Interpolation vs. Band Structure: A Practical Guide to Validating Band Gap Measurements

Accurately determining the electronic band gap is crucial for developing new materials in fields like semiconductors and photovoltaics.

Interpolation vs. Band Structure: A Practical Guide to Validating Band Gap Measurements

Abstract

Accurately determining the electronic band gap is crucial for developing new materials in fields like semiconductors and photovoltaics. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers on the two primary methods for calculating band gaps: the interpolation method used during self-consistent field (SCF) calculation and the band structure method used for post-processing. We explore the foundational principles behind each technique, detail their practical application and parameter settings, address common convergence and accuracy challenges, and introduce quantitative validation methods like Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) for rigorous comparison. This guide synthesizes troubleshooting advice and best practices to empower scientists in selecting the optimal method for their specific materials and achieving reliable, validated results.

Band Gap Fundamentals: Understanding Interpolation and Band Structure Methods

Methodological Foundations: Interpolation vs. Band Structure Calculations

Accurately predicting the band gaps of semiconductors and insulators is a fundamental challenge in materials science and computational physics. Two principal methodological approaches are band gap interpolation and ab initio band structure calculations, each with distinct theoretical foundations and applications.

Band gap interpolation is a semi-empirical approach that uses measured optical data from a few material compositions to generate the complex refractive index for arbitrary bandgaps. This method involves fitting measured complex refractive index data (real part n(λ) and imaginary part k(λ)) from representative compositions using dispersion models like Cody-Lorentz, Ullrich-Lorentz, or Forouhi-Bloomer. A linear regression is then applied to the fit parameters with respect to bandgap energy, allowing reconstruction of refractive index curves for any desired bandgap energy within the studied range. This approach is particularly valuable for high-throughput screening of material systems like lead halide perovskites where composition tuning continuously modifies bandgap energy [1].

In contrast, ab initio band structure calculations derive electronic properties from first principles without empirical fitting parameters. Among these, Density Functional Theory (DFT) methods using functionals like LDA, GGA (PBE, PBEsol), meta-GGA (SCAN), and hybrid functionals (HSE06) solve the Kohn-Sham equations to obtain Kohn-Sham eigenvalues, which are often interpreted as band structures despite the fundamental bandgap problem [2] [3]. More advanced Many-Body Perturbation Theory (MBPT) methods, particularly the GW approximation, provide a more rigorous treatment of electron-electron interactions by calculating the electronic self-energy within the framework of many-body perturbation theory [4] [2].

The GW approximation exists in several flavors with increasing computational cost and accuracy: (i) G₀W₀ using plasmon-pole approximation (PPA), (ii) full-frequency quasiparticle G₀W₀ (QPG₀W₀), (iii) quasiparticle self-consistent GW (QSGW), and (iv) QSGW with vertex corrections in the screened Coulomb interaction (QSGŴ). These methods systematically improve upon DFT by more accurately describing electron exchange and correlation effects [2].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Band Gap Determination Methods

| Feature | Band Gap Interpolation | Ab Initio Band Structure Calculations |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Semi-empirical, based on experimental measurements | First-principles, based on quantum mechanics |

| Input Data | Measured complex refractive index for reference compositions | Atomic numbers, positions, and computational parameters |

| Output | Complex refractive index for arbitrary bandgaps | Electronic band structure, density of states, band gaps |

| Computational Cost | Low (once reference data is available) | High (scales with system size and method complexity) |

| Primary Applications | Opto-electrical device modeling, high-throughput screening | Fundamental material understanding, property prediction |

| Key Limitations | Extrapolation unreliable, dependent on quality of reference data | Systematic errors depend on chosen functional/approximation |

Performance Benchmarking: Accuracy and Computational Efficiency

Comprehensive benchmarking reveals significant differences in the performance of various band gap prediction methods. A systematic study comparing many-body perturbation theory against density functional theory for 472 non-magnetic semiconductors and insulators provides crucial insights into their relative accuracy [2].

DFT functionals show a well-known trend of systematically underestimating band gaps, with the severity of underestimation dependent on the functional. The meta-GGA functional mBJ and hybrid functional HSE06 represent the best-performing DFT approaches, significantly reducing but not eliminating the systematic underestimation [2].

GW methods demonstrate substantially improved accuracy but with notable variation between different implementations. G₀W₀ calculations using the Godby-Needs plasmon-pole approximation (G₀W₀-PPA) offer only marginal accuracy gains over the best DFT methods despite higher computational costs. Replacing PPA with full-frequency integration (QPG₀W₀) dramatically improves predictions. The quasiparticle self-consistent GW (QSGW) approach removes starting-point dependence but systematically overestimates experimental gaps by approximately 15%. Adding vertex corrections to the screened Coulomb interaction in QSGŴ essentially eliminates this overestimation, producing band gaps of sufficient accuracy to reliably flag questionable experimental measurements [2].

Table 2: Quantitative Accuracy of Band Gap Prediction Methods for Solids

| Method | Mean Absolute Error (eV) | Systematic Bias | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDA/GGA DFT | ~1.0 eV (severe underestimation) | Strong underestimation | Low |

| mBJ Meta-GGA | Improved but significant error | Underestimation | Moderate |

| HSE06 Hybrid | Improved but significant error | Underestimation | High |

| G₀W₀-PPA | Moderate improvement over DFT | Slight underestimation | High |

| QP G₀W₀ (full-frequency) | Major improvement | Minor underestimation | Very High |

| QS GW | Good but overestimated | ~15% overestimation | Very High |

| QS GŴ (with vertex) | Highest accuracy | Minimal systematic error | Extremely High |

For specific material classes like atomically thin transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs including MoS₂, MoSe₂, WS₂, WSe₂), efficient GW implementations using Gaussian basis functions demonstrate exceptional performance, with computed band gaps agreeing within 50 meV with plane-wave-based reference calculations. This approach enables accurate G₀W₀ band structure calculations in less than two days on a laptop (Intel i5, 192 GB RAM) or under 30 minutes using 1024 cores, highlighting how algorithmic improvements can dramatically enhance computational efficiency [4].

The relativistic effects significantly impact band structure predictions, particularly for materials containing heavy elements. For CsPbBr₃ perovskite, non-relativistic calculations show no band gap (valence and conduction bands touch at the Fermi level), while scalar relativistic treatment opens a gap of approximately 1.2 eV. Including spin-orbit coupling becomes essential for accurate predictions in systems with heavy elements like lead [3].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Band Structure Calculation with GW Space-Time Algorithm

The GW space-time algorithm for periodic systems implements a sophisticated workflow for accurate band structure calculations [4]:

Initial DFT Calculation: Perform a self-consistent Kohn-Sham DFT calculation to obtain orbitals ψₙ(r) and eigenvalues εₙ^DFT using Eq. 1: [h₀(r) + v^xc(r)]ψₙ(r) = εₙ^DFTψₙ(r), where h₀ contains kinetic energy, Hartree potential, and external potential, while v^xc is the exchange-correlation potential.

Green's Function Construction: Calculate the single-particle Green's function G(r, r′, iτ) in imaginary time using KS orbitals and eigenvalues, with separate treatments for occupied (τ < 0) and unoccupied (τ > 0) states.

Irreducible Density Response: Compute the irreducible density response using lattice summation over neighbor cells to enable accurate treatment of crystals with small unit cells.

Screened Coulomb Interaction: Calculate the screened Coulomb interaction W using k-point sampling to handle the divergence at the Γ-point.

Self-Energy Calculation: Compute the self-energy Σ using lattice summation and solve the quasiparticle equations to obtain final band structures.

This implementation supports relativistic effects via spin-orbit coupling from Gaussian dual-space pseudopotentials and includes perturbative corrections to quasiparticle energies [4].

Band Gap Interpolation for Perovskite Materials

The band gap interpolation method for perovskite materials follows a distinct experimental protocol [1]:

Reference Data Collection: Measure complex refractive index N(λ) for several perovskite compositions with known bandgap energies using spectroscopic ellipsometry. This provides real n(λ) and imaginary k(λ) parts of the refractive index for discrete bandgap energies.

Dispersion Model Fitting: Fit the measured n(λ) and k(λ) data using different dispersion models:

- Cody-Lorentz model

- Ullrich-Lorentz model

- Forouhi-Bloomer model

Parameter Regression: Perform linear regression of the obtained fit parameters with respect to bandgap energy, establishing relationships between model parameters and bandgap.

