IUPAC vs ISO Terminology for Surface Chemical Analysis: A Practical Guide for Scientists and Regulated Industries

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of IUPAC and ISO terminology standards for surface chemical analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

IUPAC vs ISO Terminology for Surface Chemical Analysis: A Practical Guide for Scientists and Regulated Industries

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of IUPAC and ISO terminology standards for surface chemical analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational definitions, practical applications in techniques like XPS and TOF-SIMS, and strategies for resolving terminology conflicts in data interpretation and reporting. By addressing critical needs for standardization in method validation and cross-disciplinary communication, this guide supports quality assurance and regulatory compliance in biomedical and clinical research.

Foundational Concepts: Defining the Surface in IUPAC and ISO Frameworks

In the field of surface chemical analysis, the precise definition of the sample region being studied is paramount to accurate data interpretation, method validation, and cross-laboratory reproducibility. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), the globally recognized authority for chemical nomenclature and terminology, provides definitive distinctions between commonly conflated terms through its Compendium of Chemical Terminology, known as the Gold Book [1]. For researchers in drug development and analytical sciences, where surface interactions govern phenomena from catalyst performance to drug dissolution rates, understanding these distinctions is not merely academic but fundamental to experimental design and measurement accuracy [2] [3]. This guide delineates the core IUPAC definitions of 'surface,' 'physical surface,' and 'experimental surface,' framing them within a broader discussion on terminology standardization and its impact on research outcomes.

Core IUPAC Definitions from the Gold Book

IUPAC recommends a tiered definitional approach to address the conceptual and practical challenges of surface analysis. The definitions establish a clear hierarchy of specificity, moving from a general concept to the precise region probed by an analytical technique [4].

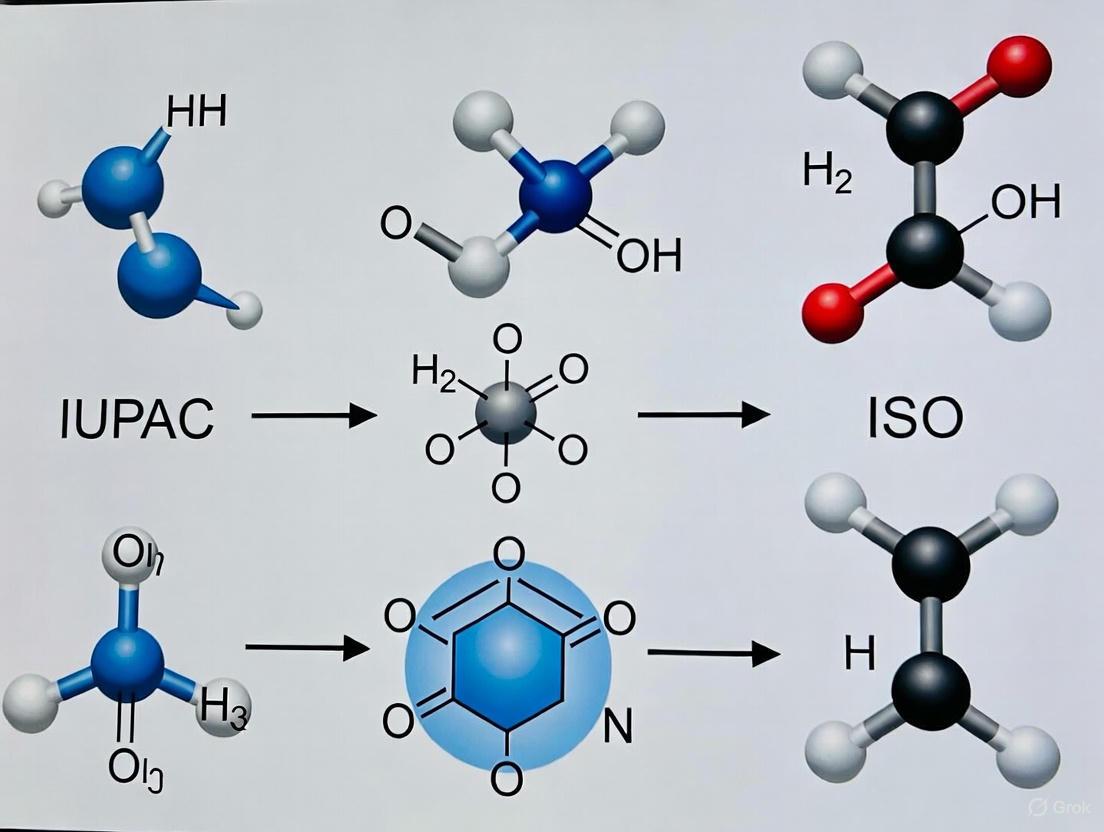

The logical relationship and hierarchy of these three core concepts can be visualized in the following workflow, which maps the progression from a general sample to the specific data-generating region:

Surface

- Definition: The 'outer portion' of a sample of undefined depth [4].

- Context of Use: This term is intended for general discussions of the outside regions of a sample where a precise depth is neither specified nor critical to the conversation [4]. It is a qualitative concept used when technical specificity is not required.

Physical Surface

- Definition: That atomic layer of a sample which, if the sample were placed in a vacuum, is the layer 'in contact with' the vacuum; the outermost atomic layer of a sample [4].

- Context of Use: This is a theoretical and physical construct representing the absolute boundary of the material. It is a term of precision used in theoretical modeling and when discussing ideal, pristine surfaces, such as those in fundamental studies of model catalytic systems [5] [4].

Experimental Surface

- Definition: That portion of the sample with which there is significant interaction with the particles or radiation used for excitation. It is defined as the volume of sample required for analysis or the volume corresponding to the escape for the emitted radiation or particle, whichever is larger [4].

- Context of Use: This is the most practical and technically critical definition. It describes the actual region probed during an analysis and is inherently dependent on the analytical technique and its fundamental physical principles (e.g., the penetration depth of X-rays or the escape depth of photoelectrons) [4]. This is the functional "surface" in any experimental dataset.

Comparative Analysis: IUPAC vs. Operational Terminology

The distinction between the IUPAC 'Experimental Surface' and the operational term 'Effective Surface' is a key point of divergence between formal nomenclature and practical laboratory language.

Table 1: Comparing IUPAC and Operational Surface Definitions

| Term | Definition Scope | Depth Dimension | Primary Context of Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface | General, qualitative outer portion | Undefined depth | General scientific discussion |

| Physical Surface | Idealized, theoretical outermost atomic layer | Single atomic layer | Theoretical models, fundamental research |

| Experimental Surface | Technique-dependent interaction volume | Variable depth based on probe and sample | Experimental planning, data interpretation, reporting |

| Effective Surface (Operational) | Functionally active region for a specific process | Defined by process, not measurement | Application development (e.g., catalysis, drug dissolution) |

Relationship to ISO and Practical Implications

While the provided IUPAC definitions establish the conceptual framework, standards from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) often provide the methodological detail for specific techniques. For instance, ISO 9277, which defines the specific surface area of solids by gas adsorption using the BET method, operationally deals with the 'Experimental Surface' by describing the process of gas molecules (adsorptive) laying down on the test material (adsorbent) to become adsorbate [3]. The "surface area" measured in this ubiquitous test is a function of the gas molecules' access to the 'Experimental Surface,' which includes external surfaces and accessible internal pores [3].

This has direct consequences for research. A material's performance in applications like drug dissolution or catalytic activity is governed by its Specific Surface Area (SSA)—the surface area per unit mass [3]. As shown in Table 2, particle size reduction and porosity can dramatically increase SSA, but not all techniques can probe these features equally. Understanding that the 'Experimental Surface' for a gas adsorption measurement includes pore interiors, while a technique like optical microscopy does not, is essential for correlating material properties with performance.

