Ion Spectroscopy Surface Analysis: Techniques, Applications, and Optimization for Biomedical Research

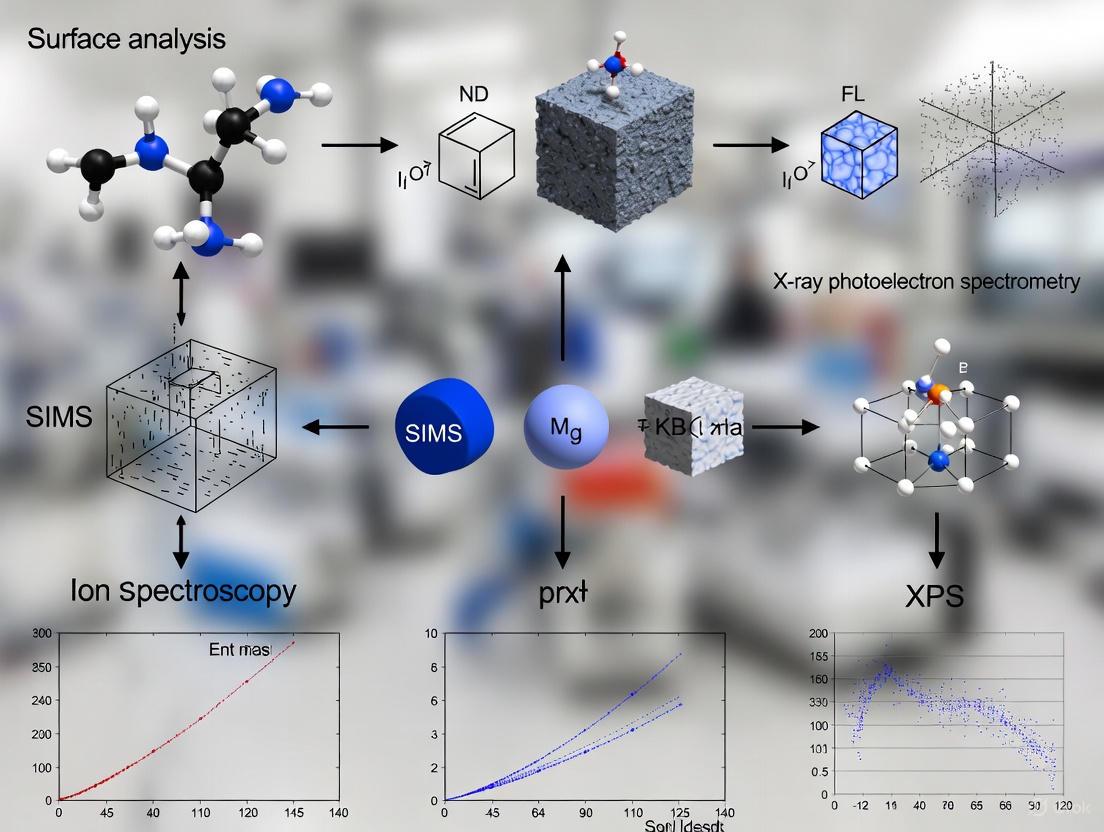

This article provides a comprehensive guide to ion spectroscopy surface analysis techniques, including XPS, AES, and SIMS, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Ion Spectroscopy Surface Analysis: Techniques, Applications, and Optimization for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to ion spectroscopy surface analysis techniques, including XPS, AES, and SIMS, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, methodological applications in pharmaceutical research like drug and metabolite imaging, common troubleshooting and optimization strategies for data quality, and a comparative analysis of technique performance for informed method selection. The content synthesizes current research and validation protocols to support advancements in biomaterial characterization and therapeutic development.

Core Principles of Surface Analysis: Understanding XPS, AES, and SIMS

Surface analysis is a critical component in materials science, chemistry, and biological research, providing detailed information about the outermost layers of a material, which often dictate its properties and performance. This application note focuses on three principal surface analysis techniques: X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS). Each technique offers unique capabilities for determining elemental composition, chemical state information, and spatial distribution of components at surfaces and interfaces. The selection of an appropriate technique depends on the specific analytical requirements, including the need for spatial resolution, chemical state information, detection sensitivity, and depth profiling capabilities. Within the broader context of ion spectroscopy research, these techniques provide complementary data that can elucidate surface-mediated processes in fields ranging from semiconductor technology to drug development.

Fundamental Principles

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) operates on the principle of the photoelectric effect. When a sample is irradiated with X-rays, electrons are ejected from inner atomic orbitals. The kinetic energy of these photoelectrons is measured, allowing for the determination of their binding energy according to the equation: Ek = hν - Eb - φ, where Ek is the kinetic energy of the emitted electron, hν is the energy of the X-ray photon, Eb is the binding energy of the electron, and φ is the work function of the spectrometer. Since binding energies are characteristic of specific elements and are influenced by chemical environment, XPS provides both elemental identification and chemical state information. The technique is highly surface-sensitive, with an information depth typically limited to the top 10 nanometers, as photoelectrons can only travel short distances in solids without losing energy [1].

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES)

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) relies on the Auger process, which involves a three-step electronic relaxation mechanism. First, a high-energy electron beam (typically 3-20 keV) strikes the sample, ejecting a core-level electron and creating an excited ion. Second, an electron from a higher energy level fills the vacancy, releasing energy. Third, this energy causes the emission of a third electron, known as an Auger electron. The kinetic energy of the Auger electron is characteristic of the element from which it was emitted and is largely independent of the incident electron beam energy. AES achieves exceptional spatial resolution, with modern instruments capable of focusing the electron beam to a diameter of 5 nm or less, enabling analysis of nanoscale features [2]. The analysis depth is approximately 5 nm, similar to XPS, making it a true surface-sensitive technique [3].

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS)

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) utilizes a focused primary ion beam (typically O-, O2-, Cs+, Au+, Bi3+, or C60+) to sputter and ionize atoms and molecules from the outermost surface of a sample. The ejected secondary ions are then analyzed by a mass spectrometer, which separates them according to their mass-to-charge ratio. SIMS operates in two primary modes: dynamic SIMS, which uses high primary ion currents for depth profiling and bulk analysis, and static SIMS, which uses low ion doses (below 1012 ions/cm2) to preserve molecular integrity and enable surface molecular analysis [4]. The technique offers exceptional sensitivity, capable of detecting elements and isotopes at parts-per-million to parts-per-billion levels, and can achieve spatial resolution below 100 nm with specialized instruments such as the NanoSIMS [4].

Technical Comparison

The following tables provide a comprehensive technical comparison of XPS, AES, and SIMS, highlighting their key characteristics, performance metrics, and application strengths.

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of XPS, AES, and SIMS

| Parameter | XPS | AES | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Probe | X-rays | Electron beam | Ion beam |

| Detected Signal | Photoelectrons | Auger electrons | Secondary ions |

| Information Depth | ~10 nm [1] | ~5 nm [3] | 1-2 monolayers |

| Spatial Resolution | ≥ 10 µm (conventional); ~1 µm (microprobe) | ≥ 8 nm [3] | 50-200 nm (NanoSIMS) [4]; ~200 nm (TOF-SIMS with C60+) [4] |

| Detection Limit | 0.1-1 at% | 0.1-1 at% | ppm-ppb (elements); < ppb (isotopes) |

| Chemical State Information | Yes | Limited | Limited (except with specialized MS) |

| Destructive | Non-destructive | Potentially damaging (electron beam) | Destructive (sputtering) |

Table 2: Applications, strengths, and limitations of XPS, AES, and SIMS

| Aspect | XPS | AES | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Strengths | Quantitative analysis, chemical state information, good for insulators | High spatial resolution, surface mapping, depth profiling | Ultra-high sensitivity, isotopic analysis, molecular information (TOF-SIMS), 3D imaging |

| Main Limitations | Lower spatial resolution, requires UHV, surface charging | Sample damage, limited chemical information, surface charging | Complex quantification, matrix effects, destructive |

| Typical Applications | Thin films, coatings, corrosion studies, catalysis, polymers [1] | Nanomaterials, failure analysis, microelectronics, grain boundary segregation [3] | Geochemistry, cell biology, pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, organic surfaces [4] |

Experimental Protocols

XPS Analysis Protocol for Battery Cathode Materials

Application: Characterization of engineered particle (Ep) battery cathodes to understand interfacial stability and degradation mechanisms [5].

Materials and Equipment:

- Thermo Fisher ESCALab QXi3 XPS instrument or equivalent [6]

- Aluminum Kα or monochromatic X-ray source

- Argon ion sputter gun for depth profiling

- Ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber (pressure < 1 × 10^-9 mbar)

- Electrical charge compensation system (low-energy electron flood gun)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mount the battery cathode material on a suitable holder using double-sided conductive tape or mounting clips. For powder samples, gently press onto indium foil to ensure electrical contact.

