Ligand Engineering for Perovskite Quantum Dots: How Functional Groups Passivate Surface Defects to Enhance Stability and Performance

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists on how ligand functional groups passivate surface defects in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs).

Ligand Engineering for Perovskite Quantum Dots: How Functional Groups Passivate Surface Defects to Enhance Stability and Performance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists on how ligand functional groups passivate surface defects in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). Surface defects on PQDs, originating from ionic nature and ligand detachment, lead to non-radiative recombination and structural degradation, critically limiting their application in optoelectronics and biomedicine. We explore the fundamental mechanisms of defect formation, detail advanced ligand engineering strategies—including ligand modification, core-shell structuring, and multifunctional molecular anchors—and present optimization techniques to overcome common challenges. The review synthesizes experimental validation and comparative performance data, establishing a clear link between specific ligand functionalities, enhanced PQD stability, and improved optoelectronic properties, offering valuable insights for developing next-generation, stable PQD-based devices.

The Science of Surface Defects: Understanding PQD Instability and Passivation Principles

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) have emerged as groundbreaking semiconductor nanomaterials with exceptional optoelectronic properties, including near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), narrow emission spectra, and exceptional defect tolerance [1]. These characteristics make them promising candidates for next-generation technologies such as light-emitting diodes (LEDs), photovoltaic cells, and photodetectors [2]. However, their widespread commercialization faces a critical bottleneck: intrinsic structural instability that leads to rapid degradation and performance deterioration [2] [1]. This instability predominantly originates from surface defects within the PQD lattice, which act as non-radiative recombination centers, quench photoluminescence, and accelerate material degradation under environmental stressors.

Understanding the root causes of these surface defects is fundamental to advancing PQD research. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the inherent instability mechanisms in PQD lattices, with particular focus on how ligand functional groups contribute to defect passivation. By examining the crystallographic origins of defects, quantitative characterization data, and experimental passivation methodologies, this document aims to equip researchers with the fundamental knowledge needed to design more stable and efficient PQD-based optoelectronic devices.

Fundamental Instability Mechanisms in PQD Lattices

Crystallographic Defects and Ion Migration

The exceptional optoelectronic properties of PQDs stem from their unique crystal structure, yet this same structure harbors inherent vulnerabilities. The perovskite lattice, with general formula APbX₃ (where A is a cation such as Cs⁺ and X is a halide anion), contains low formation energies for defect generation, particularly for halide vacancies [2]. These vacancies create shallow and deep trap states within the band gap that significantly impact charge carrier dynamics.

Low Ion Migration Energy: The minimal energy required for ion migration within the PQD lattice facilitates defect mobility and aggregation. This low activation barrier enables halide ions and vacancies to move freely through the crystal structure, especially under external stimuli such as electric fields, light, or heat [2].

Halide Vacancy Formation: Halide vacancies represent the most common and detrimental defect species in PQD systems. Their low formation energy stems from the relatively weak ionic bonding character in metal-halide frameworks. These vacancies serve as entry points for further degradation and act as centers for non-radiative recombination [2].

Interstitial Defects: The open structure of perovskite lattices allows for the formation of interstitial defects, where ions occupy non-lattice sites. These defects create localized strain fields and electronic trap states that compromise both structural integrity and optoelectronic performance [2].

Surface Defect Dynamics and Ligand Interactions

The high surface-to-volume ratio of quantum dots amplifies the impact of surface defects, making surface chemistry a critical determinant of PQD stability. Surface defects primarily arise from incomplete coordination of surface ions and dynamic ligand binding processes.

Undercoordinated Surface Ions: Surface Pb²⁺ ions lacking proper halide coordination form highly reactive sites that readily trap charge carriers. These undercoordinated sites exhibit reduced formation energy compared to bulk defects, making them predominant sources of performance degradation [1].

Ligand Detachment Dynamics: Organic ligands such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) stabilize PQD surfaces through coordinate bonding. However, their binding is inherently dynamic and reversible. The cis-configuration of carbon-carbon double bonds in these conventional ligands creates kinked molecular conformations that impose steric constraints, resulting in suboptimal surface coverage [2]. During purification processes or upon exposure to environmental stressors, these weakly-bound ligands readily dissociate, generating additional surface vacancies and exposing reactive sites.

Table 1: Primary Defect Types in PQD Lattices and Their Characteristics

| Defect Type | Formation Energy | Impact on Performance | Prevalence in Nanocrystals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Halide Vacancies (Vₕ) | Low | Non-radiative recombination, ion migration pathways | High - enhanced surface availability |

| Metal Vacancies (Vₘ) | Moderate | Hole trapping, structural instability | Moderate |

| Interstitial Halides (Iₕ) | Low to Moderate | Electron trapping, lattice strain | Moderate |

| Undercoordinated Surface Sites | Very Low | Severe non-radiative recombination, degradation initiation | Very High - surface specific |

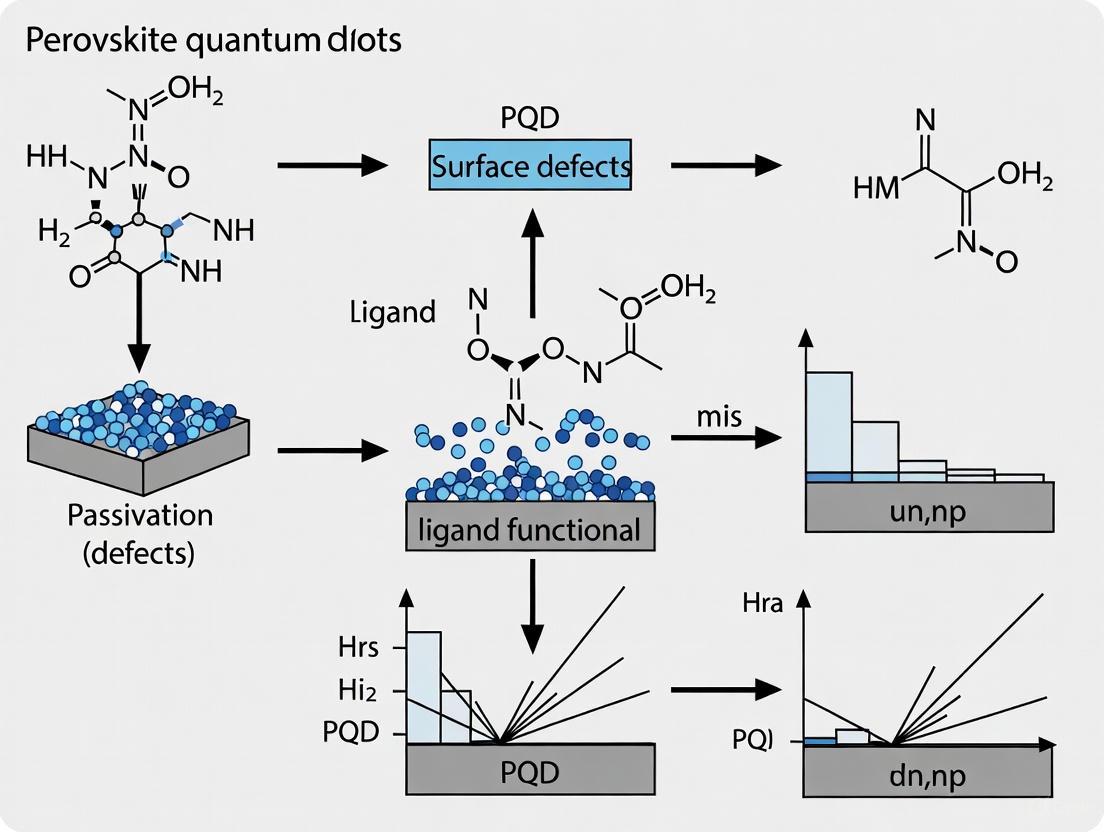

Figure 1: Root Cause Analysis of PQD Instability - This diagram illustrates the relationship between intrinsic material properties, defect formation mechanisms, and resulting performance degradation in perovskite quantum dots.

