Fundamental Principles of Heterogeneous Catalysis: From Surface Science to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the fundamental principles of heterogeneous catalysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles of Heterogeneous Catalysis: From Surface Science to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the fundamental principles of heterogeneous catalysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It begins by establishing the core concepts of surface science and active sites, then delves into modern characterization and computational methods. The content addresses critical challenges in catalyst stability and selectivity, offering troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, it covers validation through kinetic analysis and operando spectroscopy, concluding with an examination of emerging trends like single-atom catalysis and machine learning that are poised to revolutionize catalyst design for biomedical and industrial applications.

Core Concepts and the Solid-Gas Interface: Understanding the Basis of Heterogeneous Catalysis

Heterogeneous catalysis is a process where the catalyst exists in a different phase (typically solid) than the reactants (typically liquid or gaseous) [1]. This fundamental phenomenon represents a cornerstone of modern chemical technology, with more than 80% of all chemical products involving heterogeneous catalysts in at least one of their manufacturing steps [2] [3]. The field has evolved from largely empirical discoveries to a sophisticated engineering science, integrating principles from chemistry, materials science, and reaction engineering. Its importance spans from bulk chemical production and energy conversion to emerging applications in pharmaceutical synthesis and environmental protection, making it an indispensable technology for addressing global sustainability challenges [4] [1].

Historical Context and Evolution

The development of heterogeneous catalysis represents a remarkable journey of scientific and industrial innovation spanning centuries. This evolution has been driven by both scientific curiosity ("pushers") and industrial necessity ("pullers") [2].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Heterogeneous Catalysis

| Time Period | Key Development | Industrial/Societal Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Early 1900s | Haber-Bosch process for ammonia synthesis [2] | Enabled synthetic fertilizers, addressing food security concerns driven by anticipated saltpeter shortages |

| 1930s | Hydrocarbon acid cracking process by Eugène Houdry [2] | Produced more energetic gasoline, revolutionizing fuel technology |

| 1940s | Catalytic reformation and alkylation [2] | Provided powerful aviation fuel for Allied forces during World War II |

| 1960s | Hydrodesulfurization processes [2] | Initiated removal of sulfur from fuels, reducing sulfur oxide emissions |

| 1970s-1990s | Auto emission control catalysts (1974 oxidation, 1978 three-way, 1990s Pd three-way) [2] | Dramatically reduced vehicular pollution through mandatory catalytic converters |

| 1980s | Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) for power plants [2] | Enabled control of nitrogen oxide emissions from stationary sources |

| 2000s-Present | Diesel particulate elimination, urea SCR for vehicles, advanced biomass conversion [2] [5] | Addressing climate change and sustainability through cleaner emissions and renewable feedstocks |

The philosophical approach to catalyst development has also evolved significantly. The field is now transitioning from a linear economy model ("use and dispose") to a circular economy framework that emphasizes dematerialization (using less catalyst material), reduced critical raw material usage, and sustainable lifecycle management [4]. This shift is particularly evident in the growing emphasis on replacing precious metals with more abundant alternatives and developing efficient catalyst recycling protocols [4].

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

The Catalytic Process

Heterogeneous catalysis operates through a sequence of fundamental steps where reactant molecules transform into products on the catalyst surface [3]. The process begins with mass transfer of reactants to the catalyst surface, followed by adsorption of these reactants onto active sites. Subsequent surface reactions lead to the formation of products, which then desorb from the surface and diffuse away into the bulk fluid [3] [6]. The efficiency of this sequence depends critically on the catalyst's ability to bind reactants strongly enough to facilitate reaction, but weakly enough to allow product desorption.

Active Sites and Catalyst Dynamics

A fundamental concept in heterogeneous catalysis is the active site—specific locations on the catalyst surface where the reaction occurs with significantly enhanced rates [3] [7]. These sites possess distinct geometric and electronic properties that enable them to stabilize reaction intermediates and lower activation barriers. Modern research has revealed that these active sites are not static; catalysts undergo dynamic restructuring under reaction conditions, forming the true "active phase" that may differ substantially from the initial catalyst structure [8] [7]. This realization has shifted characterization paradigms toward in situ and operando techniques that probe catalyst structure under actual working conditions [8].

Major Catalytic Mechanisms

Several fundamental mechanisms describe catalytic reactions on surfaces:

- Langmuir-Hinshelwood Mechanism: Both reactants adsorb onto the catalyst surface before reacting, with the surface reaction typically being the rate-determining step [3].

- Eley-Rideal Mechanism: One reactant adsorbs onto the catalyst surface while the other reacts directly from the gas phase [3].

- Mars-van Krevelen Mechanism: Particularly relevant in oxidation catalysis, this mechanism involves the catalyst lattice (typically oxygen atoms) participating directly in the reaction, creating vacancies that are subsequently replenished by oxidizing agents [3].

Industrial Significance and Applications

Heterogeneous catalysis forms the backbone of numerous industrial sectors, contributing significantly to global economic activity. A survey of U.S. industries revealed that chemical and fuel production generates more annual revenue than any other industrial sector, with catalysis playing a critical role in most of these processes [2].

Table 2: Major Industrial Applications of Heterogeneous Catalysis

| Industrial Sector | Key Catalytic Processes | Catalyst Materials | Economic/Environmental Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refining & Petrochemicals | Fluid catalytic cracking, Catalytic reforming, Hydrodesulfurization [2] | Zeolites, Pt-Re/Al₂O₃, Co-Mo/Al₂O₃ [2] | Production of fuels, chemical feedstocks; >60% of major chemical products involve catalysis [2] |

| Environmental Protection | Automotive three-way catalysts, SCR of NOx, Diesel oxidation, VOC destruction [2] | Pt-Pd-Rh, V-W-Ti oxides, Ce-based additives [2] | Dramatic reduction of urban air pollution; compliance with stringent emissions legislation |

| Bulk Chemicals | Ammonia synthesis, Sulfuric acid production, Olefin polymerization [2] | Fe-based, Vâ‚‚Oâ‚…, Ziegler-Natta catalysts [2] | Foundation of fertilizer and chemical industries; enabled global population growth |

| Energy Conversion | Biodiesel production, Hydrogen generation, Fuel cells, Biomass conversion [1] | Solid acids/bases, Ni-based, Pt electrocatalysts [1] | Transition to renewable energy; sustainable fuel production |

| Pharmaceuticals & Fine Chemicals | Selective oxidation, Hydrogenation, C-C coupling [5] [9] | Supported metal nanoparticles, Single-atom catalysts [9] | Streamlined API synthesis; continuous flow processes; waste reduction |

The transition toward sustainable and circular economy principles is reshaping industrial catalysis, with emphasis on waste-to-value processes [5] [4]. Examples include the conversion of biomass-derived furanics to active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [5] and the upgrading of COâ‚‚ emissions into valuable fuels and chemicals [2]. These emerging applications demonstrate how heterogeneous catalysis continues to evolve in response to global sustainability challenges.

Modern Research Methodologies

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Modern heterogeneous catalysis research employs rigorous experimental protocols to ensure reproducibility and meaningful data interpretation. The CatTestHub initiative represents a community effort to standardize catalytic testing and create benchmarking databases following FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse) [6].

A representative experimental workflow for catalyst evaluation typically includes:

- Catalyst Activation: A rapid activation procedure (e.g., 48 hours under harsh conditions) to bring the catalyst to a steady state, identifying rapidly deactivating materials early [8].

- Systematic Testing Protocol:

- Kinetic Analysis: Extracting intrinsic kinetic parameters while ensuring absence of mass and heat transfer limitations through diagnostic tests [6].

Data-Centric Approaches and AI Integration

A transformative shift in catalysis research involves data-centric approaches that leverage artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to identify key "materials genes" - physicochemical parameters that correlate with catalytic performance [8]. These approaches require high-quality, consistent datasets free from experimental artifacts [8].

