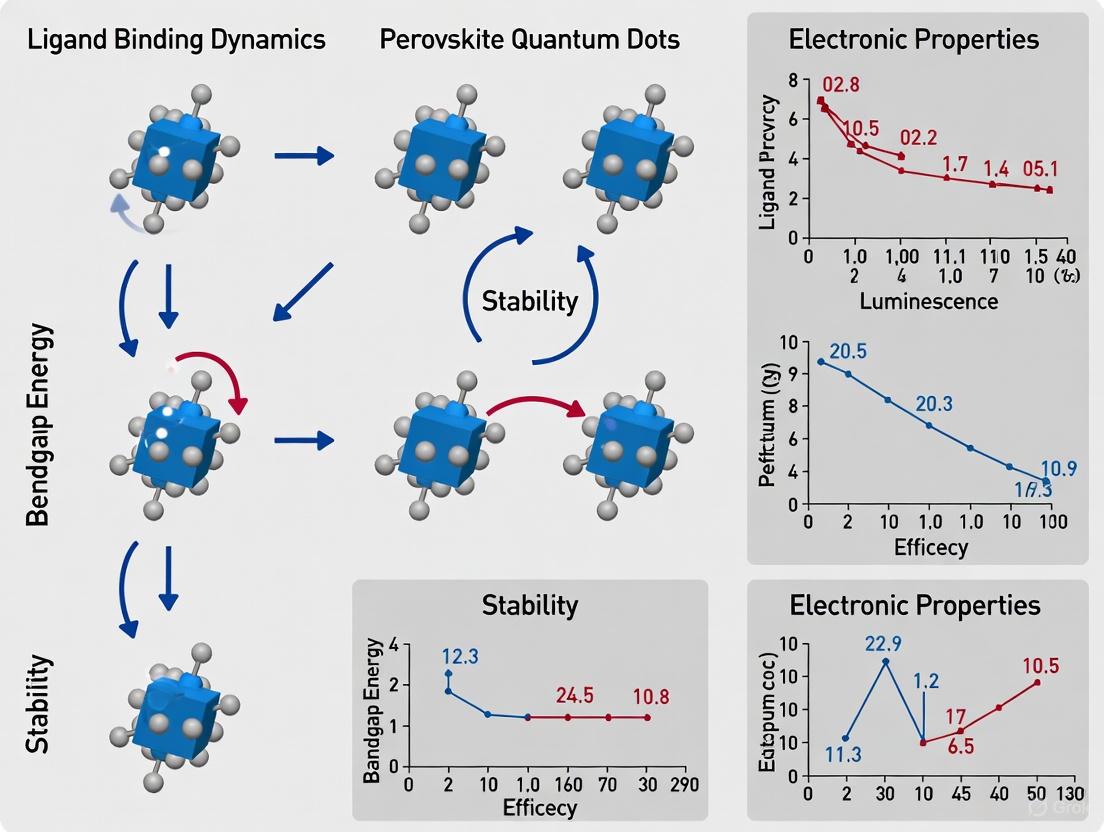

Ligand Binding Dynamics in Perovskite Quantum Dots: A Guide for Stabilizing Optoelectronic and Biomedical Applications

This article comprehensively explores the critical influence of ligand binding dynamics on the properties and performance of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), with a specific focus on implications for biomedical research...

Ligand Binding Dynamics in Perovskite Quantum Dots: A Guide for Stabilizing Optoelectronic and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the critical influence of ligand binding dynamics on the properties and performance of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), with a specific focus on implications for biomedical research and drug development. It establishes the foundational principles of how ligand structure and binding motifs dictate PQD electronic properties and stability. The content details advanced methodological strategies for surface engineering and purification, addresses key challenges in troubleshooting material degradation and toxicity, and synthesizes validation techniques for benchmarking performance. By integrating computational screening, experimental characterization, and stability optimization, this review provides researchers and scientists with a roadmap for designing robust, high-performance PQD systems for sensitive biosensing, bioimaging, and therapeutic applications.

Ligand-PQD Interactions: Unraveling the Molecular Foundations of Stability and Electronic Properties

The precise modulation of band edges is a cornerstone of modern materials design, particularly for optoelectronic applications. Within the context of perovskite quantum dot (QD) research, controlling the electronic structure at the nanoscale interface is paramount for optimizing device performance and stability. The strategic application of π-conjugated organic molecules and their functional substituents provides a powerful method for tailoring the frontier orbitals—the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM)—of semiconductor materials [1] [2]. This in-depth technical guide examines the fundamental mechanisms through which these organic components influence band edge positions and electronic properties, with a specific focus on their critical role in modulating the properties of halide perovskite QDs through ligand binding dynamics.

The defect-tolerant nature of lead halide perovskites (LHPs) makes them exceptionally responsive to surface interactions with organic ligands [2]. Unlike traditional semiconductors where surface defects often lead to charge trapping and performance degradation, LHPs can maintain high efficiencies despite defect abundance. This unique characteristic shifts the design paradigm from defect elimination to strategic electronic modification via ligand engineering. By understanding how π-conjugation length, electron donor-acceptor capabilities, and binding group selection influence band edge positions, researchers can deliberately tailor perovskite QDs for specific applications in photovoltaics, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and quantum information technologies [1] [2].

Theoretical Foundations of Band Edge Modulation

Fundamental Concepts of π-Conjugation

π-Conjugation refers to the system of overlapping p-orbitals connected by alternating single and multiple bonds in organic molecules, creating a delocalized electron cloud. This electron delocalization dramatically influences the electronic structure and optical properties of molecules, which in turn affects their interactions with semiconductor surfaces [3]. In donor-π-acceptor (D-π-A) frameworks, the π-conjugated bridge serves as a conduit for intramolecular charge transfer (ICT), facilitating electron movement from donor to acceptor groups and creating a significant molecular dipole moment [3].

The extent of π-conjugation primarily governs the energy separation between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of organic molecules. Extended π-systems lower this HOMO-LUMO gap, bringing the molecular energy levels closer to the band edges of semiconducting materials [2]. For perovskite QDs, this alignment is critical, as molecular orbitals positioned within the bandgap can introduce surface states that either facilitate charge transport or lead to detrimental charge trapping, depending on their precise energy positioning [2].

Electronic Push-Pull Dynamics

The strategic incorporation of electron-donating groups (EDGs) and electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) creates an internal "push-pull" effect within π-conjugated molecules that profoundly influences their electronic properties [3]. This polarization effect modifies the electron density distribution across the molecular framework, which directly impacts the energy and spatial distribution of frontier orbitals.

- Electron-donating groups (e.g., -NH₂, -OH, -OCH₃) raise the energy of both HOMO and LUMO orbitals, with a more pronounced effect on the HOMO level. When such molecules interact with perovskite surfaces, this can lead to an upward shift in the perovskite's effective valence band maximum through interfacial dipole formation or orbital hybridization [3] [2].

- Electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., -NO₂, -CN, -CF₃) lower the energy of molecular orbitals, particularly the LUMO, which can pull down the conduction band minimum of adjacent semiconductors. Strong EWGs like carboxylate groups, which contain electronegative oxygen atoms, significantly lower ligand orbital energies relative to perovskite states [2].

The following table summarizes the directional effects of various molecular features on electronic structure:

Table 1: Effects of Molecular Features on Electronic Structure Properties

| Molecular Feature | Primary Electronic Effect | Impact on Band Edges | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extended π-Conjugation | Reduces HOMO-LUMO gap | Brings ligand states nearer to band edges; can introduce gap states [2] | Red-shifted absorption; enhanced charge transfer [1] |

| Electron-Donating Groups | Raises HOMO/LUMO energy | Can elevate VBM; reduces hole injection barrier [3] | Increased work function; improved hole transport [3] |

| Electron-Withdrawing Groups | Lowers HOMO/LUMO energy | Can depress CBM; reduces electron injection barrier [2] | Enhanced electron affinity; improved electron injection [2] |

| Carboxylate Binding Group | Strong binding with low-lying orbitals | Lowers ligand levels relative to perovskite states [2] | Stronger coordination; potential PL quenching [2] |

| Ammonium Binding Group | Weaker binding with higher-lying orbitals | Minimal perturbation of band edges [2] | Weaker coordination; less disruptive to optics [2] |

Methodologies for Investigating Electronic Structure Modulation

Computational Approaches

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations serve as the primary computational tool for predicting and rationalizing the electronic structure modifications induced by π-conjugated ligands [3] [2]. The standard protocol involves:

- Geometry Optimization: The ligand-perovskite system is structurally relaxed using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional to establish the ground-state configuration [2]. For surface binding studies, this typically involves a perovskite slab model with one ligand molecule adsorbed at the preferred binding site.