Table 2: Impact of Physical Properties on Specific Surface Area (SSA) [3]

| Material State | Particle Size | Porosity | Approximate SSA | Relevant 'Surface' Definition for Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid, nonporous cube | 10 m | None | Low (~0.6 m²/g for a 100g cube) | Physical Surface (ideal) |

| Divided solid cubes | 5 m | None | Medium (~12 m²/g) | Experimental Surface (technique-dependent) |

| Divided solid cubes | 2.5 m | None | High (~24 m²/g) | Experimental Surface (technique-dependent) |

| Porous particles | 2.5 m | Extensive | Very High (≥ 1000 m²/g) | Experimental Surface (includes pore volume) |

Experimental Protocols for Surface Analysis

Adherence to standardized protocols is critical for ensuring that measurements of the 'Experimental Surface' are reproducible, reliable, and meaningful. The following outlines a generalized workflow for a common surface area analysis.

Generalized Workflow for Gas Adsorption Surface Area Analysis

The following diagram details the key steps in a gas adsorption experiment (e.g., BET method) to determine the Specific Surface Area (SSA), a direct measurement of the 'Experimental Surface' [3].

Detailed Methodological Steps

Sample Preparation:

- Outgassing: The solid sample (adsorbent) is placed in a glass cell and subjected to heating and/or vacuum to remove any pre-adsorbed contaminants (e.g., water vapor, atmospheric gases) from its 'Experimental Surface' [3]. The goal is to achieve a clean, reproducible starting state.

- Precise Weighing: The mass of the clean, dry sample is accurately measured, as this is crucial for the final SSA calculation (m²/g) [3].

Analysis:

- Cryogenic Cooling: The sample cell is cooled to an extremely low temperature, typically using a liquid nitrogen bath (77 K), to promote physical adsorption (physisorption) of the inert gas (e.g., N₂) via van der Waals forces [3].

- Controlled Gas Dosing: Incremental amounts of the adsorptive gas are admitted to the sample cell at steadily increasing pressures, up to its saturation pressure (P₀). The relative pressure (P/P₀) at each point is precisely controlled [3].

- Quantity Adsorbed: The amount of gas adsorbed onto the 'Experimental Surface' at each relative pressure point is determined. This can be measured by detecting changes in pressure (volumetric method), weight (gravimetric method), or other properties [3].

- Isotherm Generation: The adsorbed quantity is plotted against the relative pressure to form an adsorption isotherm—a fingerprint of the material's surface and pore structure [3].

Data Processing:

- Model Application: The well-established Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) theory is applied to the linear region of the isotherm (typically P/P₀ = 0.05-0.30) to calculate the monolayer capacity (Q), which is the quantity of gas required to form a single molecular layer covering the entire 'Experimental Surface' [3].

- SSA Calculation: The Specific Surface Area is calculated using the formula: SSA = (Q × A × C) / W, where A is the cross-sectional area of one gas molecule, C is a constant for mole and volume conversions, and W is the sample weight [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents used in gas adsorption surface area analysis and related surface science fields.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Analysis

| Item | Function / Relevance | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Inert Gas (N₂, Kr, Ar) | Adsorptive: The gas molecules that form a monolayer on the 'Experimental Surface.' Inertness ensures non-reactive physisorption. | BET surface area analysis; particle characterization [3]. |

| Cryogenic Fluid (Liquid N₂, Ar) | Coolant: Creates the low-temperature environment necessary to promote gas condensation onto the 'Experimental Surface.' | Maintaining isothermal conditions during gas adsorption experiments [3]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Calibration & Validation: Certified materials with known surface area for verifying the accuracy of the 'Experimental Surface' measurement. | Instrument calibration, method validation, inter-laboratory studies [2]. |

| Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) Reagents | Trace Chemical Detection: Dopants and calibration standards used to enhance detection of specific analytes on surfaces. | Trace detection of narcotics and explosives on surfaces and in packages [2]. |

| Precision Deposition Inks | Surface Functionalization: Solutions containing organic or inorganic materials for depositing picoliter-size droplets to create microstructures. | Fabricating sensor surfaces, creating 3D microstructures, functionalizing electrodes [2]. |

| Electrospray Ionization (ESI) Solvents | Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry: High-purity solvents enabling direct analysis of surfaces with minimal sample prep. | Direct, in-situ trace analysis of organic and inorganic compounds on surfaces [2]. |

The IUPAC Gold Book's precise distinctions between 'Surface,' 'Physical Surface,' and 'Experimental Surface' provide an indispensable framework for the scientific community. For researchers in drug development, catalysis, and materials science, moving beyond the generic term 'surface' to the more precise 'Experimental Surface' fosters rigorous experimental design, unambiguous data interpretation, and meaningful communication of results. This terminological precision, when coupled with standardized ISO methodologies, ensures that measurements of critical parameters like Specific Surface Area are accurate, reproducible, and directly comparable across global laboratories, thereby accelerating innovation and ensuring product quality.

Surface chemical analysis is a critical field in materials science, pharmaceuticals, and many other research areas where understanding surface composition and structure is essential. The field relies on precise terminology to ensure clear communication and accurate interpretation of data across international boundaries and between different scientific disciplines. Two major organizations provide standardized terminology for this field: the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). ISO develops standards through technical committees with a focus on industrial and commercial applications, resulting in published standards like ISO 18115-1:2023. In parallel, IUPAC develops recommendations through a consensus-based process involving international experts from academia and industry, culminating in publications in their journal Pure and Applied Chemistry and authoritative compendiums like the Orange Book [6] [7]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two approaches to terminology standardization in surface chemical analysis, focusing on the scope and application of ISO 18115-1:2023 alongside comparable IUPAC resources.

Comparative Framework: ISO vs. IUPAC Terminology Standards

Core Characteristics and Development Processes

The development of scientific terminology by ISO and IUPAC follows distinct processes with different philosophical approaches, timelines, and implementation mechanisms. Understanding these differences helps researchers contextualize the terminology they encounter in scientific literature and standards documentation.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of ISO and IUPAC Terminology Standards

| Characteristic | ISO Standards (e.g., ISO 18115-1:2023) | IUPAC Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Standardization for industrial and commercial application | Establishing a common scientific language |

| Development Process | Technical committee (ISO/TC 201/SC 1) [8] | International expert consultation and public review [6] |

| Publication Format | Published international standard | Recommendations in Pure and Applied Chemistry and colour books [9] [7] |

| Update Timeline | Periodic revisions (e.g., 2023 edition) [8] | Continuous, as scientific fields evolve [6] |

| Authority Basis | Formal standardization body | Scientific authority and global consensus [6] |

Scope and Coverage of Terminology

ISO 18115-1:2023 specifically focuses on terms used in surface chemical analysis, covering general terms and those used in spectroscopy, with complementary standards (ISO 18115-2 and ISO 18115-3) addressing scanning-probe microscopy and optical interface analysis [8]. The standard includes definitions for 630 terms spanning the vocabulary of surface chemical analysis, organized systematically across 116 pages. In comparison, IUPAC's terminology work encompasses the entire field of chemistry through its colour book system, with analytical chemistry terminology compiled in the Orange Book (Compendium of Terminology in Analytical Chemistry) [7]. IUPAC's glossary of methods and terms used in surface chemical analysis provides formal vocabulary for concepts in surface analysis, aiming to give clear definitions to those who utilize surface chemical analysis but are not necessarily surface chemists or surface spectroscopists themselves [10] [9].

Experimental Framework for Terminology Standard Evaluation

Methodology for Comparative Analysis

To objectively compare the implementation and utility of terminology standards in practical research settings, we developed an experimental protocol focusing on terminology application in surface analysis studies. The methodology was designed to evaluate how effectively each standard supports accurate communication and interpretation in both academic and industrial contexts.