Quantitative Analysis of Defect Impact on PQD Properties

The presence of surface defects directly correlates with measurable declines in key performance metrics across multiple PQD systems. Quantitative studies reveal systematic relationships between defect density, optoelectronic performance, and environmental stability.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Surface Defects on PQD Performance Characteristics

| PQD Material | Defect Density (a.u.) | PLQY (%) | Lifetime (ns) | Stability Retention | Measurement Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ (Unpassivated) | 1.0 | 45-65 | 8.5 | <50% (7 days) | Ambient, 25°C, 60% RH |

| CsPbBr₃ (DDAB Passivated) | 0.3 | 85-95 | 22.7 | >90% (7 days) | Ambient, 25°C, 60% RH |

| CsPbIₓBr₃₋ₓ (Unpassivated) | 1.0 | 50-70 | 6.2 | <20% (3 days) | Ambient, 25°C, 50% RH |

| CsPbIₓBr₃₋ₓ (Ion-Doped) | 0.5 | 75-85 | 14.3 | ~70% (3 days) | Ambient, 25°C, 50% RH |

| Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ (Unpassivated) | 0.8 | 25-40 | 4.5 | ~60% (7 days) | Ambient, 25°C, 60% RH |

| Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/DDAB/SiO₂ | 0.2 | 65-80 | 15.2 | >95% (7 days) | Ambient, 25°C, 60% RH |

The data demonstrates that defect passivation strategies systematically improve all key performance parameters. The most dramatic enhancements occur in lifetime measurements, where passivated samples exhibit approximately 2-3× longer photoluminescence lifetimes, indicating significant suppression of non-radiative recombination pathways [2].

Ligand Functional Groups in Defect Passivation: Mechanisms and Efficacy

Molecular Design Principles for Effective Passivation

Ligand functional groups serve as the primary interface between the PQD surface and its environment, with their molecular structure directly determining passivation efficacy. Optimal ligand design balances binding affinity, steric considerations, and electronic effects to maximize defect coverage and stability.

Binding Group Selection: Effective ligands feature functional groups with strong affinity for specific surface sites. For lead-halide perovskites, ammonium groups (in alkylammonium ligands) and carboxylic acids demonstrate particularly strong binding to halide-deficient surfaces and undercoordinated lead atoms, respectively [2]. The binding strength originates from Lewis acid-base interactions between ligand donor atoms and unsaturated surface ions.

Chain Length Optimization: Ligand alkyl chain length profoundly impacts surface coverage and charge transport. Short-chain ligands like didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) provide enhanced surface coverage compared to conventional long-chain ligands (OA/OAm) due to reduced steric hindrance [2]. However, extremely short chains may compromise colloidal stability, necessitating careful balance in molecular design.

Multidentate Approaches: Ligands featuring multiple binding groups can chelate surface sites more effectively than monodentate analogues. This multidentate binding creates more stable ligand-surface complexes that resist desorption under operational stressors, significantly improving passivation durability [2].

Specific Ligand-Surface Interactions

The passivation mechanism varies significantly depending on the specific ligand functional groups and their target surface defects:

Ammonium-Based Passivation: Quaternary ammonium compounds like DDAB demonstrate exceptional effectiveness for bromide-containing PQDs. The DDA⁺ cation exhibits strong affinity for bromide anions, effectively compensating for bromide vacancies and reducing surface trap states [2]. Studies confirm that DDAB-passivated CsPbBr₃ PQDs show increased PLQY and reduced surface defect states [2].

Carboxylic Acid and Amine Synergy: The conventional OA/OAm ligand pair operates through complementary interactions. Carboxylic acid groups bind to undercoordinated lead sites, while amine groups interact with halide-deficient regions. However, the cis-configuration of their carbon-carbon double bonds creates kinked molecular structures that limit packing density and passivation completeness [2].

Short-Chain Ligand Advantages: Compared to conventional long-chain ligands, relatively short-chain molecules like DDAB enable higher surface coverage due to their reduced steric footprint and enhanced mobility during synthesis [2]. This increased coverage directly translates to more comprehensive defect passivation and improved environmental stability.

Experimental Protocols for Defect Analysis and Passivation

Synthesis of Passivated PQDs: Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/DDAB/SiO₂ Case Study

The following protocol details the synthesis of stable, passivated lead-free perovskite quantum dots, incorporating organic and inorganic hybrid protection based on established methodologies [2]:

Materials:

- Cesium bromide (CsBr, 99.9%)

- Bismuth tribromide (BiBr₃, 99.9%)

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, anhydrous)

- Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB, 98%)

- Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, 99%)

- Oleic acid (OA, 99.5%)

- Oleylamine (OAm, 99.99%)

- Anhydrous ethanol

Synthesis Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve CsBr (0.2 mmol, 0.0426 g) and BiBr₃ (0.2 mmol, 0.1116 g) in 10 mL DMSO with vigorous stirring at 60°C until fully dissolved.

Ligand Addition: Add OA (1.0 mL) and OAm (1.0 mL) to the precursor solution under continuous stirring.

Quantum Dot Formation: Rapidly inject 1.0 mL of the precursor solution into 20 mL of toluene under vigorous stirring. Immediate formation of a colored colloid indicates PQD nucleation.

Organic Passivation: Add DDAB (10 mg in 1 mL toluene) to the crude solution and stir for 30 minutes. DDAB concentration should be optimized for specific applications.

Inorganic Encapsulation: Add TEOS (2.4 mL) to the reaction mixture and stir for 2 hours to facilitate SiO₂ shell formation through hydrolysis and condensation.

Purification: Precipitate PQDs by adding anhydrous ethanol, followed by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes. Redisperse in toluene for further characterization.

Critical Parameters:

- Reaction atmosphere: Inert gas (N₂ or Ar) recommended for oxygen-sensitive materials

- Temperature control: Maintain at 25±2°C during PQD formation

- DDAB optimization: Test concentrations from 1-10 mg to balance passivation and dispersibility

Characterization Methods for Defect Quantification

Comprehensive defect analysis requires multi-technique approaches to quantify defect density, understand passivation efficacy, and correlate structural features with optoelectronic performance:

Photoluminescence Spectroscopy: Steady-state PL measurements provide initial assessment of defect presence through quantum yield calculations and spectral shape analysis. A high PLQY indicates effective suppression of non-radiative pathways [2].

Time-Resolved Photoluminescence: PL lifetime measurements quantitatively distinguish between radiative and non-radiative recombination pathways. Biexponential fitting of decay curves yields fast (defect-related) and slow (radiative) components, with longer average lifetimes indicating superior passivation [2].

Temperature-Dependent PL Analysis: Temperature-dependent studies from 20-300 K probe exciton-phonon interactions and defect energy distribution. Reduced thermal quenching in passivated samples demonstrates suppressed non-radiative pathways at elevated temperatures [2].

Transmission Electron Microscopy: High-resolution TEM reveals morphological changes before and after passivation. For Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs, DDAB addition causes closer packing without altering quasispherical morphology, while subsequent TEOS treatment generates a protective SiO₂ shell approximately 2-5 nm thick [2].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for PQD Passivation and Characterization - This diagram outlines the sequential process for synthesizing passivated perovskite quantum dots and comprehensively evaluating their structural and optoelectronic properties.

Research Reagent Solutions for Defect Passivation Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Defect Passivation Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Research | Specific Role in Defect Passivation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Organic passivator | Compensates bromide vacancies, enhances surface coverage | Short-chain ligand for improved packing density on CsPbBr₃ and Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ [2] |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Inorganic precursor | Forms protective SiO₂ shell, prevents environmental degradation | Encapsulation of DDAB-passivated PQDs for enhanced stability [2] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand | Binds to undercoordinated metal sites, controls growth | Conventional capping ligand in initial synthesis [2] |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Surface ligand | Interacts with halide-deficient surfaces, charge balance | Conventional co-ligand in PQD synthesis [2] |

| Cesium Bromide (CsBr) | Perovskite precursor | Provides cesium cations for crystal structure | Synthesis of cesium-based PQDs [2] |

| Bismuth Tribromide (BiBr₃) | Perovskite precursor | Provides bismuth cations for lead-free alternatives | Formation of Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs [2] |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Solvent | Dissolves precursor salts, mediates crystallization | Antisolvent synthesis of PQDs [2] |

The intrinsic instability of perovskite quantum dots originates fundamentally from low defect formation energies and dynamic surface chemistry, particularly at undercoordinated lattice sites. Ligand functional groups serve as powerful tools for mitigating these defects through strategic molecular design that addresses specific surface deficiencies. The synergistic combination of organic passivation (e.g., DDAB) with inorganic encapsulation (e.g., SiO₂) represents a particularly promising approach, demonstrated by the enhanced stability and performance of lead-free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs [2].

Future research should prioritize the development of multifunctional ligands capable of simultaneously addressing multiple defect types while providing enhanced environmental resistance. Additionally, standardized protocols for quantifying defect density and passivation completeness will enable more direct comparison between different passivation strategies across research groups. As understanding of defect-passivator relationships deepens, rationally designed ligand systems will unlock the full potential of PQDs in commercial optoelectronic applications, bridging the gap between laboratory innovation and industrial implementation.