Refractive Index Reconstruction: For a desired bandgap energy, interpolate the model parameters and reconstruct the complete n(λ) and k(λ) spectra.

Model Validation: Validate the approach by comparing predicted complex refractive indices with measured data and simulating absorptance in single-junction perovskite and perovskite/silicon tandem cells.

The Forouhi-Bloomer model has demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting the complex refractive index of perovskites for arbitrary bandgaps compared to other dispersion models [1].

Computational Tools and Software Packages

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Band Structure Research

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Methodology | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT calculations | Plane-wave pseudopotentials | Materials modeling, band structure |

| Yambo | GW calculations | Many-body perturbation theory | Accurate electronic structure |

| Questaal | GW calculations | LMTO basis, all-electron | Quasiparticle self-consistent GW |

| BAND | DFT calculations | Numerical atomic orbitals | Solid-state chemistry, COOP analysis |

| VASP | DFT/GW calculations | Plane-wave basis | Materials science, surface systems |

| BerkeleyGW | GW calculations | Plane-wave basis | Nanostructures, bulk materials |

Research Reagent Solutions for Band Structure Analysis

Table 4: Essential Materials and Computational Resources

| Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Basis Sets | Localized basis functions for electronic structure | Efficient GW for 2D materials with vacuum [4] |

| Plane-Wave Basis Sets | Periodic basis functions for bulk materials | Standard solid-state calculations [2] |

| Norm-Conserving Pseudopotentials | Replace core electrons, reduce computational cost | Plane-wave DFT and GW calculations [2] |

| Godby-Needs Plasmon-Pole Approximation | Model frequency dependence of dielectric function | G₀W₀ calculations [2] |

| Full-Frequency Integration | Exact treatment of dielectric screening | QP G₀W₀ for improved accuracy [2] |

| Spin-Orbit Coupling Potentials | Include relativistic effects | Accurate band structures for heavy elements [3] |

Application-Oriented Insights for Material Classes

Different material classes present unique challenges and considerations for band gap determination:

Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (TMDCs): Monolayer TMDCs (MoS₂, MoSe₂, WS₂, WSe₂) benefit from GW implementations using Gaussian basis functions, which efficiently handle the large vacuum regions in these atomically thin materials. The lattice summation approach enables accurate treatment of crystals with small unit cells, with band gaps agreeing within 50 meV of plane-wave reference calculations [4].

Perovskites: Lead halide perovskites require careful treatment of relativistic effects. Non-relativistic calculations for CsPbBr₃ show no band gap, while scalar relativistic treatment opens approximately a 1.2 eV gap. For accurate predictions, spin-orbit coupling must be included, particularly due to the presence of heavy elements like lead [3]. Band gap interpolation methods are especially valuable for these materials due to their tunable composition and bandgap-dependent optical properties [1].

Layered Intercalation Compounds: Database approaches containing 9,004 layered intercalation compounds enable systematic studies of intercalation effects on band structures. Special k-paths consistent with host materials allow direct comparison of band structures before and after intercalation, facilitating quantitative analysis of intercalant-driven band engineering [5].

General Solids: For comprehensive screening across diverse materials, high-throughput calculations benefit from understanding method-specific error trends. While QSGŴ provides highest accuracy, its computational cost makes it impractical for large-scale screening, where efficient G₀W₀ or advanced DFT functionals may offer better trade-offs [2].

The comparative analysis of band gap determination methods reveals a complex landscape where methodological choice depends critically on research objectives, material system, and computational resources. Band gap interpolation provides an efficient, application-oriented approach particularly valuable for device modeling and compositional optimization of tunable materials like perovskites. In contrast, ab initio band structure calculations, especially advanced GW methods, offer fundamental insights and high accuracy for diverse material systems at substantially higher computational cost.

The most accurate methods like QSGŴ with vertex corrections approach sufficient accuracy to question experimental measurements, representing a significant achievement in computational materials science. However, efficient algorithm development, such as GW implementations using Gaussian basis sets, continues to narrow the performance gap, making high-accuracy calculations increasingly accessible for routine investigation of material properties.

For researchers navigating this landscape, the key consideration involves balancing accuracy requirements with computational constraints, while recognizing the distinctive strengths and limitations of each methodological approach. As both computational power and methodological sophistication continue to advance, the integration of these complementary approaches promises enhanced capabilities for understanding and designing materials with tailored electronic properties.

In the computational study of materials, determining the Fermi level and the band gap is fundamental to predicting electronic properties. These critical parameters define whether a material is a metal, semiconductor, or insulator, and influence its conductivity and optical behavior. Within first-principles calculations, two distinct methodological approaches—the k-space integration (interpolation) method and the band structure method—can be employed to calculate the band gap and, by extension, help identify the Fermi level. These methods operate on different principles and can sometimes yield differing results, making a clear understanding of their comparative strengths and limitations essential for researchers validating band gap measurements.

The band gap is rigorously defined as the energy difference between the bottom of the conduction band (BOCB) and the top of the valence band (TOVB) [6]. The Fermi level, the energy at which the probability of electron occupation is 50%, lies within this gap for intrinsic semiconductors and insulators. Accurate determination of these energies is therefore crucial. This guide provides an objective comparison of the two primary methods used within electronic structure codes, detailing their operational protocols, inherent advantages, and potential sources of error, supported by available experimental data.

Methodological Comparison: Interpolation vs. Band Structure

Core Principles and Operational Mechanisms

k-Space Integration (Interpolation) Method: This method is integrated into the self-consistent field (SCF) calculation used to determine the electron density. It relies on an analytical k-space integration scheme to compute the Fermi level and electron occupations directly [6]. The method performs a quadratic interpolation of the band energies across the entire Brillouin Zone (BZ), which is sampled with a uniform k-point grid. The band gap reported in the output file of a standard SCF calculation (e.g., the .kf file in BAND) typically comes from this method [6]. Its accuracy is highly dependent on the density of the k-point mesh (

KSpace%Quality).Band Structure Method: This is a post-processing procedure performed after the SCF cycle is complete and the electron density is converged. It involves calculating the band energies along a specific, high-symmetry path in the Brillouin Zone with a fixed potential [6]. This path is typically sampled with a very dense set of k-points (controlled by

BandStructure%DeltaK). While this method can provide a highly detailed view of the bands along the path, it cannot be used to self-consistently determine the Fermi energy or occupations and is instead used to identify the minimum gap along that path [6].

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Objective Comparison of the Two Methods for Band Gap and Fermi Level Determination

| Feature | k-Space Integration (Interpolation) Method | Band Structure Method |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Determines Fermi level & occupations during SCF; outputs band gap [6] | Post-SCF analysis of band dispersion along a path [6] |

| k-Space Sampling | Uniform grid over the entire Brillouin Zone | Dense points along a specific high-symmetry path |

| Fermi Level | Calculated self-consistently | Uses Fermi level from the prior SCF calculation |

| Band Gap | Gap between TOVB and BOCB over the entire BZ [6] | Minimum gap along the chosen path [6] |

| Key Advantage | Physically correct for BZ-wide properties; required for total energy | High resolution along path; can be more visually intuitive |

| Key Limitation | Requires dense k-grid for convergence; BZ-wide gap may be path-dependent | Risk of missing the true gap if path doesn't contain TOVB/BOCB [6] |

| Computational Cost | Higher cost for dense BZ sampling (scales with k-points^3) | Lower cost for detailed path (scales linearly with k-points) |

A critical point of discrepancy arises from their fundamental sampling differences. The interpolation method surveys the entire Brillouin Zone, so the gap it reports is the true BZ-wide fundamental gap. The band structure method, however, only reports the minimum gap found along the user-defined path. If the actual top of the valence band or bottom of the conduction band lies at a k-point not on this path, the band structure method will overestimate the fundamental band gap [6]. This makes the k-space integration method generally more reliable for obtaining the correct fundamental gap for use in further calculations, while the band structure method is excellent for analyzing band dispersion along specific directions.

Advanced Interpolation Techniques

Beyond the native interpolation within DFT codes, advanced methods have been developed to improve the accuracy and efficiency of band structure interpolation. These are particularly relevant for complex systems with entangled bands or topological materials where standard Fourier interpolation struggles.