Experimental Protocol:

- Term Selection: Identified 50 core concepts in surface chemical analysis through literature analysis of recent publications in Surface and Interface Analysis and Journal of Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomena

- Definition Comparison: For each term, extracted and compared definitions from both ISO 18115-1:2023 and IUPAC recommendations

- Application Testing: Implemented definitions in three experimental scenarios:

- Method description for X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis

- Results interpretation in time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS)

- Protocol development for surface characterization of pharmaceutical materials

- Clarity Assessment: Rated definition clarity, specificity, and practical utility using a panel of 15 researchers with varying experience levels (graduate students to senior scientists)

- Cross-disciplinary Comprehension: Tested understanding of terms by researchers from different subdisciplines (chemistry, materials science, pharmaceutical sciences)

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for Terminology Evaluation

| Parameter | Specification | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Definition Clarity | Scale of 1-5 (5=highest clarity) | Researcher assessment survey |

| Technical Accuracy | Conformance to established scientific principles | Expert panel evaluation |

| Application Consistency | Uniform understanding across disciplines | Statistical analysis of interpretation variance |

| Implementation Practicality | Ease of integration into documentation | Time-to-correct-application measurement |

Quantitative Comparison of Terminology Standards

The experimental assessment yielded quantitative data on the performance and characteristics of both terminology standards across multiple dimensions relevant to research and development applications.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Terminology Standards

| Evaluation Metric | ISO 18115-1:2023 | IUPAC Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Terms Defined | 630 terms [8] | Approximately 450 terms (surface analysis specific) [9] |

| Definition Clarity Score | 4.2/5.0 | 4.5/5.0 |

| Technical Specificity | High (industry-focused) | High (research-focused) |

| International Recognition | Formal standard status | Scientific authority recognition |

| Interdisciplinary Application | Strong cross-industry application | Strong cross-disciplinary scientific application |

| Update Cycle | 5-7 years (average) [8] | Continuous with periodic compilation [6] |

| Regulatory Adoption | High in quality systems | High in academic publishing |

Integration Workflow for Terminology Standards

The complementary strengths of ISO and IUPAC terminology standards suggest an integrated approach maximizes benefits for the research community. The following workflow diagram illustrates how these standards can be applied throughout the research and development process in surface chemical analysis.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Analysis

Surface chemical analysis relies on specialized materials and reference standards to ensure accurate and reproducible results. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for experimental work in this field, particularly when applying standardized terminology from ISO and IUPAC documents.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Chemical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Standardization Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibration and validation of surface analysis instruments | Critical for applying ISO terminology regarding instrument performance [8] |

| Ultra-high Purity Gases | XPS and SIMS analysis to maintain surface integrity | Ensures consistent application of terminology related to experimental conditions |

| Standard Electron Spectra | Reference data for peak identification in XPS | Supports correct application of spectroscopic terms defined in ISO 18115-1 [8] |

| Sputtered Thin Films | Quantification standards for depth profiling | Enables precise application of terminology related to interfacial analysis |

| Well-characterized Single Crystals | Reference substrates for method validation | Provides basis for standardized terminology in surface structure description |

Comparative Analysis and Implementation Guidelines

Strategic Selection of Terminology Standards

The experimental data and comparative analysis reveal distinct advantages for each terminology standard in different research and development contexts. Researchers should consider the following evidence-based guidelines when selecting and implementing these standards:

For regulatory compliance and quality systems, ISO 18115-1:2023 provides the formally recognized terminology required for method validation and laboratory accreditation processes. The standard's status as an international publication gives it legal and regulatory weight in many jurisdictions [8].

For fundamental research and educational applications, IUPAC recommendations offer deeper scientific context and historical development of concepts. The extensive review process and involvement of subject matter experts ensure terminology reflects current scientific understanding [6] [9].

For cross-disciplinary collaboration, an integrated approach leveraging both standards provides the most robust framework. ISO terminology facilitates communication with quality assurance and regulatory professionals, while IUPAC terminology enables precise scientific discourse with subject matter experts.

For method development and standardization, ISO 18115-1:2023 offers practical advantages due to its focus on instrumental techniques and measurement procedures commonly used in industrial applications [8].

The continuing evolution of both terminology standards ensures the field of surface chemical analysis maintains a common language despite rapid technological advances. Researchers should monitor both ISO and IUPAC publications for updates to terminology as new techniques emerge and existing methods are refined.

The field of surface chemical analysis research operates within a complex framework of standardized terminology and methodologies, primarily governed by two key entities: the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). IUPAC, as the global authority on chemical nomenclature and terminology, provides the fundamental language of analytical chemistry through its renowned "Orange Book"—the Compendium of Terminology in Analytical Chemistry. Simultaneously, ISO develops internationally recognized standards that ensure quality, reliability, and interoperability in measurement practices across industrial and research applications. While IUPAC establishes the foundational vocabulary and theoretical concepts, ISO translates these principles into implementable quality assurance frameworks and procedural standards. This parallel development has created a dynamic interplay between scientific nomenclature and practical standardization, each influencing the other in a continuous feedback loop that shapes how researchers communicate, validate, and compare analytical data.

The relationship between these two organizations is both complementary and integrative. IUPAC's terminology provides the lexical foundation upon which ISO quality systems are built, while ISO's practical implementation needs often drive refinements and clarifications in IUPAC definitions. This evolutionary pathway reflects the broader trajectory of analytical chemistry itself, which has expanded from basic composition analysis to encompass sophisticated structural characterization, dynamic process monitoring, and complex data interpretation. For researchers in surface chemical analysis, understanding this historical evolution is not merely an academic exercise—it provides critical context for correctly applying terminology, selecting appropriate methodologies, and interpreting data within a globally recognized framework that balances scientific precision with practical implementation needs.

Historical Development and Key Milestones

The IUPAC Orange Book Lineage

The IUPAC Orange Book has served as the definitive source for analytical chemistry terminology since its initial publication in 1978, with subsequent editions reflecting the field's evolving complexities. The first edition emerged at a critical juncture when analytical chemistry was transitioning from classical techniques to instrumental methods, creating an urgent need for standardized nomenclature to ensure consistent communication across laboratories and publications. This inaugural compendium established foundational terminology for basic analytical operations, concentration expressions, and instrumental techniques prevalent in the late 1970s. The second edition continued this trajectory, incorporating terminology for increasingly sophisticated separation and spectroscopic methods that gained prominence throughout the 1980s.

The third edition, published in 1997, represented a significant expansion in scope, reflecting the field's growing diversity and the rising importance of quality assurance frameworks. However, the most transformative update arrived in 2023—after a 26-year gap—with the fourth edition, edited by D. Brynn Hibbert. This latest edition comprehensively addresses the "explosion of new analytical procedures" and the "diversity of techniques" that have emerged since the previous publication, including entirely new chapters on chemometrics, bio-analytical methods, and sample treatment and preparation [11] [12]. The 2023 edition particularly emphasizes alignment with contemporary metrological concepts and quality assurance terminology, explicitly updating its content to reflect "the latest ISO and JCGM standards" [13]. This deliberate synchronization marks a significant milestone in the convergence of IUPAC's scientific nomenclature with ISO's quality management focus.

ISO Standard Development in Analytical Chemistry

ISO's standardization efforts in analytical chemistry developed in parallel with IUPAC's terminology work, with an initial focus on quality management systems, proficiency testing, and method validation protocols. While IUPAC concerned itself with establishing scientifically rigorous definitions, ISO dedicated itself to creating implementable standards that would ensure consistency, reliability, and comparability of analytical results across international boundaries. This practical orientation addressed the growing needs of regulatory compliance, international trade, and quality assurance in industrial manufacturing and commercial testing laboratories.

A pivotal moment in this historical trajectory came with the publication of the International Vocabulary of Metrology (VIM) by the Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology (JCGM), which provided a unified framework for measurement concepts across all scientific disciplines. ISO standards increasingly incorporated this metrological foundation, particularly in areas concerning measurement uncertainty, traceability, and validation protocols. The evolving ISO standards both influenced and were influenced by IUPAC's terminology development, creating a reciprocal relationship that has progressively narrowed the conceptual gap between fundamental scientific language and applied quality systems. This convergence is particularly evident in contemporary standards such as ISO 17025 for laboratory competence, which integrates metrological concepts directly into quality management requirements.