- Electronic Structure Calculation: Single-point energy calculations are performed on the optimized structure. The PBE functional is often employed due to a fortuitous cancellation of errors—its tendency to underestimate bandgaps is counterbalanced by neglecting spin-orbit coupling (SOC) effects in LHPs, yielding reasonably accurate bandgaps [2].

- Property Prediction: Key electronic properties are extracted, including:

- Projected density of states (PDOS) to identify ligand contributions to band edges

- HOMO-LUMO gaps and orbital spatial distributions

- Charge density difference maps to visualize interfacial charge transfer

- Electrostatic potential surfaces to predict dipole moments [3]

For increased accuracy, especially for molecules where SOC is less critical, hybrid functionals like CAM-B3LYP or HSE with larger basis sets (e.g., 6-31+G(d,p), def2-TZVP) can be employed [3]. These methods provide more reliable predictions of excitation energies and non-linear optical properties.

Figure 1: Computational workflow for investigating ligand effects on electronic structure using density functional theory.

Experimental Characterization Techniques

Experimental validation complements computational predictions through several key methodologies:

- Photoluminescence (PL) Quenching Studies: Measurement of PL intensity reduction provides direct evidence of charge transfer processes and the presence of midgap states introduced by ligands [2]. A significant quenching effect suggests the formation of trap states within the bandgap that non-radiatively recombine charge carriers.

- Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS): This technique directly measures the work function and valence band maximum positions, allowing quantitative assessment of band edge shifts induced by ligand treatment [1].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): High-resolution XPS analysis reveals chemical bonding information and coordination states between ligand functional groups (e.g., carboxylate oxygen, ammonium nitrogen) and perovskite surface atoms (e.g., Pb, Cs) [4].

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: Infrared spectroscopy detects shifts in vibrational frequencies of ligand functional groups upon binding, confirming coordination and characterizing binding strength [1].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electronic Structure Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ Quantum Dots | Model inorganic perovskite system for studying ligand effects [2] | Cubic phase; Size: 5-15 nm tunable; PLQY: >80% [4] [2] |

| π-Conjugated Ligands | Modulate band edges and surface properties [1] [2] | Varying π-conjugation length; Carboxylate/ammonium binding groups [2] |

| DFT Software (Wien2k, Gaussian) | Predict electronic structure changes [5] [2] | PBE, HSE functionals; 6-31+G(d,p) basis sets [3] [2] |

| Spectrofluorometer | Measure PL quenching and charge transfer efficiency [2] | Spectral range: 200-1700 nm; Time-resolved capability [2] |

| XPS/UPS System | Quantify band edge positions and chemical states [4] [1] | Monochromatic Al Kα source; He I/II UV source [1] |

Electronic Structure Modulation in Perovskite Quantum Dots

Ligand Binding Dynamics and Surface Interactions

In perovskite QD systems, ligand binding occurs primarily through two mechanisms: cationic exchange via ammonium groups replacing surface Cs⁺ ions, and coordination bonding through carboxylate groups binding to undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the [PbX₆]⁴⁻ octahedra [2]. The carboxylate group typically forms stronger bidentate chelation with lead atoms compared to the ammonium group, resulting in more pronounced electronic effects [2].

The binding interaction creates a direct electronic interface where the molecular orbitals of the ligand can hybridize with the band structure of the perovskite QD. Computational studies reveal that ligands with extended π-conjugation can have their unoccupied orbitals (LUMO) positioned close to the conduction band edge or even inside the fundamental bandgap, while their occupied orbitals (HOMO) typically remain deep within the valence band [2]. This asymmetric alignment creates potential pathways for electron transport while maintaining hole confinement within the QD core.

Band Edge Tailoring Through Molecular Design

Strategic ligand design enables precise control over perovskite QD band edges through several interconnected mechanisms:

Surface Dipole Formation: π-Conjugated molecules with strong internal push-pull character create significant interfacial dipole moments at the QD surface [1]. These dipoles electrostatically shift the effective band edges, either raising or lowering the work function depending on the dipole orientation. For instance, molecules with electron-deficient moieties positioned toward the QD surface and electron-rich groups outward typically push the band edges upward, reducing the work function and facilitating electron injection [1].

Orbital Hybridization: When ligands coordinate strongly with surface atoms, their molecular orbitals can mix with the perovskite band states, creating hybrid interface states that effectively modify the band edge composition [2]. For carboxylate-bound ligands with extended π-systems, this can result in partial extension of the QD's wavefunction onto the ligand framework, enhancing interdot electronic coupling in assembled structures [2].

Defect Passivation: Perhaps most importantly, proper ligand binding passivates undercoordinated surface atoms that would otherwise create midgap trap states [1]. By eliminating these trap states, the intrinsic band edge electronic structure is restored, leading to improved carrier mobility and reduced non-radiative recombination [1] [2].

Figure 2: Mechanisms of electronic structure modulation in perovskite quantum dots through ligand binding dynamics.

Quantitative Relationships in Electronic Modulation

Systematic computational studies have established quantitative relationships between molecular structure and electronic effects in CsPbBr₃ QD systems [2]:

- π-Conjugation Length: Increasing the conjugation length in a series of ligands (e.g., from benzene to naphthalene to anthracene derivatives) progressively lowers the LUMO energy by approximately 0.5-0.8 eV per additional aromatic ring, bringing these unoccupied orbitals closer to the QD conduction band edge [2].

- Electron-Withdrawing Strength: The incorporation of strong EWGs (e.g., -NO₂, -CN) can lower ligand LUMO levels by an additional 0.3-0.5 eV compared to unsubstituted analogues, while EDGs (e.g., -NH₂, -OCH₃) raise LUMO levels by a similar magnitude [2].

- Binding Group Effects: Carboxylate-bound ligands exhibit orbital energies approximately 0.4-0.6 eV lower than comparable ammonium-bound ligands due to the electronegativity of the oxygen atoms [2].

Table 3: Quantitative Effects of Ligand Structural Features on CsPbBr₃ QD Electronic Properties

| Ligand Structural Feature | Electronic Effect | Magnitude of Change | Impact on PLQY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Each additional aromatic ring | Lowers LUMO relative to CB | 0.5 - 0.8 eV [2] | Can decrease if states enter gap [2] |

| Strong EWG (e.g., -NO₂) | Lowers LUMO energy | 0.3 - 0.5 eV [2] | Often decreases due to midgap states [2] |

| Strong EDG (e.g., -NH₂) | Raises LUMO energy | 0.3 - 0.5 eV [2] | Minimal change if states remain outside gap [2] |

| Carboxylate vs Ammonium binding | Lowers orbital energies | 0.4 - 0.6 eV [2] | Depends on specific alignment [2] |

| Extended π-system with optimal EWG | Creates intra-gap transport states | Within 0.3 eV of CB [2] | Moderate decrease but enhances conductivity [1] |

The strategic application of π-conjugated molecules with tailored substituents provides unprecedented control over the electronic structure of perovskite quantum dots. Through a combination of surface dipole formation, orbital hybridization, and defect passivation, these molecular modulators can precisely shift band edge positions, eliminate trap states, and create designated pathways for charge transport. The insights and methodologies presented in this technical guide establish a framework for rationally designing ligand-perovskite interfaces with optimized electronic properties for specific applications. As research progresses, the integration of computational prediction with experimental validation will continue to refine our understanding of these complex interfacial interactions, enabling the development of next-generation perovskite QD devices with enhanced performance and stability for optoelectronic and quantum information technologies.

The explosive interest in lead halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) for optoelectronic applications stems from their exceptional properties, including defect tolerance, bandgap tunability, and high photoluminescence quantum yields [6]. However, the immense surface-to-volume ratio of these nanoscale materials means their optical and electronic properties are profoundly dictated by their surface chemistry. Surface ligands—organic or inorganic molecules bound to the QD surface—play a dual role: they provide colloidal stability and passivate detrimental surface defects, but their dynamic binding nature and insulating characteristics can also impede charge transport [6] [7]. Consequently, surface state engineering through rational ligand design has emerged as a critical strategy to mitigate charge trapping and unlock the full potential of PQDs in devices ranging from solar cells and light-emitting diodes (LEDs) to neuromorphic computing systems [8] [6].

This technical guide examines the fundamental interplay between ligand design and charge trapping dynamics in perovskite quantum dots. Surface ligands directly influence charge trapping through several mechanisms: they passivate ionic defects (e.g., lead and halide vacancies), modify the energy landscape at QD interfaces, dictate inter-dot coupling in solid films, and their binding stability determines the operational longevity of devices [6] [7]. We explore how advanced ligand engineering strategies, including the development of lattice-matched anchors, conductive molecular linkers, and multi-dentate binding groups, are being deployed to create a new generation of high-performance PQD devices with suppressed charge recombination and tailored charge transport properties.

