₃ crystal structure; enables good charge transport [19]. | Post-treatment of FAPbI₃ PQD films for solar cells. |

| Acetone | Moderate dipole moment and δH | Promotes formation of a hexagonal mesophase from intermediate nanoclusters, leading to fusion into 1D nanorods [17]. | Structure-directing agent for anisotropic growth. |

| Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) | Polar antisolvent | Used in purification to control ligand density and QD size; excess can introduce impurities [20]. | Purification of CsPbI₂Br QDs; optimal n-hexane:EtOAc ratio is 1:5 for low ASE threshold. |

| Excessive Polar Antisolvents | High polarity, high δH | Can cause transformation to Cs-rich non-perovskite phases; degrades emission and increases size distribution [6]. | To be avoided for stable, functional PNCs. |

The Role of Ligands and Their Density

Ligands, typically long-chain organic molecules like OA and OAm, play a dual role: they control nanocrystal growth during synthesis and passivate the surface in the final product. The chain length and density of these ligands are critical parameters.

- Ligand Chain Length: Short-chain ligands often cannot facilitate the formation of functional PQDs with desired sizes and shapes, whereas long-chain ligands like OA and OAm provide homogeneous and stable PQDs by effectively stabilizing the colloidal suspension and crystal surfaces [6].

- Ligand Density and Purification: The density of surface ligands is directly tuned during the purification process, which involves cycles of precipitation using an antisolvent and re-dispersion in a solvent. The volume ratio of solvent to antisolvent in this step is a powerful handle for controlling ligand density and, consequently, the optoelectronic properties of the PQDs [20]. For example, a ratio of n-hexane to ethyl acetate of 1:5 was found to yield CsPbI₂Br QDs with an optimal size and the lowest amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) threshold of 0.301 mJ/cm² [20].

- Ligand Exchange for Surface Passivation: Engineering the ligand shell through post-synthetic exchange is a key strategy for improving performance. Replacing native long-chain ligands with shorter or more functional molecules can enhance the electronic coupling between PQDs. In FAPbI₃ PQDs, the use of benzamidine hydrochloride (PhFACl) as a short ligand effectively filled A-site (formamidinium) and X-site (iodide) vacancies, leading to improved optoelectronic properties and a significant boost in solar cell power conversion efficiency from 4.63% to 6.4% [19].

Table 2: Impact of Ligand Engineering on Perovskite Quantum Dot Properties

| Ligand Strategy | Chemical Example | Impact on Structure & Properties | Application Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Chain Ligands | Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) | Provide colloidal stability and homogeneous nucleation; essential for basic synthesis [6]. | Enables synthesis of stable, monodisperse PQDs. |

| Short-Chain Ligand Exchange | Benzamidine Hydrochloride (PhFACl) | Fills A- and X-site vacancies on FAPbI₃ PQD surface; improves electronic coupling [19]. | Increases solar cell PCE from 4.63% to 6.4%. |

| Ligand Density Control | n-hexane:Ethyl Acetate (1:5 ratio) | Removes excess OA/OAm, increases QD size, reduces defects, and improves light scattering [20]. | Achieves lowest ASE threshold (0.301 mJ/cm²) for CsPbI₂Br QDs. |

| Excessive Ligand Removal | High antisolvent ratio | Can strip too many ligands, creating surface defects and degrading performance [19] [20]. | Leads to impurities and poor optoelectronic properties. |

The Role of Precursor and Solvent Ratios

The relative concentrations of precursors and the solvent environment establish the initial conditions for the reaction kinetics and thermodynamics.

- Precursor Stoichiometry: A stoichiometric deficiency of Cs⁺ ions (i.e., a non-equimolar Cs:Pb ratio) has been shown to promote the formation of anisotropic nanocrystals (nanorods and nanoplatelets) over zero-dimensional quantum dots [17]. Furthermore, the exact ratio of Cs-oleate to PbBr₂ precursor directly influences the monolayer thickness of the resulting nanoplatelets [17].

