Ionic Migration Dynamics on Perovskite Quantum Dot Surfaces: Mechanisms, Control Strategies, and Biomedical Applications

This article comprehensively explores the dynamics of ionic migration across the surfaces of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical factor influencing their stability and functionality.

Ionic Migration Dynamics on Perovskite Quantum Dot Surfaces: Mechanisms, Control Strategies, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the dynamics of ionic migration across the surfaces of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical factor influencing their stability and functionality. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it delves into the fundamental principles driving ion movement, advanced characterization and control methodologies, strategies for troubleshooting performance loss, and comparative analyses of effectiveness for biomedical applications. By synthesizing the latest research, this review establishes a framework for harnessing ionic migration to engineer next-generation PQD-based platforms for drug delivery, biosensing, and diagnostic imaging, bridging materials science with clinical translation.

Unraveling the Fundamentals: What Drives Ionic Migration on PQD Surfaces?

Defining Ionic Migration in the Soft Lattice of Halide Perovskites

Ionic migration refers to the movement of ions within the crystal lattice of a material under the influence of external stimuli such as an electric field, light, or heat. In halide perovskites, this phenomenon is particularly pronounced due to their intrinsic soft ionic lattice and mixed ionic-electronic conduction properties [1] [2]. The soft lattice, characterized by weak bonding and low formation energies for defects, allows for significant ionic movement, which dominates many of the anomalous phenomena observed in perovskite devices, including hysteresis, phase segregation, and slow response times [3]. Understanding and quantifying this ion migration is therefore a critical research gap that must be addressed to stabilize perovskite devices and enable their widespread commercialization [4] [1].

This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of ionic migration, framing the discussion within the broader context of ionic migration dynamics in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces research. It details the fundamental mechanisms, quantitative assessment techniques, and experimental protocols essential for researchers and scientists working to control ionic activity for enhanced device performance and longevity.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Theoretical Frameworks

Ionic migration in halide perovskites is a solid-state electrochemical phenomenon wherein vacancies and interstitial defects facilitate the hopping of ions through the crystal lattice [2]. The primary mobile species are typically halide anions (e.g., I⁻, Br⁻) and A-site cations (e.g., MA⁺, FA⁺), although the specific mobility depends on the composition and structure of the perovskite [1].

The Role of the Soft Lattice

The "soft" nature of the halide perovskite lattice, with its low elastic moduli and weak chemical bonding, results in low activation energies for defect migration. This structural softness is a double-edged sword: it contributes to the remarkable optoelectronic properties of perovskites but also makes them inherently prone to ionic movement, even under mild external biases [1] [2]. This movement can lead to deleterious effects such as:

- Chemical degradation: Ionic migration can facilitate reactions with electrode materials or environmental species [4].

- Phase segregation: In mixed-halide perovskites, ion migration can lead to the formation of halide-rich domains, undermining optoelectronic performance [3].

- Electronic band distortion: The accumulation of ions at interfaces and grain boundaries creates strong local electric fields that can distort the electronic band structure [2].

Table 1: Key Ion Migration Measurement Techniques and Representative Data

| Technique | Measured Parameter | Representative Value | Material System | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-contact PL Microscopy [2] | Ion Mobility | (2.56 ± 0.67) × 10⁻¹⁰ cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹ | Single-crystal MAPbBr₃ | Room Temperature, Non-contact |

| Light-Enhanced Transport [3] | Activation Energy (Eₐ) | 0.82 eV (dark) → 0.15 eV (light, 20 mW/cm²) | MAPbI₃ Thin Film | 17-295 K, Under Illumination |

| High-Field Poling [3] | Ionic Conductance | Obtained via cryogenic galvanostatic measurement | MAPbI₃ | Lateral Au/MAPbI₃/Au Structure |

Theoretical and Computational Toolsets

Theoretical modeling plays a crucial role in understanding ion migration. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, particularly with the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method, are widely used to calculate migration barriers (Eₘ), which correspond to the energy required for an ion to hop between two stable lattice sites [5] [1]. However, DFT-NEB can be computationally expensive and may underestimate Eₘ by 0.1–0.3 eV [5].

Empirical force fields like the Bond Valence Site Energy (BVSE) method offer a faster alternative for calculating percolation barriers, which represent the minimal energy barrier for infinite diffusion through the crystal, showing good correlation with DFT and experimental results [5]. Recently, Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as a powerful tool, enabling large-scale molecular dynamics simulations with near-DFT accuracy but at a fraction of the computational cost [5] [6]. Universal MLIPs like CHGNet and M3GNet are trained on diverse chemical spaces and can be fine-tuned for specific tasks, such as modeling the complex, charge-coupled dynamics of transition metal migration in materials like Mn-rich disordered rocksalt cathodes [6].

Quantitative Assessment and Data Presentation

Accurately quantifying ion migration is essential for understanding its impact and developing mitigation strategies. The following data, consolidated from recent studies, provides key quantitative benchmarks for the field.

Table 2: Computational Methods for Predicting Ionic Migration

| Computational Method | Key Parameter | Typical Use Case | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT-NEB [5] | Migration Barrier (Eₘ) | Precise hop barrier calculation | High accuracy for specific pathways | Computationally expensive; underestimates Eₘ by 0.1-0.3 eV |

| BVSE [5] | Percolation Barrier (Eₐ) | High-throughput screening | Fast; good correlation with DFT/experiment | Empirical force field; less precise |

| AIMD [5] | Ionic Conductivity | Direct evaluation of ionic mobility | Captures lattice dynamics & correlation effects | Extremely computationally demanding |

| uMLIP (e.g., CHGNet) [5] [6] | Migration Trajectory & Barrier | Large-scale MD simulations of complex processes | Near-DFT accuracy, lower cost | Requires fine-tuning for specific chemistries |

Experimental Protocols for Probing Ionic Migration

Non-Contact Measurement of Ion Mobility via PL Microscopy

This protocol details a method to measure intrinsic ion mobility in single perovskite particles without direct electrical contact, thereby decoupling interfacial effects from bulk ion migration [2].

- Objective: To obtain the intrinsic ion mobility of single MAPbBr₃ particles in a non-contact manner.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Interpenetrating Electrode Device: Fabricated on a quartz substrate with a 10 μm gap [2].

- MAPbBr₃ Perovskite Particles: Synthesized and spin-coated onto the device.

- PL Microscopy System: Equipped with a high-sensitivity camera and appropriate laser excitation.

- Function Generator & Voltage Amplifier: To apply a modulated electric field (e.g., square wave, 130 kV/cm).

- Data Acquisition Card: To synchronize voltage application and PL signal recording.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Spin-coat a diluted MAPbBr₃ solution onto the interpenetrating electrode device to grow isolated single particles in situ. Ensure the studied particles are on the bare quartz substrate in the middle of the electrode gap, not in direct contact with the electrodes [2].

- Electric Field Application: Apply a periodic square-wave electric field (e.g., 130 kV/cm, 30-second period) across the electrodes using the function generator and voltage amplifier.

- PL Image Acquisition: Simultaneously record the PL intensity of the individual particles under the modulated electric field. The acquisition should be synchronized with the voltage signal.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the evolution of PL intensity versus time.

- Calculate the Switching Efficiency (SE) using the formula: ( SE = (I{OFF} - I{ON}) / I{OFF} ), where ( I{OFF} ) and ( I_{ON} ) are the PL intensities with the field off and on, respectively [2].

- Analyze the polarization and recovery dynamics (time constants) from the PL intensity trajectory.

- Correlate the dynamics with particle size and electric field strength to calculate intrinsic ion mobility, which was found to be ((2.56 ± 0.67) \times 10^{-10} \, \text{cm}^2 \, \text{V}^{-1} \, \text{s}^{-1}) for MAPbBr₃ [2].

- Key Considerations: The non-contact setup is crucial for avoiding carrier injection and interfacial charge transport effects. The slow, second-scale PL dynamics are attributed to ion migration, as opposed to nanosecond-scale electronic processes [2].

Quantifying Light-Enhanced Ionic Transport

This protocol measures the influence of light illumination on ionic transport parameters, such as activation energy, across a wide temperature range [3].

- Objective: To quantitatively demonstrate the reduction of ionic transport activation energy under photoexcitation.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Lateral Device Structure: A patterned substrate (e.g., glass) with Au electrodes (e.g., 50 μm gap).

- MAPbI₃ Perovskite Film: Deposited onto the substrate covering the electrode gap.

- Cryogenic Station: Capable of maintaining temperatures from 17 K to room temperature.

- Precision Source/Measure Unit: For current-voltage (I-V) and galvanostatic measurements.

- Light Source: A fiber optic illuminator with adjustable intensity (0-20 mW cm⁻²).

- Procedure:

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate a lateral Au/MAPbI₃/Au device using a hard mask or lithography. Mount the device in the cryogenic station.