- Sample Introduction: Transfer the sample to the XPS introduction chamber and evacuate to approximately 1 × 10^-8 mbar before transferring to the analysis chamber.

- Survey Spectrum Acquisition: Collect a wide energy scan (e.g., 0-1100 eV binding energy) with pass energy of 100-150 eV to identify all elements present.

- High-Resolution Regional Scans: Acquire detailed spectra for relevant core levels (e.g., C 1s, O 1s, transition metal 2p, Li 1s) with pass energy of 20-50 eV to maximize energy resolution.

- Chemical State Analysis: Deconvolute high-resolution spectra using appropriate software to identify chemical states (e.g., different oxidation states of transition metals, various carbon species).

- Depth Profiling (if required): Perform alternating cycles of argon ion sputtering (typically 0.5-4 keV) and XPS analysis to determine composition as a function of depth.

- Data Analysis: Calculate elemental concentrations using sensitivity factors. Compare spectra from cycled and uncycled electrodes to identify degradation products.

AES Depth Profiling Protocol for Thin Film Structures

Application: Quantitative elemental and chemical state analysis from surfaces of solid materials, including depth distribution information for thin film structures [3].

Materials and Equipment:

- Physical Electronics Auger instrument or equivalent with spatial resolution ≤ 8 nm [3]

- Cylindrical Mirror Analyzer (CMA) electron analyzer

- Field emission electron gun

- Argon ion sputtering gun for depth profiling

- Charge compensation system (argon ion neutralization) for insulating samples [2]

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mount the sample securely on the holder. Ensure good electrical contact for conductive samples. For insulating samples, confirm charge neutralization system is operational.

- Instrument Setup: Align the electron beam with the analysis position. Select appropriate electron beam energy (typically 3-10 keV) and current based on spatial resolution and sensitivity requirements.

- Point Analysis: Acquire AES survey spectrum from the region of interest to identify elements present.

- Elemental Mapping: Raster the focused electron beam across the sample surface to acquire spatial distribution of elements of interest.

- Depth Profiling Setup: Define the analysis area and select sputtering parameters (argon ion energy, current, and raster size).

- Sputtering and Analysis Cycle: Program the instrument to alternate between argon ion sputtering for a predetermined time and AES analysis of selected elemental peaks.

- Data Collection: Monitor peak-to-peak intensities in the derivative AES spectrum for selected elements as a function of sputtering time.

- Data Conversion: Convert sputtering time to depth using a calibrated sputter rate for the material system.

- Interpretation: Analyze the depth profile to determine layer thicknesses, interface widths, and interdiffusion between layers.

SIMS Imaging Protocol for Single Cell Analysis

Application: Mapping of elemental distributions and tracking isotopically labeled compounds in biological systems at single-cell resolution [4].

Materials and Equipment:

- NanoSIMS instrument (e.g., CAMECA NanoSIMS) or TOF-SIMS with cluster ion source

- C60+ or Bi3+ liquid metal ion gun

- Sample stubs suitable for biological specimens

- Conductive coating materials (if required)

- Standard samples for mass calibration

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grow cells on appropriate substrates (e.g., silicon wafers). For metabolic studies, incubate with isotopically labeled compounds (e.g., 13C, 15N). Fix cells with appropriate fixative (e.g., glutaraldehyde). Dehydrate through graded ethanol series and critical point dry.

- Sample Mounting: Mount prepared samples on SIMS holders using conductive tape. Apply thin conductive coating if necessary to prevent charging.

- Instrument Setup: Select primary ion species (Cs+ for negative secondary ions, O- for positive secondary ions for NanoSIMS; C60+ or Bi3+ for TOF-SIMS). Optimize primary beam current and focus.

- Mass Calibration: Calibrate the mass spectrometer using known standards relevant to the masses of interest.

- Region of Interest Selection: Use optical microscopy or secondary electron imaging to locate cells of interest.

- Data Acquisition: Raster the primary ion beam over the selected area. For NanoSIMS, simultaneously detect up to 5-7 secondary ions with electron multipliers. For TOF-SIMS, pulse the primary beam and measure time-of-flight for mass separation.

- Image Generation: Construct elemental or isotopic maps from the acquired data by assigning counts to specific pixel locations.

- Quantification: For NanoSIMS, calculate isotopic ratios from regions of interest corresponding to specific cellular compartments. For TOF-SIMS, normalize counts to total ion count or matrix signals.

- Data Correlation: Correlate SIMS data with complementary techniques such as fluorescence microscopy (FISH) or electron microscopy for additional context [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines essential materials and reagents commonly used in surface analysis experiments across the three techniques.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for surface analysis techniques

| Item | Function/Application | Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Tapes/Carbon Tapes | Sample mounting to ensure electrical and thermal contact | XPS, AES, SIMS |

| Indium Foil | Substrate for mounting powder samples | XPS, AES |

| Argon Gas (High Purity) | Sputtering source for depth profiling and charge neutralization | XPS, AES, SIMS |

| Silicon Wafers | Clean, flat substrates for mounting samples, particularly biological specimens | SIMS |

| Isotopically Labeled Compounds (13C, 15N) | Tracers for metabolic studies in biological systems | SIMS |

| Conductive Coatings (Carbon, Gold) | Applied to insulating samples to prevent charging | AES, SIMS (if charge compensation inadequate) |

| Standard Reference Materials | Quantification calibration, mass calibration, instrument performance verification | XPS, AES, SIMS |

| Charge Neutralization Flood Gun | Provides low-energy electrons to neutralize surface charge on insulating samples | XPS |

| Ultra-pure Solvents (e.g., methanol, water) | Sample cleaning prior to analysis to remove surface contaminants | XPS, AES, SIMS |

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Combined XPS and TOF-SIMS Analysis of Battery Materials

In a study of engineered particle (Ep) battery cathodes, researchers combined XPS and TOF-SIMS to understand stabilizing effects on electrode-electrolyte interfaces. XPS provided quantitative chemical state information about the surface species, while TOF-SIMS offered high-sensitivity detection of organic and inorganic species across the interface. This combined approach revealed that Ep-coated cathodes exhibited more uniform and controlled interfaces, leading to improved battery performance and long-term stability. The TOF-SIMS data complemented XPS results by detecting trace degradation products that were below the detection limit of XPS, providing a more comprehensive understanding of degradation mechanisms [5].

NanoSIMS for Biological Systems at Single-Cell Resolution

NanoSIMS has enabled groundbreaking research in microbiology and cell biology by allowing researchers to track metabolic processes at the single-cell level. In one pioneering application, researchers used NanoSIMS to quantify N2 fixation by individual bacteria inhabiting the gills of shipworms. By introducing 15N-labeled substrates, they could measure nitrogen assimilation at unprecedented resolution. Similarly, studies on cyanobacteria used 13C and 15N tracers to track the assimilation of inorganic carbon and ammonium by individual cells, revealing significant variation in uptake rates among phylogenetically identical cells. These applications demonstrate the unique capability of SIMS to link metabolic function to phylogenetic identity in complex biological systems [4].

AES for Nanomaterials and Thin Film Characterization

AES provides critical information about surface layers and thin film structures that govern performance in various applications. With its high spatial resolution (as small as 8 nm), AES can characterize composition at nanoscale features in materials such as catalysts, semiconductors, and magnetic media. The combination of AES with ion sputtering enables depth profiling of multilayer structures, allowing researchers to determine layer thicknesses, interface quality, and interdiffusion between layers. This capability is particularly important for semiconductor devices and packaging, where nanoscale layers determine device performance and reliability [3].

XPS, AES, and SIMS represent three powerful and complementary techniques for surface analysis, each with distinct strengths and applications. XPS excels at providing quantitative elemental composition and detailed chemical state information, making it invaluable for studying surface chemistry in materials such as battery electrodes and catalysts. AES offers superior spatial resolution for mapping elemental distributions at the nanoscale, particularly useful for failure analysis and thin film characterization. SIMS provides unparalleled sensitivity for trace element and isotopic analysis, with growing applications in biological systems and materials science. The continuing development of these techniques, including improvements in spatial resolution, sensitivity, and data analysis capabilities, ensures they will remain essential tools for understanding surface and interface phenomena across numerous scientific and industrial fields.

Historical Development and Technological Evolution of Surface Analysis

Surface analysis, in analytical chemistry, is the study of the part of a solid that is in contact with a gas or a vacuum [7]. This interface dictates critical material properties and behaviors. The field has undergone a tremendous evolution since the mid-20th century, moving from classical methods that provided physical descriptions to modern spectroscopic techniques capable of providing detailed elemental and chemical state information from the outermost atomic layers [7]. This evolution has been pivotal for advancements in diverse fields, including catalysis, nanotechnology, and drug development, where understanding surface composition is essential for designing and improving materials and processes [7] [8].