- Solvent-Antisolvent Ratio: As detailed in the purification process, the volume ratio of antisolvent to solvent is a direct experimental parameter for tuning ligand density and particle size. This ratio must be carefully optimized, as excess antisolvent, while removing insulating ligands, can also introduce defects and impurities if not properly controlled [20].

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol: Tuning Ligand Density via Purification for ASE

This protocol outlines the procedure for controlling the surface ligand density of CsPbI₂Br QDs to optimize their amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) properties [20].

- Synthesis: CsPbI₂Br QDs are synthesized via the standard hot-injection method. Precursors (Cs₂CO₃, PbI₂, PbBr₂) are combined with OA and OAm in 1-octadecene (ODE) at high temperature (e.g., 160-180 °C), followed by rapid cooling in an ice-water bath.

- Purification and Ligand Density Control:

- The crude QD solution is mixed with a solvent (n-hexane).

- An antisolvent (ethyl acetate, EtOAc) is added in a controlled volume ratio to precipitate the QDs. Ratios of n-hexane to EtOAc tested range from 1:3 to 1:9.

- The mixture is centrifuged (e.g., 8000 rpm for 5 min) to separate the precipitated QDs from the supernatant containing excess ligands and unreacted precursors.

- The pellet is re-dispersed in n-hexane or another non-polar solvent for characterization and film formation.

- Optimal Condition: A volume ratio of n-hexane to EtOAc of 1:5 was found to produce QDs with a larger average size and the lowest ASE threshold (0.301 mJ/cm²), attributed to increased light scattering and a reduced defect density [20].

Protocol: Antisolvent and Ligand Engineering for FAPbI₃ PQD Solar Cells

This protocol describes the post-treatment and passivation of FAPbI₃ PQD films for application in solar cells [19].

- PQD Synthesis and Film Deposition: FAPbI₃ PQDs are synthesized via a modified hot-injection method using a FA-oleate precursor. The purified QDs are spin-coated onto a compact TiO₂/FTO substrate. This spin-coating process is repeated 3-5 times to build the active layer thickness.

- Antisolvent Post-Treatment: After each layer deposition, an appropriate amount of antisolvent (optimized to be methyl acetate, MeOAc) is dynamically dropped onto the spinning film to remove the long-chain OA ligands and densify the film.

- Surface Passivation with Short Ligands: The MeOAc treatment is followed by the application of a solution of benzamidine hydrochloride (PhFACl) in isopropanol. The PhFACl solution is spin-coated onto the PQD film. The formamidinium group in PhFACl fills A-site vacancies, while the Cl⁻ ion fills X-site vacancies, effectively passivating the PQD surface.

- Device Fabrication: After the PQD film is built and treated, the hole transport layer (e.g., Spiro-OMeTAD) is deposited, followed by the evaporation of MoO₃/Ag electrodes. The PhFACl-based devices achieved a champion PCE of 6.4%, compared to 4.63% for conventional devices [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for LARP Synthesis and Surface Engineering of PQDs

| Reagent Category & Name | Function in Synthesis/Processing |

|---|---|

| Precursors | |

| Lead Halides (PbX₂) | Source of Pb²⁺ and halide (X = I, Br, Cl) ions for the perovskite framework. |

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) / Formamidinium Acetate (FAAc) | Source of A-site cations (Cs⁺, FA⁺) when reacted with acids to form oleate salts. |

| Solvents & Antisolvents | |

| Toluene, n-Hexane, Octane | Non-polar solvents for dispersing precursors and storing final PQDs. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Moderate polarity antisolvent for post-treatment; removes ligands without damaging crystals [19]. |

| Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc), Acetone | Polar antisolvents for purification and precipitation; controls ligand density and can direct anisotropic growth [17] [20]. |

| Ligands | |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Long-chain carboxylic acid ligand; controls growth and provides colloidal stability [19] [6]. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Long-chain amine ligand; co-passivates the surface and influences crystal growth [19] [6]. |

| Benzamidine Hydrochloride (PhFACl) | Short, bifunctional ligand for surface passivation; fills A- and X-site vacancies [19]. |