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) have emerged as revolutionary semiconductor nanomaterials with exceptional optoelectronic properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), tunable bandgaps, and narrow emission peaks, making them ideal for applications in light-emitting diodes (LEDs), solar cells, and photodetectors [3] [4]. However, their significantly large surface-area-to-volume ratio makes them highly susceptible to surface defects, which act as non-radiative recombination centers, quenching photoluminescence and accelerating degradation under environmental stressors [5] [3]. The structural integrity and optoelectronic performance of PQDs are fundamentally governed by the nature and density of these surface defects, which primarily occur at cationic, anionic, and metal ion sites.

Understanding this defect landscape is paramount for developing effective passivation strategies. This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of defect vulnerabilities in PQDs, framed within the broader context of how ligand functional groups passivate these critical surface sites. We systematically categorize defect types, present quantitative data on passivation efficacy, detail experimental methodologies for defect characterization and passivation, and visualize the complex relationships within the defect-passivation ecosystem, offering researchers a foundational resource for advancing PQD-based technologies.

The Atomic-Level Defect Landscape in PQDs

The surface of PQDs is a complex terrain of under-coordinated atoms resulting from the termination of the crystalline lattice. These unpassivated sites create energy states within the bandgap that facilitate non-radiative recombination. The defect landscape can be categorized into three primary vulnerabilities, each with distinct chemical characteristics and impacts on device performance.

Metal Site (B-site) Vulnerabilities

The metal site, typically occupied by Pb²⁺ in lead-halide perovskites, is a major source of surface defects. Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions arise from incomplete [PbX₆]⁴⁻ octahedra at the crystal surface [6]. These Lewis acidic sites are potent non-radiative recombination centers. The low formation energy for generating these sites makes them a prevalent defect, particularly after synthesis or purification processes that strip protective ligands [2]. The passivation of these sites often involves Lewis base molecules that donate electron density to the vacant orbitals of the Pb²⁺ ion.

Anionic (X-site) Vulnerabilities

Halide vacancies (Vₓ) are among the most common and mobile defects in PQDs due to their low formation energy [2]. These anionic vacancies create under-coordinated Pb atoms and act as deep traps for charge carriers, severely degrading luminescence efficiency and facilitating ion migration [3] [6]. The inherent ionic nature of the perovskite lattice makes the surface halide ions particularly labile, especially when exposed to polar solvents during processing [7].

Cationic (A-site) Vulnerabilities

While less discussed than metal or halide sites, cationic vacancies (e.g., Cs⁺ sites in all-inorganic perovskites) also contribute to the defect landscape. Although their direct role as non-radiative centers may be less pronounced, they can influence electrostatic stability and ion migration pathways within the crystal [3]. The large ionic radius of A-site cations means their vacancies create significant lattice distortions.

Table 1: Summary of Primary Defect Types in Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Defect Site | Atomic Vulnerability | Chemical Nature | Impact on Optoelectronic Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Site (B-site) | Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions | Lewis Acidic | Deep trap states; strong non-radiative recombination centers [6] |

| Anionic Site (X-site) | Halide Vacancies (Vₓ) | Anionic Deficiency | Shallow and deep traps; facilitates ion migration; reduces PLQY [2] [6] |

| Cationic Site (A-site) | Cationic Vacancies (Vₐ) | Cationic Deficiency | Lattice distortion; can influence ion migration and phase stability [3] |

Ligand Passivation Mechanisms and Functional Group Efficacy

Ligand engineering serves as the primary strategy for mitigating surface defects in PQDs. The passivation mechanism is governed by the coordination chemistry between functional groups on the ligand and the specific under-coordinated sites on the PQD surface.

Fundamental Passivation Chemistry

Effective passivation relies on the formation of stable coordination complexes between ligand functional groups and surface atoms. Conventional ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) operate via a binary passivation model: the carboxylate group (-COO⁻) of OA binds to under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions, while the ammonium group (-NH₃⁺) of OAm interacts with halide anions via hydrogen bonding or electrostatic interactions [3]. However, the binding of these long-chain ligands is highly dynamic and labile, often leading to ligand desorption and re-exposure of defect sites [4] [6].

Advanced Ligand Design Strategies

Recent research has focused on developing ligands with stronger binding affinity and multifunctional capabilities:

- Multidentate and Bifunctional Ligands: Molecules like 12-aminododecanoic acid, which contain both amine and carboxylic acid groups in a single chain, offer a simplified and effective passivation approach [3]. Similarly, 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA), used for ternary AgBiS₂ nanocrystals, possesses both thiol and carboxylic acid groups, enabling comprehensive surface binding to different metal cation sites [8].

- Lewis Base Ligands: Molecules such as triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) act as strong Lewis bases, forming stable covalent bonds with under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites via their oxygen atom. This strong coordination significantly reduces surface trap density [7].

- Imide Derivatives: Ligands like caffeine have demonstrated high efficacy in passivating under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions. The atomic charge of the carbonyl oxygen in these molecules is a key descriptor, with a more negative charge correlating with stronger passivation efficacy [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Efficacy of Selected Passivation Ligands

| Ligand | Functional Group(s) | Target Defect(s) | Reported Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine | Carbonyl (C=O) | Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ | Significant improvement in PLQY and thermal stability; enabled LEDs with 130% NTSC color gamut. | [5] |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) | Phosphine Oxide (P=O) | Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ | Enhanced PCE of CsPbI₃ PQD solar cells to 15.4%; >90% initial efficiency retained after 18 days. | [7] |

| 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | Thiol (-SH), Carboxyl (-COOH) | Ag and Bi sites (in AgBiS₂) | Comprehensive surface passivation; ~12% PCE improvement in PV devices. | [8] |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Amine (-NH₂) | Halide Anions (X⁻) | Essential for initial synthesis and defect passivation; dynamic binding requires stabilization. | [3] [9] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Carboxyl (-COOH) | Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ | Essential for initial synthesis and defect passivation; dynamic binding requires stabilization. | [3] [9] |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Ammonium (R₄N⁺) | Halide Anions (X⁻) | Increased PLQY and stability in CsPbBr₃ and lead-free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs. | [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Defect Passivation and Analysis

Synthesis and Passivation Methods

Hot-Injection (HI) Method: This is a widely used colloidal synthesis technique for high-quality PQDs. A typical procedure involves injecting a Cs-oleate precursor into a hot (140–200 °C) solution of PbX₂, OA, and OAm in 1-octadecene (ODE) under an inert atmosphere [3] [4]. The reaction is quenched after a few seconds using an ice bath. Passivating ligands can be introduced in situ by including them in the precursor or reaction solution.

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP): A simpler, room-temperature method where a perovskite precursor dissolved in a polar solvent (e.g., DMF, DMSO) is rapidly injected into a poor solvent (e.g., toluene) containing capping ligands, triggering instantaneous crystallization [3].

Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange: This critical step replaces long, insulating initial ligands (OA/OAm) with shorter or more strongly binding passivants. A standard protocol involves repeatedly treating a film of pristine PQDs with a solution of the new ligand (e.g., TPPO in octane or MPA in acetonitrile) via spin-coating or dipping, followed by rinsing and centrifugation to remove ligand byproducts [7] [8].

Characterization Techniques for Defect Analysis

- Photoluminescence Spectroscopy (PL): Measuring the PL quantum yield (PLQY) and lifetime provides a direct assessment of defect density. A higher PLQY and longer lifetime indicate effective passivation of non-radiative recombination centers [5] [6].

- Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Used to confirm the binding of ligands to the PQD surface by identifying shifts in characteristic absorption bands (e.g., C=O stretch, N-H stretch) [9] [7].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Solution-state or solid-state NMR can quantify ligand density and analyze the molecular state of ligands bound to the QD surface [9].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Probes the elemental composition and chemical states at the PQD surface, helping identify the presence of under-coordinated metal ions and the nature of ligand-metal binding [2] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PQD Defect Passivation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard long-chain ligands for initial PQD synthesis and colloidal stabilization. | Used in both Hot-Injection and LARP synthesis methods to control growth and provide initial surface coverage [3] [4]. |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) | Covalent short-chain ligand for post-synthesis passivation of Pb²⁺ sites. | Dissolved in non-polar solvents (e.g., octane) to passivate ligand-exchanged CsPbI₃ PQDs without damaging the surface [7]. |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Short-chain ammonium salt for passivating halide vacancies and improving stability. | Employed to passivate lead-free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs, enhancing PL and stability for electroluminescent devices [2]. |

| Caffeine & Imide Derivatives | Lewis base molecules for targeted passivation of under-coordinated Pb²⁺. | Added during synthesis to improve optical properties and thermal stability of PQDs for high-color-gamut LEDs [5]. |

| 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | Bifunctional ligand (thiol and carboxyl) for comprehensive passivation of ternary NCs. | Used in ligand exchange for AgBiS₂ NCs to bind both Ag and Bi sites, following Hard-Soft Acid-Base principles [8]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous host matrices for spatial confinement and surface passivation of PQDs. | PCN-333(Fe) MOF used to anchor CsPbBr₃ PQDs via carboxylate groups, enhancing PL intensity and stability [6]. |

| Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (t-OABr) | Precursor for forming protective shells on PQD cores. | Used to create a core-shell structure (MAPbBr₃@t-OAPbBr₃) for enhanced stability in perovskite solar cells [10]. |

The journey to stable and high-performance perovskite quantum dots hinges on a deep and precise understanding of their atomic-scale defect landscape. The vulnerabilities at cationic, anionic, and metal sites each present distinct challenges that demand tailored passivation solutions. As this guide has detailed, the strategic selection of ligand functional groups—from conventional carboxylate and amine pairs to advanced Lewis bases and multifunctional molecules like MPA—is the most powerful tool for addressing these challenges.