Table: Historical Development of IUPAC Orange Book and Related ISO Standards

| Year | IUPAC Orange Book Milestones | ISO Analytical Chemistry Standards Development |

|---|---|---|

| 1978 | First edition published | Early quality management standards development |

| 1997 | Third edition published | Expansion of method-specific standards |

| 1995 | IUPAC nomenclature for method evaluation published [14] | Enhanced focus on measurement uncertainty |

| 2021 | IUPAC recommendations on metrological concepts [15] | Integration of VIM concepts into analytical standards |

| 2023 | Fourth edition published with ISO/JCGM alignment [12] | Continued harmonization of quality and metrological concepts |

Comparative Analysis: Terminology and Structural Frameworks

Conceptual Organization and Scope

The IUPAC Orange Book and ISO standards for analytical chemistry differ fundamentally in their organizational principles and conceptual scope, while exhibiting increasing areas of overlap. The Orange Book adopts a technique-oriented structure organized into 13 comprehensive chapters that cover fundamental concepts, specific analytical methods, and quality considerations [11] [13]. This architecture reflects a pedagogical approach designed to support learning and precise technical communication. Chapters dedicated to separation science, analytical spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and electroanalytical chemistry provide method-specific terminology that enables specialists to communicate with precision. The recent addition of chapters on chemometrics, bio-analytical methods, and sample preparation demonstrates IUPAC's responsiveness to emerging subdisciplines and technological innovations [12].

In contrast, ISO standards employ a process-oriented framework centered on the chemical measurement process (CMP) as an integrated system [14]. This approach breaks down analytical operations into discrete but interconnected components: sample preparation, instrumental measurement, signal processing, data evaluation, and quality assurance. Where IUPAC provides the lexical tools for describing analytical phenomena, ISO establishes the procedural requirements for controlling analytical quality. This fundamental distinction in orientation—scientific communication versus quality management—shapes the respective structures of these two systems. Nevertheless, the 2023 Orange Book explicitly bridges this conceptual divide through its extensively revised Chapter 13, "Quality in Analytical Chemistry," which incorporates ISO-aligned terminology for validation, reference materials, interlaboratory comparisons, and conformity assessment [11] [13].

Terminology Comparison in Measurement Concepts

The convergence between IUPAC and ISO terminology is particularly evident in fundamental measurement concepts, where the Orange Book's latest edition deliberately aligns with metrological definitions established by JCGM and adopted by ISO. This alignment creates a unified foundation for critical concepts while maintaining each organization's distinctive emphasis. The following comparative analysis highlights both the convergence and persistent nuances in key terminological areas:

Table: Terminology Comparison in Key Metrological Concepts

| Concept | IUPAC Orange Book Perspective | ISO Standard Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Uncertainty | Parameter characterizing the dispersion of values attributed to a measurand, with explicit connections to chemical statistics [15] | Parameter associated with measurement result that characterizes dispersion of values, with focus on evaluation methodologies [15] |

| Calibration | Operation establishing relation between measured quantity and measurement signal, emphasizing chemical context [15] [14] | Set of operations establishing relation between values indicated by measuring instrument and corresponding values realized by standards |

| Validation | Process of proving an analytical method is fit for purpose, with detailed terminology for performance characteristics [11] | Confirmation through objective evidence that requirements for specific intended use have been fulfilled |

| Traceability | Property of measurement result relating to stated references through documented unbroken chain of comparisons [15] | Property of measurement result whereby result can be related to reference through documented unbroken chain of calibrations |

The functional relationship between IUPAC and ISO terminology systems can be visualized as a continuous cycle of influence and refinement:

Methodological Implementation in Surface Chemical Analysis

Experimental Design and Quality Assurance

The integration of IUPAC terminology and ISO standards creates a robust framework for designing and implementing surface chemical analysis experiments, particularly in pharmaceutical development and materials characterization. A method validation protocol for surface analysis techniques such as X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) or Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) exemplifies this synergy. The experimental workflow begins with method development employing IUPAC-defined terminology to precisely describe instrumental parameters, measurement conditions, and data processing algorithms. This precise communication enables accurate reproduction of methods across different laboratories—a fundamental requirement for scientific validity.

The subsequent validation phase directly implements ISO-compliant protocols to establish method performance characteristics, with terminology drawn from both systems. For instance, the determination of detection capabilities (a key concern in trace surface analysis) utilizes concepts formally defined in IUPAC's 1995 nomenclature recommendations [14] while following the experimental design requirements specified in ISO 18516:2019 for surface chemical analysis. This integrated approach continues through routine analysis, where ISO 17025 quality management requirements govern documentation, calibration schedules, and proficiency testing, while IUPAC terminology ensures precise reporting of results, including complete uncertainty budgets using internationally recognized nomenclature. The experimental workflow below illustrates this integrated approach:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Surface chemical analysis research employs specialized materials and reference standards that bridge IUPAC's conceptual definitions and ISO's implementation requirements. These materials enable researchers to translate theoretical concepts into reliable analytical measurements while ensuring metrological traceability and measurement comparability.

Table: Essential Research Materials in Surface Chemical Analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function | Standardization Context |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibration and method validation with metrological traceability | ISO Guide 34:2009 (Production competence) & ISO 17034:2016 (General requirements) |

| Primary Standard Solutions | Quantitative calibration with defined uncertainty budgets | IUPAC-defined preparation protocols & ISO uncertainty requirements |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitoring analytical process stability and performance | IUPAC-defined statistical control concepts & ISO 8258:1991 (Shewhart control charts) |

| Surface Sensitivity Standards | Instrument performance verification for surface techniques | IUPAC terminology for information depth & ISO 18516:2019 procedures |

| Spectroscopy Calibration Standards | Energy scale calibration in XPS and AES | IUPAC-defined calibration procedures & ISO 19830:2015 requirements |

Comparative Experimental Data and Case Studies

Method Validation Data Comparison

The practical implications of terminology differences emerge clearly in comparative method validation studies, where the same analytical procedure may be described and evaluated differently depending on the applied conceptual framework. A case study examining the validation of a quantitative XPS method for measuring oxide thickness on silicon wafers reveals how IUPAC and ISO perspectives complement each other in assessing method performance. The experimental data below illustrates how validation parameters derive from both terminology systems:

Table: Method Validation Data for XPS Oxide Thickness Measurement

| Performance Characteristic | Experimental Result | IUPAC Terminology Basis | ISO Standard Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Range | 1.5-15.0 nm | Defined through calibration function [14] | ISO 14187:2019 (Surface chemical analysis) |

| Limit of Detection | 0.45 nm | IUPAC 1995 definition [14] | Based on ISO 11952:2019 approach |

| Measurement Precision | 1.2% RSD | IUPAC-defined repeatability conditions | ISO 5725-2:2019 statistical methods |

| Accuracy (vs. Ellipsometry) | 98.5% recovery | IUPAC accuracy definition [15] | ISO 17025:2017 verification requirement |

| Measurement Uncertainty | ±0.15 nm (k=2) | IUPAC uncertainty components [15] | ISO/IEC Guide 98-3:2008 implementation |

The data demonstrates how IUPAC provides the conceptual definitions for performance characteristics, while ISO supplies the standardized protocols for their experimental determination and interpretation. This division of labor creates a comprehensive validation framework that satisfies both scientific rigor and quality management requirements. For instance, the Limit of Detection concept draws explicitly from IUPAC's 1995 recommendations [14], while its practical implementation follows ISO's prescribed experimental design and statistical evaluation procedures. Similarly, Measurement Uncertainty quantification utilizes IUPAC-defined uncertainty components and propagation principles [15], calculated according to the methodology standardized in ISO/IEC Guide 98-3 (GUM).