Advanced sampling algorithms, such as topology-guided methods using persistent homology, enable efficient exploration of configuration spaces for active phase discovery [7]. These methods systematically identify potential adsorption/embedding sites across surface, subsurface, and bulk regions by analyzing topological invariants during geometric filtration processes [7]. When combined with machine learning force fields, these approaches allow rapid screening of thousands of configurations to predict active phases under realistic reaction conditions [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials in Heterogeneous Catalysis

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Examples/Specific Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Supported Metal Catalysts | Provide active metallic sites dispersed on high-surface-area supports | Pt/SiOâ‚‚, Pd/C, Ru/C for hydrogenation/dehydrogenation [6] |

| Zeolite Materials | Microporous solid acids with shape-selective properties | H-ZSM-5 for acid-catalyzed reactions; FCC catalysts in refining [6] |

| Metal Oxide Catalysts | Redox catalysts for selective oxidation | Vâ‚‚Oâ‚… for SOâ‚‚ oxidation; MoVTeNb mixed oxides for alkane oxidation [2] [8] |

| Standard Reference Catalysts | Benchmarking and cross-laboratory validation | EuroPt-1, World Gold Council standards, International Zeolite Association reference materials [6] |

| Solid Acid/Base Catalysts | Replacement for liquid acids/bases in sustainable processes | Sulfated zirconia, hydrotalcites for biodiesel production [1] |

| Single-Atom Catalysts | Maximum atom utilization with distinct electronic properties | Ptâ‚/CeOâ‚‚, isolated metal atoms on various supports [9] |

| Antibacterial agent 121 | Antibacterial agent 121, MF:C18H22N2O3S, MW:346.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kdm5B-IN-3 | Kdm5B-IN-3|Potent KDM5B Inhibitor|For Research Use |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The future of heterogeneous catalysis will be shaped by several interconnected challenges and opportunities. The transition to a circular economy demands catalytic processes that utilize renewable feedstocks, minimize energy consumption, and enable complete resource recovery [4]. Key research directions include:

- Dematerialization: Reducing the amounts of critical raw materials used in catalysts while maintaining or enhancing functionality, often through nanostructuring and single-atom designs [4] [9].

- Renewable Energy Integration: Developing catalytic processes powered by renewable electricity and sunlight for chemical synthesis [2] [1].

- COâ‚‚ Utilization: Creating efficient catalytic routes to transform COâ‚‚ from a waste product into valuable fuels and chemicals [2].

- Biomass Conversion: Designing selective catalysts for converting lignocellulosic biomass and biorefinery side streams (e.g., humins) into platform chemicals and pharmaceuticals [5].

- Advanced Characterization: Pushing the limits of in situ and operando techniques to observe catalytic surfaces at work under realistic conditions [8].

The integration of computational prediction with high-throughput experimentation will accelerate catalyst discovery, while standardized benchmarking through initiatives like CatTestHub will ensure robust evaluation and data sharing across the research community [6]. As the field addresses these challenges, heterogeneous catalysis will continue to be a cornerstone technology for building a more sustainable and resource-efficient future.

Heterogeneous catalysis, a process where the catalyst exists in a different phase from the reactants, serves as the cornerstone of numerous industrial chemical transformations and energy conversion technologies. The catalytic cycle, comprising the fundamental steps of adsorption, surface reaction, and desorption, defines the efficiency and selectivity of these processes [10]. In this cycle, reactants first bind to the catalyst surface (adsorption), then undergo chemical transformation (surface reaction), before the final products leave the surface (desorption) [11]. Traditionally, these elementary steps have been modeled as sequential processes; however, recent dynamic studies reveal that these steps can occur simultaneously in a concerted manner, challenging conventional assumptions and opening new avenues for catalyst design [10]. Understanding these fundamentals provides the necessary foundation for rational catalyst design, enabling researchers to manipulate surface active sites for selective interaction with reactant molecules [11]. This whitepaper examines the core principles of the catalytic cycle, details advanced experimental and computational methodologies for its investigation, and explores emerging trends that are redefining heterogeneous catalysis research.

Core Steps of the Catalytic Cycle

Adsorption: The Initial Reactant-Surface Interaction

Adsorption represents the critical initial step where reactant molecules in the fluid phase bind to active sites on the solid catalyst surface. This process can occur through two primary mechanisms: physisorption, involving weak van der Waals forces with minimal electronic structure change, and chemisorption, characterized by stronger chemical bonds with significant electronic rearrangement between the adsorbate and catalyst surface. The adsorption step is not merely a passive binding event but an active process that can activate molecules for subsequent reaction [11].

Recent surface modification strategies have demonstrated how adsorption properties can be precisely engineered to enhance catalytic performance. For instance, modifying catalyst surfaces with hydrophobic polymers or ionic liquids can significantly increase local reactant concentration (e.g., COâ‚‚) at the active site, thereby improving reaction efficiency [12]. Similarly, strategic surface modifications can inhibit competing side reactions like the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) in electrocatalytic COâ‚‚ reduction by controlling the adsorption behavior of key intermediates [12]. The design of adsorption sites has evolved from trial-and-error approaches to sophisticated strategies leveraging advanced materials including zeolites, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and single-atom catalysts (SACs) that provide well-defined environments for selective reactant adsorption [13].

Surface Reaction: The Chemical Transformation

Following adsorption, the activated species undergo chemical transformation through the surface reaction step. This process typically involves the breaking and forming of chemical bonds while the species are bound to the catalyst surface. The surface reaction represents the heart of the catalytic cycle, where the catalyst provides an alternative pathway with lower activation energy compared to the homogeneous reaction [11].

The surface reaction mechanism can follow various pathways, including Langmuir-Hinshelwood, where two adsorbed adjacent species react with each other, or Eley-Rideal, where a gas-phase molecule reacts directly with an adsorbed species. Recent research has revealed the dynamic nature of catalyst surfaces during this step, with reconstruction and phase transformation occurring under reaction conditions [14]. For complex reactions involving multiple electrons and protons, such as the electrochemical COâ‚‚ reduction or oxygen evolution reaction (OER), the surface reaction may comprise intricate networks of intermediate steps [12] [10]. Advanced theoretical studies now suggest that certain heterogeneous catalysts can exhibit "homogeneous-like" behavior where adsorption and desorption occur concertedly during the surface reaction, particularly in energy-intensive steps like oxygen evolution on iridium dioxide (IrOâ‚‚) surfaces [10].

Desorption: Product Release and Site Regeneration

The final step in the catalytic cycle involves desorption, where the product molecules release from the catalyst surface, regenerating the active sites for subsequent catalytic turnovers. Effective desorption is crucial for maintaining sustained catalytic activity, as strongly bound products can poison active sites and deactivate the catalyst.

The desorption process depends critically on the binding energy between the product and catalyst surface. Optimal catalysts balance sufficient adsorption strength to activate reactants with weak enough binding to allow efficient product release. Recent approaches to enhance desorption include surface modification with conductive polymers and small organic molecules that modulate electronic properties of the catalyst surface, thereby tuning the adsorption/desorption characteristics [12]. In energy-intensive reactions like oxygen evolution, the discovery of concerted adsorption-desorption mechanisms (Walden-type mechanisms) suggests that in some advanced catalyst systems, the traditional sequential model may not fully capture the complexity of the desorption process [10].

Table 1: Key Parameters in the Catalytic Cycle Steps

| Cycle Step | Key Parameters | Characterization Techniques | Modification Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Binding strength, adsorption capacity, active site density | Temperature-programmed desorption (TPD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) | Ionic liquid modification, hydrophobic polymer coatings, single-atom site engineering |

| Surface Reaction | Activation energy, reaction mechanism, intermediate stability | In situ spectroscopy, kinetic isotope effects, computational modeling | Alloying, surface doping, defect engineering |

| Desorption | Product binding energy, active site regeneration rate | Microcalorimetry, pressure swing analysis | Surface functionalization, promoter elements, coordination environment control |

Advanced Analytical Methodologies

Experimental Protocols for Mechanistic Studies

Elucidating the mechanisms of the catalytic cycle requires sophisticated experimental approaches that probe interactions at the catalyst surface under relevant reaction conditions. The following protocols represent state-of-the-art methodologies for investigating the fundamental steps of heterogeneous catalysis:

Protocol 1: Kinetic Analysis of Single-Nucleotide Incorporation for Metal Ion Role Resolution This methodology, adapted from studies on HIV reverse transcriptase, provides a framework for understanding metal ion roles in catalytic cycles [15]. The protocol begins with preparing enzyme-DNA complexes with dideoxy-terminated primers to prevent catalysis while allowing substrate binding. Researchers then employ stopped-flow instrumentation with fluorescence detection (using MDCC-labeled proteins) to monitor conformational changes in real-time [15]. By systematically varying Mg²⺠concentration (typically 0.25-10 mM) and measuring binding kinetics, the protocol distinguishes between nucleotide-bound Mg²⺠and catalytic Mg²âº. Data analysis involves fitting observed rates to a minimal pathway for nucleotide incorporation to extract kinetic parameters (Kâ‚, kâ‚‚, kâ‚‹â‚‚, k₃) for each catalytic step [15]. This approach revealed that Mg·dNTP binding induces enzyme conformational change independently of free Mg²⺠concentration, with the second catalytic Mg²⺠binding subsequently to facilitate chemistry.