Future research directions will likely focus on the design of multi-functional ligands that can simultaneously passivate multiple defect types with high binding affinity, the development of in-situ passivation protocols that integrate seamlessly with scalable fabrication processes and the exploration of cation-selective ligand strategies for complex ternary and quaternary perovskite compositions. The ultimate goal is a unified defect-passivation model that links specific functional groups to quantitative performance metrics, enabling the rational design of PQD materials for a new generation of optoelectronic devices.

The exceptional optoelectronic properties of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), including their high photoluminescence quantum yield, tunable bandgaps, and defect tolerance, have positioned them as leading materials for next-generation devices such as solar cells, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and sensors [10] [6]. However, the intrinsic ionic nature and low formation energy of perovskites result in a highly dynamic and defective surface, where unpassivated sites act as non-radiative recombination centers that quench luminescence and degrade performance [6]. The passivation of these surface defects is therefore not merely an enhancement step but a fundamental requirement for functional PQD-based technologies.

Ligand binding dynamics sit at the heart of effective surface passivation. The PQD surface is characterized by undercoordinated lead atoms (Pb²⁺) and halide vacancies, which are the primary defects that must be addressed [6]. The functional groups of ligand molecules directly anchor to these surface sites, determining the stability and electronic properties of the resulting PQD. The binding is a dynamic process; conventional ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) exhibit highly dynamic bonding at the PQD-ligand-solvent interface, leading to easy desorption and re-exposure of defects [6]. Consequently, research has shifted toward designing ligands with specific functional groups that form stronger, more stable bonds with the PQD surface. This guide examines the mechanistic roles of different functional groups in anchoring to PQD surfaces, providing a detailed technical framework for researchers aiming to design advanced passivation strategies for enhanced device performance and stability.

Fundamental Binding Mechanisms of Key Functional Groups

The interaction between a ligand's functional group and the PQD surface is primarily a coordination chemistry process. The efficacy of passivation is governed by the strength and stability of the bond formed, which in turn is determined by the electron-donating properties and steric profile of the functional group.

Carboxylate Group Coordination

The carboxylate group (-COO⁻) is one of the most prevalent and effective functional groups for passivating undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions. The binding mechanism involves the donation of lone pair electrons from the oxygen atoms of the carboxylate group to the vacant orbitals of the Pb²⁺ ion, forming a coordinate covalent bond [6]. This interaction effectively neutralizes the positive charge on the Pb²⁺ site, suppressing its activity as an electron trap.

- Binding Configuration: The carboxylate group can bind in a bidentate chelating mode, which offers superior stability compared to monodentate or physisorbed ligands. Research on CsPbBr₃ PQDs anchored to a metal-organic framework (MOF) demonstrated that the abundant carboxylate groups of the PCN-333(Fe) MOF provided lone pair electrons to coordinate with the uncoordinated Pb²⁺ on the PQD surface [6]. This specific interaction passivated surface defects, resulting in a 6.5-fold enhancement in photoluminescence intensity compared to pure CsPbBr₃ PQDs [6].

- Electron Density and Binding Strength: The binding strength is influenced by the electron density on the oxygen atoms. Electron-donating substituents on the ligand backbone can increase this density, leading to a stronger bond. The stability of the carboxylate-Pb²⁺ bond is crucial for mitigating ligand desorption under operational stresses such as heat, light, or solvent exposure.

Sulfonate Group Anchoring

Sulfonate groups (-SO₃⁻) represent a more advanced class of passivating agents due to their stronger binding affinity to the perovskite surface. The sulfonate group features three electronegative oxygen atoms, which can engage in multiple simultaneous interactions with the Pb²⁺-rich surface.

- Enhanced Binding Affinity: The sulfonate group's higher acidity (lower pKa) compared to carboxylates makes it a better leaving group and a stronger coordinator for Pb²⁺ cations. Studies on ester antisolvents have shown that sulfonate-based esters like methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) and methyl benzenesulfonate (MeBzSO₃) possess a powerful binding affinity [11]. However, their excessive polarity can lead to the instantaneous degradation of the perovskite core if not applied under carefully controlled conditions [11].

- Trade-offs in Application: While their binding is robust, the high polarity of sulfonate-based ligands presents a challenge. Their application often requires modified synthesis or post-synthesis treatment protocols to prevent damaging the ionic perovskite lattice [11].

Amine Group Interactions

Amine groups, primarily from ligands like oleylamine (OAm), play a complementary but vital role in surface passivation. Their primary function is to passivate halide anion vacancies through hydrogen bonding or direct ligand interaction [6].

- Passivation Mechanism: The nitrogen atom in the amine group, with its lone pair of electrons, can interact with exposed halide ions or fill halide vacancies. This interaction helps maintain the structural integrity of the [PbX₆]⁴⁻ octahedra and reduces halide-related defects [6].

- Synergistic Effect with Carboxylates: Amines are typically used in conjunction with carboxylic acids. The combination helps balance the surface charge and provides a more complete passivation layer. However, the bonding of conventional alkyl amines is highly dynamic, leading to susceptibility of desorption.

Advanced Ligand Designs: The Alkaline-Augmented Hydrolysis Strategy

Recent innovations focus on transforming the ligand binding environment to enhance passivation efficacy. The Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH) strategy creates an alkaline environment during the ligand exchange process, fundamentally altering the thermodynamics and kinetics of ester hydrolysis into carboxylate ligands [11].

- Mechanistic Insight: Theoretical calculations reveal that an alkaline environment renders ester hydrolysis thermodynamically spontaneous and lowers the reaction activation energy by approximately 9-fold [11]. This promotes the rapid substitution of pristine insulating oleate (OA⁻) ligands with hydrolyzed conductive counterparts.

- Quantitative Outcome: This strategy enables the substitution with up to twice the conventional amount of conductive short ligands, creating a denser and more robust conductive capping on the PQD surface. This leads to light-absorbing layers with fewer trap-states, homogeneous orientations, and minimal particle agglomerations [11].

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand-PQD Interactions

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Functional Group Efficacy in PQD Passivation

| Functional Group | Primary Binding Target | Binding Mode | Reported Binding Strength/Effect | Key Impact on PLQY | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxylate (-COO⁻) | Undercoordinated Pb²⁺ | Bidentate Chelation | Moderate to Strong | Up to 90% (with Co-doping) [12] | Dynamic bonding, susceptible to desorption |

| Sulfonate (-SO₃⁻) | Undercoordinated Pb²⁺ | Tridentate/Strong Chelation | Very Strong | N/A (often causes degradation) | High polarity can disrupt perovskite lattice |

| Amine (-NH₂, -NR₂) | Halide Anions / Vacancies | Hydrogen Bonding / Ionic | Moderate | Used in synergy with carboxylates | Weak binding, highly dynamic |

| Benzoate (from MeBz) | Undercoordinated Pb²⁺ | Chelation (Aromatic) | Enhanced (vs. Acetate) | Contributes to high PCE in PV [11] | Requires controlled hydrolysis (e.g., AAAH) |

| Acetate (from MeOAc) | Undercoordinated Pb²⁺ | Weak Chelation / Monodentate | Weak | Foundational, but limited | Weak binding, easily displaced |

Table 2: Impact of Advanced Passivation Strategies on Device Performance

| Passivation Strategy | PQD System | Key Metric Improvement | Quantitative Result | Reference/Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOF Passivation (PCN-333(Fe)) | CsPbBr₃ | Photoluminescence (PL) Intensity | 6.5x enhancement [6] | Defect passivation via carboxylate |

| MOF Passivation (PCN-333(Fe)) | CsPbBr₃ | Cu²⁺ Detection Limit (LOD) | 1.63 nM (vs. 2.89 nM for pure CsPbBr₃) [6] | Enhanced sensitivity from reduced defects |

| In Situ Core-Shell PQDs | MAPbBr₃@tetra-OAPbBr₃ | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Increased from 19.2% to 22.85% [10] | Passivation of grain boundaries |

| Alkali-Augmented Hydrolysis (AAAH) | FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ | Certified PCE | 18.3% (record for hybrid PQDSCs) [11] | Dense conductive capping layer |

| Encapsulation with EVA-TPR | CsPbBr₃ | Physical & Optical Stability | Enhanced stability and efficiency [12] | Polymer-based post-synthesis encapsulation |

Experimental Protocols for Probing Anchoring Dynamics

Post-Synthesis Surface Treatment with MOFs

This protocol details the passivation of CsPbBr₃ PQDs using a metal-organic framework (PCN-333(Fe)) as a carboxylate-group-rich substrate, as described by Li et al. [6].