Wannier Interpolation (WI): A widely used technique that projects the Hamiltonian onto a basis of maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWFs). This creates a compact, localized Hamiltonian that can be efficiently interpolated to any k-point. However, constructing MLWFs can be a nonlinear optimization problem that is sensitive to initial guesses and can be challenging for entangled bands or topological insulators [7] [8].

Hamiltonian Transformation (HT): A novel framework designed to directly localize the Hamiltonian itself, rather than the wavefunctions. It uses a pre-optimized transformation function ( f ) to smooth the eigenvalue spectrum, resulting in a Hamiltonian that is more localized than what is achieved with WI. HT avoids runtime optimization, making it faster and more robust for systems where WI fails, achieving up to two orders of magnitude greater accuracy for entangled bands [7] [8]. A key trade-off is that HT uses a slightly larger basis set and does not produce localized orbitals for chemical bonding analysis [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Interpolation Methods

| Method | Basis | Optimization Required? | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wannier Interpolation (WI) | Maximally Localized Wannier Functions | Yes (can be complex) [7] | Produces chemical insight via localized orbitals | Sensitive to initial guess; struggles with entangled bands [7] |

| Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) | Non-orthogonal numerical basis | No (uses pre-optimized ( f )) [7] | High accuracy & robustness for complex systems; faster [7] | Larger Hamiltonian; no chemical orbital output [7] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

To ensure the validity and accuracy of band structure calculations, especially when comparing methods, rigorous protocols and validation metrics are essential.

Protocol for Converged k-Space Integration

- SCF Calculation with k-Space Sampling: Perform a self-consistent field calculation with a uniform k-point grid. The initial quality (e.g.,

KSpace%Qualityin BAND) can be set to "Normal" [6]. - DOS Convergence Check: Calculate the Density of States (DOS) and progressively increase the k-space quality (e.g., to "Good" or "High"). A converged DOS will show minimal changes in the band edges and the overall shape.

- Gap Verification: The fundamental band gap from the SCF output is taken from the k-space integration method. Compare this value with the minimum gap observed in a band structure plot generated along a high-symmetry path. A significant discrepancy may indicate that the band structure path does not contain the true BOCB or TOVB.

- Final High-Accuracy Calculation: Run a final SCF calculation with the converged, high-quality k-point grid to obtain the definitive Fermi level and band gap.

Protocol for Band Structure Restart and Refinement

Modern codes like BAND allow for the restart of band structure calculations from a previous SCF run [9]. This is highly efficient for testing the sensitivity of the band structure to the k-path density.

1. Perform Converged SCF: Complete an SCF calculation with a sufficiently dense uniform k-grid.

2. Restart for Band Structure: Use the restart functionality to calculate the band structure separately.

3. Refine DeltaK: In the band structure calculation, set BandStructure%DeltaK to a smaller value to interpolate the bands onto a finer k-path [9]. This improves the visual smoothness and accuracy of the band structure plot without re-running the expensive SCF cycle.

Quantitative Validation with Error Metrics

Beyond visual comparison, quantitative error estimation is highly beneficial for validating band structures against experimental data or higher levels of theory (e.g., comparing PBE to HSE06 or GW approximations). The Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) is a standard metric for this purpose [10].

The RMSE between two band structures is calculated as: [RMSE=\sqrt{\frac{1}{N} \sum{k=1}^{Nk} \sum{i=1}^{n{bands}}\left(E2(k, i)-E1(k, i)\right)^2}] where ( N = Nk \times n{bands} ), ( E1 ) and ( E2 ) are the energies of the two band structures being compared [10].

Prerequisites for RMSE Calculation:

- Identical k-paths: Both band structures must be calculated along the same high-symmetry path with the same number of k-points [10].

- Common Energy Reference: Energies must be aligned to the same reference, typically the Fermi level or the Valence Band Maximum (VBM) [10].

- Common Energy Window: An energy window (e.g., from -10 eV to +5 eV around the Fermi level) must be selected to ensure a one-to-one mapping of bands between the two calculations, preventing deep core states from skewing the results [10].

For example, one study calculated an RMSE of 0.412 eV when comparing the band structure of AlAs in its zincblende phase calculated with the GW approximation versus the HSE06 hybrid functional with spin-orbit coupling, objectively quantifying the difference between the two methods [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Their Functions

| Tool / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| DFT Code (e.g., BAND, FHI-aims) | Performs the core self-consistent field (SCF) calculation to determine the electron density and Fermi level. |

| k-Point Grid | A uniform mesh of points in the Brillouin Zone; its density controls the convergence accuracy of the k-space integration method [6]. |

| High-Symmetry k-Path | A set of connected points along directions of high symmetry in the Brillouin Zone; used for generating plottable band structures. |

| Wannier90 Code | A widely used post-processing tool for constructing Maximally Localized Wannier Functions and performing Wannier interpolation [7]. |

| Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) | An advanced post-processing algorithm for achieving highly accurate band interpolation without orbital optimization, ideal for complex materials [7] [8]. |

| RMSE Script | A custom code (e.g., based on aimsplot_compare.py [10]) to quantitatively compare two band structures and validate computational results. |

Visualizing the Method Selection Pathway

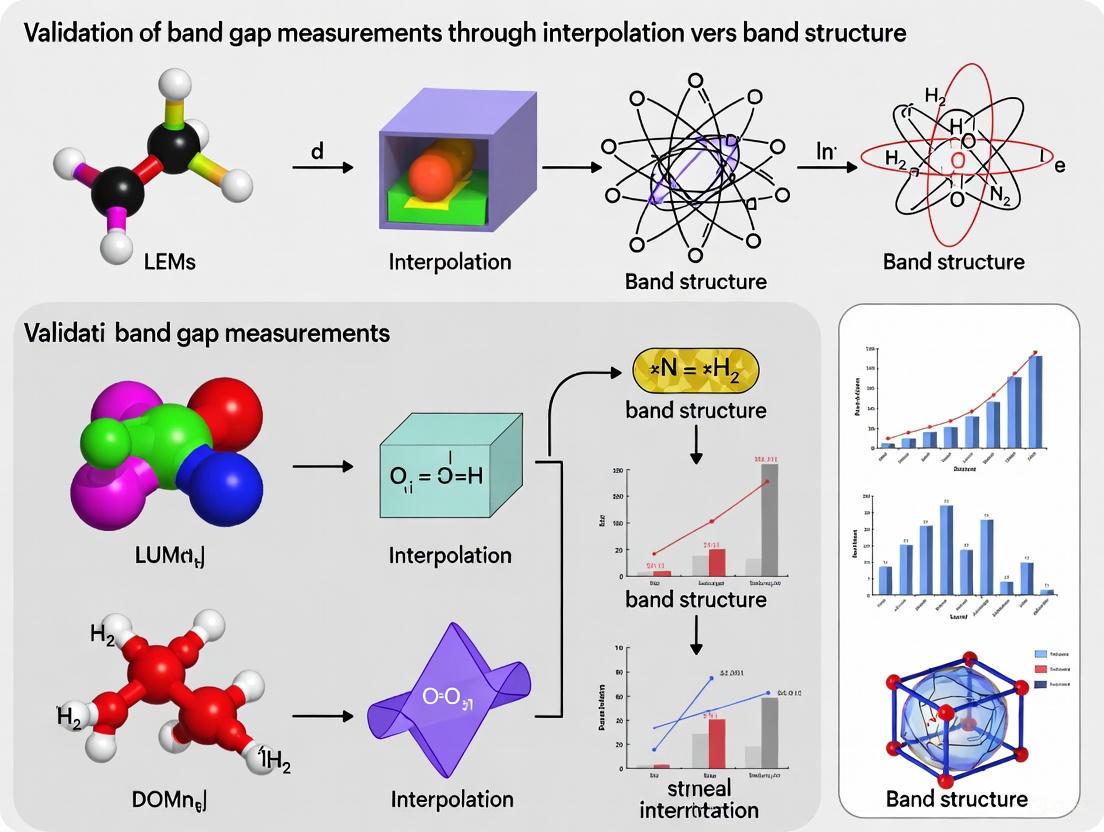

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for choosing and applying the appropriate method for determining the Fermi level and band gap, integrating both standard and advanced techniques.

