Ligand Binding Affinity in Perovskite Quantum Dots: A Comprehensive Guide to Enhancing Stability for Biomedical and Optoelectronic Applications

This article provides a detailed analysis of how surface ligand binding affinity directly dictates the structural and optical stability of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical material for next-generation optoelectronics...

Ligand Binding Affinity in Perovskite Quantum Dots: A Comprehensive Guide to Enhancing Stability for Biomedical and Optoelectronic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a detailed analysis of how surface ligand binding affinity directly dictates the structural and optical stability of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical material for next-generation optoelectronics and biomedical devices. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the fundamental principles of ligand-PQD interactions, evaluate advanced ligand engineering strategies—including bidentate and dual-ligand systems—and present methodologies for quantifying binding strength. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with the latest high-performance applications and validation techniques, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and optimizing ligands to suppress phase transition, mitigate surface defects, and achieve unprecedented device performance and operational longevity.

The Fundamental Link Between Ligand Binding and PQD Stability

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs), particularly all-inorganic CsPbX₃ (X = Cl, Br, I), have emerged as a revolutionary class of semiconductor nanocrystals for next-generation optoelectronic devices, including displays, solar cells, and photodetectors [1] [2] [3]. Their exceptional optical properties—such as high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), narrow emission bandwidth, and widely tunable bandgaps across the entire visible spectrum—enable high color purity, potentially exceeding 144% of the NTSC color standard [2] [3]. Despite this immense potential, the widespread commercial application of PQDs is critically hindered by their inherent structural instabilities [1] [3]. This review objectively compares the performance of various stabilization strategies, with a particular focus on ligand engineering, framing the analysis within a broader thesis on surface ligand binding affinity for PQD stability research.

Fundamental Structure and Roots of Instability

The foundational structure of PQDs is defined by the ABX₃ perovskite crystal lattice. In CsPbX₃, Cs⁺ (A-site) occupies the cube corners, Pb²⁺ (B-site) resides at the body center, and halide anions X⁻ (X-site) are located at the face centers, forming [PbX₆]⁴⁻ octahedra [2]. The stability of this crystal structure can be predicted using the Goldschmidt tolerance factor (t) and the octahedral factor (μ) [2].

The inherent instability of PQDs arises from two primary mechanisms: the facile migration of halide ions within the crystal lattice and the detachment of surface-passivating ligands [3]. Halide vacancies form easily due to low ionic migration energy, while commonly used long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) are only weakly bound to the PQD surface [2] [3]. These ligands readily detach during purification or upon exposure to environmental stimuli, creating surface defects that act as non-radiative recombination centers and degrade both structural integrity and optoelectronic performance [3] [4].

External factors such as humidity, temperature, light exposure, and polar solvents accelerate degradation by attacking the vulnerable ionic crystal structure and exacerbating ligand loss [2] [3]. CsPbI₃, for instance, undergoes a detrimental phase transition from a photoactive black phase (α, β, γ) to a non-perovskite yellow phase (δ) at room temperature [2].

Comparative Analysis of PQD Stabilization Strategies

Various strategies have been developed to combat PQD instability. The following table provides a performance comparison of the primary approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Strategies for Enhancing PQD Structural Stability

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Modification [2] [3] [4] | Exchanges dynamic long-chain ligands with shorter, multidentate, or covalently binding ligands to improve packing density and binding affinity. | - PLQY increased from 22% to 51% for CsPbI₃ QDs using 2-aminoethanethiol (AET) [3].- PCE of CsPbI₃ QD solar cells improved to 15.4% with TPPO ligands [4].- Maintained >95% initial PL after 60 min water/120 min UV exposure [3]. | Directly addresses surface defect origin; can be applied in situ or post-synthesis; enhances charge transport [3] [4]. | Ligand synthesis can be complex; may require optimization for different PQD compositions [2]. |

| Core-Shell Structure [3] | Encapsulates PQDs with a protective shell of polymers or inorganic materials to create a physical barrier against external stimuli (moisture, oxygen). | Improved environmental stability against moisture and oxygen [3]. | Effective isolation from environment; can be combined with other strategies [3]. | Shell growth on ionic PQD surface is challenging; may introduce interface defects; can hinder charge transport [3]. |

| Crosslinking [3] | Introduces crosslinkable ligands on the PQD surface that form a robust network via light or heat, inhibiting ligand dissociation. | Suppresses ligand dissociation and subsequent defect formation [3]. | Creates a stable, interconnected network; minimizes defect formation from ligand loss [3]. | Crosslinking process may damage PQD surface; requires careful control of reaction conditions [3]. |

| Metal Doping [3] | Incorporates metal ions with equivalent charge numbers at the A- or B-sites to strengthen the perovskite lattice and alter B-X bond lengths. | Enhances intrinsic lattice stability by changing B-X bond lengths [3]. | Improves intrinsic thermal and phase stability [3]. | Must maintain Goldschmidt tolerance and octahedral factors; typically limited to in-situ synthesis [3]. |

Experimental Protocols in Ligand Engineering

The pursuit of high-binding-affinity ligands relies on specific experimental protocols, primarily conducted through solution-based synthesis.

Synthesis Methods and Ligand Exchange

Two primary methods are used for PQD synthesis: the hot-injection method and the ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) method [2] [3]. Both methods traditionally utilize long-chain OA and OAm ligands to control nucleation and growth [2]. The subsequent ligand exchange process is critical for replacing these insulating ligands with shorter, more stable alternatives. A standard protocol involves a two-step solid-state ligand exchange for CsPbI₃ PQDs [4]:

- Anionic Ligand Exchange: Layer-by-layer deposition of PQD films followed by treatment with a solution of anionic short-chain ligands (e.g., acetate from NaOAc) dissolved in polar solvents like methyl acetate (MeOAc) to replace OA [4].

- Cationic Ligand Exchange: Post-treatment of the film with a solution of cationic short-chain ligands (e.g., phenethylammonium iodide - PEAI) dissolved in ethyl acetate (EtOAc) to replace OLA [4].

In-situ vs. Post-Synthesis Ligand Engineering

Ligand engineering strategies are categorized based on their timing:

- In-situ ligand engineering involves adding new ligands during the synthetic process, allowing them to incorporate directly as the PQDs form [2].

- Post-synthesis ligand engineering (or post-treatment) occurs after PQD synthesis and purification. This is often used to heal surface defects created during the initial ligand exchange or purification steps [3] [4]. A key advancement is using nonpolar solvents (e.g., octane) for post-treatment instead of polar solvents, which preserves the PQD surface components while allowing effective passivation with ligands like triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) [4].

Ligand Binding Affinity and Stability Relationships

The efficacy of ligand engineering is fundamentally governed by the binding affinity between the ligand and the PQD surface. Strong binding is crucial for mitigating ligand detachment and passivating surface traps.

Table 2: Comparison of Ligand Types and Their Impact on PQD Stability

| Ligand Type | Binding Mechanism | Impact on Stability & Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Long-Chain (OA/OAm) [2] [3] | Dynamic, labile binding via carboxylate/amine groups. Bent structure causes low packing density. | Poor: Low binding affinity leads to easy detachment, causing aggregation and degradation. Insulating properties hinder device performance [3] [4]. |

| Ionic Short-Chain (e.g., Acetate, PEA⁺) [4] | Ionic interaction with the PQD surface. | Moderate: Improves charge transport but binding is still relatively labile. Polar solvents used in exchange can damage the PQD surface, creating new traps [4]. |

| Multidentate/Covalent (e.g., AET, TPPO) [3] [4] | Strong, covalent-like coordination (e.g., Thiol-Pb²⁺ in AET) or Lewis-base interaction (P=O with Pb²⁺ in TPPO). | High: Strong binding affinity ensures durable passivation. TPPO in nonpolar solvent enables "nondestructive" surface stabilization, leading to high PCE (15.4%) and excellent ambient stability (>90% initial efficiency after 18 days) [3] [4]. |