- Materials:

- CsPbBr₃ PQDs: Synthesized via hot-injection or ligand-assisted reprecipitation.

- PCN-333(Fe) MOF: Chosen for its large specific surface area (~2237 m²/g) and abundant carboxylate groups.

- Solvents: n-hexane, isopropanol (IPA), isobutanol (IBA), chlorobenzene.

- Procedure:

- Synthesis of CsPbBr₃ PQDs: Dissolve CsBr, PbBr₂, OA, and OAm in organic solvents (e.g., DMF, DMSO) under inert atmosphere. Rapidly inject this precursor into a non-solvent (e.g., toluene) under vigorous stirring to induce crystallization. Purify the resulting PQDs via centrifugation.

- Preparation of PQDs/MOFs Nanocomposite: Disperse the synthesized CsPbBr₃ PQDs in a non-polar solvent like n-hexane. Prepare a separate solution of PCN-333(Fe) in a suitable solvent. Combine the two solutions and stir for several hours to allow the carboxylate groups of the MOF to coordinate with the uncoordinated Pb²⁺ on the PQD surface.

- Purification and Characterization: Collect the composite material via centrifugation and wash to remove unbound species. Characterize using:

- FTIR Spectroscopy: To confirm the formation of Pb-O bonds between the PQD and the MOF's carboxylate groups.

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: To measure the enhancement in PL intensity and quantum yield.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): To observe the uniform distribution of PQDs on the MOF matrix.

This method leverages the strong and stable chelating action of the MOF's carboxylate groups to achieve significant enhancement in optical properties and stability [6].

In Situ Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Rinsing (AAAH)

This protocol, adapted from Wang et al., describes a powerful method for enhancing ligand exchange on PQD solid films to achieve a dense conductive capping layer [11].

- Materials:

- PQD Solid Films: Films deposited via layer-by-layer spin-coating.

- Antisolvent: Methyl benzoate (MeBz) with tailored polarity.

- Alkali Source: Potassium hydroxide (KOH).

- Procedure:

- Preparation of Alkaline Antisolvent: Add a carefully regulated concentration of KOH to methyl benzoate (MeBz) antisolvent. The alkalinity must be optimized to facilitate efficient hydrolysis without degrading the PQD core.

- Interlayer Rinsing: For each layer of the deposited PQD solid film, perform a rinsing step by dynamically spraying or drop-casting the alkaline MeBz antisolvent during the spin-coating process. This step is performed under ambient humidity.

- Hydrolysis and Ligand Exchange: The alkaline environment catalyzes the hydrolysis of MeBz into benzoate anions. These short, conductive ligands rapidly substitute the pristine long-chain insulating oleate (OA⁻) ligands on the PQD surface.

- Film Formation and Post-Treatment: After depositing the desired number of layers, a final post-treatment with short cationic ligands (e.g., formamidinium, phenethylammonium) can be applied to exchange the pristine oleylammonium (OAm⁺) ligands, further enhancing charge transport.

- Key Characterization:

- FTIR and NMR: To quantify the completion of ligand exchange and the new ligand population on the surface.

- Space-Charge-Limited Current (SCLC) Measurements: To quantify the significant reduction in trap-state density.

- Grazing-Incidence Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering (GIWAXS): To confirm improved crystallographic orientation and reduced agglomeration in the film.

The AAAH strategy is notable for overcoming the thermodynamic and kinetic barriers of conventional ester hydrolysis, enabling a record-certified efficiency of 18.3% for hybrid PQD solar cells [11].

Visualization of Ligand Binding and Passivation Pathways

PQD Surface Passivation by Ligand Functional Groups

Advanced Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating PQD Ligand Binding

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research | Key Consideration / Property |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Primary carboxylate ligand for synthesis; passivates Pb²⁺ sites. | Dynamic bonding leads to easy desorption; standard for comparison. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Primary amine ligand for synthesis; passivates halide vacancies. | Used synergistically with OA; contributes to colloidal stability. |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Ester antisolvent for interlayer rinsing; hydrolyzes to benzoate. | Aromatic ring enhances binding vs. acetate; polarity must be controlled [11]. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Alkali source for AAAH strategy; catalyzes ester hydrolysis. | Concentration is critical to prevent perovskite degradation [11]. |

| PCN-333(Fe) MOF | Carboxylate-rich substrate for post-synthesis passivation. | Large surface area (2237 m²/g) provides abundant binding sites [6]. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Conventional ester antisolvent; hydrolyzes to acetate. | Benchmark for antisolvent rinsing; yields weakly-bound acetate ligands [11]. |

| Dodecylbenzene Sulfonic Acid (DBSA) | Sulfonate ligand for enhanced surface binding. | Strong chelating agent; requires careful application due to high polarity [6]. |

| Ethylene Vinyl Acetate (EVA) | Polymer for post-synthesis encapsulation and stabilization. | Provides physical barrier; enhances optical stability in composites [12]. |

The strategic selection and engineering of ligand functional groups is a decisive factor in determining the optoelectronic performance and operational stability of perovskite quantum dots. The anchoring dynamics of carboxylates, sulfonates, and amines each offer distinct advantages and challenges for passivating specific surface defects on PQDs. Moving beyond conventional ligands, advanced strategies such as using MOFs as carboxylate reservoirs or employing alkaline-augmented hydrolysis to transform antisolvents into potent passivants represent significant leaps forward.

Future research will likely focus on the precise molecular design of multi-functional ligands that combine strong anchoring groups with auxiliary functions to further enhance stability. The integration of computational screening methods, including molecular dynamics and machine learning, will accelerate the discovery of next-generation ligands tailored for specific PQD compositions and applications. As understanding of these binding dynamics deepens, the path toward PQD devices that rival and surpass the performance of their traditional counterparts becomes increasingly clear.

The Goldschmidt tolerance factor (t) stands as a foundational principle in perovskite crystallography, providing a predictive geometric framework for assessing structural stability. This whitepaper examines the intrinsic relationship between the tolerance factor and the formation of surface defects in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), establishing how thermodynamic instability predicted by t directly correlates with susceptibility to surface defect formation. Furthermore, we explore how strategic ligand engineering—utilizing functional groups such as cyano (-CN), ethylene glycol (-EG), and thienyl chains—can passivate these inevitable defects through coordination bonding and steric stabilization. By integrating theoretical prediction with practical passivation protocols, this guide provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for designing stable, high-performance PQD systems for optoelectronic applications, with particular relevance to solar cells and light-emitting devices.

The Goldschmidt tolerance factor (t) is a semi-empirical geometric parameter first proposed by Victor Moritz Goldschmidt in 1926 that predicts the stability and structural distortion of perovskite crystals based on ionic radii [13]. For a perovskite with the general formula ABX₃ (where A and B are cations and X is an anion, typically oxygen or a halogen), the factor is defined by the relationship between the ionic radii of its constituent ions.

Mathematical Definition and Structural Interpretation

The tolerance factor is calculated using the formula:

t = (r_A + r_X) / [√2 (r_B + r_X)]

where r_A, r_B, and r_X are the ionic radii of the A, B, and X ions, respectively [13] [14].

The value of t serves as a reliable predictor of the resulting perovskite crystal structure:

t ≈ 1: Indicates an ideal cubic perovskite structure with optimal ionic packing [13].t > 1: Suggests that the A cation is too large or the B cation is too small, often leading to hexagonal or tetragonal structures (e.g., BaTiO₃ with t=1.061) [13].0.9 < t < 1: Represents the stability window for the cubic perovskite structure [13] [14].0.71 < t < 0.9: Indicates that the A cation is too small to fit efficiently within the BX₆ framework interstices, resulting in orthorhombic or rhombohedral distortions (e.g., GdFeO₃, CaTiO₃) [13].t < 0.71: Suggests that A and B cations have similar ionic radii, typically leading to non-perovskite crystal structures [13] [14].