Fundamental Mechanisms: How Ligands Influence Surface States and Charge Trapping

The Nature of Surface Defects and Charge Trapping in PQDs

In perovskite quantum dots, the primary surface defects responsible for charge trapping are undercoordinated lead ions (Pb²⁺) and halide vacancies [7]. These defects introduce electronic states within the bandgap that act as traps for photogenerated electrons and holes, promoting non-radiative recombination and reducing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY). The inherent ionic character of perovskites makes these surface defects highly mobile and dynamic, complicating passivation efforts [6]. The traditional ligands oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) used in synthesis provide initial passivation but bind weakly, leading to their gradual desorption during processing or operation. This desorption re-exposes trap sites and creates channels for ion migration, ultimately degrading device performance [7].

The Dual Function of Ligands: Passivation and Charge Transport Mediation

Ligands influence charge trapping through two primary functions:

- *Defect Passivation:* Effective ligands coordinate with undercoordinated surface Pb²⁺ ions, filling vacancy sites and eliminating gap states. This is quantified by increases in PLQY and carrier lifetime.

- *Charge Transport Mediation:* In QD solids, ligands determine the physical and electronic coupling between adjacent dots. Long, insulating alkyl chains (e.g., in OA/OAm) create large inter-dot distances (>2 nm) that hinder charge transport, while short, conductive ligands facilitate wavefunction overlap and charge delocalization [9].

The binding strength and mode (e.g., monodentate vs. bidentate) determine the ligand's effectiveness under operational stresses such as electric fields, light, and heat. Strong, multidentate binding is crucial for durable passivation [7].

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Engineering Strategies

The efficacy of various ligand engineering strategies can be quantitatively assessed through key performance metrics in both materials and devices.

Table 1: Impact of Ligand Engineering on Perovskite QD Optical Properties and Device Performance

| Ligand Type / Strategy | Key Functional Groups | Reported PLQY (%) | Carrier Lifetime / Trap Density | Device Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional OA/OAm [6] | -COO⁻, -NH₃⁺ | ~59 - 85% [7] [10] | Shortened lifetime, high trap density | Baseline performance |

| Lattice-matched TMeOPPO-p [7] | P=O, -OCH₃ (6.5 Å spacing) | ~97% [7] | Significant trap elimination (theoretical) | QLED: EQE ~27%, T₅₀ > 23,000 h [7] |

| Ionic Liquid [BMIM]OTF [10] | OTF⁻, [BMIM]⁺ | ~97% [10] | τ_avg increased from 14.3 ns to 29.8 ns [10] | QLED: EQE ~21%, Response time: 700 ns [10] |

| Quaternary Ammonium (DDAB) [8] | Quaternary Ammonium Bromide | N/A | Improved carrier mobility, reduced trapping | Photosynaptic Transistor: Ultralow energy (0.16 aJ) [8] |

| Sulfide Ligands (InSb QDs) [9] | S²⁻ | N/A | Lower trap density, higher carrier mobility | SWIR Photodiode: EQE 18.5%, low dark current [9] |

Table 2: Thermodynamic Data of Ligand Binding on CsPbBr₃ QDs via ¹H NMR [11]

| Incoming Ligand | Ligand Type | Equilibrium Constant (K_eq) with Native Ligands | Bound Ligand Surface Density (nm⁻²) | Effect on PL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-Undecenoic Acid | Carboxylic Acid | 1.97 ± 0.10 (vs. Oleate) [11] | 1.2 - 1.5 (Oleate) [11] | Increase |

| Undec-10-en-1-amine | Amine | 2.52 ± 0.08 (vs. Oleylamine) [11] | 2.4 - 3.0 total ligands [11] | Increase |

| 10-Undecenylphosphonic Acid | Phosphonic Acid | Irreversible Exchange [11] | N/A | Increase |

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Exchange and Characterization

Objective: To replace native OA/OAm ligands with TMeOPPO-p to enhance passivation and stability.

Materials:

- Synthesized CsPbI₃ QDs in non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene or hexane).

- Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) ligand.

- Polar solvent for purification (e.g., ethyl acetate, methyl acetate).

- Centrifuge and centrifuge tubes.

Procedure:

- Purification: Precipitate the as-synthesized CsPbI₃ QDs by adding a polar solvent (typical volume ratio 1:1 to 1:3) and centrifuging at high speed (e.g., 8000 rpm for 5 min). Discard the supernatant to remove excess solvents and free ligands.

- Ligand Solution Preparation: Dissolve TMeOPPO-p in a mild polar solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) to a concentration of 5 mg/mL.

- Ligand Exchange: Re-disperse the purified QD pellet in the TMeOPPO-p solution. Vortex and shake the mixture for a specific duration (e.g., 1-2 hours) to allow ligand exchange.

- Purification: Precipitate the ligand-exchanged QDs by adding an anti-solvent (e.g., methanol) and centrifuging. Repeat this washing step 1-2 times to remove displaced ligands and excess TMeOPPO-p.

- Re-dispersion: Finally, disperse the functionalized QDs in an anhydrous solvent (e.g., octane) for film fabrication and characterization.

Characterization:

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Use an integrating sphere to measure absolute PLQY. Target: >95% [7].

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Observe the weakening of C-H stretching modes (2700-3000 cm⁻¹) from OA/OAm, confirming ligand replacement [7].

- XPS: A shift in Pb 4f peaks to lower binding energies indicates successful coordination of TMeOPPO-p with surface Pb²⁺ ions [7].

Objective: To incorporate ionic liquid [BMIM]OTF during synthesis to enhance crystallinity and provide co-passivation.

Materials:

- Lead bromide (PbBr₂) precursor.

- Cs-oleate precursor.

- Ionic liquid 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF).

- Solvents: Octadecene (ODE), Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm).

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve [BMIM]OTF in chlorobenzene (CB). Add this solution to the PbBr₂ precursor mixture (in ODE/OA/OAm).

- Hot-Injection Synthesis: Perform the standard hot-injection synthesis by swiftly injecting the Cs-oleate precursor into the hot (~160-180 °C) PbBr₂/[BMIM]OTF mixture.

- Purification: Allow the reaction to proceed for a short time (e.g., 10-30 s), then cool the solution in an ice-water bath. Purify the QDs by centrifugation with a polar anti-solvent.

Characterization:

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Measure the increase in average QD size (e.g., from 8.84 nm to 11.34 nm) [10].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Analyze the enhanced intensity of the (200) crystal plane peak, indicating improved crystallinity [10].

- Time-Resolved PL (TRPL): Fit the decay curve with a multi-exponential model. An increase in average lifetime (τ_avg) indicates reduced trap-assisted recombination [10].

Visualization: Ligand Engineering Workflow and Impact

The following diagram illustrates the strategic workflow for ligand engineering and its direct impact on the material's electronic properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ligand Engineering

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ligand Engineering Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Native ligands for colloidal synthesis and initial surface passivation. | Dynamic binding leads to easy desorption; baseline for comparison [6] [7]. |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) | Bulky quaternary ammonium ligand for interface optimization. | Enhances interaction with n-type polymers in photosynaptic transistors [8]. |

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) | Lattice-matched multi-site anchor for strong defect passivation. | Designed 6.5 Å O-atom spacing matches perovskite lattice for multi-dentate binding [7]. |

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF) | Ionic liquid for in-situ crystallization control and co-passivation. | Cations coordinate with Br⁻, anions coordinate with Pb²⁺; enhances QD size and crystallinity [10]. |

| Metal Halide Salts (e.g., ZnI₂, PbCl₂) | Inorganic Z-type ligands for surface passivation. | Passivates undercoordinated sites on II-VI and perovskite QDs; can introduce dynamic traps [12]. |

| Alkylphosphonic Acids | Strong-binding ligands for robust surface passivation. | Phosphonic acid group binds more strongly than carboxylic acids; can lead to irreversible exchange [11]. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Solvent for single-phase ligand exchange. | Polar, aprotic solvent suitable for metal halide ligand exchange reactions [12]. |

Surface state engineering through advanced ligand design is a cornerstone for the advancement of perovskite quantum dot technologies. Moving beyond conventional OA/OAm systems toward rationally designed ligands—featuring strong, multi-dentate binding, optimal steric profiles, and conductive backbones—has proven highly effective in suppressing charge trapping and unlocking new device performance benchmarks [8] [7] [10]. The quantitative data and protocols outlined herein provide a roadmap for researchers to systematically explore the ligand-property relationship.