The relationship between ligand binding affinity and the resulting stability pathway is logical. Stronger binding directly leads to superior surface passivation, which in turn enhances resistance to environmental factors and improves long-term performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for experimental research in PQD stabilization via ligand engineering.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Ligand Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) [2] [3] | Standard long-chain ligands for colloidal synthesis; control nucleation and growth. | Initial synthesis of high-quality, monodispersed PQDs via hot-injection or LARP [4]. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) [2] | Nonpolar solvent for dissolving precursors in high-temperature synthesis. | Used as the primary solvent in the hot-injection method [2]. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) / Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) [3] [4] | Polar solvents for dissolving ionic salts during solid-state ligand exchange. | Used in purification and layer-by-layer ligand exchange to replace OA and OAm with short-chain ligands [4]. |

| 2-Aminoethanethiol (AET) [3] | Short-chain, bidentate ligand with strong affinity for Pb²⁺ via thiolate group. | Post-synthesis ligand exchange to heal surface defects and enhance stability against water and UV light [3]. |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) [4] | Short-chain, covalent ligand that strongly coordinates to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites via Lewis-base interaction. | Post-treatment surface stabilization, dissolved in nonpolar solvents (e.g., octane) to prevent PQD surface damage [4]. |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) [4] | Short-chain, cationic ligand used to replace oleylamine. | Standard reagent in the second step of ligand exchange for fabricating conductive PQD solids for solar cells [4]. |

Defining Ligand Binding Affinity and Its Role in Surface Passivation

Ligand binding affinity, defined as the strength of the interaction between a molecule (ligand) and its target binding site, serves as a fundamental parameter in determining the effectiveness of surface passivation for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and other semiconducting nanomaterials [5] [6]. Quantitatively expressed through the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd), where lower values indicate stronger, more favorable interactions, binding affinity directly governs the stability and optoelectronic performance of functional nanomaterials [7]. In the specific context of surface passivation, high-affinity ligands form stable complexes with undercoordinated surface atoms on PQDs, effectively neutralizing defect sites that would otherwise act as centers for non-radiative recombination and material degradation [8] [9].

The pursuit of high-performance PQD-based devices necessitates a thorough comparison of ligand binding strategies, as the dynamic nature of ligand binding under operational conditions—including exposure to heat, oxygen, and moisture—presents distinct challenges beyond static binding measurements [8]. This objective analysis compares the performance of various ligand engineering approaches based on their binding affinity characteristics, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to inform material selection for enhanced PQD stability.

Theoretical Foundation: Binding Affinity Fundamentals and Passivation Principles

Key Concepts and Definitions

- Binding Affinity: The strength of the interaction between a ligand and its biomolecular target, quantitatively measured by the dissociation constant (Kd) [7] [6]. Lower Kd values indicate tighter binding.

- Dissociation Constant (Kd): The equilibrium concentration at which half of the receptor binding sites are occupied by the ligand [7]. It represents the ligand concentration required for half-maximal binding.

- Surface Passivation: The process of eliminating dangling bonds and surface defects on nanomaterials through chemical ligand binding, which improves optical properties and stability [10] [9].

- Dynamic Adsorption Affinity (DAA): A recently identified parameter describing the ligand's ability to maintain passivation under operational stressors like heat and moisture, which may be more predictive of passivation efficacy than static binding strength alone [8].

Relationship Between Binding Affinity and Passivation Efficacy

The binding affinity of a ligand towards specific surface sites on a PQD directly determines the completeness and durability of surface passivation. High-affinity binding results from strong, multidentate coordination chemistry that maximizes intermolecular forces such as ionic bonds, hydrogen bonds, and van der Waals forces [5]. For ternary nanocrystals like AgBiS2, the principle of cation-selective ligand binding becomes critically important, where different metal cations (e.g., Ag⁺ vs. Bi³⁺) exhibit distinct preferences for specific functional groups based on the Hard-Soft Acid-Base (HSAB) theory [11]. This creates a scenario where a single ligand may not comprehensively passivate all surface sites, leading to incomplete protection and instability.

Table 1: Ligand Binding Affinity Classifications and Implications for Passivation

| Affinity Classification | Theoretical Kd Range | Passivation Characteristics | Impact on PQD Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Affinity | Picomolar to Nanomolar | Stable, long-term surface coverage; resistant to displacement | High environmental stability; suppressed ion migration |

| Medium Affinity | Nanomolar to Micromolar | Reversible binding; dynamic equilibrium with solution | Moderate stability; susceptible to ligand loss under stress |

| Low Affinity | Micromolar to Millimolar | Weak, transient surface interaction; incomplete coverage | Poor stability; rapid degradation under ambient conditions |

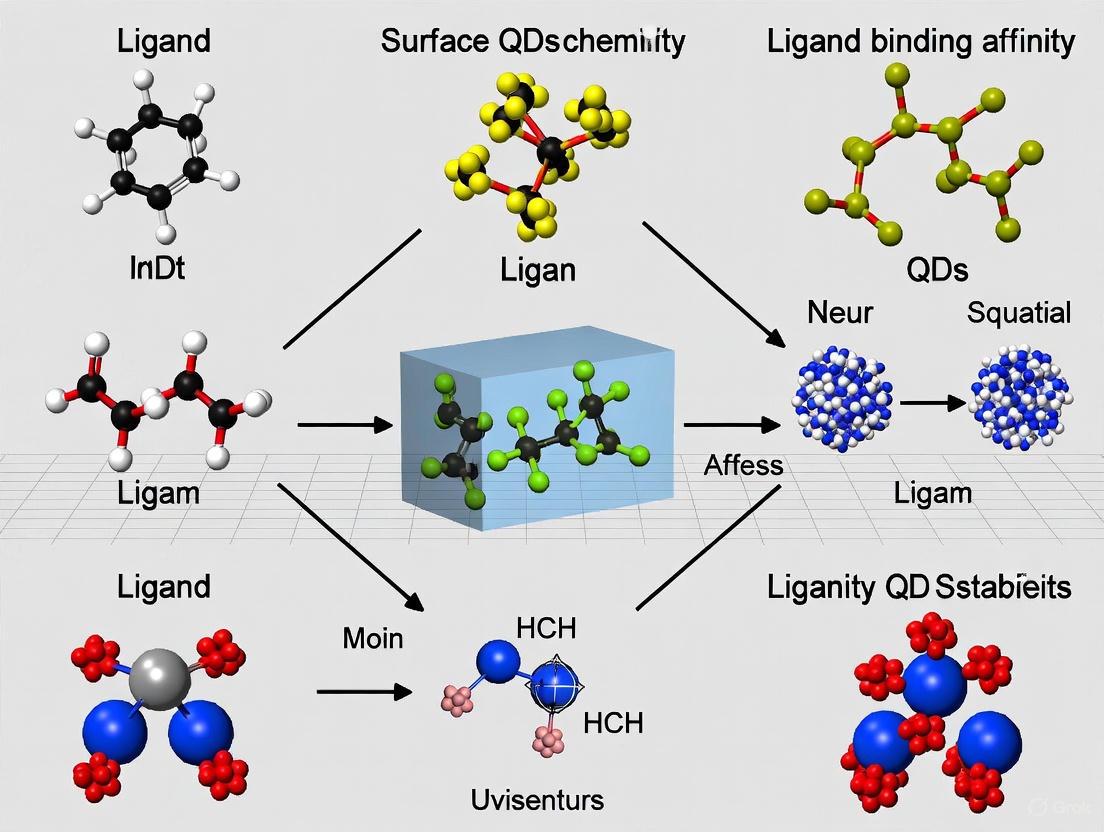

Figure 1: Logical workflow diagram illustrating the relationship between ligand binding affinity assessment and the resulting passivation outcomes for perovskite quantum dots.

Comparative Analysis of Ligand Binding Approaches

Traditional Organic Ligands vs. Advanced Passivators

Traditional long-chain organic ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) initially facilitate PQD synthesis and provide basic colloidal stability, but their labile binding nature often leads to detachment during processing or operation, creating instability issues [9]. Advanced passivation strategies employ rationally designed ligands with enhanced binding characteristics, as detailed in the comparative Table 2.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Ligand Types for PQD Surface Passivation

| Ligand Type | Example Compounds | Binding Mechanism | Reported PLQY Improvement | Stability Enhancement | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Long-Chain Organics | Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) | Dynamic L-type/X-type binding | Baseline (Reference) | Low: Rapid degradation under humidity/heat | Labile binding; insulator properties |

| Metal Salt Cations | Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺, In³⁺ with NO₃⁻/BF₄⁻ | Cationic binding to Lewis basic sites | 72-97% (various NCs) [10] | High: Stable in polar solvents | Requires non-coordinating anions; Lewis acidity |

| Multidentate Organic Ligands | 4-Aminobutylphosphonic Acid (4-ABPA) | Strong phosphonate chelation with high DAA | Significant increase in Pb-Sn perovskites [8] | Excellent: Suppressed VH formation | Complex synthesis; potential steric hindrance |

| Thiol/Carboxylic Bifunctional | 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | HSAB-compliant dual binding to Ag/Bi sites | Improved for AgBiS2 NCs [11] | High: Comprehensive ternary NC passivation | Sensitivity to oxidation (thiol group) |

Experimental Binding Affinity Data and Performance Metrics

Quantitative assessment of ligand performance reveals critical differences in passivation efficacy, with metal salt treatments and specifically designed organic molecules demonstrating superior outcomes compared to traditional approaches.