This application note details the key methodologies within surface analysis, with a particular focus on Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS) as a cornerstone technique for quantifying the atomic composition of the outermost surface. It provides structured protocols and data to support researchers in the effective application of these powerful analytical tools.

Key Techniques in Modern Surface Analysis

Modern surface analysis is characterized by a "beam in, beam out" mechanism, where a primary beam of photons, electrons, or ions interacts with the sample, and an emitted beam is analyzed to yield surface-specific information [7]. The sampling depth—a critical parameter defining surface sensitivity—varies significantly with the probe and its energy, being shallowest for ions (∼1 nm) and deepest for photons (∼1000 nm) [7]. During the 1970s and 1980s, four techniques emerged as particularly useful for real-world problem-solving due to their general applicability and ease of use [7].

Table 1: Major Surface Analysis Techniques and Their Characteristics

| Technique | Acronym | Probe In | Signal Out | Key Information | Sampling Depth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy | XPS/ESCA | X-rays (Photons) | Electrons | Elemental identity, chemical state, quantitative analysis [7] | ~1-10 nm [7] |

| Auger Electron Spectroscopy | AES | Electrons | Electrons | Elemental composition, surface mapping [7] | ~2 nm [7] |

| Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry | SIMS | Ions | Ions | Elemental and molecular composition, extreme surface sensitivity, depth profiling [7] [8] | < 1 nm |

| Ion Scattering Spectroscopy | ISS/LEIS | Ions (Noble Gas) | Ions | Atomic composition of the outermost atomic layer [9] [8] | ~0.3 nm (top monolayer) [8] |

Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS): Principles and Protocol

Core Principles of ISS

Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS), also referred to as Low-Energy Ion Scattering (LEIS), is a surface-specific technique where a beam of noble gas ions (e.g., He⁺, Ne⁺, Ar⁺) is elastically scattered by atoms on the sample surface [9] [8]. The kinetic energy of the scattered ions, ( E_s ), is measured, and the energy loss is determined by the masses of the incident ion and the target surface atom, governed by the principles of binary elastic collision and momentum conservation [9].

The fundamental equation for ISS is: [ \frac{Es}{E0} = \left( \frac{1}{1 + M2 / M1} \right)^2 \left( \cos \theta + \sqrt{ (M2 / M1)^2 - \sin^2 \theta } \ \right)^2 ] where ( E0 ) is the primary ion energy, ( M1 ) is the mass of the incident ion, ( M_2 ) is the mass of the surface atom, and ( \theta ) is the scattering angle [9]. Because the scattered ion signal is dominated by atoms in the topmost atomic layer, ISS is uniquely sensitive to the outer surface [9] [8].

Experimental Protocol for Quantitative Surface Composition Analysis

Objective: To determine the elemental composition of the outermost atomic layer of a solid sample using ISS.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function / Specification |

|---|---|

| Noble Gas Ion Source | Generates the primary ion beam (typically He⁺, Ne⁺, or Ar⁺) with energy between 0.5 - 3 keV [9] [8]. |

| Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) Chamber | Provides a clean environment (< 10⁻⁹ mbar) to prevent surface contamination during analysis [8]. |

| Sample Holder & Stage | Holds the sample and allows for precise positioning and, if available, heating or cooling. |

| Energy Analyzer | Measures the kinetic energy of the scattered ions (e.g., a hemispherical sector analyzer or time-of-flight system) [8]. |

| Standard Reference Sample | A pure, well-characterized material (e.g., gold foil) for instrument calibration [9]. |

| Charge Neutralization System | An electron flood gun for analyzing insulating samples to compensate for surface charging [8]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Sample Preparation: Introduce the sample into the UHV chamber. For powder samples, press into a clean indium foil or mount on a suitable stub. Clean the sample surface in situ via argon ion sputtering to remove adventitious carbon and contaminants, if the analysis goal permits [8].

Instrument Calibration: a. Energy Scale Calibration: Using the standard reference sample (e.g., Au), acquire a spectrum with a known primary ion (e.g., He⁺). The scattering angle ( \theta ) is a fixed parameter of the instrument (e.g., 130°) [9]. b. Primary Energy Calibration: Measure the kinetic energy of the scattered peak from the standard (( Es )). With known ( M1 ), ( M2 ), and ( \theta ), solve the ISS equation for ( E0 ) to determine the precise primary beam energy [9]. For example, with He⁺ (( M1 = 4 )) scattered from Au (( M2 = 197 )) at ( \theta = 130^\circ ) and a measured ( Es = 877 ) eV, the calculated ( E0 ) is 937 eV [9].

Data Acquisition: Direct the calibrated primary ion beam onto the sample surface. Set the energy analyzer to scan over the appropriate kinetic energy range (from just below ( E_0 ) down to zero) and collect the spectrum of scattered ion yield versus kinetic energy.

Data Interpretation: a. Peak Identification: Identify peaks in the spectrum. Each element on the surface will produce a peak at a characteristic ( Es ) [9]. b. Elemental Assignment: For each peak at energy ( Es ), use the known ( E0 ), ( M1 ), and ( \theta ) in the ISS equation to calculate the mass of the scattering atom, ( M_2 ), thereby identifying the element [9].

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Application in Corrosion Analysis

Background: Incoming coil steel stock conforming to a specified average roughness (Ra = 20-70 μin) showed unexpected corrosion after processing [10]. Analysis: 3D optical profilometry revealed that while both acceptable and rust-prone stock had similar Ra values, their 3D topography differed significantly. The rust-prone stock featured many deep valleys, whereas the acceptable stock was more isotropic [10]. ISS/SIMS Role: While surface topography parameters (Skewness, valley depth) identified the structural risk, compositional analysis via techniques like ISS or SIMS would be critical to determine if surface contaminants or specific alloying elements segregated in the valleys, contributing to the corrosion onset. Outcome: Bearing area curve analysis quantified the percentage of deep valleys that retained processing solutions, leading to flash rusting. This combined topographical and compositional analysis allowed for the development of a better quality control parameter than Ra alone [10].

Surface Engineering for Performance

Background: A new clutch plate design required optimization for friction and wear performance [10]. Analysis: Multiple plate designs with known performance were evaluated using 3D surface metrology parameters. ISS/SIMS Role: In such a study, ISS could be used to ensure the consistency of the outermost surface composition of the plates, while SIMS could depth profile to monitor the integrity of any surface coatings or modifications. Outcome: Statistical parameters like skewness (Ssk) and kurtosis were found to correlate strongly with wear and friction performance. These parameters were then used to control a novel manufacturing process, ensuring consistent and superior part performance [10].

Table 3: Quantitative Data from ISS Analysis of a Phosphor-Bronze Sample

| Element | Atomic Mass (M₂) | Theoretical ( Es/E0 ) | Measured ( E_s ) (eV) | Calculated ( Es/E0 ) | Identified? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen | 16 | 0.536 | ~400 eV (est. from fig.) | 0.427 (for E₀=937 eV) | Yes [9] |

| Copper | 63.5 | 0.837 | ~762 eV (est. from fig.) | 0.813 (for E₀=937 eV) | Yes [9] |

| Tin | 118.7 | 0.947 | ~877 eV (est. from fig.) | 0.936 (for E₀=937 eV) | Yes [9] |

Note: The table uses estimated values from a figure in [9] for a He⁺ beam (M₁=4) with a scattering angle of 130°. The primary beam energy E₀ is assumed to be 937 eV for calculation consistency.

Current Trends and Future Outlook

The field of surface analysis continues to evolve, driven by technological advancements and growing industrial adoption. Key trends shaping its future include:

- Democratization of Techniques: Instruments like XPS, SIMS, and AES are becoming more user-friendly, moving from tools exclusively operated by specialized experts to accessible resources for a broader range of scientists. This allows researchers to focus more on material exploration than instrumental complexity [11].

- Embracing Surface Engineering: Industries are increasingly using surface analysis as a general-purpose characterization tool to solve material challenges. This is particularly evident in the development of batteries, touch-screens, and medical devices, where surface properties are critical to performance [11].

- Automation and Data Integrity: The introduction of intelligent software, automation, and robust data analysis protocols is enhancing the reproducibility and integrity of surface analysis data, which is fundamental for scientific research and industrial quality control [11].