- Cryogenic Measurement: For a set of temperatures (e.g., from 17 K to 295 K), perform cryogenic galvanostatic and I-V measurements under different light intensities (0, 0.05, 1, 5, and 20 mW cm⁻²) [3].

- Conductance Separation: At each temperature and light intensity, separate the total measured conductance into its electronic and ionic components. This can be achieved by analyzing the transient response in galvanostatic measurements, where the instantaneous jump corresponds to electronic conductance and the slow relaxation corresponds to ionic conductance [3].

- Activation Energy Calculation:

- Plot the extracted pure ionic conductance as an Arrhenius plot (log of conductance vs. 1/T) for each light intensity.

- Fit the data to the Arrhenius equation. The slope of the fit is proportional to the activation energy (Eₐ) for ionic transport.

- Expected Outcome: A significant reduction in activation energy with increasing light intensity. For MAPbI₃, Eₐ decreases from ~0.82 eV in the dark to ~0.15 eV under 20 mW cm⁻² illumination [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Ion Migration Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Interpenetrating Electrode Device [2] | Creates a non-contact electric field to polarize samples for intrinsic property measurement. | Non-contact PL measurement of ion mobility in single particles. |

| Lateral Au/MAPbI₃/Au Device [3] | Standard platform for applying in-plane electric fields and measuring lateral transport. | High-field poling experiments and cryogenic I-V measurements. |

| Methylammonium Halide (MAI) [3] | Organic precursor for synthesizing hybrid organic-inorganic halide perovskites (e.g., MAPbI₃, MAPbBr₃). | Sample fabrication for ion migration studies. |

| Lead(II) Iodide (PbI₂) [3] | Inorganic precursor for perovskite synthesis. | Used in sequential deposition methods for perovskite formation. |

| Bond Valence Site Energy (BVSE) Model [5] | Empirical force field for rapid calculation of ion percolation barriers. | High-throughput computational screening of ionic conductors. |

| Universal ML Interatomic Potentials (uMLIPs) [5] [6] | Machine-learned potentials for large-scale molecular dynamics with near-DFT accuracy. | Modeling complex phase transformations and ion migration trajectories. |

Ionic migration in the soft lattice of halide perovskites is a defining characteristic that underpins both the promise and the challenges of this material class. A comprehensive understanding, achieved through the synergistic application of advanced experimental techniques like non-contact PL microscopy and robust computational tools like machine learning interatomic potentials, is paramount. The precise quantification of parameters such as ion mobility and activation energy, and the development of strategies to control ionic movement, are critical steps toward overcoming stability issues and unlocking the full potential of halide perovskites in next-generation optoelectronic devices.

Metal halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), with the general formula ABX₃ (where A is a cation, B is a metal cation, and X is a halide anion), have emerged as a revolutionary class of semiconductor nanomaterials for optoelectronic applications. Their exceptional properties—including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), tunable bandgaps, and defect tolerance—are intrinsically linked to their ionic crystal nature [7] [8]. However, this ionic character is a double-edged sword, as it facilitates ion migration within the perovskite lattice, which is a primary factor influencing both the performance and operational stability of PQD-based devices [8]. The dynamics of halide anions (I⁻, Br⁻), A-site cations (Cs⁺, FA⁺), and B-site metal ions (Pb²⁺) at surfaces and interfaces dictate critical processes such as phase segregation, non-radiative recombination, and structural degradation [9] [8]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the roles and migration behaviors of these key mobile ions, framing the discussion within the broader research context of controlling ionic dynamics to enhance the functional longevity of PQD technologies.

The Roles and Dynamics of Halide Anions (I⁻, Br⁻)

Structural and Optoelectronic Functions

Halide anions (X-site) form [BX₆]⁴⁻ octahedra, the fundamental building blocks of the perovskite crystal structure. The identity of the halide directly controls the material's bandgap and, consequently, its optical emission and absorption characteristics. Mixed halide perovskites (e.g., CsPbIₓBr₃₋ₓ) allow for continuous bandgap tuning across the visible spectrum [10] [11]. Despite their crucial role, halide ions are highly mobile due to their relatively low migration energy barriers, which makes them the most prevalent migratory species in the perovskite lattice [8].

Migration Mechanisms and Consequences

The primary mechanism for halide migration is believed to be vacancy-assisted diffusion [8]. The low formation energy of halide vacancies (Vₓ) facilitates their creation, providing pathways for adjacent halide ions to hop into these vacant sites. This process is accelerated by external stimuli such as electric fields, light, and heat [10].

Ion migration, particularly in mixed-halide systems, leads to several detrimental phenomena:

- Phase Segregation: Under illumination or electrical bias, halides can demix, leading to the formation of I-rich and Br-rich domains. This segregation causes undesirable changes in the emission spectrum and open-circuit voltage losses in solar cells [10].

- Non-Radiative Recombination: The movement of halide ions can create and mobilize deep-level traps within the bandgap, which act as centers for non-radiative recombination, thereby reducing PLQY and device efficiency [8] [11].

- Structural Instability: Progressive halide migration can initiate the decomposition of the perovskite crystal structure, ultimately leading to the formation of PbI₂ or other degradation products [9].

Table 1: Characteristics and Migration Behaviors of Key Halide Anions

| Halide Ion | Ionic Radius (Å) | Key Role | Migration Energy (eV) | Primary Instability Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iodide (I⁻) | ~2.20 | Red-shifted emission, narrow bandgap [10] | Low (est. < 0.1-0.5) | Phase segregation, photo-induced halide migration [10] |

| Bromide (Br⁻) | ~1.96 | Green emission, moderate bandgap [10] | Low (est. < 0.1-0.5) | Phase segregation in mixed halides, defect formation [8] |

The Roles and Dynamics of A-Site Cations (Cs⁺, FA⁺)

Structural Stabilization and Electronic Effects

A-site cations, situated in the cuboctahedral cavities of the [BX₆]⁴⁻ framework, are crucial for stabilizing the perovskite crystal structure. The Goldschmidt tolerance factor (t), which depends on the ionic radii of the A, B, and X ions, is a key predictor of structural stability [11]. While traditionally considered spatially confined, A-site cations, particularly smaller ions like Cs⁺, exhibit a degree of mobility that can significantly impact material properties [7] [9].

- Cesium (Cs⁺): The small ionic radius of the all-inorganic Cs⁺ cation helps stabilize the perovskite lattice against moisture-induced degradation compared to organic cations. However, Cs-rich PQDs are prone to thermally-induced phase transitions from the black γ-phase to a non-perovskite yellow δ-phase [9].

- Formamidinium (FA⁺): The larger organic FA⁺ cation contributes to a more ideal tolerance factor, often resulting in a narrower bandgap and enhanced orbital overlap, which leads to longer carrier lifetimes [7]. FA-rich PQDs exhibit stronger electron–longitudinal optical (LO) phonon coupling, which can dissociate photogenerated excitons [9].

Cation Exchange as a Migration Pathway

A prominent manifestation of A-site cation mobility is the post-synthetic cation-exchange process [7]. This reaction is driven by concentration gradients and a dynamic surface structure, allowing for the synthesis of mixed A-site (e.g., Cs₁₋ₘFAₘPbI₃) PQDs with tailored properties. The kinetics of this exchange are influenced by the surrounding chemical environment, including cation species, stoichiometric ratios, and surface ligand conditions [7]. The exchange process is theorized to proceed via a cation vacancy-assisted model, where vacancies on the A-site facilitate the exchange of cations between the solution and the crystal lattice [7].

Table 2: Comparison of A-Site Cations in PQDs

| A-Site Cation | Ionic Radius (Å) | Tolerance Factor (t) in Pb-I lattice | Key Optical Property | Thermal Degradation Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cesium (Cs⁺) | ~1.88 | ~0.89 [11] | Wider bandgap, stable blue emission [9] | Phase transition from γ-phase to δ-phase [9] |

| Formamidinium (FA⁺) | ~2.2-2.8 | ~0.99-1.06 [7] | Narrow bandgap, longer carrier lifetime [7] | Direct decomposition to PbI₂ [9] |

The Role and Stability of B-Site Metal Ions (Pb²⁺)

The B-site cation, typically lead (Pb²⁺), is the cornerstone of the perovskite octahedral structure. It forms strong covalent bonds with the surrounding halide anions, creating the [PbX₆]⁴⁻ octahedra that define the electronic band structure of the material. Pb²⁺ is responsible for the characteristic defect tolerance of lead halide perovskites, where certain intrinsic defects do not form deep-level traps within the bandgap [12] [11].