Protocol 2: In Situ/Operando Spectroscopy for Surface Intermediate Analysis This protocol employs advanced spectroscopic techniques under actual reaction conditions to monitor adsorption, surface reaction, and desorption in real-time [16]. The methodology begins with catalyst activation in a specialized reaction cell that allows simultaneous spectroscopic measurement and catalytic performance evaluation. Researchers utilize techniques including infrared spectroscopy, X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), and ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (AP-XPS) to identify adsorbed intermediates and monitor their evolution during reaction [16]. For electrochemical reactions, such as COâ‚‚ reduction, the protocol incorporates potential control while monitoring product formation through online gas chromatography or mass spectrometry [12]. Data interpretation combines spectral analysis with kinetic modeling to construct reaction mechanisms and identify rate-determining steps in the catalytic cycle.

Protocol 3: Surface Modification for Enhanced Electrocatalytic COâ‚‚ Reduction This detailed protocol from recent advances focuses on tailoring catalyst surfaces to improve COâ‚‚ reduction performance [12]. The procedure begins with catalyst synthesis (e.g., metal nanoparticles on carbon support) followed by surface modification using methods such as electropolymerization for conductive polymers, incipient wetness impregnation for ionic liquids, or self-assembled monolayer formation for small organic molecules [12]. Performance evaluation involves electrochemical testing in a sealed H-cell or flow cell with COâ‚‚-saturated electrolyte, measuring key parameters including Faradaic efficiency, partial current densities, and stability over extended operation (typically 10-100 hours). Post-characterization using electron microscopy and surface analysis techniques correlates performance changes with modified surface properties, elucidating the role of surface modification in enhancing local COâ‚‚ concentration, stabilizing intermediates, or suppressing competing reactions [12].

Computational Modeling Approaches

Computational methods have become indispensable for understanding catalytic cycles at the atomic level, providing insights that complement experimental observations:

Microkinetic Modeling combines theoretical and experimental approaches to develop quantitative models of catalytic reactions [11]. This approach integrates density functional theory (DFT) calculations of activation barriers and binding energies with experimental rate measurements to construct comprehensive reaction networks. For hydrogenation reactions, this methodology has successfully identified rate-determining steps and active site requirements, enabling rational catalyst design [11].

Generative Models represent a cutting-edge computational approach for catalyst design [14]. These models, including diffusion-based and transformer-based architectures, learn from existing catalyst datasets to generate novel surface structures with desired properties. The typical workflow involves training on databases of known catalyst structures and properties, then using the model to propose new candidates optimized for specific reactions such as CO₂ reduction or ammonia synthesis [14]. These methods effectively address the inverse design problem – finding optimal structures for target catalytic performance – moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches.

Emerging Research Frontiers

Challenging Traditional Sequential Models

Recent groundbreaking research has fundamentally challenged the long-standing assumption that adsorption, surface reaction, and desorption occur strictly sequentially in heterogeneous catalysis. Studies of the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) on iridium dioxide (IrOâ‚‚) have revealed a "Walden-like mechanism" where water adsorption and oxygen desorption occur simultaneously in a concerted manner, analogous to mechanisms observed in homogeneous catalysis [10]. This discovery suggests that the distinction between heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysis may be less rigid than previously thought, with solid catalysts capable of exhibiting molecular-like behavior under certain conditions [10].

This paradigm shift opens new possibilities for improving solid catalysts by applying principles traditionally associated with homogeneous processes. Rather than optimizing individual steps in isolation, researchers can now design catalyst systems where multiple steps cooperate synergistically, potentially reducing energy barriers and improving overall efficiency [10]. These findings are particularly relevant for energy-intensive processes like green hydrogen production, where the oxygen evolution step represents a significant efficiency bottleneck [10].

Bidirectional Catalytic Cycles

The traditional view of catalytic cycles as unidirectional processes has been expanded through research on bidirectional catalysis, particularly for multi-electron, multi-proton reactions relevant to energy conversion [17]. Studies of 2eâ»/1H⺠and 2eâ»/2H⺠cycles have revealed that efficient catalysts must facilitate reactions in both directions, with the "catalytic bias" indicating the preferred direction [17]. This understanding is crucial for reversible energy storage and conversion systems, such as electrolyzers and fuel cells.

The theoretical framework for analyzing bidirectional catalysis involves defining "catalytic potentials" (Ecatox and Ecatred) that characterize the oxidative and reductive directions of the cycle [17]. The proximity of these potentials to the equilibrium potential (Eeq) determines the catalyst's reversibility – a key design criterion for minimizing energy dissipation [17]. This sophisticated analytical approach enables researchers to deconstruct complex catalytic cycles and identify the thermodynamic and kinetic factors controlling overall efficiency.

AI-Driven Catalyst Design

Artificial intelligence is revolutionizing heterogeneous catalyst design through generative models that explore chemical space more efficiently than traditional methods [14]. These approaches include variational autoencoders (VAEs), generative adversarial networks (GANs), diffusion models, and transformer-based architectures that learn the underlying patterns in catalyst datasets to propose novel structures with desired properties [14].

For surface catalysis, generative models can propose optimal adsorption sites, predict intermediate geometries, and even identify complex transition-state structures [14]. When combined with high-throughput screening and automated synthesis, these AI approaches are accelerating the discovery of improved catalysts for applications ranging from renewable energy production to petrochemical processing [13] [14]. The integration of generative models with robotic experimentation represents a paradigm shift toward autonomous catalyst discovery, potentially reducing development timelines from years to months.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Catalytic Cycle Investigation

| Research Reagent | Function in Catalysis Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids | Surface modifiers that increase local COâ‚‚ concentration, regulate electronic structure, stabilize intermediates | Electrocatalytic COâ‚‚ reduction [12] |

| Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) | Maximize atom utilization, provide uniform active sites, enhance selectivity | Thermocatalytic reactions, energy conversion [13] |

| Zeolites | Provide confined microenvironments, shape selectivity, acidic sites | Petrochemical production, biomass conversion [13] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Tunable porous structures, well-defined active sites, high surface area | Gas separation, catalytic reactions [13] |

| Conductive Polymers | Surface modifiers that enhance electron transfer, modify adsorption properties | Electrochemical reactions, sensing applications [12] |