Table 1: Goldschmidt Tolerance Factor Values and Corresponding Perovskite Structures

| Tolerance Factor (t) | Crystal Structure | Structural Interpretation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| >1 | Hexagonal or Tetragonal | A cation too large or B cation too small | BaNiO₃, BaTiO₃ |

| 0.9-1.0 | Cubic | Ideal ionic size matching | SrTiO₃ |

| 0.71-0.9 | Orthorhombic/Rhombohedral | A cation too small for BX₆ interstices | GdFeO₃, CaTiO₃ |

| <0.71 | Different structures | A and B cations have similar ionic radii | FeTiO₃ |

Extended Applications and Modifications

While originally developed for oxide perovskites, the tolerance factor concept has been successfully extended to various material systems. A modified tolerance factor (t') incorporates electronegativity differences to improve predictive accuracy for sulfides and other chalcogenides [14]. The concept has also been expanded through the Ionic Filling Fraction (IFF), which evaluates the occupancy of constituent spherical ions in crystal structures, enabling application to arbitrary ionic compounds including complex hydrides [15].

For hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites (HOIPs) containing large and anisotropic A-cations, methodological adaptations for calculating effective ionic radii have been developed to maintain predictive accuracy [16]. These extensions demonstrate the enduring utility of the tolerance factor concept across diverse perovskite families.

Tolerance Factor and PQD Surface Defects: The Fundamental Connection

The Goldschmidt tolerance factor provides crucial insights into the intrinsic thermodynamic stability of perovskite crystals, which directly influences their propensity for surface defect formation. Understanding this relationship is fundamental to developing effective passivation strategies.

Structural Instability as a Defect Precursor

When the tolerance factor deviates from the ideal range (0.9 < t < 1), the perovskite lattice undergoes structural distortions to relieve geometric strain. These distortions create unstable crystal environments where defects are more likely to form [13] [17]. For t < 0.9, the A-site cation becomes too small to stabilize the BX₆ octahedral framework, leading to octahedral tilting and A-site vacancy formation [13]. This instability is quantitatively reflected in mechanical property calculations, where deviations from ideal t values correlate with increased elastic anisotropy and lower Debye temperatures, indicating softer lattice dynamics and higher susceptibility to defect formation [17].

The B-X Framework and Coordination Defects

The Goldschmidt tolerance factor highlights that perovskite stability can be customized through B-site and X-site components [17]. The B-X bond forms the fundamental coordination unit of the perovskite structure, and instability in this bond directly leads to under-coordinated surface sites. Density functional theory (DFT) studies reveal that the strength of B-O coordination bonds provides insight into mechanical and electronic behavior, with weaker bonds correlating with higher sensitivity and defect density [17]. In lead-halide PQDs, this manifests as halide vacancies and under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions, which act as trap states that quench photoluminescence and accelerate degradation [2] [18].

A-Site Dictation of Surface Chemistry

While the B-X framework forms the structural backbone, the A-site cation significantly influences the surface energy and defect formation kinetics. In hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites, the A-site organic cations often possess functional groups that can participate in surface passivation through hydrogen bonding or van der Waals interactions [17] [16]. Variations in hydrogen bonding between systems greatly impact structural stability and sensitivity [17]. The geometric constraints imposed by non-ideal t values can disrupt these stabilizing interactions, increasing surface energy and creating nucleation sites for defects.

Experimental Protocols: From Prediction to Passivation

Calculating Tolerance Factors for PQD Systems

Purpose: To predict structural stability and anticipate potential defect types in perovskite quantum dot formulations.

Materials and Equipment:

- Ionic radius databases (e.g., Shannon ionic radii)

- Computational resources for DFT calculations (optional)

- Crystallographic software for structure visualization

Methodology:

- Identify Component Ions: Determine the A, B, and X constituents in your target PQD composition.

- Obtain Ionic Radii: Consult standard ionic radius tables for the appropriate coordination numbers.

- Calculate Tolerance Factor: Apply the standard Goldschmidt equation:

t = (r_A + r_X) / [√2 (r_B + r_X)]. - Structural Prediction: Reference the calculated

tvalue against established structural ranges (Table 1) to predict stability and potential distortion patterns. - Defect Prognosis: Based on the

tvalue deviation from ideal, identify likely defect types:- For

t < 0.9: Anticipate A-site vacancies and under-coordinated B-site ions. - For

t > 1: Anticipate X-site vacancies and structural voids.

- For

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Passivation Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) | Surface passivator for PQDs | Provides strong halide affinity and defect passivation in Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs [2] |

| Conjugated polymers (Th-BDT, O-BDT) | Dual-function passivation and charge transport | Enhances inter-dot coupling and passivates surface defects in CsPbI₃ PQDs [18] |

| Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) | Inorganic coating precursor | Forms protective SiO₂ shells around PQD cores [2] |

| Formamidinium iodide (FAI) | Organic passivator | Participates in ligand exchange to remove long-chain organics in CsPbI₃ PQDs [18] |

| Oleic acid/Oleylamine | Standard synthesis ligands | Long-chain surfactants for PQD nucleation and growth; often replaced by shorter ligands [18] |

Defect Characterization Protocol

Purpose: To quantitatively assess surface defect density and confirm correlations with tolerance factor predictions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy system

- X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) instrument

- Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer

- Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

Methodology:

- Synthesize PQDs with varying

tvalues through A, B, or X-site compositional engineering. - Acquire PL spectra to determine trap state densities from emission linewidth and intensity.

- Perform XPS analysis of core levels (e.g., Pb 4f, I 3d, Cs 3d) to identify chemical states and detect under-coordinated species [18].

- Conduct FTIR spectroscopy to monitor ligand binding through characteristic vibrational mode shifts (e.g., ν(-CN) at ~2219 cm⁻¹ shifting to ~2224 cm⁻¹ upon Pb interaction) [18].

- Correlate defect density with calculated

tvalues to validate predictions.

Ligand Functional Groups for Targeted Passivation

Strategic selection of ligand functional groups enables targeted passivation of specific defect types predicted by tolerance factor analysis.

Coordination Bonding with Electron-Donating Groups

Ligands containing electron-donating functional groups such as cyano (-CN) and ethylene glycol (-EG) effectively passivate under-coordinated B-site ions (e.g., Pb²⁺ in lead-halide perovskites) through strong coordinate covalent bonds [18]. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy studies confirm that the ν(-CN) peak shifts from approximately 2219 cm⁻¹ to 2224 cm⁻¹ upon interaction with Pb²⁺, demonstrating strong coordination bonding [18]. Similarly, ethylene glycol functional groups exhibit characteristic C-O-C vibration shifts upon metal coordination, confirming effective passivation of under-coordinated surface sites.

Steric Stabilization with Conjugated Polymers

Conjugated polymers like Th-BDT and O-BDT functionalized with ethylene glycol side chains provide dual-function passivation by combining defect coordination with enhanced crystal packing [18]. Unlike conventional insulating ligands, these conjugated polymers facilitate preferred PQD packing through π-π stacking interactions, reducing interfacial defects and improving charge transport. The compact thienyl group in Th-BDT promotes closer inter-polymer spacing and more efficient hole transport compared to alkoxy side chains [18].

Hydrogen Bonding and Structural Integrity

Variations in hydrogen bonding between system components significantly impact structural stability and sensitivity [17]. Organic cations at the A-site can participate in hydrogen bonding networks with the BX₆ framework, enhancing structural integrity. For non-ideal tolerance factors where geometric strain threatens structural stability, strategically designed hydrogen-bonding ligands can mitigate defect formation by providing additional stabilization energy.

Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Passivation Systems

Combining organic and inorganic passivation materials creates synergistic protection systems that address multiple defect types simultaneously. For example, lead-free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs demonstrate enhanced stability when treated with both organic DDAB passivator and inorganic SiO₂ coating derived from tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) [2]. This hybrid strategy effectively passivates surface defects while forming a protective barrier against environmental degradation, addressing both intrinsic and extrinsic instability factors.

Advanced Applications and Performance Metrics

Enhanced Optoelectronic Devices

Implementation of tolerance-factor-informed passivation strategies has yielded significant improvements in PQD-based devices. CsPbI₃ PQDs passivated with conjugated polymer ligands (Th-BDT, O-BDT) achieved power conversion efficiencies exceeding 15% in solar cells, compared to 12.7% for pristine devices, with notable enhancements in short-circuit current density and fill factor [18]. These devices also demonstrated exceptional operational stability, retaining over 85% of initial efficiency after 850 hours of operation [18].

