Layer-by-Layer Solid-State Ligand Exchange for High-Efficiency CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dot Solar Cells

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the layer-by-layer (LbL) solid-state ligand exchange protocol for CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical technology for enhancing the performance and stability of...

Layer-by-Layer Solid-State Ligand Exchange for High-Efficiency CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dot Solar Cells

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the layer-by-layer (LbL) solid-state ligand exchange protocol for CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical technology for enhancing the performance and stability of next-generation solar cells. It explores the foundational principles of ligand chemistry and the limitations of long-chain insulating ligands. The content details advanced methodological approaches, including the use of short-chain organic and covalent ligands, and discusses common challenges such as surface trap generation and phase instability, offering practical optimization strategies. By validating these techniques through comparative performance metrics and stability tests, this resource offers researchers and scientists a validated framework for developing efficient and stable CsPbI3 PQD-based optoelectronic devices.

The Science of Ligand Exchange: Unlocking Charge Transport in CsPbI3 Quantum Dot Solids

The Critical Role of Surface Ligands in Colloidal CsPbI3 PQD Synthesis

The synthesis of colloidal CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) typically employs long-chain insulating ligands such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) to control crystal growth and ensure colloidal stability in non-polar solvents [1] [2] [3]. While essential for synthesis, these ligands form a detrimental insulating barrier that severely impedes charge transport in solid films, rendering them unsuitable for high-performance optoelectronic devices like solar cells [2] [3]. Consequently, a layer-by-layer (LBL) solid-state ligand exchange protocol is critical for replacing these native long-chain ligands with shorter, conductive alternatives. This process transforms the PQD film from an insulating state to a highly conductive semiconductor, enabling efficient carrier transport while simultaneously passivating surface defects to enhance both performance and environmental stability [1] [2]. This application note details the advanced protocols and key considerations for executing this vital process.

Quantitative Comparison of Ligand Exchange Strategies

The development of ligand exchange strategies has led to significant improvements in the performance of CsPbI3 PQD solar cells. The table below summarizes the key metrics for different approaches reported in the literature.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of CsPbI3 PQD Solar Cells with Different Ligand Management Strategies

| Ligand Strategy | Short Ligand Used | Key Improvement | Reported PCE (%) | Stability Retention | Citation Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEAI-LBL Exchange [1] | Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Balanced carrier transport/injection, defect passivation | 14.18 (Champion) | Excellent humidity stability (unencapsulated) | Primary research article |

| TPPO in Octane [2] | Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) | Covalent binding to uncoordinated Pb2+, non-destructive solvent | 15.4 (Champion) | >90% after 18 days (ambient) | Primary research article |

| 5A-3C Treatment [4] | 5-Aminopyridine-3-Carboxylic Acid | Multifunctional short-chain ligand, reduced vacancy defects | 15.03 (Champion) | Improved operational stability | Primary research article |

| Di-n-propylamine (DPA) [5] | Di-n-propylamine (DPA) | Simultaneous OA/OAm removal, 8x synthesis yield increase | ~15 (Approaching) | Not specified | Primary research article |

| Alkali-Augmented Hydrolysis [6] | Benzoate (from MeBz) | Doubled ligand density, fewer trap-states, homogeneous film | 18.30 (Certified) | Improved storage/operational stability | Primary research article |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard Layer-by-Layer Solid-State Ligand Exchange

This foundational protocol is essential for constructing thick, conductive PQD films for solar cells [1] [2].

- Step 1: Substrate Preparation. Pre-patterned Fluorine-doped Tin Oxide (FTO) or Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) substrates should be meticulously cleaned with ultrasonic treatment in detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropanol sequentially, each for 15-20 minutes, followed by UV-ozone or oxygen plasma treatment for 15-20 minutes to improve wettability [1].

- Step 2: Initial PQD Film Deposition. Spin-coat the synthesized CsPbI3 PQDs (capped with OA/OAm) dispersed in n-hexane or n-octane (concentration ~30-50 mg mL⁻¹) onto the substrate at 2000-3000 rpm for 20-30 seconds [2].

- Step 3: Anionic Ligand Exchange (Interlayer Rinsing). Immediately after deposition, while the film is still wet, dynamically rinse the film with methyl acetate (MeOAc) or a modified antisolvent (e.g., Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) with KOH [6]) to replace the long-chain OA ligands with short-chain acetate or benzoate ligands. This step removes the ligand shell and causes rapid supersaturation, leading to a densely packed solid film [6] [2].

- Step 4: Layer Buildup. Repeat Steps 2 and 3 for 3-5 cycles to achieve the desired film thickness (typically 300-500 nm), building the film in a layer-by-layer manner [1].

- Step 5: Cationic Ligand Exchange (Post-Treatment). After the final layer is deposited and rinsed, spin-coat a solution of short cationic ligands, such as Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) or Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) (e.g., 2-5 mg mL⁻¹ in Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) or 2-pentanol [6]), onto the completed PQD solid film. This step replaces residual OAm ligands and passivates surface defects [1] [2].

Advanced Protocol: PEAI Layer-by-Layer (PEAI-LBL) Exchange

This modified protocol integrates the cationic exchange directly into the layer-building process for superior results [1].

- Procedure: The key difference from the standard protocol is the substitution of the MeOAc rinse in Step 3 with a rinse solution containing the short cationic ligand. Specifically, after spin-coating each layer of CsPbI3 PQDs, the film is treated with a PEAI solution dissolved in EtOAc [1].

- Advantages: This method ensures more complete and uniform removal of both OA and OAm ligands throughout the entire film thickness during its construction. It promotes enhanced inter-dot coupling, superior defect passivation, and regulates balanced electron and hole transport, leading to higher open-circuit voltages and power conversion efficiencies [1].

Post-Synthetic Passivation with Covalent Ligands

This supplemental protocol can be applied after the standard ligand exchange to further enhance surface passivation and stability [2].

- Procedure: After completing the standard LBL exchange and post-treatment, spin-coat a solution of a covalent Lewis base ligand, such as Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mg mL⁻¹), dissolved in a non-polar solvent (n-octane) onto the fabricated PQD solid film [2].

- Mechanism & Benefit: The non-polar solvent prevents the dissolution or further degradation of the ionic PQD surface. The TPPO ligand covalently binds to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the PQD surface via strong Lewis acid-base interactions. This robust binding effectively reduces non-radiative recombination centers and enhances the film's resistance to moisture [2].

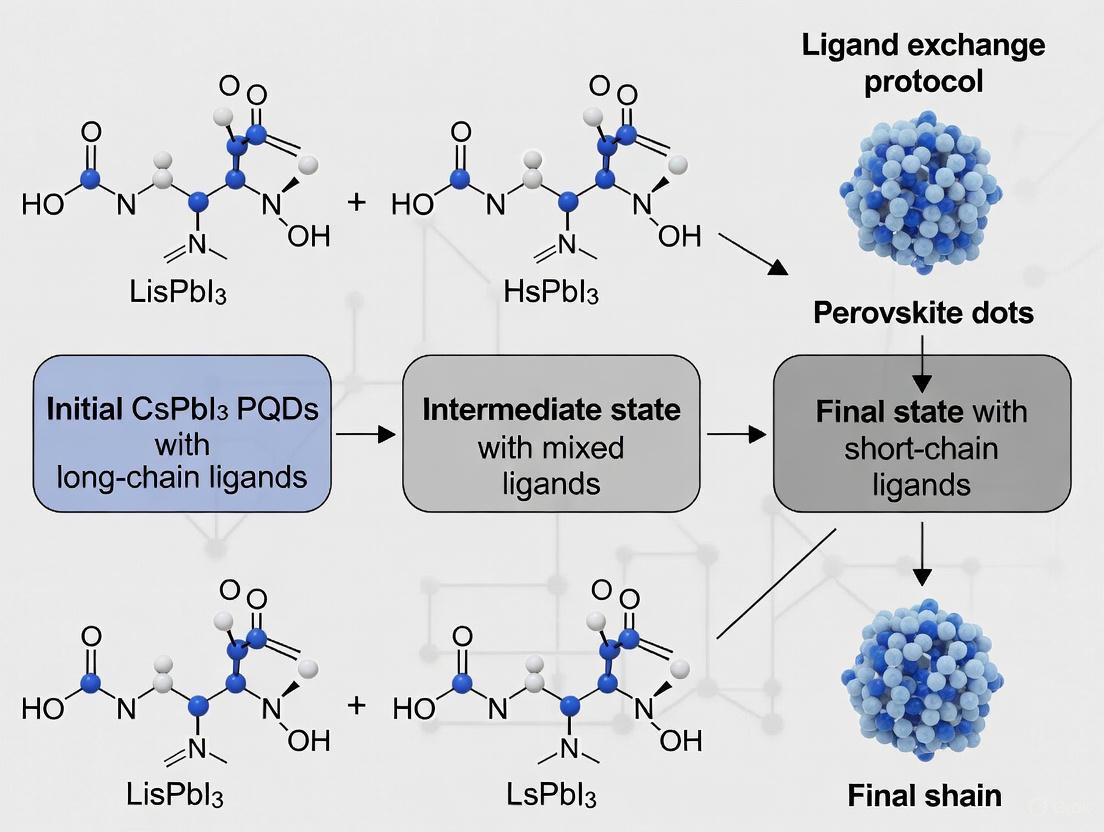

Workflow and Ligand Binding Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural and chemical decision points in the ligand management process for CsPbI3 PQD films.