The precise measurement of electrons and ions forms the cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, enabling groundbreaking research across surface science, drug development, and fundamental physics. These measurements provide critical insights into electronic structures, chemical bonding behaviors, and material properties at the atomic level. For researchers investigating surface analysis techniques, understanding these fundamental operating principles is essential for selecting appropriate methodologies and interpreting experimental data accurately. This article details the core techniques, protocols, and applications of advanced spectroscopic methods that probe the interactions of electrons and ions with matter, with particular emphasis on approaches that achieve unprecedented sensitivity for studying rare and exotic elements.

Table 1: Core Techniques for Measuring Electrons and Ions

| Technique | Measured Property | Fundamental Principle | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Photodetachment Threshold (LPT) Spectroscopy | Electron Affinity (EA) | Neutralization of anions by collinear laser photons above a specific energy threshold [12]. | Determining electron affinities of atoms/molecules, benchmarking atomic theory [12]. |

| Multi-Reflection Time-of-Flight (MR-ToF) Analysis | Mass-to-Charge Ratio (m/z) |

Separation of ions based on flight time over extended path lengths in an electrostatic trap [12]. | High-resolution mass separation, ion storage for repeated laser probing [12]. |

| Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) | Elemental Composition | Analysis of atomic emission spectra from laser-generated plasma [13]. | Surface mapping, spatial element distribution in battery and material science [13]. |

| Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) | Peptide/Protein Quantification | High-resolution, accurate-mass targeted analysis of selected precursor ions [14]. | Targeted proteomics, kinase activity profiling, biomarker verification [14]. |

Fundamental Operating Principles

Laser Photodetachment and Electron Affinity Determination

The electron affinity (EA) is defined as the energy released when an electron is added to a neutral atom to form a negative ion [12] [15]. It is a fundamental atomic property governed by complex electron-electron correlations and is a critical parameter for predicting chemical reactivity and bonding behavior [12]. Laser Photodetachment Threshold (LPT) spectroscopy determines this property by measuring the exact photon energy required to remove the extra electron from an anion, thereby neutralizing it [12] [15].

In conventional LPT, a beam of anions is overlapped collinearly with a laser beam. The laser frequency is tuned, and the number of resulting neutral atoms is monitored. When the photon energy (E) exceeds the electron affinity (EA), photodetachment occurs, releasing an electron with kinetic energy Ee = E - EA [12]. The threshold energy at which neutral atoms are detected corresponds directly to the EA of the element. The collinear overlap of the laser and ion beams extends the interaction time and reduces the Doppler broadening of the spectral line, leading to higher resolution [12].

Ion Trapping and Signal Amplification

A transformative advancement in this field is the integration of LPT spectroscopy with Electrostatic Ion Beam Traps, specifically Multi-Reflection Time-of-Flight (MR-ToF) devices [12] [15]. This approach, exemplified by the MIRACLS (Multi Ion Reflection Apparatus for Collinear Laser Spectroscopy) technique, confines ions between two electrostatic mirrors [12].

Within the MR-ToF device, anions oscillate back and forth through a field-free drift region, where they are repeatedly probed by a collinear spectroscopy laser. This "recycling" of ions—achieving approximately 60,000 passes in demonstrated experiments—increases the laser-ion interaction time by several orders of magnitude compared to single-pass setups [15]. Consequently, the probability of photodetachment for each anion is drastically increased. This enhanced sensitivity allows for state-of-the-art precision EA measurements while employing five orders of magnitude fewer anions than conventional techniques [12]. After neutralization, atoms maintain their momentum and exit the trap along a predictable path to a detector, ensuring high detection efficiency [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining Electron Affinity via MR-ToF-Enhanced LPT Spectroscopy

This protocol details the procedure for measuring electron affinity with high sensitivity using an electrostatic ion beam trap, as demonstrated for chlorine [12].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Specification |

|---|---|

| Sample Material | Element of interest (e.g., Chlorine gas for Cl⁻ production). |

| Negative Surface Ion Source | Produces a continuous beam of negative ions (Cl⁻) [12]. |

| Paul Trap | Captures, accumulates, and cools ion bunches using helium buffer gas [12]. |

| Helium Buffer Gas | Cools ions via collisions to room temperature within the Paul trap [12]. |

| High-Voltage Pulsed Drift Tube | Adjusts the kinetic energy of ion bunches for isobaric purification [12]. |

| High-Voltage Deflector | Selects ions of a specific m/z (e.g., ³⁵Cl⁻) via time-of-flight [12]. |

| MR-ToF Device | Electrostatic trap with two mirrors for confining and cycling ions [12]. |

| Narrow-Band Continuous-Wave (cw) Laser | Spectroscopy laser for photodetachment; tunable energy around the expected EA [12]. |

| Neutral Particle Detector | High-efficiency, low-background detector for neutral atoms generated upon photodetachment [12]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Ion Production and Preparation:

- Generate a continuous beam of anions (e.g.,

Cl⁻) using a negative surface ion source [12]. - Guide the anion beam into a Paul trap. Capture, accumulate, and cool the ions via collisions with room-temperature helium buffer gas to reduce their kinetic energy and emittance [12].

- Extract the ions from the Paul trap in a low-emittance bunch.

- Generate a continuous beam of anions (e.g.,

Beam Purification and Energy Adjustment:

- Pass the ion bunch through a pulsed drift tube to adjust its kinetic energy to a precise value (e.g., 20-30 keV) [12].

- Direct the energy-adjusted bunch through a high-voltage deflector. Use time-of-flight selection to isolate the specific isotope of interest (e.g.,

³⁵Cl⁻) by deflecting unwanted species away from the beam axis [12].

Ion Trapping and Laser Probing:

- Inject the purified ion bunch into the MR-ToF device. Confine the ions by reflecting them between the two electrostatic mirrors for thousands of cycles [12].

- Continuously illuminate the ions in the field-free drift section of the MR-ToF with the narrow-band cw laser. The laser beam is collinear with the ion trajectory.

- Gradually tune the laser's photon energy across the theoretical electron affinity threshold of the element.

Signal Detection and Data Acquisition:

- When the photon energy exceeds the EA, photodetachment occurs. The resulting neutral atoms are no longer confined by the electrostatic mirrors and continue on a straight path, exiting the trap [12].

- Detect these neutral atoms using a high-efficiency neutral particle detector positioned downstream [12].

- Record the neutral count rate as a function of the laser photon energy.

Data Analysis and EA Determination:

- Plot the neutral count rate versus laser photon energy. The threshold energy where the signal significantly increases corresponds to the electron affinity of the atom.

- Fit the threshold curve to determine the EA with high precision. The demonstrated precision for chlorine was 3.612720(44) eV [12].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow and ion pathways for the MR-ToF-enhanced LPT spectroscopy protocol.

Advanced Applications and Broader Context

The enhanced sensitivity of techniques like MIRACLS is pushing the boundaries of scientific inquiry. A primary application is the systematic measurement of isotope shifts and hyperfine splittings in electron affinities across isotopic chains, providing benchmarks for nuclear models [12]. Furthermore, this methodology paves the way for the first direct determination of electron affinities in superheavy elements (e.g., oganesson, Z=118), where relativistic effects are predicted to dominate and potentially颠覆 periodic table trends [12] [15].

Beyond fundamental atomic physics, these principles are vital in applied fields. In cancer research, measuring the electron affinity of rare elements like astatine and actinium is crucial for developing targeted alpha-therapy radiopharmaceuticals [15]. The technique can also be applied to molecules, providing data for theoretical calculations relevant to antimatter research and the use of radioactive molecules to probe physics beyond the Standard Model [12] [15].

The operating principles of electron and ion measurement find parallel applications in other spectroscopic methods. For instance, Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) uses a pulsed laser to create a micro-plasma, whose emitted light is analyzed to determine the elemental composition of a surface. This has proven highly effective for mapping lithium nucleation in anode-less solid-state batteries, distinguishing between electrolyte-derived lithium and in-situ formed metal anodes [13].

Table 3: Comparison of Electron/Ion Measurement Techniques

| Technique | Typical Sample Size/Intensity | Achievable Precision | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional LPT | ~10¹¹ anions per second (e.g., 600 fA for Astatine) [12] | High (for abundant samples) | Inefficient use of sample; unsuitable for very rare species [12]. |

| MR-ToF-Enhanced LPT | ~10⁶ anions per second (5 orders of magnitude fewer) [12] | State-of-the-art (e.g., 3.612720(44) eV for Cl) [12] | Requires stable anion formation and specialized trap instrumentation. |

| Photodetachment Microscopy | Large ensembles | Very High [12] | Requires high beam intensity and complex electron interference pattern analysis [12]. |

| LIBS | Microscopic surface area | Semi-Quantitative (excellent for mapping) [13] | Matrix effects can influence emission spectra and quantification [13]. |

Surface analysis techniques are indispensable tools in modern scientific research, particularly in fields requiring detailed material characterization such as drug development and materials science. These techniques provide critical data on elemental composition, chemical speciation, and spatial distribution of analytes. However, each method possesses unique capabilities alongside inherent limitations. This application note provides a detailed examination of three critical aspects—elemental detection, chemical state information, and spatial resolution—within the context of ion spectroscopy and related surface analysis techniques. By framing this discussion within experimental protocols and quantitative comparisons, this document serves as a practical resource for researchers and scientists designing characterization strategies for complex biological and material systems.