The electronic band structure is a cornerstone concept in condensed matter physics and materials science, essential for predicting and understanding a material's electronic, optical, and transport properties. The band structure method refers to the computational approach of calculating the energies of electronic states along a predefined, continuous path connecting high-symmetry points in the reciprocal space of a crystal's Brillouin zone. This path provides a representative snapshot of the electronic energy dispersion relations across different crystal momentum directions. Unlike interpolation methods, which aim to reconstruct the full band structure from a limited set of calculations, the direct band structure method involves explicit computation at numerous points along this high-symmetry path. The resulting plot of energy versus k-point position reveals critical features such as band gaps, effective carrier masses, and whether a material is a metal, semiconductor, or insulator. The accuracy of this method is paramount, as it forms the basis for validating experimental measurements and for the data-driven design of functional materials.

Core Principles and Comparative Framework

Fundamental Concepts

The band structure method leverages Bloch's theorem, which states that the wavefunctions of electrons in a periodic crystal lattice can be expressed as a plane wave modulated by a function with the same periodicity as the lattice. This theorem allows for the calculation of electronic energies at specific k-points within the Brillouin zone. A high-symmetry path is chosen to capture the most physically relevant variations in energy, typically including points like Γ (the Brillouin zone center), X, M, K, and L, whose specific definitions depend on the crystal's symmetry. The process involves performing a self-consistent field (SCF) calculation to determine the ground-state electron density, followed by a non-self-consistent calculation to compute the eigenvalues (band energies) at each k-point along the specified path.

Key Parameters and Computational Settings

The fidelity of the calculated band structure is controlled by several key parameters. The Interpolation delta-K defines the step size between k-points along the path; a smaller value (e.g., 0.02 Bohr⁻¹) results in smoother band curves but increases computational cost [11] [3]. The EnergyAboveFermi and EnergyBelowFermi parameters determine the energy window around the Fermi level for which bands are saved, ensuring that the most relevant conduction and valence bands are included in the output [11]. Furthermore, the choice of density functional approximation (e.g., LDA, GGA, hybrid functionals) significantly impacts the accuracy of the resulting band energies, particularly the band gap [2].

Method Comparison: Direct Calculation vs. Interpolation

To objectively compare the band structure method with interpolation-based approaches, it is crucial to define a framework based on accuracy, computational cost, and robustness.

- Direct Band Structure Calculation: This method involves explicit diagonalization of the Hamiltonian at many points along a continuous k-path. It is often performed after a converged SCF calculation on a uniform k-grid.

- Interpolation Methods: These techniques aim to reconstruct the full band structure from a smaller set of initial calculations. A prominent example is Wannier Interpolation (WI), which uses Maximally Localized Wannier Functions (MLWFs) to create a localized basis set, allowing for efficient Fourier interpolation of the Hamiltonian onto any k-point [7].

A novel advancement, the Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) method, has been introduced to address limitations of WI. HT enhances interpolation accuracy by applying a pre-optimized transformation to the Hamiltonian that smooths the eigenvalue spectrum, making it more localizable in real space. This method achieves up to two orders of magnitude greater accuracy for entangled bands compared to WI-SCDM (a robust Wannier function generation algorithm) and requires no complex optimization during runtime, resulting in significant computational speedups [7].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Band Structure Calculation Methods

| Feature | Direct Band Structure Method | Wannier Interpolation (WI) | Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Explicit diagonalization along a k-path | Interpolation via a localized orbital basis | Interpolation via a transformed, localized Hamiltonian |

| Accuracy | High, directly from the chosen functional | Can be limited by quality of Wannier functions | 1-2 orders of magnitude more accurate than WI-SCDM for entangled bands [7] |

| Computational Cost | High for fine k-paths, but single-shot | Lower after initial Wannierization | Rapid construction, requires a larger basis set than WI [7] |

| Robustness & Ease of Use | High, largely automated | Sensitive to initial guesses; requires user input | High; no optimization needed, more robust for complex systems [7] |

| Primary Application | Standard band structure plots | Efficient interpolation; chemical bonding analysis | Accurate interpolation of entangled/topologically complex bands [7] |

Performance and Experimental Data Comparison

The validation of band gap measurements is a central application of band structure methods. Different computational approaches yield varying results when compared to experimental data.

Accuracy of Band Gaps: DFT vs. MBPT

A systematic benchmark comparing Many-Body Perturbation Theory (MBPT), specifically the GW approximation, against Density Functional Theory (DFT) reveals critical performance differences. While meta-GGA (e.g., mBJ) and hybrid (e.g., HSE06) functionals can significantly reduce DFT's systematic band gap underestimation, their improvements can be semi-empirical [2]. In contrast, MBPT provides a more rigorous theoretical foundation.

Table 2: Band Gap Accuracy Benchmark of Computational Methods [2]

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Typical Band Gap Error | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard DFT (LDA/GGA) | Approximate density functional | Systematic underestimation | Low |

| Advanced DFT (mBJ, HSE06) | Meta-GGA/Hybrid functional | Moderate improvement over standard DFT | Moderate to High |

| G(0)W(0)-PPA | One-shot GW with plasmon-pole approximation | Marginal gain over best DFT methods [2] | High |

| Full-Frequency QPG(0)W(0) | One-shot GW with full-frequency integration | Dramatic improvement over G(0)W(0)-PPA [2] | Very High |

| QSGWĜ | Self-consistent GW with vertex corrections | Highest accuracy; flags questionable experiments [2] | Extremely High |

Case Study: Relativistic Effects in CsPbBr₃

A practical example using the perovskite CsPbBr₃ demonstrates the importance of methodological choices. A band structure calculation without relativistic treatment shows no band gap (a metal), with valence and conduction bands touching at the Fermi level. However, when a scalar relativistic treatment is applied, a band gap of about 1.2 eV opens up. Further analysis via Crystal Orbital Overlap Population (COOP) reveals that this shift is primarily due to the energetic lowering of bands with strong Pb-6s orbital character, a known relativistic effect. This case highlights how the direct band structure method, combined with specific physical approximations and analysis tools, is critical for correct material classification and understanding [3].

Detailed Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol for Direct Band Structure Calculation with Hybrid Functionals

Band-structure calculations using hybrid functionals require specific steps to handle their non-local nature [12].

- Initial SCF Calculation: Perform a self-consistent field calculation on a regular k-point mesh to obtain a converged charge density and wavefunction (e.g.,

WAVECARfile). - Define High-Symmetry Path: Determine the path through the Brillouin zone (e.g., Γ-X-M-Γ). Tools like SeekPath can automate this for any crystal symmetry.

- Supply k-Points for the Band Path:

- Option A (Explicit List): Create a

KPOINTSfile containing the irreducible k-points from the SCF mesh (with their weights) and append the high-symmetry path k-points with weights set to zero. - Option B (KPOINTS_OPT file): Use the original

KPOINTSfile for the regular mesh and create a separateKPOINTS_OPTfile in "line-mode" specifying the high-symmetry path. This method is often more convenient.

- Option A (Explicit List): Create a

- Set Coulomb Truncation: In the

INCARfile, setHFRCUT = -1to use Coulomb truncation, which avoids artificial discontinuities in the band structure. - Run Calculation: Restart the hybrid calculation from the SCF

WAVECARfile. The code will perform a new SCF cycle using the regular mesh and then compute the band energies along the specified path. - Post-Processing: Plot the band structure using visualization tools (e.g.,

py4vasp,amsbands).

Protocol for Wannier Interpolation and Hamiltonian Transformation

For interpolation-based methods, the workflow differs [7].

- Initial DFT Calculation: Perform a high-quality SCF calculation on a dense uniform k-point grid to obtain the Bloch wavefunctions.

- Projection onto Localized Basis:

- For WI: Project the Bloch states onto a trial localized orbital set (e.g., atomic orbitals) and then perform a iterative optimization to minimize the spread of the Wannier functions (maximal localization).

- For HT: Apply a pre-optimized transform function ( f ) to the Hamiltonian. This function is designed to smooth the eigenvalue spectrum, enhancing the real-space localization of the transformed Hamiltonian ( f(H) ) without any runtime optimization.

- Interpolation: Use the localized basis (MLWFs for WI, or the transformed Hamiltonian for HT) to interpolate the band energies onto any desired k-point, including a high-symmetry path.