The precise control of solvent, antisolvent, and ligand parameters is not merely a synthetic optimization but a fundamental requirement for mastering the crystal structure and properties of perovskite quantum dots. The antisolvent's physicochemical properties, particularly its dipole moment and hydrogen-bonding capacity, serve as critical levers for directing anisotropy, determining whether the synthesis yields 1D nanorods or 2D nanoplatelets [17]. Concurrently, the type and density of surface ligands govern defect passivation, electronic coupling, and ultimately, device performance, as demonstrated by significant efficiency gains in solar cells and reduced thresholds in lasers [19] [20]. The interplay of these parameters during the rapid LARP process underscores a complex but decipherable non-classical growth mechanism involving intermediate nanoclusters and mesophases [17]. Future research, aided by high-throughput experimentation and machine learning [6] [16], will continue to refine our understanding of these relationships, paving the way for the rational design of next-generation PQD-based optoelectronic devices.

The Diffusion-Limited Growth Model in Colloidal PQD Synthesis

Colloidal perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) represent a class of materials with exceptional optoelectronic properties, suitable for applications ranging from light-emitting devices to sensitive chemical sensors. Their synthesis via ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) has garnered significant attention due to its feasibility for mass production at room temperature. However, the inherent instability and fast crystallization rates of perovskites have posed substantial challenges in achieving precise size and morphology control. This whitepaper examines the diffusion-limited growth model as a fundamental mechanism for controlling the synthesis of monodisperse PQDs within the broader context of LARP methodology, providing researchers with a theoretical framework and experimental protocols to overcome current synthetic limitations.

Theoretical Framework of Diffusion-Limited Growth

Fundamental Principles

The diffusion-limited growth model posits that the growth of colloidal nanocrystals is governed by the diffusion of monomers from the solution bulk to the particle surface, rather than by the reaction rate at the surface itself. This distinction is critical for achieving monodisperse particles, as diffusion-dependent growth promotes size focusing, whereas reaction-dependent growth often leads to broadening of size distributions [21]. In the LARP process, this model becomes particularly relevant due to the rapid crystallization characteristics of perovskite materials.

The diffusion dynamics can be mathematically described using a modified Fick's law approach, where the monomer flux (J) to the particle surface is proportional to the concentration gradient between the bulk solution (Cb) and the particle surface (Cs):

J = -D * (dC/dr)

Where D represents the diffusion coefficient. Maintaining this concentration gradient within an optimal window is essential for sustained diffusion-limited growth without secondary nucleation events [21].

Role in Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation

In LARP synthesis, the diffusion-limited growth model explains how ligands influence particle size and morphology through their effect on monomer availability. Long-chain ligands such as oleylamine (OLA) and oleic acid (OA) moderate growth kinetics through several mechanisms: (1) forming coordination complexes with precursor components, (2) stabilizing nanocrystal surfaces to prevent aggregation, and (3) controlling the diffusion rate of monomers to growing crystal surfaces [6] [22].

The transition from nucleation to growth phases in LARP is exceptionally rapid for metal halide perovskites due to their low formation energy. The diffusion-limited model provides a framework for intervening in this process by manipulating precursor concentrations, ligand ratios, and solvent conditions to extend the growth phase while maintaining size uniformity [22].

Experimental Validation and Protocols

Precursor Injection Rate Studies

The critical relationship between precursor injection rate and nanocrystal growth has been systematically investigated through continuous injection syntheses of InAs quantum dots, which share analogous diffusion limitations with perovskite systems.