Diagram 1: Workflow for ligand management in CsPbI3 PQD film fabrication, highlighting strategic choices between standard and advanced exchange protocols.

The efficacy of ligand exchange hinges on the molecular interactions at the PQD surface. The following diagram categorizes common ligands and their binding modes.

Diagram 2: Classification of common short-chain ligands by their binding mechanism to the CsPbI3 PQD surface, determining film conductivity and stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of the LBL solid-state ligand exchange protocol requires careful selection of reagents. The following table lists essential materials and their specific functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CsPbI3 PQD Ligand Exchange

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Protocol | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antisolvents for Rinsing | Methyl Acetate (MeOAc), Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) | Removes OA ligands via anionic exchange; induces supersaturation & film densification [1] [2]. | Purity is critical. MeOAc is highly volatile. Efficiency relies on ambient hydrolysis [6]. |

| Advanced Antisolvents | Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) with KOH additive | Creates alkaline environment for enhanced hydrolysis; provides benzoate ligands for superior capping vs. acetate [6]. | KOH concentration must be optimized to avoid perovskite core degradation [6]. |

| Cationic Ligand Salts | Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI), Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) | Replaces OAm ligands; passivates cationic (A-site) vacancies; modulates energy levels [1] [2]. | FAI can induce phase instability if treatment is over-extended [1]. PEA+ offers better moisture resistance [1]. |

| Covalent Passivators | Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) | Strong covalent binding to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites; drastically reduces trap states [2]. | Typically dissolved in non-polar solvents (e.g., octane) to prevent PQD surface damage [2]. |

| Non-Polar Solvents | n-Octane, n-Hexane | Disperse as-synthesized OA/OAm-capped PQDs for film deposition; dissolve covalent ligands without damaging PQDs [2]. | Enable uniform film formation. Octane's higher boiling point can offer better processing control. |

Inherent Limitations of Long-Chain Insulating Ligands (OA/OAm) on Charge Transport

Colloidal quantum dots (QDs), particularly lead halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), represent a promising class of materials for next-generation optoelectronic devices, including solar cells, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and photodetectors. The solution-based colloidal synthesis of these nanomaterials typically utilizes long-chain organic ligands such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) to stabilize the nanocrystals and prevent aggregation. While these ligands are indispensable for achieving monodisperse QDs with excellent colloidal stability, they form insulating barriers around individual QDs that severely impede inter-dot charge transport. This fundamental limitation creates a significant bottleneck for optoelectronic devices that rely on efficient charge carrier extraction and injection.

For CsPbI3 PQD solar cells, which operate within a planar heterojunction architecture similar to both photovoltaic and light-emitting devices, achieving balanced electron and hole transport is essential for maximizing device performance. The presence of insulating OA/OAm ligands not only reduces overall charge mobility but also exacerbates charge recombination losses at surface defects, ultimately limiting power conversion efficiency and electroluminescent performance. This application note examines the inherent limitations of long-chain insulating ligands on charge transport and outlines methodological frameworks for addressing these challenges through advanced ligand exchange strategies.

Fundamental Limitations of OA/OAm Ligands

Interparticle Spacing and Electronic Coupling

Long-chain OA/OAm ligands create substantial physical separation between adjacent quantum dots, severely limiting electronic coupling and charge transport efficiency:

Interparticle Distance Analysis: Comparative TEM studies of CsPbBr3 nanocrystals reveal that native OA/OAM-capped QDs maintain an average interparticle distance of approximately 2.8 nm, which is more than halved to 1.3 nm following ligand exchange with compact didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDABr) [7]. This reduced spacing enhances electronic coupling between neighboring QDs, facilitating improved charge transport.

Insulating Barrier Properties: The aliphatic carbon chains of OA and OAm act as dielectric barriers that exponentially reduce the probability of carrier tunneling between quantum dots. The cis-double bond in oleic acid further reduces van der Waals interactions between hydrocarbon chains, compromising the structural integrity of the QD solid film [7].

Dynamic Ligand Binding and Surface Defects

The weak, dynamic binding characteristics of conventional OA/OAm ligands present additional challenges for charge transport:

Ligand Desorption: OA and OAm ligands bind only weakly to QD surfaces and are highly dynamic, making them prone to desorption during processing and device operation [7]. This desorption creates unsaturated coordination sites (surface defects) that act as traps for charge carriers, promoting non-radiative recombination.

Proton Transfer Effects: During purification with polar antisolvents, proton transfer between deprotonated OA (OA⁻) and protonated OAm (OAmH⁺) leads to ligand loss from QD surfaces [8]. This process generates non-radiative recombination centers that further impede charge transport and reduce photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY).

Impacts on Optoelectronic Device Performance

The compromised charge transport directly manifests in suboptimal device performance across multiple metrics:

Imbalanced Charge Injection: The inherent imbalance between electron and hole transport in OA/OAm-capped QDs enhances Auger recombination losses, reducing the efficiency of light-emitting diodes [7].

Voltage Deficits: In photovoltaic devices, insufficient charge transport contributes to open-circuit voltage (VOC) deficits by increasing trap-assisted recombination at interface states.

Electrical Inaccessibility: Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy studies confirm that reduced ligand coverage following exchange processes significantly improves the electrical accessibility of the QDs, enabling more efficient charge extraction [7].

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Effects

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Ligand Strategies and Their Impact on Charge Transport Properties

| Ligand System | Interparticle Distance | PLQY (%) | Device Performance | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native OA/OAm | 2.8 nm [7] | <70% [8] | Limited PCE, EL efficiency | Excellent colloidal stability |

| PEAI-LBL | Significantly reduced [1] | Not reported | PCE: 14.18%, VOC: 1.23 V [1] | Enhanced inter-dot coupling, defect passivation |

| DDABr | 1.3 nm [7] | Not reported | Improved LED performance [7] | Reduced interparticle spacing, improved hole injection |

| NSA/NH₄PF₆ | Not reported | 94% [8] | EQE: 26.04% [8] | Inhibition of Ostwald ripening, strong surface binding |

| Alkaline Treatment | Not reported | Not reported | Certified PCE: 18.3% [6] | Dense conductive capping, fewer trap states |

Table 2: Impact of Ligand Engineering on Electronic Properties of QD Films

| Property | OA/OAm-Capped QDs | Short-Ligand Passivated QDs | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interparticle Distance | ~2.8 nm [7] | ~1.3 nm [7] | TEM |

| Ligand Coverage | High, densely packed | Reduced, partial coverage [7] | NMR spectroscopy |

| Trap-State Density | High due to dynamic binding | Reduced through strong binding ligands [8] | FTIR, XPS, PL analysis |

| Charge Injection Balance | Limited, hole-dominated | Improved balance [1] [7] | Single-carrier devices, DFT |

| Electronic Coupling | Weak | Enhanced [1] | Spectroelectrochemistry |

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Exchange

Layer-by-Layer Solid-State Ligand Exchange with PEAI

The following protocol details the layer-by-layer (LBL) solid-state ligand exchange procedure using phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI) for CsPbI3 PQD solar cells, as demonstrated by Wang et al. [1]:

Materials and Reagents:

- CsPbI3 PQD solution in n-hexane (concentration: ~20 mg/mL)

- Methyl acetate (MeOAc), anhydrous

- PEAI solution in ethyl acetate (concentration: 0.5 mg/mL)

- Substrates (e.g., FTO/glass with appropriate charge transport layers)

- Chlorobenzene for rinsing

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean FTO substrates sequentially in detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropanol under ultrasonication for 15 minutes each. Treat with UV-ozone for 20 minutes before use.

Initial PQD Layer Deposition: Spin-coat the CsPbI3 PQD solution onto the substrate at 2500 rpm for 20 seconds. Immediately after spinning, rinse with methyl acetate (3000 rpm, 20 seconds) to remove residual solvents and initiate ligand exchange.

PEAI Treatment: While the film is still wet, spin-coat the PEAI solution (0.5 mg/mL in ethyl acetate) at 3000 rpm for 20 seconds. Allow the film to rest for 30 seconds before spinning again to remove excess solution.

Layer Buildup: Repeat steps 2-3 for 3-5 cycles to achieve the desired film thickness (typically 300-400 nm).

Final Processing: Anneal the completed film at 70°C for 5 minutes to remove residual solvents. Proceed with deposition of subsequent charge transport layers and electrodes.