Similarly, lead-free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs passivated with DDAB and SiO₂ coating enabled the fabrication of flexible electroluminescent devices emitting at 485 nm while maintaining over 90% of initial photovoltaic efficiency after 8 hours at room temperature when used as a down-conversion layer in silicon solar cells [2].

Quantitative Stability Metrics

Debye temperature calculations derived from DFT studies provide quantitative metrics for comparing perovskite stability across different compositions [17]. Nitrate perovskites (e.g., DAN-2) consistently demonstrate higher Debye temperatures, indicating stronger bonding and superior structural stability compared to periodate and perchlorate analogues [17]. These computational metrics align with tolerance factor predictions, enabling more reliable stability assessment during materials design.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Passivated PQD Systems

| PQD System | Passivation Strategy | Performance Metric | Result | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ PQDs | Conjugated polymers (Th-BDT, O-BDT) | Power conversion efficiency | >15% (vs. 12.7% control) | >85% efficiency retention after 850h [18] |

| Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs | DDAB + SiO₂ coating | Electroluminescence | Blue emission at 485 nm | >90% efficiency retention after 8h [2] |

| DAPs (Perchlorate) | B-site and X-site optimization | Debye temperature | Higher stability than DAIs | Reduced friction sensitivity [17] |

| DANs (Nitrate) | B-site and X-site optimization | Debye temperature | Highest stability among series | Superior thermal stability [17] |

The Goldschmidt tolerance factor remains an indispensable tool for predicting perovskite structural stability and guiding targeted passivation strategies. By connecting geometric constraints to specific defect types, researchers can now proactively design ligand systems with functional groups that address anticipated instability issues. The continued development of conjugated polymer ligands, hybrid passivation systems, and computational screening methods promises to further advance PQD stability and performance. As tolerance factor calculations expand to encompass more complex compositions through approaches like the Ionic Filling Fraction, their predictive power for defect engineering will continue to grow, enabling the rational design of next-generation perovskite materials for optoelectronic applications.

Ligand Engineering in Action: Strategic Functional Groups for Defect Passivation

The evolution of ligand chemistry represents a pivotal frontier in the development of advanced nanomaterials and pharmaceutical compounds. This technical review examines the fundamental transition from conventional ligand systems such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) to sophisticated short-chain and multidentate alternatives. Within the specific context of perovskite quantum dot (PQD) research, we analyze how ligand functional groups mechanistically passivate surface defects to enhance material stability and optoelectronic performance. The paradigm shift toward functional selectivity and pluridimensional efficacy in ligand design enables unprecedented control over nanomaterial properties and biological targeting capabilities, offering researchers powerful tools to engineer next-generation technologies across photovoltaics, biomedical imaging, and therapeutic development.

Ligands are molecular entities that donate lone pair electrons to form coordinate bonds with central metal atoms or ions, creating complexes with distinct physicochemical properties [19]. The conventional classification system organizes ligands by their binding sites: monodentate (single attachment point), bidentate (two coordination sites), and multidentate (multiple coordination sites), with the latter exhibiting superior binding stability through the chelate effect [20] [19]. This fundamental binding behavior directly determines a ligand's capacity to passivate surface defects, influence material crystallization, and control biological interactions.

The historical dominance of long-chain alkyl ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) in nanomaterial synthesis stems from their well-understood coordination chemistry and ability to provide steric stabilization during synthesis [21] [22]. Oleylamine, an 18-carbon unsaturated fatty amine with a cis-configured double bond, functions multifunctionally as a surfactant, solvent, and reducing agent in nanoparticle synthesis [22] [23]. Similarly, oleic acid binds strongly to nanoparticle surfaces through its carboxylate group, which offers three potential binding sites for surface attachment [23]. The OA/OAm ligand pair has demonstrated remarkable versatility in controlling size, morphology, and aggregation prevention across diverse nanoparticle systems including metal oxides, metal chalcogenides, bimetallic structures, and perovskites [21].

However, this conventional ligand approach faces significant limitations. The kinked molecular conformations resulting from the cis-configuration of carbon-carbon bonds in OA and OAm impose steric constraints that reduce ligand surface coverage on nanomaterials to suboptimal levels [2]. Furthermore, their substantial molecular length creates large interparticle spacing that impedes charge transfer—a critical drawback for optoelectronic applications [20]. These limitations have driven research toward advanced ligand architectures with tailored binding characteristics and enhanced functional efficacy.

Ligand Function in Defect Passivation of Perovskite Quantum Dots

Surface Defect Dynamics in PQDs

Perovskite quantum dots exhibit exceptional optoelectronic properties but suffer from environmental instability originating primarily from surface defects. The structural instability of APbX₃ PQDs mainly stems from ion migration and ligand detachment from the PQD surface, where weakly bound ligands dissociate to generate vacancy and interstitial defects [2]. The low ion migration energy and minimal formation energy required to generate halide vacancies in PQD lattices facilitate defect formation, while weakly bound surface ligands readily dissociate during purification or ambient exposure, accelerating structural degradation through nanoparticle aggregation [2]. This degradation promotes nonradiative recombination, reducing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and overall device performance [2].

Table 1: Common Surface Defects in Perovskite Quantum Dots and Their Impacts

| Defect Type | Formation Energy | Impact on Performance | Common Passivation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Halide vacancies | Low | Non-radiative recombination centers, ion migration pathways | Ammonium salts, thiol groups |

| Cs⁺/FA⁺ vacancies | Moderate | Lattice distortion, surface charge imbalance | Carboxylic acids, alkyl amines |

| Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites | Variable | Severe non-radiative losses, catalytic degradation | Oxygen donors, thiophene rings |

| Interstitial defects | High under illumination | Trap states, hysteresis in devices | Multidentate chelators |

Conventional Ligand Limitations in PQD Passivation

The OA/OAm ligand system, while effective for synthesis, creates fundamental limitations for PQD applications. The low mobility of long-chain alkyl ligands governs PQD crystallization, resulting in slow crystal growth kinetics that favor zero-dimensional nanostructures [2]. More critically, the suboptimal surface coverage resulting from steric constraints of these conventional ligands leaves significant portions of the PQD surface vulnerable to defect formation and environmental degradation [2]. Additionally, in electronic devices, these long-chain insulative ligands hinder interparticle charge transport, necessitating post-synthetic ligand exchange processes that often introduce further defects [24].

Advanced Ligand Architectures for Enhanced Passivation

Short-Chain Ligand Systems

Short-chain ligands address the charge transport limitations of conventional systems while providing enhanced surface passivation. Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) has emerged as a particularly effective short-chain passivator due to its strong affinity for halide anions and relatively short alkyl chain length compared to conventional OA/OAm ligands [2]. Research demonstrates that coating CsPbBr₃ PQDs with DDAB increases their photoluminescence quantum yield and reduces surface defect states [2]. The compact structure of DDAB enables tighter packing on PQD surfaces, providing more comprehensive protection while facilitating improved electronic coupling between quantum dots.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Ligand Architectures in PQD Systems

| Ligand System | Chain Length | PLQY Improvement | Environmental Stability | Charge Transport Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA/OAm (conventional) | Long (C18) | Baseline | Days (with degradation) | Poor |

| DDAB | Medium (C12) | 25-40% increase | Several weeks | Moderate |

| Succinic Acid | Short (C4) | 45-60% increase | 48-72 hours | Good |

| ThMAI | Short (aromatic) | 60-80% increase | 15 days (83% PCE retention) | Excellent |

Multidentate Ligand Systems

Multidentate ligands leverage the chelate effect to achieve superior binding affinity and defect passivation. The fundamental principle governing their enhanced performance involves the thermodynamic stabilization achieved when multiple binding sites cooperatively interact with surface atoms, creating a more energetically favorable interaction compared to monodentate alternatives [20]. Succinic acid (SA), a dicarboxylic acid containing two carboxyl groups, demonstrates this principle effectively—both carboxylic groups bind to Pb²⁺ ions on the PQD surface, causing notable enhancements in size distribution, fluorescence, and water stability properties [20].

Advanced multifunctional ligands like 2-thiophenemethylammonium iodide (ThMAI) incorporate diverse functional groups for comprehensive surface passivation. ThMAI features an electron-rich thiophene ring head group that acts as a Lewis base to robustly bind uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites, while its ammonium segment efficiently occupies cationic Cs⁺ vacancies on the PQD surface [24]. This multifaceted anchoring facilitates effective defect passivation and uniform PQD ordering. Additionally, the larger ionic size of ThMA⁺ compared to Cs⁺ helps restore surface tensile strain in PQDs, enhancing phase stability [24].