Compared to halide anions and A-site cations, the Pb²⁺ ion is significantly less mobile due to its higher charge and larger migration energy barrier [8]. Its primary role is structural integrity rather than long-range migration. However, the detachment of surface ligands can create unsaturated "dangling bonds" on Pb²⁺ atoms, which act as surface trap states, quenching luminescence and accelerating degradation [8] [11]. Furthermore, the potential release of toxic Pb²⁺ upon environmental degradation of PQDs remains a major concern for commercial applications, driving research into stable encapsulation strategies and less toxic lead-free alternatives [12] [13].

Experimental Protocols for Studying Ion Dynamics

In Situ Characterization of Ion Migration and Stability

Purpose: To directly observe the real-time structural and optical changes in PQDs induced by ion migration under external stress (e.g., heat). Materials:

- PQD Sample: Colloidally synthesized CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃ PQDs with full compositional range (x = 0 to 1) [9].

- Instrumentation: In-situ X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) equipped with a heating stage; In-situ Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy setup with temperature control; Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) [9].

- Environment Control: Argon gas flow to prevent oxidative degradation during heating [9].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Deposit a thin, uniform film of PQDs onto a suitable substrate (e.g., Pt, silicon wafer).

- Temperature Ramp: Place the sample in the characterization instrument and program a controlled temperature ramp from room temperature (e.g., 30°C) to 500°C at a defined rate (e.g., 5-10°C/min).

- Simultaneous Data Collection:

- In-situ XRD: Continuously collect XRD patterns throughout the heating process. Monitor the appearance, disappearance, and shift of diffraction peaks corresponding to the perovskite black phase (γ/α), non-perovskite yellow phase (δ), and PbI₂ [9].

- In-situ PL: Track changes in the PL intensity, peak position, and full width at half maximum (FWHM) to correlate structural changes with optoelectronic properties [9].

- TGA: Measure the sample's weight loss to identify the decomposition temperature of organic components (e.g., FA⁺, ligands) [9].

- Data Analysis: Correlate the data from all techniques to establish composition-dependent degradation mechanisms. For instance, determine that Cs-rich PQDs degrade via a γ-to-δ phase transition, while FA-rich PQDs with higher ligand binding energy decompose directly into PbI₂ [9].

Post-Synthetic Cation Exchange for Mixed A-Site PQDs

Purpose: To synthesize mixed A-site PQDs (e.g., Cs₁₋ₘFAₘPbI₃) with precise control over composition and optical properties via a cation-exchange reaction. Materials:

- Parent PQDs: Purified colloidal suspension of single-cation PQDs (e.g., CsPbI₃ PQDs) [7].

- Cation Source: Solution of formamidinium oleate (FA-OA) or a colloidal suspension of a different single-cation PQD (e.g., FAPbI₃ PQDs) [7].

- Solvents: Non-polar solvents like hexane or octane.

- Ligands: Oleic acid (OA) and Oleylamine (OAm) to maintain colloidal stability during exchange [7].

- Environment: Inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂ glovebox) to prevent degradation.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Characterize the parent PQDs (CsPbI₃) to determine initial absorption, PL, and size.

- Reaction Setup: In an inert environment, add a controlled stoichiometric amount of the FA⁺ cation source (FA-OA solution or FAPbI₃ PQD suspension) to the parent PQD solution [7].

- Kinetic Control: Stir the mixture at a controlled temperature (e.g., room temperature or slightly elevated). The exchange kinetics are regulated by factors like solvent polarity, ligand concentration, and temperature [7].

- Monitoring: Periodically extract aliquots and characterize them using UV-Vis absorption and PL spectroscopy to track the shift in the bandgap and emission peak toward longer wavelengths (red-shift) as FA⁺ incorporates into the lattice [7].

- Termination and Purification: Once the desired optical properties are achieved, terminate the reaction by adding an antisolvent (e.g., methyl acetate) to precipitate the mixed-cation PQDs. Centrifuge and redisperse the purified PQDs in a non-polar solvent [7].

Visualization of Ion Dynamics and Experimental Workflows

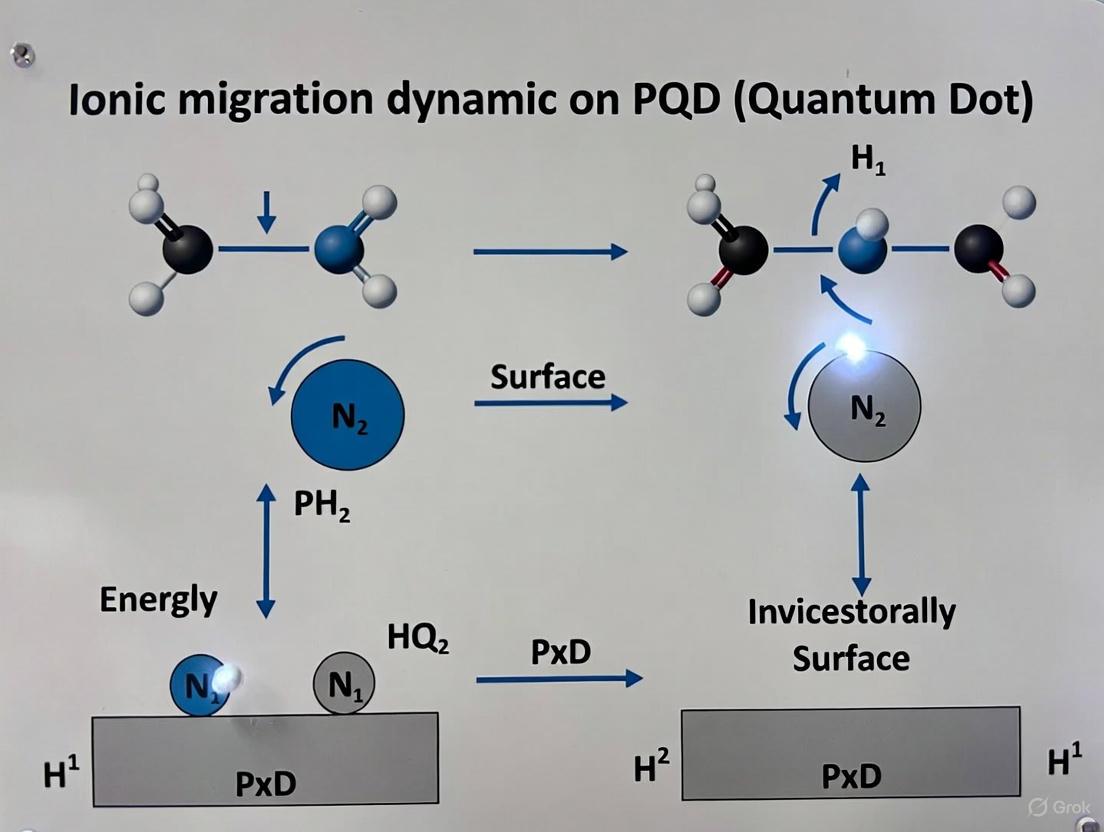

Pathways of Ion Migration in Perovskite Quantum Dots

The following diagram illustrates the primary migration pathways and key dynamic processes of ions within a PQD lattice and at its surface.

Diagram 1: Pathways of ion migration and degradation in PQDs, highlighting internal halide and A-site cation mobility, as well as surface processes like ligand detachment that lead to ion release and structural instability.

Workflow for Investigating PQD Ion Dynamics

This flowchart outlines a comprehensive experimental methodology for synthesizing PQDs, inducing ion exchange, and characterizing the resulting stability and ion dynamics.

Diagram 2: Integrated experimental workflow for probing ion dynamics in PQDs, from synthesis and modification to in-situ/ ex-situ characterization and data modeling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PQD Synthesis and Ion Exchange Studies

| Reagent / Material | Typical Function | Technical Explanation & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | A-site precursor for Cs⁺ cation. | Reacts with fatty acids (e.g., oleic acid) to form Cs-oleate, the common Cs⁺ source in hot-injection synthesis of CsPbX₃ PQDs [7]. |

| Formamidinium Acetate (FAAc) | A-site precursor for FA⁺ cation. | Used in cation-exchange reactions; the FA⁺ ion replaces a portion of Cs⁺ in pre-synthesized CsPbX₃ PQDs to form mixed-cation systems (Cs₁₋ₘFAₘPbX₃) [7]. |

| Lead Bromide/Iodide (PbBr₂/PbI₂) | B-site and halide precursor. | Provides Pb²⁺ and halide ions (Br⁻, I⁻) for the perovskite framework. The purity and stoichiometry are critical for controlling crystal growth and defect density [11]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Surface capping ligands. | Dynamic ligands that passivate surface defects, control nanocrystal growth, and provide colloidal stability. Their weak binding is a primary source of instability [8] [11]. |

| Methyl Acetate / Methyl Benzoate | Antisolvent for purification and rinsing. | Polar solvents that precipitate PQDs or rinse films to remove excess ligands without dissolving the perovskite core. They can hydrolyze to provide short-chain ligands (e.g., acetate) for X-site ligand exchange [14]. |

| 2-Aminoethanethiol (AET) | Post-synthesis ligand for stabilization. | A short-chain, bidentate ligand with a strong affinity for Pb²⁺. Used in post-treatment to replace OA/OAm, creating a dense passivation layer that enhances stability against water and UV light [8]. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Alkaline catalyst for ligand exchange. | Used to create an alkaline environment that facilitates the hydrolysis of ester antisolvents (e.g., methyl benzoate), making the substitution of long-chain insulating ligands with short conductive ones more efficient and rapid [14]. |

The dynamics of halide anions, A-site cations, and B-site metal ions are fundamental to the performance and stability of perovskite quantum dots. While halide mobility presents challenges for spectral stability, A-site cation exchange offers a powerful tool for compositional and bandgap tuning. The relative immobility of the B-site cation underpins structural integrity but necessitates careful surface passivation.

