Ligand Density and PLQY in Perovskite Nanocrystals: A Guide to Optimization and Biomedical Applications

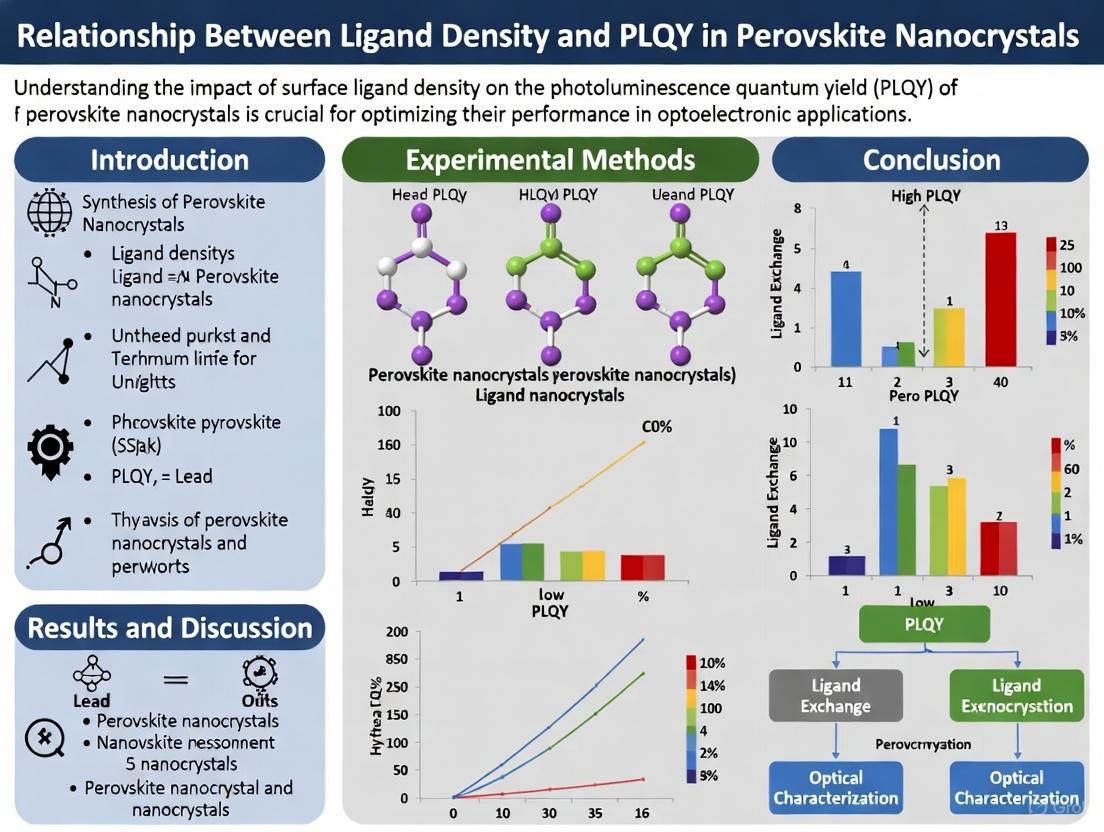

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical relationship between ligand density and photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) in perovskite nanocrystals (PeNCs), a key material for next-generation optoelectronics and biomedical...

Ligand Density and PLQY in Perovskite Nanocrystals: A Guide to Optimization and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical relationship between ligand density and photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) in perovskite nanocrystals (PeNCs), a key material for next-generation optoelectronics and biomedical imaging. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational role of ligands in surface passivation and defect control. The scope covers mechanistic insights into how ligand chemistry and density influence non-radiative recombination, advanced methodologies for precise ligand engineering, strategies to overcome common instability issues, and comparative validation of different ligand systems. By synthesizing recent scientific advances, this review serves as a strategic guide for optimizing PeNC performance for high-sensitivity diagnostics and targeted therapeutic applications.

Understanding the Fundamentals: How Ligands Govern PLQY in Perovskite Nanocrystals

Perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs) have emerged as a promising class of luminescent materials for biomedical applications due to their exceptional optical properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), narrow emission bandwidth, and tunable emission wavelengths. This technical guide explores the fundamental relationship between ligand engineering and PLQY in PNCs, providing researchers with detailed methodologies and current data to advance their application in bioimaging, biosensing, and therapeutic development.

The Fundamentals of Perovskite Nanocrystals and PLQY

Perovskite nanocrystals are semiconductor materials with the general formula ABX₃, where A is a cation (e.g., Cs⁺, FA⁺), B is a metal cation (typically Pb²⁺), and X is a halide anion (Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻). Their unique crystal structure enables exceptional optoelectronic properties, with size-tunable bandgaps and high extinction coefficients. For biomedical applications, the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) is a critical parameter defined as the ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed. A high PLQY is essential for sensitive detection in bioimaging and efficient signal generation in biosensing.

The primary challenge limiting PNC biomedical applications is their instability in physiological environments. Ionic crystal structures and dynamic ligand binding cause susceptibility to moisture, heat, and polar solvents. Surface trap states from unpassivated atoms act as non-radiative recombination centers, reducing PLQY and causing fluorescence quenching. Ligand engineering has emerged as the most effective strategy to address these limitations by providing robust surface passivation.

Ligand Engineering Strategies to Enhance PLQY

Ligand Chemical Properties and Binding Mechanisms

Surface ligands play a dual role in stabilizing PNCs and enhancing their optical properties. The binding affinity, steric effects, and chemical functionality of ligands directly influence PLQY through surface passivation efficiency.

- Binding Group Chemistry: Carboxylic acid (-COOH) and amine (-NH₂) groups are commonly used anchoring moieties that coordinate with surface Pb atoms. Recent studies show that multidentate ligands with multiple binding groups provide stronger coordination and reduce ligand desorption.

- Chain Length Optimization: Ligand alkyl chain length significantly affects passivation efficacy and material stability. Research demonstrates that dodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) with double 12-carbon chains provides optimal balance between passivation capability and steric hindrance, enhancing PLQY to 90.4% in blue-emissive CsPbCl₀.₉Br₂.₁ NCs compared to shorter or longer chain analogues [1].

- Hydrophobicity and Environmental Shielding: Long alkyl chains create a hydrophobic shell around PNCs, protecting the ionic core from aqueous environments. This is particularly crucial for biomedical applications where water-triggered degradation would otherwise occur.

The binding strength between ligands and PNC surfaces varies with A-site composition. Studies on CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃ PQDs reveal that FA-rich PQDs possess stronger ligand binding energy than Cs-rich counterparts, directly correlating with enhanced thermal stability [2].

Advanced Multifunctional Ligand Systems

Recent innovations focus on developing "all-in-one" ligands that combine surface passivation with additional functionalities. These advanced ligands address multiple challenges simultaneously:

- Photocurable Ligands: Azide-functionalized ligands with thiophene rings enable UV-induced crosslinking for patterning PNC films while maintaining high PLQY (88%) and providing charge transport capabilities [3].

- Polymer Stabilization: Incorporating polymers like poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) (PEtOx) forms Lewis acid-base interactions with Pb ions, reducing non-radiative recombination and achieving remarkable PLQY of 91% in quasi-2D perovskite films [4].

- Z-type Ligand Passivation: Lewis acid metal halide ligands (e.g., CdCl₂, ZnCl₂, InCl₃) effectively passivate anionic surface sites, dramatically increasing PLQY from 8% to 90% in CdTe quantum dots through trap state elimination [5].

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Impact on PLQY

Table 1: Ligand Engineering Strategies and Their Impact on PLQY

| Ligand Type | Material System | PLQY Improvement | Key Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDAB (C12 chain) | CsPbCl₀.₉Br₂.₁ NCs | 61.3% → 90.4% | Optimal chain length for defect passivation | [1] |

| PEtOx polymer | PBABr/CsPbBr₀.₆I₂.₄ | ~90% → 91% | Reduced non-radiative recombination | [4] |

| AzL1-Th photocurable ligand | CsPbBr₃ PNCs | High PLQY of 88% | Surface passivation + crosslinking | [3] |

| Silica encapsulation + Na⁺ doping | CsPbBr₃ PNC films | 58.0% → 74.7% | Defect reduction + environmental protection | [6] |

| Metal halide Z-ligands (InCl₃) | CdTe QDs | 8% → 90% | Effective trap state passivation | [5] |

Table 2: Ligand Chain Length Comparison and Performance Characteristics

| Ligand Chain Length | Example Compound | PLQY Achieved | Stability Performance | Key Advantages/Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short (C8) | DOAB | Lower than DDAB | Moderate | Poor hydrophobicity, weaker passivation | |

| Medium (C12) | DDAB | 90.4% (highest) | Maintains 90% PL after 10 days | Optimal polarity and binding | [1] |

| Long (C16) | DHAB | Lower than DDAB | High | Excessive steric hindrance limits passivation |

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Engineering

Ligand Exchange Methodology

Materials Required: Perovskite nanocrystal solution, novel ligand compound, non-solvent (typically ethyl acetate or methanol), toluene or hexane for redispersion, centrifugation equipment.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Preparation: Synthesize PNCs using hot-injection or ligand-assisted reprecipitation method with standard OA/OAm ligands.