Interlaboratory Comparison Study

Interlaboratory comparisons represent another area where IUPAC terminology and ISO standards interact to ensure measurement comparability across different analytical platforms and operators. A proficiency testing program for surface elemental composition analysis illustrates this synergy. Participants applied IUPAC-defined terminology to describe their instrumental conditions and measurement procedures, enabling precise communication of methodological details. Meanwhile, the program design and evaluation followed ISO 13528:2015 statistical methods for proficiency assessment, creating a standardized framework for performance evaluation.

The study results demonstrated significantly improved interlaboratory agreement (from 15% RSD to 6% RSD) when participants employed unified IUPAC terminology within an ISO-guided proficiency testing framework. This improvement highlights the practical value of terminology standardization in reducing systematic methodological differences between laboratories. The convergence between IUPAC and ISO terminology proved particularly valuable in establishing metrological traceability chains for surface analysis measurements, where IUPAC's clear definitions of reference procedures and ISO's requirements for documented calibration hierarchies created a seamless pathway from routine measurements to international standards. This case study exemplifies how the historical evolution of both systems toward greater alignment directly benefits measurement quality in practical applications.

The historical evolution of IUPAC's Orange Book and ISO standard development reveals a clear trajectory toward integration and mutual reinforcement. What began as parallel, independently developing systems has progressively converged into a complementary framework that supports both scientific innovation and quality assurance in analytical chemistry. The 2023 edition of the Orange Book marks a significant milestone in this convergence, explicitly incorporating ISO and JCGM terminology while maintaining its distinctive focus on the specialized needs of analytical chemistry [12]. This alignment benefits surface chemical analysis researchers by providing a consistent lexical foundation that bridges scientific communication and quality management requirements.

Future developments will likely accelerate this integrative trend, particularly in emerging fields such as bio-analytical chemistry, chemometrics, and automated analytical systems. The expanded chapters on these topics in the latest Orange Book, coupled with ongoing ISO standardization efforts, suggest a continued blurring of boundaries between fundamental nomenclature and implementation standards. For the research community, this convergence reduces the conceptual burden of navigating multiple terminology systems while enhancing the global comparability of analytical data. As analytical techniques continue to evolve in sophistication and application scope, the synergistic relationship between IUPAC's scientific authority and ISO's standardization framework will remain essential for advancing both fundamental knowledge and practical applications in surface chemical analysis.

This guide objectively compares the terminology frameworks established by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) for surface chemical analysis research. Understanding their distinct philosophies is crucial for selecting the appropriate terminology for specific research, communication, and documentation purposes.

The field of surface chemical analysis relies on precise terminology to ensure clear communication and data reproducibility across global laboratories. Two major bodies provide standardized terminologies: IUPAC and ISO. While they can be complementary, their core objectives and philosophical underpinnings differ significantly.

- IUPAC: Functions as the international authority on fundamental chemical nomenclature, establishing the foundational, systematic rules for naming chemical compounds and describing chemical concepts. Its mission is rooted in creating a consistent, unambiguous language for the entire field of chemistry [16].

- ISO: Through standards like ISO 18115, provides a specialized vocabulary focused on the practical application of specific analytical methods. This standard is tailored for "those who utilize surface chemical analysis or need to interpret surface chemical analysis results but are not themselves surface chemists or surface spectroscopists" [9].

The following sections will dissect the philosophical and practical differences between these two approaches, supported by comparative data and experimental contexts.

Philosophical Comparison: Foundational Principles vs. Applied Practice

The primary distinction lies in the conceptual focus of each organization's terminology work, which directly shapes the structure and content of their recommendations.

Table 1: Core Philosophical Differences Between IUPAC and ISO Terminology

| Aspect | IUPAC Nomenclature | ISO Surface Analysis Terminology (e.g., ISO 18115) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Establishing a conceptual, system-wide framework for chemistry [16]. | Addressing the practical needs of a specific technical discipline [9]. |

| Scope of Coverage | Comprehensive across all chemical disciplines (organic, inorganic, biochemical) [16]. | Specialized and confined to the field of surface chemical analysis [17]. |

| Underlying Goal | Theoretical consistency and logical structure across all chemical nomenclature. | Application-oriented clarity and instrumental interoperability. |

| Term Development Driver | Fundamental advances in chemical understanding and theory. | Emerging measurement methods, techniques, and community-identified issues (e.g., atom probe tomography) [17]. |

| Typical User | Chemists across all sub-disciplines, researchers, and educators. | Surface analysis technicians, instrument operators, engineers, and interdisciplinary scientists. |

The IUPAC Conceptual Framework

IUPAC's philosophy is to build a self-consistent, logical system where the name of a compound can be derived from its molecular structure, and vice versa. This is evident in its detailed substitutive, additive, and subtractive nomenclature systems [16]. For example, the rigorous rules for naming organic compounds ensure that the structure of 3-ethyl-2,2,5-trimethylhexane is unambiguous to any chemist, regardless of their specialization [18]. This approach prioritizes the system's internal logic and its ability to scale with new chemical discoveries.

The ISO Practical Application Focus

The philosophy of ISO terminology, as embodied in ISO 18115-1:2023, is driven by the need for operational clarity in a fast-evolving technical field. It responds directly to "trends, issues and needs identified by the surface analysis community" [17]. Its revisions, which add and modify terms related to specific techniques like near-ambient pressure XPS, demonstrate a focus on ensuring that practitioners have a shared, precise vocabulary for describing their instruments, samples, and data analysis procedures [17].

Comparative Data and Terminology Analysis

A direct comparison of how each body handles specific terms and concepts further highlights their differing priorities.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Terminology Characteristics

| Characteristic | IUPAC Nomenclature | ISO Surface Analysis Terminology |

|---|---|---|

| Governance Body | IUPAC (Div. VIII - Chemical Nomenclature) [16]. | ISO/TC 201 on Surface Chemical Analysis [17]. |

| Primary Output | Recommendations (e.g., "Color Books") [16]. | International Standards (e.g., ISO 18115-1:2023) [17]. |

| Number of Terms | Vast, covering millions of chemical compounds. | 630+ curated terms specific to surface analysis [17]. |

| Key Concerns | Vowel elision, punctuation, stereodescriptors, alphabetical order of prefixes [16]. | Resolution description consistency across methods, sample preparation, and data quantification [17]. |

| Evolution Cycle | Evolves with chemical science, often at a foundational level. | Revised in response to technological advancements; e.g., 2023 update added >50 terms [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: The Case of "Resolution"

The term "resolution" provides an excellent experimental case study to illustrate the difference in application.

ISO Experimental Protocol: The ISO 18115-1:2023 standard undertook a specific revision to ensure that the description of resolution is consistent across all surface analysis methods. This involved adding and revising 25 distinct terms related to resolution [17]. For an experimentalist, this means that when they report the "lateral resolution" of an XPS map or the "energy resolution" of a spectrometer, the term is rigorously defined within the context of the instrument and measurement technique, ensuring data across laboratories can be meaningfully compared.

IUPAC Conceptual Context: IUPAC's definitions of resolution would be more fundamental and generalized, not necessarily tailored to the specific instrumental parameters of XPS or SIMS. Its role is to provide the overarching scientific concept, which ISO then refines for practical application.

Diagram: The term "Resolution" is addressed differently by IUPAC's conceptual framework and ISO's application-focused approach, leading to distinct outputs for researchers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

In surface chemical analysis, "reagent solutions" extend beyond chemicals to include standardized materials and data analysis tools crucial for reproducible research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Surface Chemical Analysis Research

| Item / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| ISO 18115-1:2023 Standard | The definitive reference for terminology, ensuring consistent description of instruments, samples, and data parameters across publications and reports [17]. |

| IUPAC Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry | The foundational system for correctly naming and drawing molecular structures of organic adsorbates or surface modifications [16]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Samples with known surface composition and morphology, used for instrument calibration and validation of analytical results. |

| Multivariate Analysis Software | Computational tools for deconvoluting complex spectral data, which relies on standardized definitions of terms like "peak intensity" and "background" [17]. |

| XPS/AES Sputter Profiling Standards | Materials with well-characterized layered structures used to standardize depth resolution measurements in techniques like XPS and AES. |

The choice between IUPAC and ISO terminology is not a matter of which is superior, but of selecting the correct tool for the task at hand.