Critical Notes:

- Maintain relative humidity below 30% during processing to prevent PQD degradation.

- Optimize PEAI concentration to balance defect passivation and inter-dot coupling.

- The conjugated phenyl group in PEA+ enhances inter-dot coupling while providing effective surface passivation [1].

Direct Synthesis of Iodide-Passivated PbS QDs

The Iodine-Complex Directed Synthesis (ICDS) method enables direct synthesis of iodide-passivated PbS QDs, bypassing the need for post-synthetic ligand exchange [9] [10]:

Materials and Reagents:

- Lead iodide (PbI2), 99.99%

- Diphenylthiourea (DphTA), 99%

- Dimethylformamide (DMF), anhydrous

- 1-Butylamine, anhydrous

- Toluene for purification

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve PbI2 (0.5 mmol) and DphTA (0.5 mmol) in 5 mL DMF with stirring at 60°C until completely dissolved.

Nucleation and Growth: Rapidly inject 0.5 mL 1-butylamine to initiate nucleation. Maintain the reaction at 60°C for 60 seconds with vigorous stirring.

Size Control: Quench the reaction by adding 10 mL toluene. Centrifuge the mixture at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes to separate the QDs.

Purification: Redisperse the pellet in toluene and precipitate with acetonitrile. Repeat this washing step twice to remove unreacted precursors and excess ligands.

Film Formation: Deposit the PbS-I QDs directly by spin-coating without additional ligand exchange steps.

Mechanistic Insight: The ICDS method leverages iodine-complex equilibria (PbI₂ + I⁻ ⇌ [PbI₃]⁻ ⇌ [PbI₄]²⁻) to control nucleation rates and achieve in situ iodide passivation [9]. This approach eliminates long-chain insulating ligands entirely, resulting in enhanced electronic coupling between QDs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ligand Exchange Studies

| Reagent | Function | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Short conjugated ligand for LBL exchange | CsPbI3 PQD solar cells [1] | Enhances inter-dot coupling and defect passivation |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDABr) | Compact quaternary ammonium salt | CsPbBr3 NC LEDs [7] | Reduces interparticle spacing, improves hole injection |

| 2-Naphthalene Sulfonic Acid (NSA) | Strong-binding ripening inhibitor | Strong-confined CsPbI3 QDs [8] | Suppresses Ostwald ripening, enhances stability |

| Ammonium Hexafluorophosphate (NH₄PF₆) | Inorganic ligand for surface passivation | Pure-red PeLEDs [8] | Strong binding energy (3.92 eV), improves conductivity |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Ester antisolvent for alkaline hydrolysis | Hybrid A-site PQDSCs [6] | Suitable polarity, hydrolyzes to conductive ligands |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Alkali catalyst for ester hydrolysis | Enhanced ligand exchange [6] | Lowers hydrolysis activation energy ~9-fold |

Visualization of Ligand Exchange Processes

Charge Transport Limitation Mechanism

Diagram 1: Charge transport limitation mechanism caused by OA/OAm ligands

Layer-by-Layer Ligand Exchange Workflow

Diagram 2: Layer-by-layer ligand exchange workflow

The inherent limitations of long-chain insulating ligands OA and OAm on charge transport represent a fundamental challenge in quantum dot optoelectronics. The spatial barrier and electronic decoupling imposed by these ligands directly compromise device performance by reducing charge mobility and promoting recombination losses. Advanced ligand engineering strategies, including layer-by-layer solid-state exchange with short conjugated ligands, direct synthesis with compact passivants, and alkaline-enhanced hydrolysis approaches, offer viable pathways to overcome these limitations.

The experimental protocols and analytical frameworks presented in this application note provide researchers with standardized methodologies for investigating and addressing charge transport limitations in CsPbI3 PQD systems. As the field progresses, the integration of machine learning approaches for ligand design and the development of multi-functional ligands that simultaneously address passivation, coupling, and stability challenges will further advance the performance of QD-based optoelectronic devices.

Fundamental Principles of Solid-State vs. Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange

Colloidal quantum dots (CQDs) and perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) have emerged as promising semiconductor materials for next-generation optoelectronic devices, including solar cells and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). The surface properties of these nanocrystals are critically determined by their organic ligand shells. While long-chain insulating ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) are essential for achieving high-quality synthesis and colloidal stability, they severely impede charge transport between adjacent quantum dots in solid films. Ligand exchange engineering addresses this fundamental challenge by replacing long-chain ligands with shorter conductive alternatives, thereby enhancing electronic coupling and device performance. This application note examines the fundamental principles, methodologies, and applications of solid-state versus solution-phase ligand exchange processes, with particular emphasis on their implementation in CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dot (PQD) solar cell research [11] [1].

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

Core Objectives of Ligand Exchange

The primary goal of ligand exchange is to replace long-chain insulating ligands with shorter counterparts or atomic ligands to enhance inter-dot electronic coupling and charge carrier transport. This process simultaneously aims to passivate surface defects that act as trap states for charge carriers, reducing non-radiative recombination losses. In CsPbI3 PQDs, effective ligand management also contributes to phase stabilization of the photoactive black phase, which is crucial for maintaining device performance under operational conditions [11] [1] [12].

Solid-State Ligand Exchange

The solid-state ligand exchange method involves depositing a film of quantum dots capped with long-chain ligands onto a substrate, followed by surface treatment through immersion or drip-coating with a solution containing the target short-chain ligands. This approach typically employs a layer-by-layer (LBL) methodology where multiple cycles of spin-coating and ligand treatment are performed to build up thick, electronically-coupled quantum dot films [11] [1].

Key Principle: As original long-chain organic ligands are replaced with shorter target ligands, the inter-dot spacing decreases significantly, facilitating enhanced carrier transport through improved wavefunction overlap between adjacent quantum dots [11].

Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange

In solution-phase ligand exchange, quantum dots wrapped with long-chain alkyl ligands are dissolved in nonpolar solvents (e.g., octane, hexane), while short-chain ligands are dissolved in polar solvents (e.g., dimethylformamide, DMF). When these two solutions are mixed, ligand exchange occurs at the interface, transferring the quantum dots from the nonpolar to the polar solvent phase upon successful exchange. This process enables complete surface passivation before film deposition [11] [13].

Key Principle: The exchange is driven by the thermodynamic favorability of replacing weakly-coordinating long-chain ligands with strongly-binding short-chain ligands, facilitated by the phase transfer between immiscible solvents [11].

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Solid-State vs. Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange

| Parameter | Solid-State Ligand Exchange | Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange |

|---|---|---|

| Process Workflow | Layer-by-layer deposition with post-treatment | Pre-exchange in solution before film fabrication |

| Processing Time | Time-consuming due to multiple cycles | Potentially faster single-step exchange |

| Film Quality | Enables thick film fabrication | Risk of inhomogeneous agglomeration |

| Surface Passivation | May leave underlying defects unpassivated | More complete surface passivation |

| Carrier Transport | Improved but may have inhomogeneities | Enhanced inter-dot coupling and mobility |

| Scalability | Labor-intensive for large areas | More amenable to scalable ink-printing |

| Defect Formation | Dependent on treatment penetration | Minimized with optimized protocols |

The solid-state approach, particularly the layer-by-layer method, dominates CsPbI3 PQD solar cell fabrication due to its precise control over film thickness and morphology. However, this method can result in incomplete passivation of underlying layers and requires significant processing time. Solution-phase exchange offers more homogeneous passivation and streamlined fabrication but faces challenges in maintaining quantum dot stability during phase transfer [11] [1] [13].

Ligand Exchange Protocols and Methodologies

Layer-by-Layer Solid-State Ligand Exchange for CsPbI3 PQDs

Application Context: This protocol is specifically optimized for fabricating CsPbI3 PQD solar cells with enhanced photovoltaic performance and phase stability [1].

Materials Required:

- CsPbI3 PQDs synthesized with OA and OAm ligands

- Methyl acetate (MeOAc)

- Phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI) or formamidinium iodide (FAI)

- Ethyl acetate (EtOAc)

- Non-polar solvents (n-hexane, n-octane)

- Substrates (e.g., FTO glass with electron transport layer)

Experimental Procedure:

Substrate Preparation: Clean FTO substrates with transparent conductive oxide and deposit appropriate charge transport layers (e.g., TiO2 for electron transport).

PQD Ink Preparation: Disperse synthesized CsPbI3 PQDs with OA/OAm ligands in n-octane at optimal concentration (typically 10-20 mg/mL).

First Layer Deposition: Spin-coat the PQD ink onto the substrate at 2000-3000 rpm for 20-30 seconds.

Initial Ligand Treatment: During spin-coating, treat with methyl acetate (MeOAc) to partially remove original ligands and precipitate the PQD layer.

Short-Chain Ligand Treatment: After MeOAc treatment, immediately apply PEAI solution (5-10 mg/mL in EtOAc) via spin-coating or pipetting to introduce short conjugated ligands.