Future research must focus on decoupling ion migration from device operation. This will involve the development of advanced ligand systems that strongly bind to the PQD surface, suppressing both halide vacancy formation and A-site cation migration [8] [14]. Furthermore, engineering core-shell heterostructures or implementing crosslinking strategies could provide a physical barrier to ion diffusion. The insights from studying lead-based systems must also guide the design of lead-free alternatives (e.g., based on Bi³⁺ or Sn²⁺) that inherently possess higher ionic migration barriers [12] [13]. A multidisciplinary approach, integrating precise synthesis, advanced in-situ characterization, and theoretical modeling, is essential to fully understand and control ionic migration dynamics, thereby unlocking the full commercial potential of perovskite quantum dots.

Ionic migration within perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) is a double-edged sword. While it can induce deleterious degradation mechanisms in optoelectronic devices, its precise control also offers avenues for enhancing material properties and functionalities. The dynamics of these ion movements are not random; they are fundamentally governed by the nanoscale surface topography of the PQDs. This whitepaper delves into the critical, yet often overlooked, relationship between the surface energy landscape—sculpted by crystal curvature and exposed facets—and the guided pathways of ion migration. Framed within a broader thesis on ionic migration dynamics at PQD surfaces, this analysis synthesizes recent research to provide a technical guide for controlling ion transport through intelligent surface design. Understanding these principles is paramount for researchers and scientists aiming to develop next-generation PQD-based devices with unparalleled performance and operational stability.

The Surface Energy Landscape of PQDs

The surface of a perovskite quantum dot is a dynamic interface where its crystalline structure terminates, creating an environment rich in unsaturated bonds and, consequently, elevated surface energy. This energy landscape is not uniform; it is primarily determined by two interconnected geometric factors: local curvature and crystallographic facet expression.

Surface Curvature: At the nanoscale, regions with high positive curvature, such as sharp edges and vertices, exhibit a lower coordination number for surface atoms compared to flat planes. This atomic under-coordination makes these sites high-energy "hot spots." The inherent thermodynamic drive to minimize total system energy makes these sites particularly susceptible to ion adsorption, desorption, and migration. Conversely, flatter regions or negative curvatures represent lower-energy pathways or stable resting points for mobile ions. This energy gradient directly pulls ions from high-curvature to low-curvature regions.

Crystallographic Facets: A PQD is enclosed by a set of distinct crystal planes, or facets, each with a unique atomic arrangement and surface energy. For instance, in formamidinium lead iodide (FAPbI3), the (100) and (111) facets display markedly different stabilities. Research has shown that the (100) facet is significantly more susceptible to degradation from environmental factors like moisture compared to the (111) facet [15]. This implies that the activation energy for ion migration (e.g., the vacancy-mediated diffusion of iodide ions) is facet-dependent. A surface dominated by higher-energy facets will generally provide a lower-energy barrier for ionic motion, facilitating faster migration, while stable, low-energy facets can effectively pin ions in place.

The interplay between curvature and facet creates a complex energy map across the PQD surface. This map acts as a template, directing the preferential movement of ions such as iodide (I⁻), lead (Pb²⁺), and organic cations (e.g., FA⁺ or MA⁺) along specific trajectories, thereby dictating the material's evolution under operational stress.

Quantitative Data on Facet-Dependent Stability

The influence of specific crystallographic facets on PQD stability is not merely theoretical; it is quantitatively demonstrated through controlled experiments. The strategic stabilization of certain facets has led to direct improvements in key device performance metrics.

The table below summarizes empirical data on facet-dependent properties and their outcomes in solar cell devices:

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Facet-Dependent Stability in Perovskite Solar Cells

| Perovskite Material | Targeted Facet | Experimental Strategy | Key Outcome | Device Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAPbI3 [15] | (111) | Used cyclohexylamine additive to selectively promote (111) facet growth. | 95% retention of initial performance after ∼2000 hours at 30-40% relative humidity (unencapsulated). | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) of 24%. |

| FAPbI3 [15] | (100) | Control sample without facet-controlling additive. | Higher degradation rate when exposed to moisture. | Lower stability and performance compared to (111)-facet dominated samples. |

| Dion-Jacobson 2D Perovskite [15] | N/A (Phase-Pure) | Tri-solvent engineering to achieve pure-phase, oriented grains. | 95% retention for >3000 hours in air at 85°C with 60-90% relative humidity. | PCE of 17.27% for MA-free DJ 2D PSC. |

The data clearly indicates that surfaces dominated by the (111) facet in FAPbI3 exhibit superior stability against moisture-induced degradation compared to (100)-facet dominated surfaces [15]. This enhanced stability is directly linked to a reduced propensity for ion migration and structural decomposition at the surface. Furthermore, achieving phase-purity and fine control over the quantum well structure in low-dimensional perovskites, as in the Dion-Jacobson phase, represents an advanced form of facet and grain boundary engineering that profoundly suppresses ionic migration, leading to exceptional long-term stability under harsh environmental testing [15].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Ion Movement

To systematically study the connection between surface topography and ion migration, researchers employ a suite of advanced characterization and testing protocols. The following workflow outlines a typical integrated experimental approach.

Diagram 1: Integrated experimental workflow for investigating ion movement in PQDs.

Detailed Methodologies

1. Sample Synthesis and Facet Engineering

- Objective: To synthesize PQDs with controlled dominance of specific crystallographic facets.

- Protocol:

- Precursor Preparation: Prepare lead iodide (PbI₂) and formamidinium iodide (FAI) in suitable polar solvents (e.g., DMF/DMSO).

- Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation: Rapidly inject the perovskite precursor into a non-solvent (e.g., toluene) containing coordinating ligands (e.g., oleic acid and oleylamine) under vigorous stirring to induce nucleation and growth of PQDs.

- Facet Control: Introduce facet-directing agents (e.g., cyclohexylamine with a boiling point of 134°C) into the non-solvent. The additive selectively binds to certain crystal planes, inhibiting their growth and promoting the dominance of target facets like (111) [15].

- Purification: Centrifuge the resulting colloidal solution to remove unreacted precursors and aggregates. The PQD pellet is then redispersed in an anhydrous solvent for further use.

2. Structural and Surface Analysis

- Objective: To characterize the crystal structure, facet composition, and surface morphology of the synthesized PQDs.

- Protocol:

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Acquire high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images to directly observe the crystal lattice, measure interplanar spacings, and identify the dominant facets enclosing the PQDs.

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Perform XRD analysis on PQD films. The relative intensity of diffraction peaks (e.g., (100) vs. (111)) provides quantitative information on the preferred crystal orientation and facet distribution.

3. Ion Migration Assessment

- Objective: To directly probe the dynamics and pathways of ion migration.

- Protocol:

- Thermally Stimulated Current (TSC) Measurement: Place a PQD film between two electrodes. Heat the device at a constant rate while applying a DC bias. The resulting current, caused by the release of trapped ions, is measured. The temperature peaks in the TSC spectrum correspond to different ionic species and their activation energies for migration.

- Scanning Kelvin Probe Microscopy (SKPM): Use an atomic force microscope (AFM) with a conductive probe to map the surface potential of a PQD film under bias and/or illumination. Redistribution of mobile ions changes the local work function, which is detected as a shift in contact potential difference, allowing for visualization of ion migration pathways.

4. Device Fabrication and Operational Stability Testing

- Objective: To correlate surface-induced ion migration with device-level performance and degradation.

- Protocol:

- Solar Cell Fabrication: Fabricate PSCs in either n-i-p or p-i-n architecture. Spin-coat the synthesized PQDs as the active layer onto a charge transport layer (e.g., SnO₂). Deposit subsequent layers and metal electrodes as per standard procedures [15].