- Ligand Solution: Dissolve novel ligand (e.g., DDAB) in toluene at optimized concentration (typically 0.1-0.5 M).

- Mixing: Add ligand solution to PNC solution with stirring at room temperature or elevated temperature (60-80°C) for 30-60 minutes.

- Purification: Precipitate PNCs using non-solvent, followed by centrifugation at 8000-10000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Redispersion: Remove supernatant and redisperse PNCs in toluene or desired solvent.

- Characterization: Measure PLQY using integrating sphere spectrometer, analyze morphology via TEM, and confirm surface chemistry via NMR or FTIR.

Critical Parameters: Ligand concentration, reaction temperature and duration, and purification efficiency significantly impact final PLQY. Successful exchange is indicated by maintained crystal structure, improved PLQY, and reduced non-radiative decay rates in time-resolved PL measurements.

PLQY Measurement Protocol

Equipment: Spectrofluorometer with integrating sphere attachment, calibrated light source, reference standards.

Procedure:

- System Calibration: Use integrating sphere to measure all scattered and emitted photons from reference samples.

- Sample Measurement: Place PNC solution or film in the integrating sphere and measure emission spectrum under excitation.

- Data Analysis: Calculate PLQY using the equation: PLQY = (Number of photons emitted) / (Number of photons absorbed). Absolute measurements require accounting for direct excitation, emission, and scattered light components.

Validation: Compare results with time-resolved PL measurements to confirm correlation between PLQY enhancement and increased radiative recombination rates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for PNC Ligand Engineering Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Biomedical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Ligands | Oleic acid, Oleylamine | Baseline surface stabilization | Limited due to labile binding |

| Quaternary Ammonium Salts | DDAB, DOAB, DHAB | Chain length optimization studies | Enhanced stability for aqueous applications |

| Polymer Additives | Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) | Matrix formation for stability | Biocompatibility enhancement |

| Photocurable Ligands | AzL1-Th, AzL2-Th | Patterning and device integration | Biosensor microarray fabrication |

| Encapsulation Agents | Silica precursors | Environmental protection barrier | Protection in biological media |

| Dopant Sources | NaBr, Other alkali metal salts | Defect passivation at atomic level | Emission tuning for multiplexed detection |

Ligand engineering represents the most promising approach to enhance PLQY and stability of perovskite nanocrystals for biomedical applications. The relationship between ligand density, binding strength, and optical performance is fundamental to designing effective PNC-based bioprobes. Future research directions should focus on developing biocompatible ligand systems with specific targeting functionalities, understanding ligand-protein interactions in biological environments, and creating stimulus-responsive ligands for activatable imaging probes. As ligand design strategies mature, perovskite nanocrystals are poised to become powerful tools in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics.

Ligand density is a fundamental surface chemistry parameter defined as the quantity of organic ligand molecules adsorbed per unit area on a nanocrystal's surface. In the context of semiconductor nanocrystals, particularly perovskites, precise control over this parameter is not merely beneficial but essential for dictating key optoelectronic properties. The organic ligand shell, typically composed of molecules like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), serves a dual purpose: it stabilizes colloidal suspensions and passivates surface defects that would otherwise act as non-radiative recombination centers, severely compromising optical performance [7] [8]. The photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), which quantifies the efficiency of photon emission, is exquisitely sensitive to the integrity of this ligand passivation layer. High ligand density ensures effective defect passivation, directly leading to high PLQY, a critical metric for applications in light-emitting diodes (LEDs), lasers, and displays [9] [10]. This guide explores the fundamental relationship between ligand density and optical performance, detailing the experimental methods for its control and measurement, and framing these concepts within the broader objective of achieving near-unity quantum yields in perovskite nanocrystal research.

Quantitative Relationship Between Ligand Density and PLQY

The correlation between ligand density and photoluminescence quantum yield is a cornerstone of nanocrystal surface science. Experimental data consistently demonstrates that optimized ligand passivation directly translates to enhanced emissive properties.

Table 1: Experimental Data Linking Ligand Engineering to PLQY

| Ligand System / Treatment | Material | Key Finding | Achieved PLQY | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Dodecanethiol (DDT) | CsPbBr3 PQDs | X-type ligand passivation of Br vacancies | Increased from 76.1% to 99.8% | [8] |

| Lattice-matched TMeOPPO-p | CsPbI3 QDs | Multi-site anchoring eliminates trap states | Increased from 59% to 97% | [10] |

| OA/OAm Supplementation | Mixed-Halide PNCs (Green & Red) | Reinforced passivation during purification | Achieved near-unity PLQY | [9] |

| DDA-Br Exchange | CsPbBr3 NCs | Aprotic ligand shell enhances stability | ~100% | [7] |

| Alkyl Phosphonic Acids | CsPbBr3 NCs | Achieved PbBr2-terminated surface | ~100% | [7] |

The underlying mechanism is defect passivation. In lead halide perovskite nanocrystals (LHP NCs), the most common and detrimental defects are surface halide vacancies (VBr). These vacancies create uncoordinated Pb2+ ions and imperfect [PbBr6] octahedral structures, which introduce electronic trap states that promote non-radiative recombination, thereby reducing PLQY [8]. Ligands with appropriate binding groups (e.g., -COOH, -NH2, -SH, P=O) coordinate with these undercoordinated Pb2+ sites, filling the vacancies and neutralizing the trap states. This direct relationship means that a higher density of properly bound ligands leads to more complete passivation and, consequently, higher radiative recombination efficiency [7] [10].

Experimental Protocols for Controlling and Measuring Ligand Density

Controlled Synthesis and Post-Synthetic Ligand Engineering

Achieving optimal ligand density requires precise control during synthesis and subsequent processing.

Rational Ligand Design during Synthesis: The choice of ligand is paramount. For example, using alkyl phosphonic acids as the sole ligand yields CsPbBr3 NCs with a specific PbBr2-terminated surface and a near-unity PLQY [7]. Advanced design strategies involve creating lattice-matched anchoring molecules, such as Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p), where the interatomic distance of the oxygen atoms (6.5 Å) matches the perovskite lattice spacing. This multi-site anchoring provides strong interaction with uncoordinated Pb2+, leading to a PLQY of 97% [10].

Ligand-Assisted Purification Protocol: The purification process is a critical step where ligand density is often inadvertently reduced. A robust method to prevent this involves ligand supplementation [9].

- Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbBr3-xIx NCs via hot-injection using standard precursors (Cs-oleate, PbBr2/PbI2, OA, OAm) in 1-octadecene (ODE).

- Crude Solution Preparation: After reaction quenching, obtain the crude NC solution.

- Ligand Supplementation: Prior to the addition of anti-solvent, introduce a controlled amount of equimolar OA and OAm (e.g., 0.1 mL) into the crude solution. This step reinforces the ligand shell.

- Precipitation: Add a reduced volume of anti-solvent (e.g., 3 mL tert-butanol) to induce precipitation. Using less anti-solvent minimizes ligand stripping.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture at 15,000 rpm, discard the supernatant, and re-disperse the precipitate in an organic solvent like hexane or toluene [9]. This protocol has been shown to achieve near-unity PLQY for both green- and red-emissive mixed-halide PNCs.

Post-Synthetic Ligand Exchange: This method involves replacing native ligands with new ones to improve passivation or stability. For instance, reacting native oleylammonium-Br-terminated NCs with stoichiometric amounts of neutral primary alkylamines or treating Cs-oleate-terminated NCs with didodecyldimethylammonium-Br (DDA-Br) can boost PLQY to 100% and improve colloidal stability [7].

Techniques for Quantifying Ligand Density and Surface Chemistry

Accurately measuring ligand density is crucial for establishing structure-property relationships.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: NMR is a primary technique for quantifying ligand density. Purified NC samples are dispersed in deuterated solvents (e.g., toluene-d8). By integrating the characteristic proton signals from the organic ligands (e.g., -CH= from oleic acid/oleylamine) and comparing them to a known internal standard, the number of ligand molecules per NC can be calculated [7] [10]. This number, combined with the NC surface area determined via transmission electron microscopy (TEM), yields the ligand density (ligands nm-2).

Thermogogravimetric Analysis (TGA): TGA directly measures the weight loss of a dried NC sample as it is heated. The weight loss in the temperature range corresponding to ligand decomposition and desorption provides the mass fraction of the organic ligand shell. This data can be converted into the number of ligands per nanocrystal and thus the surface density [11].