Layer Buildup: Repeat steps 3-5 for 3-5 cycles to achieve desired film thickness (typically 200-400 nm).

Final Treatment: Perform a final PEAI or FAI post-treatment to ensure complete surface passivation.

Annealing: Thermally anneal the film at 70-90°C for 5-10 minutes to remove residual solvent and enhance inter-dot coupling.

Critical Parameters:

- PEAI concentration optimization (typically 5-10 mg/mL) to balance ligand coverage and charge transport

- Strict control of treatment time (10-30 seconds) to prevent undesirable phase transformation

- Relative humidity control (<30%) during processing to prevent moisture-induced degradation

- Solvent selection (EtOAc preferred over more polar solvents) to preserve PQD structure [1]

Accelerated Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange Protocol

Application Context: This methodology minimizes trap state formation during solution exchange by accelerating the exchange kinetics, particularly beneficial for PbS CQD solar cells [13].

Materials Required:

- Oleate-capped PbS CQDs in octane

- Lead halides (PbI2, PbBr2)

- Ammonium acetate

- Dimethylformamide (DMF)

- Antisolvents (acetone, ethyl acetate)

- Polar solvents for purification

Experimental Procedure:

Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve lead halides (0.1 M PbI2 and 0.02 M PbBr2) and ammonium acetate (0.04 M) in DMF.

Concentrated CQD Solution: Prepare highly concentrated oleate-capped PbS CQD solution in octane (20-30 mg/mL instead of conventional 6 mg/mL).

Rapid Mixing: Add the CQD solution to the DMF phase with vigorous vortex mixing for complete phase contact.

Accelerated Exchange: Allow the mixture to stand for only 10-30 seconds (versus minutes in conventional protocols) before centrifugation.

Phase Separation: Centrifuge at 7000-10,000 rpm for 2-3 minutes to separate exchanged CQDs in DMF phase.

Purification: Precipitate exchanged CQDs with antisolvent (acetone or ethyl acetate) and redisperse in polar solvents (DMF, butylamine).

Film Fabrication: Deposit purified CQD ink via spin-coating or inkjet printing for device fabrication.

Critical Parameters:

- High CQD concentration to maximize ligand collision frequency and exchange rate

- Minimal exposure time to polar solvents (seconds scale) to reduce surface etching

- Optimized lead halide to ammonium acetate ratio for complete ligand replacement

- Controlled centrifugation parameters to prevent irreversible aggregation [13]

Advanced Ligand Exchange Strategies

Innovative Approaches in Ligand Management

Recent advances in ligand exchange methodologies have focused on addressing specific challenges in quantum dot optoelectronics:

Proton-Prompted In-Situ Exchange: This innovative strategy for CsPbI3 PQDs utilizes hydroiodic acid (HI) to provide protons that trigger desorption of long-chain OA and OAm ligands while promoting binding of short-chain ligands like 5-aminopentanoic acid (5AVA). The protonation of amine functional groups enhances their binding to the QD surface, maintaining quantum confinement while improving conductivity and optical properties [12].

Amine-Assisted Ligand Exchange (ALE): Developed for FAPbI3 nanocrystal solar cells, this approach uses 3-phenyl-1-propylamine (3P1P) to effectively remove long ligands without increasing defect states. ALE reduces exciton-binding energy in NC films, facilitating exciton dissociation and charge transport, leading to improved short-circuit current density (17.98 mA/cm²) and power conversion efficiency (15.56%) [14].

Perovskite Ligand Engineering: Formamidinium lead iodide (FAPbI3) has been employed as a capping ligand for PbS QDs through a binary-phase ligand exchange protocol. This strategy enhances thermal stability and carrier transport while maintaining strong quantum confinement, demonstrating the potential of hybrid organic-inorganic ligands in quantum dot optoelectronics [15].

Characterization and Quality Assessment

Analytical Techniques for Ligand Exchange Validation

Table 2: Key Characterization Methods for Ligand Exchange Analysis

| Technique | Application in Ligand Analysis | Key Parameters Measured |

|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Chemical bonding analysis | Signal changes of C-H bonds in long carbon chains |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Quantitative ligand assessment | Composition and structure of surface-bound ligands |

| XPS | Surface element composition | Elemental states and ligand coverage |

| UV-Vis Absorption | Optical properties | Excitonic peak position and band tail states |

| PL Spectroscopy | Defect state analysis | Photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) |

| TRPL | Carrier dynamics | Carrier lifetime and recombination mechanisms |

| XRD | Crystal structure analysis | Phase identification and structural integrity |

| TEM/STEM | Morphology and spacing | Inter-dot distance and superlattice formation |

| FET Measurement | Charge transport | Mobility and trap state density in films |

Effective characterization is essential for validating successful ligand exchange and optimizing protocols. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy tracks the disappearance of characteristic C-H stretching vibrations from long-chain ligands, while nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) provides quantitative analysis of ligand composition. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) determines surface element composition and chemical states, confirming the incorporation of target ligands [11].

Optical characterization techniques including UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy monitor changes in excitonic features and emission properties that indicate enhanced electronic coupling. Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) reveals carrier recombination dynamics, with reduced lifetimes often indicating improved charge transfer between quantum dots. Structural techniques such as X-ray diffraction (XRD) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) verify maintained crystal structure and reduced inter-dot spacing, respectively [11] [15].

Electrical characterization through field-effect transistor (FET) measurements provides crucial information about carrier mobility and trap state density in ligand-exchanged quantum dot films, directly correlating with expected device performance [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ligand Exchange Protocols

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Ligand Exchange |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Chain Ligands | Oleic acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) | Initial stabilization during synthesis; provide colloidal stability |

| Short Organic Ligands | Phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI), 3-phenyl-1-propylamine (3P1P) | Enhance charge transport; passivate surface defects |

| Perovskite Ligands | Formamidinium lead iodide (FAPbI3), Methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) | Provide structural compatibility; enhance electronic coupling |

| Metal Halide Salts | Lead iodide (PbI2), Lead bromide (PbBr2) | Source of halide ions for surface passivation |

| Processing Additives | Ammonium acetate | Facilitate ligand removal and exchange kinetics |

| Polar Solvents | Dimethylformamide (DMF), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | Dissolve short-chain ligands; enable phase transfer |

| Non-Polar Solvents | Octane, Hexane, Chlorobenzene | Disperse original quantum dots with long-chain ligands |

| Antisolvents | Methyl acetate, Ethyl acetate, Acetone | Precipitate quantum dots during purification |

Workflow Visualization

Performance Metrics and Optimization Guidelines

Impact on Device Performance

Effective ligand exchange significantly enhances key photovoltaic parameters in quantum dot solar cells:

Open-Circuit Voltage (VOC): Proper surface passivation reduces trap-assisted recombination, increasing VOC. Accelerated solution-phase exchange has demonstrated VOC improvement from 0.650 V to 0.670 V in PbS CQD devices [13].

Short-Circuit Current Density (JSC): Enhanced inter-dot coupling and charge transport boost JSC. Amine-assisted ligand exchange in FAPbI3 NC solar cells achieved JSC of 17.98 mA/cm² [14].

Fill Factor (FF): Reduced trap state density and improved carrier mobility contribute to higher FF, with reported values exceeding 70% in optimized ligand-exchanged QD solar cells [13].

Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE): Comprehensive improvements in photovoltaic parameters through optimized ligand management have enabled CsPbI3 PQD solar cells to reach PCE values exceeding 16% [1] [12].

Optimization Guidelines

For Solid-State Exchange:

- Optimize short-ligand concentration to balance complete exchange and surface aggregation

- Control treatment time to prevent solvent-induced degradation of quantum dot structure

- Implement intermediate annealing steps to enhance ligand binding and film morphology

- Utilize mixed ligand systems for synergistic passivation of different surface sites

For Solution-Phase Exchange:

- Maximize quantum dot concentration to accelerate exchange kinetics

- Minimize exposure time to polar solvents to reduce surface etching

- Optimize ligand-to-quantum dot ratio for complete surface coverage

- Implement rigorous purification protocols to remove exchange byproducts

The selection between solid-state and solution-phase ligand exchange ultimately depends on specific research goals, material systems, and device architectures. Solid-state methods offer superior control for complex multilayer devices, while solution-phase approaches provide advantages in scalability and homogeneous passivation. Recent innovations in both methodologies continue to push the performance boundaries of quantum dot-based optoelectronic devices.

In the field of CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dot (PQD) solar cells, understanding ligand chemistry is paramount for designing efficient and stable devices. Ligands are molecules that bind to the surface of quantum dots, serving critical functions in stabilization, passivation, and charge transport. The binding mechanism—whether predominantly ionic or covalent—fundamentally influences these functions and ultimately determines device performance. Metal-ligand interactions are fundamentally Lewis acid/base reactions, where the metal center acts as the electron pair acceptor (Lewis acid) and the ligand serves as the electron pair donor (Lewis base) [16]. In CsPbI3 PQDs, the lead-rich surface provides binding sites for various ligand chemistries, creating a dynamic interface where binding strength and character dictate material properties from colloidal stability to film conductivity [17] [18].