Table 3: Quantitative Experimental Data from Key Passivation Studies

| Study System | Passivation Method | Key Measurement | Performance Outcome | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed Pb-Sn Perovskites [8] | 4-ABPA treatment | Dynamic Adsorption Affinity (DAA) | Suppressed hydrogen vacancy formation; enhanced photovoltaic performance | Ab initio MD simulations guided ligand design |

| All-inorganic NCs (CdSe/ZnS, etc.) [10] | Metal salt (Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺) treatment | Absolute PLQY | 97% (red), 80% (green), 72% (blue) in polar solvents | General strategy for intensely luminescent NCs |

| AgBiS2 NC Photovoltaics [11] | MPA ligand exchange | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | ~12% improvement over control devices | Cation-selective passivation addressing ternary NC challenges |

| CsPbX3 PQDs [9] | Various ligand engineering approaches | Structural & PL stability | Improved resistance to humidity, heat, and light exposure | Review of stability enhancement strategies |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Binding Affinity and Passivation

Protocol 1: Dynamic Adsorption Affinity (DAA) Assessment via AIMD

Objective: To evaluate ligand binding strength under operational stressors (heat, oxygen, moisture) rather than static conditions [8].

Materials:

- Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation software (e.g., VASP, CP2K)

- Model perovskite surface structures (e.g., MAI-terminated (001) mixed Pb-Sn perovskite)

- Ligand molecular structures (e.g., 4-ABPA, traditional ligands for comparison)

- Environmental stressor parameters (300K/400K temperature, O₂/H₂O molecules)

Methodology:

- Construct optimized surface slab models of the target perovskite composition

- Introduce ligand molecules at various adsorption sites on the surface

- Simulate system dynamics under controlled environmental conditions:

- Room temperature (300K) and elevated temperature (400K)

- Introduce oxygen and water molecules to simulate atmospheric stressors

- Monitor and quantify over simulation time:

- Ligand-surface bond stability and residence time

- Surface defect formation energies (e.g., hydrogen vacancies)

- Ligand desorption rates under stress conditions

- Calculate DAA metrics based on persistent binding under degradation conditions

Validation: Correlate DAA predictions with experimental stability tests (TPD-MS, operational device lifetime) [8]

Protocol 2: Surface Passivation Efficacy via Photophysical Characterization

Objective: To quantitatively measure the effectiveness of ligand passivation through optical and electronic properties.

Materials:

- Spectrofluorometer with integrating sphere

- Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectrometer

- UV-Vis absorption spectrometer

- Fabricated thin films of passivated PQDs

- Controlled atmosphere sample chamber

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Fabricate PQD films via layer-by-layer deposition with ligand treatment

- Include control samples (unpassivated or traditionally passivated) for comparison

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) Measurement:

- Use integrating sphere with calibrated spectrofluorometer

- Measure absolute PLQY values for each sample type

- Calculate improvement over baseline passivation

- Carrier Lifetime Analysis:

- Perform TRPL measurements with pulsed excitation source

- Fit decay curves to multi-exponential models

- Calculate average carrier lifetimes; longer lifetimes indicate reduced non-radiative recombination

- Stability Testing:

- Monitor PLQY and absorption under continuous illumination

- Conduct environmental testing (controlled humidity, temperature)

- Measure degradation rates over time

Data Interpretation: Higher PLQY and extended carrier lifetimes directly correlate with superior surface passivation completeness and binding affinity [10] [9].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for comprehensive assessment of ligand binding affinity and surface passivation efficacy, integrating both computational and experimental approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ligand Passivation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Ligands | Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) | Reference passivators; synthesis control | Establish baseline; dynamic binding leads to instability [9] |

| Metal Salt Treatments | Cd(NO₃)₂, Zn(BF₄)₂, In(OTf)₃ | Lewis acid site passivation; organic ligand replacement | Select based on HSAB principles; anion choice critical [10] |

| Bifunctional Ligands | 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA), 4-ABPA | Comprehensive passivation of multiple surface sites | Ideal for ternary NCs; assess oxidation sensitivity [11] [8] |

| Characterization Standards | Radiolabeled ligands, Reference quantum dots | Binding affinity quantification; method calibration | Essential for Kd and DAA validation; ensure traceability |

| Computational Tools | DFT/MD software packages, Surface modeling tools | Prediction of binding energies and DAA | Require significant computational resources; expertise-dependent |

The comparative analysis of ligand binding affinity demonstrates that strategic ligand design moving beyond traditional approaches is essential for achieving high-performance, stable PQD systems. The critical findings from current research indicate:

Binding affinity under operational conditions (Dynamic Adsorption Affinity) provides a more reliable prediction of passivation efficacy than static binding measurements alone, particularly for applications requiring environmental stability [8].

Cation-selective ligand binding presents both a challenge and opportunity for ternary nanocrystal systems, where bifunctional ligands like MPA capable of addressing multiple metal sites simultaneously demonstrate superior performance [11].

Metal salt treatments offer a promising alternative to organic ligands, providing intense luminescence while maintaining charge transport capabilities, though careful selection of cation-anion pairs is required [10].

The integration of computational prediction methods like AIMD simulations with experimental validation creates a powerful framework for accelerating the development of next-generation passivation ligands. For researchers pursuing enhanced PQD stability, prioritizing ligands with demonstrated high dynamic adsorption affinity and comprehensive surface site coverage will yield the most significant improvements in device performance and operational lifetime.

How Strong Ligand Binding Mitigates Phase Transition and Degradation

The stability of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) remains a critical challenge hindering their commercial application in optoelectronics, photovoltaics, and other advanced technologies. Among the various factors influencing stability, the binding strength of surface ligands has emerged as a pivotal determinant in mitigating two primary degradation pathways: phase transitions and material decomposition. Surface ligands are molecules that coordinate with atoms on the PQD surface, serving not only to passivate defects and prevent aggregation but also to impart profound stability against thermal and environmental stress [2]. Recent research has established a direct correlation between ligand binding energy and the thermal degradation mechanism of PQDs, revealing that strongly bound ligands can effectively suppress the detrimental phase transitions that compromise optical and electronic properties [12]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how strategic ligand engineering controls PQD stability, supported by experimental data and methodologies directly applicable to research and development settings.

Comparative Analysis: Ligand-Dependent Degradation Pathways

Thermal Degradation Mechanisms by PQD Composition

The thermal degradation pathway of CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃ PQDs fundamentally depends on their A-site cation composition and the associated ligand binding energy.

Table 1: Thermal Degradation Behavior of CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃ PQDs [12]

| PQD Composition (CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃) | Primary Thermal Degradation Mechanism | Onset Temperature Characteristics | Key Experimental Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cs-Rich (High x) | Phase transition from black γ-phase to yellow non-perovskite δ-phase | Lower degradation onset temperature | Phase transition precedes decomposition; in situ XRD shows emergence of δ-phase peaks (25.4°, 25.8°, 30.7°) |

| FA-Rich (Low x) | Direct decomposition to PbI₂ | Slightly higher thermal stability than Cs-rich counterparts | No intermediate phase transition; direct appearance of PbI₂ peaks (25.2°, 29.0°, 41.2°) at ~150°C |

The Critical Role of Ligand Binding Energy

First-principle density functional theory (DFT) calculations have quantitatively demonstrated that the binding strength of common ligands (e.g., oleylamine, oleic acid) to the PQD surface is significantly stronger for FA-rich PQDs compared to Cs-rich PQDs [12]. This higher ligand binding energy in FA-rich systems is directly correlated with their observed resistance to phase transitions and their slightly superior thermal stability, despite their hybrid organic-inorganic nature. The stronger ligand binding provides a more robust protective shell around the PQD, effectively stabilizing the perovskite structure against thermal-induced lattice rearrangements [12].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Ligand-PQD Stability

In Situ Structural and Optical Characterization

Purpose: To monitor the real-time structural and optical changes in PQDs under thermal stress, directly linking ligand binding to stability metrics.

Key Methodologies:

- In Situ X-ray Diffraction (XRD): PQD samples are heated from 30°C to 500°C under an inert argon atmosphere while continuously collecting XRD patterns. This allows for direct observation of phase transition temperatures (e.g., γ-to-δ in CsPbI₃) or the emergence of decomposition product peaks (e.g., PbI₂) [12].

- In Situ Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: Measures emission intensity, peak position, and width as a function of temperature. FA-rich PQDs exhibit stronger electron-longitudinal optical phonon coupling, suggesting higher probability of exciton dissociation by phonon scattering at elevated temperatures [12].