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: FTIR confirms the presence and binding mode of ligands on the NC surface. Shifts in the characteristic absorption bands (e.g., C=O stretch for carboxylates) indicate coordination to the surface metal atoms. A decrease in the intensity of alkyl chain C-H stretching modes after ligand exchange, as observed in TMeOPPO-p treated QDs, indicates successful modification of the ligand shell [10].

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): XPS probes the elemental composition and chemical state at the surface. A shift in the Pb 4f core level to lower binding energies after treatment with a passivating molecule like TMeOPPO-p indicates enhanced electron shielding due to strong ligand-Pb interaction, confirming successful surface passivation [8] [10]. The [Br]/[Pb] atomic ratio can also be calculated from XPS data to quantify surface halide deficiency [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Ligand Density Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | A common X-type capping ligand; binds as oleate to passivate surface sites and control growth. | Used in synthesis and purification of CsPbBr3 NCs [9]. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | A common X-type capping ligand; binds as alkylammonium to passivate surface sites. Often used with OA. | Co-ligand in standard synthesis; supplementation during purification prevents loss [9]. |

| Alkyl Phosphonic Acids | Strongly binding X-type ligands for synthesis; can yield specific surface terminations and high PLQY. | Yielded PbBr2-terminated CsPbBr3 NCs with ~100% PLQY [7]. |

| 1-Dodecanethiol (DDT) | X-type ligand for post-synthetic passivation; soft Lewis base that effectively fills Br vacancies. | Increased PLQY of CsPbBr3 PQDs from 76.1% to 99.8% [8]. |

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine Oxide (TMeOPPO-p) | Lattice-matched anchoring molecule; P=O and -OCH3 groups provide multi-site defect passivation. | Boosted PLQY of CsPbI3 QDs from 59% to 97% [10]. |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDA-Br) | Quaternary ammonium salt for ligand exchange; creates an aprotic, inert ligand shell. | Achieved near-unity PLQY and enhanced colloidal stability [7]. |

| Anti-Solvents (e.g., tert-Butanol, Methyl Acetate) | Used in purification to precipitate NCs; choice and volume critically affect final ligand density. | tert-Butanol used in ligand-assisted purification protocol [9]. |

Advanced Ligand Design: From Molecular Structure to Device Performance

Moving beyond conventional ligands, advanced molecular design is key to solving persistent challenges like operational stability in devices. The concept of lattice-matched molecular anchors represents a significant leap forward. As demonstrated with TMeOPPO-p, designing molecules where the spatial arrangement of coordinating atoms matches the spacing of binding sites on the perovskite surface allows for stronger, multi-dentate binding [10]. This enhanced interaction not only improves passivation but also stabilizes the lattice against ion migration—a major degradation pathway in perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (QLEDs). Devices incorporating such rationally designed ligands have achieved exceptional performance, including high external quantum efficiencies (EQE) of up to 27% and a dramatically extended operating half-life of over 23,000 hours [10].

Furthermore, the dynamic nature of the ligand-NC interaction must be considered. The binding equilibrium between ligands and the NC surface is influenced by the surrounding solvent environment. Studies on metal nanocrystals have shown that solvents with higher dielectric constants can cause ligand shells to adopt a more compact conformation, effectively altering the perceived ligand density and promoting aggregation [11]. This underscores that ligand density is not a static property but is influenced by the external chemical environment, which has profound implications for processing NCs into solid-state films for devices.

In conclusion, the precise definition and control of ligand density is a central theme in the pursuit of perovskite nanocrystals with optimal optical performance. The link between surface chemistry and PLQY is unequivocal: a high density of strongly-bound, well-chosen ligands is a prerequisite for achieving near-unity quantum yields. This is accomplished through rational synthesis, careful post-processing like ligand-assisted purification, and verified through a suite of characterization techniques. The ongoing development of advanced, lattice-matched ligands points the way toward not only brilliant luminescence but also the exceptional stability required for the commercial viability of perovskite-based optoelectronic devices.

In perovskite nanocrystal (PNC) research, the relationship between ligand density and Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) is a fundamental cornerstone for developing advanced optoelectronic devices. The passivation of surface defects via strategic ligand engineering directly governs the suppression of non-radiative recombination pathways, thereby enhancing light emission efficiency [12] [13]. Despite the inherent defect tolerance of lead-halide perovskites, surface defects on colloidal nanocrystals and grain boundaries in thin films remain critical performance-limiting factors, undermining both PLQY and device stability [12]. This in-depth technical guide elucidates the core mechanisms through which carefully selected and applied ligands suppress these defects, contextualized within the broader research objective of correlating ligand management with maximizing radiative recombination. We examine the latest mechanistic insights, quantitative performance data, and experimental protocols that are pivotal for researchers aiming to optimize PNC systems.

Fundamental Defect Challenges in Perovskite Nanocrystals

The high surface-to-volume ratio of perovskite nanocrystals, while beneficial for quantum confinement, also means a significant proportion of atoms reside on the surface. These surface atoms often possess incomplete coordination shells, leading to dangling bonds [14]. Common detrimental defects include:

- Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions: These Lewis acidic sites act as deep electron traps, strongly promoting non-radiative recombination [12] [10].

- Halide vacancies (Vₓ): These are shallow defects but facilitate ion migration, leading to phase segregation and spectral instability under operational stress [10] [15].

- Anti-site defects and interstitials: While less common due to higher formation energies, they can introduce mid-gap states that quench luminescence [12].

When charge carriers become trapped at these defect sites, they recombine non-radiatively, releasing energy as heat instead of photons. This process directly competes with radiative recombination, causing a precipitous drop in PLQY, reduced charge-carrier mobility, and accelerated material degradation [12] [13] [14]. The primary objective of ligand passivation is to chemically saturate these dangling bonds, thereby eliminating the associated trap states within the bandgap and restoring the intrinsic high efficiency of the perovskite material.

Ligand-Nanocrystal Interaction Mechanisms

The bonding between ligands and the perovskite NC surface can be systematically classified using the Covalent Bond Classification (CBC) method, which categorizes ligands based on their electron-pair donation and acceptance characteristics [16].

Table 1: Ligand Classification and Binding Mechanisms

| Ligand Type | Electron Donor/Acceptor Profile | Binding Mechanism | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Type Ligands | Lewis base (electron pair donor) | Donates two electrons to an uncoordinated surface metal orbital (e.g., Pb²⁺). | Oleylamine (OAm), alkyl amines [16] |

| X-Type Ligands | Forms a covalent bond | Shares a single electron with a surface site, neutralizing charge. | Oleic acid (OA), carboxylates, halides (Br⁻, I⁻) [16] |

| Z-Type Ligands | Lewis acid (electron pair acceptor) | Accepts an electron pair from a surface anion (e.g., Halide⁻). | Metal halides (e.g., PbBr₂) [16] |

Beyond this classification, the practical effectiveness of a ligand is determined by several key physicochemical properties:

- Binding Affinity and Denticity: Multidentate ligands, which feature multiple binding groups, form more stable and robust connections to the NC surface compared to dynamic, monodentate ligands like OA and OAm. This stronger binding directly translates to improved passivation durability [15] [16]. For instance, the lattice-matched anchor TMeOPPO-p, with its precisely spaced P=O and -OCH₃ groups, provides multi-site anchoring that effectively passivates complex defect sites [10].

- Ligand Chain Length and Steric Effects: The alkyl chain length of the ligand profoundly influences its packing density on the NC surface and its overall steric footprint. Research has demonstrated that ligands with intermediate chain lengths, such as dodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB), often achieve an optimal balance. They provide sufficient hydrophobicity and steric protection without excessively impairing charge transport between adjacent NCs, leading to PLQY boosts from 61.3% to 90.4% in blue-emissive CsPbCl₀.₉Br₂.₁ NCs [1].

- Polarity and Hydrophobicity: The chemical nature of the ligand tail group dictates the NC's interaction with its environment. Hydrophobic ligands, such as those with long alkyl chains, form a protective shell that significantly enhances the NC's resistance to moisture-induced degradation [1] [15].

The following diagram illustrates the flow from surface defects to the ligand-mediated passivation mechanism that ultimately enhances performance.