The strategic engineering of ligand binding mechanisms has enabled remarkable progress in PQD solar cells, with power conversion efficiencies now exceeding 17% [18]. This application note examines the fundamental principles of ionic and covalent ligand binding mechanisms within the context of layer-by-layer solid-state ligand exchange protocols for CsPbI3 PQD photovoltaics, providing researchers with practical frameworks for optimizing PQD surface chemistry.

Theoretical Foundations of Ligand Binding

Fundamental Bonding Concepts

Chemical bonds exist on a spectrum between purely ionic and purely covalent character, with most metal-ligand bonds exhibiting characteristics of both, often described as "coordinate covalent" bonds [16] [19]. In ionic bonding, electrons are effectively transferred from one atom to another, creating positively and negatively charged ions that attract each other through electrostatic forces [20] [19]. This type of bonding typically occurs between atoms with large differences in electronegativity (often metals and non-metals) and results in non-directional bonds with relatively high melting points and brittle mechanical properties [20] [19].

In covalent bonding, atoms share electron pairs, with the bond strength deriving from the reduction in kinetic energy when electrons occupy more spatially distributed orbitals [19] [21]. These bonds are directional and occur between atoms with similar electronegativities. The degree of electron sharing can vary, creating a continuum from nonpolar covalent (equal sharing) to polar covalent (unequal sharing) [21].

For PQD systems, this bonding continuum has profound implications. As one research group notes, "The bonding between metals and ligands can occur on a spectrum of covalence and strength. Some metal-ligand bonds are similar to ionic interactions, while others are essentially covalent" [16].

Electronic Effects in Metal-Ligand Complexes

The electronic structure of metal-ligand complexes directly influences their properties and functionality. Transition metal ions (such as Pb²⁺ in CsPbI3 PQDs) act as Lewis acids in metal-ligand interactions, and the resulting metal-ligand complex can itself act as a Brønsted acid [16]. This acid-base behavior means that "when a ligand has an acidic proton, interactions with a metal ion will make that acidic proton more acidic" [16], significantly impacting the chemical behavior of ligand-capped PQDs.

The directionality of covalent bonds enables the diverse coordination geometries observed in metal complexes, expanding far beyond the limited geometries available to carbon-based compounds [16]. This directionality influences how ligands arrange themselves on PQD surfaces, affecting packing density and inter-dot spacing in solid films.

Ligand Binding Mechanisms in CsPbI3 PQDs

Ionic Ligand Binding

Ionic ligand binding in CsPbI3 PQDs typically involves charge-assisted interactions between the inorganic PQD surface and ionic functional groups on ligands. These interactions are characterized by electrostatic attraction rather than shared electron pairs.

- Binding Characteristics: Ionic interactions are generally stronger in polar environments and result in more reversible binding compared to covalent linkages [16] [19]. The non-directional nature of ionic bonds allows for flexible coordination geometries but provides less control over surface arrangement.

- Common Examples: Inorganic halides (e.g., iodide, bromide) form primarily ionic bonds with the Pb²⁺ sites on CsPbI3 PQD surfaces [18] [22]. Ammonium salts (e.g., tetrabutylammonium iodide, TBAI) facilitate ionic binding through anion exchange, where the halide anion binds ionically to surface lead atoms while the ammonium cation provides electrostatic stabilization [22].

- Impact on PQD Properties: Ionic ligands typically enhance electronic coupling between PQDs by providing strong electrostatic stabilization without introducing bulky insulating barriers. This improves charge carrier transport through the PQD film, directly boosting solar cell performance [22]. As demonstrated in ZnO/PbS QD systems, TBAI-treated QD films showed superior air stability and higher short-circuit current density compared to their organic-ligand counterparts [22].

Covalent Ligand Binding

Covalent ligand binding involves shared electron pairs between the PQD surface and ligand molecules, creating directional bonds with specific bond angles and lengths.

- Binding Characteristics: Covalent bonds are generally stronger and more directional than ionic interactions, creating more stable surface attachments but potentially requiring more energy for exchange processes [16] [19]. The directionality enables precise control over ligand orientation and packing on PQD surfaces.

- Common Examples: Thiol-based ligands (e.g., 1,2-ethanedithiol, EDT) form coordinate covalent bonds with surface lead atoms [22]. Organic amines and phosphines can also form covalent bonds through donor-acceptor interactions with surface sites [16] [23]. Aromatic amines have shown particular promise in pseudo-solution-phase ligand exchange processes for CsPbI3 PQDs [23].

- Impact on PQD Properties: Covalently bound ligands typically provide robust surface passivation and enhanced environmental stability [24]. However, their strong binding and often bulky nature can increase inter-dot spacing, potentially compromising charge transport. Research has shown that "when the amide side chains of asparagine (N, Asn) and glutamine (E, Gln) bind to metals, they bind through their O atom, and not N" due to resonance stabilization [16], demonstrating how molecular structure influences binding mode in covalent interactions.

Comparative Analysis of Binding Mechanisms

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Ionic and Covalent Ligand Binding Mechanisms

| Property | Ionic Binding | Covalent Binding |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Character | Electrostatic, non-directional | Electron-sharing, directional |

| Binding Strength | Moderate to strong, environment-dependent | Strong, less environment-dependent |

| Exchange Kinetics | Faster, more reversible | Slower, less reversible |

| Common Ligands | Halide ions (I⁻, Br⁻), ammonium salts | Thiols (EDT), amines, phosphines |

| Impact on Conductivity | Higher inter-dot coupling | Often reduced conductivity due to ligand bulk |

| Role in PQD Solar Cells | Enhancing charge transport | Improving stability, surface passivation |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of CsPbI3 PQD Solar Cells with Different Ligand Chemistries

| Ligand Treatment | Bond Character | PCE (%) | Stability Retention | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBAI/EDT Bilayer | Ionic/Coordinate Covalent | 8.55 | >150 days in air | [22] |

| Aromatic Amine p-SPLE | Coordinate Covalent | 14.65 | Improved stability reported | [23] |

| Halide Exchange | Primarily Ionic | 13.4 | - | [18] |

| Bilateral Ligand Engineering | Mixed Character | 15.3 | 83% after 15 days | [24] |

| Short Choline Ligands | Ionic/Coordinate Covalent | 16.53 | - | [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Exchange

Layer-by-Layer Solid-State Ligand Exchange

The layer-by-layer solid-state ligand exchange protocol enables precise control over PQD film properties through sequential processing steps. The following methodology has been optimized for CsPbI3 PQD solar cells:

Materials Required:

- CsPbI3 PQDs synthesized with long-chain native ligands (typically oleic acid/oleylamine)

- Ionic ligand solution: 5-10 mg/mL TBAI in anhydrous methanol

- Covalent ligand solution: 0.01-0.02M 1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT) in acetonitrile

- Protic solvent (e.g., 2-pentanol) for mediating ligand exchange [17]

- Substrates (typically glass/ITO/ZnO or similar electron transport layer)

- Spin coater, annealing hotplate, nitrogen glovebox

Procedure:

- Native PQD Film Deposition: Spin-coat native CsPbI3 PQD solution (~15-20 mg/mL in hexane) onto substrate at 2000-3000 rpm for 30 seconds to form initial film.

- Ionic Ligand Treatment: Immediately flood surface with TBAI/methanol solution and let stand for 20-30 seconds, then spin-dry at 2500 rpm for 30 seconds. This replaces insulating long-chain ligands with conductive halide ions.

- Rinse Step: Flood surface with anhydrous methanol to remove excess ligands and byproducts, spin-dry.

- Repeat Layering: Repeat steps 1-3 to build desired film thickness (typically 8-12 layers).

- Covalent Ligand Treatment: For final layer, apply EDT/acetonitrile solution for 20 seconds followed by spin-drying. This creates a covalent surface passivation layer.

- Solvent-Mediated Optimization: For enhanced performance, incorporate 2-pentanol rinse step to maximize insulating ligand removal without introducing halogen vacancies [17].

- Annealing: Mild thermal treatment (70-90°C for 5-10 minutes) to improve inter-dot coupling.

Pseudo-Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange (p-SPLE)

For improved morphology control, the pseudo-solution-phase method offers advantages:

Procedure:

- Partial Ligand Exchange in Solution: Treat CsPbI3 QD solution with short organic aromatic ligands (e.g., phenylalkylammonium iodides) to partially replace long-chain ligands prior to film deposition [23].

- Film Deposition: Spin-coat partially exchanged PQD solution onto substrate.

- Solid-State Completion: Apply secondary ligand treatment (typically halide-based) to complete exchange process in solid state.

- Solvent Engineering: Utilize tailored solvent environments (e.g., 2-pentanol) to enhance ligand solubility and exchange efficiency [17].