Key Capabilities and Limitations: A Comparative Analysis

The table below summarizes the core capabilities and limitations of prominent surface analysis techniques, highlighting their performance across the three focus areas.

Table 1: Key Capabilities and Inherent Limitations of Surface Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Elemental Detection | Chemical State Information | Spatial Resolution | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIXE (Particle Induced X-ray Emission) | Quantitative mapping of metals (e.g., Fe, Mn) in biological tissues [16]. | Limited directly, often requires coupling with other techniques [16]. | ~Micrometer resolution, suitable for distinguishing brain regions like SNpc and SNpr [16]. | Requires correlation with histology for accurate anatomical location; sample preparation is critical to preserve native element distribution [16]. |

| Synchrotron XRF (X-ray Fluorescence) | Quantitative distribution of multiple elements (P, S, Cl, K, Ca, Cu, Zn) simultaneously [16]. | Can be coupled with micro-XANES to identify oxidation states (e.g., Fe(II) vs. Fe(III)) [16]. | Micro-scale resolution, capable of revealing intra-regional differences (e.g., Mn content in SNpc vs. SNpr) [16]. | Requires synchrotron radiation source; complex sample preparation using cryogenic protocols to avoid disturbing native element speciation [16]. |

| ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) | Exceptional sensitivity with detection limits in the low parts-per-trillion (ppt) range for most elements; high ionization efficiency for most metals (80-95%) [17]. | None; provides elemental composition only. | Essentially none for spatial mapping; typically a bulk analysis technique. | Overall inefficiency (~0.00002%); losses occur at nebulization, interface (sampler/skimmer cones), and in ion lenses [17]. |

| Imaging Mass Spectrometry (IMS) | Direct mapping of a wide variety of analytes, including lipids and metabolites, in thin tissue sections [18]. | Tandem MS (MS/MS) and ion/ion reactions provide specificity to differentiate isobaric and isomeric compounds [18]. | A key trade-off exists; higher chemical specificity (via ion/ion reactions) often forces lower spatial resolution (e.g., 125 µm) due to signal requirements [18]. | Differentiating isobaric/isomeric lipids is challenging; spatial resolution is inversely related to chemical specificity and limit of detection [18]. |

| Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) | Limited elemental specificity. | Can probe electronic characteristics of surfaces [19]. | Atomic-scale resolution for conductive surfaces [19]. | Requires conductive samples; primarily for topographical and electronic mapping rather than direct chemical identification [19]. |

Quantitative Data in Analytical Performance

Understanding the numerical benchmarks for sensitivity and efficiency is crucial for technique selection. The following tables consolidate key quantitative data from the literature.

Table 2: Sensitivity and Detection Limits of Mass Spectrometry Techniques

| Technique | Typical Sensitivity | Exemplary Detection Limit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrupole ICP-MS | 100-500 million counts per second per part per million (Mcps/ppm) [17]. | ~1 part per trillion (ppt) for many elements [17]. | 1 ppt corresponds to ~1.1 x 10⁹ to 4.2 x 10⁷ atoms per second introduced to the nebulizer [17]. |

| FT-ICR Imaging MS | Not explicitly quantified in results. | Enables separation of isobaric compounds [18]. | High resolving power requires long transient times [18]. |

Table 3: Component Efficiency in a Typical Quadrupole ICP-MS System

| Component / Process | Approximate Efficiency | Description of Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Nebulization & Spray Chamber | 1-2% | Majority of sample is drained to waste [17]. |

| Ionization in ICP | 40% (Hg) to >95% (most metals) | Dependent on element's first ionization potential [17]. |

| Interface (Sampler & Skimmer Cones) | ~0.04% (2% x 2%) | Intentional due to the 10⁷-fold pressure reduction from atmospheric plasma to high vacuum [17]. |

| Ion Lenses | ~50-80% | Losses from focusing and steering ions; modern "off-axis" designs improve transmission and block photons [17]. |

| Collision/Reaction Cell | Variable | Losses from space charge effects and collisional scattering [17]. |

| Quadrupole Mass Filter | ~50% | Ions filtered based on mass-to-charge ratio [17]. |

| Detector (Electron Multiplier) | ~100% (for counted ions) | One detectable pulse per ion strike [17]. |

| Overall System Efficiency | ~0.00002% | Product of individual component efficiencies [17]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Correlative Elemental and Chemical State Analysis in Brain Tissue

This protocol, adapted from a study on Parkinson's disease models, details the process for correlating quantitative metal mapping with chemical speciation and histology in specific brain regions [16].

1. Sample Preparation and Cryofixation

- Animal Perfusion and Brain Extraction: Anesthetize the animal and transcardially perfuse with a suitable buffer to remove blood. Rapidly extract the brain.

- Cryofixation: Immediately plunge the intact brain into a cooled cryogenic liquid (e.g., isopentane cooled with dry ice to -40°C) to preserve the native distribution and speciation of elements. Store cryofixed brains at -80°C [16].

- Cryo-Sectioning: Section the frozen brain on a cryostat (e.g., 10-20 µm thickness) and thaw-mount onto appropriate substrates (e.g., indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated slides for SXRF) [16].

2. Correlative Immunohistochemistry (on Adjacent Sections)

- Purpose: To unambiguously identify anatomical regions of interest (e.g., Substantia Nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and pars reticulata (SNpr)) for subsequent chemical analysis.

- Procedure: On a separate, adjacent cryo-section, perform standard tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunohistochemical staining. This provides a high-resolution anatomical map.

- Correlation: Superimpose the optical image of the stained section with the elemental maps from the analyzed section to define the regions for quantitative analysis and speciation [16].

3. Quantitative Elemental Mapping via PIXE/SXRF

- Data Acquisition: Irradiate the unstained cryo-section with a focused micro-beam of protons (PIXE) or synchrotron X-rays (SXRF). Collect the emitted X-rays to generate quantitative distribution maps for elements like Fe, Mn, P, S, K, Ca, Cu, and Zn [16].

- Spatial Registration: Use the correlated histology image to assign the elemental content to specific brain structures (SNpc, SNpr, VTA).

4. Chemical Speciation via micro-XANES

- Site Selection: Based on the correlated maps, select specific micron-scale spots within the SNpr and SNpc for speciation analysis.

- Data Collection: Acquire X-ray absorption spectra at the Fe K-edge across a range of energies around the absorption edge.

- Data Analysis: Compare the experimental XANES spectra (edge position, pre-edge features) with spectra from reference compounds (e.g., ferritin) to identify the dominant oxidation state and chemical environment of iron [16].

Protocol 2: Resolving Isobaric Lipids via Ion/Ion Reaction Imaging MS

This protocol describes a tandem MS workflow to differentiate isobaric lipids in tissue sections, addressing a key challenge in imaging mass spectrometry [18].

1. Tissue Preparation and Matrix Application

- Cryo-Sectioning: Fresh-frozen mouse brain tissue is sectioned at 10 µm thickness using a research cryostat and thaw-mounted onto ITO-coated slides [18].

- Matrix Deposition: Coat the tissue section with a matrix (e.g., 2’,5’-Dihydroxyacetophenone - DHA) using a sublimation apparatus (e.g., 3 minutes at 180°C) to ensure homogeneous crystallization [18].

2. High-Resolution Full Scan (MS1) Imaging

- Acquisition: Acquire full scan mass spectra using a MALDI-FT-ICR instrument or similar high-resolution mass spectrometer.

- Parameters: Use a high spatial resolution (e.g., 25 µm pixel spacing) to capture the detailed spatial distribution of all detectable lipids. This dataset will serve as the high-spatial-resolution input for later fusion [18].

3. Low-Resolution Ion/Ion Reaction (MS2) Imaging

- Acquisition: Acquire MS/MS images on the same tissue section using a targeted approach.

- Ion/Ion Reaction: For each pixel, isolate lipid anion precursors, mutually store them with TMODA dications from an ESI source to form Schiff base products, and perform CID to generate diagnostic fragment ions [18].

- Parameters: Use a lower spatial resolution (e.g., 125 µm pixel spacing) to compensate for the lower signal intensity resulting from the multi-step reaction and fragmentation process [18].