Quantitative Data: Ligand Impact on PLQY and Stability

The efficacy of ligand engineering is quantitatively demonstrated through significant enhancements in key optical and stability metrics. The data below summarizes findings from recent high-impact studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Ligand Passivation on PNC Performance

| Perovskite Composition | Ligand / Passivation Molecule | Key Performance Metrics | Mechanistic Insight / Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbCl₀.₉Br₂.₁ NCs [1] | Dodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) | PLQY increased from 61.3% to 90.4%; 90% PL intensity retained after 10 days. | Optimal 12-carbon chain length provides effective defect passivation and balanced charge transport. |

| CsPbI₃ QDs [10] | Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) | Near-unity PLQY of 97%; QLED EQE reached 27%; Operational lifetime >23,000 h. | Lattice-matched multi-site anchor passivates uncoordinated Pb²⁺ and suppresses ion migration. |

| CsPbBr₃ & CsPb(Br/Cl)₃ [17] | Poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-octadecene) (PMA) / KI / ZnI₂ | PLQY up to 89% (PMA); Colloidal stability >1 year (KI). | Polymer provides robust coating; inorganic halides fill vacancies more permanently. |

| CsPbBr₃ QDs [17] | Short-chain Hexyl Amine (via PLEP) | Solid-state PLQY of 82%; Hole mobility increased to 6.2 × 10⁻³ cm²V⁻¹s⁻¹. | Short-chain ligands enhance inter-dot charge transport while maintaining passivation. |

The relationship between ligand chain length and PLQY is non-monotonic, exhibiting a clear optimum. While very short chains may fail to provide adequate steric stabilization, excessively long chains can hinder charge transport and reduce passivation density. A study on CsPbCl₀.₉Br₂.₁ NCs demonstrated that DDAB (double C12-chain) outperformed both DOAB (double C8-chain) and DHAB (double C16-chain), achieving the highest PLQY [1]. This underscores that optimal ligand density and configuration, rather than mere presence, are critical for maximizing performance.

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Passivation

Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange with DDAB

This protocol, adapted from Tan et al., details the procedure for enhancing the PLQY and stability of blue-emissive CsPbCl₀.₉Br₂.₁ NCs [1].

- Primary Materials:

- Original PNCs: CsPbCl₀.₉Br₂.₁ NCs capped with oleylamine (OAm) and oleic acid (OA).

- Ligand Solution: Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) in toluene (concentration typically 0.05-0.1 M).

- Solvents: Anhydrous toluene, ethyl acetate, methanol.

- Procedure:

- Purification: The as-synthesized OA/OAm-capped PNCs are purified by centrifugation (e.g., 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes) using a non-solvent like ethyl acetate to remove excess ligands and reaction byproducts.

- Redispersion: The resulting NC pellet is redispersed in anhydrous toluene to create a stable colloidal solution.

- Ligand Addition: The DDAB solution is added dropwise to the NC solution under vigorous stirring. The typical DDAB-to-NC ratio (by lead concentration) requires optimization but often falls in a specific molar range.

- Incubation: The reaction mixture is stirred for a predetermined period (e.g., 30-60 minutes) at room temperature or slightly elevated temperatures to facilitate ligand exchange.

- Purification: The DDAB-capped NCs are precipitated by adding an anti-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) and recovered via centrifugation.

- Final Dispersion: The final product is dispersed in a suitable non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene or octane) for characterization and storage.

- Characterization Validation:

- PLQY Measurement: Use an integrating sphere to confirm the increase in absolute PLQY.

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Monitor the weakening of C-H stretches from original OA/OAm ligands, confirming ligand exchange.

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL): Observe a lengthening of the average PL lifetime, indicating suppressed non-radiative recombination [1].

Lattice-Matched Multi-Site Anchoring

This advanced protocol, based on the work in Nature Communications, uses designed molecules for superior passivation [10].

- Primary Materials:

- CsPbI₃ QDs: Synthesized via a standard hot-injection method.

- Anchoring Molecule: Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p), synthesized and purified prior to use.

- Solvent: Ethyl acetate for the treatment step.

- Procedure:

- QD Synthesis and Purification: Synthesize CsPbI₃ QDs and purify them to remove excess ligands, creating a "pristine" QD sample with active surface defects.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a TMeOPPO-p solution in ethyl acetate (e.g., concentration of 5 mg mL⁻¹).

- Surface Treatment: Add the TMeOPPO-p solution to the purified QD solution. The mixture is vortexed or stirred gently for a short duration to ensure complete mixing and interaction.

- Stabilization: The treated QDs are then stored without further purification for characterization. The binding is strong and stable.

- Characterization Validation:

- PLQY Measurement: Achieve PLQY values approaching unity (~97%).

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): A shift in the Pb 4f peaks to lower binding energies confirms strong interaction and electron density donation from the ligand to the Pb sites.

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): ¹H and ³¹P NMR spectra confirm the presence of the TMeOPPO-p molecule on the QD surface.

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate QLEDs to demonstrate a high external quantum efficiency (EQE > 26%) and operational stability [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Ligand Passivation Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) [1] | Quaternary ammonium salt for post-synthesis passivation; enhances PLQY and stability of blue PNCs. | Optimal chain length (C12) balances passivation and charge transport. |

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) [10] | Lattice-matched multi-site anchor molecule for deep trap passivation. | The 6.5 Å spacing between O atoms matches the perovskite lattice constant. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) & Oleic Acid (OA) [15] [16] | Standard L-type and X-type ligands used in initial PNC synthesis (e.g., hot-injection, LARP). | Dynamic binding leads to easy detachment, causing instability. |

| Potassium Iodide (KI) [17] | Inorganic halide salt for post-synthesis treatment; fills iodide vacancies. | Improves stability and PLQY; often used in solution or solid-state treatment. |

| Poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-octadecene) (PMA) [17] | Multidentate polymer ligand for forming a robust protective matrix around PNCs. | Enhances mechanical and environmental stability of NC films. |

| Short-chain Amines (e.g., Hexylamine) [17] | For solid-state ligand exchange to improve charge transport in PNC films. | Increases carrier mobility by reducing inter-dot separation. |

Ligand passivation is an indispensable strategy for mitigating surface defects and unlocking the full potential of perovskite nanocrystals. The mechanism is unequivocally clear: ligands function by saturating dangling bonds, eliminating trap states, and suppressing non-radiative recombination, which directly translates to heightened PLQY and operational stability [12] [13]. The critical insight for the broader thesis is that ligand density, chain length, and binding geometry are more consequential than mere ligand presence. An optimal configuration exists that maximizes surface coverage and binding affinity without compromising charge transport, as exemplified by DDAB's intermediate chain length [1] and TMeOPPO-p's lattice-matched multi-site anchoring [10]. Future research will continue to refine these relationships, driving the development of perovskite nanocrystal technologies toward their theoretical performance limits for applications in displays, lighting, and photovoltaics.

The relationship between ligand density and photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) is a cornerstone of research in perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs). Achieving high PLQY is critical for the commercial viability of PNCs in optoelectronic devices, particularly in displays where color purity and efficiency are paramount. The dynamic and unstable binding of traditional long-chain ligands often leads to their detachment during synthesis or purification, creating surface defects that act as non-radiative recombination centers, severely quenching luminescence [9] [18]. This technical guide explores the fundamental ligand properties—chain length, binding groups, and polarity—that govern surface passivation efficacy. By examining recent scientific advances, we provide a structured framework for researchers to engineer ligand systems that optimize PLQY and enhance material stability, directly contributing to the broader thesis that precise ligand management is indispensable for unlocking the full optoelectronic potential of perovskite nanocrystals.

Core Ligand Properties and Their Impact on PLQY

The Critical Role of Ligand Chain Length

The alkyl chain length of surface ligands directly influences the steric hindrance, surface coverage, and defect passivation efficiency of PNCs. An optimal chain length balances sufficient surface binding with minimal inter-particle distance, which is crucial for charge transport in films.

- Mechanism of Action: Ligands with excessively long chains can create thick insulating barriers between nanocrystals, hampering charge carrier injection and transport in electronic devices. Conversely, very short chains may provide inadequate steric stabilization, leading to NC aggregation and precipitation. Furthermore, chain length affects the ligand's hydrophobicity, which in turn influences the NCs' stability against moisture [1].

- Experimental Evidence: A seminal study on blue-emissive CsPbCl₀.₉Br₂.₁ NCs systematically investigated ligands with double alkyl chains of different lengths: double 8-carbon (DOAB), double 12-carbon (DDAB), and double 16-carbon (DHAB). The results demonstrated a non-monotonic relationship, with DDAB (12-carbon) achieving the highest PLQY of 90.4%, compared to 72.1% for DOAB and 68.5% for DHAB [1]. This indicates that a medium chain length offers the ideal compromise, providing strong binding to the NC surface and effective defect passivation without excessive steric bulk that could destabilize the ligand shell.

Table 1: Impact of Quaternary Ammonium Bromide (QAB) Ligand Chain Length on Blue-Emissive CsPbCl₀.₉Br₂.₁ NCs

| Ligand Name | Carbon Chain Length | Reported PLQY | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOAB | Double 8-carbon | 72.1% | Shorter chains lead to suboptimal passivation and lower PLQY. |

| DDAB | Double 12-carbon | 90.4% | Optimal chain length provides the best passivation and highest PLQY. |

| DHAB | Double 16-carbon | 68.5% | Longer chains may hinder effective binding and reduce passivation. |

Engineering Ligand Binding Groups for Robust Passivation

The chemical nature of the binding group determines the strength and stability of the ligand-NC interaction. Replacing traditional dynamically binding ligands with groups that form stronger, multidentate bonds is a key strategy for enhancing PLQY and stability.