Bilateral Ligand Stabilization

Recent advances demonstrate the efficacy of bilateral ligand approaches:

Procedure:

- Native Film Preparation: Deposit CsPbI3 PQD film with standard oleic acid/oleylamine ligands.

- Bilateral Ligand Treatment: Apply short, amphiphilic ligands that securely hold quantum dots from both sides, effectively "uncrumpling" distorted surfaces [24].

- Morphology Optimization: The bilateral ligands restore distorted lattice structure, significantly reducing surface defects and improving operational stability [24].

Visualization of Ligand Exchange Processes

Ligand Binding Mechanisms Diagram

Layer-by-Layer Ligand Exchange Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PQD Ligand Exchange Studies

| Reagent | Chemical Class | Primary Function | Binding Mechanism | Example Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrabutylammonium Iodide (TBAI) | Quaternary ammonium salt | Ionic ligand exchange, conductivity enhancement | Primarily ionic | 5-10 mg/mL in methanol |

| 1,2-Ethanedithiol (EDT) | Dithiol compound | Covalent surface passivation, hole extraction layer | Coordinate covalent | 0.01-0.02M in acetonitrile |

| 2-Pentanol | Protic alcohol | Solvent mediation, ligand solubility enhancement | N/A (process solvent) | Neat or blended |

| Oleic Acid/Oleylamine | Carboxylic acid/amine | Native synthesis ligands, colloidal stabilization | Ionic/Coordinate covalent | Varies by synthesis |

| Phenylalkylammonium Iodides | Aromatic ammonium salts | p-SPLE processing, surface passivation | Mixed character | 5-15 mg/mL in appropriate solvent |

| Choline Chloride | Quaternary ammonium salt | Short conductive ligand, surface binding | Ionic/Coordinate covalent | 5-10 mg/mL in 2-pentanol [17] |

The strategic manipulation of ligand binding mechanisms—from ionic to covalent and mixed-character interactions—represents a powerful approach for optimizing CsPbI3 PQD solar cell performance. Ionic binding enhances inter-dot electronic coupling and charge transport, while covalent binding provides robust surface passivation and environmental stability. The most successful strategies employ precisely engineered combinations of both mechanisms, often through sophisticated layer-by-layer processing protocols.

Future developments in PQD ligand chemistry will likely focus on increasingly sophisticated molecular designs that optimize binding strength, steric effects, and electronic properties simultaneously. Bilateral ligand approaches that address surface distortions while maintaining conductivity show particular promise [24]. Additionally, solvent-mediated exchange processes using tailored solvents like 2-pentanol will continue to evolve, enabling more complete removal of insulating ligands without introducing surface defects [17]. As research progresses, the fundamental understanding of ionic versus covalent ligand binding mechanisms will remain central to unlocking the full potential of CsPbI3 PQD photovoltaics.

Achieving Cubic Phase Stability in CsPbI3 through Surface Engineering

The metastable cubic (α) phase of cesium lead iodide (CsPbI3) possesses an ideal bandgap for optoelectronic applications. However, at room temperature, it readily transitions into a non-perovskite, optically inactive orthorhombic (δ) phase, severely limiting its practical utility. Surface engineering, particularly through advanced ligand management protocols, has emerged as a critical strategy to overcome this stability challenge. By carefully tailoring the surface chemistry of CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs), researchers can induce substantial surface strain and passivate defect sites, thereby effectively locking the material into its functionally superior cubic phase. This application note details the mechanisms, materials, and specific layer-by-layer solid-state ligand exchange protocols that have proven successful in achieving and stabilizing the α-CsPbI3 phase for high-performance solar cells.

Surface Engineering Mechanisms and Strategies

The inherent instability of the α-CsPbI3 phase stems from its ionic crystal structure and the high surface energy of its nanoscale forms. Surface engineering interventions primarily address this by:

- Inducing Constructive Surface Strain: Replacing long, insulating native ligands with shorter, chemically robust counterparts reduces the inter-dot distance. This creates a compressive surface stress on the PQD lattice, which stabilizes the cubic phase against transformation to the more relaxed δ-phase [25].

- Passivating Surface Defects: The ligand exchange process often leaves behind uncoordinated lead (Pb²⁺) ions and other surface defects that act as initiation points for phase degradation and non-radiative recombination. Effective surface engineering targets these sites with ligands having strong binding affinity, thereby removing electronic trap states and improving both stability and optoelectronic performance [2] [8].

The following table summarizes key surface engineering strategies developed for cubic phase stabilization.

Table 1: Surface Engineering Strategies for Cubic Phase Stabilization of CsPbI3 PQDs

| Strategy | Ligand / Material | Key Finding | Reported PCE | Phase Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBL Ligand Exchange [1] | Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Layer-by-layer (LBL) application enhances defect passivation & inter-dot coupling. | 14.18% | Excellent stability in high-humidity (30-50% RH) |

| Nonpolar Solvent Treatment [2] | Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) in Octane | Nonpolar solvent prevents surface dissolution; TPPO covalently passivates Pb²⁺ traps. | 15.4% | >90% initial PCE after 18 days in ambient |

| Alkali-Augmented Hydrolysis [6] | KOH with Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Alkaline environment doubles ligand density via enhanced ester hydrolysis. | 18.3% (certified) | Improved storage & operational stability |

| 3D Semiconductor Hybrid [25] | Star-Shaped Molecule (Star-TrCN) | Forms robust chemical bond with PQDs, providing a hydrophobic barrier. | 16.0% | 72% of initial PCE after 1000 h at 20-30% RH |

| Strong Binding Ligands [8] | 2-Naphthalene Sulfonic Acid (NSA) & NH₄PF₆ | Suppresses Ostwald ripening, passivates defects, and enhances conductivity. | N/A (Applied in PeLEDs) | PLQY maintained >80% after 50 days |

| Surface Stress Engineering [26] | Onium Cations | Introduces onium cations to regularize surface lattice and ameliorate surface stress. | 17.01% | Substantially improved phase stability |

Experimental Protocols: Layer-by-Layer Solid-State Ligand Exchange

The following protocol describes the fundamental layer-by-layer (LBL) solid-state ligand exchange process, which can be adapted for the specific strategies listed in Table 1.

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for LBL Ligand Exchange

| Reagent | Function / Role | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| OA/OLA-capped CsPbI3 PQDs in n-hexane | Photovoltaic Absorber Precursor | Synthesized via hot-injection method; provides monodisperse, colloidal PQDs. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Anionic Ligand Exchange Solvent | Removes oleate (OA⁻) ligands and exchanges them with acetate ions. |

| Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) | Polar Solvent for Post-treatment | Used as a solvent for cationic ligand salts (e.g., PEAI). |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) / Other Ammonium Salts | Cationic Short-Chain Ligand | Replaces residual oleylammonium (OAm⁺) ligands; passivates A-site defects. |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) in Octane | Covalent Passivation Solution | Post-treatment for strongly passivating uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites without damaging the PQD surface [2]. |

| Potassium Hydroxide in Methyl Benzoate | Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent | Facilitates rapid hydrolysis of ester, generating high density of conductive capping ligands [6]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Workflow Overview: The LBL process involves sequential deposition of PQD layers, with each layer undergoing a two-step ligand exchange to replace both anionic and cationic native ligands.

Detailed Protocol:

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with a pre-cleaned glass/FTO substrate with a deposited electron transport layer (e.g., compact TiO₂).

- Initial PQD Layer Deposition: Spin-coat a layer of OA/OLA-capped CsPbI3 PQDs dispersed in n-hexane (concentration: 20-30 mg/mL) onto the substrate at 2500-3000 rpm for 20-30 seconds.

- Anionic Ligand Exchange: Immediately after deposition, while the film is still wet, rinse it by dynamically dispensing a methyl acetate (MeOAc)-based solution (e.g., containing sodium acetate, NaOAc) during spinning. This step replaces the long-chain oleate (OA⁻) ligands with short-chain acetate ions, facilitating charge transport.

- Cationic Ligand Exchange: Following the MeOAc rinse and after the film has dried, perform a second rinse using a solution of the target cationic short-chain ligand (e.g., Phenethylammonium Iodide, PEAI, dissolved in ethyl acetate, EtOAc, at a typical concentration of 1-2 mg/mL). This step displaces the residual long-chain oleylammonium (OAm⁺) ligands.

- Layer Repetition: Repeat steps 2-4 for 3-5 cycles to build up the desired thickness of the conductive PQD solid film.

- Optional Advanced Post-treatment: Once the final layer is deposited, an additional post-treatment can be applied to further enhance passivation. For instance, spin-coat a solution of triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) in a nonpolar solvent like n-octane (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mg/mL) onto the completed film, followed by annealing at 70-80 °C for 5-10 minutes [2].

Key Operational Considerations

- Ambient Control: While some protocols are robust to moderate humidity (30-50% RH), performing the ligand exchange in an inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂ glovebox) can improve reproducibility and minimize premature degradation.