- Inverse Transformation (for HT): After diagonalizing the interpolated ( f(H) ) to obtain ( f(\epsilon) ), apply the inverse transformation ( f^{-1} ) to recover the true band energies ( \epsilon ).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

In computational materials science, the "research reagents" are the core software, functionals, and pseudopotentials that define the quality of the calculation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Band Structure Calculations

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Example Variants / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Density Functional | Defines the exchange-correlation energy; critical for accuracy. | LDA, GGA (PBE, PBEsol), meta-GGA (SCAN), Hybrid (HSE06) [3] [2] |

| Pseudopotential / Basis Set | Represents core electrons and defines the basis for wavefunctions. | Norm-conserving, Ultrasoft, PAW (Plane-Wave); TZP, QZ4P (Atomic Orbital) [11] [3] |

| k-Grid and k-Path | Samples the Brillouin zone for SCF and band structure. | Monkhorst-Pack (SCF), High-symmetry path (Band structure) [12] |

| GW Self-Energy | Calculates quasiparticle corrections beyond DFT. | G₀W₀-PPA, full-frequency QPG₀W₀, QSGW, QSGWĜ [2] |

| Localization Algorithm | Generates localized basis sets for interpolation. | Maximally Localized Wannier Functions (MLWF), SCDM, Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) [7] |

The direct band structure method, which calculates energies along a high-symmetry path, remains a fundamental and robust tool for validating band gap measurements and understanding electronic properties. Its primary strength lies in its direct connection to the underlying electronic structure theory and its relative ease of use. However, for high-throughput studies or systems with complex band topologies, advanced interpolation methods like Hamiltonian Transformation present a compelling alternative, offering superior accuracy and efficiency compared to traditional Wannier-based approaches. The choice of method ultimately depends on the specific research goal: the direct method for standard analyses and validation, and advanced interpolation or GW methods for highest accuracy or high-throughput screening. This comparative guide underscores that a careful selection of computational "reagents" and methodologies is essential for the accurate prediction and validation of electronic band structures in solid-state materials.

In the realm of computational materials science, accurately determining electronic band structures is fundamental to predicting and understanding material properties. Two predominant methodologies for this task are Full Brillouin Zone (BZ) Sampling and Targeted k-Path Analysis. Within the context of validating band gap measurements, the choice between a dense uniform mesh across the entire Brillouin zone and a focused path connecting high-symmetry points is critical, influencing both the computational cost and the physical interpretability of the results [13] [14]. This guide objectively compares these approaches, detailing their underlying principles, respective workflows, and performance in extracting key electronic properties, to serve researchers in selecting the appropriate protocol for their investigations.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Full Brillouin Zone Sampling

Full Brillouin Zone Sampling involves the use of a regular, dense mesh of k-points to discretize the entire Brillouin zone for numerical integration [13] [15]. The primary goal is to achieve converged total energy and charge density during a self-consistent field (SCF) calculation, which is a prerequisite for accurate subsequent property calculations [15]. The most common method for generating this mesh is the Monkhorst-Pack scheme [13] [15]. The quality of this sampling is controlled by the k-point mesh density, often determined by a parameter 'L' (the k-point line density), which is used to set the number of subdivisions (N₁, N₂, N₃) along the reciprocal lattice vectors [15]. Convergence is typically assessed by monitoring the total energy per cell or per atom, with a standard tolerance often set at 0.001 eV/cell [15].

Targeted k-Path Analysis

Targeted k-Path Analysis, in contrast, is a post-processing technique used for visualizing and analyzing the electronic band structure. It involves calculating eigenvalues along a specific, continuous path connecting high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone (e.g., Γ-X-W-Γ) [13] [16]. This method is not used for SCF convergence but for obtaining a momentum-resolved band dispersion, which is essential for identifying band gaps, effective masses, and van Hove singularities [16] [14]. The k-path is defined in the KPOINTS file using "line mode," specifying the start and end points of each segment and the number of points to calculate per line [13].

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Applications

Table 1: Core Functional Differences Between Full BZ Sampling and Targeted k-Path Analysis

| Aspect | Full Brillouin Zone Sampling | Targeted k-Path Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Converging total energy & charge density via SCF calculations [15] | Visualizing & analyzing band dispersion along high-symmetry lines [13] [16] |

| Typical k-point Setup | Regular (Γ-centered or Monkhorst-Pack) mesh [13] | A continuous path of points between high-symmetry points [13] |

| Key Outputs | Total energy, DOS, electron density [15] | Band structure, direct band gap, carrier effective mass [16] |

| Role in Workflow | Typically the initial, computationally intensive SCF step [15] | A subsequent, non-SCF post-processing step [13] [14] |

| Convergence Criteria | Energy per cell/atom (e.g., 0.001 eV/cell) [15] | Visual smoothness of bands & resolution of critical points [16] |

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Cost and System-Specific Considerations

| Aspect | Full Brillouin Zone Sampling | Targeted k-Path Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | High, scales with the number of k-points in the 3D mesh [15] | Lower, cost depends on the number of points along the 1D path [14] |

| Material-Specific Sensitivity | High; metals require much denser sampling than insulators [16] [15] | Lower sensitivity to insulating/metal character for visualization |

| Critical Parameters | k-point line density (L), mesh subdivisions (N₁, N₂, N₃) [15] | Choice of high-symmetry path, points per line segment [13] |

| Dependence on Cell Size | Sampling density should be inversely proportional to unit cell length [13] | Path definition is tied to the reciprocal lattice, not absolute cell size |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Full Brillouin Zone Convergence Study

A standardized protocol for converging k-points in full BZ sampling is essential for high-throughput DFT studies [17] [15].

- Initialization: Start with a coarse k-point mesh, for example, a Monkhorst-Pack grid of 4×4×4 for a cubic system [17].

- SCF Calculation: Perform a full DFT SCF calculation with this mesh to obtain the total energy.

- Iterative Refinement: Systematically increase the density of the k-point mesh (e.g., to 6×6×6, 8×8×8, etc.) and repeat the SCF calculation [17].

- Convergence Check: After each calculation, plot the total energy against the k-grid size. The energy will change sharply initially and then plateau.

- Threshold Determination: The calculation is considered converged when the energy change between two successive mesh sizes falls below a predefined threshold, for instance, 0.001 eV per cell [15]. The mesh that meets this criterion is used for production calculations.

Protocol for Targeted k-Path Band Structure Calculation

The procedure for obtaining an accurate band structure via a targeted k-path is a two-step process [13] [16].

- SCF Calculation with Full BZ Sampling: First, a converged SCF calculation must be performed using a sufficiently dense full BZ k-point mesh to obtain a reliable ground-state charge density. This is a mandatory prerequisite.

- Non-SCF Calculation on k-Path: In a second, non-self-consistent calculation, the Hamiltonian is diagonalized for the k-points along the desired high-symmetry path. The charge density is kept fixed at the converged value from the first step [13]. The KPOINTS file for this step is configured in "line mode" [13].

- Validation: For metallic systems or semiconductors like graphene, it is critical to ensure that high-symmetry points critical to the Fermi level (e.g., the K point in graphene) are included in the sampling to pin the Fermi level accurately [16].

Essential Research Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for k-point Studies

| Item / Software | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| VASP (Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package) | A widely used software suite for performing DFT calculations with plane-wave basis sets and PAW pseudopotentials [15]. |

| KPOINTS File | The input file that defines the k-point sampling scheme, whether for a full mesh or a targeted path [13]. |

| Monkhorst-Pack Method | An algorithm for generating uniform grids of k-points within the Brillouin zone for full BZ sampling [13] [15]. |

| High-Symmetry Path | A pre-defined trajectory through the Brillouin zone connecting points of high symmetry, essential for band structure plots [13]. |

| Wannier Interpolation (WI) | A physics-based interpolation method to obtain a dense band structure from a coarse k-point mesh, using maximally localized Wannier functions [7] [14]. |

| k·p Interpolation Method | An alternative interpolation technique that uses momentum matrix elements to interpolate bands from a few reference k-points [14]. |

Workflow and Logical Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for band structure calculation, highlighting the distinct roles of full BZ sampling and targeted k-path analysis.

Diagram 1: Band Structure Calculation Workflow. The workflow shows the prerequisite of a converged full BZ calculation for obtaining a charge density, which is then used for two distinct post-processing tasks: band structure calculation via a targeted k-path and DOS calculation.

Advanced Interpolation Techniques

For large or complex systems, performing direct DFT calculations on a very dense k-path can be prohibitively expensive. Advanced interpolation techniques bridge this gap by using the results from coarse full BZ calculations to predict the band structure at a much higher density.