- Traditional vs. Advanced Ligands: Conventional ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) bind ionically and dynamically, making them prone to detachment [18]. Advanced ligand systems employ multiple binding motifs:

- Multipolar Ionic Interactions: Ionic liquids like 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF) coordinate strongly with the NC surface. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations show the anion (OTF⁻) has a binding energy (Eᵦ) of -1.49 eV with Pb²⁺, significantly stronger than the -0.95 eV for a typical carboxylate (octanoic acid) [19]. The cation ([BMIM]⁺) also coordinates with Br⁻ (Eᵦ = -1.00 eV), creating a robust multipolar passivation shell that suppresses defect states and boosts PLQY to 97.1% [19].

- Conjugated Molecular Multipods (CMMs): Molecules like TPBi feature multiple surface-binding sites that adsorb via multipodal hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions [20]. This not only passivates defects but also strengthens the near-surface perovskite lattice, reducing ionic fluctuations and dynamic disorder. This approach has achieved a near-unity PLQY in films and led to light-emitting diodes (LEDs) with an external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 26.1% [20].

- Short-Branched-Chain Ligands: Ligands like 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) exhibit a stronger binding affinity toward PNCs compared to OA. When combined with acetate (AcO⁻), which also acts as a surface ligand, this system yielded CsPbBr₃ QDs with a PLQY of 99% and excellent reproducibility [21].

Solvent Polarity and Ligand-Solvent Interactions

The polarity of solvents used in synthesis and purification critically affects ligand stability. Polar solvents can compete with ligands for binding sites or strip them from the NC surface, directly impacting ligand density and PLQY.

- Purification-Induced Ligand Loss: The standard purification process using anti-solvents like tert-butanol often causes severe ligand detachment. Studies show that solvents like acetone, ethyl acetate, and n-butyl acetate compete with surface ligands, leading to their partial desorption. This creates dangling bonds and defect trap states, causing a rapid drop in PLQY—for example, from 90% to 51% within minutes of acetone exposure [22].

- Ligand-Assisted Purification Strategy: An effective countermeasure is the introduction of supplemental ligands (e.g., OA and OAm) prior to anti-solvent addition. This "pre-supplementation" reinforces the ligand shell during the high-stress purification event, effectively maintaining a high ligand density on the NC surface. This strategy has achieved near-unity PLQY for both green- and red-emissive mixed-halide PNCs, which is essential for display applications [9] [23].

- Systematic Solvent Effects: Research on 12 different polar solvents revealed a clear trend: for solvents with the same functional group (e.g., alcohols), the impact on PNCs intensifies with increasing solvent polarity. Stronger polar solvents cause more rapid PL quenching and a greater reduction in PLQY [22].

Table 2: Impact of Selected Polar Solvents on CsPbBr₃ Perovskite QDs

| Solvent | Functional Group | Impact on PQDs | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetone | Ketone | PLQY reduction from 90% to 51% | Competes for ligands, inducing defect states. |

| Ethyl Acetate | Ester | PLQY reduction to ~87.6% | Competes for ligands, causing partial detachment. |

| Methanol | Alcohol (Short-chain) | Rapid fluorescence quenching | Strong polarity completely destroys the ligand shell. |

| 1-Octanol | Alcohol (Long-chain) | Slower quenching effect | Weaker polarity has a less dramatic impact. |

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Engineering

Protocol 1: Ligand-Assisted Purification for Near-Unity PLQY

This protocol is designed to prevent ligand detachment during the purification of mixed-halide CsPbBr₃₋ₓIₓ PNCs [9] [23].

- Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbBr₃₋ₓIₓ PNCs via the hot-injection method. Lead halide precursors (PbBr₂ and PbI₂) are dissolved in a mixture of 1-octadecene (ODE), oleylamine (OAm), and oleic acid (OA) at 110 °C under a N₂ atmosphere. A pre-formed Cs-oleate solution is rapidly injected at 165 °C, and the reaction is quenched in an ice-water bath after 30 seconds.

- Ligand Supplementation: Prior to purification, add a controlled, equimolar amount of OA and OAm (e.g., 0.1 mL each) directly to the crude reaction solution. This step is critical for reinforcing the ligand shell.

- Controlled Anti-Solvent Purification: Add a reduced volume of anti-solvent (e.g., 3 mL of tert-butanol) to the ligand-supplemented crude solution to induce precipitation. Using a minimal amount of anti-solvent is key to mitigating excessive ligand stripping.

- Isolation: Centrifuge the mixture at 15,000 rpm. Discard the supernatant containing excess precursors and solvents.

- Re-dispersion: Re-disperse the final purified pellet in a non-polar solvent like hexane or toluene. The resulting PNCs should exhibit near-unity PLQY and narrow emission linewidths.

Protocol 2: Post-Synthetic Ligand Exchange to Regulate Chain Length

This protocol outlines the post-treatment of PNCs with ligands of varying alkyl chain lengths to optimize optical properties [1].

- Base NC Synthesis: Prepare blue-emissive CsPbCl₀.₉Br₂.¹ NCs capped with standard OA/OAm ligands.

- Ligand Solution Preparation: Prepare separate solutions of the quaternary ammonium bromide (QAB) ligands (e.g., DOAB, DDAB, DHAB) in a suitable solvent like toluene.

- Post-Treatment Reaction: Mix the as-prepared NC solution with the QAB ligand solution. The original OA/OAm ligands are dynamically exchanged with the QAB molecules due to their surface-binding affinity.

- Purification: Purify the ligand-exchanged NCs using an anti-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or methyl acetate) to remove the displaced ligands and any excess QAB.

- Characterization: Analyze the optical properties of the post-treated NCs. Steady-state and time-resolved photoluminescence measurements will confirm the enhancement in PLQY and exciton lifetime, with DDAB expected to yield the most significant improvement.

Schematic Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams visualize the core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Ligand Engineering in Perovskite Nanocrystals

| Reagent Category | Example Compounds | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Ligands | Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard ligands for synthesis; provide initial colloidal stability but exhibit dynamic binding. |

| Chain Length Modulators | Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB), Dimethyldioctylammonium bromide (DOAB) | To systematically study the effect of alkyl chain length on passivation, PLQY, and film conductivity. |

| Strong-Binding Ligands | [BMIM]OTF (Ionic Liquid), Acetate salts (e.g., CsOAc) | Provide stronger coordination to the NC surface than OA/OAm, leading to superior defect passivation and stability. |

| Purification Anti-Solvents | tert-Butanol, Methyl Acetate (MeOAc), Ethyl Acetate | Selective precipitation of NCs; polarity must be carefully controlled to minimize ligand stripping. |

| Stabilizing Additives | Conjugated Molecular Multipods (e.g., TPBi) | Suppress dynamic disorder and non-radiative recombination via multi-point surface binding, boosting film PLQY. |

The precise engineering of ligand properties is undeniably a decisive factor in maximizing the PLQY of perovskite nanocrystals. The evidence clearly shows that an optimal alkyl chain length (e.g., DDAB's 12-carbon chain) provides the ideal balance of passivation and stability. Furthermore, moving beyond traditional ligands to those with stronger binding groups—such as the multipolar ionic liquid [BMIM]OTF or multi-dentate conjugated molecules—significantly suppresses defect formation and non-radiative recombination, enabling PLQYs approaching 100%. Finally, the critical, often-overlooked role of solvent polarity mandates the adoption of ligand-assisted purification protocols to preserve high ligand density during processing. By systematically controlling these three interconnected properties, researchers can effectively manage the ligand density on the NC surface, directly validating the core thesis and paving the way for the development of high-performance, commercially viable perovskite-based optoelectronic devices.

The pursuit of high-performance blue-emissive perovskite nanocrystals (PeNCs) represents a critical frontier in display and lighting technologies. Despite significant advancements in green and red counterparts, the development of blue perovskites has lagged, primarily due to intrinsic challenges with achieving high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and operational stability [1]. This case study explores a pivotal investigation into how precise ligand chain length engineering enabled a remarkable PLQY enhancement from 61.3% to 90.4% in blue-emissive CsPbCl0.9Br2.1 NCs [1]. The findings provide a foundational framework for understanding the structure-property relationships between ligand architecture and PeNC performance, offering critical insights for researchers and development professionals working on advanced optoelectronic materials.

Experimental Design and Methodology

Core Hypothesis and Research Objective

The study was premised on the hypothesis that the carbon chain length of surface-bound quaternary ammonium bromide (QAB) ligands directly influences defect passivation efficiency, radiative recombination rates, and the overall optoelectronic properties of mixed-halide blue PeNCs [1]. The objective was to systematically evaluate this relationship and identify an optimal alkyl chain configuration that maximizes PLQY while enhancing environmental stability.