Future research will likely focus on deepening the fundamental understanding of ligand binding dynamics under operational conditions, further refining the design of "lock-and-key" ligand systems that perfectly match the perovskite lattice, and exploring the integration of these advanced PQDs into complex optoelectronic systems. As ligand engineering continues to mature, it will play a pivotal role in bridging the gap between laboratory innovation and the commercial application of stable, high-efficiency perovskite quantum dot devices.

The binding energetics between surface ligands and perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) fundamentally determine the optoelectronic properties and operational stability of ensuing devices. This whitepaper delineates the core principles and methodologies for quantifying these interactions, from experimental nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques that measure thermodynamic parameters to first-principles computational models that predict binding affinity. Within the context of ligand-dependent performance of perovskite quantum dots, we provide a detailed exposition of experimental protocols for ligand exchange studies, visualize the underlying workflows, and tabulate critical quantitative data. The integration of these approaches provides a robust framework for the rational design of next-generation PQD-based materials and devices.

Lead halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), with the general formula APbX₃ (A = Cs⁺, MA⁺, FA⁺; X = Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻), have emerged as a revolutionary class of semiconducting nanomaterials due to their exceptional optoelectronic properties, including size-tunable band gaps, high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), and narrow emission line widths [11] [6]. Unlike traditional II-VI QDs, PQDs possess an intrinsically ionic crystal lattice, which renders their surface chemistry exceptionally dynamic and complex. The surface ligands, typically long-chain organic molecules like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), are not mere passive stabilizers but active determinants of colloidal stability, defect passivation, charge transport, and ultimately, the efficiency and stability of PQD-based devices such as solar cells and LEDs [6].

The binding affinity and stability of these ligands are governed by fundamental thermodynamic and kinetic parameters. The highly dynamic binding nature of native ligands, however, often leads to detachment during processing or operation, causing nanoparticle aggregation, loss of photoluminescence, and device degradation [11] [6]. Therefore, a first-principles understanding of ligand binding energetics—the quantitative assessment of the strength and nature of the ligand-QD interaction—is paramount. It enables the rational selection and design of ligands to engineer more robust and efficient PQD materials, moving beyond empirical trial-and-error approaches. This guide details the experimental and computational toolkit required to probe and predict these essential properties.

Quantitative Data: Experimentally Determined Binding Parameters

Rigorous quantification is the cornerstone of understanding binding energetics. The following table consolidates key thermodynamic data obtained from solution ¹H NMR studies on CsPbBr₃ PQDs, a model system for probing perovskite surface chemistry [11].

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Thermodynamic Parameters for Ligand Exchange on CsPbBr₃ QDs

| Ligand Type | Native Ligand | Incoming Ligand | Equilibrium Constant (Kₑq) at 25°C | Energetics | Bound Surface Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxylic Acid | Oleate | 10-Undecenoate | 1.97 ± 0.10 | Exergonic | 1.2 - 1.5 nm⁻² (Oleate) |

| Amine | Oleylamine | Undec-10-en-1-amine | 2.52 ± 0.08 | Exergonic | 1.2 - 1.7 nm⁻² (Oleylamine) |

| Phosphonic Acid | Oleate | 10-Undecenylphosphonate | Irreversible | N/A | N/A |

Key Insights from Quantitative Data:

- The equilibrium constants (Kₑq) greater than 1 for carboxylic acid and amine exchanges indicate that these processes are exergonic (spontaneous) at room temperature, with the incoming ligand binding more strongly than the native one [11].

- The irreversible exchange observed with phosphonic acid ligands suggests a profoundly exergonic reaction, often associated with a much higher binding affinity, which can lead to significant improvements in photoluminescence intensity [11].

- The surface densities confirm that both oleic acid and oleylamine dynamically interact with the CsPbBr₃ QD surface, forming a dense ligand shell crucial for stabilization [11].

Experimental Protocols: Probing Binding Energetics via NMR

To obtain the quantitative data presented above, specific experimental methodologies are employed. Below is a detailed protocol for using solution ¹H NMR spectroscopy to quantify ligand exchange thermodynamics.

Protocol: Ligand Exchange Thermodynamics Studied by ¹H NMR

Principle: This method leverages the distinct NMR chemical shifts of free and bound ligand species to quantify their populations in solution at equilibrium. Ligands with terminal vinyl groups (e.g., 10-undecenoic acid) are introduced to circumvent spectral overlap with the native ligands' internal alkenyl protons [11].

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified CsPbBr₃ QD Suspension: Synthesized via a hot-injection method with controlled native ligands (e.g., oleic acid and dodecylamine to avoid spectral overlap) [11].

- Deuterated Solvent: Toluene-d⁸ for NMR spectroscopy.

- Internal Standard: Ferrocene, for precise concentration quantification.

- Incoming Ligand Solutions: Titrated amounts of 10-undecenoic acid, 10-undecenylphosphonic acid, or undec-10-en-1-amine in toluene-d⁸.

Procedure:

- QD Sample Preparation: Disperse a known concentration of purified CsPbBr₃ QDs in toluene-d⁸. Determine the QD concentration accurately using UV-Vis spectroscopy.

- Baseline NMR Acquisition: Acquire a ¹H NMR spectrum of the pure QD suspension. Identify and assign the characteristic peaks for the bound, physisorbed, and free states of the native ligands in the alkenyl region (δ = 5.4–5.9 ppm). Note the characteristic downfield shift and broadening of the bound ligand peaks.

- Ligand Titration:

- Add a small, known aliquot of the incoming ligand solution (e.g., 10-undecenoic acid) to the QD suspension.

- Mix thoroughly and allow the system to reach equilibrium.

- Acquire a new ¹H NMR spectrum.

- Repeat this titration process, acquiring a spectrum after each addition, until no further change in peak intensities is observed.

- Data Analysis:

- For each titration point, integrate the peaks corresponding to the bound and free states for both the native and incoming ligands.

- Using the internal ferrocene standard, calculate the concentrations of each species.

- For a reaction:

Bound-Oleate + Free-Incoming-Ligand ⇌ Bound-Incoming-Ligand + Free-Oleate, the equilibrium constantKₑq = [Bound-Incoming][Free-Oleate] / [Bound-Oleate][Free-Incoming]. - Plot the concentrations of bound species versus the amount of added incoming ligand to determine the average Kₑq across the titration series.

- Supplementary NMR Experiments:

- DOSY (Diffusion Ordered Spectroscopy): Perform DOSY to measure the diffusion coefficients of the ligand species. A significant decrease in the diffusion coefficient compared to the free ligand confirms interaction with the large QD surface [11].

- Selective Presaturation: Use this technique to investigate the exchange dynamics between bound and physisorbed states on a timescale of approximately 2 seconds [11].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key experimental and data analysis steps.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and materials essential for experiments focused on the surface chemistry and binding energetics of perovskite quantum dots.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Ligand Binding Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Precursor | Provides the cesium cation (Cs⁺) for the ABX₃ perovskite structure. | Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) [13] |

| Lead Precursor | Provides the lead cation (Pb²⁺) for the ABX₃ perovskite structure. | Lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂) [11] |

| Halide Precursor | Provides the halide anion (X⁻ = Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) for the ABX₃ perovskite structure. | Octylammonium bromide [6] |

| Native Ligands | Stabilize QDs during synthesis, control growth, and passivate surface defects. | Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) [11] [6] |

| Ligands for Exchange | Used to replace native ligands to improve properties like conductivity or stability. | 10-Undecenoic acid, 10-Undecenylphosphonic acid [11] |

| Non-Coordinating Solvent | Serves as the high-temperature reaction medium for QD synthesis. | 1-Octadecene (ODE), Diphenyl ether [11] [13] |

| Polar Solvent | Used in post-synthesis ligand exchange and purification processes. | Methyl acetate [6] |

| Deuterated Solvent | Required for ¹H NMR spectroscopy to analyze ligand binding. | Toluene-d⁸ [11] |

Computational Prediction: From Static Structures to Thermodynamic Ensembles

While experiments provide direct measurements, computational prediction offers a powerful tool for screening and understanding binding affinity from first principles. The central challenge lies in moving beyond static crystal structures to model the dynamic nature of binding.

The Thermodynamic Ensemble Principle

The true binding affinity (Kᵢ) is determined by the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) of the binding process, which is an ensemble property. It is theoretically defined by the equation: -RTlnKᵢ = ΔG = ΔGgas + ΔGsolv where R is the gas constant, T is temperature, ΔGgas is the gas-phase binding free energy, and ΔGsolv is the solvation free energy change [14]. A single static structure provides a limited snapshot, whereas a thermodynamic ensemble—a collection of conformations sampled from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations—approximates the full conformational space and provides a more robust foundation for predicting ΔG [14].

