Imaginary Phonons: Understanding Causes and Implementing Computational Solutions for Stable Materials

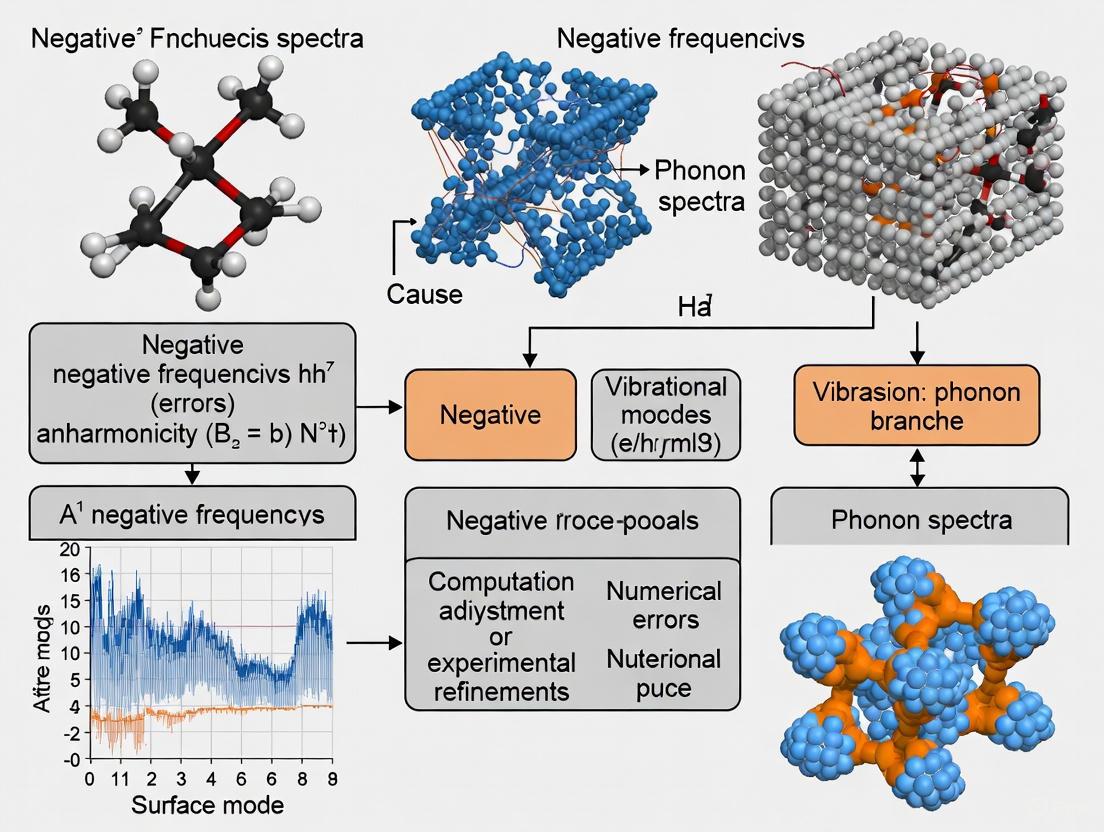

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the prevalent issue of negative (imaginary) frequencies in phonon spectra calculations.

Imaginary Phonons: Understanding Causes and Implementing Computational Solutions for Stable Materials

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the prevalent issue of negative (imaginary) frequencies in phonon spectra calculations. Covering foundational concepts to advanced methodologies, we explore the physical significance of imaginary modes as indicators of dynamic instability and the critical role of numerical convergence. The content details traditional Density Functional Theory (DFT) and modern machine learning potential (MLP) approaches, offers practical troubleshooting protocols for geometry optimization and parameter selection, and establishes validation frameworks against experimental data and high-throughput databases. This resource is essential for ensuring computational reliability in predicting material stability for applications in drug development and biomedical engineering.

What Are Imaginary Phonons? Decoding the Signal of Instability in Your Calculations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does a "negative frequency" in my phonon spectrum physically represent?

In the context of phonon spectra, a negative frequency (often reported as an imaginary frequency) is not a mathematical artifact but a signature of a physical instability within the crystal structure [1]. It indicates that the current atomic configuration is not at a minimum of the potential energy surface. Instead, the atoms experience a force driving them toward a different, more stable arrangement [2]. This can signal the existence of a phase transition, such as to a charge density wave (CDW) state or a ferroelectric distortion [1].

Q2: I've obtained negative frequencies in my Density Functional Perturbition Theory (DFPT) calculation. What is the first thing I should check?

The first step is to distinguish between a real physical instability and a numerical inaccuracy [2]. You should systematically check the convergence of your calculation with respect to key computational parameters. Small, localized negative frequencies, especially near the gamma point (Γ), are often caused by numerical issues rather than a genuine instability [2].

Q3: My phonon calculation shows small negative frequencies. Is this always a problem?

Not necessarily. The presence of small negative frequencies, particularly in the region 0 < |q| < 0.05 (in fractional coordinates) along high-symmetry lines, can be associated with poor choices of the k-point or q-point grids and is rarely a signal of a real incommensurate instability [2]. However, large and widespread negative frequencies across the Brillouin zone are a strong indicator of a physical instability.

Q4: Can adjusting computational parameters resolve negative frequencies?

Yes, in cases where negative frequencies are due to numerical imprecision. The table below summarizes key parameters to check and their typical effects. A real physical instability will persist even in a fully converged calculation [2].

Q5: Are negative frequencies always associated with low temperatures?

No, the relationship with temperature is material-dependent. In some cases, increasing the temperature can stabilize a lattice. For instance, in one reported case for SCPH calculations, increasing the temperature parameters to TMAX = 1400 and DT = 100 resolved the issue of imaginary frequencies [3]. This suggests that the instability was suppressed at higher temperatures.

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Negative Frequencies

Step 1: Verify Numerical Convergence

Before concluding a physical instability, ensure your calculation is numerically sound. Follow this workflow to check and correct common numerical issues.

Step 2: Diagnose Physical Instabilities

If negative frequencies persist after thorough convergence testing, they likely indicate a genuine physical instability. The following table outlines quantitative indicators from your calculation outputs that can help diagnose the issue [2].

| Indicator | Formula/Description | Threshold Value | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) Breaking | Largest acoustic mode frequency at Γ point before ASR imposition [2] | > 30 cm⁻¹ | Suggests poor convergence with respect to k-points or q-points [2]. |

| Charge Neutrality Sum Rule (CNSR) Breaking | max_α,β | ∑_κ Z*_κ,βα | [2] |

> 0.2 | Indicates potential convergence issues with the plane-wave cutoff or other numerical parameters [2]. |

| Localized Imaginary Modes | Presence of negative frequencies only in the region 0 < |q| < 0.05 [2] |

N/A | Often a numerical artifact, not a real instability [2]. |

| Widespread Imaginary Modes | Negative frequencies present across multiple high-symmetry paths in the Brillouin Zone. | N/A | Strong evidence of a genuine physical instability in the crystal structure [2]. |

Step 3: Implement Solutions Based on Diagnosis

Depending on the outcome of your diagnosis, implement the following solutions.

For Numerical Instabilities:

- Increase Plane-Wave Cutoff: If the CNSR breaking flag is triggered, systematically increase the plane-wave cutoff energy until the computed value falls below the 0.2 threshold [2].

- Use Denser k-point and q-point Grids: If the ASR breaking flag is triggered or imaginary frequencies are localized near Γ, use a denser grid. A standard practice is to use a grid with a density of approximately 1500 points per reciprocal atom [2].

For Physical Instabilities:

- Investigate the Low-Temperature Phase: The negative frequencies indicate that your simulated structure is unstable. You should explore the crystal structure that the phonon instability is driving the system towards, such as a distorted phase with a lower symmetry [1].

- Consider Anharmonic Effects: At higher temperatures, the harmonic approximation may break down. Techniques like the temperature-dependent effective potential method or self-consistent phonon (SCPH) calculations can account for anharmonicity. As one report noted, adjusting temperature parameters in SCPH calculations can make negative frequencies disappear [3].

- Experimental Validation: Compare your findings with experimental data, such as from Raman spectroscopy, neutron scattering, or X-ray diffraction, which can confirm the presence of a structural phase transition [1] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key computational "reagents" and parameters essential for performing stable and accurate phonon calculations.

| Item/Parameter | Function & Explanation | Recommended Value/Guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Plane-Wave Cutoff Energy | Determines the number of basis functions used to expand the electronic wavefunctions. A low value can lead to numerical inaccuracies manifesting as imaginary frequencies [2]. | Choose based on the hardest element in the compound, as suggested by pseudopotential tables (e.g., PseudoDojo) [2]. |

| k-point Grid | Samples the Brillouin zone for the electronic structure calculation. A sparse grid can cause insufficient sampling and spurious instabilities [2]. | Use a grid with a density of ~1500 points per reciprocal atom [2]. |

| q-point Grid | Samples the wavevectors for the phonon calculation in DFPT. Critical for accurately building the interatomic force constants [2]. | Use a Γ-centered grid with equivalent density to the k-point grid [2]. |

| Pseudopotential | Represents the core electrons and nucleus, replacing them with an effective potential. The choice affects the accuracy of interatomic forces [2]. | Use norm-conserving pseudopotentials from validated tables (e.g., PseudoDojo) generated with the appropriate exchange-correlation functional [2]. |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | The approximation used for quantum mechanical exchange and correlation effects. It influences the predicted lattice dynamics and stability [2]. | The PBEsol functional has proven to provide accurate phonon frequencies compared to experimental data [2]. |

| Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) | A physical constraint that the net force on the crystal from an internal displacement must be zero. Imposing it corrects for numerical drift [2]. | Should always be explicitly imposed during the phonon interpolation process [2]. |

The Critical Link Between Imaginary Phonons and Dynamic (Un)stability of Crystals

Theoretical Background: Understanding Imaginary Phonons

What are imaginary phonons and what do they signify in my calculations?

Imaginary phonons (reported as negative frequencies in computational outputs) arise when the calculated frequency squared (ω²) of a vibrational mode is negative. Mathematically, this leads to the frequency ω being an imaginary number. Physically, this indicates that the atomic structure is at a local energy maximum rather than a minimum along that vibrational coordinate. This typically signifies dynamic instability, suggesting the crystal structure may transform to a different phase or that the calculation parameters need adjustment [2] [4].

Are imaginary phonons always indicative of a real structural instability?

Not necessarily. While imaginary phonons can point to genuine structural instabilities, they can also stem from numerical inaccuracies in calculations. The key is to distinguish between "real" instabilities (indicating a structurally unstable phase) and "numerical" instabilities (caused by insufficient calculation parameters) [2]. Small imaginary frequencies near the Brillouin zone center (Γ point) often relate to numerical precision issues with k-point or q-point sampling, whereas large, persistent imaginary frequencies across multiple q-points more likely indicate genuine structural instability [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Imaginary Phonon Issues

How can I distinguish between numerical artifacts and genuine structural instability?

Follow this diagnostic workflow to identify the root cause:

What computational parameters should I adjust to resolve numerical imaginary phonons?

Increase k-point and q-point sampling density: Inadequate sampling of the Brillouin zone is a common cause of small imaginary frequencies, particularly near the Γ point. Systematic convergence testing is essential [2].

Verify strict convergence criteria: Ensure all forces on atoms are converged to below 10⁻⁶ Ha/Bohr and stresses below 10⁻⁴ Ha/Bohr³ during structural relaxation [2].

Check acoustic sum rule (ASR) and charge neutrality sum rule (CNSR) violations: Significant breaking of these sum rules (ASR > 30 cm⁻¹, CNSR > 0.2) indicates poor convergence and potentially unreliable results [2].

How can I address genuine structural instabilities in my research?

For compounds with genuine dynamic instability, several approaches have proven effective:

Apply external pressure: Hydrostatic pressure can stabilize otherwise unstable structures by modifying the potential energy surface [4].

Introduce lattice distortion: Systematically distort the crystal structure along the soft mode direction to locate the true energy minimum [4].

Adjust temperature parameters: In SCPH calculations, increasing temperature parameters (e.g., TMAX = 1400, DT = 100) has successfully eliminated imaginary frequencies in some cases [3].

Electronic smearing: Applying appropriate electronic smearing can stabilize metallic systems with states near the Fermi level [4].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table: Key Computational Tools for Phonon Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| DFPT (Density Functional Perturbation Theory) | Calculates second derivatives of energy with respect to atomic displacements and electric fields | Primary method for computing phonon spectra and related properties [2] |

| ABINIT Software Package | Implements DFPT for phonon calculations with various exchange-correlation functionals | High-throughput phonon calculations for inorganic materials [2] |

| Materials Project Database | Provides curated crystal structures and calculated properties for high-throughput screening | Source of initial structures for phonon and stability analysis [4] |

| PseudoDojo Pseudopotentials | Norm-conserving pseudopotentials optimized for specific exchange-correlation functionals | Consistent pseudopotential library for accurate DFPT calculations [2] |

| Phonon Database (phonondb.mtl.kyoto-u.ac.jp) | Repository of pre-calculated phonon band structures for various compounds | Benchmarking and reference for phonon dispersion relationships [2] |

Advanced Applications: Working with Dynamically Unstable Systems

Can compounds with imaginary phonons still be useful for materials discovery?

Yes. Recent research has shown that dynamically unstable compounds should not be automatically discarded. In some cases, these systems can exhibit enhanced electron-phonon coupling and promising functional properties. For example, Y₂C₃ with experimentally known Tc = 18K exhibits imaginary phonons related to carbon dimer "wobbly motion" that, when stabilized, carry significant electron-phonon coupling contributions [4]. Recent model Hamiltonian studies also indicate that phonon softening and anharmonicity can enhance superconducting Tc in certain systems [4].

What is the recommended workflow for investigating compounds with dynamical instability?

Quantitative Assessment: Numerical Precision Indicators

Table: Key Numerical Indicators for Assessing Phonon Calculation Reliability

| Indicator | Threshold Value | Interpretation | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) Breaking | > 30 cm⁻¹ | Significant breaking indicates poor convergence | Increase plane wave cutoff; improve k-point sampling [2] |

| Charge Neutrality Sum Rule (CNSR) Breaking | > 0.2 | Substantial deviation from charge neutrality | Verify pseudopotentials; check BEC convergence [2] |

| Imaginary Frequency Region | 0 < |q| < 0.05 | Likely numerical artifact rather than real instability | Increase q-point density; verify convergence [2] |

| Force Convergence | > 10⁻⁶ Ha/Bohr | Incomplete structural relaxation | Tighten convergence criteria during geometry optimization [2] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

The acoustic modes at my Γ point are not zero. Is this a problem?

Yes. The acoustic modes at Γ should be exactly zero due to translational invariance (acoustic sum rule). Non-zero values indicate incomplete imposition of the ASR and potential convergence issues. Most computational packages automatically impose ASR during post-processing, but significant residual acoustic frequencies (> 30 cm⁻¹ when ASR is not imposed) suggest underlying convergence problems that need addressing [2].

My calculations show small imaginary frequencies only near the Γ point. Should I be concerned?

This pattern typically indicates numerical issues rather than genuine structural instability. Focus on improving k-point and q-point sampling density and verifying plane wave cutoff convergence. These small imaginary frequencies near Γ "are hardly ever a signal of a real incommensurate instability" [2].

Can machine learning models help predict stability and handle imaginary phonons?

Yes. Advanced machine learning approaches like ALIGNN (Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network) can effectively predict material properties including those of dynamically unstable compounds. These models can be trained on datasets that include compounds with imaginary phonons (appropriately flagged), enabling more comprehensive materials discovery beyond just dynamically stable systems [4].

Are there successful examples of materials with imaginary phonons exhibiting useful properties?

Yes. Research on boron and carbon compounds has identified several promising superconducting materials that initially exhibited dynamical instability but demonstrated valuable properties after stabilization, including Ca₅B₃N₆ (predicted T_c = 35-42.4 K), Pd₃CaB (7.0 K), and various ruthenium compounds [4].

Frequently Asked Questions

What does a "negative frequency" in my phonon spectrum actually mean? A "negative frequency" does not mean the vibrational frequency itself is negative. In computational phonon analysis, it is a convention to represent an imaginary frequency, which arises from a negative eigenvalue of the dynamical matrix [5]. This matrix describes the curvature of the potential energy surface around the atomic configuration. A positive eigenvalue indicates a stable "bowl-shaped" curvature, while a negative eigenvalue indicates an unstable "saddle point," meaning the structure can lower its energy by displacing atoms along the direction of the corresponding mode [5].

My calculation yielded negative frequencies. Is my structure unstable? Not necessarily, but it is a strong indicator. Imaginary frequencies (reported as negative) often point to a structural instability [5]. This could mean that the initial structure you used for the calculation is not at a true energy minimum. The system may be trying to relax into a different, lower-energy phase, often through a phase transition [6] [7]. However, in highly anharmonic materials at high temperatures, what appears as an instability at zero Kelvin can be a sign of a dynamically stabilized phase [7].

I have confirmed a structural instability. What is the physical origin? The instability you are observing is often driven by a soft mode. This is a phonon mode whose frequency decreases (softens) significantly, often as the system approaches a phase transition [6] [7]. In the high-temperature Cmcm phase of the thermoelectric material SnSe, for instance, soft modes and strong anharmonicity lead to very low thermal conductivity [7]. The anharmonic interactions between atoms prevent the structure from settling into the symmetric arrangement that would be stable in a purely harmonic picture.

How can I resolve imaginary frequencies in my calculations? Imaginary frequencies can sometimes be resolved by adjusting calculation parameters. One documented case showed that increasing the temperature parameters in SCPH (Self-Consistent Phonon) calculations to TMAX=1400 and DT=100 eliminated all negative frequencies [3]. More fundamentally, you should ensure your structure is fully relaxed. If imaginary frequencies persist, they may be physically meaningful, indicating that the system wants to distort to a new structure. Following the soft mode distortion and re-relaxing the structure can lead to the true ground state [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Negative Frequencies

This guide outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and addressing negative frequencies in phonon calculations.

Diagnostic Procedures

1. Verify Structural Optimization

- Objective: Ensure the input crystal structure is at a local energy minimum.

- Protocol:

- Perform a full structural optimization (atomic positions and lattice parameters) using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with stringent convergence criteria for forces and stresses.

- Confirm the final structure has no residual forces on atoms.

- Expected Outcome: Small, non-physical imaginary frequencies may disappear after a rigorous relaxation [5].

2. Analyze the Soft Mode

- Objective: Determine if the imaginary frequency corresponds to a physically meaningful soft mode.

- Protocol:

- Visualize the atomic displacements of the imaginary mode using visualization software (e.g., VESTA).

- The distortion often suggests a lower-symmetry structure. Manually distort your optimized structure along this mode.

- Re-optimize the distorted structure. If it relaxes to a new, lower-energy configuration, the soft mode was indicative of a true structural instability [5].

- Expected Outcome: Identification of a stable ground-state structure, potentially related to a low-temperature phase [6].

3. Account for Strong Anharmonicity

- Objective: Correctly model materials where atomic vibrations are inherently anharmonic.

- Protocol:

- Self-Consistent Phonon (SCPH) Theory: This approach renormalizes phonons by considering anharmonic interactions to all orders. Implement SCPH calculations, which may require adjusting temperature parameters (e.g.,

TMAX,DT) to achieve convergence and eliminate unphysical imaginary frequencies [3]. - Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD): Use machine-learning accelerated MD simulations to capture the true, temperature-dependent potential energy surface. Analyze the trajectory to extract effective force constants and phonon properties [6].

- Self-Consistent Phonon (SCPH) Theory: This approach renormalizes phonons by considering anharmonic interactions to all orders. Implement SCPH calculations, which may require adjusting temperature parameters (e.g.,

- Expected Outcome: A stabilized phonon spectrum that reflects the dynamic stability of high-temperature phases, as demonstrated in SnSe and CsPbBr3 [6] [7].

Experimental Validation & Techniques

Computational predictions of soft modes and phase transitions require experimental validation. The following table summarizes key experimental methods.

| Technique | Core Function | Measurable Phonon Property |

|---|---|---|

| Inelastic Neutron Scattering (INS) [6] [8] | Probes atomic dynamics by measuring energy/momentum transfer of neutrons. | Directly measures the phonon dispersion relation (\omega(\mathbf{q})) and linewidths. |

| Inelastic X-ray Scattering (IXS) [6] | Similar to INS but uses high-energy X-rays, suitable for small samples. | Measures phonon dispersion relations, including zone-center soft modes. |

| Raman Spectroscopy [8] | Measures inelastic scattering of light by phonons. | Probes zone-center optical phonon frequencies and their linewidths as a function of temperature. |

Detailed Protocol: Inelastic Neutron Scattering (INS)

- Objective: To experimentally determine the full phonon dispersion relations, including the identification of soft modes.

- Methodology:

- A single crystal sample is mounted in a cryostat or furnace for temperature-dependent studies.

- A monochromatic beam of neutrons is directed at the sample.

- Scattered neutrons are analyzed for their energy and momentum transfer, mapping out the dynamical structure factor, (S(\mathbf{Q}, E)) [6].

- The phonon density of states and dispersion curves are extracted by modeling the (S(\mathbf{Q}, E)) data.

- Application: This technique was crucial for observing phonon anomalies in SrTiO₃ near its ferroelectric quantum critical point and for discovering dynamic octahedra rotations in CsPbBr₃ [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Investigation |

|---|---|

| Perovskite Crystals (e.g., SrTiO₃, CsPbBr₃) [6] | Model systems for studying ferroelectricity, soft modes, and anharmonic lattice dynamics. |

| Ab Initio Simulation Software (DFT) | Computes fundamental electronic structure and interatomic force constants for lattice dynamics. |

| Self-Consistent Phonon (SCPH) Code | A computational method that accounts for anharmonicity to stabilize soft modes and predict finite-temperature phonon spectra [3]. |

| Machine-Learning Potentials | Enables long-timescale molecular dynamics simulations to capture complex anharmonic behavior [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What does a negative frequency in my phonon dispersion calculation physically mean? A negative frequency, more accurately described as an imaginary frequency, does not signify a negative energy. It indicates an instability in the crystal structure. Mathematically, it arises from a negative eigenvalue of the dynamical matrix, which corresponds to negative curvature on the potential energy surface [5]. Physically, displacing the atoms along the eigenvector associated with this mode would lower the system's energy, suggesting the structure is not at a true minimum and may be a saddle point on the energy landscape [5].

My calculation was for a known, stable crystal. Why did I get imaginary frequencies? This is a common problem and often points to a numerical artifact rather than a physical instability. The most frequent causes are insufficient numerical precision in the preceding steps. A geometry optimization that did not fully converge to a minimum, or a calculation of the interatomic force constants on a q-point grid that is too coarse, can easily produce spurious imaginary frequencies [9] [10]. It is essential to ensure your structure is perfectly relaxed and your computational parameters are well-converged.

I have confirmed my crystal is unstable. How can I find the more stable structure? The eigenvectors of the unstable modes (those with imaginary frequencies) provide a direct map for structural transformation. Displacing the atomic coordinates along these eigenvectors and then re-optimizing the geometry can guide the structure to a lower-energy, stable phase [5]. This procedure is the foundation for studying structural phase transitions computationally.

Can temperature affect the presence of imaginary frequencies? Yes. In some cases, an instability may be related to a phase transition that occurs at a specific temperature. There are reports of imaginary frequencies disappearing when temperature parameters are adjusted in more advanced anharmonic calculations, such as Self-Consistent Phonon (SCP) methods, which can account for the temperature-dependent stabilization of certain modes [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing the Source of Imaginary Frequencies

Follow this workflow to systematically identify the root cause of imaginary frequencies in your phonon spectrum.

Procedure:

Verify Geometry Optimization Convergence:

- Objective: Ensure the initial structure is at a local energy minimum.

- Protocol: Scrutinize the output of your geometry optimization calculation. Most codes, like those used by the Materials Project, require forces on all atoms to converge to a very tight threshold, typically below 10⁻⁶ Ha/Bohr [9]. Any residual force can lead to unphysical instabilities.

- Solution: If not converged, restart the geometry optimization with stricter convergence settings or a different algorithm.

Check q-point Grid Density:

- Objective: Confirm that the sampling of the Brillouin Zone is sufficient.

- Protocol: The dynamical matrix is often calculated on a grid of q-points and then interpolated. A grid that is too coarse will fail to capture the subtleties of the interatomic force constants, leading to artifacts. The Materials Project, for example, uses a grid density of approximately 1500 points per reciprocal atom [9].

- Solution: Perform a convergence test by systematically increasing the density of the q-point grid (e.g., from 2x2x2 to 4x4x4) and observe if the imaginary frequencies persist.

Distinguish Artifact from Reality:

- If the imaginary frequencies disappear after achieving rigorous force convergence and using a dense q-point grid, they were likely numerical artifacts.

- If small-magnitude imaginary frequencies persist at specific q-points (especially high-symmetry points) after thorough convergence tests, a physical instability is likely [5].

Guide 2: Protocol for Resolving Numerical Artifacts

This guide provides detailed methodologies for eliminating numerically induced imaginary frequencies.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Tighten Geometry Optimization Parameters:

- In your DFT calculation input, set extreme convergence criteria. For example:

FORCE_CONVERGENCE = 1e-7 eV/Å(or equivalent in your code)ENERGY_CONVERGENCE = 1e-8 eVSTRESS_CONVERGENCE = 0.01 GPa[9]

- In your DFT calculation input, set extreme convergence criteria. For example:

Perform a q-point Convergence Study:

- Calculate the phonon dispersion using a series of increasingly dense q-point grids (e.g., 2x2x2, 3x3x3, 4x4x4). The phonon frequencies, particularly at key high-symmetry points, should not change significantly with the final increase in grid density.

Increase Basis Set or Plane-Wave Cutoff:

- Using a insufficient basis set (e.g., a low plane-wave energy cutoff) can lead to incomplete convergence of the electron density and, consequently, inaccurate forces. Consult the documentation for your pseudopotentials and increase the cutoff energy by 20-30% for a final, high-accuracy phonon calculation [9].

Data and Material Summaries

Table 1: Diagnostic Checklist for Imaginary Frequencies

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Small imaginary frequencies at general q-points | Incomplete geometry optimization | Re-optimize geometry with stricter force convergence (< 1e-6 Ha/Bohr) [9] |

| Imaginary frequencies that change with q-grid density | Insufficient Brillouin zone sampling | Increase the density of the q-point grid until the spectrum converges [9] |

| Consistent imaginary frequencies at high-symmetry points | Physical crystal instability | Displace structure along the soft mode and re-relax [5] |

| Imaginary frequencies that vanish at higher temperature | Anharmonic effect | Use self-consistent phonon (SCP) methods for accurate finite-temperature results [3] |

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

This table outlines the essential "reagents" for a successful and artifact-free phonon calculation.

| Item | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Norm-Conserving Pseudopotentials | Defines the interaction between valence electrons and ionic cores, critical for accurate forces. | PseudoDojo table [9] |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | Approximates quantum mechanical exchange and correlation effects. PBEsol is recommended for accurate phonons in solids [9]. | PBEsol [9] |

| q-point Grid | A mesh of points in the Brillouin Zone used to calculate the interatomic force constants. | A Γ-centered grid with ~1500 points/reciprocal atom [9] |

| Phonopy / ABINIT | Software packages that perform the phonon calculation using the density functional perturbation theory (DFPT) or finite-displacement method. | ABINIT (for DFPT) [9] |

From DFT to Machine Learning Potentials: Computational Strategies for Accurate Phonons

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Fundamental Concepts

What is the fundamental difference between DFPT and the finite-displacement method?

DFPT (Density Functional Perturbation Theory) computes the second derivatives of the energy (force constants) analytically by solving the Sternheimer equation for the linear response of the wavefunctions to a perturbation, such as an atomic displacement [11] [12]. In contrast, the finite-displacement method (also called the direct or frozen-phonon method) is a numerical approach. It calculates forces after displacing atoms from their equilibrium positions in a supercell and uses finite differences to obtain the force constants [13] [14].

What do "negative" phonon frequencies mean in my results?

"Negative" frequencies are a computational convention indicating imaginary frequencies [5]. They signify an instability in the structure, meaning the atomic configuration is not at a true energy minimum but rather at a saddle point on the potential energy surface. The magnitude of the imaginary frequency indicates how rapidly the energy would decrease if atoms were displaced along the direction of the corresponding eigenvector [5].

Troubleshooting Calculations

My calculation reveals negative frequencies. Does this always mean my structure is unstable?

Not necessarily. While negative frequencies often indicate a structural instability or a saddle point, they can also result from inadequate computational settings [5]. Before concluding the structure is unstable, you should verify the convergence of your calculation with respect to key parameters like the k-point grid density, plane-wave energy cutoff, and the supercell size (for finite-displacement) or q-point grid (for DFPT) [9].

For a finite-displacement calculation, how do I choose the correct displacement magnitude (ph.dr in RESCU, POTIM in VASP)?

The displacement should be small enough to remain within the harmonic regime but large enough to overcome numerical noise from the "eggbox effect." A typical value is around 0.01 Å (approx. 0.02 Bohr) [14]. It is advisable to test a range of values to ensure the results are consistent.

Why would I choose the finite-displacement method over the more efficient DFPT?

While DFPT is generally more efficient for phonons in insulators, the finite-displacement method is more versatile. It is the preferred choice for systems where DFPT is not fully implemented or robust, such as calculations involving metals, magnetic systems, ultrasoft pseudopotentials, or DFT+U corrections [15] [16]. Furthermore, new approaches like the non-diagonal supercell method can make finite-displacement calculations an order of magnitude faster [13].

Computational Setup

What is a non-diagonal supercell and how does it improve finite-displacement calculations?

A traditional (diagonal) supercell for a q-point like (n₁/m₁, n₂/m₂, n₃/m₃) requires a supercell of size m₁×m₂×m₃. The non-diagonal supercell method constructs a supercell with a volume equal to the least common multiple of m₁, m₂, and m₃, which can be significantly smaller. This reduces the computational cost substantially, making the method much faster, especially for complex systems [13].

What are the key steps in a typical DFPT workflow?

A standard DFPT workflow involves several key steps, which are visualized in the diagram below.

Comparison of Computational Methodologies

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of DFPT and the Finite-Displacement Method.

| Feature | Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT) | Finite-Displacement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Analytical calculation of force constants via linear response [12]. | Numerical differentiation of forces from atomic displacements [13]. |

| Typical Workflow | 1. Highly converged ground-state calculation.2. Self-consistent solution of DFPT equations for perturbations (e.g., rfphon).3. Post-processing with a tool like anaddb to compute phonon properties [11]. |

1. Construct a supercell.2. Generate symmetry-inequivalent atomic displacements.3. Run DFT force calculations for each displaced configuration.4. Calculate force constants and dynamical matrices to derive phonon properties [14]. |

| Key Advantage | Efficient for phonons at arbitrary q-points without large supercells [12]. | Universally applicable; works with any DFT code/functional, including DFT+U and metals [15] [16]. |

| Key Disadvantage | Implementation can be limited for certain functionals, pseudopotentials, or magnetic systems [13] [16]. | Requires large supercells for q-points beyond Γ, which is computationally expensive [13]. |

| Common Software | ABINIT [11] [9], VASP (IBRION=7/8) [16]. | Phonopy [13], PHON [13], RESCU [14], CASTEP [15]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Negative Frequencies

Problem Definition

The appearance of "negative" (imaginary) frequencies in phonon spectrum calculations signifies that the dynamical matrix has negative eigenvalues. This indicates a negative curvature of the potential energy surface in the direction of the corresponding eigenvector [5].

Diagnostic and Resolution Procedures

The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnose and resolve the issue of negative frequencies.

- Verify Ground-State Convergence: Ensure the initial DFT calculation is fully converged. Strict criteria are essential: forces should be below 10⁻⁶ Ha/Bohr and stresses below 10⁻⁴ Ha/Bohr³ for reliable phonons [9].

- Confirm Structural Optimization: The input structure for the phonon calculation must be a fully optimized equilibrium geometry. Phonon calculations on experimental or unrelaxed structures can produce spurious imaginary frequencies.

- Test Computational Parameters:

- k-points & Cutoff: Increase the density of the k-point grid and the plane-wave energy cutoff. Inadequate sampling can cause instabilities [9].

- Supercell Size (FDM): For the finite-displacement method, use a larger supercell. A cutoff radius of ~3.5 Å may be insufficient; larger values improve accuracy but increase cost [15].

- Displacement (FDM): Check that the displacement step is optimal (e.g., ~0.02 Bohr) to minimize the eggbox effect [14].

- Apply the Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR): Enforce the ASR in post-processing. This correction imposes translational invariance, which can be broken numerically, and can remove small imaginary frequencies at the Γ-point [11] [14].

- Investigate Physical Instability: If imaginary frequencies persist after thorough checks, they likely represent a genuine physical instability (e.g., a soft mode preceding a phase transition) [5]. In anharmonic systems, increasing temperature in self-consistent phonon (SCPH) calculations can also stabilize modes and remove imaginary frequencies [3].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

This table lists key software and algorithmic "reagents" used in modern phonon calculations.

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| DFPT Solvers | Computes linear response of electrons to perturbations, providing analytical force constants. | ABINIT (rfphon, rfstrs) [11], VASP (IBRION=7/8) [16], RESCU [12]. |

| Finite-Displacement Codes | Automates supercell construction, atomic displacements, and force constant calculation from finite differences. | Phonopy [13], PHON [13], RESCU (ph.mode = phonon) [14], CASTEP [15]. |

| Non-Diagonal Supercell Method | A sophisticated finite-displacement approach that uses smaller, specially shaped supercells to calculate specific q-points, drastically improving computational efficiency [13]. | ARES-Phonon [13]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) | Trains on a subset of DFT force data to predict forces in remaining displacements, reducing the number of required DFT calculations by ~90% while maintaining high accuracy [13]. | ACNN (used with ARES-Phonon) [13]. |

| Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR) Corrections | A post-processing correction that enforces that the sum of force constants for atomic displacements is zero, fixing spurious imaginary frequencies at the Γ-point [14] [5]. | Available in most analysis tools (e.g., ph.ASR=1 in RESCU [14]). |

The Rise of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) for High-Throughput Phonon Calculations

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are MLIPs and why are they important for phonon calculations? Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) are models that predict the potential energy surface of a material based on its atomic configuration. They deliver energies and forces at the level of density functional theory (DFT) but at a computational cost several orders of magnitude lower, enabling the high-throughput calculation of phonons and related properties across vast sets of materials [17].

Q2: My MLIP-based phonon calculation produces 'negative' frequencies. Does this always indicate a problem? Not necessarily. A negative frequency can signal a genuine mechanical instability of the chosen structure, meaning the system is dynamically unstable [18]. However, it can also result from technical issues, such as an MLIP that is inaccurate for the specific material or calculation parameters that are not sufficiently converged [17].

Q3: Which universal MLIP models are currently most reliable for phonon property prediction? Recent benchmarks show that models like MACE-MP-0 and CHGNet demonstrate high accuracy in predicting harmonic phonon properties [17]. The performance of various models is summarized in Table 1 below.

Q4: A common DFT phonon code fails with 'error reading file'. What should I do?

This typically indicates that the data file produced by the initial self-consistent calculation is bad, incomplete, or was produced by an incompatible version of the code. In parallel execution, ensure that if you did not set wf_collect=.true., the number of processors and pools for the phonon run matches the self-consistent run [18].

Troubleshooting Common Errors

Issue 1: Phonon calculations yield "lousy" phonons with bad or negative frequencies.

This is a common problem with multiple potential causes and solutions [18]:

Root Cause A: Violation of the Acoustic Sum Rule (ASR).

- Explanation: The ASR is never exactly verified due to the system not being perfectly translationally invariant, a condition worsened by computing the exchange-correlation energy on a discrete grid [18].

- Solution: Increasing the charge density cutoff (

ecutrho) can make the integral more exact and reduce the problem. This issue is often more severe for GGA functionals than for LDA [18].

Root Cause B: Inadequate convergence parameters.

- Explanation: The convergence thresholds for the self-consistent field (

conv_thr) or the phonon calculation itself (tr2_ph) may be too large [18]. - Solution: Systematically reduce these convergence thresholds and monitor the change in phonon frequencies.

- Explanation: The convergence thresholds for the self-consistent field (

Root Cause C: Inaccurate MLIP force predictions.

- Explanation: Some universal MLIPs, even if excellent for energies and forces near equilibrium, can be inaccurate when predicting the second derivatives of the energy (force constants) needed for phonons [17].

- Solution: Consult benchmarking studies to select an MLIP proven for phonon properties (see Table 1). For sensitive studies, fine-tuning the MLIP on a small set of high-fidelity DFT phonon calculations for your material of interest can be highly beneficial [19].

Other Checks:

- Verify that the correct atomic masses are given in the input.

- Ensure the structure is fully relaxed and reasonable.

- Check the k-point grid density, especially for metallic systems [18].

Issue 2: The phonon code stops with "occupation numbers probably wrong".

- Explanation: This warning appears when you have a metallic or spin-polarized system, but the electronic smearing method is not appropriately set [18].

- Solution: In your DFT input parameters, set the

occupationskeyword to a smearing method (e.g.,smearing='gaussian'or'mp') [18].

Issue 3: An MLIP geometry optimization fails to converge during a pre-phonon relaxation.

- Explanation: This can happen if the geometry optimization path explores regions of the potential energy surface where the MLIP yields unphysical forces, or if there are high-frequency errors in the forces [17]. This failure rate is notably higher for models where forces are predicted as a separate output and not as the exact derivative of the energy [17].

- Solution:

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Phonon Workflow with MLIPs

The following diagram illustrates a robust, high-throughput workflow for phonon calculations that integrates MLIPs and DFT validation.

Detailed Methodology:

- Geometry Relaxation: Use a universal MLIP (e.g., MACE-MP-0 or CHGNet) to fully relax the input crystal structure to its ground state. This step is critical as phonons are calculated around a stable equilibrium configuration [17].

- Harmonic Phonon Calculation: Employ the finite-displacement method on the relaxed structure. The MLIP calculates the forces for small atomic displacements, which are used to construct the dynamical matrix and solve for the phonon frequencies and eigenvectors [19].

- Stability & Property Analysis: Check the resulting phonon band structure for negative frequencies. Their absence confirms dynamic stability. Stable results can then be used to compute thermodynamic properties like the Helmholtz vibrational free energy [19].

- Troubleshooting & Validation: If negative frequencies appear, follow the troubleshooting guide. For critical results or persistent issues, validate the MLIP's force constants by performing selective DFT calculations on a small subset of supercell displacements [19] [17].

Protocol 2: Efficient Dataset Generation for MLIP Training

A key innovation in accelerating phonon calculations is the efficient generation of training data for MLIPs. The conventional finite-displacement method is computationally expensive because it requires DFT calculations on many supercells. The following protocol outlines a more efficient approach [19].

Key Details:

- Data Efficiency: This method significantly reduces the number of required supercell DFT calculations per material (e.g., down to ~6) by leveraging a data-driven approach. The model learns from a diverse dataset, identifying underlying similarities across different structures [19].

- Perturbation Strategy: Unlike displacing one atom at a time, this protocol perturbs all atoms simultaneously with small random displacements. This generates a rich set of non-zero interatomic forces with large magnitudes, providing more information per supercell calculation [19].

- Systematic Improvement: The accuracy of the resulting MLIP is systematically improvable by increasing the number of training structures and the diversity of the chemical space covered [19].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Benchmarking Universal MLIPs for Phonon Calculations

This table summarizes the performance of selected universal MLIPs in predicting phonon-related properties, based on a benchmark of ~10,000 materials. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for phonon frequencies and Helmholtz free energy provides a key metric for model selection [19] [17].

| Model Name | Key Architecture Feature | Phonon Frequency MAE (THz) | Helmholtz Free Energy MAE (meV/atom at 300K) | Dynamical Stability Classification Accuracy | Reliability Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE-MP-0 | Atomic cluster expansion descriptor [17] | ~0.18 [19] | ~2.19 [19] | 86.2% [19] | High accuracy for harmonic properties [17] |

| CHGNet | Small architecture, ~400k parameters [17] | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | High geometry optimization reliability (0.09% failure) [17] |

| M3GNet | Pioneering universal MLIP with 3-body interactions [17] | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | Good general performance [17] |

| eqV2-M | Equivariant transformers [17] | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | Lower geometry optimization reliability (0.85% failure) [17] |

| ORB | Combines SOAP with graph network [17] | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | Data Not Specified | Lower reliability; forces not energy derivatives [17] |

Table 2: Critical Parameters for Reliable Phonon Calculations

This table lists essential parameters and computational reagents that require careful attention to ensure the accuracy and stability of phonon calculations, both in DFT and MLIP frameworks.

| Item / Parameter | Function / Purpose | Recommended Settings & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ecutwfc & ecutrho | Plane-wave kinetic energy cutoffs for wavefunctions and charge density. | Must be converged. Too low values are a common cause of "lousy" or negative frequencies [18]. |

| k-point grid | Sampling of the Brillouin zone for electronic structure. | Must be dense enough, especially for metallic systems. Slow convergence can cause phonon inaccuracies [18]. |

| conv_thr | Self-consistent field (SCF) convergence threshold. | Too large a value can cause phonon errors. Tighten for more accurate forces [18]. |

| tr2_ph | Convergence threshold for the phonon SCF calculation. | Tighten if phonon frequencies are not converging or are unphysical [18]. |

| Training Dataset | Data used to train the MLIP. | Must be diverse and high-quality. Inadequate data is a primary source of discrepancy with real-world measurements [19]. |

| MLIP Architecture | The model used to represent the potential energy surface. | Choose models benchmarked for phonons (e.g., MACE). Models predicting forces separately from energy may be less reliable [17]. |

| Supercell Size | Size of the repeated cell for finite-displacement. | Must be large enough to capture long-range interatomic interactions and force constants [19]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential software and computational "reagents" required for conducting high-throughput phonon studies with MLIPs.

- Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs): Core engine for fast force evaluations. Universal models like MACE, CHGNet, and M3GNet are pre-trained on diverse materials databases and are ready for phonon predictions out-of-the-box [17].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) Codes: The source of high-fidelity training data and for final validation. Examples include VASP and Quantum ESPRESSO. Their calculations provide the energies and forces used to train MLIPs [19] [18].

- Phonon Calculation Software: Tools that use the finite-displacement or density functional perturbation theory (DFPT) methods to compute phonons from forces. Examples include PHonon (from Quantum ESPRESSO) and ALAMODE [18] [3].

- High-Throughput Frameworks: Software like atomate and dfttk that help automate and manage thousands of concurrent calculations, handling workflow execution and error checking [20].

- Curation of Diverse Training Datasets: The most crucial non-software reagent. A large, diverse, and high-quality dataset of crystal structures and their corresponding DFT-calculated forces is fundamental for training robust MLIPs that generalize well across the periodic table [19]. The dataset curated by, which includes 2,738 crystal structures with 77 elements, is an example of such a resource [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Resolving Imaginary Frequencies in Phonon Spectra

Imaginary frequencies (negative values in cm⁻¹) in phonon spectra indicate dynamical instabilities in your structure. The following table outlines common causes and evidence-based solutions based on MACE-MP-MOF0 applications.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Imaginary Frequencies

| Problem Cause | Evidence | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Dataset Sampling [21] | Imaginary modes persist across different supercell sizes. | Fine-tune the base MLIP on a curated dataset that efficiently explores the system's important dynamical modes [21]. | Check phonon band structure consistency across multiple supercells. |

| Inaccurate Potential for Non-Equilibrium Geometry | Imaginary modes appear only during geometry relaxation, not in the final structure. | Use MLIPs trained on relaxation trajectories and off-equilibrium configurations, not just final, stable geometries [22]. | Compare forces from MLIP and DFT for a set of non-equilibrium configurations. |

| Incorrect Temperature Parameters in SCPH | Imaginary modes disappear after adjusting anharmonic calculation parameters [3]. | Adjust anharmonic calculation parameters, such as increasing the maximum temperature (TMAX) in SCPH calculations [3]. | Perform SCPH calculations with progressively higher TMAX until imaginary frequencies vanish [3]. |

| Limitations of the Foundation Model | MACE-MP-0 predicts imaginary modes, but fine-tuned MACE-MP-MOF0 does not [23]. | Use the specialized MACE-MP-MOF0 model, which is fine-tuned for MOF phonon properties, instead of the general-purpose MACE-MP-0 [23]. | Compare phonon density of states from MACE-MP-MOF0 against available DFT or experimental data [23]. |

Addressing Model Transferability and Accuracy Failures

When the model fails to accurately predict energies or forces for a new MOF, use this systematic guide.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Model Transferability

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Energy/Force Check | Verify if the error for the new structure's total energy exceeds 8 kJ/mol or atomic forces exceed 50 meV/Å [24]. | Determine if the accuracy is sufficient for your target property (e.g., heat of adsorption) [24]. |

| 2. Descriptor Space Analysis | Check if the new MOF's features (elements, building blocks) fall within the diversity of the training set of 127 MOFs spanning 24 elements [23]. | Identify if the failure is due to a chemical space outlier. |

| 3. Targeted Fine-Tuning | If needed, perform additional fine-tuning on a small, targeted set of DFT data for the problematic MOF or MOF class [24]. | Achieve DFT-level accuracy on the previously failing MOFs [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is MACE-MP-MOF0 and how does it differ from MACE-MP-0?

MACE-MP-MOF0 is a machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP) specifically fine-tuned from the MACE-MP-0 foundation model for high-throughput phonon calculations in Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [23]. While the general-purpose MACE-MP-0 model can struggle with phonon properties and produce imaginary phonon modes in MOFs, the fine-tuned MACE-MP-MOF0 corrects these inaccuracies. It enables the precise prediction of phonon density of states, thermal expansion, and bulk moduli, achieving state-of-the-art agreement with DFT and experimental data [23].

Q2: Why am I getting imaginary frequencies in my phonon calculation, and does it always mean my structure is unstable?

Not necessarily. While imaginary frequencies can indicate a genuine structural instability, they often stem from limitations of the computational model itself [23] [3]. With MLIPs, a common cause is that the training dataset did not efficiently sample all the important dynamical modes of the system, leading to inaccuracies in the learned potential energy surface [21]. Before concluding the structure is unstable, verify your model's accuracy by checking its performance on known stable structures and ensuring you are using a specialized potential like MACE-MP-MOF0 that has been validated for phonon properties in MOFs [23].

Q3: What are the key criteria for a dataset to train a reliable MLIP for MOF phonon calculations?

A reliable dataset must include:

- Diverse Atomic Environments: The curated training set for MACE-MP-MOF0 contained 127 MOFs with a wide range of 24 elements in both inorganic clusters and organic linkers [23].

- Off-Equilibrium Configurations: Data must include not just optimized structures, but also strained configurations and frames from molecular dynamics trajectories to sample the potential energy surface thoroughly [23] [22].

- High-Quality Labels: All configurations must have accurate energy and atomic force labels, typically derived from DFT calculations [23] [22].

Q4: Can MACE-MP-MOF0 be used for simulating adsorption properties, like water uptake in MOFs?

Yes, the strategy of fine-tuning the pre-trained MACE model has been successfully demonstrated for predicting water adsorption in MOFs. Research shows that a fine-tuned MACE model can predict heats of adsorption and Henry coefficients in excellent agreement with experiments. These accurate predictions require the MLP to correctly describe both the adsorbate-framework interactions and the framework flexibility [24].

Q5: What accuracy thresholds should my MLIP meet for predicting properties like thermal expansion or heat of adsorption?

For reliable prediction of thermodynamic properties:

- Heat of Adsorption: The model should achieve an accuracy threshold of better than 8 kJ/mol on total energies and 50 meV/Å on atomic forces [24].

- Phonon-Derived Properties: The fine-tuned MACE-MP-MOF0 model has demonstrated the ability to predict bulk moduli and thermal expansion coefficients in agreement with DFT and experimental data, which is a key indicator of sufficient accuracy for phonon-mediated properties [23].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: High-Throughput Phonon Calculation with MACE-MP-MOF0

This protocol details the steps for computing phonon properties of a MOF using the MACE-MP-MOF0 model.

- Input Structure Preparation: Obtain a crystallographic information file (.cif) for the MOF. Ensure the structure is reasonable (e.g., check for overlapping atoms).

- Model Selection: Employ the MACE-MP-MOF0 model. Using the base MACE-MP-0 model is not recommended for phonon calculations as it may yield imaginary modes [23].

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a full geometry optimization of the unit cell and atomic positions using the MACE-MP-MOF0 potential to find the energy-minimized structure.

- Supercell Construction: Build a sufficiently large supercell (e.g., 2x2x2 or larger) to ensure accurate phonon dispersion, especially for flexible MOFs.

- Force Calculation: Use the optimized model to calculate the atomic forces for each atom displaced in positive and negative directions along Cartesian axes.

- Phonon DOS and Dispersion: Calculate the dynamical matrix and diagonalize it to obtain the phonon frequencies and eigenvectors. Plot the phonon density of states (DOS) and band structure.

- Result Analysis:

- No Imaginary Modes: A stable phonon spectrum confirms local dynamical stability.

- Imaginary Modes Present: Consult Troubleshooting Guide 1.1. Verify the result by testing different supercells. If they persist, the structure may be unstable, or the model may require fine-tuning.

Workflow: Fine-Tuning MACE-MP-0 for a Specific MOF Class

This workflow outlines the process of adapting the general MACE-MP-0 model for a specialized application, as was done to create MACE-MP-MOF0 [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Datasets for MLIP Development

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Key Features & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MACE Architecture [23] | A machine learning interatomic potential model that uses an equivariant message-passing graph tensor network. | Encodes many-body information of atomic features; forms the foundation for MACE-MP-0 and MACE-MP-MOF0 [23]. |

| Curated MOF Dataset [23] | A high-quality, diverse set of MOF structures and their corresponding DFT-level properties used for training. | The MACE-MP-MOF0 training set includes 127 representative MOFs spanning 24 elements, selected for diversity in structure and chemical building blocks [23]. |

| PubChemQCR Dataset [22] | A large-scale dataset of molecular relaxation trajectories, providing diverse off-equilibrium conformations. | Contains over 300 million molecular conformations with energy and force labels; essential for training MLIPs to handle geometry optimizations [22]. |

| Quasi-Harmonic Approximation (QHA) | A computational approach for calculating thermodynamic properties (e.g., thermal expansion) from phonon frequencies. | Used with MACE-MP-MOF0 to successfully predict properties like negative thermal expansion in MOFs [23]. |

| VASP / DFTB+ | First-principles electronic structure programs used to generate the reference data (energies, forces) for training MLIPs. | Provides the "ground truth" data. DFT is accurate but costly; DFTB is faster but may have limitations in parameterization [23]. |

Why are precise geometry and lattice optimization non-negotiable for accurate phonon spectra?

Accurate phonon spectra are entirely dependent on the quality of the input crystal structure. The phonon frequencies are obtained by diagonalizing the dynamical matrix, which is built from the second-order force constants—the derivatives of the total energy with respect to atomic displacements [25]. If the initial structure is not at its energy minimum, the forces on the atoms are not zero. This means the system is under residual stress, leading to unphysical forces that corrupt the force constants. A poorly optimized geometry often results in imaginary frequencies (often displayed as negative frequencies in plots), which can be a computational artifact rather than a sign of a real physical instability [25] [2] [26].

What are the direct consequences of a poorly optimized structure?

The primary symptom of an insufficiently relaxed structure is the appearance of spurious imaginary frequencies in the phonon spectrum.

- False Instability: Small, meaningless imaginary frequencies can appear near the Gamma point (q→0), which are typically numerical noise from a lack of convergence in k-point sampling or plane-wave cutoff [2].

- Overshadowing Real Physics: Large, pervasive imaginary frequencies can mask the true nature of the material, suggesting it is dynamically unstable when the core issue is an incorrect starting structure.

- Invalid Thermodynamics: When imaginary frequencies are present in the system, derived thermodynamic properties like the Helmholtz free energy, entropy, and heat capacity become ill-defined and cannot be reliably calculated [2].

How do I properly optimize my structure for a phonon calculation?

A robust optimization protocol is essential. The following workflow, commonly used with VASP and Phonopy, ensures a well-relaxed structure [26].

Phonon Calculation Workflow: Ensuring Structural Precision.

Step 1: Initial Relaxation

Relax both atomic positions and lattice constants using IBRION=2 and ISIF=3 in VASP. It is often advisable to turn off symmetry during this step (ISYM=0) to allow the cell to find its true minimum without constraints [26].

Step 2: Critical Symmetry Enforcement and Final Relaxation

Examine the output CONTCAR file. The relaxation in Step 1 may result in lattice constants or atomic positions that slightly break the expected crystal symmetry.

- Manually edit the

CONTCARto enforce the desired symmetry (e.g., round near-zero lattice vector components to zero) [26]. - Perform a second relaxation using the symmetrized

CONTCARas a newPOSCAR, this time withISIF=2(which fixes the lattice constants and only relaxes atomic positions) andISYM=2(enforcing symmetry). This finalizes a structure with the correct symmetry for subsequent DFPT calculations [26].

What key computational parameters ensure accurate forces and phonons?

The calculation of force constants requires highly accurate forces. The following table summarizes essential INCAR tags for VASP calculations, whether using finite-differences (IBRION=5/6) or density-functional perturbation theory, DFPT (IBRION=7/8) [27] [26].

Table 1: Essential VASP INCAR Parameters for Force and Phonon Calculations

| INCAR Tag | Recommended Setting | Function and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

PREC |

Accurate |

Ensures high accuracy in the computation of forces [27]. |

ENCUT |

At least 30% above default POTIM | Must be converged to accurately compute the stress tensor and forces [27]. |

EDIFF |

1.0E-8 |

Tight convergence criterion for the electronic energy [26]. |

LREAL |

.FALSE. |

Uses exact projection operators in real space; .FALSE. is essential for accurate forces [26]. |

ADDGRID |

.TRUE. |

Improves the accuracy of forces in some cases, with minimal computational cost [26]. |

ISMEAR |

0 (Semiconductors) |

Uses the Gaussian smearing method appropriate for semiconductors and insulators [26]. |

LEPSILON |

.TRUE. |

Calculates the Born effective charges and dielectric tensor, which are critical for LO-TO splitting in polar materials [28] [26]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

In computational materials science, the "reagents" are the software packages and computational protocols used to derive properties.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Phonon Studies

| Tool / Protocol | Function | Role in Ensuring Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | A first-principles DFT code for electronic structure calculations and force computation [28] [27]. | The primary engine for performing structural relaxations and calculating the forces needed to build the force constants. |

| Phonopy | A post-processing package for analyzing phonon properties from force constants [26]. | Takes the force constants from VASP and calculates the phonon dispersion and density of states; used to check mode symmetries. |

| DFPT (IBRION=7/8) | A method to compute second-order force constants directly in reciprocal space [28] [26]. | An efficient alternative to finite-displacements for computing the full dynamical matrix in a single calculation. |

| Finite-Differences (IBRION=5/6) | A method to compute force constants by displacing atoms in a supercell and calculating the resulting forces [27]. | The foundational method for calculating force constants; requires a well-converged supercell size. |

| Born Effective Charges & Dielectric Tensor | Physical properties quantifying the response to electric fields [28] [2]. | Must be calculated (with LEPSILON=.TRUE.) and provided as input (LPHON_POLAR=.TRUE.) to correctly model LO-TO splitting in polar materials [28]. |

How do I troubleshoot persistent imaginary frequencies?

If imaginary frequencies persist after a rigorous structural optimization, systematically check the following:

- Convergence of Computational Parameters: Phonon frequencies must be converged with respect to the plane-wave energy cutoff (

ENCUT), the k-point mesh for the electronic Brillouin zone, and the supercell size (for finite-difference methods) [28] [27]. A practical check is to monitor the Γ-point optical modes while varyingENCUTand the k-point density [27]. - Treatment of Polar Materials: For polar materials (e.g., MgO, AlN), failing to account for long-range dipole-dipole interactions will cause severe unphysical oscillations and a lack of LO-TO splitting. The solution is to set

LPHON_POLAR = .TRUE.and supply the static dielectric tensor (PHON_DIELECTRIC) and Born effective charges (PHON_BORN_CHARGES) obtained from a prior DFPT calculation (LEPSILON=.TRUE.) [28]. - Distinguishing Real from Numerical Instabilities: Small negative frequencies very close to the Γ point (|q| < 0.05) are often associated with poor choices of k-point or q-point grids and are rarely a sign of a real instability [2]. Widespread imaginary frequencies across the Brillouin zone are a stronger indicator of a genuine dynamic instability or a significantly under-relaxed structure.

Resolving Imaginary Frequencies: A Step-by-Step Troubleshooting and Optimization Protocol

A comprehensive technical guide for researchers troubleshooting instability in phonon spectra calculations.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the correct order to perform convergence tests for a DFT calculation?

A specific order is recommended to systematically converge parameters for plane-wave DFT calculations [29]:

- Kinetic energy cutoff for wavefunctions (

ecutwfcin QE,ENCUTin VASP): Converge the total energy per atom to a threshold (e.g., 0.1 mRy) with increasing energy cutoff [29]. - Kinetic energy cutoff for charge density (

ecutrhoin QE): This is typically 4 to 8 times larger than the wavefunction cutoff and must be converged similarly [29]. - K-point grid density: Converge the total energy per atom with increasingly dense k-point meshes [29].

- Smearing type and broadening: Converge the energy for decreasing broadening values (

degaussin QE) [29].

Why might my phonon calculation produce negative frequencies?

Unphysical negative frequencies in phonon spectra typically stem from two main causes [30]:

- Incomplete Geometry Optimization: The atomic structure was not fully relaxed to its minimum energy configuration before the phonon calculation.

- Insufficient Numerical Accuracy: This includes using a step size that is too large in the phonon run, or general accuracy issues related to numerical integration, k-space sampling, or fit errors [30].

Should convergence tests be repeated for DFT+U or defect calculations?

- For DFT+U: The standard convergence tests for cutoff and k-points generally do not need to be repeated, as DFT+U adds a linear correction to the Hamiltonian [29].

- For Defect Calculations: The convergence tests for cutoffs do not typically need redoing, but the k-mesh should be rechecked as it might need to be denser than for the bulk unit cell. Furthermore, a new convergence test for supercell size is essential to ensure the defect does not interact with its periodic images [29].

How do I choose an appropriate supercell size for MD or defect calculations?

The supercell must be large enough to [31]:

- Capture all long-wavelength lattice vibrations that affect the dynamics of the system.

- Minimize unphysical interactions between an atom (or defect) and its periodic images. The convergence of your property of interest (e.g., energy) with increasing supercell size should be carefully checked [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Negative Frequencies in Phonon Spectra

Negative frequencies often indicate that the forces on the atoms are not truly zero, meaning the system is not at a minimum. Follow this systematic procedure to identify and correct the issue.

Required Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Parameter | Function |

|---|---|

| Geometry Optimization | Finds the minimum energy atomic configuration, ensuring forces are near zero. |

| K-point Grid | Samples the Brillouin Zone to accurately calculate electron density and forces. |

| Plane-Wave Cutoff | Determines the basis set size for expanding wavefunctions; a higher cutoff increases accuracy. |

| Phonon Calculation Step Size | The finite displacement used to compute force constants; a too-large step causes inaccuracy. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Verify Geometric Convergence

- Ensure your initial structure is fully relaxed using a stringent force convergence criterion (e.g., forces < 1e-4 Ry/Bohr).

- Confirm the self-consistent field (SCF) calculation converged properly during the relaxation. If SCF convergence was problematic, see the guide below.

Check Numerical Parameters

- K-points: Systematically increase the k-point grid density until the total energy and forces are converged. Refer to the table in the next guide for criteria.

- Plane-Wave Cutoff: Confirm that both the wavefunction (

ecutwfc) and charge density (ecutrho) cutoffs are sufficiently high for your system's convergence.

Adjust Phonon Calculation Settings

- If the geometry and numerical parameters are sound, reduce the step size used in the phonon (finite-difference) calculation [30].

Guide 2: Achieving SCF and Geometry Convergence

SCF convergence is a prerequisite for any reliable geometry optimization or phonon calculation. The following workflow outlines a progressive strategy to tackle convergence problems.

Summary of Convergence Criteria

When performing convergence tests, use the following quantitative criteria to determine if a parameter is sufficiently converged.

| Parameter | Convergence Criterion | Typical Value / Note |

|---|---|---|

| ecutwfc | Total energy per atom change | < 0.1 mRy / ~1.36 meV [29] |

| ecutrho | Total energy per atom change | Typically 4x - 8x ecutwfc [29] |

| K-point Grid | Total energy per atom change | Varies by system symmetry |

| Geometry Optimization | Force on each atom | < 1e-4 Ry/Bohr (or stricter) |

| Supercell Size | Energy of defect formation | Constant with increasing size [31] |

Detailed Methodology

Initial Conservative Settings: For problematic SCF convergence, start with more stable settings [30]:

- Reduce the

Mixingparameter to 0.05. - In the

Diisblock, setDiMixto a lower value like 0.1 and consider settingAdaptabletofalse.

- Reduce the

Alternative SCF Solvers: If conservative mixing fails, switch the SCF method at no extra computational cost per iteration [30]:

- Use

Method MultiSecantin theSCFblock. - Alternatively, try the LIST method by setting

DiisVariant LISTi.

- Use

Improve Numerical Accuracy: Inaccurate integration grids can prevent convergence [30].

- Increase the number of radial points with

RadialDefaultsNR 10000. - Set

NumericalQualitytoGood.

- Increase the number of radial points with

Automations for Geometry Optimization: For difficult geometry optimizations, use automations to vary key parameters during the process [30]:

- Electronic Temperature: Start high (e.g., kT=0.01 Ha) to aid initial SCF convergence and ramp down to a low value (e.g., kT=0.001 Ha) as the geometry nears completion.

- SCF Criterion: Start with a loose convergence (e.g.,

1.0e-3) and tighten it (e.g.,1.0e-6) over the first 10 iterations. - SCF Iteration Limit: Increase the maximum number of SCF iterations as the calculation progresses.

Address Basis Set Dependency: If you encounter a "dependent basis" error, do not loosen the dependency criterion. Instead, fix the basis set itself by [30]:

- Using Confinement: Apply a confinement potential to reduce the range of diffuse basis functions, especially on atoms in the bulk of a material.

- Removing Functions: Manually remove the most diffuse basis functions from the set.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental cause of negative frequencies in my phonon spectrum calculation?

Negative frequencies, more accurately described as imaginary frequencies, are a direct result of a negative curvature of the potential energy surface at the atomic coordinates you provided for the calculation. They indicate that the current structure is not at a minimum of the potential energy surface (i.e., not fully relaxed) but is instead at a saddle point. Displacing the atoms along the direction of the eigenvector associated with this imaginary frequency would lower the total energy of the system [5].

Q2: My structure is fully relaxed, yet I still get negative frequencies. Why?

If your structural relaxation used force convergence criteria that were too loose, the atoms may not have reached a true minimum. The "Total force" and "Total SCF correction" values in your output should be examined. If the SCF correction is comparable to the total force, you should reduce the conv_thr parameter to better converge the self-consistent field (SCF) cycle [32]. Furthermore, stresses on the unit cell must also be converged for accurate lattice parameters, which requires a high plane-wave energy cut-off [32].

Q3: How can I systematically remove negative frequencies from my calculation?

A systematic approach involves tightening the convergence criteria for both electronic and ionic steps, and ensuring your cell size and k-point grid are appropriate. The workflow below outlines this process.

Systematic Troubleshooting Workflow for Negative Phonon Frequencies

Q4: What are the recommended convergence thresholds for forces and stresses to ensure a stable structure?

Convergence should be tested systematically, but the following table provides a guideline for target thresholds, informed by best practices in computational materials science [32].

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Threshold |

|---|---|---|

forc_conv_thr |

The convergence threshold for the maximum force on any atom during ionic relaxation. A tighter criterion is crucial for stable phonons. | 1.0E-4 Ry/Bohr or tighter [32] |

etot_conv_thr |

The convergence threshold for the total energy between ionic steps. | 1.0E-5 Ry or tighter [32] |

conv_thr |

The convergence threshold for the SCF cycle during a single electronic minimization. | 1.0E-8 Ry or tighter (if SCF correction is large) [32] |

ecutwfc |

The plane-wave kinetic energy cutoff. Must be tested for convergence of forces and stresses. | System-dependent (e.g., 40-60 Ry for carbon) [32] |

| Pressure | The stress on the unit cell after relaxation. Should be close to zero for fixed-cell calculations. | < 1.0 kbar [32] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Materials

The following table details key software and computational "reagents" essential for performing robust structural and vibrational analysis.

| Item | Function | Use Case Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO (pw.x) | A primary engine for performing DFT-based structural relaxations and force/stress calculations by solving the electronic structure problem [32]. | Used to run ionic relaxation (calculation = 'relax') with tight force convergence criteria to find a stable minimum [32]. |

| phonopy | A robust software package for calculating phonon spectra and densities of states from force constants obtained from DFT supercell calculations. | Produces the phonon band structure and Density of States (DoS); its output of "negative" frequencies flags imaginary modes [5]. |

| ALAMODE | An open-source package designed for anharmonic lattice dynamics, which can handle advanced phonon calculations beyond the harmonic approximation. | Used for more complex vibrational analyses, where issues with imaginary frequencies can sometimes be resolved by adjusting anharmonic parameters like temperature [3]. |

| Simphony | A tool for topological analysis of lattice vibrations based on Wannier tight-binding models, useful for diagnosing topology in complex materials like polar insulators [33]. | Analyzing the topological properties of phonon spectra in novel materials after a stable harmonic structure has been obtained. |

| Multi-Fidelity Bayesian Optimization (MFBO) | A machine learning framework that leverages data of different accuracies/costs to accelerate the discovery of optimal materials or molecules [34] [35]. | Using cheaper, low-fidelity calculations (e.g., lower ecutwfc) to guide more expensive, high-fidelity relaxations and phonon calculations, reducing overall computational cost. |

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide to Stable Structure Optimization