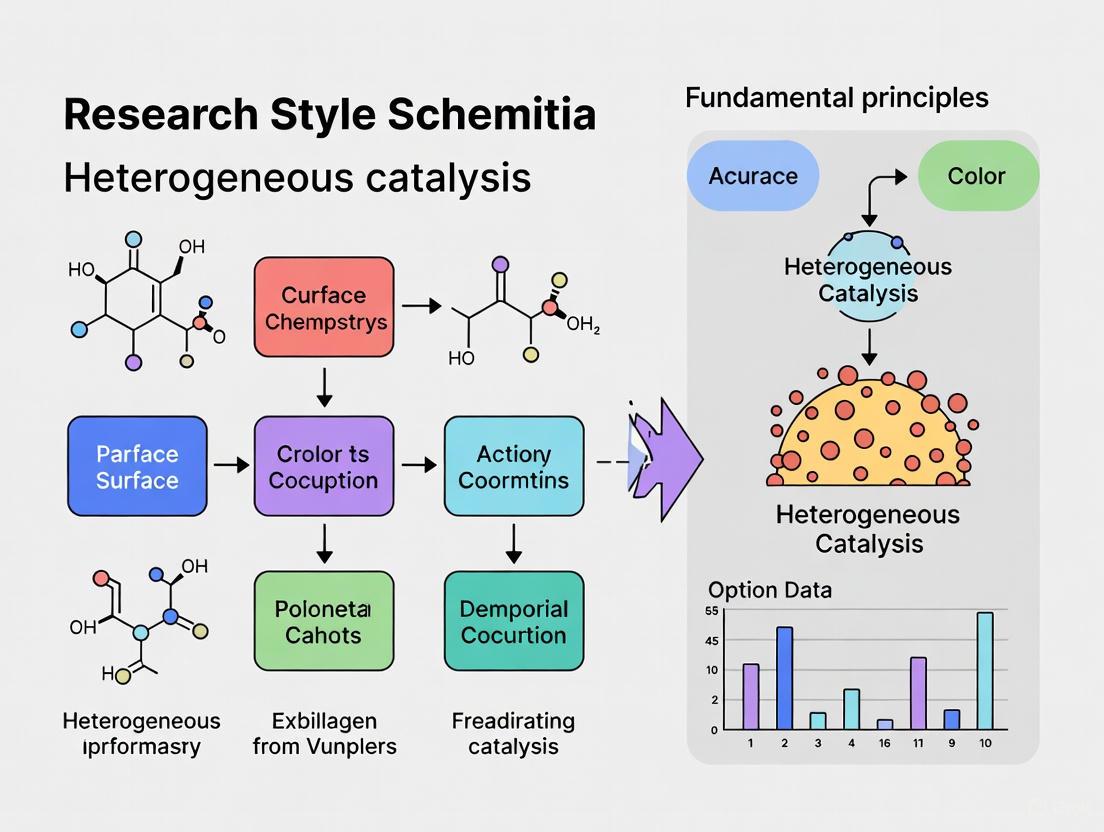

Visualization of Catalytic Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate key concepts and mechanisms in the catalytic cycle, providing visual representations of the fundamental processes.

Sequential Catalytic Cycle Model

Concerted vs Sequential Mechanisms

The fundamental steps of adsorption, surface reaction, and desorption continue to form the essential framework for understanding and designing heterogeneous catalysts. While these core principles remain valid, recent research has revealed unexpected complexities, including concerted mechanisms that blur the distinction between heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysis [10]. The integration of advanced experimental techniques, sophisticated computational modeling, and emerging AI-driven approaches is transforming catalyst design from an empirical art to a predictive science [11] [14]. These developments are particularly crucial for addressing global challenges in renewable energy [13], carbon utilization [12], and sustainable chemical production [13]. As research continues to unravel the dynamic nature of catalytic interfaces, the fundamental understanding of the catalytic cycle will continue to evolve, enabling the development of more efficient, selective, and sustainable catalytic processes for the future.

In heterogeneous catalysis, active sites are specific locations on a catalyst's surface—such as defects, step edges, kinks, or unique atomic ensembles—that possess distinct geometric and electronic structures enabling them to facilitate chemical reactions. These sites fundamentally govern catalytic performance by lowering activation energies, offering alternative reaction pathways, and ultimately determining critical parameters including reaction activity, selectivity, and stability. The composition and arrangement of atoms at these sites directly influence their ability to adsorb reactant molecules, stabilize transition states, and desorb product molecules. Understanding active sites requires a multidisciplinary approach combining surface science techniques, computational simulations, and advanced characterization methods to bridge the gap between atomic-scale structure and macroscopic catalytic function across diverse applications from chemical synthesis to environmental remediation and energy conversion [18].

Fundamental Principles of Active Sites

Geometric and Electronic Structure

The catalytic activity of a surface is predominantly governed by the interplay between its geometric structure and electronic properties. Geometrically, active sites often exist at locations where the regular periodicity of the crystal lattice is broken. These include step edges, kinks, adatoms, and vacancy defects which typically possess unsaturated coordination environments and higher surface energy compared to terraced planes. These sites facilitate stronger interactions with adsorbates and often stabilize reaction transition states more effectively than flat surfaces.

Electronically, the disrupted coordination at these sites leads to altered local electron density distributions and the presence of dangling bonds. This can result in shifted d-band centers in transition metal catalysts, directly influencing their ability to donate or accept electrons during catalytic cycles. The principles of coordination chemistry apply directly to these surface sites, where the coordination number of a surface atom determines its reactivity, with lower-coordination atoms typically exhibiting higher catalytic activity due to their more localized electron densities [19].

Metal-Support Interactions and Dynamic Behavior

The support material in heterogeneous catalysts plays a far more active role than merely providing a high surface area for metal dispersion. Metal-support interactions (MSI) can profoundly modify the electronic and catalytic properties of active sites through several mechanisms:

- Electronic Metal-Support Interaction (EMSI): Charge transfer between support and metal nanoparticles that electronically modifies the active sites.

- Strong Metal-Support Interaction (SMSI): Encapsulation of metal nanoparticles by support-derived species under specific conditions.

- Reactive Metal-Support Interaction (RMSI): Direct chemical participation of the support in the catalytic cycle.

Recent studies have revealed exceptionally dynamic behavior at metal-support interfaces under reaction conditions. For instance, in NiFe-Fe₃O₄ catalysts during hydrogen oxidation reaction, a looping metal-support interaction (LMSI) occurs where lattice oxygens react with NiFe-activated H atoms, gradually sacrificing themselves and resulting in dynamically migrating interfaces. Reduced iron atoms subsequently migrate to the {111} surface of Fe₃O₄ support and react with oxygen molecules, effectively separating the hydrogen oxidation reaction spatially on a single nanoparticle while intrinsically coupling it with the redox reaction of the support [18].

Table 1: Classification of Metal-Support Interactions in Heterogeneous Catalysis

| Interaction Type | Key Characteristics | Impact on Active Sites | Example Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Metal-Support Interaction (EMSI) | Charge transfer across interface | Modified electronic structure, adsorption properties | Pt-TiOâ‚‚, Au-CeOâ‚‚ |

| Strong Metal-Support Interaction (SMSI) | Encapsulation of metal particles by support | Physical blocking of sites, altered selectivity | Pt-TiOâ‚‚, Ni-TiOâ‚‚ |

| Reactive Metal-Support Interaction (RMSI) | Support participates directly in reaction | Bifunctional catalysis, spillover effects | NiFe-Fe₃O₄, Cu-ZnO |

| Looping Metal-Support Interaction (LMSI) | Dynamic interface migration under reaction | Continuous regeneration of active interfaces | NiFe-Fe₃O₄ (H₂ oxidation) |

Methodologies for Active Site Characterization

Computational Approaches and Potential Energy Surfaces

The concept of the potential energy surface (PES) is essential for studying material properties and heterogeneous catalytic processes at the atomic level. The PES represents the total energy of a system as a function of atomic coordinates, enabling exploration of atomic structure properties, determination of minimum energy configurations, and calculation of reaction rates. The primary challenge lies in constructing the PES both efficiently and accurately [20].

Quantum mechanical (QM) methods like density functional theory (DFT) can accurately describe molecular properties, crystal structures, and microscopic reactions but face severe computational limitations for large systems. In contrast, force field methods use simple functional relationships to establish mapping between system energy and atomic positions, offering significantly higher computational efficiency for large-scale systems such as catalyst structures, adsorption and diffusion of reaction molecules, and heterogeneous catalytic processes [20].

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Methods for Studying Active Sites

| Method | Accuracy | System Size Limit | Time Scale | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) | High | ~100-1000 atoms | Picoseconds to nanoseconds | Reaction mechanisms, adsorption energies |

| Classical Force Fields | Low to Medium | 10-100 nm | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Adsorption, diffusion, molecular dynamics |

| Reactive Force Fields | Medium | ~10,000 atoms | Nanoseconds | Bond breaking/formation, combustion |

| Machine Learning Force Fields | High (near-QM) | ~1,000,000 atoms | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Complex reaction networks, catalyst screening |

Force field methods are categorized into three main types:

- Classical Force Fields: Use simplified interatomic potential functions suited for modeling nonreactive interactions, containing 10-100 parameters with clear physical meanings.

- Reactive Force Fields: Employ complex bond-order formalisms that allow for bond formation and breaking during simulations.

- Machine Learning Force Fields: Utilize neural networks or other ML algorithms trained on QM data to achieve near-QM accuracy with significantly lower computational cost [20].