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Tracks mass loss as temperature increases, providing information on ligand desorption and decomposition events [12].

Surface Ligand Engineering and Exchange

Purpose: To replace native long-chain ligands with more strongly binding or functional alternatives to enhance stability and performance.

Layer-by-Layer (LBL) Solid-State Ligand Exchange:

- PQD Film Deposition: Spin-coat a layer of pristine PQDs (stabilized with oleic acid/OA and oleylamine/OAm) onto a substrate.

- Initial Ligand Removal: Treat the film with methyl acetate (MeOAc) to remove the original long-chain ligands and excess solvent.

- New Ligand Introduction: Introduce a solution of the new short-chain ligand (e.g., Phenethylammonium Iodide, PEA.I, dissolved in ethyl acetate) via spin-coating.

- Repetition: Repeat steps 1-3 multiple times to build a thick, electronically coupled film with complete ligand exchange [13].

Critical Parameters: The concentration of the ligand solution, treatment time, and choice of solvent are crucial. Excessive treatment time with certain ligands (e.g., formamidinium iodide, FAI) can lead to unintended cation exchange and compositional changes in the PQD [13].

Mechanisms of Ligand-Induced Stability: A Pathway Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the competing degradation pathways for PQDs under thermal stress and how strong ligand binding influences these pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ligand Stability Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for PQD Ligand Binding and Stability Studies [12] [2] [13]

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard long-chain ligands for initial PQD synthesis; provide colloidal stability. | Dynamic binding leads to easy detachment; poor charge transport in films require exchange for devices [2] [13]. |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Short-chain, aromatic ligand for post-synthesis exchange. | Enhances inter-dot coupling, passivates defects, improves moisture resistance via hydrophobic phenyl group [13]. |

| Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) | Used for ligand exchange and surface passivation. | Can induce partial cation exchange if treatment time is not controlled, altering core PQD composition [13]. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Polar solvent for washing and initial ligand removal. | Effectively removes oleate ligands without dissolving the PQD film [13]. |

| Triphenyl Phosphite (TPPi) | Strong-binding ligand for exchange. | Used in bifunctional electroluminescent solar cells to enhance both PCE and electroluminescent performance [13]. |

The strategic management of surface ligand binding affinity presents a powerful avenue for controlling the stability and degradation pathways of perovskite quantum dots. Experimental evidence conclusively demonstrates that strong ligand binding directly influences the thermal degradation mechanism, suppressing deleterious phase transitions in Cs-rich PQDs and modifying the decomposition pathway in FA-rich PQDs. The methodologies outlined—particularly in situ characterization techniques and advanced ligand exchange protocols—provide researchers with a robust framework for evaluating and improving PQD stability. As the field progresses, the rational design of multidentate and strongly-coordinating ligands will be crucial in bridging the gap between the exceptional optoelectronic properties of PQDs and the demanding stability requirements of commercial applications.

The Impact of A-Site Cation Composition on Ligand Binding Energy

The stability of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) remains a critical challenge hindering their commercial application in optoelectronics. A key determinant of this stability is the binding energy of surface ligands, which passivate the nanocrystal surface and prevent degradation. This guide objectively compares the impact of A-site cation composition (Cs⁺ vs. FA⁺) on ligand binding affinity, a fundamental relationship that directly dictates the thermal degradation pathway and ultimate device longevity. Experimental data and theoretical calculations demonstrate that A-site cation engineering is a powerful strategy for modulating surface chemistry and enhancing PQD stability.

Fundamental Concepts and Key Experimental Findings

The Role of A-Site Cations and Surface Ligands

In perovskite quantum dots with the general formula ABX₃ (e.g., CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃), the A-site is occupied by cations such as Cesium (Cs⁺) or Formamidinium (FA⁺), while the surface is capped by organic ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA). These ligands are crucial for stabilizing the nanocrystal colloid and passivating surface defects; however, their effectiveness is intrinsically linked to the chemical identity of the A-site cation. The strength of this interaction, quantified as the ligand binding energy, has been proven to be composition-dependent, thereby influencing critical properties such as phase stability and electron-phonon coupling [12].

Comparative Analysis of Binding Energy and Stability

The following table summarizes the core experimental findings on how A-site composition affects ligand binding and subsequent material properties.

Table 1: Impact of A-Site Cation Composition on PQD Properties

| Property | Cs-Rich PQDs | FA-Rich PQDs |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Binding Energy | Lower | Higher [12] |

| Primary Thermal Degradation Mechanism | Phase transition from black γ-phase to yellow δ-phase [12] | Direct decomposition into PbI₂ [12] |

| Electron-LO Phonon Coupling | Weaker | Stronger [12] |

| Implication for Exciton Dissociation | Lower probability of exciton dissociation by phonon scattering | Higher probability of exciton dissociation by phonon scattering [12] |

| Typical Experimental Phase Assignment | γ-phase (black) | α-phase (black) [12] |

A seminal in-situ study constructed a detailed picture of the temperature-dependent behavior of CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃ PQDs across the entire compositional range. The research established that the thermal degradation mechanism is not universal but depends critically on the A-site chemistry and the associated ligand binding energy. First-principles Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations directly correlated these observed stability trends with ligand binding strength, showing that the bond strength of ligands to FA-rich PQD surfaces is larger than that to Cs-rich surfaces [12].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for comparative research, this section outlines the key methodologies used in the cited investigations.

Synthesis of CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃ PQDs

Method: Hot-injection colloidal synthesis [12] [14]. Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: PbI₂ is complexed with Oleic Acid (OA) and Oleylamine (OLA) in a non-coordinating solvent (e.g., 1-Octadecene).

- Cation Injection: A pre-heated solution of Cs-oleate (for Cs⁺) or FAI (for FA⁺) in a suitable solvent is swiftly injected into the lead precursor solution.

- Reaction Quenching: The reaction is terminated by cooling the mixture in an ice-water bath after a short reaction period (5-10 seconds).

- Purification: The crude solution is centrifuged with an anti-solvent (e.g., methyl acetate) to precipitate the PQDs. The supernatant containing excess ligands and reaction byproducts is discarded. The pellet is re-dispersed in a non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene or hexane) for further use. Key Control Parameter: The molar ratio of Cs⁺ to FA⁺ in the precursor solutions is varied to achieve the desired composition across the entire range (x = 0 to 1) [12].

In-Situ Temperature-Dependent X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

Objective: To monitor structural and phase evolution in real-time under thermal stress [12]. Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: A thin film of PQDs is deposited on a suitable substrate (e.g., a silicon wafer or a Pt heater strip).

- Measurement Setup: The sample is placed in a temperature-controlled stage or chamber under an inert atmosphere (e.g., argon flow).

- Data Acquisition: XRD patterns (e.g., 2θ range of 10°-50°) are continuously collected as the temperature is ramped from room temperature (30 °C) to high temperature (up to 500 °C).

- Data Analysis: Diffraction peaks are assigned to specific crystal phases (e.g., perovskite γ-phase, δ-phase, or PbI₂). The appearance, disappearance, and shifting of peaks are tracked to identify degradation onset temperatures and mechanisms.

Theoretical Calculation of Ligand Binding Energy

Objective: To quantitatively compute the strength of the interaction between surface ligands and the PQD surface [12] [15]. Method: First-principles Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. Workflow:

- Model Construction: A slab or cluster model representing the relevant surface termination (e.g., PbI₂-terminated) of the perovskite is built.

- Geometry Optimization: The atomic positions of the model and the ligand molecule are relaxed to find the most stable configuration.

- Energy Calculation: The total energy of the optimized PQD-ligand complex (Ecomplex), the isolated PQD model (EPQD), and the isolated ligand (E_ligand) are computed.

- Binding Energy Determination: The binding energy (ΔEbind) is calculated using the formula: ΔEbind = Ecomplex - (EPQD + Eligand) A more negative value of ΔEbind indicates a stronger, more favorable binding interaction.

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationship between A-site composition, ligand binding, and material stability established through these experiments.

Diagram 1: The causal relationship between A-site cation composition, ligand binding energy, and the resulting thermal degradation pathway in perovskite quantum dots.

Advanced Ligand Engineering Strategies

The pursuit of enhanced stability has moved beyond simple ion exchange to sophisticated ligand design. A prominent strategy involves developing multi-site binding ligands that form stronger, more robust connections with the PQD surface.