4. Computational Image Fusion

- Co-registration: Spatially align the high-resolution MS1 and low-resolution MS2 imaging datasets.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) to the full MS1 dataset to reduce its complexity while retaining spatial features.

- Model Training: Use machine learning models (e.g., Linear Regression, 2-D Convolutional Neural Networks) to learn the relationship between the NMF components of the MS1 data and the specific ion/ion reaction product ion image from the MS2 data.

- Prediction: Apply the trained model to the high-resolution MS1 data to generate a predicted image of the ion/ion reaction product with a 5-fold enhanced spatial resolution (e.g., predicted at 25 µm) [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Featured Surface Analysis Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cryogenic Fluids | Rapid cryofixation of biological tissues to preserve native elemental distribution and speciation [16]. | Isopentane cooled with dry ice (-40°C to -80°C) [16]. |

| Primary Antibodies for IHC | Histological staining for anatomical correlation in correlative elemental imaging [16]. | Anti-Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH) antibody for identifying dopaminergic regions in brain tissue [16]. |

| TMODA Reagent | Gas-phase derivatization reagent for charge inversion ion/ion reactions; selectively targets phosphatidylserine lipids [18]. | Synthesized from N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethyl-1,6-hexanediamine and 6-Bromohexanal [18]. |

| MALDI Matrix | Assists in the desorption and ionization of analytes from tissue surfaces for mass spectrometry analysis. | 2’,5’-Dihydroxyacetophenone (DHA) for lipid analysis [18]. |

| Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) Coated Slides | Conductive substrate required for mounting tissue sections in imaging mass spectrometry and micro-XRF to prevent charging [18]. | -- |

| Reference Standards | Critical for calibrating quantitative analyses and for identifying chemical species via fingerprinting in XANES. | Pure ferritin for matching Fe speciation in brain tissue [16]. |

Current Trends and Publication Growth in Surface Analysis Techniques

Surface analysis is a methodical examination of a material's outermost layers to ascertain its composition, structure, and properties at atomic and molecular levels [20]. These techniques are foundational for understanding surface characteristics that dictate chemical activity, adhesion, wetness, electrical properties, corrosion-resistance, and biocompatibility [20]. The field has evolved significantly since the 1960s with the introduction of commercial instrumentation, and today encompasses a range of sophisticated techniques, the most widespread being X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Auger electron spectroscopy (AES), and secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) [21]. The growing demand for precise surface characterization in sectors like semiconductors, healthcare, and advanced materials is propelling both technological innovation and market expansion, with the global surface analysis market projected to reach between USD 9.19 billion and USD 9.38 billion by 2032 [19] [22].

This application note frames the current landscape and experimental protocols within the context of advanced ion spectroscopy and surface analysis techniques research. It is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with actionable data and methodologies to navigate this dynamic field.

Quantitative Market Growth Analysis

The surface analysis market demonstrates robust growth, driven by technological advancements and increasing demand across industrial sectors. Table 1 summarizes the quantitative market projections from key industry reports, which show some variation based on methodology and forecast periods [19] [22] [23].

Table 1: Surface Analysis Market Size and Growth Projections

| Source | Base Year Value | Projected Year Value | CAGR | Forecast Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coherent Market Insights [19] | USD 6.45 Bn (2025) | USD 9.19 Bn (2032) | 5.18% | 2025-2032 |

| The Business Research Company [22] | USD 6.61 Bn (2025) | USD 9.38 Bn (2029) | 9.1% | 2024-2029 |

| Prophecy Market Insights [24] | USD 6.1 Bn (2025) | USD 10.7 Bn (2035) | 6.3% | 2025-2035 |

| SERPVision [23] | USD 5.77 Bn (2025) | USD 14.68 Bn (2033) | 16.84% | 2026-2033 |

This growth is fueled by several macro and microeconomic factors. Key drivers include the expansion of the semiconductor and electronics industry, stringent quality control regulations in aerospace and medical devices, rising R&D investments in healthcare and nanotechnology, and government programs supporting metrology and environmental laws [19] [22] [24]. A notable restraint is the high cost of advanced equipment and a global shortage of skilled professionals to operate these sophisticated instruments [24].

Technique Adoption and Publication Growth

An analysis of publication rates reveals clear trends in the adoption and scientific application of different surface analysis techniques. As illustrated in Figure 1, the number of publications utilizing XPS (including related terms like ESCA, PES, HAXPES, and NAP-XPS) has seen a rapid and continuous increase over the past two decades. In contrast, publication rates for AES and SIMS have remained relatively constant during the same period [21]. This trend underscores XPS's position as the most commonly used technique, owing to its relatively simple spectra, ease of quantification, excellent chemical state information, and lower instrument cost compared to AES and SIMS [21].

Advanced Techniques and Methodologies

Dominant Surface Analysis Techniques

The surface analysis landscape is characterized by several powerful techniques, each with unique strengths and applications, particularly in ion spectroscopy research.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), XPS operates by irradiating a sample with X-rays and analyzing the kinetic energy of emitted photoelectrons [21] [25]. It provides quantitative data on atomic composition and chemical bonding states of the surface [25] [20]. Its key advantage is the ability to analyze various materials, both organic and inorganic, making it the most widespread technique [21] [20]. XPS cannot directly detect hydrogen or helium [21].

Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS): This technique uses a pulsed primary ion beam to desorb and ionize species from the sample surface. The secondary ions are accelerated into a time-of-flight mass analyzer, separating ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio [20]. TOF-SIMS offers extremely high surface sensitivity, can detect all elements including isotopes, and provides molecular mass information for organic compounds [21] [20]. Its spectra can be complex due to large molecular fragments.

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES): AES employs a focused electron beam to excite the sample, resulting in the emission of Auger electrons that are analyzed for their kinetic energy [21] [25]. It provides elemental and some chemical state information with very high spatial resolution, making it particularly suitable for analyzing micro-level foreign substances and for failure analysis in semiconductors and metals [25] [20].

Emerging and Specialized Methodologies

Recent years have seen the development and commercialization of several advanced XPS methodologies that address previous limitations and open new research avenues.

Hard X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (HAXPES): Traditionally conducted at synchrotron facilities, HAXPES is now available in laboratories using silver, chromium, or gallium X-ray sources instead of standard aluminum or magnesium sources [21]. The higher energy X-rays enable deeper analysis (up to several tens of nanometers), reduce the effects of surface contamination, and allow access to higher binding energy core levels, facilitating the study of buried interfaces [21] [25].

Near-Ambient Pressure XPS (NAP-XPS): A significant advancement beyond traditional ultra-high vacuum requirements, NAP-XPS allows for the chemical analysis of surfaces in reactive environments or under modest gas pressures [21]. This capability is crucial for in-situ studies of catalytic reactions, corrosion processes, and the interaction of microorganisms with surfaces [21].

XPS Depth Profiling: This technique combines controlled material removal (typically with an ion beam) with sequential XPS analysis to construct a high-resolution composition profile from the surface into the bulk [25]. The recent development of gas cluster ion sources has significantly improved the depth profiling of soft materials like organic polymers and biomaterials, which were previously damaged by monatomic ion beams [25].

Experimental Protocols for Surface Analysis

Protocol 1: XPS Analysis of Thin Film Coatings

This protocol details the procedure for characterizing the composition and chemical state of a thin film coating on a metallic substrate, relevant for biomedical implant materials.

Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Cut the sample to a maximum size of 10mm x 10mm to fit the sample holder.

- For electrically insulating materials, ensure the use of a charge compensation system [25].

- Avoid any contact with the analysis area. Use powder-free gloves and clean tweezers.

- If the sample is prone to degradation, consider rapid transfer to the introduction chamber.

Step 2: Instrument Setup

- Mount the sample on the holder using double-sided conductive tape or clamping.

- Insert the sample into the introduction chamber and pump down to ultra-high vacuum (UHV), typically ≤ 10⁻⁸ mbar [20].

- Select an Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV) for standard analysis. For HAXPES, switch to a Ag Kα or Cr Kα source [21].

- Set the pass energy to 20-50 eV for high-resolution scans (high sensitivity) and 100-200 eV for survey scans (wide energy range).

Step 3: Data Acquisition

- Acquire a survey spectrum from 0-1100 eV binding energy to identify all elements present.

- Collect high-resolution spectra for each identified element, ensuring sufficient signal-to-noise ratio.

- For non-destructive depth information, perform Angle-Resolved XPS (ARXPS) by acquiring data at emission angles from 0° (normal) to 60° [25].

- Use a step size of 0.1 eV and acquisition time of 50-100 ms/step for high-resolution spectra.

Step 4: Data Processing and Peak Fitting

- Calibrate the energy scale using the C 1s peak for adventitious carbon at 284.8 eV.

- Subtract a Shirley or Tougaard background from the high-resolution spectra.