Protocol: Predicting Affinity with MD and Machine Learning

Principle: Machine learning models, such as graph neural networks, can be trained on features extracted from MD trajectories to learn the complex relationship between protein-ligand interaction geometries and binding affinities. This approach integrates dynamic information that is missing from static structure-based models [14].

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Obtain a 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex from a database like the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Perform MD simulations (e.g., 10 nanoseconds) for the complex. Sample multiple snapshots (e.g., 100) from the trajectory to represent the thermodynamic ensemble.

- Feature Extraction: From each snapshot, extract roto-translation invariant features characterizing the protein-ligand interactions, including interatomic distances, bond angles, and types of covalent/non-covalent interactions.

- Model Training and Prediction: Train a deep learning model (e.g., Dynaformer, a graph transformer) on this curated MD dataset. The model learns to predict the experimental binding affinity by aggregating information across all snapshots of the ensemble [14].

The following diagram conceptualizes this computational workflow.

Application to PQDs: Although the Dynaformer model was developed for protein-ligand systems [14], its underlying principle is directly transferable to PQD-ligand systems. Performing MD simulations of a ligand bound to a PQD surface facet and using the resulting ensemble of snapshots to train or evaluate models can provide a powerful, dynamics-aware prediction of ligand binding affinity, moving beyond the limitations of static density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

Mastering the fundamental binding energetics of perovskite quantum dots is a critical step towards realizing their full potential in optoelectronic applications. This guide has outlined the synergistic relationship between robust experimental quantification, primarily through ¹H NMR spectroscopy, and emerging computational paradigms that leverage molecular dynamics and machine learning. The tabulated thermodynamic data and detailed protocols provide a concrete foundation for researchers to characterize ligand interactions, while the visualization of workflows demystifies the process. As the field progresses, the integration of these first-principles approaches will be indispensable for the rational design of advanced ligand schemes, paving the way for highly efficient and ultra-stable perovskite quantum dot technologies.

Advanced Surface Engineering and Purification Strategies for Enhanced Performance

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation and Purification for Near-Unity Photoluminescence Quantum Yields

The pursuit of near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) represents a cornerstone of modern optoelectronics research. Achieving PLQYs approaching 100% is essential for unlocking the full potential of PQDs in applications ranging from light-emitting diodes and lasers to solar cells and radiation visualizers. The dynamic and ionic nature of perovskite crystals presents unique challenges, where surface defects act as non-radiative recombination centers that drastically diminish luminescence efficiency. This technical guide examines the critical role of ligand binding dynamics in determining the optoelectronic properties of PQDs, with particular focus on advanced reprecipitation and purification strategies that enable near-unity PLQY. Within the broader thesis that ligand chemistry dictates PQD performance, we demonstrate how rational ligand engineering and optimized processing protocols can effectively suppress non-radiative recombination pathways while enhancing material stability and charge transport properties.

Theoretical Foundation: Ligand-PQD Interfacial Chemistry

The Role of Surface Ligands in Defect Passivation

The surface chemistry of PQDs fundamentally differs from conventional semiconductor QDs due to their intrinsically ionic lattice structure and highly dynamic ligand binding characteristics. Surface ligands on PQDs serve dual critical functions: colloidal stabilization in solvents and electronic passivation of surface defects. The high surface-to-volume ratio of QDs means that a significant proportion of atoms reside on the surface, where coordination unsaturation leads to dangling bonds that create electronic trap states. These trap states facilitate non-radiative recombination, substantially reducing PLQY [6].

The binding motifs between ligands and the PQD surface predominantly involve ionic interactions rather than covalent bonds. Common ligand classes include:

- L-type ligands (e.g., oleic acid, phosphonic acids) that donate 2 electrons

- X-type ligands (e.g., carboxylates, alkylammonium halides) that donate 1 electron

- Z-type ligands (e.g., metal carboxylates) that accept 2 electrons [6]

The binding strength and stability of these ligand classes vary significantly, with phosphonic acids exhibiting particularly strong binding affinities to PQD surfaces compared to carboxylic acids and amines [11].

Thermodynamics of Ligand Binding

Quantitative studies of ligand binding thermodynamics reveal the dynamic nature of ligand-PQD interactions. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) investigations demonstrate that both oleic acid and oleylamine native ligands dynamically interact with CsPbBr₃ QD surfaces, with individual surface densities of 1.2-1.7 nm⁻². Competitive ligand exchange experiments using 10-undecenoic acid revealed an exergonic exchange equilibrium with bound oleate (Keq = 1.97) at 25°C, while 10-undecenylphosphonic acid undergoes essentially irreversible ligand exchange due to its stronger binding affinity. Similarly, undec-10-en-1-amine exergonically exchanges with oleylamine (Keq = 2.52) at 25°C [11].

The fluxional character of ligand binding manifests in diffusion coefficients intermediate between bound and free states, confirming continuous exchange processes. This dynamic equilibrium has profound implications for purification strategies, as polar solvents can promote ligand desorption, leading to colloidal instability and PLQY degradation [11].

Advanced Ligand Engineering Strategies

Ligand Selection and Molecular Design

Table 1: Ligand Classes for High-Performance PQDs

| Ligand Class | Representative Examples | Binding Strength | Key Advantages | Impact on PLQY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain carboxylic acids | 2-Hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) | Moderate to Strong | Reduced steric hindrance, improved charge transport | Up to 99% [15] |

| Carboxylate with ancillary functions | Acetate (AcO⁻) | Moderate | Dual functionality: precursor conversion aid & surface passivation | 99% [15] |

| Phosphonic acids | 10-Undecenylphosphonic acid | Very Strong | Near-irreversible binding, excellent stability | Significant enhancement [11] |

| Short-chain amines | Dodecylamine | Moderate | Balanced surface coordination | >90% [16] |

| Halide ion pair ligands | Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) | Strong | Simultaneous halide provision and passivation | High QY with stability [17] |

Ligand Exchange and Surface Reconstruction

Strategic ligand exchange protocols enable replacement of native long-chain insulating ligands with more compact or functionally optimized alternatives. The critical considerations for successful ligand exchange include:

- Solvent polarity management to prevent PQD dissolution or degradation

- Binding affinity differential to drive complete exchange equilibria

- Steric considerations to maintain colloidal stability while enhancing inter-dot coupling

- Ancillary functionality that provides additional passivation or electronic benefits

Notably, ligand exchange with conjugated molecules can enhance charge transport in PQD solids, while multidentate ligands offer improved surface passivation through cooperative binding effects [6].

Experimental Methodologies for Near-Unity PLQY

Optimized Synthesis via Cesium Precursor Engineering

Protocol: High-Purity Cesium Precursor Preparation

- Materials: Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99.9%), oleic acid (90%), 1-octadecene (90%), 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA), acetate salts

- Procedure:

- Combine Cs₂CO₃ (0.8 mmol) with oleic acid (2.5 mL) and 1-octadecene (20 mL)

- Heat at 120°C under vacuum for 60 minutes to dissolve and dehydrate

- Under nitrogen atmosphere, add 2-HA (1.5 mmol) and acetate precursor (1.0 mmol)

- Heat at 150°C for 30 minutes with vigorous stirring until complete dissolution

- Maintain under nitrogen until use [15]

Mechanistic Insight: The acetate species (AcO⁻) serves dual functions: (1) significantly improving the complete conversion degree of cesium salt, enhancing precursor purity from 70.26% to 98.59%, and (2) acting as a surface ligand to passivate dangling bonds. Concurrently, 2-HA exhibits stronger binding affinity toward QDs compared to oleic acid, further passivating surface defects and effectively suppressing biexciton Auger recombination [15].

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation Protocol

Protocol: CsPbBr₃ QD Synthesis with Acetate/2-HA Ligand System

- Precursor Preparation:

- PbBr₂ precursor: Combine PbBr₂ (0.188 mmol) with 1-octadecene (10 mL) in a three-neck flask

- Dry under vacuum at 120°C for 60 minutes

- Add oleic acid (1 mL) and oleylamine (1 mL) under nitrogen

- Heat to 150°C until complete dissolution

- Hot-Injection Synthesis:

- Rapidly inject cesium precursor (0.4 mL) into the PbBr₂ solution at 150°C under vigorous stirring

- Maintain reaction for 30 seconds then immediately cool in an ice-water bath

- Centrifuge at 15,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 20°C

- Discard supernatant and redisperse precipitate in toluene

- Centrifuge at 8,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C

- Filter through 0.2 μm membrane [15]

Performance Outcomes: This optimized synthesis yields CsPbBr₃ QDs with uniform size distribution, green emission peak at 512 nm, narrow emission linewidth of 22 nm, and PLQY of 99%. The amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) threshold reduces by 70% from 1.8 μJ·cm⁻² to 0.54 μJ·cm⁻² compared to conventionally synthesized QDs [15].