Multi-Site Binding for Enhanced Stability

Conventional ligands like OA and OLA typically bind through a single active site, which can lead to labile passivation. Recent research has identified complexes like Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ (antimony chloride-N,N-dimethyl selenourea) that can bind to four adjacent sites on the perovskite surface via two Se and two Cl atoms [15]. DFT calculations confirm that as the number of binding sites increases, the adsorption energy becomes more negative, indicating a stronger and more stable bond. This multi-dentate binding significantly enhances moisture resistance and overall device stability, leading to record operational lifetimes for perovskite solar cells [15].

Covalent Ligands in Non-Polar Solvents

Another advanced approach addresses the destructive side-effects of conventional ligand exchange processes, which often use polar solvents that strip away surface ions and create defects. A successful mitigation strategy employs covalent short-chain ligands like triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) dissolved in non-polar solvents (e.g., octane) [4]. The TPPO ligand coordinates strongly to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites via Lewis-base interactions, while the non-polar solvent prevents the loss of surface components. This synergetic effect simultaneously improves the optoelectronic properties and ambient stability of the resulting PQD solids [4].

Table 2: Advanced Ligand Strategies for PQD Surface Passivation

| Ligand Strategy | Key Feature | Mechanism of Action | Demonstrated Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Site Binding [15] | Single molecule with multiple anchoring points (e.g., 2Se + 2Cl). | Forms multiple simultaneous chemical bonds with the perovskite surface, increasing adsorption energy. | Enhanced crystallinity, suppressed defect formation, dramatically improved thermal and operational stability. |

| Covalent Ligands in Non-Polar Solvents [4] | Covalent ligands (e.g., TPPO) processed in non-polar solvents (e.g., octane). | Strong Lewis-acid/base interaction with undercoordinated Pb²⁺; non-polar solvent preserves surface ions. | Higher PL intensity, reduced surface trap density, improved PCE and device longevity. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section catalogs key materials and reagents essential for experimental research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PQD Synthesis and Ligand Binding Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Precursor for Cs⁺ A-site cation. | Reacted with OA to form Cs-oleate injection solution. |

| Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) | Precursor for FA⁺ A-site cation. | High purity required to avoid unwanted impurities affecting crystallization. |

| Lead Iodide (PbI₂) | Source of Pb²⁺ and I⁻ in the perovskite framework. | Must be thoroughly dried and stored in a controlled environment. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OLA) | Standard long-chain surface ligands for colloidal synthesis. | Ratio and concentration control nucleation, growth, and final size of PQDs [14]. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-coordinating solvent for high-temperature synthesis. | Often purified to remove peroxides and other reactive species. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) / Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) | Polar anti-solvents for purification and ligand exchange. | Used to precipitate PQDs and for solid-state ligand exchange [4]. |

| Sodium Acetate (NaOAc) / Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Ionic short-chain ligands for ligand exchange. | Replace long-chain OA/OLA to improve inter-dot charge transport [4]. |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) | Covalent short-chain ligand for surface stabilization. | Dissolved in non-polar solvents (e.g., octane) for post-treatment passivation [4]. |

The following diagram maps the experimental workflow from synthesis to stability assessment, integrating the reagents and strategies detailed above.

Diagram 2: A comprehensive experimental workflow for synthesizing, passivating, and characterizing the stability of perovskite quantum dots.

The experimental data unequivocally demonstrates that the A-site cation composition is a powerful lever for controlling ligand binding energy in perovskite quantum dots. FA-rich PQDs exhibit higher ligand binding energy than their Cs-rich counterparts, which directly influences their thermal degradation pathway. While FA-rich compositions benefit from stronger ligand binding, they also exhibit stronger electron-phonon coupling, which may influence charge carrier dynamics. The choice of A-site cation is therefore a multifaceted decision. Future research directions highlighted in this guide, including the use of multi-anchoring and covalent ligand systems, provide a clear roadmap for overcoming current stability limitations and advancing PQD technologies toward commercialization.

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) have emerged as a revolutionary class of semiconducting nanomaterials with exceptional optoelectronic properties, including narrow-band emission, high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), and widely tunable bandgaps. These characteristics make them highly promising for applications in next-generation displays, photovoltaics, and bioimaging. However, their commercial deployment faces significant challenges due to inherent instability under environmental stressors. The ionic crystal structure of PQDs renders them particularly vulnerable to degradation from humidity, temperature fluctuations, and light exposure, leading to rapid deterioration of their optical and electronic properties.

This guide objectively compares the stability performance of various PQD stabilization strategies, with a specific focus on how surface ligand engineering modulates resilience against these key instability factors. The binding affinity and molecular structure of surface ligands directly influence defect formation, ion migration, and interfacial interactions—fundamental processes governing PQD degradation pathways. By examining experimental data across multiple studies, we provide researchers with a quantitative framework for evaluating stabilization approaches and selecting optimal ligand systems for specific application environments.

Comparative Analysis of PQD Stability Performance

Quantitative Stability Metrics Across Ligand Strategies

Table 1: Comparative performance of PQD stabilization strategies against environmental stressors

| Stabilization Strategy | Humidity Stability | Temperature Stability | Photostability | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silica Coating [16] | Greatly improved | Improved | Improved | • Maximum CRI fluctuation of 2.3 over 20 days• Maximum CCT fluctuation of 7 K• LER fluctuation of 5.2 lm/Wopt |

| Mn-Doping + Silica Shell [16] | Enhanced | Enhanced | Enhanced | • 15-day PL spectrum stability• Dual emission stability (host and Mn-related) |

| Dual-Ligand (Eu(acac)₃ & Benzamide) [17] | Excellent solvent compatibility | - | High stability | • 98.56% PLQY• 69.89 ns fluorescence lifetime• PGMEA solvent compatibility |

| Multifaceted Anchoring Ligand (ThMAI) [18] | Greatly enhanced | Enhanced black phase stability | - | • 15.3% PCE in solar cells• 83% PCE retention after 15 days |

| Traditional Long-Chain Ligands (OA/OLA) [18] | Poor | Poor black phase stability | Poor | • Rapid phase transition to δ-phase• Poor charge transport |

Impact of Relative Humidity on Material Systems

Table 2: Relative humidity effects on diverse material systems

| Material System | RH Impact | Stability Threshold | Performance Degradation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PQDs (Unprotected) | Severe degradation | Low RH environments | • PLQY reduction• Structural decomposition |

| Amorphous Solid Dispersions [19] | Variable by polymer | • HPMCAS: Most stable at high RH• PVP: Most affected at high RH | • RH significantly reduces kinetic stabilization• API solubility decreases with RH for NAP |

| Dry Eye Disease [20] | Clinical correlation | Lower RH increases risk | • Reduced RH increases relative risk of DED outpatient visits |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dual-Ligand Synergistic Passivation Engineering

The DLSPE strategy represents a sophisticated approach for simultaneously addressing bulk and interfacial defects in CsPbBr₃ PQDs [17]. The protocol involves:

- PQD Synthesis: CsPbBr₃ QDs are synthesized via hot-injection method. Cs₂CO₃ (0.3258 g, 1 mmol) and 10 mL of octanoic acid (OTAc) are loaded into a 20 mL vial and stirred at room temperature for 10 minutes to prepare the Cs precursor.

- Europium Doping: A PbBr₂ precursor solution is prepared by dissolving PbBr₂ (1 mmol), tetraoctylammonium bromide (TOAB, 2 mmol), and varying amounts of europium acetylacetonate (Eu(acac)₃ (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 mmol) in 10 mL of toluene.

- Ligand Exchange: Benzamide solution in toluene is introduced for surface ligand exchange, introducing short-chain ligands with electron-rich amide groups that coordinate with Br⁻ surface sites.

- Characterization: HR-XRD, FT-IR, XPS, and TEM analyses confirm successful incorporation of Eu(acac)₃ and benzamide, demonstrating defect suppression and structural modulation.

Multifaceted Anchoring Ligands for Phase Stability

The ThMAI ligand exchange process addresses both conductivity and stability challenges in CsPbI₃ PQD solar cells [18]:

- PQD Synthesis: CsPbI₃ PQDs stabilized with oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA) are synthesized by hot injection method, confirmed by TEM analysis to exhibit black phase with average size of 11 nm.

- Ligand Exchange: A solution of 2-thiophenemethylammonium iodide (ThMAI) in acetonitrile is used for ligand exchange, replacing initial long-chain ligands.

- Film Fabrication: PQD thin films are fabricated via layer-by-layer spin-coating with ThMAI treatment between layers.

- Device Characterization: J-V measurements, EQE spectra, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, and GIWAXS are employed to analyze photovoltaic performance, charge transport, and crystal structure.