- Solvent Polarity: The choice of solvent is critical. Using nonpolar solvents (e.g., octane) for post-treatments prevents the dissolution of the ionic PQD surface and the loss of surface components, which is a limitation of polar solvents like EtOAc [2].

- Ligand Binding Affinity: Ligands with stronger covalent binding (e.g., TPPO, NSA) or those applied in higher density (via alkaline hydrolysis) provide more durable passivation and phase stabilization compared to conventional ionic ligands like acetate [2] [6].

Ligand Binding Mechanisms at the PQD Surface

The efficacy of a ligand is determined by its binding mechanism and affinity to the PQD surface. The following diagram illustrates the binding modes of key ligand types.

Mechanism Diagram: Molecular-level interactions of different ligand classes with the CsPbI3 PQD surface.

Key to Binding Mechanisms:

- Ionic Bonding (Green): Conventional ionic short-chain ligands (e.g., acetate, PEA⁺) electrostatically bind to the PQD surface. While they improve conductivity, their binding can be labile, leading to suboptimal passivation [2].

- Covalent/Lewis Base Bonding (Blue): Ligands like TPPO and NSA act as Lewis bases, donating electron density to coordinatively unsaturated Pb²⁺ sites. This forms a stronger, more stable covalent bond, effectively neutralizing deep trap states and inhibiting Ostwald ripening [2] [8].

- Multifunctional Passivation (Red): Advanced organic semiconductors, such as the star-shaped Star-TrCN molecule, can simultaneously passivate multiple types of surface defects (e.g., both Pb²⁺ and I⁻ sites) via different functional groups, while also providing a hydrophobic barrier against moisture [25].

Achieving and maintaining cubic phase stability in CsPbI3 is paramount for its application in optoelectronic devices. The protocols outlined herein demonstrate that a meticulous, multi-stage layer-by-layer solid-state ligand exchange strategy is highly effective. Moving beyond simple ionic ligand substitution towards the use of covalently-binding ligands in nonpolar solvents, alkaline-enhanced hydrolysis for denser ligand packing, and integration with multidimensional organic semiconductors represents the cutting edge of surface engineering. These approaches collectively address the intertwined challenges of phase instability and surface defects, paving the way for the development of highly efficient and durable CsPbI3 PQD-based solar cells and other optoelectronic devices.

Protocol in Practice: A Step-by-Step Guide to LbL Ligand Exchange for Optimal Film Fabrication

Layer-by-layer (LbL) solid-state ligand exchange has emerged as a critical protocol for fabricating high-performance CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dot (PQD) solar cells. This technique enables the construction of conductive and stable PQD solid films by systematically replacing long-chain insulating ligands with short-chain conductive alternatives in a cyclic deposition process. The precise execution of spin-coating, solvent washing, and short-ligand treatment cycles directly governs the photovoltaic performance by determining charge transport efficiency and defect passivation quality. These application notes provide a detailed protocol for implementing this core LbL process within research focused on advancing CsPbI3 PQD photovoltaics.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Substrate Preparation and ETL Fabrication

The foundation of a successful LbL process begins with proper substrate preparation and electron transport layer (ETL) fabrication. For flexible substrates, employ room-temperature processes such as UV-sintered SnO2 nanocrystals. Synthesize colloidal SnO2 nanorods capped with oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), disperse them in hexane, and spin-coat onto indium tin oxide (ITO) substrates. Remove organic ligands via UV irradiation (20-30 minutes at 250-500 W power) to achieve uniform films without nanopores or shrinkage [27]. For enhanced performance, dope SnO2 with Ga³⁺ ions to reduce energy level mismatch with CsPbI3 PQDs, shifting the conduction band upward toward the vacuum level [27].

Core LbL Assembly and Ligand Exchange

The quintessential LbL process involves sequential deposition of PQD layers followed by solid-state ligand exchange. This cyclic methodology enables precise control over film thickness and optimal ligand replacement.

Diagram 1: LbL assembly workflow for CsPbI3 PQD solar cells.

Detailed Cyclic Procedure

PQD Deposition via Spin-Coating: Deposit CsPbI3 PQDs stabilized with long-chain OA/OAm ligands onto the substrate using static or dynamic spin-coating. For dynamic coating, initiate spinning first (typically 600-4000 rpm), then apply PQD dispersion (25-50 μL/cm²) using a pipette. The process involves four stages: deposition, spin-up, spin-off, and evaporation [28]. Optimize parameters to achieve uniform monolayers; higher spin speeds produce thinner films following the relationship ( hf \propto ω^{-1/2} ), where ( hf ) is final thickness and ( ω ) is angular velocity [28].

Solvent Washing Treatment: Following PQD deposition, immediately treat the film with a carefully selected solvent to initiate ligand exchange. Recent research identifies 2-pentanol as particularly effective due to its appropriate dielectric constant and acidity, which maximize removal of insulating oleylamine ligands without introducing halogen vacancy defects [17]. Apply solvent via pipette or spraying during or immediately after spin-coating, followed by a brief low-speed spin step (500-1000 rpm for 10-20 seconds) to remove excess solvent and displaced ligands.

Short-Ligand Treatment: Immediately following solvent washing, apply a solution containing short-chain ligands. For CsPbI3 PQDs, effective short ligands include choline, 5-aminopentanoic acid (5AVA), or halide ions [27] [29]. The ligand solution can be applied via spin-coating (1500-3000 rpm for 20-30 seconds) or drop-casting with subsequent spinning. For proton-promoted exchange, incorporate hydroiodic acid (HI) in the ligand solution to facilitate desorption of long-chain ligands and enhance binding of short ligands [29].

Cycle Repetition: Repeat steps 1-3 until achieving the desired PQD film thickness (typically 5-15 layers). Each cycle adds approximately one monolayer of PQDs, with thickness dependent on QD size and processing parameters.

Post-Treatment and Device Completion

After completing the LbL process, perform a final solvent wash with 2-pentanol or ethyl acetate to remove any residual unbound ligands. Subsequently, deposit the hole transport layer (HTL) and metal electrodes using thermal evaporation or additional spin-coating steps to complete the solar cell architecture [27].

Quantitative Data and Optimization Parameters

Solvent Selection Guidelines

Solvent properties critically influence ligand exchange efficiency and PQD film quality.

Table 1: Solvent Properties for LbL Processing

| Solvent | Dielectric Constant | Acidity | Optimal Application | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Pentanol | ~13.9 [17] | Protic | Solvent washing | Maximizes insulating ligand removal without defect introduction |

| Chloroform | ~4.8 [30] | Aprotic | Cubical QD deposition | Achieves ~90% monolayer coverage |

| Hexane | ~1.9 [30] | Aprotic | Spherical QD deposition | Achieves 90-100% monolayer coverage |

| Ethyl Acetate | ~6.0 [29] | Aprotic | Purification | Effective anti-solvent for PQD precipitation |

Spin-Coating Parameters for Monolayer Formation

Achieving uniform PQD monolayers requires optimization of spin-coating conditions based on QD morphology and solvent properties.

Table 2: Spin-Coating Parameters for PQD Monolayers

| QD Morphology | QD Size (nm) | Optimal Solvent | Concentration (mg/mL) | Spin Speed (rpm) | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical | 6-9 | Hexane | 10-15 | 2000-3000 | 90-100% |

| Cubical | 10-13 | Chloroform | 10-15 | 1500-2500 | ~90% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for LbL Solid-State Ligand Exchange

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium lead iodide (CsPbI3) QDs | Light absorber | Synthesize via hot-injection; maintain excess PbI₂ for defect passivation |

| Oleic acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Long-chain capping ligands | Provide colloidal stability during synthesis; require replacement for charge transport |

| 2-Pentanol | Solvent washing medium | Superior ligand solubility; appropriate dielectric constant/acidity for ligand exchange |

| Choline ligands | Short conductive ligands | Enhance interdot coupling after exchange; improve charge transport |

| 5-Aminopentanoic acid (5AVA) | Bifunctional short ligand | Amine and carboxyl groups provide effective passivation; use with HI for proton-promoted exchange |

| Gallium-doped SnO₂ nanocrystals | Electron transport layer | Room-temperature processable; Ga doping reduces energy level mismatch |

| Hydroiodic acid (HI) | Proton source for exchange | Promotes desorption of long-chain ligands; enables binding of short ligands |

Key Considerations for Implementation

Quality Control Metrics

Monitor several parameters to ensure consistent LbL processing. Film uniformity can be assessed through atomic force microscopy (AFM), with root-mean-square roughness (Rq) values below 1.5 nm indicating high-quality monolayers [30]. Verify ligand exchange efficacy through Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to confirm the reduction of hydrocarbon vibrations from long-chain ligands [27]. Employ photoluminescence quantum yield measurements to ensure the exchange process enhances rather than diminishes optoelectronic properties.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Non-uniform Films: Optimize solvent evaporation rate by controlling ambient humidity and temperature. Ensure consistent substrate wettability through proper cleaning.