Advanced Purification Techniques

Protocol: Methanol Drop-Casting Purification

- Materials: As-synthesized PQD solution in toluene, anhydrous methanol

- Procedure:

- Spin-coat PQD solution onto substrate at 1,000 rpm for 10 seconds

- While continuing spinning, drop-cast 1 mL methanol directly onto the rotating substrate

- Continue spinning for full 60 seconds to ensure complete solvent removal

- Anneal at 70°C for 5 minutes to remove residual solvents [17]

Mechanistic Insight: This approach enables simultaneous removal of excess ligands and residual reaction solvents while avoiding QD self-aggregation. Nuclear magnetic resonance analysis confirms near-complete elimination of ligand impurities, as evidenced by the disappearance of the characteristic chemical shift at 5.3-5.4 ppm corresponding to oleic acid and oleylamine [17].

Protocol: Differential Centrifugation for Size-Selective Purification

- Materials: Crude PQD solution, hexane (low polarity solvent)

- Procedure:

- Dilute crude PQDs in hexane to appropriate concentration (typically 1-5 mg/mL)

- Perform initial centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 minutes

- Collect supernatant and proceed with sequential centrifugation at increasing speeds (2,000, 4,000, 8,000, 12,000 rpm)

- At each step, separate precipitate (larger particles) from supernatant (smaller particles)

- Redisperse each fraction in fresh hexane for characterization [16]

Critical Consideration: Solvent polarity profoundly impacts separation efficacy. Low-polarity solvents like hexane (polarity 0.06) enable precise size separation with single emission peaks, whereas higher-polarity solvents (toluene: 2.4, chlorobenzene: 2.7) result in overlapping size fractions with multiple emission peaks [16].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of High-Performance PQD Systems

| Synthesis Strategy | Ligand System | Purification Method | PLQY (%) | Stability Assessment | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate/2-HA optimized precursor [15] | Acetate + 2-hexyldecanoic acid | Conventional centrifugation | 99 | Excellent reproducibility, low ASE threshold | Lasers, LEDs |

| Exploratory data analysis optimized [18] | OA/OAm ratio optimization | Standard anti-solvent precipitation | High (quantified) | Improved batch consistency | General optoelectronics |

| Template-assisted within vaterite spheres [19] | Ligand-free, rare-earth dopants | Template confinement | Near-unity | Enhanced environmental stability | Infrared visualizers |

| Glass matrix encapsulation [20] | Borosilicate glass matrix | Melt-quenching | 88.15 | Outstanding thermal/water/light stability | WLEDs, photodetectors |

| Methanol drop-casting purification [17] | OA/OAm with methanol wash | Drop-casting during spin-coating | Maintained high PL | Improved structural integrity | Memory devices |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for High-PLQY PQD Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Compounds | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cesium precursors | Cesium carbonate, Cs-oleate | Cesium cation source | Acetate addition enhances purity to 98.59% [15] |

| Lead sources | Lead bromide (PbBr₂) | Lead cation source | Requires rigorous drying before use |

| Short-chain ligands | 2-Hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) | Surface passivation | Stronger binding than OA, reduces Auger recombination [15] |

| Ancillary ligands | Acetate salts | Precursor conversion aid & passivation | Dual functionality enhances reproducibility [15] |

| Solvents | 1-Octadecene, toluene, hexane | Reaction medium | Low-polarity hexane enables effective size separation [16] |

| Purification agents | Methanol, ethyl acetate | Excess ligand removal | Methanol drop-casting effectively removes ligands without aggregation [17] |

| Stability enhancers | Rare-earth dopants [19], glass matrices [20] | Environmental protection | Enable near-unity QY in demanding conditions |

The achievement of near-unity PLQY in perovskite quantum dots through ligand-assisted reprecipitation and purification represents a significant milestone in nanomaterials engineering. The strategic integration of optimized precursor chemistry, rationally designed ligand systems, and gentle yet effective purification protocols enables unprecedented control over PQD optoelectronic properties. The profound influence of ligand binding dynamics on PQD performance underscores the critical importance of surface chemistry management throughout synthetic and processing workflows.

Future research directions should focus on several key areas:

- Precision ligand design with tailored binding motifs and steric profiles

- Multifunctional ligand systems that concurrently address passivation, charge transport, and stability

- Scalable purification technologies that maintain ligand integrity while removing impurities

- Advanced characterization techniques for real-time monitoring of ligand binding dynamics during processing

The continued refinement of ligand-assisted reprecipitation and purification methodologies will undoubtedly accelerate the commercialization of PQD technologies across photonics, electronics, and energy applications.

Workflow and System Diagrams

Lead halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) have emerged as a revolutionary class of semiconducting nanomaterials with exceptional optoelectronic properties, including tunable bandgaps, high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs), and narrow emission linewidths [6]. These characteristics make them highly promising for applications in light-emitting diodes (LEDs), solar cells, and other optoelectronic devices. However, the practical implementation of PQDs is substantially hindered by their intrinsic instability, which primarily originates from their dynamic and defect-prone surfaces [7] [6].

The surface of PQDs, characterized by a high surface-to-volume ratio, is typically capped with long-chain insulating ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) during synthesis. These ligands provide colloidal stability but bind weakly to the crystal lattice [11]. This dynamic binding leads to easy ligand desorption during processing or operation, creating surface defects such as halide vacancies and uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions [7] [21]. These defects act as non-radiative recombination centers, reducing PLQY and operational stability, and facilitate ion migration, which further degrades device performance [7] [22]. Consequently, developing robust surface passivation strategies is a critical research focus to unlock the full potential of PQD technologies.

The Principle of Multi-Site Anchoring via Lattice-Matched Design

Fundamental Concept and Mechanism

The multi-site anchoring strategy represents a paradigm shift in perovskite QD surface engineering. Unlike conventional ligands with a single binding site, multi-site anchoring molecules are designed with multiple functional groups that can simultaneously coordinate to several unsaturated sites on the QD surface [7] [23]. This multi-dentate binding dramatically enhances the molecule's binding affinity and stability on the QD surface.

The lattice-matched design is a crucial refinement of this strategy. It involves precisely engineering the spatial separation between the anchoring groups in the ligand to match the atomic spacing of the receptor sites on the perovskite crystal lattice [7]. This geometric compatibility minimizes steric hindrance and lattice strain, allowing the ligand to form strong, coherent interactions with the QD surface. For instance, in the case of tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p), the calculated interatomic distance between oxygen atoms in the P=O and para-position -OCH₃ groups is 6.5 Å, which precisely matches the lattice spacing of the target QDs [7]. This match enables the molecule to anchor effectively onto the perovskite surface, offering superior passivation.

Theoretical and Spectroscopic Evidence

The effectiveness of lattice-matched, multi-site anchoring is corroborated by theoretical calculations and spectroscopic data. Projected Density of States (PDOS) calculations reveal that while single-site anchors can eliminate some trap states, they often leave behind conspicuous trap states from uncoordinated Pb²⁺ [7]. In contrast, when a lattice-matched multi-site anchor like TMeOPPO-p is applied, the trap states and the conduction band minimum peaks connect completely, indicating effective elimination of consecutive trap states [7].

Spectroscopic techniques provide further evidence of strong ligand-QD interaction:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Shows a shift in the Pb 4f peaks to lower binding energies in target QDs, indicating enhanced electron shielding around the Pb nucleus due to strong interaction with the anchoring molecules [7].

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Shows weakened C-H stretching modes from original OA/OAm ligands, confirming that the anchoring molecules partially replace and supplement the original ligand shell [7].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: ¹H and ³¹P NMR spectra confirm the presence of the designed anchoring molecules on the QD surface, verifying successful surface binding [7].

Quantitative Performance of Multi-Site Anchoring Molecules

The following table summarizes the performance metrics of key multi-site anchoring molecules reported in recent literature, demonstrating their significant impact on PQD properties and device performance.

Table 1: Performance Summary of Multi-Site Anchoring Molecules in Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Anchoring Molecule | Key Functional Groups | Reported PLQY | Device Performance | Stability Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMeOPPO-p [7] | P=O, -OCH₃ | 97% | EQE: 27% (LED) | Operating half-life: >23,000 h |

| Benzylphosphonic Acid (BPA) [23] | P=O, P–OH | N/P | EQE: 20.6% (LED) | Device lifetime (T50): 6x of control |

| Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) [21] | Thiocyanate (S, N atoms) | Significant improvement vs. control | EQE: ~23% (NIR-LED) | Enhanced thermal & humidity stability |

| 2-Thiophenemethylammonium Iodide (ThMAI) [22] | Thiophene, Ammonium | N/P | PCE: 15.3% (Solar Cell) | 83% initial PCE after 15 days |

The efficacy of these ligands can be further understood by comparing their physical and binding properties, which are foundational to their performance.