Wannier Interpolation (WI): This method constructs a tight-binding-like Hamiltonian in a basis of maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWFs). The real-space localization of MLWFs ensures that the Hamiltonian in reciprocal space is smooth, allowing for efficient and accurate Fourier interpolation to any arbitrary k-point [7] [14]. While powerful, obtaining well-localized Wannier functions can be a nonlinear optimization problem that is sensitive to the initial guess [7].

Hamiltonian Transformation (HT): A recently proposed method that directly optimizes the localization of the Hamiltonian itself, rather than the wavefunctions. It applies a pre-optimized mathematical transformation

fto the Hamiltonian to make its real-space representation more localized, leading to highly accurate interpolation. HT is particularly effective for systems with entangled bands and can be 1-2 orders of magnitude more accurate than WI for such cases, though it uses a larger basis set [7] [18].k·p Interpolation: This method uses the momentum matrix elements

pijfrom a reference k-point to extrapolate band energies to nearby k-points [14]. A correctedk·p̃scheme has been developed to mitigate hand-shaking and band-crossing issues, enabling accurate generation of spectral functions like DOS and dielectric functions with a limited number of reference k-points, which is especially valuable for costly hybrid-DFT calculations [14].

Full Brillouin Zone Sampling and Targeted k-Path Analysis are complementary techniques, each indispensable for a different stage of electronic structure calculation. Full BZ sampling is the foundational method for achieving a converged electronic ground state, critical for total energy and DOS. In contrast, targeted k-path analysis is the specialized tool for extracting momentum-resolved band dispersions and accurate band gaps. The choice between them is not one of superiority but of purpose. For research focused on validating band gaps and effective masses, the robust protocol involves first converging the SCF calculation with a full BZ mesh, followed by a targeted k-path analysis. The emergence of advanced interpolation methods like Wannier interpolation and Hamiltonian transformation further enhances the efficiency and accuracy of this workflow, enabling high-fidelity band structure predictions from relatively coarse initial data.

Advantages and Inherent Limitations of Each Computational Approach

Accurately determining the electronic band gap of materials is a cornerstone of modern materials science, condensed matter physics, and the development of new semiconductors for optoelectronic and energy applications. The band gap, defining the energy difference between the valence and conduction bands, dictates key material properties. However, its accurate prediction from first principles remains a significant challenge. This guide objectively compares the performance of two predominant computational strategies for band gap determination: the interpolation method and the band structure method. Framed within broader research on validating band gap measurements, this analysis synthesizes current methodologies—from established density functional theory (DFT) to advanced many-body perturbation theory (MBPT) and modern interpolation techniques—to provide researchers with a clear framework for selecting the most appropriate computational tool.

Methodological Frameworks and Experimental Protocols

Understanding the foundational workflows of each approach is essential for appreciating their comparative advantages and outputs.

Band Structure Method: Direct Calculation from DFT

This method involves a direct, first-principles calculation of the electronic energies along a specific path in the Brillouin Zone (BZ). The protocol typically follows a two-step process [7]:

- Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation: A DFT calculation is first performed on a uniform k-point grid to achieve electronic ground state convergence and obtain the charge density.

- Non-SCF Band Structure Calculation: Using the fixed charge density from the SCF step, the Kohn-Sham equations are solved for a dense set of k-points along a high-symmetry path. The resulting eigenvalues are plotted to visualize the band structure.

The primary advantage of this method is its directness; it does not rely on intermediary models. However, its accuracy is intrinsically tied to the choice of the exchange-correlation functional within DFT, which is a major source of limitation, often leading to systematic band gap underestimation [2].

Interpolation Methods: Building a Compact Hamiltonian

Interpolation methods aim to construct a computationally efficient model that replicates the full DFT Hamiltonian, allowing for the calculation of eigenvalues at any k-point at a low cost. The general workflow is [7] [18]:

- SCF Calculation on a Uniform k-grid: Identical to the first step of the band structure method.

- Hamiltonian Projection: The full Hamiltonian is projected onto a localized basis set to create a compact model.

- Fourier Interpolation: This compact Hamiltonian is then interpolated onto a very dense k-point path using Fourier transforms.

A key challenge is ensuring the projected Hamiltonian remains localized in real space for accurate interpolation. Traditional Wannier Interpolation (WI) uses Maximally Localized Wannier Functions (MLWFs) as the basis, which involves a complex, non-linear optimization that can fail for systems with entangled bands or topological obstructions [7]. A modern alternative, Hamiltonian Transformation (HT), has been developed to address these limitations. HT applies a pre-optimized, invertible mathematical function f(H) to the Hamiltonian, which is designed to smooth the eigenvalue spectrum and dramatically improve localization without any runtime optimization [7] [18]. After interpolating and diagonalizing f(H), the true band energies ε are recovered via the inverse transformation f⁻¹(f(ε)).

The diagram below illustrates and contrasts the workflows for the Band Structure method, traditional Wannier Interpolation (WI), and the novel Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) method.

Performance Comparison: Accuracy, Robustness, and Efficiency

The methodologies described above yield significantly different performance outcomes in terms of accuracy, computational cost, and ease of use. The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison of different computational approaches, including advanced GW methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Band Gap Computational Approaches

| Computational Method | Key Principle | Reported Mean Absolute Error (MAE) / Accuracy | Computational Cost | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (PBE-GGA) [2] [19] | Standard DFT with semi-empirical GGA functional. | MAE: ~1.184 eV [19] (systematic underestimation) | Low | Fast; low resource use; good for geometry. | Severe band gap underestimation; delocalization error. |

| DFT (HSE06) [2] [19] | Hybrid functional mixing exact HF exchange. | MAE: ~0.687 eV [19] | High | More accurate than GGA; widely used. | High computational cost; semi-empirical. |

| DFT (mBJ) [2] | Meta-GGA functional for improved gaps. | High accuracy among DFT functionals [2] | Moderate | Better gaps without HF cost. | Can be system-dependent; not a systematic solution. |

| G₀W₀ (PPA) [2] | One-shot GW with plasmon-pole approximation. | Marginal gain over best DFT [2] | Very High | Better physics than DFT; widely implemented. | High cost/accuracy ratio; starting-point dependence. |

| G₀W₀ (Full-Freq) [2] | One-shot GW with exact frequency integration. | Dramatic improvement over PPA [2] | Very High | High accuracy; removes PPA error. | High cost; starting-point dependence. |

| QS*GW [2] | Quasiparticle self-consistent GW. | Systematically overestimates by ~15% [2] | Extremely High | Removes starting-point dependence. | Very high cost; systematic overestimation. |

| QS*GŴ [2] | QSGW with vertex corrections. | Highest accuracy; flags poor experiments [2] | Extremely High | Best theoretical framework; excellent accuracy. | Prohibitive cost for high-throughput studies. |

| Wannier Interpolation (WI) [7] | Interpolation via maximally localized functions. | High (when localization is successful) | Moderate (post-processing) | Compact Hamiltonian; provides chemical insight. | Sensitive to initial guess; fails for entangled/topological bands. |

| Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) [7] [18] | Interpolation via a localized Hamiltonian transform. | 1-2 orders of magnitude more accurate than WI-SCDM [7] | Fast (post-processing) | High accuracy & robustness; no runtime optimization. | Larger Hamiltonian size; no localized orbitals. |

Beyond the standard DFT and interpolation methods, the GW approximation of Many-Body Perturbation Theory (MBPT) represents a more advanced and physically rigorous tier. As benchmark data shows [2], while one-shot G₀W₀ calculations with simple plasmon-pole approximations (PPA) offer only marginal improvements over hybrid DFT at a much higher cost, more sophisticated GW flavors deliver superior accuracy. Full-frequency G₀W₀ and especially self-consistent schemes like QSGW and QSGŴ (which includes vertex corrections) can achieve remarkable agreement with experiment, to the point of identifying questionable experimental data [2]. However, this comes at a prohibitive computational cost that limits their use in high-throughput screening.