Machine Learning and Generative Models in Catalyst Design

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful complement to both empirical and theoretical approaches in catalysis research. By learning patterns from experimental or computed data, ML models can make accurate predictions about reaction yields, selectivity, optimal conditions, and even mechanistic pathways. The integration of ML is particularly valuable for navigating the vast multidimensional parameter spaces inherent in catalyst design [21].

Several ML algorithms have proven particularly useful in chemical applications:

- Linear Regression: Establishes direct relationships between descriptors and outcomes, serving as a baseline method.

- Random Forest: An ensemble model composed of many decision trees that provides robust predictions by combining multiple weak learners.

- Generative Models: Including variational autoencoders (VAEs), generative adversarial networks (GANs), diffusion models, and transformers that can create novel catalyst structures with desired properties.

Generative models represent a particularly promising approach for the inverse design of catalysts—directly generating candidate structures with target properties rather than screening existing databases. These models have demonstrated capabilities in property-guided surface structure generation, efficient sampling of adsorption geometries, and generation of complex transition-state structures [14]. For example, diffusion models have been tailored to confined surface systems and guided by learned forces to generate diverse and stable thin-film structures atop fixed substrates, outperforming random searches in resolving complex domain boundaries [14].

Diagram 1: Generative ML Workflow for Catalyst Design (76 characters)

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Operando Transmission Electron Microscopy for Interface Dynamics

Operando transmission electron microscopy (TEM) enables real-time observation of catalyst structural evolutions during reactions, providing atomic-scale insights into reaction mechanisms. The following protocol details the investigation of looping metal-support interaction in NiFe-Fe₃O₄ catalysts during hydrogen oxidation reaction [18]:

Materials and Synthesis

- Precursor: NiFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ (NFO) nanoparticles synthesized through sol-gel or coprecipitation methods.

- Reduction Treatment: Heat precursor in 10% H₂/He atmosphere at 400°C for 2 hours to form NiFe-Fe₃O₄ structure.

- Characterization: Confirm structural transformation using selected area electron diffraction (SAED) and high-resolution TEM.

Experimental Setup

- Microscope: Gas-celled environmental TEM equipped with quadrupole mass spectrometer.

- Reaction Conditions: Introduce reactant gas mixture (2% Oâ‚‚, 20% Hâ‚‚, and 78% He) into gas cell.

- Temperature Ramp: Gradually increase temperature to 500-700°C while monitoring structural changes.

Data Collection and Analysis

- Image Acquisition: Capture HRTEM sequence images at 5-10 frame/second during reaction.

- FFT Analysis: Determine orientational relationships between metal nanoparticles and support.

- Interface Tracking: Monitor migration of metal-support interfaces through lateral propagation of atomic ledges.

- Quantitative Analysis: Measure lattice spacing, interfacial angles, and migration rates.

This protocol revealed that the NiFe-Fe₃O₄ interface forms a preferential epitaxial relationship: NiFe (1̄12) // Fe₃O₄ (1̄1̄1̄) and NiFe [110] // Fe₃O₄ [110]. The lattice mismatch (NiFe (1̄11) = 0.20 nm vs. Fe₃O₄ (2̄24) = 0.17 nm) results in a 4.2° tilting that minimizes interfacial strain and leads to formation of lattice voids along the interface [18].

Machine Learning Force Field Development

The construction of machine learning force fields involves several key steps to ensure accuracy and transferability:

Training Data Generation

- QM Calculations: Perform density functional theory (DFT) calculations on diverse structural configurations.

- Active Learning: Iteratively select structures that maximize model improvement.

- Data Augmentation: Include various adsorption configurations, surface terminations, and defect structures.

Model Architecture and Training

- Descriptor Selection: Choose appropriate structural descriptors (e.g., atom-centered symmetry functions, SOAP features).

- Network Architecture: Implement neural networks with suitable depth and activation functions.

- Loss Function: Optimize combined energy and force predictions against QM reference data.

- Regularization: Apply appropriate regularization techniques to prevent overfitting.

Validation and Application

- Property Prediction: Validate against key catalytic properties (adsorption energies, reaction barriers).

- Molecular Dynamics: Perform extended MD simulations to study rare events and dynamic processes.

- Active Site Identification: Combine with global optimization algorithms to identify in situ active sites in heterogeneous catalysis [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Active Site Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Precursors | NiFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ nanoparticles | Model system for studying metal-support interactions | Spinel structure, well-defined reducibility |

| Support Materials | Fe₃O₄ (magnetite) | Reducible oxide support for redox reactions | {111} facet dominance, Mars-van Krevelen capability |

| Characterization Gases | 10% Hâ‚‚/He mixture | Reduction treatment and creating metal-support interfaces | Controlled redox environment |

| Reaction Gases | 2% Oâ‚‚, 20% Hâ‚‚, 78% He | Hydrogen oxidation reaction studies | Simulates industrial redox conditions |

| Computational Software | VASP, CP2K, Gaussian | Quantum mechanical calculations | DFT implementation, periodic boundary conditions |

| Force Field Packages | LAMMPS, GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulations | Classical and reactive force field support |

| Machine Learning Tools | TensorFlow, PyTorch | ML force field development | Neural network implementation |

| Generative Models | CDVAE, Diffusion models | Inverse design of catalyst structures | Latent space exploration, property guidance |

| Trk-IN-7 | Trk-IN-7, MF:C18H17FN6O2, MW:368.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Nifekalant-d4 | Nifekalant-d4, MF:C19H27N5O5, MW:409.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Diagram 2: MSI Impact on Active Site Properties (76 characters)

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of active site research is rapidly evolving with several emerging trends shaping future investigations:

Generative Models for Catalyst Discovery

Generative artificial intelligence represents a paradigm shift in catalyst design, moving from traditional forward design to inverse design approaches. These models learn the underlying distribution of known catalytic structures and properties, enabling them to generate novel candidates with desired characteristics. Notable applications include:

- Surface Structure Generation: Creating realistic surface models with complex compositions and terminations.

- Adsorption Configuration Sampling: Efficiently exploring possible adsorbate orientations and binding modes.

- Transition State Generation: Predicting likely transition state geometries for complex reaction networks.

For instance, diffusion models have demonstrated capability in generating diverse and stable thin-film structures atop fixed substrates, outperforming random searches in resolving complex domain boundaries [14]. Similarly, crystal diffusion variational autoencoder (CDVAE) models combined with optimization algorithms have generated thousands of candidate structures, leading to the discovery of new alloy compositions with high Faradaic efficiencies for COâ‚‚ reduction [14].

Dynamic and Transient Active Sites

Increasing evidence suggests that the most catalytically relevant active sites may be transient species that form under reaction conditions rather than static structural features present in the pristine catalyst. This understanding necessitates:

- Operando Characterization: Developing techniques that probe catalyst structure under actual working conditions.

- Time-Resolved Spectroscopy: Capturing short-lived intermediates and transition states.

- Multi-Scale Modeling: Connecting picosecond-scale bond breaking/formation to hour-long catalyst deactivation.

The discovery of looping metal-support interactions exemplifies this paradigm, where the continuous migration and reconstruction of interfaces under reaction conditions creates a dynamic population of active sites that cannot be predicted from the initial catalyst structure [18].

Integrated Human-Machine Catalyst Design

The future of catalyst development lies in hybrid approaches that combine human chemical intuition with machine learning capabilities. This integration enables:

- Accelerated Discovery: ML models rapidly screen vast chemical spaces to identify promising regions for human experts to investigate.

- Mechanistic Insight: ML-derived patterns provide clues about underlying physical principles and reaction mechanisms.

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Simultaneously balancing activity, selectivity, stability, and cost considerations.

As these trends continue to evolve, our understanding of active sites will progressively shift from static structural descriptions to dynamic, context-dependent entities whose properties emerge from complex interactions between catalysts, reactants, and reaction environments. This refined understanding will ultimately enable the rational design of more efficient, selective, and stable catalytic materials for addressing global energy and sustainability challenges.