Synthesis of Base Perovskite Nanocrystals

The foundational CsPbCl0.9Br2.1 PeNCs were synthesized using a established hot-injection method with standard ligands [1].

- Precursor Preparation: Cesium-oleate was prepared by reacting cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3) with oleic acid (OA) in 1-octadecene (ODE).

- Reaction Setup: Lead bromide (PbBr2) was dissolved in ODE with OA and oleylamine (OAm) as initial capping ligands.

- Nanocrystal Formation: The cesium-oleate precursor was swiftly injected into the lead halide solution at elevated temperature (150-180°C), initiating rapid nucleation and growth of CsPbBr3 NCs.

- Halide Exchange: Partial Cl-for-Br substitution was achieved through post-synthetic treatment to obtain the target blue-emissive CsPbCl0.9Br2.1 composition [1].

Ligand Engineering: Post-Treatment Protocol

The critical ligand modification step was performed via a post-synthesis ligand exchange process.

- Ligand Selection: Three QAB ligands with distinct double alkyl chains were investigated:

- Dimethyldioctylammonium bromide (DOAB): Double 8-carbon chains.

- Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB): Double 12-carbon chains.

- Dimethyldipalmitylammonium bromide (DHAB): Double 16-carbon chains [1].

- Exchange Procedure: The as-synthesized OA/OAm-capped PeNCs were dispersed in toluene. A controlled concentration of the respective QAB ligand was introduced and allowed to equilibrate, facilitating the dynamic replacement of the original long-chain ligands [1].

- Purification: Treated NCs were purified via centrifugation and re-dispersed in anhydrous toluene for subsequent characterization.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for PeNC synthesis and ligand post-treatment.

Results and Data Analysis

Impact of Alkyl Chain Length on Optical Performance

Spectroscopic characterization revealed a pronounced dependence of PLQY on the ligand's alkyl chain length, with DDAB-treated PeNCs exhibiting superior performance.

Table 1: Optoelectronic Properties of Ligand-Modified CsPbCl0.9Br2.1 PeNCs

| Ligand Type | Alkyl Chain Length | PLQY (%) | Stability (PL Intensity after 10 Days) | Relative Radiative Recombination Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA/OAm (Original) | - | 61.3 | <70% | Baseline |

| DOAB | Double C8 | 78.1 | ~85% | Moderate Increase |

| DDAB | Double C12 | 90.4 | ~90% | Highest Increase |

| DHAB | Double C16 | 75.6 | ~80% | Slight Increase |

Data synthesized from reference [1].

The data demonstrates that DDAB-treated PeNCs achieved a peak PLQY of 90.4%, significantly outperforming both shorter (DOAB) and longer (DHAB) chain analogues. Furthermore, these NCs maintained approximately 90% of their initial PL intensity after 10 days under ambient conditions, highlighting a dual benefit of enhanced efficiency and stability [1].

Exciton Dynamics and Mechanistic Insights

Time-resolved fluorescence and transient absorption spectroscopy provided deeper insight into the exciton dynamics governing the observed performance enhancements.

- Suppressed Non-Radiative Recombination: DDAB-CsPbCl0.9Br2.1 NCs exhibited a notably longer photoluminescence decay lifetime compared to other samples. This indicates more effective suppression of non-radiative decay pathways, which are often mediated by surface defects [1].

- Enhanced Radiative Recombination Rate: Analysis of exciton dynamics confirmed a substantially increased probability and rate of radiative recombination in DDAB-passivated NCs, directly correlating with the recorded PLQY boost [1].

The mechanistic role of ligand chain length can be understood through a multi-parameter influence diagram.

Diagram 2: Mechanism of alkyl chain length influence on PeNC properties and performance.

Discussion: The Structure-Property Relationship

The "Goldilocks Zone" of Alkyl Chain Length

The superior performance of DDAB underscores the existence of an optimal "goldilocks zone" for ligand alkyl chain length in blue PeNCs. This optimization balances several competing factors:

- Defect Passivation Efficiency: Ligands with excessively short chains (e.g., DOAB, C8) exhibit weaker binding affinity to the NC surface due to lower van der Waals interactions, leading to incomplete defect passivation and ligand desorption [1].

- Steric Hindrance and Polarity: Ligands with very long chains (e.g., DHAB, C16) introduce significant steric bulk. While enhancing hydrophobicity, this can impede dense packing on the NC surface, reducing passivation density. Furthermore, longer chains can exhibit lower effective polarity, potentially diminishing their ability to stabilize the ionic perovskite surface [1].

- Optimal Balance: DDAB, with its double 12-carbon chains, strikes an ideal balance. It provides sufficient chain length for stable surface binding and good hydrophobicity, while its moderate polarity promotes a stronger interaction with the PeNC surface, leading to exceptional passivation of surface defects (e.g., halide vacancies) and a dramatic reduction in non-radiative recombination centers [1] [24].

Implications for Device Performance

The translation of material-level improvements to functional devices was demonstrated by fabricating light-emitting diodes (LEDs) based on DDAB-CsPbCl0.9Br2.1. These devices showed stable electroluminescence and an extended operational lifetime, confirming the significant potential of optimally engineered PeNCs as efficient blue emitters for display backlighting and other photoelectric applications [1]. This finding aligns with broader research indicating that short-chain ligands enhance charge carrier mobility in PeNC films, which is critical for electroluminescent devices [25] [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Ligand Engineering in PeNC Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Example(s) | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Sources | Lead bromide (PbBr2) | Provides lead and halide ions for the perovskite crystal lattice [1]. |

| Cesium Sources | Cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3) | Forms cesium-oleate precursor for nucleation and growth of CsPbX3 NCs [1]. |

| Long-Chain Ligands (Synthesis) | Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) | Control NC growth during synthesis and provide initial colloidal stability [1] [24]. |

| Solvents | 1-Octadecene (ODE), Toluene | High-booint solvent for synthesis (ODE); dispersion and processing solvent (Toluene) [1]. |

| Quaternary Ammonium Ligands (Post-Treatment) | DOAB, DDAB, DHAB | Replace initial OA/OAm ligands to enhance passivation, PLQY, and stability [1]. |

| Short-Chain / Functional Ligands | Octylphosphonic acid (OPA), 3,3-Diphenylpropylamine (DPPA) | Improve charge transport in films for LED applications by reducing inter-particle distance [24]. |

| Defect Passivators | Ammonium Thiocyanate (NH4SCN) | Pseudohalide anion (SCN⁻) fills halide vacancies, suppressing non-radiative recombination in mixed-halide blue PeNCs [24]. |

This case study establishes that rational ligand engineering, specifically the optimization of alkyl chain length, is a powerful and effective strategy for overcoming the core challenges of blue-emissive PeNCs. The identification of DDAB as an optimal ligand, enabling a record PLQY of 90.4%, provides a clear and actionable design rule: maximizing performance requires a careful balance in ligand chain length to optimize surface binding affinity, defect passivation, and material stability. These findings make a substantial contribution to the broader thesis on the relationship between ligand properties and PLQY, demonstrating that ligand density and molecular architecture are inextricably linked to the photophysical outcomes in perovskite nanocrystals. Future research directions will likely focus on exploring branched-chain ligands, mixed-ligand systems, and extending these principles to lead-free perovskite compositions for broader commercial application.

Synthesis and Optimization: Methodologies for Controlling Ligand Density and Enhancing PLQY

The pursuit of high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) in metal halide perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs) is fundamentally intertwined with the precise control of their surface chemistry, particularly ligand density. PLQY, a critical metric defining the efficiency of light emission, is heavily influenced by non-radiative recombination pathways originating from surface defects. Ligands—organic molecules binding to the NC surface—play a dual role: they passivate these defects and control crystal growth during synthesis. An optimal ligand density effectively coordinates with undercoordinated lead atoms on the surface, suppressing trap states and enhancing PLQY [16] [27]. However, the relationship is complex; excessive ligand density can hinder charge transport, while insufficient coverage leads to defect-mediated PLQY degradation [28] [29]. This whitepaper delves into the advanced synthesis techniques of Hot-Injection (HI) and Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP), alongside subsequent purification strategies, framing them within the critical context of managing ligand density to achieve and maintain exceptional optical properties in PNCs.