For interpolation itself, the modern HT method demonstrates a clear performance advantage over traditional WI. HT achieves up to two orders of magnitude greater accuracy for complex systems with entangled bands and does so without the need for fragile optimization procedures, making it both more robust and computationally faster in the post-processing stage [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Selecting the appropriate "reagents" or computational tools is as critical as choosing the methodological pathway.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Band Structure Calculations

| Item / Solution | Function in Band Gap Calculation | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange-Correlation (XC) Functional | Approximates quantum many-body interactions; primary source of error in DFT. | PBE-GGA (fast, underestimates gap), HSE06 (accurate, costly), mBJ (improved gaps) [2] [19]. |

| Pseudopotential / PAW Dataset | Represents core electrons and ionic potential, reducing computational cost. | Norm-conerviing / Ultrasoft (QE), PAW (VASP). Critical for heavy elements [2]. |

| k-Point Grid | Samples the Brillouin Zone for numerical integration. | Quality (density) directly impacts SCF convergence and DOS accuracy [6]. |

| Localized Basis Set | Projects the Hamiltonian for interpolation; balance of size and quality. | Wannier Functions (WI) or the larger numerical basis in HT [7]. Avoids linear dependency issues [6]. |

Hamiltonian Transform f |

Smoothes the eigenvalue spectrum to maximize Hamiltonian localization for HT. | Pre-optimized function f_{a,n}(x) with parameters a (transition width) and n (smoothness) [7] [18]. |

| SCF Convergence Helper | Aids in achieving SCF convergence for difficult systems (e.g., metallic slabs). | Finite electronic temperature; DIIS or MultiSecant algorithms; conservative mixing schemes [6]. |

The validation of band gap measurements is a multi-faceted problem without a universal solution. The choice between interpolation and band structure methods, and the selection of the underlying electronic structure theory, involves a critical trade-off between accuracy, computational cost, and robustness.

- For rapid screening of materials or when computational resources are limited, a band structure method using a meta-GGA functional like mBJ provides a reasonable balance.

- When pursuing high accuracy for a specific material and where resources allow, MBPT/GW approaches, particularly full-frequency or self-consistent variants, are the gold standard, though they remain impractical for high-throughput studies.

- For obtaining ultra-fine band structures from a DFT calculation, interpolation methods are essential. Among them, the modern Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) approach offers superior accuracy and robustness over traditional Wannier Interpolation, especially for complex materials, making it the recommended choice for this specific task where localized orbital information is not required.

In conclusion, researchers must align their computational strategy with their specific validation goals. No single approach is flawless, but a clear understanding of the advantages and inherent limitations of each, as outlined in this guide, empowers scientists to make informed decisions and critically evaluate the resulting band gap predictions.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Implementing Both Methods in Electronic Structure Codes

The accurate calculation of electronic band structures is a cornerstone of condensed matter physics and materials science, essential for predicting and understanding material properties and phenomena [7]. In the context of validating band gap measurements, researchers often face a critical methodological choice: using direct band structure calculations or employing interpolation techniques to derive band structures from a limited set of initial calculations. Direct methods compute eigenvalues at each k-point along a specified path in the Brillouin zone through explicit diagonalization of the Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian [20]. In contrast, interpolation methods, such as Wannier interpolation (WI) and the novel Hamiltonian transformation (HT) approach, construct a localized real-space Hamiltonian from a self-consistent calculation on a uniform k-point grid, then use Fourier interpolation to obtain band energies on arbitrarily dense k-point paths [7] [18]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these approaches, detailing their configuration, parameterization, and performance to help researchers select the optimal strategy for their band gap validation projects.

Comparative Analysis of Band Structure Calculation Methods

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of band structure calculation methods.

| Method Type | Computational Principle | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Calculation | Direct diagonalization of Hamiltonian at each k-point along a path | No interpolation error, conceptually straightforward | Computationally expensive for dense k-point grids | Small systems, final production calculations |

| Wannier Interpolation (WI) | Fourier interpolation using maximally localized Wannier functions | ~100x faster than direct for dense grids, provides chemical bonding information | Sensitive to initial guesses; challenging for entangled/topological bands [7] | Systems with well-separated bands, chemical bonding analysis |

| Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) | Fourier interpolation using pre-optimized transformed Hamiltonian [18] | 1-2 orders of magnitude more accurate than WI for entangled bands; no runtime optimization [18] | Cannot generate localized orbitals; requires larger basis set [18] | Entangled bands, topological materials, high-throughput screening |

Accuracy and Performance Comparison

Table 2: Quantitative performance comparison between interpolation methods.

| Performance Metric | Wannier Interpolation (WI-SCDM) | Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) | Measurement Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interpolation Accuracy | Baseline | 10-100x improvement for entangled bands [18] | Root-mean-square error compared to direct DFT calculation |

| Computational Speed | Fast | Faster (no optimization procedure) [18] | Wall-time for interpolation construction |

| Basis Set Size | Compact (~20-100 orbitals) | ~10x larger than WI [18] | Number of basis functions required |

| Robustness | Requires careful initial guesses | High (no initial guess sensitivity) [18] | Success rate across diverse material systems |

Essential Parameters for Band Structure Calculations

Core Parameter Framework

Proper configuration of band structure calculations requires careful attention to several interdependent parameters. The primitive cell vectors define the fundamental periodicity of the system and are essential for both direct calculations and interpolation approaches. These can be specified as a 3×3 matrix (vector components), a 1×6 matrix (lengths and angles), or a 1×3 matrix (lengths only, assuming right angles) [21].

The k-point path through the Brillouin zone must be carefully designed using high-symmetry points. Different crystal structures have conventional symbol sets, such as {'G', 'X', 'W', 'L', 'G', 'K', 'X'} for FCC lattices or {'G', 'M', 'K', 'G'} for 2D hexagonal systems [21]. For unconventional structures, users must explicitly provide the fractional coordinates of each symmetry point [21].

The k-point density along the path can be controlled either by specifying the total number of points or the number for each segment between high-symmetry points [21]. Higher densities provide smoother bands but increase computation time, making this a critical parameter for balancing accuracy and efficiency.

Advanced Configuration Options

Modern DFT codes offer several specialized parameters for enhanced analysis:

Projected band calculations (

isProjected = true/false) enable decomposition of band contributions by atomic orbitals, providing crucial information for interpreting orbital character and hybridization [21].Spin polarization settings (

spinPolarization = true/false) are essential for magnetic materials and enable analysis of spin-dependent electronic structures [21].Visualization controls (

plot = true/false) automatically generate band structure plots upon calculation completion, though additional customization is typically needed for publication-quality figures [21].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol 1: Direct Band Structure Calculation

Purpose: To compute band structures through explicit diagonalization at each k-point, serving as a reference for interpolation method validation.

Workflow:

- Perform self-consistent field (SCF) calculation on a uniform k-point grid to obtain converged charge density

- Define the k-point path through the Brillouin zone using high-symmetry points

- For each k-point along the path:

- Construct the Hamiltonian matrix

- Diagonalize the Hamiltonian to obtain eigenvalues

- Store eigenvalues for the current k-point

- Repeat step 3 for all k-points along the path

- Generate the band structure plot by connecting eigenvalues across adjacent k-points

Key Parameters:

- SCF convergence criteria (typically 10^-6 eV or tighter)

- k-point grid density for SCF calculation (system-dependent, often 6×6×6 or finer)

- k-point path and density (20-50 points between high-symmetry points recommended)

Protocol 2: Hamiltonian Transformation Interpolation

Purpose: To efficiently compute accurate band structures, especially for systems with entangled bands, using the novel HT method.

Workflow:

- Perform SCF calculation on a uniform k-point grid {k} [7]

- Obtain the Hamiltonian H(k) on the uniform grid

- Apply a pre-optimized transform function f to the Hamiltonian to enhance localization [18]

- Interpolate the transformed Hamiltonian f(H) to target k-points {q} using Fourier interpolation:

H_q = (1/N_k) * Σ_{k,R} H_k * exp(i(q-k)R)[18]

- Diagonalize f(H_q) at each target k-point to obtain transformed eigenvalues f(ε)

- Apply inverse transformation f^(-1) to recover true eigenvalues ε [18]

Key Parameters:

- Transform function parameters (a, n) controlling transition width and smoothness [18]

- Uniform k-grid density (critical for interpolation quality)

- Energy cutoff ε for spectral truncation [18]

Table 3: Essential computational tools and resources for band structure calculations.