Stability Testing Protocols

Standardized stability assessment methodologies enable direct comparison between different stabilization approaches:

- Environmental Testing: PQD films and devices are subjected to controlled environmental conditions: 25°C/0% RH, 25°C/60% RH, and 40°C/75% RH [19].

- Temporal Monitoring: Long-term stability is evaluated through 15-20 day observations with regular measurements of PL spectrum, CRI, CCT, and efficiency parameters [16].

- Accelerated Aging: Devices are operated under continuous illumination or elevated temperatures to simulate extended operational lifetimes.

Mechanisms of Action and Signaling Pathways

Ligand-Mediated Stabilization Pathways

Diagram 1: Ligand-mediated stabilization pathways against environmental stressors

Dual-Ligand Defect Passivation Mechanism

Diagram 2: Dual-ligand defect passivation mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key research reagents for PQD stability studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Tetramethoxysilane (TMOS) | Silica shell precursor for encapsulation | Creates protective barrier against humidity [16] |

| Europium Acetylacetonate (Eu(acac)₃) | Trivalent dopant for bulk defect passivation | Compensates Pb²⁺ vacancies in DLSPE strategy [17] |

| Benzamide | Short-chain surface ligand | Passivates surface defects via amide coordination [17] |

| 2-Thiophenemethylammonium Iodide (ThMAI) | Multifaceted anchoring ligand | Enhances phase stability and charge transport [18] |

| Manganese Chloride (MnCl₂) | Transition metal dopant | Creates dual emission and improves structural stability [16] |

| Oleic Acid/Oleylamine | Traditional long-chain ligands | Initial stabilization but limit charge transport [18] |

| Propylene Glycol Monomethyl Ether Acetate (PGMEA) | Polar solvent for photolithography | Tests solvent compatibility in patterning processes [17] |

The strategic engineering of surface ligand binding affinity presents a powerful approach for mitigating the key instability factors affecting perovskite quantum dots—humidity, temperature, and light exposure. Experimental data demonstrate that advanced ligand strategies, particularly dual-ligand systems and multifaceted anchoring ligands, significantly outperform traditional stabilization methods across quantitative metrics including PLQY retention, phase stability, and environmental resilience.

The integration of computational design with experimental validation has enabled rational ligand development targeting specific degradation pathways. As research progresses, the continued refinement of ligand architectures promises to bridge the gap between laboratory demonstration and commercial deployment of PQD-based technologies across display, energy, and semiconductor applications.

Advanced Ligand Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Performance

The stability and optoelectronic performance of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) are critically dependent on their surface chemistry. Ligands—molecules bound to the PQD surface—play a dual role: they passivate surface defects to enhance photoluminescence and influence charge transport between neighboring dots [9]. However, conventional ligands often bind through a single functional group, leading to dynamic and labile attachment that compromises stability [15] [9]. Multifaceted anchoring ligands represent a transformative strategy, employing multiple functional groups that bind coordinatively to different surface sites simultaneously. This approach creates a more robust and stable surface passivation, significantly improving the performance and longevity of PQD-based devices such as solar cells and light-emitting diodes [18] [15].

Comparative Analysis of Multifaceted Anchoring Ligands

The following section objectively compares the performance of several advanced multifaceted ligands against conventional alternatives, with data summarized in Table 1 and binding mechanisms detailed in Table 2.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Multifaceted Anchoring Ligands in Perovskite Optoelectronics

| Ligand Name | Material/ System | Key Functional Groups | Primary Binding Mechanism | Reported Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Key Stability Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Thiophenemethylammonium Iodide (ThMAI) | CsPbI₃ PQD Solar Cells [18] | Thiophene, Ammonium [18] | Multifaceted Anchoring [18] | 15.3% [18] | Retained 83% of initial PCE after 15 days in ambient conditions [18] |

| Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ Complex | Fully Air-Processed Perovskite Solar Cells [15] | Selenourea (Se), Chloride (Cl) [15] | Multi-site (Quadruple) Binding [15] | 25.03% [15] | Projected T₈₀ shelf lifetime of 23,325 hours; T₈₀ of 5,004 h at 85°C [15] |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) | CsPbI₃ PQD Solar Cells [4] | Phosphine Oxide (P=O) [4] | Covalent L-type Binding [4] | 15.4% [4] | Maintained >90% of initial efficiency after 18 days in ambient conditions [4] |

| Conventional Ionic Short-Chain (e.g., Acetate, PEA⁺) | CsPbI₃ PQD Solar Cells [18] [4] | Carboxylate, Ammonium [18] [4] | Ionic / Labile Binding [18] [4] | 13.6% (Control) [18] | Retained only ~8.7% of initial PCE after 15 days [18] |

Table 2: Binding Mechanism and Function of Multifaceted Ligands

| Ligand | Binding Target on PQD Surface | Theoretical/Measured Binding Affinity | Secondary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| ThMAI [18] | Thiophene to uncoordinated Pb²⁺; Ammonium to Cs⁺ vacancies [18] | Strong binding energy due to reinforced dipole moment [18] | Larger ionic size of ThMA⁺ restores beneficial surface tensile strain, stabilizing the black phase [18] |

| Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ [15] | Two Se and two Cl atoms to four adjacent undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites [15] | Stronger charge transfer and more stable adsorption energy with more binding sites [15] | Forms an extended hydrogen-bonding network (NH...Cl) and fills Iodine vacancies with its Cl atoms [15] |

| TPPO [4] | Phosphine oxide group to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites [4] | Strong Lewis-base interaction (covalent) [4] | Nonpolar solvent (octane) enables nondestructive application, preserving PQD surface components [4] |

The data reveals a consistent trend: ligands capable of multi-site, coordinative binding universally outperform conventional ionic ligands. ThMAI's dual-group approach provides effective defect passivation and enhances phase stability [18]. The Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex represents the pinnacle of this strategy, with its quadruple-site binding leading to record-breaking stability metrics for air-processed devices [15]. Similarly, TPPO's strong, covalent Lewis-acid-base interaction effectively suppresses surface traps despite having a single primary binding group, especially when applied with a non-destructive solvent [4].

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Application and Analysis

Reproducible experimental protocols are fundamental for comparing ligand efficacy. Below are detailed methodologies for applying and characterizing multifaceted ligands, with the workflow for ThMAI-treated PQD solar cells visualized in Diagram 1.

Synthesis and Ligand Exchange Procedure for CsPbI₃ PQDs

- PQD Synthesis: CsPbI₃ PQDs are typically synthesized via the hot-injection method [18] [4]. A lead iodide (PbI₂) precursor is dissolved in a high-boiling-point solvent (e.g., 1-octadecene) with coordinating long-chain ligands, typically oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA), at elevated temperatures (e.g., 150-180 °C) under inert atmosphere. A cesium precursor (e.g., Cs₂CO₃-oleate) is then swiftly injected to initiate nucleation and growth of monodisperse PQDs [18] [4].

- Conventional Ligand Exchange (Two-Step): The insulating OA and OLA ligands must be replaced with shorter, conductive ligands to fabricate solid films.

- Anionic Ligand Exchange: The pristine PQD solution is spin-coated onto a substrate, followed by treatment with a solution containing short anionic ligands (e.g., acetate ions from sodium acetate) dissolved in a polar solvent like methyl acetate (MeOAc). This step replaces OA ligands [4].

- Cationic Ligand Exchange: The film is subsequently treated with a solution of short cationic ligands (e.g., phenethylammonium iodide, PEA⁺) dissolved in another polar solvent like ethyl acetate (EtOAc). This step replaces OLA ligands [4]. This two-step process is repeated in a layer-by-layer fashion to build the desired film thickness.

- Multifaceted Ligand Treatment: The innovative ligands are often applied as a post-synthesis treatment on the ligand-exchanged PQD solid.

- For ThMAI, the ligand is dissolved in a solvent like chlorobenzene or a hexane/octane mixture and dynamically spin-coated onto the fabricated PQD film [18] [21].

- For TPPO, the ligand is dissolved in a nonpolar solvent (n-octane) and applied to the ligand-exchanged PQD solids. The use of a nonpolar solvent is crucial to prevent the dissolution or degradation of the PQD surface components that can occur with polar solvents [4].

Characterization Techniques for Binding Affinity and Surface Analysis

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy: This technique verifies the successful replacement of ligands by tracking the disappearance of characteristic vibrational peaks of oleyl chains (e.g., C-H stretches) and the emergence of peaks corresponding to the new ligands [4].