Table 1: Effect of Precursor Injection Rate on Nanocrystal Growth Characteristics

| Injection Rate (mL/h) | Final Size (nm) | 1Smax Peak (nm) | Size Distribution | Growth Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | <5.0 | 1060 | Broad (High HWHM) | Early growth saturation, secondary nucleation |

| 4 | ~6.0 | 1152 | Moderate | Partial growth suppression, inhomogeneous growth |

| 2 | ~7.0 | 1300 | Narrow (12.2% size distribution) | Sustained size-focusing until suppression point |

In a representative protocol, seeds with an initial radius of 1.4 nm were synthesized via hot-injection methods, followed by slow dropwise addition of cluster-based single-source precursor to the seed solution [21]. The injection rate (Rinj) was systematically varied while maintaining constant precursor concentration and reaction volume. At high injection rates (8 mL/h), growth saturation occurred prematurely with broadened size distribution, indicating that the monomer concentration exceeded the optimal window for diffusion-limited growth. Conversely, slower injection rates (2 mL/h) maintained the monomer concentration within the diffusion-limited regime, enabling extended size-focusing growth [21].

Ligand Concentration and Chain Length Studies

The critical role of ligand engineering in diffusion-mediated growth has been demonstrated through high-throughput robotic synthesis of CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystals [6]. This approach systematically evaluated how ligand properties influence the diffusion process and consequent nanocrystal characteristics.

Table 2: Impact of Ligand Characteristics on PNC Growth and Functionality

| Ligand Type | Chain Length | PNC Morphology | Stability | Optical Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain amines/acids | Short | Irregular shapes, broad size distribution | Low (rapid degradation) | Poor emission efficiency |

| Long-chain (OLA/OA) | Long | Homogeneous nanocubes | High (weeks to months) | Bright luminescence, narrow FWHM |

| Excess amines | Variable | Cs-rich non-perovskite structures | Moderate | Poor emission, broad size distribution |

Experimental protocols for CH3NH3PbBr3 NC synthesis illustrate the precise implementation of ligand control. In a standard procedure, 0.5 mL aliquots of DMF containing variable amounts of perovskite precursors (PbBr2 and CH3NH3Br) and fixed amounts of two ligands (5 μL OLA and 50 μL OA) were quickly injected into 5 mL of toluene under vigorous stirring [22]. When precursor concentration was maintained constant while ligand concentration was increased, the resulting NCs exhibited systematic blue-shifting of photoluminescence maxima from 513 nm to 452 nm, corresponding to a reduction in particle size from approximately 4.0 nm to 2.2 nm [22].

Quantitative Analysis of Growth Trajectories

Monitoring growth trajectories provides critical validation of the diffusion-limited model. In continuous injection synthesis, quantitative comparison between experimental results and ideal growth predictions reveals distinct deviation points where growth suppression occurs. By converting experimental optical absorption data to particle radii using the Brus equation, researchers have demonstrated that diffusion-limited growth follows the predicted trajectory until a critical particle size is reached, beyond which additional precursor injection fails to produce further growth [21].

This growth suppression phenomenon occurs despite complete precursor conversion to active species, as verified by optical density measurements at 450 nm, which show agreement between measured and predicted values throughout the synthesis process. This confirms that growth limitations originate from diffusion dynamics rather than precursor conversion efficiency [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Diffusion-Controlled PQD Synthesis

| Reagent | Function | Role in Diffusion-Limited Growth |

|---|---|---|

| Oleylamine (OLA) | Coordinating ligand | Binds to crystal surfaces, moderating monomer addition rate; determines surface energy and growth kinetics |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Stabilizing agent | Forms coordination complexes with metal precursors; influences monomer diffusion through solution viscosity |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr2) | Metal precursor | Source of Pb2+ ions; concentration controls monomer flux and supersaturation level |

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs2CO3) | Cesium source | Provides Cs+ ions for perovskite formation; injection rate controls nucleation burst |

| Methylammonium Bromide (CH3NH3Br) | Organic cation precursor | Determines A-site cation composition; concentration affects crystallization kinetics |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Solvent | Dissolves precursor compounds; polarity affects ligand coordination and monomer diffusion |

| Toluene | Anti-solvent | Induces supersaturation through poor solvent environment; volume affects diffusion distance |

Diffusion Dynamics Control (DDC) Methodology

Fundamental Approach

The Diffusion Dynamics Control (DDC) methodology represents a strategic framework for overcoming the inherent size limitations in nanocrystal growth by systematically managing monomer flux through three primary parameters: reaction volume, precursor concentration, and injection rate [21]. Each parameter directly influences the concentration gradient that drives monomer diffusion to growing crystal surfaces.