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Key Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Software (Solid State) | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, SIESTA [22] | First-principles electronic structure calculations | Solid-state systems with periodic boundary conditions |

| DFT Software (Molecular) | Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA [22] | Quantum chemistry calculations | Molecular systems, clusters (often in vacuum) |

| Visualization Tools | VESTA, p4vasp, Avogadro, ChemCraft [22] | Structure modeling, results visualization, orbital analysis | Pre- and post-processing of calculation data |

| Basis Sets | Plane waves, Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs), B-splines [23] | Mathematical representation of electron wavefunctions | System-dependent choice balancing accuracy and cost |

| High-Performance Computing | CPU clusters, GPU acceleration, Cloud services (e.g., Matlantis) [22] | Computational infrastructure for resource-intensive calculations | Scaling calculations to large systems or high throughput |

The choice between direct band structure calculations and interpolation methods depends critically on the specific research context and constraints. For validation of band gap measurements, where accuracy is paramount, direct calculations provide the most reliable reference but require substantial computational resources. The emerging Hamiltonian transformation method offers an excellent compromise, delivering near-direct-calculation accuracy with significantly reduced computational cost, especially for challenging systems with entangled bands or topological characteristics [18].

When configuring these calculations, particular attention should be paid to k-path design, basis set selection, and interpolation parameters when applicable. For method validation studies, we recommend a hybrid approach: using direct calculations for benchmark systems and selected test cases, while employing advanced interpolation techniques like HT for high-throughput screening or parameter space exploration. This strategy maximizes both accuracy and computational efficiency in comprehensive band gap measurement validation studies.

In the field of computational materials science, accurately determining electronic band structures is fundamental to predicting and understanding material properties. Conventional band structure calculations within density functional theory (DFT) typically involve computationally intensive self-consistent field (SCF) calculations on a uniform k-point grid, followed by the calculation of eigenvalues on a specific path in the Brillouin zone. Band structure interpolation has emerged as a crucial technique to balance computational cost with the need for smooth, detailed band diagrams. This process relies on constructing a simplified Hamiltonian from the SCF results that can be inexpensively diagonalized at any desired k-point. The fidelity of this interpolated band structure is exceptionally sensitive to two critical input parameters: the DeltaK (Δk) value, which controls the sampling density and smoothness of the resulting bands, and the proper selection of energy windows for identifying and treating core bands separately from valence and conduction bands. These parameters are not merely technical settings; they directly control the physical accuracy of the resulting electronic structure representation, influencing subsequent predictions of optical properties, conductivity, and other electronic behaviors. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of methodologies centered on these parameters, offering experimental data and protocols for researchers validating band gap measurements through interpolation versus direct band structure methods.

Theoretical Framework: Band Structure Interpolation Methods

Fundamental Concepts and Mathematical Foundation

Band structure interpolation operates on the principle of constructing a spatially localized Hamiltonian that can be efficiently Fourier-transformed to obtain eigenvalues at arbitrary k-points. The success of this interpolation hinges on the real-space localization of the Hamiltonian matrix elements. A perfectly localized Hamiltonian would require only a small number of Fourier components, enabling perfect interpolation from a coarse k-point grid. The fundamental interpolation formula is expressed as:

$${H}{{\bf{q}}}=\frac{1}{{N}{k}}\sum {{\bf{k}},{\bf{R}}}{H}{{\bf{k}}}{e}^{{\rm{i}}({\bf{q}}-{\bf{k}}){\bf{R}}}$$

where R is the Bravais lattice vector, and N_k is the number of uniform k-points used in the SCF calculation [7]. The accuracy of this interpolation depends critically on how quickly the matrix elements H(R) decay to zero as |R| increases.

Comparative Analysis of Interpolation Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of Band Structure Interpolation Methods

| Method | Key Features | Localization Target | Computational Complexity | Accuracy for Entangled Bands | Required User Input |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wannier Interpolation (WI) | Maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWFs) as basis set | Wavefunction localization | High (non-linear optimization) | Challenging | Initial guesses, projectors, energy windows |

| WI-SCDM | Selected columns of density matrix for robustness | Wavefunction localization | Medium | Improved over WI | Energy windows, fewer initial guesses |

| Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) | Directly transforms Hamiltonian eigenvalues | Hamiltonian localization | Low (pre-optimized transform) | Excellent (1-2 orders of magnitude better) | Energy window for transformation |

| Direct Diagonalization | No interpolation, calculates at each k-point | N/A | Very High | Exact but computationally expensive | k-point path, convergence parameters |

The recently developed Hamiltonian Transformation (HT) method addresses key limitations of traditional Wannier Interpolation. While WI targets wavefunction localization through computationally demanding optimization procedures, HT employs a pre-optimized transform function f(H) designed to directly localize the Hamiltonian itself [7]. This function smooths the eigenvalue spectrum to counteract delocalization effects caused by spectral truncation during the projection onto a smaller basis set. The transform function is defined piecewise:

$${f}_{a,n}(x)=\left{\begin{array}{ll}0 & x\ge \varepsilon \ \frac{\frac{2a({e}^{-\frac{{n}^{2}}{4}}-{e}^{-\frac{{n}^{2}{(2x+a)}^{2}}{4{a}^{2}}})}{\sqrt{\pi }n}+(2x+a)\left(\,{\text{erf}}\,\left(\frac{n}{2}\right)-\,{\text{erf}}\,\left(n\left(\frac{x}{a}+\frac{1}{2}\right)\right)\right)}{4\,{\text{erf}}\,\left(\frac{n}{2}\right)} & \varepsilon -a\le x < \varepsilon \ x+a/2 & x < \varepsilon -a\end{array}\right.$$

where ε represents the maximum eigenvalue considered, a controls the width of the transition region, and n governs the function smoothness [7]. This approach eliminates the need for system-specific optimization during runtime, making it particularly effective for systems with entangled bands or topological obstructions where traditional WI struggles.

Critical Parameter 1: DeltaK for Smoothness

The Role of DeltaK in Band Structure Interpolation

The DeltaK (Δk) parameter, often referred to as the interpolation step size, determines the resolution and smoothness of the final band structure plot. It defines the spacing between consecutive k-points along the high-symmetry path in the Brillouin zone. While the initial SCF calculation converges the electron density on a uniform k-mesh, the interpolation step uses this information to calculate bands at much finer intervals specified by Δk. An appropriately chosen Δk value ensures that all relevant features of the band structure—including band crossings, avoided crossings, and extremal points—are adequately resolved without introducing computational artifacts.

Experimental Protocols and Practical Implementation

In practical implementations, the Δk parameter is explicitly defined in computational setup procedures. For example, in the BAND tutorial analyzing CsPbBr3 perovskite, the interpolation delta-K was set to 0.02 Bohr⁻¹ along the specified path Γ→X→M→R→Γ [3]. This value represents a balanced choice that captures the essential curvature variations in the bands while maintaining computational efficiency.

Protocol for Determining Optimal DeltaK:

Initial Estimation: Begin with a conservative Δk value (e.g., 0.01 Bohr⁻¹) to establish a reference band structure with high resolution.

Progressive Coarsening: Systematically increase Δk (e.g., to 0.02, 0.05, 0.1 Bohr⁻¹) while monitoring key features like band gaps, effective masses, and van Hove singularities.

Convergence Testing: Calculate the root-mean-square deviation of band energies compared to the reference structure. Optimal Δk is achieved when this deviation falls below a predetermined threshold (typically 1-10 meV).

Feature-Specific Validation: Pay particular attention to regions with high band curvature near band edges, as these require finer sampling to accurately determine effective masses for transport properties.

System-Dependent Adjustment: Consider that materials with more complex band structures (e.g., those with flat bands or strong spin-orbit coupling) generally require smaller Δk values for equivalent accuracy.

Critical Parameter 2: Energy Windows for Core Bands

The Critical Role of Energy Disentanglement

The treatment of energy windows represents perhaps the most nuanced aspect of accurate band structure interpolation. This parameter determines how electronic states are partitioned between those explicitly included in the interpolation manifold and those treated as core states. Improper window selection can lead to band entanglement, where states that should be separated in energy become mixed in the interpolated Hamiltonian, resulting in unphysical band crossings or distortions. The energy window specification typically requires setting both lower and upper bounds that encompass the bands of interest while excluding core states and high-energy unoccupied states.

Method-Specific Considerations and Protocols

The implementation of energy windows varies significantly between interpolation methodologies:

For Wannier Interpolation:

- Inner Window: Encompasses the bands to be represented as Wannier functions, typically including valence bands and possibly lower conduction bands.

- Outer Window: Defines the broader energy range from which projections are made, necessary for handling entangled bands.

- Frozen Window: For core states that remain fixed throughout the calculation.

For Hamiltonian Transformation:

- Transition Region (parameter a): Controls the width of the energy range over which the transform function provides a smooth transition, typically set proportional to the energy range of entangled bands [7].