- Incomplete Ligand Exchange: Increase solvent washing duration or optimize solvent choice. Consider proton-promoted exchange with HI for more complete ligand replacement [29].

- PQD Aggregation: Moderate short-ligand concentration and ensure thorough washing between steps to prevent uncontrolled aggregation.

- Substrate Damage: For flexible substrates, maintain all processing steps at room temperature and employ UV sintering instead of thermal annealing [27].

The LbL solid-state ligand exchange protocol comprising spin-coating, solvent washing, and short-ligand treatment represents a robust methodology for fabricating high-efficiency CsPbI3 PQD solar cells. Through meticulous optimization of solvent systems, spin-coating parameters, and ligand chemistry, researchers can achieve highly conductive and stable PQD films with controlled thickness and enhanced optoelectronic properties. This detailed protocol provides a foundation for advancing PQD solar cell research toward higher efficiencies and commercial viability.

Phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI) has emerged as a highly effective passivation agent for perovskite-based optoelectronic devices, particularly in the context of layer-by-layer solid-state ligand exchange protocols for CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dot (PQD) solar cells. This organic ammonium salt functions through a dual-site passivation mechanism: the ammonium cation (NH3+) interacts with undercoordinated Pb2+ ions, while the iodide anion (I−) fills halide vacancies within the perovskite crystal structure [31]. The rational incorporation of PEAI into CsPbI3 PQD solar cell architectures addresses critical challenges associated with surface trap states and non-radiative recombination, which typically degrade both device efficiency and operational stability [32]. By effectively mitigating these interfacial and grain boundary defects, PEAI passivation significantly enhances photovoltaic parameters, particularly open-circuit voltage (VOC) and fill factor (FF), thereby pushing the performance of quantum dot photovoltaics closer to their theoretical limits.

The application of PEAI is especially compatible with layer-by-layer processing techniques common in PQD solar cell fabrication. Its molecular structure allows for effective penetration and interaction with the quantum dot surfaces during the solid-state ligand exchange process, leading to the formation of a more ordered and electronically coupled quantum dot solid with reduced charge recombination losses [33]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of PEAI implementation protocols, quantitative performance metrics, and practical guidelines for integrating this advanced ligand system into CsPbI3 PQD research and development workflows.

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables summarize key performance metrics achieved through PEAI passivation in various perovskite device architectures, providing crucial baseline data for experimental planning and benchmarking.

Table 1: Performance Enhancement of PEAI-Passivated Perovskite Solar Cells

| Device Architecture | PCE Control (%) | PCE PEAI (%) | VOC Enhancement | FF Improvement | Stability Retention | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible planar PSCs | 12.46 | 15.20 | Significant increase | Major improvement | 80% initial PCE (2x longer) | [33] |

| CsPbI3 PQD solar cells | 14.07 | 15.72 | Not specified | Not specified | Enhanced storage stability | [34] |

| All-inorganic PVSCs | Not specified | 21.00 | Not specified | Not specified | >90% after 500h at 60°C | [35] |

Table 2: Material Properties of PEAI and Derived Perovskite Structures

| Parameter | Value | Measurement Method | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Formula | C8H12IN | Chemical analysis | PEAI compound [36] |

| Molecular Weight | 249.09 g/mol | Calculated | PEAI compound [36] |

| Appearance | White powder | Visual inspection | Pure PEAI material [36] |

| Absorption Peak | ~630 nm | UV-vis spectroscopy | (PEA)2SnI4 thin films [37] |

| Exciton Energy | 2.04 eV | Electroabsorption | (PEA)2SnI4 at 15K [38] |

| Crystal System | Triclinic | Single-crystal XRD | (PEA)2SnI4 structure [38] |

Experimental Protocols

PEAI Solution Preparation

Materials Required:

- Phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI) powder (CAS 151059-43-7) [36]

- Anhydrous solvent (isopropanol, ethanol, or ethyl acetate)

- Inert atmosphere glovebox (<1 ppm O2 and H2O)

Procedure:

- Weighing: Transfer 10-50 mg of PEAI powder into a clean glass vial inside the glovebox environment.

- Solvent Addition: Add 1 mL of anhydrous solvent to achieve a concentration range of 10-50 mg/mL.

- Dissolution: Stir the mixture at 400-600 rpm for 30-60 minutes at room temperature until complete dissolution is achieved.

- Filtration: Filter the solution through a 0.22 μm PTFE syringe filter to remove any undissolved particles or contaminants.

- Storage: Store the filtered solution in a sealed vial protected from light for immediate use (within 24 hours).

Critical Parameters:

- Solvent Selection: Isopropanol is preferred for CsPbI3 PQDs due to its effective ligand exchange capability without excessive quantum dot dissolution.

- Concentration Optimization: Testing across 10-50 mg/mL range is recommended as optimal concentration varies with specific PQD film characteristics.

- Moisture Control: Strict anhydrous conditions are essential to prevent PEAI decomposition and CsPbI3 PQD degradation.

Layer-by-Layer Solid-State Ligand Exchange with PEAI

Materials Required:

- CsPbI3 PQD solution in octane (70 mg/mL) [34]

- PEAI solution in isopropanol (concentration optimized)

- Methyl acetate (MeOAc) for washing

- Substrate (TiO2-coated FTO for n-i-p architecture)

- Centrifuge capable of 2000-8000 rpm

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean FTO/TiO2 substrates with UV-ozone treatment for 20 minutes to ensure surface wettability [34].

- Initial PQD Deposition: Spin-coat CsPbI3 PQD solution at 1000 rpm for 20 seconds followed by 2000 rpm for 15 seconds to form uniform quantum dot layer [34].

- Solid-State Ligand Exchange:

- PEAI Passivation:

- Apply 100 μL of optimized PEAI solution dynamically during spinning at 2000 rpm.

- Allow complete coverage for 30 seconds before spinning at 3000 rpm for 30 seconds to remove excess PEAI.

- Layer Buildup: Repeat steps 2-4 for 4 cycles to achieve optimal film thickness of ~400 nm [34].

- Post-treatment: Immerse the multilayer film in guanidine thiocyanate (GASCN) solution in ethyl acetate for final passivation, followed by MeOAc rinse and N2 drying [34].

Critical Parameters:

- Processing Environment: Maintain relative humidity below 10% in dry air-filled glovebox [34].

- PEAI Concentration: Optimize between 1-5 mg/mL to avoid excessive insulating layer formation.

- Application Timing: Immediate PEAI application after MeOAc treatment ensures optimal surface access.

- Centrifugation: 4000-8000 rpm for 3-5 minutes effectively separates purified QDs [34].

Schematic 1: PEAI Passivation Mechanism in Layer-by-Layer PQD Processing. The diagram illustrates the transition from initial defective quantum dot layers to fully passivated structures through coordinated PEAI interaction during solid-state processing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for PEAI-Enhanced CsPbI3 PQD Solar Cells

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes | Quality Specification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Surface passivation of PQDs | Optimize concentration (1-5 mg/mL in IPA); apply immediately after MeOAc treatment | ≥99.5% purity; white crystalline powder; store in inert atmosphere [36] |

| Cesium Lead Iodide (CsPbI3) QDs | Light-absorbing layer | Synthesize via hot-injection; 70 mg/mL in octane; size distribution 8-12 nm [34] | Phase-pure cubic perovskite; PLQY >85%; narrow emission width (<40 nm) |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Ligand exchange solvent | Use 3:1 ratio with QD solution for precipitation; anhydrous grade essential [34] | Anhydrous (99.5%); water content <50 ppm; store over molecular sieves |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) | Electron transport layer | Deposit via chemical bath at 70°C; anneal at 200°C for 30 min [34] | Compact layer; UV-ozone treatment before use for improved wettability |

| Guanidine Thiocyanate (GASCN) | Co-passivation agent | Dissolve in ethyl acetate; use after PEAI treatment for enhanced passivation [34] | ≥98% purity; effectively passivate multiple defect types synergistically with PEAI |

The integration of PEAI passivation layers within the layer-by-layer solid-state ligand exchange protocol for CsPbI3 PQD solar cells represents a significant advancement in defect management strategies. The experimental protocols outlined herein provide a reproducible methodology for achieving consistent performance enhancements, particularly in open-circuit voltage and operational stability. Researchers should prioritize meticulous control of processing atmosphere, PEAI solution concentration, and application timing to maximize the beneficial effects of this passivation approach.

Future developments in this area will likely focus on multifunctional passivation systems that combine PEAI with complementary agents such as crown ethers [35] or other ammonium salts to address a broader spectrum of defect types. Additionally, the extension of these protocols to large-area deposition techniques and tandem device architectures presents promising avenues for further research. The quantitative benchmarks provided in this application note serve as essential reference points for gauging successful implementation of PEAI-based passivation strategies in advanced CsPbI3 PQD photovoltaic research.