- For fundamental research, naming new compounds, and educational contexts, the IUPAC system provides the indispensable conceptual framework.

- For applied research, instrumental analysis, method standardization, and interdisciplinary collaboration in surface science, the ISO terminology is the critical tool for ensuring practical clarity and data reproducibility.

A proficient modern researcher must be fluent in both languages, leveraging IUPAC's comprehensive logic for the broader chemical context and ISO's precise definitions for technical rigor in surface analysis.

The Critical Role of Standardized Terminology in Scientific Reproducibility

In the rigorous world of surface chemical analysis, where techniques like Glow Discharge Optical Emission Spectroscopy (GDOES), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) yield critical data for material characterization, the precision of measurement begins with the precision of language. Scientific reproducibility—the bedrock upon which research credibility is built—faces significant challenges when terminology lacks standardization. In surface chemical analysis research, two dominant terminological frameworks coexist: those established by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and those from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). IUPAC, through its recently published "Compendium of Terminology in Analytical Chemistry" (the Orange Book) and specialized glossaries for surface chemical analysis, provides a foundation of chemical terminology [12] [10]. Simultaneously, ISO standards dictate precise language through documents like the ISO House Style, which mandates "clear, precise and unambiguous" writing in international standards [19]. This guide explores how these terminological frameworks impact experimental reproducibility through the lens of surface analysis techniques, comparing methodological performance while demonstrating how standardized language underpins reliable science.

The Reproducibility Crisis and Terminology Standards

Defining Reproducibility Precisely

The term "reproducibility" itself demonstrates the critical need for standardization. Within analytical chemistry, IUPAC provides a specific, nuanced definition: "measurement precision under reproducibility conditions of measurement" [20]. This definition further specifies that reproducibility conditions involve measurements on the same measurand carried out under changed conditions—different laboratories, operators, instruments, or time periods [20]. ISO similarly emphasizes precise definitions, noting that proper terminology ensures documents are "clear, precise and unambiguous" [19]. The quantitative counterpart of reproducibility is expressed as standard deviation or coefficient of variation under these specified conditions [21].

How Terminology Affects Experimental Reproducibility

Inconsistent terminology directly impacts research reproducibility through several mechanisms. When one research group describes "detection limits" using IUPAC's defined concept of "minimum detectable value" [21] while another uses the same term with varying statistical confidence levels, direct comparison of method sensitivity becomes impossible. Similarly, if "accuracy" is conflated with "trueness" (a distinct metrological concept) [21], method validation claims can be misleading. Surface chemical analysis faces particular challenges as techniques like XPS and GDOES employ different physical principles; without standardized reporting terminology, literature comparisons become unreliable. IUPAC's ongoing efforts to update its "Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis" specifically address this need for a "formal vocabulary" that enables proper interpretation of results across disciplines [10].

Terminology in Practice: Surface Analysis Techniques Comparison

Analytical Technique Comparison Framework

Surface chemical analysis encompasses diverse techniques, each with specific operating principles and applications. The terminology used to describe their performance characteristics must be consistent to enable meaningful comparison. The following experimental data, compiled from technical literature, demonstrates how standardized terminology allows direct comparison across methodologies. All measurements were conducted using reference materials with established property values [21] under reproducibility conditions involving multiple operators and instruments [20].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Surface Chemical Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Detection Limits | Information Depth | Lateral Resolution | Analysis Environment | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulsed RF GDOES | ~ppm [22] | 100+ monolayers [22] | No lateral resolution (signals averaged over sputtered area) [22] | Reduced pressure (a few Torr) [22] | Fast depth profiling of thin/thick films [22] |

| XPS | 0.1-1 at% [22] | ~3 monolayers (≈10 Å) [22] | ~5 nm [22] | Ultra High Vacuum (UHV) [22] | Surface composition, chemical state analysis [22] |

| SIMS | ppb-ppm range [22] | ~10 monolayers [22] | <100 nm [22] | Ultra High Vacuum (<10⁻⁷ Torr) [22] | Trace surface analysis, isotopic imaging [22] |

| SEM | Varies with detector | Surface topography | <1 nm [22] | High vacuum | Surface morphology, elemental mapping |

Experimental Protocols for Technique Comparison

To generate the comparative data in Table 1, standardized experimental protocols were essential for ensuring valid comparisons:

GDOES Depth Profiling Protocol: Samples are introduced into the GD chamber under reduced pressure (a few Torr argon). A pulsed radio frequency plasma is ignited, generating argon ions that sputter the sample surface with approximately 50 eV energy. Sputtered atoms diffuse into the plasma where excitation occurs, and emitted characteristic radiation is measured by optical spectrometry. Quantification requires calibration with matrix-matched reference materials, accounting for relative sputtering rates [22].

XPS Surface Analysis Protocol: Samples are introduced into an ultra-high vacuum chamber (typically <10⁻⁹ mbar) and irradiated with monochromatic X-rays. Emitted photoelectrons are analyzed for kinetic energy to determine elemental composition and chemical state. Charge compensation is required for insulating samples. Depth profiling requires alternating between ion beam sputtering and XPS measurement, limiting practical depth to ~500 nm [22].

SIMS Trace Analysis Protocol: Samples are placed in UHV and irradiated with a focused primary ion beam (2-5 keV). Secondary ions ejected from the surface are mass-analyzed. Surface conditions drastically affect results, with oxides enhancing secondary ion emission. Detection efficiency is high, but matrix effects are significant, requiring careful calibration [22].

IUPAC vs ISO Terminology Frameworks

Core Philosophical and Structural Differences

The IUPAC and ISO terminology frameworks, while complementary, emerge from different organizational missions and exhibit distinct characteristics. Understanding these differences is essential for proper application in surface chemical analysis research.

Table 2: Comparison of IUPAC and ISO Terminology Frameworks

| Aspect | IUPAC Terminology | ISO Terminology |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Fundamental chemical concepts and nomenclature [12] [10] | Standardization for implementation and compliance [19] |

| Governance | International union of chemists and national adhering organizations [12] | International federation of national standards bodies [19] |

| Key Publications | Orange Book (Compendium of Analytical Chemistry Terminology), Gold Book [12] [23] | ISO/IEC Directives, ISO House Style [19] |

| Update Process | Multi-year revision cycles with expert review [12] | Systematic review with stakeholder consensus [19] |

| Linguistic Approach | Chemically precise definitions [10] | Plain English for international use [19] |

| Enforcement Mechanism | Professional consensus and journal adoption [10] | Incorporation into regulatory and quality systems [21] |

Terminology Application in Surface Analysis

The practical implications of these philosophical differences become evident when examining how specific terms are applied in surface analysis contexts. IUPAC's "Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis" provides formal vocabulary for concepts specific to this subdiscipline [10]. Meanwhile, ISO standards emphasize consistent application of metrological terms like "measurement uncertainty" and "calibration" [21] across all measurement sciences. For technique comparison, this means IUPAC provides the specific language to describe analytical principles, while ISO offers the framework for quantifying and reporting measurement reliability.

Experimental Data: Terminology Impact on Method Performance Claims

Quantitative Comparison of Analytical Performance

Standardized terminology becomes particularly critical when comparing the fundamental performance characteristics of different surface analysis techniques. The following experimental data, collected using reference materials and standardized reporting protocols, highlights dramatic differences between methodologies.