The implementation of DDC has enabled the synthesis of exceptionally large InAs quantum dots with sizes exceeding 9.0 nm and absorption features reaching 1600 nm, while maintaining narrow size distribution of 12.2% [21]. Although demonstrated on III-V quantum dots, the principles of DDC are directly applicable to perovskite nanocrystal systems, where similar diffusion limitations constrain maximum achievable particle sizes.

Implementation Protocol

A standardized DDC protocol involves sequential optimization of each parameter:

Reaction Volume Optimization: Begin with systematic variation of reaction volume while maintaining constant precursor concentration and injection rate. Larger volumes typically extend the diffusion-limited growth regime by reducing the rate of concentration build-up.

Precursor Concentration Adjustment: Modify precursor concentration while monitoring for secondary nucleation events indicated by broadening of size distribution. Optimal concentration provides sufficient monomer flux without exceeding the critical supersaturation threshold.

Injection Rate Calibration: Fine-tune injection rate to match the consumption rate of monomers by growing nanocrystals. The optimal rate maintains monomer concentration between the critical levels for secondary nucleation and growth cessation.

The successful implementation of DDC requires real-time monitoring through optical spectroscopy, with particular attention to the evolution of excitonic features and absorption onset, which provide immediate feedback on size distribution and growth kinetics.

Advanced Applications and Detection Mechanisms

The enhanced control over PQD properties achieved through diffusion-limited growth principles enables sophisticated applications in sensing and detection. The synthesis of boric acid-functionalized bismuth-based non-toxic perovskite quantum dots (Cs3Bi2Br9-APBA) demonstrates this potential, where precise size control achieved through optimized LARP conditions enables highly sensitive detection of oxytetracycline with a detection limit of 0.0802 µM [23].

The detection mechanism relies on the inner filter effect (IFE), where the absorption spectrum of the target molecule (oxytetracycline) overlaps with the excitation and/or emission spectra of the PQDs, resulting in fluorescence quenching proportional to analyte concentration [23]. This application exemplifies how diffusion-controlled synthesis yields PQDs with tailored optical properties for specific sensing applications, addressing stability and toxicity concerns while maintaining exceptional detection sensitivity.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental and mechanistic pathway for diffusion-limited synthesis of perovskite quantum dots:

Diffusion Limited PQD Synthesis Workflow

The diagram illustrates the sequential process of diffusion-limited PQD synthesis, highlighting how critical parameters influence each stage. The nucleation burst initiated by anti-solvent injection transitions to diffusion-limited growth, where parameters including monomer concentration and diffusion gradient determine the progression to size-focusing regime and ultimately stable PQD formation.

The diffusion-limited growth model provides a fundamental framework for understanding and controlling the synthesis of colloidal perovskite quantum dots via ligand-assisted reprecipitation. By recognizing the critical role of monomer diffusion dynamics in determining final particle characteristics, researchers can implement strategic approaches such as Diffusion Dynamics Control to overcome traditional size limitations and distribution broadening. The experimental protocols and reagent strategies outlined in this whitepaper offer a pathway to reproducible synthesis of monodisperse PQDs with tailored optoelectronic properties, advancing their application in sensing, photonics, and beyond. As research in this field progresses, further refinement of diffusion models through high-throughput experimentation and machine learning approaches promises to unlock new dimensions of control in perovskite nanocrystal synthesis.

Advanced LARP Protocols and Biomedical Application Strategies

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) has emerged as a foundational synthesis technique for producing perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly cesium lead bromide (CsPbBr3) nanocrystals (NCs). This method leverages the differential solubility of perovskite precursors in polar solvents and non-polar antisolvents to achieve rapid nucleation and growth of nanocrystals at room temperature under ambient atmosphere [6] [24]. Unlike the hot-injection method which requires inert conditions and high temperatures, LARP synthesis offers a more accessible and scalable approach for producing high-quality PQDs [24]. The fundamental mechanism involves dissolving perovskite precursor salts in a polar solvent such as N,N'-dimethylformamide (DMF), then swiftly injecting this solution into a vigorously stirring non-polar antisolvent (e.g., toluene) containing stabilizing ligands [6]. This sudden change in solvent environment causes supersaturation, initiating nucleation and subsequent growth of nanocrystals stabilized by surface-bound ligands.