Surface science provides the fundamental principles underlying heterogeneous catalysis, a field crucial to chemical manufacturing, environmental protection, and energy conversion. Heterogeneous catalysis, characterized by catalysts existing in a different phase from reactants (typically solid catalysts with liquid or gaseous reactants), dominates industrial processes, accounting for approximately 90% of all commercially produced chemical products [22]. The development of this field rests upon pioneering work that transformed our understanding of molecular behavior at interfaces. This whitepaper examines the foundational contributions of Irving Langmuir and Gerhard Ertl, whose collective work established the mechanistic framework for modern surface science and heterogeneous catalysis research. Their investigations provided the experimental and theoretical tools to decipher complex surface processes at molecular-level resolution, enabling the rational design of catalysts with enhanced activity, selectivity, and stability [23]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these principles are increasingly relevant in areas such as catalyst-mediated synthesis of pharmaceutical intermediates and the surface-based characterization of bioactive molecules.

Fundamental Principles of Heterogeneous Catalysis

Heterogeneous catalysis involves a solid catalyst accelerating the reaction of gaseous or liquid reactants. The catalytic process occurs through a well-defined sequence of molecular events at the catalyst surface [24]. The mechanism is generally described in four key steps:

- Adsorption: Reactant molecules diffuse to and bind onto active sites on the catalyst surface [23] [25]. This often involves chemisorption, where chemical bonds form between the adsorbate and the surface, resulting in bond weakening or dissociation of the reactant molecules [24]. For example, hydrogen molecules dissociate into atoms upon adsorption on palladium surfaces [24].

- Activation: The adsorbed reactants, often in an activated or dissociated state, undergo reaction on the surface [23]. The catalyst's role is to stabilize the transition state complex, thereby lowering the activation energy of the reaction [25].

- Surface Reaction: The activated species combine to form products while still adsorbed on the surface [23].

- Desorption: The product molecules detach from the active sites and diffuse away from the surface, regenerating the catalyst for another cycle [23] [24].

A critical advantage of heterogeneous catalysts is their ease of separation from the reaction mixture, facilitating recovery and reuse, which is particularly advantageous for industrial-scale processes [26] [25]. However, their effectiveness can be limited by surface area availability, and the adsorption step is often rate-limiting [26] [25].

Contrasting Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysis

Understanding heterogeneous catalysis is aided by contrasting it with homogeneous catalysis, where the catalyst exists in the same phase as the reactants (typically liquid) [23] [22]. The distinctions are critical for selecting the appropriate catalytic approach for a given application, including stages in pharmaceutical development.

Table 1: Comparison of Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysis

| Characteristic | Homogeneous Catalysis | Heterogeneous Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Phase | Catalyst and reactants in the same phase (usually liquid) [23] [24] | Catalyst and reactants in different phases (usually solid catalyst, gas/liquid reactants) [23] [24] |

| Active Centers | All catalyst molecules [27] | Only surface atoms [27] |

| Selectivity | Typically high [27] | Often lower [27] |

| Mechanistic Understanding | Well-defined, homogeneous active sites [27] | Complex, often undefined active sites [27] |

| Catalyst Separation | Tedious and expensive (e.g., extraction, distillation) [27] | Easy (e.g., filtration) [27] [26] |

| Mass Transfer Limitations | Very rare [27] | Can be severe [27] |

Pioneers and Their Foundational Contributions

Irving Langmuir (1881-1957)

Irving Langmuir laid the cornerstone of modern surface chemistry with his systematic investigations of adsorbed films on solid surfaces. His work provided the first quantitative framework for describing adsorption, a fundamental process in heterogeneous catalysis [22].

3.1.1 Key Experimental Protocols and Models

Langmuir's pioneering methodology involved studying the adsorption of gases onto clean, planar surfaces like tungsten filaments in carefully controlled high-vacuum environments. By measuring pressure changes and surface properties, he developed the Langmuir Adsorption Isotherm. This model is based on several key assumptions [22]:

- Monolayer Adsorption: Adsorption is limited to a single molecular layer on the surface.

- Uniform Surface: All adsorption sites are energetically equivalent.

- No Interaction: No interaction occurs between adsorbed molecules.

The derived isotherm equation is:

θ = (K P) / (1 + K P)whereθis the fractional surface coverage,Kis the adsorption equilibrium constant, andPis the gas pressure.

He also proposed the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism, which describes a surface reaction where two adsorbed species react directly with each other on the catalyst surface. This mechanism remains a central concept in interpreting heterogeneous catalytic kinetics [22].

3.1.2 Research Reagent Solutions and Key Materials

Table 2: Langmuir's Key Research Materials

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Tungsten (W) Filaments | Provided a clean, well-defined solid surface for fundamental adsorption studies under high vacuum. |

| High-Vacuum Systems | Enabled the creation of ultra-clean environments necessary for studying uncontaminated surface-gas interactions. |

| Simple Gases (e.g., Hâ‚‚, Oâ‚‚) | Served as model reactants for probing fundamental adsorption and dissociation processes. |

Gerhard Ertl (b. 1936)

Gerhard Ertl built upon Langmuir's foundation by applying a suite of modern surface-sensitive techniques to unravel complex catalytic reactions at an atomic level. His work bridged the "pressure gap" between idealized ultra-high-vacuum studies and real-world industrial reaction conditions [22].

3.2.1 Key Experimental Protocols and Models

Ertl's research program was characterized by the combined use of multiple complementary surface science techniques to study model systems, most famously the Haber-Bosch process (N₂ + 3H₂ → 2NH₃) on iron single crystals.

- Surface Preparation: Using single crystal surfaces (e.g., Fe(111)) to provide a uniform array of active sites.

- In-Situ Analysis: Employing techniques like Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) to determine surface structure, X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to identify chemical states, and Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) to image individual atoms and molecules on the surface.

- Kinetic Modeling: Applying and refining surface reaction mechanisms, including the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism, to model the complex kinetics of ammonia synthesis, identifying the dissociation of nitrogen (Nâ‚‚) as the rate-determining step [22].

His studies provided a complete atomic-level picture of the catalytic cycle, from the dissociation of N₂ and H₂ on the iron surface to the formation and desorption of NH₃.

3.2.2 Research Reagent Solutions and Key Materials

Table 3: Ertl's Key Research Materials

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Iron (Fe) Single Crystals | Model catalysts with defined surface structures (e.g., Fe(111)) to correlate activity with specific atomic sites. |

| Promoted Iron Catalysts | Industrial-style catalysts (e.g., with K, Ca, Al oxides) to study promoter effects on activity and selectivity [22]. |

| High-Purity Reactant Gases (Nâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚) | Used to study the mechanism of the Haber-Bosch process under controlled conditions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Methodologies

The progression from Langmuir to Ertl exemplifies the evolution of the surface scientist's toolkit. The following workflow visualizes a generalized experimental approach for probing a heterogeneous catalytic system, integrating methodologies pioneered by these key figures.

Diagram Title: Surface Science Investigation Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details critical reagents and materials used in advanced surface science experiments for heterogeneous catalysis research.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Surface Science Studies

| Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Model Catalyst Surfaces | Single crystals (Pt(111), Fe(110)), supported metal nanoparticles (Pt/Al₂O₃) | Provide well-defined structures to correlate activity with specific surface sites (terraces, steps, kinks). |

| Promoter Compounds | Potassium carbonate (K₂CO₃), Aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃) [22] | Additives that enhance catalyst activity, selectivity, or longevity without being active themselves. |

| Surface-Sensitive Probe Molecules | Carbon monoxide (CO), Nitric oxide (NO) | Used in spectroscopy (e.g., IRAS) to characterize the nature and density of active sites. |

| High-Purity Reactant Gases | Hydrogen (Hâ‚‚), Oxygen (Oâ‚‚), Nitrogen (Nâ‚‚), Carbon Monoxide (CO) | Ensure reproducible results by avoiding poisoning of sensitive catalyst surfaces by impurities. |

| Reference Standards | Sputtering targets (Ar⺠ions), Binding energy reference foils (Au, Cu) | Essential for cleaning surfaces and calibrating spectroscopic equipment like XPS. |

| DNA Gyrase-IN-5 | DNA Gyrase-IN-5, MF:C25H15BrClN5, MW:500.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Degarelix-d7 | Degarelix-d7, MF:C82H103ClN18O16, MW:1639.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantitative Data and Comparative Analysis

The quantitative data derived from the studies of Langmuir, Ertl, and subsequent researchers provides the basis for comparing catalytic systems and optimizing industrial processes.