Table 2: Structural and Binding Properties of Anchoring Ligands

| Ligand | Binding Group Type | Binding Energy / Strength | Key Functional Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMeOPPO-p [7] | Multi-site, Lattice-matched | High (Calculated) | Precise 6.5 Å O-atom spacing matches QD lattice |

| FASCN [21] | Bidentate, Liquid | -0.91 eV (DFT); 4x higher than OA/OAm | Short chain, high surface coverage, prevents desorption |

| ThMAI [22] | Multifaceted Anchoring | High binding energy | Large ionic size restores tensile strain; dipole moment |

| Oleate (OA) [21] | Single-site | -0.22 eV (DFT) | Dynamic binding, prone to desorption |

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Synthesis and Application

Synthesis of CsPbI₃ Perovskite Quantum Dots

Modified Hot-Injection Method [7]:

- Preparation of Cs-oleate precursor: Dissolve 0.814 g of Cs₂CO₃ in 40 mL of 1-octadecene and 2.5 mL of oleic acid. Heat the mixture at 120°C under vacuum until the Cs₂CO₃ is completely dissolved.

- Preparation of Pb-halide precursor: Load 0.069 g of PbI₂, 5 mL of 1-octadecene, 0.5 mL of oleic acid, and 0.5 mL of oleylamine into a flask. Dry the mixture under vacuum at 120°C for 1 hour.

- QDs synthesis: Under a nitrogen atmosphere, rapidly inject 0.4 mL of the preheated Cs-oleate precursor (at 120°C) into the Pb-halide precursor solution maintained at 170°C.

- Reaction termination: Cool the reaction mixture immediately using an ice-water bath after 5-10 seconds of reaction.

- Purification: Centrifuge the crude solution at high speed and wash the precipitated QDs with a mixture of methyl acetate and ethyl acetate to remove excess ligands and unreacted precursors.

- Ligand solution preparation: Dissolve the purified CsPbI₃ QDs in ethyl acetate to form a solution with a concentration of 5 mg mL⁻¹.

- Anchoring molecule addition: Add TMeOPPO-p to the QD solution. The molecule's concentration can be optimized, but a typical treatment involves a sufficient molar ratio to ensure complete surface coverage.

- Incubation and mixing: Stir the mixture for a predetermined period to allow for complete ligand exchange.

- Purification: Precipitate the QDs, recover them via centrifugation, and re-disperse them in a suitable solvent for film fabrication or device integration.

Characterization Techniques for Validation

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Use an integrating sphere to measure the absolute PLQY of the QD solutions or films. TMeOPPO-p-treated QDs have shown near-unity PLQYs of 97% [7].

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Characterize the morphology, size distribution, and lattice fringes of the QDs. Lattice-matched anchors yield uniform and cubic morphologies with clear lattice fringes [7].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Confirm the crystalline phase and structure. Effective passivation should not alter the main diffraction peaks of the perovskite cubic phase [7].

- 1H NMR Spectroscopy: Quantify the bound and free fractions of ligands on the QD surface, providing insights into ligand binding dynamics and surface coverage [11].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for multi-site ligand application and validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Site Anchoring Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) [7] | Lattice-matched multi-site anchor for defect passivation | P=O and -OCH₃ groups with 6.5 Å O-atom spacing. |

| Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) [21] | Bidentate liquid ligand for full surface coverage | Short carbon chain (<3), high binding energy (-0.91 eV). |

| 2-Thiophenemethylammonium Iodide (ThMAI) [22] | Multifaceted anchoring ligand for strain and defect management | Thiophene ring (Lewis base) and ammonium group. |

| Benzylphosphonic Acid (BPA) [23] | Multi-site anchor for phase distribution regulation | P=O and P–OH groups, strong P–O–Pb bond. |

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) [7] [22] | Cesium precursor for QD synthesis | High purity (99.99%) for controlled stoichiometry. |

| Lead Iodide (PbI₂) [7] [22] | Lead and halide precursor for QD synthesis | High purity (99.999%) to minimize impurities. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) [7] [22] [21] | Native surface ligands for initial QD synthesis and stabilization | Long-chain, dynamic binding. |

| Anhydrous Solvents (e.g., 1-Octadecene, Toluene, Ethyl Acetate) [7] [11] | Reaction medium and purification solvents | Anhydrous to prevent perovskite degradation. |

Molecular Anchoring Mechanisms and Impact on QD Properties

The superior performance of multi-site anchoring ligands stems from their specific molecular interactions with the perovskite QD surface, which fundamentally alter the material's electronic properties and structural integrity.

Diagram 2: Molecular interactions between anchoring ligands and QD surface defects, and their resulting property enhancements.

The development of multi-site anchoring ligands represents a significant advancement in the surface engineering of perovskite quantum dots. The lattice-matched design strategy, exemplified by molecules like TMeOPPO-p, moves beyond simple defect passivation to create a stable, coherent interface between the organic ligand and the inorganic perovskite lattice [7]. This approach successfully addresses the fundamental challenges of poor stability and charge transport inefficiencies that have plagued PQD applications.

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas:

- Computational Discovery: Leveraging machine learning and high-throughput DFT calculations to design novel multi-site ligands with optimized binding energies, lattice matching, and charge transport properties.

- Multi-Functional Ligands: Designing ligands that not only passivate defects but also actively contribute to charge transport or provide enhanced environmental barrier properties.

- Systematic Exploration: Expanding the library of anchoring functional groups and backbone structures to develop tailored ligand systems for specific perovskite compositions (e.g., all-inorganic CsPbI₃, FAPbI₃, or mixed halide perovskites) and target applications (LEDs, solar cells, detectors).

The integration of rational ligand design, guided by a deep understanding of perovskite surface chemistry and lattice parameters, is poised to unlock the next generation of high-performance and durable perovskite-based optoelectronic devices.

Innovative Cesium Precursor Recipes and Short-Chain Ligands for Improved Reproducibility

The reproducibility and optoelectronic performance of lead halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) are critically limited by dynamic surface ligand interactions and imperfect cesium precursor conversion. This whitepaper details a novel cesium precursor formulation that integrates dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) and the short-branched-chain ligand 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA). The optimized recipe enhances cesium precursor purity from 70.26% to 98.59%, achieving a near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 99% and a 70% reduction in the amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) threshold. Framed within the broader context of ligand binding dynamics, this guide provides detailed methodologies and data analysis to empower researchers in synthesizing high-fidelity PQDs for advanced optoelectronic applications.

The intrinsic ionic crystal lattice of lead halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) makes their surface chemistry and optoelectronic properties exceptionally sensitive to ligand binding dynamics. Unlike traditional II-VI semiconductor QDs, the binding of surface ligands on PQDs is highly dynamic and labile; polar solvents can readily promote ligand desorption, leading to colloidal instability and loss of photoluminescence (PL) efficiency [11] [6]. This fluxional nature of ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) results in batch-to-batch inconsistencies, poor reproducibility, and serious non-radiative recombination, which have hampered their industrial adoption [24] [25] [6].

The core challenge extends to the cesium precursor itself. Conventional precursor recipes often suffer from incomplete conversion, yielding significant by-products that introduce variability and defects during nucleation and growth [24]. Therefore, innovative ligand engineering and precursor design are not merely incremental improvements but foundational to unlocking the commercial potential of PQDs in lasers, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and solar cells.

This technical guide focuses on a breakthrough strategy that addresses both precursor purity and ligand binding affinity simultaneously. By designing a novel cesium precursor recipe and employing short-chain ligands with stronger binding motifs, this approach directly stabilizes the PQD surface, suppresses Auger recombination, and sets a new benchmark for reproducibility and performance.

Core Mechanism: Dual-Functional Acetate and Short-Chain Ligands

The presented innovation hinges on a two-pronged molecular strategy targeting both precursor chemistry and surface passivation.

Dual-Functional Acetate (AcO⁻) as a Reaction Modifier and Surface Passivator

The introduction of acetate anions (AcO⁻) into the precursor recipe serves two critical, sequential functions:

- Enhanced Precursor Purity: AcO⁻ significantly improves the complete conversion degree of cesium salt during the precursor preparation phase. It suppresses the formation of reaction by-products, elevating the purity of the cesium precursor from a baseline of 70.26% to 98.59% [24]. This directly addresses the root cause of batch-to-batch inconsistency.

- Surface Passivation: Beyond its role in the precursor, AcO⁻ acts as a surface ligand, directly passivating dangling bonds on the synthesized PQD surface. This dual functionality fosters enhanced homogeneity and reproducibility from the very first stage of the reaction [24].