The simplicity and efficacy of LARP synthesis have made it instrumental in advancing basic research on PQDs, enabling fundamental studies of crystallization kinetics, surface chemistry, and structure-property relationships [6]. The method's versatility allows for precise control over nanocrystal size, morphology, and composition through manipulation of reaction parameters including ligand chemistry, precursor ratios, and antisolvent selection [25]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of LARP synthesis methodology, from fundamental CsPbBr3 NC preparation to advanced heterostructure formation, equipping researchers with the protocols necessary to exploit this technique for both fundamental investigation and applied technology development.

Experimental Protocols: Core Methodologies

Fundamental Synthesis of OA–OAm Capped CsPbBr3 NCs

The following protocol details the synthesis of standard oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) capped CsPbBr3 NCs via the LARP method [24]:

Step 1: Precursor Solution Preparation Prepare separate precursor solutions by dissolving 0.16 mmol of each salt (CsBr, PbBr2, and ZnBr2 for doped NCs) in 2 mL of anhydrous DMF in individual glass vials. For pure CsPbBr3 NCs, omit ZnBr2. Add 0.16 mmol of n-octylammonium bromide (OCABr) to 2 mL DMF in a separate vial. Stir each solution vigorously until complete salt dissolution is achieved.

Step 2: Final Precursor Mixture Combine the following volumes in a new glass vial: 800 μL CsBr precursor, 200 μL OCABr precursor, 1 mL PbBr2 precursor, 100 μL OAm, and 200 μL OA. For Zn-doped NCs, include 400 μL ZnBr2 precursor at this stage. Mix thoroughly to obtain a clear, homogeneous final precursor solution.

Step 3: Nucleation and Growth Swiftly inject 1 mL of the final precursor solution into a round-bottom flask containing 20 mL of toluene under vigorous stirring (500-700 rpm). Continue stirring for 15 minutes to allow complete nanocrystal growth.

Step 4: Purification and Collection Transfer the colloidal NC solution to a centrifuge tube. Add 4 mL of acetonitrile (ACN) as a non-solvent to precipitate the NCs. Centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes. Discard the supernatant and redisperse the pellet in fresh toluene for storage and characterization. The purified NCs are designated as CPB@OA NCs [24].

Advanced Coating and Functionalization Protocols

PVP Encapsulation of CsPbBr3 NCs [24]: Dissolve 20 mg of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, MW ~40,000) in 500 μL of ethanol. Add this PVP solution to 20 mL of toluene in a round-bottom flask. Inject 1 mL of the final precursor solution (from Step 2 above) dropwise into the flask under vigorous stirring. Continue the reaction for 15 minutes. Purify following the standard centrifugation protocol (Step 4). The resulting PVP-coated NCs are designated as CPB@OA@PVP NCs.

Silica Coating of CsPbBr3 NCs [24]: Add 20 μL of (3-aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane (APTMS) directly to 1 mL of the final precursor solution (from Step 2) and mix thoroughly. Swiftly inject this mixture into 20 mL of toluene under vigorous stirring. React for 15 minutes before purification via standard centrifugation. This yields silica-coated Zn-doped CsPbBr3 NCs.

Methyl Acetate Purification for Enhanced Stability [26]: Substitute conventional non-solvents (methanol, acetone) with methyl acetate (MeOAc) during the purification step. Add 4-5 mL MeOAc to the NC solution after synthesis and centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes. MeOAc undergoes hydrolysis in the presence of PQDs, generating acetate anions that partially replace original surface ligands without damaging the NC cores, resulting in enhanced stability and suppressed non-radiative recombination.