- For peak fitting, use appropriate line shapes (asymmetric for metals, symmetric for oxides/polymers) and apply correct constraints for spin-orbit doublets (e.g., fixed area ratio and separation for the Pt 4f doublet) [21].

- Report the atomic concentrations calculated from the peak areas using instrument-specific sensitivity factors.

Protocol 2: TOF-SIMS Depth Profiling for Organic Interfaces

This protocol is optimized for investigating the vertical distribution of organic molecules in a multilayer drug-eluting film.

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Handling

- Prepare samples as described in Protocol 1, Step 1.

- Due to the extreme surface sensitivity of TOF-SIMS, ensure samples are not exposed to volatile organic compounds.

- For non-conductive samples, a thin metal coating (e.g., ~10 nm Au) may be necessary, unless using a charge compensation system designed for SIMS.

Step 2: Instrument Configuration

- Select a bismuth (Biₙᵐ⁺) liquid metal ion gun as the primary analysis beam for high yield of molecular ions.

- Use a cesium (Cs⁺) or argon (Arₙ⁺) gas cluster ion source for sputtering to minimize damage to the organic matrix [25].

- Optimize the primary ion beam current and focus for the desired spatial resolution.

- Set the time-of-flight analyzer for high mass resolution (M/ΔM > 10,000).

Step 3: Depth Profiling Acquisition

- Set the analysis area and ensure it is smaller than the sputter crater to avoid crater edge effects.

- Alternate between short pulses of the analysis beam (Biₙᵐ⁺) and continuous etching with the sputter beam (Cs⁺ or Arₙ⁺).

- Adjust the sputter beam energy and current to achieve a suitable erosion rate. Calibrate the depth scale post-analysis using a profilometer.

- Acquire positive and negative ion spectra at each depth increment.

Step 4: Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Reconstruct 2D chemical images from the ion data for specific depths.

- Extract intensity profiles for characteristic molecular ions and fragments as a function of sputter time/depth.

- Use multivariate analysis techniques (PCA, MCR) to deconvolute complex spectral data from overlapping layers.

- Correlate the SIMS depth profile with XPS data from Protocol 1 for comprehensive chemical and molecular information.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful surface analysis requires careful selection of reagents and materials. Table 2 lists key solutions and items crucial for preparing and analyzing surfaces, especially in a pharmaceutical or biomaterials context.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Analysis

| Item/Reagent | Function/Application | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents (e.g., HPLC-grade Water, Ethanol, Toluene) | Sample cleaning and residue removal prior to analysis. | Prevents introduction of contaminants from solvents that could adsorb onto the surface. |

| Conductive Adhesive Tapes (Carbon, Copper) | Mounting powder or irregularly shaped samples onto holders. | Ensures good electrical and thermal contact between sample and holder, critical for non-conductive samples. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Instrument calibration and quantification. | Required for validating analytical results; includes pure metal foils (Au, Ag, Cu) for energy scale calibration. |

| Charge Compensation Source (Low-energy Electron Flood Gun) | Neutralizing surface charge on insulating samples. | Essential for analyzing polymers, ceramics, and pharmaceutical powders to prevent peak shifting and broadening in XPS [25]. |

| Sputter Ion Sources (Argon, Cesium, Gas Clusters) | Surface cleaning and depth profiling. | Monatomic ions (Ar⁺) for inorganic materials; gas clusters (Arₙ⁺) for organic and soft materials to reduce damage [25]. |

| Standardized Substrata (e.g., Silicon Wafers) | Model surfaces for method development and calibration. | Provides a well-defined, atomically flat, and reproducible surface for validating analytical protocols [26]. |

| Cryogenic Preparation Stage | Sample preparation and transfer for volatile or biological samples. | Preserves the native state of samples containing liquids or sensitive biomolecules by freezing. |

A critical consideration, particularly for biological samples, is that cell preparation protocols—including centrifugation, washing, desiccation (air-drying or freeze-drying), and contact with hydrocarbons—can severely modify the physicochemical properties of cell surfaces [26]. Therefore, preparation methods must be critically investigated for each microorganism to ensure results reflect the in-situ cell surface as closely as possible.

The field of surface analysis is characterized by consistent growth in both market value and scientific publication output, with XPS maintaining its dominant position. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for data interpretation and automation is a key trend enhancing precision and efficiency [19] [24]. Furthermore, the development of more accessible specialized techniques like HAXPES and NAP-XPS is expanding the boundaries of what can be studied, allowing researchers to probe buried interfaces and operate in reactive environments [21].

For researchers in drug development and material science, this translates to an increasingly powerful toolkit for solving complex problems related to surface composition and reactivity. However, challenges remain, including the high cost of instrumentation, the need for skilled operators, and pervasive issues with data interpretation, as evidenced by incorrect peak fitting in a significant portion of XPS publications [21] [24]. Addressing these challenges through improved training, robust data analysis software, and the development of more cost-effective instruments will be crucial for the future advancement and accessibility of these indispensable analytical techniques.

Practical Applications in Drug Development and Material Characterization

Mass Spectrometric Imaging (MSI) for Drug and Metabolite Distribution in Tissues

Mass Spectrometric Imaging (MSI) has emerged as a transformative analytical technique in pharmacology and toxicology, enabling the direct detection and spatial mapping of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), their metabolites, and endogenous biomarkers directly from biological tissue sections [27]. Unlike traditional analytical methods that require tissue homogenization, MSI preserves the spatial context of molecular distributions, providing crucial insights into drug distribution, metabolism, and target engagement at the site of action [27]. This capability is particularly valuable for understanding tissue pharmacokinetics, which often offers a more accurate representation of drug activity than plasma measurements alone [27].

The fundamental strength of MSI lies in its label-free, multiplexed capability to simultaneously detect parent compounds, known and potential metabolites, and endogenous biomarkers in a single experiment without the need for radioactive labeling or fluorescent tags [27]. When integrated with traditional histology techniques such as haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry (IHC), MSI creates a comprehensive picture that combines analytical and spatial information [27]. This integration provides researchers with a powerful tool to optimize dosing strategies, mitigate off-target effects, and identify reliable biomarkers for early toxicity detection [27].

Application Notes: Key MSI Approaches

Quantitative MSI (qMSI) for Neurotransmitters

Overview and Principle: Precise quantitation of endogenous compounds in heterogeneous tissue samples presents significant challenges due to matrix effects and variations in ionization efficiency [28]. Advanced MALDI-MSI protocols employing a standard addition approach have been developed to address these limitations, enabling accurate spatial quantification of neurotransmitters and their metabolites in rodent brain tissue [28]. These methods involve homogeneous spraying of standard solutions onto tissue sections to minimize matrix effects associated with spatially heterogeneous samples [28].

Experimental Workflow: The quantitative workflow incorporates two distinct methods. Method A utilizes spraying of deuterated analogues of neurotransmitters across all tissue sections for normalization, with calibration standards applied quantitatively to consecutive tissue sections [28]. Method B employs two stable isotope-labeled compounds: one for calibration and the other for normalization [28]. Both methods demonstrated strong linearity between signal intensities and analyte concentrations across brain tissue sections, with values comparable to those obtained using high-performance liquid chromatography-electrochemical detection [28].

Key Advantages: The standard addition approach significantly enhances quantitation accuracy by accounting for tissue-specific matrix effects, providing a robust method for spatial quantification of neurotransmitters in complex brain tissue environments [28]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying neuropharmacology and the distribution of neuroactive compounds.

Tissue-Expansion Mass Spectrometry Imaging (TEMI)

Technology Principle: TEMI represents a recent innovation that addresses the longstanding challenge of low spatial resolution in conventional MSI [29]. This method involves chemically anchoring proteins into a hydrogel synthesized in situ, followed by controlled swelling of the tissue-hydrogel material to achieve physical expansion of the tissue sample [29]. By eliminating the proteolysis, detergent, and high-temperature treatments used in conventional expansion methods, TEMI better retains biomolecules including lipids, metabolites, peptides, and N-glycans through interactions with anchored, native-state proteins [29].

Performance Characteristics: TEMI achieves single-cell spatial resolution without sacrificing voxel throughput, enabling the profiling of hundreds of biomolecules simultaneously [29]. Through optimized protocols involving multiple rounds of gel embedding without denaturation, TEMI achieves expansion factors of approximately 2.5–3.5-fold linearly, resulting in effective lateral resolutions of ~20 μm down to ~2.9 μm [29]. This enhanced resolution enables visualization of individual Purkinje cells in mouse cerebellum and reveals previously unknown spatial heterogeneity in lipid distributions across cerebellar layers [29].