Hot-Injection (HI) Synthesis

Principles and Methodology

The hot-injection (HI) method is a cornerstone for synthesizing high-quality, monodisperse perovskite nanocrystals. This technique involves the rapid injection of a precursor into a hot solvent containing ligands, triggering instantaneous nucleation and controlled growth [16]. The process is characterized by its requirement for high temperatures (typically 140-200 °C) and an inert atmosphere, often achieved using a Schlenk line [28]. The key principle is the creation of a temporary supersaturation condition, leading to a short, burst nucleation event, after which the crystal growth proceeds at a lower temperature. The ligands present in the reaction mixture, such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (Olam), immediately coordinate to the newly formed nanocrystal surfaces, governing final particle size, morphology, and passivating surface defects [28] [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: CsPbBr3 NCs via HI

Materials:

- Precursors: Lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂, 98%), Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99.9%)

- Solvents: 1-Octadecene (ODE)

- Ligands/Surfactants: Oleylamine (Olam, technical-grade, 70%), Oleic acid (OA, technical-grade, 90%), Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB, 98%), Octylphosphonic acid (OPA, 98%)

- Other: Trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO, 90%)

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: 26 mg of PbBr₂ (0.075 mmol) is dispersed in 2 mL of ODE in a three-necked flask.

- Ligand Addition: Depending on the desired surface chemistry, ligation and solvation agents are added.

- Dehydration and Heating: The mixture is dried under vacuum for 30-60 minutes at 100-120 °C to remove residual water, then placed under an inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂).

- Cesium Precursor Preparation: In a separate vial, 0.2 mmol of Cs₂CO₃ is dissolved in 1-1.5 mL of OA and ODE, heated until clear, and preheated to 100-120 °C.

- Injection and Reaction: The PbBr₂/ligand mixture is heated to the target reaction temperature (typically 150-180 °C). The Cs-Oleate precursor is swiftly injected. The reaction is quenched after 5-10 seconds by immersing the flask in an ice-water bath.

- Purification: The crude solution is centrifuged (e.g., 8000 rpm for 10 minutes) to separate the nanocrystals from unreacted precursors and large aggregates. The supernatant is discarded, and the pellet is redispersed in an anhydrous solvent like toluene or hexane [28].

Impact of Ligand Density on PLQY in HI

In HI synthesis, ligand type and concentration directly determine the final ligand density on the NC surface, which is a critical factor for PLQY. While traditional Olam/OA ligands provide good initial passivation, the resulting ligand shell is labile, leading to ligand loss and PLQY degradation over time [28]. Replacing primary alkylammonium salts like Olam with quaternary ammonium salts like DDAB, which lacks protons and is less prone to desorption, has been shown to grant better surface passivation and improved stability, thereby maintaining high PLQY [28]. Furthermore, the use of phosphonic acids (e.g., OPA), which strongly coordinate to Pb²⁺ sites, can lead to a more robust ligand shell, further suppressing non-radiative recombination [28]. The diffusion-controlled growth environment in HI often results in high reaction yields and good size control, though the optical properties can be affected by bromide-deficient conditions if the ligand/precursor balance is not optimized [28].

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) Synthesis

Principles and Methodology

Ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) is a versatile and cost-effective synthesis method performed at room temperature and under ambient atmosphere [30] [31]. Its core principle relies on solubility differences between solvents. Precursor salts (e.g., CsBr and PbBr₂) are first dissolved in a polar solvent like dimethylformamide (DMF) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). This precursor solution is then rapidly injected into a poorly soluble, miscible antisolvent (e.g., toluene) under vigorous stirring [31]. The sudden drop in solubility creates a high supersaturation level, triggering the instantaneous nucleation and growth of perovskite NCs. The ligands added to the precursor solution (e.g., OA and Olam) immediately coordinate to the nascent nanocrystals, controlling their growth, stabilizing the colloidal suspension, and passivating surface defects [30]. The simplicity, scalability, and low energy requirements of LARP make it highly appealing for industrial applications [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: CsPbBr3 NCs via LARP

Materials:

- Precursors: Cesium bromide (CsBr, 99.999%), Lead bromide (PbBr₂, ≥98%)

- Solvents: N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, 99.8%), Toluene (99.8%)

- Ligands: Oleic acid (OA, 95%), Oleylamine (OAm, 70%)

Procedure:

- Precursor Dissolution: A mixture of CsBr (0.085 g, 0.4 mmol) and PbBr₂ (0.147 g, 0.4 mmol) is dissolved in 10 mL of DMF. This solution is stirred at 1000 rpm for a controlled dissolution time (10-25 minutes). The dissolution time is a critical parameter influencing precursor concentration and final NC size [31].

- Ligand Introduction: After dissolution, 1 mL of OA and 0.5 mL of OAm are injected into the precursor solution and allowed to react for 10 minutes.

- Precipitation and NC Formation: 0.5 mL of the precursor-ligand solution is swiftly injected into 10 mL of toluene with vigorous stirring. The formation of brightly luminescent NCs is immediate.

- Purification: The crude NC solution is typically centrifuged at low speed (e.g., 3000-5000 rpm for 5-10 minutes) to remove any large aggregates or precipitate. The supernatant, containing the dispersed NCs, is then used or stored [31]. The formation of bulk crystals as a precipitate can limit the maximum achievable concentration of NCs in LARP [28].

Impact of Ligand Density on PLQY in LARP

The ligand density and dynamics in LARP-synthesized NCs are profoundly influenced by processing parameters. High-throughput studies have revealed that long-chain ligands (e.g., OA/OAm) facilitate the formation of homogeneous and stable NCs with high PLQY, whereas short-chain ligands often fail to produce functional NCs [30]. The ligand-to-precursor ratio is a decisive factor. A study varying precursor dissolution time demonstrated that a decreasing ligand-to-precursor ratio (achieved by longer dissolution times) promotes NC growth, resulting in larger sizes and redshifted emission [31]. This ratio directly affects surface coverage and passivation efficacy. Furthermore, excessive amines or highly polar antisolvents can induce a transformation of the NCs into non-perovskite structures with poorer emission properties [30]. The diffusion rate of ligands during the reaction is crucial; optimal diffusion ensures effective surface coverage and defect passivation, leading to high PLQY [30]. LARP often excels in producing NCs with excellent initial emission properties, likely due to bromide-rich conditions from the solvation agents [28].

Comparative Analysis of HI and LARP Techniques

The choice between HI and LARP significantly impacts the properties of the resulting perovskite nanocrystals, particularly in terms of ligand density, optical performance, and scalability. The table below provides a structured comparison of these two core techniques.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of Hot-Injection vs. LARP synthesis methods

| Aspect | Hot-Injection (HI) | Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Conditions | High temperature (140-200 °C), inert atmosphere [28] [16] | Room temperature, ambient air [30] [31] |

| Key Chemical Parameters | Ligand type (OA, Olam, DDAB, PA), temperature, precursor ratio [28] | Ligand-to-precursor ratio, dissolution time, antisolvent polarity [30] [31] |

| Typical NC Size (CsPbBr₃) | Diffusion-controlled, tunable via ligand and temperature [28] | 5.7 - 6.6 nm, tunable via dissolution time/ligand ratio [31] |

| PLQY Performance | High, but can be affected by bromide-deficient conditions [28] | High, often with excellent initial emission due to bromide-rich conditions [28] |

| Reaction Yield | High [28] | Limited by bulk crystal precipitation [28] |

| Scalability & Industrial Appeal | Moderate, due to complex setup and energy cost [16] | High, due to simplicity, low cost, and ambient conditions [28] [16] |

| Ligand Shell Stability | Can be engineered for high stability (e.g., using DDAB, PA) [28] | Susceptible to ligand desorption due to polar solvent residue [30] |

Ligand-Assisted Purification and Surface Management

The Necessity of Purification

Following synthesis, perovskite NCs require purification to remove unreacted precursors, excess ligands, and solvent impurities that can instigate Ostwald ripening and degrade optical performance [16]. However, the purification process itself poses a risk to ligand density. Conventional centrifugation and washing can cause ligand desorption, creating undercoordinated surface sites that act as trap states and quench PLQY [27]. Therefore, purification must be viewed as a critical step for surface management, aimed at refining the ligand shell without compromising passivation.

Advanced Purification and Ligand Management Strategies

To mitigate ligand loss, several advanced strategies have been developed:

- Ligand Exchange and Engineering: This involves replacing the original, labile ligands (e.g., Olam/OA) with more tightly bound alternatives after synthesis. The use of bidentate ligands (e.g., dicarboxylic acids) that bind to the NC surface with two anchor groups offers significantly stronger adhesion and better surface coverage, effectively reducing defect density and maintaining high PLQY through purification and aging [16] [27].

- Post-Synthesis Passivation: This strategy involves treating the purified NCs with additional ligand solutions to "heal" the surface defects created during purification. A prominent method is the use of metal bromide–ligand solutions (e.g., PbBr₂ with oleic acid), which can replenish lead and halide vacancies on the surface, leading to a notable recovery and enhancement of PLQY [27].

- Use of Zwitterionic Ligands: Zwitterionic ligands, which contain both positive and negative charges within the same molecule, exhibit strong electrostatic binding to the perovskite surface. This interaction enhances ligand density and stability, helping the NCs withstand the rigors of purification while preserving their optical properties [27].