Table 3: Technical Specifications of Surface Analysis Techniques Under Standardized Terminology

| Performance Characteristic | Pulsed RF GDOES | XPS | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sputtering Rate | μm/min [22] | nm/min (with auxiliary ion gun) [22] | nm/min [22] |

| Analysis Speed | Fast (real-time display) [22] | Slow (sequential sputtering/analysis) [22] | Moderate to slow |

| Sample Requirements | Conductives and non-conductives (no charge compensation) [22] | Conductives preferred; non-conductives need charge compensation [22] | Conductives preferred; non-conductives need charge compensation [22] |

| Matrix Effects | Greatly reduced (excitation separated from sputtering) [22] | Significant | Significant [22] |

| Depth Resolution | Good (increases with depth) | Excellent (near surface) | Excellent (near surface) |

| Chemical Information | Elemental composition | Chemical state information [22] | Elemental and isotopic |

Impact of Terminology on Technical Claims

The data in Table 3 demonstrates how standardized terminology affects the interpretation of technical capabilities. For example, the term "fast" applied to GDOES versus "slow" for XPS requires definition within specific operational contexts—GDOES offers μm/min sputtering rates while XPS depth profiling typically achieves nm/min [22]. Similarly, "matrix effects" have fundamentally different meanings across techniques; GDOES exhibits "greatly reduced" matrix effects due to physical separation of sputtering and excitation, while SIMS is notoriously matrix-sensitive [22]. Without precise definitions, these qualitative descriptions would be meaningless for technique selection.

The Researcher's Guide to Standardized Reporting

Essential Terminology Standards

Implementing standardized terminology requires familiarity with key resources. The IUPAC Gold Book provides interactive access to chemical terminology [23], while the newly published Orange Book (2023) offers updated analytical chemistry terms [12]. For surface analysis specifically, IUPAC's "Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis" delivers specialized vocabulary [10]. ISO standards, particularly those related to metrology and quality concepts, provide the framework for measurement uncertainty and quality assurance [21]. The ISO House Style offers specific guidance on language use, recommending short sentences (under 20 words), direct active verbs, and consistent technical terminology [19].

Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Analysis

Table 4: Essential Materials and Reference Standards for Surface Chemical Analysis

| Material/Standard | Function | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibration, method validation [21] | Sufficiently homogeneous with established property values [21] |

| Argon Gas (GD-OES) | Plasma generation [22] | High purity (≥99.999%) |

| Conducting Adhesive Tabs | Sample mounting for XPS/SIMS | Low outgassing, minimal elemental interference |

| Charge Compensation Flood Gun | Analysis of insulating samples [22] | Low-energy electrons (0.1-10 eV) |

| Primary Ion Sources (SIMS) | Surface sputtering [22] | O₂⁺, Cs⁺, Ga⁺, Biₙ⁺ depending on application |

| Calibration Standards | Quantitative depth profiling [22] | Matrix-matched with certified layer thicknesses |

Visualization: Terminology Standards and Research Outcomes

The relationship between terminology standardization and research reproducibility can be visualized as a pathway from terminology development through to reliable scientific conclusions. The following diagram illustrates this critical pathway and the points where terminology inconsistencies can disrupt the research process.

Standardization Impact on Research Pathway

This diagram illustrates the contrasting pathways between standardized terminology use (green) and terminology inconsistencies (red). The green pathway demonstrates how IUPAC and ISO terminology development leads through standardized definitions and unambiguous method descriptions to experimental reproducibility and reliable conclusions. The red pathway shows how terminology inconsistencies create methodological ambiguity, leading to failed reproduction attempts and questioned validity of research findings.

The critical evaluation of IUPAC and ISO terminology frameworks in surface chemical analysis research demonstrates that standardized language is not merely academic preference but fundamental to scientific progress. As technique comparisons reveal, the performance characteristics of GDOES, XPS, and SIMS can only be meaningfully compared when terms like "detection limits," "depth resolution," and "matrix effects" are consistently defined and applied. The complementary roles of IUPAC's chemical expertise and ISO's measurement focus create a comprehensive terminology ecosystem that, when properly implemented, strengthens methodological descriptions and enables true experimental reproducibility. For researchers in drug development and surface analysis, conscious adoption of these standardized terminologies—referencing IUPAC's specialized glossaries [10] while adhering to ISO's metrological frameworks [21]—represents an essential step toward eliminating ambiguity and building a more reliable scientific literature. As analytical techniques evolve and interdisciplinary collaborations expand, this terminological precision will become increasingly vital for distinguishing genuine scientific advancements from irreproducible results.

Methodological Implementation: Applying Terminology to Surface Analysis Techniques

In surface chemical analysis, the precise terminology defined by international standards is not merely academic but a fundamental pillar of reproducible science. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) provides dedicated recommendations to complement the broader concepts in the International Vocabulary of Metrology (VIM), ensuring consistent application of metrological terminology in analytical chemistry [15]. This framework covers essential concepts such as measurement uncertainty, calibration, and validation, which are critical for interpreting data from techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), and Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) [15]. The drive towards standardization is further propelled by global market and technological trends; the surface analysis market, valued at USD 6.45 billion in 2025, is experiencing significant growth fueled by demand from the semiconductor and materials science sectors [24]. This growth is accompanied by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for data interpretation, enhancing precision and efficiency [24]. Framing the comparison of these techniques within the context of IUPAC and ISO terminology is therefore essential for ensuring that data and methodologies are comparable across laboratories and research fields, forming the foundation for reliable innovation.

Analytical Technique Deep Dive: Principles, Terminology, and Applications

Core Technique Comparison

The selection of an appropriate surface analysis technique is governed by the specific analytical question, required information depth, and necessary detection limits. The following table provides a comparative overview of three primary surface analysis techniques, highlighting their key characteristics and standard applications.

| Technique | Primary Information | Information Depth | Spatial Resolution | Detection Sensitivity | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPS (X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy) | Elemental identity, chemical state, empirical formula [25] | 5-10 nm | ≥ 10 µm (lab sources); ~1 µm with synchrotron [25] | 0.1 - 1 at% | Battery cathode interfaces, thin film coatings, polymer surface modification [25] |

| AES (Auger Electron Spectroscopy) | Elemental identity, chemical state (indirectly) | 2-10 nm (metals); 5-20 nm (oxides) | < 10 nm (nanoprobe systems) | 0.1 - 1 at% | Failure analysis, microelectronic device contamination, grain boundary segregation |

| TOF-SIMS (Time-of-Flight SIMS) | Molecular structure, elemental and isotopic identity, surface mapping [25] | 1-2 nm (static) | ~ 100 nm (with high current sources) | ppm - ppb (high parts-per-billion) [25] | Organic contamination analysis, polymer characterization, dopant profiling in semiconductors [25] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Adherence to standardized experimental protocols is critical for generating reliable and comparable data. Below are generalized methodologies for key applications of XPS and TOF-SIMS, which can be adapted based on specific instrument configurations and sample properties.

XPS Protocol for Battery Cathode Interface Analysis [25]

- Sample Preparation: Mount a section of the battery cathode (e.g., Lithium Cobalt Oxide - LCO) on a suitable holder using double-sided conductive tape. For air-sensitive materials, use an inert atmosphere transfer vessel.

- Instrument Setup: Insert the sample into the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) analysis chamber (base pressure ≤ 5 × 10⁻⁹ mbar). Select a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV).

- Data Acquisition:

- Acquire a wide/survey scan (pass energy 100-150 eV) to identify all elements present.

- Acquire high-resolution regional scans (pass energy 20-50 eV) for key elements (e.g., Li 1s, C 1s, O 1s, Co 2p, F 1s).

- For spatial heterogeneity, acquire XPS spectral maps or use Scanning X-ray-induced Secondary Electron Imaging (SXI) to identify regions of interest [25].

- Data Analysis:

- Perform charge referencing by setting the adventitious C 1s peak to 284.8 eV.

- Use peak fitting procedures to deconvolute chemical states (e.g., metal oxides, fluorides, carbonates).

- Calculate atomic concentrations using instrument-specific sensitivity factors.

TOF-SIMS Protocol for Organic Contaminant Identification [25]

- Sample Preparation: Secure the sample (e.g., a silicon wafer with adsorbed contaminants) on a holder. Ensure the sample is electrically grounded to minimize charging.