Table 5: Quantitative Parameters in Catalytic Surface Science

| Parameter | Description | Formula / Example | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover Frequency (TOF) | Number of reaction cycles catalyzed per active site per unit time [22]. | Molecule reacted / (site × second) | Intrinsic activity of an active site, independent of catalyst mass or volume. |

| Surface Coverage (θ) | Fraction of available adsorption sites occupied by adsorbates [22]. | θ = (K P) / (1 + K P) (Langmuir Isotherm) | Determines reaction rate; many reactions follow Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics dependent on θ. |

| Adsorption Energy (Eâ‚dâ‚›) | Energy released upon adsorption of a molecule on a surface. | Typically measured in kJ/mol. | Strength of interaction between adsorbate and surface; dictates stability of adsorbed species. |

| Rate Determining Step (RDS) | The slowest elementary step in a catalytic cycle that limits the overall rate. | Nâ‚‚ dissociation in Ammonia synthesis [22]. | Guides catalyst design; efforts focus on accelerating the RDS. |

| Selectivity | The fraction of converted reactant that forms a specific desired product. | (Moles of desired product / Total moles of reactant converted) × 100% | Crucial for economic and environmental efficiency, minimizing byproducts. |

The journey from Langmuir's foundational adsorption isotherms to Ertl's atomically-resolved catalytic mechanisms represents the maturation of surface science into a predictive discipline. Langmuir provided the thermodynamic and kinetic framework, while Ertl developed the experimental toolkit to visualize and validate these principles at the atomic scale. Their work collectively demonstrated that complex macroscopic catalytic phenomena are governed by the precise arrangement and dynamics of atoms and molecules at interfaces.

The legacy of these pioneers directly informs contemporary research frontiers. The integration of heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysis approaches, known as hybrid catalysis, seeks to combine the best features of both—such as the easy separation of heterogeneous systems with the high selectivity of homogeneous catalysts [27] [28]. Furthermore, advancements in in-situ and operando spectroscopy, high-throughput experimentation, and computational modeling are now tasked with bridging the "materials gap," moving from idealized single crystals to complex, practical catalysts under working conditions [29]. For scientists in drug development and related fields, the principles of surface interaction and catalyst design established by Langmuir and Ertl provide a robust conceptual framework for understanding and manipulating molecular interactions at the heart of technological innovation.

The Dynamic Nature of Catalysts Under Reaction Conditions

The conventional view of catalysts as static entities has been fundamentally overturned by recent advances in operando characterization techniques. It is now established that catalysts are dynamic systems, whose structures and active sites evolve in response to the reaction environment [18]. This paradigm shift recognizes that the working state of a catalyst is not necessarily its pre-synthesized form, but rather a configuration dictated by the complex interplay of reactants, temperature, pressure, and support interactions [30]. Understanding these dynamic processes is crucial for the rational design of heterogeneous catalysts with enhanced activity, selectivity, and stability.

These dynamic phenomena occur across multiple length and time scales, from atomic-level migrations at metal-support interfaces to macroscopic restructuring of catalyst pellets. Within the broader thesis of fundamental principles in heterogeneous catalysis research, this dynamic nature represents a critical bridge between idealized catalyst design and practical catalytic performance. The implications extend across chemical synthesis, energy conversion, and environmental remediation, demanding a reevaluation of traditional structure-activity relationships [18].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Catalyst Dynamics

Metal-Support Interactions and Interface Migration

The interface between metal nanoparticles and their oxide supports serves as a highly active and dynamic region where complex interactions govern catalytic behavior. Recent studies have identified a looping metal-support interaction (LMSI) in NiFe-Fe₃O₄ catalysts during hydrogen oxidation reactions [18]. This phenomenon involves spatial and temporal separation of redox processes across a single nanoparticle:

- Hydrogen Activation: H₂ molecules dissociate on NiFe nanoparticle surfaces, with hydrogen atoms spilling over to the NiFe-Fe₃O₄ interface.

- Lattice Oxygen Reaction: Spilled-over hydrogen reacts with lattice oxygen atoms from Fe₃O₄, gradually consuming the support material and causing interface migration.

- Metal Atom Migration: Reduced iron adatoms migrate substantial distances across the Fe₃O₄ surface to {111} facets.

- Oxygen Activation: Migrated iron atoms facilitate Oâ‚‚ molecule activation at support sites distant from the original interface.

This continuous cycle of reduction, migration, and oxidation creates a dynamic catalytic system where the metal-support interface constantly reforms, maintaining catalytic activity through spatially separated redox cycles [18].

Structural Evolution and Phase Transformations

Catalyst structures undergo significant transformations under operating conditions that differ markedly from their as-synthesized states. For example, during ammonia synthesis, robust agglomerates of iron oxides transform into porous skeletal structures with dramatically increased specific surface areas [30]. Similarly, in NiFe-Fe₃O₄ systems, encapsulated overlayers that characterize the classical Strong Metal-Support Interaction (SMSI) state retract under reactant gas mixtures, exposing active sites for catalysis [18].

These structural changes are governed by principles of energy minimization under specific reaction conditions. Coherent, semicoherent, and incoherent interfaces at metal-support junctions exhibit different surface energies (0-200 mJ·mâ»Â², 200-500 mJ·mâ»Â², and 500-1000 mJ·mâ»Â² respectively), which strongly influence reactant chemisorption and catalytic activity [30]. The dynamic nature of these interfaces enables continuous optimization of active site configurations during reaction conditions.

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Catalyst Dynamics

Operando and In Situ Characterization Techniques

The direct observation of catalyst dynamics requires techniques that can probe atomic-scale structural changes under realistic reaction conditions. Operando transmission electron microscopy (OTEM) has emerged as a powerful methodology for visualizing these processes in real-time [18].

Table 1: Key Operando Characterization Techniques for Catalyst Dynamics

| Technique | Information Obtained | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operando TEM | Real-time visualization of structural changes, interface migration, particle dynamics | Atomic-scale | Seconds to minutes | Metal-support interactions, nanoparticle sintering, surface reconstruction |

| Environmental TEM | Catalyst behavior in gas atmospheres | Atomic-scale | Seconds | Phase transformations, redox processes |

| Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry (coupled to OTEM) | Gas composition analysis, reaction products | N/A | Milliseconds | Correlation of structural changes with catalytic activity |

| Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) | Crystallographic phase identification | Nanoscale | Seconds | Phase transitions, structural evolution |

Experimental Protocol for Operando TEM Studies of Metal-Support Interactions:

Catalyst Synthesis: Prepare NiFe-Fe₃O₄ catalysts through partial reduction of NiFe₂O₄ (NFO) precursor in 10% H₂/He at 400°C [18].

Structural Validation: Confirm catalyst structure using Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) to verify transformation from NFO to NiFe-Fe₃O₄ composition.

Operando Reaction Conditions: Introduce reactant gas mixture (2% Oâ‚‚, 20% Hâ‚‚, 78% He) into ETEM gas cell with temperature control.

Temperature Ramping: Gradually increase temperature to operational range (500-700°C) while monitoring structural changes.

Real-Time Imaging: Capture high-resolution TEM sequence images at frame rates sufficient to resolve interface migration (typically 1-10 frames per second).

Quantitative Analysis: Measure interface migration rates, particle dynamics, and structural transformations using image analysis software.

Product Analysis: Correlate structural changes with reaction products using integrated mass spectrometry.

Theoretical Validation: Complement experimental observations with density functional theory (DFT) calculations to understand energy landscapes and migration barriers.

This methodology enables direct visualization of dynamic processes such as the layer-by-layer dissolution of Fe₃O₄ support along (111) planes and the subsequent migration of reduced Fe atoms to {111} surface facets [18].

Kinetic and Transport Phenomenon Analysis

Understanding catalyst dynamics requires careful discrimination between intrinsic kinetic phenomena and mass/heat transport effects. Proper experimental design must ensure measurement of intrinsic reaction rates free from transport limitations [31].