Table 2: Ligand types and their functions in perovskite nanocrystal synthesis and passivation

| Ligand Type | Example Compounds | Function & Mechanism | Impact on PLQY & Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Type (Lewis Base) | Oleylamine (Olam), Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Electron pair donation to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites [16]. | Provides initial passivation; labile binding can lead to PLQY degradation [28]. |

| X-Type (Anionic) | Oleic Acid (OA), Alkylphosphonic Acids (PA) | Forms a covalent bond with surface sites; often used with amines [16]. | Good passivation; stronger binding with phosphonic acids improves stability [28]. |

| Z-Type (Lewis Acid) | Lead Oleate | Accepts electron pairs from surface halide anions [16]. | Can contribute to surface passivation but is less common. |

| Quaternary Ammonium | Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Ionic bonding to surface halides; lacks protons, preventing facile desorption [28]. | Enhances stability and maintains PLQY in polar environments [28]. |

| Bidentate/Multidentate | Dicarboxylic acids, alkyl phosphonic acids | Multiple binding points to the NC surface, creating a chelating effect [16] [27]. | Significantly improves ligand density and stability, leading to high and durable PLQY [27]. |

Visualization of Synthesis Workflows and Ligand Impact

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for the HI and LARP synthesis methods and the logical relationship between synthesis parameters, ligand density, and final NC properties.

Diagram 1: Synthesis workflows and parameter-property relationships for HI and LARP methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table provides a consolidated list of key reagents used in the synthesis and passivation of perovskite nanocrystals, detailing their specific functions.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for perovskite nanocrystal synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salts | Cs₂CO₃, CsBr, PbBr₂ | Provide the elemental constituents (Cs, Pb, Br) for the perovskite crystal lattice (ABX₃) [28] [31]. |

| Solvents | 1-Octadecene (ODE), Toluene, DMF | ODE: High-boiling non-polar solvent for HI. Toluene: Non-polar antisolvent for LARP. DMF: Polar solvent to dissolve precursors in LARP [28] [31]. |

| Acidic Ligands (X-type) | Oleic Acid (OA), Nonanoic Acid (NA), Octylphosphonic Acid (OPA) | Bind to surface cations (Pb²⁺); control growth and provide steric hindrance. Phosphonic acids offer stronger binding [28] [16]. |

| Basic Ligands (L-type) | Oleylamine (Olam), Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Bind to surface halide anions; crucial for controlling crystallization and passivating halide vacancies [28] [16]. |

| Quaternary Ammonium Salts | Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB), Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (TOAB) | Provide halide ions and passivate surface via ionic bonding; more stable due to lack of exchangeable protons [28]. |

| Multidentate Ligands | Dicarboxylic acids, alkyl diphosphonic acids | Provide multiple anchoring points to the NC surface, creating a highly stable ligand shell that resists desorption during purification [16] [27]. |

The advanced synthesis techniques of Hot-Injection and Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation, coupled with sophisticated ligand-assisted purification strategies, provide a powerful toolkit for engineering high-performance perovskite nanocrystals. The central theme unifying these methodologies is the critical need to control ligand density at the NC surface. Whether through the high-temperature, controlled environment of HI or the room-temperature, parameter-driven approach of LARP, the ultimate goal is to achieve a optimally passivated surface that suppresses non-radiative recombination pathways. The ongoing development of robust ligands, such as quaternary ammonium salts and multidentate ligands, along with post-synthesis treatment protocols, is pivotal for translating the exceptional initial PLQY of lab-scale PNCs into the long-term stability required for commercial optoelectronic devices. A deep understanding of the intricate relationship between synthesis parameters, ligand chemistry, and final nanocrystal properties is essential for driving this field forward.

In the pursuit of high-performance perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs) for optoelectronic applications, post-synthetic ligand engineering has emerged as a pivotal strategy for optimizing key performance metrics, most notably the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY). The density and binding affinity of surface ligands directly govern the passivation of surface defects that act as non-radiative recombination centers, thereby exerting a fundamental influence on PLQY [29] [32]. While initial ligand shells from synthesis provide colloidal stability, they often feature dynamic binding and incomplete surface coverage, leaving a high density of unpassivated sites such as under-coordinated lead (Pb²⁺) and halide ions [33] [34]. Post-synthetic strategies—including ligand exchange, supplementation, and functionalization—enable the construction of a refined, robust ligand matrix that enhances defect passivation, suppresses ion migration, and improves environmental stability, collectively driving PLQY toward its theoretical limits. This technical guide delineates the core principles, methodologies, and quantitative outcomes of these strategies, framing them within the critical context of modulating ligand density to maximize radiative recombination efficiency.

Fundamental Principles Linking Ligand Chemistry to PLQY

The Role of Surface Defects in PLQY Quenching

The photoluminescence efficiency of PNCs is primarily limited by non-radiative recombination at surface defects. Due to their high surface-to-volume ratio, nanocrystals possess a significant population of surface atoms that can become charge carrier traps if improperly coordinated. Common defects include:

- Halide Vacancies (V₋): Act as deep electron traps, strongly promoting non-radiative recombination [33].

- Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites: Function as hole traps, reducing charge carrier lifetime [29].

- Cation Vacancies (e.g., Cs⁺ or FA⁺): Disrupt the local electronic structure and facilitate ion migration [34].

These defects create mid-gap states that provide alternative pathways for exciton relaxation without photon emission. The central premise of ligand engineering is that a high density of well-chosen ligands effectively passivates these defects, restoring high-efficiency radiative recombination [29] [32].

Ligand Binding Dynamics and Surface Coverage

Traditional long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA) bind to the NC surface through relatively weak ionic interactions. This labile binding results in a dynamic equilibrium where ligands frequently detach, creating temporary unpassivated defects that flicker between ON and OFF states in single-particle PL studies [32]. This manifests as PL flickering and blinking, directly observed at the single-particle level, which averages to a reduced ensemble PLQY [32].

The relationship between ligand surface density (ρ) and PLQY can be conceptually described by a model where the non-radiative recombination rate (kₙᵣ) is proportional to the density of unpassivated defects, which in turn decreases with increasing ρ. Consequently, PLQY, which is given by kᵣ/(kᵣ + kₙᵣ) where kᵣ is the radiative rate, increases with higher ligand density and improved binding strength [29] [35].

Core Post-Synthetic Ligand Engineering Strategies

Ligand Exchange: Replacing Long-Chain Insulating Ligands

Ligand exchange involves the partial or complete displacement of native, often long-chain, insulating ligands with shorter or more functional ligands after synthesis and purification. This strategy is crucial for applications like photovoltaics, where efficient charge transport between NCs is essential.

Solvent-Mediated Ligand Exchange for Photovoltaics: A seminal study demonstrated the use of tailored solvents to maximize the removal of insulating oleylamine ligands from CsPbI₃ PQD surfaces. The protic solvent 2-pentanol was identified as optimal due to its appropriate dielectric constant and acidity, facilitating the exchange with short choline ligands without introducing halogen vacancy defects. This process resulted in a champion PQD solar cell efficiency of 16.53%, attributed to enhanced charge transport and improved defect passivation [36].

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Ligand Exchange Strategies

| Perovskite System | Original Ligand | New Ligand | Key Metric | Performance Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ QDs | Oleylamine | Choline | Solar Cell Efficiency | 16.53% (champion device) | [36] |

| CsPbBr₃ QDs | OA/OLA | Benzamide | PLQY | Increased to 98.56% | [33] |

| FAPbBr₃/MAPbBr₃ NCs | TOPO/alkylphosphinic acid | Phosphoethanolamine (PEA) | Single-particle ON fraction | 94% (minimal blinking) | [35] |

Ligand Supplementation: Dual-Ligand Synergistic Passivation

Ligand supplementation involves introducing additional passivants to the existing ligand shell to address specific defect types, creating a multi-component, synergistic passivation system.

Dual-Ligand Synergistic Passivation Engineering (DLSPE): This advanced strategy simultaneously targets bulk and surface defects. In a representative study on CsPbBr₃ QDs:

- Europium acetylacetonate (Eu(acac)₃) was incorporated to compensate for Pb²⁺ vacancies in the lattice and stabilize the crystal framework.

- Benzamide was introduced via surface ligand exchange, its electron-rich amide groups coordinating with under-coordinated Br⁻ ions on the surface [33].

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations confirmed strong and selective binding of these ligands to specific defect sites. This dual approach resulted in a near-unity PLQY of 98.56% and a dramatically shortened fluorescence lifetime of 69.89 ns, indicating highly suppressed non-radiative decay [33]. Furthermore, this strategy improved solvent compatibility, enabling the integration of PQDs into photolithography processes for high-resolution patterning (20.7 μm linewidth) [33].

Ligand Functionalization: Advanced Zwitterionic Ligands

Ligand functionalization focuses on designing and deploying novel ligand architectures with enhanced binding and steric properties.