- Maximum Power Point (MPP) Tracking: Operate the encapsulated or unencapsulated devices at their MPP under continuous simulated sunlight (e.g., 1 sun illumination at AM 1.5G). Monitor the PCE as a function of time (e.g., over 1000-2000 hours) to assess operational stability [15]. The decay rate is a direct indicator of the robustness of the PQD surface against ion-migration-induced degradation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental pursuit of stable PQDs requires a carefully selected toolkit of reagents and materials. The following table catalogues essential items used in the featured research for controlling surface properties and mitigating ion migration.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Surface and Ion Migration Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclohexylamine [15] | A high-boiling-point amine additive that acts as a facet-directing agent. | Selectively promotes the growth of the stable (111) facet in FAPbI3 perovskites, thereby reducing surface energy and enhancing moisture resistance. |

| Uracil [15] | A biomolecule used as a multi-functional binder and passivant. | Strengthens grain boundaries and effectively passivates surface defects, improving the mechanical and ionic stability of perovskite films. |

| Oleic Acid & Oleylamine | Common surface-capping ligands used in colloidal nanocrystal synthesis. | Coordinate to surface atoms during PQD growth, controlling size and shape, and providing initial stabilization against aggregation and oxidation. |

| Guanabenz Acetate Salt [15] | A chemical agent used for ambient-air fabrication. | Prevents perovskite hydration by shielding the surface from water molecules, obviating both anion and cation vacancies that facilitate ion migration. |

| β-poly(1,1-difluoroethylene) (β-pV2F) [15] | A polymer with an ordered dipolar structure. | Used in strain-engineering to stabilize the perovskite black phase and control energy alignment at interfaces, reducing ionic mobility under thermal cycling. |

| Alkyl Ammonium Iodide Salts [16] | Ligands used for surface exchange and passivation. | Employed in ligand exchange strategies to create a dense, conductive PQD film with well-passivated surfaces, crucial for high-efficiency solar cells. |

The surface energy landscape of perovskite quantum dots, defined by the intricate interplay of curvature and crystallographic facets, serves as the fundamental master planner for ionic migration. This whitepaper has established that a profound understanding of this relationship is not merely academic but is instrumental in developing actionable strategies for enhancing PQD stability. By deliberately engineering surfaces towards low-energy, stable facets like (111) in FAPbI3, and by employing sophisticated passivation and ligand engineering techniques, researchers can effectively construct energy barriers that suppress detrimental ion movement. The experimental frameworks and reagent tools outlined herein provide a pathway for continued exploration and optimization. As the broader thesis of ionic migration dynamics evolves, the deliberate design of the surface energy landscape will undoubtedly remain a central tenet, guiding the development of robust, high-performance PQD technologies that can finally transition from laboratory marvels to commercial realities.

The operational stability and performance of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) in optoelectronic devices are intrinsically limited by the complex interplay between ionic migration and surface defects. This technical guide delves into the atomistic origins of surface traps and their dynamic relationship with ion migration, a critical challenge identified in current research on PQD surfaces. While PQDs exhibit exceptional optoelectronic properties such as high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY) and tunable bandgaps, their intrinsic instability remains a major obstacle to commercialization [17]. This review synthesizes recent findings on the mechanisms of defect formation and ion migration, provides detailed methodologies for their experimental and computational investigation, and offers a toolkit for researchers aiming to mitigate these detrimental phenomena. The insights framed within this document contribute to the broader thesis that understanding and controlling these interfacial dynamics is paramount for developing next-generation, stable perovskite-based technologies.

Low-dimensional halide perovskites, including quantum dots, nanowires, and nanosheets, hold significant promise for optoelectronic applications due to their distinctive quantum confinement effects, adjustable bandgaps, and superior carrier dynamics [17]. However, their practical application is severely constrained by two interrelated phenomena: surface defects and ionic migration. Surface traps, which are ubiquitous in nanoscopic semiconductor materials, originate from the lower coordination of surface atoms compared to bulk atoms, leading to localized electronic states that act as centers for non-radiative recombination [18]. Concurrently, the soft, ionic lattice of perovskite materials facilitates the migration of ions (such as halide anions and A-site cations) under operational stresses like electric fields and light illumination.

The interplay between these processes creates a feedback loop: ionic migration can modify the surface chemistry and passivation of PQDs, leading to the formation of new trap states, while existing surface defects can act as preferential sites for ion accumulation and nucleation of degradation. This synergy ultimately accelerates the degradation of perovskite optoelectronic devices, impacting their efficiency and operational lifetime [17]. Understanding this coupling is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a critical requirement for engineering robust materials.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Atomistic Origins

Classification and Chemistry of Surface Defects

Surface traps can be classified as either shallow or deep midgap states, with the latter being particularly detrimental for device performance as they provide efficient pathways for non-radiative exciton recombination [18]. The atomistic origin of these traps is best understood by considering specific benchmark systems:

- In CsPbI₃ PQDs: The surface chemistry is highly dynamic. Trap states can form due to the displacement of surface ions or the adsorption/desorption of ligand species. Computational models using charge-balanced chemical formulas like [ABX₃]ₘ(AX)ₙ are crucial for reliably simulating these systems without introducing spurious electronic states from unrealistic stoichiometries [18].

- In PbS QDs: The formation of trap states is often linked to non-stoichiometric surfaces. For instance, the removal of two iodide ligands to form molecular iodine can lead to an n-doped QD (Ndop = -2 in the Charge Balance Model), with excess electrons filling the conduction band and creating a doped system that differs from the intrinsic, defect-free material [18].

The Charge Balance Model (CBM) and Covalent Bond Classification (CBC) scheme provide complementary frameworks for describing the QD's electronic structure and surface chemistry, respectively [18]. The CBM evaluates charge balance by treating the QD as an ionic species, counting the number of excess or deficient valence electrons. A condition of Ndop = 0 typically indicates an intrinsic, charge-balanced QD with a clean band gap. The CBC scheme, conversely, describes the chemical bonding at the surface using neutral species and classifies ligands as L-type (2-electron donors), X-type (1-electron donors), or Z-type (0-electron donors, often Lewis acidic metal complexes) [18]. Proper ligand passivation, often using a combination of these types, is essential for achieving a stable, trap-free surface.

The Ionic Migration Pathway

Ionic mobility (μ) or diffusivity (D) in a crystalline solid is exponentially dependent on the migration barrier (Em) for ionic motion, as described by the equation: D = f·g·a²·ν·exp(-Em/kBT) [19]

Here, f is the correlation factor, g is the geometric factor describing diffusion channel connectivity, a is the hop distance, ν is the pre-factor dependent on vibrational frequencies, and kB and T are the Boltzmann constant and temperature, respectively. Among these factors, the migration barrier (Em) is the most dominant, as it has an exponential influence on diffusivity [19]. Identifying materials with high ionic mobility therefore hinges on accurately predicting and minimizing Em.

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing Ionic Migration Barrier (Em) in Solids

| Factor | Description | Impact on Migration Barrier (Em) |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Structure & Connectivity | Geometric factor (g) and hop distance (a); connectivity of diffusion channels. | Em is often lower in structures with open, connected pathways and optimal transition state geometry that avoids face-sharing polyhedra [19]. |

| Migrating Ion-Anion Distance | The distance between the migrating ion and the surrounding anions in the lattice. | Shorter distances often lead to higher Em due to stronger repulsive interactions during the hop [19]. |

| Coordination Environment Change | The change in coordination number of the migrating ion between its initial and transition states. | A significant change in coordination number typically leads to a higher Em [19]. |

Ionic migration in perovskites is not a random walk but occurs through specific pathways within the crystal lattice, often involving vacancy-mediated mechanisms. The energy landscape for these pathways is dictated by the surrounding lattice and the local chemical environment, which can be significantly altered by the presence of surface defects.

Coupling Dynamics: How Defects and Migration Interact

The relationship between vacancies, traps, and ion migration is cyclic. First, vacancies are a prerequisite for ion migration; without vacant lattice sites, ions cannot readily hop. Second, the migration of ions can itself generate defects. For example, when an ion migrates from a lattice site to an interstitial position, it creates a vacancy-interstitial pair (Frenkel defect). If the migrating ion is subsequently trapped at the surface, it can leave behind a vacancy cluster in the bulk. Third, existing surface defects act as sinks for migrating ions. Ions such as I⁻ can accumulate at surface trap sites, leading to localized chemical decomposition, such as the formation of PbI₂, which is a common degradation product observed in lead-halide perovskites [17]. This accumulation not only passivates the trap state but also creates new ones, altering the surface's electronic structure and potentially triggering further ion migration to restore local charge balance.

Experimental and Computational Characterization Methods

A multi-pronged approach is required to probe the complex interplay between ionic migration and surface defects. The following workflows and protocols outline key methodologies.

Computational Workflow for Predicting Migration Barriers

Diagram 1: Workflow for computing ionic migration barriers.

Detailed Protocol: Density Functional Theory - Nudged Elastic Band (DFT-NEB) Calculation

The DFT-NEB method is considered the state-of-the-art for accurately estimating Em by modeling the minimum energy path (MEP) of atomic migration [19].