Hybrid Passivation Strategies

The most effective PQD stabilization approaches combine organic and inorganic passivation methods. Research demonstrates that lead-free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs benefit significantly from a hybrid protection strategy involving organic passivation using DDAB combined with inorganic SiO₂ coating [2]. This approach synergistically enhances environmental stability by combining the defect-passivating capabilities of short-chain organic ligands with the complete encapsulation provided by inorganic oxide shells. The organic component effectively passivates specific surface defects, while the SiO₂ coating forms a dense, amorphous protective layer that preserves intrinsic luminescent properties while providing a barrier against environmental degradants [2].

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Exchange and Evaluation

Ligand Exchange Methodology for PQDs

Short-Chain Ligand Incorporation Protocol:

- Synthesize CsPbX₃ PQDs using hot-injection method with OA/OAm ligands as previously described [24].

- Precipitate PQDs using centrifugation at 9000 rpm for 10 minutes with antisolvent (ethyl acetate).

- Redisperse pellet in hexane and recentrifuge at 6000 rpm for 5 minutes to remove excess long-chain ligands.

- For DDAB incorporation: Resuspend cleaned PQDs in toluene containing 5-10 mg/mL DDAB and stir for 30 minutes.

- Precipitate DDAB-capped PQDs with ethyl acetate and centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 8 minutes.

- Redisperse final product in anhydrous toluene for characterization [2].

Multidentate Ligand Exchange Procedure:

- Clean pristine CsPbBr₃ PQDs (with OA and OAm) through standard precipitation/redispersion cycle.

- Ligand exchange with succinic acid (SA): Dissolve SA in anhydrous DMSO at 10 mg/mL.

- Add SA solution to PQD dispersion in 2:1 volume ratio and stir vigorously for 2 hours.

- Precipitate SA-PQDs using toluene as antisolvent and centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes.

- For NHS activation: Resuspend SA-PQDs in water containing 15 mM NHS and stir for 1 hour.

- Purify via dialysis against deionized water for 4 hours to remove unreacted NHS [20].

Characterization Techniques for Ligand Efficacy

Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: Measure PL quantum yield (PLQY) using integrating sphere method. Calculate defect density through non-radiative recombination rates derived from PL decay kinetics. Higher PLQY and longer carrier lifetimes indicate effective defect passivation [2] [24].

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Image PQDs before and after ligand exchange to evaluate morphological changes, size distribution, and aggregation state. High-resolution TEM can reveal lattice fringes and surface structure modifications [2].

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Analyze surface elemental composition and binding energies to verify ligand attachment and identify specific surface interactions. Shifts in Pb 4f and Br 3d peaks indicate successful coordination with surface atoms [24].

FTIR Spectroscopy: Confirm ligand binding through characteristic functional group vibrations. Carboxylate stretching frequencies between 1500-1650 cm⁻¹ demonstrate binding mode to surface metal atoms [20].

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Quantify ligand surface coverage by measuring weight loss during thermal decomposition. Higher decomposition temperatures indicate stronger ligand binding [23].

Pathway Visualization: Ligand Evolution in PQD Passivation

Diagram 1: Defect Passivation Strategy Evolution. This pathway illustrates the transition from conventional ligand limitations to advanced solutions addressing specific PQD surface defects.

Research Reagent Solutions for Ligand Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Ligand Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Ligands | Baseline synthesis, steric stabilization | Long alkyl chains, monodentate binding | Oleic acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) |

| Short-Chain Ammonium Salts | Defect passivation, enhanced charge transport | Compact structure, strong halide affinity | Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) |

| Bidentate Carboxylic Acids | Stronger surface binding, chelate effect | Two carboxyl groups, short chain length | Succinic acid (SA), Glutamic acid |

| Multifunctional Aromatic Ligands | Comprehensive defect passivation | Multiple functional groups, π-conjugation | 2-Thiophenemethylammonium iodide (ThMAI) |

| Silica Coating Precursors | Inorganic encapsulation, environmental barrier | Hydrolytic condensation, optical transparency | Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) |

| Bio-conjugation Agents | Biomolecule attachment, sensing applications | NHS ester formation, aqueous compatibility | N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) |

The strategic evolution from conventional OA/OAm ligands to advanced short-chain and multidentate systems represents a fundamental paradigm shift in nanomaterial surface engineering. This transition addresses the critical limitation of traditional ligands—their inability to simultaneously provide comprehensive surface passivation while maintaining efficient charge transport. The emerging ligand design principles emphasize multifunctional anchoring capabilities, appropriate steric profiles, and tailored binding group chemistry to specifically target prevalent surface defects in quantum-confined systems.

Future developments will likely focus on dynamic ligand systems that adapt to environmental conditions, stimuli-responsive ligands for programmable assembly, and bio-inspired designs mimicking natural molecular recognition elements. The integration of computational screening with high-throughput experimental validation will accelerate the discovery of next-generation ligands tailored for specific applications from high-efficiency photovoltaics to sensitive biomedical detection platforms. As ligand design grows increasingly sophisticated, the distinction between "passive" stabilizers and "active" functional components will continue to blur, opening new possibilities for engineered materials with precisely controlled interfacial properties.

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule with a functional group that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex through the formal donation of one or more of the ligand's electron pairs [25]. The metal-ligand bond order can range from one to three, and ligands are typically viewed as Lewis bases [25]. In the specific context of semiconductor perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), ligands are indispensable for surface passivation, significantly influencing optical properties, stability, and charge transport characteristics [3] [4].

The Covalent Bond Classification (CBC) method categorizes ligands into three fundamental types based on their electron-pair donation characteristics [25]. L-type ligands are neutral Lewis bases that donate two electrons to the metal center. In PQD systems, common L-type ligands include alkyl amines (e.g., oleylamine - OAm) and phosphines (e.g., trioctylphosphine), which coordinate through their lone pair electrons [26] [4]. X-type ligands are anionic species that donate one electron to the metal center, formally functioning as radicals. This category includes carboxylates (e.g., oleate - OA⁻ from oleic acid) and halides, which compensate for excess cationic charge on the PQD surface [26] [3]. A third category, Z-type ligands, act as Lewis acids and accept electron pairs from the metal center, such as metal carboxylates like Pb(OA)₂ [26].

This guide examines the critical role of X-type and L-type ligands in passivating surface defects on PQDs, a fundamental requirement for enhancing both the performance and environmental stability of next-generation optoelectronic devices.

Ligand Classification and Binding Mechanisms

Fundamental Ligand Types

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of X-type and L-type Ligands

| Ligand Type | Electron Donation | Chemical Nature | Common Examples | Primary Binding Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-type | 1-electron | Anionic | Oleate (OA⁻), Halides (Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻), Thiolates | Ionic/covalent bonding to metal cations (Pb²⁺) on PQD surface |

| L-type | 2-electron | Neutral | Oleylamine (OAm), Trioctylphosphine, Alkyl Amines | Coordinate covalent bonds through lone electron pairs |

Surface Defect Passivation Mechanisms

Perovskite quantum dots possess a high surface-to-volume ratio, resulting in a significant population of surface atoms with uncoordinated bonds (dangling bonds) that create trap states [3]. These trap states can capture photoinduced charge carriers, leading to nonradiative recombination and photoluminescence quenching [3].

The binary ligand strategy employing complementary X-type and L-type ligands has proven highly effective for comprehensive surface passivation [3]. This approach creates a synergistic effect where:

- X-type ligands (e.g., carboxylates) passivate cationic surface sites (A⁺ or B²⁺) through ionic interactions [3]

- L-type ligands (e.g., amines) passivate anionic surface sites (X⁻) through coordination bonding and hydrogen bonding [4]

For CsPbBr₃ PQDs, the standard passivation involves oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) combinations [4]. The carboxylic acid group (-COOH) of OA chelates with surface lead atoms, while the amine group (-NH₂) of OAm binds to halide ions [4]. This binary system creates a stable ligand shell that suppresses surface defect formation and enhances photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY).

Table 2: Defect Passivation Capabilities of Different Ligand Chemistries

| Ligand Chemistry | Targeted Defect Sites | Binding Strength | Impact on PLQY | Stability Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxylates (X-type) | Pb²⁺ sites, Cation vacancies | Moderate to Strong | Significant improvement | Colloidal stability, reduced ion migration |

| Alkyl Amines (L-type) | Halide vacancies | Moderate | Enhancement | Surface defect healing |