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: This is a key metric for assessing defect passivation. A significant increase in PL intensity and carrier lifetime after treatment with a multifaceted ligand indicates successful reduction of non-radiative recombination centers (surface traps) [18] [4].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Used to analyze the crystal structure and phase stability of the PQDs. Ligands like ThMAI that impart tensile strain can help stabilize the metastable black perovskite phase (α-, β-, γ-phase) against transformation into a non-perovskite yellow phase (δ-phase) [18] [9].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations: Theoretical modeling is indispensable for understanding the binding mechanism at the atomic level. DFT can calculate adsorption energies of different ligand configurations, map charge transfer, and determine the most stable binding modes, such as the quadruple-site binding of Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Multifaceted Ligand Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Thiophenemethylammonium Iodide (ThMAI) [18] | Multifaceted anchoring ligand for defect passivation and strain engineering in PQD films. | Primary ligand in Seo et al. study for enhancing CsPbI₃ PQD solar cell performance and stability [18] [21]. |

| Antimony Chloride-N,N-dimethyl Selenourea Complex (Sb(SU)₂Cl₃) [15] | Multi-site (quadruple) binding passivator for bulk perovskite films, suppressing defects. | Key additive in fully air-processed perovskite solar cells, achieving high efficiency and record stability [15]. |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) [4] | Covalent short-chain ligand for passivating uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites via Lewis-base interaction. | Used as a post-treatment on ligand-exchanged CsPbI₃ PQD solids, dissolved in nonpolar octane [4]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OLA) [18] [4] [9] | Standard long-chain ligands for the initial synthesis and stabilization of colloidal PQDs. | Universally used in the hot-injection synthesis of CsPbI₃ PQDs; later replaced via ligand exchange [18] [4]. |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) [4] | Conventional short-chain cationic ligand used in standard ligand exchange procedures. | Used in the control group and as part of the initial ligand exchange before advanced ligand treatment [4]. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) / Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) [4] | Polar solvents used in the conventional two-step ligand exchange process. | Employed to dissolve ionic short-chain ligands (e.g., acetate, PEAI) and wash away long-chain ligands [4]. |

| n-Octane [4] | Nonpolar solvent for dissolving covalent ligands in post-synthesis treatments. | Used to dissolve TPPO for a nondestructive surface treatment that preserves PQD surface components [4]. |

The strategic development of multifaceted anchoring ligands marks a significant leap forward in perovskite material science. By moving beyond single-site, labile binding to multi-functional, coordinative anchoring, researchers can simultaneously address the critical challenges of surface defect passivation, inter-dot charge transport, and phase stability. As demonstrated by ThMAI, TPPO, and the sophisticated Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ complex, this approach enables devices that combine high performance with exceptional durability, a crucial combination for commercial applications. Future research will likely focus on designing even more complex ligands with tailored binding groups, exploring lead-free perovskite systems, and scaling up synthesis and application protocols for industrial manufacturing.

In the pursuit of high-performance perovskite quantum dot (PQD) optoelectronics, surface ligand engineering has emerged as a critical frontier. The central challenge lies in overcoming the inherent trade-off between surface passivation for stability and efficient charge transport for device performance. Long-chain insulating ligands used in synthesis provide excellent colloidal stability but severely hinder inter-dot charge transport, while short-chain ligands often suffer from incomplete coverage and weak binding. Within this landscape, bidentate anchoring ligands represent a transformative strategy, simultaneously addressing the dual requirements of robust surface passivation and enhanced electrical conductivity through their unique coordination geometry and strong binding affinity.

This review objectively compares the performance of emerging bidentate and multifaceted ligand systems, focusing on quantitative metrics critical for PQD device advancement. We examine experimental data on binding energies, conductivity enhancement, and device performance, providing researchers with a structured comparison of ligand strategies that are pushing the boundaries of PQD applications in photovoltaics and light-emitting devices.

Experimental Approaches in Ligand Performance Evaluation

Evaluating ligand performance requires a multifaceted experimental approach to quantify both binding strength and its impact on material properties. Standard protocols include:

Binding Energy Calculation via Density Functional Theory (DFT)

- Protocol: First-principles DFT calculations are performed on cluster or slab models of the PQD surface. The binding energy (Eb) is calculated as Eb = Etotal - Esurface - Eligand, where Etotal is the energy of the surface-ligand complex, Esurface is the energy of the pristine surface, and Eligand is the energy of the isolated ligand. More negative values indicate stronger, more favorable binding [22] [23].

Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) Measurement

- Protocol: PQD films are excited at their absorption band edge using a monochromatic light source. The integrated intensity of the emitted photons is compared against a calibrated reference standard using an integrating sphere. PLQY = (number of photons emitted / number of photons absorbed) × 100%. Higher PLQY indicates superior passivation of non-radiative recombination centers [22] [23].

Two-Terminal Device Conductivity Measurement

- Protocol: Ligand-exchanged PQD films are deposited onto substrates with pre-patterned electrodes. Current-voltage (I-V) characteristics are measured under dark conditions. Electrical conductivity (σ) is calculated from the slope of the I-V curve, factoring in film geometry. This directly quantifies improved inter-dot charge transport after ligand exchange [22] [23].

The experimental workflow below illustrates how these characterization techniques are integrated to evaluate ligand performance from molecular binding to final device functionality.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating ligand performance in PQD applications

Comparative Performance of Ligand Systems

Bidentate Ligands for Near-Infrared Perovskite LEDs

The application of formamidine thiocyanate (FASCN) as a bidentate liquid ligand demonstrates remarkable improvements in near-infrared PQD-LEDs. The comparative data reveals its superior performance against conventional ligands.

Table 1: Performance comparison of FASCN versus conventional ligands in FAPbI₃ PQDs

| Parameter | Oleate (OA) | Oleylammonium (OAm) | FAI | MAI | FASCN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Energy (eV) | -0.22 | -0.18 | -0.31 | -0.30 | -0.91 |

| Relative Binding | 1× | 1× | 1.4× | 1.4× | 4.1× |

| Film Conductivity (S/m) | Baseline | Baseline | - | - | 8× improvement |

| Exciton Binding Energy (meV) | 39.1 | 39.1 | - | - | 76.3 |

| LED External Quantum Efficiency | ~11.5% | ~11.5% | - | - | ~23% |

| Turn-on Voltage at 776 nm | - | - | - | - | 1.6 V |

FASCN's bidentate coordination through soft sulfur and nitrogen atoms enables fourfold higher binding energy than oleate ligands and threefold higher than formamidine iodide (FAI) and methylammonium iodide (MAI) [22] [23]. This tight binding prevents ligand desorption during film preparation, eliminating interfacial quenching centers. The short carbon chain (<3 atoms) enables eightfold higher film conductivity compared to control samples, while the liquid characteristics of FASCN avoid the need for high-polarity solvents that could damage PQD surfaces [22] [23].

Multifaceted Anchoring Ligands for Perovskite Quantum Dot Photovoltaics

In photovoltaic applications, the ligand design strategy expands to include multifaceted anchoring groups that simultaneously address multiple surface defects.

Table 2: Performance comparison of anchoring ligands in CsPbI₃ PQD solar cells

| Ligand | Anchor Groups | Binding Affinity | PCE (%) | Stability (Initial PCE Retained) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ThMAI | Thiophene + Ammonium | High (Dipole-enhanced) | 15.3% | 83% after 15 days | Multifaceted anchoring, tensile strain restoration |

| TPPO | Phosphine Oxide | Strong (Covalent/Lewis base) | 15.4% | >90% after 18 days | Nonpolar solvent compatibility, strong Pb²⁺ coordination |

| Conventional Ionic Short-chain | Single ammonium/carboxylate | Labile/Weak | 13.6% | <9% after 15 days | Baseline for comparison |

The electron-rich thiophene ring in ThMAI acts as a Lewis base that strongly binds to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites, while the ammonium segment efficiently occupies cationic Cs⁺ vacancies [18]. This multifaceted anchoring, reinforced by charge separation and strong dipole moment, enables effective defect passivation and uniform PQD ordering. The larger ionic size of ThMA⁺ compared to Cs⁺ helps restore surface tensile strain, enhancing black-phase stability [18].

Triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) employs a different strategy, using covalent short-chain ligands dissolved in nonpolar solvents to avoid damaging the ionic PQD surface [4]. The TPPO ligand strongly coordinates with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites via Lewis acid-base interactions, while the nonpolar solvent octane completely preserves PQD surface components. This approach yields a PCE of 15.4% with excellent ambient stability [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents for bidentate ligand research in perovskite quantum dots

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) | Bidentate liquid ligand for NIR PQD-LEDs | Short chain (<3C), liquid state, S/N coordination |

| 2-Thiophenemethylammonium Iodide (ThMAI) | Multifaceted anchor for PQD photovoltaics | Thiophene + ammonium groups, large ionic size |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) | Covalent ligand for surface stabilization | Lewis base, nonpolar solvent compatibility |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OLA) | Standard long-chain ligands for PQD synthesis | Provides initial stability, requires replacement |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) / Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) | Polar solvents for conventional ligand exchange | Removes long-chain ligands, can damage PQD surface |

| Octane | Nonpolar solvent for nondestructive ligand treatment | Preserves PQD surface components during treatment |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Short cationic ligand for comparison studies | Conventional short-chain ligand, ionic nature |

Molecular Coordination Mechanisms

The superior performance of bidentate ligands stems from their fundamental coordination chemistry with the PQD surface. The diagram below illustrates how these ligands achieve enhanced surface coverage and stability compared to conventional monodentate ligands.

Figure 2: Molecular coordination mechanisms of ligand classes on PQD surfaces

Bidentate ligands like FASCN form chelate complexes with surface metal atoms, achieving significantly higher binding energies (-0.91 eV) compared to monodentate ligands (-0.18 to -0.31 eV) [22] [23]. This chelate effect dramatically reduces ligand desorption during processing. Multifaceted anchors like ThMAI further enhance this approach through dipole-enhanced binding, where charge separation between electron-rich thiophene and electron-deficient ammonium groups creates stronger surface adhesion [18].

The strategic implementation of bidentate and multifaceted anchoring ligands represents a paradigm shift in perovskite quantum dot surface engineering. The experimental data clearly demonstrates that these advanced ligand architectures simultaneously address the historical challenges of surface passivation and charge transport that have limited PQD device performance.

Through strong chelation, short conductive chains, and multifunctional anchoring, these ligands enable record device efficiencies—achieving ~23% EQE in NIR-LEDs and over 15% PCE in photovoltaics—while significantly enhancing operational stability. The fundamental coordination chemistry of these systems provides a versatile foundation for further innovation, offering researchers a expanding toolkit to tailor PQD surfaces for specific applications. As the field progresses, the continued refinement of bidentate ligand design promises to unlock the full commercial potential of perovskite quantum dot technologies.

In the evolving landscape of nanoscience and drug development, complementary dual-ligand systems represent an advanced paradigm where two distinct ligand molecules work synergistically to enhance material performance and functionality. Unlike single-ligand approaches that often address stability or binding affinity in isolation, dual-ligand systems integrate complementary functionalities that collectively overcome individual limitations. This strategy is particularly valuable in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) stabilization, where environmental vulnerability has historically constrained practical application. By engineering ligand pairs with cooperative interactions, researchers can create robust nanostructures that maintain optical excellence while withstanding harsh operational conditions.

The fundamental thesis governing this approach posits that strategic ligand pairing can produce emergent properties—benefits that transcend the simple summation of individual ligand contributions. These systems typically combine one ligand providing strong surface attachment with another offering steric protection or additional functional capabilities. This guide examines the comparative performance of leading dual-ligand and encapsulation strategies, providing experimental data and methodologies to inform research directions in PQD stabilization and surface ligand binding affinity optimization.

Comparative Analysis of Dual-Ligand and Encapsulation Strategies

The pursuit of PQD stability has yielded various strategic approaches, from surface ligand engineering to complete nanostructure encapsulation. The table below systematically compares the performance characteristics of two prominent strategies documented in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of PQD Stabilization Strategies

| Strategy & Materials | Stability Performance | Optical Properties | Key Advantages | Experimental Affinity Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Encapsulation [24] | Maintains 99.8% PL intensity after 2 hours water immersion | Amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) with ultralow threshold of 1.72 μJ cm−2; Emission intensity 10× stronger than conventional PL | Waterproof protection; Ultrahigh-speed monitoring capability (108 fps) | Superior linearity (R² = 0.999) for concentration quantification (0–3.5 μM tartrazine) |

| Metal-Organic Framework (UiO-66) Encapsulation [25] | Luminescence maintenance over 30 months ambient; Several hours underwater | Strong exciton-polariton coupling; Anti-crossing behavior in dispersion curves; Identifiable lattice fringes (0.58 nm) = (100) plane of CsPbBr₃ | Long-term environmental stability; Enhanced exciton-phonon interaction | BET surface area decreases from 1,510 m²/g (UiO-66) to 320 m²/g (PQD@UiO-66) confirms pore filling |

The experimental data reveal that both encapsulation strategies successfully address PQD instability through distinct mechanisms. The PDMS encapsulation creates a protective barrier that enables exceptional retention of photoluminescence (99.8%) in aqueous environments while enhancing optical gain properties [24]. Conversely, the UiO-66 framework provides nanoscale confinement within its porous structure, offering remarkable long-term stability over 30 months while maintaining strong light-matter interactions [25]. These encapsulation approaches differ fundamentally from traditional surface ligand binding by creating physical barriers that shield PQDs from environmental degradants while preserving—and sometimes enhancing—their innate optical properties.

Experimental Protocols for Dual-Ligand System Validation

PDMS Encapsulation Methodology for PQDs

The PDMS encapsulation process follows a sequential fabrication approach that prioritizes interfacial compatibility between the quantum dots and polymer matrix [24]:

PQD Synthesis Preparation: Synthesize CsPbBr₃ PQDs using standard hot-injection methods, with precise control over precursor ratios and reaction temperatures to achieve uniform size distribution.

Surface Ligand Treatment: Implement a dual-ligand surface engineering step using oleic acid and oleylamine to ensure optimal dispersion compatibility with the PDMS matrix.

PDMS Matrix Formation: Prepare a transparent PDMS precursor by thoroughly mixing silicone elastomer base and curing agent in a 10:1 ratio, followed by degassing under vacuum to remove entrapped air bubbles.

PQD-PDMS Integration: Combine PQD solution with PDMS precursor using gradual titration (approximately 1:4 volume ratio) with continuous mechanical stirring to ensure homogeneous distribution without aggregation.

Curing Protocol: Cure the composite material thermally at 65°C for 4 hours, followed by post-curing at 85°C for 2 hours to achieve optimal cross-linking density without damaging the PQDs.

Film Fabrication: For sensor applications, spin-cast the uncured composite onto glass substrates at 2000 rpm for 30 seconds before implementing the curing protocol to create uniform thin films.

The critical validation step involves water immersion testing, where encapsulated films are submerged in deionized water while monitoring photoluminescence intensity at regular intervals using a fluorescence spectrometer. The exceptional stability (99.8% PL retention after 2 hours) confirms effective encapsulation [24].

MOF Encapsulation via Self-Limiting Solvothermal Deposition

The UiO-66 encapsulation employs a confinement-based stabilization strategy through a multi-step process [25]:

UiO-66 Matrix Synthesis: Prepare UiO-66 powder with missing-linker defects by combining zirconium chloride and terephthalic acid in N,N-dimethylformamide with acetic acid as modulators, followed by solvothermal reaction at 120°C for 24 hours.

Activation and Purification: Activate the synthesized UiO-66 by solvent exchange with methanol and subsequent thermal activation under vacuum at 150°C for 12 hours.

Lead Ion Functionalization: Create Pb-UiO-66 through self-limiting solvothermal deposition (SIM method) where Pb²⁺ ions coordinate on hexa-zirconium nodes of the MOF, forming metal-oxygen bonds between guest metal ions and the cluster.

Perovskite Crystallization: Introduce CsBr precursor solution to the Pb-UiO-66 powder mixture, initiating reaction that breaks Pb-O bonds and generates CsPbBr₃ QDs within the MOF pores.

Purification and Characterization: Remove excess precursors through repeated centrifugation and washing cycles, followed by characterization through XRD, TEM, and BET surface area analysis.

Validation of successful encapsulation includes BET surface area analysis showing reduction from 1,510 m²/g (pristine UiO-66) to 320 m²/g (PQD@UiO-66), confirming pore filling with perovskite QDs [25]. Additional confirmation comes from TEM imaging showing lattice fringes with 0.58 nm spacing corresponding to the (100) plane of CsPbBr₃.

Analytical Techniques for Binding Affinity Assessment

Binding Affinity Measurement Methods

Quantifying ligand interactions remains fundamental to understanding dual-ligand system efficacy. The table below compares established techniques for evaluating binding affinity.

Table 2: Analytical Methods for Binding Affinity Assessment

| Method | Working Principle | Sample Requirements | Affinity Range | Key Applications in Ligand Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) [26] | Fluorescence variation measurement in response to temperature gradients | Minimal (10 μL volume); nM target concentration; One fluorescent partner | pM-mM | Ligand/receptor binding in native membranes; D2R/spiperone-Cy5 affinity (5.3 ± 1.7 nM) |