- Supercell Construction: Build a crystallographic supercell of the material of sufficient size to prevent interaction between periodic images of the defect/vacancy. A 2x2x2 or 3x3x3 supercell is typical.

- Geometry Optimization: Use DFT to fully relax the atomic positions and lattice vectors of the supercell to its ground-state configuration. This provides the initial (IS) and final (FS) states for the migration hop.

- Pathway Initialization: Construct a series of intermediate "images" (typically 5-9) between the IS and FS. A simple linear interpolation of atomic coordinates is often used for initial path guess.

- NEB Calculation: Perform the NEB calculation using a DFT code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO). The images are connected by spring forces and optimized simultaneously. The climbing-image NEB variant is recommended to ensure the highest-energy image converges to the saddle point.

- Energy Barrier Extraction: The migration barrier (Em) is calculated as the total energy difference between the saddle point image and the initial state image.

Protocol Notes: This method is computationally intensive, with cost scaling with system size. The choice of exchange-correlation functional can impact accuracy. For high-throughput screening, machine learning models like graph neural networks (GNNs) fine-tuned on DFT-NEB data can predict Em swiftly and accurately, achieving R² scores >0.7 on diverse test sets [19].

Experimental Workflow for Trap State Analysis

Diagram 2: Experimental characterization of traps and ion migration.

Detailed Protocol: Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) and Lifetime Decay

PLQY is a direct indicator of the efficiency of radiative recombination and, by extension, the density of non-radiative trap states [18].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a stable, optically clear dispersion of PQDs in a suitable solvent. Ensure the optical density at the excitation wavelength is low (e.g., <0.1) to avoid inner-filter effects.

- Absolute PLQY Measurement: Use an integrating sphere coupled to a spectrometer and a calibrated light source. The sample is excited inside the sphere.

- Measure the spectrum of the excitation light with only the solvent in place (Iex(λ)).

- Measure the spectrum with the PQD sample in place. This contains both the transmitted excitation light and the photoluminescence (Iem(λ)).

- The absolute PLQY is calculated as: PLQY = ∫Iem(λ)dλ / [∫Iex(λ)dλ - ∫Isample(λ)dλ], where Isample(λ) is the transmitted excitation light measured with the sample.

- Time-Resolved PL (TRPL) Measurement: Use a time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) system with a pulsed laser source (e.g., picosecond diode laser).

- Record the decay of photoluminescence intensity after pulsed excitation.

- Fit the decay curve to a multi-exponential model: I(t) = Σ Aᵢ exp(-t/τᵢ). The amplitude-weighted average lifetime (⟨τ⟩ = Σ Aᵢτᵢ / Σ Aᵢ) is often reported.

- Interpretation: A high PLQY (approaching 100%) and a long average PL lifetime are indicative of low trap state density and effective surface passivation [17]. A multi-exponential decay suggests a distribution of carrier dynamics, often due to trapping and detrapping from surface states.

Protocol Notes: For measuring ionic mobility, Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a key technique, though it can be resource-intensive and sensitive to sample preparation [19].

Table 2: Key Characterization Techniques for Defects and Ion Migration

| Technique | Measured Property | Information on Defects/Migration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Resolved PL (TRPL) | Photoluminescence decay lifetime | Dynamics of charge carrier trapping and non-radiative recombination; trap-assisted recombination rates. | Requires multi-exponential fitting; sensitive to surface chemistry. |

| FTPS/SPS (Frequency/Photo-thermal Deflection Spectroscopy) | Sub-bandgap absorption | Density and energy distribution of trap states within the bandgap. | Highly sensitive to shallow and deep traps; requires specialized setup. |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Complex impedance as a function of frequency | Ionic conductivity, diffusion coefficients, and activation energy for migration (Em). | Analysis can be complex; requires modeling with equivalent circuits. |

| DFT-NEB Calculations | Total energy along a migration path | Atomistic migration pathway and energy barrier (Em). | Computationally expensive; accuracy depends on exchange-correlation functional. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for PQD Surface Defect and Ion Migration Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Precursors (e.g., Pb(OAc)₂, PbI₂) | Source of Pb²⁺ cations for the perovskite inorganic framework. | PbI₂ is a common precursor for CsPbI₃ QD synthesis via hot injection [17]. |

| Cesium Oleate | Source of Cs⁺ cations. | Injected into lead-halide precursor solution to nucleate and grow CsPbX₃ QDs [17]. |

| Oleic Acid & Oleylamine | L-type and X-type ligands. | Primary surface ligands that passivate under-coordinated surface atoms (Pb²⁺ and I⁻) during synthesis, suppressing trap formation [18]. |

| Halide Salt Precursors (e.g., NH₄X, ZnX₂) | Source of halide anions (X = Cl, Br, I); used for anion exchange. | Enables post-synthetic tuning of bandgap and PL emission [17]. Can also be used to treat halide-deficient surfaces. |

| Bidentate Ligands (e.g., 2-Bromohexadecanoic Acid - BHA) | Advanced surface passivators. | Bidentate ligands bind more strongly to surface atoms, effectively passivating surface defects and leading to high PLQY (>97%) even under prolonged UV irradiation [17]. |

| Z-type Passivators (e.g., CdX₂, PbX₂) | Electron-withdrawing Lewis acid species. | Passivate under-coordinated halide anions (Lewis bases) on the QD surface, as described by the CBC scheme, helping to achieve charge balance [18]. |

| Metal Halide Salts (e.g., KI, ZnBr₂) | Post-synthetic healing agents. | Used in solution or solid-state treatments to fill halide vacancies, a common defect that acts as a trap and facilitates I⁻ migration [18]. |

The intricate dance between ionic migration and surface defects lies at the heart of the stability challenge in perovskite quantum dots. As detailed in this guide, surface traps originating from under-coordinated atoms and non-stoichiometric surfaces create midgap states that quench luminescence and degrade performance. Simultaneously, the low migration barriers for ions in the soft perovskite lattice enable a dynamic redistribution of species that can both create new defects and be guided by existing ones. Breaking this detrimental cycle requires a holistic approach that combines advanced synthesis with precise passivation and thoughtful material design.

Future research must focus on several key areas:

- Developing Unified Models: Creating computational models that can simultaneously describe electronic structure (defects) and ion dynamics, bridging the gap between static and dynamic descriptions of the PQD surface.

- In Situ/Operando Characterization: Applying techniques like in situ spectroscopy and diffraction under operational conditions (light, bias) to observe the interplay between defects and migration in real-time.

- Multi-modal Passivation Strategies: Designing and implementing robust passivation schemes that use a combination of L-, X-, and Z-type ligands to comprehensively address all possible surface defect types, thereby stabilizing the surface against both ionic attack and ligand loss [18].

- Exploiting Machine Learning: Leveraging accurate graph neural network models and other ML tools to rapidly screen for new compositions and heterostructures with inherently low ion migration barriers and high defect tolerance, accelerating the discovery of stable materials [19].

By deepening our understanding of the fundamental mechanisms outlined in this review and leveraging the detailed protocols and tools provided, researchers can make significant strides toward overcoming the primary barriers to the commercialization of high-performance, durable perovskite quantum dot technologies.

Ionic migration, the movement of charged atoms or molecules, is a fundamental process governing functionality in a wide range of advanced materials, from energy storage systems to novel sensing platforms. Within the specific context of perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces research, controlling this migration is paramount for enhancing device performance and stability. External stimuli such as light, electric fields, and heat provide powerful, non-invasive means to precisely activate and direct ion transport. This control enables the tuning of material properties on-demand, facilitating breakthroughs in applications like photovoltaics, chemical sensing, and bioelectronic medicine. A deep understanding of these triggers is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for designing the next generation of adaptive and high-performance technologies. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the mechanisms and methodologies by which these external triggers govern ionic movement, framed within the ongoing research on ionic migration dynamics at PQD surfaces.

The Role of Light in Ion Transport

Light energy, particularly in the visible spectrum, can induce ion transport through direct photon-matter interactions that alter the energy landscape within a material. A prominent mechanism involves light-induced ligand dissociation in metal-organic complexes.

Mechanism of Visible-Light-ContMetal-Ligand Coordination

Research has demonstrated that Ru(II) complexes, such as [Ru(tpy-COOH)(biq)(H2O)](PF6)2 (denoted Ru-H2O), can undergo reversible ligand substitution controlled by visible light [20]. In this system:

- Thermal Substitution (in the dark): A coordinated water molecule in the Ru-H2O complex can be replaced by a functional thioether ligand (e.g., MeSC2H4-R1), forming a stable Ru–thioether coordination bond.

- Photosubstitution (under light): Upon irradiation with visible light (e.g., 530 nm at 50 mW cm⁻²), the coordinated thioether ligand is cleaved and replaced by a water molecule [20].