The emulsion LARP approach emphasizes critical balancing of OA and OLA (oleylamine) ligands:

- Prepare precursor solutions as in standard LARP

- Systematically vary the OA:OLA ratio between 1:1 and 1:2 while maintaining total ligand volume

- Optimize reaction temperature between 20-30°C

- Control injection rate to 1 mL/min for controlled emulsion formation

- Balance is achieved when sharp excitonic emission at ~510 nm with FWHM <25 nm is obtained

Table 1: Critical Synthesis Parameters and Their Impact on NC Properties

| Parameter | Typical Range | Impact on NC Properties | Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| OA:OAm Ratio | 1:1 to 1:2 | Defines surface passivation, optical properties [25] | ~1:1.5 (vol/vol) |

| Reaction Time | 5-30 min | Controls nucleation & growth completion [6] | 15 min |

| Precursor Concentration | 0.08-0.2 M | Determines NC size, size distribution [6] | 0.16 M |

| Antisolvent:Solvent Ratio | 15:1 to 25:1 | Affects supersaturation, nucleation rate [6] | 20:1 |

| Temperature | 20-30°C | Influences reaction kinetics, crystal quality [25] | 25°C |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Materials for LARP Synthesis and Their Functions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salts | CsBr, PbBr₂, ZnBr₂ | Provides metal and halide ions for perovskite crystal formation [24] |

| Solvents | DMF, Toluene, Acetonitrile | DMF: Dissolves precursors; Toluene: Antisolvent for reprecipitation; ACN: Purification non-solvent [24] |

| Ligands | Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm), n-Octylammonium Bromide (OCABr) | Surface passivation, size control, colloidal stability [24] [25] |

| Coating Materials | PVP, APTMS (for silica) | Enhances stability, enables functionalization [24] |

| Alternative Non-solvents | Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Gentler purification, maintains structural integrity [26] |

Visualization of Synthesis Workflows and Mechanisms

LARP Synthesis Workflow

Diagram 1: LARP Synthesis Workflow

Ligand Function and Charge Transfer Mechanism

Diagram 2: Ligand Function Mechanism

Shell-Dependent Charge Transfer in Heterostructures

Diagram 3: Shell-Dependent Charge Transfer

Data Presentation: Quantitative Analysis of NC Properties

Table 3: Optical Properties and Performance Metrics of LARP-Synthesized NCs

| NC Type | PLQY (%) | PL Peak (nm) | FWHM (nm) | Stability | Charge Transfer Rate | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPB@OA NCs | >80 [24] | ~515 [24] | <25 [25] | Moderate [24] | Fast [24] | LEDs, Lasers [27] |

| CPB@OA@PVP NCs | >75 [24] | ~518 [24] | ~26 [24] | High [24] | Moderate [24] | Bio-imaging, Color-converted LEDs [24] |

| Silica-coated NCs | >70 [24] | ~520 [24] | ~28 [24] | Very High [24] | Slow [24] | harsh environment sensors [24] |

| MeOAc-washed MAPbBr3 | High maintenence [26] | ~525 [26] | ~25 [26] | Enhanced [26] | Not reported | Stretchable color filters [26] |

Advanced Applications and Heterostructure Engineering

The LARP-synthesized CsPbBr3 NCs serve as building blocks for advanced heterostructures with tailored charge transfer properties. Studies have demonstrated that combining CsPbBr3 NCs with nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots (NCQDs) creates heterostructures where the charge transfer rate depends critically on shell thickness [24]. Thin-shelled NCs (OA/OAm capped only) facilitate faster charge transfer due to direct bonding between N-states of NCQDs and Pb-atoms in the CsPbBr3 structure [24]. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations reveal that electron acceptor states of N-atoms in NCQDs lie below the conduction band of perovskite NCs, enabling efficient charge separation [24].

These heterostructures enable various applications including:

- Photocatalysis and CO2 reduction: Enhanced charge separation improves catalytic efficiency [24]

- Solar cells: Type-II band alignment facilitates electron-hole pair separation [24]