Application Potential: The significantly improved spatial resolution offered by TEMI facilitates uncovering metabolic heterogeneity in tumors and detailed mapping of biomolecule distributions across various mammalian tissues [29]. This advancement opens new possibilities for studying drug distribution at cellular resolution and investigating subcellular compartmentalization of pharmaceuticals and their metabolites.

MSI for Toxicological Investigations

Integration in Drug Safety Assessment: MSI plays an increasingly important role in toxicological investigations by providing spatial context for drug-induced injury [27]. The technique helps establish mechanistic hypotheses of toxicity, guiding critical go/no-go decisions in drug development by balancing therapeutic benefits against potential risks [27]. MSI integrates seamlessly with histopathology, clinical chemistry, pharmacodynamics, and drug metabolism data to provide a comprehensive understanding of drug safety profiles [27].

Strategic Implementation: Incorporating MSI into toxicological studies requires careful planning and collaboration across multidisciplinary teams including toxicology, histopathology, drug metabolism, bioanalysis, and quality assurance [27]. The initial step involves determining the MSI limit of detection (LOD) for the parent drug and its metabolites [27]. Prospective studies offer greater flexibility for optimizing necropsy timing and flash-freezing of tissues for MSI analysis with input from study toxicologists and histopathologists [27].

Case Example: A recent study demonstrated MSI's ability to distinguish biliary toxicants by revealing distinct pharmacokinetics within hepatocytes and bile duct cells, informing the development of safer alternatives [27]. This application highlights how spatial distribution data can provide crucial insights into organ-specific toxicity mechanisms that might be missed using traditional analytical approaches.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantitative MALDI-MSI with Standard Addition

This protocol describes a robust method for absolute quantification of drugs and metabolites in tissue sections using a standard addition approach to account for matrix effects [28].

Materials and Equipment

- Biological Samples: Fresh-frozen tissue specimens (e.g., rodent brain, liver)

- Chemical Standards: Deuterated or stable isotope-labeled analogues of target analytes, calibration standards (e.g., dopamine, norepinephrine, 3-methoxytyramine)

- Matrix Compounds: FMP-10, 1,5-diaminonaphthalene (DAN), 9-aminoacridine (9-AA)

- Solvents: HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile, deionized water, 0.1 N HCl/50% MeOH (1/9 v/v)

- Equipment: Cryostat, robotic sprayer (e.g., TM-sprayer, HTX-Technologies), MALDI-FTICR-MS instrument (e.g., Solarix XR 7T-2Ω)

Step-by-Step Procedure

Tissue Preparation

- Surgically remove tissue and snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen or over dry ice.

- Store at -80°C in appropriate containers to maintain spatial integrity.

- Cut sagittal tissue sections at 12 μm thickness using a cryostat.

- Mount sections centrally on ITO-coated slides with sufficient distance between sections to avoid cross-contamination.

Standard Solution Preparation

- Prepare stock solutions of neurotransmitters and corresponding SIL analogues in 0.1 N HCl/50% MeOH (1/9 v/v).

- Sonicate for 20 minutes to ensure complete dissolution.

- Dilute calibration standards and SIL compounds for normalization in 50% methanol.

Standard Application via Robotic Sprayer

- Apply SIL internal standards (e.g., DA-d4, 3-MT-d3, NE-d6) over sagittal mouse brain tissue sections in six passes to achieve a concentration of 7.2 pmol/mg tissue.

- For Method A: Spray different concentrations of calibration standards in four passes over intended brain tissue sections, while covering other tissues with a coverslip.

- For Method B: Prepare samples similarly to Method A, but use different stable isotope-labeled compounds as calibration standards.

- Use the following spraying parameters: nozzle temperature 90°C, solvent flow rate 70 μL/min, nozzle velocity 1100 mm/min, nitrogen gas pressure 6 psi, track spacing 2.0 mm.

- Calculate the density of deposited standard using: ( w = n \times C \times \frac{F}{V \times d} ), where ( n ) is number of passes, ( C ) is solution concentration, ( F ) is flow rate, ( V ) is sprayer head velocity, and ( d ) is track spacing.

Matrix Deposition

- Vacuum-dry samples for 10 minutes after standard application.

- Apply derivatizing MALDI matrix FMP-10 (4.4 mM in 70% acetonitrile) using 20 passes with horizontal lines.

- Use spraying parameters: solvent flow rate 80 μL/min, nozzle temperature 90°C, nozzle velocity 1100 mm/min, nitrogen gas pressure 6 psi, track spacing 2 mm.

MALDI-MSI Acquisition

- Perform imaging using a MALDI-FTICR-MS instrument equipped with a Smartbeam II 2 kHz Nd:YAG laser.

- Acquire data in positive ion mode using quadrature phase detection (QPD) mode over a mass range of m/z 150-1500.

- Record spectra by summing signals from 100 laser shots per pixel.

- Use a matrix-derived peak at m/z 555.2231 as a lock mass for internal m/z calibration.

- Utilize red phosphorus for external calibration.

Data Analysis and Quantification

- Convert acquired data to imzML format using flexImaging, then to msIQuant format for quantitative analysis.

- Extract signal intensity values of neurotransmitters and metabolites from specific regions of interest.

- Plot data against amounts of added analytes and perform least-squares analysis.

- Determine endogenous concentration of each analyte from the x-intercept of the trend line.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of MALDI-MSI for Neurotransmitters

| Analyte | Linear Range | R² Value | Tissue Region | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine (DA) | Not specified | >0.99 | Striatum | HPLC-ECD |

| Norepinephrine (NE) | Not specified | >0.99 | Striatum | HPLC-ECD |

| 3-Methoxytyramine (3-MT) | Not specified | >0.99 | Striatum | HPLC-ECD |

| 5-HT | Not specified | >0.99 | Striatum | HPLC-ECD |

| 5-HIAA | Not specified | >0.99 | Striatum | HPLC-ECD |

Protocol 2: Tissue-Expansion MSI (TEMI)

This protocol describes the TEMI method for achieving single-cell resolution in mass spectrometry imaging through physical expansion of tissue samples [29].

Materials and Equipment

- Biological Samples: Fresh mammalian tissues (e.g., mouse cerebellar tissue)

- Hydrogel Components: High-monomer, high-toughness gel components

- Solutions: 30% sucrose solution, 1× PBS, deionized water

- Matrix Compounds: 1,5-diaminonaphthalene (DAN), 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid

- Equipment: Cryostat, MALDI-MS instrument with high spatial resolution capability

Step-by-Step Procedure

Tissue Preparation and Hydrogel Embedding

- Chemically anchor proteins into a hydrogel synthesized in situ using a high-monomer, high-toughness gel formulation.

- Avoid proteolysis, detergent, or high-temperature treatments to maximize retention of biomolecules.

- Perform a second round of gel embedding to create an interpenetrating gel network with sufficient toughness for isotropic expansion.

Controlled Expansion

- Expand embedded tissue slices approximately 2.5–3.5-fold linearly in 1× PBS.

- Avoid full expansion in deionized water to prevent cracks or macroscale gel deformation.

- Lay expanded gels flat before freezing without macroscopic tissue distortion.

Cryosectioning

- Use 30% sucrose for optimal cryosectioning of expanded tissue-gel material.

- Cut sections at 30 μm thickness, as thinner sections become increasingly difficult to obtain intact.

- Ensure even surface without uneven hydrogel layers that could interfere with MALDI laser penetrance.

Matrix Application and MALDI-MSI Acquisition

- Apply appropriate MALDI matrix (e.g., DAN for lipids in positive and negative ionization modes).

- Perform imaging with 50-μm raster laser scan for ~2.5-fold expanded tissue, resulting in effective lateral resolution of ~20 μm.

- For higher resolution, image 3.5-fold expanded tissue sections with 10-μm raster laser scan, achieving ~2.9-μm effective scanning resolution.

Data Analysis

- Identify lipid molecules specifically enriched in different tissue structures and functional layers.

- Generate spatial distribution maps revealing biomolecular heterogeneity.

- Correlate molecular distributions with tissue morphology and cellular features.

Table 2: TEMI Performance Characteristics for Different Biomolecule Classes

| Biomolecule Class | Spatial Resolution | Key Findings | Tissue Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids | ~2.9 μm effective | Revealed PC(32:0), PC(38:1), PC(38:6) enrichment in distinct cerebellar layers | Mouse cerebellum |

| Metabolites | ~20 μm effective | Identified 187 metabolite features with distinctive spatial organization | Mouse cerebellum |

| Peptides/Proteins | ~2.9 μm effective | Detected 57 features including myelin basic protein and histone H2B groups | Mouse cerebellum |

| N-glycans | ~2.9 μm effective | Spatial distribution mapping of N-linked glycans | Mouse cerebellum |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MSI Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|