This reversible process, cyclable over at least 10 times with approximately 80% coordination efficiency per cycle, effectively acts as a molecular "screwdriver" for reconfiguring surface functions and controlling ionic species [20]. The equilibrium constant (K) for the coordination reaction with a model thioether like 2-(methylthio)ethanol (MTE) is 107 ± 4 M⁻¹ at 298 K, indicating a strong, yet reversible, binding affinity [20].

Experimental Protocol: Light-Induced Ligand Exchange on Surfaces

Objective: To functionalize and subsequently reconfigure a surface using visible-light-controlled Ru–thioether coordination.

Materials:

- Quartz or silicon substrate.

- (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES).

- Ru-H2O complex.

- Coupling agents: N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC).

- Aqueous solutions of functional thioether ligands (e.g., MeSC2H4-R1, MeSC2H4-R2).

- Solvents: Water, acetone.

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean the substrate thoroughly (e.g., with oxygen plasma or piranha solution) to ensure a hydrophilic surface.

- Silanization: Immerse the substrate in a 2% v/v solution of APTES in toluene to form an amine-terminated surface. Rinse and cure.

- Ru Complex Grafting: React the aminated surface with the Ru-H2O complex using standard NHS/EDC carbodiimide chemistry to form amide bonds, creating a

Ru-H2O-modified substrate[20]. - Initial Functionalization (Thermal Substitution): Immerse the Ru-H2O-modified substrate in an aqueous solution of the first functional thioether (MeSC2H4-R1, 10 mM) for 40-60 minutes in the dark. Rinse gently with water to remove unbound ligand.

- Ligand Removal (Photosubstitution): Irradiate the functionalized surface with green light (530 nm, 40-50 mW cm⁻²) for 10 minutes in an aqueous environment to cleave the thioether ligand. Wash with water and acetone to remove the dissociated ligand.

- Re-functionalization (Thermal Substitution): Immerse the substrate in a solution of a second functional thioether (MeSC2H4-R2, 10 mM) in the dark for 40-60 minutes to attach the new functionality. Rinse.

Characterization: The success of each functionalization and de-functionalization step can be monitored using UV-vis absorption spectroscopy, observing the characteristic blueshift in the metal-to-ligand charge transfer band upon thioether coordination [20].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for reconfiguring a surface using this light-controlled coordination chemistry.

The Role of Electric Fields in Ion Transport

Electric fields provide a direct means to exert force on charged particles, enabling precise spatial and temporal control over ion transport. This principle is leveraged in both sensing and bioelectronic applications.

Mechanism of Ion-Selective Membrane Cuff Operation

A key innovation is the multimodal ion-selective membrane (ISM) cuff for focused ion depletion in vivo. The operating principle involves:

- Ion Depletion: When a current is applied across an ISM that is selective for a specific ion (e.g., Ca²⁺), the target ion is depleted in the electrolyte volume where current enters the membrane [21].

- Confinement: The cuff architecture physically confines the electrolyte volume around a nerve, focusing the ion depletion effect and preventing rapid dissipation into surrounding tissue. A transport model predicted that applying -20 µA for 5 minutes could reduce Ca²⁺ concentration in the cuff's lumen from 2 mM to below 0.5 mM [21].

- Nerve Sensitization: Depleting extracellular Ca²⁺ concentrations affects the gating of voltage-gated sodium channels, sensitizing the nerve and lowering its threshold for activation by electrical stimulation [21].

Experimental Protocol: In Vivo Nerve Sensitization via Focused Ca²⁺ Depletion

Objective: To modulate the sensitivity of a sciatic nerve to electrical stimulation in a live rat model using an ISM-cuff for localized Ca²⁺ depletion.

Materials:

- Implantable ISM cuff electrode (screen-printed carbon-polymer contacts, one coated with a Ca²⁺-selective membrane).

- Surgical setup for rat sciatic nerve exposure.

- Bipolar electrode for electrical stimulation.

- Recording equipment for compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) from target muscles (e.g., gastrocnemius, tibialis anterior).

Procedure:

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate the cuff electrode with carbon-polymer contacts. Coat one contact with a Ca²⁺-selective membrane cocktail containing an ionophore [21].

- Surgical Implantation: Anesthetize the rat and acutely expose the sciatic nerve in the gluteal region. Carefully place the ISM cuff around the nerve.

- Baseline Threshold Search: Prior to ion modulation, determine the baseline threshold current required to elicit a CMAP in the target muscles using the cuff's uncoated stimulation electrode.

- Ion Depletion Phase: Apply a depletion current of -20 µA to the ISM-coated contact for 5 minutes. The transport model and direct measurements confirm this reduces Ca²⁺ to ~0.5 mM within the cuff lumen [21].

- Post-Depletion Threshold Search: Immediately after the depletion phase, repeat the threshold search from Step 3 to measure the change in nerve sensitivity.

- Data Analysis: Compare the stimulation thresholds and CMAP amplitudes before and after Ca²⁺ depletion to quantify the sensitization effect. Evidence suggests this effect can selectively influence different nerve fascicles, improving functional selectivity [21].

Characterization: The Ca²⁺ depletion performance of the ISM cuff can be directly measured in vitro using a calibrated sensing technique, verifying a drop from 2 mM to 0.5 mM within 100 s of applying -20 µA [21].

The diagram below outlines the key components and operating principle of the ISM-cuff device.

The Role of Heat in Ion Transport

Thermal energy influences ion transport by increasing ionic mobility and, in some material systems, inducing phase transitions that create new transport pathways or alter existing ones.

Mechanism of Thermal Phase Evolution in Hollandite Nanorods

In situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies on silver hollandite (AgyMn8O16) nanorods have visualized the phase evolution and ion transport dynamics during lithiation, processes highly influenced by thermal conditions.

- Two-Stage Lithiation: The process involves two distinct regimes:

- β-regime: Characterized by fast Li⁺ diffusion along the nanorod's long axis with minimal volume change, resulting in a lithiated phase with an orthorhombic distortion (

LixAg1.6Mn8O16, x~1) [22]. - γ-regime: Initiated by a slower-moving reaction front, this stage involves substantial volume expansion (over 27% radially), the formation of polyphase lithiated hollandite, and the expulsion of face-centered-cubic silver metal (Ag⁰) nanoparticles (x>6 in

LixAg1.6Mn8O16) [22].

- β-regime: Characterized by fast Li⁺ diffusion along the nanorod's long axis with minimal volume change, resulting in a lithiated phase with an orthorhombic distortion (

- Inter-Nanorod Transport: A key finding was the first direct observation of lateral Li⁺ transport between individual nanorods in the a–b plane, not just along a single rod's c-axis. This indicates that ion transport in one-dimensional materials is not necessarily confined to a single particle [22].

Experimental Protocol: In Situ TEM Visualization of Li⁺ Transport

Objective: To observe in real-time the lithium-ion transport pathways and associated phase evolution within and between Ag1.6Mn8O16 nanorods.

Materials:

- Synthesized

Ag1.6Mn8O16nanorods (e.g., via hydrothermal or reflux-based synthesis). - In situ TEM scanning/transmission electron microscope (S/TEM) holder equipped with a nanomanipulator and a lithium metal tip.

- Lithium metal counter electrode.

- Synthesized

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Disperse the synthesized

Ag1.6Mn8O16nanorods in a solvent and drop-cast them onto a specialized in situ TEM chip with micro-electrodes. - Setup Assembly: Load the chip into the TEM holder. Using the nanomanipulator, bring a sharp lithium metal tip into contact with a selected nanorod or a bundle of nanorods.

- In Situ Lithiation: Apply a small bias potential between the Li tip (anode) and the chip's electrode (cathode) to initiate electrochemical lithiation while the holder is inside the TEM column.

- Real-Time Imaging & Diffraction: Record real-time video (e.g., 1 frame per second) to monitor morphological changes, such as the propagation of reaction fronts and volume expansion. Simultaneously, acquire selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns and electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) spectra from specific regions (pristine, β-regime, γ-regime, reaction front) to correlate structural and chemical evolution [22].

- Data Analysis: Measure the velocity of reaction front propagation (observed at ~5 nm/s along the c-axis). Quantify volume changes from image analysis. Identify crystalline phases present in different regimes from diffraction patterns.