2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) as a High-Affinity Surface Ligand

The recipe replaces the conventionally used oleic acid with 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA), a short-branched-chain ligand.

- Stronger Binding Affinity: Compared to oleic acid, 2-HA exhibits a stronger binding affinity toward the CsPbBr₃ QD surface [24].

- Suppression of Auger Recombination: This robust binding more effectively passivates surface defects and, crucially, suppresses biexciton Auger recombination—a major loss mechanism in optical gain applications. This leads to an improved spontaneous emission rate [24].

The synergistic effect of these two components is illustrated in the following diagram, which contrasts the conventional and innovative synthesis pathways.

Diagram: Comparative Workflow of Conventional and Innovative PQD Synthesis

Quantitative Performance Data

The efficacy of this innovative recipe is validated by stark improvements in key performance metrics, as summarized in the table below.

Table: Quantitative Performance Comparison of CsPbBr₃ QDs

| Performance Metric | Conventional Method | Innovative Method (AcO⁻ + 2-HA) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cesium Precursor Purity | 70.26% | 98.59% | +28.33% [24] |

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Not specified (Baseline) | 99% | Near-unity [24] |

| ASE Threshold | 1.8 μJ·cm⁻² | 0.54 μJ·cm⁻² | -70% [24] |

| Emission Linewidth (FWHM) | Not specified | 22 nm | Narrow [24] |

| Green Emission Peak | Not specified | 512 nm | Defined [24] |

The data demonstrates that QDs prepared with the new recipe exhibit a uniform size distribution, a narrow emission linewidth of 22 nm, and a high PLQY of 99% with excellent stability. The most striking improvement is in the amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) performance, where the threshold energy density required to achieve ASE was reduced by 70%, a critical advancement for laser applications [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This section provides a step-by-step methodology for synthesizing high-quality CsPbBr₃ QDs using the innovative precursor recipe.

Synthesis of the Novel Cesium Precursor

- Reagent Preparation: In a controlled atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen glovebox), combine cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) with a mixture containing 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) and acetic acid (the source of AcO⁻) in a molar ratio optimized for complete conversion. The exact molar ratios are proprietary but are designed to achieve a precursor purity of >98% [24].

- Reaction and Solubilization: Heat the mixture to 100-120°C under continuous stirring until the Cs₂CO₃ is fully dissolved and the solution becomes clear, indicating the formation of the cesium carboxylate (Cs-2HA/CsOAc) complex. The reaction time is typically 1-2 hours.

- Precursor Storage: The resulting cesium precursor solution is cooled to room temperature and can be stored in a sealed vial under an inert atmosphere for future use.

Hot-Injection Synthesis of CsPbBr₃ Quantum Dots

- Preparation of PbBr₂ Precursor: In a three-neck flask, combine lead bromide (PbBr₂) with 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) and oleylamine (OLAm) in 1-octadecene (ODE). Degas the mixture under vacuum at 100°C for 30-60 minutes to remove water and oxygen.

- Reaction Initiation: Under an inert nitrogen atmosphere, raise the temperature of the PbBr₂ precursor to 160°C. Rapidly inject the pre-synthesized novel cesium precursor (from Step 4.1) into the vigorously stirring lead precursor solution.

- Nucleation and Growth: The reaction proceeds immediately upon injection, evidenced by a rapid color change. Allow the reaction to proceed for 5-10 seconds to control the QD size.

- Reaction Quenching: Quickly cool the reaction flask by placing it in an ice-water bath to terminate nanocrystal growth.

Purification and Post-Treatment

- Precipitation: Add an excess of methyl acetate or ethyl acetate to the crude QD solution to precipitate the QDs.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture at high speed (e.g., 8,000 rpm for 5 minutes). Discard the supernatant containing unreacted precursors and free ligands.

- Washing and Redispersion: Re-disperse the QD pellet in a non-solvent like hexane or toluene. Repeat the precipitation and centrifugation steps at least twice to remove excess ligands and reaction by-products thoroughly.

- Final Dispersion: Disperse the final purified QDs in anhydrous toluene or hexane to form a stable colloidal solution for characterization and device fabrication.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for the Innovative PQD Synthesis Protocol

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Technical Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Provides the cesium cation (Cs⁺) source for the perovskite crystal structure. | High purity (99.9%) is recommended to minimize impurity introduction. |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | Short-branched-chain carboxylic acid ligand; replaces oleic acid for stronger binding and better defect passivation. | Its branched structure prevents dense packing, enhancing colloidal stability [24]. |

| Acetic Acid | Source of acetate (AcO⁻) anions; acts as a dual-functional agent to improve precursor purity and passivate surface defects. | Anhydrous grade is critical to prevent unwanted hydrolysis reactions. |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Source of lead (Pb²⁺) and bromide (Br⁻) ions for the CsPbBr₃ perovskite lattice. | Must be thoroughly dried before use to remove adsorbed water. |

| Oleylamine (OLAm) | Co-ligand that assists in solubilizing precursors and passivating surface sites during synthesis. | Typically used in conjunction with carboxylic acids [11]. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-coordinating high-boiling-point solvent for the hot-injection synthesis. | Must be degassed and dried to ensure an oxygen- and water-free environment. |

Ligand Binding Dynamics and Thermodynamic Underpinnings

The success of this innovative recipe is deeply rooted in the fundamental thermodynamics of ligand binding. Quantitative studies using ¹H NMR spectroscopy have been pivotal in understanding these interactions.

- Dynamic and Reversible Binding: Solution ¹H NMR reveals that native ligands like oleate dynamically interact with the CsPbBr₃ QD surface, with a significant fraction of ligands being physisorbed or in rapid exchange between bound and free states [11].

- Quantifying Binding Strength: Ligand exchange experiments with molecules containing terminal vinyl groups allow for precise quantification. The exchange equilibrium constant (Keq) for a carboxylic acid replacing bound oleate can be exergonic, with Keq values around 1.97 at 25°C, indicating a favorable thermodynamic drive for the incoming ligand [11].

- Correlation with Performance: Increases in steady-state PL intensities are directly correlated with more strongly bound conjugate base ligands, providing a clear link between thermodynamic binding strength and optoelectronic performance [11].

The following diagram visualizes the competitive ligand exchange process that governs the QD surface state, a core concept in ligand binding dynamics.

Diagram: Thermodynamics of Competitive Ligand Exchange on QD Surface

The strategic optimization of the cesium precursor recipe using dual-functional acetate and the short-chain ligand 2-hexyldecanoic acid presents a robust solution to the long-standing challenges of reproducibility and performance in perovskite QDs. By directly targeting precursor purity and leveraging the thermodynamics of strong ligand binding, this method yields CsPbBr₃ QDs with near-perfect PLQY and significantly reduced lasing thresholds.

Future research directions in ligand engineering will likely focus on multi-site, lattice-matched anchoring molecules. Recent studies demonstrate that designed molecules, such as tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p), whose binding groups match the atomic spacing of the perovskite lattice (e.g., 6.5 Å), can provide multi-site anchoring, eliminate trap states more completely, and further enhance device efficiency and operational stability [7]. The convergence of high-purity precursor chemistry and advanced, rationally designed ligand anchors will continue to drive the development of perovskite QDs from laboratory curiosities toward commercial-ready optoelectronic devices.

The translation of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) from exceptional optoelectronic materials to reliable biomedical platforms hinges almost entirely on mastering their surface chemistry. While inorganic lead halide perovskite quantum dots, notably CsPbX₃ (X = Cl, Br, I), possess optical properties that are nearly ideal for bioimaging and biosensing—including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), narrow emission linewidths, and easily tunable bandgaps—their inherent ionic crystal structure renders them susceptible to rapid degradation in aqueous physiological environments [4] [26]. This instability, coupled with concerns regarding lead toxicity, has historically impeded their biomedical application.

Ligand engineering emerges as the indispensable strategy to overcome these challenges. Ligands are molecules that cap the PQD surface, originally facilitating synthesis and controlling crystal growth [27]. However, their dynamic binding nature often leads to detachment, causing aggregation, loss of luminescence, and ultimately, structural decomposition [27] [6]. For biomedical translation, ligand engineering focuses on replacing these transient, hydrophobic ligands with robust, functional ligands that confer colloidal stability, aqueous dispersibility, biocompatibility, and targeting capability [26] [28]. The binding dynamics of these ligands—their affinity, coordination mode, and density—directly dictate the stability, optical performance, and ultimate biological fate of PQDs, forming the core thesis of this review. By strategically designing the ligand shell, researchers can transform fragile PQDs into stable, functional probes capable of long-term operation within complex biological systems.

Fundamental Principles of PQD Surface Chemistry and Ligand Binding

Crystal Structure and Surface Defect Sites