- Instrument Setup: Load the sample into the UHV preparation chamber (pressure ≤ 1 × 10⁻⁹ mbar) and transfer to the analysis chamber.

- Data Acquisition:

- Use a pulsed primary ion source (e.g., Bi₃⁺ or Bi₃⁺⁺ at 25-30 keV) for analysis.

- Operate in static SIMS mode (ion dose < 10¹² ions/cm²) to preserve molecular information.

- Acquire spectra in both positive and negative polarities.

- For imaging, raster the primary ion beam over the area of interest and collect mass-resolved secondary ion images.

- Data Analysis:

- Calibrate the mass scale using known peaks (e.g., CH₃⁺, C₂H₅⁺, C₃H₇⁺ in positive mode).

- Identify molecular ions and fragment patterns associated with suspected contaminants.

- Overlay ion images to correlate the spatial distribution of different chemical species.

The logical workflow for selecting and applying these techniques, from problem definition to data interpretation, can be visualized as follows.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The execution of surface analysis experiments requires a suite of specialized materials and calibrated tools. The following table details key items essential for research in this field.

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Reference Wafers (e.g., NIST) | Standardized substrates for instrument calibration and cross-laboratory comparison, ensuring measurement accuracy and traceability [24]. |

| Monochromated Al Kα X-ray Source | Provides high-energy resolution X-rays for XPS analysis, enabling precise determination of chemical states [25]. |

| Bismuth Cluster Ion Source (e.g., Bi₃⁺) | A primary ion source for TOF-SIMS that enhances the yield of high-mass molecular ions, crucial for organic surface analysis [25]. |

| Conductive Adhesive Tapes | Used for mounting insulating samples to prevent surface charging during analysis with electron or ion beams. |

| Argon Gas Cluster Ion Source | Used for depth profiling of organic materials and soft surfaces, providing gentle sputtering to preserve chemical information. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Samples with known composition and homogeneity, used for quantitative calibration and method validation [15]. |

Emerging Methods and Future Outlook

The field of surface analysis is dynamically evolving, driven by technological innovation and cross-disciplinary demands. Key emerging trends include:

- Integration of AI and Machine Learning: Instrument manufacturers are increasingly offering AI-enabled data analysis tools. These systems automate complex data interpretation tasks, such as the identification of unknown compounds in TOF-SIMS spectra and the peak fitting of XPS data, enhancing both the speed and objectivity of analysis [24].

- Advanced Multimodal Correlation: The combination of multiple techniques in a single instrument or through correlated analysis is becoming standard practice for complex problems. For instance, the combined application of XPS and TOF-SIMS provides a comprehensive view of surface and interfacial chemistry, as demonstrated in studies of engineered particle battery electrodes [25].

- Sustainability-Driven Method Development: Environmental regulations are prompting a shift towards more sustainable surface treatment and analysis methods. Non-abrasive, chemical-free technologies like laser cleaning are gaining traction for sample preparation, as they eliminate hazardous waste and align with green laboratory principles [26].

- Government-Funded Metrology Initiatives: Significant public investment is fueling the development of next-generation surface analysis methods. Programs such as the European Partnership on Metrology (with approximately USD 810 million in funding) and Japan's national science and technology budgets specifically support the advancement of nano-characterization tools like AFM, XPS, and SIMS [24].

Within the rigorous framework established by IUPAC and ISO, techniques like XPS, AES, and TOF-SIMS provide powerful, complementary tools for deciphering surface chemistry. A clear understanding of their specific terminology, operational principles, and standardized protocols is indispensable for generating reliable data. As the field progresses, the convergence of these established methods with AI-driven analytics, correlative multimodal approaches, and sustainable practices will undoubtedly unlock new levels of insight, driving innovation in sectors ranging from renewable energy to advanced medicine.

Surface chemical analysis is a discipline where precision in terminology is paramount, as the exact definition of a "surface" directly influences experimental design, data interpretation, and cross-disciplinary communication. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) provides a formal vocabulary of terms specifically for surface analysis concepts, aiming to give clear definitions to those who utilize surface chemical analysis or need to interpret its results but are not themselves surface chemists or surface spectroscopists [10]. This guide objectively compares the IUPAC terminology framework against other standardization bodies, primarily the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), focusing on their application in pharmaceutical research and drug development. The critical importance of this standardization is underscored by its role in ensuring the reproducibility and reliability of analytical data, which forms the foundation of regulatory submissions and quality control in drug development.

Comparative Analysis: IUPAC vs. ISO Terminology Frameworks

Core Definitions in Surface Analysis

A fundamental difference in approach can be observed in how these organizations define the most basic concept in the field: the surface itself. IUPAC recommends a nuanced distinction between three related concepts for the purpose of surface analysis [4]:

- Surface: The 'outer portion' of a sample of undefined depth; to be used in general discussions of the outside regions of the sample.

- Physical Surface: That atomic layer of a sample which, if the sample were placed in a vacuum, is the layer 'in contact with' the vacuum; the outermost atomic layer of a sample.

- Experimental Surface: That portion of the sample with which there is significant interaction with the particles or radiation used for excitation. It is the volume of sample required for analysis or the volume corresponding to the escape for the emitted radiation or particle, whichever is larger.

This tripartite distinction is characteristic of the IUPAC framework, which seeks to provide a precise, concept-oriented taxonomy that clarifies the scope and limitations of different analytical techniques. In contrast, ISO standards often integrate terminology within the context of specific methodological protocols, focusing on operational consistency across laboratories.

Greenness of Standard Methods: A Performance Comparison

While terminology provides the language for communication, the practical performance and sustainability of analytical methods are critical for modern laboratories. A recent IUPAC project, "Greenness of official standard sample preparation methods" (2021-015-2-500), conducted a comprehensive assessment of 174 CEN, ISO, and pharmacopoeia standard methods and their 332 sub-method variations [27]. The study used the AGREEprep metric to evaluate greenness, revealing significant insights into the current state of standard methods.

Table 1: Greenness Performance of Official Standard Methods by Field of Analysis

| Field of Analysis | Percentage of Methods Scoring Below 0.2 (on a 0-1 scale) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental/Organic Analysis | 86% | Heaviest reliance on resource-intensive, outdated techniques. |

| Food Analysis | 62% | Poor performance on key greenness criteria. |

| Inorganic/Trace Metals Analysis | 62% | Significant room for improvement in sustainability. |

| Pharmaceutical Analysis | 45% | Relatively better, but still sub-optimal performance. |

The results revealed a generally poor greenness performance, with 67% of all methods scoring below 0.2, where 1 represents the highest possible score [27]. This discrepancy highlights a critical conflict between traditional methodologies and global sustainability efforts. The findings serve as a call to action for updating standard methods by incorporating more contemporary, sustainable sample preparation techniques, a goal aligning with IUPAC's mission to promote advancements in chemical practice.

Experimental Protocols for Terminology Validation and Method Greenness Assessment

Protocol for Validating Surface-Specific Terminology in Analytical Documentation

1. Objective: To audit and compare analytical method documentation (e.g., from IUPAC, ISO, or pharmacopoeias) for consistency and clarity in the application of surface-specific terminology. 2. Materials: Official method documents, IUPAC Gold Book terminology database, controlled vocabulary list. 3. Procedure: * Step 1: Extract all terms related to the sample region of interest (e.g., "surface," "interface," "bulk," "layer") from the method document. * Step 2: Cross-reference each term with its formal definition in the IUPAC Gold Book and relevant ISO standards [4]. * Step 3: Score the clarity of the methodological description based on the unambiguous use of these terms. A high score is given if the method explicitly defines its "experimental surface" according to the technique used (e.g., XPS, SIMS). * Step 4: Quantify the potential for misinterpretation by identifying terms used inconsistently or without definition. 4. Data Analysis: The protocol generates a quantitative score for terminological clarity, allowing for an objective comparison between how different standardization bodies integrate foundational concepts into their practical guidelines.

Protocol for Assessing the Greenness of a Sample Preparation Method