- Sample Preparation: Disperse the synthesized

Characterization: Key metrics include reaction front velocity, radial expansion percentage, and identification of crystalline phases (tetragonal hollandite, distorted lithiated phases, fcc Ag⁰) via EDPs [22].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from the research discussed in this whitepaper.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of External Trigger Mechanisms

| Trigger Mechanism | Key Metric | Value / Range | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light (Ru-Complex) | Photosubstitution Efficiency | ~80% per cycle | Reversible coordination of MTE to Ru-H2O over 10 cycles [20] |

| Equilibrium Constant (K) | 107 ± 4 M⁻¹ | Coordination of MTE with Ru-H2O at 298 K [20] | |

| Irradiation Parameters | 530 nm, 50 mW cm⁻², 1 min (soln) / 10 min (surface) | Green light-induced ligand dissociation [20] | |

| Electric Field (ISM Cuff) | Depletion Current | -20 µA | Current applied to ISM contact for Ca²⁺ depletion [21] |

| Ca²⁺ Concentration Reduction | 2.0 mM → <0.5 mM | In the cuff lumen after 5 min of -20 µA current [21] | |

| Electrode Impedance | 341 ± 36.9 Ω | Screen-printed carbon-polymer contacts [21] | |

| Heat (Ion Transport) | Reaction Front Velocity | ~5 nm/s | Propagation along nanorod c-axis during lithiation [22] |

| Volume Expansion (Radial) | >27% | In γ-regime of lithiated hollandite nanorods [22] | |

| Lithiation Stoichiometry (x in LixAg1.6Mn8O16) | β-regime: x~1; γ-regime: x>6 | Determined via EELS analysis [22] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

[Ru(tpy-COOH)(biq)(H2O)](PF6)2 (Ru-H2O) |

Photoswitchable molecular "screwdriver"; core complex for reversible ligand coordination. | Light-controlled surface reconfiguration [20] |

| Functional Thioethers (MeSC2H4-R) | Molecular "bits"; provide specific surface functionalities (e.g., wettability, protein affinity). | Light-controlled surface reconfiguration [20] |

| Ca²⁺-Selective Ionophore Membrane | Selectively filters and depletes Ca²⁺ ions from a mixed electrolyte upon application of current. | Electrochemical nerve sensitization [21] |

| Screen-Printed Carbon-Polymer Contacts | Biocompatible, low-impedance electrodes for electrical stimulation and iontronic delivery in vivo. | ISM Cuff fabrication [21] |

| Silver Hollandite (Ag1.6Mn8O16) Nanorods | Tunnel-structured electroactive material for visualizing Li⁺ transport and phase evolution. | In situ TEM lithiation studies [22] |

Integrated Trigger Effects and Research Applications

The interplay of multiple external triggers often yields synergistic effects. For instance, the fabrication of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) themselves, which are highly relevant to ionic migration surface research, often involves heat (e.g., hot-injection synthesis at elevated temperatures) to control crystallization and defect formation [12]. These PQDs, particularly lead-based variants like CsPbX3, are then deployed as nanosensors, where their interaction with light (high photoluminescence quantum yield) is modulated by the presence of target ions, enabling ultrasensitive heavy metal detection with limits as low as 0.1 nM [12]. Furthermore, the performance of related devices, such as perovskite solar cells (PSCs), is enhanced by strategies that manage ion migration under operational stresses combining electric fields and heat, achieving remarkable stabilities exceeding 8 months and power conversion efficiencies over 26% [15].

The fundamental insights and advanced methodologies detailed in this whitepaper—from light-controlled molecular reconfiguration to in situ visualization of ion transport—provide a powerful toolkit for researchers. These approaches are directly applicable to the broader thesis of understanding and controlling ionic migration dynamics at the surfaces of perovskite quantum dots and other advanced functional materials, paving the way for innovations in sensing, energy storage, and bioelectronic medicine.

Tools and Techniques: Probing and Harnessing Surface Ion Dynamics

Advanced Spectroscopy for Direct Ionic Motion Observation

Ionic motion, the migration of ions within a material's lattice or across its surface, is a fundamental process that dictates the performance and stability of numerous advanced technologies. In the context of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs)—a class of materials with exceptional optoelectronic properties—controlling ionic migration is a central challenge for achieving commercial viability. The inherent ionic nature of perovskite crystals, characterized by relatively low ionic migration energy barriers, facilitates the easy formation of halide vacancies and leads to structural degradation under external stimuli such as heat, light, or electrical bias [23]. This ionic mobility, while potentially exploitable in certain applications, often results in phase segregation, accelerated aging, and diminished device performance in solar cells and light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [14] [23]. Directly observing these ionic dynamics is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a critical endeavor for diagnosing failure mechanisms and guiding the rational design of more robust materials.

This technical guide details advanced spectroscopy techniques capable of probing ionic motion directly, with a specific focus on methodologies relevant to PQD surfaces. The ability to track ion movement with high spatial and temporal resolution provides invaluable insights into the fundamental dynamics that underpin device operation and degradation. For PQDs, surface ions are particularly susceptible to migration due to incomplete passivation and the presence of dangling bonds, making the surface a primary site for initiating structural failure [23]. The techniques outlined herein enable researchers to move beyond indirect performance metrics and observe the core ionic processes in real-time, thereby framing the discussion within the broader thesis of understanding and controlling ionic migration dynamics in PQD research.

Core Spectroscopy Techniques

A range of sophisticated spectroscopic methods has been developed to characterize ionic motion, each with unique mechanisms, advantages, and operational domains. The following table summarizes the key techniques of relevance to PQD studies.

Table 1: Core Spectroscopy Techniques for Observing Ionic Motion

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Key Measurable | Spatial/Temporal Resolution | Primary Application in PQD Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry (IMS-MS) | Separates ions in a buffer gas under an electric field based on their size, charge, and shape [24]. | Collision Cross Section (CCS, Ω), a measure of ionic gas-phase size [24]. | Millisecond separation timescale; compatible with chromatographic pre-separation [24]. | Probing the surface ligand shell and identifying labile ionic species desorbed from PQD surfaces [24]. |

| Impedance Spectroscopy (IS) | Applies a small AC voltage and measures the current response across a frequency range to deconvolute different electrochemical processes [25]. | Ionic conductivity, defect relaxation times, and interfacial charge transfer resistances [25]. | Bulk measurement; frequency-dependent, typically mHz to MHz range [25]. | Quantifying bulk ionic conductivity and characterizing the energy of ion migration within PQD films [25]. |

| Precision Laser Spectroscopy | Uses quantum logic with co-trapped atomic ions to prepare, control, and measure the quantum states of a single molecular ion [26]. | Rovibrational state transitions, dipole moments, and state lifetimes with ultra-high precision [26]. | Quantum-state resolution; sub-part-per-trillion spectral resolution achievable [26]. | Fundamental studies of ion-molecule interactions and electric field effects on single ions, providing benchmark data [26]. |

Technical Deep Dive: IMS-MS Methodologies

Among these techniques, IMS-MS deserves particular attention for its ability to separate and identify ionic species directly. The core principle, as defined by the Mason-Schamp equation, links the measured ion mobility (K) to the collision cross section (CCS, Ω), which is a normalized measure of the ion's gas-phase size [24]. The equation is:

[ \Omega = \frac{3}{16} \frac{ze}{N0} \left( \frac{2\pi}{\mu kB T} \right)^{1/2} \frac{1}{K_0} ]

Here, (ze) is the ion charge, (N0) is the buffer gas density, (\mu) is the reduced mass of the ion and buffer gas, (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, and (T) is the drift region temperature [24]. This allows researchers to distinguish between isomeric species and conformational states that would be indistinguishable by mass alone, making it powerful for analyzing the complex mixture of ligands and surface-bound ions on PQDs.

Different IMS platforms offer distinct advantages:

- Drift-Tube IMS (DTIMS): Considered the "classic" model, DTIMS uses a uniform electric field in a pressurized drift region. Its primary advantage is the ability to measure CCS as a primary method from first principles using the Mason-Schamp equation, without requiring calibration [24]. However, its pulsed nature can lead to a low duty cycle (e.g., ~6.7%), though multiplexing strategies like the Hadamard Transformation can increase this to ~50% [24].

- Traveling Wave IMS (TWIMS): This platform, which popularized IMS-MS, uses a series of dynamic voltage waves to propel ions through the gas. While it offers continuous ion introduction and high sensitivity, it is a secondary method that requires calibration with ions of known CCS values measured by DTIMS [24].

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol: Impedance Spectroscopy for Ionic Conductivity

Impedance Spectroscopy is a cornerstone technique for quantifying ionic motion in solid-state materials like perovskite films. A harmonized procedure is critical for obtaining reproducible and reliable results, as highlighted in a cross-laboratory study on ceramic electrolytes [25].

Sample Preparation:

- Material Synthesis: Prepare PQD films or solid electrolyte pellets (e.g., LLZO:Ta:Al or LATP) using standardized synthesis protocols to ensure consistent stoichiometry and phase composition [25].

- Electrode Integration: Integrate the sample into an appropriate cell housing, such as a coin cell. Sputter or evaporate ionically-blocking electrodes (e.g., gold or platinum) onto both sides of the pellet to ensure well-defined electrical contact [25].

Data Acquisition: