Hydrophobic Ligand Engineering: Conquering Humidity Instability in CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dots

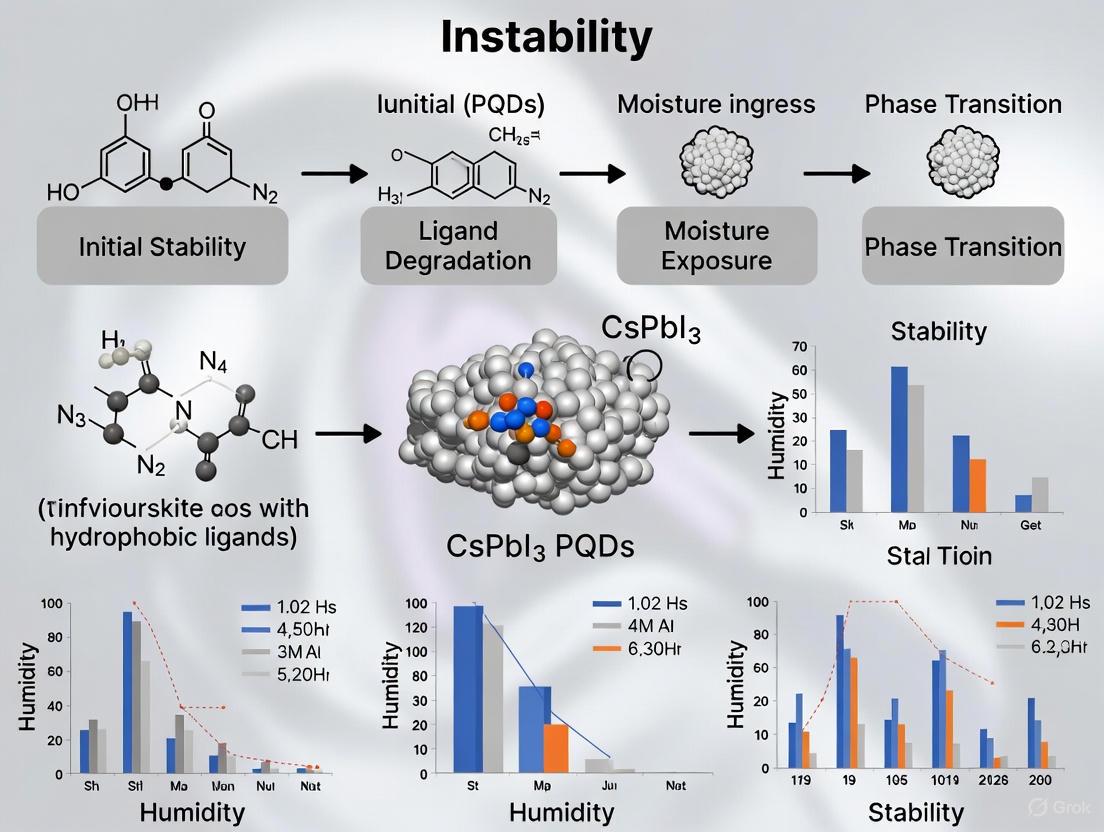

The humidity-induced degradation of cesium lead iodide perovskite quantum dots (CsPbI3 PQDs) poses a significant challenge to their practical application in optoelectronics and biomedicine.

Hydrophobic Ligand Engineering: Conquering Humidity Instability in CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dots

Abstract

The humidity-induced degradation of cesium lead iodide perovskite quantum dots (CsPbI3 PQDs) poses a significant challenge to their practical application in optoelectronics and biomedicine. This article comprehensively explores the strategic use of hydrophobic ligands to enhance environmental stability. We first establish the fundamental instability mechanisms of the CsPbI3 crystal structure. The core of the discussion details various ligand engineering methodologies, including in-situ and post-synthesis treatments, showcasing effective ligands like phenethylammonium and star-shaped molecules. The article further provides troubleshooting guidelines for optimizing ligand exchange processes and validates these strategies through comparative analysis of performance metrics and long-term stability data. Finally, we synthesize key takeaways and project future research directions for deploying robust CsPbI3 PQDs in clinical and biomedical settings.

The Inherent Challenge: Understanding CsPbI3 PQD Instability and the Hydrophobic Defense Mechanism

FAQs: Understanding CsPbI3 Instability

Q1: What are the different crystal phases of CsPbI3, and why does the black phase degrade?

CsPbI3 exists in several crystal phases. The photoactive black phases (α, β, γ) have a perovskite structure suitable for optoelectronics, while the yellow δ-phase is a non-perovskite, photo-inactive structure [1]. The instability stems from the fact that the black phases are metastable at room temperature and spontaneously transform into the more stable δ-phase [1]. This transition is triggered by environmental factors like moisture and temperature, and is driven by the small ionic radius of the cesium ion, which leads to an unfavorable Goldschmidt's tolerance factor (t ≈ 0.8), making the perovskite structure inherently unstable [1].

Q2: What is the atomic-level pathway for the detrimental phase transition?

Research has clarified that the transition from the photoactive γ-phase to the non-perovskite δ-phase is not a single step. It is a multiple-step transition with three intermediate states [2]. The lowest-energy pathway is: γ (3D perovskite) → Pm (3D) → Cmcm (2D) → Pmcn (1D) → δ (1D non-perovskite) [2]. The first step (γ-to-Pm) is the performance-controlling step, with a surprisingly low energy barrier of only about 31 meV/atom, explaining why the transition occurs so readily [2].

Q3: How does humidity specifically accelerate the degradation of CsPbI3 films?

Humidity directly facilitates the transition to the δ-phase. Moisture reduces the energy barrier for the phase transition [3]. When CsPbI3 is exposed to prolonged moisture, water molecules interact with the crystal lattice, catalyzing the rearrangement from the 3D perovskite structure into the 1D chain structure of the δ-phase, which is more stable in the presence of water [3] [4]. This process is often observed as a color change from black to yellow in the film.

Q4: What are the most effective strategies to inhibit the phase transition and improve stability?

The primary strategies, often used in combination, include [1]:

- Ion Doping: Substituting Pb²⁺ with other divalent cations (e.g., via nickel acetate incorporation) can strain the lattice and increase the transition barrier [5] [2].

- Surface Ligand Engineering: Coating the CsPbI3 nanocrystals or films with hydrophobic ligands, polymers, or quantum dots (e.g., 1,8-diaminooctane or nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots) creates a protective shield against moisture [3] [4].

- Strain Engineering: Applying compressive strain, particularly along the [010] crystal axis, has been predicted as an effective way to increase the transition barrier and stabilize the photoactive phase [2].

- Composite Formation: Forming heterostructures with materials like ZnO or TiO2 can enhance stability and provide synergistic effects [6] [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Rapid Phase Degradation to Yellow δ-phase During Fabrication

Problem: The CsPbI3 film turns yellow during or immediately after the annealing process, indicating a transition to the non-perovskite δ-phase.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Ambient Humidity [3] | Monitor relative humidity (RH) in the fabrication environment. XRD to confirm δ-phase peaks at ~10.27°, 13.43° [4]. | Control the annealing environment. Optimize annealing time for the specific RH; e.g., at RH 60%, a shorter annealing time (6 min) may be optimal [3]. |

| Insufficient or Inefficient Annealing [3] [5] | Use TGA to study additive volatilization. Check for residual DMAI or solvent via XRD/Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy [3]. | Precisely optimize annealing temperature and duration. For DMAI-based recipes, ensure complete evaporation. Consider additives like Ni(AcO)₂ to drive crystallization at lower temperatures [5]. |

| Incorrect Stoichiometry or Precursor Composition | Perform EDS to check Cs:Pb:I ratio (target 1:1:3) [4]. | Ensure precise precursor weighing and fresh chemicals. Explore additive engineering (e.g., dimethylammonium iodide) to stabilize the intermediate phase [3]. |

Issue 2: Poor Long-Term Stability Under Ambient Conditions

Problem: Devices or films degrade over time (hours to days) when stored in ambient air.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Surface Passivation [3] [4] | Perform SEM to examine film morphology and grain boundaries. XPS to detect unpassivated Pb²⁺ surface defects. | Implement post-synthesis passivation with long-chain alkyl ligands (e.g., 1,8-diaminooctane) or hydrophobic quantum dots (e.g., N-GQDs) to create a moisture-resistant layer [3] [4]. |

| Intrinsic Structural Instability | Conduct long-term XRD monitoring to track phase purity. | Employ ion doping (e.g., with Ni²⁺) to internally stabilize the perovskite lattice [5]. Use encapsulation strategies to shield the device from environmental factors [7]. |

| Weak Interfacial Contacts in Device Stack | Analyze J-V curves for increased series resistance or reduced shunt resistance. | Optimize charge transport layers (e.g., TiO₂, spiro-OMeTAD) to ensure efficient charge extraction and reduce interfacial recombination [8]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Hydrophobic Ligand Passivation with 1,8-Diaminooctane (DAO)

This protocol outlines the surface passivation of CsPbI3 films using DAO to enhance humidity stability [3].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- 1,8-Diaminooctane (DAO): A diamine with a long alkyl chain. Functions as a bidentate ligand that binds to undercoordinated Pb²⁺ on the CsPbI3 surface, reducing surface defects and providing a hydrophobic barrier.

- Dimethylammonium Iodide (DMAI): Additive used in the precursor to facilitate the formation of the black perovskite phase at lower temperatures.

- Anhydrous Solvents (e.g., Toluene, Isopropanol): Used for dissolving passivators to prevent premature degradation of the perovskite layer.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- CsPbI3 Film Fabrication: Fabricate the CsPbI3 perovskite film on your substrate using your standard method (e.g., spin-coating from a precursor containing CsI, PbI₂, and DMAI).

- Annealing: Anneal the film at the optimized temperature and time for your specific humidity condition (e.g., 6 minutes at ~100°C for RH 60%) until a black film forms [3].

- DAO Solution Preparation: Prepare a passivation solution by dissolving DAO in an anhydrous solvent like toluene at a concentration of ~1 mg/mL.

- Passivation Treatment: While the film is still hot (approximately 100°C), spin-coat the DAO solution onto the film surface.

- Post-Treatment Annealing: Perform a brief secondary anneal (e.g., 5 minutes at 100°C) to ensure proper ligand binding and solvent removal.

- Characterization: Confirm successful passivation via Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (observe NH₂ stretching), water contact angle measurement (increased hydrophobicity), and XPS (reduction in uncoordinated Pb²⁺ signal).

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this passivation process.

Protocol 2: Stabilization via Nickel Acetate Additive Incorporation

This protocol describes a DMAI-free, green synthesis method to stabilize the γ-CsPbI3 phase using nickel acetate (Ni(AcO)₂) as a phase-directing additive [5].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Nickel Acetate Tetrahydrate (Ni(AcO)₂·4H₂O): Serves as a crystallization agent and stabilizer. It helps form a γ-CsPbI3 nanocomposite, improving film crystallinity and phase stability without the need for volatile organic additives.

- DMSO Solvent: Used as a greener, alternative solvent to common toxic solvents like DMF.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve CsI and PbI₂ in pure DMSO to create the CsPbI3 precursor solution.

- Additive Incorporation: Add Ni(AcO)₂·4H₂O to the precursor solution at an optimal concentration (e.g., 0.1 M, 7.1 mol%) and stir until fully dissolved.

- Film Deposition: Spin-coat the Ni(AcO)₂-containing precursor solution onto the substrate.

- Crystallization & Annealing: Anneal the film at a moderate temperature (e.g., ~180°C) to facilitate the formation of the black γ-CsPbI3 phase. The nickel acetate matrix aids in low-temperature crystallization.

- Characterization: Use XRD to confirm the formation of the γ-CsPbI3 phase and the absence of δ-phase or residual PbI₂ peaks. SEM can be used to observe the enlarged grain size and improved film morphology.

The following table summarizes key phase transition barriers and stability data from recent studies.

Table 1: Phase Transition Barriers and Stabilization Effects in CsPbI3

| Material/Intervention | Phase Transition Pathway | Energy Barrier / Key Metric | Impact on Stability | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undoped CsPbI3 | γ → δ | ~31 meV/atom (very low) | Explains spontaneous transition at room temperature [2]. | [2] |

| Ion Doping | γ → δ (with various dopants) | Volcano-shaped barriers | Barrier height depends on dopant ionic radius; optimal dopant size maximizes stability [2]. | [2] |

| Strain along [010] | γ → δ | Barrier increased with strain | Compressive strain is an effective method to raise the transition barrier [2]. | [2] |

| DAO Passivation | - | Retains 92.3% initial PCE after 1500 min at 30% RH | Significantly improves operational humidity stability without encapsulation [3]. | [3] |

| Ni(AcO)₂ Additive | - | >600 hours MPP stability (inert atm) | Stabilizes γ-phase, enables DMAI/HI-free green synthesis [5]. | [5] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CsPbI3 Phase Stabilization

| Reagent | Function / Role in Stabilization | Key Property / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethylammonium Iodide (DMAI) | Aids in forming black phase at low temperatures by creating an intermediate; volatilizes during annealing [3]. | Volatilization rate is humidity-dependent; requires precise annealing control [3]. |

| 1,8-Diaminooctane (DAO) | Hydrophobic surface passivator. Diamine groups chelate undercoordinated Pb²⁺, long alkyl chain repels water [3]. | Creates a hydrophobic, moisture-resistant film, enhancing operational stability [3]. |

| Nickel Acetate (Ni(AcO)₂) | Phase-directing additive. Promotes and stabilizes γ-CsPbI3 in a nanocomposite structure without organic cations [5]. | Enables a greener, DMSO-only synthesis; reduces global warming potential of fabrication [5]. |

| Nitrogen-Doped Graphene QDs (NGQDs) | Aqueous-stable passivator. Enables dispersion of δ-CsPbI3 in water for photocatalysis by surface coating [4]. | Can be used to stabilize the otherwise wasted δ-phase for applications in aqueous environments [4]. |

Phase Transition Pathway Visualization

The atomic-level pathway of the γ-to-δ phase transition is complex. The following diagram summarizes the multi-step process and key stabilization strategies that act upon it.

Core Concept: What is the Goldschmidt Tolerance Factor?

The Goldschmidt tolerance factor is a simple geometric parameter used to assess the stability and likely crystal structure of perovskite materials. It evaluates how well the constituent ions fit together in the ABX₃ perovskite structure, predicting structural distortions and phase stability based on ionic radii [9] [10].

The Mathematical Expression

The tolerance factor ((t)) is calculated using the ionic radii of the constituent ions [9] [11]:

(t = \frac{rA + rX}{\sqrt{2}(rB + rX)})

Where:

- (r_A) = radius of the A-site cation

- (r_B) = radius of the B-site cation

- (r_X) = radius of the anion (typically oxygen in oxides, or halogens like I⁻ in halide perovskites)

Interpretation of Tolerance Factor Values

The calculated value of t provides a direct indication of the expected perovskite structure and its stability [9] [11]:

Table 1: Goldschmidt Tolerance Factor and Corresponding Perovskite Structures

| Tolerance Factor (t) | Crystal Structure | Explanation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| >1 | Hexagonal or Tetragonal | A ion too large or B ion too small | BaTiO₃ (t=1.061) [9] |

| 0.9 - 1.0 | Cubic | Ideal ion size matching | Ideal cubic perovskite [9] |

| 0.71 - 0.9 | Orthorhombic/Rhombohedral | A ions too small for B ion interstices | GdFeO₃, CaTiO₃ [9] |

| <0.71 | Different non-perovskite structures | A and B ions have similar ionic radii | Ilmenite structure (e.g., MgTiO₃) [11] |

For halide perovskites like CsPbI₃, the tolerance factor and octahedral factor (μ = rB / rX) together determine stability. CsPbI₃ has a tolerance factor of approximately 0.89 and an octahedral factor of 0.47, which places it within the stable perovskite region but close to instability boundaries, explaining its propensity for phase transitions [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do I calculate the tolerance factor for my specific perovskite composition?

To calculate the tolerance factor for your material, follow this detailed protocol:

- Determine Ionic Radii: Obtain the ionic radii for your A-site cation, B-site cation, and X-site anion. Use a consistent and reliable source, such as Shannon's ionic radii database, and pay close attention to the coordination number for each ion [11]. For halide perovskites, ensure you use radii appropriate for halide environments.

- Apply the Formula: Input these values into the standard tolerance factor formula: (t = \frac{rA + rX}{\sqrt{2}(rB + rX)}).

- Consider Coordination Numbers: For accurate calculations, the coordination numbers should be 12 for the A-site ion, 6 for the B-site ion, and 6 for the X-site ion in an ideal cubic structure [11].

- Interpret the Result: Refer to Table 1 to correlate the calculated

tvalue with the expected crystal structure and stability.

My calculated 't' is ideal (~1), but my CsPbI₃ film is still unstable. Why?

This is a common issue in halide perovskite research. An ideal tolerance factor is a necessary but not sufficient condition for stability, especially for CsPbI₃. Other critical factors include [13] [12] [14]:

- Entropic Factors: The stability of the black perovskite phase (α, β, γ) is temperature-dependent. At room temperature, the non-perovskite yellow δ-phase is often thermodynamically favored, leading to spontaneous phase transition even with a suitable

t[14]. - Surface Energy and Ligand Dynamics: The surface of perovskite crystals and quantum dots (PQDs) has a high surface energy. Traditional long-chain ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) used in synthesis are dynamically bound and can detach, creating surface defects and under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites that initiate degradation [12].

- Environmental Stressors: Humidity and polar solvents directly attack the ionic crystal lattice. Water molecules penetrate the structure, leading to hydration and eventual decomposition into CsI and PbI₂ [15].

Can the tolerance factor guide ligand selection for stabilizing CsPbI₃ PQDs?

While the classic tolerance factor applies to the bulk crystal, the principle of steric compatibility is central to ligand engineering. The goal of using hydrophobic ligands is to passivate the surface without straining the crystal lattice. Ligands must [16] [12]:

- Coordinate Strongly with surface sites (e.g., Pb²⁺ ions) to reduce defect density.

- Provide a Hydrophobic Barrier to shield the ionic core from water molecules.

- Maintain a Balance between improved stability and charge transport; overly bulky ligands can inhibit inter-dot conductivity.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Phase Degradation of CsPbI₃ in Ambient Humidity

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Table 2: Troubleshooting Phase Degradation in CsPbI₃

| Problem Cause | Recommended Solution | Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Weak/Detachable Surface Ligands | Implement post-synthesis ligand exchange with multidentate, hydrophobic ligands. | 1. Synthesize CsPbI₃ PQDs using standard hot-injection or LARP methods. 2. Prepare a solution of short, robust ligands (e.g., choline, diaminoligands like 1,8-diaminooctane (DAO)) in a tailored solvent like 2-pentanol. 3. Treat the PQD solid film with this solution to replace native insulating ligands [16] [3]. |

| Intrinsic Thermodynamic Instability | Apply external stimuli or incorporate additives to stabilize the metastable perovskite phase. | 1. High-Pressure Treatment: Subject the δ-phase CsPbI₃ to 0.1-0.6 GPa of pressure, heat to induce the α-phase, and rapidly cool to preserve the γ-phase at ambient conditions [14]. 2. Ionic Incorporation: Introduce minor dopants during synthesis to subtly adjust the average ionic radii and optimize the local tolerance factor without significantly altering the bandgap [13]. |

| High Defect Density at Grain Boundaries | Use surface passivation treatments to heal defects. | After film deposition, spin-coat a solution of a passivating agent (e.g., DAO). The diamine groups chelate under-coordinated Pb²⁺ defects, reducing non-radiative recombination sites and improving moisture resistance by forming a hydrophobic layer [3]. |

Problem: Poor Charge Transport in Ligand-Stabilized PQD Films

Possible Cause: The insulating nature of the long-chain or newly introduced ligands used for stabilization creates barriers between PQDs, hindering carrier transport.

Solutions:

- Ligand Exchange with Short Conductive Ligands: Replace native long-chain ligands (OA/OAm) with shorter, conjugated, or charged ligands that provide both stability and improved electronic coupling [16] [12].

- Solvent Engineering for Optimal Exchange: Use a tailored solvent system (e.g., protic 2-pentanol) that effectively removes insulating ligands without damaging the PQD surface or introducing halogen vacancies [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Stabilizing CsPbI₃ Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 1,8-Diaminooctane (DAO) | A diamine ligand for surface passivation. The amine groups chelate under-coordinated Pb²⁺ defects, while the long alkyl chain provides hydrophobicity [3]. | Effective in post-synthesis treatment of solid films to enhance moisture stability and boost PV performance [3]. |

| Choline Ligands | Short, conductive ligands used to replace insulating native ligands (e.g., oleylamine) [16]. | Improves charge carrier transport in PQD films for solar cells. Often applied using a tailored solvent. |

| 2-Pentanol | A protic solvent tailored for ligand exchange. Its appropriate dielectric constant and acidity maximize the removal of insulating ligands without creating halogen vacancies [16]. | Superior to other solvents for mediating effective ligand exchange while preserving the PQD structure. |

| Dimethylammonium Iodide (DMAI) | An additive used in precursor solutions to facilitate the formation of CsPbI₃ perovskite films, especially in ambient air [3]. | Its volatilization during annealing is humidity-dependent. Requires precise optimization of annealing time and temperature based on ambient RH [3]. |

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

The following diagram visualizes the decision-making process for diagnosing and addressing CsPbI₃ instability, integrating the use of the Goldschmidt Tolerance Factor with practical stabilization strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental cause of the black-to-yellow phase transition in CsPbI₃ PQDs? The transition is driven by the low thermodynamic stability of the photoactive black perovskite phases (cubic α-, tetragonal β-, or orthorhombic γ-phase) at room temperature. These phases are metastable and have a natural tendency to transition to the more thermodynamically stable, non-photoactive yellow orthorhombic (δ-) phase. This intrinsic instability is quantified by a critical Goldschmidt tolerance factor (t ≈ 0.8) and a high revised tolerance factor (τ ≈ 4.99), which fall outside the ideal range for stable perovskite structures [13] [1]. Moisture significantly accelerates this thermodynamically favored process.

Q2: How exactly does water molecules initiate the degradation of the perovskite structure? Water molecules attack the crystal surface, leading to a facet-dependent dissolution process. The polar crystal facets dissolve at a higher rate than the more stable (100) facets. This uneven degradation, driven by the solvation of ions (Cs⁺, Pb²⁺, I⁻) into the water, causes a morphological transformation from well-defined nanocubes to nanospheres and ultimately the collapse of the perovskite crystal structure [17]. This process is illustrated in the diagram below.

Q3: Why are long-chain ligands like Oleic Acid (OA) and Oleylamine (OAm) insufficient for preventing moisture-induced degradation? While OA and OAm are essential for synthesizing high-quality PQDs, they exhibit dynamic and weak binding to the PQD surface. This makes them prone to detach over time, leaving behind unpassivated surface defects [18]. Furthermore, these long-chain ligands are insulating, which impedes charge transport between neighboring QDs in a film, limiting device performance. Their inability to form a robust, hydrophobic shield makes them inadequate for long-term stability [19] [20].

Q4: What are the key characteristics of an effective hydrophobic ligand for stabilizing CsPbI₃ PQDs? Effective hydrophobic ligands typically possess the following characteristics:

- Strong Coordinating Groups: Functional groups like phosphonic acid (-PO(OH)₂) or multiple amine groups (-NH₂) that bind more strongly to the Pb ions on the PQD surface than OA/OAm [19] [3].

- Short or Rigid Chains: Shorter carbon chains or rigid aromatic structures that improve charge transport by reducing the inter-dot distance, unlike insulating long chains [19].

- Hydrophobic Moieties: Components like benzyl rings or long alkyl chains that create a water-repellent shell around the PQD, physically blocking moisture penetration [19] [20] [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Rapid Phase Degradation During Film Storage in Ambient Conditions

Possible Cause: Inefficient surface passivation and lack of a hydrophobic barrier, allowing moisture to penetrate the film and trigger the phase transition.

Solution: Implement a Stepwise Ligand Exchange Protocol. This protocol involves introducing robust, short-chain ligands during both the synthesis and the film-forming process to ensure complete surface coverage and passivation [19].

- Step 1: Initial Ligand Exchange in Solution. To the crude CsPbI₃ PQD solution (synthesized via the standard hot-injection method), add a methyl acetate (MeOAc) washing solvent that contains your target short-chain ligand (e.g., Benzylphosphonic Acid - BPA). Centrifuge and redisperse the QDs [19].

- Step 2: Secondary Ligand Exchange During Film Formation. Employ a layer-by-layer spin-coating technique. After depositing each layer of PQDs, use a washing solvent (e.g., MeOAc) that contains the same short-chain ligand (BPA) to treat the film. This step ensures the replacement of any remaining long-chain ligands and completes the surface passivation directly on the substrate [19].

- Verification: Successful ligand management will result in films that maintain their black color and show no signs of yellowing (δ-phase) in XRD patterns after being stored in ambient air for hundreds of hours [19].

Problem 2: Poor Charge Transport in PQD Films Despite High Phase Stability

Possible Cause: The presence of residual long-chain, insulating ligands (OA/OAm) on the PQD surface, which creates energy barriers for charge carrier movement between adjacent QDs.

Solution: Employ Short-Chain Conductive Ligands or Molecular Bridges. Replace the insulating ligands with molecules that not only passivate the surface but also facilitate electronic coupling.

- Option A: Short-Chain Ligands like Acetate or Benzylphosphonic Acid. These ligands shorten the distance between QDs, enabling better wavefunction overlap and charge transport. For example, BPA-modified CsPbI₃ QD solar cells have shown significantly improved electrical transport properties [19].

- Option B: 3D Star-Shaped Conjugated Molecules. Molecules like Star-TrCN can bond robustly with the PQD surface, passivating defects while simultaneously creating a cascade energy band structure that improves charge extraction. This approach has boosted solar cell efficiency to 16.0% while enhancing moisture stability [20].

Problem 3: Inconsistent Film Formation and Phase Purity under High Humidity

Possible Cause: Uncontrolled volatilization of precursors (e.g., Dimethylammonium Iodide - DMAI) and sensitivity to ambient moisture during the annealing process, leading to mixed phases.

Solution: Precisely Control the Annealing Conditions Relative to Humidity. The annealing time and temperature must be optimized for the specific relative humidity (RH) of your fabrication environment.

- Guideline: The volatilization rate of common additives like DMAI is humidity-dependent. At higher RH, the evaporation occurs faster.

- Verification: Use UV-Vis spectroscopy to confirm the target bandgap (~1.7 eV for CsPbI₃) and XRD to check for the absence of the δ-phase peak at ~11.8° [3]. Over-annealing or under-annealing at a given humidity will result in incomplete conversion or the formation of the yellow phase.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents used in advanced strategies for stabilizing CsPbI₃ PQDs against moisture.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Stabilizing CsPbI3 PQDs against Moisture

| Reagent Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Key Outcome/Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Benzylphosphonic Acid (BPA) | Short-chain ligand with strong P=O coordination group. Used in a stepwise process to replace OA/OAm, providing defect passivation and a hydrophobic barrier [19]. | PCE of 13.91% in solar cells; retains 91% initial efficiency after 800 h in atmosphere [19]. |

| Star-TrCN | 3D star-shaped organic semiconductor. Acts as a molecular bridge, passivating defects and creating a cascade energy band for improved charge extraction [20]. | PCE boosted to 16.0%; retains 72% initial PCE after 1000 h at 20-30% RH [20]. |

| 1,8-Diaminooctane (DAO) | Diamine passivator with a long alkyl chain. The two amine groups chelate with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ defects, while the alkyl chain provides hydrophobicity [3]. | PCE of 17.7%; retains 92.3% initial efficiency after 1500 min operational tracking at 30% RH [3]. |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Halide ion pair ligand. Provides effective edge passivation, altering degradation trajectories and preserving cubic morphology upon water exposure [17]. | Reduces overall degradation rate and maintains crystal shape in the initial stages of water attack [17]. |

| Dimethylammonium Iodide (DMAI) | Additive used in precursor solution. Facilitates the formation of a intermediate phase that converts to CsPbI₃ upon annealing, enabling fabrication under high humidity [3]. | Enables formation of high-quality CsPbI₃ films at up to 60% relative humidity [3]. |

Comparative Data of Stabilization Strategies

The table below summarizes quantitative data from recent studies on different CsPbI₃ PQD stabilization strategies, providing a benchmark for expected performance.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of CsPbI3 PQD Stabilization Strategies

| Stabilization Strategy | Device Type | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Stability Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzylphosphonic Acid (BPA) Ligand Exchange | QD Solar Cell | 13.91% | 91% of initial PCE after 800 h storage in atmosphere; 92% after 200 h continuous light exposure. | [19] |

| Star-TrCN Hybridization | QD Solar Cell | 16.0% | >72% of initial PCE retained after 1000 h at 20-30% relative humidity. | [20] |

| 1,8-Diaminooctane (DAO) Passivation | Perovskite Solar Cell | 17.7% | 92.3% of initial PCE retained after 1500 minutes of maximum power point tracking at 30% RH without encapsulation. | [3] |

| Moisture-Assisted Fabrication (DMAI) | Carbon-based Perovskite Solar Cell | 16.05% | A new record for inorganic carbon-based PSCs, demonstrating that controlled H₂O can be beneficial during fabrication. | [21] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental conflict presented by native ligands on CsPbI₃ PQDs? Native long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) are essential for synthesizing stable, colloidal CsPbI₃ PQDs and preventing their aggregation [12]. However, these same ligands are electrically insulating and create a barrier between quantum dots in a film, severely limiting charge transport and leading to poor performance in optoelectronic devices [22] [23].

FAQ 2: How does ligand engineering improve moisture stability? Ligand engineering replaces hygroscopic or dynamically detaching native ligands with more robust, hydrophobic alternatives. For instance, exchanging native ligands with aromatic ring-based phenethylammonium (PEA) cations creates a hydrophobic protective layer that shields the PQDs from moisture penetration, significantly enhancing stability under ambient conditions [22].

FAQ 3: What are the trade-offs between different ligand exchange strategies? Conventional ligand exchange often trades stability for performance. Replacing long-chain OLA with short-chain formamidinium (FA) improves charge transport but removes the hydrophobic layer, making the films susceptible to moisture [22]. Advanced strategies using ligands like PEA or diaminocarbon chains (e.g., 1,8-diaminooctane, DAO) aim to simultaneously enhance both charge transport and moisture resistance by providing short, conductive, and hydrophobic groups [22] [3].

FAQ 4: Why is CsPbI₃ particularly susceptible to humidity? CsPbI₃ is highly sensitive to moisture because humidity reduces the energy barrier for a phase transition, causing the photoactive black perovskite phase (α- or γ-phase) to degrade into a non-photoactive yellow orthorhombic phase (δ-phase) [3]. This process is accelerated by surface defects and the detachment of native ligands [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Problem: Poor Charge Transport in PQD Films

Symptoms: Low device current density, low fill factor in solar cells, reduced electroluminescence efficiency in LEDs. Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insulating Native Ligands: A dense layer of long-chain OA/OAm ligands acts as an insulating barrier [22] [12]. | Perform post-synthetic ligand exchange with short-chain ligands like acetate (Ac) or phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI) to improve dot-to-dot coupling [22]. |

| Ineffective Ligand Exchange: Incomplete replacement of native ligands leaves insulating residues. | Optimize the concentration and reaction time of the post-treatment solution. Use spectroscopic techniques (FT-IR, NMR) to confirm ligand exchange [22]. |

| Introduction of Hygroscopic Ligands: Using ligands like FA⁺ improves transport but harms moisture stability [22]. | Employ hydrophobic short-chain ligands (e.g., PEA⁺) that do not compromise moisture resistance while improving charge transport [22]. |

Common Problem: Rapid Degradation under Ambient Humidity

Symptoms: Phase transition from black to yellow δ-phase, decrease in photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), color fading in films. Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Ligand Detachment: Dynamic binding of OA/OAm ligands causes them to detach, exposing the PQD surface to moisture [12]. | Implement ligand engineering with multidentate or chelating ligands (e.g., dicarboxylic acids, diammonium chains) that bind more strongly to the PQD surface [12] [3]. |

| Lack of Hydrophobic Protection: Removal of native ligands during exchange without introducing a new hydrophobic layer [22]. | Anchor hydrophobic ligands such as PEA or DAO during the exchange process. These create a moisture-resistant shell around the PQDs [22] [3]. |

| Surface Defects: Undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the PQD surface act as entry points for moisture and accelerate degradation [3]. | Apply a passivation layer with molecules that bond with these defects. For example, 1,8-diaminooctane (DAO) can coordinate with undercoordinated Pb, reducing defects and improving hydrophobicity [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Stability and Performance

Protocol 1: Post-Synthetic Ligand Exchange with Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI)

This protocol is adapted from research demonstrating simultaneous improvement in photovoltaic performance and moisture stability [22].

1. Materials and Reagents

- CsPbI₃ QD stock solution: Synthesized via hot-injection or LARP method.

- Solvents: Anhydrous n-hexane, anhydrous acetonitrile, chlorobenzene.

- Ligand Exchange Solution: 10 mM PEAI in anhydrous acetonitrile.

- Acetate Salt: Sodium acetate (NaAc) or ammonium acetate (NH₄Ac).

- Equipment: Centrifuge, vortex mixer, nitrogen glove box.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. Initial Purification: Precipitate the native CsPbI₃ QDs from the stock solution by adding acetate salt (e.g., NaAc) as a polar antisolvent. Centrifuge to obtain a QD pellet. This step replaces anionic oleate ligands with shorter acetate groups [22]. 2. Redispersion: Redisperse the acetate-capped QD pellet in anhydrous n-hexane or n-octane. 3. Film Casting: Spin-coat the redispersed QD solution onto a substrate to form a thin film. 4. Cationic Ligand Exchange: While the film is still wet, drop-cast the 10 mM PEAI in acetonitrile solution onto the film. Allow it to react for 30-60 seconds. 5. Rinsing and Annealing: Spin-off the excess solution and rinse the film with anhydrous acetonitrile to remove byproducts and unbound ligands. Anneal the film on a hotplate at 70-90°C for 5-10 minutes.

3. Key Parameters for Success

- Timing: The PEAI post-treatment must be performed on a wet film to facilitate cation exchange.

- Concentration: Optimal PEAI concentration is critical; too high may cause dissolution, too low results in incomplete exchange.

- Solvent Choice: Acetonitrile is used as it is a polar solvent that does not redissolve the CsPbI₃ QD film.

Protocol 2: Surface Passivation with 1,8-Diaminooctane (DAO)

This protocol is for enhancing moisture stability and reducing surface defects, enabling fabrication under high humidity [3].

1. Materials and Reagents

- CsPbI₃ perovskite film: Fabricated using precursors like CsI, PbI₂, and dimethylammonium iodide (DMAI).

- Passivation Solution: 1 mg/mL 1,8-diaminooctane in anhydrous isopropanol.

- Equipment: Spin coater, hotplate.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure 1. Film Preparation: Fabricate a CsPbI₃ perovskite film using your standard method (e.g., one-step spin-coating with DMAI additive). 2. Annealing: Anneal the film to form the black perovskite phase. 3. Passivation: Immediately after annealing and while the film is still hot (e.g., 80-100°C), spin-coat the DAO solution in isopropanol onto the film at 4000-5000 rpm for 30 seconds. 4. Post-treatment Annealing: Anneal the film again at 70-80°C for 1-2 minutes to remove residual solvent and strengthen the interaction between DAO and the perovskite surface.

3. Key Parameters for Success

- Application on Hot Surface: Applying the DAO solution on a hot film improves the binding efficiency to undercoordinated Pb²⁺ defects.

- Solution Concentration: A low concentration (e.g., 1 mg/mL) is sufficient to form a monolayer and avoid insulating layer formation.

- Solvent: Isopropanol is chosen as it does not damage the perovskite film.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Ligand Exchange and Passivation Workflow

Mechanism of Hydrophobic Ligand Stabilization

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents used in the featured ligand engineering protocols.

| Research Reagent | Function / Role in Experiment | Key Outcome / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Short-chain, hydrophobic cationic ligand for post-synthetic exchange. Replaces insulating OLA [22]. | Simultaneously improves charge transport (short chain) and moisture resistance (hydrophobic aromatic ring). Preserves inorganic composition and bandgap [22]. |

| 1,8-Diaminooctane (DAO) | Bidentate ligand for surface passivation. Coordinates with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ defects [3]. | Creates a hydrophobic surface, reduces non-radiative recombination, and enhances operational stability under humidity [3]. |

| Acetate Salts (e.g., NaAc) | Anionic ligand source for initial purification and exchange. Replaces long-chain oleate ligands [22]. | Provides initial shortening of ligand shell, improving film conductivity and preparing QDs for subsequent cationic exchange [22]. |

| Dimethylammonium Iodide (DMAI) | Additive in CsPbI₃ film fabrication. Facilitates the formation of the perovskite phase at lower temperatures [3]. | Enables the formation of high-quality CsPbI₃ films, but can leave behind DMAI-rich surfaces with undercoordinated Pb defects [3]. |

CsPbI₃ Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) possess exceptional optoelectronic properties, making them promising for solar cells and light-emitting devices. However, their commercial viability is severely limited by an intrinsic instability: high susceptibility to moisture, which causes degradation and a detrimental phase transition from a photoactive black phase to a non-photoactive yellow phase [7] [13] [24]. Within the broader context of research addressing the humidity instability of CsPbI₃ PQDs, the strategic use of hydrophobic ligands has emerged as a primary defense mechanism. These ligands function by creating a protective, moisture-resistant barrier around the quantum dots, physically shielding them from environmental water molecules and thereby enhancing their operational lifetime and performance [22] [24].

Experimental Protocols: Implementing Ligand Strategies

Protocol 1: Short-Chain Ligand Exchange with Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI)

This protocol replaces insulating long-chain ligands with shorter, hydrophobic aromatic ammonium cations to simultaneously improve charge transport and moisture resistance [22].

- Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbI₃ QDs using standard hot-injection methods with oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) as native ligands.

- Initial Ligand Exchange: Perform a solid-state ligand exchange on the QD thin films to replace anionic oleate ligands with acetate (Ac) anions.

- Hydrophobic Cation Incorporation: Treat the Ac-exchanged CsPbI₃ QD thin films with a solution of Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI).

- Mechanism: The phenethylammonium (PEA) cations replace the remaining oleylammonium (OLA) ligands on the QD surface. The aromatic ring provides enhanced hydrophobicity, creating a stable moisture-resistant layer without altering the QD's inorganic composition or size [22].

- Validation: Characterize using Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) and H NMR spectroscopy to confirm successful ligand exchange.

Protocol 2: Stepwise Ligand Management with Benzylphosphonic Acid (BPA)

This two-step strategy uses a short-chain ligand with strong coordinating groups to achieve defect passivation and hydrophobicity during both QD preparation and film formation [19].

- Primary Passivation during Synthesis: Introduce Benzylphosphonic Acid (BPA) into the crude CsPbI₃ QD solution immediately after synthesis. The P=O group strongly coordinates to the QD surface, initiating the replacement of long-chain OA/OAm.

- Film Deposition and Secondary Treatment: Prepare QD films using a layer-by-layer spin-coating technique.

- Final Ligand Exchange: For each deposited layer, use a washing solvent of methyl acetate (MeOAc) incorporated with BPA. This step completely removes residual long-chain ligands and performs a final surface passivation.

- Mechanism: The strong coordination of BPA passivates surface defects and the short hydrocarbon chain improves inter-dot charge transport. The benzyl group enhances the overall hydrophobicity of the QD film [19].

Protocol 3: Surface Post-Processing with Cysteine (Cys)

This method employs a multi-functional biomolecule for effective surface defect passivation and stability enhancement [25].

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve cysteine in an ethyl acetate solution.

- Post-Processing: Add the synthesized CsPbI₃ QDs to the cysteine ligand solution and treat with ultrasound for several minutes.

- Purification: Centrifuge the mixture, discard the supernatant, and re-disperse the precipitate in hexane for further use.

- Mechanism: Cysteine acts as a tridentate ligand, coordinating to the QD surface through its carboxylate (–COO⁻), amino (–NH₂), and thiol (–SH) groups. This multi-dentate binding effectively suppresses surface defects and enhances the binding energy, leading to a more robust and photoluminescent QD [25].

Performance Data: Quantitative Comparison of Ligand Strategies

The effectiveness of various ligand strategies is quantified through key performance metrics in solar cells and light-emitting devices, as summarized in the tables below.

Table 1: Photovoltaic Performance and Stability of CsPbI₃ PQD Solar Cells with Different Ligand Treatments

| Ligand Strategy | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Stability Retention (Unencapsulated) | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenethylammonium (PEA) [22] | 14.1% | >90% after 15 days in ambient air | Simultaneous improvement in moisture stability and charge transport. |

| Benzylphosphonic Acid (BPA) [19] | 13.91% | 91% after 800 hours in atmosphere; 92% after 200 hours of continuous light. | 1.9x increase in hole mobility; 46% reduction in trap state density [19] [26]. |

| 1,8-Diaminooctane (DAO) [3] | 17.7% | 92.3% after 1500 minutes of operation at 30% relative humidity. | Effective passivation of undercoordinated Pb defects; enhanced humidity stability during fabrication. |

| Aluminum Isopropoxide (IPA-Al) [26] | N/A (For LED applications) | 2.15x enhancement in operational half-life for LEDs. | Forms a covalent Al-I bond and inert Al-O-Al layer, boosting conductivity and stability. |

Table 2: Optical Property Enhancement of CsPbI₃ PQDs from Ligand Passivation

| Ligand / Treatment | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Defect Reduction & Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Cysteine Post-Processing [25] | 70.77% (vs. 38.61% for pristine) | Fewer surface defects; tridentate binding (carboxyl, amino, thiol). |

| Benzylphosphonic Acid (BPA) [19] | Significant improvement reported | Passivates defects via P=O coordination; inhibits non-radiative recombination. |

| Standard Oleic Acid / Oleylamine | Low after purification | High defect density due to ligand loss during processing. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Reduced Charge Transport After Ligand Exchange

- Potential Cause: The new short-chain ligands, while improving conductivity, may still form an insulating layer if too densely packed or if they partially aggregate.

- Solution: Optimize the ligand concentration and reaction time. Consider ligands that form thinner, more conductive layers, such as organic covalent metal salts (e.g., IPA-Al) [26].

Problem: Quantum Dot Aggregation During Ligand Exchange

- Potential Cause: The use of short-chain ligands with poor solubility in non-polar solvents (like octane or toluene) used for QD dispersion can destabilize the colloid [26].

- Solution: Prioritize ligands with high solubility in non-polar solvents. Alternatively, employ a stepwise ligand exchange strategy where the initial exchange is performed in a crude solution before purification to minimize aggregation during film formation [19].

Problem: Incomplete Ligand Exchange or Passivation

- Potential Cause: The washing solvent (e.g., methyl acetate) may have insufficient polarity to fully remove long-chain native ligands or to introduce the new short-chain ligand effectively [19] [22].

- Solution: Increase the polarity of the washing solvent slightly or add the new ligand directly into the washing solution. Confirm exchange success with FT-IR or NMR spectroscopy [22].

Problem: Phase Instability Persists After Treatment

- Potential Cause: Surface iodide vacancies, which are not fully passivated by organic ligands, can act as nucleation sites for the non-perovskite δ-phase [27].

- Solution: Implement a dual passivation strategy. Combine your hydrophobic organic ligand with halide-rich salts like CsI or CdI₂ to fill the surface iodide vacancies and further slow the phase transition kinetics [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Hydrophobic Ligand Management in CsPbI₃ PQD Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Hydrophobic cationic ligand for A-site surface exchange [22]. | Aromatic ring provides hydrophobicity; short chain aids charge transport. |

| Benzylphosphonic Acid (BPA) | Short-chain ligand for defect passivation and ligand exchange [19]. | Phosphonic acid group (P=O) has strong coordinating ability to the QD surface. |

| Cysteine | Multi-functional biomolecule for tridentate surface passivation [25]. | Provides carboxylate, amino, and thiol groups for strong coordination. |

| Aluminum Isopropoxide (IPA-Al) | Organic covalent metal salt ligand [26]. | Forms covalent Al-I bonds and an inert Al-O-Al layer; highly soluble in non-polar solvents. |

| Dimethylammonium Iodide (DMAI) | Additive for facilitating CsPbI3 film formation under humidity [3]. | Volatilizes during annealing, aiding in the crystallization of the perovskite phase. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Common washing solvent for layer-by-layer QD film deposition [19]. | Polarity is sufficient to remove some ligand byproducts without dissolving the QDs. |

Visualizing the Workflow and Mechanism

The following diagrams illustrate the general workflow for a stepwise ligand exchange and the molecular mechanism by which hydrophobic ligands protect the perovskite core.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't we just use the long-chain ligands from synthesis for moisture protection? While long-chain ligands like oleic acid provide initial colloidal stability, they are dynamically bound and easily detach during purification and film processing. This leaves behind surface defects and fails to provide a consistent hydrophobic barrier. Furthermore, these long-chain ligands are insulating, which severely limits charge transport between QDs in a film, hampering device performance [19] [7].

Q2: What is the key trade-off in hydrophobic ligand design? The primary trade-off is between hydrophobicity/stability and charge transport efficiency. Long, densely packed hydrocarbon chains offer excellent moisture resistance but are highly insulating. Short chains improve electrical conductivity but may offer less robust protection and can cause QD aggregation. Advanced ligand design focuses on molecules that are both hydrophobic and conductive, or that form thin, dense layers [26] [22].

Q3: How do iodide vacancies contribute to moisture-induced degradation? Surface iodide vacancies are critical nucleation sites for the phase transition to the non-perovskite δ-phase [27]. Water molecules strongly solvate these vacancy sites, accelerating the structural collapse. Therefore, an effective stability strategy must combine hydrophobic shielding with surface defect passivation, particularly of iodide vacancies, using halide-rich salts or ligands with strong coordinating atoms [27] [25].

Q4: Can these ligand strategies enable fabrication in ambient air? Yes, that is a key direction of recent research. By using advanced ligands and additives like DMAI or DAO, researchers have successfully fabricated CsPbI₃ solar cells under relatively high humidity (e.g., 45-60% RH) without a controlled inert atmosphere [3]. This demonstrates the potential for reducing manufacturing costs and scaling up production.

Ligand Engineering in Action: Synthesis, Exchange, and Application Strategies

In-Situ Ligand Engineering During Hot-Injection Synthesis

Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Why are my CsPbI3 PQDs unstable and losing luminescence quickly after synthesis?

A: Rapid degradation is often caused by ligand detachment and Ostwald ripening. Traditional long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) bind weakly to the QD surface, leading to detachment that exposes ionic sites and accelerates degradation [28]. This manifests as emission wavelength shifting from target pure-red (∼623 nm) to crimson (∼639 nm) and decreased photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) [28].

- Solution: Introduce strong-binding ligands during synthesis. 2-Naphthalene sulfonic acid (NSA) shows higher binding energy (1.45 eV) than OAm (1.23 eV) [28]. For CsPbBr₃ QDs, dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid (DBSA) controls nucleation and suppresses Ostwald ripening, maintaining 89% PL after six months [29].

Q2: How can I achieve pure-red emission (620-635 nm) from CsPbI3 PQDs?

A: Obtaining emission below 635 nm requires strong quantum confinement with QD radius less than 5 nm [28]. Uncontrolled Ostwald ripening during synthesis causes small QDs to dissolve and larger ones to grow, weakening quantum confinement.

- Solution: Inject NSA ligand after nucleation. With 0.6 M NSA, PL peak blue-shifts to 626 nm with 89% PLQY and narrow size distribution [28]. Post-synthesis ligand exchange with ammonium hexafluorophosphate (NH₄PF₆) further blue-shifts emission to 623 nm and boosts PLQY to 94% [28].

Q3: Why does my product have low photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY)?

A: Low PLQY indicates surface defects acting as non-radiative recombination centers. Halide vacancies are common defects, and weak ligand binding fails to passivate them effectively [30].

- Solution: Create halide-rich environment and repair lattice vacancies. For CsPbI3 QDs, guanidinium iodide (GAI) additive repairs iodine vacancies and replaces surface Cs atoms, suppressing non-radiative Auger recombination to achieve 27.1% external quantum efficiency in LEDs [30]. For CsPbBr₃, ZnBr₂ passivates bromide vacancies and enhances DBSA adsorption, achieving 90.7% PLQY [29].

Q4: My PQDs aggregate during purification – how can I prevent this?

A: Aggregation occurs because polar anti-solvents used in purification trigger ligand loss through proton transfer between OA⁻ and OAmH⁺ [28].

- Solution: Incorporate strong-binding ligands before purification. NSA treatment promotes debonding of weak OA/OAm ligands and provides steric hindrance to inhibit fusion [28]. NH₄PF₆ exchange during purification provides strong binding (3.92 eV binding energy) to prevent aggregation and maintain dispersion [28].

Experimental Protocols

This protocol produces 4.3 nm CsPbI3 PQDs with 94% PLQY and 623 nm emission.

Materials: Lead iodide (PbI₂, 99.999%), cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99.99%), 1-octadecene (ODE, 90%), oleic acid (OA, 90%), oleylamine (OAm, 90%), 2-naphthalene sulfonic acid (NSA), ammonium hexafluorophosphate (NH₄PF₆), hexane, methyl acetate.

Procedure:

- Standard CsPbI3 QD Synthesis: Use hot-injection method at 170-185°C with Cs-oleate precursor [28].

- NSA Treatment: Immediately after nucleation, inject 0.6 M NSA dissolved in toluene. NSA replaces weak OAm ligands and suppresses Ostwald ripening through stronger Pb binding and steric hindrance.

- Growth Monitoring: Monitor via in-situ PL spectroscopy. NSA-treated QDs show blue-shifted emission and enhanced intensity versus controls.

- Purification: Centrifuge crude solution and redisperse in hexane. Add NH₄PF₆ solution (10 mg/mL in methanol) during purification for ligand exchange.

- Washing: Precipitate with methyl acetate, centrifuge, and redisperse in hexane. Repeat twice.

- Storage: Store in anhydrous hexane at 4°C in inert atmosphere.

This protocol produces 2.6 nm CsPbBr₃ QDs with 90.7% PLQY and 461 nm emission.

Materials: PbBr₂ (99.9%), ZnBr₂ (99.9%), dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid (DBSA), standard CsPbBr₃ precursors.

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Mix DBSA and ZnBr₂ with standard precursors in three-neck flask [29].

- Hot-Injection: Perform at 160°C under nitrogen. DBSA regulates nucleation rate while ZnBr₂ passivates bromide vacancies.

- Reaction Monitoring: DBSA suppresses Ostwald ripening, maintaining ultra-small QD size.

- Purification: Standard centrifugation with anti-solvent.

- Characterization: Confirm 2.6 nm size, 461 nm emission, and 90.7% PLQY.

Materials: Phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI), sodium acetate (NaAc), standard CsPbI3 QD precursors.

Procedure:

- Acetate Exchange: First replace native OLE ligands with acetate via solid-state ligand exchange [22].

- PEAI Treatment: Deposit PEAI solution (1.5 mg/mL in isopropanol) on Ac-exchanged CsPbI3-QD thin films via spin-coating.

- Annealing: Anneal at 70°C for 1 minute to incorporate PEA cations onto QD surfaces.

- Validation: Confirm PEA incorporation via FT-IR and H NMR. PEA-incorporated solar cells retain >90% initial PCE after 15 days ambient conditions [22].

Table 1: Ligand Performance Comparison for CsPbX3 PQDs

| Ligand System | QD Type | Emission (nm) | PLQY (%) | Stability Performance | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSA + NH₄PF₆ [28] | CsPbI₃ | 623 | 94 | 80% PLQY after 50 days | Pure-red emission, high charge transport |

| DBSA + ZnBr₂ [29] | CsPbBr₃ | 461 | 90.7 | 89% PL after 6 months | Blue emission, superior photostability |

| PEA Incorporation [22] | CsPbI₃ | - | - | >90% PCE after 15 days | Enhanced moisture resistance |

| Guanidinium Iodide [30] | CsPbI₃ | - | - | T₅₀: 1001 min @ 100 cd/m² | Defect passivation, lattice repair |

| OA/OAm (Control) [28] | CsPbI₃ | 635-639 | <80 | Rapid degradation | Baseline reference |

Table 2: Stability Performance Under Different Conditions

| Ligand Strategy | Storage Stability | Thermal Stability | Moisture Resistance | Photostability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSA + NH₄PF₆ [28] | 80% PLQY after 50 days | - | - | - |

| DBSA + ZnBr₂ [29] | 89% PL after 6 months | - | - | 65% intensity after 80 min UV |

| PEA [22] | - | - | >90% PCE after 15 days ambient | - |

| Siloxane Passivation [31] | Stable in nonpolar solvents | - | - | Enhanced PLQY |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for In-Situ Ligand Engineering

| Reagent | Function | Key Properties | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Naphthalene Sulfonic Acid (NSA) [28] | Strong-binding ligand, Ostwald ripening inhibitor | Binding energy: 1.45 eV; steric hindrance | Use at 0.6 M concentration post-nucleation |

| Ammonium Hexafluorophosphate (NH₄PF₆) [28] | Post-synthesis ligand exchange | Binding energy: 3.92 eV; enhances conductivity | Add during purification in methanol solution |

| Dodecylbenzenesulfonic Acid (DBSA) [29] | Nucleation control, size regulation | Suppresses Ostwald ripening; enables <3 nm QDs | Use synergistically with ZnBr₂ |

| Zinc Bromide (ZnBr₂) [29] | Halide vacancy passivation | Bifunctional agent; enhances ligand adsorption | Critical for bromide-rich environment |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) [22] | Hydrophobic stabilizer | Short-chain, hydrophobic cation | Incorporates without changing QD size/composition |

| Guanidinium Iodide (GAI) [30] | Lattice repair, surface passivation | Modifies tolerance factor; repairs iodine vacancies | Creates halide-rich environment |

Ligand exchange is a fundamental process in materials chemistry where the original organic ligands surrounding a nanocrystal are replaced with new ligands to alter the nanocrystal's properties. For CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), this process is critical for enhancing environmental stability, particularly against humidity, and improving optoelectronic performance for device applications. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers implementing these techniques.

Core Ligand Exchange Techniques

Solid-State Ligand Exchange

Solid-state ligand exchange is performed on quantum dot films after deposition. In this method, a film of QDs with original long-chain ligands is treated with a solution containing the desired replacement ligands.

Experimental Protocol for Solid-State Exchange on PbS QDs [32]:

- Film Preparation: Deposit a film of oleic acid (OA)-capped QDs onto a substrate via spin-coating or other methods.

- Ligand Solution Preparation: Dissolve tetrabutylammonium iodide (TBAI) in methanol at a typical concentration of 10 mg/mL.

- Treatment: Immerse the QD film in the TBAI solution for 20-30 seconds.

- Rinsing: Rinse the film thoroughly with fresh methanol to remove excess ligands and reaction by-products.

- Drying: Dry the film under a nitrogen stream. This process is typically repeated multiple times in a layer-by-layer (LBL) fashion to build up film thickness.

Key Considerations:

- Incomplete Exchange Challenge: A major limitation is that the exchange can be incomplete, leaving residual OA ligands that adversely affect charge transport. The efficiency depends on factors like film thickness, ligand concentration, and exchange time [32].

- Pre-Washing Optimization: Research shows that post-synthesis washing of QDs (e.g., with an ethanol-methanol mixture) prior to film formation can reduce the initial OA load, leading to more complete subsequent solid-state exchange and improved device performance [32].

Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange

Solution-phase exchange occurs in a biphasic mixture where QDs are transferred from a non-polar solvent to a polar solvent as ligands are replaced, enabling purification and processing directly from solution.

Experimental Protocol for Accelerated Solution-Phase Exchange [33]:

- Polar Phase Preparation: Dissolve lead halides (0.1 M PbI₂ and 0.02 M PbBr₂) and ammonium acetate (0.04 M) in dimethylformamide (DMF).

- QD Phase Preparation: Use a highly concentrated solution (~6 mg/mL) of oleate-capped PbS CQDs in octane.

- Mixing: Add the QD solution to the DMF solution and mix vigorously using a vortex mixer for a short duration (seconds).

- Phase Separation: Allow the mixture to separate. QDs with successfully exchanged ligands will transfer to the bottom DMF phase.

- Purification: Separate the DMF phase and precipitate the QDs by adding an anti-solvent (e.g., toluene or chloroform), then centrifuge.

Key Considerations:

- Exchange Rate: Using highly concentrated QD solutions accelerates the ligand exchange, minimizing surface exposure to the polar solvent and reducing the formation of trap states [33].

- Acid-Catalyzed Mechanism: For lead chalcogenide QDs, the exchange of carboxylate ligands (like oleate) with iodide is an acid-catalyzed reaction. The cation of the iodide salt (e.g., NH₄⁺, CH₃NH₃⁺) plays a role in the reaction efficiency, with acidic cations facilitating more complete ligand removal [34].

Technique Comparison and Selection Guide

Table 1: Comparison of Solid-State and Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange Techniques

| Feature | Solid-State Exchange | Solution-Phase Exchange |

|---|---|---|

| Process Workflow | Layer-by-layer deposition and treatment [35] | Single-step exchange and phase transfer before film formation [35] |

| Throughput | Time-consuming for thick films [35] | Reduces labor and time requirements [35] |

| Film Quality | Risk of incomplete exchange and cracking in thick films [32] | Improved homogeneity and reduced agglomeration [33] |

| Trap State Density | Higher risk of sub-bandgap trap states due to incomplete passivation [32] | Better passivation and minimized surface defects achievable [33] |

| Best Applications | Thin-film devices, research-scale prototyping | Thick-film devices, scalable processing, high-performance photovoltaics |

Quantitative Data on Ligand Performance

The choice of ligand directly impacts the optical properties and stability of the resulting quantum dot films.

Table 2: Impact of Different Ligands on CsPbI3 PQD Properties [36]

| Ligand | Photoluminescence (PL) Enhancement | Key Stability Performance | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | 18% | -- | Surface passivation of undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions |

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | 16% | -- | Surface passivation of undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions |

| l-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | 3% | Retained >70% of initial PL after 20 days of UV exposure | Superior photostability and defect suppression |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Ligand Exchange Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Short-Chunk Inorganic Ligands | Provides n-type passivation, enhances charge transport, and improves air stability [32] [34] | Tetrabutylammonium iodide (TBAI), Ammonium Iodide (NH₄I), Methylammonium Iodide (MAI), Lead Iodide (PbI₂) |

| Polar Solvents | Medium for solid-state treatment or polar phase in solution exchange [32] [33] | Methanol (MeOH), Dimethylformamide (DMF) |

| Non-Polar Solvents | Dispersion medium for as-synthesized QDs with original ligands [33] | Octane, Hexane, Chloroform |

| Precipitation Anti-Solvents | Used to purify QDs after solution-phase exchange [32] [33] | Toluene, Acetone |

| Metal Salts & Additives | Source of metal-halide complexes; catalysts for exchange reaction [33] | Lead Bromide (PbBr₂), Ammonium Acetate (NH₄Ac) |

Workflow and Decision Diagrams

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Incomplete Ligand Exchange

Q: My solid-state ligand exchanged films show poor conductivity. I suspect incomplete exchange of the original oleic acid ligands. How can I improve this?

- Cause: The native oleic acid ligands are not fully removed and replaced by the target short-chain ligands, creating a barrier for charge transport [32].

- Solution:

- Pre-Wash QDs: Implement multiple post-synthesis washing cycles of the QDs using an ethanol-methanol mixture before film deposition. This reduces the initial ligand load, facilitating more complete subsequent exchange [32].

- Optimize Salt & Solvent: Use iodide salts with acidic cations (e.g., NH₄I or MAI instead of TBAI) in methanol, as the protonated environment catalyzes the removal of oleate [34].

- Adjust Processing: Increase the concentration of the ligand solution and/or the immersion time, though this must be balanced against the risk of film degradation [32].

FAQ 2: Trap State Formation

Q: After solution-phase exchange, my QD films exhibit high trap state density and low photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY). What is the cause and how can it be mitigated?

- Cause: Slow exchange kinetics can expose the QD surface to the polar solvent for an extended period, leading to surface etching and the formation of unpassivated sites (dangling bonds) [33].

- Solution:

- Accelerate Exchange: Use a highly concentrated solution of the starting QDs. This maximizes the contact area between QD surfaces and incoming ligands, drastically reducing the exchange time from minutes to seconds and minimizing surface damage [33].

- Confirm Passivation: Use Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to verify the removal of OA and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to confirm the successful binding of the new halide ligands to the QD surface [32].

FAQ 3: Film Cracking and Morphology

Q: My films crack during the solid-state ligand exchange process, leading to poor device performance. How can I achieve crack-free, thick films?

- Cause: Incomplete ligand removal can cause inconsistent spacing and clustering of QDs, building up stress that results in cracking [32].

- Solution:

- Ensure Complete Exchange: Follow the solutions for "Incomplete Ligand Exchange" above to remove the bulky OA ligands more thoroughly, allowing for a more uniform contraction of the film.

- Leverage Solution-Phase Exchange: Consider switching to solution-phase exchange, which allows for the formation of dense, crack-free thick films in a single deposition step, as the ligand shell is already optimized before film formation [35] [33].

FAQ 4: Choosing the Right Ligand

Q: For my CsPbI3 PQDs, which ligand should I use to maximize both stability and optoelectronic performance?

- Guidance: The optimal ligand depends on the primary property you wish to enhance. Refer to Table 2 for quantitative data [36].

- For maximum photoluminescence intensity, TOPO is the most effective.

- For superior long-term photostability, L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) is the best choice, as it retains over 70% of its initial PL intensity after 20 days of UV exposure.

- For charge transport in electronic devices, short inorganic ligands like iodides (I⁻) are typically necessary to reduce inter-dot spacing and tunneling barriers [35] [32]. A combination of ligands may be required to balance these properties.

Phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI) is an aromatic ammonium salt with the chemical formula C8H12IN and a molecular weight of 249.09 g/mol [37]. It appears as a white crystalline powder with a melting point of 283°C [38] [39]. In perovskite research, particularly with fully inorganic CsPbI3 perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), PEAI serves a critical function as a short-chain, hydrophobic ligand that replaces native long-chain insulating ligands, thereby simultaneously enhancing charge transport and moisture stability [22].

The primary challenge in CsPbI3 PQD development involves the inherent trade-off between charge transport and environmental stability. Native long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA) provide colloidal stability and initial moisture resistance but severely hinder charge transport between quantum dots [22] [40]. PEAI addresses this dilemma by providing short-chain characteristics that improve electronic coupling while maintaining hydrophobic protection through its aromatic ring structure [22]. This unique combination makes it particularly valuable for improving the performance and durability of perovskite-based optoelectronic devices, including solar cells and light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

Experimental Protocols: Incorporating PEAI into CsPbI3 PQDs

Standard Ligand Exchange Procedure with PEAI

The incorporation of PEAI typically follows a two-step ligand exchange procedure on pre-synthesized OA/OLA-capped CsPbI3 PQDs:

Step 1: Anionic Ligand Exchange

- Prepare a solution of sodium acetate (NaOAc) in methyl acetate (MeOAc) [40].

- Treat the OA/OLA-capped CsPbI3 PQD thin films with the NaOAc solution to replace anionic OA ligands with acetate ions [40].

- Repeat this process in a layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly to achieve the desired film thickness [40].

Step 2: Cationic Ligand Exchange with PEAI

- Prepare a solution of PEAI in ethyl acetate (EtOAc) [40].

- Post-treat the acetate-exchanged CsPbI3 PQD solids with the PEAI solution to replace residual cationic OLA ligands with PEA cations [40].

- The treatment time and concentration must be optimized to ensure complete exchange without damaging the PQD structure [22].

Key Considerations:

- The polar solvents (MeOAc and EtOAc) are essential for dissolving ionic salts and removing long-chain ligands but may potentially remove surface components from PQDs if not properly controlled [40].

- Successful incorporation can be confirmed through Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, which shows decreased IR peak intensities of oleyl groups and carboxylate groups, along with increased aromatic double bonding peaks [40].

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for the PEAI ligand exchange process:

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics of PEAI-Modified CsPbI3 PQDs

Table 1: Performance comparison of CsPbI3 PQD solar cells with different ligand treatments

| Ligand Treatment | PCE (%) | VOC (V) | Stability Retention | Stability Duration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEAI incorporation | 14.1 | ~1.2 | >90% | 15 days (ambient) | [22] |

| PEAI stabilization | 17.0 | 1.33 | 94% | 2000+ hours (low humidity) | [41] |

| Conventional FA-based treatment | 13.4 | Lower than PEAI | Poor stability | N/A | [22] |

| PEAI with TPPO co-treatment | 15.4 | >1.2 | >90% | 18 days (ambient) | [40] |

Table 2: Moisture stability comparison of different CsPbI3 PQD formulations

| Stabilization Method | Humidity Condition | Performance Retention | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEAI ligand exchange | Ambient conditions | >90% after 15 days | Simultaneous charge transport & stability [22] |

| PEAI + 2D perovskite formation | Low-humidity environment | 94% after 2000+ hours | Record VOC of 1.33V [41] |

| PEAI + TPPO in octane | Ambient conditions | >90% after 18 days | Reduced surface traps [40] |

| Conventional FA treatment | Ambient conditions | Poor stability | Improved charge transport only [22] |

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Q1: Why does my PEAI-treated CsPbI3 PQD film show decreased photoluminescence (PL) intensity after ligand exchange?

- Cause: The conventional ligand exchange process using polar solvents can generate surface traps, particularly uncoordinated Pb2+ sites, which act as non-radiative recombination centers [40].

- Solution: Implement a secondary surface stabilization using covalent short-chain ligands like triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) dissolved in nonpolar solvents (e.g., octane). This approach passivates surface traps without further damaging the PQD surface [40].

Q2: How can I prevent phase transformation from black cubic-phase (γ-CsPbI3) to yellow orthorhombic-phase during PEAI treatment?

- Cause: Moisture penetration during processing accelerates phase transformation, especially when hydrophobic OLA ligands are removed [22].

- Solution:

Q3: Why is the open-circuit voltage (VOC) of my PEAI-incorporated CsPbI3 PQD solar cell lower than expected?

- Cause: Incomplete ligand exchange or hybridization of fully inorganic CsPbI3 with organic cations can reduce bandgap and consequently VOC [22].

- Solution:

- Optimize PEAI concentration and processing time to prevent excessive incorporation

- Verify preserved bandgap through UV-Vis spectroscopy

- Use complementary passivation strategies (e.g., 2D perovskite formation with lead acetate) to suppress charge recombination [41]

Q4: How can I verify successful PEA cation incorporation onto CsPbI3 PQD surfaces?

- Characterization Methods:

Advanced Optimization Strategies

Q5: What is the optimal method for combining PEAI with other ligands for enhanced performance?

- Strategy 1: Combine PEAI with TPPO dissolved in nonpolar solvents. TPPO strongly coordinates with uncoordinated Pb2+ sites while PEAI provides hydrophobic protection [40].

- Strategy 2: Use PEAI with 2D perovskite formation by controlling lead acetate ratio, creating a protective barrier that suppresses charge recombination [41].

- Strategy 3: Implement PEAI treatment after strong-binding NSA (2-naphthalene sulfonic acid) ligands to inhibit Ostwald ripening during synthesis [28].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents for PEAI-based CsPbI3 PQD experiments

| Reagent | Function | Specifications | Supplier Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI) | Short-chain hydrophobic ligand for cation exchange | Purity: ≥98%, White powder, CAS: 151059-43-7 [38] [37] | Greatcell Solar Materials, Sigma-Aldrich [38] [37] |

| Cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3) | Cesium source for PQD synthesis | Purity: 99.99% [22] [20] | Alfa Aesar [22] [20] |

| Lead iodide (PbI2) | Lead source for PQD synthesis | Purity: 99.999% [22] [20] | Alfa Aesar [22] |

| Oleic acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OLA) | Native long-chain ligands for initial PQD stabilization | OA: 90%, OLA: 70% [22] [20] | Sigma-Aldrich, Alfa Aesar [22] |

| Sodium acetate (NaOAc) | Short anionic ligand for initial ligand exchange | Purity: 99.995% [22] [20] | Sigma-Aldrich [22] |

| Triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) | Covalent short-chain ligand for surface stabilization | For surface trap passivation [40] | Sigma-Aldrich [40] |

| Methyl acetate & Ethyl acetate | Polar solvents for ligand exchange | Anhydrous, ≥99.8% [40] | Sigma-Aldrich [40] |

Technical Support Center

FAQs: Ligands and Perovskite Quantum Dot Stability

What are multidentate ligands and how do they improve stability?

Multidentate ligands are molecules that can attach to a central metal atom or ion at multiple points using two or more donor atoms [42] [43]. This multi-point binding creates a chelating effect, forming a ring structure [43]. The chelating effect describes the enhanced affinity these ligands have for a metal ion compared to a collection of similar monodentate (single-point) ligands. This stronger binding leads to significantly improved complex stability [43]. In the context of CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs), using multidentate ligands reduces ligand detachment, which is a primary cause of structural degradation under environmental stress [12].

Why should I consider star-shaped ligands?

Star-shaped polymers are a subclass of branched polymers characterized by a single branch point from which three or more linear chains (arms) emanate [44]. The key advantage of this architecture is the presence of multiple functional end groups (like hydroxyls) that can serve as initiation sites for polymerization or as binding points. This multifunctionality can be exploited to create a dense or cross-linked ligand shell around a nanocrystal, enhancing its environmental stability and modifying its physical properties, such as reducing crystallinity and increasing viscosity compared to linear analogues [44].

How can ligand modification specifically address the humidity instability of CsPbI3 PQDs?

CsPbI3 PQDs are highly susceptible to degradation from environmental factors like humidity [12] [36]. Traditional long-chain ligands (e.g., oleic acid and oleylamine) provide initial stability but are dynamically bound and can detach, leaving the surface vulnerable [22] [12]. Ligand engineering tackles this by:

- Introducing Hydrophobicity: Exchanging native ligands with short-chain, hydrophobic molecules like phenethylammonium (PEA) creates a moisture-resistant shell without compromising charge transport. Research has shown that PEA-incorporated CsPbI3-QD solar cells retained over 90% of their initial performance after 15 days under ambient conditions [22].

- Enhancing Binding with Multidentate Ligands: Using ligands with multiple binding groups (e.g., L-Phenylalanine) strengthens the attachment to the PQD surface. This effective passivation of undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions and surface defects suppresses non-radiative recombination and improves stability against moisture, oxygen, and light [36].

Troubleshooting Guide: Ligand Exchange and Stability

Problem: Rapid degradation of CsPbI3 PQD films under ambient humidity.

- Potential Cause 1: Weak binding of monodentate ligands.

- Solution: Replace monodentate ligands with multidentate alternatives. For example, use trioctylphosphine (TOP) or trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO), which are L-type ligands that coordinate more strongly with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the PQD surface. One study showed TOP and TOPO passivation led to PL intensity enhancements of 16% and 18%, respectively [36].

- Potential Cause 2: Hydrophilic surface due to ligand choice.

- Solution: Perform a post-synthesis ligand exchange with a short-chain hydrophobic ligand. A proven protocol is the incorporation of phenethylammonium (PEA) cations. This replaces long-chain, insulating oleylammonium ligands with short-chain, hydrophobic PEA, simultaneously improving charge transport and forming a protective layer against moisture [22].

- Potential Cause 3: Incomplete surface coverage leading to defect sites.