Table 2: Essential Requirements for Kinetic Studies of Catalyst Dynamics

| Parameter | Requirement | Experimental Validation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Isothermality | Uniform temperature throughout catalyst bed | Multiple thermocouples at different bed positions; criteria: ΔT < 1-2°C |

| Flow Pattern | Ideal plug flow or perfectly mixed | Residence time distribution studies; tracer pulse experiments |

| Transport Limitations | Absence of intra- and inter-particle mass transfer resistance | Weisz-Prater criterion for internal diffusion; Mears criterion for external diffusion |

| Catalyst Particle Size | Minimal size for intrinsic kinetics; larger for industrial relevance | Test with varying particle sizes; select smallest practical size without transport effects |

| Catalyst Representation | Proper representation of industrial catalyst form | Compare crushed particles vs. full-size pellets |

Experimental Protocol for Assessing Transport Limitations:

Particle Size Variation: Conduct kinetic experiments with progressively smaller catalyst particle sizes while maintaining constant catalyst mass.

Rate Comparison: Compare observed reaction rates across different particle sizes. Consistent rates indicate absence of internal diffusion limitations.

Flow Rate Variation: Perform experiments at different volumetric flow rates while maintaining constant space velocity.

External Diffusion Assessment: Unchanging conversion with increasing flow rate indicates absence of external diffusion limitations.

Weisz-Prater Criterion Application: Calculate Φ = (robs × R²)/(Deff × Cs) where robs is observed rate, R is particle radius, Deff is effective diffusivity, and Cs is surface concentration. Values of Φ << 1 indicate no internal diffusion limitations.

These methodologies ensure that observed catalyst dynamics reflect intrinsic chemical processes rather than experimental artifacts [31].

Computational Modeling and Data Science Approaches

Language Models for Synthesis Protocol Analysis

The growing complexity of catalyst synthesis literature has prompted the development of specialized computational tools for information extraction. Transformer-based language models, such as the ACE (sAC transformEr) model, can convert unstructured synthesis protocols into structured, machine-readable action sequences [32].

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Catalyst Synthesis Language Models

| Metric | Score | Interpretation | Implication for Catalyst Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levenshtein Similarity | 0.66 | Captures 66% of protocol information | Enables large-scale analysis of synthesis-condition-performance relationships |

| BLEU Score | 52 | High-quality translation of synthesis steps | Facilitates database creation for dynamic behavior prediction |

| Time Reduction | 50-fold | From 500+ hours to 6-8 hours for 1000 papers | Accelerates identification of dynamic stability trends |

These models significantly reduce literature review time from approximately 30 minutes per paper to under 1 minute, enabling researchers to identify patterns in catalyst stability and dynamic behavior more efficiently [32].

Guidelines for Machine-Readable Synthesis Reporting

To maximize the effectiveness of computational approaches, standardized reporting guidelines for catalyst synthesis have been developed:

Structured Action Sequences: Define synthesis steps using standardized action terms (mixing, deposition, pyrolysis, filtering, washing, annealing).

Parameter Standardization: Consistently report critical parameters (temperature, ramp rates, atmosphere, duration, precursors).

Composition Specification: Clearly identify metal speciation, support materials, and final composition.

Condition Documentation: Detail all synthesis conditions, including solvent systems, concentrations, and time parameters.

Adoption of these guidelines improves machine-readability of synthesis protocols from approximately 66% to much higher fidelity, enabling better correlation between synthesis conditions and catalyst dynamic behavior [32].

Implications for Catalyst Design and Reactor Engineering

The dynamic nature of catalysts under reaction conditions has profound implications for both catalyst design and reactor engineering strategies. Recognizing that working catalysts may bear little resemblance to their as-synthesized precursors enables more rational design approaches:

Stabilization of Dynamic Interfaces: Rather than designing rigid structures, focus on creating systems that maintain activity through controlled dynamic processes. The LMSI phenomenon demonstrates how cyclic restructuring can sustain catalytic activity through spatial separation of redox functions [18].

Design for Evolution: Catalyst design should account for predictable structural changes under operation conditions. For example, the transformation of iron catalysts during ammonia synthesis from oxides to porous metallic structures significantly enhances surface area and activity [30].

Reactor Configuration Selection: The choice of reactor type must accommodate catalyst dynamics. Suspension reactors, fixed-bed reactors, and flow microreactors each present different advantages for managing evolving catalyst systems, depending on molecular diffusivity, reaction exothermicity, and operating conditions [30].

These principles highlight the importance of studying catalyst behavior under authentic operational conditions rather than relying exclusively on ex situ characterization of fresh catalysts.

Visualization of Dynamic Catalyst Processes

Looping Metal-Support Interaction Mechanism

Diagram 1: Looping metal-support interaction mechanism showing spatially separated redox processes.

Operando Characterization Workflow

Diagram 2: Operando characterization workflow for studying catalyst dynamics.

Research Reagent Solutions for Dynamic Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Studying Catalyst Dynamics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiFeâ‚‚Oâ‚„ Precursor | Model catalyst system for MSI studies | Looping metal-support interaction studies | Controlled composition for reproducible interface formation |

| Hâ‚‚/He Gas Mixtures | Reduction agent and carrier gas | Catalyst pre-treatment and in situ reduction | Purity >99.999% to prevent contamination |

| Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚/He Reaction Mixtures | Redox environment simulation | Hydrogen oxidation reaction studies | Precise composition control for reproducible redox cycling |

| Fe₃O₄ Support Material | Reducible oxide support | Metal-support interaction studies | Controlled facet exposure, particularly {111} surfaces |

| Single-Atom Catalyst Precursors | Well-defined active sites | Dynamic stability studies of SACs | Controlled anchoring to prevent aggregation |

| Functionalized Support Materials | Modified surface chemistry | Hybrid catalyst dynamics | Controlled functional group density |

| TEM Grids with MEMS Heaters | In situ observation platform | Operando TEM studies | Thermal and mechanical stability under reaction conditions |

The dynamic nature of catalysts under reaction conditions represents a fundamental shift in our understanding of heterogeneous catalysis. Through mechanisms such as looping metal-support interactions, structural evolution, and spatial decoupling of redox processes, catalysts demonstrate remarkable adaptability to their chemical environment. The integration of advanced operando characterization techniques with computational modeling and standardized data reporting provides unprecedented insights into these dynamic processes. This knowledge enables the rational design of next-generation catalytic systems that leverage, rather than resist, their dynamic nature for enhanced performance and stability. As research in this field progresses, embracing catalyst dynamics as a fundamental principle will be essential for advancing sustainable catalytic technologies across chemical synthesis, energy conversion, and environmental protection.

Characterization, Computational Design, and Real-World Applications

Advanced Operando Spectroscopy for Studying Catalysts at Work

The rational design of next-generation heterogeneous catalysts is fundamentally dependent on a thorough mechanistic understanding of how they function under realistic working conditions. Operando spectroscopy, defined as the simultaneous measurement of catalyst structure and catalytic activity under real reaction conditions, has emerged as a powerful methodology to elucidate these reaction mechanisms and establish concrete links between a catalyst's physical/electronic structure and its activity [33]. Unlike traditional in situ techniques that probe catalysts under simulated reaction conditions, operando methods require that the catalyst's activity is being measured simultaneously under conditions as close as possible to actual operation, including considerations of mass transport, gas/liquid/solid interfaces, and product formation [33]. This approach is particularly valuable because catalysts are dynamic entities that undergo significant transformations during reactions, meaning their static, pre-reaction structure often differs substantially from their active state [34] [35].

The fundamental principle underlying operando spectroscopy is the correlation between spectroscopic signals and catalytic performance metrics acquired simultaneously. This dual measurement capability enables researchers to move beyond simple structural snapshots to establishing genuine structure-activity relationships that account for the dynamic nature of catalytic systems [36]. As heterogeneous catalysis involves phenomena across different time and length scales, no single spectroscopic method can provide a complete picture, necessitating the development of multi-technique approaches and advanced reactor designs [36] [33]. The ultimate goal of these advanced characterization efforts is to identify the true active sites, reveal reaction intermediates, and understand deactivation mechanisms, thereby providing the scientific foundation for designing more efficient, selective, and stable catalysts for applications ranging from chemical production and energy conversion to environmental protection [35].

Core Operando Characterization Techniques

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy probes atom-specific structural and electronic details of catalysts through the examination of X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) [34]. XANES provides information about the electronic configuration, oxidation state, and symmetry of the absorber atom, while EXAFS yields details on the local coordination environment, including bond distances and coordination numbers [34] [33]. This technique is particularly valuable for studying amorphous or nanoscale materials where long-range order is absent.